Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/22/117. The contractual start date was in August 2012. The draft report began editorial review in December 2019 and was accepted for publication in September 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2022. This work was produced by Gilbert et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2022 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this report have been reproduced with permission from Gilbert et al. 1 Reproduced from Thorax, Gilbert FJ, Harris S, Miles KA, Weir-McCall JR, Qureshi NR, Campbell Rintoul R, et al. , 2021, with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Background and rationale

Although the incidence of lung cancer is slowly reducing in the UK, the number of new cases diagnosed each year is > 47,000. 2 A proportion of patients with lung cancer present with a solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN) on diagnostic imaging tests; these patients form an important subgroup, as early-stage disease has excellent survival rates following surgical resection. 3 However, not all SPNs are due to lung cancer and the accurate characterisation of SPNs is an ongoing diagnostic challenge with significant associated health costs. A 2010 observational study4 found that the average US Medicare expenditure for clinical management of a patient with a SPN was US$50,233 (£30,363) when the SPN was malignant and $22,461 (£13,577) when it was benign. With the advent of NHS England’s Targeted Lung Health Checks programme,5 piloting low-dose computerised tomography (CT) lung cancer screening in England, the number of patients with a SPN requiring further investigation will increase substantially. A previous Health Technology Assessment (HTA) review6 noted that CT screening is associated with a relatively high false-positive rate and that subsequent investigations constitute a significant cost. Furthermore, SPNs are a common finding in whole-body screening CT examinations offered to asymptomatic individuals by independent sector providers. Typically, the costs of follow-up investigations from these examinations are incurred in the public sector (UK National Screening Committee, appendix 17). Novel cost-effective approaches to the assessment of SPNs would be of value to the NHS.

Imaging techniques

The presence of calcification in a SPN on a CT scan is strongly predictive of a benign cause. However, morphological features used to evaluate non-calcified SPNs by conventional CT show considerable overlap between benign and malignant nodules. Widely adopted clinical guidelines8,9 for the investigation of SPNs recommend serial CT scans for nodules of ≤ 8 mm in diameter to look for growth. For nodules of > 8 mm, the recommendation is to perform one of the following: short-term interval CT scans or fluorine-18-labelled-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography–computerised tomography (PET/CT) (referred to hereafter as PET/CT rather than 18F-FDG-PET/CT) and/or biopsy, depending on local expertise. 10

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) currently recommends PET/CT for the assessment of SPNs in cases when a biopsy is not possible or has failed, depending on nodule size, position and CT characterisation. 11 PET/CT acquires images of the body following intravenous injection of a radioactive glucose analogue. PET/CT characterises SPNs on the basis of uptake of glucose. Radionuclide uptake can be assessed qualitatively or quantitatively, with a standardised uptake value (SUV) of > 2.5 implying malignancy. A 2018 meta-analysis12 confirmed the accuracy of PET/CT as a non-invasive means of characterising SPNs, with a pooled sensitivity of 89% [95% confidence interval (CI) 87% to 91%] and specificity of 70% (95% CI 66% to 73%). In a 2013 audit of a local PET/CT service serving a population of 1 million, with an annual lung cancer incidence of 695 patients, 44 PET/CT scans were requested per year to characterise SPNs. 13 Extrapolated to the UK population, the present demand for PET/CT to characterise SPNs is ≈ 2700 examinations per year, equivalent to almost 15% of NHS-funded PET/CT scans performed annually in the UK.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced computerised tomography (DCE-CT) is a rapid series of CT images acquired following intravenous administration of conventional iodinated contrast media. In comparison with PET/CT, which characterises nodules based on their metabolic activity, DCE-CT characterises SPNs on the basis of their vascularity, measured through the amount of enhancement and wash-out. A 2008 meta-analysis14 identified 10 studies reporting the ability of DCE-CT to characterise SPNs, with a pooled sensitivity of 93% (95% CI 88% to 97%) and specificity of 76% (95% CI 68% to 97%). Owing to the low cost, high sensitivity and negative predictive value (NPV) of DCE-CT, this technique may be particularly valuable in the assessment of non-calcified SPNs in patients who have a low prior probability of malignancy. Despite the comparable diagnostic accuracy in meta-analyses, however, DCE-CT is not widely used in the UK.

As identified in a 2006 HTA review,6 there are no agreed guidelines for the further diagnostic investigation of SPNs identified in a CT lung cancer screening programme. The current NICE guidelines11 for the diagnosis and management of lung cancer were constructed for patients presenting symptomatically or incidentally, and modifications are now required, with CT screening likely to be adopted in the future. The prevalence of malignancy among positive screenings (1.8–3.2%) is significantly lower than for SPNs presenting clinically, for which the rate is closer to 48%. 6,15 As a result, NICE has suggested that imaging approaches may be more appropriate than biopsy for low-risk patients; therefore, imaging approaches are likely to be particularly valuable for the assessment of SPNs identified in a CT screening programme. The results of the UK lung cancer screening randomised controlled trial16 have demonstrated the potential of a CT screening programme to detect early-stage lung cancer and deliver curative treatment in a high-risk cohort. This HTA-funded pilot study concluded that a single screening in those 60–75 years would be clinically effective and cost-effective at reducing lung cancer-related mortality among high-risk smokers. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of screen detection, compared with symptomatic detection, was £6325 per life-year gained, and £8500 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained. Among this cohort, 27% required either early CT follow-up or referral to a multidisciplinary team (MDT) for further workup, and 3.2% had nodules of ≥ 10 mm that were suitable for PET/CT or DCE-CT analysis.

The English 14-site pilot of low-dose CT screening is inviting > 600,000 people aged 55–74 years, over 4 years, who have a high risk of lung cancer as result of their smoking status. Based on this, this cohort alone could annually yield ≈ 4500 additional non-calcified SPNs, of ≥ 10 mm in size, suitable for imaging evaluation with PET/CT or DCE-CT. This demand would represent a significant additional burden on the currently limited availability of PET/CT in the UK, which could potentially be reduced by adoption of management strategies incorporating DCE-CT.

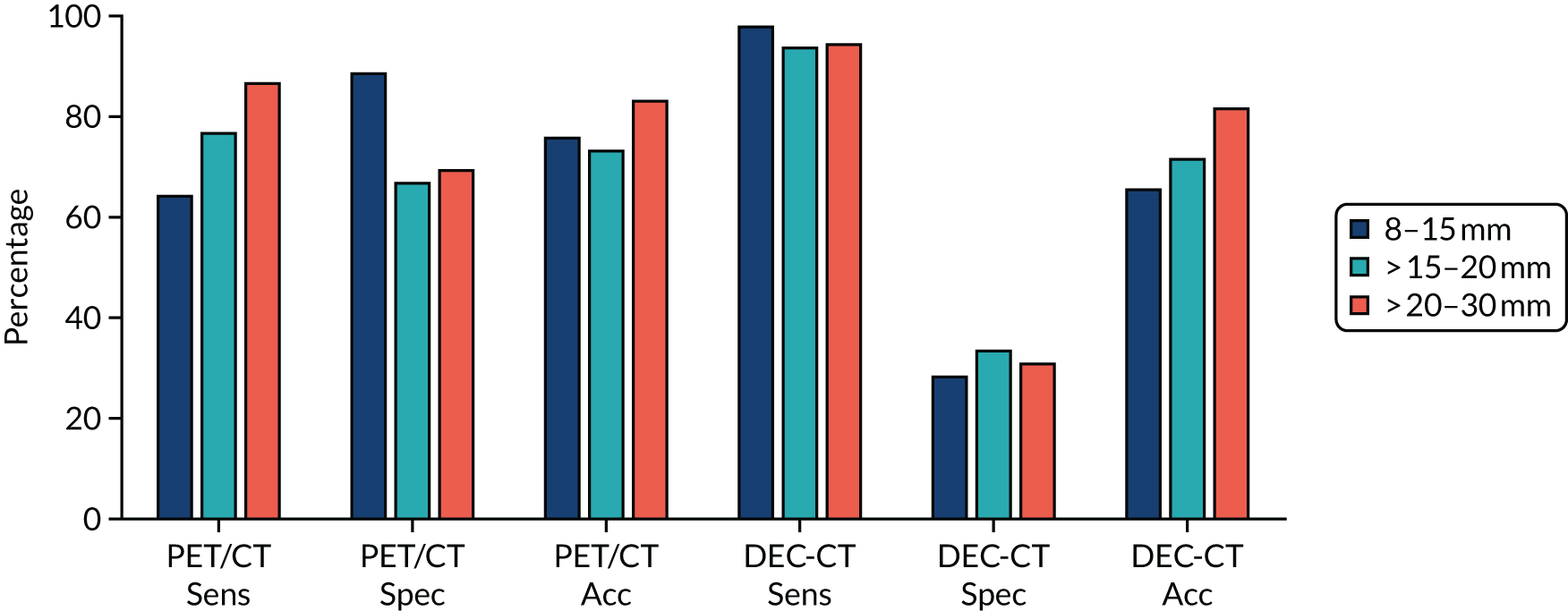

To date, only three studies17–19 have directly compared the diagnostic performances of PET/CT and DCE-CT in the same cohort of patients. Pooled data from these studies (217 SPNs) indicate that PET/CT and DCE-CT have sensitivities of 92% and 87%, and specificities of 90% and 83%, respectively. As of yet, no comparative studies of PET/CT [neither dedicated positron emission tomography (PET) nor PET/CT] and DCE-CT have been performed in the UK, to our knowledge. Therefore, in this study, objective 1 was to determine, with high precision, the diagnostic performances of DCE-CT and PET/CT in the NHS for the characterisation of indeterminate SPNs.

Therapeutic impact and cost-effectiveness of imaging for solitary pulmonary nodules

A single study19 has included an assessment of the therapeutic impact of PET/CT in the characterisation of SPNs. This study found that PET/CT either contributed to or was very important in reaching management decisions in 31 out of 112 cases (28%). 19 There have been several studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of management strategies that include PET/CT for the characterisation of SPNs, in comparison with conventional CT-based watch-and-wait strategies. 20–25 These studies indicate that PET/CT is either cost-saving or cost-effective across several health-care systems for a wide range of prior probabilities of malignancy. A range of effectiveness measures have been adopted in these studies, including accuracy of management, life expectancy and, in one case, quality-adjusted life expectancy. In general, strategies with PET/CT and those without PET/CT have demonstrated similar effectiveness, but with significant differences in cost. However, these studies used neither diagnostic performance data derived from integrated PET-CT systems nor NHS cost structures.

A single study26 has compared the cost-effectiveness of strategies that include DCE-CT with that of conventional CT- and PET-based strategies. DCE-CT was found to offer a potentially cost-effective diagnostic approach, with savings of up to £2000 per patient compared with conventional CT-based strategies. Furthermore, a strategy in which patients underwent PET/CT only if the DCE-CT result was positive for malignancy was consistently less expensive, but with similar effectiveness when compared with a PET/CT-based strategy. The cost benefits of DCE-CT were greatest when the prevalence of malignancy was low; therefore, this approach may be particularly advantageous in the evaluation of SPNs found during CT screening. However, the analysis in this study was limited by the lack of direct comparative diagnostic accuracy data for DCE-CT and integrated PET/CT at the time of writing, as well as the omission of final outcome measures. Using the diagnostic performance data obtained in fulfilling objective 1, we undertook decision-analytic modelling to assess the likely costs and health outcomes resulting from the incorporation of DCE-CT into management strategies for patients with SPNs (objective 2).

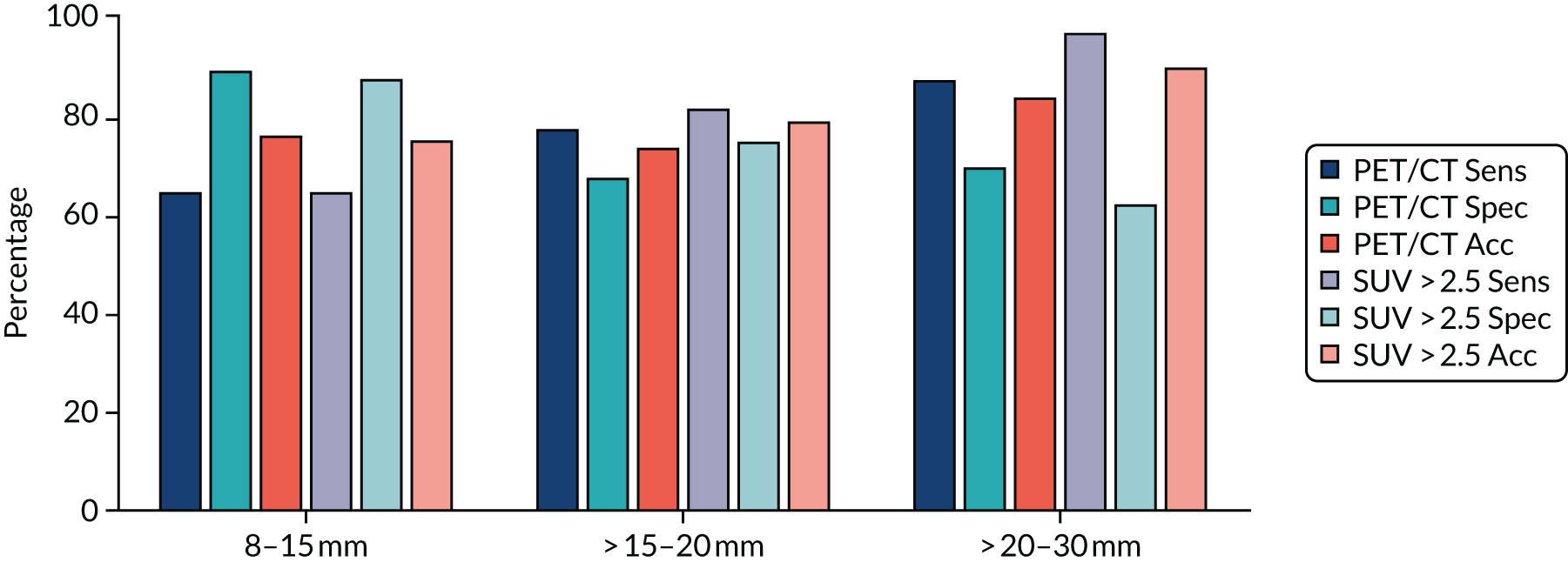

Incremental value of incorporating computerised tomography appearances of a solitary pulmonary nodule into the interpretation of integrated positron emission tomography–computerised tomography

Previous economic evaluations of PET/CT for SPNs have been based on diagnostic performance data for dedicated PET systems, rather than integrated PET/CT. 20–22,24–28 Two studies29,30 have shown a small incremental improvement in the diagnostic performance of PET/CT, compared with PET alone, in the characterisation of SPNs. Incorporating the CT appearances of the nodule into the diagnostic interpretation reduced the false-positive rate for SPNs with moderate fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake, thereby improving diagnostic specificity from 71% to 77%29 and from 82% to 89%. 30 This incremental improvement in diagnostic accuracy has the potential to affect the cost-effectiveness of PET/CT, but, at the start of this study, had not been demonstrated in an NHS setting, to our knowledge. Therefore, a secondary objective of this study was to assess, in an NHS setting, the incremental value of incorporating the CT appearances of a SPN into the interpretation of integrated PET/CT examinations.

Combined dynamic contrast-enhanced computerised tomography and positron emission tomography–computerised tomography

Current integrated PET-CT systems allow for the performance of both PET/CT and DCE-CT in a single examination. 31 None of the currently published studies comparing these techniques in the assessment of SPNs has proposed diagnostic criteria that combine features from both modalities, and discrepant cases are poorly reported. 17,18,32–37 It is feasible that combined parameters of FDG uptake and contrast enhancement could improve the diagnostic performance of PET/CT by discriminating between benign and malignant nodules with mildly increased FDG uptake (i.e. SUV of 2.5–4.9). From the few data currently available, inflammatory nodules with moderate FDG uptake would be likely to exhibit higher FDG uptake/contrast-enhancement ratios than malignant nodules. Furthermore, the NPV of a benign result on both PET/CT and DCE-CT could be sufficiently strong to reduce the need for subsequent imaging surveillance. Thus, a further secondary objective of this study was to assess whether or not combining DCE-CT with PET/CT is more accurate and/or more cost-effective in the characterisation of SPNs than either test used alone or in series.

Incidental extrathoracic imaging findings

Incidental extrathoracic findings are not uncommon in both the PET and CT components of PET/CT examinations performed for thoracic malignancy. 38 These incidental abnormalities have the potential to add to the health outcomes and cost implications of the use of PET/CT in the characterisation of pulmonary nodules, but would remain undetected by DCE-CT, for which image acquisition is limited to the nodule itself. To date, economic evaluations of PET/CT in the characterisation of SPNs have not included this potential impact. 20–22,24–28 Therefore, an additional secondary objective of this study was to document the nature and incidence of incidental extrathoracic findings on PET/CT scans, undertaken for the characterisation of SPNs, and to model their impact on cost-effectiveness.

Rationale

Solitary pulmonary nodules form a substantial investigative burden, which is likely to increase in the wake of recent positive lung screening trials. PET/CT, although currently the main investigative strategy for early-stage lung cancer and pulmonary nodules, is a limited and expensive resource. Alternative strategies using current NHS infrastructure, such as DCE-CT, may provide a more streamlined and cost-effective diagnostic strategy. However, a large multicentre trial comparing DCE-CT with PET/CT was required to assess the diagnostic and economic validity of such an approach. 39

Aims and objectives

The aims of this study were to compare the diagnostic accuracy of DCE-CT with that of PET/CT for the detection of malignancy in SPNs, and the comparative cost-effectiveness of a diagnostic strategy involving either or both of these imaging techniques.

Primary objectives

-

To determine, with high precision, the diagnostic performances of DCE-CT and PET/CT in the NHS for the characterisation of SPNs.

-

To use decision-analytic modelling to assess the probable costs and health outcomes resulting from incorporating DCE-CT into management strategies for patients with SPNs.

Secondary objectives

-

To assess, in an NHS setting, the incremental value of incorporating the CT appearances of a SPN into the interpretation of integrated PET/CT examinations.

-

To assess whether or not combining DCE-CT with PET/CT is more accurate and/or cost-effective in the characterisation of SPNs than either test used alone or in series.

-

To document the nature and incidence of incidental extrathoracic findings on PET/CT and DCE-CT undertaken for the characterisation of SPNs, and to model their cost-effectiveness.

Chapter 2 Observational study methods

Trial design

The trial was designed in accordance with the guidance for the methods of technology appraisal issued by NICE40 and adopted by NICE in formulating its guidance for the use of PET in the staging of lung cancer.

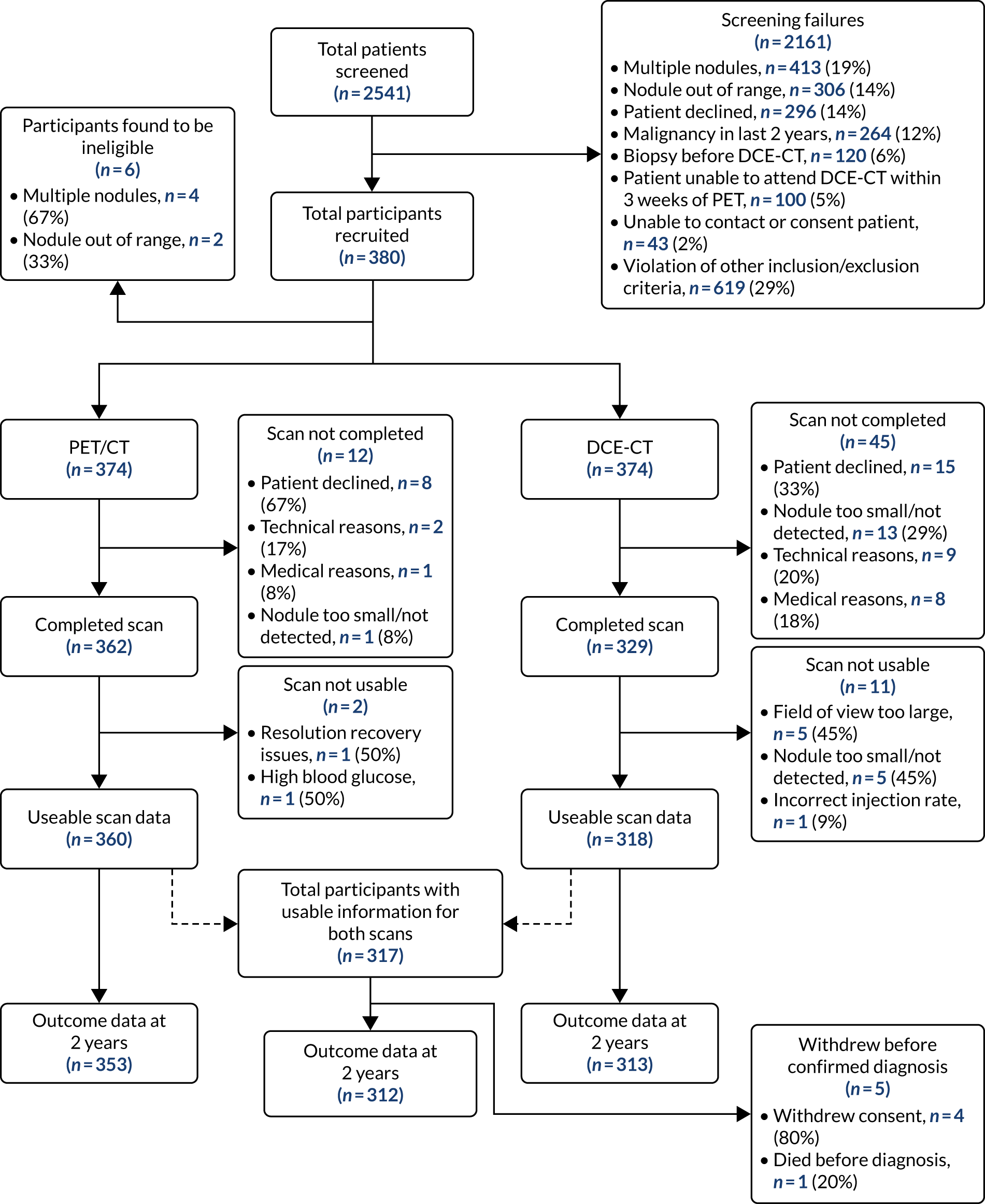

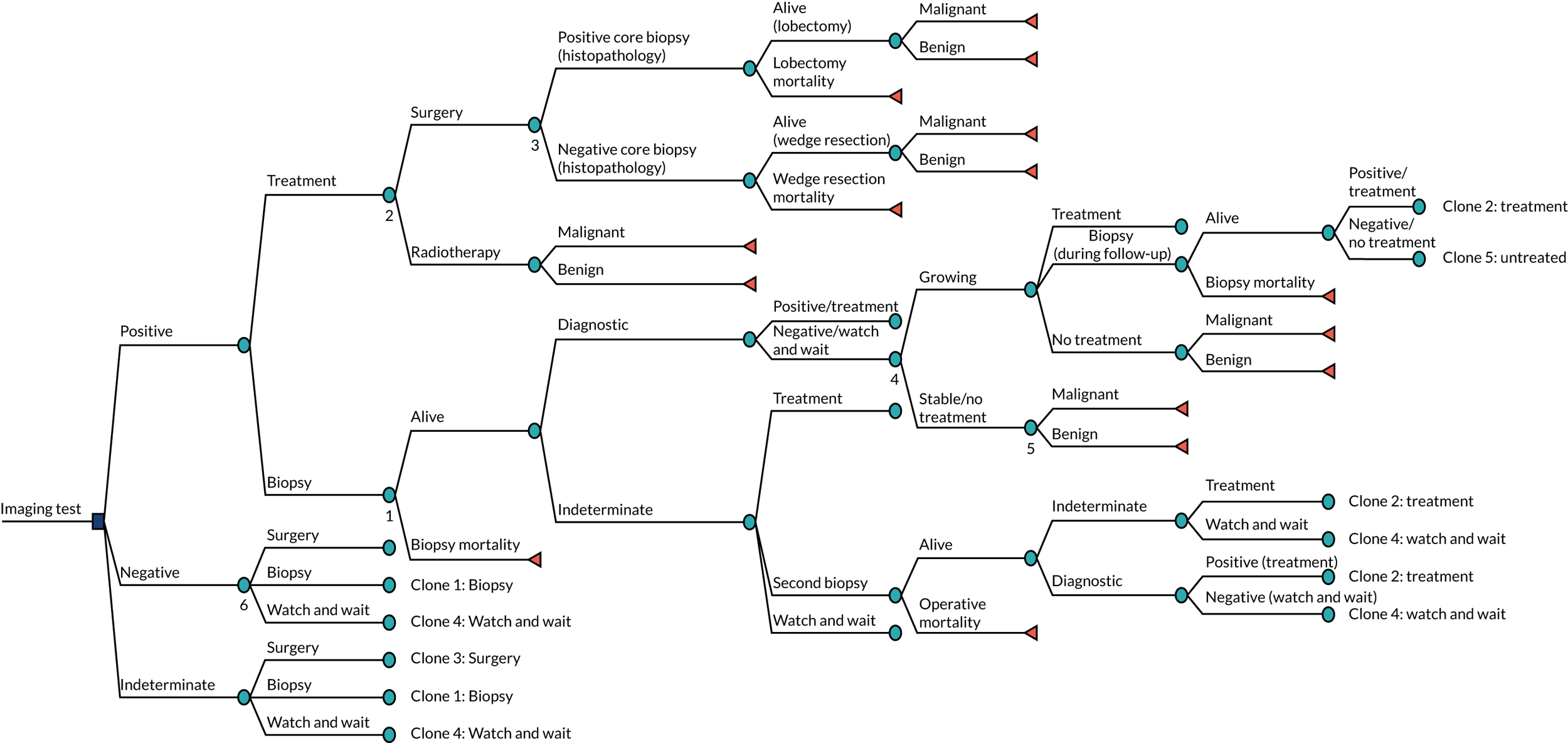

The trial was designed as a prospective observational study to assess the diagnostic performance and incremental value of DCE-CT by the addition of this modality to PET/CT in a cohort of 375 patients with a SPN, with the trial protocol previously published. 39 The trial flow diagram is presented in Figure 1.

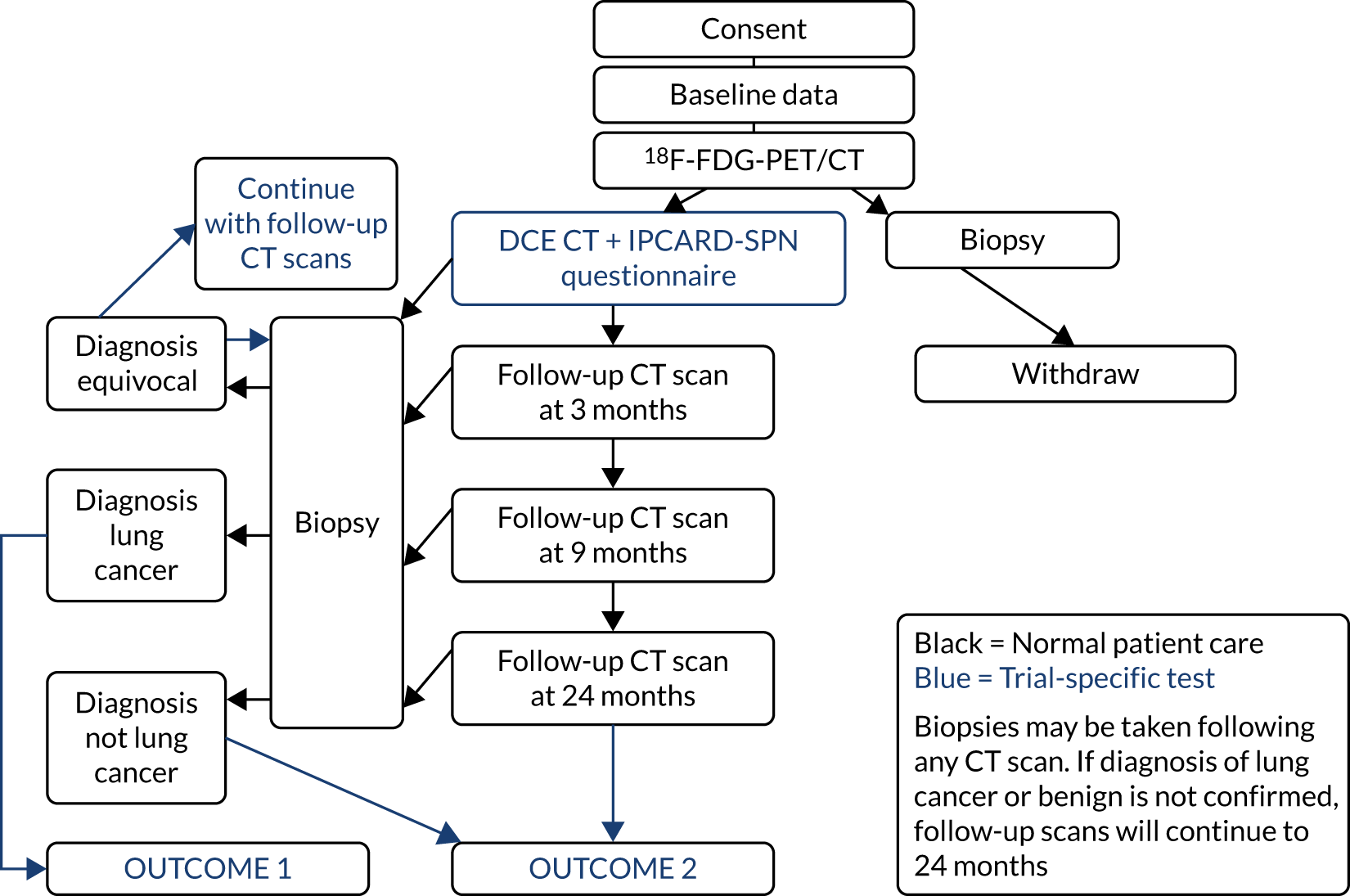

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the SPUtNIk trial. IPCARD-SPN, Identifying symptoms that Predict Chest And Respiratory Disease – Solitary Pulmonary Nodule; SPUTniK, Single PUlmonary Nodule Investigation.

Participants

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

A soft-tissue solitary dominant pulmonary nodule of ≥ 8 mm and ≤ 30 mm on the axial plane:

-

measured on lung window using conventional CT

-

no other ancillary evidence strongly indicative of malignancy (e.g. distant metastases or unequivocal local invasion).

-

-

If clinicians and reporting radiologists believe that the patient is being treated as having a single pulmonary nodule and there are other small lesions of < 4 mm that would normally be disregarded, the patient should be included in the trial.

-

Nodules already under surveillance could be included, provided that the patient had recently undergone or had scheduled PET/CT.

-

Aged ≥ 18 years at the time of providing consent.

-

Able and willing to consent to the study.

Exclusion criteria

-

Pregnancy.

-

History of malignancy in the previous 2 years.

-

Confirmed aetiology of the nodule at the time of the qualifying CT scan. As this was a diagnostic study, should the aetiology of the nodule be confirmed by investigation such as PET/CT or bronchoscopy prior to consent, the patient remained eligible, as the decision to include is made on the analysis of the qualifying CT scan.

-

Biopsy of nodule before DCE-CT.

-

Contraindication to potential radiotherapy or surgery.

-

Contraindication to imaging techniques (assessed by local practice).

All patients meeting the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria were eligible and were recruited consecutively to the study. In giving consent, they were expected to follow the procedures summarised in Table 1.

| Screening and recruitment visit(s) | Baseline and diagnostics visit 1a | Visit 2b | Visit 3b | Visit 4c | Visit 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day(s) | –14 to –1 | 0 | ||||

| Month(s), range | 3 months or local practice | 9 months or local practice | 12–18 months | 24 months | ||

| Information sheet provided | ✗ | |||||

| Informed consent | ✗ | |||||

| Review inclusion/exclusion criteria | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Recruit to study | ✗ | |||||

| Check contraindications of contrast | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| 4- to 6-hour fasting glucosed | ✗ | |||||

| Resource assessment | ✗ | |||||

| Substudy IPCARD-SPN questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| PET/CTd,e,f | ✗ | |||||

| DCE-CTe,f | ✗ | |||||

| Chest CTf,g | ✗ | ✗ | ✗c | |||

| Concomitant medications | ✗ | |||||

| Adverse eventsh | ✗ |

Changes to eligibility criteria after commencement of the trial

As noted previously, changes to inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Inclusion criteria – to include nodules that were already under surveillance, and single nodules when smaller lesions of < 4 mm exist, but they would normally be disregarded by the radiologist.

-

Exclusion criteria – ensuring that the criterion for entering the trial is unknown aetiology at the time of CT.

Setting and recruitment pathway

Patients were identified at local MDT meetings, at the time of referral for investigation of a SPN, or at referral to the PET centres for PET/CT on the basis of having a single dominant pulmonary nodule on a CT scan with uncertain aetiology.

An invitation letter and patient information sheet were sent to potential patients, along with their PET/CT appointment letter, inviting them to participate in the study.

Local research and NHS staff approached potential patients either in clinic or by telephone to:

-

explain the study and/or provide the patient information sheet

-

note the age, sex and smoking history of a patient

-

confirm eligibility for the study.

Patients were given an appointment for PET/CT, and were booked for DCE-CT on either the same day or within 14 days of the PET/CT appointment. (Note that, if there were scheduling issues, appointments could be up to a maximum of 21 days apart.) Some sites chose to make the DCE-CT appointment at the time of the PET/CT appointment, following consent, if there were constraints on scanner time.

The Single PUlmonary Nodule Investigation (SPUtNIk) study patient information sheets and Identifying symptoms that Predict Chest And Respiratory Disease – Solitary Pulmonary Nodule (IPCARD-SPN) questionnaire were given to patients either in clinic or by post.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

This study had two co-primary outcomes. The first was to assess the diagnostic test characteristics [sensitivity, specificity, NPV, positive predictive value (PPV) and overall diagnostic accuracy (ODA)] for PET/CT and DCE-CT, in relation to a subsequent diagnosis of lung cancer within a 2-year time frame. The second was to assess the cost-effectiveness of each imaging technique. The outcome measures used in the economic model include accuracy, estimated life expectancy and QALYs. Costs were estimated from an NHS perspective. ICERs (reported as the incremental cost per correctly treated malignancy and the incremental cost per correctly managed case) compare management strategies with DCE-CT against management strategies without DCE-CT.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcome measures include diagnostic test characteristics for PET/CT with incorporation of CT appearances and combined DCE-CT plus PET/CT. The incidence of incidental extrathoracic findings on PET/CT, subsequent investigations and costs were determined.

Adverse events

All adverse events ocurring within the 30 days following the study DCE-CT were reported to the SPUtNIk database. For full details, see the SPUtNIk study protocol. 39

Registration

Sites registered patients to the SPUtNIk study by sending a signed registration form via fax or e-mail attachment to the Southampton Clinical Trials Unit (SCTU). Sites were given a block of SPUtNIk codes. Patients were allocated trial identifier codes consecutively, following consent. On registration, SCTU staff checked eligibility and confirmed the patient trial identifier code by e-mail. Registration and DCE-CT could not take place before informed consent was signed; however, registration with SCTU could take place before or after DCE-CT, because there was a possibility that some clinics would schedule the DCE-CT outside office hours.

Blinding

The study was a non-randomised diagnostic accuracy and comparative health economic effectiveness trial; therefore, blinding was not necessary to meet the trial objectives. However, the results of the DCE-CT were not reported to the participants’ clinicians, so as not to bias the assessment of the diagnostic accuracy of DCE-CT.

Data collection

Baseline and evaluative procedures (visit 1, day 0)

If both imaging techniques were performed on the same day, PET/CT was performed first, with no waiting time between imaging. If they were performed on separate days, either imaging technique could be performed first, provided that patient consent and registration took place before DCE-CT (e.g. in the case of a delay in PET/CT).

Ideally, PET/CT and DCE-CT were performed within 14 days, with an absolute maximum of 21 days allowed between imaging techniques when sites had difficulty with scheduling.

Follow-up

Following the PET/CT and DCE-CT investigations, management of the SPN was directed by the local/specialist lung MDT.

In many cases, a nodule biopsy or excision biopsy was undertaken and the histopathological outcome recorded. Cases shown to be due to lung cancer (or other malignancy) were managed according to local protocols. Follow-up/outcome data were collected by case report form (CRF).

Patients with a high pre-test probability of cancer, who were unfit for surgery or for whom a biopsy was non-diagnostic/not possible, were considered for stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) or nodule ablation. For the purposes of this study, these patients were considered to have cancer as per British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines. 8

In some cases, nodule surveillance was appropriate (with or without prior biopsy). 8,9 In these cases, recommended follow-up was performed at:

-

3 months

-

9 months

-

24 months.

Deviation from these time points, based on clinical need, was at the discretion of the MDT. For instance, if a nodule resolved during follow-up, then continued imaging was not necessary. During the course of the trial, the BTS guidelines changed, such that nodules stable at 12 months on volumetric analysis (< 25% change in volume) are considered benign, requiring no further follow-up. When the technology to undertake this analysis was available to the MDT, follow-up could be terminated before 24 months.

At each study visit, the following were performed:

-

chest CT (low dose, thin section, unenhanced), unless the MDT felt that it was inappropriate

-

recording of any biopsy samples taken

-

recording of health resource use information.

At 2 years:

-

Health resource data were collected from patient records (this included additional findings that came to light while investigating the SPN with PET-CT, treatment associated with the SPN and tests, and treatment related to these additional intra- or extrathoracic findings).

-

The end-of-study CRF was completed in the clinical database.

-

The principal investigator (PI) signed off a patient’s electronic CRF record and the database was locked for that patient.

Procedure when nodule was reduced in size or not visible on the dynamic contrast-enhanced computerised tomography scan

Occasionally, a nodule that was eligible (i.e. was 8–30 mm in size) on the lung window on the qualifying CT scan had reduced in size or was not visible when DCE-CT was performed. This was likely to be related to the inflammatory/infective nature of the nodule. In this case, the following procedures were undertaken:

-

If the nodule was not visible on the DCE-CT locating scan, contrast was not administered. If the nodule had reduced in size but was still > 8 mm, contrast was given.

-

If the nodule was < 8 mm, a local decision was made by the supervising radiologist.

Withdrawal criteria

A patient could withdraw consent at any time and was not asked to give a reason:

-

If a patient withdrew from undergoing PET-CT or DCE-CT or both, but did not specifically withdraw consent to collect data from hospital notes, collection of relevant data from their hospital notes and general practitioner contact continued.

-

If consent was completely withdrawn, results were recorded on CRFs for procedures performed prior to the withdrawal of consent.

Sample size

For the primary outcome measures in this study, the diagnostic characteristics for DCE-CT and PET/CT were used for the sample size calculations. Use of the other outcome measures that are related to the economic analyses was prevented by the prior need for detailed characterisation of the decision trees. We consider the sample size needed to detect particular accuracy for each test, separately, and then when the tests are used in conjunction.

Consideration for each test separately

Published sensitivity for PET/CT for the characterisation of SPNs varies between 77% and 96% (pooled weighted average: 92%) and specificity varies between 76% and 100% (pooled weighted average: 90%). 14,17,18,21,23,29,30,32,41,42 Published sensitivity and specificity values for DCE-CT vary between 81% and 100% (pooled weighted average: 87%) and between 29% and 100% (pooled weighted average: 83%), respectively. 14,17,18,21,23,29,30,32,41,42 Based on two previous UK studies, the mean prevalence of malignancy in indeterminate SPNs has been reported as 68.5%. 22 At this prevalence, a sample size of 375 participants will produce approximately 257 malignant and 118 benign SPNs. This gives 95% confidence limits for the sensitivity and specificity of DCE-CT of 87% ± 4.1% and 83% ± 6.8%, respectively, with sensitivity and specificity values for PET/CT of 92% ± 3.3% and 90% ± 5.4%, respectively. These estimates will provide sufficiently narrow confidence limits to allow precise economic modelling based on the results. For the purposes of economic analyses, we also considered combining our data with the meta-analysis results from our systematic review (see Chapter 8) of previous studies of 217 patients who had undergone both techniques. 12,14,15 Recruitment rates were anticipated to be high (70%) because DCE-CT was additional, rather than an alternative, to normal care, and is readily incorporated into the existing PET-CT examination. We expected to recruit the required sample size (n = 375) in 18 months. Assuming that only 70% of patients would meet all inclusion criteria, it was anticipated that we would need to screen 375/0.7 = 536 patients.

Consideration for when both tests are used together

Consideration has to be given to both tests being used together. In particular, (1) those with a negative result on a DCE-CT scan are classed as benign, and (2) those with a positive result on a DCE-CT scan then undergo PET/CT; those with a positive result on the PET/CT are classed as ‘malignant’ and those with a negative result on a PET/CT scan are classed as ‘benign’. The specificity of this process is the same as that of using PET/CT alone. So, the key interest is estimating the sensitivity of this joint-test classification strategy, compared with PET/CT alone. Based on previous data of 130 malignant tumours, 114 tumours give a positive DCE-CT scan result and a positive PET/CT scan result; this suggests that the sensitivity of the joint testing procedure is 114/130 = 0.877. Compared with the PET/CT sensitivity, thought to be 0.92 (as noted previously), the joint-testing approach is projected to reduce sensitivity by about 4%. Based on the sample size formula of Alonzo et al. ,43 to detect that the joint DCE-CT–PET/CT approach has at least a 4% reduction in sensitivity, compared with the PET/CT sensitivity of 0.92, a total sample size of 288 participants is required (including 197 with a malignant tumour); this calculation assumes an 80% power, 5% significance level, and prevalence of malignancy of 0.685. Thus, by including 375 participants, as per our previous sample size calculations, our study is also powered to detect at least a 4% decrease in sensitivity for the joint-testing approach.

Statistical methods and data analysis

We considered the diagnostic accuracy of positive PET/CT and DCE-CT scan results, both separately and in conjunction, in relation to a diagnosis of lung cancer by 2 years. In these analyses, we will be able to include only those patients in whom the presence of lung cancer by 2 years is confirmed.

Initially, the separate diagnostic performance of PET/CT and DCE-CT were examined using the predefined diagnostic criteria. For PET/CT, this was based on the combined PET grade and CT grade (see Table 3 for grade breakdown). This was classified as positive for malignancy if one of the following criteria was met: grade 4 on PET or CT, or grade 3 on both PET and CT, or grade 2 on PET and grade 3 or 4 on CT. For DCE-CT, 15-Hounsfield unit (HU) enhancement is prevalent in the literature when scanning patients at an X-ray energy of 120 kVp. We proposed scanning patients at 100 kVp to obtain a higher signal-to-noise ratio. The attenuation of iodine increases with decreasing photon energy. Phantom measurements verified that an iodine concentration measuring 15 HU at 120 kVp measured approximately 20 HU at 100 kVp; as a result, 20 HU was chosen as the prespecified threshold for malignancy.

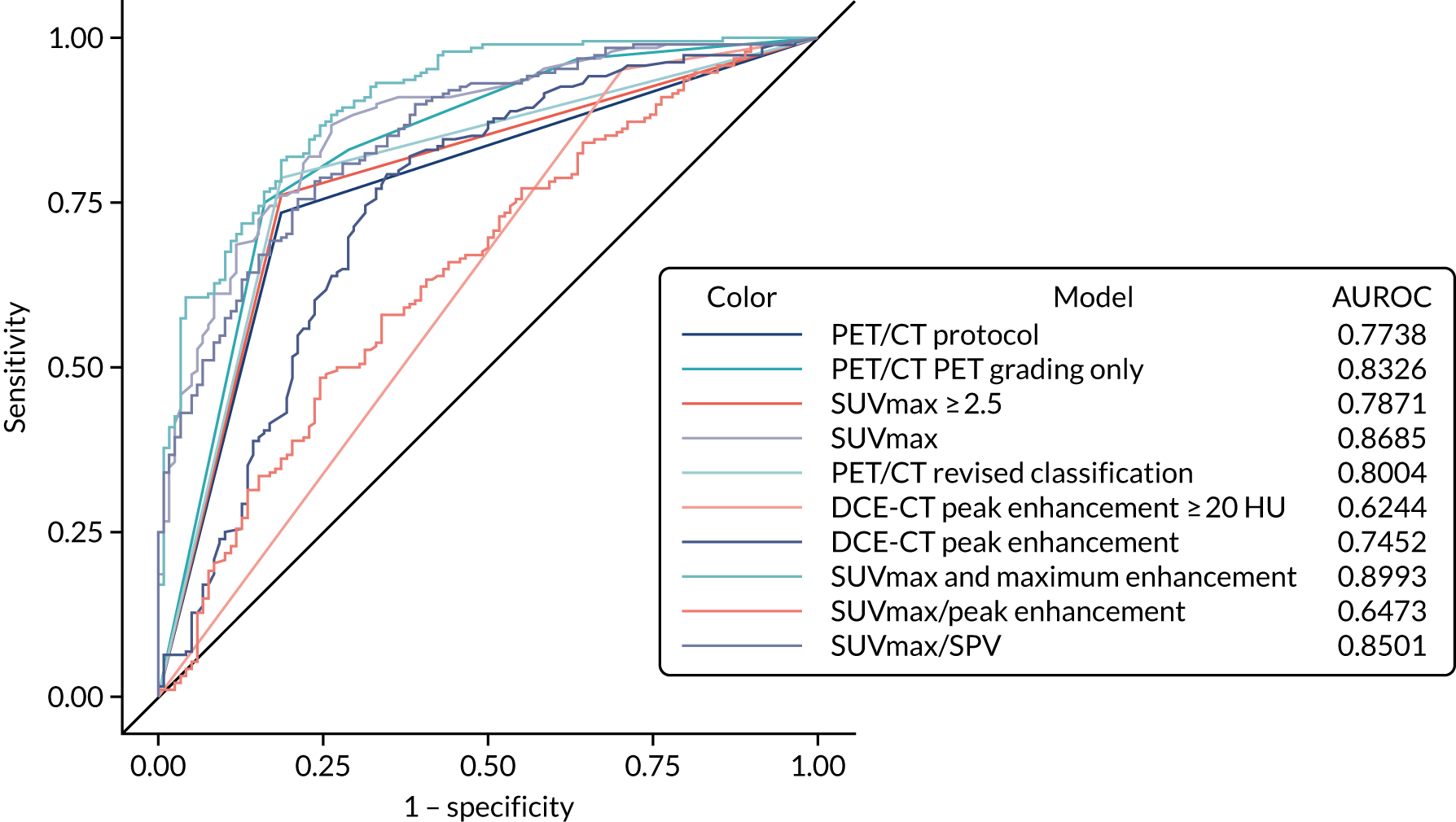

In addition, we examined the full range of possible threshold values to see if performance could be improved. This involved using the grading of individual CT and PET images, as well as the maximum and mean SUV from the PET image, peak enhancement, peak and mean HU from the DCE-CT and the reporting radiologist’s classification of the SPN from the PET/CT and DCE-CT results. The classification produced by the site radiologists was their expert opinion and was based on all available information from either the PET/CT or DCE-CT (correspondingly), as well as any prior information from the initial staging CT. An indeterminate option was available here. At each threshold, sensitivity and specificity were estimated (with 95% CIs), and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve calculated. The optimal cut-off point from the range of values is reported based on keeping the sensitivity above 90% and maximising specificity within this limitation. An alternative cut-off point that provides the best trade-off in sensitivity and specificity is also reported. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and ODA at these cut-off points, as well as the pre-defined values, are presented with 95% CIs in this report. When translating sensitivity and specificity to PPVs and NPVs, we assumed a particular prevalence, using the value seen in our study. We report PPVs and NPVs for a range of other prevalences reported in the literature, identified from our systematic review. The ODA is the percentage of cases that are correctly classified, regardless of whether they were cancers or non-cancers.

The diagnostic performance of PET/CT and DCE-CT combined was examined using the same techniques as previously described, with patients classed as ‘positive’ if they had both PET/CT and DCE-CT positive scan results, and all other patients classed as ‘negative’.

A logistic regression model was undertaken, including key diagnostic elements from both PET/CT and DCE-CT. This included (but was not limited to) the individual imaging components that were described previously, size measures from each of the scans and predefined measures such as the standardised perfusion value (SPV). The SPV is the maximum enhancement multiplied by the subject’s body weight and divided by the dose of iodine received. These variables were used on their original scale as covariates in a logistic regression to produce a risk score and predicted probability of lung cancer for each individual, based on their specific test values. This predicted probability came from a transformation of the linear predictor from the logistic regression model: the predicted ‘risk’ for each individual. A cut-off value was used to decide a high-risk score (which predicts an adverse outcome) and a low-risk score (predicting a good outcome). The calibration of the model was assessed by grouping patients into deciles ordered by predicted risk and considering the agreement between the mean predicted risk and the observed number of true lung cancer cases in each decile (sometimes referred to as the expected vs. observed statistic). The derived diagnostic rule was cross-validated by comparing the classification of each patient with their outcome of confirmed lung cancer, allowing an estimate of the sensitivity and specificity of the prediction model. By varying the chosen cut-off level, a ROC curve was produced, summarising the sensitivity and specificity of the predictive rule across the full range of cut-off points. The overall discriminatory ability was summarised as the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve with 95% CI. The most suitable cut-off level was selected using the same rules as before. The internal validity of the final model was assessed by the bootstrap resampling technique to adjust for overoptimism in the estimation of model performance due to validation in the same data set that was used to develop the model itself. These models will be exploratory only and, before they can used or considered useful, they would require external validation in a separate data set.

If these methods showed poor accuracy performance (in terms of calibration and/or discrimination), then the logistic regression model was extended to include additional patient-level covariates (such as time from 18F-FDG injection to PET/CT scan) in addition to test results. Demographic information was considered, as well as clinical and imaging features considered indicative of a higher likelihood of SPN malignancy. The performance of the model was also evaluated at the site level, when possible, to ascertain whether or not model performance is consistent in each site or, if it is not, the variability in performance across sites, and whether or not this can be improved by tailoring the prevalence in each site.

Interim analysis and data storage

No interim analysis was planned for this study, although there were a series of Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee meetings that occurred throughout the duration of the data collection process.

Data and all appropriate documentation will be stored for a minimum of 15 years after the completion of the trial, including the follow-up period.

Accreditation of positron emission tomography centres

Methods

Centres performing PET for the SPUtNIk study underwent an accreditation process using procedures established for multicentre trials by the UK PET Core Lab. 44 For centres to be accredited by the UK PET Core Lab, they had to submit the following data:

-

PET/CT acquisition and reconstruction of the International Electrotechnical Commission image quality phantom following a standard protocol; when possible, the local clinical protocol was accredited

-

submission of 8 weeks’ phantom data to demonstrate ongoing scanner stability

-

evidence of ongoing PET and CT quality control (QC) as part of a quality assurance (QA) system

-

evidence of calibration of the patient weighing scales used to determine SUVs

-

evidence of traceability of the radionuclide calibrator used to measure injected activity

-

two anonymised patient scans for visual assessment of image quality by two experienced PET clinicians.

To ensure that image quality was maintained throughout the trial, each scanning centre was required to submit a scan of the image quality phantom to the UK PET Core Lab for analysis on an annual basis. In total, 16 hospitals recruited patients as part of the study. Not all recruiting hospitals had access to a fixed PET/CT scanner on-site, so patients were either scanned in a mobile PET/CT unit or sent to the nearest PET centre. Appendix 2, Table 27, shows a summary of the recruiting sites and the fixed PET centres (n = 17) or mobile units (n = 8) used.

To improve recruitment, patients with nodules already under surveillance were included in the trial if PET had been performed recently. In some cases, this meant that non-accredited PET scanners were used at the time of the PET. In all but one case, the scanners were retrospectively accredited.

Accreditation of dynamic contrast-enhanced computerised tomography centres

Centres performing DCE-CT for the SPUtNIk study underwent an accreditation process developed specifically for this trial and conducted by the Radiation Protection Department of the Mount Vernon Cancer Centre, East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trust.

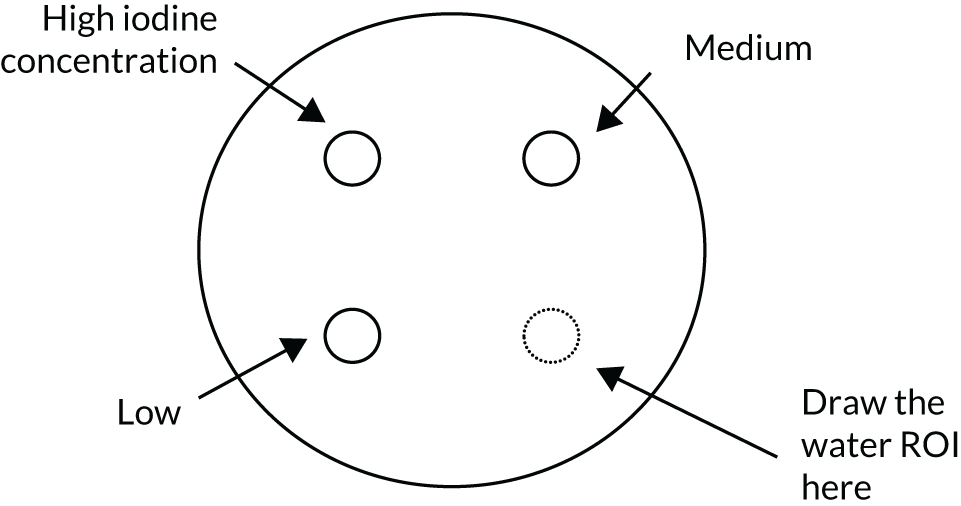

Two phantom types were designed for the trial. The SPUtNIk chest-equivalent phantom (Figure 2) was constructed by the Clinical Physics Department at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, and the SPUtNIk water-filled Radiographer QA Phantom (Figure 3) was constructed by the Bioengineering Department at the Mount Vernon Cancer Centre.

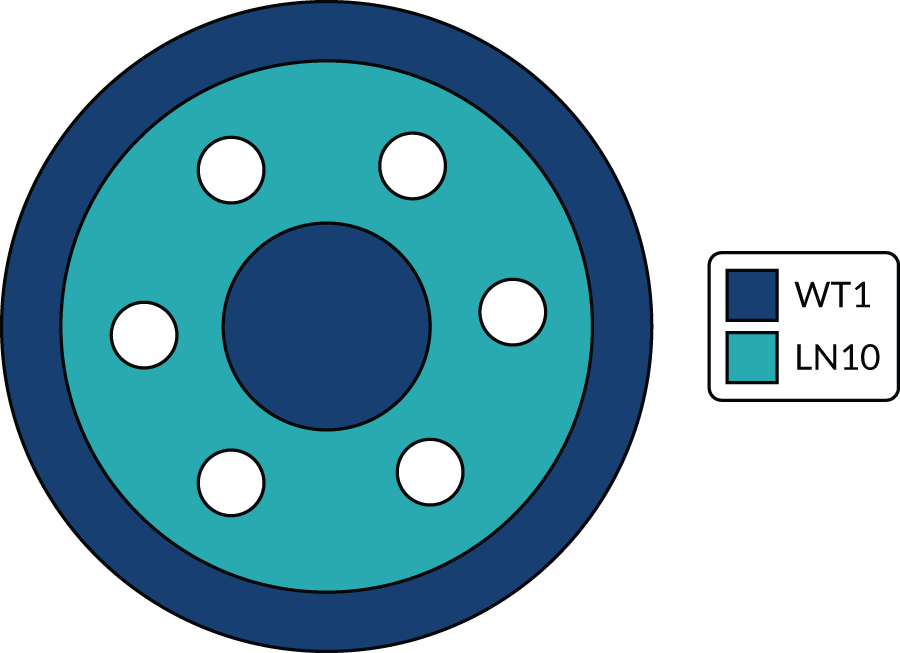

FIGURE 2.

The SPUtNIk chest-equivalent phantom. Outer annulus, diameter 290 mm, composed of water-equivalent material WT1 (Clinical Physics Department, St Bartholomew’s Hospital); middle annulus, diameter 240 mm, composed of lung-equivalent material LN10; central circle, diameter 100 mm, composed of water-equivalent material WT1. Six holes, each 30 mm in diameter, designed to hold a vial containing iodine solution at the following concentrations: 0.0, 0.3, 0.6, 1.6, 2.4 and 4.7 mg/ml. Phantom thickness: 100 mm.

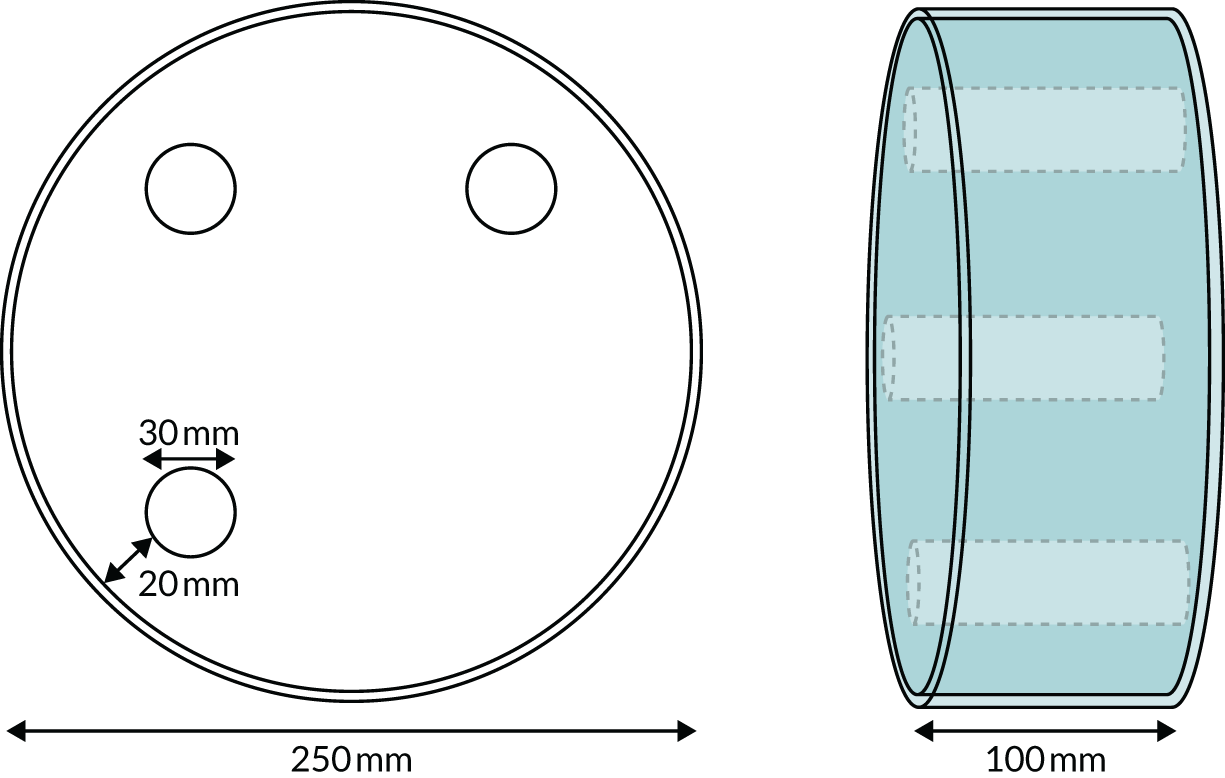

FIGURE 3.

The SPUtNIk water-filled radiographer quality assurance phantom. Perspex cylinder: 250 mm outer diameter, 244 mm internal diameter. Water filled with release plug to fill/empty phantom. Three internal chambers, each of 30 mm internal diameter, with plugs to fill/empty with iodine solution at the following concentrations: 0.6, 1.6 and 2.4 mg/ml.

A clinical scientist from the DCE-CT accreditation team visited each site and, with the lead radiographer, entered the weight-dependent trial protocols into the scanner and saved them with clearly identifiable names. The chest-equivalent phantom was scanned under the trial protocol (see the SPUtNIk study protocol39). One SPUtNIk water-filled radiographer QA phantom was issued to the centre and scanned, as per the QA protocol (see the SPUtNIk study protocol39). Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine- (DICOM-)standard images of both phantoms were saved to a compact disc for later analysis. The peak energy (in kVp) and half-value layer of the X-ray beam at 100 kV were measured using the RaySafe™ Xi R/F Detector (RaySafe, Billdal, Sweden), positioned in the scan plane and using a scout projection, taking care to avoid attenuation by the table/couch.

Information and instruction were given to the lead radiographer for QA for the SPUtNIk trial and for data anonymisation and transfer to the PET Core Lab for storage and further analysis of patient images. Images exported from each scanner were checked to ensure that the correct scan protocol had been set up. The mean and standard deviation in CT number in the iodine inserts of both the chest-equivalent phantom and the Radiographer QA phantom were extracted using IQWorks [http://iqworks.org/ (accessed 12 October 2018)]. The line of best fit between CT number and iodine concentration in each phantom was assessed using Microsoft Excel® 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), and the gradient was taken as the iodine calibration factor at 100 kV. Sites were issued a certificate of accreditation and informed of the iodine calibration factor in the SPUtNIk chest phantom for their scanner.

All scanners were required to undergo regular planned preventative maintenance and CT number calibration, at frequencies recommended by the manufacturer.

Fourteen sites recruited patients as part of the study. Participants underwent DCE-CT on one of 16 scanners, as summarised in Appendix 2, Table 28.

The mean iodine calibration factor in the lung-equivalent phantom was 32.2 HU/(mg/ml), with a coefficient of variation across the scanners of 6.6%. The mean iodine calibration factor in the water-filled radiographer phantom was 30.0 HU/(mg/ml), with a coefficient of variation of 4.5%.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced computerised tomography acquisition design

The DCE-CT acquisition settings were chosen to reasonably standardise dose and image quality across all manufacturers and models of scanner. The full procedure is listed in the SPUtNIk study protocol. 39

Computerised tomography scans taken at 120 kVp are prevalent in the literature; however, by scanning at a lower photon energy, the increased attenuation of iodine could be exploited. For a given iodine concentration, the increased attenuation at low energy results in a higher CT number. Scans of phantoms simulating patients of different weight explored the use of 100 kVp and 80 kVp. At 80 kVp, the X-ray tube current required to maintain a desired signal-to-noise ratio was sufficiently high to exclude most CT scanners. However, at 100 kVp, a good signal-to-noise ratio could be achieved for all phantom sizes. Therefore, 100 kVp was chosen.

Tube current modulation alters the X-ray current, and, consequently, the photon intensity, with variation in patient attenuation during CT. The variation in manufacturer approach to tube current modulation would have resulted in differences in dose and image quality, depending on patient weight and scanner type. Standardisation of tube current modulation between manufacturers was beyond the scope of this trial; therefore, fixed tube currents were used across three weight categories: < 60 kg = 200 mA, 60–90 kg = 350 mA and > 90 kg = 500 mA. These tube currents were chosen to maintain a signal-to-noise ratio independent of patient weight.

At the time of trial inception, 64 × 0.6 mm collimation was representative of modern scanners. Slice thickness and interval were chosen to provide adequate noise statistics for the measurement of CT number enhancement, with enough sensitivity to choose the slice position and with maximum enhancement for nodules of > 8 mm in diameter. A reconstruction kernel with similar appearance and noise level across each manufacturer was chosen.

Although some scanners included in the trial had an option of iterative reconstruction, this was not used, so as to standardise the dose and image quality of all CT systems, regardless of scanner model and manufacturer.

Chapter 3 Site quality control

Accreditation of positron emission tomography centres and technical quality control of positron emission tomography scans

Imaging protocols with guidance for performing the PET/CT (see SPUtNIk protocol39) were provided to sites, with local clinical protocol followed if the PET/CT was carried out as standard of care prior to study entry. Of the 380 patients recruited to the study, 373 were eligible for the study and underwent PET/CT imaging from January 2013 to December 2016. The scans were sent to the UK PET Core Lab, St Thomas’ Hospital, for technical checks (Table 2).

| Technical checks performed | Ideal range |

|---|---|

| Scanner acquisition and reconstruction matched to accredited parameters | Any deviations noted and reviewed by PET expert |

| Patient blood glucose | < 11 mmol/l |

| Fasting status | ≥ 6 hours |

| Uptake time | 60 minutes (± 10 minutes) |

| Scan range | Angle of jaw to mid-thigh |

| DCE-CT intravenous contrast | To be administered after PET if performed in the same session |

| Injected activity | Dependent on scanner and total scan time (diagnostic reference level 400 MBq) |

Any deviations from the expected patient preparation, image acquisition or scan processing were flagged for discussion with a PET expert. A total of 370 (99.2%) PET scans were submitted for technical review. The results of technical review were as follows:

-

Sixteen scans used a new reconstruction not accredited for the study called point-spread function (PSF) modelling.

-

Patient blood glucose was not measured/not provided for seven patients; one patient had a blood glucose level of > 11 mmol/l.

-

Fasting status was not provided for 27 scans, nine patients fasted for < 6 hours, but all fasted for at least 4 hours and their blood glucose was within the expected range.

-

All scans covered at least the angle of jaw to mid-thigh.

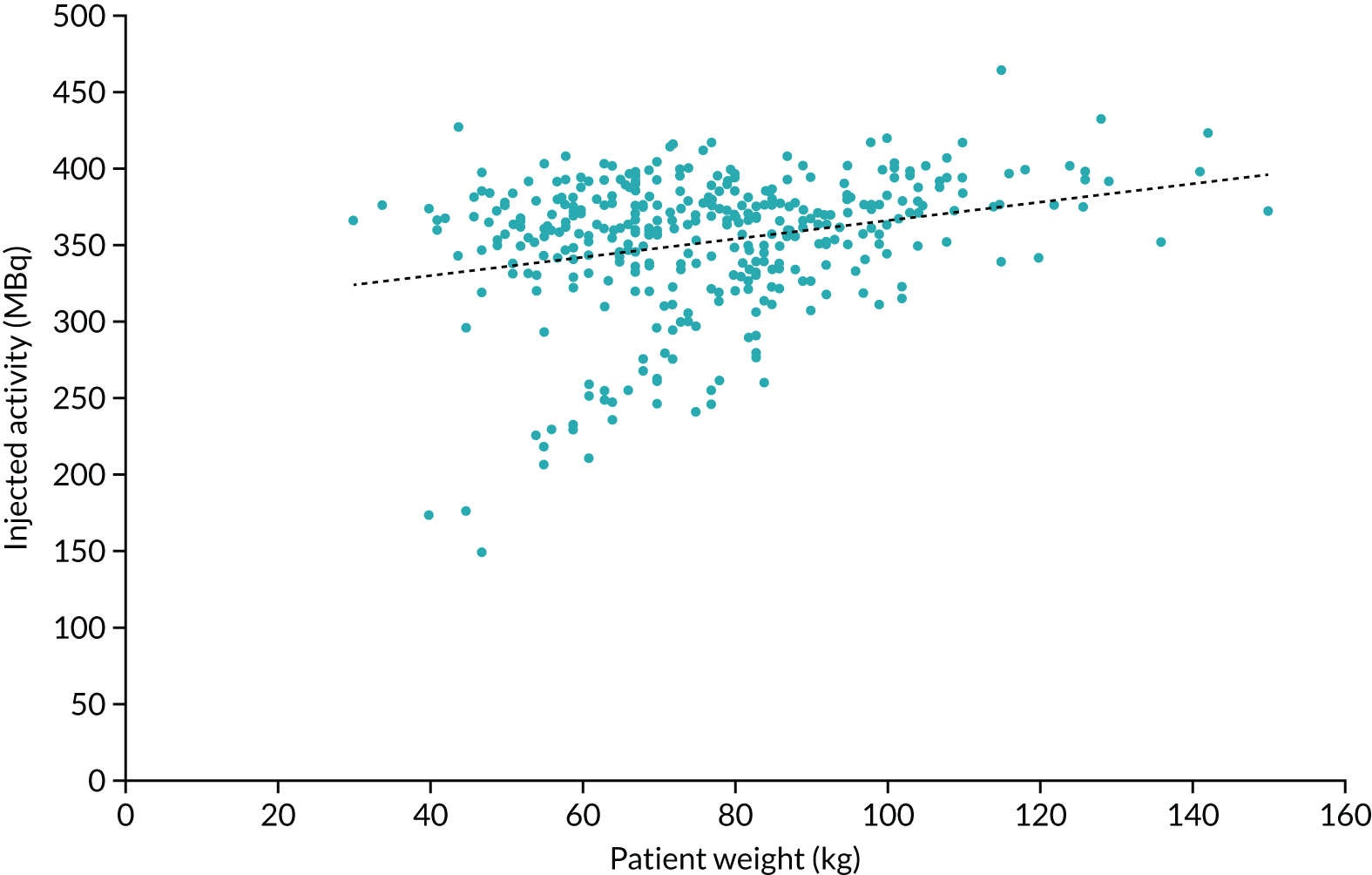

The mean injected activity was 352.6 MBq (range 148.1–464.0 MBq). The national diagnostic reference level (DRL) for 18F-FDG is 400 MBq and it is recommended to use a weight-based protocol of 4.5 MBq/kg, with a minimum injected activity that is dependent on the scanner model and acquisition parameters used. The mean injected activity used for the SPUtNIk patients was 4.9 MBq/kg (range 2.5–12.2 MBq/kg) and patient weight ranged from 30 to 150 kg (mean 76.8 kg). A plot of the injected activity as a function of patient weight is shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Injected activity as a function of patient’s weight for all patients.

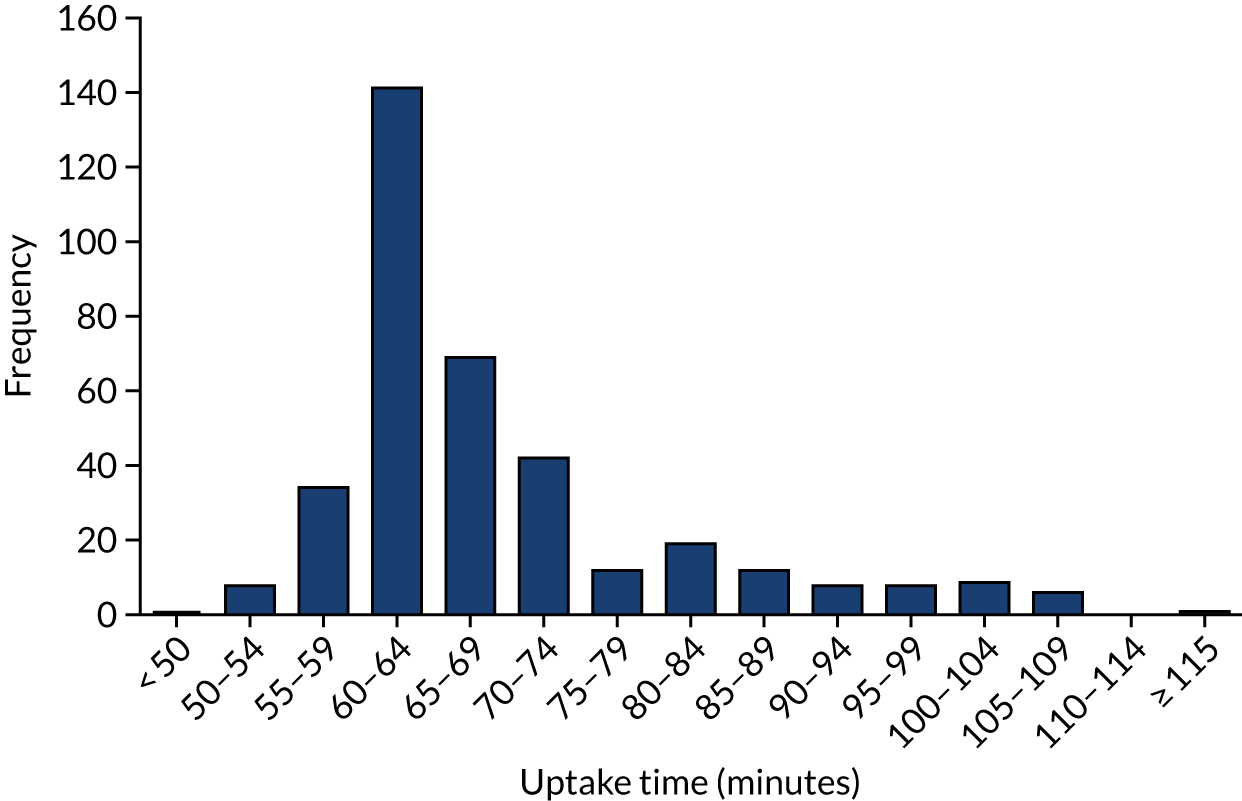

The mean uptake time was 68.6 minutes (range 49.0 to 117 minutes). The distribution of uptake times is shown in Figure 5; for 72% (n = 267) of PET scans, the uptake time was within 60 ± 10 minutes. For 80% (n = 295) of scans, the uptake time was within 50–75 minutes. Only one scan had an uptake time of < 50 minutes, and 74 had an uptake time of > 75 minutes. The standard-of-care protocol for one centre was a 90-minute uptake time, rather than the 60-minute uptake time in the other sites.

FIGURE 5.

Uptake time (time between injection and PET scan start) for all patients.

Radiation dose

In general, a dose of 7.6 mSv is quoted for the radiotracer injection based on 400 MBq and 6.5 mSv for the CT part, based on national DRLs for CT as part of a PET-CT. This gives a total of 14.1 mSv for the PET-CT. However, local practice varies and the expectation is that the PET injected dose is lower for SPUtNIk, as many sites used weight-based injected activities.

Radiographer-led quality control of dynamic contrast-enhanced computerised tomography scanners

Each site was issued with a water-filled radiographer QA phantom and shown how to carry out tests on its scanner. Baseline measurements were performed by the clinical scientist, who then created a radiographer QA spreadsheet with tolerances and pass/fail criteria for the site. All results were logged on the QA spreadsheet, a copy of which was sent to Mount Vernon for analysis at regular intervals throughout the trial. To ensure that QA was not excessively burdensome at participating sites, the frequency of DCE-CT radiographer QA phantom scans was set to either weekly (for sites with a high trial patient volume) or before each patient scan (for less frequent trial scans). QA was not carried out within 7 days of trial DCE-CT on 24 occasions.

Across the 14 sites, QA was carried out a total of 753 times. This ranged from 148 instances at one site to just four at another. Some sites carried out radiographer QA more often than the trial required, whereas other sites, with particularly low recruitment, carried out QA a few times only. In total, there were just six (0.8%) instances when the measured iodine calibration factor fell outside ± 5% of the baseline calibration factor measured at the accreditation visit.

There was no marked variation in iodine calibration factor over time for any of the scanners. The maximum difference between baseline calibration factor (measured at accreditation) and mean calibration factor (over the length of the trial) was –2.1%, with the mean variation being 0.2%. There were no systematic trends.

Sites were asked to record any new tubes that were installed in the scanners. Only one new tube was reported during the trial. The baselines and tolerances for QA measurements were reset following installation of the new tube. Although the measured CT numbers in the phantom did change slightly, the enhancement relative to water was not significantly different and the iodine calibration factor did not change. The cause of the tube change was not ascertained; however, the changes in tube output or beam quality that might be expected prior to the failure of an X-ray tube had no effect on the radiographer QA results or iodine calibration factor. There was one other step-change in CT numbers during the trial. No explanation for this could be found. The enhancement relative to water and iodine calibration factor did not change, so the scanner remained in the trial.

Technical quality control of dynamic contrast-enhanced computerised tomography scans

Deviation log

Of the 329 completed DCE-CT sessions carried out during the trial, a number of scans deviated from the scan protocol (see Appendix 4, Table 30). Protocol deviations were reviewed by radiologists and clinical scientists to determine if patients should be excluded from the final analysis. The following sections are a list of deviations and the rationale for determining inclusion/exclusion in the trial. The aim was to be pragmatic and inclusive, and to recognise that the imaging was being conducted at multiple NHS sites, reflecting real-life practice. In total, 12 scans were deemed unusable.

Reconstructed field of view

A significantly larger reconstructed field of view will affect how accurately the region of interest (ROI) is drawn within the nodule and the number of voxels included in the CT number measurement. Four scans had a field of view within a few mm of the 150 mm required in the protocol. This had little effect on the ROI or CT number measurement. These patients were included. Nine scans were reconstructed with a significantly larger field of view (303–426 mm) than specified in the protocol. The nodule diameter for these scans was reviewed against the reconstructed field of view to determine the number of voxels contained within the ROI. If the value was greater than would be measured for an 8-mm nodule with the protocolled 150-mm field of view, the scan data were included for analysis. Five scans were excluded on this basis, as relatively small nodules were scanned on a large field of view. This combination of small nodule and large field of view resulted in fewer voxels sampled for measurement of average CT number, thereby reducing the confidence and accuracy of the CT number measured.

Reconstructed slice thickness and slice interval

One scan was reconstructed with a slice interval of 2.5 mm, one scan with a slice thickness of 2 mm and 18 scans with an interval of 3 mm (protocol 2.5- or 3-mm slices with a 2-mm interval). This could have a small effect on the choice of central slice of the nodule for CT number measurement. The deviations are not significant, and all scans were included for final analysis.

Contrast-enhanced imaging times

Contrast-enhanced CT scans should have been acquired at 60, 120, 180 and 240 seconds post iodine injection. Three patients were scanned at incorrect time points. One patient was scanned with an additional 23-second delay to the 2-, 3- and 4-minute time points. Iodine uptake usually takes place within the first minute; the short delay to the final three acquisitions was thought to have little effect on the measured CT number, so this scan was included. A second patient had the 60-second post-contrast scan carried out correctly, but the remaining three acquisitions were carried out at 174, 209 and 270 seconds. The patient effectively had no 2-minute scan, and the peak CT number may have been missed. This scan was excluded from analysis. A third patient had the 60-second post-contrast scan in the wrong location, not including the nodule. The remaining three acquisitions were carried out at the correct times and location. The peak enhancement value was 29.9 HU, which is greater than the predicted 20 HU threshold for malignancy. This scan was included in the analysis.

X-ray tube current and patient mass

The DCE-CT protocol has three weight-based mA settings: < 60 kg = 200 mA, 60–90 kg = 350 mA and > 90 kg = 500 mA. Seven patients were scanned with the wrong mA value. When a patient received a higher current than intended, the image quality was improved and the scans were included in the trial. When a patient’s weight was slightly over or under a weight boundary, the data were included for analysis. One patient was scanned with automated tube current modulation. The mA value delivered for the central slice of the nodule was compared with the protocol mA value. The patient was included, as the enhancement value was significantly lower than the expected threshold for malignancy; therefore, a lower-dose (higher-noise) scan would not have altered the status of this patient’s data.

Radiation dose

A high-dose DCE-CT strategy was used to keep the image noise low and get more accurate enhancement values. Imaging was undertaken at multiple post-contrast time points. The total effective dose for an average patient for the whole DCE-CT examination (whole-chest scan to locate nodule, then one pre-contrast and four post-contrast nodule scans) is ≈ 30 mSv. This was calculated using the ImPACT CT dose calculator [www.impactscan.org/ (accessed 1 October 2018)].

Reconstruction kernel

Royal Papworth Hospital installed a new Siemens Force CT scanner (Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany) during the trial. The Force CT scanner does not have the same reconstruction kernels as other Siemens scanners used in the trial. During the protocol set-up visit, a variety of reconstruction kernels were reviewed. The kernel with noise statistics most similar to the B30 kernel in the trial protocol was selected.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced computerised tomography injection rate

Four patients had DCE-CT examinations using a contrast injection rate of 3 ml/second, rather than the 2 ml/second prescribed in the protocol. A linear-systems approach (see Report Supplementary Material 1) was used to determine patient-specific correction factors to compensate for this difference in injection rate. The model showed that the faster contrast injection rate could have significantly affected the enhancement values for images acquired at 60 seconds, but the impact on later time points would be minimal. As three of the four cases showed significant nodular enhancement at later time points, it was considered unlikely that their DCE classification as benign or malignant would have been affected by the incorrect contrast injection rate. The remaining cases were excluded from the trial as a result of analysis failure for other reasons.

Window centre and width

In addition to the deviations above, 19 scans were viewed with a window width of 400 HU (protocol is 350 HU). This has no significant impact on how the nodules are visualised; therefore, all scans were included in the final analysis.

Measurement software for contrast enhancement

Site accreditation involved measurement of iodine CT number on CT scanner workstations to determine the iodine calibration of each scanner, and also on reporting workstations or picture archiving and communication systems. The measurement of iodine CT number was tested on both CT workstation and reporting workstation to ensure that no additional processing was applied to the images that might affect the trial.

Phantom scans were compared at eight different sites with three different manufacturers of scanner (seven different scanner models) and four different reporting workstation manufacturers. The radiographer QC phantom contains three inserts of varying iodine contrast concentration, equivalent to approximately 20, 50 and 70 HU (at 100 kV) embedded in a larger volume of water. The CT number, standard deviation and enhancement relative to water were compared for measurements taken on the CT scanner and reporting workstation. Measurements for three slices in the phantom were taken, with care taken to avoid air bubbles.

The maximum deviation in CT number for a given slice was 1.4 HU for the highest iodine concentration. At the clinically relevant threshold of 20 HU, the maximum deviation seen was 1.0 HU. There was no overall positive or negative trend in the values, and the differences seen were within the standard deviation (typically 6–10 HU) of the sample of CT numbers within each ROI.

There was no evidence of a difference between the measured CT number and the enhancement value for measurements taken on the CT scanner or reporting workstations.

Positron emission tomography and dynamic contrast-enhanced computerised tomography interobserver variability: site versus core read

Positron emission tomography

Nuclear medicine specialists or dual-trained radiologists read the PET/CT examinations. For the SUV, the ROI was placed using the threshold technique, as in standard practice.

Originally, 10% (n = 41 to account for potential losses due to missing data) of the total patients undergoing PET were selected for a second read by a core laboratory. Owing to high variability between the recruiting sites, documented results and the core laboratory read results, a full core read of all the PET data sets was performed. The original site reads were performed by the reporting physician at each of the study centres. Image analysis was performed using the onsite software used in routine clinical practice. All core laboratory reads were performed by a single radiologist who was not involved in the primary reads. The core laboratory read was blinded to the original diagnostic CT, the DCE-CT and the original site’s read. A ROI was defined based on the nodule size and location, with alterations made when there was a discordance in the location of the PET uptake relative to the nodule on the CT that could be attributed to motion/respiration. Quantitative assessment of the nodule uptake was performed using the maximum standardised uptake value (SUVmax) and the mean standardised uptake value (SUVmean). The nodule CT and PET characteristics were semiquantitatively graded based on visual inspection, as described in Table 3.

| Grade | Significance | PET/CT | Attenuation correction CT |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | No evidence of malignancy | No visible uptake | Round, well-defined lesion with laminated or popcorn calcification |

| 1 | Low probability of malignancy | Uptake less than mediastinal blood pool | Inflammatory features, for example air bronchograms, enfolded lung |

| 2 | Indeterminate | Uptake comparable to mediastinal blood pool | Smooth well-defined margins, uniform density |

| 3 | High probability of malignancy | Uptake greater than mediastinal blood pool | Lobulated, spiculated or irregular margins |

| 4 | Very high probability of malignancy | Evidence of distant metastases (i.e. M1 disease) | Evidence of distant metastases (i.e. M1 disease) |

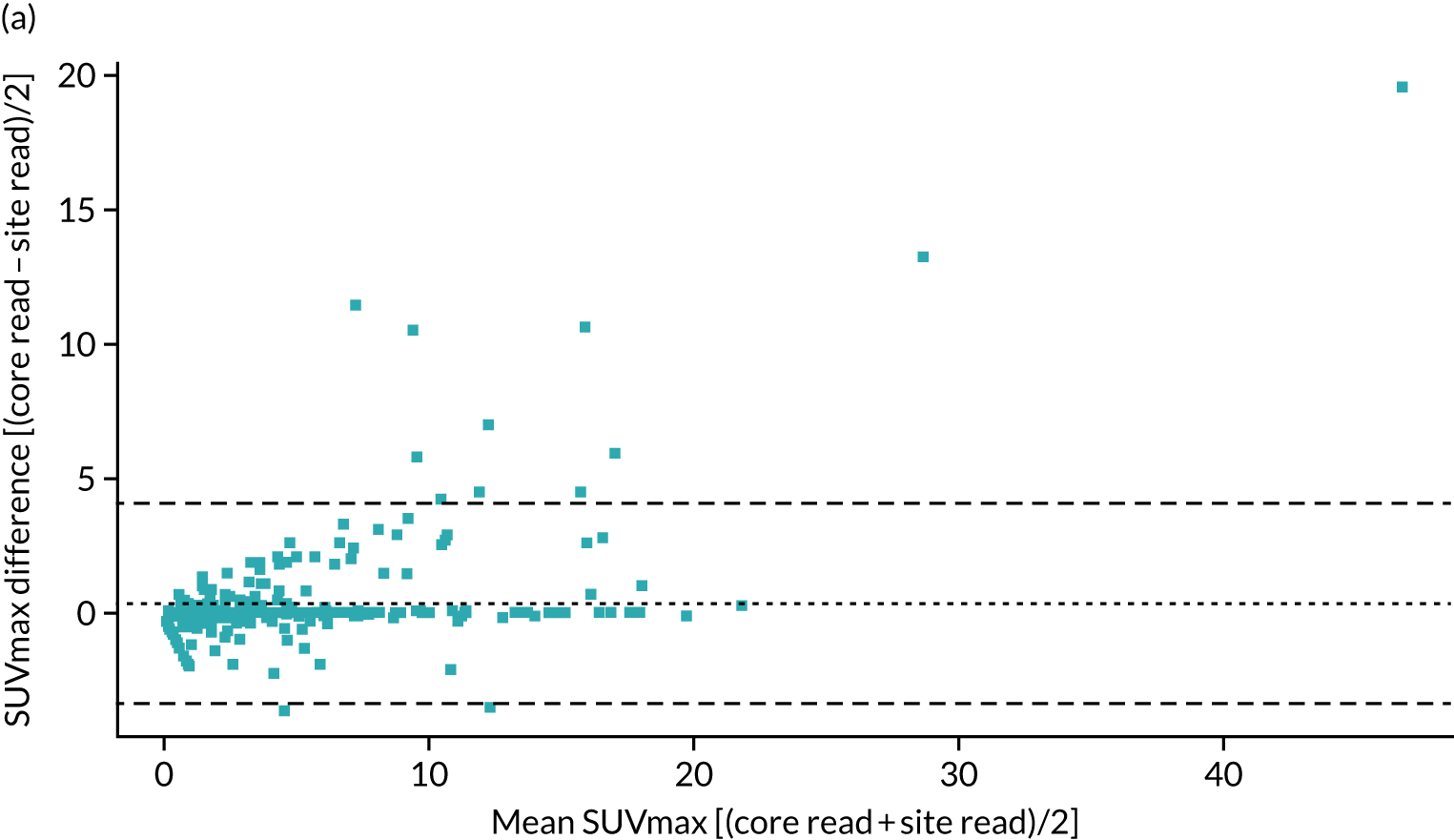

A total of 354 cases were included in the reproducibility analysis for the SUVmax, with six excluded because of lack of an identifiable nodule, multiple nodules or missing data. The SUVmax demonstrated a small, but significant, bias between the site read and core laboratory read, and high variability between the two reads with wide limits of agreement (LOAs) (mean difference 0.37, LOA –3.36 to 4.11; paired t-test p < 0.001). Despite this, when considering a threshold for the SUVmax of > 2.5 as being malignant, there was excellent agreement between the site read and core laboratory read [κ (unweighted): 0.93; p < 0.001].

As the SUVmax LOAs were wider than expected, we further reviewed the steps in the scanning and analysis. Several sites were identified to be using PSF reconstruction algorithms, which can result in an increase in SUVmax of up to 25%. Data submitted to the core laboratory were all reconstructed using the standard algorithms, but the reporting sites would have had access to both; therefore, it is possible that the values from the PSF reconstruction would have been recorded. When the 108 cases from those sites were excluded, leaving 247 cases in the analysis, the mean difference was –0.06 (LOAs –2.29 to 2.42; paired t-test p = 0.41), producing significantly improved LOAs and the loss of bias.

Figure 6 contains the Bland–Altman plots for the site and core laboratory reads for the SUVmax, with and without PSF sites included.

FIGURE 6.

Bland–Altman plot comparing the SUVmax obtained at the recruiting site with that obtained at the core laboratory. (a) Across all sites; and (b) excluding those with PSF.

A total of 339 cases were included in the reproducibility analysis for the SUVmean, with 15 cases excluded because of lack of documentation of site read of the SUVmean. There was a small, but significant, bias in the SUVmean between the site read and the core laboratory read, with wider LOAs than those for the SUVmax (SUVmean: mean difference –0.38, LOAs –4.41 to 3.67; paired t-test p < 0.001).

Intraobserver variability was also examined, using two different software packages [Xeleris™ (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) and ADW 4.4 (GE Healthcare)], with a minimum of 4 months between reads to minimise the chances of retention between scans. This showed high levels of agreement for the SUVmax (mean difference –0.04, LOAs –0.28 to –0.21; paired t-test p = 0.07), and reasonable agreement for the SUVmean, with higher variability (mean difference 0.34, LOA –1.81 to –2.49; paired t-test p = 0.06). The two outliers in both cases were nodules that lay close to the heart or to the diaphragm, making accurate measurement challenging because of the proximity of the nodule to adjacent structures, and, therefore, prone to variability.

There was excellent agreement between the sites on the visual semiquantitative grading of the PET uptake [κ (with squared weighting): 0.87; p < 0.001]. The greatest variation in scoring occurred around grade 2, which is ‘uptake equivalent to the mediastinum’. Only eight (2.3%) cases were called as equivalent to the mediastinum at the sites, whereas 41 (11.6%) cases were called as equivalent to the mediastinum at core laboratory read. Given that the SUVmax agreement was tight in and around a SUVmax of 2–2.5, which is typically equivalent to the mediastinal blood pool, this suggests that it is very subjective as to when the visual uptake becomes greater, or less, than the mediastinum.

There was fair agreement in the CT visual grading of the nodules [κ (with squared weighting): 0.33; p < 0.001], with disagreement between site read and core read most pronounced for grade 2 lesions. As the original CT was blinded to the core laboratory, but not to the site readers, it may be that subtle spiculation, lobulation or heterogeneity of attenuation not evident on the low-dose attenuation-corrected CT scan may, in fact, have been determined by the standard CT scan, causing this marked upgrade in scoring. Alternatively, it may be that determining whether there is true spiculation or simply background parenchymal lung disease causing contour irregularity is a poorly reproducible finding on CT.

The combined 18F-FDG-PET/CT assessment was classified as positive for malignancy if one of the following criteria was met:

-

grade 4 on 18F-FDG-PET/CT

-

at least grade 3 on both PET and CT appearances

-

grade 2 on PET and grade 3 or 4 on CT.

Based on this grading, there was good overall agreement on the presence of malignancy [κ (unweighted): 0.70, p < 0.001).

Based on the above, the SUVmax appears to be the most robust measurement across sites. It has both a lower mean difference and narrower LOAs than the SUVmean. Using a SUVmax cut-off point of 2.5 yielded significantly higher agreement between sites and the core read for malignancy than visual grading of the lesions. CT grading was particularly prone to high observer variability, which affected the diagnosis of malignancy in a large number of cases.

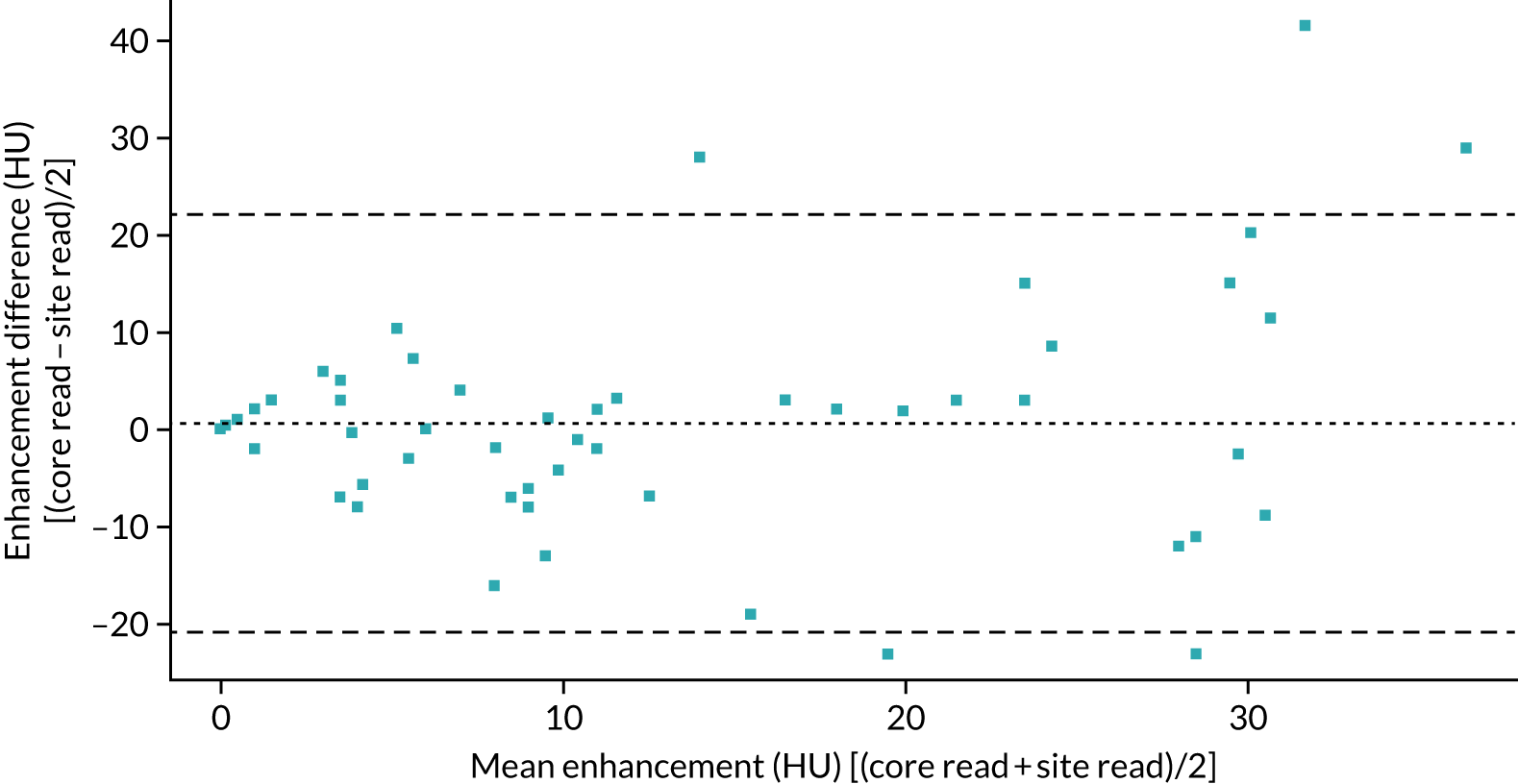

Dynamic contrast-enhanced computerised tomography

Thoracic radiologists or dual-trained radiologists read the DCE-CT. Training was given using a manual and a short video. The ROI was placed using mediastinal settings (window width: 400 HU, window level: 40 HU) in the axial plane with the largest diameter of the nodule. The two-dimensional size was measured in millimetres by taking the longest diameter of the lesion and the perpendicular diameter in the axial plane.

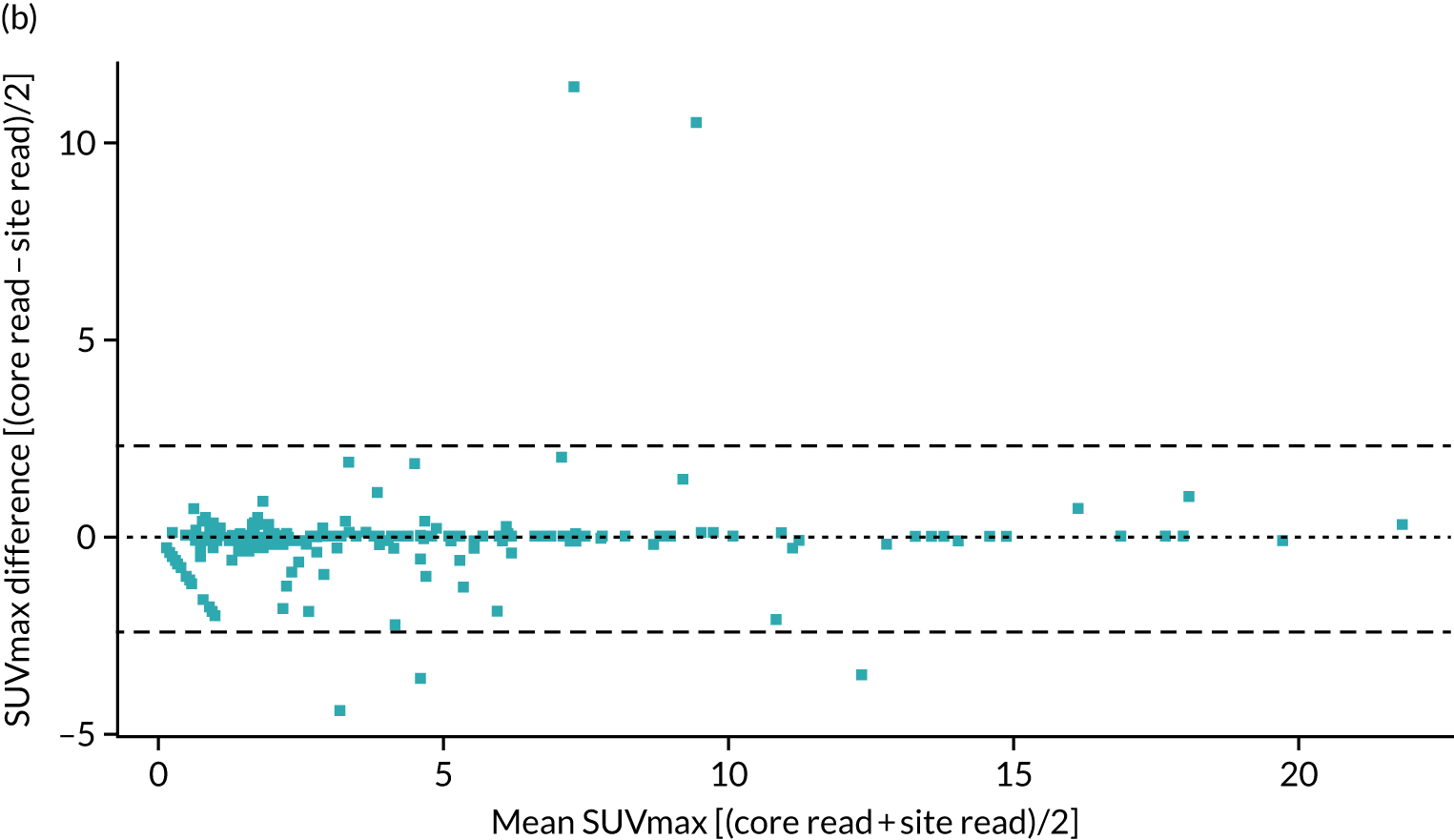

Twenty per cent (n = 66 to account for potential losses due to missing data) of the total DCE-CT scans were selected for a second read. A larger number of DCE-CT scans were chosen to reflect the fact that DCE-CT was not generally used in routine practice, and thus was potentially more prone to variability in the analysis. A training video was prepared to ensure that site readers were analysing the DCE-CT scans using a similar technique, with the technique used in the study as previously published. 45 The selection criteria were weighted to ensure that all centres had at least one scan second read and that the number of scans selected from each centre was representative of the proportion of the total scans performed at that centre. The individual scans from each centre were randomly selected. The site reads were performed using the on-site software used in routine clinical practice. All central reads were performed on a single software platform (syngo.via, Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany) by a single reader. The second reader was blinded to the original diagnostic CT, the PET/CT and the original site read. Quantitative assessment of the nodule enhancement was performed using maximum enhancement.

Maximum enhancement was comparable in 63 of the 66 cases (three cases had missing data). There was no significant difference between the site read and the core laboratory read (mean difference 2.57 HU, LOAs –34.5 to 39.6; paired t-test p = 0.29). The Bland–Altman plot for maximum enhancement is shown in Figure 7.

FIGURE 7.

Bland–Altman plot comparing maximum enhancement obtained at the recruiting site with that obtained at the core laboratory.

Considering a threshold of maximum enhancement of ≥ 20 HU as being malignant, there was good agreement between the site read and the core laboratory read [κ (unweighted): 0.75; p < 0.001].

There was no systematic bias in the values obtained by the DCE-CT central read and the sites in either the maximum enhancement of the nodules or the wash-out. There were, however, wide LOAs between the two measures, suggesting substantial variability in the technique. Further work is required to determine if this is due to differences in analysis software/scanners, or due to variations in the size and precise location of each of the ROIs at each of the time points.

Chapter 4 Diagnostic accuracy systematic review and meta-analysis

Methods

The study was prospectively enrolled in PROSPERO (CRD42018112215). The study has been reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies (PRISMA-DTA) statement. 46

The condition to be studied was the diagnostic test accuracy of SPNs. The inclusion criterion was studies examining SPNs being worked up for malignancy; studies that included participants aged < 18 years and studies of pure ground glass nodules were excluded. The intervention of interest was DCE-CT. CT scans were included as long as there was a minimum of both a pre-contrast-enhanced and post-contrast-enhanced CT data set for the quantification of the degree of enhancement. The gold standard against which the test was examined was required to be histological diagnosis of malignancy obtained from either needle biopsy or surgical resection, with benign status confirmed either histologically, or with follow-up imaging showing no growth at 2 years or resolution. We considered both prospective and retrospective diagnostic accuracy studies that contained sufficient data to construct contingency tables in order to assess true-positive, false-positive, true-negative and false-negative results.

To identify articles of interest for review, MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched from their inception until October 2018 for published studies on the diagnostic accuracy of DCE-CT in the characterisation of pulmonary nodules. The full search strategy is documented in Appendix 5. Titles and abstracts of studies retrieved using the search strategy, and those from additional sources, were all independently screened by two reviewers (Jonathan R Weir-McCall and Stella Joyce) to identify studies that potentially met the inclusion criterion. The full texts of these potentially eligible studies were retrieved and independently reviewed by the two reviewers to assess eligibility. When there was a disagreement between the reviewers, a consensus was reached through discussion. The references of the retrieved full-text articles were screened for further articles of interest; if any articles were found, these were retrieved if they had not been identified by the original search strategy.

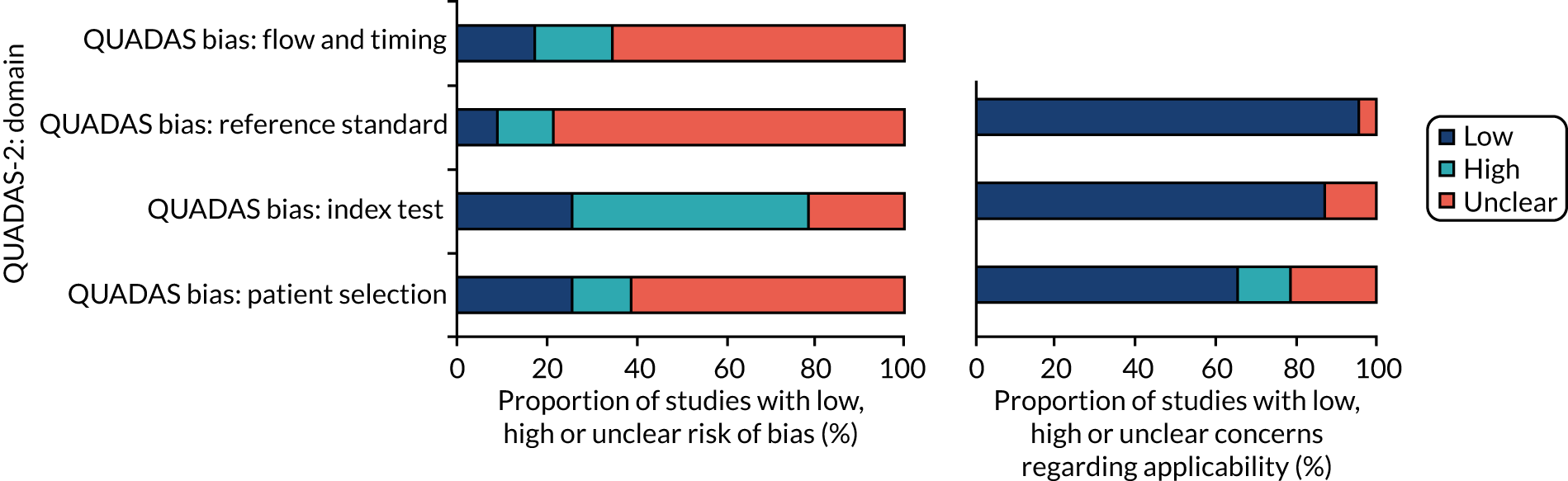

A single reviewer (Jonathan R Weir-McCall) used a standardised, pre-piloted form to extract data from the included studies for assessment of study quality and evidence synthesis. Extracted information included study population, participant demographics and baseline characteristics; details of the CT scanning hardware, scanning technique and diagnostic threshold used; study methodology; nodule size range and eventual diagnosis; diagnostic accuracy metrics; and radiation dose. Two reviewers authors (Jonathan R Weir-McCall and Stella Joyce) independently assessed the risk of bias in the included studies through the use of the second version of the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) questionnaire. 47 Discordance in the scoring of bias between the two reviewers was resolved by a third reviewer (Lena-Marie Dendl).

Two deviations occurred from the original pre-registered protocol. A size threshold was not prespecified in the original protocol, yet, during the literature review, it became readily apparent that the upper size limit included in studies varied markedly. Although the Fleischner9 and BTS8 guidelines state that the upper limit of a SPN size is 30 mm, we allowed up to 40 mm for the purpose of this analysis because of the high quality of many of the studies using this threshold, and the granularity it would provide the review. An analysis was performed to compare studies with nodules of > 30 mm with studies with nodules of ≤ 30 mm, as described in Statistical analysis, to determine the effect this might have on the results. The original protocol called for the analysis of SPNs; several studies recruited based on the detection of a SPN, but, if an additional nodule was detected at the time of the index test, they included, analysed and followed up both lesions. Despite not being SPN studies, these were included in the analysis as they reflect routine clinical practice whereby new lesions can frequently be detected on interval studies, or picked up when CT is performed following detection of a nodule on chest radiographs.

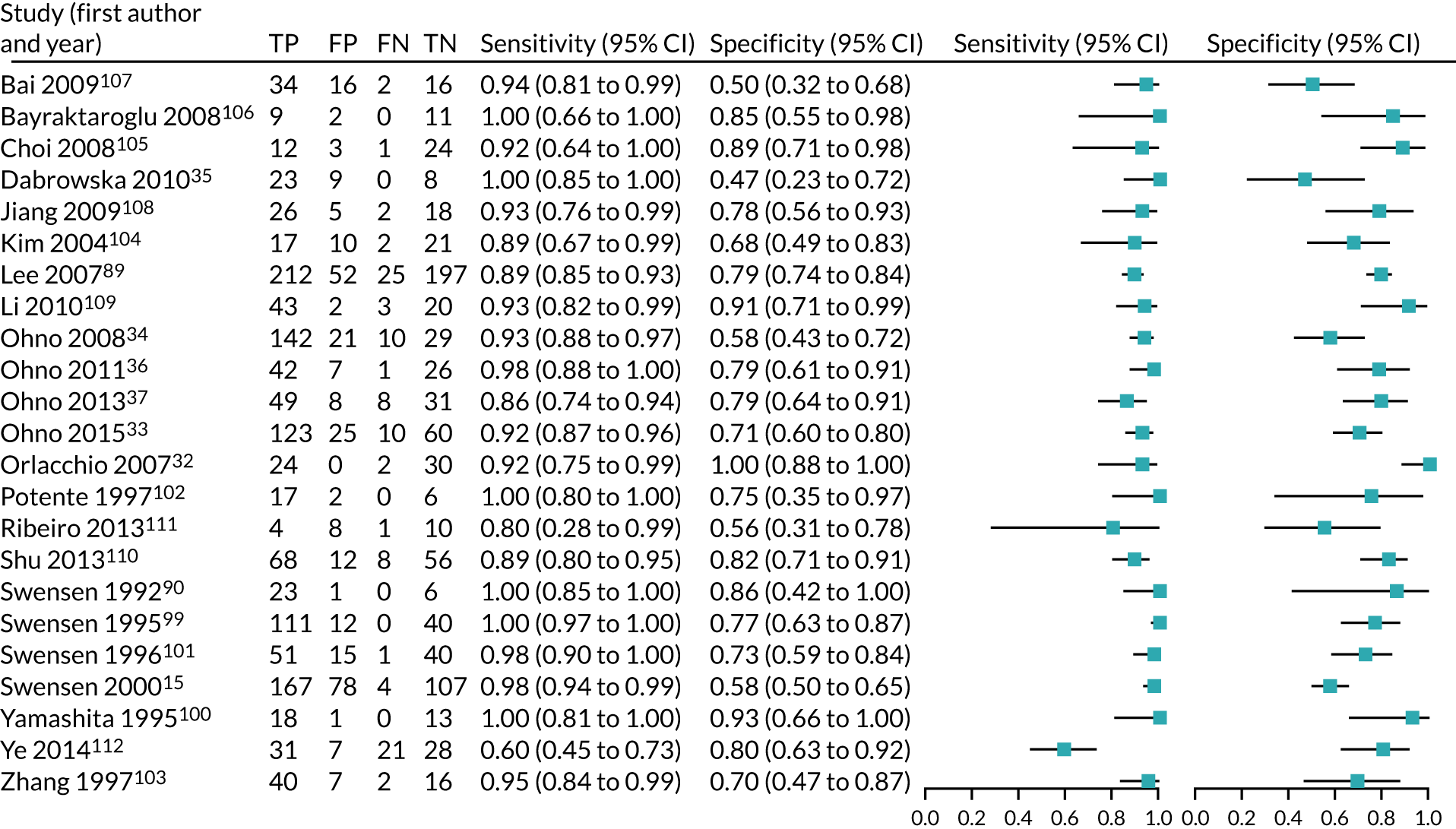

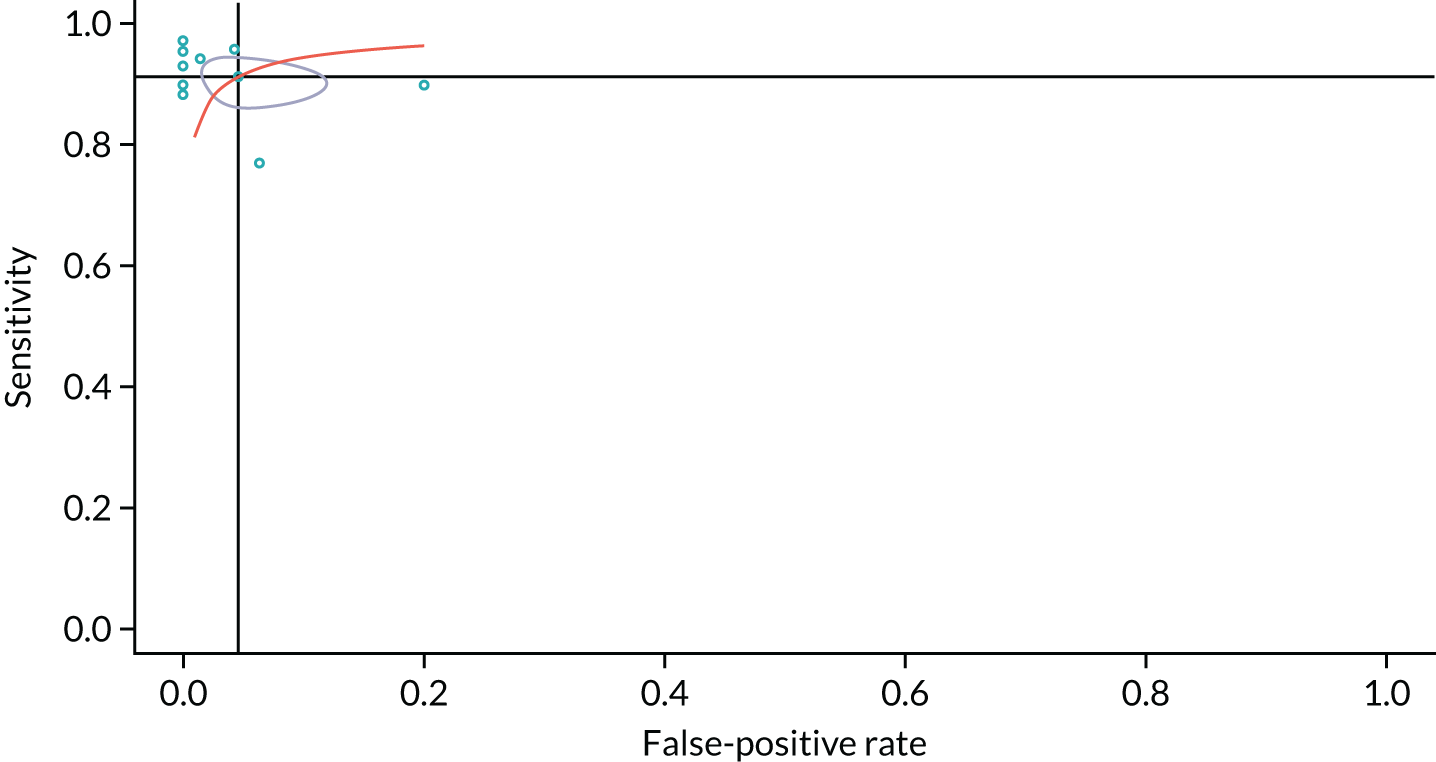

Statistical analysis

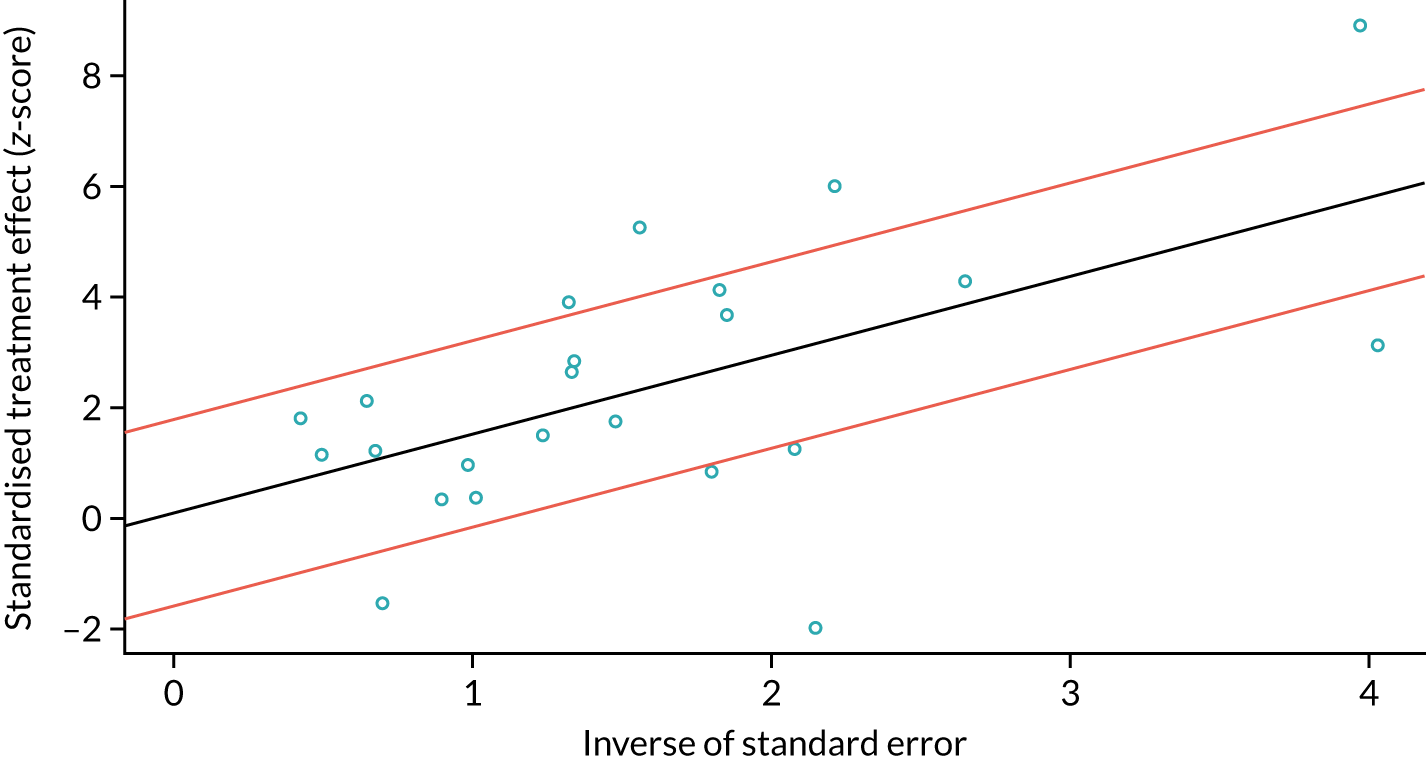

Numbers of true positives, false positives, true negatives and false negatives were extracted from the studies and used to form 2 × 2 contingency tables, which were used to derive sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLR), negative likelihood ratio (NLR) and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR). Results were pooled using the lme4 package in R (Rstudio, version 1.1.463, RStudio, Inc. Boston, MA, USA; R, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) to perform a bivariate binomial random-effects meta-analysis. 48 This uses a binary (logit) generalised linear mixed-model fit by maximum likelihood (using a Laplace approximation). Bivariate summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curves were constructed using the bivariate random-effects model outputs to populate the SROC plot in Review Manager version 5.3. (RevMan, The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). To identify potential sources of heterogeneity, we stratified a secondary analysis into subgroups according to characteristics such as sample size, lesion size, risk of bias (low vs. high/indeterminate), diagnostic thresholds and whether or not the diagnostic threshold was prospectively set. These were included as covariates, in turn, in a meta-regression analysis, with analysis of statistical significance between models performed using a likelihood ratio test of nested models. For sample size, the threshold at which to split the data was arbitrarily set at 100, to represent larger samples that were less likely to be prone to bias due to outliers. For mean nodule size, the sample was split at 20 mm, to provide a reasonable split of the data. For maximum nodule size, the data were split based on whether or not the study included nodules of > 30 mm, as the 30-mm diameter is considered by most guidelines as the upper threshold for a lesion to be called a nodule, after which it is considered to be a mass. The effect of publication date was examined by splitting on the median (2008), with studies published in the previous decade considered to be more representative of modern CT technology. In studies reporting the diagnostic accuracy of multiple thresholds, the optimal threshold was used in the primary analysis.

In the secondary analyses examining different thresholds, studies were included in each subgroup analysis if they had reported the threshold of interest. Thresholds with one or two studies reporting the same threshold were not considered for meta-analysis. To test for study publication bias and heterogeneity, a Galbraith plot was created to examine the interaction between the efficient score and variance, with the Harbord test used to test for funnel plot asymmetry. 49 All statistical analyses were performed using RStudio version 1.1.463. Forest plots and SROC curves were generated using RevMan version 5.

Results

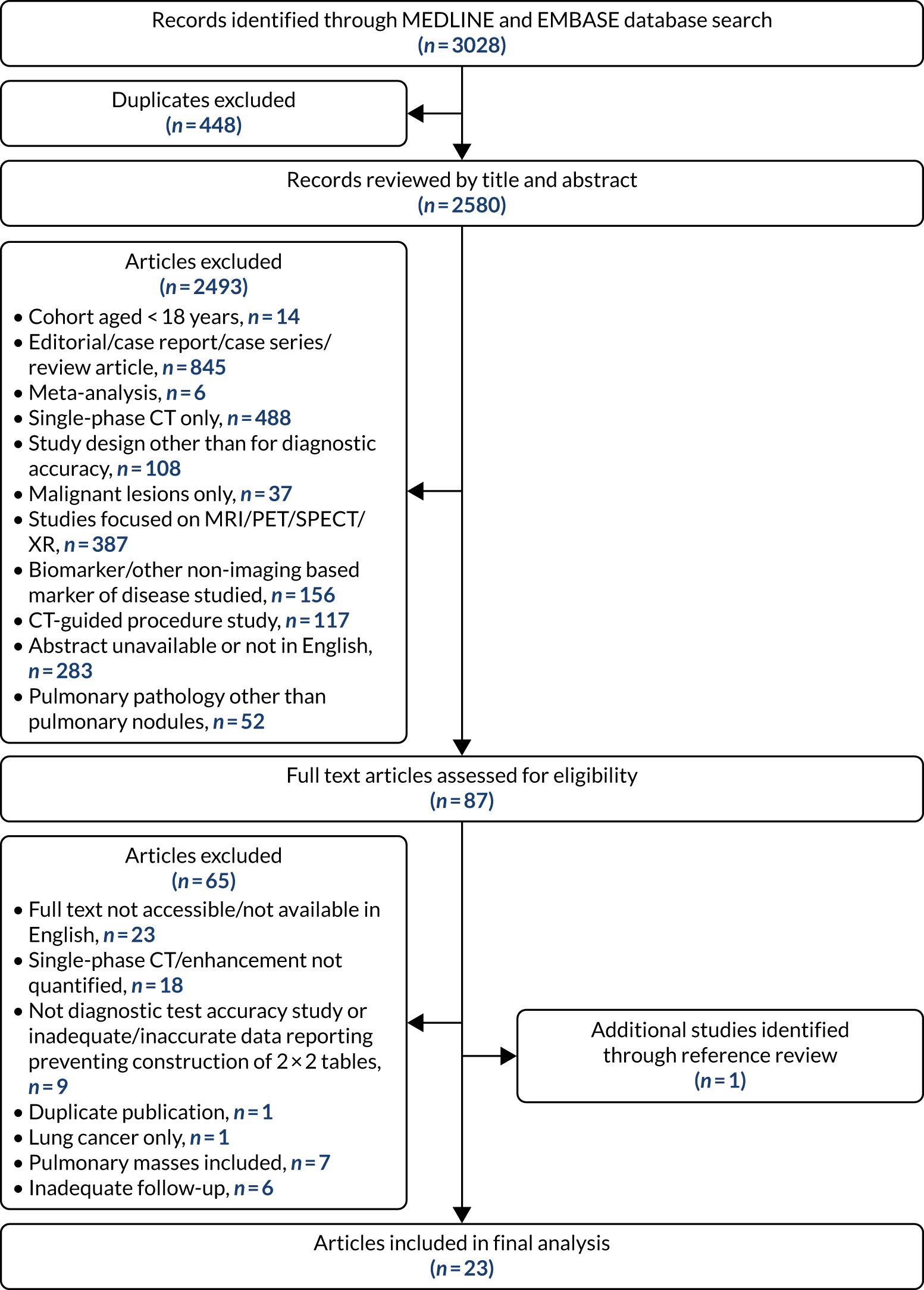

Of 3028 potential papers identified by the literature review, 22 met the inclusion criterion. An additional study was located from the references of the included papers, resulting in 23 studies in the final analysis. Figure 8 details the study flow diagram of the studies identified and screened for eligibility, and the reasons for study exclusion.

FIGURE 8.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the papers identified by the literature search, screened for eligibility and included in the final study. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SPECT, single-photon emission computerised tomography; XR, X-ray.

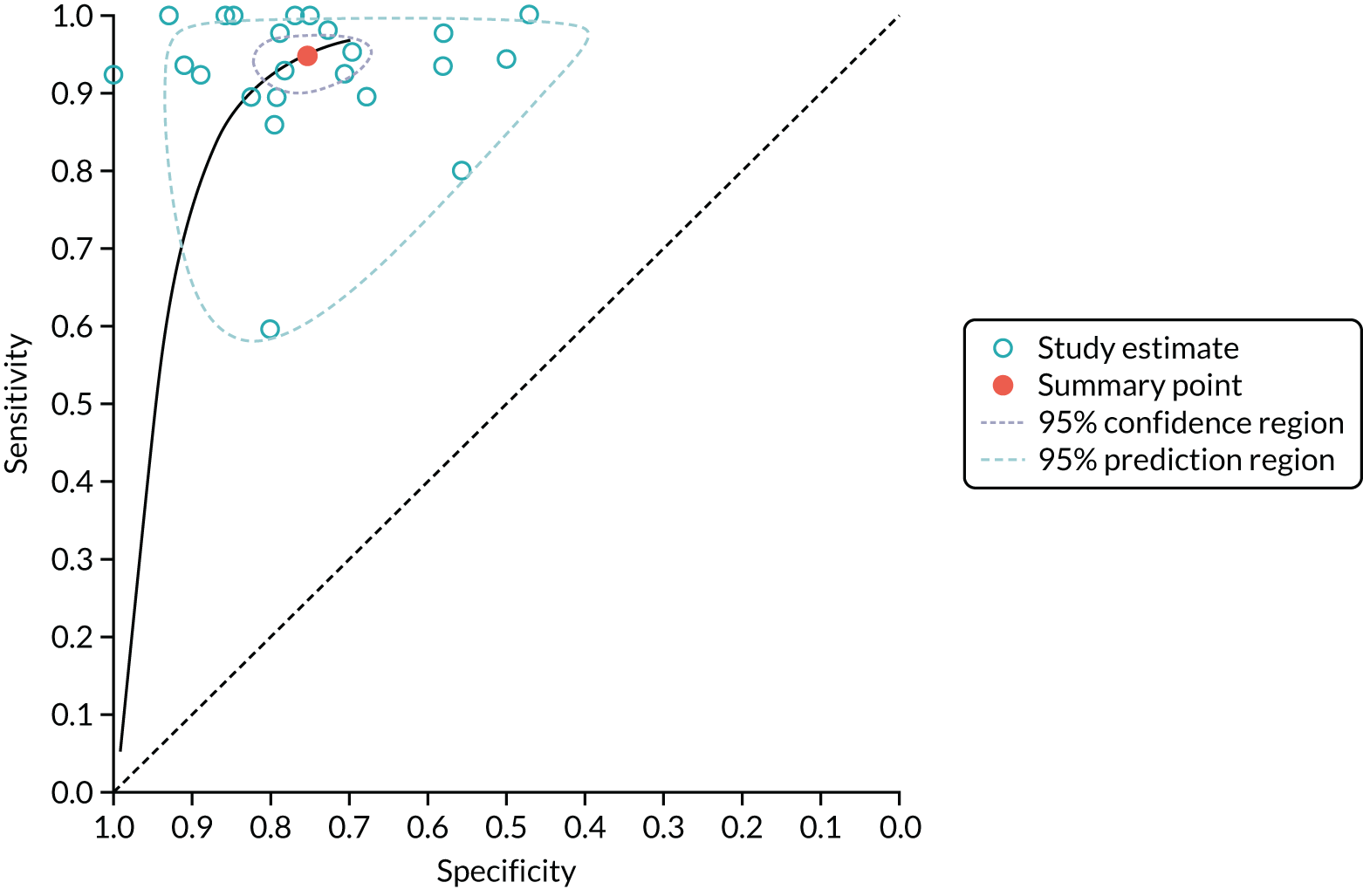

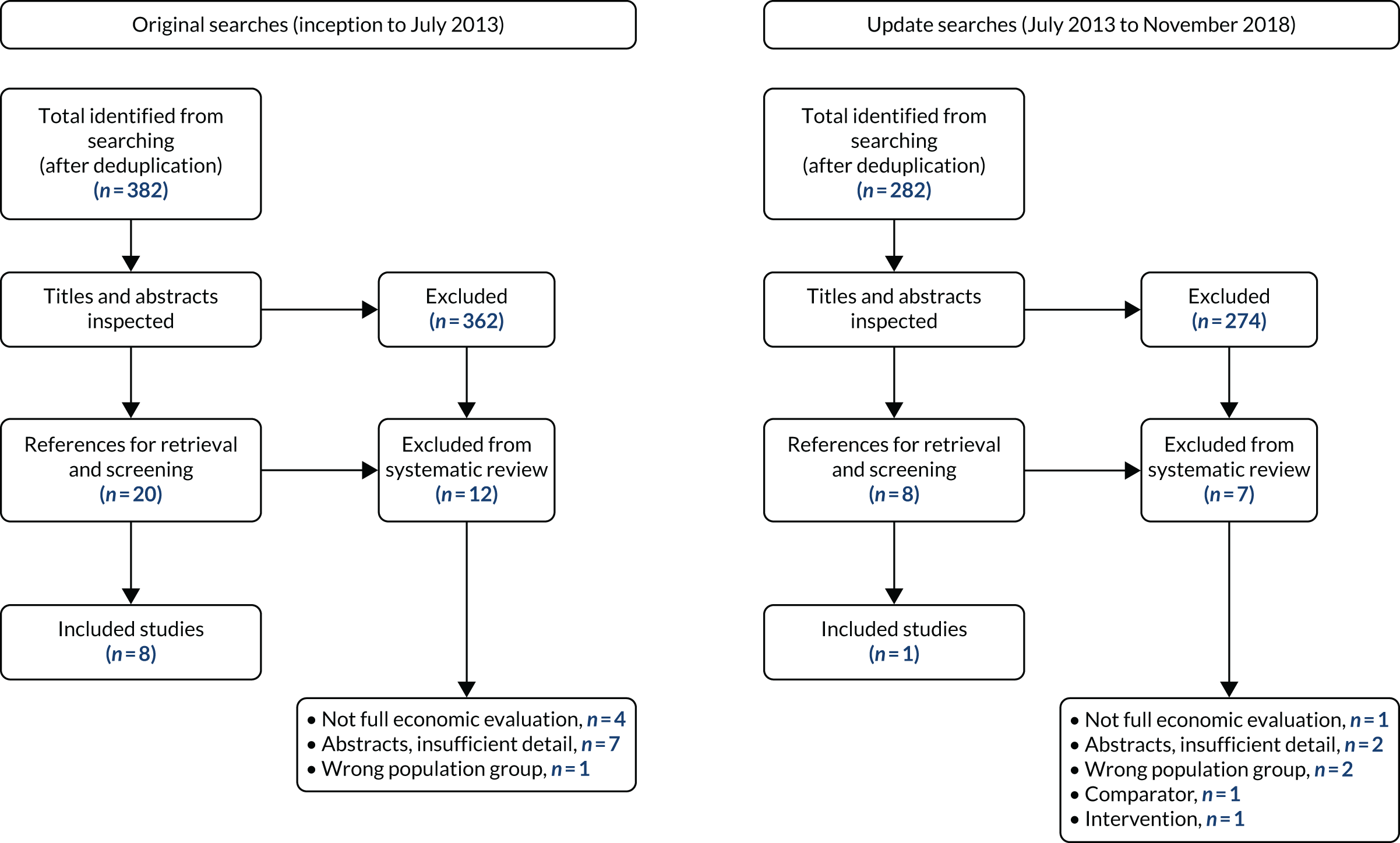

The 23 included studies incorporated data from 2397 patients with 2514 nodules. Out of 2514 nodules, 1389 (55.3%) were malignant. The studies were predominantly retrospective single-centre studies. Appendix 5, Tables 31 and 32, details the study characteristics of each of these studies and the scanning technique, injection protocol and reconstruction algorithm used in each.