Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/160/02. The contractual start date was in February 2017. The draft report began editorial review in August 2020 and was accepted for publication in April 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Devall et al. This work was produced by Devall et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Devall et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted with permission from Chu et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license, which permits others to copy and redistribute this work, for non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Clinical background

Miscarriage is a common complication of pregnancy (15–25% of pregnancies; approximately 125,000 miscarriages per year in England). 2,3 Miscarriage is associated with not only physical harm, such as excessive bleeding, infection and uterine perforation during surgery, but also substantial psychological impact on patients; studies have shown that distress from miscarriage is equivalent to that from the stillbirth of a term-born baby,4,5 and miscarriage is estimated to cost the NHS £81M per year. 6

There are two main types of miscarriage that require medical intervention: missed miscarriage and incomplete miscarriage. 6 A missed miscarriage, also known as a delayed or silent miscarriage, is diagnosed when a non-viable pregnancy is identified on ultrasound scan during the first 14 weeks of gestation. Commonly, women who suffer missed miscarriage are asymptomatic or experience small amounts of vaginal bleeding or pain before the diagnosis is made. 6–8 All pregnancy tissue is retained in the uterus in a missed miscarriage. In contrast, an incomplete miscarriage is diagnosed when pregnancy tissue has already been partly expelled by the uterus. 6

Management of miscarriage can be expectant (i.e. waiting for natural miscarriage), medical (i.e. with drugs) or surgical. A UK survey conducted by this study team has shown that 25% of women opt for medical management. However, there is uncertainty about the optimal drug regimens for medical management. Misoprostol is a prostaglandin analogue used for the medical management of miscarriage to induce myometrial contractions to aid the expulsion of pregnancy tissue. 9 However, misoprostol alone is not always effective, and 15–40% of women require an additional dose of misoprostol, thus prolonging the duration of treatment. 10–14 This treatment failure can culminate in the need for surgical management, which can be particularly undesirable to women who have actively chosen to have medical management. 15,16 To strengthen the effect of misoprostol, a steroidal anti-progestogen called mifepristone (Mifegyne®, Exelgyn, Paris, France) is sometimes used in combination with misoprostol. Mifepristone is a competitive progesterone receptor antagonist that primes the myometrium before prostaglandin exposure. 9

The reported effectiveness of combination treatment with mifepristone and misoprostol for the medical management of missed miscarriage in previous clinical trials ranges from 64% to 84%. 17–19 However, given the lack of placebo-controlled studies, the usefulness of mifepristone in the management of missed miscarriage has remained unclear. Before National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline CG154 was published in 2012,20 common practice was to use a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol (MifeMiso combination). The 2012 NICE guideline, however, recommended that misoprostol alone should be given to women undergoing medical management. 20 This recommendation was based on very limited evidence from one study of 115 women,17 which found no difference between MifeMiso combination and misoprostol alone. Recognising the limited available evidence, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) issued a commissioned call for a trial investigating the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mifepristone in combination with misoprostol compared with misoprostol alone in the management of first-trimester miscarriage.

Existing evidence

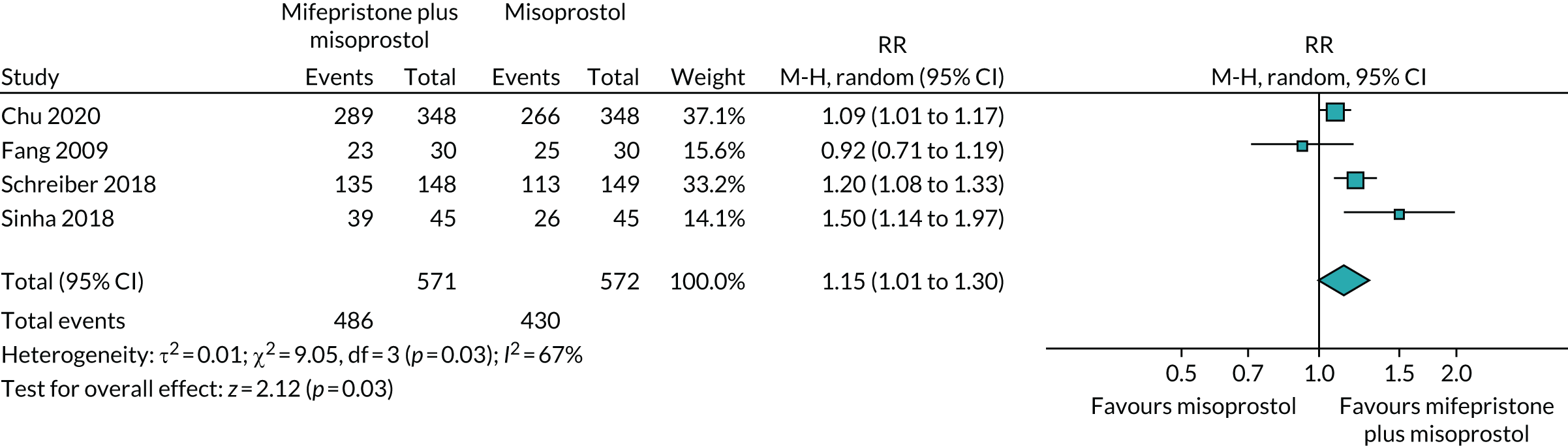

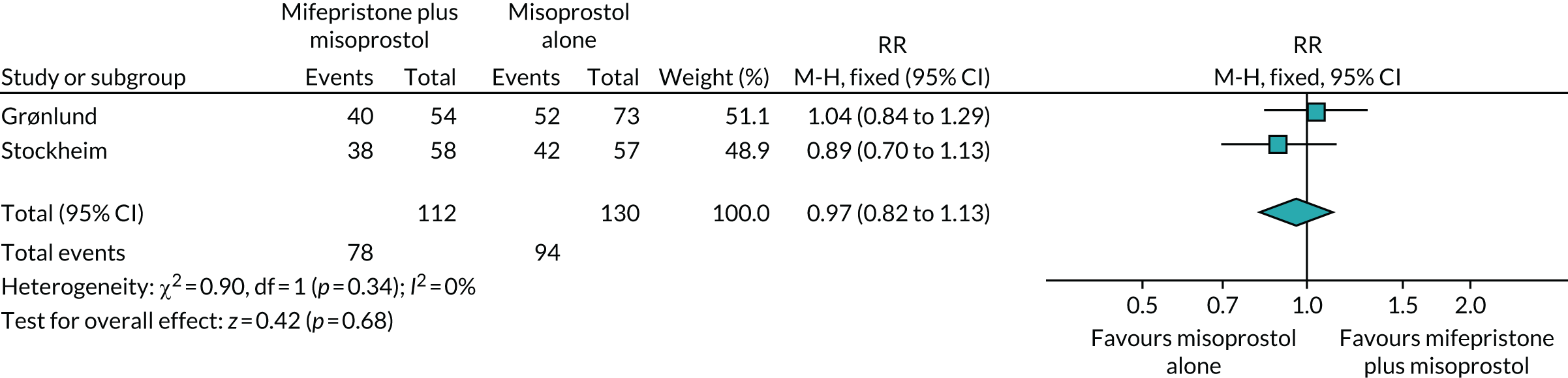

We conducted a systematic review of trials investigating the use of mifepristone and misoprostol in women with miscarriage to gain a better understanding of studied interventions, outcomes and resolution rates. These studies are listed in Table 1. In addition to the publication by Stockheim et al. ,17 one more trial was identified,18 which compared MifeMiso combination with misoprostol alone in the missed miscarriage population. Together, the two trials included a total of 242 patients treated with MifeMiso or misoprostol alone. Meta-analysis of the results showed no significant difference between the two trial groups for outcome of resolution of miscarriage [risk ratio (RR) 0.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.82 to 1.13] (Figure 1). However, given the imprecision that inevitably accompanies such small sample sizes, it is not possible to draw any firm inferences.

| Study (first author and year of publication) | Intervention | Comparison | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grønlund 200218 (n = 127) | 600 mg of oral mifepristone and 400 µg of misoprostol 48 hours later | 400 µg of vaginal misoprostol and 200 µg of misoprostol 2 hours later if no vaginal bleeding occurred | Centres randomised to treatment regimens with crossover every 4 months; allocation concealment inadequate; no blinding of patients and study personnel |

| Stockheim 200617 (n = 115) | 600 mg of oral mifepristone and 800 µg of oral misoprostol 48 hours later | 800 µg of oral misoprostol and 800 µg of oral misoprostol 48 hours later | Method of randomisation clear; no allocation concealment; no blinding of patients and study personnel |

FIGURE 1.

Forest plot of completed trials comparing MifeMiso combination with misoprostol alone for the medical management of missed miscarriage, for the outcome of resolution of miscarriage.

Rationale

A trial comparing MifeMiso to misoprostol alone for the medical management of missed miscarriage was required because:

-

NICE guideline CG154 called for a definitive trial to evaluate whether or not there is any benefit in using mifepristone in addition to misoprostol.

-

A patient survey supported the study. The survey (n = 188) showed that 66% of women would consider taking part in the study.

-

A UK clinician survey supported the study. In the survey of 152 practitioners, 79% believed that a clinical trial was needed to investigate whether or not the mifepristone and misoprostol combination is more effective than misoprostol alone in the medical management of missed miscarriage.

-

The Association of Early Pregnancy Units, the Early Pregnancy Clinical Studies Group, the Miscarriage Association and Tommy’s Charity supported the research.

-

If benefit was confirmed in the MifeMiso trial, women and the NHS stand to gain substantially. On the other hand, if mifepristone was found to be ineffective, treatment with mifepristone could be avoided.

-

Mifepristone treatment is cheap (£17.55 per 200-mg oral tablet), and if benefit was confirmed, rapid uptake of this intervention was expected.

Specific objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective of the MifeMiso trial is to test the hypothesis that treatment with mifepristone plus misoprostol is superior to misoprostol alone for the resolution of miscarriage within 7 days in women diagnosed with missed miscarriage by pelvic ultrasound scan in the first 14 weeks of pregnancy.

Key secondary objective

To test the hypothesis that the addition of mifepristone reduces the need for surgical intervention to resolve the miscarriage up to discharge from early pregnancy unit (EPU).

Other secondary objectives

-

To evaluate if the addition of mifepristone reduces the need for further doses of misoprostol.

-

To evaluate if the addition of mifepristone improves other clinical outcomes, including surgical intervention up to and including 7 days post randomisation and after 7 days post randomisation, duration of bleeding, infection, negative pregnancy test at 21 days post randomisation, time from randomisation to discharge from EPU care, side effects and complications.

-

To evaluate if the addition of mifepristone improves patient satisfaction.

-

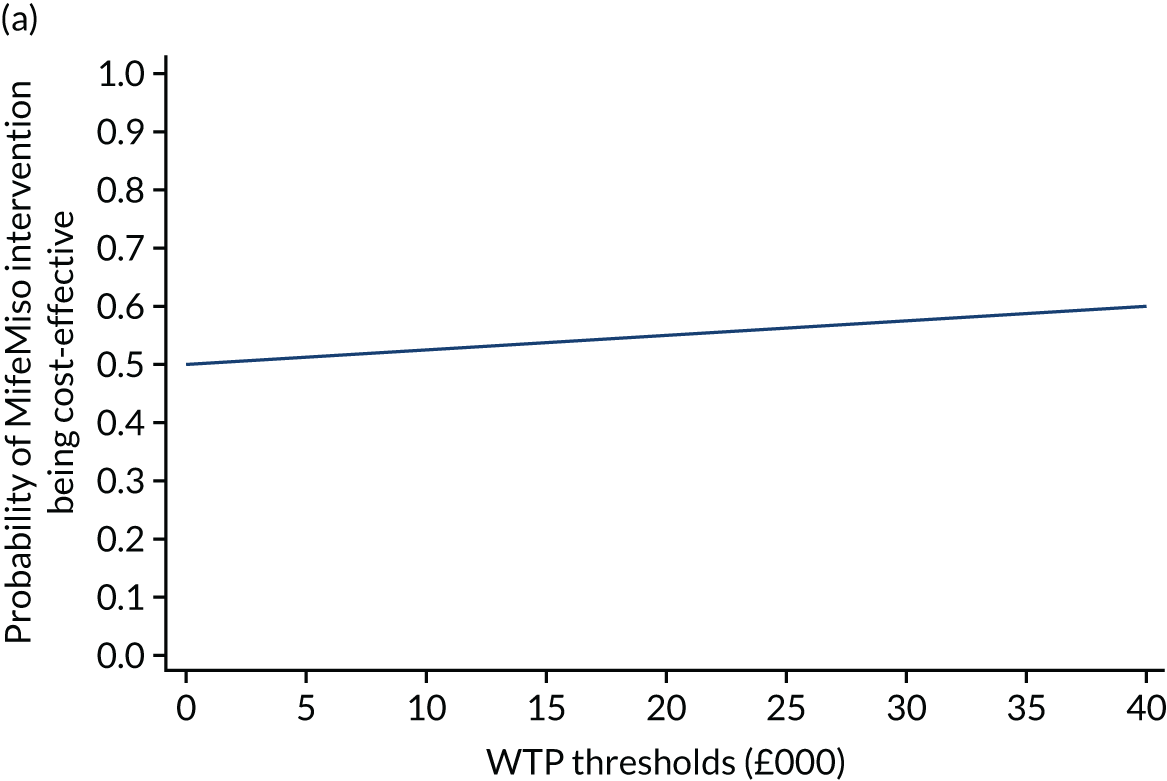

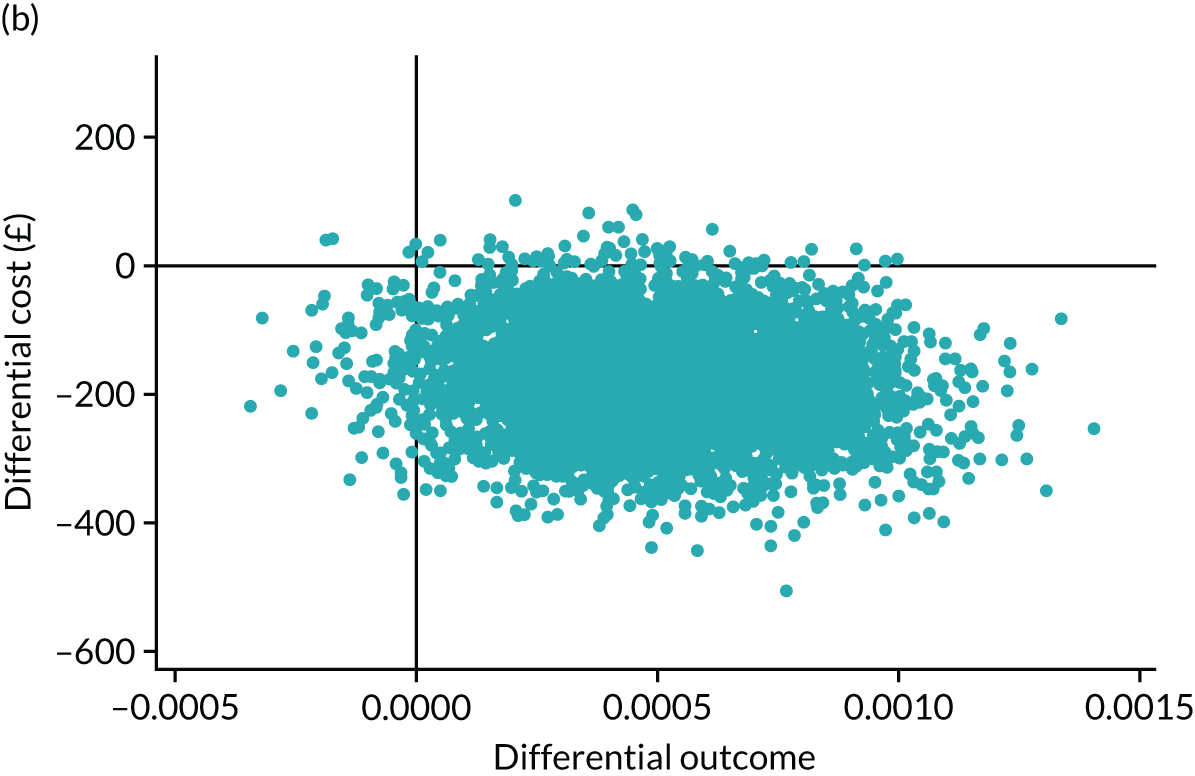

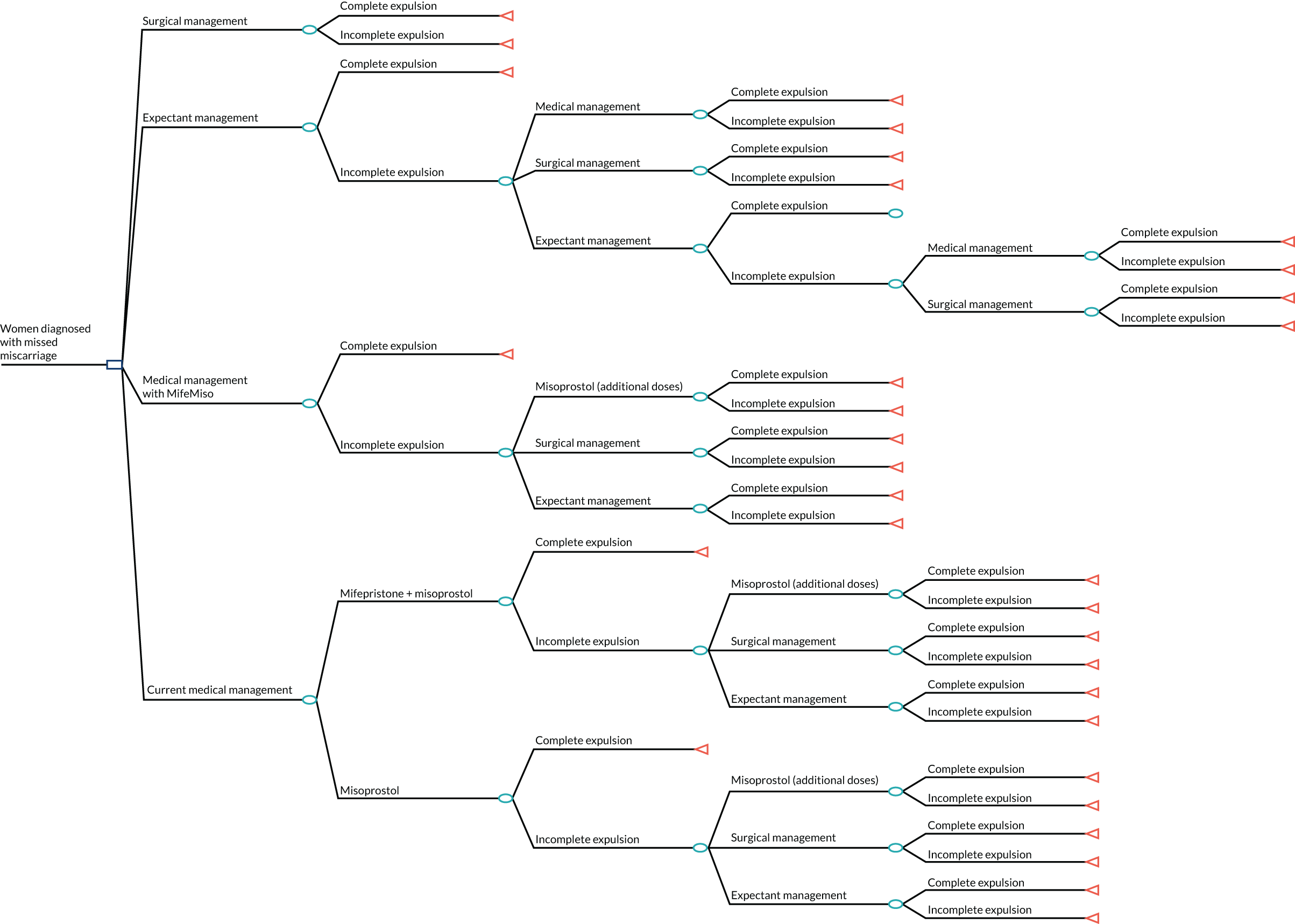

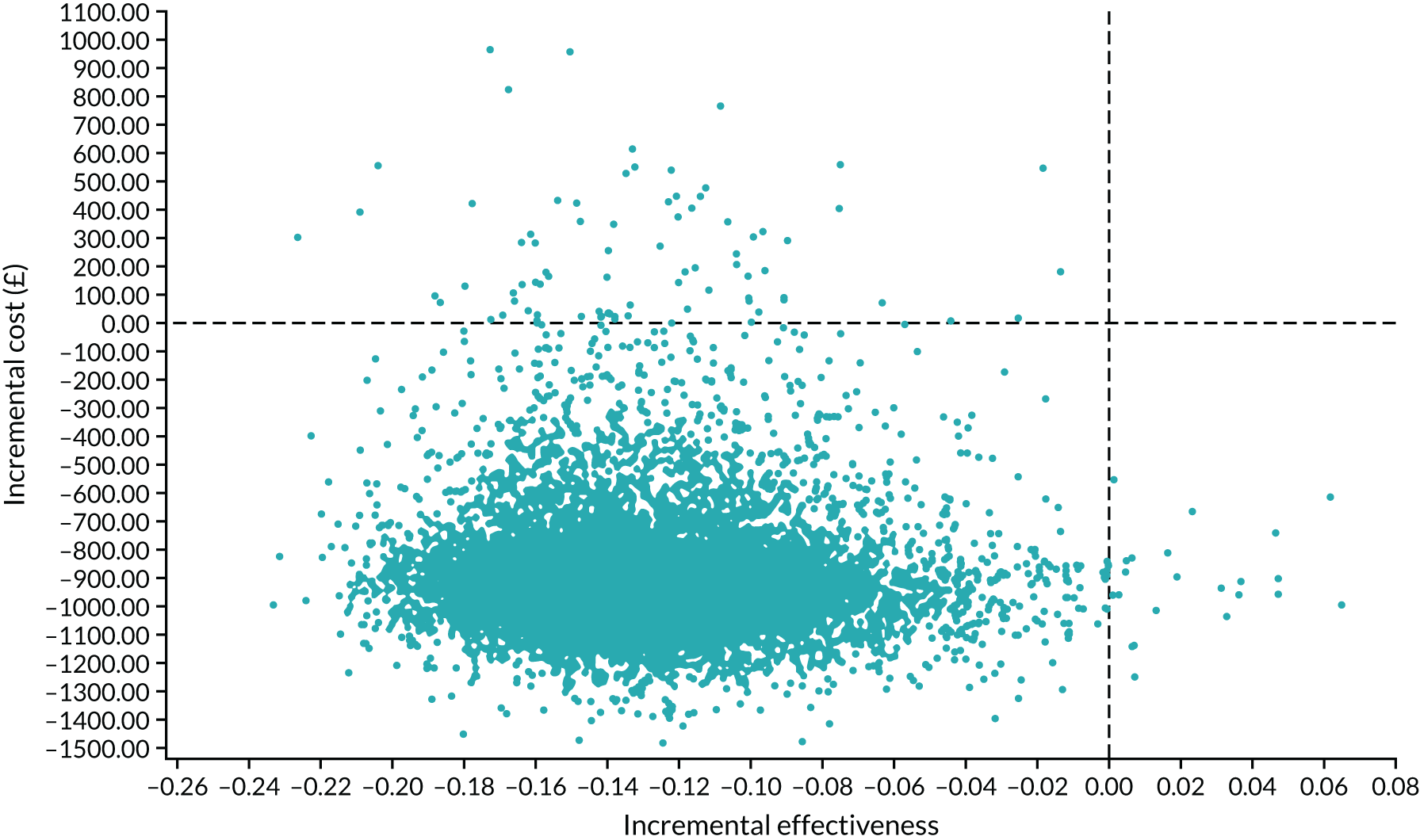

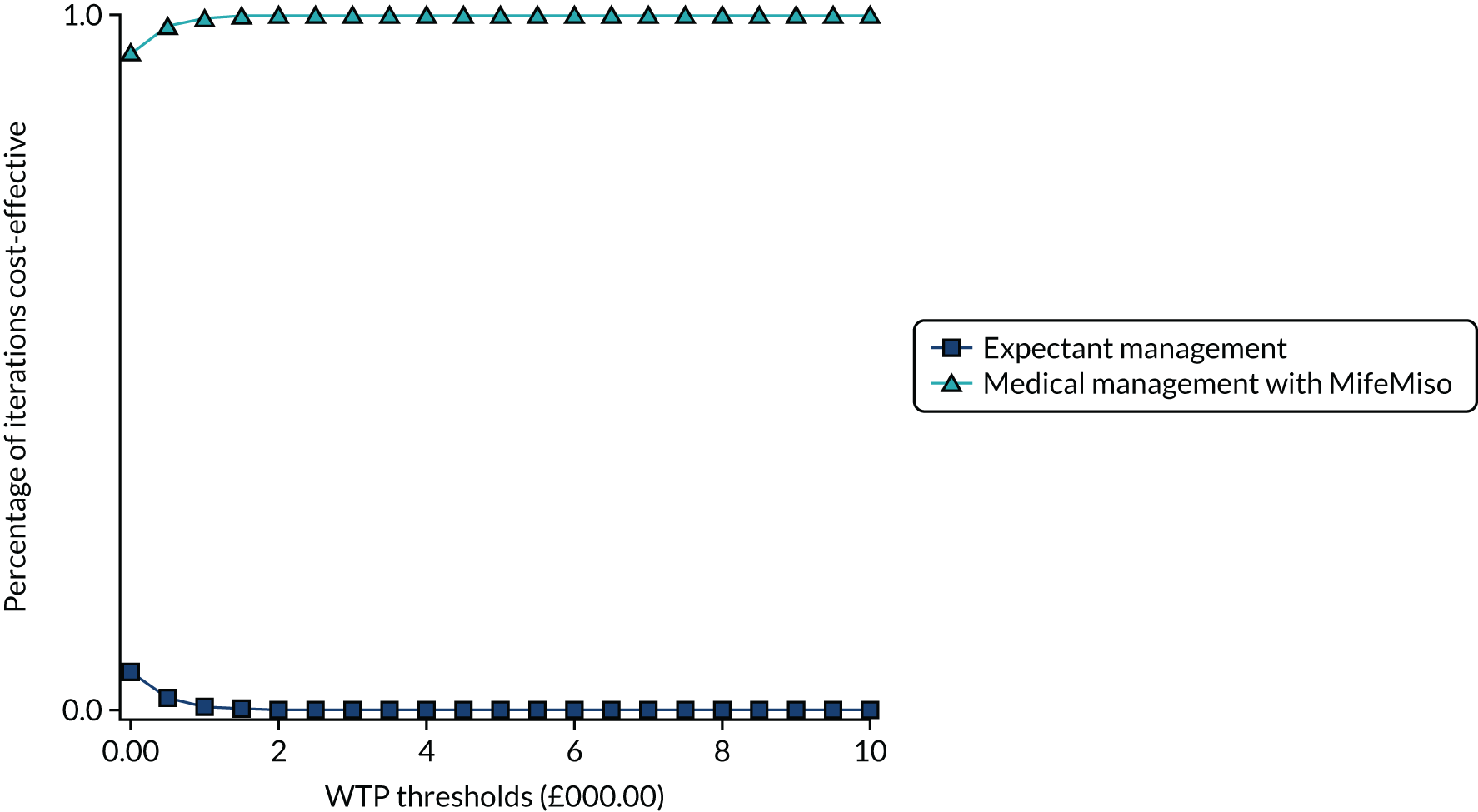

To assess the cost-effectiveness of the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol in the medical management of missed miscarriage.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted with permission from Coomarasamy et al. 21,22 Contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

Our study registration is published on www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03065660. 23

Design

The MifeMiso trial was conducted as a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial of mifepristone and misoprostol compared with misoprostol alone in the medical management of missed miscarriage. The trial had a favourable ethical opinion from National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee West Midlands – Edgbaston. The final protocol version was v5.0, 27 June 2019.

Participants

Potential participants were women attending EPUs in secondary or tertiary care NHS hospitals located across the UK. They were eligible for the MifeMiso trial if they fulfilled the following criteria (see Recruitment for more details on the recruitment process):

-

A missed miscarriage had been diagnosed by pelvic ultrasound scan in the first 14 weeks of pregnancy and they had opted for medical management of miscarriage.

-

They were aged ≥ 16 years.

-

They were willing and able to give informed consent.

Potential participants could not be included if any of the following criteria were applicable:

-

They had opted for alternative methods of miscarriage management (expectant or surgical).

-

They had a diagnosis of incomplete miscarriage.

-

They were suffering life-threatening bleeding.

-

They had contraindications to mifepristone or misoprostol use (e.g. chronic adrenal failure, known hypersensitivity to either drug, haemorrhagic disorders and anticoagulant therapy, prosthetic heart valve or history of endocarditis, existing cardiovascular disease, severe asthma uncontrolled by therapy or inherited porphyria).

-

They were currently participating in another blinded, placebo-controlled trial of investigational medicinal products (IMPs) in pregnancy.

-

They had previously participated in the MifeMiso trial.

-

They were not able to attend for a day 6–7 ultrasound scan.

Recruitment

Potential participants were identified from dedicated EPUs and approached by clinic doctors, research nurses and midwives, who had received appropriate training relating to the trial.

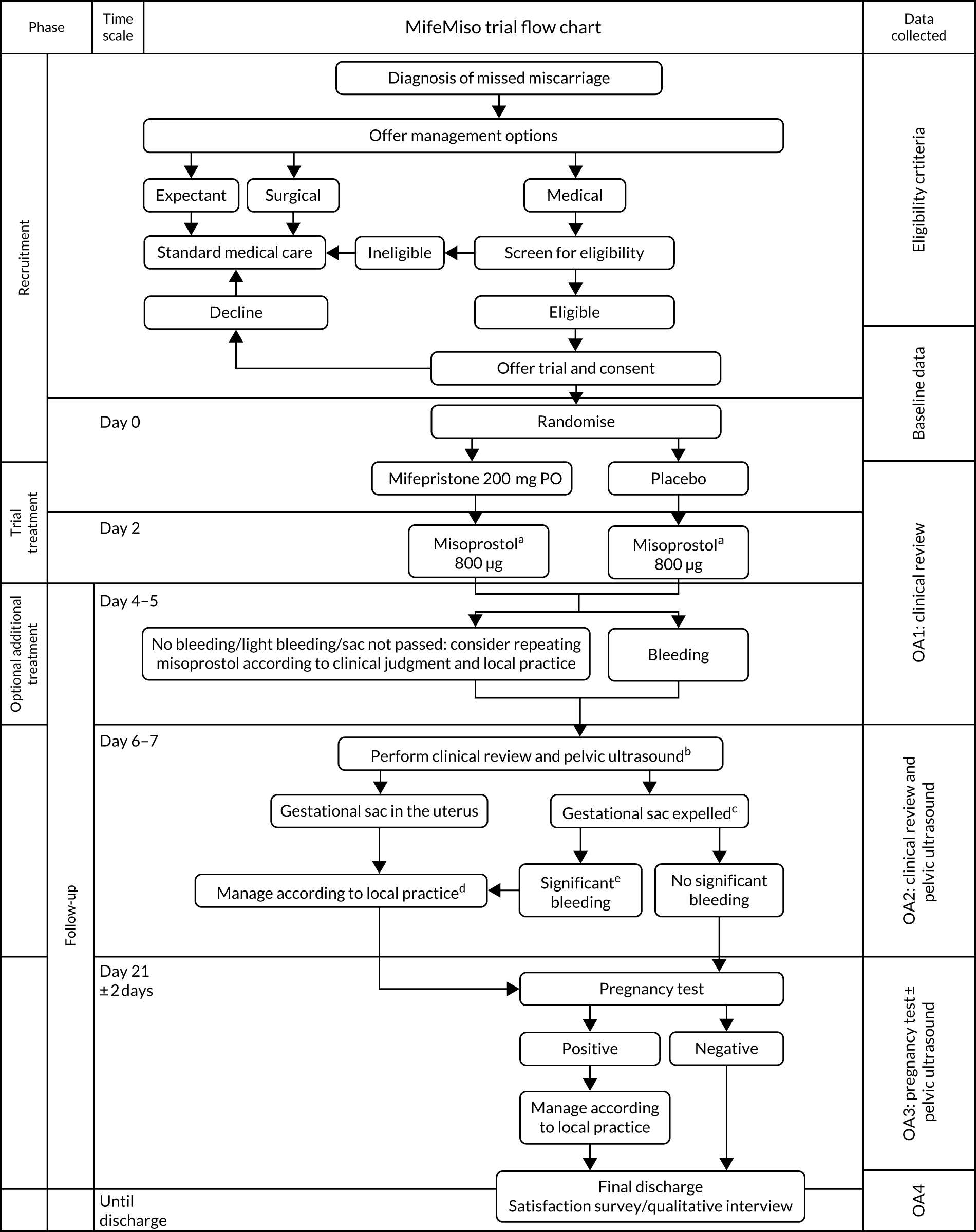

The participant eligibility pathway to recruitment and randomisation is illustrated in Figure 2. Eligible women were given verbal and written explanations about the trial. They were informed clearly that participation in the trial was entirely voluntary, with the option to withdraw at any stage, and that participation or non-participation would not affect their usual care. They were provided with a participant information sheet (PIS) (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Eligible women were then given the opportunity to decide if they wished to participate, if they needed more time to consider their decision or if they did not wish to participate. In all three scenarios, the decision of the woman was respected. If a woman needed more time to consider her potential involvement, the research nurse or midwife contacted her after the initial discussion to follow this up. If an initially undecided woman decided later to participate, the research nurse or midwife arranged a mutually convenient opportunity for the woman to be consented, providing she still met the eligibility criteria. A written consent form (see Report Supplementary Material 2) was provided to each woman who agreed to participate in the trial. The investigator and the participant both signed the consent form. The original copy was kept in the investigator site file, one copy was given to the participant, one copy was retained in the woman’s hospital records and one copy was returned to the MifeMiso trial office at Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit. Baseline demographic and medical data were collected, anonymised and stored in an electronic integrated trial management system (ITMS). Any identifying information was collected and stored in a password-protected local database on a secure computer with restricted access. We made provision for translation, if necessary, to communicate with non-English speakers and accommodate any special communications requirements of potential study participants.

FIGURE 2.

MifeMiso trial flow chart. a, If gestational sac has been passed before the scheduled time for misoprostol, misoprostol can be omitted; b, if scan performed earlier than day 6–7 and sac passed then repeat scan at day 6–7 not required; c, primary outcome; d, advice: avoid surgical evacuation unless clinically indicated; e, according to clinical judgement.

Randomisation

Confirmation of eligibility according to inclusion and exclusion criteria was provided by a medically trained doctor and all the necessary information was gathered before randomisation. Participants were randomised online to receive the trial intervention (either mifepristone or placebo) via a purpose-designed ITMS. Each authorised member of the research team was provided with a unique username and password to the ITMS for this purpose. Online randomisation was available 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, apart from short periods of scheduled maintenance.

Sequence generation and minimisation

Participants were randomised online via a secure internet facility. This third party independent ITMS was designed, developed and delivered by MedSciNet® (London, UK) according to standards of the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) 27000 and the requirements of the US Food and Drug Administration CFR21:11.

Participants were randomised to receive mifepristone or placebo in a 1 : 1 ratio. A ‘minimisation’ procedure using a computer-based algorithm was used to avoid chance imbalances in important stratification variables. The stratification variables used for minimisation are listed below:

-

Maternal age (< 30 or ≥ 30 years). The aim was to achieve a balance in the number of participants from younger and older age groups. However, there is no known biological reason why the intervention should lead to differing efficacy in women aged < 30 or ≥ 30 years.

-

Body mass index (BMI) (< 35 or ≥ 35 kg/m2). It was postulated that the pharmacokinetics and metabolism of mifepristone and misoprostol may be different in women with a BMI that is < 35 or ≥ 35 kg/m2.

-

Previous parity (nulliparous, parous women). It was postulated that parous women may be able to complete their missed miscarriage at a higher resolution rate than nulliparous women. The aim was, therefore, to achieve balance in the participants according to their previous parity.

-

Gestational age (< 70 or ≥ 70 days). It was postulated that women with a gestational age of < 70 days may have a higher resolution rate than women with a gestational age of ≥ 70 days.

-

Amount of bleeding [Pictorial Blood loss Assessment Chart (PBAC) score: ≤ 2 or ≥ 3]. It was proposed that women with a PBAC score of ≥ 3 may achieve a higher resolution rate than those with a score of ≤ 2, as an increased amount of bleeding would suggest that the miscarriage was more likely to resolve with the allocated intervention.

-

Randomising centre. It was hypothesised that different centres may respond to patients with different ultrasonography findings in different ways. For example, some centres may have a quicker recourse to miscarriage than others. Therefore, the aim was to achieve balance in the number of participants randomised to mifepristone and misoprostol and placebo and misoprostol at each recruiting centre.

Allocation

When all the eligibility criteria and baseline data items were entered online, the ITMS generated a trial number that took into account the minimisation variables recorded for the individual and was linked to a specific trial intervention pack. The pack number was revealed via e-mail to the local principal investigator (PI), the relevant trial pharmacist (see Blinding) and the research nurse or midwife performing the randomisation. The trial intervention pack was dispensed to the patient by the clinical trial pharmacist at the randomising hospital. Each trial intervention pack contained either mifepristone or an identical-looking placebo tablet.

Interventions

Each participant in the MifeMiso trial received either a mifepristone or placebo tablet, to be administered orally. Both products were supplied by MODEPHARMA Limited (Beckenham, Greater London, UK), a pharmaceutical wholesaler and project management company with a Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) wholesale dealer’s licence, in compliance with good manufacturing practice (GMP) standards, good clinical practice (GCP) requirements and Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004. MODEPHARMA Limited also provided qualified person (QP) release of the trial drug under the requirements of the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004.

Mifepristone tablets

The IMP was mifepristone at a single dose of 200 mg, taken following randomisation. Mifepristone was based on licensed and commercially available Mifegyne (Mifepristone) 200-mg tablets.

Placebo tablets

Placebo tablets were oral tablets, composed of Pearlitol 200SD Dev, Microcrystalline Cellulose NF, Ph. Eur.; DAB, Crospovidone, NF/Ph. Eur.; Magnesium Stearate, Ph. Eur.; and Quinoline Yellow produced in the same form as the IMP, and identical in colour, shape and weight, for use in the control group of the MifeMiso trial. The dose, route and timing of administration were also identical to those in the active mifepristone group of the study.

Dose

The dose of 200 mg of mifepristone was chosen as it is the most commonly used dose for the medical management of miscarriage when used with misoprostol and it is the most commonly studied dose in published trials investigating its efficacy in the medical management of miscarriage.

Concomitant non-trial treatments

Concomitant therapy was provided at the discretion of the care-providing clinicians, and all concomitant treatment and medications were documented via the ITMS. Other than identified contraindicated drugs (see Participants), the initiation of treatment for another indication did not necessitate withdrawal from the MifeMiso trial.

Blinding

Participants, investigators, research nurses, midwives and other attending clinicians remained blind to the trial drug allocation throughout the duration of the trial.

In the case of any serious adverse event (SAE), the recommendation was to initiate management and care of the participant as though the woman had taken mifepristone. The occurrence of any adverse event considered serious, unexpected and possibly, probably or definitely related to the trial intervention (for more information please see additional documentation: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1516002/#/documentation; accessed September 2021) led to unblinding as appropriate. In any other circumstances, investigators and research nurses and midwives remained blind to drug allocation while the participant remained in the trial. However, if medical management required clinicians to know a participant’s drug allocation, then this could be requested from the central trial team 24 hours per day, 7 days per week.

Compliance assessment and treatment withdrawal

Compliance monitoring

The dispensing of the MifeMiso trial drug was recorded in the pharmacy drug accountability log. Ingestion of the drug was observed by a health-care professional (HCP) and documented in the patient’s notes. Compliance to trial treatment was defined as taking the allocated mifepristone or placebo tablet on day 0 (day of randomisation) and subsequently misoprostol on day 2 unless the gestational sac had passed before the scheduled time for misoprostol; in the latter case, the patient was deemed to be compliant to the trial medication as long as the allocated mifepristone or placebo tablet was taken on day 0.

Withdrawal from trial

Participants could voluntarily withdraw their consent to study participation at any time. If a participant did not return for a scheduled visit, attempts were made to contact them and (when possible) to review compliance and adverse events (AEs). We documented the reason(s) for self-withdrawal when possible. Each woman remained able to change her mind about withdrawal, and re-consent to participate in the trial, at any time. If a participant explicitly withdrew consent to any further data recording then this decision was respected and recorded via the ITMS. All communications surrounding the withdrawal were noted in the study records and no further data were collected for such participants.

Outcomes and assessment

Primary outcome

Failure to spontaneously pass the gestational sac within 7 days after randomisation.

Secondary outcomes

Key secondary outcome: surgical intervention to resolve the miscarriage (collected up to discharge from EPU care).

Additional secondary outcomes are as follows (as a proportion of those randomised unless stated):

-

Surgical intervention to resolve the miscarriage up to and including day 7 post randomisation.

-

Surgical intervention to resolve the miscarriage after day 7 post randomisation to discharge from EPU care.

-

Need for further doses of misoprostol up to day 7 post randomisation.

-

Need for further doses of misoprostol up to discharge from EPU care.

-

Overall patient satisfaction score [measured using the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) questionnaire and collected at discharge from EPU care].

-

Patient quality of life (index value and overall health status measured using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), questionnaire and collected on date of randomisation, day 6–7 post randomisation or day of follow-up ultrasound scan if different from day 6–7 and day 212 days post randomisation. If a woman obtains an initial positive pregnancy test result at day 21 ± 2 days post randomisation, then a further EQ-5D-5L questionnaire is collected (at discharge from EPU care).

-

Duration of bleeding reported by woman (days) (collected up to discharge from EPU care).

-

Diagnosis of infection associated with miscarriage requiring outpatient antibiotic treatment (collected up to discharge from EPU care).

-

Diagnosis of infection associated with miscarriage requiring inpatient antibiotic treatment (collected up to discharge from EPU care).

-

Negative pregnancy test result 21 days (± 2 days) after randomisation.

-

Time from randomisation to discharge from EPU care (described using summary statistics only).

Safety outcomes:

-

blood transfusion required (collected up to discharge from EPU care)

-

side effects (collected up to discharge from EPU care)

-

death (collected up to discharge from EPU care)

-

any serious complications (collected up to discharge from EPU care).

Mixed-methods evaluation resource use outcomes

These are detailed in Chapter 4.

Resource use outcomes

These are detailed in Chapter 5.

Future outcomes

Women’s consent was sought for future evaluation of themselves and any subsequent pregnancies using their health records. Although long-term follow-up was outside the scope of this trial, we plan to conduct further studies on outcomes such as subsequent successful pregnancies post-miscarriage resolution.

Outcome generation

Details of how outcome measures were generated are given in Table 2. The ITMS was utilised to capture baseline and outcome data, and to maintain an audit trail. Relevant trial data were transcribed directly into the ITMS. Source data comprised the research clinic notes, hospital notes, self-reports, the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire completed at 21 days post randomisation and subsequently at discharge (for women who obtained an initial positive pregnancy test result), the patient satisfaction survey completed at discharge, and the transcript of the in-depth qualitative interviews. All case report forms are provided in the additional documentation (see Report Supplementary Material 4).

| Outcome assessed | When? | How? | By whom? | PD or SP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline data: EQ-5D-5L questionnaire | Day 0 | Face-to-face clinical appointment with participant | Self-administered questionnaire | PD |

| OA1: clinical review | Day 4–5 | Telephone or face-to-face clinical appointment with participant | Local research nurse/midwife or doctor | SP and PD |

| OA2: clinical review ± pelvic ultrasound, to determine whether or not the gestation sac has been expelled | Day 6–7 | Face-to-face clinical appointment with participant | Local research nurse/midwife or doctor | PD (and SP in some hospitals depending on trust policy) |

| OA2: EQ-5D-5L questionnaire | Day 6–7 | Face-to-face clinical appointment with participant | Self-administered questionnaire | PD |

| OA3: pregnancy test | Day 21 ± 2 days (point of discharge for women with negative pregnancy test result) | Clinical records and/or telephone interview or face-to-face clinical appointment with participant | Local research nurse/midwife or doctor | SP |

| OA3: EQ-5D-5L questionnaire | Day 21 ± 2 days (point of discharge for women with negative pregnancy test result) | Telephone or face-to-face clinical appointment with participant | Self-administered questionnaire | PD |

| OA4: final discharge | At discharge | From clinical records or interview with the participant | Local research nurse/midwife or doctor | SP |

| OA4: EQ-5D-5L questionnaire (if initial positive pregnancy test result) and patient satisfaction survey | At discharge | Telephone or face-to-face clinical appointment with participant | Self-administered questionnaires | PD |

| OA4: semistructured qualitative interview | Within 6 weeks of discharge | Face-to-face, via telephone or via video call with participant | Qualitative/mixed-methods researcher | PD |

First outcome assessment (day 6–7 post randomisation)

At the time of randomisation, arrangements for an ultrasound appointment through EPU were made for day 6–7 post randomisation. The research nurse or midwife assisted with booking an appointment if necessary, and was responsible for ensuring that the details of the scan were recorded in the ITMS. If the woman did not have a scan for any reason, this was recorded in the ITMS. If the woman did not attend for an ultrasound scan, or attended for a scan after day 7 post randomisation, then the research nurse or midwife asked the woman if she could provide the date of passing the gestational sac.

Blinded Endpoint Review Committee assessment of the primary outcome

For women who did not undergo an ultrasound scan on day 6 or 7 and had not already passed their gestational sac according to an earlier scan, a Blinded Endpoint Review Committee (BERC) was convened to assess whether or not the primary outcome had been met. The BERC consisted of four medical members of the central trial management group and an independent nurse specialist who works in early pregnancy. All members of the committee were blinded to treatment allocation and were required to sign the BERC charter before the meeting taking place (see Report Supplementary Material 5). The committee was convened at a face-to-face meeting following the end of trial recruitment to review participant data for women who had not undergone ultrasound scanning within 7 days of randomisation.

Before the committee meeting, a medical member of the central trial management group contacted these women to ask when they had experienced their vaginal bleeding and pelvic pain following the trial medications. The date when the participant experienced miscarriage symptoms and the date of any subsequent scan were used to determine whether the gestational sac was passed by day 7. The committee needed to agree unanimously that the participant could have primary outcome data collected. Please see below for some examples of participants who underwent BERC assessment.

Example 1

A participant reported vaginal bleeding and pain for 2 days starting from the day of misoprostol administration and then experienced no further bleeding and underwent ultrasound scan on day 8. The committee agreed that this meant that the participant would have passed the gestational sac by day 7.

Example 2

A participant reported vaginal bleeding on the day of misoprostol administration and no further bleeding thereafter. The ultrasound scan was performed on day 9, and the gestational sac was seen in situ. The committee agreed that this meant that the participant failed to pass the gestational sac by day 7.

The BERC adhered to the prespecified committee charter and convened to discuss the clinical details of each of these participants. The decision of whether or not the primary outcome was met needed to have been decided unanimously by the committee.

Second outcome assessment (day 21 ± 2 days post randomisation)

The second outcome assessment was conducted at 21 days (± 2 days) post randomisation. The research nurse or midwife at each study site contacted the participant to obtain their pregnancy test result. If the result was negative, this was used as the point of discharge from EPU care. If the pregnancy test result was positive, the participant was asked to repeat the pregnancy test until a negative test result was obtained. Several clinical outcomes were collected up to discharge from EPU care, including requirement for surgical intervention, duration of bleeding, requirement for blood transfusion and diagnosis of infection associated with miscarriage. The research nurse or midwife obtained the duration of bleeding by asking the participant and collected the remaining information from clinical notes.

Definition of the end of the trial

The interventional phase of the trial ended when the last woman recruited had taken her last dose of the trial treatment. The observational phase of the trial to assess clinical outcomes ceased and the primary analysis was scheduled to occur when the final outcome of the last woman recruited had been completed and data had been entered onto the database and validated as being ready for analysis.

Notes on adverse events and serious adverse events

All the trial participants were asked to report any hospitalisations, consultations with other medical practitioners, disability, incapacity or any other AEs to their local research team; if the local study nurse or midwife was unavailable for any reason, the participants were able to report the events to the trial manager via telephone at any time. Moreover, at the time of each outcome assessment, investigators and research nurses and midwives at each study centre proactively asked each participant about any AEs in the preceding weeks. AEs were assessed by clinical investigators, further reported as appropriate, and recorded on the ITMS.

Serious AEs and serious adverse reactions (SARs) were recorded on a purpose-designed SAE form. Local investigators notified the trial manager within 24 hours of the local investigators becoming aware of these events. In addition, local investigators were responsible for reporting SAEs to their host institutions, in accordance with local regulations, and instituting supplementary investigations as appropriate based on clinical judgement of the causative factors. SAEs and SARs were followed up until resolution even if this was beyond the participant’s discharge date from EPU care. The trial manager reported all SAEs to the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) approximately once every 6 months. The DMC viewed data blinded to treatment, but was able to review unblinded data if requested.

Sample size

The MifeMiso trial investigators believed that it was important to ensure that the study was large enough to detect reliably moderate but clinically important treatment effects. The sample size was calculated using the Sample Size Tables for Clinical Studies Software application based on a chi-squared test for comparing two proportions. Our calculations indicated that 670 women would be required to detect a minimally important difference (MID) of a 10% reduction in the rate of failure to spontaneously pass the gestational sac within 7 days (i.e. from 25% to 15%), assuming 90% power and a type I error rate of 5%. However, assuming and adjusting for a worst case scenario of 5% attrition, the total number of participants required was 710 (355 participants in each group). The 25% (95% CI 23% to 27%) control group estimate was taken from our systematic review (unpublished data) and the 10% MID was the most popular selection from our HCP survey (41% of those surveyed). The estimate of the control group rate was monitored throughout the recruitment period by the independent DMC to ascertain if any deviations from this assumption had an impact on the sample size calculation.

Statistical methods

A comprehensive statistical analysis plan (SAP) was drawn up before any analysis and provided to the independent DMC for review. All analyses were prespecified in a SAP. Full details of the statistical analysis can be found in the SAP (see Report Supplementary Material 6).

All women randomised were included in the analysis and were analysed in the group into which they were randomly allocated, regardless of treatment received (an intention-to-treat analysis).

For all binary outcomes, a log-binomial regression model was used to calculate the adjusted RRs and 95% CIs. For continuous outcomes, a linear regression model was used to estimate adjusted mean differences and 95% CIs. All estimates of treatment effects between groups were adjusted for the minimisation variables where maternal age, BMI and gestational age were treated as continuous fixed effects, parity and bleeding score as categorical fixed effects, and randomising centre as a random effect. If covariate adjustment was not possible (i.e. due to lack of convergence when carrying out the modelling procedure), alternative models were explored. The clustering effect of randomising centres was accounted for by using robust standard errors at centre level. When required, p-values from the associated models were produced and used to assess statistical significance.

A hierarchical testing procedure was prespecified to allow for multiple comparisons: the null hypothesis for the primary outcome was tested first and, if it was statistically significant at the 5% level, the key secondary outcome would be tested. Otherwise, no further hypothesis testing would be performed. For all safety outcomes, to assess any signal within specific organ groups, p-values are presented unadjusted for multiple testing. The results from all other secondary outcomes are treated as exploratory rather than confirmatory. No adjustments for multiple testing were made for CIs.

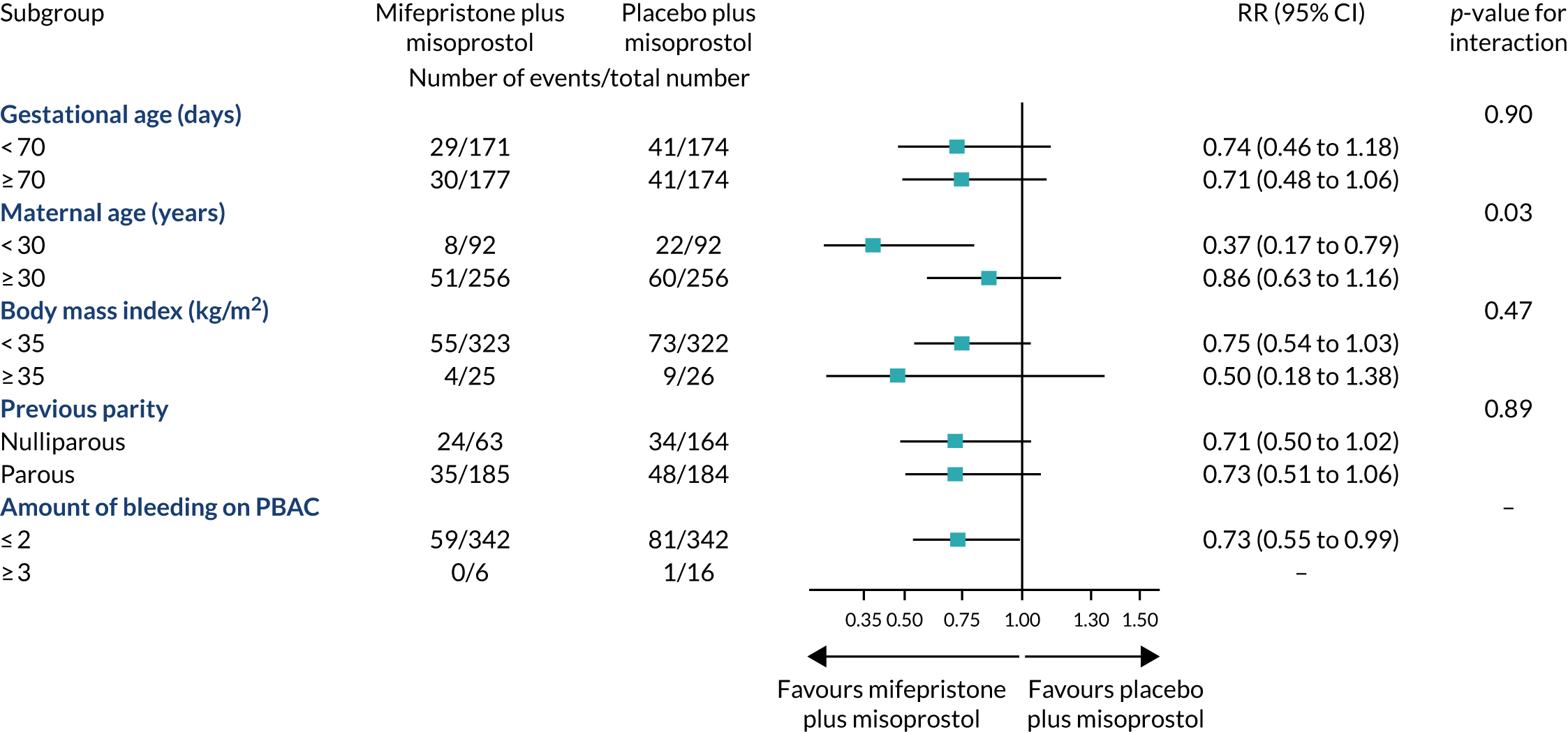

We analysed the treatment effect for the primary outcome in prespecified subgroups defined according to maternal age (< 30 or ≥ 30 years), BMI (< 35 or ≥ 35 kg/m2), previous parity (nulliparous or parous women), gestational age (< 70 or ≥ 70 days) and amount of bleeding (PBAC score,24 ≤ 2 or ≥ 3). The subgroup defined by gestational age was prespecified as of special interest; the results of other subgroup analyses are treated with caution and used for the purposes of hypothesis generation only. 25 The effects of these subgroups were examined by adding the variables for the interaction of subgroup with trial group to the regression model; an F-test was used to determine whether or not the effects of mifepristone and misoprostol differed to the effects of placebo and misoprostol in the various subgroups.

Analyses of principal safety and effectiveness outcomes were performed on behalf of the DMC by the trial statistician (who remained unaware of the treatment assignments) on two occasions during the recruitment period. Because these analyses were performed with the use of the Peto principle,26 no adjustment was made to the final p-values presented.

Trial oversight

Study oversight was provided by a Trial Steering Committee (TSC) (chaired by Mr Rajendra Rai, Imperial College London) and a DMC (chaired by Dr Abha Maheshwari, University of Aberdeen).

The TSC provided independent supervision for the trial, providing advice to the chief investigator, co-investigators and the sponsor on all aspects of the trial throughout the study. The DMC adopted the DAMOCLES27 charter to define its terms of reference and operation in relation to oversight of the MifeMiso trial. The DMC met on an approximately 6-monthly basis during the study.

Chapter 3 Results

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted with permission from Chu et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license, which permits others to copy and redistribute this work, for non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

This chapter reports the results of the MifeMiso trial. It starts with a description of the flow of participants through the trial and is followed by demographic information and results of the primary and secondary outcomes including safety outcomes. The clinical findings from this trial have been previously published in The Lancet. 1

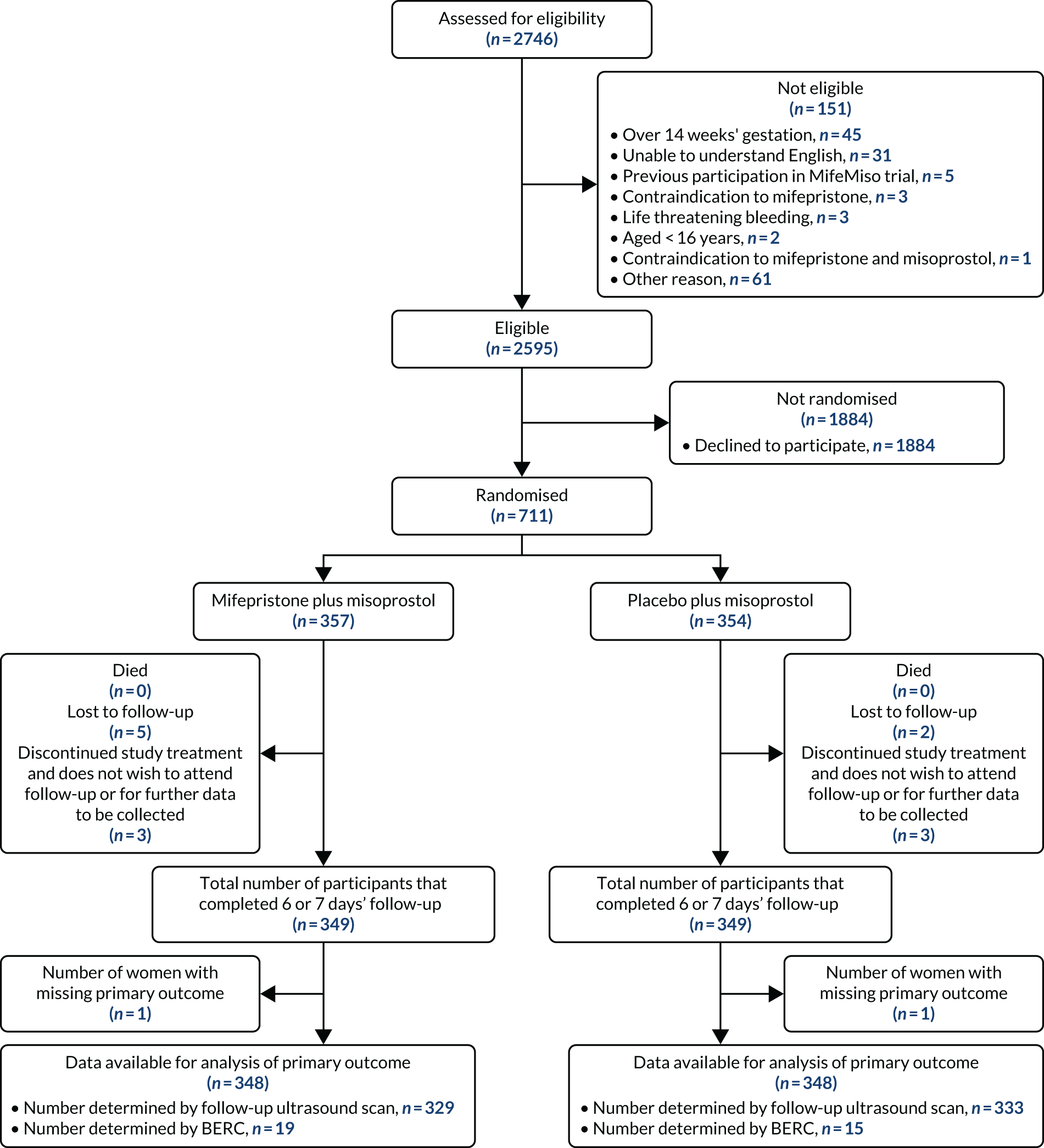

Participant flow

Participant flow is illustrated in Figure 3. A total of 2746 participants were screened for eligibility to take part in the MifeMiso trial, of whom 151 were not eligible for randomisation and a further 1884 declined to participate in the trial. A total of 711 women proceeded to randomisation, with 357 allocated to the mifepristone and misoprostol group and 354 allocated to the placebo and misoprostol group. Six participants were withdrawn from the study, a further seven were lost to follow-up and two had missing primary outcome data. This meant that 696 participants (98% of those randomised) were available for analysis of the primary outcome.

FIGURE 3.

The MifeMiso trial CONSORT flow diagram.

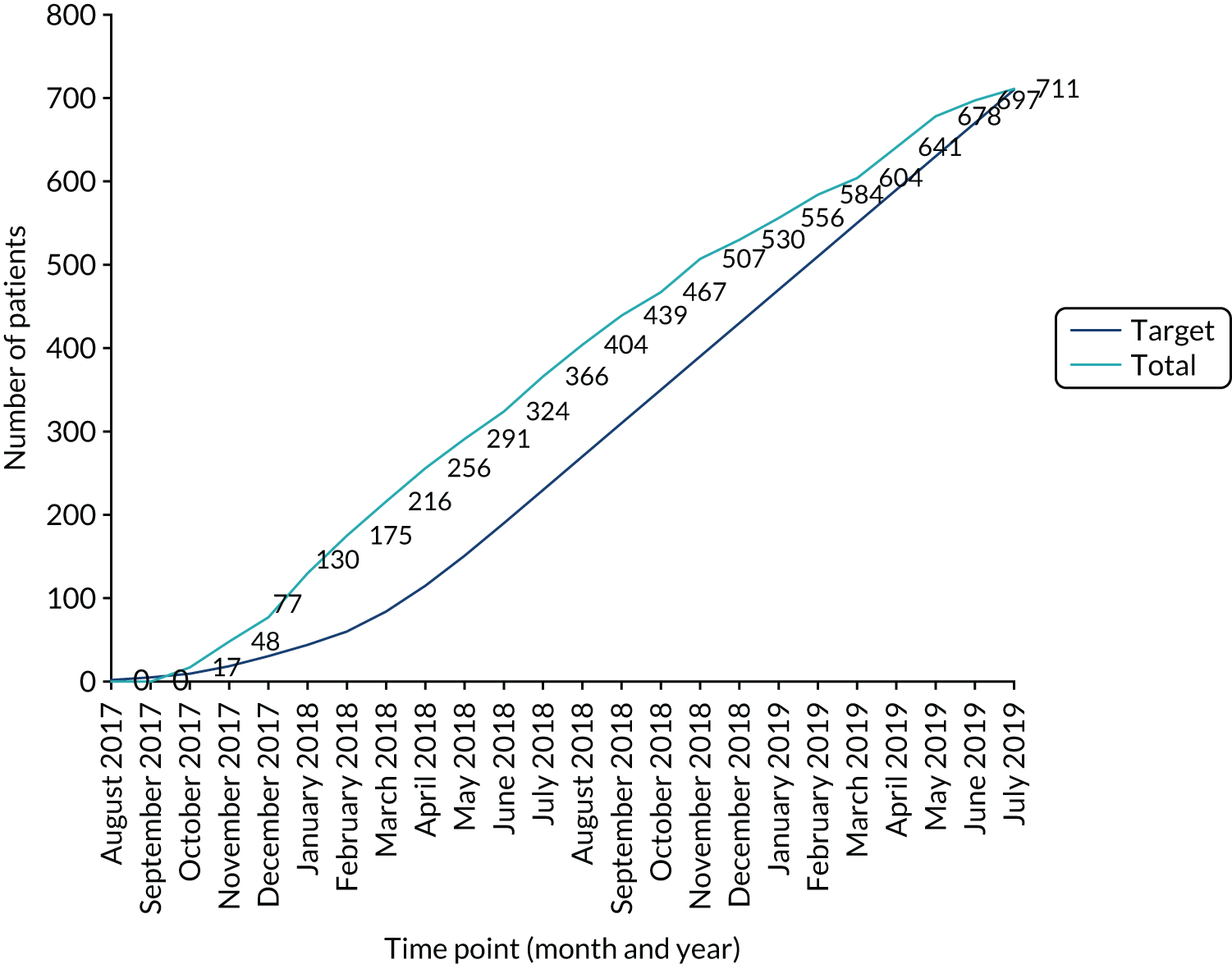

Recruitment

Recruitment and randomisation took place over 22 months in 28 UK NHS hospitals (Figure 4, Table 3) from October 2017 to July 2019 (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

Map of the MifeMiso trial recruiting sites. Map data © Google 2021.

| Centre | PI | Activation date | Total recruitment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunderland Royal Hospital | Amna Ahmed | 25 September 2017 | 108 |

| University College London Hospital | Joel Naftalin | 27 September 2017 | 60 |

| West Middlesex University Hospital | Natalie Nunes | 29 November 2017 | 59 |

| St Michael’s University Hospital | Abigail Oliver | 25 September 2017 | 49 |

| Queen Alexandra Hospital | Nirmala Vaithilingam | 20 September 2017 | 47 |

| University Hospital Coventry | Feras Izzat | 25 September 2017 | 38 |

| Singleton Hospital | Frances Hodge | 11 January 2018 | 31 |

| Burnley General Hospital | Kalsang Bhatia | 5 April 2018 | 30 |

| St Thomas’ Hospital | Judith Hamilton | 2 October 2017 | 28 |

| Birmingham Women’s Hospital | Yadava Jeve (previously Ismail Hassan) | 17 November 2017 | 28 |

| Southmead Hospital | Jane Mears | 1 June 2018 | 25 |

| Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham | Shilpa Deb | 20 September 2017 | 20 |

| Liverpool Women’s Hospital | Linda Watkins (previously Penny Robshaw) | 9 October 2017 | 18 |

| Chelsea and Westminster Hospital | Natalie Nunes | 29 November 2017 | 18 |

| Princess Royal Hospital, Telford | Martyn Underwood | 6 December 2017 | 18 |

| King’s College Hospital | Jackie Ross | 1 February 2018 | 18 |

| Princess Anne Hospital, Southampton | Ying Cheong | 9 October 2017 | 17 |

| Glasgow Royal Infirmary | Chitra Kumar | 26 October 2017 | 16 |

| Queen Elizabeth University Hospital | Stewart Pringle | 25 October 2017 | 13 |

| Birmingham Heartlands Hospital | Pratima Gupta | 30 November 2017 | 13 |

| Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle | Meenakshi Choudhary | 29 September 2017 | 12 |

| St Helier Hospital | Sangeetha Devarajan | 5 April 2018 | 12 |

| Whipps Cross University Hospital | Anupama Shahid | 2 October 2017 | 11 |

| Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh | Andrew Horne | 3 October 2017 | 11 |

| Royal London Hospital | Anupama Shahid | 11 October 2017 | 4 |

| Epsom Hospital | Sangeetha Devarajan | 8 May 2018 | 4 |

| Princess of Wales Hospital | Frances Hodge | 11 January 2018 | 2 |

| Newham University Hospital | Anupama Shahid | 2 November 2017 | 1 |

FIGURE 5.

Cumulative recruitment to the MifeMiso trial.

Baseline data

The baseline demographic characteristics of participants in the two groups were comparable, with the minimisation algorithm ensuring balance for the factors indicated in Table 4.

| Characteristic | Mifepristone plus misoprostol group (N = 357) | Placebo plus misoprostol group (N = 354) | Overall (N = 711) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimisation variables | |||

| Maternal age (years) | |||

| < 30, n (%) | 95 (27) | 95 (27) | 190 (27) |

| ≥ 30, n (%) | 262 (73) | 259 (73) | 521 (73) |

| Mean (SD) | 32.8 (5.6) | 32.7 (5.7) | 32.8 (5.6) |

| Median [IQR] | 33 [29–37] | 33 [29–36] | 33 [29–37] |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| < 35, n (%) | 332 (93) | 328 (93) | 660 (93) |

| ≥ 35, n (%) | 25 (7) | 26 (7) | 51 (7) |

| Mean (SD) | 25.8 (5.6) | 26.5 (5.5) | 26.1 (5.6) |

| Median [IQR] | 24.4 [22.1–27.8] | 25.5 [22.3–29.7] | 24.8 [22.2–28.9] |

| Previous parity, n (%) | |||

| Nulliparous | 167 (47) | 168 (47) | 335 (47) |

| Parous | 190 (53) | 186 (53) | 376 (53) |

| Gestational age (days) | |||

| < 70, n (%) | 176 (49) | 175 (49) | 351 (49) |

| ≥ 70, n (%) | 181 (51) | 179 (51) | 360 (51) |

| Mean (SD) | 70.5 (13.1) | 70.7 (13.8) | 70.6 (13.4) |

| Median [IQR] | 70 [61–81] | 70 [63–82] | 70 [62–82] |

| Amount of bleeding, n (%) | |||

| PBACa score ≤ 2 | 351 (98) | 348 (98) | 699 (98) |

| PBACa score ≥ 3 | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 12 (2) |

| Other demographic and clinical characteristics | |||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 296 (83) | 280 (79) | 576 (81) |

| Black | 10 (3) | 17 (5) | 27 (4) |

| Asian | 38 (11) | 42 (12) | 80 (11) |

| Mixed | 5 (1) | 8 (2) | 13 (2) |

| Other ethnic group | 7 (2) | 7 (2) | 14 (2) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| Progesterone levels | |||

| Mean (SD) | 17.0 (4.2) | 22.8 (12.8) | 20.9 (10.6) |

| Median [IQR] | 17.0 [14.0–20.0] | 26.0 [12.7–33.0] | 19.5 [14.0–33.0] |

| Not measured, n (%) | 355 (99) | 350 (99) | 705 (99) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| Pregnancy-related pain score at randomisationb | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.0 (1.8) | 1.2 (2.0) | 1.1 (1.9) |

| Median [IQR] | 0 [0–1] | 0 [0–2] | 0 [0–2] |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| Number of gestational sacs, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 351 (98) | 348 (98) | 699 (98) |

| 2 | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 12 (2) |

| ≥ 3 | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| Missing | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| Days from date of ultrasound scan diagnosing missed miscarriage to randomisation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.5 (3.3) | 1.9 (4.6) | 1.7 (4.0) |

| Median [IQR] | 0 [0–1] | 0 [0–1] | 0 [0–1] |

| Not measured | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| Current concomitant medication, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 71 (20) | 80 (23) | 151 (21) |

| No | 285 (80) | 274 (77) | 559 (79) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| If yes, type of medication,c n (%) | |||

| Analgesic | 7 (10) | 6 (8) | 13 (9) |

| Antibacterial | 5 (7) | 5 (6) | 10 (7) |

| Anticonvulsant | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 3 (2) |

| Antidepressant | 8 (11) | 7 (9) | 15 (10) |

| Antifungal | 0 (–) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Anti-inflammatory agents | 1 (1) | 0 (–) | 1 (1) |

| Blood glucose regulators | 4 (6) | 6 (8) | 10 (7) |

| Blood products/modifiers/volume expanders | 1 (1) | 0 (–) | 1 (1) |

| Cardiovascular agent | 2 (3) | 4 (5) | 6 (4) |

| Dermatological agent | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Gastrointestinal agent | 3 (4) | 4 (5) | 7 (5) |

| Hormonal agents, stimulant/replacement/modifying (sex hormones/modifiers) | 3 (4) | 9 (11) | 12 (8) |

| Hormonal agents, stimulant/replacement/modifying (thyroid) | 12 (17) | 10 (13) | 22 (15) |

| Immunological agent | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 3 (2) |

| Migraine | 1 (1) | 0 (–) | 1 (1) |

| Respiratory tract agent | 12 (17) | 15 (19) | 27 (18) |

| Sedative/hypnotic | 0 (–) | 2 (3) | 2 (1) |

| Antiplatelet | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 3 (2) |

| Medical history, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes | |||

| Yes | 4 (1) | 7 (2) | 11 (2) |

| No | 352 (99) | 347 (98) | 699 (98) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| Renal disease | |||

| Yes | 3 (1) | 1 (< 1) | 4 (1) |

| No | 353 (99) | 353 (99) | 706 (99) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| Cardiac disease | |||

| Yes | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) |

| No | 355 (99) | 353 (99) | 708 (99) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| Chronic hypertension | |||

| Yes | 2 (1) | 1 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) |

| No | 354 (99) | 353 (99) | 707 (99) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| Thyroid disease | |||

| Yes | 12 (3) | 13 (4) | 25 (4) |

| No | 344 (96) | 341 (96) | 685 (96) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| Cancer | |||

| Yes | 2 (1) | 0 (–) | 2 (< 1) |

| No | 354 (99) | 354 (100) | 708 (99) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| Other | |||

| Yes | 46 (13) | 44 (12) | 90 (13) |

| No | 310 (87) | 310 (88) | 620 (87) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| Number of previous pregnancies, n (%) | |||

| Live birth | |||

| 0 | 63 (18) | 70 (20) | 133 (19) |

| 1 | 111 (31) | 118 (33) | 229 (32) |

| 2 | 45 (13) | 39 (11) | 84 (12) |

| ≥ 3 | 25 (7) | 23 (7) | 48 (7) |

| No previous pregnancies | 112 (31) | 104 (29) | 216 (30) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| Stillbirth | |||

| 0 | 238 (67) | 246 (69) | 484 (68) |

| 1 | 6 (2) | 3 (1) | 9 (1) |

| 2 | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) |

| ≥ 3 | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| No previous pregnancies | 112 (31) | 104 (29) | 216 (30) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| Miscarriage | |||

| 0 | 120 (34) | 121 (34) | 241 (34) |

| 1 | 62 (17) | 77 (22) | 139 (20) |

| 2 | 29 (8) | 24 (7) | 53 (7) |

| ≥ 3 | 33 (9) | 28 (8) | 61 (9) |

| No previous pregnancies | 112 (31) | 104 (29) | 216 (30) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| Ectopic pregnancy | |||

| 0 | 231 (65) | 241 (68) | 472 (66) |

| 1 | 13 (4) | 9 (3) | 22 (3) |

| 2 | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| ≥ 3 | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| No previous pregnancies | 112 (31) | 104 (29) | 216 (30) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| Molar pregnancy | |||

| 0 | 244 (68) | 249 (70) | 493 (69) |

| 1 | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) |

| 2 | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| ≥ 3 | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| No previous pregnancies | 112 (31) | 104 (29) | 216 (30) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| Termination | |||

| 0 | 191 (54) | 192 (54) | 383 (54) |

| 1 | 44 (12) | 45 (13) | 89 (13) |

| 2 | 7 (2) | 10 (3) | 17 (2) |

| ≥ 3 | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 5 (1) |

| No previous pregnancies | 112 (31) | 104 (29) | 216 (30) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

| Pregnancy of unknown location | |||

| 0 | 241 (68) | 250 (71) | 491 (69) |

| 1 | 3 (1) | 0 (–) | 3 (< 1) |

| 2 | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| ≥ 3 | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| No previous pregnancies | 112 (31) | 104 (29) | 216 (30) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) | 1 (< 1) |

Compliance with treatment

Adherence with the treatment regimen was high in both groups: 94% (337/357 women) in the mifepristone plus misoprostol group and 96% (341/354 women) in the placebo plus misoprostol group (Table 5).

| Outcome | Mifepristone plus misoprostol group (N = 357) | Placebo plus misoprostol group (N = 354) |

|---|---|---|

| Number adherent to treatment regimena | 337 (94) | 341 (96) |

| Number non-adherent | 20 (6) | 13 (4) |

The route of administration for the first dose of misoprostol was vaginal for the vast majority of women who needed to take this intervention [89% (286/321) in the mifepristone plus misoprostol group and 90% (299/334) in the placebo plus misoprostol group]. The number of women who received oral or sublingual misoprostol for their first dose was small, and the same in each group (Table 6).

| Description of interventions | Mifepristone plus misoprostol (N = 357) | Placebo plus misoprostol (N = 354) |

|---|---|---|

| Mifepristone or placebo taken, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 354 (99) | 350 (99) |

| No | 2 (1) | 4 (1) |

| If no, reason, n (%) | ||

| Woman changed her mind | 2 (100) | 3 (75) |

| Sac already passed | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| Othera | 0 (–) | 1 (25) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) |

| Misoprostol taken, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 321 (90) | 334 (94) |

| No | 35 (10) | 20 (6) |

| If no, reason, n (%) | ||

| Woman changed her mind | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| Woman did not attend hospital | 3 (9) | 0 (–) |

| Sac already passed | 27 (77) | 16 (80) |

| Other | 5 (14)b | 4 (20)c |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) |

| If yes, route of administration of first dose of misoprostol, n (%) | ||

| PV | 286 (89) | 299 (90) |

| PO | 30 (9) | 28 (8) |

| Sublingual | 5 (2) | 7 (2) |

| Missing | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| Additional doses of misoprostol taken | ||

| Yes, n (%) | 50 (14) | 65 (18) |

| One additional dose | 40 (80) | 51 (78) |

| Two additional doses | 7 (14) | 12 (18) |

| Three or more additional doses | 3 (6) | 2 (3) |

| Mean number of additional doses (SD) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.6) |

| Median number of additional doses [IQR] | 1 [1–1] | 1 [1–1] |

| No, n (%) | 271 (76) | 269 (76) |

| First dose not taken | 35 (10) | 20 (6) |

| Missing | 1 (< 1) | 0 (–) |

| If yes, route of administration of first additional dose, n (%) | ||

| PV | 36 (72) | 46 (71) |

| PO | 7 (14) | 11 (17) |

| Sublingual | 7 (14) | 8 (12) |

| Missing | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| If yes, dose of first additional dose (µg) | ||

| Mean (SD, n) | 656.0 (185.3, 50) | 692.3 (169.8, 65) |

| Median [IQR] | 800 [400–800] | 800 [600–800] |

| Missing | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| If yes, days since mifepristone/placebo of first additional dose | ||

| Mean (SD, n) | 6.7 (6.6, 50) | 6.2 (6.8, 64) |

| Median [IQR] | 4 [3–7] | 4 [4–7] |

| Missing | 0 (–) | 1 (2) |

Primary outcome results

The proportion of participants who did not pass the gestational sac spontaneously within 7 days was 17% (59/348 women) in the mifepristone plus misoprostol group and 24% (82/348 women) in the placebo plus misoprostol group (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.98; p = 0.04) (Table 7).

| Mifepristone plus misoprostol group (N = 357) | Placebo plus misoprostol group (N = 354) | RRa (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome – failure to pass the gestational sac spontaneously within 7 days of randomisation | ||||

| Yesb | 59 (17.0) | 82 (23.6) | 0.73 (0.54 to 0.98) | 0.035 |

| No | 289 (83.0) | 266 (76.4) | ||

| Missing | 9 | 6 | ||

Secondary outcome results

For the prespecified key secondary outcome, the proportion of participants who required surgical intervention to resolve the miscarriage was 17% (62/355 women) in the mifepristone plus misoprostol group, as compared with 25% (87/353 women) in the placebo plus misoprostol group (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.94; p = 0.02) (Table 8). Among the women who underwent surgery, the most common reason for surgery was pregnancy tissue remaining in the uterus: 89% (55/62 women) in the mifepristone plus misoprostol group, and 91% (79/87 women) in the placebo plus misoprostol group.

| Mifepristone plus misoprostol group (N = 357) | Placebo plus misoprostol group (N = 354) | RRa (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key secondary outcome – surgical intervention to resolve the miscarriage up to discharge from EPU | ||||

| Yesb | 62 (17) | 87 (25) | 0.70 (0.52 to 0.94) | 0.019 |

| No | 293 (83) | 266 (75) | ||

| Missing | 2 | 1 | ||

| Reason for surgeryc | ||||

| Pregnancy tissue remaining | 55 (89) | 79 (91) | ||

| Significant bleeding | 19 (31) | 14 (16) | ||

| Other | 8 (13) | 6 (7) | ||

| Missing | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | ||

| Outcome of surgery | ||||

| Complicatedc | 4 (6) | 5 (6) | ||

| Bleeding at surgery | 4 (100) | 3 (60) | ||

| Uterine damage | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | ||

| Need for extensive surgical intervention | 2 (50) | 0 (–) | ||

| Other | 1 (25) | 4 (80) | ||

| Missing | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | ||

| Uncomplicated | 58 (94) | 82 (94) | ||

| Missing | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | ||

| Surgical intervention to resolve the miscarriage up to and including day 7 post randomisation | ||||

| Yesb | 23 (6) | 19 (5) | 1.23 (0.68 to 2.21)d | |

| No | 332 (94) | 334 (95) | ||

| Missing | 2 | 1 | ||

| Surgical intervention to resolve the miscarriage after day 7 and up to discharge from EPU | ||||

| Yesb | 39 (11) | 68 (19) | 0.56 (0.39 to 0.79) | |

| No | 316 (89) | 285 (81) | ||

| Missing | 2 | 1 | ||

| Need for further doses of misoprostol within 7 days after randomisation | ||||

| Yesb | 34 (10) | 48 (14) | 0.73 (0.45 to 1.18) | |

| No | 322 (90) | 306 (86) | ||

| Missing | 1 | 0 (–) | ||

| Need for further doses of misoprostol up to discharge from EPU care | ||||

| Yesb | 50 (14) | 65 (18) | 0.78 (0.54 to 1.12) | |

| No | 307 (86) | 289 (82) | ||

| Missing | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | ||

| Infection requiring outpatient antibiotic treatment | ||||

| Yesb | 8 (2) | 11 (3) | 0.72 (0.29 to 1.78)d | |

| No | 343 (98) | 340 (97) | ||

| Missing | 6 | 3 | ||

| Infection requiring inpatient antibiotic treatment | ||||

| Yesb | 5 (1) | 4 (1) | 1.10 (0.30 to 4.01)d | |

| No | 346 (99) | 347 (99) | ||

| Missing | 6 | 3 | ||

| Negative pregnancy test result 21 days (± 2 days) after randomisation | ||||

| Yesb | 237 (77) | 230 (76) | 1.02 (0.93 to 1.11)e | |

| No | 71 (23) | 72 (24) | ||

| Test not provided | 33 | 28 | ||

| Missing | 16 | 24 | ||

| Overall patient satisfaction score (CSQ-8)f | ||||

| Mean (SD, N) | 29.1 (3.8, 265) | 29.2 (3.8, 256) | –0.05 (–0.50 to 0.40) | |

| Median [IQR] | 31 [27–32] | 31 [28–32] | ||

| Duration of bleeding reported by woman (days) | ||||

| Mean (SD, N) | 16.0 (12.6, 326) | 16.3 (15.2, 330) | –0.44 (–2.73 to 1.84) | |

| Median [IQR] | 13 [8–19] | 12.5 [7–19] | ||

| Time from randomisation to discharge from EPU care (days) | ||||

| Mean (SD, N) | 27.0 (14.2, 340) | 27.3 (14.4, 337) | ||

| Median [IQR] | 21 [21–28] | 21 [21–27] | ||

The proportion of participants who required further doses of misoprostol up to discharge was 14% (50 out of 357 women) in the mifepristone plus misoprostol group, as compared with 18% (65 out of 354 women) in the placebo plus misoprostol group (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.12). The mean time from randomisation to discharge was 27 days (SD 14.2) in the mifepristone plus misoprostol group, as compared with 27.3 days (SD 14.4) in the placebo plus misoprostol group. There was no evidence of a subgroup effect according to gestational age, which was prespecified as a subgroup of special interest (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Subgroup analyses.

There was no evidence of a between-group difference in the proportions of participants experiencing a SAE: 5 out of 357 women (1%) in the mifepristone plus misoprostol group and 2 out of 354 women (1%) in the placebo plus misoprostol group. Similarly, there was no evidence of a difference in the proportions of participants experiencing an AE: 26 out of 357 women (7%) in the mifepristone plus misoprostol group and 24 out of 354 women (7%) in the placebo plus misoprostol group (Table 9). For further detailed information on AEs, see Report Supplementary Material 7.

| Mifepristone plus misoprostol group (N = 357) | Placebo plus misoprostol group (N = 354) | Adjusted RRa (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood transfusion requiredb | ||||

| Yes | 11 (3) | 5 (1) | 2.15 (0.76 to 6.12)c | 0.150 |

| No | 341 (97) | 346 (99) | ||

| Missing | 5 | 3 | ||

| Any side effects (AEs)b,d | ||||

| Yes | 26 (7) | 24 (7) | 1.11 (0.77 to 1.61) | 0.576 |

| No | 331 (93) | 330 (93%) | ||

| Deathd | ||||

| Yes | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | Unable to calculate | Unable to calculate |

| No | 357 (100) | 354 (100) | ||

| Any serious complications (SAEs)b,d | ||||

| Yes | 5 (1) | 2 (1) | 2.33 (0.45 to 11.95)c | 0.311 |

| No | 352 (99) | 352 (99) | ||

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to exclude the 34 cases that were included in the primary outcome analysis following review by the BERC. This analysis showed that the proportion of participants who did not pass the gestational sac spontaneously within 7 days was 18% (59 out of 348 women) in the mifepristone plus misoprostol group and 24% (81 out of 348 women) in the placebo plus misoprostol group (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.00; p = 0.05) (Table 10).

| Mifepristone plus misoprostol group (N = 357) | Placebo plus misoprostol group (N = 354) | RRa (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome – failure to pass the gestational sac spontaneously within 7 days of randomisation | ||||

| Sensitivity analysis – excluding women requiring primary outcome information provided by BERC | ||||

| Yesb | 59 (17.9%) | 81 (24.3%) | 0.75 (0.56 to 1.00) | 0.052 |

| No | 270 (82.1%) | 252 (75.7%) | ||

| Number excluded | 19 | 15 | ||

| Missing | 9 | 6 | ||

Interpretation of the clinical findings

Our large multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed that the combination treatment of mifepristone plus misoprostol resulted in an increase in the number of missed miscarriages that were completed within 7 days compared with misoprostol alone. There were also fewer incidences of surgical management to complete miscarriage in the mifepristone plus misoprostol group than in the placebo plus misoprostol group. These findings are consistent with other previously published trials. 19,28,29 The results from our trial show clearly the importance of optimising the medical management of missed miscarriage using the combined mifepristone and misoprostol treatment regimen, which improves outcomes and safety by increasing the proportion of women who have miscarriage resolution and by reducing the need for surgical management. Women choosing medical management of missed miscarriage often wish to have expedited treatment and resolution of their miscarriage while also avoiding the risks of surgery. 30 The risks of miscarriage surgery are dependent on the clinical context, the setting in which the procedure is performed, the surgeon and the available equipment. Complications of miscarriage surgery are rare, but can include bleeding, infection and uterine perforation requiring more extensive surgery, which carries significant morbidity. 30 Our trial findings demonstrate that the combination treatment of mifepristone and misoprostol reduces the need for surgery after medical management and this is likely to be of great importance to women wishing to undergo medical management of missed miscarriage.

It is also important to note that the women who received placebo and misoprostol can be considered to have had an extra 2 days of expectant management compared with women receiving mifepristone and misoprostol. If the mifepristone was not found to have a beneficial effect in achieving passage of the gestational sac, one would have expected either similar rates of miscarriage resolution by day 7 or higher miscarriage resolution rates in the placebo and misoprostol group.

The strengths of this study include its multicentre approach, increasing generalisability across a wide range of settings, and the placebo-controlled design with high adherence to treatment, enhancing the trial’s internal validity. A pragmatic trial design was used in our study, which also adds to the generalisability of our findings. In particular, the route of administration of misoprostol reflects standard UK clinical practice and NICE guidance for the medical management of missed miscarriage. 6 The majority of our participants received vaginal misoprostol and it is important to note that the route of misoprostol administration was similar in both trial groups. The primary outcome used in the MifeMiso trial was carefully selected through a consultation and survey of clinicians working with women diagnosed with miscarriage and the women themselves through patient and public involvement (PPI). We were able to collate near-complete data for primary outcome, which was aided by the use of a BERC. The committee convened using a strict charter and considered each individual participant’s clinical data in turn. The clinical data were collected on a standardised case report form and the decision as to whether or not the participant had met the primary outcome could only be made unanimously. The sensitivity analysis excluding the findings of the BERC does not alter the conclusions of our trial and is consistent with the primary analysis, showing a similar treatment effect and 95% CI.

Some limitations of our study should also be considered. We studied the effect of mifepristone and misoprostol in missed miscarriage; therefore, these results are not generalisable to patients diagnosed with incomplete miscarriage, who will already have passed some pregnancy tissue. The biological rationale for focusing exclusively on missed miscarriage in this trial is that the antiprogestogenic effect of mifepristone is less likely to be relevant in incomplete miscarriage, as in this case the expulsion of pregnancy tissue has already begun. 31

Chapter 4 Women’s perspectives on the acceptability of and their satisfaction with medical management of missed miscarriage: a nested qualitative study

Introduction

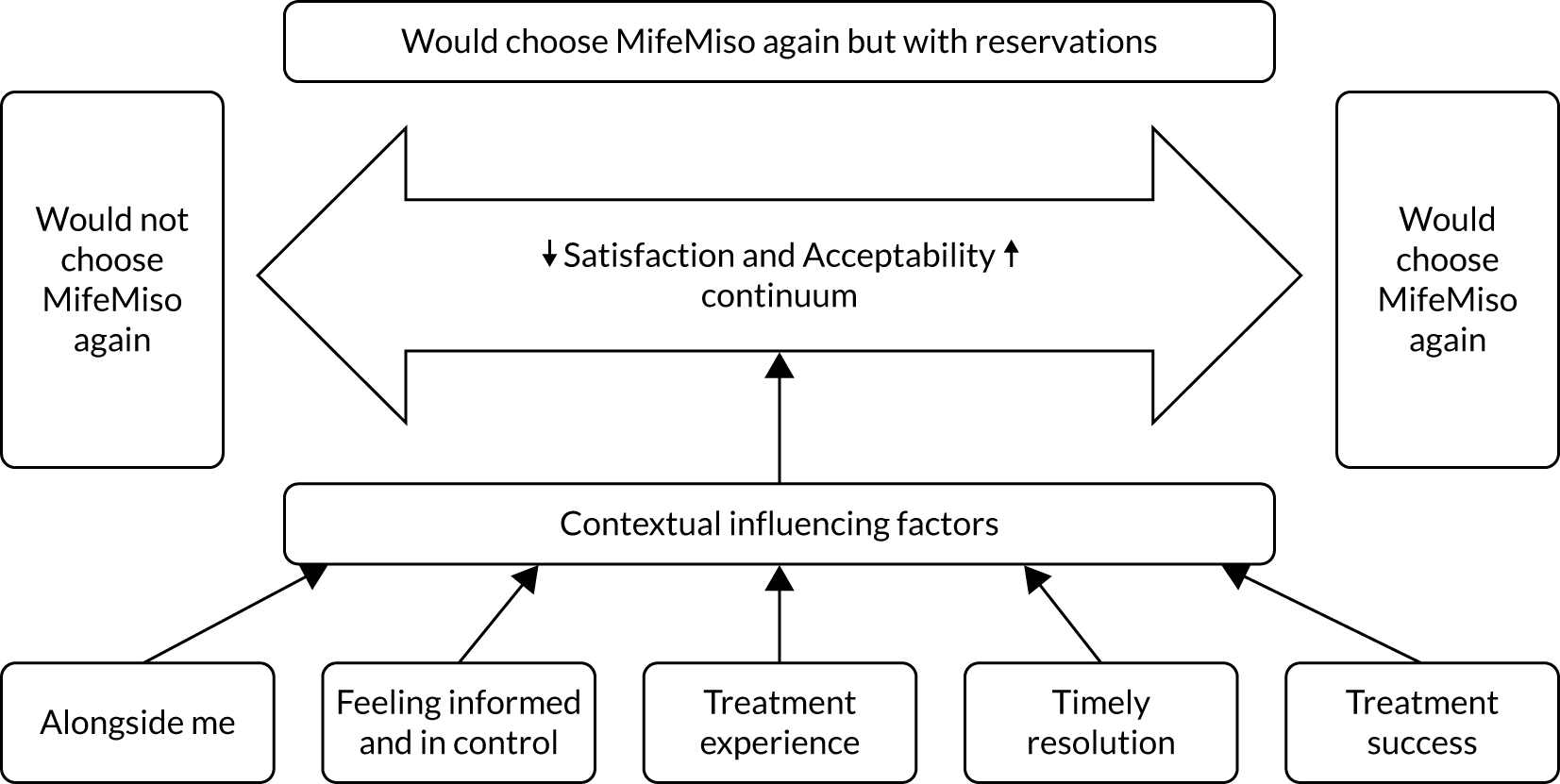

Medical management of miscarriage was introduced as an alternative to surgical or expectant management > 20 years ago. 32 Quantitative studies exploring the efficacy of medical management, with administration of either misoprostol or a combination of misoprostol and mifepristone, have also considered women’s satisfaction with the treatment and the factors influencing acceptability. 32–38

These studies have established that medical management is an effective alternative to surgical management or expectant management. 19,34,35,38,39 Furthermore, they have identified benefits to medical management, including lower health-care costs,35,40 and avoidance of risks associated with surgical management. 34 Medical management has also been found to offer an alternative to expectant management that is responsive to women’s increasing preference for a timely resolution to the miscarriage. 41

However, research has also highlighted that women’s satisfaction with medical management may be limited in certain contexts. In particular, it is suggested that satisfaction is dependent on the success of medical management in achieving a complete resolution to the miscarriage. 32,36,37,42 These studies have shown that women who experience treatment failure resulting in the need for surgical intervention experience lower quality of life36 and lower satisfaction with treatment37,42 and are less likely to say that they would choose medical management again in the event of further miscarriages. 32,37 This finding is further reinforced in a nested qualitative study within a trial of different types of miscarriage management that explored women’s experiences of management options. 34,43 Smith et al. 43 found that, although medical management is viewed as an acceptable alternative to surgery, women’s view of it becomes negative when it fails and surgery is then required. This finding contrasts directly with women’s perspectives after expectant management had failed, where they did not perceive the resulting need for surgery as a negative outcome. 43 It seems possible that lower satisfaction may at least in part reflect the need for two forms of active management as opposed to only one, in the case of women who initially opted for expectant management, particularly as women had expressed concerns about the lengthy duration of the process of medical management. 43

Qualitative and mixed-methods studies have considered aspects of the experience of miscarriage treatment, and some of these have addressed factors influencing the acceptability of medical management. 41,43–46 The results suggest that acceptability is influenced by a range of factors, including the wish to avoid the risks associated with surgical intervention, such as adhesions or scarring, and a fear of either anaesthesia or hospital intervention. 41,43,44 Women may also choose medical management because they perceive it to be more aligned with a natural experience of miscarriage, including being able to grieve and experience the loss. 41,43 In addition, it seems possible that medical management provides some women with a greater sense of control than can be achieved with expectant management, particularly given that women express the desire to bring an end to the miscarriage in a timely manner. 43

However, in both qualitative and quantitative studies, women report negative side effects associated with medical management, including significant levels of pain, cramping and bleeding as well as nausea and sickness. 43,47,48 It has also been reported that bleeding, pain and prolonged treatment reduce the acceptability of medical management to women, particularly if the treatment is subsequently unsuccessful. 35,36

It is also important to recognise that satisfaction and acceptability of medical management cannot be viewed in isolation of the care process within which it is delivered. Both UK and international qualitative studies exploring women’s perceptions of miscarriage care have found that choice about treatment options, adequate information-giving, control over where treatment takes place, the environment of care and follow-up support can also significantly influence the acceptability of and satisfaction with treatment for miscarriage. 43,44 Women and their partners have also reported the value of empathic, sensitive and responsive HCPs in assisting them to cope with the miscarriage and promote their recovery from the psychological and physical consequences. 49,50 However, many of these studies evaluate all forms of management; thus, it is difficult to determine those aspects of satisfaction that are specific to medical management.

It is evident that satisfaction with and acceptability of medical management of miscarriage is a complex area, with many possible factors influencing women’s choice of medical management, their experience of it and whether or not they would choose it again. However, limited literature exists that specifically explores in depth women’s perspectives on the process of medical management and considers which factors may be important to women in determining the acceptability of medical management and their satisfaction with it.

Furthermore, different forms of miscarriage occur in the first trimester of pregnancy, including missed or silent miscarriage. 51 Missed miscarriage is defined as the presence of a pregnancy either with a fetus but no evidence of fetal heart activity or with an empty gestational sac. 51,52 In missed miscarriage, women may not have experienced any signs of miscarriage until later in the first trimester and may not know the baby has died until the dating scan, even though fetal death may have occurred some weeks before. Some women will have had a feeling that something is wrong, but these concerns may have been dismissed by themselves or by HCPs. 52,53 In addition, some women continue to experience pregnancy symptoms even though their baby has died. 51–54

Although medical management is recommended for missed miscarriage,55 there is limited evidence of differences in satisfaction between women diagnosed with different types of miscarriage and how this might influence their choices and experience of treatment. One recent study54 concluded that the type of treatment was more important than the type of pregnancy loss in all miscarriages, with treatment effectiveness and timeliness strongly influencing recovery. However, other studies have suggested that the experience of missed miscarriage may be different from that of other types of miscarriage. 53,56 For example, Adolfsson et al. 56 found that women experiencing a missed miscarriage have prolonged and greater levels of grief and difficulty coping than women experiencing other forms of miscarriage. It seems plausible that the features of missed miscarriage, such as those mentioned above, may create particular challenges in emotional processing of the diagnosis. They may also influence decision-making and experience of treatment, given that unspoken emotional considerations have been found to influence women’s decision-making about miscarriage treatment. 44 However, as far as we are aware, an in-depth understanding of women’s experience of the process of medical management of missed miscarriage and their satisfaction with it has not been explored. Consequently, further in-depth research is required to develop our understanding.

Aim of the study

To explore women’s satisfaction with and acceptability of medical management of missed miscarriage for those who complete the MifeMiso trial protocol.

Research questions

-

Why do women choose medical management?

-

Why do women choose to participate in the trial?

-

What is their lived experience of the process of treatment and care?

-

What factors influence the acceptability of and satisfaction with the treatment they have received?

-

Does receipt of mifepristone with misoprostol influence women’s satisfaction with and acceptability of medical management?

-

What implications does this have for the care offered to women and their partners?

Methods

Study design and rationale

To address the identified aim and research questions, we undertook a qualitative study nested within the MifeMiso trial, which sought to develop an understanding of:

-

women’s experience of the trial treatment, considering the structures, resources and processes occurring during their participation as well as their perceptions concerning the treatment itself

-

the contextual factors influencing women’s experience of the trial treatment and their satisfaction with it. 57,58

In conducting this study, we therefore sought to contribute an in-depth understanding to the overall findings of the trial, by addressing aims that illuminate aspects of women’s experience that are currently less well understood but that may influence their satisfaction with medical management and its acceptability. 57 Results such as this can make substantial contributions to the implementation of findings of the trial in the future. 57,59

The primary source of data collection was qualitative, semistructured interviews. Semistructured interviews are a widely used method of data collection in studies that explore people’s personal experiences and which aim to develop a deep understanding of their attitudes, perceptions and beliefs. Interviews are particularly suited to discussing sensitive topics when an open-ended approach is needed. 60

Two additional sources of data collection were utilised. All participants taking part in the MifeMiso trial were asked to complete the CSQ-8. 61 This questionnaire was designed for use in health studies and has been used recently in treatment studies for miscarriage. 42 The CSQ-8 has eight questions, each of which offers responses ranging from quite dissatisfied (scoring 1 point) to very satisfied (scoring 4 points). A total score of 32 can, therefore, be achieved. The higher the total score, the more satisfied the woman is with the treatment she has received. In this study, the CSQ-8 was utilised as a sampling frame when selecting participants for interview. In addition, participants completing the CSQ-8 were invited to provide additional thoughts concerning their satisfaction in a free-text box at the end of the questionnaire. These free-text comments were used as an additional source of data.

Methodological approach

We have framed this qualitative study within an epistemological position of constructivism62 and an ontological position of critical realism. 63 Constructivist theory proposes that there is no single unassailable truth; rather, meaning is constructed by individuals to make sense of their world, and these meanings are constantly being revised and re-interpreted. 64,65 By using a constructivist epistemology, we seek to understand the multiple realities and meanings that individuals create, by asking questions that relate to complicated features of human activity. 57,65 In applying constructivism in this study, we seek to understand how medical management of missed miscarriage is perceived by women and why they experience the treatment as acceptable or unacceptable. Although constructivism is grounded in relativism, it is argued that qualitative health-care research is commonly based on assumptions about the objective existence of specific conditions, such as, in this research, miscarriage. 63 Willig63 therefore suggests that it is appropriate to adopt a critical realist ontology alongside a constructivist epistemology, in which it is accepted that miscarriage exists, but that what we are concerned with is how medical management of miscarriage is constructed and understood by the women who experience it.

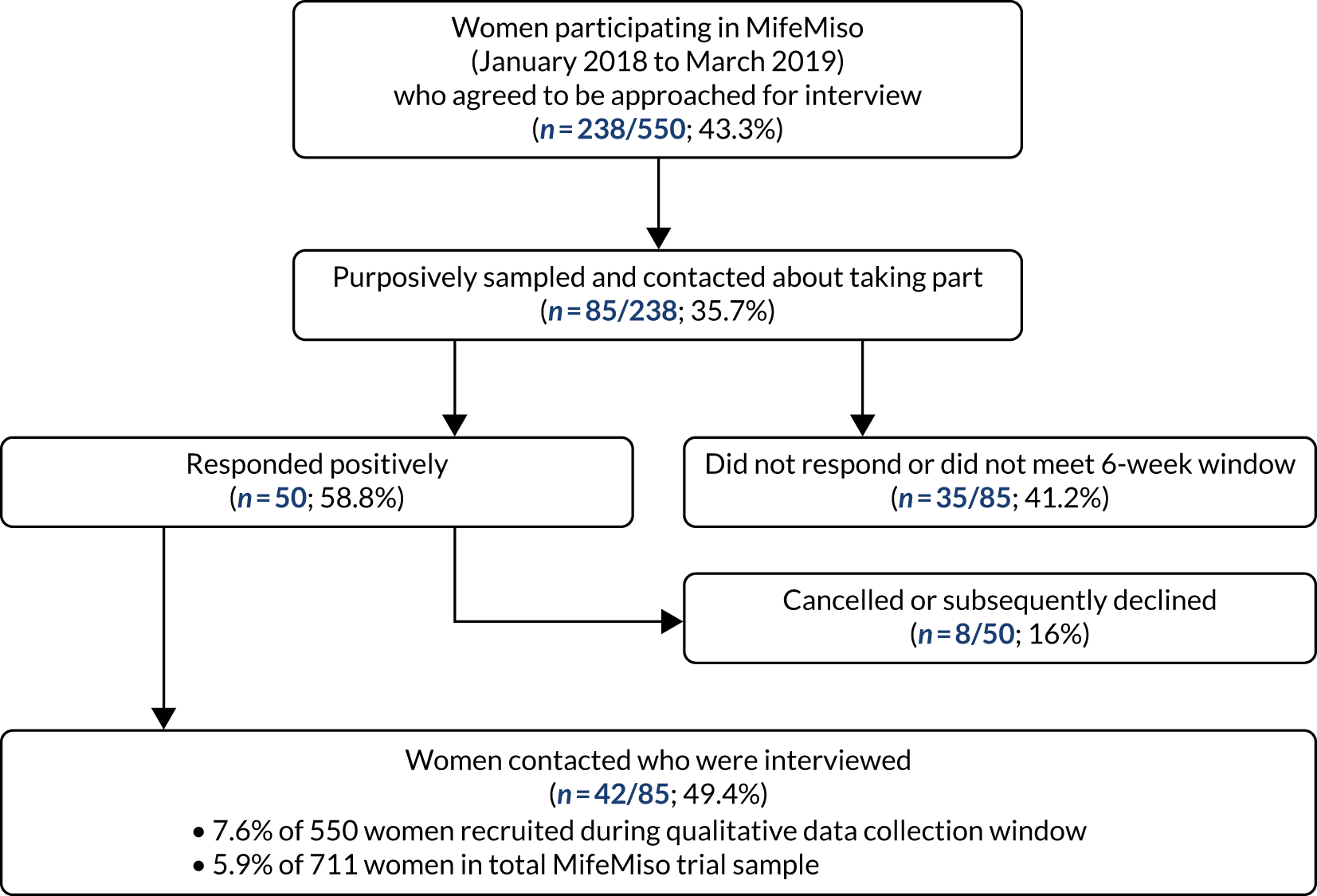

Recruitment

Recruiting HCPs provided eligible women with a PIS and informed them about the opportunity to participate in a qualitative interview when they were approached to take part in the trial. A subsequent invitation was provided at day 21, when they were asked to complete the CSQ-8 satisfaction survey. At this point, women self-selected to be approached for participation in the interviews by providing their contact details and indicating their agreement to be contacted by the qualitative research team. Satisfaction survey questionnaires were returned directly to the trials office along with signed permission to be contacted about an interview. These contact details were then passed onto the qualitative research team (JLFP and LJ).

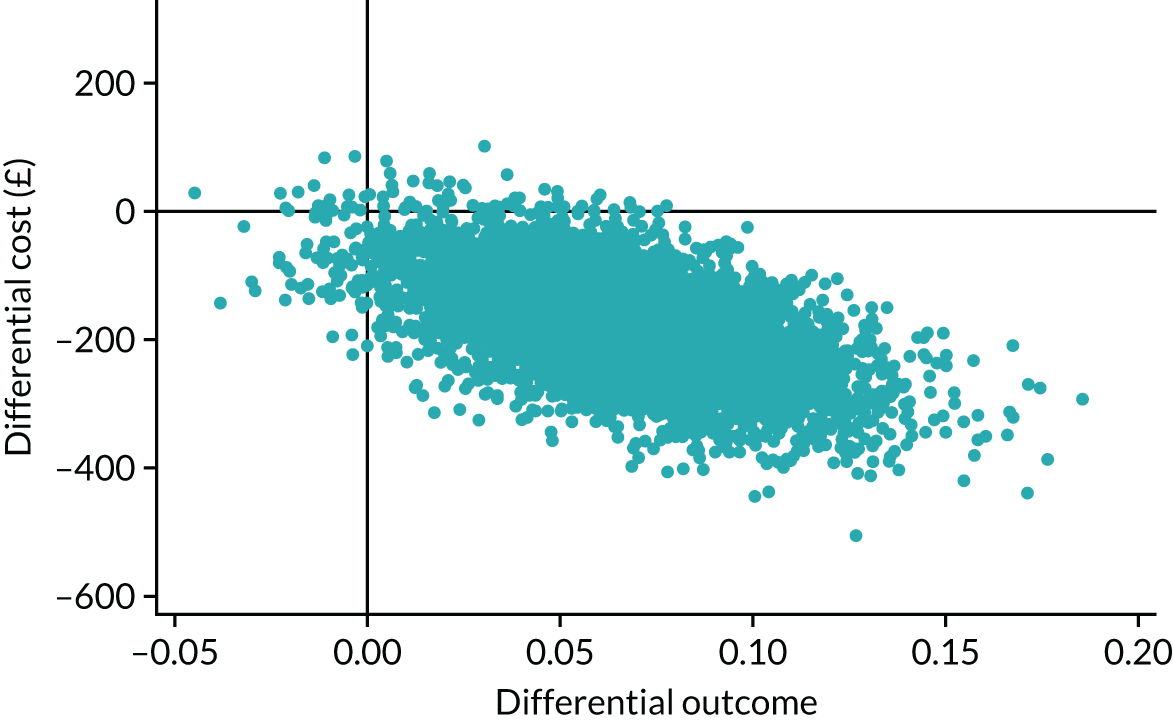

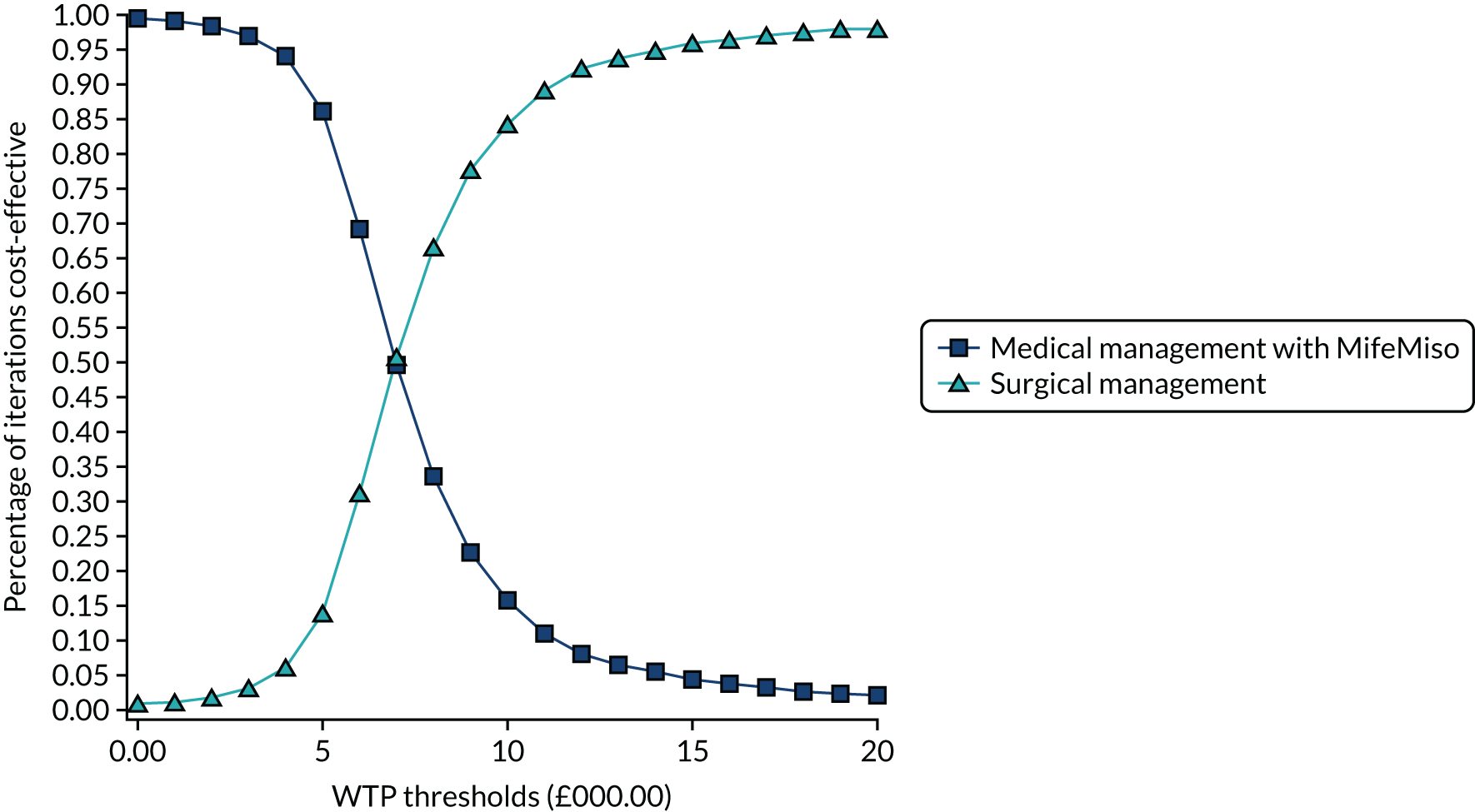

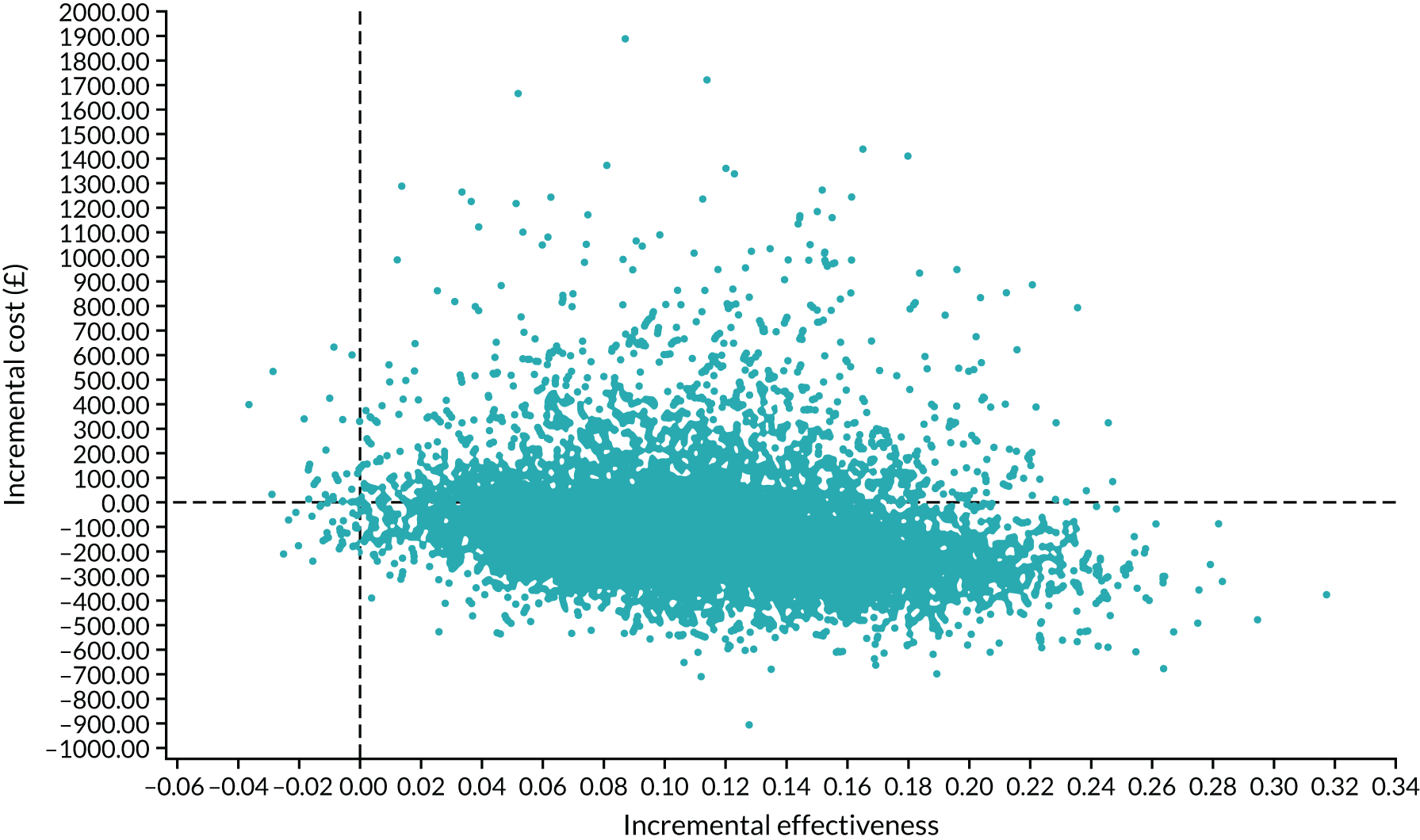

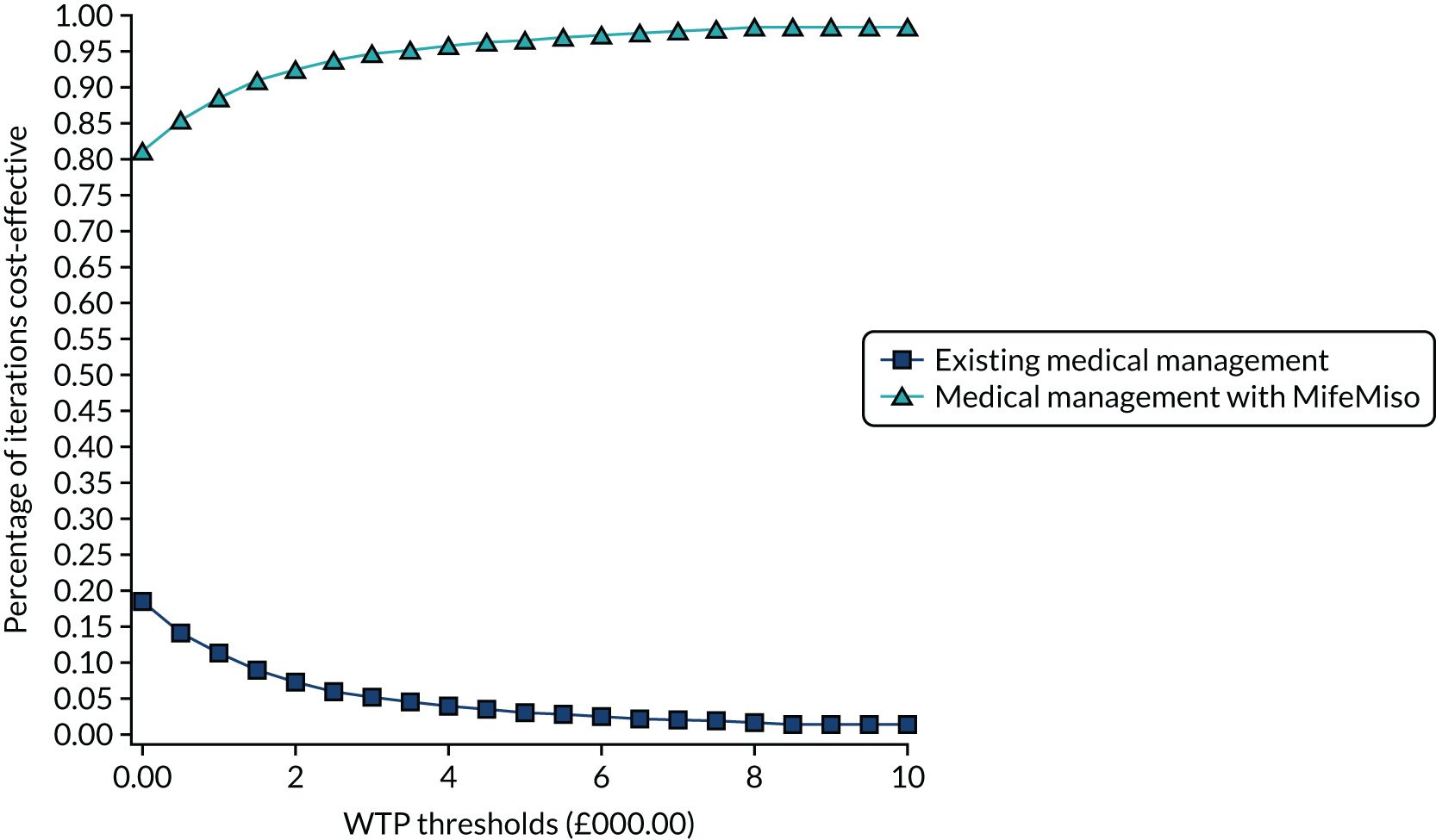

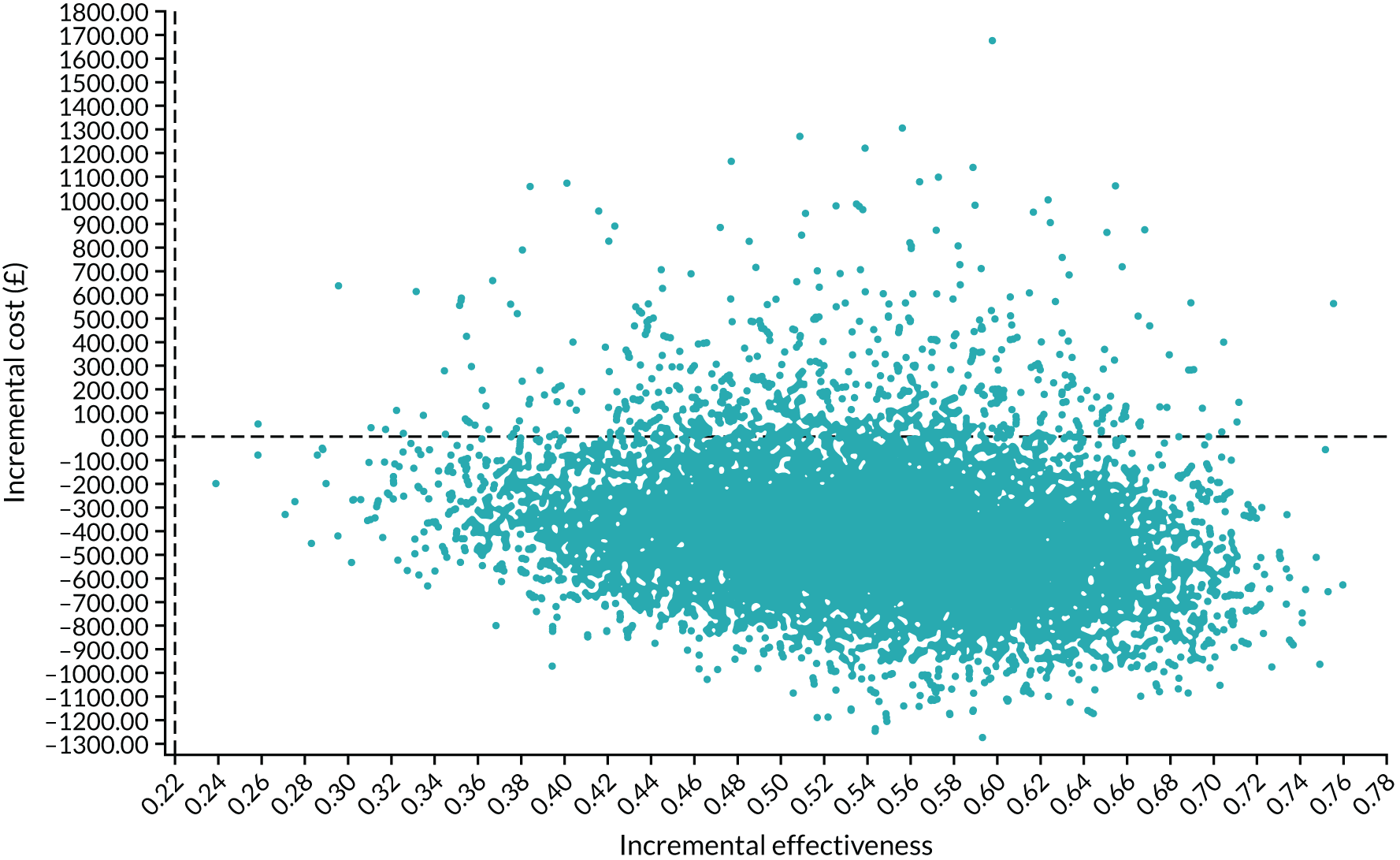

Satisfaction scores were used as an initial sampling frame. We purposively selected participants from those who were satisfied/found the treatment acceptable, and those who did not. We also sought to increase the diversity by purposively recruiting a maximum variation sample of participants according to trial site, age, BMI, gestational age, parity and ethnicity. Within this context we sought to achieve diversity in the sample to ensure that a broad range of views, characteristics and experiences of participation were obtained.