Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/26/01. The contractual start date was in October 2014. The draft report began editorial review in October 2019 and was accepted for publication in June 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. This report has been published following a shortened production process and, therefore, did not undergo the usual number of proof stages and opportunities for correction. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Brealey et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Frozen shoulder

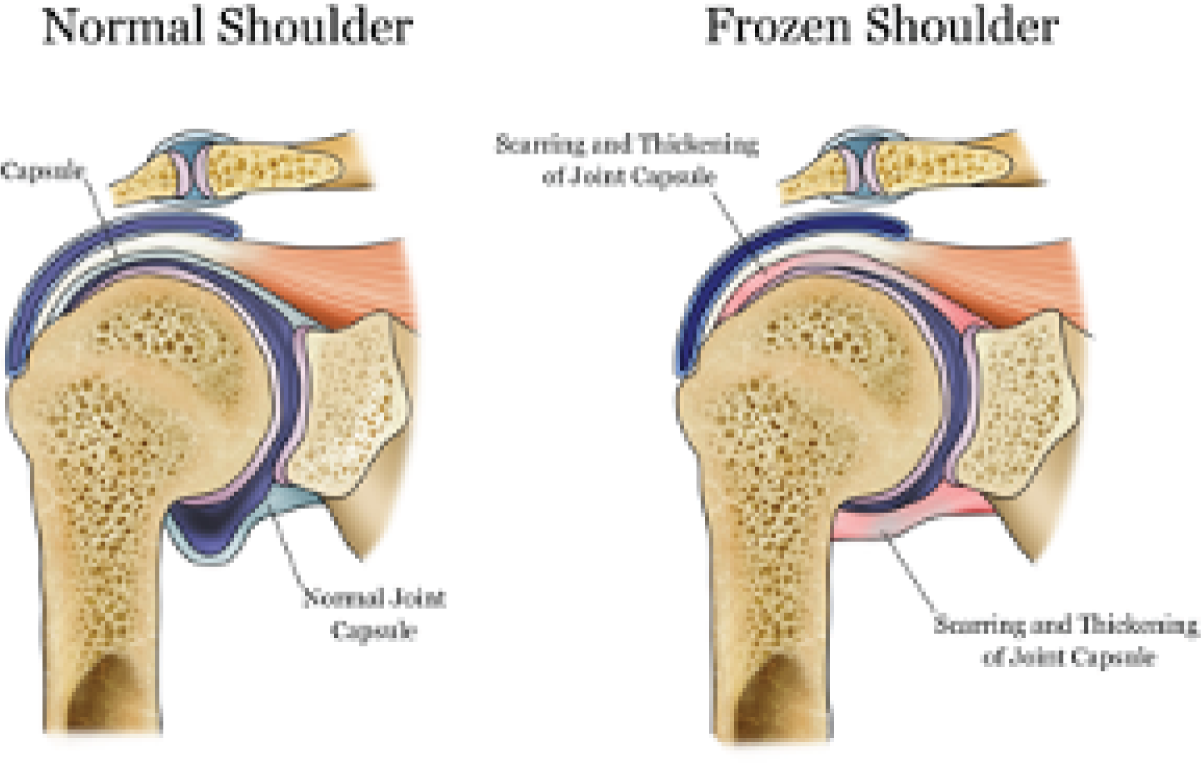

Frozen shoulder (also known as adhesive capsulitis) occurs when the capsule, or soft tissue envelope, around the ball-and-socket shoulder joint becomes inflamed and then scarred and contracted. This makes the shoulder very painful, tight and stiff. It starts with pain, which increases in intensity as stiffness develops. 1 The exact cause of this condition is unknown. Reported associations include diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, trauma, stroke, neurosurgery and thyroid disease. 1 In the absence of a known association, the condition is labelled by clinicians as ‘idiopathic’ or ‘primary’ frozen shoulder. The pathology of the capsule involves chronic inflammation, and proliferative fibrosis has been reported. 2 Myofibroblasts contribute to matrix deposition and fibrosis, with the underlying pathology considered similar to Dupuytren’s contracture. 2,3 The macroscopic appearance of these changes can be seen in the shoulder during arthroscopic visualisation of the rotator interval capsule. People with this condition may struggle with basic daily activities, suffer serious anxiety and have sleep disturbance due to shoulder pain. There is a tendency for spontaneous resolution, but recovery may be slow or incomplete. Even after an average of ≥ 4 years from onset, around 40% of patients can have mild to severe symptoms. 4 Figure 1 illustrates the pathology of frozen shoulder.

FIGURE 1.

Diagram showing site of pathology of frozen shoulder. This figure has been re-used from www.local-physio.co.uk/articles/shoulder-pain/frozen-shoulder/ with permission from the copyright holders.

Three clinical phases have historically been recognised for this condition,5 where the duration of each phase is indicative but varies considerably between patients:

-

painful phase, which may last 3–9 months

-

adhesive phase, with stiffness lasting for 4–6 months

-

phase of resolution or ‘thawing’, lasting for 5–24 months.

These phases have considerable overlap, and therefore the current favoured terminology is ‘pain predominant’ and ‘stiffness predominant’ phases. 6

The cumulative incidence of frozen shoulder is estimated at 2.4 per 1000 population per year, based on a Dutch general practice sample. 7 Frozen shoulder most commonly affects individuals in their sixth decade of life, and a large primary care-based study in the UK found that frozen shoulder affects 8.2% of men and 10.1% of women of working age. 8 By contrast, an incidence of 1% was reported by a UK shoulder surgeon in his specialist hospital practice. 9 This discrepancy in estimated incidence can be explained by the use of different populations as the denominators in the different studies. 6 Although not clearly established, when associated with diabetes mellitus, frozen shoulder is considered to be more resistant to treatment. 10

Diagnosis of frozen shoulder

A diagnosis of frozen shoulder is based on clinical criteria that include history of insidious onset deep-seated pain in the shoulder and upper arm with increasing stiffness, as well as clinical findings of limited active and passive external rotation in the absence of crepitus. 11 Radiographs are reported as not routinely required,6 but are usually performed in secondary care to exclude pathology like glenohumeral arthritis or posterior glenohumeral dislocation that could manifest with similar clinical signs. There is no reference standard for comparison, which explains the lack of diagnostic test accuracy data. 11 The key examination findings were originally described by Codman as restriction of elevation and external rotation. 12 As visual estimation of external rotation has fair to good reliability,13 restrictions (typically with pain) in both passive and active external rotation have been used as diagnostic criteria in clinical studies. 11,14–17 It can be difficult, however, to correctly diagnose the problem, as highlighted in a qualitative study of patients’ perceptions and priorities when living with primary frozen shoulder. 18 This accords with other studies, which have found that general practitioners (GPs) in the UK and the USA lack confidence in making shoulder diagnoses. 19,20

Treatments for frozen shoulder

The aims of treating a patient with frozen shoulder are to provide advice, education and reassurance; achieve pain relief; improve shoulder mobility; reduce the duration of symptoms; and facilitate return to normal activities. 21 Generally, less invasive treatments are provided in a primary care setting in the UK to those in the earlier phases of the disease, particularly for controlling pain. These may include oral analgesia, physiotherapy, acupuncture, and glucocorticoid (steroid) injection. 21 The treatments utilised in secondary care, when stiffness has become more established, were confirmed in a UK survey of health professionals conducted in 2009 as physiotherapy, manipulation under anaesthesia (MUA) and arthroscopic capsular release (ACR). 22

Physiotherapy treatment includes combinations of advice, exercises, therapist-applied mobilisation techniques, and thermo- and electrotherapies. The modalities of treatment recommended for use are described in the UK national physiotherapy guidelines for frozen shoulder,6 which are based on a systematic review. These are provided either in isolation or as a supplement to other interventions, such as intra-articular corticosteroid injection or surgical interventions (MUA or ACR). Intra-articular corticosteroid injection helps reduce inflammation of the joint capsule and reduce pain, which may facilitate the performance of exercises and hence enhance the effects of physiotherapy. Intra-articular corticosteroid injection has been shown to provide short-term benefits, with better improvements in pain, function and range of movement (up to 6–7 weeks for all three improvements) than placebo13 and probably than isolated manual therapy and exercise. 6

Manipulation under anaesthesia is a procedure the surgeon undertakes when the patient is under general anaesthesia. The affected shoulder joint is manipulated in a controlled fashion to stretch and tear the tight shoulder capsule. The joint is often injected with corticosteroid as part of this procedure. MUA is thought to facilitate recovery by releasing the tightness in the capsule, with the injection helping control capsular inflammation and pain. This is followed by physiotherapy for mobilisation of the arm and shoulder to restore mobility and function.

Arthroscopic capsular release is a ‘keyhole’ surgical procedure performed under general anaesthesia. The keyholes are used to view the joint and divide (release) the contracted capsule using typically arthroscopic radiofrequency ablation. This is thought to allow more accurate and controlled release of the tight capsule. The procedure is completed by performing MUA to complete and confirm full release of the contracted capsule. ACR is also followed by physiotherapy of the arm and shoulder to restore mobility and function.

Rationale for the UK FROzen Shoulder Trial

It is unknown whether a combination of physiotherapy and steroid injection or either of the surgical interventions (MUA or ACR) followed by physiotherapy is more effective. 13 Similarly, there is uncertainty about the benefits of MUA compared with other treatment options,23,24 and only limited evidence on ACR is available from randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 13,25

Systematic reviews have identified large gaps in the evidence base and uncertainty about the effectiveness of treatments for frozen shoulder and, therefore, a need for high-quality primary research. 26 In a systematic review13 commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, 28 RCTs, one quasi-experimental study and two case series were included. The review found insufficient studies with a similar intervention and comparator to quantify effectiveness. Most studies were rated as having a high risk of bias, did not report adequate methods of randomisation, allocation concealment and outcome assessment, and seemed to be inadequately powered. Few studies reported collecting data on harms.

In view of the paucity of high-quality evidence to guide current practice, considerable uncertainties remain about the management of frozen shoulder. With the intention of facilitating quicker recovery, more invasive surgical interventions (MUA and ACR) are being used in spite of the lack of good evidence. 13 There is a clear need for a well-designed, high-quality RCT to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of commonly used interventions for the treatment of frozen shoulder.

The findings of a national survey22 of health-care professionals in the UK, conducted in 2009, were used to determine the most commonly used interventions that need to be tested in a RCT in a secondary care setting. Physiotherapy, MUA and ACR were those that health-care professionals recommended be compared in a RCT. Only 6% of respondents at the time suggested using hydrodilatation as a comparator in a trial, which did not make this a feasible intervention to test in a RCT. This survey informed our decision to compare early structured physiotherapy (ESP) combined with intra-articular steroid injection with the two most frequently used, invasive and costly surgical interventions, namely MUA and ACR. 22 It is important to emphasise that, although physiotherapy is a common treatment in NHS practice, the ESP intervention was a specifically designed and standardised physiotherapy pathway to test the optimal delivery of physiotherapy in the NHS. As evidence about patients’ experiences of frozen shoulder is also limited,18 participants were interviewed about their experience and the acceptability of treatment, as were health professionals (physiotherapists and surgeons).

Aim and objectives

The strategic aim of UK FROST (UK FROzen Shoulder Trial), underpinned by the key treatment uncertainties, was to provide evidence of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of three common interventions currently provided in the UK NHS for the treatment of frozen shoulder in a hospital setting. The following objectives were defined to achieve this overarching aim:

-

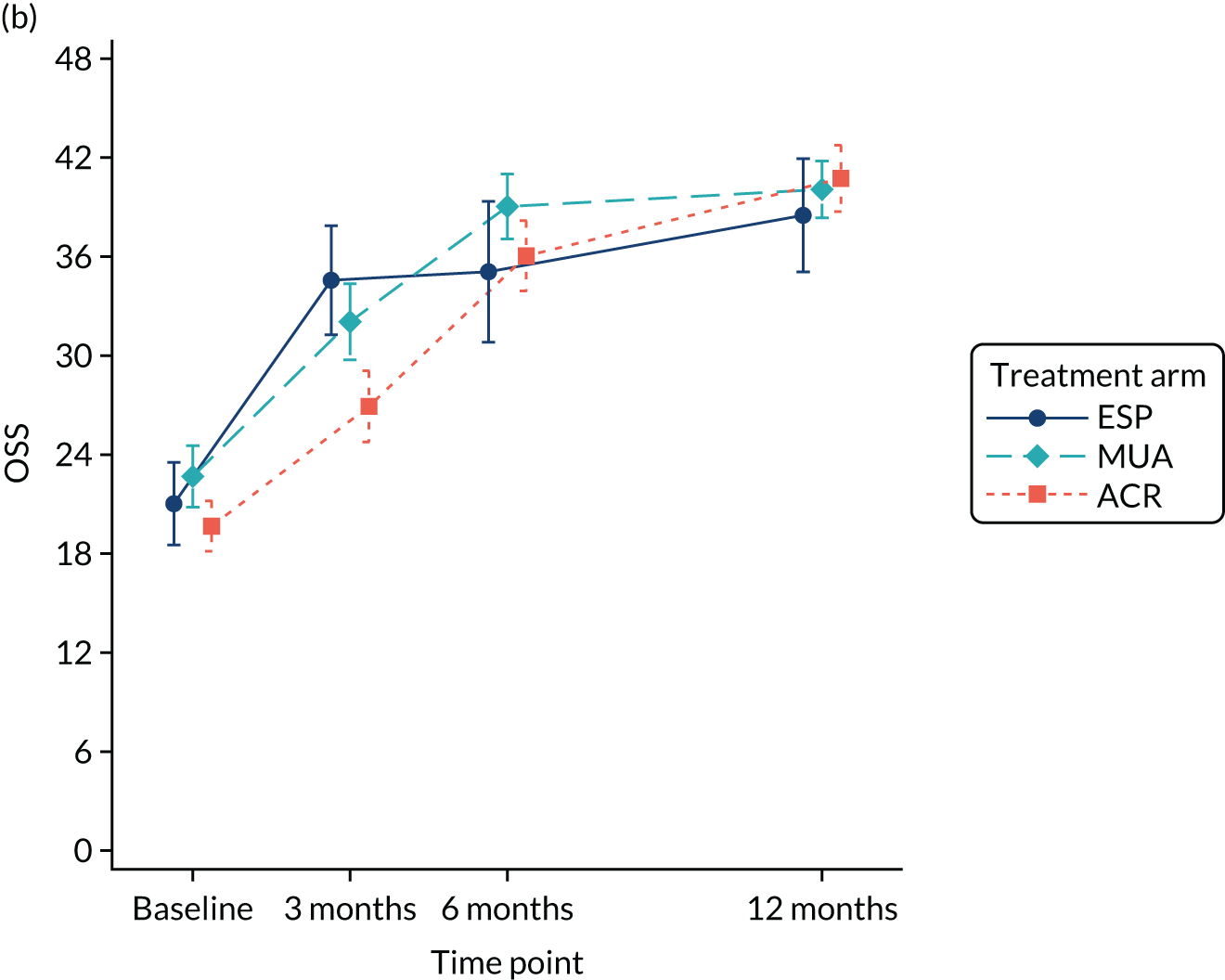

The primary objective was to determine the effectiveness of ESP compared with MUA compared with ACR for patients referred to secondary care for the treatment of frozen shoulder. This was achieved using a parallel-group RCT, with the Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) (a patient-reported outcome measure) as the primary outcome at 3, 6 and 12 months. The primary time point was 12 months after randomisation.

-

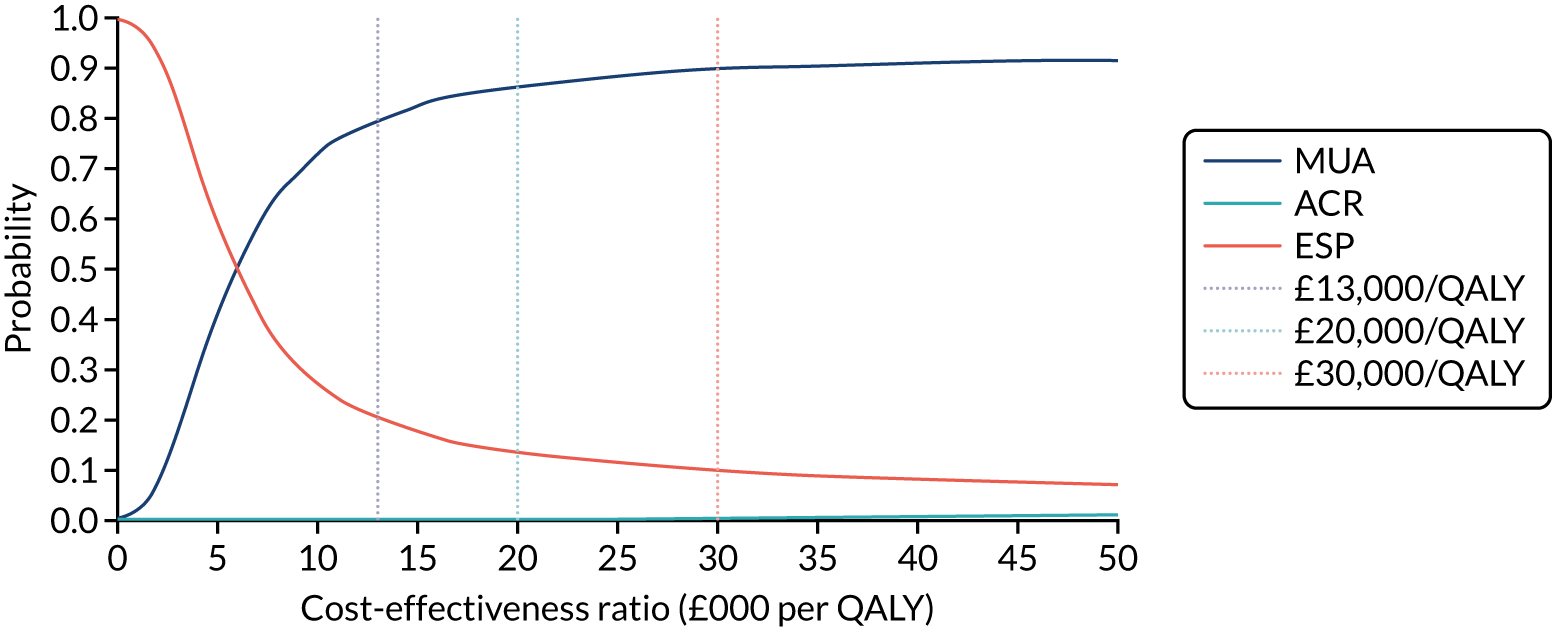

To compare the cost-effectiveness of the three interventions, to identify the most efficient provision of future care, and to describe the resource impact that the various interventions for frozen shoulder would have on the NHS.

-

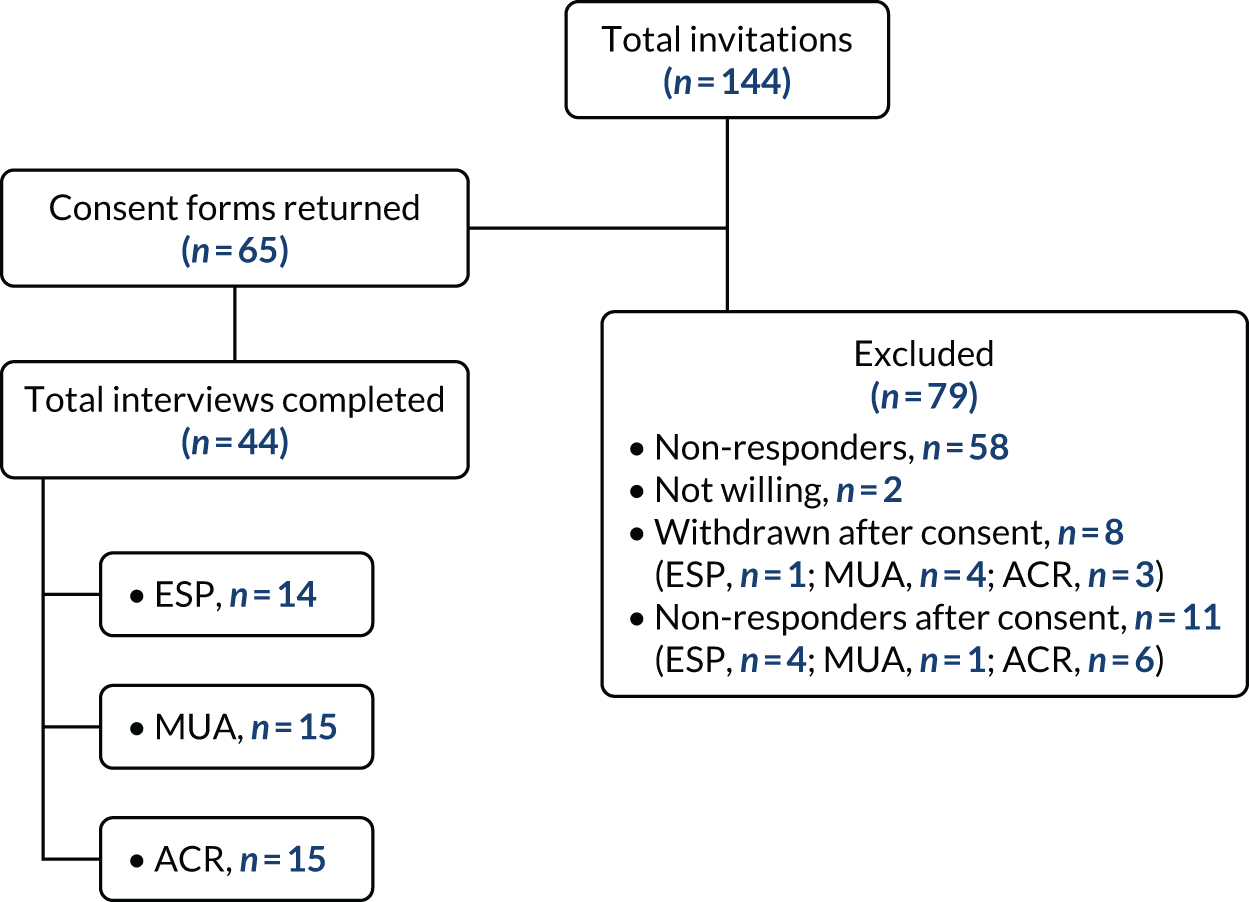

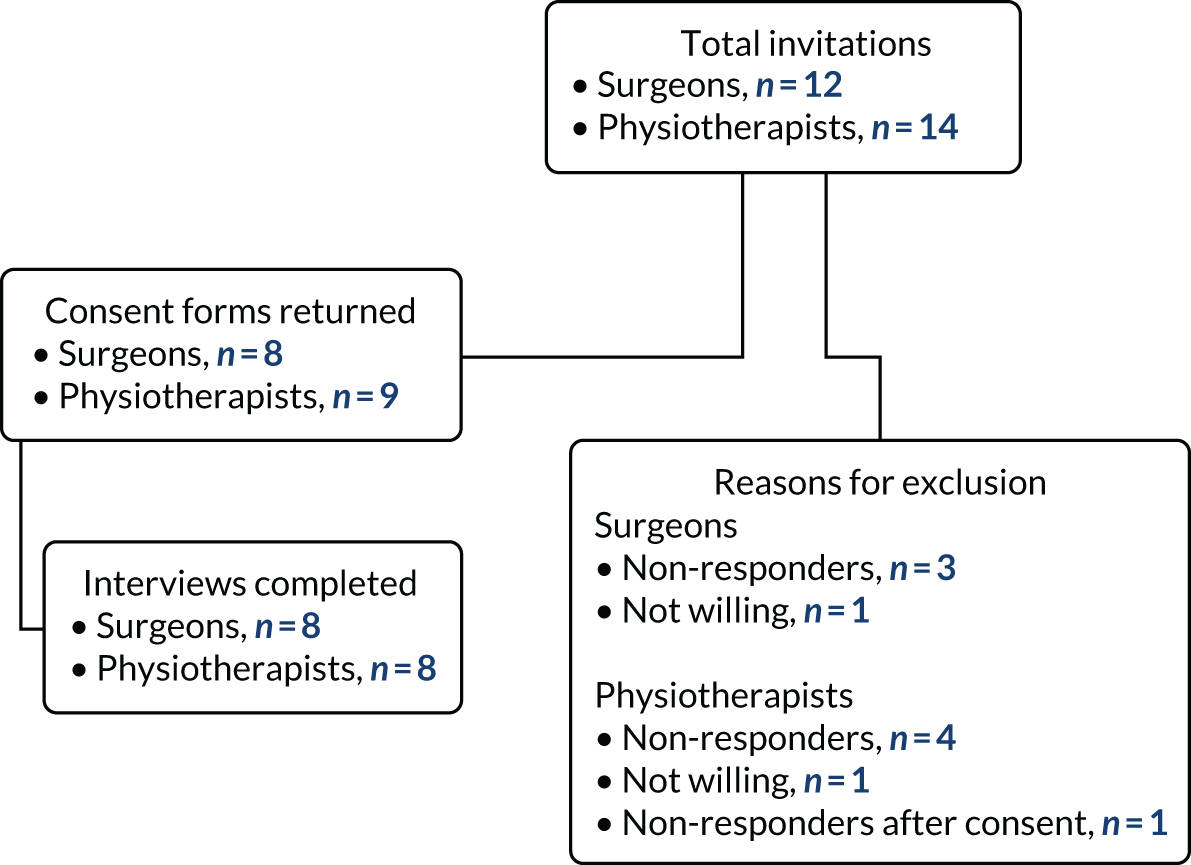

To qualitatively explore the acceptability of different interventions for frozen shoulder to patients and health-care professionals and to provide important patient-centred insight to further guide clinical decision-making.

-

To update the HTA programme-funded systematic review examining the management of frozen shoulder by assessing current RCT evidence for the effectiveness of interventions used in secondary care. This would allow the trial findings to be considered in the context of the existing evidence for the interventions under evaluation.

-

To widely disseminate the findings of this study to all stakeholders through networks of health-care professionals, patients, health service managers and commissioning groups. This would be in addition to publishing the results of the study in key journals and publishing the National Institute for Health Research HTA report.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

This chapter describes the trial design and methods used to address the objectives about the clinical effectiveness of the health-care interventions being compared. The methods of the health economic evaluation and the nested qualitative study are described in the corresponding chapters. The trial protocol has been published. 27

Trial design

This was a pragmatic, multicentre, stratified (diabetes present or not) superiority trial comparing three parallel groups (MUA vs. ACR vs. ESP, with unequal allocation of 2 : 2 : 1) in adult patients referred to secondary care in England, Wales and Scotland for the treatment of primary frozen shoulder, and for whom surgery was being considered.

Participants

Patients with primary frozen shoulder were identified through clinical examination and plain radiographs. 28 To minimise diagnostic uncertainty, clinical examination included the key diagnostic assessment of restriction of passive external rotation in the affected shoulder,29 for which there is evidence of good inter-rater agreement on whether or not restriction is present30 and a high threshold (50% restriction of movement) for inclusion. Plain radiographs (anteroposterior and axillary projections) were obtained routinely for all patients to see whether or not these were normal and could allow the exclusion of glenohumeral arthritis and other pathology that could lead to similar clinical presentation (e.g. locked posterior dislocation).

Inclusion criteria

Patients, including those with diabetes, were eligible if:

-

they were aged ≥ 18 years

-

they presented with a clinical diagnosis of frozen shoulder characterised by restriction of passive external rotation in the affected shoulder to < 50% of that of the contralateral shoulder

-

they had radiographs that excluded other pathologies.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if:

-

they had a bilateral concurrent frozen shoulder

-

their frozen shoulder was secondary to trauma that necessitated hospital care (e.g. fracture, dislocation, rotator cuff tear)

-

their frozen shoulder was secondary to other causes (e.g. recent breast surgery, radiotherapy)

-

any of the trial treatments (e.g. unfit for anaesthesia or corticosteroid injection) were contraindicated

-

they were not resident in a catchment area of a trial site

-

they lacked the mental capacity to understand the trial.

Setting

The trial recruited from the orthopaedic departments of 35 NHS hospitals in the UK across a range of urban and rural areas. This comprised 28 hospitals in England, six in Scotland and one in Wales. Two additional hospitals in England screened for patients but did not recruit into the trial. Recruitment started in April 2015 and the final follow-up was in December 2018. All 37 participating hospitals are listed in Appendix 1.

Interventions

The components and standardisation of the surgical trial interventions were informed by a survey of 53 surgeons, who were the principal investigators of two multicentre shoulder surgical RCTs. 31,32 The standalone physiotherapy and post-procedural physiotherapy programmes were developed using evidence from a systematic review,13 UK guidelines,6 previous surveys of UK physiotherapists33,34 and consensus of expert shoulder physiotherapists in secondary care derived from a Delphi survey specific to UK FROST. 18 Ethics approval for the last of these was obtained from the School of Health and Social Care Research Governance and Ethics Committee of Teesside University on 23 May 2014 (Research Ethics Committee reference 069/14). The physiotherapy programmes developed are available online. 35 It is important to emphasise that, although physiotherapy is a common treatment in NHS practice, the ESP intervention was a specifically designed, standardised, new physiotherapy pathway to test the optimal delivery of physiotherapy in the NHS based on the best available evidence and expert consensus.

Participants assigned to either of the two surgical procedures were placed on the surgical waiting list and underwent routine preoperative screening. In keeping with NHS waiting time targets, both surgical procedures were expected to be performed within 18 weeks of randomisation. Participants would undergo these procedures under general anaesthetic and were expected to be admitted as day cases.

Physiotherapy was delivered by qualified physiotherapists (i.e. not students or assistants), and participating surgeons were familiar with the surgical procedure(s). There was no minimum number of surgical procedures that the surgeon had to have performed, and no grades of surgeon were excluded. Which surgeon operated on participants and whether or not the individual surgeon needed to be supervised by a consultant was at the discretion of the participating site, and followed normal care pathways and practices. The experience of physiotherapists and surgeons delivering the trial treatments was quantified and recorded in terms of their salary bands and the number of frozen shoulder patients they treated in a typical month.

Manipulation under anaesthesia with an intra-articular steroid

The affected shoulder was manipulated to stretch and tear the tight capsule and to improve range of movement. Intra-articular injection of corticosteroid to the glenohumeral joint was to be administered while the participant was under the same anaesthetic, unless the injection was contraindicated at the time of surgery. Postoperative analgesia, including nerve blocks, was provided as per usual care in the treating hospital. The details of MUA were collected prospectively using the MUA surgery form (see Report Supplementary Material 1). In the unlikely event that the MUA was judged to be incomplete, it was recommended that the surgeon should not cross over intraoperatively to capsular release. The need for this was to be reviewed at another clinic appointment to allow the outcome of the MUA to be assessed and the need for any further intervention to be decided. Details of any further intervention were collected prospectively.

Arthroscopic capsular release with manipulation under anaesthesia

Arthroscopic release of the contracted rotator interval and anterior capsule was performed, followed by MUA to complete the release of the inferior capsule. Additional procedures such as posterior capsular release or subacromial decompression were permitted at the operating surgeon’s discretion. Steroid injections, which slightly increase the risk of infection and morbidity, were permitted at the surgeon’s discretion. 36 Postoperative analgesia, including nerve blocks, was provided as per usual care in the treating hospital. The details of ACR were collected prospectively using the ACR surgery form (see Report Supplementary Material 2).

Nested shoulder capsular tissue and blood samples study

At six selected hospitals, 16 participants allocated to ACR who had not had a steroid injection within 6 weeks from the day of surgery were included in an exploratory nested capsular tissue and blood study. This was undertaken between January 2017 and December 2017 and had the following objectives:

-

to determine molecular and cellular abnormalities in tissue obtained during surgery from patients with frozen shoulder

-

to determine serum protein and cytokine signatures in patients with frozen shoulder

-

to correlate any tissue and serum abnormalities detected with clinical presentation and response to treatment.

When the date of surgery was known, the research nurse posted a letter about the nested study, a patient information leaflet and a consent form. Written informed consent was obtained at the participant’s pre-surgery assessment. A tissue sample of capsule from the rotator interval, which is routinely incised or removed as part of ACR, and a venous blood sample were obtained for analysis. All samples were fresh frozen, stored on dry ice and transported securely by courier to the Oxford Musculoskeletal Biobank at the University of Oxford, and housed at the Botnar Research Centre for formal analysis. The biopsy material was small (2 mm by 2 mm) and obtained with the use of arthroscopic graspers, and biopsy was not expected to have any significant effect on patient outcomes. The results of this study have been published. 37

Early structured physiotherapy

Participants received up to 12 sessions of structured physiotherapy, comprising essential ‘focused physiotherapy’ and optional supplementary physiotherapy, over a period of up to 12 weeks. The focused physiotherapy package included an information leaflet (see Report Supplementary Material 3) providing education and advice on pain management and function; an intra-articular steroid injection; and hands-on mobilisation techniques, increasingly stretching into the stiff part of the range of movement as the condition improved. 38,39 Participants received supervised exercises and were provided with instructions for a graduated home exercise programme (see Report Supplementary Material 4), progressing from gentle pendular exercises to firm stretching exercises according to stage, as is accepted good practice. All participants randomised to ESP underwent all elements of the focused physiotherapy package unless there was a specific clinical reason for them not to do so (e.g. a steroid injection might be withheld from a participant with currently uncontrolled diabetes, or from a participant with a stiff but painless and non-irritable shoulder).

Supplementary physiotherapy comprised those interventions that were non-essential but permissible additions, allowing physiotherapists some flexibility. These interventions, which may have been omitted from the national guidelines because they were outside their scope (e.g. acupuncture) and/or because there was a lack of evidence of their effectiveness in the primary academic literature (e.g. hydrotherapy, soft-tissue release techniques), were explored using a Delphi process.

Participants who did not improve with ESP were referred for further treatment in consultation with the treating clinician following a 12-week assessment. When further treatment after ESP involved surgical intervention, participants were placed on the normal surgical waiting list. Any further treatment provided was recorded. Participants allocated to ESP were offered reimbursement of their travel expenses. The ESP given during each session (e.g. injection, advice and education, gentle active exercise) was recorded in the structured physiotherapy log book (see Report Supplementary Material 5).

Post-procedural physiotherapy

Following MUA or ACR, participants underwent up to 12 weeks of physiotherapy, normally commencing within 24 hours of the procedure. The aim was to reduce pain and aid with regaining/maintaining the mobility achieved by the operation. The post-procedural physiotherapy (PPP) differed from ESP to suit its very different context. As the research literature was uninformative, two essential ‘focused physiotherapy’ interventions were prespecified, based on established good practice. These were:

-

an information leaflet giving education and advice on pain management and function

-

instructions for a graduated home exercise programme.

All participants randomised to MUA or ACR were to undergo all elements of this focused physiotherapy package unless there was a specific clinical reason for them not to do so. The Delphi survey, which was interpreted as had been done for ESP, provided optional, supplementary interventions. A steroid injection was to be avoided where possible during PPP. The PPP log book (see Report Supplementary Material 6) was used to record the PPP given during each session.

Steroid injections

Steroid injections were administered with or without imaging guidance, depending on the usual practice of the hospital site. Current evidence does not support the superiority of either approach. 40

Modifications to interventions

There were no explicit criteria for modifying, discontinuing or crossing over from the assigned trial treatment. The clinician and participant discussed whether or not to continue with the assigned treatment for reasons such as the patient having poorly controlled diabetes or no longer requiring the treatment.

Adherence to interventions

Adherence to the trial treatments was explained in the trial site manual and during site initiation visits. A requirement of the internal pilot was to check the feasibility of delivering the ESP programme. This was expanded to include the surgical interventions and PPP. Every month, a designated trial co-ordinator extracted data from the hospital case report forms (CRFs) and updated a spreadsheet to record information about aspects of the treatments. The spreadsheet was reviewed for treatment adherence by the chief investigator, a consultant orthopaedic surgeon and the lead physiotherapist, who decided whether or not any action was required at a site. This was further monitored by the Trial Management Group (TMG), the independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC).

Concomitant care

Analgesia for pain relief, general advice on care of the arm (e.g. axillary hygiene) and general advice to prevent further stiffness in the limb were all permitted at part of the management of a participant awaiting surgery. Specific home exercise programmes, such as that provided with the structured physiotherapy intervention, were not permitted. Steroid injections were avoided, as these were considered active interventions.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the OSS, a patient-reported measure of functional limitation following shoulder surgery. The development and validation of this measure included patients with frozen shoulder,41 and it has been used in the follow-up of these patients. 4 The OSS is a 12-item measure with five response categories and a range of scores from 0 (worst) to 48 (best). 42 It has been validated against the professionally endorsed Constant score43 and the SF-36 (Short Form questionnaire-36 items),44 and its responsiveness over a 6-month period following surgical intervention has been established. 45

Participants completed the OSS at baseline prior to randomisation. The questionnaire was then posted to the participants 3, 6 and 12 months after randomisation. The primary end point was 12 months after randomisation, allowing the interventions and co-treatment interventions to be delivered and the majority of complications to be treated. The OSS was also completed at the hospital at the start of treatment. This was either the day of the operation or, for participants allocated to ESP, the day when the steroid injection was given or at the first visit to physiotherapy, whichever was first. The OSS was then posted to participants for them to complete 6 months from when treatment started.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were collected at baseline and at 3, 6 and 12 months from randomisation, unless otherwise stated.

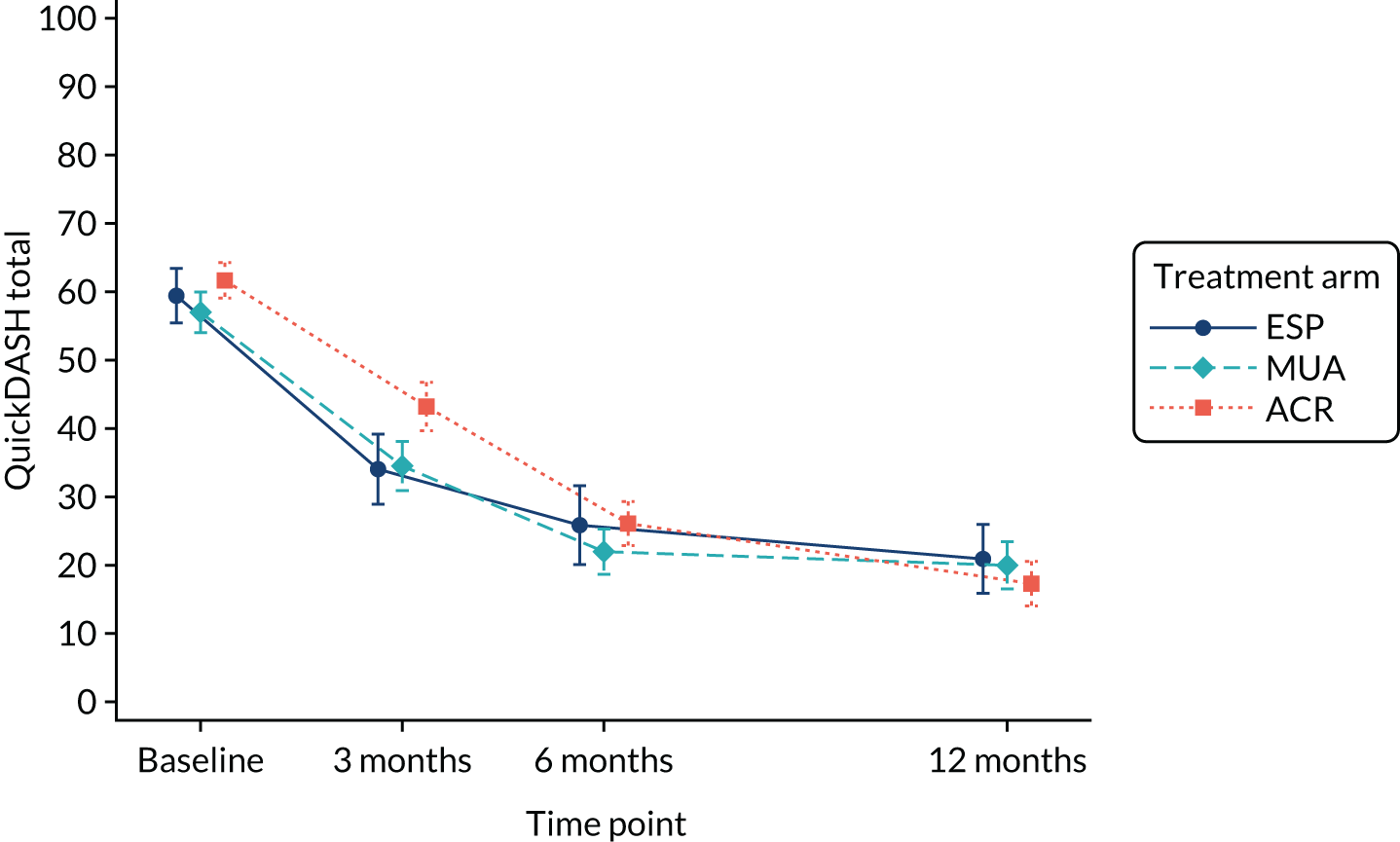

Quick Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand

The DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand) is a well-validated and reliable measure of symptoms and functional limitation in the upper extremity. 46 To minimise responder burden, the validated 11-item short version, the QuickDASH (Quick Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand), was used. 47 This is scored from 0 to 100, and an 8-unit improvement in scores has been defined as the minimum clinically important difference for patients with shoulder problems. 48 Its validity with and responsiveness to frozen shoulder has been established. 49

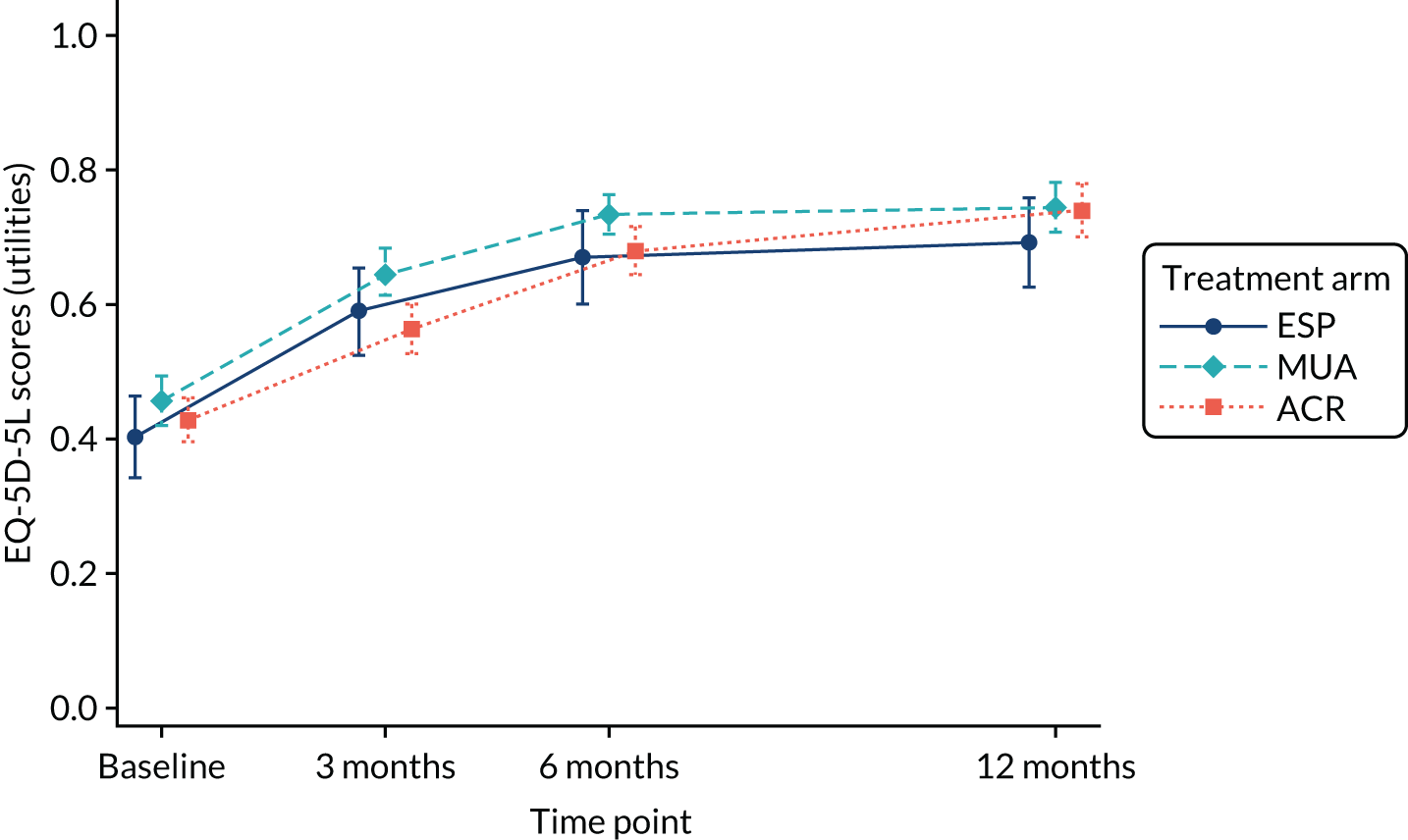

EuroQol-5 Dimension, five-level version

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) is a validated, generic and health economic, self-completed, patient-reported outcome measure covering five health domains with three response options. 50,51 The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), consists of the same five domains as the original EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), but with five levels rather than three to help overcome problems with ceiling effects and to improve sensitivity. 52,53 The EQ-5D-3L has been validated for use with a range of shoulder conditions. 54,55 The EQ-5D-5L provides a simple descriptive profile of health status that can be used to estimate quality-adjusted-life-year (QALY) scores in economic evaluations.

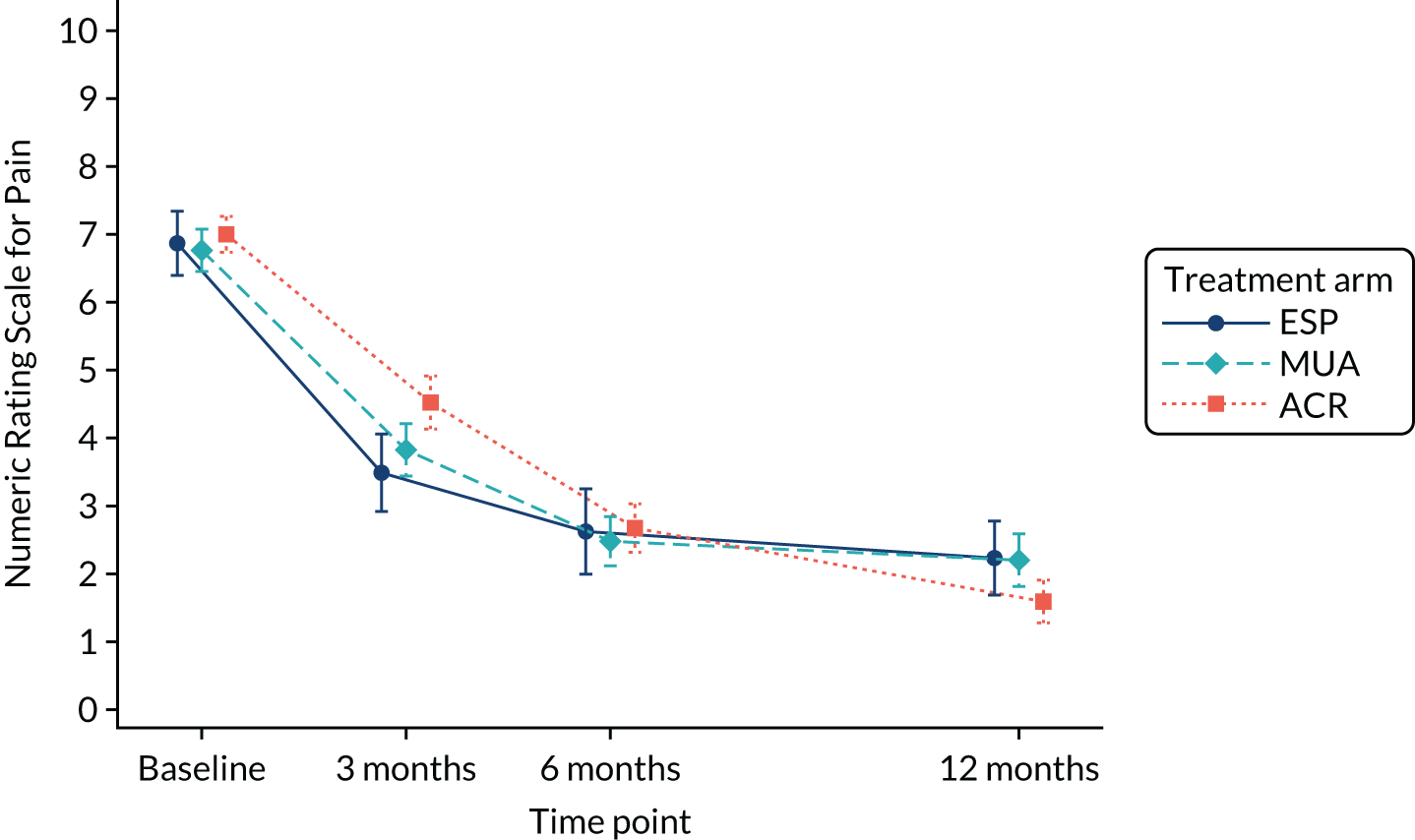

Pain

Shoulder pain ‘during the past 24 hours’ was measured using the Numerical Rating Scale for pain,56 a single 11-point numerical scale on which 0 represents ‘no pain’ and 10 represents ‘worst possible pain’. This measure is considered the most valid for use in this population. 57

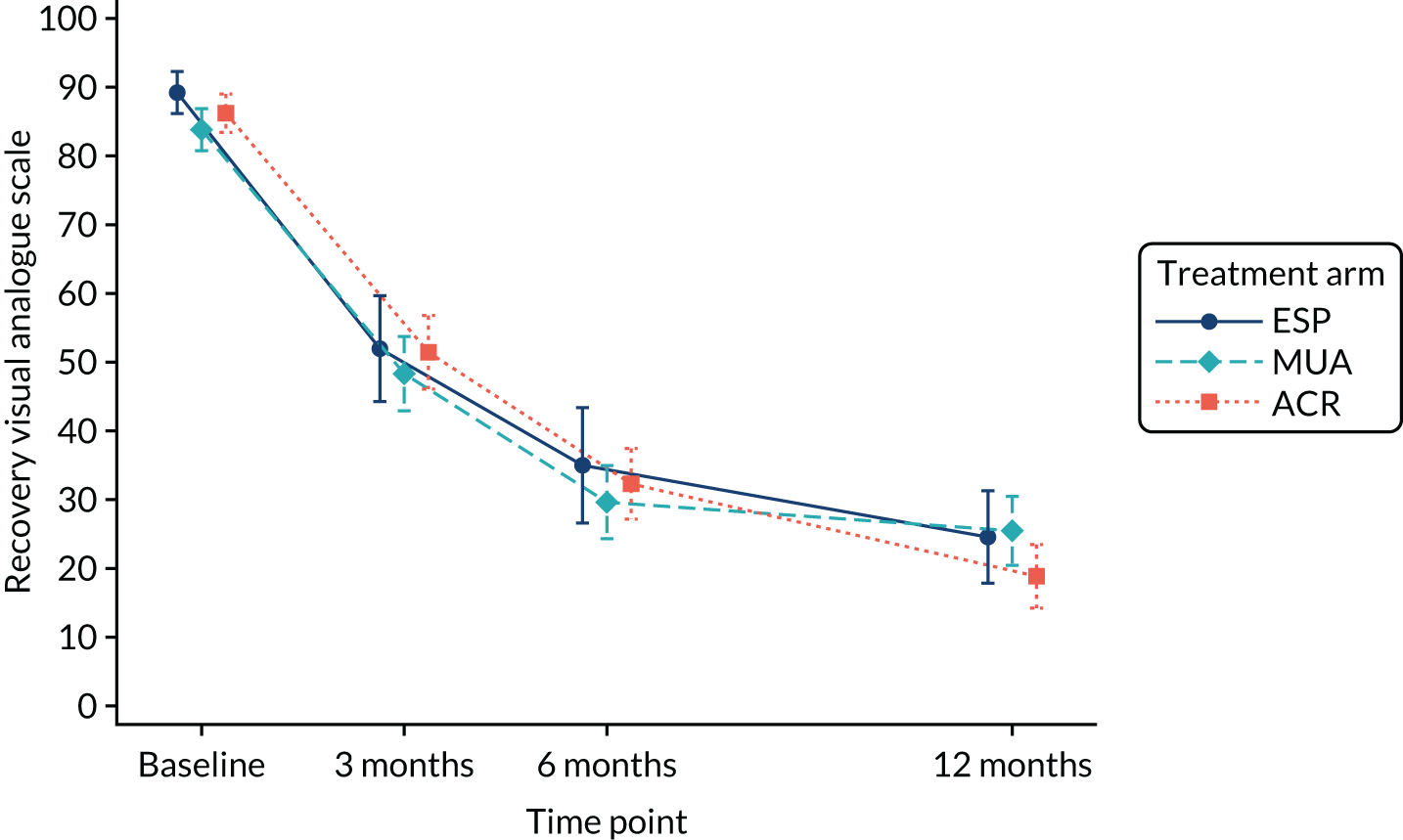

Extent of recovery

A simple subjective global question asked to what extent the participant’s frozen shoulder symptoms in the past 24 hours had affected their assessment of needing treatment. This informed the extent to which symptoms resolved over time. Responses were measured using a visual analogue scale with anchors from 0 to 100 (e.g. 0, no need to ask for treatment; 100, definitely ask for treatment).

Complications

At 12 months, sites recorded all expected and unexpected complications on the 52-week complication forms (see Report Supplementary Material 7). Infection was defined as for the ‘surgical site infection’ audit. 58 Delayed wound healing was defined as any wound that had not healed by 2 weeks post surgery. Complex regional pain syndrome was defined as pain, swelling and stiffness of the affected shoulder, and arm and/or hand restrictions limiting the full tuck of the fingers. In addition, nerve, blood vessel, tendon or bone injury and complications related to steroid injection, including steroid flare and septic arthritis, were recorded.

Adverse events

A non-serious adverse event (AE) was defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a trial participant related to the affected shoulder up to 12 months from randomisation. A serious adverse event (SAE) was defined as any untoward medical occurrence that resulted in death, threat to life, hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, persistent or significant disability or incapacity, a congenital abnormality or birth defect, or any other medical condition that may require medical or surgical intervention to prevent any of these from occurring.

Sample size

The primary trial outcome was the OSS, and this was assessed for three treatment comparisons: ESP with MUA, ESP with ACR, and MUA with ACR.

Data suggest that a 5-point improvement can be found on the OSS (standard effect size of 0.42) between surgically and non-surgically treated patients,59 with a stable standard deviation (SD) of 12 points across different populations. This larger effect size was required to justify the higher costs and potential risks associated with surgery when comparing ESP with MUA, and ESP with ACR. 42 A smaller difference of 4 points on the OSS (standard effect size of 0.33) was expected to distinguish between MUA and ACR.

To observe the above effect sizes with 90% power and 5% two-sided significance, adjusting for a moderate estimate (r = 0.4) of the correlation between OSS over 12 months and allowing for 20% attrition, a total sample size of 500 patients was required (MUA, n = 200; ACR, n = 200; ESP, n = 100). The sample size calculation was not adjusted for multiple comparisons owing to the a priori specified sequence of treatment comparisons and the analysis of the primary outcome in a single analysis model. 60

There were no planned interim analyses for the trial or stopping guidelines. An internal pilot from which data contributed to the final analyses was performed to confirm the feasibility of the trial, and this is explained in the following section.

Internal pilot study

There were two phases of the internal pilot study.

Phase 1 (months 4–9)

It was important to critically test our assumptions after 6 months of recruitment by reviewing the number of sites set up and the number of eligible patients identified, approached and consented. This was to help inform the number of participating sites required to achieve the recruitment target. Secondary reasons for undertaking this phase of the pilot were to review (1) whether or not the participating sites were being provided with enough training and documentation; (2) the number of reasons why patients were not eligible for the trial; (3) the length of time it took to consent a patient and the reasons why patients did not take part; (4) whether or not all clinicians at a site were actively taking part in the trial, and, if not, why not; and (5) patient adherence to treatment allocation.

The independent oversight committees assessed the success of phase 1 based on the following objectives:

-

to have a minimum of four sites recruiting during the 6 months that had recruited 24 patients (i.e. evidence that sites could recruit the expected one participant per month)

-

to ensure that adequate progress was made with setting up other sites to recruit in order to have 12 sites set up (i.e. 50% of sites).

Phase 2 (months 10–27)

This phase of the internal pilot continued for a further 18 months and was reviewed at 6-monthly intervals with the independent oversight committees. Patients were likely to have already suffered from frozen shoulder for several months and received physiotherapy in primary care before their referral to hospital. There was concern that this could have an impact on patient consent and adherence to the ESP intervention, which were threats to both the feasibility and the validity of the trial. Evidence from simulation work was that, with 80% power, a true treatment effect size of 0.2 or 0.4 and 30% non-compliance, the power is reduced to 54%. 61 In UK FROST, with a sample size that had 90% power and effect sizes of around 0.3–0.4, 20–30% non-compliance in the ESP arm was expected to reduce the power to between 60% and 70%. Therefore, if at the 24-month review, when 50% of the patients were expected to have been recruited, the non-compliance in the ESP arm was between 20% and 30%, the oversight committees would advise on whether to continue with a three-arm trial or with the surgical comparisons only. The following were also monitored:

-

reasons for patient non-consent to participate in the trial, their treatment preferences and a member of the trial team to informally discuss this with willing patients

-

whether or not all 25 sites were set up and had recruited 250 patients (50% of our target)

-

waiting times at sites from randomisation to intervention, with consideration of the need to replace sites that were not meeting the waiting time targets agreed in the protocol (i.e. the surgical procedure being performed within 18 weeks of randomisation).

Recruitment

Initial estimates for recruitment were based on Hospital Episode Statistics for NHS hospitals in England in 2009/10 and 2010/11. These excluded post-trauma or secondary referrals from other specialties, giving a stable rate of 210 per million patients treated for frozen shoulder. Assuming that 50% of frozen shoulder patients presenting in secondary care met the inclusion criteria and 40% of these consented, this left around 40 patients per million to be recruited into the trial. It was estimated that, to recruit 500 trial participants from trusts each serving catchment areas of around half a million people, 25 hospitals would be required to recruit for a minimum of 1 year. This assumed that there would be no delays in set-up or problems at any subsequent time point, that all surgeons at the sites would be willing to participate and that all potential participants would be screened for eligibility. Following the pilot phase, the number of sites required was increased to ensure that recruitment was achieved to target.

Patients who had been referred for a frozen shoulder to an outpatient hospital clinic were identified by the research nurse or assessing clinician. In the clinic, a designated individual within the shoulder team (e.g. surgeon or physiotherapist) completed the study eligibility form (see Report Supplementary Material 8) to confirm whether or not the patient was eligible and, when applicable, approached the patient about the study. The research nurse then provided the patient with an information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 9) and answered any questions. The patient was able to consent at that time or they could take up to 1 week to decide. When a patient consented (see Report Supplementary Material 10), he or she was asked to complete the baseline form (see Report Supplementary Material 11). The research nurse completed the consent status form (see Report Supplementary Material 12) to confirm the patient’s status.

When a patient did not consent, the research nurse recorded the reason and the treatment plan in another section of the consent status form. The patient was also offered an optional patient preference form (see Report Supplementary Material 13) to complete if they wanted to provide more information about why they chose not to take part.

Training in recruitment was provided to hospital staff as part of the site initiation visit, and a trial site manual was prepared that included guidance on consenting patients into the trial and how to answer questions that might arise during consent-taking. In addition, a poster was provided to publicise the trial to hospital staff and patients. During the trial, training and reminders were implemented using regular e-mail bulletins and face-to-face meetings with principal investigators and research nurses, with trial co-ordinators providing support and guidance to staff as required.

Randomisation

The randomisation sequence was based on a computer-generated randomisation algorithm provided by a remote randomisation service (telephone or online access) at York Trials Unit, University of York. The unit of randomisation was the individual patient, allocated to the trial interventions MUA, ACR and ESP in the ratio of 2 : 2 : 1, stratified by the presence of diabetes,62 using random blocks sizes of 10 and 15. The research nurse used the remote randomisation service to register eligible and consenting patients before computer generation of the allocation. This ensured treatment concealment and immediate unbiased allocation.

The research nurse then informed the treating clinician and the patient of the treatment allocation.

Blinding

Given the nature of the trial treatments, comparing surgical and non-surgical treatment options, the blinding of participants and clinicians to treatment allocation was not possible or desirable in this pragmatic trial. Therefore, patients and clinicians were informed of the treatment allocation after randomisation. The statistician was blind to treatment allocation until after data were hard locked and no further changes could be made.

Statistical methods

Analyses were conducted for the three treatment comparisons of interest, ACR with ESP, MUA with ESP, and ACR with MUA, according to the principle of intention to treat (ITT). All analyses were conducted in Stata® version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) using two-sided statistical significance at the 0.05 level. The statistical analyses plan was completed prior to completion of data collection on 12 February 2019.

Trial progression

The characteristics (age, sex, diabetes, symptom duration, laterality and patient preferences) of ineligible and non-consenting patients were compared with the randomised patient population. Reasons for exclusion and non-consent were tabulated, including free-text entries summarised by the trial team. The agreed treatment for excluded patients was tabulated. The flow of participants from eligibility and randomisation to follow-up and analysis of the trial was presented in a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram.

Baseline characteristics

All participant baseline characteristics were summarised descriptively by trial arm both for participants ‘as randomised’ and for those ‘as analysed’. The ‘as analysed’ population comprised all participants included in the primary analysis (i.e. patients who had complete data for the baseline covariates and outcome data for at least one post-randomisation time point). No formal statistical comparisons were undertaken between arms. Continuous measures were summarised using numbers, mean, SD, median, minimum and maximum, and categorical data were reported as counts and percentages.

Intervention delivery/fidelity

Details of the interventions as delivered were presented, including time to treatment, receipt of steroid injections, and optimal or suboptimal release achieved during surgery, as well as number and content of physiotherapy sessions. Fidelity was reported descriptively by trial arm, with baseline characteristics tabulated for each arm. Reasons for not receiving randomised treatment, alternative treatments and any further recorded treatments were tabulated by trial arm. Caseload by site and surgeon/physiotherapist were reported descriptively. The grades/bands and experience of treating surgeons and physiotherapists were presented.

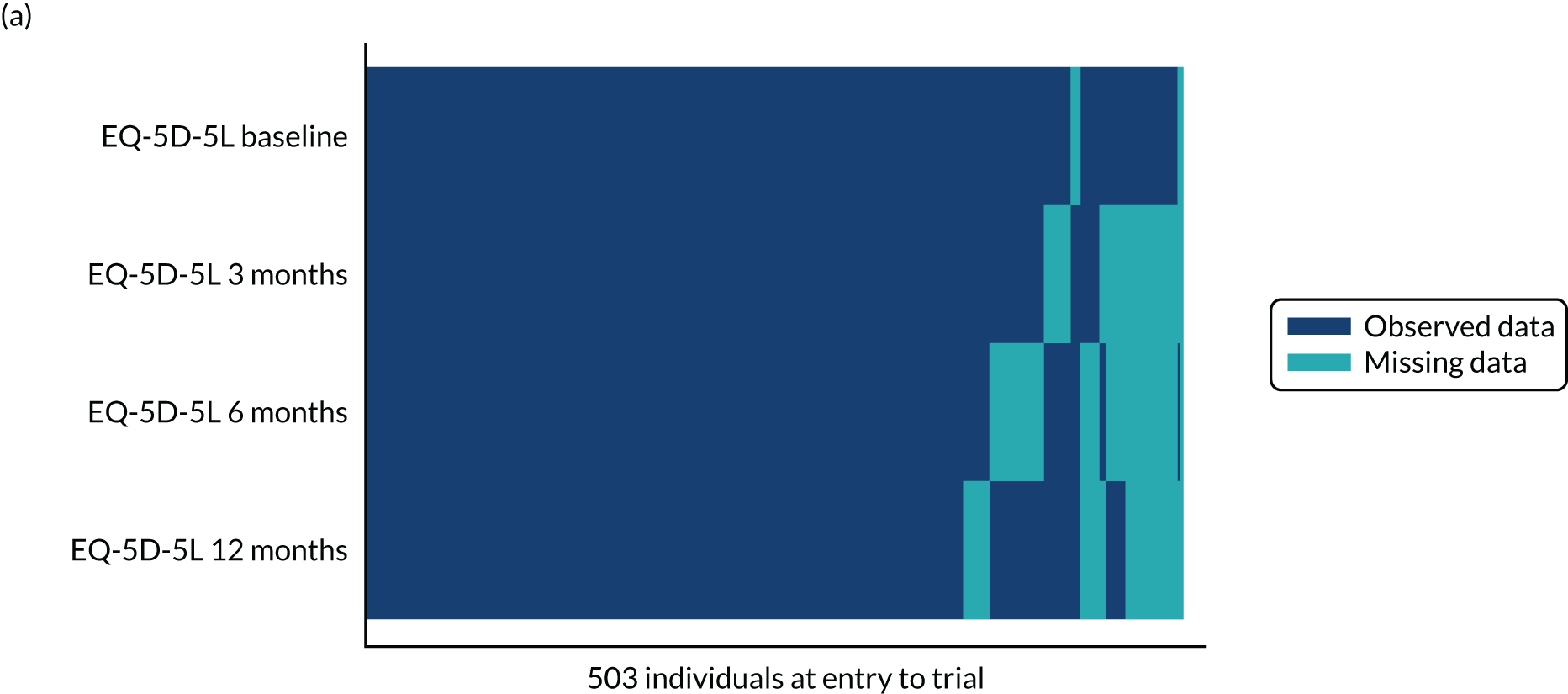

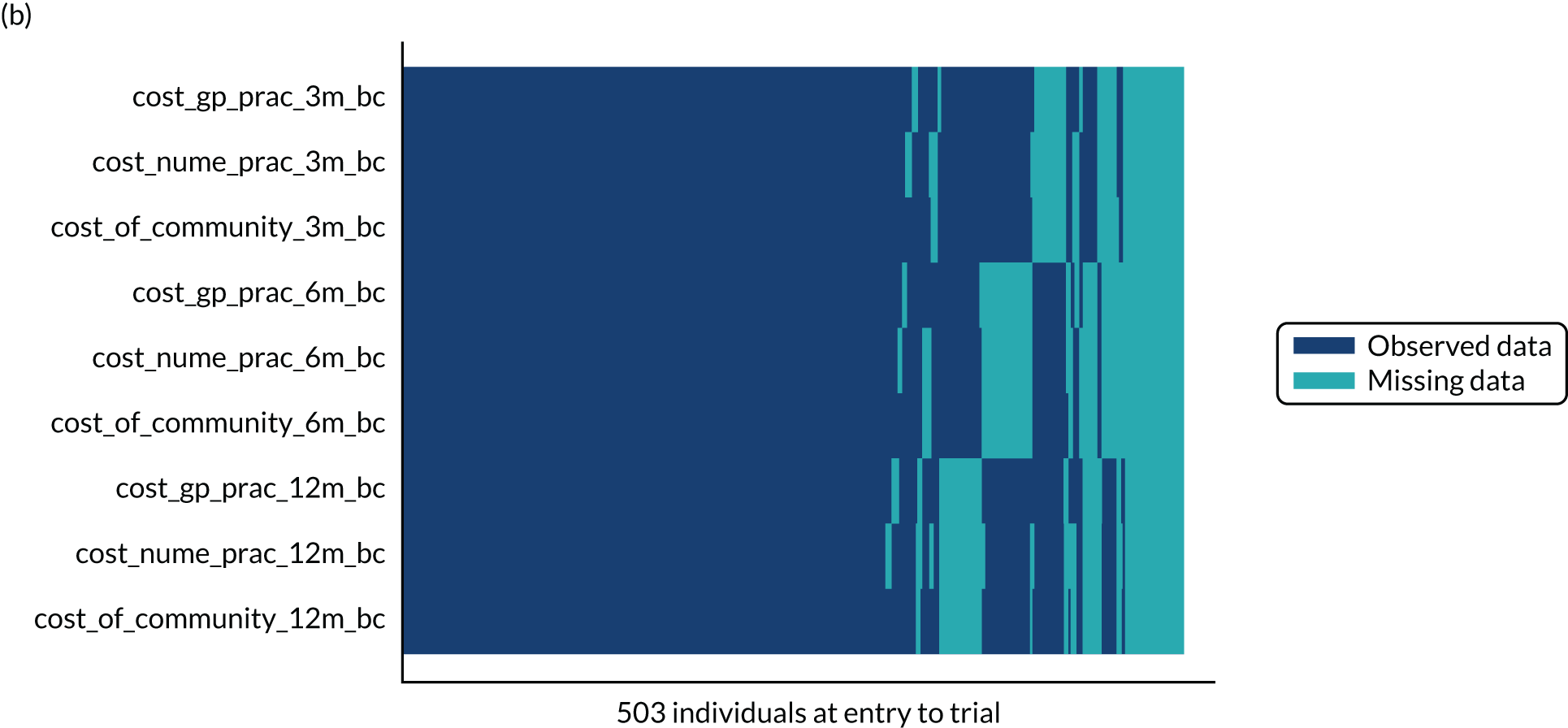

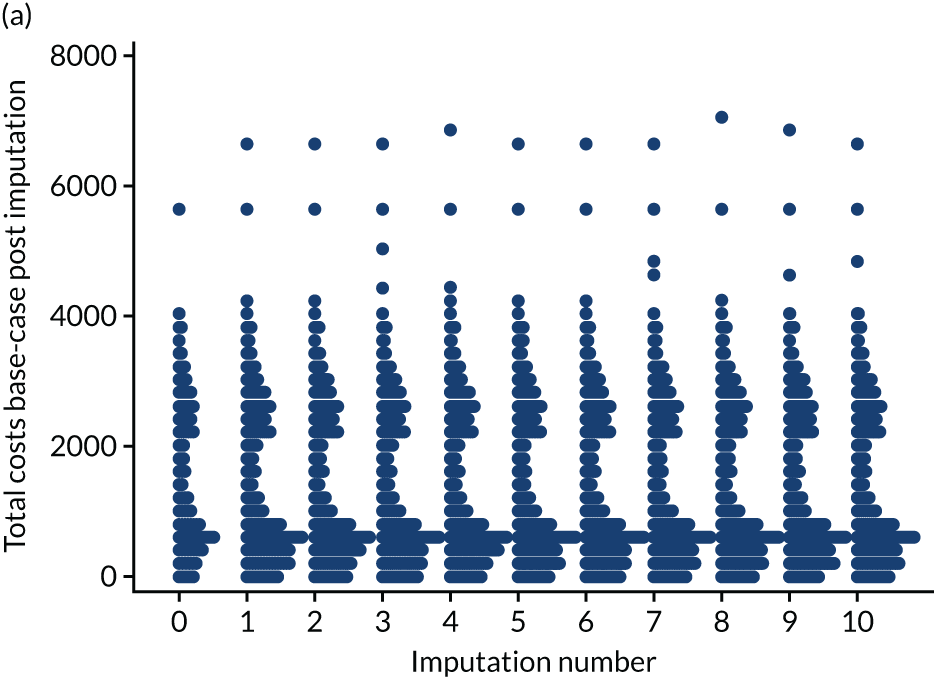

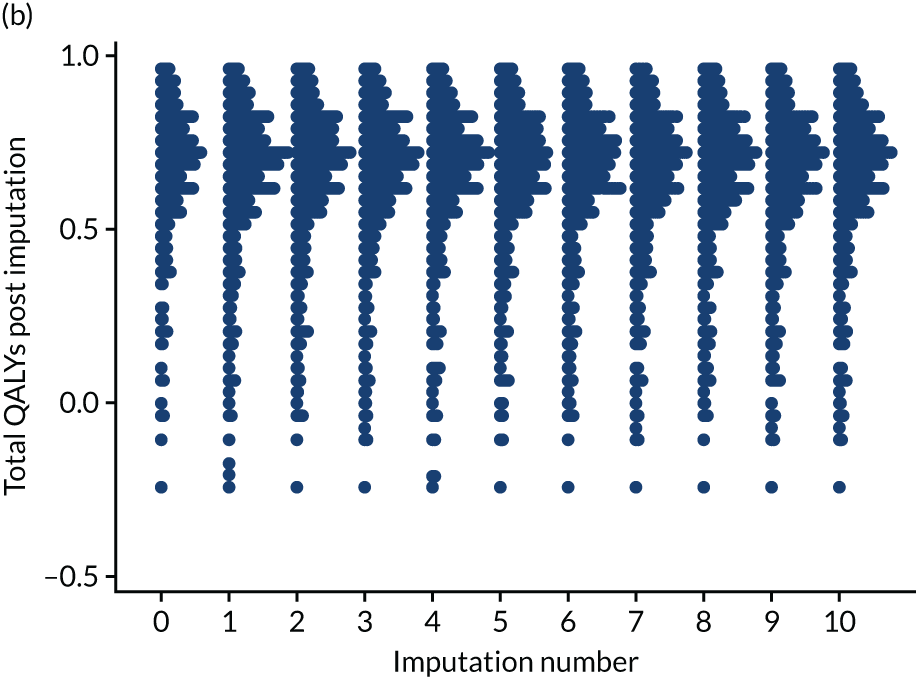

Missing data

Item-level missing data for individual outcomes (OSS and QuickDASH) were managed according to the instrument scoring guidance, and patterns of missing items were reported by trial arm. As the follow-up dates for the 6-month CRF and 6-month post-treatment CRF were in proximity for some participants, OSS data from these CRFs were used as a substitute if data were available for one and missing for the other, and if the two CRFs had been sent to the participant within 4 weeks (28 days). Missing baseline covariates for the primary analysis were imputed for the purpose of the analysis if participants provided follow-up data for at least one time point. Two participants with follow-up data had missing OSS baseline scores. Using the QuickDASH as a proxy, their scores were imputed as the median OSS of any participants with the same QuickDASH value.

Primary outcome (Oxford Shoulder Score) analysis

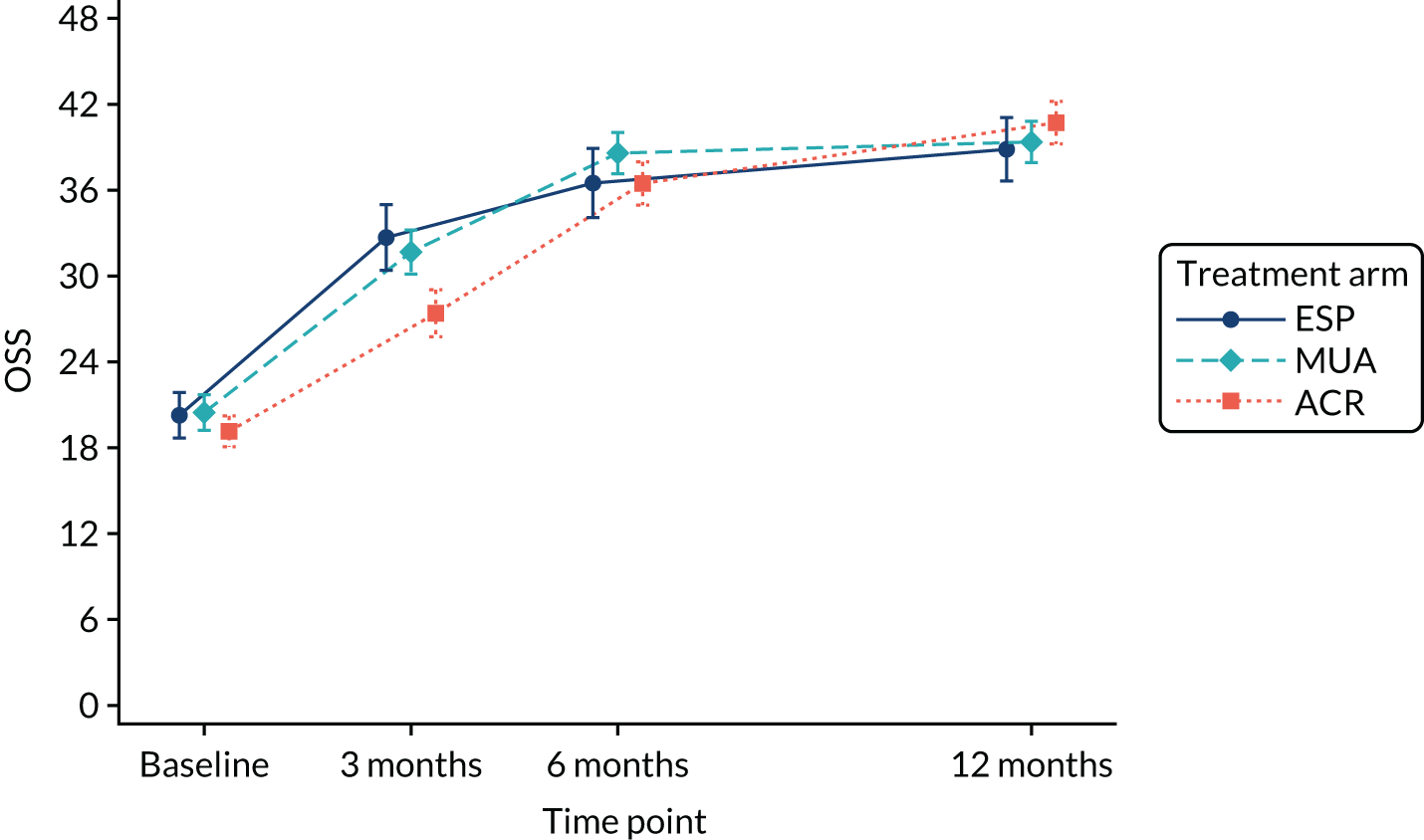

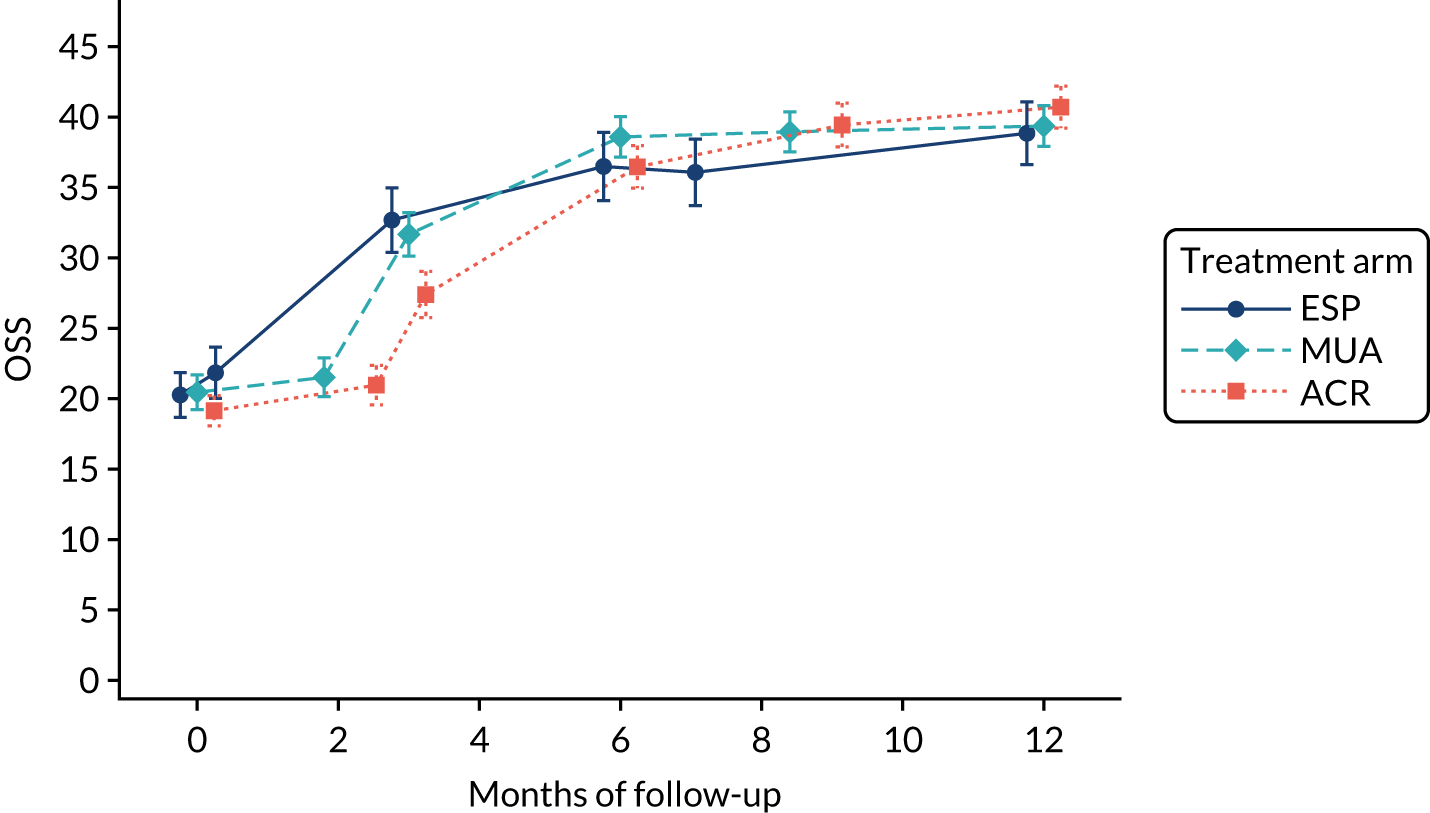

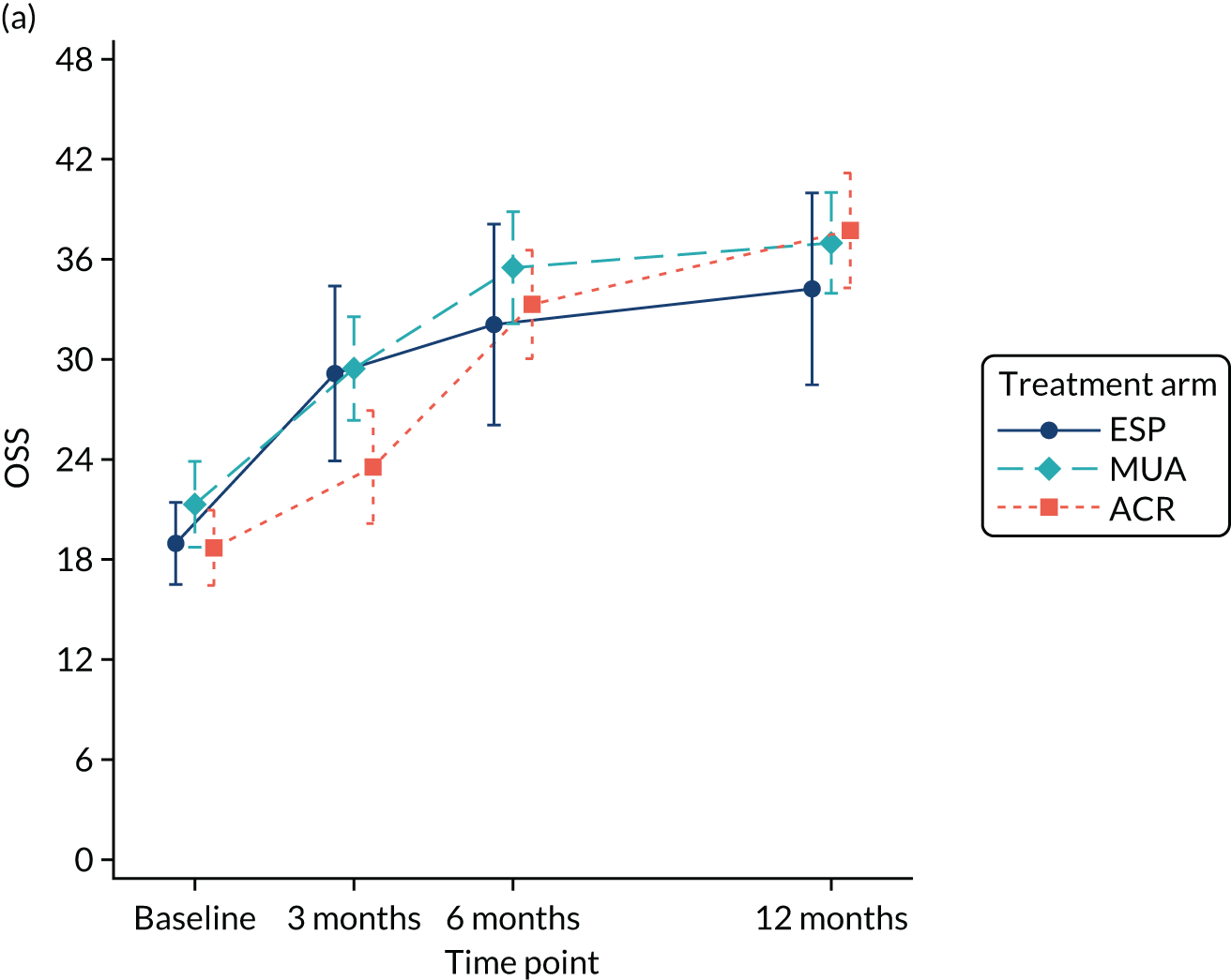

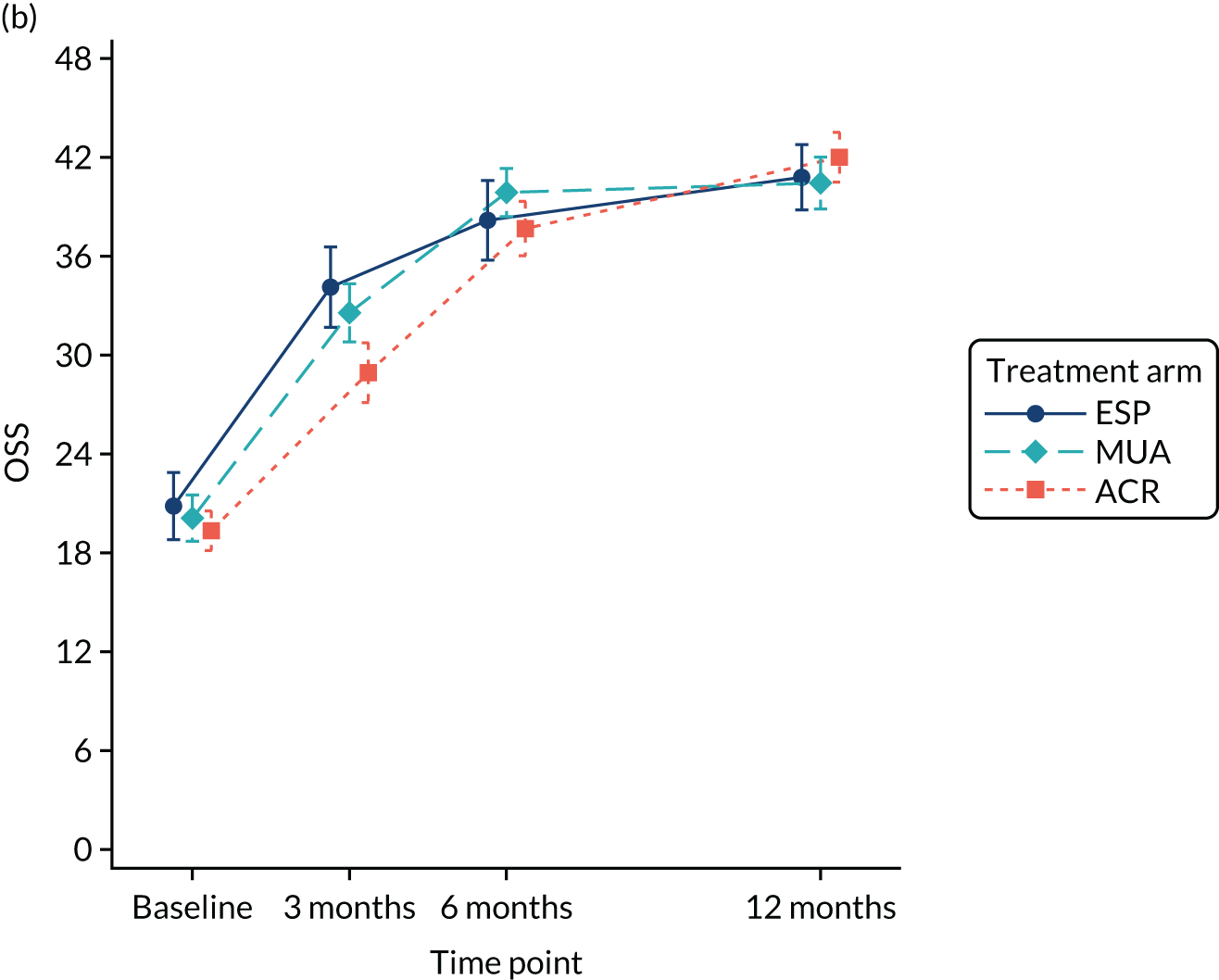

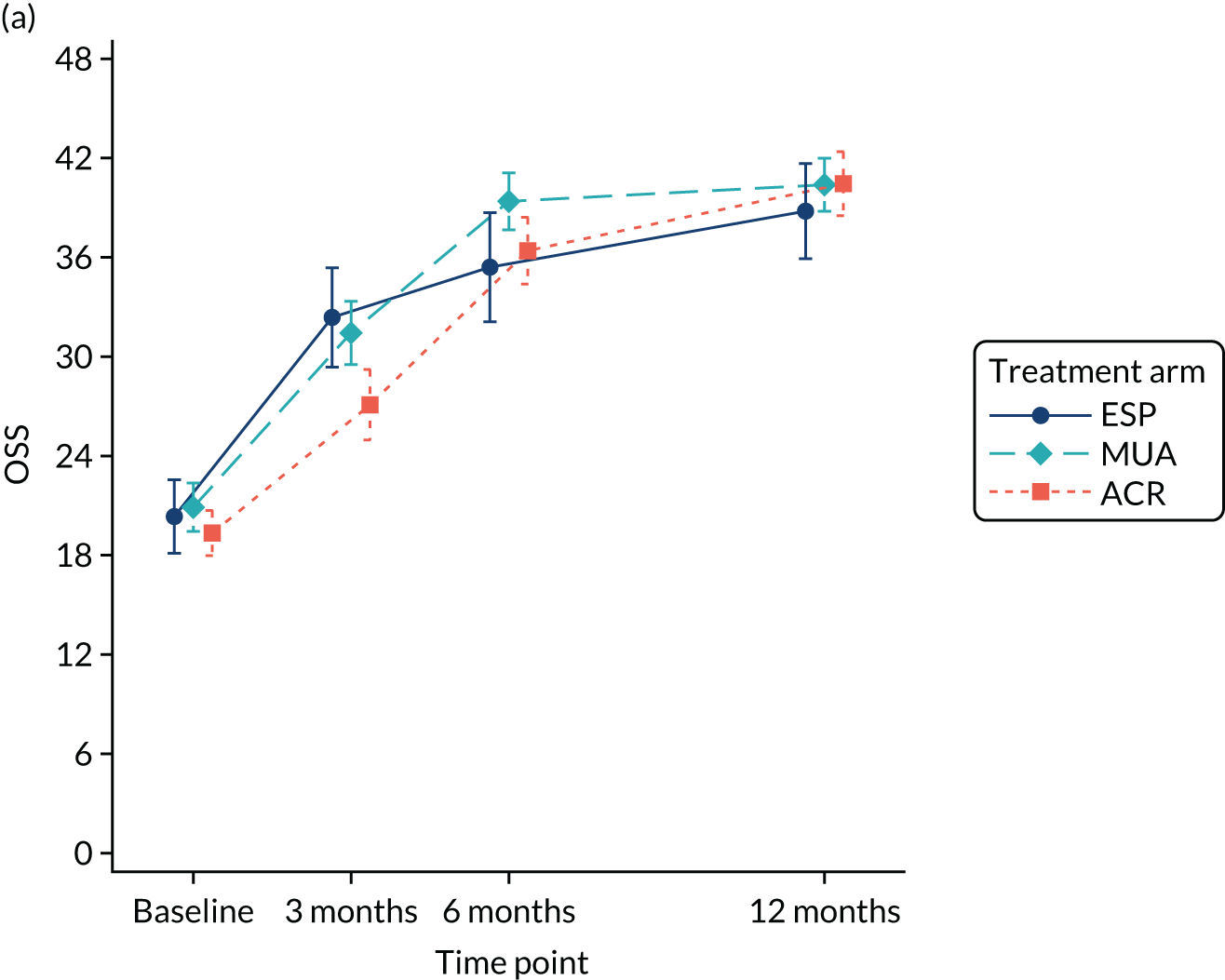

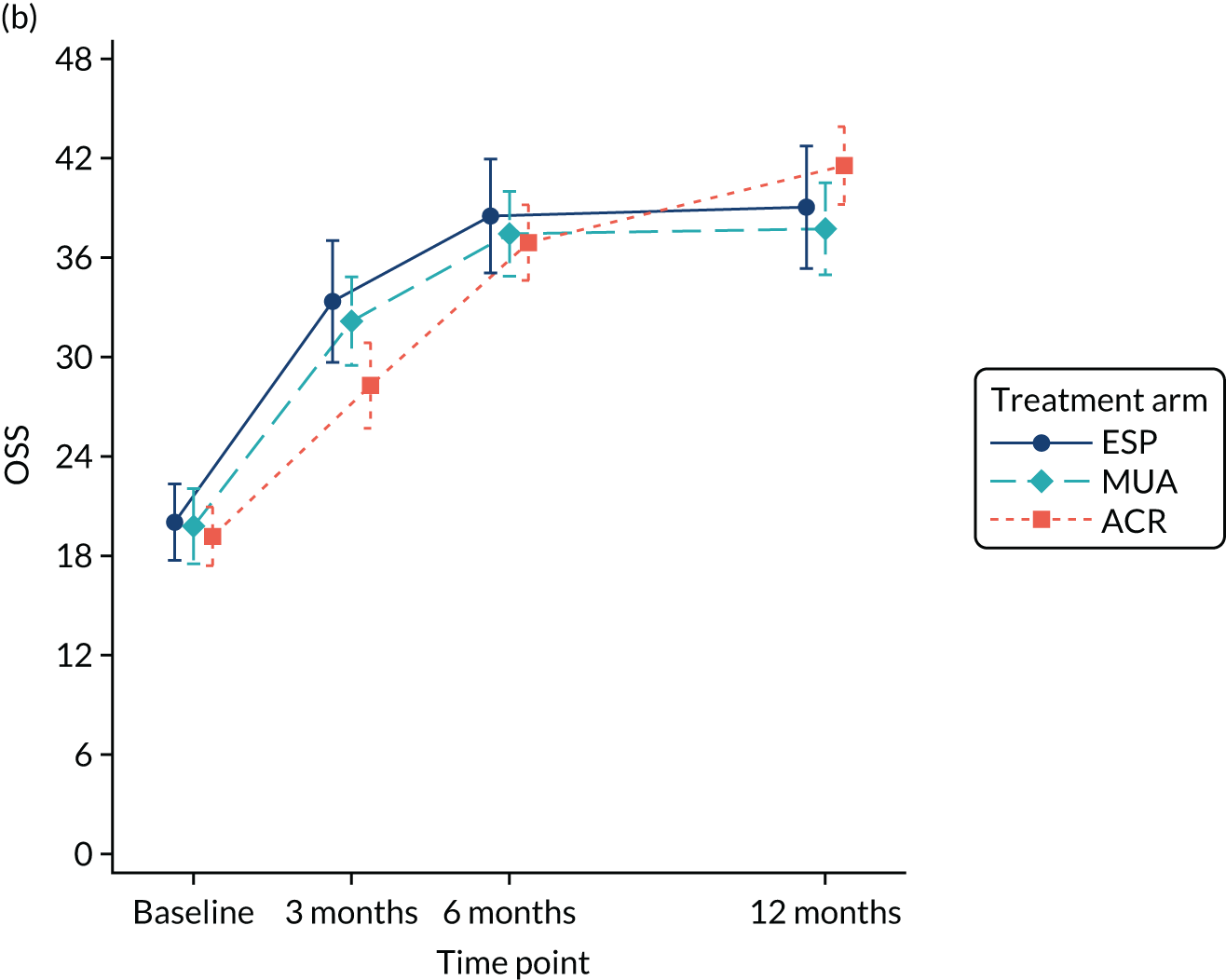

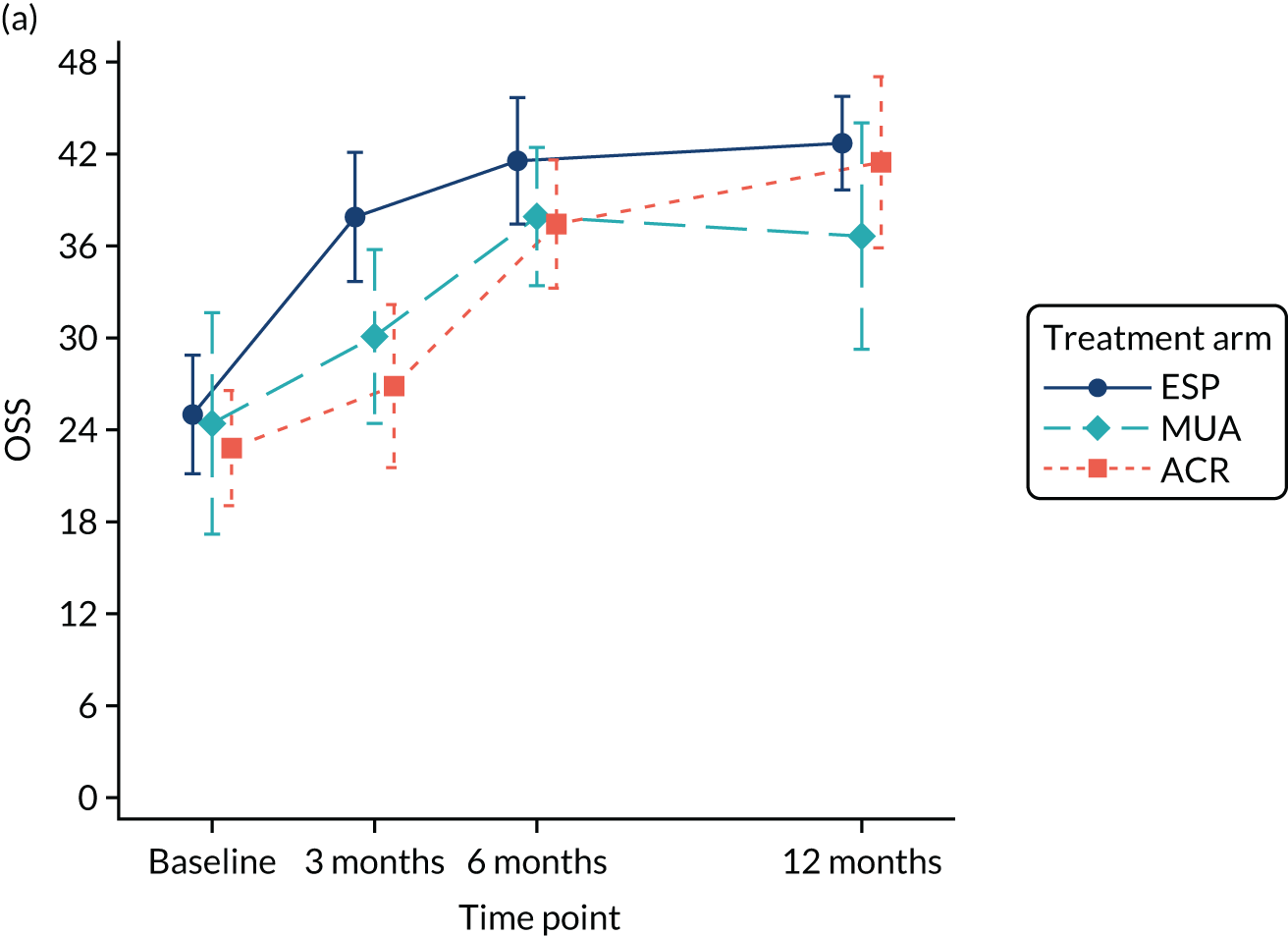

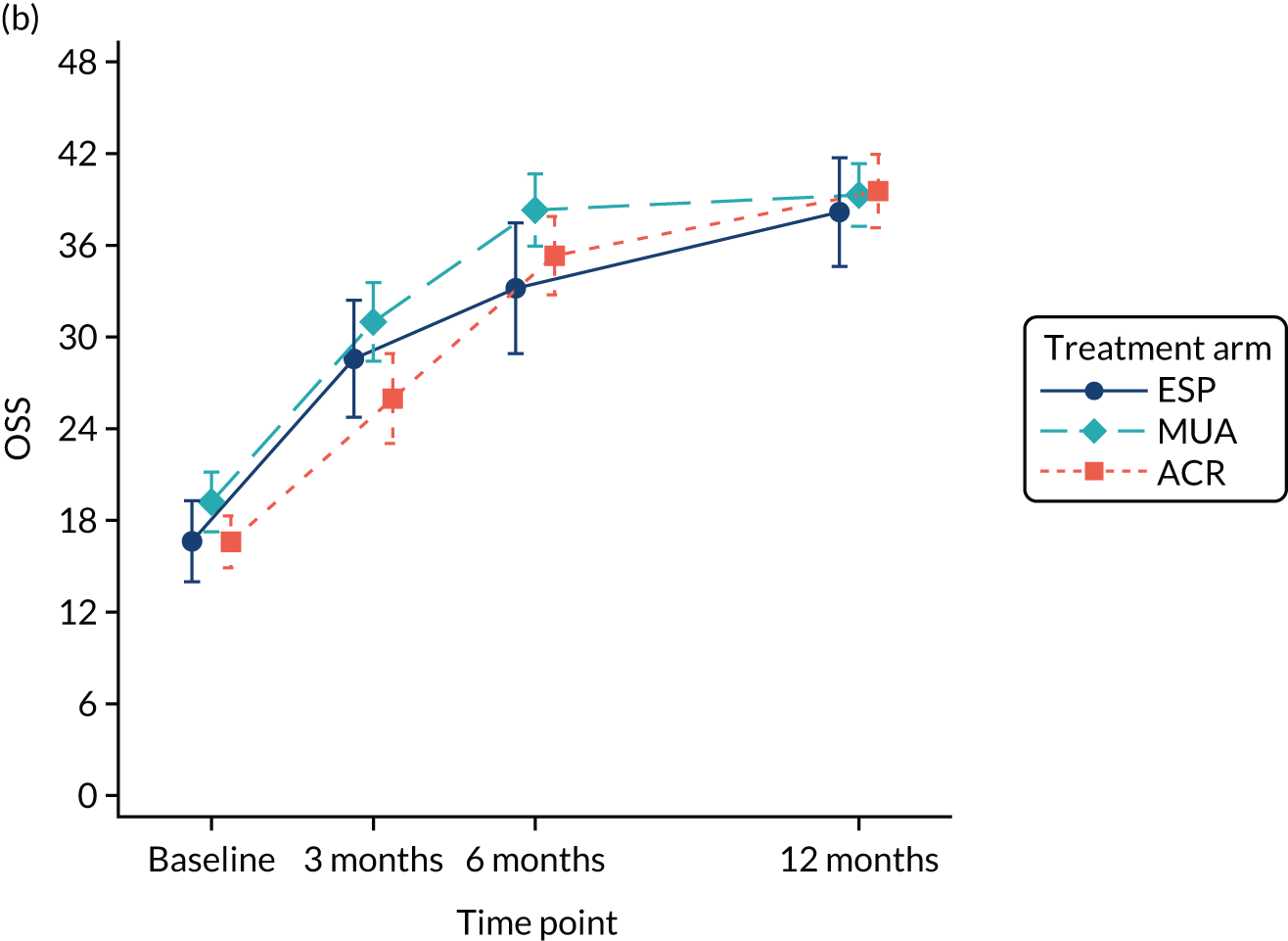

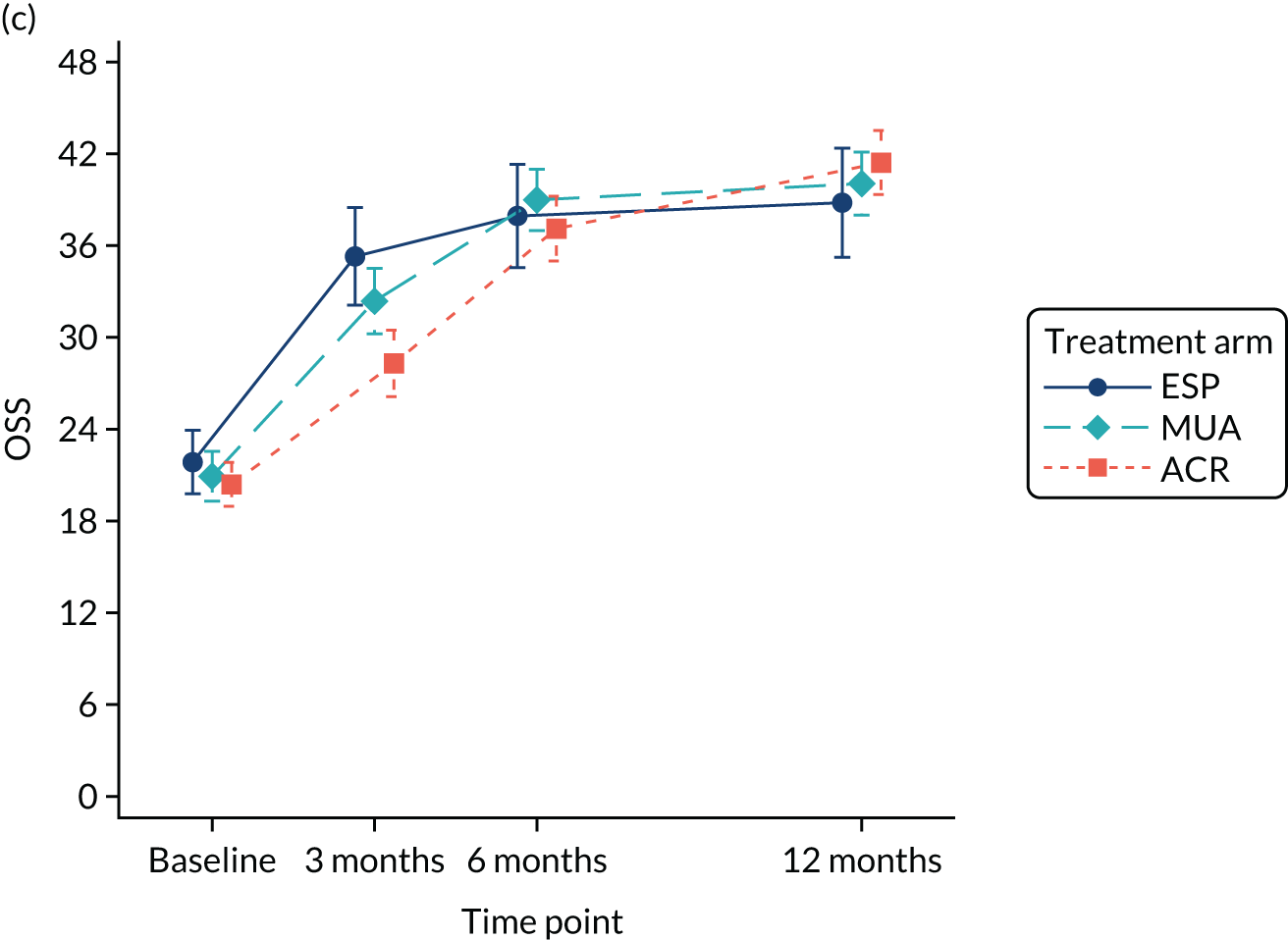

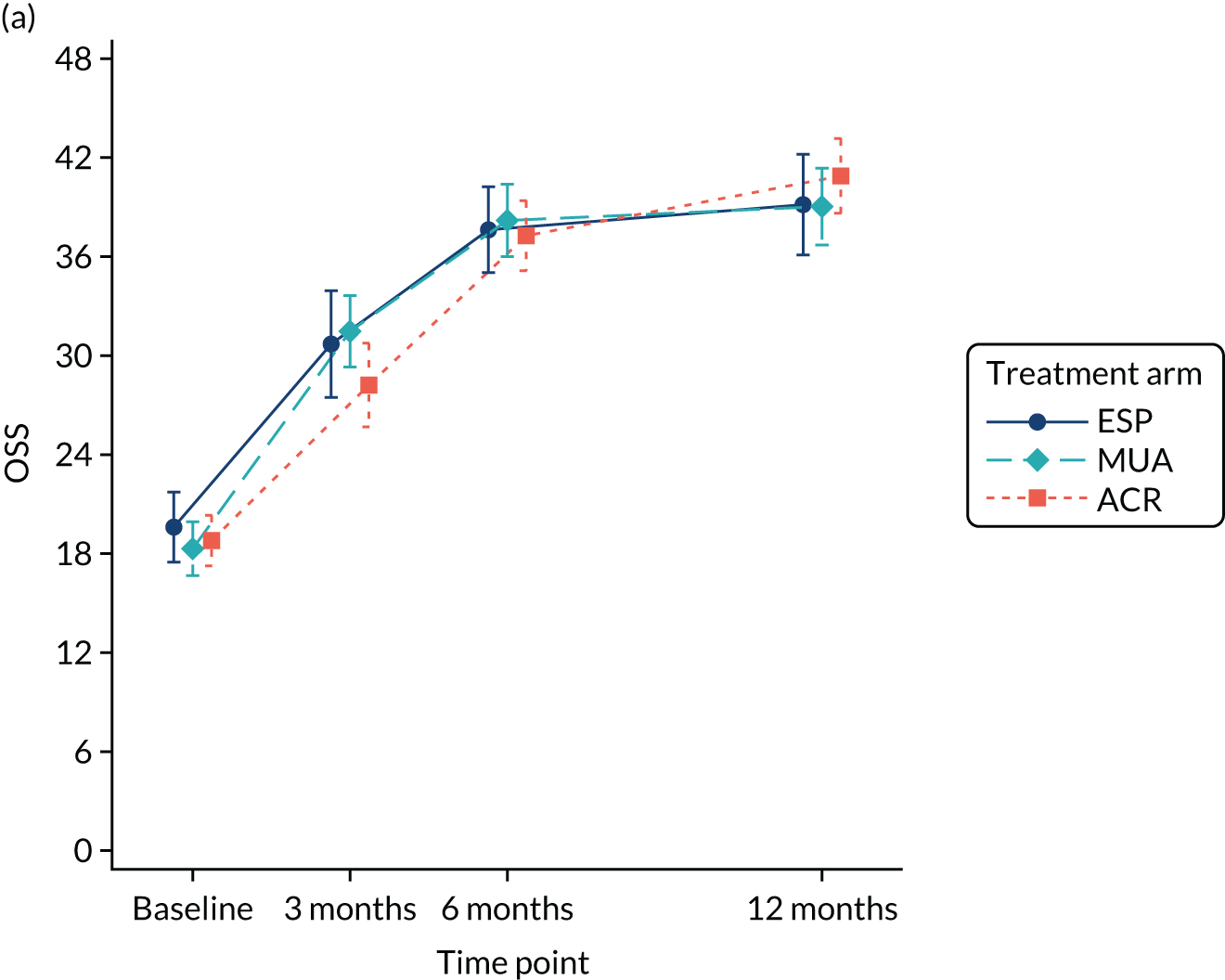

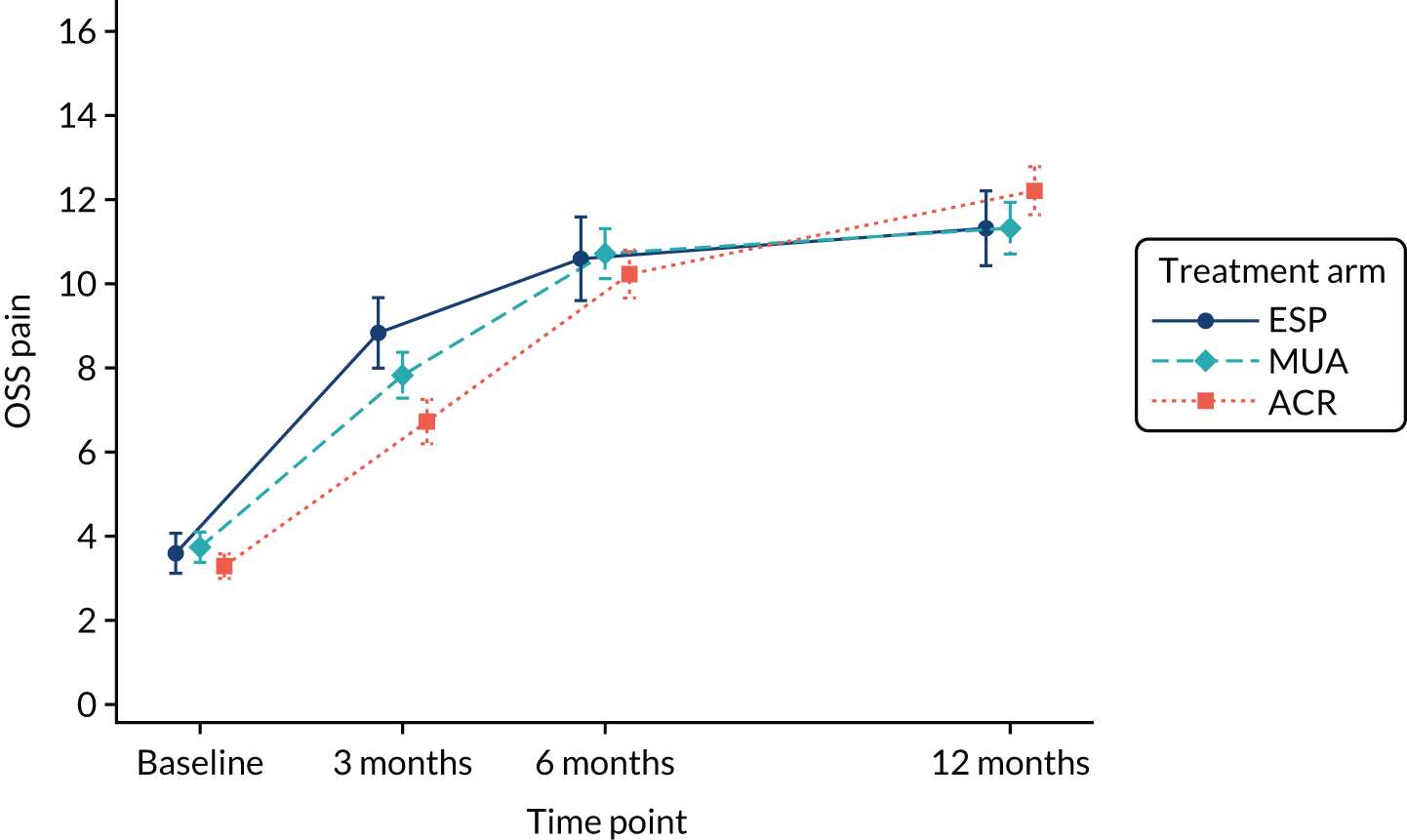

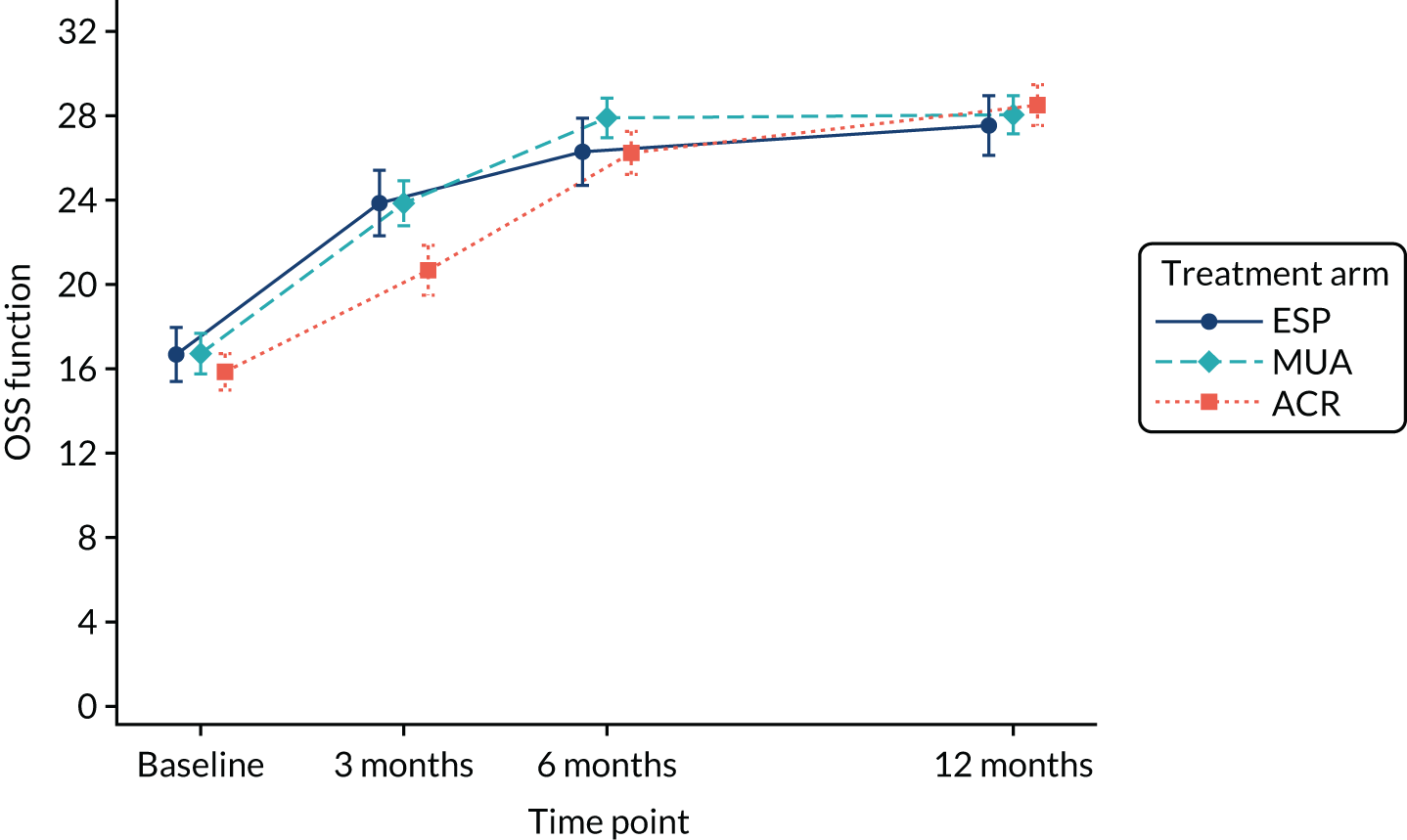

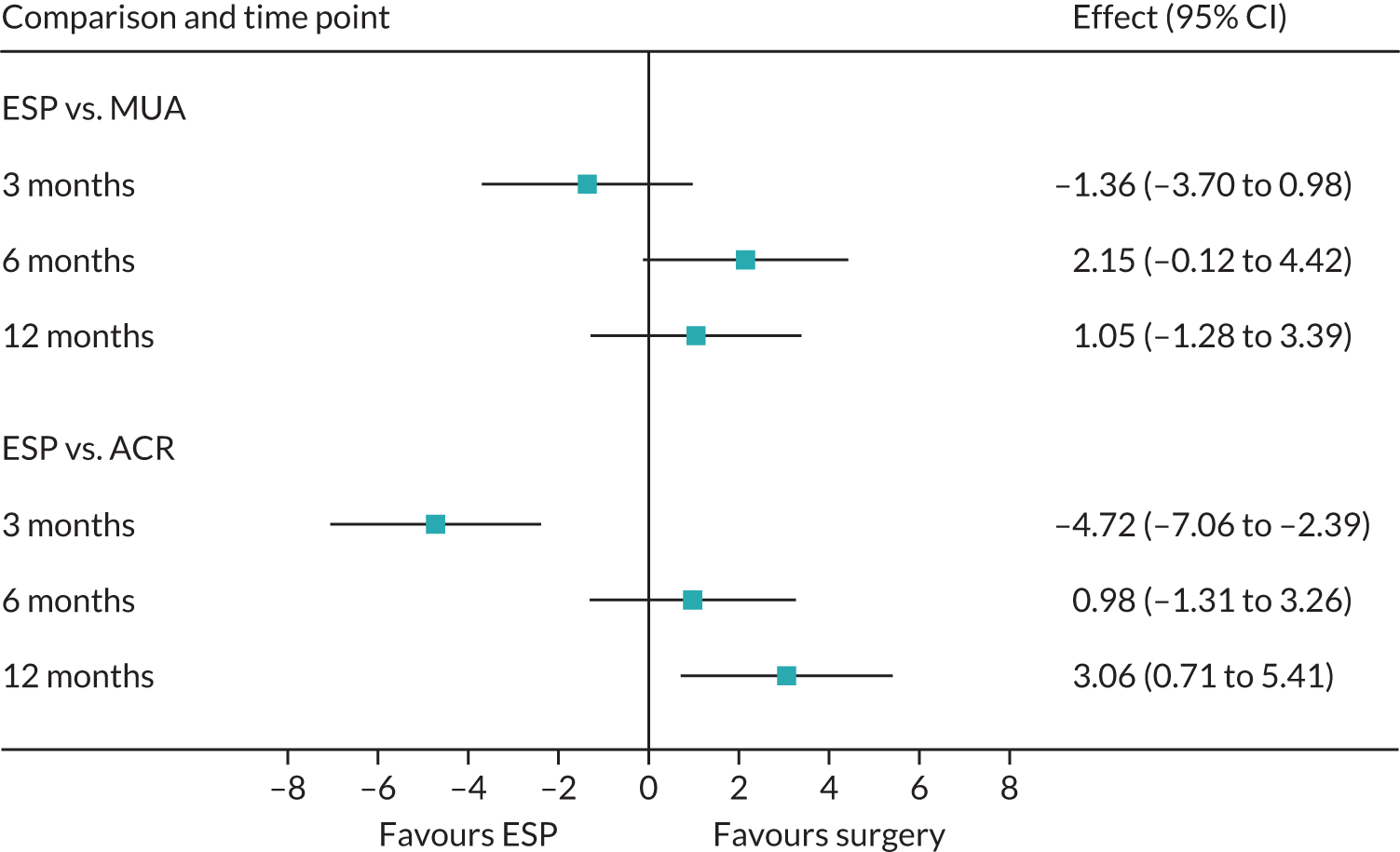

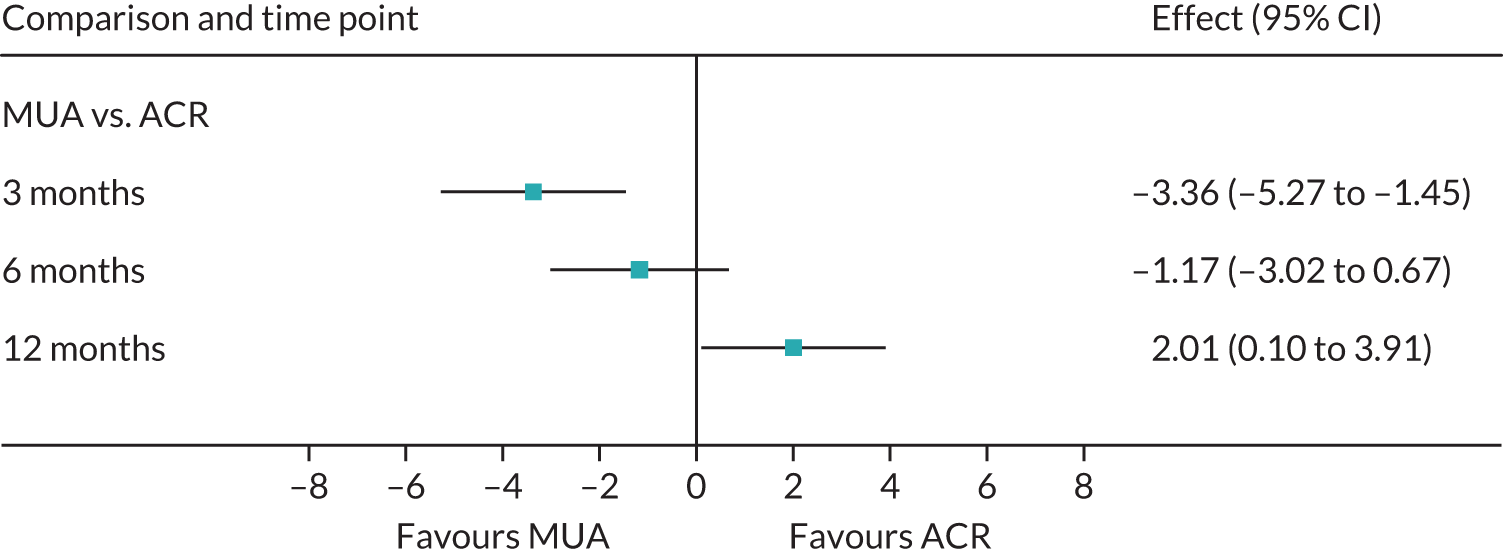

The OSS was summarised descriptively at each collected time point by trial arm, and mean scores and confidence intervals (CIs) were illustrated graphically.

The primary analysis was conducted on an ITT basis, including patients in the treament arm to which they were randomised. The primary analysis compared the OSS between treatment arms at 12 months. The primary outcome, OSS, was analysed using a covariance pattern linear mixed model, including assessments at all available time points with reference to the date of randomisation (3, 6 and 12 months, thereby increasing power) and treating patients as a random effect. The model was adjusted for OSS at baseline and included as further fixed effects: treatment arm, time, arm-by-time interaction, age, sex and diabetes. Differences in local practice and expertise were accounted for by including recruitment site as a random effect in the model. Given the low individual practitioner caseload (designated surgeon or physiotherapist in the shoulder team) expected in this multicentre trial, surgeons or physiotherapists were not specifically adjusted for.

For the modelling of repeated measurements, the best-fitting (based on Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion), simple (not significantly different from an unstructured pattern) covariance pattern was selected. For all three treatment comparisons, the model provided estimates at individual time points (the estimate at the 12-month time point served as the primary end point for each of the three treatment comparisons), as well as an overall treatment effect over 12 months. These are reported as mean differences between treatment arms, with 95% CIs and associated p-values.

Data were assumed missing at random (MAR). Model assumptions were checked, and, if they were in doubt, the data were transformed prior to analysis or alternative non-parametric analysis methods were explored.

Secondary analyses

Analysis adjusted for treatment compliance

To take account of an expected degree of participant non-compliance with the allocated treatment, a secondary complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis was carried out. This retains the initial randomised assignments but overcomes the problems of a per-protocol analysis. Given the three active treatments under investigation with different adherence criteria and the multiple alternative treatment pathways for each participant, not all comparisons were suitable for CACE analysis. Therefore, only compliance with ESP (minimum of eight ESP sessions or participant/physiotherapist satisfied with progress) was assessed using instrumental variable regression, predicting OSS at the primary end point at 12 months. The analysis adjusted for covariates of the primary analysis model. Assuming that the same proportion of participants in the comparator arm would have adhered to the intervention if they had been offered it (which should be achieved by way of randomisation), the group differences from this model provided an estimate of the treatment effect among participants who adhered to the treatment.

Analysis adjusted for waiting times

A separate secondary ITT random intercept linear mixed-model analysis including pre-treatment OSS and OSS 6 months from the start of treatment in addition to the 3- and 6-month post-randomisation data was conducted, including the same covariates as the primary analysis. Time was included as a continuous variable in order to explicitly model participant trajectories over time using all available data and thereby explore the influence of variable waiting times on the results of the study. Treatment effect estimates and p-values were derived at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation.

Missing data

The extent and pattern of missing outcomes over time were explored by trial arm. Logistic regression models were used to identify predictors of non-response and included all baseline data and primary outcome assessments before any missing values as potential predictors. Any variables found to be predictive of non-response were included in a repeat of the model specified for the primary analysis. Analysis by multiple imputation was considered if missing data exceeded the planned level of attrition (i.e. at least 20% of missing total OSS scores at 12 months).

Analysis using data close to intended follow-up points

If > 5% of all questionnaires were returned outside their intended time of follow-up [general follow-up: on or after 6 weeks, i.e. after the telephone reminder; pre-treatment form (see Report Supplementary Material 14); day of operation or the earlier of first day of physiotherapy or steroid injection], then the primary analysis and analysis adjusted for waiting times were repeated with data from such questionnaires excluded.

Analysis adjusting for baseline imbalances

The UK FROST DMEC observed an imbalance of employment status between randomised treatment arms during the monitoring of the trial. On its recommendation, a binary variable of working status (working vs. not working) was included as a covariate in the same model as the primary analysis if it was found to be associated with the OSS outcome.

Subgroup analyses

To explore differences in treatment response for different participant populations, three planned exploratory subgroup analyses were conducted: one exploring the influence of whether or not the participant was diabetic (yes/no), one exploring whether or not the participant had been in previous receipt of physiotherapy (yes/no) and one exploring patient treatment preferences as expressed at baseline (allocated to preferred treatment/not allocated to preferred treatment/had no preference). In addition, the TSC proposed a further subgroup analysis based on the duration of frozen shoulder symptoms at baseline (using the median of less than/more than 9 months as the cut-off point). For each analysis, a treatment-arm-by-subgroup interaction term was included in the primary analysis model, and the p-value of the interaction term was reported along with descriptives of the primary outcome for each subgroup–treatment arm pairing.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

QuickDASH, pain, extent of recovery

Continuous secondary outcomes were reported descriptively (unadjusted mean, SD, median, minimum and maximum). ITT linear mixed models were conducted for each outcome, adjusting for the same covariates as the primary analysis.

Pain or stiffness

As part of physiotherapy, the participant’s predominant problem, pain or stiffness, was recorded at each session. Equal pain and stiffness was classified, managed and recorded as pain. The proportion of each category at the first and last recorded physiotherapy session for each participant was presented by treatment arm.

Complications/adverse events

Based on the overlap between recorded complications and AE data, these data sets were reviewed, and a single list of serious and non-serious AEs was compiled to avoid duplication in reporting. These events were then summarised by type for each treatment arm. A logistic regression model was used to determine treatment arm differences in having experienced at least one AE if the number of participants with one or more events exceeded 10 in each arm. The same covariates as those used in the primary analysis were adjusted for.

Other analyses

Treatment preferences

Patient and clinician treatment preferences were explored for non-consenting patients where this information was provided.

Baseline patient preferences and expectations of randomised patients were explored descriptively by trial arm as well as for patients who had and patients who had not received prior physiotherapy and for patients who did and patients who did not receive their allocated intervention. Any change in preferences was explored by tabulating participants’ preferences at the 12-month follow-up against their baseline preferences and against their allocated treatment.

Oxford Shoulder Score change scores

Patients’ comparative shoulder assessment at 12 months (e.g. slightly better or much better) was matched with their change in OSS between baseline and 12 months in order to explore the magnitude of meaningful differences in the outcome in the study population.

Oxford Shoulder Score subdomains

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of OSS from a population of patients with rotator cuff tears in the UKUFF trial63 identified reliable OSS subdomains of pain (items 1, 8, 11 and 12) and function (items 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10). To further explore the nature of shoulder outcomes, descriptive statistics and associated graphs were presented for OSS subdomains of pain and function by treatment arm at each time point.

Outcomes for participants receiving no treatment

The OSS and QuickDASH scores were summarised descriptively at baseline and at all follow-up points for participants who did and participants who did not receive any treatment as indicated on their change in status form (see Report Supplementary Material 15). Where available, the average time to the decision of no treatment was reported for this group.

Update of systematic review

To place the trial findings in the context of current evidence, the HTA systematic review about the management of frozen shoulder was updated. 13 MEDLINE/PreMEDLINE, CENTRAL, EMBASE, PEDro, Science Citation Index, Clinicaltrials.gov and WHO International Clinical Trials Registry were searched from January 2010 to December 2018 and studies reported prior to 2010 obtained from our previous HTA review. The updated review focused only on evidence from RCTs and the interventions and outcomes collected in UK FROST. Hydrodilatation, however, was also included, as its popularity has increased since a survey was undertaken to inform the design of UK FROST. 22 Moreover, during the qualitative interviews with health-care professionals in the nested study, some surgeons and physiotherapists commented that hydrodilatation could have been a treatment option in the trial. The review protocol has been registered (PROSPERO CRD42019122999).

Data management

A central database at York Trials Unit was used to manage data collection, including the sending and return of participant questionnaires (see Report Supplementary Material 16) and hospital CRFs. This included automated e-mail reminders to participating sites to help ensure the timely return of hospital CRFs. Participant questionnaires and hospital CRFs were designed using TeleForm software (version 10; Cardiff Software, Cambridge, UK) and marked up with variable names and appropriate scoring. To maximise data quality, when hospital CRFs were returned to York Trials Unit the key variables required for the statistical analysis and checking adherence in the delivery of the treatments were reviewed for completion and accuracy by a research data administrator, who resolved any queries with the research nurse at the site. The hospital site was reimbursed for the completion of all CRFs up to a maximum value of £124.00. This was agreed by the trust and trial sponsor using a clinical trial agreement during the site set-up. No checks of the quality of data in the postal questionnaires were made on return of the questionnaires to York Trials Unit, although a trial co-ordinator checked whether the participant had given extreme responses to the last EQ-5D-5L question and/or given a free-text response that indicated they could be at harm. When either of these occurred, the principal investigator, research nurse and chief investigator were notified by e-mail. After this initial check, all postal questionnaires and hospital CRFs passed through a process of scanning in the TeleForm software, second checking and validating against predetermined rules.

Active and systematic follow-up of all randomised participants by post included pre-notification reminders, 2- and 4-week letter reminders and the option to complete an abridged questionnaire (a minimum of the OSS and EQ-5D) over the telephone after 6 weeks. At 12 months, the primary end point, an unconditional incentive of £5 was included. If the patient agreed at the time of consent, text messages were sent on the day the participant was sent the postal questionnaire64 and newsletters were circulated to trial participants. 65 Trial participants could withdraw entirely from the study at any time for any reason, but any data collected up to that point were included in the analysis. The participant could agree to being withdrawn from only postal questionnaire collection or from only hospital CRF collection.

Essential trial documentation were kept with the trial master file and investigator site files, allowing the conduct of the trial and quality of the data produced to be evaluated. The documentation will be retained for a minimum of 5 years after the conclusion of the trial. The postal questionnaires and hospital CRFs will be stored for a minimum of 5 years after the conclusion of the trial as paper records, and for a minimum of 20 years in electronic format.

Adverse event management

All AEs and SAEs were recorded by the site principal investigator or delegated clinician and returned to the trial office on a CRF (see Report Supplementary Materials 17 and 18). In accordance with good clinical practice, SAEs were reported within 24 hours and AEs were reported within 5 days of the investigator becoming aware.

Once this information was received, the chief investigator determined causality and expectedness. The Research Ethics Committee was notified of SAEs that were unexpected and related to the trial within 15 days for a non-life-threatening event and within 7 days for a life-threatening event. For non-serious AEs, the central office was notified within 5 days of the event being known. All AEs and SAEs were reported to the DMEC, TSC and TMG. Expected AEs for this shoulder condition included infection; bleeding; delayed wound healing; conversion of a planned day-case procedure to an overnight stay for control of pain; post-procedural worsening of shoulder pain; injury to adjacent structures such as nerve, tendon, bone or joint; recurrent stiffness requiring further treatment; transient hyperglycaemia, steroid flare or joint sepsis following corticosteroid injection; and injuries related to the heating or cooling of tissues. The chief investigator reviewed follow-up reports 1 month later (see Report Supplementary Material 19) to ensure that adequate action had been taken and progress had been made.

Ethics approval and monitoring

Ethics committee approval and any changes to the project protocol

National Research Ethics Service Committee North East – Newcastle and North Tyneside 2 approved the study on 18 November 2014 (Research Ethics Committee reference 14/NE/1176). Health Research Authority approval for the study with an existing UK-wide review was granted on 15 June 2016. A summary of the changes made to the protocol since the original Research Ethics Committee approval is in Appendix 2.

Trial Management Group

The day-to-day management of the trial was overseen by the TMG, which met quarterly. A representative of the sponsor attended when available. These meetings monitored progress with recruitment (e.g. enrolment, consent, eligibility), allocation to study groups, adherence of the trial interventions to the protocol, retention of trial participants, monitoring of AEs/SAEs and reasons for participant withdrawal. The review of progress was undertaken at a participating site level and, as necessary, feedback was given to the principal investigator and research nurses at each site.

Trial Steering Committee

A TSC was appointed by the funding body to provide overall supervision of the trial and to advise on its continuation. The membership of the TSC is listed in the Acknowledgements.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

The DMEC was appointed by the funding body and had access to the unblinded comparative data as provided by a statistician at York Trials Unit who was independent of the trial team. The DMEC monitored the data and made any recommendations about (dis)continuation of the trial to the independent TSC. The membership of the DMEC is listed in the Acknowledgements.

Patient and public involvement

Two patients who had previously received treatment for frozen shoulder at the lead site (James Cook University Hospital) and the independent patient representative member of the TSC were invited to comment on the patient information leaflet, the patient-facing data collection forms and the consent process for trial participation. The need to develop a leaflet to provide general information about frozen shoulder was identified following a qualitative study of patients with frozen shoulder using semistructured interviews. 18 The two patient representatives were invited to attend the TMG during the early stages of the study and it was later agreed to seek their opinion outside the meetings when necessary. Recruitment was steady and the target was met on time. The retention of participants also went well and the target was exceeded. Therefore, there was little further contact with the two patient representatives during the trial, although they did advise on the newsletters to be sent to trial participants.

Following the initial analyses of the study results, we sought the advice of the two patient representatives and a wider group of seven patients with frozen shoulder at the lead site. Study results, associated risks for individual trial treatments and their health economic impact were discussed. Members shared their thoughts on their preferred choice of treatment based on the study results and agreed to support the trial team with dissemination to various platforms. This included contributing to the Plain English summary of this report, journal publications and web-based outputs, such as updating the entry about management of frozen shoulder on Wikipedia and helping to develop content for other appropriate web pages. These patients will also meet with local (shoulder research users group) and national shoulder patient groups (British Elbow and Soulder Society patient liaison group) to ensure that the current evidence base for treatment options is available and disseminated appropriately to patients and the wider public.

Chapter 3 Trial results

This chapter begins with a summary of the findings of the internal pilot study and the nested shoulder capsular tissue and blood samples study. It then summarises recruitment, the flow of participants through the trial, the characteristics of participants at baseline and the results of analyses of the primary and secondary outcomes, as well as the integration of the findings into the existing literature.

Summary findings of the internal pilot

The objective of phase 1 of the internal pilot (months 4–9) was to have a minimum of four sites recruiting during the 6 months that had recruited 24 patients (i.e. evidence that they could recruit the expected one participant per month). To ensure that adequate progress had been made with setting up sites to recruit, 12 sites were to be set up (i.e. 50% of the total sites). At the end of month 9, we had recruited 20 patients (i.e. 83% of the target). This was in spite of not starting recruitment until month 7 and having only three of the four pilot sites set up. There were, however, two sites at which we were waiting on approval, and 16 out of 26 sites with which we had held a preliminary meeting.

We also reviewed other aspects of the study. In summary, of the 34 patients who had a clinically confirmed frozen shoulder, four met the exclusion criteria, 10 did not consent and 20 consented. Early data showed that treatment preference was the reason for all non-consent, rather than patients being too busy or not wanting to be involved in research. The time taken to consent ranged from 15 minutes to 1 hour. Participating sites had confirmed that they had received sufficient training and supporting documentation. Except at one of the four pilot sites, all surgeons were supportive of the study. At this one site, one surgeon was taking part, another surgeon felt that he did not see a sufficient number of patients to take part, and a third surgeon lacked equipoise to consent patients. All three surgeons, however, had agreed to deliver the surgical interventions to which patients were allocated. No patient non-compliance with treatment had yet been reported.

Although we had not met our patient recruitment or site set-up targets, both oversight committees were satisfied with the overall progress made during phase 1.

The primary objective of phase 2 was to review the feasibility of the ESP intervention and whether non-compliance in the ESP arm did not exceed 20–30%. At the end of this phase (month 27), of the 65 trial participants who had been allocated to ESP, 37 had ended their treatment and could be assessed for non-compliance. The remaining 28 participants either had started their treatment or were waiting to start treatment. Of the 37 participants who had ended their treatment, 29 (78%) met our criteria for completing the intervention as had been agreed with the trial team and independent committees: the participant had attended eight sessions or more (n = 19); or had attended fewer than eight sessions but both the participant and the physiotherapist were satisfied with their progress (n = 9); or had attended fewer than eight sessions and declined to attend more because they were satisfied with their progress, their ability to manage independently, or both (n = 1). Therefore, non-compliance with the ESP intervention applied to 22% of participants, which was within the threshold of 20–30%. The oversight committees agreed that this was an acceptable degree of non-compliance and that the trial should continue with all three treatment arms.

Another aspect of trial feasibility that was reviewed at month 27 was non-consent into the trial. This was because there was concern that patients would often have already received physiotherapy in primary care and that this could affect their decision to take part in the trial, given that the ESP intervention was one of the treatment options. It was found that 55% (n = 72) of the 131 reasons for patients not taking part was because they either ‘want surgery’ or ‘do not want physiotherapy’. This compared with 18% (n = 24) of patients who ‘want physiotherapy’ or ‘do not want surgery’. Other reasons for non-consent were infrequent. The main treatment that non-consenting patients went on to have was keyhole surgery (45%, n = 67). Of patients randomised into the trial, the majority had no treatment preference (53%, n = 159), over one-third preferred surgery (39%, n = 116) and the rest preferred physiotherapy (8%, n = 25). Despite the preferences for surgery, this did not have an impact on the feasibility of the trial, with 36 sites set up, compared with the target of 25 sites, and 325 participants recruited against the target of 250 participants. We also reviewed the timing of the delivery of interventions, which confirmed that only one site had regularly failed to deliver surgery on time because of local pressures. The local trial team and principal investigator were very engaged and responsive to the trial team’s concerns and prioritised the trial participants for the surgical procedures.

In short, UK FROST was being delivered on time and to target, with an acceptable degree of non-compliance with the ESP intervention. The oversight committees were satisfied with the progress of all aspects of the trial and for it to continue as planned.

Summary findings of the shoulder capsule tissue and blood samples study

The primary aim of this nested study was to determine the key molecular processes and changes seen in the shoulder capsular tissue of patients with frozen shoulder in order to better understand these processes; and to determine the relationship between tissue changes, serum biomarkers and clinical symptoms and signs at presentation. This was done by determining the molecular and cellular abnormalities in shoulder capsular tissue obtained during surgery, by determining serum protein and cytokine signatures, and by correlating any tissue and serum abnormalities detected with the clinical presentation.

Following research ethics approval from the Oxford Musculoskeletal Biobank (09/H0606/11) and National Research Ethics Service Committee Newcastle and North Tyneside (14/NE/1176), appropriate informed consent was sought from UK FROST participants randomised to receive the ACR intervention. For a small sample of 16 patients who consented to the study, the shoulder capsular tissue and a venous blood sample were collected. The findings from the analysis of the capsular tissue samples were then compared with data available in the Oxford Tissue Biobank of findings from both healthy and diseased rotator cuff tendon tissues.

Inflammation signatures differed between tissue from frozen shoulder and that from tendon tears. Compared with tendon tear tissue, frozen shoulder capsular tissue showed reduced expression of nuclear factor-κB response genes, including TNFA, IL6 and IL8, and increased expression of IL10, CD14, CD163 and C1QA messenger RNA. The fibroblast activation markers podoplanin (PDPN), CD106 (VCAM1) and CD248 and the fibroblast activation protein were highly expressed in adhesive capsulitis and torn tendons, compared with healthy tendons. However, fibroblast activation marker CD90 was significantly reduced in adhesive capsulitis compared with healthy and diseased tendon tissue. Proresolving receptors mediating resolution of inflammation, including ALX/FPR2, CMKLR1 and GPR32, were highly expressed in frozen shoulder capsular tissue. 37

This study in patients of a similar age has provided some insight into why inflammation ultimately resolves in frozen shoulder but persists in tendon tears. This study suggests that the phenotypes of fibroblast subsets populating diseased shoulder tissues differ between conditions with self-limiting and and those with persistent inflammation. CD90 therefore represents an important pathogenic marker and possible molecular checkpoint regulating persistent stroma-mediated inflammation in common soft tissue diseases of the shoulder. Proresolving proteins were highly expressed in frozen shoulder tissue compared with established shoulder tendon tears. These findings have provided a novel insight into the disease mechanism of frozen shoulder, which points towards a resolving inflammatory environment. Further studies to better understand the biological mechanisms governing successful resolution of inflammation should inform new therapeutic strategies to accelerate disease resolution in frozen shoulder.

Recruitment into UK FROST

A total of 37 sites screened patients for the UK FROST trial, of which 35 randomised at least one patient. Appendix 3 presents the number of patients screened and randomised at each site, as well as the number of participants who withdrew before the end of the study.

Flow of participants

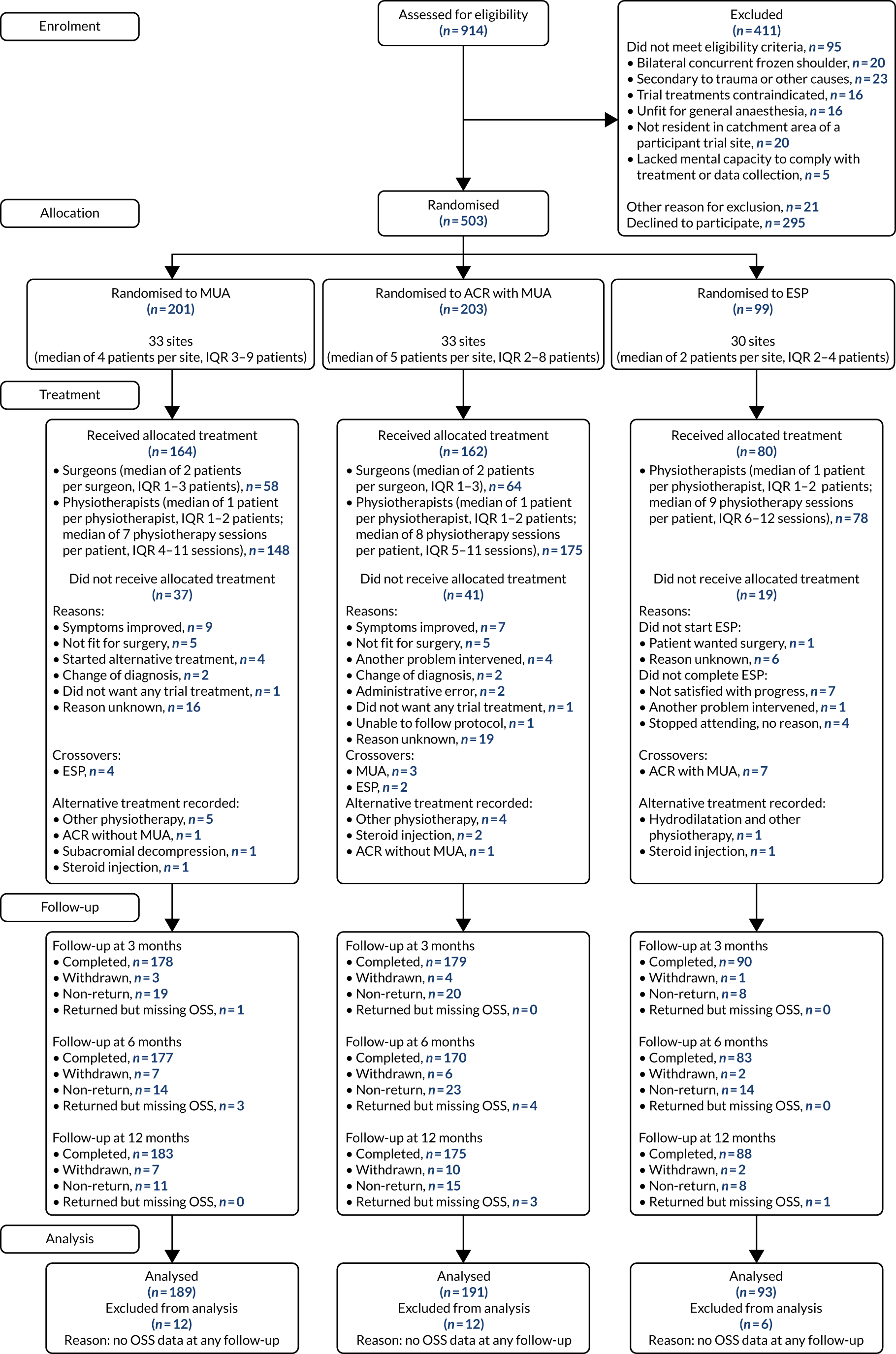

The flow of participants from screening to randomisation, treatment, follow-up and analysis is illustrated in the CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 2). Of 914 screened patients, 503 were randomised into the UK FROST trial. The reasons for exclusion were not meeting eligibility criteria (n = 95), non-consent (n = 295) and other reasons (n = 21). The most frequent reason for exclusion was having frozen shoulder symptoms secondary to trauma that required hospital care. Most patients who provided information about why they were not willing to join the trial said that this was because they had already had physiotherapy and wanted to have surgery (Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram. IQR, interquartile range.

| Reason | Number excluded | Per cent of total excluded (N = 411) |

|---|---|---|

| Trial exclusion criteria (n = 116; more than one reason possible) | ||

| Bilateral concurrent frozen shoulder | 20 | 4.9 |

| Frozen shoulder secondary to trauma (i.e. trauma to the shoulder that required hospital care, e.g. fracture, dislocation, rotator cuff tear) | 23 | 5.6 |

| Frozen shoulder secondary to other causes (e.g. recent breast surgery or radiotherapy) | 16 | 3.9 |

| Any of the trial treatments are contraindicated (e.g. patient is unfit for anaesthesia or corticosteroid) | 16 | 3.9 |

| Not resident in a catchment area of a participating site | 20 | 4.9 |

| Lacks mental capacity and unable to understand the trial or instructions for treatment | 5 | 1.2 |

| Other reason | 21 | 5.1 |

| Patient non-consent (n = 295; grouped free-text information from screening form) | ||

| Wanted surgery | 79 | 19.2 |

| Did not want surgery | 40 | 9.7 |

| Wanted physiotherapy | 22 | 5.4 |

| Did not want physiotherapy | 48 | 11.7 |

| Wanted steroid injection | 2 | 0.5 |

| Wanted clinician to decide | 3 | 0.7 |

| Wanted no further treatment | 2 | 0.5 |

| Could not travel to trial site | 1 | 0.2 |

| Was too busy to take part | 7 | 1.7 |

| Too many questionnaires | 1 | 0.2 |

| Did not want to take part | 29 | 7.1 |

| Unclear/no reason given | 61 | 14.8 |

| Patient non-consent (n = 295; selection of possible reasons from list of preference form if agreed to complete, more than one reason possible) | ||

| I wanted the treating clinician to make a decision for me | 13 | 3.2 |

| I have already had physiotherapy | 84 | 20.4 |

| I do not want physiotherapy | 38 | 9.2 |

| I do not want surgery | 36 | 8.8 |

| I do want physiotherapy | 28 | 6.8 |

| I do want surgery | 75 | 18.2 |

| I am too busy to take part in research | 10 | 2.4 |

| I do not want to be involved in research | 6 | 1.5 |

| I thought there were too many questionnaires to complete | 1 | 0.2 |

| I just did not want to take part | 10 | 2.4 |

| Other | 29 | 7.1 |

| Did not agree to complete preference form | 109 | 26.5 |

Treatment allocations were 2 : 2 : 1 to MUA with steroid injection (n = 201), ACR with MUA (n = 203), and ESP with steroid injection (n = 99). Follow-up rates at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation were between 85% and 89%, above the target of 80% assumed in the sample size and with no evidence of differential dropout in any of the treatment arms. The primary analysis at 12-month follow-up included all participants with OSS outcome data at one or more follow-ups, and therefore 94% of participants could be included in the analysis.

Baseline characteristics

Eligible patients who did and eligible patients who did not consent to participate in the trial were comparable in their baseline characteristics (Table 2). The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants at baseline are presented in Table 3, comparing the profile of the total patients randomised (n = 503) with that of participants included in the primary analysis (n = 473). No systematic differences between the two populations were evident. The characteristics of patients in the three randomised arms were broadly similar, with the exception of a greater number of participants in the MUA arm being currently in paid work and some group imbalance in having had a similar shoulder problem on the opposite side to the reference shoulder.

| Characteristic | Eligible but non-consenting (N = 295) | Eligible and randomised (N = 503) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 200 (68) | 319 (63) |

| Age (years) | ||

| n | 293 | 503 |

| Mean (SD) | 53.7 (8.0) | 54.3 (7.7) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 53 (32, 82) | 54 (30, 77) |

| Diabetic, n (%) | ||

| No | 219 (74) | 353 (70) |

| Type 1 | 23 (8) | 29 (6) |

| Type 2 | 51 (17) | 121 (24) |

| Missing | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Affected shoulder, n (%) | ||

| Left | 181 (61) | 304 (60) |

| Right | 110 (37) | 196 (39) |

| Missing | 4 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Duration of symptoms (months) | ||

| n | 288 | 495 |

| Mean (SD) | 10.5 (7.0) | 10.9 (9.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 9 (6–12) | 8 (6–12) |

| Minimum, maximum | 1, 48 | 0, 96 |

| Duration of symptoms (grouped), n (%) | ||

| < 9 months | 135 (46) | 249 (50) |

| ≥ 9 months | 153 (52) | 246 (49) |

| Missing | 7 (2) | 8 (2) |

| Characteristic | As randomised (N = 503) | As analysed (N = 473) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MUA | ACR | ESP | MUA | ACR | ESP | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Female | 129 (64) | 126 (62) | 64 (65) | 121 (64) | 117 (61) | 62 (67) |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| n | 201 | 203 | 99 | 189 | 191 | 93 |

| Mean (SD) | 54.5 (7.7) | 53.9 (7.7) | 54.5 (7.8) | 54.4 (7.3) | 54.4 (7.6) | 54.8 (7.8) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 54 (30, 75) | 54 (33, 76) | 53 (39, 77) | 54 (30, 75) | 55 (33, 76) | 53 (39, 77) |

| Diabetic, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 141 (70) | 143 (70) | 69 (70) | 131 (69) | 135 (71) | 66 (71) |

| Type 1 | 12 (6) | 12 (6) | 5 (5) | 12 (6) | 11 (6) | 5 (5) |

| Type 2 | 48 (24) | 48 (24) | 25 (25) | 46 (24) | 45 (24) | 22 (24) |

| Affected shoulder, n (%) | ||||||

| Left | 127 (63) | 121 (60) | 56 (57) | 119 (63) | 114 (60) | 54 (58) |

| Right | 73 (36) | 80 (39) | 43 (43) | 69 (37) | 75 (39) | 39 (42) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Duration of symptoms (months) | ||||||

| n | 196 | 201 | 98 | 185 | 190 | 92 |

| Mean (SD) | 10.5 (8.6) | 11.3 (10.0) | 10.8 (8.8) | 10.7 (8.7) | 11.3 (10.1) | 11.0 (9.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 8 (6–12) | 9 (6–12) | 8 (6–12) | 8 (6–12) | 9 (6–12) | 8 (6–12) |

| Minimum, maximum | 2, 60 | 0, 96 | 2, 72 | 2, 60 | 2, 96 | 2, 72 |

| Duration of symptoms (grouped), n (%) | ||||||

| < 9 months | 103 (51) | 95 (47) | 51 (52) | 96 (51) | 90 (47) | 48 (52) |

| ≥ 9 months | 93 (46) | 106 (52) | 47 (47) | 89 (47) | 100 (52) | 44 (47) |

| Missing | 5 (2) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 4 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Radiographs, n (%) | ||||||

| Anteroposterior view | 200 (100) | 201 (99) | 99 (100) | 188 (99) | 190 (99) | 93 (100) |

| Axillary view | 174 (87) | 179 (88) | 86 (87) | 163 (86) | 169 (88) | 80 (86) |

| Modified axillary | 29 (14) | 24 (12) | 14 (14) | 27 (14) | 24 (13) | 14 (15) |

| Ethnicity summary, n (%) | ||||||

| White British | 187 (93) | 185 (91) | 84 (85) | 176 (93% | 175 (92) | 80 (86) |

| Other | 13 (6) | 17 (8) | 15 (15) | 12 (6) | 15 (8) | 13 (14) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) |

| Education, n (%) | ||||||

| Left school before 16 years old | 33 (16) | 28 (14) | 15 (15) | 31 (16) | 26 (14) | 14 (15) |

| Left school at 16 years old | 75 (37) | 74 (37) | 37 (37) | 70 (37) | 71 (37) | 34 (37) |

| Left education at 18 years old | 27 (13) | 28 (14) | 14 (14) | 25 (13) | 26 (14) | 12 (13) |