Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/192/90. The contractual start date was in July 2016. The draft report began editorial review in January 2019 and was accepted for publication in December 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Hall et al. This work was produced by Hall et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 The authors

Chapter 1 Introduction

Acute appendicitis is the most common surgical emergency in children. 1 The lifetime risk of developing appendicitis is 7–8% and the most common age point for developing appendicitis is the early teens. Appendicectomy is considered by most surgeons to be the gold-standard treatment for acute appendicitis. As a result, in 2017–18, there were 8105 emergency appendicectomies in England in children aged < 16 years.

Although appendicectomy is usually a simple procedure, it requires a general anaesthetic and an abdominal operation with inherent risks. Many parents find the proposal that their child needs emergency surgery frightening, and one that they are keen to avoid if an alternative is available. Work we undertook with patients and their families before the current study confirmed this. Families frequently ask ‘Does my child really need an operation?’.

An additional burden of paediatric appendicitis is the financial aspect. Treatment of children with appendicitis in England costs in excess of £21M per year. Appendicectomy also requires significant resource use, including need for out-of-hours surgery (45% of all paediatric appendicectomies are performed between 18.00 and 08.00).

An alternative approach to the treatment of children with acute appendicitis is treatment with antibiotics, without an appendicectomy. Although there is growing scientific interest in the use of non-operative treatment with antibiotics, we do not yet know whether or not this approach is safe and effective. However, there are several potential benefits of a non-operative approach over surgery, including:

-

avoiding the trauma, physiological stress, psychological distress and physical scarring of an operation

-

avoiding complications as a result of surgery or general anaesthesia

-

reduced NHS resource use with the potential for significant savings if non-operative treatment is effective.

However, such an approach would be acceptable only if antibiotic treatment is safe, if it is successful in the majority of cases and if the risk of recurrent appendicitis is low.

Although it has been known for some time that acute appendicitis can been treated successfully with antibiotics alone, in the context of remote environments without surgical service capability,2 the role of non-operative treatment as primary therapy within an established health-care system has only recently come under consideration. This was initially in adults,3–10 and only more recently in children. 11–13 Although a number of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted among adults with acute appendicitis, extrapolating the findings of research in adults to children is problematic as there are key differences in appendicitis occurring in adults compared with children. Paediatric-specific research is necessary because appendicitis presents differently in children and adults. The intra-abdominal inflammatory response of adults is different to that of children;14,15 the inflammatory response in children may be more amenable to antibiotic treatment alone, and the psychosocial and economic impacts of appendicitis in children affect the whole family, rather than just the individual.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the existing literature relating to non-operative treatment of appendicitis in children was undertaken prior to this study. 16 This identified 10 articles reporting just 413 children who received non-operative treatment. There was just one RCT, which was a pilot RCT, and therefore was not powered to compare the efficacy of non-operative treatment with that of surgery, but was conducted to inform the design of a large multicentre RCT, including North America, that is currently recruiting.

The systematic review concluded that further research into the clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness of non-operative treatment compared with appendicectomy in the form of RCTs was needed to inform future decision-making for this group of patients. Importantly, none of the existing studies of non-operative treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis in children has identified any safety concerns regarding the intervention. 11,13,17–20

Given the current clinical interest, the evidence of the success of non-operative treatment and clear demand from patients, we believe that the time is right for a well-designed trial comparing non-operative treatment, namely antibiotics, with appendicectomy for acute uncomplicated appendicitis in children. However, prior to this, we identified a need for a feasibility study to inform the design and delivery of such a trial. A number of factors mean that a feasibility study is prudent prior to committing the resources to a full effectiveness trial. Such factors include a lack of experience of non-operative treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis in the UK, meaning that surgeons may not be willing to recruit; a challenging recruitment profile (children with appendicitis present to hospital as an emergency, often out of routine working hours and at the weekend), meaning that specific arrangements would have to be put in place to enable recruitment; a complex pattern of outcomes of interest to different stakeholder groups, meaning that identification of a primary outcome for an effectiveness trial is not clear; and a need to engage with relevant stakeholders to optimise the design and delivery of a trial.

We therefore designed a feasibility study, the aim of which was to answer the research question: is it feasible and acceptable to conduct a multicentre RCT testing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a non-operative treatment pathway for the treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis in children?

The specific objectives of this initial feasibility study were to:

-

assess the willingness of parents and children to be enrolled in, and surgeons to recruit to, a randomised trial comparing operative with non-operative treatment and to identify anticipated recruitment rate

-

identify strategies to optimise surgeon–family communication to inform the future RCT

-

enhance the design of a future RCT from the perspectives of stakeholders at participating sites (children, parents, surgeons and nurses)

-

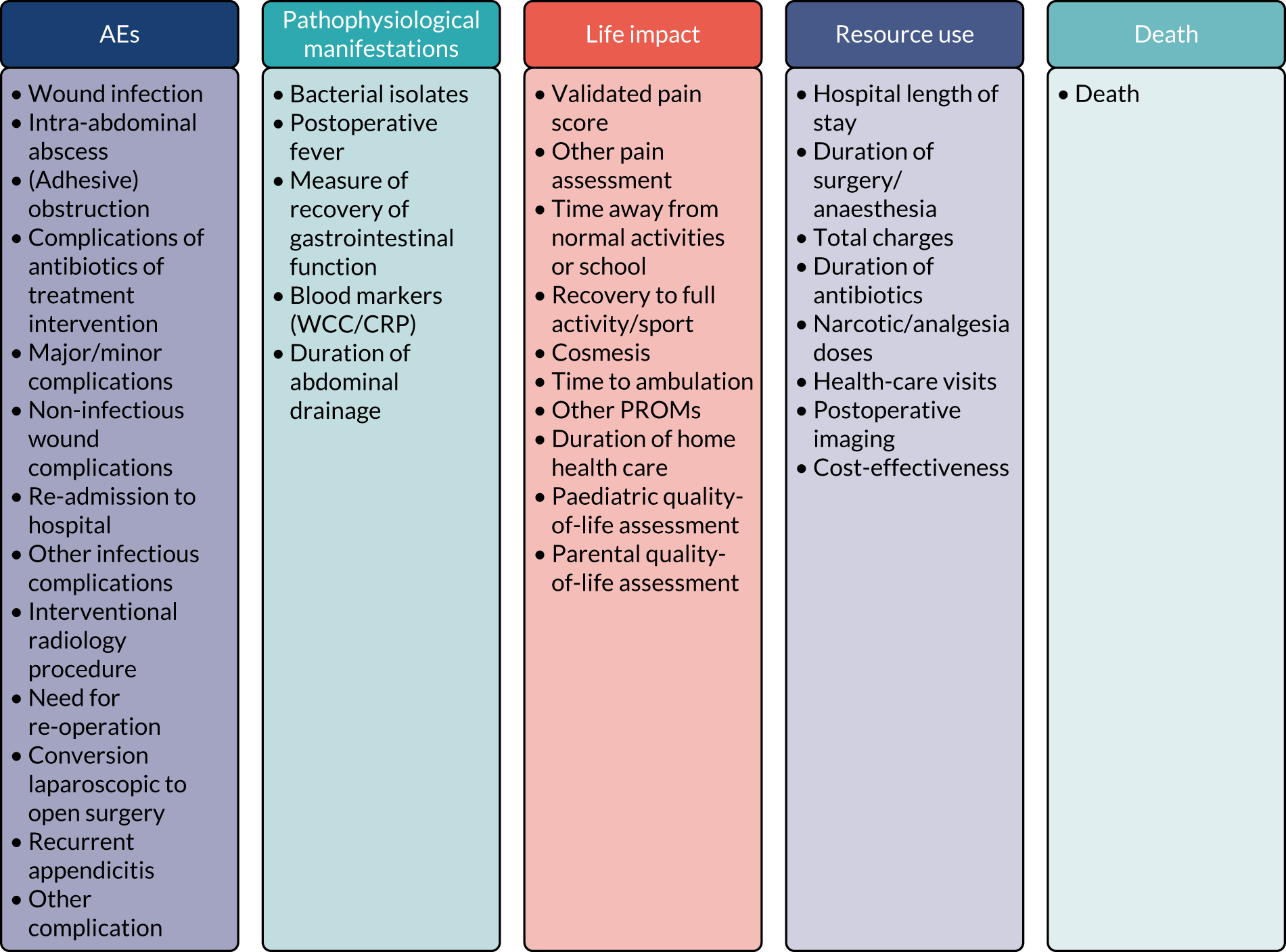

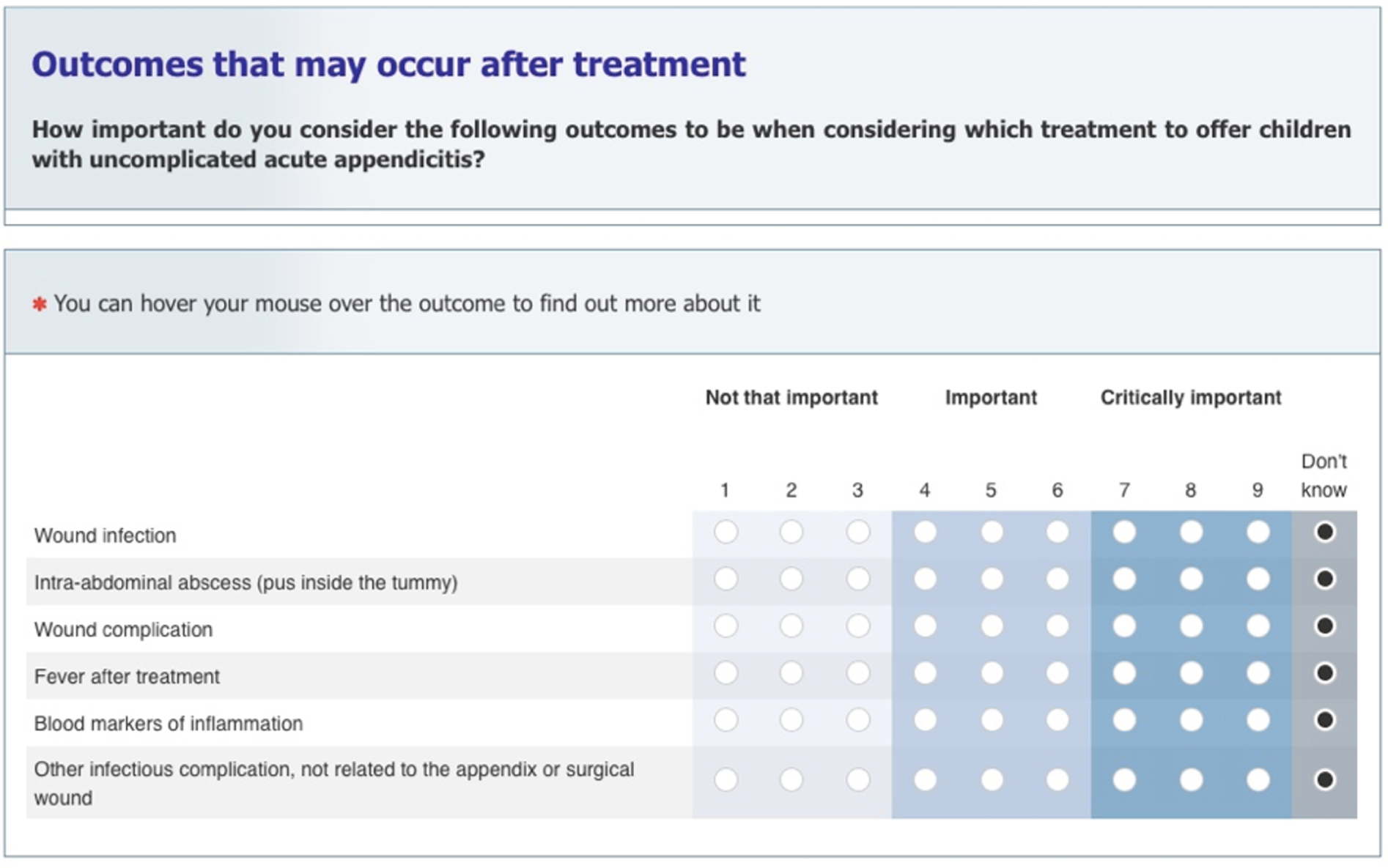

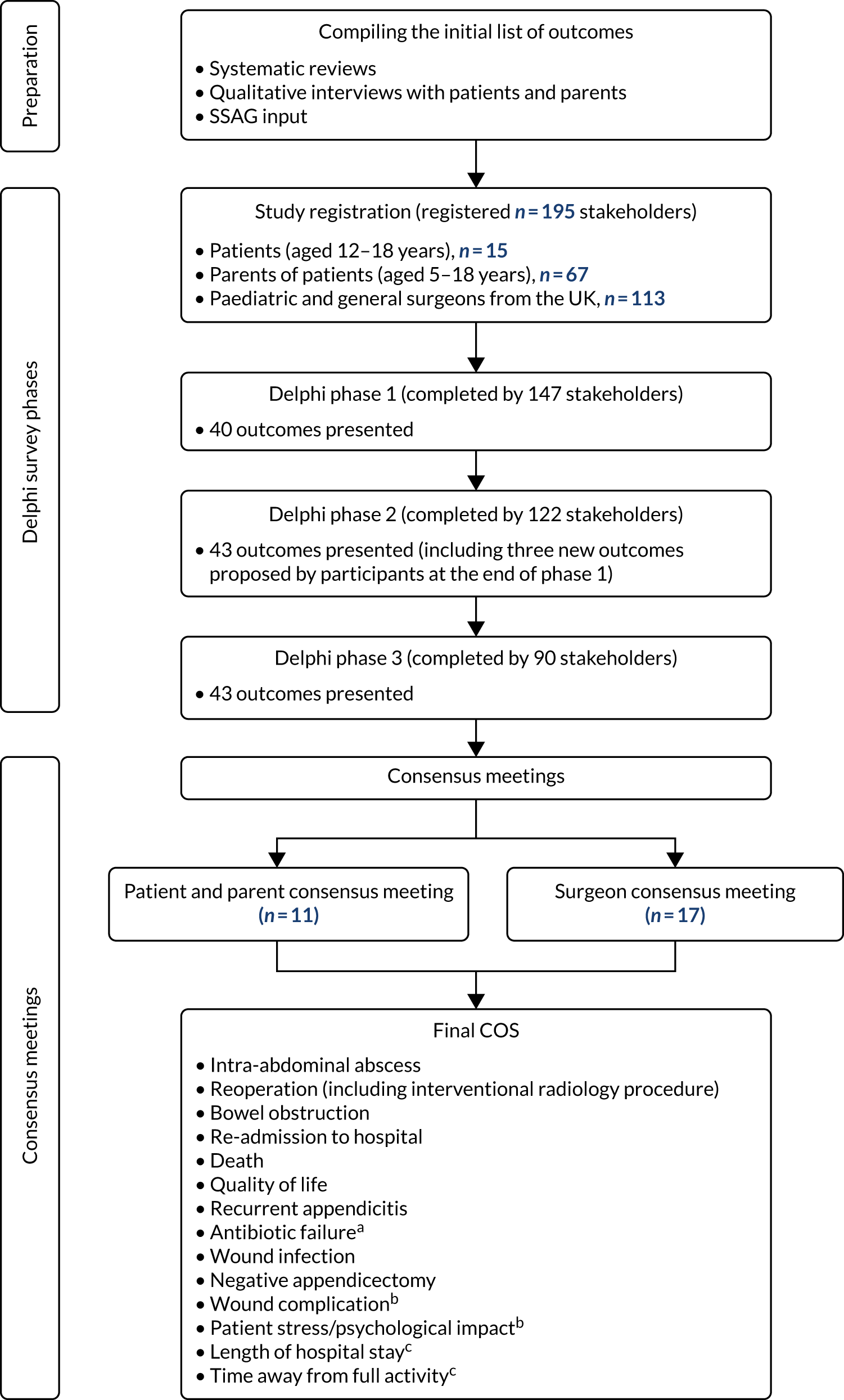

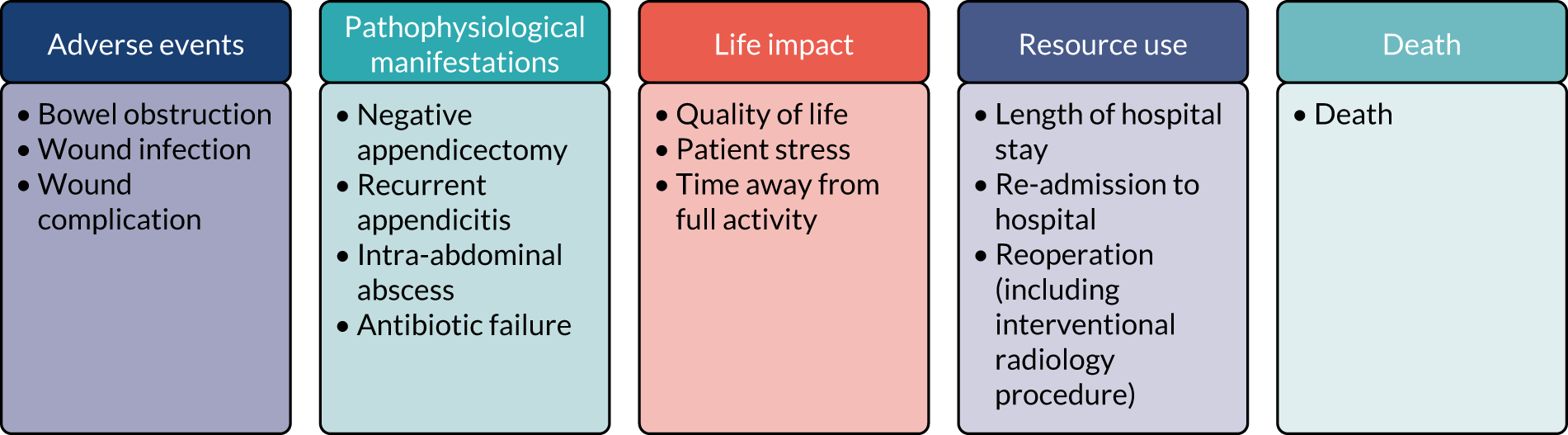

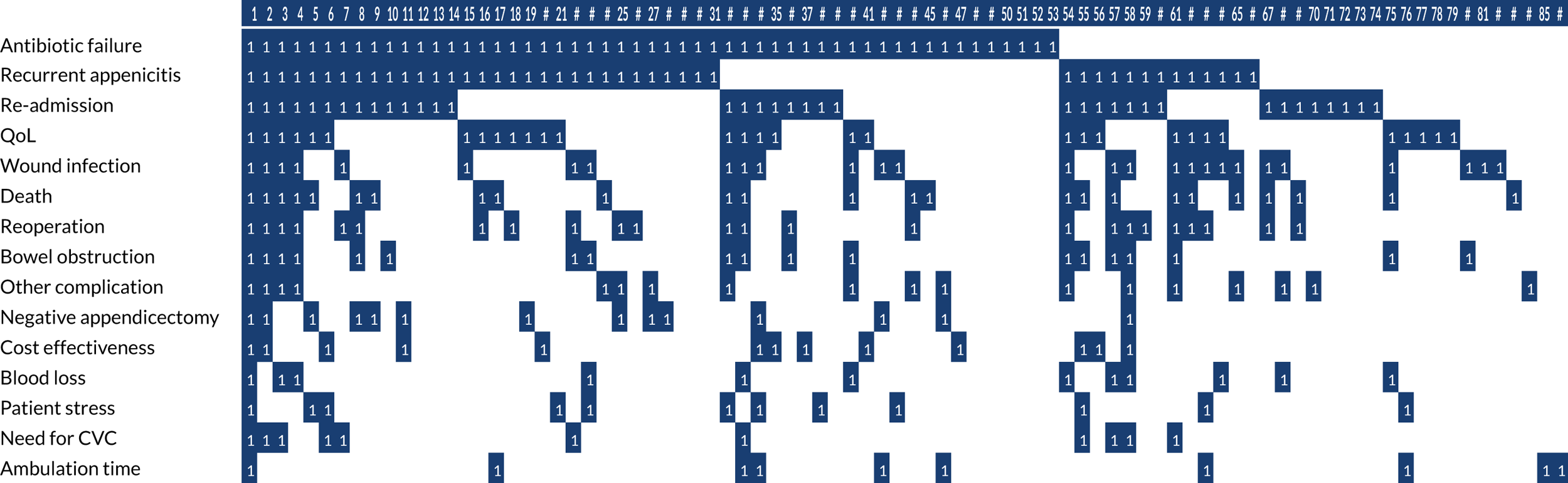

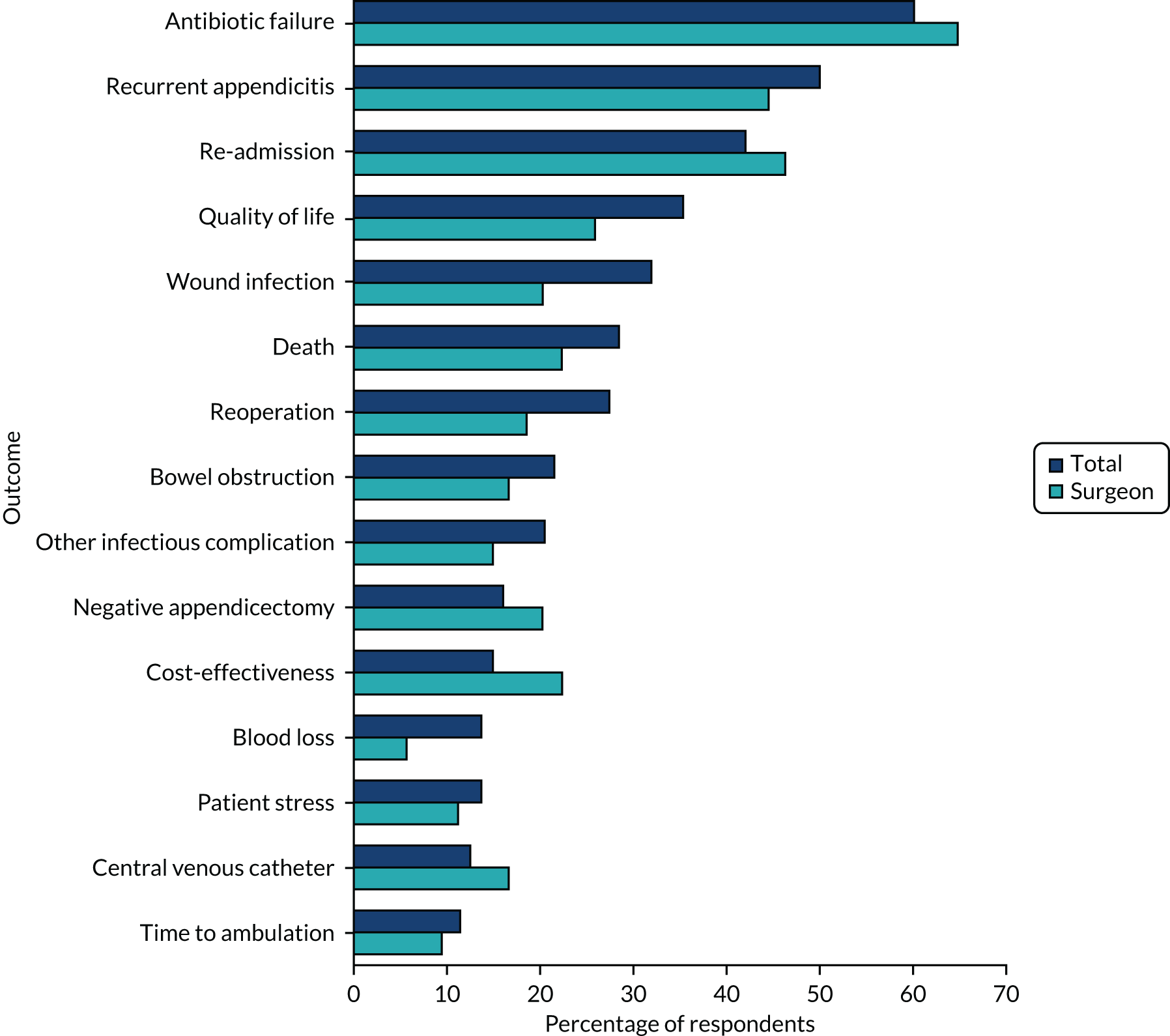

identify what core outcomes family members and surgeons regard as important to measure in a future RCT and to develop a core outcome set (COS)

-

assess the equipoise and willingness of UK paediatric surgeons to participate in a future RCT

-

generate data to allow for the design of a definitive RCT, including sample size calculation and identification of key cost drivers and other parameters necessary to perform a full economic analysis

-

examine clinical outcomes of children with acute appendicitis treated without an operation, including an initial assessment of efficacy and safety of this treatment pathway in our centres

-

ensure that the whole of the research programme is well informed by a group of children and parents [the study-specific advisory group (SSAG)].

The CONservative TReatment of Appendicitis in Children a randomised controlled Trial (CONTRACT) feasibility study comprised a number of inter-related elements, carefully designed to fulfil the following objectives:

-

A randomised controlled feasibility trial of children with appendicitis comparing a non-operative treatment pathway with appendicectomy.

-

A detailed programme of embedded qualitative and quantitative research to optimise recruitment to the feasibility RCT. This was designed to inform the design and conduct of any future RCT of non-operative treatment versus appendicectomy in the treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis in children.

-

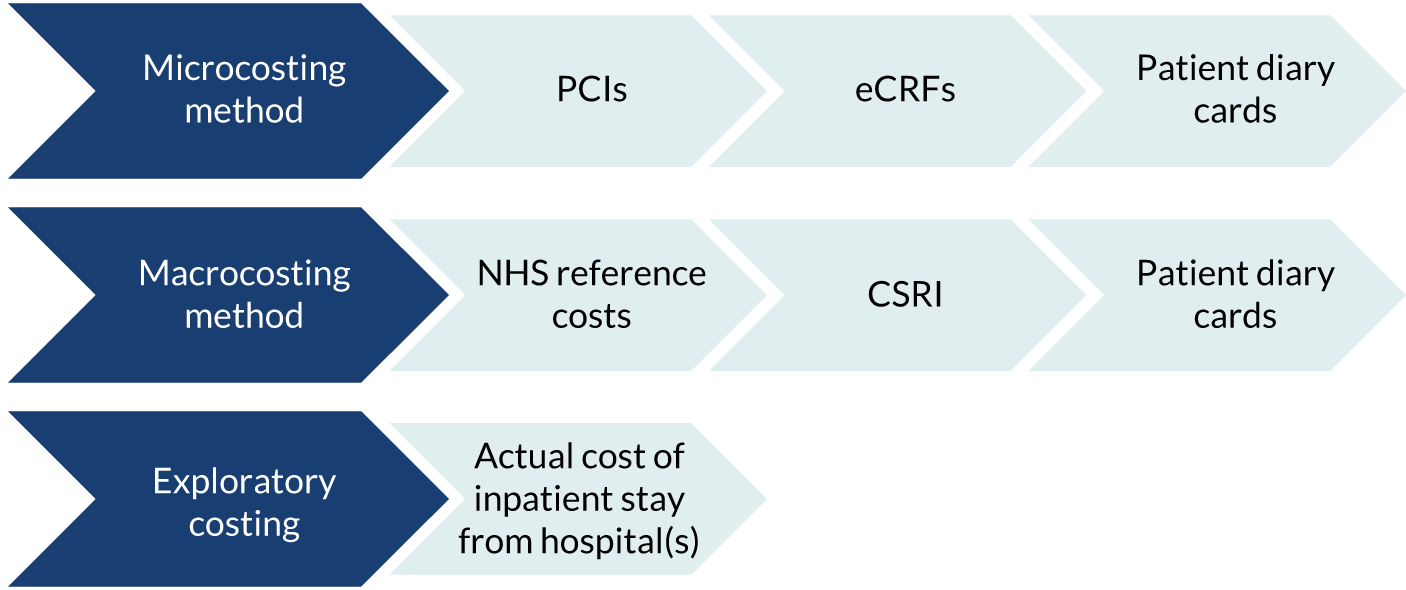

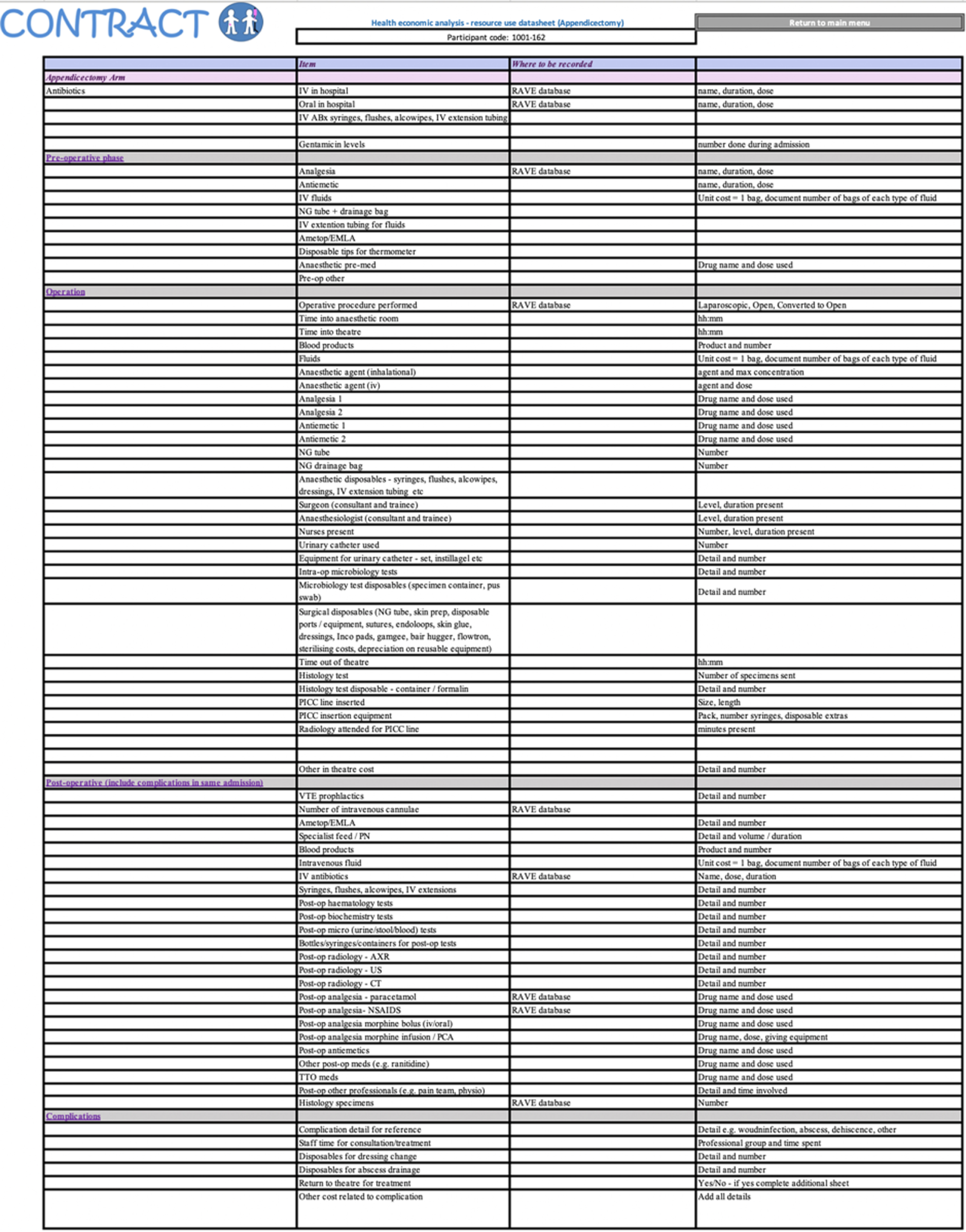

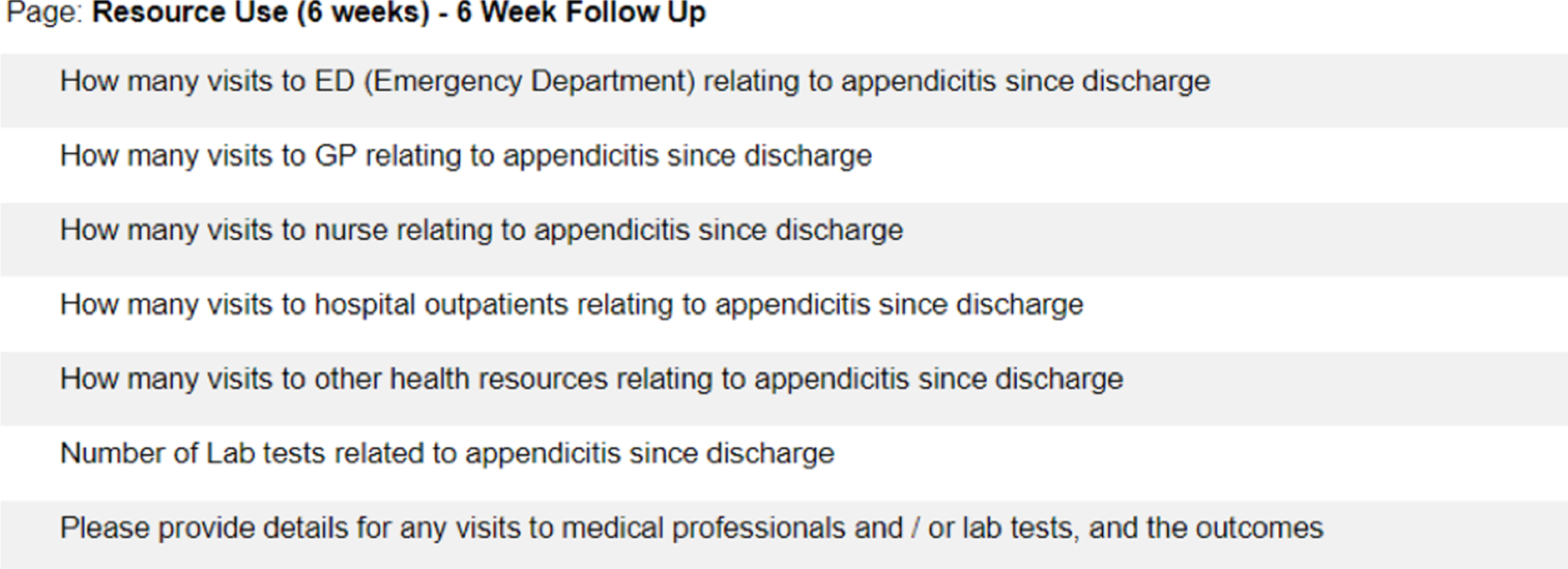

A health economics feasibility study to allow the identification of key cost drivers and other parameters necessary to perform a full economic evaluation in a future RCT. This included the design and piloting of data collection tools and the adoption of a microcosting approach.

-

The development of a COS for the treatment of children with uncomplicated acute appendicitis for use in the future RCT as well as the wider research community.

-

A patient and public involvement (PPI) workstream that reciprocally fed into elements 1, 2 and 4 (above). A SSAG was formed, made up of children who have had acute uncomplicated appendicitis, children who have not and parents.

Chapter 2 Methods of the feasibility randomised controlled trial

This chapter is focused on the methodology of the clinical component of the feasibility RCT. The methodology of the other elements of the wider study is described in the relevant later chapters.

Trial design

We performed a prospective feasibility RCT comparing appendicectomy with non-operative treatment in children with acute uncomplicated appendicitis. Recruitment lasted for 12 months and was open in three specialist paediatric surgery centres in England.

Participants

Participants were children aged 4–15 years inclusive with a clinical diagnosis of acute appendicitis, who would normally be treated with an appendicectomy as part of their standard care.

Inclusion criteria

-

Children aged 4–15 years.

-

Clinical diagnosis, either with or without radiological assessment, of acute appendicitis that, prior to study commencement, would be treated with appendicectomy.

-

Written informed parental consent, with child assent if appropriate.

Exclusion criteria

-

Clinical signs or radiological findings to suggest perforated appendicitis.

-

Presentation with appendix mass.

-

Previous episode of appendicitis or appendix mass treated non-operatively.

-

Major anaesthetic risk precluding allocation to the appendicectomy arm.

-

Known antibiotic allergy preventing allocation to the non-operative treatment arm.

-

Antibiotic treatment started at referring institution (defined as two or more doses administered).

-

Cystic fibrosis.

-

A positive pregnancy test.

-

Current treatment for malignancy.

Interventions

Non-operative treatment arm

Children randomised to non-operative treatment were treated according to a clinical pathway designed specifically for this trial. This treatment pathway comprised fluid resuscitation, a minimum of 24 hours of broad-spectrum intravenous (i.v.) antibiotics (per local antimicrobial policy), a minimum of 12 hours of nil by mouth (NBM) and regular clinical review to detect signs and symptoms of significant clinical deterioration, including, but not limited to, increasing fever, increasing tachycardia and increasing tenderness. After the initial 12-hour period of NBM, oral intake was advanced as tolerated. Children successfully treated without an operation were converted to oral antibiotics (per local policy) once they were afebrile for 24 hours and tolerating oral intake.

Clinical reviews were completed at approximately 24 and 48 hours post randomisation. Any children who showed signs of significant clinical deterioration by 24 hours, or at any point during the trial, were treated with appendicectomy. Children who were considered stable or improving continued with non-operative treatment. At 48 hours, any child who had not shown clinical improvement underwent an appendicectomy. The decision to continue non-operative treatment at these time points, or to recommend discontinuation of non-operative treatment and to recommend appendicectomy instead, was made by the treating consultant and based on clinical judgement rather than any specific features that are not evidence based. All reasons for a change in treatment were recorded in detail to guide a clinical pathway in a future trial.

Any child who received an appendicectomy for an incomplete response to non-operative treatment followed a standardised postoperative treatment regime already in use at each institution and identical to that used in the appendicectomy arm. The reason for having an appendicectomy was recorded.

Children treated non-operatively received a total of 10 days of antibiotics following randomisation, unless decided otherwise by the treating clinician. Children who received non-operative treatment were not routinely offered interval appendicectomy, but were counselled about the risk of recurrence.

Appendicectomy treatment arm

Children randomised to the appendicectomy arm underwent either open or laparoscopic appendicectomy at the surgeon’s discretion, performed by a suitably experienced trainee (as per routine current practice) or a consultant.

Participants received i.v. antibiotics from the time of diagnosis and were treated postoperatively with i.v. antibiotics according to existing institutional protocols; however, the following recommended regime was used to guide practice: children with acute uncomplicated appendicitis or a macroscopically normal appendix received no further antibiotics. Children with a perforated appendix (defined as a faecolith or faecal matter in the peritoneal cavity, or visualisation of a hole in the appendix) continued to receive i.v. antibiotics for a minimum of 3 days, and received a minimum total course of antibiotics of 5 days (i.v. and oral). The duration of antibiotic therapy was not standardised beyond this owing to anticipated variation in intraoperative findings and in response to treatment. The type of antibiotics used was identical to those used in the non-operative treatment arm in each centre. Any child failing to respond to first-line antibiotics was treated as was clinically appropriate with a longer course of antibiotics or a change in antibiotic therapy, with the choice of antibiotic determined by intraoperative swab or fluid culture.

Postoperatively, children with uncomplicated acute appendicitis or a normal appendix did not routinely have a nasogastric tube or a urinary catheter. They received oral intake as tolerated after surgery.

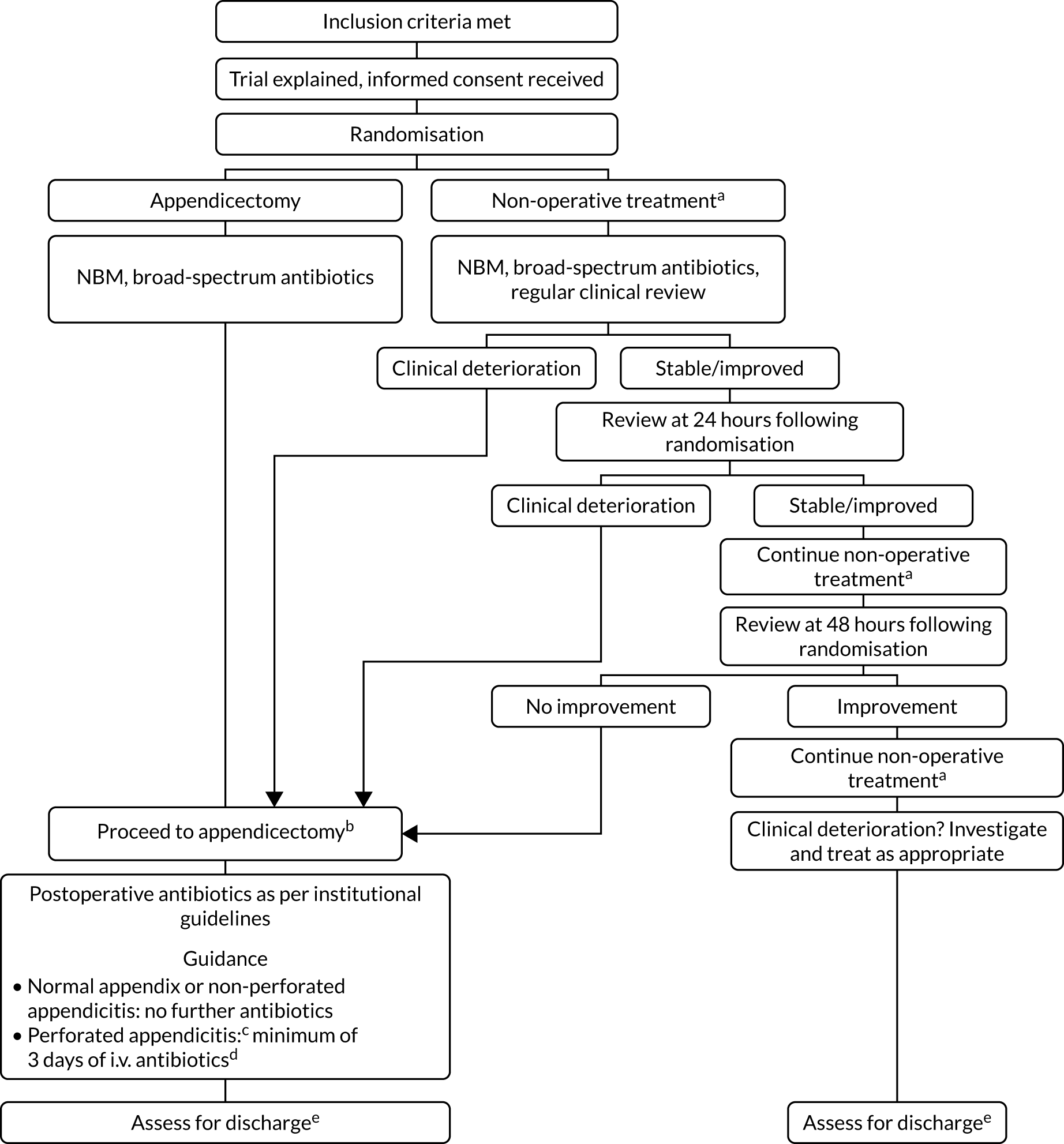

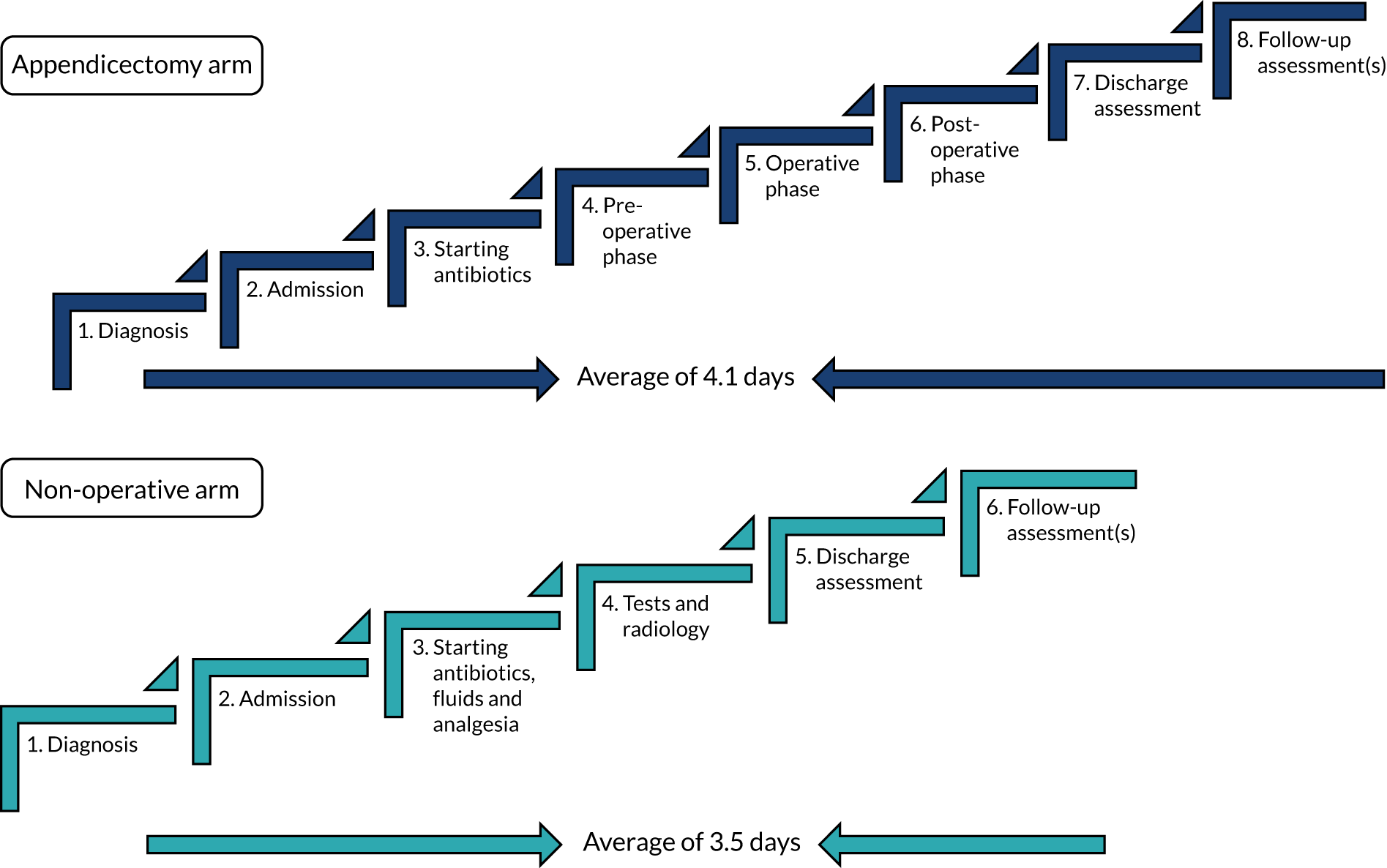

The participant flow through the two treatment arms is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the trial pathway. a, Non-operative treatment: NBM/sips for the initial 12 hours, minimum, then advance diet as tolerated; i.v. antibiotics for 24 hours, minimum, change to oral once afebrile for 24 hours, total course 10 days; and analgesia; b, appendicectomy group: no routine use of nasogastric tube or urinary catheter, advance diet as tolerates; c, defined as either seeing a hole in the appendix or seeing faecal matter/faecolith in the peritoneal cavity; d, continue i.v. antibiotics until afebrile for 24 hours, then change to oral; minimum 5 days total on antibiotics; e, criteria for discharge include vital signs within normal limits, tolerating light diet, adequate oral analgesia and mobile.

Discharge assessment

Criteria for discharge home were identical in both treatment arms and were as follows: vital signs within normal limits for age, afebrile for ≥ 24 hours, tolerating light diet orally, adequate oral pain relief and able to mobilise. We aimed to determine the feasibility of a blinded discharge assessment in a future RCT by attempting to complete a blinded discharge assessment for each participant as follows. Once a decision to discharge the child had been made, a member of the clinical team who had not been involved directly in the child’s treatment was asked to complete a discharge assessment. This assessor did not have prior knowledge of the randomisation or treatment received by the child. On completion of the discharge assessment, the assessor ‘guessed’ which treatment the child received. If the assessor became unblinded during the assessment, this was recorded.

Follow-up

All participants were given a diary card [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1419290/#/ (accessed February 2020)] to complete for the 14 days immediately following discharge from hospital and provided with a stamped addressed envelope to return this to the clinical trials unit on completion. This assessed whether or not the child had taken antibiotics and analgesia medication on each day following discharge, as well as an assessment of their recovery based on their ability to complete normal or full daily activities and attend school (if applicable). Finally, it also assessed whether or not parents had had to miss work as a result of their child’s illness. Follow-up appointments for all participants took place at 6 weeks and at 3 and 6 months following discharge, either in the outpatient clinic or in the clinical research facility at each centre. If a face-to-face appointment was not possible, the 3- and 6-month follow-ups were completed by telephone. Following an analysis of follow-up rates during the trial, we introduced an incentive in an attempt to improve follow-up rates. This was introduced in March 2018. All participants who attended all remaining follow-up visits from that point onwards were offered a £10 voucher.

Randomised controlled trial processes

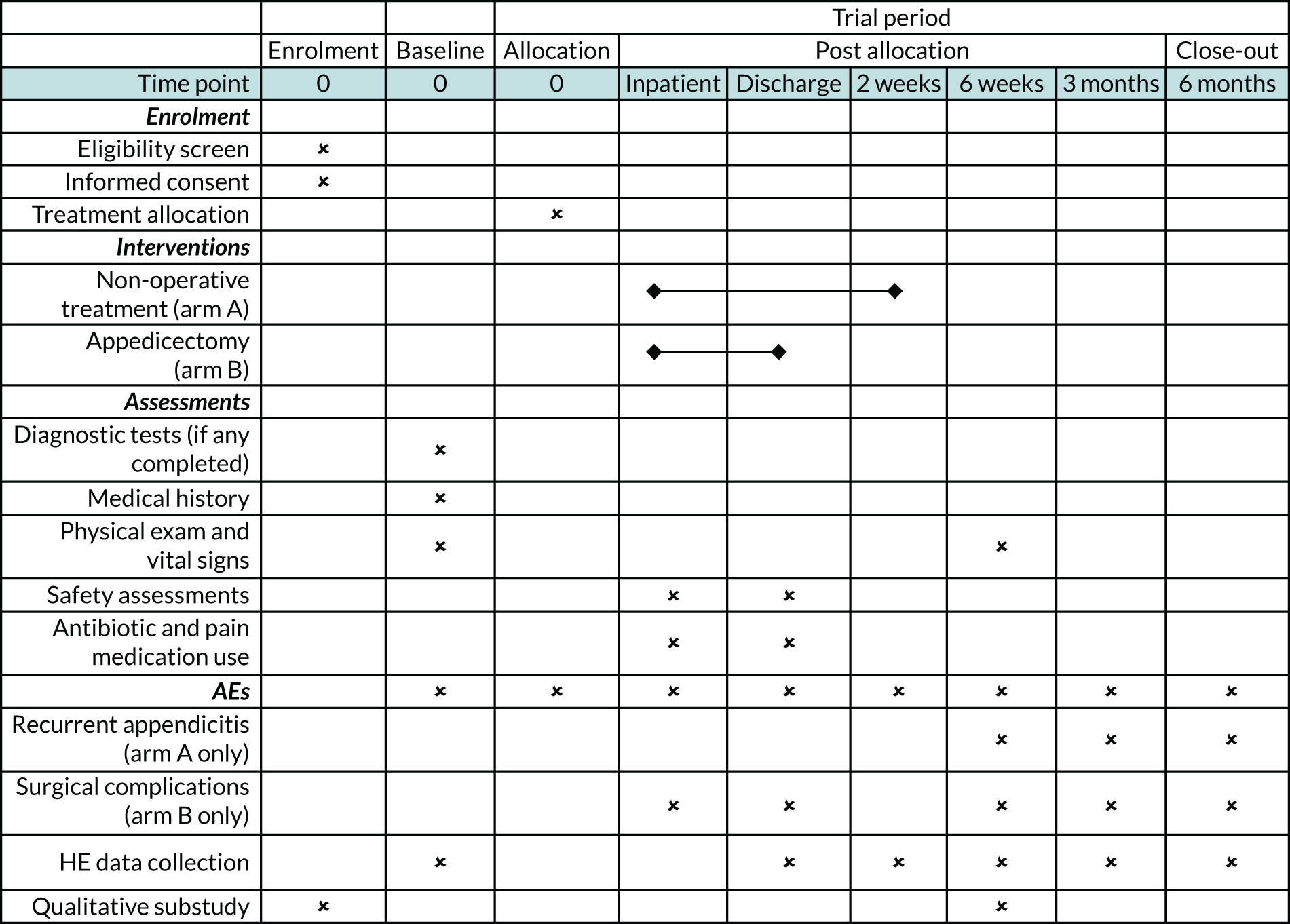

The schedule of enrolment, interventions and follow-up is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Overview of trial activity. AE, adverse event; HE, health economics.

Participant identification and recruitment

Participants were identified by the clinical team at the time of diagnosis and their eligibility was confirmed by the research team as soon as possible. Eligible patients were approached by the treating clinical teams with support from dedicated research nurses. Potential participants were provided with written information about the trial [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1419290/#/ (accessed February 2020) and shown a short video describing the study (see http://tinyurl.com/contract-f]. From the time of first discussing the trial with potential participants and their families, a maximum of 4 hours was permitted before a decision could be made regarding participation. This was to ensure that there was no delay in providing treatment as a result of considering trial participation. After receiving written informed consent (and assent from children aged ≥ 12 years who wished to give it), a member of the trial team randomised the participant to one of two treatment groups in a 1 : 1 ratio via an independent web-based system [TENALEA (Alea Clinical, Abcoube, the Netherlands)]. This online system allowed complete pre-randomisation concealment of treatment allocation and provided instant assignment to either the appendicectomy group or the non-operative treatment group. Minimisation was used to account for recruiting centre and to ensure balance between the groups in factors that may affect diagnostic accuracy and outcome of treatment. The factors taken into account were (1) sex, (2) age (4–8 years or 9–15 years), (3) duration of symptoms (onset of pain to recruitment to trial: < 48 hours or ≥ 48 hours) and (4) recruiting centre. In addition to the data required to complete randomisation, limited additional data were collected at baseline, including the use of any diagnostic imaging, and an Alvarado score21 (a scoring system used to help predict the severity of appendicitis) was calculated for each participant. This was used to provide an overview of the severity of illness of each child as a descriptive term; it was not used as a minimisation variable nor was a minimum Alvarado score used in the eligibility criteria.

Data collection and analysis

Data were recorded by dedicated research nurses at each site directly into an electronic, secure, web-based case report form (Medidata Rave® database; Medidata Solutions, Inc., New York, NY, USA). Data analysis was performed by the study statistician, who was blinded to treatment allocation by the use of coded data. As this is a feasibility study, all analyses were treated as preliminary and exploratory and data are reported descriptively. Feasibility outcomes (number of eligible patients, recruitment/retention rates, reasons for non-participation, success of blinding of the discharge assessor), treatment outcomes and complications are presented as simple summary statistics with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Clinical outcomes were compared between treatment groups in an exploratory analysis.

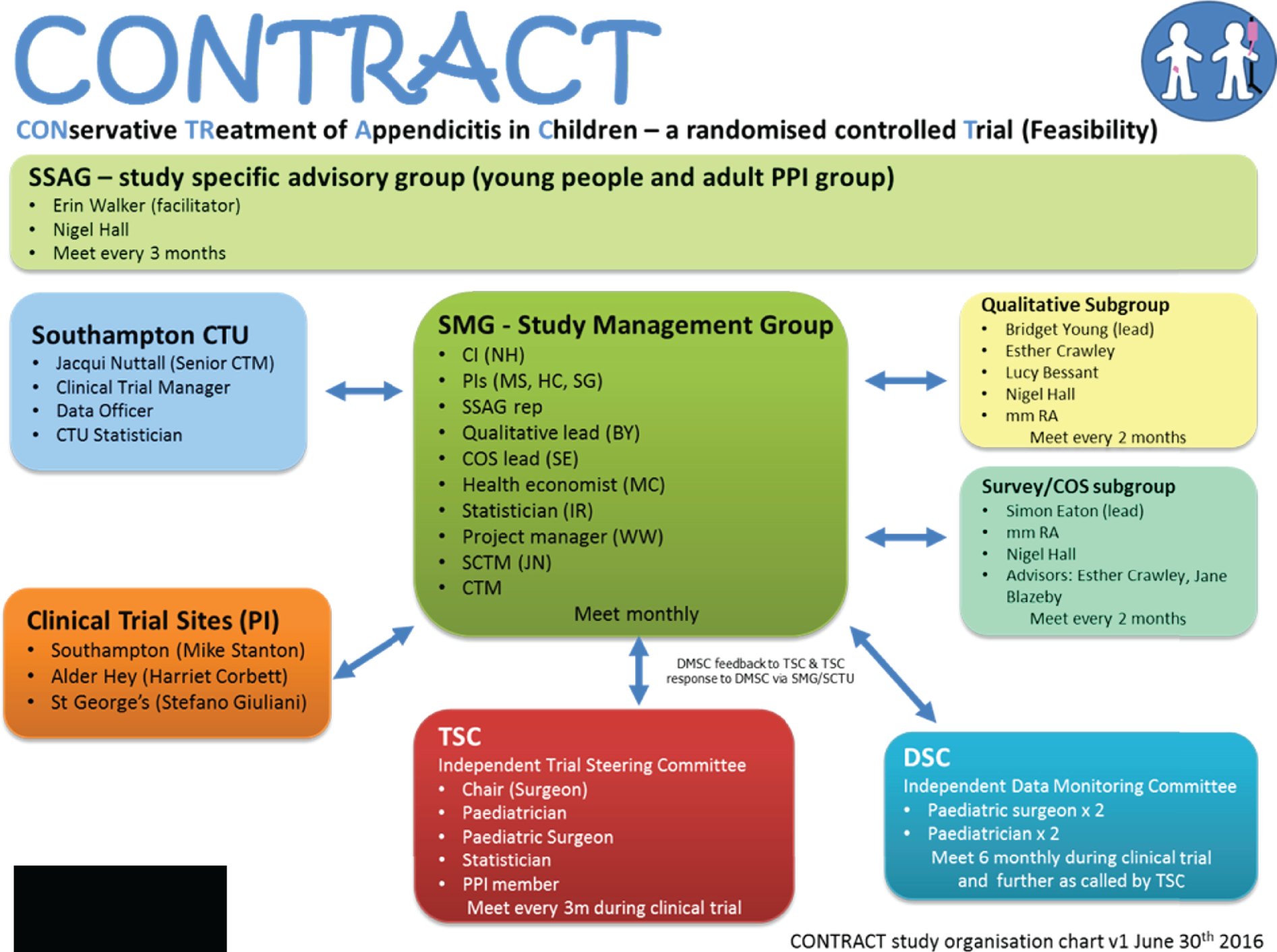

Trial oversight

A Study Management Group (SMG) was responsible for overseeing the day-to-day management of the trial. An independent Trial Steering Committee and Data Monitoring and Safety Committee were convened to provide oversight of the trial. Their roles and responsibilities, which included adverse event (AE) monitoring, were agreed at the beginning of the trial and documented in specific charters. Specific processes to report AEs in a timely manner to the relevant committee were agreed.

Protocol, registration and ethics approval

The trial was carried out in accordance with a published protocol22 that was developed in accordance with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials – Children (SPIRIT-C) guidance,23 and was registered prior to recruitment of the first participant (International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number: ISRCTN15830435). The overall study was given ethics approval by the Hampshire A Research Ethics Committee (reference number 16/SC/0596). The study is reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials 2010 statement. 24

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was to assess the feasibility of conducting a multicentre RCT testing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a non-operative treatment pathway for the treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis in children. This was evaluated as the proportion of eligible patients who were approached and recruited to the study over 12 months.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were predominantly centred on the qualitative and COS substudies, contributing to the development of a future RCT. Those specifically relating to the RCT are marked with an ‘*’:

-

*Determine the willingness of parents, children and surgeons to take part in a randomised trial comparing operative treatment with non-operative treatment, and identify the anticipated recruitment rate. This was assessed from audio-recorded family–surgeon recruitment consultations; interviews with patients, parents, surgeons and nurses; surgeon surveys; and focus groups.

-

Identify strategies to optimise surgeon–family communication using the consultation and interview data.

-

Design a future RCT from the perspectives of stakeholders at participating sites (children, parents, surgeons, nurses, etc.), informed by the consultation and interview data, surgeon surveys and focus groups.

-

Assess the equipoise and willingness of UK paediatric surgeons to participate in a future RCT through surgeon surveys and focus groups.

-

*Assess the clinical outcomes of trial treatment pathways, including (1) overall success of initial non-operative treatment (measured as the number of participants who were randomised to non-operative treatment and discharged from hospital without appendicectomy), (2) complications of disease and treatment (measured during hospital stay and during the 6-month follow-up period) and (3) the rate of recurrent appendicitis during the 6-month follow-up period.

-

*Assess the performance of the study procedures, including retention of participants for the duration of the trial and the feasibility of outcome-recording and data collection systems.

Sample size

Participants were recruited from three centres for 12 months. It was expected that each centre would treat 80–100 children with acute appendicitis per year, with an estimate that at least 130 would be eligible out of the 240–300 potential patients. As this was a feasibility study, we did not specify a specific sample size, but aimed to define our recruitment rate within an approximate 10% margin of error. Based on an anticipated study population available for recruitment of approximately 130 participants, we would be able to estimate a true 40% recruitment rate with a 95% CI of 31% to 49% and a true 50% recruitment rate with a 95% CI of 41% to 59%. These numbers of participants in the feasibility RCT would be adequate to test treatment pathway procedures, data collection methods and loss to follow-up.

Changes to the original protocol

Version 2, 10 April 2017

-

Minor clarification of serious adverse event (SAE) exceptions in section 6.2.1.

-

Addition of ISRCTN reference on front page.

Version 3, 4 July 2017

-

Change to co-investigator at St George’s Hospital.

-

Reference to online patient video access.

-

Consent process oversight by Southampton Clinical Trials Unit (SCTU).

-

Telephone consent process for qualitative substudy.

-

Specification of office hours for randomisation backup.

-

Timeline for questionnaire completion.

-

Time frame for AE reporting.

-

Update to COS protocol.

Version 4, 8 March 2018

-

Addition of an incentive during the follow-up stage of the trial.

Chapter 3 Feasibility randomised controlled trial results

Trial timelines and recruitment

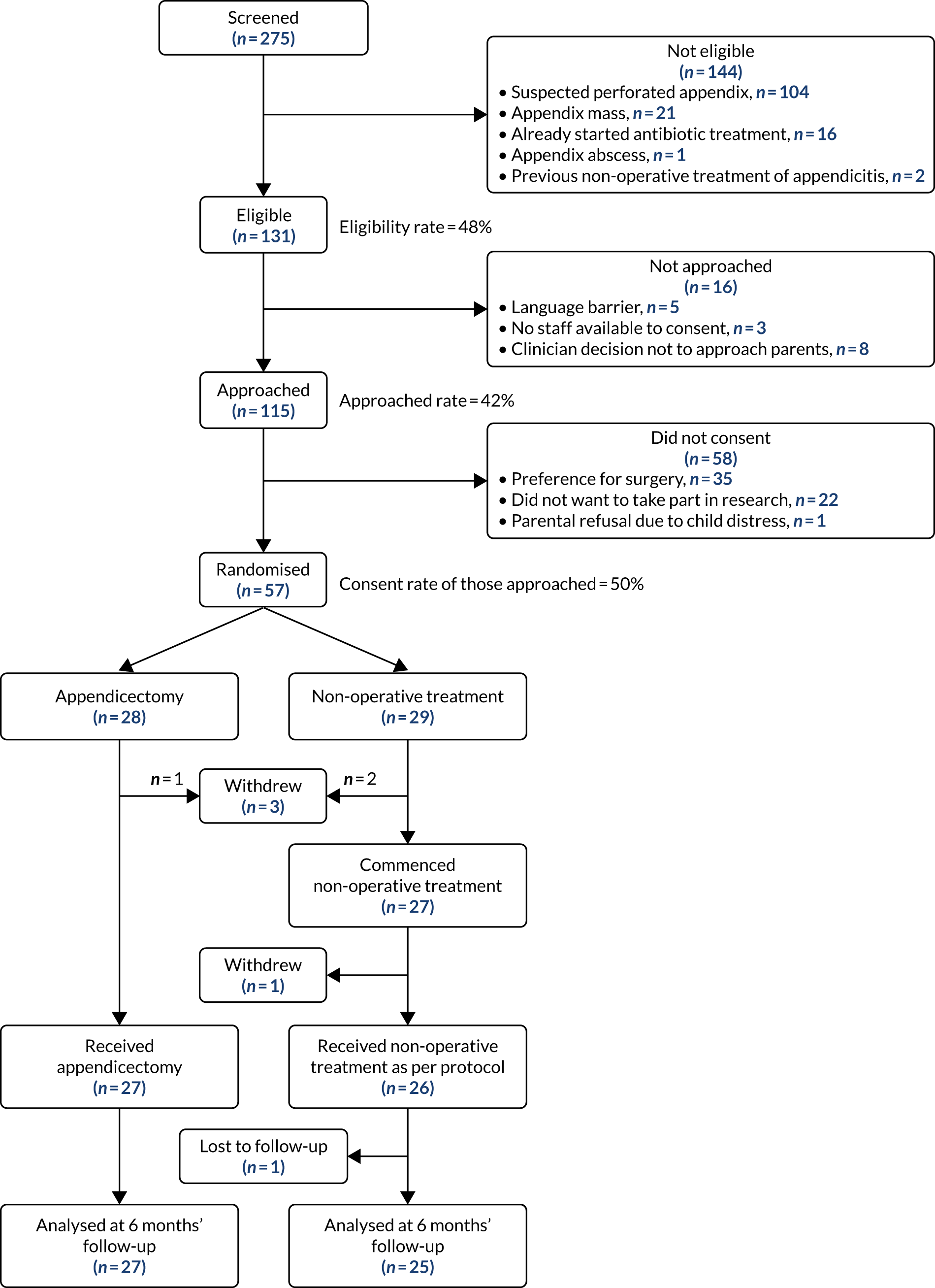

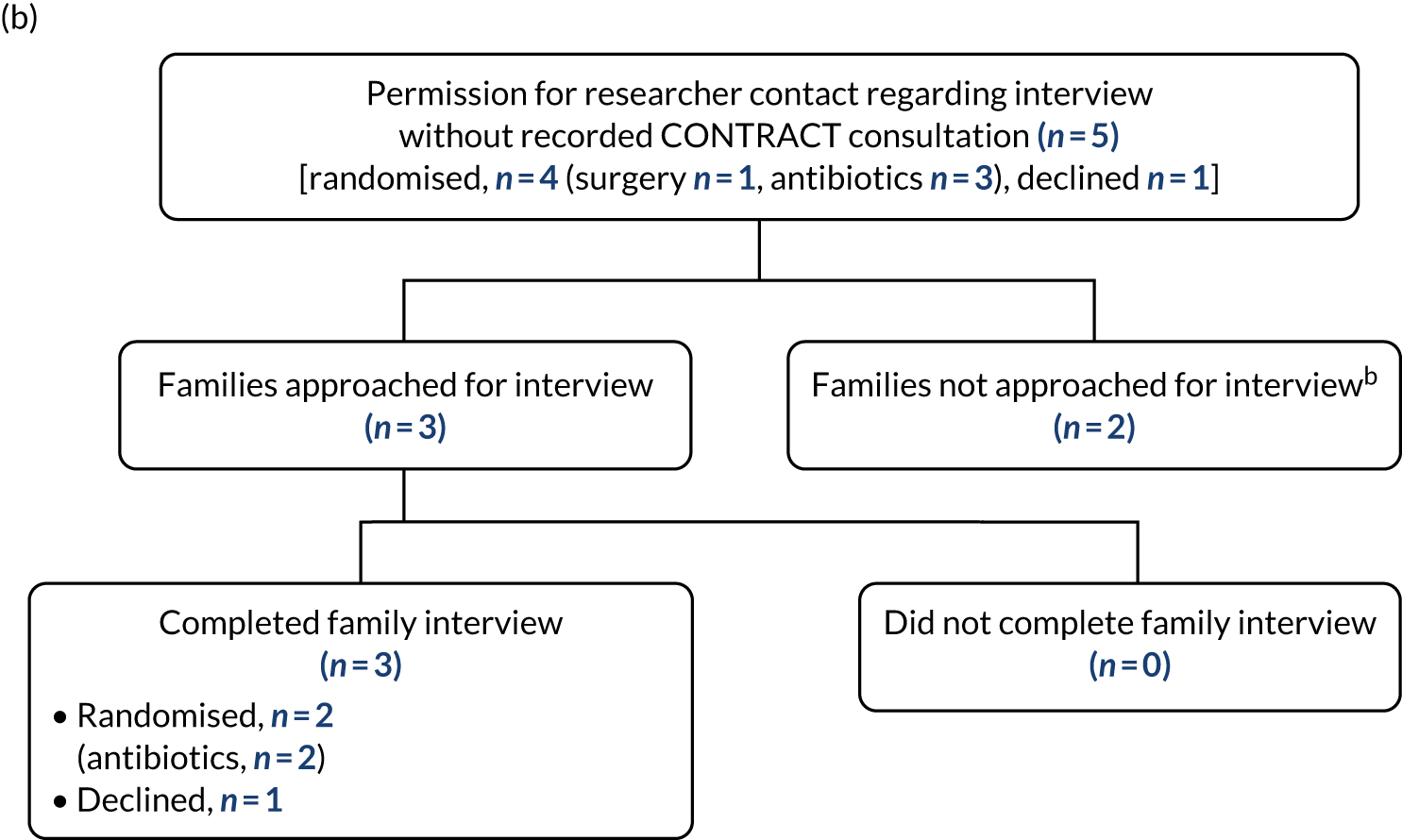

Pre-trial education and training visits, as well as site initiation visits, took place between December 2017 and February 2018. All three centres opened to recruitment simultaneously on 1 March 2017 at midnight. All three centres were open to recruitment for 12 months until midnight on 28 February 2018. During this time, a total of 275 children with acute appendicitis between the ages of 4 and 15 years, inclusive, presented to the three participating centres. Of these, 144 were ineligible for inclusion for the reasons shown in Figure 3. The remaining 131 children met the eligibility criteria for the CONTRACT feasibility RCT (48%, 95% CI 40% to 59%). Of these, 16 were not approached because they did not speak adequate English, no recruiting staff were available to approach the parents for consent or there was an active clinical decision not to approach the parents regarding the trial (typically in the presence of an additional medical comorbidity in the potential participant). A total of 16 children (12%) were therefore not approached despite meeting the eligibility criteria. The remaining 115 children (88% of those eligible) were all approached for participation in the trial: 57 agreed to participate and were successfully randomised. The remaining 58 did not consent to the trial because of a preference for surgical treatment (n = 35), because they did not want to take part in research (n = 22) or, in one case, because the parents were unable to consider the trial because they felt that their child was too distressed. Overall, 44% (57/131) of all eligible patients were recruited and the overall recruitment rate of those approached over the 12 months of the trial was 50% (95% CI 40% to 59%).

FIGURE 3.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram of the CONTRACT feasibility RCT.

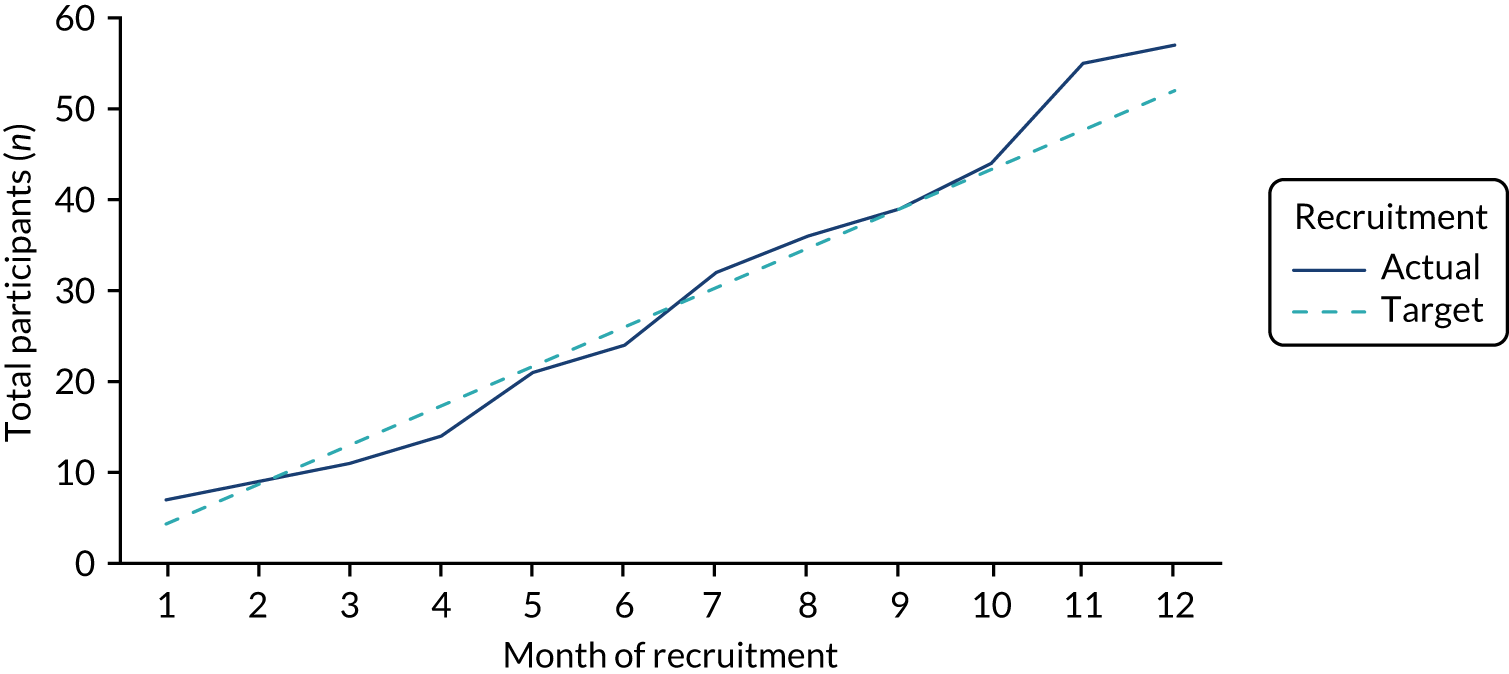

Feasibility of trial recruitment

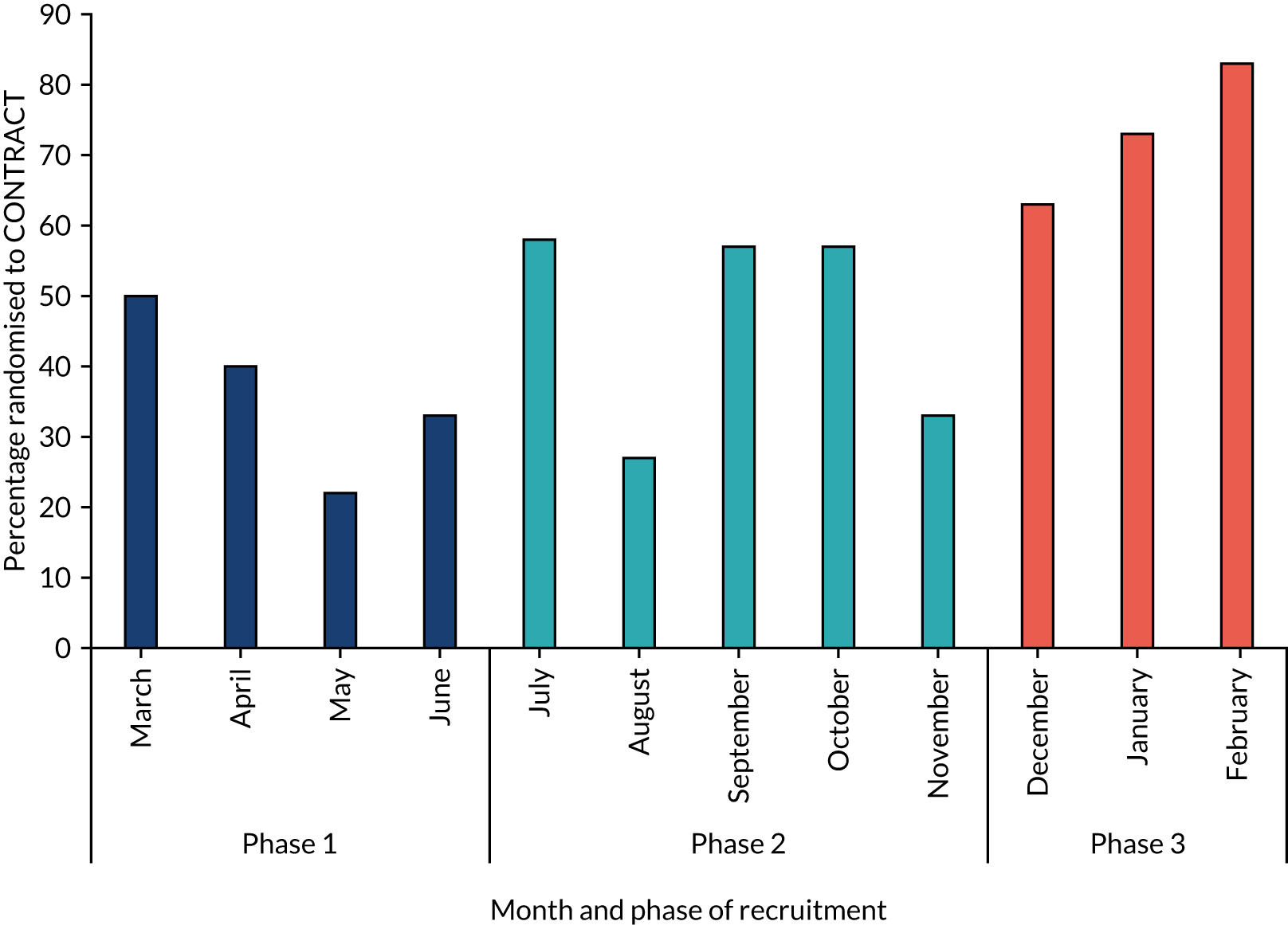

The first participant was recruited to the trial on 2 March 2017, and recruitment continued for the 12-month duration of the study, as shown in Figure 4. Although no formal recruitment target was set for this trial, based on the anticipated number of eligible participants and anticipated recruitment rate, we aimed to recruit 52 participants. Overall, the number of participants recruited to this feasibility trial exceeded this ‘target’, and the recruitment rate of 50% (95% CI 40% to 59%) was at the upper end of the pre-trial target recruitment range of 40–50%.

FIGURE 4.

Trial recruitment by month.

Following the initial recruitment training prior to the start of recruitment, further training was completed at all three centres in early July 2017 (month 5) and November 2017 (month 9). The relationship between retraining and recruitment rate is explored fully in Chapter 4. Recruitment rate during the initial 4 months of the trial was 38%, rose to 47% in months 5–9 and rose further to 72% in months 10–12.

Of note, all three centres were actively involved in screening and recruiting patients for the duration of the study (Table 1). The overall recruitment rate exceeded 40% at all three participating centres.

| Details | Total | Trial centre | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alder Hey | Southampton | St George’s | ||

| Total patients screened (n) | 275 | 145 | 78 | 52 |

| Eligible patients who entered trial (n) | 57 | 25 | 21 | 11 |

| Eligible patients who were approached but did not enter trial (n) | 58 | 27 | 16 | 15 |

| Recruitment rate (%) | 50 | 48 | 57 | 42 |

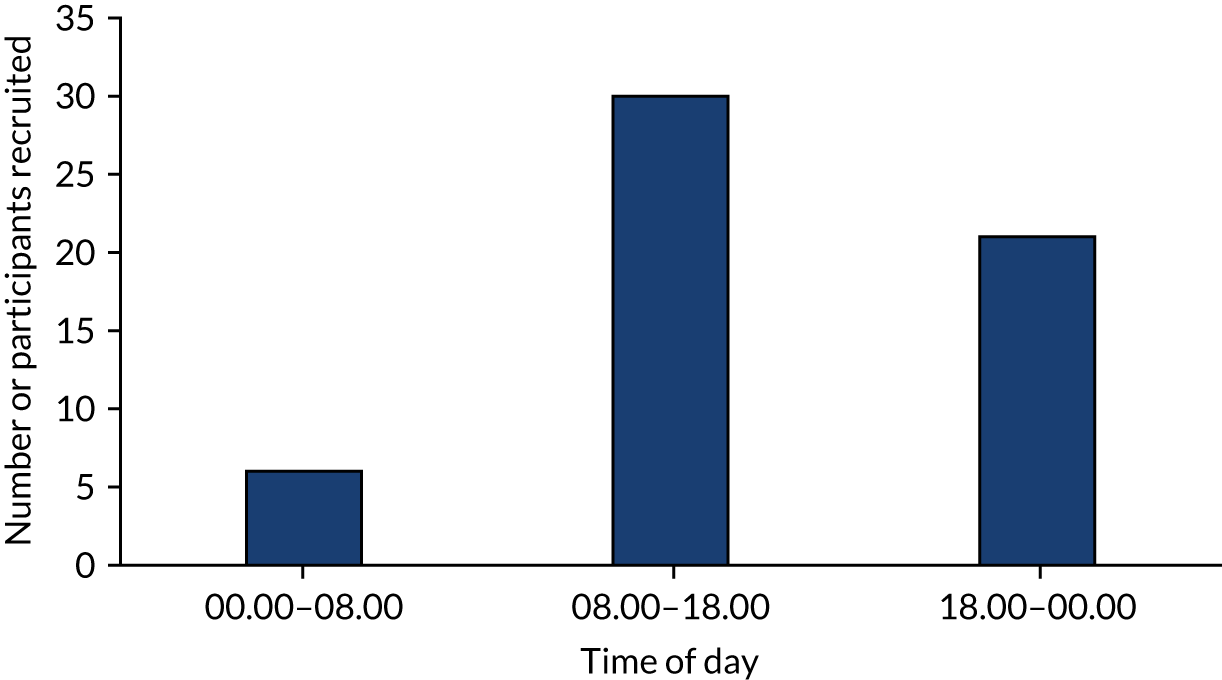

Of note, particularly in relation to the feasibility of a future trial, recruitment was successfully completed by over 21 different surgeons across the three centres. Furthermore, participants were successfully recruited to the trial outside normal working hours. Three-fifths of participants were recruited during working hours, and the remaining two-fifths were recruited either between the hours of 18.00 and 00.00 or between 00.00 and 08.00 (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Number of participants recruited at different times of day.

Adherence to treatment allocation and protocol, trial retention and other feasibility outcomes

Figure 3 shows participant flow through the clinical trial. Three participants withdrew consent soon after randomisation and formally withdrew from the trial. Reasons given for this were dissatisfaction with the treatment allocated (n = 2) and being too overwhelmed with the diagnosis to continue in the trial (n = 1). The remaining 27 participants in the appendicectomy arm and 27 participants in the non-operative treatment arm commenced the assigned intervention. All 27 participants in the appendicectomy arm received the treatment as allocated; there was one protocol deviation in the non-operative treatment arm: the parents of one child withdrew consent for the study and requested appendicectomy 8 hours after randomisation, but did not withdraw consent for continued data collection.

A total of 34 out of 54 eligible children (63%) underwent a blinded discharge assessment. For the remaining 20 children, this was not possible owing to non-availability of appropriate members of staff. Data relating to the blinded discharge assessment are shown in Table 2. In one case, the assessor was unblinded during the assessment. In the remaining cases for which an assumed treatment was provided, the assessment was correct in 61% (n = 20) of cases and incorrect in 39% (n = 13) of cases. This is not statistically significantly different from the 50% accuracy that one would anticipate achieving by chance alone (p = 0.28; chi-squared test).

| Actual treatment allocation | Assumed treatment by blinded assessor (n) | Unblinded (n) | Total (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appendicectomy | Non-operative treatment | |||

| Non-operative treatment | 6 | 13 | 0 | 19 |

| Appendicectomy | 7 | 7 | 1 | 15 |

| Total | 13 | 20 | 1 | 34 |

Following discharge, 26 out of 54 (48%) participants returned a diary card: 15 in the appendicectomy arm and 11 in the non-operative treatment arm. Of the 11 in the non-operative arm who returned data, one completed the diary card until only day 4 following discharge. Thus, fewer than half of all participants in the study at the time of discharge from hospital (26/54 = 48%) returned diary card data for analysis. This equates to a total of 380 days of reporting.

One child was completely lost to follow-up: they did not attend any follow-up appointment and could not be contacted by telephone. This child was withdrawn from the study after the 3-month follow-up time point as they were known to have moved overseas. The remaining participants attended follow-up appointments or were contacted by telephone at 6 weeks (48/54, 89% of those remaining in the study), 3 months (46/54, 85%) and 6 months (n = 45/53, 85%). All other participants either did not attend or did not respond to repeated requests for contact by telephone. During the study, in an attempt to increase the follow-up rate, we added an incentive for completion of all remaining follow-up attendances by an individual participant in the form of a £10 shopping voucher. None of the 6-week follow-up appointments was incentivised owing to the time when the incentive was introduced. Of the 3-month follow-up appointments, 47 were not incentivised and were completed by 39 participants (83%, 95% CI 72% to 93%), whereas seven were incentivised and all seven were completed (100%, 95% CI 59% to 100%). Of the 6-month follow-up appointments, 34 were not incentivised and were completed by 28 participants (83%, 95% CI 65% to 93%), and 19 were incentivised and were completed by 17 participants (89%, 95% CI 67% to 99%).

Compliance with outpatient antibiotic treatment

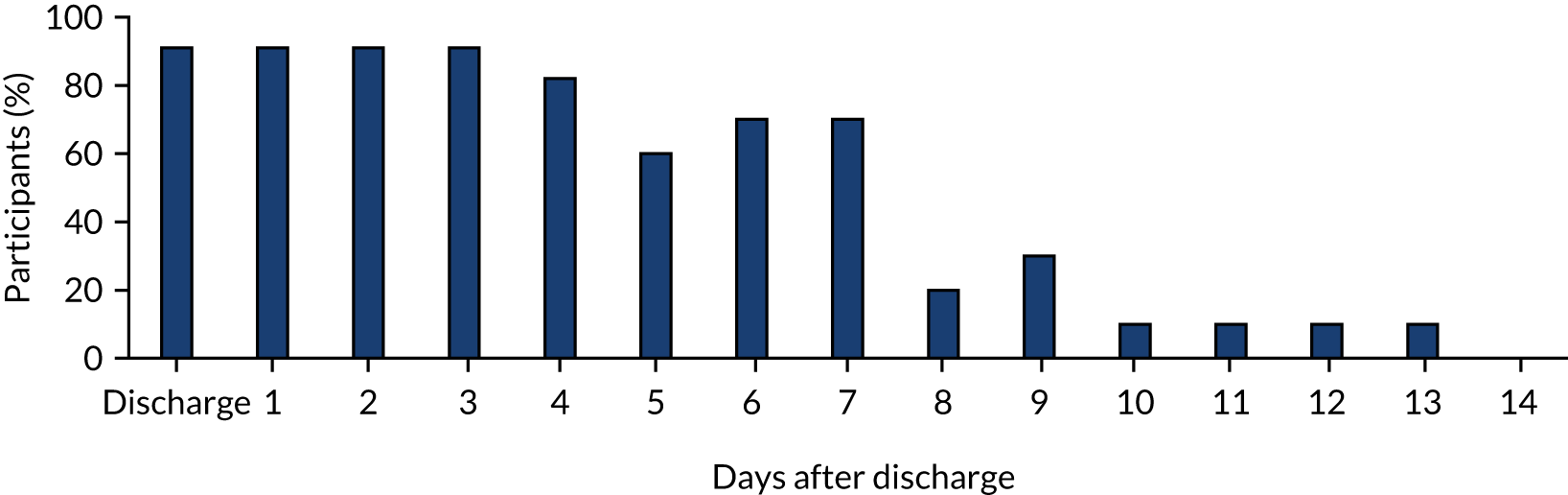

We had initially planned to assess compliance with outpatient antibiotic treatment in the non-operative treatment arm through the use of diary cards. However, owing to the low diary card completion rate and higher than anticipated crossover to appendicectomy during initial hospital admission, these data should be interpreted with some caution. They are included here for completeness (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Compliance with oral antibiotics after discharge in the non-operative treatment arm (n = 11 until day 3, n = 10 thereafter). Proportion of participants in the non-operative treatment arm who reported taking antibiotics at or following discharge.

Clinical aspects of the feasibility trial

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics for the participants overall and described by treatment allocation are shown in Table 3.

| Characteristic | Treatment arm | Total (N = 57) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appendicectomy (N = 28) | Non-operative treatment (N = 29) | ||

| Age, median (range) | 10 years and 7 months (6 years and 4 months–13 years and 6 months) | 10 years and 3 months (5 years and 0 months–15 years and 11 months) | 10 years and 5 months (5 years and 0 months–15 years and 11 months) |

| Sex, male : female (n) | 18 : 10 | 18 : 10a | 36 : 20a |

| Duration of symptoms (hours),b median (range) | 32 (12–63) | 34 (12–79) | 33 (12–79) |

| Ultrasonography during diagnostic workup,c n (%) | 8 (29) | 8 (28)a | 16 (28) |

| Alvarado score,d median (range) | 5 (3–8) | 5 (3–8) | 5 (3–8) |

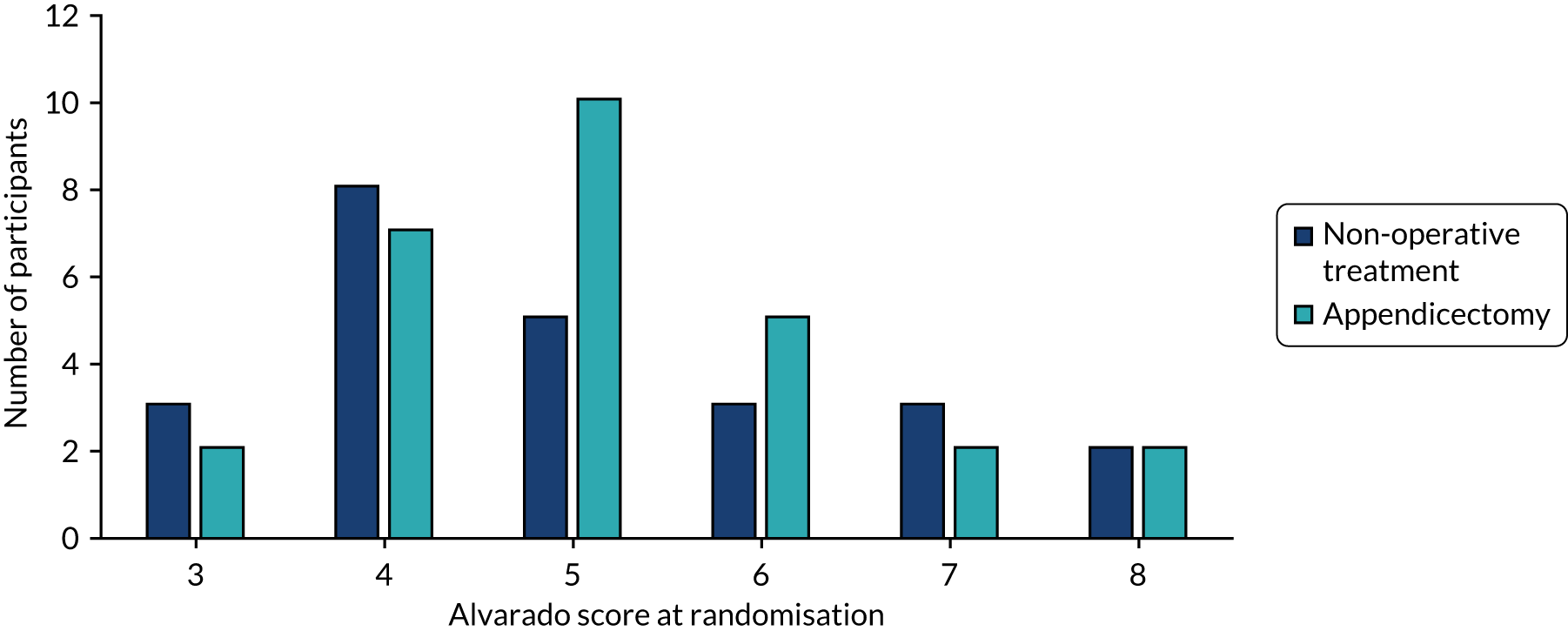

The distribution of Alvarado scores between groups is shown in Figure 7.

FIGURE 7.

Distribution of Alvarado scores across treatment arms.

Treatment received and outcome

In the appendicectomy arm, all 27 children received the allocated intervention and were treated according to the clinical pathway. Histological diagnosis of the resected appendix revealed simple acute appendicitis in 17 participants (63%), perforated appendicitis in eight participants (30%) and a normal appendix in two participants (7%).

In the non-operative treatment arm, 19 of the 27 children (70%) responded to non-operative treatment successfully, followed the clinical pathway and were successfully discharged from hospital. The remaining eight children underwent appendicectomy during their initial hospital admission. Reasons for appendicectomy were parental choice (withdrawal from treatment arm, as discussed in Adherence to treatment allocation and protocol, trial retention and other feasibility outcomes) at 8 hours following randomisation (n = 1), deterioration in clinical condition (according to protocol) at range 12.3–44.4 hours following randomisation (n = 6) and no improvement after 48 hours of non-operative treatment (in accordance with protocol) (n = 1). For the children whose clinical condition deteriorated (n = 6), reasons for deterioration included persistent fever and pain, worsening peritonism and worsening pain. For the one child who did not have any symptomatic improvement after 48 hours, the primary persisting complaint was that of ongoing severe abdominal pain. All eight patients underwent successful appendicectomy during the initial hospital admission. Histological findings were simple acute appendicitis in four and perforated appendicitis in four.

Clinical outcomes related to hospital stay are reported on an intention-to-treat basis and are shown in Table 4. Both decision to discharge and actual time of discharge were recorded as there may be non-medical factors (e.g. availability of transport or other social factors) that delay actual discharge.

| Time from randomisation to | Total time (hours), median (range) | Time by treatment arm (hours), median (range) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-operative treatment | Appendicectomy | ||

| Decision to discharge | 67 (20–196) | 57 (21a–188) | 65 (20–196) |

| Actual discharge | 69 (21–196) | 76 (34–194) | 63 (21–196) |

For participants in the non-operative treatment group, the time from randomisation to discharge from hospital for children who responded to non-operative treatment and for those who underwent appendicectomy during the initial hospital admission are shown in Table 5.

| Time measure | Time (hours), median (range) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 27) | Successful non-operative treatment (n = 19) | Appendicectomy during admission (n = 8) | |

| Randomisation to actual discharge | 76 (34–194) | 61 (34–125) | 116 (40–194) |

Of the 35 appendicectomies performed on participants in the trial during the initial hospital phase, 33 were performed laparoscopically, one was open surgery and one was laparoscopic converted to open surgery.

Early post-discharge outcomes

Data relating to early post-discharge recovery obtained from diary cards are summarised in Figures 8–10. A total of 26 diary cards were returned: 15 from the appendicectomy arm and 11 from the non-operative treatment arm. For one of the 11 participants in the non-operative treatment arm, data were reported up to and including day 4 only. For the remaining participants who returned diary cards, data were complete.

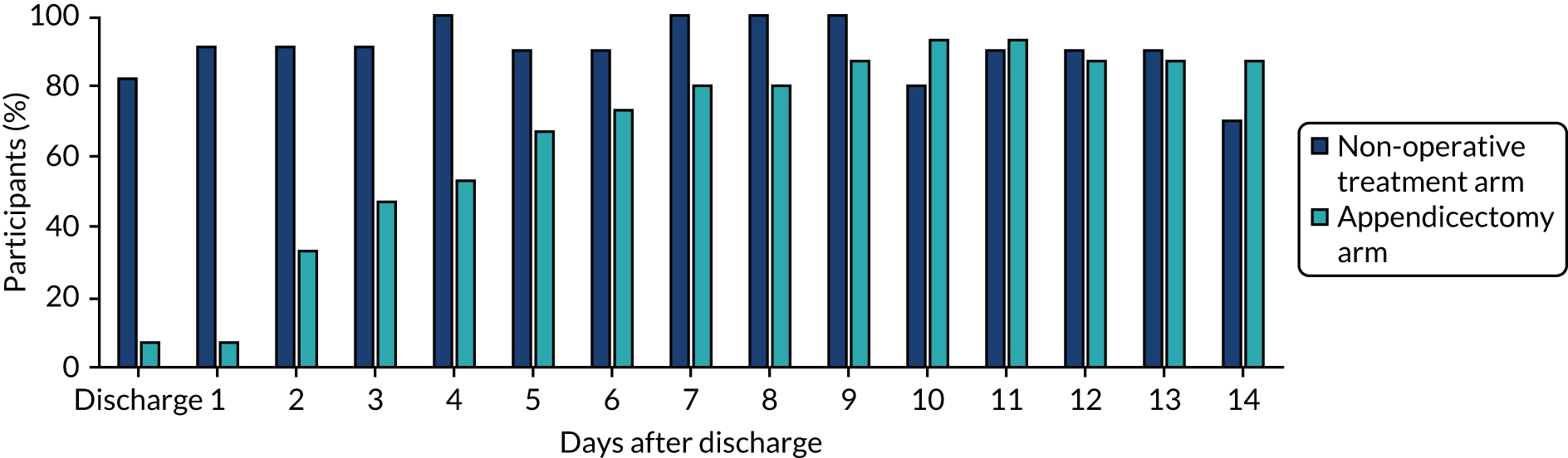

Pain medication after discharge home

The proportion of participants in each treatment arm who reported taking pain medication at and on the days following discharge home is shown in Figure 8. These data clearly suggest that analgesia use following discharge was lower following non-operative treatment than following appendicectomy. In accordance with the protocol, we have not performed a formal comparative analysis of these data.

FIGURE 8.

Analgesia use following discharge from hospital as reported in diary cards.

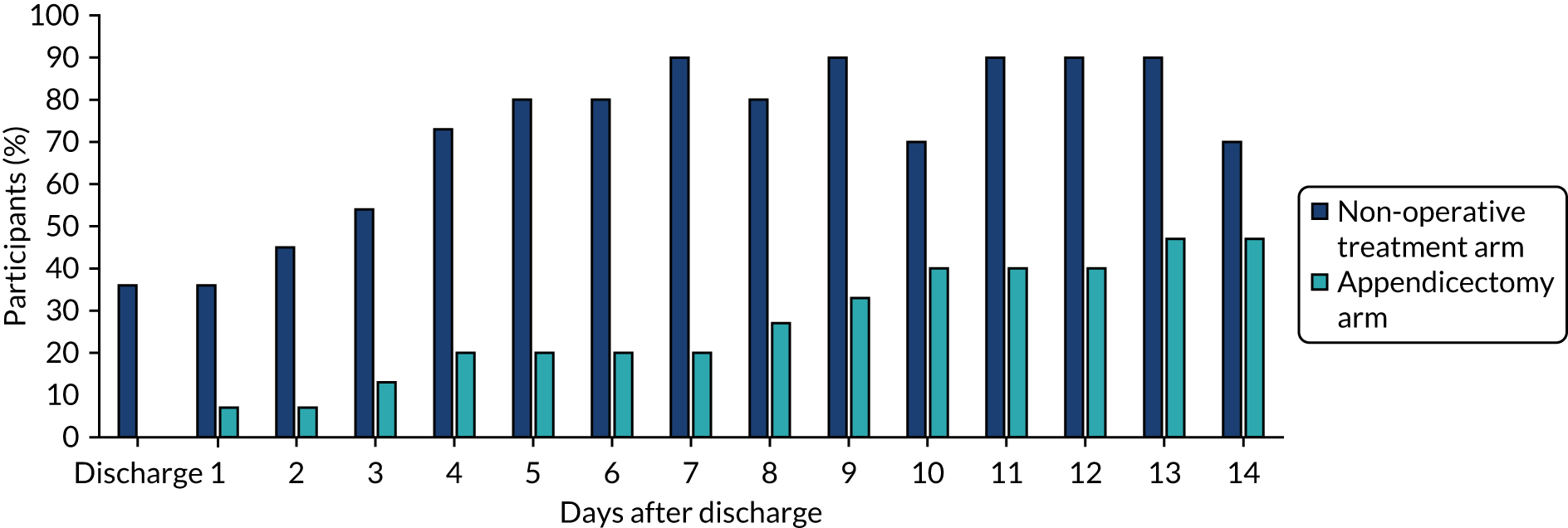

Return to normal activities

The proportion of participants in each treatment arm who reported being able to return to normal daily activities at and on the days following discharge home is shown in Figure 9. These data suggest that trial participants were able to return to normal activities faster following non-operative treatment than following appendicectomy.

FIGURE 9.

Return to normal activities as reported in diary cards.

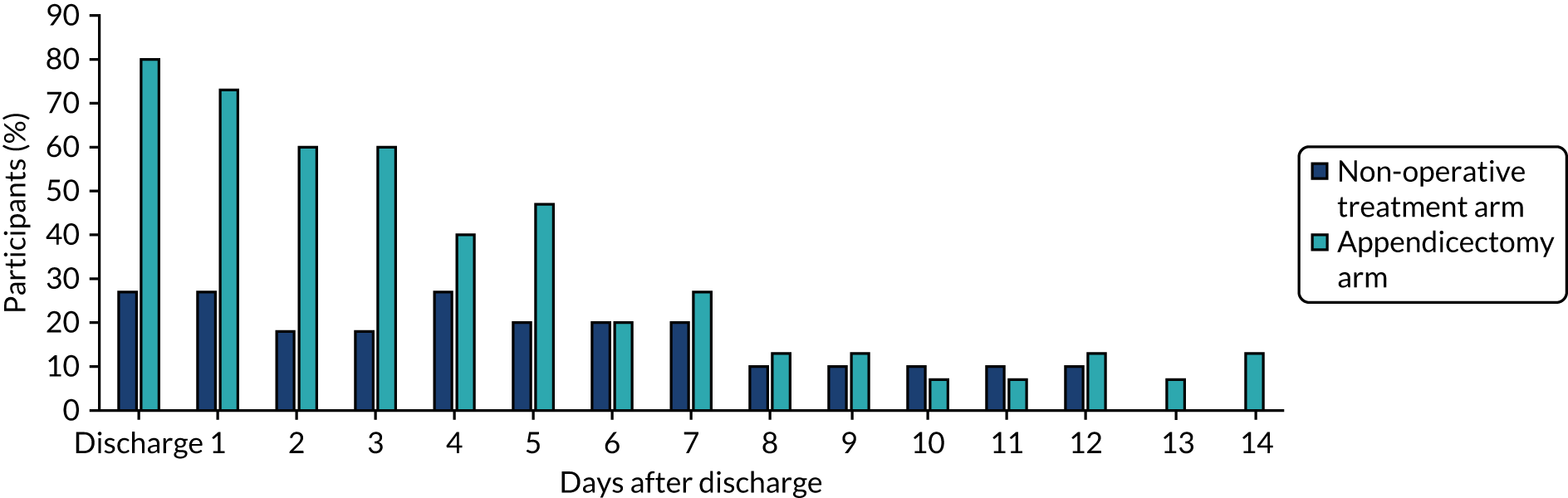

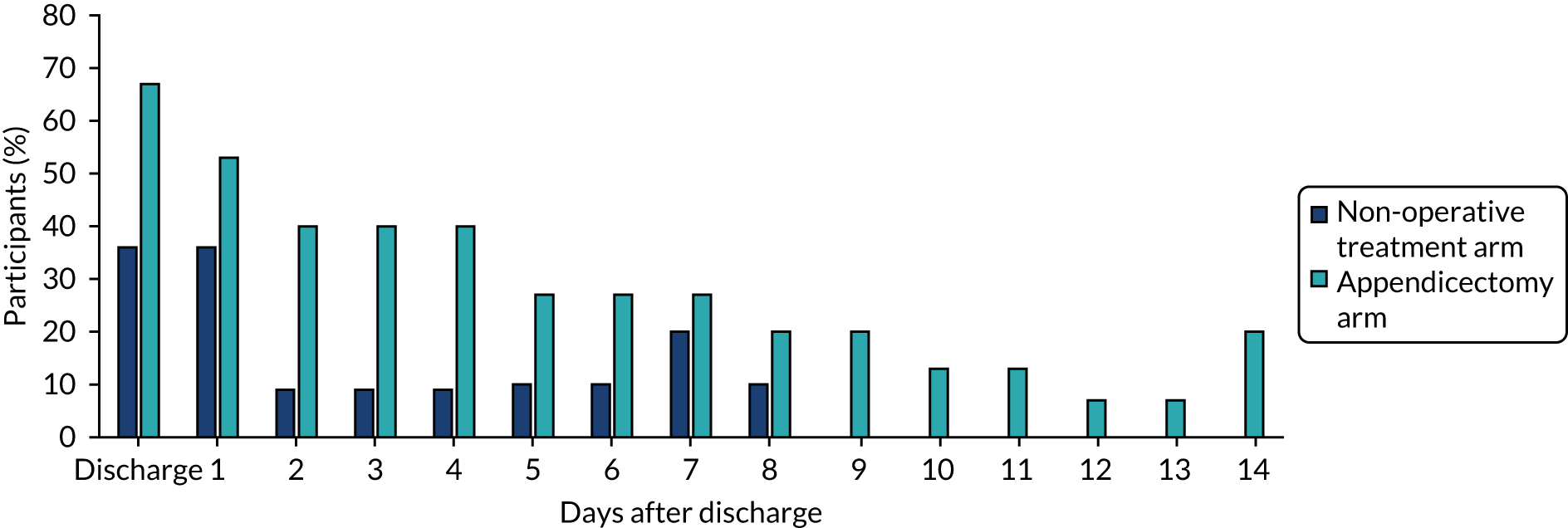

Return to full activities

The proportion of participants in each treatment arm who reported being able to return to full activities at and on the days following discharge home is shown in Figure 10. Like the data on return to normal activities, these data suggest that trial participants were able to return to full activities faster following non-operative treatment than following appendicectomy.

FIGURE 10.

Return to full activities as reported in diary cards.

Parental absence from work

The proportion of participants in each treatment arm whose parents reported missing work as a result of their child’s illness or recovery is shown in Figure 11. These data suggest that parents were able to return to work more quickly if their child was allocated to non-operative treatment than if their child was allocated to appendicectomy. All parents of children allocated to non-operative treatment and who completed diary cards had returned to work by 9 days following discharge, whereas the parents of some children allocated to appendicectomy had not returned to work 2 weeks after discharge.

FIGURE 11.

Parental absence from work as reported in diary cards.

The 6-month follow-up

During the 6-month follow-up period, a total of seven children, all of whom were randomised to non-operative treatment, developed recurrent appendicitis. This equates to 24% of the total number randomised to non-operative treatment and 37% of the 19 participants who initially responded to non-operative treatment and were discharged from hospital without having had an appendicectomy. Of these seven children, six underwent appendicectomy (laparoscopic or open); histological findings were simple acute appendicitis in four of these children and perforated appendicitis in the remaining two. The remaining participant presented with an appendix mass at the time of recurrence, which was successfully treated non-operatively, and subsequently underwent interval laparoscopic appendicectomy. At the final follow-up of the trial, 11 children initially randomised to receive non-operative treatment (41%) had not undergone appendicectomy.

In the appendicectomy arm, three children (11%) were re-admitted to hospital following initial discharge for investigation and/or treatment of potential complications related to appendicectomy.

Adverse events

Adverse events during the 6-month follow-up period were captured and are summarised in Appendix 1, Tables 15 and 16. In the appendicectomy arm, 22 AEs were reported in eight participants; in the non-operative treatment arm, 24 AEs were reported in 15 participants. A small number of these AEs were assigned as being ‘possibly’ or ‘definitely’ attributable to the trial intervention.

In the non-operative treatment arm, the AEs included a rash at the time of receiving antibiotics in two participants. In the appendicectomy arm, three children developed wound complications (one dehiscence, one infection and one suture complications); one child developed a postoperative intra-abdominal abscess requiring percutaneous drainage and a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) for prolonged antibiotics; and one child had intra-abdominal fluid collection, which was treated with intravenous antibiotics. Other AEs, including sickness, pain, visits to the general practitioner (GP), visits to the emergency department and investigations through blood tests and ultrasonography, occurred in both treatment groups. Overall, three children in the appendicectomy arm and eight children in the non-operative treatment arm were re-admitted to hospital. All hospital re-admissions in the non-operative treatment arm were for treatment of recurrent appendicitis, which resulted in appendicectomy for seven participants and a PICC for one participant.

Discussion

This feasibility RCT was undertaken to address a number of specific objectives of the overall CONTRACT feasibility study. The feasibility of a future trial will be dependent on a number of factors, including the willingness of parents and children to be enrolled in a RCT in the context of uncomplicated acute appendicitis; the willingness of surgeons to recruit to such a trial (having been appropriately trained); an acceptable overall recruitment rate; a satisfactory and acceptable trial design, particularly with reference to a non-operative treatment pathway that is safe and usable; and continued justification for the underlying research question. In conducting this feasibility RCT, we have been able to address the majority of these objectives, but acknowledge that some remain outstanding.

We have clearly demonstrated that it is possible to train surgeons to approach children and families at the time of an emergency admission, discuss the trial with them and recruit to a RCT. This has been achieved equally successfully at several centres, suggesting that the procedures put in place to facilitate this are generalisable and not centre specific. We have also demonstrated that it is possible to recruit children with acute uncomplicated appendicitis to this trial outside normal working hours, an important consideration as children with appendicitis frequently present outside routine working hours, including at night and at weekends. It is also evident that there is adequate interest from parents and children to be involved in a trial, as half of all those approached with information about the study agreed to participate. Findings from the parallel communication study (see Chapter 4) confirmed continued interest from families.

Overall, the recruitment rate achieved across the 12 months of this feasibility RCT was 50% of those approached (95% CI 40% to 59%). This is at the upper end of our predicted recruitment target range and is in excess of the recruitment rate seen in other clinical trials involving either an emergency presentation or a complex intervention. We have no doubt that our embedded qualitative work (see Chapter 4) to understand the barriers to and facilitators of recruitment enhanced recruitment to this feasibility RCT. The sequential data on recruitment rate across the lifespan of this trial (rising from 38% to 47% to 72%) would support a role for iterative learning and retraining in improving trial recruitment; although, clearly, a causative relationship between retraining and an increased recruitment rate cannot be proven. Nonetheless, these findings suggest a continued role for qualitative methods in a future effectiveness trial, albeit at a reduced level. It is most likely that the qualitative methods would be particularly advantageous in new recruiting centres.

Following recruitment to the trial, a small number of participants withdrew, most likely because of dissatisfaction with the treatment to which they had been allocated. Although efforts were made to explore treatment preference during recruitment consultations, it is possible that, in some cases, a residual family preference for one treatment remained, and that this contributed towards the immediate withdrawal of three participants. To minimise this, it would be important that future recruitment consultations include adequate discussion and exploration of treatment preference to attempt to recruit only those families that are genuinely accepting of either treatment intervention, and therefore less likely to withdraw from the trial following randomisation. A further aspect that came to light during the running of this feasibility RCT was what children undergoing non-operative treatment were likely to experience ongoing pain despite not having surgery. Pain was cited as a reason for undergoing appendicectomy during the initial hospital admission in a number of cases in the non-operative treatment arm. Following identification of pain as an issue in the embedded qualitative research, we suggested that recruiters specifically discuss pain during recruitment consultations. In particular, we aimed to ensure that parents should anticipate that a certain amount of ongoing abdominal pain would continue with non-operative treatment, as it appeared that the discussion of ongoing pain was absent from recruitment consultations prior to that point. Data obtained from recruiting centres for participants randomised to non-operative treatment and whose clinical condition did not improve by 48 hours after randomisation showed that ongoing abdominal pain was a contributing factor in at least one case. Therefore, it is possible that some (but probably not all) appendicectomies during the initial hospital admission in the non-operative treatment arm may have been avoided with improved explanation about ongoing pain, and perhaps improved pharmacological pain management.

The data on blinded discharge assessment were collected to determine if it would be possible to collect outcome data in a blinded fashion in a future effectiveness trial, if desired. Clearly, in a trial such as this, it is impossible to blind those providing the intervention, those receiving the intervention and those caring for the patients from treatment allocation. Therefore, blinded outcome assessment remains a possible means of collecting outcome data in a blinded way. There were limitations to availability to do this in this feasibility RCT, mainly the fact that we required a member of nursing staff who did not have any familiarity with the trial participant to be available at the time of discharge and to remain blinded before, during and after the discharge assessment. In many cases, owing to staff non-availability, it was not possible to obtain a blinded discharge assessment. However it was possible in 34 out of 54 eligible cases; in just one of these 34 cases, the assessor became unblinded. Of the remaining cases, the assessor ‘guessed’ the treatment correctly 61% of the time, which is not statistically significantly different from what would be anticipated by chance (50%). It is therefore likely that, if a future trial were to require a blinded discharge assessment to minimise bias, this would be possible.

Overall adherence to inpatient treatment pathways by clinical teams and patient (family) compliance with home antibiotic consumption were good. Having agreed to recruit participants into the feasibility RCT, surgeons were accepting of the non-operative treatment pathway and generally compliant with it. In just one case, a decision was made (by a clinician) that was not in keeping with the clinical pathway: to perform an appendicectomy on a child whose clinical symptoms had not improved at 44 hours rather than at 48 hours, as defined in the treatment pathway. However, on closer review of the timelines, this appears to be a pragmatic decision related to the time of the day at which randomisation took place. Therefore, we have not recorded this as a protocol deviation. All participants allocated to the appendicectomy arm received the allocated intervention.

Rates of adherence to follow-up following trial discharge were variable across the different time points. We provided participants with a diary card to enter data on a daily basis following discharge from hospital in an attempt to record outcomes related to ongoing pain and time taken to return to normal and full daily activities, as well as an assessment of parental caring. Compliance with outpatient antibiotic use was also assessed by diary cards. Only 48% of diary cards were returned after a 2-week period, suggesting that this is not a useful method for recording this type of data. Interestingly, however, the majority of diary cards that were returned were fully completed, suggesting that the minority of parents who completed a diary card were engaged in the process. It is likely that a future effectiveness trial will require an alternative means of recording outcomes during the early discharge period, if desirable. The use of a mobile electronic data-capture platform, such as a smartphone-based application, may be a solution to this, although a previous paediatric study25 using such an approach suggested that data accuracy would need to be ascertained.

In this feasibility RCT, we aimed to follow up patients at 6 weeks and at 3 and 6 months following randomisation. Current routine clinical practice varies between sites and surgeons, but, at a maximum, would comprise a single follow-up visit. A key reason for multiple follow-up assessments in this feasibility RCT was for the purpose of optimising the design of a cost-effectiveness analysis in a future effectiveness trial. For the purposes of collecting relevant clinical outcomes, it is likely that an initial follow-up assessment followed by a longer-term assessment (most likely at approximately 1 year after randomisation) would be adequate. The optimal design of a potential cost-effectiveness study alongside a future effectiveness trial is further discussed in Chapter 6. Of note, completion of follow-up visits at 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months was relatively high (> 80% at all time points), but was below what would be needed to achieve an acceptable ‘lost to follow-up’ rate in a future effectiveness trial. Interestingly, the offer of an incentive to those who completed all outstanding follow-up appointments seems to have increased compliance with follow-up (92% vs. 83%) and would probably be worth considering for a future effectiveness trial. Although we did not formally study the effect of this incentive in a randomised way, the findings are in keeping with the previous literature on questionnaire return rates and retention in trials. 26–28

A specific objective of this study was to assess the safety of the treatment interventions, and of the non-operative treatment pathway in particular, because non-operative treatment is not standard practice for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in the majority of UK centres. Overall, a similar number of AEs were reported in each treatment group, although more participants in the non-operative treatment arm than in the appendicectomy arm experienced AEs. AEs specifically related to treatment intervention were as anticipated and relatively infrequent. Other, less treatment-specific, AEs occurred in both treatment groups; there were no specific concerns about the safety of either treatment intervention. Of note, no unexpected SAEs were reported. During this feasibility trial, we encountered some challenges with the reporting and assignment of severity of AEs; as a result, the reporting pathways were altered. This experience will be valuable when proceeding to a future effectiveness trial.

Regarding the clinical features and outcomes of participants in this feasibility RCT, the baseline characteristics of trial participants were in keeping with those anticipated from the existing literature of children with acute appendicitis. Children allocated to receive appendicectomy were treated in accordance with the guidance of the clinical pathway provided for this trial. Of note, 30% of children were found to have perforated appendicitis and 7% were found not to have appendicitis at all (negative appendicectomy). Overall, postoperative outcomes in this group were as expected, given the operative findings. Of note, three participants had AEs related to their surgical wound, four had assessment with an abdominal ultrasonography and two had localised intra-abdominal fluid collection, of whom one was treated with percutaneous drainage.

In participants allocated to receive non-operative treatment, a higher proportion (30%) received appendicectomy during their initial hospital admission than had been anticipated based on the existing data on efficacy of non-operative treatment. In one case, this was due to parental withdrawal from the treatment allocation, but, in the remaining seven, it was due to non-response to non-operative treatment in accordance with the trial protocol. At surgery and on histology, the findings were simple acute appendicitis in four of these cases and perforated appendicitis in the remaining four. Despite this higher than anticipated non-response rate, overall clinical outcomes related to initial hospital admission were similar between treatment groups. Unsurprisingly, children allocated to receive non-operative treatment who subsequently underwent appendicectomy had a longer initial hospital stay than participants for whom non-operative treatment was successful.

Although data obtained from diary cards are limited by the low return rate, the data available suggest that there may be differences in recovery between the treatment arms (see Figures 8–11). Participants in the non-operative treatment arm appeared to stop taking analgesia sooner and were able to return to normal and, subsequently, full daily activities sooner than participants in the appendicectomy arm. Furthermore, their parents reported being able to return to work earlier. It will be important to capture these post-discharge outcomes in a future effectiveness trial. The potential for such differences in outcomes between treatment arms provides additional justification for pursuing an assessment of the relative efficacy of these two treatments. It also acts as a reminder that differences between treatment arms may exist beyond the initial hospital admission and therefore not immediately apparent to treating clinicans. Importantly, these outcomes may be of great interest and relevance to children and their families. Of note, few previous studies of non-operative treatment of children with acute uncomplicated appendicitis have reported outcomes relating to return to function or burden on the family. Only the study by Minneci et al. 29 reported a measure of ‘disability days’, which they defined as the sum of the length of stay (in days); the number of days of normal activity missed for the child; the number of days of normal activity missed for the parent or guardian; and clinic, emergency department and inpatient visits. Interestingly, they also reported fewer disability days for patients receiving non-operative treatment than for patients undergoing appendicectomy, but their study was not randomised. 29 Although Hartwich et al. 30 used a measure of quality-adjusted life-months in a cost–utility analysis of non-operative treatment, this was based on a measure of overall quality of life (QoL), rather than the specific detail relating to recovery time.

Although we have demonstrated that recruitment to a RCT is feasible from a number of perspectives, it is important to consider whether or not the clinical outcomes achieved in this feasibility RCT are compatible with a future effectiveness study of this population of children using the current clinical pathway. First, there was no evidence of an adverse safety profile of the non-operative treatment pathway. However, when considering clinical effectiveness, there are a number of differences between the clinical outcomes achieved in participants in both treatment arms and the existing comparative literature. Prior to undertaking this feasibility RCT, we performed a systematic review of the existing literature related to successful non-operative treatment of children with acute appendicitis and identified an initial success rate (defined as being discharged from hospital following initial hospital admission) of 97%. 16 However, in the current feasibility RCT, just 70% of children randomised to non-operative treatment were successfully discharged from hospital without receiving appendicectomy. Similarly in our feasibility RCT, the rate of recurrent appendicitis was higher, at 37%, than that reported in the previous literature. Of note, the difference in clinical outcomes between this feasibility RCT and previous studies is not confined to the non-operative treatment pathway, for instance the overall hospital length of stay is longer than is typically reported following appendicectomy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis. The probable explanation for this is that we have inadvertently recruited to our study more children with perforated appendicitis than we had intended to. Of the 57 children recruited to the study, 12 were known to have had perforated appendicitis at the time when they underwent appendicectomy. It is well recognised that children with perforated appendicitis have a more prolonged and complicated clinical course than children with acute uncomplicated appendicitis. It is interesting that, despite this, the overall hospital length of stay between groups was similar; however, there is no doubt that non-operative treatment in this feasibility RCT was not as clinically effective (however defined) as the previous literature suggests. 16

The likely explanation for this discrepancy is that our inclusion and exclusion criteria were too loose to allow the accurate identification of children who had acute uncomplicated appendicitis as opposed to more advanced disease. We deliberately designed this trial to be pragmatic to optimise its acceptability to surgeons, in particular. No alteration to current diagnostic pathways was made when designing this trial. In the UK, it is recognised that only a minority of children undergo diagnostic ultrasonography as part of their work-up when presenting with abdominal pain. 31 This is important as one of the pieces of information to be gained from ultrasonography may be a more reliable distinction between children with acute uncomplicated appendicitis and those with perforated appendicitis than can be achieved with clinical judgement alone. In our feasibility RCT, the exclusion of children suspected to have perforated appendicitis was based on clinical judgement alone, rather than on any specific physical signs, laboratory parameters or ultrasonograph findings. We continue to justify the absence of radiological parameters in our exclusion criteria because, even in this feasibility RCT, just 30% of enrolled participants underwent diagnostic ultrasonography. However, for a future effectiveness trial to be acceptable to all stakeholders, it will be necessary to determine, with a greater precision, children who have acute uncomplicated appendicitis as opposed to more advanced disease. Importantly, this should be done without the use of diagnostic imaging, as any such change would be a significant departure from current routine UK practice, would have logistical and cost implications, may decrease the acceptability of the trial to UK clinicians and would limit the generalisability of any findings. Therefore, we are in the process of using the data obtained during the screening process of this feasibility RCT to perform an analysis intended to identify a set of criteria that can be used in the setting of a child with a confirmed diagnosis of appendicitis (based on tests used in routine care). This set of criteria aims to assist with the judgement of whether the child is likely to have uncomplicated acute appendicitis or more advanced disease. We anticipate that, after adequate testing, the use of such criteria may facilitate the accurate identification of children with acute uncomplicated appendicitis so that a population in whom non-operative treatment can be anticipated to be of greater efficacy can be identified and enrolled in a future trial.

As a result of the alteration in trial design that will be necessary before proceeding to a future effectiveness trial, it is not valid to use outcome data recorded in this feasibility trial for the purposes of informing a sample size calculation for a future effectiveness trial. Such a RCT will therefore require an internal pilot phase as a minimum to test assumptions on which any provisional sample size calculation is based, as a result of these enhancements in trial design.

Chapter 4 Communication substudy: a qualitative study to optimise trial recruitment

Background

Recruitment of patients to RCTs is often challenging. Poor recruitment has been suggested as the most common reason for premature trial discontinuation,32 and almost half of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme and Medical Research Council trials require additional funding, time extensions or both. 33

The CONTRACT feasibility RCT included several factors that can complicate or impede recruitment. The study compared surgical treatment with non-surgical treatment. Recruitment to trials that include such markedly different treatments is known to be particularly difficult because of treatment preference issues. 34,35 This is especially pertinent as the surgical treatment arm in CONTRACT (appendicectomy) has been a mainstay of treatment for acute appendicitis for more than 100 years. 36 Recruiting children (as opposed to adults) to trials is also challenging, because it is necessary to consider the needs of both child and parent(s),37 and children’s capacities to contribute to the decision-making process can vary markedly. 38 Recruitment to trials during an unscheduled hospital admission, as in CONTRACT, can also be complex owing to uncertainties regarding a patient’s clinical condition, the demanding clinical working environment and time limitations associated with the urgent need to deliver the treatments under investigation. 39 Furthermore, potential CONTRACT participants often present to hospital outside normal working hours, when the availability of recruiting staff is limited.

Trial recruitment can be optimised by embedding qualitative studies in the trials to identify barriers to recruitment and strategies to address these difficulties over the course of the trial. 40–42 Some strategies that have previously been identified via qualitative studies as important in optimising recruitment focus on communication are changes to the order of presenting treatments, avoiding misinterpreted terms, exploring patients’ treatment preferences42–45 and identifying the ‘hidden challenges’ to recruitment, such as a lack of clinical equipoise among health professionals. 46 Patients’ treatment preferences are complex, dynamic and may not always be well founded. Treatment preference exploration offers an opportunity to emphasise equipoise and address treatment preferences founded on misconceptions, thus making trial treatment arms more acceptable42 and optimising informed consent and recruitment. 43,44

Previous research in this field has focused on optimising recruitment to adult trials by embedding qualitative studies. The current embedded qualitative study (communication study) was needed as CONTRACT was a paediatric trial being conducted in an urgent care setting. It was anticipated that strategies to optimise recruitment and consent would need to be adapted to this specific setting, and, similarly, that lessons for future pilot and definitive trials would need to take account of the particularities of this paediatric setting.

This chapter describes the key findings of the communication study: how it informed recruitment to CONTRACT, how it informed the training delivered to health professionals and an evaluation of the training. The chapter documents the impact of the communication study on CONTRACT and outlines key messages for optimising recruitment to any future definitive trial comparing surgical with non-surgical treatment for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in children. More broadly, the findings can be used to inform the development and design of trials comparing surgical with non-surgical treatment, paediatric trials and research conducted in an acute setting.

Aims

The communication study aimed to:

-

systematically examine how families and health professionals communicated about and experienced CONTRACT

-

identify strategies to optimise trial recruitment to CONTRACT and to a future definitive trial.

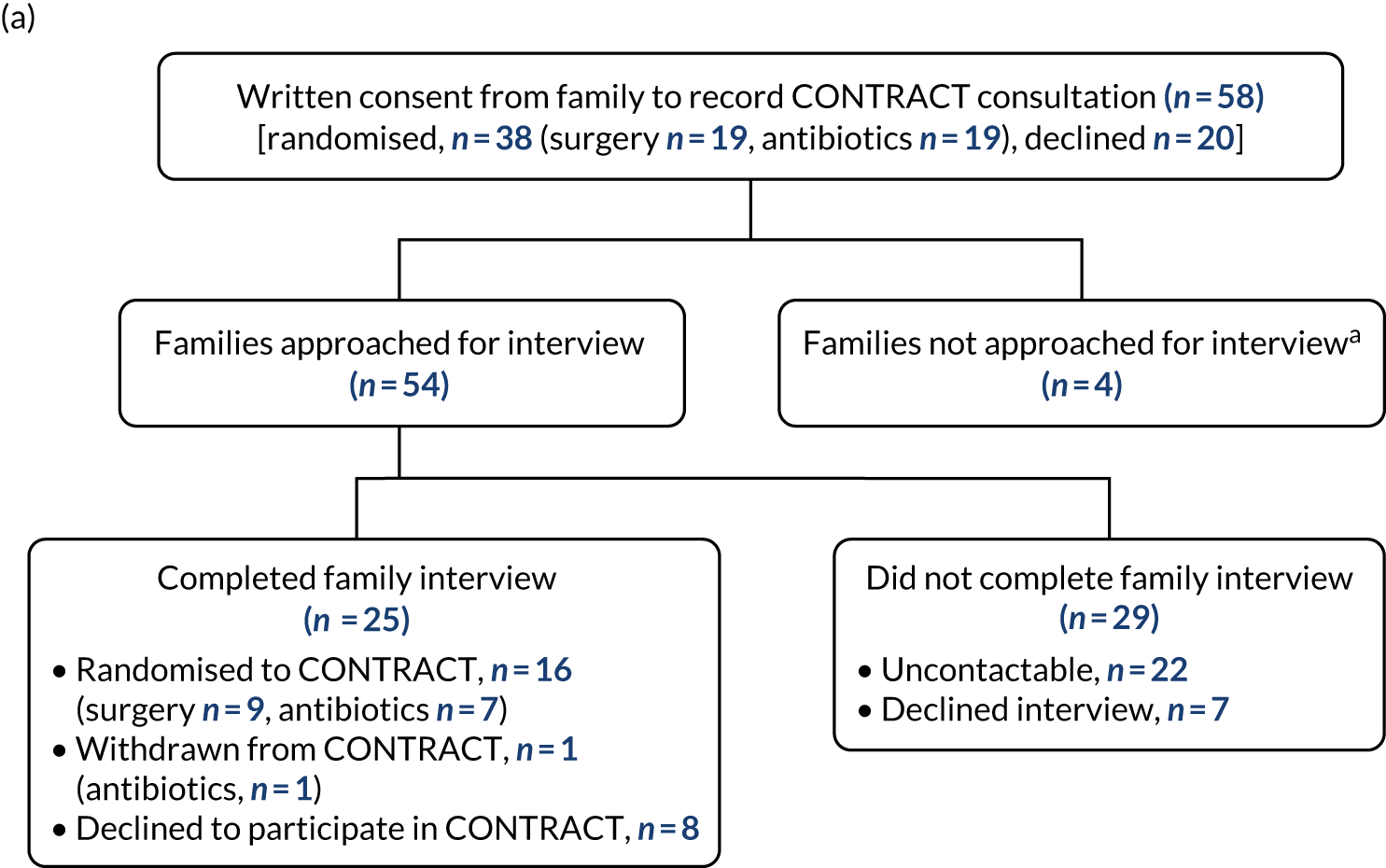

Methods

Overview

We drew on an integrative qualitative communication approach, involving analysis of audio-recordings of CONTRACT consultations and in-depth interviews with parents, patients (i.e. children and young people) and health professionals. 47 This integrative qualitative communication approach is particularly suited to explore clinical communication in trials. The consultation recordings allowed us to explore how health professionals explained CONTRACT during consultations with families, and the interviews allowed us to explore children’s, parents’ and health professionals’ perspectives on communication about CONTRACT. 42 The communication study was included in the ethics approval given for CONTRACT. Patients and parents were provided with a summary of the results on completion of the study and we received no subsequent feedback from participants regarding the findings.

Recruitment training and phases

CONTRACT recruited for 12 months from March 2017 and the communication study ran concurrently. Before recruitment began, we delivered generic recruitment training in December 2016. We analysed the qualitative data iteratively throughout the CONTRACT recruitment period (and afterwards), and these ongoing analyses informed the development of bespoke recruitment training. While the trial was ongoing, we delivered two bespoke recruitment training sessions at all three CONTRACT sites in July 2017 and November 2017. We therefore classified ‘phase 1’ of recruitment as March–June 2017, ‘phase 2’ as July–October 2017, and ‘phase 3’ as November 2017–February 2018. We refer to these phases in Results. All training sessions involved Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) presentations and discussion between the communication study team and health professionals at each individual site. The recruitment training that was delivered at the end of phases 1 and 2 was specifically informed by the ongoing analyses of the qualitative data. Health professionals were asked to complete training evaluation forms (available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1419290/#/) pre training, and after training sessions 1 (generic recruitment training), 2 and 3 (bespoke recruitment training sessions). Finally, we provided health professionals with written ‘hints and tips’ on ways to optimise CONTRACT consultation communication. We updated this information periodically in the light of the ongoing qualitative analysis.

Participants

Health professionals approached families of children who were eligible for CONTRACT at one of three UK hospitals. The families of all children who were eligible for CONTRACT were eligible for the communication study. During this period, we also approached and interviewed health professionals who had been involved in CONTRACT at one of the three sites.

Procedure

Sampling

Health professionals were invited for interview if they had either approached families about CONTRACT or been involved in other aspects of recruitment or patient care. Parents were invited for interview if they had been approached about CONTRACT. Children aged 7–15 years who had been approached about CONTRACT were also invited for interview. The sampling strategy for both consultation recordings and interviews aimed for diversity in CONTRACT participation status [including those who had consented or declined, child age, family socioeconomic status, health professional’s role (i.e. surgeon or nurse) and NHS site].

Consultations

Health professionals sought verbal permission to audio-record trial consultations at each of the study sites. If permission was granted, the audio-recorder was activated (the health professional subsequently sought written consent from parents and assent from children for the audio-recording to be included in the study). Consultations typically entailed health professionals describing the various elements of CONTRACT and the communication study, providing the relevant information sheet(s) and showing families a video about CONTRACT. Families then had time to decide before consenting to CONTRACT and/or the communication study; in the CONTRACT protocol, the proposed time given to decide was a maximum of 4 hours from the initial discussion until consent was obtained. Families were eligible for the communication study whether they declined or consented to CONTRACT. Consultation recordings and communication study consent forms were uploaded directly to a secure server. The recordings were subsequently transcribed by a professional agency and then anonymised and checked by the communication study team prior to analysis.

Interviews

Families who expressed an interest in being interviewed and provided written consent for their contact details to be forwarded were telephoned by a member of the communication study team. The team member attempted to contact the family up to three times by telephone to invite them to participate. The team member explained this part of the study to the family and forwarded them the relevant information sheet(s). If the family was interested in participating, an interview was provisionally scheduled. Family interviews were typically completed 1–4 weeks following discharge from hospital.

Health professionals were eligible for interview if they were involved in CONTRACT, although we were particularly interested in interviewing health professionals who had experience of inviting families to participate in CONTRACT. The communication study team typically obtained health professionals’ contact details via the local principal investigator and then contacted the health professional to provide the health professional information sheet and offer more information about the study, before obtaining consent and conducting the interview.

Before telephone interviews, informed consent and assent was audio-recorded; before face-to-face interviews, informed consent and assent was obtained in writing. Two experienced qualitative researchers (LB and FCS) with health research backgrounds conducted the semistructured interviews with children, parents and health professionals. Interviews were topic guided to ensure exploration of key topics (see Appendix 2), yet conversational to allow participants to raise issues of importance to them. As some of the concepts explored were rather complex, only children aged 7–15 years were eligible for interview. We devised separate topic guides for parents, health professionals and children, and used materials to facilitate the children’s interviews, such as art pads, pens and stickers. Topic guides were initially developed through consultations with the SSAG and adapted throughout the course of the study in response to developing analyses.

All interviews were audio-recorded, then transcribed by a professional agency. Transcripts were pseudo-anonymised (replacing names and places with codes) and checked by the study team prior to analysis. Sampling for interviews ceased when data saturation was reached. 48

Qualitative analysis

Salmon et al. 47 advocate an analytical approach that borrows from several methodological traditions when analysing data involving consultations and interviews. This involves two interlinked strands of analysis: a cross-case strand and a within-case integrative strand.

In cross-case strand analysis, consultation analysis focused on the interaction between recruiter and potential participants and information provision, communication techniques, intervention preferences and trial participation decisions. We analysed interview data for evidence of the needs, priorities and goals of families in relation to recruitment, randomisation, treatment preferences, their experiences and acceptability of the intervention and views regarding which outcomes are important. The analysis of interviews with health professionals at sites focused on their perceptions and experiences of recruitment, as well as their perceptions of the interventions and which outcomes they viewed as important (for information on outcomes of importance, see Chapter 5).

Within-case integrative strand analysis allowed us to explore associated consultations and interviews for each individual case [i.e. consultation and interviews with the parent(s), child and health professional present in the aforementioned consultation]. We produced narratives for each case by drawing on the codes and themes that arose from the cross-case analysis, allowing us to test and develop those codes and themes, and integrate the strands of analysis.

We analysed the recruitment consultations by listening to these as well as by reading the transcripts. If analyses of the audio-recordings suggested that recruitment difficulties were potentially linked to communication during the recruitment consultation, the communication study research group discussed the issue and integrated it into the health professional training sessions.

The analysis of recruitment consultations used content analytic methods to describe what was said by whom and how often in the audio-recordings of recruitment sessions. 49 More flexible constant comparison methods were used to identify common or divergent themes, particularly focusing on the impact of statements by the recruiter on parent responses and views. Thematic analysis was used to focus in great detail on certain sections of the transcripts, for example in the interactions during which randomisation was offered. 50 Families that declined randomisation or that did not accept their randomisation allocation were noted.

Again, analysis of all interview data drew on the principles of the constant comparative method and thematic analysis. 50

Members of the qualitative research team (FCS and LB) initially read and double-coded approximately 10% of consultations, health professional and family interview transcripts, and led a process of ‘cycling’ between the developing analysis and new data. Other members of the qualitative study team (BY) read a selection of transcripts and helped to develop and test the analysis by periodic discussion (LB, FCS, EC, NJH and BY) of detailed reports of the developing analysis.

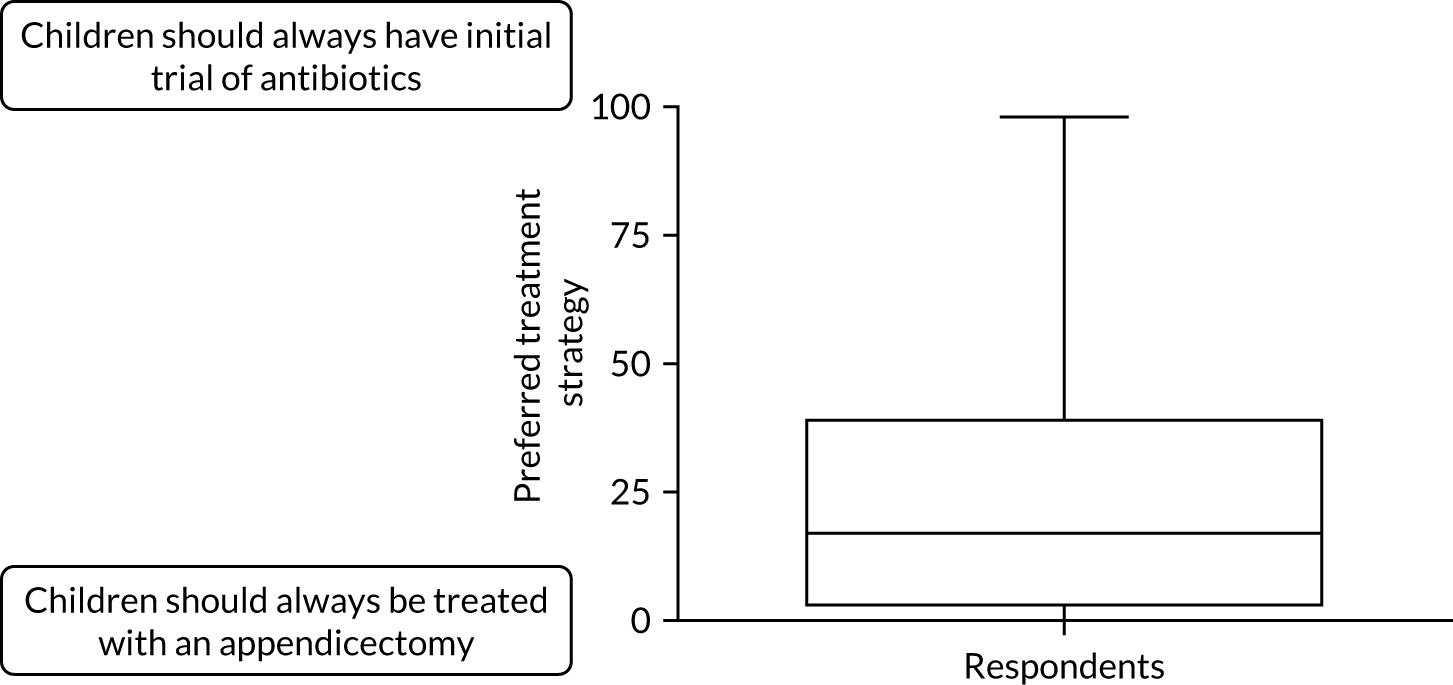

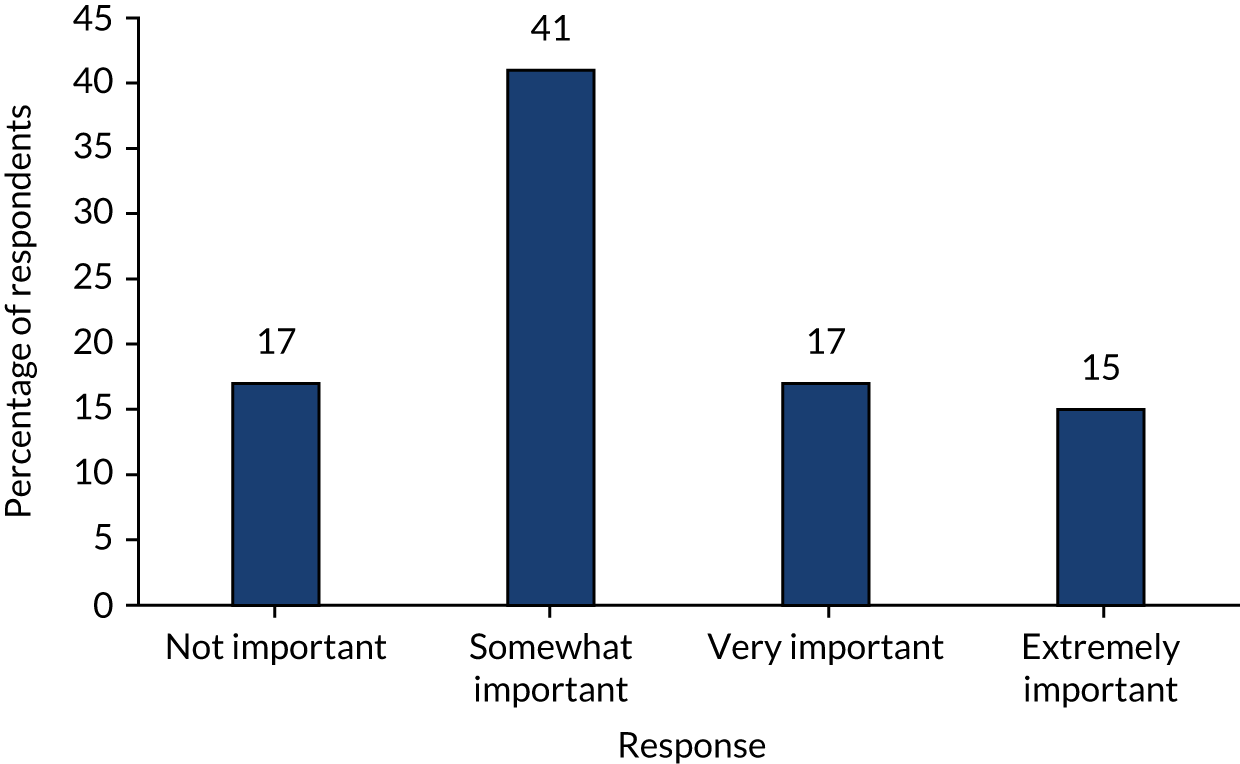

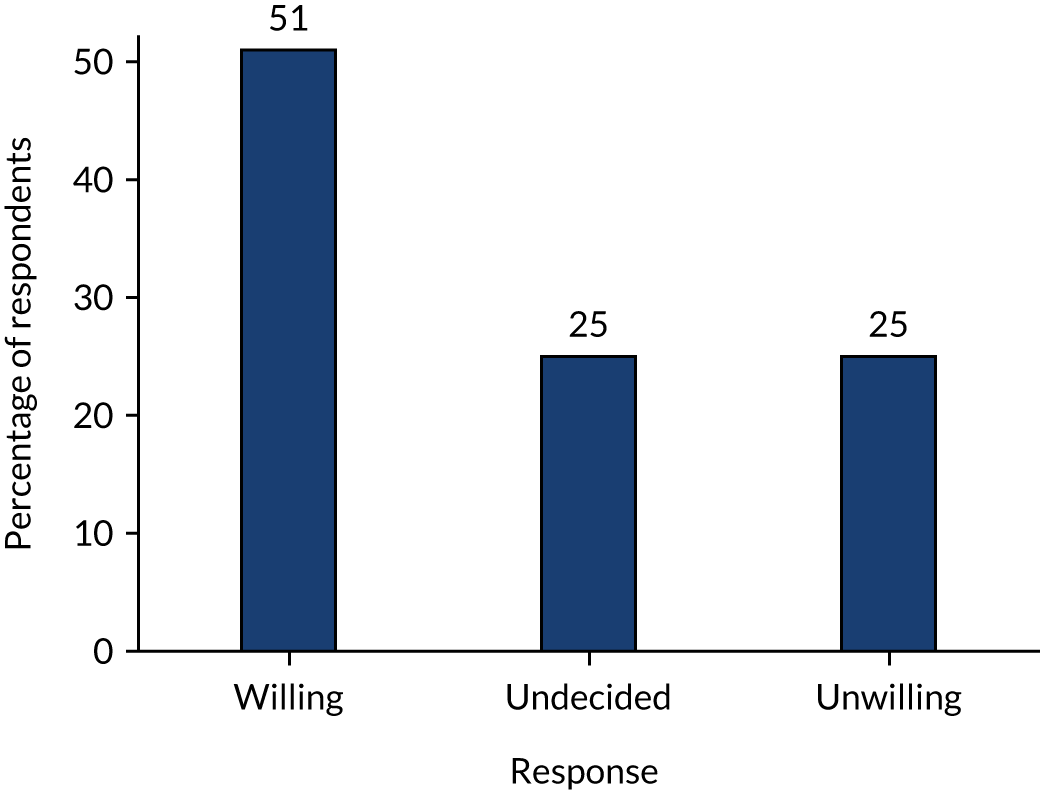

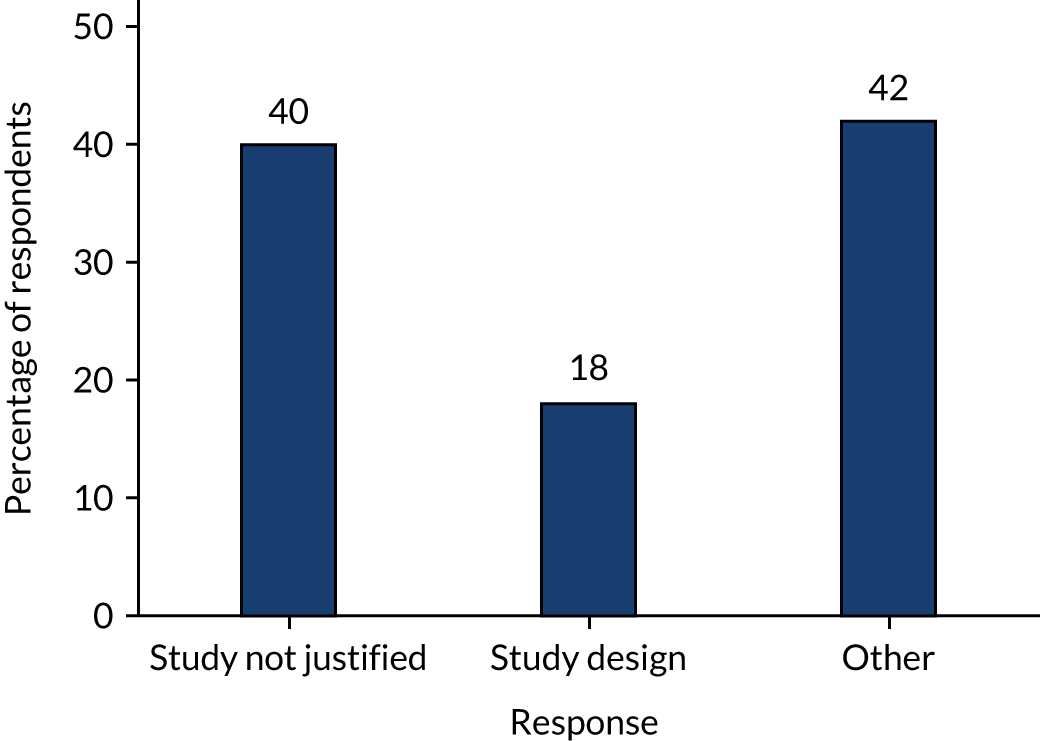

Initially, each transcript was read several times (by LB/FCS) before developing open codes to describe each relevant unit of meaning, although coding occurred at multiple levels, from detailed descriptions of communication and experiences of the trial, to the general orientation of participants towards clinical research. Through comparison within and across the transcripts, the open codes were developed into categories to reflect and test the developing analysis.