Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/09/06. The contractual start date was in August 2016. The draft report began editorial review in December 2017 and was accepted for publication in July 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Luke Vale is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board and co-ordinating editor of Cochrane Incontinence. Ash Monga was a paid speaker for Astellas Pharma (Tokyo, Japan), SEP Pharma Ltd (London, UK), Boston Scientific (Boston, MA, USA) and Atlantic Pharma Ltd (Bedford, UK). Phil Mackie is a member of the Scottish Independent Review of Transvaginal Mesh Implants.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Brazzelli et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of underlying health problem

Urinary incontinence (UI) is defined as an involuntary loss of urine. It is a common condition that is believed to affect millions of people. There are several types of UI; the focus of this research is stress urinary incontinence (SUI). SUI is the loss of urine when coughing, laughing, sneezing or exercising. It is a common and distressing condition, greatly affecting quality of life. The prevalence of SUI varies during life but is greater in women who have had children and in older women (20–50%). 1 The physical changes resulting from pregnancy, childbirth and menopause often contribute to SUI. For many women, SUI can worsen during the week before the menstrual period. Lower oestrogen levels can lead to lower muscular pressure around the urethra, which in turn increases the chances of leakage. Many women access conservative treatment with physiotherapy to deliver pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and bladder training initially but, if this fails, surgery is the mainstay of treatment. Data suggest that women have a 10% lifetime risk of having continence surgery. 1

The aim of surgery is to support or partially obstruct the bladder neck and/or urethra, thus blocking the leakage of urine on exertion or coughing. Women with mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) (a combination of SUI and urgency UI) may also be helped because they are better able to defer voiding and leakage. However, urinary urgency and urgency UI can be both caused by and made worse by SUI surgery. 1

Incontinence varies in degree of severity from several drops of urine to complete bladder emptying. It may occur daily, many times a day or only occasionally, perhaps once a month. It may be predictable or very unpredictable. These different factors – severity, frequency and predictability – all play a role in evaluating the impact of incontinence on behaviour, treatment choice, quality of life and economic burden. The precise economic burden has proved difficult to calculate. One published UK study suggests an estimated total figure for combined health, personal and societal expenditure of £818M for SUI at 1999/2000 prices (upwards of £1.1B at 2017 prices),2 whereas another study published in 2004 suggests a health-care cost to the UK NHS (SUI only) of £117M per year. 3

One of the main purposes of this research is to comparatively draw together all the relevant evidence from published randomised controlled trials (RCTs), accomplished through a network meta-analysis (NMA) and associated economic model. This allows all the available surgical treatments to be simultaneously compared with each other, for what we believe to be the first time, to determine which treatments should be offered in clinical practice on the basis of being the most clinically effective, safest and most cost-effective.

Description of current service provision

Women are likely to have tried many things prior to presenting to their general practitioner (GP), including lifestyle changes, PFMT and incontinence pants or pads. Embarrassment stops many seeking help from their GP until symptoms become unmanageable or begin to have a greater impact on everyday life. The treatment offered within primary care will depend on the type and severity of incontinence. Conservative treatments are usually tried first before moving on to medication. Conservative treatments can overlap with treatments tried by women prior to presenting and may include lifestyle changes (e.g. reduced caffeine intake, adjusted fluid intake, weight loss); PFMT, which can be aided by biofeedback, vaginal cones or electrical stimulation; and bladder training.

If these treatments are unsuccessful, medication is available. For SUI only one medication is available: duloxetine. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends (as of September 2013) that duloxetine not be routinely offered as first-line treatment and that it be offered as second-line therapy only to women wishing to avoid other therapy (i.e. surgery). The guidelines further state that women should be counselled regarding the drug’s side effects. The evidence for duloxetine is uncertain. The drug failed to receive Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for SUI owing to concerns over liver toxicity and suicidal events. In the UK, as mentioned previously, it is currently recommended as an add-on medication for SUI instead of surgery. Its safety and utility for SUI have been evaluated in a number of meta-analyses, the latest of which, published in 2016 and based on clinical trial reports, found that, although effective for SUI, duloxetine’s associated harms were high and, when individual patient data were analysed, outweighed the benefits. 4

There are several surgical treatment options for the management of women who have failed first-line treatment for SUI. Furthermore, there are a number of variations on most techniques, but, essentially, they fall into nine distinct categories:

-

anterior vaginal repair (anterior colporrhaphy)

-

bladder neck needle suspension

-

open abdominal retropubic colposuspension

-

laparoscopic retropubic colposuspension

-

traditional suburethral retropubic sling procedures

-

mid-urethral sling (MUS) procedures

-

retropubic MUS

-

transobturator MUS

-

-

single-incision sling procedures (‘mini-slings’)

-

periurethral injection (injectable bulking agents).

One of the earliest operations described for SUI was anterior repair with urethral buttressing sutures (Kelly sutures). Although curing over half of women, the high failure rate (and that of another operation, bladder neck needle suspension) led to the development of colposuspension, which is an open abdominal method of elevating the bladder neck. The evidence base suggested that this was more effective but with greater morbidity and a longer recovery time than the previous options. Laparoscopic colposuspension, although a minimally invasive variation of colposuspension, was considered slightly less effective than open surgery. These issues led to the development of traditional suburethral sling procedures, in which a piece of material, which could be biological (such as a rectus sheath graft) or synthetic (such as a polypropylene mesh sling), is placed under the urethra and the free ends secured in one of a number of different ways. The advent of a new minimally invasive technique that enabled the sling to be placed without tension ushered in a new era of simpler, effective and cheaper treatment. This brief summary of the evidence concurs with the conclusions of the Cochrane reviews that have collated the relevant evidence for these types of procedures. 5–12

The number of women having surgery has been rising and the choice of operations has changed over the past decade. In 2013–14, Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data for England show that around 12,000 women had a MUS operation, with around 500 having another type of continence procedure (colposuspension, ≈300; traditional slings, ≈200) and just over 700 having periurethral injections. In contrast, 10 years earlier just under 7000 women had a MUS operation, ≈1400 had a colposuspension and ≈250 had a traditional sling. There is no single database that records how many vaginal mesh implants are implanted or removed each year in women with SUI, making an assessment of trends difficult. However, it would appear that, until recently, there had been a shift towards minimally invasive MUS, with the majority of women choosing this procedure, which in turn led to a substantial increase in the total number of women having continence surgery. These trends are likely to have been driven, in part, by the perception of improved effectiveness and safety.

In 2014 the American Urogynecologic Society and Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction published a position statement: ‘The polypropylene mesh mid-urethral sling is the recognized worldwide standard of care for the surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence. The procedure is safe, effective, and has improved the quality of life for millions of women’. 13 However, subsequent international media publicity regarding supposed long-term severe adverse effects from vaginal mesh procedures has caused anxiety in women, many of whom have decided, owing to high levels of uncertainty, to avoid any type of surgery involving synthetic material, including MUS, despite the lack of any robust new evidence to support this view.

Women’s concerns about the safety of vaginal mesh implants led to a patients’ campaign, which in turn led to an independent enquiry and the suspension of use of any vaginal mesh (including MUSs) in Scotland, UK parliamentary questions, a mandatory national audit and a national campaign, Hear Our Voice (www.scottishmeshsurvivors.com/). The debate encompasses the wider use of vaginal mesh in conditions not being considered in this report. There remains a lot of uncertainty surrounding the optimal choice of surgery, especially related to long-term safety, with recent news and media headlines adding to the ambiguity that clinicians and women face when making decisions regarding treatment options. It is likely that the trend in the use of minimally invasive MUSs has taken a downwards turn; however, what is currently unclear is the strength of evidence to support the choice of any one of the other surgery options.

Description of technologies under assessment

The technologies under assessment are the surgical techniques anterior vaginal repair (anterior colporrhaphy); bladder neck needle suspension; open abdominal retropubic colposuspension; laparoscopic retropubic colposuspension; traditional suburethral retropubic sling procedures; retropubic MUS; transobturator MUS; and single-incision sling procedures (mini-slings).

Decision problem

Currently there is no clear evidence to indicate which surgery is the best choice. It is unclear if the older operations that were previously available (such as anterior repair and colposuspension) really result in equivalent or better outcomes than the polypropylene MUS. However, the feeling of our clinical experts who used to offer colposuspension and traditional slings is that these techniques had more frequent and severe associated complications and returning to them may be detrimental to women. To enable women to make an evidence-based choice and inform practice guidelines, it is essential to collect reliable evidence in a transparent, concise manner to allow impartial counselling of women regarding the benefits and risks of the alternative surgical operations for the management of SUI.

The wide range of surgical operations available, the different techniques used to perform these operations and the lack of a consensus among surgeons make it challenging to establish which procedure is the most effective. The existing evidence base, including the Cochrane systematic reviews, has focused on discrete two-way comparisons, with no attempt being made to collate all of the evidence on the surgical options available and rank them in terms of clinical effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness. This has resulted in a piecemeal evidence base that is difficult for women and clinicians to interpret. This assessment includes an evidence synthesis of all available RCTs to determine the relative clinical effectiveness and safety of interventions, a discrete choice experiment (DCE) to explore women’s preferences, an economic decision model to determine the most cost-effective treatment and a value-of-information (VOI) analysis to help inform the focus of further research.

Aims and objectives of the research

The aim of this project was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of surgical treatment for SUI and stress-predominant MUI in women.

The key objectives were to:

-

undertake an evidence synthesis using systematic review methods, including a NMA to estimate the relative clinical effectiveness of the different types of surgery and inform key clinical parameters for a decision model

-

undertake a review of safety/adverse effects associated with each type of surgical intervention

-

undertake a DCE to explore the preferences of women

-

develop a decision model to estimate the cost-effectiveness of surgical treatments for SUI and stress-predominant MUI

-

utilise the decision model to undertake a VOI analysis to assess the need for further primary research.

Chapter 2 Methods of clinical effectiveness review(s)

This chapter reports the methods used for conducting an objective synthesis of the current evidence for assessing the clinical effectiveness and safety of surgical interventions for the treatment of SUI or stress-predominant MUI in women. The evidence synthesis was carried out according to the general principles of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidance for undertaking reviews in health care,14 the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions15 and the NICE guide to the methods of technology appraisal16 and was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). 17 The methods were prespecified in a research protocol (PROSPERO database registration number CRD42016049339).

Search strategy

Literature searching was performed in two stages. First, relevant studies were identified from the existing relevant Cochrane systematic reviews published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Second, the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register was searched to identify new studies added since the publication of the Cochrane systematic reviews (henceforth ‘updated literature searches’).

The Cochrane Incontinence Group has published eight systematic reviews assessing nine distinct surgical procedures for the treatment of SUI in women. Two Cochrane systematic reviews that were obtained through personal communication and were in the process of being updated (review on traditional suburethral slings for UI in women: Dr Lucky Saraswat, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, 2016; review on laparoscopic colposuspension for UI in women: Dr Muhammad Imran Omar, University of Aberdeen, 2016) were also used as source data. Both reviews have currently completed the peer-review process. On approval, the final versions of these systematic reviews are expected to be published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

We used these Cochrane systematic reviews to identify studies that met our prespecified inclusion criteria. To avoid duplicates, the studies were taken from the reviews in the following order:

-

Lapitan et al. 5 – open retropubic colposuspension for UI in women

-

Ford et al. 8 and Ogah et al. 18 – MUS operations for SUI in women

-

Nambiar et al. 9 – single-incision sling operations for UI in women

-

Saraswat et al. 7 and Rehman et al. 19 – traditional suburethral sling operations for UI in women

-

Freites et al. 6 and Dean et al. 20 – laparoscopic colposuspension for UI in women

-

Glazener and Cooper11 – bladder neck needle suspension for UI in women

-

Glazener and Cooper10 – anterior vaginal repair for UI in women

-

Kirchin et al. 12 – urethral injection therapy for UI in women.

There was a certain degree of overlap between systematic reviews, with some primary studies included in more than one review. The additional reports of primary studies included as second/multiple publications were checked across reviews.

The Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Trials Register was searched (date of last search: 8 June 2017) using the terms given in Appendix 1 to identify studies published since the conduct of the Cochrane systematic review. The Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Trials Register is updated regularly and contains studies from the following databases and other sources:

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) [via Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CRSO)] (inception to 15 May 2017) (searched 15 May 2017)

-

MEDLINE (via OvidSP) (1946 to April week 3 2017)

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via OvidSP) (covering 28 April 2017)

-

MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print (via OvidSP) (covering 2 May 2017)

-

ClinicalTrials.gov via Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS) standalone

-

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)

-

hand-searching of journals and conference proceedings.

EMBASE is not included in the above list because the Cochrane Centralised Search Service already searches EMBASE for identification of RCTs and adds them to CENTRAL. Details of the search methods used to build the Specialised Register are available from the group’s module in The Cochrane Library. 21

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials or quasi-RCTs (using alternate allocation) were eligible for the assessment of clinical effectiveness. There was no restriction on the trials’ publication status (published or unpublished) or on the year or the language in which they were reported.

Population

The type of participants considered for this assessment were adult women with SUI or stress-predominant MUI. Either a clinical or a urodynamic diagnosis of SUI was considered suitable. We accepted the diagnoses as defined by the authors of the included trials. Women who underwent continence surgery as a primary or repeated procedure, women with SUI and concomitant prolapse and women who received concomitant prolapse surgery were deemed suitable for inclusion. Studies that did not specify the type of incontinence (stress, urge, mixed) or the predominant MUI symptoms (stress or urge) were excluded.

Interventions

The interventions detailed below were deemed suitable for inclusion. There are a number of variations on most surgical techniques, but, essentially, they fall into nine distinct categories, each of which has been previously evaluated in systematic reviews published in The Cochrane Library:

-

retropubic MUS operations

-

transobturator MUS operations

-

open retropubic colposuspension

-

laparoscopic colposuspension

-

traditional suburethral sling procedures

-

single-incision sling operations

-

anterior vaginal repair

-

bladder neck needle suspension

-

urethral injection therapy (periurethral injections/injectable bulking agents).

To be eligible for inclusion, studies had to compare two or more of the surgical interventions listed above. Studies that compared a surgical intervention with PFMT were also considered suitable for inclusion as they were useful for the development of a NMA treatment diagram for assessing direct and indirect treatment comparisons. For the purpose of this assessment, we considered eligible for inclusion PFMT programmes taught and monitored by health professionals, clinicians or instructors (defined as ‘supervised PFMT’). 22 PFMT programmes for which instructions were delivered using written material only (e.g. leaflets or flyers delivered to women), without any interaction or face-to-face contact with health-care professionals, were considered to be equivalent to no treatment and, therefore, excluded from this assessment.

We excluded, post hoc, studies that compared surgery with pharmacological treatments or no treatment, as they were not considered useful for the development of the treatment network diagram. We did not include studies comparing specific technical variations of the relevant surgical techniques (e.g. inside-out vs. outside-in transobturator MUS operations, or one injectable agent vs. another) as it was beyond the scope of this review to assess specific technical approaches within each surgical category.

Outcomes

The following outcome measures were considered.

Primary outcomes

-

Number of women cured (defined as resolution of clinical symptoms).

-

Number of women cured or improved (henceforth referred to as ‘improvement’).

Secondary outcomes

-

Long-term data:

-

number of women having repeated continence surgery.

-

-

Adverse events:

-

haemorrhage/major vascular complications, including haematoma

-

infection, including wound infection and urinary tract infection (UTI)

-

infection related to use of synthetic mesh

-

de novo symptoms of urgency or urgency incontinence

-

voiding difficulties including urinary retention

-

bladder or urethral perforation

-

tape/mesh/implant exposure

-

tape/mesh erosion or extrusion

-

persistent pain or discomfort, including osteitis, which is pertinent to the Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz procedure

-

dyspareunia (pain with intercourse)

-

death.

-

-

Resource use:

-

operating time

-

length of hospital stay.

-

We considered outcomes measured at 12 months or the nearest time point available as well as longer-term outcomes (e.g. at 2 years or 5 years). Studies with a time point of < 2 weeks were excluded.

The measurement of these outcomes was not used as an eligibility criterion for selecting studies for inclusion in this assessment.

Primary outcomes (cure and improvement) were defined in many different ways. For example, authors of individual studies defined cure as ‘no stress incontinence symptoms’, ‘negative testing’ or subjective reports of being ‘continent’, ‘dry’, ‘satisfied’ or ‘very much improved’. To have a more consistent definition of cure, we checked the original definitions used by the authors of each included study to ensure that ‘cure’ was used to refer to the resolution of SUI symptoms. We also accepted cases where authors reported resolution of ‘incontinence symptoms’ without specifying stress symptoms. Any indication of satisfactory improvement in SUI symptoms was defined as ‘improvement’.

A variety of measures could be used to define cure or improvement in SUI symptoms, including subjective (women-reported) measures such as women’s observations and objective measures such as quantification of symptoms (e.g. pad tests) and urodynamic tests. We chose to extract data based on a hierarchy of reported outcomes. For ‘cure’, women’s self-report of cure was given priority when available. When this measure was not available, a composite measure (a combination of women-reported and objective measures) was used instead. Pad test and urodynamic test results were considered only when the previous two outcome measures were not available. For ‘improvement’, the women’s self-report of improvement was preferred but if this was not available the women’s satisfaction rate was used as a proxy. If satisfaction rate was also not available, we considered improvement rates based on pad tests and then on urodynamic tests. Cough stress tests or diaries were considered less reliable measures for the assessment of cure and improvement.

Adverse event outcomes were extracted verbatim from the relevant Cochrane systematic reviews. The classification of secondary outcomes and time points of outcome measurements were only consistent within each Cochrane systematic review, but not necessarily across different Cochrane systematic reviews. For example, in certain reviews pain outcomes were classified by time (short term and long term) whereas in others this was by location (e.g. groin or abdominal). Haematoma was reported as either a distinct outcome (haematoma) or part of a group of outcomes (e.g. perioperative complications). Though some outcomes were redefined by Cochrane authors to facilitate meta-analysis, the definitions used were not always clearly reported. No attempt was made to standardise adverse event outcomes extracted from different Cochrane systematic reviews.

The GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach,23 which takes into account five criteria – study design (judged according to the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool), inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias24 – was used for rating the quality of evidence of the two primary outcomes included in the NMA (cure and improvement). The following steps were taken: (1) assess the quality of evidence of direct treatment effect (head-to-head comparison), when available; (2) assess the quality of evidence of indirect treatment effect (i.e. two pairwise comparisons contributing to the first-order loop; the lower confidence rating of the two pairwise comparisons was used to indicate the overall quality of indirect treatment effect); (3) use the higher of the two quality ratings when both direct and indirect estimates of treatment effect are available; and (4) when only a direct or indirect estimate of treatment effect is available, base the network quality on that estimate. As GRADEpro GDT (McMaster University and Evidence Prime Inc, Hamilton, ON, Canada; https://gradepro.org) is a web-based tool that does not support assessment of the quality of evidence of network meta-analyses, we used Microsoft Excel® 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). There are four levels of quality of evidence: high, moderate, low or very low. ‘High quality’ means that the authors have a lot of confidence that the true effect lies close to that of the estimated effect. ‘Moderate quality’ means that the authors believe that the true effect is probably close to the estimated effect but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. ‘Low quality’ means that the true effect might be markedly different from the estimated effect. ‘Very low quality’ means that the true effect is probably markedly different from the estimated effect.

Owing to the lack of suitable data and the fact that the risk-of-bias assessment in the relevant Cochrane systematic reviews was not always provided for individual outcomes, it proved unfeasible to use the GRADE approach for grading the quality of other outcomes.

Data collection

Selection of studies

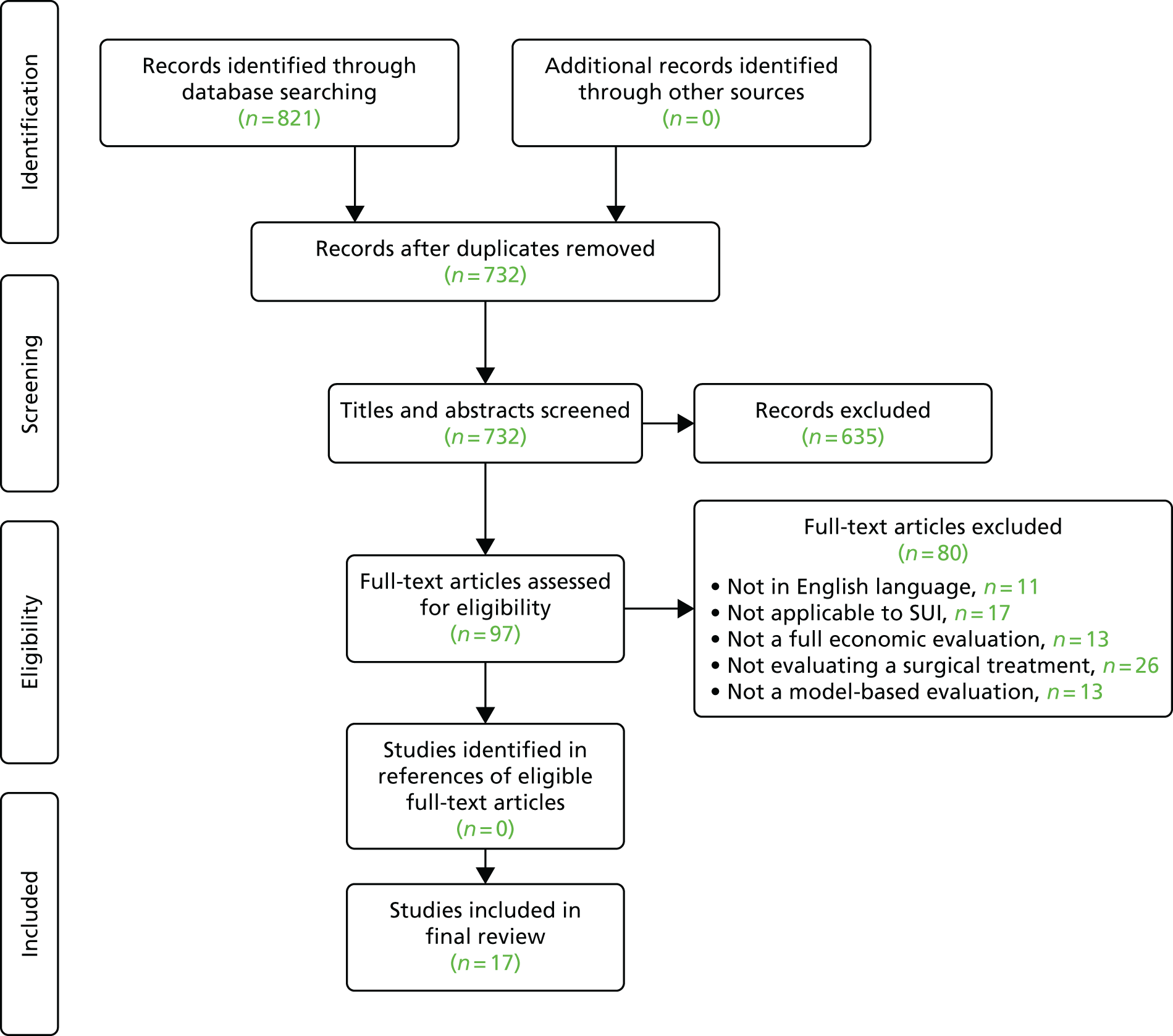

The selection of studies included in the Cochrane systematic reviews was established by one reviewer (SW) and checked by a second reviewer (MI). Screening of the titles and abstracts of all citations identified by the updated literature searches was conducted by one reviewer (SW). Full text copies of all potentially relevant reports were retrieved by the same reviewer for eligibility and checked by a second reviewer (MI or MS) to ensure that they met the prespecified inclusion criteria.

Data extraction

Studies selected from Cochrane systematic reviews

The original data extraction performed by the authors of the individual Cochrane systematic reviews was used as a basis for the assessment of clinical effectiveness. The characteristics of included studies were extracted as reported in the relevant Cochrane systematic reviews. Outcome data presented in forest plots of each Cochrane systematic review were exported using RevMan version 5.3 (Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). Of these, data for primary outcomes (cure and improvement) were cross-checked against the original study reports and supplementary information (such as definitions and time points) was extracted to enable the performance of a NMA.

Cross-checking of secondary outcome data was performed only when there was inconsistency in the extracted data or when studies were originally included as abstracts in the Cochrane systematic reviews but subsequently published in full (eight studies). 25–32 In other cases, adverse event data were accepted as reported in the Cochrane reviews.

Some Cochrane systematic review authors attempted to contact the corresponding authors of included studies to obtain key missing data or have full-text copies of non-English-language translations. Any relevant information retrieved in such a manner was included in this assessment. In some cases, reports published in languages other than English were translated by the authors of the Cochrane reviews. When a translation could not be arranged, the information used in the Cochrane reviews was limited to the content of the English abstracts.

Studies identified by the updated literature searches

For new studies identified by the updated literature searches, data extraction was carried out by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer (MI and MS) for errors or inconsistencies. Any disagreement was resolved through consensus or arbitration by a third party. A data extraction form was designed and piloted for the purpose of this assessment (see Appendix 2). Details related to study design, characteristics of participants, settings, characteristics of interventions and outcome measures were recorded. Outcome data were extracted as needed to allow calculation of summary statistics and measures of variance. Numbers of events and total number of participants in each treatment group were extracted for the assessment of dichotomous outcomes, and means and standard deviations (SDs) were extracted for the assessment of continuous outcomes. Missing data were not imputed and there was no attempt to contact study authors for missing data.

Risk-of-bias assessment of included studies

Studies selected from Cochrane systematic reviews

We relied on the original risk-of-bias assessments performed by the authors of the Cochrane systematic reviews. Assessment criteria varied across different Cochrane systematic reviews, which were accepted as reported. We updated the risk-of-bias assessments using the new criteria described below only for those studies that were initially included in the Cochrane systematic reviews as abstracts but subsequently published in full (eight studies). 25–32

Studies identified by the updated literature searches

For the studies identified by the updated literature searches, the Cochrane risk-of-bias assessment tool was used. 15 Critical judgments were made for the following domains: selection bias (random sequence generation, allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessor), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), reporting bias (free of selective reporting) and other bias. Each included study was judged to be at ‘low risk of bias’, ‘high risk of bias’ or ‘unclear risk of bias’. The assessment was conducted by one reviewer (MI or MS) and checked by a second reviewer (MI or MS). Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or arbitration with a third reviewer (MB). Studies were not included or excluded on the basis of their methodological quality.

Data analysis

Network meta-analysis

Network meta-analysis aims to synthesise all of the available evidence within a distinct framework. It enables the integration of direct evidence with indirect evidence from a network of studies involving all possible intervention comparisons. Direct evidence is obtained from all possible head-to-head comparisons between the different interventions, whereas indirect evidence is obtained from comparisons of two or more interventions that share a common comparator. For example, direct evidence from comparing intervention A with B and B with C can be combined to provide indirect evidence for intervention A versus C.

We conducted a NMA to assess the effects of the surgical interventions for SUI in terms of the number of women who were cured or experienced an improvement in their incontinence symptoms (primary outcomes). Studies that reported 100% events in all arms (all participants were cured or improved) were excluded from the analysis as they provide no evidence for the analysis. The NMA included outcomes measured at 12 months or at a time point closest to 12 months (studies with a time point of < 2 weeks or > 36 months were excluded).

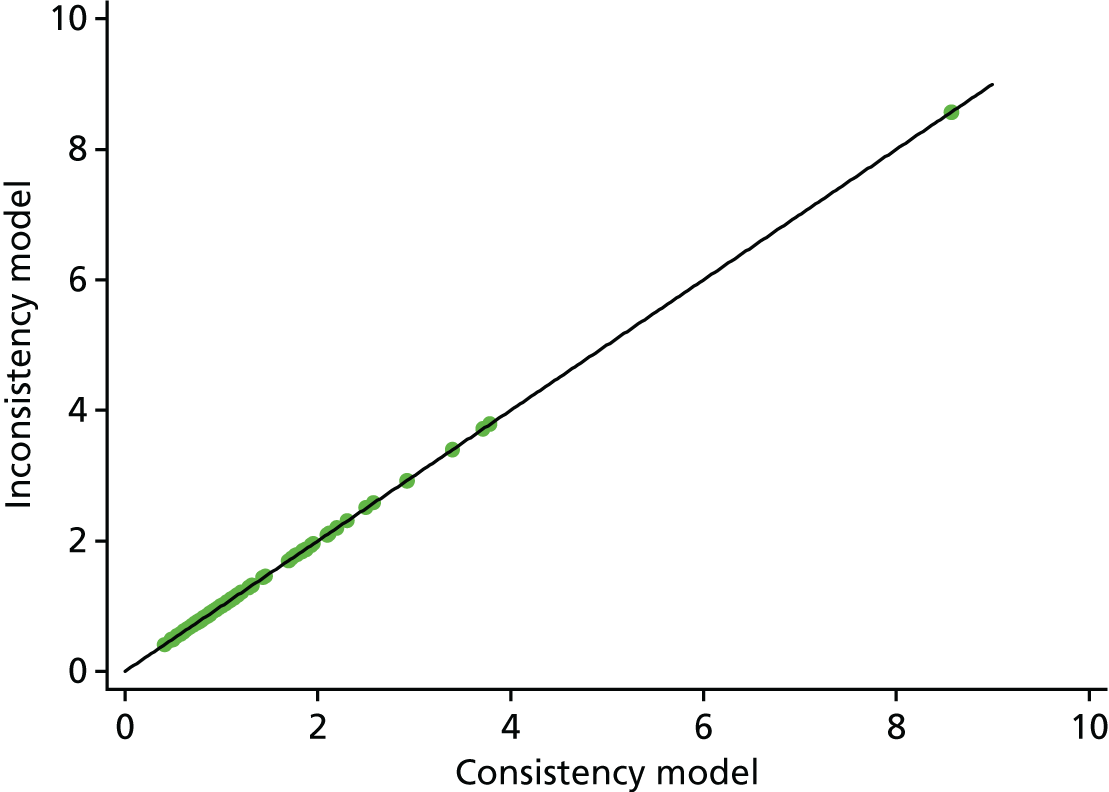

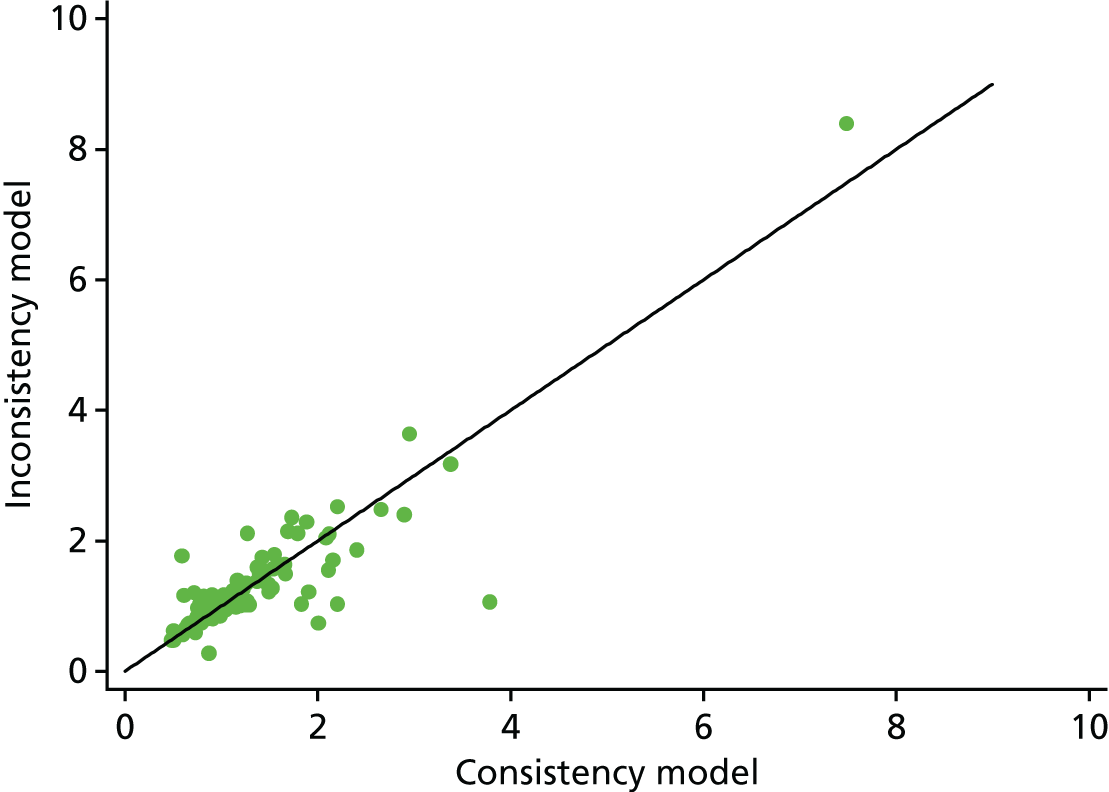

Convergence was assessed using Brooks–Gelman–Rubin plots, trace plots and autocorrelation plots. The NMA analysis was undertaken within a Bayesian framework, using WinBUGS 1.4.3 (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK)33 and using code provided by Dias et al. 34 (see Appendix 3). The analysis used vague uniform prior and adjusted for multi-arm trials using conditional distributions. Consistency, which is where direct and indirect evidence are in agreement, was assessed by comparing the individual data point’s posterior mean deviance contributions for the consistency and inconsistency model and node splitting analysis35 using R 3.4.1 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

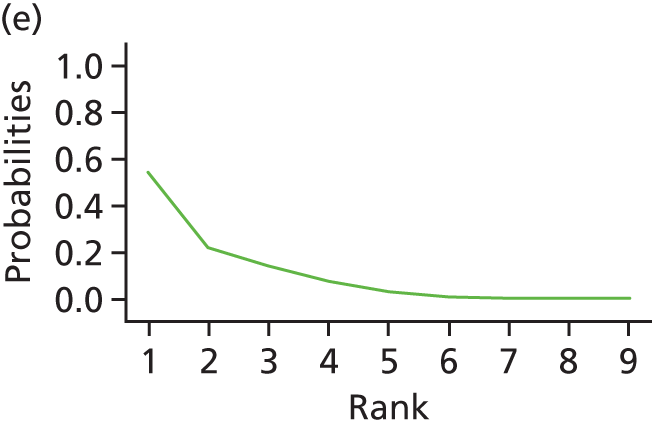

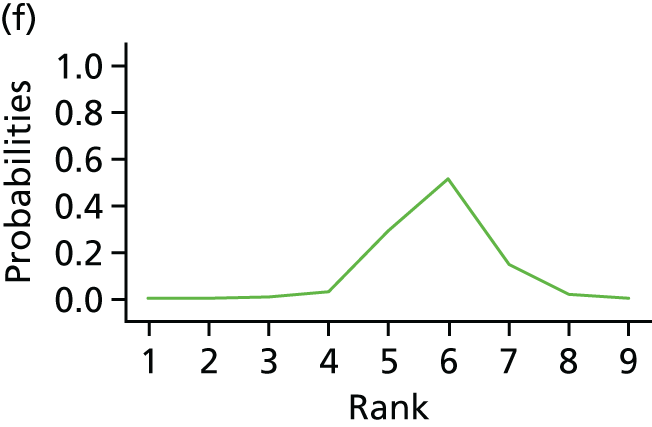

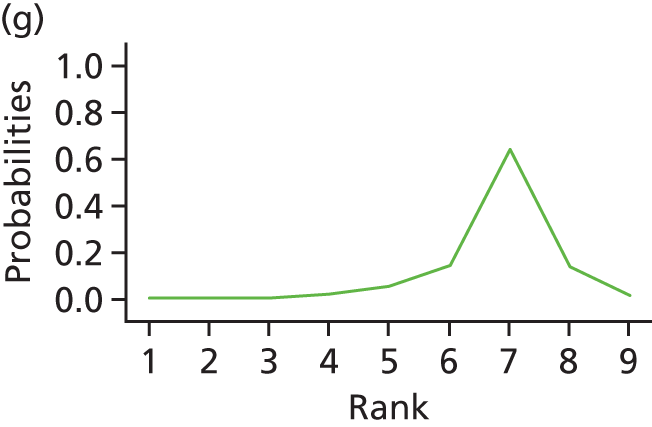

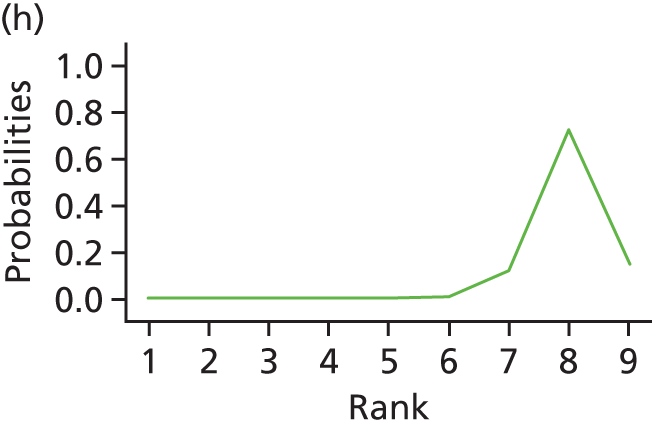

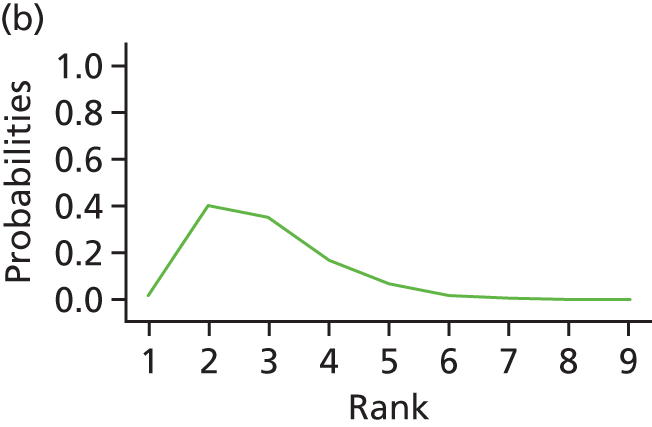

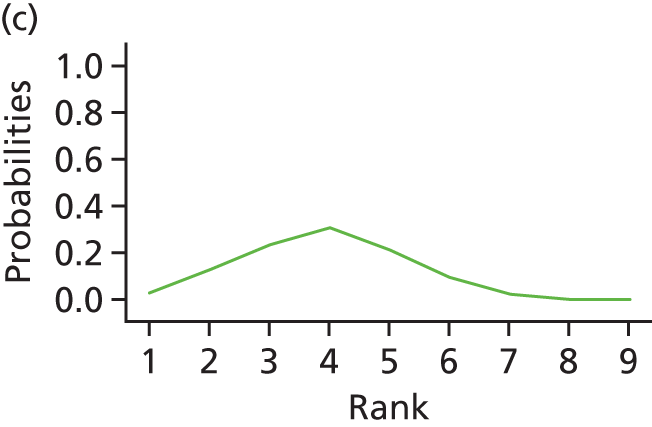

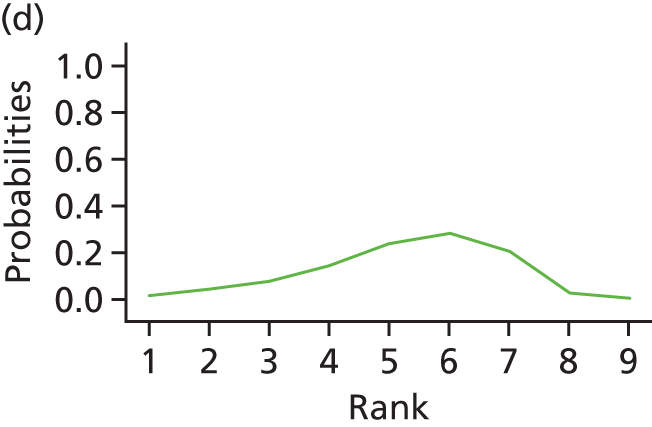

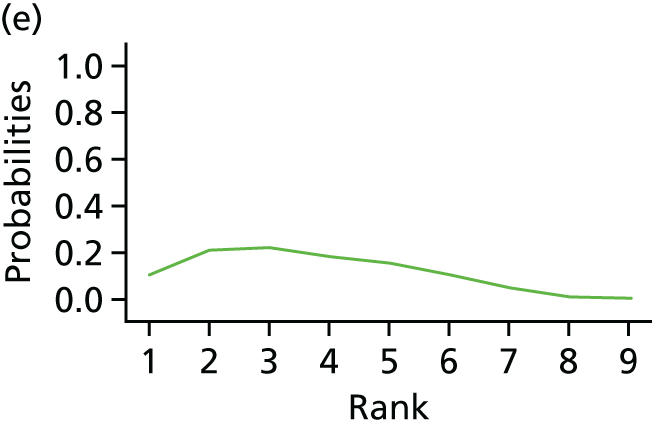

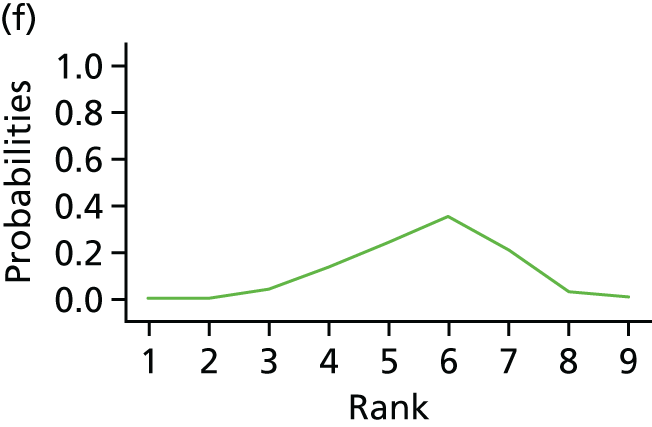

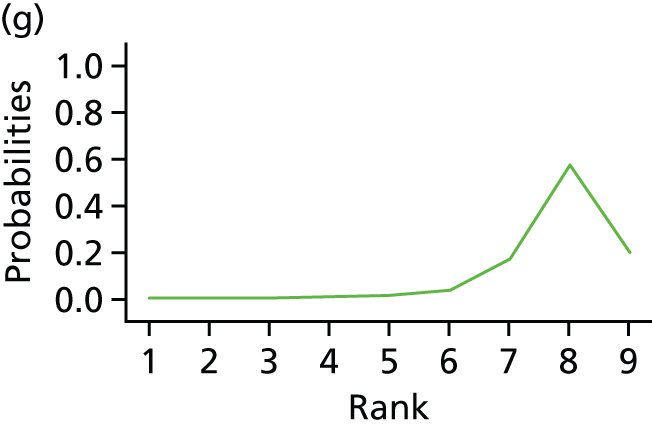

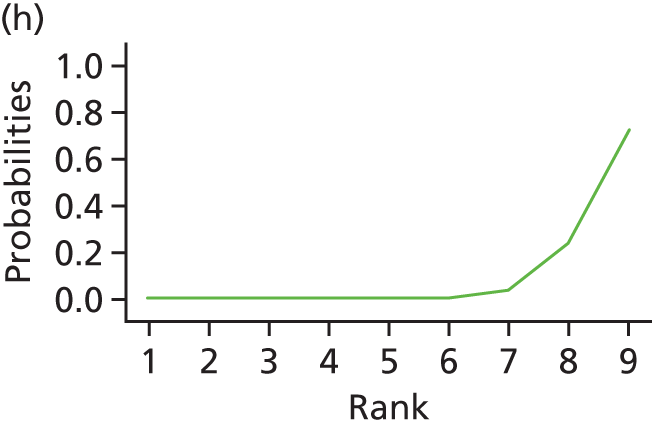

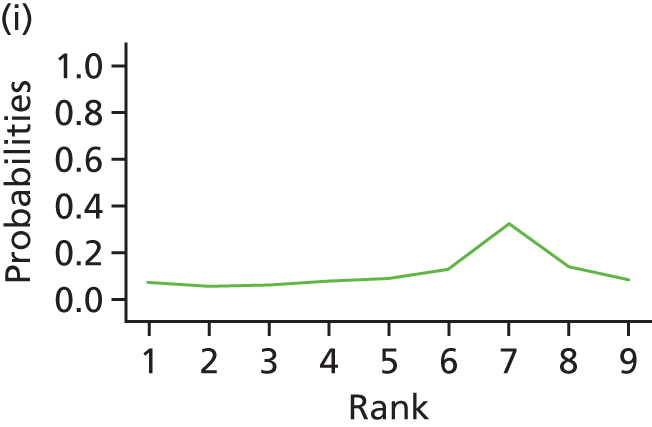

In the results section, network diagrams are presented for each outcome and effect sizes are reported as posterior median odds ratios (ORs) and 95% credible intervals (Crls). We also present rankograms for all surgical interventions, which gives probabilities of an intervention being ranked 1 (the highest) to 9 (the lowest) as well as reporting the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA), which is a numerical presentation of the overall ranking and presents a single number associated with each intervention. SUCRA values range from 0% to 100%. The closer to 100% the SUCRA value, the more likely that an intervention is in the top rank or one of the top ranks; the closer to 0 the SUCRA value, the more likely that an intervention is in the bottom rank or one of the bottom ranks. 36

Direct pairwise (head-to-head) meta-analyses

Adverse event outcomes as well as cure and improvement were summarised as direct head-to-head comparisons using a random effects model. Effect sizes are reported as ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous outcomes and as mean differences with 95% CI for continuous outcomes. When data were available, meta-analyses assessing adverse events were performed at different time points (e.g. 6 months, 12 months, 24 months). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. Analyses were performed using Stata version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Subgroup analysis

We planned to undertake subgroup analyses for the following groups: women with stress-predominant MUI versus women with SUI alone; repeated surgery (after failed previous continence surgery) versus primary procedures; women with and without coexisting vaginal prolapse/having concomitant prolapse surgery. However, these were not performed owing to the lack of available data. For example, lack of clarity in some trial reports made it difficult to decipher whether study participants had SUI, MUI or both. Moreover, outcome data for each patient subgroup were not reported separately in all trials. Owing to such inconsistencies and limited reporting of suitable data in the included studies, we were unable to perform these analyses.

Chapter 3 Results of clinical effectiveness review(s)

Number of studies identified

Studies identified from Cochrane systematic reviews

From the eight published Cochrane systematic reviews that provided data suitable for this assessment, a total of 166 studies (in 443 reports) were initially selected as potentially relevant. Of these, 147 studies (in 406 reports) were included as they met the prespecified inclusion criteria for this assessment, 17 studies were excluded and one was merged with another study. 37 The number of included studies from each Cochrane systematic review is shown in Table 1.

| Source of studies | Number of studies selected |

|---|---|

| (a) Selected from published Cochrane systematic reviews | |

| Lapitan et al.:5 open retropubic colposuspension for UI in women | 47 |

| Ford et al.8 and Ogah et al.:18 MUS operations for SUI in women | 68 |

| Nambiar et al.:9 single-incision sling operations for UI in women | 24 |

| Saraswat et al.7 and Rehman et al.:19 traditional suburethral sling operations for UI in women | 6 |

| Freites et al.6 and Dean et al.:20 laparoscopic colposuspension for UI in women | 1 |

| Glazener and Cooper:11 bladder neck needle suspension for UI in women | 1 |

| Glazener and Cooper:10 anterior vaginal repair for UI in women | 0 |

| Kirchin et al.:12 urethral injection therapy for UI in women | 0 |

| Subtotal | 147 |

| (b) Identified via updated literature searches | |

| Subtotal | 28 |

| Total number of included studies (a + b) | 175 |

Studies identified from updated literature searches

The updated literature searches identified 591 potentially relevant titles and abstracts from which 216 reports were selected for full-text evaluation. Of these, 65 reports (describing 28 new studies) were considered suitable for inclusion. In addition, 100 reports were identified as additional references of studies already included in the relevant Cochrane systematic reviews and two reports were additional references of studies originally included in the Cochrane systematic reviews but subsequently excluded from the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of surgical treatments for women with stress urinary incontinence (ESTER) report. A total of 26 reports of 23 ongoing trials were also identified and two further reports were included as ‘awaiting assessment’ and 21 reports were excluded.

In total, 175 studies were included in the assessment of clinical effectiveness. Of these, 43 studies were available only as conference abstracts. 38–80 A PRISMA flow chart summarising the study selection process is provided in Appendix 4. The list of included studies and associated references is reported in Appendix 5. Reasons for exclusion for a sample of excluded studies are described in Appendix 6. The list of ongoing trials is provided in Appendix 7.

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of the included studies are detailed in Appendix 8. The included studies involved a total of 21,598 women, with a median follow-up of 12 months, ranging from 1 month80 to 126 months. 81 Sample size ranged from 1570 to 65582 participants, with a median of 91 participants per study. There were 25 studies with a sample size of ≥ 200 participants. 28,37,61,65,72,82–101 The largest study assessed 655 women treated with either open colposuspension or traditional slings. 82 The mean or median age of women ranged from 34.338 to 65.0102 years.

There were 10 quasi-randomised trials (out of 175 included studies; 6%) considered to be at high risk of selection bias, as participants were allocated to treatment by alternation,103–110 date of birth111 or medical history numbers. 112

The primary references of the included studies (either the first publication or the first full-text publication) were published between 1978105 and 2016. 65,91,113–115 Around 10% (17 out of 175) of the included studies were published before 2000, 81 (46%) were published between 2000 and 2009 and 77 (44%) were published in 2010 or thereafter. All of those published before 2000 compared open colposuspension with other surgical procedures, whereas those published from 2000 onwards tended to include MUSs (retropubic or transobturator route) or single-incision slings as one of the study arms.

The number and type of intervention comparisons are shown in Table 2. Altogether, the included studies reported 21 treatment comparisons. The majority of included studies involved MUSs (retropubic or transobturator route) as part of their interventions. The most common intervention comparisons were between retropubic MUSs and transobturator MUSs (58 studies) and between transobturator MUS and single-incision slings (39 studies). The latter comparisons included 17 new studies, nearly two-thirds of the 28 new studies identified by the updated literature searches (17 out of 28; 61%). Another common comparison was between open colposuspension and other surgery (46 studies), followed by laparoscopic colposuspension (21 studies) and traditional slings (20 studies). Few studies were available for most other comparisons.

| Intervention | Number randomised | Number of studies | Number of new studies | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (control) | 2 (experiment) | ||||

| Retro-MUS | Transob-MUS | 8876 | 58 | 4 | Darabi Mahboub et al.,26 Tarcan et al.,31 Wang,37 Cervigni et al.,41 Choe et al.,42 de Oliveira et al.,44 Diab et al.,45 El-Hefnawy et al.,48 Elshawaf and Al bahaie,49 Hammoud et al.,56 Kamel,58 Leanza et al.,61 Mansoor et al.,64 Palomba and Zullo,70 Riva et al.,71 Rudnicki et al.,72 Salem et al.,73 Aigmüller et al.,83 Aniuliene,84 Araco et al.,86 Chen et al.,90 Krofta et al.,94 Laurikainen et al.,96 Meschia et al.,97 Rechberger et al.,98 Richter et al.,99 Enzelsberger et al.,104 Lee et al.,107 Nerli et al.,110 Wang et al.,116 Andonian et al.,117 Chen et al.,118 Scheiner et al.,119 Alkady and Eid,120 Aniuliene et al.,121 Barber et al.,122 Barry et al.,123 David-Montefiore et al.,124 deTayrac et al.,125 Deffieux et al.,126 El-Hefnawy et al.,127 Freeman et al.,128 Jakimiuk et al.,129 Karateke et al.,130 Kiliç et al.,131 Kim et al.,132 Liapis et al.,133 Mehdiyev et al.,134 Nyyssönen et al.,135 Porena et al.,136 Ross et al.,137 Schierlitz et al.,138 Tanuri et al.,139 Teo et al.,140 Wang et al.,141 Wang et al.,142 Zhang and Zhu143 and Zullo et al.144 |

| Retro-MUS | Open colpo | 1240 | 13 | 0 | Trabuco et al.,32 Drahoradova et al.,46 Elshawaf and Al bahaie49 Halaska et al.,55 Han,57 Koelbl et al.,60 O’Sullivan et al.,69 Ward et al.,100 Liapis et al.,108 Bai et al.,145 Foote et al.146 and Paraiso et al.147 |

| Retro-MUS | Lap colpo | 651 | 8 | 0 | Adile et al.,39 Maher et al.,63 Mirosh and Epp,67 Foote et al.,146 Paraiso et al.,147 Persson et al.,148 Ustün et al.149 and Valpas et al.150 |

| Retro-MUS | Trad sling | 868 | 9 | 0 | Abouhashem et al.,38 Sharifiaghdas and Mortazavi,81 Guerrero et al.,92 Kondo et al.,106 Bai et al.,145 Amaro et al.,151 Arunkalaivanan and Barrington,152 Basok et al.153 and Song et al.154 |

| Retro-MUS | Single incision | 1092 | 9 | 3 | Lee et al.,62 Rudnicki et al.,72 Barber et al.,87 Wang et al.,116 Abdelwahab et al.,155 Andrada Hamer et al.,156 Basu and Duckett,157 Gopinath et al.158 and Ross et al.159 |

| Retro-MUS | Ant repair | 53 | 1 | 0 | Wadie et al.160 |

| Transob-MUS | Open colpo | 272 | 4 | 0 | El-Din Shawki et al.,47 Elshawaf and Al bahaie,49 Bandarian et al.161 and Sivaslioglu et al.162 |

| Transob-MUS | Lap colpo | 35 | 1 | 0 | Samiee et al.163 |

| Transob-MUS | Trad sling | 141 | 3 | 1 | Al-Azzawi,164 Silva-Filho et al.165 and Tcherniakovsky et al.166 |

| Transob-MUS | Single incision | 4612 | 39 | 17 | Bianchi et al.,25 Djehdian et al.,27 Lee et al.,28 Schweitzer et al.,29 Smith et al.,30 Dati et al.,43 Enzelsberger et al.,50 Fernandez et al.,52 Friedman,54 Kim et al.,59 Melendez Munoz et al.,65 Merali et al.,66 Rudnicki et al.,72 Seo et al.,74 Shawky et al.,75 Van Rensburg et al.,79 Yoon et al.,80 Gaber et al.,91 Masata et al.,101 Amat I Tardiu et al.,112 Jurakova et al.,113 Pastore et al.,114 Xin et al.,115 Wang et al.,116 Masata et al.,167 Oliveira et al.,168 Sottner et al.,169 Enzelsberger et al.,170 Foote,171 Hinoul et al.,172 Hota et al.,173 Mackintosh,174 Maslow et al.,175 Campos et al.,176 Schellart and Roovers,177 Sivaslioglu et al.,178 Tang et al.179 and Tommaselli et al.180 |

| Transob-MUS | Ant repair | 120 | 2 | 1 | El-Din Shawki et al.47 and Salari and Sohbati181 |

| Transob-MUS | PFMT | 460 | 1 | 1 | Labrie et al.95 |

| Open colpo | Lap colpo | 1402 | 12 | N/A | Burton et al.,40 Fatthy et al.,51 Morris et al.,68 Stangel-Wojcikiewicz,76 Summitt et al.,77 Ankardal et al.,85 Carey et al.,89 Kitchener et al.,93 Mak et al.,182 Su et al.,183 Tuygun et al.184 and Ustün et al.185 |

| Open colpo | Trad sling | 922 | 7 | N/A | Fischer et al.,53 Albo et al.,82 Demirci and Yucel,103 Henriksson and Ulmsten,105 Bai et al.,145 Enzelsberger et al.186 and Sand et al.187 |

| Open colpo | Bladder neck needle | 639 | 7 | N/A | Bergman et al.,88 Mundy,109 Athanassopoulos and Barbalias,111 Bergman et al.,188 Gilja et al.,189 German et al.190 and Palma et al.191 |

| Open colpo | Ant repair | 690 | 8 | N/A | El-Din Shawki et al.,47 Bergman et al.,88,188 Berglund and Lalos,192 Colombo et al.,193 Holmes et al.,194 Kammerer-Doak et al.195 and Liapis et al.196 |

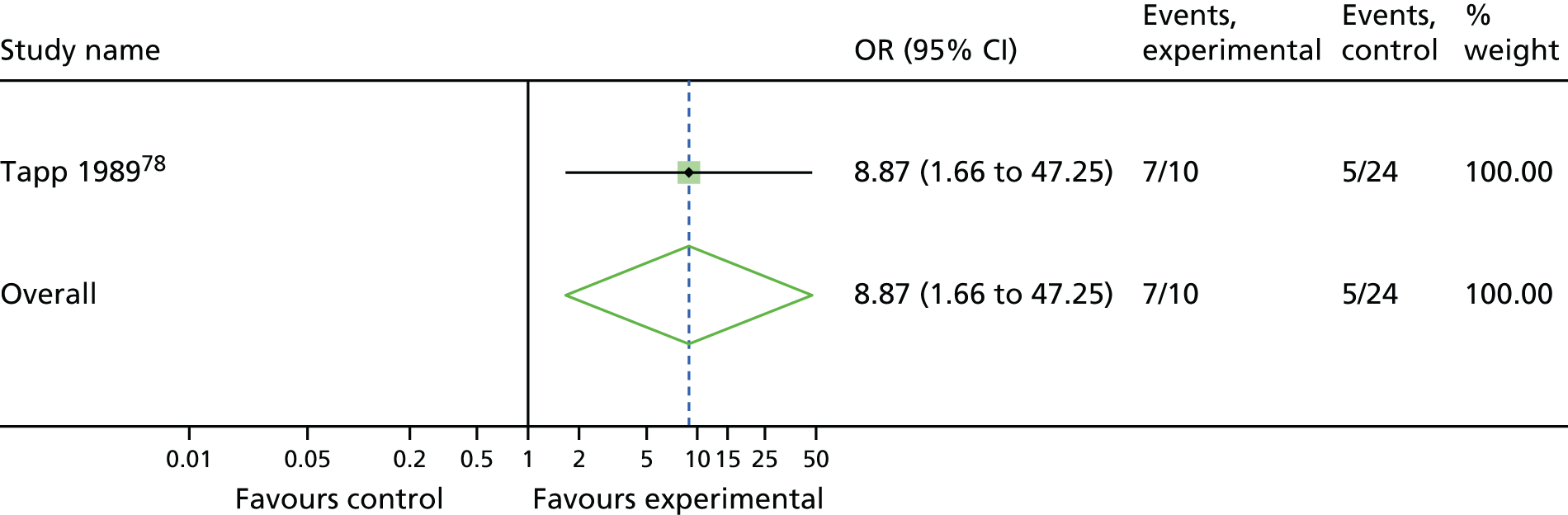

| Open colpo | PFMT | 45 | 1 | N/A | Tapp et al.78 |

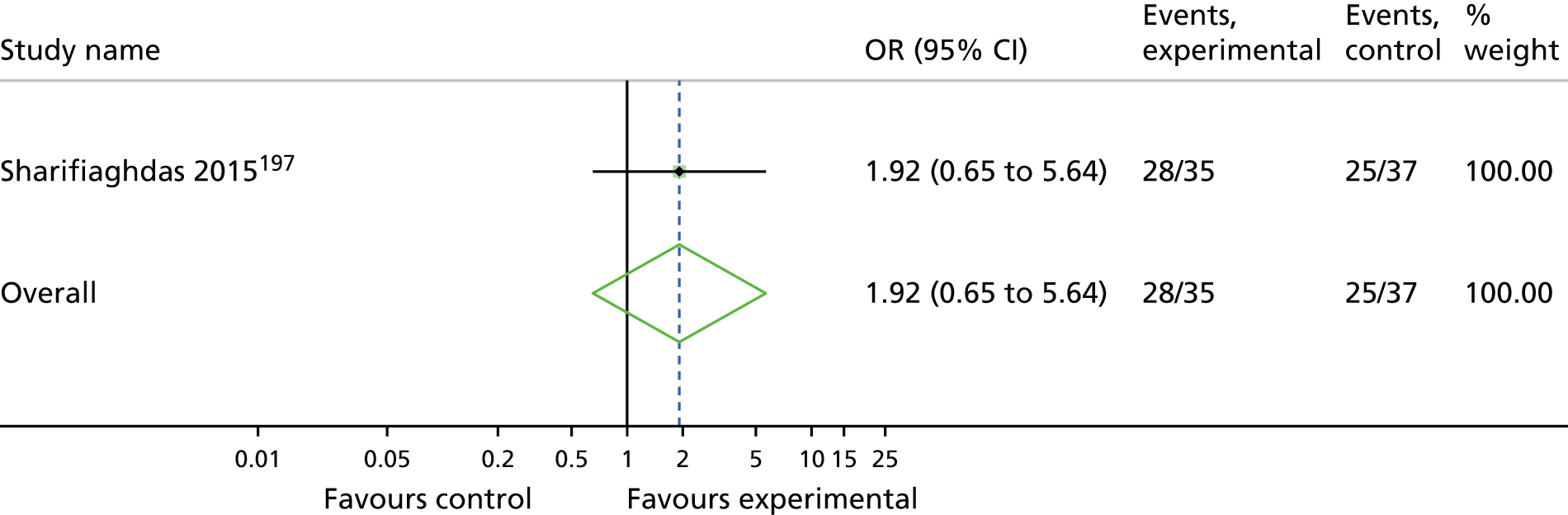

| Trad sling | Single incision | 72 | 1 | 1 | Sharifiaghdas et al.197 |

| Trad sling | Injectable | 45 | 1 | N/A | Maher et al.102 |

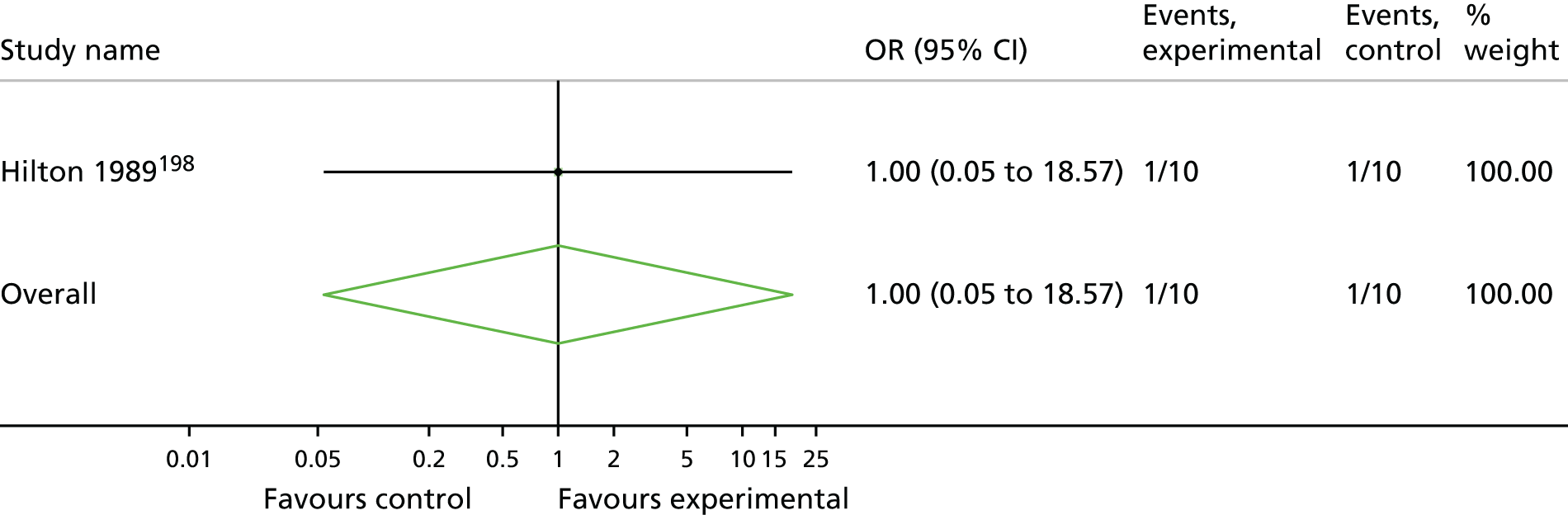

| Trad sling | Bladder neck needle | 20 | 1 | N/A | Hilton198 |

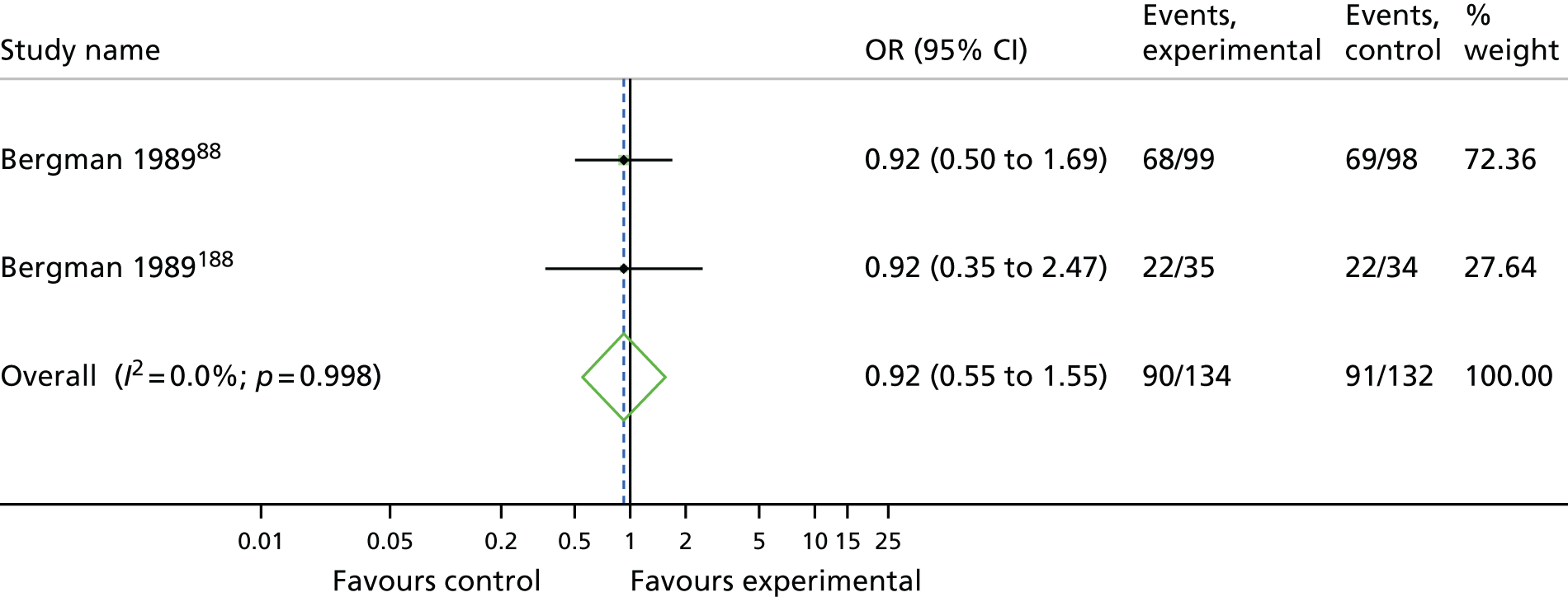

| Bladder neck needle | Ant repair | 346 | 3 | N/A | Bergman et al.88,188 and Di Palumbo199 |

Six trials were based on a three-arm design. 47,49,88,116,145,188 One four-arm trial was also converted to a three-arm trial because two of the four arms compared two variations of the same treatment and were therefore combined [i.e. tension-free vaginal tape-obturator (TVT-O) and transobturator tape (TOT) were combined as transobturator MUS]. 72

Some of the three-arm trials were converted into two-arm trials because either two of the three treatment arms compared two variations of the same surgical operation,91,92,117–119,167–169,189,200 or one of the three arms assessed a treatment that did not meet our inclusion criteria [e.g. de Olivera et al. 44 included pre-pubic tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) and Tapp et al. 78 included PFMT plus electrical stimulation].

The characteristics of the participants enrolled in the included studies are summarised in Table 3. The majority of studies (91 out of 175; 52%) included women with urodynamically confirmed SUI. 25,30,31,37,39,40,43,49,51,53–55,57,58,60,61,67–69,76–78,81,83,85,87–93,97,100–103,106,107,109,111,113,115,118,122–131,138,140–142,145–152,155,160–162,166,167,171,173,178,180,182,183,185,187–190,193–196,198,201–203 Eight studies included women with a clinical diagnosis based on either urodynamic tests or symptoms of SUI27,28,120,157,165,168,172,191 and the remaining studies appeared to use a diagnosis based on symptoms of SUI.

| UI diagnosis | Number of studies |

|---|---|

| Urodynamically confirmed stress incontinence | 91 |

| Symptom diagnosis of stress incontinence | 76 |

| Either urodynamic or symptom diagnosis of stress incontinence | 8 |

| MUI | |

| SUI/USI only, no MUI | 23 |

| SUI/USI or MUI | 53 |

| SUI/USI, unclear if MUI is included or excluded | 99 |

| Previous UI surgery | |

| Excluded | 81 |

| Excluded specific surgery only | 16 |

| Included | 31 |

| Not reported | 47 |

| Co-existing prolapse at recruitment | |

| Excluded | 11 |

| Excluded ≥ 2 degree only | 28 |

| Excluded ≥ 3 degree only | 28 |

| Excluded ‘major’ or ‘significant’ prolapse only | 11 |

| Included | 36 |

| Not reported | 61 |

| Concomitant prolapse surgery performed | |

| No | 39 |

| Yes | 35 |

| Yes (hysterectomy) | 6 |

| Not reported | 95 |

In general, it was difficult to determine from the relevant Cochrane systematic reviews whether or not the patient populations had other specified characteristics (e.g. mixed incontinence or mixed symptoms, previous incontinence surgery, co-existing prolapse) as information on participants’ characteristics was not reported consistently across reviews.

It was ascertained that, based on the reported information, 23 studies included women with SUI alone37,60,67,78,90,91,94,104,105,108,114,118,129,139,142,143,161,162,178,179,181,192,201 as they specifically mentioned exclusion of urgency UI or MUI. A total of 53 studies included women with SUI as well as some with MUI. 26,30–32,48,52,56,72,79,81,82,85,87,89,99,101,106,107,110,112,113,115–117,119,120,122,124–128,135,136,148,153,154,156,159,160,164,167–169,173,174,176,180,187,194,198,199

The majority of studies excluded women with any previous UI surgery (81 out of 175 studies)29–31,38,39,43,52,58,67,69–72,78,85,86,88,89,91,92,94–97,100,101,103,104,108,113–116,118,120,126,128–130,133,136,137,140,141,143,144,147,148,155–157,159–163,165,167,168,170,172,174–178,180–185,188,192–194,196,201–204 or certain types of incontinence surgery (16 out of 175 studies). 28,65,77,83,87,93,102,119,121,122,127,135,146,150,171,173 A total of 31 studies (out of 175; 18%) included women presenting with recurrent incontinence after failed surgery. 25,27,32,37,51,56,63,79,82,84,99,106,107,109,117,123–125,138,139,142,151,152,166,186,187,190,191,195,197,198 Of these, one study included only recurrent cases. 186 The remaining studies (47 out of 175) did not indicate whether study participants had primary or recurrent incontinence, or both.

In 45% of the studies (78 out of 175) women presenting with coexisting prolapse were excluded either completely (11 studies)60,63,86,104,105,107,113,125,129,149,203 or if they presented with moderate to severe prolapse (67 studies). Six studies included exclusively women with coexisting prolapse. 32,70,88,181,193,199 A total of 30 studies included a proportion of women with prolapse of varying degrees28,30,37,41,48,52,61,64,79,82,87,90,91,99,108,111,112,117,119,122,123,142,154,166,173,176,184,192,194,195 and the remaining 61 studies did not specify whether women with prolapse were included or excluded.

A total of 39 studies did not allow concomitant prolapse surgery to be performed. 39,50,60,63,67,77,81,83,85,86,93,94,100–102,104,105,107,113,116,125,126,129,133,135,137,146,148–150,156,159,167,171,174,179,186,188,203 Three studies reported that prolapse surgery was performed in all included women32,41,88 and 32 studies reported that some women received prolapse surgery. 28,30,31,37,43,48,52–54,61,79,82,87,89,99,106,112,117,119,120,122,123,127,138,160,173,176,185,187,193,195,196 Six studies explicitly reported that hysterectomy was performed. 103,147,182,183,194,199 The remaining 95 studies did not indicate whether or not concomitant prolapse surgery was performed.

The source of funding and the setting of included studies were not consistently reported in the relevant Cochrane systematic reviews. Out of the 36 studies with available information (28 studies identified by the updated searches and eight studies identified from the Cochrane systematic reviews), five studies appeared to be funded by industry28,29,159,176,177 and seven studies were conducted in more than one clinical centre. 28,72,79,95,159,176,177

The clinical experience of the surgeon performing the procedures was not consistently reported in the Cochrane systematic reviews. Among the 36 studies providing this information, the surgeon’s clinical experience varied from ‘having inserted a minimum of one sling prior to the study’29 to ‘having performed 200 surgical procedures’. 115 Five studies reported that surgeons tended to be less experienced in performing sling procedures than the comparator surgical intervention. 25,101,113,159

Risk-of-bias assessment of included studies

There is wide variation across Cochrane systematic reviews in the number and types of criteria (domains) used to assess risk of bias. For example, the number of risk-of-bias domains was four,7,11 five,8,9,18 six5 or seven6 across reviews. The 28 new studies identified by the updated literature searches, and the eight studies originally included as abstracts in the Cochrane systematic reviews and subsequently updated based on new full-text reports, were assessed using the current version of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool, which involved a total of nine domains. An overall assessment of risk of bias is presented in Table 4 below. Appendix 9 provides the risk-of-bias results for all individual studies included in this assessment.

| Items | Risk, n (%) | Number of studies assessed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Unclear | High | ||

| 1. Random sequence generation (selection bias) | 85 (49) | 80 (46) | 10 (6) | 175 |

| 2. Allocation concealment (selection bias) | 49 (28) | 116 (66) | 10 (6) | 175 |

| 3. Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | 8 (5) | 123 (73) | 37 (22) | 168 |

| 4a. Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): all outcomes | 20 (15) | 107 (81) | 5 (4) | 132 |

| 4b. Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): patient reported outcomes | 4 (11) | 17 (47) | 15 (42) | 36 |

| 4c. Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): clinician-measured outcomes | 8 (22) | 20 (56) | 8 (22) | 36 |

| 5. Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | 1 (14) | 6 (86) | 0 (0) | 7 |

| 6a. Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias): all outcomes | 54 (39) | 76 (55) | 9 (6) | 139 |

| 6b. Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias): patient-reported outcomes | 18 (50) | 16 (44) | 2 (6) | 36 |

| 6c. Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias): clinician-measured outcomes | 21 (58) | 13 (36) | 2 (6) | 36 |

| 7. Selective reporting (reporting bias) | 24 (65) | 7 (19) | 6 (16) | 37 |

| 8. Other bias | 0 (0) | 82 (100) | 0 (0) | 82 |

Selection bias (adequate sequence generation/allocation concealment)

For all 175 included studies, risk of selection bias was assessed in two domains: random sequence generation and allocation concealment. A total of 43 studies (out of 175; 25%) reporting both adequate sequence generation and adequate allocation concealment were considered to have an overall low risk of selection bias. 25,27–29,32,51,63,64,83,86,87,92,93,96,97,100,101,116,120,122,124–126,128,135–137,140,144,147,148,150,157,159,160,167,174–176,182,183,185 A further six studies (out of 175; 3%) reported adequate allocation concealment but they did not describe the method used for random sequence generation. 77,85,127,156,173,199 A total of 40 studies (out of 175; 23%) reported adequate sequence generation but did not provide information on allocation concealment. 26,30,31,37,41,52,60,65,72,79,82,88,89,91,94,99,101,114,119,129,130,138,141,143,146,162,164,172,178,180,181,186–189,194–196,198,203 Two studies (out of 175; 1%) with adequate random sequence generation specifically mentioned that the treatment allocations were not concealed. 95,193

There were eight quasi-randomised trials (out of 175 included studies; 5%) in which treatment allocation was based on a method of alternation103–107,109,110 or on date of birth. 111 These were considered to be at high risk of selection bias in terms of both allocation sequence generation and concealment of allocation. Two further studies (out of 175; 1%) allocated participants by alternation108 or by medical history numbers112 and were considered to be at high risk of selection bias, although allocation concealment was considered to be at unclear (rather than high) risk of bias by the authors of the Cochrane systematic reviews. 5,9 The remaining studies (74 out of 175; 42%) did not provide this information.

Performance and detection bias (blinding)

Blinding of patients and personnel provides a safeguard against performance bias and blinding of outcome assessors protects against detection bias. It is worth noting that, owing to the nature of the interventions, blinding of participants and personnel, especially the surgeon performing the operation, is not possible. Blinding of outcome assessment for patient-reported outcomes would similarly be difficult in this clinical context (with unblinded patients being the assessors), although it should be possible to blind health-care professionals who assess clinical outcomes.

In seven studies identified from the Cochrane systematic reviews assessing traditional slings7 and bladder neck needle suspension,11 risk of performance bias and detection bias was assessed using a single criterion (whether or not a lack of blinding could introduce performance and detection bias). One study (out of 7; 14%) was judged to be at low risk of bias92 and the other six studies (86%) at high or unclear risk of bias. 38,81,102,166,198,199

Risk of performance and detection bias was assessed separately in the 168 included studies identified from sources other than the two Cochrane reviews mentioned above. With respect to the assessment of whether or not lack of blinding of patients and personnel could introduce performance bias, eight studies (out of 168; 5%) were judged to be at low risk of bias87,89,117,128,129,151,157,191 and the other 160 studies (95%) were judged to be at high or unclear risk of bias. 25–32,37,39–80,82–86,88,90,91,93–101,103–114,116,118–127,130–150,152–156,158–165,167–190,192–197,201–203

Risk of detection bias in the 132 studies identified from Cochrane systematic reviews on MUS,8,18 open colposuspension,5 laparoscopic colposuspension6 and single-incision slings9 was assessed in terms of whether or not lack of blinding of outcome assessors could affect results. A total of 20 studies (out of 132; 15%) were judged to be at low risk of bias37,86,87,89,94,117,122,125,127,130,136,141,142,144,148,156,174,178,191,204 and the remaining 112 studies (85%) were judged to be at high or unclear risk of bias. 39–42,44–47,49,51,53–61,63,64,67–71,73,74,76–78,80,82–85,88,90,93,96–100,103–112,116,118–120,123,124,126,128,129,131–135,137–140,145–147,149–155,157,160–163,165,167–170,172,173,180,182–190,192–196,201–203

Detection bias in the 36 studies identified from other sources (e.g. new studies from the update literature searches) was assessed on a per outcome basis in terms of whether or not lack of blinding of outcome assessors could affect effect estimates of patient-reported outcomes such as subjective perception of cure of UI (where outcomes are assessed directly by women) and of clinician-measured outcomes such as urodynamic tests (where outcomes are assessed by care providers). One study (out of 36; 3%) was judged to be at low risk for patient-reported outcomes,159 five studies (14%) at low risk for clinician-measured outcomes,25,115,143,175,181 and three studies (8%) at low risk for both patient-reported and clinician-measured outcomes. 29,32,91 The remaining 27 studies (75%) were judged to be at high or unclear risk for either outcome. 26–28,30,31,43,48,50,52,62,65,66,72,75,79,95,101,113,114,121,158,164,171,176,177,179,197

Attrition bias (incomplete outcome data)

In 139 studies included in the relevant Cochrane systematic reviews, risk of bias was assessed for all outcomes concerned. A total of 54 were judged to be at low risk of attrition bias, with missing data either balanced between treatment groups or imputed using appropriate methods, or with no missing data;37,40,41,54,67,81–84,88,92–94,96–98,100,102,106,116,119,120,122,123,126–128,130,133,135–137,139,141,142,144,147–150,155,157,160,162,166,168,170,174,178,184,185,193,198,199 nine were judged to be at high risk of bias;86,87,112,140,156,172,173,180,189 and 76 were judged to be at unclear risk of bias. 38,39,42,44–47,49,51,53,55–61,63,64,68–71,73,74,76–78,80,85,89,90,99,103–105,107–111,116–118,124,125,129,131,132,134,138,145,146,151–154,161,163,165,167,169,182,183,186–188,190–192,194–196,201–203

In 36 studies identified from other sources (e.g. new studies from the updated literature searches), risk of attrition bias was assessed on a per outcome basis in terms of patient-reported outcomes and clinician-measured outcomes. Of these, 18 studies were judged to be at low risk for both patient-reported and clinician-measured outcomes,25,27,30,52,91,95,101,113,114,121,143,159,164,171,176,177,179,181 three studies were judged to be at low risk for clinician-measured outcomes but unclear for patient-reported outcomes,66,72,75 two studies were judged to be at high risk for both patient-reported and clinician-measured outcomes29,175 and the remaining 13 studies were judged to be at unclear risk of bias for both outcomes. 26,28,31,32,43,48,50,62,65,79,115,158,197

Reporting bias (free of selective reporting)

Few of the relevant Cochrane systematic reviews assessed the risk of reporting bias. Information was available from one study identified from the Cochrane systematic review assessing laparoscopic colposuspension6 and from 36 further studies (28 new studies and the eight studies originally included as abstracts in the Cochrane systematic reviews and subsequently published in full). Of these, 24 studies (out of 37; 65%) were judged to be at low risk of reporting bias on the basis that all outcomes specified in the methods section were reported in the results section of the study report,25,27–32,52,62,65,79,95,101,113–115,143,159,171,175,177,179,181,197 six studies (16%) were judged to be at high risk of bias on the basis that they did not report the results for all the outcomes specified in the method section of the study report,26,43,72,75,91,176 and the remaining seven studies (19%) did not provide sufficient information to formulate a judgement. 48,50,66,121,158,163,164

Other sources of bias

Information on which to assess ‘other sources of bias’ was available for 82 of the included studies. In these studies, there was no clear evidence that other sources of bias were present. 25–32,40,43,46–53,55,57,60,62,65,66,68,69,72,75–79,82,85,88,89,91,93,95,100,101,103,105,108,109,111,113–115,121,143,145,158,159,161–164,171,175,177,179,181–195,197,200–203

Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Network meta-analysis of primary outcomes: number of women cured and number of women who experienced an improvement in their incontinence symptoms

Technical information about the model

The NMA included eight surgical procedures for SUI:

-

retropubic MUS operations

-

transobturator MUS operations

-

open colposuspension

-

laparoscopic colposuspension

-

traditional sling operations

-

single-incision sling operations

-

bladder neck needle suspension

-

anterior vaginal repair.

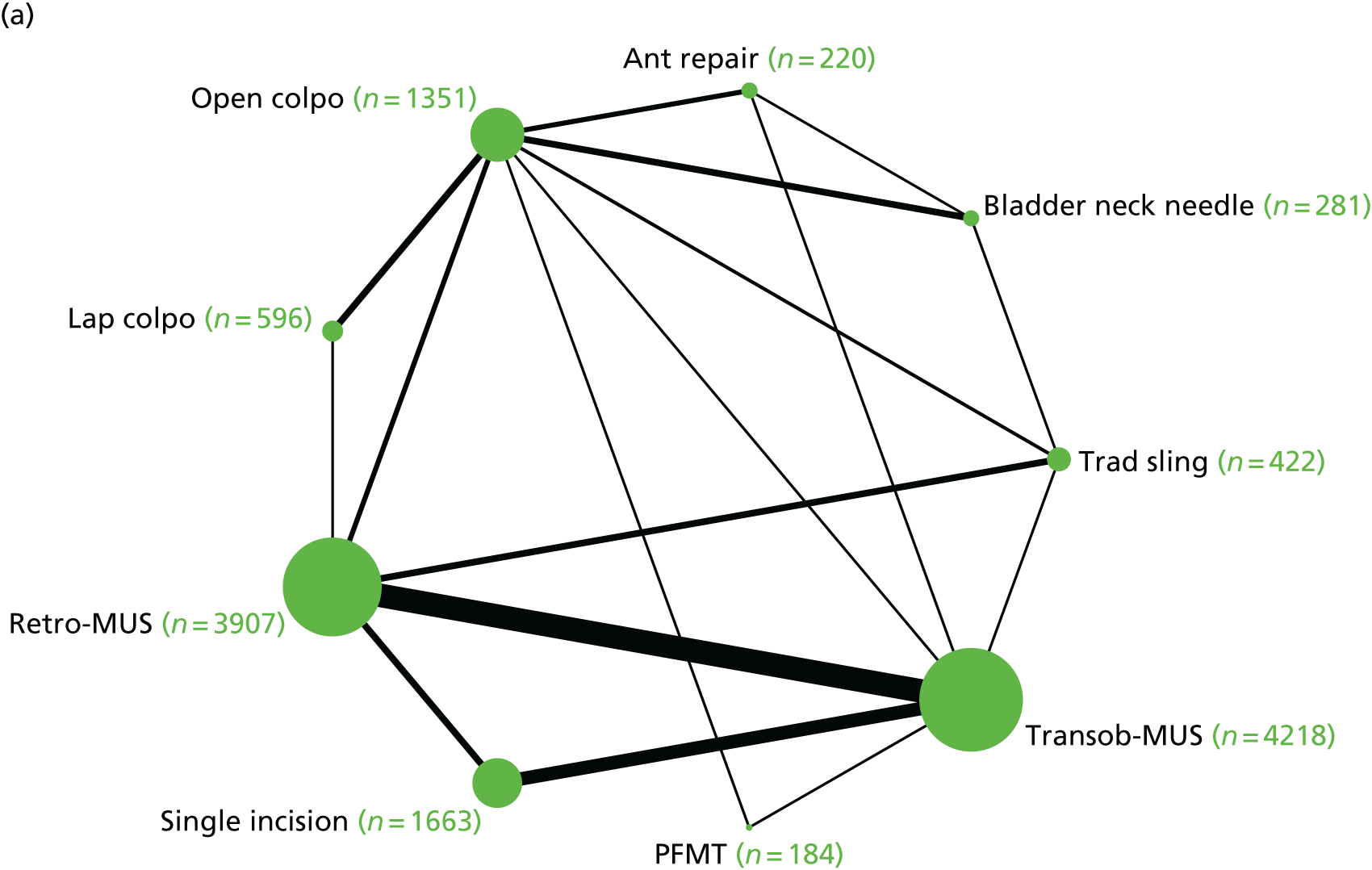

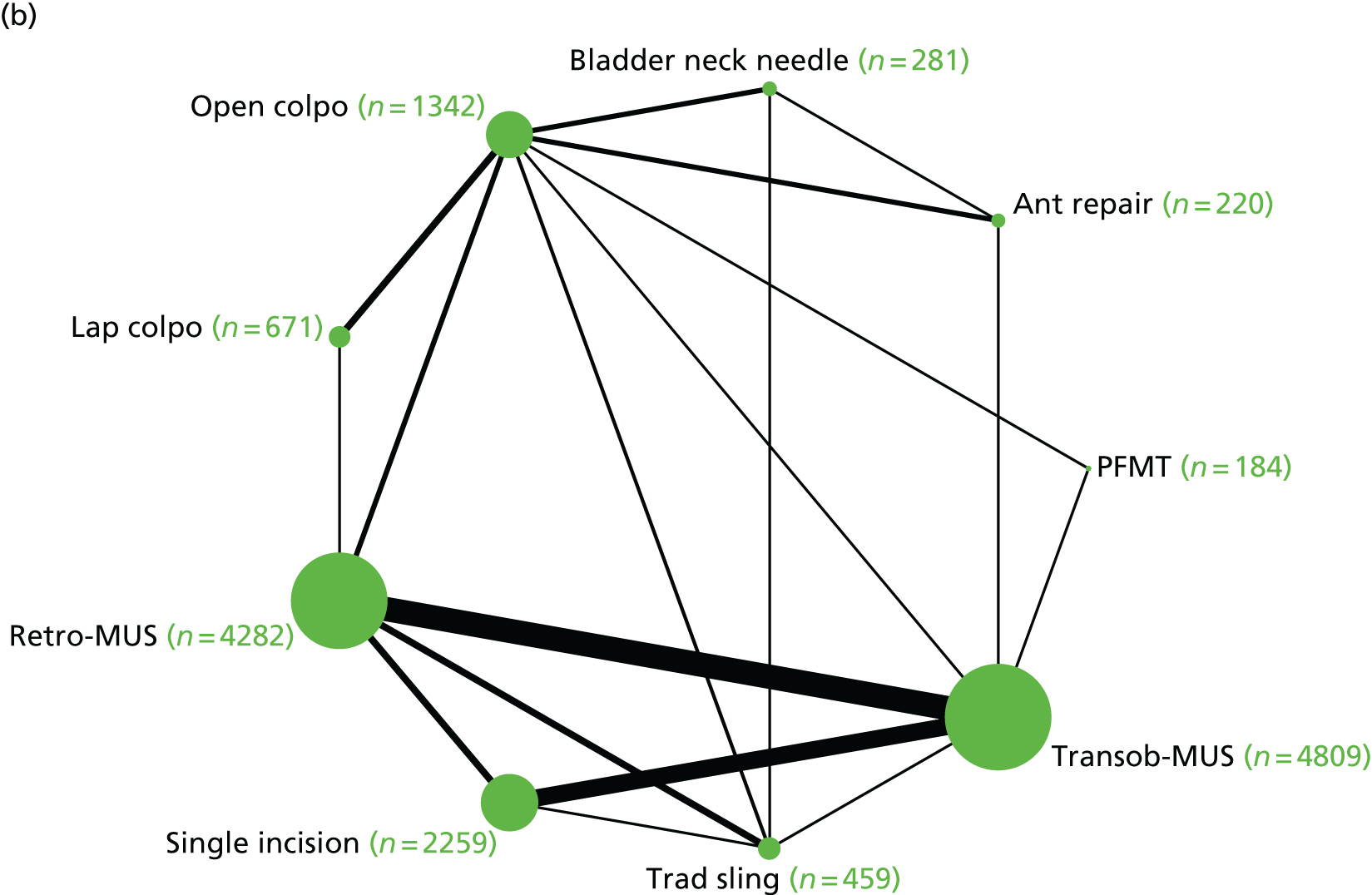

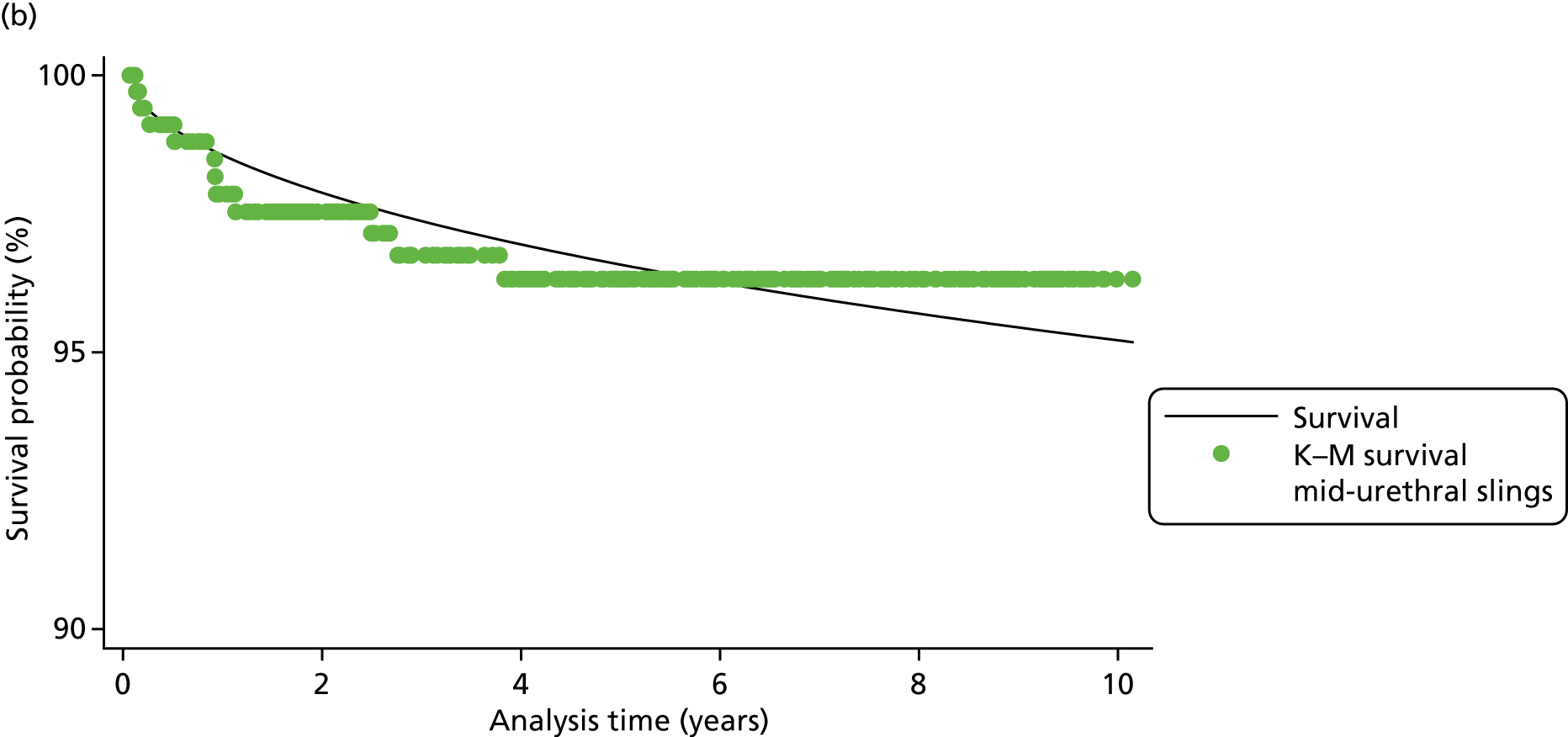

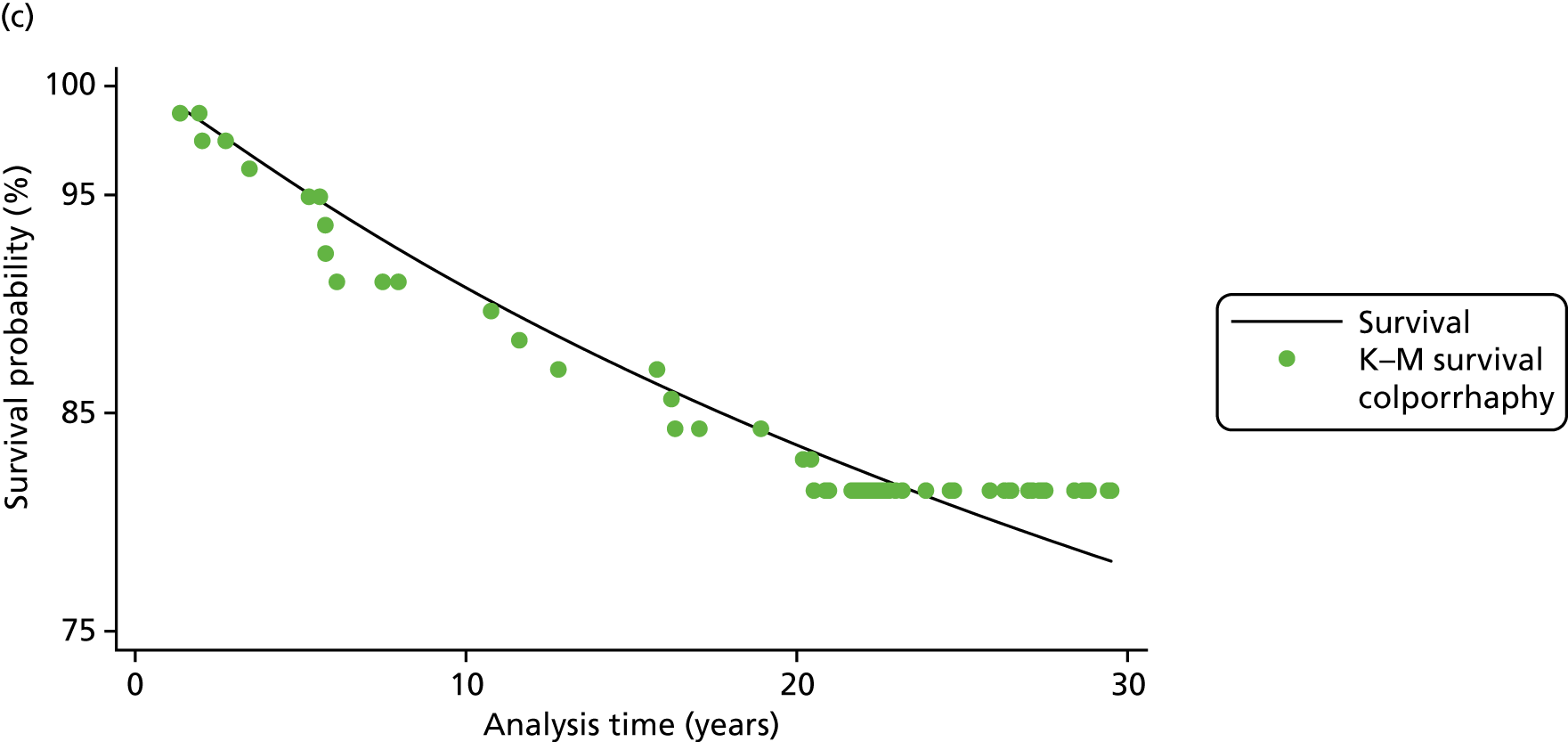

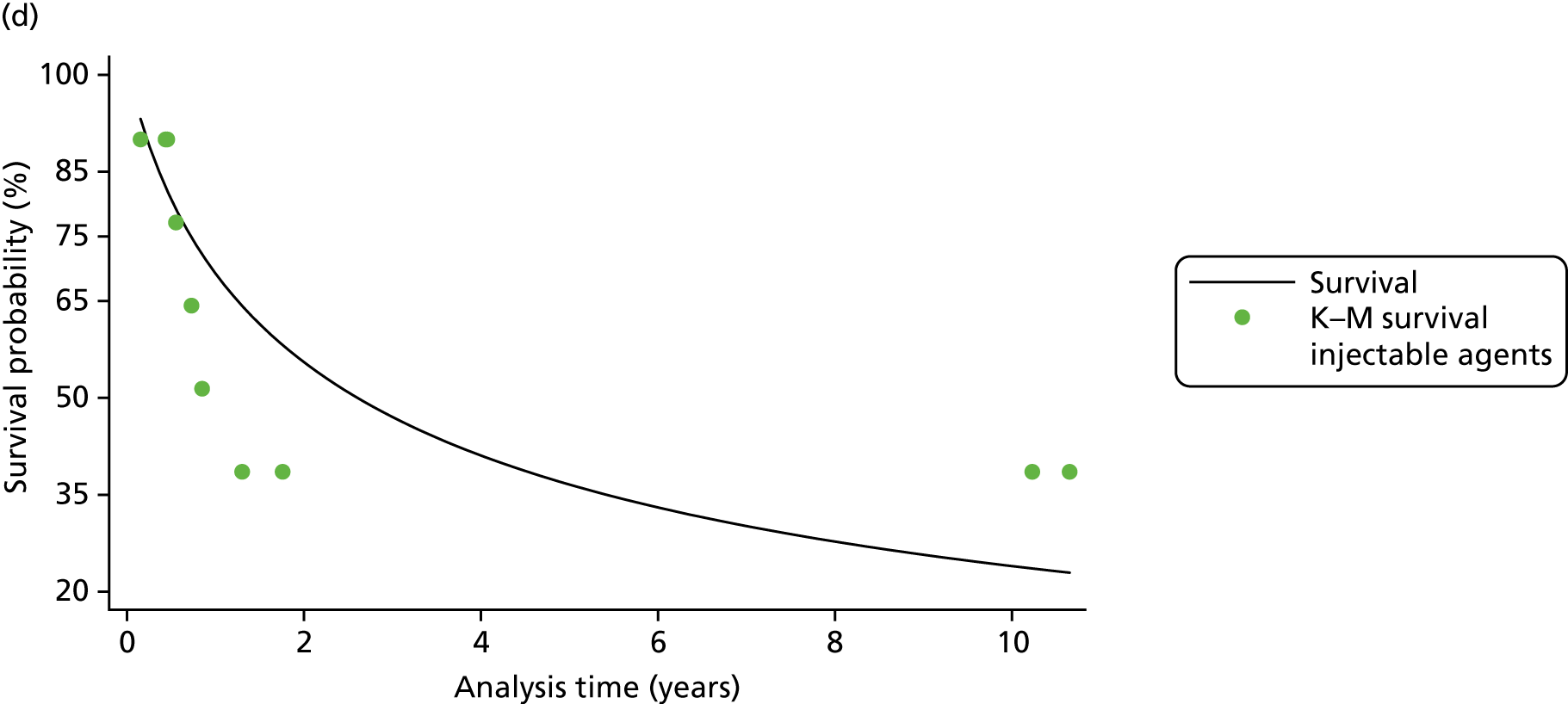

The ninth procedure, urethral injection therapy, did not add any information to the network and was excluded from analysis (for the cure outcome analysis, urethral injection therapy was only connected to one intervention). Separate models were developed for the two primary outcomes: the number of women cured (defined as resolution of symptoms) and the number of women improved (defined as women experiencing an improvement in their incontinence symptoms, including cure). Figure 1 shows the network diagrams for the number of women cured and improved, respectively. The size of the circles reflects the number of participants and the line width reflects the number of direct comparisons. Figure 1 also includes the total number of women for each surgical intervention included in the NMA.

FIGURE 1.

Network plot for (a) the number of women cured; and (b) the number of women improved. Note: circle size reflects the number of participants; line width reflects the number of direct comparisons. Ant repair, anterior vaginal repair; bladder neck needle, bladder neck needle suspension; open colpo, open colposuspension; lap colpo, laparoscopic colposuspension; retro-MUS, retropubic MUS; single incision, single-incision sling; trad sling, traditional sling; transob-MUS, transobturator MUS.

Cure or improvement of incontinence symptoms was assessed subjectively (by the woman), objectively (by a clinician) or by a combination of subjective and objective measures (composite measure). When more than one of these outcome measures were reported within a study, only one measure was included in the NMA. This measure was selected in the following order: women’s self-report assessment was given priority and, if this was unavailable, the composite outcome measure followed by the objective outcome measure were chosen as a proxy. The NMA included outcomes measured at 12 months or at a time point closest to 12 months.

The number of studies providing direct head-to-head (pairwise) evidence for each intervention that contributed data to the NMA is shown in Tables 5 and 6. The searches identified 125 trials that reported cure or improvement, or both. Three trials67,76,105 were excluded from the cure data set and four trials67,76,105,124 from the improvement dataset because they reported ‘100% events’ in all treatment arms (i.e. all participants in the study were cured or improved), providing no information for the NMA. Thus, 105 trials contributed to the NMA for assessing the number of women cured, and 120 trials were included in the analysis assessing the number of women improved. For ‘cure’, the analysis included four three-arm trials and 101 two-arm trials and generated a total of 17 direct comparisons, whereas for ‘improvement’ the analysis included five three-arm trials and 115 two-arm trials and generated a total of 18 direct comparisons. Appendix 10 shows the total number of trials for each treatment comparison for the assessment of both primary outcomes.

| Treatment | Direct evidence | NMA | GRADE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Number of trials | ORa | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CrI | |

| Transob-MUS | Retro-MUS | 36b | 0.83 | 0.71 to 0.97 | 0.74 | 0.59 to 0.92 | Moderate |

| Open colpo | Retro-MUS | 6b | 0.95 | 0.68 to 1.32 | 0.85 | 0.54 to 1.33 | Low |

| Lap colpo | Retro-MUS | 2 | 0.40 | 0.11 to 1.45 | 0.58 | 0.31 to 1.05 | Low |

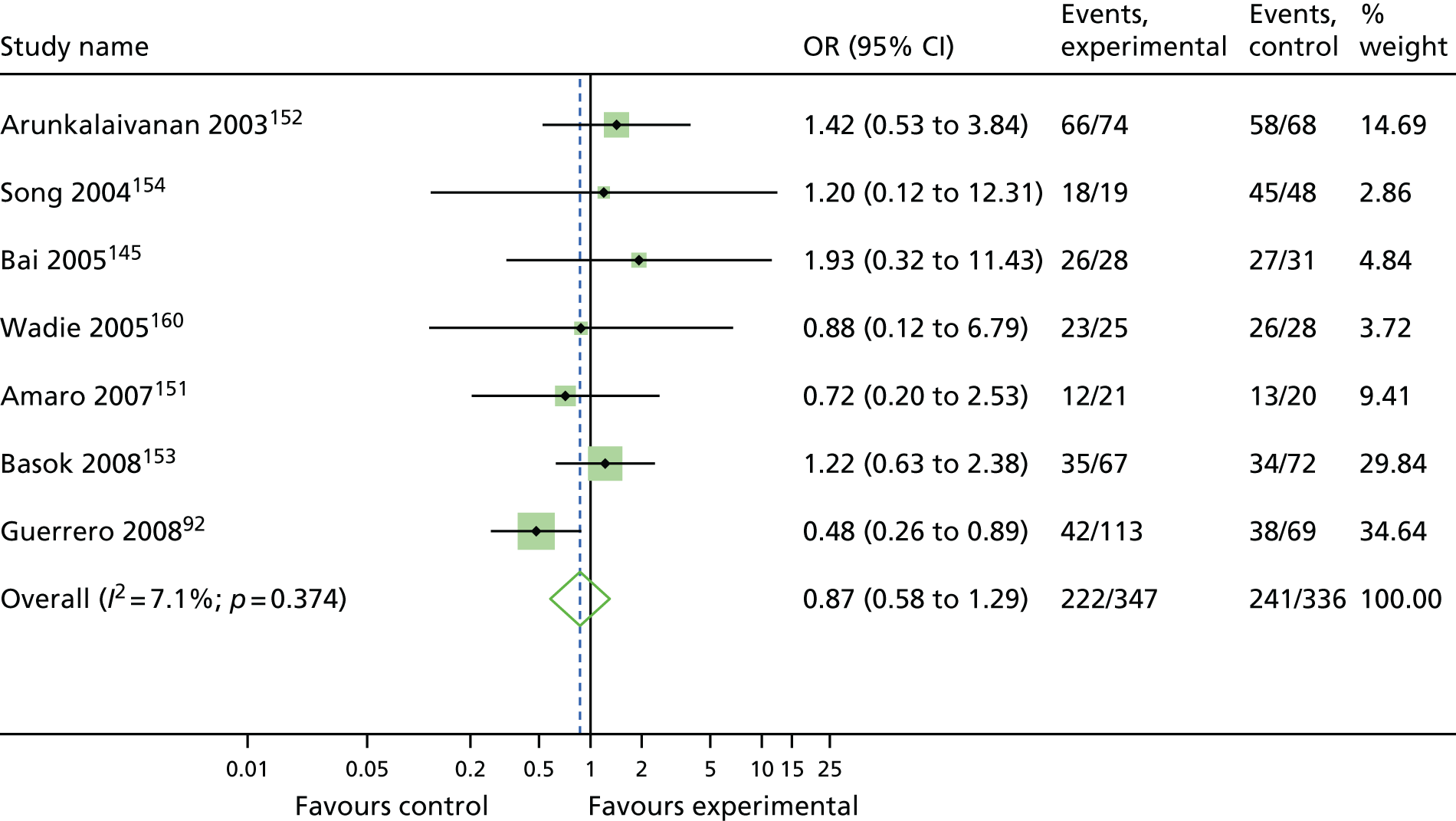

| Trad sling | Retro-MUS | 6b | 0.87 | 0.58 to 1.29 | 1.06 | 0.62 to 1.85 | Very low |

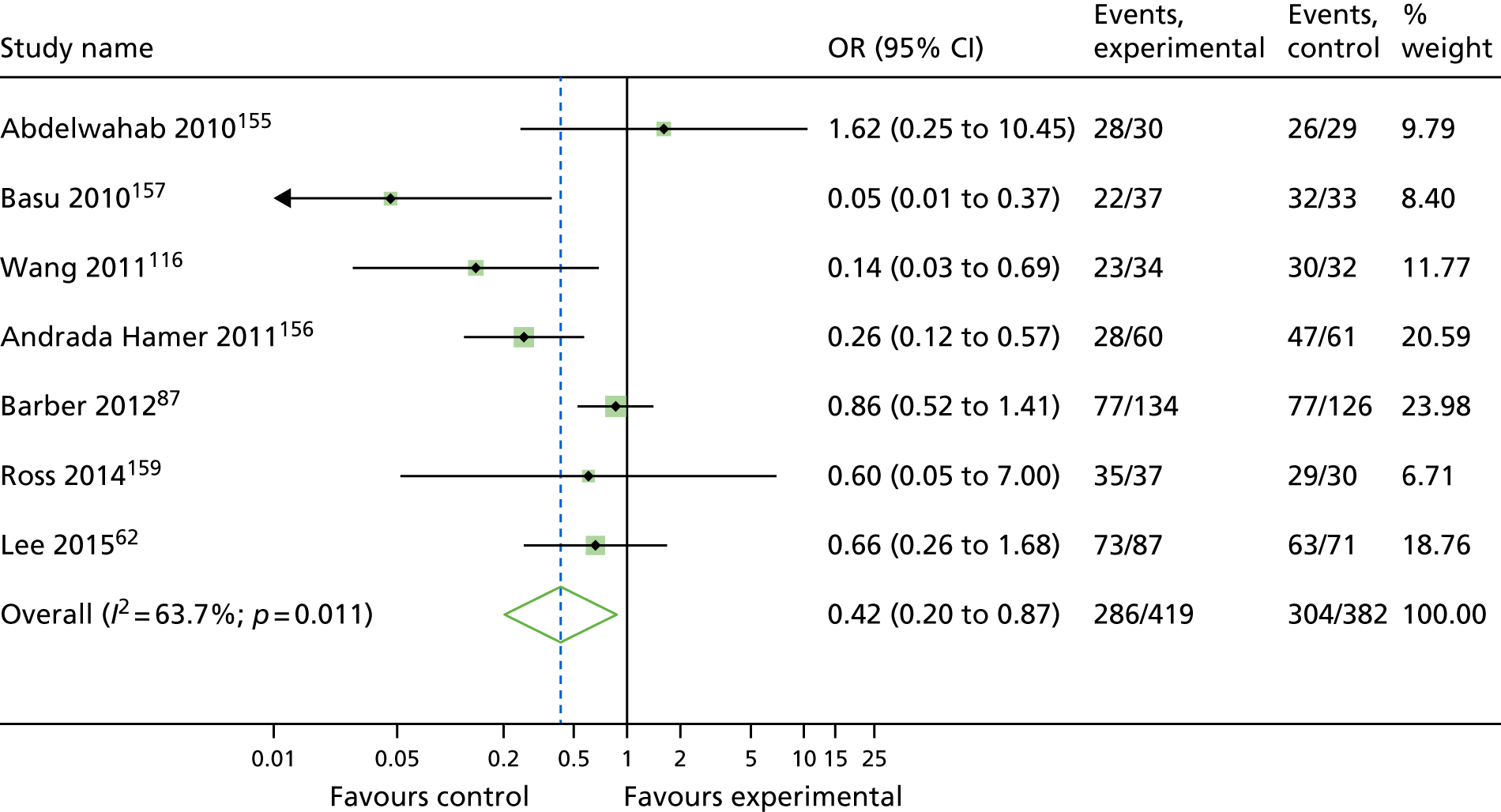

| Single incision | Retro-MUS | 6b | 0.42 | 0.20 to 0.87 | 0.50 | 0.36 to 0.70 | Low |

| Bladder neck needle | Retro-MUS | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.34 | 0.15 to 0.75 | Low |

| Ant repair | Retro-MUS | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.22 | 0.10 to 0.45 | Very low |

| PFMT | Retro-MUS | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.12 | 0.04 to 0.32 | Low |

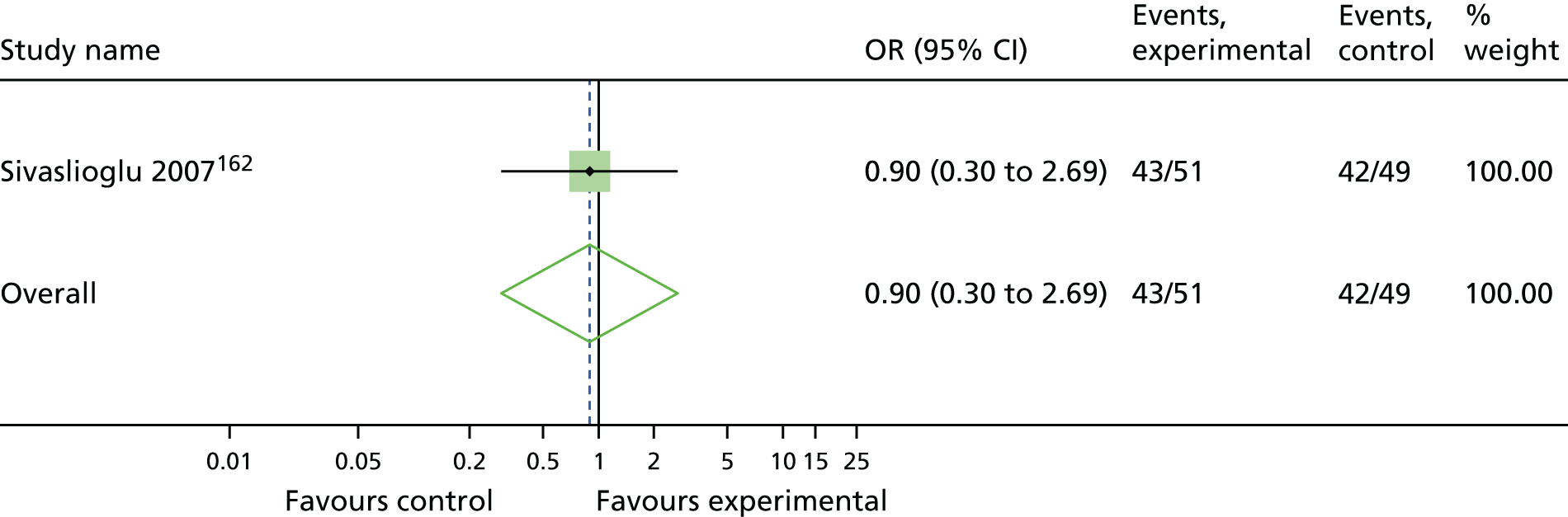

| Open colpo | Transob-MUS | 1 | 0.90 | 0.30 to 2.69 | 1.16 | 0.72 to 1.86 | Low |

| Lap colpo | Transob-MUS | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.79 | 0.42 to 1.46 | Low |

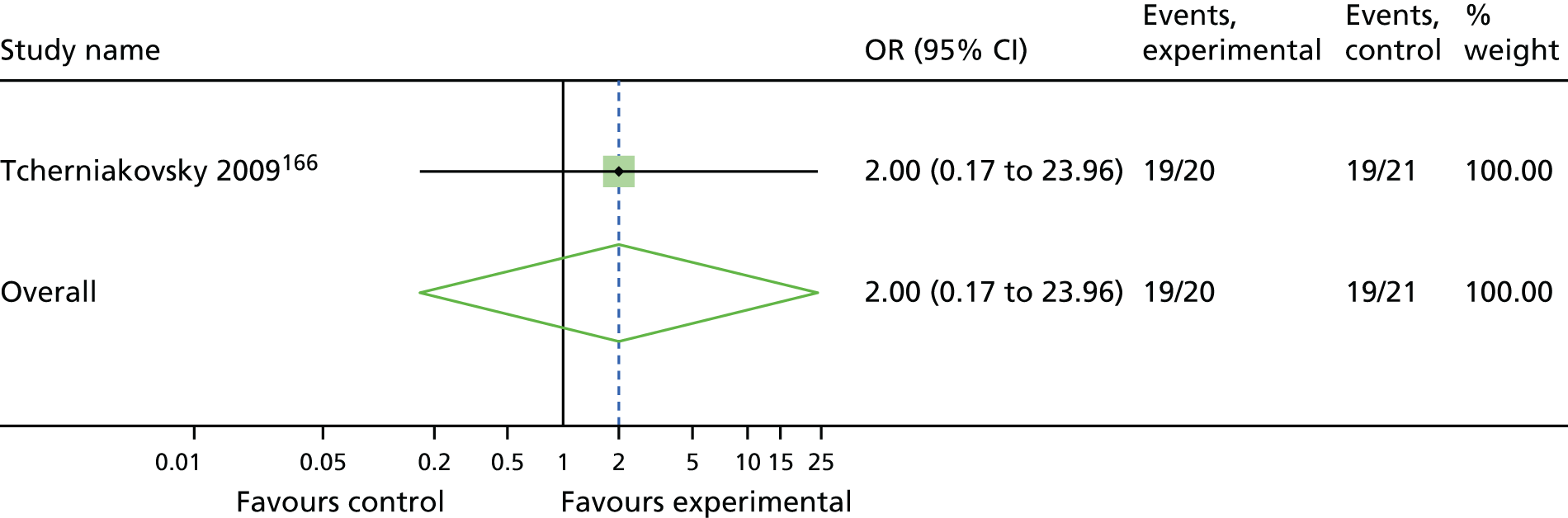

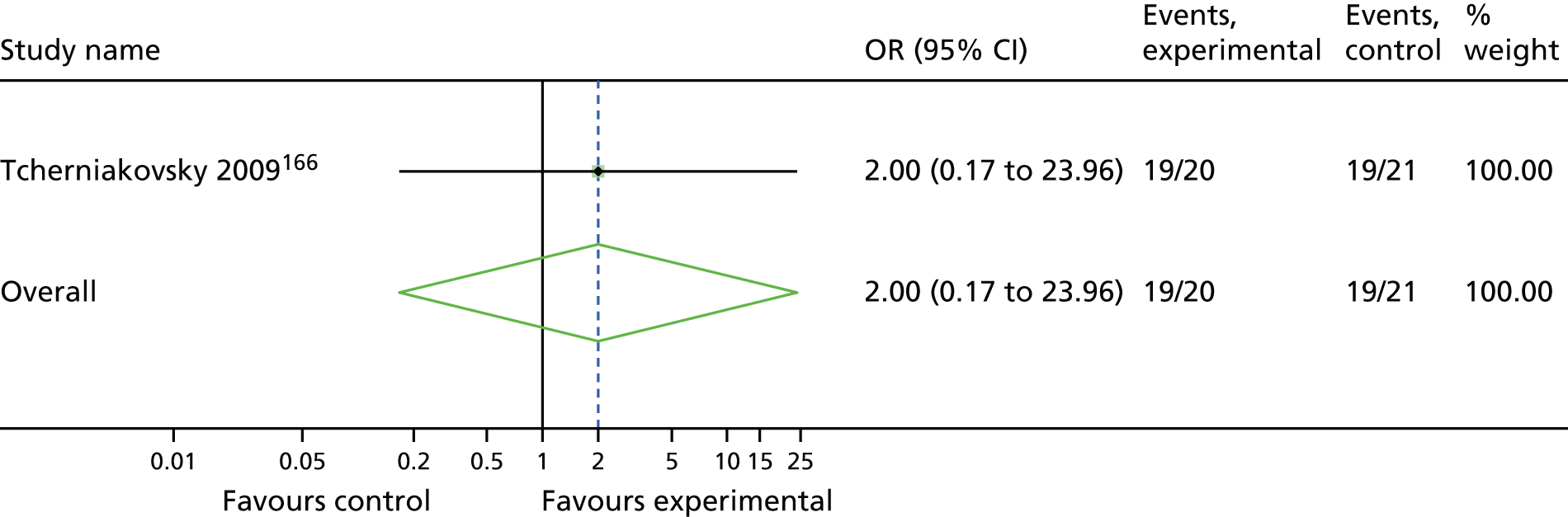

| Trad sling | Transob-MUS | 1 | 2.00 | 0.17 to 23.96 | 1.44 | 0.81 to 2.62 | Very low |

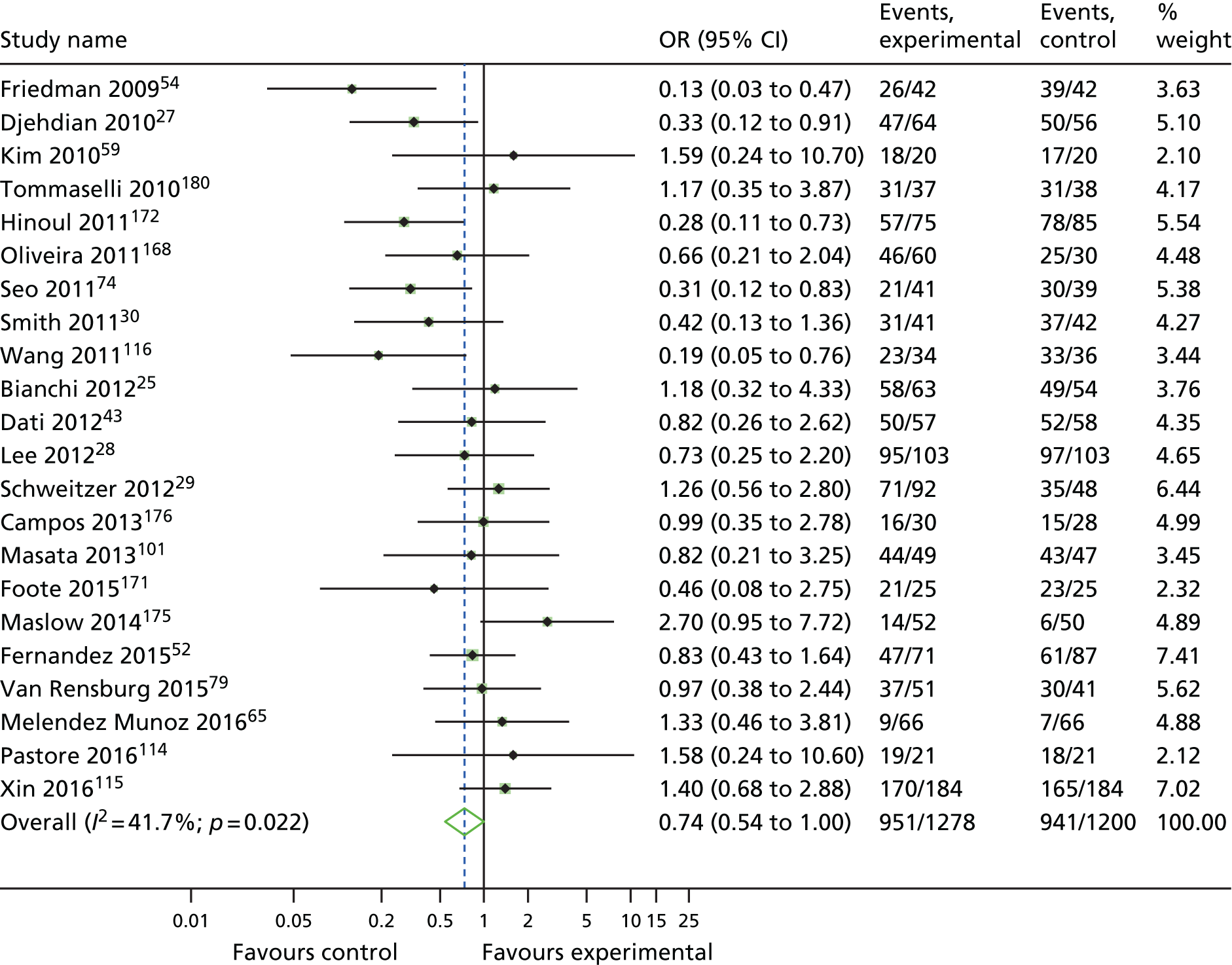

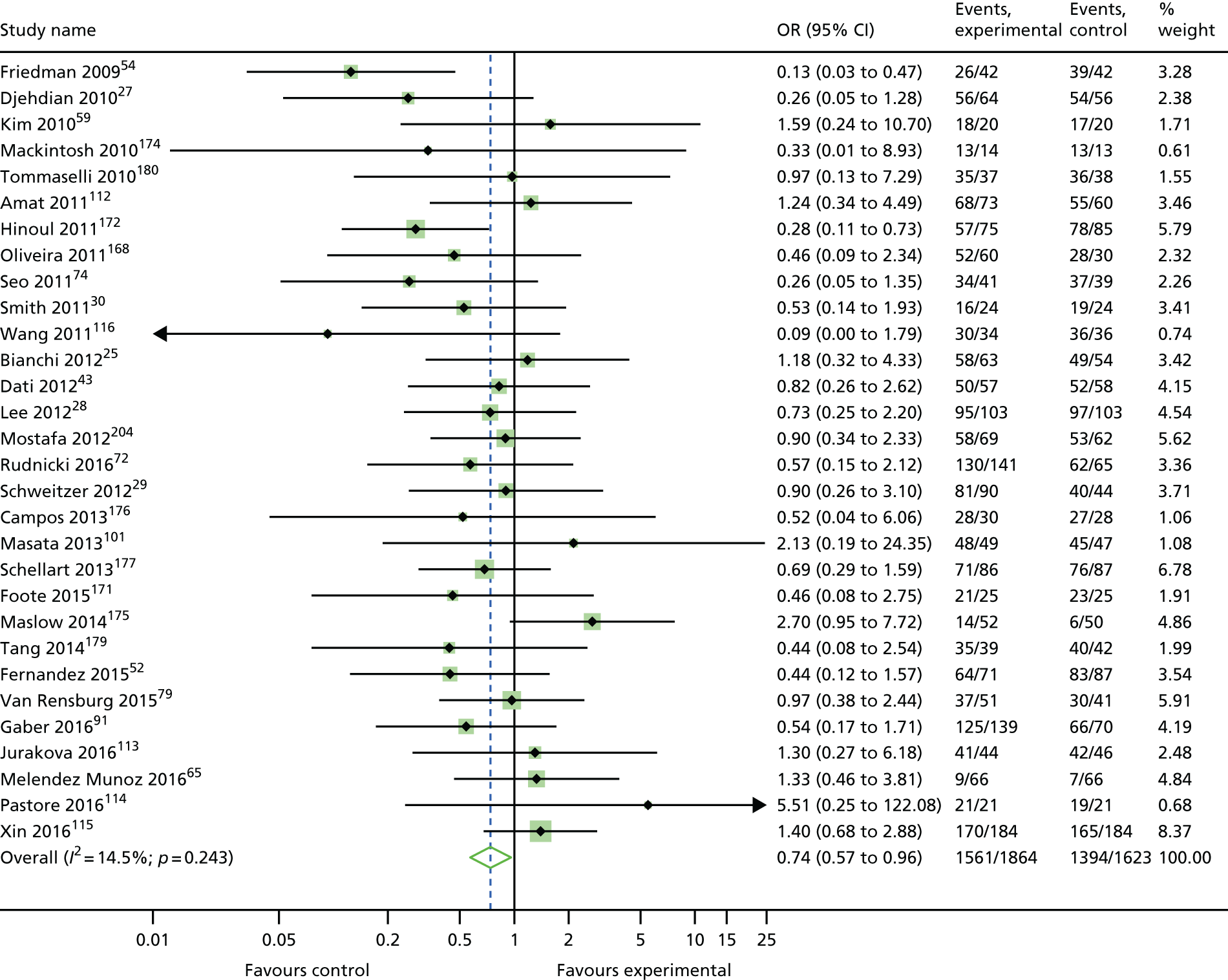

| Single incision | Transob-MUS | 21b | 0.74 | 0.54 to 1.00 | 0.68 | 0.51 to 0.91 | Low |

| Bladder neck needle | Transob-MUS | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.46 | 0.21 to 1.02 | Very low |

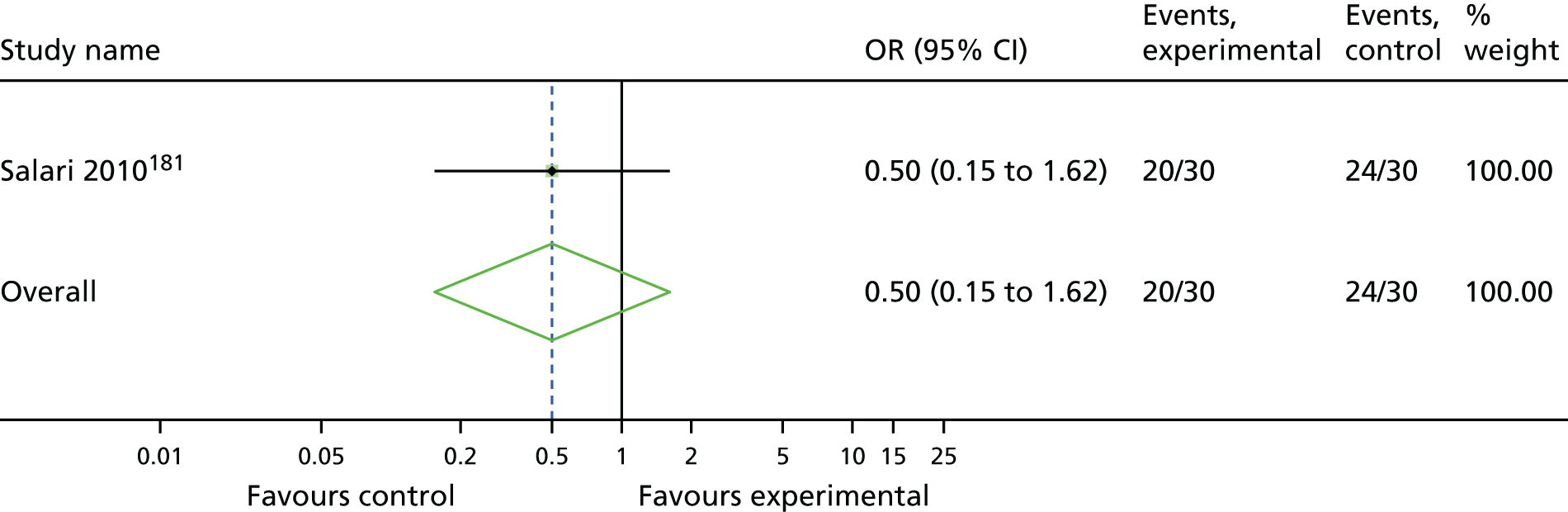

| Ant repair | Transob-MUS | 1 | 0.50 | 0.15 to 1.62 | 0.30 | 0.14 to 0.62 | Very low |

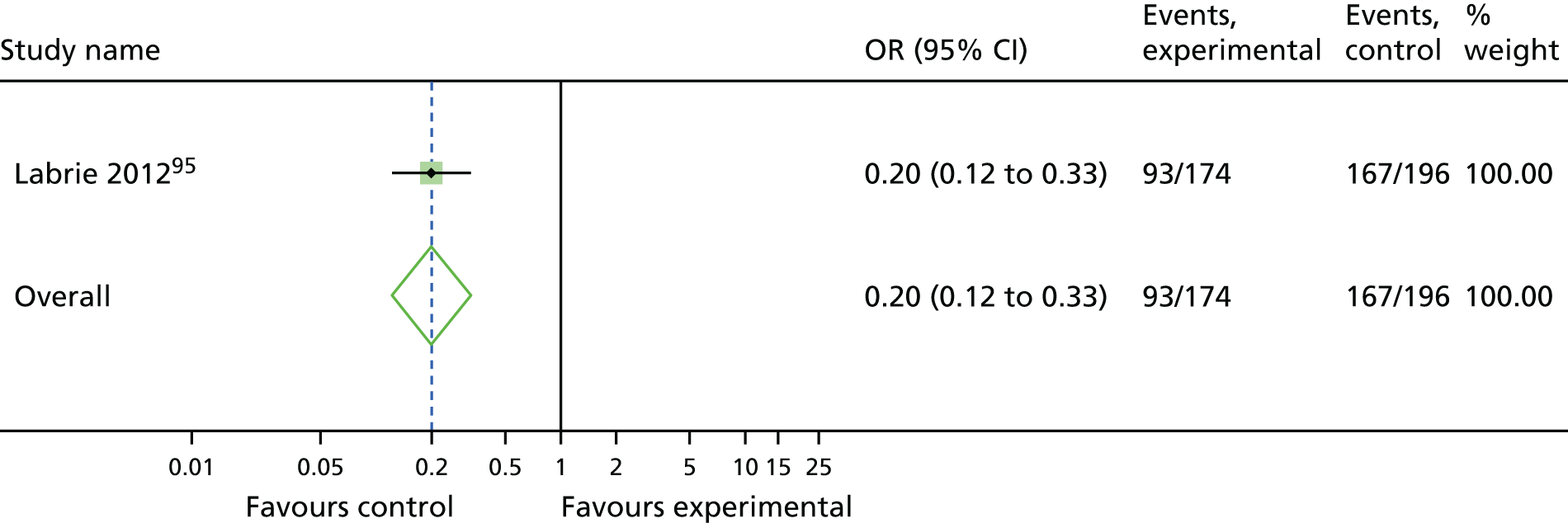

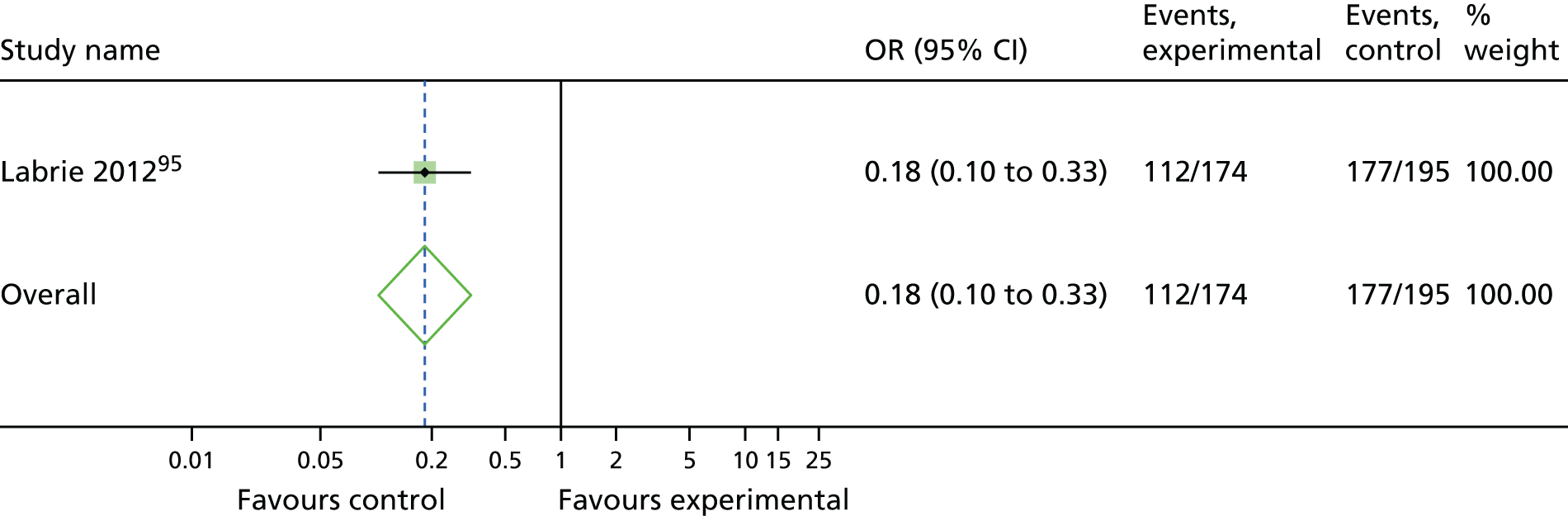

| PFMT | Transob-MUS | 1 | 0.20 | 0.12 to 0.33 | 0.16 | 0.06 to 0.43 | Low |

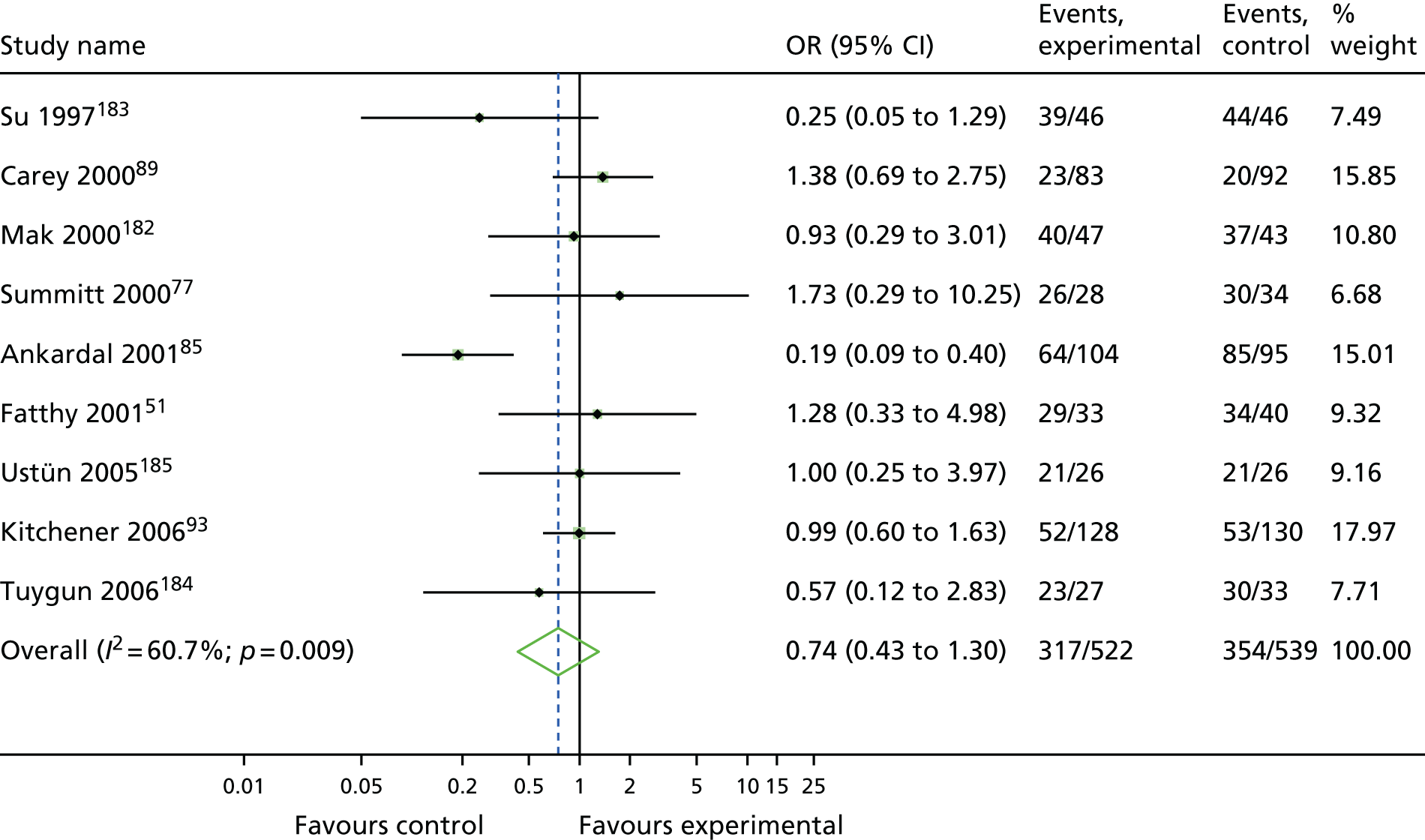

| Lap colpo | Open colpo | 9 | 0.74 | 0.43 to 1.30 | 0.68 | 0.42 to 1.08 | Low |

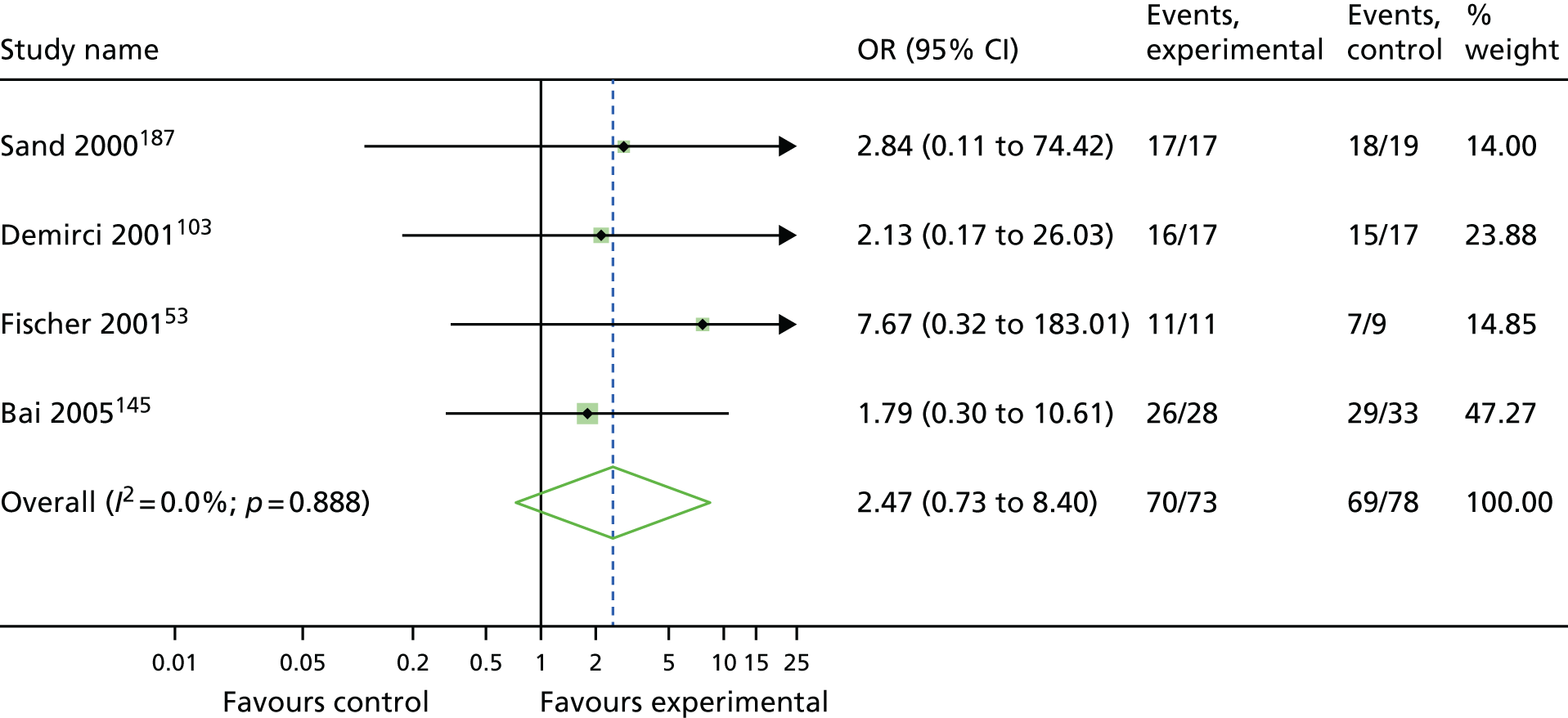

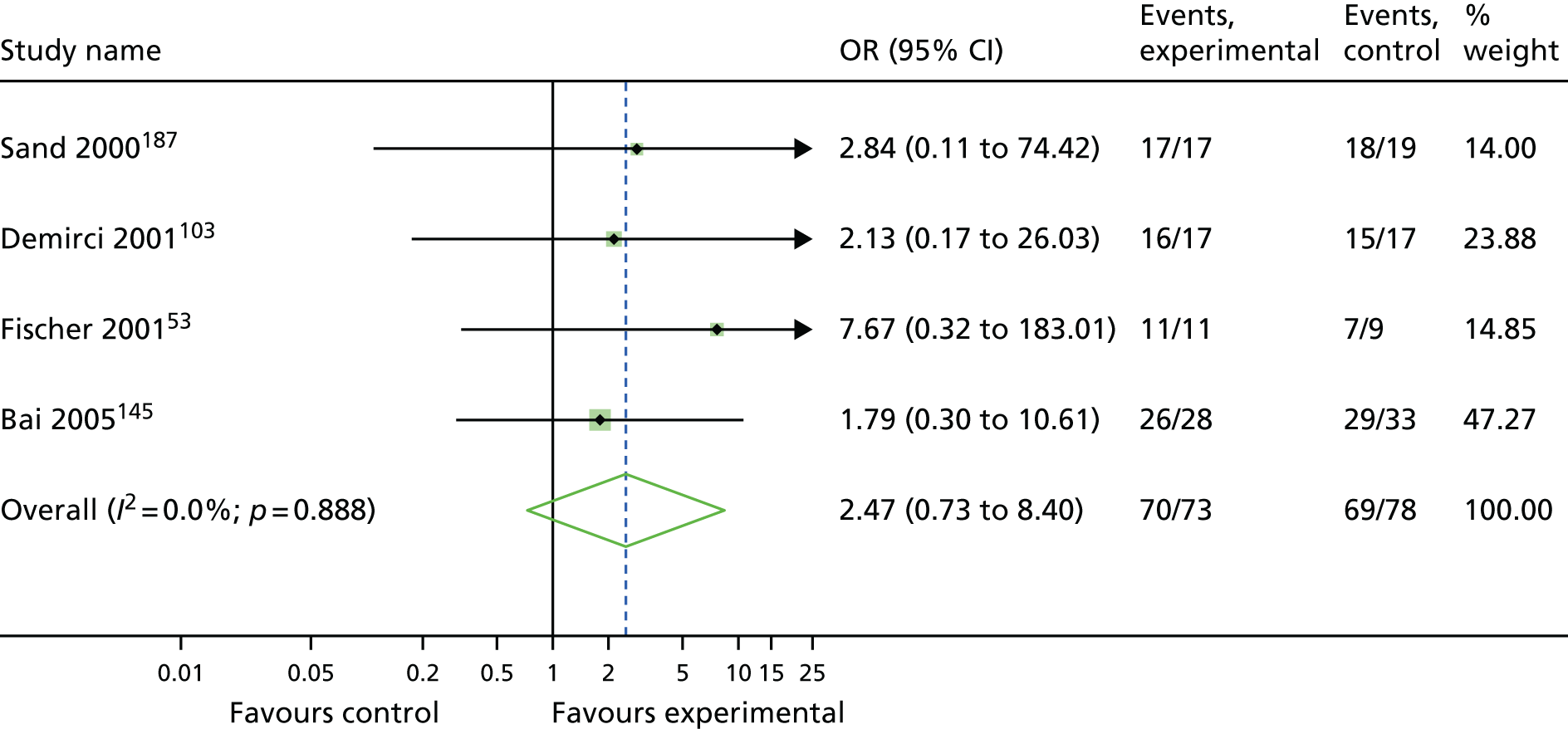

| Trad sling | Open colpo | 3b | 2.47 | 0.73 to 8.40 | 1.24 | 0.66 to 2.45 | Very low |

| Single incision | Open colpo | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.59 | 0.34 to 1.01 | Low |

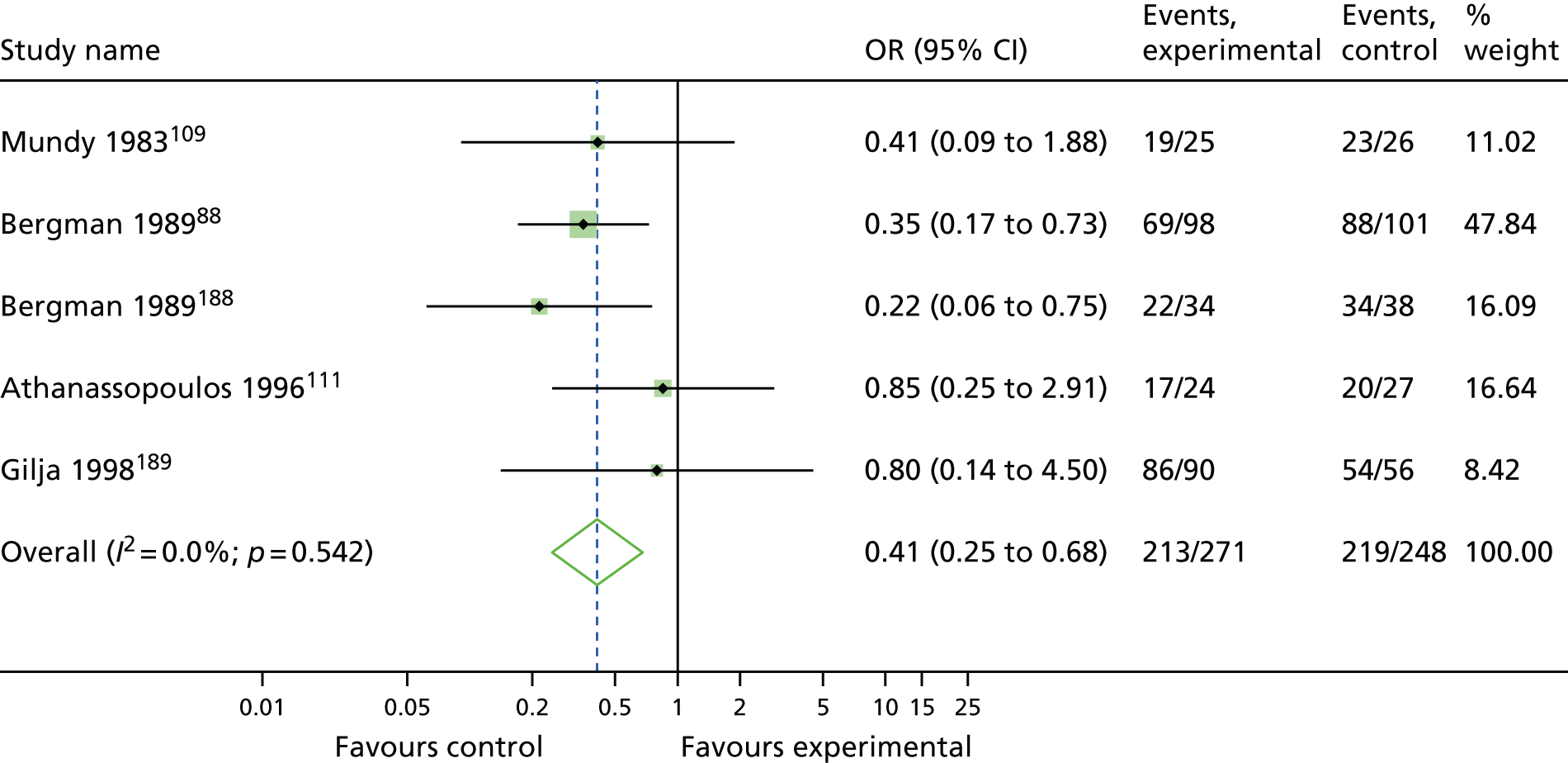

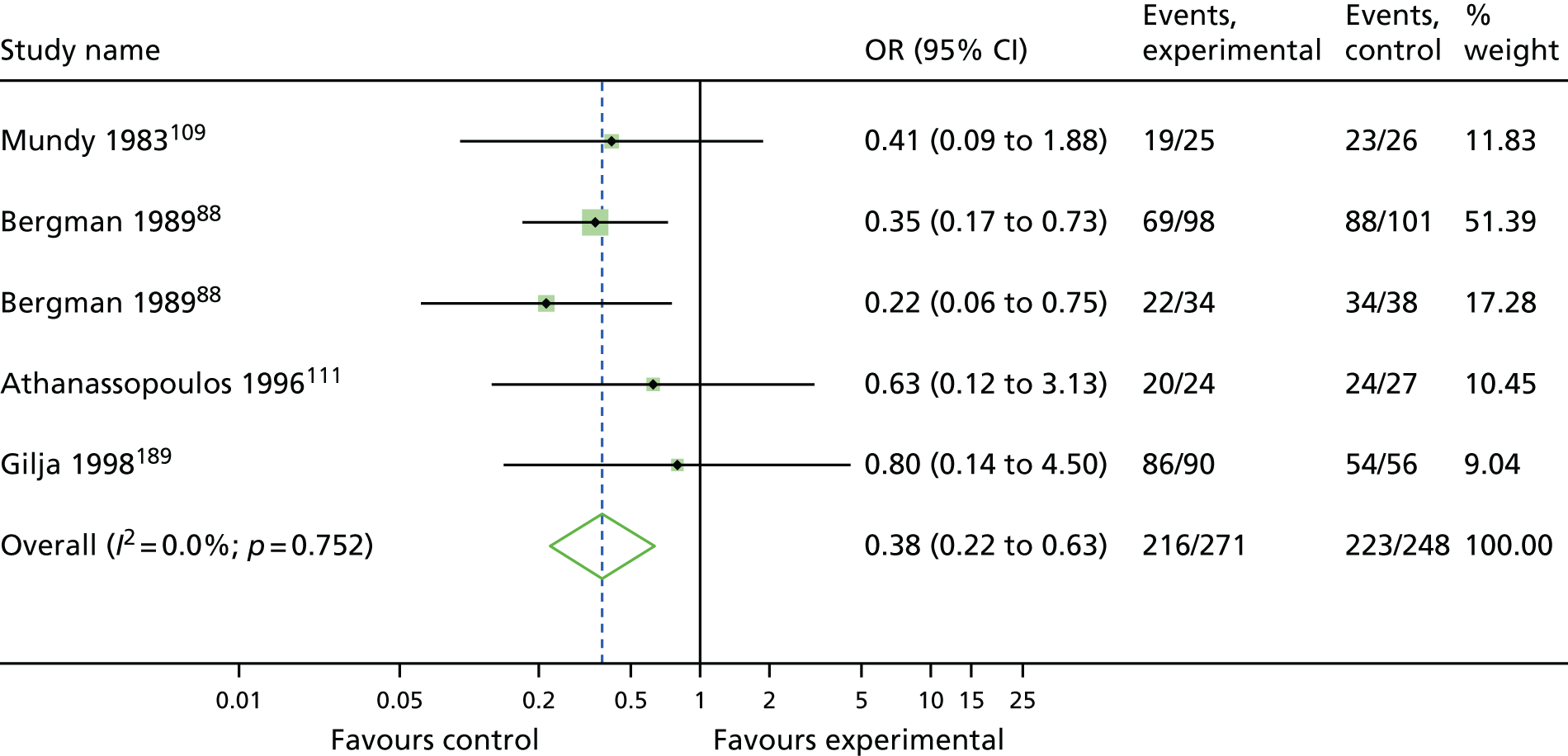

| Bladder neck needle | Open colpo | 3b | 0.41 | 0.25 to 0.68 | 0.40 | 0.20 to 0.78 | Low |

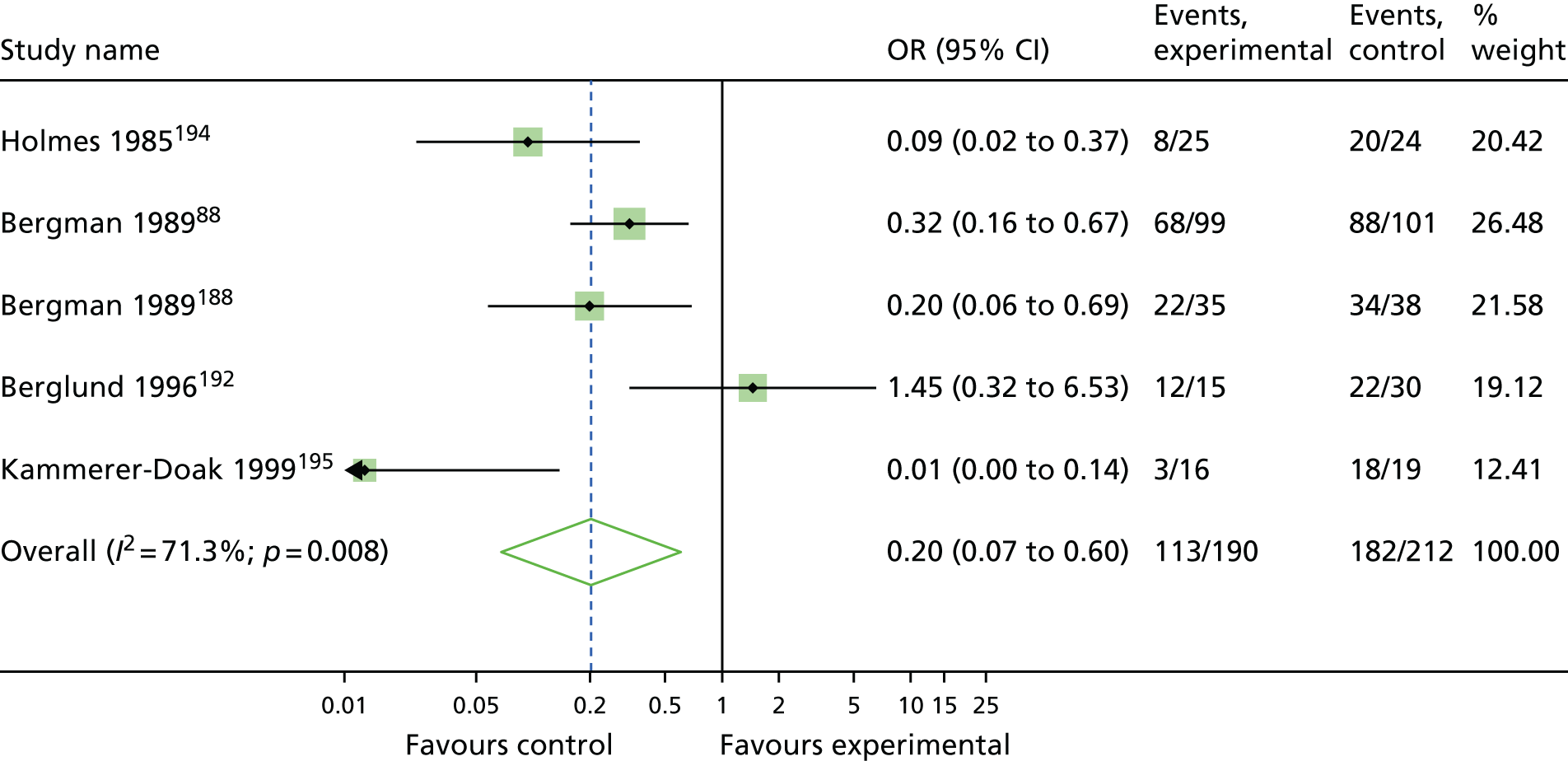

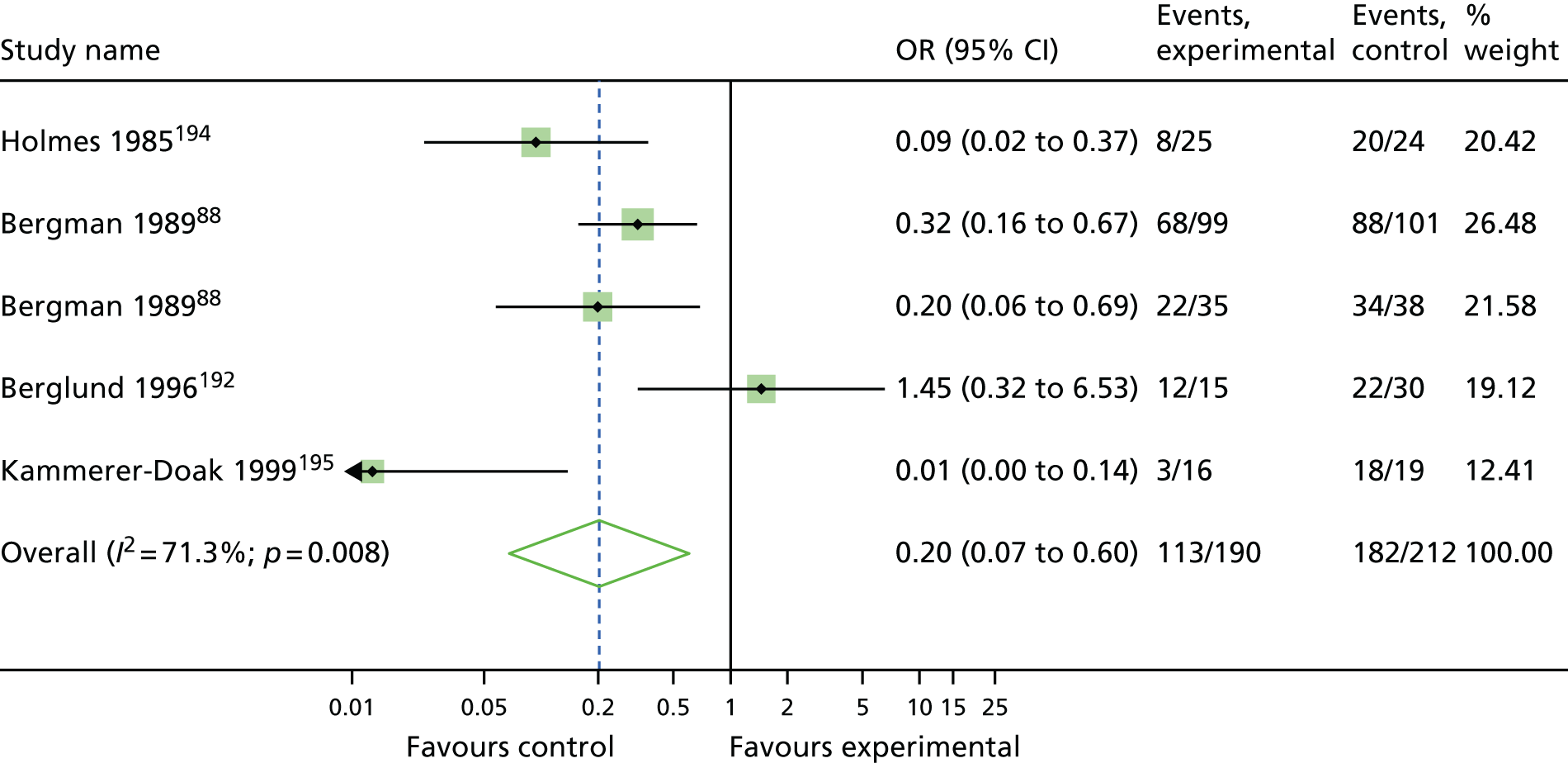

| Ant repair | Open colpo | 3b | 0.20 | 0.07 to 0.60 | 0.26 | 0.14 to 0.48 | Very low |

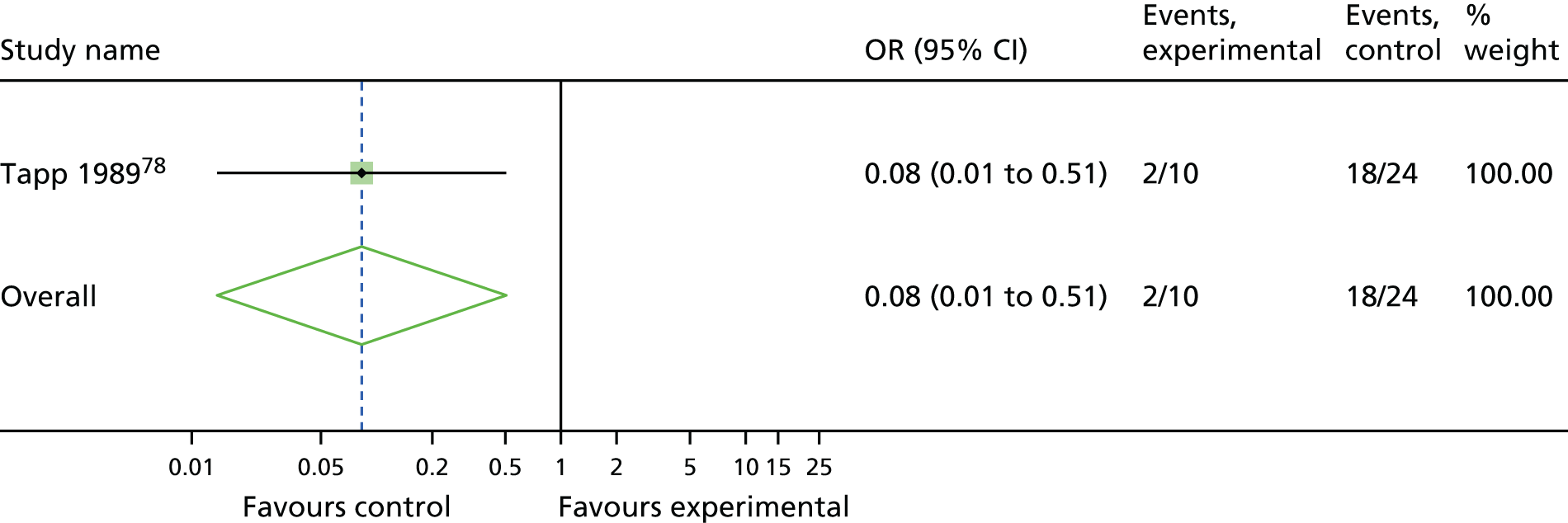

| PFMT | Open colpo | 1 | 0.08 | 0.01 to 0.51 | 0.14 | 0.05 to 0.39 | Low |

| Trad sling | Lap colpo | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.83 | 0.86 to 4.04 | Very low |

| Single incision | Lap colpo | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.87 | 0.44 to 1.70 | Low |

| Bladder neck needle | Lap colpo | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.59 | 0.26 to 1.33 | Very low |

| Ant repair | Lap colpo | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.38 | 0.18 to 0.82 | Very low |

| PFMT | Lap colpo | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.21 | 0.07 to 0.63 | N/A |

| Single incision | Trad sling | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.47 | 0.25 to 0.88 | Very low |

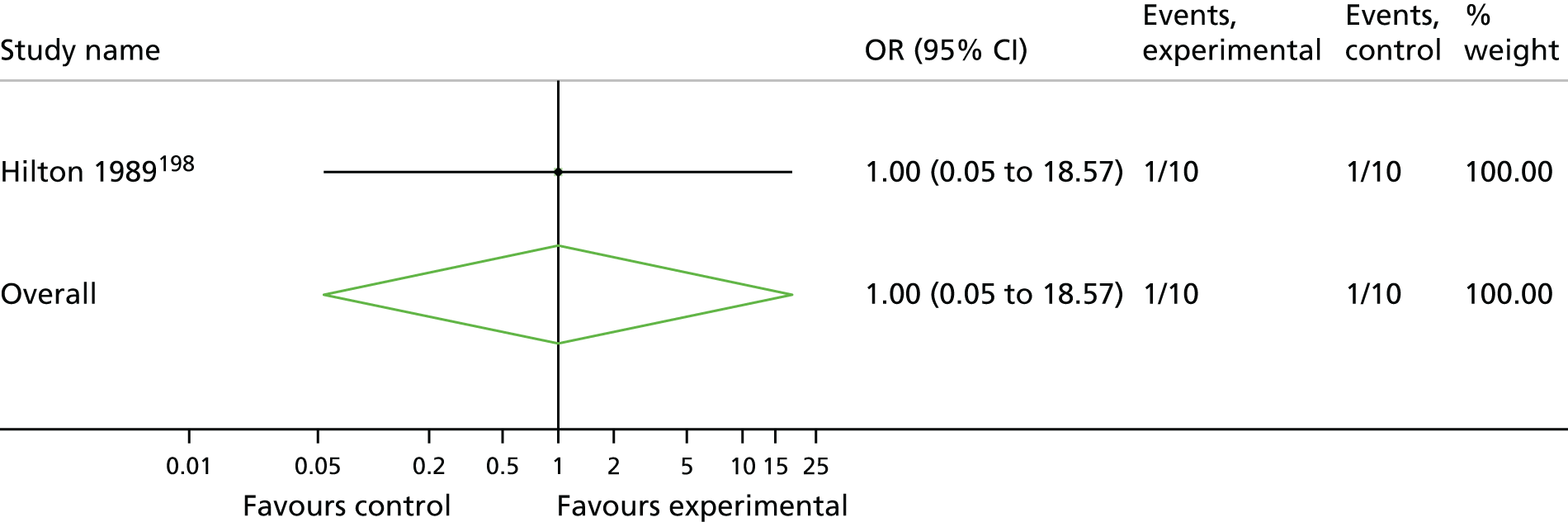

| Bladder neck needle | Trad sling | 1 | 1.00 | 0.05 to 18.57 | 0.32 | 0.13 to 0.79 | Very low |

| Ant repair | Trad sling | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.21 | 0.09 to 0.49 | Very low |

| PFMT | Trad sling | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.11 | 0.04 to 0.34 | Very low |

| Bladder neck needle | Single incision | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.67 | 0.29 to 1.56 | N/A |

| Ant repair | Single incision | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.44 | 0.20 to 0.96 | Very low |

| PFMT | Single incision | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.24 | 0.08 to 0.65 | Low |

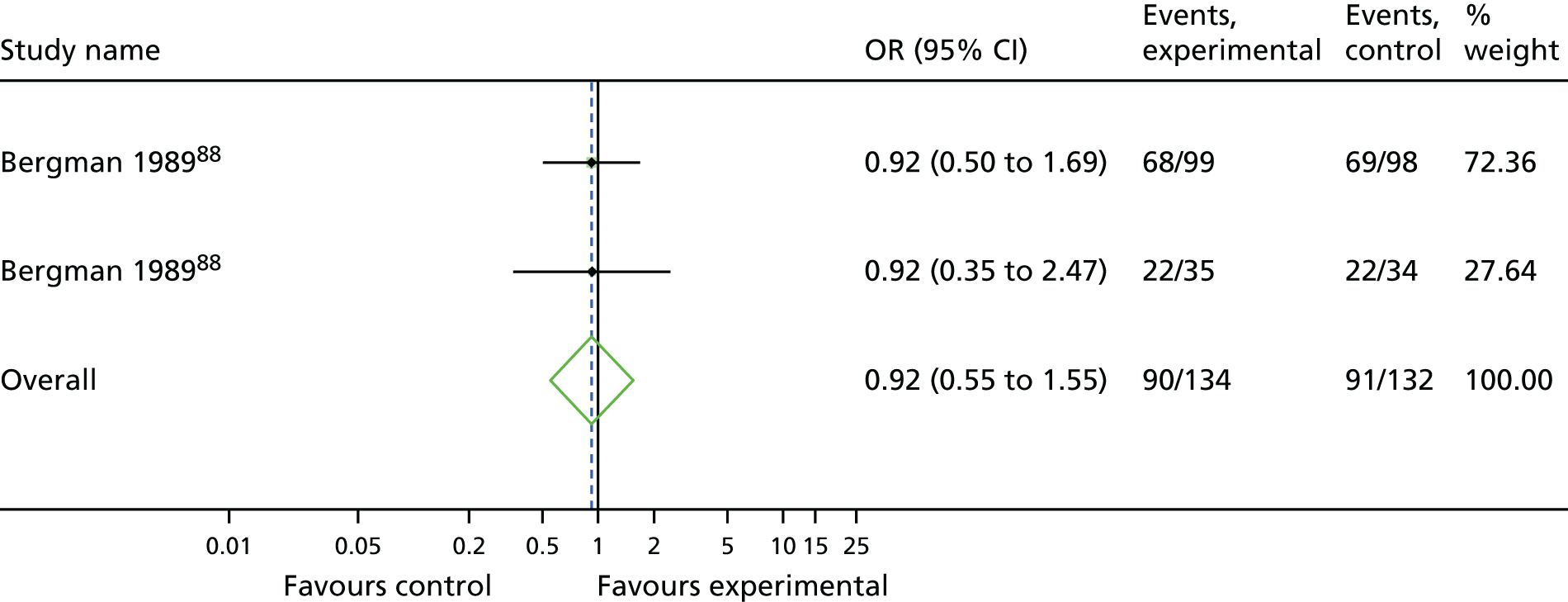

| Ant repair | Bladder neck needle | 1b | 0.92 | 0.55 to 1.55 | 0.65 | 0.30 to 1.36 | Very low |

| PFMT | Bladder neck needle | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.35 | 0.10 to 1.17 | Low |

| PFMT | Ant repair | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.55 | 0.17 to 1.77 | Very low |

| Treatment | Direct evidence | NMA | GRADE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Number of trials | ORa | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CrI | |

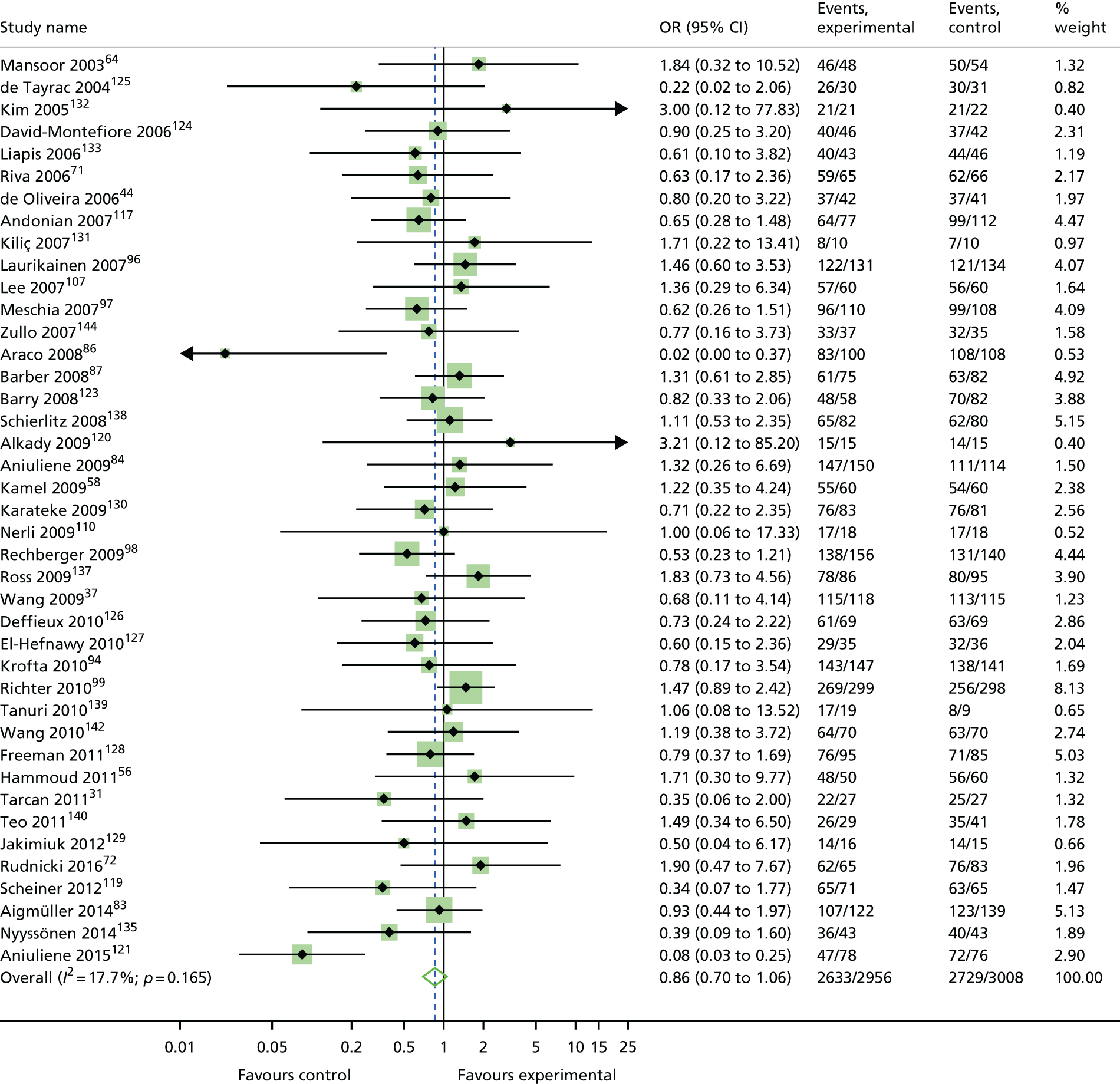

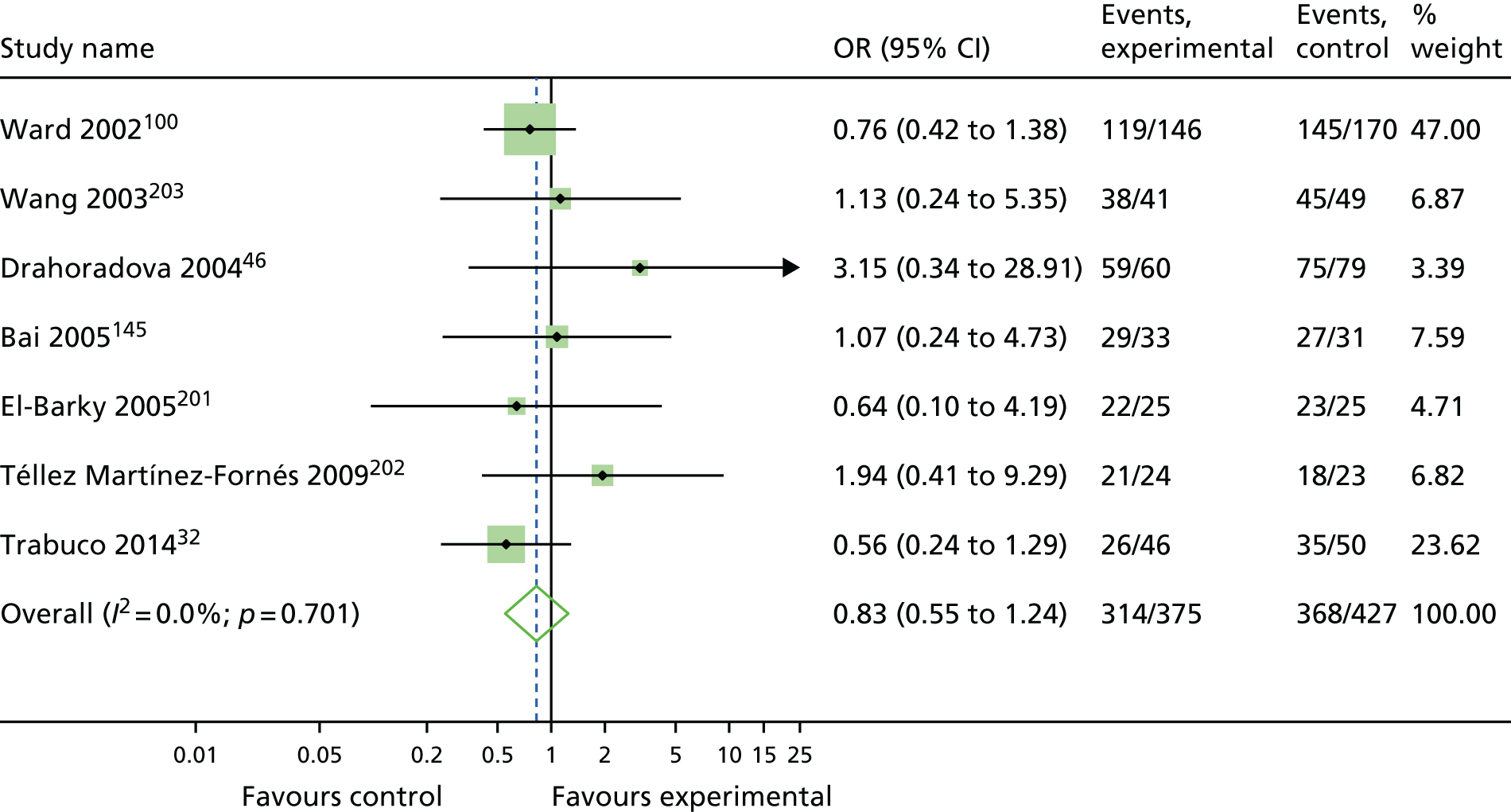

| Transob-MUS | Retro-MUS | 40b | 0.86 | 0.70 to 1.06 | 0.76 | 0.59 to 0.98 | Moderate |

| Open colpo | Retro-MUS | 6b | 0.83 | 0.55 to 1.24 | 0.65 | 0.41 to 1.02 | Low |

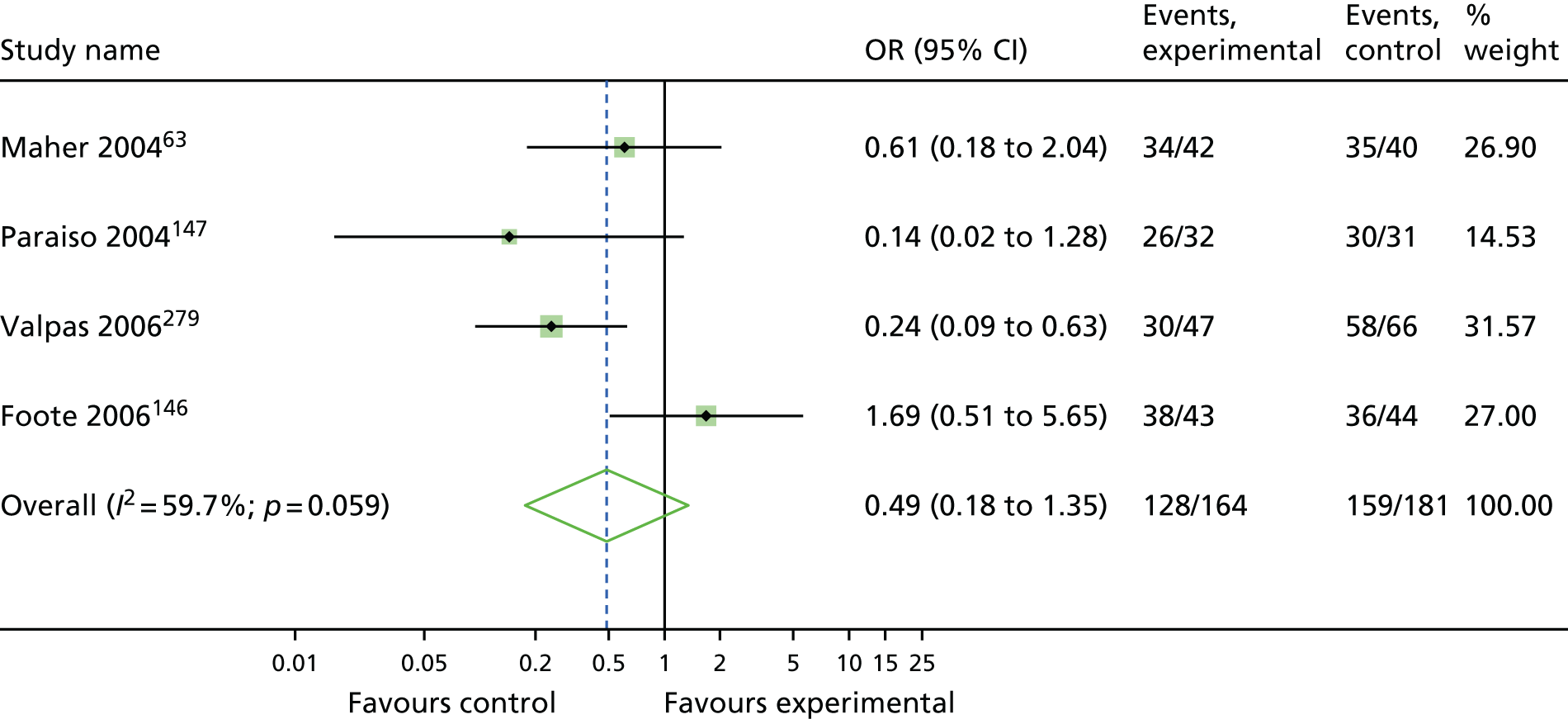

| Lap colpo | Retro-MUS | 4 | 0.49 | 0.18 to 1.35 | 0.52 | 0.29 to 0.91 | Low |

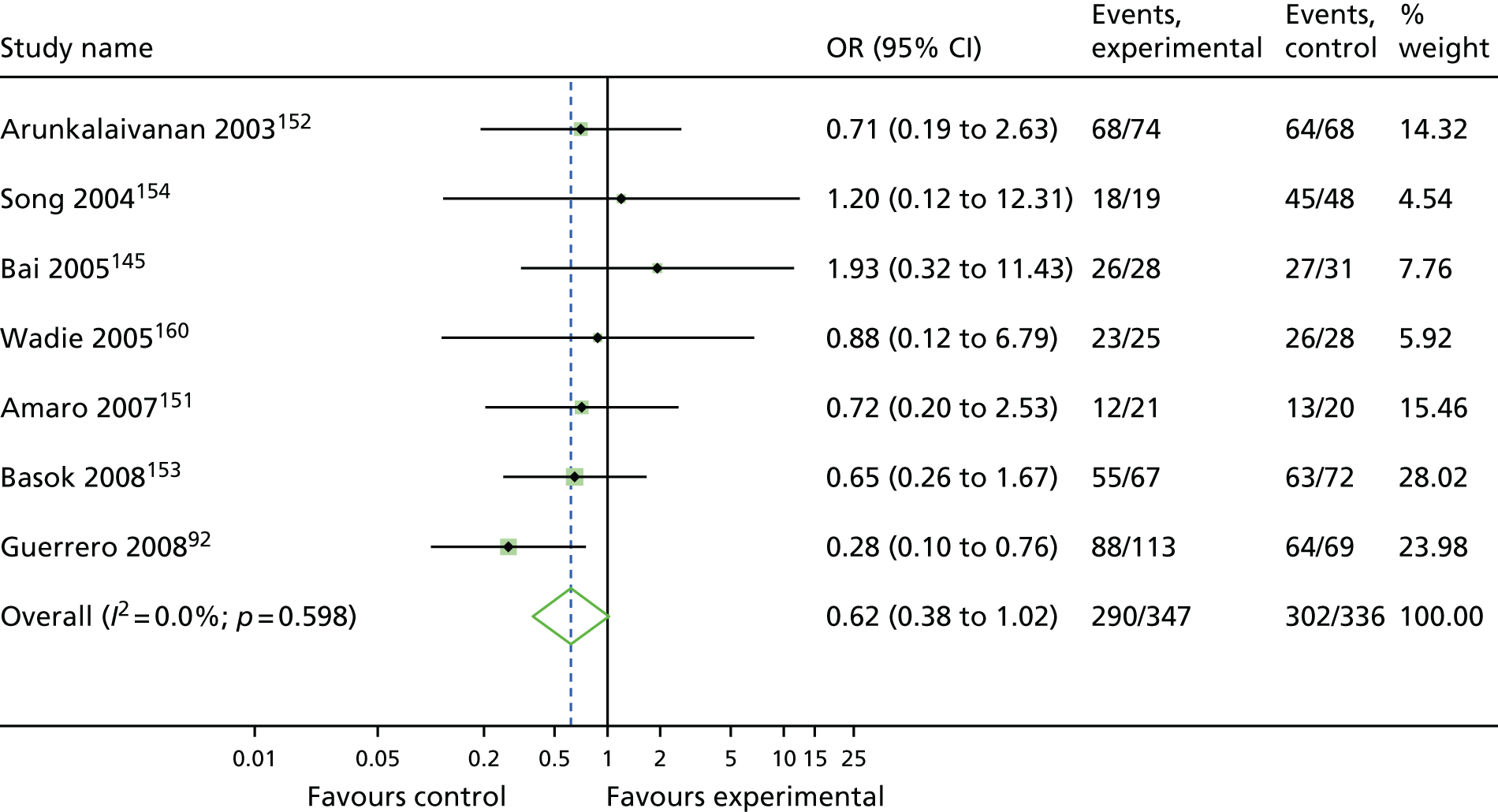

| Trad sling | Retro-MUS | 6b | 0.62 | 0.38 to 1.02 | 0.69 | 0.39 to 1.26 | Low |

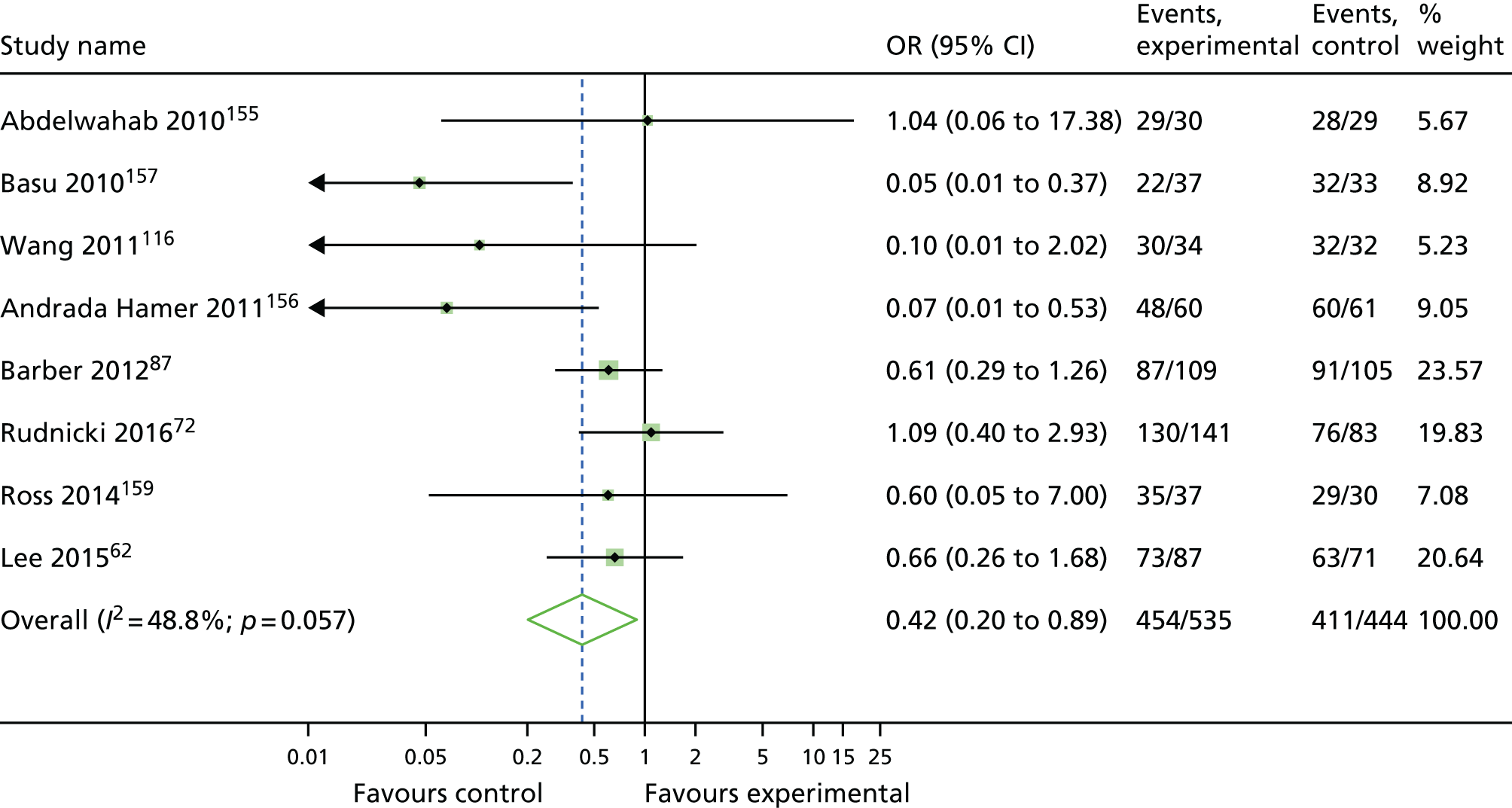

| Single incision | Retro-MUS | 6b | 0.42 | 0.20 to 0.89 | 0.50 | 0.35 to 0.71 | Moderate |

| Bladder neck needle | Retro-MUS | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.25 | 0.11 to 0.58 | Low |

| Ant repair | Retro-MUS | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.18 | 0.08 to 0.39 | Very low |

| PFMT | Retro-MUS | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.43 | 0.14 to 1.37 | Low |

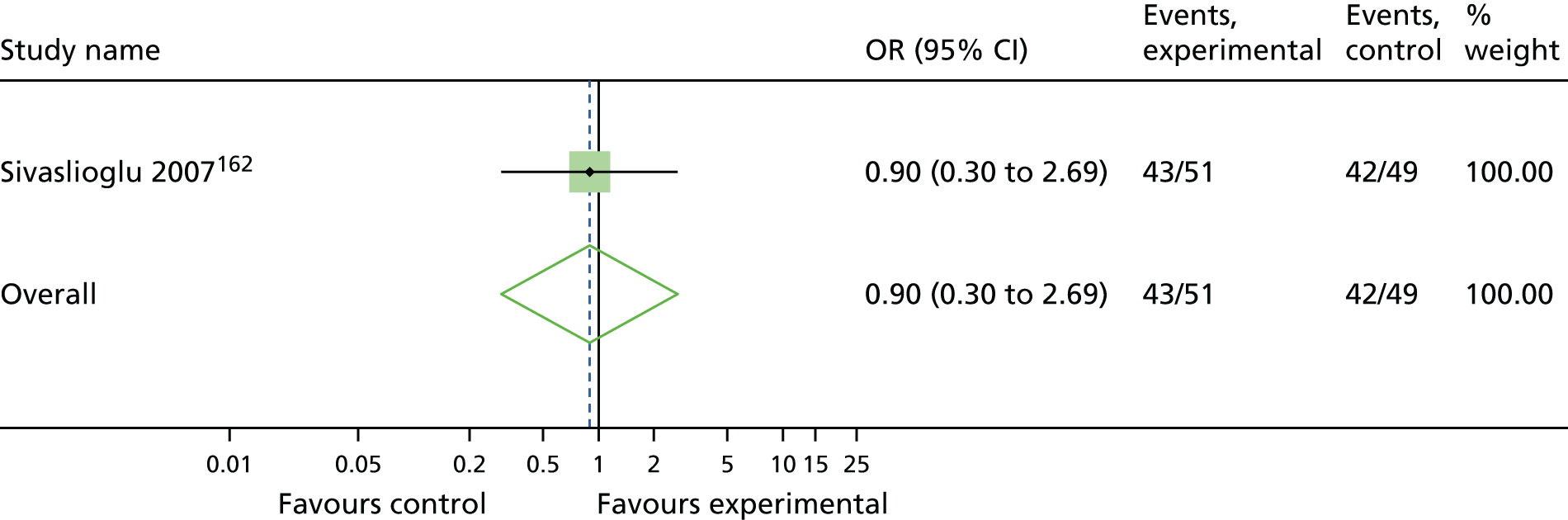

| Open colpo | Transob-MUS | 1 | 0.90 | 0.30 to 2.69 | 0.85 | 0.52 to 1.41 | Low |

| Lap colpo | Transob-MUS | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.69 | 0.37 to 1.26 | Low |

| Trad sling | Transob-MUS | 1 | 2.00 | 0.17 to 23.96 | 0.91 | 0.49 to 1.72 | Very low |

| Single incision | Transob-MUS | 28b | 0.74 | 0.57 to 0.96 | 0.66 | 0.49 to 0.89 | Moderate |

| Bladder neck needle | Transob-MUS | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.33 | 0.14 to 0.79 | Very low |

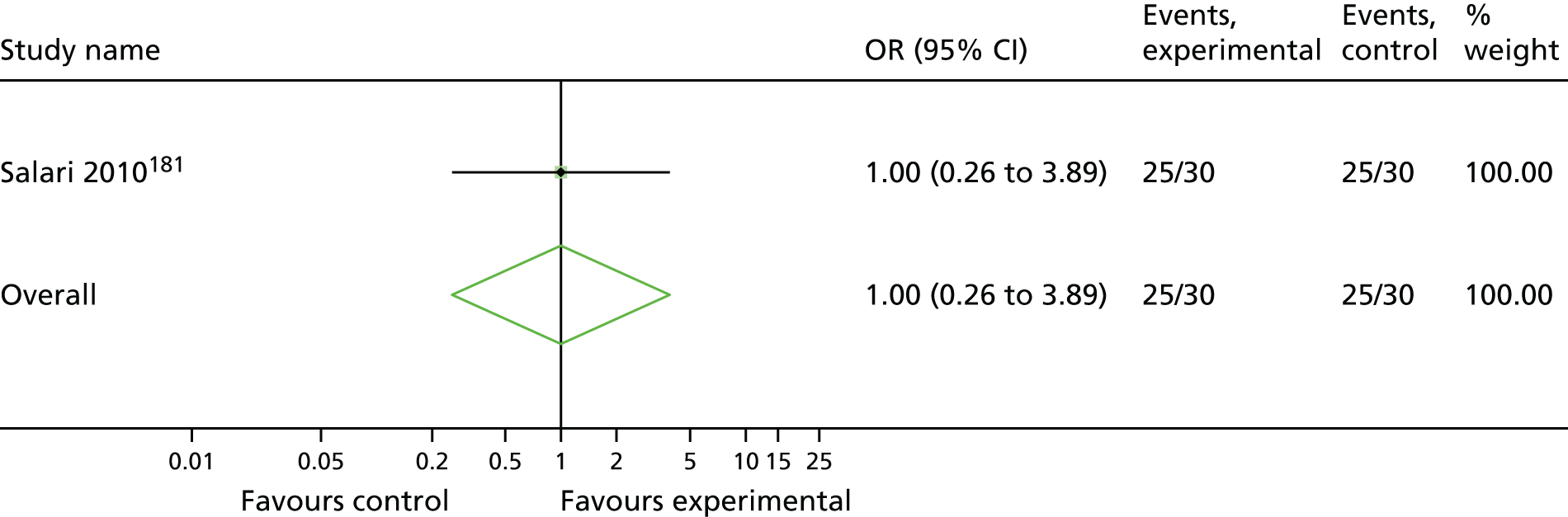

| Ant repair | Transob-MUS | 1 | 1.00 | 0.26 to 3.89 | 0.24 | 0.10 to 0.53 | Very low |

| PFMT | Transob-MUS | 1 | 0.18 | 0.10 to 0.33 | 0.56 | 0.19 to 1.78 | Low |

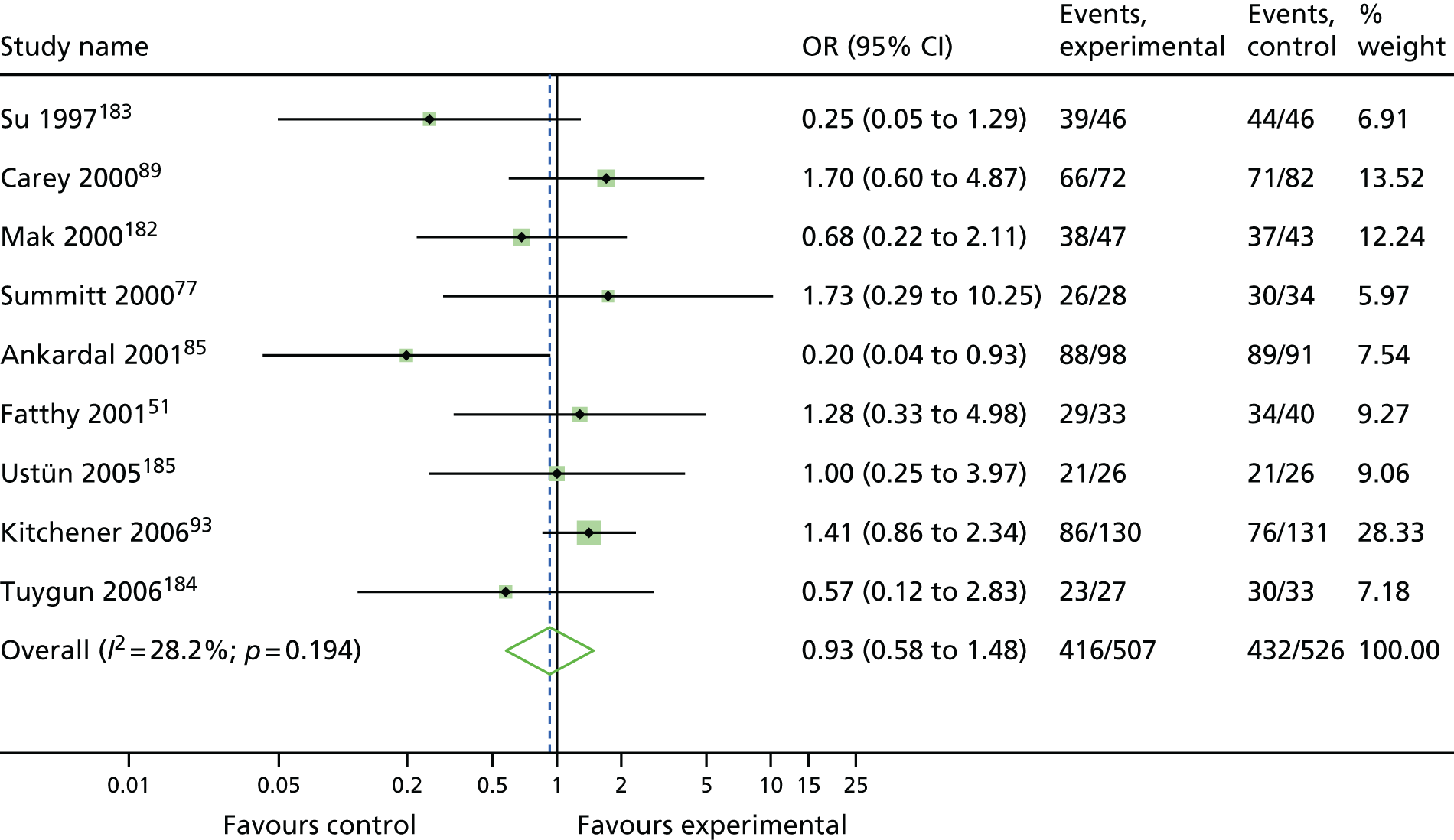

| Lap colpo | Open colpo | 9 | 0.93 | 0.58 to 1.48 | 0.81 | 0.49 to 1.31 | Low |

| Trad sling | Open colpo | 3b | 2.47 | 0.73 to 8.40 | 1.07 | 0.54 to 2.15 | Low |

| Single incision | Open colpo | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.78 | 0.44 to 1.36 | Low |

| Bladder neck needle | Open colpo | 3b | 0.38 | 0.22 to 0.63 | 0.38 | 0.18 to 0.81 | Low |

| Ant repair | Open colpo | 3b | 0.20 | 0.07 to 0.60 | 0.28 | 0.14 to 0.55 | Very low |

| PFMT | Open colpo | 1 | 8.87 | 1.66 to 47.25 | 0.66 | 0.21 to 2.16 | Low |

| Trad sling | Lap colpo | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.32 | 0.62 to 2.98 | Low |

| Single incision | Lap colpo | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.97 | 0.50 to 1.87 | Low |

| Bladder neck needle | Lap colpo | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.47 | 0.20 to 1.17 | Very low |

| Ant repair | Lap colpo | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.34 | 0.15 to 0.79 | Very low |

| PFMT | Lap colpo | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.82 | 0.25 to 2.88 | Very low |

| Single incision | Trad sling | 1 | 1.92 | 0.65 to 5.64 | 0.73 | 0.37 to 1.39 | Low |

| Bladder neck needle | Trad sling | 1 | 1.00 | 0.05 to 18.57 | 0.36 | 0.13 to 0.95 | Very low |

| Ant repair | Trad sling | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.26 | 0.10 to 0.65 | Very low |

| PFMT | Trad sling | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.62 | 0.18 to 2.18 | Very low |

| Bladder neck needle | Single incision | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.49 | 0.20 to 1.24 | Very low |

| Ant repair | Single incision | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.36 | 0.15 to 0.82 | Very low |

| PFMT | Single incision | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.84 | 0.28 to 2.78 | Low |

| Ant repair | Bladder neck needle | 1b | 0.92 | 0.55 to 1.55 | 0.72 | 0.31 to 1.63 | Very low |

| PFMT | Bladder neck needle | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.72 | 0.45 to 6.89 | Low |

| PFMT | Ant repair | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.38 | 0.65 to 9.30 | Very low |

The direct pairwise analyses showed some heterogeneity in four direct comparisons for the number of women cured (single-incision sling vs. retropubic MUS; single-incision sling vs. transobturator MUS; laparoscopic colposuspension vs. open colposuspension; and anterior vaginal repair vs. open colposuspension) and one comparison for the number of women improved (laparoscopic colposuspension vs. retropubic MUS) (see Appendices 10 and 11).

Number of women cured

Table 5 shows the estimates of treatment effect from the direct pairwise meta-analyses and the NMA for the number of women cured (the direct meta-analysis results for all the included studies are presented in Appendix 11). The NMA showed that, on average, women who underwent a traditional sling or retropubic MUS operation were more likely to be cured compared with those who had other surgical procedures. Some of the comparisons had a limited number of studies and there is considerable uncertainty around the estimates of effect, for example for the comparison between retropubic MUS and traditional sling [OR 1.06, 95% CrI 0.62 to 1.85 (quality of evidence: very low)], between retropubic MUS and open colposuspension [OR 0.85, 95% CrI 0.54 to 1.33 (quality of evidence: very low)] and between retropubic MUS and laparoscopic colposuspension [OR 0.58, 95% CrI 0.31 to 1.05 (quality of evidence: very low)].

Number of women who experienced an improvement in their incontinence symptoms

Table 6 shows the estimates of treatment effect from the NMA and the overall estimates from the direct pairwise meta-analyses for the number of women with improvement in incontinence symptoms (the full set of direct meta-analyses results is presented in Appendix 12). The NMA showed that women who had retropubic MUS or transobturator MUS were more likely to experience an improvement in their incontinence symptoms. However, there is some uncertainty around the estimates of effect for some of the comparisons, for example the comparisons between retropubic MUS and open colposuspension [OR 0.65, 95% CrI 0.41 to 1.02 (quality of evidence: low)] and between retropubic MUS and traditional sling [OR 0.69, 95% CrI 0.39 to 1.26 (quality of evidence: low)].

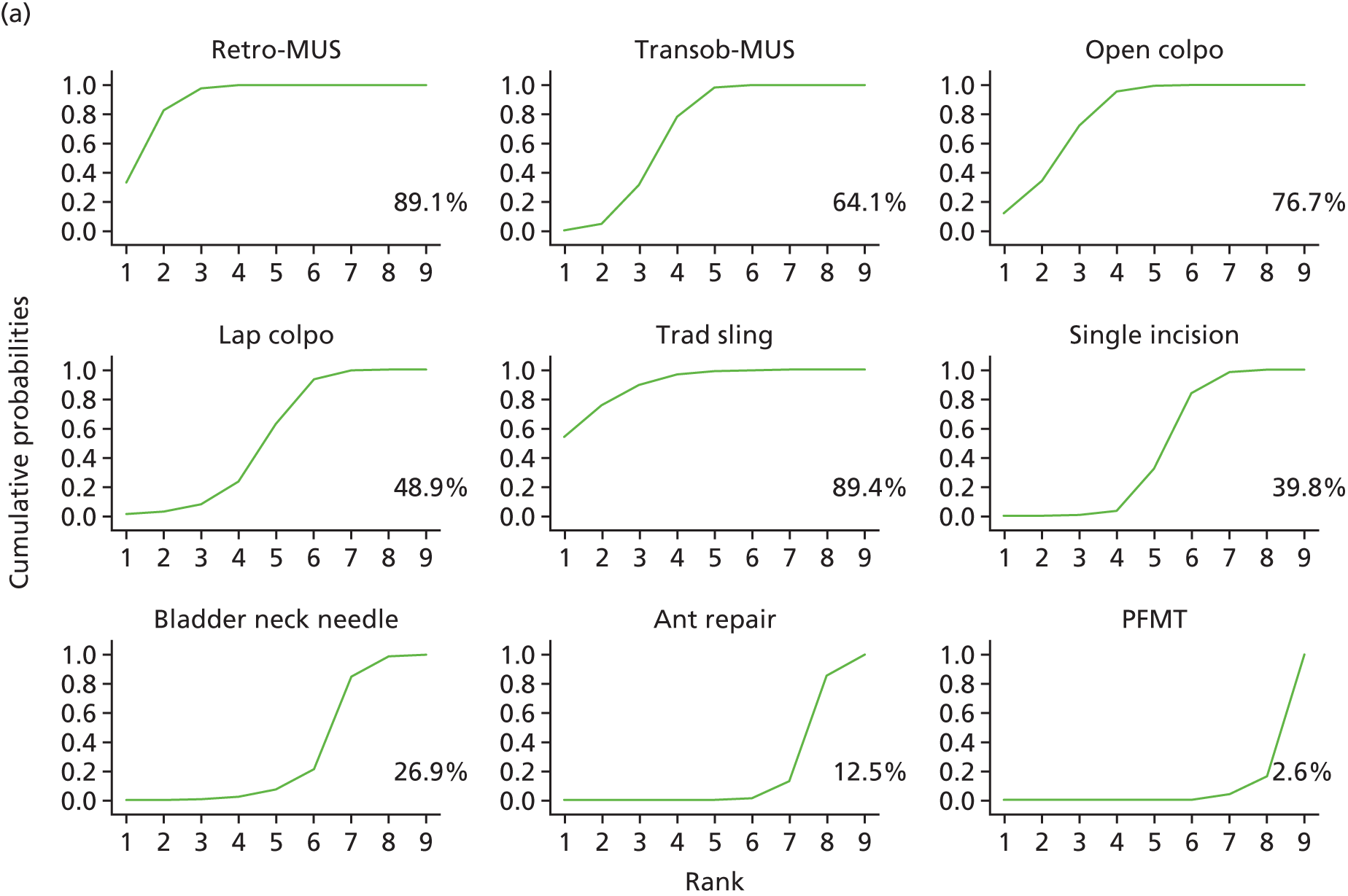

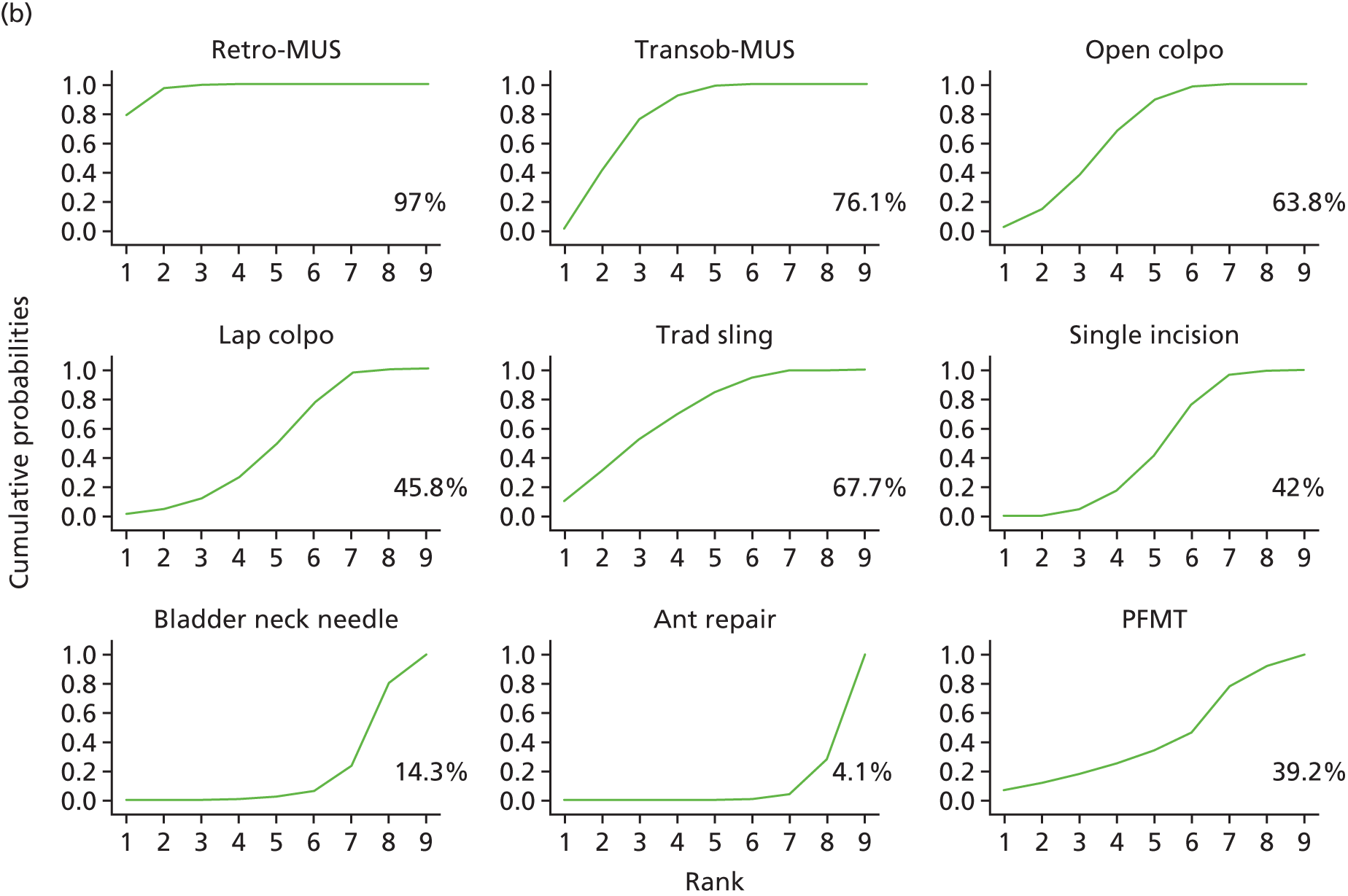

Ranking of treatment effectiveness

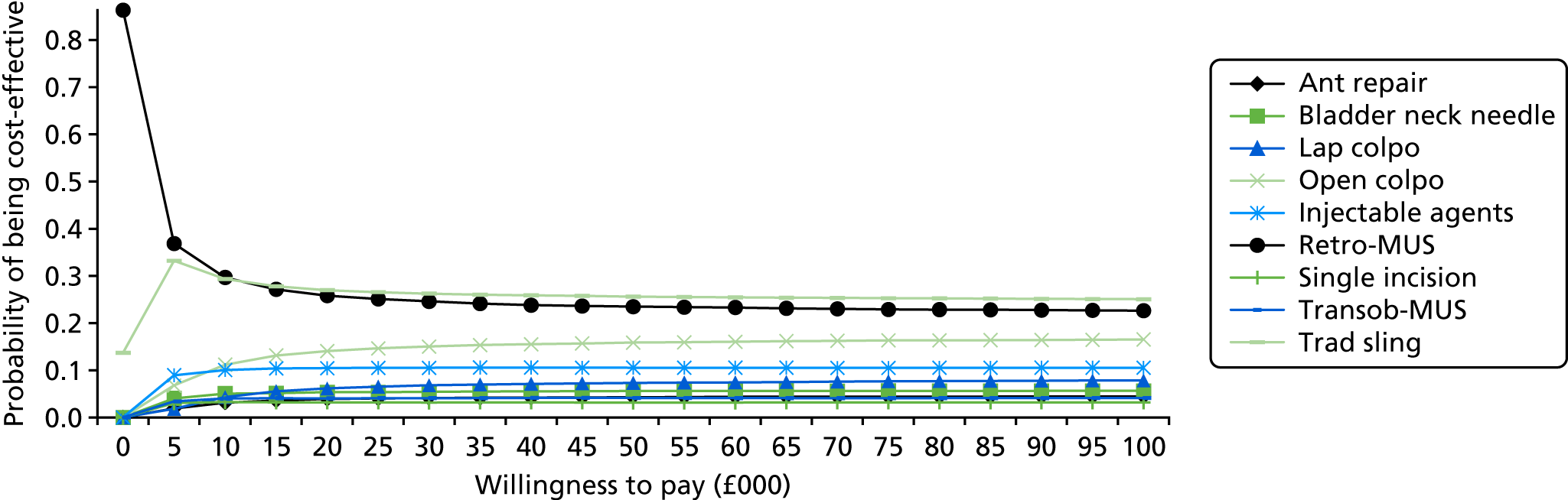

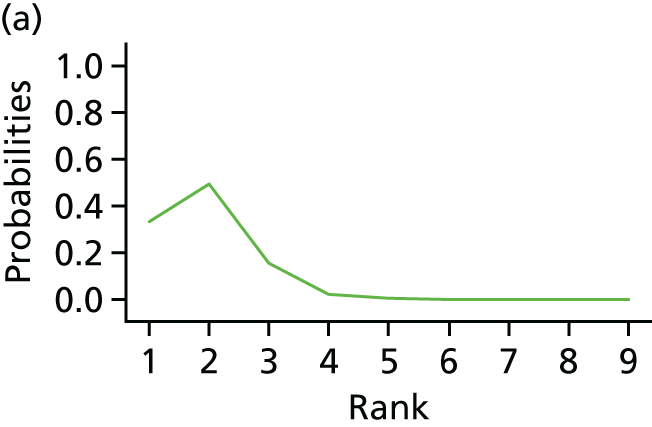

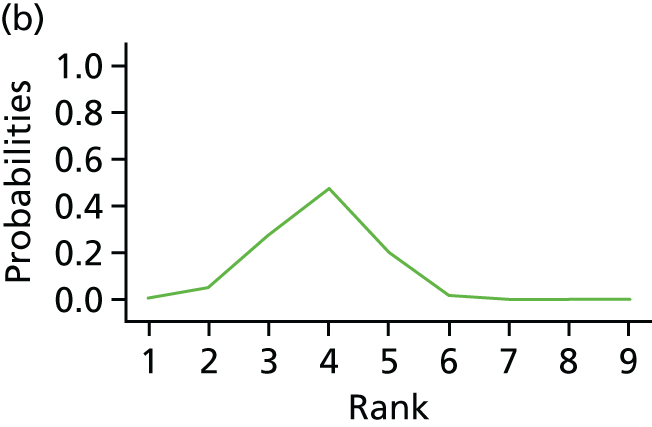

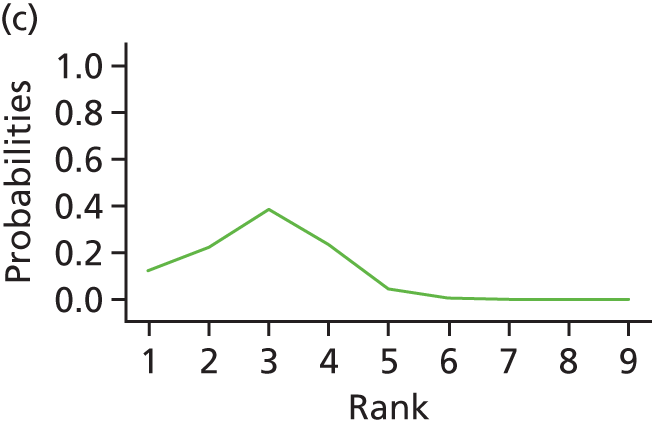

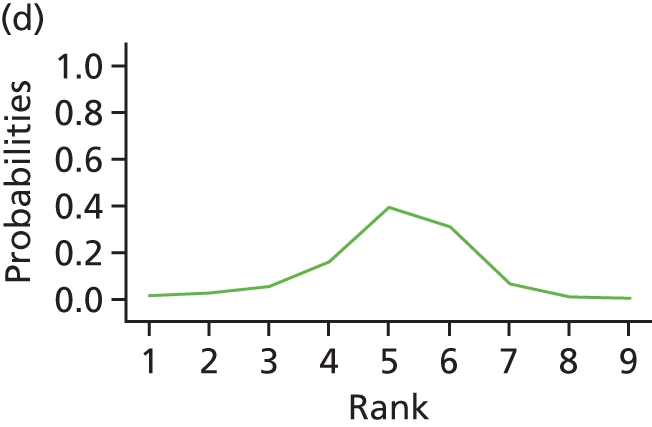

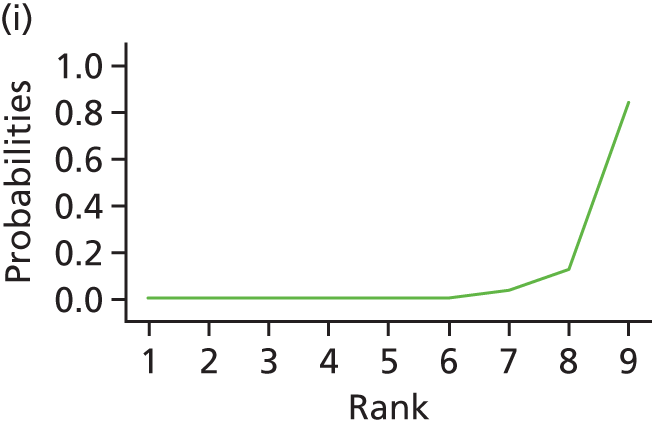

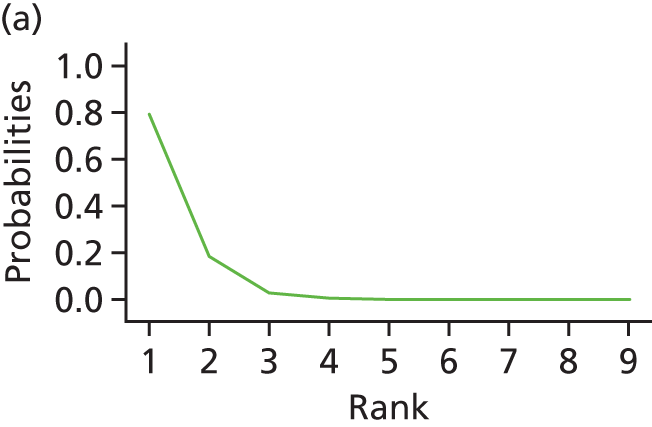

Figure 2 shows the SUCRA values for all surgical interventions. The rankograms are reported in Appendix 13.

FIGURE 2.

Surface under the cumulative ranking curve values for (a) the number of women cured; and (b) the number of women improved. Ant repair, anterior vaginal repair; bladder neck needle, bladder neck needle suspension; open colpo, open colposuspension; lap colpo, laparoscopic colposuspension; retro-MUS, retropubic MUS; single incision, single-incision sling; trad sling, traditional sling; transob-MUS, transobturator MUS.

Traditional sling and retropubic MUS (see Figure 2a) are the treatments most likely to result in the highest proportion of women cured (89.4% and 89.1%, respectively), followed by open colposuspension (76.7%), transobturator MUS (64.1%), laparoscopic colposuspension (48.9%), single-incision sling (39.8%), bladder neck needle suspension (26.9%), anterior vaginal repair (12.5%) and PFMT (2.6%). On the other hand, retropubic MUS (97.0%) and transobturator MUS (76.1%) are the most likely treatments to result in the highest proportion of women with an improvement in their incontinence symptoms (see Figure 2b), followed by traditional sling (67.7%), open colposuspension (63.8%), laparoscopic colposuspension (45.8%), single-incision sling (42.0%), PFMT (39.2%), bladder neck needle suspension (14.3%) and anterior repair (4.1%).

Consistency between direct and indirect evidence

In the NMA there was no evidence of inconsistency for the cure outcome (see Appendix 14, Figure 45 and Table 33 for full details) and some evidence of inconsistency for the improvement outcome (see Appendix 14, Figure 46 and Appendix 14, Table 34). Consistency assessed using the node-splitting method (see Appendix 14, Table 34) showed inconsistencies for PFMT compared with transobturator MUS and for traditional sling and PFMT compared with open colposuspension. However, caution is required here, as the node splitting method can have low statistical power to detect inconsistency.

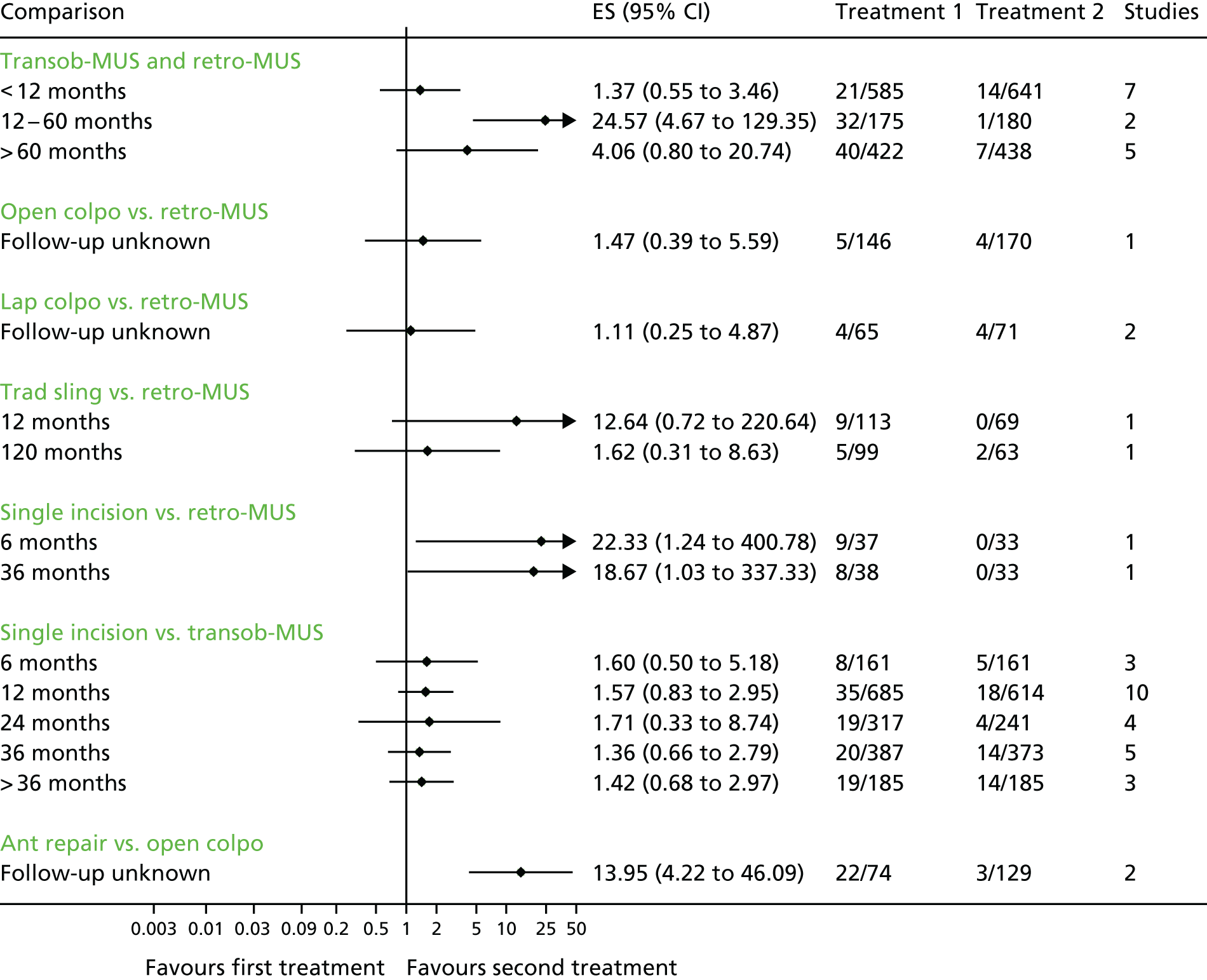

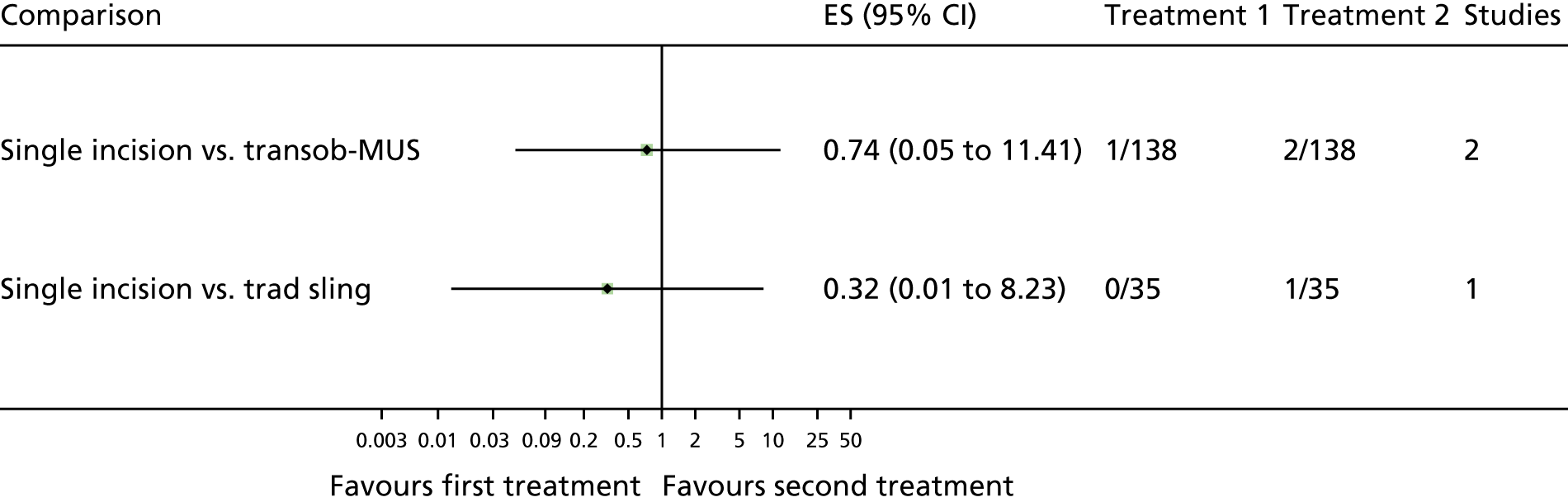

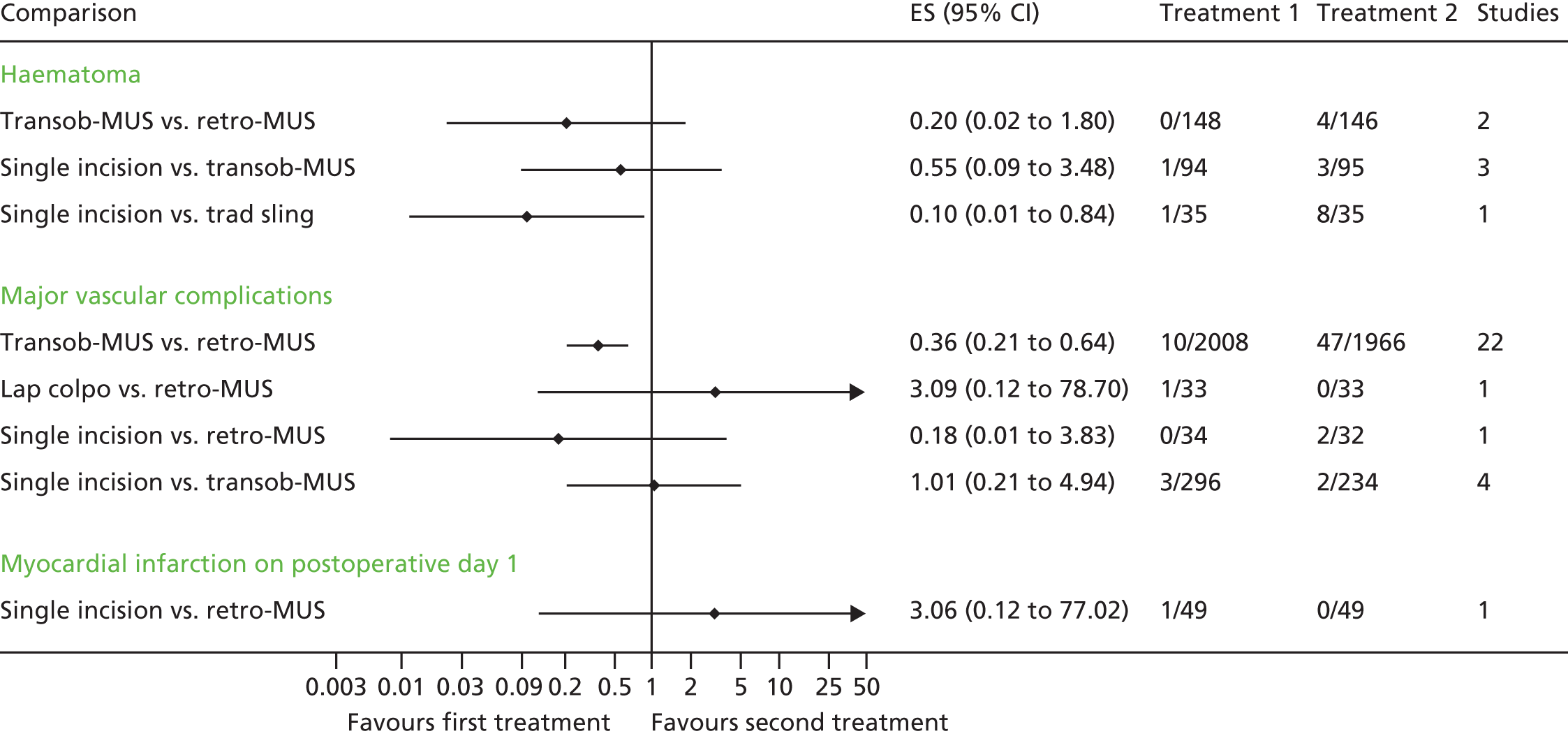

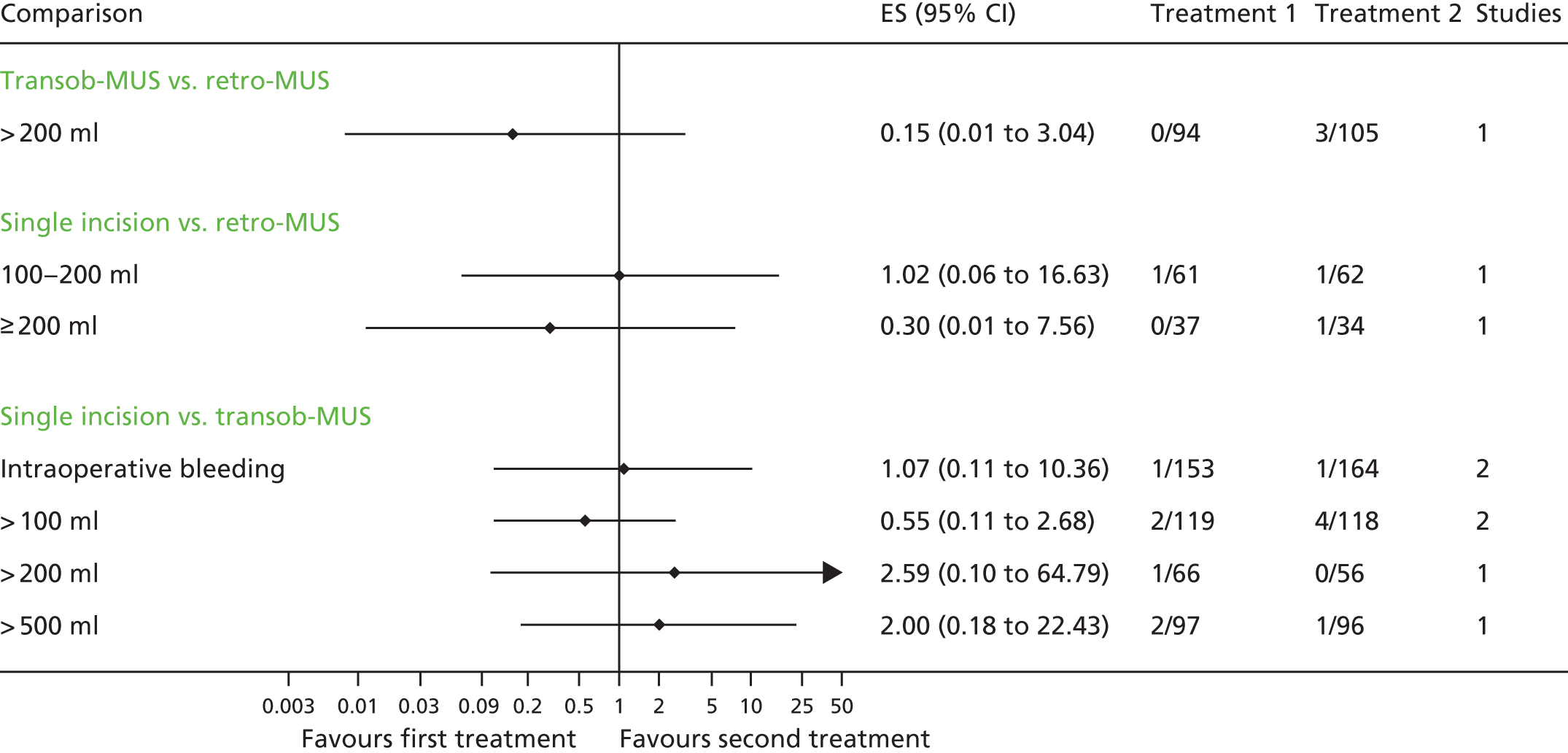

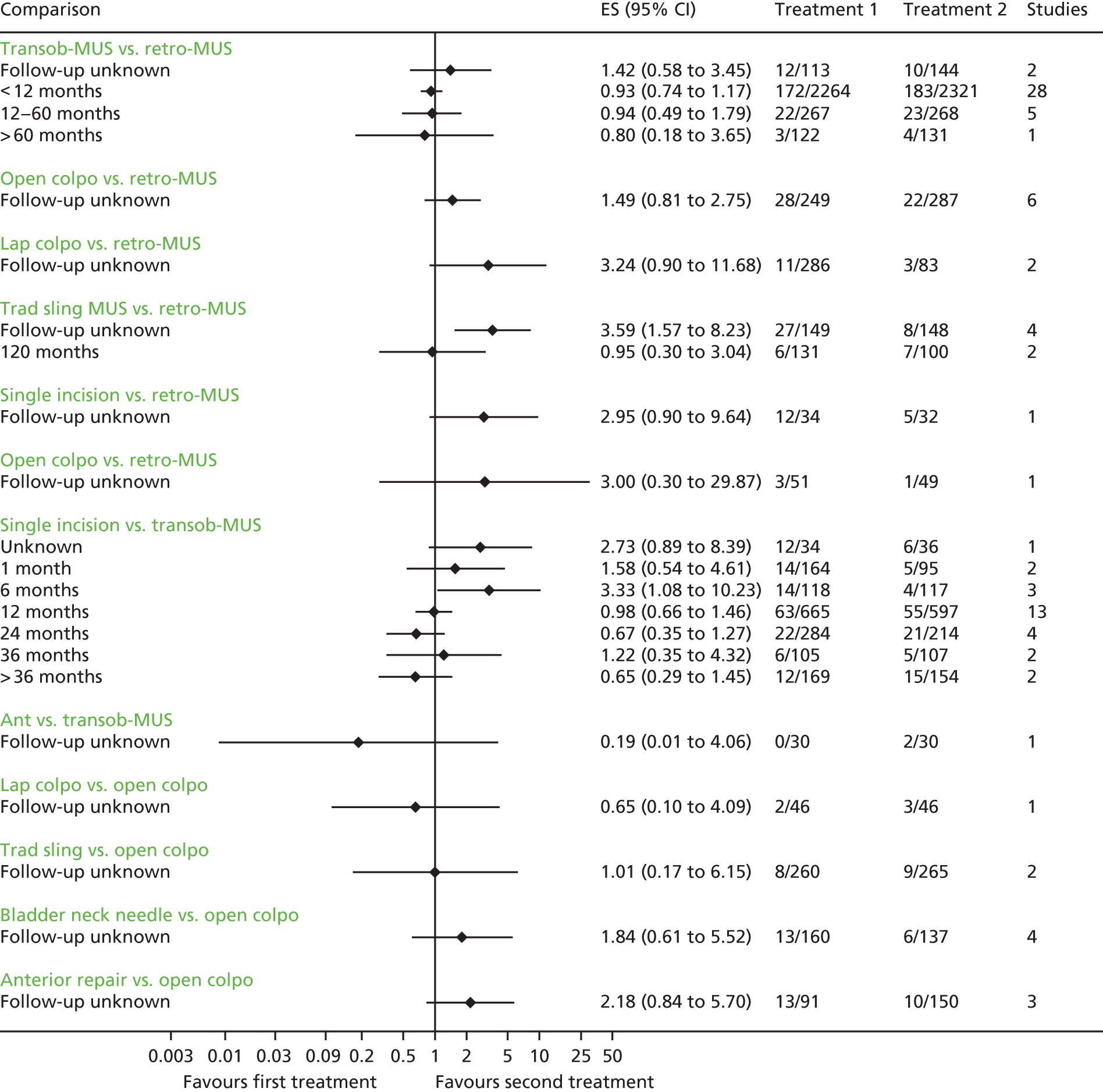

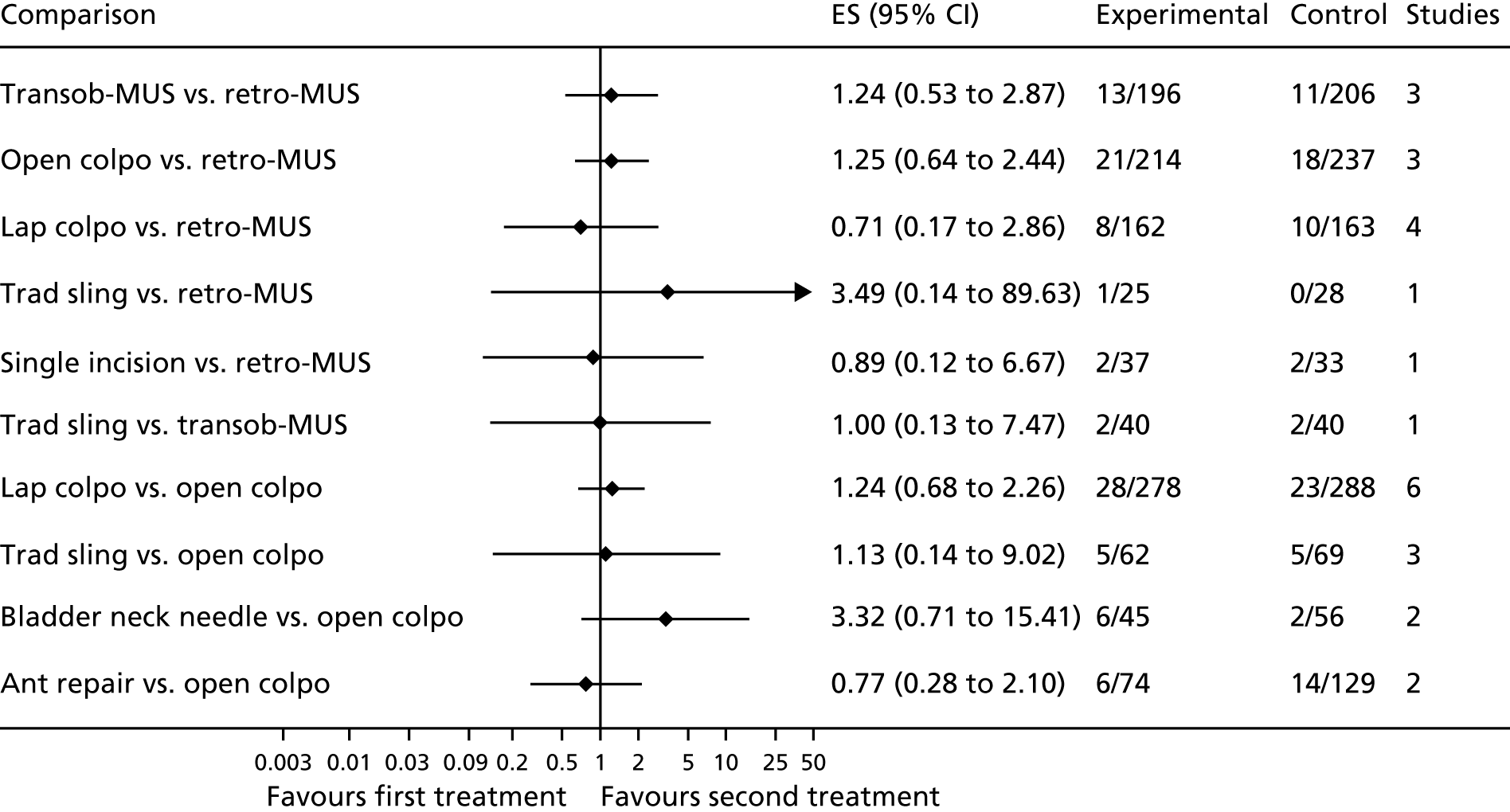

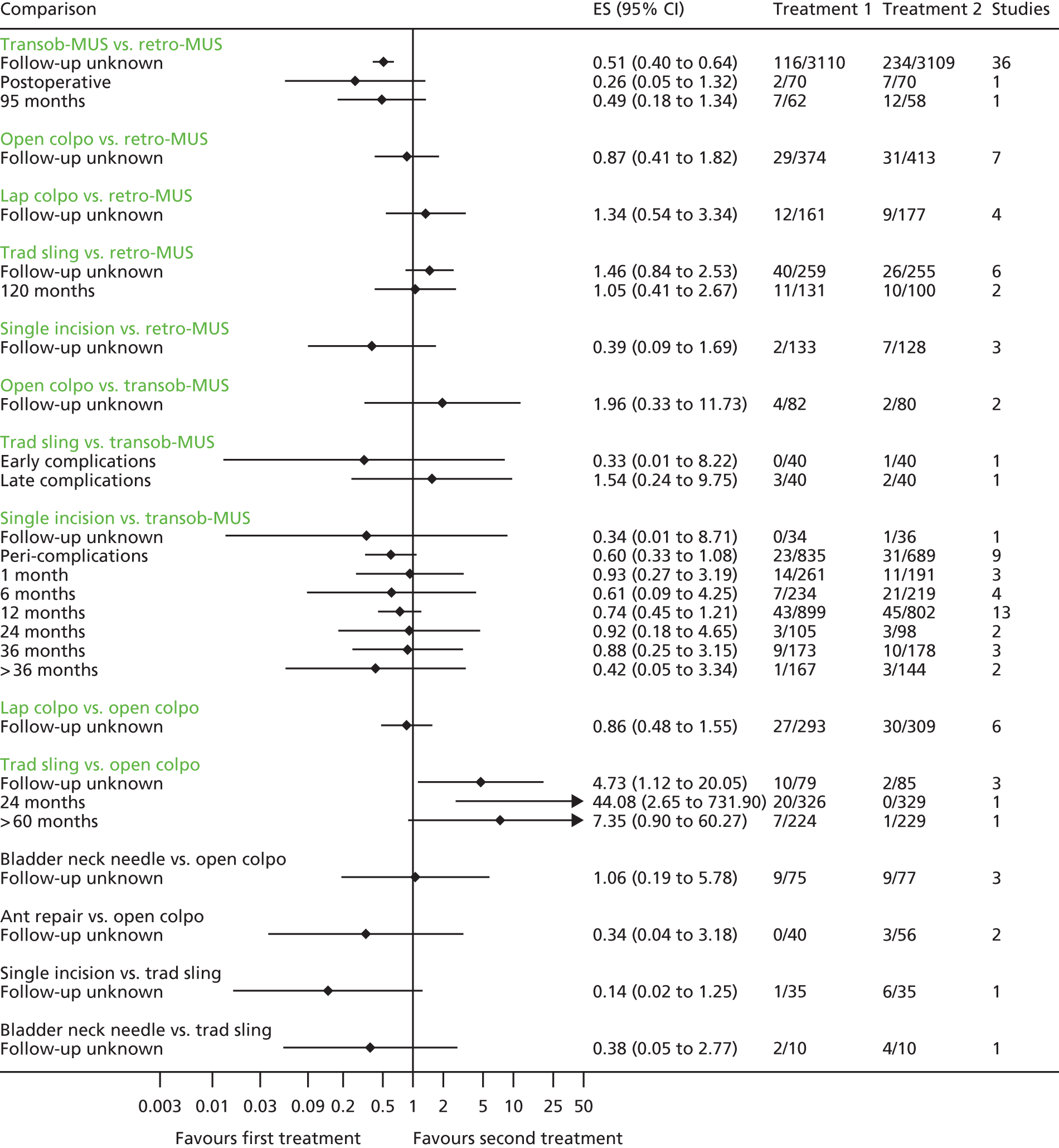

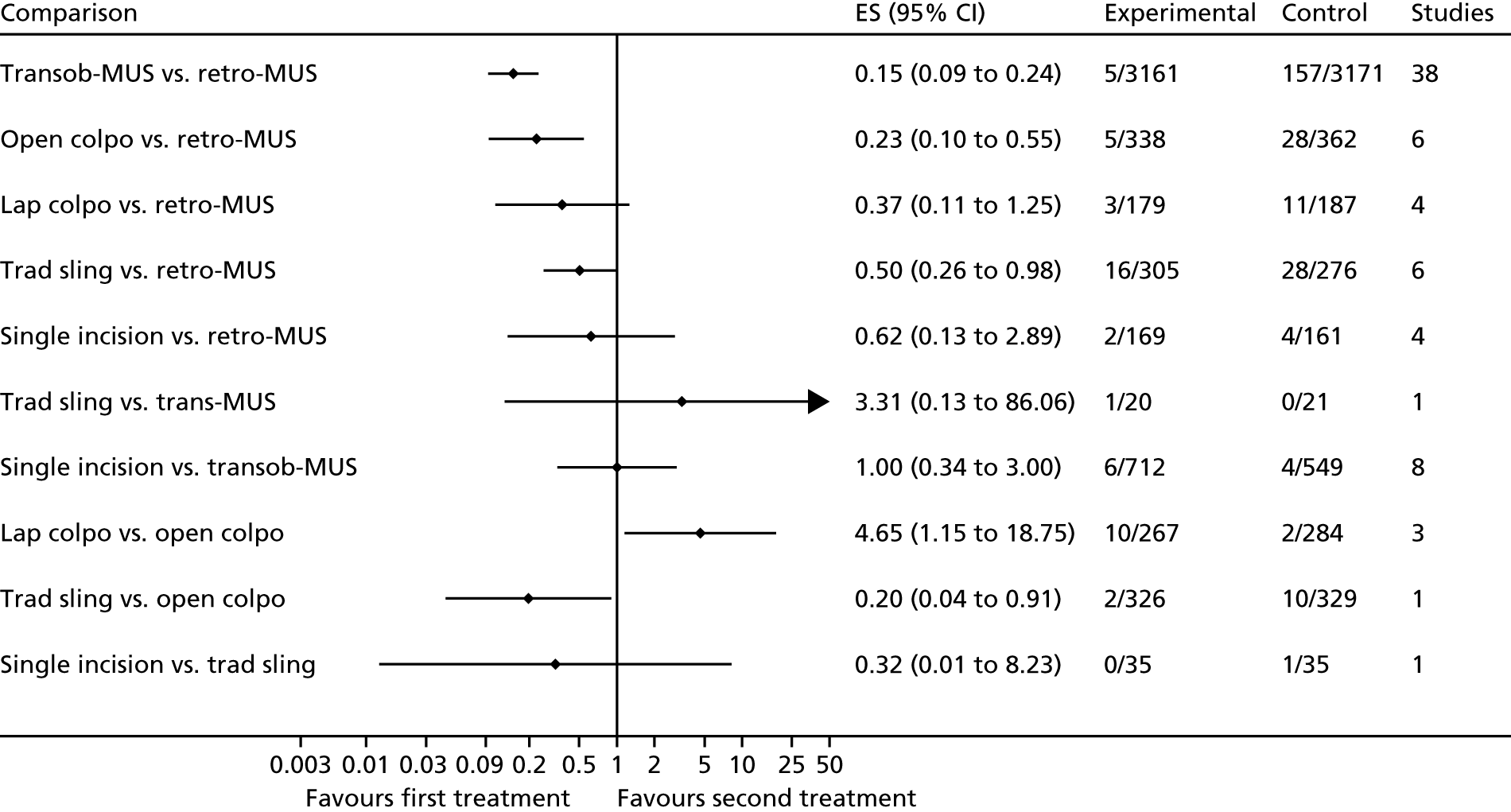

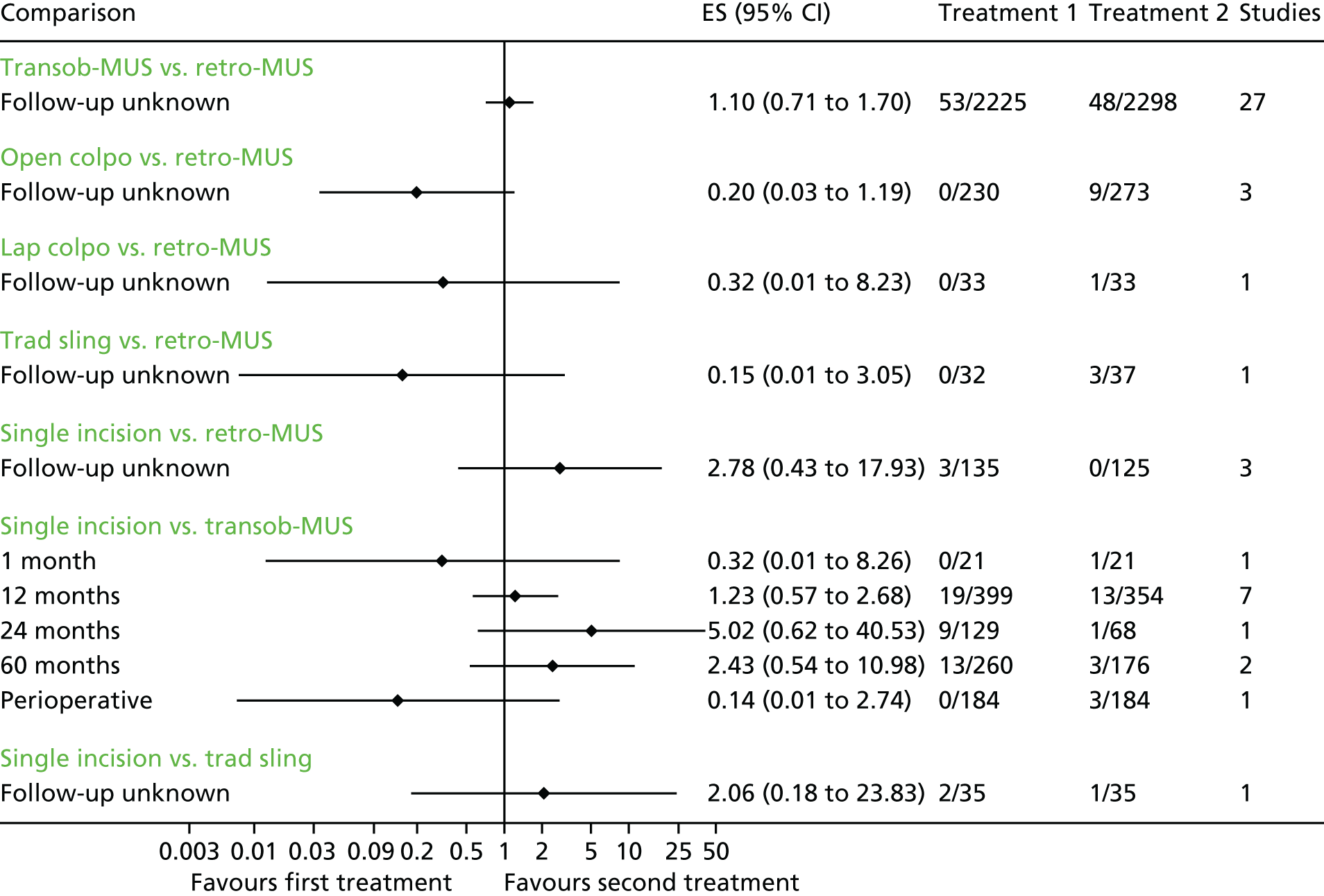

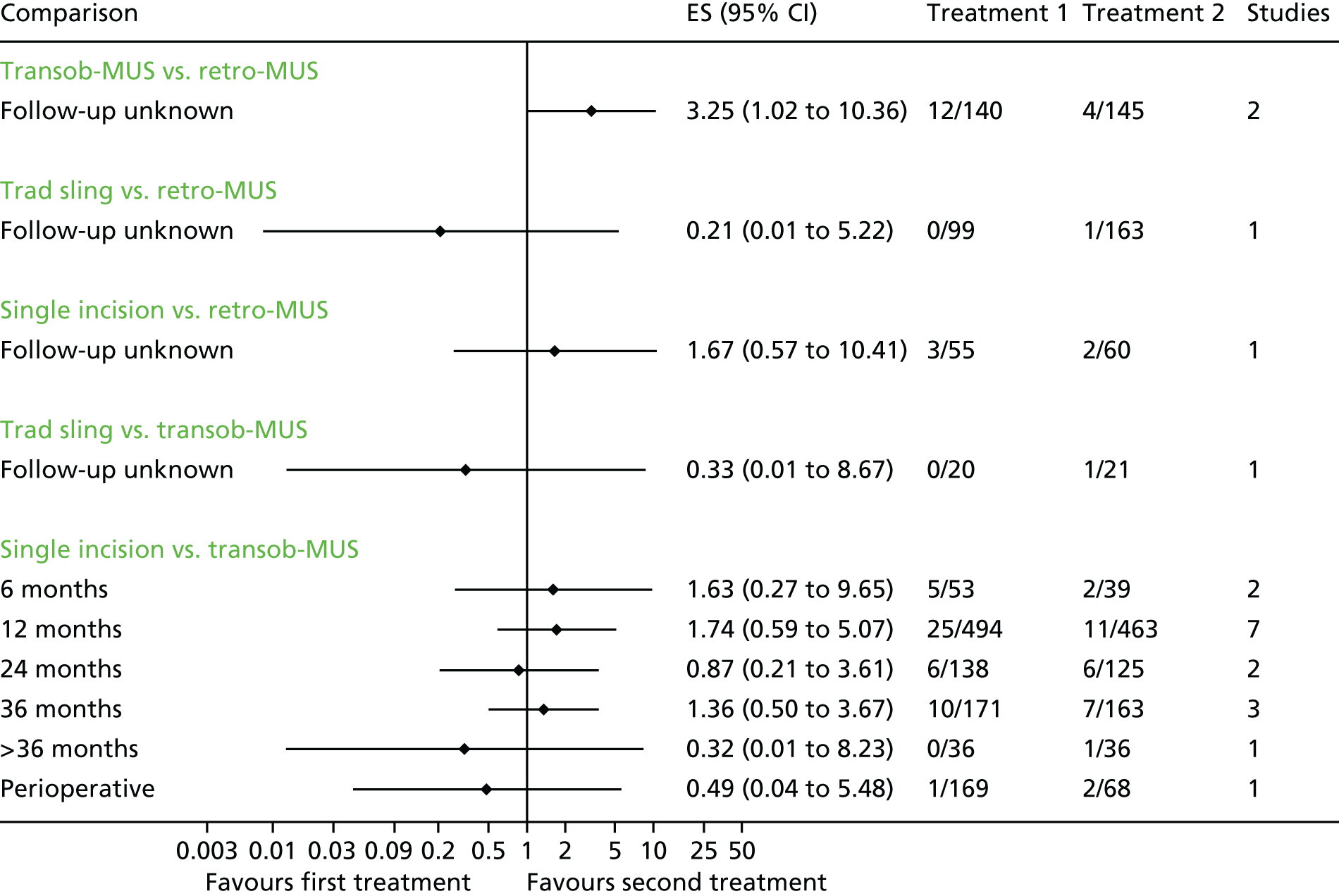

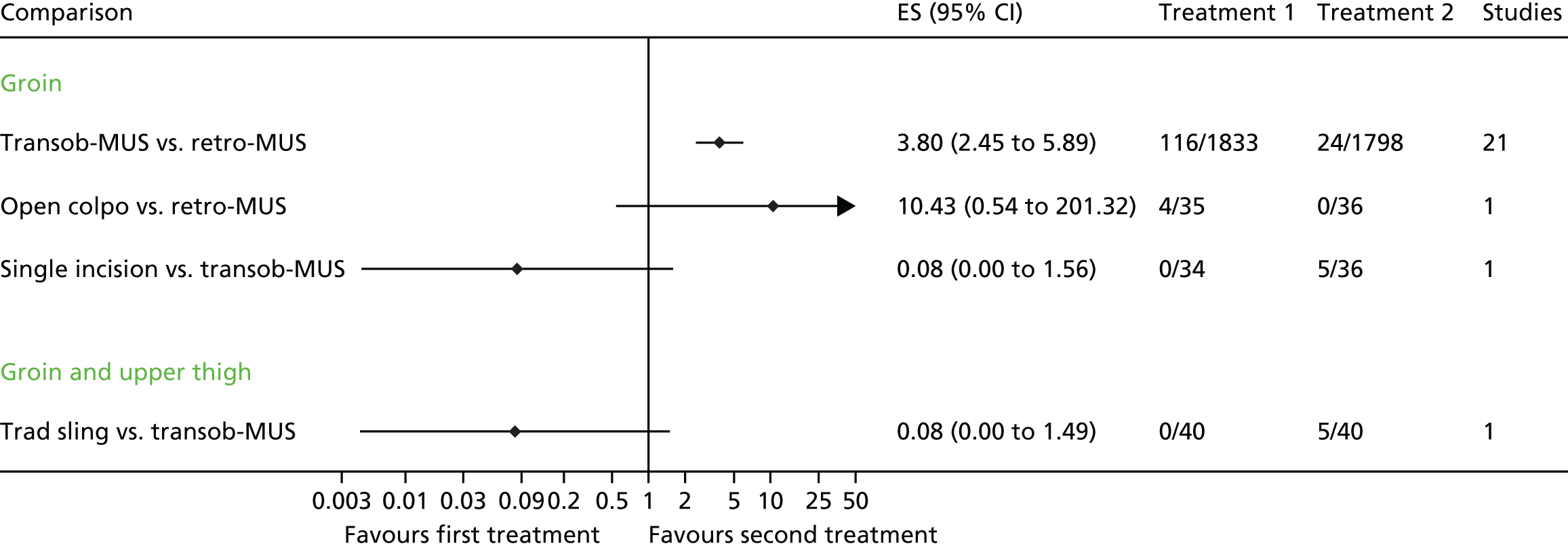

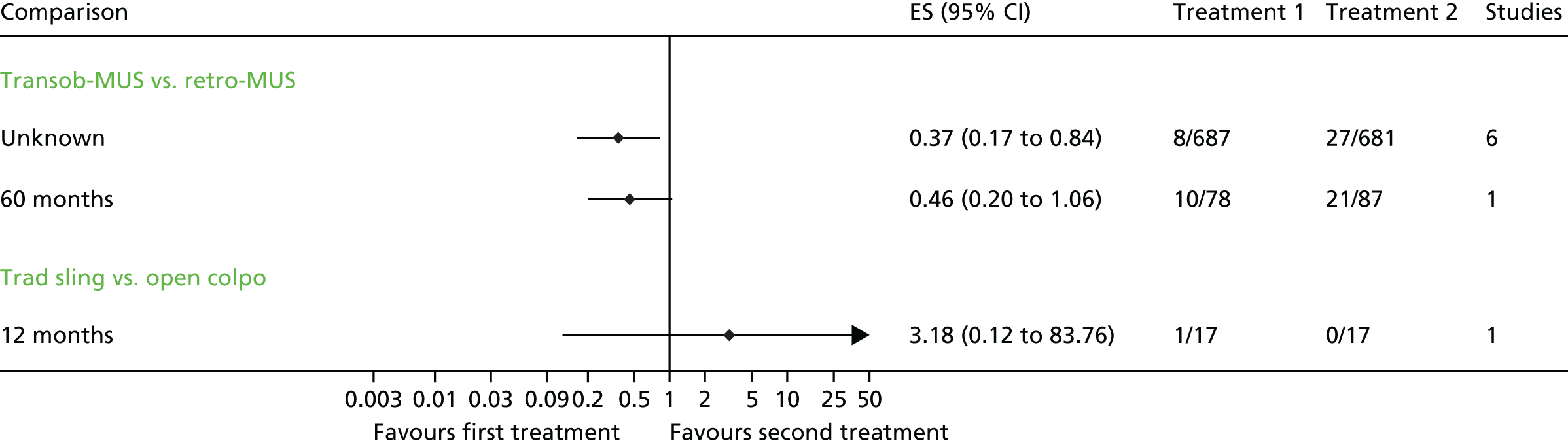

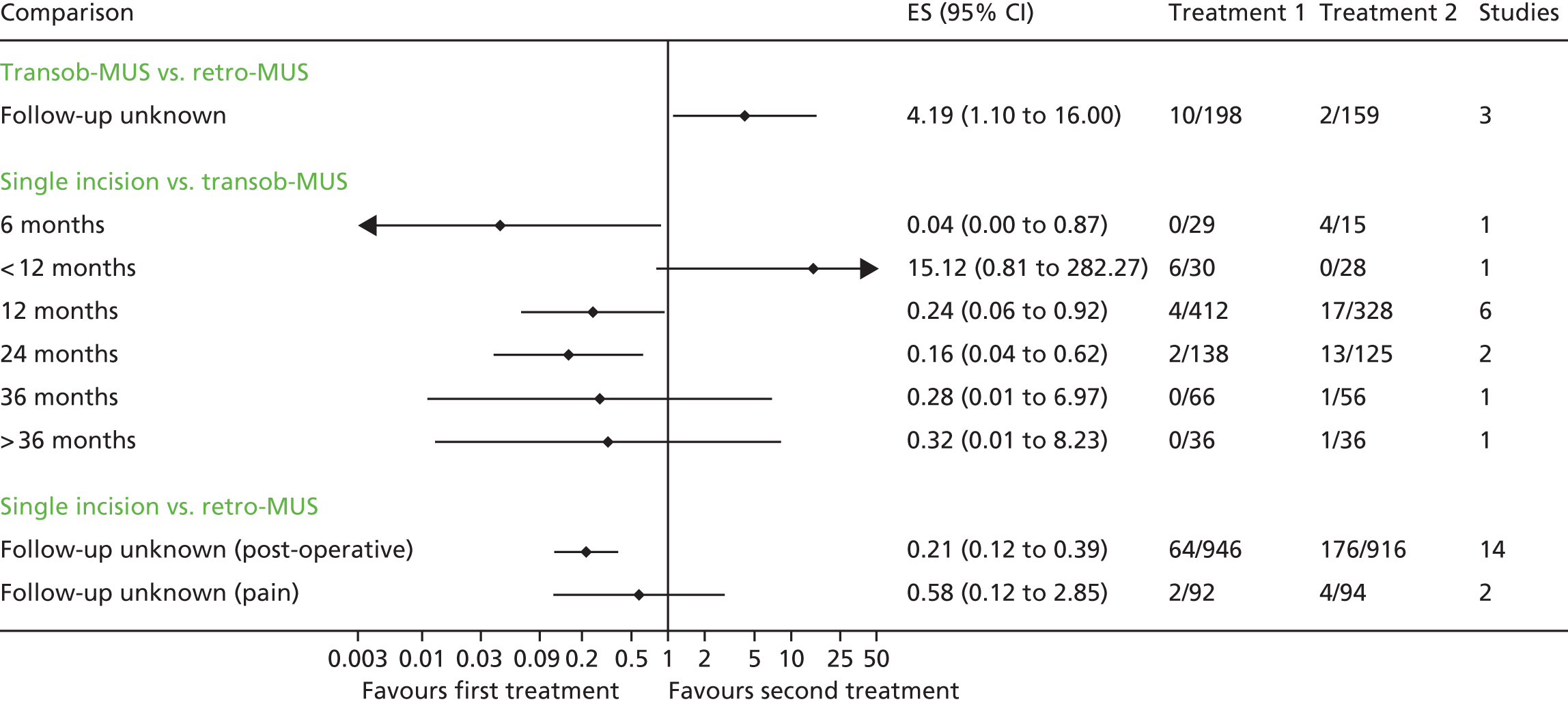

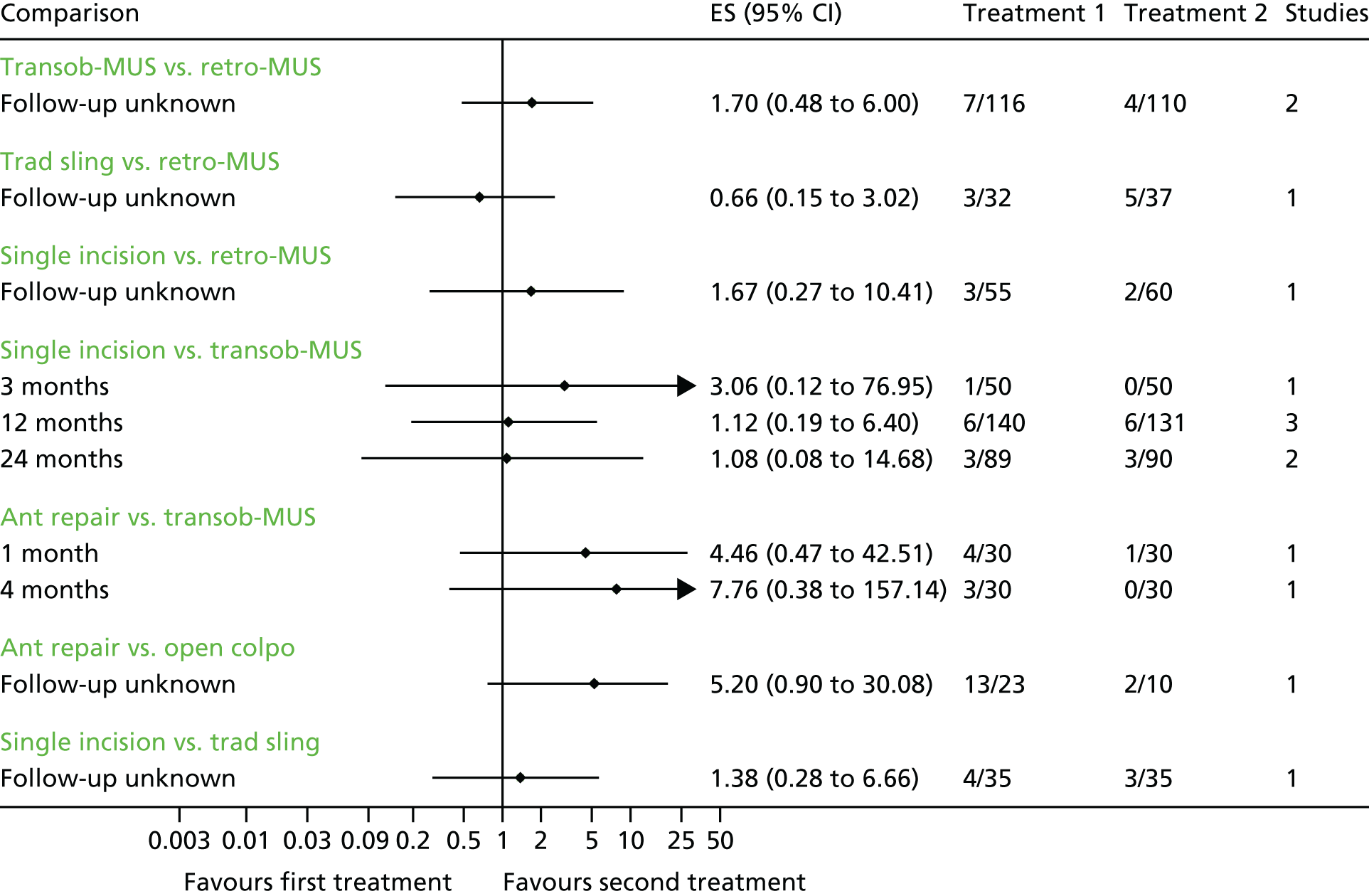

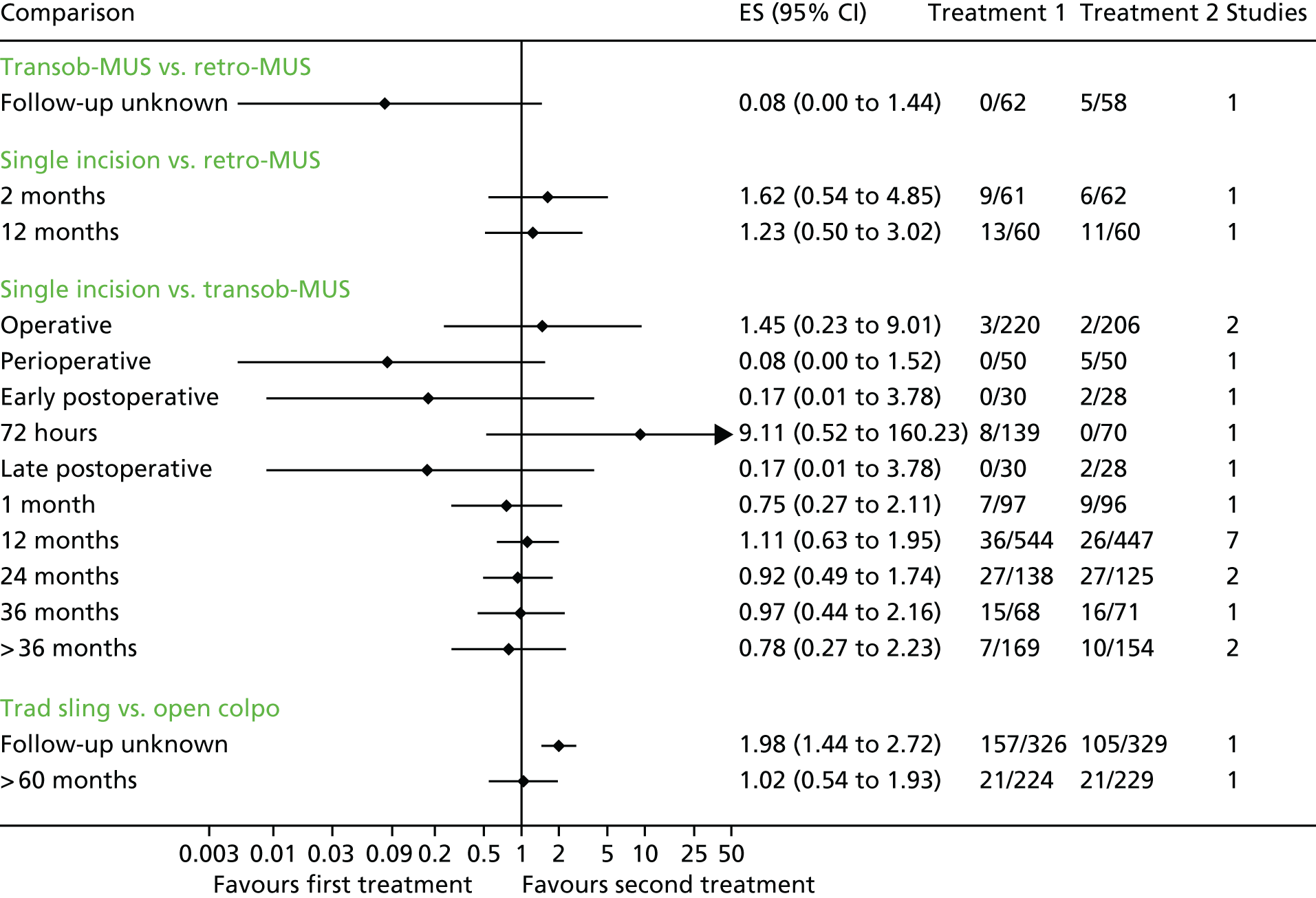

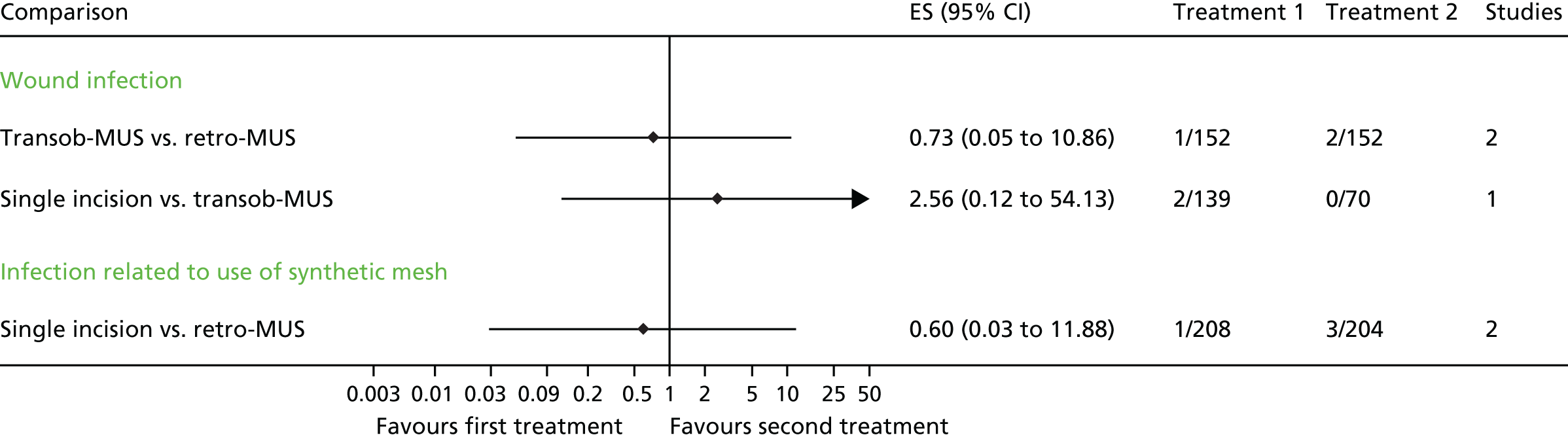

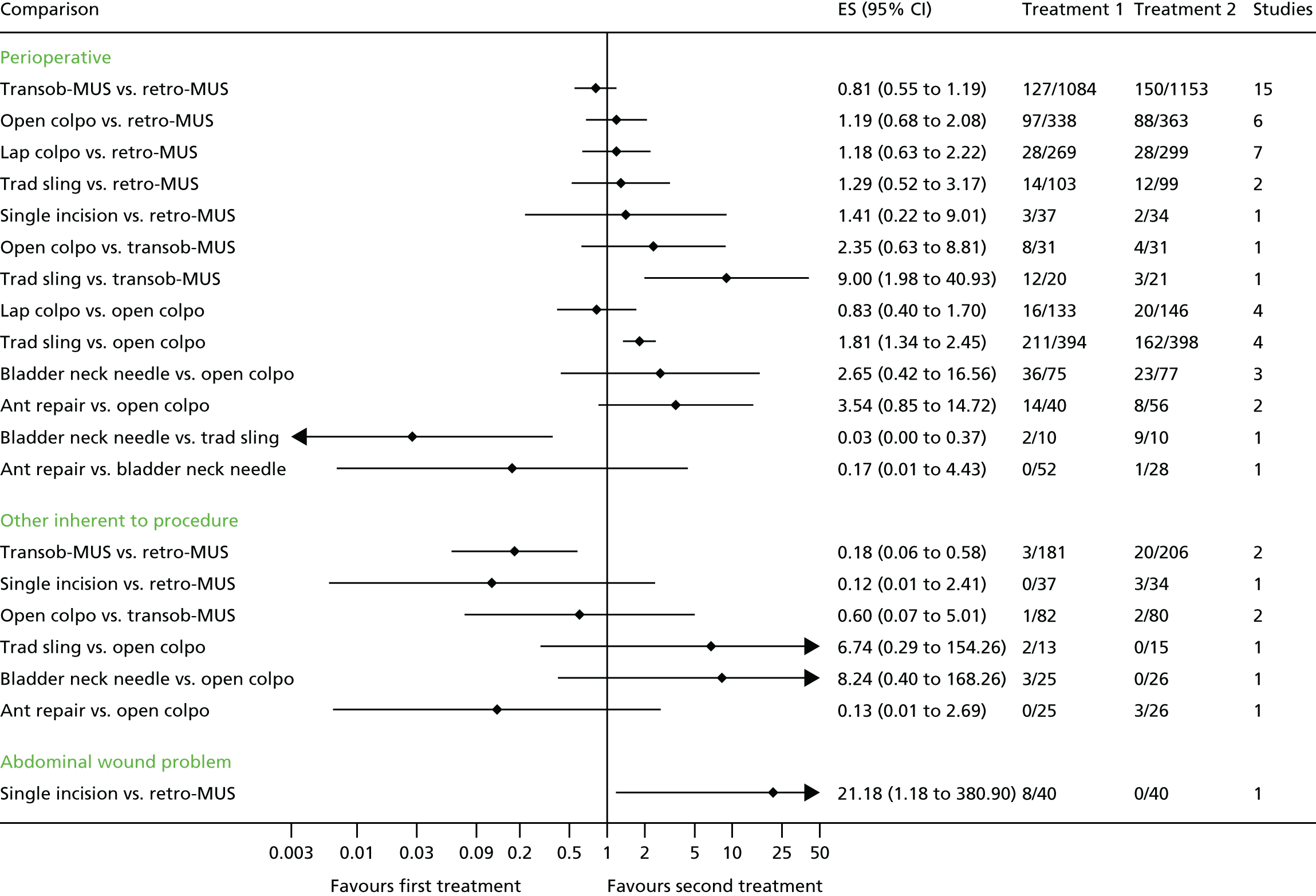

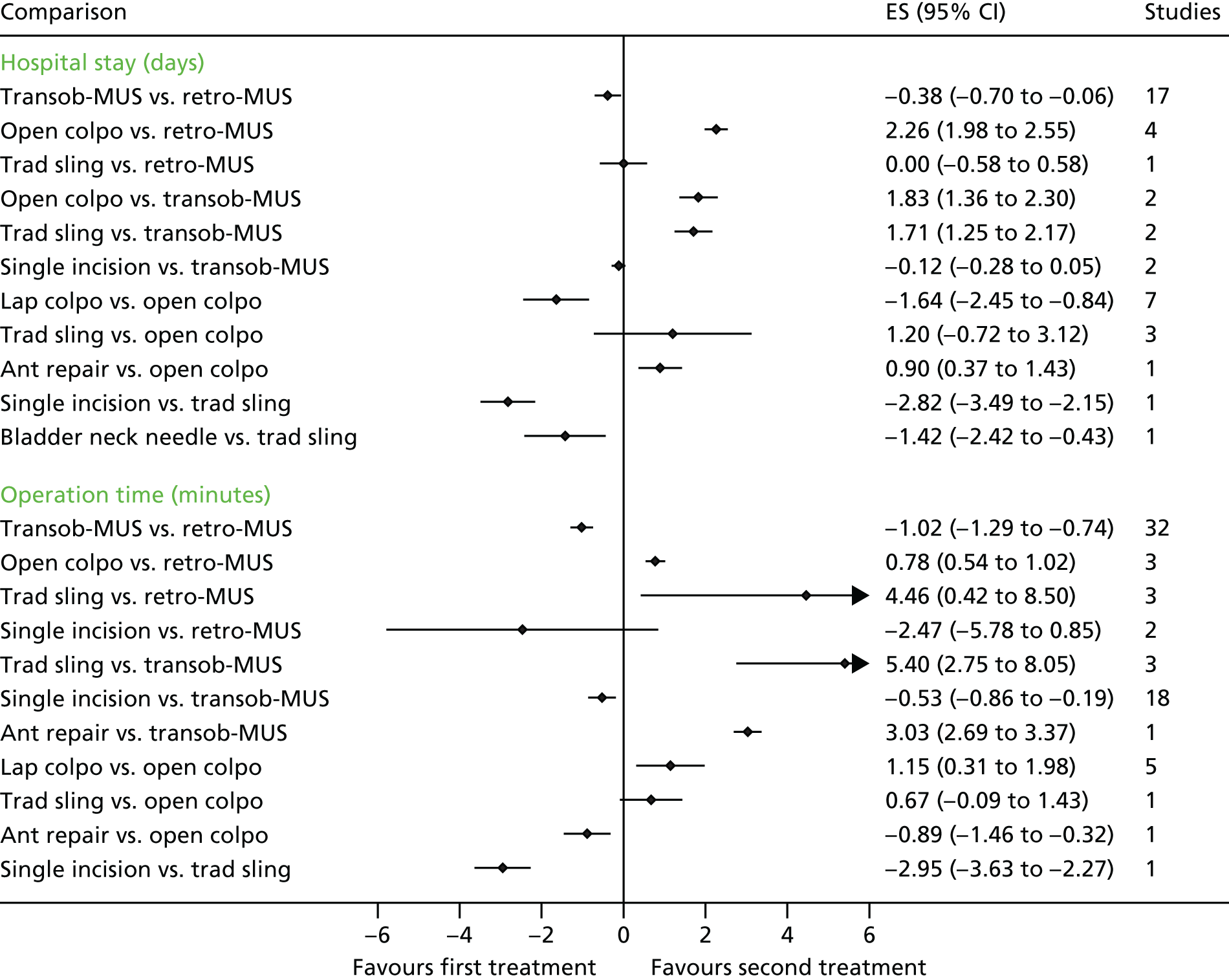

Adverse events: direct pairwise comparisons

The adverse event results are shown in Appendix 15. Full meta-analyses results for all included studies are available in Report Supplementary Material 1.