Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/49/149. The contractual start date was in June 2016. The draft report began editorial review in January 2020 and was accepted for publication in July 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Cockayne et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Material throughout this chapter has been reproduced from Cockayne et al. 1 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2018. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Material throughout this chapter has been reproduced from Cockayne et al. 2 © 2021 Cockayne S et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Burden of falls and falling in the UK

Falls and fall-related fractures are highly prevalent among older people and are a major contributor to morbidity and cost to individuals and society. 3 Approximately one-third of people aged ≥ 65 years, and half of those aged > 80 years living in the community, will have a fall each year. 4,5 Although not all falls will have an impact on the individual, approximately one-fifth of all falls will require medical attention and 5% will result in a fracture,6 often a hip fracture. A significant number of falls (85%) occur within the home. 7 Older people who fall once are two to three times more likely to fall again within 1 year. Repeated falls tend to be experienced by frail older people aged ≥ 75 years. 4 These falls may lead to a loss of independence, resulting in the need for institutional care. It is likely that this burden will further increase, given the ageing population in the UK, with projections that the proportion of people aged ≥ 65 years is set to rise from 18% to 24% between 2016 and 2042. 8 The financial cost of treating injurious falls has been estimated at £2B per year, mainly as a result of the cost of treating hip fractures. 9

Risk factors for falling

Falls occur as a result of a complex interaction of risk factors. These risk factors can be separated into three broad categories: intrinsic, extrinsic and behavioural. Intrinsic risk factors are person-related and include factors such as having had a previous fall or fracture, impaired vision or impaired balance/gait. 10 Extrinsic risk factors are related to the environment, such as the presence of clutter, trip hazards or poor lighting. Behavioural risk factors include risk-taking activities, for example climbing on chairs, drinking alcohol, or having poor intake of nutrition or fluids.

Environmental hazards (extrinsic risk factors) are frequently attributed by older people as the primary causal factors in their fall and are also cited in the literature as a major contributor to falls. In a review by Rubenstein11 of 12 studies, environmental factors were identified as the primary cause of approximately one-third of falls (mean 31%, range 1–53%, n = 36,280). Similarly, in Talbot et al. ’s12 retrospective study, environmental factors were perceived by older people as the second most common cause of falls, with key contributors identified as objects on the floor, external forces and wet, uneven and icy surfaces. The latest Cochrane review in this area13 reported that home safety assessment and modification was effective in reducing the risk of falling [relative risk of falling 0.88, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.80 to 0.96]. It also concluded that the intervention was more effective in people at higher risk of falling, including those with visual impairment, and if it was delivered by an occupational therapist (OT). 14

Environmental assessment and modification to reduce falls

The person–environment–occupation occupational therapy conceptual model of practice purports that the person, their environment and the activities in which they engage continually interact in ways that enhance or diminish the individual’s occupational performance. Environmental hazards constitute dynamic entities, which occur through the interaction between these three elements, and occupational therapy practice aims to restore a balance between these elements. Occupational therapy-led environmental interventions, therefore, comprise a comprehensive assessment of the older person, their environment and the tasks they perform, with intervention strategies focused on the person, their environment and their task performance.

At the time of applying for funding for this study, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance15 recommended the delivery of a home hazard assessment and safety intervention/modification for those receiving treatment in hospital as a result of a fall. It was recommended that the assessment should be undertaken by a ‘suitably trained professional’, in conjunction with follow-up and appropriate interventions. However, no such guidance existed for older people living in the community who had an elevated risk of falling but had not yet necessarily received hospital treatment as a result of falling. This was despite a pilot trial, undertaken by one of the authors,16 that assessed the effectiveness of a home hazard assessment and environmental modification in this population reporting a reduction in the number of falls as a secondary outcome in the study.

Consequently, the Occupational Therapist Intervention Study (OTIS) was undertaken to find out if these preliminary findings could be confirmed and to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the intervention. If home hazard assessment and environmental modification were shown to be clinically effective and cost-effective, it would be likely that these would be implemented more widely, and could lead to important public health gains in preventing or delaying disability in the older population.

Research aims and objectives

OTIS was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme in response to a call for efficient study designs. The aim of OTIS was to establish the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a home hazard assessment and environmental modification, delivered by OTs, on the number of falls among older, community-dwelling people at risk of falling.

The main objectives of OTIS were to:

-

investigate the clinical effectiveness of a home hazard assessment and environmental modification for falls prevention

-

investigate the cost-effectiveness of a home hazard assessment and environmental modification for falls prevention

-

explore the barriers to and facilitators of implementing the intervention among OTs and the wider community (e.g. commissioners of services).

Chapter 2 Methods

Material throughout this chapter has been reproduced from Cockayne et al. 1 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2018. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Material throughout this chapter has been reproduced from Cockayne et al. 2 © 2021 Cockayne S et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Study design

OTIS was a modified cohort, pragmatic, two-armed, open randomised controlled trial (RCT), with an economic evaluation and nested qualitative study. In a cohort RCT (cRCT) design, participants are recruited to an observational cohort, and eligible participants are then randomised into an embedded RCT, following a period of outcome data collection. 17 Participants are unaware of when they have been randomised into the embedded RCT, and only those in the intervention group are informed that they have been offered the treatment. In our definition of a modified cRCT, participants were recruited into a cohort, but all were informed about the embedded RCT and that allocation to the intervention group and the usual-care group would be decided by chance. We implemented a run-in period for data collection before randomisation and a process for rescreening, after a period of time, the cohort participants who were not immediately eligible for the trial. We successfully used this design to improve recruitment rates and potentially minimise post-randomisation attrition in a previous NIHR-funded falls prevention RCT. 18 We therefore expected to observe similar benefits in this trial, as the previous trial not only was conducted in a comparable population, but also evaluated a falls prevention intervention.

The first benefit of using a modified cRCT design was the anticipated increase in recruitment rates in comparison with a traditional RCT design. Some participants would be immediately eligible for the trial and could be randomised straight after the initial ‘run-in’ period of data collection. Others who fulfilled all of the eligibility criteria apart from having had a fall within the previous 12 months were rescreened at a later date and could subsequently become eligible (e.g. if they had fallen in the meantime), in which case they could be randomised. These additional participants would have been lost to recruitment had a traditional RCT design been used. Second, we expected that this design would minimise post-randomisation attrition and the possibility of reporting bias. In a traditional RCT design, as participants can access usual care outside the trial, the only incentive to take part in the trial, apart from altruism, is the possibility of receiving the intervention. In this modified design, all participants were informed on enrolment to the cohort that they could at some point be offered a home assessment visit by an OT. The home assessment visit was offered to those participants subsequently randomised into the intervention group of the RCT; however, those in the usual-care group were not explicitly notified of their group allocation, as would have been the case in a traditional RCT. We expected that this would reduce attrition caused by ‘resentful demoralisation’ and minimise the risk of participants in the usual-care group biasing the trial, either knowingly or unknowingly, by reporting the number of falls they had experienced more or less conscientiously than those allocated to the intervention group. Finally, to ensure that participants were engaging with the study, and to reduce post-randomisation attrition and the risk of selection bias, we used a ‘run-in’ period to collect falls data prior to participants being randomised. Participants had to return their baseline questionnaire and at least one falls calendar before they could be randomised. As participants were required to provide a falls calendar each month for 1 year after being randomised, we hoped that only including those who had a proven track record of returning a calendar would reduce the chance that participants would not return calendars during the course of the trial.

Participants were randomised to either the usual-care group or the intervention group. The usual-care group continued to receive usual care from their general practitioner (GP) or other health-care professional and were sent a falls prevention leaflet. The intervention group received usual care and the falls prevention leaflet and were also offered a home assessment visit by an OT. Participants were allocated to a group using an unequal randomisation ratio (generally 2 : 1) in favour of the usual-care group in order to reduce costs and minimise the OT burden of delivering the intervention. The trial included an economic evaluation (see Chapter 4) and a nested qualitative study to explore treatment fidelity and the OTs’ experiences of delivering the intervention (see Chapter 5). The trial protocol has been published in full. 1

Public involvement

OTIS was informed throughout by the involvement of older people with a history of falls. Patient and public representatives were identified from the cohort of participants who had taken part in previous studies led by the study team. The group consisted of four older people, who met with the study team each year during the course of the study at face-to-face meetings held at the University of York. They also provided input over the telephone, if required. They helped develop the design and conduct of the study by providing feedback on the grant application submitted to the funder. They identified falls as an area of concern affecting many older people and agreed that reducing falls was an important issue. They further considered that strategies aimed at reducing falls was an area of research worth undertaking. During the trial, further advice was given on recruitment methods and on the phrasing and content of participant-facing documents, such as the participant information sheet, case report forms and newsletters. The group considered the burden of completing the trial documentation and whether or not it would be acceptable to trial participants. In addition, they reviewed the plain English summary in this report and advised on the dissemination of findings to a lay audience. They will provide input into the summary of results letter that will be sent to participants. One of the public involvement group members was also a member of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC)/Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). She attended meetings via teleconference and contributed from a non-medical perspective to ensure that the trial maintained its priorities of being patient focused and pragmatic.

Regulatory approvals and research governance

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee (REC) 3 (REC reference number 16/WS/0154) on 8 August 2016. The study was approved by the Health Research Authority on 8 September 2016. The University of York Department of Health Sciences Research Governance Committee approved the study on 20 May 2016. Approval and ‘Confirmation of Capacity and Capability’ was obtained for each participating NHS trust prior to the commencement of the trial at that site (see Appendix 1). Substantial amendments to approve changes to the protocol and study documentation were submitted to the REC, the Health Research Authority, the Department of Health Sciences Research Governance Committee and each site’s research and development office as required during the course of this study. The trial sponsor was the University of York, and responsibilities were delegated to York Trials Unit (YTU).

Trial registration

The trial was assigned the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) ISRCTN22202133 on 21 June 2016.

Setting

Recruitment of participants took place across eight NHS trusts based in primary and secondary care in England. OTs employed in these trusts delivered the trial intervention. Fifteen GP surgeries within the geographical area covered by six of these NHS trusts mailed out invitation packs to their patients as part of the recruitment process.

Participant recruitment

Participants were first recruited to the OTIS cohort. Potential participants for the cohort were identified by one of the following methods:

-

A database search of existing trial cohorts held at YTU19–21 and the Yorkshire Health Study. 22 To be eligible for the mail-out, participants had to be aged ≥ 65 years and live in an OT catchment area. Participants known to live in residential or nursing homes were excluded from the mail-out.

-

A database search of the patient lists at GP surgeries within OT catchment areas. To be eligible for the mail-out, patients had to be aged ≥ 65 years. Patients known to have dementia or who lived in residential or nursing homes were excluded.

-

Advertising the study in GP surgeries, newspapers, faith magazines, posters, University of the Third Age (London, UK) and flyers.

-

Opportunistic screening undertaken by health-care professionals (GPs and podiatrists).

The recruitment methods used at each individual trust are reported in Appendix 2. As we planned to mail out a large number of invitation packs in order to recruit sufficient participants, we took the opportunity to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions designed to increase recruitment to studies. 23,24 As we were sending out large numbers of postal questionnaires to participants for follow-up data, we also took the opportunity to evaluate interventions aimed at improving response rates to postal questionnaires. 25,26

Any potential participant identified using one of the above strategies was sent a study recruitment pack consisting of an invitation letter (see Report Supplementary Material 1), a participant information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 2), a consent form (see Report Supplementary Material 3), a screening questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 4) and a freepost envelope for returning the completed paperwork. For potential participants invited through a GP mail-out, the invitation letter was from their GP surgery, while those approached from the YTU cohorts and the Yorkshire Health Study were sent an invitation letter from YTU or the Yorkshire Health Study, respectively.

Potential participants who wished to take part in OTIS were requested to return a completed consent form and screening questionnaire by post to YTU. The research team assessed the forms to confirm the participant had given consent to take part in the study and for eligibility.

Consenting participants

Participation in OTIS was voluntary. Potential participants were given written information about the study and contact details for the research team if they, or a family member or friend, had any queries. The participants were asked to complete a consent form to indicate that they wanted to take part in the research and were willing to receive a home visit from an OT if this was offered. At the consent stage, participants were able to register their interest in helping the study team with other similar related studies. If willing, participants could opt in to being sent details about future research. On receipt of written consent for this study, researchers at YTU assessed participants’ responses to the screening questionnaire for eligibility in accordance with the criteria listed below.

Participant eligibility

Inclusion criteria for OTIS cohort

-

Aged ≥ 65 years.

-

Willing to receive a home assessment from an OT.

-

Community-dwelling.

-

Had had at least one fall in the past 12 months or reported a fear of falling on their screening questionnaire (for at least some of the time).

Exclusion criteria for OTIS cohort

-

Unable to walk 10 feet (3.05 m), even with the use of a walking aid.

-

Unable to give informed consent, for example due to dementia.

-

Lived in a residential or nursing home.

-

Unable to read or speak English and had no friend or relative to translate/interpret for them.

-

Had had an OT assessment for falls prevention in the previous 12 months or were on the waiting list for an OT assessment.

Participants who met any of the exclusion criteria for the study or did not meet the first three inclusion criteria were notified in writing that they were ineligible and no further correspondence was sent. Participants deemed eligible (i.e. those who met all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria) were sent a baseline questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 5) and a pack of monthly falls calendars (18 months’ worth; see Report Supplementary Material 6). Participants were eligible to be randomised once they had returned a completed baseline questionnaire and at least one falls calendar in the preceding 3 months. Participants who had neither had a fall in the past 12 months nor reported a fear of falling but were otherwise eligible for the study were deemed as ‘pending’ in terms of their eligibility and were followed up every 3 months for falls data. If individuals reported a fall, and were still willing to be in the study, they became eligible and were sent a pack of falls calendars and a baseline questionnaire to complete. If individuals did not report a fall by the end of the recruitment period, they were sent a letter to inform them that recruitment to the study had closed and that they were ineligible for the study.

Sample size

We proposed to recruit and randomise 1299 participants to OTIS in a 2 : 1 ratio (i.e. 866 to usual care and 433 to the intervention). This number allowed for 10% attrition and provided 90% power (using two-sided significance at the 5% level) to show a difference in the percentage of participants who experienced at least one fall in the 12 months following randomisation from 60% in the usual-care group to 50% in the intervention group, accounting for the unequal randomisation (Stata Statistical Software Release 13, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). In the REFORM (REducing Falls with ORthoses and a Multifaceted podiatry intervention) trial,19 which was conducted by some of the authors, an absolute difference of 5% was observed in the percentage of participants experiencing a fall (intervention group, 50%; usual-care group, 55%), with an upper CI limit of 13%; therefore, the decision was made to power OTIS for a 10% absolute difference.

The sample size is based on the proportion of participants experiencing at least one fall over 12 months, which is a key secondary outcome, rather than on the primary outcome, which is a count variable (number of falls). Powering a trial for count data is more complex and requires greater assumptions and so a binary approach to the sample size calculation was taken.

Randomisation

Participants were enrolled into the cohort study if they fulfilled the eligibility criteria and provided written consent to take part. They were then randomised to either the intervention group or the usual-care group once they had returned a valid baseline questionnaire and at least one falls calendar within 3 months prior to randomisation. Randomisation was carried out using YTU’s secure web-based randomisation service and was based on an allocation sequence generated by an independent data systems manager, who was not involved in the recruitment of participants. A ‘batch’ of participants from a particular centre was randomised at a time in a single block, most commonly in a 2 : 1 ratio in favour of the usual-care group (to reduce costs), according to when centres had the capacity to undertake intervention appointments and how many participants were available to be randomised. In some instances, the allocation ratio used per ‘batch’ varied (range 1 : 1 to 9.7 : 1) depending on the OTs’ capacity to carry out the assessments and the number of participants available to randomise at that centre (the overall ratio was, ultimately, 2.1 : 1). Unequal randomisation in favour of the usual-care group was used for two reasons. First, it reduced the cost of delivering the intervention arm of the study. Second, it reduced the OTs’ burden of having to deliver the home assessment visits. There was a total of 12 centres; some of the trial sites were split into two or three centres, according to the geographical areas covered by the OTs, for the purposes of randomisation. By nature of the procedure, the median time from completion of the eligibility form to randomisation was around 2.5 months. We did not repeat eligibility checks or baseline data collection before randomisation as we did not anticipate that many participants’ circumstances were likely to change in this short time frame such that they would become ineligible. This avoided further delays. Once intervention group participants had been randomised, they were sent a letter informing them of their group allocation and confirmation that an OT would be in contact to arrange a home assessment visit. Participants who were allocated to the usual-care group were not informed of their group allocation in order to minimise potential attrition and the possibility of resentful demoralisation. YTU wrote to all participants’ GPs (both the intervention and the usual-care groups) informing them of the participant’s study participation after they had been randomised and advised them of the possibility that the participant could be offered a home assessment.

Blinding

Owing to the nature of the intervention, participants in the intervention group were not blinded to group allocation. This was an open trial with an unequal allocation ratio; therefore, it was not possible to blind members of the research team who were actively involved in the administration of the study, the statistician or the health economist. Data entry staff were, however, blind to group allocation.

Group allocation

Usual-care group

Participants allocated to the usual-care group continued to receive usual care from their GP and other health-care professionals, which may have included referrals to falls clinics. They were sent a falls prevention leaflet produced by Age UK27 with their baseline questionnaire in the post.

Intervention group

In addition to the usual care and the falls prevention leaflet given to the usual-care group, the participants in the intervention group were offered home environmental assessment and modification to identify personal fall-related hazards. The assessment was undertaken by an OT registered with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC). The OT used the Westmead Home Safety Assessment (WeHSA) tool28 to structure their assessment visit. The WeHSA was developed in Australia in 1997 for older adults and is a validated tool. It comprises a 57-item functional assessment organised into 15 domains: internal/external traffic ways, general indoors, living area, seating, bedroom, toilet area, bathroom, kitchen, laundry, mobility aid, footwear, pets, medication management and safety call systems. The assessment consisted of an initial discussion about the participant’s history of falling, lifestyle, patterns of usage of areas in the home, risk-taking behaviour, strategies already adopted to reduce falls, environmental changes made and functional vision. The participant and the OT then moved through the home and identified potential falls hazards. The OT encouraged the participant to identify potential strategies to mitigate any hazards, but offered suggestions if needed. A list of recommendations was agreed and, if needed, the OT would either refer on to other agencies or liaise with family members regarding the provision of equipment and modifications or refer on to other health-care services as deemed clinically appropriate. The Timed Up and Go test29 was also conducted. The Timed Up and Go test is a standardised tool used as a falls risk indicator, with scores of > 14 seconds indicating a high risk of falling. These data were collected to allow secondary analysis to be undertaken once the main findings of the study are published. A second visit by the OT could have been undertaken if deemed clinically necessary, but, to our knowledge, none was. The OT contacted the participant 4–6 weeks after the home visit to collect data on whether or not the recommendations had been acted on. To document the activities undertaken at the visit, the OT completed an OT booklet (see Report Supplementary Material 7).

Occupational therapist training to deliver the intervention

The OTs delivering the intervention attended a 1-day face-to-face training session on how to conduct the assessment before conducting the home visits with participants. A standardised training package was developed by the co-applicant who had undertaken the pilot study16 (Alison Pighills) in collaboration with Professor Lindy Clemson, who originally developed the WeHSA. A standardised approach was used to ensure that the OTs who delivered the intervention did so consistently across all of the trial sites. The training materials included a presentation with detailed notes, a training manual and videos of older people undertaking activities of daily living, which the OTs assessed using the WeHSA. The training covered the following 10 domains: prevalence of falls; evidence underpinning environmental assessment and modification; falls risk factors; the person–environment–occupation conceptual model of practice and occupational performance;30 background on falls – categories, types and locations; environmental assessment; equipment and ideas for falls prevention; adherence to recommendations; action-planning; and scoring a video of an older person carrying out functional tasks at home using the WeHSA. Self-efficacy was addressed in the OT training in relation to its influence on participants’ confidence in their ability to engage in activities without falling, and the potential for low self-efficacy to lead to activity avoidance and deconditioning. OTs were encouraged to address both falls self-efficacy and fear of falling with participants as a component of the visit. The OT training addressed grading the demands that activities placed on the individual, particularly in the context of ‘environmental press’, which is the demand that the environment places on the individual, and reducing that demand for frail older people to enhance their self-efficacy. The initial training session was led by the co-applicant (Alison Pighills) who conducted the pilot trial. Two other HCPC-registered OTs and study co-applicants (Shelley Crossland and Avril Drummond) were also trained to facilitate the training at subsequent training sessions using a ‘train the trainer’ approach. 31,32 These face-to-face training sessions were audio-recorded for the purpose of evaluating training fidelity. The face-to-face training was supplemented by an online training module. 33 Those who could not attend the face-to-face training undertook the online training course in addition to attending ‘cascade’ training delivered by one of the OTs who had attended the face-to-face training sessions. These ‘cascade’ trainers were provided with the same training package used in the face-to-face sessions, which included extensive notes. All OTs trained to deliver the intervention were supported by Shelley Crossland, Avril Drummond and Alison Pighills, who addressed any queries or points for clarification raised during the training or throughout the trial.

Participant follow-up

All participants in OTIS were followed up with monthly falls calendars for 12 months post randomisation, and follow-up was completed by August 2019. If a participant did not return their falls calendar within 10 days of the due date, a member of the research team either contacted them by telephone (Monday to Friday between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m.) or sent a letter to collect falls data. Participants could also ring a freephone number to report a fall (participants could leave a message outside office hours or when a research team member was not available). Any participant who reported falling using their falls calendar was contacted by the research team in order to collect additional information about the fall(s) (see Report Supplementary Material 8). Participants occasionally gave permission for a relative or carer present to talk on the telephone to the researcher on their behalf. Permission for the study team to talk to a relative or carer was documented on the participant’s consent form. The relative or carer was asked to report on the participant’s own views. The relative or carer did not have to provide their own written consent.

Participants were also sent follow-up questionnaires in the post at 4, 8 and 12 months post randomisation along with a freepost return envelope (see Report Supplementary Material 9–11). Any participant who provided a mobile phone number and agreed to receive text messages was sent one Short Message Service text at the time they were expected to receive their questionnaire. Any participant who did not return their follow-up questionnaire within 21 days was sent a reminder letter together with an additional copy of the questionnaire. Participants were also sent a group-specific newsletter at 3 months post randomisation and 2 weeks before their final 12-month follow-up questionnaire. The newsletter informed participants of the study’s progress and aimed to minimise attrition and improve response rates to the postal questionnaires. The content of the newsletter was informed by issues raised by study participants and the public involvement group during the course of the trial. All participants were sent an unconditional £5 in cash with their 12-month questionnaire to cover any incidental expenses that they may have incurred when completing the questionnaires and in recognition of their participation in the study.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

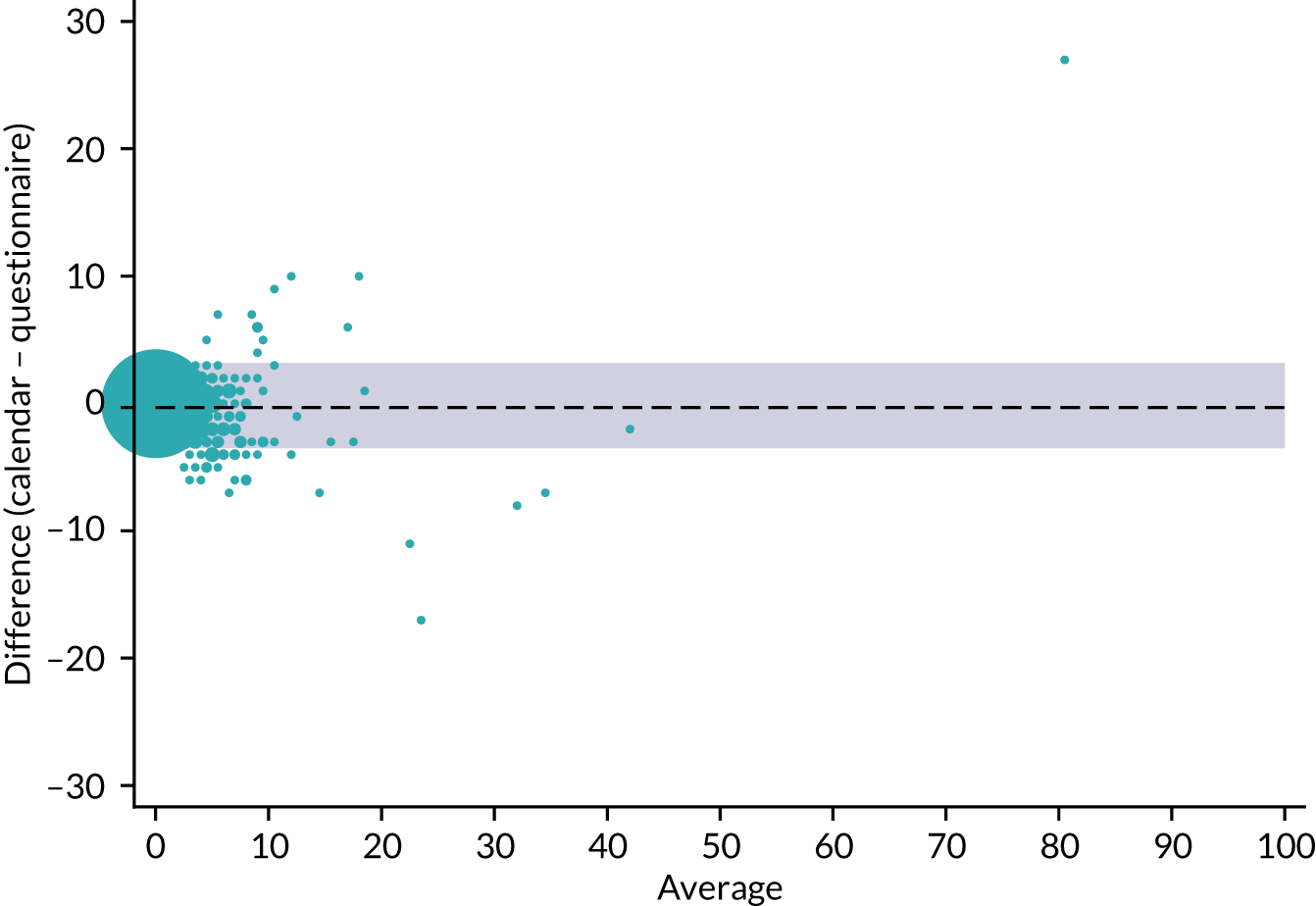

The primary outcome of the trial was the number of falls per participant over the 12 months from randomisation. A fall was defined as ‘an unexpected event in which the participant comes to rest on the ground, floor or lower level’. 34 Data were collected from self-reported monthly falls calendars, on which participants were asked to mark the number of falls they had on each day or to indicate that they had not fallen that month. An explanation of what the researchers considered to be a fall was included in the participant information sheet and on the falls calendars. If a participant was uncertain whether an event would be classed as a fall, they were encouraged to ring the research team at YTU to discuss it. Participants who indicated on their falls calendar that they had a fall were contacted by the research team for further information. Information collected about the falls included the date and number of falls, the location of the fall, what the participant was doing when they fell (i.e. the cause/reason for the fall), injuries from the fall (e.g. superficial wounds, such as bruising, sprain, cuts, abrasions or fractures, including type of fracture) and any hospital admissions (see Report Supplementary Material 8).

Data collected on the 4-, 8- and 12-month post-randomisation follow-up participant questionnaires included the number of falls in the previous 4 months and were used to calculate the falls rates for participants who did not return any monthly falls calendars.

Secondary outcomes

All secondary outcomes were self-reported by the participant and collected using questionnaires at baseline and at 4, 8 and 12 months post randomisation, or on monthly falls calendars. The secondary outcomes were:

-

proportion of participants reporting at least one fall in the 12 months from randomisation

-

proportion of participants reporting multiple (two or more) falls in the 12 months from randomisation

-

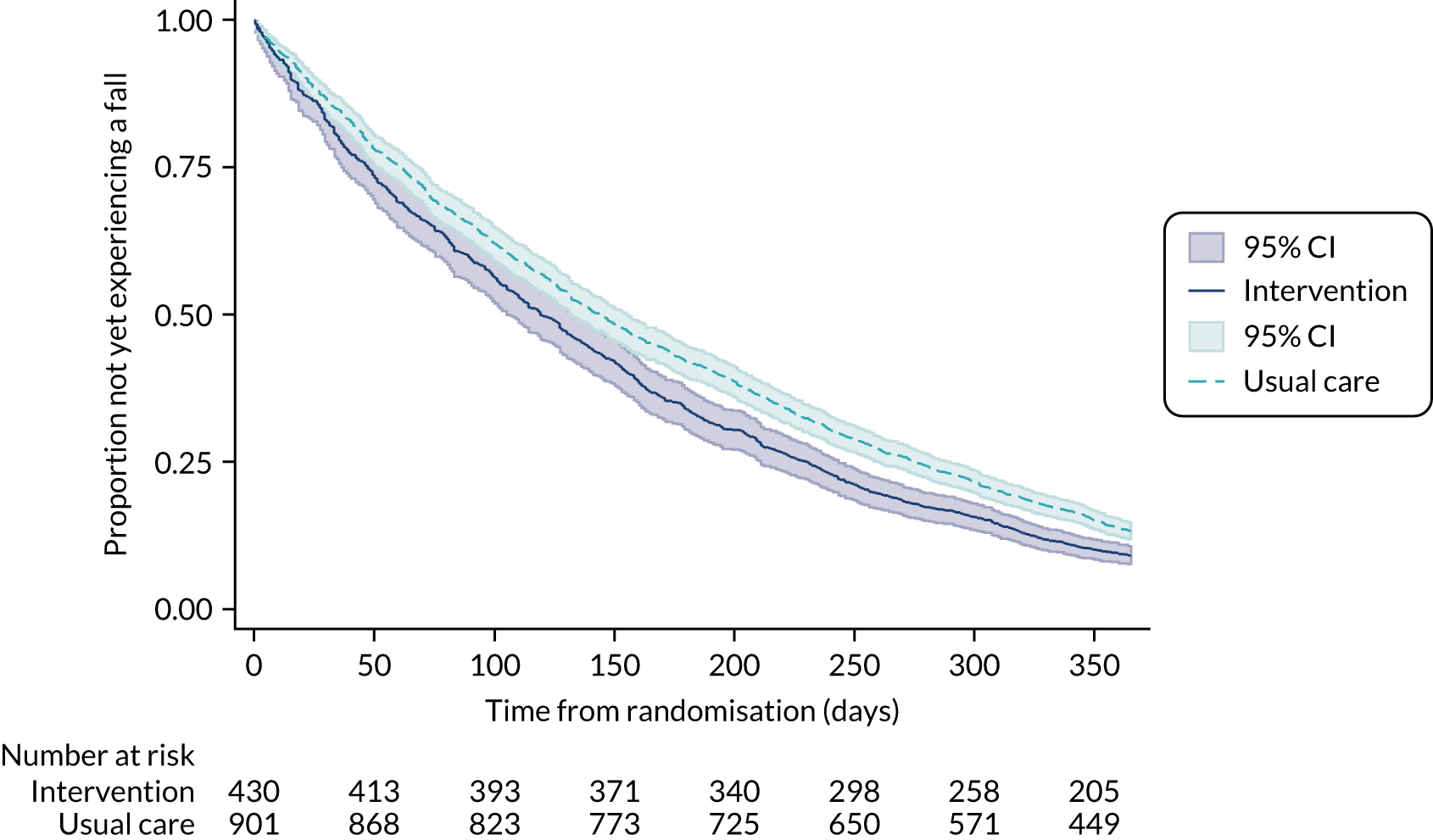

time to first fall from date of randomisation and between subsequent falls

-

fracture rate

-

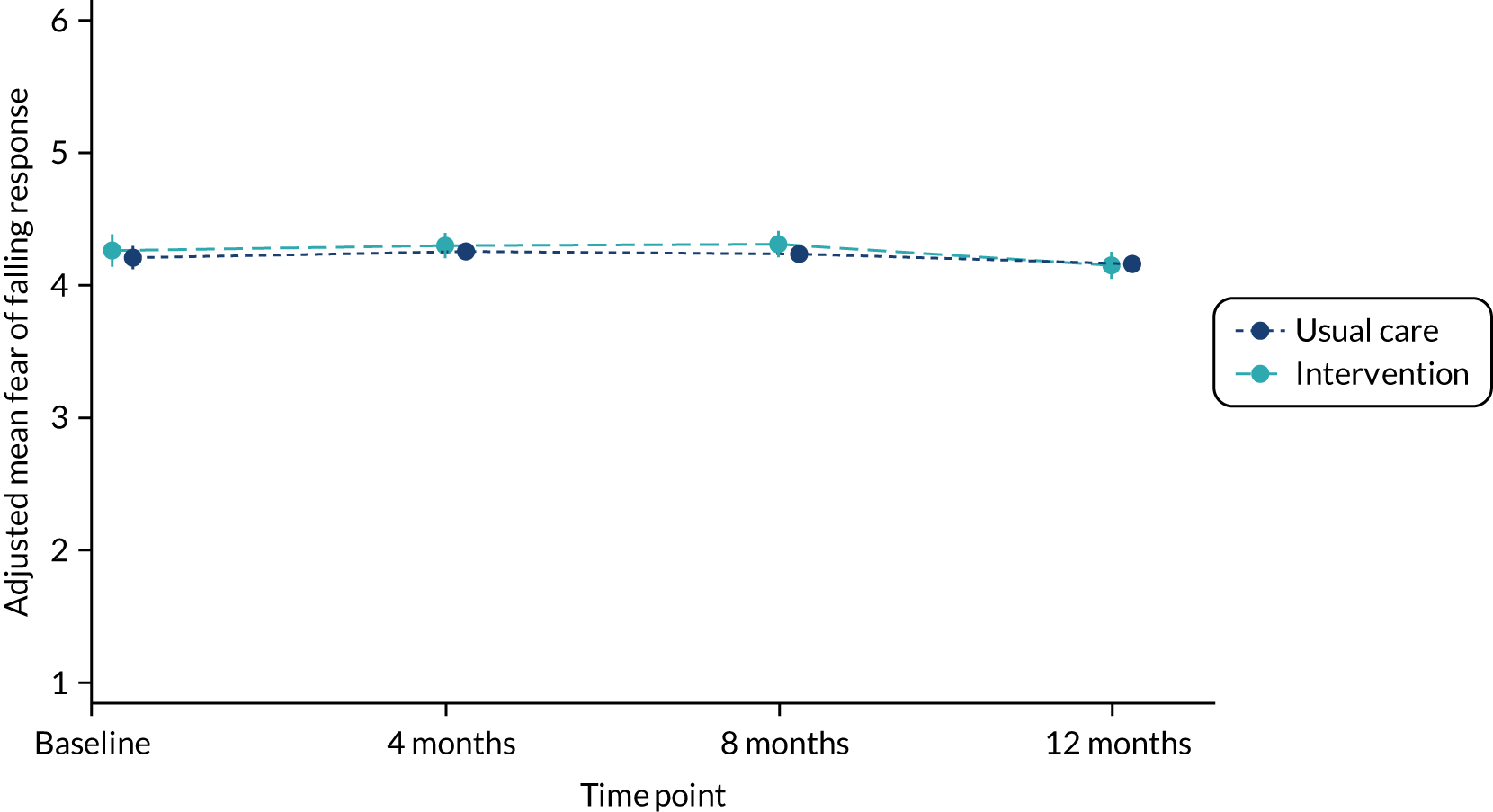

fear of falling

-

health-related quality of life, as measured using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)

-

health service utilisation.

Scoring of instruments

Fear of falling

Fear of falling was measured using the question ‘During the past 4 weeks have you worried about having a fall?’ Response categories were all of the time, most of the time, a good bit of the time, some of the time, a little of the time, and none of the time. These were scored from one to six, respectively, and treated as continuous data in the analysis. This measure has not been validated yet but was used by some of the authors in the earlier REFORM trial,18 where it correlated moderately well (r = 0.6) with the validated Short Falls Efficacy Scale (Short FES-I).

Other data collected

Items to identify participants with a history of falling or balance problems

We incorporated items into the baseline questionnaire that asked about history of falling or balance problems. These included selecting which of the following statements best applies: My balance is good and I want to keep it that way; My balance is quite good but I would like to improve it; or I have some problems with balance that I want to overcome. Additionally, we asked ‘Do you have any difficulties with your balance whilst walking or dressing?’, with the following response categories: yes, often or always; or no, or just occasionally. This item, in addition to asking about the number of falls sustained in the previous 12 months and the severity of problems doing usual activities (as part of the EQ-5D-5L), allowed us to construct a measure of risk of falling (adapted from a balance screening survey developed in the PreFIT study35). Participants reporting balance problems while walking or dressing or at least moderate problems doing usual activities, or those reporting one or more fall in the previous 12 months, were categorised as being at intermediate or high risk of falling. Conversely, those who reported no falls in the previous 12 months and no balance problems while walking or dressing and no or only slight problems doing usual activities were deemed to be at a low risk of falling.

Other important data

The following data were also collected during the study: date of birth, sex, ethnicity, height, weight, living arrangements, health problems, broken bones since the age of 18 years, number of medications prescribed by a doctor (≤ 4 vs. > 4), and difficulties with balance and, for intervention participants only, Timed Up and Go test scores and duration of home assessment.

Adverse events

With approval from the REC and the joint TSC and DMEC, it was agreed that only unexpected events that were related to taking part in the study had to be reported. Details of any adverse events reported directly to YTU by the participant, by a member of their family or by the OT who delivered the intervention were recorded on an OTIS adverse event form (see Report Supplementary Material 12). Participants reported adverse events by writing details of the event in the free-text comment section of a follow-up questionnaire, or they or a family member could report the event during a telephone call with a member of the study team. OTs were instructed to inform the study team by telephone if they found out that the participant had experienced an adverse event during their follow-up telephone call to elicit data on whether their recommendations had been actioned. Adverse events were categorised by two members of the study team, the trial manager and the chief investigator and reviewed by the Trial Management Group. Any serious adverse event judged to have been related and unexpected was required to be reported to the REC under the current terms of the standard operating procedures. The reporting period began as soon as the participant consented to being in the study and ended 12 months after they had been randomised.

In this study, a serious adverse event was defined as any untoward occurrence that:

-

resulted in death

-

was life-threatening

-

required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

consisted of a congenital anomaly or birth defect

-

was otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator.

Owing to the age of the participants, expected events included incidences of hospitalisations, disabling/incapacitating/life-threatening conditions, ageing-associated diseases (e.g. cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, arthritis, osteoporosis or dementia), other common illnesses such as depression, falls and deaths.

The occurrence of adverse events was monitored during the trial by an independent TSC/DMEC. Adverse event data are summarised descriptively by treatment group.

Non-consenting participants

Participants who did not wish to take part in the study were not required to return any forms to YTU; however, some chose to complete the screening questionnaire, and thus provided some demographic information about their age, sex, falls in the previous 12 months and fear of falling.

Participant withdrawal

Participants could withdraw from the trial at any point during the course of the study. If a participant indicated that they wanted to withdraw from the study, they were asked whether they wished to withdraw from the intervention only (i.e. withdrawal from treatment if allocated to the intervention group, only if withdrawal was requested before OT visit was received) or withdraw fully from the study. When withdrawal was only from the intervention, follow-up data continued to be collected. Data provided by participants who fully withdrew were retained for analysis, up to the point at which they withdrew. A member of the research team completed a change of circumstance form for any participant who changed status during the trial (see Report Supplementary Material 13).

Trial completion and exit

Participants completed the trial once they had completed the 12-month follow-up period post randomisation. Participants exited the trial if they had fully withdrawn (i.e. no further follow-up), were lost to follow-up or died.

Data analysis

All outcomes were analysed collectively after follow-up had ended. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA), following the principles of intention-to-treat (ITT), with outcomes analysed according to the participants’ original randomised group irrespective of deviations based on non-compliance. Statistical tests were two-sided at the 5% significance level, and 95% CIs are used.

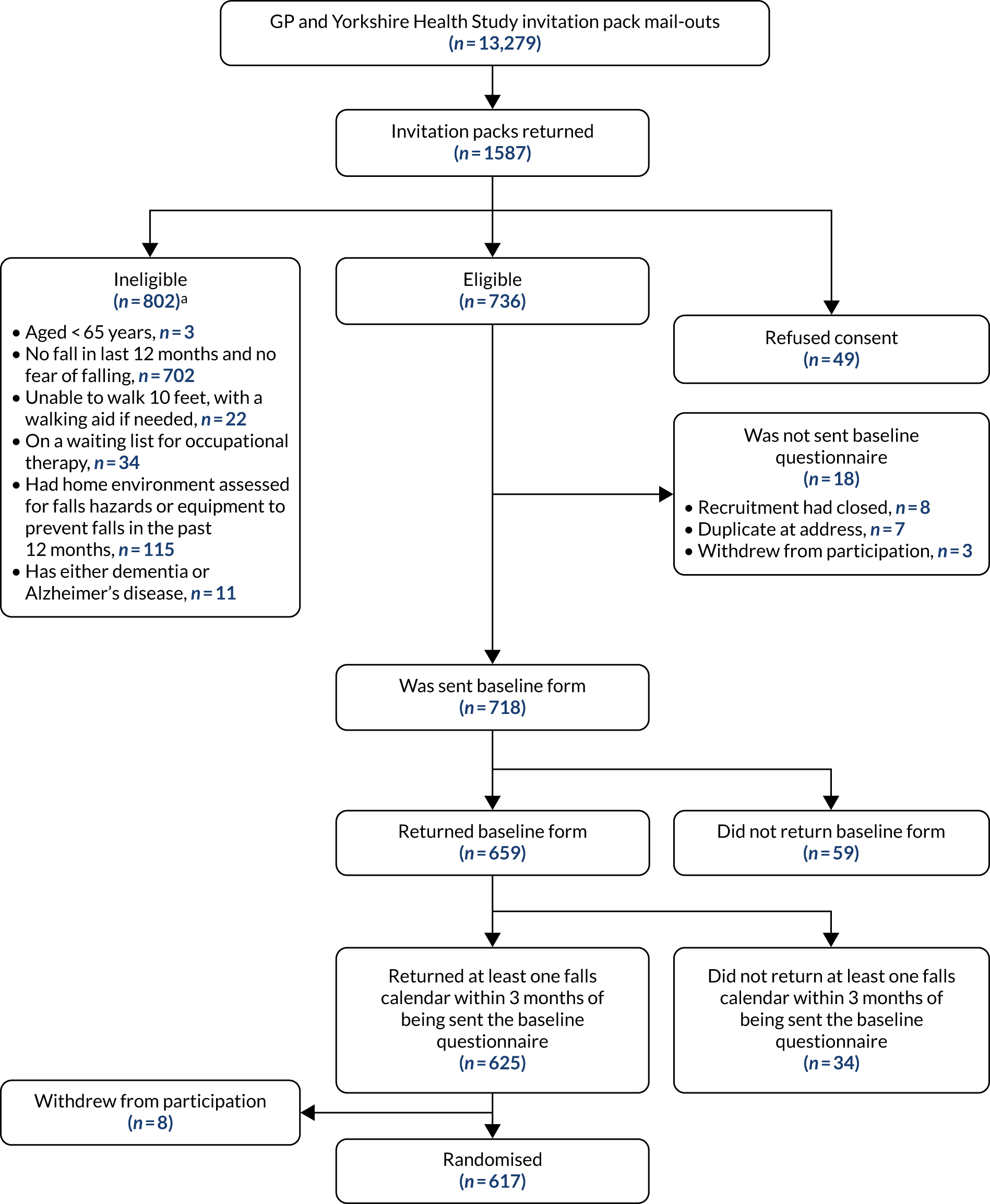

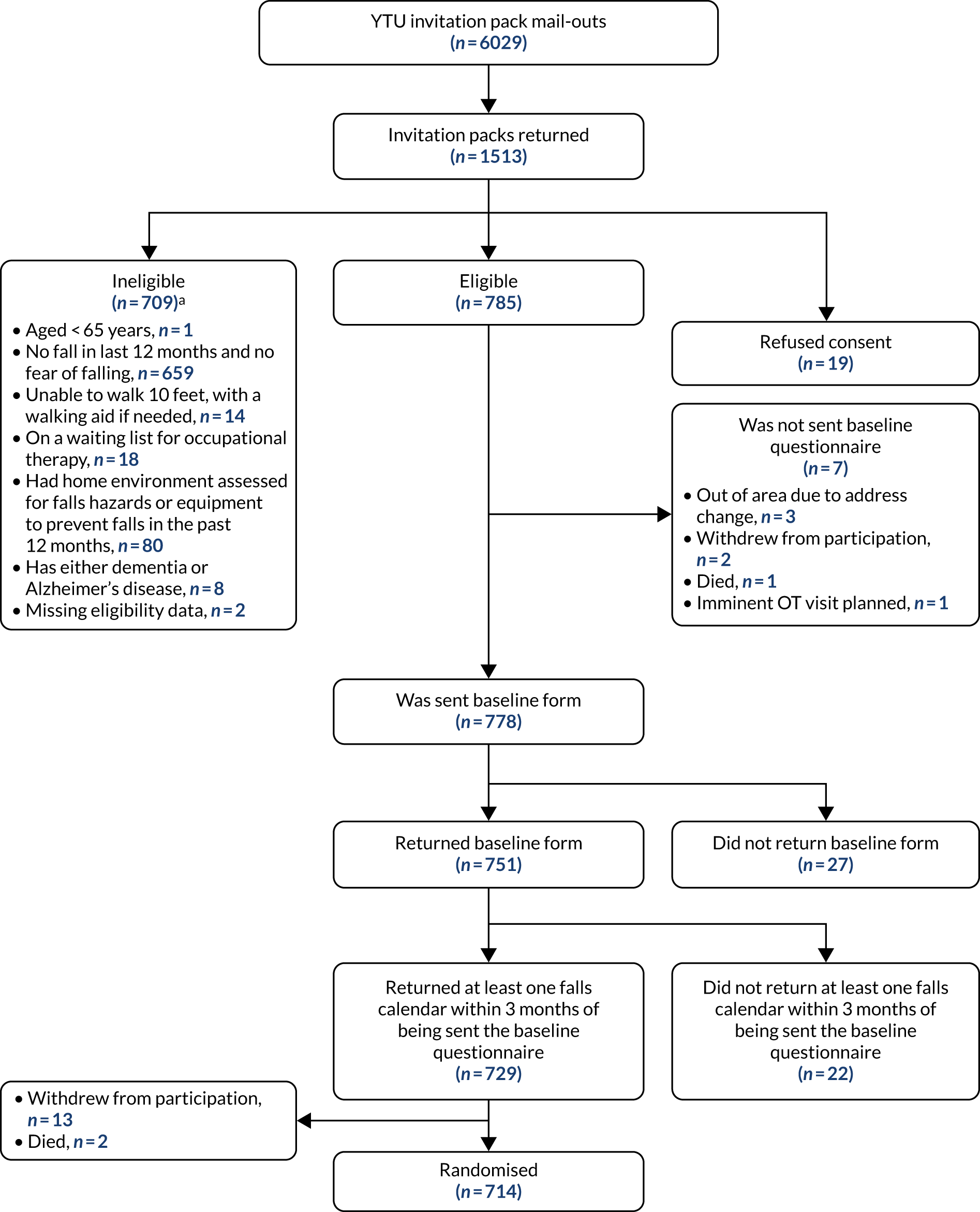

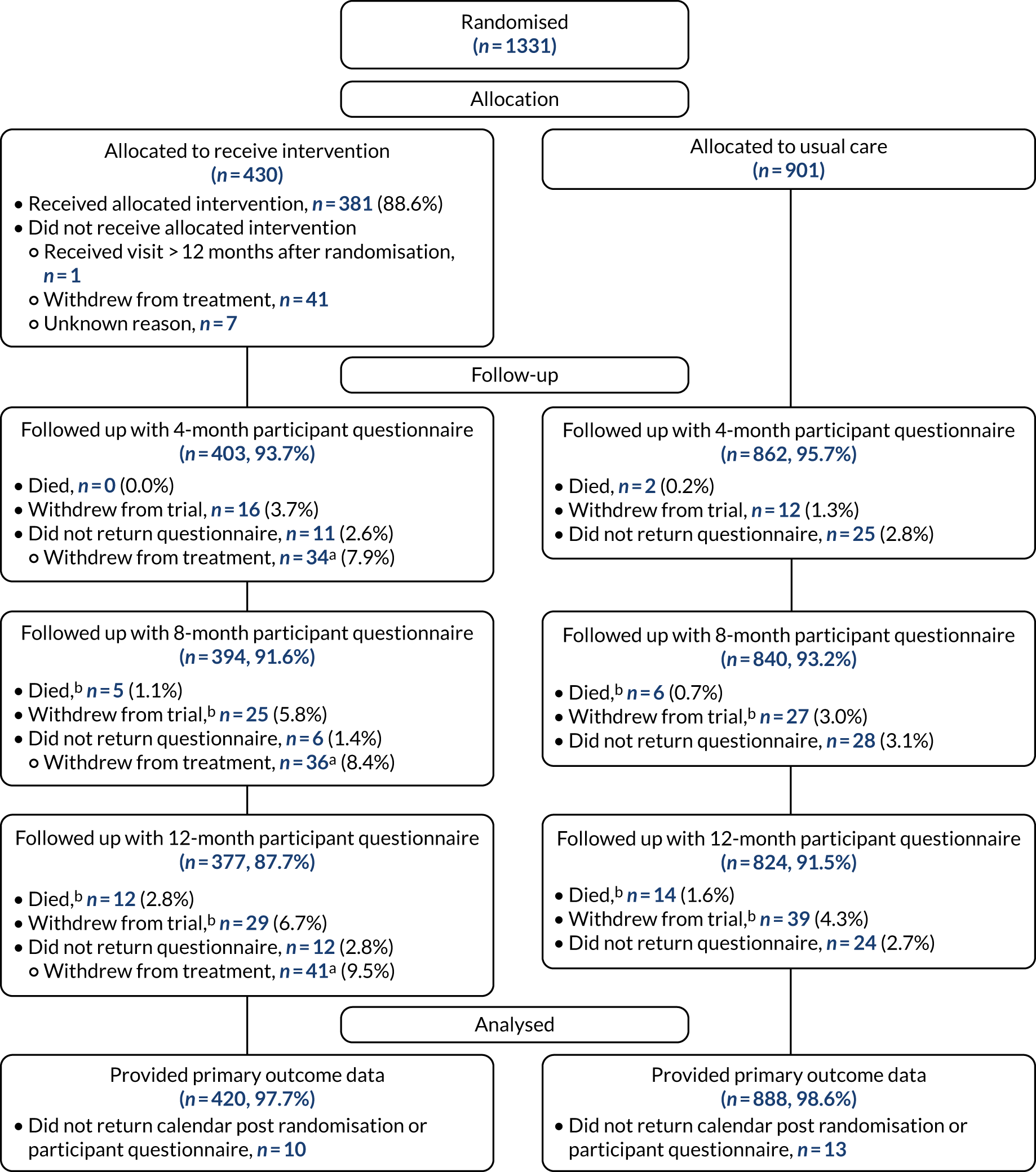

Three Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagrams depict the flow of participants through the trial; one presents the recruitment of participants via GP and Yorkshire Health Study cohort mail-outs and another presents the recruitment of participants via the YTU cohort mail-outs, up to the point of randomisation; the third presents the flow of participants from randomisation onwards.

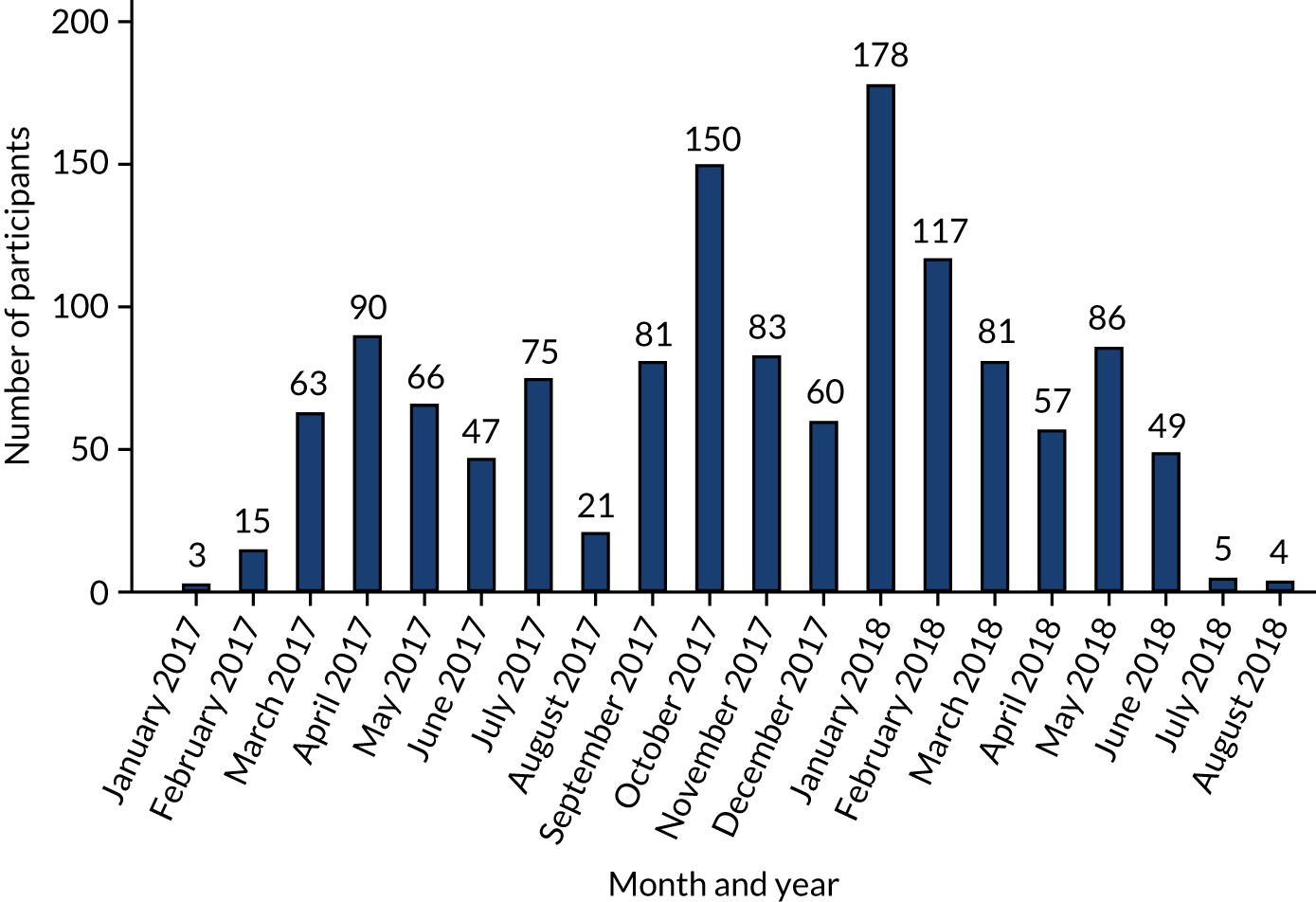

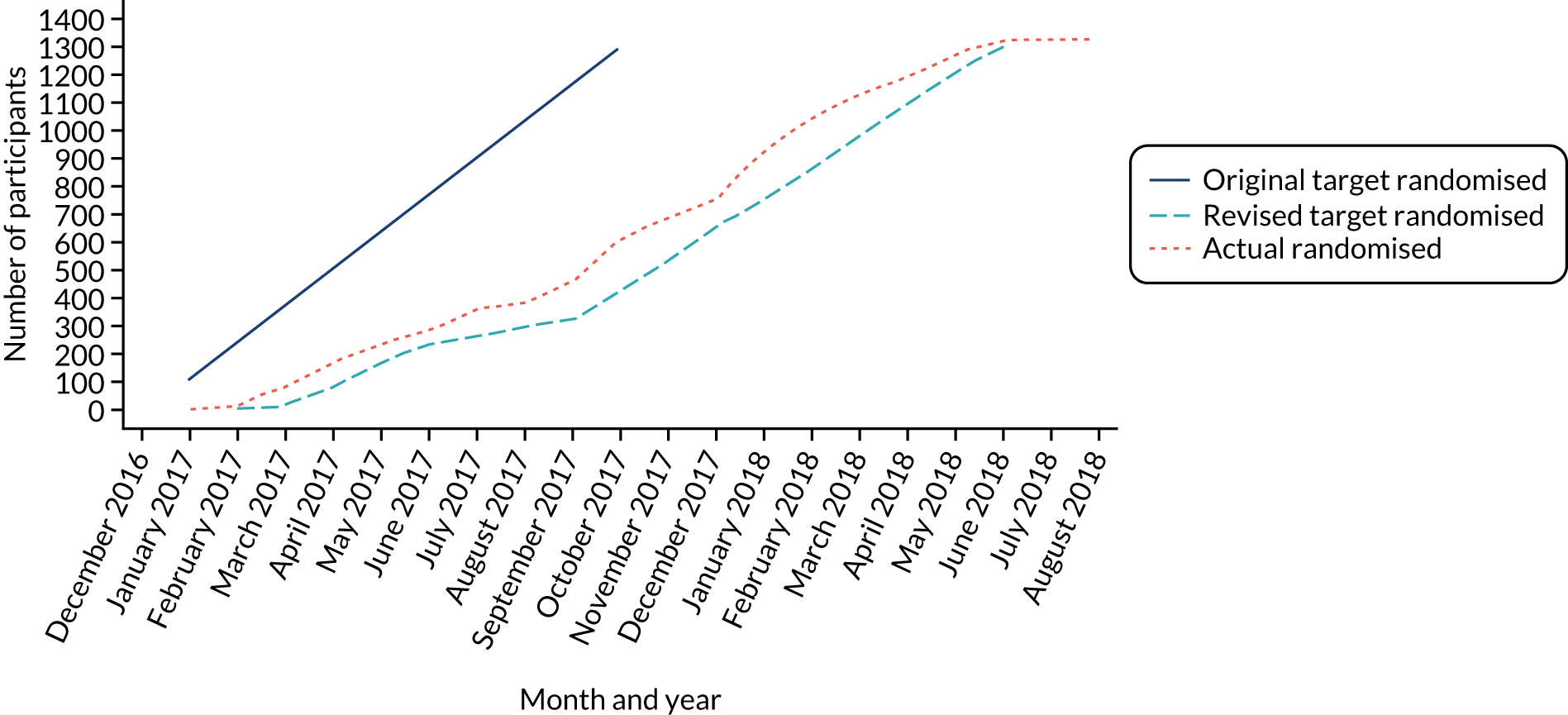

Recruitment graphs present the overall recruitment by month, and the actual compared with the target recruitment.

All participant baseline data are summarised descriptively by trial arm. No formal statistical comparisons were undertaken. Continuous measures are reported as means, standard deviations (SDs), median, minimum and maximum, and categorical data are reported as counts and percentages.

Follow-up response rates to the monthly falls calendars and the participant questionnaires (including time to response) are summarised overall and by treatment group. Details about the falls (e.g. cause, location) are also summarised.

The number of intervention participants receiving the OT home assessment and the time taken from randomisation to the home visit are also summarised.

Participant withdrawals (number, type and timing) are presented overall and by treatment group.

Primary analysis

The number of falls per person was analysed using mixed-effects negative binomial regression adjusting for sex (male/female), age at randomisation (continuous), history of falling and the allocation ratio used to randomise the participant as fixed effects, and centre as a random effect. Participants were classified into two groups for the history of falling covariate: (1) one or no falls in the 12 months prior to completion of the screening questionnaire; and (2) two or more falls reported in the 12 months prior to completion of the screening questionnaire. The model included an exposure variable for the number of months that the participant returned a monthly falls calendar (i.e. the number of months’ worth of falls they report).

The point estimate for the treatment effect in the form of an adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR) is provided, along with its associated 95% CI and p-value.

This analysis primarily included falls data from the falls calendars, but, where no post-randomisation calendars were returned, data from the 4-, 8- and 12-month participant questionnaires were used for a participant, where available. When no falls data were provided at all, an assumption of zero falls over a negligible follow-up time of 0.1 months was made for the participant in the analysis.

Analysis of the primary outcome was checked and verified by a second statistician.

Sensitivity analyses

Non-compliance

The primary analysis follows the principles of ITT and thus estimates the effect of the offer of an OT visit; however, not all intervention participants received the home assessment. A complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis to assess the impact of compliance on the primary treatment estimate was undertaken. 36–38 CACE analysis allows an unbiased treatment estimate of, in this case, receipt of an OT home assessment visit, in the presence of non-compliance. It is less prone to biased estimates than the more commonly used approaches of per-protocol or ‘on-treatment’ analysis, as it preserves the original randomisation and uses the randomisation status as an instrumental variable to account for the non-compliance. Compliance was defined as receiving the OT home assessment visit within 12 months of randomisation. A two-stage instrumental variable regression approach was used with negative binomial regression to reflect the primary analysis.

Post hoc adjustment for Parkinson’s disease

A chance imbalance in the proportion of participants in the two groups with Parkinson’s disease at baseline was observed. We therefore decided, as an unplanned, post hoc analysis, to consider the impact of this imbalance on the primary treatment estimate in a sensitivity analysis. We repeated the primary analysis including whether or not the participant had Parkinson’s disease as an additional fixed effect.

Missing data

A logistic regression model was used to predict non-response (no falls data received post randomisation either via monthly falls calendars or on the participant follow-up questionnaires), including all variables collected prior to randomisation. The primary analysis was then repeated, including as covariates all variables found to be statistically significantly predictive of non-response, to determine if these affected the parameter estimates and study conclusions.

Therapist effects

In some centres, more than one therapist delivered the intervention visits to the participants. We therefore have clustering by therapist in the intervention group. The value of the intervention may depend on the skill/experience of the therapist and their relationship with the participant. Therefore, to account for this potential variation between therapists, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using an artificial cluster method. With this method, every participant (whether allocated to the intervention group or to the usual-care group) was associated with a therapist. For intervention participants, their trial therapist was known; however, for usual-care participants, we assigned them a counterfactual therapist, that is, one they could have seen had they been randomised to the intervention group. For centres where only one therapist delivered the visits, all of the usual-care participants were assigned this therapist. For centres that had more than one trial therapist, the usual-care participants were randomly assigned one of these therapists in the proportion that the therapists saw intervention participants. Each therapist then had their own cluster of usual-care and intervention participants. Therapist (rather than centre) was then included as a random effect in the primary analysis model.

Subgroup analysis

The primary analysis was repeated including an interaction term between the treatment allocation and whether or not a participant received care in a hospital (outpatient appointment, day case, accident and emergency (A&E) presentation, or hospital admission) as a result of a fall in the 4 months prior to completion of the baseline questionnaire.

Secondary analyses

The following secondary outcomes were analysed by mixed-effects logistic regression adjusting for sex, age, history of falls and allocation ratio as in the primary analysis, and centre as a random effect:

-

proportion of participants who fell at least once over the 12 months from the date of randomisation*

-

proportion of multiple fallers (participants who had two or more falls in the 12 months from randomisation)*

-

proportion of participants who reported that they worried about falling at least some of the time at 12 months post randomisation

*using data from monthly falls calendars except where no post-randomisation calendars were returned, in which case data from the 4-, 8- and 12-month participant questionnaires were used, where available.

Adjusted odds ratios (OR) for the intervention effect and their associated 95% CIs and p-values are provided.

The primary and secondary analyses relating to falls (number of falls and proportion of single and multiple fallers) were also repeated using data only from participant follow-up questionnaires.

The proportion of participants having at least one fracture or multiple fractures resulting from a fall are reported but were not formally analysed owing to the rarity of these events.

Fear of falling was also analysed in its continuous form using a covariance pattern model incorporating all post-randomisation time points and adjusting for baseline fear of falling, sex, age, history of falling, allocation ratio, treatment group, time, and a treatment group-by-time interaction. The correlation of observations within participants over time was modelled using participant and centre as random effects. The Akaike information criterion was used to compare models specifying different correlation structures (smaller values were preferred). 39 An unstructured covariance structure was used in the final model. Model assumptions were checked visually. The normality of the standardised residuals was checked using a Q–Q plot, and homoscedasticity was assessed using a scatterplot of the standardised residuals against fitted values. There was no evidence to suggest a violation of the underlying assumptions, so data were not transformed. Adjusted mean differences in fear of falling between the two groups at 4, 8 and 12 months are provided, with their 95% CIs and p-values.

The time to the first fall was derived as the number of days from randomisation to the first fall reported on the monthly falls calendars. The time between any subsequent falls was also calculated. Participants who did not have a fall were treated as censored at their date of trial exit, or the date of their last available assessment, or 365 days or trial cessation, as appropriate. For months for which no calendar was returned, it is assumed, by default, that no falls were experienced in these months. The proportion of participants yet to experience a fall was summarised using a Kaplan–Meier survival curve for each group. Time to fall was analysed using the Andersen and Gill method40 for analysing time to event data when the event can be repeated. The analysis treats each time to event or censoring as a separate observation. The data were analysed by Cox proportional hazards regression, using robust standard errors to account for dependent observations by participant and adjusting for the same covariates as in the primary analysis model. Adjusted hazard ratios and their associated 95% CIs and p-values are provided.

Summary of changes to the protocol

Recruitment

The original funding application stated that we planned to randomise 1299 participants to OTIS over a 10-month period. Participants would be identified from either cohorts of participants held at the University of York and the University of Sheffield or direct mail-out to patients on GP lists. However, study commencement was delayed by approximately 4 months because of contractual issues and delays in obtaining regulatory approvals. As the trial progressed, recruitment fell below the expected level, due, in the main, to the delay in setting up sites. Approval was obtained from the funder to extend the study by 12 months to a total of 43 months (June 2016 to December 2019). This permitted the set-up of additional sites and mail-out of recruitment packs to potential participants from GP surgeries. Details of the recruiting sites and the dates that research and development departments confirmed their capacity and capability to undertake the study can be found in Appendix 1. To facilitate recruitment, approval to use additional recruitment strategies, namely opportunistic screening by OTs and other health-care professionals, media advertising for participants and rescreening participants, was received in January 2017, May 2017 and March 2017, respectively.

Treatment fidelity

In July 2017, additional strategies were included in the protocol to assess treatment fidelity. Discussions about fidelity strategies were guided by the TSC/DMEC and agreed by the funder. Additional strategies included some observational work of the OTs delivering the intervention and a review of the OT booklets to ensure that key elements of consultations had been included.

Intervention: undertaking the follow-up telephone call

In October 2017, a change to the protocol allowed members of the research team as well as OTs to undertake the follow-up telephone call to check participants’ adherence to the recommendations suggested in the home visit. This was intended to relieve some of the burden on the OTs; however, in the end the OTs had capacity to undertake all of the follow-up calls.

Chapter 3 Clinical effectiveness results

Material throughout this chapter has been reproduced from Cockayne et al. 2 © 2021 Cockayne S et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Participant flow

Participants were mainly enrolled into OTIS via mail-outs from GP surgeries or from previous trial cohorts. The flow of participants is illustrated in the CONSORT flow diagrams in Figures 1–3. Across the eight participatory sites (East Coast Community Healthcare, East Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust, Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust, Humber Teaching NHS Foundation Trust, Leeds Community Healthcare NHS Trust, Northern Lincolnshire and Goole NHS Foundation Trust, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust), 12 ‘centres’ were formed. These centres were formed for logistical reasons to stratify the randomisation and were based on the geographical areas covered by the OTs.

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram, up to randomisation, for GP and Yorkshire Health Study cohort mail-outs. a, More than one reason can apply.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram, up to randomisation, for YTU existing trial cohort mail-outs. a, More than one reason can apply. Reproduced with permission from Cockayne et al. 2 © 2021 Cockayne S et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

FIGURE 3.

The CONSORT flow diagram depicting the flow of participants from randomisation. a, Includes withdrawals from trial/death where this was before the intervention was received; b, withdrawals and deaths over time are cumulative.

General practitioner mail-outs

A total of 11,965 recruitment packs were mailed or handed out to potential participants between March 2017 and April 2018 from GP surgeries, via opportunistic screening or through the University of the Third Age. The geographical locations covered included Harrogate, York and Elvington, Sheffield, Grimsby, East Coast Community (across Norfolk and Suffolk) and East Sussex.

Yorkshire Health Study

A recruitment pack was sent to 1314 participants from the Yorkshire Health Study cohort between April and July 2017.

Existing trial cohorts

A total of 6029 potentially eligible participants from previous trials conducted at YTU were mailed between October 2016 and March 2018: 3142 (52.1%) from CASPER (CollAborative care and active surveillance for Screen-Positive EldeRs),20 1741 (29%) from SCOOP (screening of older women for prevention of fracture)21 and 1146 (19.0%) from REFORM. 19

Recruitment

Recruitment commenced in October 2016 and ceased when the final participant was randomised in August 2018. Overall, 19,308 recruitment packs were distributed. Among these, no response was received to 15,491 (80.2%), 162 were returned as ‘addressee unknown’, 159 people had died, seven participants received more than one pack (duplicates), three packs were returned too late to be included in the trial, and two participants were out of area. A further 384 people returned incomplete documentation. In total, 3100 (16.1%) potential participants returned a screening questionnaire and a valid consent form and were assessed for eligibility; 68 (2.2% of 3100) declined to participate, 1468 (47.4%) were immediately eligible and 1564 (50.4%) were initially ineligible. The most predominant reason for ineligibility was not having had a fall in the previous 12 months or not having a fear of falling (n = 1361, 87.0%), although this was usually not the only reason (Table 1).

| Reason (not mutually exclusive) | n (% of 1564) |

|---|---|

| Aged < 65 years | 4 (0.3) |

| No fall in last 12 months and no fear of falling | 1361 (87.0) |

| Unable to walk 10 feet, with a walking aid if needed | 36 (2.3) |

| On a waiting list for occupational therapy | 52 (3.3) |

| Had home environment assessed for falls hazards or equipment to prevent falls in the past 12 months | 195 (12.5) |

| Had dementia | 19 (1.2) |

| Missing eligibility data | 2 (0.1) |

Based on their initial screening, 1289 participants were otherwise eligible except that they had not had a fall in the previous 12 months or did not have a fear of falling. These participants were eligible to be rescreened. A rescreening questionnaire was sent to 965 people (among the rest, they either declined to be rescreened or recruitment had closed before they were due to be rescreened). Of the 147 participants who returned a rescreening form, 53 (36.1%) subsequently became eligible (43 of whom went on to be randomised). Eligible and consenting participants were sent a baseline questionnaire and a pack of falls calendars (n = 1496). Twenty-five eligible, consenting participants were not sent a baseline pack because the trial had closed to recruitment (n = 8); the participant was at a duplicate address (n = 7); the participant withdrew consent (n = 5); the participant lived outside an area that an OT could visit (n = 3); an imminent OT visit was planned (n = 1); and the participant had died (n = 1). Of the 1410 participants (94.3% of 1496) who returned a baseline questionnaire, 1354 (96.0% of 1410) also returned at least one falls calendar. Of these 1354 participants, 1331 were randomised [the remaining 23 either withdrew (n = 21) or died (n = 2) before they were randomised].

The overall randomisation rate, from the total number of recruitment packs sent out, was 6.9%. The rate varied according to the mode of recruitment. From 6029 recruitment packs mailed out from YTU trial cohorts, 714 (11.8%) participants were randomised, relative to 59 out of 1314 (4.5%) from the Yorkshire Health Study and 558 out of 11,965 (4.7%) from GP surgeries.

Randomisation

The first participant was randomised on 31 January 2017 and the last was randomised on 2 August 2018 (Figure 4), with follow-up ending in August 2019. Participants were randomised in 168 batches of between 2 and 32 patients. In total, 1331 participants were randomised into OTIS: 430 (32.3%) to the intervention group and 901 (67.7%) to the usual-care group (see Figure 3). We therefore exceeded our target of 1299 by 32 participants (Figure 5), albeit with the requirement of an extension to the recruitment period from October 2017, by which time we initially had hoped to complete recruitment, to August 2018. A median of 66 participants were recruited from each of the 12 centres (range 19–312 participants).

FIGURE 4.

Monthly recruitment to the OTIS trial.

FIGURE 5.

Actual and target recruitment to the OTIS trial.

There was a median of 27 days (interquartile range 20 to 40 days) between completion of the screening questionnaire and completion of the baseline questionnaire. Participants were randomised a median of 44 days (interquartile range 25–73 days) after completing their baseline questionnaire. This allowed them time to return at least one falls calendar and for the OTs to confirm their capacity to deliver the intervention visits.

Baseline data

Baseline data for the 1331 randomised participants are presented in Tables 2 and 3. The mean age of participants was 80 years (range 65–98 years), and two-thirds (n = 872, 65.5%) were female. Three-quarters (n = 999) of the participants had sustained a fall in the 12 months prior to enrolment, among whom one in five (19.7%) had attended a hospital for treatment following their fall. The two groups were comparable on all baseline characteristics, except for a chance imbalance in the proportion of participants with Parkinson’s disease. Participants in the intervention group (n = 14, 3.3%) were more likely to have Parkinson’s disease than those in the usual-care group (n = 9, 1.0%).

| Characteristic | Intervention group (N = 430) | Usual-care group (N = 901) | Total (N = 1331) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 79.9 (6.4) | 80.2 (6.3) | 80.1 (6.3) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 79.7 (67.3, 98.0) | 80.3 (65.5, 98.7) | 80.1 (65.5, 98.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 145 (33.7) | 314 (34.9) | 459 (34.5) |

| Female | 285 (66.3) | 587 (65.1) | 872 (65.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 27.0 (5.4) | 26.8 (5.2) | 26.9 (5.3) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 26.3 (14.0, 59.7) | 26.0 (14.7, 63.8) | 26.1 (14.0, 63.8) |

| Taking > 4 medications prescribed by a doctor, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 212 (49.3) | 455 (50.5) | 667 (50.1) |

| No | 216 (50.2) | 437 (48.5) | 653 (49.1) |

| Missing | 2 (0.5) | 9 (1.0) | 11 (0.8) |

| Living arrangements, n (%)a | |||

| Alone | 202 (47.0) | 443 (49.2) | 645 (48.5) |

| With friend or relative | 20 (4.7) | 49 (5.4) | 69 (5.2) |

| With partner or spouse | 212 (49.3) | 417 (46.3) | 629 (47.3) |

| In sheltered accommodation | 8 (1.9) | 26 (2.9) | 34 (2.6) |

| Comorbidities, n (%)a | |||

| Osteoporosis | 67 (15.6) | 136 (15.1) | 203 (15.3) |

| High blood pressure | 192 (44.7) | 415 (46.1) | 607 (45.6) |

| Pain | 219 (50.9) | 452 (50.2) | 671 (50.4) |

| Angina or heart troubles | 94 (21.9) | 194 (21.5) | 288 (21.6) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 14 (3.3) | 9 (1.0) | 23 (1.7) |

| Arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis/osteoarthritis) | 226 (52.6) | 461 (51.2) | 687 (51.6) |

| Anxiety or depression | 55 (12.8) | 115 (12.8) | 170 (12.8) |

| Stroke | 25 (5.8) | 67 (7.4) | 92 (6.9) |

| Urinary incontinence | 89 (20.7) | 167 (18.5) | 256 (19.2) |

| Chronic lung disease | 34 (7.9) | 54 (6.0) | 88 (6.6) |

| Diabetes | 81 (18.8) | 153 (17.0) | 234 (17.6) |

| Ménière’s disease/conditions affecting balance/dizziness/vertigo | 32 (7.4) | 86 (9.5) | 118 (8.9) |

| Poor vision | 83 (19.3) | 178 (19.8) | 261 (19.6) |

| Cancer | 51 (11.9) | 65 (7.2) | 116 (8.7) |

| Other | 159 (37.0) | 341 (37.8) | 500 (37.6) |

| Characteristic | Intervention group (N = 430) | Usual-care group (N = 901) | Total (N = 1331) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fall in last 12 months, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 323 (75.1) | 676 (75.0) | 999 (75.1) |

| If yes, number of falls | |||

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 1 (1, 40) | 1 (1, 24) | 1 (1, 40) |

| If yes, did you attend hospital for any of the falls?, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 60 (18.6) | 137 (20.3) | 197 (19.7) |

| History of falling in previous 12 months, n (%) | |||

| No or one fall | 283 (65.8) | 568 (63.0) | 851 (63.9) |

| Two or more falls | 147 (34.2) | 333 (37.0) | 480 (36.1) |

| Fear of falling, n (%) | |||

| All of the time | 13 (3.0) | 37 (4.1) | 50 (3.8) |

| Most of the time | 31 (7.2) | 75 (8.3) | 106 (8.0) |

| A good bit of the time | 67 (15.6) | 114 (12.7) | 181 (13.6) |

| Some of the time | 120 (27.9) | 279 (31.0) | 399 (30.0) |

| A little of the time | 117 (27.2) | 229 (25.4) | 346 (26.0) |

| None of the time | 82 (19.1) | 167 (18.5) | 249 (18.7) |

| Broken bone since age of 18 years, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 192 (44.7) | 378 (42.0) | 570 (42.8) |

| No | 235 (54.7) | 518 (57.5) | 753 (56.6) |

| Missing | 3 (0.7) | 5 (0.6) | 8 (0.6) |

| Judgement of balance, n (%) | |||

| Good and want to keep it that way | 116 (27.0) | 241 (26.7) | 357 (26.8) |

| Quite good but would like to improve it | 166 (38.6) | 327 (36.3) | 493 (37.0) |

| Some problems with balance that want to overcome | 144 (33.5) | 328 (36.4) | 472 (35.5) |

| Missing | 4 (0.9) | 5 (0.6) | 9 (0.7) |

| Difficulties with balance while walking or dressing, n (%) | |||

| Yes, often or always | 109 (25.3) | 274 (30.4) | 383 (28.8) |

| No, or just occasionally | 312 (72.6) | 611 (67.8) | 923 (69.3) |

| Missing | 9 (2.1) | 16 (1.8) | 25 (1.9) |

| Risk of falling, n (%) | |||

| High/intermediatea | 373 (86.7) | 775 (86.0) | 1148 (86.3) |

| Low | 52 (12.1) | 119 (13.2) | 171 (12.8) |

| Missing | 5 (1.2) | 7 (0.8) | 12 (0.9) |

Comparing randomised participants with ineligible or non-consenting participants, non-randomised participants tended to be very slightly younger (mean age 78.5 years) and less likely to be female (58.0%).

Number of falls calendars returned

The response rates for the monthly falls calendars, where month 0 is the month of randomisation, are presented in Table 4. Overall, the response rate per month was consistently > 90%; however, the response rate is lower in the intervention group each month than in the usual-care group. This difference increases from 1.2% (97.2% compared with 98.4%) at month 0 to 3.4% (87.9% compared with 91.3%) at month 12.

| Month post randomisation | Intervention group (N = 430), n (%) | Usual-care group (N = 901), n (%) | Overall (N = 1331), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 418 (97.2) | 887 (98.4) | 1305 (98.0) |

| 1 | 414 (96.3) | 879 (97.6) | 1293 (97.1) |

| 2 | 410 (95.3) | 877 (97.3) | 1287 (96.7) |

| 3 | 408 (94.9) | 870 (96.6) | 1278 (96.0) |

| 4 | 403 (93.7) | 862 (95.7) | 1265 (95.0) |

| 5 | 399 (92.8) | 855 (94.9) | 1254 (94.2) |

| 6 | 398 (92.6) | 851 (94.5) | 1249 (93.8) |

| 7 | 398 (92.6) | 852 (94.6) | 1250 (93.9) |

| 8 | 394 (91.6) | 846 (93.9) | 1240 (93.2) |

| 9 | 391 (90.9) | 843 (93.6) | 1234 (92.7) |

| 10 | 388 (90.2) | 834 (92.6) | 1222 (91.8) |

| 11 | 378 (87.9) | 828 (91.9) | 1206 (90.6) |

| 12 | 378 (87.9) | 823 (91.3) | 1201 (90.2) |

Participant questionnaire return rates

Within 4 months of randomisation, there were two reported deaths (both in the usual-care group) and 28 withdrawals from the trial [16 (3.7%) in the intervention group and 12 (1.3%) in the usual-care group]. These participants were therefore not sent a 4-month participant questionnaire [1301 (97.8%) were sent] (Table 5). Between 4 and 8 months post randomisation, a further nine deaths (intervention group, n = 5; usual-care group, n = 4) and 24 withdrawals (intervention group, n = 9; usual-care group, n = 15) were reported. Between 8 and 12 months post randomisation, 15 deaths (intervention group, n = 7; usual-care group, n = 8) and 16 withdrawals (intervention group, n = 4; usual-care group, n = 12) were reported. Therefore, at 12 months, 389 (90.5%) participants randomised to the intervention group and 848 (94.1%) in the usual-care group were sent a follow-up questionnaire. Overall, participant response rates to the follow-up questionnaires at 4, 8 and 12 months were consistently above 90%. The response rates, with the number sent as the denominator, were similar between the two groups across all three time points; however, when using the number randomised as the denominator, the response rates decrease over time and are lower in the intervention group than in the usual-care group. At 12 months, 87.7% of the intervention group returned a questionnaire compared with 91.5% of the usual-care group. This reflects that the intervention group had a higher withdrawal rate and so a higher proportion of participants in this group were not sent the questionnaire.

| Participant questionnaire | Intervention group (N = 430) | Usual-care group(N = 901) | Total (N = 1331) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 months | |||

| Sent (% randomised) | 414 (96.3) | 887 (98.5) | 1301 (97.8) |

| Received (% sent) | 403 (97.3) | 862 (97.2) | 1265 (97.2) |

| Received (% randomised) | 403 (93.7) | 862 (95.7) | 1265 (95.0) |

| Median time to response (interquartile range), days | 9 (8, 13) | 10 (8, 14) | 9 (8, 14) |

| 8 months | |||

| Sent (% randomised) | 400 (93.0) | 868 (96.3) | 1268 (95.3) |

| Received (% sent) | 394 (98.5) | 840 (96.8) | 1234 (97.3) |

| Received (% randomised) | 394 (91.6) | 840 (93.2) | 1234 (92.7) |

| Median time to response (interquartile range), days | 9 (8, 13) | 9 (8, 14) | 9 (8, 13) |

| 12 months | |||

| Sent (% randomised) | 389 (90.5) | 848 (94.1) | 1237 (92.9) |

| Received (% sent) | 377 (96.9) | 824 (97.2) | 1201 (97.1) |

| Received (% randomised) | 377 (87.7) | 824 (91.5) | 1201 (90.2) |

| Median time to response (interquartile range), days | 9 (8, 13) | 9 (7, 13) | 9 (7, 13) |

Occupational therapist-delivered environmental assessment and modification visits

A total of 382 participants allocated to the intervention group received an environmental assessment and modification visit from an OT. Of these participants, 362 (94.8%) completed the Timed Up and Go test, with a mean of 15.6 seconds (SD 8.4 seconds, range 5 to 70 seconds); 159 (43.9%) scored over 14 seconds, indicating a high risk of falling. The assessments were conducted by 23 OTs (median 16 visits per OT, range 1 to 54 visits per OT). Nineteen of the OTs attended a face-to-face training session, and four were ‘cascade’ trained by another OT who had attended face-to-face training. The visits took place between 1 and 411 days after randomisation (median 27 days), and lasted a median of 90 minutes (range 25 to 180 minutes). Nearly two-thirds of the intervention group (277/430, 64.4%) had received the visit within 6 weeks of being randomised, and 381/430 (88.6%) received it within 12 months. The delays in delivering the visits were due to availability of the participant and, despite agreeing to the number of participants to be randomised at a given time, OT capacity. One participant received the visit beyond 12 months after they were randomised as they lived on the border of two trusts and it could not be agreed which trust should undertake the visit. A total of 48 participants did not receive a visit.

Of the 48 participants randomised to the intervention group who did not receive a visit, 25 withdrew from the intervention and 16 withdrew fully from the trial before receiving a visit. Reasons for withdrawing from the intervention were as follows: the participant did not feel that they would benefit from an OT visit (often as they felt that they were fit and well), n = 12; an OT visit was not appropriate (house was well equipped/had ongoing renovations/was a rental property/had been already assessed and adapted for needs of spouse), n = 4; the OT was unable to arrange visit, n = 3; the participant lived outside the area that the OT would attend, n = 3; no reason given, n = 2; and the participant did not want a visit due to ill health, n = 1. Reasons for full withdrawal among these participants were broadly similar, as it was common for participants to inform the OT when they came to arrange the appointment that they did not want the visit (i.e. they were withdrawing from treatment). These participants were then asked if they would be willing to continue to provide outcome data, which some declined to do; hence, they were fully withdrawn from the trial.

Seven participants appeared to remain in full participation with the trial but did not receive an environmental assessment. It is possible that these participants received a home visit but, as no documentation relating to the visit was received for them, we have conservatively assumed these participants did not receive the intervention.

Primary outcome

Raw data

In total, 1303 (97.9%) trial participants returned at least one falls calendar following randomisation (intervention, n = 419, 97.4%; usual care, n = 884, 98.1%), with 1204 (90.5%) returning a complete 12 months’ worth of calendars post randomisation (intervention, n = 377, 87.7%; usual care, n = 827, 91.8%). Of the 28 participants who did not return any falls calendars, five (four usual care, one intervention) provided falls data on at least one of the 4-, 8- and 12-month participant questionnaires. These data were used in the analysis for these participants. In total, 2260 falls were reported: 826 in the intervention group (mean 1.9 falls, SD 5.5 falls; median 1 fall, range 0–94 falls) over an average of 338 days (median 365 days), and 1434 in the usual-care group (mean 1.6 falls, SD 3.0 falls; median 1 fall, range 0–41 falls) over a mean of 345 days (median 365 days).

At least some information, such as the location and perceived cause, was available for 2037 (90.1%) falls (intervention, n = 700, 84.7%; usual care, n = 1337, 93.2%; Table 6). Just over half of falls for which there was available location information occurred indoors (53.4%), with the majority (85.7%) of these occurring inside the participant’s own home rather than inside another premises. About half of the falls resulted in a superficial injury or worse, with 2.8% of the falls resulting in a broken bone (from 16 falls in the intervention group and 41 falls in the usual-care group), most frequently in the wrist or the hand (17/57, 29.8%).

| Details of fall | Intervention group (N = 700) | Usual-care group (N = 1337) | Total (N = 2037) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Where did you fall?, n (%) | |||

| Inside own home | 289 (41.3) | 590 (44.1) | 879 (43.2) |

| Inside, not in own home | 59 (8.4) | 88 (6.6) | 147 (7.2) |

| Outside own home | 136 (19.4) | 259 (19.4) | 395 (19.4) |

| Outside, beyond own home | 180 (25.7) | 322 (24.1) | 502 (24.6) |

| Missing | 36 (5.1) | 78 (5.8) | 114 (5.6) |

| What were you doing when you fell?, n (%)a | |||

| Getting in/out of bed, chair, bath, toilet, shower | 79 (11.3) | 150 (11.2) | 229 (11.2) |

| Turning | 41 (5.9) | 105 (7.9) | 146 (7.2) |

| Going up/down stairs or steps | 82 (11.7) | 142 (10.6) | 224 (11.0) |

| Walking | 323 (46.1) | 550 (41.1) | 873 (42.9) |

| Reaching/bending | 69 (9.9) | 161 (12.0) | 230 (11.3) |

| Rushing | 30 (4.3) | 38 (2.8) | 68 (3.3) |

| Unknown/cannot recall | 80 (11.4) | 160 (12.0) | 240 (11.8) |

| Other | 56 (8.0) | 138 (10.3) | 194 (9.5) |

| What caused you to fall?, n (%)a | |||

| Trip, did not pick up feet, fell over something | 205 (29.3) | 391 (29.2) | 596 (29.3) |

| Slip, skid | 69 (9.9) | 104 (7.8) | 173 (8.5) |

| Uneven surface | 59 (8.4) | 99 (7.4) | 158 (7.8) |

| Slippery surface | 50 (7.1) | 85 (6.4) | 135 (6.6) |

| Steps/gradient | 99 (14.1) | 179 (13.4) | 278 (13.6) |

| Access | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) |

| Legs gave away, just went over | 53 (7.6) | 154 (11.5) | 207 (10.2) |

| Dizzy, woozy, groggy, light-headed, passed out | 48 (6.9) | 115 (8.6) | 163 (8.0) |

| Lost balance | 221 (31.6) | 420 (31.4) | 641 (31.5) |

| Knocked, pulled or blown over | 12 (1.7) | 36 (2.7) | 48 (2.4) |

| Footwear issue | 19 (2.7) | 19 (1.4) | 38 (1.9) |

| Poor visibility/lighting | 24 (3.4) | 36 (2.7) | 60 (2.9) |

| Obstacle/obstruction/pet | 55 (7.9) | 110 (8.2) | 165 (8.1) |

| Unknown/cannot recall | 50 (7.1) | 121 (9.1) | 171 (8.4) |

| Other | 22 (3.1) | 51 (3.8) | 73 (3.6) |

| Injuries suffered, n (%)a | |||

| No injury | 343 (49.0) | 646 (48.3) | 989 (48.6) |

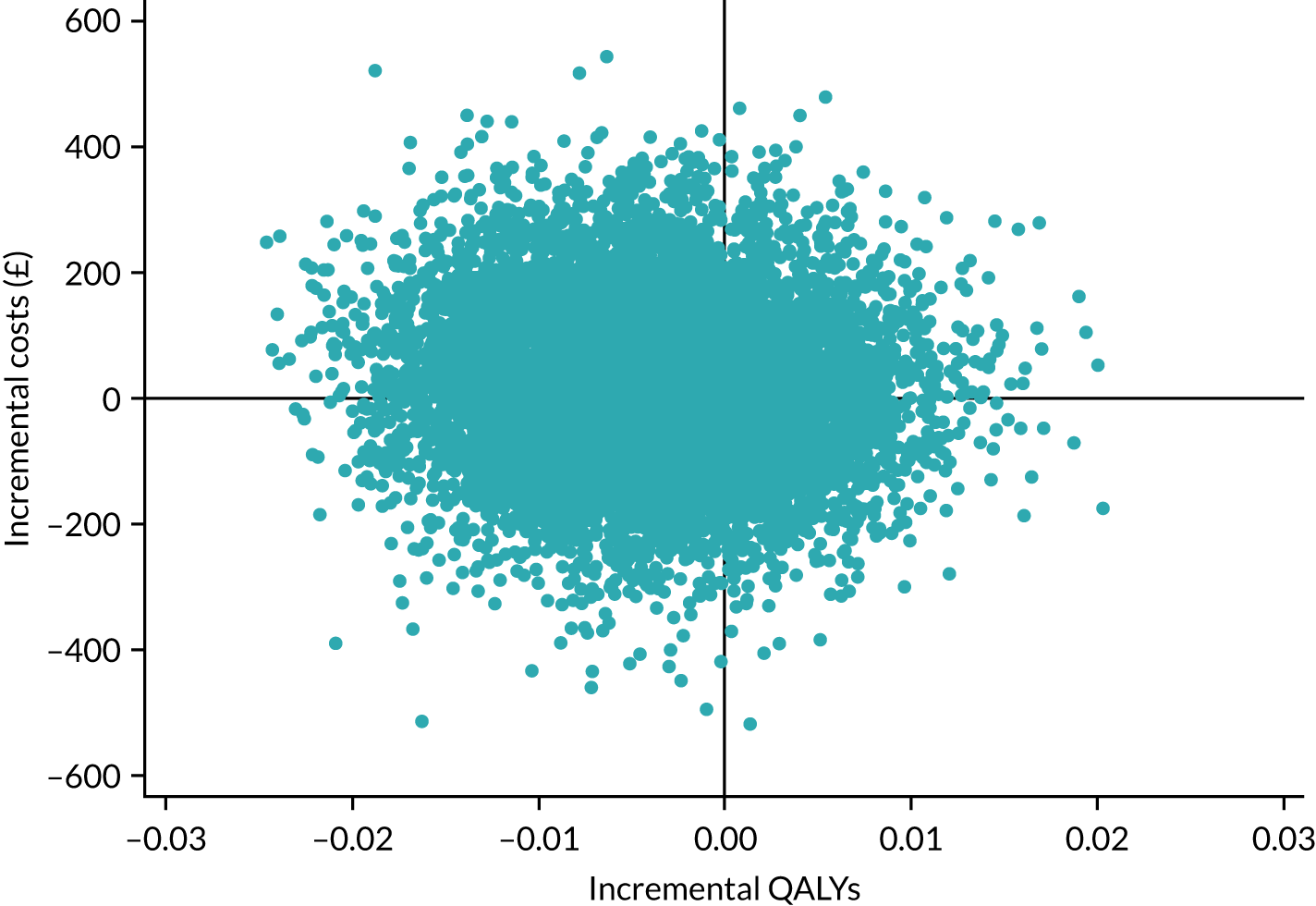

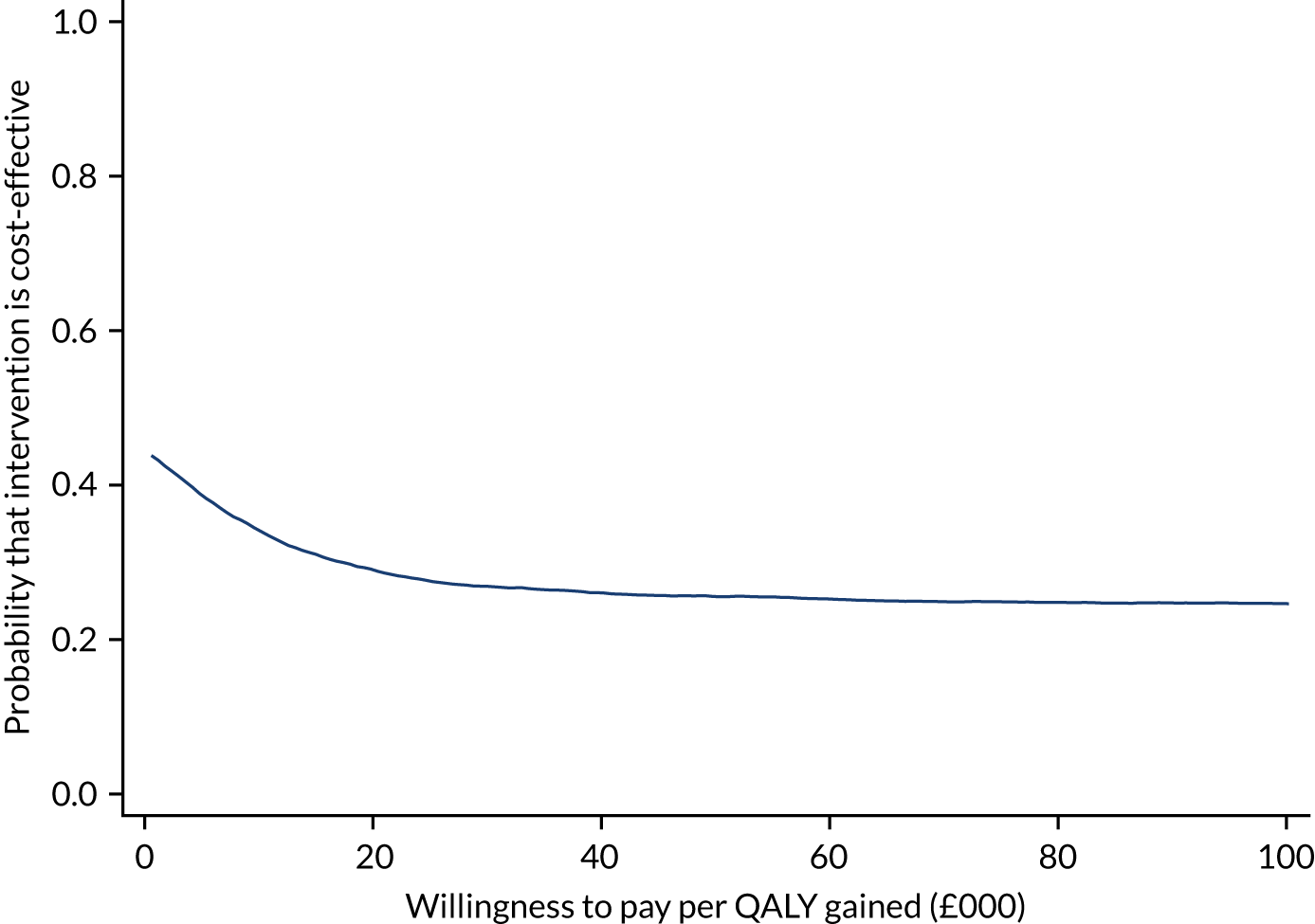

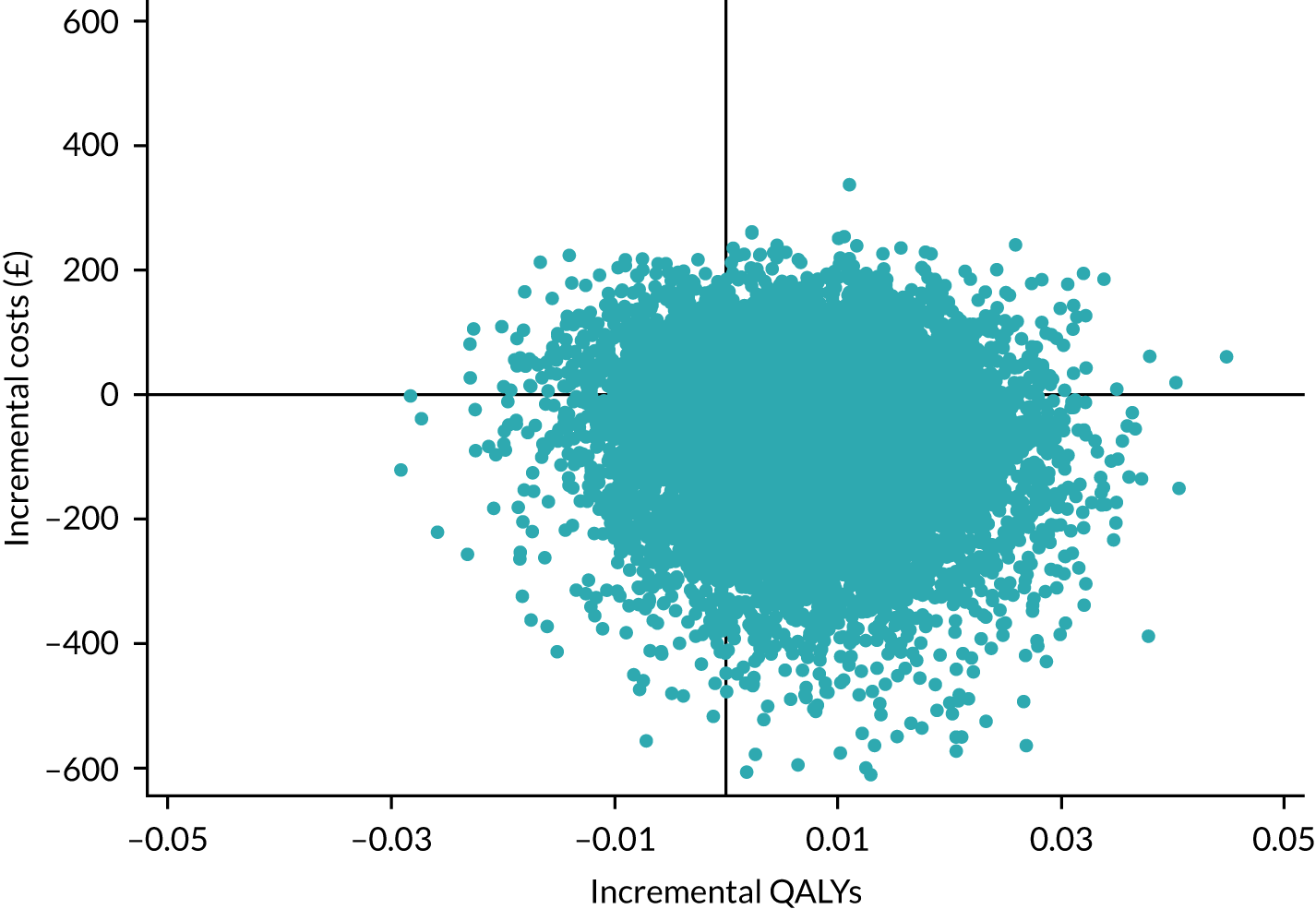

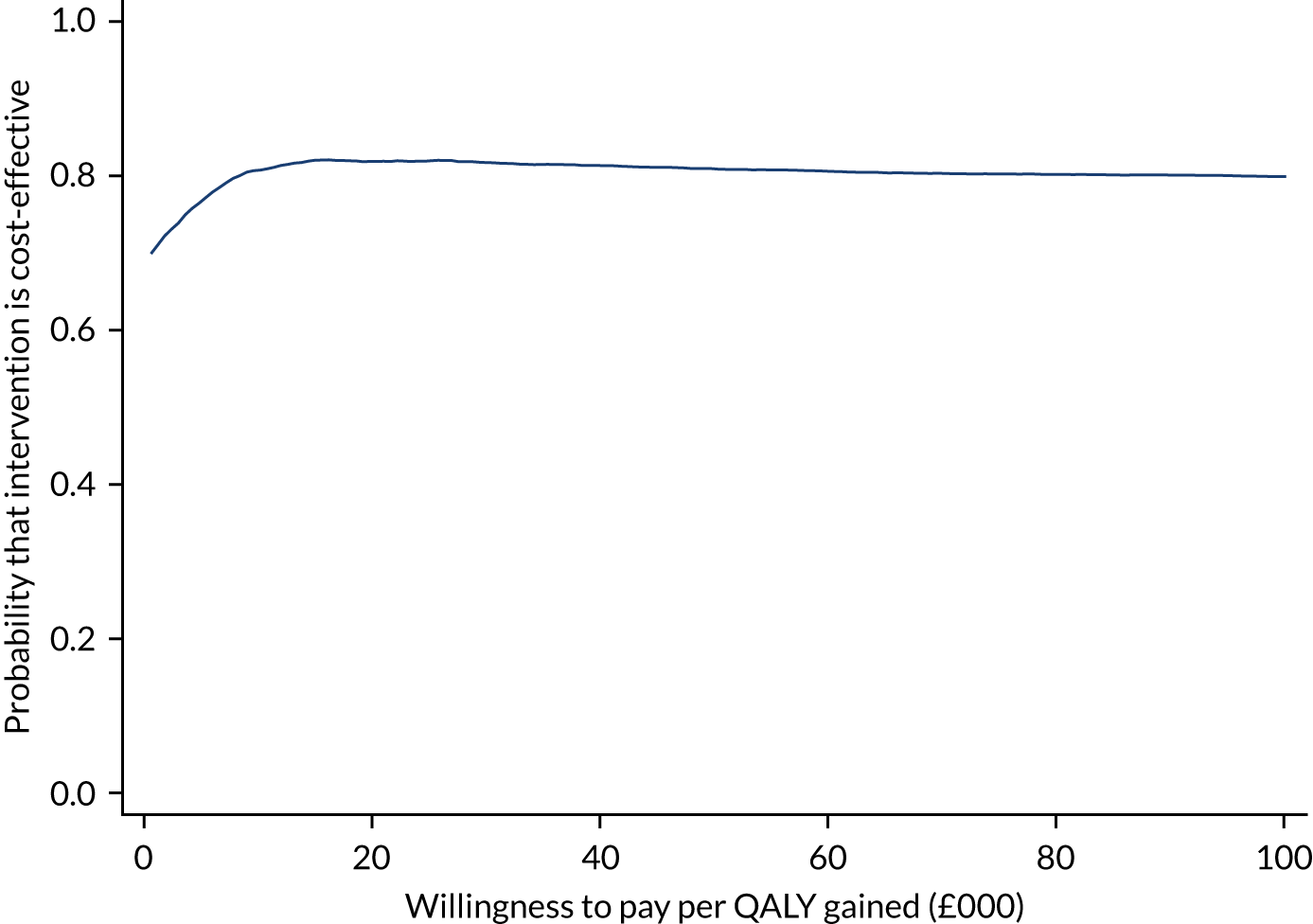

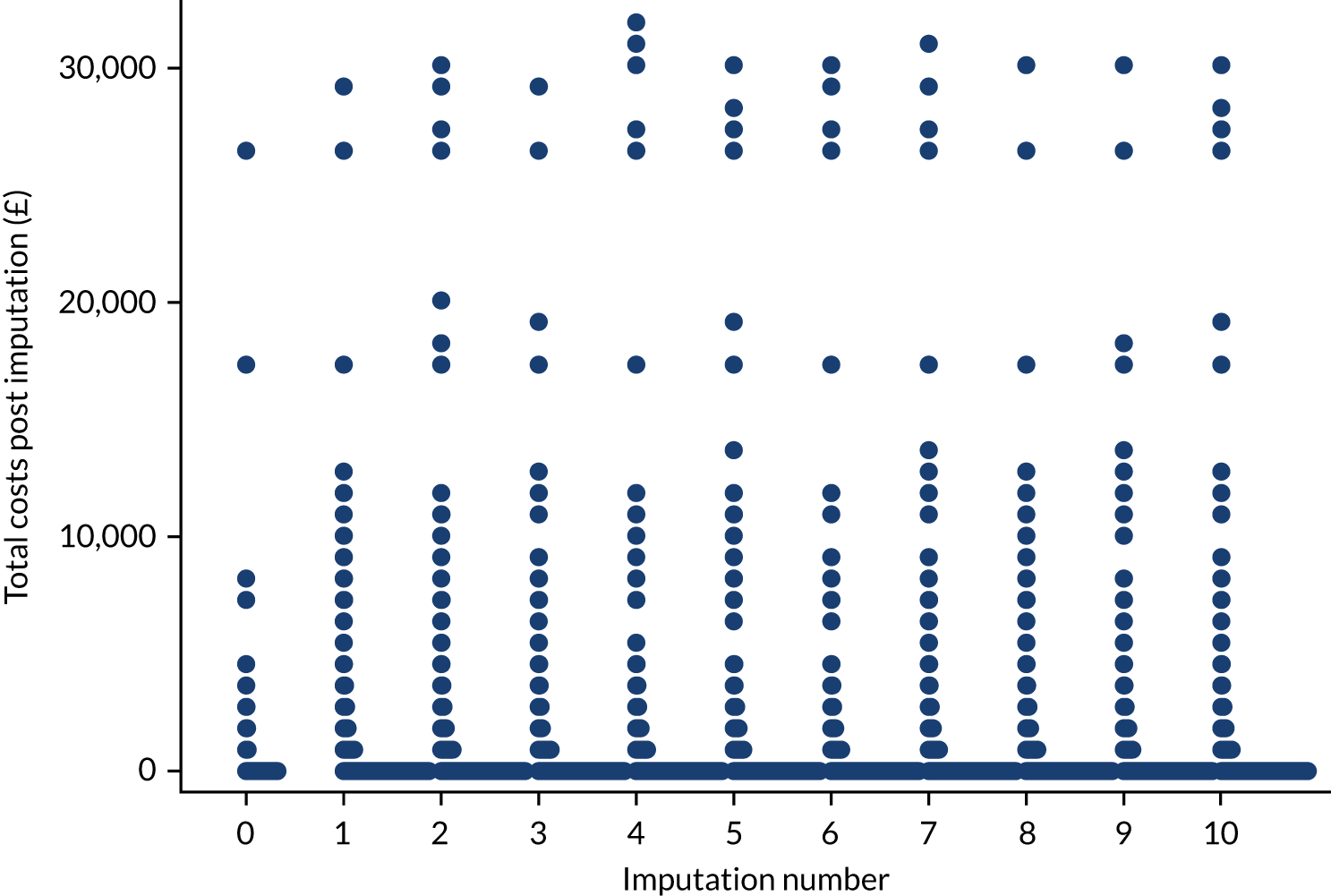

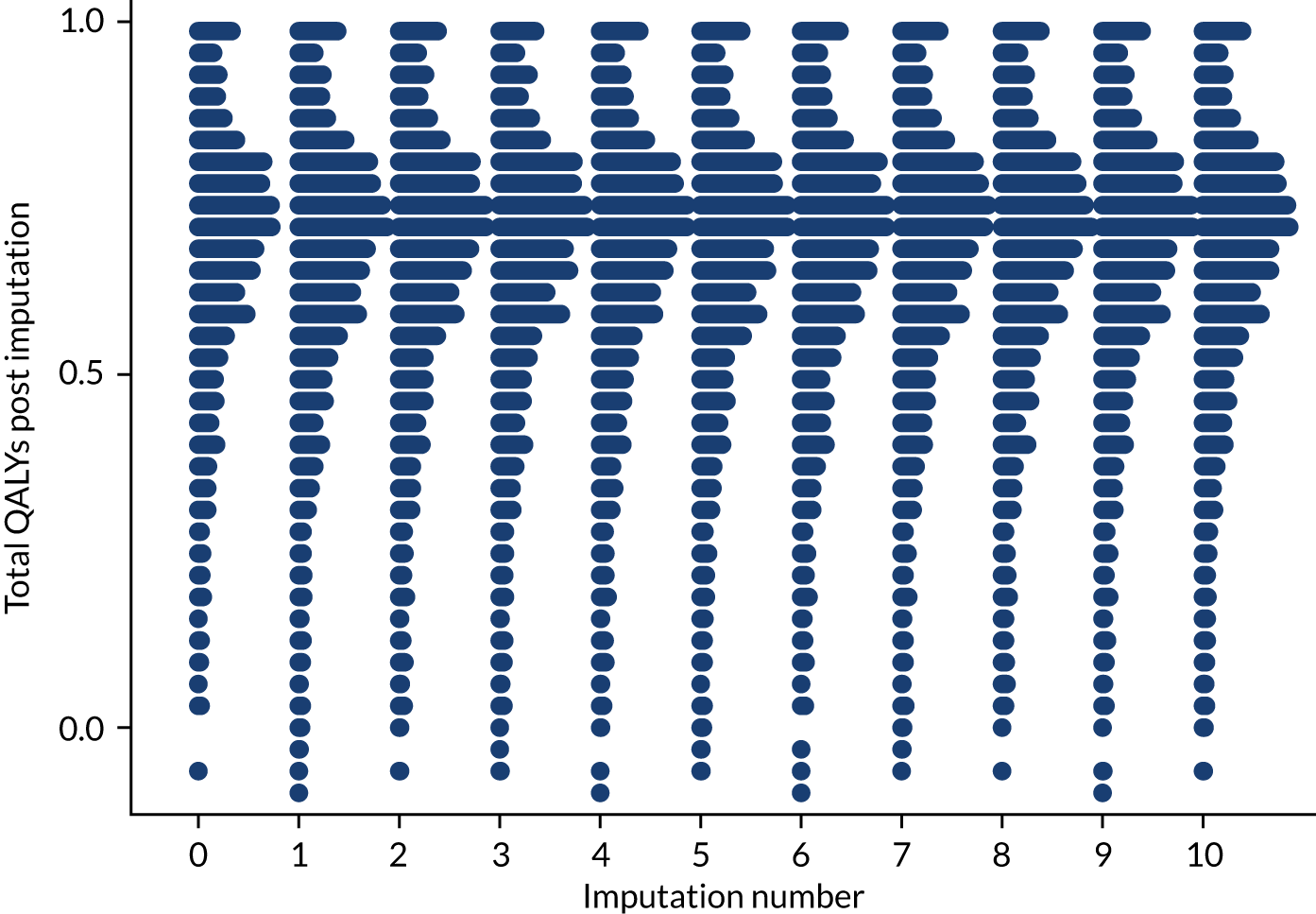

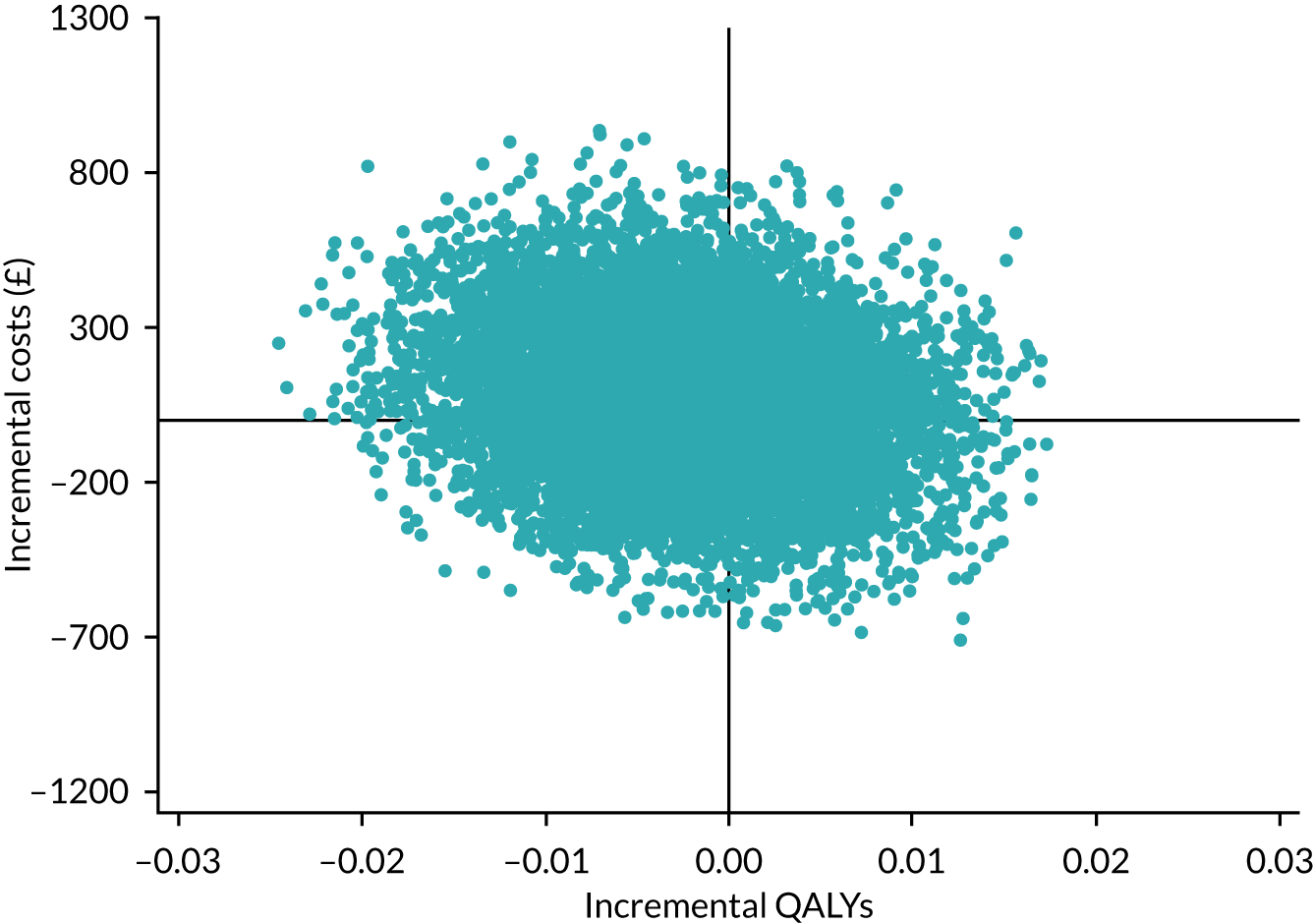

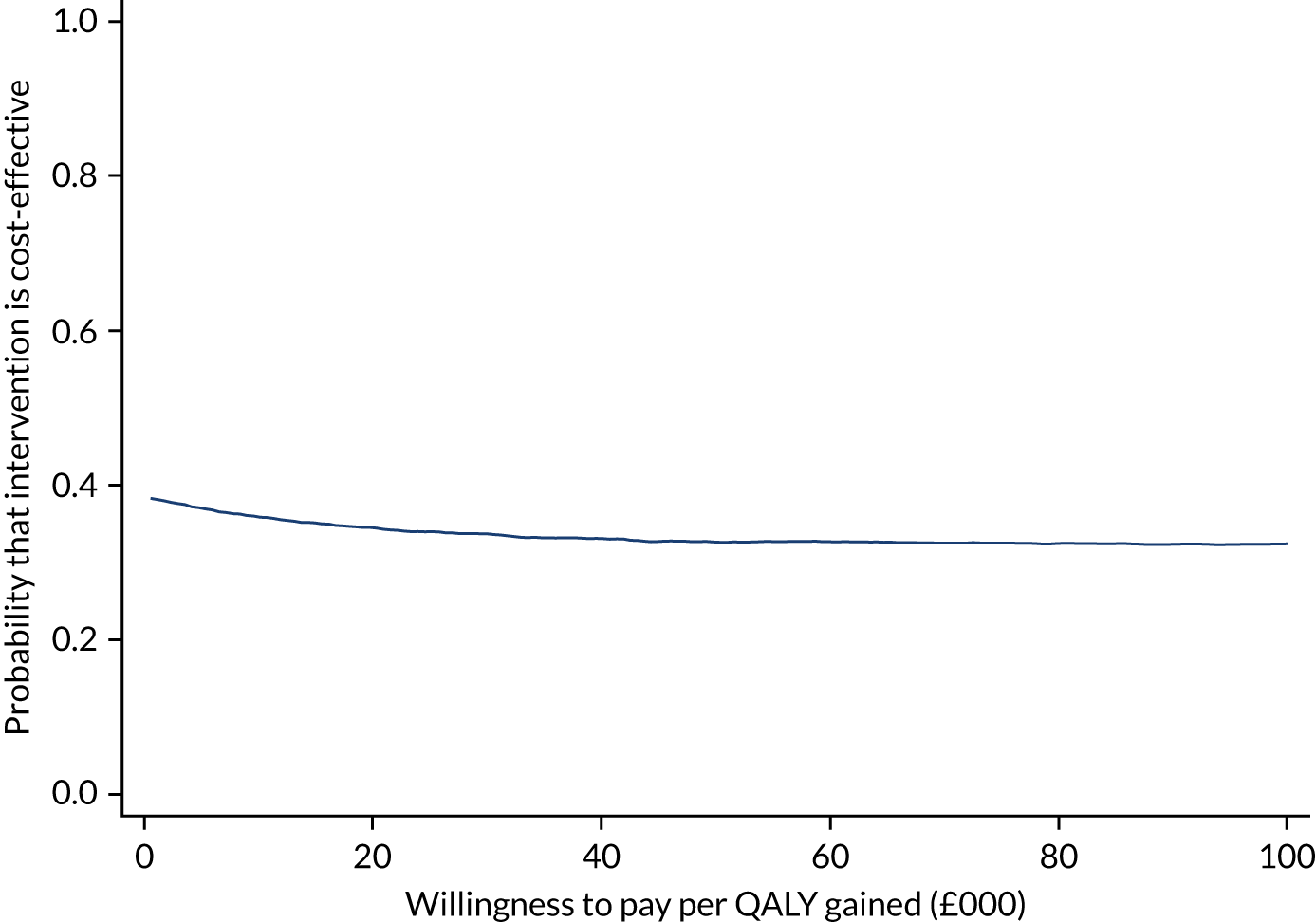

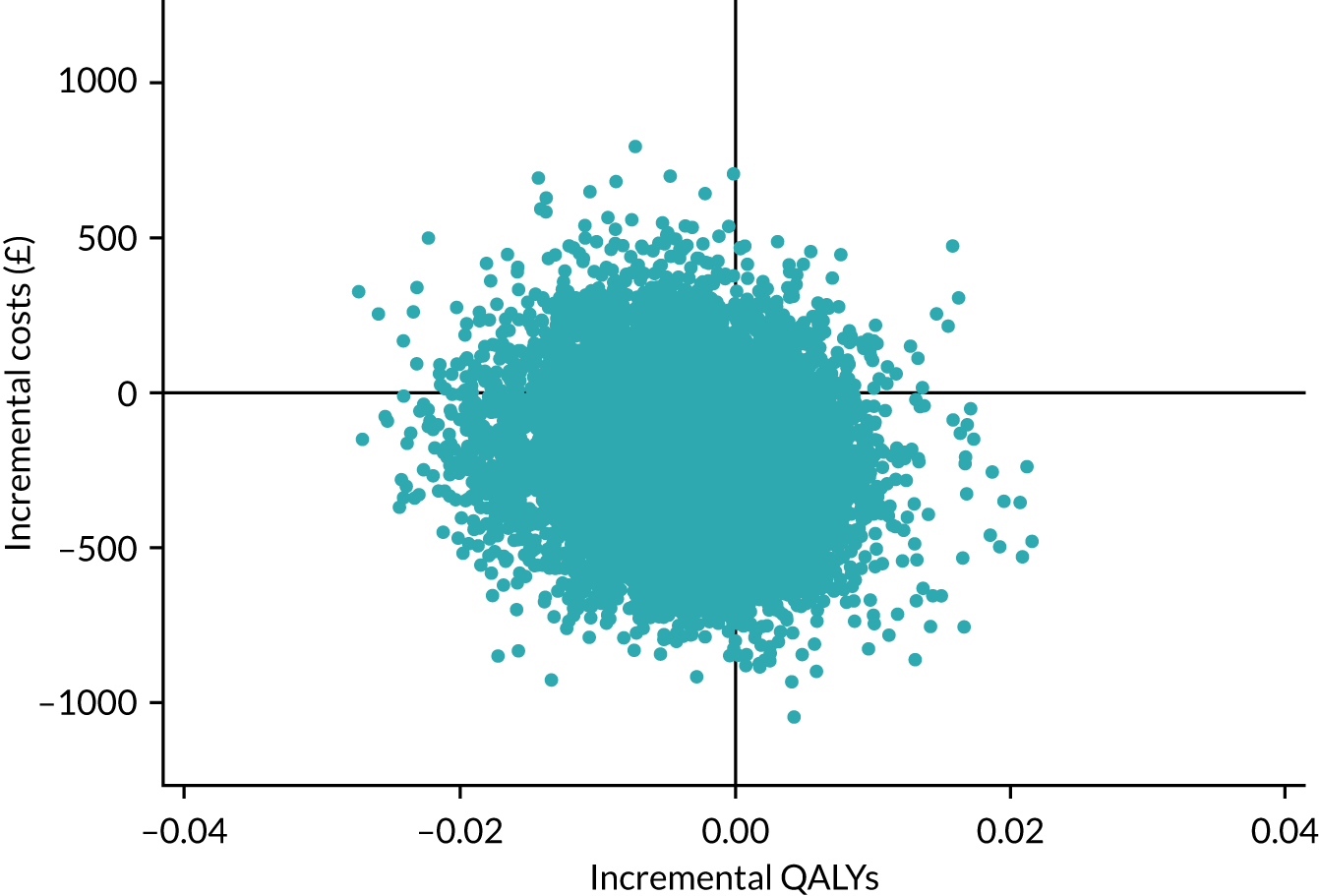

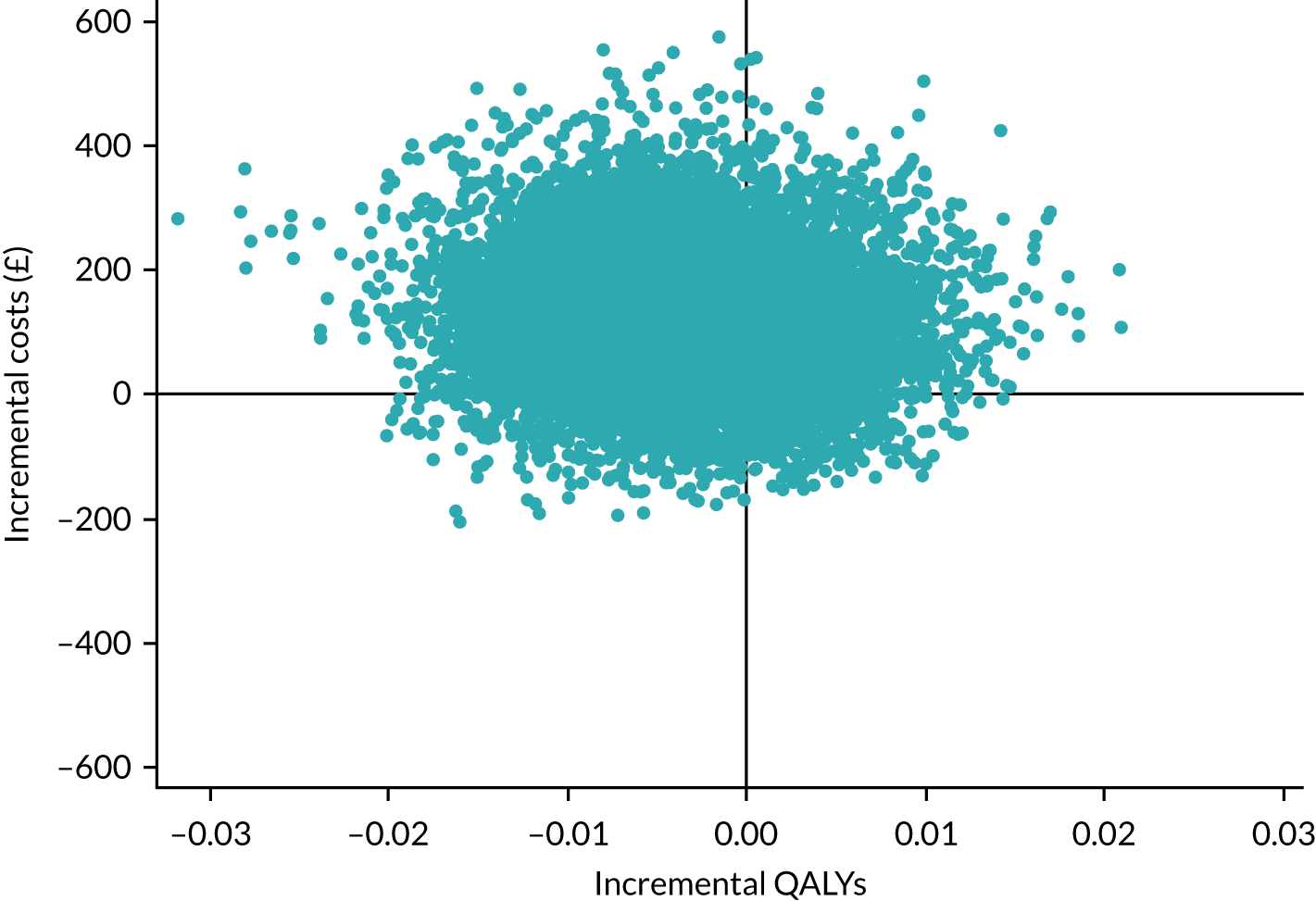

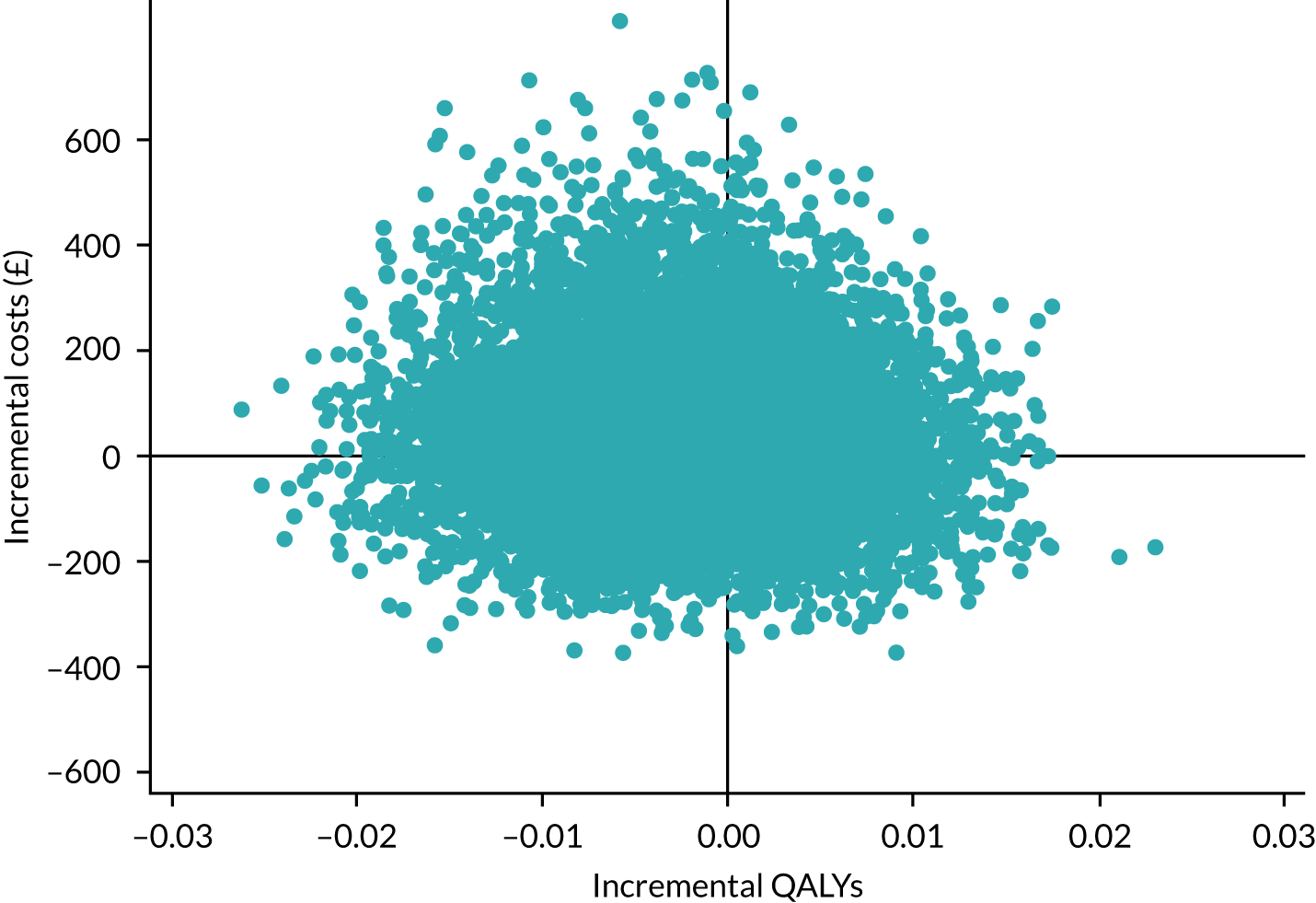

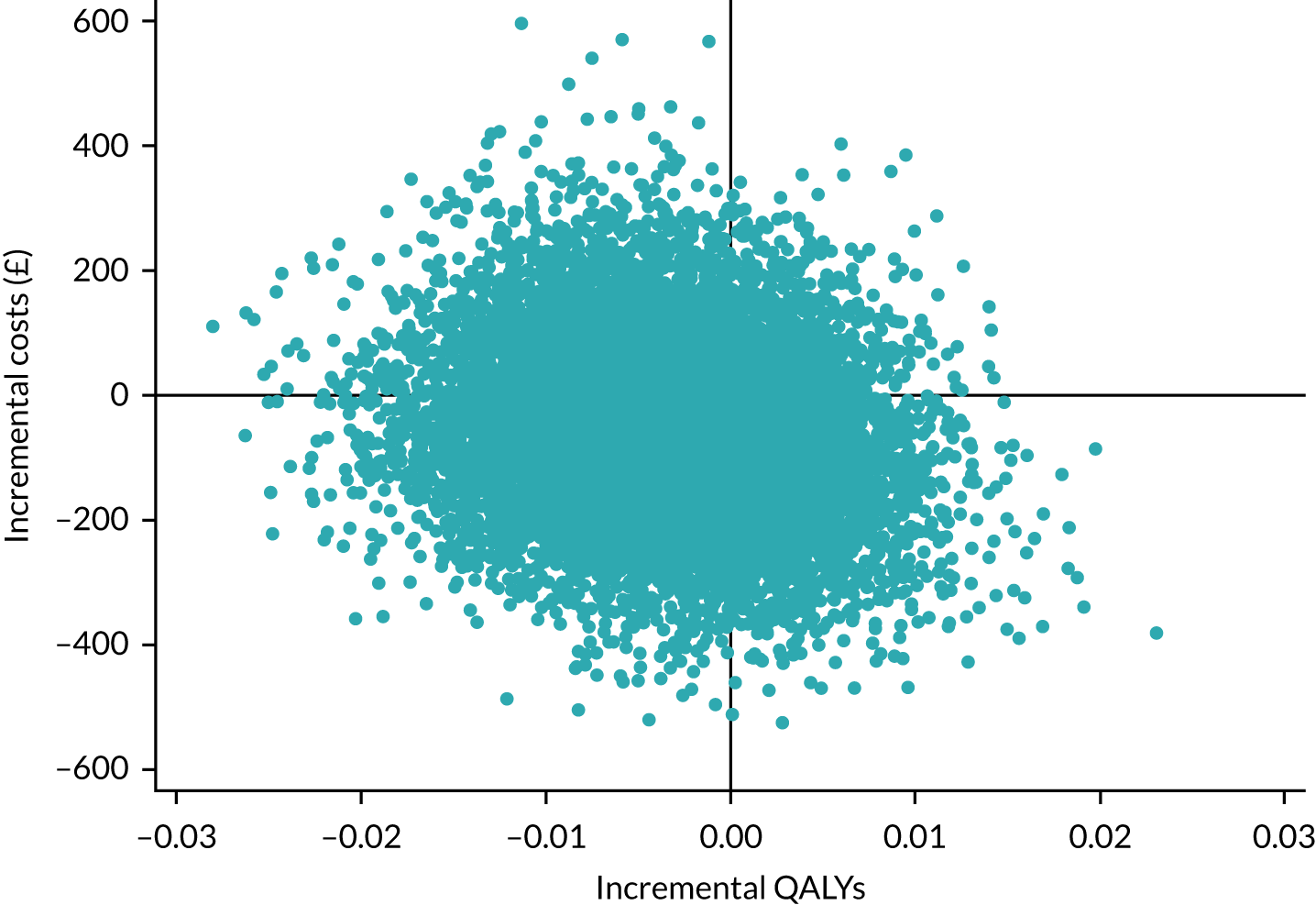

| Superficial wounds (e.g. bruising, sprain, cut, abrasion) | 287 (41.0) | 582 (43.5) | 869 (42.7) |