Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/143/01. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The draft report began editorial review in September 2017 and was accepted for publication in July 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

David Price reports board membership fees paid to the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute from Aerocrine AB, Amgen Inc., AstraZeneca plc, C.H. Boehringer Sohn AG & Ko. KG, Chiesi Farmaceutici S.p.A., Mylan N.V., Mundipharma GmbH, Napp Pharmaceutical Group Ltd, Novartis Pharmaceutical Company and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd; consultancy agreement fees paid to the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute from Almirall S.A., Amgen Inc., AstraZeneca plc, C.H. Boehringer Sohn AG & Ko. KG, Chiesi Farmaceutici S.p.A., GlaxoSmithKline plc, Mylan N.V., Mundipharma GmbH, Napp Pharmaceutical Group Ltd, Novartis Pharmaceutical Company, Pfizer Inc., Teva Pharmaceutical Industries and Theravance Biopharma; grants from Aerocrine AB, AKL Research and Development Ltd, AstraZeneca plc, C.H. Boehringer Sohn AG & Ko. KG, the British Lung Foundation, Chiesi Farmaceutici S.p.A., Mylan N.V., Mundipharma GmbH, Napp Pharmaceutical Group Ltd, Novartis Pharmaceutical Company, Pfizer Inc., the Respiratory Effectiveness Group, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Theravance Biopharma, the UK National Health Service and Zentiva N.V.; lecture/speaking engagement fees paid to the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute from Almirall S.A., AstraZeneca plc, C.H. Boehringer Sohn AG & Ko. KG, Chiesi Farmaceutici S.p.A., Cipla Ltd, GlaxoSmithKline plc, KYORIN Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Mylan N.V., Merck & Company, Inc., Mundipharma GmbH, Novartis Pharmaceutical Company, Pfizer Inc., Skyepharma and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries; manuscript preparation fees paid to the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute from Mundipharma GmbH and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries; travel expenses fees paid to the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute from Aerocrine AB, AstraZeneca plc, C.H. Boehringer Sohn AG & Ko. KG, Mundipharma GmbH, Napp Pharmaceutical Group Ltd, Novartis Pharmaceutical Company and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries; funding for patient enrolment or completion of research fees paid to the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute from Chiesi Farmaceutici S.p.A., Novartis Pharmaceutical Company, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries and Zentiva N.V.; and payment for developing educational materials fees paid to the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute from Mundipharma GmbH and Novartis Pharmaceutical Company. David Price is a peer reviewer for grant committees for the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programmes. He has stock/stock options from AKL Research and Development Ltd that produces phytopharmaceuticals, and owns 74% of the social enterprise Optimum Patient Care Ltd (in Australia, Singapore and the UK) and 74% of the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute Pte Ltd (Singapore). Ian Pavord reports grants from GlaxoSmithKline during the conduct of the study; has received speaker’s honoraria from AstraZeneca plc, C.H. Boehringer Sohn AG & Ko. KG, Aerocrine AB, Almirall S.A., Novartis Pharmaceutical Company and GlaxoSmithKline; has received honoraria for attending advisory board panels from Almirall S.A., AstraZeneca plc, C.H. Boehringer Sohn AG & Ko. KG, Dey Pharma, L.P., GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Schering-Plough, Novartis Pharmaceutical Company, Napp Pharmaceutical Group Ltd and RespiVert Ltd; and has received sponsorship for attending international scientific meetings from AstraZeneca plc, C.H. Boehringer Sohn AG & Ko. KG, GlaxoSmithKline and Napp Pharmaceutical Group Ltd. Mike Thomas received speaker’s honoraria for speaking at sponsored meetings or satellite symposia at conferences from Aerocrine AB, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis Pharmaceutical Company. He has received honoraria for attending advisory panels with Aerocrine AB, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis Pharmaceutical Company and Pfizer Inc. during the conduct of the study. He reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research during the conduct of the study; being a member of the HTA Primary Care Community and Preventative Interventions Panel during the conduct of the study; and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis Pharmaceutical Company, Boehringer Ingelheim and Aerocrine AB outside the submitted work. He is a member of the British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network’s Asthma Guideline Steering Group and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s Asthma Diagnosis and Monitoring Guideline Development Group. Christopher Brightling received payment via his institution of grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca plc/MedImmune, LLC, GlaxoSmithKline plc, F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG/Genentech, Inc., Novartis Pharmaceutical Company, Chiesi Farmaceutici S.p.A., Pfizer Inc., Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Sanofi S.A./Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, Mologic Ltd and Vectura Group plc.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by McKeever et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Extracts of text, figures and tables throughout this chapter have been published in Skeggs et al. 1 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background

Asthma is one of the commonest chronic diseases in the world, affecting an estimated 300 million people. Acute exacerbations of asthma cause considerable morbidity and account for a large component of the direct and indirect costs of asthma.

Previous studies have shown that the widespread use of an asthma self-management plan can reduce exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids and emergency health-care utilisation, as well as reduce time away from work or school because of poorly controlled asthma. However, although written self-management plans are recommended for all patients with asthma, many patients are not provided with one. Reasons for not being provided with a self-management plan include a lack of time and confusion about what to include in the plan when asthma control is deteriorating but before there is a need for oral corticosteroids.

Two large randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials2,3 found no benefit from doubling the dose of a patient’s usual inhaled corticosteroid2 or doubling the dose of inhaled budesonide3 when asthma control starts to deteriorate. However, other studies have suggested that higher doses (e.g. a fivefold increase4 or 1 mg of inhaled fluticasone propionate twice daily5) may be effective for the treatment of established exacerbations. A previous single-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial carried out by the chief investigator explored whether or not asthma exacerbations could be prevented with a self-management plan that recommended quadrupling the dose of inhaled corticosteroid at the time when asthma control starts to deteriorate (n = 403). 6 The results showed that for those participants who started on the study inhalers (n = 94) quadrupling the dose of inhaled corticosteroid led to a 36% reduction in asthma exacerbations (per-protocol analysis, p = 0.004). Unfortunately, the number of participants starting on the study inhaler varied between the two groups and the primary outcome in the intention-to-treat analysis was not significant. There is no evidence to suggest that a higher dose (i.e. a fivefold increase) is any more effective and would be associated with greater systemic activity.

In view of the limited evidence for quadrupling the dose of inhaled steroid at the point when asthma control starts to deteriorate, the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme issued a funding call in February 2010 and, subsequently, commissioned the Fourfold Asthma Study (FAST) (reference number 10/143/01).

Objectives

Primary objective

-

Determine whether or not the proposed asthma self-management plan reduces asthma exacerbations requiring oral steroids or unscheduled health-care consultations for asthma, compared with the usual self-management plan.

Secondary objectives

-

Determine whether or not the proposed asthma self-management plan reduces the deterioration in asthma control, compared with the usual self-management plan.

-

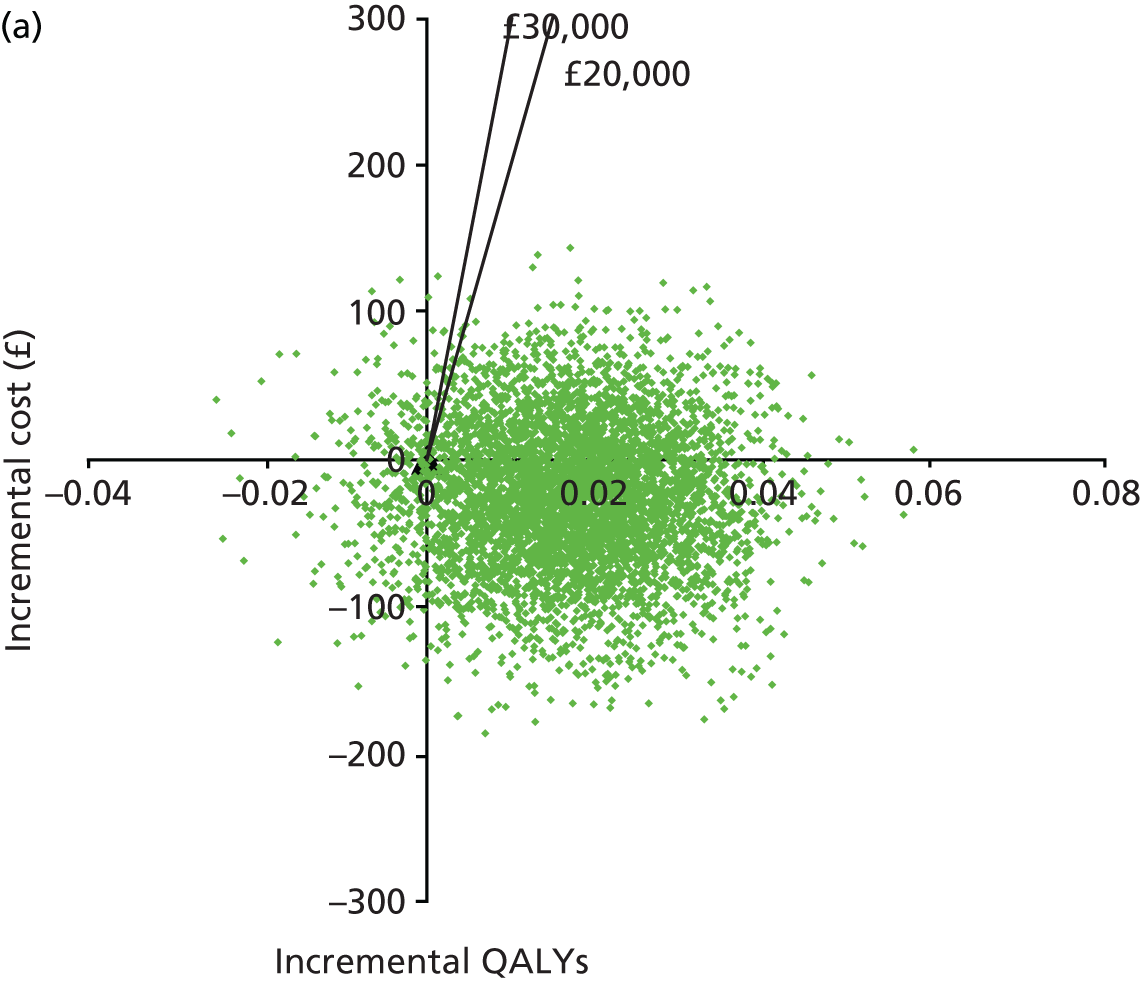

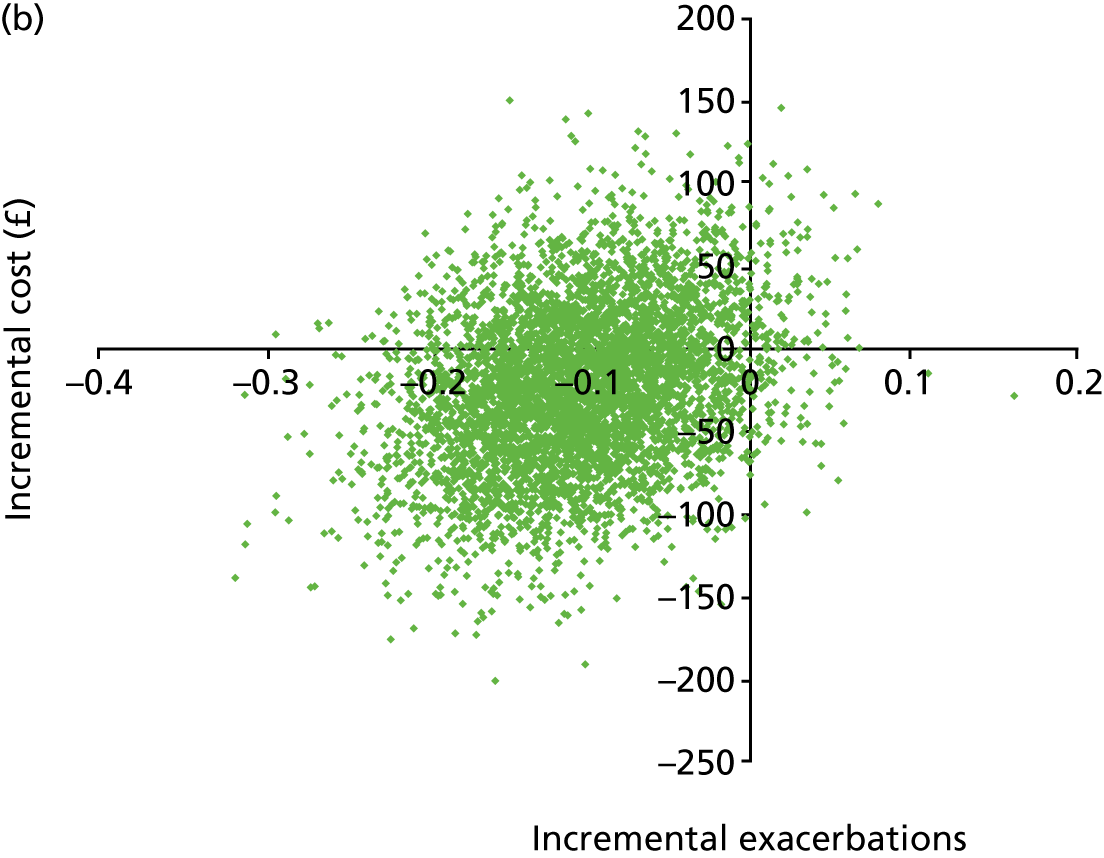

Determine if the proposed asthma self-management plan is cost-effective to the NHS and society overall, compared with the usual self-management plan.

Role of the funder

The study was funded by the NIHR HTA programme. The NIHR had input into the trial design through peer review of the proposal, but did not have a role in data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or the writing of the final report. The corresponding author had access to all the data and was responsible for the decision to submit the final report.

Chapter 2 Methods

Extracts of text, figures and tables throughout this chapter have been published in Skeggs et al. 1 and in the International Standard Registered Clinical/soCial sTudy Number (ISRCTN) Registry as ISRCTN15441965. 7 These are open access articles distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Trial design

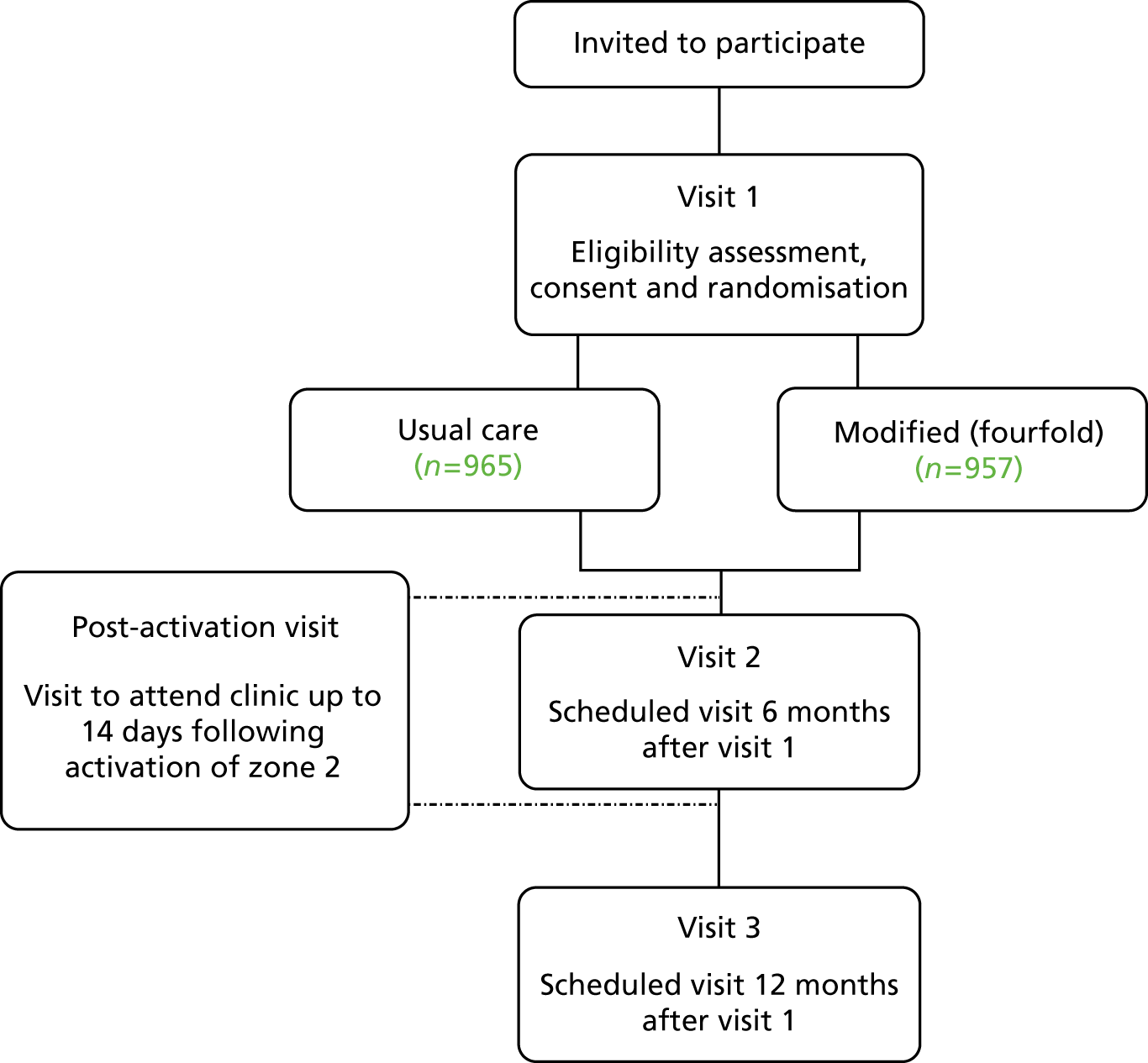

The FAST was a multicentre, pragmatic, normal care-controlled, randomised controlled trial (RCT) of 12 months’ duration (Figure 1). Adult asthma patients were randomised (1 : 1) to one of two asthma self-management plans: usual care or modified. Both self-management plans were identical at zones 1, 3 and 4, but at zone 2 (worsening of asthma symptoms) the usual-care group was advised to follow the current guidelines of increasing bronchodilator medication when asthma control begins to deteriorate. The modified self-management plan advised participants to increase bronchodilator medication and quadruple their inhaled corticosteroid dose. Both self-management plans advised participants to increase their medication for a maximum of 14 days, or for a shorter duration if asthma symptoms started to improve, before returning to their normal treatment, which was actively promoted in both self-management plans.

FIGURE 1.

Trial visit flow chart.

Participants were expected to attend three scheduled visits: baseline, 6 months and 12 months. These visits were conducted at the participants’ local general practitioner (GP)’s clinic or hospital (or via the telephone if easier for the participant). During these visits the research nurse reviewed the participant’s diary card to assess their adherence to the self-management plan and use of inhaled steroids, reviewed the participant’s asthma control to determine if there had been any unreported activation of zones 2, 3 or 4 since the previous visit and asked participants to complete the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), questionnaire and Service Use Questionnaire (see Appendix 1).

In addition to the scheduled visits, participants were expected to attend post-activation visits no less than 14 days after activating zone 2 of the asthma self-management plan; for some participants multiple visits took place in the 12-month participation period. Prior to the visit participants were expected to complete a diary card. For FAST two diary cards were used: one diary card for those participants who used corticosteroid inhalers and a second for those on combination inhalers. The participants used the diary cards to record peak flow, to record the asthma medication used to manage symptoms (including the number of puffs of usual preventer inhaler, of extra corticosteroid inhaler and of reliever inhaler and whether or not any systemic corticosteroids were taken) and to document whether they had an asthma-related GP or hospital appointment. The diary cards acted as an aide-memoire during the post-activation visit; the research nurse reviewed the daily peak flow measurements, any health-care consultations attended, the use of inhaled corticosteroids and systemic corticosteroids, ascertained if any adverse events (AEs) had occurred and assessed the participant’s adherence to the asthma self-management plan. Participants were also asked to complete the Juniper et al. Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (Mini AQLQ). 8 The study assessments are outlined in Table 1.

| Study assessments | Named trial visit | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1/screening | Activation of zone 2 (days 0–14) | Post-activation visit (14 days)a | Visit 2 (6 months after visit 1) | Visit 3 (12 months after visit 1) | |

| Demographics/eligibility, consent | ✓ | ||||

| Randomisation | ✓ | ||||

| Asthma diary card completionb | ✓ | ||||

| Mini AQLQc | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Issue asthma diary card | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| EQ-5D-3Ld | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Service Use Questionnairee | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Adherence to the self-management planf | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Asthma diary card review | ✓ | ||||

| Asthma review | ✓ | ✓ | |||

In addition, it was planned that the first 200 participants recruited at the Nottingham and Liverpool sites would have the option (if they agreed) to have their inhaled corticosteroid inhaler fitted with a smart inhaler electronic dose counter for adherence purposes. The main purpose of this was to compare an electronic record of inhaler use with the participants’ self-reported inhaler use and, therefore, the overall adherence to their allocated self-management plan. The smart inhaler was planned to be used to independently validate the accuracy of the participants’ self-reported adherence.

The implementation of the smart inhaler was challenging and, unfortunately, some technical issues (the smart inhaler not working correctly and a short battery life) prevented the implementation of the initial batch of devices into the trial.

Following a period of uncertainty around delivery and the reliability of new devices to replace those that did not function accurately, it was the unanimous view of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), at a meeting held in July 2014, that it was not practical to pursue further use of monitoring devices as the chance of any informative data being obtained from them prior to the end of the study was low. As a result, the planned interim analysis to determine whether or not self-reported adherence to adjustments to inhaled steroid dose was similar to that captured by the electronic devices was not conducted.

Recruiting centres

Recruitment took place in both primary and secondary care across England and Scotland. There were 10 secondary care sites: Nottingham City Hospital, Leicester Glenfield Hospital, Freeman Hospital Newcastle, Aintree University Hospital, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Royal Liverpool University Hospital, King’s Mill Hospital, Arrowe Park Hospital, Blackpool Victoria Hospital and Bradford Royal Infirmary. In addition, there were 171 primary care Research Initiative Sites (RISs) across 11 CRN regions: North East and North Cumbria, North West Coast, Greater Manchester, East Midlands, West Midlands, West of England, Thames Valley and South Midlands, Eastern, Kent, Surrey, Sussex, Wessex and South West Peninsula.

Participants were identified through secondary care and primary care. In secondary care, participants were identified from patients attending respiratory outpatient appointments at the individual recruiting centres and also through running database searches of participants who had previously participated in asthma studies and had given consent to be contacted again for future studies. In Scottish centres, the Scottish Primary Care Research Network identified potential participants in primary care who were subsequently recruited at local secondary care sites. In primary care, local CRNs liaised directly with GP practices that acted as RISs that performed a database search to identify potential participants. Potentially eligible participants were sent a participation invitation pack that included an invitation letter flyer about the trial and, in some practices, a copy of the Participant Information Sheet.

A local press release was issued at the start of the trial. Posters and flyers were displayed in recruiting centres and, where possible, a digital flyer was displayed in recruiting centre waiting areas. Posters were also displayed in pharmacies in the Nottinghamshire area and information flyers were placed in the bags of patients who were collecting prescriptions for asthma medication. The trial was also promoted online by Asthma UK.

General practitioner surgeries local to the recruiting hospitals were used as Participant Information Centres (PICs) by displaying posters and flyers.

Participants

Patients were considered eligible for entry into the trial if the following inclusion criteria were met:

-

men or women aged ≥ 16 years

-

clinician-diagnosed asthma treated with a licensed dose of inhaled corticosteroid [i.e. steps 2–4 of the British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (BTS/SIGN) guidelines]2

-

one or more exacerbations in the last 12 months requiring treatment with systemic corticosteroids

-

current smokers could be included provided that the recruiting centres had good evidence of underlying asthma (i.e. a life-long history of asthma, a > 12% forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) reversibility, or sputum or blood eosinophilia).

In addition, patients were not entered into the trial if any of the following exclusions applied:

-

a history more in keeping with smoking-related chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (i.e. smoked > 20 pack-years, without evidence of significant reversibility or eosinophilia)

-

on maintenance systemic corticosteroids (i.e. step 5 of the BTS/SIGN guidelines2)

-

using a combination inhaler for both maintenance and relief treatment

-

experienced an exacerbation within 4 weeks of randomisation

-

women who were pregnant, breastfeeding or who were planning to become pregnant.

Interventions

Asthma self-management plans

The asthma self-management plans used in the trial were based on the plan that was available from Asthma UK9 and were widely used at the time of the trial’s design and protocol development. All participants were randomised to either the usual-care or modified self-management plans, which differed only in instruction at zone 2, which in the modified plan recommended a quadrupling of inhaled corticosteroid dose.

Zone 1 described the participant with well-controlled asthma and simply recommended that they continue their usual treatment. Zone 3 described the development of an exacerbation and when to start systemic corticosteroids and seek medical intervention and zone 4 described what to do with life-threatening exacerbations. Both plans had the same wording so that participants in each group should, on average, have started systemic corticosteroids at the same threshold.

Zone 2 included the current area of uncertainty and the research question under investigation.

Usual self-management plan

Participants in the usual-care group who reached zone 2 were instructed to use additional bronchodilator medication to relieve asthma symptoms, as outlined in their individual asthma self-management plan.

Modified self-management plan

Participants in the modified self-management group who reached zone 2 were instructed to use additional bronchodilator medication to relieve asthma symptoms and to increase their inhaled corticosteroid treatment fourfold, either by increasing the number of puffs of their current inhaler, if they used a corticosteroid inhaler (refer to Table 2), or by adding a corticosteroid inhaler to their treatment if they used a combination inhaler (Table 3), as outlined in their individual asthma self-management plan. Those participants on combination inhalers were not asked to simply increase the number of puffs because this would have led to an increase in long-acting beta-agonist dose as well as the corticosteroid dose.

| Current number of puffs per dose | Number of puffs per dose to achieve quadrupled dose |

|---|---|

| 1 o.d. | 4 o.d. |

| 2 o.d. | 8 o.d. |

| 1 b.i.d. | 4 b.i.d. |

| 2 b.i.d. | 8 b.i.d. |

| And so on | And so on |

| Current treatment | Additional treatment options | |

|---|---|---|

| Option 1 | Option 2 | |

| Seretide® MDI 50/25 (GlaxoSmithKline, Uxbridge, UK), 2 puffs b.i.d. | FP 50, 6 puffs b.i.d. | FP 125, 3 puffs b.i.d. |

| Seretide MDI 125/25, 2 puffs b.i.d. | FP 125, 6 puffs b.i.d. | FP 250, 3 puffs b.i.d. |

| Seretide MDI 250/25, 2 puffs b.i.d. | FP 250, 6 puffs b.i.d. | N/A |

| Seretide Accuhaler® 100/50 (GlaxoSmithKline, Uxbridge, UK), 1 puff b.i.d. | FP Disk 100, 3 puffs b.i.d. | N/A |

| Seretide Accuhaler 250/50, 1 puff b.i.d. | FP Disk 250, 3 puffs b.i.d. | N/A |

| Seretide Accuhaler 500/50, 1 puff b.i.d. | FP Diskhaler 500, 3 puffs b.i.d. | N/A |

| Symbicort® Turbo® 100/6 (AstraZeneca UK Ltd, Luton, UK), 1 puff b.i.d. | Bud Turbo 100, 3 puffs b.i.d. | N/A |

| Symbicort Turbo 100/6, 2 puffs b.i.d. | Bud Turbo 100, 6 puffs b.i.d. | Bud Turbo 200, 3 puffs b.i.d. |

| Symbicort Turbo 200/6, 1 puff b.i.d. | Bud Turbo 200, 3 puffs b.i.d. | N/A |

| Symbicort Turbo 200/6, 2 puffs b.i.d. | Bud Turbo 200, 6 puffs b.i.d. | Bud Turbo 400, 3 puffs b.i.d. |

| Symbicort Turbo 200/6, 4 puffs b.i.d. | Bud Turbo 400, 6 puffs b.i.d. | N/A |

| Symbicort Turbo 400/12, 1 puff b.i.d. | Bud Turbo 400, 3 puffs b.i.d. | N/A |

| Symbicort Turbo 400/12, 2 puffs b.i.d. | Bud Turbo 400, 6 puffs b.i.d. | N/A |

| Fostair MDI 100/6 (Chiesi Ltd, Manchester, UK), 1 puff b.i.d. | Qvar MDI 100, 3 puffs b.i.d. | N/A |

| Fostair MDI 100/6, 2 puffs b.i.d. | Qvar MDI 100, 6 puffs b.i.d. | N/A |

| Flutiform® MDI 50/5 (Napp Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Cambridge, UK), 2 puffs b.i.d. | FP MDI 50, 6 puffs b.i.d. | N/A |

| Flutiform MDI 125/5, 2 puffs b.i.d. | FP MDI 125, 6 puffs b.i.d. | FP MDI 250, 3 puffs b.i.d. |

| Flutiform MDI 250/10, 2 puffs b.i.d. | FP MDI 250, 6 puffs b.i.d. | N/A |

It was perceived at the outset of the trial that all participants enrolled in the trial would benefit, as their self-management plan would be explained to them in detail and monthly texts would be sent to prompt them to adhere to it (if participants consented to this). It was believed that this would increase the participant’s awareness of their asthma symptoms and allow them to implement their self-management plan more reliably.

During the baseline visit, a member of the research team randomised each participant to their self-management plan and talked through the allocated plan with the participant to ensure that they fully understood the guidance at each zone. Those participants who were randomised to usual self-management were instructed to ‘use your reliever inhaler to relieve your symptoms and continue your preventer medication at your normal dose’. Those participants randomised to the modified self-management plan were instructed to ‘use your reliever inhaler to relieve your symptoms and increase your preventer medication as described below’ and then implement the zone 2 dose instructions in the self-management plan according to either:

-

option 1: how to achieve a quadrupling dose for participants on an inhaled corticosteroid-only inhaler

-

option 2: how to achieve a quadrupling dose for participants on a combination inhaler.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of ‘time to first asthma exacerbation’ was defined as the need for systemic corticosteroids (for at least 3 consecutive days) and/or unscheduled health-care consultations for asthma (i.e. reaching zone 3 or 4 of the Asthma UK self-management plan).

Secondary outcomes

-

Number of participants who had an acute exacerbation of asthma.

-

Total number of exacerbations.

-

Number of participants using systemic corticosteroids for an acute exacerbation of asthma.

-

Number of participants requiring unscheduled health-care consultations for asthma.

-

Total number of courses of systemic corticosteroids for an acute exacerbation of asthma.

-

Total number of unscheduled health-care consultations for asthma.

-

Time to participants requiring systemic corticosteroids for an acute exacerbation of asthma.

-

Time to unscheduled health-care consultations for asthma.

-

Area under the morning peak flow curve over 2 weeks from the point of activating zone 2 of the asthma plan.

-

Change in Mini AQLQ score 2 weeks after activating zone 2 of the self-management plan.

-

Cumulative dose of inhaled and systemic corticosteroids used in the 12 months after randomisation.

-

Cost and resource audits of both trial arms, reported as incremental cost per asthma exacerbation prevented and cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained.

Safety outcomes

Known side effects of inhaled corticosteroids were collected because of the quadrupling of the dose of inhaled corticosteroid in the modified self-management group.

Data collection

Trial data generated by all centres were entered by site staff directly into a web-based bespoke database, designed and maintained by the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU). Access to the trial database was controlled by user logins, and users could enter or edit data only for their regional centre. Participant questionnaires, completed at clinic visits, were entered into the trial database by site staff. If participants had not activated zone 2 of their self-management plan and were unable to attend the 6- and/or 12-month visit in person, site staff contacted participants via telephone and completed the trial database directly with the information provided to them over the telephone. Any missing and/or ambiguous data were queried with site staff, by the NCTU team, and resolved wherever possible.

Participants were asked to complete their diary cards prior to attending their post-activation visit. This diary card is where the participants recorded peak flow and the asthma medication used to manage symptoms (including the number of puffs of usual preventer inhaler, extra corticosteroid inhaler, reliever inhaler and whether or not any systemic corticosteroids were taken) and documented whether they had an asthma-related GP or hospital appointment. The diary was reviewed by the site staff at each clinic appointment and this information was used to complete the relevant sections of the trial database.

Site staff were also required to assess the participant’s adherence to the asthma self-management plan by reviewing the diary card and discussing, during the visit, whether or not, and how, participants changed their inhaled treatment since activating zone 2 of their self-management plan. Site staff completed the adherence assessment directly into the web-based bespoke system. Initially, there was the option for the first 200 participants recruited to measure their actuation adherence with the smart inhaler. The participant’s corticosteroid inhaler would be fitted with the electronic dose counter to record the date and time of each actuation. The data would then be directly downloaded from the device during the participant’s visit and uploaded to a separate database. The smart inhaler devices were not implemented because of the challenges described in Trial design and all adherence data were assessed by the site staff.

The web-based bespoke system generated automated notification e-mails for sites to remind them of upcoming and overdue 6- and 12-month visits. These notification e-mails were sent to sites on a monthly basis on the first day of every month during the recruitment and follow-up phase of the trial.

Those participants who provided additional consent, were sent monthly text reminders to remind them to adhere to their asthma self-management plan. The text message service was automated, with text messages automatically initiated on the first day of every month at approximately noon. To maintain confidentiality the participant’s mobile phone number was entered on to the database by site staff at the point of consent. These data were then encrypted and stored confidentially. Only research staff at their own specific site had access to their participants’ mobile phone numbers. If the participant withdrew, was lost to follow-up or had completed the trial, then the text messages automatically stopped being sent to the participant.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained for all participants prior to any trial procedures being undertaken. Consent to receive a summary of the results of the study and for the research team to send monthly reminder text messages to the participant was included as optional.

Sample size

A reduction of one-third in the number of people requiring treatment with oral corticosteroids was considered an important treatment effect by a group of local GPs, asthma nurses and asthma experts.

With 1000 participants per group, a log-rank test (at the two-sided 5% significance level) provided at least 90% power to detect a difference of 30% (relative effect), assuming an exacerbation rate of 13% in the control group. A 13% exacerbation rate requiring systemic corticosteroids was the lowest level seen in the control group of previous studies of this type6,10 and so provided a conservative estimate. The study initially proposed to recruit 2300 participants to allow for participants lost to follow-up (i.e. approximately 15% lost to follow-up). The study was not powered for the subgroup analysis performed on smoking status or dose of maintenance inhaled steroid dose at baseline.

The power calculation was revised in March 2015 in consultation with the NIHR HTA programme. The overall event rate in the first 226 participants recruited was higher (around 50%) in those reaching the 12-month follow-up time point. The exacerbation rate at this time was thought to be high because of more participants being recruited from secondary care and, therefore, having more severe asthma; hence, a lower exacerbation rate was used to revise the sample size calculation. Assuming an exacerbation rate in the control group of 17% and 90% power, and still estimating a one-third reduction in the fourfold increase group, then a sample size of 1542 participants was needed for analyses. Allowing for 20% of participants being lost to follow-up, the study aimed to recruit between 1774 and 1850 participants before the close of recruitment on 31 January 2016.

For those participants who were lost to follow-up, where possible, site staff reviewed participant computerised medical records to document if they had had an asthma-related GP appointment, if their asthma had exacerbated or if they had been prescribed systemic steroids.

Stopping rules and discontinuation

Ongoing adherence to the self-management plans was assessed by the Data Monitoring Committee in accordance with the criteria outlined in Table 4.

| Level of adherence in both groups | Proposed action |

|---|---|

| ≥ 50% of participants with moderate or good adherence with self-management compliance | Continue with trial as planned |

| ≤ 49% – ≥ 30% of participants with moderate or good adherence with self-management compliance | Implement pragmatic strategies for improvement |

| ≤ 29% of participants with moderate or good adherence with self-management compliance | Stop trial unless rectifiable solution can be readily implemented |

Randomisation

Randomisation was stratified by regional centre (Box 1), smoking status (yes/no) and maintenance inhaled corticosteroid dose (high/low dose; Table 5). Participants were allocated with equal probability to the two trial treatment groups. Recruiting sites were grouped into regional centres, which grouped practices to the appropriate CRN regions or secondary hospital care sites (Box 1). The treatment group to which a participant was assigned was determined by a computer-generated pseudo-random code, with random permuted blocks of randomly varying size, that was created by the NCTU in accordance with its standard operating procedure. The data were held on a secure University of Nottingham server.

-

Aberdeen Royal Infirmary.

-

Aintree University Hospital.

-

Arrowe Park Hospital.

-

Blackpool Victoria Hospital.

-

Bradford Royal Infirmary.

-

East of England.

-

Freeman Hospital, Newcastle.

-

Hetton Group Practice.

-

Kent.

-

King’s Mill Hospital.

-

Leicester Glenfield Hospital.

-

Nottingham City Hospital.

-

Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals.

-

Southampton.

-

South West Peninsula.

-

Surrey and Sussex.

-

Thames Valley and South Midlands.

-

West Midlands (South).

-

West of England.

-

Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester.

| Steroid | Device and formulation | Dose (mcg/day) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| BDP | Non-proprietary | 100–1000 | > 1000–2000 |

| BDP | Clenil® (Chiesi Ltd, Manchester, UK) MDI | 100–1000 | > 1000–2000 |

| BDP | Qvar MDI | 50–500 | > 500–800 |

| Budesonide | MDI | 100–1000 | > 1000–1600 |

| Budesonide | Turbuhaler | 100–800 | > 800–1600 |

| Fluticasone propionate | MDI/Accuhaler | 50–500 | > 500–2000 |

| Ciclesonide | MDI | 80–320 | |

| Seretide | MDI/Accuhaler | 50–500 | > 500–1000 |

| Symbicort | Turbuhaler | 100–800 | > 800–1600 |

| Fostair | MDI | 400 | |

| Flutiform | MDI | 50–500 | > 500–1000 |

Research nurses accessed the randomisation website by means of a remote, internet-based randomisation system developed, and maintained, by NCTU. Access was controlled by unique user logins. The sequence of treatment allocations was concealed until interventions had all been assigned and recruitment and data collection were complete. The chief investigator, trial team and trial statisticians were blinded to treatment allocations until the database was locked.

Blinding

Owing to the nature of the self-management plans allocated in the trial, it was not possible to blind site staff or participants to their treatment allocation. Efforts were made to minimise the expectation bias by detailing in the trial documents that the evidence supporting the quadrupling of the inhaled dose of corticosteroid at the time of worsening asthma symptoms was limited, and it was not yet known whether or not the intervention offered any benefit over usual care. Both groups were also provided with tailored self-management plans that were explained to them in detail, ensuring that both groups received similar instruction on how to best use their asthma self-management plan.

Throughout the trial, prior to database lock, the blinding allocation was preserved for the chief Investigator, trial statisticians, the trial team and TSC members.

Full details of blinding arrangements are summarised in Table 6.

| Role within trial | Blinding status | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Not blinded | Not possible to blind participants, efforts made to minimise expectation bias |

| Research nurses and principal investigators | Not blinded | Acted as the main point of contact for participants. Not possible to blind research staff, efforts made to minimise bias |

| Trial staff at NCTU | Blinded | Acted as the main point of contact for recruiting centres. All trial documentation finalised prior to revealing treatment codes |

| Statisticians | Blinded | Statisticians finalised the statistical analysis plan prior to revealing the treatment codes |

| Chief investigator | Blinded | Finalised all documentation prior to revealing treatment codes |

Statistical analysis

Analyses are detailed in the statistical analysis plan (www.nottingham.ac.uk/nctu/trials/respiratory.aspx#FAST), which was finalised prior to database lock and release of the treatment allocation codes for analysis.

All analyses were based on the intention-to-treat principle, for example analysed as randomised regardless of adherence to self-management plan. All analyses were carried out using Stata®/SE 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics of demographic and clinical measures were used to examine balance between the randomised groups at baseline.

Descriptive analyses

The number of participants activating zone 2 or above of the self-management plan was derived from the following information on the electronic Case Report Form (eCRF): summary pages for diary cards, post-activation visit pages, summary pages for oral corticosteroid use for asthma, summary pages for health-care consultations for asthma and a question about unreported activations at the scheduled visits. Therefore, the source of the date of the first activation, diary card completion and post-activation visit attendance for the first activation to zone 2 is tabulated by allocated group. The research nurse rating of adherence is described with frequencies and percentages for the first activation to zone 2. Adherence information is unknown for participants who did not report their activation to zone 2 or complete their diary card.

Asthma exacerbation outcomes

An asthma exacerbation was defined as the need for a course of systemic corticosteroids and/or an unscheduled health-care consultation for asthma. A course of systemic corticosteroids was defined as taking 3 consecutive days or more of corticosteroids. Health-care consultations and courses of systemic corticosteroids were counted as part of the same exacerbation if they were within 14 days of the previous health-care consultation or course of systemic corticosteroids for asthma.

Similarly, for the derivation of the total number of courses of systemic corticosteroids, corticosteroids started within 14 days of the last date of the previous course of corticosteroids were counted as within the same course. For the derivation of the total number of unscheduled health-care consultations, GP/hospital visits were classed as one unscheduled health-care visit if they were within 14 days of the previous visit.

The analysis population for the asthma exacerbation outcomes (including systemic corticosteroids and unscheduled health visits) was all participants apart from those with whom there was no further contact after randomisation and, therefore, information was unavailable about oral steroid use or unscheduled health-care consultations for asthma (i.e. questions on eCRF answered as unknown or not answered). Attendance at a scheduled or post-activation visit or a completed diary card was considered as contact after randomisation.

The questions about oral corticosteroid use or unscheduled health-care consultations for asthma on the eCRF were not expected to be answered as unknown, as the protocol specified that health-care records could be checked for participants who did not complete the 12-month follow-up visit but who did not withdraw consent. Some sites, however, did not have access to health-care records if the participant had moved surgery or if the participant was recruited from a secondary care site. In these circumstances, the questions could be answered as unknown.

Primary outcome: time to first asthma exacerbation

For the analysis of time to first asthma exacerbation, the start time was the date of randomisation and the end time was either:

-

the date of first starting to take systemic corticosteroids (provided these were taken for at least 3 consecutive days) or the date of the first unscheduled health-care consultation for asthma (if within 365 nights after randomisation) (whichever happened first)

-

censored for participants who did not take systemic corticosteroids for more than 3 consecutive days or have an unscheduled health-care consultation (or if this occurred more than 365 days after randomisation) at the:

-

12-month follow-up date for participants who completed the trial (or 365 days if the 12-month follow-up date was after this)

-

date of withdrawal for participants who withdrew consent

-

date of death for participants who died

-

date of last contact in the case of participants who moved to another GP practice during the trial

-

scheduled 12-month follow-up date (i.e. 365 days after randomisation) for all other participants who did not complete the trial as a result of being lost to follow-up or other reasons (sites were asked to check GP records for these participants to ascertain the primary outcome over the trial period).

-

-

censored for participants where it was unknown if they took any systemic corticosteroids or had an unscheduled health-care consultations at the:

-

last date the participant was known to be in the trial, that is, whichever was last of the latest dates from the diary [provided peak expiratory flow (PEF) data or some information on the number of puffs on inhalers was recorded], post-activation visit date or 6-month visit date

-

randomisation date for all other scenarios.

-

The number of participants with an asthma exacerbation, the total number of person-years to first exacerbation and the rate for first asthma exacerbation are summarised by allocated group. The time to first asthma exacerbation is presented in Kaplan–Meier plots, with a table showing the number at risk.

The hazard ratio for an asthma exacerbation in the modified self-management group compared with the usual-care group was calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression (using the Breslow method for tied failure times), including the randomisation stratification variables dose of inhaled corticosteroid (high/low) and smoking status (never, former, current) as covariates and using a shared frailty model to account for stratification by regional centre. 11 In addition, the unadjusted hazard ratio is reported.

The proportional hazards assumption was tested by using a log–log plot of survival and using Schoenfeld’s residuals.

Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome

The hazard ratio for time to asthma exacerbation was further adjusted for age, sex and peak flow at screening. These were chosen based on previous literature as being strong predictors of asthma exacerbation.

Prespecified subgroup analyses for the time to first asthma exacerbation for smoking status at trial entry (never, former, current) and dose of inhaled corticosteroid at trial entry (high/low) were conducted by including an interaction term with allocated group in the Cox proportional hazards regression model, adjusting for randomisation stratification variables.

The main analysis of the primary outcome specified above was repeated for the per-protocol population. The per-protocol population was defined as participants who activated zone 2 and had good adherence to their self-management plan during their first activation, as assessed by the research nurse, and participants who completed the study as planned (i.e. attended the 12-month follow-up) and did not activate zone 2. Note that this is a non-randomised comparison and, therefore, should be interpreted with caution.

Exploratory analyses were also performed to examine the robustness of the conclusions from the main analysis to the date of censoring for the participants who did not complete the 12-month visit.

Secondary outcomes

For secondary outcomes, the same approach for analyses was taken as for the primary outcome. The results are summarised by allocated group and the analysis models (used to estimate the intervention effect) included the randomisation stratification variables of corticosteroid dose, smoking status and regional centre as covariates.

Secondary exacerbation outcomes

The time to participants requiring a course of systemic corticosteroids and time to participants requiring an unscheduled health-care consultation were analysed using the methods described above for the primary outcome.

The difference in the percentage of participants with an asthma exacerbation requiring a course of corticosteroids and requiring an unscheduled health-care consultation was compared between the two allocated groups using generalised estimating equations with the binomial family and:

-

an identity link to estimate the risk differences

-

a log-link to estimate the risk ratios.

An exchangeable correlation matrix was used to account for randomisation being stratified by regional centre.

The total number of asthma exacerbations per participant, the total number of courses of systemic corticosteroids and the total number of unscheduled health-care consultations per participant were summarised in the two allocated groups and compared with a negative binomial model using generalised estimating equations to account for randomisation being stratified by regional centre. The number of days in the trial was used as time at risk in the negative binomial model. Incidence rate ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented.

Area under the morning peak flow curve over 2 weeks from the point of activating zone 2 of the asthma plan

The area under the peak flow curve was specified as a secondary outcome to explore whether or not the severity of the deterioration in asthma control differed between the allocated groups. After zone 2 activation, peak flow data were to be collected on the diary cards for 14 days.

The percentage baseline peak flow was used for analysis and was calculated as actual PEF × 100/(screening visit PEF). The area under the curve for each participant was calculated in Stata using the cubic spline method. 12

Participants with a diary card completed for the first activation to zone 2 and with a PEF measurement on day 1, at least one PEF measurement on or after day 10 and at least one PEF measurement in between day 1 and 10 were included in the analysis. The area under the curve was calculated for the two analysis populations:

-

participants with a PEF measurement on day 1, at least one PEF measurement on or after day 10 and at least one PEF measurement in between days 1 and 10

-

participants with a PEF value recorded on day 1 and day 14 and at least six PEF values between days 1 and 14.

For both of the analyses above on days when PEF was not recorded in the diary, the PEF value was imputed using the last PEF value recorded.

Linear regression with a random effect for regional centre was used to compare the area under the percentage baseline morning peak flow curve. Baseline PEF was also included as a covariate (along with the randomisation stratification variables), as this was felt likely to be prognostic for PEF values during activation to zone 2.

Change in the Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire score 2 weeks after activating zone 2 of the self-management plan

The Mini AQLQ measures the functional problems (symptoms, activities, emotions and environment) that are most troublesome to adults with asthma. It has 15 items each with seven response options (where 1 indicates severely impaired and 7 indicates not at all impaired) and a recall period of 2 weeks. The Mini AQLQ score was calculated from the mean of all 15 responses. The mean score for participants with missing items was calculated if no more than two items were missed. If more than two items were missed, the Mini AQLQ score was not calculated.

Participants with a Mini AQLQ for the first activation to zone 2 completed within 28 days of the start of the activation (because of the time window for the post-activation visit in relation to activation of zone 2) were included in the analysis of change in the Mini AQLQ. Mini AQLQ questionnaires completed more than 28 days after first activating zone 2 were not included.

The overall Mini AQLQ score is summarised at baseline and 2 weeks after activating zone 2 or above. In addition, the score was compared between allocated groups using a linear regression model adjusting for the Mini AQLQ score at baseline [i.e. analysis of covariance (ANCOVA)] and randomisation stratification variables with a random effect for regional centre.

If the Mini AQLQ score was missing at baseline, for inclusion in the regression analysis the score was imputed using the mean baseline score at the participant’s regional centre. 13

Cumulative dose of inhaled and systemic steroids used in the 12 months after randomisation

Participants attending and completing the 12-month follow-up visit were included in the analysis of cumulative dose of inhaled and systemic steroids.

The cumulative dose of inhaled corticosteroids was derived from the information collected at visits (scheduled and post activation) about permanent asthma medication, including changes in medication, and from the information entered from the diary cards about inhaler use during activation to zone 2 or above. Participants were assumed to have taken their normal number of puffs on their preventer inhaler for days when no information was recorded on the diary card.

The cumulative doses of inhaled corticosteroids and systemic corticosteroids taken per participant over the 365 days from randomisation are summarised descriptively by allocated group. The cumulative dose of systemic corticosteroids taken is summarised for all participants and includes only participants who took systemic corticosteroids.

Safety

Adverse events were reported during the 14 days following activation of zone 2 of the self-management plan; therefore, safety data are summarised for participants activating zone 2 or above of their self-management plan on at least one occasion.

The number and percentage of participants experiencing a serious adverse event (SAE), seriousness criteria, total number of SAEs, SAE description [using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA)14 terminology-preferred term] and classification (not related to trial treatment, related to trial treatment – not unexpected) are summarised by allocated group.

The number and percentage of participants experiencing a non-serious AE, total number of non-serious AEs, AE description (using the MedDRA-preferred term) and relationship to inhaled steroids are summarised by allocated group. Non-serious AEs reported that were not considered to be known side effects of inhaled corticosteroids (e.g. displaced fractures) are not included in the summaries.

Summary of changes to the protocol

The full protocol and statistical analysis plan are available on the NCTU’s website (www.nottingham.ac.uk/nctu/trials/respiratory.aspx#FAST). A summary of changes made to the protocol after the start of recruitment is listed in Appendix 2.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

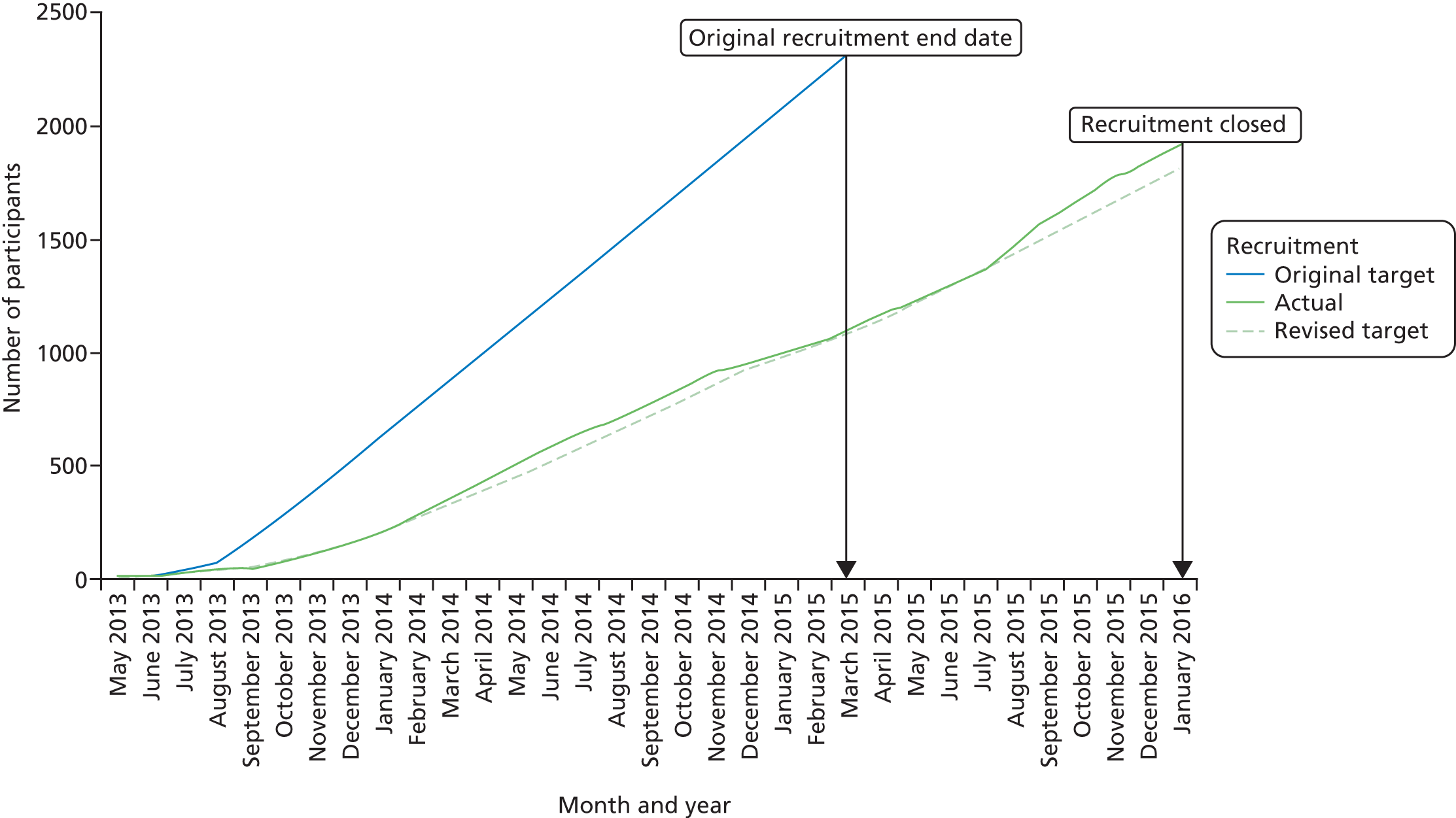

Recruitment to the trial took place between 17 May 2013 and 29 January 2016 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative recruitment.

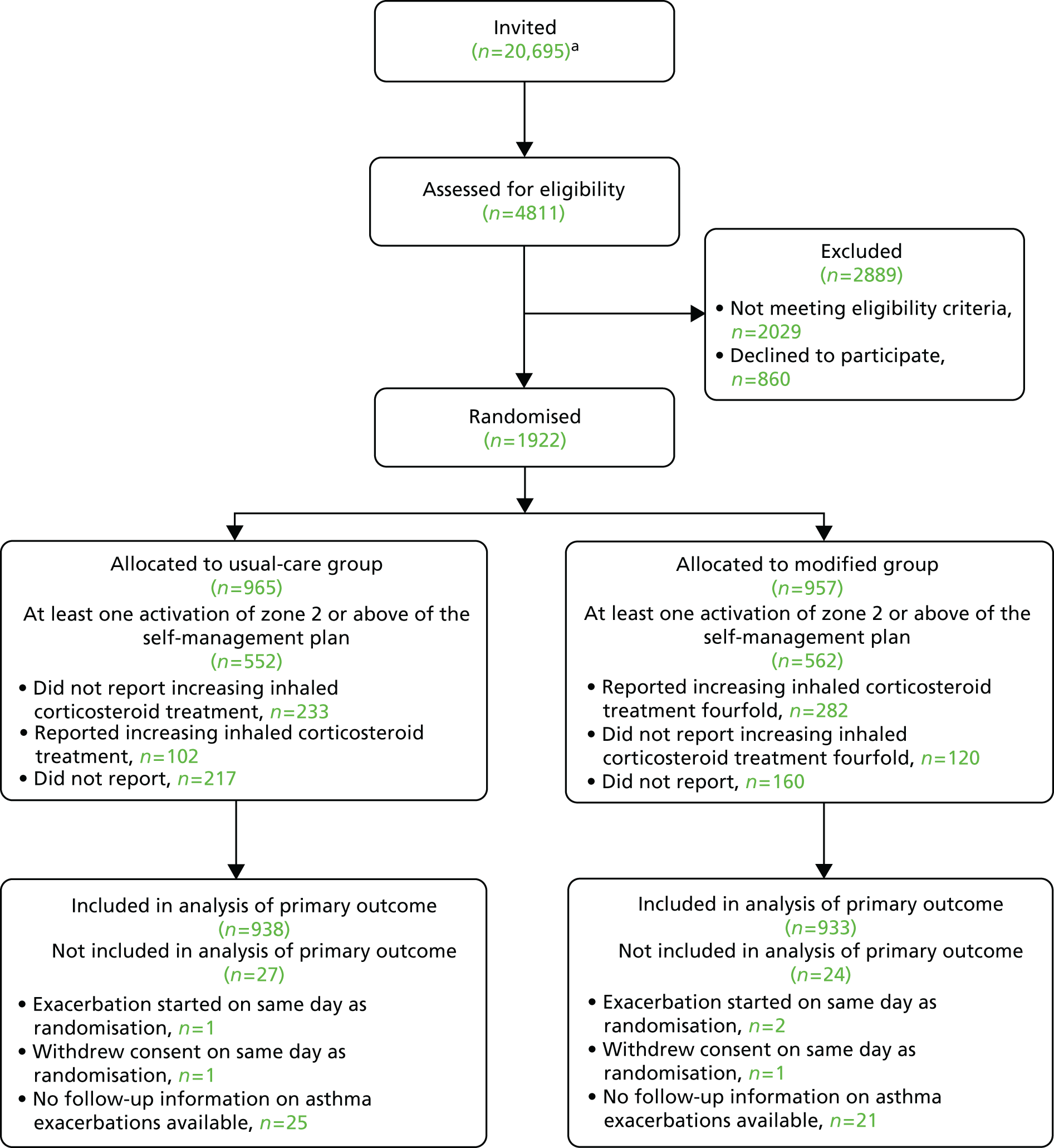

During this time 20,695 asthma patients were contacted and invited to take part in the study (patient contact data were not provided by 77 of the initiated sites). Of these, 4811 were assessed for eligibility and 1922 were subsequently randomised (Figure 3). Of the 2889 participants who were screened but not randomised, 860 (30%) declined to participate and 2029 (70%) failed to meet the eligibility criteria (Table 7).

FIGURE 3.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) participant flow diagram. a, Invited figure reflective of the data provided by 132 initiated sites at the time of reporting.

| Reason for not meeting eligibility criteria | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| No systemic corticosteroids in the past year | 594 |

| On maintenance corticosteroids | 340 |

| Exacerbated in the last 4 weeks | 47 |

| SMART regimen | 365 |

| COPD | 577 |

| Other | 106 |

| Pregnant/breastfeeding | 20 |

| Mental/learning difficulties | 39 |

| Unlicensed dose of inhaled steroid | 11 |

| On Relvar® Ellipta (GlaxoSmithKline UK Ltd, Brentford, UK) | 5 |

| No reason given | 31 |

Initially, recruitment was slow, and after 6 months was only 25% of the target as a result of a combination of delays with contracting and a higher than expected rate of non-eligibility. Following review of site recruitment and recruitment trends in primary and secondary care, focus was shifted to concentrate on primary care RISs. Although the RISs were initially achieving target after around 6 months, the pool of potential participants was exhausted and recruitment dropped. In February 2014, FAST’s Trial Management Group met the trial funders to agree on a strategy that new RISs should be opened to replace sites as they became inactive. Following the meeting, an ambitious initiation plan was undertaken, with 54 sites opening between March and December 2014 and a further 107 sites opening in 2015.

In order to meet recruitment targets the NIHR HTA programme agreed to an 11-month recruitment extension (January 2015). The trial completed recruitment on 31 January 2016 with 1922 randomised participants and 196 RISs and 11 secondary care sites initiated throughout the recruitment period. At the outset of the study it was envisaged that approximately 80% of participants would be recruited from primary care (i.e. PICs). In total, 81% of participants were recruited from primary care (63% RISs and 18% PICs) and 19% from secondary care sites. The number of participants randomised to each group was well balanced across regional randomisation centres (Table 8).

| Region | Intervention arm, n (% of total) | Total (N = 1922), n (% of total) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 965) | Modified (N = 957) | ||

| 1 | 133 (14) | 132 (14) | 265 (14) |

| 2 | 45 (5) | 45 (5) | 90 (5) |

| 3 | 31 (3) | 31 (3) | 62 (3) |

| 4 | 9 (1) | 9 (1) | 18 (1) |

| 5 | 77 (8) | 76 (8) | 153 (8) |

| 6 | 92 (10) | 93 (10) | 185 (10) |

| 7 | 99 (10) | 100 (10) | 199 (10) |

| 8 | 179 (19) | 176 (18) | 355 (18) |

| 9 | 22 (2) | 23 (2) | 45 (2) |

| 10 | 8 (1) | 8 (1) | 16 (1) |

| 11 | 5 (1) | 6 (1) | 11 (1) |

| 12a | 5 (1) | 5 (1) | 10 (1) |

| 13 | 38 (4) | 35 (4) | 73 (4) |

| 14 | 25 (3) | 25 (3) | 50 (3) |

| 15 | 103 (11) | 104 (11) | 207 (11) |

| 16 | 13 (1) | 13 (1) | 26 (1) |

| 17 and 18 | 12 (1) | 10 (1) | 22 (1) |

| 19 | 37 (4) | 35 (4) | 72 (4) |

| 20 | 29 (3) | 28 (3) | 57 (3) |

| 21 | 3 (< 0.5) | 3 (< 0.5) | 6 (< 0.5) |

Baseline data

Participants

The characteristics of the participants at baseline were well balanced between the usual-care and modified self-management groups (Table 9).

| Characteristic | Intervention arm | Total (N = 1922) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 965) | Modified (N = 957) | ||

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 56.7 (15.2) | 56.2 (15.5) | 56.5 (15.3) |

| Min., max. | 19, 94 | 16, 91 | 16, 94 |

| Sex, n (% of total) | |||

| Male | 316 (33) | 301 (31) | 617 (32) |

| Female | 649 (67) | 656 (69) | 1305 (68) |

| Recruited from, n (% of total) | |||

| Primary care | 774 (80) | 785 (82) | 1559 (81) |

| Secondary care | 191 (20) | 172 (18) | 363 (19) |

| PEF (l/minute) at screening | |||

| Mean (SD) | 381.1 (112.2) | 386.9 (110.8) | 384 (111.5) |

| Type of inhaler, n (% of total) | |||

| Corticosteroid | 303 (31) | 275 (29) | 578 (30) |

| Combination | 662 (69) | 682 (71) | 1344 (70) |

| Maintenance dose of inhaled corticosteroids (mcg/day of BDP) | |||

| Median (25th, 75th centiles) | 800 (400, 1000) | 800 (400, 1000) | 800 (400, 1000) |

| Min., max. | 100, 4000 | 80, 4000 | 80, 4000 |

| Maintenance dose of inhaled corticosteroids (used in randomisation stratification), n (% of total) | |||

| Low (≤ 1000 mcg/day of BDP) | 752 (78) | 743 (78) | 1495 (78) |

| High (> 1000 mcg/day of BDP) | 213 (22) | 214 (22) | 427 (22) |

| BTS step of asthma treatment, n (% of total) | |||

| Step 2 – regular preventer therapy | 259 (27) | 221 (23) | 480 (25) |

| Step 3 – initial add-on therapy | 363 (38) | 345 (36) | 708 (37) |

| Step 4 – persistent poor control | 330 (34) | 374 (39) | 704 (37) |

| Step 5 – omalizumab | 3 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 5 (0.3) |

| Not knowna | 10 (1) | 15 (2) | 25 (1) |

| Smoking status, n (% of total) | |||

| Never | 552 (57) | 564 (59%) | 1116 (58) |

| Current | 66 (7) | 59 (6) | 125 (7) |

| Former | 347 (36) | 334 (35) | 681 (35) |

| Pack-years for current or former smokers | |||

| n | 413 | 393 | 806 |

| Mean (SD) | 13.9 (16.1) | 12.3 (14.5) | 13.1 (15.4) |

| Mini AQLQ overall scoreb | |||

| n | 959 | 944 | 1903 |

| Mean (SD) | 5 (1.2) | 5.1 (1.2) | 5.1 (1.2) |

The mean age of participants was 57 years [standard deviation (SD) 15 years] and 1305 (68%) were female. Of those enrolled, 1344 (70%) were prescribed combination inhalers, and 1495 (78%), the majority of participants, were on a low dose of maintenance steroid [≤ 1000 mcg/day of beclometasone dipropionate (BDP)]. Overall, 1125 participants (59%) reported not taking any other respiratory medication at randomisation (Table 10).

| Medication | Intervention arm, n (% of total) | Total (N = 1922), n (% of total) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 965) | Modified (N = 957) | ||

| None | 572 (59) | 553 (58) | 1125 (59) |

| At least one medication reported | 360 (37) | 363 (38) | 723 (38) |

| Unknown | 33 (3) | 41 (4) | 74 (4) |

| Preventer medication | |||

| Theophylline/aminophylline | 16 (2) | 21 (2) | 37 (2) |

| Sodium cromoglycate | – | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) |

| Omalizumab | 3 (< 0.5) | 2 (< 0.5) | 5 (< 0.5) |

| Reliever medication | |||

| Long-acting beta agonist | 12 (1) | 14 (1) | 26 (1) |

| Long-acting muscarinic antagonist | 38 (4) | 39 (4) | 77 (4) |

| Leukotriene antagonist | 81 (8) | 94 (10) | 175 (9) |

| Nebulised beta agonist | 3 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) | 4 (< 0.5) |

| Nebulised anticholinergic | 7 (1) | 8 (1) | 15 (1) |

| Short-acting beta agonist (not nebulised) | 311 (32) | 312 (33) | 623 (32) |

| Other respiratory medication | |||

| Antibiotics | 6 (1) | 5 (1) | 11 (1) |

| Oral/inhaled corticosteroids | 99 (10) | 112 (12) | 211 (11) |

| Other | 42 (4) | 47 (5) | 89 (5) |

Follow-up

Scheduled follow-up visits

Attendance by participants at the scheduled visits was good. In the usual-care group, 772 (80%) participants attended the 6-month visit, decreasing to 700 (73%) at the 12-month visit. Attendance was similar in the modified self-management group, with 773 (81%) participants attending the 6-month visit and 679 (71%) attending the 12-month visit.

A total of 67 (7%) participants in the usual-care group and 80 (8%) in the modified self-management group withdrew consent from the trial, 15% of participants were lost to follow-up and 5% of participants in each group were marked as not completing the trial for other reasons (Table 11). The other reasons reported for participants not attending the 12-month visit included moving area or GP surgery, being advised to switch to a Single inhaler Maintenance And Reliever Therapy (SMART) regimen, and a variation or stopping in inhaled steroid dose.

| Attendance | Intervention arm, n (% of total) | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 965) | Modified (N = 957) | |

| Attended | 700 (73) | 679 (71) |

| Did not attend | 260 (27) | 274 (29) |

| No information | 5 (0.5) | 4 (0.4) |

| Reason if did not attend 12-month visit | ||

| Lost to follow-up | 147 (15) | 145 (15) |

| Withdrawal of consent | 67 (7) | 80 (8) |

| Other | 44 (5) | 47 (5) |

| Deatha | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| No information | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

Activation to zone 2 or above of the self-management plan

A total of 1114 participants (58%) activated zone 2 or above of the self-management plan in the year after randomisation, with similar numbers in the two groups (552 in the usual-care group and 562 in the modified self-management group). The baseline characteristics of the participants who activated zone 2 or above were similar in the two groups (Appendix 6). However, a greater percentage of participants completed a diary card and attended the post-activation visit for the first activation of zone 2 in the modified self-management group than in the usual-care group (Table 12).

| Activation | Intervention arm, n (% of total) | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 552) | Modified (N = 562) | |

| Source of date of first activation | ||

| Diary card | 328 (59) | 400 (71) |

| Post-activation visit | 2 (< 0.5) | 3 (1) |

| Health-care consultation or oral corticosteroid use for asthma | 203 (37) | 137 (24) |

| Date not known (unreported activationa) | 19 (3) | 22 (4) |

| Post-activation visit attended for first activation to zone 2 or above | 263 (48) | 341 (61) |

| Diary card completed for first activation to zone 2 or aboveb | 334 (61) | 403 (72) |

Nurse-assessed adherence to the allocated intervention

Adherence to the allocated self-management plan was rated by research nurses using either information entered in diaries or, if the diary was not completed, participant recall of this information at post-activation visits. The ratings were based on the criteria specified in the protocol and are shown in Table 13.

| Rating | Intervention arm | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual care | Modified | |

| Poor | Fourfold increase in maintenance dose | No or minimal change in medication |

| Moderate | Increase in maintenance dose, but less than fourfold | Change, but as fourfold or as instructed |

| Good | No change in inhaled corticosteroid dose | Fourfold change and followed instructions |

Adherence to the self-management plan was assessed as good (i.e. fourfold increase in corticosteroid dose as per instructions) for the first activation of zone 2 or above for 282 (50%) of the participants in the modified self-management group (Table 14). In the usual-care group, adherence for 15 participants (3%) was assessed as poor (i.e. used a fourfold increase in maintenance corticosteroid dose during first activation to zone 2) (Table 14).

| Adherence | Intervention arm, n (% of total) | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 552) | Modified (N = 562) | |

| Poor | 15 (3) | 31 (6) |

| Moderate | 87 (16) | 89 (16) |

| Good | 233 (42) | 282 (50) |

| Not known | 217 (39) | 160 (28) |

Adherence information was unknown for 377 participants: 331 participants, first activation to zone 2 or above was an asthma exacerbation (health-care consultation or oral corticosteroid use for asthma; Table 12), 41 participants had an unreported activation and five participants had diary data but no nurse assessment of adherence entered on to the database. Adherence information is unknown for a greater percentage of participants who activated zone 2 or above in the usual-care group than in the modified self-management group (39% and 28%, respectively) (Table 14), as the percentage of participants completing diary cards was lower in the usual-care group.

Inclusion in the analysis of the primary outcome

There were 938 participants (97%) in the usual-care group and 933 participants (97%) in the modified self-management group included in the primary analysis of the primary outcome (Table 15). Of these, 134 and 158 participants in the usual-care and modified self-management group, respectively, were censored for the primary outcome as they did not have an exacerbation of asthma or complete the 12-month visit (Table 15).

| Primary outcome status | Intervention arm, n (% of total) | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 965) | Modified (N = 957) | |

| Unknown information about oral corticosteroid use or unscheduled health-care consultations for asthma after randomisation – not included in analysis of primary outcome | 26 (3) | 22 (2) |

| Participant had asthma exacerbation and/or completed the 12-month follow-up visit | 805 (83) | 777 (81) |

| Exacerbation started on day of randomisation – not included in analysis of primary outcomea | 1 | 2 |

| Participant did not have asthma exacerbation and did not complete the 12-month follow-up visit – censored for primary outcome | 134 (14) | 158 (17) |

| Censored at | ||

| Date of death | 1 | 0 |

| Date withdrew consent | 32 | 34 |

| Date left surgery | 3 | 5 |

| Scheduled 12-month visit date | 91 | 107 |

| 6-month visit date | 6 | 10 |

| Post-activation visit date | 1 | 2 |

No information was collected after randomisation for 26 participants (3%) in the usual-care group and 22 (2%) in the modified self-management group (Table 15). Therefore, these participants could not be included in the analysis of the primary outcome.

Three participants had asthma exacerbations that started on the same day as randomisation. These participants are not included in the analysis of the primary outcomes, but are included in other analyses relating to exacerbations of asthma.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Primary outcome: time to first asthma exacerbation

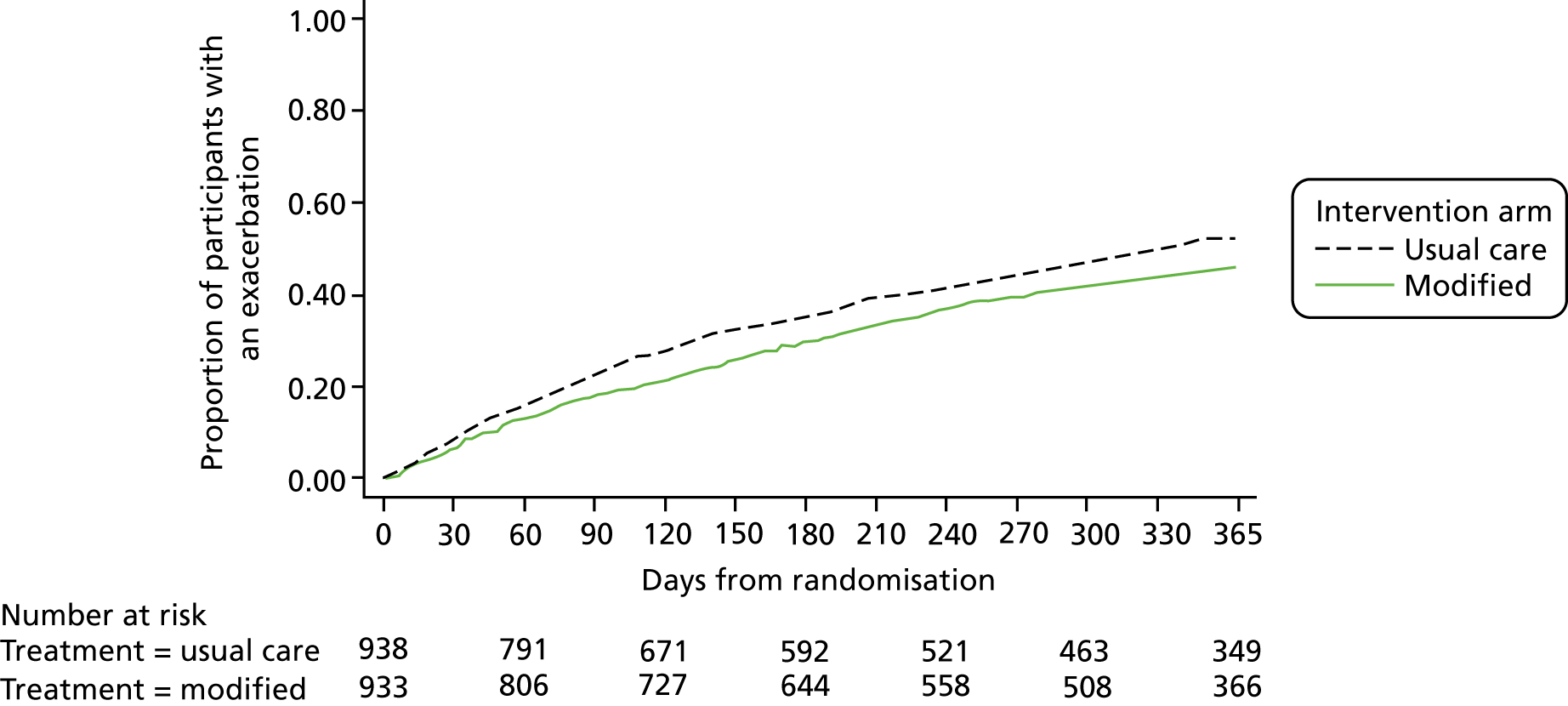

Primary analysis

The number of participants having an exacerbation of asthma in the year after randomisation was 484 (51.6%) in the usual-care group and 420 (45.0%) in the modified self-management group (Figure 4). Kaplan–Meier curves for the time to first asthma exacerbation are shown in Figure 4. The adjusted hazard ratio for the time to first asthma exacerbation in the modified self-management group compared with the usual-care group was 0.81 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.92; p = 0.002; Table 16).

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves for the time to first asthma exacerbation by allocated group.

| Primary outcome | Intervention arm | Adjusted hazard ratioa (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 938) | Modified (N = 933) | ||

| Total number (% of total) with exacerbation | 484 (51.6%) | 420 (45.0%) | |

| Total follow-up time (person-years) | 610.3 | 649.8 | |

| Rate (per person-years) | 0.79 | 0.65 | 0.81 (0.71 to 0.92); p = 0.002 |

Secondary analysis for the primary outcome

Additional adjustment

The hazard ratio for the time to first asthma exacerbation in the modified self-management group compared with the usual-care group with additional adjustment for age, sex and PEF at screening was 0.80 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.92; p = 0.001).

Varying censoring time

If participants in both groups who did not complete the 12-month visit and did not exacerbate were censored at their date of last contact (either the 6-month visit date, last post-activation visit date or last completed diary card date), instead of as described in Table 15, the adjusted hazard ratio was 0.81 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.95; usual care, n = 860, and modified, n = 850).

If participants in the usual-care group were censored, as described in Table 15, and participants in the modified self-management group were censored at their date of last contact (i.e. favouring the usual-care group), the adjusted hazard ratio was 0.93 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.06; usual care, n = 938, and modified, n = 850).

Per-protocol analysis

Just over 50% of participants were included in the per-protocol population: 491 (51%) participants in the usual-care group and 524 (55%) participants in the modified self-management group (Table 17). A greater number of participants included in the per-protocol population in the modified self-management group had an activation to zone 2 or above.

| Inclusion | Intervention arm, n (% of total) | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 965) | Modified (N = 957) | |

| Included in per-protocol population | 491 (51%) | 524 (55%) |

| Good adherence during the first activation to zone 2 or abovea | 233 | 281 |

| Did not activate zone 2 or aboveb | 258 | 243 |

For the participants included in the per-protocol population, 197 in the usual-care group and 189 in the modified self-management group had an asthma exacerbation, with an adjusted hazard ratio for the time to first asthma exacerbation of 0.83 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.01; p = 0.06).

Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome

There was no evidence of a difference in the hazard ratio for time to asthma exacerbation in the modified self-management group compared with the usual-care group according to smoking status or dose of maintenance inhaled steroid dose at baseline (Table 18).

| Subgroup | Adjusted subgroup specific hazard ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted interaction effect (95% CI) | p-value for interaction effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking status | |||

| Never smoked | 0.78 (0.66 to 0.93) | 0.80 | |

| Current | 0.92 (0.55 to 1.54) | 1.18 (0.68 to 2.03) | |

| Former | 0.83 (0.67 to 1.04) | 1.07 (0.80 to 1.41) | |

| Dose of maintenance inhaled corticosteroids | |||

| Low | 0.84 (0.72 to 0.98) | 0.37 | |

| High | 0.73 (0.57 to 0.94) | 0.87 (0.65 to 1.17) | |

Secondary outcomes

Unscheduled health-care consultations and the use of systemic corticosteroids for asthma

Time to first use of systemic corticosteroids for asthma and time to first unscheduled health consultation for asthma

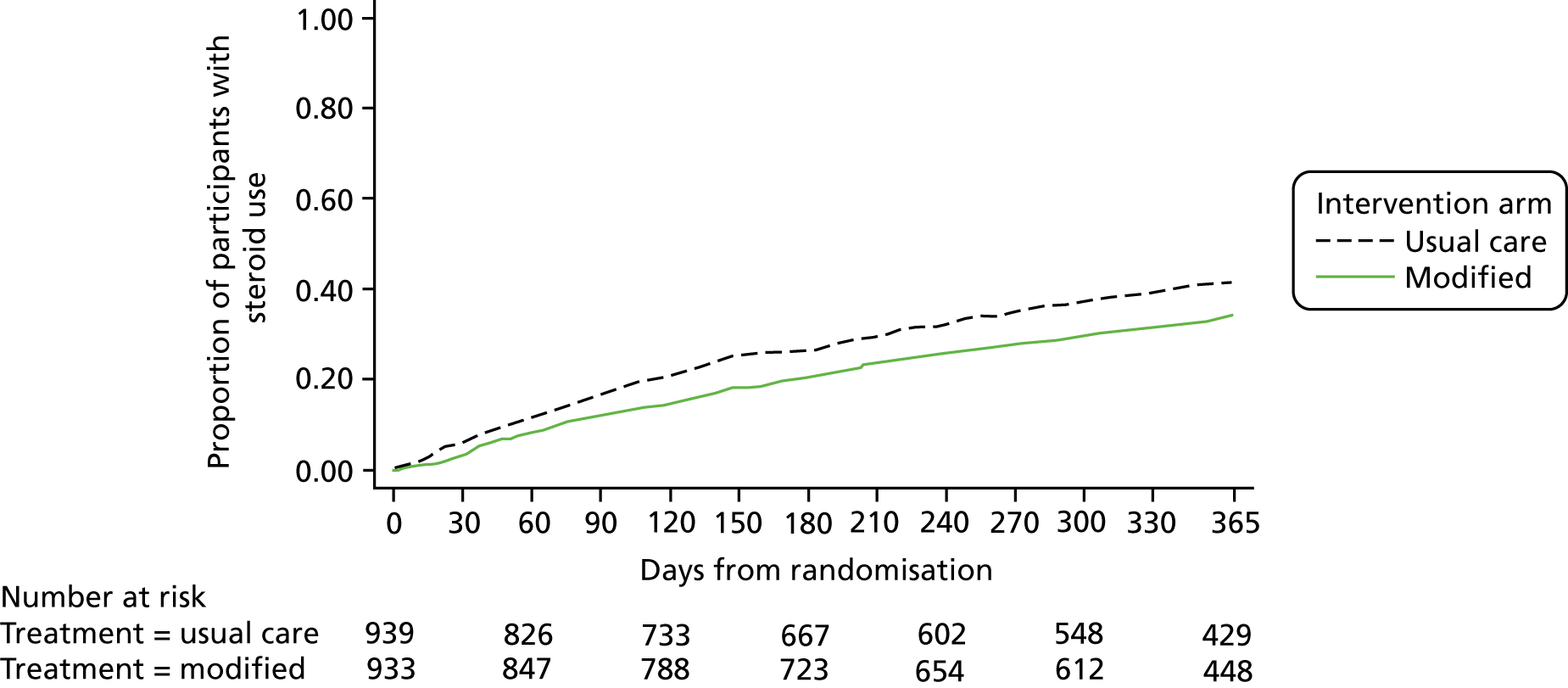

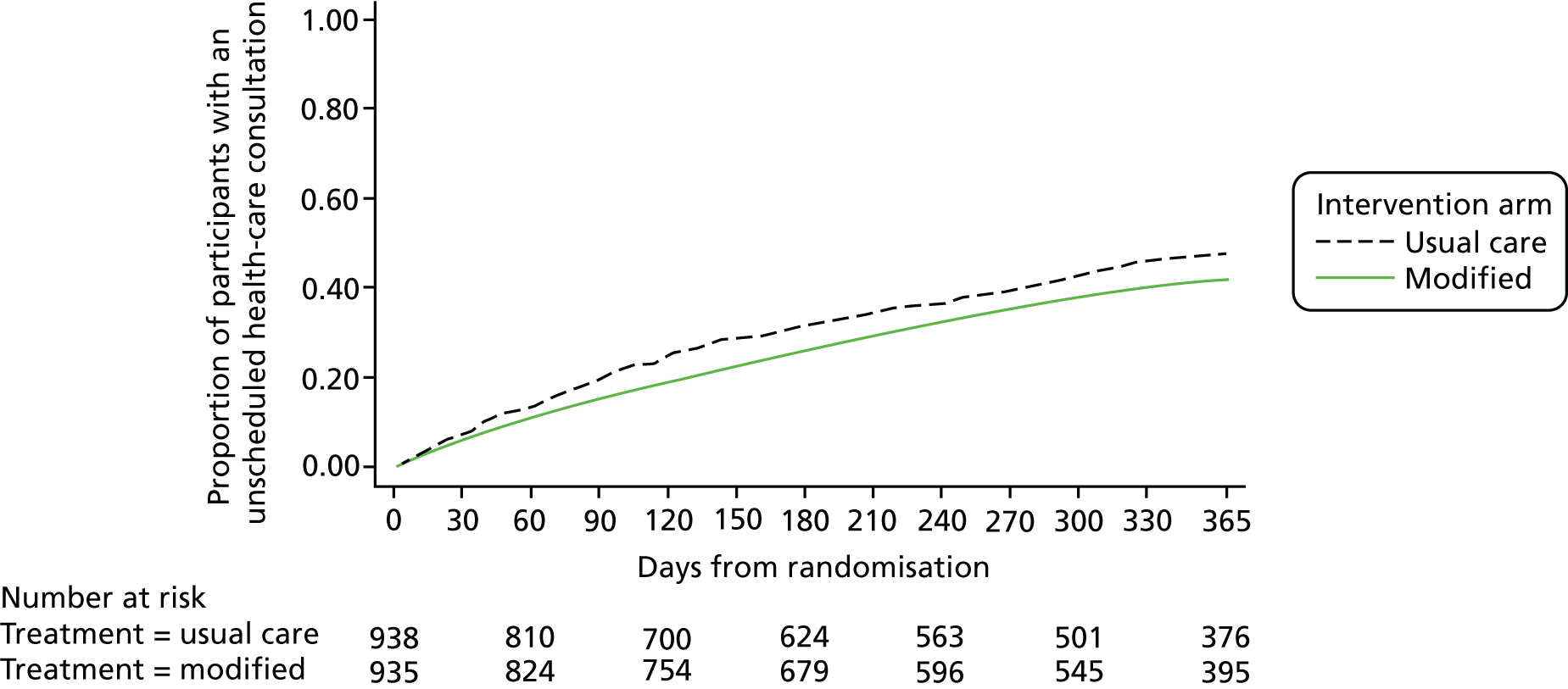

Figure 5 shows the Kaplan–Meier curves for the time to first use of systemic corticosteroids and the time to first unscheduled health-care consultation is shown in Figure 6. The adjusted hazards ratios are 0.76 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.88; p < 0.001) for the use of systemic corticosteroids and 0.82 (95% CI 0.70 to 0.92; p = 0.002) for unscheduled health-care consultations.

FIGURE 5.

Kaplan–Meier curves for the time to first requiring systemic corticosteroids for asthma by allocated group.

FIGURE 6.

Kaplan–Meier curves for the time to first unscheduled health-care consultation for asthma by allocated group.

Total number of courses of systemic corticosteroids for asthma, unscheduled health consultations and exacerbations for asthma

Table 19 shows that the number of participants using systemic corticosteroids, having an unscheduled health-care consultation and an exacerbation (systemic corticosteroids or unscheduled health-care consultation), was lower in the modified self-management group than in the usual-care group.

| Secondary outcome | Intervention arm | Adjusted intervention effecta (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 939) | Modified (N = 935) | |||

| Use of systemic corticosteroids | ||||

| Any courses, n (% of total) | ||||

| No | 552 (59) | 614 (66) | Risk difference –7.0% (–11.3% to –2.7%) | Risk ratio 0.83 (0.74 to 0.93) |

| Yes | 377 (40) | 311 (33) | ||

| Not knownb | 10 (1) | 10 (1) | ||

| Total number of courses | n = 929 | n = 925 | Incidence rate ratio 0.82 (0.70 to 0.96) | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.61 (0.93) | 0.5 (0.86) | ||

| 1, n (% of total) | 254 (27) | 212 (23) | ||

| 2, n (% of total) | 82 (9) | 68 (7) | ||

| 3 or more, n (% of total) | 41 (4) | 31 (3) | ||

| Any unscheduled health-care consultations | ||||

| Any, n (% of total) | ||||

| No | 490 (52) | 543 (58) | Risk difference –6.8% (–11.1% to –2.4%) | Risk ratio 0.86 (0.78 to 0.95) |

| Yes | 442 (47) | 379 (41) | ||

| Not knownb | 7 (1) | 13 (1) | ||

| Total number of unscheduled health-care consultations | n = 932 | n = 922 | Incidence rate ratio 0.86 (0.75 to 0.99) | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.84 (1.23) | 0.73 (1.19) | ||

| 1, n (% of total) | 261 (28) | 224 (24) | ||

| 2, n (% of total) | 96 (10) | 83 (9) | ||

| 3 or more, n (% of total) | 85 (9) | 72 (8) | ||

| Exacerbation: use of systemic corticosteroids and/or unscheduled health-care consultation for asthma | ||||

| Any exacerbations, n (% of total) | ||||

| No | 445 (47) | 499 (53) | Risk difference –6.7% (–11.2% to –2.3%) | Risk ratio 0.87 (0.80 to 0.95) |

| Yes | 485 (52) | 422 (45) | ||

| Not knownb | 9 (1) | 14 (1) | ||

| Total number of exacerbations | n = 930 | n = 921 | Incidence rate ratio 0.88 (0.77 to 1.01) | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.95 (1.29) | 0.84 (1.26) | ||

| 1, n (% of total) | 270 (29) | 235 (25) | ||

| 2, n (% of total) | 119 (13) | 97 (10) | ||

| 3 or more, n (% of total) | 96 (10) | 90 (10) | ||

Similarly, the total number of courses of systemic corticosteroids, unscheduled health-care consultations and exacerbations per participant was lower in the modified self-management group than in the usual-care group (Table 19).

Area under the percentage baseline morning peak flow curve over 2 weeks from the point of activating zone 2 (or above) of the asthma self-management plan

A higher percentage of participants who activated zone 2 or above of the self-management plan in the modified self-management group were able to be included in the analysis of the area under the PEF curve analysis (i.e. 54% compared with 41% in the usual-care group) as a result of a higher percentage of participants completing a diary card in the modified self-management group (Table 20). In both groups, however, there are high numbers of missing data for this analysis (Table 20). This is mainly due to participants not completing diaries for the first activation to zone 2 or not recording PEF values on or after day 10.

| Inclusion | Intervention arm, n (% of total) | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 552); at least one activation to zone 2 or above | Modified (N = 562); at least one activation to zone 2 or above | |

| Included in analysis | 226 (41) | 303 (54) |

| Not included in analysis | 326 (59) | 259 (46) |

| Reason not included | ||

| No diary for first activation to zone 2 or above | 224 | 162 |

| No PEF values recorded in diary | 24 | 8 |

| PEF not recorded on day 1 | 17 | 17 |

| No PEF recorded on or after day 10 | 60 | 72 |

| PEF recorded on day 1 and 10, but no days in-between | 1 | – |

For the participants who did record sufficient PEF information on their diary cards, the area under the percentage baseline PEF curve in the 2 weeks from the point of first activating zone 2 or above of the self-management plan was slightly higher in the modified self-management group than in the usual-care group (Table 21).

| Analysis | Intervention arm | Adjusted difference in meansa (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 552); at least one activation to zone 2 or above | Modified (N = 562); at least one activation to zone 2 or above | ||

| Analysis 1 | n = 226 | n = 303 | |

| Mean (SD) | 1130 (155) | 1166 (142) | 38 (13 to 62) |

| Median (25th, 75th centiles) | 1146 (1025, 1238) | 1165 (1073, 1258) | |

| Min., max. | 687, 1669 | 558, 1781 | |

| Analysis 2 | n = 197 | n = 269 | |

| Mean (SD) | 1133 (152) | 1164 (136) | 32 (7 to 59) |

| Median (25th, 75th centiles) | 1151 (1030, 1242) | 1158 (1069, 1249) | |

| Min., max. | 687, 1669 | 805, 1781 | |

Change in Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire 2 weeks after activating zone 2 (or above) of the self-management plan

The percentage of participants who activated zone 2 (or above) of the self-management plan was higher in the modified self-management group than in the usual-care group and who could be included in the analysis of change in the Mini AQLQ score (i.e. 51% compared with 39% in the usual-care group) because of a higher percentage of participants in the former attended the post-activation visit in the modified self-management group (Table 22). In both groups, however, there are substantial numbers of missing data for this analysis (Table 22).

| Mini AQLQ status | Intervention arm, n (% of total) | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 552); at least one activation to zone 2 or above | Modified (N = 562); at least one activation to zone 2 or above | |

| Mini AQLQ within 28 days | 216 (39) | 284 (51) |

| More than two items missed, score not calculated | 0 | 1 |

| Mini AQLQ completed after 28 days | 36 (7) | 40 (7) |

| Mini AQLQ not done | 29 (5) | 38 (7) |

| Post-activation visit not attended | 60 (11) | 42 (7) |

| No post-activation record | 211 (38) | 158 (28) |

For the participants who did complete the Mini AQLQ within 28 days of the first activation to zone 2, the Mini AQLQ scores were slightly higher in the modified self-management group than in the usual-care group (Table 23).