Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 17/09/04. The contractual start date was in January 2019. The draft manuscript began editorial review in December 2022 and was accepted for publication in February 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 McDermott et al. This work was produced by McDermott et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 McDermott et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

There is worldwide concern about the prevalence of young people’s mental health problems and the COVID-19 pandemic has catapulted young people’s mental health to the top on the global health agenda. UNICEF’s The State of the World’s Children 2021: On My Mind report concentrated for the first time on promoting, protecting and caring for children’s mental health. They argue that mental health is a global issue and little attention has been paid to either the problem or its potential solutions. 1

The consensus from the UN, UNICEF and WHO is that there is a fundamental relationship between human rights and mental health. UNICEF (UK) argue that ‘it is key that local government, services and professionals frame good mental health as a basic human right, one all children and young people are entitled to’. 1,2 In addition, the consensus posits that the most effective, human-rights-enhancing approach to young people’s mental health care should be based on public health and psychosocial support rather than overmedicalisation and institutionalisation. 3 WHO Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan (2013–30) states:4

Children and adolescents with mental disorders should be provided with early intervention through evidence-based psychosocial and other non-pharmacological interventions based in the community, avoiding institutionalization and medicalization. Furthermore, interventions should respect the rights of children in line with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and other international and regional human rights instruments. (p.11)

This report presents the results of a multi-methods study conducted between 2019 and 2022, examining mental health early intervention services and self-care support for LGBTQ+ young people with common mental health problems in the UK. The aim was to generate evidence about what works, why, for whom and in what context.

First, we provide an overview of evidence concerning mental health inequalities for LGBTQ+ young people in the UK and the paucity of existing evidence concerning how services can best meet the needs of this population. Chapter 2 covers the methodology for this multi-methods study in detail, describing the three distinct stages of the research. The following chapters focus on the results of each of these distinct stages. Chapter 3 details the meta-narrative review (MNR) conducted to synthesise existing evidence, from which we produced an initial theoretical model of what works to effectively support, at an early point, LGBTQ+ young people’s mental health. This chapter presents an in-depth review of the evidence on early intervention mental health support for LGBTQ+ young people. In Chapter 4, we map the services identified providing mental health early intervention and self-care support for LGBTQ+ young people in the UK and present a resulting typology of service provision. Chapter 5 provides details of the collective case study evaluation conducted and the model for effective support developed based on data from 12 case study sites that provided mental health support to LGBTQ+ young people. The concluding chapter brings together the results of each stage of the study to deliver our overarching arguments, outline recommendations for policy, practice and future research, and provide details of the impact and dissemination of the research.

Mental health inequalities and LGBTQ+ young people

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer/questioning, plus young people report significantly higher rates of depression, self-harm, suicidality and poor mental health than cisgender and heterosexual youth. 5–8 The evidence demonstrating this mental health prevalence inequality has been consistent in the UK over the last 20 years. In 2003, findings were published for the first large-scale UK study examining mental health and quality of life for lesbians and gay men living in England and Wales. These findings highlighted greater levels of psychological distress among lesbians and gay men compared to heterosexual women and men respectively, across age brackets, including young people aged 16–24 years. 9

This mental health inequality continues to be reported in subsequent research. In 2019, an analysis of online survey data from 677 UK participants aged 16–25 years in the ‘Youth Chances’ community study highlighted higher rates of poor mental health, suicidality and experiences of victimisation among trans and non-binary young people than in the wider population. 10 A 2016 pooled analysis of 12 UK population surveys showed that lesbian, gay and bisexual identified people under the age of 35 years were twice as likely to report symptoms of poor mental health compared with heterosexual peers. 8 As the severity of mental health problems worsens, this disparity between LGBTQ+ youth and cisgender youth increases. A recent meta-analysis of studies comparing suicidality in youth found that compared to cisgender and heterosexual youth, trans youth were six times, bisexual youth five times and LG youth four times more likely to report a history of attempted suicide. 11 Longitudinal evidence also demonstrates that in the UK, these mental health disparities start as early as 10 years old increasing throughout adolescence and peaking between the ages of 13 and 19 years. 6

Explaining LGBTQ+ poor mental health

The most prominent model in explaining these mental health inequalities is ‘minority stress’12 whereby experiences of stigma, prejudice and discrimination create hostile environments, leading to mental health problems. Being LGBTQ+ means young people do not conform to expectations or ‘norms’, that is, that you are heterosexual and cisgender (non-transgender). LGBTQ+ young people are marginalised through lack of mainstream visibility, discrimination, (micro)aggression, bullying and victimisation they experience. 13,14 Even within LGBTQ+ communities, young people may come up against assumptions and pressures about the ‘right’, ‘normal’ or ‘best’ ways to be LGBTQ+, such as stereotypes about bisexual people,15,16 or what it means to be ‘trans enough’. 17,18 Young people may also experience the erasure of their identities within service settings and in their interactions with adults, that is, where it is not considered that they could be LGBTQ+ and cis-heterosexuality is presumed. 19

A 2020 systematic review of qualitative research into LGBTQ+ young people’s mental health identified isolation and rejection, LGBTQ+ phobic victimisation and discrimination, and marginalisation as key factors impacting mental health. 20 Parent/carer and family rejection has been identified as a profound factor informing depression21 and suicidality. 22 Parental rejection has also been identified as an important factor driving elevated rates of homelessness among LGBTQ+ young people, with experiences of homelessness being associated with hopelessness, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). 23 These mental health risks are often compounded by intersecting minority stressors of racism and poverty. 24 The negative mental health impacts of family rejection have been exacerbated for LGBTQ+ young people during COVID-19. 25,26

School and education are also key sites of exclusion and victimisation for LGBTQ+ young people. A 2021 systematic review identified victimisation as a key factor impacting self-harm and suicidality among LGBTQ+ young people. 20,27 A quarter of the LGBTQ+ young people surveyed for Stonewall’s 2017 School Report experienced being ignored and isolated as a pattern of bullying. 28 Experiences of victimisation and discrimination at school have been identified as a prominent risk factor for depression, self-harm, suicidality, PTSD and school absence. 21,27,29,30

Unsurprisingly, evidence regarding protective factors for LGBTQ+ young people’s mental health indicates safe and supportive school environments,21,29,31 and parent/carer and family support and affirmation29,32,33 can protect mental health. In addition, social connectedness and belonging20,21,29 (including the presence of LGBTQ+ support movements and communities),33,34 and being able to talk to a trusted adult32,35 are key factors promoting resilience and reducing poor mental health for LGBTQ+ young people.

The mental health inequalities faced by LGBTQ+ young people have been exacerbated by COVID-19 and the impact of national and regional lockdowns, with evidence emerging that lockdowns have led to high levels of stress and depressive symptoms reported by LGBTQ+ people, especially young people. 36,37 Among 1140 LGBTQ+ young people surveyed for research commissioned by the charity organisation ‘Just Like Us’, 68% reported that their mental health worsened during the pandemic; 55% reported worrying daily about their mental health, rising to 65% for black LGBTQ+ young people, trans and gender-diverse young people, and disabled LGBTQ+ young people. 37

Underutilisation of mental health services

Despite this mental health inequality, LGBTQ+ young people have elevated unmet mental health needs compared to their cis-heterosexual peers and underuse mental health services. 38–42 Findings from a UK study indicated that in a sample of 789 LGBTQ+ young people, only one-fifth of participants had sought help for their mental health difficulties. 42 Through interviews and survey data, the study found that LGBTQ+ young people were reluctant to access statutory or third-sector mental health services because of experiences of homophobia, biphobia and transphobia; cis-heteronormativity (fear their sexual orientation or gender identity would be scrutinised or blamed for their mental health problems); difficulties disclosing their sexual and/or gender identity; fears of being misunderstood or judged by adults because they were young; and stigma related to having mental health problems. 41–44

Importantly, studies show that LGBTQ+ youth will seek mental health help online and from peers13,41,45 and prefer accessing LGBTQ+ organisations for mental health support. 42,46 There is a limited understanding of why asking for help for mental health problems is problematic for LGBTQ+ youth.

Poor mental health service experience

In addition to the underutilisation of mental health services,47 studies suggest LGBTQ+ young people have poor overall experience of mental health services and school-based support. 10,13,38,43,48,49 Discriminatory and marginalising experiences include service staff using the incorrect name or pronouns for the young person, it being assumed that every young person is cisgender and heterosexual by default, and service staff asking inappropriate questions. 49,50

Limited staff awareness and understanding of LGBTQ+ issues and minority stresses is a problem raised by both LGBTQ+ young people and staff working in mental health services. 42 A 2020 study involving data produced with a sample of 2064 LGBTQ+ young people aged 14–25 years found that practitioners’ lack of knowledge was perceived as increasing the risk that LGBTQ+ identities would be pathologised and framed as a ‘cause’ or ‘symptom’ of mental health problems. 51 Evidence indicates that, in response to this inadequate knowledge base, LGBTQ+ young people feel responsible for educating professionals and practitioners about LGBTQ+ identities, taking up time during which they should be receiving support. 50,52

Lacking knowledge and awareness within services also means that some LGBTQ+ young people feel unable to be open about their experiences, identities and emotions as a whole, detracting from the efficacy of mental health support. 42,50 This self-censorship is connected to fears of negative response53 and being ‘outed’ by the service to parents/carers or other family, peers, or other services. 51 LGBTQ+ young people’s experiences of mental health services are also characterised by a profound loss of autonomy and exclusion from decisions about their own support. 42,51

Research suggests the competence of healthcare staff to provide appropriate care to LGBTQ+ young people is a vital factor in ensuring access. For example, a 2020 EU study found that the barriers to health care for LGBTQ+ people are exacerbated by two related assumptions held by healthcare professionals. First, the assumption that patients are heterosexual and cisgender and, second, the assumption that LGBTQ+ people do not experience significant problems due to their LGBTQ+ identity, meaning that LGBTQ+ identity is viewed as incidental or irrelevant to the delivery of appropriate health care. 19

While it is unhelpful (and harmful) for the importance of the LGBTQ+ experience to be dismissed, it is also damaging for mental health practitioners to overemphasise LGBTQ+ identities in excessive or pathologising ways. When staff have limited understanding and awareness about LGBTQ+ identities, this can manifest as the attribution of mental distress and poor mental health exclusively to a young person’s being LGBTQ+, particularly when the young person is trans or gender diverse. 13,49

Newman et al. 52 suggest that it is necessary to pay attention to the ‘affective dimensions of healthcare engagement’ (p. 1) in order to understand how to develop inclusive health care for LGBTQ+ youth. The authors argue for a model of care that goes beyond ‘tolerant inclusivity in which sexually and gender-diverse people are framed as different in spaces governed by normative practices, concepts, representations, language, and hierarchies’ (p. 2). Their research suggests ‘belonging’ is important to inclusive health care for LGBTQ+ youth, where there is an unconditional acceptance and recognition of gender and sexual diversity. 13

Despite the recognition that LGBTQ+ youth are less likely to access mainstream mental health services and have a poor experience, the evidence base examining LGBTQ+ youth mental health support needs and service preferences is very limited. A systematic review found that research was more likely to identify barriers to accessing mental health support rather than facilitators to encourage engagement. 20 In addition, there is an absence of focus on intersectional factors such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status and disability in LGBTQ+ youth mental health care. 14,52,54

The current study aims to address this knowledge gap by examining ‘what works best?’ for supporting the mental health of LGBTQ+ young people with common mental health problems at an early stage.

Rationale for the current study

According to the Early Intervention Foundation, the central principle of early intervention is effectively identifying and providing early and preventive support to children and young people who are more at risk of poor mental health outcomes. 55 This strategy has been emphasised further in light of COVID-19 and the impacts on children and young people’s mental health since the first UK lockdown in early 2020. 56–58

The importance of early and preventive support for the long-term development of young people is included in the UK government’s Health and Social Care (HSC) Committee’s 2021 report on children and young people’s mental health, which advocates for radical action to focus mental health provision on early intervention and prevention. 56 Drawing on research conducted by the National Children’s Bureau and UCL59 and by the charity Stonewall,28 the HSC committee affirms the need for targeted strategies to increase protective factors for LGBTQ+ young people.

Ensuring better mental health outcomes for LGBTQ+ young people requires long-sighted, innovative and creative approaches. Here, we use ‘early intervention’ to refer to mental health services that LGBTQ+ young people can access before reaching a crisis point. While the focus of the Queer Futures 2 project was young people aged 12–25 years, there is evidence that mental health inequalities for LGBTQ+ young people start as early as age 10 years. 6 Early intervention more broadly covers all stages of a child’s development from birth onwards.

The UK evidence base examining LGBTQ+ young people’s early intervention mental health support needs and services is very limited. Consequently (and despite this manifest inequality and underutilisation of mental health services), there is no research in the UK on how to develop appropriate mental health early intervention and supported self-care provision to this vulnerable group. This study delivers rigorous evidence to fill this gap, address this inequality and fulfil the requirements of NHS mental health strategic direction.

Research objectives

-

To produce a synthesis of the evidence on mental health early intervention services and self-care support to LGBTQ+ young people.

-

To identify service models for mental health early intervention and supported self-care which are accessible and acceptable to LGBTQ+ young people.

-

To develop a programme theory of how, why and in what context mental health early intervention services and self-care support work for LGBTQ+ young people.

-

To increase understanding of LGBTQ+ young people’s access to and navigation of formal and informal mental health early intervention services and self-care support.

-

To generate commissioning guidance (including service costs) on mental health early intervention and supported self-care services for LGBTQ+ young people.

Research questions

-

What evidence exists on mental health early intervention services and supported self-care for LGBTQ+ young people?

-

What type of service models for mental health early intervention and supported self-care to LGBTQ+ young people are currently provided?

-

How, why and in what context do mental health early intervention services and supported self-care work for LGBTQ+ young people?

-

In what ways do LGBTQ+ young people access and navigate formal and informal mental health early intervention services and self-care support?

-

How can LGBTQ+ young people be encouraged to access and engage with mental health early intervention services and self-care support?

Chapter 2 Methodology

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from McDermott et al. 60 and Pattinson et al. 61 These are Open Access articles distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

This research project is a multi-methods theory-led case study evaluation with three distinct stages answering the key study objectives:

-

Stage 1. A systematic review of existing literature concerning early mental health interventions and self-care support for LGBTQ+ young people.

-

Stage 2. A service mapping study to identify existing UK LGBTQ+ youth-specific mental health interventions and support.

-

Stage 3. A theory-led case study evaluation of 12 case study sites (CSS) to establish the components of appropriate, quality early intervention mental health and self-care support for LGBTQ+ young people.

In this chapter, the rationale for a multi-methods approach is provided, followed by a description of the review, mapping and case study evaluation stages of the research. This chapter also contains details of the study’s research governance and ethics approval, and an overview of patient and public involvement (PPI).

Study design

The study used a theory-driven evaluation methodology, as appropriate when there is little evidence on the effectiveness or acceptability of services and interventions. 62,63 There is a paucity of UK research examining mental health early intervention services and supported self-care provision for LGBTQ+ young people. Consequently, we designed a study that recognises we are at the first stage of understanding the ways in which mental health services might support LGBTQ+ young people. This initial ‘innovation stage’ required evaluation methods capable of ‘discovering’, ‘describing’ and providing a theoretical understanding of why, how and in what context a service might work. 64

Experimental designs are excellent for assessing the effectiveness of services and interventions, but they cannot assess how or why services achieve particular outcomes in a variety of contexts. 65,66 Theory-driven evaluation approaches seek to not only understand why a service may work but also detail the underlying logic or theory of why it may work. 63,66 In order to develop health services which are likely to be effective, sustainable and scalable, evaluations need to understand not just whether, but how, why and in what contexts a service has a particular outcome. 64,67 Theory-led evaluation methods acknowledge that healthcare delivery takes place in complex social systems with potentially multiple pathways to the provision of services that work. 67,68

It is now widely recognised that theory is important to health services research because it aids the development of generalisable and robust knowledge and builds a scientific understanding of healthcare quality. 68 Case study design has been criticised because of concerns regarding external validity, that is that a single case study is a poor basis for generalising. However, the Medical Research Council, among others,62,69,70 have argued it is possible to generate ‘cumulative knowledge’ about the factors that influence healthcare delivery by adopting a theoretically driven method. We utilised Yin’s62 ‘analytical generalisation’ approach whereby the programme theory established in an evidence synthesis is ‘tested’ during the case study data analysis. This means a case study evaluation research design does not generalise results to the population as a whole but generalises to theoretical propositions on how or why a service/intervention may work. 62 We used a case study evaluation to generate a theoretical understanding of the mechanisms by which mental health early intervention services and self-care provision can support LGBTQ+ young people with common mental health problems.

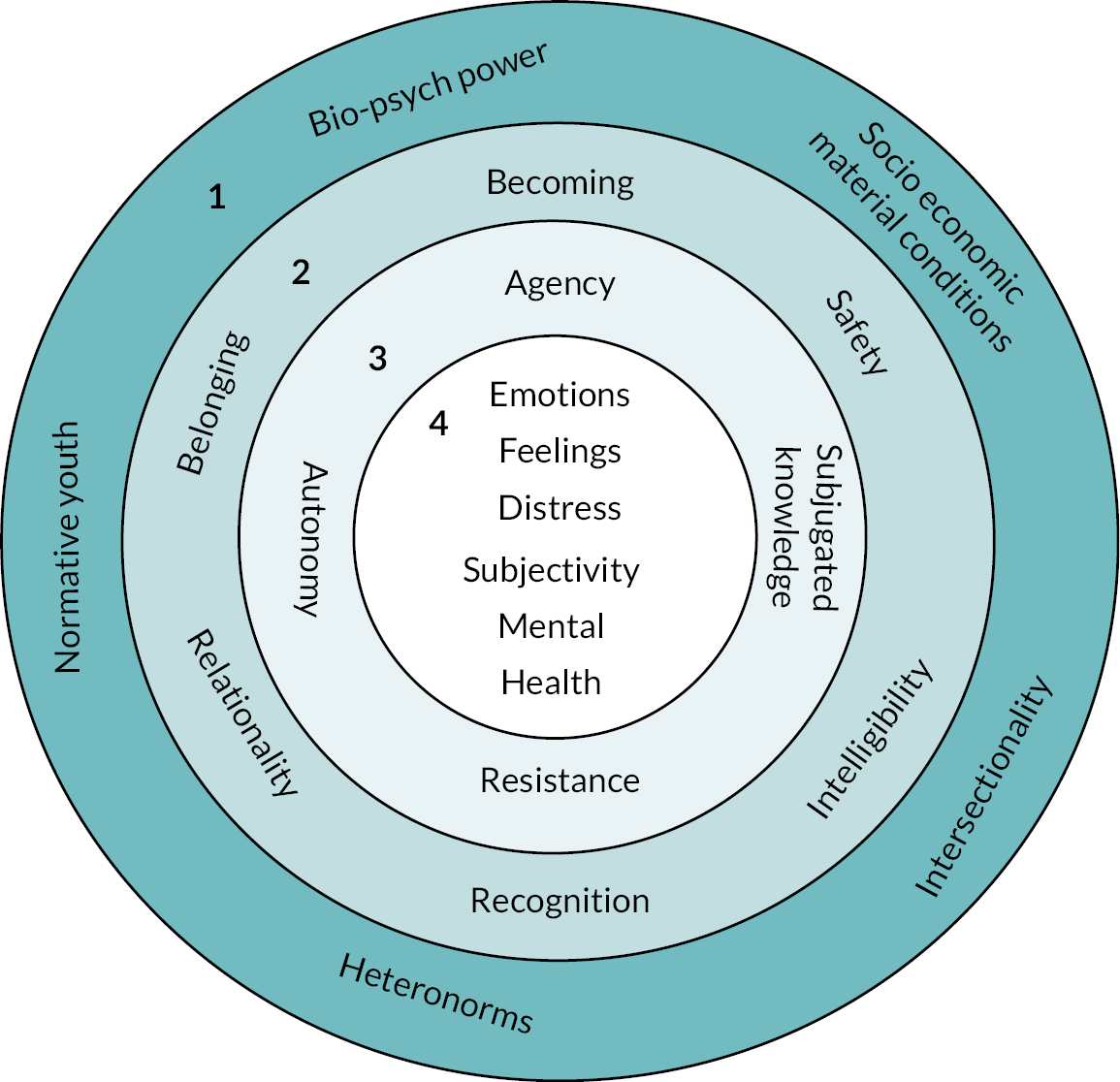

Theoretical framework

The lack of research on LGBTQ+ young people and their use of mental health services has resulted in few theoretical explanations for why current services may be inappropriate. Members of the research team have been at the forefront of developing theories to explain why LGBTQ+ populations have elevated rates of mental health problems. 13,71 This work builds on Meyer’s72 minority-stress model that explains LGBTQ+ individual mental health and well-being in terms of experiences of discrimination/victimisation/stigma and is a plausible explanation for poor experiences of mental health service provision. 13

McDermott (CI) and Johnson’s (CA) theoretical perspective uses the concept of cis-heteronormativity (the dominance of cis-heterosexuality where gender identities and bodies align and everyone is assumed heterosexual)73 as a central lynchpin to understanding why LGBTQ+ young people may face additional burdens on their mental health. Young people, particularly in the early stages of non-normative gender and sexual identity development, can feel alienated from traditional forms of support (family, friends)72 and at odds with normative expectations of cis-heterosexuality. 13,74,75 This isolation will often be underpinned by deep feelings of shame which are implicated in both poor mental health and a reluctance to access formal support services. 71,76,77

The study is theoretically framed using an intersectional perspective and draws on Collins’78 definition of intersectionality, which positions race, class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nation, ability and age as interconnected phenomena that produce and shape social inequalities. When thinking about the experience and impacts of oppression, identity categories are often conceived as discrete from each other and static. LGBTQ+ identities are often represented in homogeneous ways, structured by homo- and trans norms that centre whiteness, heterosexuality, class privilege and being non-disabled in relation to the ‘right’ ways to be LGBTQ+. 79,80 We utilised Collins and Bilge’s 81 intersectional approach to centre relations of power across structural, cultural, disciplinary and interpersonal domains in our understanding and operationalisation of intersectionality.

Theories and models that explain why LGBTQ+ young people are hesitant to ask for help for their mental health problems are crucial to the development of early intervention mental health service models that are acceptable and accessible to LGBTQ+ youth. We utilised models of young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems that go beyond the barriers/facilitators model that is commonly used in research. Our approach drew from Biddle et al. ’s82 ‘cycle of avoidance’ model that conceptualises help-seeking in relation to normalising and coping. McDermott’s development of this model13,40,41 posits that LGBTQ+ young people are hesitant to ask for help because they are afraid of being judged and humiliated in relation to normative expectations of adolescent development, cis-heteronormativity and mental health, and, as a result, they minimise their mental health problems and try to cope alone. 13,40–42,76 However, LGBTQ+ young people will look for support from places/people where they feel they are not judged, such as peers, LGBTQ+ individuals/organisations and online,40,42 and this provides some initial evidence for the development of appropriate service models.

Thus, theories for understanding the need for appropriate mental health early intervention services for LGBTQ+ young people were informed by models of youth help-seeking,13,40,41 youth psychology,74 theories of sexuality and gender13,71 and developmental approaches to identity,71 rather than narrowly defined sexual orientation labels. 83

The study has worked with the definition of early intervention and supported self-care that included any health, social care or educational intervention, service or technology provided by the public, private or third sectors that aims to facilitate LGBTQ+ young people (or carers) taking action to address their mental health problems. This included services that specifically target both the LGBTQ+ young people and the services that have adapted their delivery to meet the mental health needs of LGBTQ+ young people. Throughout the report, we use ‘mental health support’ as shorthand for ‘early mental health intervention and supported self-care’.

Stage 1: systematic review method

The first stage of the study addressed research question 1:

-

What evidence exists on mental health early intervention services and supported self-care for LGBTQ+ young people?

And objective 1:

To produce a synthesis of the evidence on mental health early intervention services and self-care support to LGBTQ+ young people

Scoping review

An initial scoping review conducted by the research team confirmed the nascent nature of existing research on early intervention support for mental health of LGBTQ+ youth. The primary aim of the scoping review was to assess the size of the available published literature on LGBTQ+ youth mental health early intervention services/support research. Scoping review methodology can be used to identify knowledge gaps, scope a body of literature and provide a roadmap for a subsequent full systematic review. 84 We searched four main databases, from 2005, for research examining LGBTQ+ youth and mental health services, and research on mental health interventions aimed at LGBTQ+ youth. We located 55 relevant studies and no systematic reviews on the topic. The scoping review revealed a body of literature from divergent research paradigms such as medicine, clinical psychology, psychiatry, sociology, cultural studies, education, youth studies, social work and queer theory.

For this reason, a configuring systematic review methodology68,85 was utilised rather than hypothesis testing systematic review methodology. A configuring approach is suitable as our scoping review did not find any randomised control trials and very few large-scale studies that are used to test causal hypotheses and ask ‘what works’?86 Use of a configuring rather than aggregative approach to the systematic review87,88 is appropriate for reviews with heterogenic literature, and it specifically aims to broaden understanding of particular services/interventions, asking instead, ‘what happens?’. 86 This discovery informed our decision to utilise the MNR method because it offers a strategy to make use of a conflicting body of research from diverse research paradigms. 89

Meta-narrative review rationale

Research on LGBTQ+ youth mental health early intervention services and self-care support is an emerging field of investigation. The nascent nature of existing literature, and limited theoretical explanations of why existing interventions and services are inappropriate for LGBTQ+ young people, guided our view that a theory-led systematic review methodology will be more fruitful than the traditional Cochrane and Campbell collaborations approach which are typically focused on forms of a meta-analysis. 90 Theory-driven approaches seek to detail the underlying logic or theory of how, why and in what contexts a service or intervention may work,63,68 which is necessary to ensure they are effective, sustainable and scalable. This underlying theoretical explanation is often overlooked but is, in fact, crucial to ensure that interventions that have been successful in their original contexts can be ‘meaningfully replicated’68 in other settings.

We chose to utilise the MNR method rather than other theory-led review methods (e.g. realist review, meta-ethnography, thematic synthesis) for two reasons. First, the scoping review revealed a heterogeneous body of literature consisting of disparate research paradigms with different epistemological and ontological perspectives that have produced a disjointed empirical evidence base. Second, our aim was to produce a theoretical explanation of mental health early intervention support for LGBTQ+ youth that could be tested within a case study evaluation methodology. A MNR is a distinct systematic theory-driven technique developed by Greenhalgh et al. 91 that is used to generate understanding from heterogeneous, complex, often contradictory evidence across diverse disciplines. 89,92

There are six guiding principles that inform MNR, and these were incorporated into each step of the review process from the outset. These are listed below (taken from Greenhalgh and Wong;93 Wong et al. 85):

-

Pragmatism – being guided by evidence most likely to promote sense-making.

-

Pluralism – explored from multiple perspectives and the quality appraised according to the discipline of origin.

-

Historicity – attention to how the tradition within which the research evidence was generated has unfolded over time.

-

Contestation – analysis and sense-making about conflicting evidence.

-

Reflexivity – individual and team of reviewers continually reflect on emerging findings.

-

Peer review – testing findings with external reviewers.

In addition to the six guiding principles, quality standards and training materials92,93 have been developed to ensure MNR are conducted in a systematic way ‘according to an explicit, rigorous and transparent method’91 (p. 418).

Specifically, MNRs make sense of complex interventions/services by exploring the implications of different conceptualisations of a given topic across a range of research paradigms over time. The underlying assumption is that key constructs, in our case ‘sexual orientation’, ‘gender identity’, ‘mental health’, ‘youth’ and ‘help-seeking’, are conceptualised, theorised and empirically studied differently among research paradigms. A MNR is premised upon a constructivist epistemological approach that suggests that knowledge is produced within particular research traditions (e.g. sociological, psychological, biomedical). Consequently, a MNR aims to make sense of heterogeneous bodies of literature by identifying, comparing and analysing the belief systems that exist within different research paradigms. The aim of this MNR was to obtain a theoretical understanding of how early intervention mental health services can support LGBTQ+ youth with common mental health problems. The review questions addressed were:

-

What empirical studies have been undertaken on mental health early intervention services and self-care support for LGBTQ+ young people?

-

What are the theoretical propositions for how and why these services may work?

Multidisciplinary team

Consultation throughout the review process with a wider team for the purposes of reflexivity and peer review of findings are central principles in a MNR. 93 A multidisciplinary research team is important to conducting MNR because it enables pluralism of approaches and an appreciation of distinct research traditions. 89 The Queer Futures Research Team included people from a variety of disciplines (such as clinicians, mental health nursing, psychology, public health, health economics, health science, sociology) and were involved throughout the MNR.

We also took the view that user involvement is key to conducting systematic reviews to ensure they will produce meaningful outcomes for all stakeholders. 90 The Queer Futures 2 study Project Advisory Group was consulted about the review at regular intervals. The Project Advisory Group comprised health service staff and commissioners; clinicians; voluntary sector practitioners who work with the population group; and a service user representative. We also conducted extensive PPI with LGBTQ+ young people recruited from different sites across the UK.

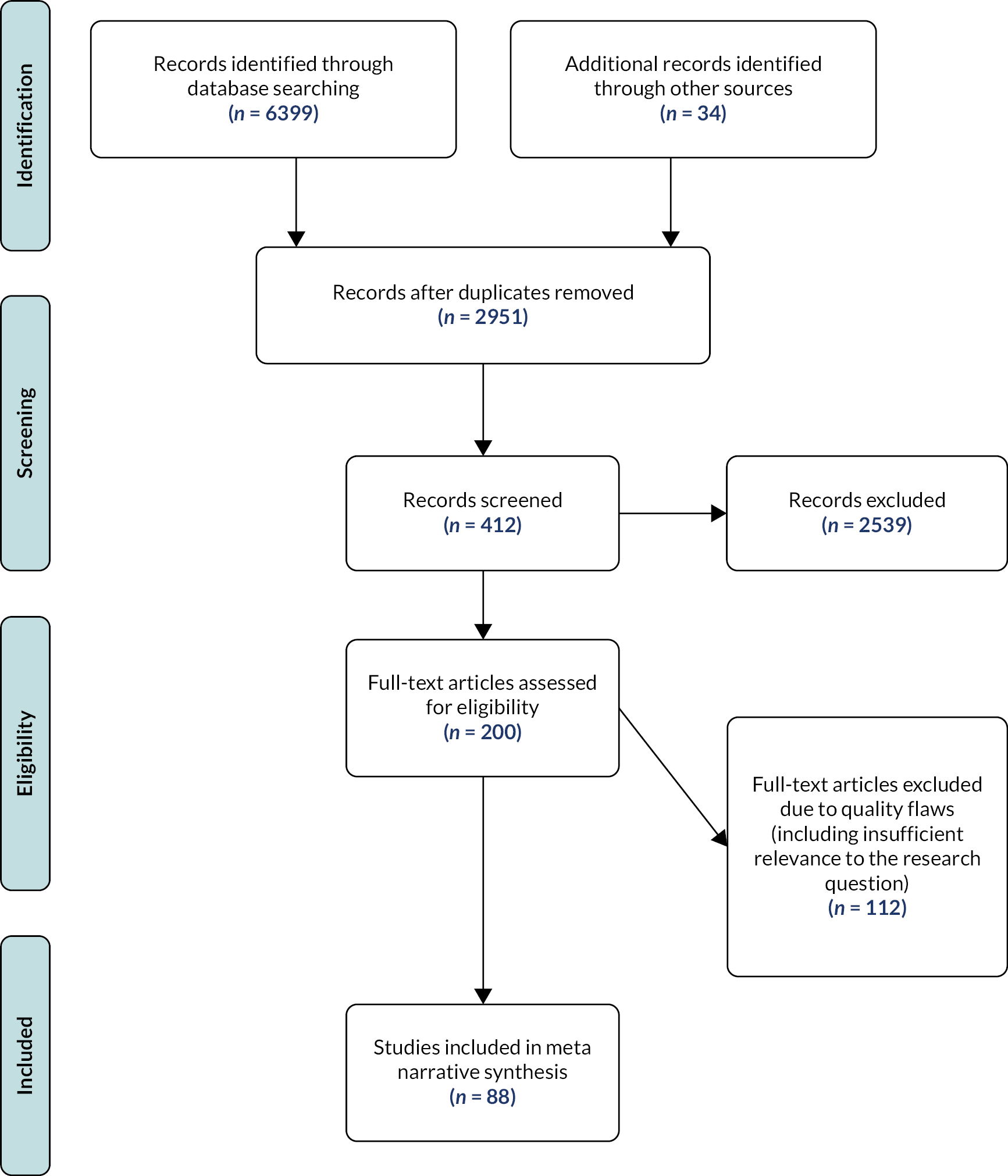

Search strategy

The aim of the search strategy, consistent with the MNR, is to identify documents that are conceptually or empirically relevant to the research questions. 85 Using the RAMESES85 standards for MNRs the protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42019135722). The search terms (Table 1) were developed in four domain categories: (1) sexual orientation and gender identity, (2) age, (3) mental health and (4) intervention/service. Searching was then undertaken via relevant electronic databases including both discipline-specific databases and multidisciplinary databases to increase the scope. These included, for example, MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Academic Search Ultimate, Web of Science, British Education Index, NHS Evidence, Social Care Online (see Appendix 1, Tables 17 and 18). The electronic database search was supplemented by expert informants, journal hand searching, citation tracking, and informant-led grey literature online searches. All identified papers were then subject to the review procedure.

| Sexual orientation and gender identity | Age | Mental health | Intervention/service |

|---|---|---|---|

| lesbian OR | Youth OR | “mental health” OR | Support OR service OR program* OR |

| gay OR | adolescen* OR | “mental disorder” OR | “early intervention” OR |

| bisexual OR | teen* OR | “mental* ill*” OR | “help seeking” OR |

| transgend* OR | “young people” OR | “mental* distress*” OR | CAMHS OR |

| same-sex OR | “young adult” OR | wellbeing OR | “Child and adolescent mental health service*” OR Thrive OR “CYP-IAPT” OR |

| “sexual minorit*” OR | “young person” | “well being” OR | IAPT OR mindfulness OR “primary care” OR outpatient OR |

| homosexual* OR | psycholog* OR | “cognitive therapy” OR CBT OR | |

| “sexual orientation” OR | psychiatr* OR | “behavio# * therapy” OR | |

| sexualities OR | depress* OR | Therap* OR | |

| queer* OR | “low mood” OR | counselling OR | |

| “gender atypicality” OR | anxiet* OR | school OR college OR | |

| “sexual identit*” | “self injur*” OR | university OR “higher education”? OR | |

| “self-harm” OR | “community–based” OR | ||

| “emotional problem*” OR | “social care” OR “social work” OR | ||

| “emotional difficult*” OR | “youth group” OR “youth service” OR | ||

| “emotional* distress*” OR | “peer support” OR “self manag*” OR | ||

| “emotional dysregul*” | “self car*” OR “self help*” OR | ||

| online OR virtual OR web OR internet OR | |||

| digital OR cyber OR “social media” OR | |||

| technolog* |

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The inclusion/exclusion criteria (Table 2) were based upon the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study (PICOS) framework. However, in comparison to other forms of systematic reviews, MNR does not pre-define a ‘preferred’ study design. This is consistent with the principle of pragmatism, that is, that evidence most likely to promote sense-making about the phenomenon (LGBTQ+ youth mental health support) and be most useful to the ‘intended audience’, is selected. 93 Thus, Table 2 represents PICOS criteria adapted to capture the diversity of possible search results that is acceptable for inclusion within a MNR.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

|

|

| Intervention |

|

|

| Findings |

|

|

| Study details |

|

|

The selection of papers for a MNR is an interpretative process that attempts to make sense of the literature to produce an account of how the research traditions develop over time. This MNR selection process was iterative, that is, it required a series of judgements within the research team about the relevance of particular research within that tradition. Papers published before 1990 were excluded because research published before this date were unlikely to be relevant given substantial changes in attitudes, policies and laws towards LGBTQ+ populations. The United Nations94 defines ‘youth’ as referring to people aged 15–24 years, but the age definition of youth varies across nations, disciplines and policies. Research written in English, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and French were included because these languages are spoken within the research team. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied independently by two members of the research team.

Quality assessment

The systematic review methodology does not have a standard quality appraisal framework. We drew on the EPPI-Centre ‘Weight of Evidence Framework’95 and recommendations for theory-led systematic reviews96 to devise a quality appraisal tool (Table 3) that focused on the relevance to the review question and the quality standard in relation to the discipline of origin. The tool was applied by two members of the research team.

| Relevance to the review question |

|

| Quality standard in relation to the discipline of origin |

|

Data extraction

Data extraction and synthesis were simultaneously conducted using the data analysis software Atlas.ti. Three members of the research team developed a data extraction and synthesis coding schema (Table 4), and this was applied to the included studies. The use of Atlas.ti enabled easy comparison and contrast of the extracted data across the included studies for the synthesis of the literature.

| Data extraction code and definition | Subcodes |

|---|---|

| Synthesis code and definition | Subcodes |

| Context: Describes the setting in which the research or discussion about mental health support takes placeFinding: Any findings in the papersStudy design: Explicit research design statedTheoretical perspective: Explicit statement about the theoretical orientation of the studyIntervention/service: The intervention or support service that the study involves | Clinical, Community, Online, Other, SchoolConceptual, EmpiricalQuantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Method, Systematic Review, Other, for example clinical case |

| Help-seeking: Conceptualization of help-seeking LGBTQ+ Identities: Conceptualization of relationship between LGBTQ+ identities and mental healthMental Health: Conceptualization of mental healthYouth: Conceptualization of youth | Access, Autonomy, Barriers, Cycle of avoidance, Health behaviour, Health information, Other, Power(lessness), StigmaDecompensation model, Essentialist, Heteronormativity, Homophobia, Intersectionality, Marginalisation, Minority Stress, Psychological Mediation Framework, VictimizationBiomedical, Critical, Individualising, Other, Pathologising, Psychological, Psycho-social. Adolescent psychological development, Autonomy, Biological, Other |

Data synthesis

It is usual in the synthesis stage of a MNR to have two interpretative phases. In the first phase, reviewers aim to identify and map out specific meta-narratives for each research tradition, focusing in particular on the concepts, theories, methods and instruments, which have characterised the tradition. The second stage involves comparing the meta-narratives asking what insights can be drawn by combining and contrasting findings from different traditions. 85 We outline the two phases below.

In stage one of the synthesis, multiple research team members used the extracted data to identify the research paradigms and map each meta-narrative. In this way, the different research traditions ‘become the unit of analysis’. 89 For each research paradigm, we asked key questions:

-

How has each tradition conceptualised the topic?

-

What theoretical approaches and methods did they use?

-

What are the main empirical findings?85

The synthesis process was informed ‘a priori’ by the research team’s familiarity with the key concept areas of the research project: (1) LGBTQ+ identities, (2) youth, (3) mental health and (4) help-seeking. Therefore, theoretical understandings of these concept areas were used analytically to inform an interpretive reading of all the research tradition meta-narratives created. Emergent theories were recorded transparently as with other stages of the MNR process. 85

Stage 2 of the synthesis compared the key dimensions across the research paradigms to generate a higher-order theoretical understanding of how and why interventions/services might work. In particular, we attended to the conflicts that arise between the theories, concepts and findings underpinning research from different traditions. This is consistent with the principle of ‘contestation’ – the commitment of MNR ‘to engage in disagreements’97 (p. 732). This second phase of the synthesis was conducted iteratively, using five distinct analytical steps that were guided by the principles of a MNR: pragmatism, pluralism, historicity, contestation, reflexivity, and peer review91 (Table 5). We moved between these five steps and the key question we asked across the research paradigms was ‘what are the implications of the contested concepts for developing early intervention mental health support for LGBTQ+ youth?’

| Step | Analytical strategy | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Historical theory building | Identification for each meta-narrative of the theories and models that seek to explain poor mental health in LGBTQ+ populations. From these we generated a draft theoretical framework for the entire stage 2 synthesis |

| 2 | Contestation | The key concepts (mental health, youth, LGBTQ+ identities, help-seeking interventions/services and findings) were compared across the meta-narratives. Attending to the conflicts that arose between the theories, concepts and findings underpinning the meta-narratives, and then comparing these to the draft theoretical framework |

| 3 | Pragmatism | As a result of the ‘contestation’ of the research traditions, we asked ‘what are the implications of the contested concepts for developing early intervention mental health support for LGBTQ+ youth?’ |

| 4 | Reflexivity | Reflecting both individually and as a team, we iteratively moved between ‘contestation’ and ‘pragmatism’ steps, the raw data (literature), the research questions and the draft theoretical framework. To supplement this thinking, we performed three additional cross-sectional analyses of the included data with a focus on LGBTQ+ youth of colour, trans and gender diverse youth, and bisexual youth |

| 5 | Peer review | The draft theoretical framework was further developed through discussion with the research team (including LGBTQ+ youth) and practitioners from the health, education, and voluntary sector |

The multidisciplinary research team developed a robust theory68 consistent with the pluralism and peer review principles of MNR. 93 The theoretical explanation of mental health early intervention services and self-care support for LGBTQ+ young people with common mental health problems derived from the MNR was then ‘tested’ during the case study data analysis in stage 3 of the overall study design.

Stage 2: service mapping method

The second stage of the study addressed research question 2:

-

What type of service models for mental health early interventions and supported self-care to LGBTQ+ young people are currently provided?

And objective 2:

-

To identify service models for mental health early intervention and supported self-care which are accessible and acceptable to LGBTQ+ young people

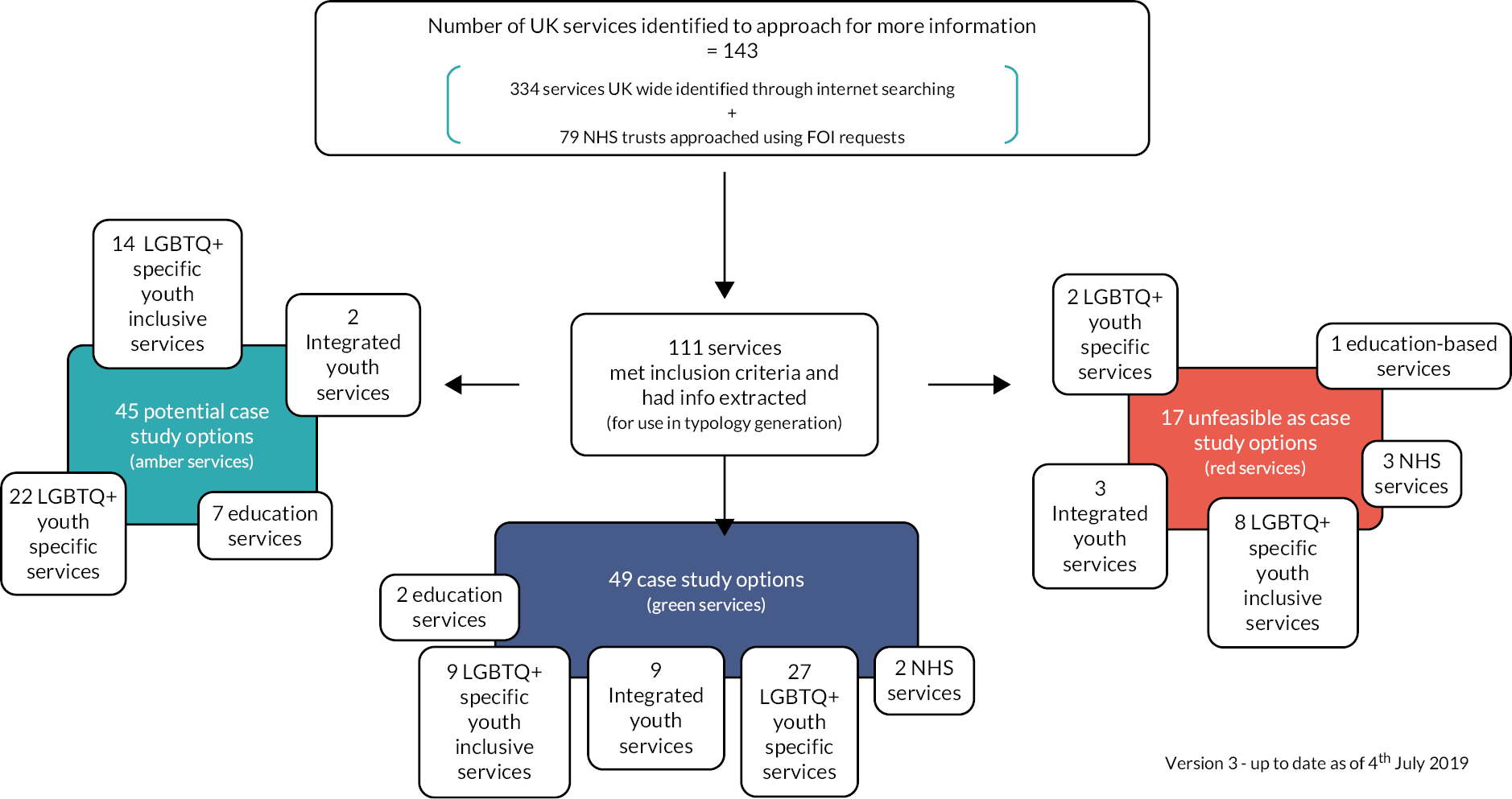

Method overview

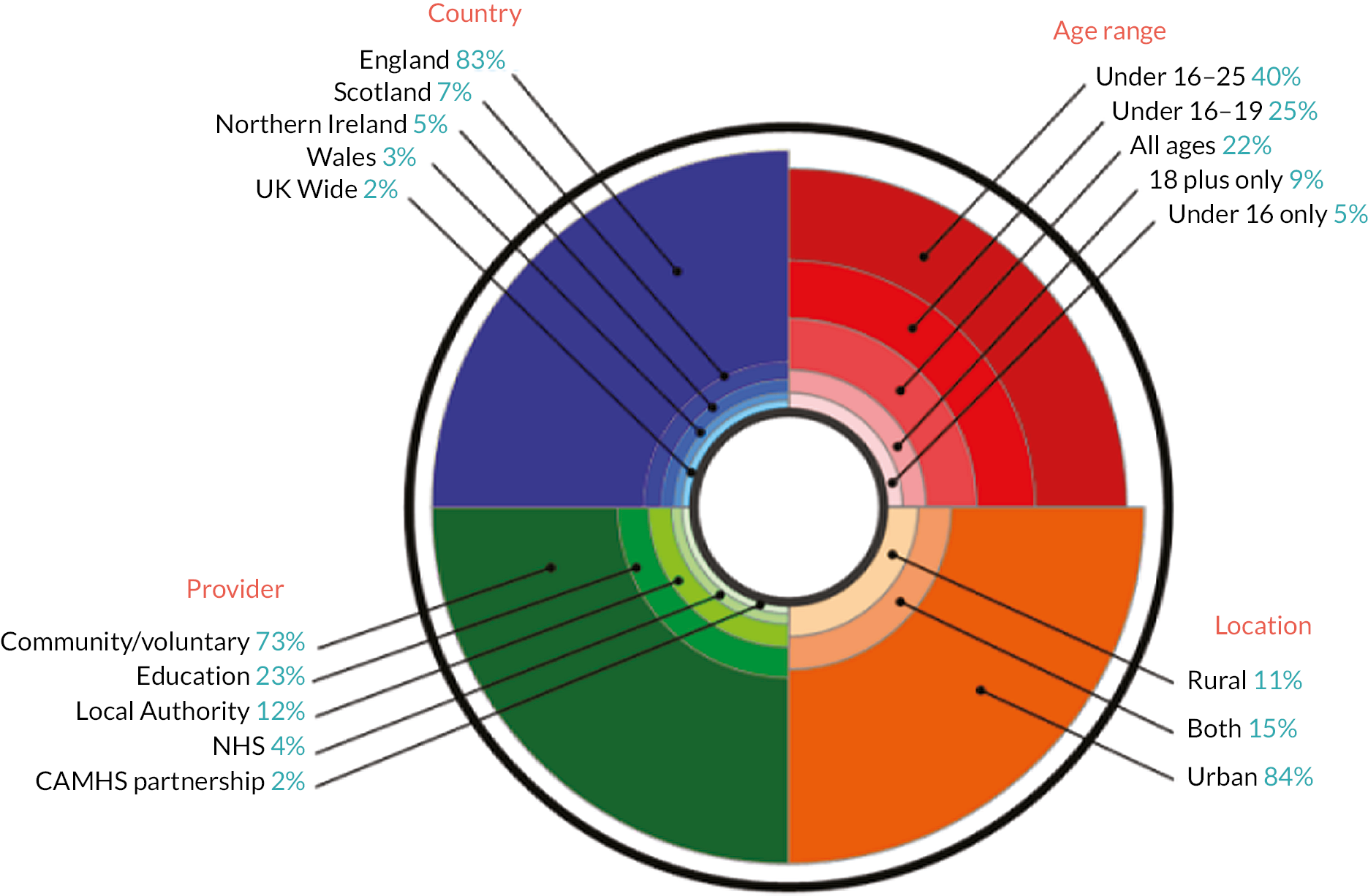

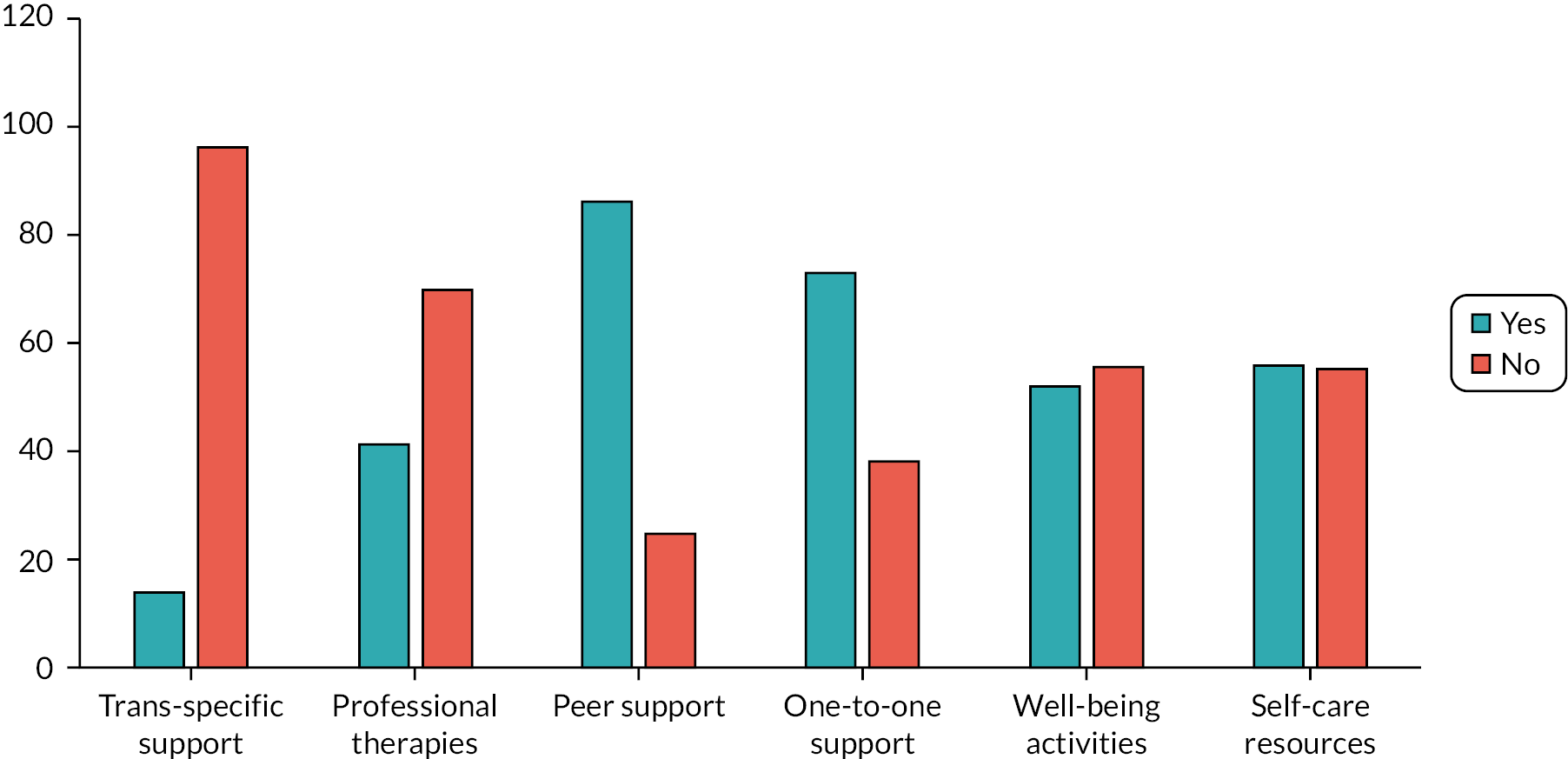

This stage of the study drew on the successful mapping methods used in Pryjmachuk et al. ’s children and young people mental health self-care research. 98 Between February 2019 and February 2020, we employed systematic online and offline search strategies to identify services of various types for example self-care, peer-support, digital support, clinical; in a range of service settings for example health, local authority, third sector. Data collection was desk based and basic details (e.g. target population, mode of delivery, theoretical approach) of potential services obtained from any source were extracted and entered into an Excel spreadsheet. The service mapping data were tested against inclusion criteria in the information extraction phase and a final typology was generated to describe service provision across the UK. A full summary of the mapping data then produced a typology of services which was used to inform the selection of the CSS in stage 3 evaluation.

Search strategy

The search strategy was devised as both online and offline to identify services in the UK where youth, sexuality or gender identity, and mental health were a focus.

Online search strategy

During online searching, Google (the internationally most used search engine) and Bing (the default search engine for the respective organisation’s IT systems) were used to locate websites of interest using the following search phrases:

-

LGBTQ+ Young People Mental Health Services [ADD GEOGRAPHICAL AREA].

-

LGBTQ+ CAMHS [ADD GEOGRAPHICAL AREA].

-

LGBTQ+ Youth Group [ADD GEOGRAPHICAL AREA].

These search phrases were selected and piloted with LGBTQ+ young people and service providers, to ensure they reflected the type of search term used when looking for mental health support for themselves or a service user. The rationale for this search strategy was that current active services would need to be discoverable to potential service users in a basic web search and therefore these phrases should illuminate most of the available service options. The first 10 sites yielded through these search terms were checked for available services. Information about the service and provision offered was also gathered through specific websites, forums, blogs, and relevant social networking sites. Online searches were also conducted for local Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) transformation plans, which were likely to detail current and planned services for LGBTQ+ young people. In addition, a search for LGBTQ+-associated charter marks (e.g. Stonewall Champions, The Rainbow Flag Award to identify potential school services) was undertaken. The online search was supplemented by standard systematic search strategies including expert informants (academics and service providers) and subject-specific hand searching of print media (March 2019 issues of DIVA, Attitude and Gay Times). 87

Services that clearly offered support for LGBTQ+ youth mental health and those which were likely to support LGBTQ+ youth mental health were recorded. In the latter case, ‘likely’ meant that there was good reason to think the service supports LGBTQ+ youth mental health in some capacity including:

-

LGBTQ+ youth services, many of which had basic websites or Facebook groups and did not give detailed account of their activities in online information, including how they offer mental health support.

-

LGBTQ+ mental health services that did not explicitly state they offered targeted work to young people but were available to under 26-year-olds.

-

Youth mental health services that did not advertise LGBTQ+ specific work but are important providers of mental health support to this age group (e.g. Young Minds).

-

Services known through expert informants to support the mental health of LGBTQ+ young people.

Offline search strategy

The offline search included the use of print-only media such as magazines, newspapers and free periodicals that do not necessarily have an online format to facilitate in-depth search at a local level. The use of offline print media allows for the identification of any potential smaller, more marginalised groups or services that may utilise small advertising for discretion. The offline search will also be facilitated through the following key contacts and networks such as:

-

LGBTQ+ third sector service providers, for example MindOut, Viva LGBTQ+ youth (Wales), Gendered Intelligence, The Proud Trust

-

LGBTQ+ third sector national umbrella organisations, for example National LGB&T Partnership, Stonewall, Stonewall Cymru, LGBTQ+ Foundation, LGBTQ+ Consortium, LGBTQ+ Youth Scotland, Cara-friend [Northern Ireland (NI)]

-

Key third sector youth organisations, for example 42nd Street, Barnardo’s

-

Key third sector mental health organisations for example Young Minds, Self Harm UK

-

Key expert informants, that is professionals developing LGBTQ+ youth mental health services

-

Professional groups such as the Royal Colleges of Nursing, General Practice and Psychiatrists, Schools and Students Health Education Unit, CAMHS Nurse Consultants network, British Psychological Society

-

NIHR clinical research networks, for example primary care, mental health

-

All primary care trusts and mental health trusts

-

All directors of children’s services in local authorities

-

National third sector umbrella organisations, for example, NCVO (The National Council for Voluntary Organisations), National Youth Agency.

We made a Freedom of Information (FOI) request directly to all NHS trusts delivering CAMHS in the UK (n = 79) to enquire about any LGBTQ+ youth-specific mental health service provision as CAMHS have a minimal online presence, and we were unable to obtain service information via webpages. FOI request contained the following questions:

-

Does your trust provide a specific mental health service for LGBTQ+ young people?

-

Are your staff offered LGBTQ+ awareness training?

-

Do you deliver the training in house or is it provided by an external partner?

-

Do you have a specific policy for working with LGBTQ+ people?

Trusts were asked to provide contact details for a staff member who would be able to provide more information about any services identified.

Inclusion/exclusion of services

The identified services were considered against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Determining whether services meet the inclusion criteria was an iterative process, dependent on the information available through the website and informal conversations with expert informants and the services directly. This was applied by two research team members. The inclusion/exclusion criteria are detailed in Table 6.

| Domain | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Mental health | Provide support for common mental health conditions for example depression, anxiety, self-harm | Crisis servicesNo mental health problems |

| Age | Targeted to 12- to 25-year-olds | Services for exclusively under 12 years oldServices exclusively for over 25 years old |

| Sexuality/gender | Targeted to LGBTQ+ young peopleYouth mental health support within gender identity services | No LGBTQ+ youth provisionGender identity services (physical health services) |

| Service operation | Moderated by an agent, for example service staff memberActive during February 2019–February 2020Delivered in the UK (England, Scotland, Wales, NI) | Services where no agent/staff were involved, for example self-help appsNot active between 1 February 2019 and 31 December 2019Delivered exclusively outside the UK |

Data extraction

Detailed information (Table 7) about the operation of the eligible mental health services was collected using the service website, online resources, key contacts, and direct contact with the service via telephone or e-mail and entered into an Excel spreadsheet by two members of the study team.

| Data type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Service name | All names the service has operated under |

| Service provider | NHS, Local Authority, School, Private, Voluntary/Charity, Community Interest Company |

| Sexual orientation | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Queer, Questioning, Asexual, Aromantic, Fluid, Pansexual, Skoliosexual; and any other sexual orientations |

| Gender identity | Transgender, Gender Fluid, Non-Binary, Agender, Bigendered, Genderqueer, Intersex, Transman, Transwoman; and any other gender identities |

| Target group | Demographic details of who attends the services |

| Mental health condition | Common mental health conditions: Anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, self-harm, PTSD, emerging personality disorders |

| Theoretical approach | This will be determined by grouping the services at the end of the mapping exercise |

| Mode of delivery | How is the service delivered? For example, face-to-face, online, groups, one-to-one |

| Tools/techniques | What tools/techniques does the service use to provide mental health support? For example, counselling, arts therapy, sports, exercise |

| Self-care element | What is done by the service user to improve their mental health (usually an activity of some sort, for example reading materials, practising an action, learning a technique) |

| Support element | What is done by the staff member to support the improvement of young people’s mental health (coaching, facilitating, giving feedback and encouragement) |

| Setting | Where is the service delivered? For example, clinic, community, home, online |

| Rural/urban | What is the geographic location of the service? Urban or rural |

| Length of contact | What is the average length of time a young person is involved in the service? |

| Frequency of contact | How often on average is a young person involved in the service? |

| LGBTQ+ training | Does the service offer LGBTQ+ training? Is it voluntary or mandatory? |

| LGBTQ+ policy | Does the service have a specific LGBTQ+ policy? |

| Facility adaptations | Have there been any adaptions to the facility to make it more suitable for LGBTQ+ young people? For example, gender-neutral toilets |

| Country/county | Where is the service based? Country (England will be split into counties) |

| Duration running | How long has the service been operational? |

| Commissioned specifically? | Is the LGBTQ+ mental health support specifically funded as part of somebody’s job description? |

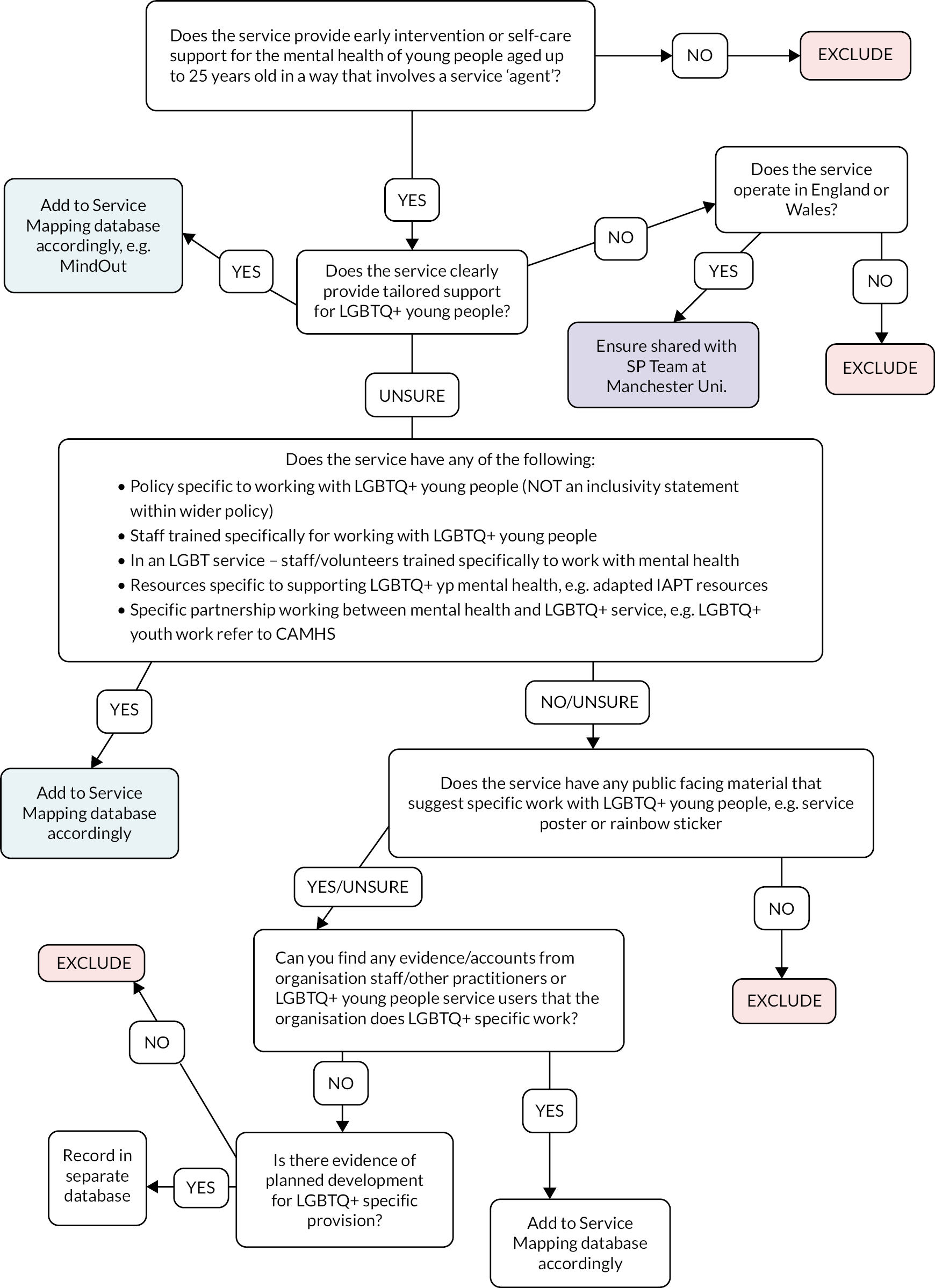

Frequently it was difficult to determine from the information available during the searching phase (e.g. via websites) whether a service definitely met the inclusion criteria. In these cases, services were contacted via telephone or e-mail by the researchers for further information. Thus, the searching and information extraction was more of an iterative than linear activity and these activities overlapped considerably in practice. To assist in determining if services were relevant for inclusion, a flow chart was created in consultation with the Project Advisory Group (see Appendix 2).

Once services were deemed to meet the inclusion criteria, detailed information was collected about their operation. This information was extracted either from materials available in the public domain such as service websites and promotional materials or by requesting the information via telephone, e-mail or by asking a service representative to complete an online form. All information extracted was inputted into a spreadsheet for each of the categories in Table 7.

Typology generation

The typology of early intervention mental health service/support for LGBTQ+ young people was developed by five members of the research team. Framework analysis was used to create the typology of services from the information extracted during the mapping process. 98,99 Framework analysis consists of five processes: familiarisation, identification of thematic framework, indexing, charting, followed by interpretation. 100

During the familiarisation process, the researchers highlighted themes and similarities between the services. These initial observations along with the findings of the MNR informed the creation of the thematic framework, which provided the basis of the indexing and charting. A matrix format was utilised for the indexing and charting processes to a group of services. 98 The grouping of services informed the development of the service typology. Finally, the research team along with the wider project advisory group discussed the criteria for the service typology and produced a simple typology that identified the type of service provision available in the UK.

Case study selection

Case study sites were selected from each category of the service typology. The case study selection criteria were developed by five members of the research team and are outlined in Table 8. The criteria were developed to reflect the capacity of the service to participate in the research and to include a diversity of service models in a range of settings at a variety of geographical sites. The CSS were determined in consultation with the project advisory group and LGBTQ+ young people. Twelve CSS were selected.

| Criteria | Criteria description |

|---|---|

| Type of service | There should be a case study site for each of the services in the typology |

| Theoretical approach/model | Case study sites should include a range of approaches/models of mental health support, for example, CBT, person-centred, affirmative, activist/advocacy, youth work, peer-led, pedagogical, empowerment, social model, clinical model |

| Geography | At least one site in the four nations – England, Scotland, Wales and NI |

| Capacity | Case study sites must be robust enough to undergo an evaluation and can demonstrate:

|

| Operation | Case study sites are operational for the 12 months of the data collection period |

| Urban/rural | Case study sites should include a mix of urban and rural provision |

| Age | The 12 case study sites include the full age range of the study (12–25 years old) |

| Trans/gender diversity | One to two of the case study sites should be trans/gender specific |

Stage 3: case study evaluation method

The third stage of the proposed study addressed research questions 3–5:

-

How, why and in what context do mental health early intervention and supported self-care work for LGBTQ+ young people?

-

In what ways do LGBTQ+ young people access and navigate formal and informal mental health early intervention services and self-care support?

-

How can LGBTQ+ young people be encouraged to access and engage with mental health early intervention services and self-care support?

And objectives 3–5:

-

To develop a programme theory of how, why and in what context mental health early intervention services and self-care support work for LGBTQ+ young people.

-

To increase understanding of LGBTQ+ young people’s access to and navigation of formal and informal mental health early intervention services and self-care support.

-

To generate commissioning guidance (including service costs) on mental health early intervention and supported self-care services for LGBTQ+ young people.

Methods overview

The third stage of the project comprised a collective case study evaluation of mental health early intervention and self-care support services for LGBTQ+ youth across 12 case studies. A case study is an empirical enquiry that focuses on a single phenomenon in its real-life context, especially useful (as in our circumstances) when a description or explanation is required. 101 Collective case studies are those in which multiple cases are studied simultaneously or sequentially in an attempt to generate a broad appreciation of a particular issue. 69 Yin62,101 defines a ‘case’ as a ‘bounded entity’, a broad and flexible definition that allows the case to be as varied as an event, an individual, a service or a policy. In this project, we have defined the case as ‘mental health early intervention and self-care support service for LGBTQ+ young people in the UK’.

The 12 case studies were purposively102 selected from services identified in stage 2 (service mapping) to reflect the different dimensions of the stage 2 service typology. We estimated that 12 would be an adequate number of cases to capture the range of services identified in stage 2. Data were collected from key stakeholders in each of the CSS (n = 12) to examine factors such as service acceptability, gaps in provision, barriers/facilitators to access, views on service improvement and encouraging access/engagement. At each case study site, data were collected via:

-

Online interviews with LGBTQ+ young people, family members and service staff (n = 10)

-

Documentary review

-

Non-participant observation

-

Data were collected on service cost.

Case study evaluation is a theory-driven evaluation methodology and therefore the data analysis strategy is theoretical using the ‘explanation-building’ (EB) analytical technique. 62 The findings from each case study site were used to gradually refine the theoretical model developed in stage 1 of the study to produce an overarching theoretical understanding of how, why and in what context mental health early intervention services and self-care support work for LGBTQ+ young people. 69

Sampling and recruitment

A purposive sampling strategy64 was used to select participants within the case study sites to ensure that a diverse range of appropriate stakeholders (LGBTQ+ youth, parents and carers, health, social care and education professionals, and volunteers) were invited to participate.

For service staff, the inclusion criteria were that they worked for the case study service and had experience supporting the mental health of LGBTQ+ young people. For parent/carers inclusion criteria were that they had experience caring for an LGBTQ+ young person with common mental health difficulties who had sought mental health support. For LGBTQ+ young people, the eligibility criteria were as follows:

-

12–25 years old

-

Identifies as LGBTQ+

-

Experience of seeking support for a common mental health difficulty

-

Currently engaged with the case study service

-

Not in crisis.

Recruitment of LGBTQ+ young people was via digital flyers and posters circulated by the service staff. In some cases, research staff went along to online youth group sessions to introduce Queer Futures 2 and invite participation. In other cases, support workers passed the digital flyers directly to individuals they thought may be interested and safe to take part. Individual LGBTQ+ young people were selected purposively to ensure we involved a diverse range of LGBTQ+ young people including in relation to gender and sexual identity, ethnicity, poverty and disability. Recruitment of service staff was also purposive to gain diverse insights into LGBTQ+ youth mental health support depending on job role. Parents/carers were recruited only where there was a specific parent/carer support group.

In total 93 participants took part in the study: 45 LGBTQ+ young people, 42 service staff, 6 parents/carers (see Table 9 for demographic characteristics of participants).

| Variable | Classification | Young people (n = 45) | Service staff/volunteers (n = 42) | Parents/carers (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12–16 | 11 | ||

| 17–20 | 23 | 2 | ||

| 21–25 | 11 | 4 | ||

| 26–35 | 16 | |||

| 36–45 | 12 | 1 | ||

| 46–55 | 6 | 5 | ||

| 56–65 | 2 | |||

| Gender | Man/boy | 18 | 13 | |

| Woman/girl | 8 | 23 | 6 | |

| Non-binary | 13 | 3 | ||

| Othera | 6 | 3 | ||

| Are you trans? | Yes | 32 | 7 | |

| No | 8 | 33 | 6 | |

| Unsure | 2 | 1 | ||

| Prefer not to say | 3 | 1 | ||

| Ethnicity | Black African | 1 | ||

| Black British | 1 | 1 | ||

| Black Caribbean | 1 | |||

| Chinese | 1 | |||

| Irish | 3 | |||

| Latino | 1 | |||

| Mixed ethnicity white/Asian | 2 | 2 | ||

| Mixed ethnicity white/Black Caribbean | 3 | |||

| Other | 1 | |||

| Other (mixed ethnicity)a | 2 | 2 | ||

| Pakistani | 1 | |||

| Prefer not to say | 1 | |||

| White (other) | 5 | 2 | 1 | |

| White English/Irish/Scottish/Welsh/British | 29 | 29 | 4 | |

| Sexual orientation | Asexual | 7 | ||

| Bisexual | 6 | 7 | 2 | |

| Gay | 8 | 9 | ||

| Heterosexual | 2 | 10 | 4 | |

| Lesbian | 2 | 6 | ||

| Pansexual | 4 | 1 | ||

| Queer | 9 | 7 | ||

| Questioning | 2 | 1 | ||

| Othera | 5 | 1 | ||

| Are you disabled? | Yes | 21 | 6 | |

| No | 20 | 35 | 6 | |

| Prefer not to say | 4 | 1 | ||

| Type of disability | Chronic illness | 2 | 2 | |

| Learning disability | 9 | 1 | ||

| Mental health condition | 27 | 4 | ||

| Mobility impairment | 4 | 1 | ||

| Neurodiversity | 12 | |||

| Othera | 1 | |||

| Prefer not to say | 1 | |||

| Sensory impairment | 4 | |||

| Undiagnosed mental health condition | 26 | |||

| Highest qualification | No qualifications | 6 | ||

| GCSE | 16 | |||

| AS levels | 1 | 1 | ||

| A levels | 15 | 2 | 2 | |

| HE diploma | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| First degree | 2 | 20 | 1 | |

| Higher degree | 2 | 15 | 2 | |

| Trade apprenticeship | 1 | |||

| Prefer not to say | 2 | |||

| Employment | Student | 28 | 2 | |

| Unemployed | 9 | |||

| Full-time employment | 1 | 26 | 5 | |

| Part-time employment | 4 | 12 | 1 | |

| Other | 3 | 1 | ||

| Prefer not to say | 1 | |||

| Parent degree | Yes | 23 | ||

| No | 16 | |||

| Unsure | 6 | |||

| Free school meals | Yes | 18 | ||

| No | 19 | |||

| Unsure | 8 |

Data collection

Semistructured online interviews

We conducted semistructured qualitative interviews with three groups of participants:

-

Service staff using online video apps – Zoom or Microsoft Teams

-

Parent/carers using online video apps – Zoom or Microsoft Teams

-

LGBTQ+ young people via WhatsApp (text only).

The aim of the interviews was to generate in-depth, exploratory data from the perspectives of the participants. 103 The rationale for employing different modes of interviewing were the difficulties of researching a marginalised group, collecting data during the COVID-19 pandemic and the sensitivity of the topic. There are difficulties recruiting samples because participants may be unwilling to be open about their LGB or T and/or mental health status. Previous studies, including the lead author’s, have demonstrated that online interviews can be successfully used to examine LGBTQ+ youth’s mental health. 13,42,104 This is because a virtual interface provides unique access to LGBTQ+ youth who may not otherwise participate in research,105 and the internet is an important vehicle by which LGBTQ+ youth seek information and support regarding their sexual orientation, gender identity and mental health. 104,106

The decision to use WhatsApp as a method of interviewing LGBTQ+ young people was based on consultation with LGBTQ+ young people. While Instagram was popular too, WhatsApp offered superior data security via end-to-end encryption. WhatsApp also offered functionality for sending picture messages and links to, for example, the demographic survey and participant information video. Finally, the anonymity afforded to LGBTQ+ young people and the mode of answering questions, that is, via typing text, was desirable as it was likely that many would be taking part from their domestic environments during lockdown. WhatsApp offered privacy that was not otherwise available via video interviewing. Albeit limited, there was also some published evidence about the effectiveness of using WhatsApp for interviewing young people about mental health topics. 107,108

All topic guides for the individual interviews were informed by stage 1 (existing evidence review) and piloted with our PPI groups. Questions were standardised and made friendly and accessible for LGBTQ+ young people through the use of images (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Qualtrics was used to collect demographic information and service cost data (see Report Supplementary Material 2). The links to online forms for completion were forwarded through WhatsApp or e-mail (for staff/parents or carers) as part of the interviews.

The online video interviews were recorded and converted to audio only for transcription. The WhatsApp interviews were downloaded direct to Lancaster University’s secure encrypted cloud storage – Microsoft OneDrive. Non-professional participants (e.g. young people and parents/carers) were offered £20 in gift vouchers as a token of thanks for participation.

Non-participation observation

Most case study sites at the point of data collection were providing an online service. Data from these sites were collected via ‘netnographic’ non-participation observation. Netnography is a form of ethnography that has been used in the study of online health behaviour,109 and similar to ethnography, it is concerned with everyday routine behaviours in a natural setting. 110 This method is appropriate for the observation of services that may operate entirely online. All non-participant observation was recorded in a case study workbook template that was designed to standardise data collection across the sites. Data was collected, for example, on the manner in which the service was run, duration, timings, model of mental health provision, staff and volunteer organisation, partnerships and relationships.

Documentary review

Where available, relevant documentary evidence was collected from each site such as operational manuals, service evaluations, administrative service datasets, strategic plans, intervention protocols, information leaflets. This documentary evidence largely served to provide a contextual background to, and additional understanding of, the 12 case studies. All documentary data were recorded in a case study workbook template that was designed to standardise data collection across the sites.

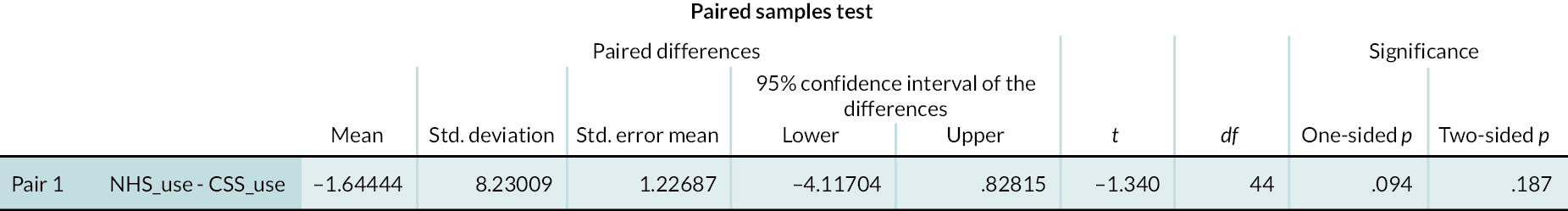

Service cost data

Information on resource use was collected from individuals when interviewed via an online survey tool, shared via a weblink at the end of the interview (see Report Supplementary Material 2). This was done for the purpose of supporting the development of the NHS commissioning guidance only. The aim of the health economic analysis was to determine the pattern of service use by LGBTQ+ young people and generate average service costs per user. Utilising a combination of the findings of the stage 2 service mapping and feedback from PPI, participants were asked about their use of a wide range of healthcare and social services visits such as general practitioner (GP), nurse at GP surgery, psychiatrist, community mental health/psychiatrist nurse, other mental health services and other service use. Each participant was also asked about their use of services in the case study site including 1 : 1 sessions, peer support, activity sessions and other sessions. Participants self-reported their use of services using a survey developed for this study with a recall period of 4 weeks.

Costs were considered for health care provided in primary care, community mental health services, emergency services, social care services and other services. We also considered the care-provided case study sites. All costs are presented in pounds sterling using 2021 available costs.

Data analysis

First, the data sets – interview transcripts, non-participant observation and documentary evidence – from each individual case study site were imported into Atlas.ti.9 computer software designed to assist in the organisation and analysis of qualitative and multi-methods data (the service cost data were not included).

The resulting data set was extensive and diverse as is characteristic of case study research. This volume of data needs to be managed systematically62,101,111 with a clear analytical data strategy in place prior to data collection. 111 Case study evaluation is a theory-driven evaluation methodology, and therefore, we drew on Yin’s EB data analysis strategy that is designed for case studies with multiple case sites (like ours) and aims to build a general explanation that fits each individual case.

Yin111 (p. 142) states this is ‘analogous to creating overall explanation, in science, for findings from multiple experiments’. EB is used where ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions (i.e. causal questions) are regarding complex topics that are difficult to measure. The explanation is therefore narrative and more robust if there is a central theoretical proposition. The theoretical framework/model developed from stage 1 MNR provided this and a coherent orientation for our case study data analysis. Generally, this approach has been poorly operationalised and described by other studies and therefore we relied upon insights from Yin. 111 There are three fundamental aspects of case study data analysis that informed our strategy:

-

This is a deductive and inductive approach

Explanation building is partly deductive because we had a theoretical model from stage 1 that we proposed explains early intervention mental health support for LGBTQ+ youth. This model came from the literature/evidence, and we were ‘testing this’ with our 12 case study sites. EB is also partly inductive because we suspected the model was inadequate and we were using data from the case study sites to revise and improve the model.

-

Includes within-case analysis and cross-case synthesis

What is important to case study analysis is a whole-case approach. In a sense, the case study site is the unit of analysis. This means for each case study site we conducted a ‘within-case’ analysis, followed by cross-case synthesis comparing whole-case study sites. The aim was to retain the integrity of each entire case study site. In this way, the findings from each case study site data analysis were used to gradually refine the theoretical model developed in stage 1 to produce an overarching theoretical understanding of the mechanisms by which mental health early intervention services can support LGBTQ+ young people with common mental health problems.

-

Uses a series of iterations

The iterative nature of EB is central to the approach of a case study with multiple case study sites. Eventual explanation results from a series of iterations, and if done in relation to a theoretical proposition increases the trustworthiness of the findings. The findings from each case study site were examined and compared to the theoretical model from stage 1 which was then revised, and the evidence examined again. This iterative process was important to ensure other plausible explanations were considered in the process. 62

In this way, the findings from each case study site data analysis were used to gradually refine the theoretical model developed in stage 1 to produce an overarching theoretical understanding of the mechanisms by which mental health early intervention services and self-care can support LGBTQ+ young people with common mental health problems.

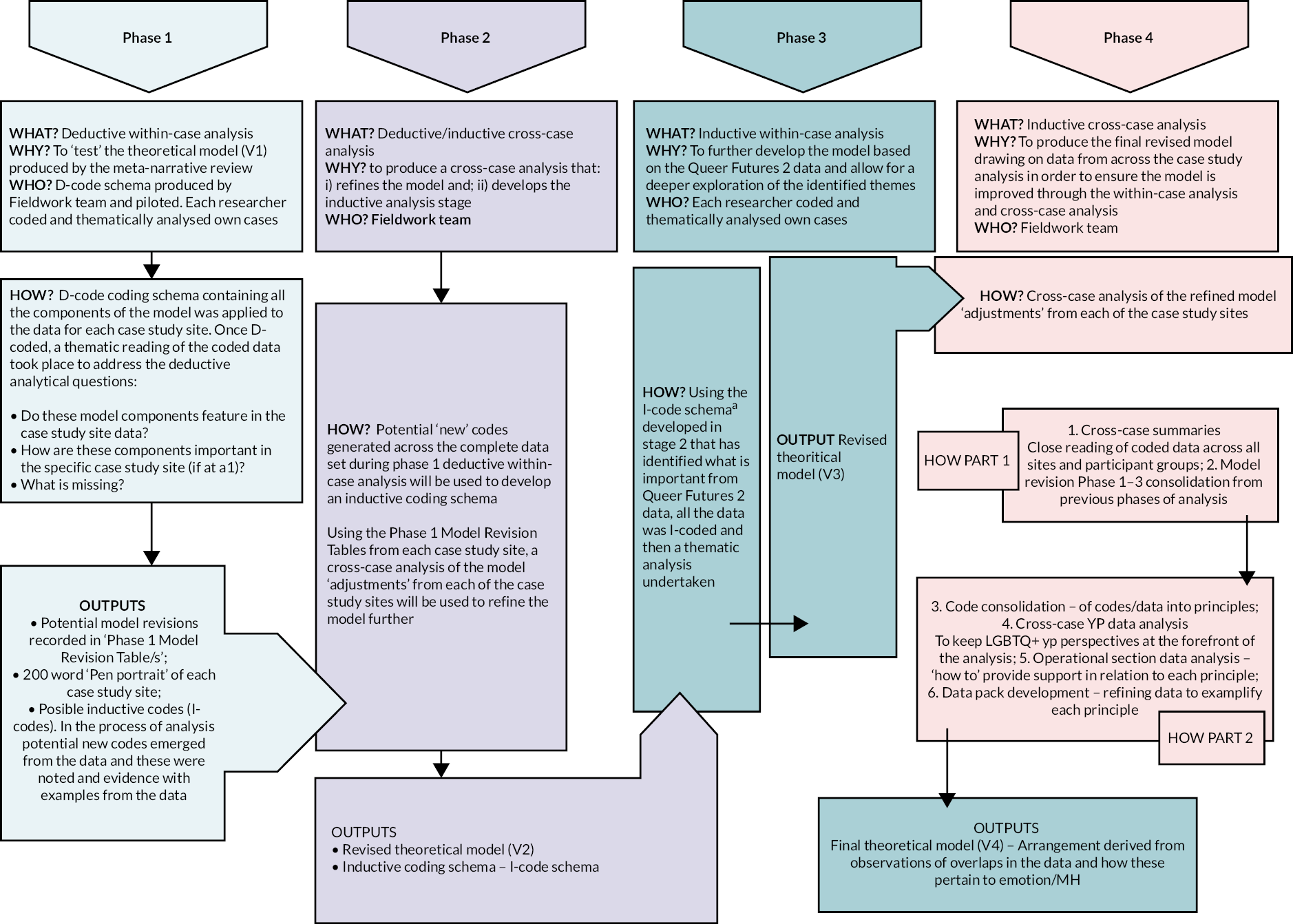

Operationalising EB data analysis in a case study evaluation with multiple case study sites is difficult because we had a large amount of complex data. Our analysis was conducted on each site only when all data had been collected for that individual case study site. The iterations of analysis were in four phases as follows:

-

Deductive within-case analysis Revision of model

-

Deductive/inductive cross-case analysis Revision of model

-

Inductive within-case analysis Revision of model

-

Inductive cross-case analysis Final revision of the model.

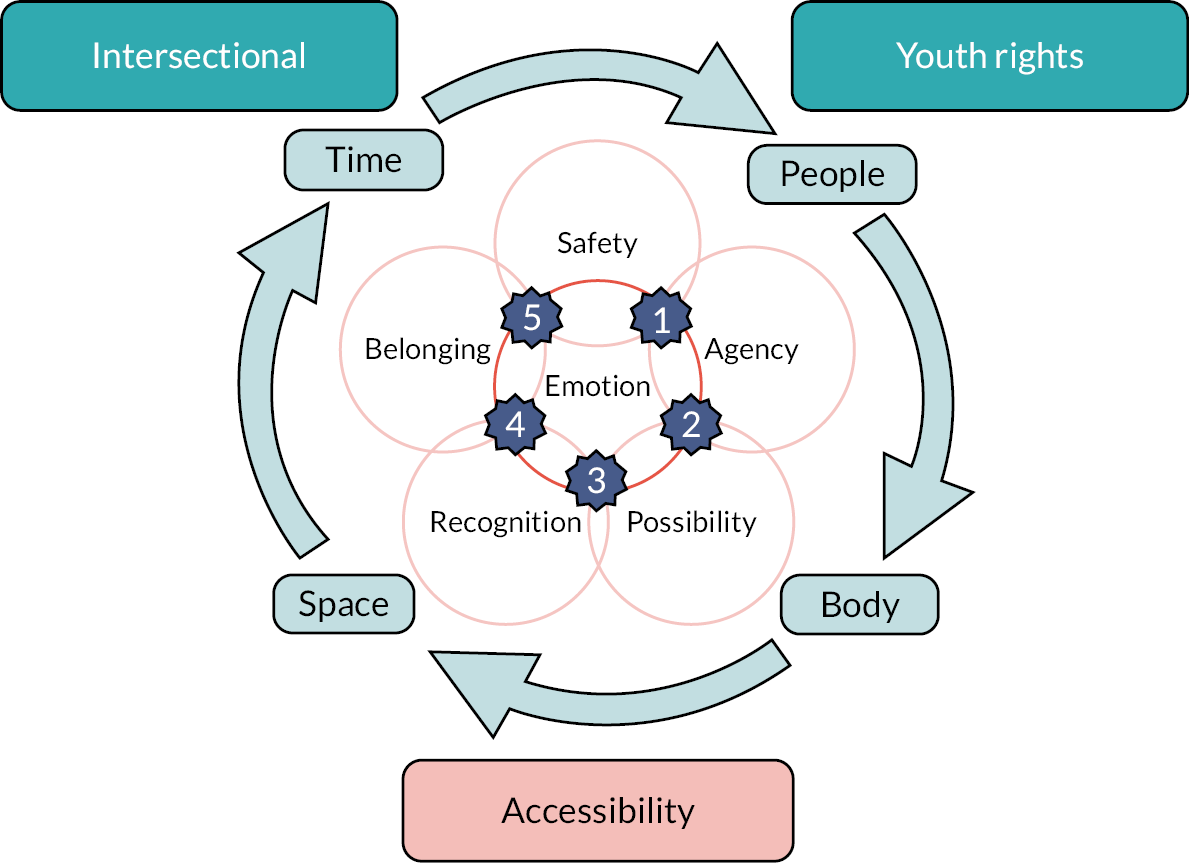

The four phases of the case study analysis process are represented in Figure 1.