Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/112/03. The contractual start date was in November 2010. The draft report began editorial review in April 2012 and was accepted for publication in May 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Meads et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Aim of the report

The aims of this project were as follows:

-

To determine the accuracy of sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy with technetium-99 (99mTc) enhanced and/or blue dye lymphoscintigraphy for diagnosis of inguinofemoral lymphadenopathy (IFL) in vulval cancer through systematic review.

-

To assess, through systematic review, the diagnostic and therapeutic impact of SLN biopsy with 99mTc enhanced and/or blue dye lymphoscintigraphy in:

-

changing disease staging

-

changing planned treatment

-

reducing complications associated with IFL

-

improving morbidity and disease-free survival.

-

-

To determine the effectiveness of various interventions [e.g. surgery, radiotherapy (RT) and chemotherapy] in the management of vulval cancer.

-

To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of SLN biopsy with 99mTc enhanced and/or blue dye lymphoscintigraphy versus IFL using decision-analytic modelling.

The original protocol for the project is in Appendix 1.

Chapter 2 Background

Description of underlying health problem

Vulval cancer is a relatively rare gynaecological malignancy diagnosed mainly among elderly patients. In 90% of cases it develops as a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and the remaining 10% are melanomas, Paget's disease, Bartholin's gland tumours, adenocarcinomas and basal cell carcinomas. 1 Lesions mainly occur on the inner edges of the labia majora (around 50% of the cases), less often in the labia minora and very rarely on the clitoris or in the Bartholin glands. The symptoms of vulval cancer include a lump on the vulva, vulval bleeding, itching, pain or ulceration, and approximately 90% of women present with a visible tumour. 1 Diagnosis is by biopsy with histological examination of the sample. Histological examination can include immunohistochemical analysis which may enable more a precise interpretation of the degree of dysplasia compared with conventional haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. 2

Vulval cancer can be locally invasive and can spread via the lymphatic system to the inguinal or femoral nodes. If the primary tumour is laterally located in the vulva, spread may be only to that side; if the tumour is central, spread may be to either side. Lymphatic spread is strongly related to lesion size: metastasis is present in 20–30% of tumours < 2 cm in diameter and in 44% of tumours > 2 cm. 3 Correlation of lymph node status with depth of invasion is also important. Tumours with a < 1-mm depth of invasion have a < 1% risk of nodal spread. 4,5 Lymph node status is regarded as an important predictor of survival. 6 Malignancy in the lymph nodes can result in invasion of the blood vessels of the groin, including rupture of the femoral blood vessels. Distal spread via the bloodstream is relatively rare. 2

Once vulval cancer is diagnosed, staging is important in order to plan treatment and estimate prognosis. Two staging systems are frequently used, one developed by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO)7,8 and one by the tumour node metastasis (TNM) classification of malignant tumours7 (Tables 1 and 2). Both staging systems have gradually evolved over time. Table 3 gives a comparison of FIGO and TNM staging. 2

| Stage | FIGO staging 1969 | FIGO staging 1988 | FIGO staging 2000 | FIGO staging 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical staging | Surgical staging | Surgical staging | Surgical staging | |

| 0 | Carcinoma in situ | Carcinoma in situ | Carcinoma in situ | Carcinoma in situ |

| I | Tumour confined to vulva, 2 cm or less in largest diameter and no suspicious groin nodes | Tumour confined to vulva or perineum, < 2 cm in greatest dimension and nodes are negative | Ia: tumour confined to vulva or vulva and perineum, 2 cm or less in greatest dimension and with stromal invasion no greater than 1 mm. Nodes are negative Ib: tumour confined to vulva or vulva and perineum, 2 cm or less in greatest dimension and with stromal invasion greater than 1 mm. Nodes are negative |

IA: lesions ≤ 2 cm in size, with depth of invasion ≤ 1 mm IB: lesions > 2 cm in size, with depth of invasion > 1 mm |

| II | Tumour confined to vulva, more than 2 cm in diameter and no suspicious groin nodes | Tumour confined to vulva or perineum, > 2 cm in greatest dimension, nodes are negative | Tumour confined to vulva or vulva and perineum, more than 2 cm in greatest dimension. Nodes are negative | Tumour of any size with extension to adjacent perineal structures: one-third lower urethra, one-third lower vagina, anus. No lymph node metastases |

| III | Tumour of any size with (1) adjacent spread to the urethra and/or vagina, perineum, and anus, and/or (2) clinically suspicious lymph nodes in either groin | Tumour of any size with (1) adjacent spread to the lower urethra or anus, and/or (2) unilateral regional lymph nodes metastases | (1) Tumour invades any of the following: lower urethra, vagina, anus (2) Unilateral regional lymph nodes metastases |

Tumour of any size, with or without extension to adjacent perineal structures, with positive lymph nodes IIIA: one lymph node metastasis (≥ 5 mm) or 1–2 lymph node metastases (< 5 mm) IIIB: at least two lymph node metastases (≥ 5 mm) or at least three lymph node metastases (< 5 mm) IIIC: lymph node metastases with extracapsular spread |

| IVa | IV: tumour of any size, (1) infiltrating the bladder mucosa or the rectal mucosa, or both, including the upper part of the urethral mucosa, and/or (2) fixed to the bone, and/or (3) other distant metastases | Tumour invasion of any of the following: upper urethra, bladder mucosa, rectal mucosa, pelvic bone and/or bilateral regional node metastasis | Any size tumour with bilateral regional lymph node involvement or with invasion of any of the following: upper urethra, bladder or rectal mucosa, pelvic bone | Tumour invades any of the following: upper urethral and/or vaginal mucosa, bladder or rectal mucosa, or fixed to the pelvic bone. Or fixed or ulcerated lymph nodes |

| IVb | – | Any distant metastasis, including pelvic lymph nodes | Any distant metastasis, including pelvic lymph nodes | Any distant metastases including pelvic nodes |

| Stage | TNM 1969 | TNM 1988 | TNM 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical staging | Surgical staging | Surgical staging | |

| Tx | – | Primary tumour cannot be assessed | Primary tumour cannot be assessed |

| T0 | – | No evidence of primary tumour | No evidence of primary tumour |

| Tis | – | Carcinoma in situ | Carcinoma in situ |

| T1 | Tumour confined to the vulva, 2 cm in largest diameter | Tumour confined to the vulva and/or perineum, ≤ 2 cm in greatest dimension | T1a: tumour confined to the vulva and/or perineum, ≤ 2 cm in greatest dimension and with stromal invasion no greater than 1 mm T1b: tumour confined to the vulva and/or perineum, ≤ 2 cm in greatest dimension and with stromal invasion > 1 mm |

| T2 | Tumour confined to the vulva, 2 cm in largest diameter | Tumour confined to the vulva and/or perineum, > 2 cm in greatest dimension | Tumour confined to the vulva and/or perineum, > 2 cm in greatest dimension |

| T3 | Tumour of any size with adjacent spread to the urethra, and/or vagina, and/or perineum and/or anus | Tumour involves any of the following: the lower urethra, vagina, anus | Tumour invades any of the following: the lower urethra, vagina, anus |

| T4 | Tumour of any size infiltrating the bladder mucosa, and/or the rectal mucosa, or including the upper part of the urethral mucosa and/or fixed to the bone | Tumour involves any of the following: bladder mucosa, rectal mucosa, upper urethra, pelvic bone | Tumour invades any of the following: bladder mucosa, rectal mucosa, upper urethral mucosa or is fixed to bone |

| Nx | Regional (i.e. femoral and inguinal) lymph nodes cannot be assessed | Regional (i.e. femoral and inguinal) lymph nodes cannot be assessed | |

| N0 | No nodes palpable | No lymph node metastases | No lymph node metastases |

| N1 | Nodes palpable in either groin, not enlarged, mobile (not clinically suspicious for neoplasm) | Unilateral regional lymph node metastases | Unilateral regional lymph node metastases |

| N2 | Nodes palpable in either groin, enlarged, firm and mobile (clinically suspicious for neoplasm) | Bilateral regional lymph node metastases | Bilateral regional lymph node metastases |

| N3 | Fixed or ulcerated nodes | – | – |

| Mx | – | Distant metastases cannot be assessed | Distant metastases cannot be assessed |

| M0 | No clinical metastases | No distant metastases | No distant metastases |

| M1 | M1a: palpable deep pelvic lymph nodes M1b: other distant metastases |

Distant metastases, including pelvic lymph node metastases | Distant metastases, including pelvic lymph node metastases |

| FIGO stage | TNM status | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour | Node | Metastases | |

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| IA | T1a | N0 | M0 |

| IB | T1b | N0 | M0 |

| II | T2 | N0 | M0 |

| III | T3 | N0 | M0 |

| T3 | N1 | M0 | |

| T1 | N1 | M0 | |

| T2 | N1 | M0 | |

| IVA | Ta | N2 | M0 |

| T4 | Na | M0 | |

| IVB | Ta | Na | M1 |

The grade of malignancy refers to the extent of differentiation seen on microscopic examination and gives an indication of how fast the malignancy is likely to develop. In vulval cancer three grades are defined:

-

Grade 1: cells are low grade or well differentiated and histologically look very much like normal vulval cells.

-

Grade 2: cells are medium grade or moderately differentiated and look more abnormal than grade 1 cells, but not so much as grade 3 cells.

-

Grade 3: cells are high grade or poorly differentiated or can be undifferentiated, they are very unlike normal vulval cells.

Premalignant conditions

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is a precancerous condition that can occur in the vulval area and may present as pigmented lesions. There are two main types of VIN, each with their own distinctive clinical and pathological features. The classifications in use are the World Health Organization (WHO)’s classification that refers to human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated VIN as warty/basaloid VIN and grades the disease as VIN1, VIN2 and VIN3. The International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) has proposed a newer classification referring to VIN usual type and VIN differentiated type. The more commonly referred to classical or usual-type VIN is a disease of relatively young women and is associated with HPV. HPV deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), mostly type 16, is present in up to 90% of classical VIN. Typically, classical VIN involves the vulva multifocally and is associated with multicentric involvement of the vagina and cervix. Classical VIN progresses to cancer in only 3–10% of treated patients. The other type of VIN is referred to as simplex or differentiated VIN and was described in the 1960s, but added to ISSVD classification in 2004/5. It constitutes 2–10% of VIN diagnoses, but is seen adjacent to up to 60% of vulval cancers. It characteristically occurs in postmenopausal women and is associated with lichen sclerosis. Histologically, it is a subtle lesion and is likely to be underdiagnosed because of its high degree of differentiation. 9–14

Aetiology

Several factors increase the risk of developing cancer of the vulva, but none confers high risk. Factors increasing risk of malignancy include HPV infection, smoking, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and other factors.

Smoking

Smoking is a risk factor for the development of many malignancies, including vulval cancer. 15,16 For women already infected with HPV, smoking further raises the risk of neoplasia. It has been reported that cigarette smoking increases the risk of vulval cancer development by 25 times for women smoking ≥ 20 cigarettes a day who also have serological evidence of HPV-16 infection. 16 Another study reported that active smoking was associated with an increased risk of developing vulval cancer [relative risk (RR) 2.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.3 to 3.2]. 17

Human papillomavirus infection

Human papillomavirus infection is thought to cause up to half of vulval cancers, mostly in women under the age of 50 years. HPV is less likely to be a risk factor in older women. Vulval carcinoma development is associated with infection of high-risk HPV types. A case–control study found that over 30% of examined tumours contained HPV DNA of types 16, 18 or 33. Moreover, HPV DNA was found in 61% of tumours with adjacent intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN III) and in 13% of tumours without associated VIN III. 18 The prevailing evidence favours HPV as one causative factor in genital tract carcinoma. 19

Human immunodeficiency virus infections

Human immunodeficiency virus causes the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Owing to its destructive effect on the human immune system, women burdened with it are more prone to a HPV infection, which, in turn, may be easily linked with vulval cancer development. 20

Other factors

A higher risk of vulval cancer is associated with lower socioeconomic status and fewer years of education. 21 It has been found that a prior history of lichen sclerosus of the vulva and inflammation of the vulva or vagina are significantly associated with vulval cancer development. Some other evidence suggests that environmental exposures may also play an important role in vulval carcinogenesis. 22 In addition, some studies have shown a link between the risk of vulval cancer occurrence and psoriasis,23 or vulval cancer occurrence and transplant immunosuppression. 24

Epidemiology

Vulval cancer accounts for approximately 3–5% of all gynaecological malignancies and 1% of all cancers in women. 25 The worldwide prevalence of vulval cancer is around 3% and it is estimated that 27,000 women are diagnosed each year. 21 In the UK, the lifetime risk of developing vulval cancer is 1 in 316. 21 According to a recent report, the highest rate of occurrence is in North America, South America and Europe, with incidence rates of between 1 and 2 per 100,000 per year. 26

Vulval cancer is very rare in young women aged < 25 years. Incidence rates are around 1.1 per 100,000/year, among women aged 25–39 years, rising to 3.8 per 100,000/year in those aged 60–64 years and peaking at 24.5 per 100,000/year in women aged ≥ 85 years. The proportion of women diagnosed with vulval cancer under the age of 50 years has risen from 7% in the 1970s to 14% in 2006–8. 21

Each year in the UK, there are, on average, 373 deaths from vulval cancer. The European age-standardised death rate for vulval cancer in the UK was 0.64 per 100,000 female population over the 5-year period 2004–8. The mortality rate for vulval cancer is 0.1 per 100,000 women aged 25–44 years and 0.5 for women aged 45–64 years, rising to 6 per 100,000 women aged ≥ 65 years and 12 per 100,000 women aged ≥ 80 years. Mortality rates for vulval cancer in the UK have declined steadily since the early 1970s. The rate fell by almost half (48%) between 1971 and 2008, from 1.3 per 100,000 female population to 0.7 per 100,000. 27

Prognosis

Vulval cancer is highly curable when diagnosed at an early stage. 28 Survival is most dependent on primary lesion diameter and the pathological status of the inguinal nodes. 1 Linking staging to survival is not precise if it is unclear whether the nodes are involved (which would be stage III) or not (which would be stage II). In a study of 588 patients treated in 1977–84,29 survival of patients with FIGO stage I, II, III and IV disease was 98%, 87%, 75% and 29%, respectively. If nodes are involved, survival is linked to the number of nodes involved and unilaterality versus bilaterality. In patients with tumour diameter > 8 cm and three or more unilateral or two bilateral metastatic nodes, the relative survival at 5 years was 0%. 29 The following aspects have been accounted as the risk factors for node metastasis: clinical node status, age, degree of differentiation, tumour stage, tumour thickness and depth of stromal invasion. 29,30 The presence of capillary–lymphatic space invasion is associated with increased local recurrence in the vulva but not with increased risk of groin node metastases. 1

Another early study gave 5-year survival rates for RT of only 13.0%, simple vulvectomy of 30.8%, vulvectomy and RT of 32.5%, radical vulvectomy with IFL of 55.7% and radical vulvectomy with inguinal, femoral and pelvic lymphadenectomy of 63.3%. 31

Current treatment options

Since the late 1960s, the treatment of choice for vulval cancer has been surgical removal of the tumour and affected lymph nodes. 1 The actual treatment used for SCC depends on the stage of tumour found (Table 4). 3 Surgical management of non-SCC cancers vary by type of cancer. For carcinoma of the Bartholin's gland, treatment follows that for SCC tumours but the tumours are more likely to be deep and metastatic. For basal cell and verrucous carcinomas, wide local excision is usually used as metastases are rare. For malignant melanoma (MM), wide local excision is preferred, but there is a high rate of relapse. 1

| Stage | Definition | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Carcinoma in situ and less advanced precancerous changes, e.g. VIN | Laser surgery, wide local excision, or a skinning vulvectomy; alternatively fluorouracil ointment may be prescribed or imiquimod |

| I | Treatment depend on the size and depth of the cancer and VIN occurrence | – |

| IA – depth of invasion of 1 mm or less, and there are no other areas of cancer or VIN | Wide local excision. The cancer is being removed along with a 1-cm margin of the normal tissue surrounding | |

| IB – lesions > 2 cm in size with depth of invasion > 1 mm | Wide local excision/hemi/radical vulvectomy and inguinal lymph node dissection SLN biopsy may be performed instead of lymph node dissection when tumour size is < 4 cm and is unifocal |

|

| II | Cancer spread to structures near the vulva area | Partial radical vulvectomy |

| Optional removal of the lymph nodes in the groin on both sides of the body | ||

| If cancer cells are present near the margins the radiation therapy to the area of surgery is performed | ||

| Radiation therapy with surgery in order to remove remaining cancer tissues. Chemotherapy with fluorouracil and/or cisplatin | ||

| III | Cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes | Surgical removal of cancer and lymph nodes in the groin optionally followed by radiation therapy. Radiation and chemotherapy are applied for patients not able to undergo surgery |

| IVA | Cancer spread to organs and tissues in the pelvis: rectum, bladder, pelvic bone, upper part of the vagina and urethra. Tumours of type T1 and T2 with less severe nearby spread but with extensive spread to nearby lymph nodes | Removal of as much as possible of the affected tissue with possible pelvic exenteration. Usually operation includes vulvectomy, removal of the pelvic lymph nodes or, alternatively, lower colon, rectum, bladder, uterus, cervix and vagina Gold standard: combination of surgery, radiation and chemotherapy |

| IVB | Cancer spread to lymph nodes in the pelvis or to organs and tissues outside the pelvis | None of the approaches is assumed to cure the malignancy though they may be helpful in relieving some symptoms emerging from the disease |

| Recurrent | Cancer recurrence | Treatment depends on the recurrence time and location. Local recurrence: surgery or combination of three approaches. Unresectable recurrence: chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy |

Surgery to the vulva can be radical vulvectomy (complete removal of the vulva), hemivulvectomy or, more commonly, wide local excision. 1 If necessary, skin grafting using skin from the thigh can be used. The intention of surgery is complete removal of the lesion with a minimum margin of 15 mm disease-free tissue on all sides of the specimen. The side effects of vulvectomy are extensive pain, disfigurement and the risk of sphincter damage leading to urinary or faecal incontinence. There can be considerable psychological trauma and loss of psychosexual function. 32

Because of the risk of lymphatic spread to the groin nodes, lymphadenectomy of the inguinal and femoral nodes, either unilaterally or bilaterally, is usually undertaken, depending on the stage of the disease and the laterality of the tumour. IFL can be omitted safely if the tumour depth of invasion is < 1 mm. Unilateral IFL is performed for lateral tumours that are at least at a 1-cm distance from the midline of the vulva. Bilateral IFLs are performed for tumours encroaching within 1 cm of the midline. Complications affect over 50% of patients having IFL, including infection of groin wounds, subsequent wound breakdown, lymphoedema and cellulitis. 33–35 If the groin breaks down, patients need to stay in hospital for several days longer than otherwise and will need antibiotics and community care once discharged. As patients are often elderly, this additional morbidity can compromise overall recovery. Lymphoedema may be the most aggravating as it significantly limits overall mobility,36 is disfiguring, causes difficulties in daily living, can lead to lifestyle becoming severely limited and may also result in psychological distress. Over the last 20 years, use of the triple-incision technique in the groin, for which three cuts are made, leaving skin bridges between so that the skin can heal more quickly than one longer single (butterfly) incision, has reduced postoperative stay and improved recovery from IFL. 37

Patients with poor prognostic features may additionally receive RT covering the pelvis, groin and the perineum area. In cases of locally advanced disease, standard management includes surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy (sequentially or in combination). 1 If patients are unable to withstand surgery, RT alone or, occasionally, chemotherapy alone can be used.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy

Currently, clinical examination for the determination of metastatic involvement of groin lymph nodes is insufficiently accurate, particularly when the nodes may contain micrometastases but appear clinically normal. Out of all patients with clinically normal lymph nodes, between 16% and 24% will go on to develop metastases;30,38 therefore, interest has been shown in the use of imaging modalities and SLN biopsy in order to determine lymphatic spread and thereby more accurately stage vulval cancer and reduce the need for unnecessary surgery. If IFL is undertaken and nodes are negative for metastases, there is considerable morbidity from the IFL, which is associated with longer hospital stays. If IFL is not undertaken and there were micrometastases that were missed, survival rates are reduced. So IFL is a surgical procedure that serves to obtain lymph nodes for histopathology as a diagnostic test for metastases and IFL can also remove clinically suspicious enlarged nodes to improve treatment success rates.

A SLN refers to any lymph node that receives drainage directly from the primary tumour and is the first in the chain of lymph nodes in the groin and, therefore, has the highest probability of containing cancer cells from the tumour in the vulva. 39 SLNs can be identified by using a dye called isosulfan blue or a radioactive tracer called 99mTc in a procedure called lymphoscintigraphy. Blue dye and 99mTc can be used alone or in combination. 40 The blue dye/99mTc procedure only detects the SLN, but cannot determine whether or not the SLN has metastatic deposits. For this, histopathological examination is required. This is best done by routine histopathology using H&E staining, although, in some centres, frozen sections may also be used. Lymph nodes can be cut in a variety of slices, with thinner slices known as ultrastaging. Immunohistochemical techniques that will enhance the ability to detect metastatic deposits can also be used.

There is a risk with SLN biopsy that malignancy may be missed. It may be that the first draining lymph node was missed, or that the malignancy developed not in the SLN but in any of the groin nodes other than the SLNs biopsied and examined with histology. There has been one small survey of vulval cancer patients evaluating the acceptability of SLN biopsy compared with IFL at different levels of risk. 41 This 106 patients who were surveyed had fully recovered from vulval cancer (99 questionnaires could be evaluated) and had received IFL as part of their treatment. 41 It was found that 66% would recommend IFL if the risk of missing metastasis from SLN biopsy was 1 in 80, and 84% would recommend IFL if the risk of missing metastasis from SLN biopsy was one in eight. Age and the presence or degree of side effects experienced by the patients surveyed, which included severe lymphoedema in 39% and with severe pain in 28%, did not affect preferences for each procedure.

The extent of SLN biopsy being undertaken in the NHS for vulval cancer is currently unclear. The most recent guideline from the UK Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists states that ‘Dye studies and lymphoscintigraphy may be of value in the detection of SLNs although the outcome of this type of intervention is awaiting the outcome of controlled clinical evaluation’. 1

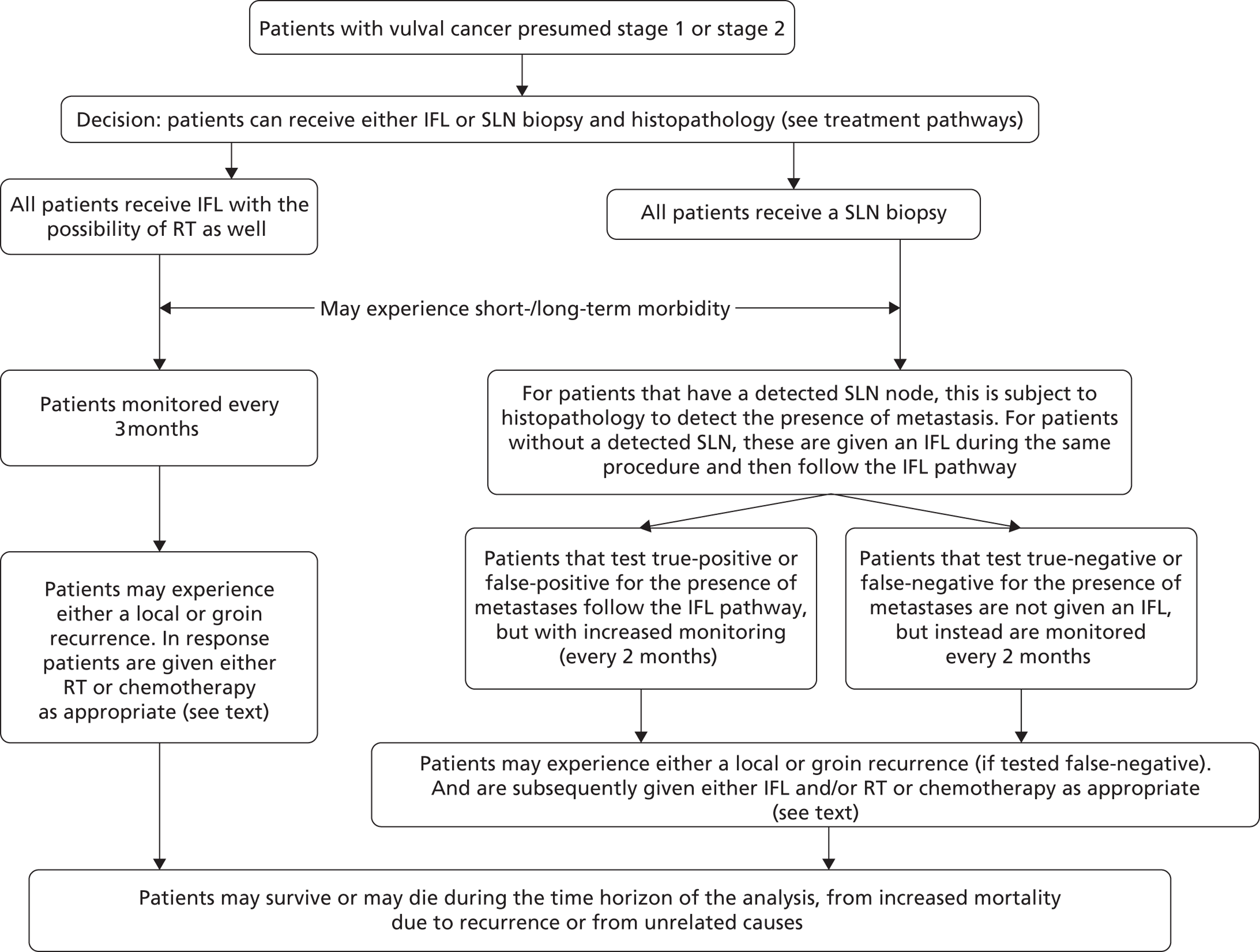

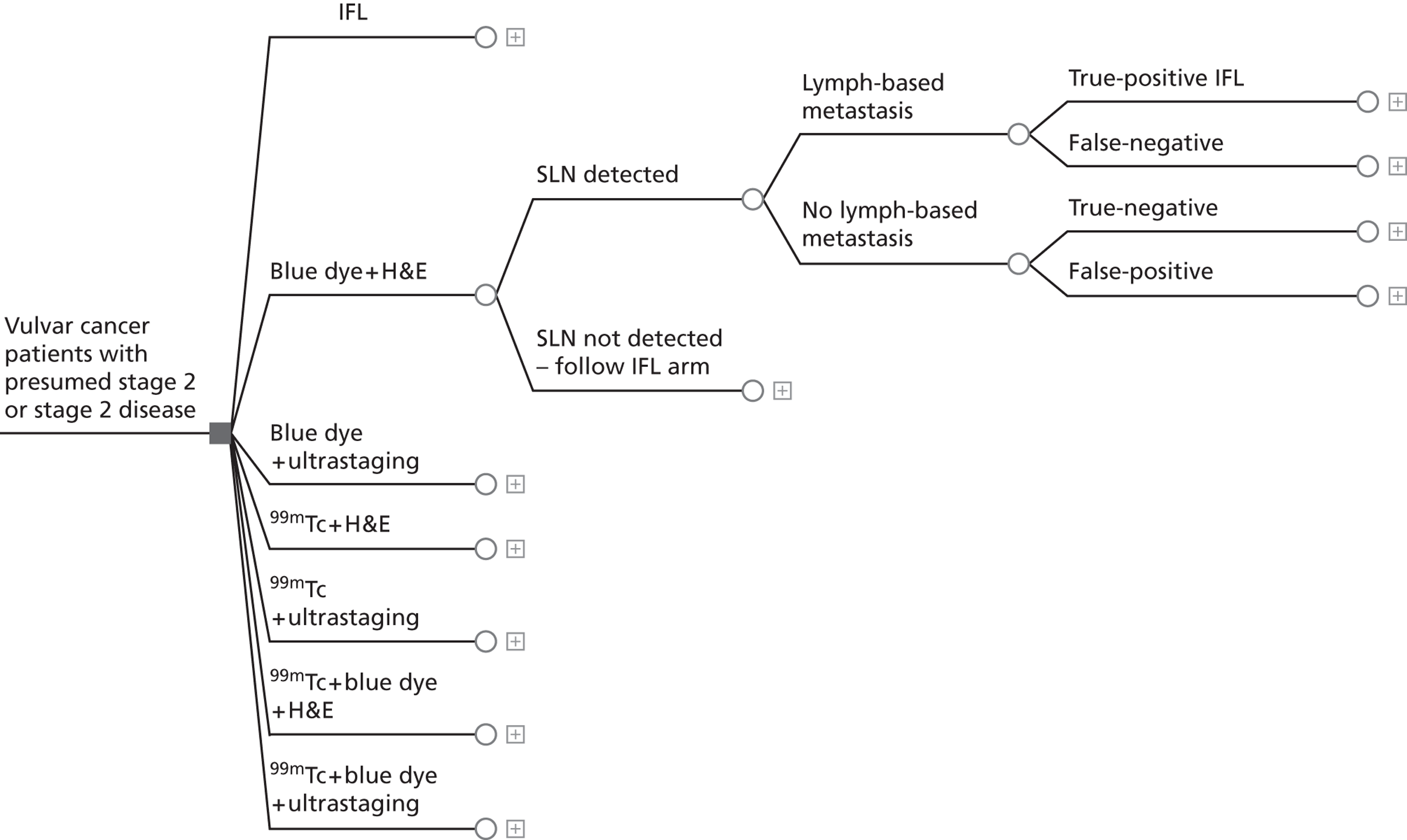

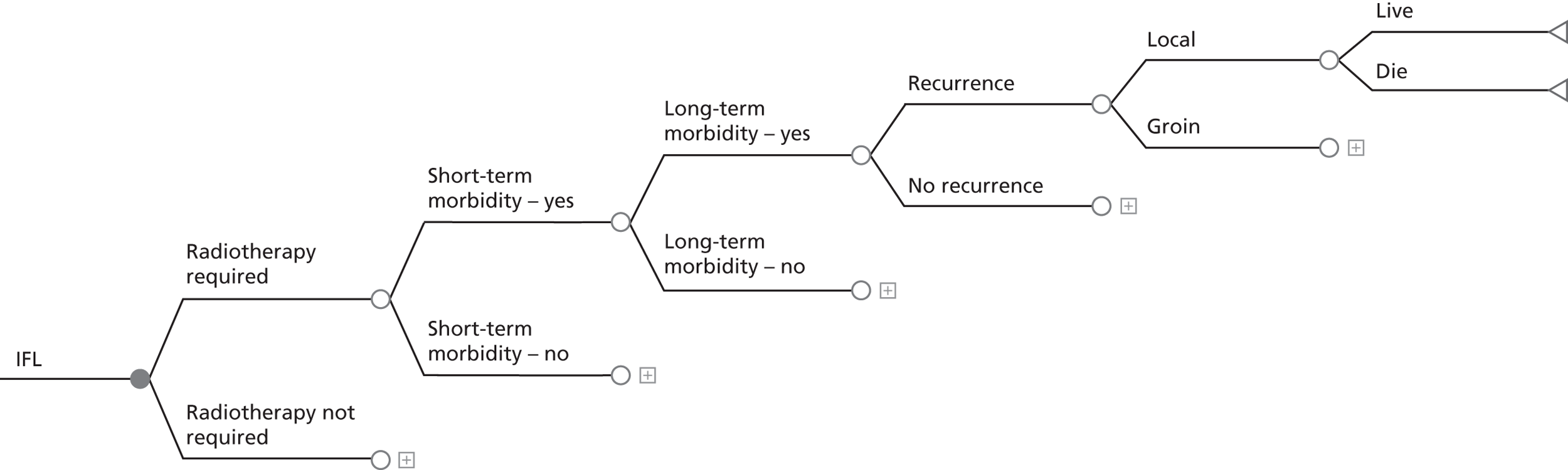

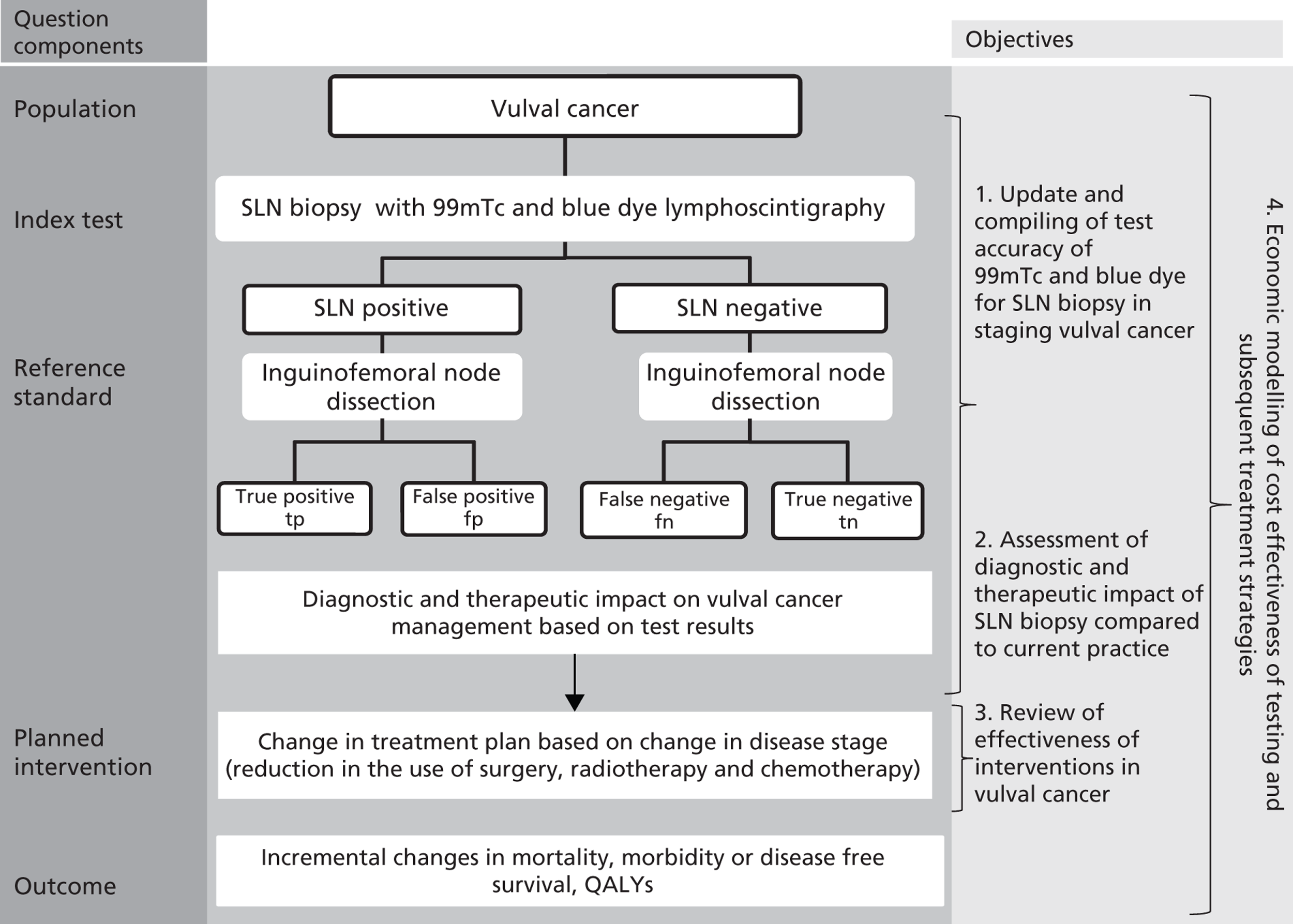

Chapter 3 Definition of the decision problem

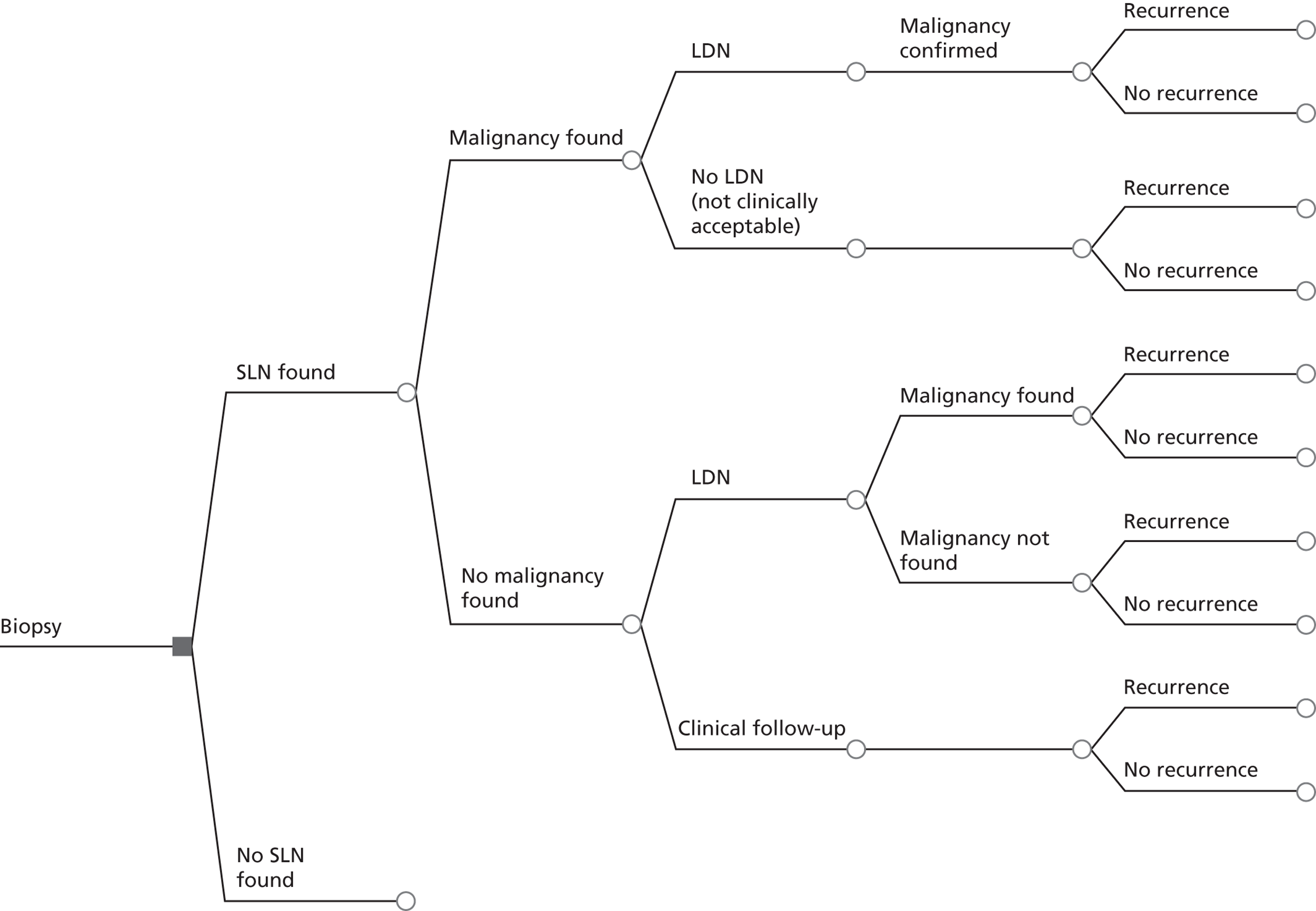

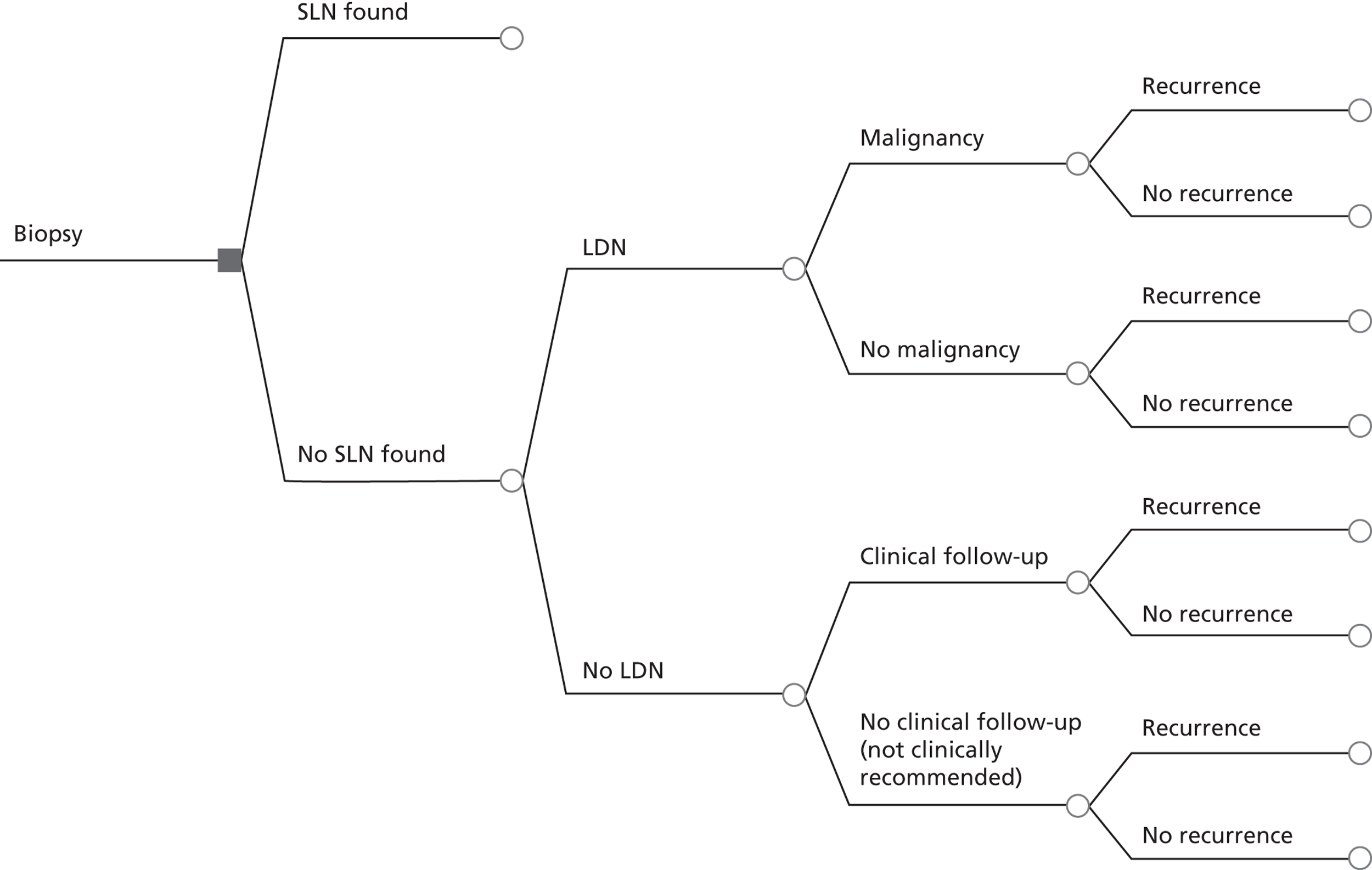

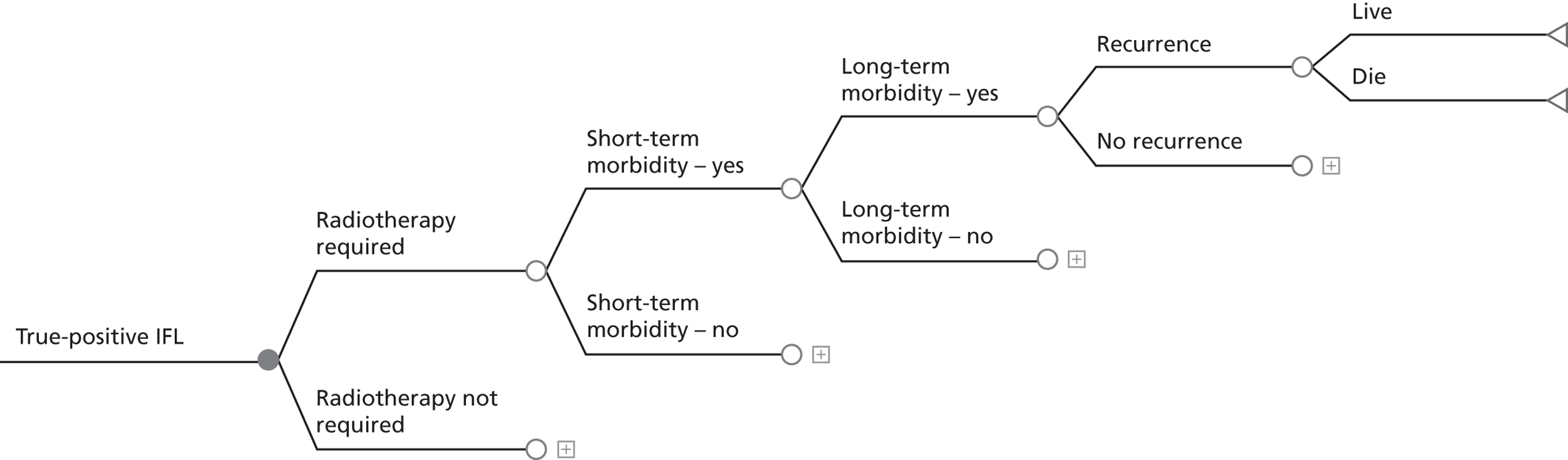

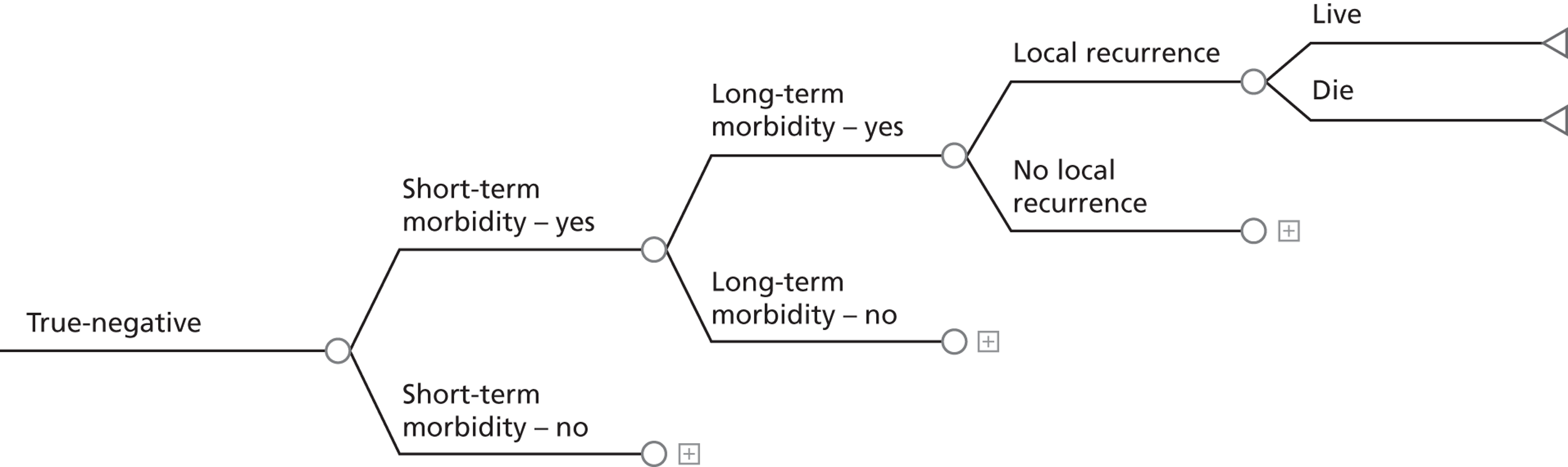

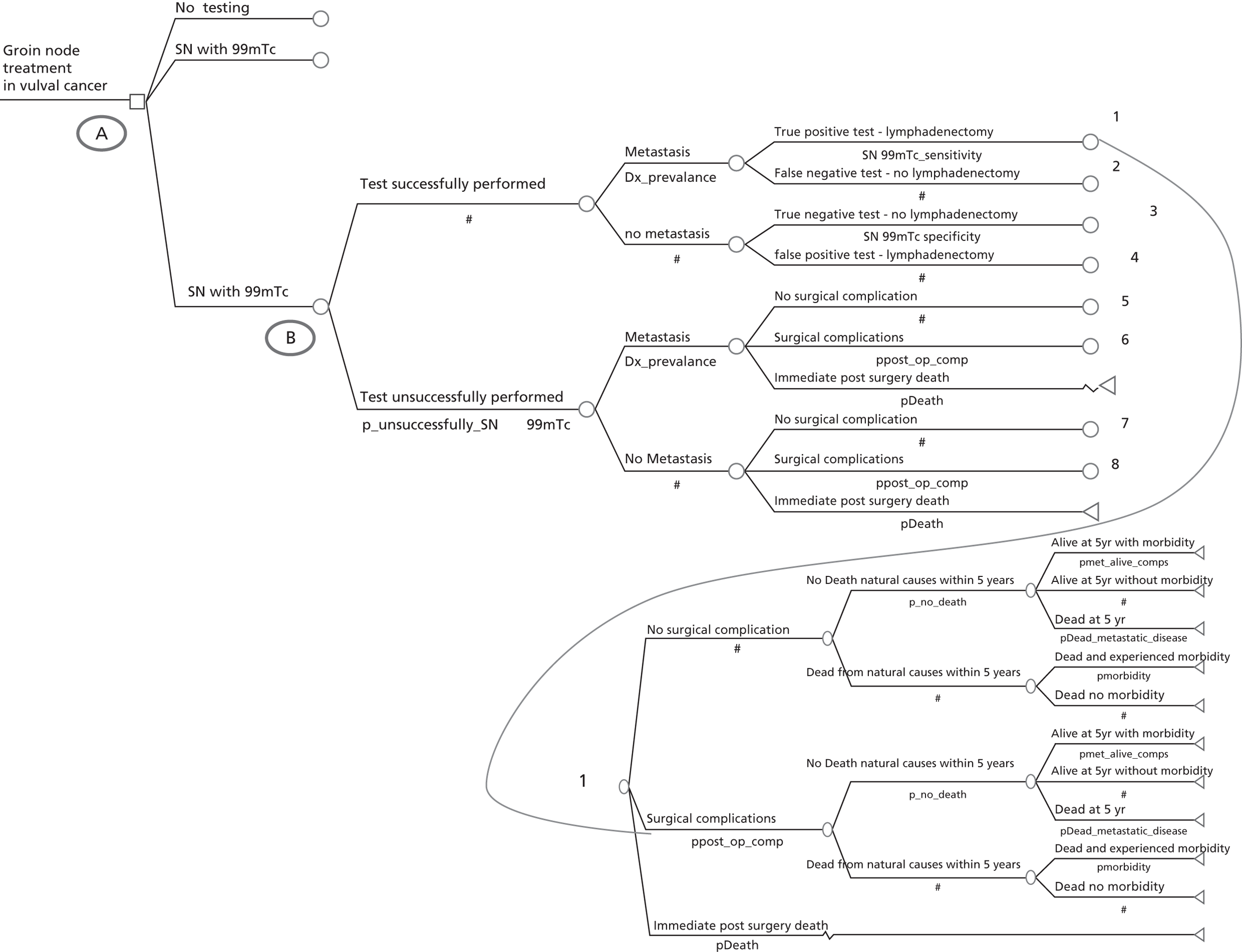

If SLN biopsy could accurately identify those patients in whom cancer has spread to the groin nodes without extensive surgical removal of all of the groin nodes, this would be extremely valuable. If this technique was very accurate in detecting no metastases, no radical treatment would be necessary. In order to test the accuracy of SLN biopsy, the reference standard can be IFL for all node-positive and -negative patients. Alternatively, clinical follow-up could be used for node-negative patients if SLN was considered to be sufficiently accurate not to miss patients with metastases in the lymph nodes. The different possibilities are illustrated in Figure 1 for the situations in which a SLN was found at biopsy and Figure 2 in the case that a SLN was not found at biopsy. The histopathology of the SLN biopsy should ideally be compared with the same type of histopathology used for all of the lymph nodes examined after IFL because the histopathology is part of the SLN biopsy test as well as the reference standard. If frozen sections or immunohistochemistry were used for the SLN histopathology and routine histological techniques such as H&E staining were used only for the IFL nodes, then that would, in effect, mean a different reference standard was being used.

FIGURE 1.

Decision tree for SLN biopsy (part 1).

FIGURE 2.

Decision tree for SLN biopsy (part 2).

In the decision trees, recurrence refers to groin recurrence; however, any recurrence is important, and both groin and distant recurrence may be reduced following IFL, but not local recurrence in the vulva.

The aim of this health technology assessment (HTA) was to determine the test accuracy and cost-effectiveness of SLN biopsy in vulval cancer by systematic reviews and decision-analytic modelling.

Chapter 4 Systematic review methods

Protocol development and overview of review methods

A protocol was developed for undertaking systematic reviews of test accuracy, diagnostic and therapeutic impact and effectiveness of treatment for vulval cancer (see Appendix 1). Scoping searches for relevant systematic reviews were conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE and The Cochrane Library [systematic reviews, HTA, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)] (see Appendix 2).

Systematic reviews were carried out using established methods in line with the recommendations of the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination and the Cochrane Collaboration,42,43 including those of the Cochrane Methods Working Group on Screening and Diagnostic Tests. 44 Presentation of results is according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 45

Inclusion of studies, data extraction and quality assessment were carried out in duplicate, with differences resolved by consensus and/or arbitration involving a third reviewer. The selection process was piloted by applying the inclusion criteria to a sample of papers first. A two-stage process was then followed. First titles and abstracts were screened, then, for all references categorised as ‘include’ or ‘uncertain’ by both reviewers, the full text was retrieved wherever possible and final inclusion decisions were made based on the full paper. Reference Manager version 12.0 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA) software was used to construct a database of citations for all systematic reviews.

Clinical, methodological and statistical data extraction was conducted into data extraction sheets by at least two reviewers and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. If consensus could not be reached, disagreements were resolved by arbitration by a third reviewer. For diagnostic studies, information regarding study design and methods, characteristics of participants, SLN biopsy and comparison tests, and outcomes of interest were extracted using data extraction forms (see Appendix 3). For the effectiveness review, separate data extraction forms were used for different study designs: comparative experimental study (part A), comparative observational study (part B) and non-comparative study (part C). The data extraction sheets used are shown in Appendix 4. The quality assessment questions for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included in the data extraction sheet, but a separate form was used for case series (see Appendix 4). Data extraction was managed with Microsoft Word 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and Microsoft Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Quality was also assessed independently by two reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or by arbitration by the third reviewer. For each review a comprehensive master database of articles was constructed using Reference Manager 12.0 software.

Methods for test accuracy, diagnostic and therapeutic impact review

Search strategy

A sensitive search was conducted to identify all relevant published and unpublished studies and studies in progress. All databases were searched from inception to January 2011. Search strategies were designed from a series of test searches and discussions of the results of those searches among the review team. Both medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and text words were used and included ‘vulva cancer’, ‘sentinel lymph node biopsy’ and ‘lymphoscintigraphy’. Search strategies can be found in Appendix 5. Literature was identified from several sources, including:

-

General health and biomedical databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), Science Citation Index; and medical diagnostic studies database (MEDION).

-

Checking of reference lists of review articles and papers.

-

Specialist search gateways [Organizing Medical Networked Information (OMNI) and The National Cancer Institute], general search engine (Google) and metasearch engine (Copernic).

-

Searching a range of relevant databases including Clinical Trials.com and UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio to identify information about studies in progress, unpublished research or research reported in the grey literature.

-

Hand-searching of Gynecologic Oncology journal (1980 to January 2011).

-

Contact with authors of the included studies for information on any relevant published or unpublished studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population

Included were:

-

women with early stages of vulval cancer: at least 75% of population with FIGO stage I and II or TNM categories T1–2, N0, M0.

Excluded were:

-

all patients with vulval melanomas

-

advanced stage vulval cancer (FIGO stage IV), inoperable tumours, tumours unsuitable for primary surgery

-

patients with clinical suspicion of metastases, i.e. with palpable inguinofemoral lymph nodes, enlarged lymph nodes (> 1.5 cm) on imaging or cytologically proven inguinofemoral lymph node metastases at the start of the study.

Index tests and comparator tests

Included were:

-

SLN biopsy with 99mTc, blue dye or combined technique (99mTc with blue dye), with histopathology by frozen section or other routine histopathological techniques. Where studies reported any of ultrastaging, serial sections, multiple slices, additional sections or step sections, these were all classified as ultrastaging.

Excluded were:

-

imaging modalities such as ultrasonography

-

novel techniques such as reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

Reference standard

Included were:

-

histopathology of inguinofemoral node dissection

-

follow-up for groin recurrence.

Excluded were:

-

imaging modalities such as ultrasonography.

Outcomes

Included were:

-

diagnostic accuracy

-

diagnostic impact: change in staging after SLN biopsy

-

therapeutic impact: change in treatment plan including avoidance of full IFL after SLN biopsy

-

complications

-

morbidity

-

mortality and disease-free survival

-

quality of life (QoL)

-

impact on surgeon's and team’s skills and experience (learning curve).

Excluded were:

-

non-clinical outcomes

-

outcomes reported per groin only.

Study design

Included were:

-

any prospective or retrospective test accuracy study designs

-

studies investigating the diagnostic and therapeutic impact with or without concurrent assessment of test accuracy

-

prospective cohort studies of outcomes of patients tested with 99mTc, blue dye or combined technique for SLN biopsy.

Excluded were:

-

case studies

-

studies with 10 or fewer patients.

Quality assessment

Test accuracy quality assessment followed the quality of diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS) guidelines46 and diagnostic and therapeutic impact followed those suggested by Meads and Davenport. 47 The items of methodological quality listed in the QUADAS guidelines are representative spectrum, selection criteria clearly described, acceptable reference standard, acceptable delay between tests, partial verification avoided, differential verification avoided, reference standard independent of the index test, index test described in sufficient detail, reference standard described in sufficient detail, index test results blinded, reference standard results blinded, relevant clinical information available, uninterpretable results reported and withdrawals explained. 46

These were tailored to assess the included studies because different aspects of quality are applicable to different topic areas. The actual quality items used for this report are listed below. For acceptable delay between tests, this included delay between the index test and reference standard (within 1 month). There will inevitably be a delay between index test and clinical follow-up (when available). Study quality was summarised in a table (see Table 10). No additional issues were thought to be useful in interpretetion of the results of these studies. The following items were included in study summaries and assessed using the three criteria listed under each item. 44

1. Representative spectrum

Yes: If patients were women in early-stage squamous cell vulval cancer.

No: If a few patients were in a higher stage of vulval cancer (T3–T4) or some patients had vulval melanoma or another type of cancer rather than squamous cell cancer.

Unclear: If there is insufficient information available to make a judgement about the spectrum of patients.

2. Selection criteria clearly described

Yes: If the selection criteria are described.

No: If the selection criteria are not described.

Unclear: If there is insufficient information available to clearly know the selection criteria.

3. Acceptable reference standard

Yes: Whether or not the reference standard used (histopathology, clinical follow-up) was adequately described to permit sufficient replication and was appropriate according to advice from our clinical experts (e.g. ultrastaging used, immunohistochemistry used).

No: The reference standards used do not include ultrastaging or immunohistochemistry.

Unclear: It is unclear exactly what reference standard was used.

4. Acceptable delay between sentinel lymph nodes biopsy and histopathology

Yes: If the time between tests was shorter than 1 month, at least for an acceptably high proportion of patients.

No: If the time between tests was longer than 1 month for an unacceptably high proportion of patients.

Unclear: If information on timing of tests was not provided.

5. Partial verification avoided

Yes: If all patients, or a random selection of patients, who received the index test went on to receive verification of their disease status using a reference standard, even if the reference standard was not the same for all patients.

No: If some of the patients who received the index test did not receive verification of their true disease state, and the selection of patients to receive the reference standard was not random.

Unclear: If this information is not reported by the study.

6. Differential verification avoided

Yes: If the same reference standard was used in all patients.

No: If the choice of reference standard varied between individuals.

Unclear: If it is unclear whether or not different reference standards were used.

7. Incorporation avoided

Yes: If the index test did not form part of the reference standard.

No: If the reference standard formally included the result of the index test.

Unclear: If it is unclear whether or not the results of the index test were used in the final diagnosis.

8. Whether or not there was sufficient information to replicate index test and reference standard

Yes: Sufficient information available.

No: Insufficient information available.

Unclear: If it is unclear whether or not there is enough information to permit replication.

9. Reference standard/index test results blinded

Yes: If test results (index or reference standard) were interpreted blind to the results of the other test or blinding is dictated by the test order.

No: If it is clear that one set of test results was interpreted with knowledge of the other.

Unclear: If it is unclear whether or not blinding took place.

10. Relevant clinical information

Yes: If the same clinical data available when test results were interpreted as would be available when the test is used in practice.

No: If clinical data usually available was withheld or if more information than is usually available was provided.

Unclear: If information about the clinical data available was not stated.

11. Uninterpretable results reported

Yes: If the number of uninterpretable test results is stated or if the number of results reported agrees with the number of patients recruited (indicating no uninterpretable test results).

No: If it states that uninterpretable test results occurred or were excluded and does not report how many.

Unclear: If it is not possible to work out whether or not uninterpretable results occurred.

12. Withdrawals explained

Yes: If it is clear what happened to all patients who entered the study, for example, if a flow diagram of study participants is reported explaining any withdrawals or exclusions, or the numbers recruited match those in the analysis.

No: If it appears that some of the patients who entered the study did not complete the study, i.e. did not receive both the index test and reference standard, and these patients were not accounted for.

Unclear: If it is unclear how many patients entered and, hence, whether or not there were any withdrawals.

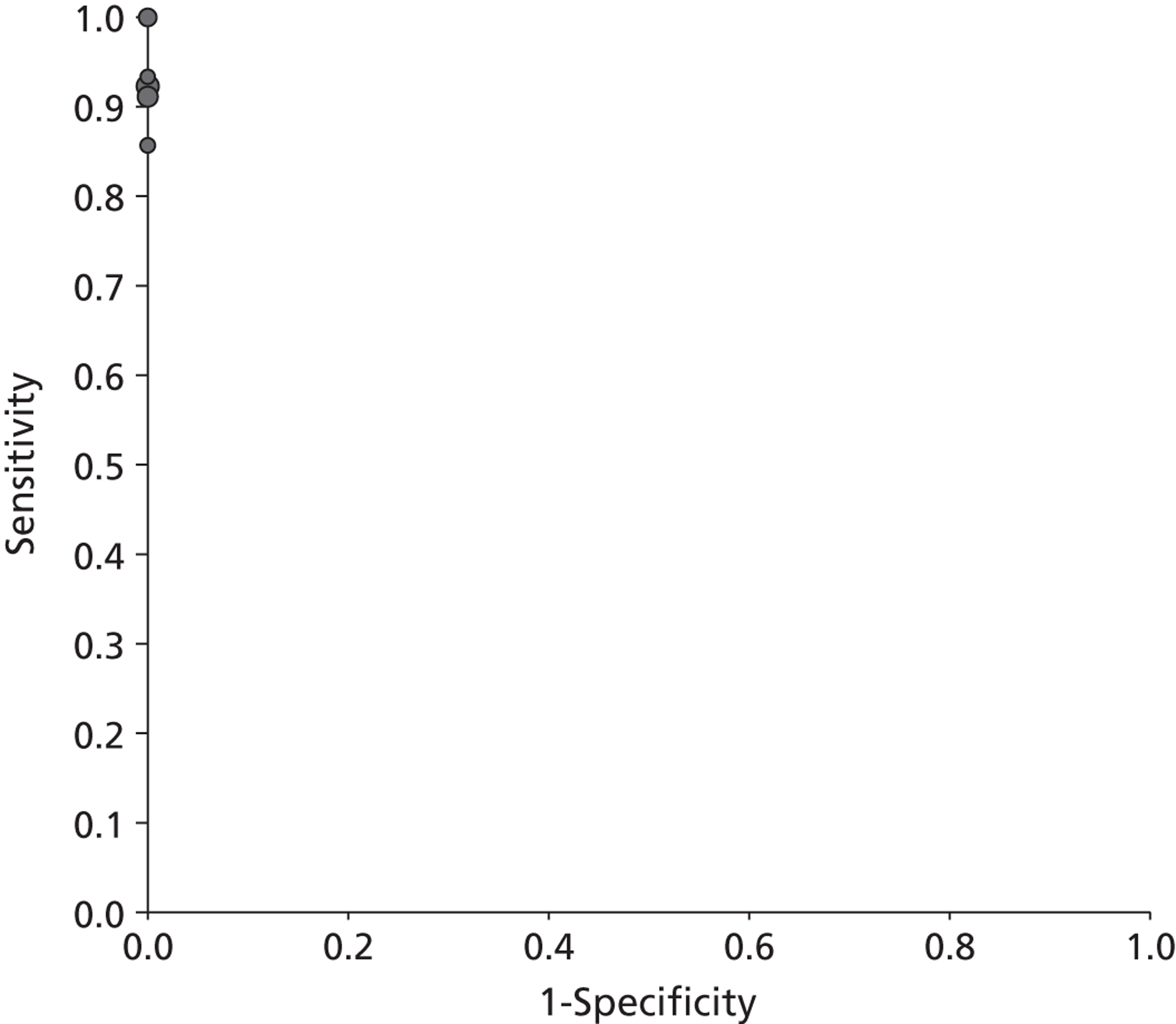

Methods of statistical analysis

RevMan version 5.0 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used in the statistical analyses and Meta-Disc statistical package version 1.4 (Javier Zamora, Madrid, Spain) was used to conduct meta-analysis. Sensitivity, specificity, true-positives (TPs), false-positives (FPs), true-negatives (TNs) and false-negatives (FNs) were taken directly from the source papers. If that was not possible, values were calculated from data provided. Based on an investigation of heterogeneity, summary estimates of sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratios (LRs) were derived as appropriate. Results are displayed graphically on summary receiver operator curve plots (see Figure 4). Summary SLN detection rates and their 95% CIs were calculated using Meta-Disc. Methods for meta-analysis used by Meta-Disc are as follows. Sensitivity and specificity are pooled by the formulae:

where a are TPs and d are TNs, D is total number with disease and ND is the total number without disease. These formulae correspond to weighted averages in which the weight of each study is its sample size. The CIs of sensitivity and specificity are calculated using the F distribution method to compute the exact confidence limits for the binomial proportion (x/n) and are given by the formulae below where LL is the lower limit and UL is the upper limit:

Bivariate meta-analysis can only be conducted when there are more than four studies. Only one group of studies were eligible [IFL for all, 99mTc with blue dye – ultrastaging with immunohistochemistry (see Table 16)]. However, the diagnostic test results for all of the studies have no FPs, so STATA (version 12.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) will only run a bivariate meta-analysis if a continuity correction is added (changing 0 to 1 in some of the studies). This was done for the last five studies (see Table 16).

Methods for effectiveness reviews

Search strategy

A sensitive search was conducted to identify all relevant published and unpublished trials and trials in progress. All databases were searched from inception to January 2011. Search strategies were designed from a series of test searches in a multistep process. Both MESH terms and text words were used and included a variety of synonyms for vulval cancer and the interventions (surgery, RT, chemotherapy). Search strategies can be found in Appendix 6. Studies were identified from several sources, including:

-

General health and biomedical databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid).

-

Specialist electronic databases: The Cochrane Library, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), DARE and HTA Database.

-

Checking of reference lists of review articles and papers.

-

Searching a range of relevant databases including ClinicalTrials.com and UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio to identify information about studies in progress, unpublished research or research reported in the grey literature.

-

Hand-searching (Gynecologic Oncology) from 1980 to January 2011.

-

Specialist search gateways (OMNI and the National Cancer Institute), general search engine (Google) and metasearch engine (Copernic) in January 2011.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population

Included were:

-

women with early stages of vulval cancer (including squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, vulval Paget's disease, Bartholin's gland cancer): at least 75% of population with FIGO stage I and II or TNM categories T1–2, N0–1, M0.

Excluded were:

-

all patients with vulval melanomas or VIN only

-

patients with advanced vulval cancer, inoperable tumours and those unsuitable for primary surgery

-

patients with clinical suspicion of metastases, i.e. with palpable inguinofemoral lymph nodes, enlarged lymph nodes (> 1.5 cm) on imaging or cytologically proven inguinofemoral lymph node metastases at the start of the study only

-

patients with multifocal tumours only

-

studies with 25% or more patients with clinical stages more advanced than FIGO stages I and II or TNM T1–2, N0–1, M0, unless the subgroup with these characteristics were clearly indicated and results given separately

-

studies with all patients treated before 1980.

Intervention

Included were:

-

surgery: vulvectomy (any form, with or without IFL)

-

RT (any type, to vulval area or groin).

Excluded were:

-

diagnostic treatment studies.

Comparator (when available)

Included were:

-

surgery (any form) with RT (adjuvant or neoadjuvant) or chemotherapy.

Excluded were:

-

same surgery as intervention. We did not include studies comparing different types of vulval excision for vulval cancer, as this was not relevant to the primary question to be addressed.

Outcomes

Included were:

-

deaths, overall survival, disease-free survival (presented as raw numbers, survival curves, etc.)

-

morbidity

-

recurrence

-

QoL

-

early and late complications.

Excluded were:

-

psychosexual outcomes.

Study design

Included were:

-

RCTs

-

non-RCTs

-

observational studies (cohort, case–control or case series).

Excluded were:

-

studies with five or fewer patients in the therapeutic group

-

studies in which the majority of patients were enrolled in 1970s or earlier.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was performed appropriate to study designs. For RCTs, quality assessment was according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions43 (Table 5). In all cases, a ‘yes’ answer indicated a low risk of bias and a ‘no’ indicated a high risk of bias. ‘Unclear’ was used if details were insufficient. Quality of studies was summarised in tables (see Tables 34 and 35). Case–control studies were evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale48 (Table 6). A study was awarded with maximum one star [*] for each numbered item within the ‘selection’ and ‘exposure’ categories and a maximum of two stars [**] in the ‘comparability’ category. Each evaluated study could obtain a maximum of nine stars (four for the selection part, two for the comparability part and three for the exposure part). Qualitative description was also used. The detailed coding manual for this scale is in Appendix 7. Quality assessment of case series used criteria from a recent HTA report on methodological characteristics of case series. 49 A checklist composed of 13 items in five categories was used, and this is reproduced in Appendix 8.

| Section | Description | Question |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence generation | Describe the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether or not it should produce comparable group | Adequate sequence generation? |

| Allocation concealment | Describe the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to determine whether or not intervention allocations could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment | Allocation concealment? |

| Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors | Describe all measures used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. Provide any information relating to whether or not the intended blinding was effective | Blinding? (Self-reported outcomes) |

| Blinding? (Objective outcomes) | ||

| Incomplete outcome data | Describe the completeness of outcome data for each main outcome, including attrition and exclusions from analysis. State whether or not attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers in each intervention group (compare with total randomised participants), reasons for attrition/exclusions when reported and any reinclusions in analyses performed by the review authors | Incomplete outcome data addressed? |

| Selective outcome reporting | State how the possibility of selective outcome reporting was examined by the review authors and what was found | Free of selective reporting? |

| Other sources of bias | State any important concerns about bias not addressed in the other domains in the tool | Free of other bias? |

| Section | Number | Question |

|---|---|---|

| Selection | 1. | Is the case definition adequate? |

| 2. | Representativeness of the cases | |

| 3. | Selection of controls | |

| 4. | Definition of controls | |

| Comparability | 1. | Comparability of cases and controls on the basis of the design or analysis |

| Exposure | 1. | Ascertainment of exposure |

| 2. | Same method of ascertainment for cases and controls | |

| 3. | Non-response rate |

Methods of statistical analysis

Separate analyses were performed on randomised and observational studies. RevMan version 5.0 was used in the statistical analyses. Information was analysed based on the group to which the participants were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. For dichotomous data, results are presented as summary RR with 95% CI (for comparative observational studies odds ratios were calculated when appropriate). For case–control studies and case series, a narrative summary of the findings is presented along with the numerical results.

Chapter 5 Diagnostic review

Study selection

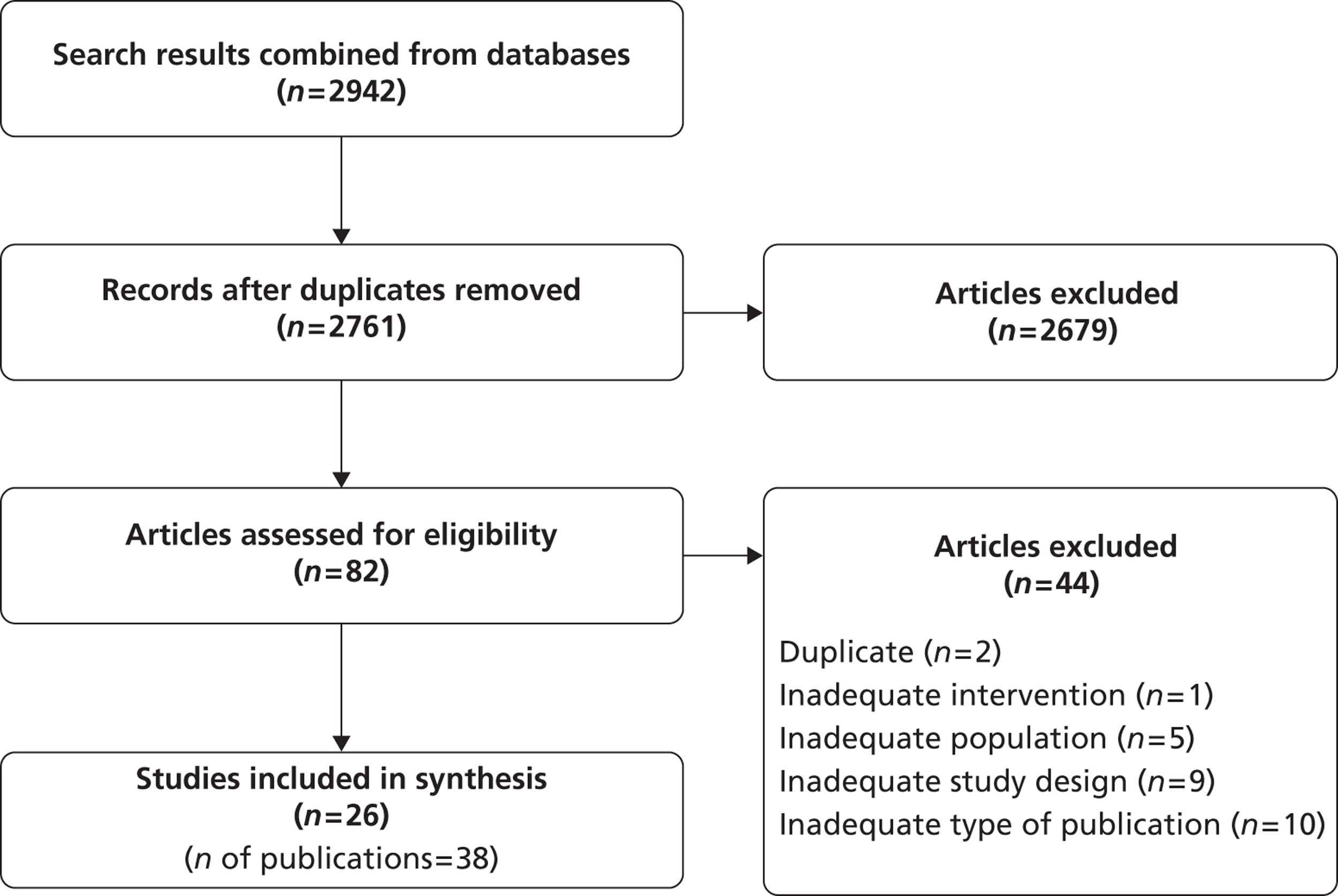

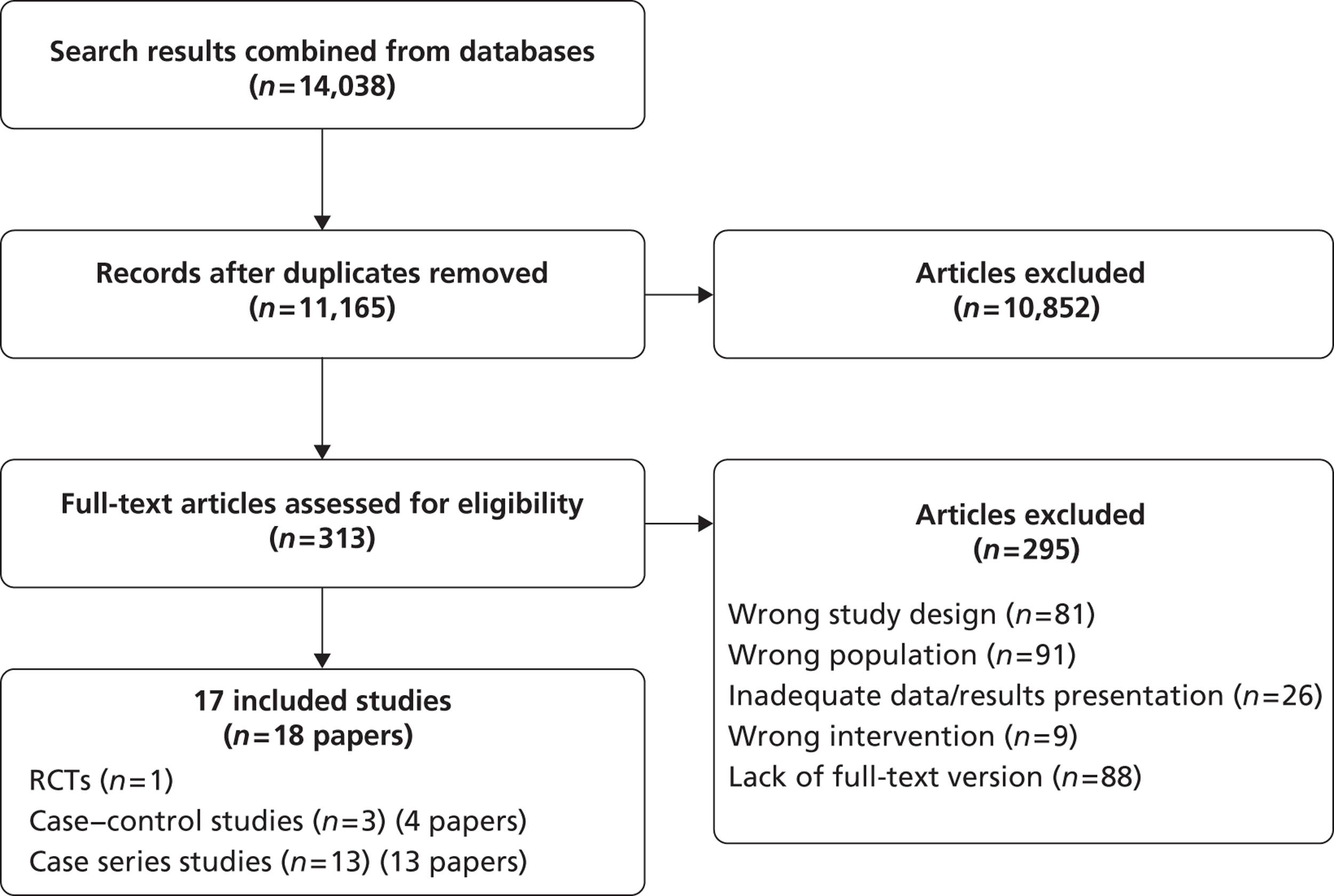

From the searches, 2942 citations were identified, of which 82 full papers were obtained. Included were 26 relevant studies (38 publications) (Figure 3). Excluded full-text articles are listed in Appendix 9 with reasons for exclusion, which were mostly because of small sample size or type of publication (reviews, abstracts). Some studies were excluded because they gave results only per groin rather than per patient.

FIGURE 3.

A PRISMA diagram for diagnostic review.

Characteristics of included studies

Index tests and histopathological techniques used for the index tests and reference standards used in each of the studies are given in Table 7. Although both 99mTc and blue dye were used in a number of studies, how the results were presented varied considerably. In some studies, only one was used. For example, De Cicco et al. ,55 Merisio et al. 64 and Vidal-Sicart et al. 74 used only 99mTc and Levenback et al. 61 used only blue dye. In six studies,39,52,62,66,67,69 a proportion of SLNs were diagnosed with blue dye or 99mTc separately and a proportion with both (see Table 7); the results for malignancy were given for the whole cohort irrespective of the test or tests actually used to find the malignancy. In such cases, only the sensitivity and specificity results can be given for the combination of tests used rather than only blue dye or 99mTc separately or only both used together in all patients. However, for the other 20 studies,50,51,53–61,63–65,68–74 detection rates per groin can be given for each test separately and both tests combined (see Table 7). It is noticeable that the histopathological techniques used for the full IFL specimens were either not given or were less detailed than those used for the SLNs. Only De Cicco et al. ,55 Johann et al. 59 and Radziszewski et al. 68 appeared to use the same techniques and very little detail is given in the first two. More details of index tests and reference standards used are given in Appendix 10.

| Study | 99mTc | Blue dye | Both together | Histopathological techniques: SLN | Histopathological techniques: remaining nodes | Type of surgery given (or RT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achimas-Cadariu et al., 200950 | – | – | ✗ | H&E, ultrastaging | NR | Radical vulvectomy (58%), modified (41%) |

| Basta et al., 200551 | ✗a | ✗a | ✗ | SLN immunochemical stain for micrometastases | NR | NR |

| Brunner et al., 200852 | ✗ (91%) | – | ✗ (9%) | Frozen sections, H&E and, if negative, immunohistochemistry for cytokeratins | Routine techniques | NR |

| Camara et al., 200953 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Frozen section | NR | NR |

| Crosbie et al., 201054 | – | – | ✗ | H&E and, if negative, with additional sections and immunohistochemistry for cytokeratins AE1–3 | NR | Radical excision (47%), unclear (53%) |

| De Cicco et al., 200055 | ✗ | – | – | H&E | H&E | Wide radical excision, hemivulvectomy or radical vulvectomy (percentages not given) |

| de Hullu et al., 200056 | – | ✗ | ✗ | H&E and, if negative, with additional sections and immunohistochemistry for cytokeratins AE1–3 | H&E | Radical excision (100%) |

| Hampl et al., 200857 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | H&E and, if negative, with additional sections and immunohistochemistry for panycytokeratin antibody | NR | Hemivulvectomy (35%), vulvectomy (35%), local tumour resection (30%) |

| Hauspy et al., 200758 | ✗ | – | ✗ | Frozen section then serial sections H&E and immunohistochemistry for cytokeratins AE1–3 for some sections | H&E | Wide local excision (76%), radical vulvectomy (20%), RT (5%) |

| Johann et al., 200859 | – | – | ✗ | Step sectioning | Step sectioning | Radical vulvectomy (30%), hemivulvectomy (57%), wide excision (13%) |

| Klat et al., 200960 | – | – | ✗ | H&E, ultrastaging and immunohistochemistry for cytokeratins AE1–3 | NR | Radical surgery (100%) |

| Levenback et al., 200161 | – | ✗ | – | Frozen section if suspicious, step sectioning and some immunohistochemistry using several protocols | NR | NR |

| Lindell et al., 201039 | – | ✗ (22%) | ✗ (78%) | Step sections, H&E and if negative, immunohistochemistry for cytokeratin MNF116 | H&E | Vulvectomy (47%), hemivulvectomy (31%), wide local excision (22%) |

| Louis-Sylvestre et al., 200662 | ✗ (21%) | – | ✗ (79%) | Serial sections, H&E and immunohistochemistry for cytokeratins AE1 and AE3 | NR | NR |

| Martinez-Palones et al., 200663 | – | – | ✗ | 0.2 mm sections, H&E and if negative, immunohistochemistry for cytokeratin and membrane epithelial antigen | NR | NR |

| Merisio et al., 200564 | ✗ | – | H&E, ultrastaging, immunohistochemistry for cytokeratins in 50% of samples | Standard techniques | Radical vulvectomy or radical vulval excision (percentages NR) | |

| Moore et al., 200865 | – | – | ✗ | H&E and ultrastaging | NR | Radical vulvectomy or radical vulval excision (percentages NR) |

| Nyberg et al., 200766 | – | ✗ (20%) | ✗ (80%) | Histopathology | NR | NR |

| Pityński et al., 200367 | – | ✗ (14%) | ✗ (86%) | NR | NR | NR |

| Radziszewski et al., 201068 | – | – | ✗ | Multiple slices, H&E in 50% slices, H&E and immunohistochemistry in the other 50% of slices | H&E in 50% slices, H&E and immunohistochemistry in other 50% slices | NR |

| Rob et al., 200769 | – | ✗ (27%) | ✗ (73%) | Frozen section then serial sections, H&E, and immunohistochemistry on every third slide | H&E | NR |

| Terada et al., 200670 | – | – | ✗ | Multiple slices, H&E then if negative, immunohistochemistry with cytokeratin antigen | NR | NR |

| Vakselj et al., 200771 | – | – | ✗ | NR | NR | Tumour excised (100%) |

| Van den Eynden et al., 200372 | – | – | ✗ | H&E then if negative, ultrastaging and immunohistochemistry for cytokeratins AE1 and AE3 | NR | NR |

| Van der Zee et al., 200873 | – | – | ✗ | Frozen section or routine histopathology, ultrastaging | H&E | Radical excision (100%) |

| Vidal-Sicart et al., 200774 | – | – | ✗ | Multiple slices, H&E then if negative, H&E with immunohistochemistry | H&E | Radical vulvectomy or radical vulval excision (percentages NR) |

Details of included studies and baseline characteristics are presented in Tables 8 and 9. The studies were conducted in a variety of European countries and in the USA and Canada. The majority were small and from single centres. The largest was a recent multicentre study by Van der Zee et al. from the Netherlands [the GROningen INternational Study on Sentinel nodes in Vulvar cancer (GROINSS-V)],73 which included 403 patients recruited between the years 2000 and 2006. Inclusion and exclusion criteria of the studies are given in Appendix 10.

| Study | Publications | Setting | Study design/patient selection | Recruitment dates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achimas-Cadariu et al., 200950 | Achimas-Cadariu et al., 200950 | Dr Horst Schmidt Klinik, Wiesbaden, Germany | Retrospective/consecutive | June 2000 to May 2008 |

| Basta et al., 200551 | Basta et al., 200551 | Department of Gynaecology, Obstetrics and Oncology, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Krakow, Poland | Prospective | NR |

| Brunner et al., 200852 | Brunner et al., 2008;52 Sliutz et al., 2002;75 Hefler et al., 200876 | Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria | Retrospective/consecutive | January 2001 to August 2007 |

| Camara et al., 200953 | Camara et al., 200953 | Friedrich-Schiller-University of Jena, Jena, Germany | Prospective | February 2003 to March 2007 |

| Crosbie et al., 201054 | Crosbie et al., 201054 | Gynaecology Clinic at The Christie NHS Foundation Trust in Manchester, Manchester, UK | Prospective | 2002–6 |

| De Cicco et al., 200055 | De Cicco et al., 200055 | San Gerardo Hospital, Monza, Italy | Prospective/consecutive | May 1996 to September 1998 |

| de Hullu et al., 200056 | de Hullu et al., 1998;77 de Hullu et al., 200056 | Groningen University Hospital, Groningen and Academic Hospital Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, the Netherlands | Prospective/consecutive | July 1996 to July 1999 |

| Hampl et al., 200857 | Hampl et al., 200857 | Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics of Heinrich Heine Universit (Dusseldorf), University of Jena, Medizinischen Hochschule Hannover and Women's Hospital, Regional Hospital of Altötting, Germany | Prospective/consecutive | 2003–6 |

| Hauspy et al., 200758 | Hauspy et al., 200758 | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada | Prospective | April 2004 to September 2006 |

| Johann et al., 200859 | Johann et al., 200859 | Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and of Nuclear Medicine, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland | Retrospective | January 1990 to March 2007 |

| Klat et al., 200960 | Klat et al., 200960 | University Hospital Ostrava, Ostrava, Czech Republic | Prospective | May 2004 to November 2007 |

| Levenback et al., 200161 | Levenback et al., 1994;78 Levenback et al., 1995;79 Levenback et al., 2001;61 Frumovitz et al., 200480 | Anderson Cancer Center and Southwestern Medical Centre, University of Texas, TX, USA | Prospective | 1993–9 |

| Lindell et al., 201039 | Lindell et al., 201039 | Department of Women's and Children's Health, of Pathology and Oncology and of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden | Retrospective | 2000–7 |

| Louis-Sylvestre et al., 200662 | Louis-Sylvestre et al., 200662 | Centre Hospitalier Intercommunal Créteil, Créteil, France | Prospective | April 2002 to December 2005 |

| Martinez-Palones et al., 200663 | Martinez-Palones et al., 200663 | Hospital Materno-infantil Vall d'Hebron, Barcelona, Spain | Prospective/consecutive | January 1995 to July 2005 |

| Merisio et al., 200564 | Merisio et al., 200564 | Gynaecology Units of University of Parma and of Policlinico S Matteo of Pavia, Italy | Prospective | May 1999 to May 2003 |

| Moore et al., 200865 | Moore et al., 200865 | Women and Infants' Hospital, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA | Prospective/consecutive | 2002–7 |

| Nyberg et al., 200766 | Nyberg et al., 200766 | Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, Finland | Retrospective | 1 January 2001 to 30 June 2005 |

| Pityński et al., 200367 | Pityński et al., 200367 | Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics and of Nuclear Medicine, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Krakow, Poland | Prospective | NR |

| Radziszewski et al., 201068 | Radziszewski et al., 201068 | Maria Sklodowska-Curie Memorial Cancer Centre and Institute of Oncology, Warsaw, Poland | Prospective/consecutive | January 2002 to December 2006 |

| Rob et al., 200769 | Rob et al., 2006;81 Rob et al., 200769 | Motol University Hospital, Second Medical Faculty, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic | Prospective/consecutive | December 2001 to December 2005 |

| Terada et al., 200670 | Terada et al., 200670 | Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Cancer Research Center, University of Hawaii School of Medicine, and Department of Pathology, Queens Medical Centre, Honolulu, HI, USA, | Retrospective | 1996–2003 |

| Vakselj et al., 200771 | Vakselj et al., 200771 | Institute of Oncology Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia | Prospective/consecutive | March 2006 to December 2006 |

| Van den Eynden et al., 200372 | Van den Eynden et al., 200372 | Department of Obstetrics-Gynaecology, University Hospital of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium | Retrospective | November 1999 to December 2002 |

| Van der Zee et al., 200873 | Van der Zee et al., 2008;73 Oonk et al., 2009;82 Oonk et al., 201083 | 15 centres registered at the University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands | Prospective/consecutive | March 2000 to May 2006 |

| Vidal-Sicart et al., 200774 | Vidal-Sicart et al., 2002;84 Vidal-Sicart et al., 2007;74 Vidal-Sicart et al., 2009;85 Puig-Tintore et al., 200386 | Section of Gynecologic Oncology, Instituto Clínic de Ginecología, Obstetrícia y Neonatología, Hospital Clinic, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain | Prospective | May 1998 to June 2005 |

| Study | n | Percentage of patients in early stage available for analysis | Age, years (median or mean, range) | Tumour location (n) | Histological type of tumour (n) | TNM (n) | FIGO stage (I–IV) (n) | Grade (1–3) (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achimas-Cadariu et al., 200950 | 46 | 95% | Median 66, range 34–94 | Midline: 17; lateral: 29 | SCC: 46 | T1–16, T2–28, T3–2 | I: 16; II: 19; III: 7; IV: 4 | 1: 8; 2: 29; 3: 9 |

| Basta et al., 200551 | 39 | 100% | NR | NR | NR | NR | All stage I and II | NR |

| Brunner et al., 200852 | 44 | 100% | Mean 70 | Midline: 34; lateral: 10 | SCC: 44 | T1–30, T2–14/N0–27, N1–17 | NR | 1: 14; 2: 27; 3: 3 |

| Camara et al., 200953 | 17 | 94.1% | Median 75, range 37–83 | NR | SCC: 16; melanoma: 1 | T1–7, T2–9, T3–1, N1–9, N2–8 | NR | NR |

| Crosbie et al., 201054 | 32 | 100% | Median 67, range 34–94 | Midline: 17; lateral: 15 | SCC: 32 | NR | I: 7; II: 5; III: 4; IV: 3 | NR |

| De Cicco et al., 200055 | 37 | 100% | NR | Midline: 19; lateral: 18 | SCC: 37 | T1–17, T2–20 | NR | NR |

| de Hullu et al., 200056 | 59 | 100% | Median 69, range 33–92 | NR | SCC: 59 | T1–25, T2–34 | NR | NR |

| Hampl et al., 200857 | 127 | 94.4% | Mean 61.4 | Midline: 33; lateral: 49 | SCC: 126; other: 1 | T1–56, T2–62, T3–7, N1–88, N2 + N3–39 | NR | 1: 15; 2: 86; 3: 23 |

| Hauspy et al., 200758 | 41 | 95% | Mean 65, range 34–92 | NR | SCC: 39; melanoma: 2 | T1–22, T2–19 | NR | 1: 18; 2: 17; 3: 4 |

| Johann et al., 200859 | 23 | 86% | Median 68.4, range 34.1–86.5 | NR | SCC: 23 | T1–9, T2–11, T3–3, N1–11, N2–11, N3–1 | NR | 1: 3; 2: 14; 3: 6 |

| Klat et al., 200960 | 23 | 100% | Median 67.5, range 38–92 | Midline: 18; lateral: 5 | SCC: 23 | T1–11, T2–12 | NR | NR |

| Levenback et al., 200161 | 52 | 87% | Median 58, range 18–92 | Midline: 25; lateral: 27 | SCC: 35; melanoma: 7; other: 10 | T1–22, T2–23, T3–7/N0–39, N1–9, N2–4 | NR | NR |

| Lindell et al., 201039 | 77 | 98% | Mean 71.2, range 40–92 | Midline: 22; lateral: 55 | SCC: 77 (other: 1a) | T1 + T2–76, T3–1 | NR | 1: 18; 2: 28; 3: 31 |

| Louis-Sylvestre et al., 200662 | 38 | 100% | Mean 66, range 34–90 | Midline: 26; lateral: 12 | NR | T1–29, T2–9, N1–32, N2–6 | NR | NR |

| Martinez-Palones et al., 200663 | 28 | 92.9% | Mean 71.3 ± 12, 7 (SD), range 30–84 | NR | SCC: 26; melanoma: 2 | T1–9, T2–19 | I: 9; II: 19 | 1: 19; 2: 6; 3: 1 |

| Merisio et al., 200564 | 20 | 100% | Mean 75, range 49–95 | Midline: 11; lateral: 9 | SCC: 20 | T1–9, T2–11/N0–20 | NR | NR |

| Moore et al., 200865 | 36 | 100% | Median 63, Mean 64, range 29–87 | NR | SCC: 35 | NR | I: 24; II: 8; III: 3; IV: 1 | NR |

| Nyberg et al., 200766 | 47 (results for 25 stage I and II only) | 100% | NR | NR | NR (full sample SCC: 46, other: 1) | NR | I: 11; II: 14 | 1: 15; 2: 8; 3: 2 |

| Pityński et al., 200367 | 37 | 100% | NR | NR | NR | NR | All stage I or II | NR |

| Radziszewski et al., 201068 | 62 | 100% | Median 68, range 37–94 | NR | SCC: 62 | T1–20, T2–42, N1–62 | NR | NR |

| Rob et al., 200769 | 43 | 100% | Median 70.9, range 26–95 | Midline: 21; lateral: 22 | SCC: 43 | T1–25, T2–18 | NR | NR |

| Terada et al., 200670 | 21 | 100% | Mean 72, range 42–86 | NR | SCC: 21 | T1–21 | NR | NR |

| Vakselj et al., 200771 | 35 | 92% | Median 65.8, range 36–88 | NR | SCC: 32; melanoma: 1; other: 2 | NR | I: 18; II: 6 | 1: 1; 2: 4; 3: 2b |

| Van den Eynden et al., 200372 | 32 | 100% | Mean 67, range 32–96 | NR | SCC: 31; other: 1 | T1 – 16, T2 – 16, N1 – 24, N2 + N3–8 | NR | NR |

| Van der Zee et al., 200873 | 403 | 100% | NR | Midline: 151; lateral: 252 | NR | T1 or 2–403, N0–276, N1–27 | NR | NR |

| Vidal-Sicart et al., 200774 | 50 | 86% | Mean 75, range 41–95 | NR | SCC: 50 (other: 8a) | NR | Ib: 23; II: 20; III: 8 | NR |

Data collection was prospective in 19 studies and retrospective in seven. Patients were recruited consecutively in 11 studies, prospectively in nine and retrospectively in two. Achimas-Cadariu et al. 50 described their study as retrospective, but data were collected prospectively from an in-house tumour registry. Recruitment dates varied between 1990 and 2008 and were not given in two studies51,67 (see Table 8). The percentage of patients with early-stage disease varied between 86% and 100%, being 100% in 16 studies. Median or mean ages varied between 58 and 75 years and individual ages varied between 18 and 95 years. Medians were given in most studies as vulval cancer is relatively rare in younger women. Where reported, tumour locations were relatively evenly spread between midline or lateral positions. The most commonly reported tumour type was SCC. Five studies included one or two melanomas53,58,61,63,71 and seven included other tumour types. 39,57,61,66,71,72,74 Either TNM, FIGO or grade staging, alone or in combination, was given in all studies. Most included patients with disease of varying severity and a few only included patients with early-stage disease, such as Terada et al. 70

Quality of included studies

Quality assessment is reported in Table 10. Of the 26 studies included, four53,66,67,71 provided no information about the histological staining method used. Brunner et al. ,52 Camara et al. ,53 Hauspy et al. 58 and Rob et al. 69 used frozen section as the reference standard, rather than more routine histopathological techniques. In 16 studies, on receipt of negative results by H&E procedures, immunohistochemical tests using specific protein antibodies such as AE1, AE3, S-100, human melanoma black monoclonal antibody (HMB)-45, monoclonal antibody, cytokine myocyte nuclear factor (CKMNF), cytokine (CK)-88 and epithelial membrane antigen were conducted. In others, ultrastaging was used if samples were negative by H&E staining and standard sectioning. The thickness of slices varied from one study to another so that some studies were more likely to find small metastatic deposits than others because of the thinner sections taken.

| Study | Quality factors | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| Achimas-Cadariu et al., 200950 | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Basta et al., 200551 | U | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | N | Y | Y |

| Brunner et al., 200852 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N |

| Camara et al., 200953 | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Crosbie et al., 201054 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | U | U | Y | Y |

| De Cicco et al., 200055 | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y |

| de Hullu et al., 200056 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hampl et al., 200857 | N | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y | N |

| Hauspy et al., 200758 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Johann et al., 200859 | N | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y | N |

| Klat et al., 200960 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Levenback et al., 200161 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y | N |

| Lindell et al., 201039 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N |

| Louis-Sylvestre et al., 200662 | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | N | U | U | Y | N |

| Martinez-Palones et al., 200663 | N | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Merisio et al., 200564 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Moore et al., 200865 | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Nyberg et al., 200766 | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | U | Y | Y |

| Pityński et al., 200367 | U | U | U | U | U | Y | Y | N | U | N | Y | Y |

| Radziszewski et al., 201068 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | N |

| Rob et al., 200769 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N |

| Terada et al., 200670 | Y | Y | N | U | Y | N | Y | N | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Vakselj et al., 200771 | N | N | U | Y | Y | N | Y | N | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Van den Eynden et al., 200372 | Y | U | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | U | Y | Y | N |

| Van der Zee et al., 200873 | Y | Y | N | U | Y | N | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N |

| Vidal-Sicart et al., 200774 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N |

There were four studies50,65,70,73 in which, if the SLN was found to be negative, no IFL was performed but patients were followed up clinically instead. In a study by Van den Eynden et al. ,72 10 out of 32 patients had a SLN biopsy plus full IFL. In the remaining 22 patients, an IFL was performed only if the SLN was positive or not found. In a study by Johann et al. 59 and another by Vidal-Sicart et al. ,74 some patients had SLN biopsy and full IFL regardless of node statistics and some only had IFL if the SLN was positive, but the results for the two groups were reported separately. Only the results for SLN biopsy and full IFL are reported here. In Crosbie et al. ,54 Klat et al. ,60 Martine-Palonez et al. ,63 Vakselj and Bebar71 and Vidal-Sicart et al. ,74 clinical follow-up was reported, and, for all except Vidal-Sicart et al. ,74 this was reported according to whether patients had been SLN positive or negative.

Because the main aim of the included studies was the analysis of diagnostic procedures, most did not report information about the number of patients who had undergone specific types of surgery or other treatment procedures (see Appendix 10, Table 53, for treatment descriptions). Usually, patients underwent radical vulvectomy, wide local excision or hemivulvectomy. RT was performed in only six studies (as adjuvant therapy in Hauspy et al. ,58 Levenback et al. ,61 Moore et al. ,65 Vakselj and Bebar71 and Van der Zee et al. 73 or as palliative treatment in Terada et al. 70). Additionally, a study by Levenback et al. 61 mentioned that, in one patient in whom SLN was grossly positive after SLN biopsy, the surgeon aborted IFL in favour of RT. Adverse events (AEs) were reported in five studies54,65,70,72,73 (see Appendix 10, Table 55).

With regard to blinding of index and reference test results, it would have been possible for the SLN and the full IFL nodes to be examined by different pathologists blind to each other's reports, but only de Hullu et al. 56 achieved this, and only De Cicco et al. 55 mentioned that they had not blinded pathologists. The remaining studies did not mention any blinding.

Test accuracy results

Results of test accuracy studies for which all patients had IFL as the reference standard are given in Table 11 and for which IFL was the reference standard in test positives and clinical follow-up in test negatives is given in Table 12. Most of the studies reported their results per groin rather than per patient; therefore, teasing out the results per patient was difficult in several of the papers (noted as numbers unclear in the comments column of Tables 11 and 12).

| Study | n | No. of patients with one or more SLNs found | No. of patients with SLN containing malignancies (frozen section) | No. of patients with SLN containing malignancies (histopathology) | No. with SLN found but negative and malignancy found at ILN | No. with no SLN found | No. with no SLN and malignancy from ILN (frozen section) | No. with no SLN and malignancy from ILN (histopathology) | No. with clinical follow-up | No. with malignancies at follow-up | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basta et al., 200551 | 39 | 38 | – | 12 | 0 | 1 | – | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| Brunner et al., 200852 | 44 | 44 | 17 | 0 | 3 | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | Numbers unclear |

| Camara et al., 200953 | 17 | 15 | 7 | - | 0 | 2 | – | 1 | 0 | – | Both |

| 17 | 13 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 99mTc | |

| 17 | 9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Blue | |

| Crosbie et al., 201054 | 32 | 31 | – | 6 | 0 | 1 | – | 1 | 32 | SLN negative: 0 SLN positive: 5 |

– |

| De Cicco et al., 200055 | 37 | 37 | – | 8 | – | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| de Hullu et al., 200056 | 59 | 59 | – | 20 | 0 | 0 | – | - | 0 | – | – |

| Hampl et al., 200857 | 127 | 125 | 0 | 36 | 3 | 2 | – | 0 | 0 | – | Numbers unclear |

| Hauspy et al., 200758 | 41 | 39 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | – | – |

| Johann et al., 200859 | 23 | 23 | ? | 10 | 1 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | Numbers unclear |

| Klat et al., 200960 | 23 | 23 | – | 14 | 1 | 0 | – | - | 23 | SLN positive: 3 SLN negative: 1 |

– |

| Levenback et al., 200161 | 52 | 46 | – | 11 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 0 | – | Numbers unclear | |

| Lindell et al., 201039 | 77 | 75 | – | 21 | 2 | 2 | – | 0 | 0 | – | Numbers unclear |

| Louis-Sylvestre et al., 200662 | 38 | 36 | – | 11 | – | 2 | – | ? | 0 | – | Numbers unclear |

| Martinez-Palones et al., 200663 | 28 | 27 | – | 6 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 28 | SLN positive: 4 SLN negative: 3? No SLN: 1 |

|

| Merisio et al., 200564 | 20 | 20 | – | 3 | 1 | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – |

| Nyberg et al., 200766 | 25 (47)b | 25 | 4 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | Stage I and II only | |

| Pityński et al., 200367 | 37 | 37 | – | 11 | 0 | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | |

| Radziszewski et al., 201068 | 56 | 56 | – | 21 | ? | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | Six patients with metastases on FNA, numbers unclear |

| Rob et al., 200769 | 43 | 43 | 13 | 14 | 0 | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | Both |

| 16 | 11 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 | - | 1 | 0 | – | Blue only, numbers unclear | |

| Vakselj et al., 200771 | 35 | 35 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | – | – | 35 | SLN positive: 6 SLN negative: 3 |

– |

| Vidal-Sicart et al., 200774 | 50 | 49 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 1 | – | Not found | (70)a | Total: 5 | – |

| Study | n | No. of patients with 1 or more SLNs found | No. of patients with SLN with malignancies (frozen section) | No. of patients with SLN with malignancies (histopathology) | No. with SLN found but negative and malignancy found at ILN | No. with no SLN found | No. with no SLN and malignancy from ILN (frozen section) | No. with no SLN and malignancy from ILN (histopathology) | No. with clinical follow-up | No. with malignancies at follow-up | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achimas-Cadariu et al., 200950 | 46 | 43 | – | – | – | 3 | – | – | 46 | 8 | Mostly per groin analysis |

| Moore et al., 200865 | 36 | 35 | – | 4 | 0 | 1 | – | 0 | 31 (negative SLN) | SLN negative: 2 | – |

| Terada et al., 200670 | 21 | 21 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | – | – | 21 | SLN positive: 2 SLN negative: 0 |

– |

| Van den Eynden et al., 200372 | 32 | 27 | – | 10 | 5 | 5 | – | ? | 17 | SLN negative: 4 | Numbers unclear |

| Van der Zee et al., 200873 | 403 | 403 | – | 127 (135 in Oonk et al. 201083) |

36 (micromets from 33 immunohistochemistry of SLN, Oonk et al. 201083) | 0 | – | – | 276 | SLN negative: 8 groin, 34 local SLN positive: 11 groin, 34 local, 7 distant |

Numbers unclear |

For calculation of sensitivity and specificity, studies have been categorised by the reference standards used, the index test used and the histopathological techniques used as follows:

-

IFL for all

-

99mTc with blue dye

-

99mTc only

-

blue dye only

-

immunohistochemistry (Table 20).

-

-

-

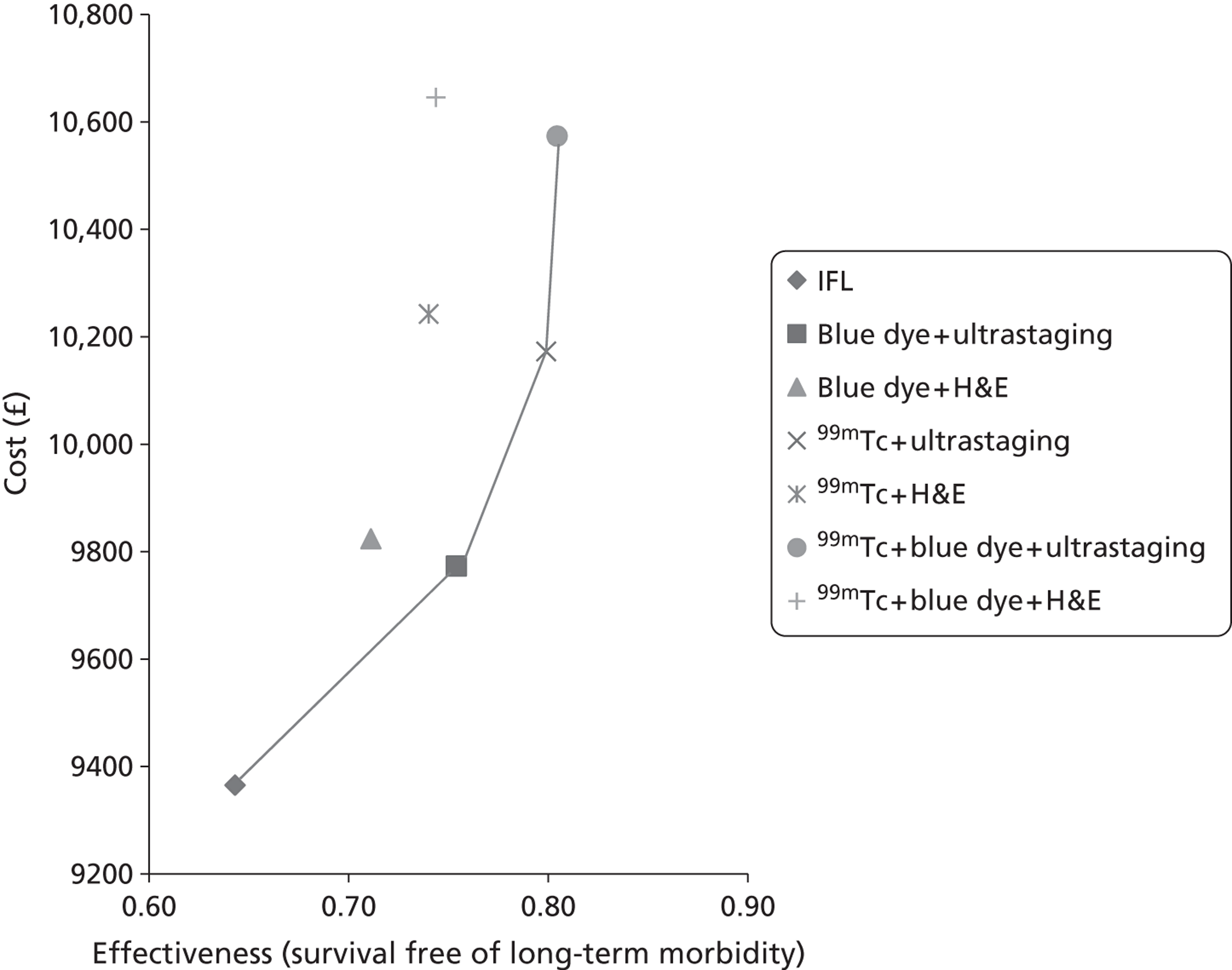

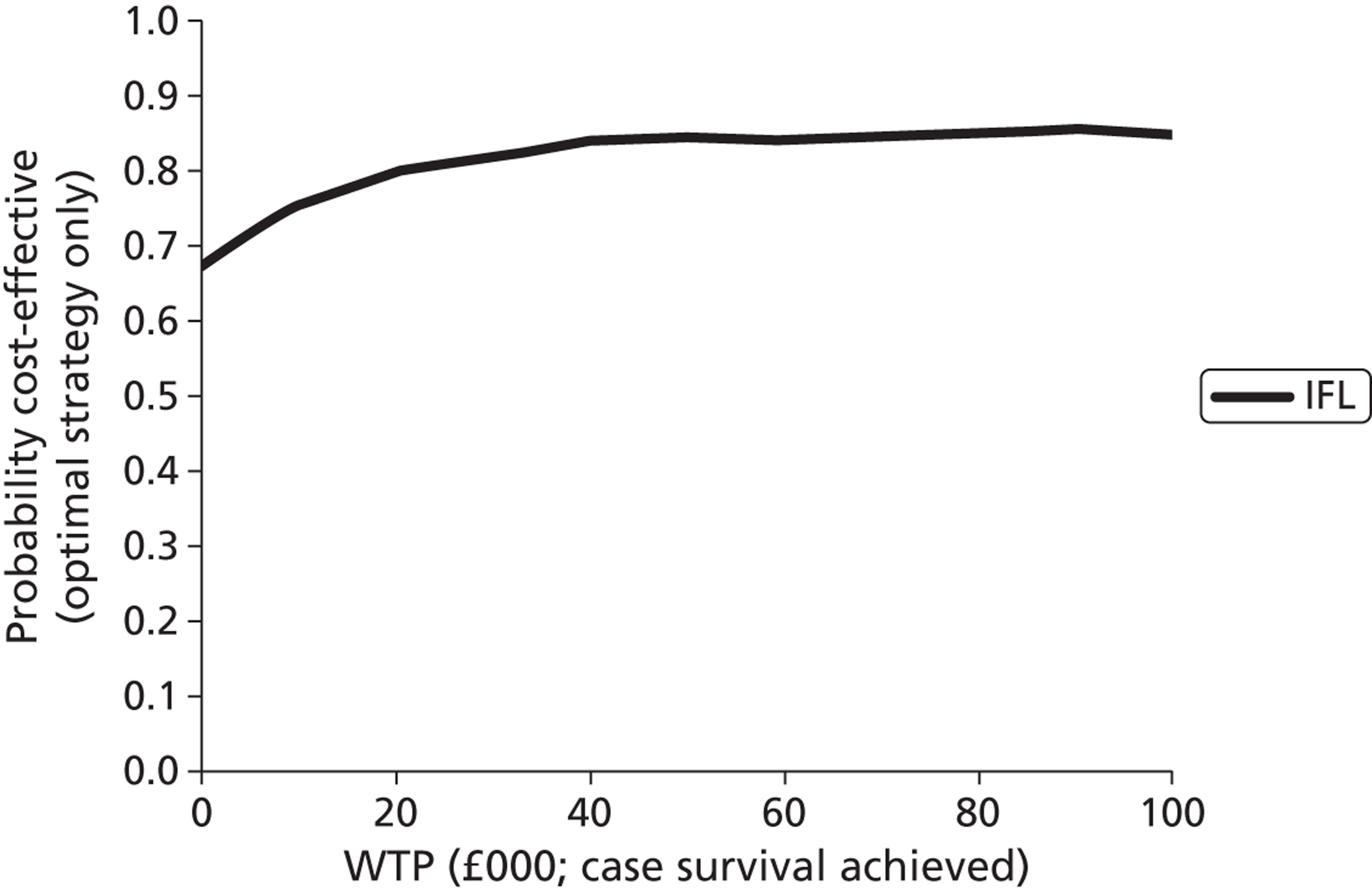

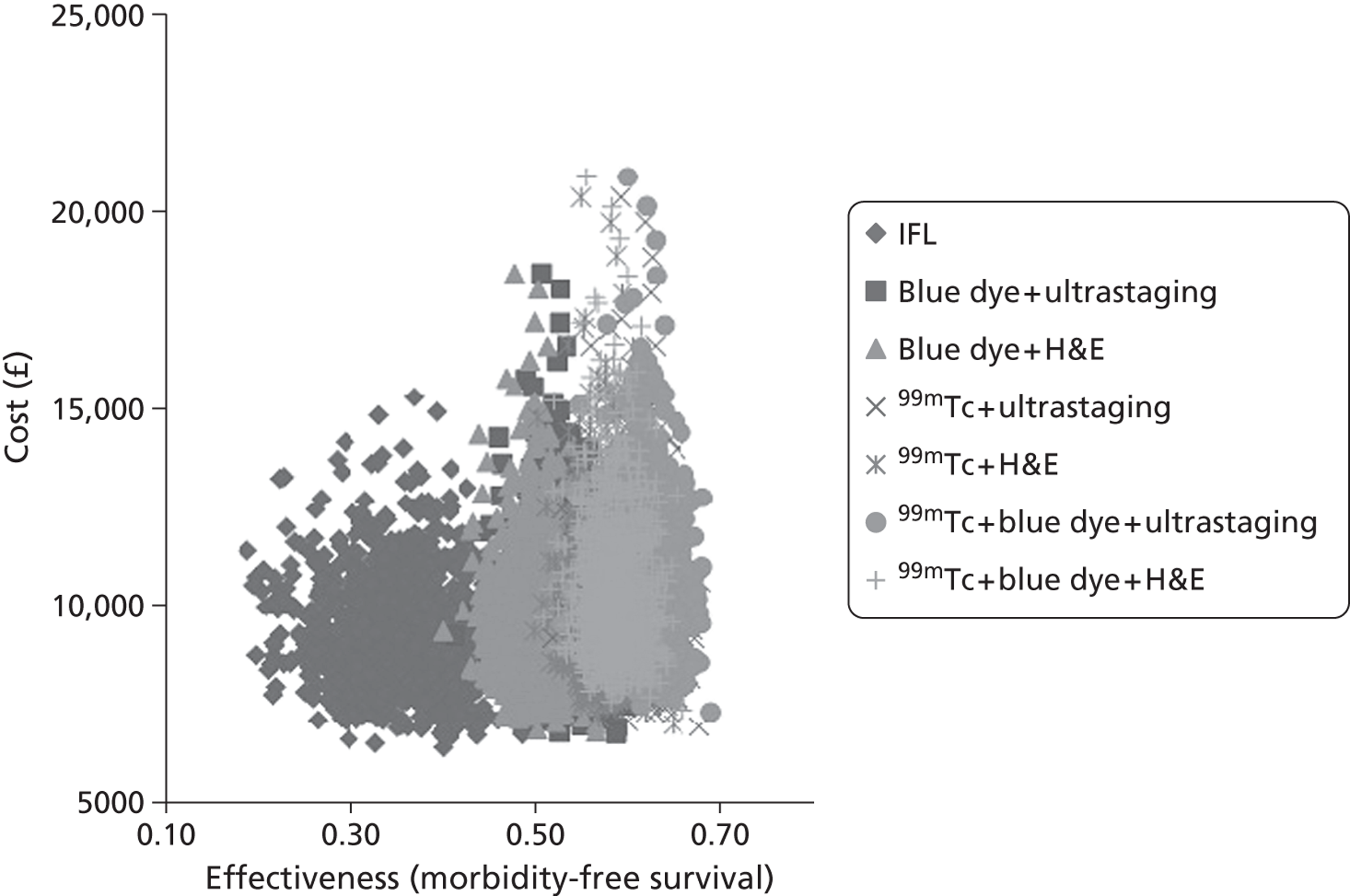

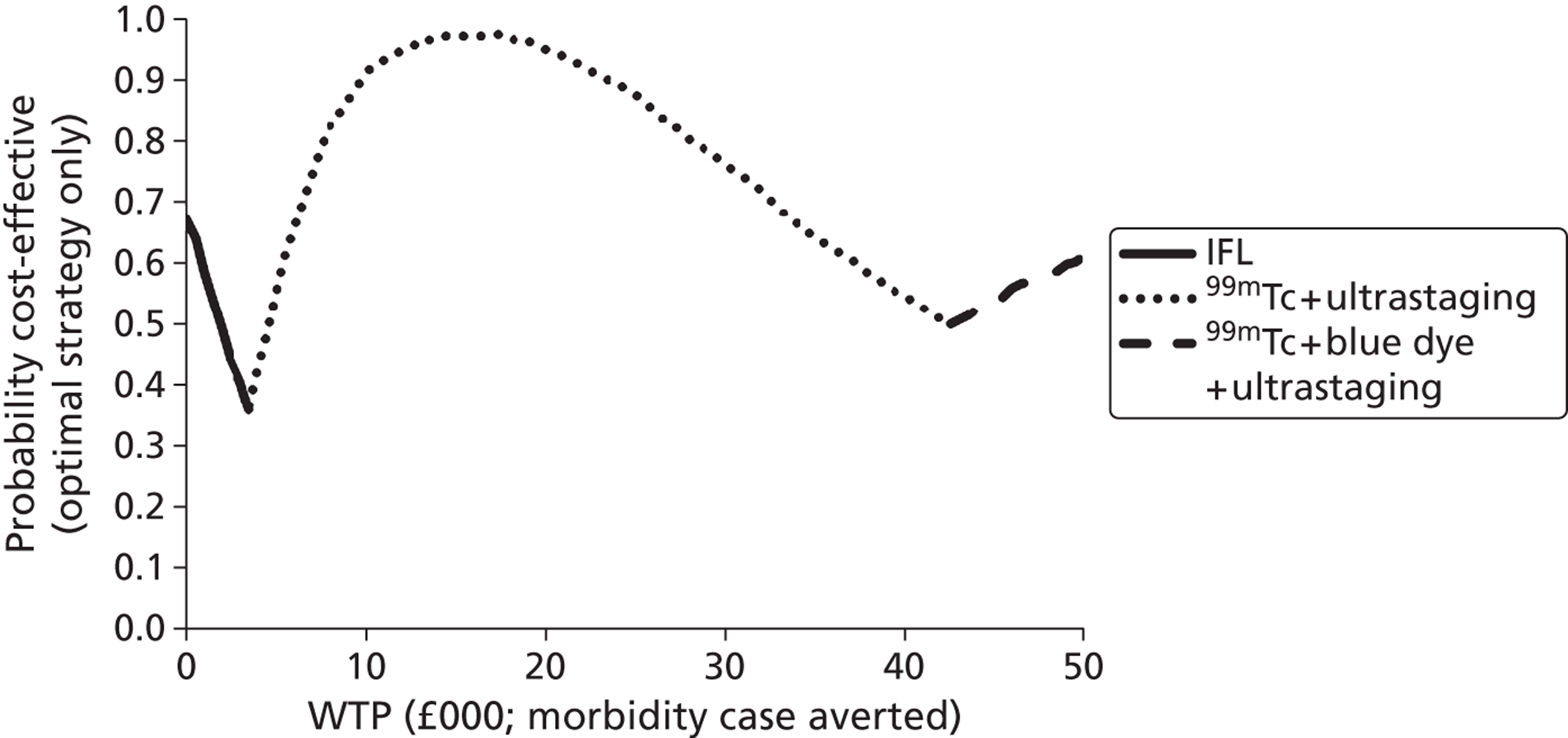

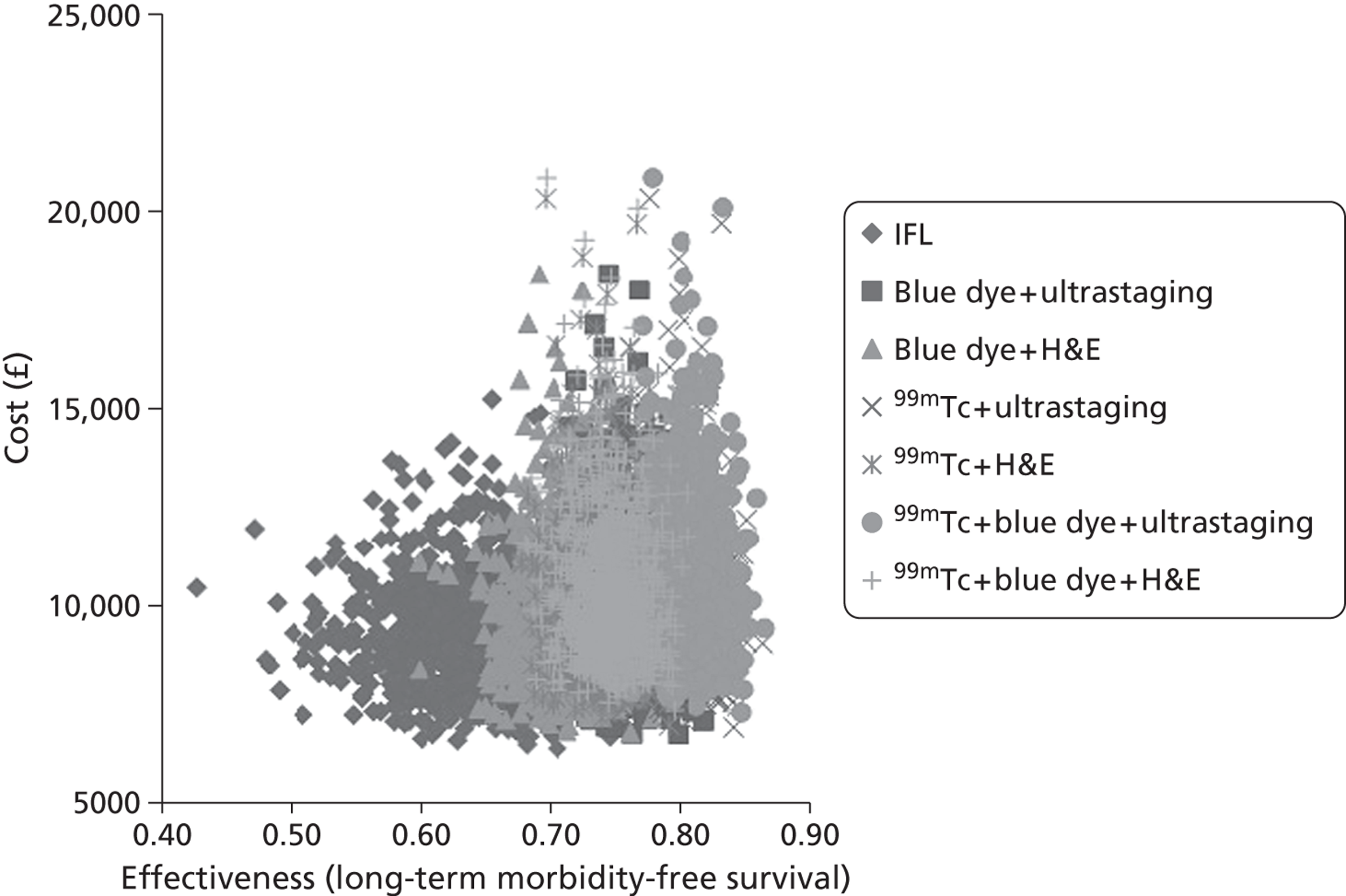

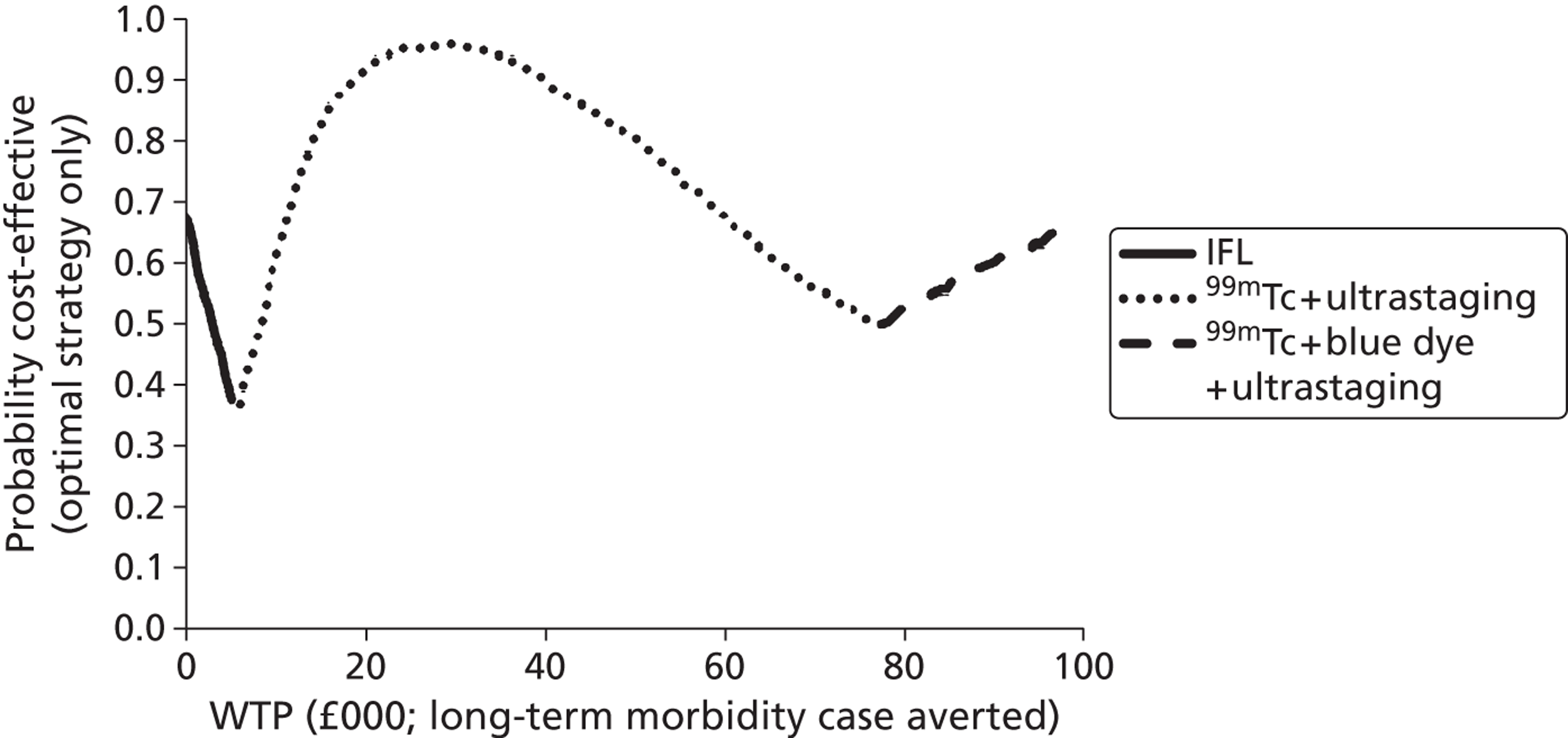

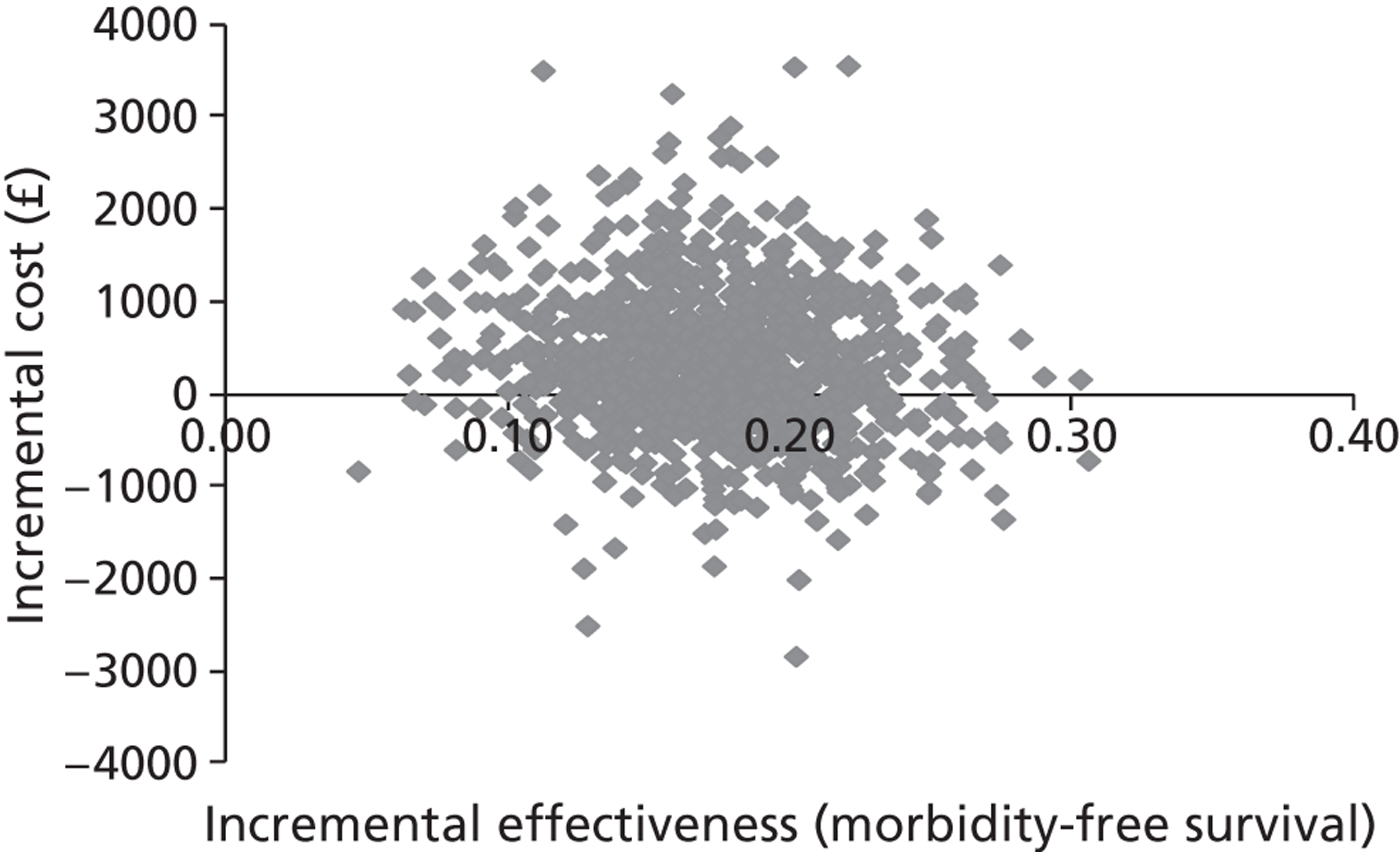

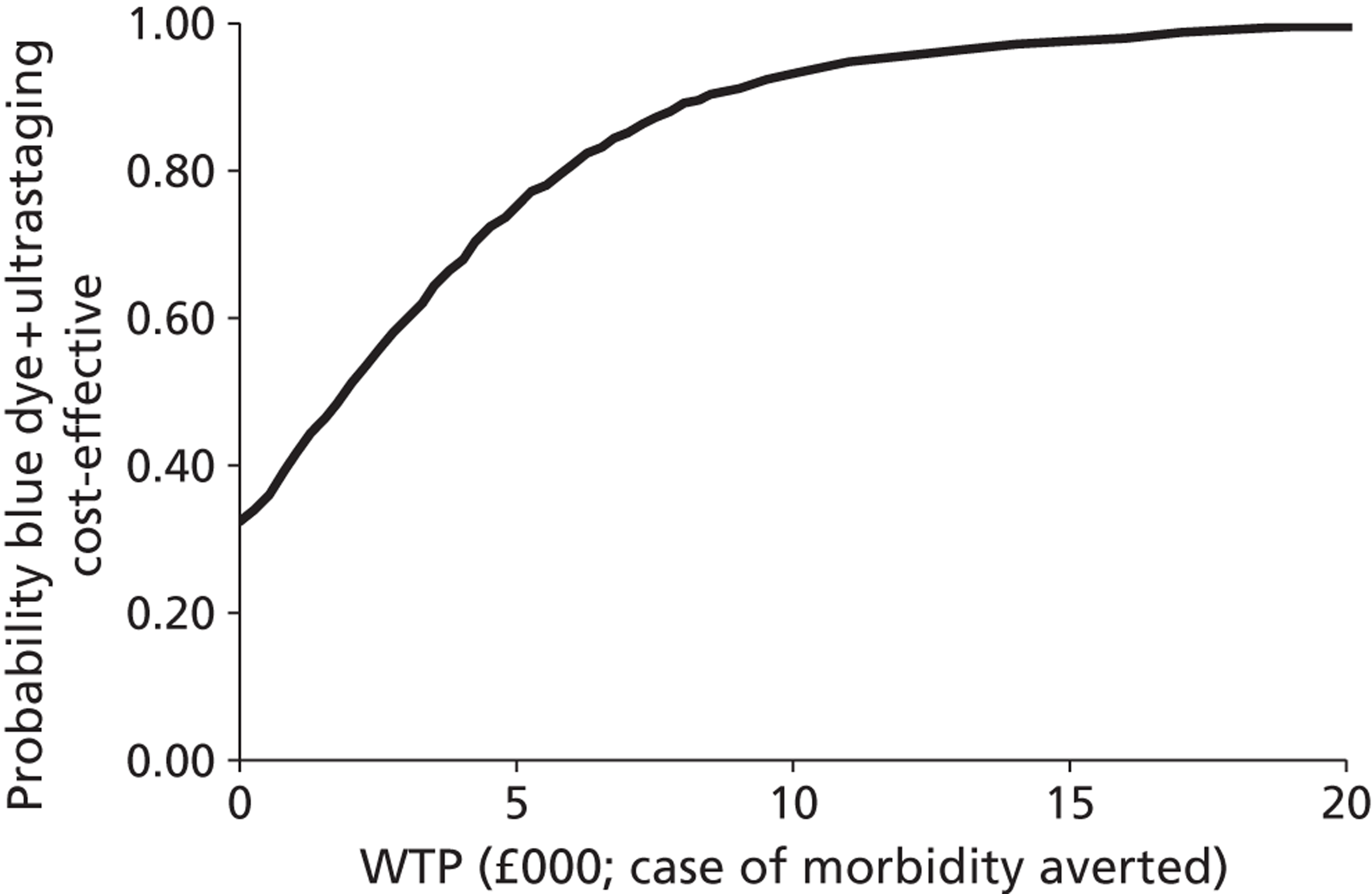

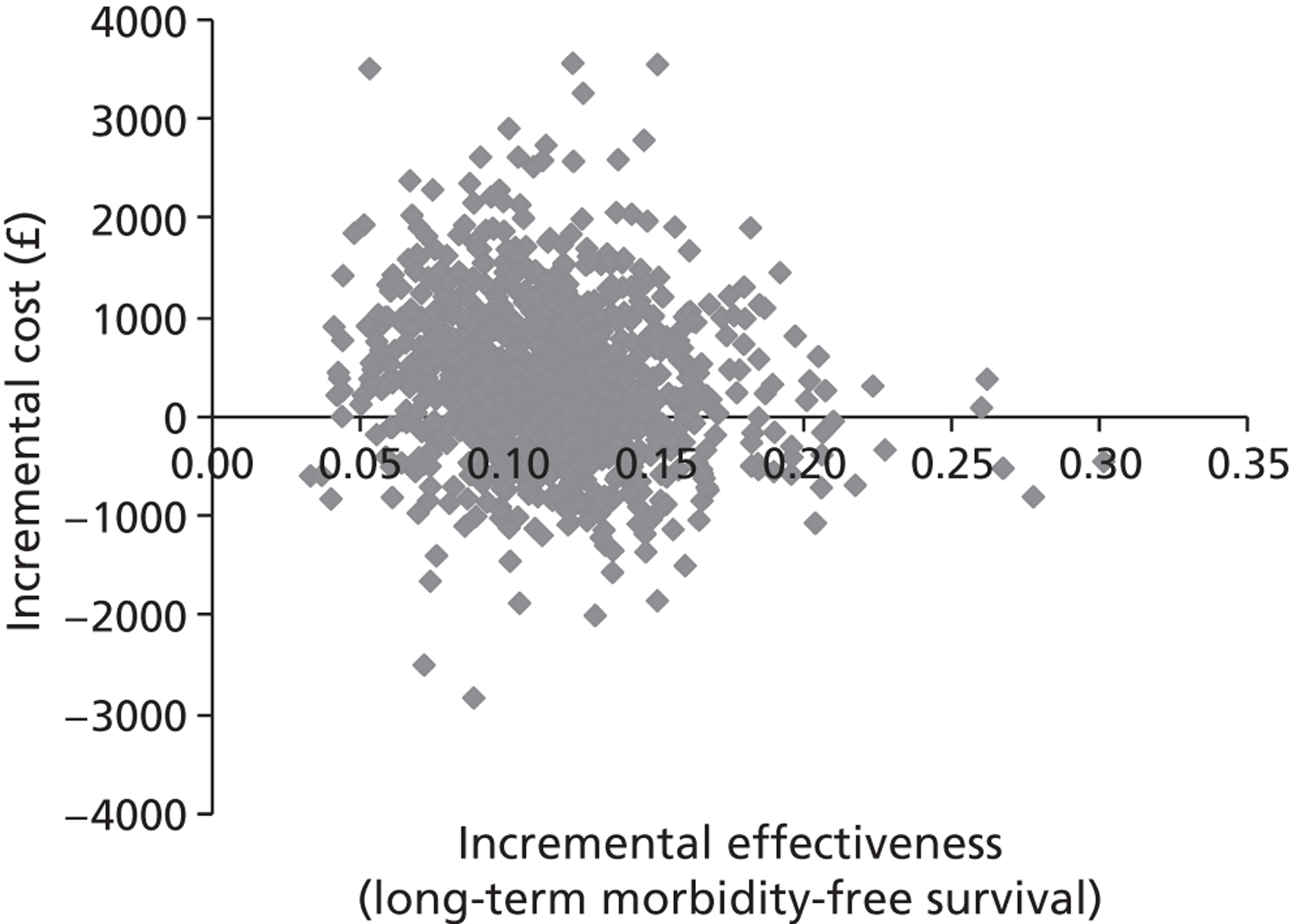

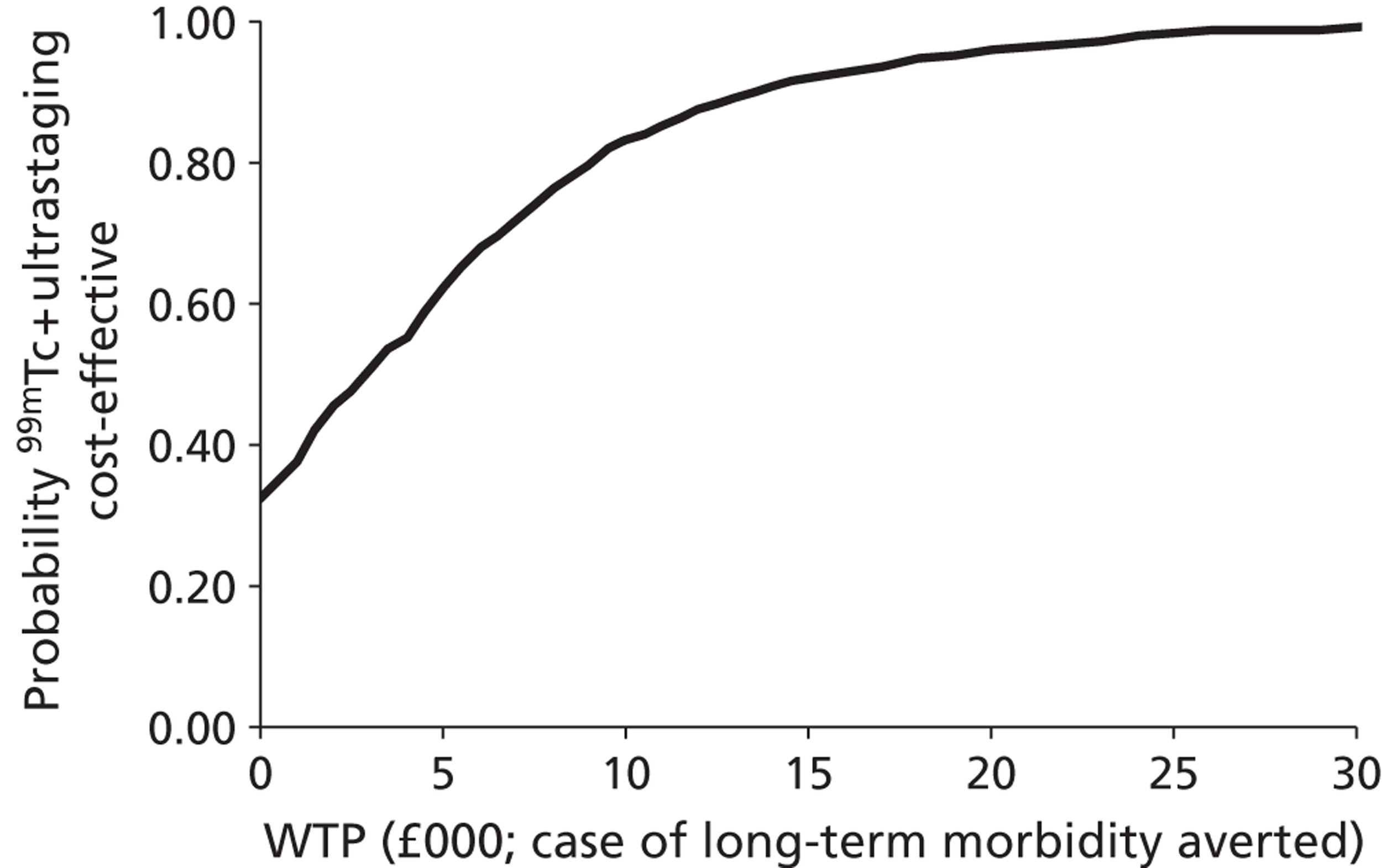

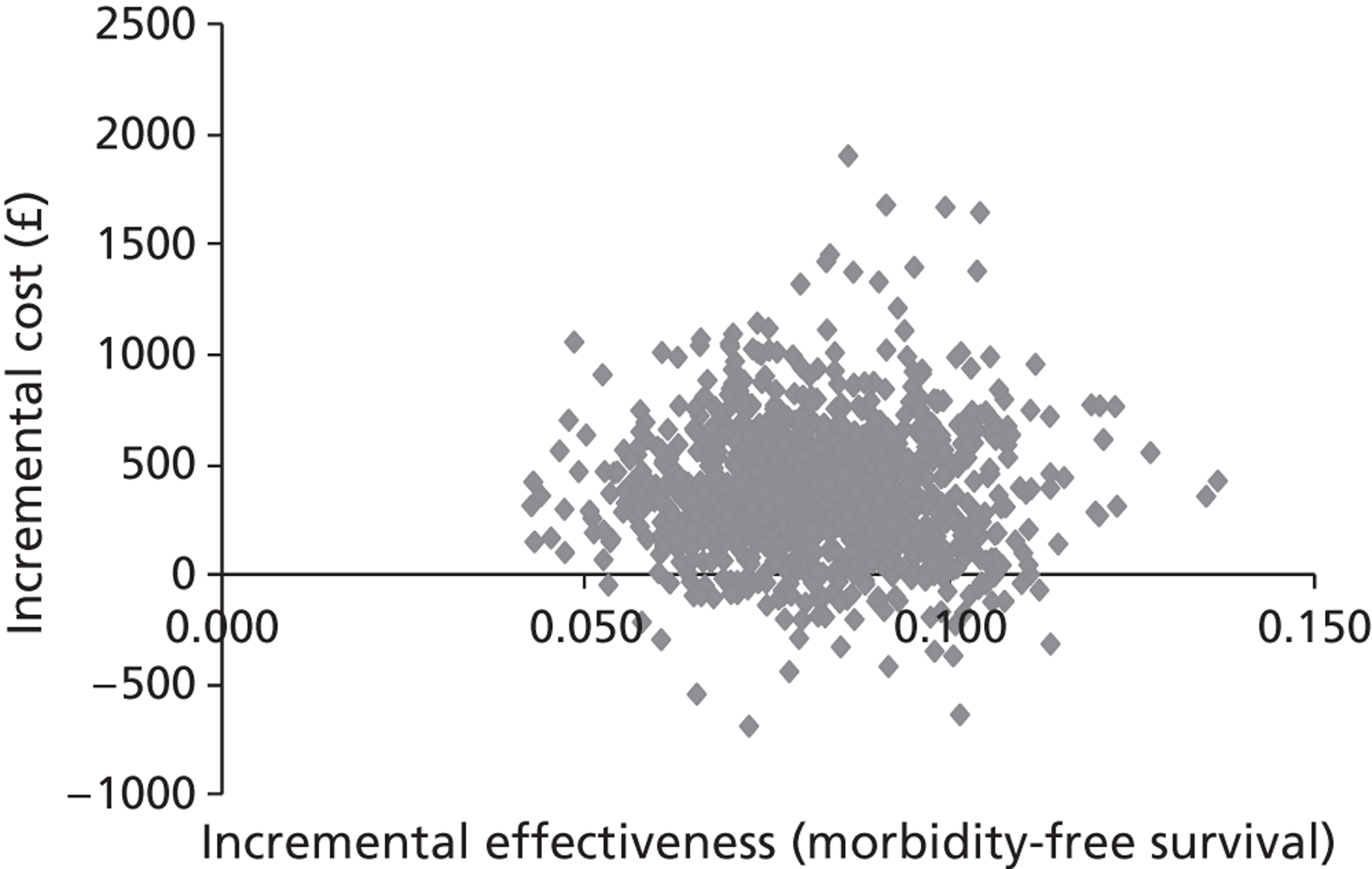

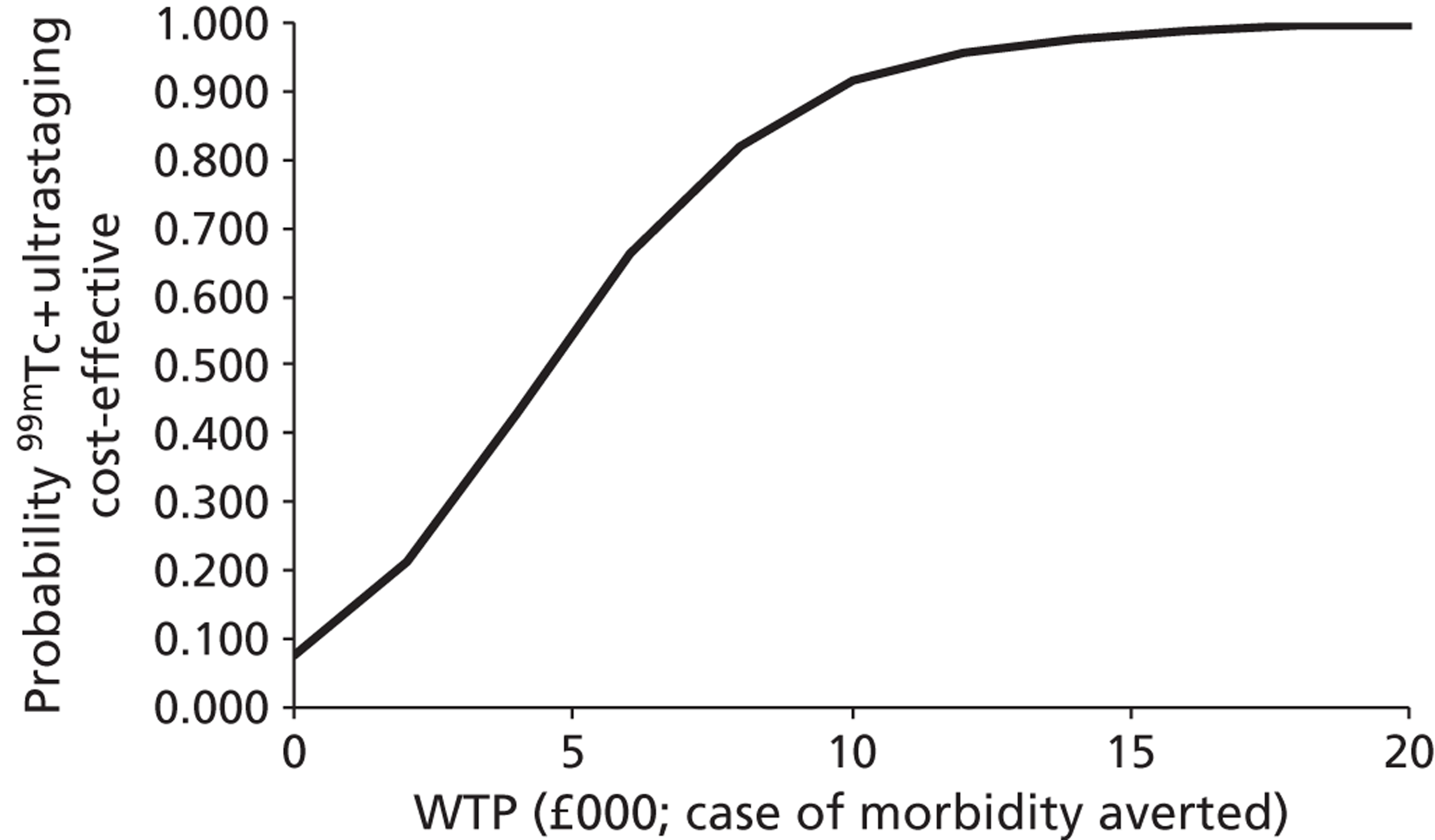

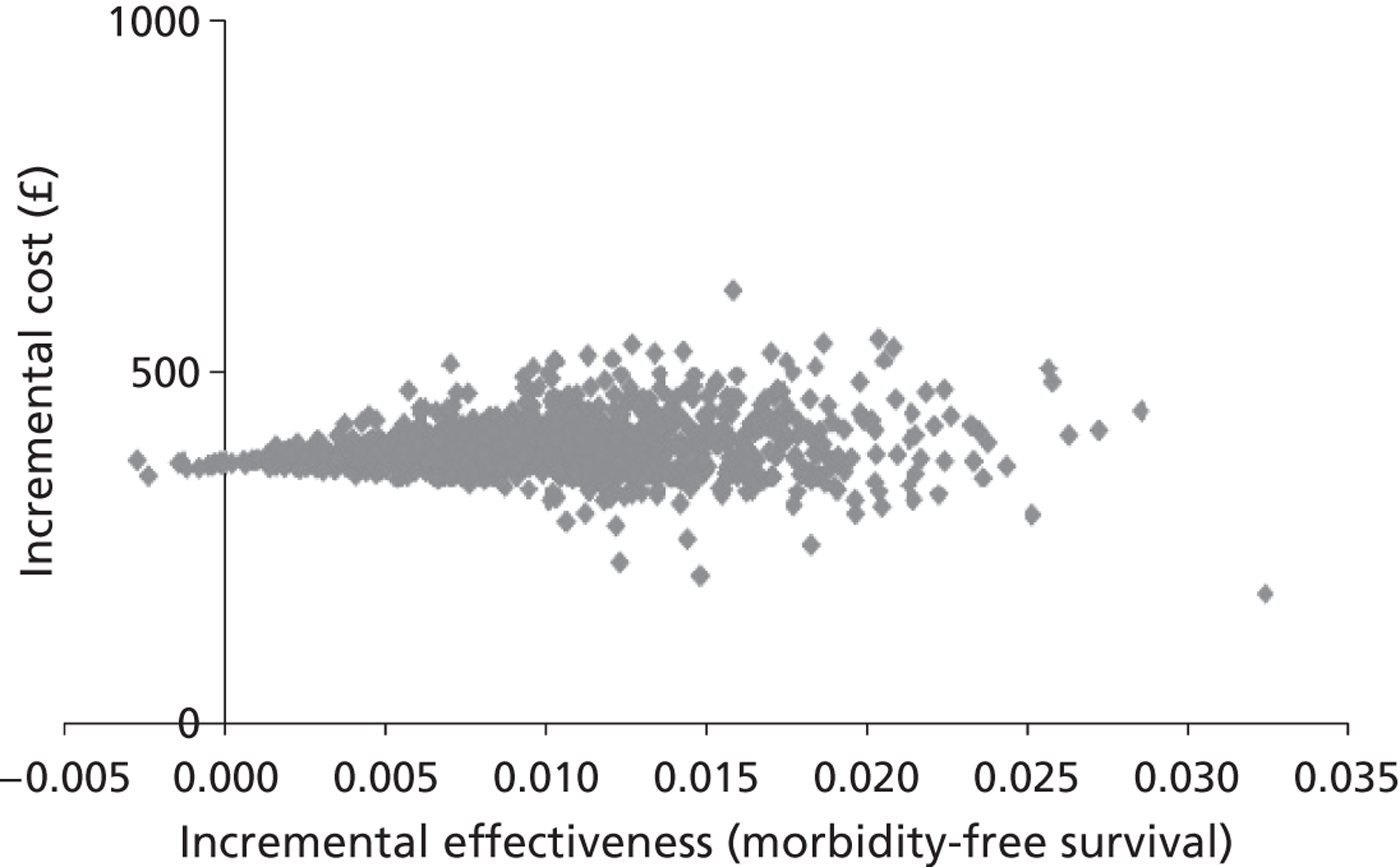

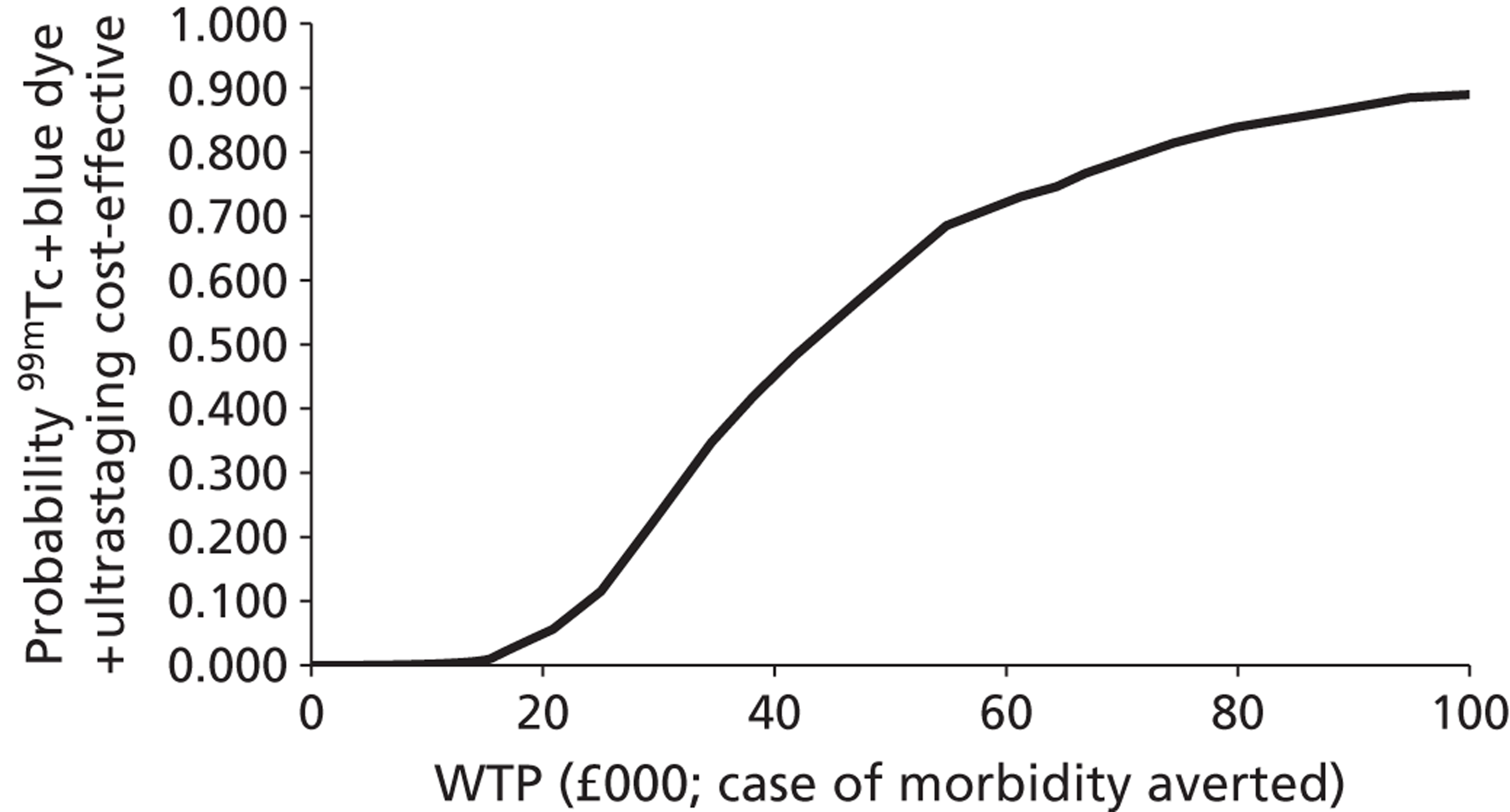

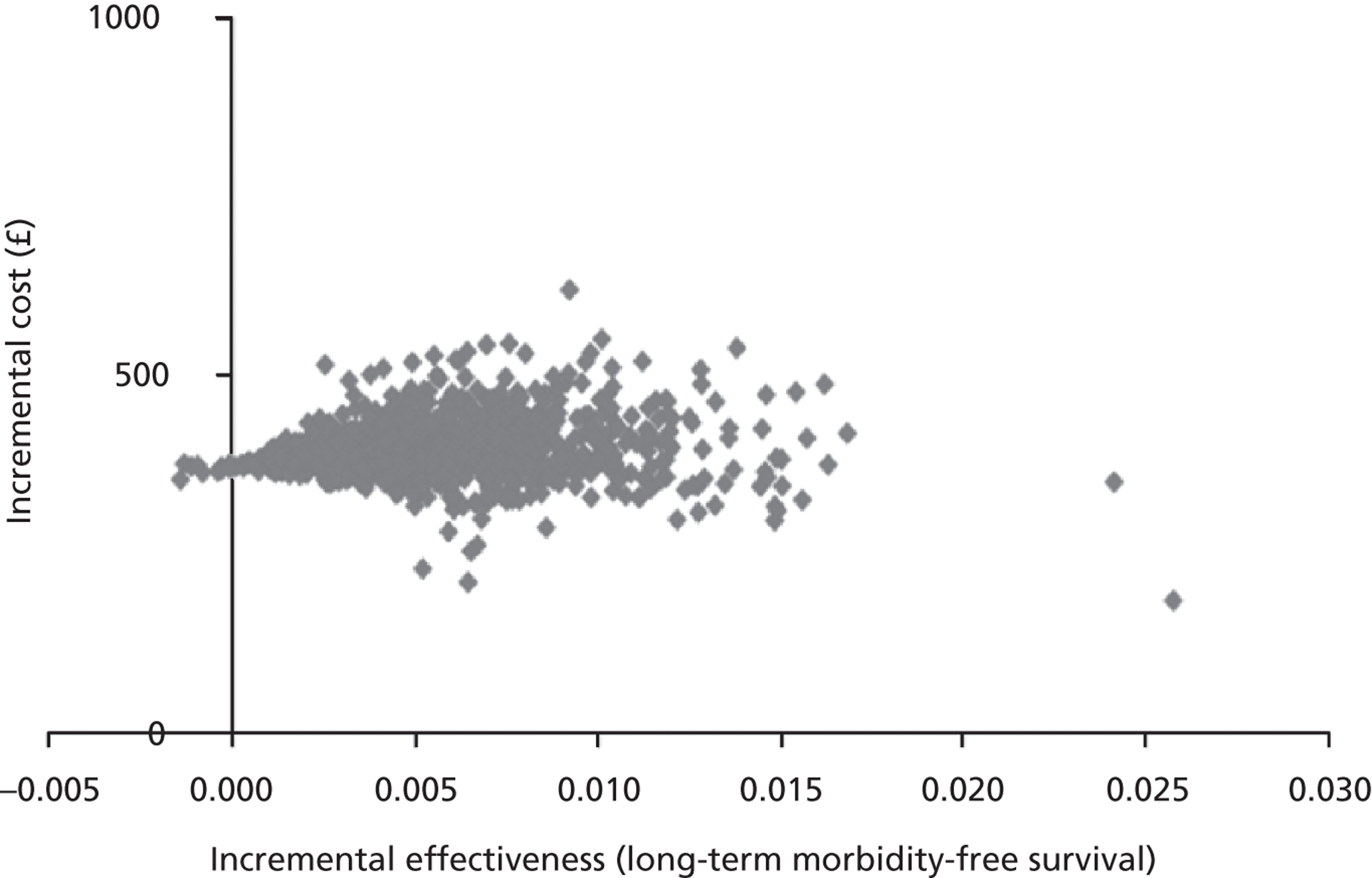

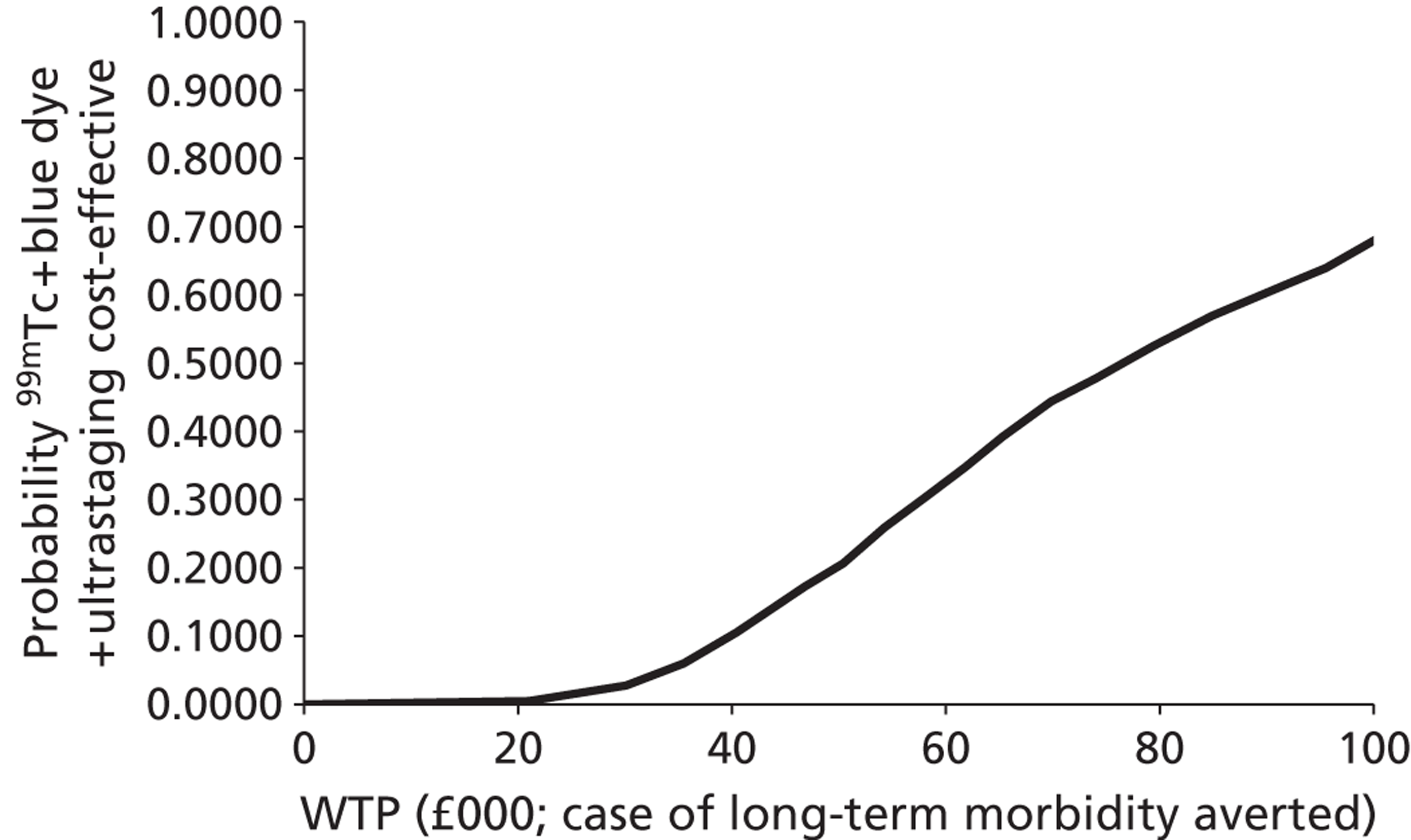

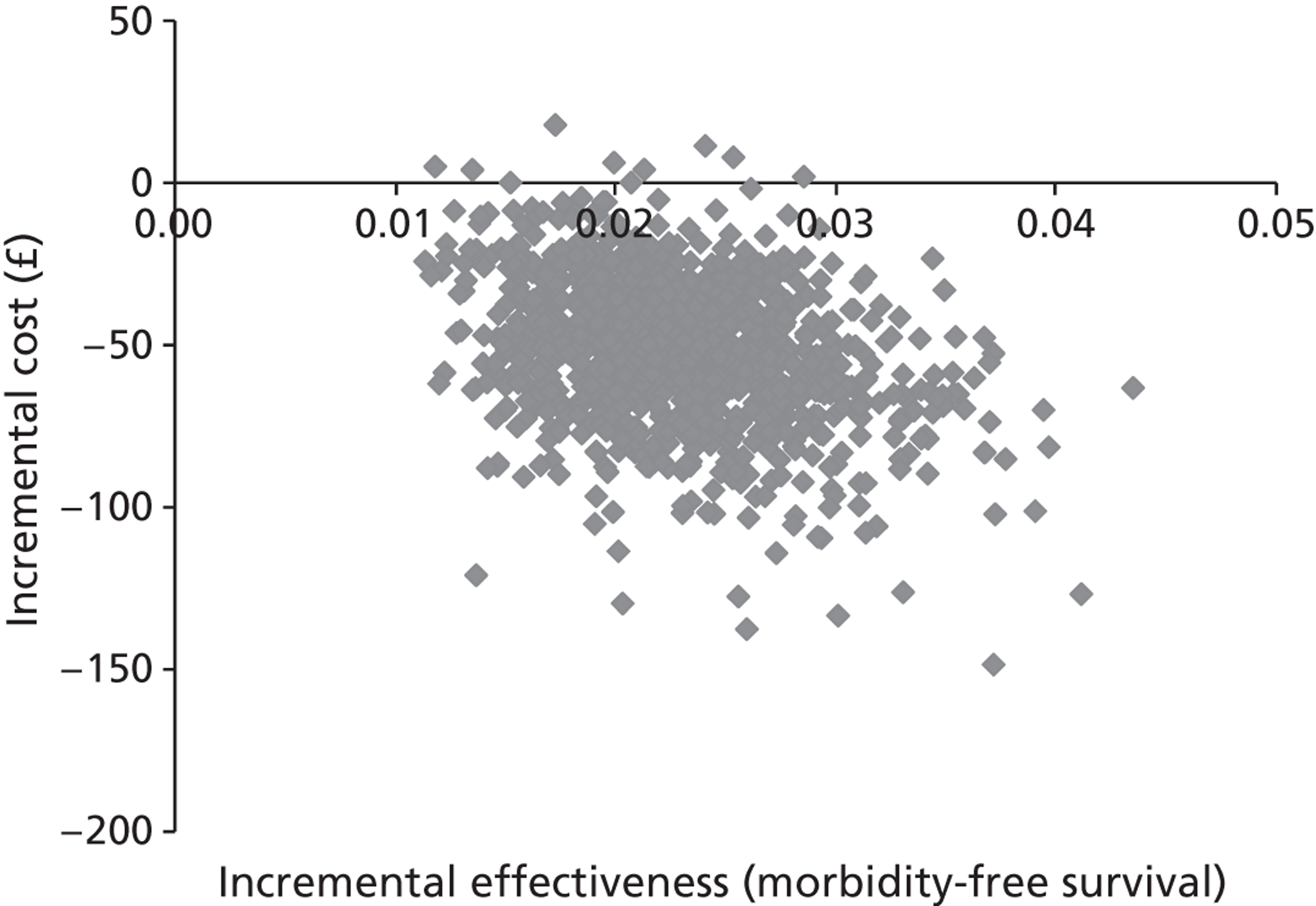

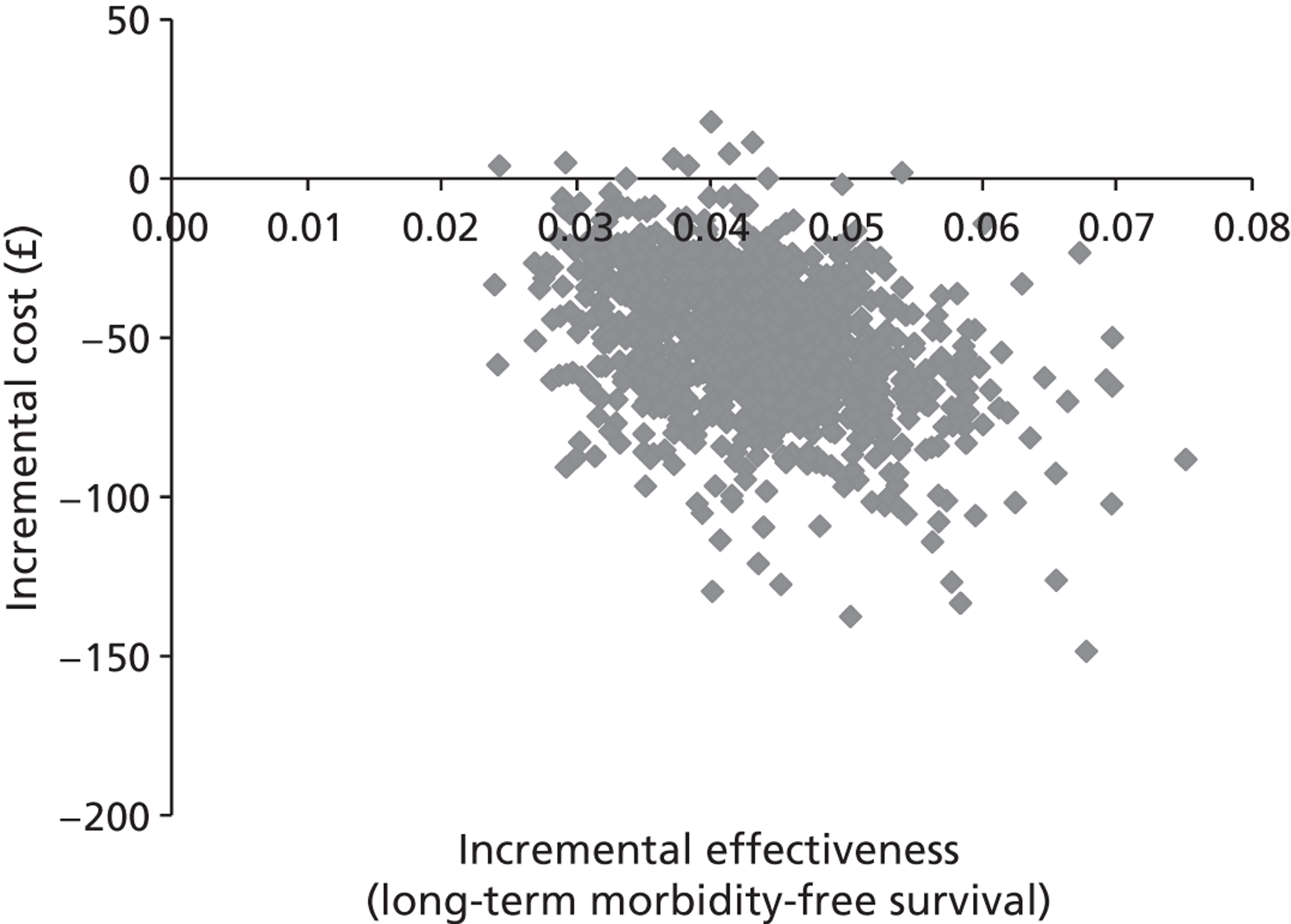

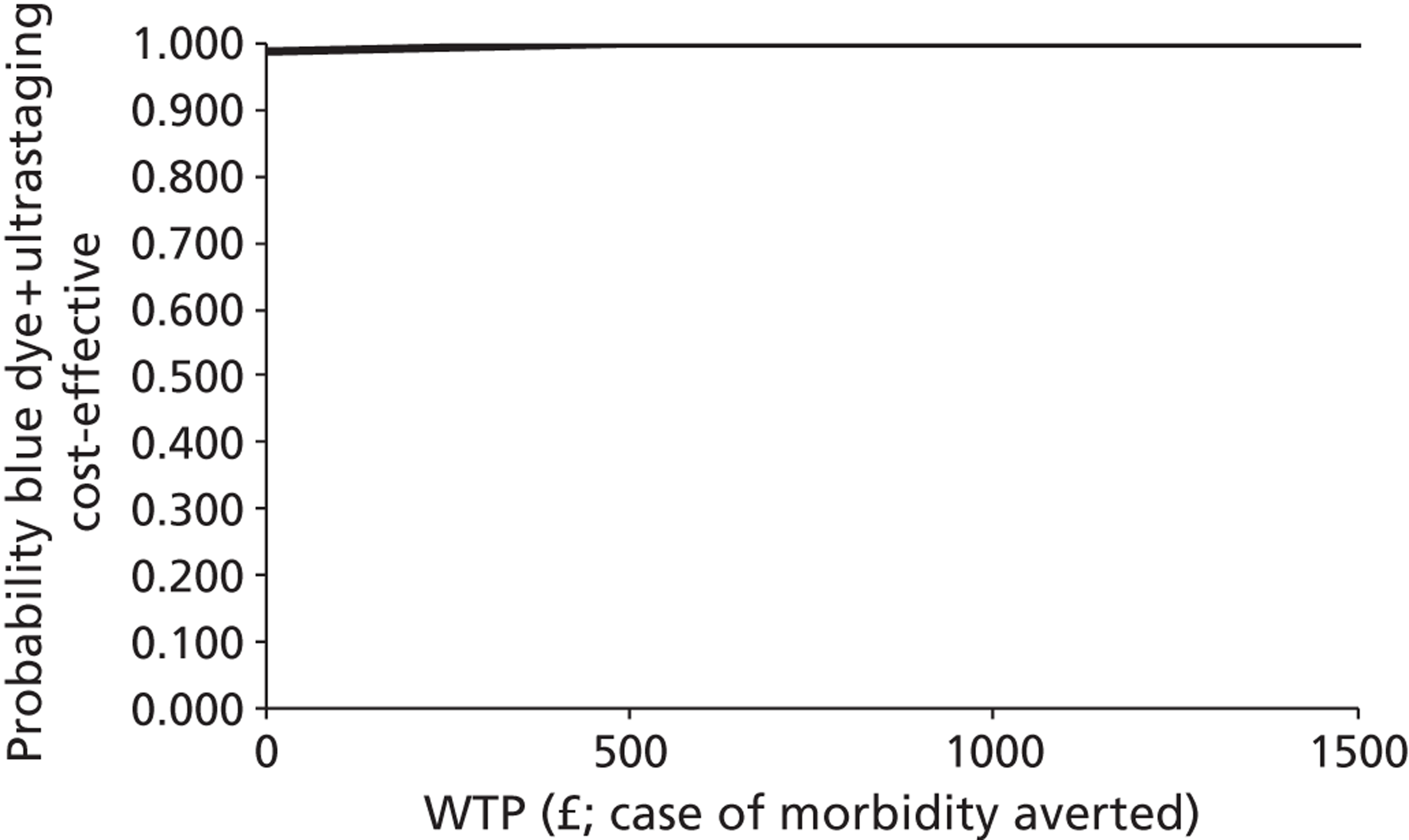

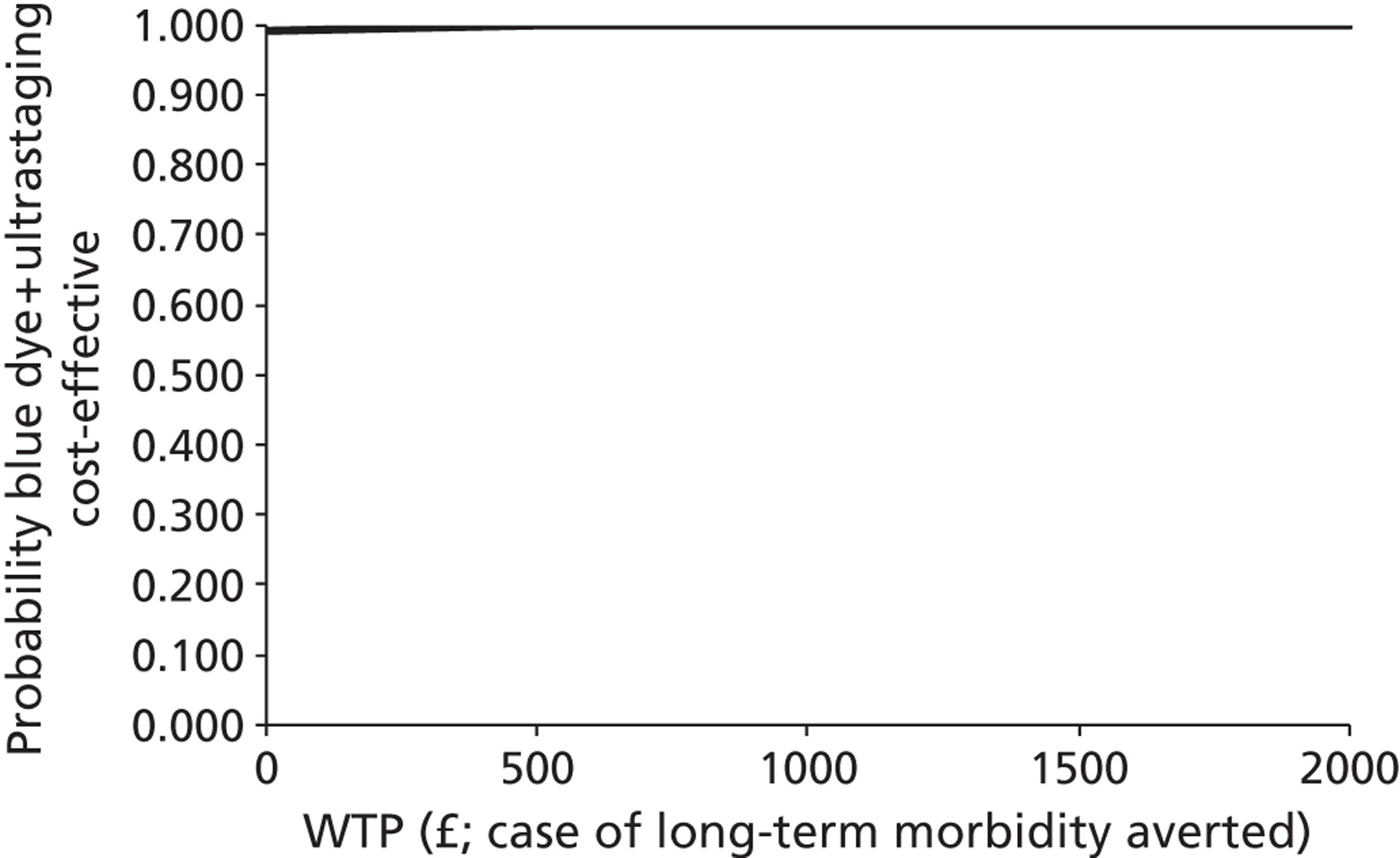

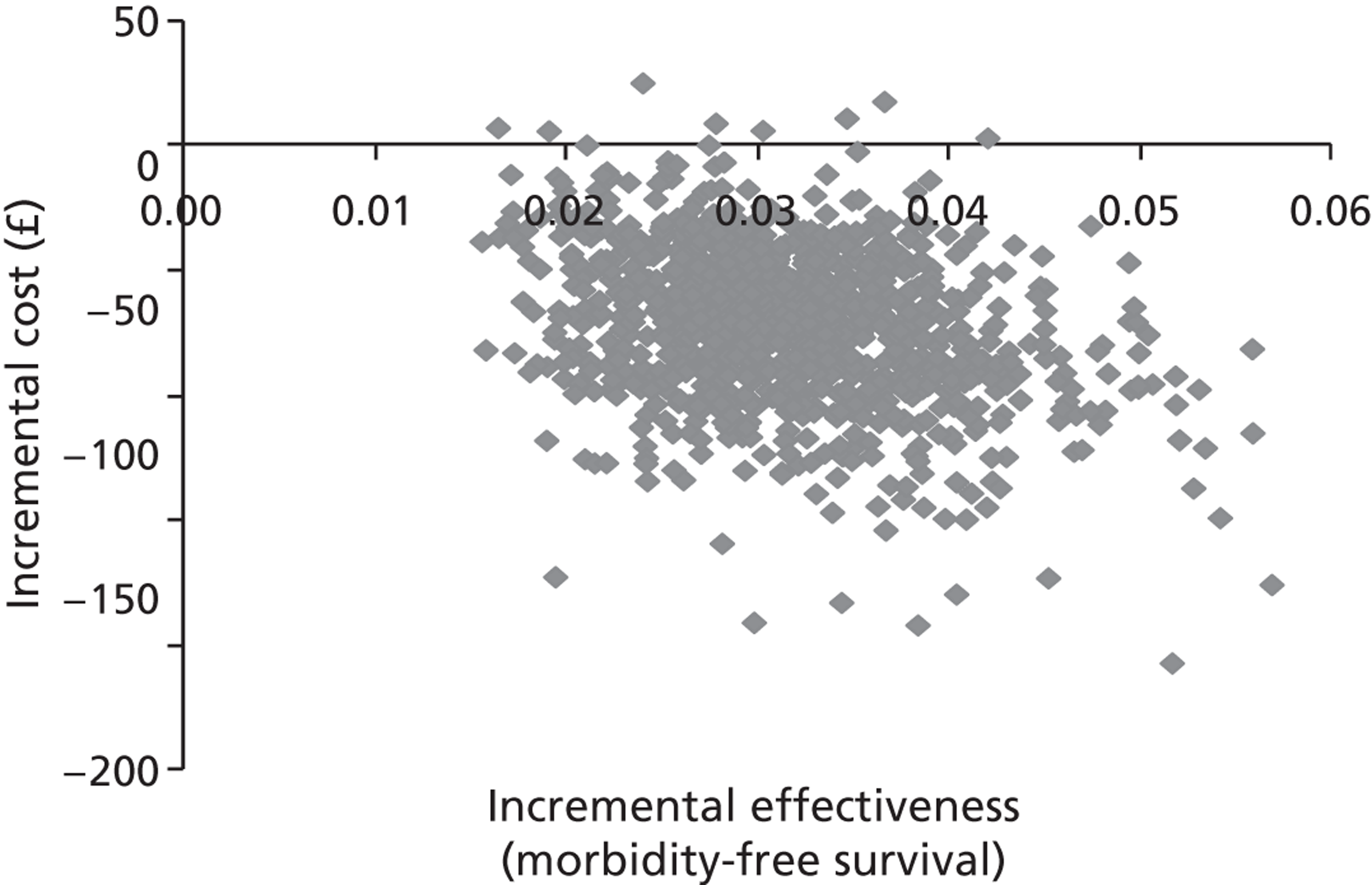

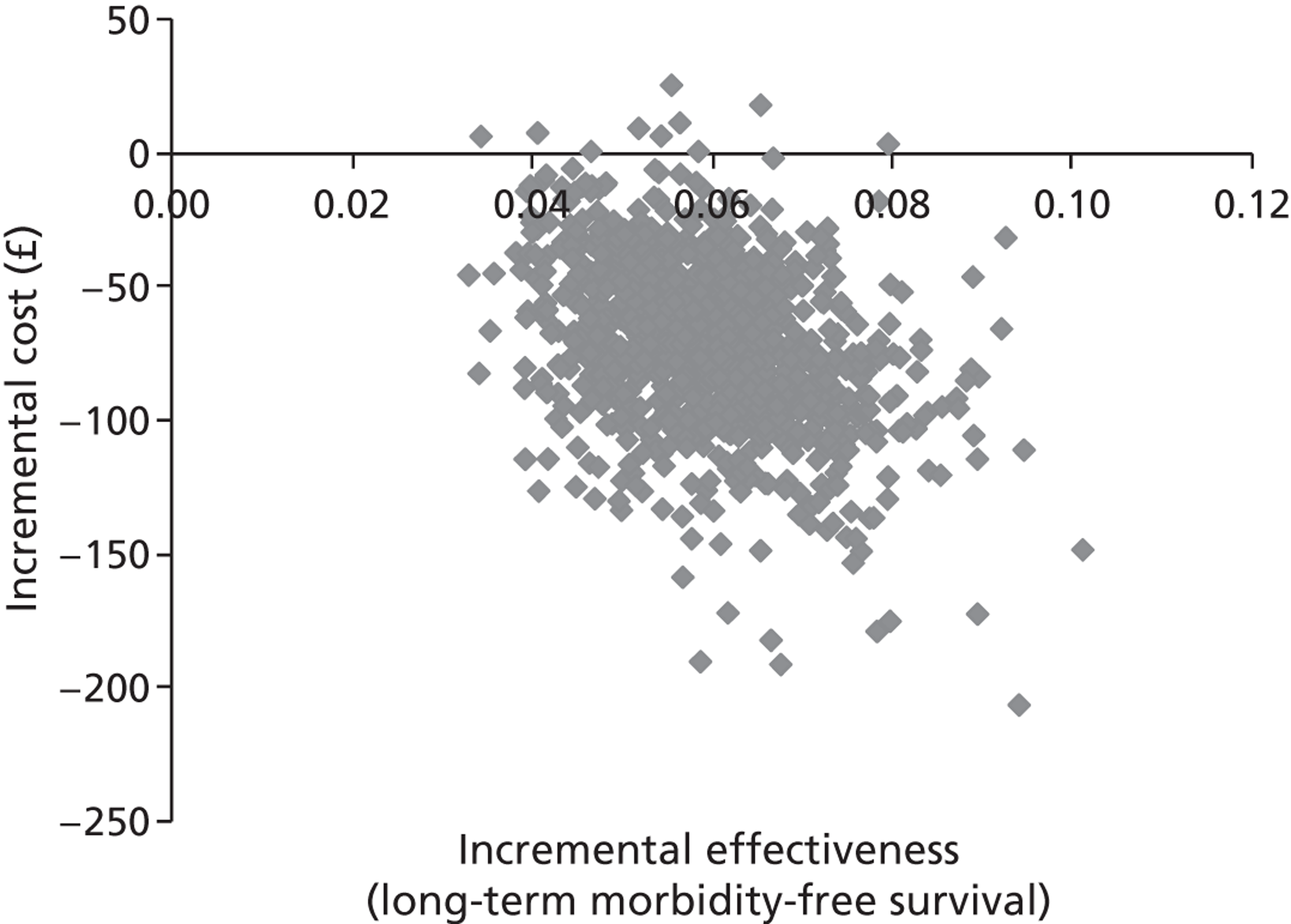

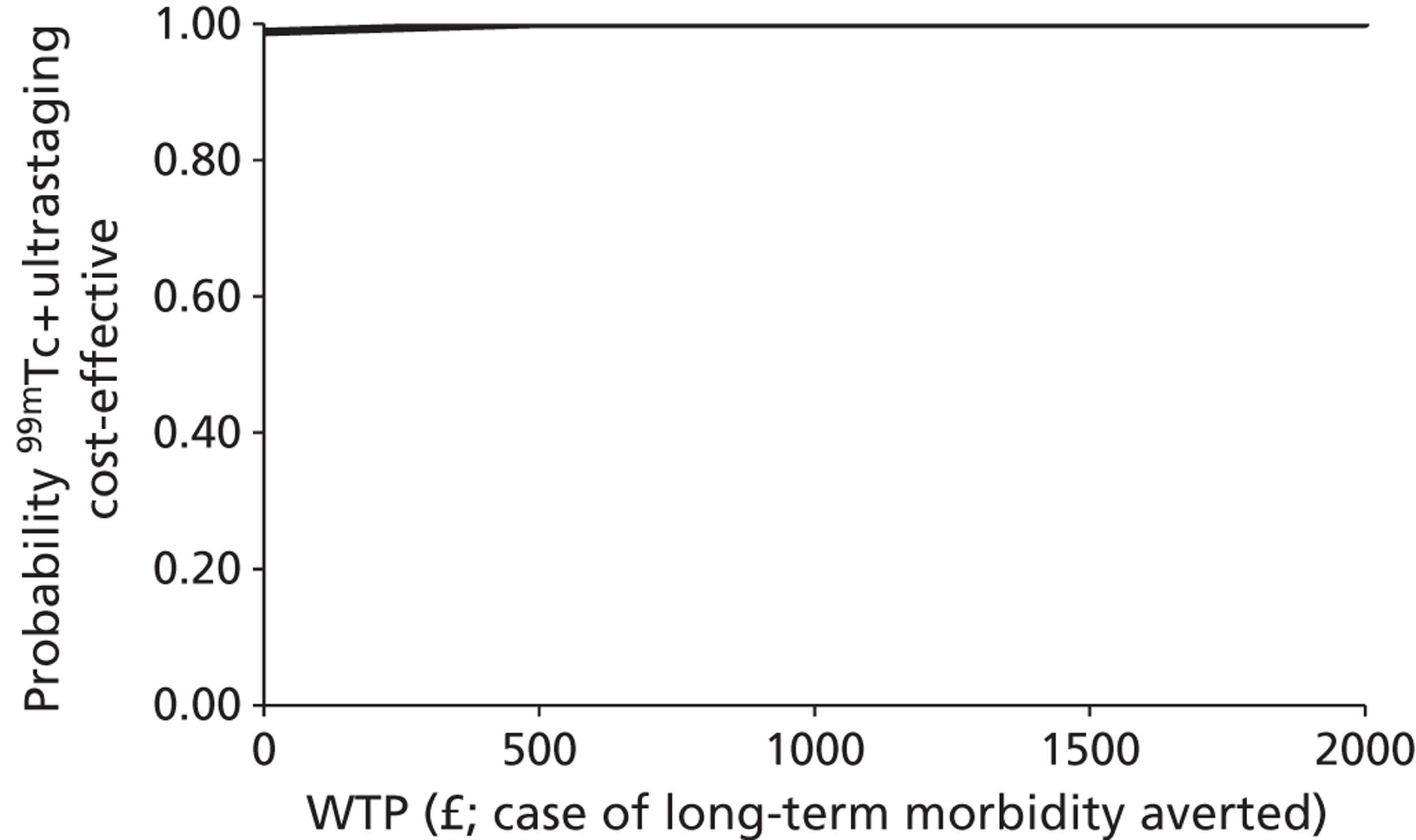

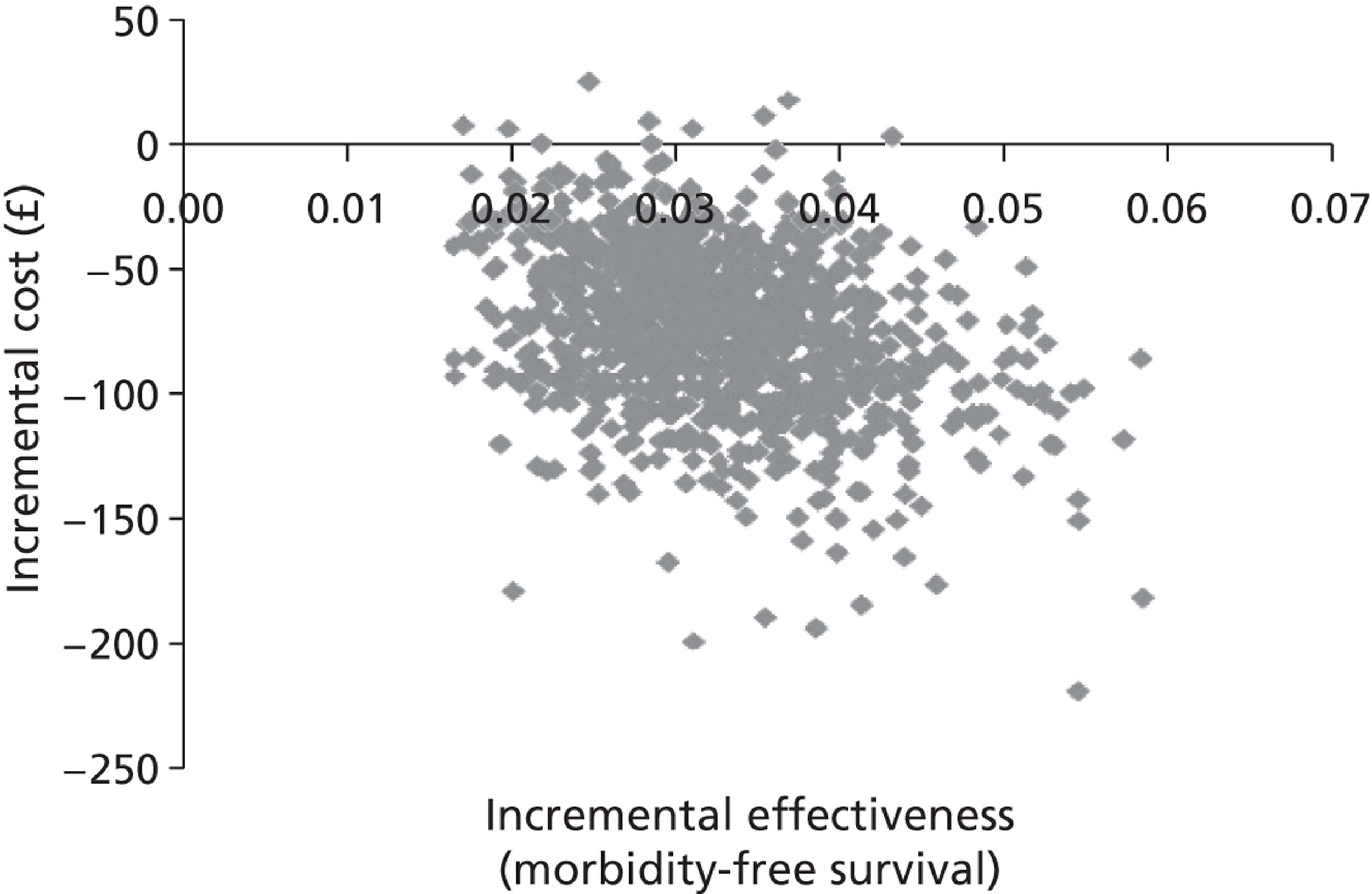

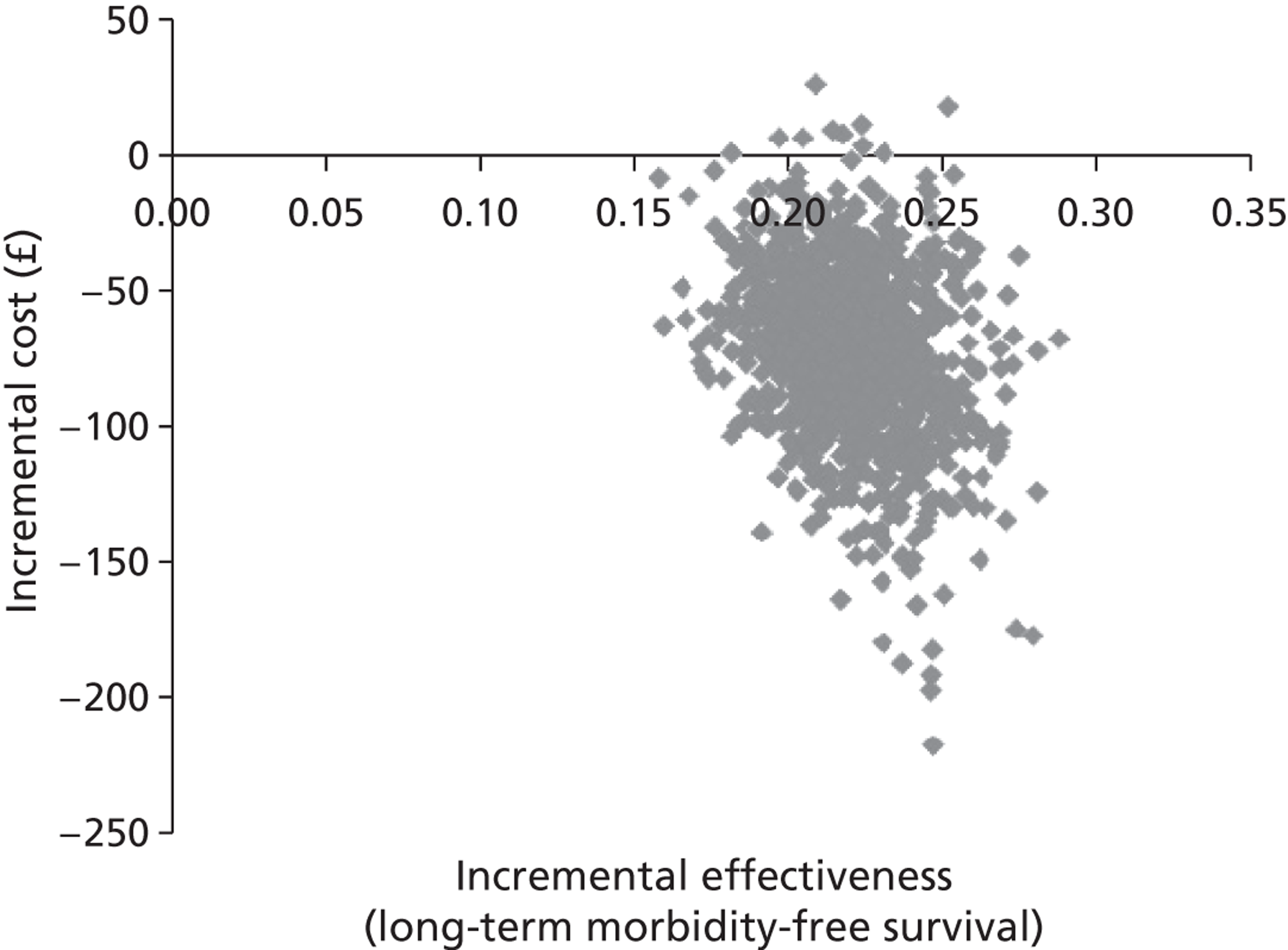

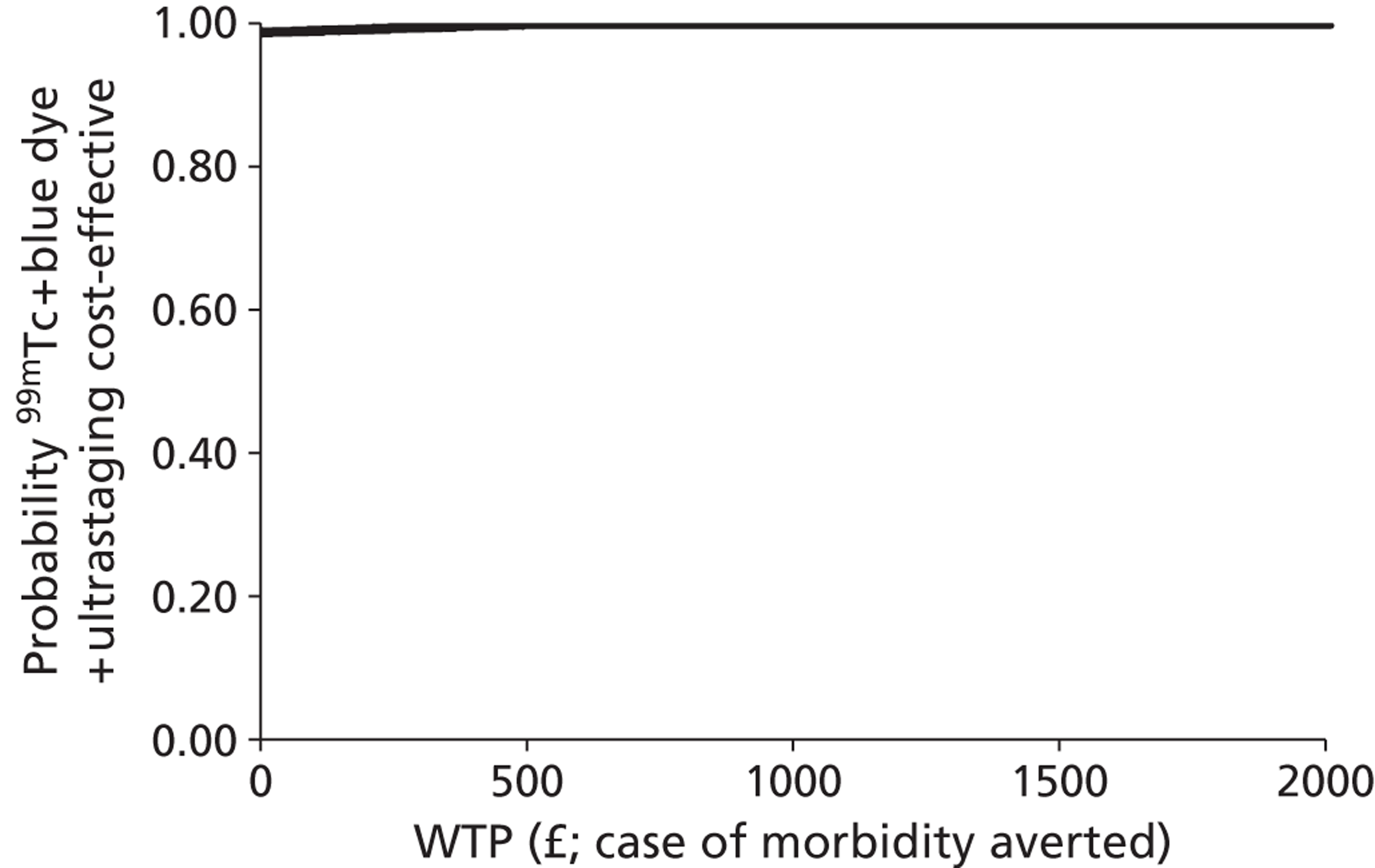

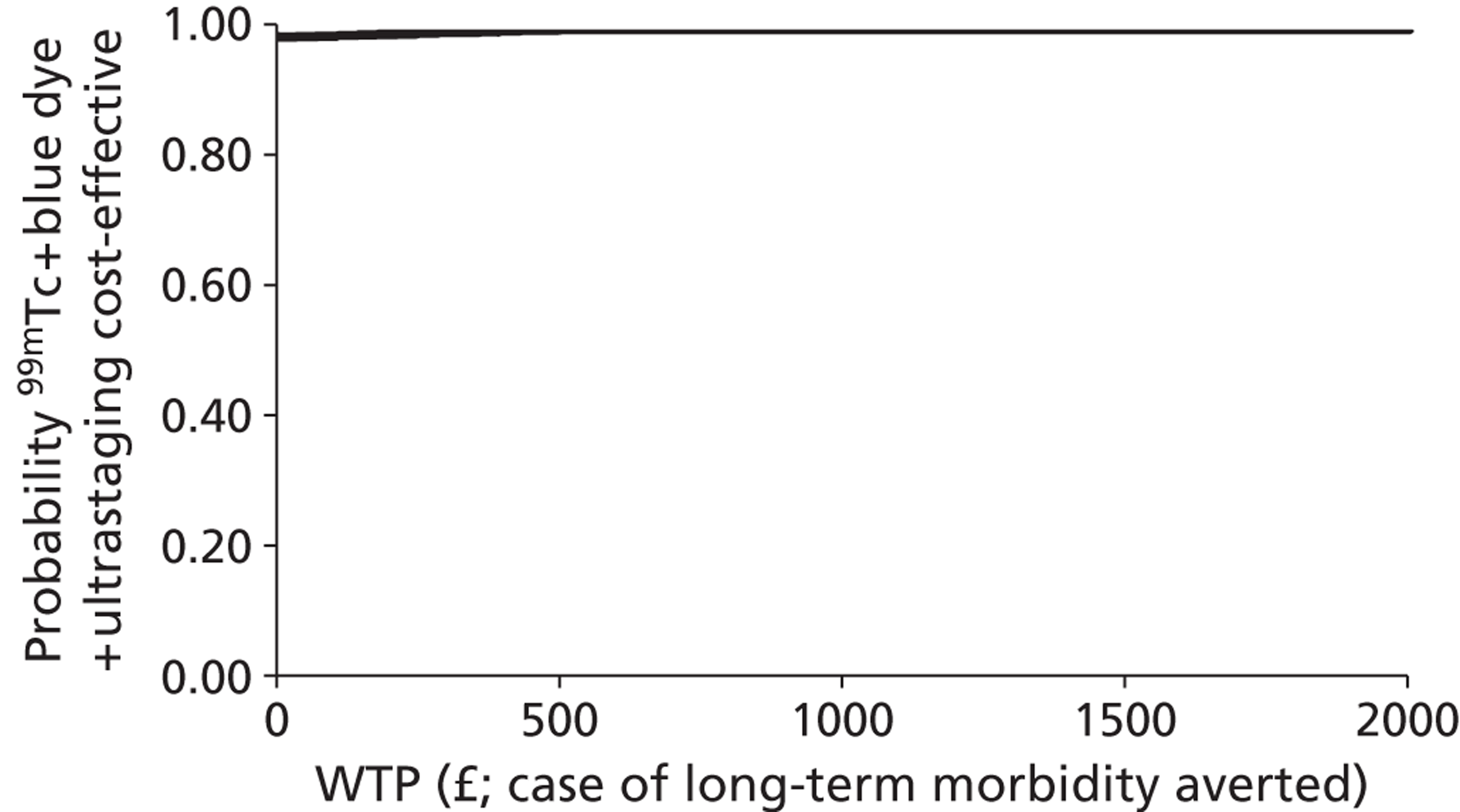

IFL for SLN positive and clinical follow-up for SLN negative