Notes

Article history

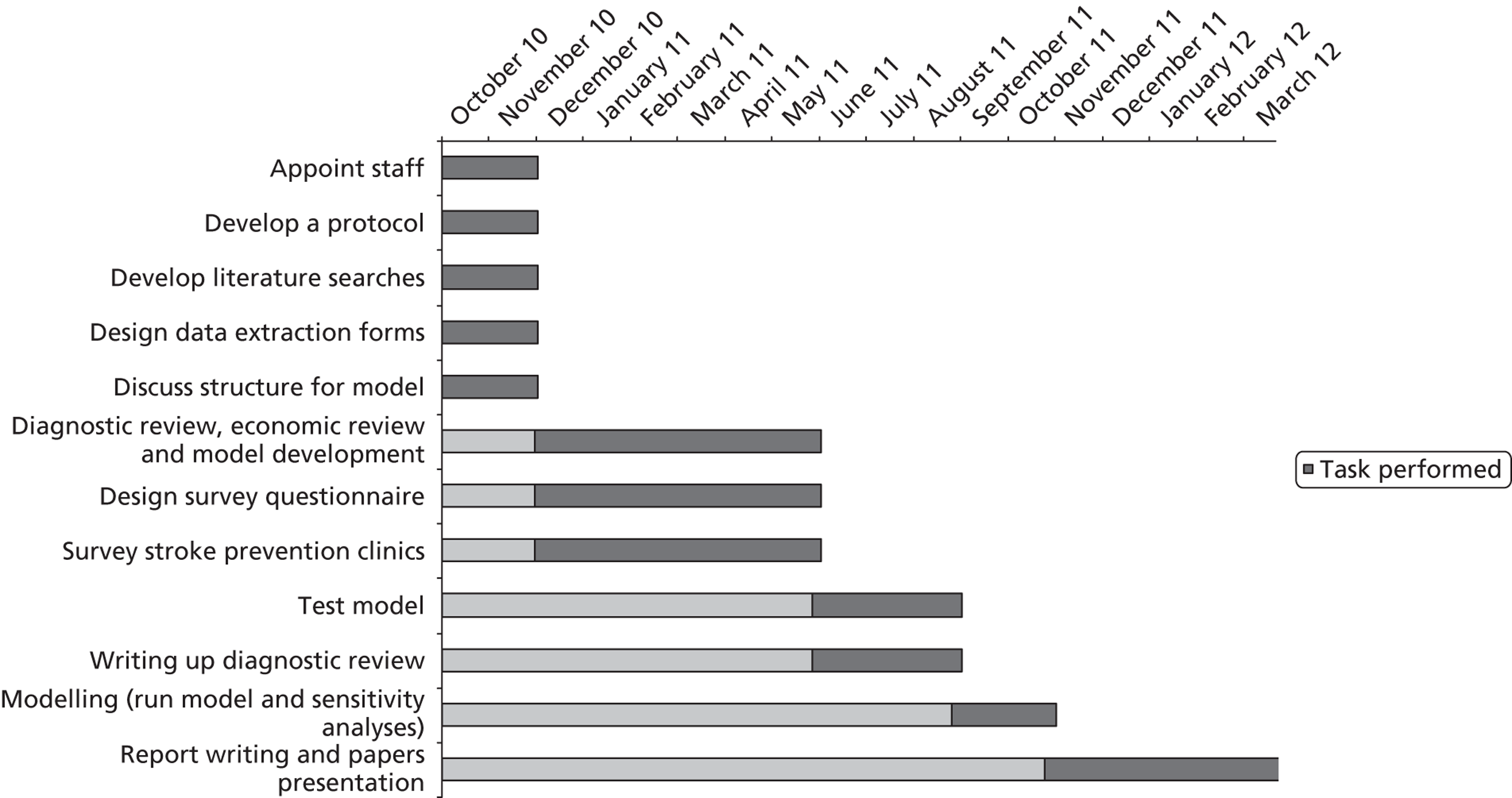

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/22/169. The contractual start date was in October 2010. The draft report began editorial review in August 2012 and was accepted for publication in January 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors:

none

Corrections

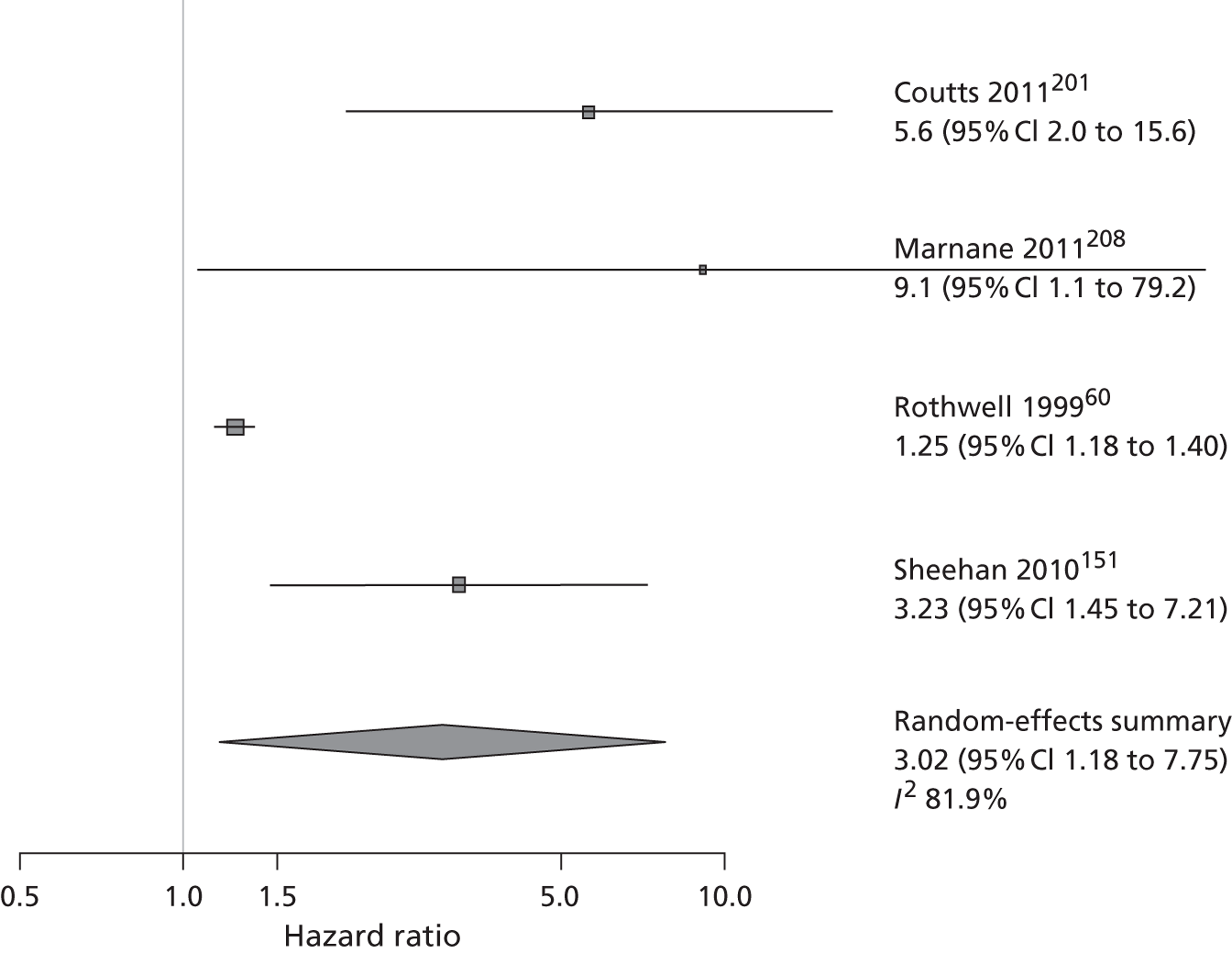

-

This article was corrected in September 2015. See Wardlaw J, Brazzelli M, Miranda H, Chappell F, McNamee P, Scotland G, et al. Erratum: An assessment of the cost-effectiveness of magnetic resonance, including diffusion-weighted imaging, in patients with transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke: a systematic review, meta-analysis and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2015;18(27):369–370. http://dx/doi.org/10.3310/hta18270-c201509

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Wardlaw et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

In the UK, about 150,000 people have a stroke each year. About 30% die within 6 months and another 30% survive dependent on others for everyday activities, making stroke the commonest cause of dependency in adults and the second commonest cause of death in the world. 1,2 Stroke is estimated to cost the NHS between £4.6B3 and £7B per year. 4 Stroke is also one of the major causes of disability in adults. 5 Eighty per cent of strokes are ischaemic, and most (75%) ischaemic strokes are due to an artery in the brain becoming blocked by atherothromboembolism. Treatment of ischaemic stroke is limited to thrombolysis, which can be used only in the first few hours after the stroke,6 a minor effect of aspirin, and co-ordinated stroke unit care, so prevention is vital.

About 20–40% of people have a warning transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or minor non-disabling ischaemic stroke shortly before they have a major disabling stroke. 7,8 In the UK, there are estimated to be 80,000–90,000 TIAs per year. 9 If these people can be assessed quickly, potential stroke causes identified and treated appropriately to reduce risk, then many of these disabling strokes can be prevented. 10 Based on these figures, the average regional hospital serving a population of around 750,000 will see about 1000 suspected TIA/minor stroke cases per year, i.e. about 20 per week. Delivering effective stroke prevention to this number of people is challenging and requires highly organised stroke services that are able to respond rapidly, accurately and effectively for stroke prevention, while avoiding adverse affects on other services within finite resources. The personal, societal, public health and financial burden of stroke in the UK is such that every effort should be made to limit the damaging effects of having a major disabling stroke, and to determine how to make best use of our available resources. 5,11–13

Transient ischaemic attack is defined as ‘a sudden loss of focal cerebral or monocular function lasting less than 24 hours due to inadequate cerebral or ocular blood supply as a result of low blood flow, thrombosis or embolism associated with disease of the arteries, heart or blood’. 14 Although the definition of TIA purely on the basis of clinical grounds is the subject of debate,15,16 and a tissue-based definition has been proposed,17 for the present time we have used the clinical definition. Patients with minor stroke, which differs from TIA only by symptoms or signs lasting more than 24 hours, are also at high risk of early recurrent stroke and need the same assessment and treatment as for patients with TIA to prevent a further disabling stroke or death. A small proportion of TIA/minor stroke (< 5%)18–20 is actually due to a small haemorrhage in the brain but this can be distinguished from ischaemic stroke only by brain scanning.

The period of highest risk of disabling stroke is in the first few hours and days after a TIA/minor stroke, thus making suspected TIA/minor stroke a medical emergency:8,14,21,22 the Oxford Vascular Study (OXVASC) suggested that between 8.0% and 11.5% of patients will have a recurrent stroke by 1 week, and between 11.5% and 15.0% by 1 month after TIA/minor stroke unless effective secondary prevention is started. 9 In the USA, there are about 240,000 TIAs per annum, of whom 25% had experienced a further TIA, a stroke or died by 3 months. 23 Prevention of recurrent ischaemic stroke is by rapid identification of underlying risk factors [such as ipsilateral tight carotid artery stenosis, atrial fibrillation (AF), hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension] and implementation of optimal medical (antiplatelet agents, statins, antihypertensive drugs or anticoagulant drugs where necessary)10,14,24 and surgical treatment (endarterectomy for symptomatic moderate to severe carotid stenosis). 25

Hence, patients with definite acute ischaemic stroke are now given standard quadruple preventative therapy [antiplatelet agent, statin, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and diuretic drug] and patients who present with suspected TIA/minor stroke are started on quadruple therapy pending specialist investigation and treatment. It is therefore important to ensure that the patients whose symptoms after due investigation are proven not to be caused by acute ischaemic cerebrovascular (CV) disease, particularly the small proportion (≈5%) whose symptoms are due to a small haemorrhage, then avoid inappropriate, ineffective, expensive, unnecessary or possibly hazardous26–30 drug treatment.

The conventional brain scanning technique for stroke and TIA is computed tomography (CT), now widely available in the NHS. Although CT excludes tumours and haemorrhage if performed acutely,31 it is insensitive to small ischaemic lesions, so does not ‘positively’ diagnose TIA/minor stroke. 32 CT demonstrates an infarct in a maximum of 50% of minor acute strokes33 and 43% of mixed minor stroke and TIA,34 although the sensitivity may be lower in older patients with brain tissue loss and leukoaraiosis. Nonetheless, the presence of an infarct on CT in patients presenting with TIA is associated with increased short-term risk of stroke,35 CT has high specificity for ischaemia,36 visible infarction on CT is an independent predictor of poor outcome (dependency or death) after ischaemic stroke of all severities,33,37 CT is very accurate for haemorrhage within the first 5 days of symptoms32,36 and for tumours and other non-vascular causes of sudden neurological symptoms, giving it many advantages to balance its two disadvantages: the low sensitivity for acute ischaemic stroke and for small haemorrhages that are > 5 days old. 31

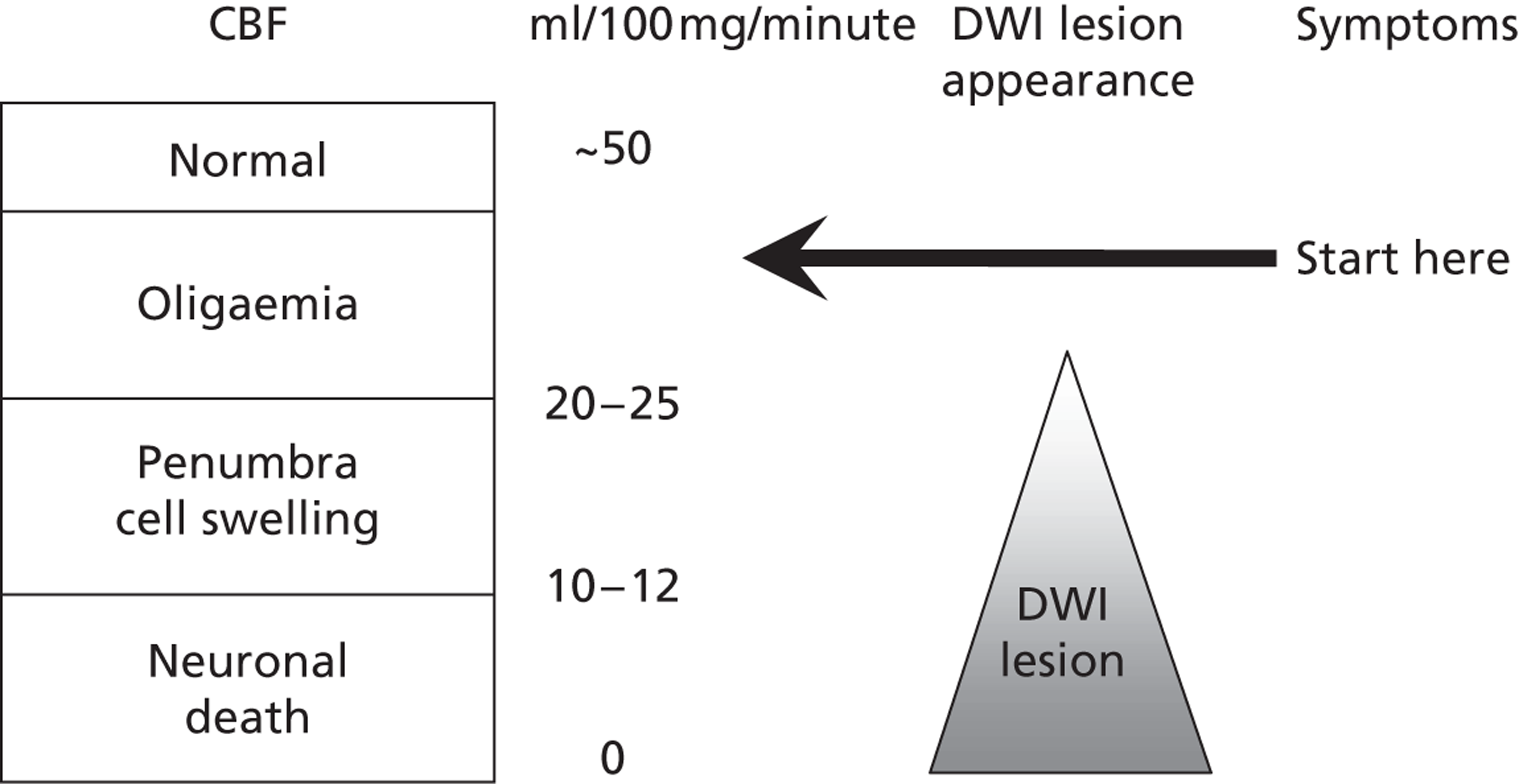

Magnetic resonance with diffusion-weighted imaging (MR DWI) is very sensitive to ischaemia. 38 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is widely used to investigate many neurological disorders, musculoskeletal problems and in oncology. MRI is very versatile because different sequences can be used to highlight different types of pathology relevant to stroke. For example, DWI is very sensitive to changes in the mobility of water in the brain; one of the earliest changes in the brain at the onset of ischaemia is cell swelling, which reduces the extracellular space and hence restricts water movement. Thus, early ischaemia shows up well on DWI, even very early after the symptoms start and even in very small lesions causing mild symptoms38 if the effects of the ischaemic insult are sufficient to cause enough cell swelling to change the DWI signal. When considering how to use and interpret any brain imaging, it is important not to forget about the pathophysiological steps in ischaemia, knowledge that has been available since the early 1970s (Figure 1): the first step at the start of an ischaemic insult is that neurons cease their electrical activity when blood flow drops below about 35 ml/100 mg/minute (which is when the neurological symptoms start), well above the level required to precipitate loss of ion pump activity and cell swelling (about 20 ml/100 mg/minute) or cell death (10 ml/100 mg/minute). 39 It is therefore perfectly possible to have symptoms without any visible lesion on even the most sensitive scans, such as DWI, if the ischaemic insult is enough to drop the flow below the electrical shutdown level, but not so as to precipitate cell swelling or even on perfusion imaging if the amount of brain affected by the loss of flow is below the resolution of current perfusion imaging methods. If the flow recovers rapidly and never reached the level of causing cellular oedema then the symptoms will resolve and there will never be a lesion visible on the scan. If the flow recovers rapidly even after falling to a nadir below the cell oedema stage but not for long enough to result in cell death then the DWI-visible lesion will resolve rapidly as the cell swelling resolves and no lesion will be seen on the scan. 40 Only if the flow reduction persists for long enough and is low enough to have caused significant amounts of cell death will the scan show a positive lesion – the DWI lesion will last for variable times depending on the amount of tissue damage. 41 The chances of seeing an acute ischaemic lesion on DWI increase with increasing stroke severity,42,43 but even in patients with moderate to severe initial stroke symptoms the DWI hyperintensity/apparent diffusion coefficient reduction may disappear within a few days to a week and leave little evidence of permanent damage. 44 Permanent damage would appear on other sequences, notably T2-weighted, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) or T1-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) images or CT, but after a week or so, when any acute swelling has disappeared, the recent lesion would be difficult to differentiate from an old prior lesion. 45 This physiological explanation is one of several valid and probably quite common reasons for having true ischaemic disease but a negative DWI even on acute scanning. Other reasons include delays to scanning, variation in sensitivity of sequences on individual MR machines and between MR machines of the same field strength and of different field strengths and generation of manufacture. 46

FIGURE 1.

Critical flow thresholds for development of symptoms and MR DWI imaging lesions.

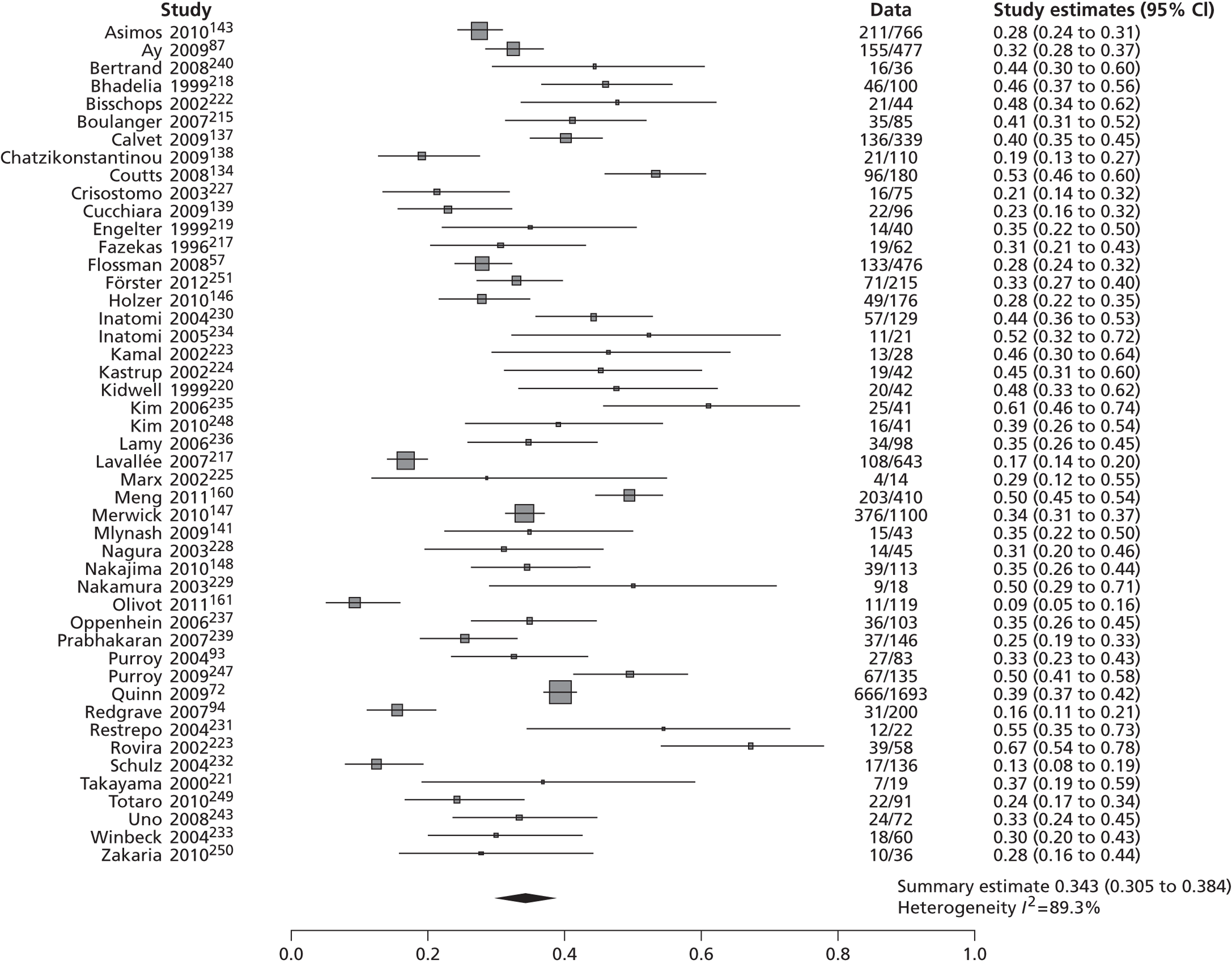

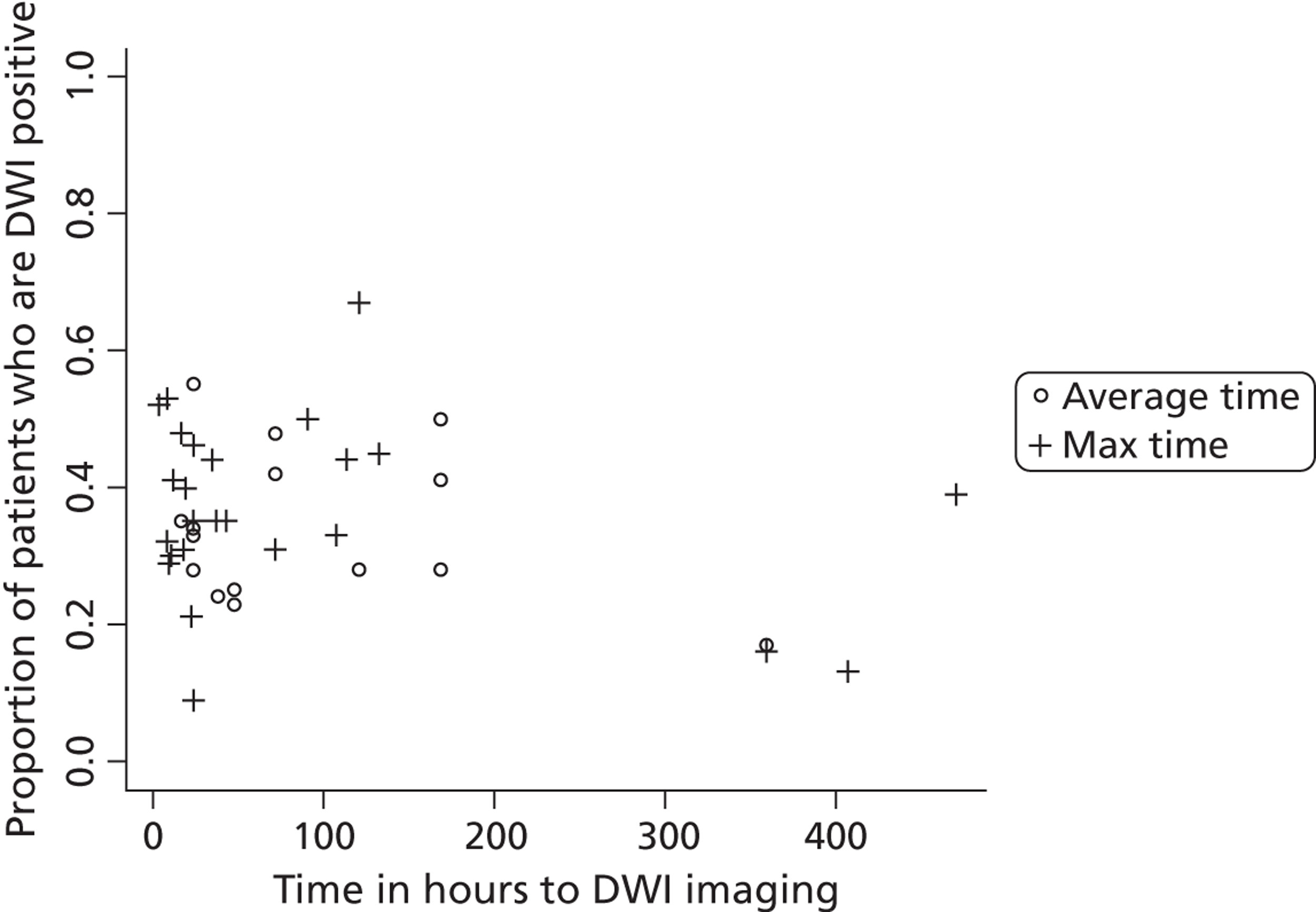

Diffusion-weighted imaging primarily displays ischaemic areas as white on a dark background, so ischaemic lesions when present are much more obvious than they are on CT scanning, where ischaemic lesions appear as dark on a dark background. Thus even very tiny ischaemic lesions stand out on MR DWI (with the above caveat) soon after symptom onset in 16–67% of TIAs (mean 37%)47,48 and about 70–90% of minor strokes overall, even if scanned weeks after the event in some minor stroke patients. 36,38,45,48–50 However, in general, the chance of finding an ischaemic lesion on DWI falls rapidly with increasing time after symptoms,45,50 and probably most rapidly for small cortical ischaemic lesions,44 meaning that delays to scanning of even a few days will reduce the sensitivity of MR DWI to small ischaemic lesions. Currently, with CT scanning, if the scan provides no positive evidence of an ischaemic lesion, the diagnosis of ischaemia is often assumed if the scan has excluded haemorrhage and stroke mimics. By contrast, MR including DWI could help make a ‘positive’ diagnosis of brain ischaemia in TIA/minor stroke if it showed positive findings of ischaemia in a large proportion of patients, although a diagnosis of TIA/minor stroke would still have to be assumed if the DWI were negative and no alternative diagnosis could be made clinically.

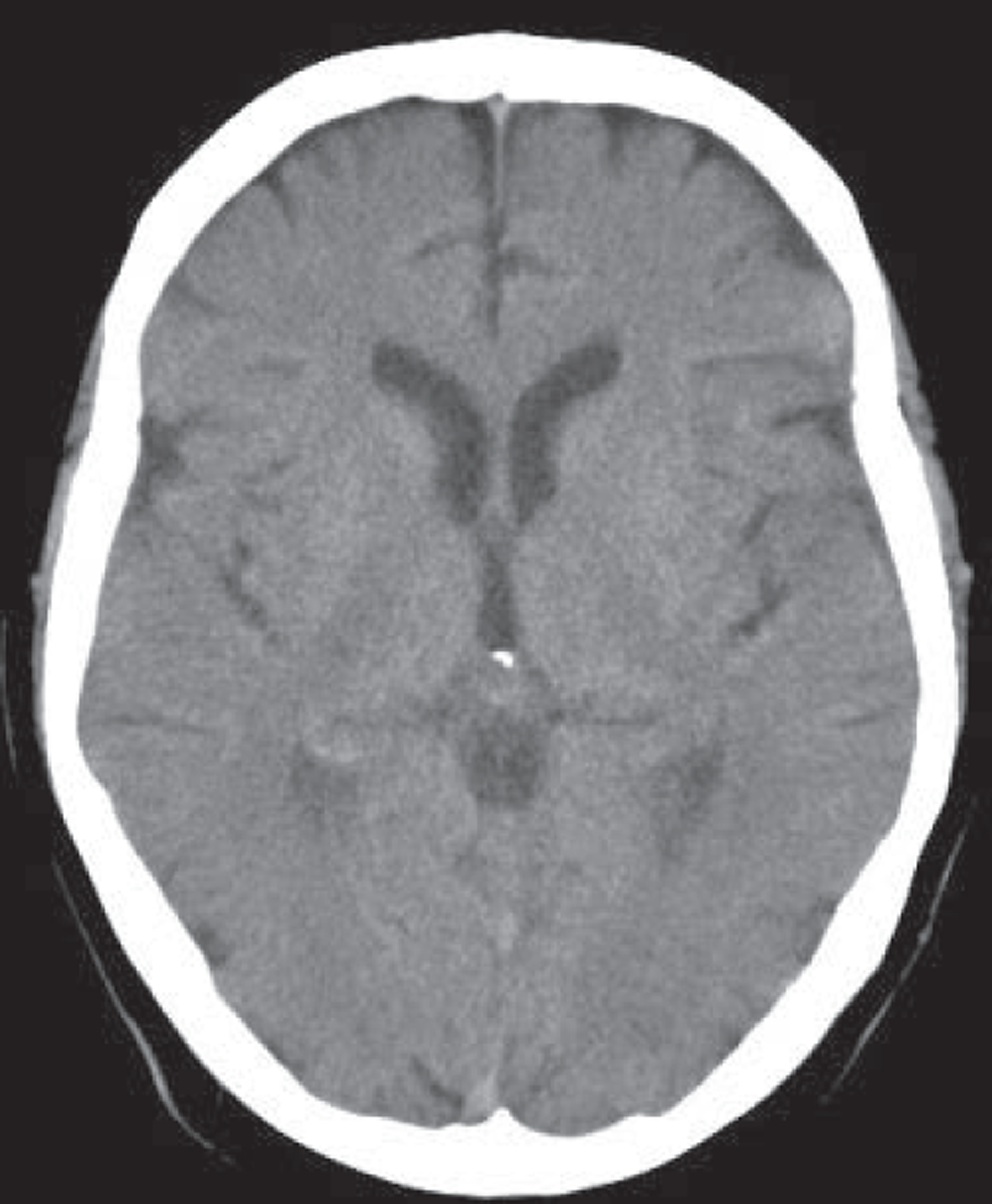

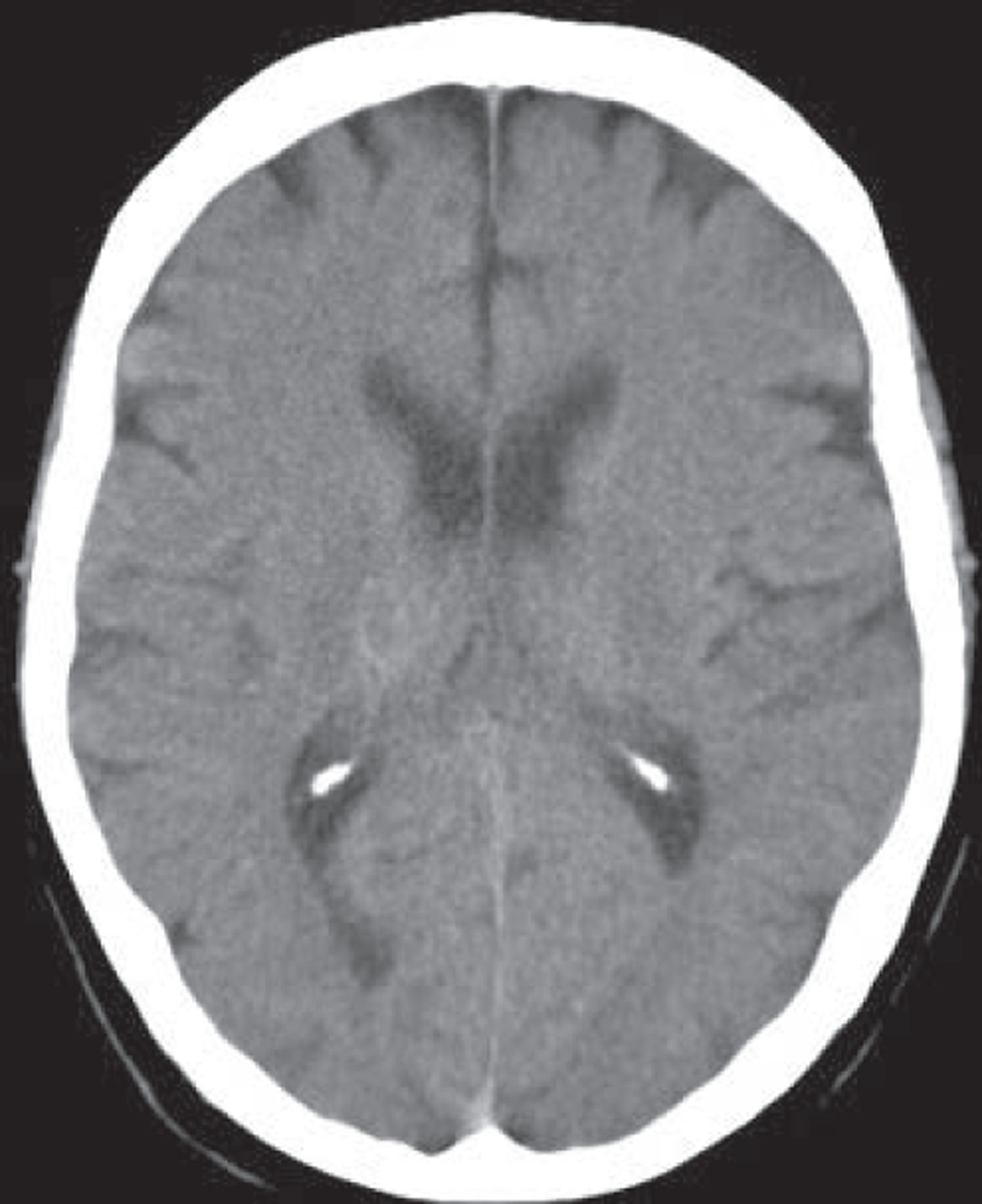

MR, if it includes T2*-weighted imaging or equivalent, is very sensitive to haemorrhage, even years after the event. 51 Other commonly used MR sequences (T2-weighted, T1-weighted and, particularly, FLAIR imaging) are much less sensitive. 51 Very acute haemorrhage (i.e. within the first few hours after symptom onset) is less easy to identify on MR and may be mistaken for ischaemia or a mass lesion until the characteristic paramagnetic features of blood breakdown products have had time to form. 52,53 In contrast, CT is very sensitive to acute haemorrhage54 but cannot reliably detect haemorrhage in patients who first present at > 5 days after a minor ischaemic stroke (Figure 2). 31 The high sensitivity of MR T2* sequences for haemorrhage is essential to diagnose haemorrhage correctly51,55,56 in patients who present late to medical services to avoid inappropriate use of antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants and carotid endarterectomy in patients with haemorrhagic stroke.

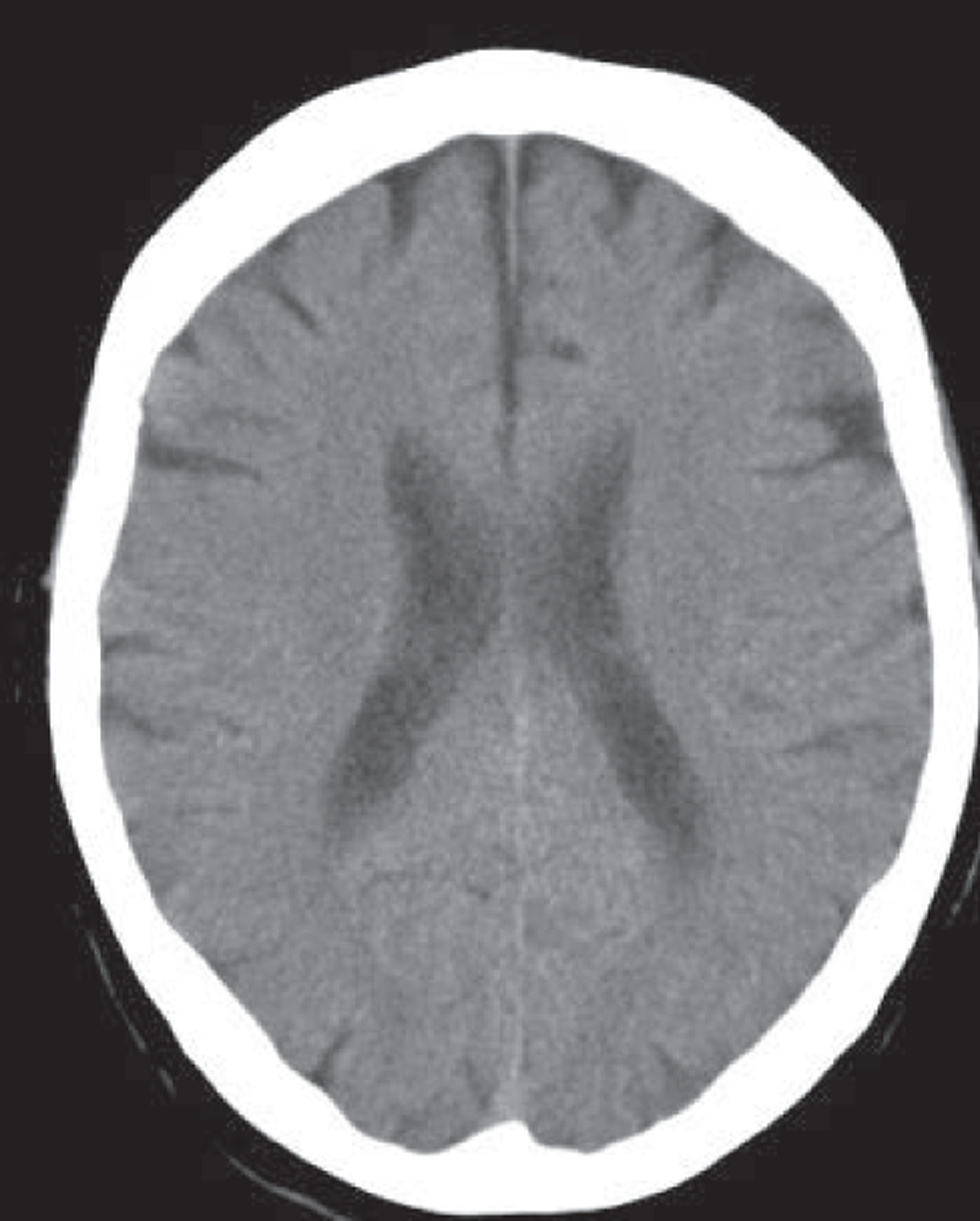

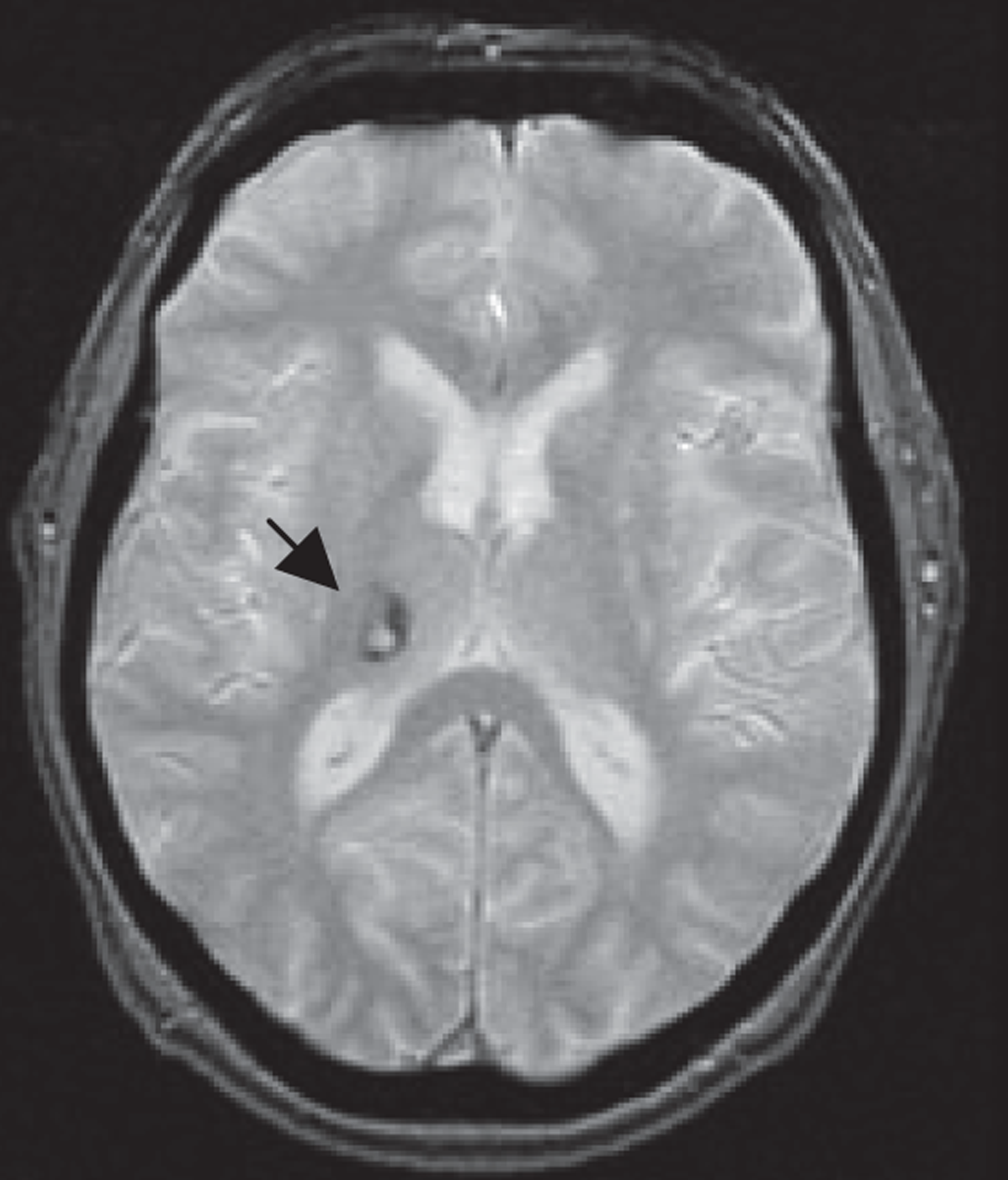

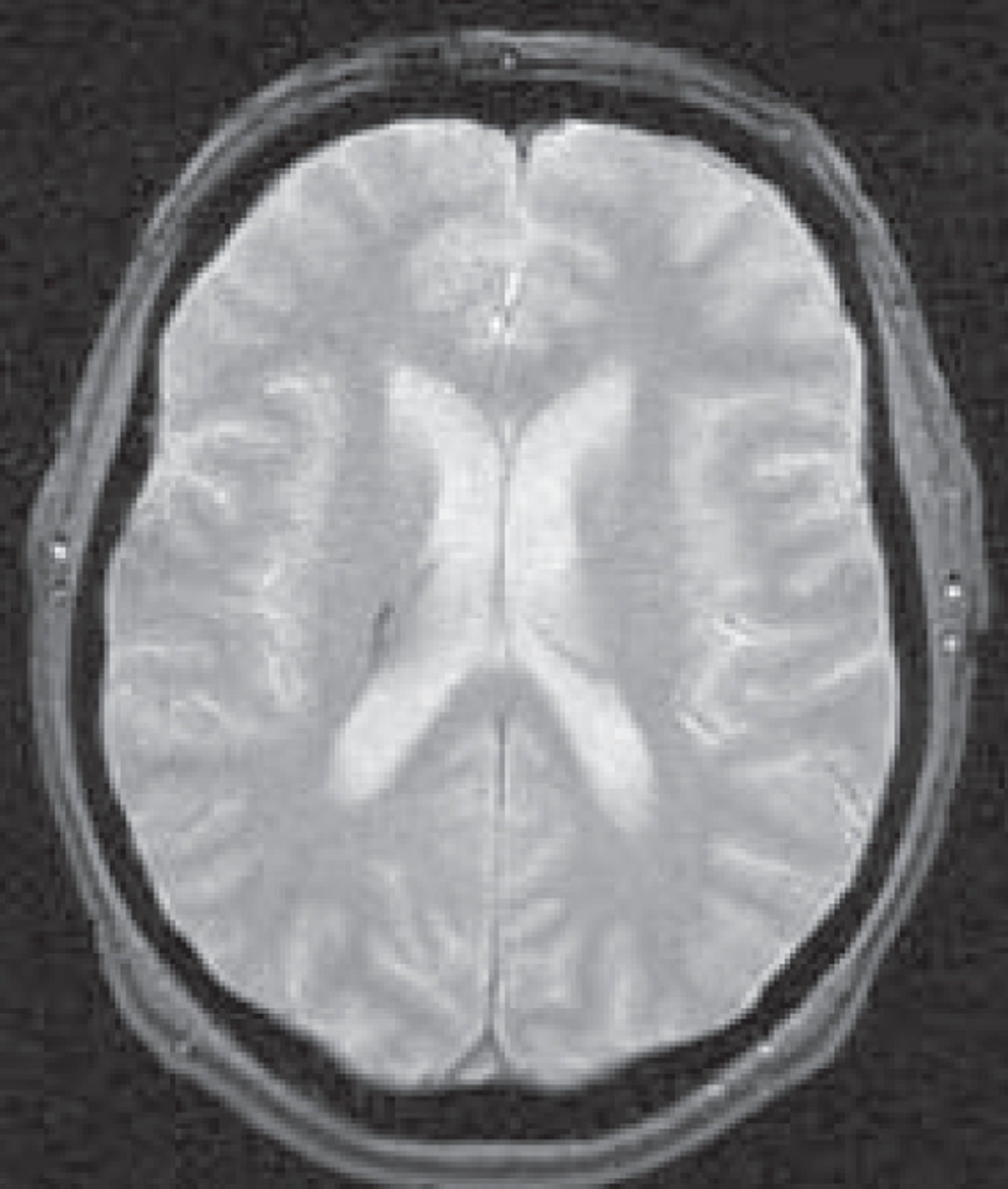

FIGURE 2.

Images from a patient presenting 8 days after developing mild left arm and leg numbness: top row, CT; bottom row, T2* MRI. Images from a patient presenting 8 days after developing mild left arm and leg numbness. CT is almost completely normal (a thin white circle is visible in the central image in the superior right thalamus, indicating a small resolving haemorrhage, arrow middle top image) but MR T2* clearly shows the low signal (black circle, arrow left bottom image) characteristic of a haemorrhage.

Magnetic resonance DWI could also help management in other ways. In some patients with carotid stenosis it is difficult to decide if the clinical event occurred in the territory of that artery or not. 57 DWI is helpful if it can confirm that a TIA/minor ischaemic stroke was in the territory of a tight carotid stenosis, so leading to endarterectomy. 57 The presence of lesions in several territories would indicate a need to search a more proximal source of embolism, for example in the heart. 58

The ability of MR to differentiate common stroke mimics from true ischaemic events is unclear. MR DWI is not specific to acute ischaemia: multiple sclerosis (MS), migraine, postictal changes, hypoglycaemia and even infection can produce high signal lesions on DWI (and reduced apparent diffusion coefficient). Many mimics do not produce any abnormality on either CT or MR brain imaging.

If MR is proven also to have high sensitivity and specificity for ischaemic events then by helping to exclude acute ischaemic CV disease as the cause of symptoms, and if in a large enough proportion of patients, it will potentially have a greater role in avoiding unnecessary or inappropriate treatment. However, if there is an over-reliance on the sensitivity of MR DWI to detect minor ischaemic change such that physicians start to think that patients presenting with suspected TIA/minor stroke without an acute ischaemic lesion on DWI do not have a TIA/minor stroke and therefore assign alternative diagnoses and do not implement secondary stroke prevention measures then greater use of MR could actually have a net damaging effect on stroke prevention. Similarly, if more MR is used – but without including all relevant sequences required to reliably identify haemorrhage,51,56 as well as ischaemia and any structural lesions acting as a mimic as the cause of symptoms – then it may also result in no benefit or net harm if patients with haemorrhage are misdiagnosed and given drugs that increase bleeding risk.

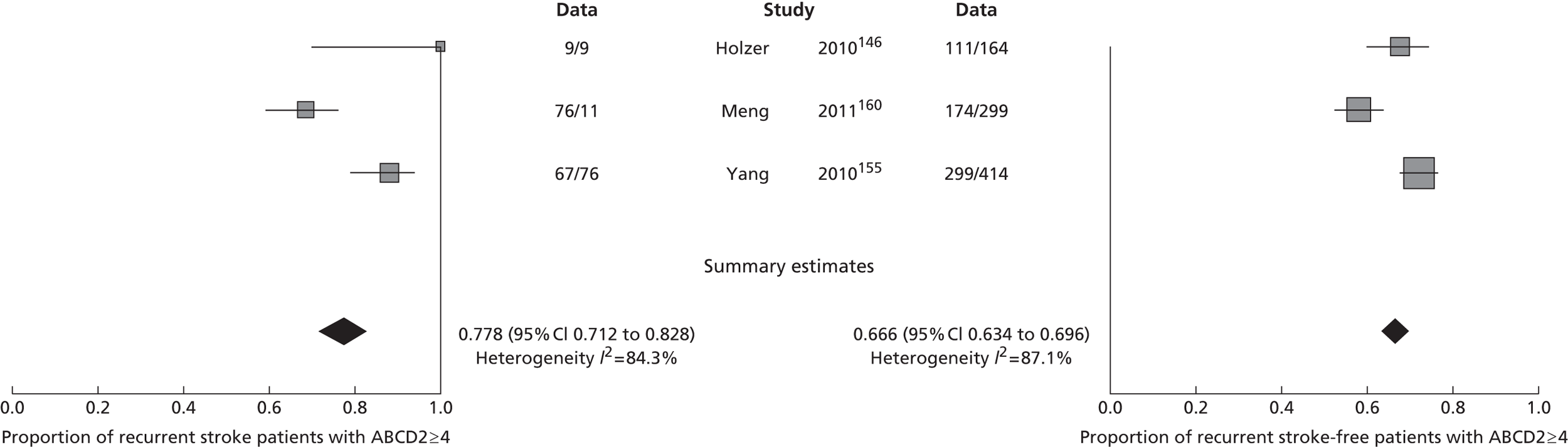

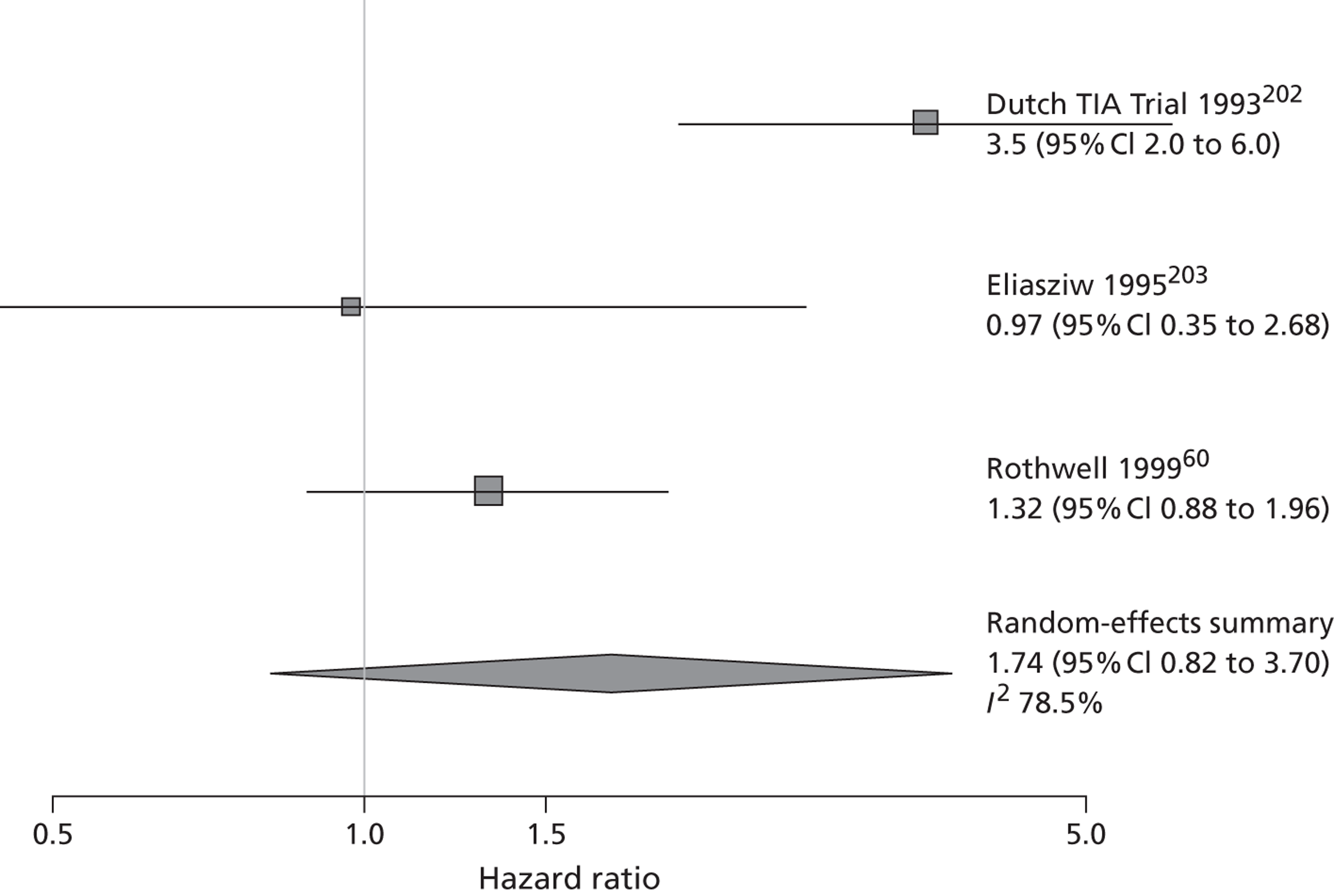

Several clinical scoring systems have been devised that aim to improve identification of patients at high risk of disabling recurrent stroke after TIA/minor stroke. 59–65 These scores could help to reduce delays to reaching medical attention and to triage patients,66 so that those needing most rapid treatment, such as carotid endarterectomy, would reach surgery more quickly. They might also improve the accuracy of clinical diagnosis of TIA by non-stroke physicians, thereby also making better use of resources. Not all of these have been externally validated. All except two60,64 use only simple clinical features so are rapid and easy to apply without needing complex technologies. 59,61,62,65 For example, the ABCD2 score uses age, blood pressure, clinical features, duration of symptoms and diabetes to derive a score from 0 to 7. The ABCD2 score has been adopted in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines to aid patient triage in the UK:67 those with a score of ≥ 4 to be prioritised for assessment and treatment within 24 hours of reaching medical attention; those with a score of < 4 within 1 week.

Many of these scores performed well in the population from which they were derived and often also in initial testing in a different cohort68,69 but then wider use uncovered difficulties. For example, independent testing of the ABCD and ABCD2 scores62 has not been universally positive. 70,71 Although in OXVASC the ABCD2 score was highly predictive of recurrent stroke within 7 days of TIA (p < 0.01), it did not predict stroke at between 8 and 90 days, because in this group, patients with lower scores had a higher risk of stroke than those with high ABCD2 scores (p = 0.04). 71 The ABCD2 score also did not predict recurrent stroke in patients with minor stroke (as opposed to TIA). Thus TIA clinical risk prediction scores may not usefully predict stroke risk at > 7 days after TIA and may be of limited value in patients with minor stroke. Most scores were devised and tested in highly selected populations of patients with definite TIA/minor stroke such as randomised multicentre trials or observational studies after screening by a stroke expert where the patient had to have a definite TIA/minor stroke to get into the study. However, this is not the population of suspected TIA/minor stroke that typically presents to the ‘front door’ of the hospital. In this unselected population, up to 50% do not ultimately turn out to have had a TIA/minor stroke and therefore should have a low risk of recurrent stroke. 72 However, the net effect of applying a clinical risk score in this mixed population was that many true TIA/minor strokes were given a low ABCD2 score and therefore would have missed rapid access to stroke services. 72 In this sense, the use of a clinical risk score could actually lead to a net failure to prevent recurrent stroke. This reflects a general limitation of low specificity scoring or screening systems – namely that while they may detect the small proportion of patients with particularly high risk of recurrent stroke, many recurrent strokes actually occur in patients deemed to be at moderate or low risk only (because there are many more of them). Widespread use of clinical risk scores in this setting could therefore put at risk patients in a ‘slow stream’ who would then potentially not receive treatment quickly enough to prevent stroke and has not been tested.

Part of the problem may be that (1) the clinical diagnosis of TIA/minor stroke is difficult73–75 and (2) the clinical findings have low specificity for the likely underlying cause, but the future stroke risk is closely related to the cause. The clinical diagnosis of TIA and minor stroke is made difficult, especially for non-experts, by the high proportion of patients (up to 50%)5,72,76–78 who actually have common mimics of TIA/minor stroke. Common mimics include migraine, transient global amnesia, epilepsy, simple faints, tumours, functional disorders, etc. 72,77 It is not possible to determine the cerebral pathological cause of symptoms, i.e. whether infarct, haemorrhage or mimic (e.g. tumour), without a brain scan, although most mimics do not show specific positive findings on imaging, meaning that accurate diagnosis still rests heavily on clinical skills. 26,79

Some have questioned the usefulness of scores that do not incorporate significant carotid disease or other potential cardioembolic sources. 80,81 Two scoring systems that included carotid stenosis as part of the risk prediction60,64 found that adding tight carotid stenosis did improve risk prediction. Carotid imaging is an integral part of the assessment of TIA and minor stroke to identify those with ipsilateral tight carotid stenosis who will benefit from carotid endarterectomy. 82 The cost-effectiveness of carotid imaging was assessed in a previous Health Technology Assessment (HTA)-funded project by our group. 5 This work showed that rapid access to carotid imaging to identify and measure carotid stenosis was the most cost-effective way of using carotid imaging, and that the four non-invasive imaging methods functioned similarly in terms of accuracy83,84 and stroke prevention, although ultrasound was the most cost-effective of the four techniques if used early after TIA/minor stroke. 85 The focus of the present application is on how to improve stroke prevention through use of brain imaging techniques, so comparative carotid imaging will not be considered further.

The evidence on the contribution of MR to diagnosis, stroke prediction and hence potential for patient management and cost-effectiveness after TIA/minor stroke is uncertain – it could be very useful if used within its limitations in a targeted way, or it could be potentially harmful if used indiscriminately and without including all relevant sequences. No studies have considered these points or addressed the cost-effectiveness of using MR including DWI and T2* in TIA/minor stroke. Most studies of cost-effectiveness of imaging in stroke have either concentrated on hyperacute disabling stroke26,86 or on carotid imaging for carotid stenosis5 as part of carotid endarterectomy. 86 There are no clinical trials of diagnostic accuracy or effect on prediction of prognosis of MR including DWI, only observational studies using DWI in populations of patients with TIA/minor stroke. Many publications come from the same few research groups meaning there is likely to be data duplication: at the start of this project, all published studies were from single centres so lacked generalisability; some were retrospective; many only included a modest proportion of their TIA population (e.g. 53%)87 so were prone to various biases. 88–90 An acute lesion on DWI may be associated with increased risk of recurrent stroke and helps to confirm a positive diagnosis of stroke, but the additional prognostic value over clinical scoring, the role of carotid imaging, the effect of sample biases, etc., had not been evaluated thoroughly and was therefore unclear. 87,87,91–94 The accuracy of MR for common mimics of TIA/minor stroke was unclear, as most publications excluded patients who turned out after further testing not to have had a stroke.

There are barriers to the wider use of MR in stroke prevention. In addition to limitations owing to study methodological factors, listed above, MR is more expensive than CT scanning (about £400 for MR vs. £150 for CT brain scanning)5 and less available than CT in the UK, with long waiting lists even for patients with established indications for MR. There is limited capacity to provide rapid access to MR for people with TIA and stroke. MR delayed even by a few days would be of little value, as the patient would miss the period of highest recurrent stroke risk95 and the chance of finding an ischaemic lesion on DWI falls rapidly with increasing time after symptoms. 45,50 In the mid-2000s, although 75% of UK hospitals had MR on site, < 10% were able to scan patients early after stroke. 95 Similarly, across the EU, only 5% of hospitals met criteria for stroke care, which included availability of MR for stroke (and surprisingly the UK had the highest proportion of hospitals with MR for stroke). 96 Current availability is not known. Any increase in use of MR for stroke prevention could result in reduced availability for patients with MS, cancer and many other conditions for which MR is of established benefit. Some patients cannot have MR because of contraindications, for example having a pacemaker, claustrophobia or metal implant, so there would always be a need for CT. In one recent study, 90/904 patients (10%) considered for MR had contraindications and only 477/904 (53%) of all patients presenting with TIA actually underwent MR; of those having MR only 155/477 (33%, or 17% of the initial cohort) had a DWI-positive lesion. 87 Not all TIA patients have CT at present, so MR including DWI would partly replace, and partly be an additional investigation, if it proved to be cost-effective in stroke prevention.

What do guidelines say?

The 2008 UK NICE Guidelines advocate use of DWI in about 50%97 of TIA/minor stroke patients (www.dh.gov.uk/stroke). 67

Specifically, what is the guidance?

The objective for brain imaging for TIA is:4 ‘To confirm the diagnosis and/or vascular territory affected in those patients where either is unclear.’

Imaging for TIA (p. 8)

5. About 50 per cent of suspected TIAs require MRI of the brain. The diagnosis of TIA is difficult and doubt often remains, even after expert clinical assessment, whether or not the event was a TIA. Of patients presenting with symptoms suggesting a TIA, about half prove to have some other cause. For those who have had a TIA, the location of the lesion (damaged tissue) may not be known.

6. Computed Tomography (CT) is not sufficiently sensitive to demonstrate the small lesions found in TIA. MRI of the brain with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is needed where the diagnosis or location of the lesion remains in doubt. The MRI may answer the question of whether the lesion is in vertebral (brain/brainstem) or carotid neck territory, prompting further carotid investigation where appropriate. If multiple lesions are found, this may suggest a cardiac source of the clot(s), and prompt investigation of the heart.

8. Carotid imaging should ideally be performed at initial assessment and should not be delayed for more than 24 hours after first clinical assessment of TIA for those at higher risk of stroke (i.e. ABCD2 score ≥ 4) or in those with non-cardioembolic carotid-territory minor stroke. Those people who are found to have carotid stenosis will require carotid intervention within 48 hours of presentation.

9. For those people at lower risk of subsequent stroke (i.e. ABCD2 score of < 4), carotid imaging should be performed within 7 days. If they are found to have carotid stenosis, they should have carotid intervention within two weeks of presentation.

10. Expert clinical assessment coupled with appropriate imaging provides the best diagnostic pathway for patients with TIA.

Furthermore, the Executive Summary states:

5. Imaging services managing TIA and stroke will need to be able to provide the following services:

5.1 TIA

MRI/MRA brain for those patients requiring it available 7 days a week with Contrast Enhanced MRA (CEMRA) for first-line carotid imaging. This requires MR software for diffusion weighted and gradient echo imaging and CEMRA, and a pump injector for CEMRA; and

Carotid imaging seven days a week, which will ideally include CEMRA and duplex ultrasound, and CT angiography.

5.2 Stroke

24-hour access to CT;

Rapidly accessible MRI, with the features described above, for those patients who require it; and

Ability to undertake more complex imaging examinations for stroke subtypes as required.

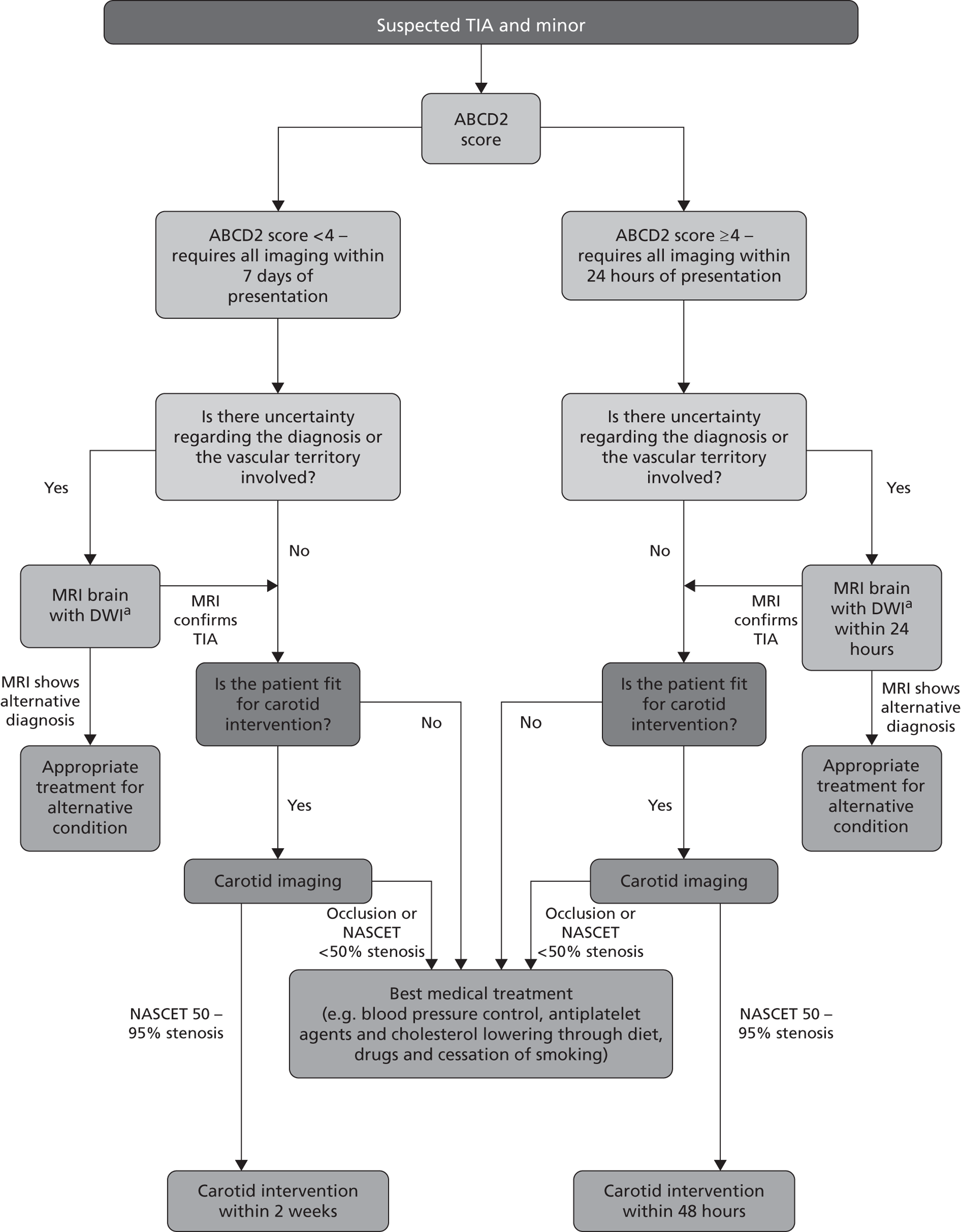

This policy is summarised in the NICE flow chart (Figure 3). 67 Whether or not this policy would reduce recurrent stroke and improve quality of life after TIA, or simply flood the system with large numbers of patients with negative MR scans while displacing others with diagnoses for which MR does have a clear indication, is uncertain. Since the start of this project, NHS Improvement in England have introduced tariffs to encourage the establishment of stroke prevention clinics that meet key performance criteria, and additional tariffs for rapid assessment and treatment of patients with high ABCD2 scores and for performing MRI in TIA patients (amount payable £450–634 per patient). 98,99

FIGURE 3.

Summary of current NICE guidance on investigation and management of patients with suspected TIA and minor stroke. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government License v1.0. NASCET, North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial. a, Unless MRI contraindicated, in which case ct should be used.

Enthusiasm for a policy of more MR is expressed in many other guidelines. The American Heart Association (AHA)100 and related organisations101 stated that ‘TIA patients should undergo neuroimaging evaluation within 24 hours of symptom onset, preferably with magnetic resonance imaging including diffusion sequences’. 17 The revised National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke,102 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) Guidelines 2008,103 and European Guidelines104 are more cautious but still advocate immediate brain imaging and use of MR, including DWI in large proportions of patients especially those with mild stroke. Therefore, there is a ‘mismatch’ between national and international guidance on the one hand,17,97 and convincing evidence to support this approach,47,48 information to guide precise usage,105 details of cost-effectiveness and available technology to deliver it on the other,95,96 resulting in confusion about what to do in routine practice. This is mirrored in the NHS Purchasing and Supply Agency 2008 report, which stated only that ‘DWI shows significant potential in the study of TIA/minor stroke’, but also called for ‘more evidence’. 105 The limited evidence has also led some reviewers to call for more data on imaging to guide physicians treating TIA patients. 106,107

In summary, MR including DWI could make a substantial impact as a positive diagnostic test for TIA/minor stroke by improving diagnosis of the cause of stroke; efficient patient selection for medical secondary prevention in patients with a proven diagnosis; conversely, the avoidance of unnecessary treatment in patients in whom acute ischaemic CV disease was reliably excluded; and best use of carotid endarterectomy (especially where stroke expertise is limited). There are potential cost implications. TIA/minor stroke is so common that MR would be in daily use in every hospital if such a strategy were adopted wholeheartedly, but the direct costs to the NHS would be substantial – £16M per year to scan just the 50% of TIA patients suggested in recent UK guidelines, not including the minor strokes and all of the TIA mimics, assuming that MR were available. The opportunity cost to meet the demand by increasing MR scanning capacity, (without which there would also be substantial disadvantage to other MR users). It is not clear if the potential diagnostic and prognostic advantages of MR outweigh the disadvantages of the obvious expense, limited availability, failure to make a positive diagnosis of ischaemic lesion in up to 66% of TIA patients, unquantified accuracy for other stroke-related diagnoses, and possibility that the strokes that we are trying to prevent might occur during the wait for a scan if availability cannot be rapidly increased. Any strategy to increase MR usage would have to factor in the effect of varying delays introduced because of waiting for MR. We are not aware of any large or multicentre studies ongoing on this topic, although it is likely that single centre studies are ongoing.

This study aimed to resolve this controversy by summarising all available data on MR including DWI, diagnosis and stroke prediction, and modelling the cost-effectiveness of using MR including DWI in a range of stroke prevention strategies.

Our primary research objective is to determine whether MR DWI as well as other relevant structural and blood-sensitive sequences is cost-effective in the majority of patients with TIA or minor stroke to guide diagnosis and secondary stroke prevention, compared with the current alternative of CT brain scanning.

Second, to determine the cost and cost-effectiveness of increased use of MR including DWI and blood-sensitive sequences in patients presenting at > 5 days after TIA/minor stroke when CT will not be able to identify haemorrhage as the cause of stroke reliably.

Third, to estimate if ‘one-stop’ brain and carotid imaging is more cost-effective than individual separate brain and carotid examinations, in what proportion of patients a ‘one-stop’ approach could be used, and the practical and cost implications.

Fourth, to determine physicians and radiologists current attitudes to increased use of MR in TIA/minor stroke, the availability, barriers to greater use, costs of increasing availability, and net effect on other patient groups in whom MR is commonly used.

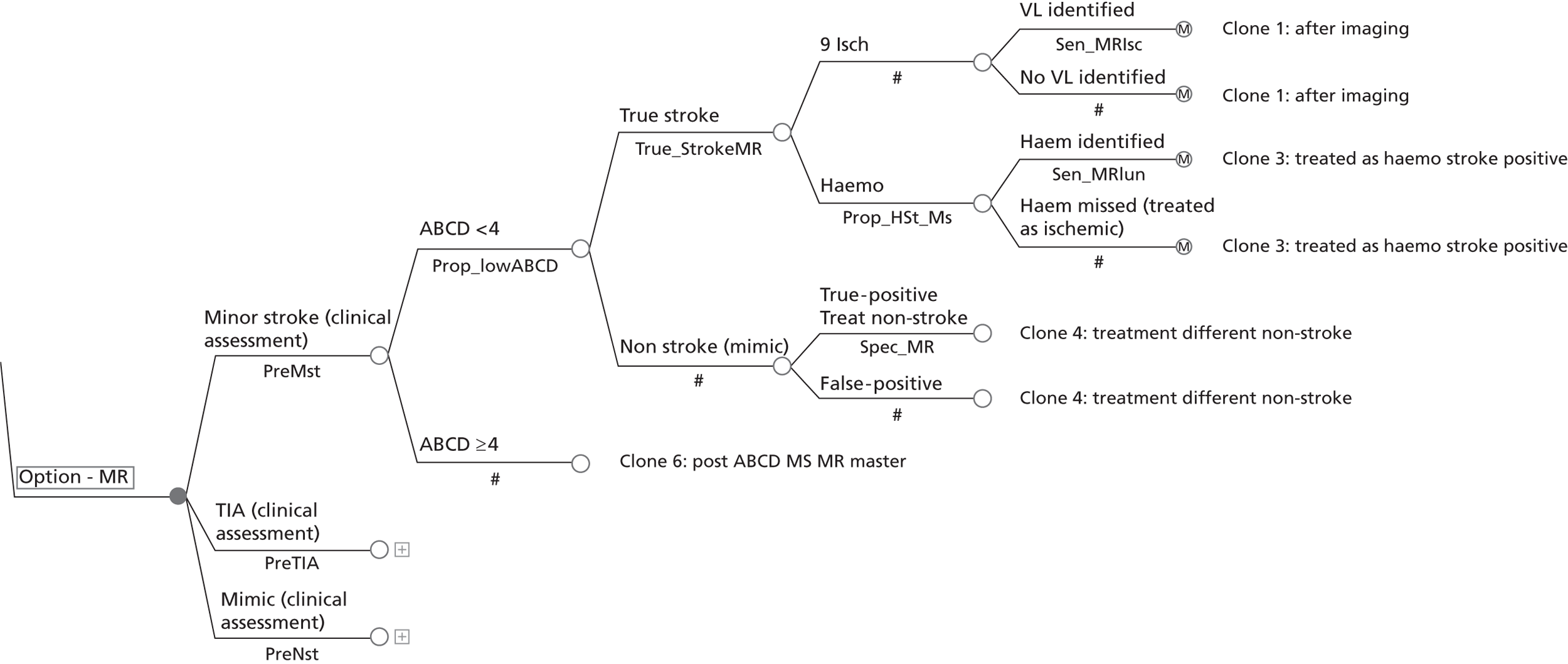

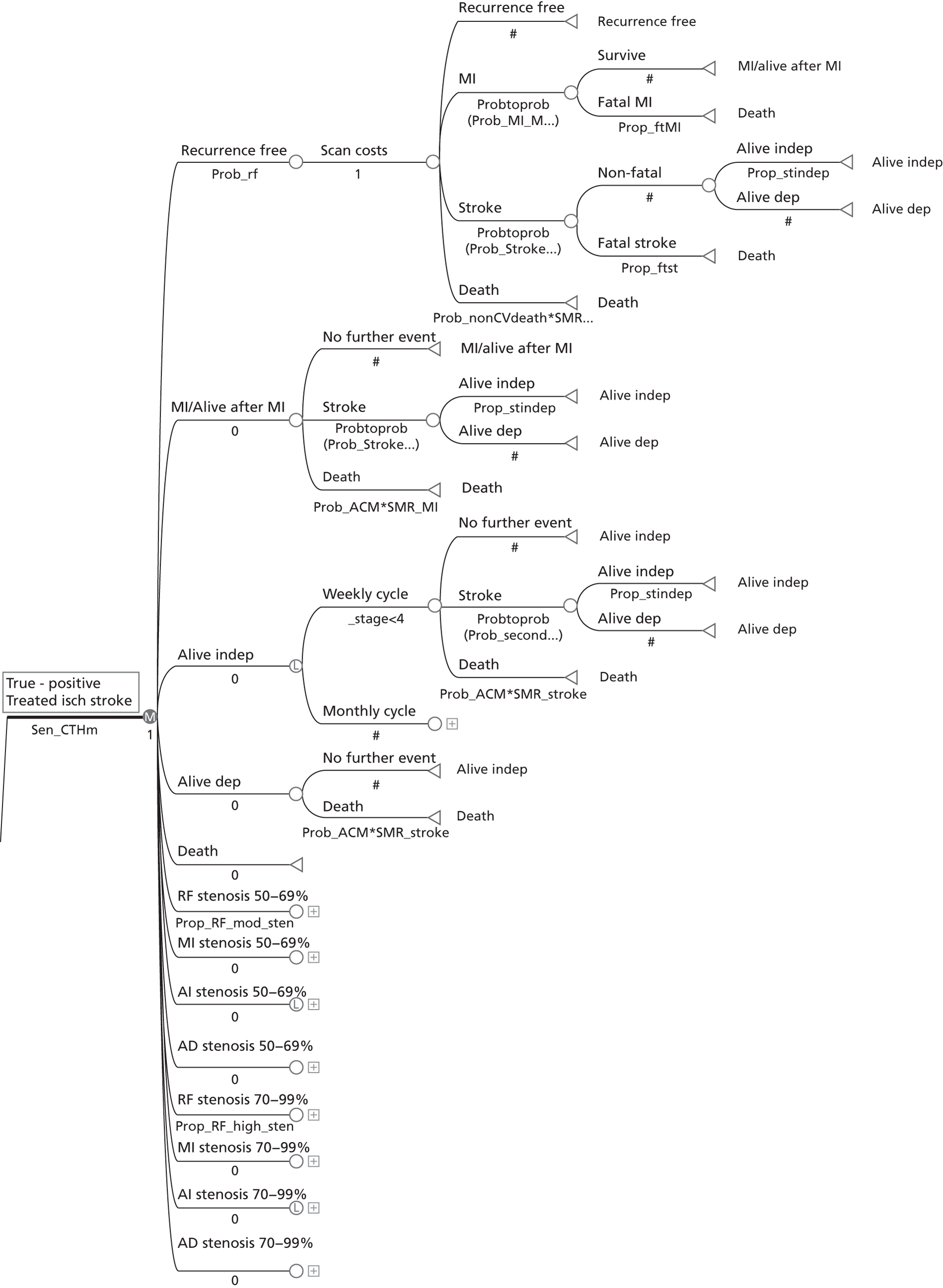

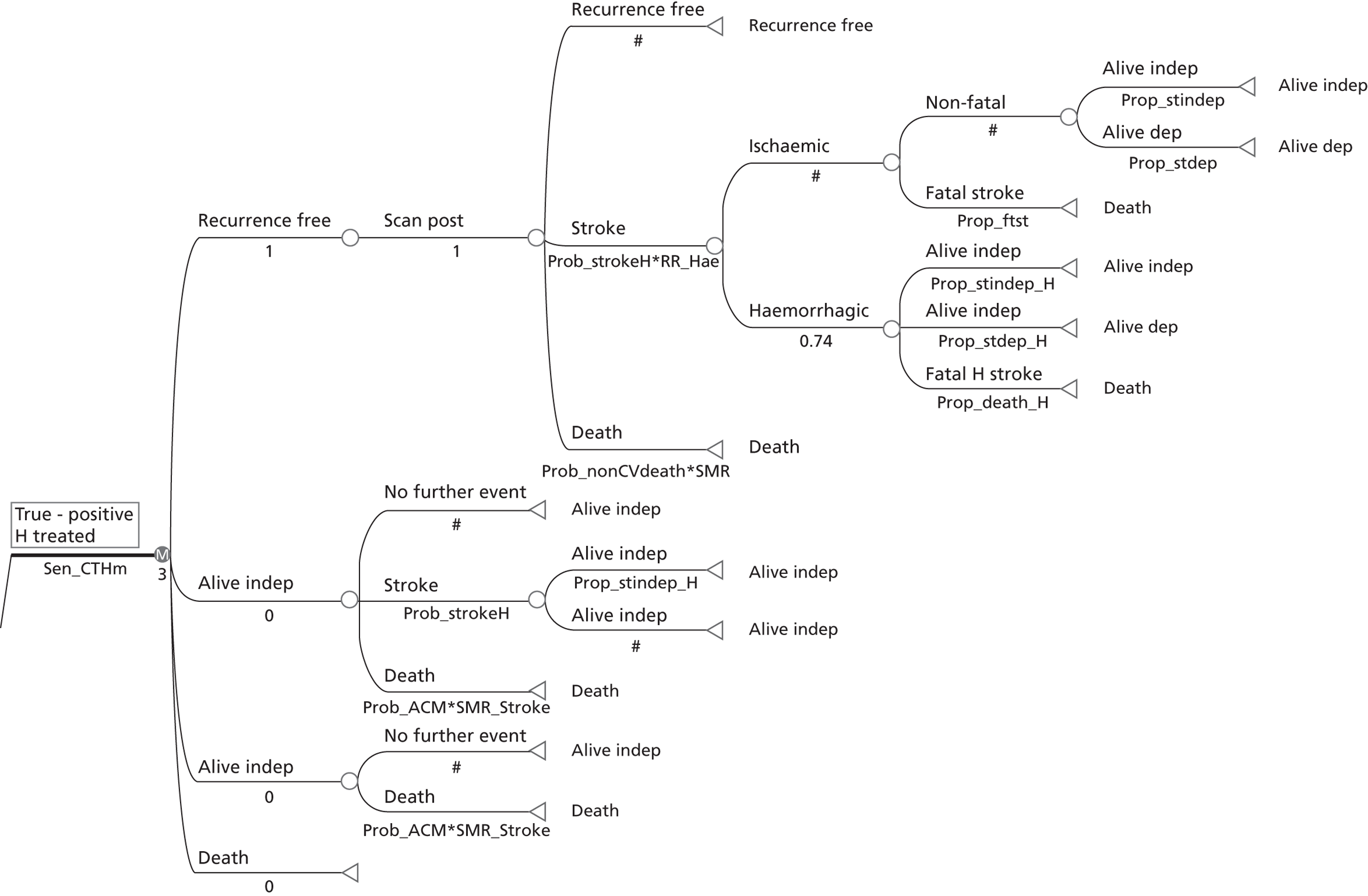

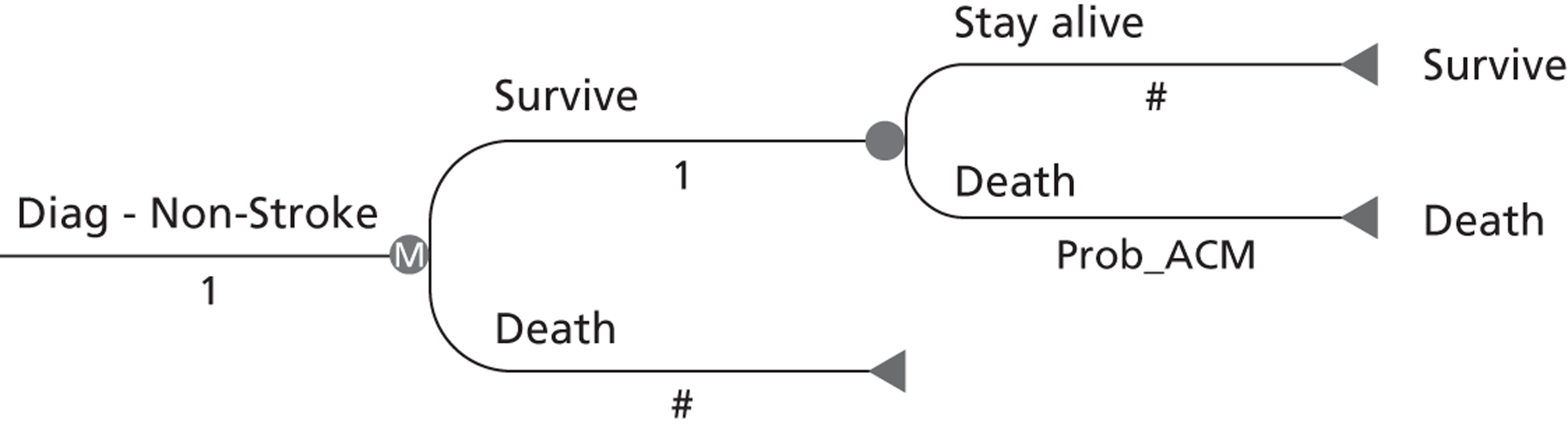

We planned to do this by using health economic decision-analytic modelling to assess the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and practical implications of using MRI in different proportions of patients with TIA or minor stroke at different times after symptom onset, obtaining data from systematic reviews of the relevant literature, surveys of current practice and costs, existing stroke registry and cohort data. If MR cannot be justified in all patient then our aim was to determine in which subgroups of patients the use of MR is cost-effective. We aimed to provide a range of options reflecting the effect of using MR in different proportions of TIA/minor stroke patients at different times after TIA/minor stroke to guide decision-making by health service purchasers. We anticipated that the health economic modelling would be a hybrid of methods used in two previous HTA-funded cost-effectiveness analyses in stroke: a decision-analytic tree model to reflect the initial diagnosis of TIA/minor stroke compared with mimic, and ischaemic stroke compared with haemorrhagic stroke from work on the cost-effectiveness of CT scanning in acute stroke,26 followed by a probabilistic time-based model to reflect the varying risk of recurrent stroke and other vascular events following TIA/minor stroke, over a long time horizon from the work on cost-effectiveness of different carotid imaging methods in stroke prevention. 5

Chapter 2 General methods

Introduction

The research involved gathering information from many sources. This chapter provides a short résumé of the main objectives of the work and a brief general summary of the methods used. More detailed methods specific to the question being addressed are provided in each relevant chapter or section.

Objectives

Our primary research objective was to determine whether MR DWI and additional relevant structural and blood-sensitive sequences is cost-effective in the majority of patients with TIA or minor stroke to guide diagnosis and secondary stroke prevention, compared with the current alternative of CT brain scanning.

Our second objective was to determine the cost and cost-effectiveness of increased use of MR including DWI and blood-sensitive sequences in patients presenting at > 5 days after TIA/minor stroke when CT will not be able to identify haemorrhage as the cause of stroke reliably.

Our third objective was to estimate if ‘one-stop’ brain and carotid imaging was more cost-effective than individual separate brain and carotid examinations, in what proportion of patients a ‘one-stop’ approach could be used, and the practical and cost implications.

Our fourth objective was to determine physicians’ and radiologists’ current use of imaging in stroke prevention and attitudes to increased use of MRI in TIA/minor stroke, the availability, barriers to greater use, costs of increasing availability and net effect on other patient groups in whom MR is commonly used.

We undertook this work using a range of tools. We modelleding the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and practical implications of using MRI in different proportions of patients with TIA or minor stroke at different times after symptom onset, using systematic reviews of the relevant literature, surveys of current practice and costs, and existing stroke registry and cohort data. If MRI could not be justified in all patients then we aimed to determine in which subgroups of patients the use of MR was cost-effective. We aimed to provide a range of options reflecting the effect of using MRI in different proportions of TIA/minor stroke patients so as to guide decision-making by health service purchasers. The extent to which these objectives would be fulfilled would depend on the amount of relevant evidence available in the literature on use of imaging in patients with TIA and minor stroke and mimics.

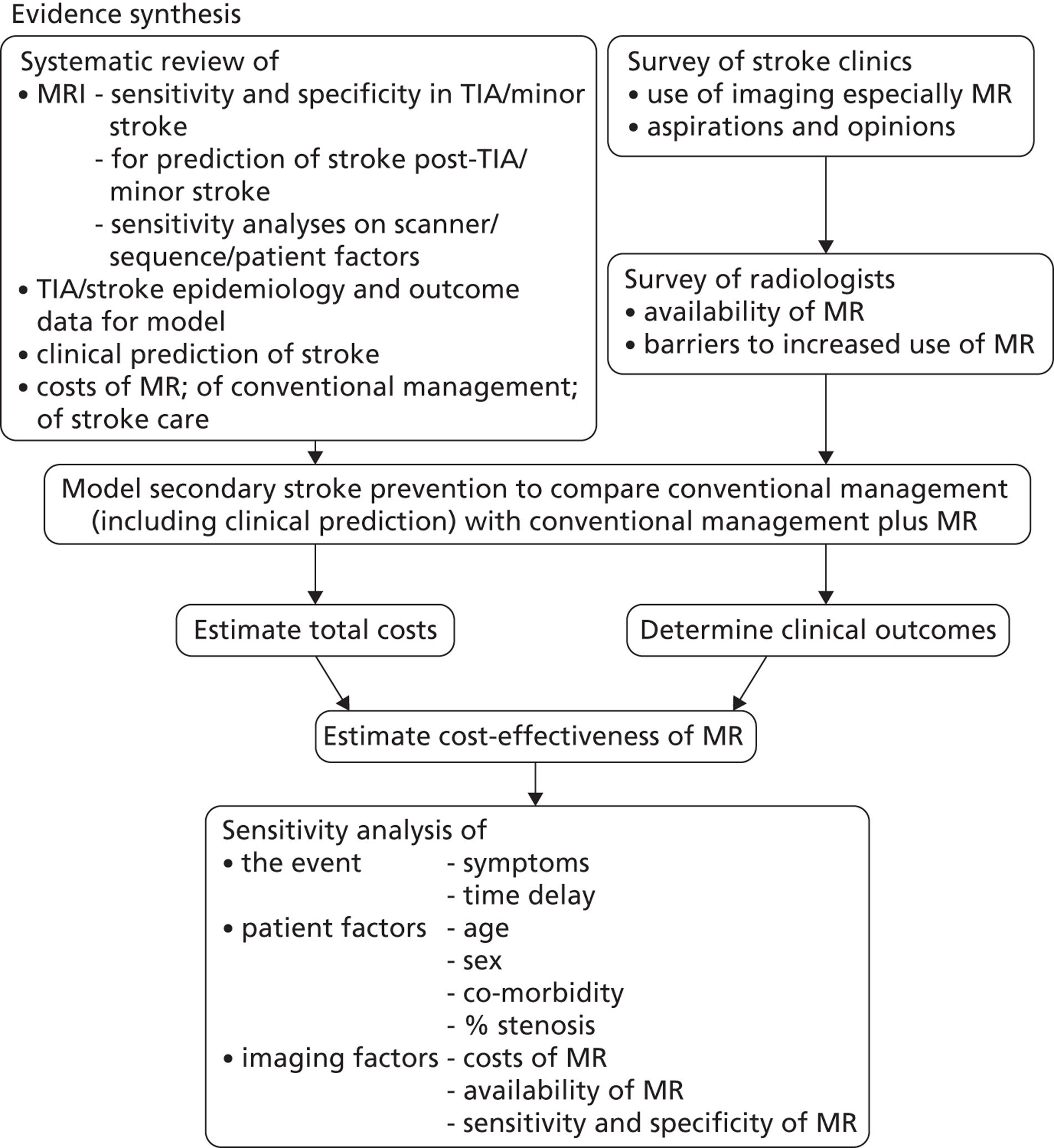

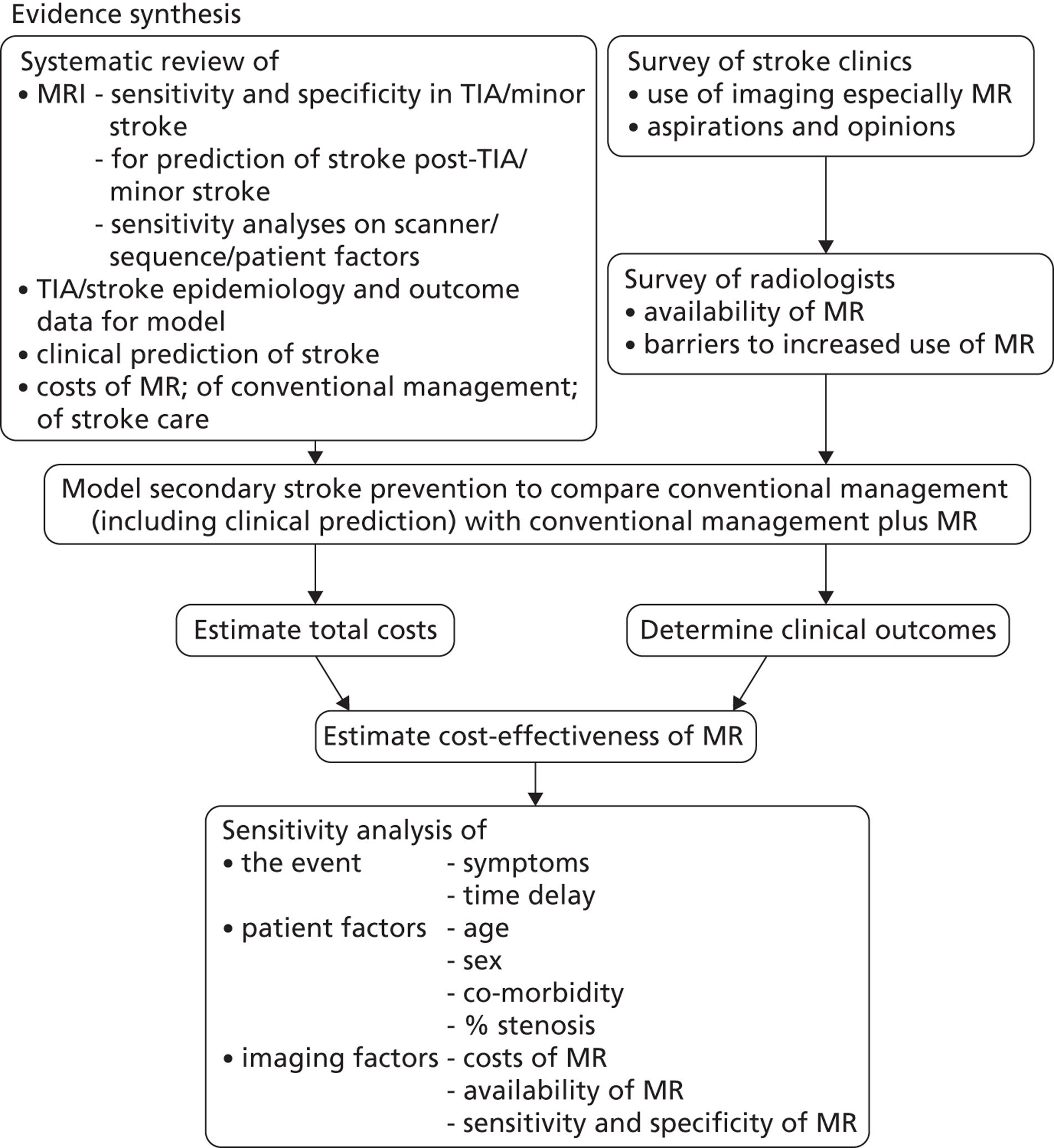

Design

The study was an evidence synthesis of data from the literature, new surveys of current UK practice and costs, and health economic modelling with sensitivity analyses of important variables (Figure 4). Further details on the following are given in relevant chapters.

-

Systematic reviews We systematically reviewed the literature to:

-

summarise the risk of recurrent stroke after TIA and minor stroke by time period (see Chapter 3)

-

summarise clinical risk scoring systems and in particular the ABCD2 score and its predictive accuracy (see Chapter 4)

-

estimate the sensitivity/specificity of CT and MR including DWI sequences in TIA/minor stroke, including the arterial territory; and

-

assess their role in prediction of stroke after TIA (see Chapters 5 and 6)

-

estimate the proportion of suspected TIA/minor stroke patients who are diagnosed as a mimic (see Chapter 7)

-

assess previous studies of cost-effectiveness of imaging in stroke prevention (see Chapter 9)

-

gather all of the data required to model stroke prevention after TIA, including estimating costs of CT and MR (summarised to 2003 in Wardlaw et al. 26 but requiring updating) (see Chapters 10 and 11).

-

-

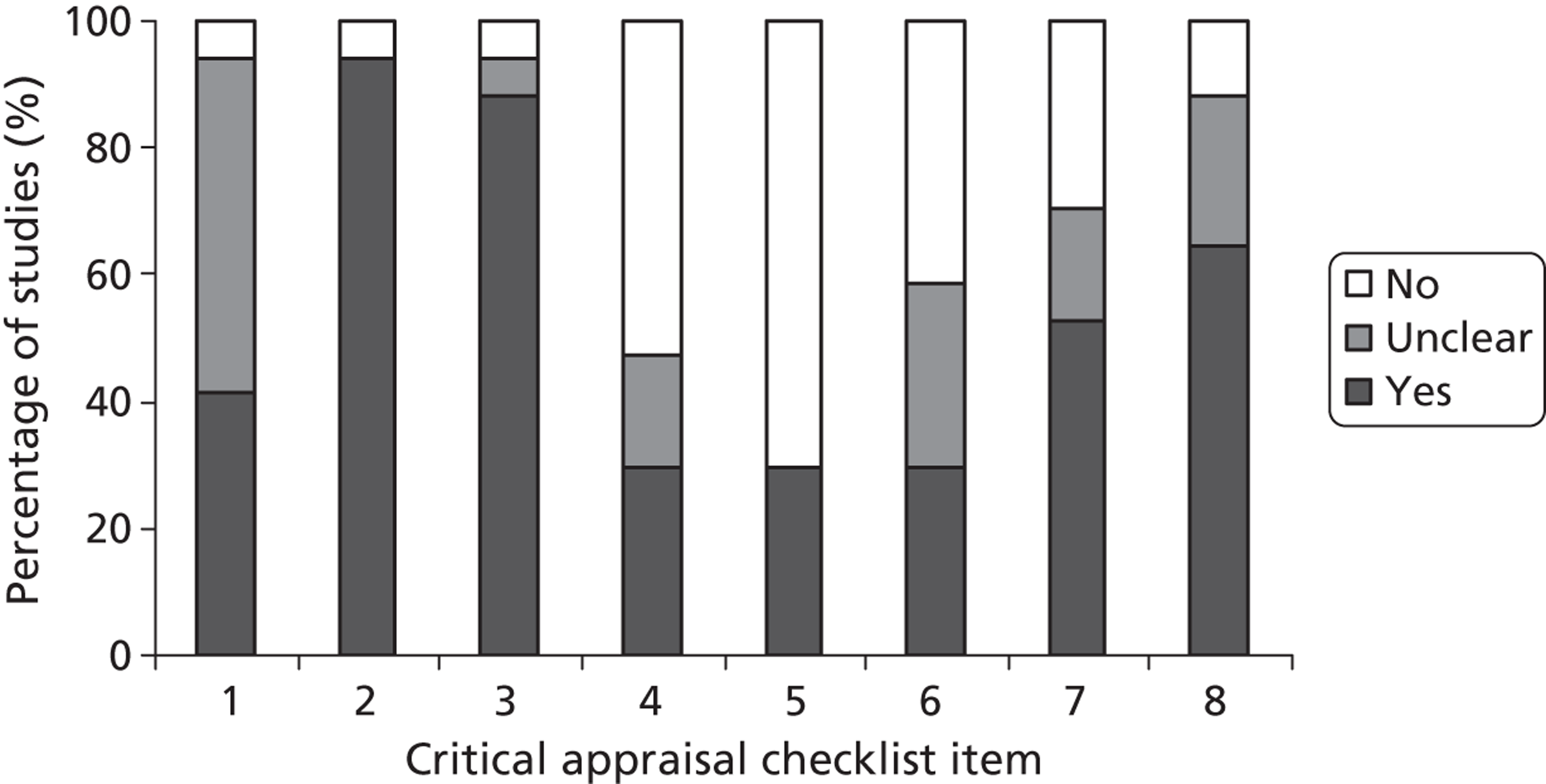

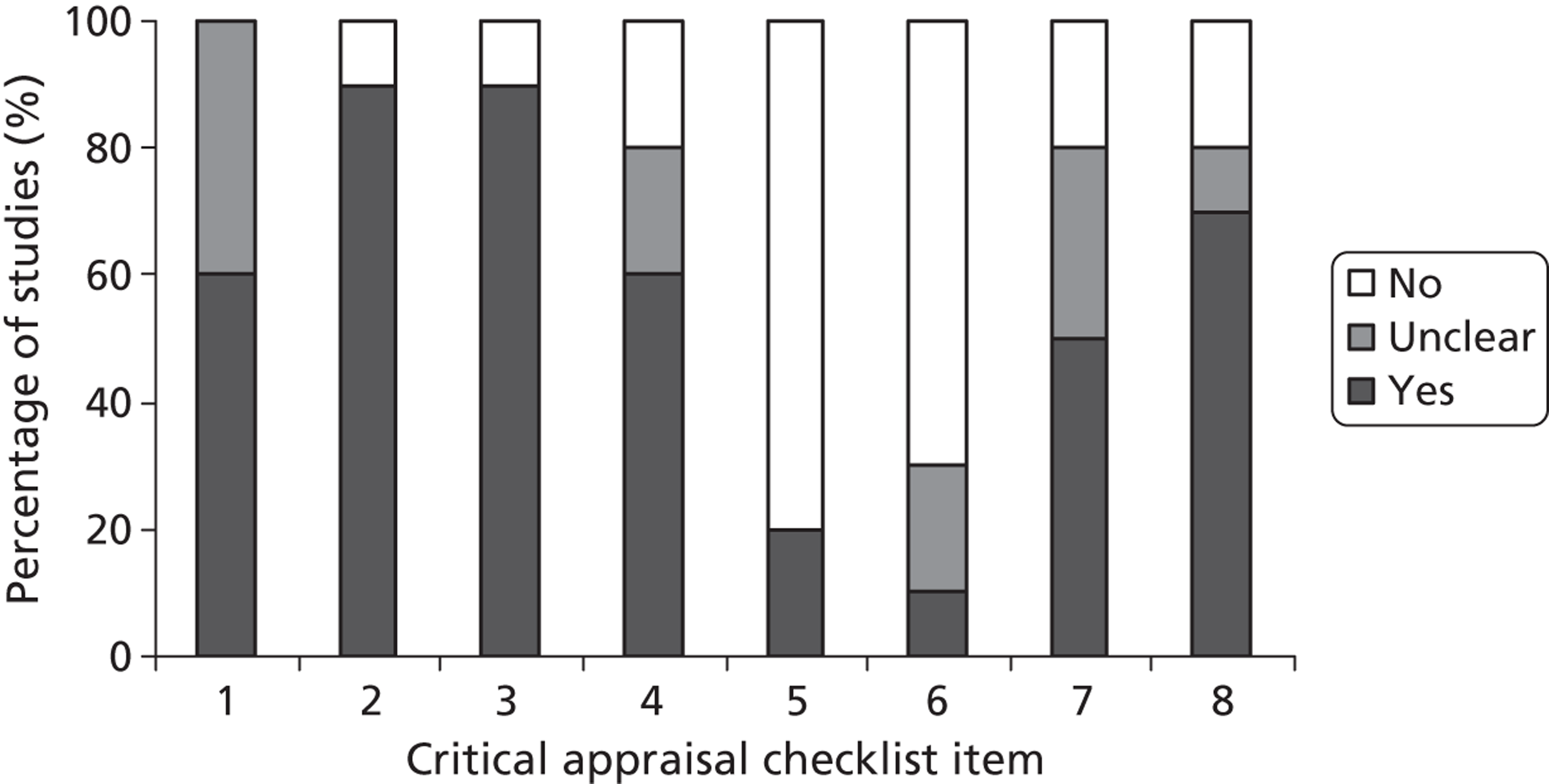

All aspects of these systematic reviews, including literature searching, quality assessment, data extraction, and evidence synthesis were performed according to the Cochrane Collaboration and Stroke Group standards, including recommendations from the Screening and Diagnostic Tests Methods Group. 5,36 Occasionally we were not able to apply Cochrane methodology, and wherever this occurred, we give the reasons why and describe any alternative methodology used. The methods for evidence synthesis (meta-analyses performed according to the summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve methodology or separate meta-analyses of sensitivity and specificity estimates) were determined by the data obtained and we used the most appropriate method, as described in each relevant chapter/section. 108 We explored heterogeneity by examination of forest plots and I2-statistics. 109 However, we did not use meta-regression, i.e. meta-analyses with covariates to explain heterogeneity, due to limited numbers of studies and a lack of information on relevant covariates. Where possible, we used a standardised quality assessment instrument [i.e. the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Studies (QUADAS) tool],110 adapted to the topic in question as appropriate. 26,83 For chapters on prediction or prognosis, we created bespoke tools to suit the clinical context as there are no universally accepted instruments. Details are given as required in each chapter. As studies may be reported in multiple publications, we took care to include data from any given cohort only once in the reviews.

-

We obtained data on demographics, risk factors, medications, recurrent stroke and death in patients with TIA/minor stroke relevant to the UK, treatments and their effects, data on quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and utility weights and in order to construct the health economic model (see Chapters 10 and 11). We used existing data sets where possible, for example large stroke and TIA registries,111 individual patient data sets and routinely collected anonymised national audit data, as in previous work. 5,26

-

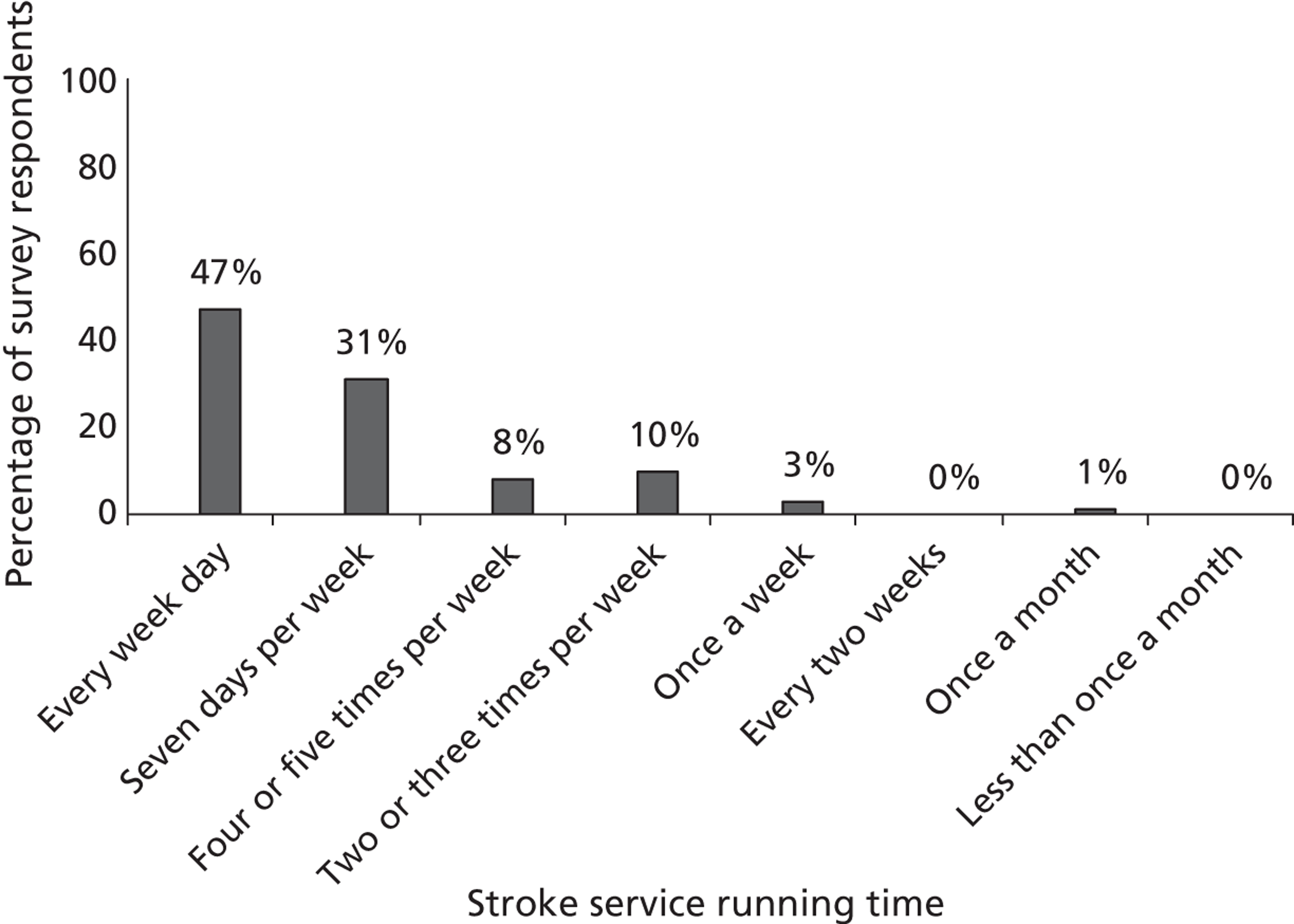

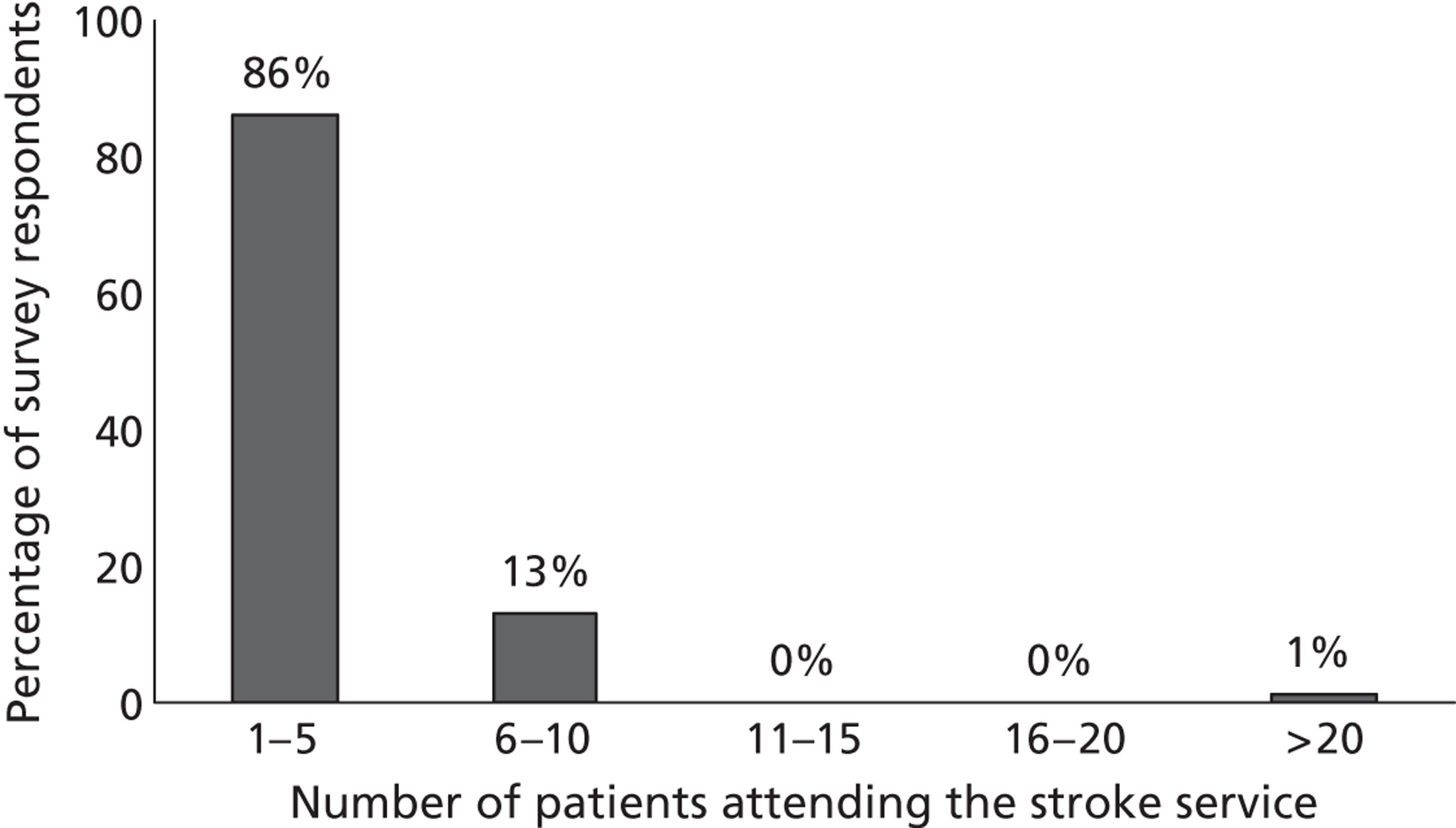

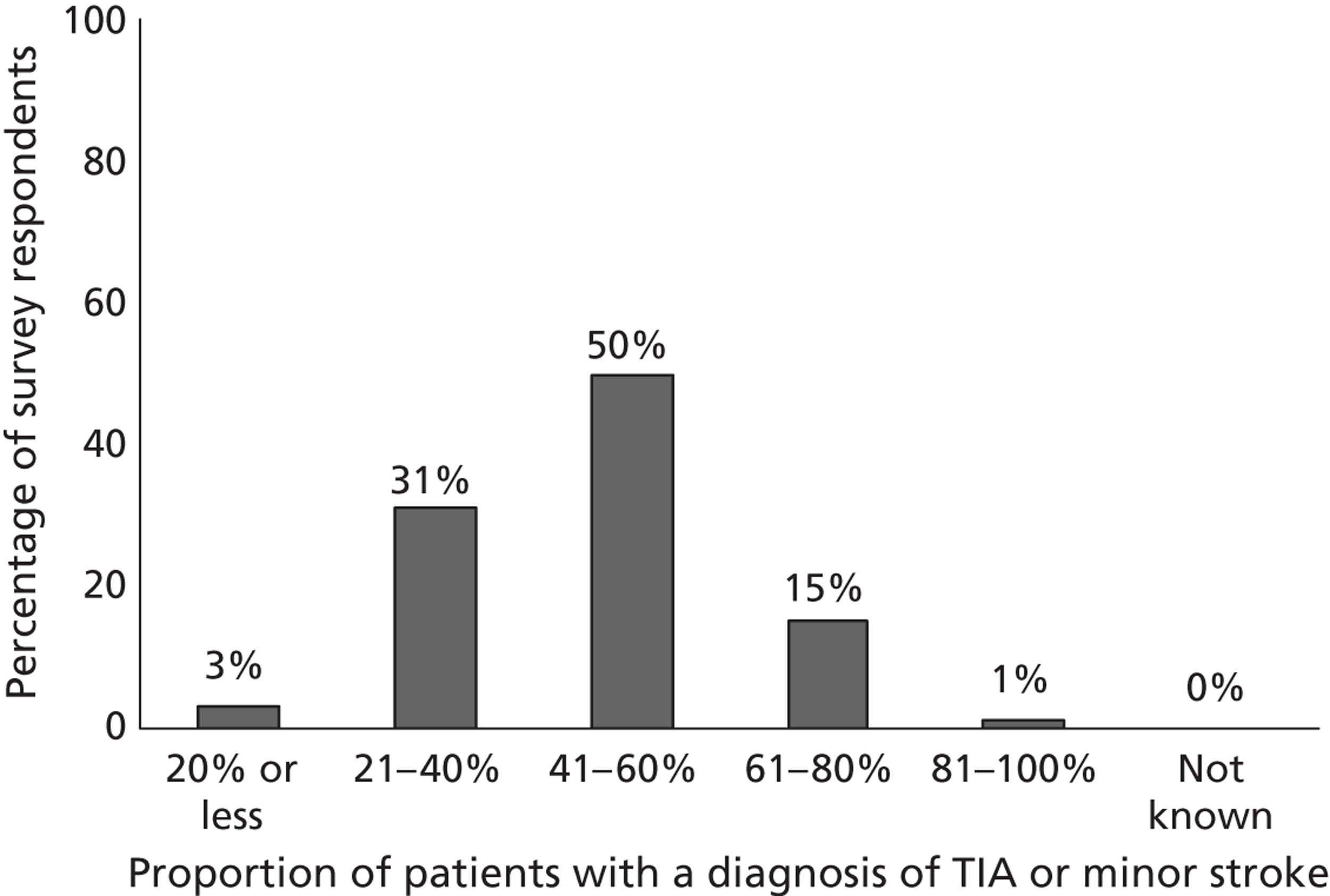

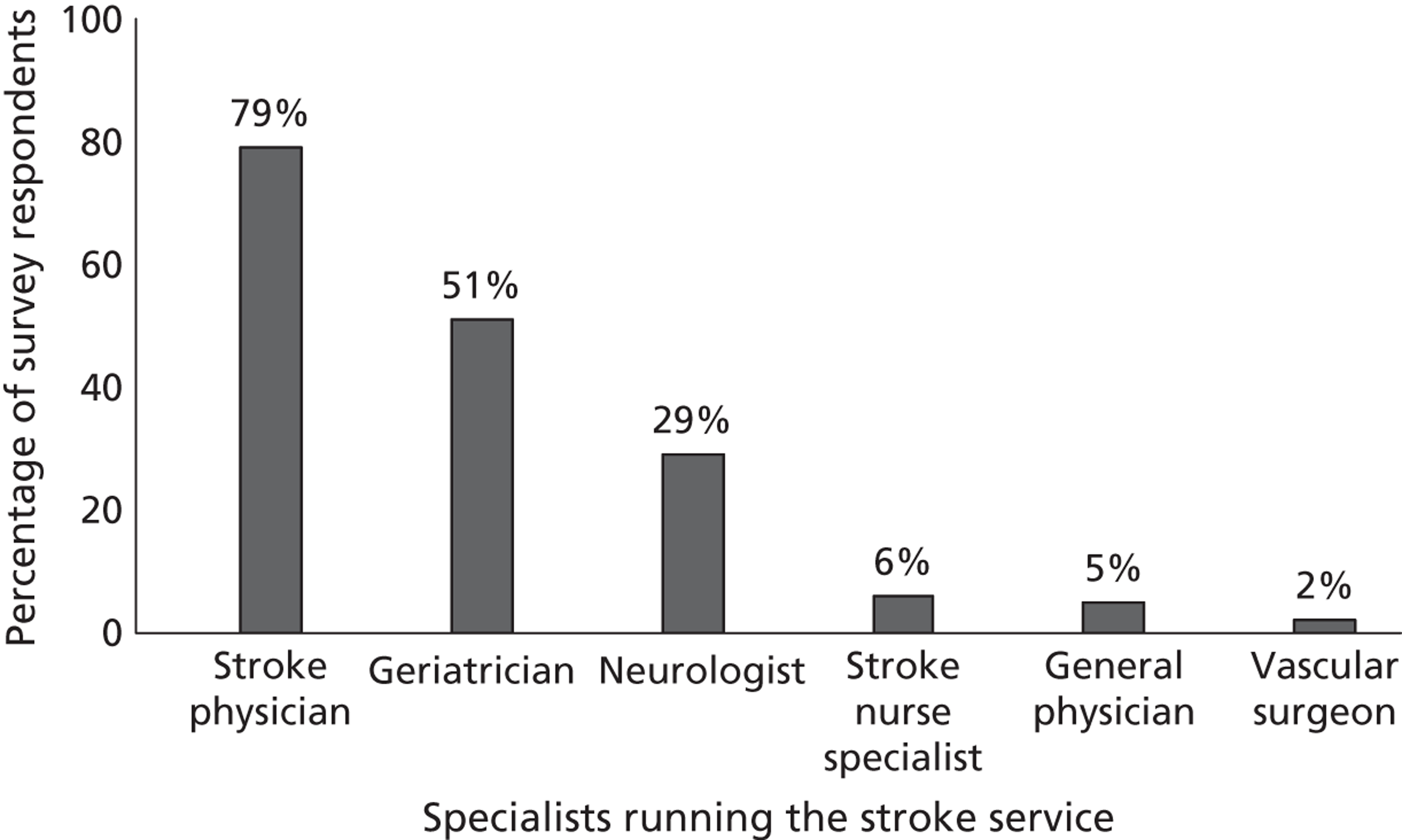

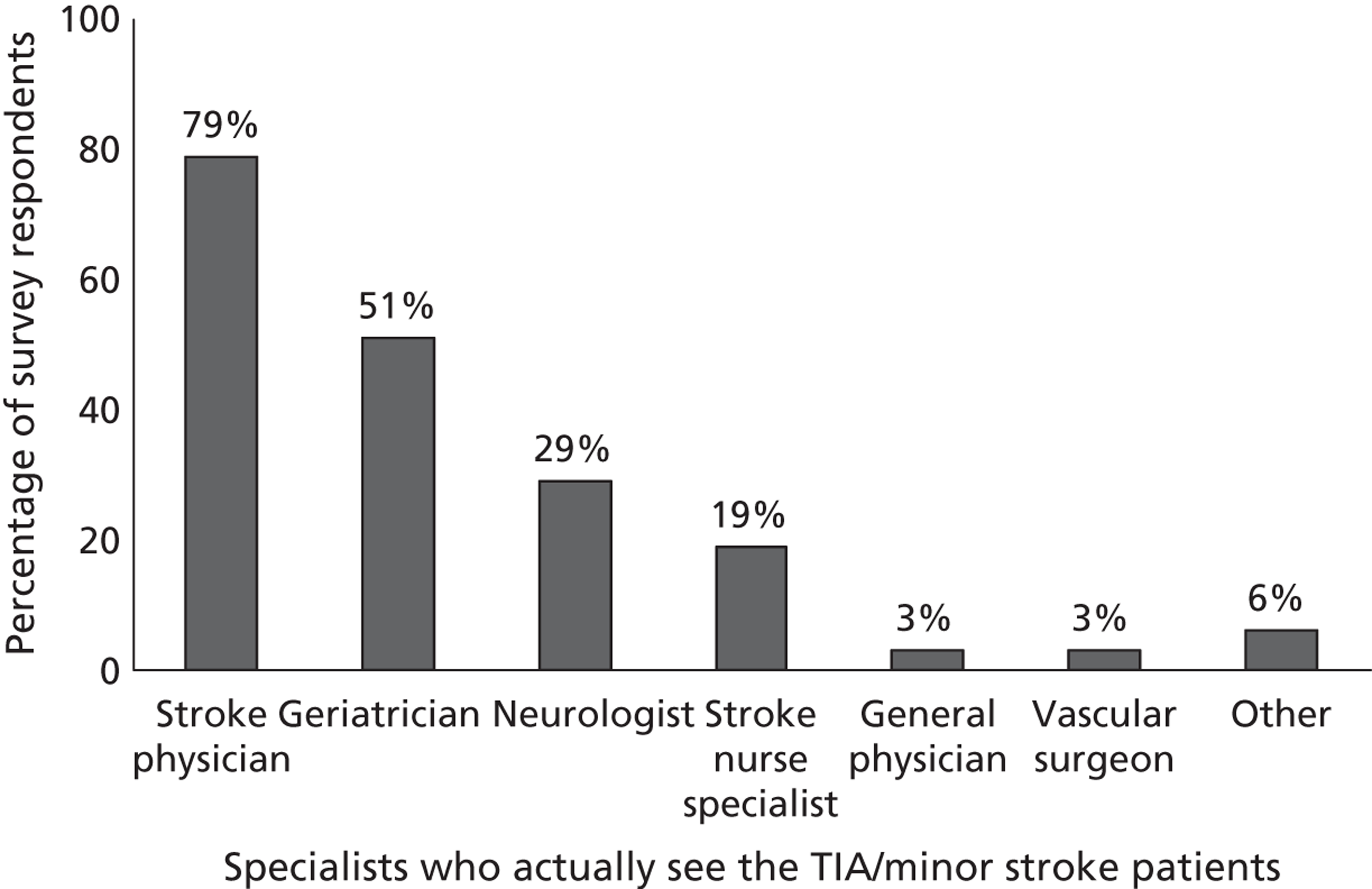

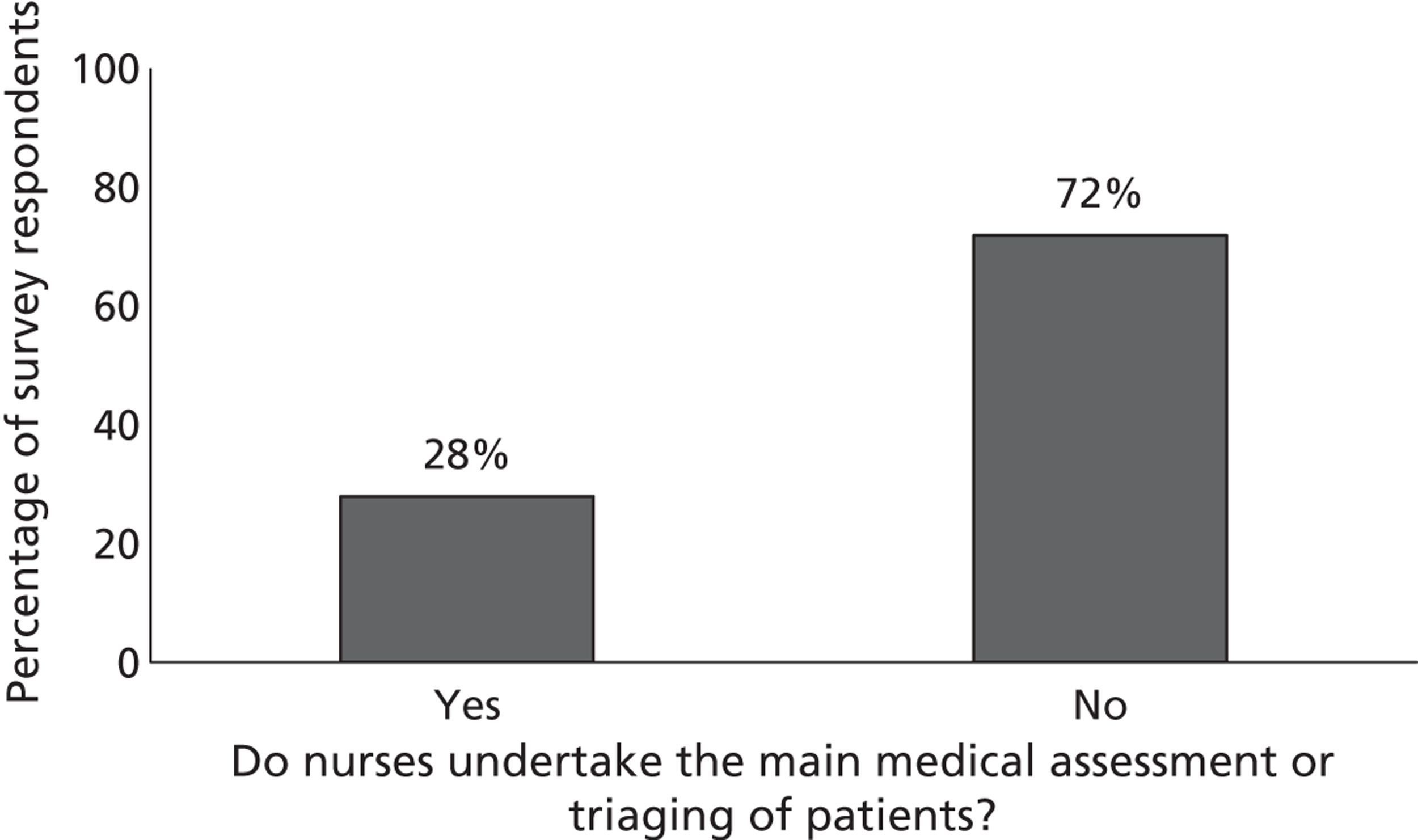

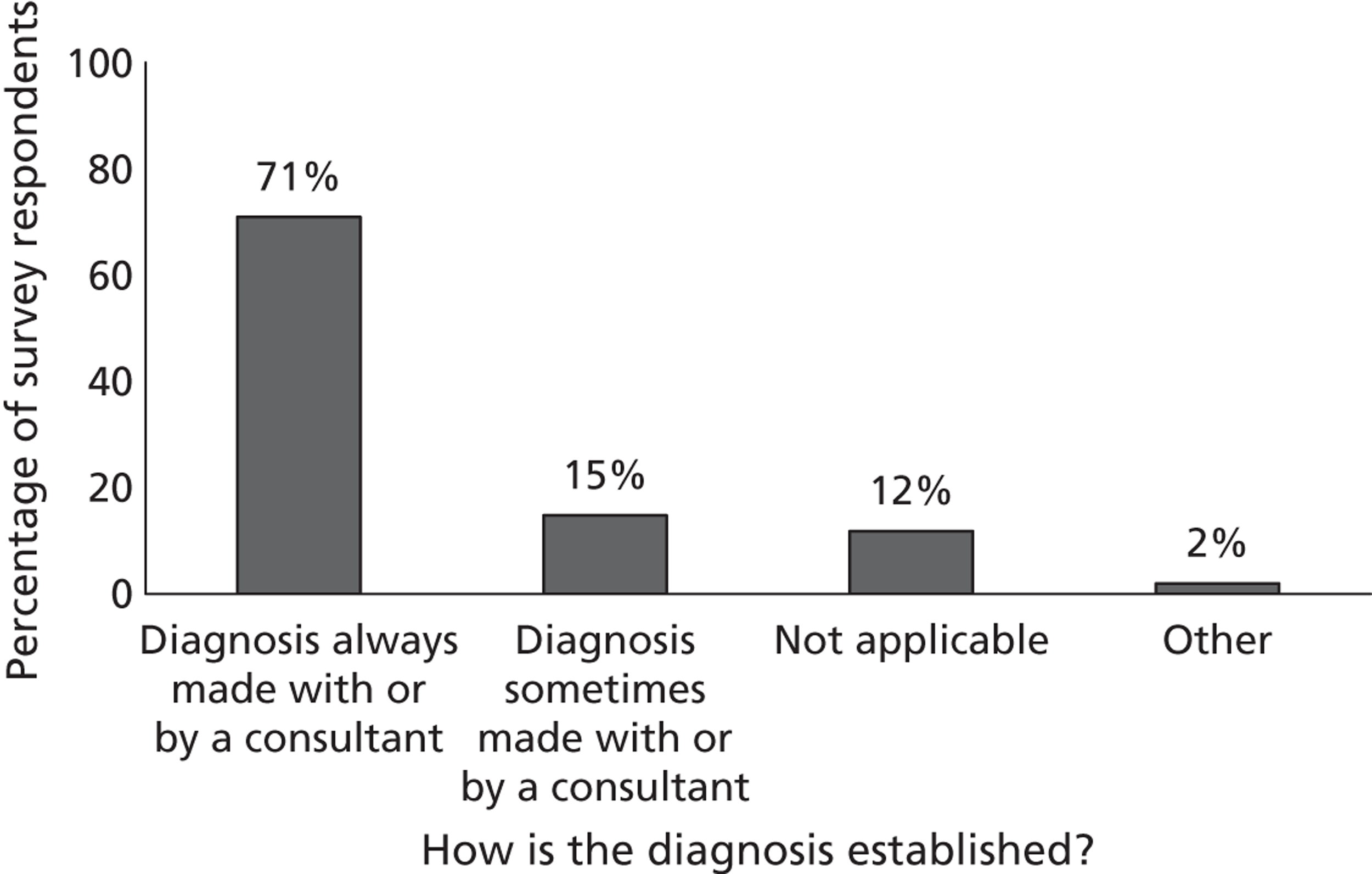

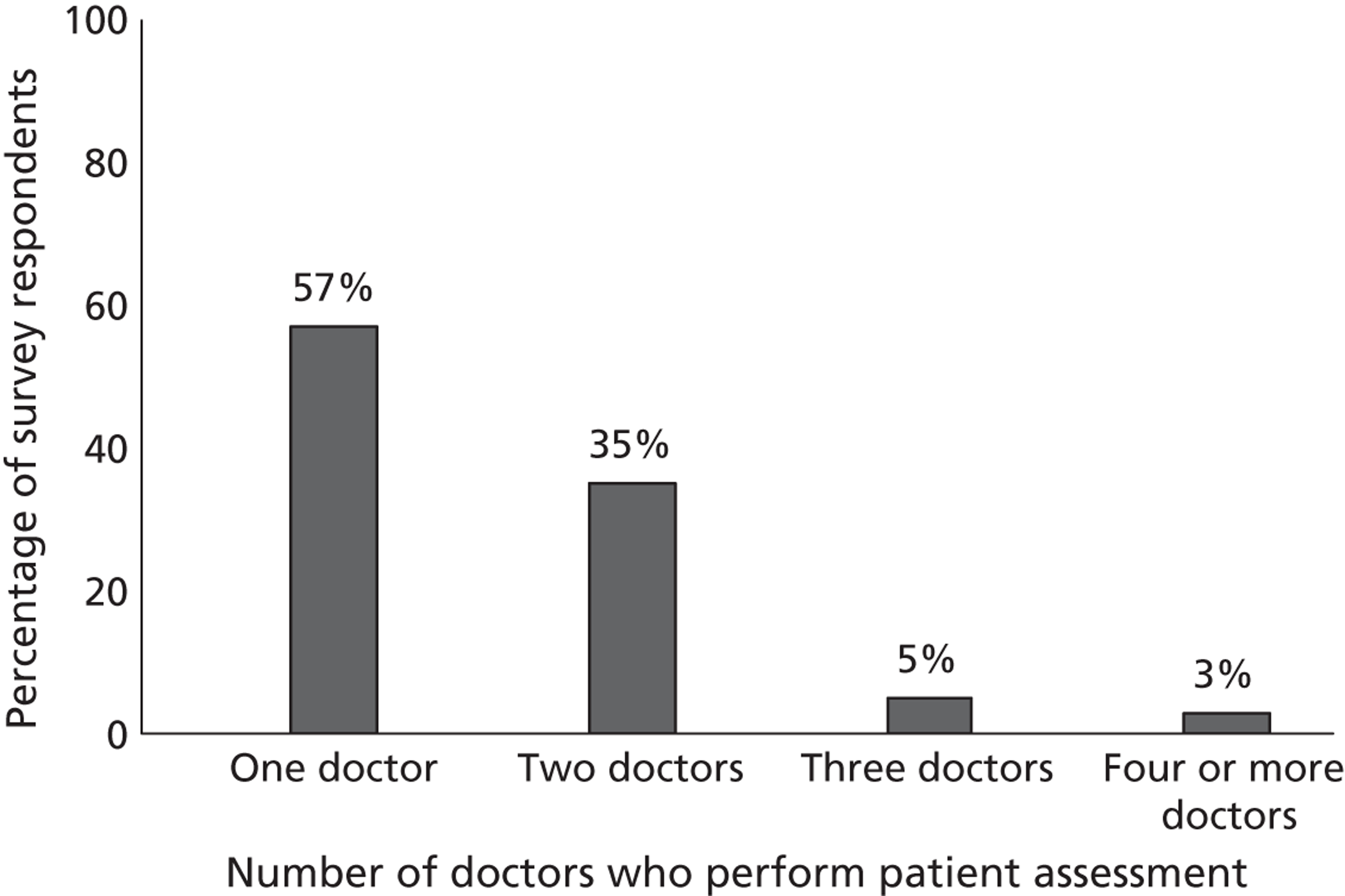

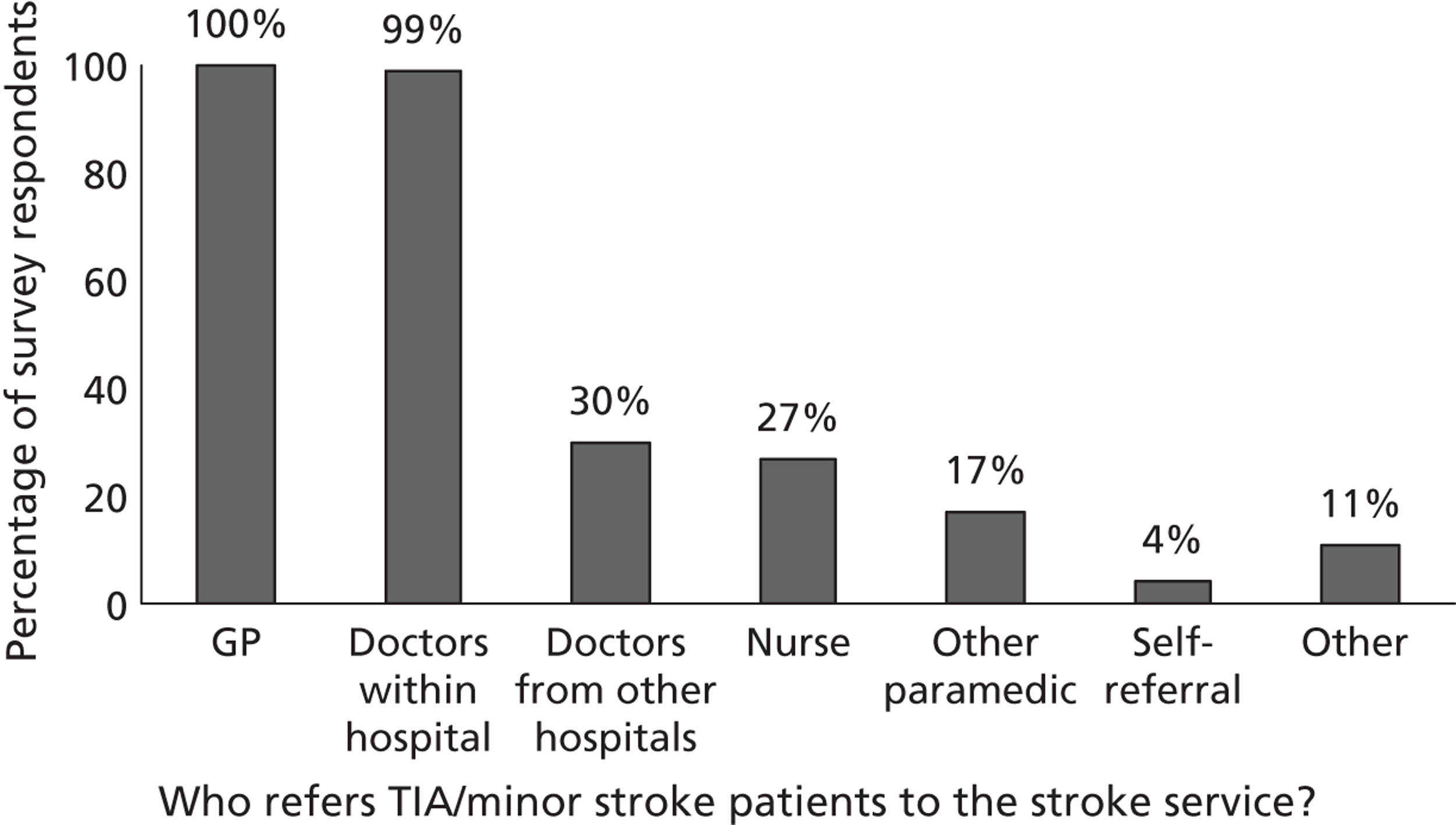

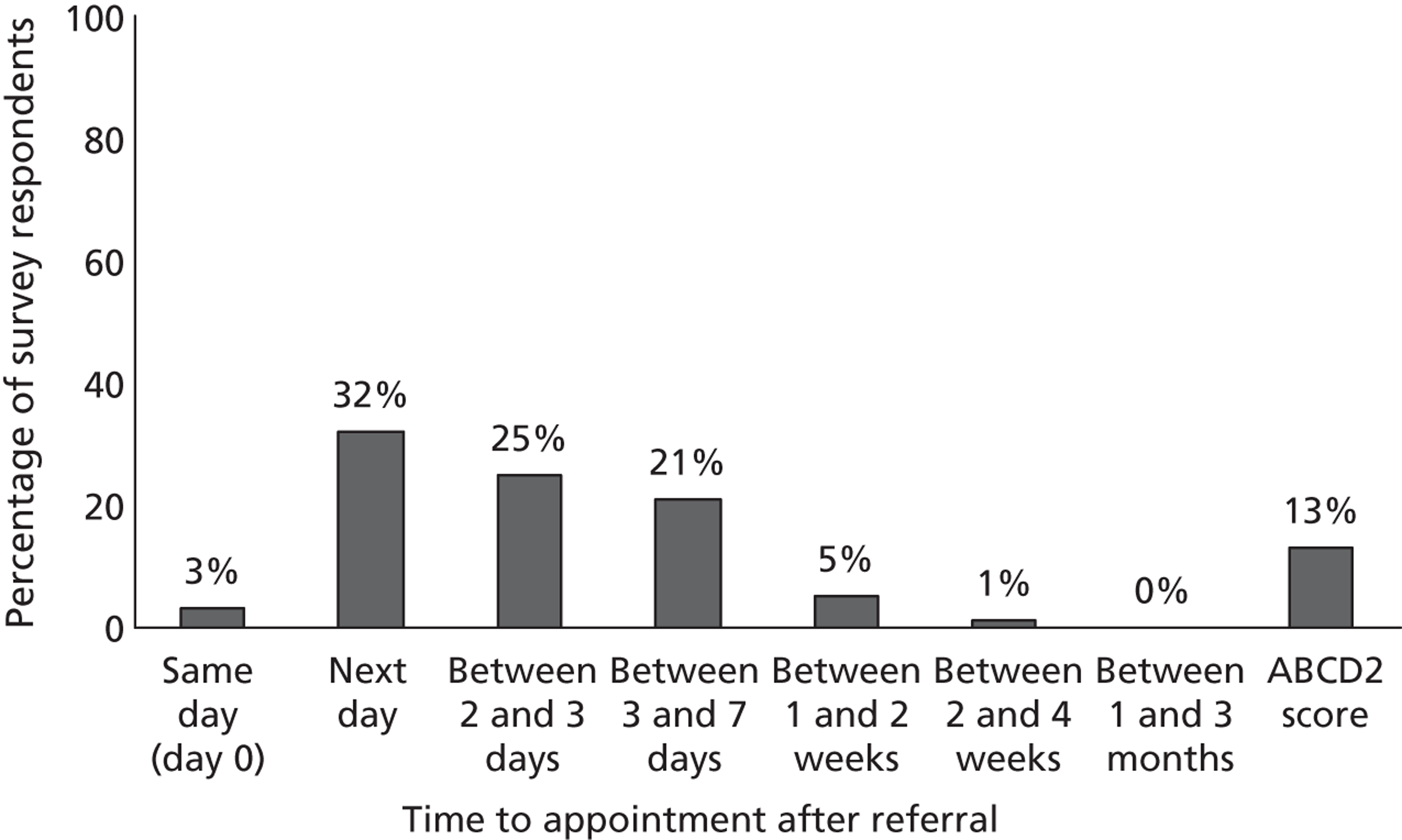

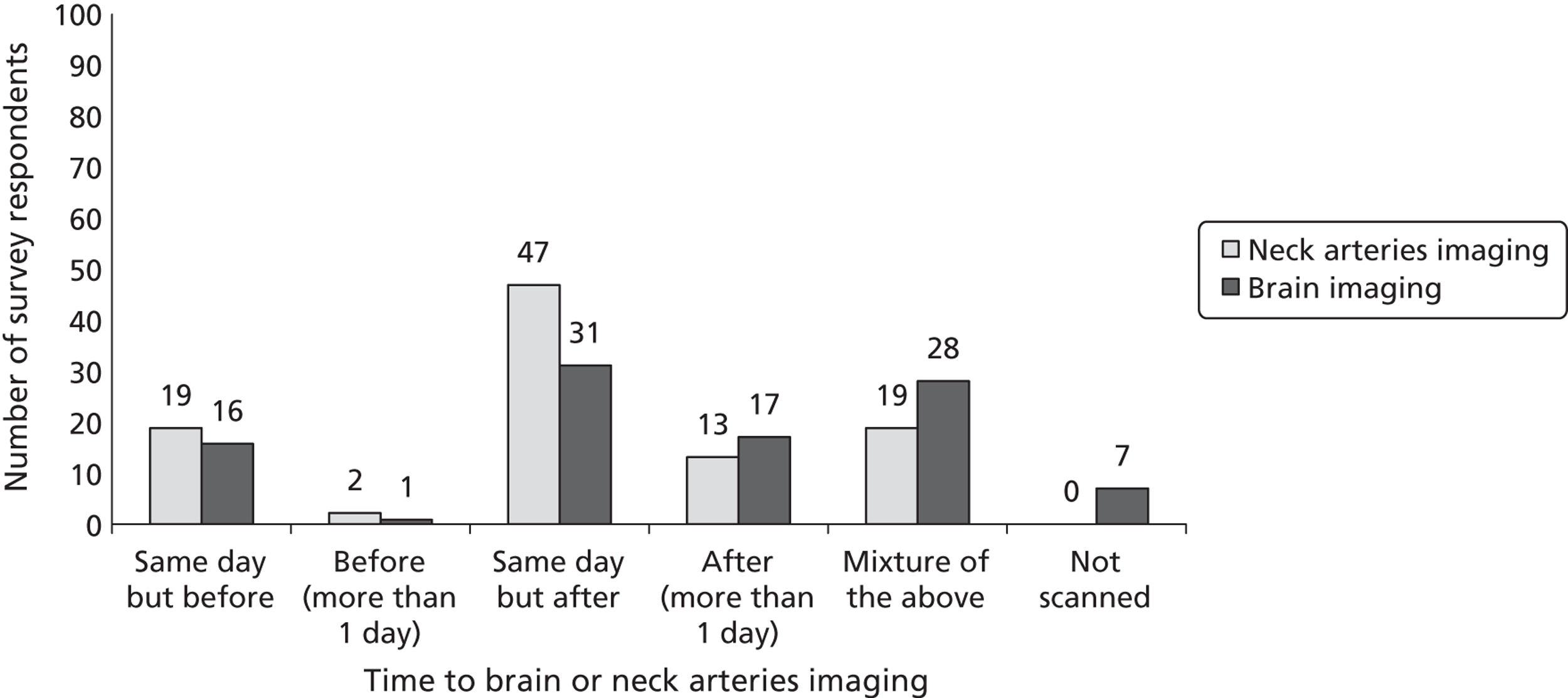

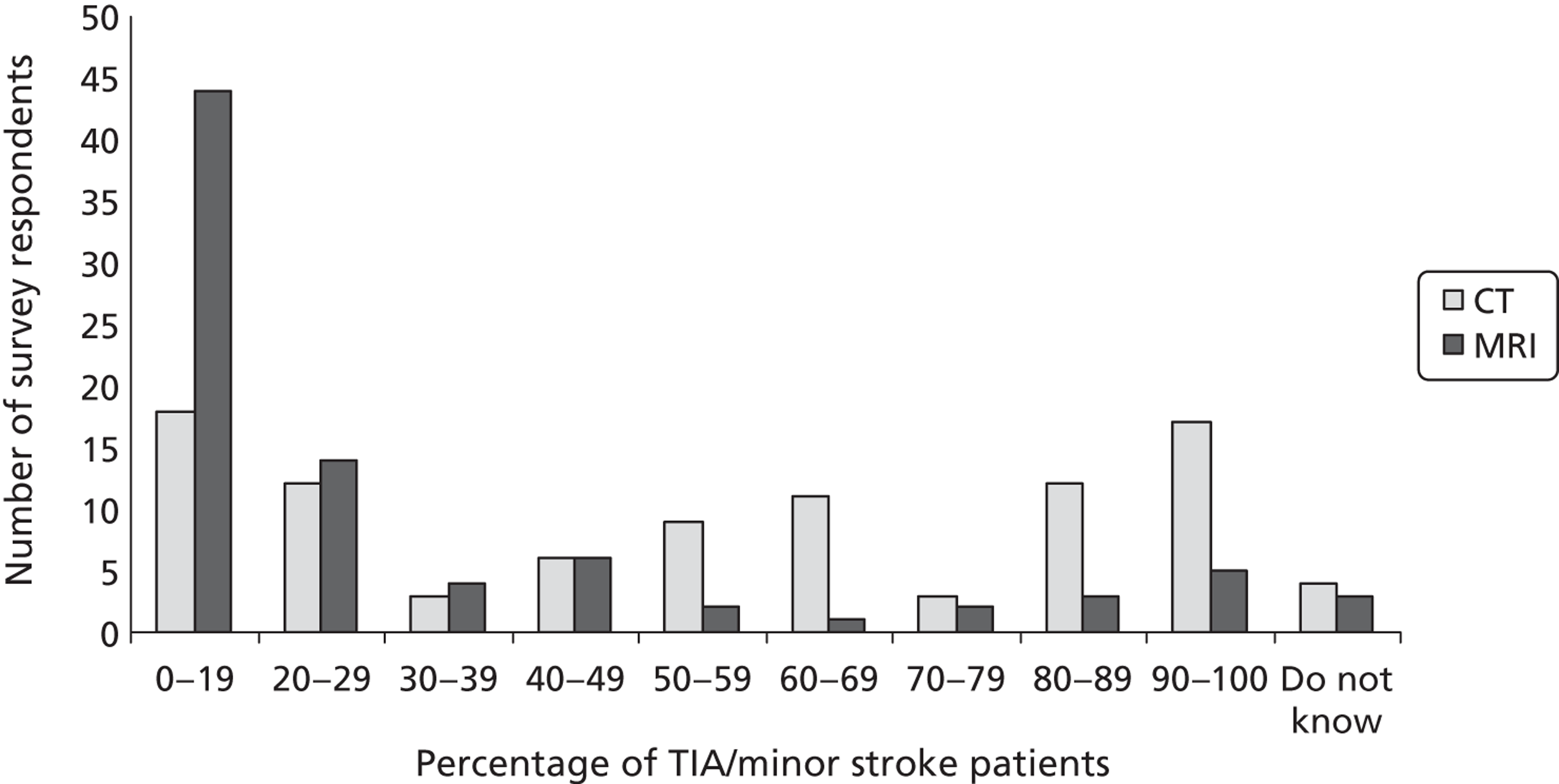

We surveyed UK stroke physicians through the Royal College of Physicians Stroke Audit and NHS Health Improvement,5 to ask about stroke prevention clinics including current access to and use of MR sequences, including DWI in patients with TIA/minor stroke in the NHS, aspirations and consensus on role of MR, and to gather additional unpublished data on MR including DWI in TIA/minor stroke (see Chapter 8).

-

We surveyed UK radiology departments across the UK to determine current use of imaging for stroke, types of imaging used, what capacity there is for increased throughput of TIA and minor stroke patients, and to identify the perceived major barriers to increased or faster throughput of TIA/minor stroke patients and what additional resources would be required to provide additional access for these patients (see Chapter 8).

-

We obtained UK data on imaging costs from the NHS Department of Health (DOH) NHS Reference Costs database, the literature and CT and MR from individual radiology departments,5,26 and the health-care costs associated with management of stroke patients by literature review of relevant electronic databases3 and by interrogation of specific sources, such as stroke registry data as in previous work (see below for specific details). 5,26 We also sought costs of stroke care by outcome and stroke prevention treatments (see Chapter 11).

-

We obtained data on quality of life after stroke for key subgroups from the literature, from previous work, unpublished sources and from our local stroke register data (see Chapter 11). 112

-

We built a model to reflect key stages and outcomes in secondary stroke prevention after TIA/minor stroke, including all data on assessments, medical and surgical interventions, outcomes, and timings, populated with representative data from TIA/stroke services in the UK. The timelines in the model were stratified by time after symptoms, key patient characteristics, use of prognostic scores (ABCD2),62 including conventional routinely available investigations (brain CT, carotid imaging), the comparator MRI and treatment decisions, and key outcomes of non-disabling and disabling stroke and death at various time intervals out to a lifetime time horizon (see Chapter 11).

-

We modelled the incremental cost-effectiveness of implementing MR including DWI with or without T2* instead of usual care in the diagnosis of TIA/minor stroke and a range of different strategies where proportions of patients would vary by key characteristics and timing of investigations, etc. in sensitivity analyses. We estimated the effect of using MR or CT also to diagnose carotid stenosis as a ‘one-stop’ investigation using magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or CT angiography (CTA), respectively, instead of performing the MR or CT of the brain scan and separately performing carotid imaging with, for example, ultrasound. We used data from our previous HTA report (see Chapter 12). 5,84

-

We summarised the effect of different investigative approaches on recurrent stroke, costs, and QALYs, and hence the probability that the new diagnostic strategy is more cost-effective than usual care. The results are presented for a cohort of patients presenting to stroke prevention clinics with suspected TIA/minor stroke. Various analyses were conducted to investigate the worth of commissioning further research on the cost-effectiveness of MR DWI imaging and inform the design of any future research. All modelling work was performed according to recommended guidance (www.equator-network.org) (see Chapter 12). 113

FIGURE 4.

Study design.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We modelled a typical population of patients presenting with suspected TIA/minor stroke including mimics based on existing data reflecting current demographic, pre-stroke medications, and stroke treatments using information from the literature and a large national stroke audit.

These data sources included:

-

the North Edinburgh Stroke Study and Lothian Stroke Register (LSR, n = 2598, a hospital-based registry of all inpatients and outpatients with TIA and stroke presenting to the hospital between 1992 and 2000 with demographic information, imaging and laboratory investigations, past medical history, medications prior to and following the TIA/stroke, and quality-of-life data) and followed up to 4 years for recurrent stroke, cardiac events and death and used in two previous HTA reports5,26

-

the Edinburgh Stroke Study (ESS, n = 1367, a hospital-based registry of all inpatients and outpatients with TIA and stroke presenting to the hospital between 2002 and 2005 with the same information except quality of life) and so far followed up to 4 years after the stroke111

-

the Scottish Stroke Care Audit Study (SSCAS), a Scottish national routine collection of anonymised audit data from TIA and stroke services

-

data from other studies of stroke and TIA with more detailed imaging, including a study comparing CT and MR scans in minor stroke between 1998 and 2001 (n = 230) conducted as part of a previous HTA-funded project31

-

a study of patients with mild cortical and lacunar stroke between 2005 and 2007 (n = 250), all with MR DWI and T2* imaging114

-

audit data of TIA and stroke mimics from stroke prevention services in Leicester (Eveson; obtained through NHS Improvement)

-

data on quality of life at 6 months after stroke by functional outcome Oxford Handicap Score from the Clots in Legs Or sTockings after Stroke (CLOTS) trials. 115

Ethical arrangements

The use of existing anonymised data to populate the model and perform other analyses did not require additional ethics approvals. All data used in the proposed modelling were anonymised.

Proposed sample size

We modelled the effect of incremental change in proportions of TIA/minor stroke patients undergoing MRI for a typical UK population of 1000 patients. The existing data sets included several thousand patients with TIA, minor and major stroke, with initial clinical and imaging assessment, and data on functional status, stroke recurrence and death at 6 months, 1 year and later. We provide the results in the form of ‘events per a cohort of 1000 patients presenting to hospital with suspected TIA and minor stroke’.

Statistical analyses

Systematic review of diagnostic accuracy

Indices of diagnostic performance were extracted or derived from data presented in each primary study for each imaging test. Where data were available, we constructed 2 × 2 contingency tables of test results compared with reference standard to show the cross-classification of disease status and test outcome. We calculated sensitivity and specificity with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each imaging test for each study where possible. To describe and visualise the data, we used forest plots showing the pairs of sensitivity and specificity estimates for each study. We also used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plots, random-effects SROC curves, survival curves, and various other meta-analytic techniques as appropriate. All reviews, analysis of observational data and other types of analysis including critical appraisal were conducted according to the established relevant recommendations (www.equator-network.org). 110,116

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the incremental cost-effectiveness of MR scanning compared with CT for the whole population. Secondary outcome measures included the number of strokes prevented per strategy, costs and QALYs. We tested the effect of substituting MR for CT in key subgroups by time to imaging, ABCD2 score, assuming that DWI-negative TIA patients did not have a TIA/minor stroke, and combining carotid and brain imaging in one examination. We tested the effect of changing the proportion of patients with TIA/minor stroke with a visible ischaemic lesion on ‘MR including DWI’ and CT brain scanning and the association with key clinical variables; whether adding information from brain scanning to clinical risk scoring improves prediction of future risk of stroke or death; the association between a positive or negative brain scan and risk factors for stroke, such as carotid stenosis; delays to diagnosis, delays to starting medical or surgical treatment if MR including DWI were to replace CT brain scanning; the number of disabling strokes prevented at 6 months, 1 and 5 years after TIA/minor stroke if ‘MR including DWI’ were to be used in most patients for a cohort of 1000 patients. We tested the effect of QALYs stratified by key patient groups. We will provide a range of options reflecting effect of using MR in different proportions of TIA/minor stroke patients to guide decision-making by health service purchasers.

A brief discussion of the specific aspects of each chapter is provided at the end of each chapter and a discussion of the whole project and main findings in Chapter 13.

Chapter 3 A systematic review and meta-analysis of stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack

Introduction

The early risk of recurrent stroke after TIA has been underestimated for many years. Approximately 15–20% of ischaemic strokes are preceded by a TIA117 and the appropriate detection and urgent diagnostic work-up for patients with TIA can avoid a further disabling stroke if the correct treatment is indicated. A retrospective study of consecutive patients attending emergency departments (EDs) within 24 hours after TIA demonstrated that the stroke risk after the index event was higher than previously thought; the stroke rate was 10.5% at 90 days, with half of the events (5.3%) occurring within 2 days of symptoms onset. 8 A further analysis of a population-based TIA incidence study [Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project (OCSP)] also reported a high stroke rate after index TIA, with risks of 8.6% at 7 days and 12.0% at 30 days. 21 Several studies have been published after these publications. With respect to stroke immediately after TIA, in a prospective population-based incidence study of TIA and stroke (OXVASC), in 488 patients with a first TIA the risks of stroke at 6, 12 and 24 hours were 1.2% (95% CI 0.2% to 2.2%), 2.1% (0.8% to 3.2%) and 5.1% (3.1% to 7.1%), respectively. Furthermore, 42% of all stroke during the 30 days after a first TIA occurred within the first 24 hours. 118 Different studies have reported conflicting stroke rates after TIA, and cohorts from Oxford, UK and northern Portugal have published very high risks of stroke at 7 days (11% to 13%) and 90 days (17% to 21%), respectively. 9,119 A systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 observational studies reporting the early risk of stroke after TIA (total n = 7238), showed that risks of stroke ranged from 1.4–9.9% at 2 days, 3.2–17.7% at 30 days, and 3.9–17.3% at 90 days, with significant heterogeneity for all periods considered. Using a random-effects model, the pooled estimate of risk was 3.5% (95% CI 2.1% to 5.0%) at 2 days, 8.0% (5.7% to 10.2%) at 30 days, and 9.2% (6.8% to 11.5%) at 90 days; the risk was higher when the methodology of the studies involved active ascertainment of stroke outcome (9.9%, 13.4% and 17.3%, respectively). 120 Another systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting the risk of stroke exclusively within 7 days of TIA (total 18 cohorts, n = 10,126 patients) showed pooled risk of stroke of 3.1% (95% CI 2.0% to 4.1%) at 2 days and 5.2% (3.9% to 6.5%) at 7 days, with a substantial heterogeneity across studies for both pooled risk estimates. The risks of stroke after TIA observed in patients treated urgently by specialist stroke services were 0.6% (95% CI 0.0% to 1.6%) at 2 days, and 0.9% (95% CI 0.0% to 1.9%) at 7 days compared with 3.6% (95% CI 2.4% to 4.7%) at 2 days and 6.0% (95% CI 4.7% to 7.3%) at 7 days from other cohorts. 121

Recent studies24,122 included in the systematic review by Giles and Rothwell121 have reported very low risks of recurrent stroke for patients in whom a secondary prevention treatment [mainly antiplatelet drugs and blood pressure (BP)-lowering drugs] was started immediately after confirmed diagnosis of TIA or minor stroke. An early detection of medical conditions with a high risk of early stroke recurrence, such as severe carotid stenosis or a cardiac source of embolism requiring specific treatments (i.e. carotid endarterectomy or anticoagulant therapy) can also explain the significant reductions in stroke rates in those cohorts.

Methods

Objectives

For the purpose of this HTA project we have conducted a systematic review considering all primary studies reporting the overall rate of stroke in TIA patients. Recent published systematic reviews on stroke risk after TIA (e.g. Wu and colleagues120 and Giles and Rothwell121) were used only as a source of relevant references. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for systematic reviews of studies that evaluate health-care interventions to conduct this review. 123 We aimed to identify all published studies reporting the risk of recurrent stroke among patients with TIA and/or minor stroke irrespective of the clinical setting or type of study design.

Identification of studies

We searched indexed records that appeared in MEDLINE (Ovid) from January 1995 to November 2011. It is worth noting that for the purpose of this systematic review we combined the comprehensive literature searches we developed for Chapter 6 (DWI in patients with TIA and minor stroke) and for Chapter 4 (clinical prediction score and risk of stroke after TIA and minor stroke) of this assessment. The MEDLINE search strategy included both subject headings [medical subject headings (MeSH) terms] and text words for the target condition (e.g. stroke, TIA, minor stroke). We adapted the MEDLINE search to search EMBASE. In particular, we ‘translated’ the MEDLINE MeSH terms into the corresponding terms available in the Emtree vocabulary. We did not apply any language restrictions. The searches were initially run in November 2010 and updated in November 2011. Full details of the MEDLINE and the EMBASE search strategies are presented in Appendix 1. We imported all citations identified by the MEDLINE and EMBASE search strategies into the Reference Manager bibliographic database version 11 (ISI Research Software, San Francisco, CA, USA). We hand-searched all proceedings of the International Stroke Conference (2011) and the European Stroke Conference (2011, 2012). We also contacted experts in the field and perused the reference lists of all relevant articles to identify further published studies for possible inclusion in the review. Only full-text articles were deemed suitable for inclusion. 124

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

One review author (MB) examined the identified titles and abstracts and retrieved all potentially relevant citations in full. Full-text articles were assessed by two reviewer authors (MB, HM) and retained if they reported the number and proportion of patients with stroke recurrence at 7 days, 90 days, and/or > 90 days after index TIA. We analysed all studies regardless of whether they reported recurrent stroke at 7 days, 90 days or > 90 days. We excluded non-English articles for which a full-text translation was not available.

Quality assessment and data extraction

Two review authors (MB, HM) independently conducted data extraction and review the methodological quality of selected studies using the primary papers. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or referred to a third author (JMW) if necessary. We recorded data on study methods (e.g. setting, study design) characteristics of patients (first vs. recurrent TIA), and outcomes (stroke events at 7, 90 and > 90 days). We also collected information on the following methodological aspects, which we considered more likely to introduce potential biases: prospective compared with retrospective study design, data source for cohort identification (e.g. registries, databases, medical notes), patients’ selection criteria, definition of TIA and recurrent event, timing of clinical assessment, evaluating clinicians, and method of outcome ascertainment (active vs. passive).

Data synthesis

For each study we calculated the total number of patients with stroke recurrence after index event (first or recurrent TIA). The pooled proportion of TIA patients with stroke recurrence was calculated by means of a univariate random-effects meta-analysis with within-study variance modelled as binomial. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed visually by inspection of the forest plots and by calculating I2-statistics. 109 Data were analysed in R version 2.14.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) (cran.r-project.org).

Results

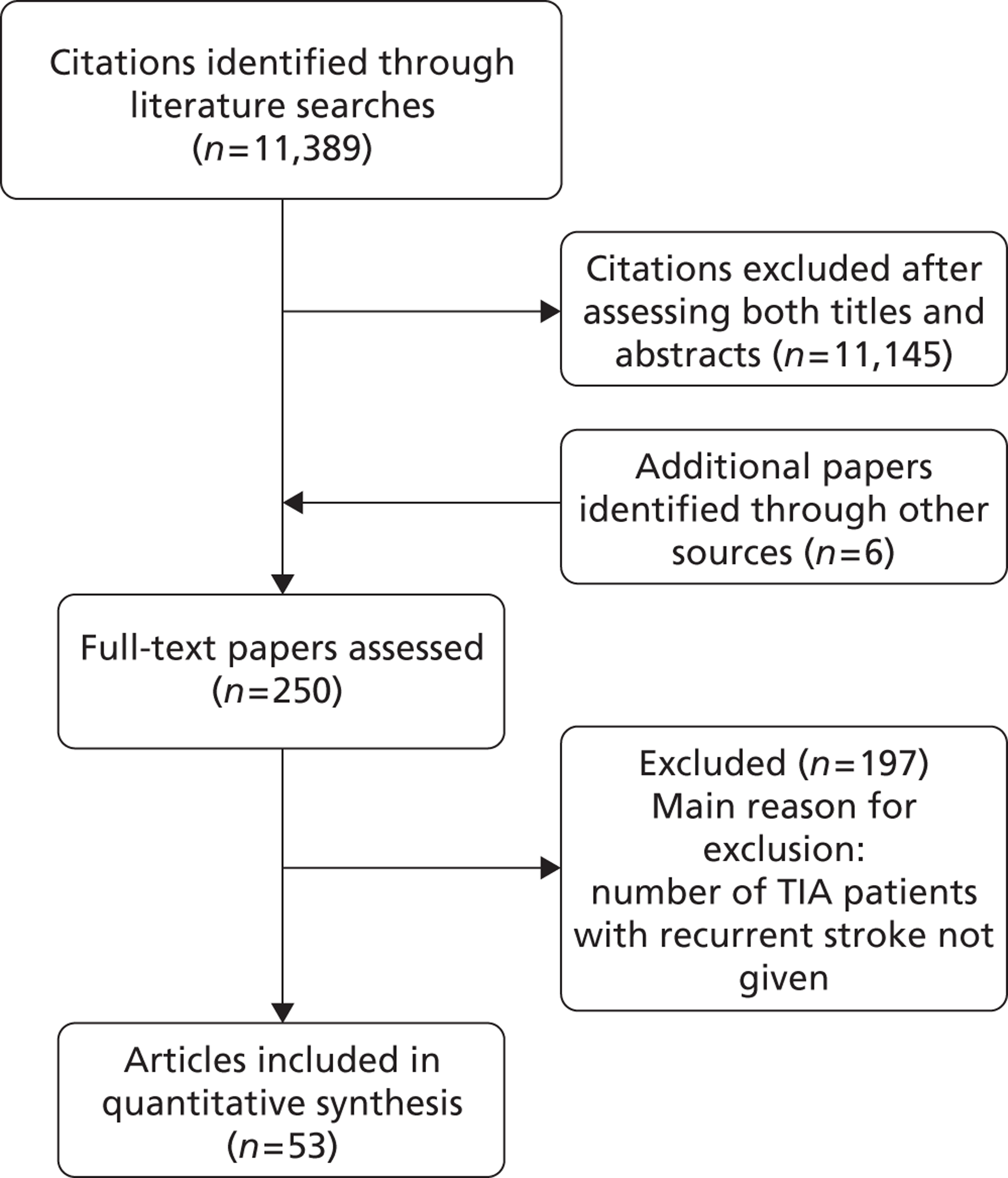

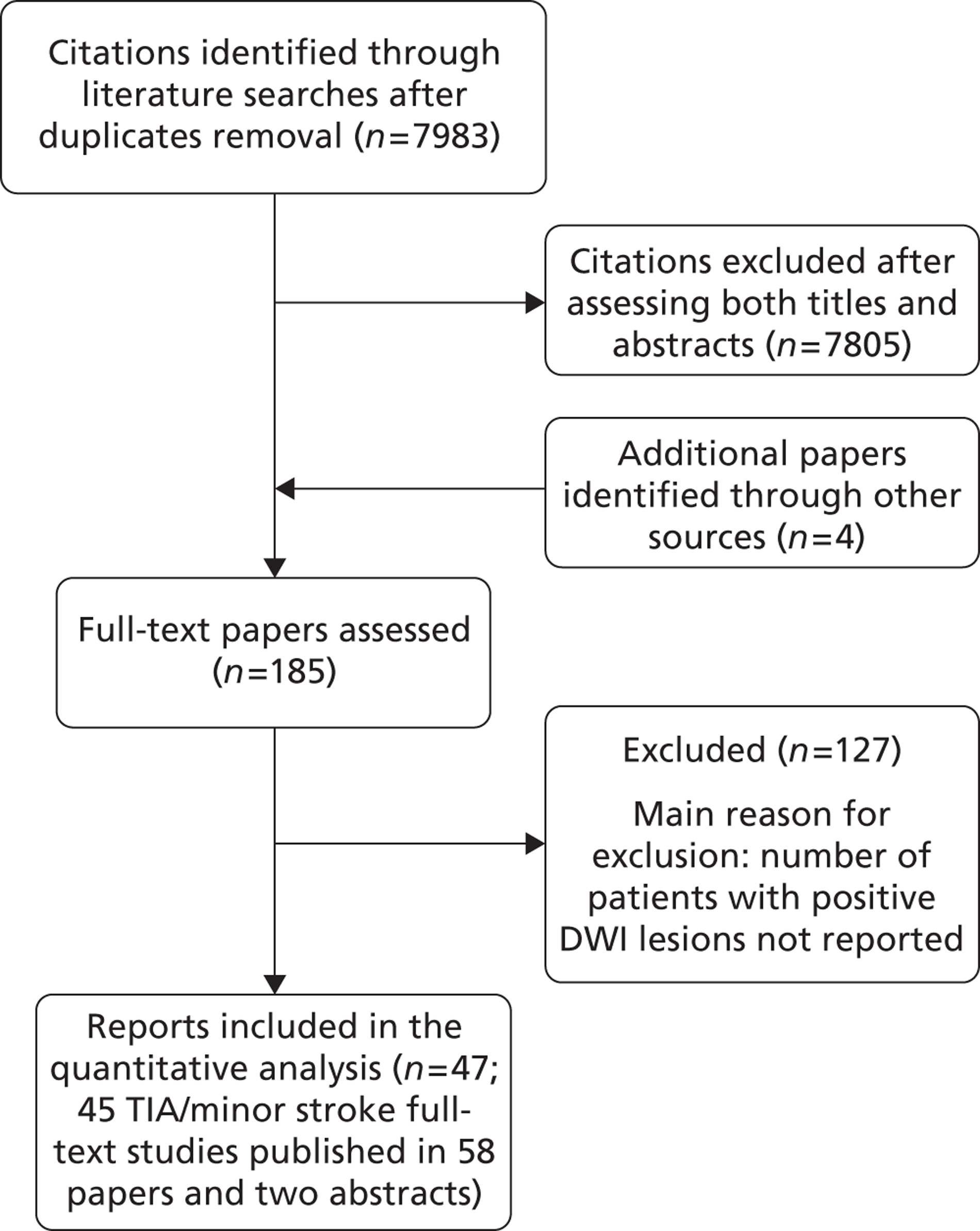

Number of included/excluded studies

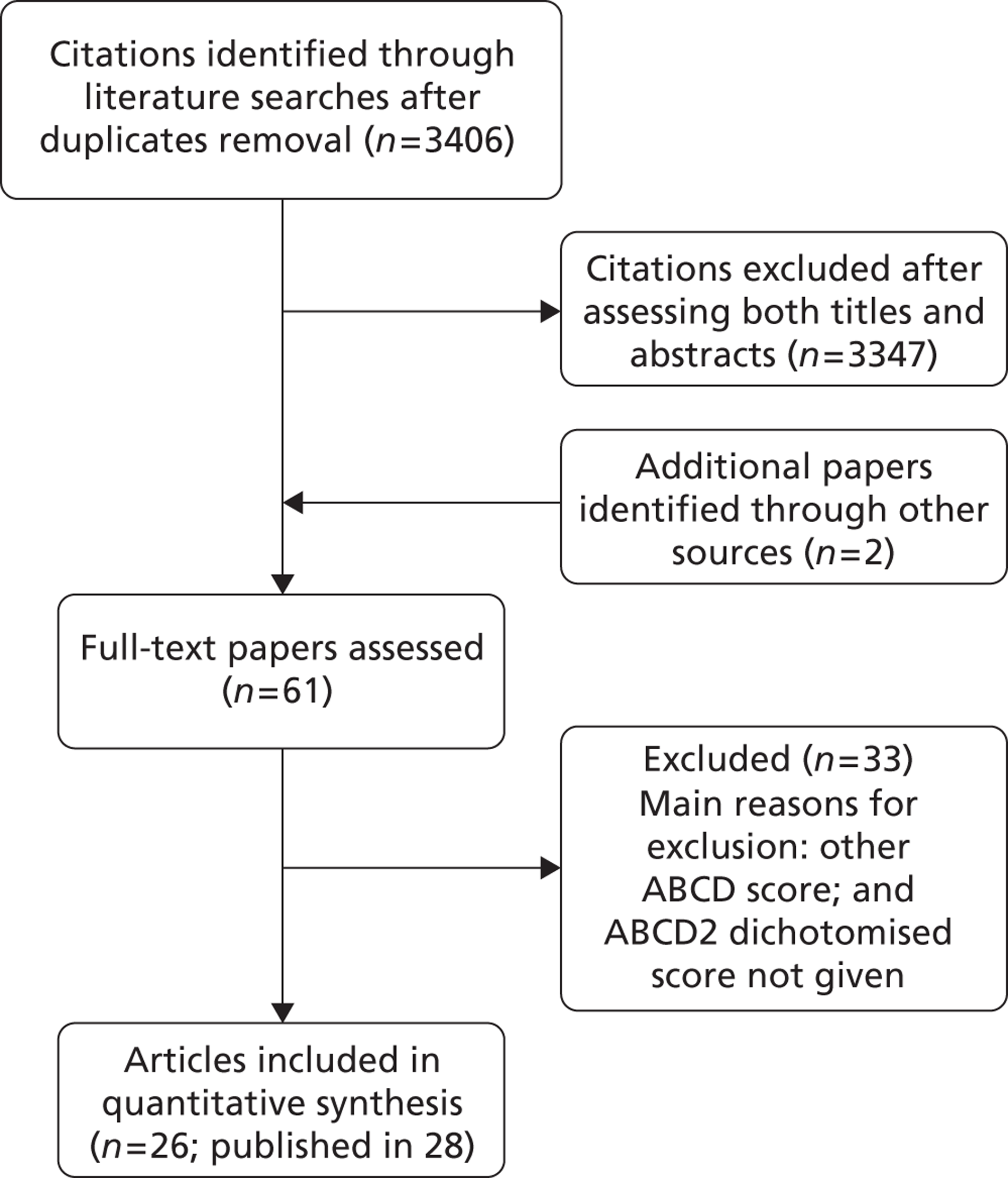

The literature searches identified 11,389 citations. After initial screening of titles and abstracts we selected 248 citations for full-text retrieval. Two additional studies published in 2005 were included after hand-searching of reference lists of relevant studies, yielding a total of 250 studies. After full-text examination, 197 studies were excluded, leaving 53 studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The main reason for exclusion was that the number of recurrent events was not clearly reported (Figure 5). We translated one report published in Spanish; all other included reports were originally published in English. We observed, as have others,125 that some studies come from the same TIA cohorts (i.e. Oxford, north Dublin, California, Massachusetts, Lleida and Paris cohorts) and we experienced difficulty in avoiding double counting of the same patient data appearing in multiple publications. Many studies were published from the same research groups and the same cohorts of patients were described in multiple reports – with some reports assessing more than one patient cohort (i.e. Oxford, north Dublin, California, Massachusetts, Lleida and Paris cohorts). Even although we attempted to exclude multiple publications we found it challenging to identify which cohort was assessed in which study, as precise information were somehow lacking. When a single study included separate cohorts (e.g. community-based TIA patients and patients from specialist unit) for the purpose of the analyses we considered the separate cohorts as coming from separate studies.

FIGURE 5.

Identification and selection of studies.

Characteristics of included studies

The methodological characteristics of selected studies are shown in Table 1.

| Study ID | Setting | Study design | TIA definition | Recurrent TIA included | Time from symptoms onset | Evaluating clinician | Consecutive patients | Follow-up | Recurrence definition (type of events) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lovett and colleagues, 200321 | Population based | Prospective | Time based | No | Median 7 days | Neurologist | Yes | In person | Stroke |

| Lisabeth and colleagues, 2004126 | Population based (multiple EDs) | Prospective | Time based | Yes | NR | Neurologist (records) | No | Clinical records | Stroke (6.8% haemorrhagic) |

| Hill and colleagues, 2004127 | Population based (multiple EDs) | Retrospective | ICD 9 definition | Yes | NR | Emergency medicine physician | No | Clinical records (using ICD codes) | Stroke (1.2% haemorrhagic) |

| Coull and colleagues, 20049 | Population based | Prospective | Time based | Yes | Assessed ‘as soon as possible’ | Neurologist | Yes | In person | Stroke |

| Eliasziw and colleagues, 2004128 | NASCET | Prospective | Time based | Yes (first recorded event considered) | Within 180 days | Neurologist | No | In person | Stroke |

| Gladstone and colleagues, 2004129 | ED | Prospective | Time based | Yes | Median 120 minutes | Emergency medicine physician | Yes | Clinical records | Stroke |

| Kleindorfer and colleagues, 200523 | ED | Retrospective | Time based | Yes | NR | Emergency medicine physician, neurologist (records review) | Yes | Clinical records | Stroke |

| Rothwell and colleagues, 200561 | Population based | Prospective | Time based | Yes | Assessed ‘as soon as possible’ | Neurologist | Yes | In person | Stroke |

| Whitehead and colleagues, 2005130 | TIA clinics | Retrospective | NR | NR | NR | Stroke physician | Yes | Clinical records | Not clear |

| Van Wijk and colleagues, 200565 | Hospital | Prospective | Time based | NR | Within 3 months (near 23% within 7 days) | Neurologist | No | In person, letters, records | Stroke |

| Correia and colleagues, 2006119 | Population based | Prospective | Time based | No | 48% < 48 hours and 62% < 7 days | Neurologist | Yes | In person | Stroke |

| Bray and colleagues, 2007131 | ED | Retrospective | Time based | NR | Median 135 minutes | Emergency medicine physician | Yes | Clinical records (64%), telephone (36%) | Stroke |

| Johnston and colleagues, 200762 | ED | Retrospective | Time based | Yes | < 24 hours | Emergency medicine physician | Yes | Clinical records | Stroke (distinguishable from index TIA) |

| TIA clinic | Prospective | Time based | Yes | Assessed ‘as soon as possible’ | Neurologist | Yes | In person | Stroke | |

| Koton and colleagues, 2007132 | Population based | Prospective | Time based | Yes | Assessed ‘as soon as possible’ | Neurologist | Yes | In person | Stroke |

| Lavallée and colleagues, 2007122 | Specialist unit | Prospective | Time based | Not clear; patients with past medical history of CV disease included | 61% with < 48 hours and 75% with < 7 days of symptoms | Neurologist | Yes | In person, telephone | Stroke |

| Rothwell and colleagues, 200724 | TIA clinic | Prospective | Time based | Yes | 57% within 24 hours | Neurologist | Yes | In person | Stroke |

| Wu and colleagues, 2007120 | Hospital | Retrospective | NR | Yes | Immediately | NR | Yes | Clinical records | Probably stroke |

| Atanassova and colleagues, 2008133 | Hospital | Prospective | Time baseda | No | NR | Neurologist | Yes | In person | Stroke |

| bCoutts and colleagues, 2008134 | ED | Prospective | Time based | Yes | < 12 hours | Neurologist | Yes | In person | Stroke |

| bJosephson and colleagues, 2008135 | ED | Retrospective | Time based | Yes | < 24 hours | Emergency medicine physician | Yes | Clinical records | Stroke (distinguishable from index TIA) |

| Ois and colleagues, 200881 | Hospital | Prospective | Time based | Yes | Median 12 hours | Neurologist | Yes | In person, telephone | Stroke |

| Sciolla and Melis, 200869 | ED | Prospective | Time based | Not clear; patients with past medical history of CV disease were included | < 24 hours | Neurologist | Yes | In person, telephone | Stroke |

| Asimos and colleagues, 2009136 | ED | Prospective | Time based | Yes (first TIA included) | < 24 hours | Emergency medicine physician | No | Clinical records | Disabling stroke (mRS ≥3) |

| Ay and colleagues, 200987 | ED | Retrospective | Time based | NR | < 24 hours | Neurologist | Yes | Clinical records | Stroke |

| Calvet and colleagues, 2009137 | Specialist unit | Retrospective | Time based | Yes | < 48 hours | Neurologist | Yes | In person, telephone | Stroke |

| Chatzikonstantinou and colleagues, 2009138 | Specialist unit | Prospective | Time based | Yes | < 24 hours | NR | Yes | In person | Stroke |

| Cucchiara and colleagues, 2009139 | Specialist unit | Prospective | Time based | NR | < 48 hours | Neurologist | Yes | In person, telephone | Stroke |

| bFothergill and colleagues, 2009140 | Population based | Retrospective | Time based | No | < 72 hours | Neurologist (records) | Yes | Clinical records | Stroke |

| Mlynash and colleagues, 2009141 | Specialist unit | Prospective | Time based | Yes | < 48 hours | Neurologist | Yes | NR | Stroke |

| Tan and colleagues, 2009142 | Hospital | Prospective | Time based | NR | < 48 hours | Neurologist | Yes | NR | Stroke |

| Asimos and colleagues, 2010143 | ED | Prospective | Time based | Yes (first TIA included) | < 24 hours | Emergency medicine physician | No | Clinical records | Stroke |

| Chandratheva and colleagues, 2010144 | Population based | Prospective | Time based | Yes | Assessed ‘as soon as possible’ | Neurologist | Yes | In person | Stroke |

| Harrison and colleagues, 2010145 | TIA clinic | Retrospective | NR | NR | Median 15 days | Stroke physician | Yes | Clinical records | Stroke (ICD-9 definition) |

| Holzer and colleagues, 2010146 | Specialist unit | Retrospective | Time based | Yes | NR | Neurologist | Yes | Telephone, interview, medical records | Stroke |

| Merwick and colleagues, 2010147 | Population based | Retrospective | Time based | Yes | NR | Stroke physician | Yes | In person, telephone- clinical records | Stroke |

| Nakajima, and colleagues, 2010148 | Hospital | Prospective | Time based | Yes | NR | Neurologist | Yes | Clinical records, telephone interview | Stroke (TIA – asymptomatic brain infarction excluded) |

| Ong and colleagues, 2010149 | ED | Retrospective | Time based | NR | NR | Emergency medicine physician | Yes | In person | Stroke |

| Purroy and colleagues, 2010150 | Specialist unit | Prospective | Time based | Yes | < 48 hours | Neurologist | Yes | In person | Stroke |

| Sheehan and colleagues, 2010151 | Population based | Prospective | Time based | Yes | Median time 24 hours | Stroke physician | Yes | In person | Stroke |

| Tsivgoulis and colleagues, 2010152 | Hospital | Prospective | Time based | Yes | NR | Neurologist | Yes | In person | Stroke |

| Wasserman and colleagues, 2010153 | ED | Prospective | NR | NR | Within 7 days (68% < 24 hours) | Emergency medicine physician | No | Telephone questionnaire, records | Stroke |

| Weimar and colleagues, 2010154 | Specialist unit | Prospective | Time based | Yes | < 24 hours in 92%c | Neurologist | Yes | Telephone, paper questionnaire | Stroke |

| Yang and colleagues, 2010155 | Hospital | Retrospective | NR | Yes | NR | NR | Yes | In person, telephone | Stroke |

| Amort and colleagues, 2011156 | ED | Prospective | Time based | NR | NR | Neurologist | Yes | In person, telephone | Stroke |

| Arsava and colleagues, 2011157 | ED | Retrospective | Transient symptoms + DWI visible infarct | Yes | < 24 hours | Neurologistd | Yes | Clinical records | Stroke (new symptoms + visible DWI lesion) |

| Bonifati and colleagues, 2011158 | ED | Retrospective | Time based | Yes | NR | Neurologist and emergency medicine physician | Yes | Telephone interview, clinical records | Stroke (confirmed by brain imaging) |

| Kim and colleagues, 2011159 | ED | Retrospective | Time based | Yes | NR | Emergency medicine physician | No | Clinical records | Stroke (distinguishable from index TIA) |

| Meng and colleagues, 2011160 | Hospital | Prospective | Time based | Yes | Within 7 days | Neurologist | Yes | In person, clinical records | Stroke |

| Olivot and colleagues, 2011161 | ED | Prospective | Time based | NR | < 24 hours in 92% | Neurologist, stroke physician | Yes | In person, telephone interview | Stroke |

| Sanders and colleagues, 2011162 | Hospital | Retrospective | Time based | NR | NR | Emergency medicine and stroke physician | Yes | Clinical records, telephone | Stroke |

| Stead and colleagues, 2011163 | ED | Retrospective | Time based | Yes | NR | Mainly emergency medicine physician | Yes | Telephone interview, clinical records | Stroke |

| Amarenco and colleagues, 2012164 | Specialist unit | Prospective | Time based | Not clear; patients with past medical history of CV disease included | NR | Neurologist | Yes | In person, telephone interview | Stroke |

| Purroy and colleagues, 2012165 | Specialist unit | Prospective | Time based | Yes | < 48 hours | Neurologist | Yes | In person | Stroke |

The 53 studies varied in their primary objectives. Eleven were population-based studies including cohorts from the UK (Oxford), Ireland (Dublin), USA (Texas and Minnesota), Canada (Alberta) and northern Portugal. 9,21,61,119,126,127,132,140,144,147,151 Seventeen were ED-based studies,23,69,87,129,131,134–136,143,149,153,156–159,161,163 three were focused on TIA clinics (one included OXVASC participants),24,130,145 10 were hospital-based studies (the authors of which did not describe characteristics of the hospital unit),65,81,120,133,142,148,152,155,160,162 10 recruited patients admitted to a specialist unit [including stroke unit, neurological ward or highly-specialised neurovascular (NV) clinics],122,137–139,141,146,150,154,164,165 one focused on patients attending ED and TIA clinics (including OXVASC participants)62 and one128 recruited patients as part of a hospital-based clinical trial. The 53 studies included a total of 30,558 participants. The risk of recurrent stroke at 7 days was reported in 28 studies (30 cohorts) of 12,332 participants, 34 studies (35 cohorts) of 19,769 participants reported the stroke risk at 90 days and nine studies of 8699 participants reported the stroke risk > 90 days. For studies reporting the stroke risk > 90 days, the length of follow-up ranged from 6 months to 14 years.

The study design was prospective in 33 studies9,21,24,61,65,69,81,119,122,126,128,129,132–134,136,138,139,141–144,148,150–154,156,160,161,164,165 and retrospective in 19;23,87,120,127,130,135,137,140,145–147,149,155,157–159,162,163 one study62 included two cohorts recruited prospectively and retrospectively. Participants were included consecutively in 45 studies. The diagnosis of TIA was made by a neurologist or stroke physician in 36 studies,9,21,24,61,65,69,81,87,119,122,126,128,130,132–134,137,139–142,144–148,150–152,154,156,157,160,161,164,165 by an emergency medicine physician in 10 studies,23,127,129,131,135,136,143,149,153,159 and by both in four;62,158,162,163 in three studies120,138,155 this information was not reported.

With respect to the timing of patient assessment after the index event, in 10 studies TIA patients were assessed within 24 hours of symptoms onset,62,69,87,134–136,138,143,155,161 in six studies within 48 hours,137,139,141,142,150,165 in one study140 within 72 hours and in one study160 within 7 days. Another four studies9,61,132,144 reported that ‘patients were assessed as soon as possible after the event’ but did not give a time. One study62 (including two cohorts) assessed patients within 24 hours and ‘as soon as possible after the event’, another study120 assessed patients ‘immediately’ after the event, and in three studies65,128,145 the timing of assessment was beyond 7 days. The remaining 27 studies did not clearly provide this information (see Table 1). Four studies included patients with first-ever TIA, 34 included either first-ever or recurrent TIA, and in 15 studies the authors did not report this information.

The majority of studies (n = 46) used a time-based definition of TIA (see Table 1), one study145 recruited patients retrospectively from clinical records using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Ninth Edition, definition of TIA, one study157 included just patients with transient symptoms and DWI visible lesion, in five studies the information was not reported. One study128 included a highly selected sample of patients with TIA and carotid stenosis, and three studies65,141,155 excluded patients with specific conditions [i.e. cardioembolic events or blood coagulation disorders, AF and posterior circulation TIAs, respectively].

The ascertainment of stroke events after TIA was carried out by face-to-face patient assessment or telephone interviews in 25 studies,9,21,24,61,69,81,119,122,128,132–134,137–139,144,149–152,155,156,161,164,165 by medical records in 15 studies,23,62,87,120,126,127,129,130,130,135,136,140,143,145,157,159 by mixed methods involving face-to-face assessment plus another method (i.e. telephone interviews, medical records, letters) in 11 studies,65,131,146–148,153,154,158,160,162,163 and was not reported in two studies. 141,142

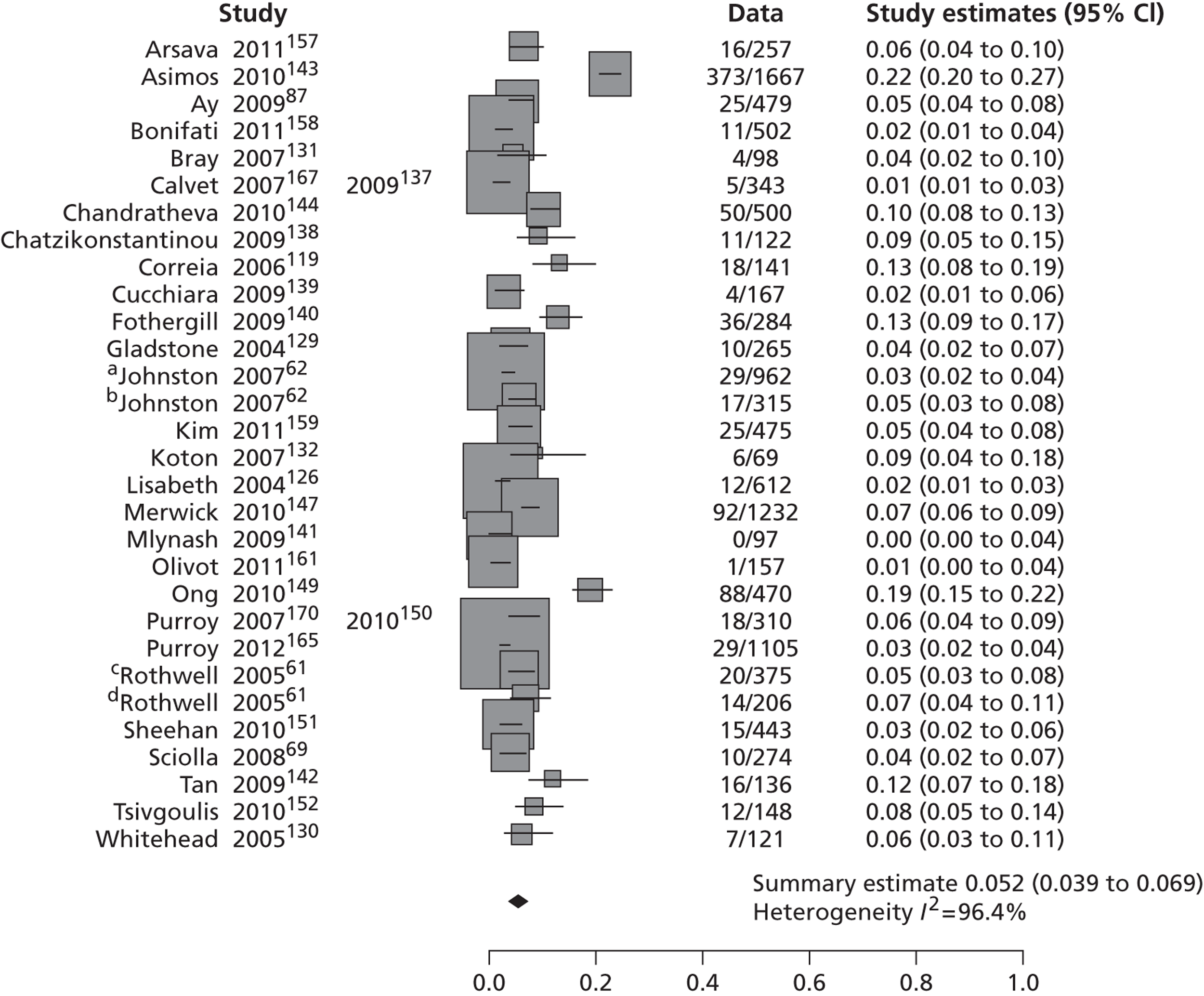

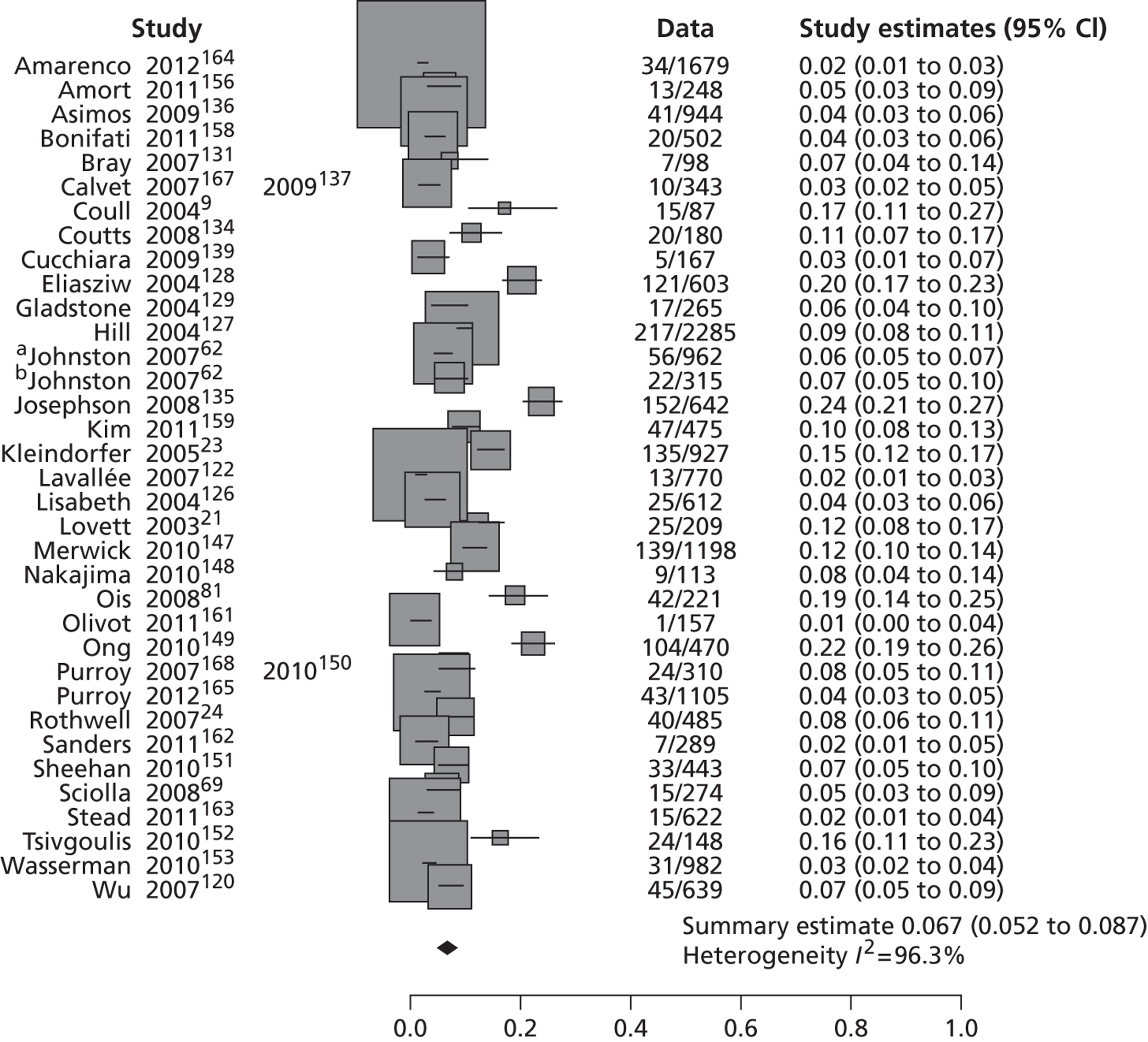

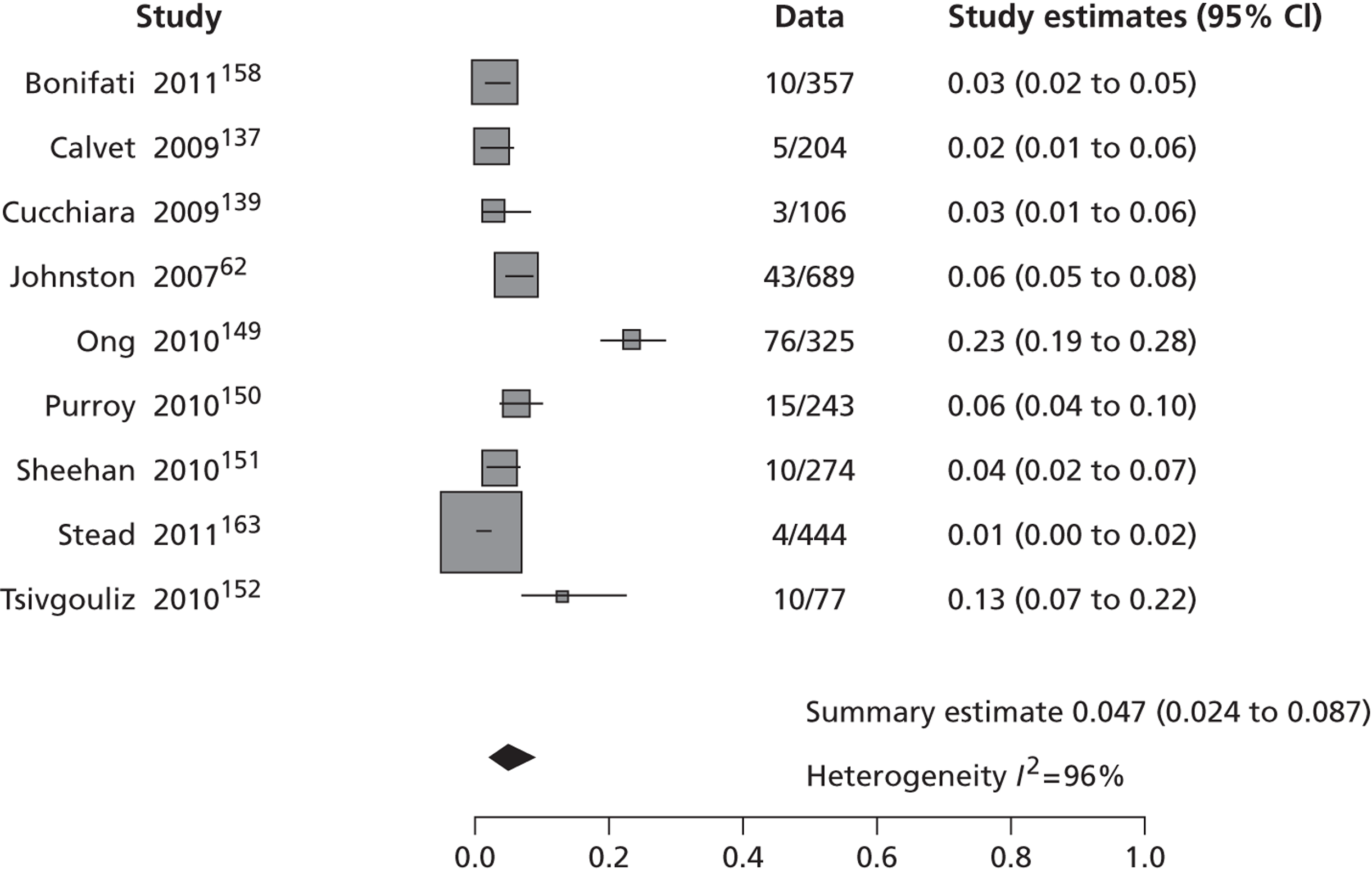

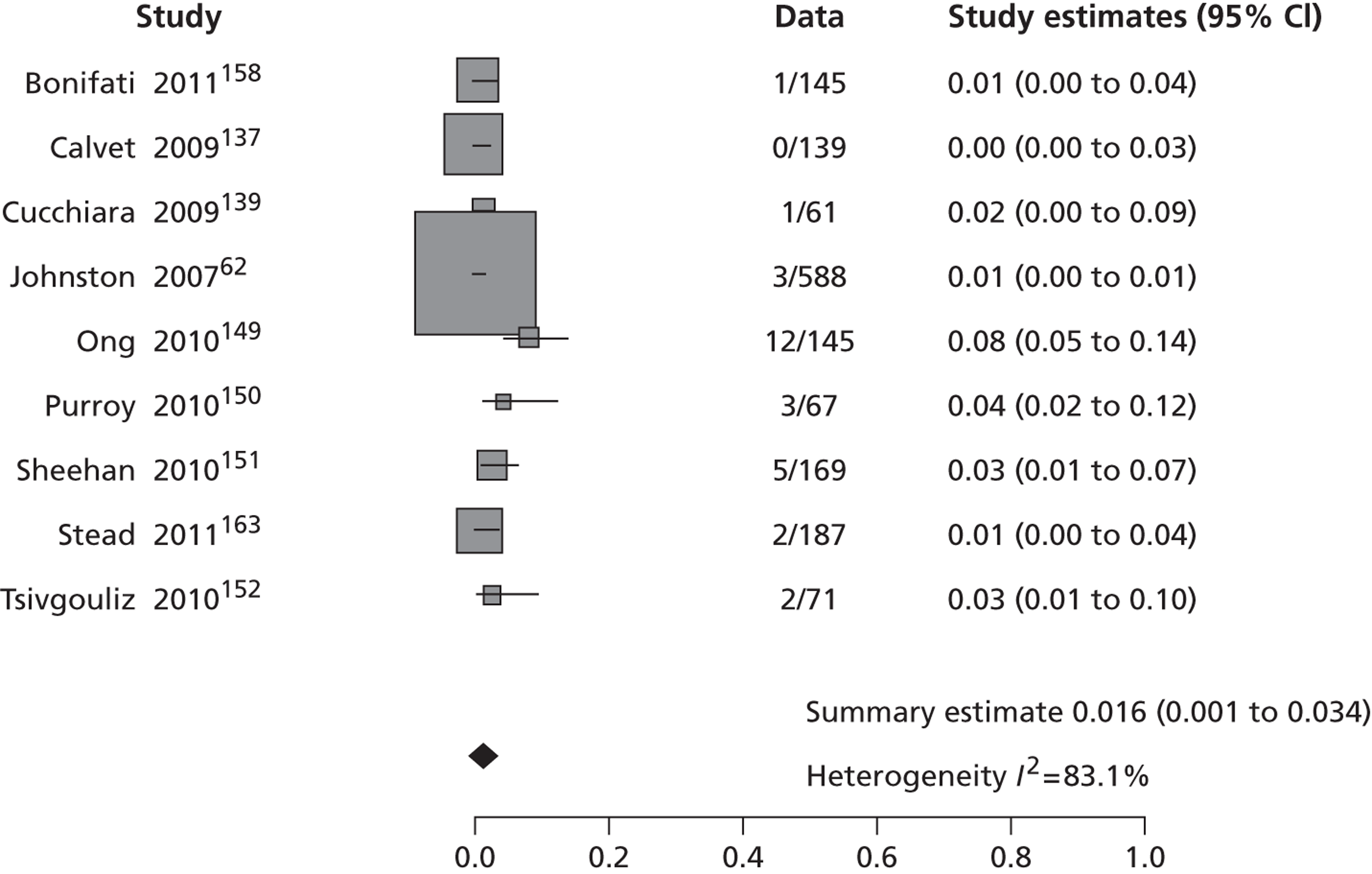

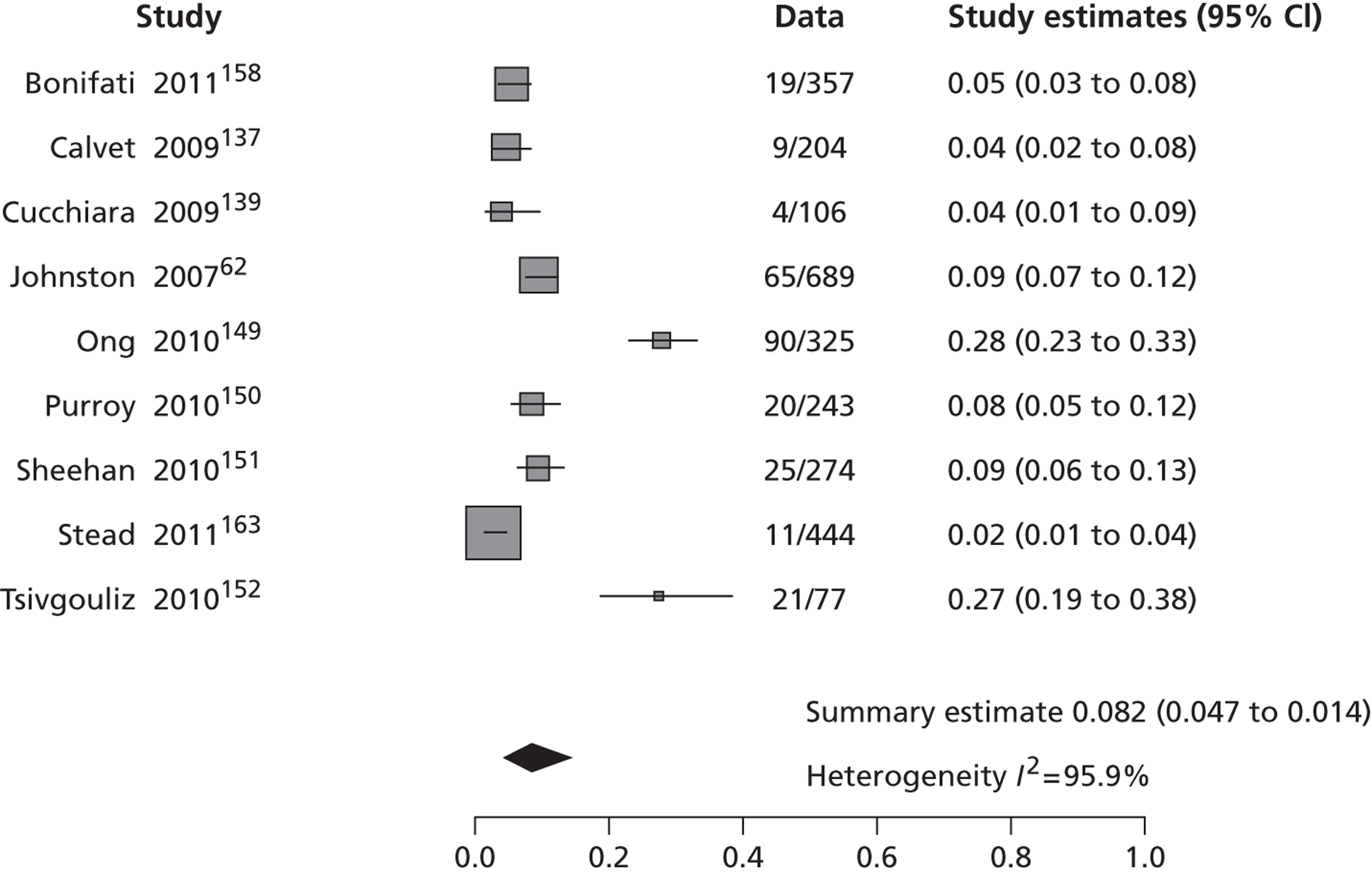

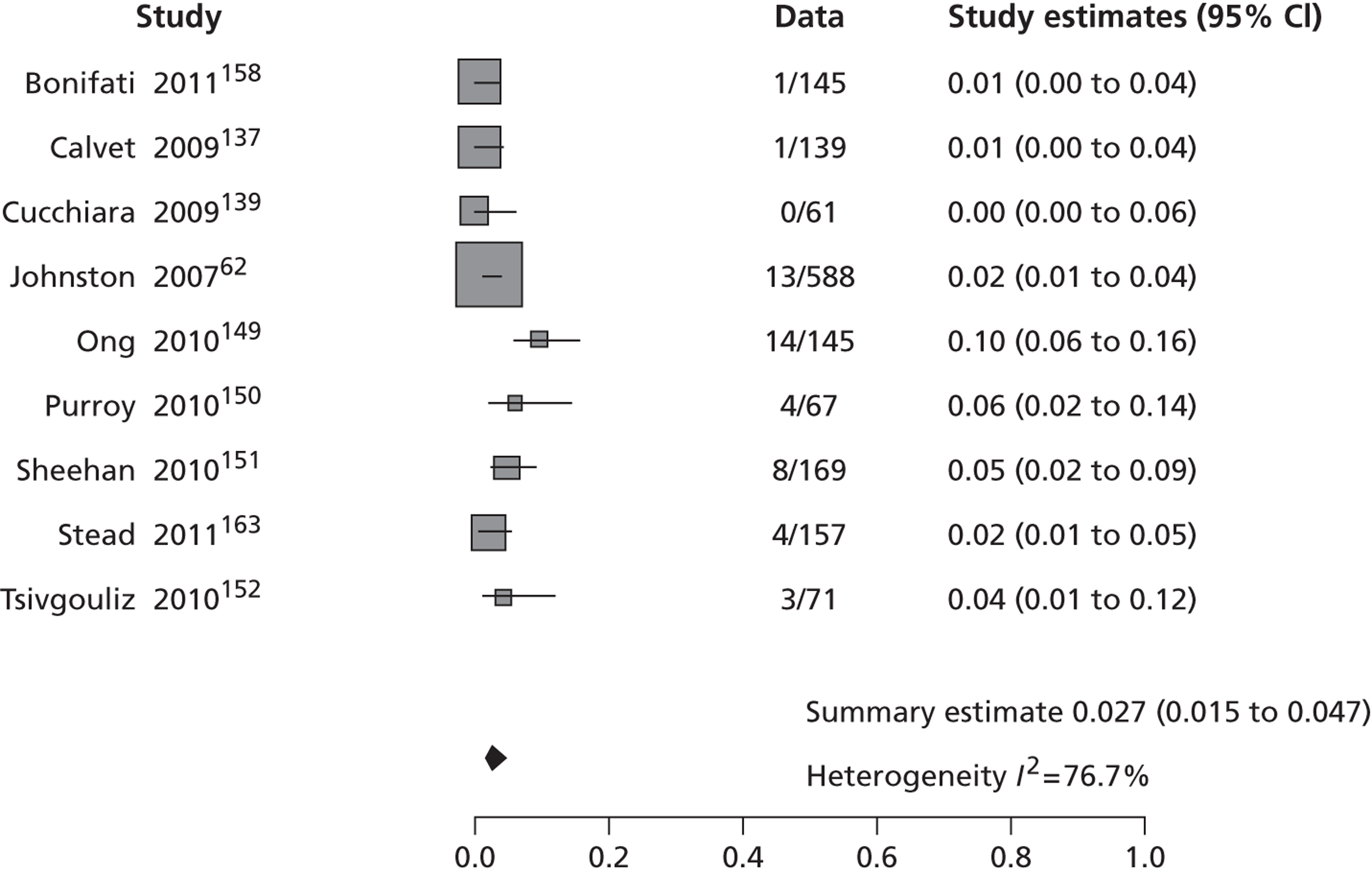

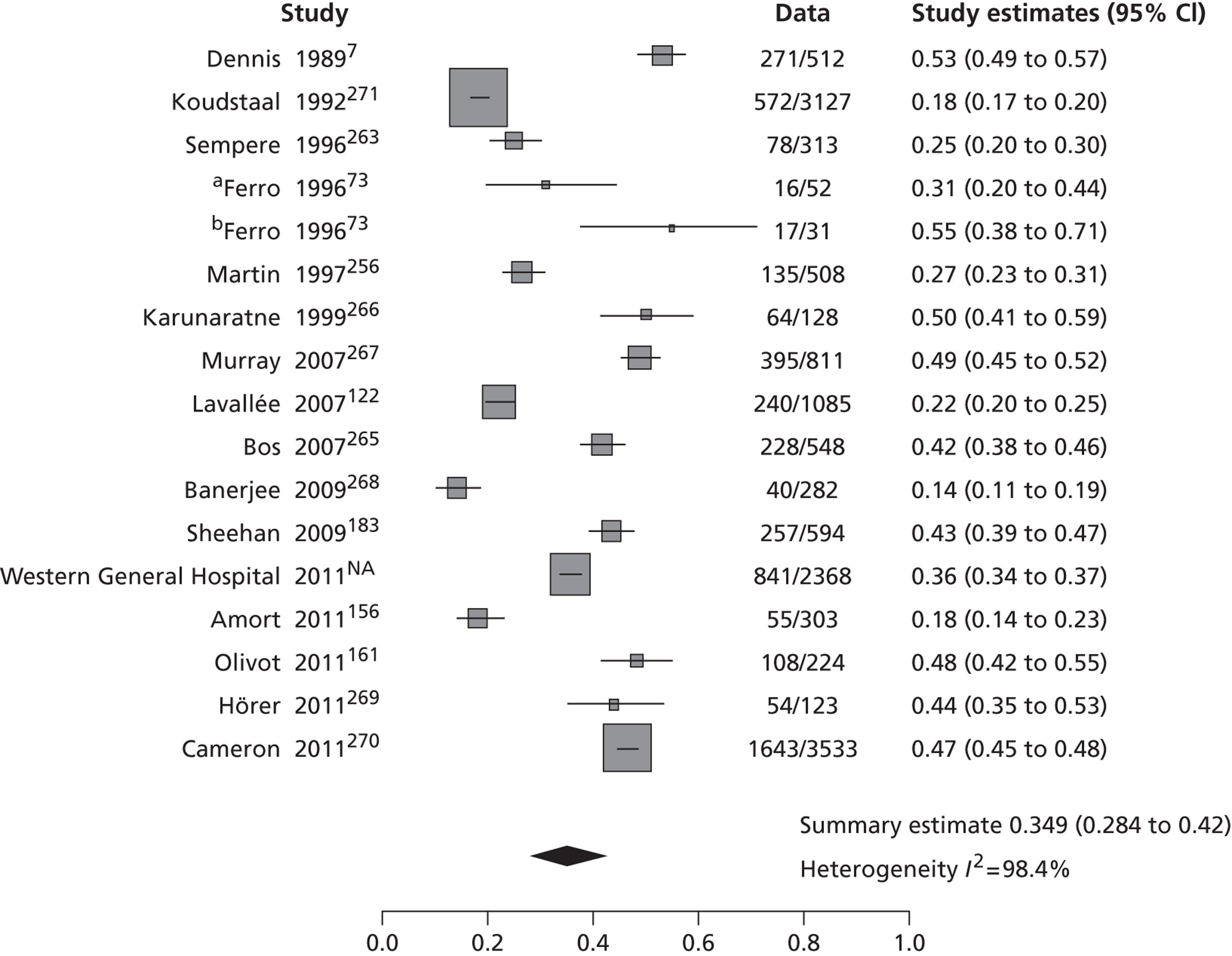

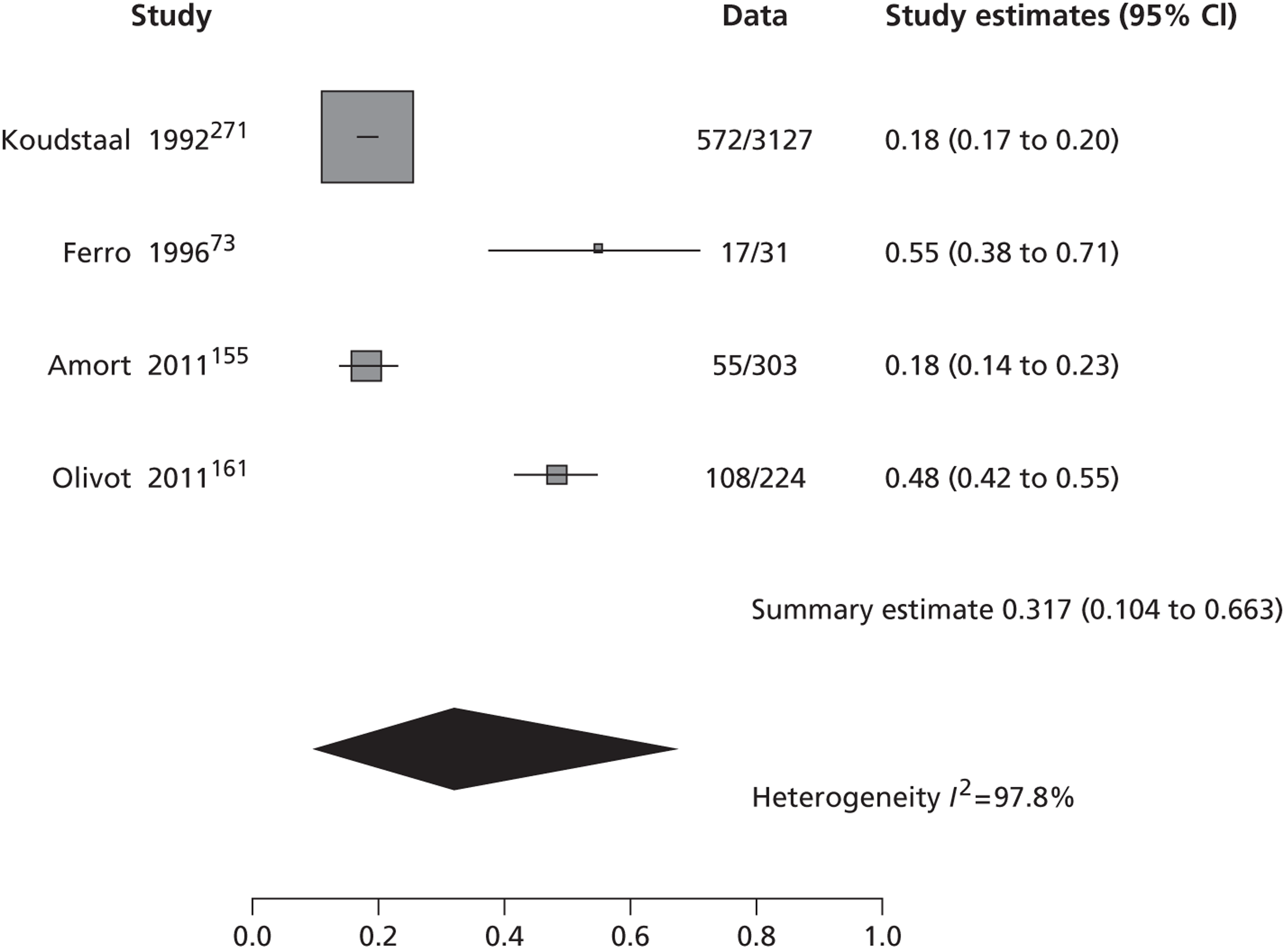

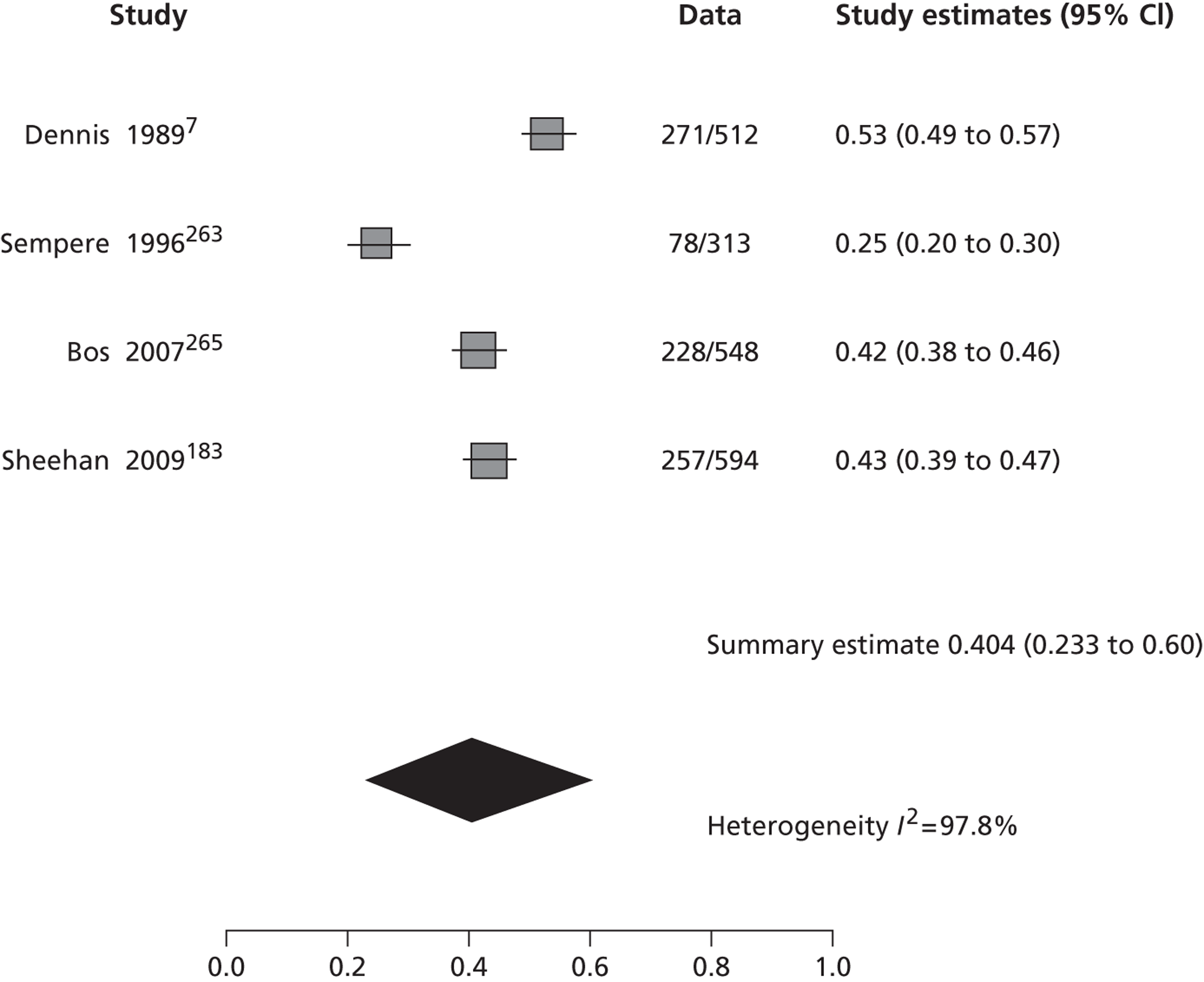

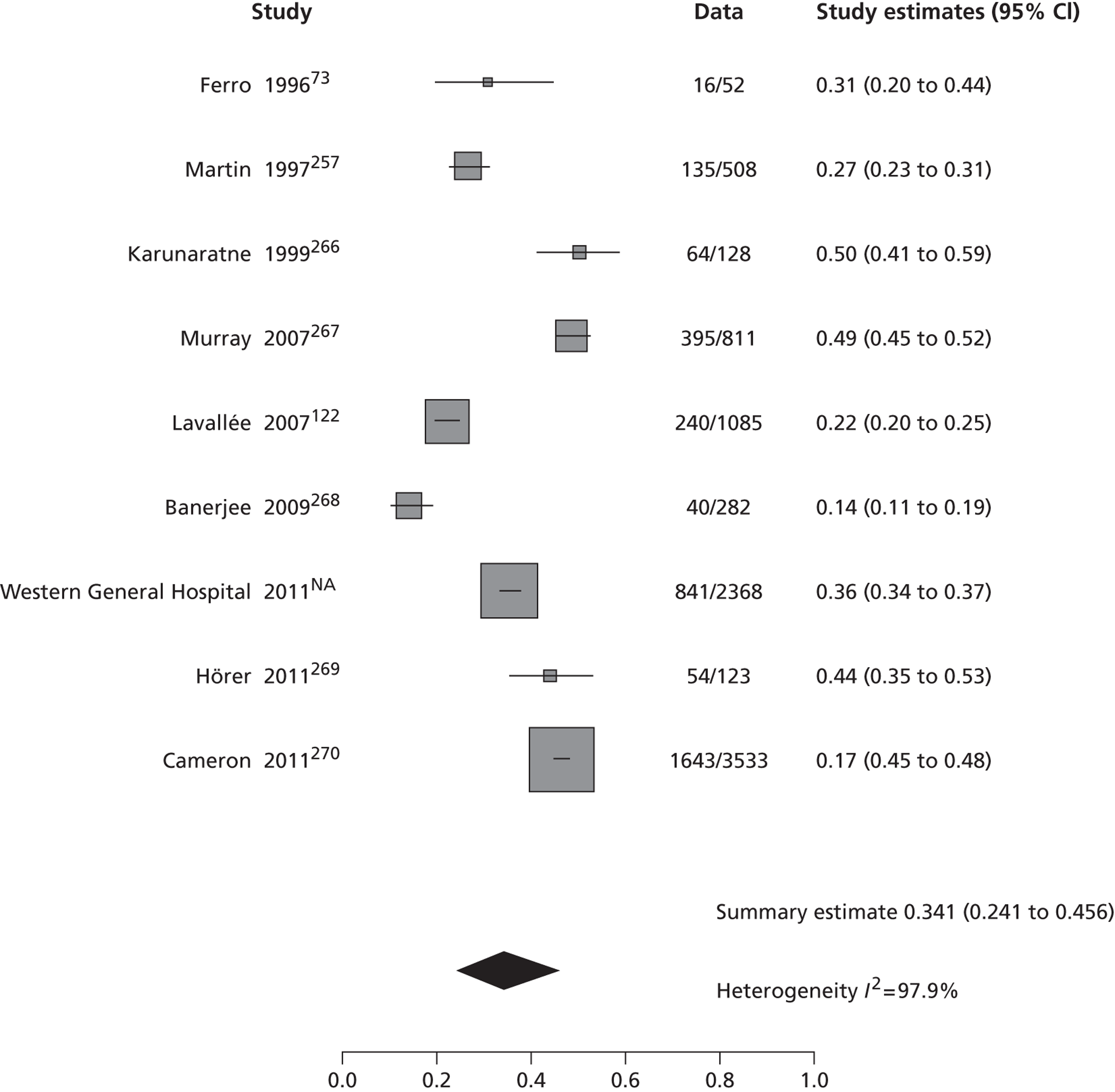

Main findings

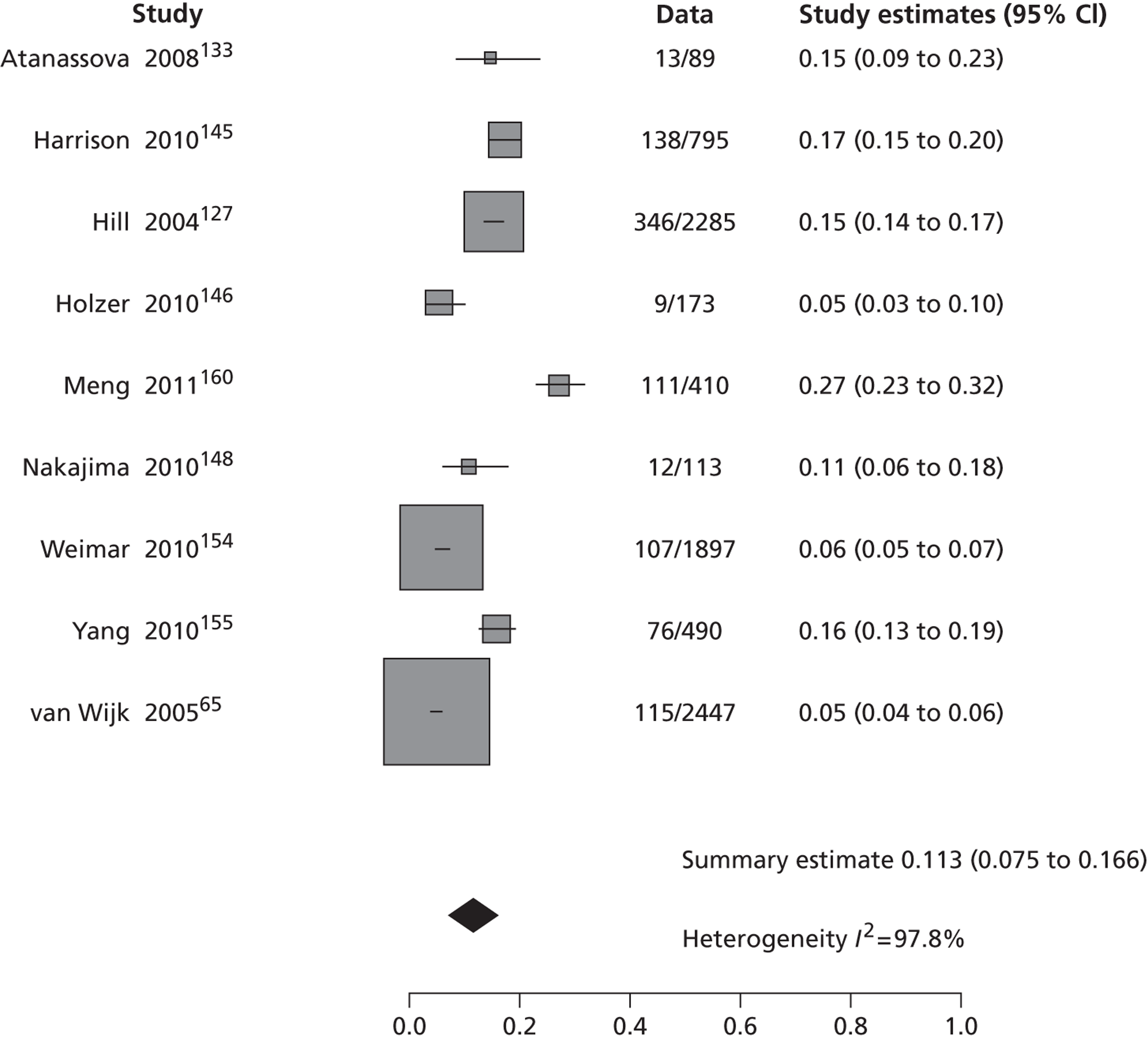

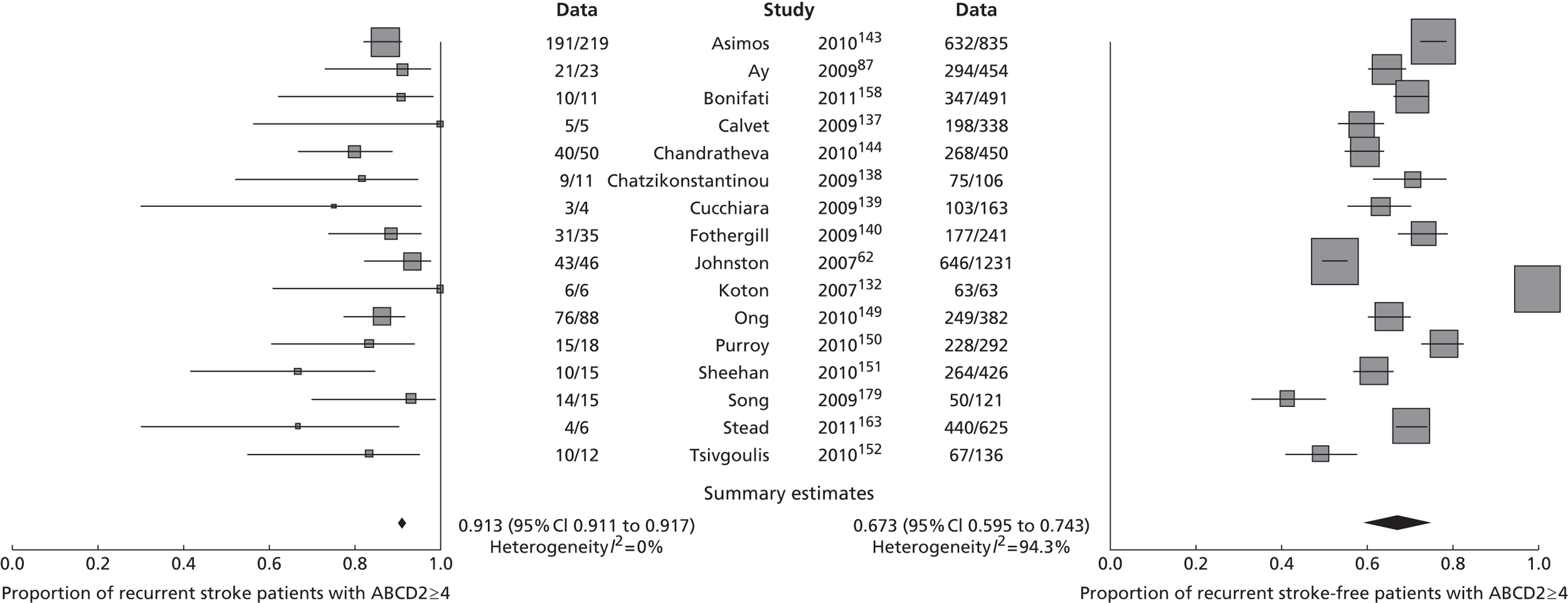

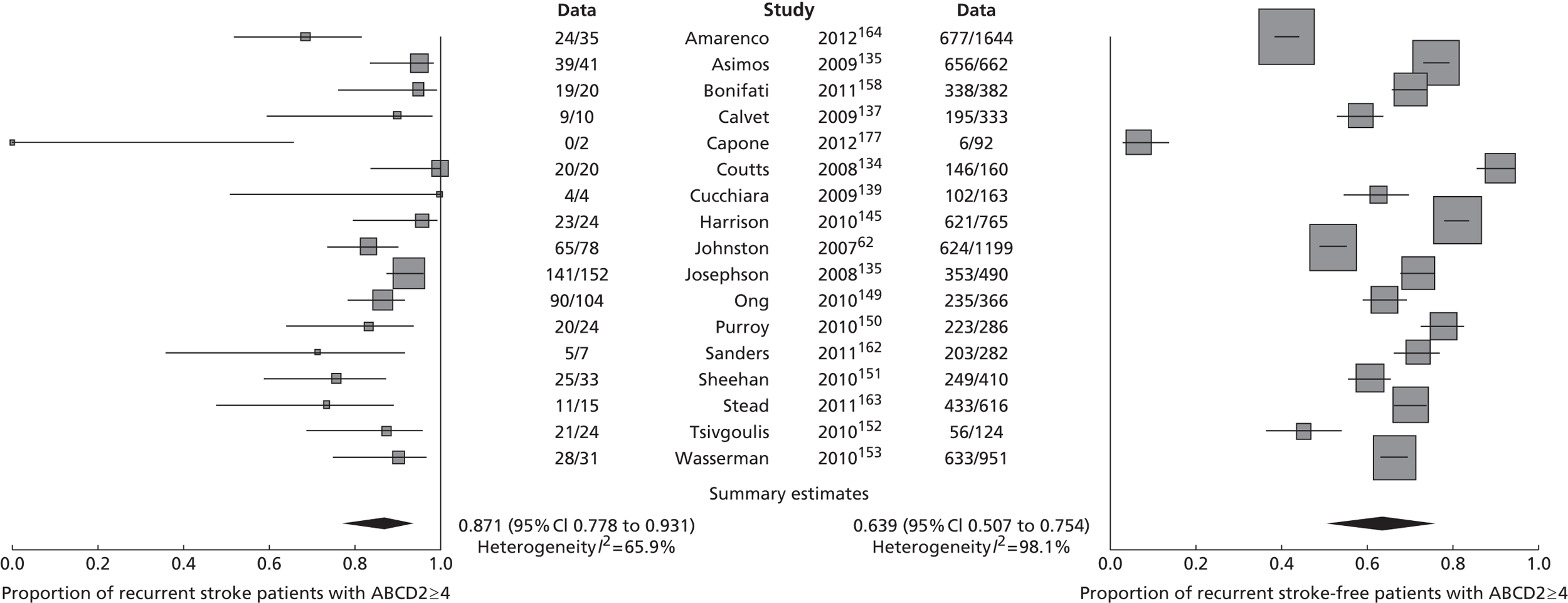

Table 2 shows the proportion of patients with stroke recurrence reported in all studies at different time points. The number of events was 974 out of 12,332 patients for studies reporting stroke risk at 7 days, 1567 out of 19,803 patients for risk at 90 days, and 927 out of 8699 patients for risk > 90 days. The risk of stroke reported across studies ranged from 0.0% to 22.4% at 7 days, 0.6% to 23.7% at 90 days, and 4.7% to 27% at > 90 days. There was evidence of significant heterogeneity between studies; the I2-statistics were 96.4%, 96.3%, and 97.8% for stroke risk at 7, 90 and > 90 days, respectively. Using random-effects meta-analysis, the pooled risk of stroke was 5.2% (95% CI 3.9% to 5.9%) at 7 days, and 6.7% (95% CI 5.2% to 8.7%) at 90 days. For stroke risk at > 90 days the pooled estimate was 11.3% (95% CI 7.5% to 16.6%). Figures 6–8 show the forest plots for studies reporting the proportion of patients with stroke recurrence at 7, 90 and > 90 days after index TIA.

| Study ID | Size | Setting | Study design | Percentage of stroke recurrence (n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 days | 90 days | > 90 days | |||||||

| Lovett and colleagues, 200321 | 209 | Population based | Prospective | 12.0 | (25) | ||||

| Lisabeth and colleagues, 2004126 | 612 | Population based | Prospective | 1.9 | (12) | 4.0 | (25) | ||

| Hill and colleagues, 2004127 | 2285 | Population based | Retrospective | 9.5 | (217) | 15.1 | (346) | ||

| Coull and colleagues, 20049 | 87 | Population based | Prospective (OXVASC) | 17.2 | (15) | ||||

| Eliasziw and colleagues, 2004128 | 603 | NASCET | Prospective | 20.1 | (121) | ||||

| Gladstone and colleagues, 2004129 | 265 | ED | Prospective | 3.8 | (10) | 6.4 | (17) | ||

| Kleindorfer and colleagues, 200523 | 927 | ED | Retrospective | 14.6 | (135) | ||||

| Rothwell and colleagues, 200561 | 375 | Population based | Prospective (OXVASC) | 5.3 | (20) | ||||

| 206 | Prospective (TIA clinic) | 6.8 | (14) | ||||||

| Whitehead and colleagues, 2005130 | 121 | TIA clinics | Retrospective | 5.8 | (7) | ||||

| Van Wijk and colleagues, 200565 | 2447 | Hospital | Prospective | 4.7 | (115) | ||||

| Correia and colleagues, 2006119 | 141 | Population based | Prospective | 12.8 | (18) | ||||

| Bray and colleagues, 2007131 | 98 | ED | Retrospective | 4.0 | (4) | 7.1 | (7) | ||

| Johnston and colleagues, 200762 | 962 | ED | Retrospective (California) | 3.0 | (29) | 5.8 | (56) | ||

| 315 | TIA clinic | Prospective (Oxford) | 5.4 | (17) | 7.0 | (22) | |||

| Koton and colleagues, 2007132 | 69 | Population based | Prospective (OXVASC) | 8.7 | (6) | ||||

| Lavallée and colleagues, 2007122 | 770 | Specialist unit | Prospective | 1.7 | (13) | ||||

| Rothwell and colleagues, 200724 | 485 | TIA clinic | Prospective (OXVASC) | 8.2 | (40) | ||||

| Wu and colleagues, 2007120 | 639 | Hospital | Retrospective | 7.0 | (45) | ||||

| Atanassova and colleagues, 2008133 | 89 | Hospital | Prospective | 14.6 | (13) | ||||

| aCoutts and colleagues, 2008134 | 180 | ED | Prospective | 11.1 | (20) | ||||

| aJosephson and colleagues, 2008135 | 642 | ED | Retrospective (California) | 23.7 | (152) | ||||

| Ois and colleagues, 200881 | 221 | Hospital | Prospective | 19.0 | (42) | ||||

| Sciolla and Melis, 200869 | 274 | ED | Prospective | 3.6 | (10) | 5.5 | (15) | ||

| Asimos and colleagues, 2009136 | 944 | ED | Prospective (North Carolina) | 4.3 | (41) | ||||

| Ay and colleagues, 200987 | 479 | ED | Retrospective (Boston) | 5.2 | (25) | ||||

| Calvet and colleagues, 2009137 | 343 | Specialist unit | Retrospective | 1.5 | (5) | 3.0 | (10) | ||

| Chatzikonstantinou and colleagues, 2009138 | 122 | Specialist unit | Prospective | 9.0 | (11) | ||||

| Cucchiara and colleagues, 2009139 | 167 | Specialist unit | Prospective | 2.4 | (4) | 3.0 | (5) | ||

| aFothergill and colleagues, 2009140 | 284 | Population based | Retrospective | 12.7 | (36) | ||||

| Mlynash and colleagues, 2009141 | 97 | Specialist unit | Prospective | 0.0 | (0) | ||||

| Tan and colleagues, 2009142 | 136 | Hospital | Prospective | 11.8 | (16) | ||||

| Asimos and colleagues, 2010143 | 1667 | ED | Prospective (North Carolina) | 22.4 | (373) | ||||

| Chandratheva and colleagues, 2010144 | 500 | Population based | Prospective (OXVASC) | 10.0 | (50) | ||||

| Harrison and colleagues, 2010145 | 795 | TIA clinic | Retrospective | 17.4 | (138) | ||||

| Holzer and colleagues, 2010146 | 173 | Specialist unit | Retrospective | 5.2 | (9) | ||||

| Merwick and colleagues, 2010147 | 1232 | Population based | Retrospective (OXVASC and Dublin) | 7.5 | (92) | 12.0 | (139) | ||

| Nakajima and colleagues, 2010148 | 113 | Hospital | Prospective | 8.0 | (9) | 10.6 | (12) | ||

| Ong and colleagues, 2010149 | 470 | ED | Retrospective | 18.7 | (88) | 22.1 | (104) | ||

| Purroy and colleagues, 2010150 | 310 | Specialist unit | Prospective | 5.8 | (18) | 7.8 | (24) | ||

| Sheehan and colleagues, 2010151 | 443 | Population based | Prospective (Dublin) | 3.4 | (15) | 7.5 | (33) | ||

| Tsivgoulis and colleagues, 2010152 | 148 | Hospital | Prospective | 8.1 | (12) | 16.2 | (24) | ||

| Wasserman and colleagues, 2010153 | 982 | ED | Prospective | 3.2 | (31) | ||||

| Weimar and colleagues, 2010154 | 1897 | Specialist unit | Prospective | 5.6 | (107) | ||||

| Yang and colleagues, 2010155 | 490 | Hospital | Retrospective | 16.0 | (76) | ||||

| Amort and colleagues, 2011156 | 248 | ED | Prospective | 5.2 | (13) | ||||

| Arsava and colleagues, 2011157 | 257 | ED | Retrospective (Boston) | 6.2 | (16) | ||||

| Bonifati and colleagues, 2011158 | 502 | ED | Retrospective | 2.2 | (11) | 4.0 | (20) | ||

| Kim and colleagues, 2011159 | 475 | ED | Retrospective (California) | 5.3 | (25) | 9.9 | (47) | ||

| Meng and colleagues, 2011160 | 410 | Hospital | Prospective | 27.0 | (111) | ||||

| Olivot and colleagues, 2011161 | 157 | ED | Prospective | 0.6 | (1) | 0.6 | (1) | ||

| Sanders and colleagues, 2011162 | 289 | Hospital | Retrospective | 2.4 | (7) | ||||

| Stead and colleagues, 2011163 | 622 | ED | Retrospective | 2.4 | (15) | ||||

| bAmarenco and colleagues, 2012164 | 1679 | Specialist unit | Prospective (SOS-TIA) | 2.0 | (34) | ||||