Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 03/14/03. The contractual start date was in December 2004. The draft report began editorial review in March 2010 and was accepted for publication in August 2010. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2011. This work was produced by Glazener et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

In 2003, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme called for a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to determine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle exercises, with and without biofeedback, for men with urinary incontinence at 6 weeks after prostate surgery. This report describes the research that was commissioned.

The Men After Prostate Surgery (MAPS) study was a major multicentre UK trial that aimed to establish whether a structured programme of conservative physical treatment, delivered personally by a trained health professional (therapist), resulted in better urinary and other outcomes compared with standard management with no professionally delivered pelvic floor muscle exercise regimen in men who were incontinent after prostate surgery. Men having (1) transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) for benign prostatic hypertrophy and (2) radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer were randomised independently in separate trials but using common outcome measures.

Description of the underlying health problem

Urinary incontinence after prostate surgery and effect on well-being

Urinary incontinence is a debilitating condition that can be an iatrogenic consequence of prostate surgery. 1 The effect of urinary incontinence on quality of life can be profound. The economic costs can be personal (such as the need to use pads or devices and the deleterious effect on quality of life) and societal (use of health services and the need for residential or nursing home care). The effect on quality of life of urinary incontinence is greater than that of erectile dysfunction, another possible iatrogenic consequence of prostate surgery. 2

Continence mechanisms in men

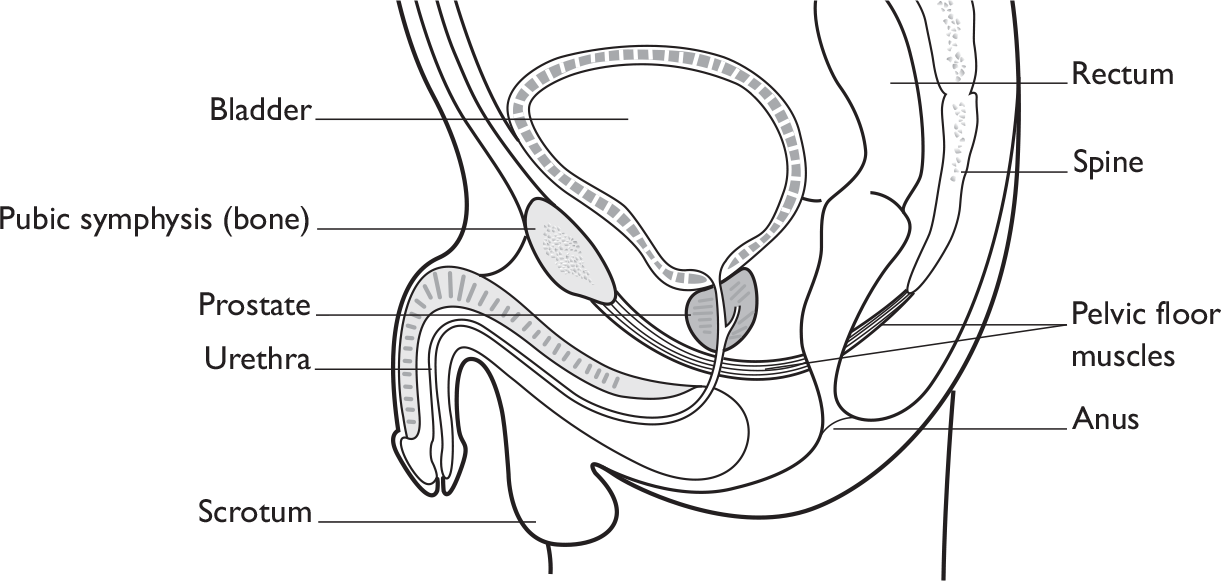

Urinary continence in men is achieved by the interaction of anatomical structures (bladder, urinary sphincter, urethra and the pelvic floor muscles; Figure 1) and neurological control. Continence is maintained by contraction of the sphincter and pelvic floor muscles and relaxation of the bladder muscle (detrusor muscle), while controlled, appropriate urination requires the relaxation of the sphincter and pelvic floor muscles at the same time as the bladder muscle contracts. This process is under neurological control. Failure in either muscle or neurological function or both will result in incontinence or urinary retention.

The male urinary sphincter may be divided into two functionally separate units, the proximal sphincter (nearest the bladder, consisting of the bladder neck, prostate and the portion of the urethra that passes through the prostate) and the distal sphincter (further away from the bladder, just below the prostate at the level of the pelvic floor muscles). The pelvic floor muscles contribute to the ability of the distal sphincter to keep the urethra closed.

Radical prostatectomy physically disrupts the integrity of both the muscles and the nerves, thus resulting in urinary incontinence. The proximal sphincter is removed during prostatectomy, and may also be damaged by radiation to the prostate. After prostatectomy, men achieve continence using the distal sphincter and the pelvic floor muscles that surround it. Thus, following prostatectomy, continence depends on the distal sphincter mechanism, which includes soft tissue supporting structures, the muscles of both the sphincter and the pelvic floor, and their intact innervation (both autonomic via the pelvic nerve and somatic via the pudendal nerve). In addition, the disruption of the nerve supply to the penis can interfere with normal erectile and hence sexual function.

Transurethral surgery for benign prostatic hypertrophy, while theoretically not disrupting the distal sphincter or the nerve supply to the pelvic floor muscles, does remove the proximal urethral sphincter. Such sphincter injury can result in incontinence.

Thus, urinary incontinence can be an iatrogenic outcome of prostate surgery. However, incontinence may also result from bladder dysfunction, which may persist from before surgery or be of new onset. Before surgery, men with benign prostatic hypertrophy have difficulty in emptying their bladders owing to bladder outlet obstruction. This may manifest as the lower urinary tract symptoms of frequency, urgency and urgency urinary incontinence. Detrusor overactivity may be demonstrated by urodynamic studies. While these symptoms are relieved by prostatectomy in over 75% of men,3,4 residual overactivity or incontinence may be accounted for by a variety of mechanisms, including persistent obstruction (38%), impaired contractility of the bladder detrusor muscle (25%) and sphincter deficiency (8%). 3

For a detailed description of the continence mechanisms and incontinence resulting from prostatic disease and its treatment see Koelbl et al.,5 pp. 299–308.

Definition of urinary incontinence

The MAPS study has used methods, definitions and units that conform to the standards jointly recommended by the International Continence Society and the International Urogynaecology Association, except where specifically noted. 6 These replace those formerly in use. 7

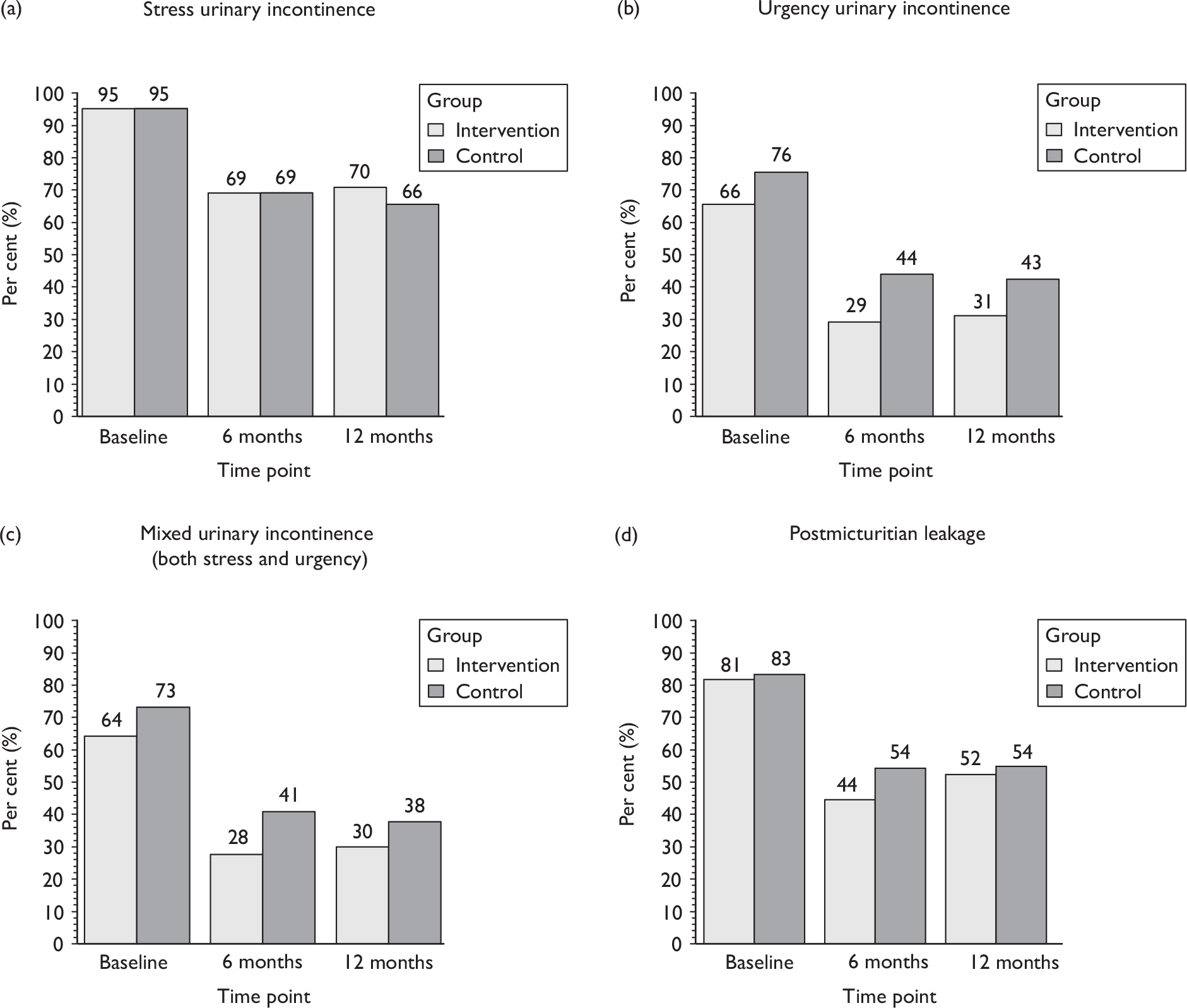

Urinary incontinence is defined as the ‘complaint of involuntary loss of urine’. 6 This can be subcategorised as follows:

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) Complaint of involuntary loss of urine on effort or physical exertion (e.g. sporting activities) or on sneezing or coughing.

Urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) Complaint of involuntary loss of urine associated with urgency.

Mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) Complaint of involuntary loss of urine associated with urgency and also with effort or physical exertion or on sneezing or coughing.

Postmicturition leakage Complaint of a further involuntary passage of urine following the completion of micturition.

Urgency Complaint of a sudden compelling desire to pass urine that is difficult to defer.

In the MAPS study these were differentiated according to the men’s responses to questionnaires. Men could also categorise their incontinence as ‘other’ if they were incontinent under other circumstances, but we did not ask for clarification of the type of incontinence.

Incontinence can be further categorised according to the results of urodynamic studies (cystometry). These are:

Urodynamic stress incontinence (USI) Involuntary leakage of urine during filling cystometry, associated with increased abdominal pressure, in the absence of a detrusor contraction.

Detrusor overactivity (DO) Involuntary detrusor contractions occurring during filling cystometry. The symptoms of urgency and/or urgency incontinence may or may not occur.

However, we did not require the type of incontinence to be defined using urodynamics in MAPS.

Prevalence and natural history

The prevalence of urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy is widely reported, ranging from 2% to 60%, albeit at varying times after operation. 8 The wide range in estimates of the incidence of postprostatectomy urinary incontinence may be explained by factors such as differences in populations, type of study, type of operation, definition of incontinence and time of assessment relative to surgery. Estimates of incontinence soon after radical operation are much higher (e.g. 82% in 1013 men9). The technique of radical prostatectomy also affects continence rates: the perineal approach,1 use of laser,10 preservation of the neurovascular bundle11 and bladder neck preservation12 have all been shown to be associated with lower urinary incontinence rates. The incidence also varies according to who measures it: doctors may underestimate urinary incontinence rates by as much as 75%. 13 The incidence of urinary incontinence decreases with time, and seems to plateau at 1 to 2 years after surgery,14 emphasising the need for long-term follow-up. 8 Other factors sometimes associated with postprostatectomy urinary incontinence include older age, previous TURP, preoperative lower urinary tract symptoms, obesity, clinical stage, race and ethnic differences. 8

In contrast, the prevalence of urinary incontinence after TURP is less widely reported. Based on a population audit of over 3000 men, an estimated 11% needed to use pads at 3 months after endoscopic resection of the prostate. 15

Significance in terms of ill health

Extent of problem in the UK

The number of men undergoing surgery for prostate disease is changing: in 2000–1, the number of TURPs in NHS hospitals in England was just under 30,000, while there were about 2000 open excisions of prostate (of which the majority would have been for prostate cancer). 16 By 2008–9, the number of TURPs had fallen to just over 25,000 (of which 2700 were with laser), while over 4000 open operations were performed. Thus, prostate surgery and its sequelae represent a considerable use of health resources and a health burden to men.

Description of standard management

Existing guidelines

For men who have undergone prostate cancer treatment, the current National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines acknowledge that urinary incontinence has been reported as a result, most especially stress incontinence (which is mentioned as either temporary or permanent). NICE highlights that incontinence may be a problem after brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy, as well as in those men who have also had a TURP.

NICE guidelines highlight some of the treatments available to men, including physical (pelvic floor muscle re-education, bladder retraining), medical (drug therapy) or surgical (injection of bulking agents, artificial urinary sphincters or perineal sling) interventions, and they give the following recommendations for urinary incontinence management following prostate cancer treatment. 17

Current recommendations from NICE

-

Men experiencing troublesome urinary symptoms before treatment (of their prostate problem) should be offered a urological assessment.

-

Men undergoing treatment for prostate cancer should be warned of the likely effects of the treatment on their urinary function.

-

Health-care professionals should ensure that men with troublesome urinary symptoms after treatment should have access to specialist continence services for assessment, diagnosis and conservative treatment. This may include coping strategies, along with pelvic floor muscle re-education, bladder retraining and pharmacotherapy.

-

Health-care professionals should refer men with intractable stress incontinence to a specialist surgeon for consideration of an artificial urinary sphincter.

-

The injection of bulking agents into the distal urinary sphincter is not recommended to treat stress incontinence after prostate surgery in men.

No guidelines could be found for the treatment of urinary incontinence associated with either benign prostatic hypertrophy or TURP.

Treatment options

Treatment options for men with urinary incontinence after prostate surgery include:

-

containment using continence products, including absorbent products, sheaths, urine drainage bags, mechanical devices such as penile occlusive devices or clamps, and catheters (see Cottenden et al. 18 for a comprehensive review)

-

conservative options such as advice to modify lifestyle factors and pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) (see Hay-Smith et al. 19 for a comprehensive review)

-

surgery using injectable urethral bulking agents, a male sling, an adjustable balloon device or an artificial urinary sphincter or, as a last resort, creation of a catheterisable continent stoma by bladder neck closure or urinary diversion into a rectal reservoir or ileocaecal pouch with a catheterisable stoma (see Herschorn et al. 20 for a comprehensive review).

However, few of these options are supported by reliable research evidence.

The decision to test conservative treatment

One of these options, PFMT, was the subject of a Cochrane review first published in 1999. 21 The review found that, although conservative treatment based on PFMT is offered to men with urinary incontinence after either type of prostate surgery, there was insufficient evidence to evaluate its effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and effect on quality of life. In the first version of that review, data from three small trials involving a total of 232 men provided estimates of the effects of PFMT on the chance of having incontinence after radical prostatectomy at 1 year: the relative risk of incontinence, comparing PFMT plus biofeedback versus control, was 0.55 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.24 to 1.23]. 22–24 However, some of the men in two of these trials were not incontinent at baseline, and the trials were all small. Thus, the data did not provide conclusive evidence about whether conservative treatment might reduce incontinence at 1 year after operation.

As a consequence, the NIHR HTA programme commissioned primary research (the MAPS trial) to provide reliable evidence about the effectiveness of PFMT in this population.

In three subsequent updates of the Cochrane review (in 2001, 2004 and 2007), there was still insufficient evidence to guide the practice of providing men with PFMT after prostate surgery. The current (as yet unpublished) update (2011) will have an additional 16 included RCTs, but even after inclusion of data from these trials, no clear conclusions can be drawn.

The questions addressed by this study

The following questions were addressed, primarily in terms of regaining urinary continence at 12 months after recruitment:

-

For men with urinary incontinence 6 weeks after radical prostatectomy, what is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of active conservative treatment delivered by a specialist continence physiotherapist or a specialist continence nurse compared with standard management?

-

For men with urinary incontinence 6 weeks after TURP, what is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of active conservative treatment delivered by a specialist continence physiotherapist or a specialist continence nurse compared with standard management?

The hypothesis tested in each group of men (in two parallel but separate trials) was that active conservative management would result in a difference of 15% between the groups in the proportion of incontinent men at 1 year after recruitment. The two groups were considered independently because the underlying pathological mechanisms, the rates of incontinence and the chance of regaining continence were expected to be different in the two clinical populations. We recognised that standard management for the control arm in both trials was likely to include non-specialist advice about pelvic floor exercises, including leaflets. Men also had access to any normal care provided locally for men with urinary incontinence, such as pads and advice from continence nurse specialists on continence aids.

Chapter 2 Methods of study

This chapter will describe the methods used to identify and enrol the men in the two trials, and describe the methods of statistical and economic analysis.

Study design and populations

The MAPS study involved men who had urinary incontinence after prostate surgery. Two parallel but separate RCTs were conducted, amongst:

-

men having a radical prostatectomy, usually for prostate cancer

-

men having TURP, usually for benign prostatic hypertrophy.

Approval for this UK study was obtained from the Scottish Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (reference number MREC/04/10/01) and confirmed by each centre’s local research ethics committee and research and development department. The study was conducted according to the principles of good practice provided by research governance guidelines.

Local clinical centres

Centres willing to participate in MAPS were identified from a survey of members of the British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS), through personal communication [with urological surgeons and with staff from the Radiotherapy and Androgen Deprivation in Combination After Local Surgery (RADICALS) trial] and through the inclusion of the study on the National Cancer Research Network (NCRN). Each centre had a local principal investigator (lead urologist), who co-ordinated the activities of the local recruitment officer(s) and the local therapist(s). All men from all consultants providing prostate surgery in each centre were eligible, but there were some centres that agreed only to the recruitment of men having radical surgery, while others agreed only to the inclusion of those having TURP. Four centres recruited only to the radical prostatectomy trial: three of these sites recruited during the last 6 months of the recruitment period and included only men recruited to the radical prostatectomy trial at the request of the central office, in order to maximise the numbers in that trial. The fourth site had such a large throughput of men having radical prostatectomies that it did not have the capacity to recruit to the TURP trial as well. Seven centres recruited only men having TURP. This was due, in five of these seven, to existing local services for all men having radical surgery that included explicit teaching of PFMT: the staff were reluctant to ‘unpick’ this element of their service for fear of delivering lower-quality care than before (despite the service not being evidence based). Men were not recruited to the radical prostatectomy trial in the other two sites because of lack of capacity and low numbers of prostate procedures being undertaken locally.

Therapists and training

The therapists could be either specialist continence physiotherapists or nurses with specialist continence or urology training. All therapists received standardised bespoke instruction in the use of PFMT and bladder training for the conservative treatment of male urinary incontinence and PFMT for erectile dysfunction. Therapists used MAPS study instruction materials and documentation to further ensure standardisation of the intervention (see Chapter 3).

Participants

Men were approached at the time of admission for their prostate surgery or at pre-operative assessment clinics. They were initially asked for their consent to receive a screening survey questionnaire sent by post 3 weeks after their operation. Men who indicated in that questionnaire that they were incontinent were invited to participate in the appropriate RCT. Their eligibility was reviewed against the following criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

Urinary incontinence at 6 weeks after prostate surgery (incontinence was defined as a response indicating a loss of urine to either of two questions in the screening questionnaire: ‘how often do you leak urine?’ and ‘how much urine do you leak?’.

-

Full informed consent.

-

Ability to comply with intervention.

Exclusion criteria

-

Formal referral for physiotherapy or teaching PFMT related to prostate surgery.

-

Radiotherapy planned or given during the first 3 months after surgery for men with prostate cancer.

-

Transurethral/endoscopic resection of prostate carried out as palliation for outflow obstruction in advanced prostate cancer (known as ‘channel TURP’).

-

Inability to complete study questionnaires.

Men with prostate cancer diagnosed at transurethral resection of the prostate

The literature suggested that approximately 15% of men have incidental prostate cancer when the prostatic chips removed at TURP are examined for pathology. 25 Within MAPS, men were still considered eligible for randomisation if the initial management plan did not include formal treatment (a wait and see policy). If the cancer was identified before randomisation, and either radiotherapy or radical prostatectomy was planned within the following 3 months, the man was not eligible for the TURP trial. However, men who were not randomised but subsequently readmitted for radical prostatectomy were eligible to be recruited as new participants to the radical prostatectomy group (after signing a new consent form and completing a new screening questionnaire after surgery). If cancer was diagnosed after randomisation, the men remained in the group to which they had been allocated even if radiotherapy or radical prostatectomy was carried out subsequently. These men could still have the MAPS intervention, if the timing of the new treatment allowed, and were followed up as per the MAPS protocol.

Thus, the MAPS study consisted of two stages: stage 1, the screening survey (used to identify eligible men), and stage 2, the two RCTs.

Screening for postoperative urinary incontinence (stage 1, the screening survey)

Potential MAPS participants were identified by recruitment officers in each clinical centre from amongst all men admitted to the urological ward(s) for prostate surgery. A log was kept of potentially eligible men, categorising reasons if they subsequently became ineligible or did not consent to receive a screening questionnaire. Each man was given a MAPS hospital information sheet (see Appendix 1.1) by the recruitment officer, and then, if interested in the study, each man was asked for his consent to be sent the screening questionnaire at 3 weeks after surgery. The hospital patient information sheet, the screening consent form (see Appendix 2.1) and the screening questionnaire (see Appendix 3.1) all included information about being contacted about further research.

The screening questionnaire was sent to men from the study office in Aberdeen at 3 weeks after the date of operation. A reminder letter with a second copy of the questionnaire was sent after 2 weeks to non-responders. If the returned questionnaire indicated that a man had urinary incontinence, he became eligible for stage 2 of MAPS.

Recruitment to the randomised controlled trial of conservative treatment (stage 2, the randomised controlled trials)

Each man who indicated on his screening questionnaire that he had urinary incontinence was sent an RCT patient information sheet (see Appendix 1.2), a baseline questionnaire (see Appendix 3.2), a urinary diary (see Appendix 3.5) and an RCT consent form (see Appendix 2.2) by the study office in Aberdeen. Men who were willing to be contacted by telephone were telephoned around a week later by a dedicated recruitment co-ordinator based at the MAPS study office in Aberdeen. The purpose of this call was to answer the men’s questions about the trial, to confirm eligibility and to obtain verbal consent to randomisation. Upon receipt of the signed RCT consent form, men were randomised to the intervention or standard care group. Men who did not respond within 14 days after the initial mailing-out were reminded by post and/or telephone.

Withdrawal

Men were free to withdraw from the study at any point without giving a reason. Verbal consent was obtained from men who initially agreed to enter the trial, but later decided to withdraw, to enable relevant data to be retained or collected through central NHS resources.

Randomisation and allocation to group

When the baseline questionnaire and the consent form were received, the Aberdeen MAPS study office randomised the man to the intervention or standard care group.

Randomisation was by computer allocation using the randomisation service of the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT, in the Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen). Allocation was stratified by type of operation (radical prostatectomy or TURP) and minimised using centre, age and pre-existing urinary incontinence. The process was independent of all clinical collaborators.

The study office informed all men of their allocation by post. All groups received a lifestyle advice leaflet (see Appendix 4.2). For men allocated to the intervention group, the study office arranged for the local therapist (physiotherapist or continence nurse) to send out the necessary appointments. A letter and GP information sheet were sent to each participant’s GP. Copies of the GP’s letter and the consent form were sent to the hospital urological consultant for filing in the man’s hospital notes.

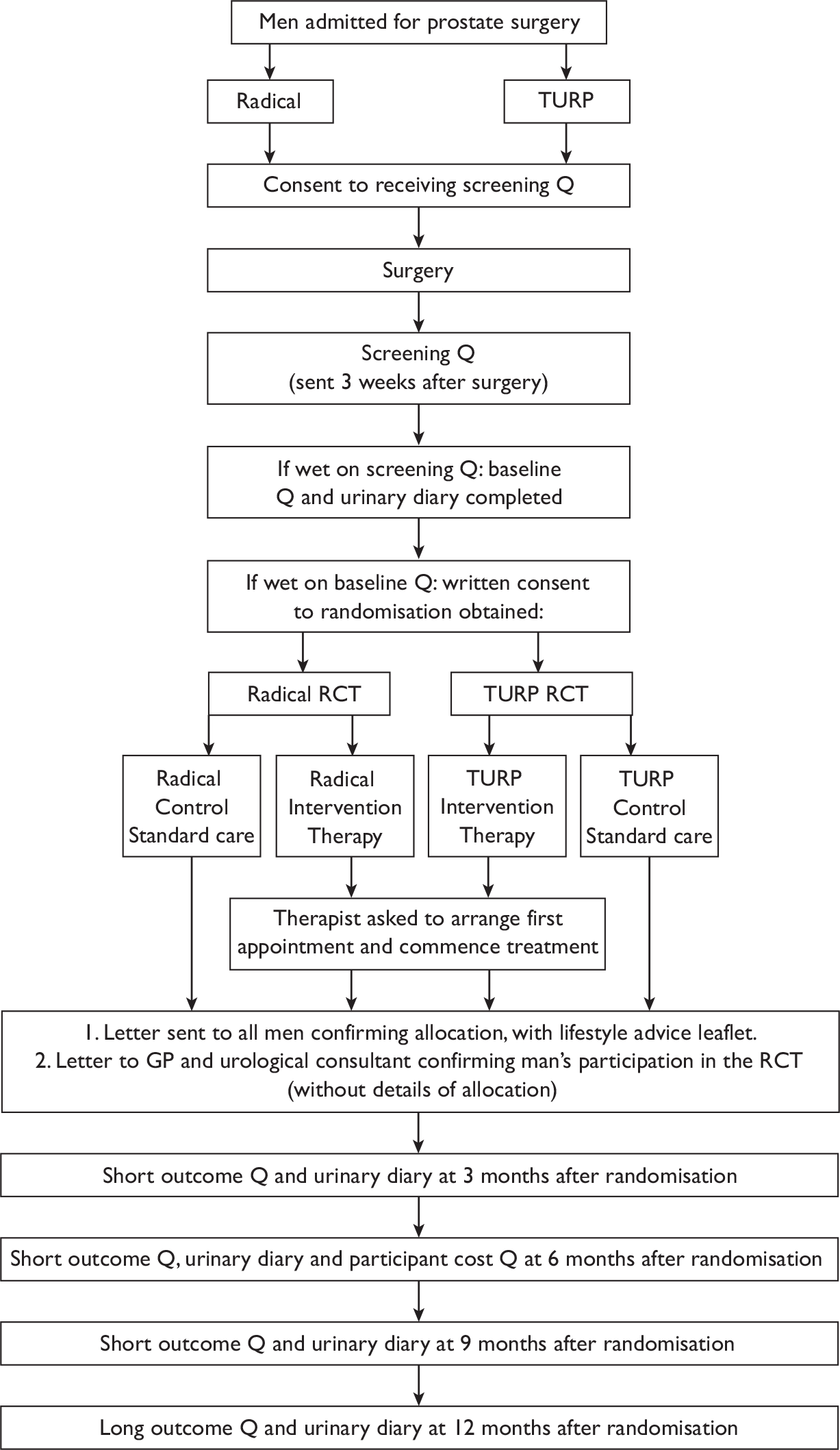

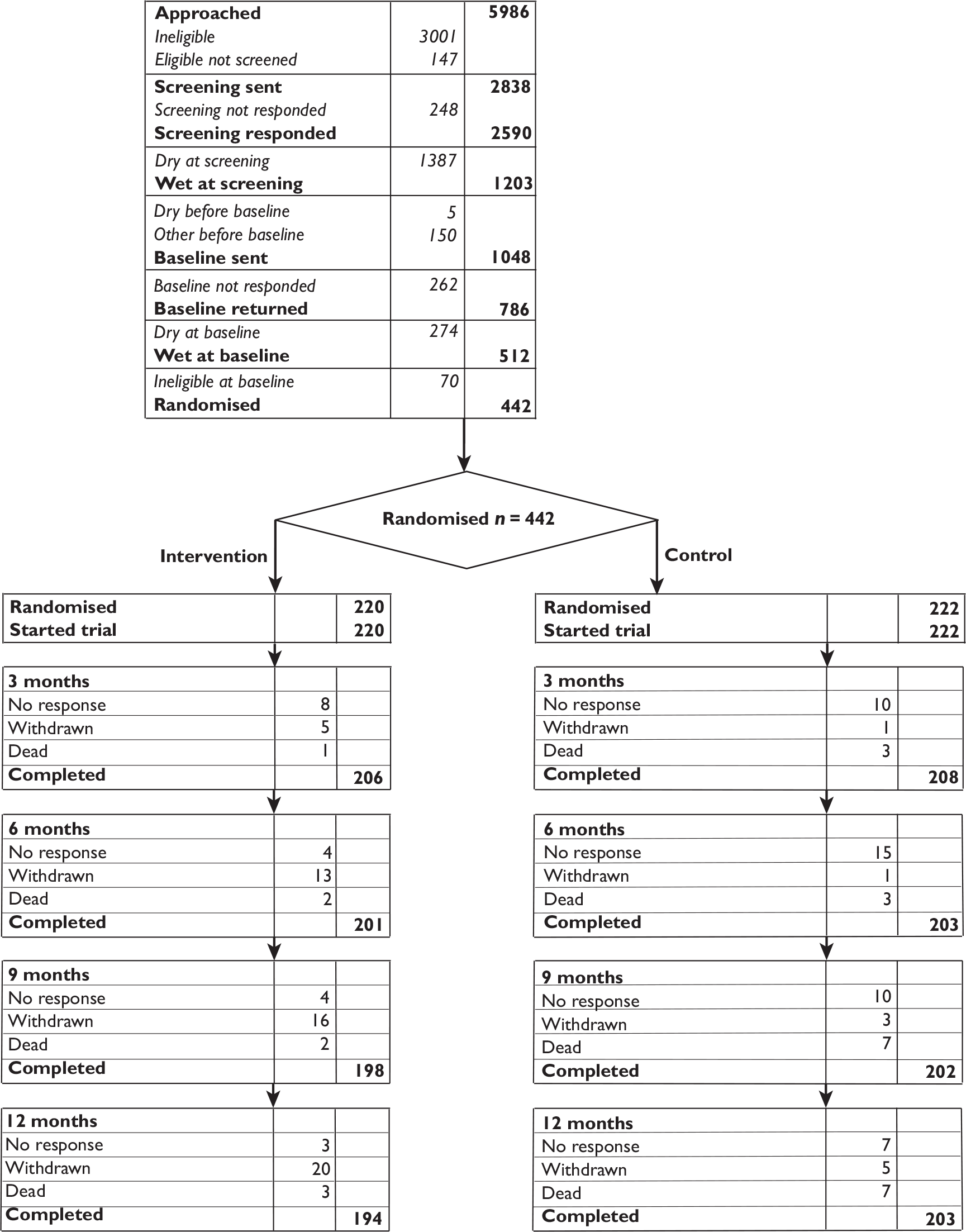

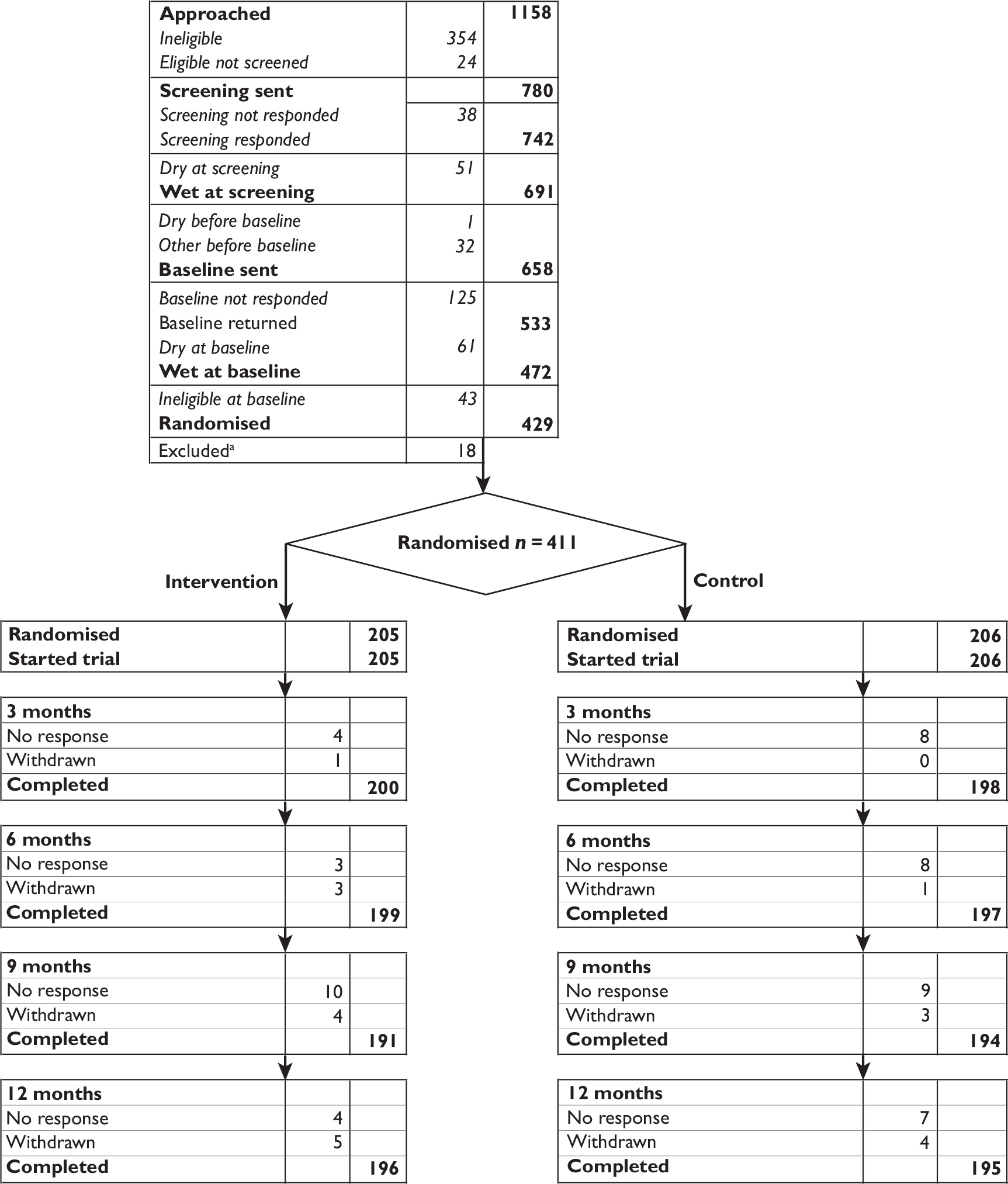

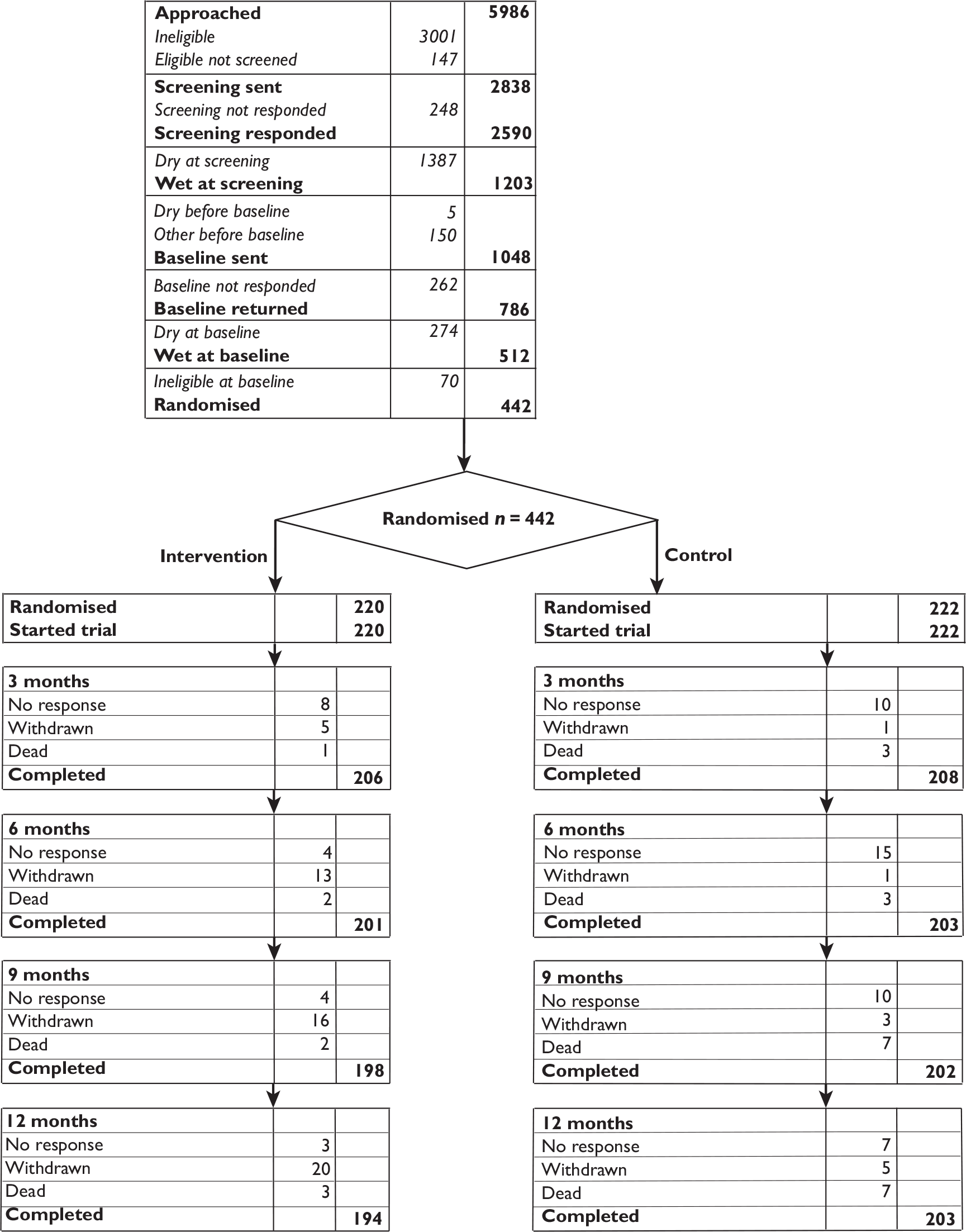

A flow chart summarising the trial recruitment processes and procedures is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart of the trial recruitment processes and procedures. Q, questionnaire.

Interventions

Intervention arm

The men in the intervention group attended for a MAPS therapist assessment of their symptoms after randomisation (see Chapters 6 and 11). The first appointment, for an hour, consisted of assessment and training, including customised goal setting for home practice of exercises. The men then attended a further three appointments, each lasting approximately 45 minutes, at around 2, 6 and 12 weeks after the first appointment. They were taught PFMT, with bladder training for men with urgency or urge incontinence. 26 This was supplemented by a booklet containing reminder instructions for PFMT and bladder training (see Pelvic Floor Exercises for Men Taking Part in the MAPS Study; Appendix 4.3). Men also received the lifestyle advice leaflet sent to the men in the standard care arm (see Appendix 4.2).

Biofeedback using digital anal examination was used to teach correct contraction technique and to monitor the strength of contractions. Although biofeedback used for diagnosis or training (repetitive exercising with machine-led feedback on the effectiveness of contractions) was not used routinely in the trial, therapists could use this at their discretion in individual cases. Further details of the intervention are given in Chapter 3.

Control arm

Men in the control group received standard care and a booklet containing supportive lifestyle advice only (without reference to PFMT) by post after randomisation (see Appendix 4.2). Men did not receive any formal assessment or treatment but were able to access usual care and routine NHS services if they felt they needed help with incontinence. This could include written advice if this was part of routine hospital care (such as leaflets containing instructions on PFMT).

Both arms

Use of NHS services, use of pads and practice of PFMT were documented in both groups using information from questionnaires (see Appendix 3.4) and 3-day urinary diaries (see Appendix 3.5) issued at baseline and 3, 6, 9 and 12 months after randomisation.

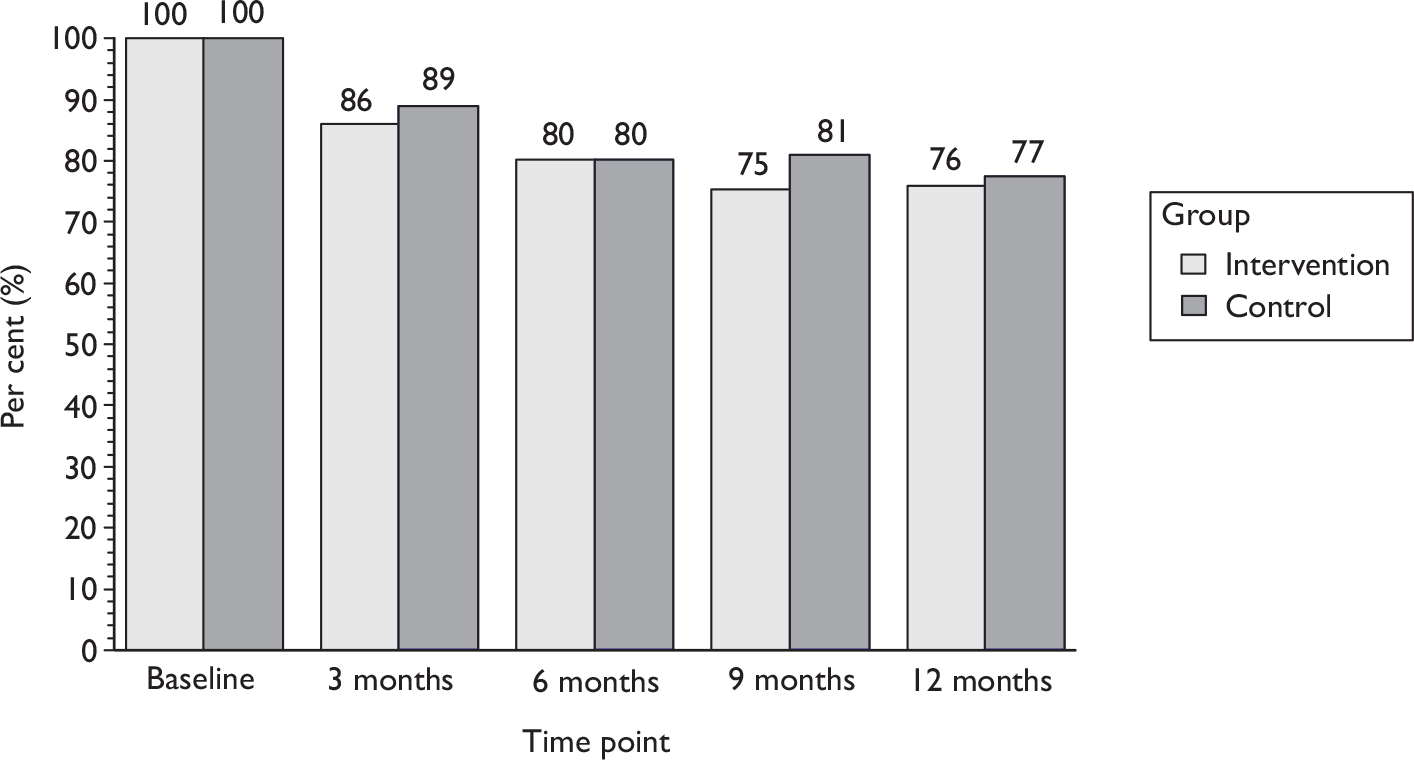

Data collection and processing

Men were recruited between January 2005 and September 2008. Follow-up continued with 3-monthly questionnaires and urinary diaries for 12 months from the date of the last randomisation, at which time the primary end point (incontinent or not) was measured using the International Consultation on Incontinence (ICI) Short Form questionnaire (ICI-SF). 27 Consent was sought to continue follow-up into the future. The men were also asked to consent to be contacted about other relevant research studies.

Questionnaires (see Appendices 3.1–3.4)

Men were sent postal questionnaires at baseline and 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. An additional health-care unit cost questionnaire was sent only at 6 months. The short questionnaires at 3 and 9 months contained only brief urinary incontinence, exercise and health-care utilisation questions.

Urinary diaries (see Appendix 3.5)

Men were asked to keep diaries at baseline and 3, 6, 9 and 12 months after randomisation, kept for 3 days at each time period.

Data processing

Data from the various sources outlined above were sent to the study office in Aberdeen for processing. Staff in the study office carried out extensive range and consistency checks to enhance the quality and accuracy of the data. Essential missing data were sought from the recruitment officers at the centres, or the men, by post, telephone or email as appropriate.

Outcomes

The primary clinical outcome was subjective report of urinary continence at 12 months. 27

Incontinence was defined as a response indicating a loss of urine to either of two questions in the screening questionnaire, ICI-SF: ‘how often do you leak urine?’ and ‘how much urine do you leak?’

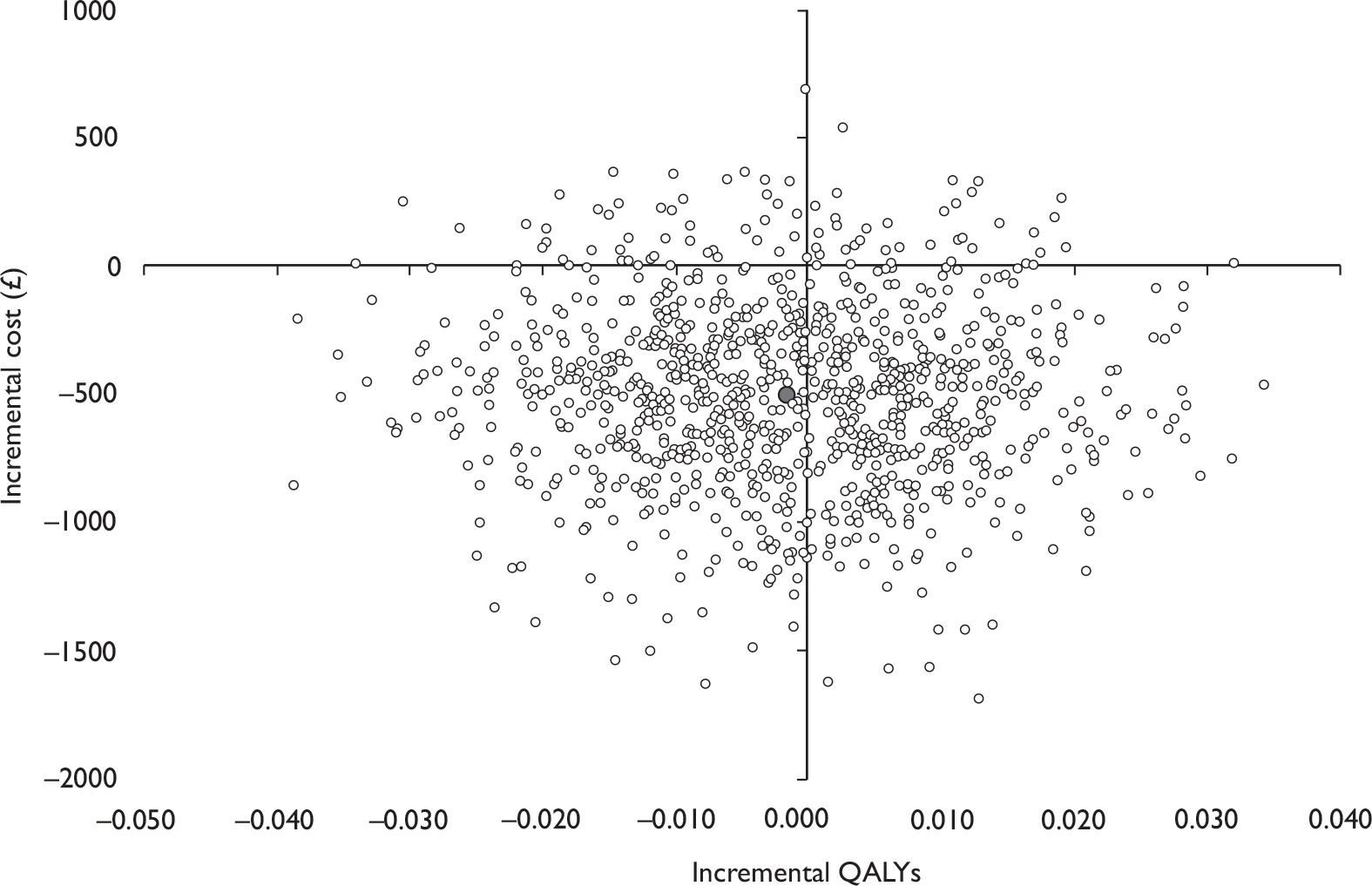

The primary measure of cost-effectiveness was incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

Secondary outcome measures were as follows.

Clinical

-

Subjective report of continence or improvement of urinary incontinence at 3, 6 and 9 months after randomisation, and improvement at 12 months.

-

Number of incontinent episodes in previous week (objective, from diary).

-

Use of absorbent pads, penile collecting sheath, bladder catheter or bed/chair pads.

-

Number and type of incontinence products used.

-

Coexistence, cure or development of urgency or urge incontinence.

-

Urinary frequency.

-

Nocturia.

-

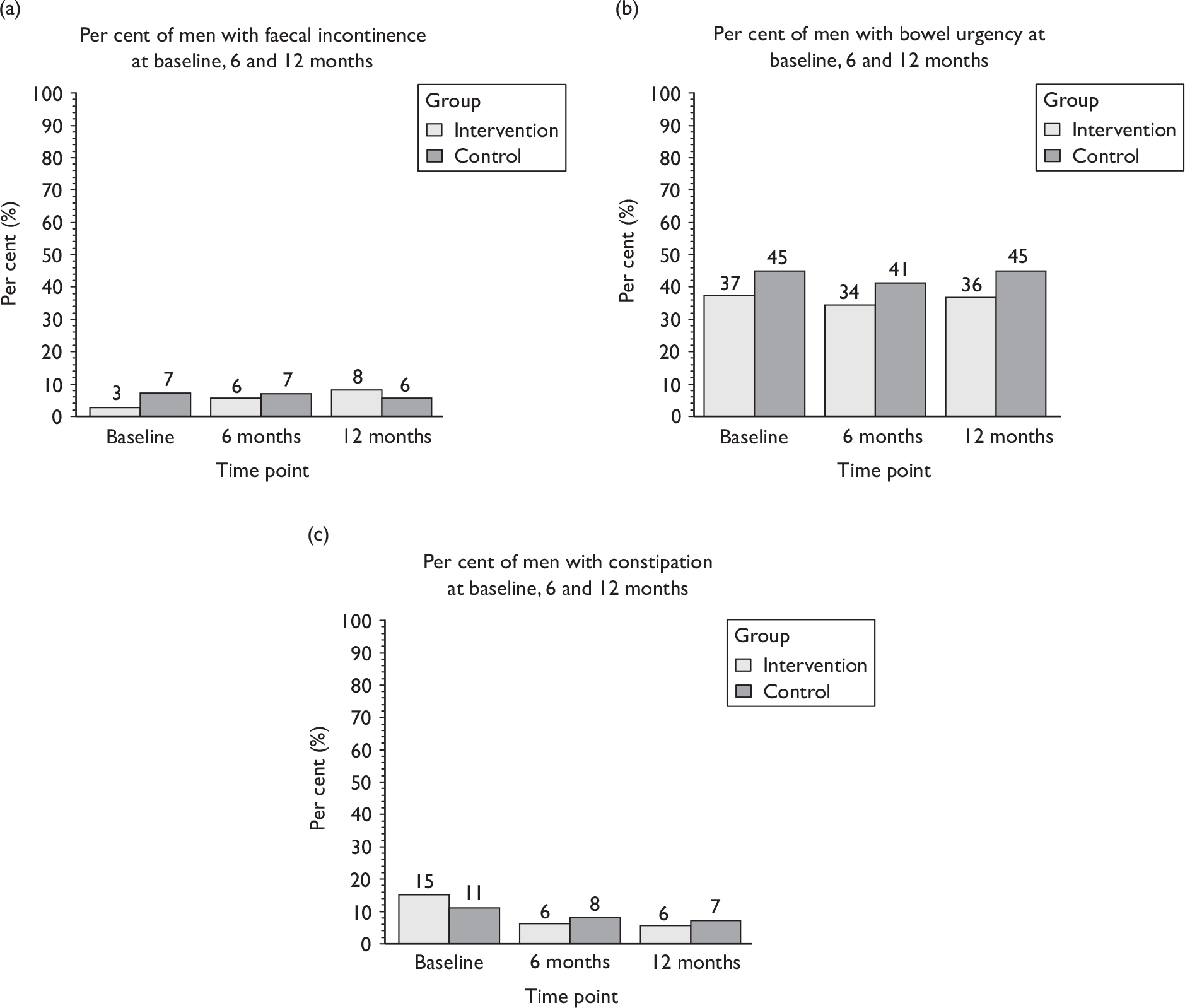

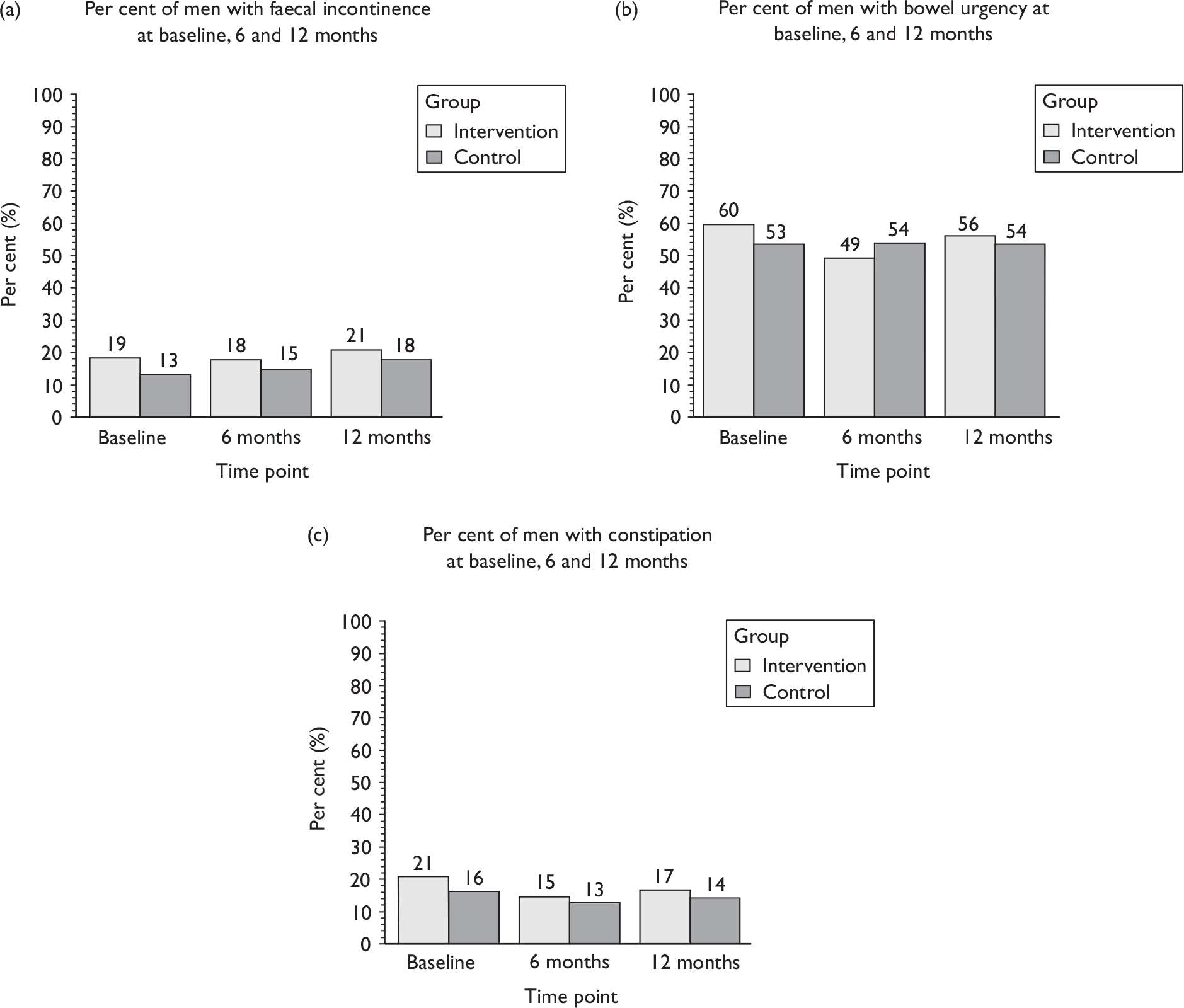

Faecal incontinence (passive or urge).

-

Other bowel dysfunction (urgency, constipation, other bowel diseases).

-

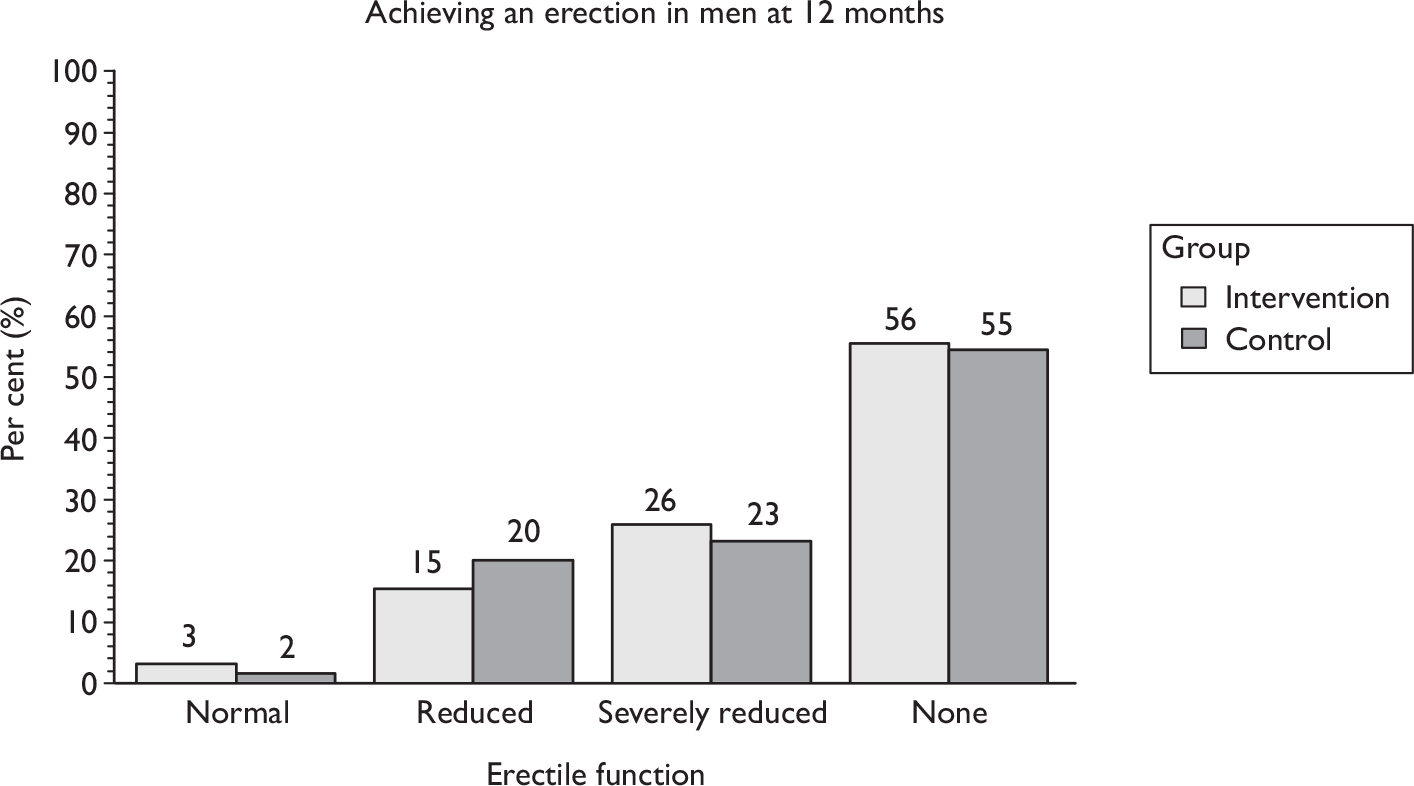

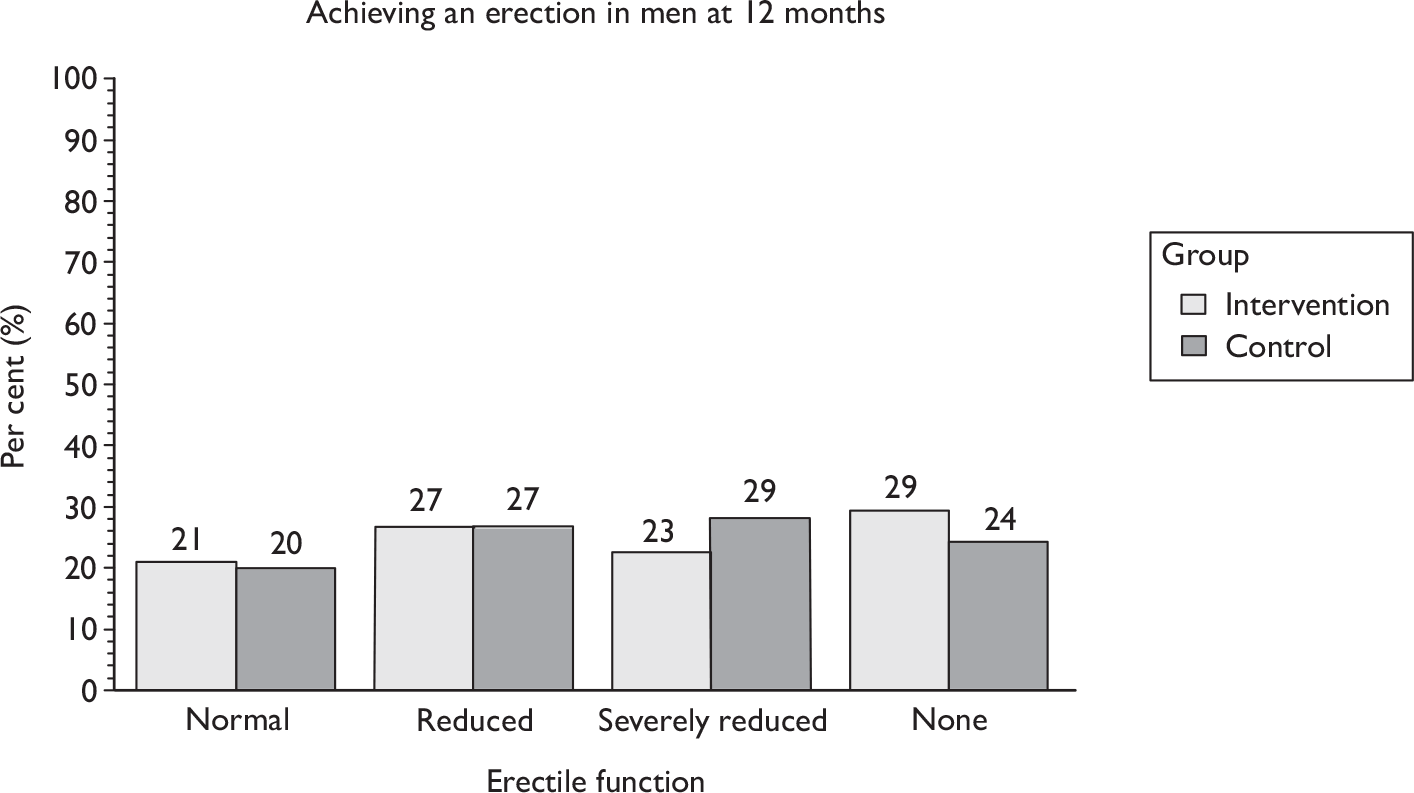

Sexual function at 12 months (including information about erection, ejaculation, retrograde ejaculation, pain, change in sex life and reason for change).

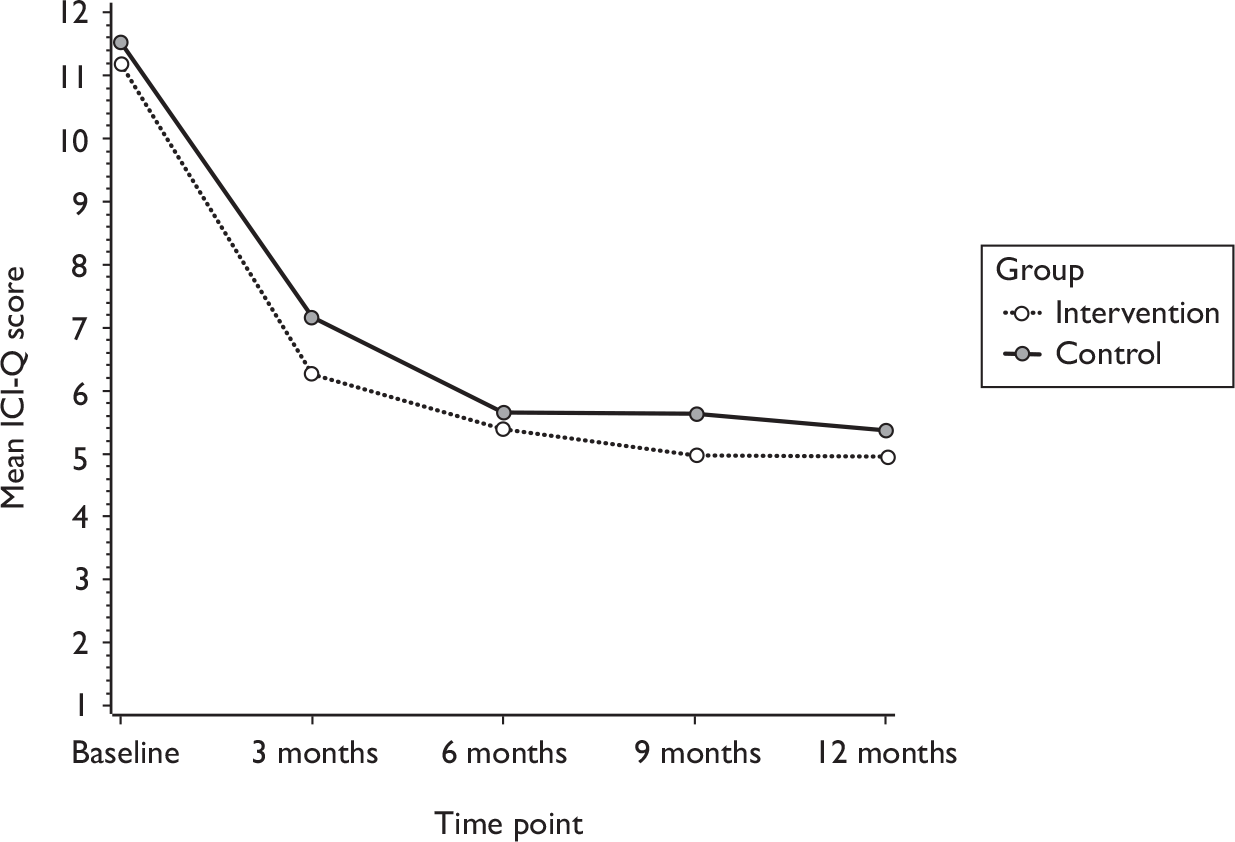

Quality of life

-

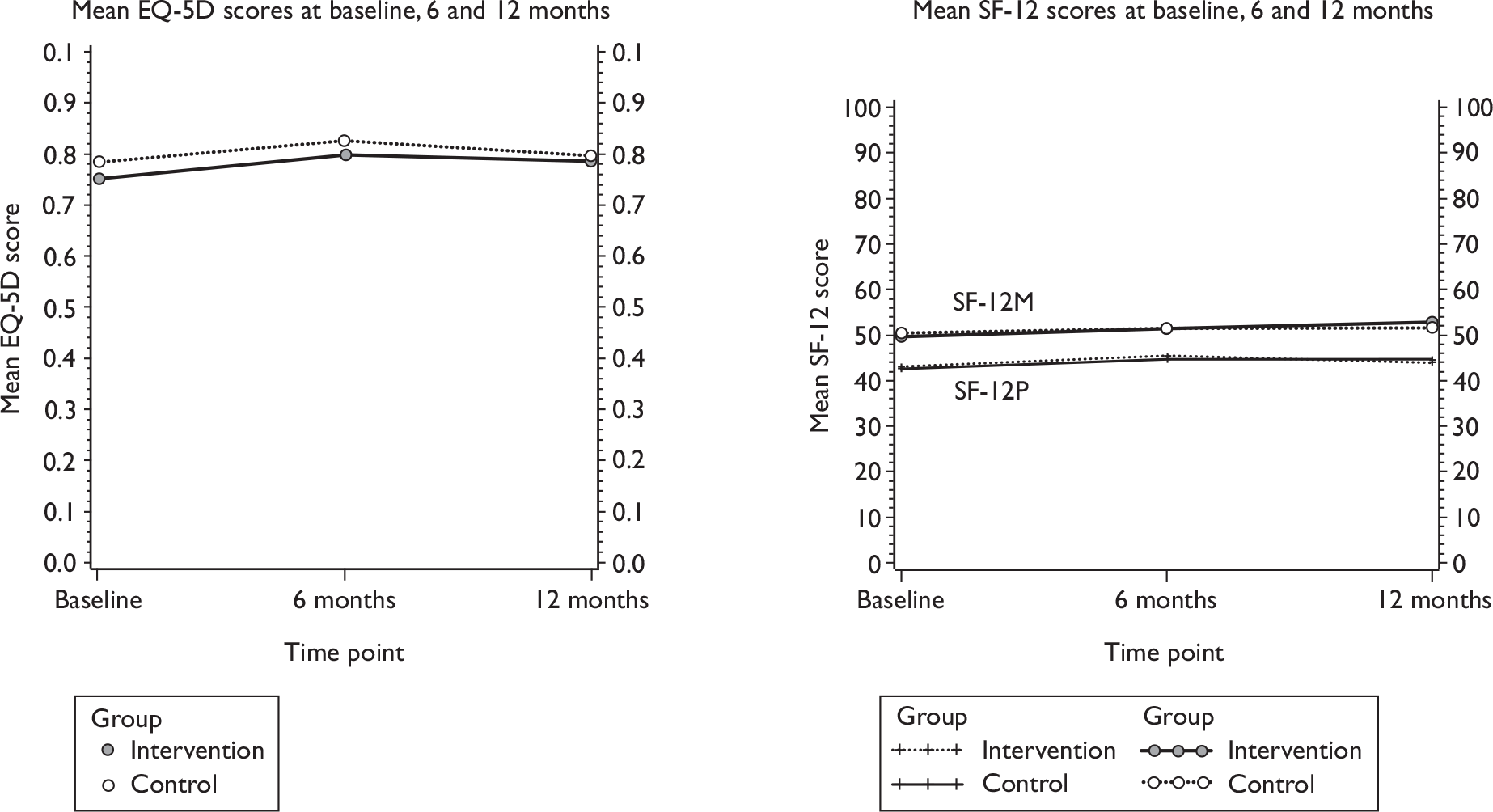

Incontinence-specific quality of life outcome measure (10-point scale, ICI-Q). 27

-

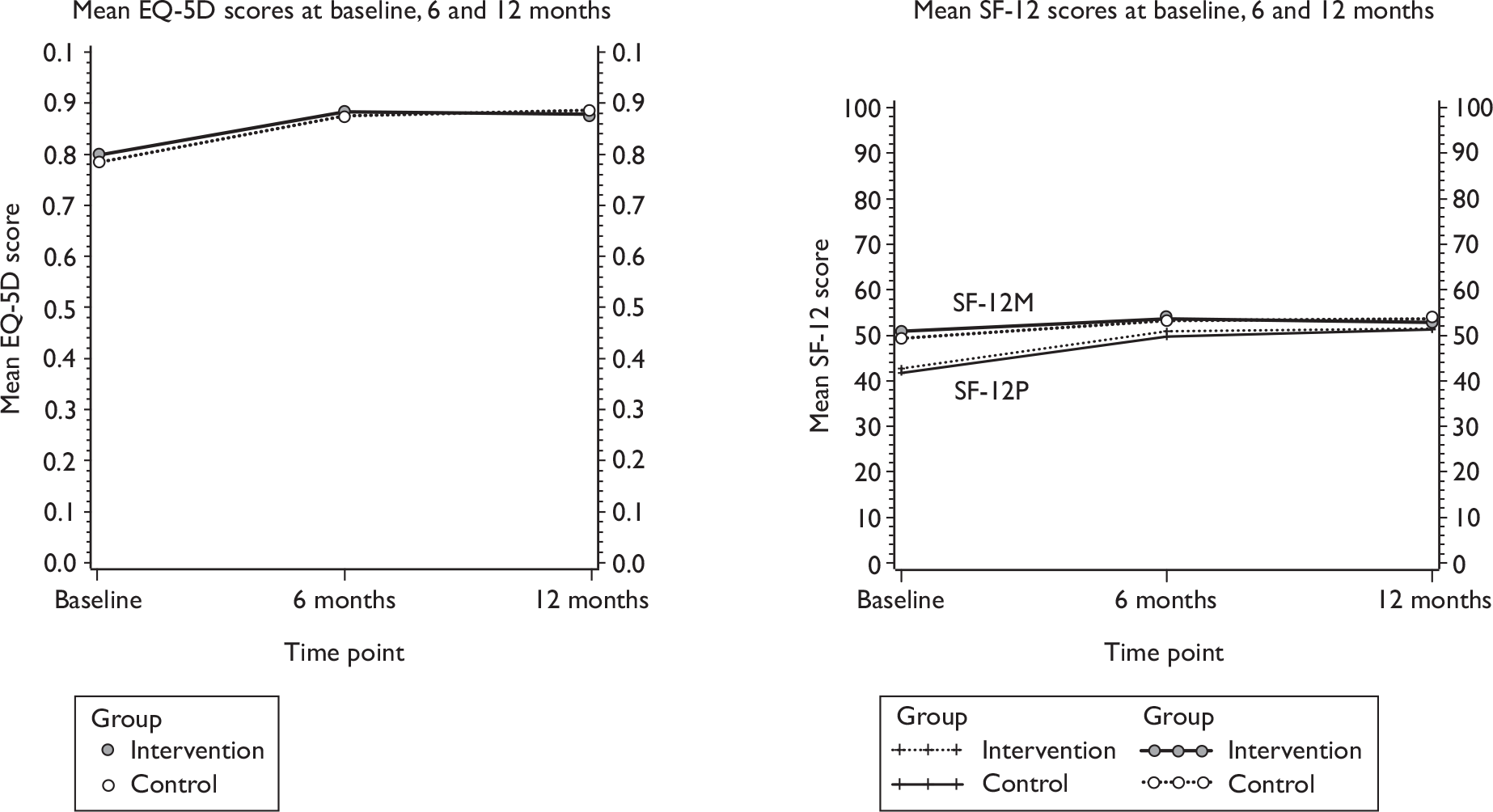

General health measures (Short Form questionnaire-12 items, SF-12, and European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions, EQ-5D).

Use of health services for urinary incontinence

-

Need for alternative management for incontinence (e.g. surgery, drugs).

-

Use of GP, nurse, consultant urologist, physiotherapist.

-

Satisfaction with treatment of incontinence after prostate surgery.

Other use of health services

-

Visits to GP.

-

Visits to practice nurse.

Effects of interventions

-

Use of PFMT.

-

Lifestyle changes (weight, constipation, lifting, coughing, exercise).

Economic measures

-

Patient costs [e.g. self-care (e.g. pads, laundry), travel to health services, sick leave].

-

Cost of conservative trial treatment.

-

Cost of alternative or additional NHS treatments [e.g. pads, catheters, drugs (e.g. adrenergic agonists, anticholinergics, oral medication for erectile dysfunction), hospital admissions or further surgery].

-

Other measures of cost-effectiveness (e.g. incremental cost per additional man continent at 12 months).

Table 1 provides a summary of which study measures and outcomes were collected at each time point in the study.

| Study measure | Screening | Baseline | Month 3 | Month 6 | Month 9 | Month 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consent/randomisation | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ✓ | |||||

| Operative details | ✓ | |||||

| Clinical characteristics | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Follow-up (outcome) questionnaires | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Urinary diaries | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Urinary outcomes (primary) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Other urinary outcomes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Health-care utilisation questions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| SF-12, EQ-5D | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Exercise, including practice of PFMT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Bowel outcomes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Participant cost questionnaire | ✓ | |||||

| Sexual function outcomes | ✓ | |||||

| Lifestyle change outcomes | ✓ | |||||

| Satisfaction with treatment for incontinence | ✓ | |||||

| Further treatment for incontinence | ✓ |

Blinding

As the trial arm to which men were allocated could not be concealed after randomisation had occurred from either the man or the therapist, blinding of participants to intervention was not possible. However, outcome measures were assessed using questionnaires that were processed by MAPS study office staff who were not aware of the randomisation.

The statistician responsible for the final analyses was not the same as the one who performed the interim analyses for the Data Monitoring Committee. All statistical coding and results were agreed before the allocation was revealed.

Sample size

Based on the aim of detecting an absolute difference between intervention and control groups of 15% (30% to 15%) in the number of men who are still incontinent at 12 months, we calculated that we would need 174 men per arm of each trial to give 90% power to detect a significant difference at the 5% level. This would allow detection of a difference of 0.30 of a standard deviation (SD) at 80% power for continuous measures such as quality of life. Should the proportion of men who are incontinent be more than 30%, we would still have 80% power to detect a 15% change from 40% to 25%.

Allowing for a 13% dropout rate after enrolment in the RCT, we planned to recruit 200 men per arm. This would amount to 400 men in each of the two parallel trials, who would come from 615 incontinent men, assuming that 65% agree to join the trial. Based on conservative assumptions of 50% and 5% incontinent at 6 weeks after radical prostatectomy and endoscopic resection of prostate, respectively, and 80% response rates to the screening questionnaire, 1540 and 15,400 men would need to be approached. If a typical centre undertook 30 radical prostatectomies and 300 endoscopic resections of prostate each year, about 26 centres would be required for each trial recruiting over an average of 2 years.

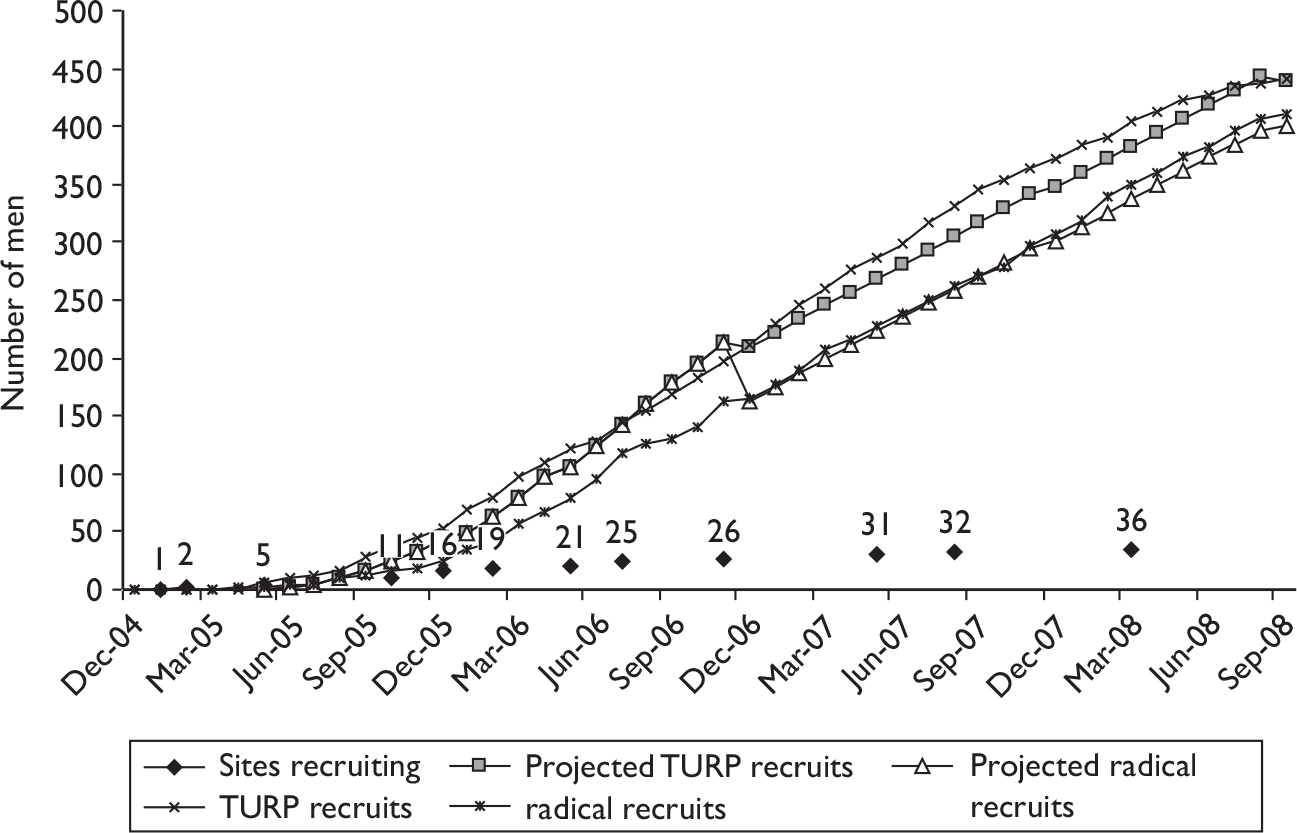

Table 2 shows the number of men whom we estimated we would need to approach and hence the number of ‘typical sized’ clinical centres that would be required. In summary, we needed to screen around 17,000 men in stage 1 of the study, making conservative assumptions about likely response and participation rates. Based on these figures, a 2-year recruitment period in 26 centres would have been needed.

However, towards the end of planned recruitment (end September 2007), it became apparent that we would fall short of our minimum targets for men randomised. We therefore applied for a 9-month extension to recruitment, based on more accurate estimates of recruitment rates. In consultation with the Data Monitoring Committee and representatives of the HTA programme, recruitment was extended to July 2008 and, as a result, randomisation finished on 23 September 2008. There were no changes to the effective sample size sought (174 in each group at 12-month follow-up).

| Estimate | Radical prostatectomy | TURP |

|---|---|---|

| Men needed per arm (minimum) | 174 | 174 |

| Allowing for 13% dropout | 200 | 200 |

| Total men needed in two arms | 400 | 400 |

| Assuming 65% willing to enter RCT, no. of incontinent men needed | 615 | 615 |

| Percentage incontinent at 6 weeks (stage 2) | 50% | 5% |

| No. of men needed to reply to survey | 1230 | 12,300 |

| Assuming 80% response to survey, no. needed for survey (stage 1) | 1540 (approx.) | 15,400 (approx.) |

| No. of operations per typical centre | 30 | 300 |

| No. of typical centres needed in 2 years | 26 | 26 |

Statistical methods

Trial analyses

The principal comparisons in each trial were between men allocated to active therapy (up to four visits to a therapist plus the lifestyle advice leaflet) and men allocated to the control group (lifestyle advice leaflet only). The two populations of men (having radical prostatectomy or TURP) were analysed as separate trials. The primary outcome measure (urinary incontinence at 12 months) and secondary outcome measures were analysed using general linear models that adjusted for the minimisation covariates (age and pre-existing urinary incontinence) and, when possible, the baseline measure of the outcome. For the primary outcome only, unadjusted analyses were also reported. All analyses used 95% CIs. For the binary outcomes, a Poisson link function was used to estimate relative risks (instead of estimating odds ratios from a logistic model) and robust standard errors were used to estimate the CIs. 28 For illustrative purposes, the relative risk of the primary outcome was also transformed to a risk difference.

The primary statistical analysis was based on all men as randomised, irrespective of subsequent compliance with the treatment allocated (intention to treat). The intention-to-treat approach gives the least biased estimate of effectiveness of the two interventions. Given that it was likely that some of the participants would not attend the therapy sessions (e.g. because they were continent), a secondary comparison was conducted to estimate the efficacy of the treatment received (i.e. what is the effect if the participants actually received the treatment they were allocated to?). The so-called ‘per-protocol’ approach for estimating efficacy of treatment, in which compliers with treatment in each group are compared with each other, can have substantial selection bias. A more robust method is to use a latent variable approach. 29 We used the method of adjusted treatment received as described by Nagelkerke et al. 30 The method used a two-stage least squares approach, whereby treatment received and the residuals from that model were used as an independent variable in a second model together with the treatment received to estimate the effects on the primary outcome.

Missing items in the health-related outcome measures were treated as per the instructions for that particular measure. No further imputation for missing values was undertaken. The ways in which the data were analysed were prespecified in the statistical analysis plan, which was agreed in advance with the MAPS Trial Steering Committee.

Timing and frequency of analyses

A single principal analysis was carried out at 15 months after the last man was recruited. The Data Monitoring Committee considered confidential interim analyses of data on three occasions during the data collection period (January 2006 – 31 randomised to radical prostatectomy and 48 randomised to TURP; January 2007 – 180 randomised to radical prostatectomy and 200 randomised to TURP; January 2008 – 297 randomised to radical prostatectomy and 364 randomised to TURP). The Data Monitoring Committee did not recommend any amendments to the protocol on any occasion.

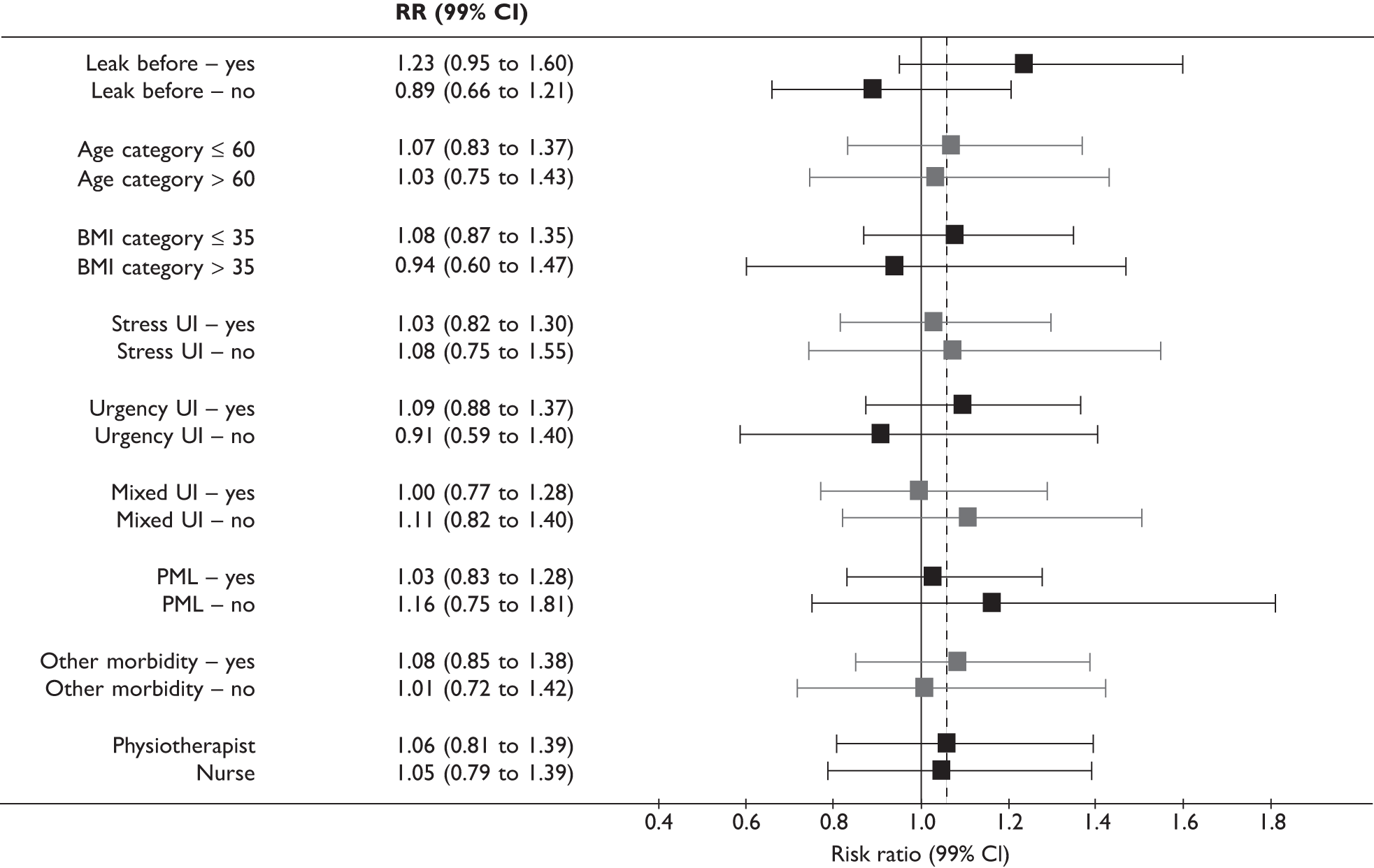

Planned secondary subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses (separately for the two populations) explored the effect on urinary incontinence at 12 months after randomisation of:

-

pre-existing urinary incontinence (before prostate surgery)

-

age (up to 60 years, 61 years and over for radical prostatectomy; up to 70 years, 71 years and over for TURP)

-

body mass index (BMI) (up to 30 kg/m2, 30–34.9 kg/m2, 35 kg/m2 or greater)

-

type of incontinence at trial entry (SUI, UUI, MUI, postmicturition leakage)

-

other morbidity

-

type of therapist (physiotherapist or nurse)

-

centres with and without biofeedback machines.

Stricter levels of statistical significance (2p < 0.01) were sought, reflecting the exploratory nature of these analyses.

Ancillary analyses

Screening data

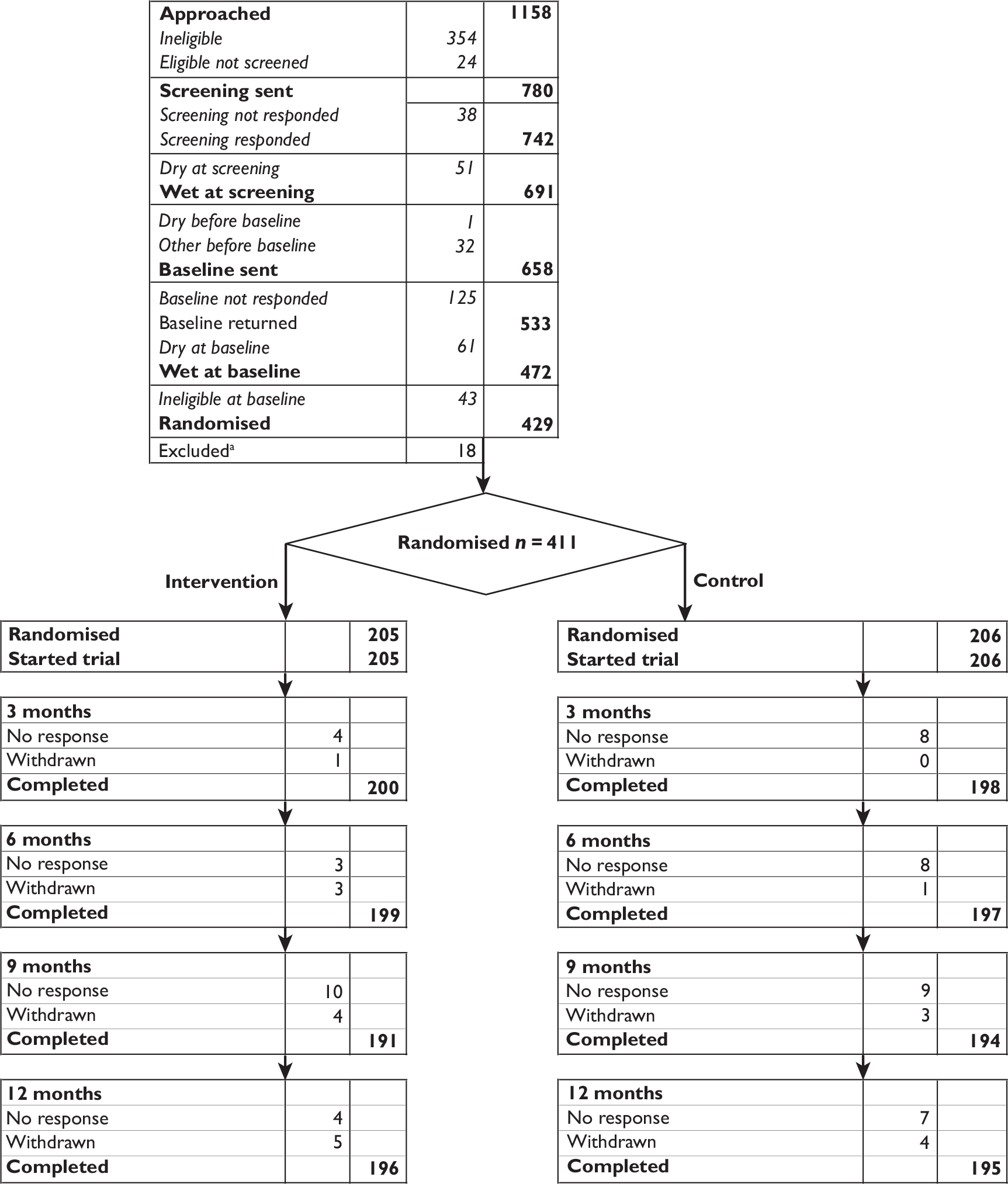

Descriptive statistics were tabulated to describe the derivation of the trial groups from the screening procedures, and included comparison of those who responded versus those who did not respond to the screening.

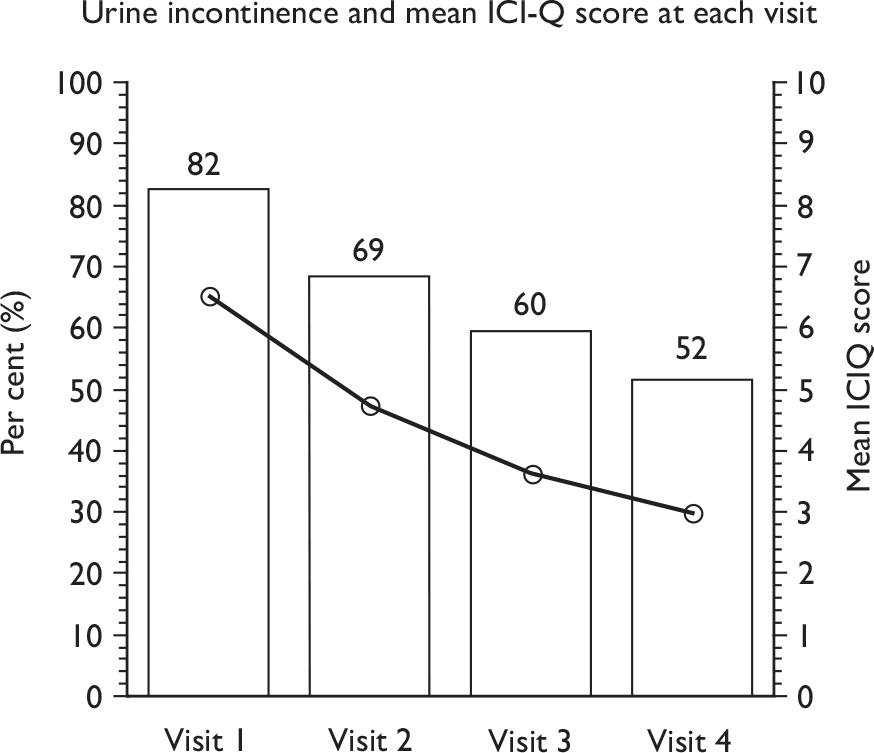

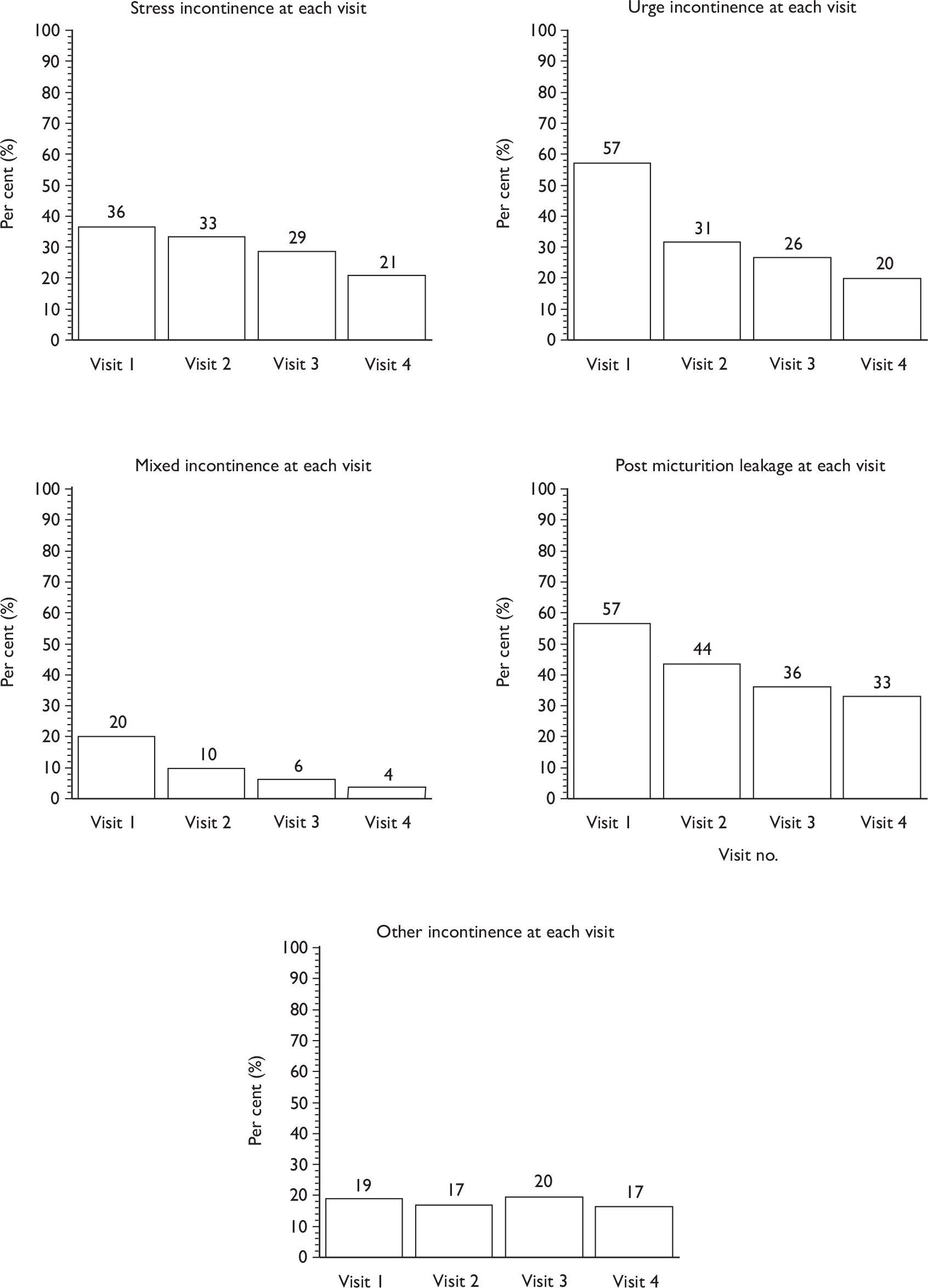

Therapist data

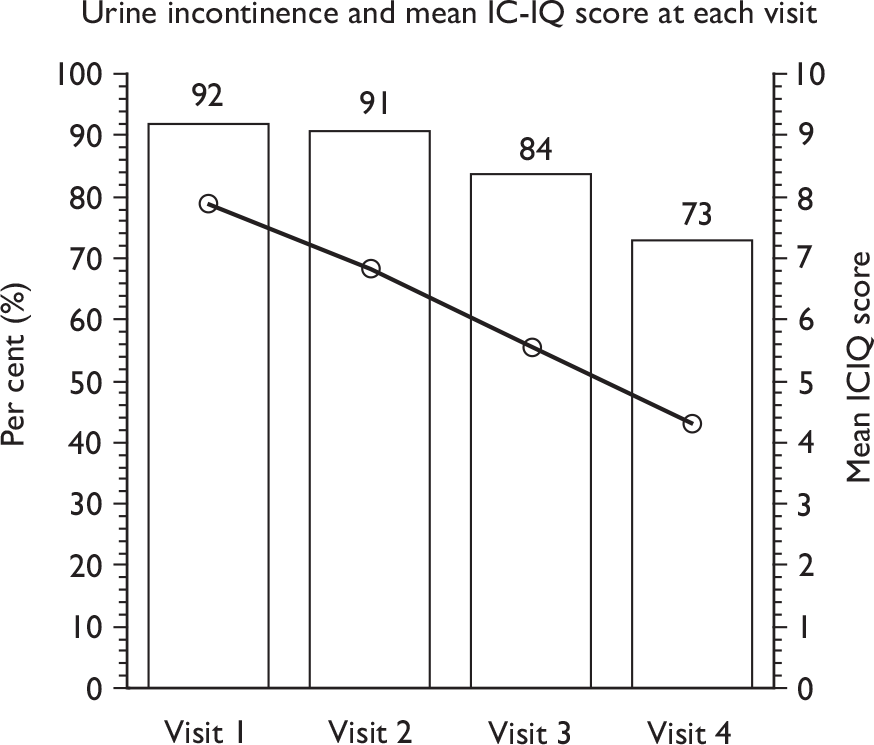

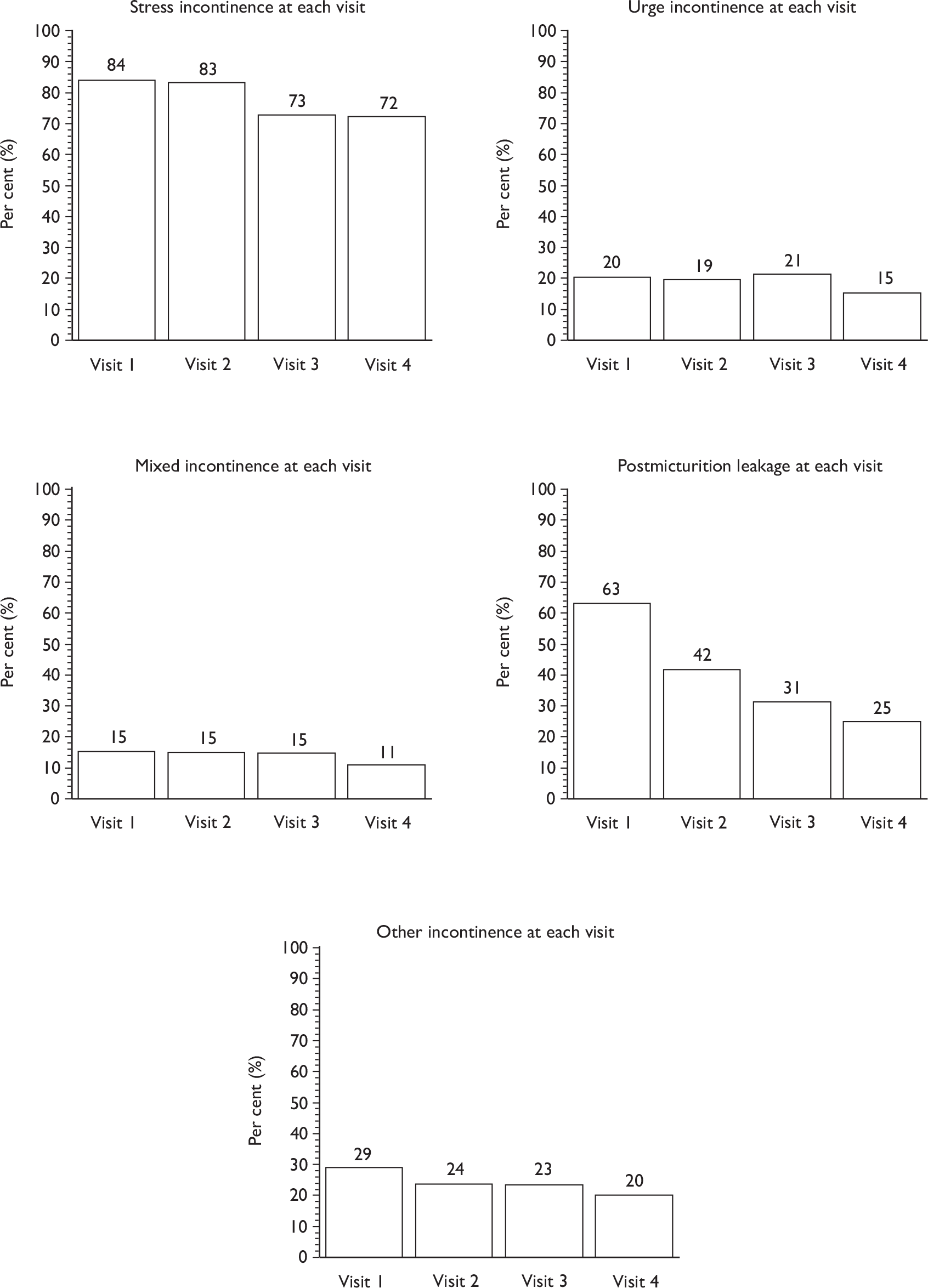

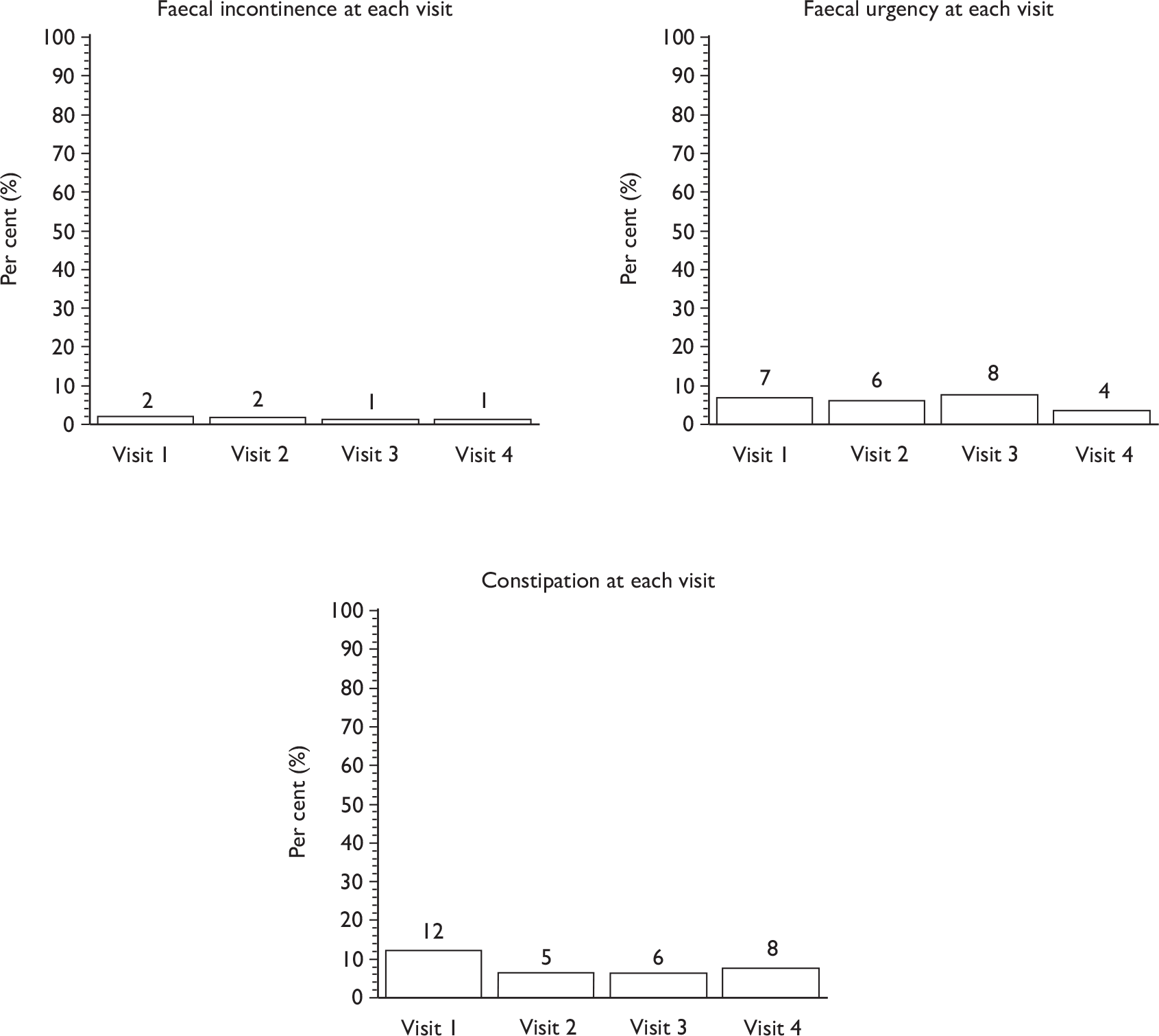

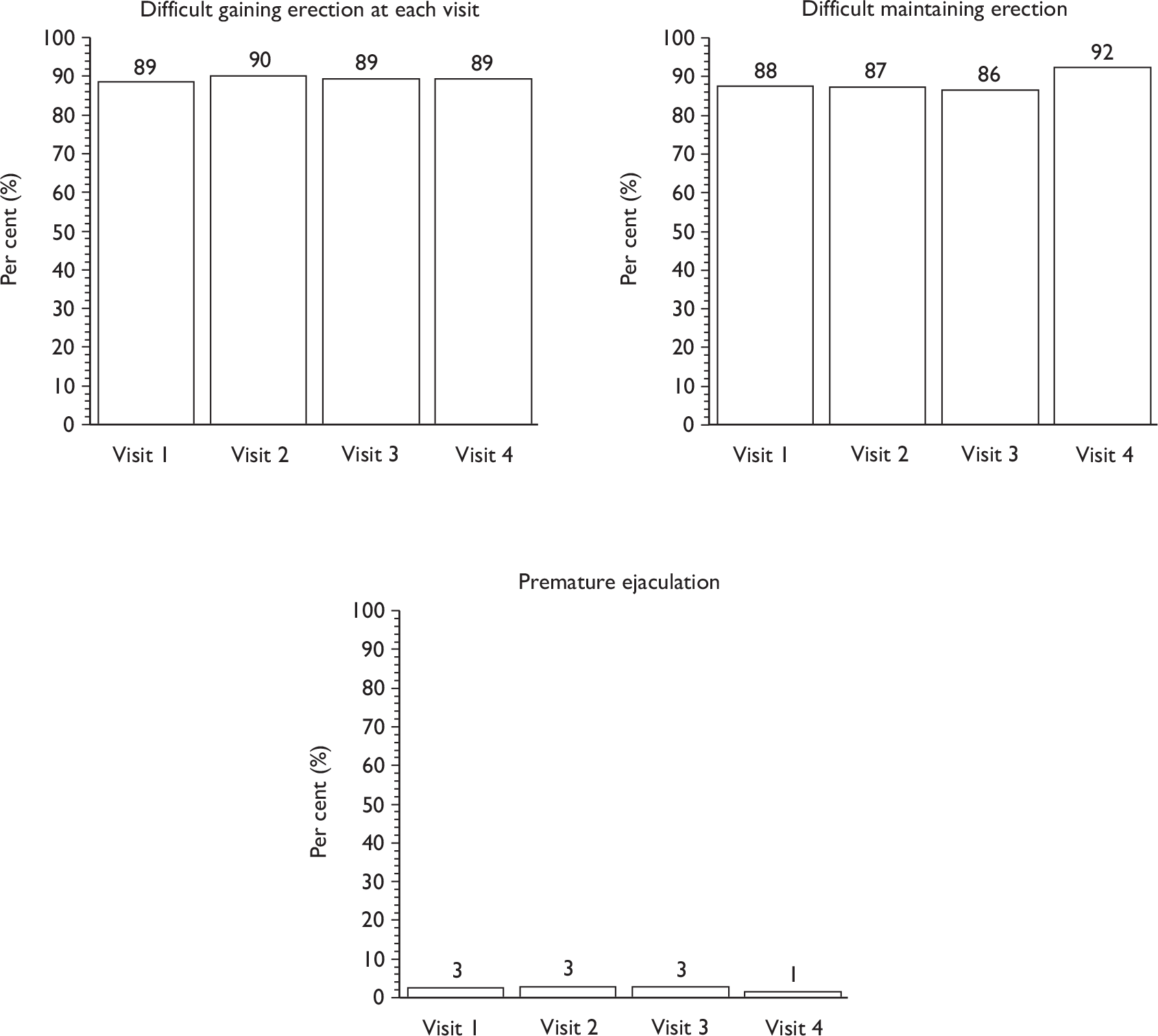

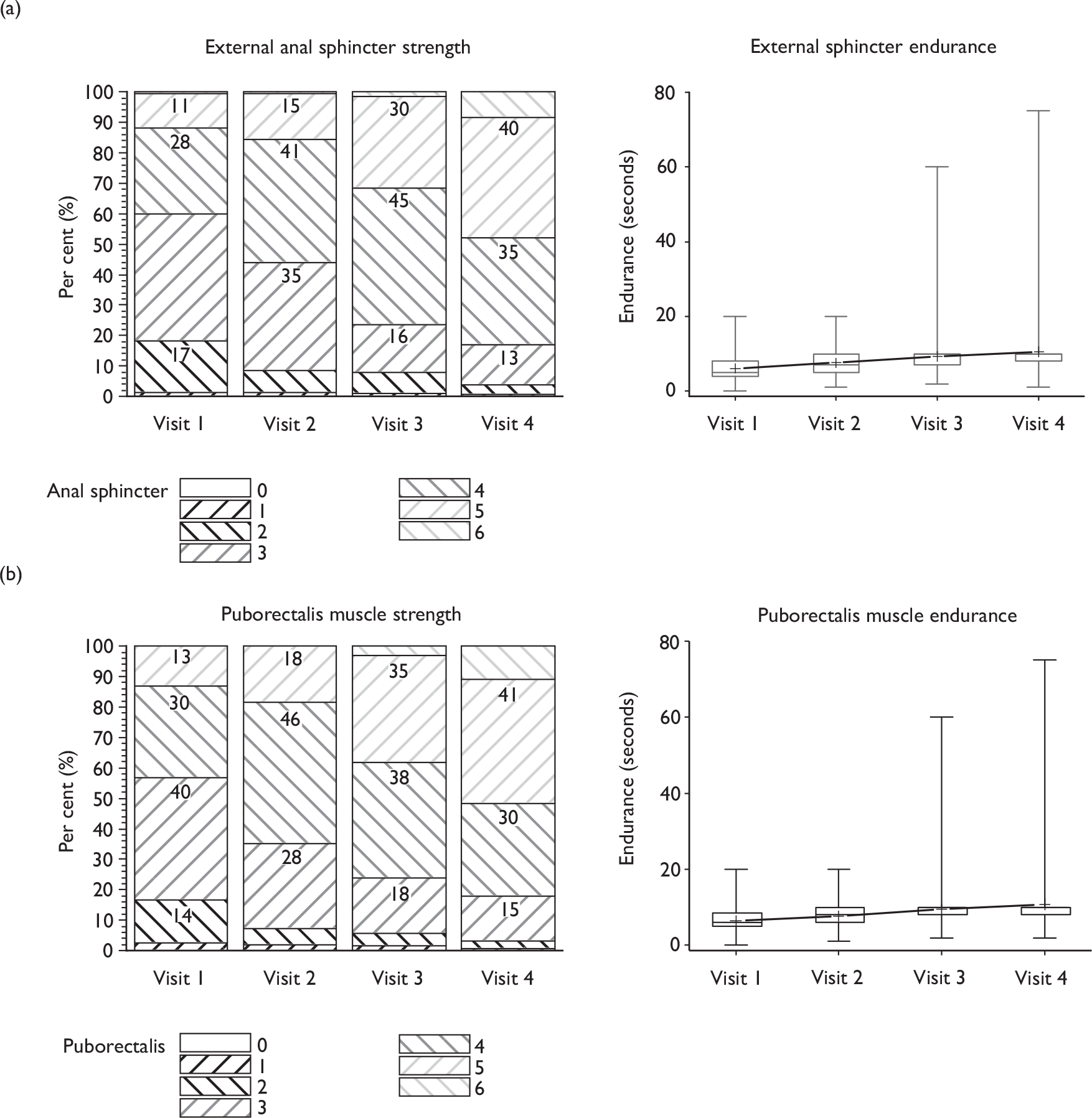

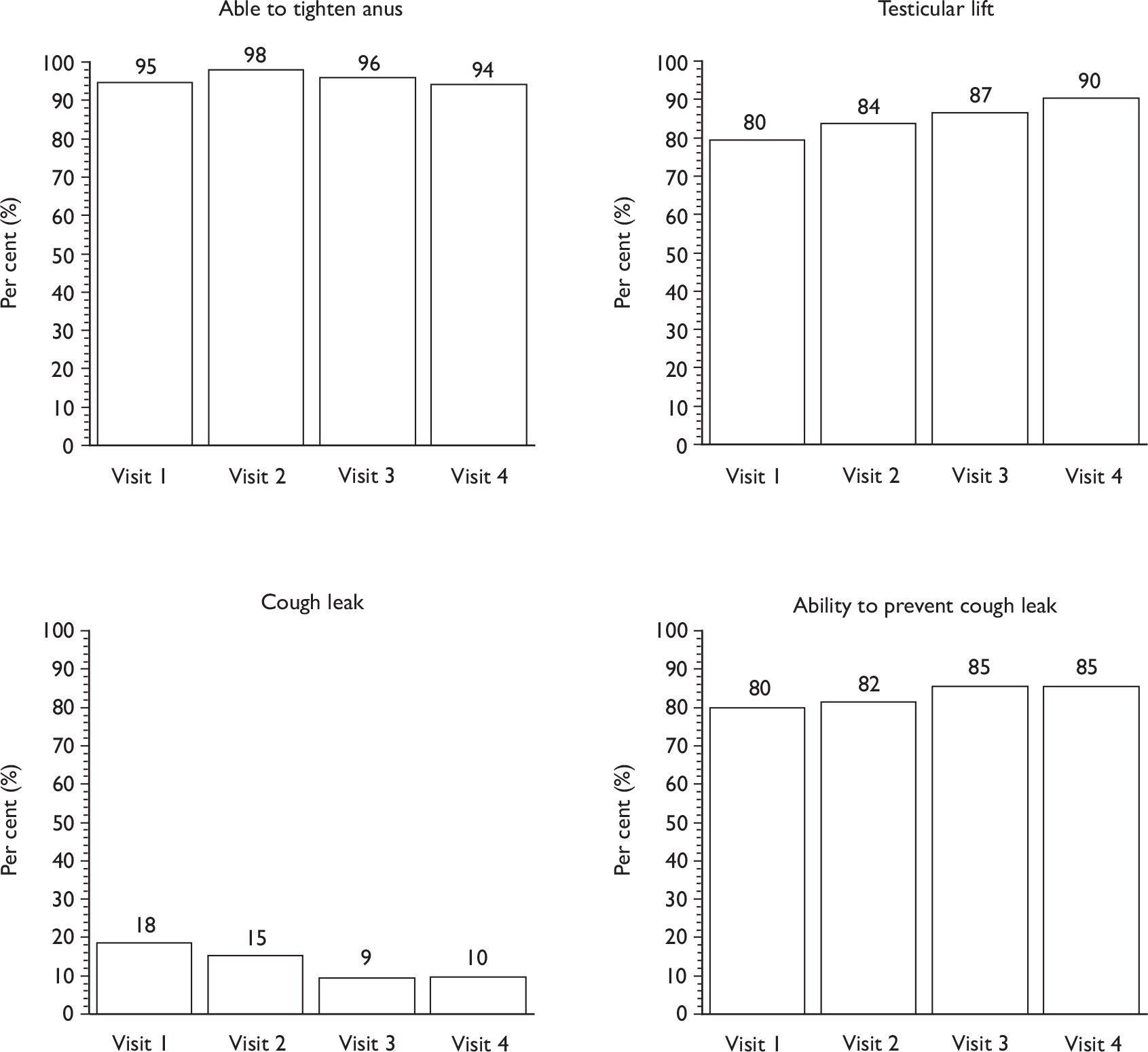

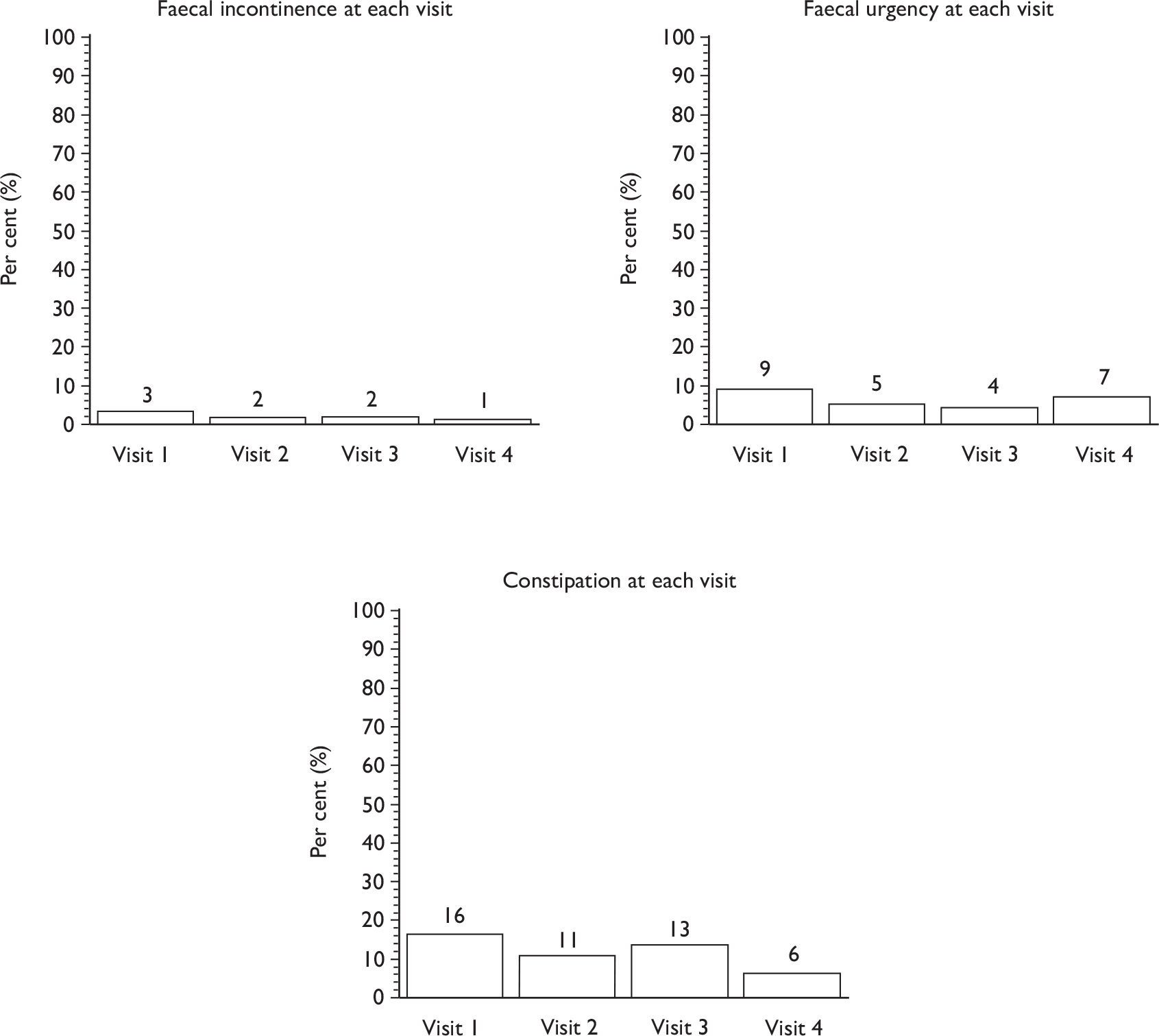

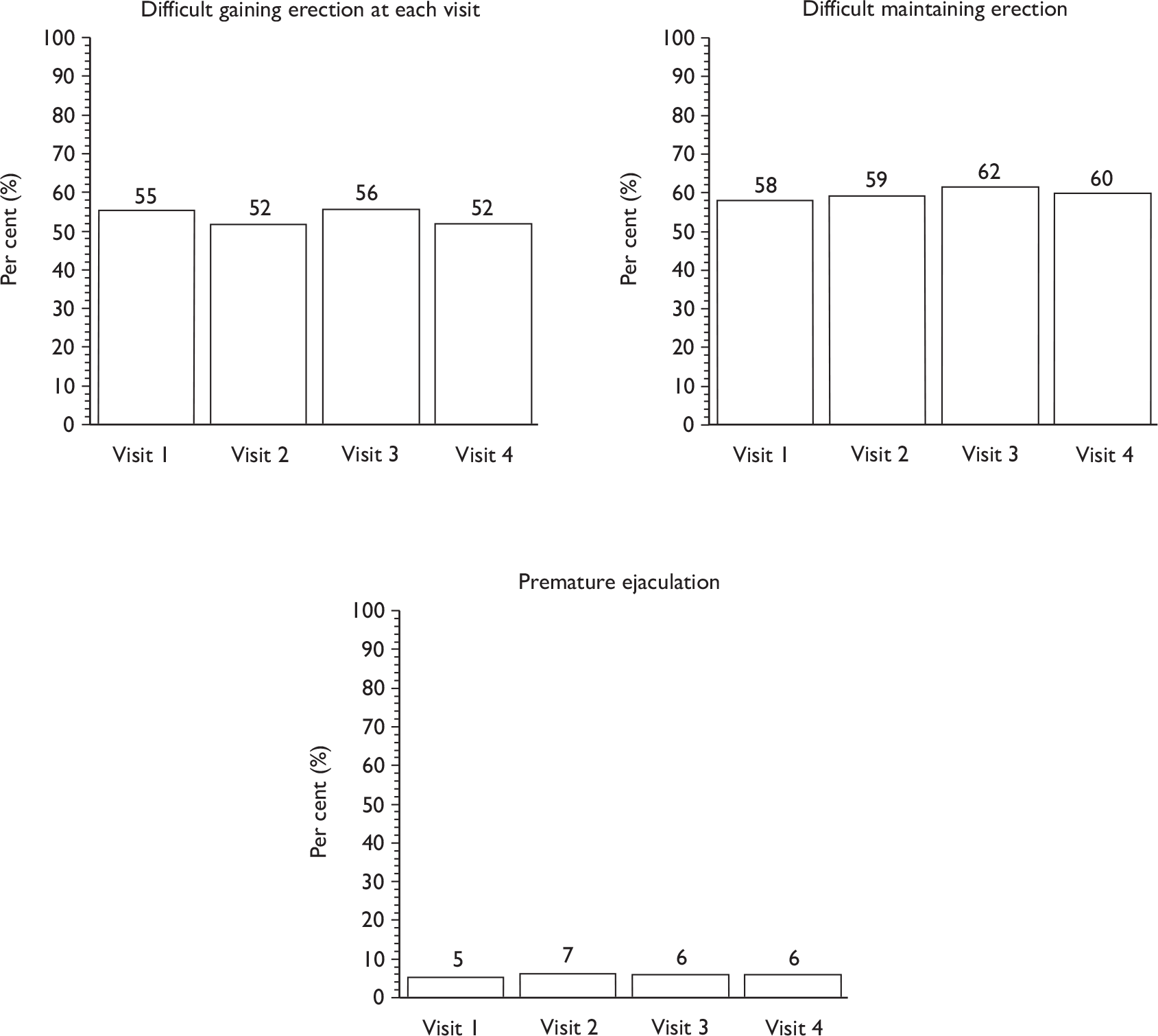

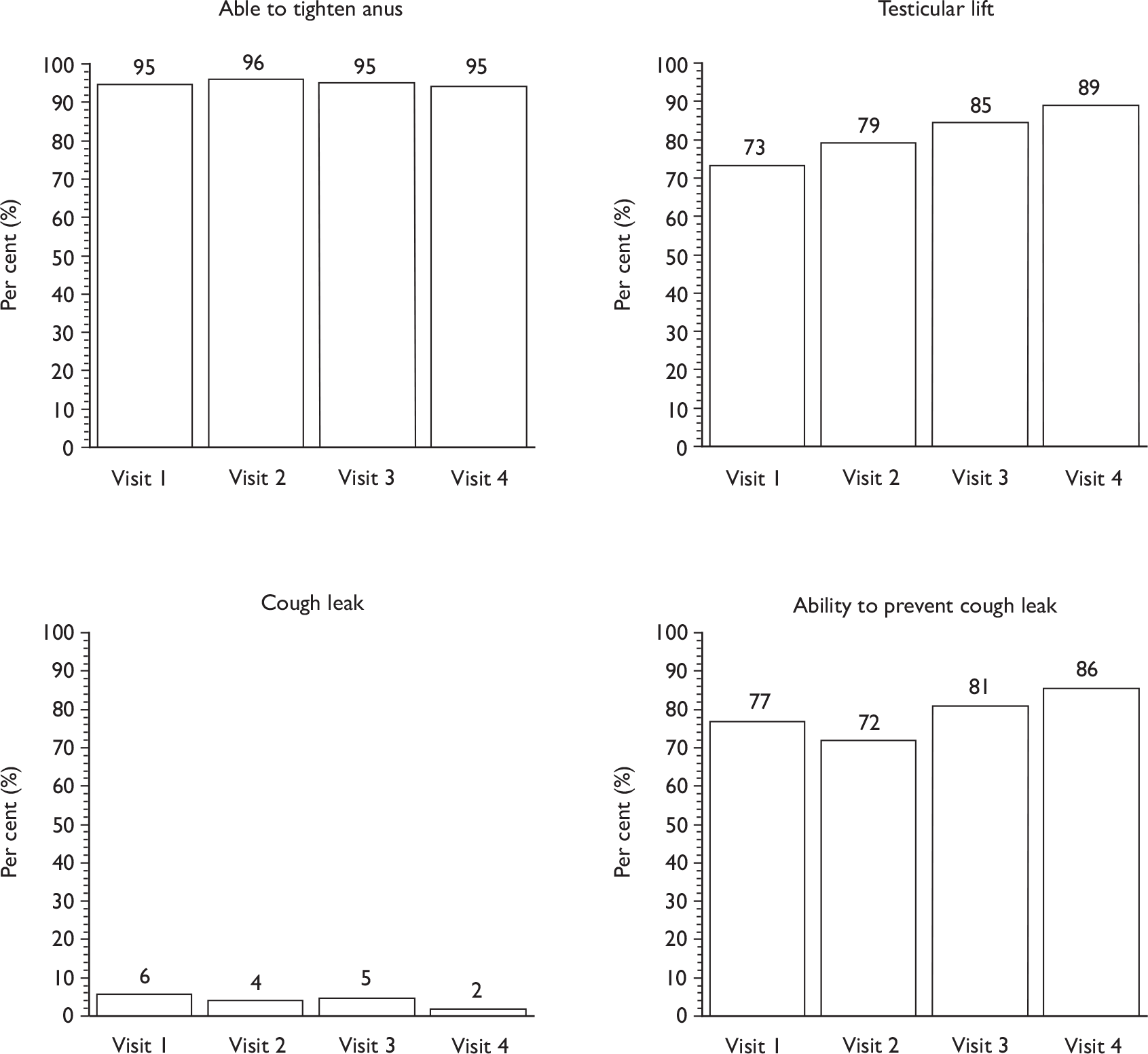

Descriptive data were tabulated to describe how the therapy intervention was implemented in each of the trials. This included a comparison across therapy visits (one to four) on incontinence, bowel and sexual problems and pelvic floor muscle performance.

Economics methods

Introduction

The economic evaluation was based on a within-trial analysis at 12 months after recruitment for men with urinary incontinence 6 weeks after radical prostatectomy or TURP. The question addressed was: what is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of active conservative treatment delivered by a specialist continence physiotherapist or a specialist continence nurse compared with usual management? The perspective of the study was based on a societal viewpoint and included both the costs of the health service provider (the NHS) and those of the patients.

Measurement of resource use

The use of health services as a consequence of being incontinent was recorded prospectively for every participant in the study. Resource utilisation data were collected using questionnaires and urinary diaries. These data were collected using questionnaires sent to the participants at baseline, and 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. Resource utilisation data collected also included the intervention, i.e. the number of visits to the therapists, who were either specialist continence physiotherapists or continence nurse specialists. According to the protocol, PFMT intervention comprised four sessions. Details of the intervention are provided in Chapter 3. The first session of PFMT was 1 hour and the other three sessions were approximately 45 minutes each. Each session was conducted in a hospital department. The consumables required per session were gloves, K-Y Jelly, wipes and paper towels. No additional resources were required for the biofeedback as no equipment was used; verbal biofeedback was used to teach the men how to contract their muscles optimally and advise them on improvement from previous appointments.

Primary care and outpatient resource use included visits to the GP as well as to the outpatient department. The number of GP visits and the contact (doctor or nurse) were obtained from the 3-, 9- and 12-month follow-up questionnaires. Number of outpatient visits was obtained from the 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month follow-up questionnaires. For the length of stay, the number of days the men were admitted was recorded. Other resource use included the number and type of drugs the patients were prescribed for their incontinence problems, the number of pads used and, finally, the number of bed and chair protectors used. The data reported by the patients were used to calculate the average and total resource use per patient.

The information generated from these questionnaires entailed manipulation of the data to perform the comparative analysis. Details of methods used to estimate resource use collected are included in Table 3.

| Resource | Relevant variables | Source | Reported outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient management | Physiotherapist 1st visit | DA | Number attending |

| Physiotherapist 2nd–4th visit | DA | Number attending | |

| GP visits | PQ | Number | |

| Primary care | Nurse visits | PQ | Number |

| Outpatient visits | PQ | Number | |

| Secondary care | Inpatients days | PQ | Number |

| Physiotherapy | PQ | Number | |

| Medications, e.g. tolterodine tartrate | PQ | Type and number | |

| Other | Pads | PQ | Type and number |

| Chair/bed protectors | PQ | Type and number | |

| Catheters | PQ | Type | |

| External sheaths | PQ | Type |

Identification of unit costs

As described above, costs focused on the direct health service costs associated with each treatment. Unit cost data were extracted from the literature or from relevant sources such as manufacturers’ price lists (British National Formulary, BNF)31 and NHS Reference Costs. 32 The year of the cost data is 2008 and the currency is pounds sterling (£).

The costs of the intervention included the cost of PFMT sessions. These comprised the costs of the staff involved, consumables and overheads. The costs of producing the leaflets for the trial were not included in the analysis as all the men in the trial received leaflets. Men in both groups received a booklet containing supportive lifestyle advice (without reference to PFMT) by post after randomisation (see Appendix 4.2). Men in the intervention group also received a MAPS pelvic floor exercise leaflet (see Appendix 4.3) from the therapist at the first visit. The booklet aimed both to support and to reinforce the anatomy teaching received during MAPS therapy appointments, as well as the exercise programme that had been set. It was therefore assumed that the costs would be the same for both groups. The cost of training that therapists received (1-day course) was included in the intervention costs because it was low and was not likely to impact on the overall costs.

The cost of the follow-up management comprised the cost per visit to both primary (GP and nurse appointments) and secondary (outpatient appointments and number of inpatient days) health-care providers. Unit costs for GP’s visits were obtained from the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) unit costs of community care. 33 Unit costs for outpatient services were obtained from the Scottish Health Service Costs (SHCS) (Information and Statistics Division website34) for the primary analysis and the national reference costs in a sensitivity analysis (Department of Health website35). The inpatient costs were those of the wards to which the men were admitted.

Other costs considered included containment products. These comprised all the products that participants used, such as absorbent pads, penile collecting sheaths, bladder catheters and bed and chair protectors. The unit costs of these items were taken from the providers of these items or from the NHS suppliers, where available. The unit cost of sheaths is based on a weekly cost of sheaths, estimated assuming that one sheath is used each day, the reusable leg bag is used for 3 days and one night bag is used each night. The unit costs of the catheter were based on the assumption that the catheter was used over a 3-month period, and similar assumptions were made for the leg and night bags. The unit cost of the medications was taken from the BNF,31 and the cost per patient in terms of medication use was calculated by multiplying the unit cost by each number of units consumed for each patient. The costs considered were those of the drugs, not the prescription charges. Table 4 provides a summary of the unit costs for the resources used.

| Resource use | Unit cost (£) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Staff costs | 67 | Based on cost per hour of patient contact for Band 6 of the October–December 2007 NHS staff earnings estimates for qualified nurses33 |

| Cost of consumables | 0.90 | Based on cost of gloves, K-Y Jelly, couch roll, paper towels, wipes for four visits |

| Medications | Various | Cost based on recommended dosage |

| GP doctor visit | 36 | Per surgery consultation lasting 11.7 minutes33 |

| GP nurse visit | 11 | Based on cost per consultation33 |

| Physiotherapist visit | 31 | Based on cost of nurse-led clinic33 |

| Outpatient visit | 75 | Based on cost34 |

| Inpatient visit | 157 | Based on the average cost per day in a urology specialty ward34 |

| Pads | 0.17 | Cost per pad |

| Chair/bed protector | 0.15 | Cost per protector |

| Sheath | 8.46 | Weekly cost of sheath (condom) catheter, reusable leg bag and disposable night bag |

| Catheter | 2.73 | Weekly cost of catheter, reusable leg bag and disposable night bag |

The data describing the resource utilisation of participants were combined with estimates of unit costs for each of the areas of management considered. This allowed for estimation of total cost for each participant, as well as the average cost for each area of resource utilisation and average total cost. The results are reported in Chapters 8 and 13.

Participant costs of urinary incontinence

As the perspective of the study was the NHS and patient, those costs borne by participants and their families were also considered. Participants’ resource use was taken as time taken to access services (e.g. attend GP, physiotherapist, outpatient or inpatient appointments), travel costs and the time taken off usual activities owing to poor health. Similar costs were included for spouses, relatives or friends who accompanied them to their appointments. Travel costs to patients and their families were based on actual fares when public transport was used and published mileage rates in the case of those who used their own vehicles (HM Revenue and Customs website36). These data were collected through postal questionnaires administered at 12 months.

In the case of patients who would have been engaged in employed work, the value of their time was taken as the gross average full-time wage rate for men (Office for National Statistics website37). The value for those who were not in formal employment was based on 57% of the average national rate and 43% for those who may have been involved in leisure activities. 38 The costs of friends/relatives accompanying patients to hospital were estimated in the same way. These unit time costs, measured in terms of their natural and monetary terms, were combined with estimates of number of health-care contacts derived from the health-care utilisation questions. Self-purchased health care included items such as pads bought by the participant, prescription medicines and over-the-counter medications. Information about these was collected through the health-care utilisation questions. Patients’ time and travel costs were based on the information collected, and are described in Table 5.

| Resource | Resource use | Unit cost |

|---|---|---|

| Use of personal car to GP | Distance travelled | Cost per mile/km |

| Use of personal car to hospital | Distance travelled | Cost per mile/km |

| Use of public transport to GP | Ticket | Return cost of ticket |

| Use of public transport hospital | Ticket | Return cost of ticket |

| Medication purchased | Type and number | Cost of medicines |

| Loss of earnings | Number of days off work | Daily wage |

Quality of life

Effectiveness within the trial was measured in terms of QALYs and subjective continence at 12 months (assessed using data from the ICI-SF). Quality of life data were collected at baseline and 6 and 12 months. This was generated using generic health status measurement tools, the EQ-5D and SF-12, included in the questionnaires. The EQ-5D measure divides health status into five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Each of these dimensions has three levels, therefore 243 possible health states exist. 39 Responses of the patient EQ-5D questionnaires were transformed using a standard algorithm to produce a health state utility at each time point for each patient. The utility scores obtained at baseline and 6 and 12 months were used to estimate the mean QALY score for each group. The estimation of QALYs took account of the mortality of study participants. Participants who died within the study follow-up were assigned a zero utility weight from their death until the end of the study follow-up. QALYs before death were estimated using linear extrapolation between the QALY scores at baseline and all available EQ-5D scores up to death.

As described below in the section on the sensitivity analysis, the responses from the SF-12 questionnaire were also used as the basis of QALYs, and were mapped on to the existing Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D) measure using the algorithm by Brazier et al. 40 to allow utility values to be estimated for each time point. These utility scores were transformed into QALYs using the methods described above to provide an alternative measure of QALYs for each patient.

Incremental cost-effectiveness

Data collected on costs and effects of the interventions were combined to obtain an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). This was performed by calculating the mean difference in costs between the interventions and control groups over the difference in effect between the interventions and control groups. This gives us the cost per additional QALY gained for the new interventions relative to standard practice.

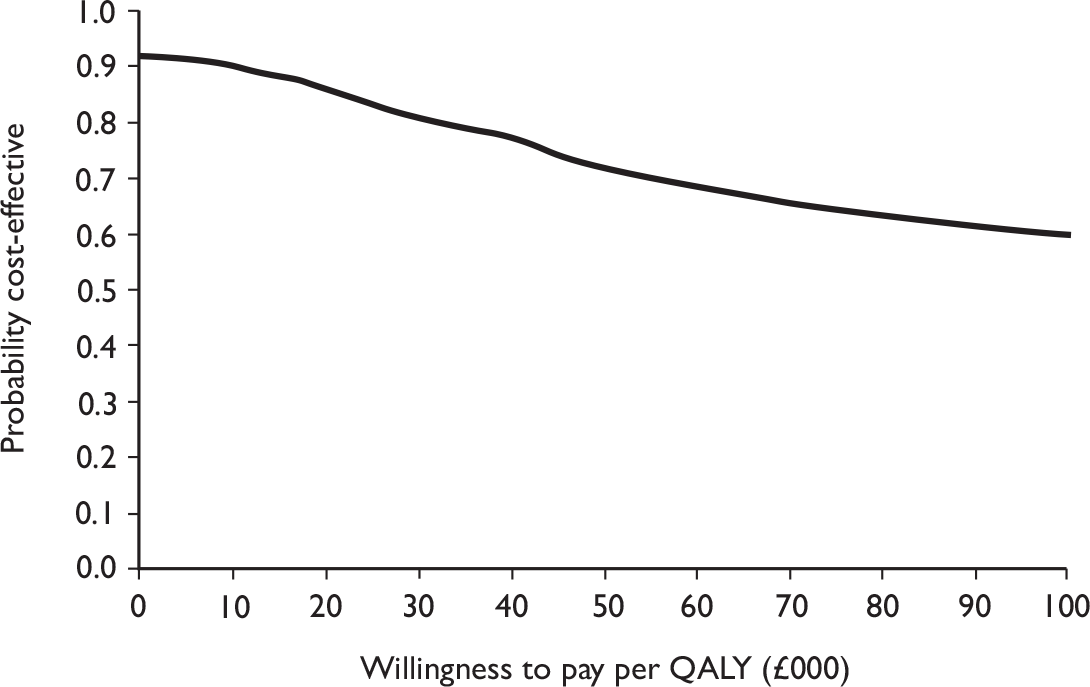

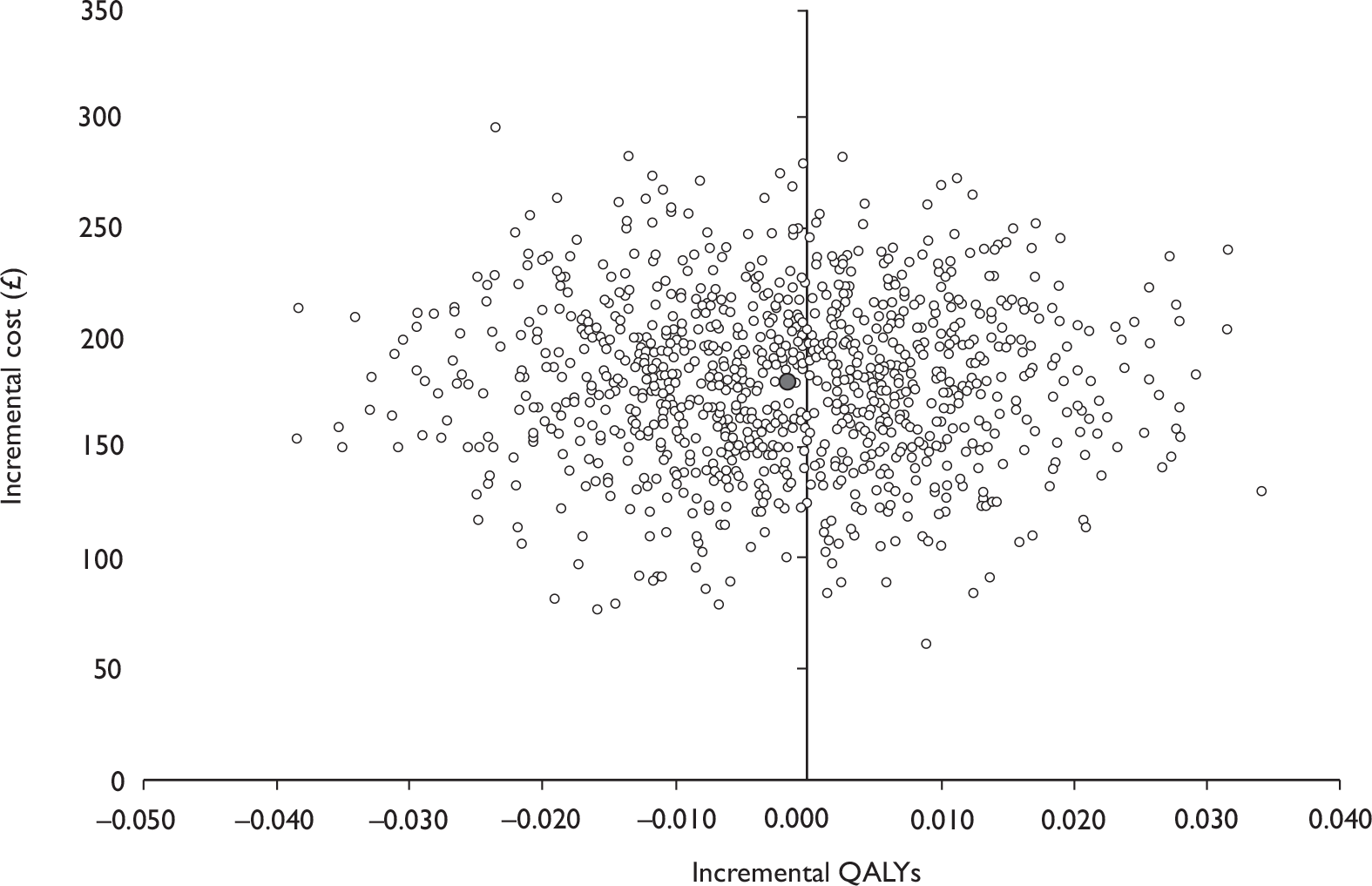

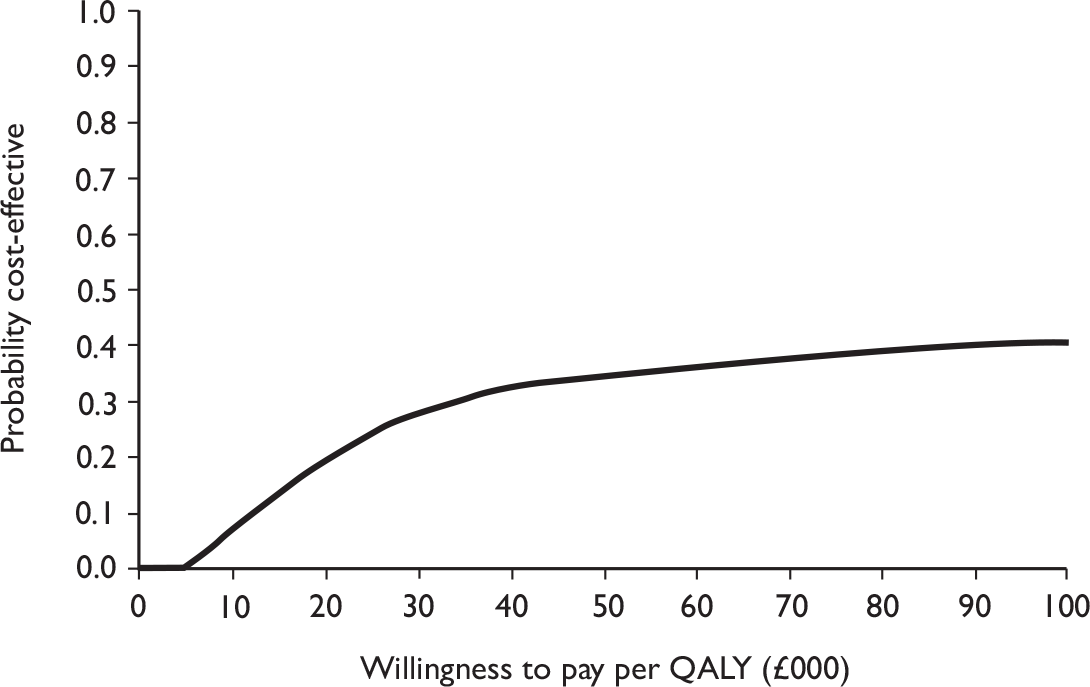

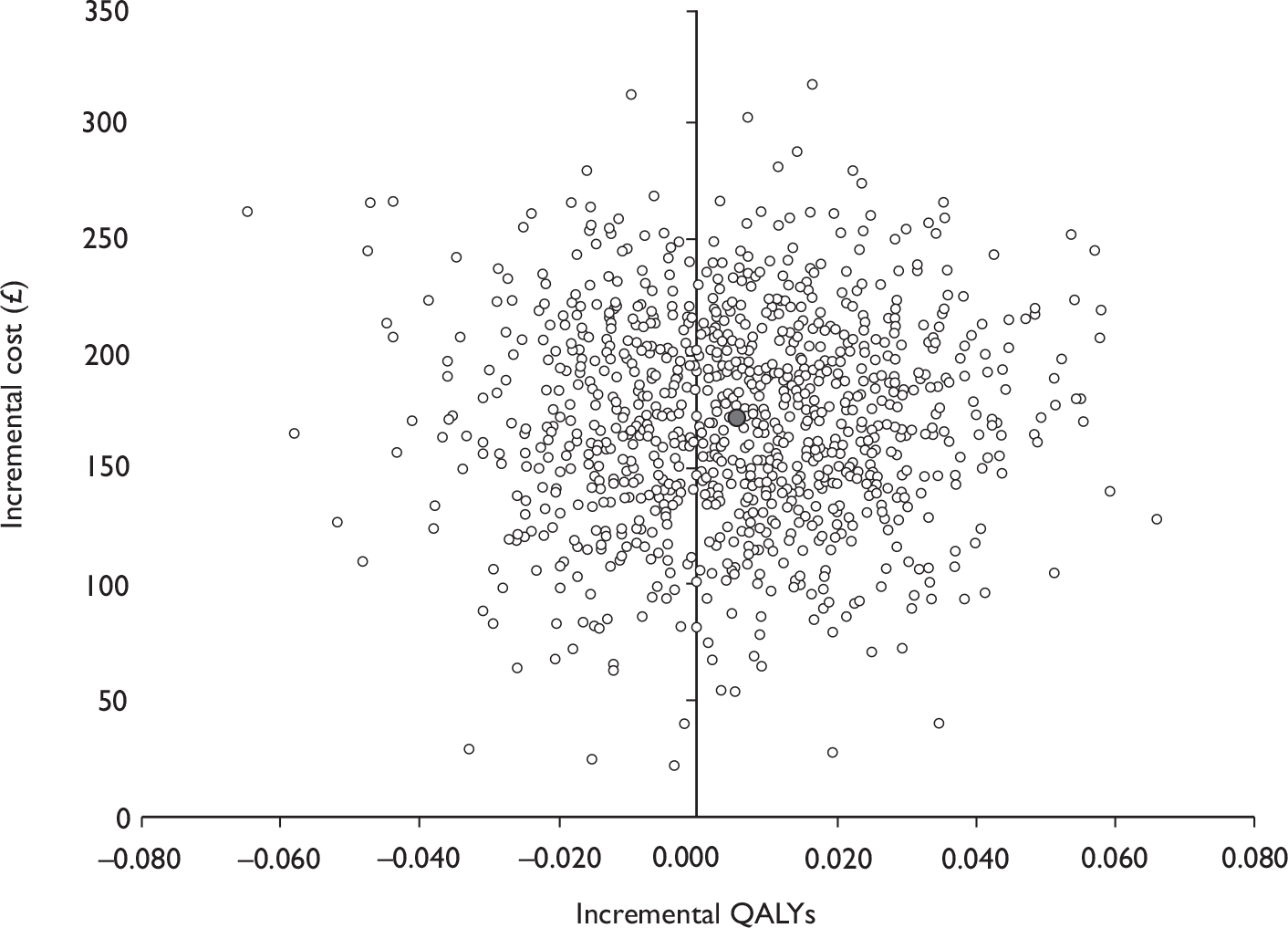

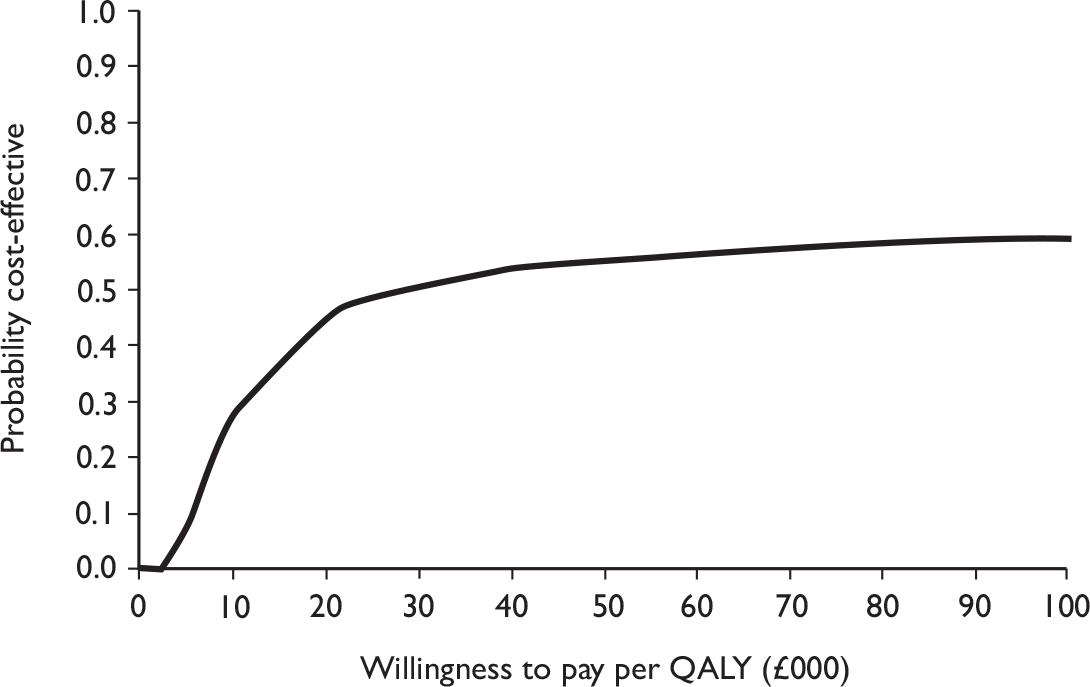

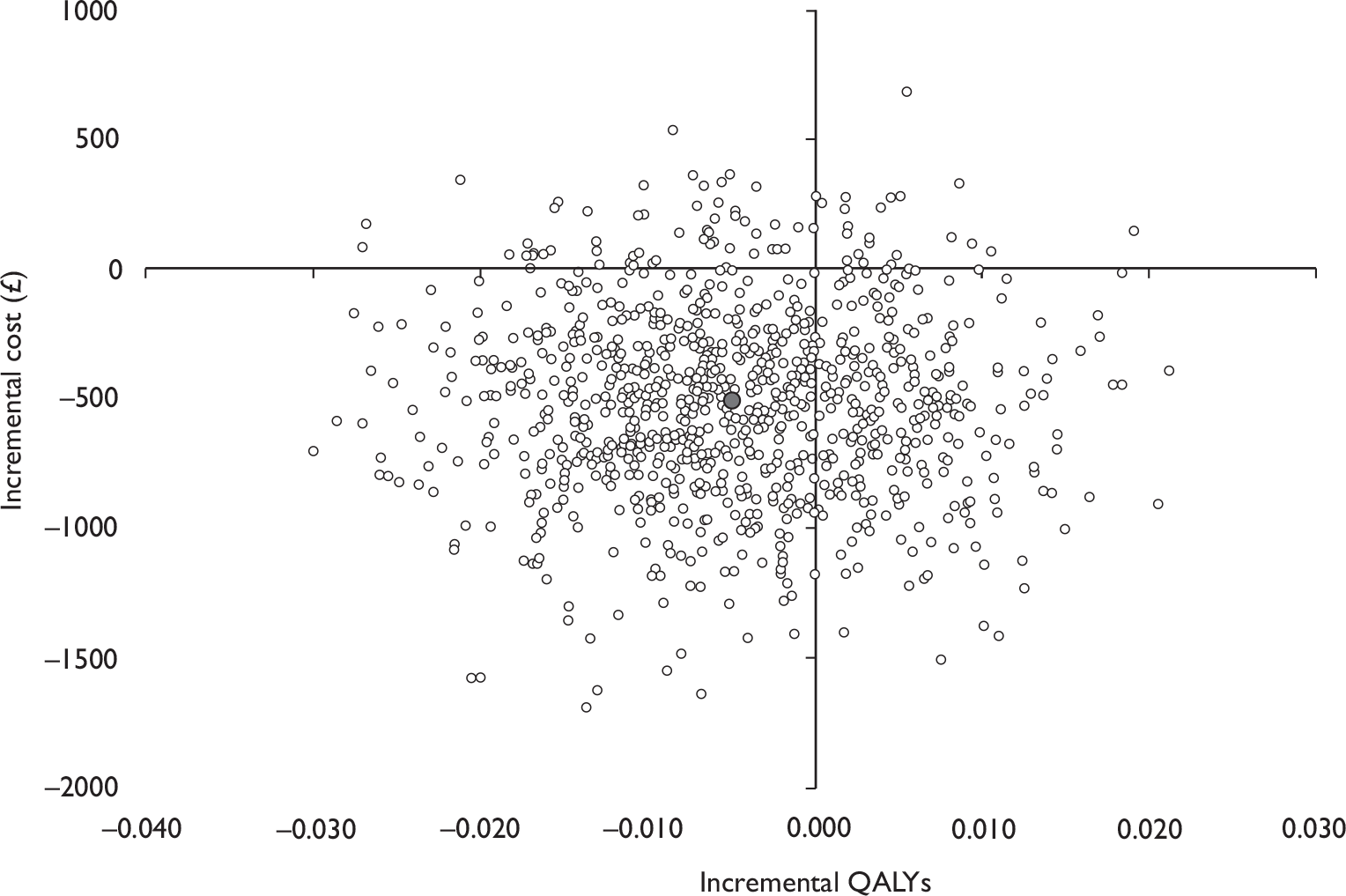

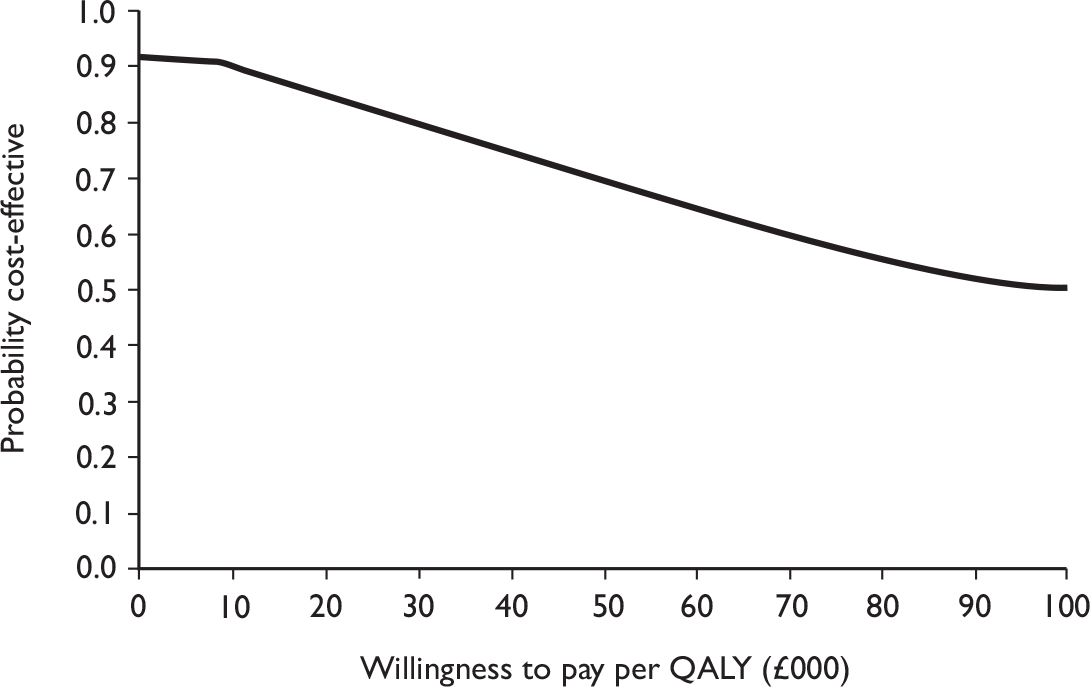

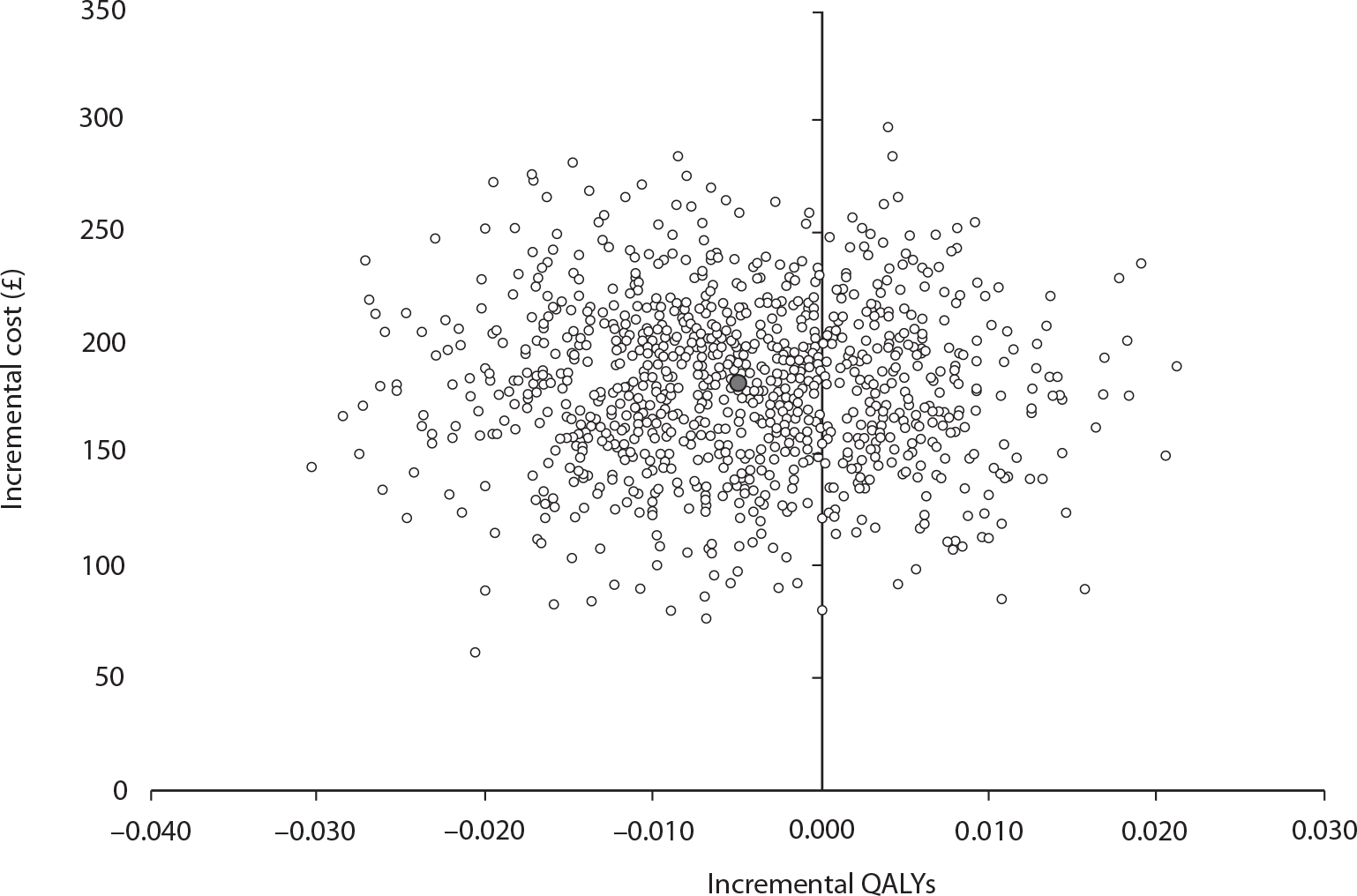

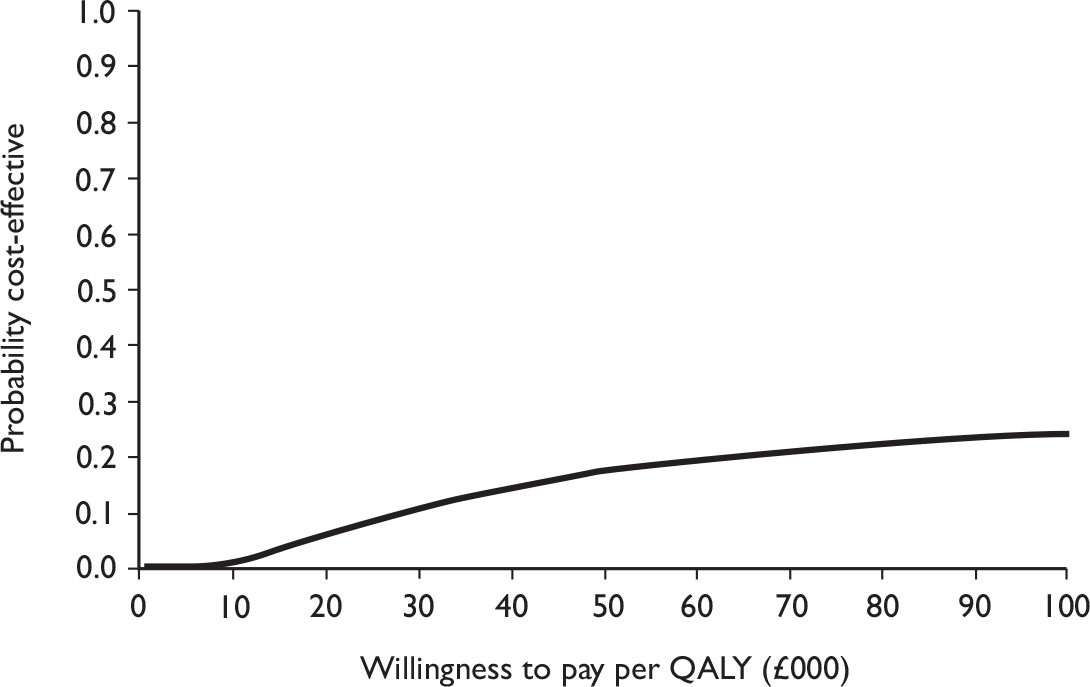

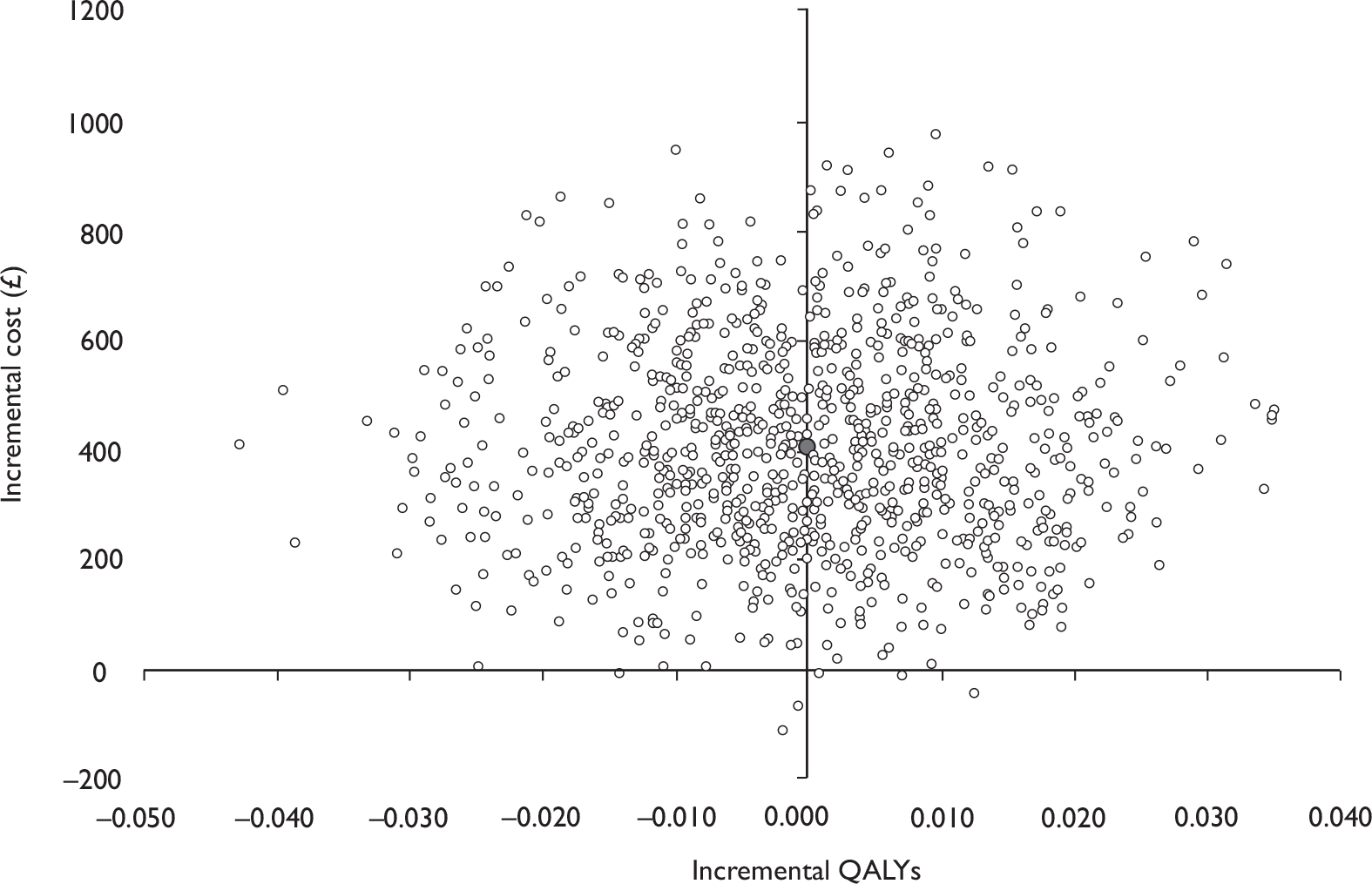

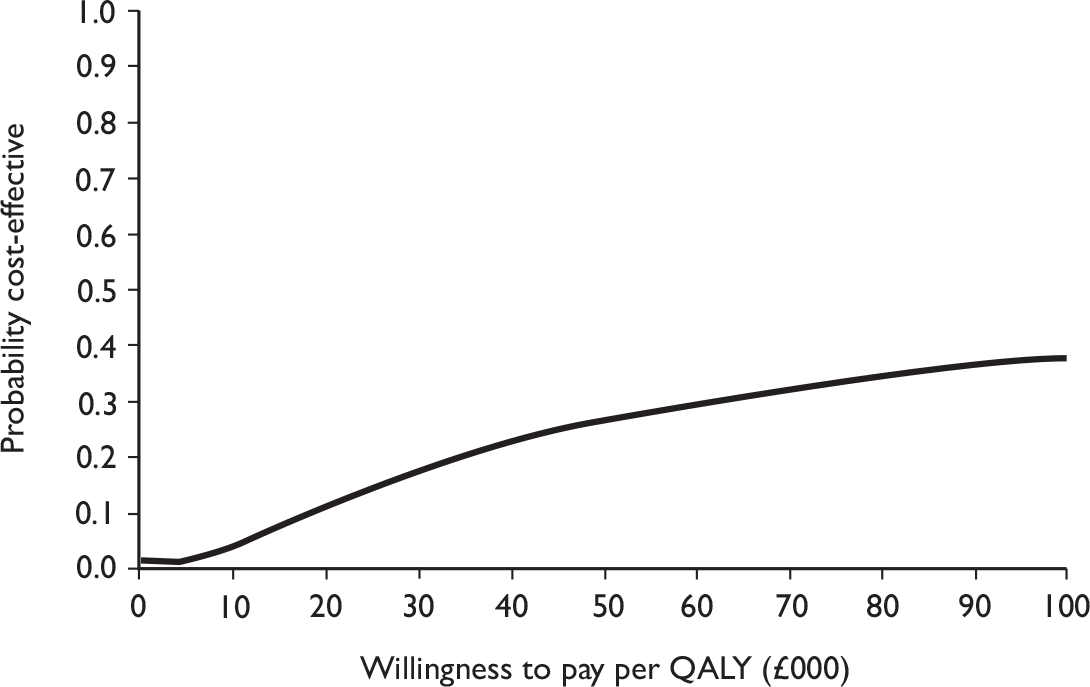

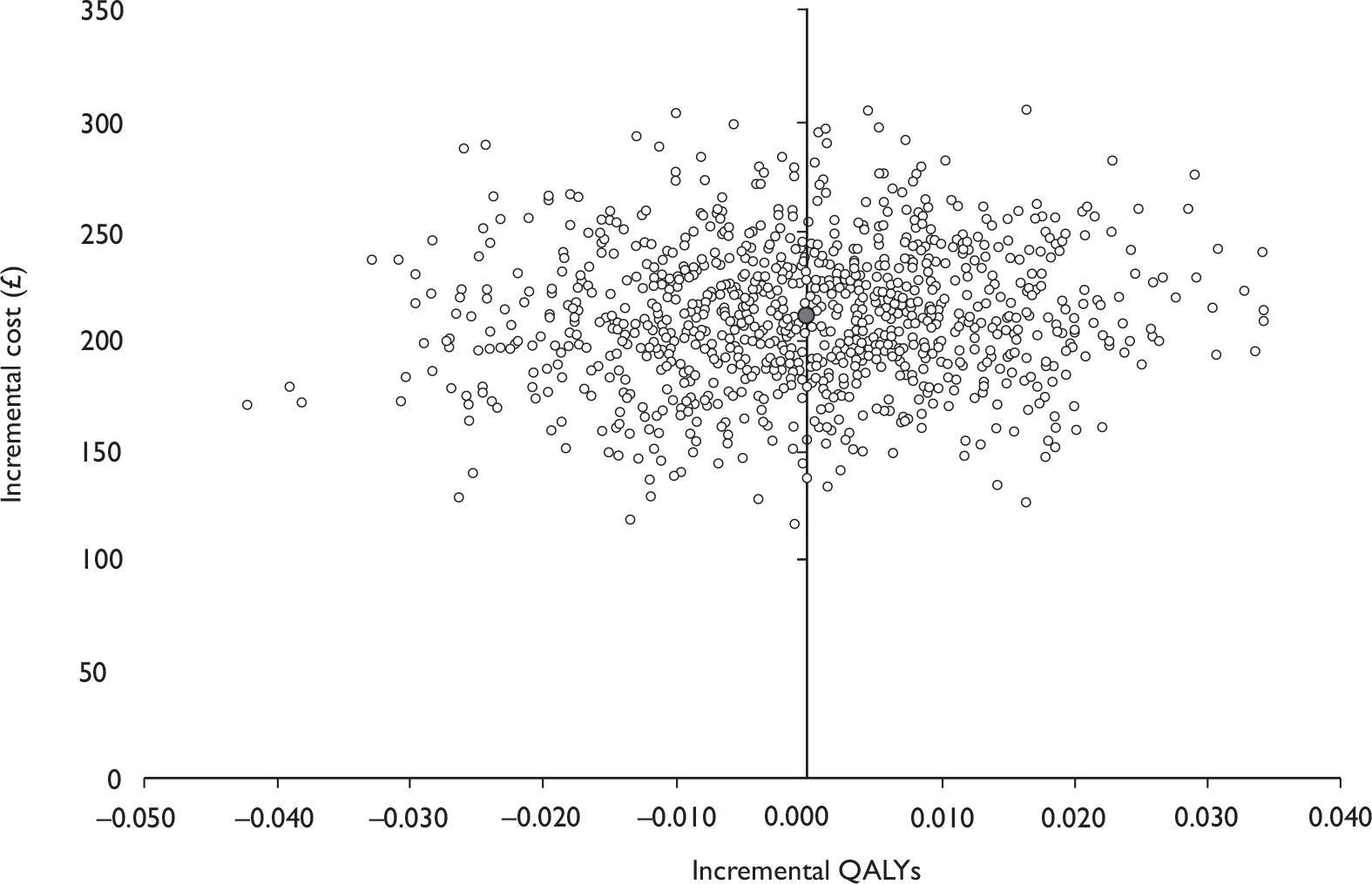

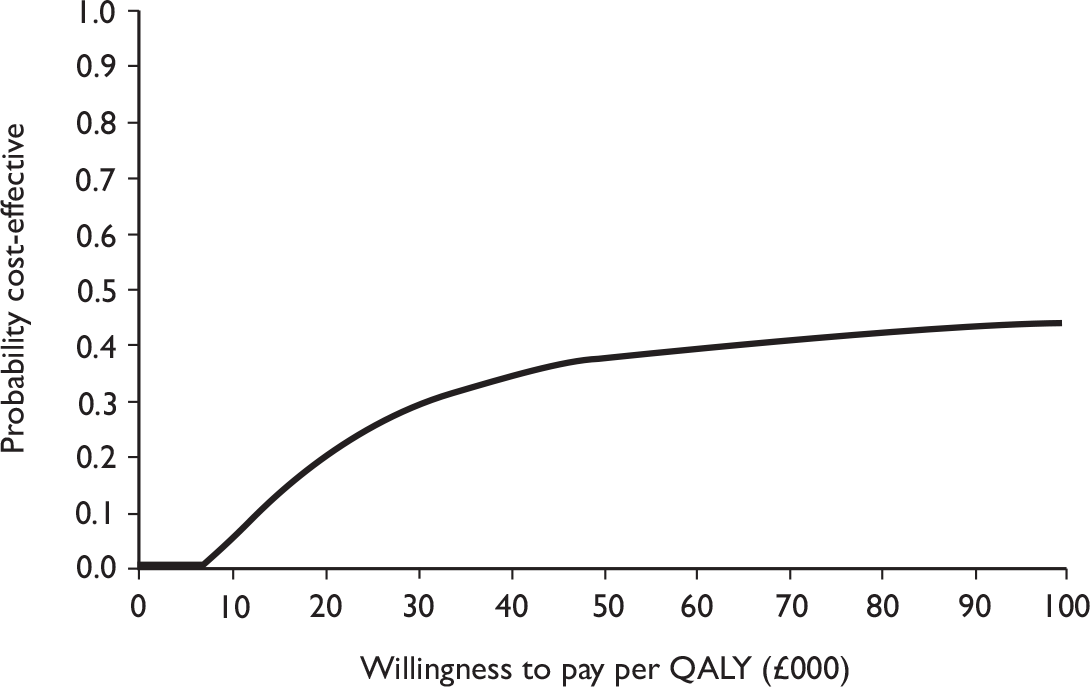

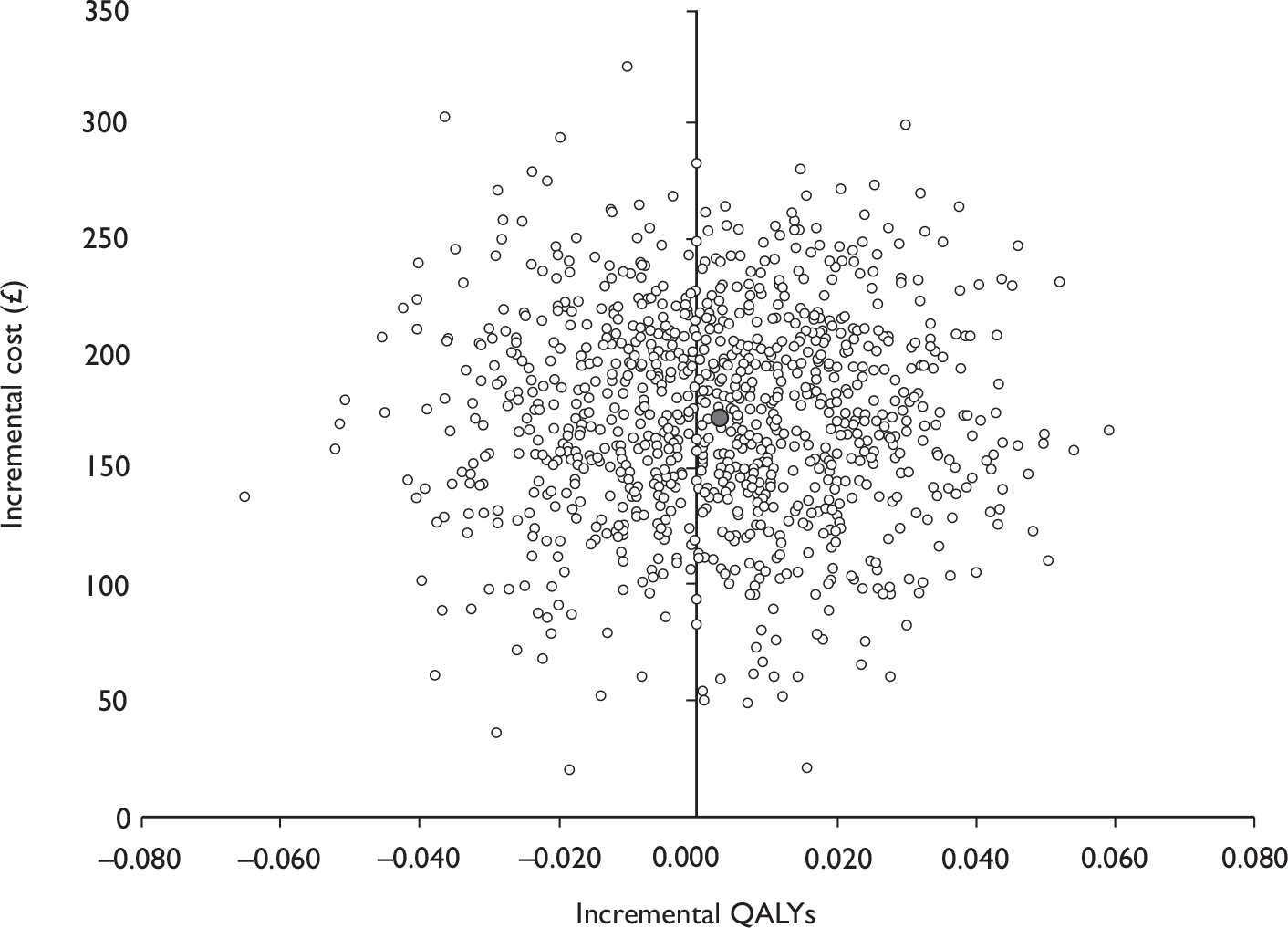

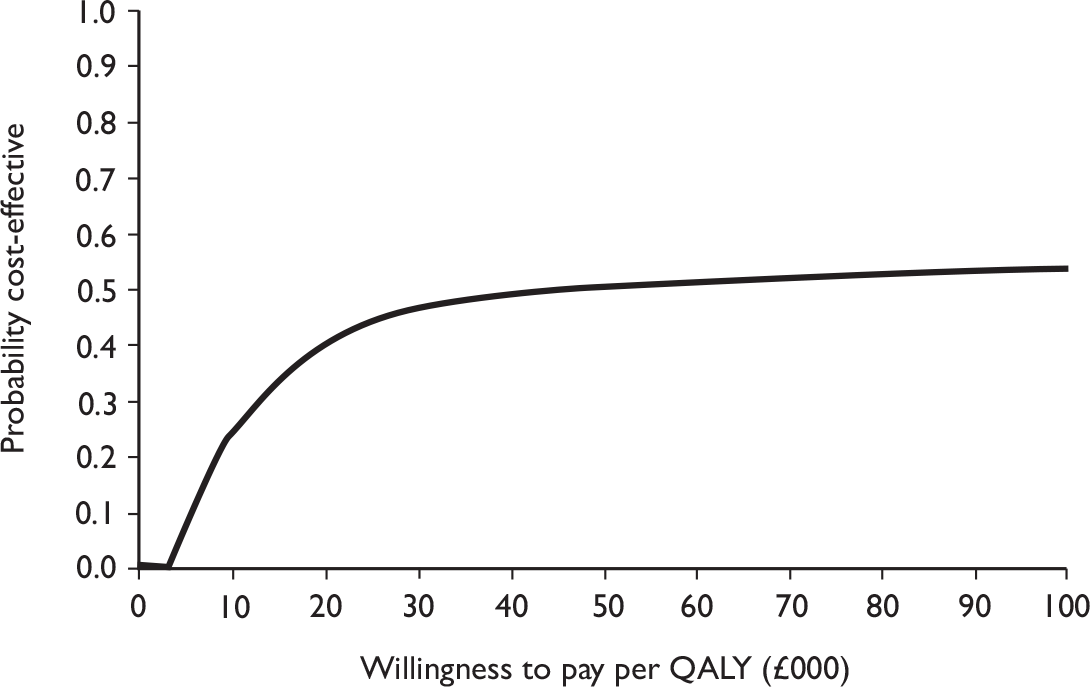

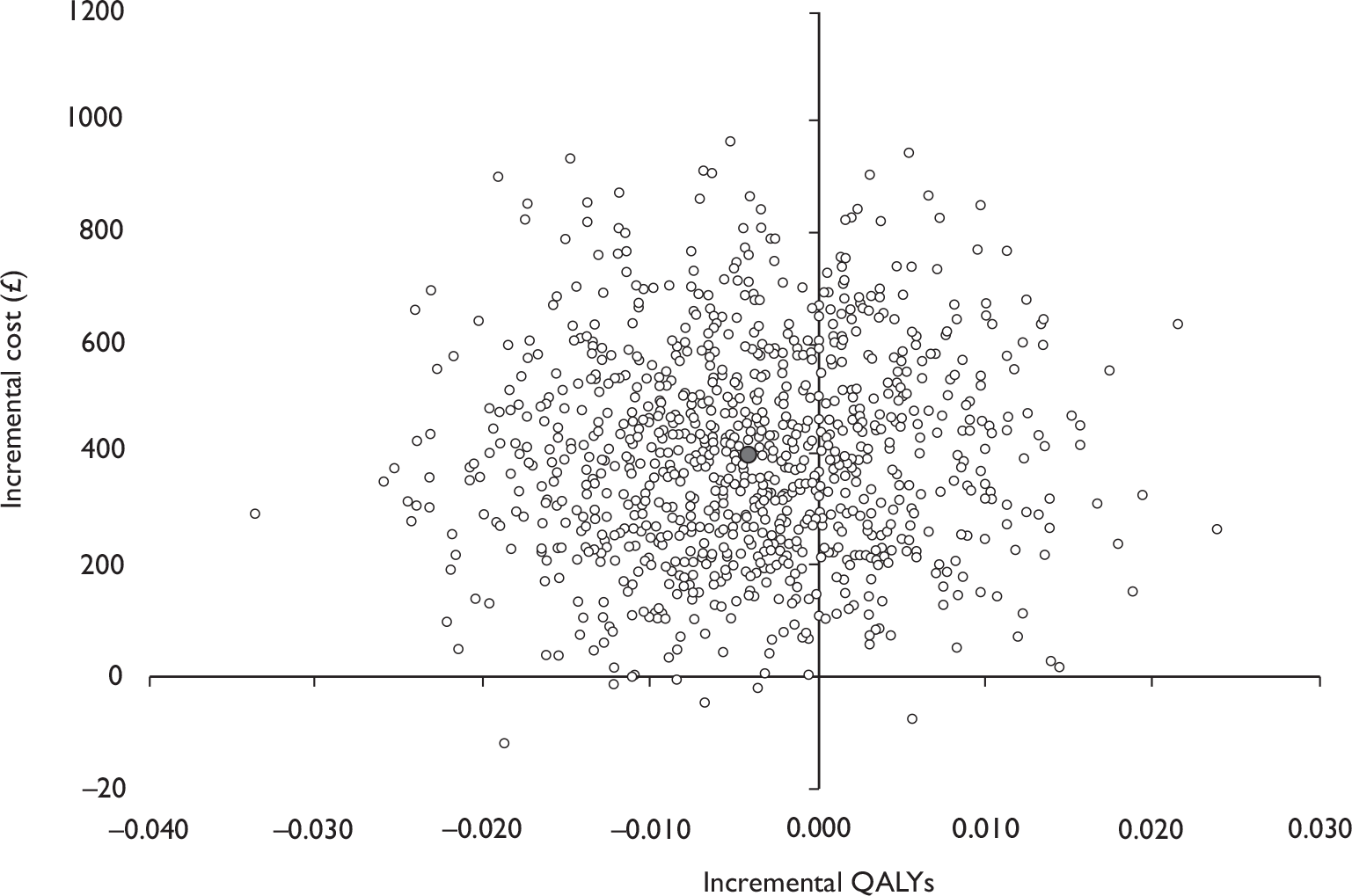

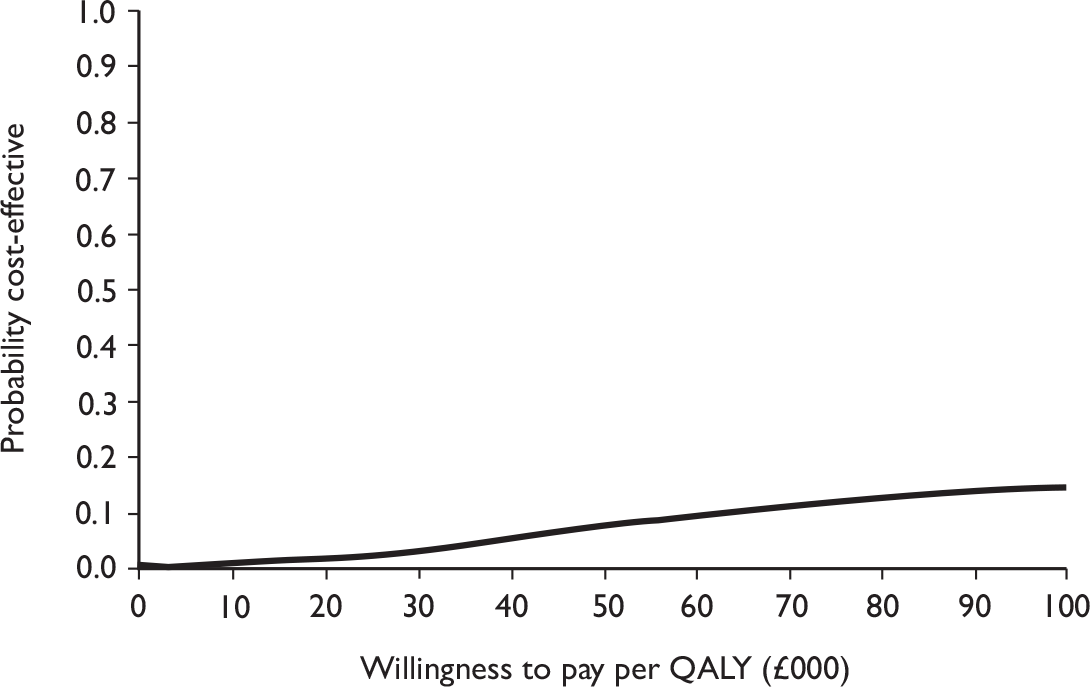

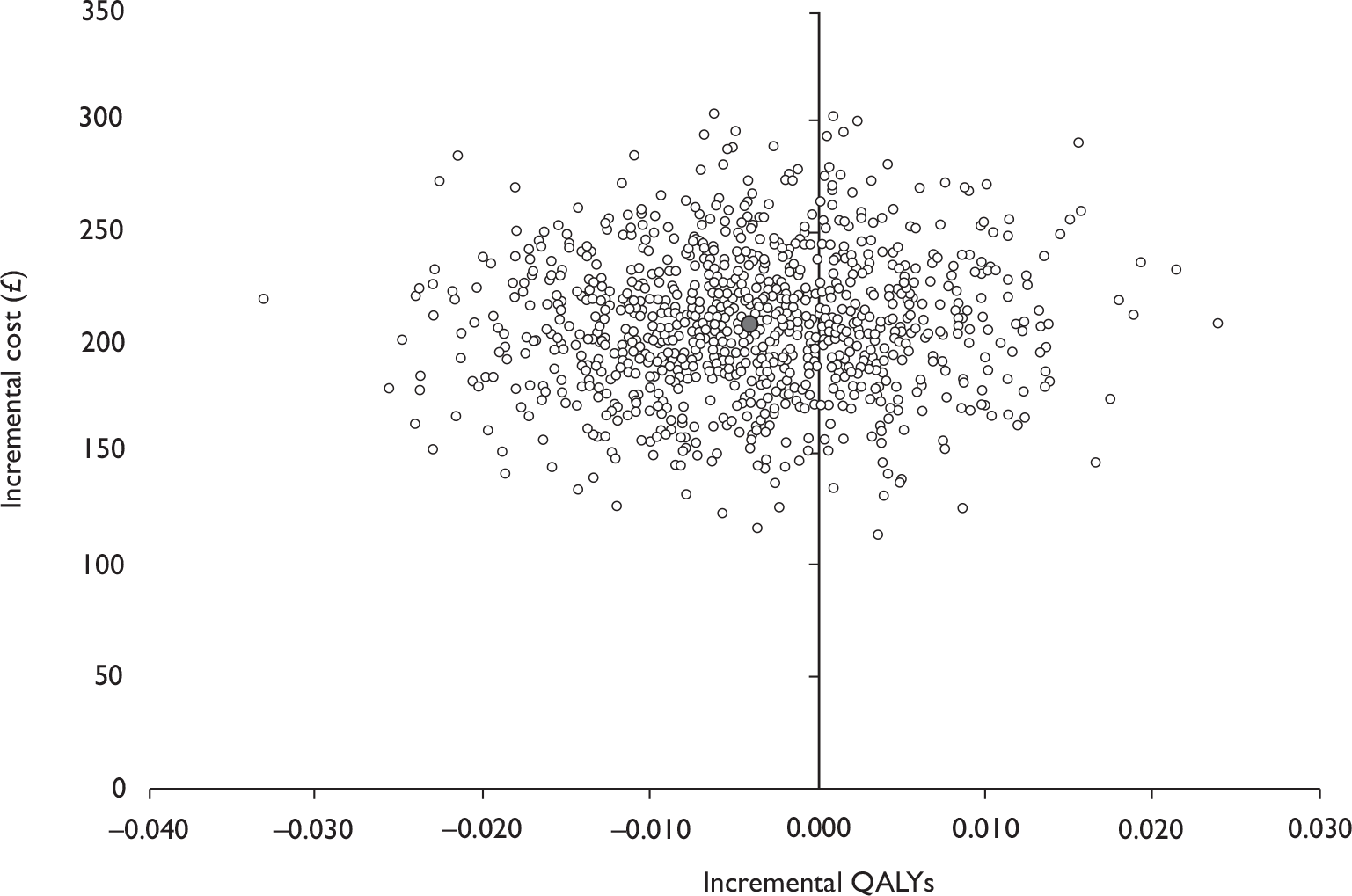

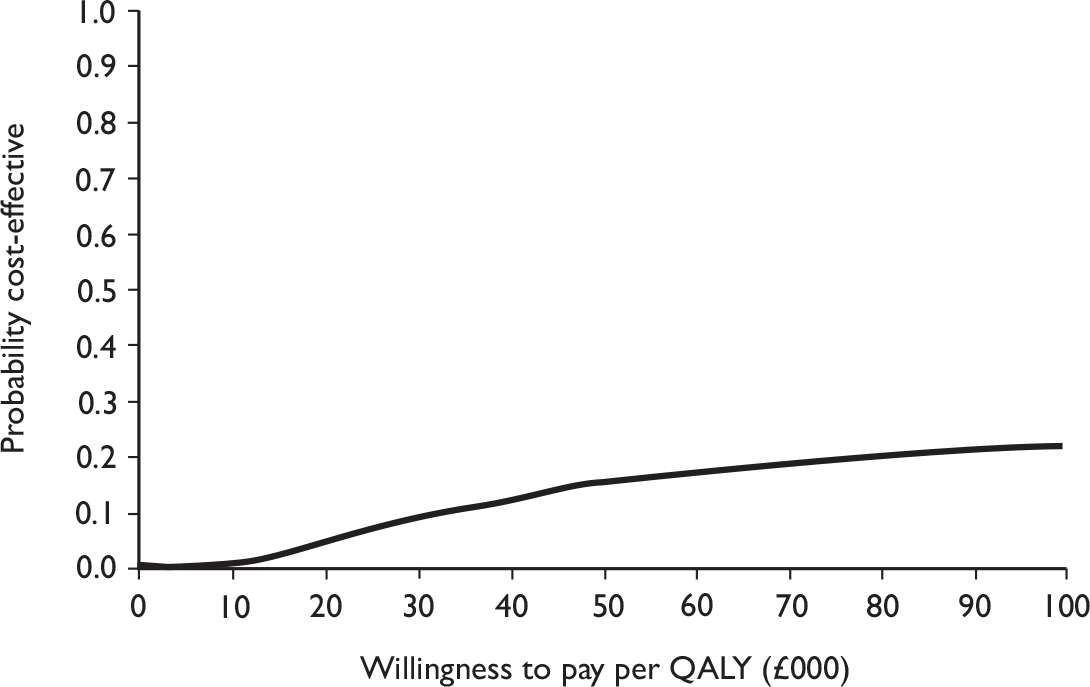

The primary analysis was based on the 1-year follow-up of the trial and the outcome was the incremental cost per QALY. This outcome was chosen to reflect a societal decision-making perspective. The results are presented as point estimates of mean incremental costs, proportion of men continent, QALYs and cost per QALY. Measures of variance were based upon bootstrapped estimates of costs, QALYs and incremental cost per QALY. Incremental cost-effectiveness data are presented in terms of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs).

Data analysis (economics)

As data were collected over a 1-year period, discounting was not carried out. The numbers of missing data for each variable used in the analyses of cost were quite low, and data that were missing were considered to be missing completely at random. Data reported as mean costs for both cases and controls were derived for each item of resource use and then compared using unpaired t-tests and linear regression adjusted for baseline values. As the data were not normally distributed, non-parametric bootstrapping was used to estimate confidence limits around the difference in cost for each area of resource use and total costs.

Sensitivity analysis

With all parameter estimates there are elements of uncertainty owing to the lack of available information. In order to explore the importance of such uncertainties and assumptions, various sensitivity analyses were conducted by varying some of the assumptions or estimates used in the analysis. Two types of sensitivity analyses were performed: one-way sensitivity analysis and threshold analysis.

The base-case analyses in terms of utilities were adjusted for patient outcomes at baseline to account for variability that might be present amongst the intervention groups. An unadjusted analysis was also performed to highlight the importance of this base-case assumption.

There is uncertainty around the QALY estimates as they were derived using one generic instrument, the EQ-5D. There is some debate over whether the dimensions in the EQ-5D are sensitive enough to capture the loss in quality of life for chronic health states of which the worst effects occur during acute episodes. Therefore, the responses from the SF-12 questionnaire were mapped on to the existing SF-6D measure using the algorithm by Brazier et al. 40 to allow utility values to be estimated for each time point. These utility scores were then transformed into QALYs using the same methods as used for the EQ-5D scores to provide an alternative measure of QALYs for each patient.

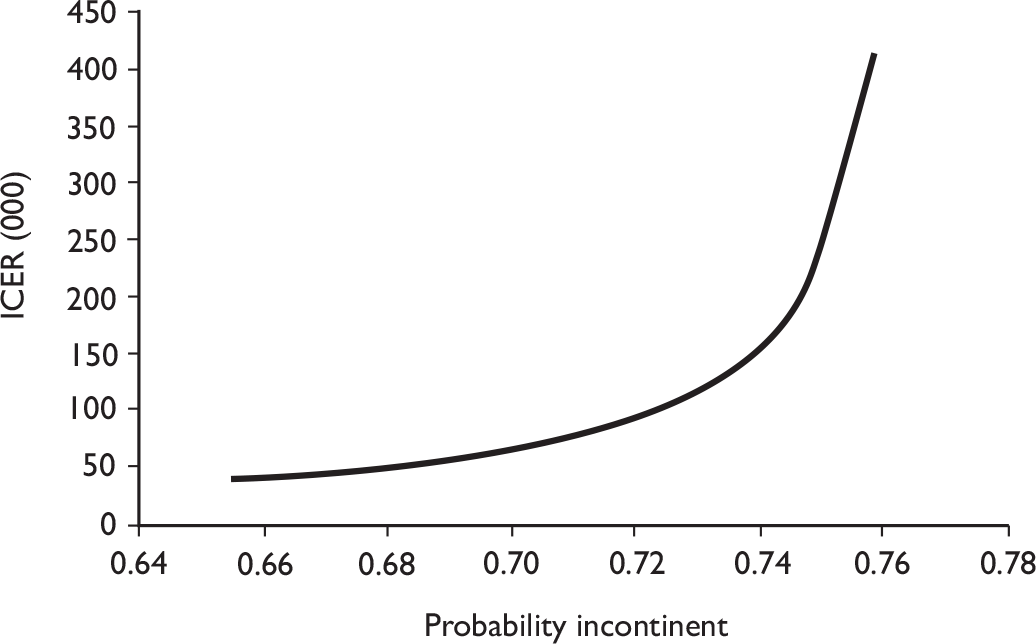

Modelling

Additional information for policy-makers was derived from a simple economic model that considers what difference in continence rates would result in a change in the conclusions about which treatment would be cost-effective. This analysis was performed from the perspective of the NHS.

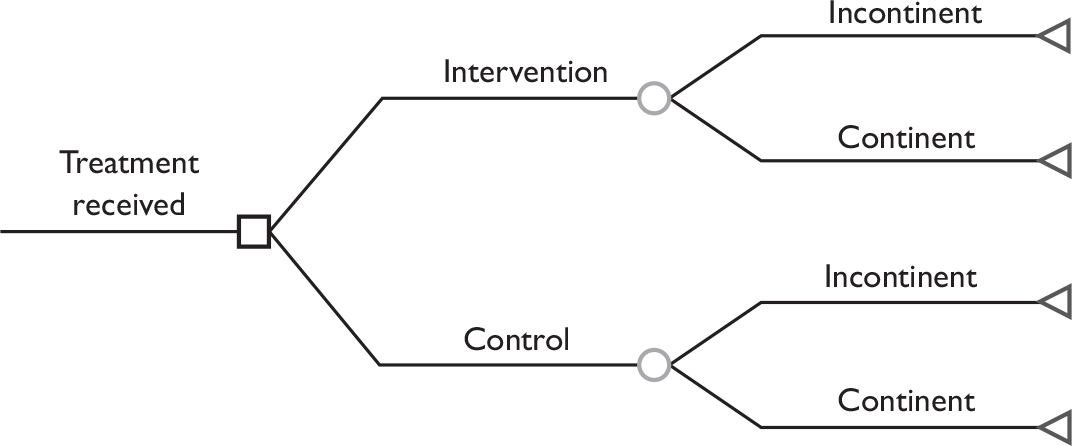

The data used to populate the model were based on the trial patient data, to inform on the probability of being incontinent at the end of 12 months, and the cost data. The data also included QALYs and costs derived for each participant, based on the group they were allocated to (intervention or control) The model is illustrated in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Structure of the model used in economic analyses.

Management of the study

The MAPS study office, working in conjunction with our trials unit, and CHaRT in the Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen, provided support for the clinical centres, randomisation, management of data collection, follow-up, data processing and analysis. The MAPS Project Management Group (grant holders and representatives from the study office) met formally at least monthly during the course of the study to discuss key trial issues.

The study was overseen by an independent Trial Steering Committee with an independent chairman and three other independent members. The remaining members were the grant holders. The Trial Steering Committee met annually on six occasions. An independent Data Monitoring Committee was also established, comprising an independent chairman and three other independent members, who met on three occasions. The trial statistician supplied, in strict confidence, interim analysis results for their consideration.

The University of Aberdeen assumed the role of sponsor for the study.

Table 6 shows the substantive changes to the MAPS study protocol since its first approval by the MREC: they were approved on the dates shown.

| Change to protocol | Date approved |

|---|---|

| Nomenclature: the operation types for the two groups of men are referred to as ‘radical’ and ‘TURP’ | 31 May 2005 |

| Nomenclature: intervention will be delivered by ‘therapists’ rather than ‘physiotherapists’ | 31 May 2005 |

| Formal referral to a therapist delivering PFMT before or after operation added as a specific exclusion criterion | 31 May 2005 |

| Multiple sclerosis or Parkinson’s disease no longer a specific exclusion criterion | 31 May 2005 |

| Trial Steering Committee concluded that the study should still aim to enrol 25–30 centres as this would allow for sites withdrawing and rates dropping off | 30 November 2005 |

| Amendment relating to the diagnosis of unsuspected prostate cancer in men undergoing TURP, and how this would be handled in the MAPS study | 30 November 2005 |

| New sponsor: University of Aberdeen | 30 November 2007 |

| Revised extension timings | 30 November 2007 |

Chapter 3 Intervention design, centres, therapists and therapy

In this chapter, the rationale for the intervention, the methods used to train the therapists in order to standardise the intervention and the types of therapists at each centre are described.

Introduction

The purpose of the MAPS trial was to compare return to continence with or without a structured PFMT programme, delivered by a trained therapist, in men after TURP or radical prostatectomy. Both groups received written information on recovery after surgery. The primary outcome was self-reported urinary incontinence at 12 months after randomisation.

Following radical prostatectomy, some degree of iatrogenic urinary incontinence is a recognised complication in up to 90% of men. 9 Following TURP for benign prostatic hypertrophy, the figure is around 10%. 15

Some physiotherapists already use PFMT and bladder training (BT) or urge suppression (US) techniques to treat men with urinary incontinence following prostate surgery, despite Cochrane reviews clearly showing that there is currently insufficient evidence to confirm whether or not these are effective. 26,41 Uncertainty also surrounds the most effective PFMT and BT/US protocols for specific clinical indications.

MAPS control protocol

All participants received a lifestyle advice leaflet (see Appendix 4.2) (control and intervention groups). Face and content validity were established by review of the literature,19 with a consumer representative of men who had urinary incontinence, and with health-care professionals. The final copy contained information about moderating fluid intake (avoiding too much or too little), and information on caffeine, cranberry juice, diet and obesity, constipation, general fitness, lifting, smoking, chest problems and urinary tract infections and was based on clinical practice recommendations. The control group had no further contact with the research team, apart from follow-up by questionnaires.

MAPS intervention protocol

In addition to the leaflet described above, all men in the intervention group received a structured PFMT intervention. The protocol was based on one used in a previous trial using PFMT to increase pelvic floor muscle strength for men with erectile dysfunction. 42 The BT/US techniques were based on those typically used in clinical practice for UUI and summarised in a Cochrane review. 43 The advice on fluid intake was based on standard clinical practice. 44

Constituent elements of the intervention protocol

Assessment of pelvic floor strength

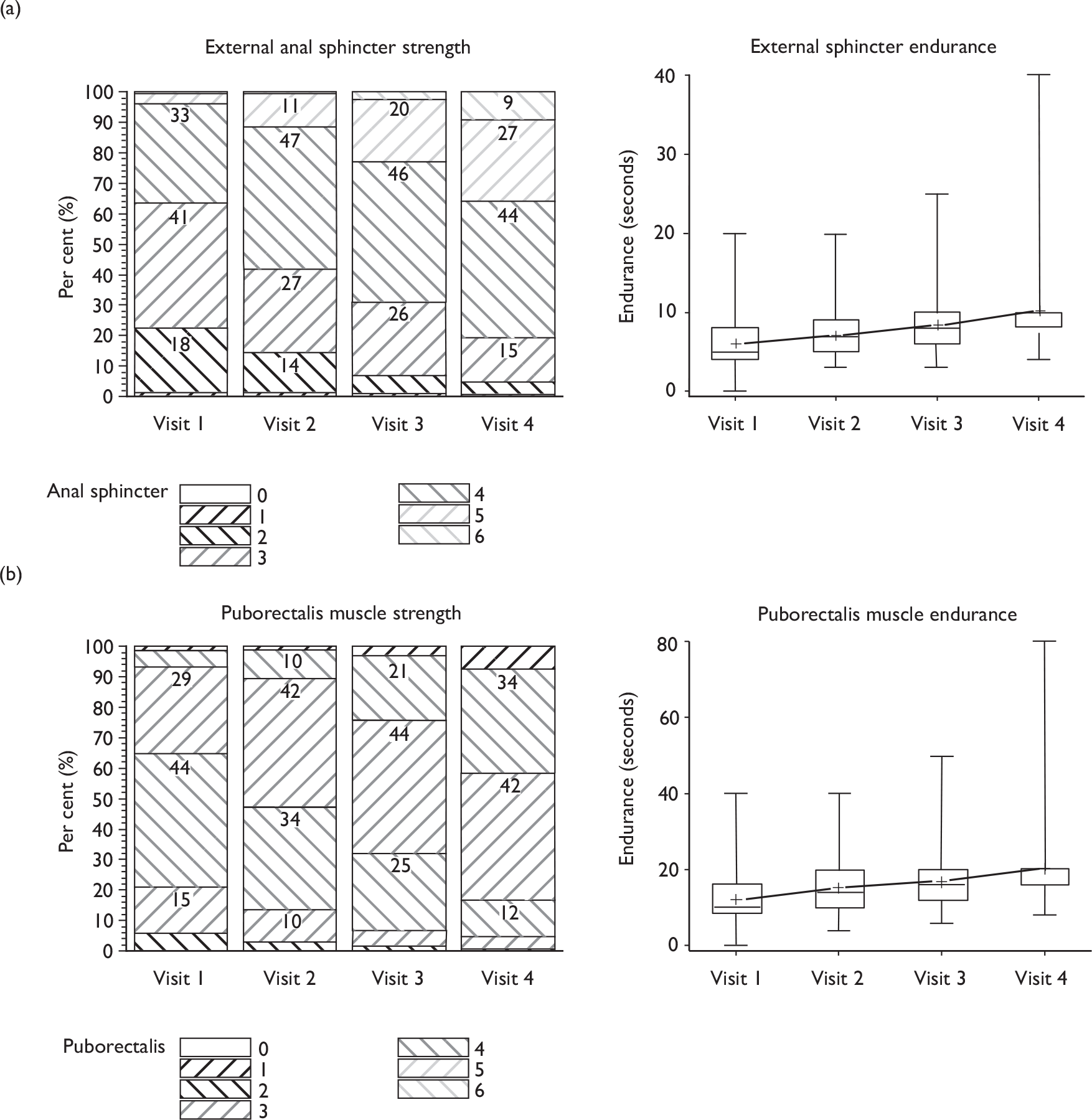

During each therapy appointment, pelvic floor muscle contraction strength was evaluated by a digital anal examination using the Oxford score (graded 0–5). 45 An additional grade (6) was added to define a very strong anal squeeze. 46 The new grading system was used to assess separately the strength of both the external anal sphincter and the deeper puborectalis muscle (taken to represent the pelvic floor muscles). The external anal sphincter was assessed at 1–2 cm from the anal meatus, and the puborectalis at 3–4 cm from the anal meatus.

Verbal biofeedback from this examination was used to teach the men how to contract their muscles optimally, and advise them on improvement from previous appointments. At each assessment, the maximum duration of each contraction was timed by counting.

Pelvic floor muscle therapy regimen

PFMT was aimed at improving the strength of the pelvic floor muscles to allow effective contraction during exertion to prevent urinary leakage. PFMT consisted primarily of three maximum-strength contractions with a 10-second break between each one, practised in three positions (lying, sitting and standing) twice daily (see Appendix 4.3). Targets were set for the duration of each contraction, up to a maximum of 10 seconds, and revised in successive appointments if progress had been made. In addition, men were taught to carry out a sustained submaximal contraction of the pelvic floor muscles during walking and to perform a strong contraction before and during any event that might cause leakage, such as coughing or rising from sitting (‘the knack’). 47 Men were advised to eliminate urine remaining in the bulbar urethra by using a strong contraction after urination was finished, in order to prevent postmicturition dribble. 42 Contracting the pelvic floor muscles during sexual activity was also recommended to achieve, maintain or improve erectile strength.

Bladder training/urge suppression

Men with urgency or UUI were taught urge suppression techniques in order to avoid rushing to the toilet when the bladder was starting to contract (see Appendix 4.3). Fluid advice, including avoiding or reducing caffeine, was also offered.

Written supplementary guidance

The MAPS PFMT leaflet (see Appendix 4.3) aimed both to support and to reinforce the anatomy teaching received during appointments, as well as the exercise programme that had been set. To maximise understanding, careful consideration was given to the language and terminology used in this leaflet, taking into account the sensitive nature of incontinence and erectile dysfunction. The use of medical and anatomical terms was minimised in favour of a plain English approach (‘urine leakage’ for incontinence). 48

Drafts of the leaflets were reviewed for face and content validity by lay persons and health-care professionals with knowledge of men’s health and continence issues.

Understanding strategies selected for the MAPS intervention

In order to clarify key aspects of the rationale behind elements of the MAPS standardised intervention, the following areas were addressed.

Rationale for performing a digital anal examination

A digital anal examination was undertaken to assess the strength and endurance of, firstly, the external anal sphincter and, secondly, the puborectalis muscles. Wyndaele and Van Eetvelde49 demonstrated the reproducibility of assessing the puborectalis by anal assessment using grades 0–5. By assessing puborectalis muscle strength, the strength of the surrounding pelvic floor muscles would also be graded. The muscles were graded from 0 to 6, with 0 being ‘no flicker or contraction’ and 6 being ‘very strong, unable to withdraw finger. 42 Repeating the examination at subsequent visits enabled therapists to provide verbal feedback to men that their exercises were effective in building up muscle strength and to monitor progress.

Rationale for asking men to perform pelvic floor exercises in three positions

Pelvic floor muscles support the abdominal contents and prevent urinary leakage. The three positions provided a graded method of increasing the effect of gravity, in order to provide extra muscle work load. The pelvic floor muscles were recruited initially in a lying position, without the effect of gravity. As strengthening occurred, pelvic floor muscles were subject to a higher load by recruiting them in a sitting position, where the downwards descent of the pelvic floor would be partly prevented by the seat of the chair. A greater load would be placed on the pelvic floor during standing, when gravitational forces opposed the elevation of the pelvic floor during exercise. MAPS adopted this regimen for the intervention supported by evidence from four previously documented trials, which found it to be convenient, acceptable and comfortable for patients. 24,50–52 It was believed that men needed to be able to tighten their pelvic floor muscles in a number of positions, so that they could recruit them speedily during coughing and sneezing.

Rationale for performing three pelvic floor muscle contractions

The PFMT programme was aimed at increasing pelvic floor muscle strength in order to counteract increases of abdominal pressure during exertion. Based on clinical research of quadriceps strengthening using a progressive resistance machine, repeated computerised readings showed that the first contraction gave the patient the feel of the movement but failed to achieve maximum power. The second contraction attained maximum power, whilst the third failed to reach maximum power owing to fatigue. 53 Kegel54 stated that maximum power was a key element to gaining increased muscle strength. These principles informed the PFMT programme, considering that the maximum power of pelvic floor contraction would be attained using three muscle contractions in each position held for up to 10 seconds. The target was individually adjusted as performance improved.

Rationale for performing the regimen twice a day

Kegel54 recommended 300–400 pelvic floor muscle contractions a day to treat SUI in women.However, clinical practice has shown that patients find this level of commitment to be too arduous, resulting in attrition and demotivation. The principles of muscle building show that it is the quality of the contraction that is more important than the quantity. 53,55

The MAPS intervention was therefore designed to provide targets that were achievable in order to motivate men to maintain the regimen within the constraints of the protocol. In a previous trial,42 55 men were asked to perform their exercise sets only twice a day. After 3 months, all except one (who had severe back pain) showed a statistically significant increase in pelvic floor muscle strength. We therefore felt that this regimen had a proven ability to increase pelvic floor muscle strength.

Rationale for contracting the muscles as strongly as possible

The pelvic floor muscles consist of two-thirds slow-twitch continually tonic muscle fibres and one-third fast-twitch muscle fibres, which can be speedily recruited when extra support is needed during activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure. 56 Both fibre types are recruited during maximum contraction of the pelvic floor muscles. In order to achieve an increase in muscle bulk, the MAPS intervention used maximum voluntary effort, which was expected to result in the hypertrophy of muscles and an increase in local blood supply. 53,55

Rationale for functional use of muscles

Pelvic floor muscles need to be recruited to prevent leakage of urine during activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure. ‘The Knack’ is the technique, or learned skill, of tightening just before and during these activities. 47 Owing to its significant role in contributing to continence, teaching of ‘the Knack’ was therefore included as an element in the MAPS intervention.

Reasons for increasing pelvic floor muscle endurance

Slow-twitch muscle fibres fulfil a number of important functions: pelvic floor support, bladder and bowel control, sexual activity, posture and respiration. The upright posture stimulates the pelvic floor reflex, which results in contraction of the slow-twitch fibres in response to the weight of the abdominal contents. 57 In order to meet this demand, the pelvic floor muscles need to have sufficient muscle endurance to prevent urinary leakage. By encouraging the patient to tighten the pelvic floor muscles slightly during walking (as taught in the MAPS intervention), a functional method of potentially increasing the use of slow-twitch fibres and hence muscle endurance was achieved.

Rationale for tightening the pelvic floor muscles after urinating

One of the superficial pelvic floor muscles, the bulbocavernosus muscle, encircles the proximal 50% of the penis and tightens by reflex action at the end of micturition to facilitate emptying of the bulbar portion of the urethra. 58 Teaching men to contract their pelvic floor muscles strongly after they have completed micturition will result in the recruitment of the bulbocavernosus muscle along with the other pelvic floor muscles. 42 This muscle contraction will then facilitate the evacuation of residual urine from the bulbar urethra. This may restore or develop the reflex postvoid milking mechanism identified by Wille et al. 58 and termed the ‘urethrocavernosus reflex’ by Shafik and El-Sibai. 59 Thus, as an additional strategy to attain continence, participants were taught to perform consciously a pelvic floor muscle contraction immediately after micturition.

Rationale for tightening the pelvic floor muscles during sexual activity

The superficial bulbocavernosus and ischiocavernosus muscles are active during penile erection. 60 The bulb of the penis sits on the inferior aspect of the deeper layer of the pelvic floor muscles, which form a firm base for the erect penis. The bulbocavernosus muscle prevents blood from escaping through the deep dorsal vein during an erection. One study has shown that pelvic floor exercises can restore erectile function in 40% of men and improve it in a further 36%. 42 As this is another potential benefit of PFMT, it was decided that it would be appropriate to include erectile function in the MAPS intervention materials and be measured as a secondary outcome. However, it is not yet clear whether men will benefit after radical prostatectomy as the amount and degree of nerve damage caused by surgery is likely to be variable. Erectile function was a secondary outcome of the study.

Rationale for choice of urge suppression techniques

A detrusor contraction produces a desire (urge) to empty the bladder. If urgency sensations cannot be overcome, urinary incontinence may occur. The resulting fear of leakage can cause anxiety, breath-holding and descent of the diaphragm, which, coupled with abdominal muscle contraction, can produce early inappropriate micturition. A retrospective study in women has reported that effective urge suppression techniques include keeping calm, sitting down or standing still and waiting 1 minute until the initial urge sensation disappears. 46 PFMT can be used to strengthen the pelvic floor musculature and, together with urge suppression techniques, can help to restore bladder control.

Rationale for giving fluid, dietary and lifestyle advice

All men received fluid, dietary and relevant lifestyle advice as part of the therapy appointments, supplemented by written information (see Appendix 4.2). Advice included information that reducing fluid intake (underdrinking) to avoid leakage may lead to urinary tract infections, constipation and dehydration. 61 Conversely, drinking excessive amounts (in the belief that this is beneficial for health) may have adverse effects such as an increased risk of leakage. 62 However, men experiencing nocturia were advised that avoiding fluids 2 hours before bedtime may be helpful.

Drinks containing caffeine or alcohol may cause increased risk of urgency and men were advised to reduce or avoid them. 61 Anecdotal evidence has shown that certain foods (e.g. onions, spicy foods and curries) can cause increased gut peristalsis, which may also have an effect on the bladder, causing it to be overactive and contractile. Other risk factors for an overactive bladder were highlighted, including the effect of constipation, smoking and obesity. 63 Information on all these elements was included in the MAPS lifestyle advice leaflet (see Appendix 4.2).

Rationale for four appointments in 12 weeks

The value of psychological support for men following radical prostatectomy has been stressed in the literature,52 as has the intrinsic value of therapist contact in order to maintain patient motivation. 64 Within MAPS, therefore, a schedule of four appointments (at baseline, 2 weeks, 6 weeks and 12 weeks) was considered sufficient to monitor postsurgical muscle strength development and maintain motivation but not be too burdensome on patients or costly in terms of resources (chiefly therapist time).

Pelvic floor muscle strength can improve over a 3-month period of PFMT. 42 Men in the study received four appointments and were encouraged to continue their exercise regimen for life, with particular emphasis on functional work (e.g. contracting during activity or counteracting increases in intra-abdominal pressure by use of ‘the Knack’). A previous trial by van Kampen et al. 24 using pelvic floor exercises and functional use of these muscles showed significant reduction in urinary incontinence at 1, 6, and 12 months after radical prostatectomy, demonstrating that improvement was maintained while men continued to perform their exercises.

Summary of rationale for design of intervention

The MAPS intervention, combining PFMT, BT/US and fluid advice, was evidence based wherever possible. Where evidence was lacking, the intervention was based on expert clinical practice. The rationale underpinning the intervention was published in 2009. 65

The trial compared the structured PFMT intervention with standard care, in order to add to the current evidence base. This, in turn, should inform practice and treatment decisions for therapists, men with incontinence after prostate surgery, and providers of care.

Training for the therapists

Therapists were either specialist continence physiotherapists or specialist continence nurses. The intervention protocol was standardised by systematically training all the therapists during a bespoke training day programme, and by use of common trial forms for recording assessment and treatment data. Some therapists were trained on a one-to-one basis if they joined the study late. During the training day, an overview provided information on the anatomy and physiology of the lower urinary tract, the pelvic floor muscles and the abdominal muscles, together with information on how prostate surgery affects normal urine control. Therapists received instruction on the MAPS PFMT protocol including:

-

assessment and examination of men in a systematic manner

-

the diagnosis of SUI, UUI, postmicturition dribble and erectile dysfunction by history

-

grading the strength of the pelvic floor muscles during a digital anal examination by evaluating the anal sphincter and also the puborectalis sling at each visit

-

affirmation that all the pelvic floor muscles (including the transversus abdominis) should tighten during a maximum contraction and that, if the contraction was strong, they would see a scrotal lift and the penis moving slightly into the body

-

description of the MAPS-approved method of teaching PFMT

-

instruction in BT/US techniques

-

advice about fluid intake and other lifestyle advice corresponding to the leaflet

-

the role of PFMT in the treatment of erectile dysfunction

-

graded goal-setting for the men in terms of gradually increasing endurance of pelvic floor muscle contractions

-

documenting the treatment given at each visit.

Summary of the MAPS intervention

At the baseline assessment visit, the men were taught PFMT. BT/US techniques were included if men described urgency or UUI. The men had reinforcement sessions on three further occasions over 3 months – at around 2 weeks, 6 weeks and 12 weeks after the first appointment. Anal examination was repeated at each visit to document changes in pelvic floor muscle strength, and to provide feedback to the men on their progress.

Pelvic floor muscle training

Men in the intervention group were instructed:

-

to carry out three maximum pelvic floor contractions in three positions (lying supine with knees bent and feet on the couch, sitting with knees apart and standing with feet apart) twice per day

-

to ‘lift’ their pelvic floors slightly while walking

-

to tighten their pelvic muscles before activities that might cause them to leak, such as coughing

-

to tighten after urinating to eliminate the last few drops.

Biofeedback