Notes

Article history paragraph text

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 01/01/03. The contractual start date was in June 2003. The draft report began editorial review in June 2010 and was accepted for publication in November 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

H Barr received money from pharmaceutical companies for consultancy, travel and accommodation.

Dedication

We dedicate this report to the memory of Ceri Margaret Bray (1957–2008), first trial manager, whose energy and dedication were crucial to COGNATE's success.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Russell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

In the UK, cancer of the upper gastrointestinal tract (oesophageal or gastric, or both) affects some 13,000 patients each year. Gastro-oesophageal cancer is the fifth most frequently occurring cancer in the UK and the fourth most common cause of cancer death. 1,2

Many Western series have described recent changes in the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal cancer, characterised by reduced incidence of distal gastric cancer and increased incidence of proximal gastric and distal oesophageal cancer. 3 Furthermore the incidence of these cancers varies between regions, with more oesophageal adenocarcinoma in Scotland (18 per 100,000) than in England (13 per 100,000). 1,4

Most community-based series show that cancer of the stomach or oesophagus mostly affects the elderly and often causes significant morbidity. The Scottish Audit of Gastric and Oesophageal Cancer (SAGOC)4 reported a median age of 72 years for patients with gastric or oesophageal cancer; this was similar to that in the recent National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Audit (NOGCA) in England and Wales, initiated by the Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland (AUGIS). 5 In both studies, tumours were unusual in patients who were < 40 years old. About 40% of patients with upper gastrointestinal cancer have significant comorbid disease at presentation and about one-sixth are in bed for more than half of the time.

The general prognosis of patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer is poor, with a median survival after diagnosis among all patients in 1997–99 of 8 months. 4 Although survival had improved by 2005, 5-year survival remained poor at 7% for oesophageal cancer and 12% for gastric cancer. 6 However survival depends on tumour stage and patient characteristics, and there have been many advances in the treatment of these tumours, both curative and palliative. So it is important to select the most appropriate management plan for each patient.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS; or endosonography) is a medical procedure performed by gastroenterologists, radiologists or surgeons with specialised training. Endosonography combines endoscopy – the insertion of a probe into the upper gastrointestinal tract – with ultrasonography. It places a high-frequency ultrasound probe mounted on the end of the endoscope in direct contact with oesophageal or gastric tumours. This provides good images of the structures of the bowel wall and local lymph nodes, but is less good at identifying distant metastases. To patients it feels very similar to normal endoscopy, unless it includes ultrasound-guided biopsy of deeper structures. Although biopsy may increase risk, the basic procedure is no more risky than an endoscopy.

The literature review (see Literature review) shows that EUS has potential to provide accurate staging of gastric and oesophageal tumours, rather than associated nodes. It can therefore provide important prognostic information to guide management. However, as the link between better staging and better management is not proven, the benefit of EUS is not clear.

So we designed the trial known as Cancer of Oesophagus or Gastricus: New Assessment of Technology of Endosonography (COGNATE) to evaluate, not the accuracy of EUS, but the effect it has on patient management and thus outcome. Accordingly the choice of treatment was an important intermediate outcome. It was also crucial to follow patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer who had not been selected for surgery as well as those selected; if EUS leads to more or less surgery, it is as important to measure effects on patients who do not receive surgery as on patients who do. Although this comprehensive approach is a central feature of COGNATE, the literature review (see Literature review) shows that many assessments of the effect of staging lack this breadth.

The COGNATE trial therefore monitored the outcome of treatment to detect increased mortality or morbidity. If it generates evidence that EUS improves choice of treatment, this will benefit, not only individual patients, but the whole population of patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer, through better targeting of scarce resources. Thus the National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment (NCCHTA) commissioned COGNATE to evaluate whether EUS is effective and cost-effective in the management of gastro-oesophageal cancer. There is no other published or current randomised trial that addresses this issue of importance to the care of cancer in the NHS. In short, COGNATE aims to estimate the value of EUS in managing gastro-oesophageal cancer.

Literature review

Treatment

Endoscopic treatment

For patients with early gastro-oesophageal cancer, endoscopic treatments, notably endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), can achieve long-term cure without the risk and morbidity of surgery. The risk of a major complication (e.g. perforation or bleeding) is approximately 1%. 7 If the tumour is localised to the mucosa, EMR is likely to lead to long-term survival with a 5-year disease-free survival rate of 99% and a general 5-year survival rate of 84%. 8 Even in patients with early submucosal changes, EMR may be the treatment of choice. As the tumour invades deeper, however, there is an increased risk of lymphatic involvement needing a surgical approach. 9–11

Surgery

Surgery for gastro-oesophageal cancer is a major therapeutic intervention with substantial postoperative morbidity and mortality. Even in patients surviving surgery, quality of life deteriorates and may take several months to recover to the preoperative state. Indeed patients who die within 2 years of oesophageal surgery seldom recover their preoperative quality of life. 12,13 Hence it is important to restrict surgery with curative intent to patients likely to achieve long-term survival. Both the ability of surgeons to achieve complete resection of the tumour (R0) by removing all macroscopic and microscopic lesions and the outcome of that surgery depend on the fitness of the patient and the extent of the tumour at the time of surgery.

Patients in whom complete resection is possible have a significant survival advantage over those whose resections are incomplete. 4 Indeed incomplete resection of oesophageal cancers increases neither length nor quality of survival. 14 The most common reason for incomplete resection in patients with oesophageal cancer is residual tumour in the resection margins. 15,16 The presence of metastases in lymph nodes also reduces general and disease-free survival. 4

Neo-adjuvant therapy

The development of effective chemotherapy regimens for patients with advanced disease has led to the introduction of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy before surgery for both oesophageal and gastric cancer. A Cochrane review of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in oesophageal cancer, based on 2000 patients in 11 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), showed a survival advantage at 5 years for chemotherapy before surgery compared with surgery alone. 17 However the two largest trials included in this review yielded conflicting results. The Medical Research Council (MRC)-funded trial of fluorouracil (5FU) and cisplatin before surgery compared with surgery alone showed a median survival advantage of 4 months in the neo-adjuvant arm. 18 However a similar trial from the USA19 failed to show any effect of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. Nevertheless meta-analysis of all trials shows a survival advantage after 5 years for neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in operable oesophageal cancer.

In gastric cancer, meta-analysis of trials of chemotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone showed a small survival benefit from chemotherapy, particularly for lymph-node-positive disease; however toxicity was significant. 20 A large RCT comparing surgery alone with chemoradiotherapy after surgery showed a survival benefit from chemoradiotherapy, but sustained criticism for not controlling the quality of surgery. 21 The MRC-funded trial of chemotherapy before and after surgery compared with surgery alone showed significantly better 5-year survival in the chemotherapy group – 36% compared with 23%. 22

Multimodal treatment

Although surgery-based treatment remains the norm for the treatment of gastro-oesophageal cancer, external-beam radiotherapy alone has achieved excellent results for oesophageal cancer. 23–25 Concomitant chemoradiotherapy is also effective for oesophageal cancer. 26–28 However there is no evidence that external-beam radiotherapy alone is adequate for gastric cancer. The few RCTs comparing external-beam radiotherapy with surgery alone have been underpowered. Similarly, the two RCTs that have compared chemoradiotherapy before surgery with chemoradiotherapy alone have not shown any benefit to either treatment. 29,30 A study from China31 showed no difference between surgery and chemoradiotherapy alone for the treatment of squamous cell oesophageal cancer.

In advanced localised oesophageal cancer there is good evidence that chemoradiotherapy is superior to external-beam radiotherapy alone in achieving long-term survival and improving swallowing. 28,32,33 In gastric cancer, however, radiotherapy is more difficult.

Staging and treatment selection

It is clear from both SAGOC4 and NOGCA5 that there is variation in the selection of patients for different treatments. Operation rates in the Scottish audit varied by tumour type: oesophageal cancer 31%; gastro-oesophageal junction tumours 38%; and gastric cancers 51%. There was even greater variation between centres in operation rates: oesophageal cancer 20–42%; junction cancer 25–64%; and gastric cancer 32–63%. 4 The NOGCA report5 showed similar variation in patients selected for curative surgery.

The general criteria for treatment selection are stage of the tumour at presentation, along with patient's fitness, and ability and willingness to undergo specific treatments. Patient fitness depends on comorbid disease. Management decisions depend on the interaction of all of these factors. In addition they increasingly depend on markers of the biological behaviour of a tumour. For gastro-oesophageal cancer these may include tumour differentiation, growth characteristics, response to chemotherapy and molecular mechanisms.

Tumour staging

Accurate assessment of tumour stage at presentation will inform subsequent management decisions by indicating likely prognosis and the feasibility of specific treatments.

For gastro-oesophageal cancer the issues are:

-

Is EMR treatment likely to be possible?

-

Does surgical resection have a high probability of complete resection?

Staging is also important for meaningful comparisons between trials. Much of the uncertainty in comparing treatment options arises from inaccurate staging.

Tumour staging summarises anatomical measurements of the extent of direct invasion by a tumour (T); the involvement of lymph nodes (N); and the presence of distant metastases (M). The most common staging investigations used for patients with upper gastrointestinal cancer are computed tomography (CT) scanning, and EUS. In SAGOC4 69% of patients received CT. In NOGCA5 most patients received CT but the rate fell with increasing age and in patients with poor performance status. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and integrated positron emission tomography and computed tomography (PET-CT) scanning are less common. For gastric cancer, laparoscopy can add considerably to these imaging techniques.

Endoscopic ultrasound

Endoscopic ultrasonography was introduced in the early 1980s. However it became accepted practice only in the 2000s. For example the EUS rate was 3% in SAGOC undertaken in the late 1990s,4 but 48% (gastric) and 58% (oesophageal) in NOGCA5 undertaken some 10 years later. In this review we consider the accuracy of EUS for both gastric and oesophageal cancers, and for both T and N stages.

Search strategy

The first systematic review of EUS in gastro-oesophageal cancer dates from 2001. 34 Two recent updates on EUS in oesophageal35 and gastric cancer36 reviewed studies up to 2006. As these reviews used similar search strategies, we used that strategy to identify articles up to October 2009. Specifically, we searched MEDLINE, PubMed, Ovid journals and The Cochrane Library for articles including all the following terms: endoscopic ultrasound or endosonography; oesophageal cancer or gastric cancer; tumour staging; invasion and surgery. We excluded studies that did not define tumour location clearly, those that did not confirm findings by surgery and those with fewer than 10 patients. Of studies from the same centre reporting the same data, we included only the most up-to-date reports. In contrast to previous systematic reviews, we classified tumours of the gastro-oesophageal junction as oesophageal cancers.

Gastric cancers

We identified 29 studies, with 2500 patients, that reported on the accuracy of EUS staging for gastric cancer between 1988 and 2009;37–65,21,37–41,43–45,47,48,50–53,56,57,59,62–65 used radial ultrasound probes, three49,58,60 used linear array probes and five42,46,54,55,61 did not report the type of probe (Table 1). As the reported accuracy of linear array probes for both T and N stages did not differ from that of the rest, we include them here.

| Study | Design | Number of patients | Transducer | Accuracy (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T stage | N stage | ||||

| Murata 198853 | Prospective | 146 | Radial | 79 | 88 |

| Tio 198959 | Prospective | 72 | Radial | 84 | 66 |

| Botet 199143 | Prospective | 50 | Radial | 92 | 78 |

| Saito 199157 | Prospective | 110 | Radial | 86 | Unspecified |

| Akahoshi 199138 | Prospective | 74 | Radial | 81 | 50 |

| Rosch 199265 | Consecutive | 41 | Radial | 71 | 75 |

| Grimm 199348 | Prospective | 147 | Radial | 78 | Unspecified |

| Dittler 199345 | Consecutive | 254 | Radial | 83 | 66 |

| Ziegler 199364 | Prospective | 108 | Radial | 86 | 74 |

| Caletti 199344 | Prospective | 42 | Radial | 91 | 69 |

| Perng 199654 | Consecutive | 69 | Unspecified | 71 | 65 |

| Massari 199652 | Prospective | 65 | Radial | 89 | 68 |

| Francois 199646 | Consecutive | 29 | Unspecified | 79 | 79 |

| Hunerbein 199649 | Consecutive | 60 | Linear | 65 | 73 |

| Wang 199861 | Consecutive | 119 | Unspecified | 70 | 65 |

| Willis 200062 | Consecutive | 116 | Radial | 78 | 77 |

| Xi 200363 | Prospective | 35 | Radial | 80 | 69 |

| Shimoyama 200458 | Consecutive | 45 | Linear | 71 | 80 |

| Polkowski 200455 | Prospective | 88 | Unspecified | 63 | 47 |

| Javaid 200450 | Consecutive | 112 | Radial | 83 | 64 |

| Bhandari 200442 | Prospective | 48 | Unspecified | 88 | 79 |

| Tsendsuren 200660 | Consecutive | 41 | Linear | 68 | 66 |

| Arocena 200640 | Prospective | 17 | Radial | 35 | 42 |

| Potrc 200656 | Prospective | 82 | Radial | 68 | 57 |

| Ang 200639 | Prospective | 57 | Radial | 77 | 60 |

| Ganpathi 200647 | Consecutive | 109 | Radial | 80 | 78 |

| Bentrem 200741 | Prospective | 225 | Radial | 57 | 50 |

| Lok 200851 | Prospective | 123 | Radial | 64 | 75 |

| Ahn 200937 | Prospective | 68 | Radial | 90 | 90 |

The pooled accuracy of EUS for gastric T stage was 76.2% (range 35–92%). Accuracy was 71.2% for studies reported before 2000, and slightly but not significant less than 80.4% for studies after 2000. This is consistent with Puli et al. ,36 who reported no difference between studies published in the 1980s, 1990s or 2000s. 36 Their review also compared the sensitivity and specificity of EUS at different T stages of gastric cancer with the pathology from resected specimens in 22 studies with 1900 patients (Table 2).

| T stage | Pooled sensitivity (range) | Pooled specificity (range) |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | 88.1 (84.5–91.1) | 100 (99.7–100) |

| T2 | 82.3 (78.2–86.0) | 95.6 (94.4–96.6) |

| T3 | 89.7 (87.1–92.0) | 94.7 (93.3–95.9) |

| T4 | 99.2 (97.1–99.9) | 96.7 (95.7–97.6) |

Thus sensitivity for tumour invasion is high for T1, lower for T2, and then improves as tumours become more advanced. In contrast, specificity is very high for all stages of disease, but highest for T1. Hence if EUS shows T1 disease, the patient probably has anatomical T1 disease. In contrast, if EUS shows T2 disease, the patient may have anatomical T1 disease. So EUS can result in overtreatment, subjecting patients to resectional surgery rather than EMR in the first instance.

The pooled diagnostic accuracy of EUS for nodal staging of gastric cancers was 67.9% (range 42–90%), lower than for T stage as reported in previous studies. 34,36 However it is likely that the use of linear array probes and fine-needle cytology increases that accuracy.

Comparison of endoscopic ultrasound and computed tomography

Six studies compared the diagnostic accuracy of CT with that of EUS for both T and N stages (Table 3). Diagnostic accuracy for both T and N staging was higher for EUS than for CT. However the last two studies showed high levels of diagnostic accuracy for both EUS and CT, probably because they were the only studies to use multi-detector row-computed tomography (MDCT). The superiority of MDCT over conventional CT is also apparent in a review by Kwee and Kwee,66 assessing different imaging modalities for lymph node status in gastric cancer. Nevertheless this review concluded that neither EUS nor MDCT reliably excluded or confirmed the presence of lymph node metastases in gastric cancer. In a separate review, Kwee and Kwee67 concluded that EUS was the best imaging modality for T staging of gastric cancer.

Influence of endoscopic ultrasound on management

Although the accuracy of EUS in staging gastric cancer is thus well reported, there are few studies examining the effect of EUS staging on subsequent management. Dittler and Siewert45 found that EUS predicted complete (R0) resection of gastric tumours in 81% of 254 consecutive gastrectomies, close to the achieved complete resection rate of 78%. Javaid et al. 50 also describe a high complete resection rate in patients predicted by EUS. A Chinese study of only 35 patients reported that the sensitivity of EUS for resection rates was 88% and the specificity 100%. 63

However the accuracy of EUS for T1 tumours is less than for T4 tumours. With conventional 7.5-Hz or 12-Hz endoscopic transducers it is difficult to determine whether a tumour is limited to the gastric mucosa or invading the submucosa and to what extent. It is this distinction that enables EUS to predict the success of EMR. The review by Kwee and Kwee68 of the few studies that address this point is uncertain whether EUS can accurately differentiate between mucosal and deeper gastric cancers.

Oesophageal cancers

We identified 40 studies, with 2600 patients, which reported on the accuracy of EUS staging for oesophageal cancer between 1986 and 2009 (Table 4). 48,49,53,59,65,69–103 The pooled accuracy for T stage was 78.5% (range 59–93%) and for N stage 76.3% (range 60–90%). As with gastric cancer, there was no significant evidence that accuracy improved with time. Indeed the studies with the highest diagnostic accuracy were all undertaken before 2000.

| Study | Design | Number of patients | Accuracy (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T stage | N stage | |||

| Murata 198853 | Consecutive | 173 | 88 | 88 |

| Tio 198959 | Prospective | 91 | 90 | 82 |

| Vilgrain 199069 | Consecutive | 46 | 73 | Unspecified |

| Botet 199170 | Prospective | 50 | 92 | 88 |

| Rice 199171 | Consecutive | 22 | 59 | 70 |

| Ziegler 199172 | Prospective | 37 | 89 | 69 |

| Rosch 199265 | Consecutive | 44 | 82 | 70 |

| Dittler 199373 | Consecutive | 167 | 86 | 73 |

| Grimm 199348 | Prospective | 63 | 86 | 86 |

| Hordijk 199374 | Consecutive | 41 | 76 | Unspecified |

| Yoshikane 199477 | Consecutive | 28 | 75 | 72 |

| Greenberg 199475 | Prospective | 16 | 85 | 60 |

| Peters 199476 | Consecutive | 34 | 76 | 82 |

| Binmoeller 199578 | Prospective | 38 | 89 | 79 |

| McLoughlin 199579 | Consecutive | 15 | 86 | Unspecified |

| Hasegawa 199680 | Consecutive | 22 | 76 | 67 |

| Holden 199681 | Consecutive | 15 | 87 | 73 |

| Hunerbein 199649 | Consecutive | 19 | 84 | 88 |

| Massari 199783 | Prospective | 55 | 90 | 87 |

| Natsugoe 199682 | Consecutive | 37 | Unspecified | 86 |

| Pham 199884 | Consecutive | 28 | 61 | 75 |

| Vickers 199885 | Prospective | 50 | 92 | 86 |

| Bowrey 199986 | Prospective | 30 | 93 | 80 |

| Catalano 199987 | Prospective | 145 | Unspecified | 73 |

| Nishimaki 199988 | Consecutive | 166 | Unspecified | 72 |

| Salminen 199989 | Consecutive | 26 | 66 | 72 |

| Heidemann 200090 | Consecutive | 68 | 79 | 79 |

| Nesje 200091 | Prospective | 54 | 70 | 90 |

| Vazquez 200192 | Consecutive | 64 | Unspecified | 70 |

| Kienle 200293 | Prospective | 117 | 69 | 79 |

| Chang 200394 | Prospective | 60 | 83 | 89 |

| Wu 200395 | Prospective | 31 | 84 | 71 |

| DeWitt et 200596 | Prospective | 102 | 72 | 75 |

| Lowe 200597 | Prospective | 75 | 71 | 81 |

| Moorjani 200799 | Prospective | 50 | 64 | 72 |

| Shimpi 2007100 | Prospective | 42 | 76 | 89 |

| Kutup 200798 | Prospective | 214 | 66 | 64 |

| Sandha 2008102 | Prospective | 16 | 80 | 81 |

| Mennigen 2008101 | Prospective | 97 | 73 | 74 |

| Takizawa 2009103 | Prospective | 159 | Unspecified | 64 |

In a systematic review of EUS in the staging of gastro-oesophageal cancer, Kelly et al. 34 found that non-traversability of oesophageal cancers and tumours at the gastro-oesophageal junction reduced diagnostic accuracy of EUS staging, but not significantly. In contrast Hordijk et al. 74 found that accuracy was about 90% whether tumours were traversable or not, but fell to 46% for tumours that had been dilated. Accordingly we postulate that differences between studies may arise from the percentage of non-traversable tumours and the method of dealing with these. Two other studies78,85 found a significant reduction in diagnostic accuracy in stenosed oesophageal tumours and suggested that this may be because all the tumours were T3 or T4 with a high rate of lymph node involvement. Kelly et al. 34 also identified junctional tumours as a potential, but not statistically significant, source of diagnostic inaccuracy owing to the difficulty in getting contact between the probe and the tumour surface. As few studies report the exact location of tumour sites, there is uncertainty whether this is a confounding variable.

As with gastric cancer, the accuracy of EUS was better in more advanced oesophageal cancers; specificity is high at all tumour stages, whereas sensitivity increases for T3 and T4 tumours (Table 5). 35 This suggests a slight tendency for EUS also to overestimate oesophageal T stage.

| T stage | Pooled sensitivity (range) | Pooled specificity (range) |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | 81.6 (77.8–84.9) | 99.4 (99.0–99.7) |

| T2 | 81.4 (77.5–84.8) | 96.3 (95.4–97.1) |

| T3 | 91.4 (89.5–93.0) | 94.4 (93.1–95.5) |

| T4 | 92.4 (89.2–95.0) | 97.4 (96.6–98.0) |

Two meta-analyses35,104 have reported sensitivities above 80% and specificities about 80% for EUS in estimating lymph node involvement in patients with oesophageal cancer. Puli et al. 35 also found four studies that combined EUS with fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and increased sensitivity to 97% (range 92–99%) and specificity to 95% (range 91–98%). In contrast, Van Vliet et al. 104 found no improvement in accuracy by combining FNAC and EUS. However they did find five studies that analysed results for mediastinal lymph nodes separately from those for coeliac lymph nodes, which had a higher sensitivity of 85% (range 72–99%) and a higher specificity of 96% (range 92–100%). It is likely that these high accuracies for FNAC and coeliac nodes were in specialised centres. The identification of coeliac lymph node involvement may have greater potential to improve management as this suggests metastatic disease in patients with oesophageal cancer, and thus precludes surgery.

Endoscopic ultrasound compared with computed tomography scanning

Endoscopic ultrasound staging consistently has higher diagnostic accuracy than CT staging for both T and N stages (Table 6). Unlike gastric cancer, there is no reported comparison of EUS with the most up-to-date CT techniques. Although there are few studies comparing EUS with MRI or PET scanning, these are not generally more accurate than CT for local regional upper gastrointestinal cancers.

| Study | Number of patients | Stage | EUS (%) | CT (%) | MRI (%) | PET (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botet 199170 | 50 | T | 92 | 60 | ||

| N | 88 | 74 | ||||

| Ziegler 199172 | 37 | T | 89 | 51 | ||

| N | 69 | 51 | ||||

| Greenberg 199475 | 28 | T | 85 | 15 | ||

| N | 60 | 50 | ||||

| Holden 199681 | 15 | T | 87 | 40 | ||

| N | 73 | 33 | ||||

| Massari 199783 | 55 | T | 90 | 50 | ||

| N | 87 | 39 | ||||

| Kienle 200293 | 117 | T | 69 | 33 | ||

| N | 79 | 67 | ||||

| Wu 200395 | 31 | T | 84 | 68 | 60 | |

| N | 71 | 78 | 64 | |||

| Lowe 200597 | 69 | T | 71 | 42 | 42 | |

| N | 81 | 80 | 76 | |||

| Sandha 2008102 | 16 | T | 80 | |||

| N | 81 | 69 | 56 |

Influence of endoscopic ultrasound on management

The accuracy of EUS staging is as well reported for oesophageal cancer as for gastric cancer. Again, however, there are few studies examining the effect of EUS staging on subsequent management. In their systematic review, Dyer et al. 105 acknowledged that drawing conclusions from observational studies, rather than RCTs, was open to bias, but estimated that EUS appeared to change management in 24–29% of patients. Two retrospective,106,107 and therefore suspect, studies examined the effect of EUS staging on patient survival. The first study106 reported significantly better survival and reduced recurrence rate following better selection of patients for surgery and neo-adjuvant treatment; although the second study107 found no advantage from EUS staging, it omitted to report on patients declined for surgery. Neither study reported on quality of life.

Summary

Many studies have assessed the accuracy of EUS in the staging of gastro-oesophageal cancer. The pooled rates for T stage suggest accuracy of 76% for gastric cancer and 78% for oesophageal cancer; those for N stage suggest accuracy of 68% for gastric cancer and 76% for oesophageal cancer. Furthermore accuracy improves for more advanced tumours. These estimates of accuracy are consistently better than those achieved with other imaging modalities, most often CT scanning. However there is little rigorous evidence as to whether increased accuracy translates into improvements in patient management, still less patient outcomes.

However the management of gastro-oesophageal cancer depends, not only on staging accuracy, but also on patient factors like fitness and willingness for treatment, and treatment factors like benefits and risks. Many patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer have substantial comorbid disease. Often this determines treatment selection irrespective of tumour stage. For other patients the differentiation between T2 and T3 tumours may have little influence on treatment selection, as it is unclear how this affects prognosis or whether treatment should differ between these tumours. So increased accuracy from EUS may be most valuable in discriminating between T3 and T4 tumours and judging whether complete resection is feasible; and between T1 and T2 tumours and judging whether endoluminal treatment is feasible.

Nodal status is another important prognostic indicator for gastro-oesophageal cancer, but it is less clear how this should affect management decisions. Patients with tumours that are N-positive and T3 or T4 will generally fare worse than those with less advanced tumours. Nevertheless we do not know whether and how the outcome for patients with more advanced tumours depends on the choice between curative and palliative treatment.

In short, the known accuracy of EUS in staging gastro-oesophageal cancer makes it important to evaluate whether this staging modality significantly affects the management of gastro-oesophageal cancer. Only a RCT of all patients eligible for EUS can answer that question.

Philosophy

Evaluative paradigm

There has been no formal evaluation of EUS, merely recommendations that it was essential in staging oesophageal cancers. 108 Nevertheless the 2008 NOGCA5 showed that even cancer networks do not universally use EUS to stage oesophageal cancers. Staging non-traversable tumours is difficult;34 the majority are T3 or T4 lesions, which need good staging to avoid non-curative resections. EUS is least accurate in carcinomas around the gastro-oesophageal junction,34 incidence of which is increasing rapidly. Another problem is that there are few studies comparing the cost-effectiveness of EUS with that of modern CT protocols. 34

In summary, although there is evidence that EUS improves anatomical staging of patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer, it is not clear how it affects patient management, even less how it affects patient outcome. SAGOC showed that between 1997 and 2000 few patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer underwent EUS. 4 The subsequent growth in use of EUS in gastro-oesophageal cancer, documented in NOGCA, reinforces the case for evaluating the contribution of EUS to management.

It is also important to study which patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer benefit from EUS. At first sight three types of cancer have the best chance:

-

T1 tumours localised to the mucosa, in which endoscopic treatment may avoid unnecessary surgery.

-

Tumours for which EUS may predict the outcome of ‘curative’ surgery, in particular the risk of residual disease.

-

T3 or T4 tumours in which EUS may encourage multimodal treatment, taking the form of chemotherapy alone, radiotherapy alone, both or neither, depending on clinical circumstances.

To address all these issues comprehensively needs a pragmatic randomised trial that assesses patients by a conventional staging algorithm and then randomises them between EUS and not. In designing such a trial, we started from the seminal writing of Schwartz and Lellouch109 (Table 7).

| Topic | Type of trial | |

|---|---|---|

| Fastidious | Pragmatic | |

| Objective | To acquire information relevant to defined scientific hypotheses and, thus, to draw scientific conclusions | To decide between two treatments in clinical practice rather than under ideal conditions |

| Definition of treatment | Rigid and equalised; in particular the trial protocol defines treatments so that psychosomatic or placebo effects are the same for each treatment | Flexible and optimal; in particular the protocol defines treatments so that each makes the best of psychosomatic or placebo effects |

| Experimental conditions | Tightly controlled laboratory conditions | Normal clinical practice |

| Definition of patients | The trial protocol strictly defines those patients eligible for all trial treatments prospectively, but may revise that definition retrospectively. Patients who withdraw from allocated treatments thereby withdraw from the analysis | The trial protocol defines patients eligible for all trial treatments flexibly but irrevocably once randomisation has occurred. Patients who withdraw from their allocated treatments after randomisation remain in the analysis |

| Number of criteria | No constraint on the number of criteria provided the trial protocol defines all criteria in advance | Only one; hence, if there are many potential criteria, the trial protocol must give them empirical weights so as to yield a single decision function, for example cost per QALY |

| Method of analysis | Traditional significance test for each hypothesis (but no formal relationship between significance tests) | Select treatment which gives the best weighted decision function (but no formal significance test) |

At a time when randomised trials were much rarer than today, Schwartz and Lellouch prepared the way for ‘health technology assessment’ by distinguishing between two distinct scientific paradigms for clinical trials: ‘fastidious’ trials aim to test defined scientific hypotheses and ‘pragmatic’ trials aim to choose between alternative technologies. 109

In practice, trials that keep to either column of Table 7 are rare. For example the proposal that pragmatic trials need no significance test is feasible only if the protocol specifies how analysis will combine the potential criteria to yield a single decision function, and there is enough information about that function to ensure that the resulting sample size calculation yields the required statistical confidence in the simple decision to choose the technology that performed best on that function in the trial. Since trials rarely fulfil both of these conditions, pragmatic trials usually borrow from the left-hand column of Table 7 by specifying the significance tests that they will undertake.

These far-sighted distinctions influenced the pragmatic design of the COGNATE trial in at least four ways:

-

While fastidious trials mimic the laboratory conditions associated with scientific investigation, pragmatic trials take place in normal clinical practice.

-

While fastidious trials define treatments rigidly, so as to keep hypothesis tests free from external influence, pragmatic trials define treatments flexibly because they seek the best decision for the complexities of normal clinical practice.

-

While fastidious trials seek to equalise placebo or non-specific effects, so as to compare like strictly with like, pragmatic trials seek to optimise these effects as one does in clinical practice

-

While fastidious trials exclude from analysis participants who violate the protocol in any way (‘analysis per protocol’), pragmatic trials seek to analyse all participants according to their allocated treatment whatever subsequently happens (‘analysis by treatment allocated’). 110

The value of EUS in staging patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer is not proven. Hence the only ethical means of evaluating this investigation is a randomised trial. As the funders – the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) – aim to inform decision-making in the NHS, and EUS was already widespread across the NHS, the trial has to be pragmatic. Accepting these arguments, the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (MREC) for Scotland approved this pragmatic protocol on 14 June 2004. Thus the scientific validity of the COGNATE trial lies in its adherence to the pragmatic scientific paradigm rather than the fastidious scientific paradigm.

It is intrinsic in the pragmatic scientific paradigm that, after randomisation between alternative interventions (in this trial, alternative diagnostic pathways and their therapeutic sequelae), multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) and individual clinicians make optimal clinical decisions for trial participants. Thus the COGNATE trial is evaluating, not an isolated EUS scan seen as a simple diagnostic intervention, but the ‘complex intervention’111 comprising the entire sequence of clinical decisions that flow from that intervention. In particular, the COGNATE economists seek to cost all the consequences for the use of NHS resources that lie downstream from the focal EUS scan or its absence.

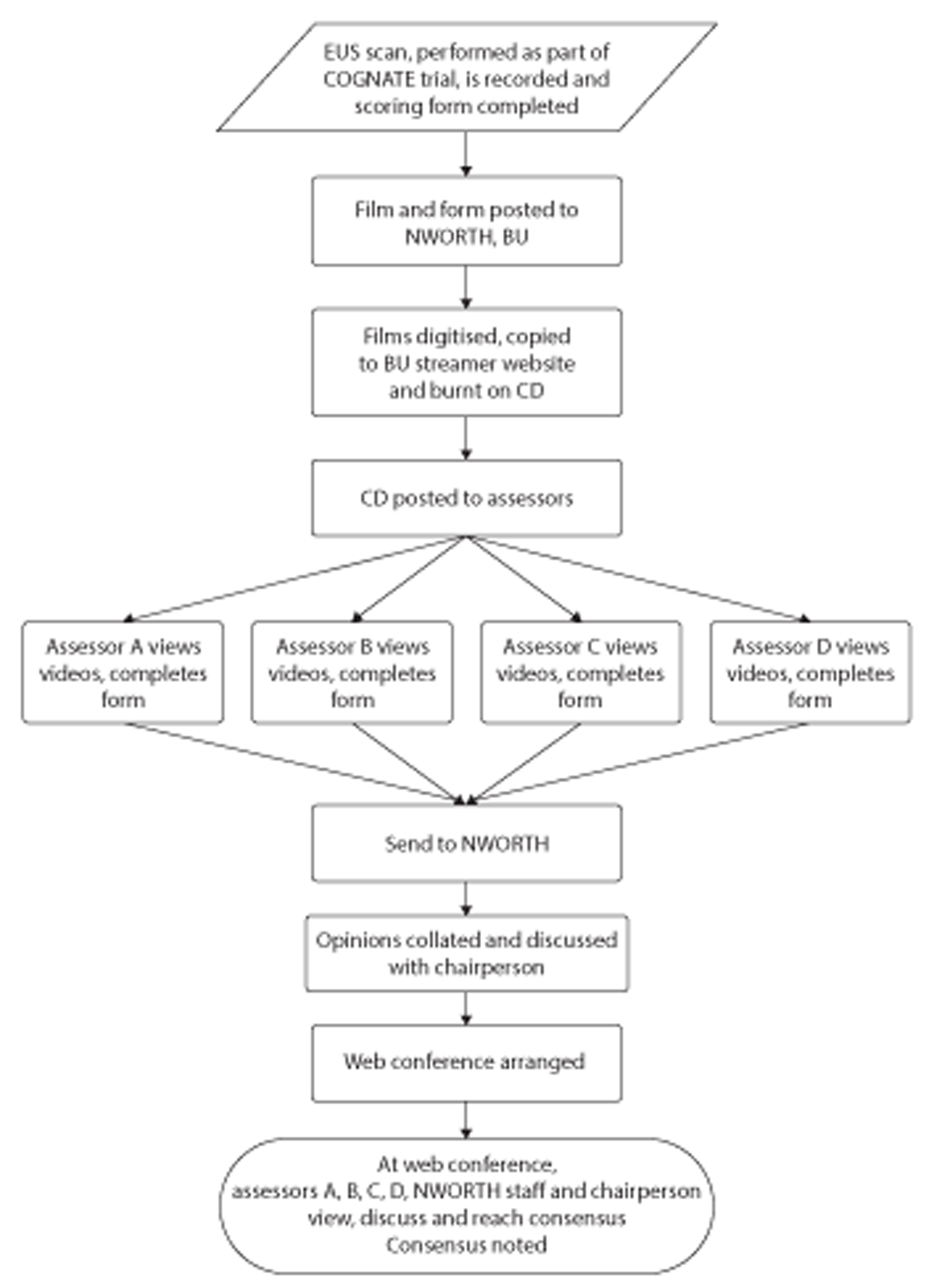

Quality assurance

Little guidance is available for assuring the quality of the clinical processes in clinical trials. Most trials, including COGNATE, follow standard operating procedures (SOPs)112 providing rigorous guidance on the conduct of the trial itself. However there is little if any scientific literature on ensuring the quality of the clinical process that is being tested. As EUS is an operator-dependent skill, it was important to assess the quality of the scanning process within the COGNATE trial.

Variation in the interpretation of scans has three main sources. First there are concerns over the accuracy of EUS scans36 and the learning curve of those who interpret them. 113 Secondly the equipment to record and store images is not consistent between centres. Thirdly analytical interpretation of scans varies among observers and even over time by the same observer. Hence the COGNATE trial aimed to develop and report on a prospective system of peer review to assure the quality of EUS scans. In particular, it reviewed the quality of the reports and recommendations made by reporting clinicians.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

We conducted a pragmatic multicentre randomised trial to evaluate the (clinical) effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of EUS as a technology to improve the staging and thus the management of gastro-oesophageal cancer. In planning the trial, we assessed tools for estimating quality of life in patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer. The ensuing psychometric analysis of data collected at baseline and after 1 and 3 months enabled us to develop an appropriate outcome measure for quality of life, which we used in the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analyses. To ensure that the trial evaluated ‘current best practice’ in endosonography, we initiated a rigorous quality assurance process.

Intervention

We designed the COGNATE trial to test the effect on quality-adjusted survival of undergoing EUS within the staging process. Before the trial began, we developed a pragmatic, and therefore advisory, staging algorithm from normal clinical practice as characterised by SAGOC:4

-

All patients should receive biochemistry, haematology, pulmonary function tests and cardiac assessment, not least to exclude patients whose World Health Organization (WHO) status is 3 or 4, or who are medically unsuitable for either surgery or chemotherapy.

-

Patients who are medically fit for surgery without evidence of metastases should undergo CT following an agreed protocol using spiral scanner and intravenous contrast.

-

Patients with any suspicion of peritoneal disease should undergo laparoscopy as the best means of detecting peritoneal tumour deposits.

-

Fit patients with localised tumours and no contraindications were eligible for randomisation to EUS or not.

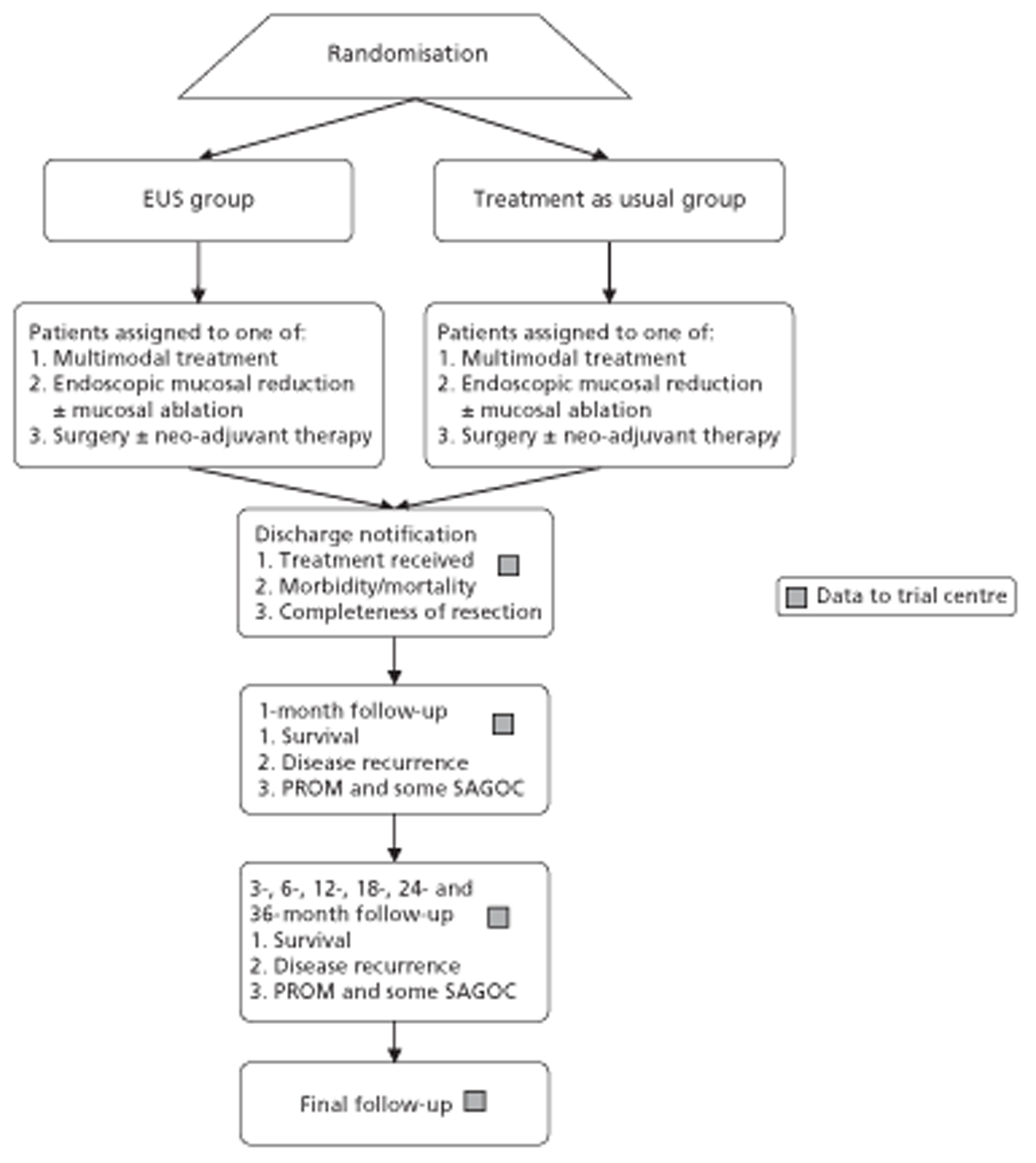

In the resulting control group (or ‘non-EUS group’ in tables), the choice of treatment depended on the results of the completed initial staging investigations, revisited if necessary. In the resulting intervention group (or ‘EUS group’ in tables), the final choice of treatment followed the EUS scan. At the end of staging, with or without EUS, MDTs assigned patients to one of three treatment options. Patients with:

-

tumours that were adjudged to be mucosal underwent EMR with or without argon-beam ablation of the surrounding mucosa

-

tumours that were adjudged to be resectable underwent surgery with or without neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, typically with cisplatin and 5FU

-

advanced localised disease, for which complete resection was adjudged to be impossible, received multimodal treatment, possibly including palliative surgery for gastric cancers.

Thus we randomised no patients who then had evidence of metastases or then had plans for palliative treatment or were then known to be medically unfit for surgery. In a pragmatic trial, of course, subsequent changes in all this information cannot invalidate the randomisation.

Trial flow chart

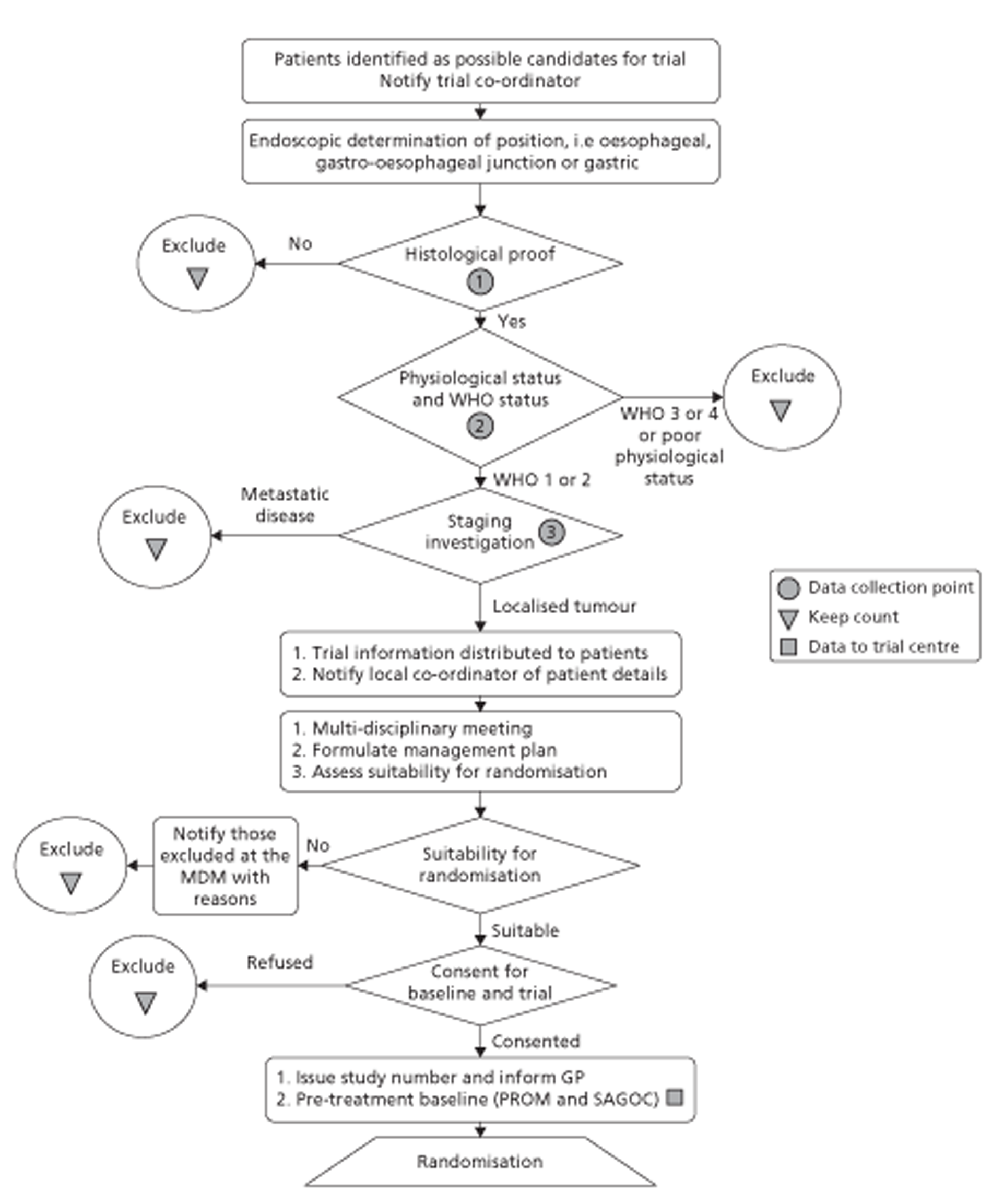

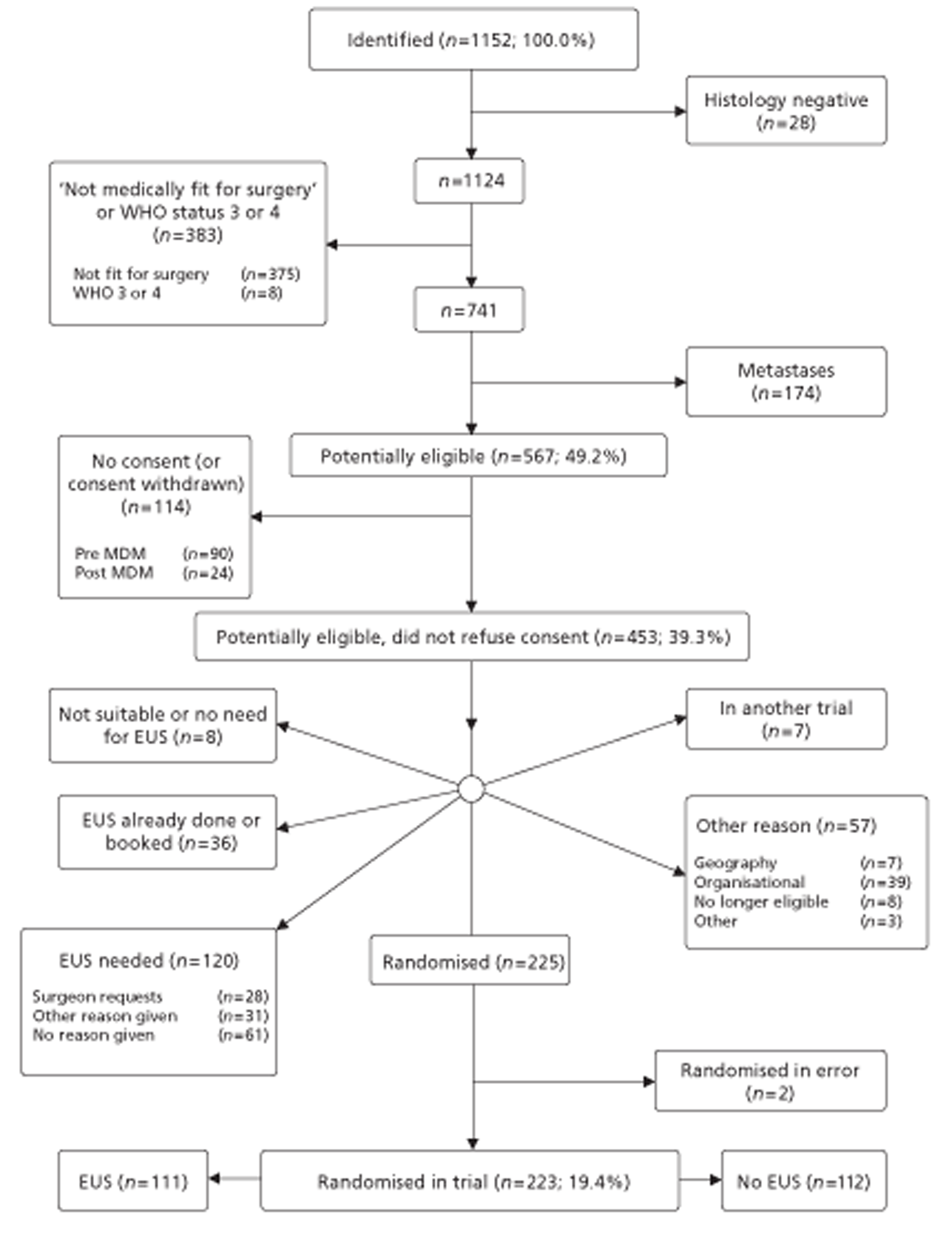

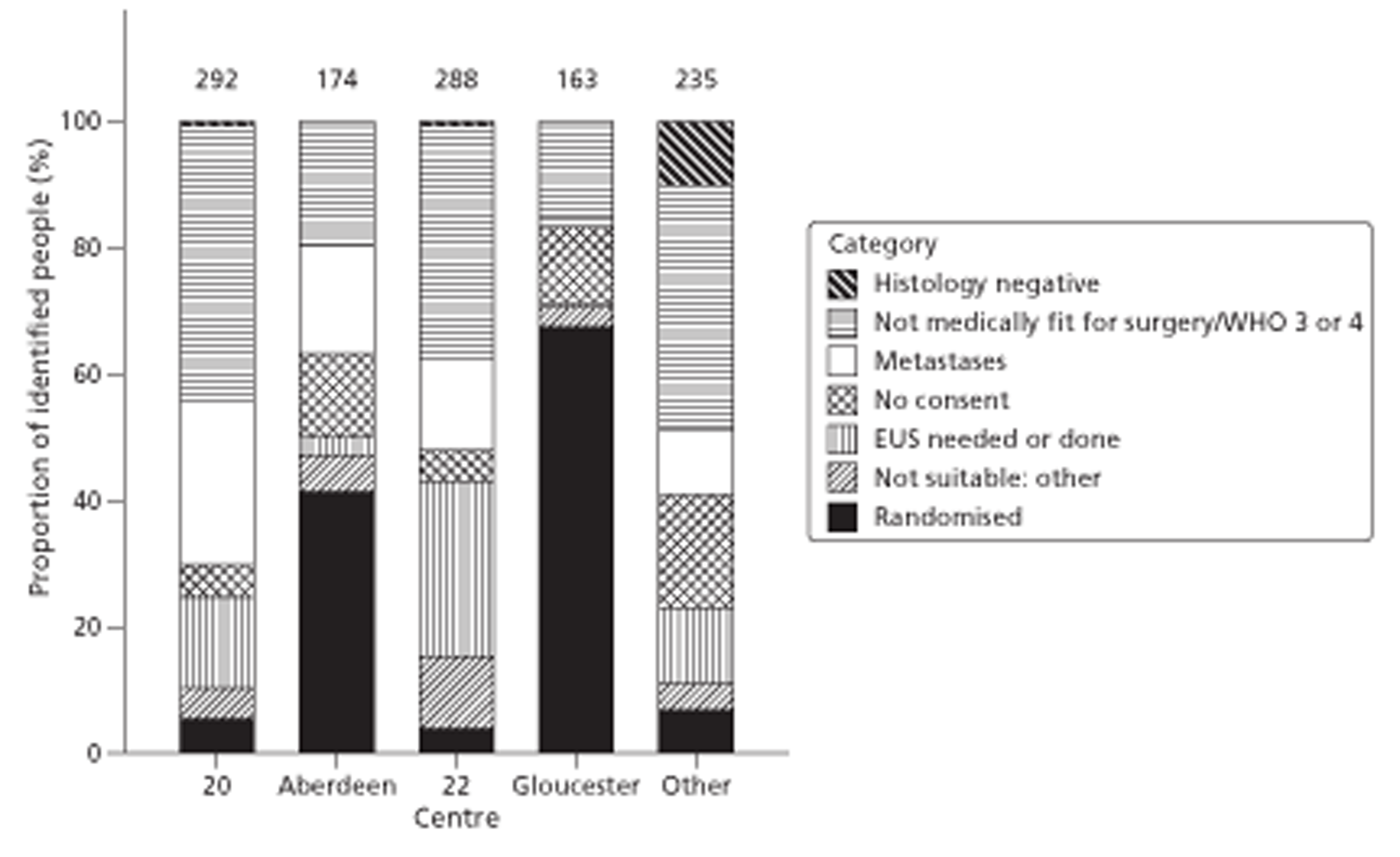

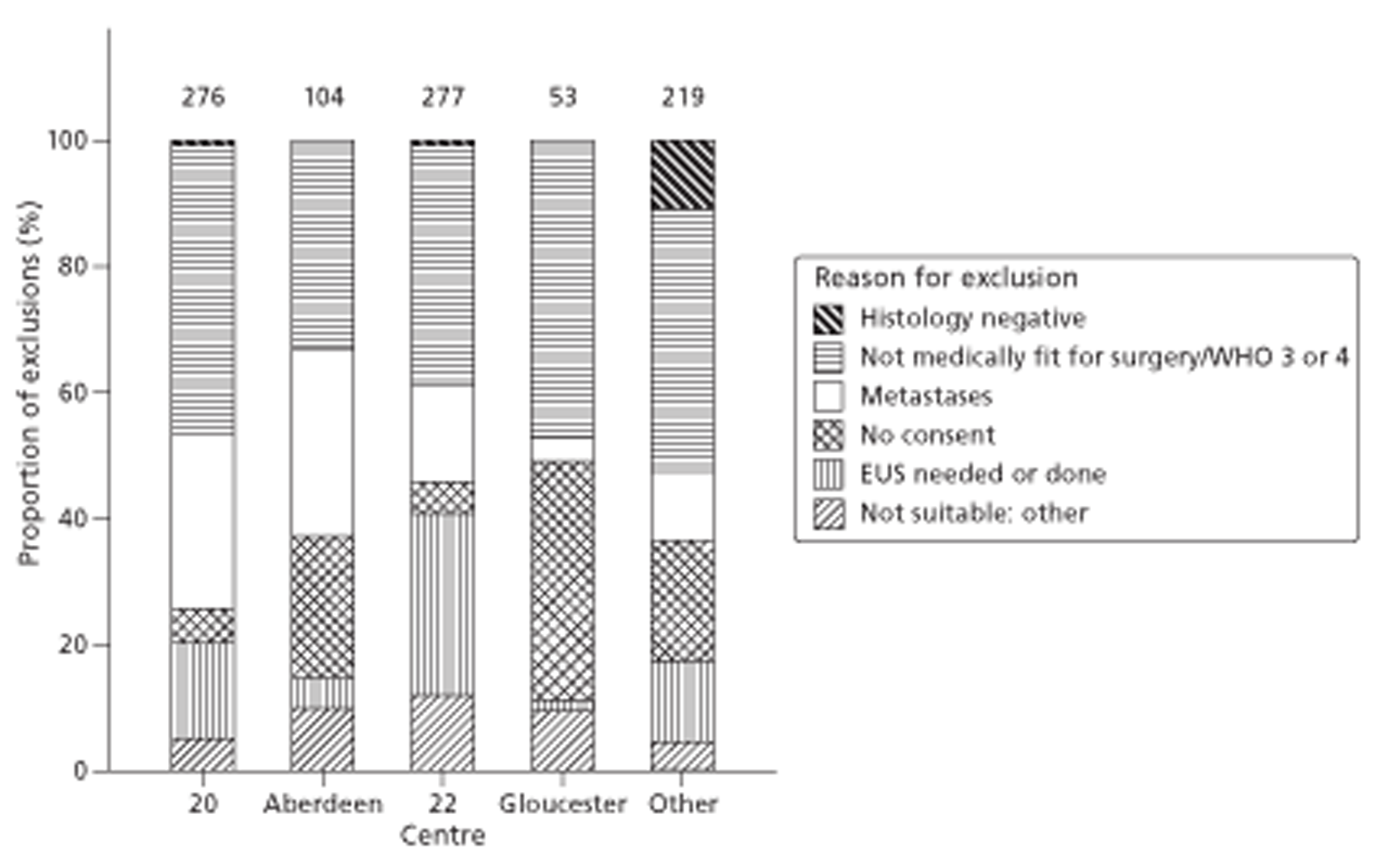

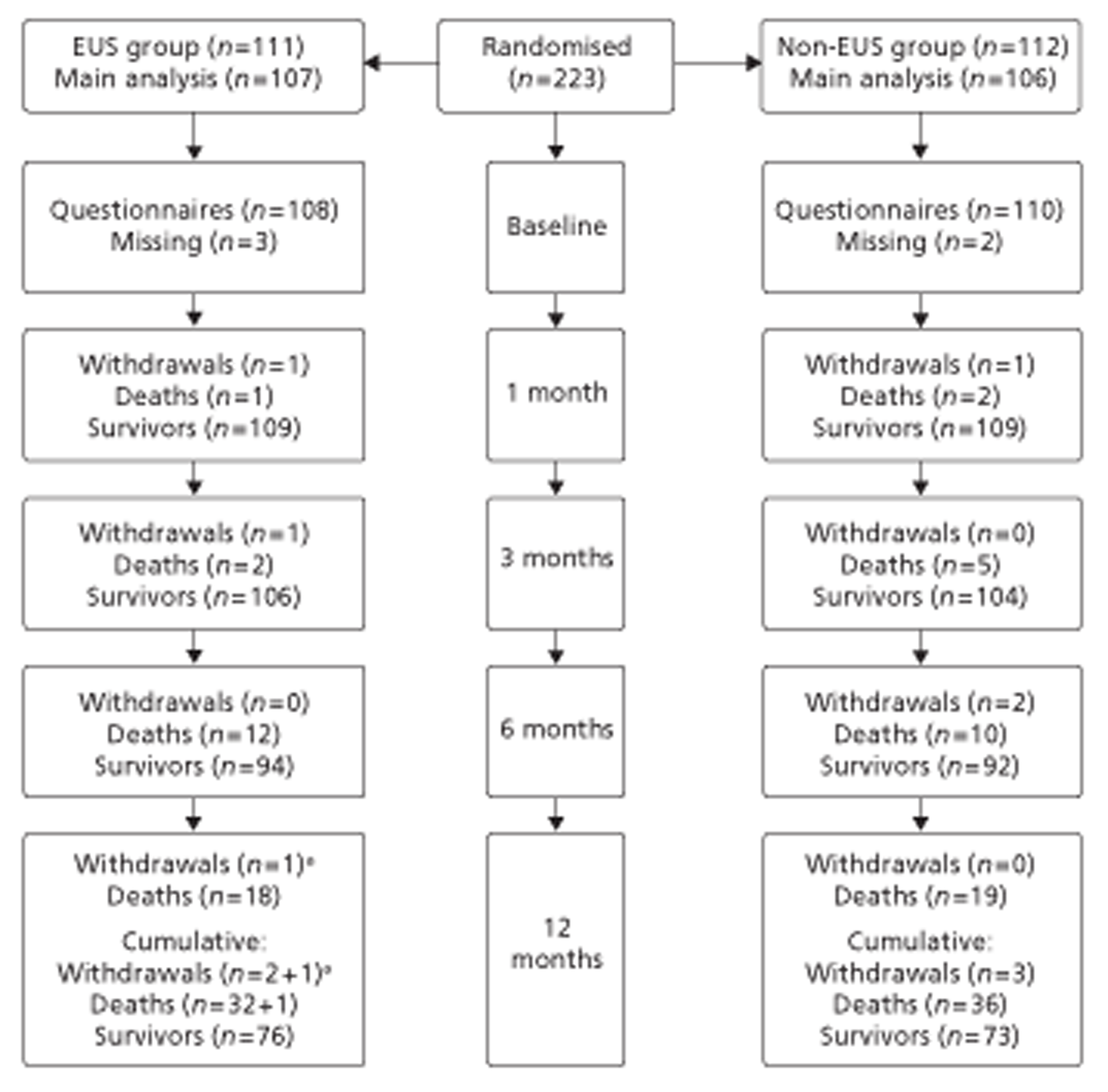

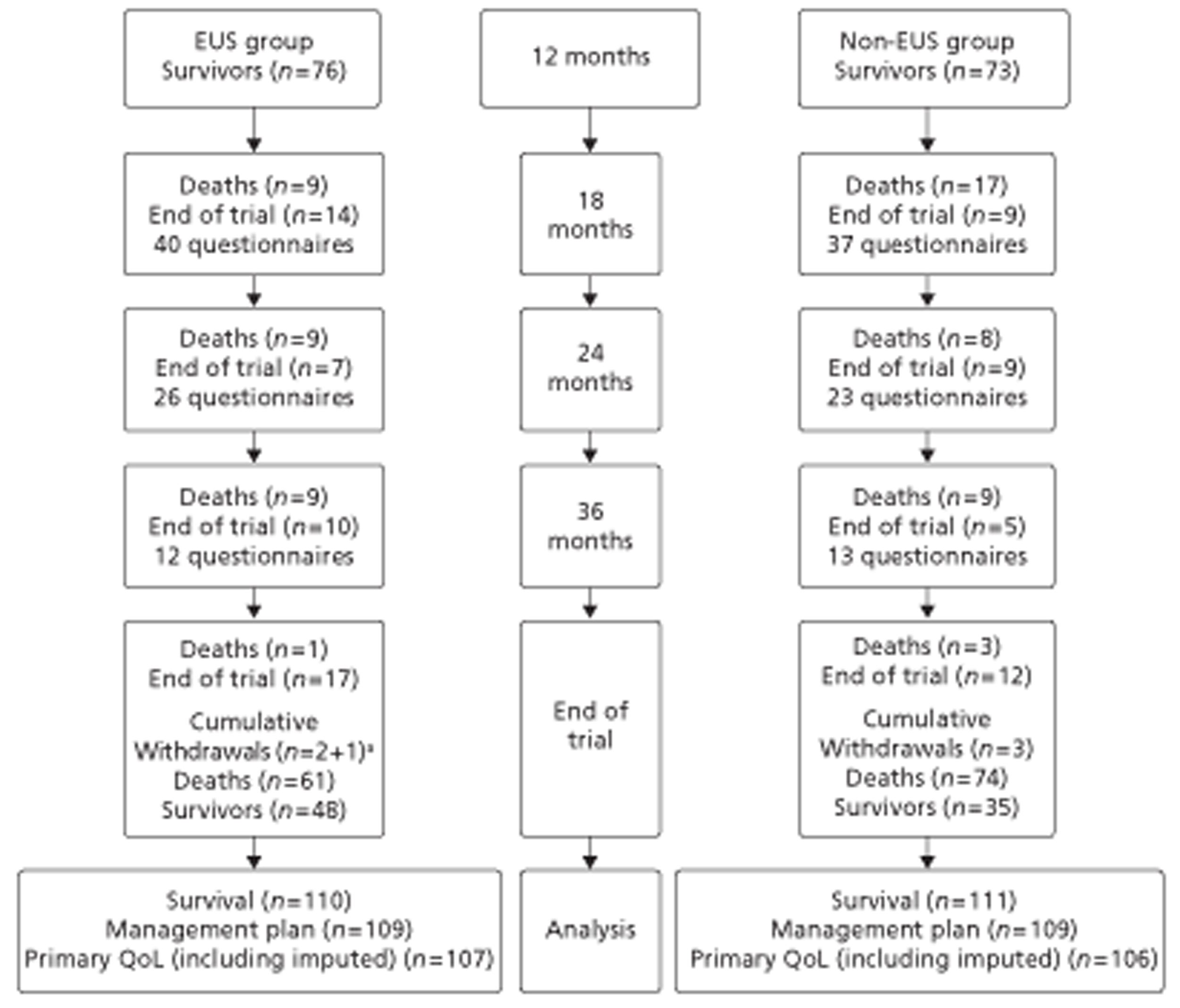

Figures 1 and 2 summarise the trial design. Randomisation took place after review of the initial staging investigations by the MDT. Clinicians agreed a conditional management plan, sought informed consent and randomised patients between receiving EUS and proceeding to the agreed management plan. They also reported to the North Wales Organisation for Randomised Trials in Health (NWORTH), Bangor University's Registered Clinical Trial Unit, all patients whom the MDT decided not to randomise with reasons for exclusion. These included patients for whom they considered EUS either essential or inappropriate.

FIGURE 1.

Trial design: start to randomisation. MDM, multidisciplinary meeting. PROM, patiented-reported outcome measure.

FIGURE 2.

Trial design: randomisation to conclusion. PROM, patient-reported outcome measure.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The COGNATE trial was a trial of patients with proven cancer of the oesophagus, stomach or gastro-oesophageal junction. To be eligible for the trial, patients had to be fit for both surgery and chemoradiotherapy as well as free of metastatic disease. Both their ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) grading114 and their WHO performance status115 had to be 1 or 2 (see Figure 1). Following initial staging, clinicians could exclude patients from the trial for clinical reasons.

Patient information and informed consent

Before randomisation, the research professionals or clinicians invited eligible patients to participate in the COGNATE trial, gave them the patient information sheet approved by the Scotland MREC, and allowed them time to consider it and ask questions. We explained the nature of EUS and the process of randomisation to these patients. We stressed that the choice of treatment after EUS was the same in both groups. We then asked consenting patients to sign the consent form.

Randomisation

Once an eligible patient had consented and completed the baseline quality-of-life questionnaire, the recruiting centre telephoned NWORTH in Bangor. NWORTH staff confirmed eligibility and asked for information on both stratifying variables: centre and tumour location – gastric, oesophageal or the gastro-oesophageal junction. As we included only participants with good WHO performance status, we did not need to stratify for this. NWORTH then randomised the participant between intervention and control groups using a dynamic randomisation algorithm designed to prevent subversion. 116,117 We reported regularly on recruitment to the National Clinical Research Network and NCCHTA. NWORTH confirmed the allocation by e-mail to the recruiting centre, which either booked an EUS scan for intervention participants or continued the agreed management plan for control participants.

Sample size

Our original application proposed to consent, randomise and follow up a total of 700 patients in a trial in which the primary outcome was survival. We soon discovered that most centres in the UK wanted to use EUS to stage gastro-oesophageal cancer. Conscious that early participants were able and happy to report on their health-related quality of life (HRQoL), however, we decided with the support of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the approval of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme to change the primary outcome to quality-adjusted survival. This effectively combines the components of health that EUS might improve – survival through better staging and HRQoL through reassurance arising from better staging and planning – in principle reducing the sample size needed.

As there is no easy means of calculating the power of a sample for the primary outcome of quality-adjusted survival, we calculated power for two simple but plausible scenarios. First, if there were no difference between groups in quality of life, the combination of a sample of 400 participants and a log-rank test using a 5% significance level would yield 80% power of detecting a hazard ratio of 0.6, equivalent to a difference between 60% survival at 12 months [derived from SAGOC:4Appendix 1 and Figure 2] and 73% survival. Second, if there were no difference between groups in survival, the combination of the sample of 400 and a t-test using a 5% significance level would yield more than 80% power of detecting a ‘small’ effect size of 0.3118 in quality of life. As the groups were more likely to differ in both survival and quality of life, the power of our primary analysis of quality-adjusted survival would be correspondingly greater. At worst, if we were able to randomise and follow-up only 220 patients, that scenario would yield 80% power to detect a hazard ratio of 0.5 (equivalent to a difference between 60% and 78% in survival at 12 months) or an effect size of 0.4 in quality of life, still ‘small’. 119

Quality-of-life instruments

The COGNATE trial used two instruments to gather information on quality of life as the basis for evaluating both effectiveness and cost-effectiveness: the European Quality of Life – 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and its visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS); and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) comprising FACT – General (FACT-G) and FACT – Additional Concerns (FACT-AC). Centres administered the questionnaires, including these instruments at baseline and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after randomisation and at 18, 24 and 36 months where possible.

We used the EQ-5D, developed by the EuroQol Group,120,121 to measure patients’ HRQoL and to ascribe utilities to their health states. The EQ-5D is a preference-based generic measure comprising five domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and discomfort, and anxiety and depression. Each domain has three levels: no problems, some problems and a lot of problems. The EQ-5D scoring system defines 245 possible health states, namely 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 × 3, plus two additional states – dead and unconscious. EQ-5D gives death a utility of zero and ‘best imaginable health’ a utility of one. For each participant it converts the five item scores into a summary utility based on the ‘time trade-off’ preferences of a UK-wide random sample of 3000 respondents. 122 Some health states have negative utility (‘worse than death’). We included the EQ-5D in our outcome portfolio as the primary means of adjusting survival for quality of life. EQ-5D complements its five items with a visual analogue scale (VAS); this is a single thermometer-like generic quality-of-life scale with zero representing ‘worst imaginable health’ and 100 representing ‘best imaginable health’, on which respondents mark their perceived current health directly. Scores, therefore, require no further processing.

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy is a psychometric instrument measuring cancer-specific quality of life. 123,124 The current version of FACT-G comprises four subscales: Physical Well-Being (seven items), Social or Family Well-Being (seven items), Emotional Well-Being (six items) and Functional Well-Being (seven items). FACT sums scores on these subscales to give FACT-G. The COGNATE team derived its FACT-AC scale from Gastric Additional Concerns,125 comprising 19 items, and Oesophageal Additional Concerns,126 comprising 17 items, by removing overlapping items and psychometrically weak items using methods described by Streiner and Norman. 119 In this way we effectively merged the Gastric Additional Concerns and Oesophageal Additional Concerns scales to form a single integrated Gastro-Oesophageal Concerns scale for easy use by all trial patients. We also assessed the extent to which this provided information over and above that provided by EQ-5D.

Data collection

Centres collected data on the due day when possible, but otherwise within a window. Although pre-randomisation data could be collected up to 3 days before randomisation, randomisation could not proceed without these data. Data due at 1, 3 and 6 months could be collected up to 14 days after the due date; data due at 12, 18, 24 and 36 months could be collected up to 28 days after the due date. To avoid bias, for example by anticipating a major event, we did not collect data before the due date except for pre-randomisation data. Similarly, we did not collect data for 7 days after a major procedure.

Our preferred mode of administration was a rigorously defined face-to-face interview. In our experience interviews reduce biases due to sicker patients not responding. Trained research professionals read each question while participants followed laminated versions. The researchers entered their responses directly into a laptop computer. If a face-to-face interview was not possible, we conducted the interview by telephone, having posted the questionnaire to the participant in advance. As a last resort, the participant could complete the questionnaire and return it by post; with that exception, research nurses were interviewers not observers. The researchers also recorded the mode of completion: face to face, telephone or postal. Although we know that interviewers affect responses to questionnaires, there is strong evidence [from a recent systematic review to which two of us (DKI, ITR) contributed] that this effect is consistent across trial arms. 127 Furthermore FACT itself is robust against interviewer effects. 128

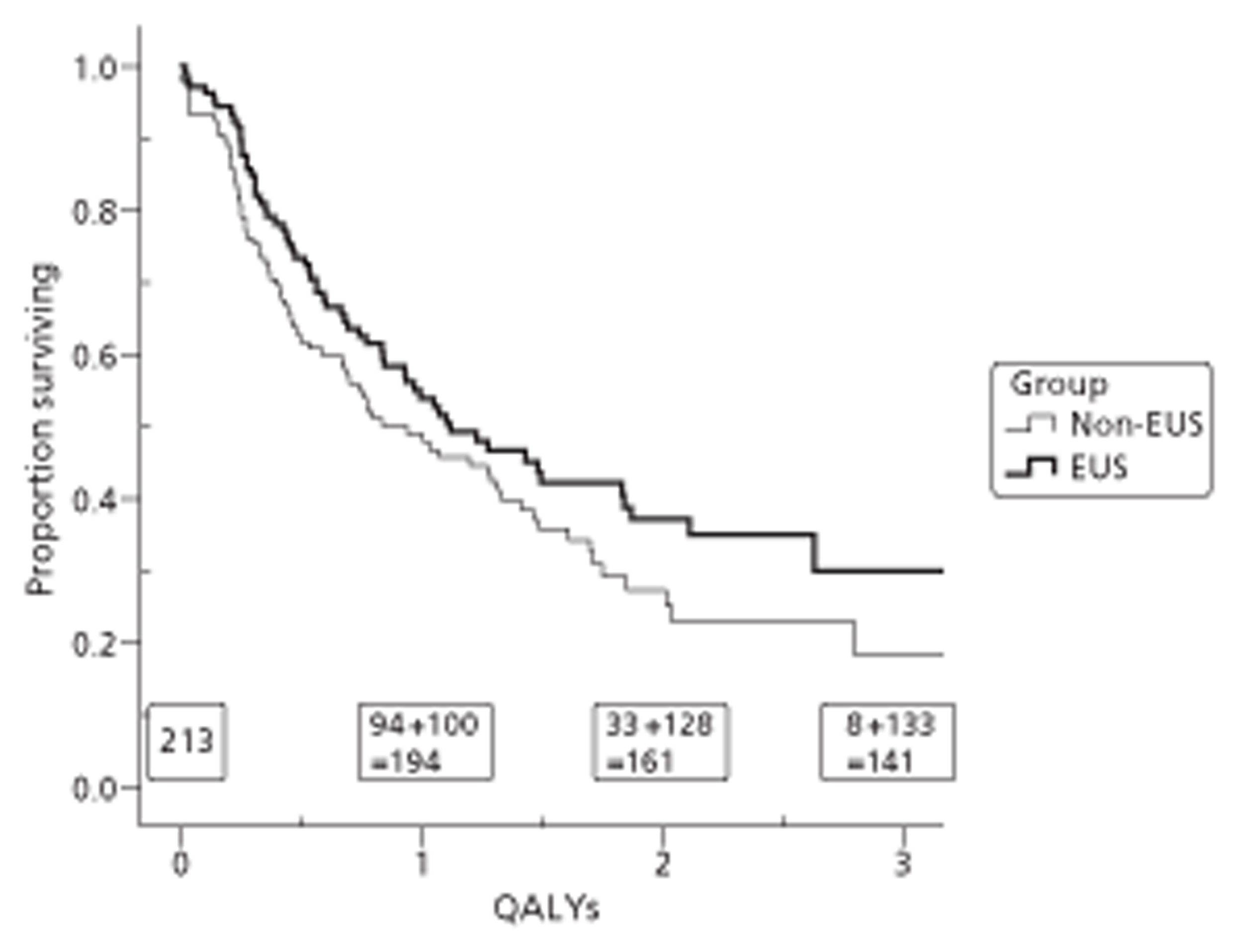

Primary outcome measure: quality-adjusted survival

The primary outcome measure was quality-adjusted survival, using the EQ-5D health index to adjust for the quality of life of survivors. We integrated outcomes over time for individuals by calculating the ‘area under the curve’ (AUC). This avoids multiple testing of correlated outcomes. We calculated this area from the graph of HRQoL (EQ-5D or FACT) against time by joining all the intermediate points derived from the follow-up interviews, drawing vertical lines to the horizontal (time) axis at randomisation and at death, complete withdrawal or censoring at the end of the trial (August 2009), whichever occurred soonest, and then calculating the area of the resulting polygon. This area is the standard measure of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) in cost-utility analysis. 129

Secondary outcome measures

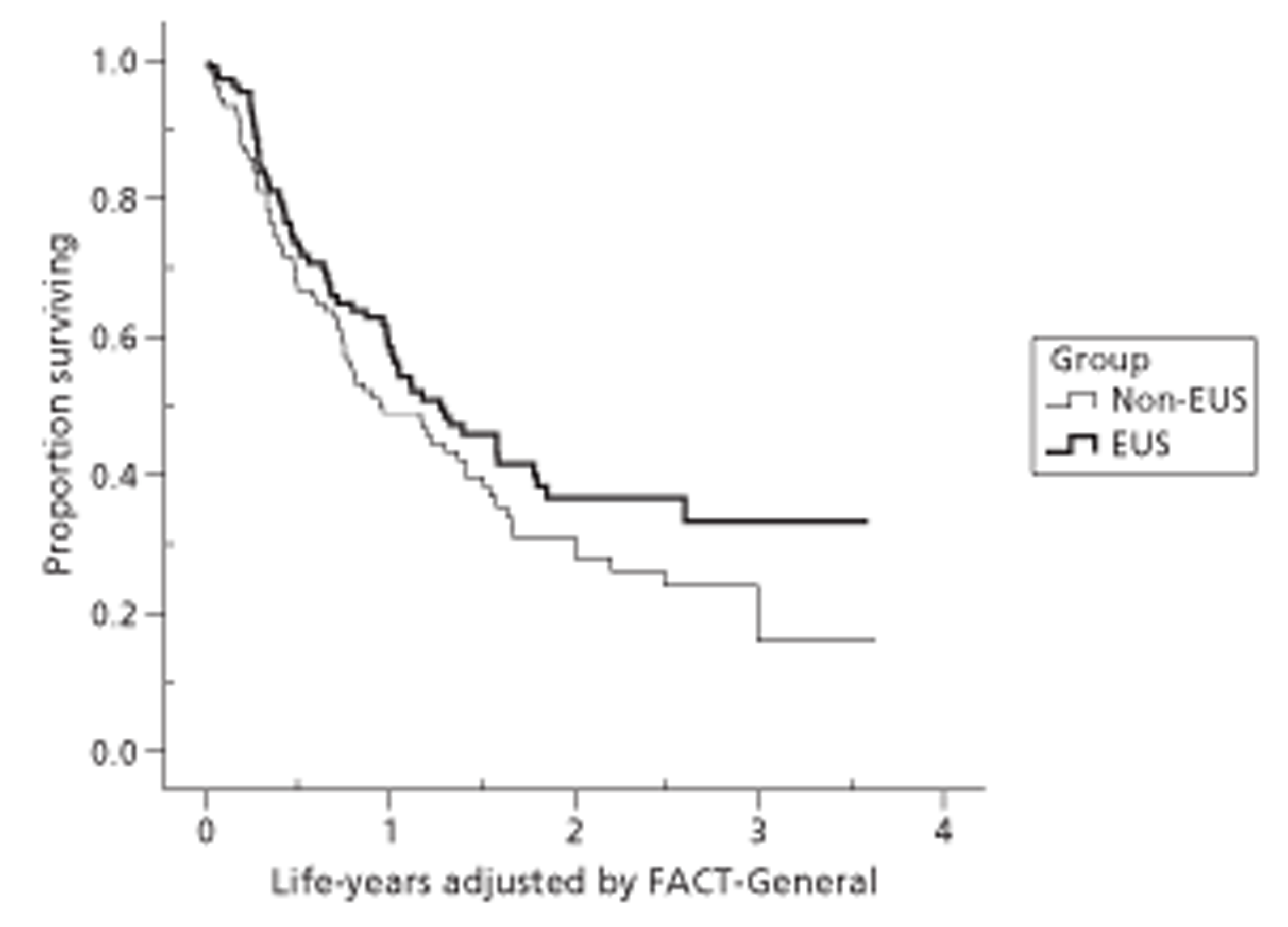

Survival adjusted by FACT

It is possible to use quality-of-life measures other than EQ-5D to adjust survival for quality of life. We used AUC summaries of the two main FACT scores, FACT-G and the combined Additional Concerns (FACT-AC), as cancer-specific and site-specific versions of quality-adjusted survival. We converted both measures to a scale with minimum 0 (worst quality of life) and maximum 1 (best quality of life) before calculating the AUC.

Survival from randomisation

However standard survival analysis uses only available information on participants' survival, including those withdrawing from the trial, and takes account of variable follow-up by censoring observations. Hence no imputation is necessary. The maximum observation time was 12 months for those last randomised and 58 months for those first randomised to the pilot study.

Quality of life at 12 months

We compared all three measures – EQ-5D, FACT-G and FACT-AC – between intervention and control groups at the 12-month interview. This was the minimum planned length of follow-up between randomisation and the end of the trial. Data from later interviews could be compared only on subsamples recruited nearer the start of the trial.

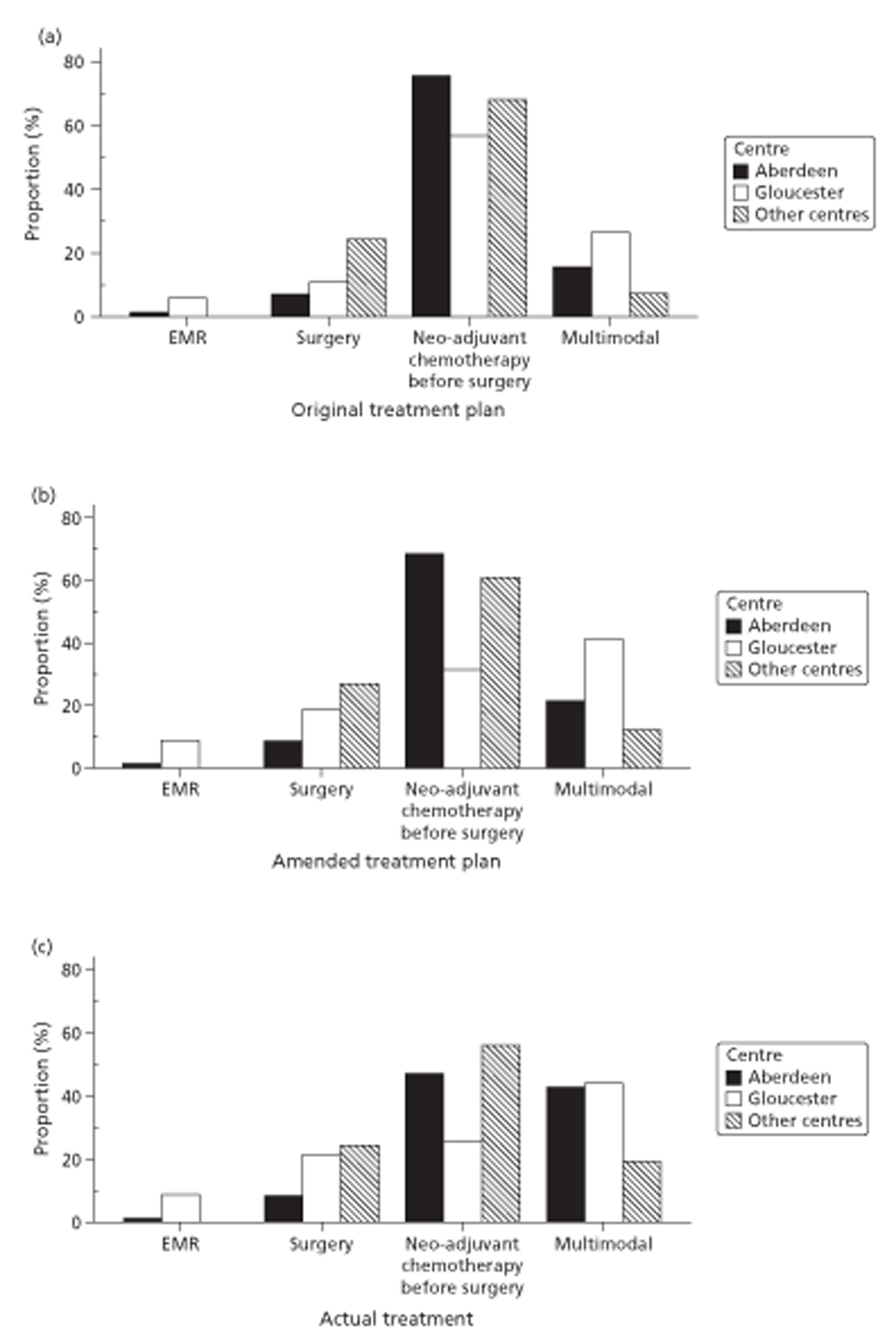

Management plan changes

We recorded changes to the management plan agreed by the MDT that occurred after randomisation and the treatment actually received.

Quality of treatment

-

Complete resection, defined as the removal of all macroscopic and microscopic lesions, was recorded by participating centres for the whole sample on the trial database. For the few participants for whom this conclusion was missing, the three clinical members of the trial team independently assessed all other information about excision and reached consensus while blind to allocated treatment.

-

Pathological reporting of resected specimens using SAGOC criteria. 4

-

Morbidity and mortality potentially caused by EUS. We asked participating centres to record all complications of EUS (including deaths in hospital within 30 days) that might have been related to the investigation. There were no such complications. Indeed the only early death of an intervention participant occurred after palliative surgery without any suspicion that EUS played any role.

Cancer mortality according to the SAGOC definitions

For all deaths we classified the cause as EUS related, completely or partly cancer related, related to cancer treatment, or unrelated to any of these. We also recorded all diagnoses of metastases, either during life or at death.

Follow-up

We followed patients until death or the end of data collection, which was between 12 and 58 months after the end of recruitment for all patients. We collected data at discharge from hospital after initial treatment and at follow-up clinics after 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months.

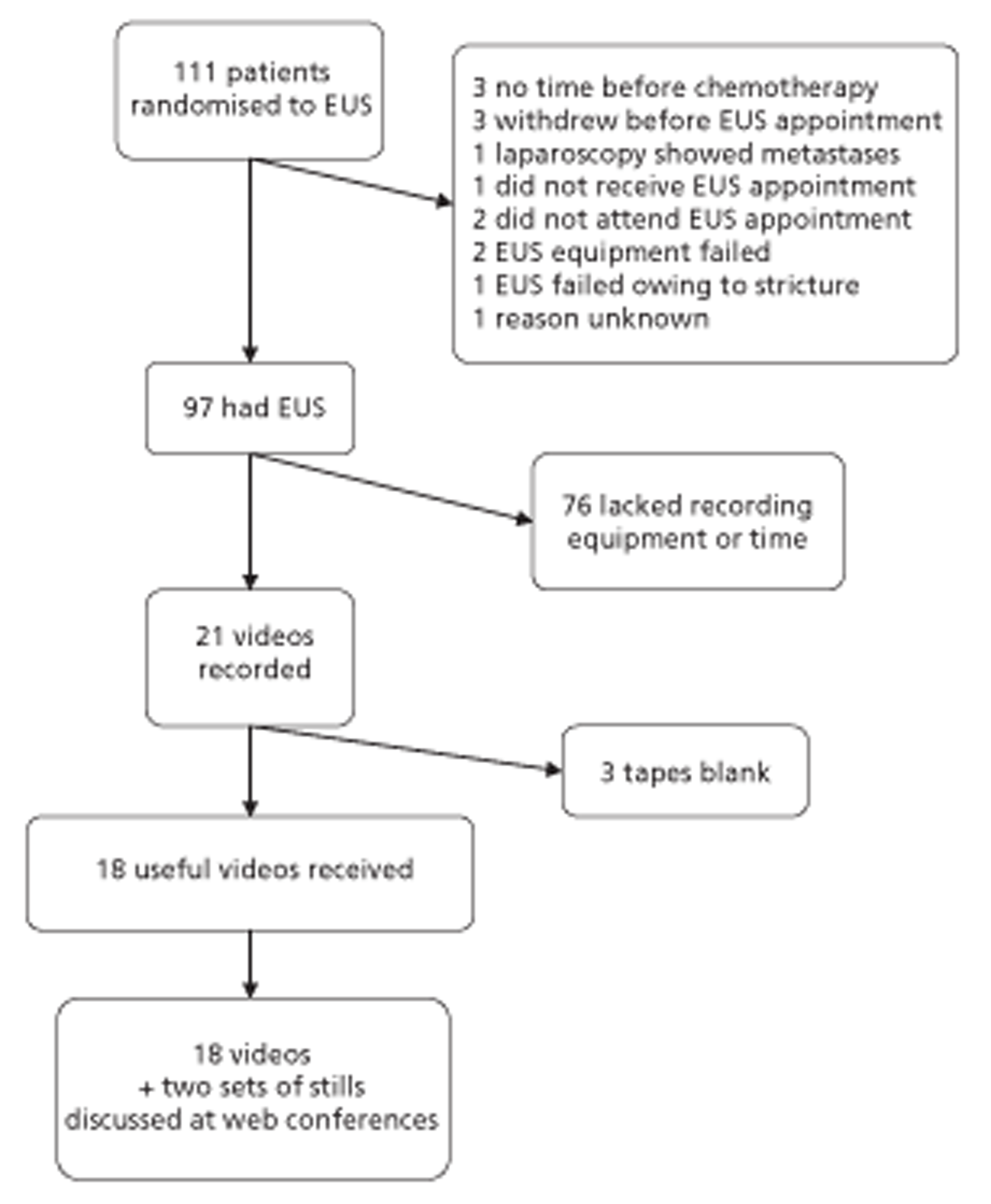

Quality assurance of endoscopic ultrasound scans

The COGNATE team asked investigators to record EUS scans on videotapes and to record staging and explanatory comments on a trial proforma. Anonymised videos of selected EUS scans of intervention participants were reviewed by a panel of investigators during a series of web conferences, each of which reached a blinded consensus on the staging of four tumours. We compared the staging decisions of the individual peer reviewers, their consensus decision and the staging decision of an international expert as external reviewer with that of the original investigator who performed the scan. We used Cohen's kappa or weighted kappa130 to test for agreement.

Independent trial monitoring

The COGNATE trial had a TSC comprising an independent chairperson, two independent members and four members of the COGNATE Trial Executive Group (TEG). Principal investigators (PIs) in each centre reported to the TSC through the TEG. The Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC), comprising three independent members with the trial statistician in attendance, acted as a subcommittee of the TSC, reporting to the TSC. Appendix 3 lists members of the TSC and DMEC.

Trial management

North Wales Organisation for Randomised Trials in Health managed the trial. A Trial Management Group comprising the two chief investigators, trial statistician, health economist, outcomes specialist, data manager, trial manager and trial administrator met monthly at NWORTH. Telephone access was available to other investigators by invitation. Minutes were taken and stored in the Trial Master File.

Ethics and participating sites

The COGNATE trial was approved by the Scotland MREC A and 10 Local Research Ethics Committees (LRECs) and associated research governance units for a total of 16 hospital sites. Two centres did not recruit any patients, one owing to competing workload and the other (who had obtained ethical approval from four LRECs for seven hospitals in that area) owing to lack of commitment from staff. Appendix 2 gives details of the eight recruiting hospitals.

One centre screened many patients but randomised only one into the COGNATE trial, and later asked to withdraw from the study. They agreed that their COGNATE patient, if willing, could receive continuing follow-up through a nurse from the local Cancer Research Network. This arrangement was accepted by the patient and the local Research Governance Department.

Protocol amendment

The proposal to change the primary outcome measure from survival to the more sensitive measure of quality-adjusted survival, which reduced the target sample size from 700 to a maximum of 400 and a minimum of 220, was agreed by the DMEC and TSC in April 2006 and reported to the NCCHTA in December 2006. A 6-month, no-cost extension was agreed by the DMEC and TSC in April 2007 and by the NCCHTA in November 2007. The final protocol is in Appendix 1.

Electronic data collection and storage

All data identified patients only by a unique trial number. Each trial centre kept its own index linking trial numbers to patients' names and addresses separate from the laptop computers used to store and transfer trial data, and protected that index by key and password. The trial co-ordinating centre in Bangor had no access to these local indices. Those analysing data had no access to which group of participants received the intervention until the TSC had scrutinised and approved the methods and findings of the main statistical analysis.

North Wales Organisation for Randomised Trials in Health designed a Microsoft Access database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to enable each centre to collect COGNATE data on their trial laptop computer. The electronic forms for data entry were designed to be friendly to local staff. When local staff suggested an improvement to display the dates of tests already entered into the database, the database designer programmed the change and the trial manager implemented it on the next suitable occasion – monitoring visit, investigators’ meeting or over the telephone.

Centres transferred data to NWORTH by electronic file transfer protocols every 2 months throughout the trial. This allowed the data manager and trial manager to monitor data completeness and report to the research team. As Bangor University updated file transfer protocols twice during the COGNATE trial, this necessitated retraining of local staff in methods of data transfer. By all of these means the COGNATE trial can fairly claim to have been a generally paperless trial.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis plan

To avoid bias, we wrote our statistical analysis plan, and the TSC approved it, during the recruitment phase. Although participants and their clinicians knew their randomised allocation, we kept the methodological chief investigator and trial statistician blind to all these allocations until they had presented blinded findings to the TSC in September 2009.

Primary analysis was by ‘whether allocated to endoscopic ultrasound’. 109,110 This reflects the pragmatic nature of the trial, and its primary goal of evaluating that health technology in informing decisions in the real world. We also undertook secondary analysis by ‘endoscopic ultrasound received’ to explore the implications of clinical decisions that diverged from the random allocation.

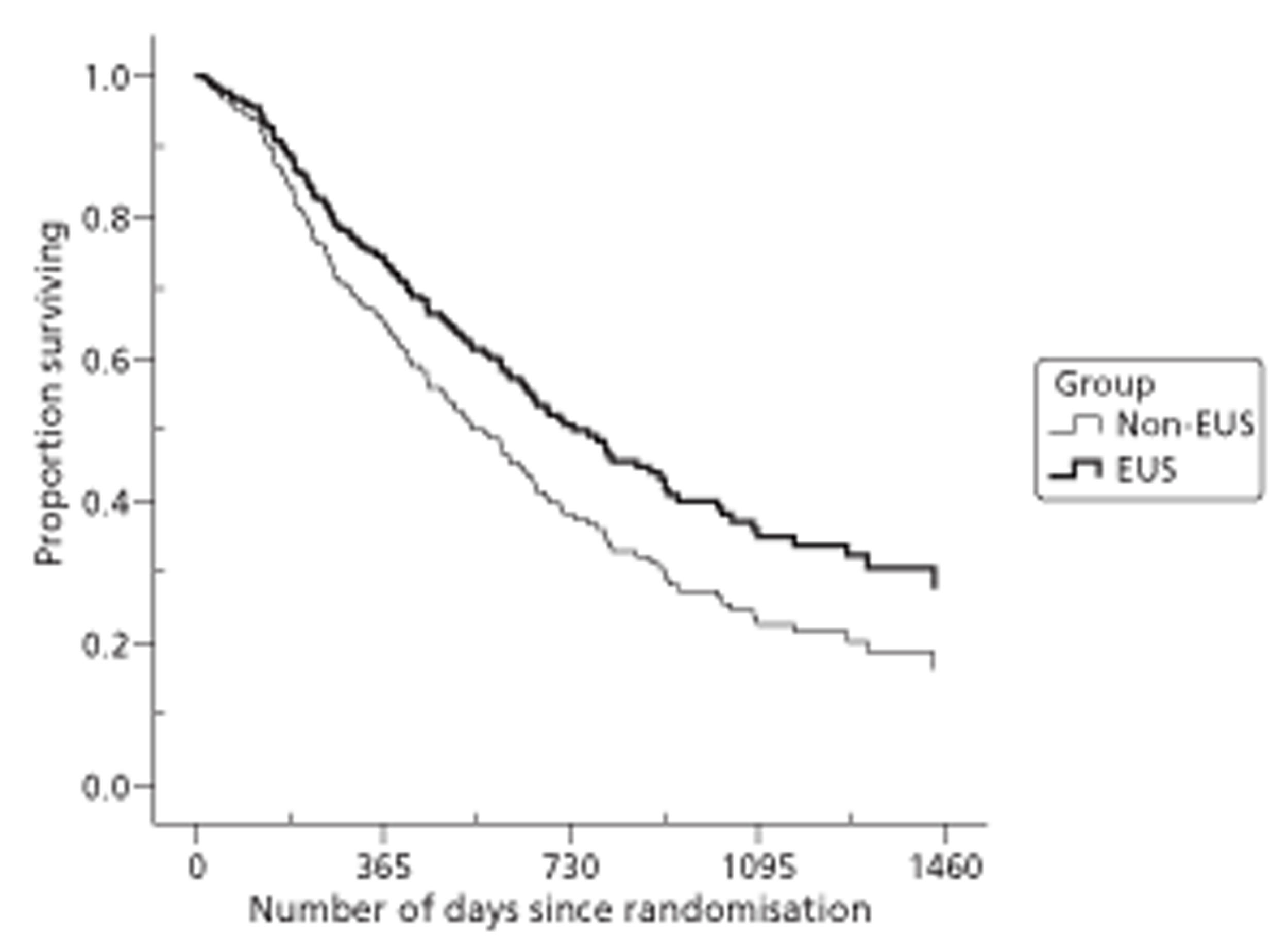

Quality-adjusted survival (primary outcome) and survival

The primary outcome measure (survival adjusted by EQ-5D), and survival-based secondary outcome measures (unadjusted survival, survival adjusted by FACT-G, and survival adjusted by FACT-AC) all analysed the time between randomisation and the end of the trial or death (if it occurred before the end of the trial). Thus surviving participants recruited at the end of the trial were censored at 12 months, while those recruited near the beginning of the trial were censored only if they survived 48 months or more.

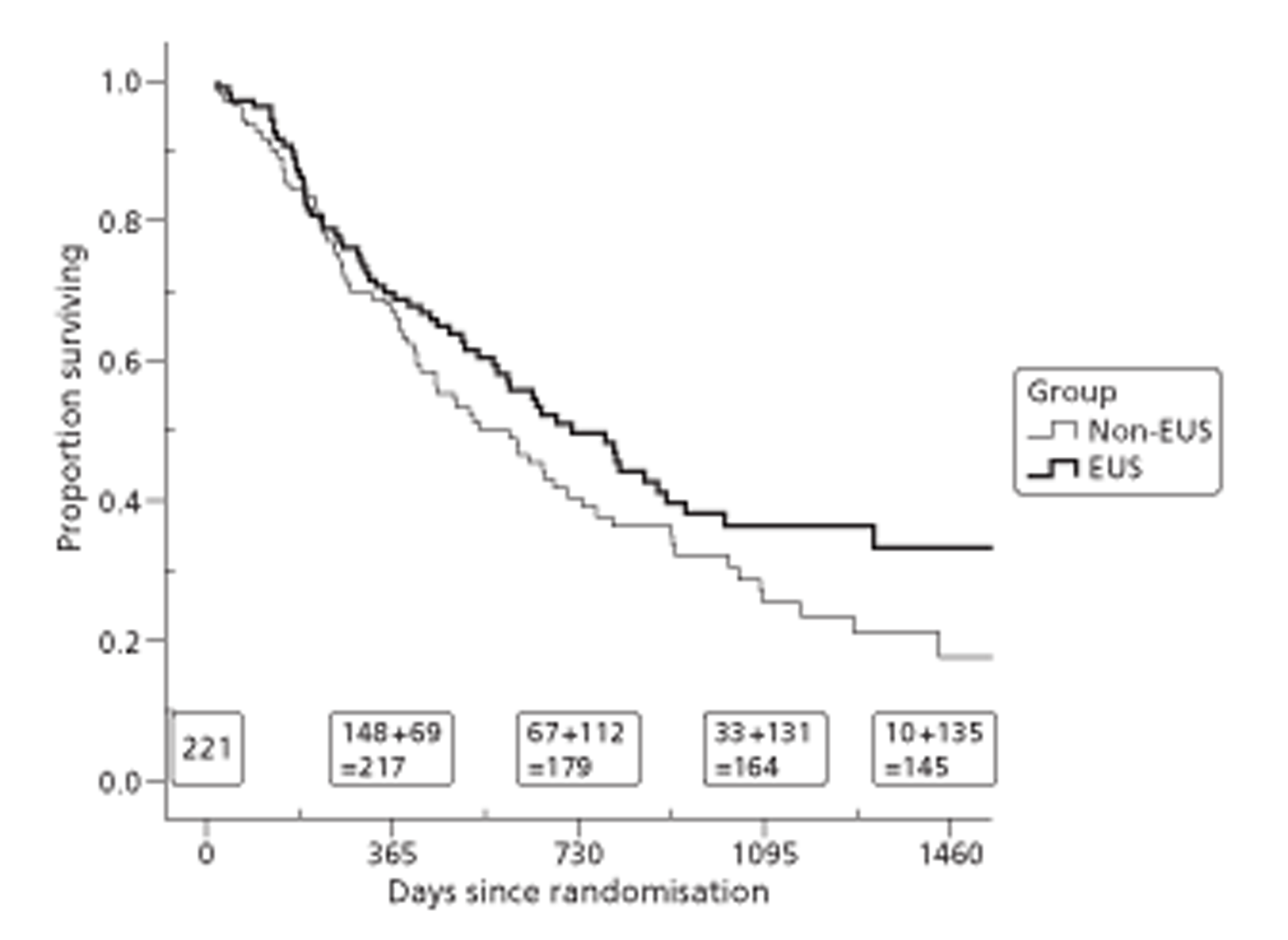

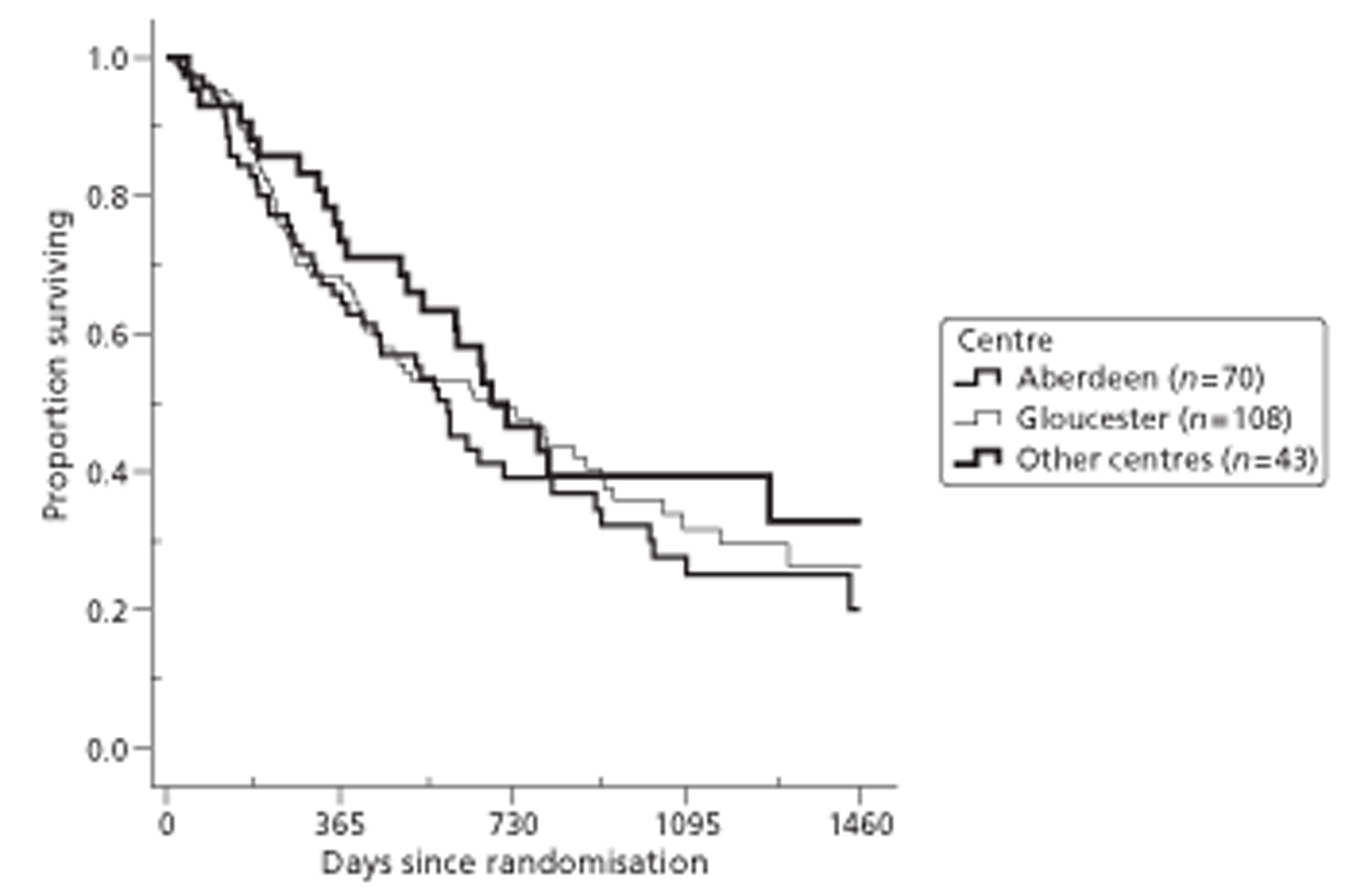

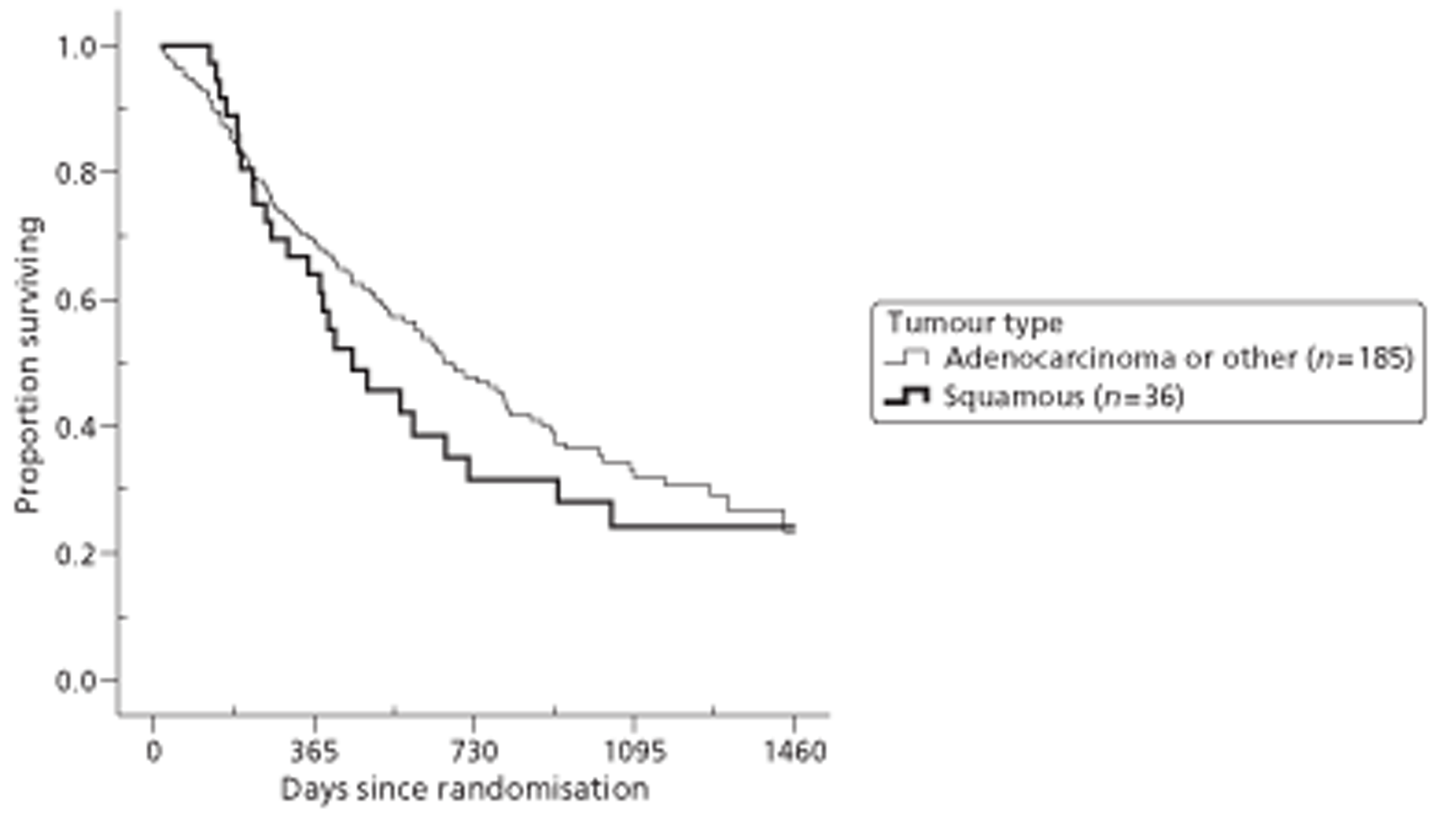

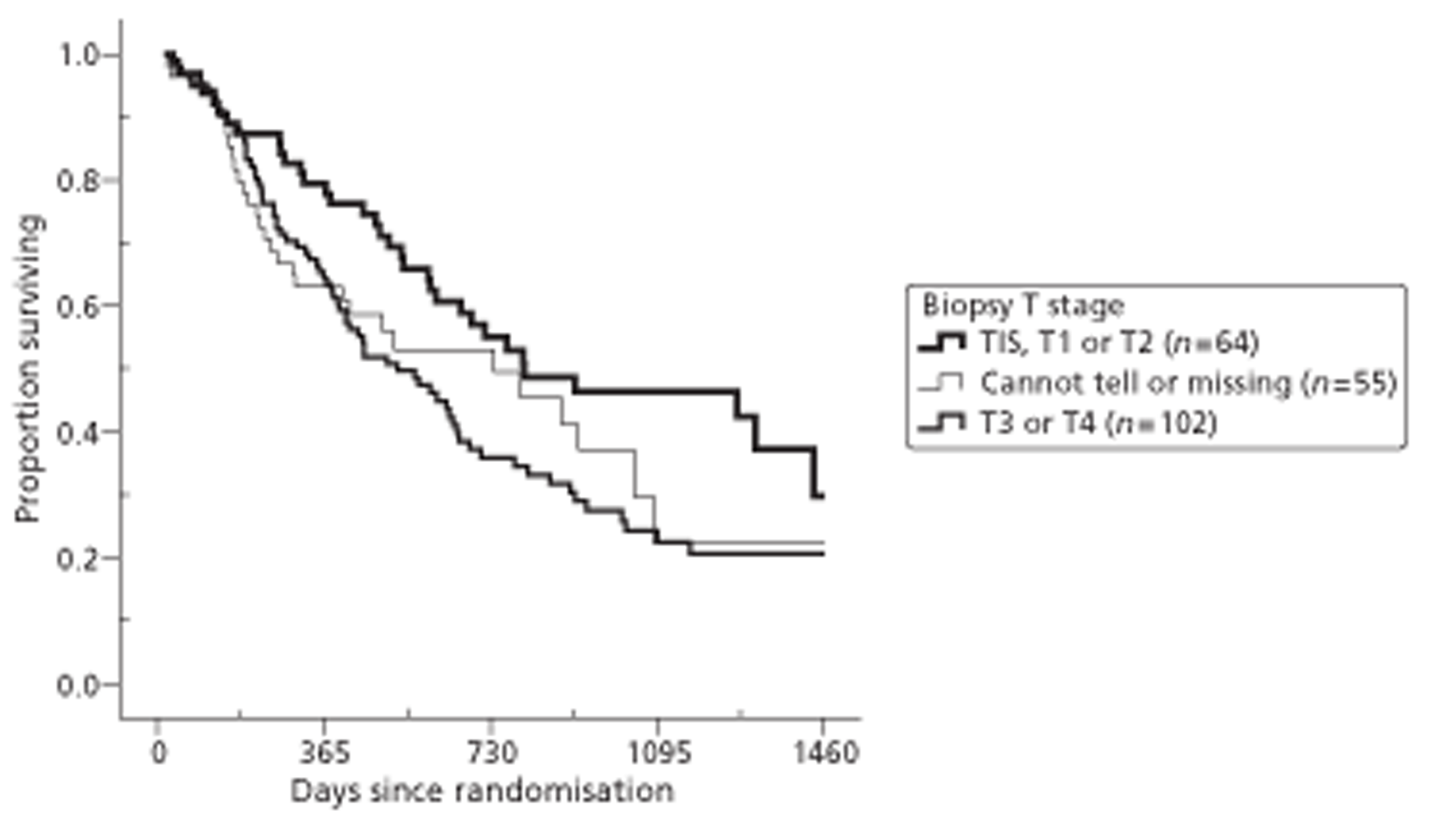

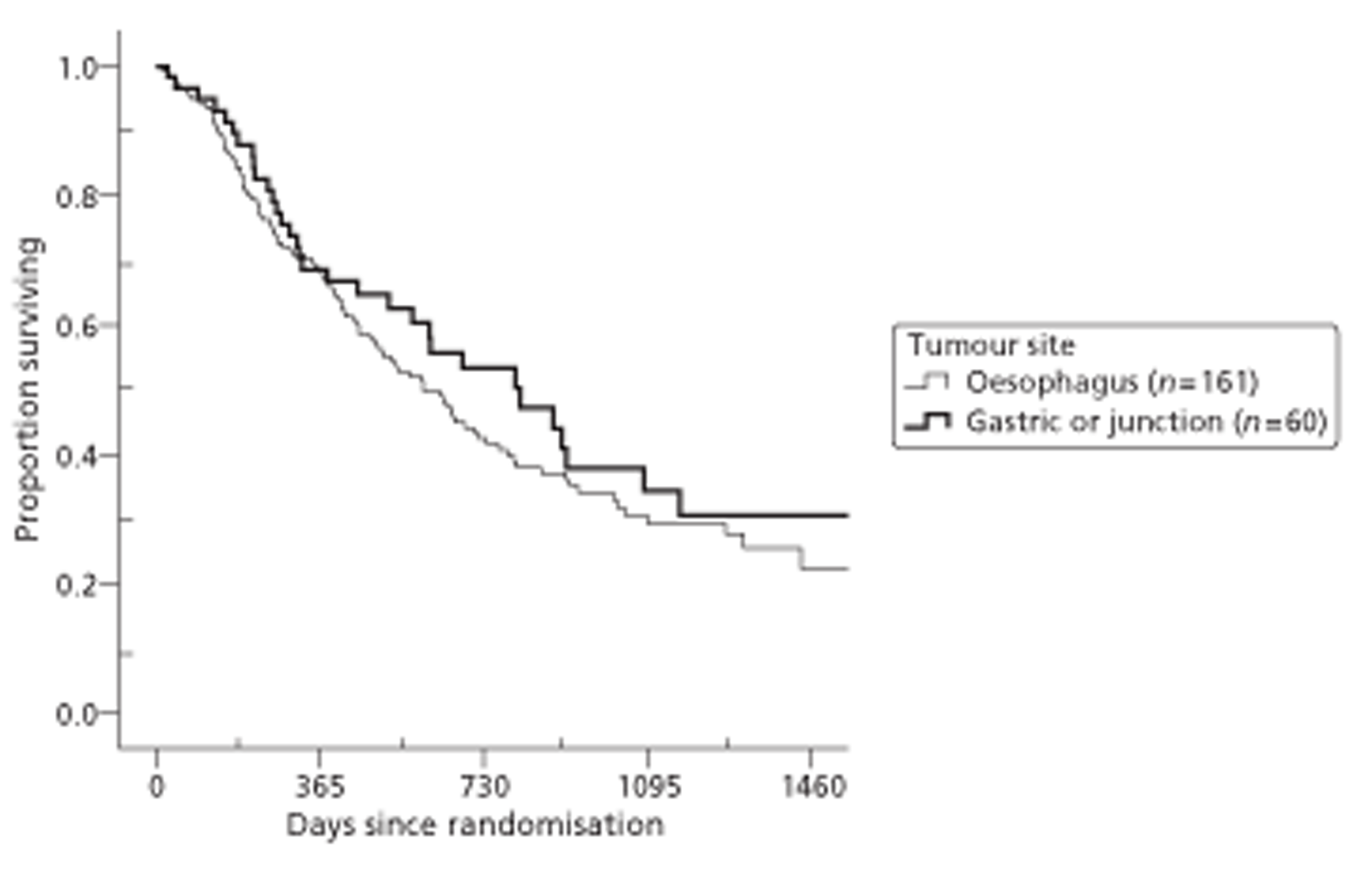

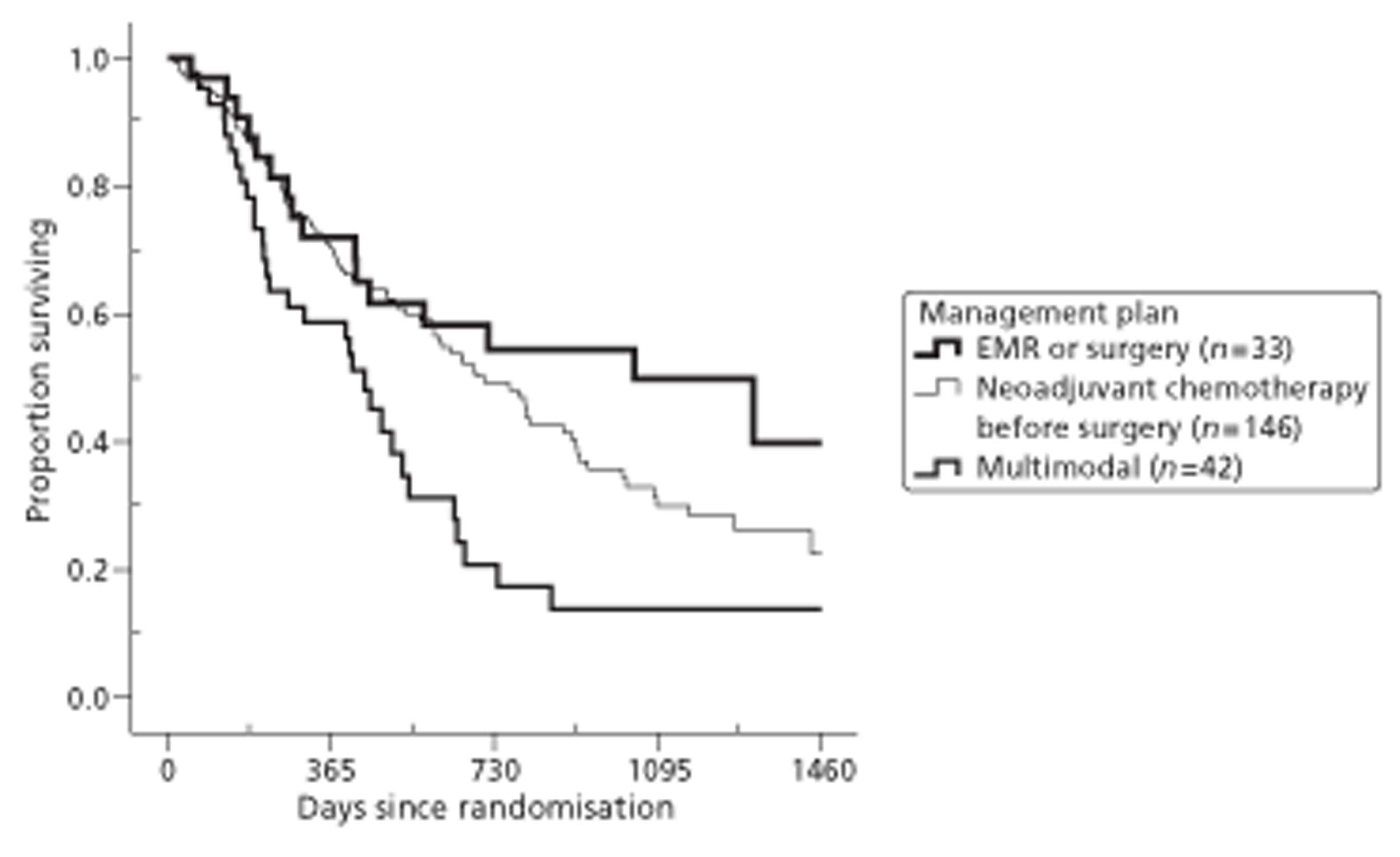

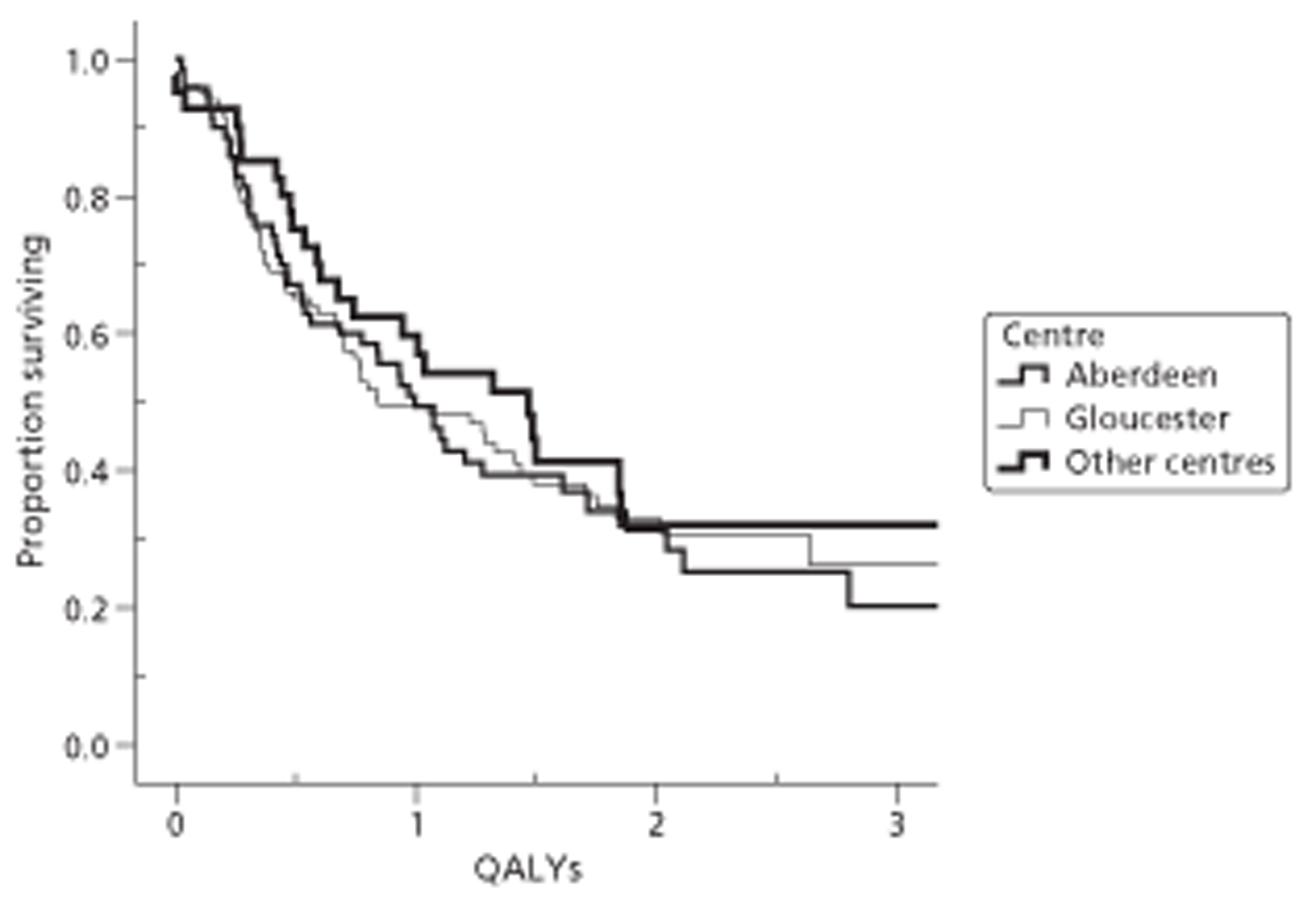

Because of the variable follow-up, applying standard analysis of variance methods or t-tests to these measures is biased against the group with better survival. There are a range of survival analysis methods, all of which allow for censored observations and thus avoid this bias. For descriptive comparisons, we used Kaplan–Meier estimates of mean and median length of survival as numerical summaries, survival curves as graphical summaries, and log-rank tests to compare the survival experience of different groups. However we used Cox regression, which models the simultaneous effect on survival of several characteristics, for the main (quality-adjusted) survival comparisons.

Both primary quality-adjusted survival analysis and secondary survival analyses using Cox Regression models considered several baseline characteristics, including EQ-5D and FACT baseline scores, for inclusion as covariates. We did this, not only to take account of any baseline imbalance between groups despite stratification, but also to improve the precision and generalisability of the model. We always included centre, condensed to three groups of similar size: Aberdeen, Gloucester and the rest. We always used the baseline score of a given measure to predict a later score of that measure. Other characteristics considered in step-wise model building included: age and gender; site, stage and type of tumour; the initial management plan agreed before randomisation; but not WHO status, as most participants had a WHO status of 1. To get the best from ‘initial management plan’ in predicting outcomes, we created a binary variable to distinguish between conservative prior plans (namely chemotherapy, radiotherapy, both or neither) and therapeutic prior plans (namely endoscopic resection or surgery in some form). As we had expected, this later proved very good at predicting outcomes. As conservative plans choose between all possible combinations of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, we followed the example of many MDTs by describing this and the resulting binary variable as ‘multimodal’.

Quality of life at 12 months: sensitivity analysis of primary outcome

We analysed EQ-5D, FACT-G and FACT-AC scores at 12 months by general linear models, using the same approach to covariates as in survival analyses. Although all follow-up times contributed to the EQ-5D- or FACT-adjusted survival analyses, we reported these three measures, and the four FACT subscales, at all follow-up times only descriptively to reduce multiple testing. As in the Cox regressions, we supplemented model-based analyses with basic summaries and graphs.

For cost-effectiveness analysis, we extended the primary QALYs measure beyond the end of the trial to 48 months for all participants by a combination of survival modelling and imputation. When all censored individuals have the same follow-up time, survival analysis methods are no longer needed. Hence this fully imputed measure, and the equivalent truncated to the minimum follow-up of 12 months, were analysed in the same way as the quality-of-life measures at 12 months. This provides both a sensitivity analysis for the main effectiveness measure and a link to the cost-effectiveness analysis.

Other outcome measures

We compared changes in management plan, complete resection rates and cause of death between groups and centres by chi-squared tests of the appropriate proportions. In response to referees, we also investigated the relationship between changes in management plans and selected other outcomes (survival, quality of life, cost and complete resection) for the two allocated groups.

Modelling: covariates and interactions

We used analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) in general, and Cox regression models specifically for survival and quality-adjusted survival, to improve comparisons between intervention and control groups. These techniques enhance the basic analytical techniques – t-tests and log-rank tests respectively – by making allowance for covariates, namely participant characteristics that affect outcome. Most covariates have similar effects on intervention and control groups, therefore including them in models corrects for baseline imbalances if present, and thus improves estimates of the effect of EUS. Whether or not there are any baseline imbalances, covariates can also explain some of the intrinsic uncertainty and thus reduce it.

In choosing covariates we followed the analysis plan that we had defined prospectively and the independent TSC had approved, also prospectively. This plan considered as potential covariates only the pre-randomisation variables listed above [see Quality-adjusted survival (primary outcome) and survival]. First we entered centre and baseline values of the outcome under analysis. Secondly we sought covariates that affect that outcome directly; to avoid subjective choices, we used a step-wise procedure and included only covariates that increased the precision of the estimated effect of EUS.

However covariates may also interact with the effect of EUS in the sense that changing the value of the covariate changes the estimated difference between an intervention participant and a control participant with the same characteristics. Thus an interaction indicates which participants derive the most benefit from EUS. The first two analytical steps we have just described used covariates without interactions. The third step added interactions between the treatment allocated and the covariates chosen in the previous two steps if they improved the model significantly. In the only change to this analysis plan after the TSC had approved it, we also investigated whether or not the unexpected interaction between the effect of EUS on survival adjusted by EQ-5D and the baseline EQ-5D also applied to survival adjusted by FACT and the baseline EQ-5D.

Imputation and missing values

To avoid bias in analysis by treatment allocated, it is desirable not to exclude participants for whom some outcome data are missing;129,131 whenever possible, therefore, we imputed these data from known data about these participants and other participants whose outcome data are known. 132,133

The main trial recruited for 3.5 years. To maximise statistical power, therefore, we followed all participants for as long as possible, namely between 1 and 4.5 years. The main aim of imputation for the effectiveness analysis was to achieve complete data within this design rather than to extend data beyond 31 July 2009, the end of the trial and thus the censoring date. However the bootstrap methods used to assess cost-effectiveness required us to estimate costs and benefits for all participants for the same period. We chose two follow-up times: 12 months, the minimum unless a participant withdrew from the trial; and 48 months, which took account of all information on both survival (as there were no subsequent deaths) and quality of life (as the last questionnaire to participants was at 36 months). Sensitivity analyses of both effectiveness and cost-effectiveness provide explicit links between the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness sections of this report.

Potentially there was complete information for all participants who died during follow-up. Dead participants did not use any more resources, and we set their subsequent quality of life to zero, rather than missing. We also received survival data on all participants up to complete withdrawal or the end of the trial. As survival analysis allows for variable follow-up, it does not need imputation.

Data were of two types:

-

Clinical data, including demographic and resource use, abstracted by research professionals from hospital notes and entered retrospectively onto the electronic database. In general we did not need to impute these data, because we asked research professionals to collect complete data except for pre-randomisation tumour stage, for which we permitted ‘missing’. However we imputed resource use in secondary care from the end of the trial to 48 months.

-

Patient-reported outcome measures at baseline and follow-up. We imputed the few missing data for the main effectiveness analysis. For the cost-effectiveness analysis and effectiveness sensitivity analysis, we needed to impute quality of life to 48 months.

We imputed missing quality-of-life data in three phases. Each phase used SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) Missing Values Analysis (MVA) procedure,132 which simultaneously estimates all missing values in a data set, on one or more data sets. The final phase also used estimated survival probabilities from the Cox regression model that we have described.

Imputing quality of life: phase 1 – psychometric and effectiveness analyses

Phase 1 used all quality-of-life items (27 in FACT-G covering four subscales; 33 in FACT-AC; five in EQ-5D, one for each domain; and EQ-VAS, a single item) answered in interviews at the same time to estimate the missing items in those interviews. This yielded a complete set of responses for existing interviews. Initial psychometric analyses, using responses at 0, 1 and 3 months, reduced the number of items in FACT-AC by two, after which we repeated phase 1. We used the resulting data to calculate scores for EQ-5D and FACT scales and subscales for all existing interviews.

Imputing quality of life: phase 2 – until 12 months

We then discarded item scores, except EQ-VAS, in favour of scale scores across time. We created a single data set comprising all 213 participants and set scale scores to zero after death. To this data set we added the allocated treatment, and baseline characteristics to improve estimates. Phase 2 used only time points up to 12 months, the minimum period of follow-up in the trial. We used MVA to impute scale scores at times without interviews for those who were still alive at 12 months, and then for those who had died by 12 months. This yielded a complete imputed data set with all quality-of-life scores at all times up to 12 months. Three participants withdrew before 12 months. While phase 2 included them among survivors, phase 3 adjusted their estimated quality of life at times after withdrawal to take account of the probability of death.

Imputing quality of life: phase 3

No more participants withdrew completely after 12 months. Beyond 12 months, however, the survival status of progressively more participants is unknown because of censoring at the end of the trial. Phase 3 therefore estimated both the probability of being alive at each of the three remaining times and the quality of life of the participant if alive. Multiplying these two estimates yields the expected quality of life. This procedure adapts to quality-of-life data the process for imputing censored cost data described by Lin et al. 133

In the first part of phase 3, we derived the probability of censored participants being alive at 18 months from the Cox regression model for survival. We calculated similar probabilities at 24 and 36 months, and also at 48 months for use in cost-effectiveness analysis and effectiveness sensitivity analysis. In the second part of phase 3, we used three separate MVA imputations to extend the data set from phase 2 to 18 months, 24 months and 36 months for those not known to be dead at those times. We multiplied each imputation by the probability that each participant would have been alive at this time. Finally we set quality-of-life scores for people known to be dead to zero, or the equivalent for FACT-AC, for which 0 is the best possible score.

By the end of phase 3, we had complete quality-of-life information for all 213 participants at all time points before the end of the trial, and survival status at that date, enabling us to estimate QALYs for primary analysis. We also had expected quality-of-life scores, but not survival status, for all 213 participants at all time points up to 36 months, for cost-effectiveness analysis and fully imputed sensitivity analysis for effectiveness.

Imputing: phase 4 – secondary care costs

We combined data on resource use in secondary care into six periods – up to 12 months, 12–18 months, 18–24 months, 24–36 months, 36–48 months and 48–60 months. We costed and summed unimputed frequency data to give the total cost in each period for each participant. However we were able to discard the final period because by 48 months only 10 participants were still in the trial, none of whom reached 60 months. For each of the first five periods we imputed the expected cost for unobserved participants by adapting the method of Lin et al. ,133 although not exactly as we had adapted it to quality-of-life data in phase 3 above.

Of these four phases of data imputation, phase 1, which imputes missing answers to questions within a scale from answers to related questions in the same scale, is not appropriate to costs because costs have no ‘related questions within a scale’ in the psychometric sense. Phase 2 was not necessary because we observed costs until censoring at 12 months or later. As with Lin et al. ,133 our costs were spread over intervals, while we had collected and imputed quality-of-life scores at exact time points, which included the ends of the cost intervals. Hence, although the survival probabilities were exactly the same in Phases 3 and 4, we used two for each cost interval – those of being alive at the start and the end of the interval. Unlike quality-of-life scores, however, costs are highly skewed and unsuitable for the MVA procedure. 129 In general, therefore, we estimated costs in unobserved intervals from the mean cost among people in the same allocated treatment group who were alive and observed throughout the interval. Nevertheless we used separate estimates for the cost of the year before death, because they are consistently and considerably higher than all years other than the first.

Psychometric methods to refine quality-of-life assessment

Rationale

We assessed quality of life by the EuroQol120,121 and FACT123,124 (see Design, Quality of life instruments). We chose the EQ-5D as the primary means of adjusting survival for quality of life. We included the EQ-VAS as a natural adjunct to the EQ-5D. We added FACT as an alternative means of adjusting survival, conditional on psychometric analysis within the trial. When the primary outcome measure changed from survival to quality-adjusted survival during the trial, thorough quality-of-life assessment became even more crucial.

The standard way to score FACT data is as follows. Each subscale is the sum of its items. FACT-G is the sum of Physical, Social, Emotional and Functional subscales. FACT Total is the sum of FACT-G and Additional Concerns. FACT Trial Outcome Index (TOI) is the sum of Physical, Functional and Additional Concerns. The rationale for the TOI is:

It is a common endpoint used in clinical trials, because it is responsive to change in physical or functional outcomes. While social and emotional well-being are very important to quality of life, they are not as likely to change as quickly over time or in response to therapy. 134

To assess the best use of FACT in the COGNATE trial, we posed three research questions and conducted psychometric analyses separately on the data collected before randomisation, and at 1 and 3 months, when enough individuals attempted the questionnaires to make the analyses feasible.

Questions and corresponding analyses

How to score FACT-AC?

The COGNATE trial combined the two ‘Additional Concerns’ scales – Gastric and Oesophageal – so that all participants completed both scales. This could have resulted in some redundancy among the items measuring each construct. Although the scoring method for FACT-AC– summing the items – implies a single dimension, this has not been systematically tested. Therefore we decided to examine the factor structure of the Additional Concerns items, and to consider the implications for scoring. We subjected the FACT-AC items to principal components analysis using SPSS version 16,135 basing the number of components to be retained on the scree plot of eigenvalues and on the meaningfulness of the solution. We rotated these components orthogonally.

How to score FACT-G?

The scoring method of FACT-G – summing item scores to produce four subscale scores that can be summed into a single score – implies four intercorrelated dimensions. Previous factor analyses have typically found such a structure. 136 However we felt it prudent to check the factor structure of the FACT-G items and to consider the implications for scoring. We achieved this by subjecting the FACT-G items, that is to say the Physical, Functional, Social, and Emotional subscales, to confirmatory factor analyses with maximum likelihood estimation, using AMOS™ version 16137 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The factors were free to correlate. For each model, we considered the global fit, the residual covariances, the loadings of items on their intended factors, the modification indices for the loadings of items on their non-intended factors, and the correlations between factors. We measured global fit by the comparative fit index (CFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardised root-mean-square residual (SRMR). Values of CFI above 0.9, SRMR below 0.10 and RMSEA below 0.08 represent adequate fit. 138 Ideally, we sought a significance level of at least 0.05 for the RMSEA test of close fit, where close fit is defined as an RMSEA value no greater than 0.05. We modified models only when there was both statistical and theoretical justification for so doing.

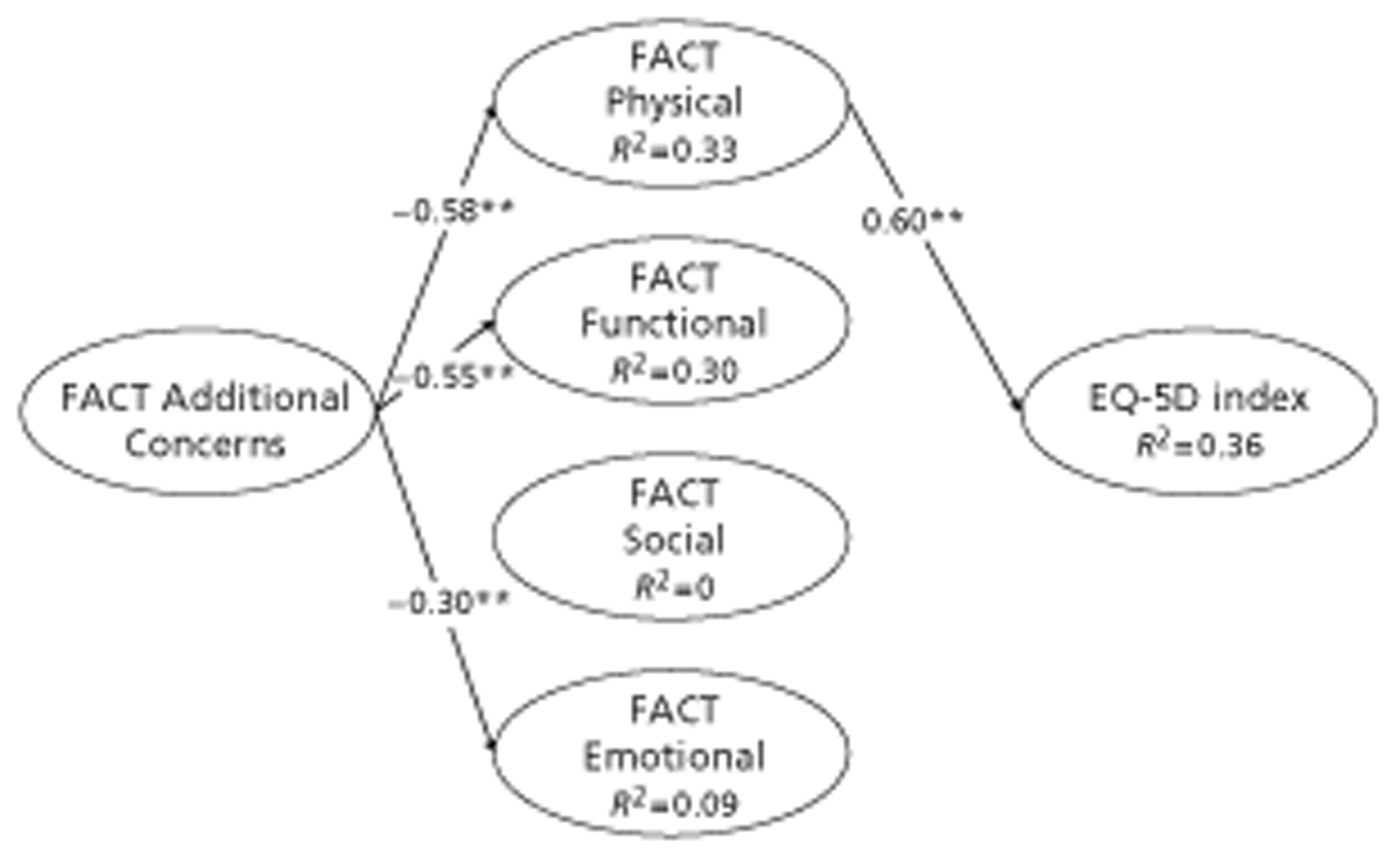

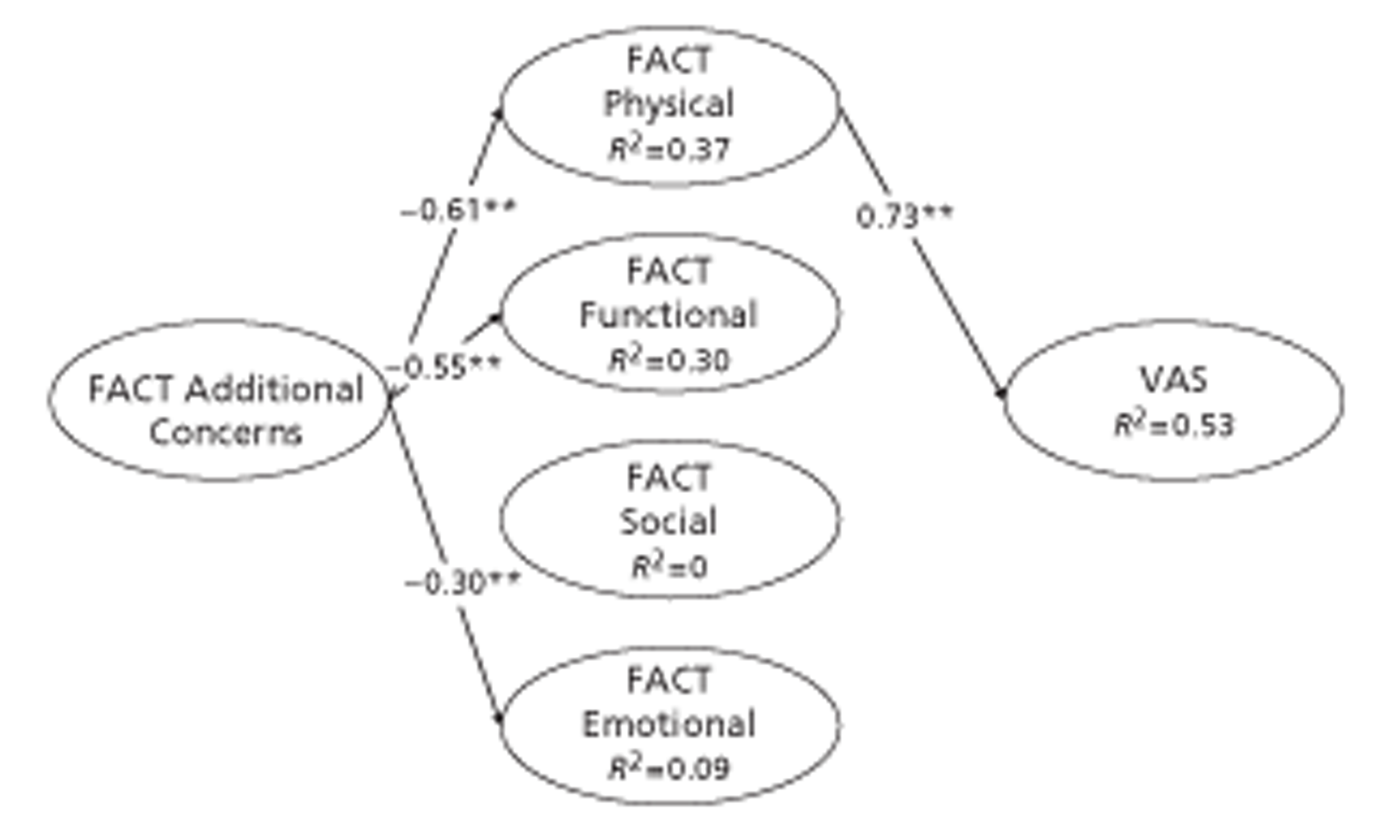

What FACT summary measure to use in COGNATE?