Notes

Article history paragraph text

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 97/10/99. The contractual start date was in May 2007. The draft report began editorial review in October 2011 and was accepted for publication in July 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Adrian Grant has received salary support from the NIHR as director of the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research programme.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Grant et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Executive summary

Background

In the Health Technology Assessment (HTA)-commissioned REFLUX trial, laparoscopic fundoplication for people with chronic symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) was shown to significantly improve reflux-specific and general health-related quality of life (HRQoL) at least up to 12 months after surgery. However, cost-effectiveness was uncertain without more reliable information about longer-term costs and benefits. Here, we report the findings from longer-term follow-up of the REFLUX trial.

Objective

To evaluate, at 5 years after surgery, the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and safety of a policy of relatively early laparoscopic surgery compared with continued medical management among people with GORD symptoms that are reasonably controlled by medication and who are judged suitable for both surgical and medical management.

Methods

Design

-

Long-term follow-up of a pragmatic randomised controlled trial (with parallel non-randomised preference groups) comparing a laparoscopic surgery-based policy with a continued medical management policy to assess relative clinical effectiveness.

-

An economic evaluation of laparoscopic surgery for GORD to compare the cost-effectiveness of the two management policies, based on a within-trial (5-year) economic analysis and exploration of the need for a longer-term model.

Setting

Participants had originally been recruited in 21 UK hospitals through local partnership between surgeon(s) and gastroenterologist(s) who shared the secondary care of patients with GORD. After operation (surgical groups) and after optimisation of anti-reflux therapy (medical groups), participants were returned to the care of their general practitioners (GPs). Follow-up was by annual postal questionnaire and selective case notes review when questionnaires indicated reflux-related health-care events.

Participants

Participants in this study were questionnaire responders among the 810 original participants. At trial entry, all had both documented evidence of GORD and symptoms for > 12 months. Annual questionnaire response rates (years 1–5) were 89.5%, 77.5%, 76.7%, 69.8% and 68.9%.

Intervention

Of the 810 participants, 357 were recruited to the randomised comparison (178 randomised to surgical management and 179 randomised to continued medical management) and 453 to the parallel non-randomised preference arm (261 surgical management and 192 medical management). The type of fundoplication was left to the discretion of the surgeon.

Main outcome measures

The principal outcome measure was a disease-specific instrument (the REFLUX questionnaire developed specifically for this study). Secondary measures were the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36), the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), surgical events including complications, reflux medication use, GP visits, hospital outpatient consultations, day and overnight hospital admissions, and their costs.

Results

At entry to the original trial, participants had been taking GORD medication for a median of 32 months and had a mean age of 46 years, and 66% were men; the randomised groups had been well balanced. Responders at 5 years were older, had been on medication for a shorter time prior to trial entry and had higher baseline quality-of-life scores than non-responders; however, the randomised groups of responders were similar in baseline characteristics. Primary analyses were based on the ‘intention-to-treat’ (ITT) principle, with secondary per-protocol analyses based on those who, at 1 year, had received their allocated treatment.

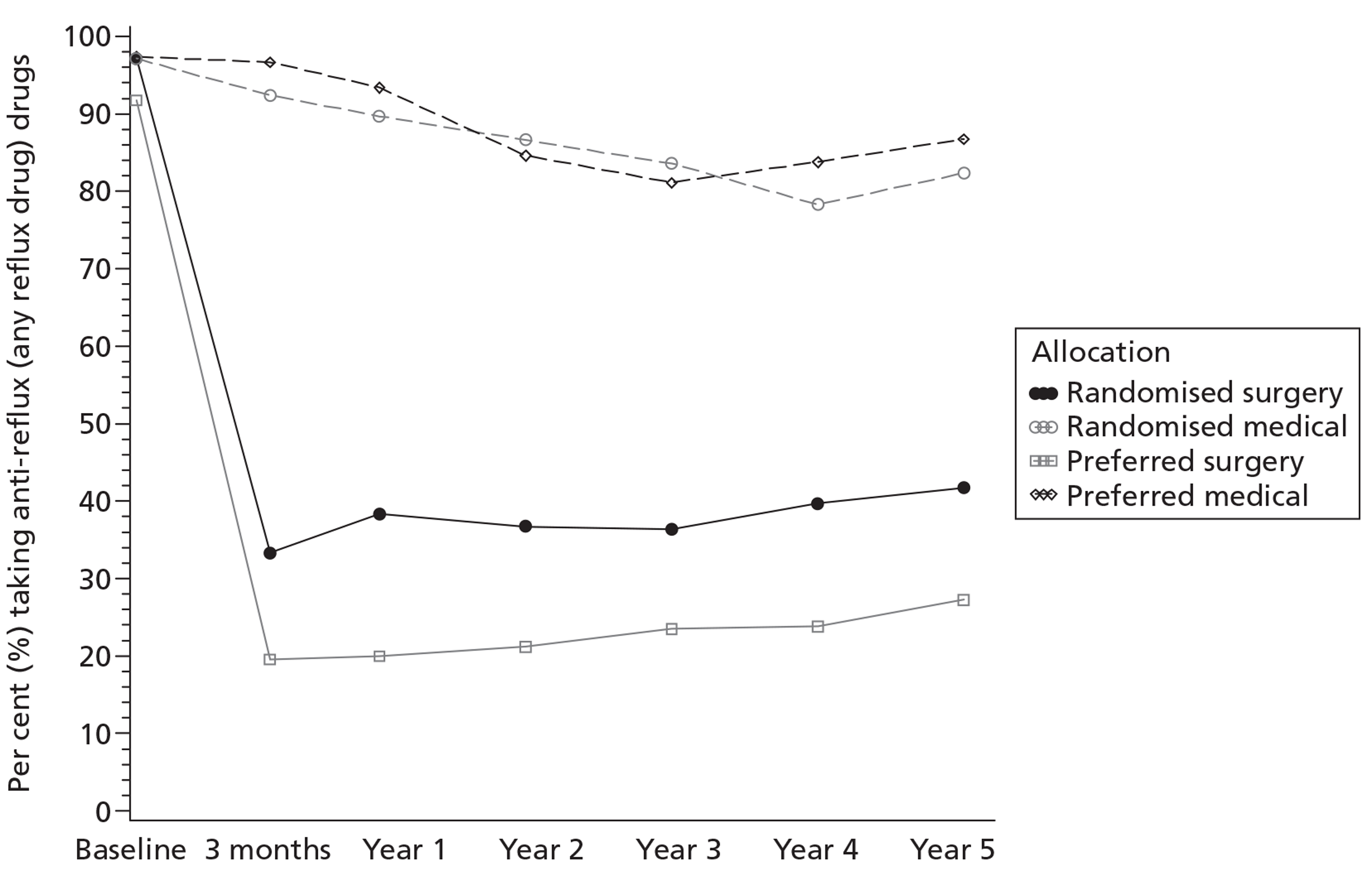

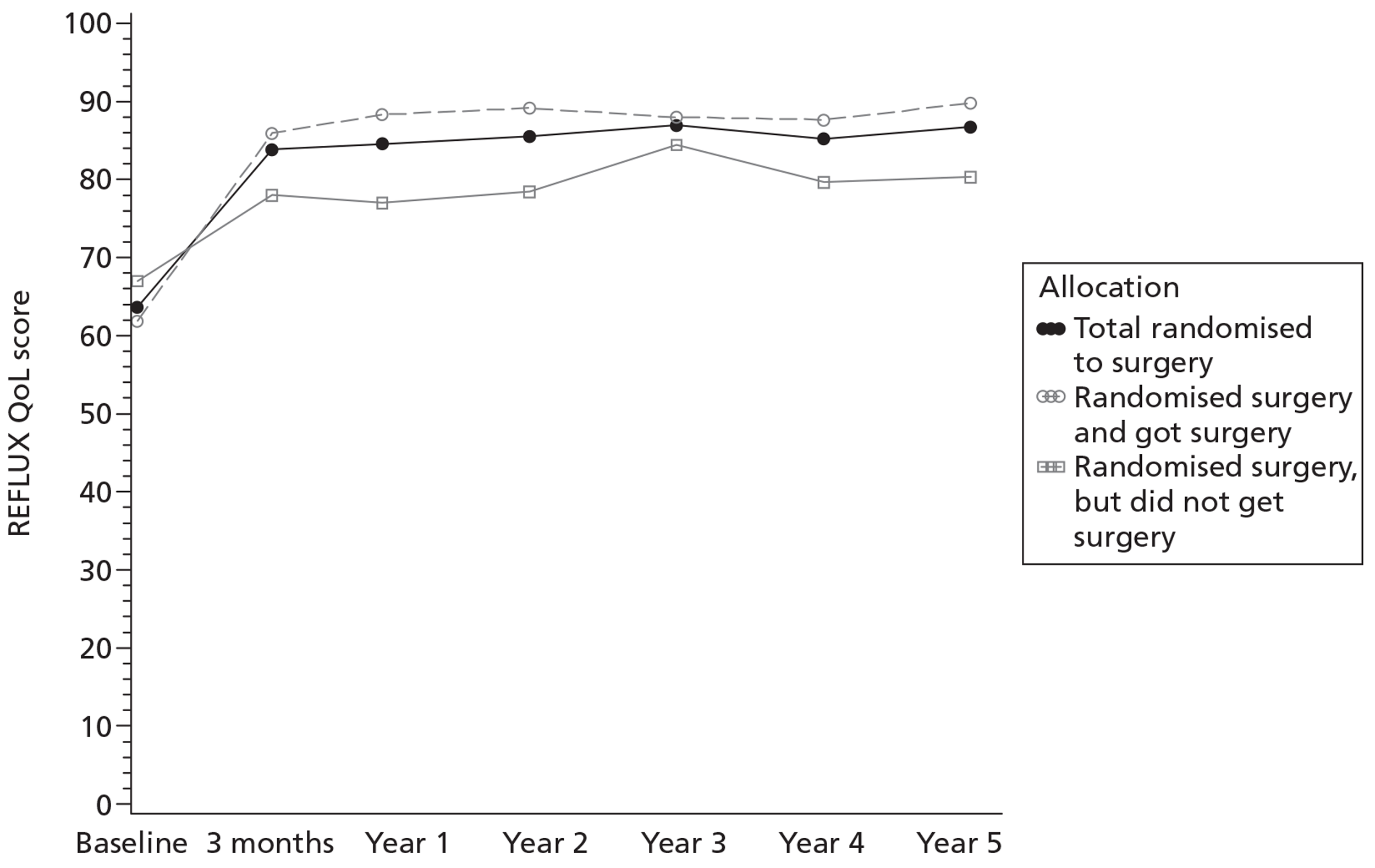

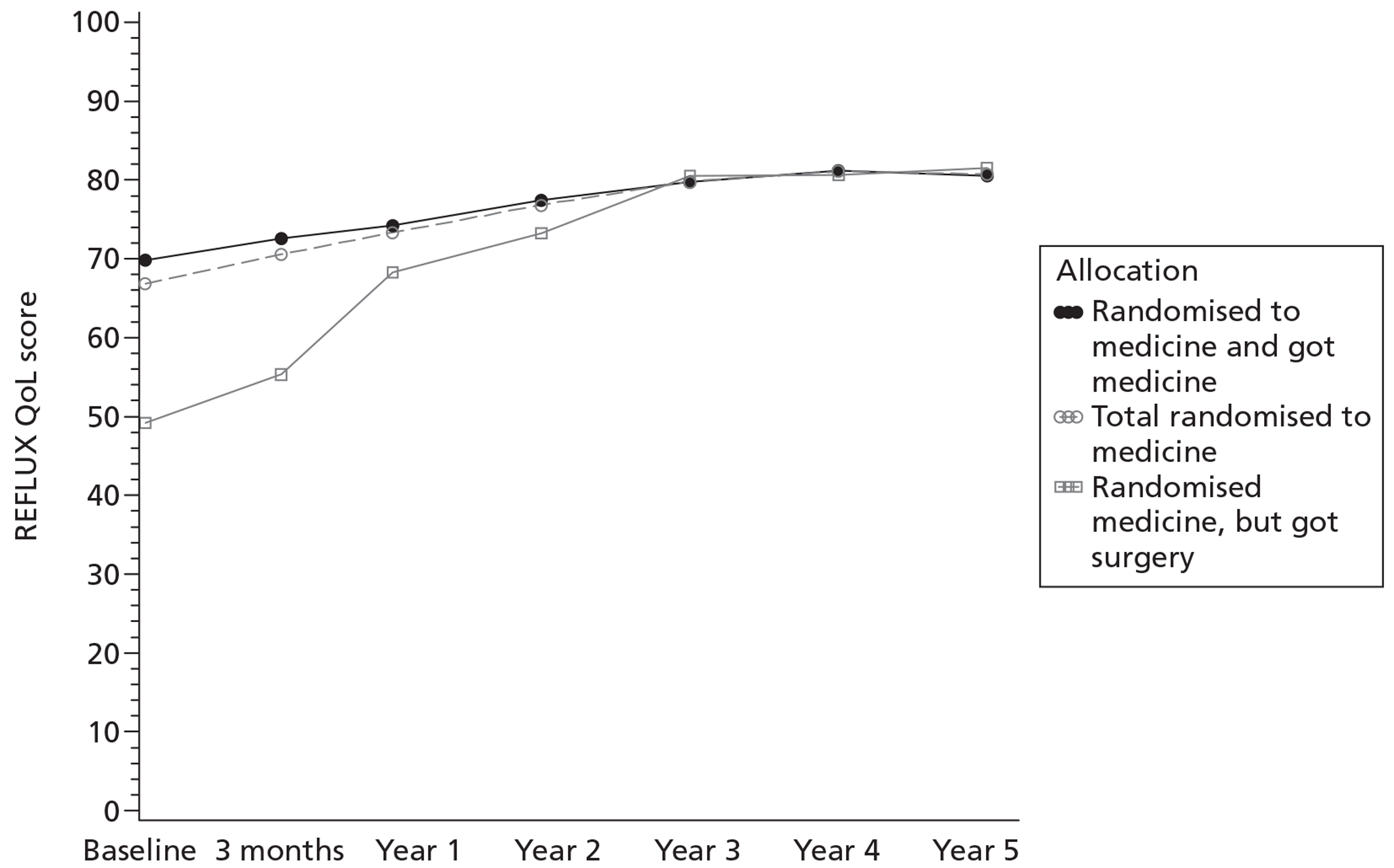

By 5 years, 63% (n = 112) of the 178 randomised surgery participants and 13% (n = 24) of the 179 randomised medical management participants had actually received fundoplication (equivalent figures in the preference groups were 85% and 3%). There had been a mixture of clinical and personal reasons for those allocated surgery not receiving it, sometimes related to long waiting times. A total or partial wrap procedure had been performed depending on surgeon preference; perioperative complications had been uncommon with no deaths associated with surgery.

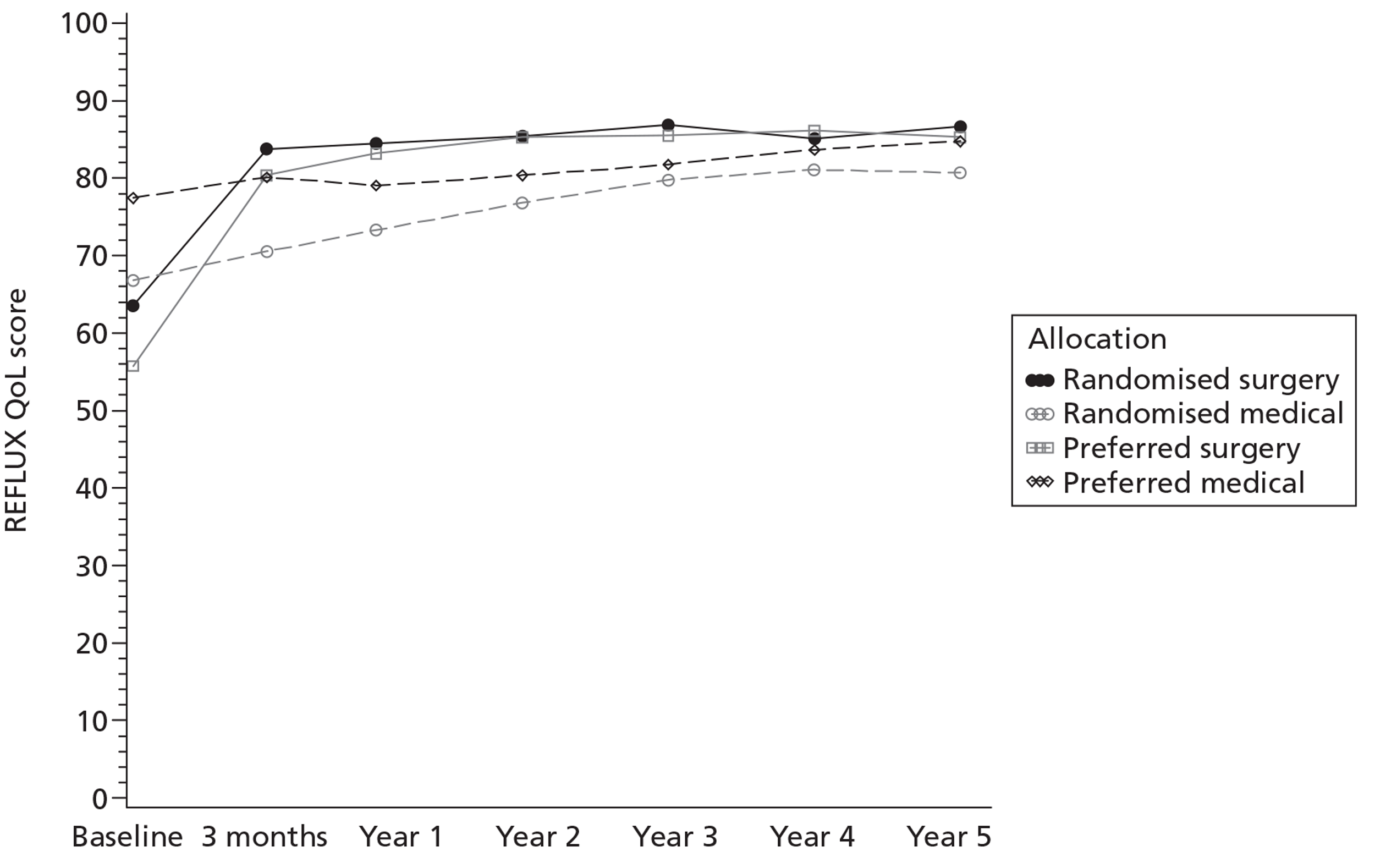

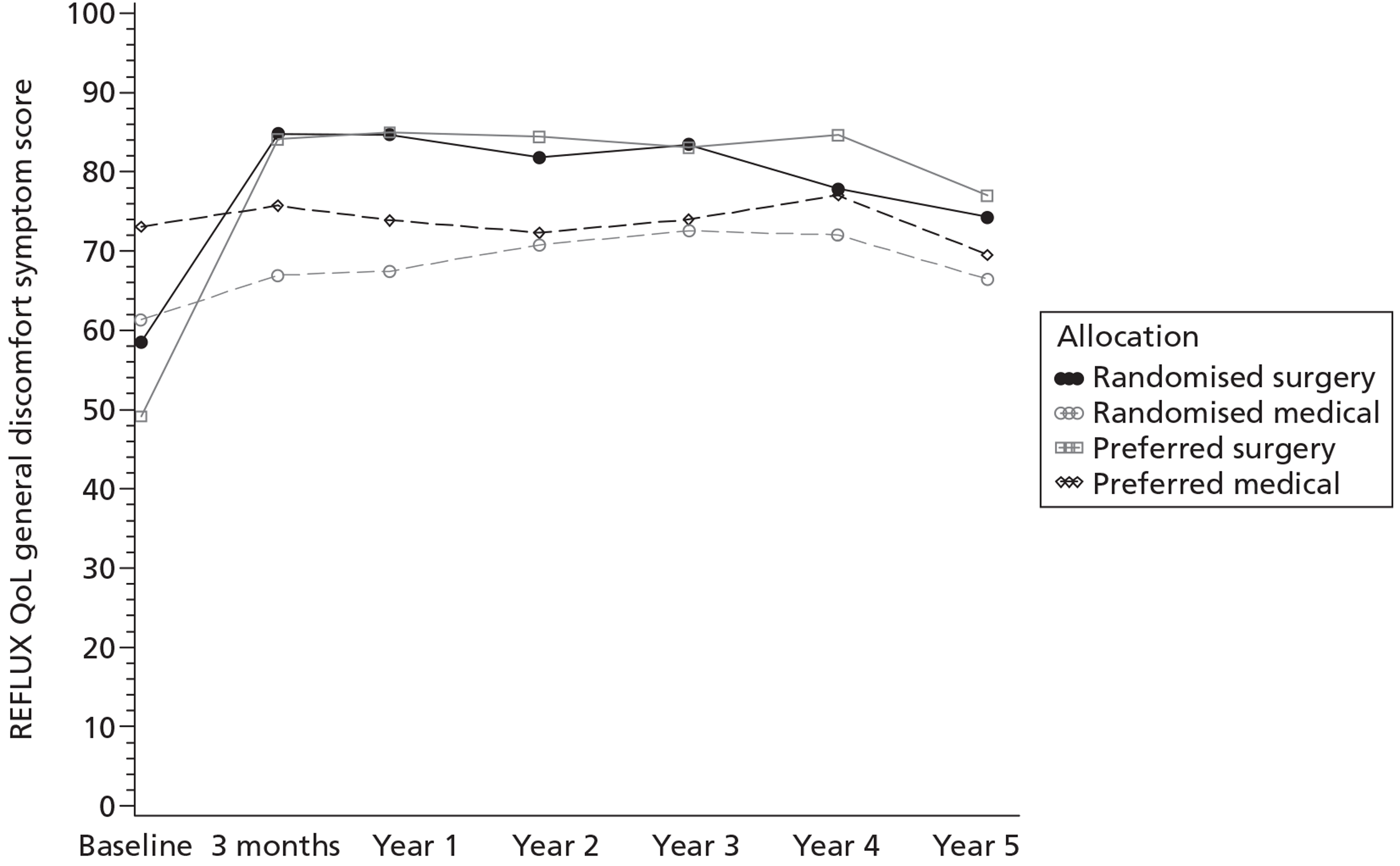

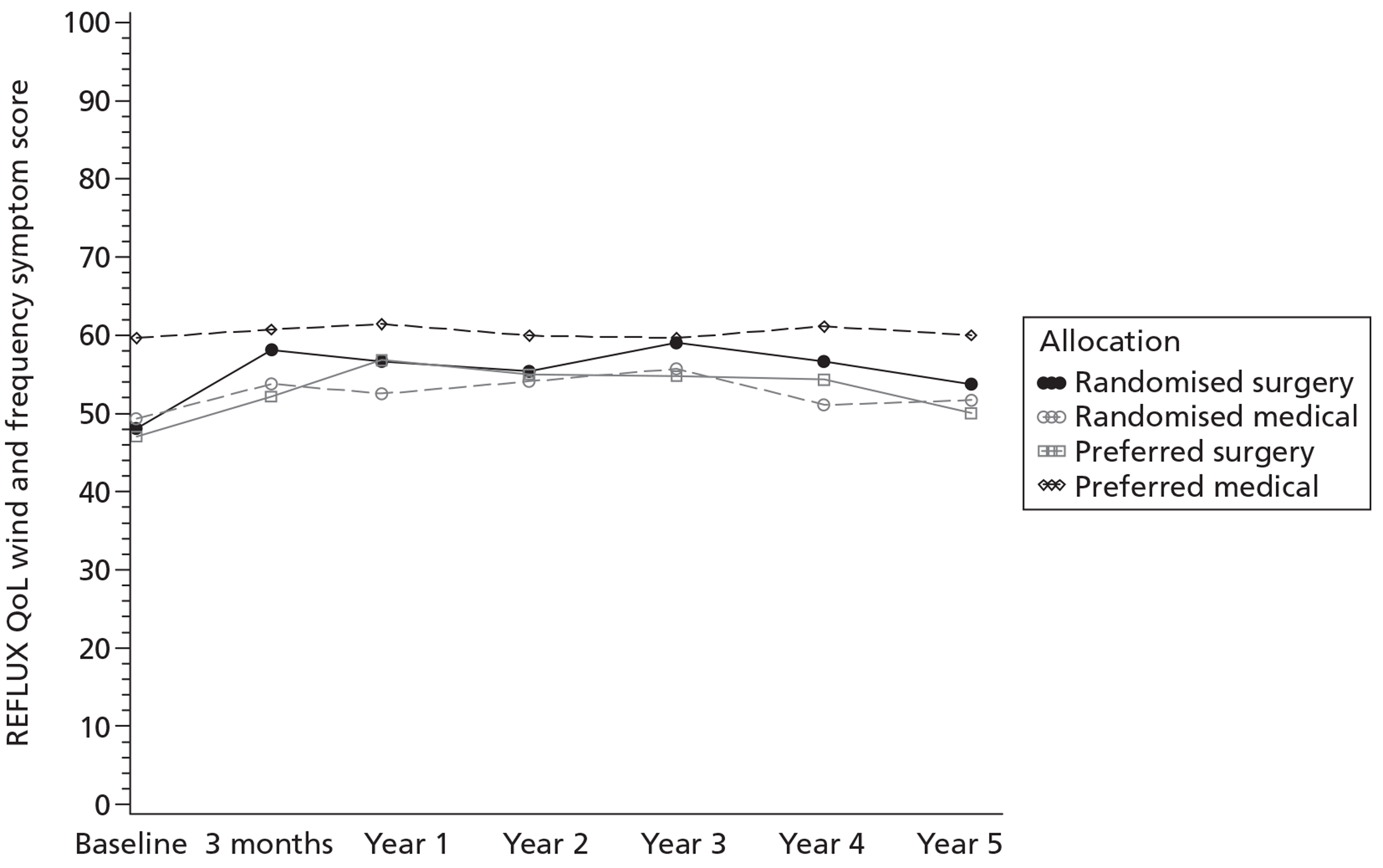

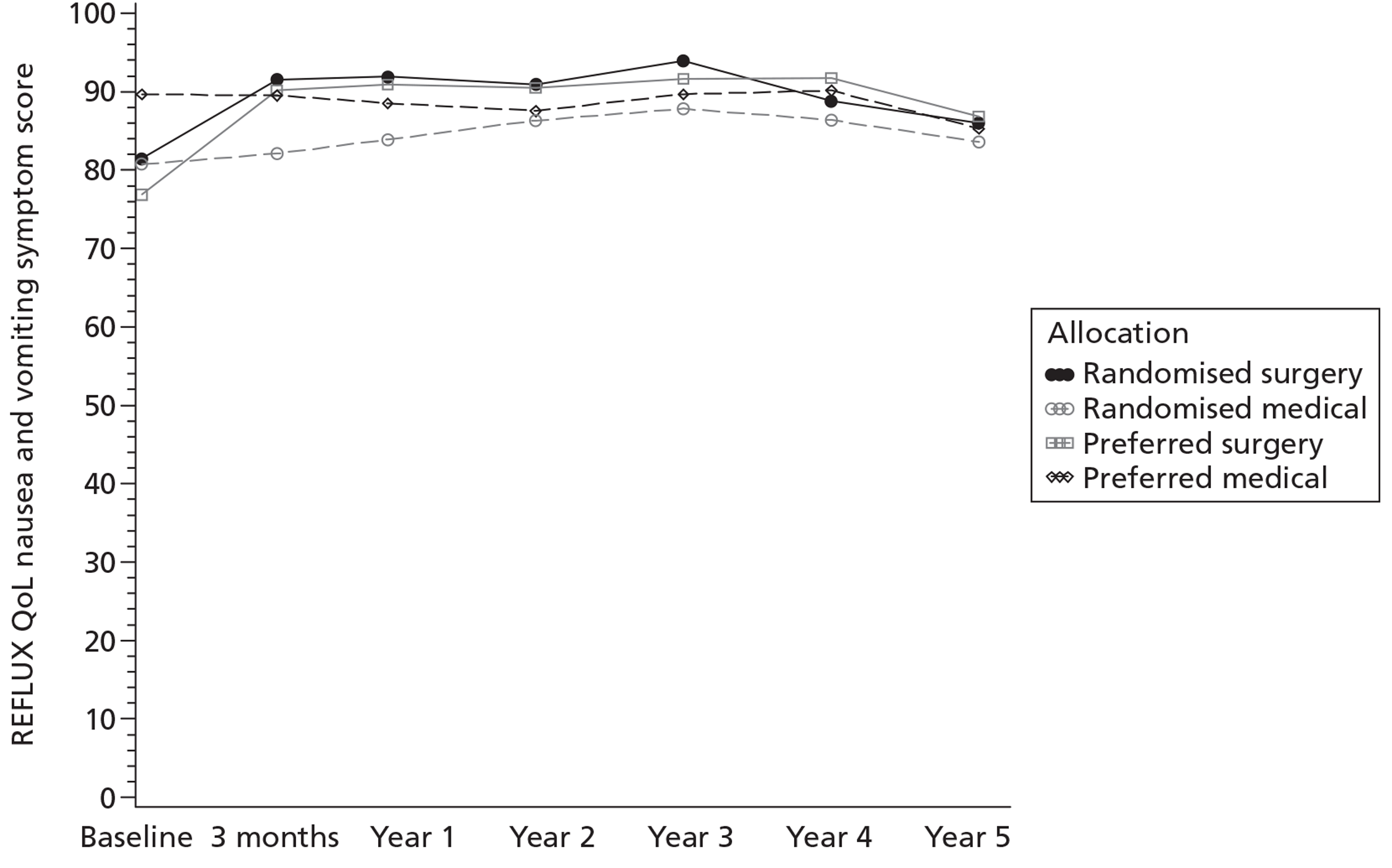

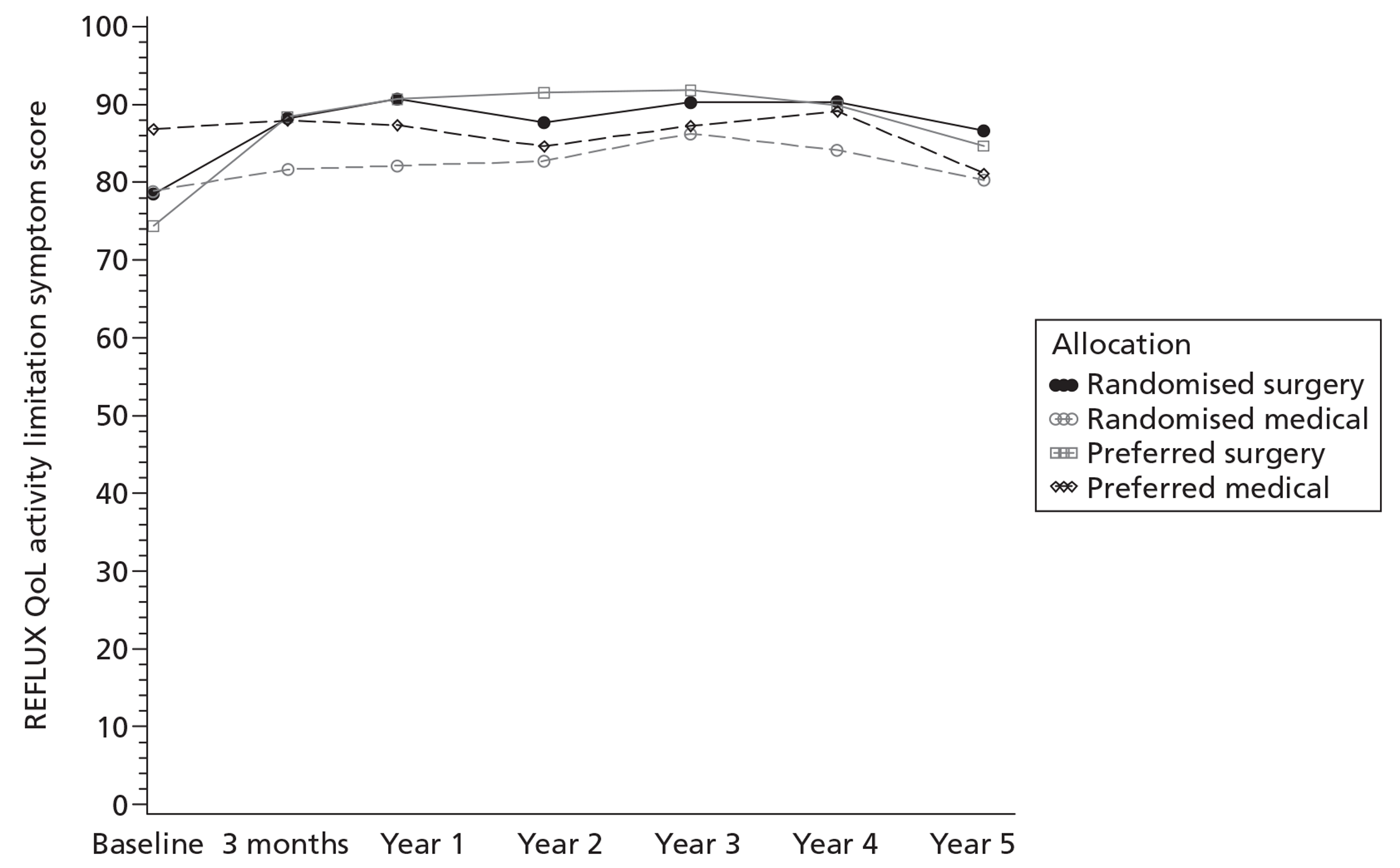

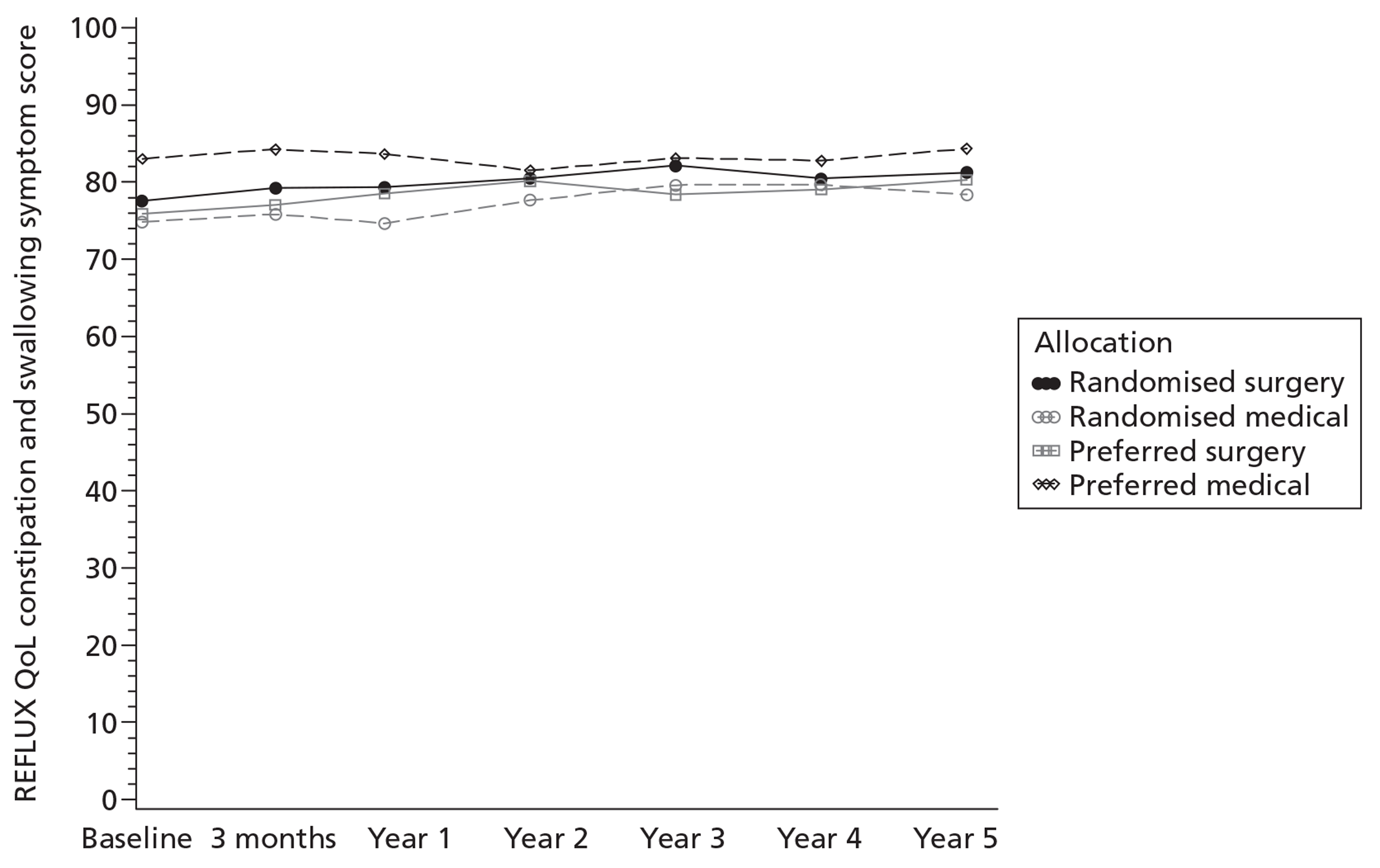

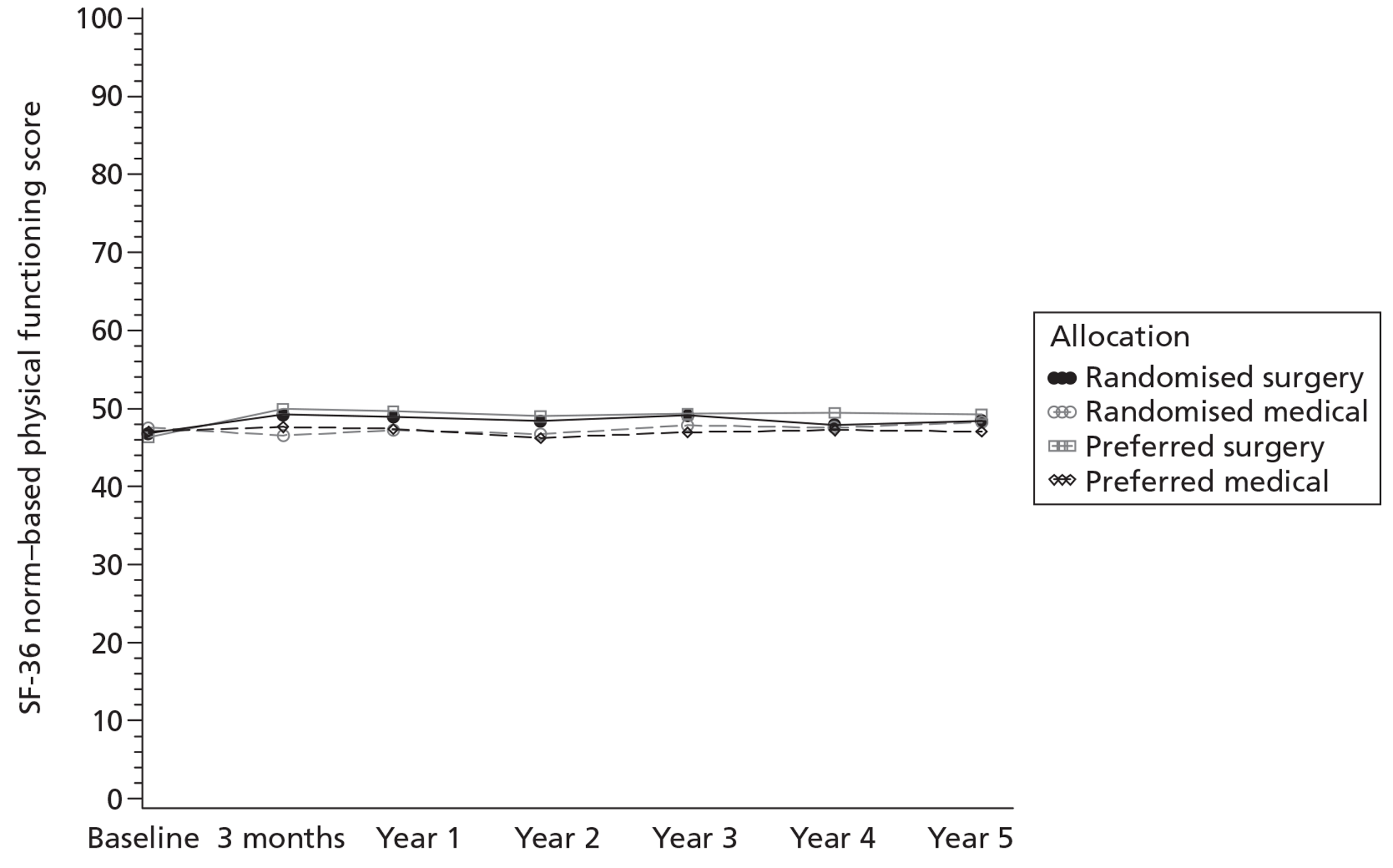

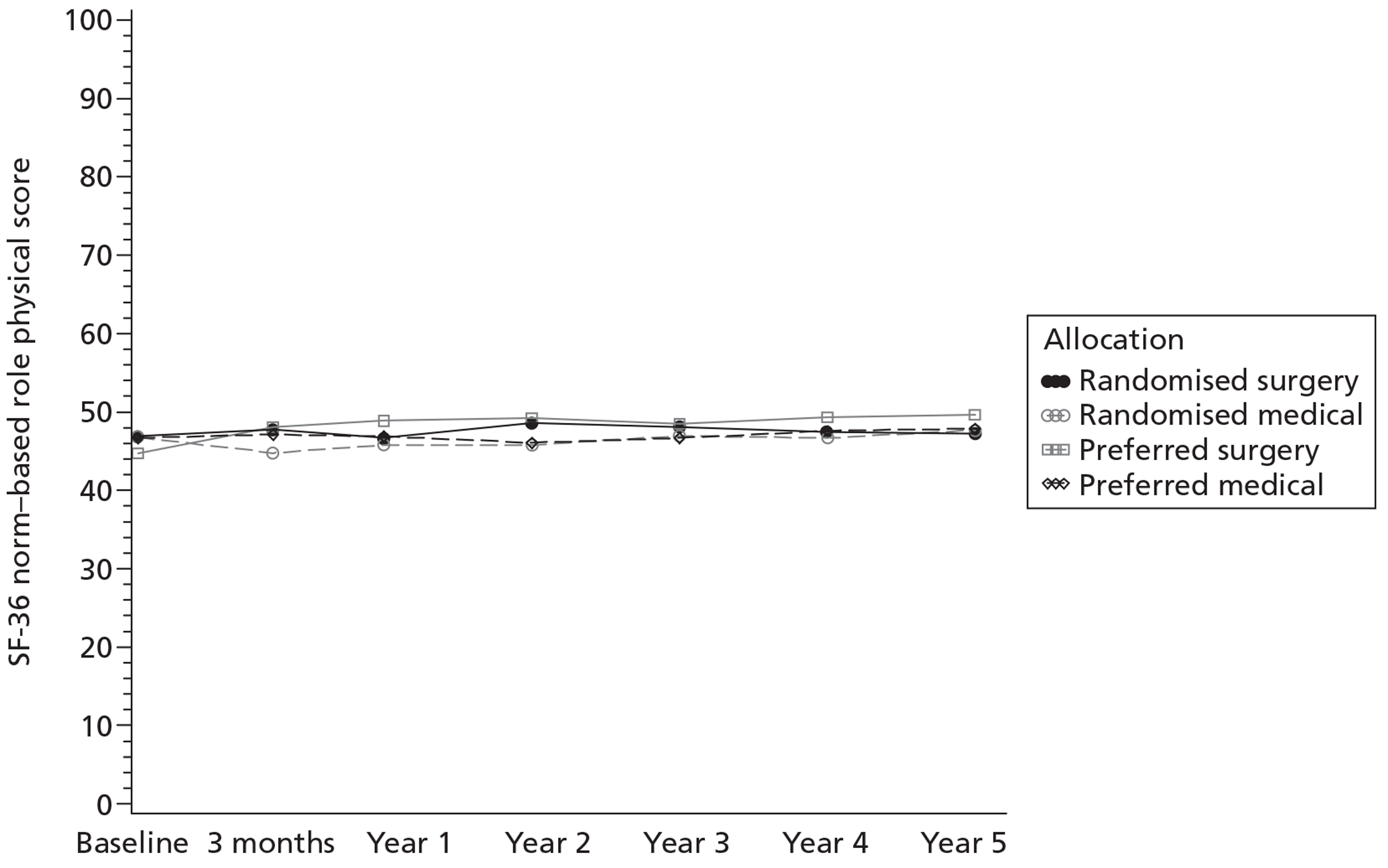

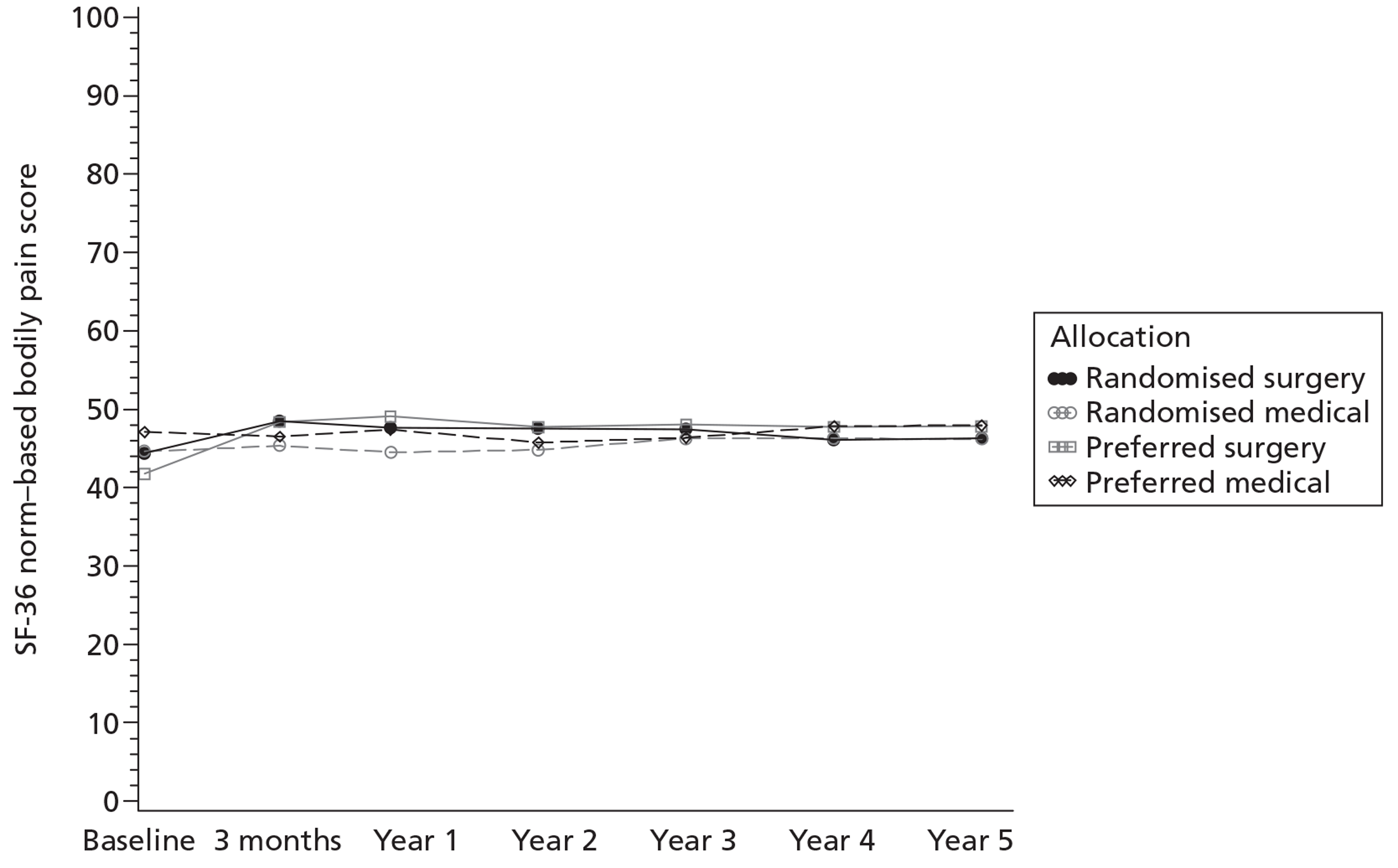

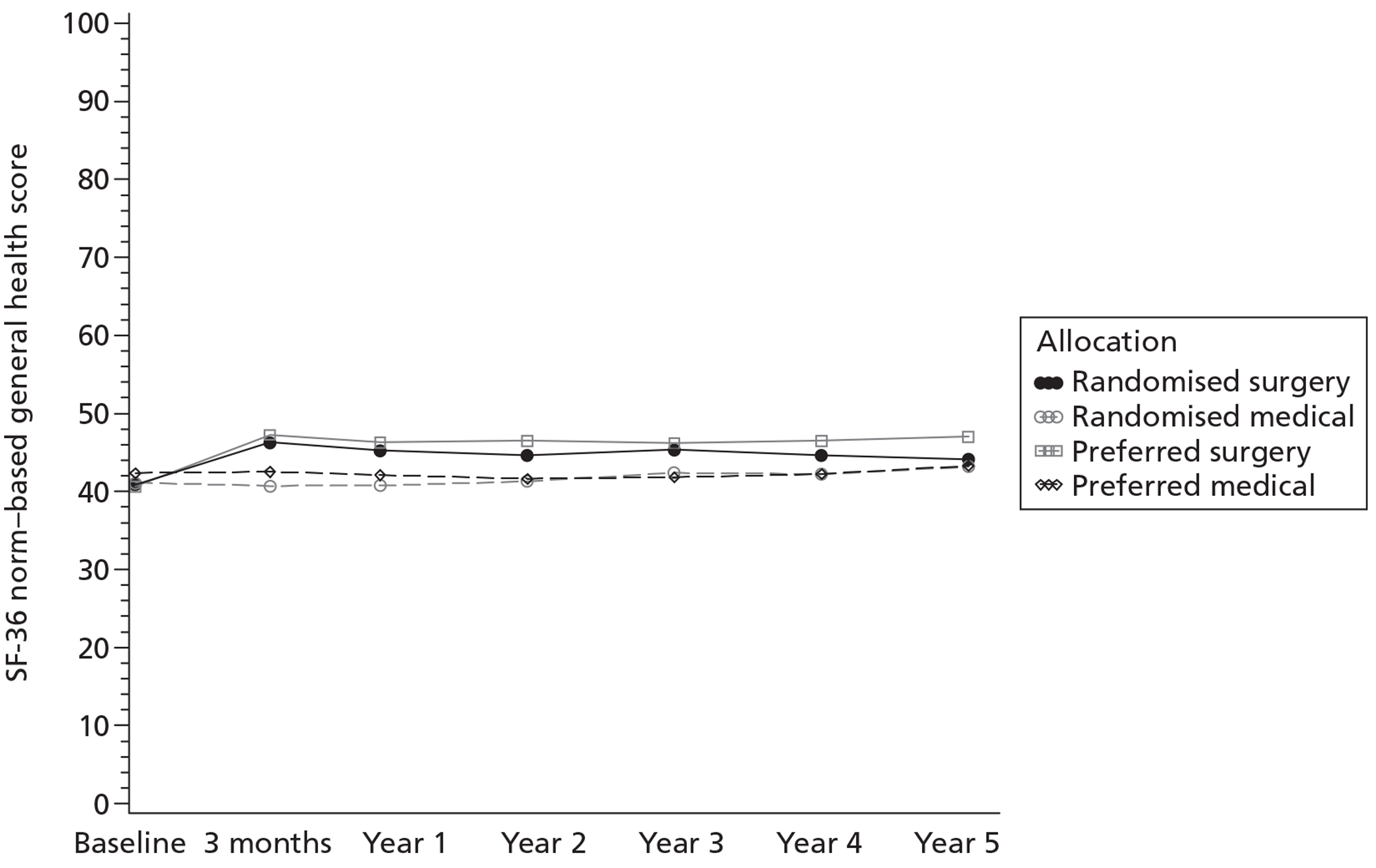

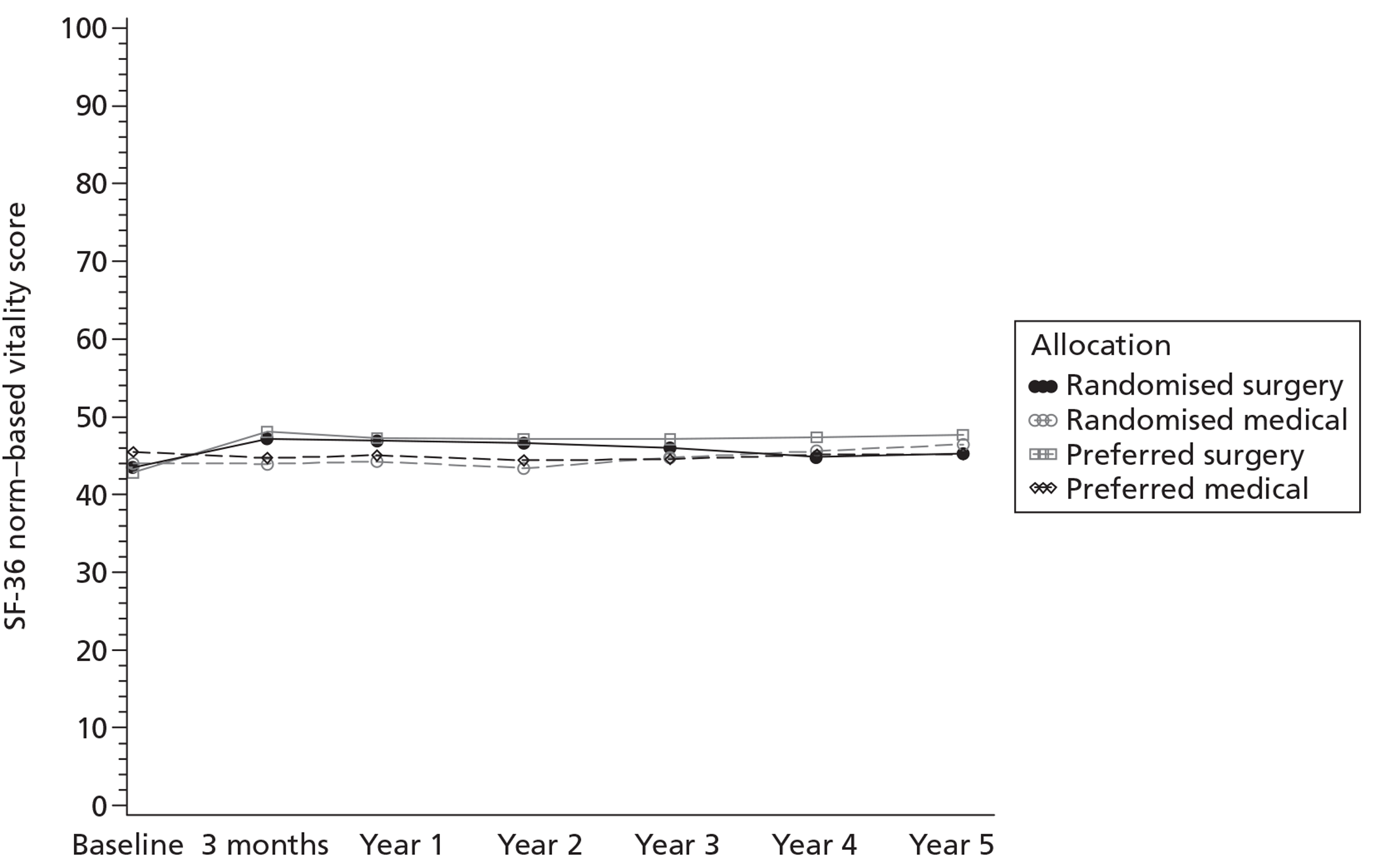

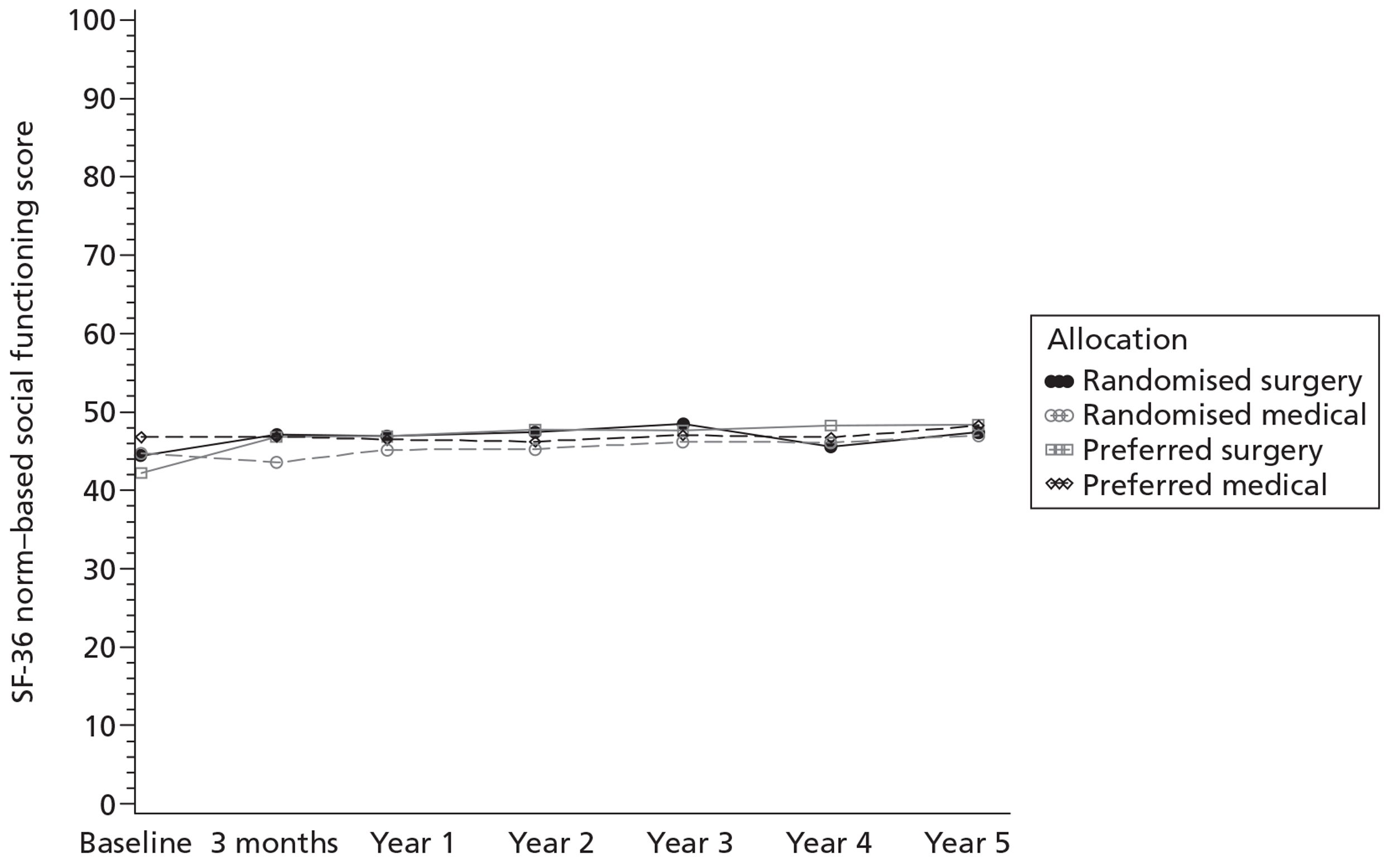

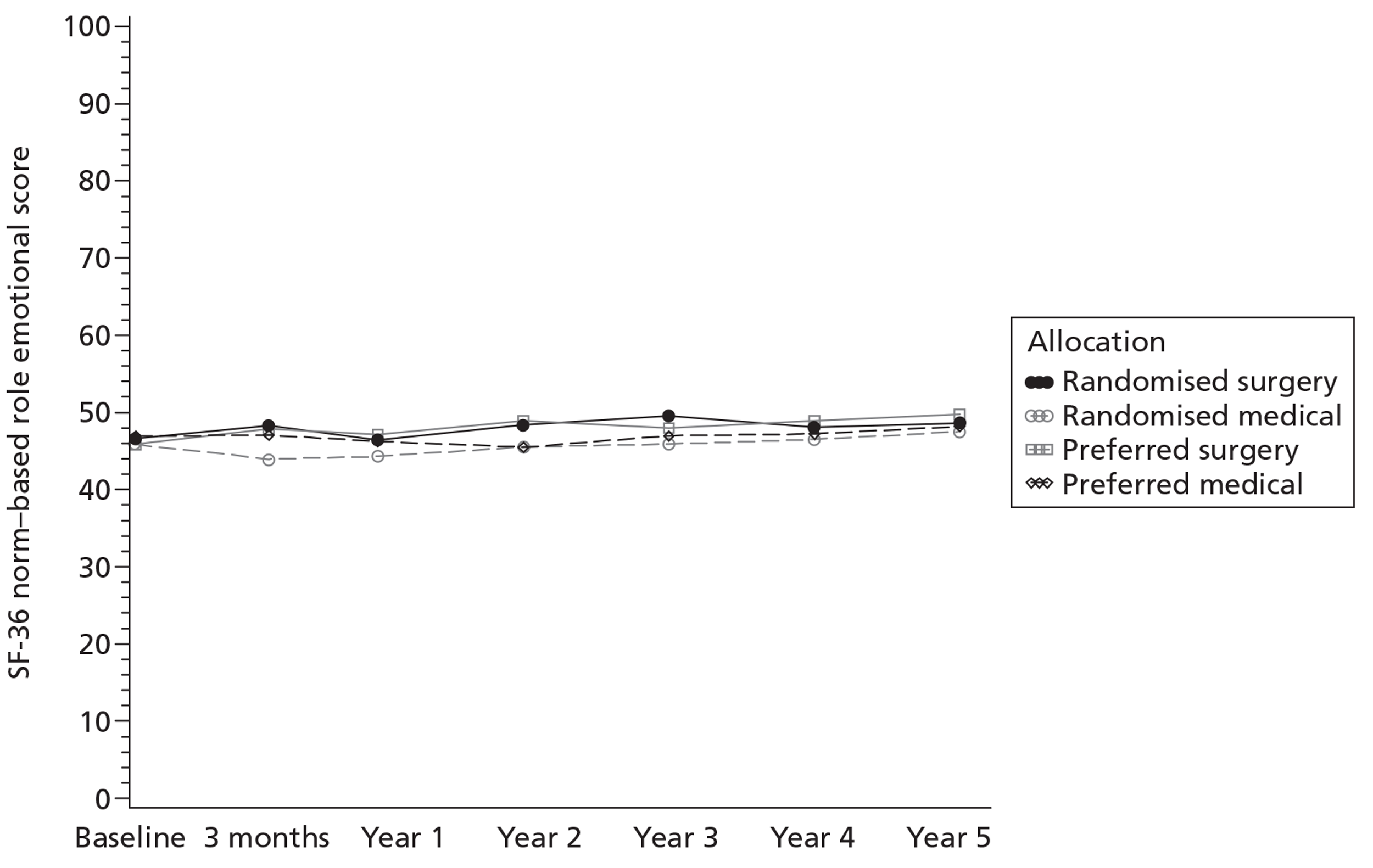

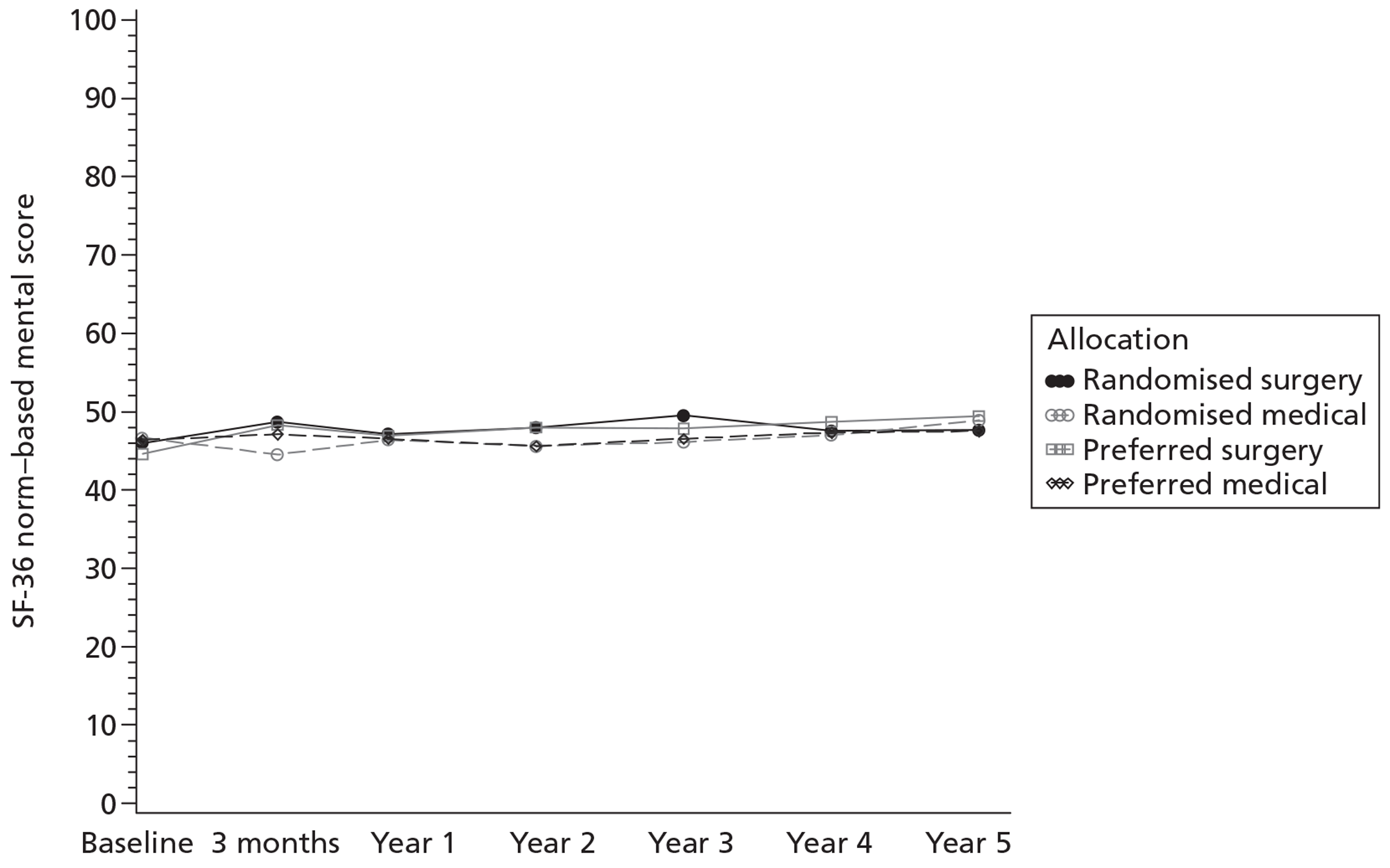

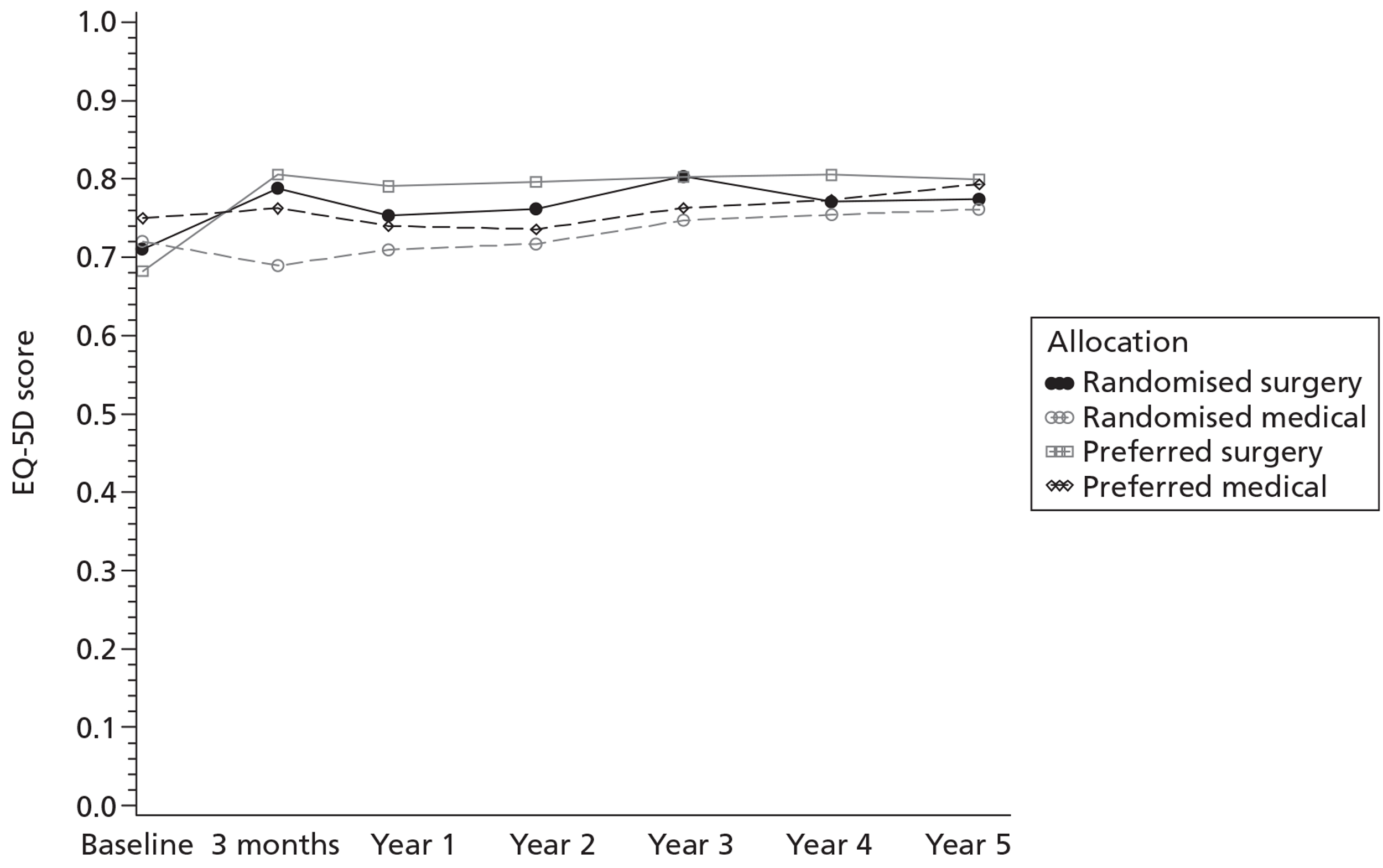

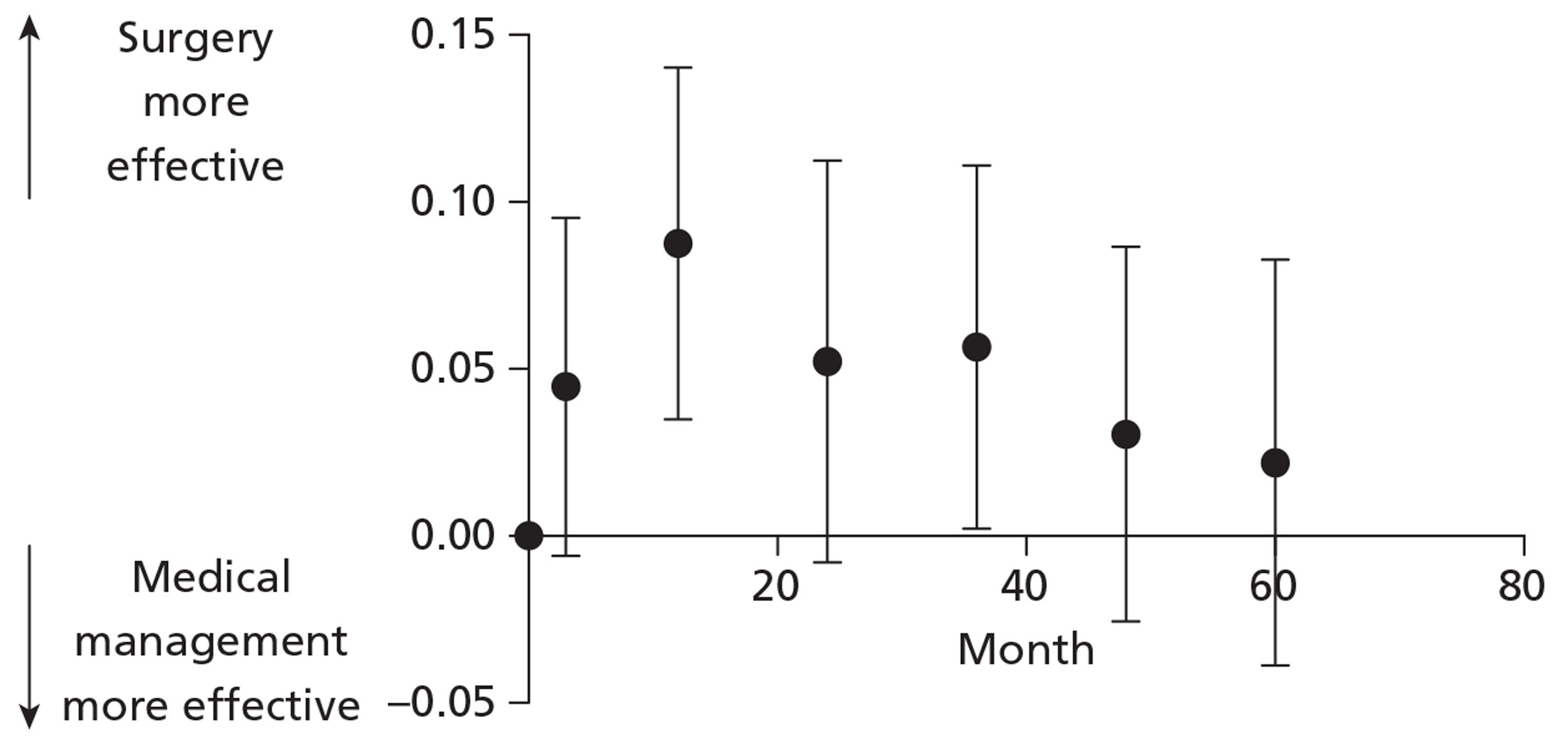

At each year, there were significant differences in the REFLUX score (a third of a SD; p < 0.01 at 5 years) favouring the randomised surgical group, reflecting differences in general discomfort (particularly), wind and frequency, nausea and vomiting, and activity limitation subscores. SF-36 and EQ-5D scores also favoured the randomised surgical group, especially SF-36 norm-based general health, but differences attenuated over time and were generally not statistically significant at 5 years [EQ-5D difference (ITT) 0.047, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.013 to 0.108; p = 0.13]. The lower the REFLUX score and hence the worse the symptoms at trial entry, the larger the benefit observed after surgery. Post hoc exploratory analyses showed that those randomly allocated to medical management who subsequently had surgery had worse symptoms (lower baseline scores) than those who continued on medical management as allocated; following surgery, the scores of these patients markedly improved and this explains, at least in part, why differences in outcome between the randomised groups became less marked over time.

The preference surgical group also had low REFLUX scores at baseline. These scores improved substantially after surgery and at 5 years they were slightly better than those in the preference medical group.

Overall, 4% (n = 16) of the total 364 in the study who had fundoplication had a subsequent reflux-related operation, of whom two had a further (i.e. third) operation. Reoperation was most often conversion to a different type of wrap or a reconstruction of the same wrap. There were only two cases of reversal of the fundoplication and neither was in the randomised comparison. In total, 3% (n = 12) of those who had fundoplication required surgical treatment for a complication directly related to the original surgery, including oesophageal dilatation (n = 4) and repair of incisional hernia (n = 3). Patterns of ‘difficulty swallowing’, flatulence and ‘wanting to vomit but being physically unable to do so’ – all problems that have previously been associated with anti-reflux surgery – were similar in the two randomised groups.

Economic evaluation

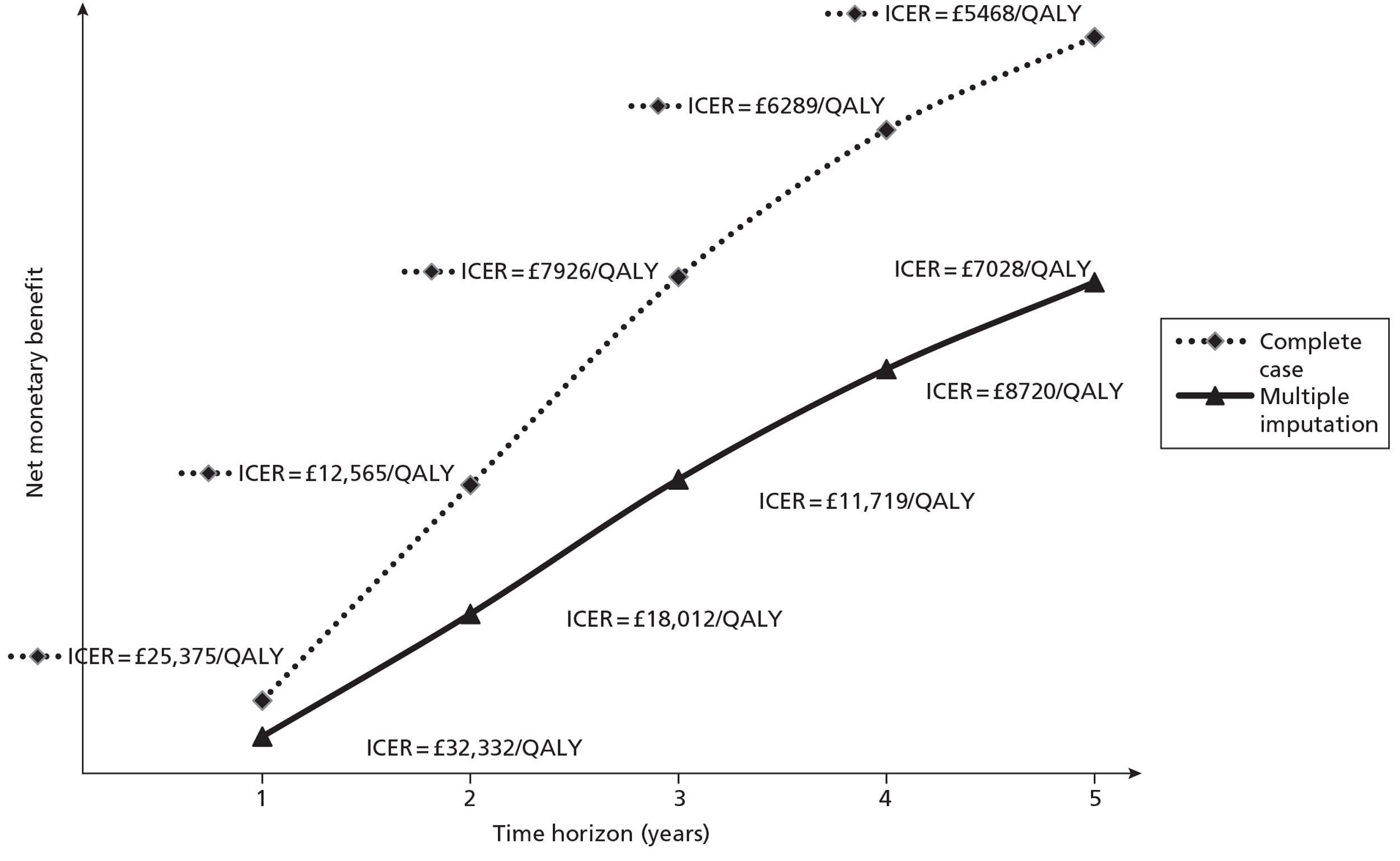

Differences in mean costs and mean quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) at 5 years were used to derive an estimate of the cost-effectiveness of laparoscopic fundoplication and continued medical management from the perspective of the NHS. Conventional decision rules were used to estimate incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs). Sensitivity analysis (including probabilistic sensitivity analysis) was used to explore and quantify uncertainty in the cost-effectiveness results.

Health-care resource-use data were collected prospectively as part of the clinical report forms and patient questionnaires at each follow-up point. The cost for each individual patient in the trial was calculated by multiplying their use of NHS resources by the associated unit costs (from published sources) and discounting at an annual rate of 3.5%. For the base-case analysis, total costs constituted the costs of surgery, complications due to surgery, reoperations, reflux-related prescribed medication, reflux-related visits to and from the GP and reflux-related hospital inpatient, outpatient and day visits. For the sensitivity analysis, all GP visits and all hospital admissions were included in the calculation of total costs. Health outcomes were expressed in terms of QALYs. HRQoL was assessed at each follow-up point using the EQ-5D. Incremental mean QALYs between randomised treatment groups were estimated with and without adjustment for baseline utility, using ordinary least squares regression.

The extent of missing data throughout the trial follow-up was significant; for this reason, the base case drew on the multiple imputed data set ITT analysis. A separate scenario – the complete-case analysis, in which only participants who returned all questionnaires and completed all EQ-5D profiles are included – was employed for both ITT and per-protocol analyses. Multiple imputation provides unbiased estimates of treatment effect if data are missing at random. Sensitivity analysis was used to test the impact on the cost-effectiveness results if data were missing not at random, that is, if patients with worse outcomes or greater costs were more likely to have missing data.

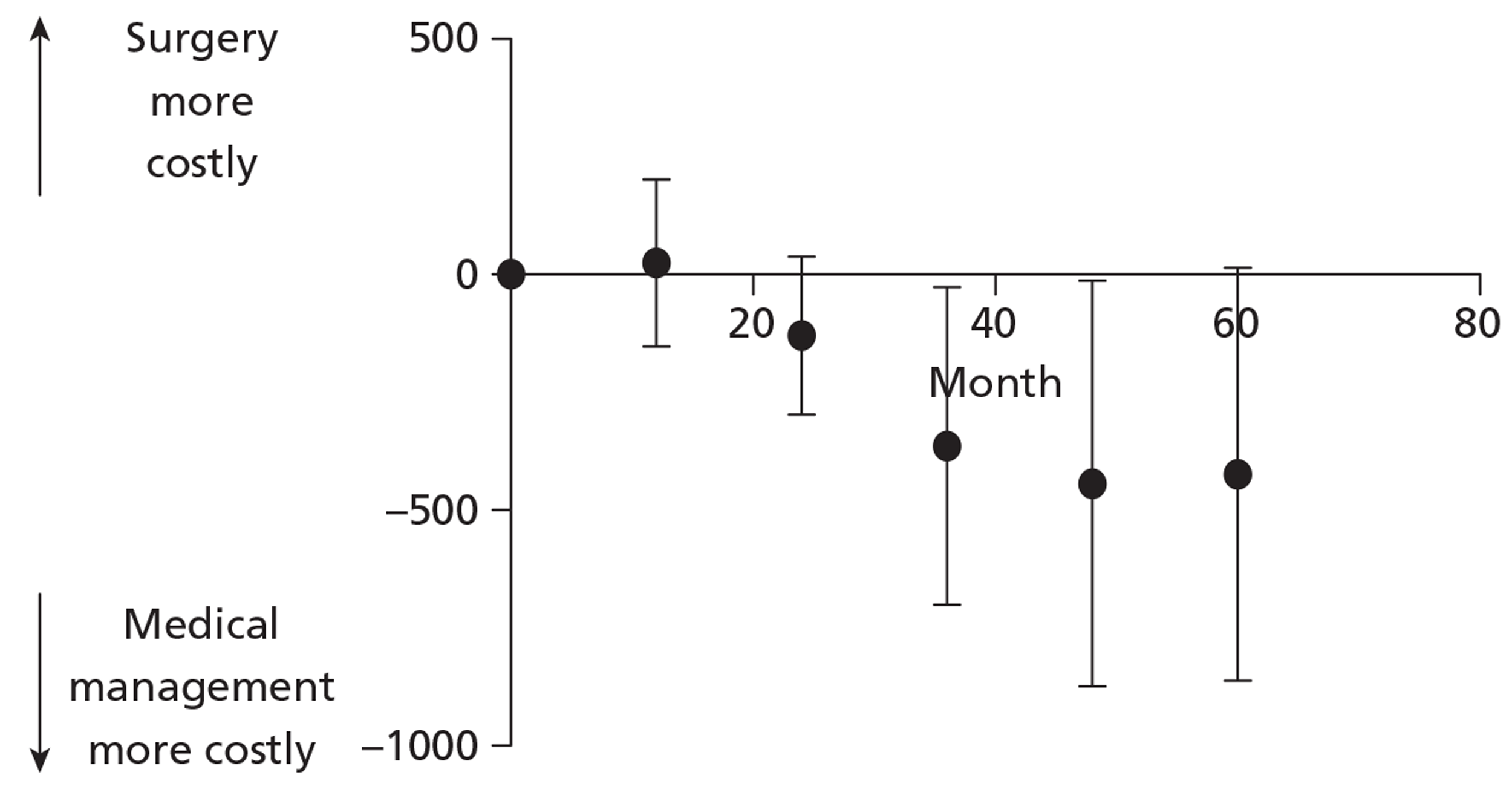

The results show that, for the base-case analysis (multiple imputed data set), the participants randomised to fundoplication accrued greater costs (incremental mean cost £1518; 95% CI £1006 to £2029) but also reported greater overall HRQoL (incremental mean QALYs 0.2160; 95% CI 0.0205 to 0.4115) than participants randomised to continued medical management. Laparoscopic fundoplication is a cost-effective strategy for GORD patients eligible for the REFLUX trial on the basis of the range of cost-effectiveness thresholds used by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (£20,000–30,000 per additional QALY). The results for the complete-case analysis concurred with the multiple imputed data set: across analyses adjusted and unadjusted for baseline EQ-5D, ICERs ranged between £5468 and £8410, well below the NICE cost-effectiveness thresholds. For both data sets (multiple imputation and complete case), the probability of surgery being the more cost-effective intervention was > 0.82 for incremental analyses unadjusted for baseline EQ-5D and > 0.93 once incremental QALYs were adjusted for baseline EQ-5D.

A sensitivity analysis was carried out comparing the groups according to their ‘per-protocol’ status at 1 year. A per-protocol analysis compares the efficacy of the treatments received, whereas an ITT analysis compares the effectiveness of the strategies as offered to patients. The per-protocol analysis (in complete cases) suggested that surgery was more cost-effective than medical management. Other sensitivity analyses were carried out using a wider set of resource-use data. The results of the first alternative scenario, using the costs of primary care visits for any reason rather than only reflux-related reasons, increased the ICER slightly in relation to the base case. Nevertheless, the ICER remains well below conventional thresholds, and the probability of surgery being cost-effective was > 0.85 for both adjusted and unadjusted analyses. In the second alternative scenario, replacing reflux-related hospital costs by all hospital costs, medical management was ‘dominated’ by the surgical policy; the probability of surgery being cost-effective was > 0.90.

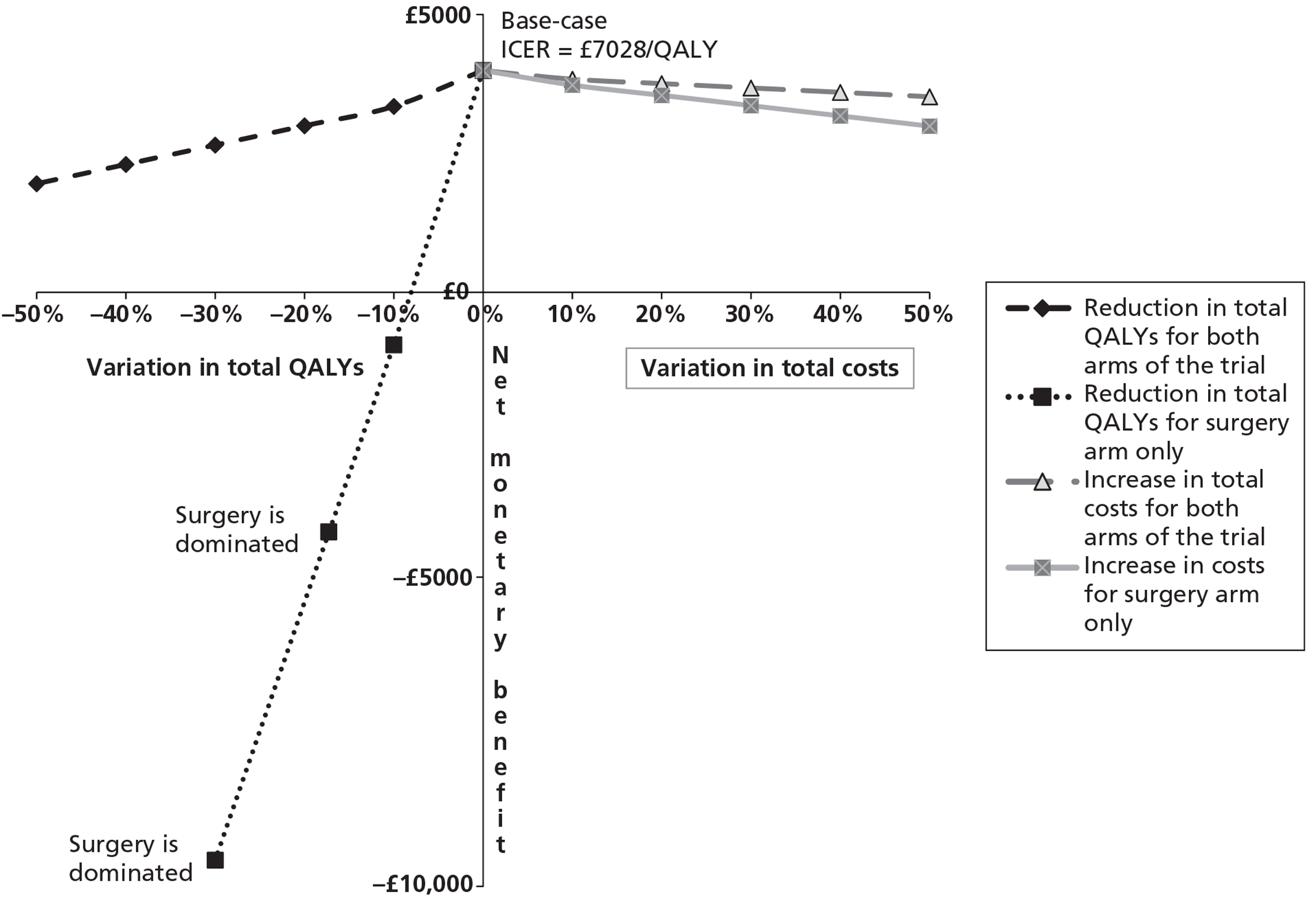

The base-case analysis imputes missing data. This assumes that missing data are missing at random, that is, their values can be predicted (with uncertainty) from observed data. This assumption is impossible to confirm or repute but its effect on the results can be tested in sensitivity analysis. The base-case analysis may be biased if the values of a missing variable are different from the observed values (for given values of other covariates). Sensitivity analysis using the multiple imputation data set showed that the cost-effectiveness of surgery was relatively insensitive to any increase in costs: cost-effectiveness changed little when costs were increased for patients with missing data in both treatment groups and when costs were increased just for patients randomly allocated surgery with missing data. A similar result was observed after reducing the total QALYs for all patients with missing data. In contrast, the cost-effectiveness of surgery was highly sensitive to the assumption that patients randomly allocated surgery with missing data experience lower HRQoL than patients with complete data. A 10% decrease in QALYs for patients randomised to surgery with missing data results in the cost-effectiveness increasing above £20,000 per QALY gained. This scenario shows that missing data can have an impact on the results. Nevertheless, although it is impossible to empirically confirm or refute this scenario from the data in the trial, it would seem improbable in practice that surgical patients with poor quality of life are less likely to respond to follow-up questionnaires than similar participants undergoing medical management.

Comparison with similar randomised trials

The findings of the REFLUX trial were considered in the context of the three other randomised trials that have compared laparoscopic surgery with medical management. In respect of benefits, the trials consistently show better relief of GORD symptoms following surgery, with parallel, though less marked, improvements in generic HRQoL. The four trials are also consistent in respect of complications of surgery, with small numbers having associated visceral injuries, postoperative problems and dilatation of the fundoplication wrap. The REFLUX trial suggests that 4.5% have a reoperation and the other trials are broadly consistent with this. Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), flatulence and bloating have been linked with fundoplication in the other trials. In contrast, although a small number of REFLUX participants had a dilatation of the fundoplication wrap, responses to the questionnaires did not show a difference between those randomised to surgery and those randomised to medical management in these respects.

Conclusions

After 5 years' follow-up, a policy of relatively early laparoscopic fundoplication among patients for whom reasonable control of GORD symptoms requires long-term medication and for whom both surgery and medical management are suitable continues to provide better relief of GORD symptoms with associated better quality of life. Complications of surgery were rare. Despite being initially more costly, a surgical policy is likely to be more cost-effective for such patients suffering from GORD who were eligible for the REFLUX trial.

Implications for health care

Extending the use of laparoscopic fundoplication to people whose GORD symptoms require long-term medication for reasonable control and who would be suitable for surgery would provide health gains that extend over a number of years. The longer-term data reported here indicate that this would also be a cost-effective use of resources. The more troublesome the symptoms, the greater the potential benefit from surgery.

Recommendations for research

Most patients taking anti-reflux medication are managed in general practice. It is uncertain how many of these people might be suitable for surgery and hence what the most efficient provision of future care might be. Further research to explore the feasibility and resource impact of alternative policies for fundoplication within the NHS is therefore recommended.

Trial registration

This study is registered as ISRCTN15517081.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Health Technology Assessment programme of the National Institute for Health Research.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This report describes the long-term follow-up of the REFLUX trial assessing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of laparoscopic surgery compared with continued medical management for people with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). This comparison was identified as a priority for research by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, which funded the trial in two stages. The first stage, encompassing preliminary economic modelling, outcome development, trial recruitment, initial clinical management, follow-up to a time equivalent to 1 year after surgery and modelling of cost-effectiveness based on results available at that time, was reported in 2008. 1–5 The second stage, reported here, describes analyses based on further follow-up to 5 years after surgery.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

The lower oesophagus, at its junction with the stomach, normally acts as a sphincter to prevent the contents of the stomach flowing back up the oesophagus. When the sphincter does not work adequately, the acid stomach contents leak, or ‘reflux’, into the oesophagus. The commonest symptom that this causes is heartburn, a burning sensation in the chest or throat. GORD has been defined through an international consensus process as ‘a condition which develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications’; in this consensus, symptoms were considered ‘troublesome’ ‘if they adversely affected a patient's well-being’. 6

Symptoms caused by gastro-oesophageal reflux are common: between 20% and 30% of a ‘Western’ adult population experience heartburn and/or reflux intermittently. 7–9

Treatment of GORD includes both medical and surgical management, the options depending on the severity of symptoms. The majority of people with reflux have only mild symptoms and require little, if any, medication. The simplest is self-administered antacids with advice to alter lifestyle factors such as dietary modification, smoking cessation and weight reduction. A minority have severe symptoms and develop overt complications, despite full medical therapy, and require surgical intervention. Among the remainder, control of symptoms requires regular or continuous acid-suppression therapy using either histamine receptor antagonists (H2RAs) or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs); initial high-dose therapy may be followed by maintenance treatment using these drugs either intermittently or continuously at a reduced dose sufficient to suppress symptoms. It is from this intermediate group of patients with significant disease requiring maintenance medical treatment that most of the treatment costs for the health service arise.

Laparoscopic fundoplication

Interest in surgery as an alternative to long-term medical therapy for GORD has been considerable since the introduction of the minimal access laparoscopic approach in the early 1990s. 10 Randomised trials conducted comparing laparoscopic with open surgery showed similar improvement in symptoms but with clear benefits of the laparoscopic approach in terms of recovery and fewer postsurgical complications.11 As a consequence, surgery was suggested as an alternative to long-term maintenance medical treatment with anti-reflux drugs.

The operative method, whether using an open or a laparoscopic approach, involves performing a fundoplication by wrapping the fundus of the stomach around the lower oesophagus to create a high-pressure zone, thus reducing gastro-oesophageal reflux. The wrap created can be either complete (360°) or partial. Many operative variants have been described. The commonest operation is a 1-cm complete wrap fashioned over a large bougie, the so-called ‘short-floppy Nissen’. 12,13 There has been debate about the use of a partial rather than a total fundoplication. The partial approach has a number of potential advantages (such as fewer postoperative complications) but several controlled studies have shown broad equivalence between the two approaches;14 for the purpose of this study they were therefore regarded as equivalent. Although fundoplication is reported to produce resolution of reflux symptoms in upwards of 90% of patients, like all surgery it carries risks and can have side effects. There is also uncertainty about the durability of benefit and frequency and severity of side effects following surgical therapy. Long-term follow-up to 12 years after open reflux surgery suggested attenuated but continuing better control of reflux symptoms; however, other symptoms such as difficulties swallowing (dysphagia), rectal flatulence and inability to belch or vomit were more common in surgical patients. 15 An important objective of this study was to determine if the long-term pattern of symptoms following laparoscopic surgery was similar.

Medical management

Proton pump inhibitors, sometimes supplemented with prokinetics or alginates, are the most effective medical treatment for moderate to severe GORD. Once started on PPIs, the majority of patients with significant GORD remain on long-term treatment. 16 It is estimated that around 1% or more of the UK adult population are prescribed PPI maintenance therapy. 17–19 The cost to the NHS of medical management of GORD is considerable. In England alone, the cost of PPIs is estimated to be £220M per year. 20 Of this budget, most of this prescribing occurs within the primary care setting. 21,22

Although PPIs are generally considered safe, there is increasing acknowledgement of their possible adverse effects. 23,24 Gastric acid suppression predisposes to enteric infections and the sustained hypergastrinaemia resulting from PPI use causes rebound acid hypersecretion and the development of acid-related symptoms if the drug is stopped. Acute severe hypomagnesaemia has been recognised relatively recently as a rare adverse reaction to PPIs; the mechanism underlying it is not known. The clinical significance of impaired vitamin B12 and iron absorption due to PPIs is uncertain; there is also controversy about the risk of fractures and pneumonia and about the occurrence and significance of gastric mucosal atrophy and intestinal metaplasia, which have been seen in Helicobacter pylori-positive patients taking PPIs. Drug–drug interactions have also been a cause for concern,25 although unequivocal evidence of their occurrence does not in itself establish clinical significance.

For the purpose of this study, medical therapy was taken to mean long-term therapy with PPIs (or H2RAs if intolerant to PPIs).

Rationale for the study design

The original study design was based on the belief that decisions about the management of GORD should be made using unbiased, statistically precise comparisons of alternative policies. At study entry all patients fulfilled three criteria: they were on long-term acid suppression with PPIs; they had symptoms that were thought to be adequately controlled; and they were suitable in terms of fitness and comorbidity for either surgical or continuing medical treatment for their GORD. At the time that the study was planned, the consensus opinion of clinicians was that these three criteria identified GORD patients for whom surgical and continuing medical treatment could be considered equally acceptable treatment options and that, consequently, the comparison should be undertaken in patients meeting these criteria.

The most likely sources of bias were in the ways in which the groups being compared were selected; how their outcomes were assessed; and how the management was actually delivered. This is the basis for using a pragmatic randomised controlled trial (RCT) design. Random allocation protected against selection bias. Confining the trial to those with no clear treatment preference limits biased patient-centred assessment of outcome, and pragmatic comparison of alternative policies [with intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis] avoids bias introduced by individual cases of non-compliance. This approach had limitations, however, and for this reason we chose to incorporate two parallel, non-randomised preference groups.

Including those with a clear preference for one policy or the other allows broader extrapolation and generalisability. Study of this group may give insights into the reasons for preference and hence give pointers to patient choices after the study. 26 Furthermore, preference may influence outcome and, if so, this may also help when making treatment decisions. 26,27 A third reason for the parallel, non-randomised preference groups28 was that the addition of data from the preference groups may reduce imprecision around the estimates from the randomised comparison and this may be particularly useful for rare events, such as complications that can be confidently ascribed to one or other treatment. (The limitation is that the preference groups are not derived by random allocation, and hence the comparisons are exposed to the biases of non-randomised studies.)

Reliable comparisons within and between randomised and preference groups require valid measurement of treatment outcome. Although there were a number of quality-of-life (QoL) tools available, none was sufficiently specific to assess the spectrum of gastrointestinal symptoms associated with the treatment of GORD, particularly those due to surgery. For this reason we developed and validated a new outcome measure (the REFLUX questionnaire). We have continued to use this as the primary outcome measure in the longer-term follow-up reported here. Details of the REFLUX questionnaire and its derivation have been described elsewhere. 1,4

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and its management represent a very significant call on NHS resources. Although clinical effectiveness, acceptability and safety will be important determinants of future policy, the issues of cost and resource use may be over-riding. This is the reason for the economic evaluation component of this study. Policy should be guided by both assessment of the relative cost-effectiveness of alternative policies and assessment of the impact that possible policy changes would have for the NHS and for patients with GORD.

The cost of laparoscopic fundoplication appears to be equivalent to the cost of 2–3 years of maintenance treatment with PPIs, although it is acknowledged that the costs of PPIs are falling. 29 The costs of surgery are related largely to two factors: the incidence of complications/length of hospital stay and the number of patients requiring long-term medical interventions after surgery.

We addressed cost-effectiveness in our report of the first phase of the REFLUX trial. 1 We reported both a within-trial cost-effectiveness analysis based on the results up to 12 months after surgery and an extended cost-effectiveness model that explored a number of scenarios beyond 12 months. The within-trial analysis related the extra mean costs associated with the surgical policy to the estimated increase in mean quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) associated with surgery up to that time. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was around £19,000 when the ITT analysis was used. Taking into account the uncertainties around the estimates of both costs and utilities, it was calculated that the chance that the surgical policy would be cost-effective at a threshold of £20,000 per QALY was 46%. This indicated considerable uncertainty at thresholds that are currently commonly applied to costs per QALY. The limitations of the within-trial analysis were discussed in detail in the earlier report, in particular that it ignored costs and benefits that accrued after 1 year.

The economic model was designed to address the limitations of the within-trial analysis. It explored a range of scenarios of varying lifetime benefits and costs, and analyses gave a wide range of incremental costs per QALY of £1000–44,000, again indicative of wide uncertainty. The factors contributing most to this uncertainty were the projected health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) parameters and the long-term uptake of medication following surgery.

Thus, although data available up to a time equivalent to 1 year after surgery provided promising evidence that surgical management might well be cost-effective, there was too much uncertainty, especially about longer-term costs and benefits, to provide clear guidance for decision-makers. This was the justification for the longer-term follow-up to 5 years reported here.

Chapter 2 Methods

Original study design

The study had two complementary components:

-

a multicentre, pragmatic30 RCT (with parallel non-randomised preference groups) comparing a laparoscopic surgery-based policy with a continued medical management policy to assess their relative clinical effectiveness

-

an economic evaluation of laparoscopic surgery for GORD to compare the cost-effectiveness of the two management policies, identify the most efficient provision of future care and describe the resource impact that various policies for fundoplication would have on the NHS.

Eligible patients who consented to participate in the RCT were randomly allocated to either laparoscopic surgery or continued medical management. Those patients who had a strong preference for one or other of the two treatment options could be recruited to the preference study. Clinical history was recorded at study entry. Participants completed health status questionnaires at the time of recruitment to the study and then at specified times equivalent to 3 and 12 months and then 2, 3, 4 and 5 years after surgery.

Approval for this study was obtained from the Scottish Multicentre Research Ethics Committee and the appropriate Local Research Ethics Committees.

Clinical centres

Clinical centres were based on local partnerships between surgeons with experience of laparoscopic fundoplication and gastroenterologists, with whom they shared the secondary care of patients with GORD. Centres were eligible if they included:

-

a surgeon who had performed at least 50 laparoscopic fundoplication operations

-

one or more gastroenterologists who agreed to collaborate with the surgeon(s) in the trial.

Study population

Eligible patients were those for whom care had been provided by a participating clinician who was uncertain which management policy (surgical or medical) was better. In addition, patients had to have documented evidence of GORD (based on endoscopy and/or manometry/24-hour pH monitoring) as well as symptoms for >12 months requiring maintenance PPI therapy for reasonable symptom control. Patients who were intolerant to PPIs and therefore required H2RA therapy to control their symptoms were also eligible. Patients who were morbidly obese [body mass index (BMI) > 40 kg/m2] or who had Barrett's oesophagus of > 3 cm or evidence of dysplasia, a paraoesophageal hernia or an oesophageal stricture were all excluded.

Eligible patients who did not want to take part in the randomised trial because of a strong preference for one type of management or the other were invited to take part in the preference arm of the study. For logistical reasons and to maintain a balance between the sizes of the randomised and the preference groups, we aimed to cap the numbers of participants recruited to the preference arms to 20 per arm in each centre.

All participants gave their informed consent.

Health technology policies being compared

Laparoscopic surgery policy

For those participants allocated to the randomised surgical group or recruited to the preference surgical group of the trial, subsequent deferring or declining of surgery, by either the participant or the surgeon, was always an option (i.e. even after trial entry), particularly among those recruited by a gastroenterologist and referred to a surgeon for consideration of surgery within the trial. Participants who had not had manometry/pH studies underwent these tests before surgery to exclude achalasia.

The surgery was performed either by an experienced surgeon who had undertaken > 50 laparoscopic fundoplications or by a less experienced surgeon working under the supervision of an experienced surgeon. It was recommended that crural repair be routine and that non-absorbable synthetic sutures (not silk) be used for the repair. The type of fundoplication used was left to the discretion of the experienced surgeon. For the purposes of the main comparisons, the different surgical techniques for laparoscopic fundoplication were considered as part of a single policy. The study design, however, allowed for indirect comparisons between techniques.

Medical management policy

Those allocated to the medical management policy had their therapy reviewed and adjusted as necessary by the local gastroenterologist to be ‘best medical management’. It was recommended that management conformed to the principles of the Genval Workshop Report. 31 These include stepping down antisecretory medication in most patients to the lowest dose that maintained acceptable symptom control. Following the therapy review by the gastroenterologist, trial participants had their medication managed by their general practitioner (GP). Although, in general, trial participants allocated to medical management were managed in this way, the protocol did include the option of surgery if a clear indication for it subsequently developed.

Study registration (and treatment allocation when randomised)

The treatment allocation for participants in the randomised component of the trial was computer generated; it was stratified by centre, with balance in respect of other key prognostic variables – age (18–49 years or 50+ years), sex (male or female) and BMI (≤ 28 or > 29 kg/m2) – by a process of minimisation. Randomisation was organised centrally at the Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen, and was independent of all clinical collaborators.

Clinical management

Participants who were allocated to surgical management were invited to a consultation with the collaborating surgeon. During this consultation, the surgeon confirmed that there was no contraindication to surgery and discussed the operation in more detail, before arranging an operation date. The surgeon recorded intraoperative details on specially designed study forms. All other in-hospital data collection was the responsibility of the local study nurse. In all respects, other than the trial interventions, clinical management was left to the discretion of the clinician responsible for care. This continued to be the case in the extended follow-up phase, which is the focus of this report, with GPs monitoring subsequent care needs throughout the follow-up period.

Data collection

Follow-up by postal questionnaire was first performed at 3 months after surgery, or at an equivalent time among those who did not have surgery, and then annually. The questionnaire used for the follow-up at 2–5 years was similar to the questionnaire that had been used in the earlier phase of the trial up to 12 months after surgery. Non-responders received up to two reminder telephone calls or letters to encourage return of their postal questionnaires. On occasion, and at the participants' convenience, a shortened version of the questionnaire was completed over the telephone.

From around half-way through the 5-year follow-up, participants were sent a £5 gift voucher with their final postal reminder to compensate for their time in completing the questionnaire. This decision was taken based on the findings of a systematic review of the effects of incentives on postal questionnaire return32 and specific randomised trials that evaluated the use of vouchers. 33–35

All data were sent to the trial office in Aberdeen for processing. A random 10% sample of all data was double-entered to check accuracy and no significant errors were identified. Extensive range and consistency checks further enhanced the quality of the data.

The principal study outcome measure

The primary outcomes for measuring the differences in effects between medical and surgical management were:

-

a ‘disease-specific’ measure incorporating assessment of reflux and other gastrointestinal symptoms and the side effects and complications of both therapies (the REFLUX questionnaire was developed specifically for this study4)

-

NHS costs including treatments, investigations, consultations and other contacts with the health service.

The secondary outcome measures were:

-

HRQoL – measured using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)36 and Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36)37

-

patient costs, including loss of earnings, reduction in activities and the costs of prescriptions and travel to health care

-

other serious morbidity, such as operative complications

-

(further) anti-reflux surgery

-

mortality.

An example of the annual questionnaire used for collecting this information is provided in Appendix 1.

Sample size

The original aim was to recruit 600 participants to the randomised trial to give 80% power to identify a difference between the two groups of 0.25 of a standard deviation (SD) in respect of the disease-specific instrument and other continuous variables such as EQ-5D and SF-36, using a significance level of 5%. Based on the same arguments, it was planned that 300 people would be recruited to each arm of the preference study. The cost savings of a surgical policy largely depend on the number of patients managed surgically who no longer require PPI treatment, and a trial with 300 surgically managed patients would have estimated this proportion to within about 5% with 95% statistical confidence.

However, prompted by a lower rate of recruitment than expected, this target was revised in January 2003 in consultation with the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) and representatives of the HTA programme. It was agreed that a larger benefit (0.3 of a SD) was clinically plausible based on improvements seen after surgery in the accruing literature among more severely affected people (who were not eligible for the trial). This was calculated to require 196 in each group to give 80% power (2p = 0.05).

Statistical considerations

This report describes analyses of annual questionnaire data up to 5 years after surgery (or an equivalent time if managed medically). As a general rule, in the tables and analyses presented in this report, the participants in the randomised groups are separate from those in the preference groups. A sizeable group of patients allocated to surgery did not receive surgery. Therefore, to investigate the potential influence of this non-compliance with allocation, summary statistics in the results tables are given for four main analysis populations (comprising eight groups of participants):

-

Randomised ITT population (groups that were randomised to either surgery or medical management).

-

Per-protocol (PP) population (groups that were either randomised to surgery and received surgery in the first year or randomised to medical management and did not receive surgery in the first year).

-

Preference ITT population (groups that preferred either surgery or medical management at recruitment).

-

Preference PP population (groups that either preferred surgery at recruitment and received surgery in the first year or preferred medical management and did not receive surgery in the first year).

The primary outcome measure (REFLUX QoL score) and secondary outcome measures (SF-36, EQ-5D, REFLUX symptom scores, anti-reflux surgery and use of reflux-related drugs) were analysed using general linear models. The analyses adjusted for the minimisation covariates (age, BMI and sex) and where appropriate (defined by significant at the 5% significance level) also adjusted for baseline measures and baseline measures by treatment interaction. A secondary, pre-stated subgroup analysis explored the differential effects of surgeon's preferred operative procedure on the primary outcome measure. All analyses were reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

The primary analysis of the randomised groups was by ITT. The ITT approach sustains the integrity of the randomisation and gives the least biased estimate of effectiveness of the two forms of management. Given that a sizeable minority of the randomised surgical participants did not receive surgery, we were also interested in estimating the efficacy of the initial treatment received as a secondary comparison (i.e. commonly known as a PP analysis). In an open trial design a PP analysis can have substantial selection bias. To minimise the effects of selection bias we used the method of ‘adjusted treatment received’ as described by Nagelkerke et al. 38 and others. 39,40 The method used a two-stage least-squares approach whereby treatment randomised was regressed onto treatment received and the residuals from that model were used as an independent variable in a second model, together with the treatment received, to estimate the effects on the various primary and secondary outcome measures.

For the preference study, only the primary outcome was analysed statistically. The analysis compared the preference surgical group with the preference medical group and adjusted for the minimisation factors. As described above, for logistical reasons and to maintain balance between the randomised and preference groups, we capped the number of preference participants at 20 per group per centre. The study design was not therefore a true comprehensive cohort. We did consider modelling differences between the randomised and preference groups; however, it is not universally accepted that formal modelling is appropriate in this context. In this case we knew from the randomised arms that there was a strong interaction between treatment effects and baseline REFLUX QoL, and in addition we knew that there was a large difference in QoL between preference arms at baseline (and patient demographics such as age and sex). We therefore decided that formal modelling of the arms would add little to the comparison given the large confounding between preference groups.

Sensitivity analyses

The sensitivity of the primary outcome analysis result was investigated using two approaches – the effect of excluding a large centre and the effects of missing data. In the first approach the largest recruiting centre, Aberdeen, was excluded and the analysis as described above was rerun. Second, previous work demonstrated that the primary outcome was likely missing at random (MAR) or missing completely at random (MCAR) and that a repeated measures analysis (using all available data) was an appropriate statistical method for analysing data up to 12 months. 41 We therefore used a repeated measures analysis on the primary outcome across all of the follow-up data (12 months to 5 years) to investigate the effect of incorporating a profile of measures for each participant. No further imputation for missing values was necessary.

Data monitoring

During recruitment, an independent DMC met on three occasions and each time saw no reason to recommend any fundamental changes to the protocol. The committee did not meet after recruitment was completed.

Chapter 3 Trial results and clinical effectiveness

Recruitment to the trial

Participants were recruited in 21 clinical centres, all within the UK (their locations are listed on the left-hand side of Table 1). Recruitment to the trial was open from March 2001 until the end of June 2004, although not all centres enrolled over the total period because of the staggered introduction of centres and early closure for logistical reasons in a few places. 1

| Randomised participants, n (%) | Preference participants, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical (n = 178) | Medical (n = 179) | Surgical (n = 261) | Medical (n = 192) | |

| Aberdeen: Aberdeen Royal Infirmary | 38 (21.3) | 40 (22.3) | 20 (7.7) | 21 (10.9) |

| Belfast: Royal Victoria Hospital | 15 (8.4) | 14 (7.8) | 4 (1.5) | 20 (10.4) |

| Bournemouth: Royal Bournemouth Hospital | 4 (2.2) | 3 (1.7) | 20 (7.7) | 3 (1.6) |

| Bristol: Bristol Royal Infirmary | 12 (6.7) | 11 (6.1) | 18 (6.9) | 20 (10.4) |

| Bromley: Princess Royal Infirmary | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.7) | 20 (7.7) | 17 (8.9) |

| Edinburgh: Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh | 11 (6.2) | 11 (6.1) | 1 (0.4) | 15 (7.8) |

| Guildford: Royal Surrey County Hospital | 10 (5.6) | 10 (5.6) | 17 (6.5) | 10 (5.2) |

| Hull: Hull Royal Infirmary | 7 (3.9) | 7 (3.9) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.0) |

| Inverness: Raigmore Hospital | 7 (3.9) | 8 (4.5) | 2 (0.8) | 8 (4.2) |

| Leeds: Leeds General Infirmary | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) | 10 (3.8) | 3 (1.6) |

| Leicester: Leicester Royal Infirmary | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) |

| London: St Mary's Hospital | 8 (4.5) | 7 (3.9) | 4 (1.5) | 10 (5.2) |

| London: Whipps Cross Hospital | 4 (2.2) | 3 (1.7) | 16 (6.1) | 5 (2.6) |

| Poole: Poole Hospital | 10 (5.6) | 10 (5.6) | 25 (9.6) | 13 (6.8) |

| Portsmouth: Queen Alexandra Hospital | 10 (5.6) | 10 (5.6) | 15 (5.7) | 1 (0.5) |

| Salford: Hope Hospital | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 6 (2.3) | 3 (1.6) |

| Stoke-on-Trent: North Staffordshire Hospital | 5 (2.8) | 6 (3.4) | 20 (7.7) | 9 (4.7) |

| Swansea: Morriston Hospital | 8 (4.5) | 8 (4.5) | 14 (5.4) | 9 (4.7) |

| Telford: Princess Royal Hospital | 11 (6.2) | 12 (6.7) | 24 (9.2) | 8 (4.2) |

| Yeovil: Yeovil District Hospital | 9 (5.1) | 8 (4.5) | 18 (6.9) | 8 (4.2) |

| York: York District Hospital | 5 (2.8) | 5 (2.8) | 3 (1.1) | 6 (3.1) |

| Total | 178 (100) | 179 (100) | 261 (100) | 192 (100) |

A total of 357 participants were recruited to the randomised component: 178 allocated to surgery and 179 allocated medical management. 453 participants agreed to join the preference component: 261 choosing surgery and 192 choosing medical management. Table 1 shows recruitment by centre. Around one-fifth of the randomised participants were enrolled in Aberdeen; no centre contributed > 10% of participants in the preference component.

Analysis populations

Throughout the analyses presented later in this chapter, the participants in the randomised component are kept separate from those in the preference component (other than for rare surgical events). The numbers of participants in each of the four main analysis populations are shown in Table 2. All 357 who joined the randomised component are in the randomised ITT population; only the 280 within this group who actually received their allocated management over the first year are in the randomised PP population. All 453 participants who joined the preference component are in the preference ITT population; the 407 of these who, by the end of the first year, were managed as originally chosen were in the preference PP population.

| Surgical, n (%) | Medical, n (%) | Total, n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised ITT | 178 (49.9) | 179 (50.1) | 357 |

| Randomised PP | 111 (39.6) | 169 (60.4) | 280 |

| Preference ITT | 261 (57.6) | 192 (42.4) | 453 |

| Preference PP | 218 (53.6) | 189 (46.4) | 407 |

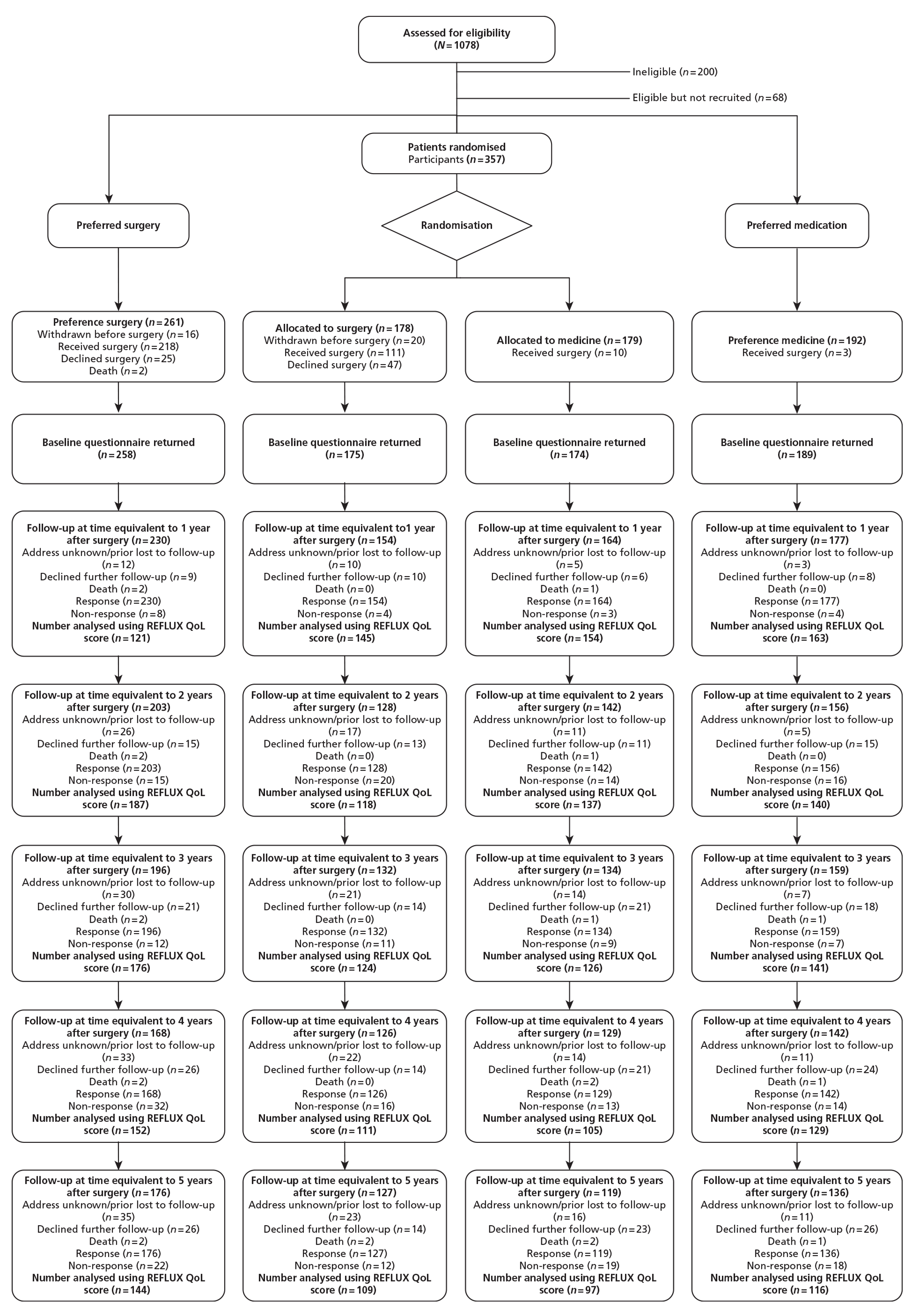

Trial conduct

The derivation of the main study groups and their progress through the stages of follow-up in the trial are shown in Figure 1. This is in the form of a CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) flow diagram. In total, 1078 patients were considered for trial entry and 200 of these were found not to meet one or more of the eligibility criteria. Of the 68 patients eligible for the study but not recruited, 51 declined to participate, six were subsequently deemed inappropriate for the study by the surgeon responsible for care and the remaining 11 were missed.

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT diagram.

Details of the clinical management actually received are described later in this chapter.

The mean (SD) time intervals in months between the receipt by the trial office of each subsequent annual postal questionnaire are shown in Table 3; all were near 12 months, as would be expected. There was, however, a difference between the randomised groups in the time interval between the 1-year and the 2-year questionnaires (mean 12.2 months surgical group vs 13.9 months medical group). In part, this was due to more late returns in the medical management group – the median intervals were closer: 12.00 and 13.00 months respectively. As described previously,1 early follow-up was adjusted to be at a time equivalent to 3 and 12 months after surgery. The adjustments in the medical group to match this could be only approximate and this is the explanation for the difference that remained between the randomised groups. An advantage of long-term follow-up to 5 years is that any difference in the timing of follow-up becomes proportionately smaller over time.

| Randomised participants | Preference participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical | Medical | Surgical | Medical | |

| ITT (n = 178) | ITT (n = 179) | ITT (n = 261) | ITT (n = 192) | |

| 1 year to 2 years | 12.2 (1.9) | 13.9 (3.1) | 12.4 (1.8) | 12.9 (4.6) |

| 2 years to 3 years | 11.8 (1.2) | 11.6 (1.2) | 11.6 (1.5) | 11.8 (1.2) |

| 3 years to 4 years | 12.0 (1.5) | 12.0 (1.4) | 12.1 (1.2) | 12.0 (1.1) |

| 4 years to 5 years | 11.8 (1.3) | 12.0 (1.3) | 12.1 (1.5) | 12.0 (1.3) |

More details of the response rates to the annual questionnaires are provided in Table 4. The overall rates of return of annual follow-up questionnaires (years 1–5) were 89.5%, 77.7%, 76.7%, 69.8% and 68.9% of the study participants. Seven participants are known to have died up to the end of the 5-year follow-up; equivalent response rates among those not known to have died are 89.8%, 77.9%, 77.0%, 70.2% and 69.5%. There were no substantive differences in response rates between the groups.

| Year | Category | Randomised participants, n (%) | Preference participants, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical (n = 178) | Medical (n = 179) | Surgical (n = 261) | Medical (n = 192) | ||

| 1 | Responded | 154 (87) | 164 (92) | 230 (88) | 177 (92) |

| Declined further follow-up | 10 (6) | 6 (3) | 9 (3) | 8 (4) | |

| Deceased | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Address unknown/lost to follow-up | 10 (6) | 5 (3) | 12 (5) | 3 (2) | |

| Non-responder | 4 (2) | 3 (2) | 8 (3) | 4 (2) | |

| 2 | Responded | 128 (72) | 142 (79) | 203 (78) | 156 (81) |

| Declined further follow-up | 13 (7) | 11 (6) | 15 (6) | 15 (8) | |

| Deceased | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Address unknown/lost to follow-up | 17 (10) | 11 (6) | 26 (10) | 5 (3) | |

| Non-responder | 20 (11) | 14 (8) | 15 (6) | 16 (8) | |

| 3 | Responded | 132 (74) | 134 (75) | 196 (75) | 159 (83) |

| Declined further follow-up | 14 (8) | 21 (12) | 21 (8) | 18 (9) | |

| Deceased | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Address unknown/lost to follow-up | 21 (12) | 14 (8) | 30 (11) | 7 (4) | |

| Non-responder | 11 (6) | 9 (5) | 12 (5) | 7 (4) | |

| 4 | Responded | 126 (71) | 129 (72) | 168 (64) | 142 (74) |

| Declined further follow-up | 14 (8) | 21 (12) | 26 (10) | 24 (13) | |

| Deceased | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Address unknown/lost to follow-up | 22 (12) | 14 (8) | 33 (13) | 11 (6) | |

| Non-responder | 16 (9) | 13 (7) | 32 (12) | 14 (7) | |

| 5 | Responded | 127 (71) | 119 (66) | 176 (67) | 136 (71) |

| Declined further follow-up | 14 (8) | 23 (13) | 26 (10) | 26 (14) | |

| Deceased | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Address unknown/lost to follow-up | 23 (13) | 16 (9) | 35 (13) | 11 (6) | |

| Non-responder | 12 (7) | 19 (11) | 22 (8) | 18 (9) | |

Three participants died before the 1-year follow-up was reached: two in the preference surgery group and one in the randomised medical group. None of these participants actually had surgery. Four died subsequently; there is no evidence linking these deaths to trial participation.

Description of the groups at trial entry

Sociodemographic and clinical factors

Table 5 provides a description of the groups at trial entry. The main division within the table is between participants in the randomised component and those in the preference component. These two halves of the table are further divided according to the allocation of participants and then subdivided according to ITT or PP.

| Characteristic | Randomised participants | Preference participants | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical | Medical | Surgical | Medical | |||||

| ITT (n = 178) | PP (n = 111) | ITT (n = 179) | PP (n = 169) | ITT (n = 261) | PP (n = 218) | ITT (n = 192) | PP (n = 189) | |

| Baseline questionnaire returned, n (%) | 175 (98.3) | 111 (100.0) | 174 (97.2) | 165 (97.6) | 256 (98.1) | 216 (99.1) | 189 (98.4) | 186 (98.4) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 46.7 (10.3) | 46.3 (10.2) | 45.9 (11.9) | 45.9 (11.9) | 44.4 (12.0) | 44.5 (12.2) | 49.9 (11.8) | 50 (11.7) |

| Male, n (%) | 116 (65.2) | 68 (61.3) | 120 (67.0) | 115 (68.0) | 170 (65.1) | 139 (63.8) | 111 (57.8) | 110 (58.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 28.5 (4.3) | 28.7 (4.1) | 28.4 (4.0) | 28.3 (4.0) | 27.7 (4.0) | 27.5 (3.7) | 27.4 (4.1) | 27.4 (4.1) |

| Duration of prescribed medication for GORD (months), median (IQR) | 33 (15–83) | 30 (16–76) | 31 (16–71) | 30 (15–71) | 35 (14–71) | 36 (14–65) | 27 (13–60) | 26.5 (13–60) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||||||||

| Employed full-time | 116 (66.3) | 72 (65.5) | 110 (61.8) | 104 (61.9) | 168 (65.1) | 138 (64.2) | 100 (52.4) | 97 (51.6) |

| Employed part-time | 13 (7.4) | 12 (10.9) | 16 (9.0) | 15 (8.9) | 35 (13.6) | 29 (13.5) | 20 (10.5) | 20 (10.6) |

| Student | 5 (2.9) | 3 (2.7) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.8) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.9) | 3 (1.6) | 3 (1.6) |

| Retired | 12 (6.9) | 9 (8.2) | 22 (12.4) | 20 (11.9) | 18 (7.0) | 16 (7.4) | 35 (18.3) | 35 (18.6) |

| Housework | 11 (6.3) | 6 (5.5) | 10 (5.6) | 10 (6.0) | 17 (6.6) | 15 (7.0) | 15 (7.9) | 15 (8.0) |

| Seeking work | 6 (3.4) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.2) | 5 (1.9) | 5 (2.3) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.1) |

| Other | 12 (6.9) | 7 (6.4) | 14 (7.9) | 14 (8.3) | 13 (5.0) | 10 (4.7) | 16 (8.4) | 16 (8.5) |

| Age (years) left full-time education, n (%) | ||||||||

| ≤ 16 | 110 (62.5) | 68 (62.4) | 108 (60.7) | 102 (60.7) | 151 (58.5) | 128 (59.3) | 105 (55.3) | 104 (55.6) |

| 17–19 | 38 (21.6) | 24 (22.0) | 40 (22.5) | 40 (23.8) | 63 (24.4) | 51 (23.6) | 45 (23.7) | 43 (23.0) |

| 20+ | 28 (15.9) | 17 (15.6) | 30 (16.9) | 26 (15.5) | 44 (17.1) | 37 (17.1) | 40 (21.1) | 40 (21.4) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 46 (25.8) | 29 (26.1) | 40 (22.3) | 36 (21.3) | 71 (27.2) | 61 (28.0) | 39 (20.3) | 39 (20.6) |

| Erosive oesophagitis, n (%) | 85 (54.8) | 48 (50.0) | 97 (62.2) | 91 (62.3) | 104 (46.4) | 80 (43.2) | 87 (50.9) | 86 (51.2) |

| Comorbidity: Helicobacter pylori status, n (%) | ||||||||

| Positive (subsequently treated) | 12 (9.0) | 5 (6.1) | 14 (10.4) | 13 (10.3) | 18 (8.4) | 14 (7.9) | 15 (10.5) | 15 (10.7) |

| Positive (subsequently untreated) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.2) | 3 (2.4) | 8 (3.7) | 8 (4.5) | 2 (1.4) | 2 (1.4) |

| Negative | 75 (56.4) | 48 (58.5) | 73 (54.1) | 67 (53.2) | 118 (54.9) | 101 (56.7) | 74 (51.7) | 72 (51.4) |

| Uncertain | 45 (33.8) | 29 (35.4) | 45 (33.3) | 43 (34.1) | 71 (33.0) | 55 (30.9) | 52 (36.4) | 51 (36.4) |

| Hiatus hernia present, n (%) | 94 (57.3) | 64 (61.0) | 102 (60.4) | 94 (59.1) | 168 (68.9) | 146 (71.2) | 101 (59.8) | 99 (59.6) |

| Asthma, n (%) | 21 (11.9) | 14 (12.7) | 21 (11.8) | 19 (11.3) | 30 (11.5) | 23 (10.6) | 36 (18.8) | 36 (19.0) |

Randomised arms

Within the randomised groups there were no apparent imbalances between the medical and surgical intervention arms. The patients were, on average, 46 years old, 66% were men, around two-thirds were in full employment and participants had been on GORD medication for a median of 32 months. The baseline characteristics in the randomised PP groups were similar.

Preference arms

The sociodemographic characteristics of the preference participants were broadly similar to those of the randomised participants. However, preference medical participants tended to be older (mean age 50 years) and were more likely to be female, fewer were in full-time employment and participants had been on GORD medication for a shorter period (approximately 6 months less than randomised participants).

Prescribed medications

The prescribed medications at the time of trial entry are shown in Table 6. There was a similar profile of prescribed medications across the randomised and preference groups. As would be expected, nearly all participants reported taking a reflux-related drug in the previous 2 weeks. Over 90% had taken a PPI, of which lansoprazole was the most common.

| Medication | Randomised participants | Preference participants | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical | Medical | Surgical | Medical | |||||

| ITT (n = 178) | PP (n = 111) | ITT (n = 179) | PP (n = 169) | ITT (n = 261) | PP (n = 218) | ITT (n = 192) | PP (n = 189) | |

| PPIs, n (%) | ||||||||

| Any PPI | 161 (92.0) | 105 (94.6) | 162 (93.1) | 153 (92.7) | 225 (87.9) | 191 (88.4) | 173 (91.5) | 170 (91.4) |

| Omeprazole | 46 (26.3) | 32 (28.8) | 46 (26.4) | 43 (26.1) | 49 (19.1) | 36 (16.7) | 61 (32.3) | 61 (32.8) |

| Lansoprazole | 77 (44.0) | 47 (42.3) | 72 (41.4) | 69 (41.8) | 100 (39.1) | 92 (42.6) | 69 (36.5) | 66 (35.5) |

| Pantoprazole | 6 (3.4) | 6 (5.4) | 11 (6.3) | 11 (6.7) | 21 (8.2) | 17 (7.9) | 11 (5.8) | 11 (5.9) |

| Rabeprazole | 12 (6.9) | 6 (5.4) | 13 (7.5) | 13 (7.9) | 21 (8.2) | 16 (7.4) | 14 (7.4) | 14 (7.5) |

| Esomeprazole | 20 (11.4) | 14 (12.6) | 20 (11.5) | 17 (10.3) | 37 (14.5) | 33 (15.3) | 18 (9.5) | 18 (9.7) |

| H2RAs, n (%) | ||||||||

| Any H2RA | 14 (8.0) | 6 (5.4) | 12 (6.9) | 9 (5.5) | 22 (8.6) | 16 (7.4) | 13 (6.9) | 13 (7.0) |

| Ranitidine | 13 (7.4) | 6 (5.4) | 8 (4.6) | 6 (3.6) | 11 (4.3) | 7 (3.2) | 11 (5.8) | 11 (5.9) |

| Famotidine | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Cimetidine | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nizatidine | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.2) | 3 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Over-the-counter H2RA | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.3) | 3 (1.8) | 7 (2.7) | 4 (1.9) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) |

| Prokinetics, n (%) | ||||||||

| Any prokinetics | 12 (6.9) | 7 (6.3) | 8 (4.6) | 6 (3.6) | 11 (4.3) | 10 (4.6) | 5 (2.6) | 4 (2.2) |

| Domperidone | 8 (4.6) | 5 (4.5) | 4 (2.3) | 3 (1.8) | 7 (2.7) | 6 (2.8) | 4 (2.1) | 3 (1.6) |

| Metoclopramide | 4 (2.3) | 2 (1.8) | 4 (2.3) | 3 (1.8) | 4 (1.6) | 4 (1.9) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Any reflux-related drug, n (%) | 170 (97.1) | 108 (97.3) | 169 (97.1) | 160 (97.0) | 235 (91.8) | 198 (91.7) | 184 (97.4) | 181 (97.3) |

| Other prescribed drugs, n (%)a | ||||||||

| Alginates | 22 | 12 | 21 | 18 | 37 | 33 | 14 | 13 |

| Antispasmodics (e.g. dicycloverine) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Chelates (e.g. sucralfate) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other ulcer-healing drugs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Mucogel® (Chemidex) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Asilone® (Thornton & Ross) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-gastrointestinal | 7 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Anti-nausea | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Health status

Randomised arms

The HRQoL scores at study entry are displayed in Table 7. The scores were broadly similar in the randomised surgical and randomised medical groups, although they were slightly higher (better health) in the randomised medical group. When the DMC first met after the initial 143 participants had been recruited to the randomised component, the committee did ask us to change the enrolment procedure to ensure that baseline questionnaires were completed before formal entry and randomisation. We understand that this was because they were concerned about an apparent imbalance between the randomised groups in baseline health status at that time. After satisfying themselves that this was not due to a breakdown in the randomisation procedure, the DMC surmised that this might be due to prior knowledge of the treatment allocation affecting questionnaire responses (with those allocated surgery tending to project worse health status than those allocated medical management). Certainly, the groups based on the first 143 participants were well balanced in other respects, and there was subsequently good balance in health status as well. The apparent small imbalance between the randomised groups in health status measures is therefore likely to be a reflection of the imbalance in the first 143 participants.

| HRQoL instrument | Randomised participants | Preference participants | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical | Medical | Surgical | Medical | |||||

| ITT (n = 178) | PP (n = 111) | ITT (n = 179) | PP (n = 169) | ITT (n = 261) | PP (n = 218) | ITT (n = 192) | PP (n = 189) | |

| REFLUX QoL, mean (SD) | 63.6 (24.1) | 61.9 (24.5) | 66.8 (24.5) | 68.2 (24.2) | 55.8 (23.2) | 55.9 (23.2) | 77.5 (19.7) | 78.0 (19.1) |

| REFLUX symptom score, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| General discomfort symptom score | 58.5 (24.5) | 57.1 (25.1) | 61.3 (25.8) | 62.4 (25.7) | 49.1 (24.4) | 48.7 (25.2) | 73.1 (21.3) | 73.6 (20.9) |

| Wind and frequency symptom score | 48.1 (20.9) | 46.2 (20.9) | 49.3 (21.4) | 49.5 (21.7) | 47.1 (21.4) | 47.5 (21.2) | 59.6 (22.7) | 59.8 (22.7) |

| Nausea and vomiting symptom score | 81.5 (19.5) | 81.6 (18.8) | 80.7 (21.9) | 81.6 (21.7) | 76.9 (19.9) | 77.5 (19.5) | 89.7 (13.6) | 90.1 (12.9) |

| Activity limitation symptom score | 78.5 (16.9) | 77.6 (16.3) | 78.9 (17.3) | 79.5 (17.1) | 74.4 (16.1) | 73.9 (16.2) | 86.8 (13.0) | 87.0 (13.0) |

| Constipation and swallowing symptom score | 77.5 (19.9) | 77.3 (20.3) | 74.8 (21.0) | 75.6 (20.4) | 75.8 (22.0) | 74.8 (22.6) | 83.0 (17.7) | 83.3 (17.6) |

| SF-36 score, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Norm-based physical functioning | 46.8 (10.2) | 46.1 (10.3) | 47.5 (10.5) | 47.7 (10.5) | 46.3 (9.4) | 46.1 (9.3) | 47.1 (10.8) | 47.0 (10.9) |

| Norm-based role physical | 46.9 (10.7) | 46.6 (10.8) | 46.8 (10.6) | 47.0 (10.4) | 44.7 (10.9) | 44.6 (10.7) | 46.7 (10.9) | 46.6 (10.9) |

| Norm-based bodily pain | 44.4 (10.1) | 44.1 (9.9) | 44.6 (10.4) | 44.9 (10.3) | 41.8 (9.5) | 41.9 (9.6) | 47.1 (9.8) | 47.2 (9.8) |

| Norm-based general health | 40.9 (9.9) | 40.2 (9.6) | 41.1 (10.6) | 41.4 (10.6) | 40.6 (10.2) | 40.8 (10.0) | 42.4 (10.0) | 42.4 (9.9) |

| Norm-based vitality | 43.5 (10.5) | 43.9 (10.3) | 44.0 (11.7) | 44.4 (11.4) | 42.8 (11.1) | 42.8 (11.3) | 45.5 (10.7) | 45.6 (10.7) |

| Norm-based social functioning | 44.4 (11.1) | 44.1 (10.6) | 44.7 (11.7) | 45.2 (11.5) | 42.2 (11.6) | 42.1 (11.5) | 46.8 (10.2) | 46.7 (10.2) |

| Norm-based role emotional | 46.6 (11.5) | 47.2 (11.5) | 45.8 (12.9) | 46.3 (12.6) | 45.9 (12.2) | 46.1 (12.1) | 46.9 (11.8) | 46.8 (11.8) |

| Norm-based mental health | 46.0 (11.6) | 46.9 (11.0) | 46.7 (11.6) | 47.1 (11.3) | 44.6 (11.4) | 44.6 (11.6) | 46.4 (10.7) | 46.3 (10.8) |

| EQ-5D, mean (SD) | 0.711 (0.258) | 0.718 (0.239) | 0.720 (0.255) | 0.732 (0.246) | 0.682 (0.259) | 0.679 (0.259) | 0.750 (0.223) | 0.752 (0.222) |

| EQ-5DVAS, mean (SD) | 68.6 (17.1) | 69.2 (15.9) | 70.5 (18.1) | 71.2 (17.6) | 67.2 (18.5) | 67.0 (18.5) | 71.3 (16.7) | 71.5 (16.6) |

The most prevalent reflux symptoms (those with lowest scores) were general discomfort and wind. The participants had lower SF-36 and EQ-5D scores than a normal UK population with the same average age and sex characteristics (SF-36 population norm approximately 50 for all domains; EQ-5D norm 0.88).

Preference arms

The preference for surgery participants reported worse REFLUX QoL scores and worse health in general than the preference for medicine participants. It can be seen from Table 7 that the randomised participants reported QoL measures in between these two extremes.

Baseline characteristics of groups compared at 5 years

There were differences in baseline characteristics between those who had completed a questionnaire at 5 years and those who had not (Table 8). For example, responders had a higher mean age (47.9 years vs 43.6 years), had been on prescribed medication for a shorter period at recruitment to the REFLUX trial (50.5 months vs 60.2 months) and had higher QoL scores at baseline (measured on the disease-specific REFLUX instrument, EQ-5D and SF-36).

| Characteristic | Responder (max. n = 558) | Non-responder (max. n = 252) | p-value (two- sided) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD), n | 27.9 (4.0), 557 | 28.2 (4.3), 252 | 0.37 |

| Age (years), mean (SD), n | 47.9 (11.2), 558 | 43.6 (12.2), 252 | < 0.01 |

| Sex, n/N (%) | |||

| Male | 343/558 (61) | 174/252 (69) | 0.04 |

| Female | 215/558 (39) | 78/252 (31) | – |

| Duration of prescribed medication (months), mean (SD), n | 50.5 (62.9), 544 | 60.2 (65.2), 250 | 0.05 |

| Erosive oesophagitis, n/N (%) | |||

| Yes | 262/493 (53) | 111/213 (52) | 0.78 |

| No | 231/493 (47) | 102/213 (48) | |

| Helicobacter pylori status, n/N (%) | |||

| Positive (subsequently treated) | 39/440 (9) | 20/186 (11) | 0.81 |

| Positive (subsequently untreated) | 9/440 (2) | 5/186 (3) | – |

| Negative | 238/440 (54) | 102/186 (55) | – |

| Uncertain | 154/440 (35) | 59/186 (32) | – |

| Hiatus hernia, n/N (%) | |||

| Yes | 330/524 (63) | 135/222 (61) | 0.58 |

| No | 194/524 (37) | 87/222 (39) | – |

| Age (years) left full-time education, n/N (%) | |||

| ≤ 16 | 304/552 (55) | 170/250 (68) | < 0.01 |

| 17–19 | 143/552 (26) | 43/250 (17) | – |

| 20+ | 105/552 (19) | 37/250 (15) | – |

| Employment status, n/N (%) | |||

| Full-time | 348/551 (63) | 146/251 (58) | 0.01 |

| Part-time | 65/551 (12) | 19/251 (8) | – |

| Student | 6/551 (1) | 7/251 (3) | – |

| Retired | 62/551 (11) | 25/251 (10) | – |

| Housework | 32/551 (6) | 21/251 (8) | – |

| Seeking work | 10/551 (2) | 6/251 (2) | – |

| Other | 28/551 (5) | 27/251 (11) | – |

| REFLUX QoL, mean (SD), n | 66.6 (24.2), 533 | 61.3 (24.1), 226 | < 0.01 |

| REFLUX symptom score, mean (SD), n | |||

| General discomfort symptom score | 61.1 (25.5), 544 | 55.4 (25.4), 231 | < 0.01 |

| Wind and frequency symptom score | 51.5 (21.7), 546 | 48.9 (23.0), 235 | 0.13 |

| Nausea and vomiting symptom score | 83.8 (18.3), 549 | 77.1 (21.5), 239 | < 0.01 |

| Activity limitation symptom score | 79.9 (16.1), 547 | 77.5 (17.4), 232 | 0.06 |

| Constipation and swallowing symptom score | 78.8 (20.0), 550 | 75.2 (21.7), 236 | 0.03 |

| EQ-5D, mean (SD), n | 0.735 (0.234), 544 | 0.662 (0.279), 239 | < 0.01 |

| SF-36 score, mean (SD), n | |||

| SF-36 physical | 45.2 (9.5), 530 | 44.0 (9.7), 232 | 0.10 |

| SF-36 mental | 46.3 (11.2), 530 | 42.7 (12.9), 232 | < 0.01 |

| Norm-based physical functioning | 47.2 (9.9), 545 | 46.1 (10.7), 239 | 0.15 |

| Norm-based role physical | 46.6 (10.7), 546 | 45.0 (11.0), 238 | 0.06 |

| Norm-based bodily pain | 45.1 (10.1), 546 | 42.3 (9.9), 236 | < 0.01 |

| Norm-based general health | 42.0 (9.8), 544 | 39.3 (10.7), 236 | < 0.01 |

| Norm-based vitality | 44.3 (10.8), 549 | 42.8 (11.4), 237 | 0.07 |

| Norm-based social functioning | 45.5 (10.8), 542 | 41.8 (12.0), 237 | < 0.01 |

| Norm-based role emotional | 47.0 (11.5), 543 | 44.5 (13.2), 239 | 0.01 |

| Norm-based mental health | 47.0 (10.6), 549 | 42.9 (12.4), 237 | < 0.01 |

| Any PPI, n/N (%) | 508/552 (92) | 213/242 (88) | 0.07 |

| Any reflux drug, n/N (%) | 530/552 (96) | 225/242 (93) | 0.07 |

However, the baseline characteristics of those in the randomised surgical and randomised medical groups who completed a questionnaire at 5 years were very similar, with the only notable difference being in BMI (Table 9). The mean baseline BMI among responders in the randomised surgical group was higher (29.0 kg/m2) than that for responders in the randomised medical management group (27.7 kg/m2). As described in Chapter 2, these results confirmed that a repeated measures analysis assuming no differential loss to follow-up could be considered.

| Characteristic | Surgical (max. n = 127) | Medical (max. n = 119) | p-value (two-sided) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD), n | 29.0 (4.3), 127 | 27.7 (3.8), 119 | 0.01 |

| Age (years), mean (SD), n | 48.5 (9.3), 127 | 46.4 (11.6), 119 | 0.12 |

| Sex, n/N (%) | |||

| Male | 79/127 (62) | 76/119 (64) | 0.79 |

| Female | 48/127 (38) | 43/119 (36) | – |

| Duration of prescribed medication (months), mean (SD), n | 57.2 (63.4), 124 | 46.3 (60.1), 117 | 0.17 |

| Erosive oesophagitis, n/N (%) | |||

| Yes | 63/111 (57) | 68/107 (64) | 0.35 |

| No | 48/111 (43) | 39/107 (36) | – |

| Helicobacter pylori status, n/N (%) | |||

| Positive (subsequently treated) | 6/96 (6) | 10/91 (11) | 0.52 |

| Positive (subsequently untreated) | 1/96 (1) | 2/91 (2) | – |

| Negative | 55/96 (57) | 45/91 (49) | – |

| Uncertain | 34/96 (35) | 34/91 (37) | – |

| Hiatus hernia, n/N (%) | |||

| Yes | 73/117 (62) | 71/114 (62) | 0.99 |

| No | 44/117 (38) | 43/114 (38) | – |

| Age (years) left full-time education, n/N (%) | |||

| ≤ 16 | 77/125 (62) | 70/119 (59) | 0.46 |

| 17–19 | 27/125 (22) | 31/119 (26) | – |

| 20+ | 21/125 (17) | 18/119 (15) | – |

| Employment status, n/N (%) | |||

| Full-time | 86/124 (69) | 76/118 (64) | 0.77 |

| Part time | 13/124 (10) | 10/118 (8) | – |

| Student | 2/124 (2) | 1/118 (1) | – |

| Retired | 9/124 (7) | 13/118 (11) | – |

| Housework | 4/124 (3) | 7/118 (6) | – |

| Seeking work | 4/124 (3) | 3/118 (3) | – |

| Other | 6/124 (5) | 8/118 (7) | – |

| REFLUX QoL, mean (SD), n | 65.9 (23.7), 121 | 68.6 (24.0), 110 | 0.38 |

| REFLUX symptom score, mean (SD), n | |||

| General discomfort symptom score | 60.1 (24.1), 123 | 63.9 (25.2), 115 | 0.23 |

| Wind and frequency symptom score | 48.0 (19.7), 125 | 48.7 (20.9), 117 | 0.78 |

| Nausea and vomiting symptom score | 82.9 (18.9), 125 | 84.7 (18.9), 117 | 0.46 |

| Activity limitation symptom score | 79.9 (15.2), 124 | 79.9 (16.8), 117 | 0.99 |

| Constipation and swallowing symptom score | 78.2 (19.2), 124 | 75.9 (20.0), 118 | 0.35 |

| EQ-5D, mean (SD), n | 0.736 (0.223), 122 | 0.755 (0.228), 118 | 0.51 |

| SF-36 score, mean (SD), n | |||

| SF-36 physical | 44.8 (10.0), 121 | 46.1 (9.1), 114 | 0.30 |

| SF-36 mental | 46.6 (11.0), 121 | 46.5 (11.1), 114 | 0.98 |

| Norm-based physical functioning | 46.8 (10.0), 123 | 48.4 (10.2), 117 | 0.22 |

| Norm-based role physical | 46.9 (10.8), 124 | 47.0 (10.8), 116 | 0.96 |

| Norm-based bodily pain | 44.6 (10.1), 123 | 45.7 (10.1), 117 | 0.39 |

| Norm-based general health | 41.4 (9.4), 124 | 42.4 (10.2), 116 | 0.41 |

| Norm-based vitality | 43.9 (10.4), 125 | 44.9 (11.2), 117 | 0.47 |

| Norm-based social functioning | 45.4 (10.5), 124 | 46.4 (10.8), 115 | 0.45 |

| Norm-based role emotional | 47.2 (11.4), 124 | 46.7 (12.1), 116 | 0.74 |

| Norm-based mental health | 47.3 (10.9), 125 | 48.0 (10.6), 117 | 0.60 |

| Any PPI, n/N (%) | 120/125 (96) | 109/118 (92) | 0.23 |

| Any reflux drug, n/N (%) | 124/125 (99) | 113/118 (96) | 0.08 |

Surgical management

Table 10 summarises the use of surgery in the four study groups over the full 5-year follow-up period. At the end of the first year, 111 participants (62.4%) randomised to surgery had actually undergone fundoplication. Over the next 4 years, one more member of this group had fundoplication, bringing the total to 112 (62.9%). In the randomised medical group, 10 participants (5.6%) had fundoplication in the first year, with a further 14 participants having fundoplication in subsequent years, bringing the total at 5 years to 24 (13.4%). In the preference surgical group, 218 participants (83.5%) had fundoplication in the first year, with four more in the period up to 5 years, taking the percentage to 85.1%. Surgical management applied to only three participants (1.6%) in the preference medical group in the first year, with a further three being operated on in the subsequent 4 years (total 3.1%).

| Surgery | Randomised participants | Preference participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical (n = 178) | Medical (n = 179) | Surgical (n = 261) | Medical (n = 192) | |

| First fundoplication in first year, n (%) | 111 (62.4) | 10 (5.6) | 218 (83.5) | 3 (1.6) |

| First fundoplication after first year, n | 1 | 14 | 4 | 3 |

| In second year | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| In third year | 0 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| In fourth year | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| In fifth year | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Fundoplication at any time during 5-year follow-up, n (%) | 112 (62.9) | 24 (13.4) | 222 (85.1) | 6 (3.1) |

Information about the reasons why participants allocated surgery did not receive it in the first year is available for 47. For 25 of these 47, this was a clinical decision, most commonly the surgeon deciding that surgery was not appropriate; most of the other 22 changed their minds about surgery for a variety of work- or home-related reasons. A further 20 withdrew for unknown reasons. There is no doubt, however, that a number of these participants suffered long delays before being formally offered surgery, and this was an important factor in their eventual decision to choose not to have surgery after all. The trial was conducted at a time when there was great pressure on surgical services in the NHS, with long delays for elective surgery for non-life-threatening benign conditions being common. Indeed, the average time between trial entry and surgery in the trial was 8–9 months. 1

Details of the surgery received by the 111 participants (62.4%) randomised to surgery and the 218 preference participants (83.5%) who actually received surgery in the first year, the perioperative complications that they experienced and their hospital stay have been reported previously but are summarised in Appendix 2 for completeness. There were no perioperative deaths.

Table 11 shows the numbers of those who had fundoplication who subsequently had a second reflux-related operation during the 5 years of follow-up. Overall, this applied to 16 participants (4.4%) among the 364 who had a first operation: five (4.5%) in the randomised surgery group; one (4.2%) in the randomised medical group; eight (3.6%) in the preference surgery group; and two (33.3%) in the preference medical group. In total, five of the 16 operations were reconstructions of the same wrap, three were repairs of hiatus hernia only, six were conversions to a different type of wrap and two were reversals of the fundoplication. Two of these 16 participants had a third reflux-related operation; both were in the preference surgery group – one a reconstruction of the same wrap and one a repair of hiatus hernia only.

| Surgery | Randomised participants | Preference participants | Total cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical (n = 178) | Medical (n = 179) | Surgical (n = 261) | Medical (n = 192) | ||

| First fundoplication operation at any time, n | 112 | 24 | 222 | 6 | 364 |

| Second reflux-related reoperation, n (%) | 5 (4.5) | 1 (4.2) | 8 (3.6) | 2 (33.3) | 16 (4.4) |

| Reconstruction of same wrap | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Repair of hiatus hernia only | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Conversion of type of wrap | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 6 |

| Reversal of fundoplication | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Third reflux-related reoperation, n | |||||

| Reconstruction of same wrap | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Repair of hiatus hernia only | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Conversion of type of wrap | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reversal of fundoplication | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Late postoperative complications

Table 12 describes late postoperative complications among those participants who had surgery, in each of the study groups and overall. Of the total 364 who had fundoplication, 12 (3.3%) had a late complication: four (1.1%) were oesophageal dilatations/stricture dilatations; three (0.8%) were repairs of incisional hernias; and five (1.4%) were a heterogeneous group of other complications as detailed in the table.

| Complication | Randomised participants | Preference participants | Total cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical (n = 178) | Medical (n = 179) | Surgical (n = 261) | Medical (n = 192) | ||

| First fundoplication operation at any time | 112 | 24 | 222 | 6 | 364 |

| Late postoperative complications (within first year of original operation), n | |||||

| Oesophageal dilatation/stricture dilatation | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Repair of incisional hernia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Other (admission for deep-vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Late postoperative complications (within second year following operation), n | |||||

| Oesophageal dilatation/stricture dilatation | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Repair of incisional hernia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other (pain from operation; hole between stomach and liver) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Late postoperative complications (beyond second year), n | |||||

| Oesophageal dilatation/stricture dilatation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Repair of incisional hernia | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |