Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/04/13. The contractual start date was in January 2018. The final report began editorial review in December 2020 and was accepted for publication in July 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Willis et al. This work was produced by Willis et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Willis et al.

Chapter 1 Background, rationale and objectives

Clinical and health services research continually produces new evidence that can benefit patients. However, this evidence does not reliably find its way into everyday NHS practice. 1 There are frequent failures to introduce effective new interventions and clinical practices quickly enough, consistently use those already proven to be effective, or stop using those found to be ineffective or even harmful. The resulting inappropriate variations in health care and outcomes are well documented and pervasive across different settings and specialities. 2–9 The gap between evidence and practice is a strategically important problem for policy-makers, health-care systems and research funders because it limits the health, social and economic effects of research. 10

Audit and feedback (A&F) aims to improve the uptake of recommended practice by reviewing clinical performance against explicit standards and directing action towards areas not meeting those standards. 11 It is a widely used foundational component of quality improvement in health-care systems internationally, including within around 60 National Clinical Audit (NCA) programmes in the UK. 12 These programmes address a range of priorities (e.g. diabetes, cancer) and therefore play key roles in both measuring the extent of inappropriate variations and using feedback to promote improvement.

The most recent Cochrane review of 140 randomised trials found that A&F had modest effects on patient processes of care, leading to a median 4.3% absolute improvement [interquartile range (IQR) 0.5–16%] in compliance with recommended practice. 11 One-quarter of A&F interventions had a relatively large positive effect on quality of care, whereas another quarter had a negative or null effect. The review found that feedback may be more effective when the source is a supervisor or colleague, it is provided more than once, it is delivered in both verbal and written formats, and it includes both explicit targets and an action plan. Given the relative paucity of head-to-head comparisons of different methods of providing feedback and comparisons of A&F with other interventions, it remains difficult to recommend the use of one feedback strategy over another on empirical grounds. 13

Strategies to promote the uptake of recommended practice need to take account of the cost-effectiveness of implementation interventions. 14 Given that health-care and research resources are finite, it is important to determine how to enhance the effects and reliability of A&F to maximise population benefit. There is little evidence about the cost-effectiveness of implementation strategies, including A&F. 15,16 Although NCAs may appear to be relatively costly, any modest effects can potentially be cost-effective if audit programmes build in efficiencies. For example, the increasing availability of routinely collected data on quality of care provides opportunities for large scale, efficient A&F programmes. 17,18 Effective use of feedback offers potential advantages over other quality improvement approaches (e.g. educational outreach visits or inspections) in terms of reach and cost-effectiveness,14 particularly given the scope to enhance impact on patient care within existing resources and systems. There are further opportunities to improve the alignment of A&F with national and local quality-improvement drives, such as aligning audits more closely with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance and standards.

We have identified, through expert interviews, systematic reviews and our own experience with providing, evaluating and receiving practice feedback, 15 state-of-the-science, theory-informed suggestions for effective feedback interventions (Box 1). 19 These suggestions relate to the nature of the desired action (e.g. improving the specificity of recommendations for action), the nature of the data available for feedback (e.g. providing more rapid or multiple feedback), feedback display (e.g. minimising cognitive load for recipients) and delivery of feedback (e.g. addressing credibility of information). These represent practical ways to bring about tangible improvements in feedback methods that can maximise the value of existing national audit programmes and health-care infrastructures and, hence, improve patient care and outcomes.

-

Recommend actions that are consistent with established goals and priorities.

-

Recommend actions that have room for improvement and are under the recipient’s control.

-

Recommend specific actions.

-

Provide multiple instances of feedback.

-

Provide feedback as soon as possible and at a frequency informed by the number of new patient cases.

-

Provide individual (e.g. practitioner-specific) rather than general data.

-

Choose comparators that reinforce desired behaviour change.

-

Closely link the visual display and summary message.

-

Provide feedback in more than one way.

-

Minimise extraneous cognitive load for feedback recipients.

-

Address barriers to feedback use.

-

Provide short, actionable messages followed by optional detail.

-

Address the credibility of the information.

-

Prevent defensive reactions to feedback.

-

Construct feedback through social interaction.

We (NI, JG) undertook a cumulative meta-analysis of A&F trials included in the Cochrane review. 20 The effect size and associated confidence intervals (CIs) stabilised in 2003 after 51 comparisons from 30 trials. Cumulative meta regressions suggested that new trials were contributing little further information on the impact of common effect modifiers, indicating that this field of research has become ‘stagnant’. Research needs to shift its focus from asking whether or not A&F can improve professional practice towards how to optimise its effects. We identified a research agenda for A&F at an international meeting in Ottawa in 2012. 21 Our research built on this agenda and sought to revitalise A&F research and reduce research waste. We aimed to improve patient care by optimising the content, format and delivery of feedback from NCAs through three linked objectives.

Objective 1: to develop and evaluate, within an online randomised screening experiment, the effects of modifications to feedback on intended enactment, user comprehension, experience, preferences and engagement

Research questions

Out of a set of recent, state-of-the-science, theory-informed suggestions for improving feedback, which are the most important and feasible to evaluate further within national audit programmes?

What is the effect of such modifications to feedback on intended enactment, comprehension, engagement among clinicians and managers targeted by national audits, user experience and preferences under ‘virtual laboratory’ conditions?

The 15 suggestions for improving feedback indicate a way forward but require further development and evaluation. 19 Rigorous evaluation methods, such as well-conducted cluster randomised trials, can establish the relative effectiveness of following such modifications to feedback. However, varying only five elements of feedback (e.g. timing, frequency, comparators, display and information credibility) produces 288 combinations – not allowing for replication of studies or the addition of other interventions, such as education meetings of outreach visits. 22 Given the multiplicity of factors that would need to be addressed, such an approach is not feasible; more efficient ways are needed to prioritise which of these to study. In objective 1, we undertook a fractional factorial screening experiment, building on current evidence and knowledge of behaviour change, and produced a statistical model to predict the effects of a large number of single and combined feedback modifications. This model can subsequently guide choices for further evaluation, as well as suggest practical ways of adapting feedback to enhance NCA impacts.

Objective 2: to evaluate how different modifications of feedback from national audit programmes are delivered, perceived and acted on in health-care organisations

This included feedback modifications identified in objective 1 and allowed for more organisationally focused modifications not amenable to online experimentation.

Research question

How do health-care organisations act in response to modifications of feedback from national audit programmes under ‘real-world’ conditions?

Our overall approach was consistent with the development, feasibility and (early) evaluation stages of the UK Medical Research Council guidance on complex interventions. 23 Having identified the most promising single and combined feedback modifications in a virtual experiment, we aimed to investigate how they work in ‘real-world’ conditions.

Our earlier programme, AFFINITIE (Audit and feedback interventions to increase evidence-based transfusion practice),24 evaluated the separate and combined effects of enhanced content of feedback and enhanced support following delivery of feedback with the National Clinical Audit of Blood Transfusion (NCABT). We identified marked variations in local NHS trust responses to blood transfusion audits, including a lack of clarity about who feedback should target and who is responsible for action;25,26 such problems are likely to apply to other national audits. Objective 2 aimed to evaluate how our different modifications of feedback from national audit programmes were delivered, perceived and acted on in health-care organisations, guided by Clinical Performance Feedback Intervention Theory (CP-FIT). 27 We worked with two national audit programmes that were introducing changes to how they delivered feedback.

The COVID-19 pandemic halted all non-essential research in the NHS, forcing us to abandon this objective in the early stages of fieldwork. With funder approval, we therefore modified our approach and drew on ‘expert’ interviews and CP-FIT to identify the strengths of the two national audit programmes, how their planned changes would strengthen their audit cycles, and further scope for strengthening their audit cycles.

Objective 3: to explore the opportunities, costs and benefits of national audit programme participation in a long-term international collaborative to improve audits through a programme of trials

Research question

What are the opportunities, costs and benefits of national audit programme participation in an international collaborative to improve audits through a programme of trials?

Large scale improvement initiatives, such as national audit programmes, continually aim to enhance their impacts, often by making incremental changes over time (e.g. in use of comparators, feedback displays). Given that such changes usually result in small to modest effects on patient care and outcomes, it is difficult to judge whether or not they are effective in the absence of rigorous experimental evaluations. There are potential significant returns on investment from NCA participation in a co-ordinated programme of research to improve effectiveness. We have proposed ‘implementation laboratories’ that embed research within existing large-scale initiatives such as national audit programmes. 28 Close partnerships between health-care systems delivering implementation strategies at scale and research teams hold the potential for a more systematic approach to identify and address priorities, sequential head-to-head trials comparing modifications to improvement strategies (e.g. of A&F), promoting good methodological practice in both improvement methods and evaluation, enhancing the generalisability of research and demonstrating the impact of improvement programmes. However, there is very limited experience of establishing such implementation laboratories. Objective 3 explored the opportunities, costs and benefits of national audit programme participation in a long-term international collaborative to improve audits through a programme of trials.

Collaborating National Clinical Audit programmes

We conducted this work in partnership with five NCA programmes:

-

NCABT

-

the Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network (PICANet)

-

the Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP)

-

the Trauma Audit & Research Network (TARN)

-

the National Diabetes Audit (NDA).

These national audit programmes offered diversity in audit methods, topics and targeted audiences, thereby increasing confidence that our outputs would be relevant to the wider range of national audit programmes. All participated in objectives 1 and 3, whereas objective 2 focused on TARN and the NDA. The five programmes are summarised next.

Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project

This project collects data from admissions in England, Wales and Northern Ireland for myocardial infarction. It aims to improve clinical care through the audit process and to provide high-resolution data for research. 29

Data span the course of patient care, from the moment the patient calls for professional help through to hospital discharge and rehabilitation. Clinicians and clerical staff in hospitals collect data on patient demographics, medical history, clinical assessment, investigations and treatments. Pseudonymised records are uploaded centrally to the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research. In total, 206 hospitals submit more than 92,000 new cases to MINAP annually. The database currently holds approximately 1.5 M patient records. Vital status following hospital discharge is obtained via linkage to data from the Office for National Statistics. An annual report is compiled using these data, including individual hospital summary data.

National Diabetes Audit

The NDA programme is made up of four modules: the National Diabetes Core Audit, the National Pregnancy in Diabetes Audit, the National Diabetes Footcare Audit and the National Inpatient Diabetes Audit. 30 The NDA helps improve the quality of diabetes care by enabling participating NHS services and organisations to assess local practice against NICE guidelines, compare their care and outcomes with similar services and organisations, identify gaps or shortfalls that are priorities for improvement, identify and share best practice, and provide comprehensive national pictures of diabetes care and outcomes in England and Wales.

Our study focused on the National Diabetes Core Audit. For this, general practices and specialist services participate through the General Practice Extraction Service. Secondary care and structured education providers submit data manually via the Clinical Audit Platform. Audit reports provide national-level information for prevalence, care process completion, treatment target achievement, referral and attendance at structured education, comparisons for people with a learning disability, comparisons for people with a severe mental illness and complication rates. Reports also provide local-level information for registrations, demographics, complications, care process completion and treatment target achievement.

Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network

PICANet was established to develop and maintain a secure and confidential high-quality clinical database of paediatric intensive care activity to identify best clinical practice, monitor supply and demand, monitor and review outcomes of treatment episodes, facilitate health-care planning and quantify resource requirements, and study the epidemiology of critical illness in children. 31

PICANet collects data from 30 hospitals providing specialist care. The core data set of demographic and clinical data on all admissions allows comparison of PICU activity at a local level with national benchmarks such as Paediatric Intensive Care Standards. This data set provides an important evidence base on outcomes, processes and structures that permits planning for future practice, audit and interventions. Each year, PICANet produces audit reports to show changes and comparisons over the 3-year reporting period.

Trauma Audit and Research Network

TARN is the NCA for traumatic injury and is the largest European Trauma Registry, holding data on > 800,000 injured patients, including > 50,000 injured children. 32 It aims to monitor processes and outcomes of care to demonstrate the impact of trauma networks, providing local, regional and national information on trauma patient outcomes and, thereby, help clinicians and managers to improve trauma services.

TARN collects data from 220 hospitals across England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Individual patient data are inputted manually at the trauma unit to an online data collection, validation and in-built reporting system, aiming to be available within 25 days of patient discharge or death. TARN produces annual national reports, triannual hospital network-level reports, triannual performance comparisons (e.g. hospital survival rates), quarterly patient-reported outcome measures (e.g. patient experience, return to work), and quarterly trauma dashboards for benchmarking against peers. TARN also provides continuous reporting and ad hoc analyses.

National Comparative Audit of Blood Transfusion

This programme of clinical audits examines the use and administration of blood and blood components in NHS and independent hospitals in the UK. 33 The programme aims to provide evidence that blood is being prescribed and used appropriately and administered safely, and highlight where practice is deviating from the guidelines to the possible detriment of patient care.

There is a rolling programme of audits and re-audits, with two or three taking place each year. Recent topics include the management of major haemorrhage, transfusion-associated circulatory overload, and patient blood management in adults undergoing elective, scheduled surgery. The NCABT contrasts with most other national clinical audit programmes, which consistently focus on a core, limited set of indicators. Consequently, the NCABT has to develop and implement different audit criteria and methods for the collection, validation and analysis of data within relatively short periods of time. The resultant feedback reports are subsequently uploaded and delivered to the hospital transfusion team via a hospital-specific NCA web page.

Chapter 2 The development of feedback modifications for an online randomised screening experiment (objective 1)

Background

Many proposed ways of improving feedback require further development and evaluation. 19 The Multiphase Optimisation Strategy (MOST) offers a methodological approach for building, optimising and evaluating multicomponent interventions, such as audit and feedback. 34 MOST comprises three steps: preparation, to lay the groundwork for optimisation by conceptualising and piloting components; optimisation, conducting optimisation trials to identify the most promising single or combined intervention components; and evaluation, a definitive randomised trial to assess intervention effectiveness.

Work in objective 1 most closely corresponded with the first and second steps of MOST and included a screening experiment, previously used in implementation research to identify and prioritise the most promising ‘active ingredients’ for further study. 35,36 In this type of study, components of an intervention are systematically varied within a randomised controlled design in a manner that simulates a real situation as much as possible. Interim end points (e.g. behavioural intention, behavioural simulation) are measured rather than changes in actual behaviour or health-care outcome. These experiments can be conducted virtually (e.g. online) with targeted participants using interim outcomes. One design, the fractional factorial experiment, can produce a statistical model to predict the effects of a large number of single and combined intervention components and, hence, guide choices for further evaluation.

We therefore undertook an online fractional factorial experiment to investigate the single and combined effects of ways of delivering feedback. We based these ways of delivering feedback on the 15 suggestions for improving feedback, and refer to them as feedback modifications. In consultation with our patient and public involvement (PPI) panel, we considered and added a further suggestion that involved incorporating ‘the patient voice’ in feedback.

We assessed the effects of these feedback modifications on health professionals’ intended enactment of audit standards, user comprehension, experience, and engagement. We first describe the development of the feedback modifications and the building of the interface for the online experiment, before describing the experiment methods and results.

Methods

We used a two-step process to select and then design the feedback modifications.

Step 1 was priority setting. A consensus process guided team discussions on which feedback modifications to prioritise for development.

Step 2 was user-centred design (UCD). Through iterative UCD, we developed modifications from high-level suggestions through to implementation. UCD is an iterative design approach that focuses on users and their needs. It emphasises initial user research to define system requirements, followed by repeated phases of design and evaluation with users to deliver progressively more usable system designs. This ensured that our priorities and choices reflected those of the people planning, delivering or receiving feedback from NCAs. In parallel, we held regular research team discussions around the feasibility and detailed design of the evolving feedback modifications.

Step one: priority setting

Design

We used a structured consensus process to guide the selection of feedback modifications for inclusion in the experiment. 37 Our method involved face-to-face meetings and discussion to elicit all views and promote transparent decision-making.

Participants

We used an 11-member reference panel. Consensus processes gain relatively little in reliability by exceeding this number. 37 Panel members brought a range of perspectives from patient and public, national audit, clinical, behavioural science and research backgrounds. This helped to ensure that shared deliberations took account of service, public and research priorities. The reference panel comprised:

-

an active member of a patient participation group in general practice and former paediatric epidemiologist who helped establish PICANet

-

a cardiology specialist registrar associated with MINAP

-

a national audit operational manager for PICANet

-

a haematology consultant specialising in transfusion (former lead for NCABT)

-

a member of the public with experience in marketing

-

a consultant neonatologist with a lead role in the National Neonatal Audit Programme

-

a behavioural scientist with interests in patient safety and audit and feedback in surgical contexts

-

a behavioural scientist with interest in audit and feedback (also a member of the research team; FL)

-

an academic general practitioner with experience of leading a regional A&F programme (also a member of the research team; SA)

-

an academic general practitioner with an interest in A&F and informatics (also a member of the research team; BB)

-

an academic foundation year medical trainee.

Procedure

We sent reference panel members a document outlining the rationale for and examples of candidate feedback modifications. At the first meeting, we presented and summarised key features of each proposed modification and invited requests for clarification. We then asked panellists to consider each modification against the following criteria:

-

current evidence and need for further research, prioritising modifications for which there was greater uncertainty of effectiveness

-

feasibility of adopting and embedding modifications within NCA materials and processes

-

the extent to which feedback modifications combine with other data and quality improvement processes to the best effect.

Panel members independently rated each modification item on a 1–9 scale, where ‘1’ indicated the lowest support and ‘9’ indicated the highest support. We collated the scores for each modification and presented the median and range to all panel members at a second face-to-face meeting. We categorised low overall agreement as at least three raters scoring the item 1–3 and at least three scoring it 7–9, moderate agreement as at least two raters scoring the item 1–3 and at least two scoring it 7–9, and high agreement as one or no raters scoring the item 1–3 and one or zero scoring it 7–9. The second meeting focused on modification items with low levels of agreement. The panel found the third criterion (‘the extent to which feedback modifications can be combined with other data and quality improvement processes to the best effect’) difficult to operationalise consistently. We therefore dropped this criterion. Following discussion, panellists independently re-rated the modifications.

We reviewed reference panel outputs at Project Management Team meetings, at an A&F MetaLab meeting that included our Canadian-based co-investigators in Toronto (May 2018), and at a UCD workshop held at City, University of London (June 2018), generally prioritising those with higher scores for further evaluation.

We were aware that it would be problematic to develop and apply online versions of all proposed modifications (e.g. construct feedback through social interaction) or to test them within a single online experiment (e.g. provide multiple instances of feedback). We also had to ensure that each feedback modification included in the online experiment was compatible with other modifications to fulfil the requirements of the fractional factorial design. Based on these considerations, we excluded nine modifications from further consideration and took seven modifications forward into the UCD activity.

Step 2: user-centred design

Design

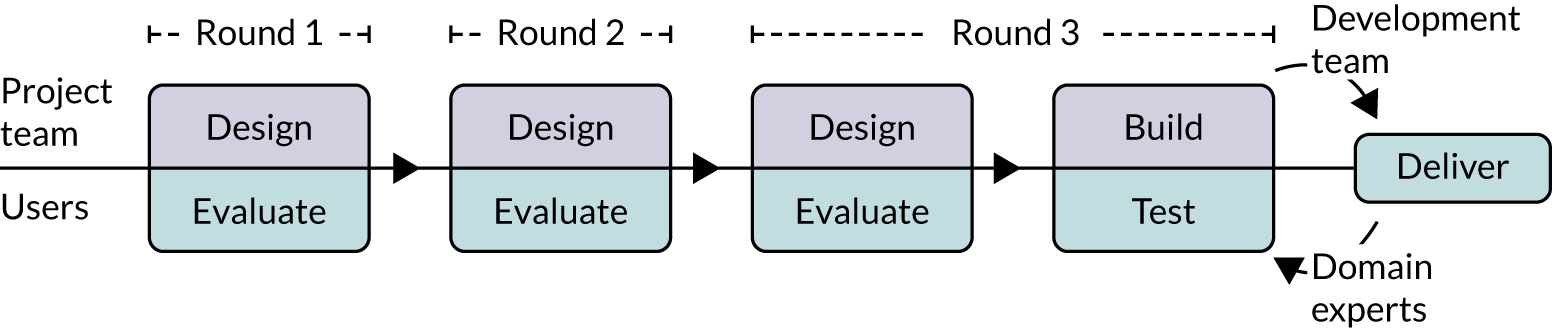

Our approach followed human–computer interaction processes of UCD38 to design both the online versions of the modifications and other aspects of the experiment, including a questionnaire to measure participant responses. We started with two UCD workshops at City, University of London (May 2018 and June 2018), then undertook three iterative rounds of design and evaluation (summarised in Figure 1), followed by testing by the research team. Each of the three iterative rounds of UCD comprised designing a set of prototypes in consultation with team members familiar with each of the national audits, followed by formative evaluation of the prototypes with participants using the think-aloud technique. 39 This qualitative approach to design was intended to assess functionality, usability and user experience to optimise modification content and format.

FIGURE 1.

User-centred design process.

Throughout the development process, we held regular face-to-face, teleconference and e-mail discussions as a research team around the feasibility and detailed design of the candidate and evolving online modifications. We took notes and kept records of these exchanges.

User-centred design workshops

The first UCD workshop brought research team members together with human–computer interaction researchers. We employed the creative techniques of constraint removal and analogical reasoning40 to generate ideas for ways of delivering the modifications in the online experiment. By imagining that various operational and design constraints did not exist, team members could think creatively about ways to remove or work around the issues identified. Analogical reasoning was used to draw on researchers’ experiences of how web-based technologies were used in other domains (e.g. online shopping) to inspire design ideas.

The second UCD workshop considered findings from the priority setting process and defined the design brief for the UCD of the modifications. We started by considering how people typically receive, use and share feedback. We assumed that most feedback recipients work in high-pressure environments with constrained resources and competing priorities on time. We also assumed that computing equipment for staff in health-care settings might be of variable age and capability. We considered designing the online experiment for hand-held devices, but decided against this for three reasons: (1) some feedback reports might only be delivered via secure NHS systems; (2) full rather than small screens might be more conducive to viewing any tables and graphs; and (3) the additional programming required to configure the experiment for multiple hand-held devices was beyond our means. Likely computing limitations and the unacceptability of audio output in shared working environments also precluded adding audio to feedback modifications.

We considered whether to present feedback modifications within full feedback reports or as isolated excerpts. Although the former would have greater ecological validity, developing realistic, fictitious, whole feedback reports for five national audits, all incorporating randomised combinations of six modifications, would not have been feasible. However, we recognised that the online experiment would still need to present contextual information about each NCA and present baseline formatting and content that would be reasonably familiar to participants. We therefore identified the information architecture of a ‘typical’ feedback report in the five participating NCAs and mapped key sections onto the modifications. The key sections identified were About this audit, Audit standard (criteria), Results (feedback), Recommendations for action, Further information, and Patient story.

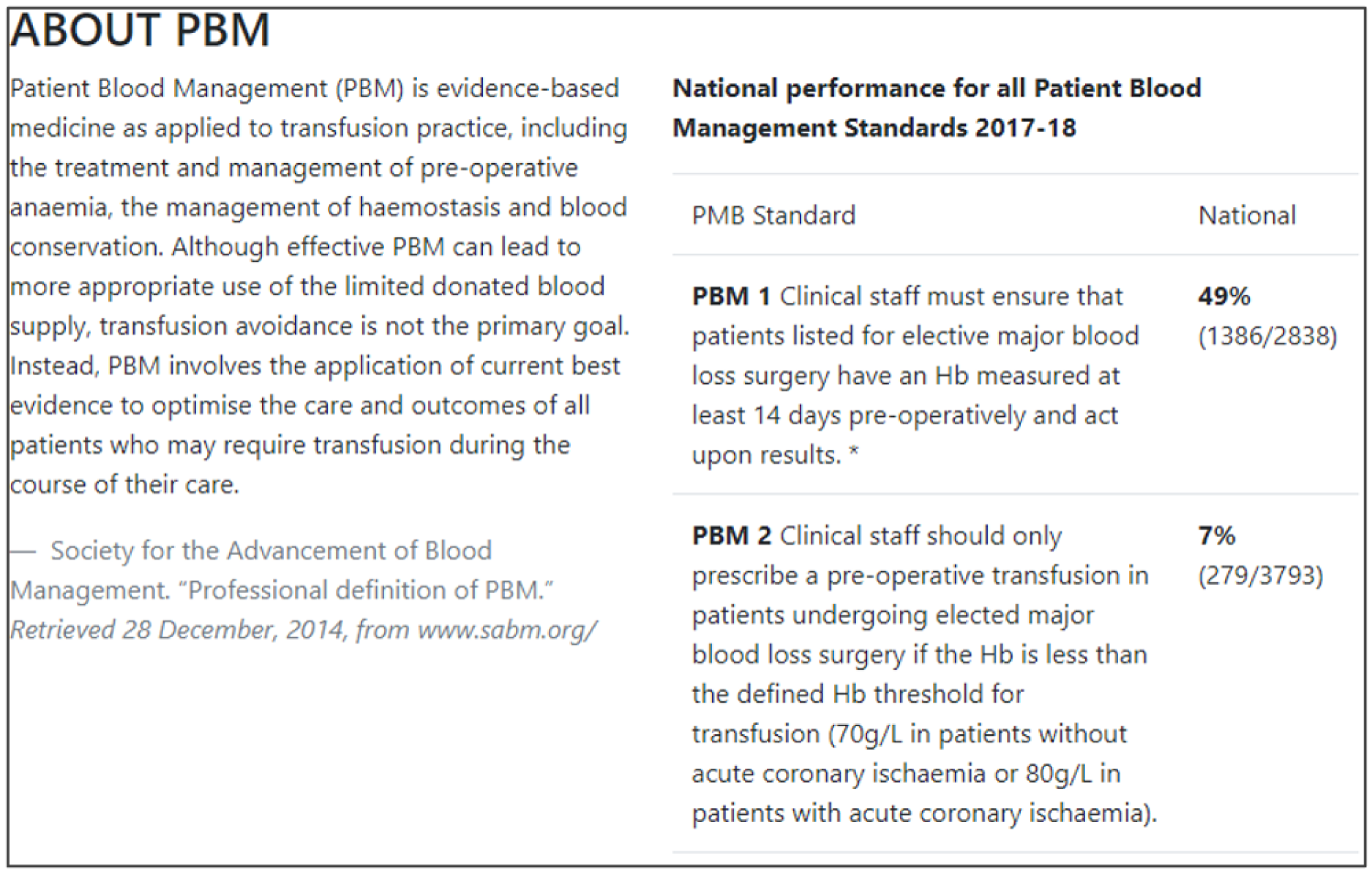

We considered the feasibility of including multiple audit criteria within each online report. We opted to present results for one main audit criterion within each online report to reduce participant burden and simplify outcome assessment for the experiment. We aimed to ensure that the audit criterion selected for each NCA would be perceived as valid and credible by experiment participants. We therefore selected the main audit criterion with advice from relevant national audit collaborators (Box 2).

Patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction or unstable angina who have an intermediate or higher risk of future adverse cardiovascular events are offered coronary angiography (with follow-on percutaneous coronary intervention if indicated) within 72 hours of first admission to hospital.

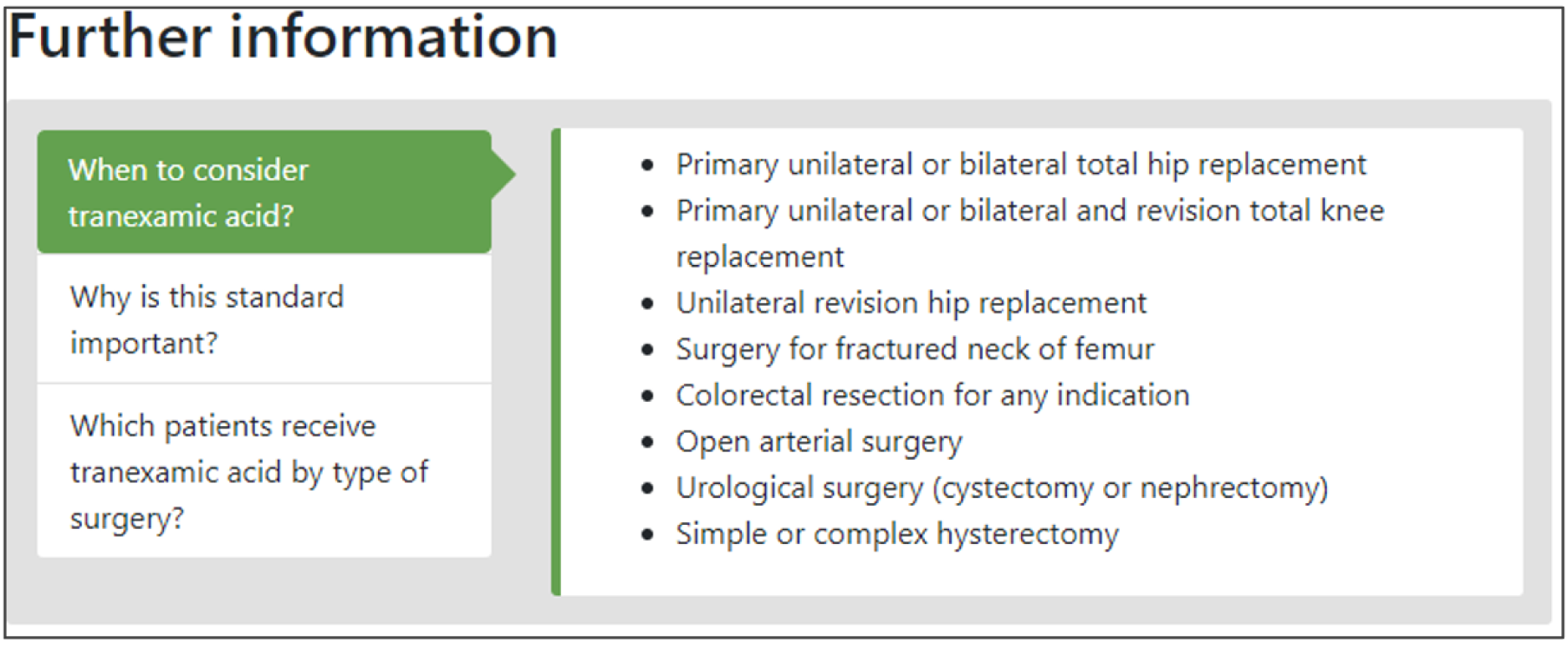

National Clinical Audit of Blood TransfusionClinical staff should prescribe tranexamic acid for surgical patients expected to have moderate or more significant blood loss unless contraindicated.

National Diabetes AuditPatients with type 2 diabetes whose HbA1c level is ≥ 58 mmol/mol (7.5%) after 6 months with single-drug treatment are offered dual therapy.

Paediatric Intensive Care Audit NetworkMinimising the number of unplanned extubations for paediatric intensive care patients per 1000 days of invasive ventilation.

Trauma Audit and Research NetworkPatients who have had urgent three-dimensional imaging for major trauma have a provisional written radiology report within 60 minutes of the scan.

HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c.

Participants

The UCD participants comprised professionals typically involved in developing or targeted by national audits, identified via our collaborating audit programmes. We e-mailed invitations and scheduled evaluation sessions for those who expressed an interest in the study. We obtained informed consent and conducted evaluation sessions face to face at the most convenient site for the participants, such as their place of work or at one of our partner universities.

We held a total of 17 evaluation sessions, involving 13 participants, over 8 months between July 2018 and February 2019. Seven participants were involved in round 1, four in round 2 and six in round 3 (Table 1). Four participants were associated with MINAP, three with NCABT, three with PICANet, two with NDA and one with TARN.

| Interview number | Participant ID | UCD round | Audit | Session date | Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | P01 | 1 | MINAP | 24 July 2018 | Nurse |

| 02 | P02 | 1 | MINAP | 8 August 2018 | Consultant cardiologist |

| 03 | P03 | 1 | MINAP | 9 August 2018 | Consultant cardiologist |

| 04 | P04 | 1 | NCABT | 16 August 2018 | Lead transfusion practitioner |

| 05 | P05 | 1 | MINAP | 16 August 2018 | Radiology matron |

| 06 | P06 | 1 | NCABT | 17 August 2018 | Risk and compliance manager |

| 07 | P07 | 1 | TARN | 23 August 2018 | Network manager |

| 08 | P08 | 2 | NDA | 16 October 2018 | Senior quality improvement lead (diabetes) |

| 09 | P09 | 2 | PICANet | 17 October 2018 | Data and audit manager |

| 10 | P10 | 2 | PICANet | 23 October 2018 | Consultant in intensive care |

| 11 | P11 | 2 | NCABT | 6 November 2018 | Acting clinical lead |

| 12 | P04a | 3 | NCABT | 20 December 2018 | Lead transfusion practitioner |

| 13 | P07a | 3 | TARN | 14 January 2019 | Network manager |

| 14 | P08a | 3 | NDA | 16 January 2019 | Senior quality improvement lead (diabetes) |

| 15 | P12 | 3 | NDA | 18 January 2019 | GP |

| 16 | P13 | 3 | PICANet | 5 February 2019 | Consultant paediatrician |

| 17a | P08a | 3 | PICANet | 21 February 2019 | Data manager |

Procedure

We undertook three rounds of UCD using prototypes of increasing fidelity to the intended online modifications (Table 2). The evaluation sessions employed a variety of techniques to gather information about current feedback report usage and elicit preferences for modification content, user interface elements, naming and ordering (‘information architecture’) of key sections of the audit report, the design of the online questionnaire, and the e-mail invitation to take part in the experiment.

| Round | Modifications | Materials | Protocol | Data type | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Multimodal feedback (M9) | Paper prototypes of modifications created using Balsamiq Mockups41 | Think-aloud | Audio | Sentiment data (positive, negative, mixed/neutral responses to modifications) |

| Cognitive load (M10) | Sketches of report structure and different navigation options | Semistructured interviews | Observational notes | Insights into people and process | |

| Optional detail (M12) | |||||

| Patient voice (M16) | |||||

| 2 | Controllable actions (M2) | Semi-interactive, web-based prototypes of modifications and mock-ups of invitation e-mail published through Github Pages (Github, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) | Think-aloud | Audio and video | Sentiment data (positive, negative, mixed/neutral responses to modifications) |

| Specific actions (M3) | Semistructured interviews | Observational notes | Insights into people and process | ||

| Effective comparators (M7) | |||||

| Multimodal feedback (M9) | |||||

| Cognitive load (M10) | |||||

| Optional detail (M12) | |||||

| Patient voice (M16) | |||||

| 3 | Specific actions (M3) | Prototypes of interactive website, including landing pages, audit report, questionnaire page and thank you page built using Bootstrap (https://getbootstrap.com) and published on Github | Usability testing | Audio | Usability reports and change logs |

| Effective comparators (M7) | Scenarios | Observational notes | Sentiment data (positive, negative mixed/neutral responses to modifications) | ||

| Multimodal feedback (M9) | Think-aloud | Issue log | Insights into people and process | ||

| Cognitive load (M10) | Semistructured interviews | ||||

| Optional detail (M12) | Unmoderated team testing of rules/checks and randomisation | ||||

| Patient voice (M16) |

Four of the seven modifications required user interface-related design work only; the other three required the creation of audit-specific content. Round 1 included only the four user-interface-related modifications to reduce preparation time and session run-time. We created ON and OFF versions of each modification: ON versions where the modifications had been applied and OFF versions where the modifications had not been applied. We identified a list of possible design patterns and principles as starting points for operationalising the modifications.

Round 1: design and evaluation of sets of paper-based prototypes exploring the modifications and the design of the online audit report

Semistructured interviews gathered information about roles and typical audit report usage patterns, including familiar formats, navigational behaviour and attitudes to audit. Then, think-aloud interviews explored designs for an online audit report, including information architecture and navigational elements. Finally, think-aloud interviews evaluated prototypes of four of the seven selected modifications. We iterated content and designs between evaluation sessions.

Round 2: design and evaluation of sets of online prototypes refining modifications and the design of the study invitation e-mail, report iconography and terminology

Semistructured interviews gathered further information about roles, typical audit report usage patterns, including familiar formats, navigational behaviour and attitudes to audit. Think-aloud interviews gathered responses to online prototypes for all seven modifications. We also tested responses to a mock-up e-mail invitation, and a screen showing different icons paired with common audit terms.

Round 3: design and evaluation of a complete online prototype, refining the content, data, flow, and presentation of all screens in the experiment

We conducted ‘end-to-end’ usability testing of the prototype experiment to identify issues in the flow between screens, page interactions and content to ensure that the right information was passed between various components of the experiment.

Expert testing

Project team members, including those familiar with each national audit, undertook comprehensive ‘expert reviews’ of the live online experiment to identify programming bugs and usability issues and to ensure fidelity to modifications as intended ahead of the online launch. This involved several rounds of team testing of all aspects of the website, including rules and checks, randomisation and editorial content. Data were captured via self-reported issue logs and addressed by the web development team.

Data collection and analysis

We took observational notes and audio- or video-recorded, transcribed and anonymised all evaluation sessions with UCD participants. We thematically analysed these data using NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to identify emergent themes, usability issues and design suggestions. We took a two-step approach to coding for each round of UCD. Step 1 consisted of initial a priori coding of participants’ responses to the modification versions, categorised by sentiment (mixed or neutral, negative, positive). Step 2 consisted of inductive coding to understand context of use (not reported here) and to inform the design and usability of the website that would host the online experiment. We undertook these analyses as integral elements to the development process to improve the designs in the subsequent round of UCD.

Results

We present integrated findings from the consensus and UCD processes for each of the 16 modifications. For each modification, we report its underpinning rationale, evidence base, need for further research, feasibility of incorporating it within NCAs, selection for online experiment and proposed application, and illustrations of final versions. Appendix 1 provides details of the three UCD rounds of the modifications selected for online development. Appendix 2 shows the final designs for the six selected modifications for all five audits. Table 3 summarises the first and second round median ratings from the consensus process.

| Suggested modification | Current evidence and need for further research, median score (range) | Feasibility of adoption by national clinical audit programmes, median score (range) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 1 | Round 2 | |

| 1: recommend actions consistent with established goals and prioritiesa | 7 (3–9) | 7 (3–9) | 7 (4–8) | 7.5 (6–8) |

| 2: recommend actions that can improve and are under the recipient’s controlb | 5 (4–8) | 6 (3–8) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) |

| 3: recommend specific actions | 6 (3–7) | 6 (4–7) | 7 (6–9) | 8 (6–9) |

| 4: provide multiple instances of feedbacka | 7 (3–8) | 7 (3–8) | 6 (4–8) | 7 (4–8) |

| 5: provide feedback as soon as possible and at a frequency informed by the number of new patient casesa | 5 (3–8) | 6 (4–8) | 7 (3–8) | 7 (4–8) |

| 6: provide individual rather than general dataa | 7 (3–8) | 7.5 (5–8) | 3 (1–8) | 4.5 (2–8) |

| 7: choose comparators that reinforce desired behaviour change | 8 (3–9) | 8 (7–9) | 8 (2–9) | 8 (7–9) |

| 8: closely link the visual display and summary messagea | 6 (3–9) | 6 (3–9) | 8 (5–9) | 8 (5–9) |

| 9: provide feedback in more than one way | 5 (3–8) | 6 (4–8) | 7 (4–9) | 7 (5–9) |

| 10: minimise extraneous cognitive load for feedback recipients | 6 (3–8) | 7 (3–8) | 6 (1–9) | 6 (3–9) |

| 11: address barriers to feedback usea | 6 (2–8) | 6 (4–8) | 3 (2–6) | 4.5 (3–6) |

| 12: provide short, actionable messages followed by optional detail | 7 (4–8) | 7 (4–8) | 7 (5–9) | 8 (7–9) |

| 13: address credibility of informationa | 6 (3–7) | 6.5 (5–7) | 7 (4–8) | 7 (5–8) |

| 14: prevent defensive reactionsa | 6 (3–8) | 6.5 (3–8) | 3 (3–7) | 3 (3–7) |

| 15: construct feedback through social interactiona | 7 (4–8) | 7 (5–8) | 6 (3–8) | 6 (3–8) |

| 16: incorporate the patient voice | 7 (2–9) | 8 (6–9) | 5 (2–9) | 7 (4–9) |

Recommend actions that are consistent with established goals and priorities

Rationale

Setting goals promotes behaviour change in various ways, such as priority setting, focusing attention and effort, and reinforcing commitment. 42 Subsequent intention (or motivation) is a reasonable predictor of behaviour. In contrast, individuals who do not intend to enact a given behaviour are less likely to enact the behaviour than those who do. Goals that are compatible with professional, team or organisational goals and priorities are more likely to be achieved than those that are not.

Evidence base

Feedback is more effective when it includes both explicit targets and an action plan, according to the Cochrane review metaregression. 11 For example, a Dutch randomised trial demonstrated that feedback accompanied by an implementation toolbox suggesting a range of actions improved pain management in intensive care units. 43

Need for further research

Although the reference panel rated the need for further research as relatively high (7, high agreement), the second UCD workshop considered the need for further research to be low; it is unlikely that an audit programme would ever not want to do this or that further research would produce novel findings.

Feasibility within national audits

The panel rated the feasibility of incorporating this feedback modification within a national audit programme as relatively high (7.5, high agreement). The panel also recognised a difference between having goals and setting action plans; feedback recipients might need more guidance and support to carry out effective action planning.

Selection for online experiment

No.

Recommend actions that can improve and are under the recipient’s control

Rationale

Feedback needs to target recipients who have control over the actions required to improve practice. The degree of control over an action may vary among recipients. For example, feedback that requires action at an organisational level or additional resources to improve performance might be better directed at a hospital clinical lead or senior manager than at individual clinicians, as clinicians are unlikely to have the power to make such changes. There should also be scope for improvement on existing levels of practice, although feedback can also help to maintain high levels of performance.

Evidence base

Feedback is more effective when baseline performance is low. 11

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as moderate (6, high agreement). The second UCD workshop considered that the level of control of the recipient was of interest as the limited evidence suggests its importance.

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as high (7, high agreement).

Shorthand reference

Controllable actions (M2).

Selection for online experiment

No. There were two components to this suggested modification: first, recommending actions that can improve (e.g. low as opposed to high performance at baseline) and, second, recommending actions under the control of recipients (e.g. processes of care as opposed to patient outcomes). We considered the latter to be of greater interest to the online experiment.

During an e-mail exchange with co-investigators, we agreed that process of care audit criteria might generally be under the control of clinicians targeted by feedback [e.g. if a general practitioner (GP) is asked to consider prescribing antihypertensive agents for blood pressure levels above a given threshold]. In this case, an outcome audit criterion such as the proportion of patients with adequately controlled blood pressure might be less under the control of the GP, given the variable patient physiological and behavioural responses to treatment. This issue was pertinent to the experiment because the perceived fairness of the audit criterion may affect recipient responses (e.g. recipients might disengage from acting on feedback for audit criteria that they consider outside their control). We planned to operationalise controllable actions (M2) by randomising recipients to either process of care or outcome indicators in the online experiment.

We encountered two practical problems with operationalising controllable actions (M2) in the online experiment:

-

Paired process of care and outcome indicators were not available for all five NCA programmes participating in the experiment.

-

Operationalising both process of care and outcome indicators would have prohibitively increased the complexity of content and programming for the online experiment (e.g. in requiring differently worded feedback excerpts and outcome measures).

We therefore dropped this modification during the UCD work and included only one audit criterion per national audit.

Recommend specific actions

Rationale

Specification of a desired behaviour can facilitate intentions to perform that behaviour and enhance the likelihood of subsequent action. 44 The action, actor, context, target, time (AACTT) framework45 can guide specification by defining the:

-

action required – a discrete observable behaviour (i.e. ‘what’ needs to be done)

-

actor(s) performing the behaviour (i.e. ‘who’)

-

context in which the behaviour is enacted (i.e. ‘where’)

-

individuals or population targeted by the behaviour (i.e. ‘to/with whom’)

-

required timing (period and duration) of the behaviour (i.e. ‘when’).

For example, a GP (actor) might offer brief smoking cessation advice (action) to a patient who smokes (target) when time permits in a consultation (context) during an annual review of asthma medicines (timing). There are a number of ways to promote specific actions, such as providing feedback that is linked to or automatically generates lists of patients requiring clinical action.

Evidence base

Two randomised trials indicated that feedback accompanied by patient-specific risk information or by specific action plans was more effective than feedback without this information. 43,46 One observational study found that vaguely worded clinical practice recommendations were associated with lower compliance. 47 A further observational study examining changes in compliance following feedback found no relationship with specificity of wording. 48

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as moderate (6, high agreement). UCD workshop 2 considered that, although it is unlikely that an audit programme would ever not want to specify actions, further research could inform the value of explicitly operationalising this modification.

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as high (8, high agreement).

Selection for online experiment

Yes. The panel acknowledged that defining specific and context-sensitive actions was often challenging in practice, especially within NCA programmes dealing with complex clinical behaviours performed by multiple ‘actors’.

We recognised that the relevance and specificity of recommended actions would vary by recipient (e.g. considering the different needs of clinicians responsible for delivering individual patient care and managers responsible for service delivery). In practice, these distinctions may be blurred given that senior clinicians, often targeted by NCA feedback, are also responsible for service delivery. We paid attention to this issue later when designing questionnaire items for the experiment.

We also noted that the ability to operationalise this modification in one way, by providing links to (fictional) names of patients requiring action, was contingent on the clinical context. This is feasible when managing patients with long-term conditions (e.g. diabetes), when clinical actions can be prompted within ongoing management, but is unlikely to be practical in acute management (e.g. for immediate trauma care).

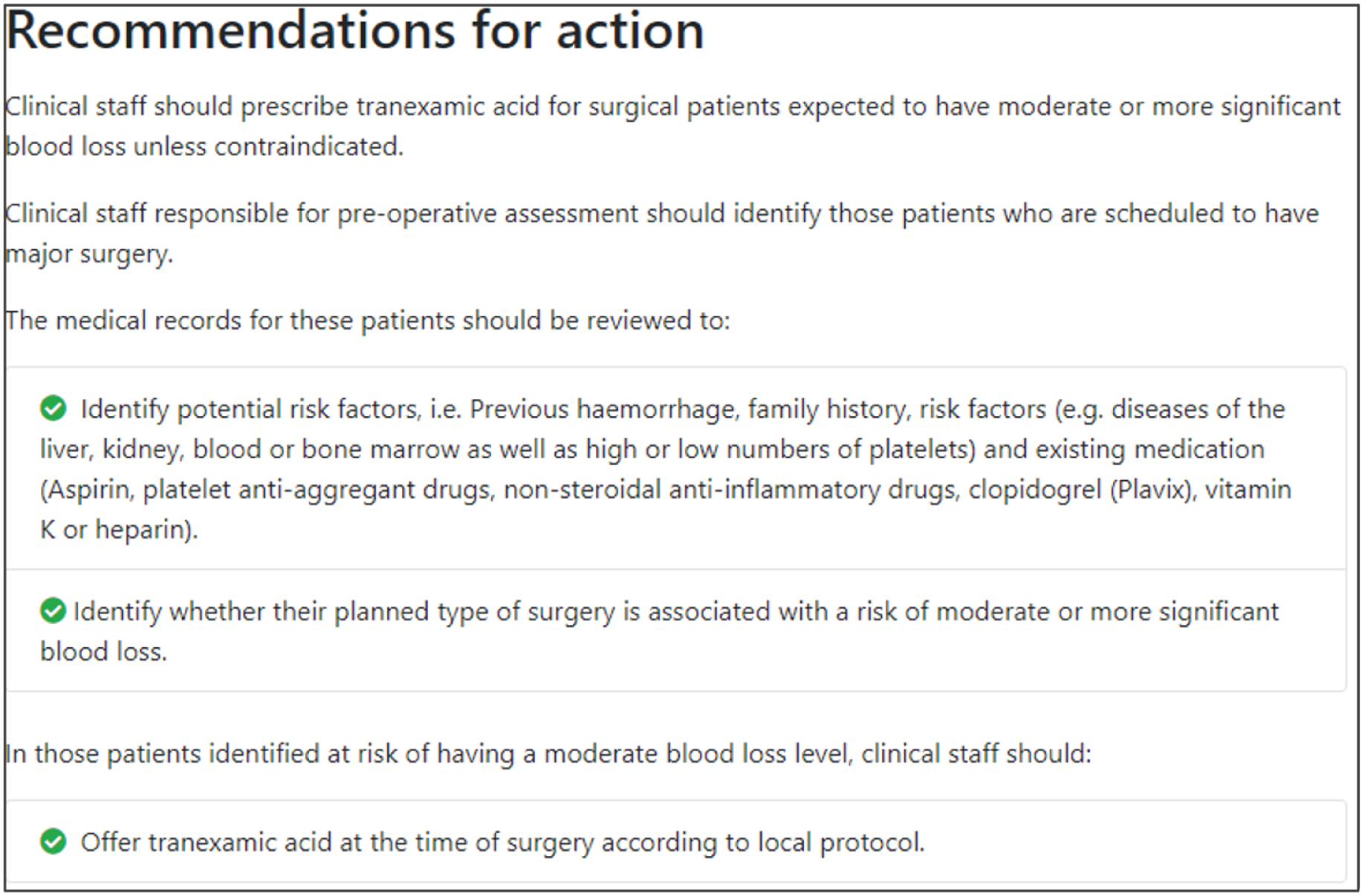

The modification would be ON if the feedback included recommendations for action that specified the action required, the actor(s) who should perform the action, the context in which the action is taken, the targeted individuals or population, and the required timing of the action. The modification would be OFF in the absence of these specifications, with any recommendations for action vaguely worded. Figure 2 illustrates the final design.

Shorthand reference

Specific actions (M3).

FIGURE 2.

Screenshot example of final ON version of modification specific actions (M3) (NCABT).

Provide multiple instances of feedback

Rationale

Multiple rounds of feedback encourage a feedback loop, wherein the recipient can receive the initial feedback, attempt a change in practice and then observe whether or not the change has been effective. 49 Consistency in feedback format over time fosters familiarity with the data format, increasing the likelihood of engagement where the data are considered useful.

Evidence base

Feedback may be more effective when it is provided more than once. 11

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as high (7, high agreement).

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as high (7, high agreement).

Selection for online experiment

No, as it would not be feasible to randomise participants so that one group received repeated instances of feedback.

Provide feedback as soon as possible and at a frequency informed by the number of new patient cases

Rationale

The interval between data collection and feedback should be as short as possible to reinforce the relevance of data to recipients; delays in providing feedback can allow recipients to discount findings as being no longer relevant to current practice. 50 However, the time between data collection and feedback needs to be long enough to allow a sufficient number of new cases to accumulate for audit (ensuring data reliability) and to allow time for recipients to have acted on previous feedback and observed the benefits of any such action.

Evidence base

One randomised trial found that immediate reminders were more effective than monthly feedback reports in promoting internal medicine specialists’ adherence to preventative care protocols. 51

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as moderate (6, high agreement).

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as high (7, high agreement).

Selection for online experiment

No, as it would not be feasible to operationalise within the online experiment.

Provide individual (e.g. practitioner-specific) rather than general data

Rationale

Providing individual feedback strengthens accountability and offers recipients fewer options for discounting performance data that they may initially disagree with. It facilitates corrective actions, such as reviewing the care of individual patients and reviewing decision-making. In practice, giving individual-level feedback is often not feasible because most health care is delivered by teams. However, feedback should generally be fed back at the lowest feasible level (e.g. team rather than organisation, organisation rather than system).

Evidence base

Feedback data specific to an individual recipient are usually more effective than those that apply to a group,52 although there is little evidence from health-care settings.

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as high (7.5, high agreement).

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as medium (4.5, moderate agreement). There is limited scope for changing practice as national audits already typically aim to give feedback at the most individual level (including team or organisation) feasible.

Selection for online experiment

No, as it would be difficult to include such a change within most current NCAs, which typically can collect data at team or organisational levels only.

Choose comparators that reinforce desired behaviour change

Rationale

Feedback is typically given in the context of a comparator. Comparators can include one or more of:

-

recipient performance, usually how performance changes over time

-

formal standards, such as a target level of achievement

-

a peer group, such as mean performance of similar individuals, teams or organisations.

Comparators should be selected according to their ability to change or reinforce the desired behaviour. However, care is needed in choosing or tailoring comparators. 53 For example, if providing feedback to high performers, positive feedback may either lead to reduced effort or increased motivation. Audit programmes may also consider switching attention to new topics where performance is poorer, but this risks inducing fatigue in higher performers. Yet attempts to improve already high levels of performance may be less fruitful than switching attention to alternative priorities. For many clinical actions, there is a ‘ceiling’ beyond which health-care organisations’ and clinicians’ margins for improvement are restricted because they are functioning at or near their maximum capabilities. Comparators are also challenging to set for low performers, who may be demotivated by feedback indicating that they are far below the average or top centile.

Evidence base

There is relatively little evidence about which comparators should be chosen under which circumstances. 13

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as high (8, high agreement).

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as high (8, high agreement).

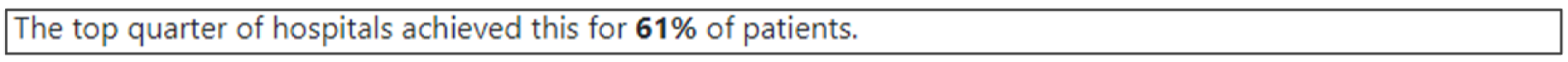

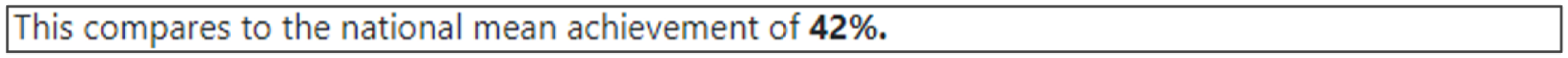

Selection for online experiment

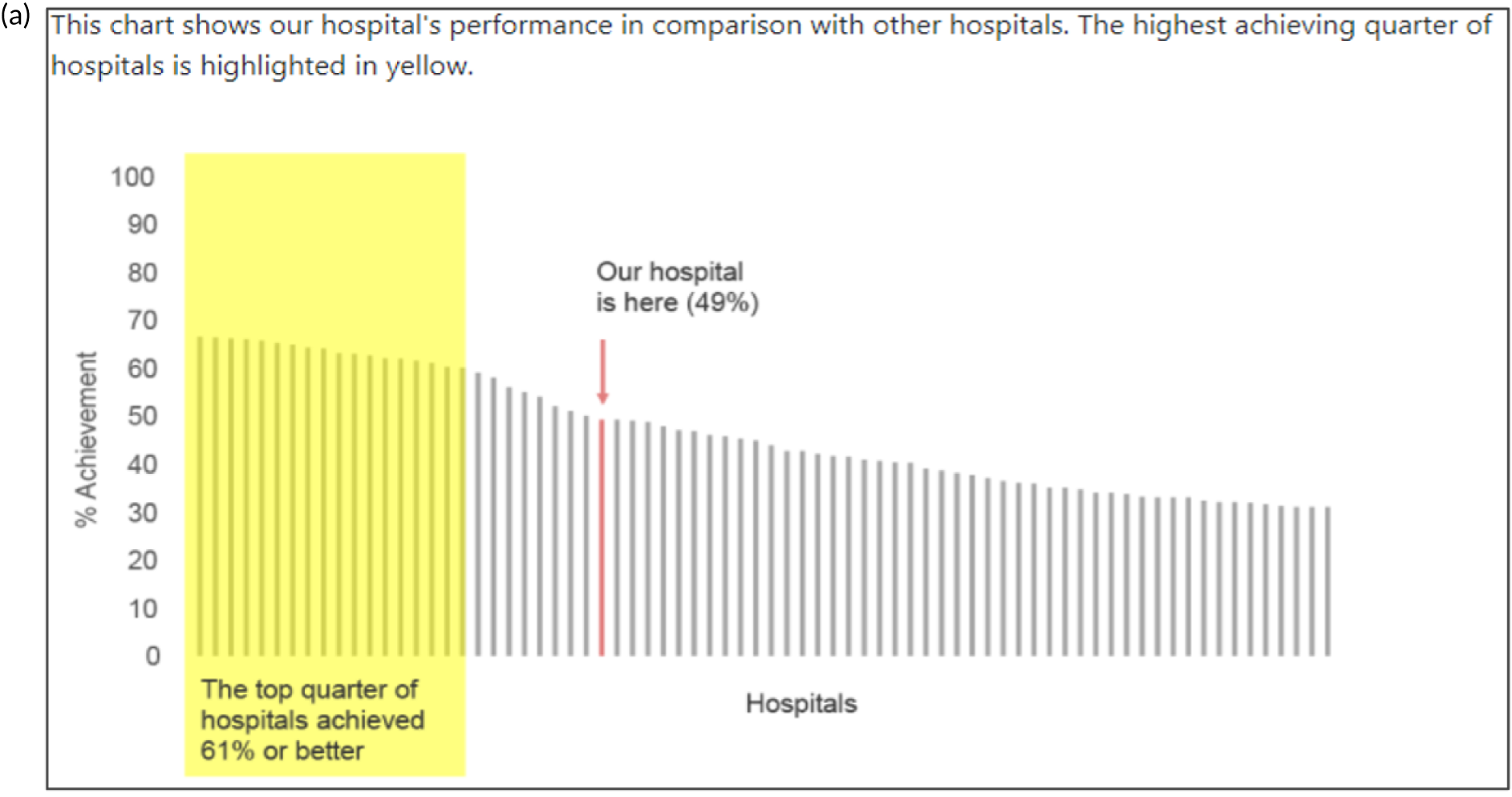

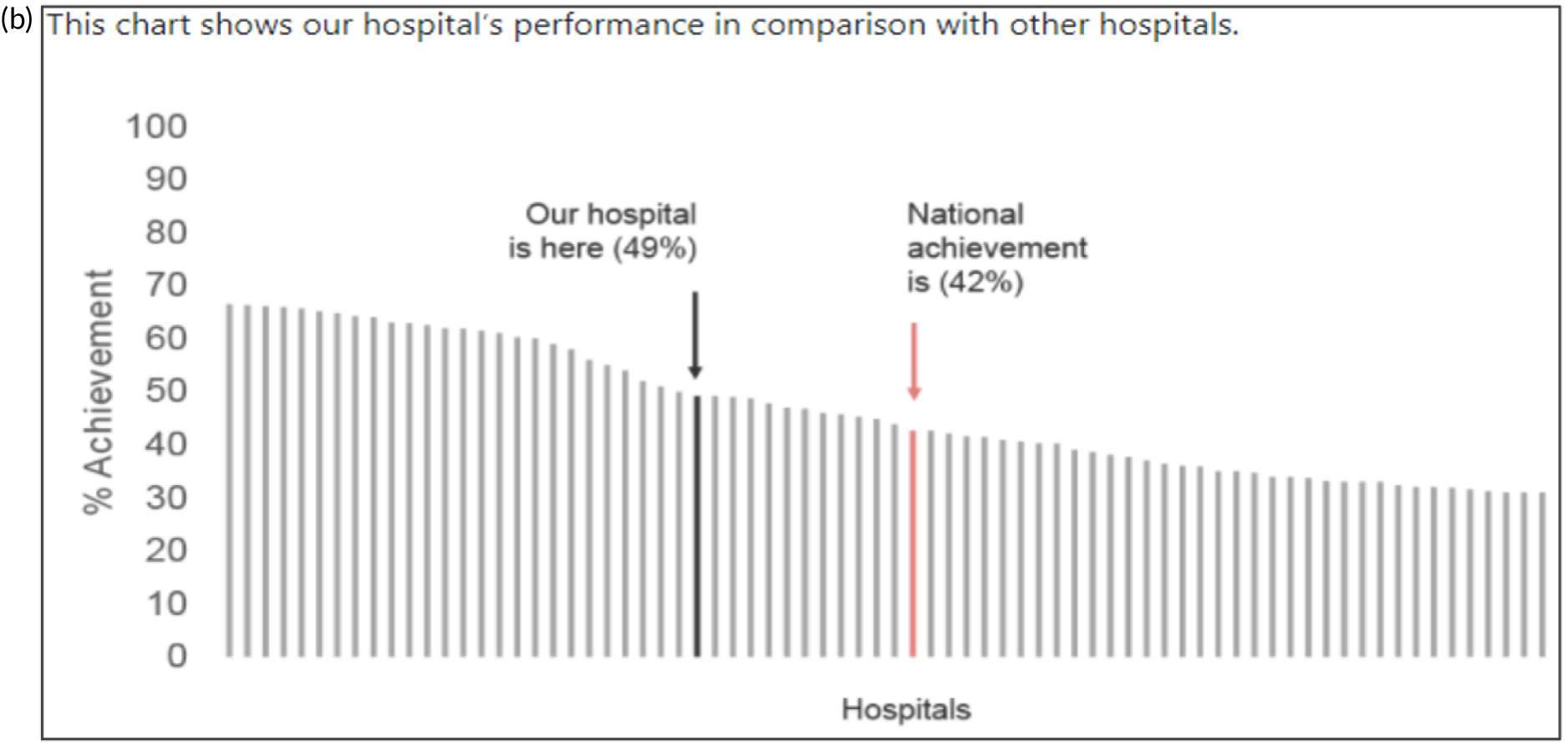

Yes. Effective comparators (M7) would be ON if the feedback comparator showed recipient performance against that of the top 25% nationally. The modification would be OFF if the feedback comparator showed recipient performance against the mean average.

There was a wide range of options for varying comparators, including several variants of each of recipient performance over time, formal targets and peer comparisons. Although using several comparators might risk creating mixed messages for recipients, it might also maximise impact if the comparators are thoughtfully aligned. For example, recipients may see progress over time, note how this compares to others and be further motivated by explicit targets. We generated a (non-exhaustive) range of questions:

-

Is a tailored approach (e.g. those below the mean see the mean, those above the mean see the top 10%) more effective than a standard approach (where all recipients see the same feedback)?

-

Is adding an explicit target to peer comparisons more effective than not?

-

Is adding individual peer performance scores (e.g. histogram in which the mean/top 10% is also marked) more effective than only the mean/top 10% summary statistics?

-

Are identifiable peers more effective than anonymous peers (given that comparison is a social process?)

-

Is feedback more effective if it is compared with summary statistics from one reference group (i.e. national) or multiple groups (e.g. national, regional)?

-

Is a comparator more effective than no comparator?

The key issue for any such variant is which best focuses attention for driving behaviour change. Figure 3 illustrates the final design.

FIGURE 3.

Screenshot examples of final ON and OFF versions of effective comparators (M7) (NCABT).

Shorthand reference

Effective comparators (M7).

Closely link the visual display and summary messages

Rationale

Summary text can be accompanied by graphical elements in close proximity, with both reinforcing the same message. The messages can also be linked stylistically.

Evidence base

There is little evidence from health-care settings. 19

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as moderate (6, high agreement).

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as high (8, high agreement).

Selection for online experiment

No, although the second UCD workshop recognised that this would be feasible.

Provide feedback in more than one way

Rationale

Presenting feedback in different ways may help recipients develop a more complete and memorable mental model of the information presented, allow them to interact with the feedback in a way that best suits them and reinforce memory by repetition. 19

Evidence base

Feedback may be more effective when it combines both written and verbal communication. 11

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as moderate (6, high agreement).

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as high (7, high agreement).

Selection for online experiment

Yes. The modification would be ON if the feedback included a graphical display of performance data along with the textual information for effective comparators (M7). The modification would be OFF in the absence of a graphical display of performance data. Figure 4 illustrates the final designs.

FIGURE 4.

Screenshot examples of final versions of multimodal feedback (M9) when effective comparators (M7) is switched (a) ON and (b) OFF (NCABT).

Shorthand reference

Multimodal feedback (M9).

Minimise extraneous cognitive load for feedback recipients

Rationale

Feedback recipients are generally time poor and need to cope with competing priorities for attention. Poorly presented and excessively complex feedback risks being misunderstood, discounted or ignored by recipients. 54 Reducing cognitive load entails minimising the effort required to process information and can be supported by prioritising key messages, reducing the number of data presented, improving readability and reducing visual clutter. Graphical elements should be as simple as possible and use features such as colour coding to amplify messages (e.g. ‘traffic lights’).

Evidence base

There is little evidence from health-care settings.

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as high (7, high agreement). The second UCD workshop recognised that, although no national audit programme would deliberately attempt to add extraneous cognitive load to feedback reports, we had encountered variable content and format. 26

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as moderate (6, high agreement).

Selection for online experiment

Yes. In the second UCD workshop and subsequent team discussions, we debated the feasibility of operationalising extraneous cognitive load within an online experiment, recognising issues in standardisation and interpretation. We decided to develop a modification for the online experiment in which the control condition would comprise feedback with extraneous cognitive load. However, we had to be careful to ensure that the control condition was not degraded so much as to be unrepresentative of typical practice. We were also limited by programming capacity in how much we could achieve; increasing or reducing cognitive effort might require having two versions (ON and OFF) of all feedback pages and modifications. We therefore focused on ways of changing the content to increase or decrease cognitive load.

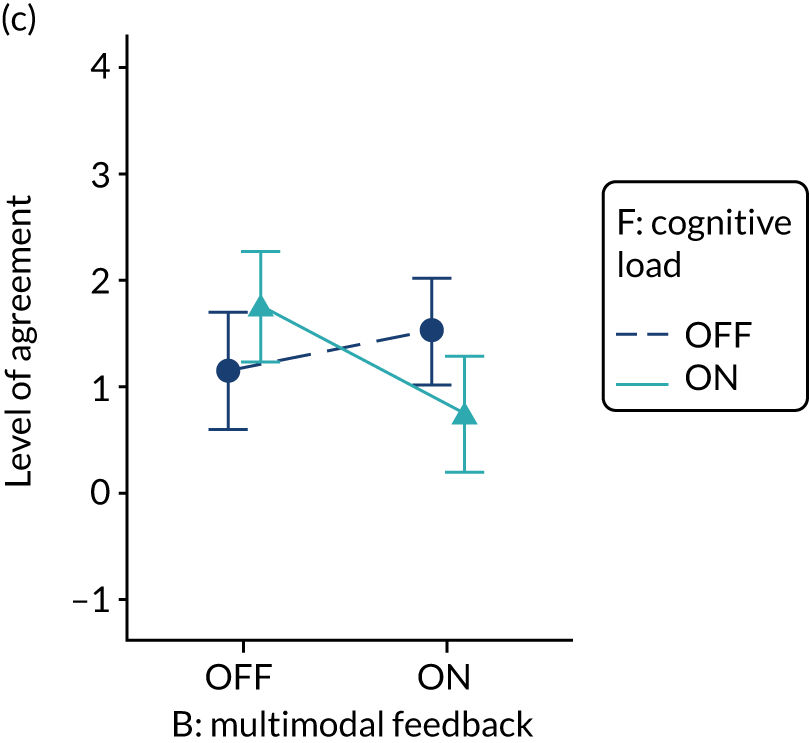

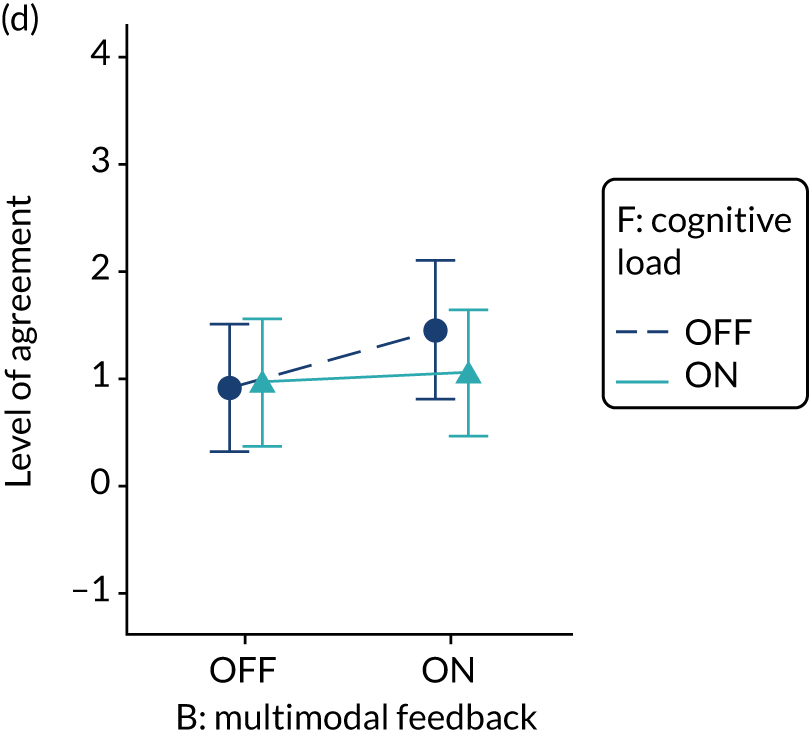

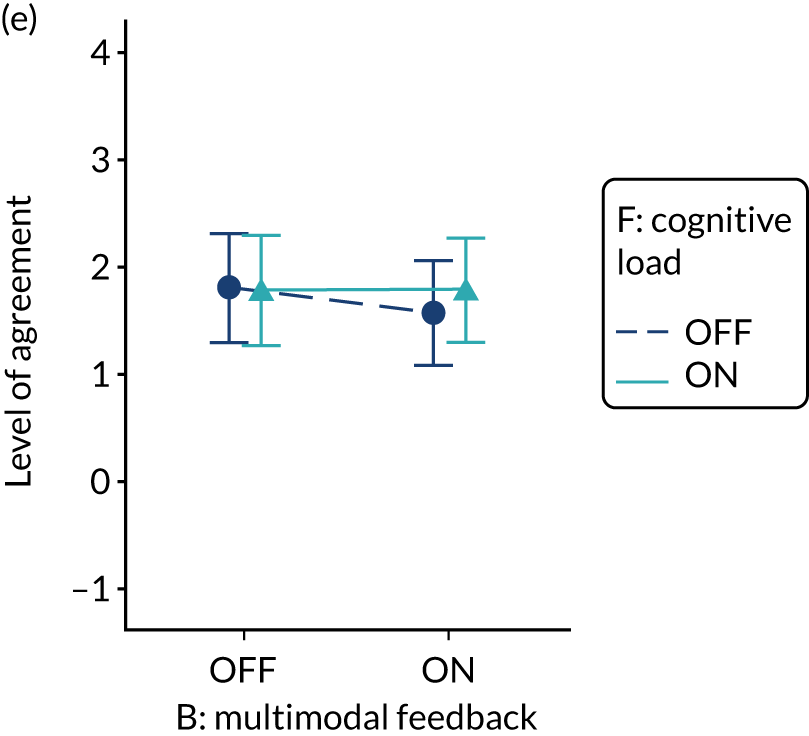

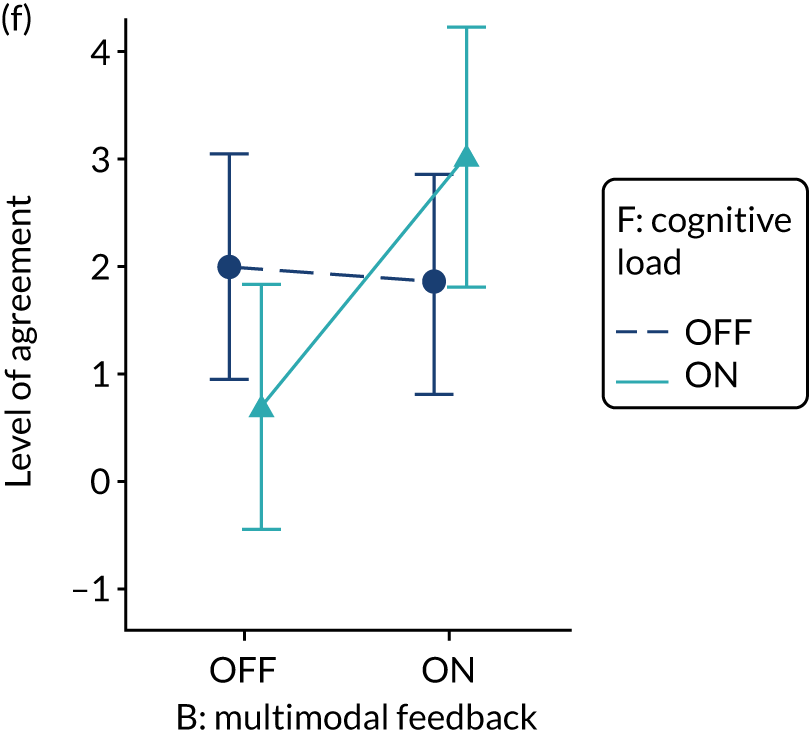

The modification would be ON in the absence of distracting detail. The modification would be OFF in the presence of distracting detail, such as additional general text not directly related to the audit criterion and feedback on other audit criteria. We recognised that this modification might interact with multimodal feedback (M9) and therefore anticipated a negative interaction in the analysis of the online experiment. Figure 5 illustrates the final design for the OFF version (high cognitive load).

FIGURE 5.

Screenshot example of a section of the final OFF version of cognitive load (M10) (NCABT).

Shorthand reference

Cognitive load (M10).

Address barriers to feedback use

Rationale

Although recipients may receive and read feedback, they may not feel or be able to act on it. Barriers to effective action may exist across individual (i.e. professional or patient), clinical team, organisation or system levels. 55 For example, a GP receiving feedback on prescribing anticoagulants for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation might be uncertain about how to initiate and monitor treatment in the absence of clearly defined local pathways for doing so. 56 Therefore, feedback may need to include specific advice on how to do this and be accompanied by organisational initiatives to define and disseminate recommended clinical pathways. Feedback effects may be enhanced by supported interventions based on systematically identified barriers to and enablers of recommended practice.

Evidence base

A Cochrane review57 suggests that tailored interventions to address identified determinants of practice can change professional practice, although they are not always effective and, when they are, the effect is small to moderate.

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as moderate (6, high agreement).

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as moderate (4.5, high agreement).

Selection for online experiment

No. The second UCD workshop suggested that addressing barriers to use would be most relevant following delivery of feedback.

Provide short, actionable messages followed by optional detail

Rationale

Feedback reports can be lengthy documents that are onerous for recipients and of uncertain value for changing behaviour. Providing short, actionable messages, with optional information available for interested recipients, allows those who only have the time or inclination to glean the main messages to do so. Other recipients may demand more detailed information to check the validity and relevance of feedback data or consider the evidence base underpinning a particular recommendation for action. Feedback credibility may be enhanced if recipients can ‘drill down’ to better understand their data.

Evidence base

Little research has addressed this in the context of feedback. One randomised experiment found that a ‘graded-entry’ approach improved clarity and accessibility for clinical guideline summaries. 58 A review of health technology assessments recommended ‘structured decision-relevant summaries’. 59 Interaction designers refer to this technique as progressive disclosure and use it to disguise system complexity and to declutter the user interface of higher-end functionality in a way that supports both casual and advanced users. 60

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as high (7, high agreement).

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as high (8, high agreement).

Selection for online experiment

Yes. The modification would be ON if the feedback included short messages with links to explanatory detail related to the audit criterion. The modification would be OFF in the absence of links to explanatory detail. This modification partly overlaps with specific actions (M3) and we anticipated a negative interaction in the online experiment. Similarly, this modification might also negatively interact with cognitive load (M10), given that adding information might distract participants. Figure 6 illustrates the final design.

FIGURE 6.

Screenshot example of final ON version of modification 12 (NCABT).

Shorthand reference

Optional detail (M12).

Address the credibility of the information

Rationale

Feedback effects may be compromised if recipients consider the data erroneous or irrelevant to their own practice. Approaches to counter such beliefs include involving recipients in the selection of audit criteria and data collection, being transparent about the strengths and limitations of feedback data, and highlighting how the data are relevant to recipients’ practice and circumstances.

Evidence base

Feedback delivered by a supervisor or colleague is more effective than feedback delivered by other sources. 11

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as moderate (6.5, high agreement).

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as high (7, high agreement).

Selection for online experiment

No. We judged that most NCAs already take reasonable measures to explain the credibility of their data and it would not be feasible to embed additional delivery by a colleague or supervisor within the online experiment.

Prevent defensive reactions to feedback

Rationale

Negative feedback may naturally elicit defensive responses, especially if the targets set for improvement are perceived as unattainable. 61,62 Repeated negative feedback coupled with unattainable targets for change may demotivate and disengage recipients. Encouraging reflection on success with an emphasis on extending such success to other arenas (‘feedforward’) may be more motivating. 62,63 Actively guiding recipients’ reflections on the feedback away from defensive reactions may also be beneficial.

Evidence base

Few studies on feedforward for clinicians exist. 19

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as moderate (6.5, high agreement).

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as low (3, high agreement).

Selection for online experiment

No. The second UCD workshop noted that most national audits probably attempt such measures routinely, although we recognised the potential for experimental work framing messages in different (positive and negative) ways.

Construct feedback through social interaction

Rationale

Educational research suggests that social interaction offers opportunities for recipients to actively work with feedback and go beyond superficial responses. Approaches to increase such interaction include asking recipients to self-assess performance prior to feedback, promoting dialogue about the meaning and implications of feedback, and taking part in facilitated discussions to develop action plans. 64–66

Evidence base

There is little in the feedback literature about interaction between the feedback providers and recipients,19 although qualitative research suggests that approaches promoting self-assessment can be motivating. 67

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as high (7, high agreement).

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as moderate (6, high agreement).

Selection for online experiment

No. The second UCD workshop considered that this might be problematic to operationalise convincingly within an online experiment.

Incorporate ‘the patient voice’

Rationale

Patient and public involvement can help ensure the relevance of audit programmes to patient and public needs and provide alternative perspectives to those of health-care professionals. Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) guidance for best practice in clinical audit recommends PPI throughout the audit process as a marker of quality. 68 Although none of the previous 15 suggestions for effective feedback specifically mentioned PPI, we proposed including it in the online experiment given its policy salience. We analysed 27 national audit reports in 2018 and found that five included sections directly written by patients about their experiences of care or the audit. None was specifically linked to audit criteria. Yet, in principle, such attempts to incorporate ‘the patient voice’ may highlight the importance of providing high-quality care to feedback recipients and, hence, increase their motivation to improve practice.

Evidence base

We were unaware of any research directly addressing this suggestion.

Need for further research

The need for further research was rated as high (8, high agreement).

Feasibility within national audits

Feasibility within national audits was rated as high (7, high agreement).

Selection for online experiment

Yes. The modification would be ON with the addition of a quotation from and a photograph of a fictional patient. The text would describe their experience of care, where possible, directly related to the audit criterion.

We aimed to embed one or more of the following behavioural change techniques69 in the quotation:

-

feedback on outcome(s) of behaviour (i.e. stating how the patient benefited from clinical care consistent with recommended clinical practice).

-

anticipated regret (i.e. suggesting that the feedback recipient might regret not following recommended practice).

-

vicarious consequences [i.e. prompting observation of consequences for others (including rewards and punishments) when recommended practice is or is not followed].

-

information about others’ approval (i.e. stating how the patient approves of the recipient following recommended practice).

The modification would be OFF in the absence of this information. Figure 7 illustrates the final design.

FIGURE 7.

Screenshot example of final ON version of M16: patient story (NCABT).

Designing the online experiment

System scope

The experiment was to be delivered as a custom-built website that participants would access by clicking on a link in an e-mail invitation. The core functionality was to present participants with an audit page composed of the audit standard and combinations of ON or OFF versions of the 6 modifications (Appendix 2), followed by a questionnaire to measure their response. We decided to embed this functionality within a linear series of pages in designing the experiment (Table 4).

| Step | Page description | Page type | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Welcome page | Static content | User orientation, study purpose, graphical overview and funders/collaborators |

| 2 | Consent form and participant information | Form | Capture informed electronic consent and present patient information sheet. Form including validation |

| 3 | Select your audit page | Form and patient information sheet | Allocate user identifier and modification combinations. Capture role and organisations type |

| 4 | Audit report page | Feedback display | User view of baseline and combined audit report content Page metrics, including Google Analytics ® (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) |

| 5 | Questionnaire | Form | Multiple-choice ratings scale capturing outcome data |

| 6 | Thank-you page | Form | Capture e-mail address for incentive fulfilment and unlinked name for certificate download. User view of ‘tips for effective feedback’ |

Requirements

The website was required to welcome the participant (step 1), obtain informed consent (step 2), allocate participants to one condition in the fractional factorial experiment (step 3), present feedback modifications (step 4), provide a questionnaire to collect outcome data for the experiment (step 5), allow participants to download ‘evidence-based tips’ for effective feedback and to claim a voucher and certificate upon completion (step 6). The website was also required to gather metrics, including time to completion and page visits. To maintain participant anonymity, the personal data required for making the voucher claim would not be linked to research data. We designed for anticipated behaviour, preventing user errors and a degree of misuse (e.g. we wanted to be able to detect repeat attempts from voucher request logs).

Evolution over user-centred design rounds

Round 1 sketches

We identified typical and salient content types from national reports published by our five collaborating national audits. We began to scope the information architecture for an interactive online version of the feedback excerpts (which effectively corresponded to a ‘mini-audit report’). We designed seven paper prototypes for ways of presenting an online audit report. We selected five sketches that best fulfilled our brief. The sketches illustrated ways that common online navigational design patterns could be applied to audit content. The sketches included a single scrollable web page with a hyperlinked table of contents, a website with a classic global navigation bar, one with a task-led dashboard, one with step navigation (‘next’ and ‘back’ buttons), and one with side tabs and ‘breadcrumb trail’ navigation. Breadcrumbs are a dynamic trail of links that allow users to traverse back through drilled content. We illustrated inline features to prioritise, sort and ‘bookmark’ recommendations, and buttons or links to related content (Table 5).

| UCD Round | Sketch version and description | Overall sentiment, by participant | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||

| 1 | S1.0 single scrollable page, hyperlinked table of contents and pared-back content, i.e. a mini-report | n/c | N | M | M | M | N | M | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 1 | S1.1 step navigation with guidelines first | N | N | N | M | N | P | M | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 1 | S1.2 task-focused navigation and breadcrumb trail | N | N | M | N | N | P | M | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 1 | S1.3 classic global navigation bar and left-hand secondary navigation, ‘add to basket’ recommendations and linked results/content | P | N | M | M | M | M | M | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 1 | S1.4 side tabs and breadcrumb trail navigation, inline links to related content and ‘favourites’ | M | M | M | M | P | M | M | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2 | E-mail invitation | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | N | P | M | M | – | – |

Round 1 findings

We received a broad mix of responses relating to the styles of navigation presented. The single scrolling page was deemed to be typical but not necessarily user-friendly. Participants responded positively to task-focused navigation and the classic global navigation with side-tabs. Participants gave mixed responses to the step navigation owing to the lack of signposting or menu in our sketch. They could not see how deep the system was or what information it contained. Participants also reported suitable or expected names for sections in order of importance, with the most salient information, ‘results’, presented first. Participants reacted positively to prioritisation features.

Round 1 requirements

The website was designed to:

-

clearly convey the scope of the experiment and set respondent expectations before consent

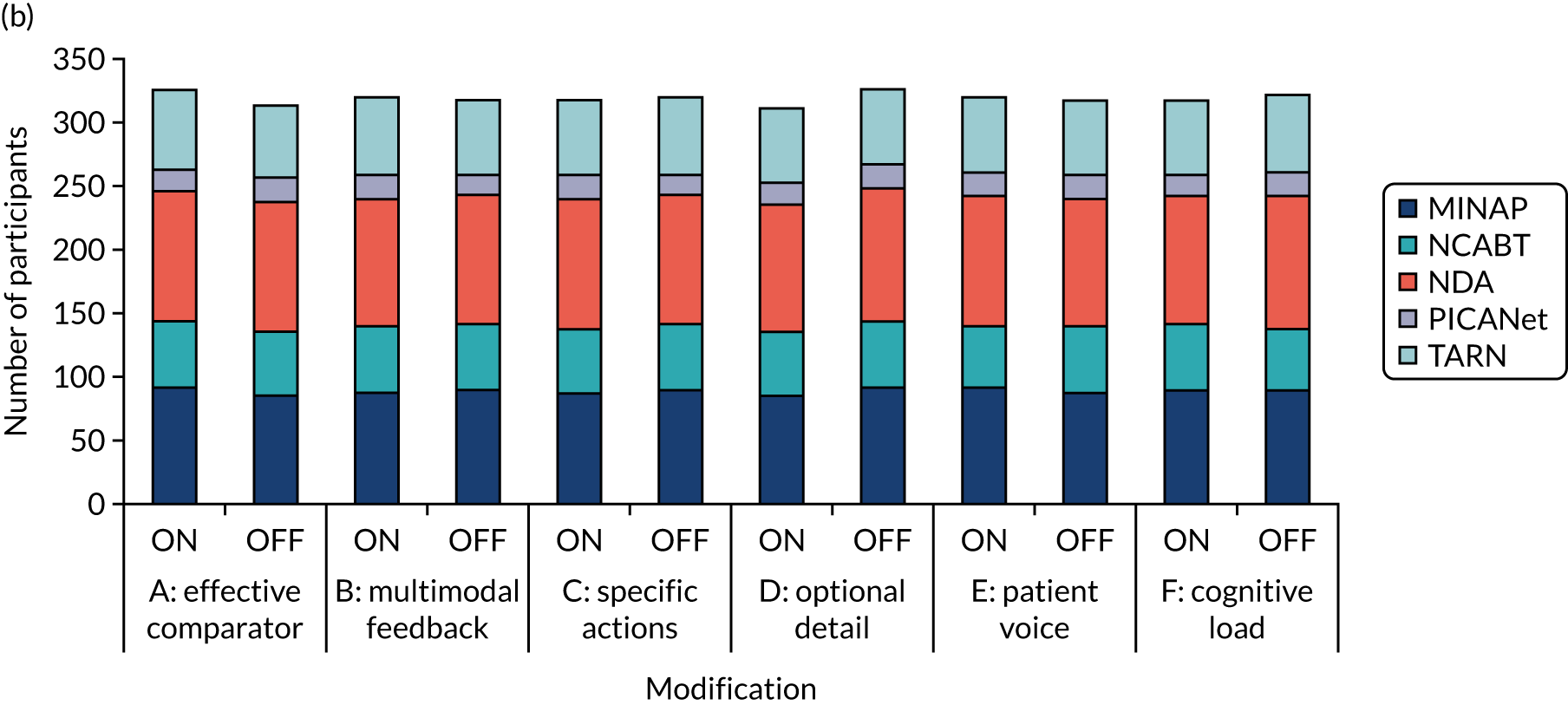

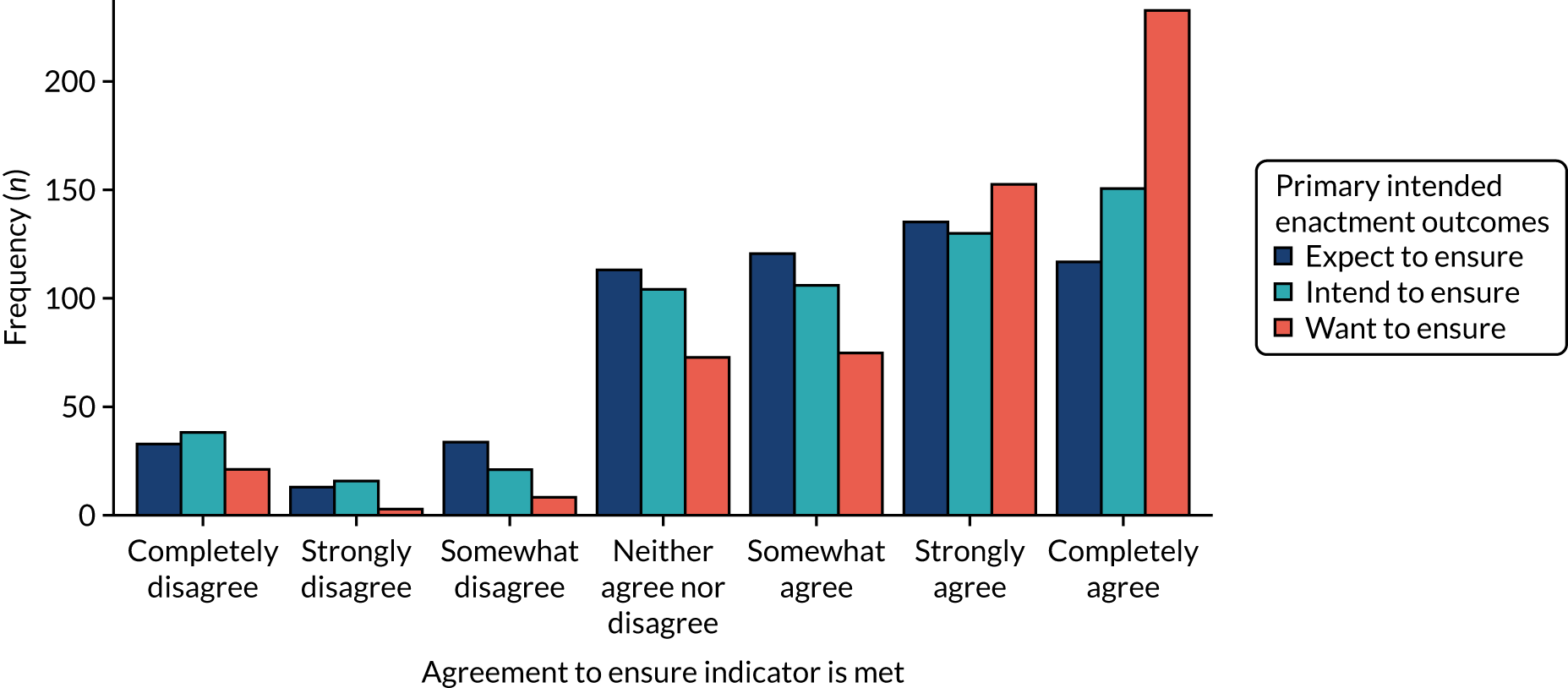

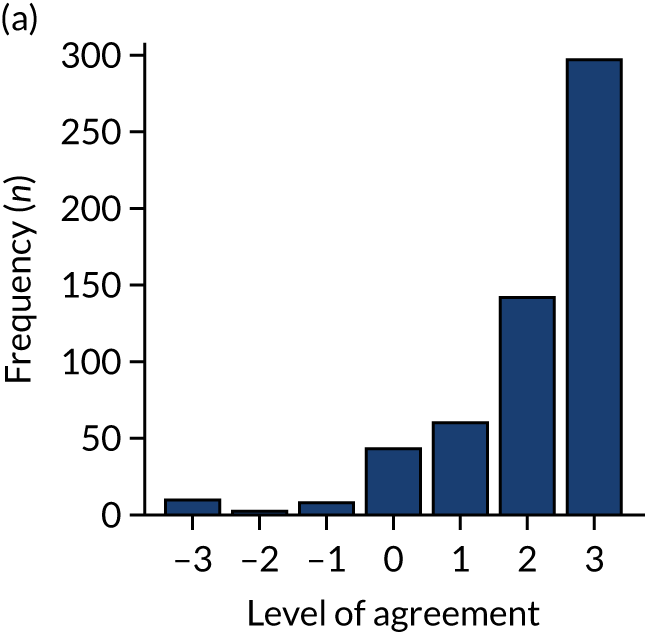

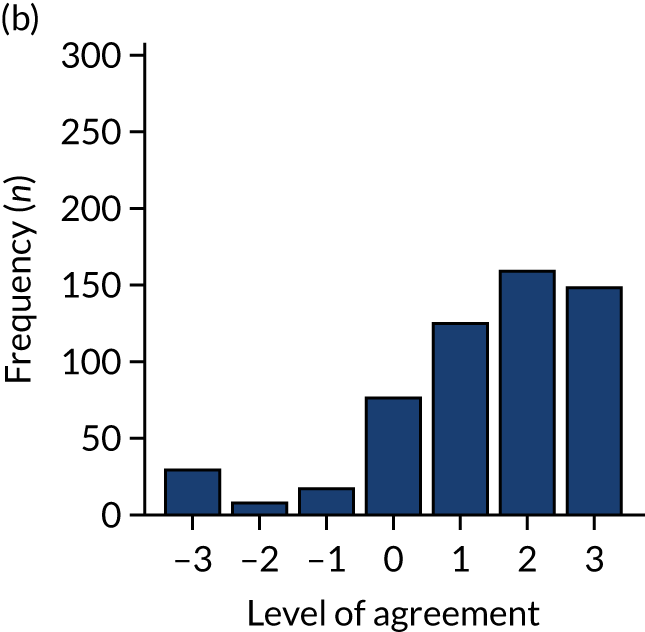

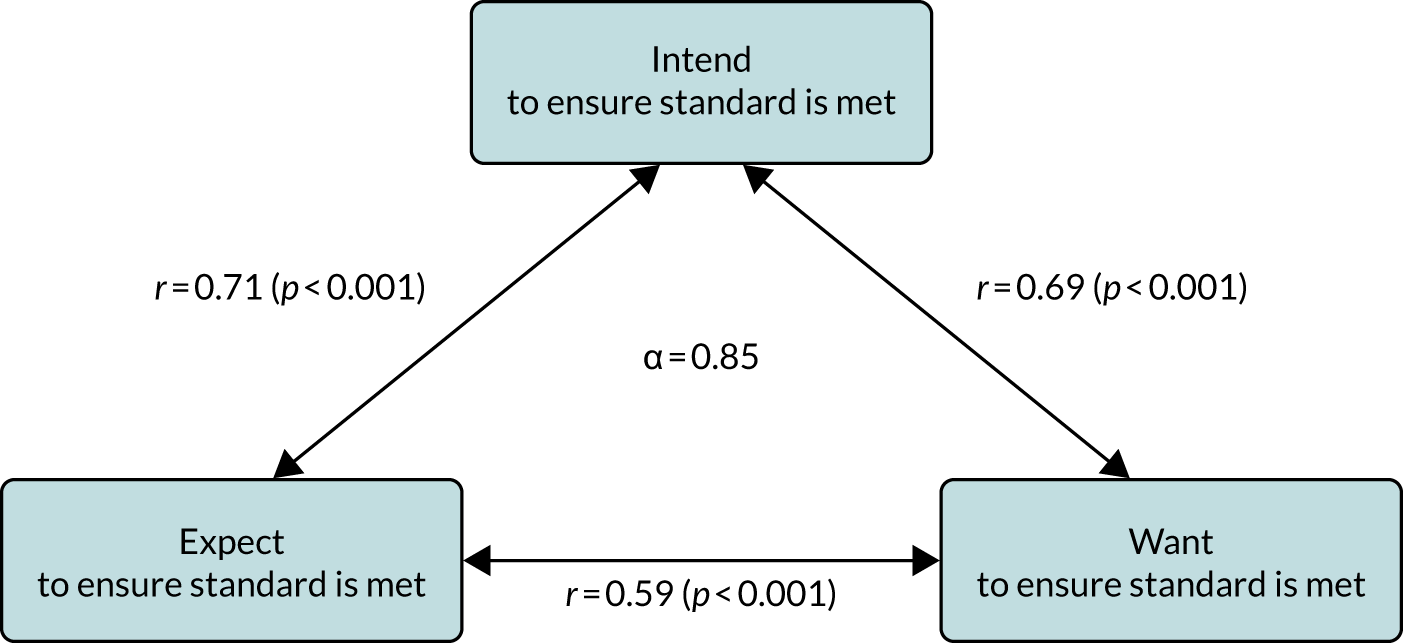

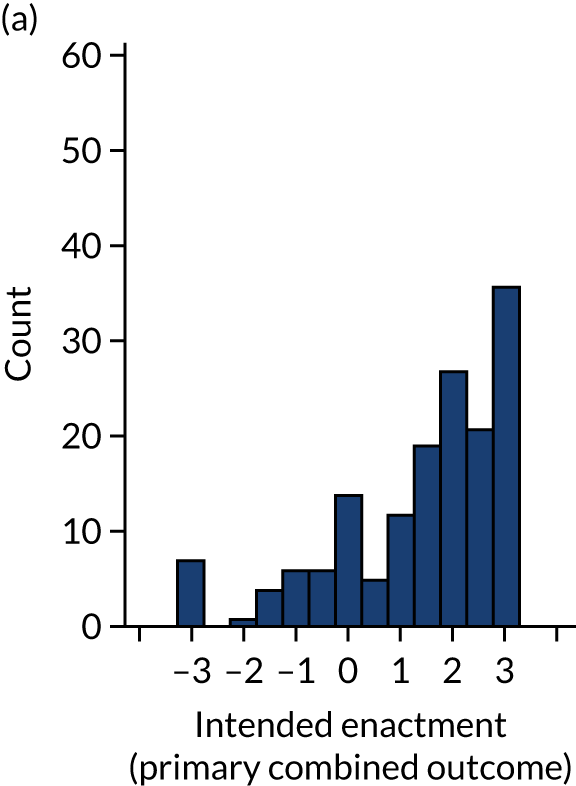

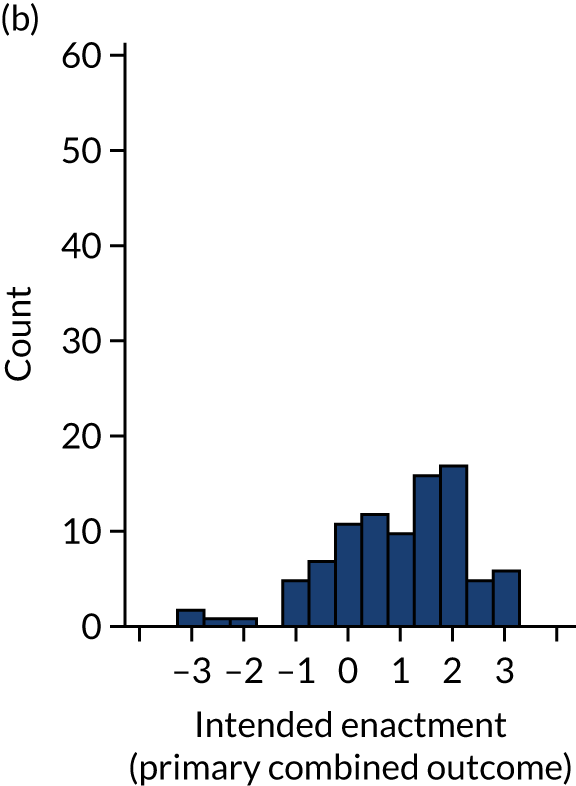

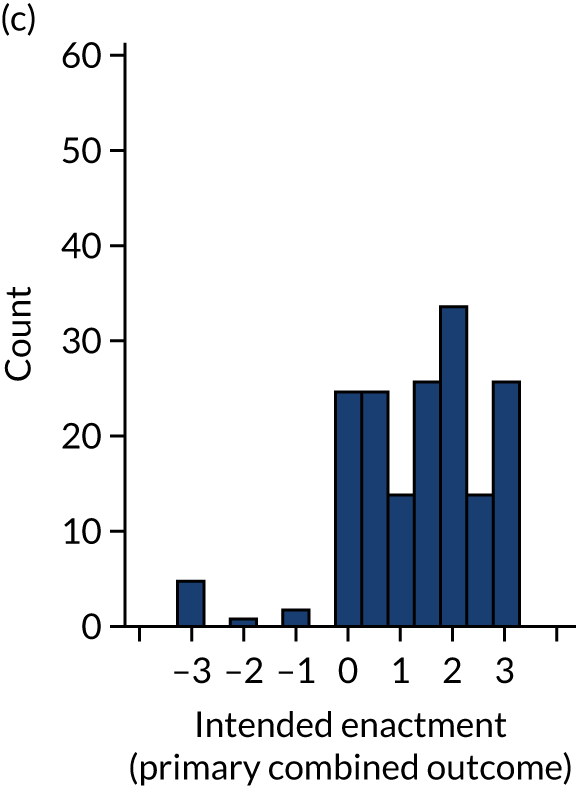

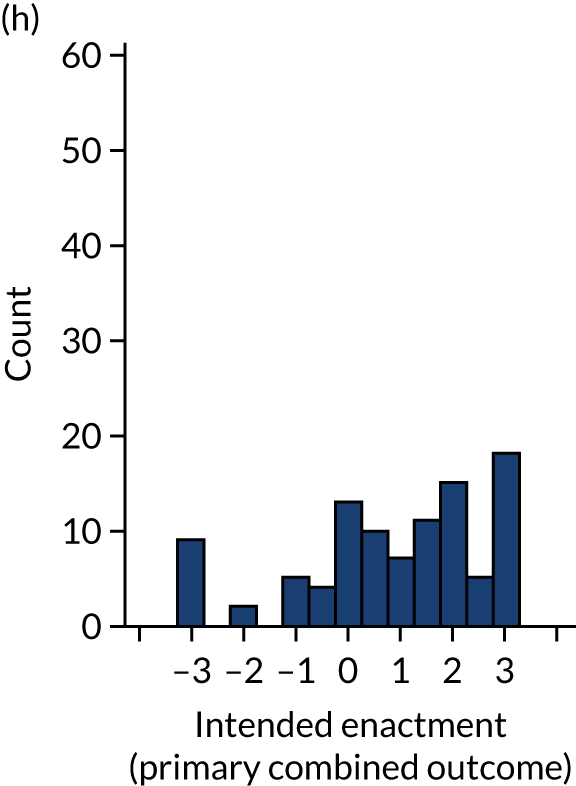

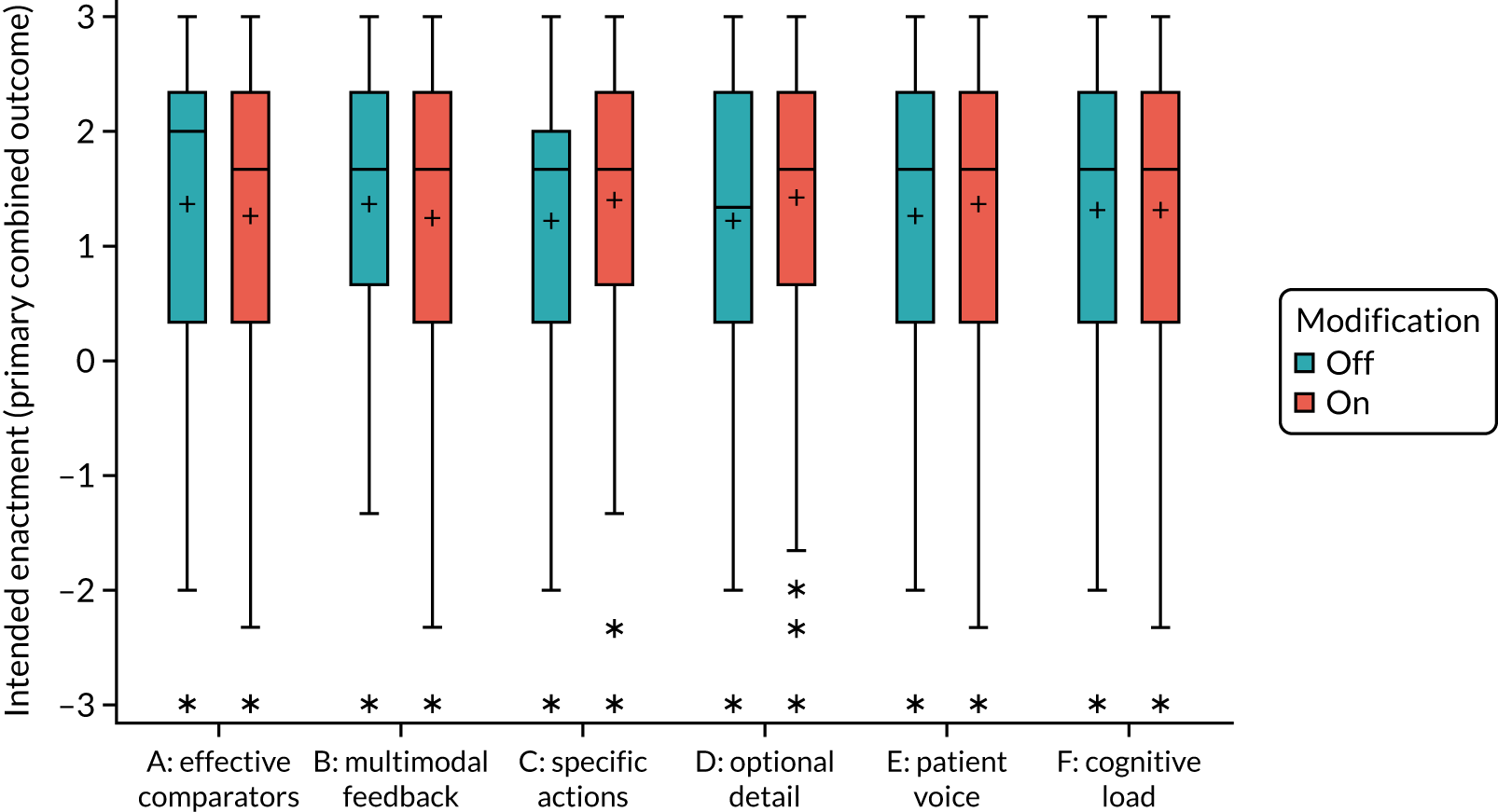

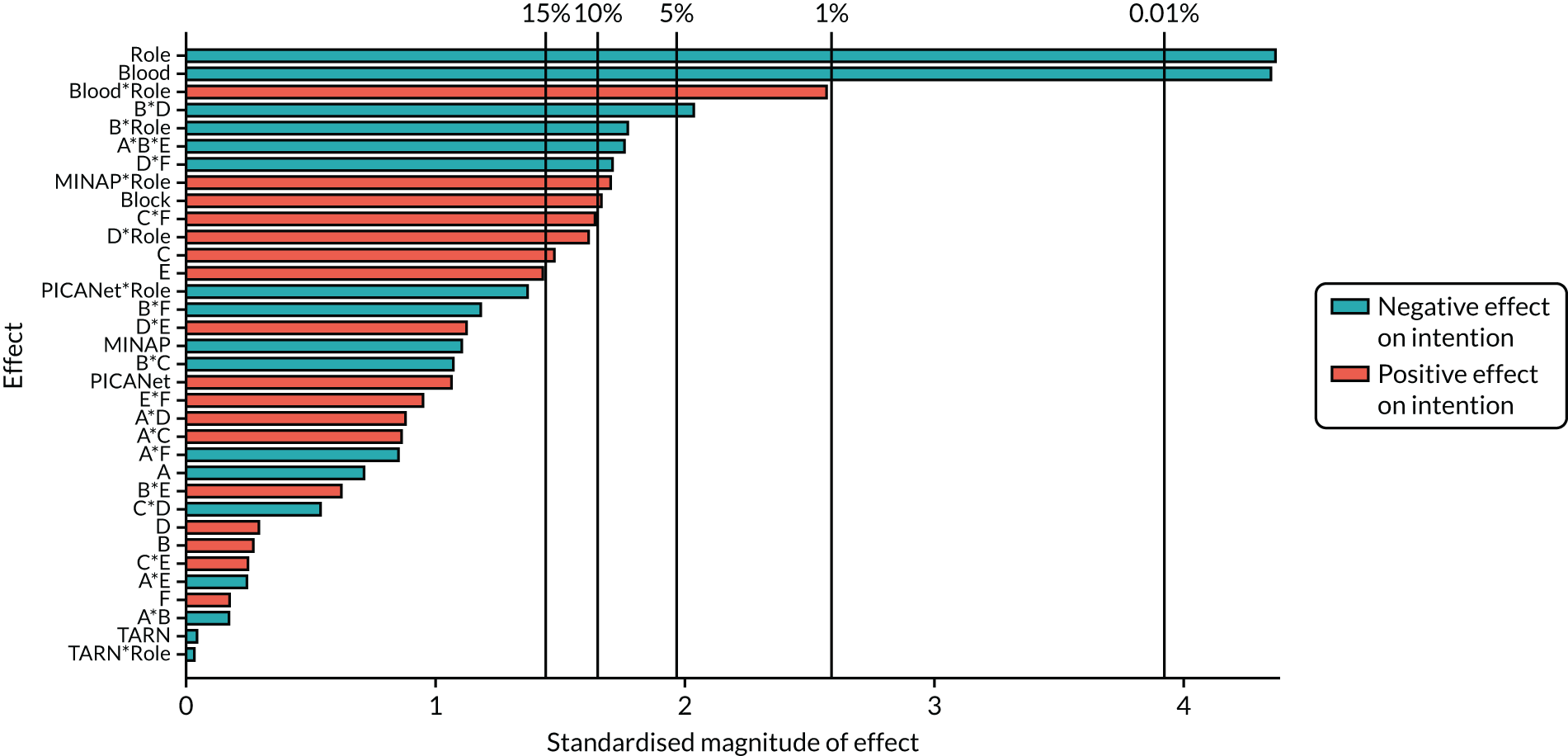

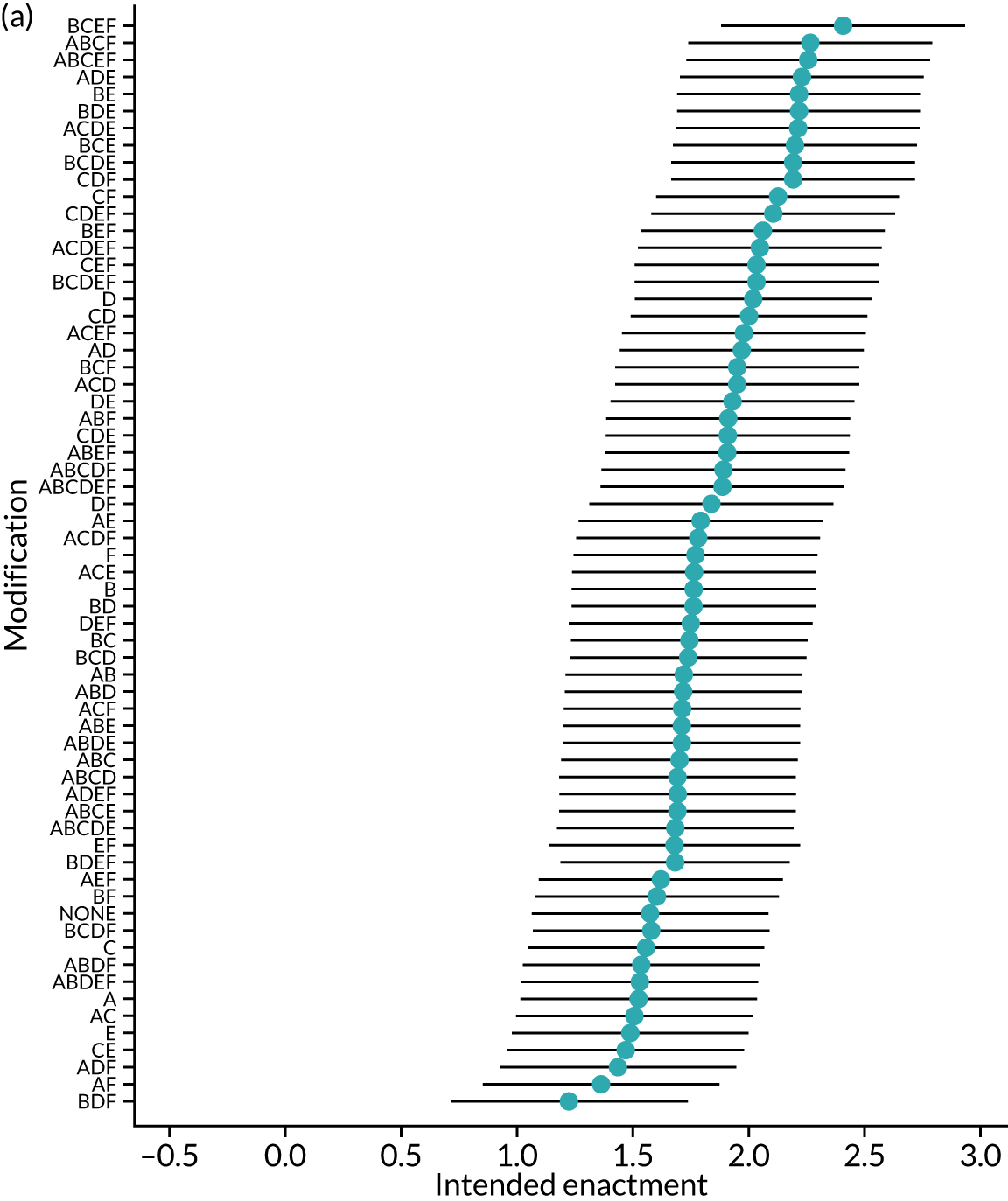

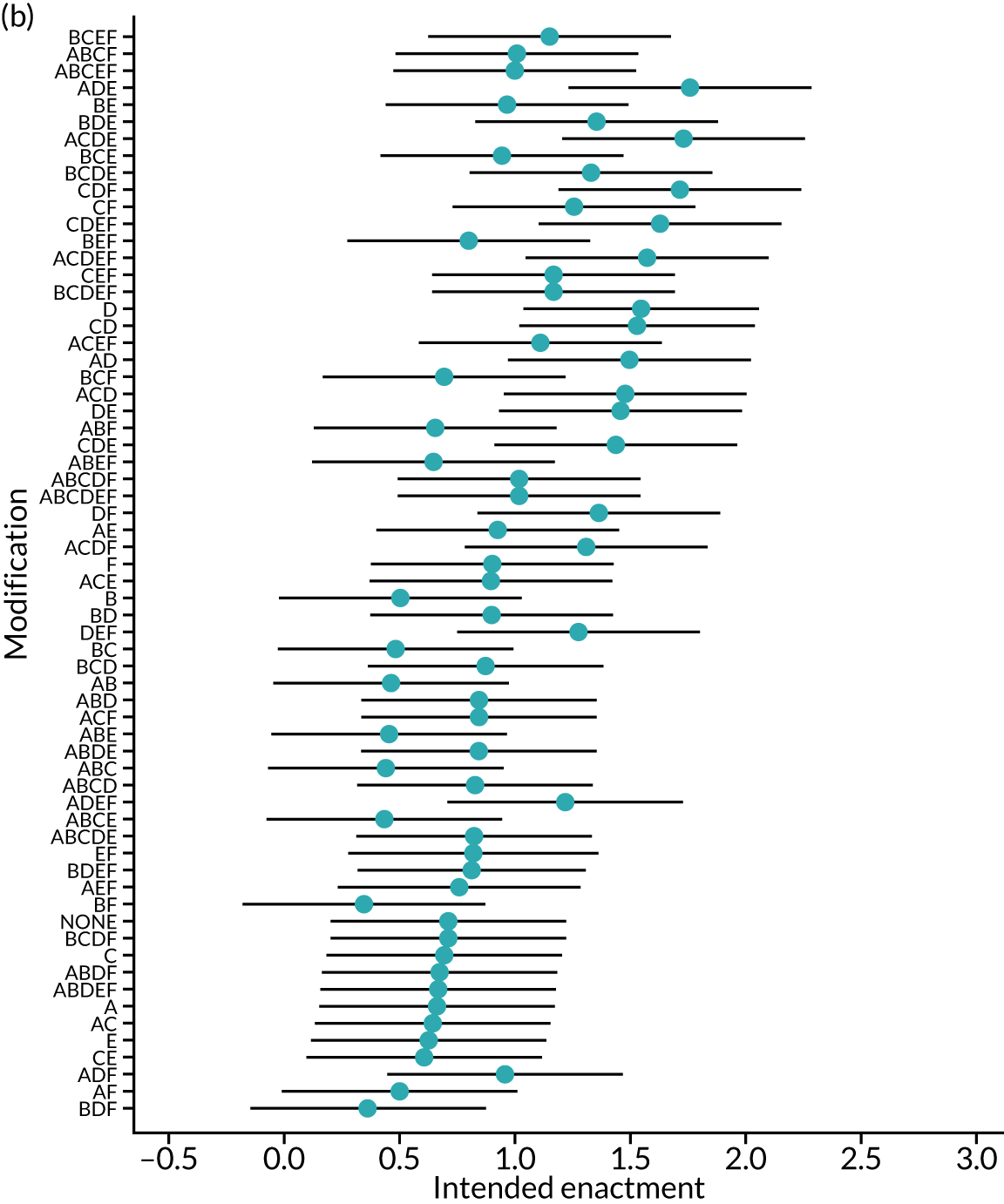

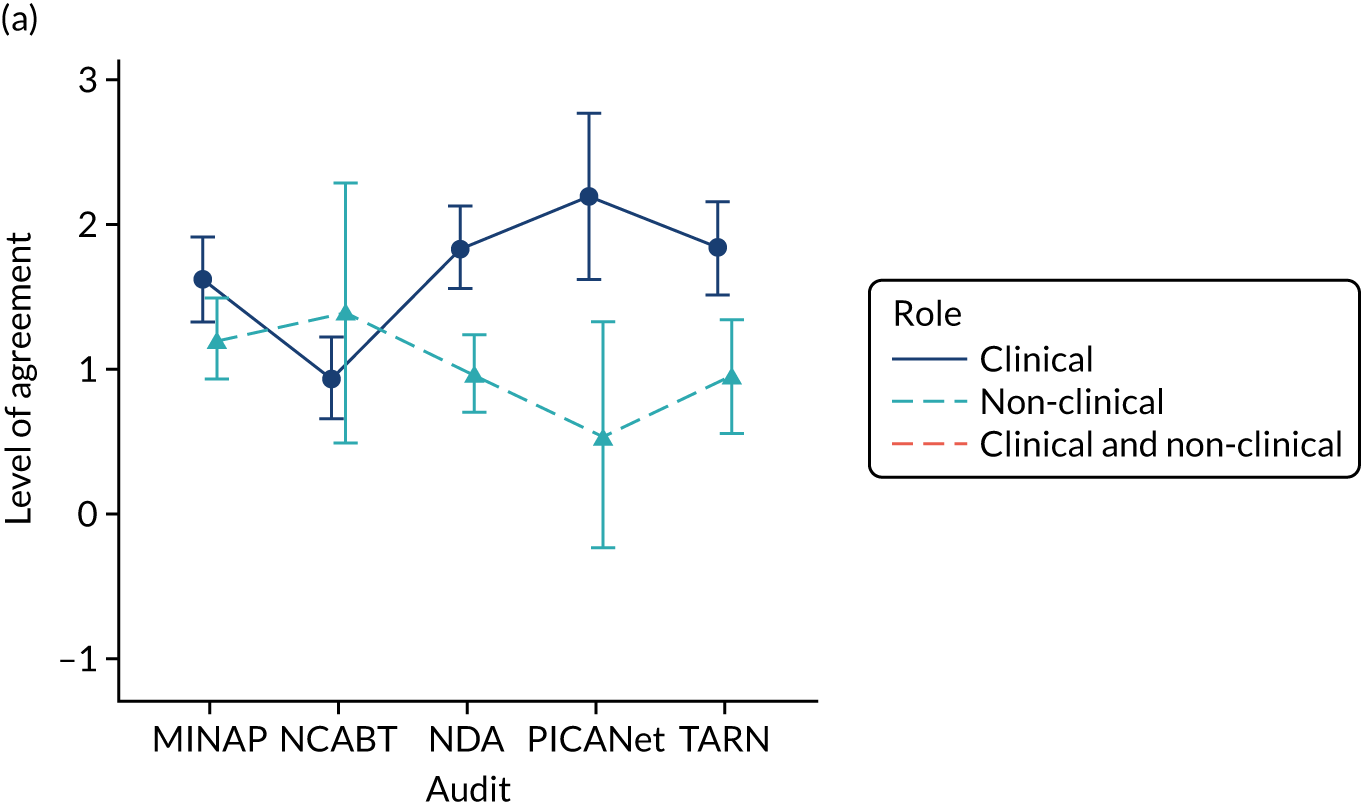

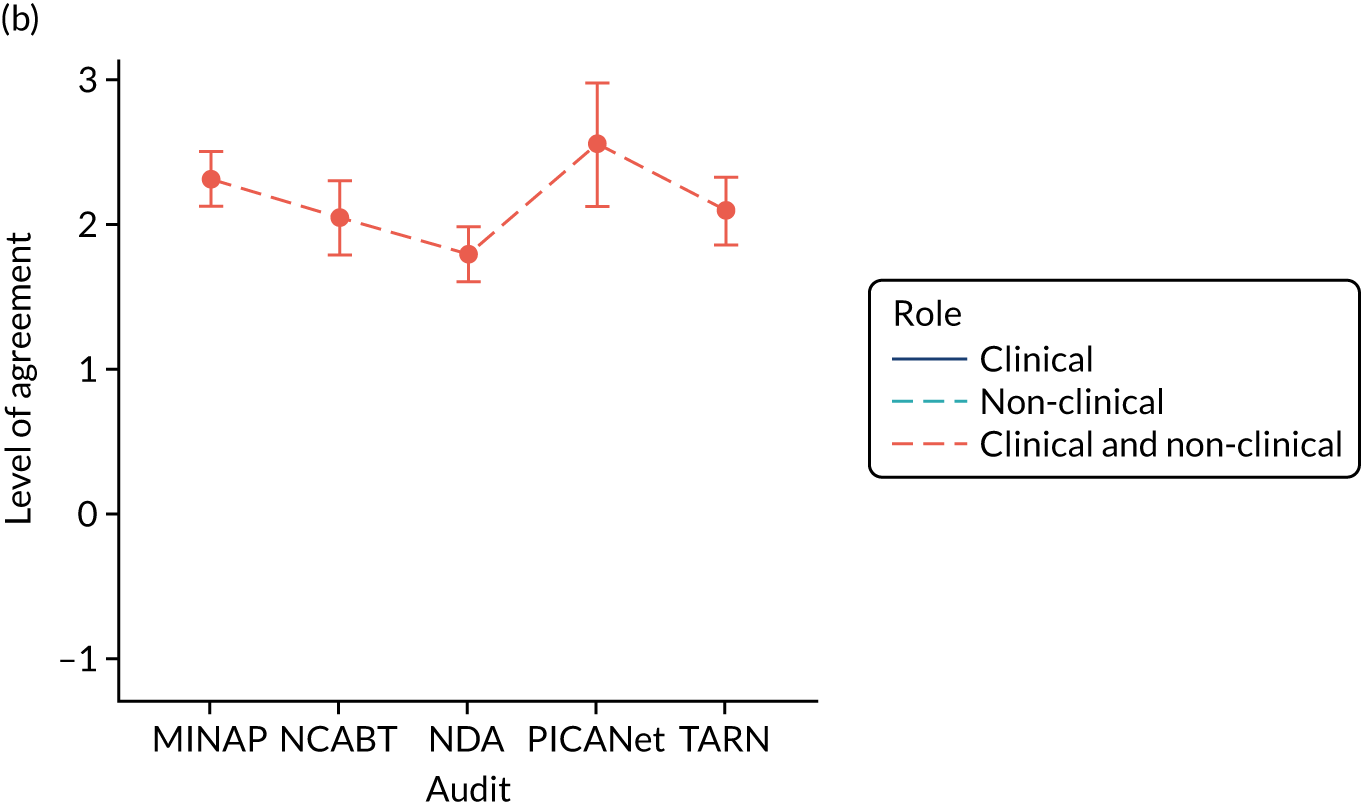

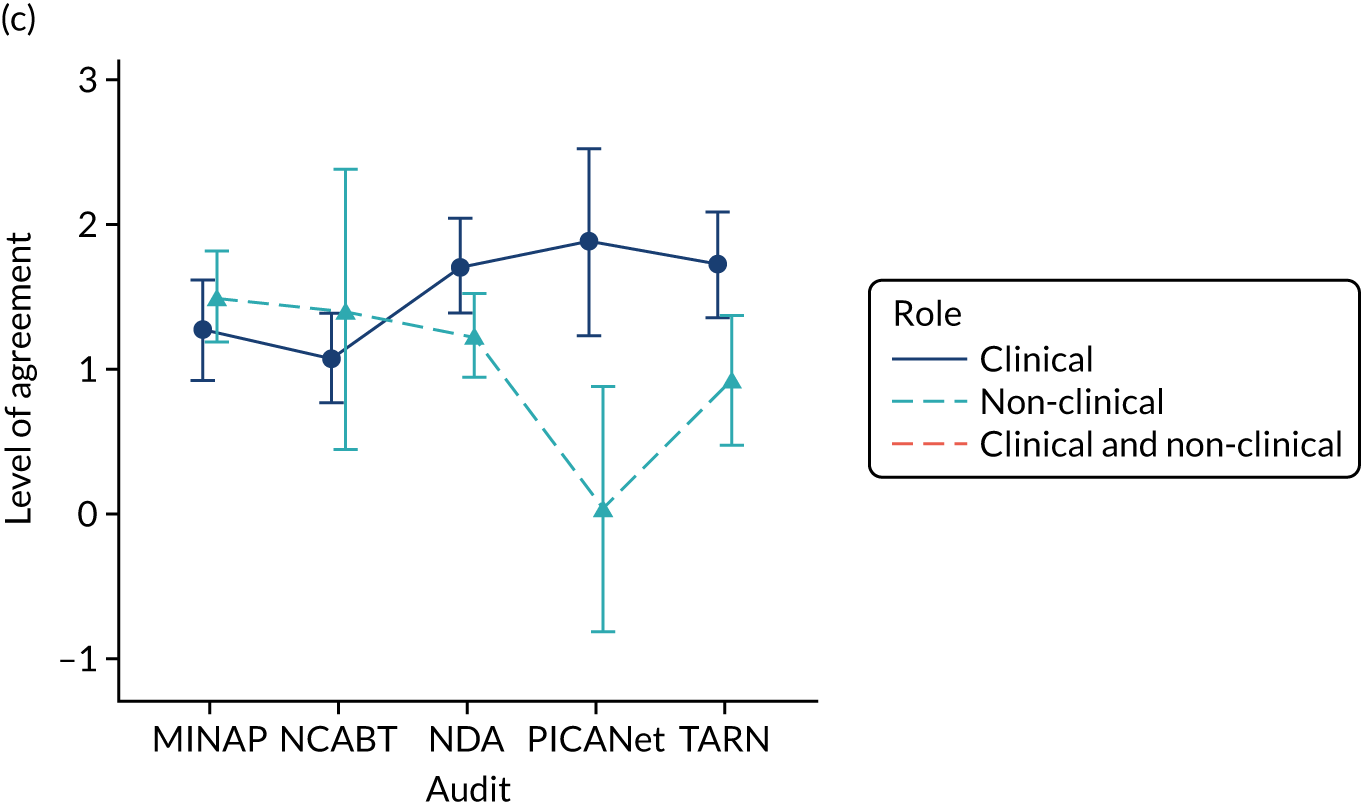

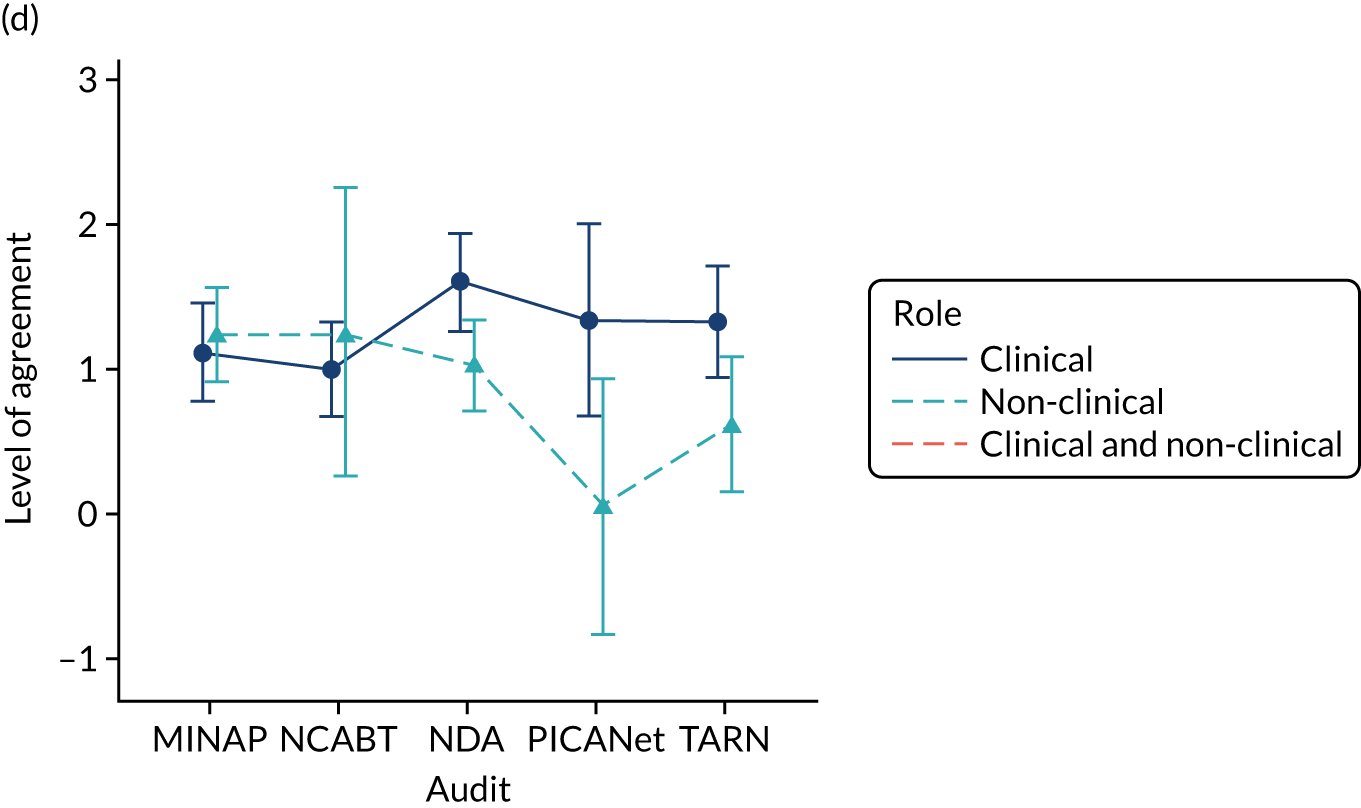

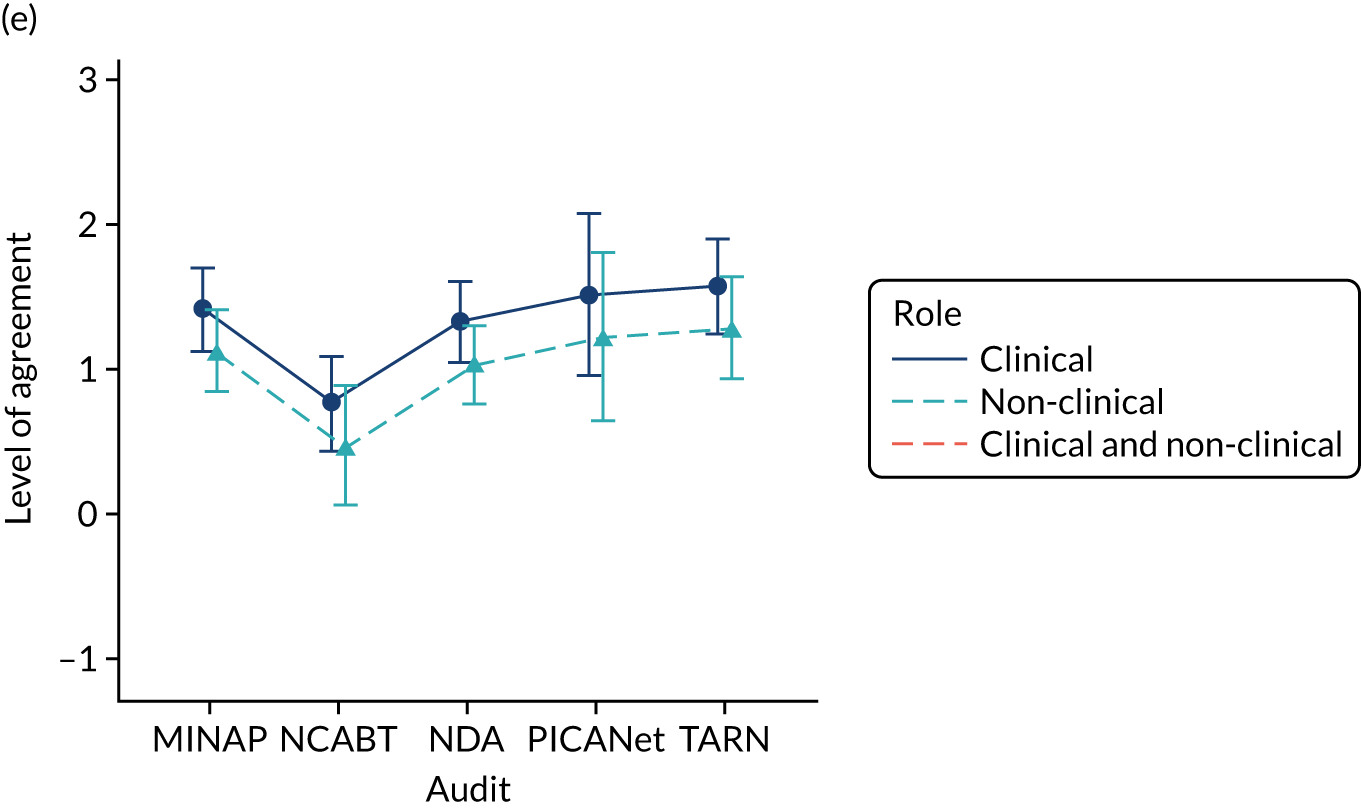

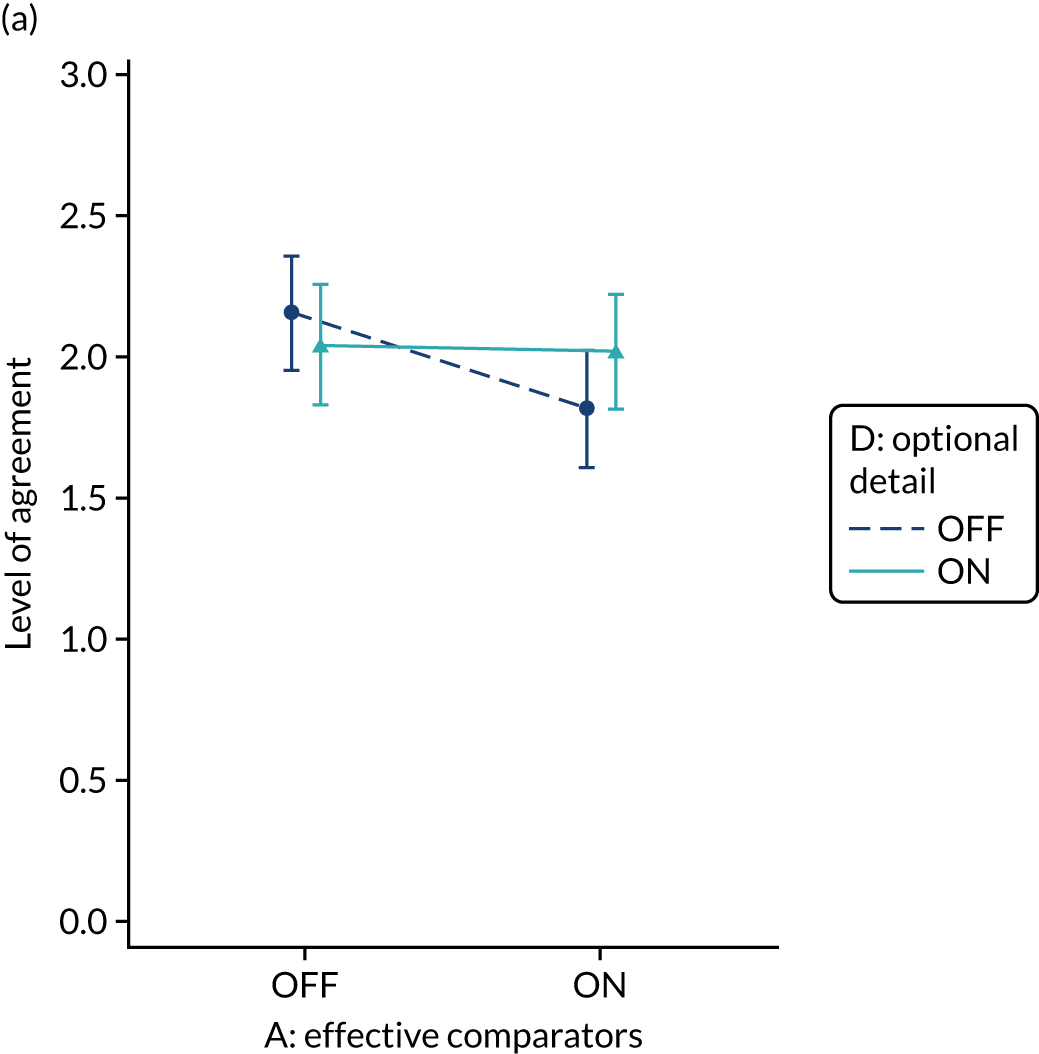

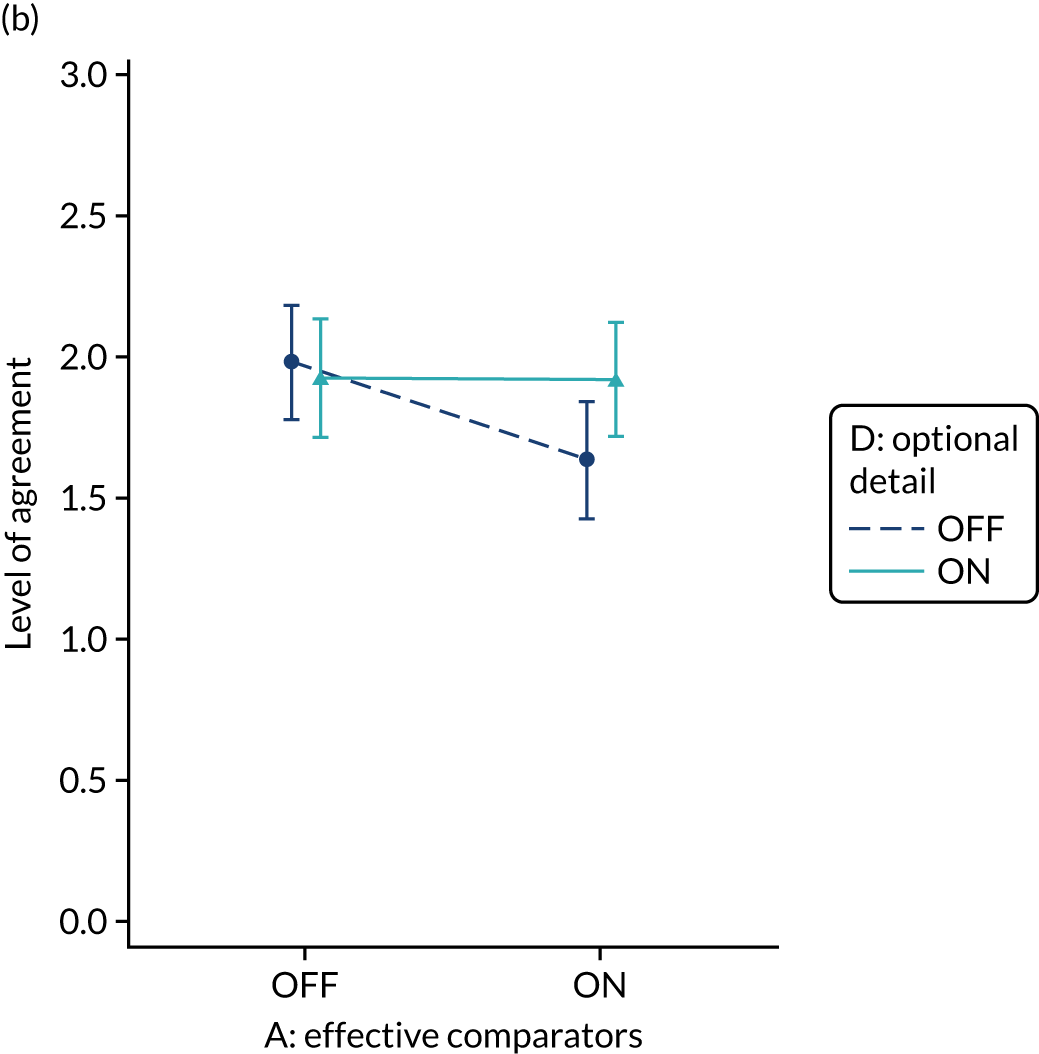

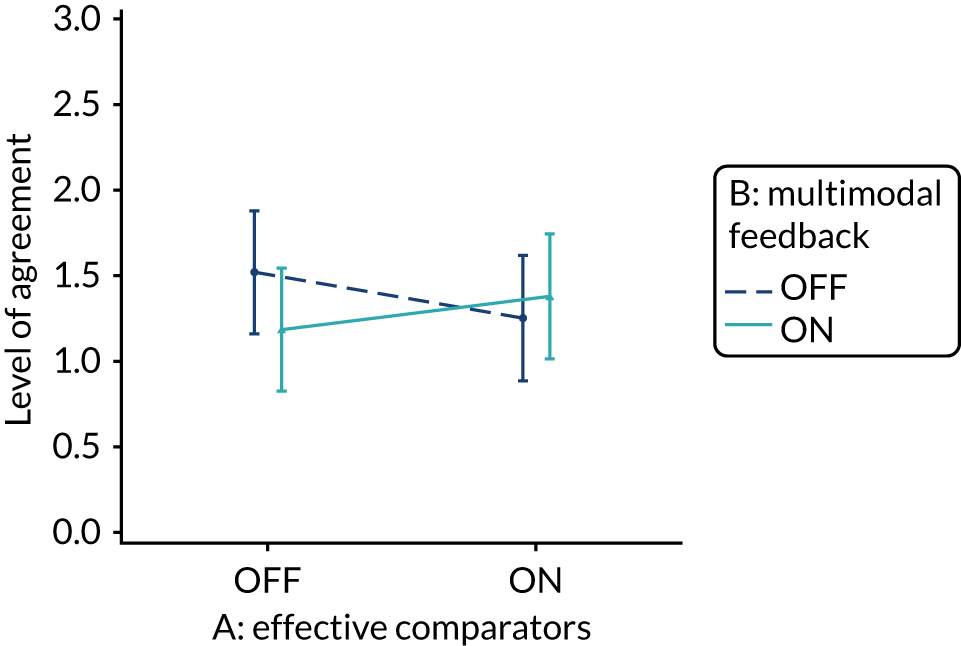

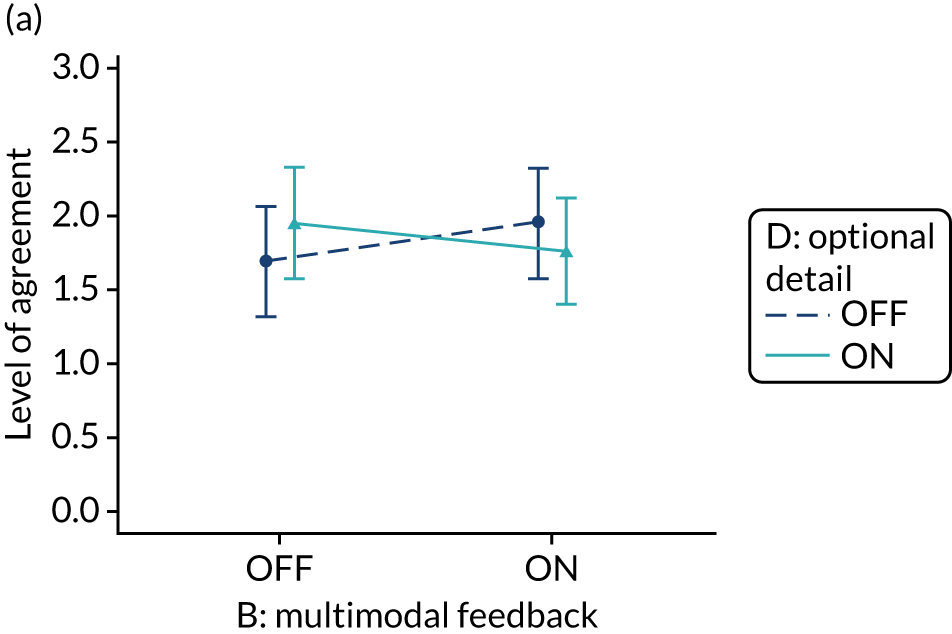

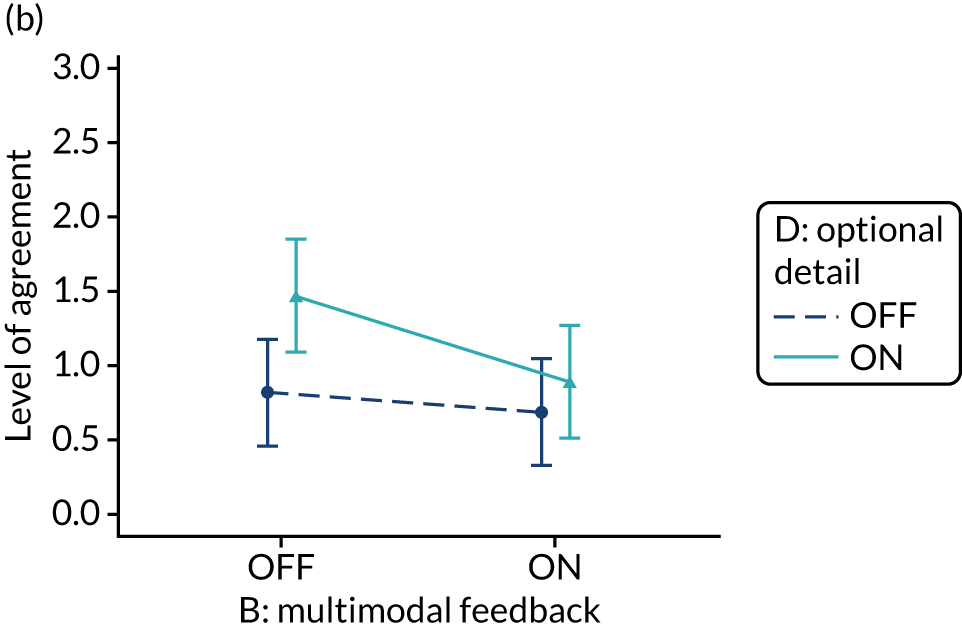

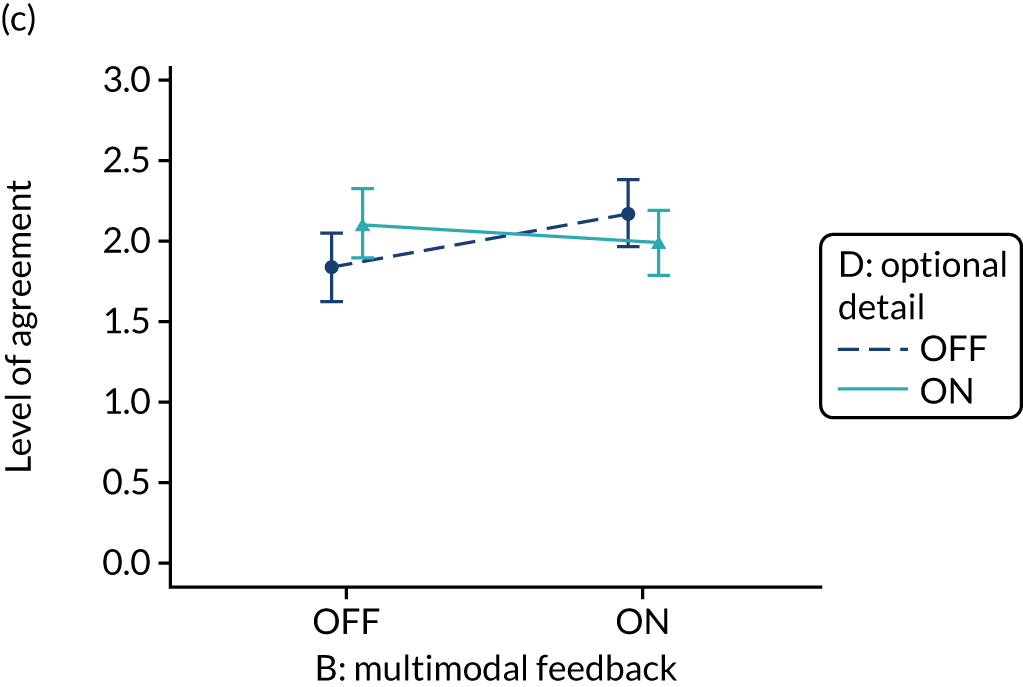

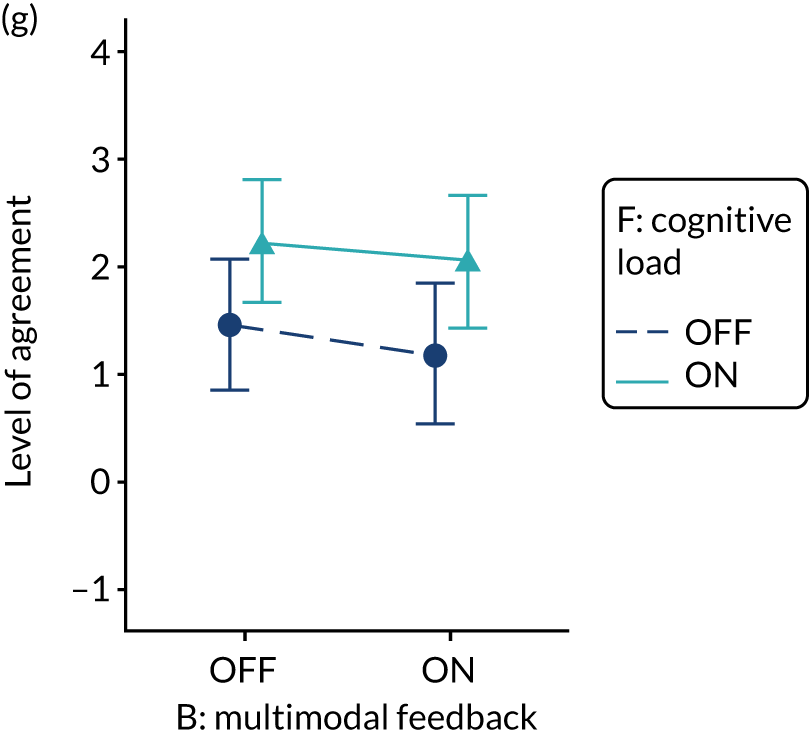

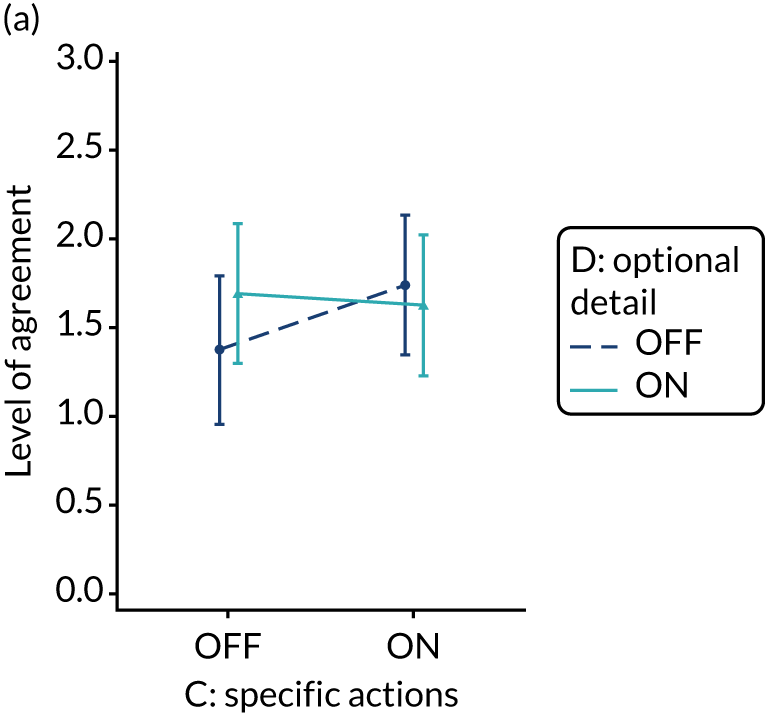

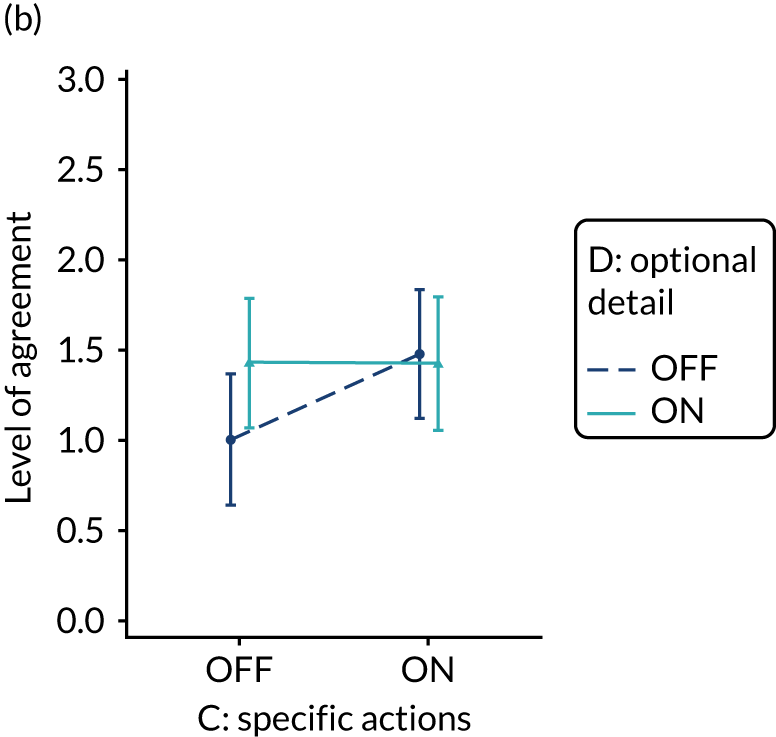

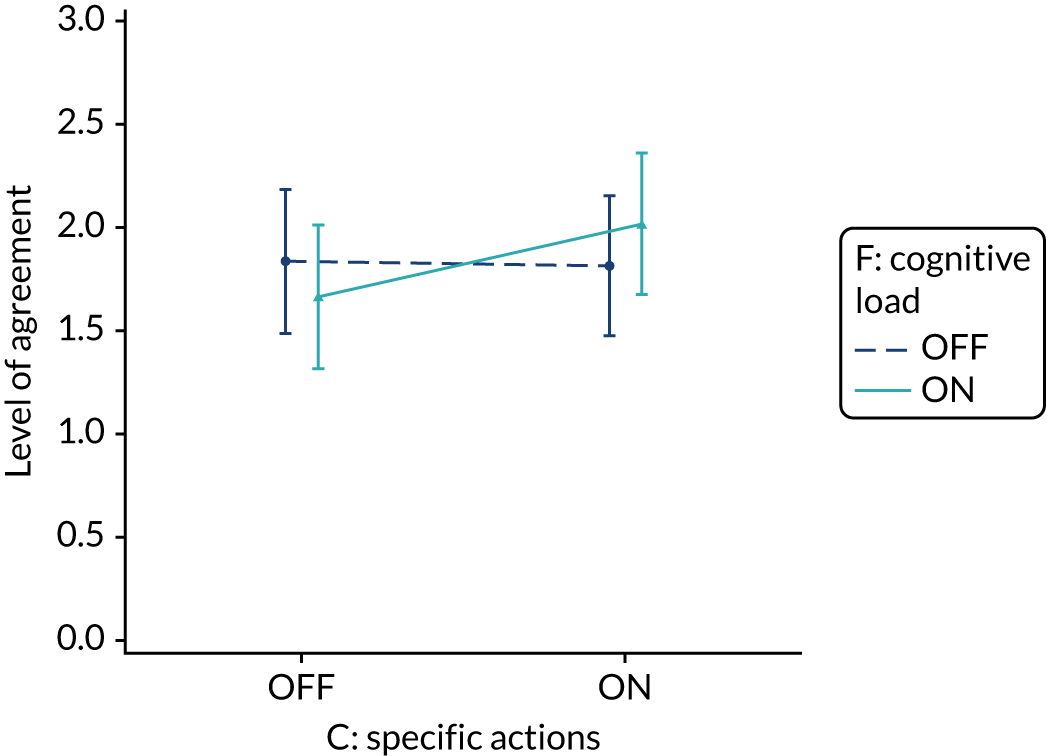

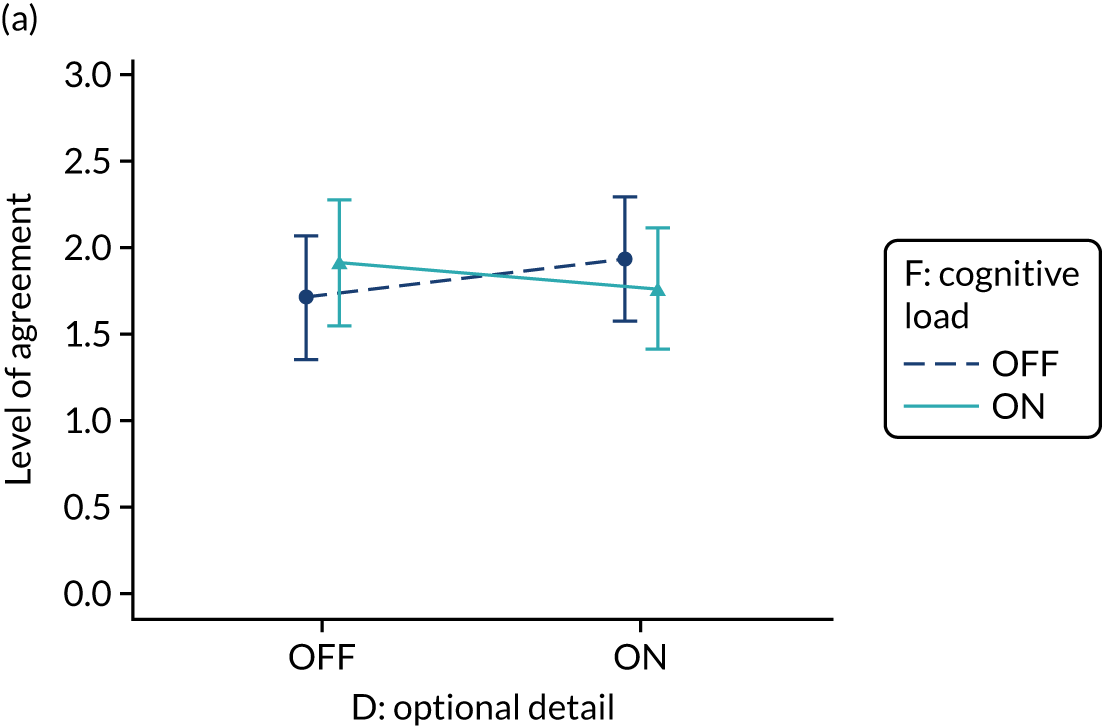

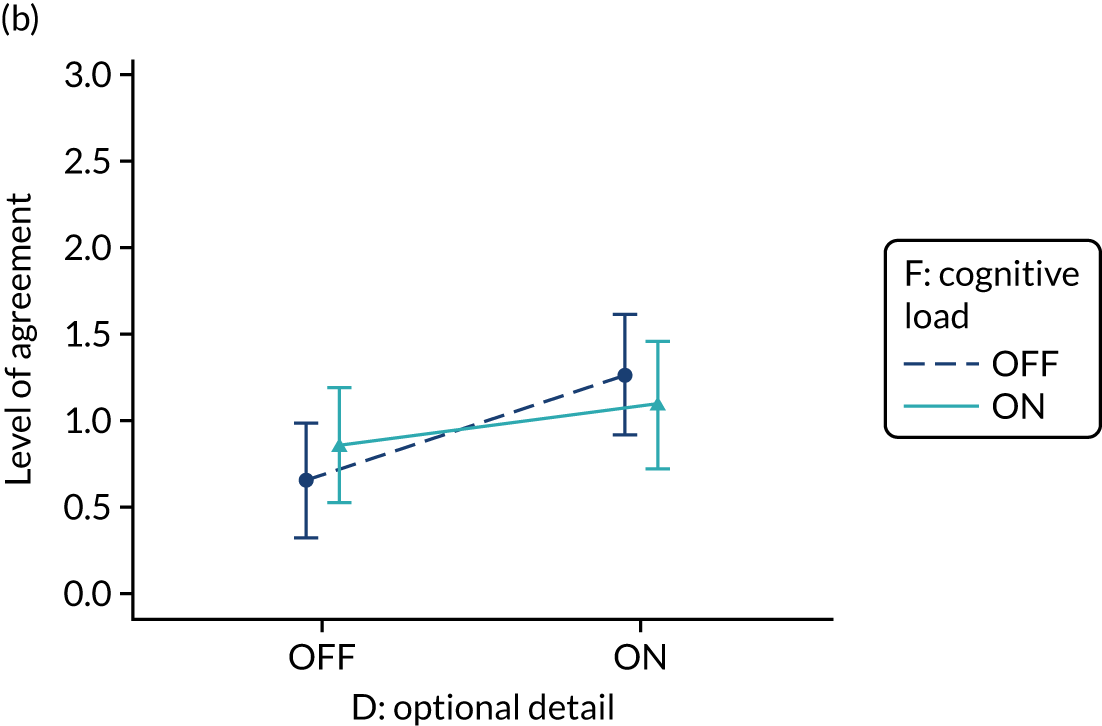

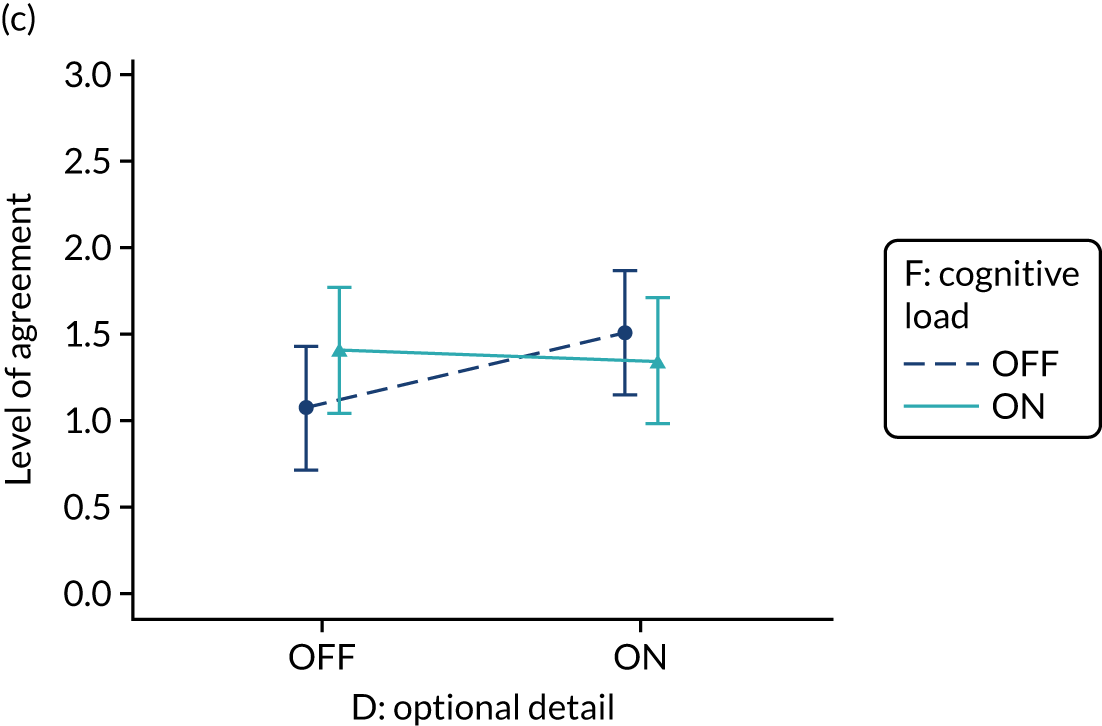

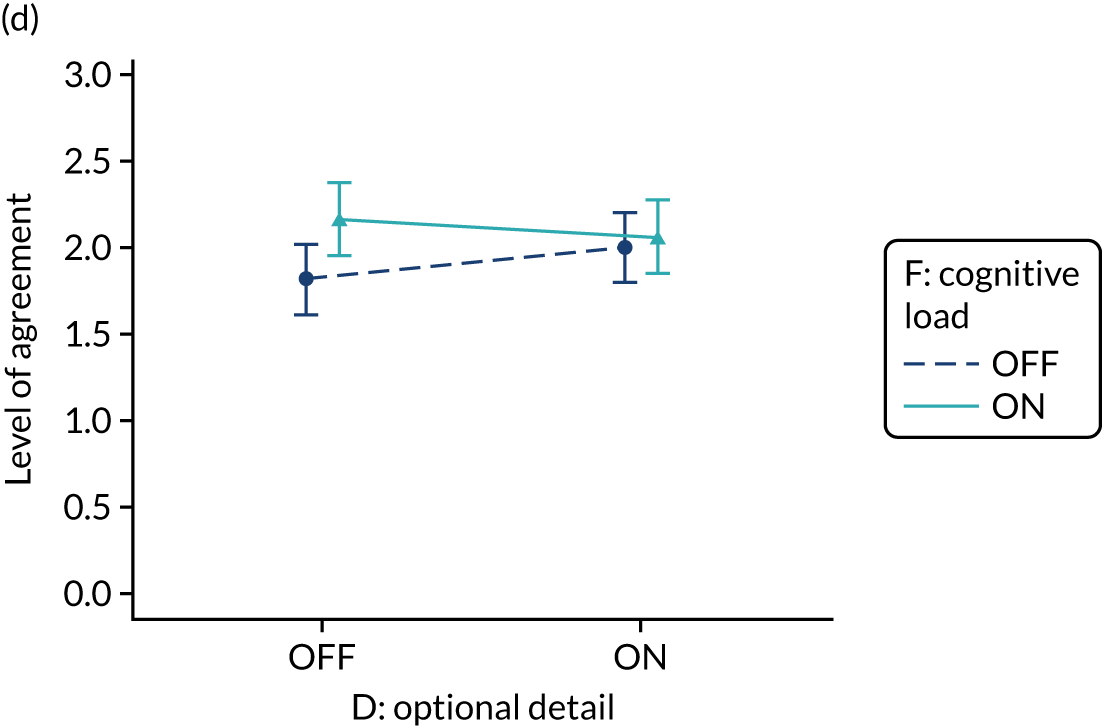

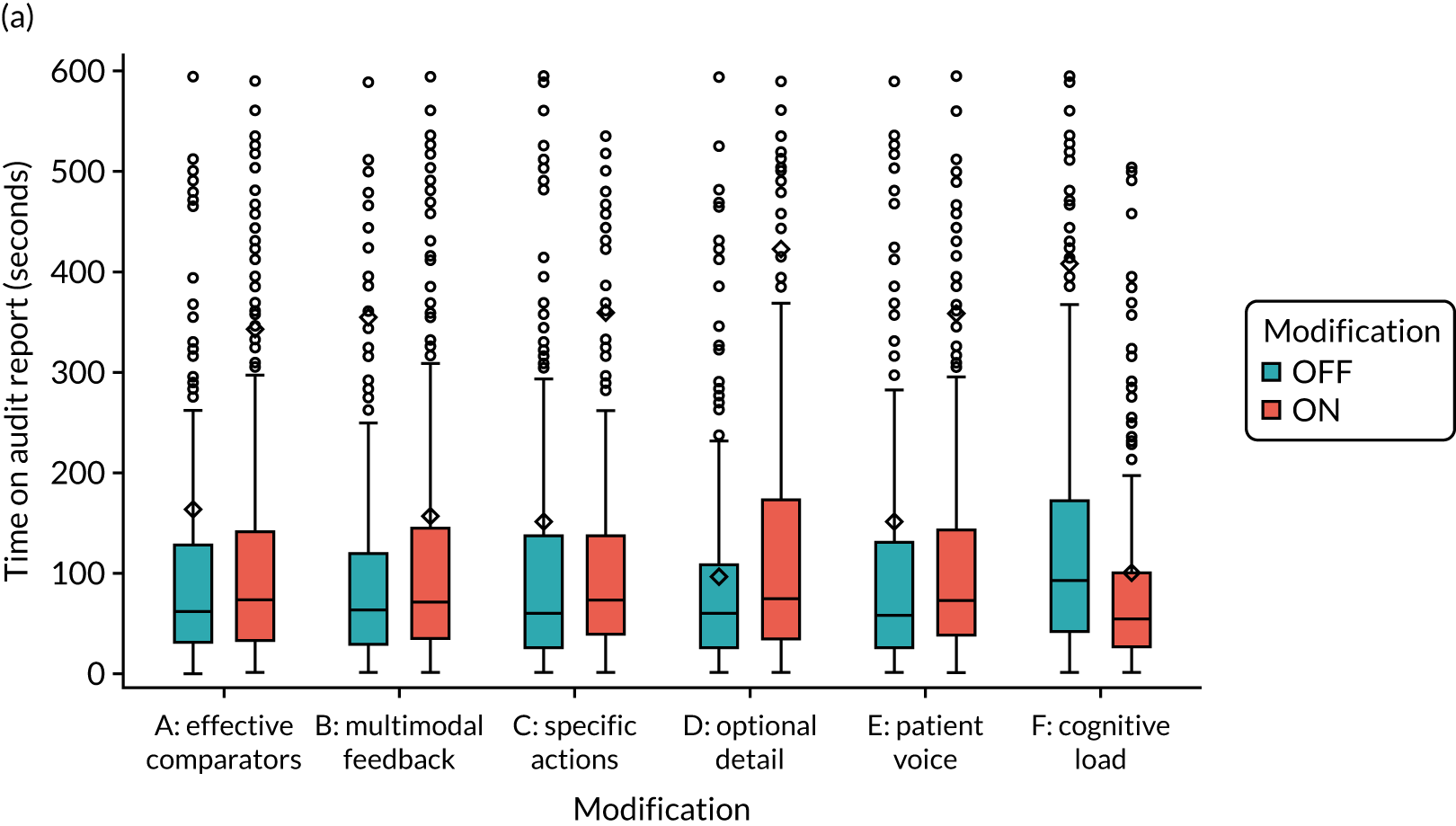

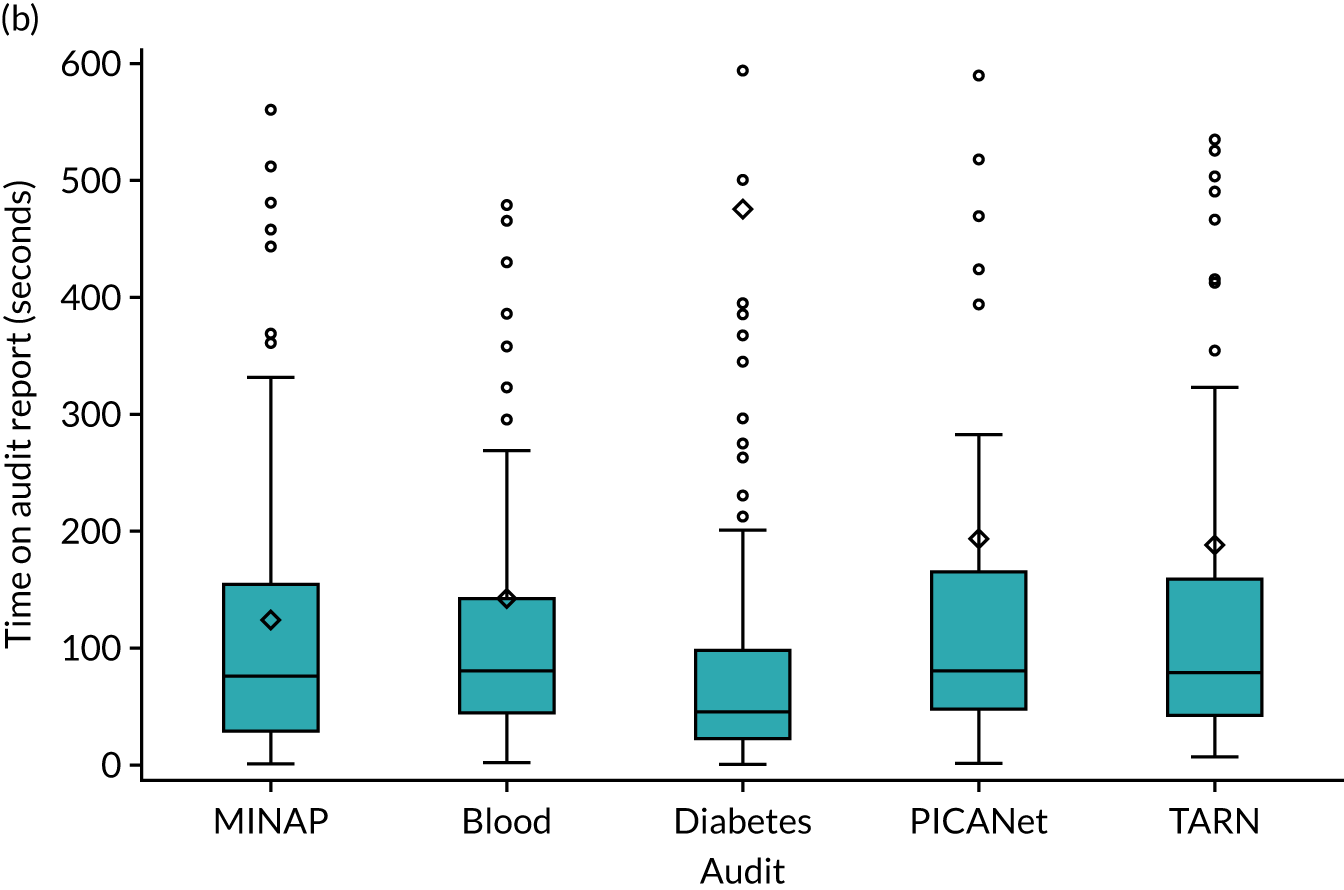

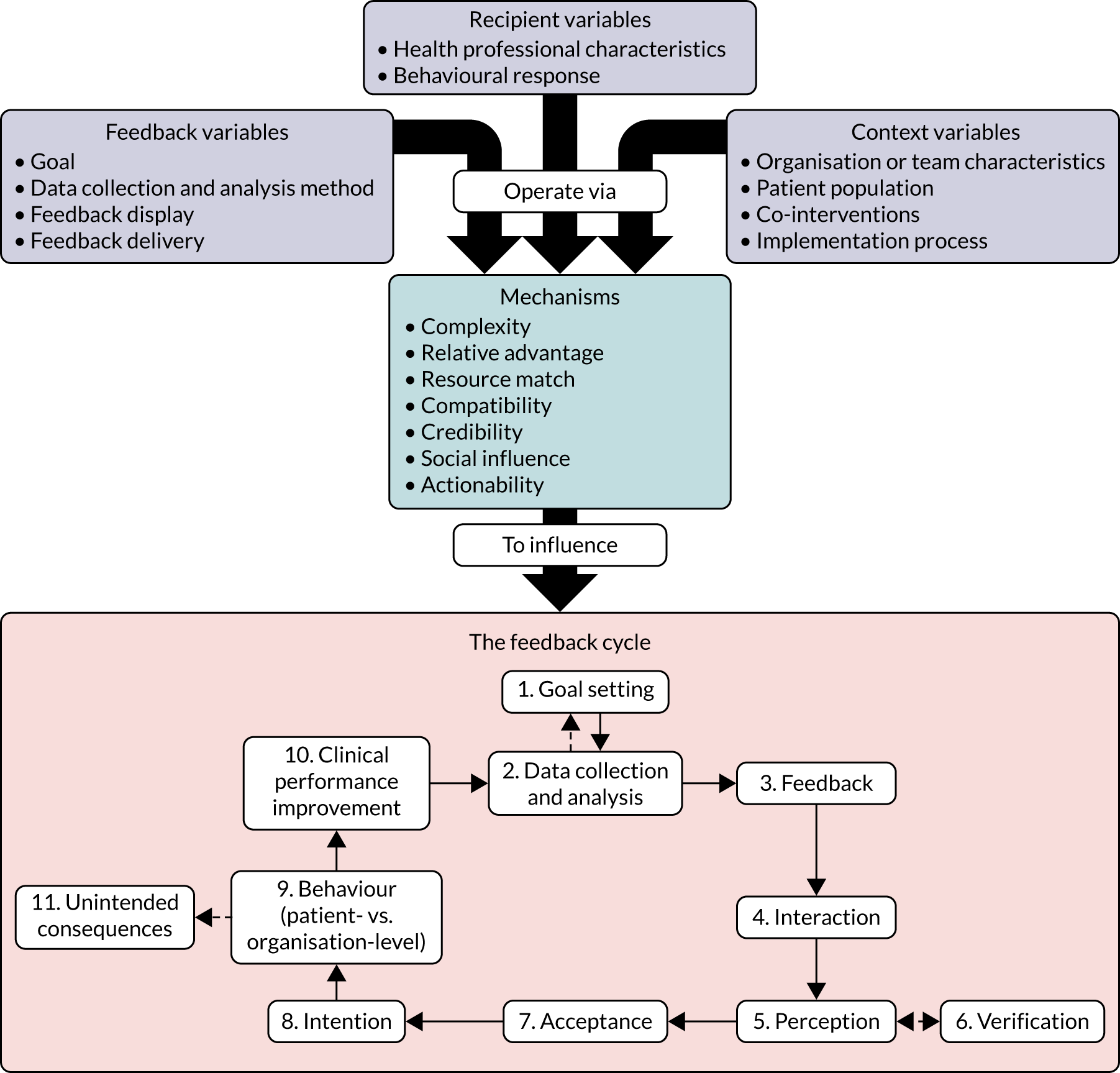

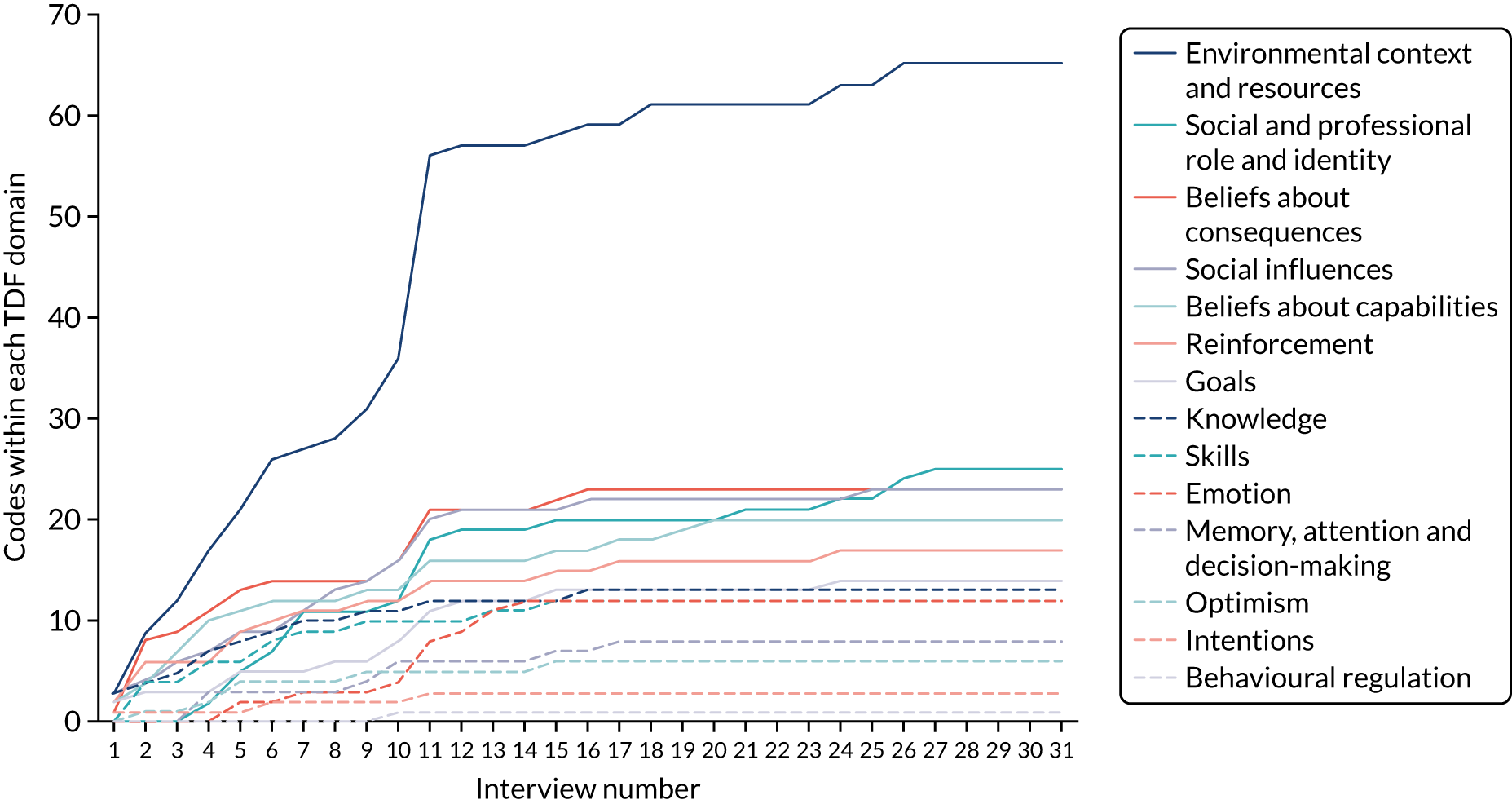

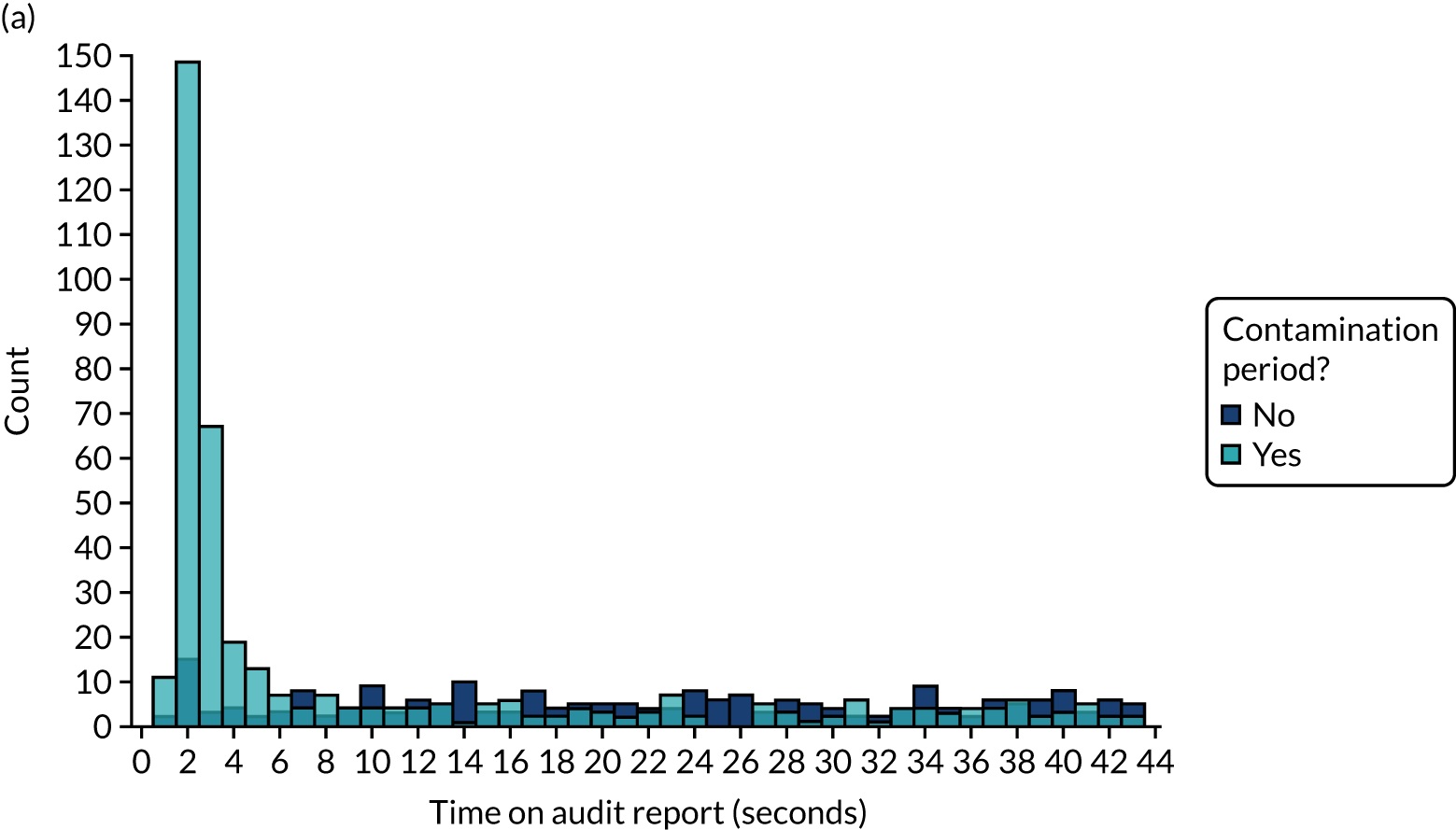

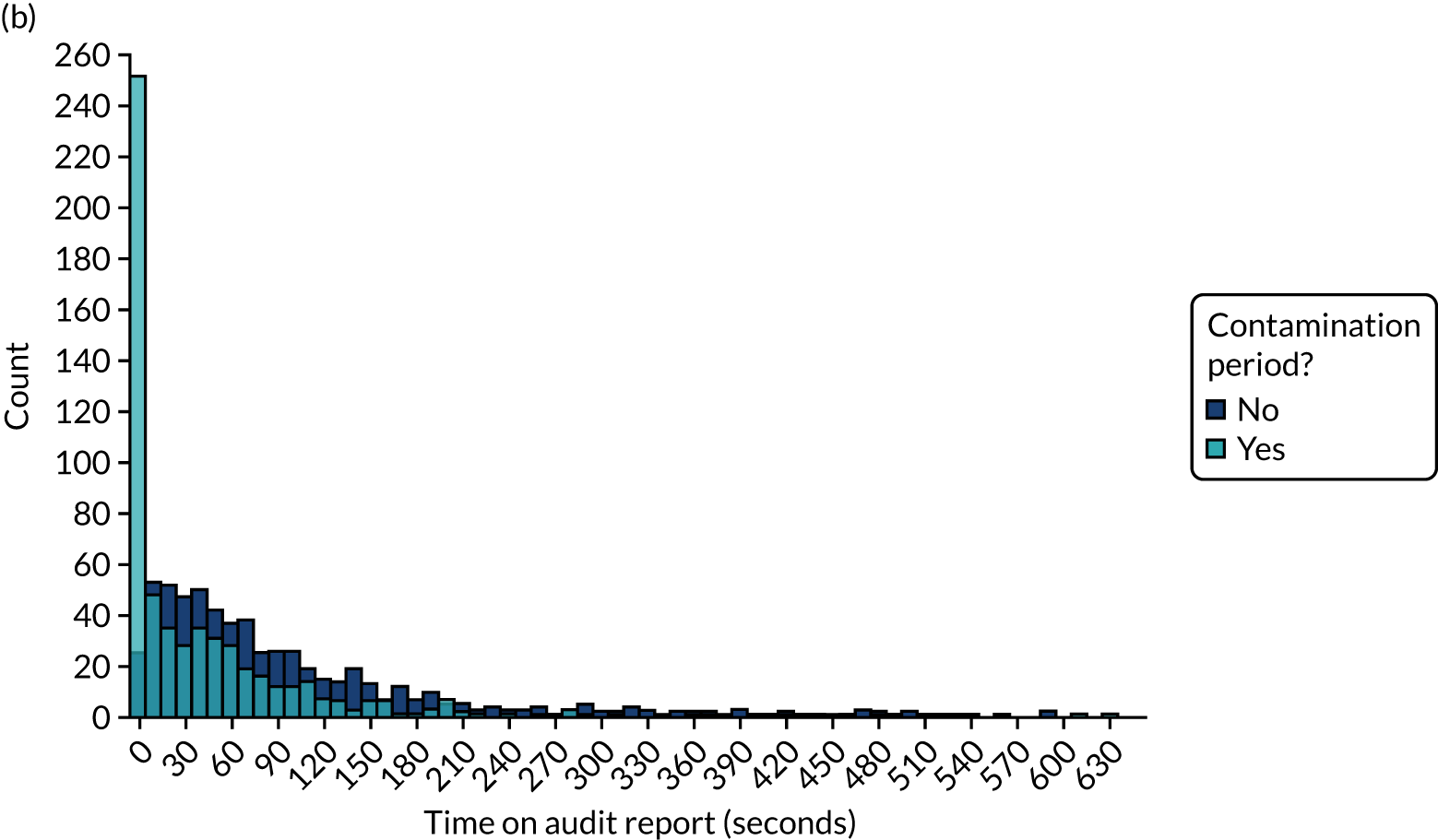

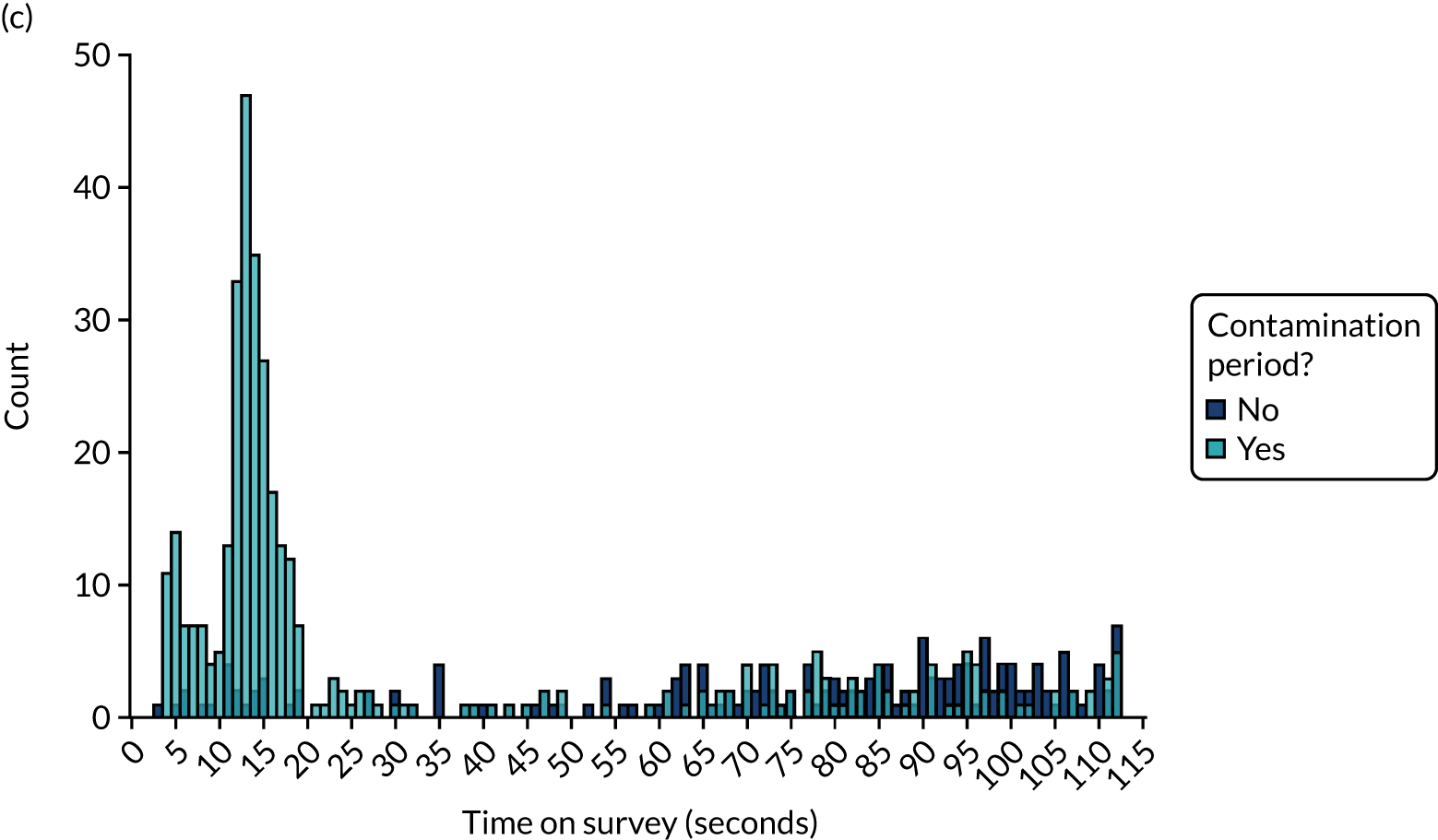

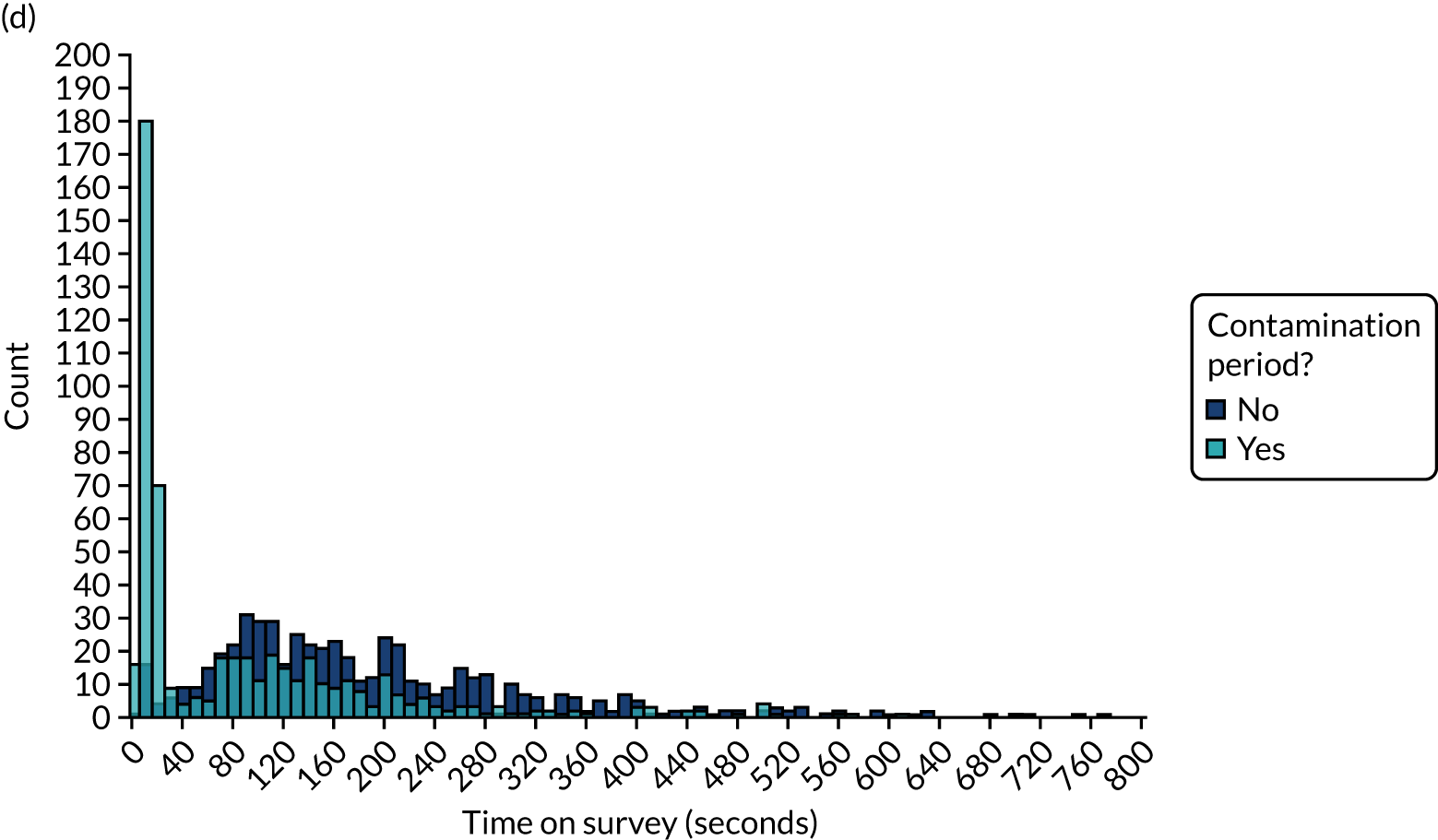

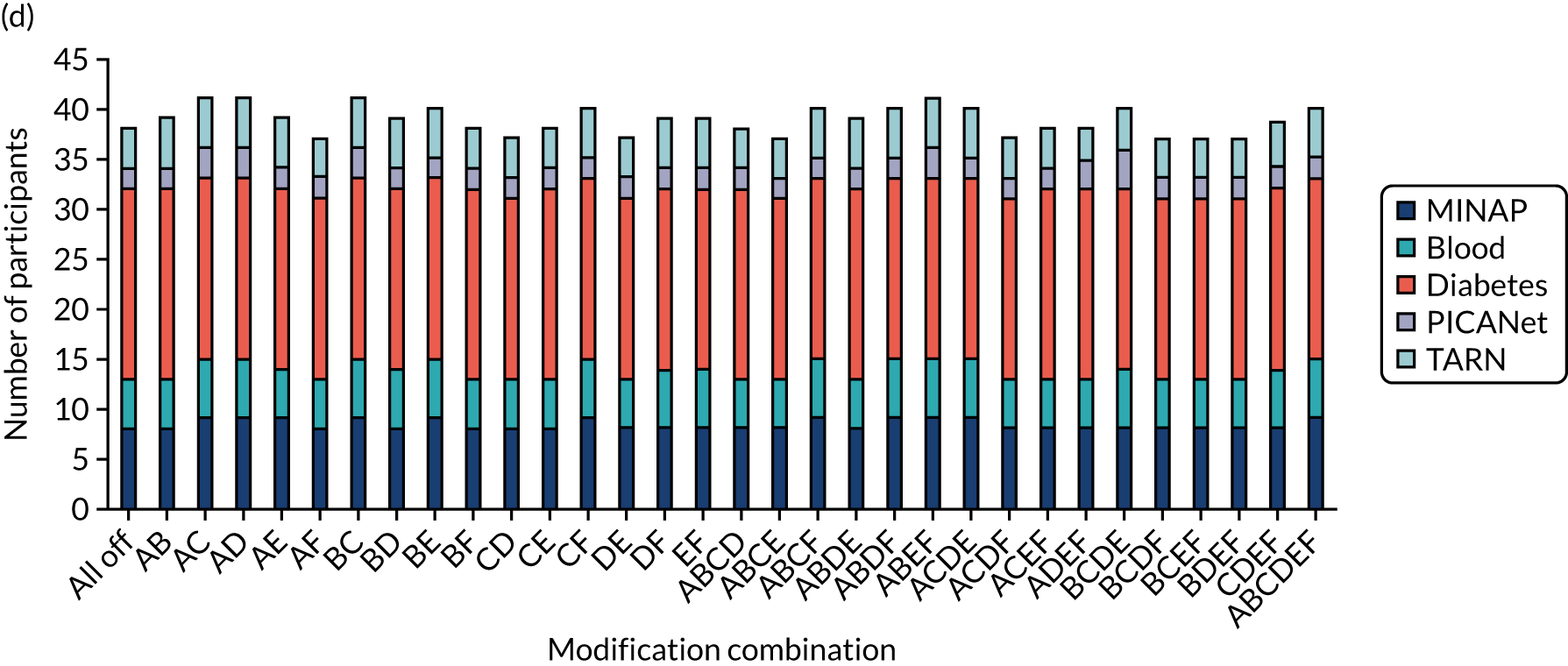

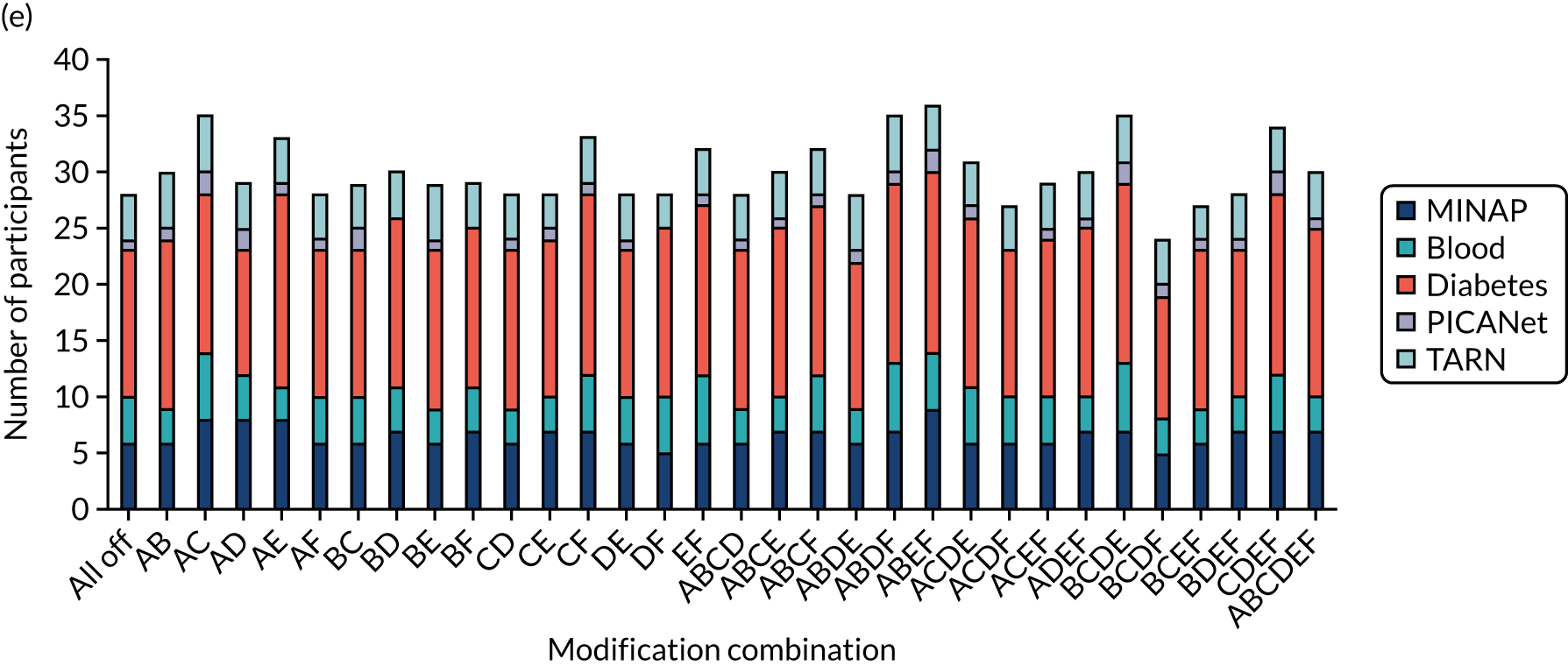

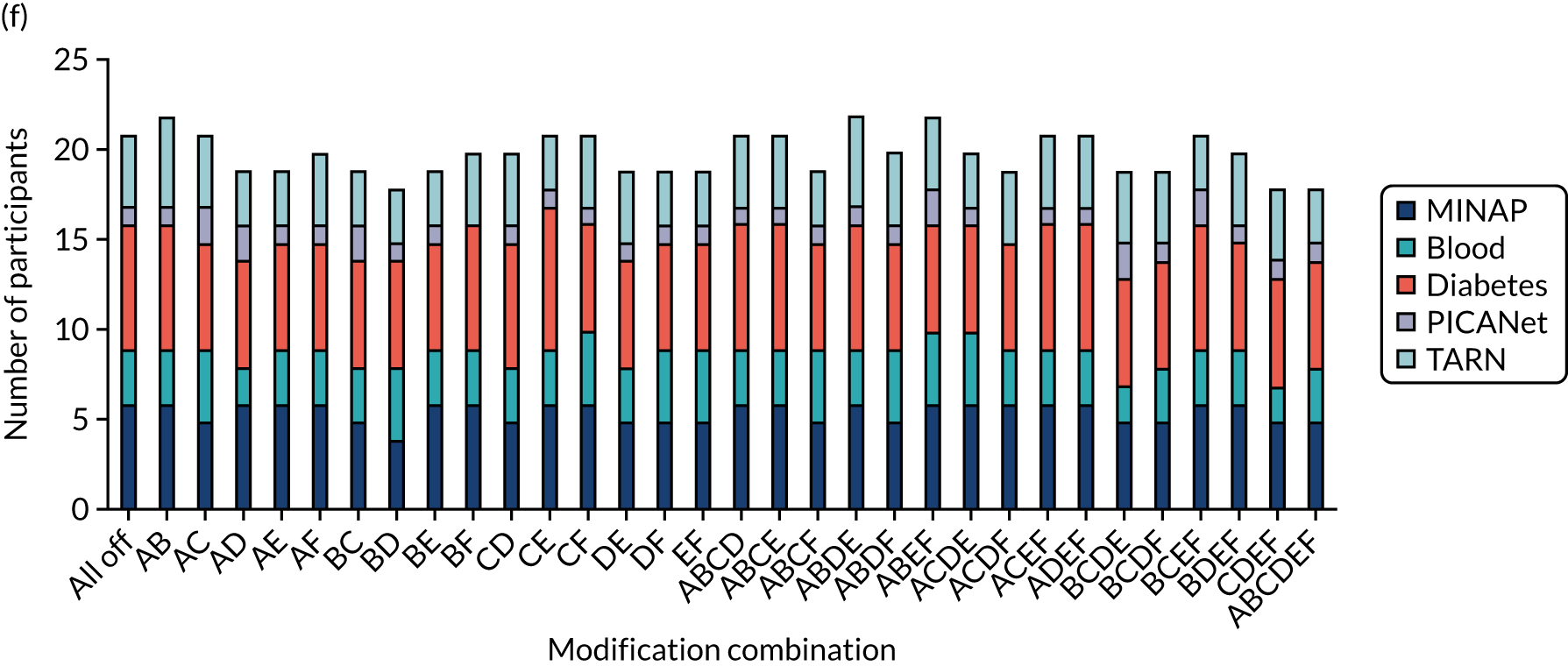

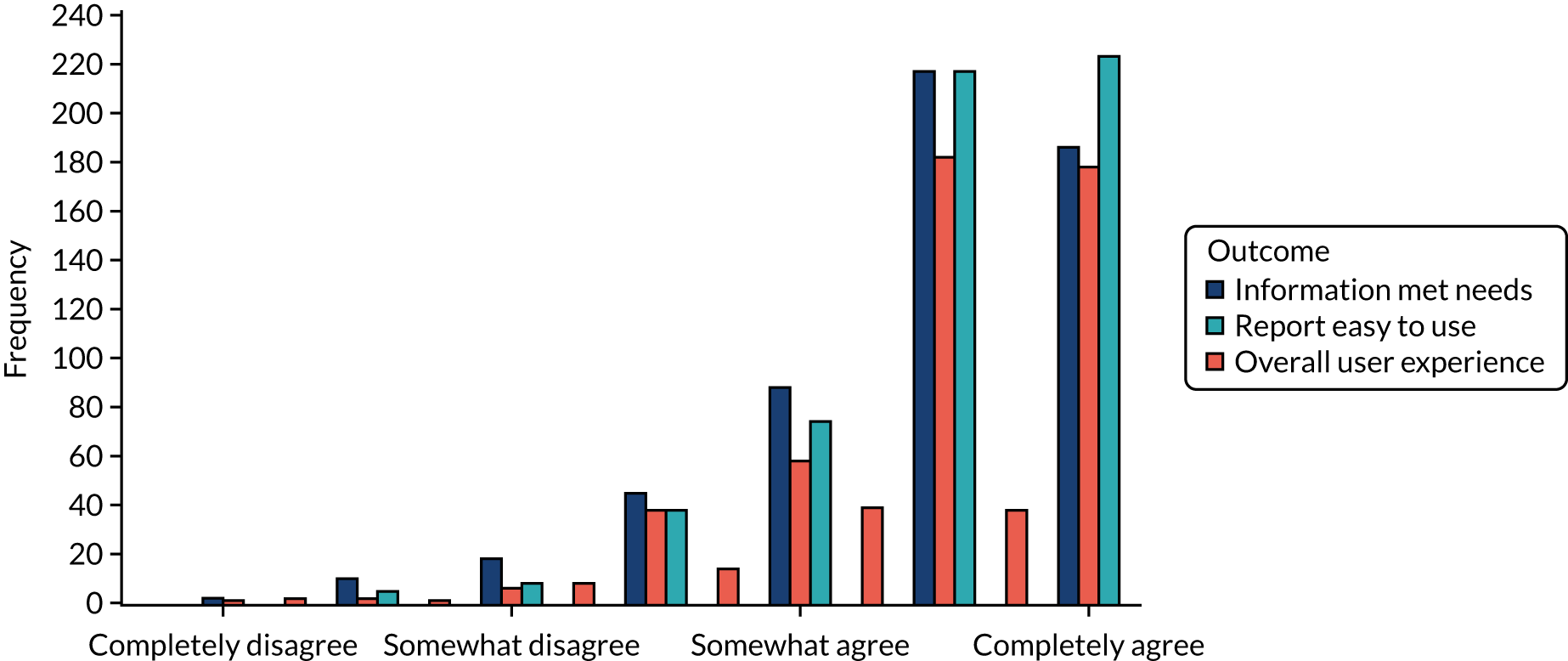

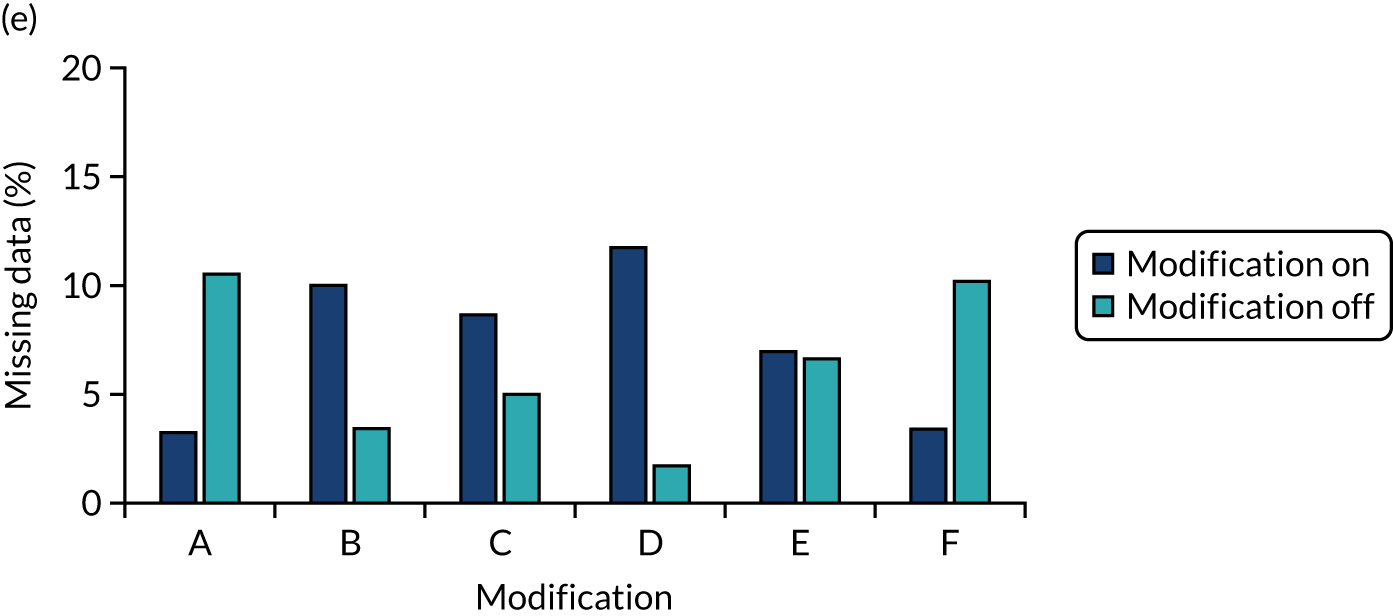

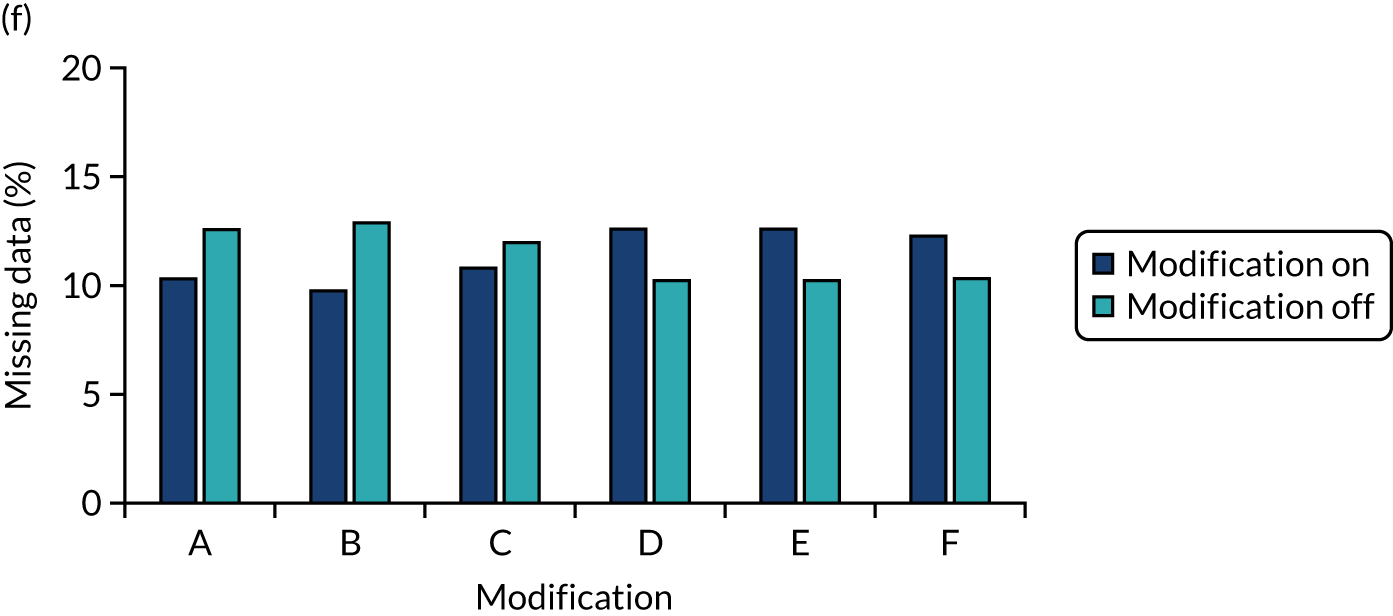

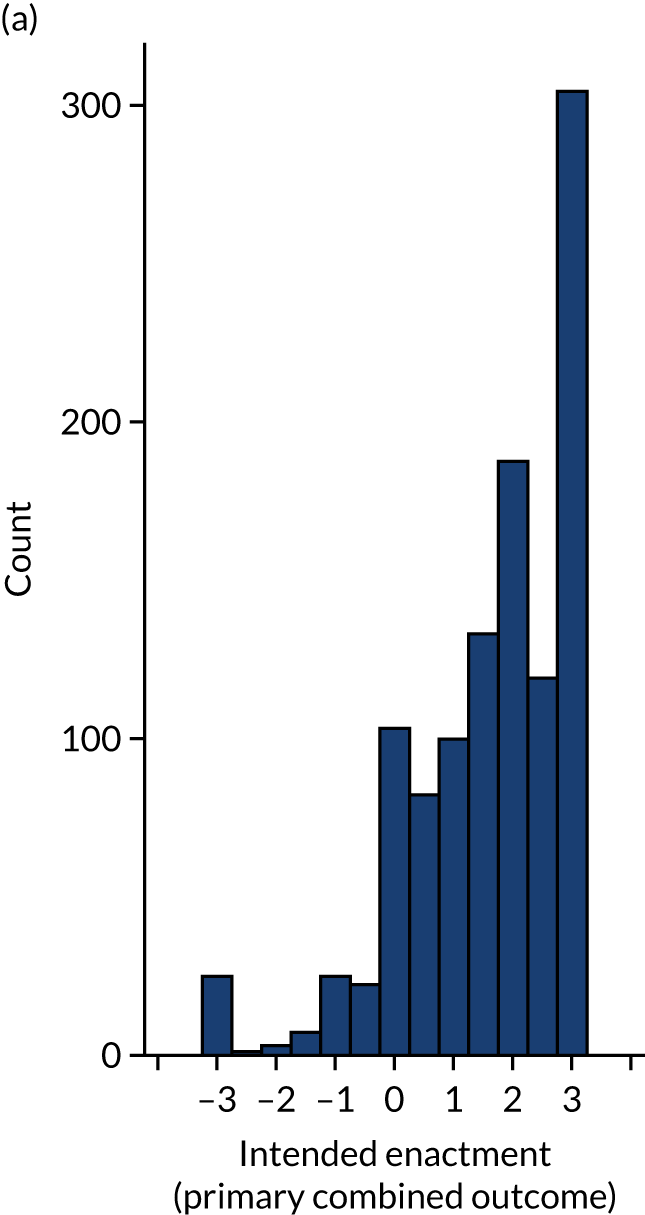

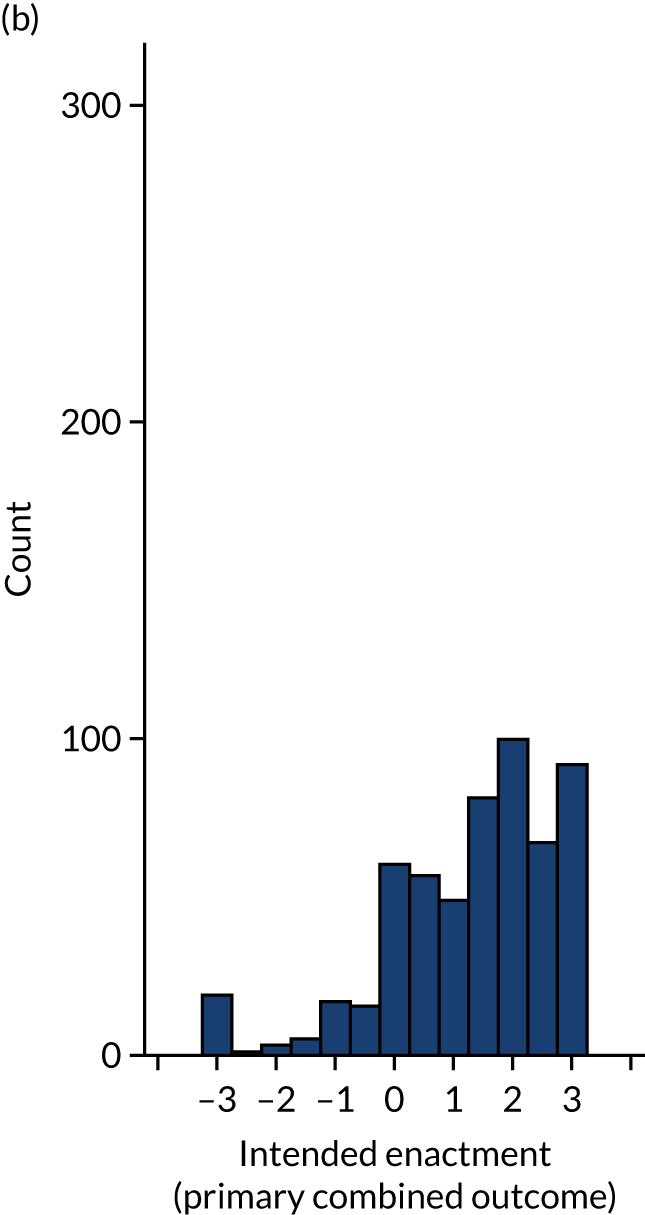

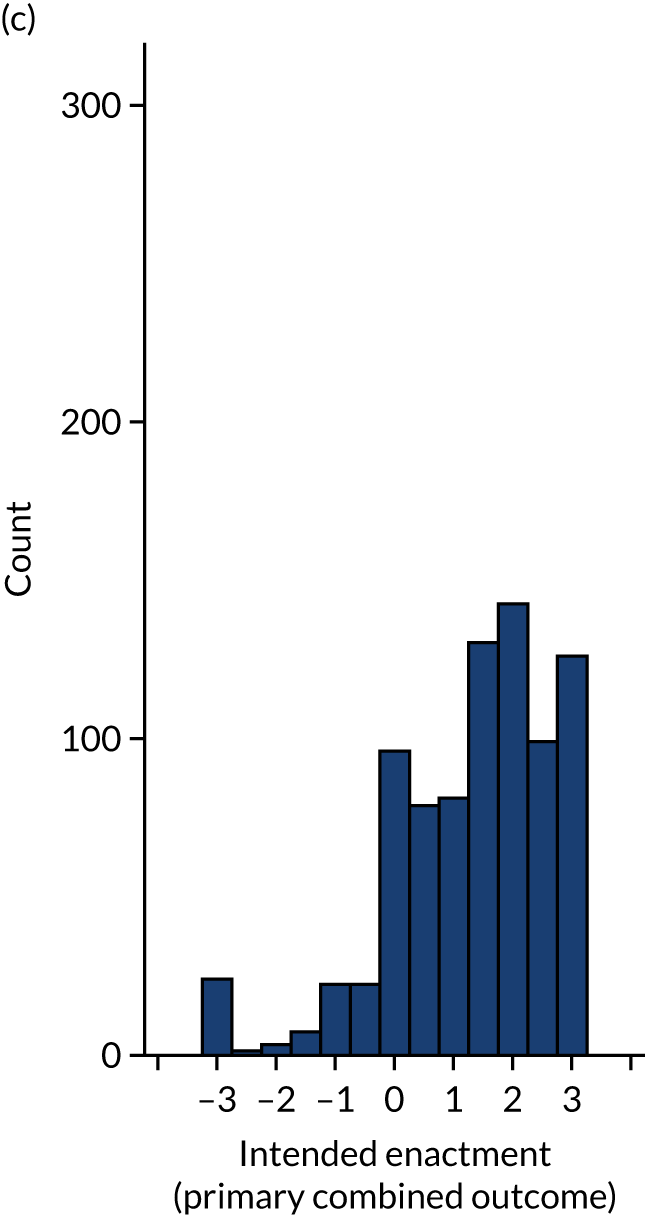

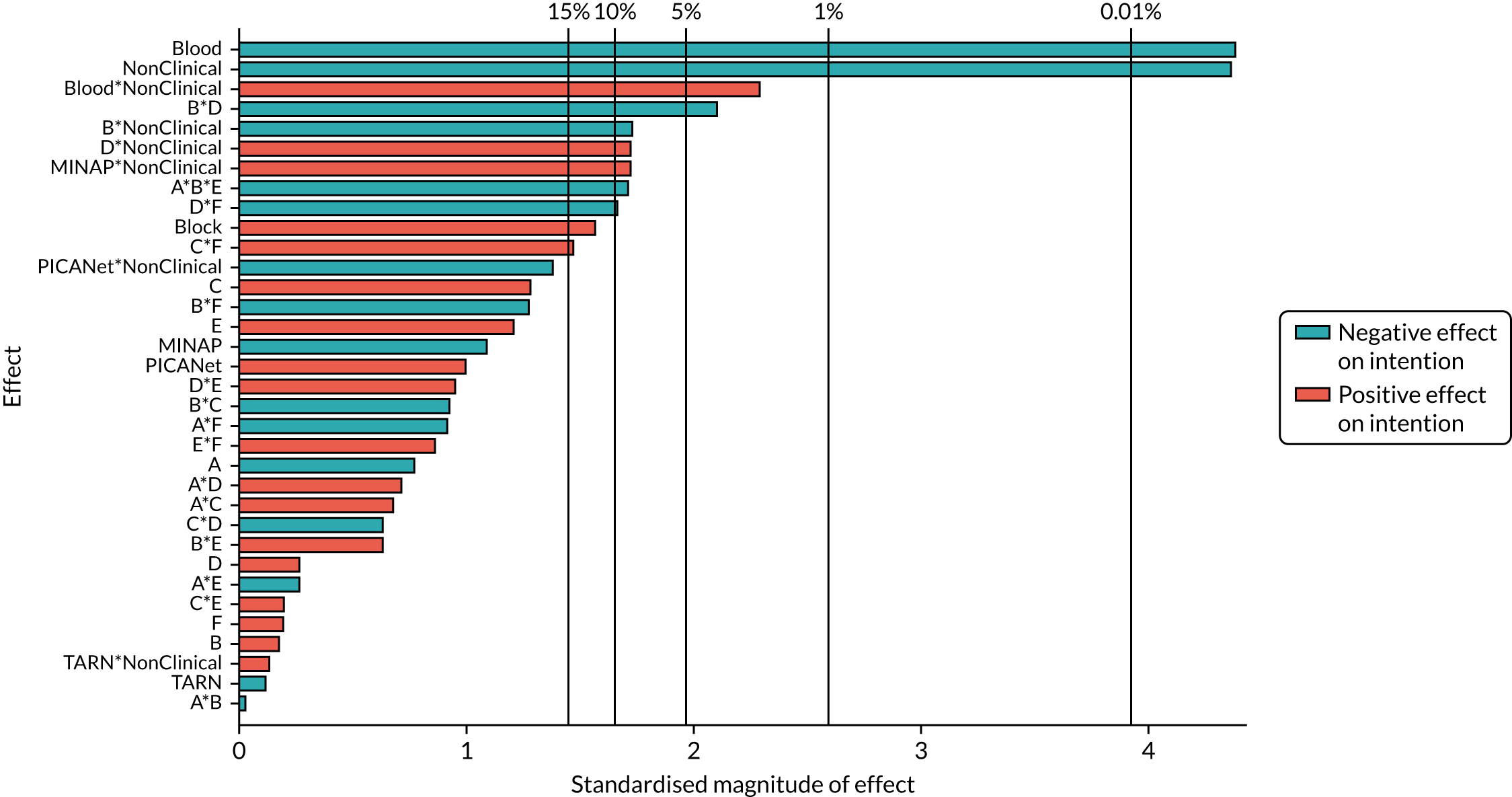

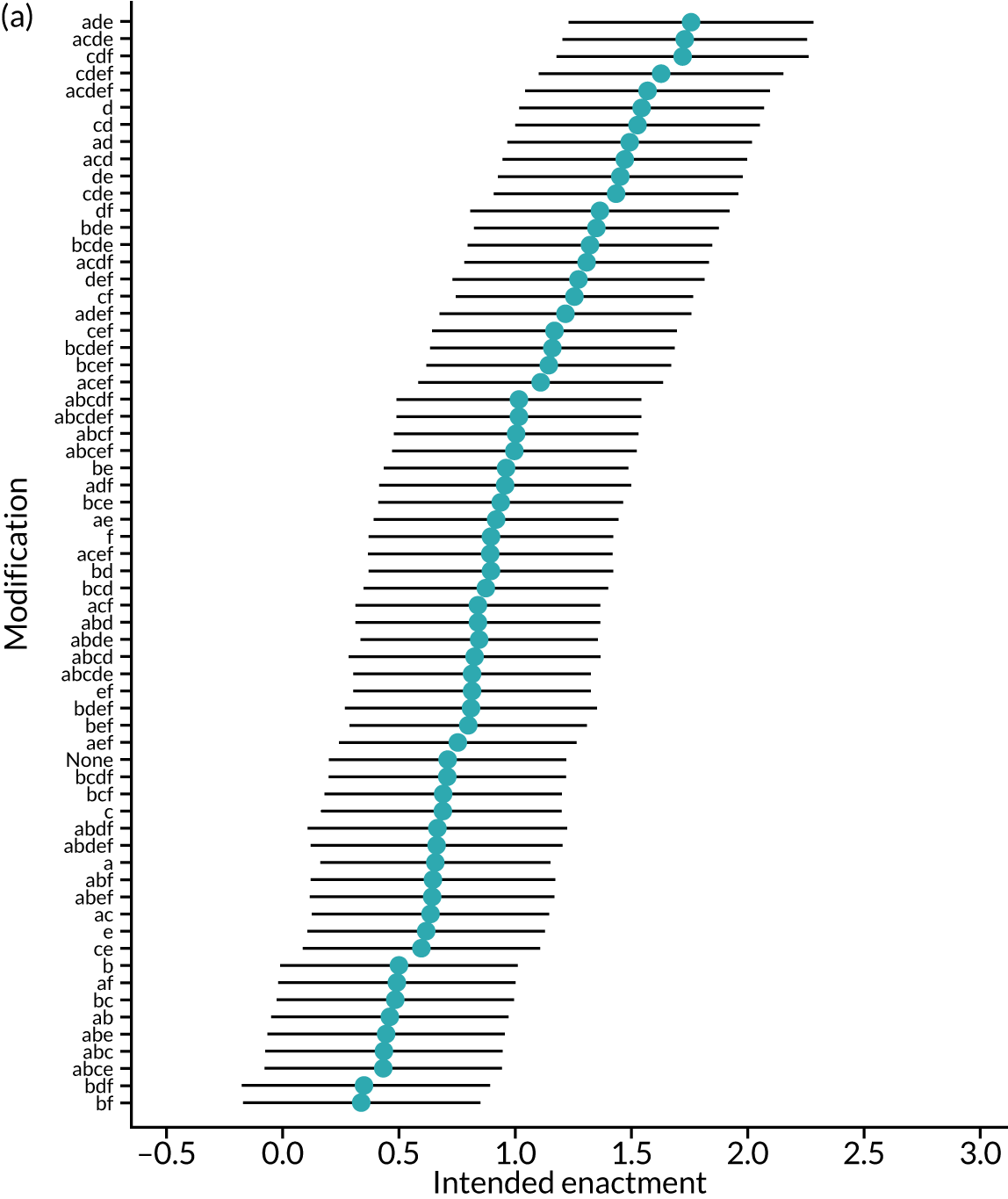

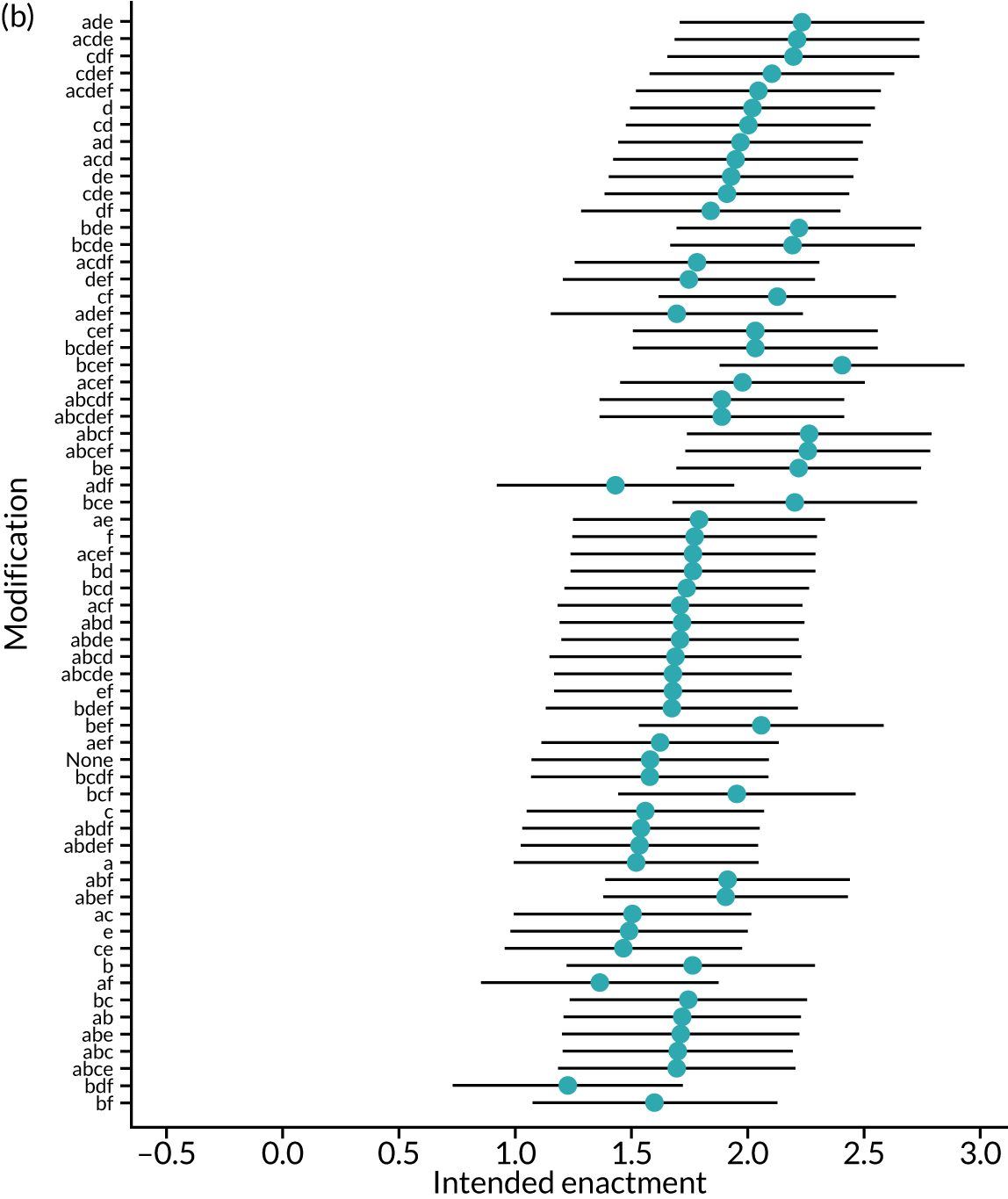

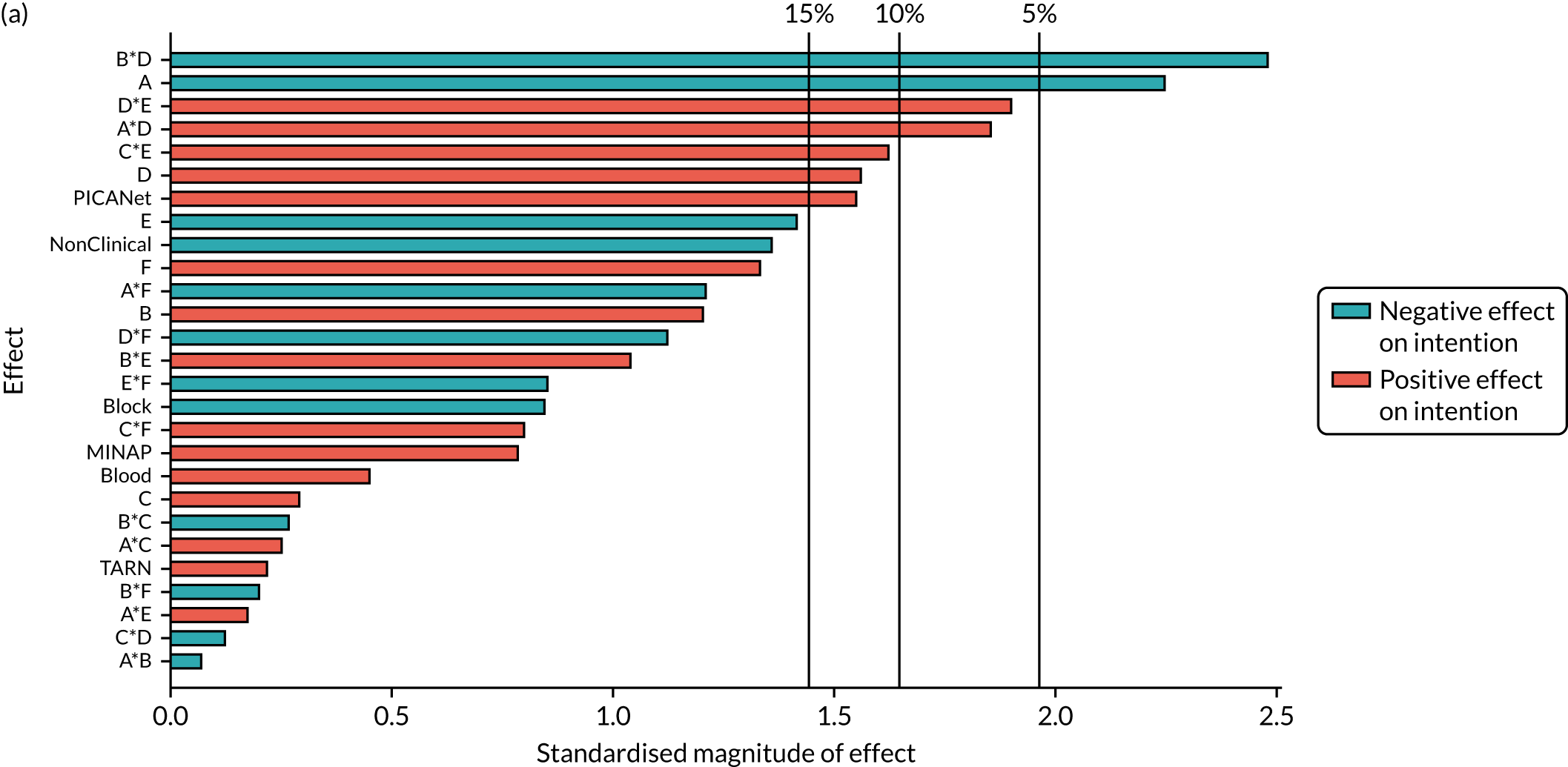

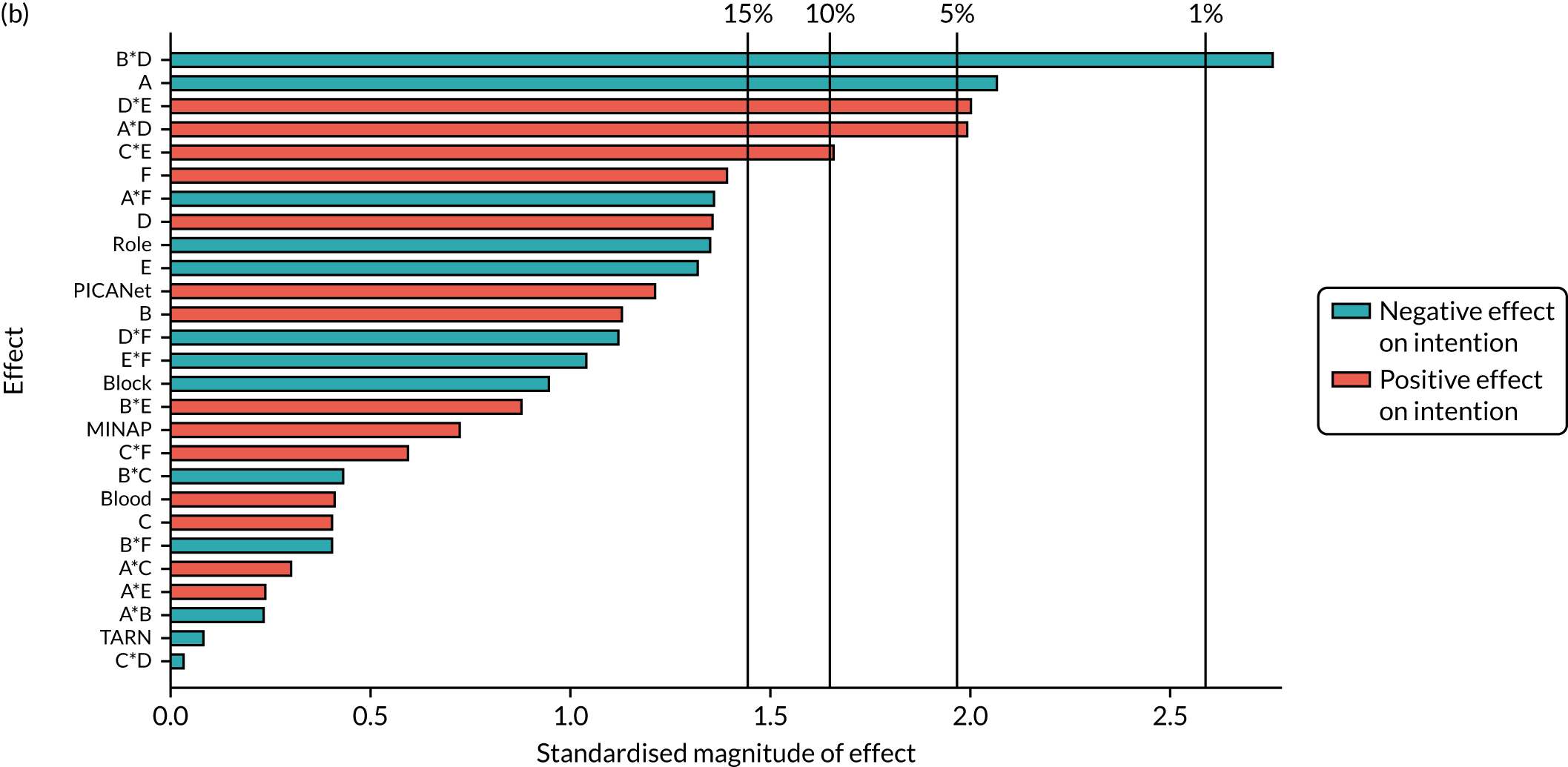

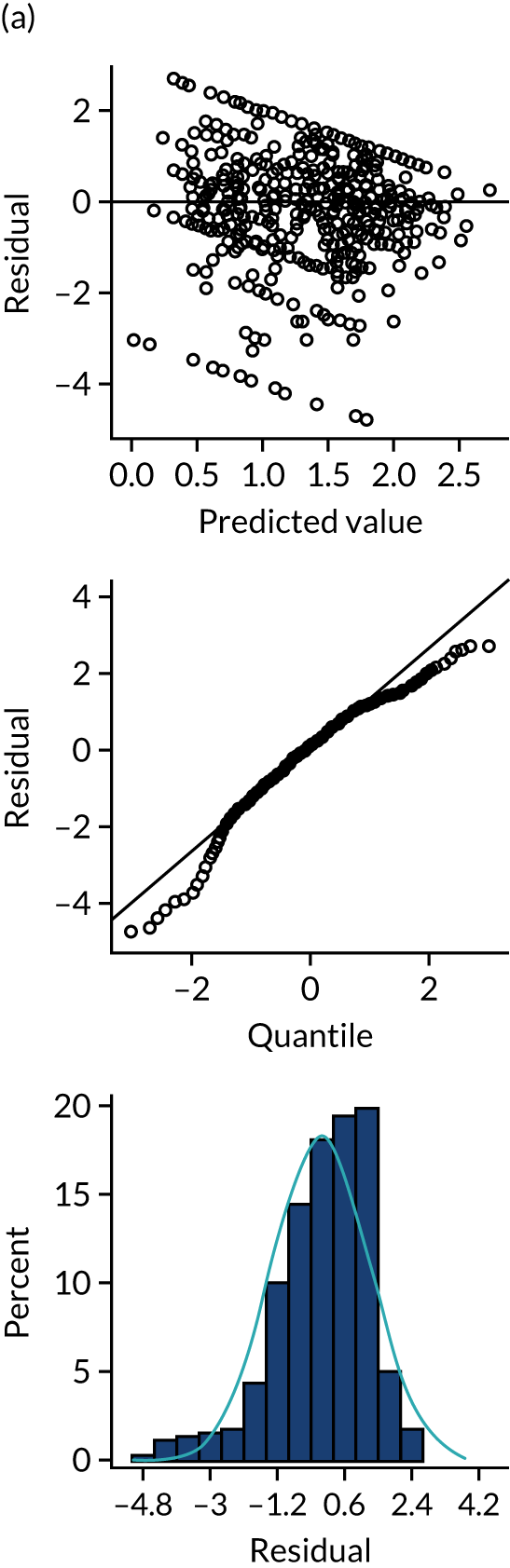

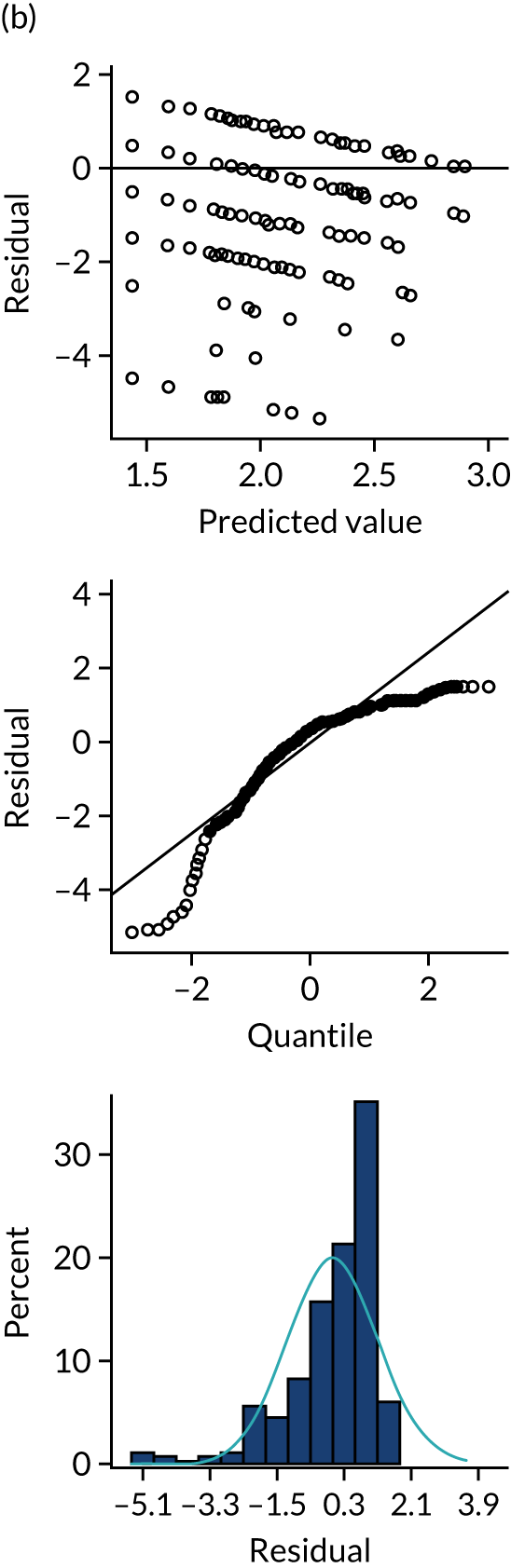

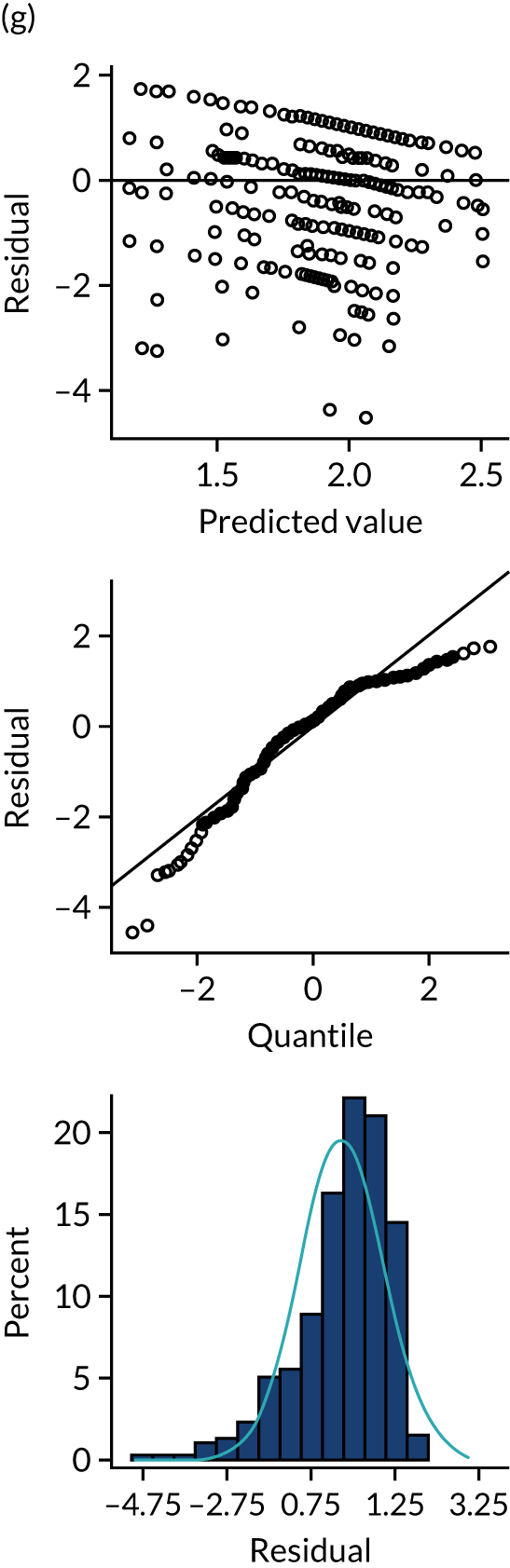

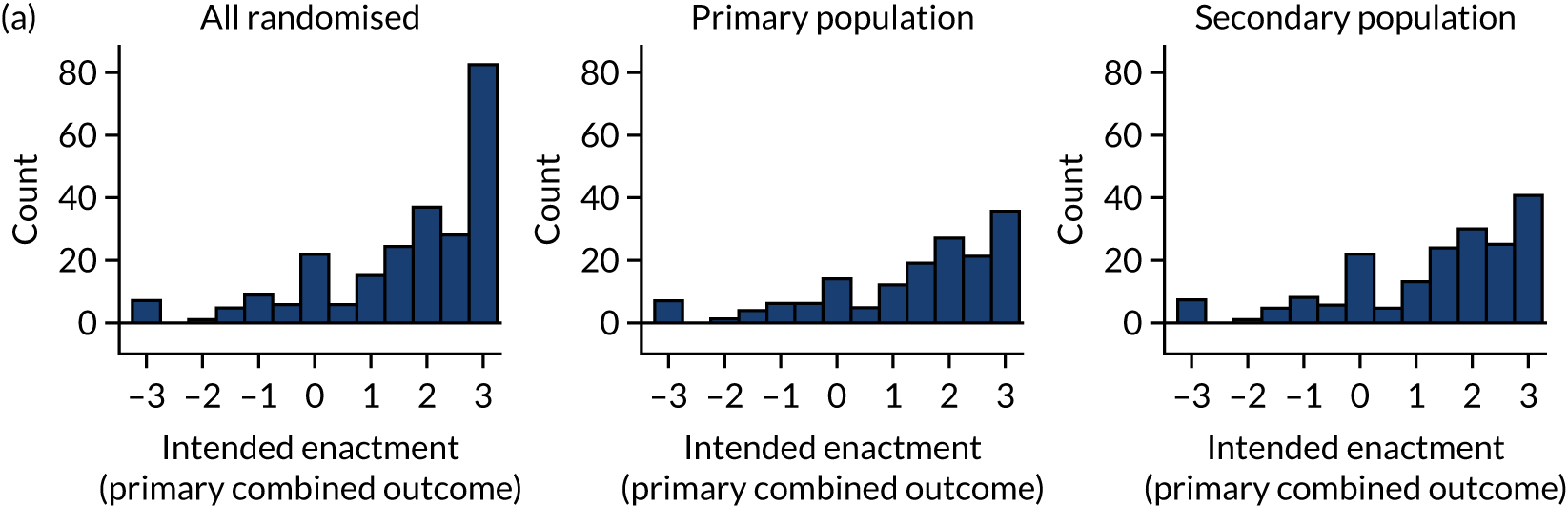

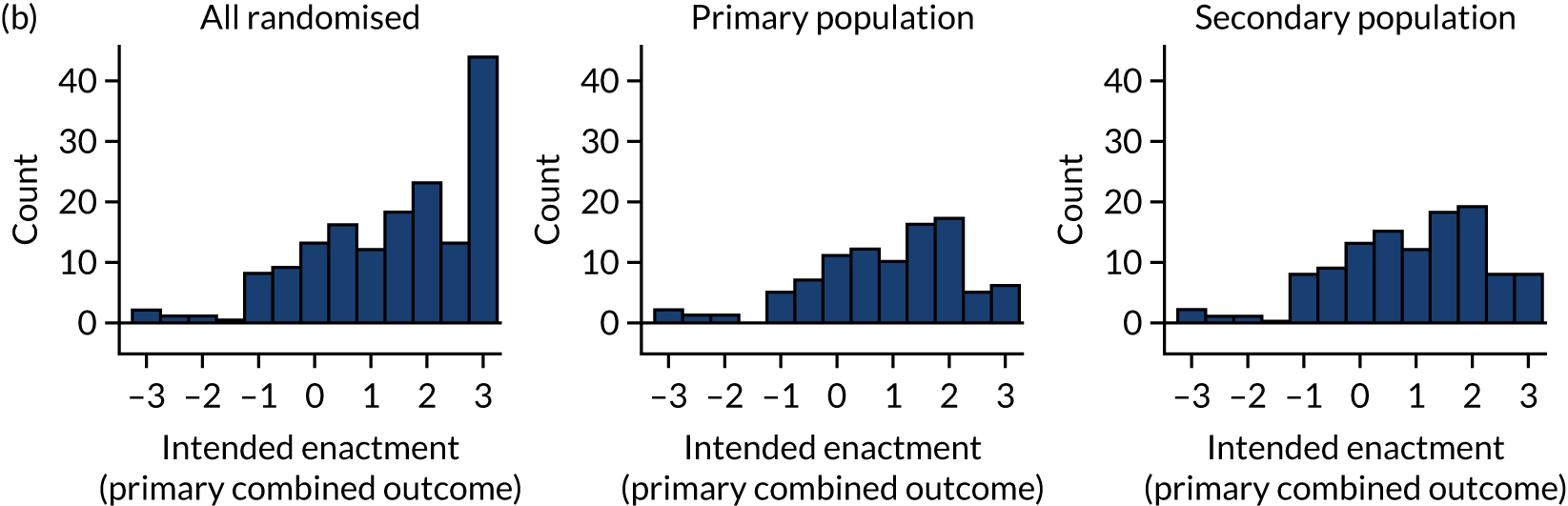

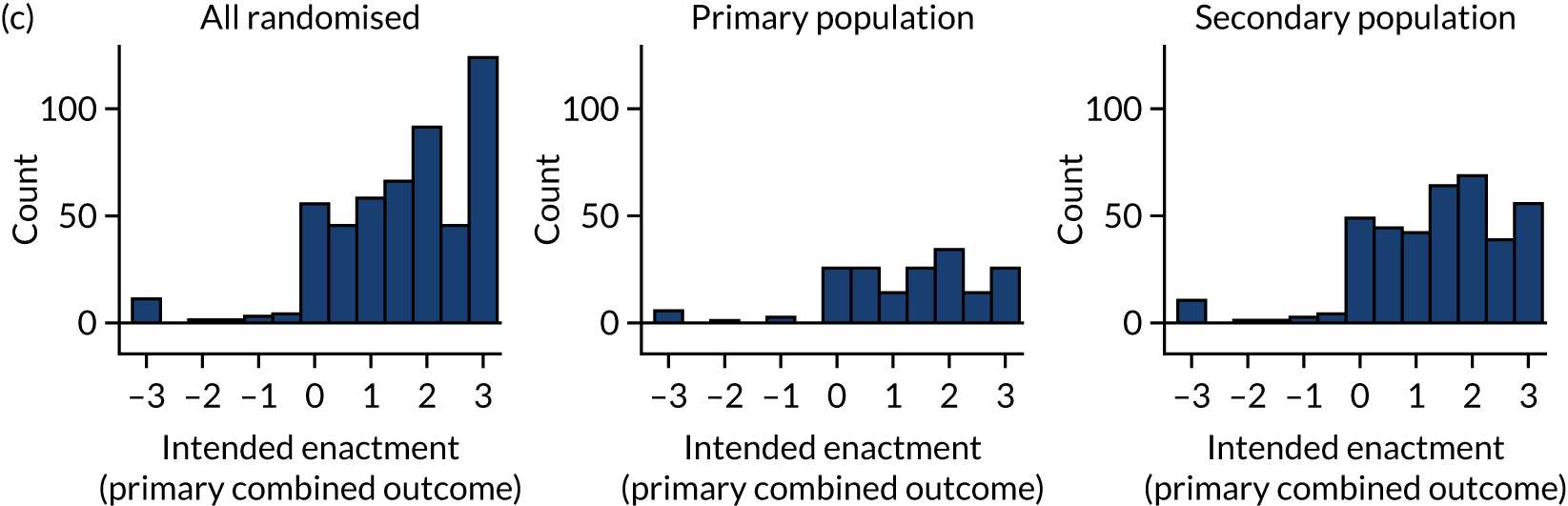

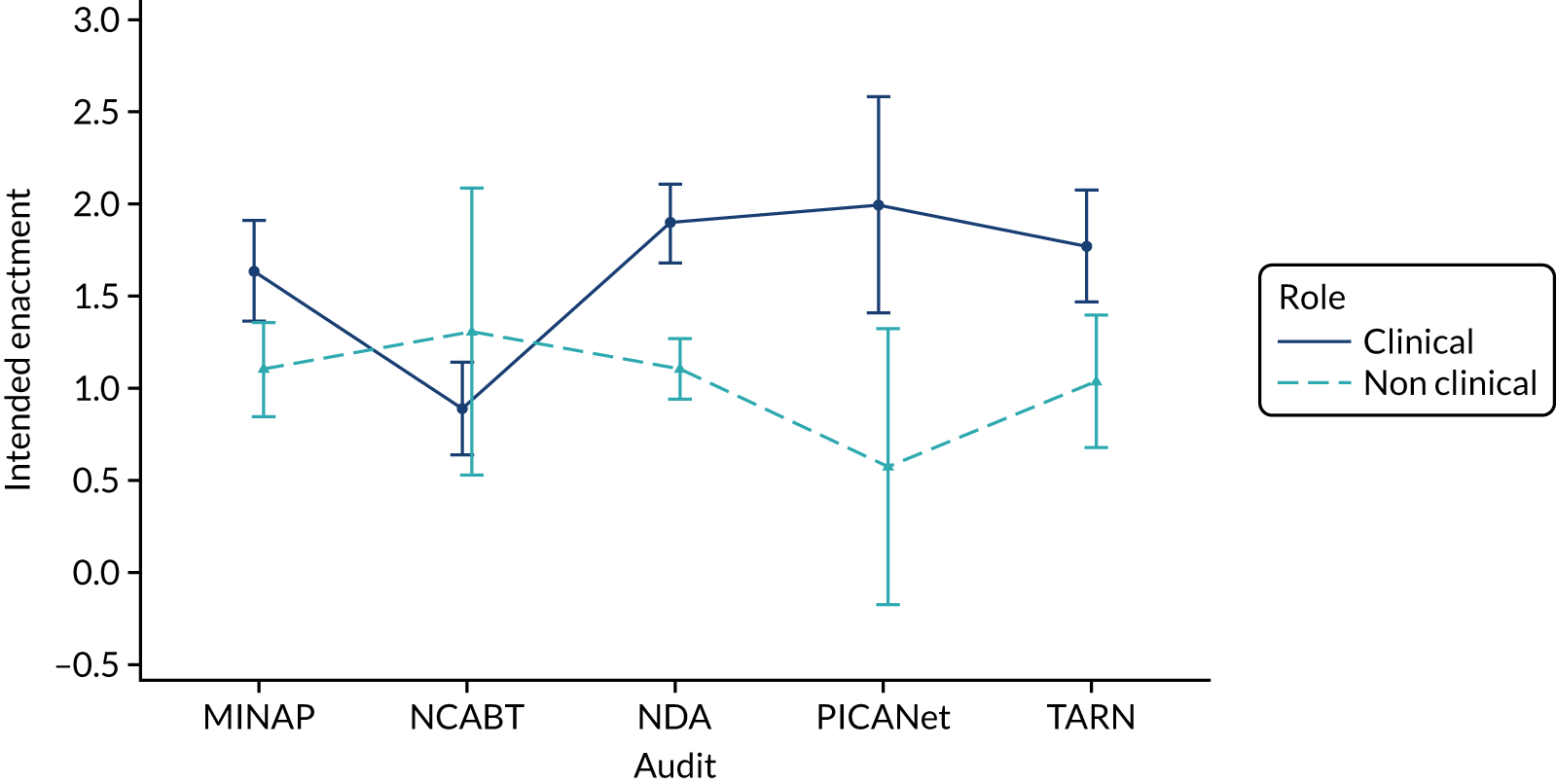

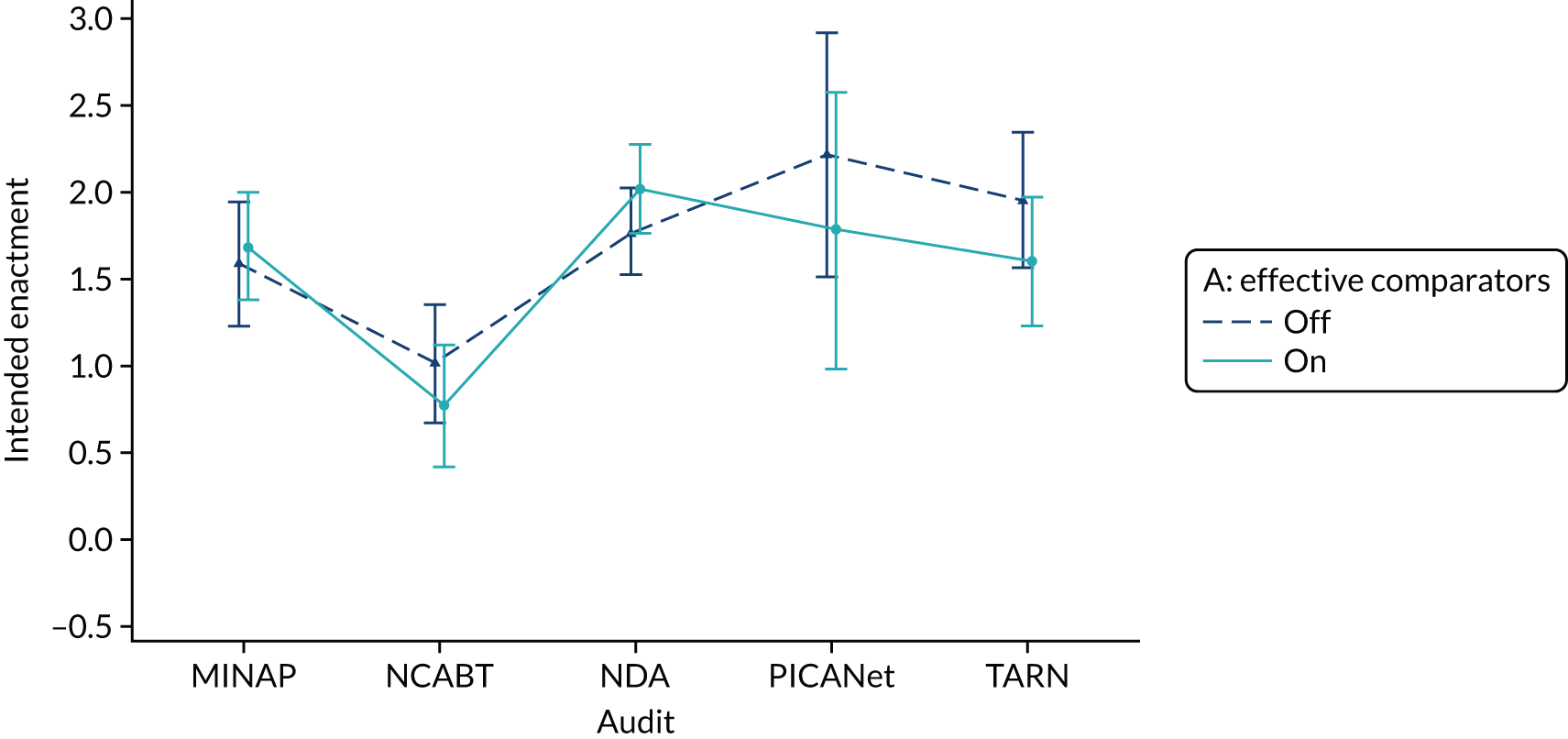

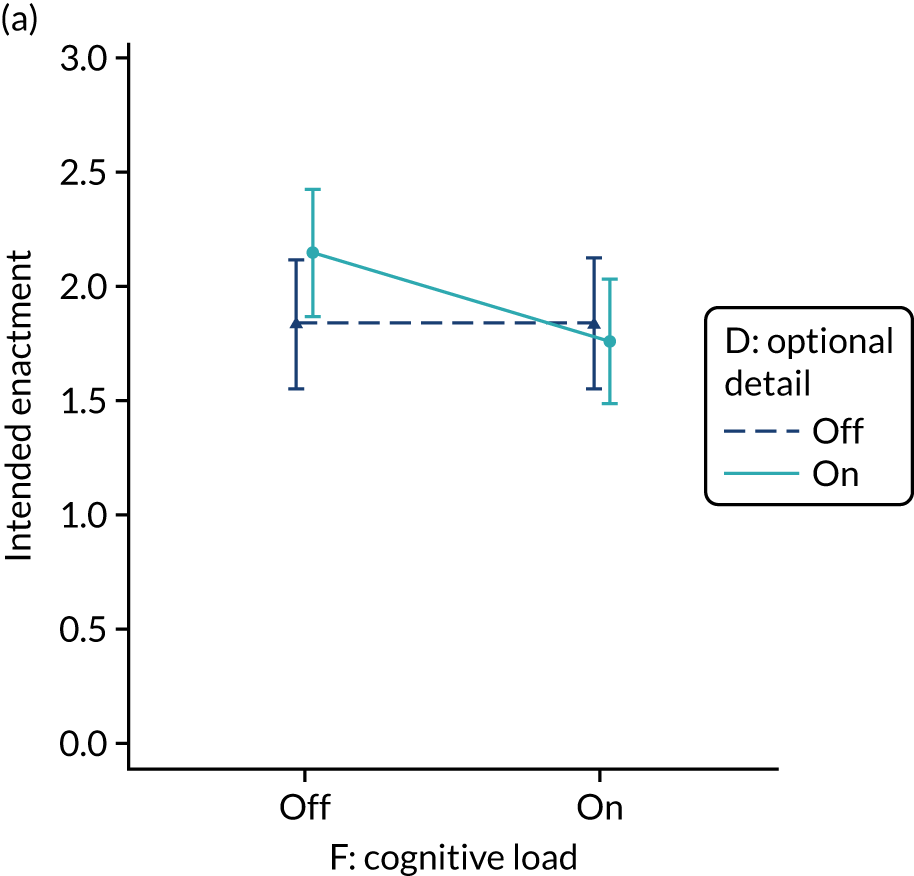

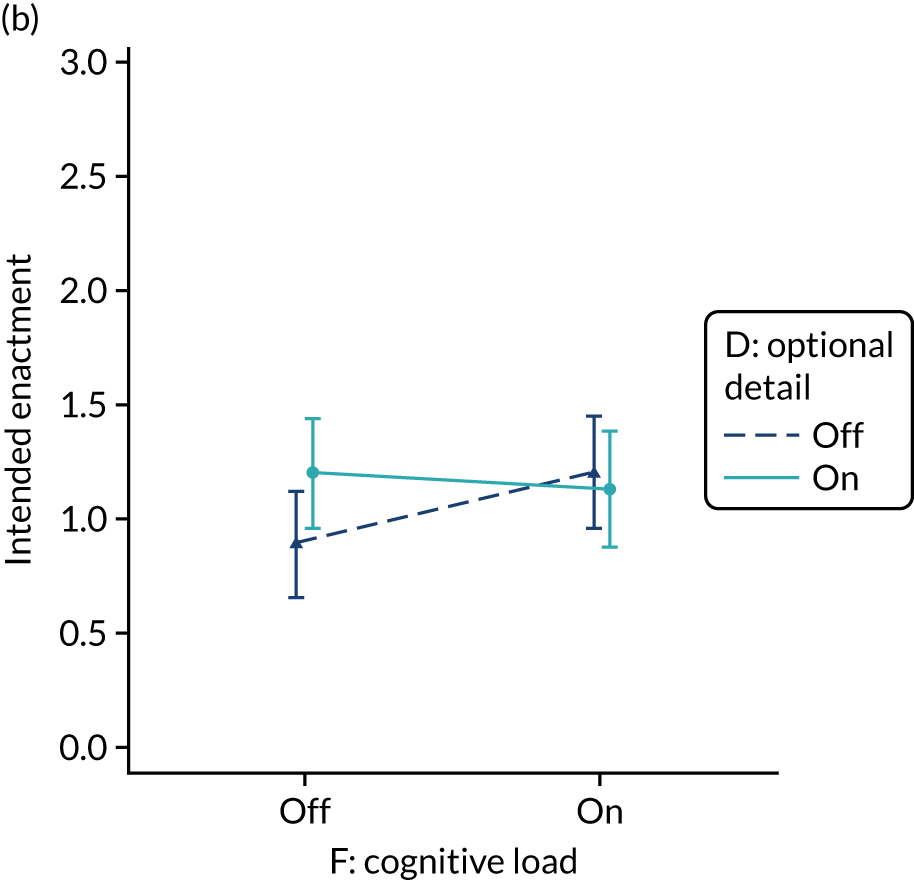

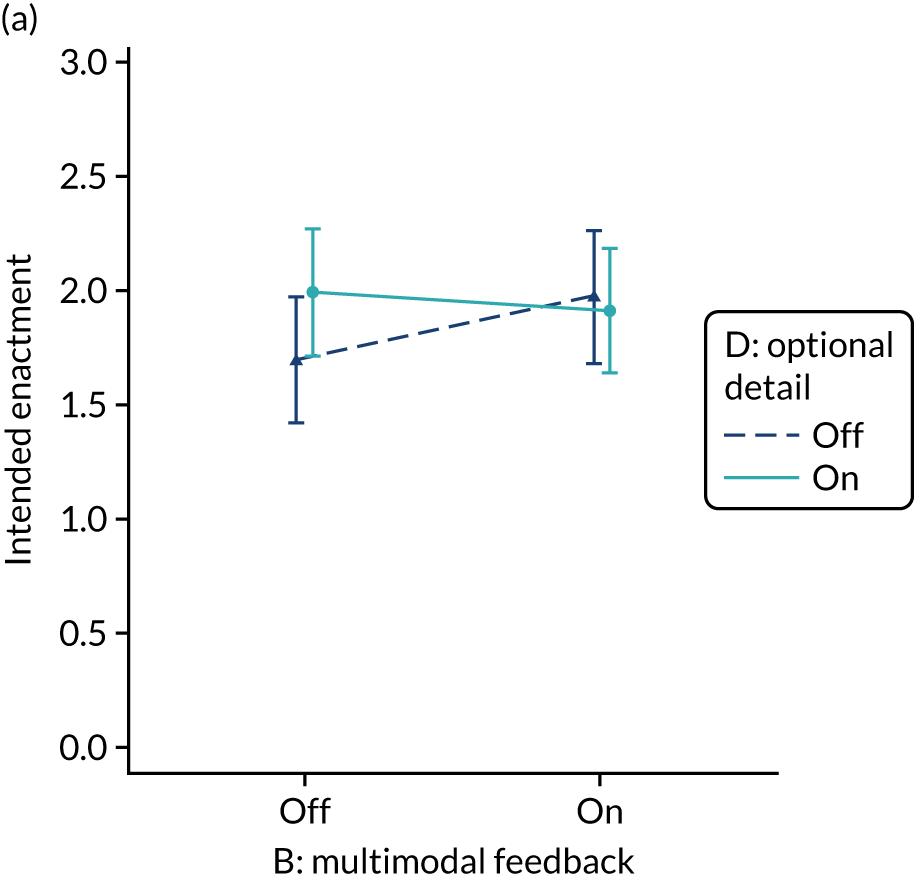

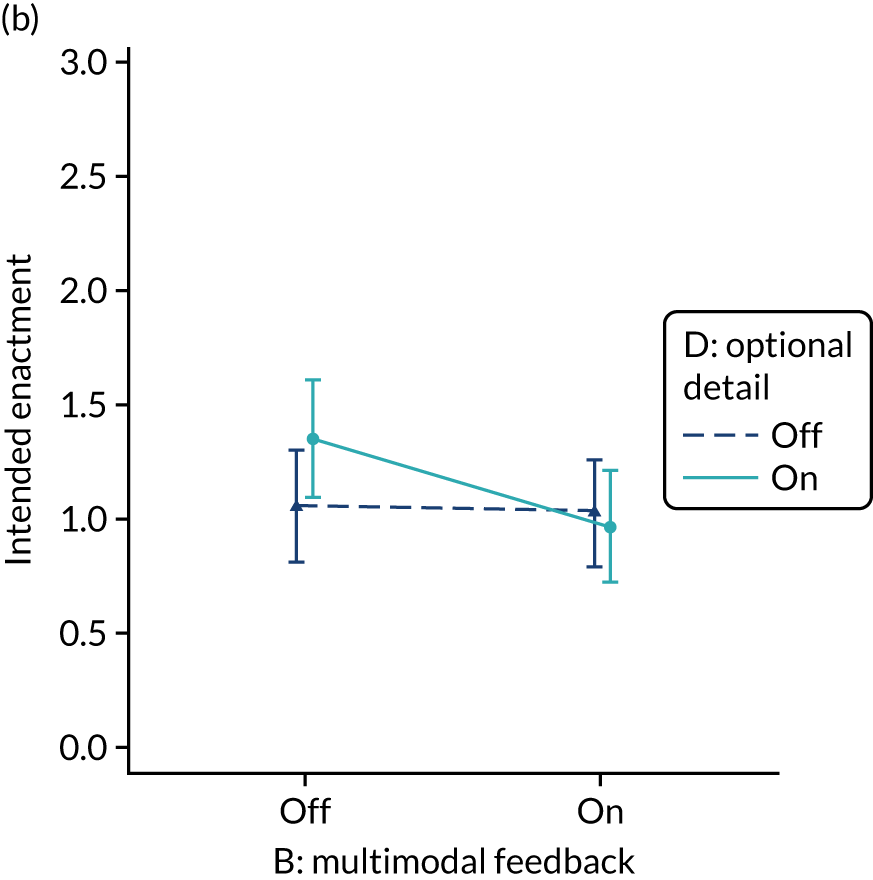

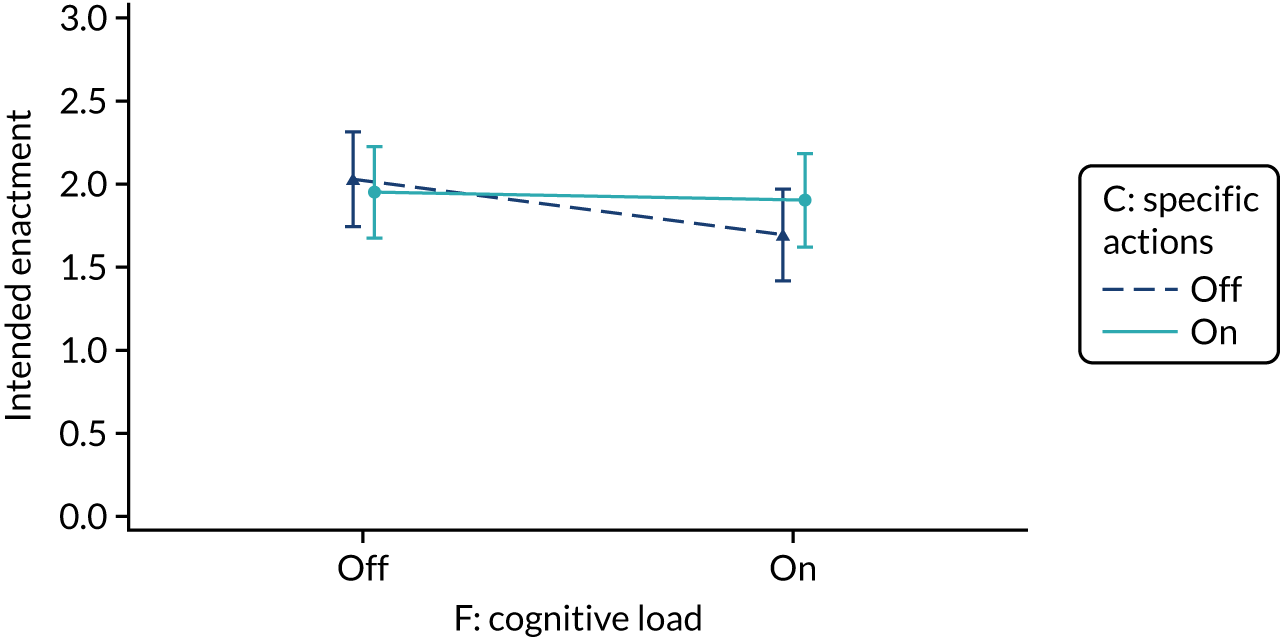

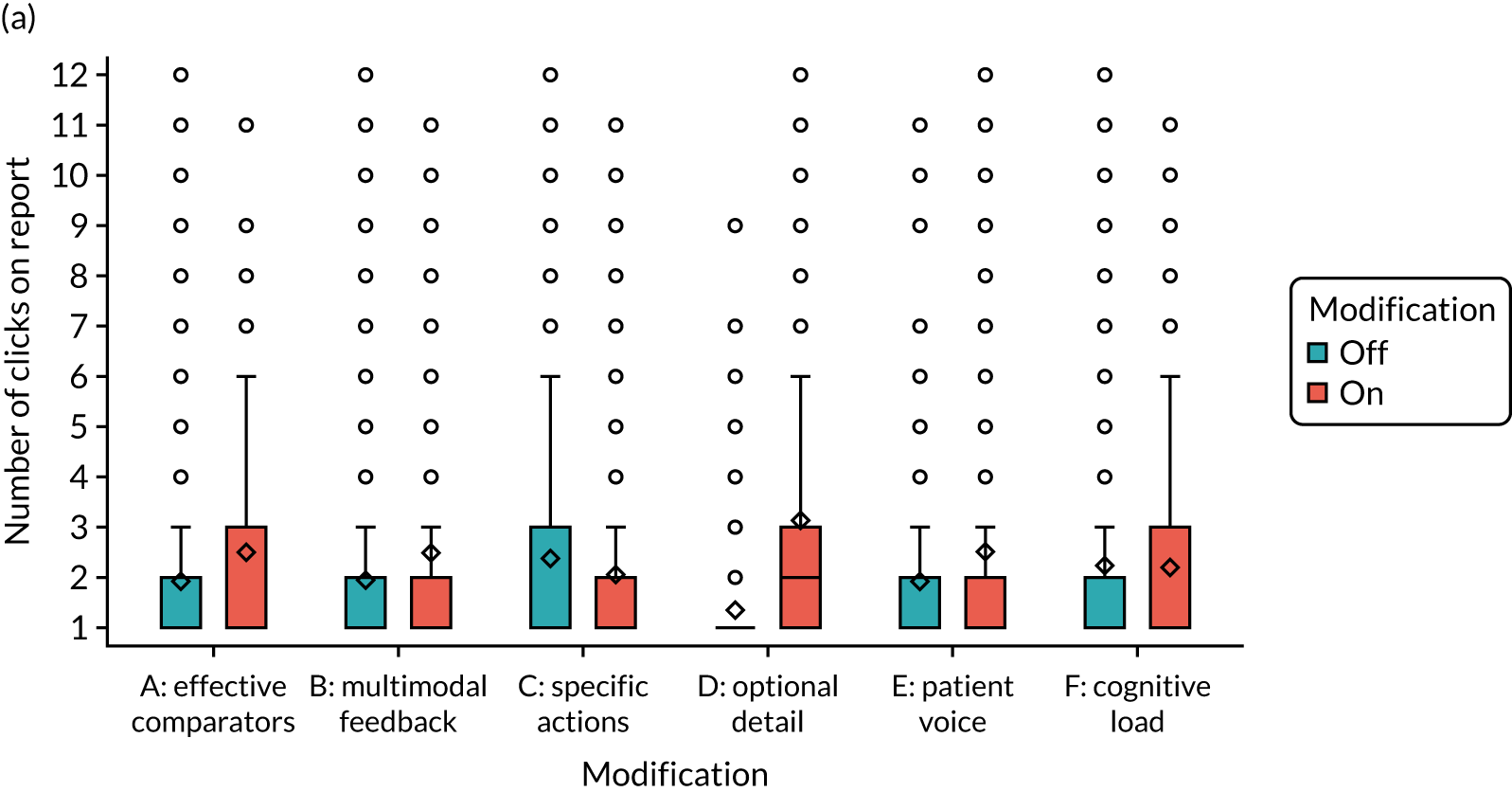

-