Notes

Article history

This themed issue of the Health Technology Assessment journal series contains a collection of research commissioned by the NIHR as part of the Department of Health’s (DH) response to the H1N1 swine flu pandemic. The NIHR through the NIHR Evaluation Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC) commissioned a number of research projects looking into the treatment and management of H1N1 influenza. NETSCC managed the pandemic flu research over a very short timescale in two ways. Firstly, it responded to urgent national research priority areas identified by the Scientific Advisory Group in Emergencies (SAGE). Secondly, a call for research proposals to inform policy and patient care in the current influenza pandemic was issued in June 2009. All research proposals went through a process of academic peer review by clinicians and methodologists as well as being reviewed by a specially convened NIHR Flu Commissioning Board.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background to, research governance for and, participation in SwiFT

Introduction

In April 2009, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the outbreak of confirmed human cases of pandemic influenza A 2009 (H1N1) in Mexico and the USA and raised the pandemic alert level initially to Phase 4 (sustained human-to-human transmission) and subsequently to Phase 5 (widespread human infection). The first two UK cases of H1N1 were confirmed in Scotland.

In May 2009, the first case of human-to-human transmission in the UK was confirmed with laboratory-confirmed cases reported in Northern Ireland and Wales, leading to confirmed cases across the UK.

In June 2009, the WHO raised the pandemic alert level to Phase 6, the highest level (on 11 June 2009), and the total number of UK cases reached 100 with the first UK death attributed to H1N1 (on 15 June 2009). 1

This advent of a new strain of influenza A, known as swine ’flu, presented an opportunity for research to be commissioned both to inform patient management during the pandemic and, possibly, to inform future pandemics.

The objective of this chapter is to describe the research governance process and report on the ability to initiate and co-ordinate an essential research study efficiently, within the NHS, in a pandemic situation.

Methods

The Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre (ICNARC) was approached by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC), on 12 June 2009, with a view to them commissioning research from the ICNARC. The aim of the proposed research was to provide information, early on in the pandemic, to guide critical care clinicians and policy-makers. The first objective of the proposed research was to use both existing critical care and early pandemic data to inform care during the pandemic (with a possible use for triage – if the situation arose where demand for critical care seriously exceeded capacity). The second objective was to be able to monitor the impact of the H1N1 pandemic on critical care services, in real time, with regular feedback to critical care clinicians and other relevant jurisdictions to inform ongoing policy and practice. The NETSCC encouraged internal prioritisation of this research within the ICNARC (i.e. diversion of any required, senior and junior, research and operational staff from ongoing audit and research projects).

Two ICNARC senior staff members (KMR, DAH) conceived, designed and wrote the Swine Flu Triage study (SwiFT) proposal. An outline proposal for SwiFT was submitted to the NETSCC on 12 June 2009, a full proposal (the first and final draft) with basic costs was submitted on 25 June 2009 and provisional funding was approved by the NETSCC on 9 July 2009. Following detailed response to Board/reviewers’ comments and submission of full costs, final funding for SwiFT was approved on 27 July 2009.

In early August 2009, the Chief Investigator (KMR) travelled to Australia to link up with the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) to learn from their H1N1 experience, its impact on critical care services and their registry. 2,3 A further opportunity for international communication/collaboration occurred between the ANZICS and Canadian registries, with SwiFT (KMR) at the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine meeting in Vienna in October 2009.

Results

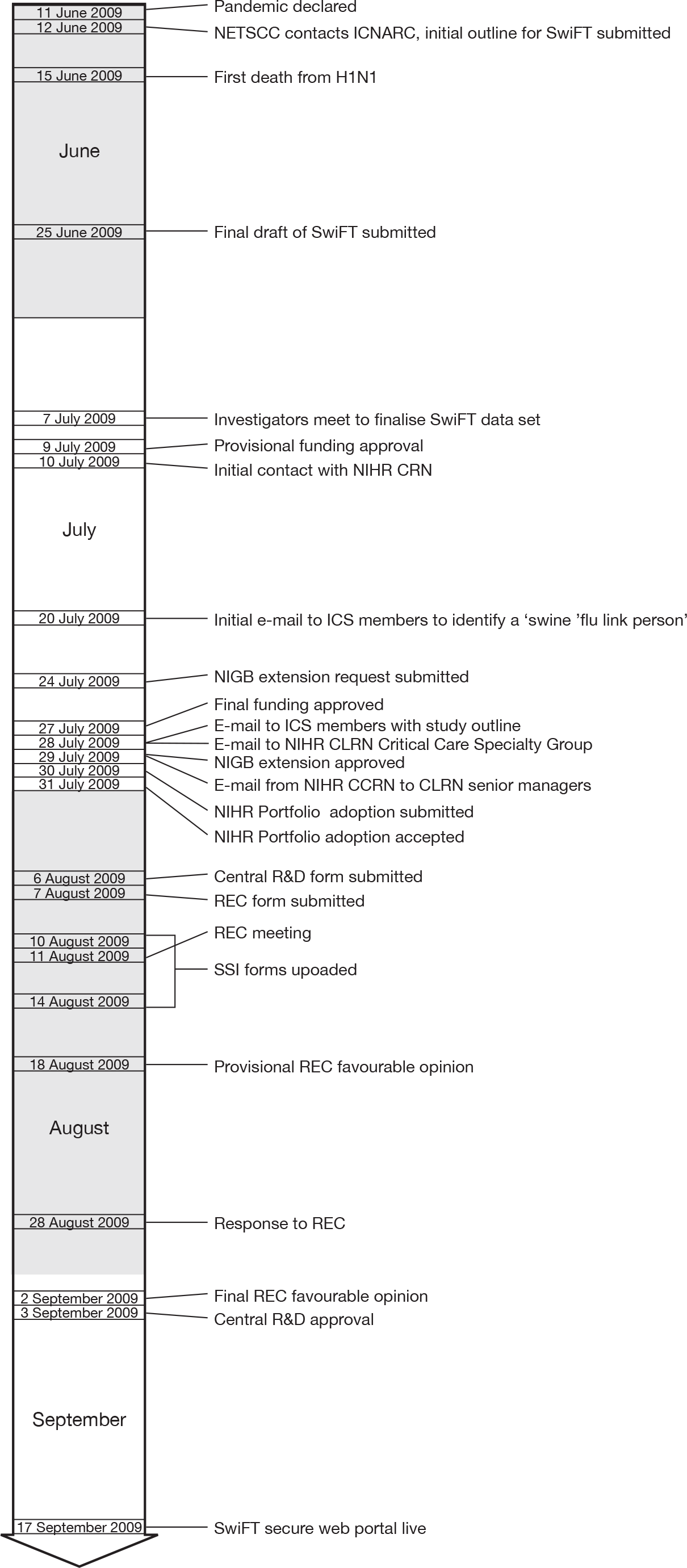

Figure 1 summarises the key events.

FIGURE 1.

The SwiFT timeline. CLRN, Comprehensive Local Resarch Network; CRN, Clinical Research Network; ICS, Intensive Care Society; NIGB, National Information Governance Board; REC, Research Ethics Committee; SSI, site-specific information.

Study infrastructure

On 7 July 2009, prior to provisional funding approval, five co-investigators (KMR, DAH, DFMcA, GDP and DKM) met to discuss and agree the proposed data set for primary collection of pandemic-related data. Using the ICNARC’s existing international links, data collection forms from Mexico, Canada and Australasia were used to inform the SwiFT data set and to enable compatibility between common variables for international comparison. 2 From this, the final data set specification was developed by the two ICNARC co-investigators (DAH and KMR). Three members of the ICNARC information technology staff immediately commenced development of a secure, web-based, data entry system for SwiFT. Following comprehensive testing by ICNARC staff members, the SwiFT secure, web-based, data entry system went live on 17 September 2009.

In parallel with internal study infrastructure work, central and local research governance approvals were required for approximately 220 organisations (Trusts, Health Boards, etc.) in five countries [England, Wales, Northern Ireland, Scotland and the Republic of Ireland (ROI)]. Five senior members of ICNARC staff, supported by the entire staff, were allocated responsibility for research governance in each of the five countries.

The ICNARC used every opportunity to promote and outline the objectives of SwiFT, either directly as presentations on SwiFT or indirectly by mentioning SwiFT at other ICNARC audit/research study meetings. SwiFT was presented at: the Scottish Intensive Care Society meeting on 4 September 2009; a national critical care meeting on the H1N1 pandemic on 10 September 2009; the twelfth Current Controversies in Anaesthesia & Peri-Operative Medicine meeting (Dingle, Ireland) on 15 October 2009; and a national meeting on infection in critical care on 4 November 2009. SwiFT was also highlighted at data collection training courses for the national clinical audit of adult critical care co-ordinated by the ICNARC, the Case Mix Programme (CMP), and for ongoing ICNARC research studies, Fungal Infection Risk Evaluation (FIRE, 07/29/01) and Risk Adjustment In Neurocritical care (RAIN, 07/37/29) at five courses in September 2009, one in October 2009 and one in November 2009.

Research governance

England

Information governance

Primary data collection for SwiFT was considered, and submitted, as an extension to the National Information Governance Board (NIGB) Ethics and Confidentiality Committee approval for the CMP under Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006. On 24 July 2009, the ICNARC applied for this extension of Section 251 support and this was confirmed for England and Wales on 29 July 2009 (see Appendix 1).

Portfolio adoption

Details of clinical research studies which meet specific eligibility criteria are recorded in a database known as the UK Clinical Research Network (UK CRN) Portfolio, which comprises the NIHR CRN Portfolio in England and the corresponding portfolios in Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland. On 30 July 2009, SwiFT was submitted for adoption by the NIHR CRN Portfolio in England and this was duly granted (reference 7396) on 31 July 2009 (see Appendix 1).

Central research and development approval

Once provisional funding was approved, on 10 July 2009, the Chief Investigator (KMR) was contacted directly by the NIHR CRN regarding the expedited process for gaining NHS permissions for national H1N1 research studies using the NIHR Coordinated System for gaining NHS Permission (CSP). On the same day, the Central and East London Comprehensive Local Research Network (CLRN), the original Lead CLRN for SwiFT, led on agreement with the CSP Unit (CSPU) for an appropriate subset of the usual global and local governance checks to be applied. SwiFT was submitted to the NIHR CSP on 31 July 2009, identifying Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust as Lead NHS Trust, and West Anglia CLRN assumed Lead CLRN status. On 6 August 2009, the main research and development (R&D) form was submitted with a list of local collaborators, sourced from the Intensive Care Society (ICS) link person spreadsheet (see Local research and development approval), for 125 of 157 acute Trusts in England. Central R&D approval was gained on 3 September 2009 following ethics approval (see Ethics approval).

Local research and development approval

In consultation with the CSPU, it was agreed that as SwiFT was a research study, site-specific information (SSI) forms for all acute hospitals were needed to process through the system. However, it was agreed that one SSI could be written and then duplicated > 150 times – one for each NHS Trust. West Anglia CLRN provided support to assist with the uploading of the local collaborator details, solely amending the NHS Trust for each SSI form. A spread sheet containing all the Local Collaborators was supplied to facilitate West Anglia CLRN supporting this process. SSI forms for 152 NHS Trusts were uploaded in batches from 10 to 14 August 2009.

To expedite the identification of local collaborators, on 20 July 2009, the ICS (the professional organisation for intensive/critical care clinicians) e-mailed all its members requesting details for a ‘swine ‘flu link person’ for each critical care unit. This was followed up, on 28 July, with a second e-mail, drafted by the ICNARC, outlining the objectives and local resourcing for SwiFT and indicating that the details of the link person would be passed to the ICNARC for the purposes of rapidly facilitating the local approval process for SwiFT. The ICNARC contacted the nominated link person (n = 125 of 165 NHS Trusts in England) and included the details in the local collaborators’ spread sheet provided to West Anglia CLRN for populating the SSI forms.

Ethics approval

The National Research Ethics Service (NRES) activated an emergency policy allowing Research Ethics Committees (RECs) to consider applications quickly. The REC application for SwiFT in England, Wales and Northern Ireland was expedited by the application, received by the NRES on the 7 August 2009, being diverted to the next available REC meeting – the North West REC on 11 August 2009. Provisional approval was provided on 18 August 2009 highlighting a number of issues, relating to the triage modelling and proposed use of a triage model, which required a detailed response (see Appendix 1). This was submitted on 25 August 2009. Final opinion was chased by the ICNARC on 1 September 2009, and a final favourable opinion was received on 2 September 2009 facilitating central R&D approval for SwiFT on 3 September 2009 (see Appendix 1).

Local resources

On 28 July 2009, an e-mail was sent to all members of the NIHR CRN Critical Care Specialty Group describing and outlining the objectives of SwiFT. On 29 July 2009, as part of a series of ongoing ‘early warning’ alerts regarding national H1N1 research studies, the NIHR Comprehensive Clinical Research Network contacted all CLRN clinical directors and senior managers, identifying the NHS support requirements for SwiFT and requesting each CLRN team to review capacity and provide acute hospitals/critical care units support to collect SwiFT data. This included an indication that funding for the data collection exercise could be available from the national contingency, if required (see Appendix 1). The Chairperson of the NIHR CRN Critical Care Specialty Group, one of the SwiFT coinvestigators (TSW), facilitated the process of trying to achieve local resources for participating acute hospitals. In addition, SwiFT co-investigators within England (GDP, BLT and DKM) acted as ambassadors for SwiFT within their own CLRNs.

Wales

Local research and development approval

Without a central co-ordinating centre for governance checks in Wales, NHS permission for acute hospitals in Wales had to be gained through their existing processes. The CSPU made the global governance report available to the ICNARC to help facilitate this process. Contact with the senior managers for the three Research Practitioner Networks (RPNs), North Wales, South East Wales and South West Wales, (akin to the CLRNs in England) proved straightforward and the global governance report was shared with them. Senior individuals within the RPNs led and facilitated the identification of acute hospitals/local collaborators and local R&D approval. Despite enthusiasm from the RPNs, the local approval process proved to be slow.

Local resources

Being outside the CLRN system meant that local resources were not available for supporting SwiFT in Wales. Discussions were held with the RPNs regarding availability of local resources. The RPNs did not appear to think local resourcing would be an issue; however, no formal response was provided. It appeared that each RPN approached this on an individual acute hospital/local level.

Northern Ireland

Information governance

As NIGB approval applied only to England and Wales, on 17 August 2009, contact was made with the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS) in Northern Ireland who, in the absence of equivalent legislation, indicated that because SwiFT was very much in the public interest it was acceptable for clinicians to contribute data without the patient’s consent. Following information security checks, Dr Michael McBride, Chief Medical Officer wrote to all Chief Executives of Health and Social Care (HSC) Trusts, on 25 August 2009, indicating that ‘whilst individual organisations and clinicians can still make their own decisions about whether or not they wish to contribute patient data to the study, it is the view of the DHSSPS that Northern Ireland should contribute data as the study is very much in the public interest’ (see Appendix 1).

Local research and development approval

Rather than the expedited SSI form process for England, SSI forms had to be individually generated and checked with each of the five individual NHS Trusts, prior to submission. Along with the dedicated ICNARC staff member, one of the co-investigators (DFMcA) acted as ambassador and facilitated local approvals by helping to identify local collaborators for SwiFT in Northern Ireland.

Local resources

Being outside the CLRN system meant that local resources were not available for supporting SwiFT in Northern Ireland.

Scotland

Information governance

As NIGB approval applied only to England and Wales, on 4 August 2009, contact was made with the Information Governance Lead at the eHealth Directorate in the Scottish Government who, in the absence of equivalent legislation, indicated that each Caldicott Guardian for each individual NHS Health Board would need to be approached about SwiFT. It was acknowledged, by them, that this would be a time-consuming and challenging process with no standardised system or forms. Despite significant investment, centrally and locally, information governance approval proved to be slow.

Local research and development approval

On 28 July 2009, an e-mail was sent to all members of the Scottish ICS describing and outlining the objectives and local resourcing requirements for SwiFT. On 18 August 2009, the NHS Research Scotland Coordinating Centre (NRSCC) agreed to help co-ordinate all the Scottish R&D departments and streamline local approvals for SwiFT. The CSPU provided all the study documents and global checks governance directly to the NRSCC on 8 September 2009. The NRSCC provided R&D contacts for each of the 14 NHS Health Boards. Rather than the expedited SSI form process for England, SSI forms had to be individually generated and checked with each of the 14 individual NHS Health Boards, prior to submission. Along with the dedicated ICNARC staff member, one of the co-investigators (TSW) acted as ambassador and facilitated local approvals by helping to identify local collaborators for SwiFT in Scotland.

As part of the collaborative effort, requested by the NIHR between all national H1N1 research studies, the ICNARC provided the completed SSIs for the 14 Scottish Health Boards, from SwiFT, to facilitate the approval process for a separate genetics study on H1N1 in Scottish critical care units.

Ethics

The REC application for Scotland was received by the Scotland A REC on 24 August 2009, considered at its meeting on 24 September 2009 and a response, received on 28 September 2009, dismissed SwiFT as not requiring ethics approval – ‘the Committee was of the opinion that this was audit linked to service development and delivery rather than research, and therefore did not require ethical approval from an NHS research ethics committee’ (see Appendix 1).

Local resources

Being outside the CLRN system required a different approach to attempt to secure local resources for supporting SwiFT in Scotland. Attempts to secure local resources through the Scottish ICS Audit Group, part of the Information Services Division (NHS National Services, Scotland), were unsuccessful. Contact was made by one of the co-investigators (TSW) with the Director and Deputy Director of the Chief Scientist Office (CSO) which resulted in SwiFT being included in a joint letter from the Chief Medical Officer and the Director of the CSO. The letter, dated 31 August 2009, to all Chief Executives and R&D Directors of NHS Health Boards, REC Chairpersons and Directors of R&D networks, indicated that, for the three studies listed (SwiFT being one), ‘it will be very helpful if each Health Board reviewed the capacity of the intensive care units to collect this data and, where such capacity is limited, plan to put in place adequate capacity. If necessary, we expect staff from any CSO NHS infrastructure budget to assist these projects as a priority over their normal responsibilities’ (see Appendix 1). The CSO committed central support if this was not identified at the local level. Local investigators attempted to facilitate the process of trying to achieve local resources for participating acute hospitals with their individual, local R&D departments with variable success; some, but not all, committed support. Despite the CSO offer of central support, no additional central funding was requested.

Republic of Ireland

Information governance

As NIGB approval applied only to England and Wales, using existing critical care clinical contacts in the ROI, on 17 August 2009, contact was made with the Health Service Executive (HSE) lead for critical care H1N1 planning and the information communications technology lead on information governance. Detailed information was provided by the ICNARC about data security (physical, logical and network), including a copy of the system level security policy for SwiFT. Though no final verdict was provided, by 8 September 2009, it appeared that there were no major information governance issues to Irish acute hospitals participating in SwiFT. Along with the dedicated ICNARC staff member, a clinical contact, Dr Brian Marsh, acted as ambassador and facilitated HSE and local approvals for acute hospitals in the ROI.

Local research and development approval/ethics

Without a central co-ordinating centre for governance checks in the ROI, local R&D/ethics permission for acute hospitals in the ROI had to be gained through their existing processes, including gaining individual hospital ethics approvals.

Local resources

Being outside the CLRN system meant that local resources were not available for supporting SwiFT in the ROI.

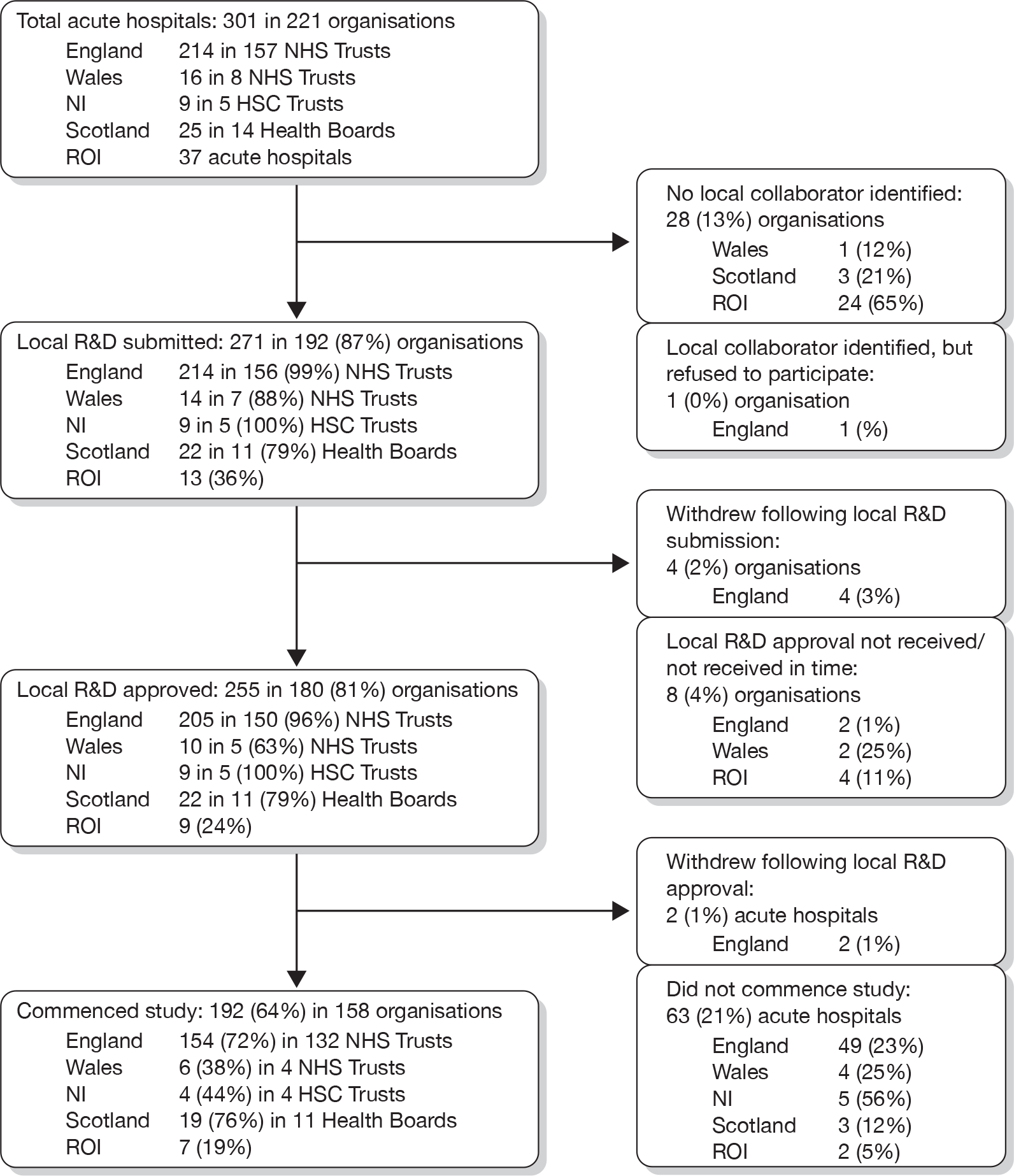

Participation

Local R&D approval was gained at the organisational level (e.g. Trust, Health Board, etc.). Of the 221 organisations identified, submission for local R&D approval was achieved for 192 (87%; see Figure 2). The main reason for not submitting for local R&D approval was failure to identify a local collaborator to lead SwiFT. Only in one Trust (Stockport NHS Foundation Trust – Stepping Hill Hospital) did an identified local collaborator (the clinical lead for the critical care unit) actually refuse to participate. Local R&D approval for participation in SwiFT was received for 81% of organisations representing 85% of acute hospitals (Figure 2). Local R&D approval converted into actual commencement of data collection in only 64% of the 301 identified acute hospitals.

FIGURE 2.

Research governance and participation in SwiFT. NI, Northern Ireland.

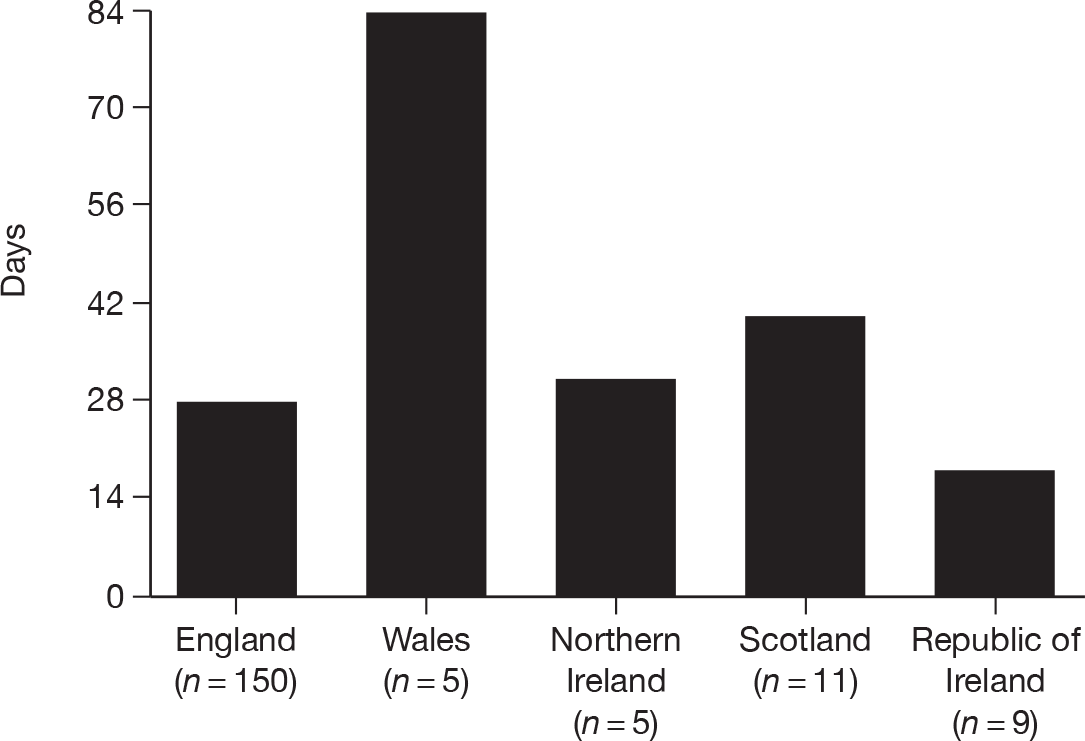

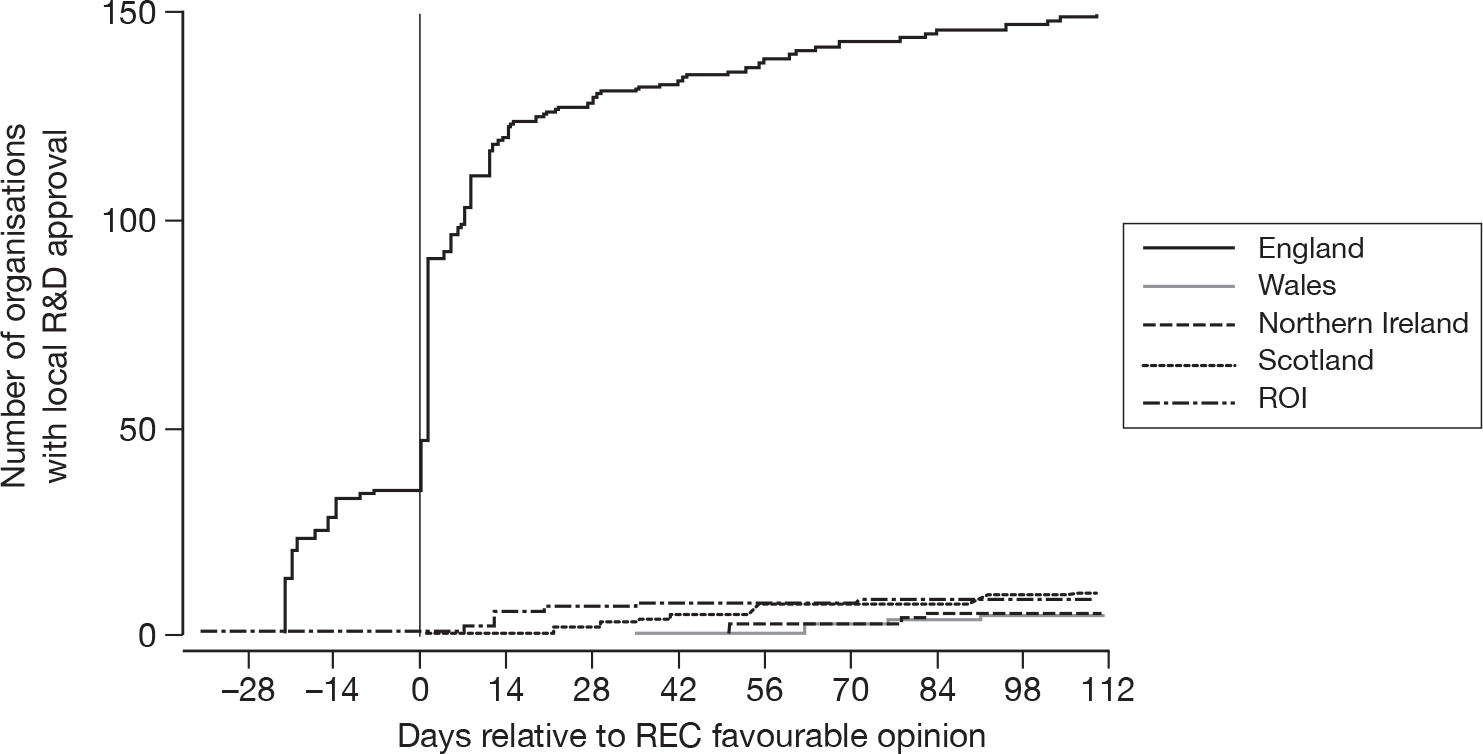

Local R&D approval was quickest in the ROI, but for only a small number (n = 9, 24%) of acute hospitals. England achieved both quick (Figure 3) and timelier (Figure 4) local R&D approval for a much larger number of NHS Trusts (n = 150, 96%) – with 35 English NHS Trusts providing local R&D approval pending central R&D approval (REC approval) and a further 56 providing local R&D approval within 1 day of central R&D approval. Northern Ireland was similarly quick to gain local R&D approval, but for a much smaller number of only five HSC Trusts. Scotland appeared slower for their 11 Health Boards but, as the decision on REC approval for Scotland (i.e. it was ultimately deemed not to be required) did not occur until day 25, local R&D approval was delayed by this fact. The five NHS Trusts in Wales took much longer to gain local R&D approval.

FIGURE 3.

Mean time (days) to obtain local R&D approval for organisations for SwiFT.

FIGURE 4.

Timeliness of local R&D approval for SwiFT – day 0 indicates central R&D approval for England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

SwiFT commenced in 192 (64%) acute hospitals in 158 organisations (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

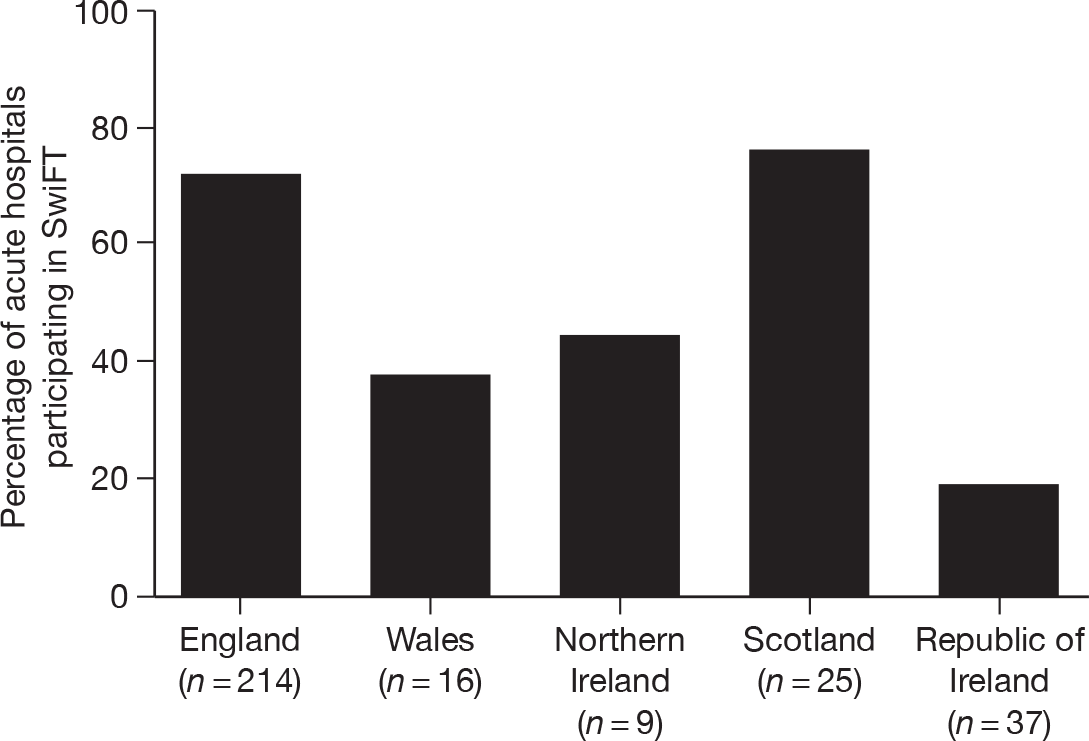

Participation of acute hospitals in SwiFT.

Discussion

Attempting to gain permissions for, and initiate SwiFT in, 221 organisations across five countries was challenging even with the existing networks of, and expertise within, the ICNARC. Despite this, SwiFT only achieved low acute hospital coverage for the ROI (19%), Wales (38%) and Northern Ireland (44%). A question has to be posed as to whether the time attempting to gain permissions/initiate SwiFT in these countries was time well spent? In addition, despite the huge effort of the ICNARC research team to obtain central research and information governance approvals in as short a time scale as possible, local approvals were still slow and the figures illustrate the difficulty in achieving such an ambitious research study, even with the added impetus of a pandemic. A further question has to be posed, therefore, as to whether the timelines for governance achieved in SwiFT are acceptable during a pandemic?

The process of attempting to achieve comprehensive participation of acute hospitals in SwiFT identified a number of facilitators and barriers.

Facilitators

-

Accelerated research governance The accelerated processes, developed by/for the NIHR CRN, CSPU/CSP, NIGB and NRES/REC, which were activated in England appeared to deliver for SwiFT. 4

-

ICNARC The ICNARC had the infrastructure (staff skilled in research design, data set development, web-based data entry development/testing, data validation, analysis and reporting), knowledge (in conducting research, in navigating the research governance system and in critical care), contacts, relationships, trust and track record to conceive, design and deliver SwiFT. In addition, the ‘permission’ from the NETSCC to divert required ICNARC staff members, without worry of the knock-on effect to other ongoing research studies, allowed for rapid initiation of SwiFT. Despite the existing heavy workload at the ICNARC, ICNARC staff were motivated by the challenge and topical nature of SwiFT and every individual, at every level in the organisation, played a role in supporting its set-up and co-ordination.

-

External support External support came from four main sources: first, through direct access to individuals with high levels of authority to make decisions in the situation where any potential barriers in the research governance system were identified; second, from the professional organisations, the UK and national Societies, who supported SwiFT; third, from the members of the UK CRN Critical Care Specialty Group and from the directors and leads for Research Management and Governance in the CLRNs (or their direct/indirect equivalents in Wales, Northern Ireland, Scotland and the ROI) who supported acute hospitals in identifying and accessing local resources; and, fourth, from the critical care staff, who rose to the challenge that SwiFT posed.

Barriers

-

Failure to identify local collaborators With respect to national clinical audit, the ICNARC has a remit solely for adult critical care in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. While the Scottish co-investigator (TSW) helped to facilitate identification of local collaborators in Scotland, the absence of an existing network of contacts in the ROI (and no ROI co-investigator) potentially hindered participation in SwiFT there. Paediatric critical care colleagues were also more reticent about participating owing to insufficient time for the degree of involvement/negotiation being requested by the professional society, the Paediatric ICS, for them to fully endorse and advertise SwiFT.

-

Method of identifying local collaborators The usual mode of engaging clinicians in a specific research study (i.e. identifying them, engaging their interest and jointly submitting for approval, etc.) was circumnavigated in the interest of speed for SwiFT in England. SSI forms were populated with individuals, probably busy owing to the impending pandemic, whose interest in SwiFT had not previously been identified. While most engaged with the pandemic situation, the speed of the process and the failure to engage up-front did put a few ‘noses out of joint’. However, the process followed was not unreasonable and was the only practicable way to get the R&D process ‘up and running’, in such a large number of acute hospitals, over such a short time frame.

-

Lack of local resources Accessing local resources to support SwiFT appeared to be much harder in countries outside England, leading to much lower participation in these countries. The exception was Scotland, where participation was higher owing to two apparent reasons – first, the efforts of the Scottish co-investigator (TSW) and second, the existence of a genetic H1N1 study in Scottish critical care units to which SwiFT linked to supply the phenotype data for patients, thus avoiding duplicate data requirements.

-

The existence of the CLRN system enhanced participation in England; however, following local R&D approval, the main reason cited for not participating appeared to be the absence of local resources. This appeared to be as much down to a lack of knowledge of acute hospital staff in how to access these resources, possibly due to the newness of the system and the staff’s newness to research, than to a refusal to provide the resources.

-

Lack of an integrated, centralised system for research governance The relative effort required to gain approvals for acute hospitals outside England was immense. While Scotland had a centralised system for R&D approvals, gaining information governance clearance for each NHS Health Board from each Caldicott Guardian proved very time-consuming; one individual could hold up a number of acute hospitals ready to start for some considerable time.

-

Other competing activities The European Society of Intensive Care Medicine initiated a European H1N1 registry which was promoted to the UK critical care community. The UK Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) Consortium had their own H1N1 initiative and acute hospitals providing ECMO tended not to, or only partially, participate in SwiFT. The Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network was pooling data on paediatric critical care unit admissions with H1N1.

The next chapters present the results of SwiFT.

Chapter 2 Exploration of potential physiological models to triage patients requiring critical care using existing (pre-pandemic) data

Introduction

In the earliest stages of the pandemic, it was clear that H1N1 had the potential to cause life-threatening illness. However, the likely impact of the pandemic on critical care capacity in the UK was unknown. Estimates of the attack rate, hospitalisation rate and case fatality rate were extremely uncertain.

In the light of these uncertainties, based on data available to 14 June 2009, Ercole et al. 5 attempted to model the likely impact of an H1N1 pandemic, lasting 12 weeks, on critical care in England. Based on disease severity data from the USA6 and from Mexico,7 attack rates of 61% for age < 15 years and 29% for age ≥ 15 years, with a hospital admission rate from 0% to 2%, were assumed. The latter exceeded the then current hospital admission rate (0%) for the first 752 cases in England and, yet, the US hospital admission rate at this time was 9%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 7% to 12%. The assumed impact was that 36% of hospital admissions would require critical care and that 50% of these would require ventilatory support. Using age-stratified data for the English population, the peak requirement for critical care for H1N1 cases was estimated to be between 0% and 250% of current capacity (assumed to be the sum of total adult Level 3 beds and total paediatric intensive care beds). Peak ventilator usage was estimated to be between 0% and 120% of current capacity (assumed to be equal to the number of beds). Focusing solely on H1N1 cases, these estimates suggested that existing critical care resources, including any surge capacity gained through expansion into Level 2 beds and theatre/recovery settings, could be vastly exceeded.

Excessive demand, where resources are finite, creates an ethical dilemma and many emergency plans apply a utilitarian approach (to do the most good for the greatest number), sacrificing individual benefits for the greater good. 8 However, the Committee on Ethical Aspects of Pandemic Influenza, established by the Chief Medical Officer in 2006, rejected this as the driving principle for ethical decision-making, favouring instead a principle of ‘equal concern and respect’. 9 Within this framework, a key component of treatment decisions is fairness (‘everyone with an equal chance of benefitting from an intervention should have an equal chance of receiving it’9). In this situation, the principles of biomedical ethics and international law dictate that triage be used to guide equitable and efficient resource allocation and that the rationale for triage should be fair and transparent and meet the principles of distributive justice – the fair distribution of scarce resources. 8,10

Triage could be required at several steps in the care pathway for patients with H1N1: first, in primary care, to determine which patients required hospital assessment; second, in the emergency department, to determine which patients needed hospital admission; and third, in hospital, to determine which patients needed critical care. These three triage steps would require different triage thresholds and, most probably, different triage models. It is important to note that SwiFT only considered the third step in the care pathway for H1N1 patients.

For obvious reasons, no triage models specifically designed in the context of H1N1 existed. However, the threat of H5N1 avian influenza had initiated the development of triage models. 11–16 These existing, proposed models for triage of patients considered for critical care were based on: expert opinion;11 existing severity scores for either general critical care, e.g. the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA),12,13 or pneumonia, e.g. CURB-65 (confusion, urea, respiratory rate, blood pressure, age 65+ years);14 or developed and/or validated using small, single-centre populations of patients presenting to emergency departments with either community-acquired pneumonias15 or suspected infection. 16

Many existing triage models relied on data relating to chronic health conditions,11–15 which may be difficult to assess reliably during the peak of a pandemic. In addition, many models used laboratory parameters,11–14 the measurement of which is resource-intensive and may delay a triage decision.

Guidance from the Department of Health, released at the start of the H1N1 outbreak, recognised that there was no universally accepted system available for triage in this context. 17 The guidance focused on the use of a SOFA-based system, but acknowledged that further research in this area was required and that, in the event that a more robust tool was developed, the guidance would be updated.

An ideal triage tool needs to be simple enough to be applied quickly and consistently during the peak of the pandemic (which may not be the case for SOFA-based tools),13 but also be complex enough to be ‘scaleable’, i.e. the decision criteria could be adjusted in order to match demand against capacity. 10 It also needs to be able to match inevitable staff shortages (from staff sickness as well as increased demand) and suboptimal staff expertise (arising from the need to redeploy staff to critical care), against the actual clinical demands posed by patients.

Approaches based specifically on models for patients with respiratory infections (e.g. CURB-65) may be inappropriate, as triage decisions would need to be made for all patients considered for critical care and not only those with H1N1, as a single pool of resources would have to be shared among all patients. 10,12

In a pandemic, triage decisions would need to be made for patients who would be admitted to the critical care unit under usual (non-pandemic) circumstances. The decision problem being considered in this chapter was therefore: of the patients admitted to a critical care unit in usual (non-pandemic) circumstances, was it possible to develop a triage model that could reliably divide patients into the following three groups:

-

Those who required a low degree of organ support and might be safely managed in non-critical care areas or temporary critical care areas (e.g. theatre/recovery areas upgraded to provide basic critical care facilities).

-

Those who required a significant degree of organ support within a critical care unit but, with such support, would survive to leave acute hospital.

-

Those who, despite full critical care support, would not survive to leave acute hospital and for whom, in pandemic circumstances, critical care may need to be denied on the grounds of futility.

Methods

Selection of data

The CMP is the national, comparative audit of patient outcomes from adult, critical care units in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, co-ordinated by the ICNARC. The CMP is a voluntary performance assessment programme using high-quality clinical data to facilitate local quality improvement through routine feedback of comparative outcomes and key quality indicators to clinicians/managers in adult critical care units. The CMP recruits predominantly adult, general critical care units, either standalone intensive care units or combined intensive care/high-dependency units. Currently, approximately 90% of adult, general critical care units in England, Wales and Northern Ireland are participating in the CMP.

The CMP-specified data are recorded prospectively and abstracted retrospectively by trained data collectors according to precise rules and definitions, set out in the ICNARC CMP Dataset Specification. Data collectors from each unit are trained prior to commencing data collection, with retraining of existing staff or training of new staff also available. CMP training courses are held at least four times per year.

The CMP-specified data are collected on consecutive admissions to each participating critical care unit and are submitted to the ICNARC quarterly. Data are validated locally, on data entry, and then undergo extensive central validation for completeness, illogicalities and inconsistencies, with data validation reports returned to units for correction and/or confirmation. The validation process is repeated until all queries have been resolved and then the data are incorporated into the CMP Database (CMPD).

The CMPD has been evaluated according to the quality criteria of the Directory of Clinical Databases (www.icapp.nhs.uk/docdat/) and scored highly. 18

All admissions in the CMPD to adult, general critical care units in England, Wales and Northern Ireland from 1 January 2007 to 31 March 2009, collected to Version 3.0 of the ICNARC CMP Dataset Specification, incorporating the Department of Health Critical Care Minimum Data Set (CCMDS),19 were extracted.

Impact of cancelled/postponed elective and scheduled surgery

Critical care unit admissions that could potentially be avoided by the cancellation/postponement of elective and scheduled surgery were identified by the following criteria:

-

admissions direct from theatre with a classification of surgery as ‘elective’ or ‘scheduled’

-

all subsequent admissions during the same hospital stay of patients identified from criterion (1)

-

admissions for pre-surgical preparation.

The impact of cancellation/postponement of these admissions was estimated by:

-

the percentage of admissions avoided/postponed

-

the percentage of calendar days of critical care saved

-

the percentage of calendar days at Level 3 saved

-

the percentage of days of advanced respiratory support saved,

both overall and across units.

Exclusions

For the purpose of developing the triage models, the following admissions were excluded:

-

admissions associated with elective/scheduled surgery (as defined above)

-

admissions missing all basic vital signs (temperature, systolic blood pressure, heart rate and respiratory rate)

-

admissions missing status at ultimate discharge from acute hospital

-

readmissions of the same patient within the same acute hospital stay.

Patient cohorts

Models were developed using both the following two cohorts:

-

(a) all admissions, except those excluded based on the criteria listed above

-

(b) admissions for acute exacerbations of respiratory illness, defined by the presence of any of the following conditions as the primary or secondary reason for admission to the critical care unit:

-

– acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [‘non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema (ARDS)’]

-

– pneumonia (‘bacterial pneumonia’; ‘viral pneumonia’; ‘pneumonia, no organism isolated’)

-

– acute exacerbations of chronic airways disease [‘chronic obstructive pulmonary/airways disease (COPD/COAD)’; ‘chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with acute lower respiratory infection’; ‘chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with acute exacerbation, unspecified’; ‘emphysema’; ‘asthma attack in new or known asthmatic’].

-

Note: complete identification of such cases was dependent on the recording of one of the above conditions as either the primary (mandated) or secondary (optional) reason for admission. Primary and secondary reasons for admission to the critical care unit are coded using the ICNARC Coding Method,20 which was developed specifically for the CMP. It is a five-tiered, hierarchical method for coding reasons for admission or underlying conditions in critical care consisting of the type of condition (surgical/non-surgical), body system, anatomical site, pathological/physiological process and specific condition.

The case mix of admissions in the two cohorts was described by their age, sex, source of admission to the critical care unit, Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II Acute Physiology Score and APACHE II score,21 ICNARC Physiology Score,22 and, for cohort B, CURB-65 (new onset confusion; urea > 7 mmol l-1; respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths per minute; systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≤ 60 mmHg; age ≥ 65 years). 23

Triage modelling

The primary outcome for the triage models was an ordinal outcome on the following scale:

-

Potentially avoidable admission: admission did not receive advanced respiratory support, advanced cardiovascular support, renal support, neurological support or liver support (as defined by the CCMDS)19 at any time during the stay in the critical care unit and survived to leave acute hospital.

-

Critical care required: admission survived to leave acute hospital but was not a ‘potentially avoidable admission’ (i.e. received advanced respiratory support, advanced cardiovascular support, renal support, neurological support and/or liver support at any time during the stay in the critical care unit).

-

Death: admission did not survive to leave acute hospital.

The following routine physiological variables, termed ‘core variables’, measured and recorded during the first 24 hours following admission to the critical care unit, were included in the modelling:

-

highest temperature (central or, if no central available, non-central)

-

lowest systolic blood pressure

-

highest heart rate

-

highest respiratory rate

-

neurological status, using Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) to approximate AVPU (Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive) categories of Alert (GCS 15), Voice (GCS 10–14), Pain (GCS 7–9) and Unresponsive (GCS 3–6)24 and a separate category for patients for whom GCS could not be assessed owing to sedation.

In addition, the effect of adding the following variables, termed ‘additional variables’, to the model (alone or in combination) was explored:

-

lowest partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2), associated fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) or PaO2 : FiO2 ratio

-

base excess (calculated from the arterial blood gas with the lowest pH and from the lowest haemoglobin)

-

highest blood lactate

-

highest serum urea.

The physiological variables were divided into categories using small intervals at round values (e.g. multiples of 5 or 10, dependent on the scale of the variable).

Finally, the effect of incorporating severe comorbidity and/or age into the triage models was explored by selecting the preferred model based on physiological variables only and adding severe comorbidity (either in five individual organ systems or overall) and age (as a linear term).

Models were fitted using ordered logistic regression, with the primary performance measure of interest being the ability of the model to discriminate between the three outcome categories. Discrimination was assessed by Harrell’s concordance statistic, a natural generalisation of the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for binary logistic regression. 25 A concordance of 1 corresponds to perfect discrimination – that is, for any pair of admissions with different outcomes, the admission with the worse outcome will have the higher score. A concordance of 0.5 corresponds to discrimination that is no better than chance. Concordance values > 0.7 are generally considered to be ‘satisfactory’, > 0.8 ‘good’ and > 0.9 ‘excellent’. 26 The standard error of the concordance statistic was calculated using a jack-knife procedure adjusted for clustering of the outcome at the unit level. As the models were developed and validated on the same data set, performance measures may be subject to ‘shrinkage’. Efron’s optimism bootstrap (with 200 bootstrap samples) was used to estimate the optimism in the concordance due to overfitting. 27

The effect of using a model to triage patients with low or high scores was explored by modelling potential outcomes for triaged patients. For patients with low scores triaged to temporary critical care areas, it was assumed that those with outcomes classified as ‘potentially avoidable admissions’ would be managed safely in the temporary critical care area and discharged alive, but that those classified as ‘critical care required’ or ‘death’ would subsequently be transferred to the critical care unit. The number of bed days saved by this approach was therefore the bed days of critical care occupied by the diverted admissions that were ‘potentially avoidable’. For patients with high scores triaged to no critical care, it was assumed that those with outcomes classified as ‘potentially avoidable admissions’ would survive without critical care, but that those classified as ‘critical care required’ or ‘death’ would die, with the ‘critical care required’ group representing deaths that were potentially avoidable if more critical care capacity had been available.

All analyses were performed using stata/version 10.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA). The concordance statistic was calculated using the somersd package. 28

Results

Selection of data

Data were extracted from the CMPD for 105,397 admissions to 148 adult, general critical care units in England, Wales and Northern Ireland from 1 January 2007 to 31 March 2009. Excluding admissions whose last known status was still in the critical care unit (n = 7), admissions missing the date of discharge from, or death in, the critical care unit (n = 2), and admissions with inconsistencies in CCMDS data (n = 8) left 105,380 admissions to 148 units (99.98%) included in the analysis.

Impact of cancelled/postponed elective and scheduled surgery

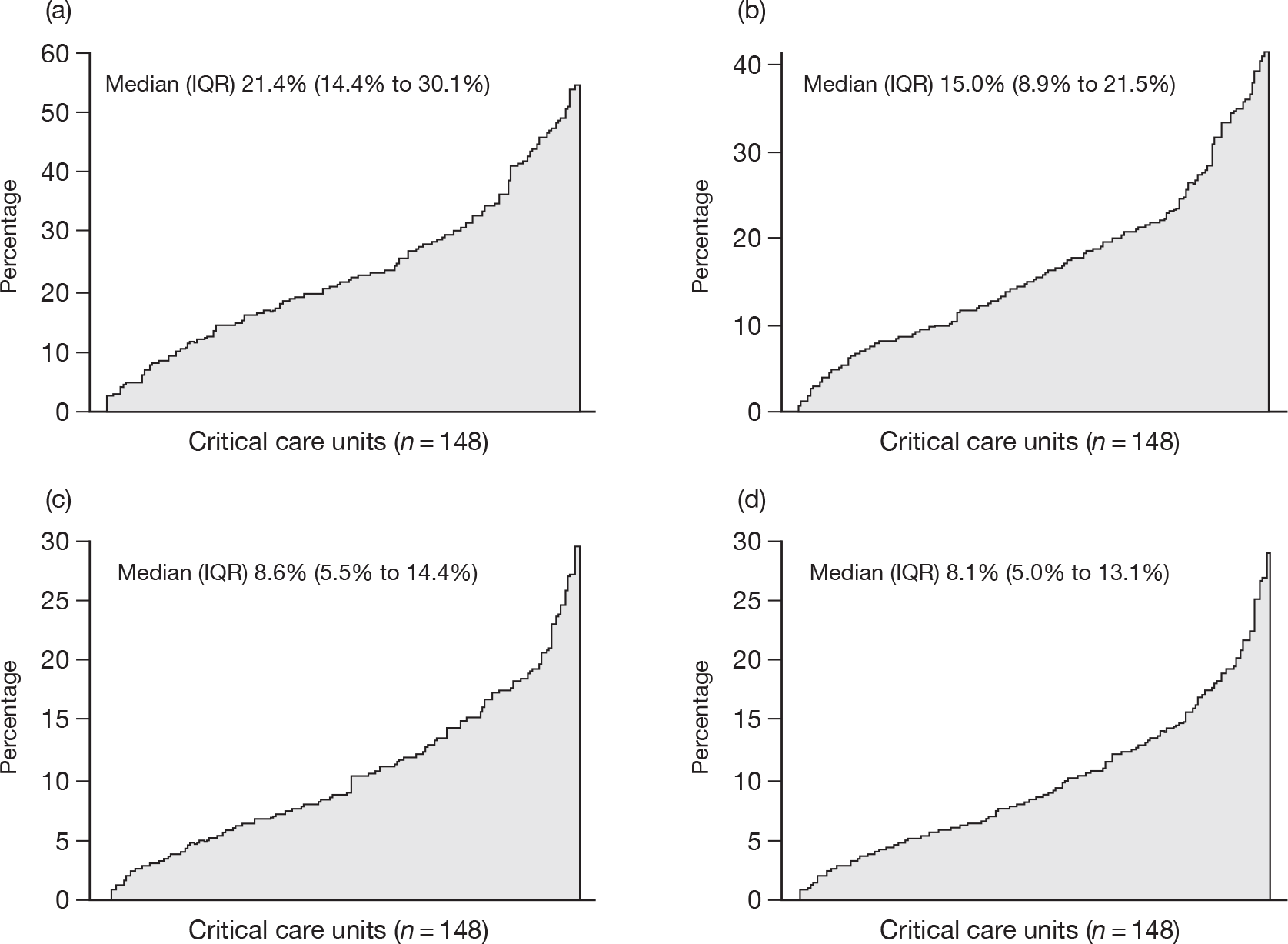

Overall, 25,828 (24.5%) admissions were associated with elective/scheduled surgery. These consisted of 23,548 admissions from theatre, 1240 subsequent readmissions, and 1040 admissions for pre-surgical preparation. Cancellation/postponement of these admissions would result in saving 17.0% of calendar days of critical care, 10.9% of calendar days of Level 3 care and 9.9% of calendar days of advanced respiratory support.

There was considerable variation in admissions associated with elective/scheduled surgery across the 148 critical care units (Figure 6). The median number of admissions in the available data from these units for elective/scheduled surgery was 611 [interquartile range (IQR) 368 to 973; and range 44 to 1966, respectively] and the median number of calendar days of critical care delivered was 3490 (IQR 2280 to 5526; and range 326 to 12,361, respectively).

FIGURE 6.

Variation across 148 adult, general critical care units in (a) the percentage of admissions prevented, and (b) calendar days of critical care, (c) Level 3 care and (d) advanced respiratory support saved by cancellation/postponement of elective/scheduled surgery.

Exclusions

After exclusion of admissions associated with elective/scheduled surgery, a total of 79,552 admissions remained. For triage modelling, the following additional admissions were excluded: admissions missing status at ultimate discharge from acute hospital (n = 867, 1.1%); readmissions to the critical care unit within the same acute hospital stay (n = 3475, 4.4%); admissions missing all basic vital signs (n = 700, 0.9%). A total of 74,510 admissions to 148 adult, general critical care units remained for analysis.

Patient cohorts

Of 74,510 admissions included in the analysis, 15,996 (21.5%) admissions were identified as admissions for acute exacerbations of respiratory illness. A brief summary of the case mix of all admissions and of admissions for acute exacerbations of respiratory illness is presented in Table 1.

| All admissions (N = 74,510) | Acute exacerbations of respiratory illness (N = 15,996) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 58.8 (19.7) years | 61.1 (17.8) years |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 33,246 (44.6) | 7414 (46.3) |

| Male | 41,264 (55.4) | 8582 (53.7) |

| Source of admission to the critical care unit, n (%) | ||

| Emergency department/not in hospital | 24,239 (32.5) | 4794 (30.0) |

| Theatre (following emergency/urgent surgery) | 17,876 (24.0) | 539 (3.4) |

| Ward or intermediate care | 27,474 (36.9) | 9032 (56.5) |

| Other critical care unit | 4921 (6.6) | 1631 (10.2) |

| APACHE IIa | ||

| Acute physiology score, mean (SD) | 13.3 (6.6) | 14.2 (6.3) |

| APACHE II score, mean (SD) | 17.4 (7.5) | 18.9 (7.2) |

| ICNARC physiology score, mean (SD) | 19.7 (9.8) | 21.8 (9.4) |

| CURB-65, n (%) | ||

| 0 | – | 420 (2.6) |

| 1 | – | 2645 (16.5) |

| 2 | – | 4507 (28.2) |

| 3 | – | 5147 (32.2) |

| 4 | – | 2682 (16.8) |

| 5 | – | 595 (3.7) |

Triage modelling

Of 74,510 admissions, 19,557 (26.2%) were classified as ‘potentially avoidable’, 31,074 (41.7%) as ‘critical care required’, and the remaining 23,879 (32.0%) died before discharge from acute hospital. Of 15,996 admissions with acute exacerbations of respiratory illness, 4098 (25.6%) were classified as ‘potentially avoidable’, 5800 (36.3%) as ‘critical care required’ and 6098 (38.1%) died before discharge from acute hospital.

The concordance statistics for triage models based on the core variables only, and core variables plus one or more additional variables, are shown in Table 2. Data on blood lactate were only available for 57,551 admissions to 118 units (12,144 with acute exacerbations of respiratory illness), therefore models incorporating blood lactate were restricted to these data. The model based on core variables alone produced a concordance of 0.75 (which may be considered ‘satisfactory’). Incorporating all additional variables raised this to a maximum of 0.79. The discrimination of the models among admissions with acute exacerbations of respiratory illness was generally worse, with concordance statistics ranging from 0.71 to 0.75. Among all admissions, the single additional variables that added most discriminatory ability to the core variables were FiO2 and urea (each raising the concordance to 0.77). Among admissions with acute exacerbations of respiratory illness, the addition of urea marginally outperformed the addition of FiO2 (concordance 0.74 vs 0.73), supporting the presence of urea within the CURB-65 score for community-acquired pneumonia. However, the difficulty in obtaining a urea value quickly enough to use as the basis for a triage decision has previously been identified as a limitation of using CURB-65 for triage. 15 It was proposed, therefore, that the most practical physiology-based triage model should be based on the core variables plus FiO2. Applying Efron’s optimism bootstrap to this model indicated that the anticipated degree of shrinkage when applying this model in future populations was small. The estimated optimism (95% CI) in the concordance was 0.00054 (0.00036 to 0.00073) for all admissions and 0.00099 (0.00055 to 0.00144) for admissions with acute exacerbations of respiratory illness. Adjusted estimates of the concordance for this model were therefore 0.769 and 0.727, respectively.

| Variables in model | Concordance (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| All admissions (n = 74,510) | Acute exacerbations of respiratory illness (n = 15,996) | |

| Core variablesa only | 0.752 (0.746 to 0.757) | 0.712 (0.703 to 0.721) |

| Core variables plus... | ||

| … PaO2 | 0.761 (0.754 to 0.767) | 0.722 (0.713 to 0.730) |

| … FiO2 | 0.770 (0.763 to 0.776) | 0.728 (0.719 to 0.736) |

| … PaO2 : FiO2 | 0.766 (0.760 to 0.772) | 0.728 (0.719 to 0.736) |

| … Base excess | 0.763 (0.757 to 0.770) | 0.722 (0.713 to 0.731) |

| … Urea | 0.771 (0.766 to 0.776) | 0.738 (0.730 to 0.747) |

| … FiO2 and urea | 0.784 (0.778 to 0.790) | 0.747 (0.738 to 0.755) |

| … FiO2, base excess and urea | 0.786 (0.781 to 0.792) | 0.749 (0.741 to 0.758) |

| Core variables onlyb | 0.751 (0.744 to 0.757) | 0.712 (0.702 to 0.722) |

| Core variables plus… | ||

| … Blood lactateb | 0.766 (0.761 to 0.772) | 0.715 (0.707 to 0.724) |

| … FiO2, base excess, urea and blood lactateb | 0.791 (0.786 to 0.796) | 0.752 (0.743 to 0.760) |

Incorporating severe comorbidity into the triage model based on core variables and FiO2 resulted in a negligible improvement in concordance (Table 3). Incorporating age into the triage model, in addition to comorbidity, produced a small improvement in concordance to 0.788 for all admissions and 0.761 for admissions with acute exacerbations of respiratory illness.

| Variables in model | Concordance (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| All admissions (n = 74,510) | Acute exacerbations of respiratory illness (n = 15,996) | |

| Core variablesa and FiO2 only | 0.770 (0.763 to 0.776) | 0.728 (0.719 to 0.736) |

| Core variables and FiO2 plus… | ||

| … severe comorbidity in five separate organ systemsb | 0.773 (0.767 to 0.779) | 0.734 (0.725 to 0.742) |

| … severe comorbidity (any/none) | 0.773 (0.767 to 0.779) | 0.734 (0.725 to 0.742) |

| … severe comorbidity in five separate organ systemsb and age (linear) | 0.788 (0.783 to 0.794) | 0.761 (0.753 to 0.768) |

| … severe comorbidity (any/none) and age (linear) | 0.788 (0.783 to 0.793) | 0.760 (0.753 to 0.768) |

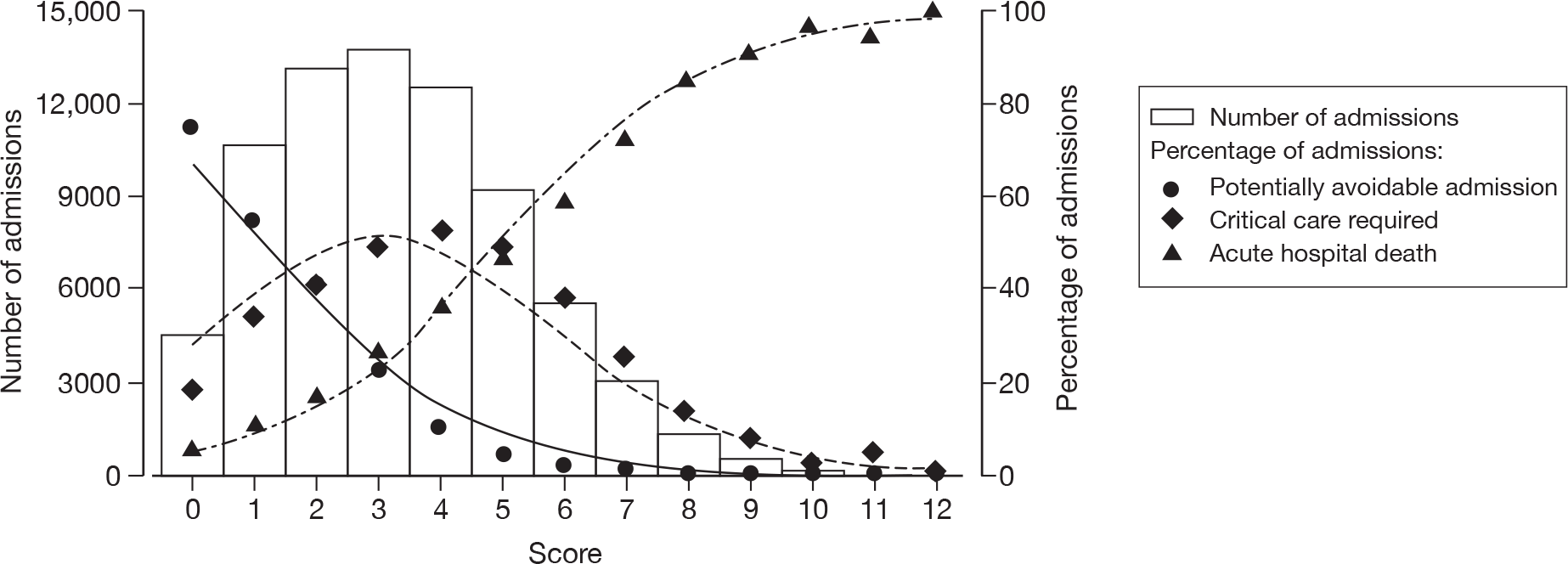

A potential simple, physiology-based, triage model is described in Table 4. This model produced a score with a range from 0 to 12. The distribution of the score and associated outcomes are illustrated in Figure 7. As a result of combining adjacent categories from the original fine categorisation to produce this score, there was some loss of discrimination, resulting in a concordance statistic for the score of 0.754 (95% CI 0.747 to 0.760) among all admissions and 0.713 (95% CI 0.705 to 0.721) among admissions with acute exacerbations of respiratory illness. By comparison, the concordance statistic for CURB-65 among admissions with acute exacerbations of respiratory illness was 0.680 (95% CI 0.671 to 0.688).

| Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 95+ | 75–94 | 60–74 | <60 |

| Temperature (°C) | 36.5+ | 36–36.4 | < 36 | |

| Heart rate (minute-1) | < 130 | 130+ | ||

| Respiratory rate (minute-1) | 12–35 | < 12 or 36+ | ||

| Neurological status | A, GCS 15 | V, GCS 10–14 | P,a GCS 7–9 | U, GCS 3–6 |

| FiO2 | 0.21 | 0.22–0.49 | 0.50+ | |

FIGURE 7.

Distribution of the score (bars) and relationship with outcomes (line: predicted by model; points: observed) for a 12-point triage score based on core variables plus FiO2.

The effect of using this model to triage patients with low and high scores is shown in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. Although the strategy of diverting patients with a low score to temporary critical care areas may seem appealing in terms of initially diverting a relatively large proportion of admissions from the critical care unit, the effect on bed occupancy is much less as the ‘potentially avoidable admissions’ generally had short stays in the critical care unit. The upper limit of any such strategy would be to save the 12.5% of bed days occupied by ‘potentially avoidable admissions’ overall. By comparison, although triaging patients with high scores diverts a much smaller proportion of admissions, the effect in critical care unit bed days saved is greater as these patients had longer stays in the critical care unit. However, the savings in terms of bed days would be small and the cost of these savings would potentially be a substantial number of avoidable deaths.

| Scores on which triage occurs | Percentage of admissions diverted | Potential outcomes for diverted admissions | Percentage of critical care unit bed days saveda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical care unit admission avoided | Subsequent admission to critical care unit – survives | Subsequent admission to critical care unit – dies | |||

| 0 | 6.0% | 74.5% | 18.8% | 6.6% | 1.8% |

| 0–1 | 20.3% | 60.6% | 29.5% | 9.9% | 5.1% |

| 0–2 | 38.0% | 51.5% | 34.9% | 13.6% | 8.8% |

| 0–3 | 56.5% | 42.1% | 39.8% | 18.1% | 11.1% |

| Scores on which triage occurs | Percentage of admissions diverted | Potential outcomes for diverted admissions | Percentage of critical care unit bed days saveda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Likely survivor | Avoidable death | Unavoidable death | |||

| 10–12 | 0.3% | 0.0% | 3.0% | 97.0% | 0.1% |

| 9–12 | 1.1% | 0.1% | 6.8% | 93.1% | 0.4% |

| 8–12 | 2.9% | 0.1% | 11.4% | 88.4% | 1.7% |

| 7–12 | 6.9% | 0.7% | 20.1% | 79.2% | 5.7% |

| 6–12 | 14.4% | 1.5% | 30.0% | 68.5% | 15.4% |

Discussion

A simple, physiology-based, triage model was developed that had ‘satisfactory’ concordance for distinguishing between outcome categories. The model outperformed CURB-65 among admissions with acute exacerbations of respiratory illness. These results seem to support findings from an emergency department cohort that CURB-65 is an unreliable triage tool in this setting. 29 Some of the poor performance of CURB-65 could be attributed to the fact that it was developed to triage patients for admission to hospital (a different triage step in the care pathway to that considered in SwiFT).

It is unsurprising that the performance of the simple, physiology-based triage model was not better as, even using much more detailed laboratory and diagnostic data available within the critical care unit, complex risk prediction models produce concordance estimates in the range 0.82–0.87 for distinguishing hospital survivors from non-survivors. 22,30 Even with this higher level of concordance it has been suggested that such risk models should not be routinely relied on, in isolation, for making life and death decisions for individual patients. 31

The development of the simple, physiology-based, triage model was limited by the available data in the CMPD. In particular, the most extreme physiological measurements from the first 24 hours following admission to a critical care unit were assumed to be representative of pre-admission values that would be used to make a triage decision. Using these more extreme physiological values from a wider time period could falsely enhance the apparent performance of the model. Addition of severe comorbidity had only a small effect while the addition of age had a moderate effect, though the concordance of the model was still only satisfactory. The incorporation of age into a triage model potentially raises ethical concerns. 8

The utility of a score, derived from the simple, physiology-based, triage model, to triage patients for critical care in a pandemic seems to be minimal. Under the most extreme conditions considered, i.e. triaging patients with a score of 0–3 to a temporary critical care area, admitting patients with a score of 4 or 5 and denying critical care to patients with a score of ≥ 6, a saving of only 26.5% of critical care bed days would be achieved. However, for every 100 patients triaged:

-

57 patients would initially be managed in a temporary critical care area, but 33 of these would subsequently require transfer to the critical care unit and the subsequent effect of this delayed transfer on critical care resource utilisation and outcome cannot be quantified

-

29 patients would be admitted to the critical care unit as usual

-

14 patients would be denied critical care, and of these, four patients would die who would otherwise have survived if admitted to the critical care unit.

While there may be some scope for using such scores for triage to critical care during a pandemic, it seems clear that: (1) these scores are not sufficiently discriminatory to be relied upon in isolation; and (2) the resultant savings in terms of critical care unit bed days would not be substantial. More data are required to explore this in further detail. Data on all acute hospital admissions potentially requiring critical care would be required to enable a fuller exploration of decision-making around critical care admission. Data on the duration and trajectory of critical illness would enable exploration of triage models to consider earlier discontinuation of critical care for patients initially admitted to critical care.

In conclusion, it must be recognised that triage may be required at several steps in the care pathway for patients with H1N1 and each step probably requires different triage models. SwiFT focused on the decision to admit to critical care only and, more specifically, on identifying which patients not to admit, when resources are scarce, from among those who would be admitted under usual (non-pandemic) circumstances. Given this, the failure of the simple, physiology-based triage model to reliably identify patients who are unlikely to benefit from critical care suggests that: (1) further research into triage methods, at each step in the care pathway, should be a high priority; and (2) pandemic planning should not be based on assumptions that a reliable triage tool is available for any step.

Chapter 3 The impact of H1N1 on critical care in the UK

Introduction

The objective of the main phase of SwiFT was to provide regular reporting to policy-makers and to clinicians to guide immediate policy and practice on the use of critical care services during the pandemic. This chapter describes the impact of the pandemic on critical care services and patients’ care and outcomes.

Methods

Coverage

All acute hospitals in England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the ROI were encouraged to participate in SwiFT. As soon as each site completed governance checks, data were collected on consecutive patients meeting the inclusion criteria until SwiFT closed to recruitment on 31 January 2010 (in consultation with the Department of Health). At the end and following completion of recruitment, the local collaborator at each site signed a final declaration, confirming the period of recruitment and indicating that all consecutive, eligible patients had been recruited, or reporting any exceptions. The overall coverage of SwiFT across sites in England was assessed by comparing data from SwiFT with weekly prevalence figures for critical care compiled and published by the Health Protection Agency (HPA) from daily situation report data submitted to the Department of Health from individual NHS Trusts in England. The coverage of SwiFT, relative to the pandemic as a whole, was estimated by comparing the numbers of confirmed H1N1 cases recruited in SwiFT with the total numbers of intensive care unit and high-dependency unit admissions reported by the Department of Health and the devolved administrations. 1

Inclusion criteria

All patients (adult or paediatric) were included in SwiFT if they were either:

-

confirmed or suspected pandemic H1N1 patients referred and assessed as requiring critical care; or

-

non-H1N1 patients referred and assessed as requiring critical care (under usual/non-pandemic circumstances), but not admitted to a critical care unit in the hospital where referred and assessed.

Data collection

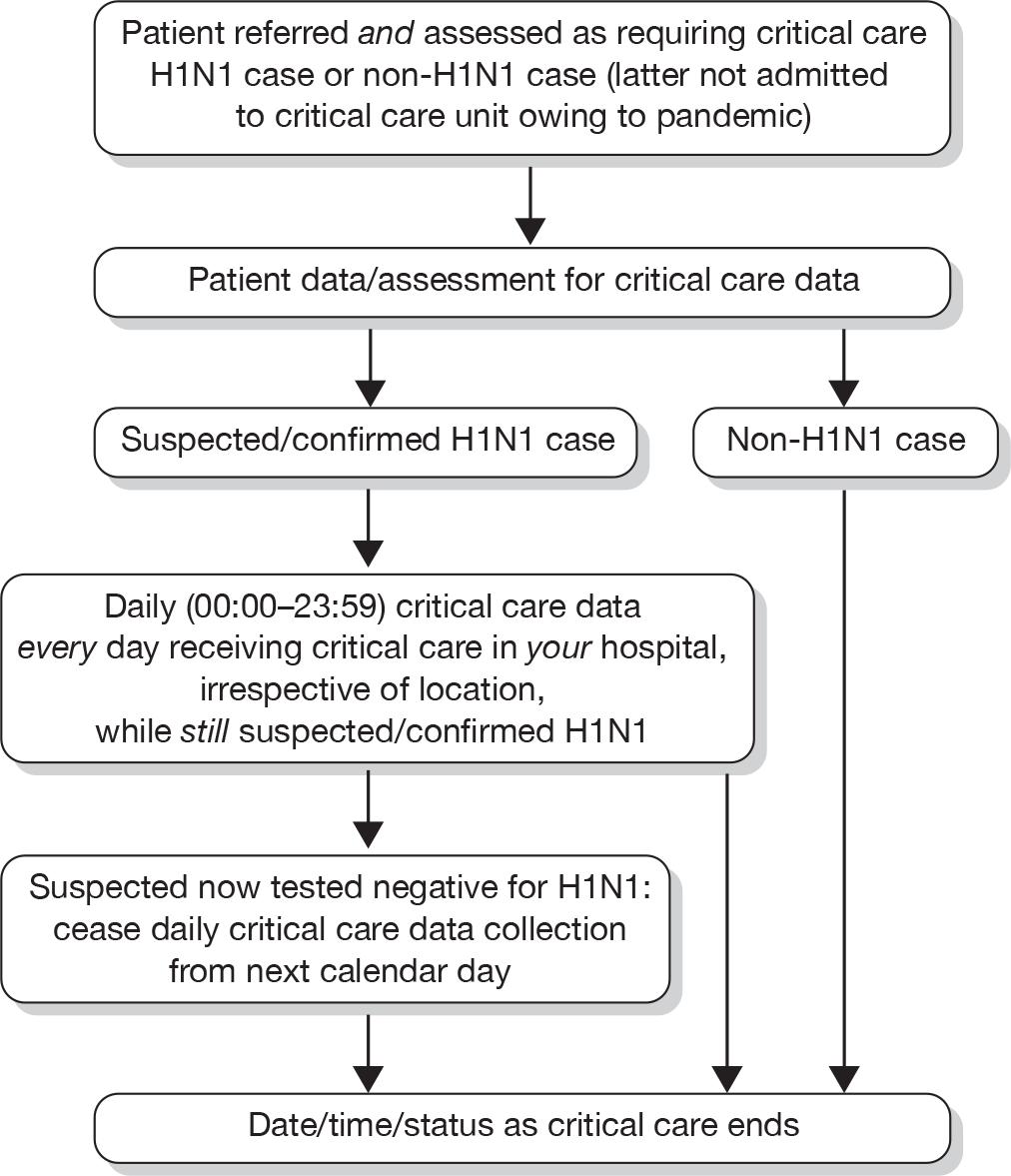

Selected clinical data were collected from both the point of referral and assessment for critical care and daily (calendar day 00:00–23:59) while receiving critical care. Daily data collection continued until either tested negative for suspected H1N1 cases or critical care ended for confirmed H1N1 cases (Figure 8). Confirmed H1N1 was defined as tested positive for H1N1 by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or viral culture from upper respiratory swabs or tracheobronchial aspirate. Suspected H1N1 was defined as any patient believed to have H1N1 and managed as such. Tested negative for H1N1 was defined as at least one negative real-time PCR from both upper respiratory swabs and tracheobronchial aspirate. Date, time and status when critical care ended were collected for all suspected H1N1, confirmed H1N1 and non-H1N1 cases.

FIGURE 8.

Overview of data collection for SwiFT.

Assessment data included event (date, time and location of assessment); sociodemographic (age, sex and ethnicity); body composition [ranges of body mass index (BMI)]; pregnancy status; H1N1-related (status, vaccine status, antivirals and presentation); chronic organ dysfunction (mild/severe); responsiveness (Alert/Voice/Pain/Unresponsive, confusion); vital signs (temperature, blood pressure, heart and respiratory rate); oxygenation (oxygen saturation and fraction of inspired oxygen); and selected results (base excess, blood lactate, serum urea and creatine kinase). All elements to calculate the CURB-65 assessment of severity of pneumonia score23 were included.

Daily data included H1N1-related (status and antivirals); organ support (by body system including type of ventilatory support); selected drugs; responsiveness (lowest GCS); vital signs (lowest systolic blood pressure and highest heart rate); oxygenation (lowest PaO2 with associated FiO2); selected results (highest bilirubin, lowest platelet count, highest blood lactate and highest creatinine) and fluids (total urine output and overall balance). All elements to calculate the SOFA score32 were included.

SwiFT data were entered onto a secure web-based data entry system developed and hosted by the ICNARC. Data collection manuals and forms (see Appendix 2), definitions (either as help text or as answers to frequently asked questions) and error checking were either available for download or built into the design of the web portal.

Reporting during the pandemic

Once a suitable sample size of cases had been accrued in the SwiFT database, weekly reports were circulated to policy-makers and to critical care clinicians. Key policy-makers receiving the reports included the Department of Health Pandemic Flu Team, Chief Medical Officer, Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, Pandemic Influenza Clinical and Operational Group, Director General responsible for Pandemic Influenza, Director of NHS Flu Resilience, Scientific Pandemic Influenza sub-group on Modelling Operational group, Influenza Clinical Information Network, and Swine Flu Critical Care Clinical Group. To maximise access to all clinicians, the weekly reports were uploaded onto the SwiFT web portal to provide regular updates on the evolving pandemic.

The content of the reports was developed initially by two SwiFT co-investigators (KMR, DAH) and circulated to key policy-makers and clinicians for comment and input.

System capacity

The impact of the H1N1 pandemic on critical care system capacity was assessed by: the numbers of patients refused critical care (owing to either perceived futility or the lack of available staff and/or beds); the numbers of patients managed in extended critical care areas or in non-critical care areas; and the numbers transferred to receive critical care in another acute hospital.

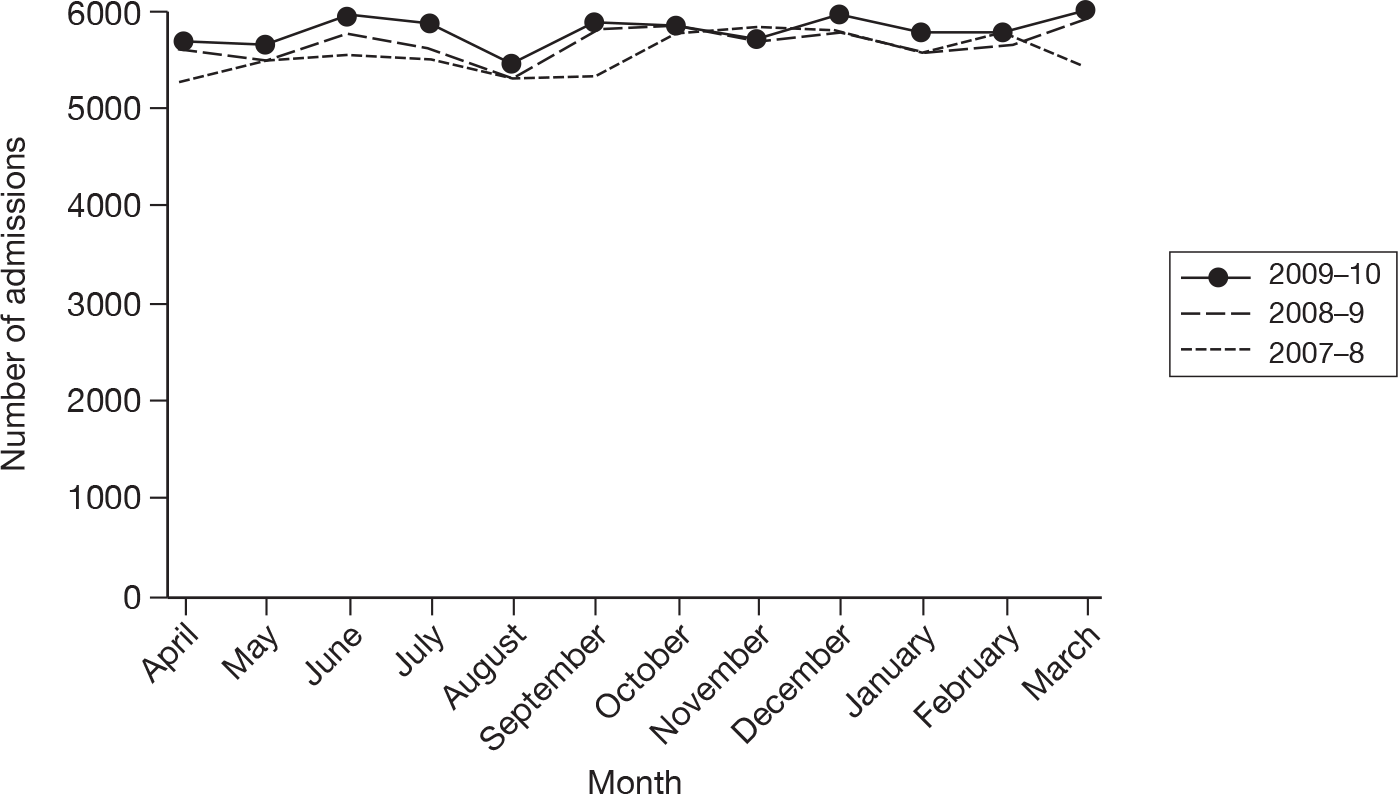

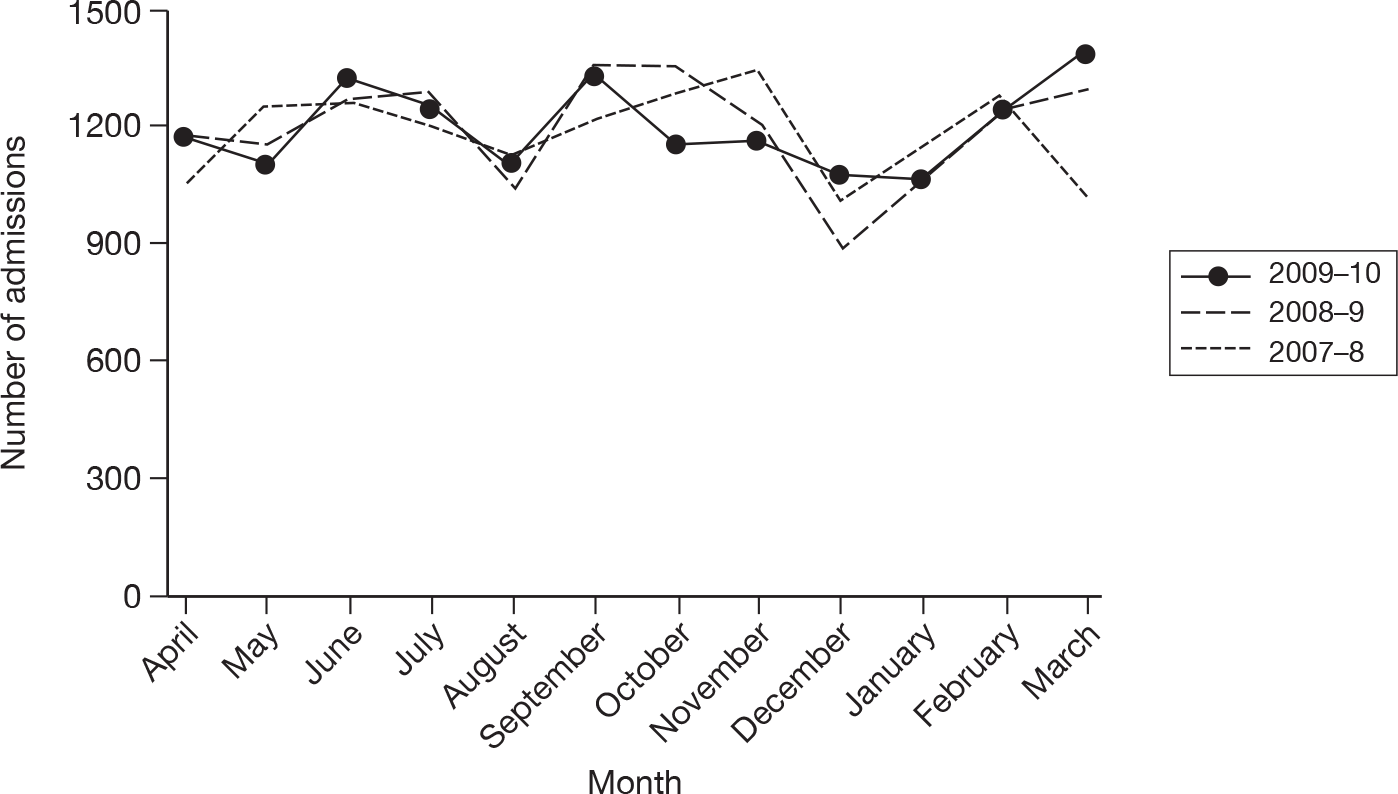

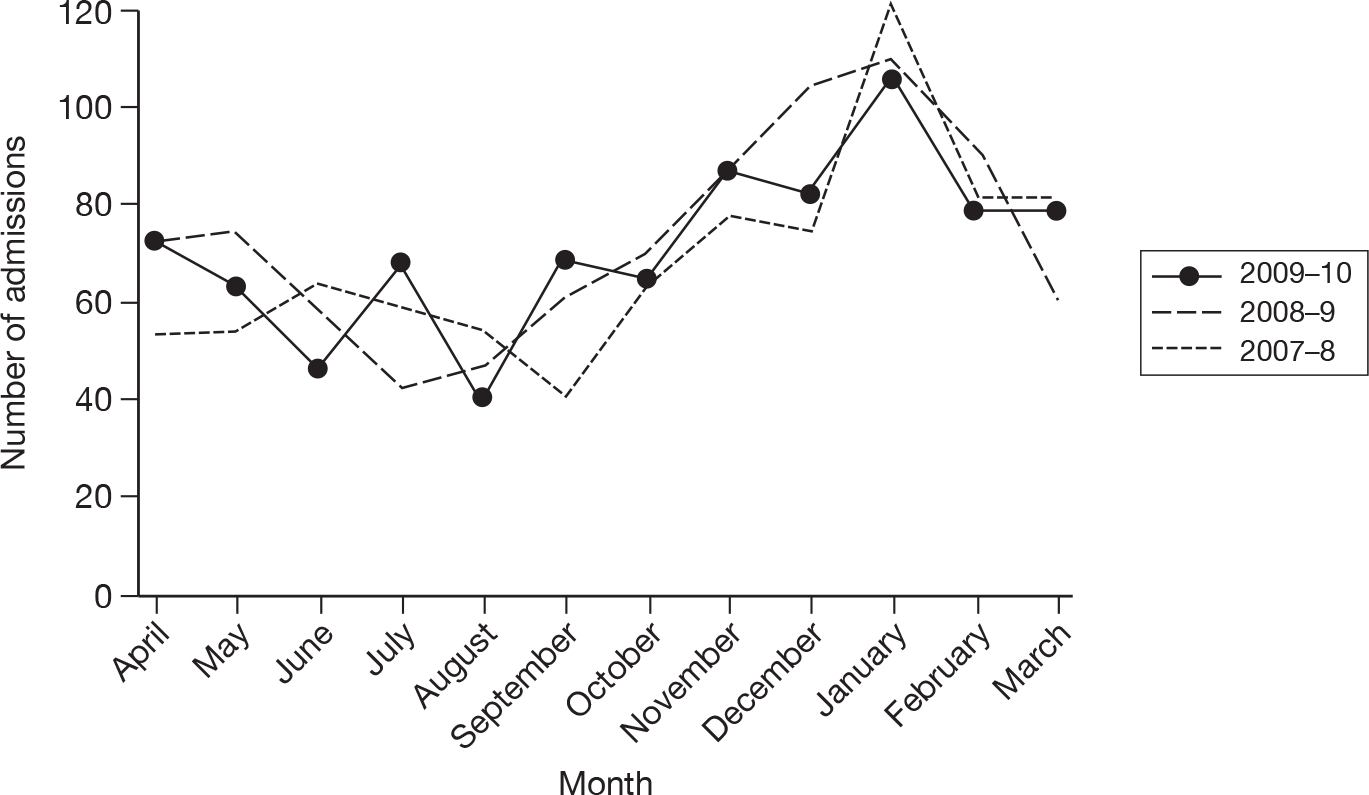

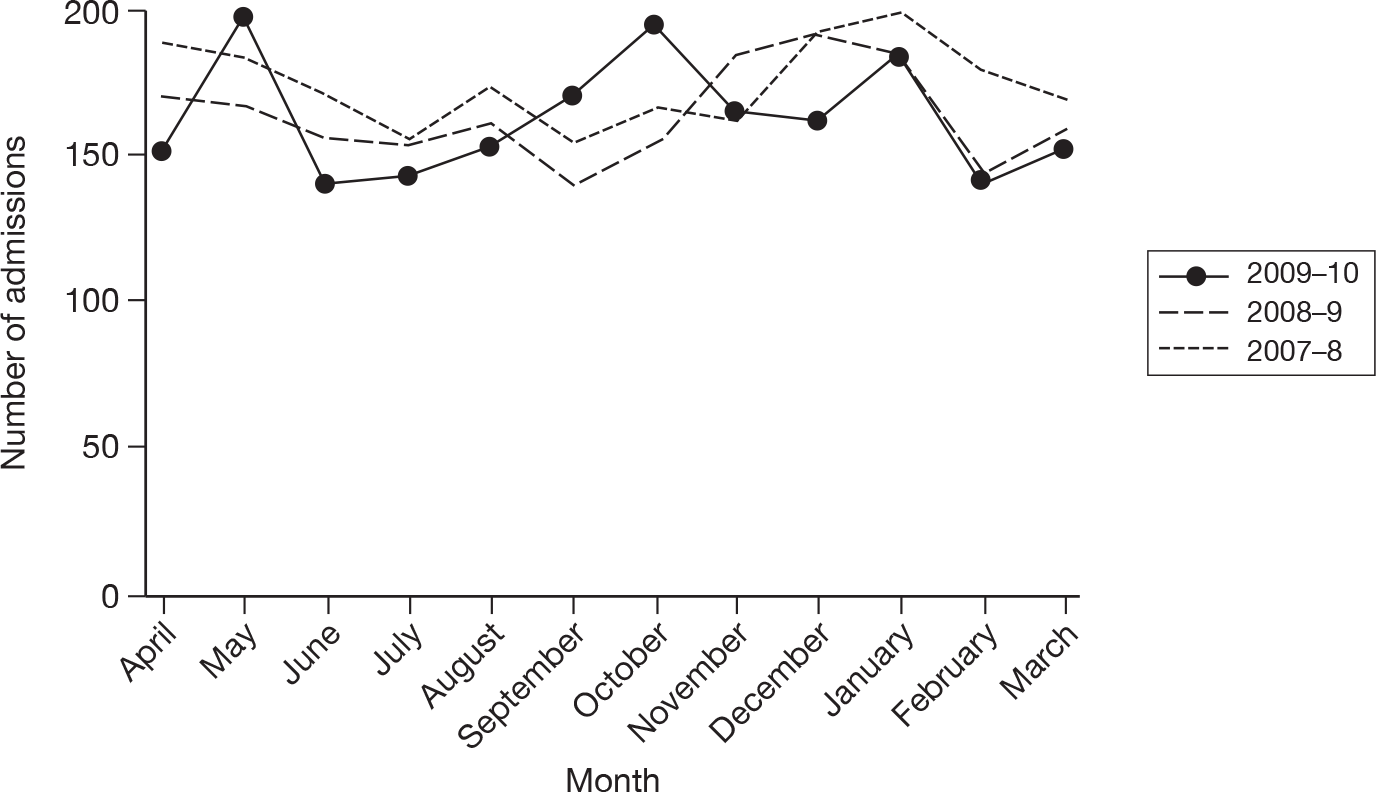

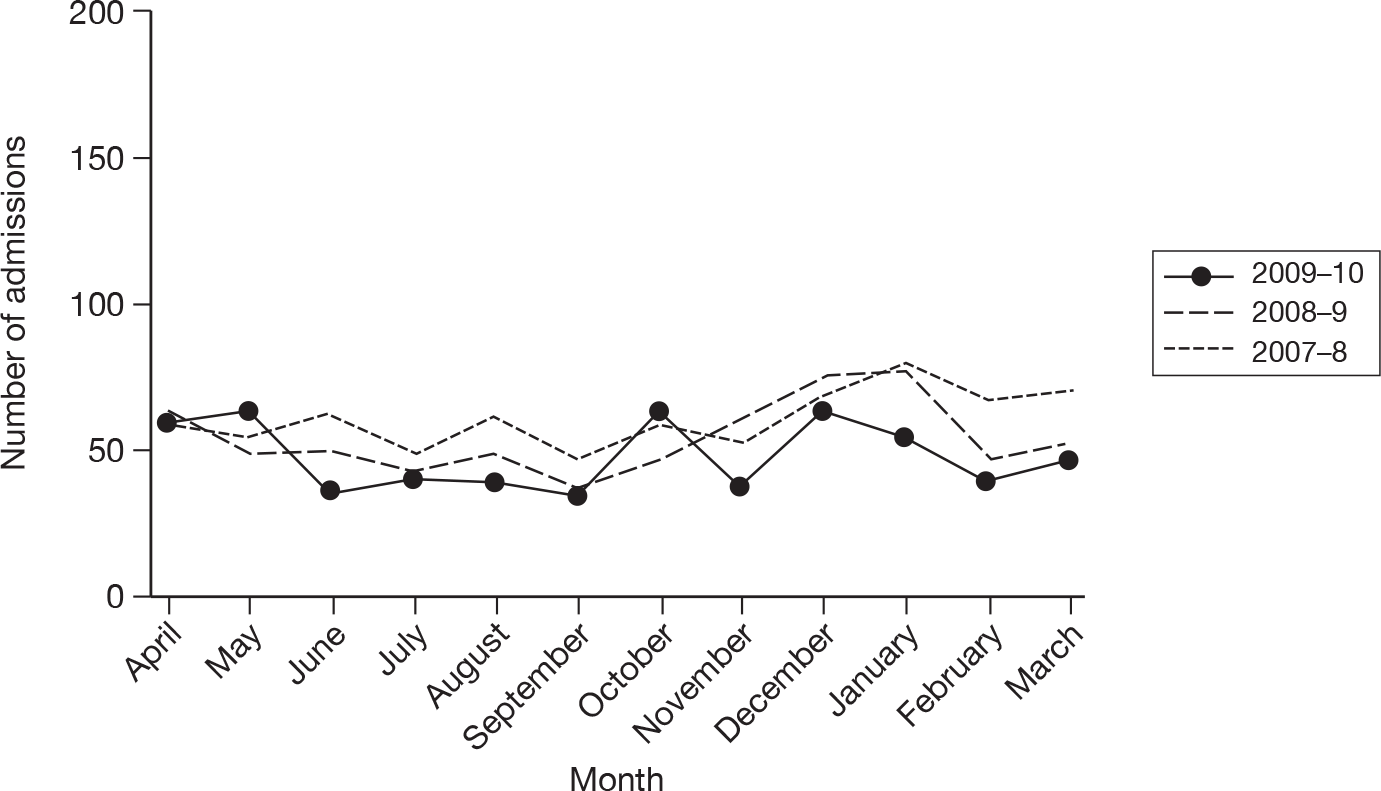

The wider impact of the H1N1 pandemic was assessed by evaluating data from the CMPD for the year April 2009 to March 2010 compared with the previous 2 years. Data were extracted for all adult, general critical care units with complete data for the entire 3-year period, and the following were plotted for each month: total number of admissions; number of admissions direct from theatre following elective or scheduled surgery; number of admissions from recovery only (representing use of recovery as an extended critical care area); number of admissions transferred to a critical care unit in another hospital; and the number of these transfers that were for non-clinical reasons (i.e. not for more specialised critical care or repatriation).

Description of cases

Suspected/confirmed H1N1 cases were classified, for presentation, into the following three categories:

-

Confirmed: H1N1 confirmed either on initial assessment or at any time during critical care.

-

Suspected: H1N1 suspected on initial assessment, but never confirmed nor tested negative.

-

Tested negative: H1N1 suspected on initial assessment, but never confirmed and subsequently tested negative.

The patients identified in these three categories were described and compared by the following factors.

Patient demographics were described by age on initial assessment, ethnicity, sex, pregnancy status and body composition. Ethnicity was reported by collapsing the ethnic categories, as used in the 2001 UK census, into the following five groups: white (A, B, C); mixed (D, E, F, G); Asian or Asian British (H, J, K, L); black or black British (M, N, P); other ethnic groups (R, S); or not stated (Z). Pregnancy status was recorded as currently pregnant, recently pregnant (within the past 42 days), or neither. Body composition was assessed, either objectively by calculation of BMI or subjectively, and categorised as: very thin (BMI < 16 kg m-2); thin (BMI 16–18.5 kg m-2); acceptable weight (BMI 18.6–24.9 kg m-2); overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg m-2); obese (BMI 30–39.9 kg m-2); or morbidly obese (BMI ≥ 40 kg m-2).

Chronic health status was described by reported chronic organ dysfunction of respiratory, cardiovascular, renal, hepatic and neurological systems (classified as either moderate or severe) and by the presence of immunocompromise (due to disease or therapy). For respiratory and cardiovascular organ dysfunction, moderate dysfunction was defined as outpatient management and severe dysfunction as severe impairment in activities of daily living. For renal organ dysfunction, moderate dysfunction was defined as outpatient management and severe dysfunction as requiring chronic renal replacement therapy. For hepatic organ dysfunction, moderate dysfunction was defined as compensated liver disease and severe dysfunction as decompensated liver disease or awaiting transplantation. For neurological organ dysfunction, moderate dysfunction was defined as some impairment in activities of daily living and severe dysfunction as severe impairment in activities of daily living.

Reported presentation was classified as: viral pneumonitis/ARDS; secondary bacterial pneumonia; exacerbation of airflow limitation, e.g. COPD or asthma; or another intercurrent illness with H1N1 (coded with the ICNARC Coding Method20).

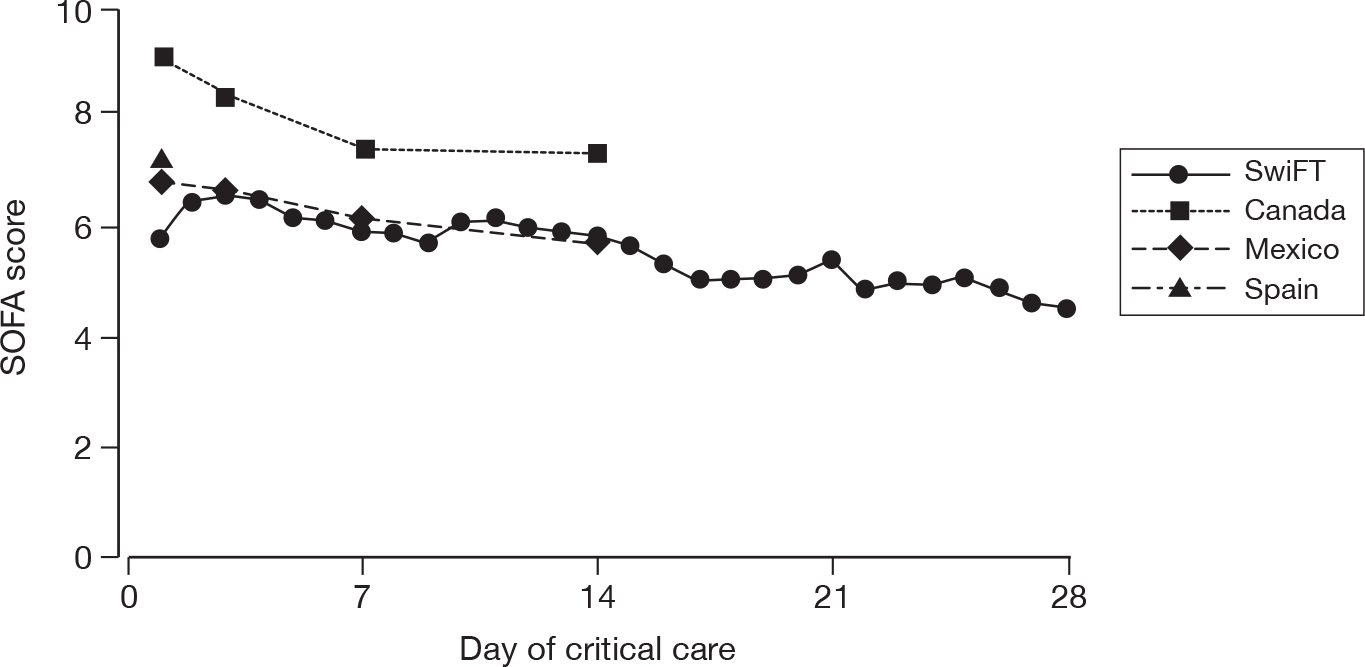

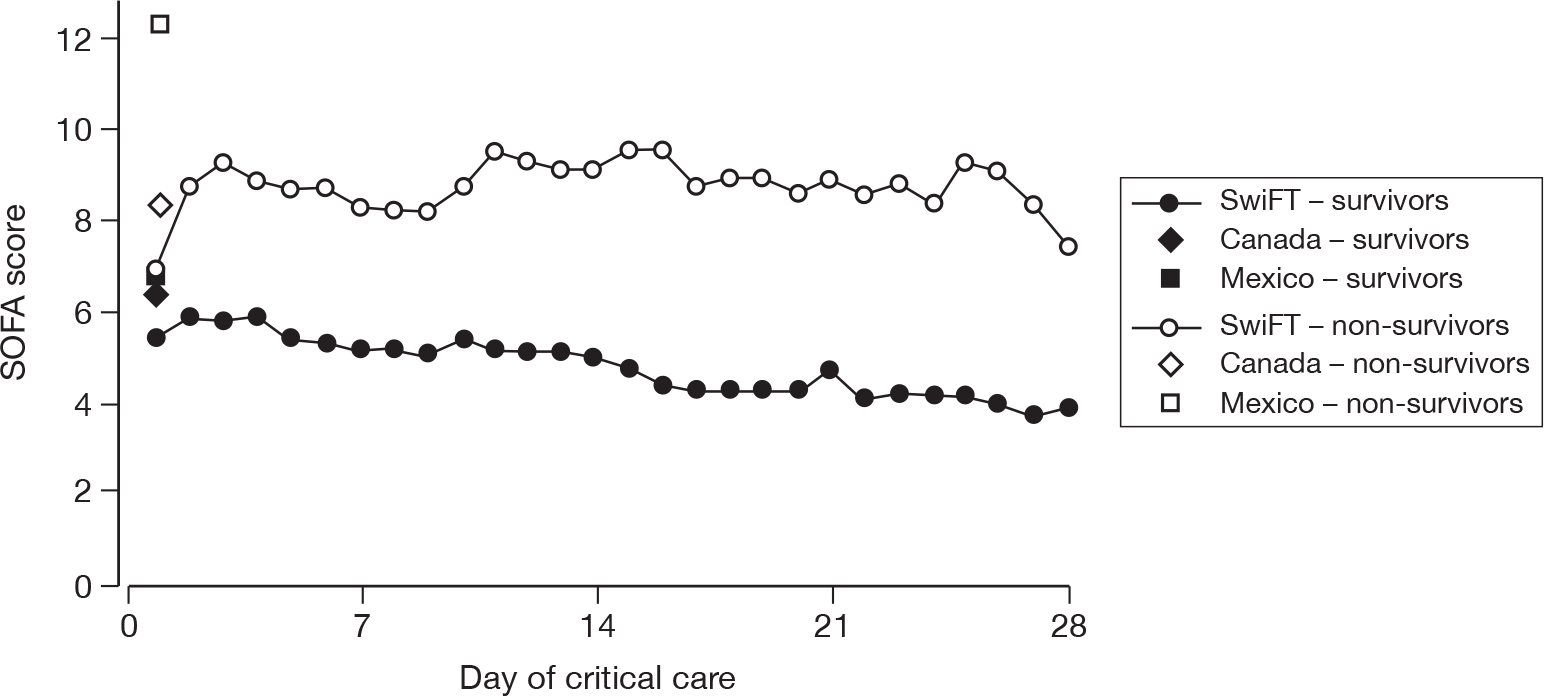

Acute severity on initial assessment was described by the CURB-65 score,23 which is a severity assessment score for community-acquired pneumonia. It consists of five points, one point each for the presence of new onset confusion, urea > 7 mmol l-1, respiratory rate of ≥ 30 breaths minute-1, low systolic (< 90 mmHg) or diastolic (≤ 60 mmHg) blood pressure, and age ≥ 65 years. Acute severity on the first calendar day of critical care was summarised by the SOFA score. 32 The SOFA score is a scoring system summarising the degree of organ dysfunction with 0–4 points assigned to each of: respiratory (PaO2 : FiO2 and mechanical ventilation); cardiovascular (mean arterial pressure and administration of vasopressors); renal (creatinine and urine output); hepatic (bilirubin); neurological (GCS); and coagulation (platelets), giving a total score ranging from 0 to 24.

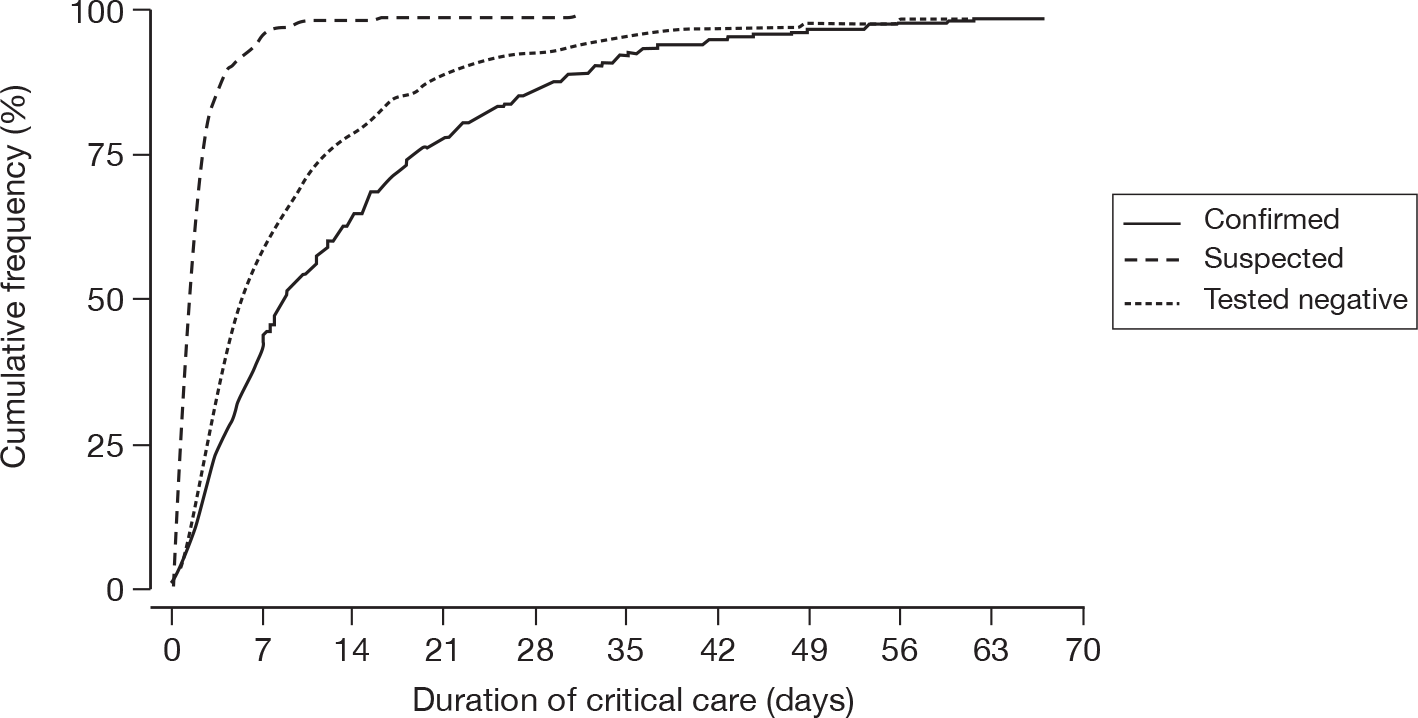

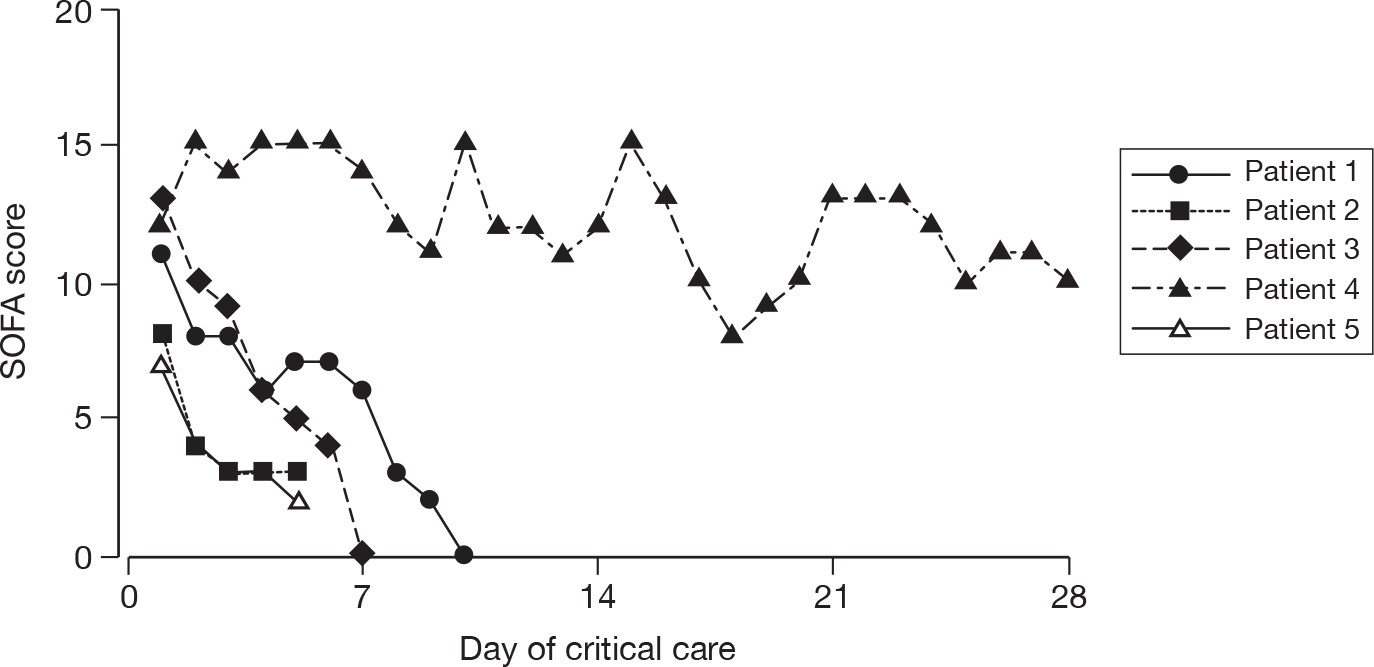

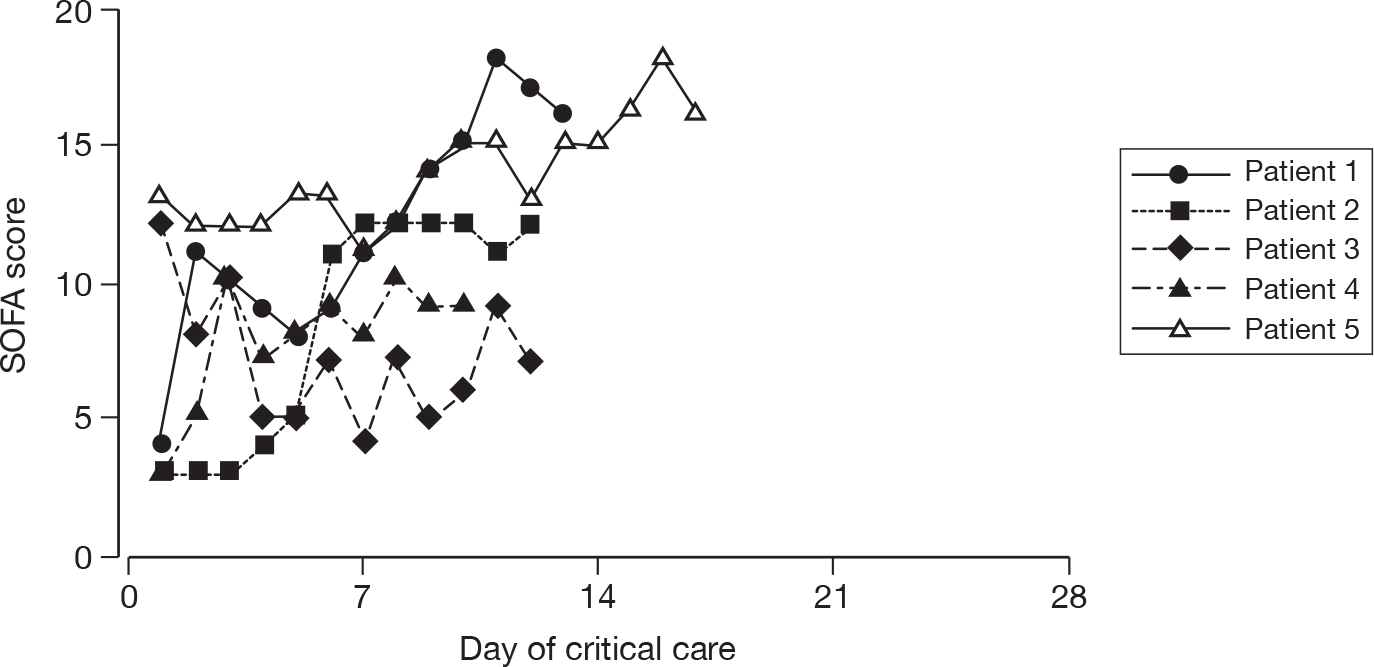

For patients receiving critical care, the duration of critical care was calculated from the date and time critical care commenced to the date and time critical care ended. The duration of critical care was displayed graphically by cumulative frequency plots and summarised by the median and mean. The survival status for the three groups was summarised at the end of critical care within the original hospital.

Performance of triage models

The performance of the simple physiology-based triage model developed was assessed among patients with confirmed or suspected H1N1 at initial assessment for critical care and compared with that of CURB-65. The outcome variable differed slightly from that used to derive the model, as follow-up was available only to the end of critical care and not to ultimate discharge from acute hospital. This may therefore be considered to represent the performance of the model under the assumption that all those patients surviving the critical care episode would go on to leave acute hospital alive. [Note: data from all adult, general critical care admissions in the CMP indicate that, of those who survive to leave the critical care unit, a further 8% die before discharge from acute hospital.]

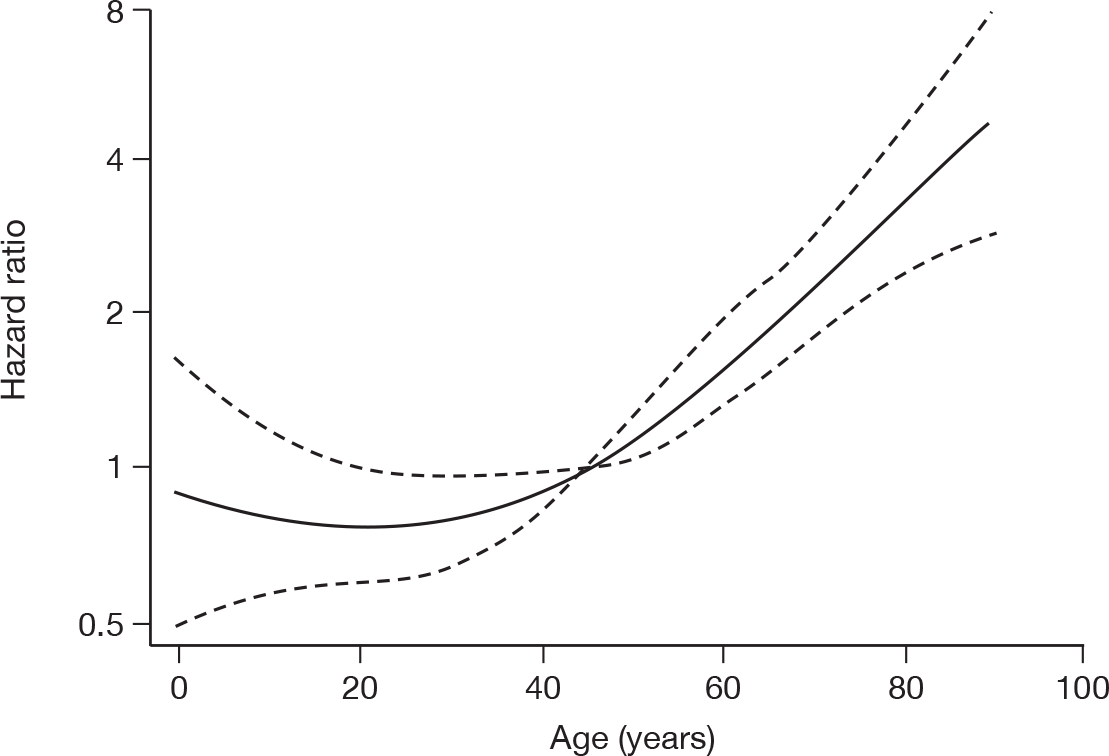

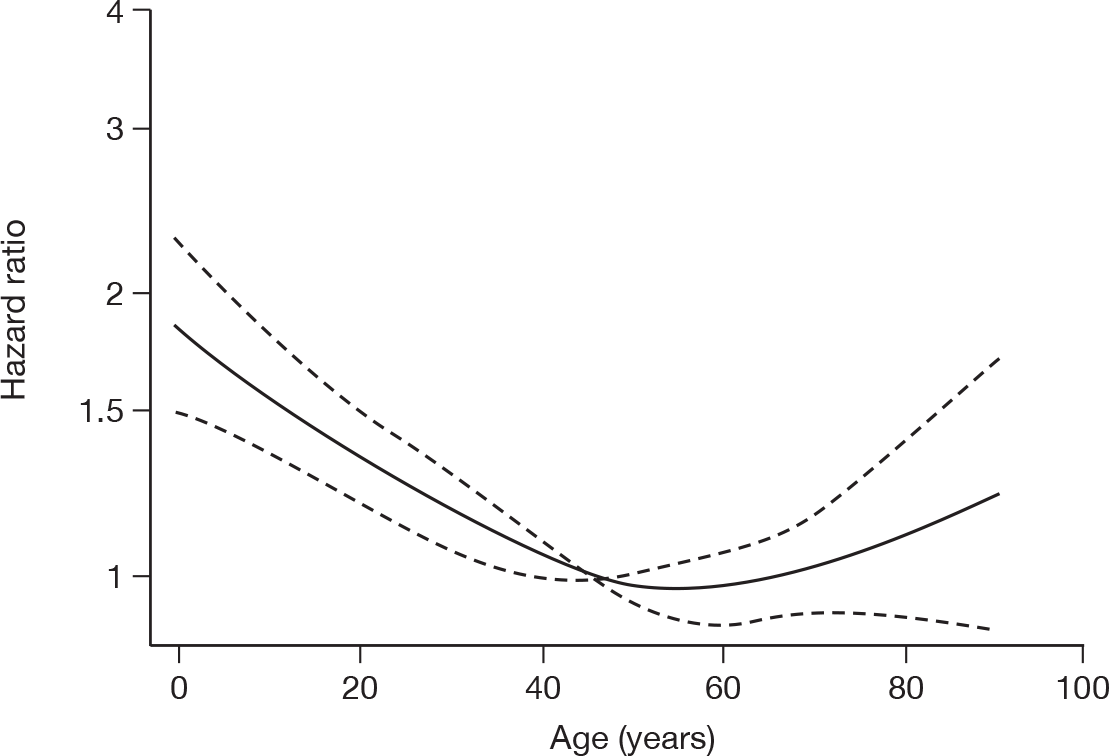

Risk factors for death and duration of critical care

For patients receiving critical care within the original hospital, risk factors for death, while receiving critical care within the original hospital, were assessed with a Cox proportional hazards regression model. The outcome for the model was the time to death while receiving critical care. Patients ending critical care or lost to follow-up (owing to incomplete daily data) were treated as censored. The potential risk factors included in the model were: age (non-linear relationship fitted using restricted cubic splines); sex; pregnancy status; ethnicity (white vs non-white); H1N1 status (confirmed vs suspected) on initial assessment; reported presentation; location of assessment (emergency department vs other); chronic organ dysfunction (any severe vs any moderate vs none); being immunocompromised; and SOFA score on first calendar day of critical care.

For patients surviving to the end of critical care within the original hospital, risk factors for longer duration of critical care were assessed with a Cox proportional hazards model. The outcome for the model was time to end of critical care. Deaths were excluded and patients lost to follow-up were treated as censored. The same potential risk factors were explored as listed for time to death while receiving critical care (above).

Results

Coverage

SwiFT received central research governance approval on 3 September 2009 and the secure, web-based, data entry system went live on 17 September 2009. A total of 192 acute hospitals participated in SwiFT, including 154 of 214 acute hospitals in England (72%), 6 of 16 in Wales (38%), 4 of 9 in Northern Ireland (44%), 19 of 25 in Scotland (76%) and 7 of 37 in ROI (19%). Owing to the very variable time taken to complete local governance checks, participation increased over time.

Final declaration forms were received from the local collaborators representing 188 (98%) of the 192 acute hospitals that commenced recruitment. Of the returned declarations, 64 (34%) indicated that not all paediatric cases were included, owing to a misunderstanding of the inclusion criteria and only recording data for patients admitted to the adult critical care unit (n = 59), owing to lack of resources (n = 3) or owing to cases being missed (n = 2). Capture of all confirmed and suspected H1N1 cases was reported as complete for 178 (95%) acute hospitals, with 10 reporting potentially incomplete capture owing to either lack of resources (n = 3) or cases being missed (n = 7). Capture of non-H1N1 cases affected by the pandemic was reported as complete for 170 (90%), with 18 reporting potentially incomplete capture owing to a misunderstanding of the inclusion criteria (n = 11), to lack of resources (n = 5), or to cases potentially being missed (n = 2).

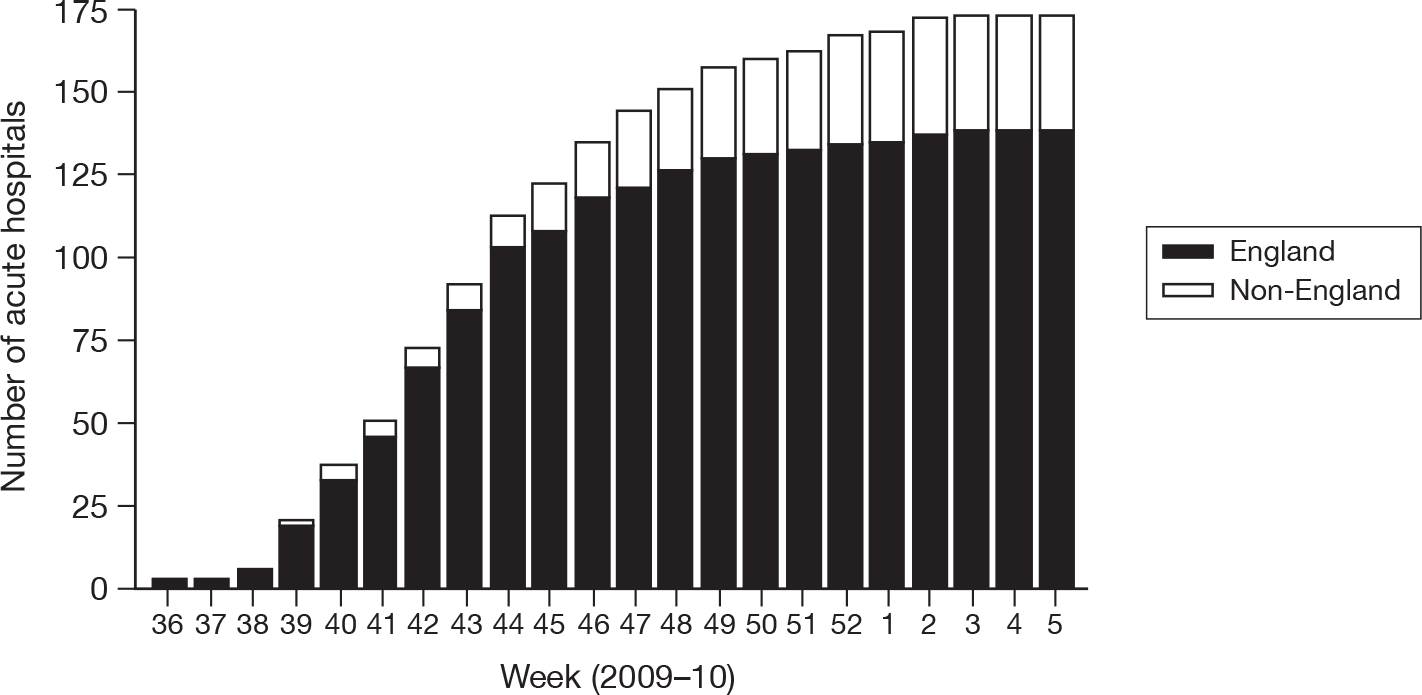

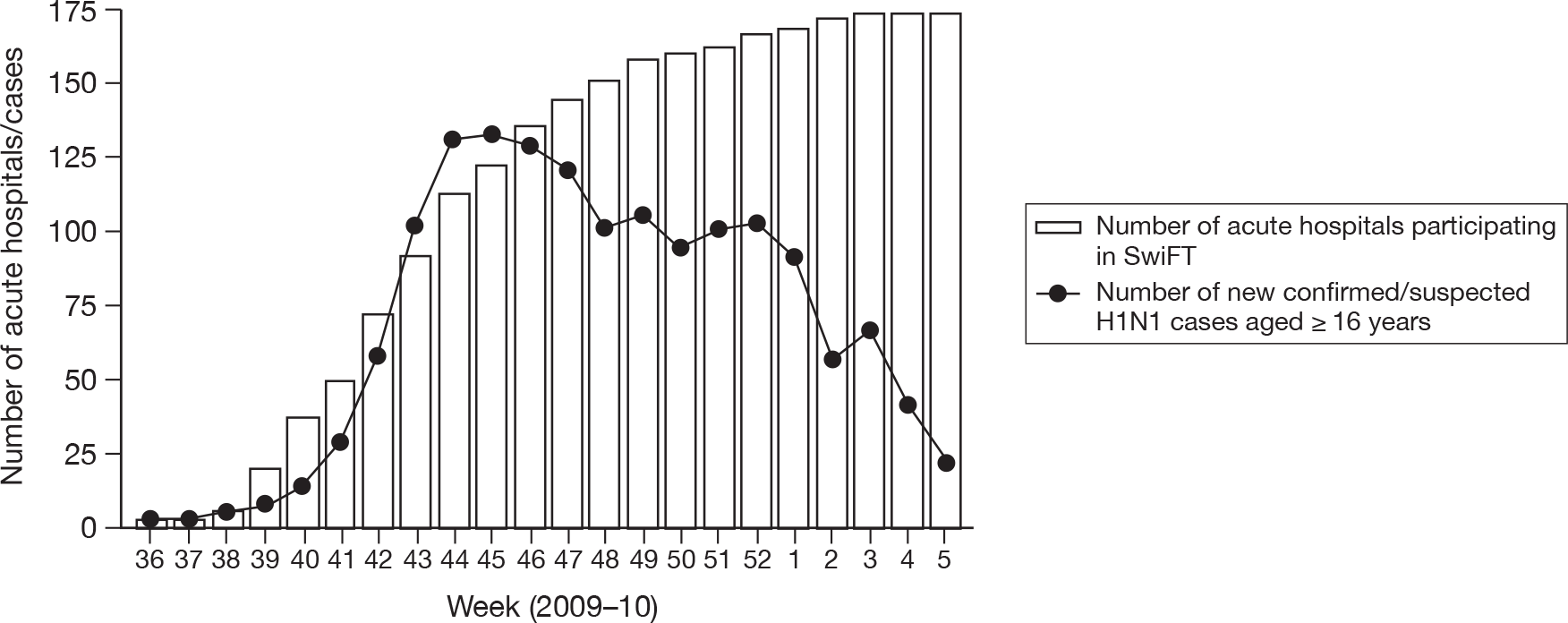

The number of acute hospitals participating by week, of the 174 acute hospitals admitting adult patients and returning completed final declaration forms confirming periods of continuous screening for eligible cases, is shown in Figure 9 (four paediatric hospitals that actively participated in SwiFT have been excluded from this figure owing to the lack of complete capture of paediatric cases in other hospitals). Extrapolating from these figures indicated overall coverage of 39% (46% in England) of acute hospitals with adult critical care facilities for the period 3 September 2009 to 31 January 2010. Figure 10 shows the number of new adult cases by week compared with the number of participating hospitals.

FIGURE 9.

Number of acute hospitals admitting adult patients participating in SwiFT by week (week 36 = week commencing 31 August 2009).

FIGURE 10.

Number of new confirmed/suspected H1N1 cases (aged ≥ 16 years) in SwiFT, by week, compared with number of participating acute hospitals (week 36 = week commencing 31 August 2009).

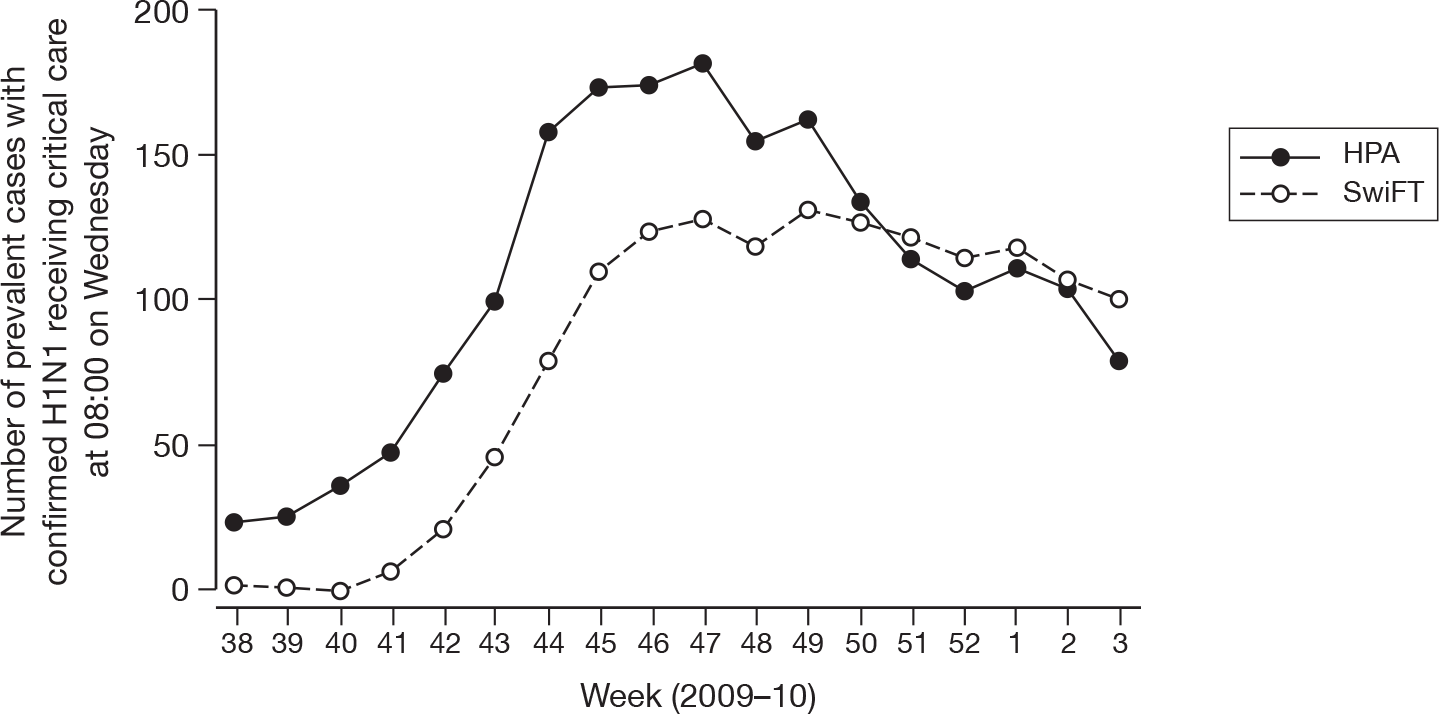

Initial coverage of SwiFT in England was low compared with the weekly prevalence figures published by the HPA. However, by the end of SwiFT, a greater number of prevalent cases were identified from SwiFT than were reported by the HPA (Figure 11).

FIGURE 11.

Weekly reported prevalent cases of confirmed or suspected H1N1 receiving critical care in England from SwiFT compared with HPA figures (week 38 = week commencing 14 September 2009).

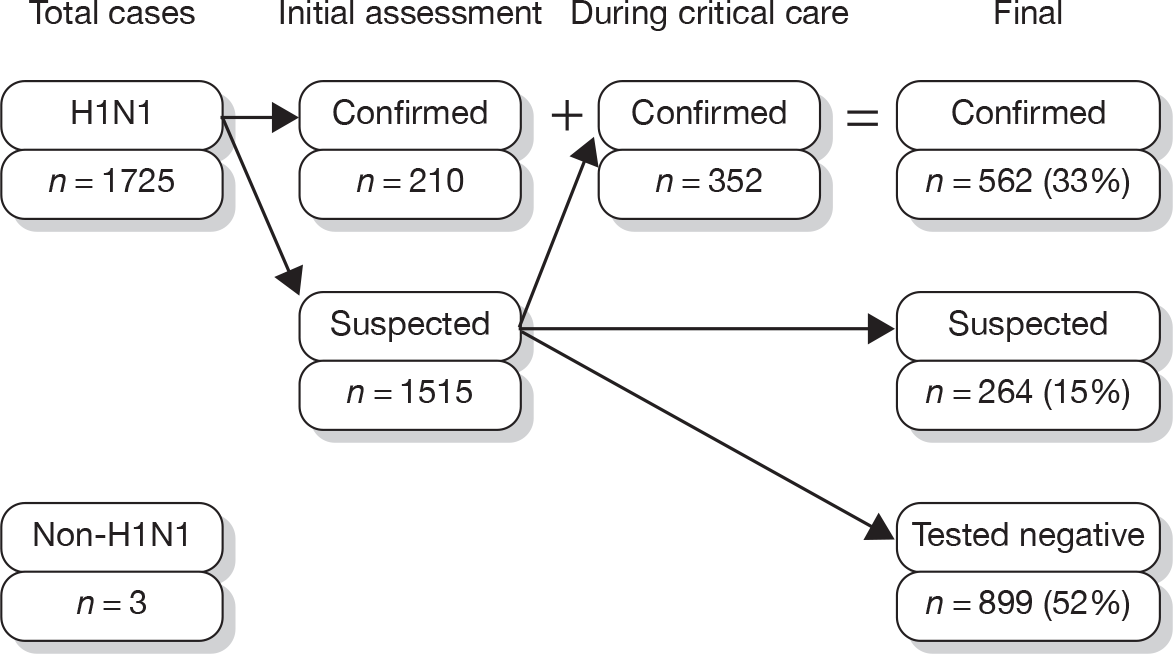

All cases, including those added to the portal after the close of recruitment, were included in this report. Overall, 1,725 confirmed or suspected H1N1 cases and three non-H1N1 cases were reported in SwiFT (Figure 12). Of these, 268 (16%) cases and 2,098 (19%) daily assessments (of a final total of 11,322) were added to the web portal after 31 January 2010, when SwiFT closed to new cases.

FIGURE 12.

SwiFT case flow.

Of the 1725 H1N1 cases, 562 (33%) were confirmed to have H1N1, either on initial assessment or at any time during critical care, 899 (52%) tested negative for H1N1 having initially been suspected, and 264 (15%) suspected cases were neither confirmed nor tested negative. Of 1679 cases assessed with information on location available, 603 (36%) assessments took place on the ward, 506 (30%) took place in the emergency department, 521 (31%) took place in a critical care or extended critical care area, and 49 (3%) took place in other locations.