Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number DTC-RP-PG-0311-12001. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The final report began editorial review in May 2019 and was accepted for publication in March 2021. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 O’Brien et al. This work was produced by O’Brien et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 O’Brien et al.

SYNOPSIS

Introduction

Lewy body dementia (LBD) is a term used to describe two closely related conditions: dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD). They form the second most common neurodegenerative dementia (after Alzheimer’s disease), but it is recognised that they are underdiagnosed. Diagnosis has important implications for management, as those with LBD present with a range of variable clinical features, including cognitive impairment, motor symptoms, autonomic symptoms, sleep problems and neuropsychiatric features.

We undertook this programme because little is known regarding the prevalence or diagnostic practice of LBD in the UK and, although national management guidelines [e.g. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 20181] do recognise the importance of both DLB and PDD and make some limited management recommendations, there are no systematic approaches to management or recognised care pathways. DIAMOND-Lewy (Improving the DIAgnosis and Management of Neurodegenerative Dementia of Lewy body type) was a comprehensive, multidisciplinary 5-year programme of work seeking to investigate and implement ways to improve both the diagnosis and management of LBD (i.e. both DLB and PDD) within the NHS.

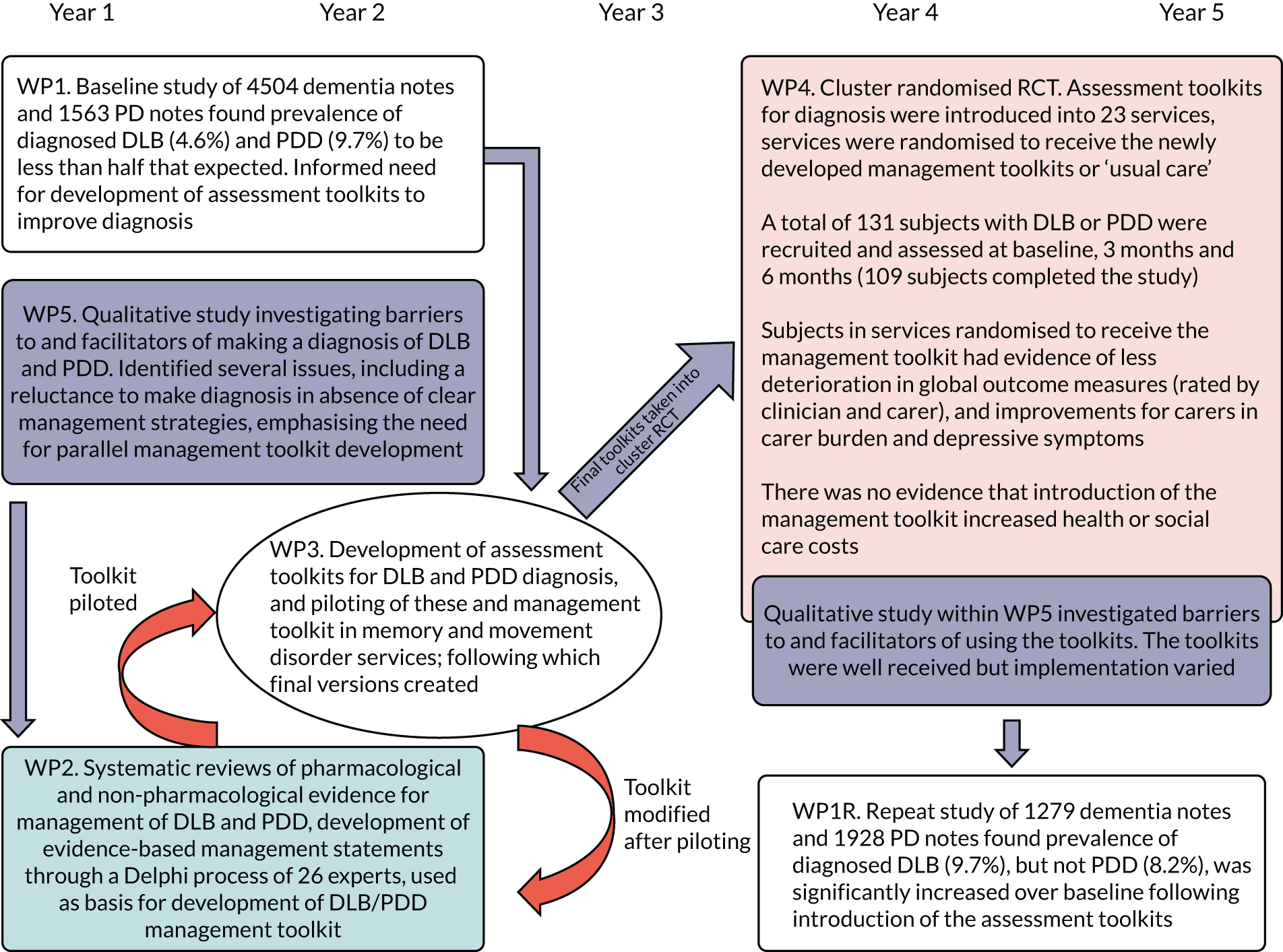

We achieved this through a number of interlinked work packages (WPs), with a very strong patient and public involvement (PPI) core running throughout the programme. In this synopsis, we first describe our approach to PPI and how this influenced the design of the programme. In WP1, we undertook a retrospective case note study to investigate current practice in secondary care NHS services with regard to the diagnosis and management of LBD. In WP2, we undertook systematic reviews of pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of LBD and used this evidence, supplemented by a Delphi study of expert clinicians, to produce an evidence-based management toolkit. In WP3, we developed assessment toolkits for the diagnosis of LBD and, incorporating the management toolkit from WP2, piloted these assessment and management toolkits in routine NHS memory assessment and movement disorder services. In WP4, we introduced the assessment and management toolkits more broadly within a pilot cluster randomised trial. WP5 was a series of qualitative studies with three components: (1) an investigation of the barriers to and facilitators of making a diagnosis and managing LBD, (2) exploration of views on the assessment and management toolkits and (3) exploration of implementation of the assessment and management toolkits in clinical practice. Finally, in WP1 repeated (WP1R), we undertook a repeat assessment of DLB and PDD diagnostic rates following introduction of the assessment toolkits in some of the same services that had participated in WP1.

A research pathway diagram showing how these WPs linked together is provided (Figure 1). Each WP will now be discussed in turn after a description of the PPI core running throughout the programme.

FIGURE 1.

Research pathway diagram. PD, Parkinson’s disease; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Patient and public involvement throughout the DIAMOND-Lewy programme

Introduction

Patient and public involvement is seen as fundamentally important to the quality and relevance of research. In the light of calls for greater transparency and consistency in reporting PPI, we have followed the GRIPP2-SF (Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public 2–short form) reporting guidelines, highlighting the impacts of PPI and critically reviewing our approach to PPI. 2–4 Much of this section of the report was drafted collaboratively with members of the PPI group.

Aim

The aim was to use PPI to inform all phases of the study from patient and carer perspectives.

Methods

Patient and public involvement in this programme started very early, during the development of the proposal, with one PPI member (Derek Forster) being a co-applicant. Once the programme started, we established a PPI group that met regularly throughout the programme. Potential volunteers were sought through a public meeting organised by the North East Dementias and Neurodegenerative Research Network (DeNDRoN) in July 2013 and through the existing networks of Derek Forster and the DeNDRoN PPI co-ordinator. Three PPI representatives agreed to join the group with Derek Forster, and all four members contributed throughout the programme. All members’ lives have been touched by neurodegenerative diseases, either as a patient or as a carer. In addition, members were motivated by their desire to ‘give something back’, interest in medical research and enthusiasm to help progress research into LBD. Experience of PPI varied. One member had been involved in PPI for > 10 years; however, for another this was their first PPI experience. All members received training on research through DeNDRoN. This was supplemented by an introductory session on LBD by Ian McKeith. One of the co-applicants (CB) facilitated the group and meetings were held on university premises. We followed the INVOLVE guidance on reimbursing group members for their time and expenses. 5

The first PPI meeting focused on how to achieve the desired aim. This led to agreement that the group would:

-

share personal knowledge and experience of DLB, Parkinson’s disease (PD) and PDD

-

comment on the practicalities and pressures that participating in the research could create for patients and carers (safeguarding)

-

ensure that information was user-friendly and did not alarm potential participants

-

ensure that a patient/carer focus was included in developing the management toolkit

-

contribute to study newsletters.

Members agreed that the timing and duration of PPI meetings should reflect the needs of the programme. Although the group thought it was unnecessary to link individual PPI members to specific WPs, they were keen to embed PPI into the programme management structures. To achieve this, Derek Forster attended both the PPI group and the Programme Management Group (PMG) and Valerie Argent joined the Programme Steering Committee (PSC) as a lay member.

In addition to the PPI group, two PPI workshops were convened to inform the development of the management toolkit (see Work package 2: development of management toolkits for Lewy body dementia). Potential participants were identified by team members through patient and carer interviews conducted during WP5 and local contacts. One member of the PPI group (Anne Lister) also attended the PPI workshops for WP2. The content of the workshops is described in Work package 2: development of management toolkits for Lewy body dementia.

Outcomes of patient and public involvement

The PPI group met 20 times, with full attendance at nearly all meetings. The number of meetings ranged from one to five per year. Members often prepared for meetings by reading documents, and commented on documents by e-mail between meetings. The initial expectation of group members and the research team was that the group would adopt a consultation approach, with an emphasis on ensuring that documents would make sense to patients and carers, including advising on the feasibility and acceptability of the study procedures. Over time, however, the group grew in confidence and were proactive in developing and expanding their role, adopting collaborative and user-controlled approaches at different times. 6 For example, rather than commenting on the public version of the study newsletter (which was initially drafted by the research team), members took ownership of the newsletter by redesigning the layout, introducing a new structure and writing much of the content themselves.

A user-controlled approach was adopted to obtain feedback on participants’ experiences of taking part in the pilot trial. Rather than inviting a single participant to describe their experience at the PPI dissemination event in the North East, members were keen to present a broader range of experiences. This led to the development and inclusion of some open questions about study participation with the letter inviting participants to the PPI event. Overall, 28 detailed responses were received. Two members of the group (VA and AL) reviewed and collated the information and presented their findings at the PPI dissemination event. Key themes were the interpersonal skills of the interviewers and having an opportunity to talk about their situation. Everybody found the home visits convenient and > 70% of respondents said that they would be willing to take part in a similar study. These comments provided useful feedback for the researchers and highlight aspects of study design, which may maximise recruitment and retention in future studies. Furthermore, the comments highlighted the lack of support available after diagnosis, suggesting new avenues for research and intervention.

Key activities undertaken by both the PPI group and the PPI workshops in WP2 are related to the research cycle7 and are summarised in Table 1.

| Stage of the research cycle7 | Example outcomes |

|---|---|

| Identifying and prioritising the research agenda | Future research priorities were highlighted by the PPI workshops for WP2 and the feedback collected for the PPI event |

| Study design |

Advised on consent procedures for clinic observation (WP5) and for notes review (WP1) Reviewed outcome measures to ensure that they were appropriate and relevant (WP4) |

| Development of the grant proposal |

Reviewed draft proposal Contributed to lay summary Included as a co-applicant (DF) |

| Undertaking/managing research |

Reviewed PIS and consent forms (WPs 1, 2, 4 and 5) Advised on most appropriate order of questions in assessment toolkit (WP3) and outcome measures (WP4) Shared experiences of PD and LBD with a new researcher to raise awareness and understanding prior to data collection (WP5) Advised on eliciting feedback on the toolkits (WP5) Identified key principles to underpin the management toolkit (WP2) Advised on appropriate ways of thanking study participants (WP4) Wrote a thank-you letter for study participants (WP4) Member of PMG (DF) Member of PSC (VA) |

| Analysing and interpreting |

Reviewed qualitative interview data (WP5) Collected and analysed data on participants’ experiences of the pilot trial (WP4) |

| Dissemination and implementation |

Produced biannual programme newsletters Produced lay summaries of published papers for the programme website Drafted annual progress reports and this section of the report Contributed to the organisation of PPI events Presented at the North East PPI event |

| Monitoring and evaluation |

Reflected on their role Made recommendations for PPI in future research |

Having highlighted some of the successful contributions made by PPI during the programme, we also acknowledge that its impact in some areas was limited. Owing to uncertainty about which outcome measures would prove sensitive to changes resulting from the introduction of the management toolkit, the team proposed a range of measures. Reconciling the perspectives of PPI members and those of the research team was sometimes challenging, for example in relation to the number of outcome measures and the perceived burden of these on participants, and in relation to the wording of questions in the assessment toolkit, some of which were considered to be inaccessible to patients and carers. However, there was limited scope to make changes because they were validated measures.

Discussion and conclusions

Using more than one approach to PPI in the programme proved effective. While the PPI group provided continuity throughout the programme, the workshops enabled the inclusion of a broader range of perspectives, including those of people with dementia. By combining a ‘fully intertwined’ approach to PPI and the ‘one-off’ approach for the workshops, we were able to include patients and carers who did not wish to commit to ongoing input. 8 The inclusion of PPI members on the PMG and PSC ensured opportunities for communicating with the full team. The detailed understanding of the programme developed through the PPI group, facilitated the ability of the PPI members to contribute confidently and effectively to meetings.

All members of the PPI group continued to be involved throughout the programme. This continuity helped the group to develop in confidence and expertise. Although we have benefited from stable group membership throughout the programme, members recognise that this may be unusual, as the health or circumstances of PPI members may deteriorate over a 5-year period, particularly if they are directly affected by the condition.

A limitation of the PPI group was the homogeneity of members in terms of ethnicity and class, and the lack of ability to alter some validated questions that members thought contained complex and inaccessible terms. Previous studies have emphasised the challenges of ensuring diversity in PPI, in particular the inclusion of people with dementia. 9 None of the members of the PPI group had dementia (although two had PD). Although caring for a spouse with LBD clearly provides significant insight into living with the condition, this is not the same as first-hand experience. 9 Despite the efforts of the DeNDRoN PPI co-ordinator, no people with dementia were identified for the PPI group. This partly reflects the low diagnostic rates and delays in diagnosing LBD (see Work package 1: baseline study of the diagnosis and management of Lewy body dementia). The situation was exacerbated by the high demand for PPI members in Newcastle upon Tyne, a Centre of Excellence in LBD research.

Reflections

Recent publications on PPI have emphasised the need for increased understanding of effective approaches to PPI. 4,8,10 Unfortunately, we did not obtain formal feedback from workshop participants, although the attendance of several participants at the subsequent PPI dissemination event suggested an ongoing interest in the programme. The perception of the PPI group was that although not everyone in the research team initially recognised the potential value of PPI, their contributions were increasingly valued as the programme progressed. Although no formal evaluation or opportunities for reflection were planned at the outset, the process of drafting newsletters, giving presentations at the PPI event and drafting this section for the final report prompted the group to recognise their wide-ranging contributions and reflect on their experiences of this approach to PPI. Key factors thought to contribute to the success of the PPI group were as follows:

-

having a simple two-page overview of the programme to help members understand the different WPs and how they were interlinked

-

having regular meetings to maintain interest and understanding of the programme

-

working together in a group and sharing ideas

-

having a facilitator

-

attending to practical issues, for example ease of access, free parking, timely reimbursement of expenses and flexibility over the timing of meetings

-

having access to a computer and large screen to enable the group to produce or edit documents collaboratively during meetings

-

having stability of group membership

-

ensuring that meetings were business-like, but enjoyable.

Several of these factors are consistent with those identified in previous studies. 8 Three suggestions were made for facilitating PPI contributions to future projects. The first concerned the importance of all team members recognising and valuing the different perspectives offered by PPI members, even when these challenged their own views. The second related to greater clarity over the responsibilities and remit of the PPI member within the PSC and finally the group emphasised the need for the chairperson of the PSC to explicitly invite comments from the PPI member.

After 5 years, members of the PPI group are surprised at their continuing levels of enthusiasm and commitment. Reflecting on this, members attribute their loyalty to the relevance of the programme to their lives, compatibility of members and the appreciative facilitation. In terms of personal benefit, members have valued the opportunity to keep up with research, maintain mental agility and develop new skills. Although the programme has now ended, the PPI group is planning to share their experiences to wider audiences through a conference presentation and an article for lay audiences.

In summary, the inclusion of PPI throughout the programme was extremely valuable and added very positively to the design of the DIAMOND-Lewy programme, its conduct and outcome, with PPI members making key contributions that affected the design and administration of the assessment and management toolkits. PPI also played a key role in dissemination and feedback of the study to participants, with members taking ownership of content for regular study newsletters, designing suitable methods for thanking participants and playing key roles in the co-design and delivery of the programme dissemination events.

Work package 1: baseline study of the diagnosis and management of Lewy body dementia

The aim of this WP was to undertake a baseline study of diagnosis and management of LBD in NHS secondary care services.

Introduction

The accurate recognition of dementia and the diagnosis of dementia subtype helps ensure appropriate management, and are central to improving patient care. LBD, comprising both DLB and PDD, is the second most common cause of neurodegenerative dementia in older people, accounting for between 15% and 20% of all cases of dementia, according to autopsy studies. 11 However, clinical and epidemiological studies suggest rates of only 5–7%. 12 This suggests that a considerable number of people with LBD go undiagnosed and so are not offered potentially beneficial management strategies. More worryingly, incorrect diagnosis risks inappropriate management with drugs such as antipsychotics, which, even at a low dose, can have serious side effects and cause mortality in those with LBD. 11

Currently, the proportion of cases of dementia diagnosed with DLB and PDD in NHS secondary care services is not known, nor has there been any systematic study of diagnostic practice or management in secondary care, although a US-based retrospective survey indicated frequent erroneous diagnosis and delays to a final correct diagnosis. 13 This is an essential first step to improving care. Therefore, this WP sought to establish the baseline for current diagnostic rates for DLB and PDD, providing a foundation for the other WPs. The WP was split into two parts: (1) WP1A examined diagnostic and management practice for DLB and took place in old age psychiatry and memory services, and (2) WP1B examined diagnostic and management practice for PDD. This latter element was undertaken in movement disorders services run by neurologists and geriatricians.

Initially, the plan had been to undertake WP1 solely in services in one geographic region of the UK (the north-east of England). However, there arose an opportunity to undertake a much more informative two-region study, whereby diagnostic rates for DLB and PDD could be ascertained in both the North East and East Anglia, two representative but clearly separate UK regions. This change also allowed some comparison of whether or not any variation in diagnostic rates and practice existed between regions.

Work package 1A: baseline study of the diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies

Methods

This WP took place over the first 2 years of the programme, with the aim of comparing rates of current clinical diagnosis of DLB with expected prevalence figures, confirming the accuracy of DLB diagnosis and comparing diagnostic and management pathways of those with DLB with those with non-DLB dementia. The hypothesis was that the actual rate of diagnosis of DLB would be ≤ 5% and that pathways to diagnosis of DLB would be longer and more complex than for non-DLB dementia.

The study had two phases: (1) a case note-screening phase to obtain information on consecutive referrals to services and (2) a phase involving detailed case note examination by clinical members of the research team (specialty registrars). Ethics approval was obtained for both phases from National Research Ethics Service Committee North East – Newcastle and North Tyneside 1 (reference 13/NE/0268). In addition, we obtained approval from the Confidentiality and Advisory Group to allow the extraction of some information during phase 1 without the explicit consent of the person with dementia [reference CAG 8.03(PR8)/2013].

We included nine old age psychiatry/memory services across four NHS trusts (two in East Anglia and two in the North East). Approvals were obtained from all trust research and development departments. Referral lists were obtained over an 18-month period and consecutive case notes screened by the research team, with key data extracted, including age, sex, diagnosis and Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score. Those with a DLB diagnosis who were alive and felt to be well enough by the clinical team (105/207 cases identified) were approached for their consent to be included in a more detailed study of their notes, with the extraction of information regarding diagnostic and management pathways collected using a standardised case report form. To describe the management pathway for each participant, data were collected on the use of services, spanning several years of clinical records before and after final diagnosis. Data collected included the number of appointments before and after diagnosis, and the number and type of diagnostic investigations undertaken before and after diagnosis.

For each DLB participant who consented, a non-DLB control participant was recruited by selecting the next participant seen in the respective service who was diagnosed with non-DLB dementia, matched for age (± 5 years), sex and MMSE score (in three bands: 0–10, 11–20 and 21–30) and who consented to participate. To assess the accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of DLB, a panel of three expert clinicians (not involved in the original diagnoses) independently reviewed clinical documentation and applied the 2005 international DLB consensus criteria to each case,14 with a primary diagnosis of probable or possible DLB taken as agreement with a clinician diagnosis of DLB. The expert panel agreed with the clinical diagnosis in 99% of cases of DLB (74/75) and 97% of cases with non-DLB dementia (72/74). One DLB case was excluded because the panel felt that there was insufficient evidence to assign any dementia subtype. Two non-DLB cases were excluded: one because the panel felt that the case had a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and the other because the diagnosis was thought most likely to be PDD.

The data on use of services were combined with unit cost data taken from routine sources, including NHS reference costs15 and Personal Social Services Research Unit costs. 16 This enabled the cost of service use to be estimated and comparison between the cost of pathways to diagnosis and post-diagnosis care for DLB participants compared with control participants. Full details of the methods for this are included in Appendix 1. This study (and WP1B) were approved by the North East – Newcastle & North Tyneside 1 Research Ethics Committee (reference 13/NE/0268) and the Confidentiality and Advisory Group [reference 8.03(PR8)/2013].

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were assessed using t-tests, with chi-squared tests used for categorical data. Differences in costs between DLB and non-DLB participants were explored using independent-samples t-tests with unequal variance for normally distributed variables, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous non-normally distributed variables and chi-squared tests were used to explore differences in proportions. Differences in average cost between those with DLB and controls in the costs of diagnosis and of post-diagnosis treatment were estimated using marginal effects from a generalised linear model of costs. The generalised linear model was specified with a gamma distribution and a log-link function to account for skewness in the distribution of costs.

Results

We identified 9449 consecutive referrals, of whom 4504 received a diagnosis of dementia. Of those patients receiving a diagnosis of dementia, 207 (4.6%) received a diagnosis of DLB and of these, 74 DLB patients and 72 non-DLB dementia control patients consented for more detailed study of their notes (see Appendix 1, Table 8, for details of cohort characteristics).

Dementia with Lewy bodies was diagnosed in 4.6% of all those with dementia and there was evidence of a difference in diagnostic rates between the two regions, with the rate in the North East being higher (5.6%) than in East Anglia (3.3%) (χ2 = 13.6; p < 0.01). There were differences in the number of core diagnostic features for DLB between the North East and East Anglia, with more clinical features being present in DLB cases diagnosed in East Anglia, suggesting a higher ‘threshold’ for diagnosis, which would be consistent with the lower rates of diagnosis. Use of biomarkers, such as dopaminergic imaging, was also significantly different between the two areas, with the use of biomarkers being much less common in East Anglia. Overall, there was evidence of an impact of age, with younger participants taking longer to receive an accurate DLB diagnosis than older patients. Those with DLB were more likely to have received another diagnosis before DLB (mean alternative diagnoses before final dementia diagnosis 1.1 vs. 0.6; p = 0.003). DLB participants also had significantly more clinical assessments and imaging tests prior to their diagnosis than those with non-DLB dementia (Table 2). Data on costs were estimated over a time of 6.4 years for DLB participants compared with 5.1 years for non-DLB participants. Overall, the average cost of care for DLB participants was £6557, compared with £3425 for non-DLB participants [mean difference £2868, 95% confidence interval (CI) –£68 to £4013; p = 0.055] (see Appendix 1, Table 9). After controlling for sex, time since diagnosis, total resource use time and other patient characteristics, having a DLB diagnosis resulted in an increase of £3600 in total costs compared with non-DLB participants (p < 0.001). For DLB participants, medical history costs represented the largest contribution, with an average across participants of 40% of total costs compared with 27% for non-DLB participants (p = 0.042) (see further details in Appendix 1, Tables 10 and 11).

| Results: regional diagnostic variation | North East, n | East Anglia, n | Statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core features of DLB at time of diagnosis (mean) | 1.5 | 2.1 | –2.78 (Student’s t-test) | 0.007 |

| Suggestive features of DLB at time of diagnosis, including DaT scans (mean) | 0.8 | 0.4 | 2.63 (Student’s t-test) | 0.0011 |

| Abnormal DaT scans prior to diagnosis | 24 | 1 | 12.9 (chi-squared test) | 0.001 |

| DaT scans prior to diagnosis (including normal) | 31 | 1 | 20.6 (chi-squared test) | < 0.001 |

| Total diagnostic features (core and suggestive) of DLB at time of diagnosis | 2.4 | 2.6 | 0.80 (Student’s t-test) | 0.42 |

| Time between first secondary care appointment and final diagnosis (years) | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.03 (Student’s t-test) | 0.31 |

Work package 1B: baseline study of the diagnosis and management of Parkinson’s disease dementia

This study, also undertaken over the first 2 years of the programme, looked at diagnostic and management practice in those with PDD, with the aim of establishing baseline diagnostic rates for PDD and comparing investigations, assessment and management of those with PDD with control participants (i.e. patients with PD without dementia).

Methods

We included five PD or movement disorder services, each from a separate trust, comprising two geriatric medicine services and three services that combined geriatric medicine and neurology expertise. The research team reviewed notes of all referrals to services over an 18-month period. Those patients identified with PDD who were alive and felt to be well enough by the clinical team (44/151 identified) were approached for consent for a more detailed study of their notes, with the extraction of information with regard to diagnostic and management pathways collected using a case report form. For each PDD participant who consented, a person with PD but without dementia (control) was recruited by selecting the next case seen in the respective service who was diagnosed with PD, matched for age (± 5 years) and sex, and who consented to participate.

Similar methods of analysis as those described for WP1A (see Work package 1A: baseline study of the diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies) were used to collect and analyse data, and ethics, Confidentiality Advisory Group and research and development approvals were sought and obtained.

Results

The research team identified 2263 referral patients, of whom 1563 had a diagnosis of PD. Of these patients, 151 (9.7%) had received a diagnosis of PDD and of these, 38 PDD patients and 35 PD control patients were approached and consented for detailed review of their notes (see Appendix 1, Table 8, for details of cohort characteristics). For PDD, unlike DLB, there was no evidence of a difference in diagnostic rates between the two regions (p = 0.2), although mean MMSE scores at time of diagnosis were lower in East Anglia than in the North East (p = 0.008).

Examining the management pathways, there was evidence that dementia was probably present well before the diagnosis of PDD was made. For example, 46% of those with PDD had impaired activities of daily living due to cognitive impairment, with a mean intervening time of 1.5 years prior to diagnosis. Cognitive impairment in multiple domains was present in 57% of patients at a mean period of 2 years before diagnosis and 39% of patients had received an antidementia drug at an average of 1.75 years before a dementia diagnosis.

Data on costs were available for an average of 9.3 and 7.8 years of management for PDD patients and PD control patients, respectively. There was no evidence of a difference in average total costs between PDD and PD controls (average difference £2024, 95% CI –£3598 to £5548; p = 0.462) (see Appendix 1, Table 9). After controlling for sex, time since diagnosis, total resource use time and other patient characteristics, PDD participants had an average total cost of care of £7655 more than PD controls (95% CI £3676 to £11,634; p < 0.001). PDD participants had higher average costs of investigations (£250 more, on average, 95% CI £237 to £306; p = 0.001) and higher post-diagnosis management costs (£570 more, 95% CI £281 to £808; p = 0.001) (see Appendix 1, Tables 10 and 11).

Discussion

Our results showed, in keeping with our expectations, that DLB and PDD were diagnosed at around half (or less) the rates that one would expect them to be, based on prior epidemiological and pathological studies. 12 There was clear evidence of differences in diagnostic practice between different services and different regions, with a higher threshold for diagnosing DLB being, unsurprisingly, associated with lower diagnostic rates. For PDD, there was evidence that the diagnosis was delayed, with those diagnosed by services in one region having a significantly lower MMSE score at point of diagnosis than the other, and those diagnosed with PDD had evidence of dementia being present up to 2 years before the actual diagnosis was made. Our study had limitations, including the use of retrospective data and sampling of only some services in two geographical regions. Services were not randomly selected, but selected on the basis of geography. For the detailed case note assessment of subjects, we were able to obtain only a modest number of cases and there may have been selection bias, as we could consent only people who were alive and not deemed too unwell by their clinical teams to approach. The diagnostic rate findings have been fully published17 and the differences in pathways to diagnosis and management are currently in preparation. In terms of costs for both DLB and PDD groups, there was evidence that after controlling for sex, time since diagnosis, total resource use time and other patient characteristics that the costs of care were higher for both DLB and PDD groups than their respective controls.

Work package 2: development of management toolkits for Lewy body dementia

Objectives

The objectives of WP2 were to (1) complete a systematic review of evidence about the management of LBD and (2) use this to develop a clinical guideline, using a Delphi process incorporating the views of a multidisciplinary panel of independent experts combined with two facilitated PPI workshops.

Systematic reviews

At the time that these reviews were undertaken and to the best of our knowledge, no evidence-based reviews of the comprehensive management of LBD existed. As a consequence, little formal management guidance for LBD was offered in the NICE dementia guideline used at that time,18 despite the fact that this group of patients has multiple symptoms requiring treatment. Clinical guidance at the time appeared solely in the form of pharmacological reviews and expert consensus opinion statements. 14,19,20 This was an unsatisfactory situation for prescribers, health-care providers and recipients of care. We therefore conducted systematic reviews on pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of DLB.

Methods

The first of our two systematic reviews21 examined research on treatment effects and costs, and patient and carer views of pharmacological management strategies for LBD. Studies were identified through bibliographic databases, trials registers, grey literature, reference lists and experts. The review protocol is provided in Appendix 2. 22 In brief, we used the keywords ‘Lewy or parkinson’ and ‘dementia’, conducting searches until March 2015, without restrictions on publication date or language. Titles and abstracts were screened, with non-English-language papers screened by native speakers, and criteria used were (1) participants who had a diagnosis of DLB, PDD or LBD, (2) studies examined pharmacological strategies and (3) outcome measures and scores were specified. No restrictions were placed on study design, but opinion papers were excluded. Data were extracted in relation to participant demographic characteristics, selection criteria, study design, management strategies, outcome measures and scores, adverse events and withdrawals. Studies were grouped and analysed according to pharmacological strategy. Methodological quality was assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (QATQS) [URL: www.ephpp.ca/tools.html (accessed April 2021)]. The QATQS examines selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawals and drop-outs. Domains are rated as being of weak, moderate or strong quality, which feeds into an overall rating of study quality.

Meta-analyses were conducted and, when studies could not be combined, summaries were provided. The level of evidence and grade of recommendations for each management strategy were assessed using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine criteria. 23

Forty-four studies examining 22 strategies were included in the review. Meta-analysis indicated beneficial effects of donepezil and rivastigmine for cognitive and psychiatric symptoms. Rivastigmine, but not donepezil, was associated with greater risk of adverse events. Meta-analysis of memantine suggested that it is well tolerated, but with few benefits. Descriptive summaries provided some evidence of benefits for galantamine, modafinil, levodopa, rotigotine, clozapine, duloxetine, clonazepam, ramelteon, gabapentin, zonisamide and yokukansan. Piracetam, amantadine, selegiline, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone and citalopram did not appear to be effective. Methodological quality was rated as weak for 41% of included studies, moderate for 39% and strong for 20%. This review concluded that high-level evidence related to pharmacological strategies for managing LBD is rare and that strategies for important areas of need in LBD, such as autonomic symptoms and carer burden, had not been investigated, nor had the views of patients and carers about pharmacological strategies.

This review21 of pharmacological management was published in the American Journal of Psychiatry (impact factor = 13.6) and by the end of 2018 had been cited 92 times, with an Altmetric Attention Score of 26 placing it in the top 5% of all research outputs scored. It formed the basis for the subsequent development of the management guideline and the first round of statements for Delphi panel evaluation.

Our second systematic review in WP2 regarded the non-pharmacological management of LBD. 24 Details of the search strategy are described in Appendix 3. As with pharmacological management, the literature and guidance available about LBD management available to clinicians and families at that time was virtually non-existent and mainly accessed through not-for-profit support organisations. Bibliographic databases were searched using a wide range of search terms and no restrictions were placed on study design, language or clinical setting. We used the search terms [(Lewy OR Park*) and Dementia]. Interventions were any non-pharmacological treatment and identified using a wide range of terms covering individual non-pharmacological therapies: activit*, acupuncture, alternative, animal, aromatherapy, art therapy, assisted, balance, behav*, bicycle, calisthenics, carer intervention, caregiver intervention, CBT, Chi gong, cognit*, cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, counsel*, creative arts, dance, dancing, diet, direct current stimulation, drama, ECT, educat*, electroconvulsive therapy, enhanc*, environmental intervention, environmental modification, exercise, flexibility, humor therapy, humour therapy, hydrotherapy, intervention*, leisure, light therapy, management, martial arts, massage, meditation, Montessori, multisensory, music, non-pharm*, nonpharm*, nutrition, occupational therapy, pet therapy, physical activity, physical therapy, physiotherapy, pilates, psychoeducation, psychol*, psychosocial, psychotherapy, Qi gong, reality orientation, recreation*, reminiscence, resistance training, run*, sensory, simulated presence, stimulation, Snoezelen, support*, support group*, swim*, tai chi, therap*, therapeutic activity, TMS, training, training carers, training caregivers, transcranial magnetic stimulation, treatment*, validation, weight training, yoga. Searches were conducted on 30 October 2016.

The search identified 21 studies [including two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with available subgroup data], seven case series and 12 case studies. Most studies reported beneficial effects of the interventions used, although the only sizeable study was on dysphagia, showing a benefit of honey-thickened liquids. Given the heterogeneity of interventions and poor quality of the studies overall, no quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) was possible. Overall, identified studies suggested possible benefits of non-pharmacological interventions in LBD, but the small sample sizes and low quality of studies meant that no definite recommendations could be offered. This work underscored the clear and urgent need for future research on this topic.

The review of non-pharmacological management was published in Psychological Medicine24 (impact factor = 5.4) and was also subsequently incorporated into the development of the management toolkit.

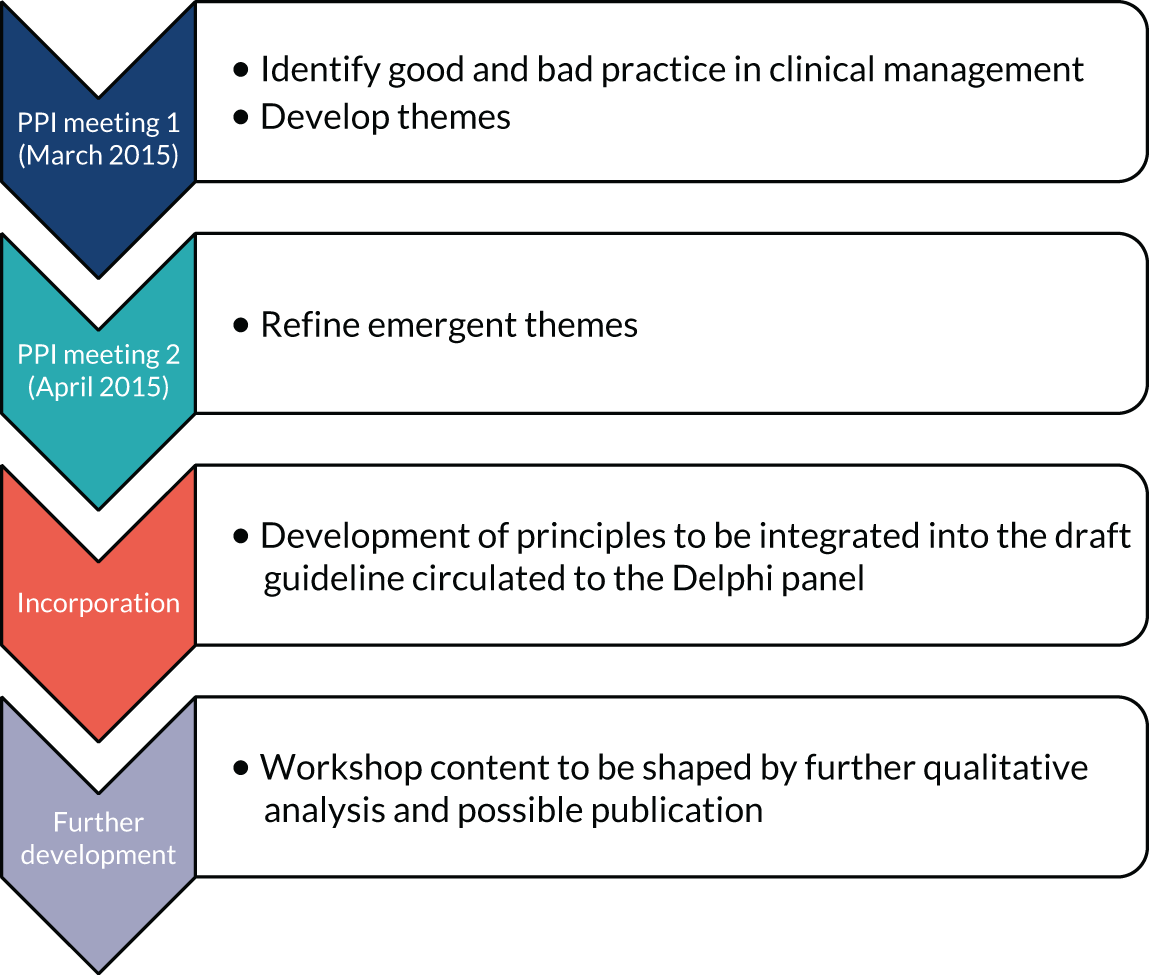

Public–patient workshops

Two public–patient workshops were held, with the participation of 38 people with LBD and their family/carers. The first event focused on identifying best practice in LBD clinical management, based on their own experiences. The content of the workshops is shown in Figure 2. The emergent themes were developed further in the second event and refined into a set of guiding principles.

FIGURE 2.

Workshops and content.

Some of the key themes that were held to be important are listed in Table 3. The themes were structured in such a way as to help the clinical team deliver the guideline recommendations in a user-friendly format.

| Management principle | Summary of discussion point |

|---|---|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

From our work, a core element was the recognition that the carer is often the expert on the person with dementia and they need to feel that this is recognised. Although people want to be told what the clinician feels would be best for them, they also expressed concern about doctors treating what they know best, rather than following patient and carer preferences, or seeking help from other types of expert. Carer diaries were often mentioned as a useful way of dealing with these issues. Opinions were divided as to whether or not the patient and carer should be seen together by the clinical team, separately or offered both. Some issues, such as increased carer stress, which is high in LBD, probably need to be explicitly discussed with the carer on their own.

Although the advantages of developing and working through a problem list were recognised, it was also said that a long list of problems could be demoralising, something that is particularly relevant for LBD where there are often many symptoms, not all of which may need to be formulated as problems. It was noted as helpful that an expert experienced in LBD is often able to offer reassurance that these symptoms can be expected as part of the disorder and not part of another illness.

Carer and peer support groups are very valuable for support and practical help, providing people have similar conditions. Support groups are one source of practical information at an early stage on important general matters, including power of attorney, attendance allowance and council tax. Where geographical distance is a problem, telephone or e-mail contact may still be helpful.

A clear message throughout the PPI consultations was that although they appreciated the levels of care and concern that clinical teams offered, they often had difficulty in obtaining and understanding information about LBD. A lack of post-diagnostic support, advice and counselling was frequently mentioned, as was a shortage of easily accessible materials. As a result, the guideline that we produced contained links to what were judged to be the best-quality information sources at the time of writing, and it is hoped that these will be made freely available to those attending our NHS services and that they will, in turn, be replaced by improved versions and adapted for local use.

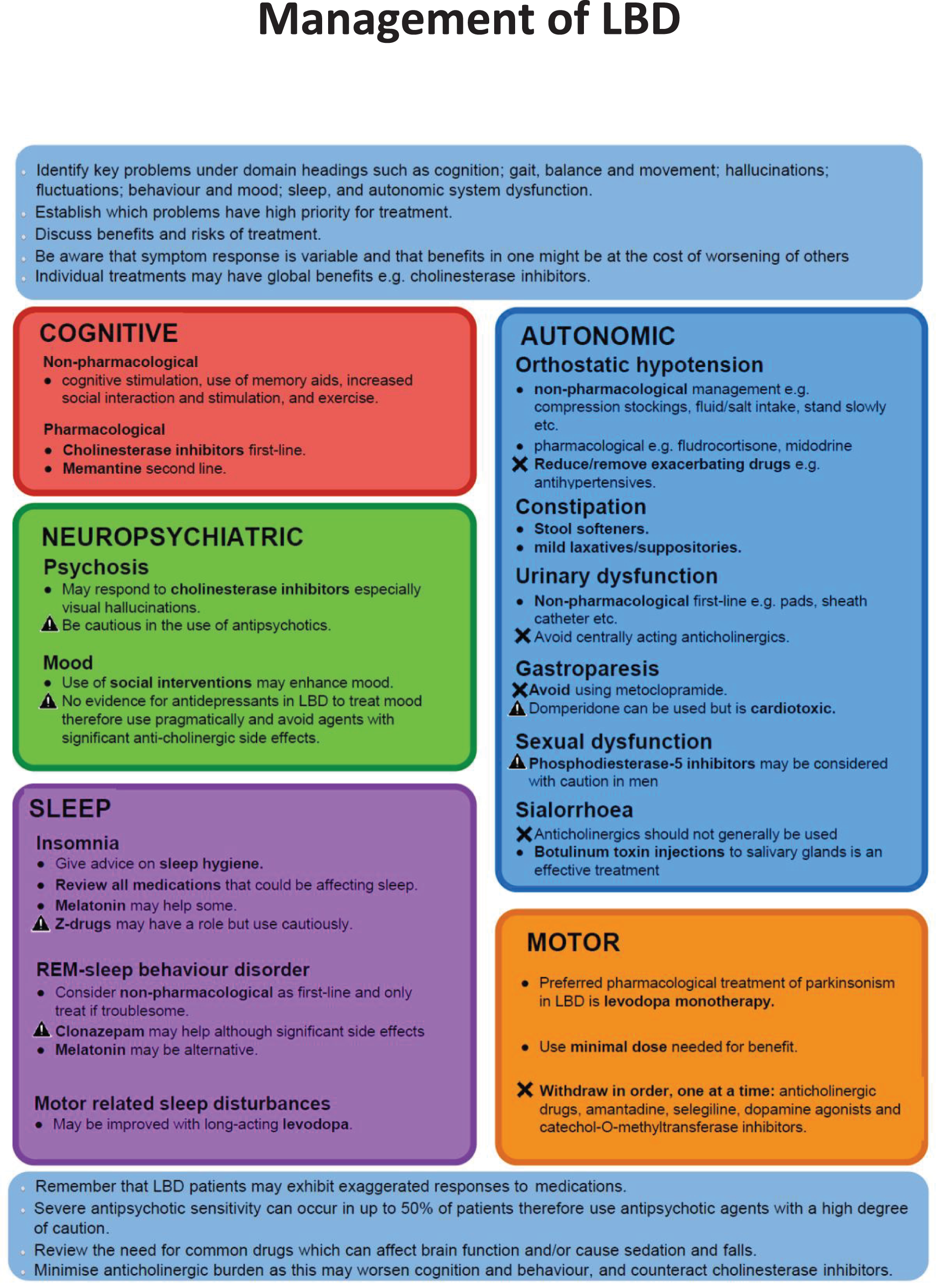

Guideline development

Using the systematic reviews and public–patient feedback, an initial draft of the guidelines was developed by two authors (J-PT and IMcK). Statements relating to symptom domains were created and, using an anonymised online platform, reviewed by the Delphi panel. The panel comprised experts in the field (n = 26), including psychology, geriatrics, psychiatry, neurology, primary care, physiotherapy, nursing and academic experts and some key international opinion leaders (see Appendix 4 for list of contributors), who were identified through consultation with relevant stakeholder groups and supported by an extensive publication search and/or their role as keynote speakers on management of LBD at conferences. The Delphi process was undertaken over three rounds. A high level of agreement was sought across the three rounds (85% for rounds 1 and 2, and 75% for round 3). Controversial statements were modified on the basis of feedback and rerun in the subsequent round or removed. Of 252 original statements, 161 were kept, with 78 of these (48.4%) gaining full consensus panel agreement for inclusion, 52 (32.3%) with 90–99% consensus agreement and 31 (19.3%) agreed by 75–89% of the panel. After this process, the guideline statements were re-collated and formulated into one document. More controversial statements (but still meeting majority consensus opinion of > 50%) were included as clarifying footnotes, where appropriate, in the guideline document.

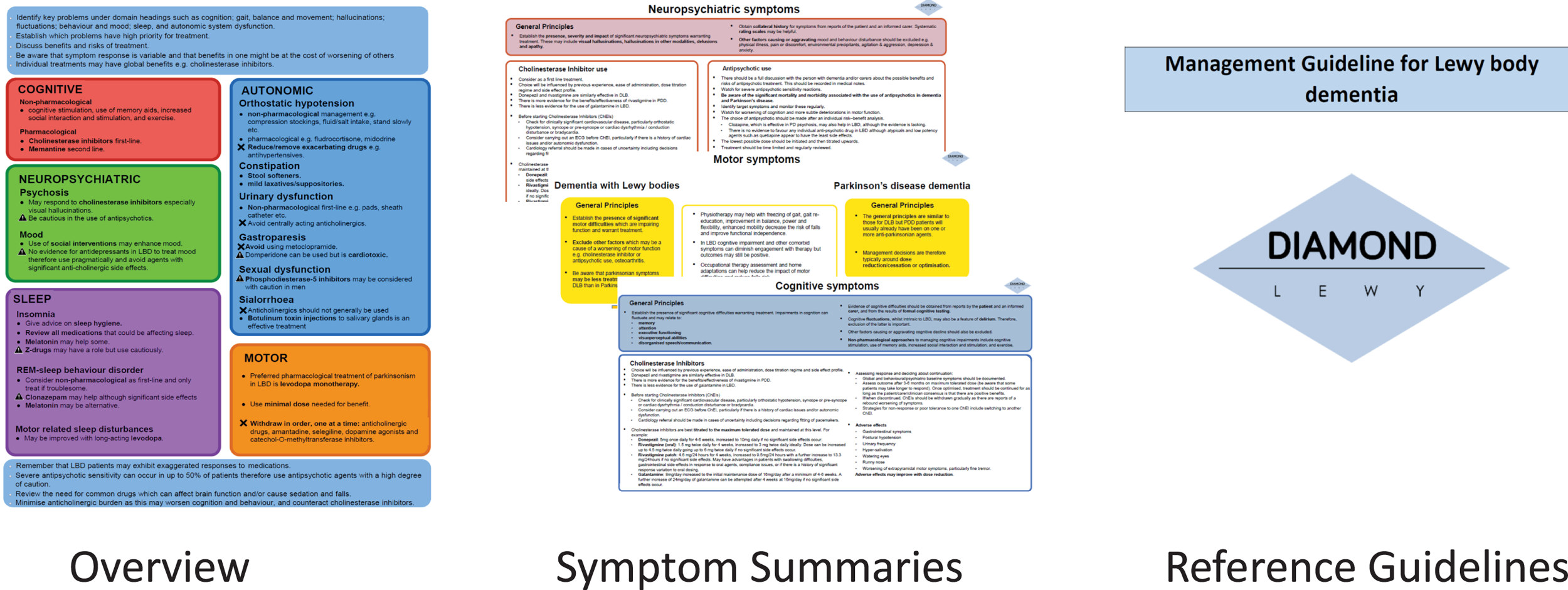

The guideline statements were then supplemented by summary management sheets (one overall summary figure and separate summary figures for each key symptom domain, produced by J-PT and IMcK, with input from the DIAMOND-Lewy team) that accompanied the written guideline, with the whole package being called the management toolkit. This toolkit was then subjected to further evaluation and feedback in WP3 and typological corrections or clarification of guideline statements (although no change to content or meaning) were made based on the feedback from clinicians.

The management toolkit was finalised at this point and put forward for evaluation in WP4 (see Report Supplementary Material 1). The toolkit comprised an overview (see Appendix 5), brief summaries for each symptom area and the management guideline.

Dissemination of the toolkit

Our major output has been the acceptance of an authoritative management review,25 which contains reference to the Delphi statements and the evidence base used to produce the management toolkit, in Lancet Neurology (impact factor = 27.14). This has made the findings from our guidelines accessible for adaption and implementation in clinical services internationally.

Specific to the UK and NHS context, we have a dissemination plan, including:

-

making the management toolkit freely available via our website

-

embedding the use of the management toolkit in significant national educational fora (e.g. the British Association of Psychopharmacology)

-

developing an online learning resource with video discussing management approaches in LBD.

Work package 3: development of assessment toolkits for the diagnosis of Lewy body dementia

Introduction

Work package 3 was developed because the accurate recognition of LBD is crucial to ensuring appropriate management and, therefore, central to improving patient care in dementia. 26–28

Prior to this programme, there was no single simple-to-administer toolkit that incorporated assessment of all the symptoms needed to make a diagnosis of DLB and PDD. Therefore, WP3 aimed to develop such assessment toolkits to improve the recognition and diagnosis of both DLB and PDD.

Methods

We developed the final LBD assessment toolkits in three stages: (1) identifying validated assessments for different symptoms and signs needed for a LBD diagnosis to make a pilot instrument, (2) obtaining feedback on the acceptability and feasibility of the toolkit through interviews with clinicians and the programme PPI group, and (3) piloting the toolkits in memory and movement disorder services prior to producing a final version to be used in WP4.

Stage 1: development of pilot assessment toolkits

Following funding, the DIAMOND-Lewy PMG first discussed the basic approach to the problem and, in particular, whether one overall assessment and assessment toolkit should be developed or two separate ones, one for DLB (aimed at memory services) and one for PDD (aimed at movement disorder services or neurology and geriatric medicine services that also see people with movement disorders). It was concluded that two different instruments would be needed that matched the international diagnostic criteria for DLB14 and PDD. 29 The clinical experts in the DIAMOND-Lewy programme (AT, J-PT, IMcK, LA, DB and JOB) then reviewed the published literature and supplemented this with their expert knowledge to identify available validated assessment instruments26–28,30 that would form the contents of the toolkits. The PMG identified appropriate components for each toolkit from the identified assessment instruments.

For the DLB toolkit, the aim was to improve identification of the core and suggestive diagnostic symptoms, as diagnosis of cognitive impairment and dementia in specialist memory services is not a concern. At the time of toolkit development, there were six core and suggestive symptoms for diagnosing DLB. One was dopaminergic imaging, which would not form part of a clinical assessment tool, and another was neuroleptic sensitivity, which can only be identified following exposure to antipsychotic drugs, which is now a rare event. 31,32 Therefore, the focus was on assessment of the four remaining symptoms: (1) persistent complex visual hallucinations, (2) spontaneous cognitive fluctuations, (3) spontaneous parkinsonism and (4) rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behaviour disorder. The following components of the instrument were identified:

-

cognitive fluctuation – four questions to carers from the Dementia Cognitive Fluctuation Scale28

-

REM sleep behaviour disorder – a single screening question to carers from the Mayo Sleep Questionnaire27

-

visual hallucinations – two core questions for patients and two for carers from the North East Visual Hallucinations Inventory30

-

motor features of parkinsonism – five items from the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. 26

For the PDD toolkit, the aim was to improve identification of cognitive impairment and to facilitate matching of symptoms to the PDD diagnostic criteria. 29 The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was identified as most appropriate for brief cognitive assessment in this context. 33

Stage 2: feedback and modification of toolkits

During 2014, as WP3 lead, Alan Thomas put together the two instruments and there followed a period of iteration with the rest of the PMG. This led to the formulation of draft versions of the toolkits, which were then sent to the PPI panel for feedback in early 2015. PPI panel feedback was incorporated into a revised version, which was again commented on by the PMG and PPI members until final agreed versions of the toolkits and text were agreed for the pilot study. These iterative rounds led to changes in the wording of questions to try to improve clarity. In addition, a major change suggested was to separate the PDD toolkit into one version for use with carers and one for use with patients, based on how patients present to PD services where they may or may not have a carer present. After final iterations between PMG and PPI groups, three final assessment toolkits were produced for the pilot and feasibility study.

Stage 3: pilot and feasibility of assessment toolkits

During early 2015, as the final versions of the toolkits were developed and by mid-2015, the necessary research ethics approval was obtained from Yorkshire and The Humber – Bradford Leeds Research Ethics Committee (reference 15/NE/0028). Trust research and development approval was also obtained prior to the start of the study.

In the autumn of 2015, we conducted the pilot study of the feasibility of the assessment toolkits in memory and PD services at Gateshead Health NHS Foundation Trust. Details are published in Thomas et al. 34 Briefly, we obtained engagement from medical and nursing staff in these services who administered the toolkits to > 20 patients, with individual clinicians using the toolkits between zero and seven times in patients with and without LBD. Feedback on acceptability and thoughts on improvement were obtained by direct comments to the WP lead (AT) and the research nurse by comments written on the toolkits and from qualitative interviews with patients, carers and clinicians.

Clinicians found the toolkits straightforward to use, although in the PD service they found attempting the cognitive assessment to be a problem because of time constraints. These clinicians were also keen to have the questions about core symptoms of DLB included in the toolkit for PD services. Patients and carers had no concerns about their use or how the questions were phrased. Therefore, following the pilot, a revision of the toolkits was produced that took these comments into account. Specifically, we produced a single assessment toolkit (the LBD toolkit) for PD services, which included the questions from the DLB toolkit for identifying core DLB features. Finally, by this time, the revised DLB consensus diagnostic criteria were being published,11 which led to a few final minor changes to these toolkits to ensure that they were aligned with the revised criteria. Details of these changes were published. 35

Use of the toolkits in work package 4

These final published versions of the DIAMOND-Lewy toolkits (see Report Supplementary Material 2) were utilised in WP4 of the programme, with all services, whether randomised to intervention or usual care, being supported in using the toolkits. The toolkits were published online in 2016 and in print in 2017,34 and this contributed to making these toolkits publicly available through open access. In parallel, the toolkits have also been made available through the DIAMOND-Lewy study website [URL: https://research.ncl.ac.uk/diamondlewy/ (accessed April 2021)].

Work package 4: a pilot cluster randomised trial of the management toolkit

This WP involved the introduction of the assessment toolkits (developed in WP3) to memory/old age psychiatry and PD/movement disorder services, with the aim of facilitating diagnosis of DLB and PDD, and the introduction through a cluster randomised trial (randomised at the individual service level) of the management toolkit (developed in WP2) into half of the services taking part, with the other half continuing with standard care. The objectives of the pilot RCT were to (1) see if such a study was feasible [i.e. that we could recruit subjects with DLB and PDD (target n = 120) and retain them for 6 months] and (2) obtain data to inform power calculations for future studies.

Methods

We included 11 services in four NHS trusts in the North East and 12 services in four NHS trusts in East Anglia. The trial was supported by the Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit, which undertook the randomisation via a statistician blinded to other aspects of the study. One service in the North East was subsequently unable to recruit any patients and withdrew part-way through the study. This study was approved by the West Midlands – Coventry and Warwickshire Research Ethics Committee (reference 16/WM/0025).

Assessment toolkits and, for services randomised to the intervention arm, the management toolkit were introduced during an in-person site initiation visit undertaken by the research team. The site initiation visits comprised standardised presentations and handouts followed by a question and answer session. The site initiation visits included as many clinical team members as were able to attend and all those involved in the diagnosis and management of those with DLB and PDD were encouraged to use the diagnostic and management toolkits. Follow-up support and further sessions were provided as required, and the study team maintained regular contact with all services during the course of the recruitment and follow-up period.

Assessment and management toolkits were provided as paper copies, with laminated copies of the overview and symptom summary sheets for the management toolkit. Some sites requested electronic [Portable Document Format (PDF)] versions and, where these were requested, they were supplied. If services had questions regarding the assessment or management toolkits, they were free to ask members of the research team. Regular trial newsletters that contained a ‘frequently asked questions’ section were sent to services to facilitate engagement with the study. Questionnaires regarding the value and use of the management toolkit were sent to services in the intervention arm halfway through the study and at the study end. Qualitative interviews (see Work package 5: qualitative studies throughout the DIAMOND-Lewy programme) were conducted to ascertain barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of both the diagnostic and management toolkits.

In all services, patients with DLB and PDD were recruited for data collection at baseline, 3 months and 6 months. A carer/informant was recruited for all but two patients. The full study protocol, which includes all the assessments undertaken, is available on the DIAMOND-Lewy website. 36 In brief, assessments included those of cognition (MMSE and MoCA), neuropsychiatric symptoms (Neuropsychiatric Inventory and Geriatric Depression Scale), fluctuations (Cognitive Fluctuation Scale), activities of daily living (Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale), motor symptoms [Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part 3 (UPDRS)] and quality of life [DEMQOL (Dementia Quality of Life) and EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)]. Current management and use of health care and personal/social care services were collected on a bespoke questionnaire. Global outcome scales were completed by the visiting researcher and the carer/informant. Informant assessments included quality of life of the carer (EQ-5D-5L), carer burden (Zarit Burden Interview) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

All baseline and 3- and 6-month assessments were undertaken by members of the Clinical Research Network DeNDRoN teams in the North East and East Anglia, who were unaware of the service allocation (to management toolkit or standard care).

Data entry was completed by those undertaking the assessments, and central checking and quality assurance followed double-entry at local sites with an error rate of < 0.1% (all errors noticed were, of course, corrected). Database integrity was therefore felt to be very good. Identical shell databases were completed in the North East and East Anglia and then merged and sent to the study statistical team.

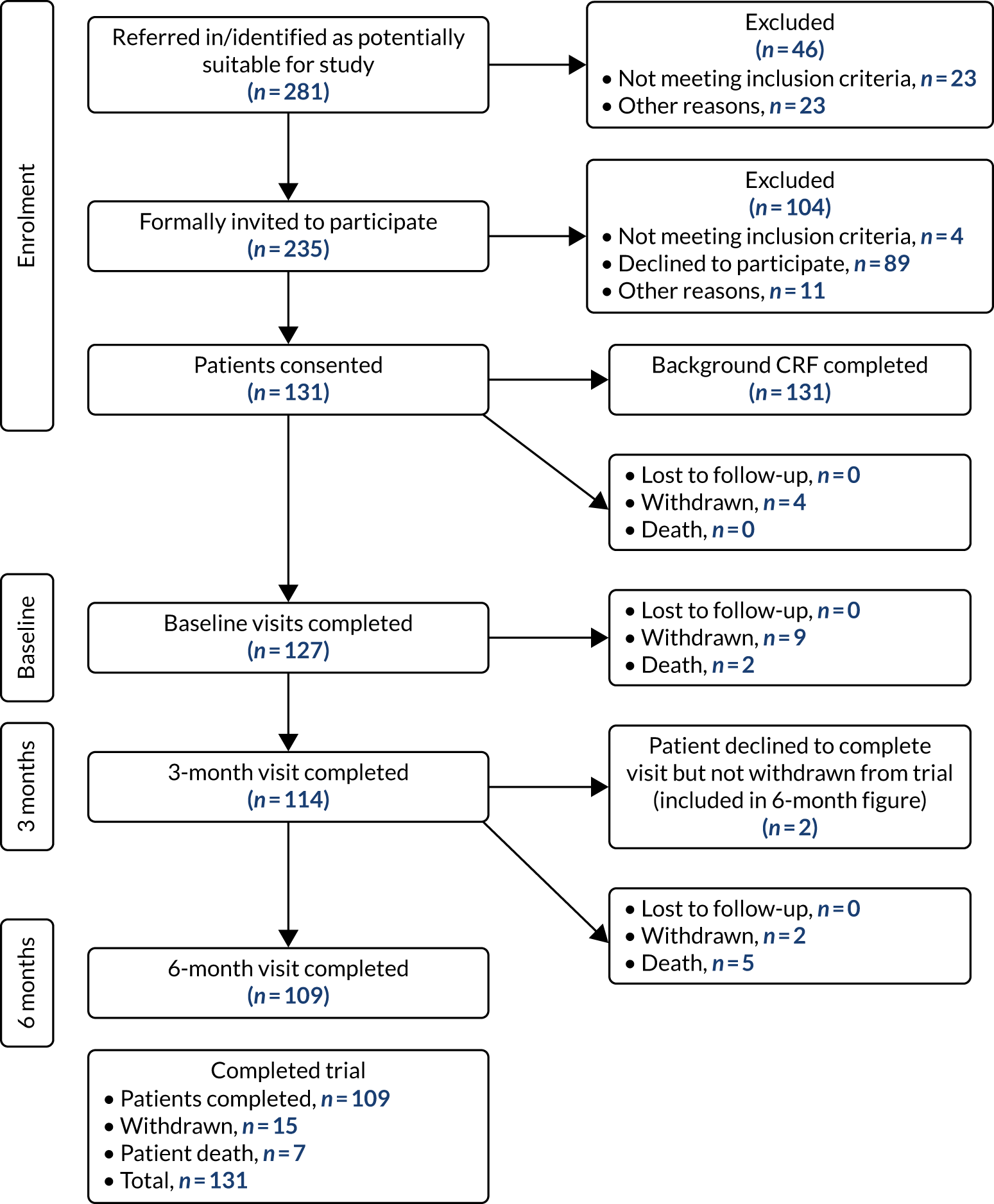

Results

One hundred and thirty-one participants consented to take part in the study. A CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) flow diagram, indicating patient progression through the study, is shown in Figure 3. One hundred and twenty-seven participants underwent a baseline assessment, and 6-month data were available for 109 participants (86% of those who completed baseline, 83% of all participants who consented). Eighteen participants were lost to follow-up, seven of whom died (four in the intervention arm, three in the control arm). Those lost to follow-up were similar in demographic characteristics to those remaining in the study except for age, with those lost to follow-up being significantly older (median age of 83 vs. 77 years).

FIGURE 3.

DIAMOND-Lewy WP4 CONSORT flow diagram of participants’ completion rate (27 March 2019). CRF, case report form.

The recruitment target was more than achieved. We aimed to recruit 120 patients and actually recruited 131. Patient characteristics at baseline are shown in Table 4. Participants randomised to receive the intervention did not differ significantly from those randomised to the control group on any of the baseline measures except for carer-reported DEMQOL and carer anxiety symptoms as assessed on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

| Characteristic | Control (N = 52) | Intervention (N = 75) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of sites | 11 | 12 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 77.0 (7.59) | 79.3 (6.97) | 0.086 |

| Median | 77.0 | 79.0 | 0.094 |

| Interquartile range | 72.0–83.0 | 75.0–84.0 | |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.846 | ||

| DLB | 31 (59.6) | 46 (61.3) | |

| PDD | 21 (40.4) | 29 (38.7) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.642 | ||

| Female | 10 (19.2) | 17 (22.7) | |

| Male | 42 (80.8) | 58 (77.3) | |

| DEMQOL | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.76 (0.13) | 0.78 (0.12) | 0.229 |

| Median | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.215 |

| Interquartile range | 0.70–0.82 | 0.70–0.88 | |

| Carer DEMQOL-proxy | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.70 (0.14) | 0.76 (0.12) | 0.021 |

| Median | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.026 |

| Interquartile range | 0.55–0.82 | 0.67–0.85 | |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory | |||

| Mean (SD) | 25.0 (17.5) | 20.0 (18.0) | 0.125 |

| Median | 22.0 | 15.0 | 0.038 |

| Interquartile range | 12.0–31.0 | 9.0–24.0 | |

| UPDRS | |||

| Mean (SD) | 43.7 (19.1) | 38.2 (18.6) | 0.112 |

| Median | 41.0 | 35.5 | 0.137 |

| Interquartile range | 28.0–55.0 | 26.0–51.0 | |

| Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia | |||

| Mean (SD) | 9.31 (6.10) | 7.41 (4.85) | 0.056 |

| Median | 9.0 | 7.0 | 0.104 |

| Interquartile range | 4.0–13.0 | 4.0–11.0 | |

| Geriatric Depression Scale | |||

| Mean (SD) | 5.7 (3.5) | 5.6 (3.3) | 0.899 |

| Median | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.952 |

| Interquartile range | 3.0–7.0 | 3.0–7.0 | |

| MMSE | |||

| Mean (SD) | 20.8 (6.1) | 21.4 (6.1) | 0.581 |

| Median | 22.0 | 22.0 | 0.503 |

| Interquartile range | 17.0–25.0 | 19.0–26.0 | |

| MoCA | |||

| Mean (SD) | 15.1 (4.9) | 15.6 (6.0) | 0.644 |

| Median | 15.5 | 16.0 | 0.690 |

| Interquartile range | 12.0–19.0 | 12.0–19.0 | |

| EQ-5D-5L | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.67 (0.27) | 0.67 (0.21) | 0.998 |

| Median | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.516 |

| Interquartile range | 0.55–0.85 | 0.57–0.80 | |

| EQ-5D-5L (proxy) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.55 (0.27) | 0.56 (0.27) | 0.769 |

| Median | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.929 |

| Interquartile range | 0.37–0.73 | 0.40–0.77 | |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: anxiety | |||

| Mean (SD) | 6.7 (4.2) | 5.2 (4.1) | 0.052 |

| Median | 6.0 | 4.0 | 0.037 |

| Interquartile range | 3.0–9.0 | 2.0–8.0 | |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: depression | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.6 (3.8) | 4.2 (3.5) | 0.553 |

| Median | 3.0 | 3.5 | 0.610 |

| Interquartile range | 1.0–7.0 | 1.0–7.0 | |

| Zarit Burden Interview | |||

| Mean (SD) | 27.5 (15.6) | 22.6 (15.3) | 0.082 |

| Median | 26.0 | 18.0 | 0.070 |

| Interquartile range | 14.5–38.5 | 10.0–33.0 | |

| Carer EQ-5D-5L | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.80 (0.20) | 0.81 (0.19) | 0.822 |

| Median | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.902 |

| Interquartile range | 0.72–1.0 | 0.69–1.0 | |

Health economics

The main objective of the economic component of the pilot RCT was to rehearse the methods for a future definitive economic evaluation of the new management toolkit compared with the usual care provided for dementia. As is typical for pilot trials, the modest sample size meant that a full economic evaluation was not appropriate because estimates would be both imprecise and unreliable. Therefore, the focus of the economic component was restricted to provide a descriptive analysis of the costs and outcomes. Data on costs and outcomes for each patient sample (DLB and PDD) were examined separately, as it was expected that the different diagnoses would lead to a differential use of services and outcomes.

Deviations from protocol

The protocol, and the analysis plan (see Report Supplementary Material 3), which was based on the protocol, stated that a cost-effectiveness analysis would be conducted, reporting an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. A stochastic analysis, reporting results in the form of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves and cost–quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) plots, was also planned. However, because of the smaller number of data collected than expected, this analysis was not conducted to avoid reporting imprecise and unreliable results.

A full report of the economic component can be found in Appendix 6. A summary of the key results is presented below.

Costs

Costs were examined from the perspectives of the UK NHS and Personal Social Services, which includes costs of medications and health and social service use. Costs incurred by other sectors (e.g. local authorities) were not included; however, private costs incurred by patients and carers for attending health-care services were included. Data on costs using a service use questionnaire administered to the carer were collected at baseline and at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Data on private costs to patients were collected using a time and travel questionnaire at the 6-month follow-up.

Health care and social service resource use

In both patient samples, mean costs associated with health and social service use decreased in the intervention arms between baseline and the 6-month follow-up. However, in the control groups, costs increased. There is a substantial amount of imprecision around the service use cost data, however, and median values are considerably smaller than the mean values, which suggests that there is a substantial right skew to the data, with some participants incurring much higher costs than the remainder of the sample (see Appendix 6, Table 12).

Medication costs

There was little variation in mean medication costs between baseline and the 6-month follow-up in both patient samples. There was a trend towards increasing costs for both arms over the follow-up period. A greater increase in mean medication costs can be observed in the intervention arms of both patient samples than in the control arms. However, the increase is larger for the PDD patients (see Appendix 6, Table 13).

Intervention delivery costs

The cost of the intervention included the production of the management toolkits and training staff to use them. The total delivery cost was divided by the number of participants in the intervention arm in both patient groups combined (n = 75) to estimate a mean delivery cost per participant receiving the intervention. The mean intervention delivery cost was estimated at £76.32 per participant in the intervention arms and £0 for those not receiving the intervention (i.e. control arms) (see Appendix 6, Table 14).

Total costs

Total costs included health and social service use, medication costs and intervention delivery costs (to illustrate cumulative costs at that time point they were added to the cumulative costs, estimated at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups only). The health and social care use costs made up the largest proportion of the total cost. In both patient samples, there was an overall increase in total costs between baseline and the 6-month follow-up in the control arms, whereas total costs at the 6-month follow-up were lower than baseline in both sample intervention arms (see Appendix 6, Table 15). There remains substantial imprecision in the total cost values because of the small sample size and, therefore, the total costs are, at best, illustrative.

Private costs

Private costs included the cost of travelling to inpatient services, outpatient appointments, general practitioner (GP) visits and community dementia service visits for both patients and carers who may have accompanied patients. The cost of time spent travelling to each appointment and the cost of time spent at each appointment were also estimated. Costs were attributed to time based on activity rates for various activities, using estimates published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS)37 (see Appendix 6 for further details). For both patients and carers, mean travel costs decreased between baseline and the 6-month follow-up in both trial arms and patient samples. An exception to this was the control group of the PDD sample, which incurred higher mean costs at the 6-month follow-up than at baseline.

With reference to the cost of patients’ time spent attending health-care services, the intervention groups of both patient samples incurred lower mean costs over the 3-month period between the 3- and 6-month follow-ups than during the 3-month period prior to baseline data collection, whereas the control groups had a higher mean cost for the same 3-month period prior to the 6-month follow-up than at baseline (see Appendix 6, Table 16). A similar pattern was observed for costs to carers, with the exception that carers in the control group of the DLB sample incurred lower mean costs at the 6-month follow-up than at baseline (see Appendix 6, Table 17).

Quality of life

Patients’ generic quality of life was derived from the responses to the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire,38 completed at baseline and at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups (missing EQ-5D-5L data at each time point are recorded in Appendix 6, Table 18). Responses to the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire were transformed into health state utilities, using tariffs derived from the UK population. 39 Using the change from baseline approach, the health state utilities were used to estimate generic QALYs for each participant so that the change in QALYs between baseline and the 6-month follow-up was estimated.

Overall, changes in QALYs in each trial arm for each sample were small to modest, but with consistent decreases in mean and median scores for those with DLB, indicating a benefit for those in the intervention arm. An extremely small decrease in QALYs was observed in the intervention arm of the PDD sample, compared with a small increase in mean QALYs for the control arm (see Appendix 6, Table 19).

Discussion

This study demonstrated the feasibility of successfully recruiting a large number of participants with DLB and PDD over an 18-month period from 23 sites, and we more than achieved the recruitment target (target, n = 120; recruited, n = 131). Follow-up rates were good (85%), given the condition under study, as LBD is known to be associated with more rapid functional decline and increased mortality than other dementias. 11,40 Completion rates of assessments for both patients and carers were high.

Using results from this study to inform a power calculation (80% power, alpha 0.05) gives a required sample size of 726 for outcome based on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory {18.8 [standard deviation (SD) 19.3] in the intervention and 22.6 [SD 16.3] in the control group}. Assuming 80% completion rates, the recruitment sample would need to be 908 for the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. However, given that the toolkits are already evidence based and associated with some positive outcomes, even in this pilot study, it is not clear that a larger trial based around demonstrating efficacy of the toolkits is needed. Instead, an approach focused more on their routine implementation, through service improvement or other approaches, may be preferable.

Taking account of the cost of implementing the management toolkits, the health economic analysis indicated that the total costs for both DLB and PDD increased over the course of the study in the control arms and decreased in the intervention arms, despite a slight increase in medication costs in intervention groups. With such a modest sample size, data were insufficient to draw conclusions, although there is no indication that the intervention increased costs. Data indicated that further study on health economic consequences in a larger sample is needed.

The qualitative studies (see Work package 5: qualitative studies throughout the DIAMOND-Lewy programme) indicate that implementation and use of the management toolkit varied considerably between individual clinicians and between services. Limitations of the study are that we were not able to standardise or measure this, nor – because this was randomised at a cluster level – could we directly associate the impact of the management toolkit on patient outcomes at the individual patient level. Further study should investigate these issues, but our results strongly support the need for a large, definitive trial of the management toolkit and indicate that its introduction is not associated with increased costs.

Work package 5: qualitative studies throughout the DIAMOND-Lewy programme

The reasons for underdiagnosis and suboptimal management of LBD have not previously been empirically investigated using qualitative methods. Research has focused on clarifying diagnostic criteria, identifying biomarkers or screening tools to facilitate diagnosis, with little attention to potential barriers to diagnosis. The emphasis has therefore been on identifying technical solutions, rather than considering the full range of factors that might contribute to the underdiagnosis of LBD. There is growing recognition of the contribution qualitative research can make to feasibility studies, pilot trials and RCTs,41,42 for example by understanding the context into which interventions are to be introduced, optimising interventions, understanding factors influencing the implementation of the intervention and facilitating the interpretation of findings. 41,43,44 In the DIAMOND-Lewy programme, the objectives of the qualitative work were to:

-

understand current practice in diagnosing and managing LBD (WP5.1)

-

explore stakeholder views on the acceptability of the toolkits (WP5.2)

-

explore the implementation of the assessment and management toolkits in routine NHS practice (WP5.3).

A range of theories are available to assess the likelihood of a new intervention being successfully embedded into routine practice. 45 Normalisation process theory (NPT) is a well-established theory of implementation, which has been used extensively in studies of health-care interventions. 46 NPT considers factors that affect implementation in relation to four key areas: (1) how people make sense of a new practice (coherence), (2) the willingness of people to sign-up and commit to the new practice (cognitive participation), (3) their ability to take on the work required of the practice (collective action) and (4) activity undertaken to monitor and review the practice (reflexive monitoring) [URL: www.normalizationprocess.org (accessed April 2021)]. 47

The qualitative work aimed to generate practical knowledge to inform subsequent stages of the programme (e.g. by providing feedback that could be used in revising toolkits, proposing an implementation strategy to address key barriers and proposing change mechanisms for the study findings). Ethics and research governance approvals were sought in two phases. Favourable ethics opinion for phase 1 was obtained from the Newcastle and North Tyneside 1 Research Ethics Committee (reference 13/NE/0322). Subsequent research and development and Caldicott approvals were granted from each participating site. Favourable ethics opinion for phase 2 was obtained from Wales Research Ethics Committee 5 (reference 16/WA/0098). Health Research Authority approval for phase 2 was obtained on 29 June 2016.

Methods

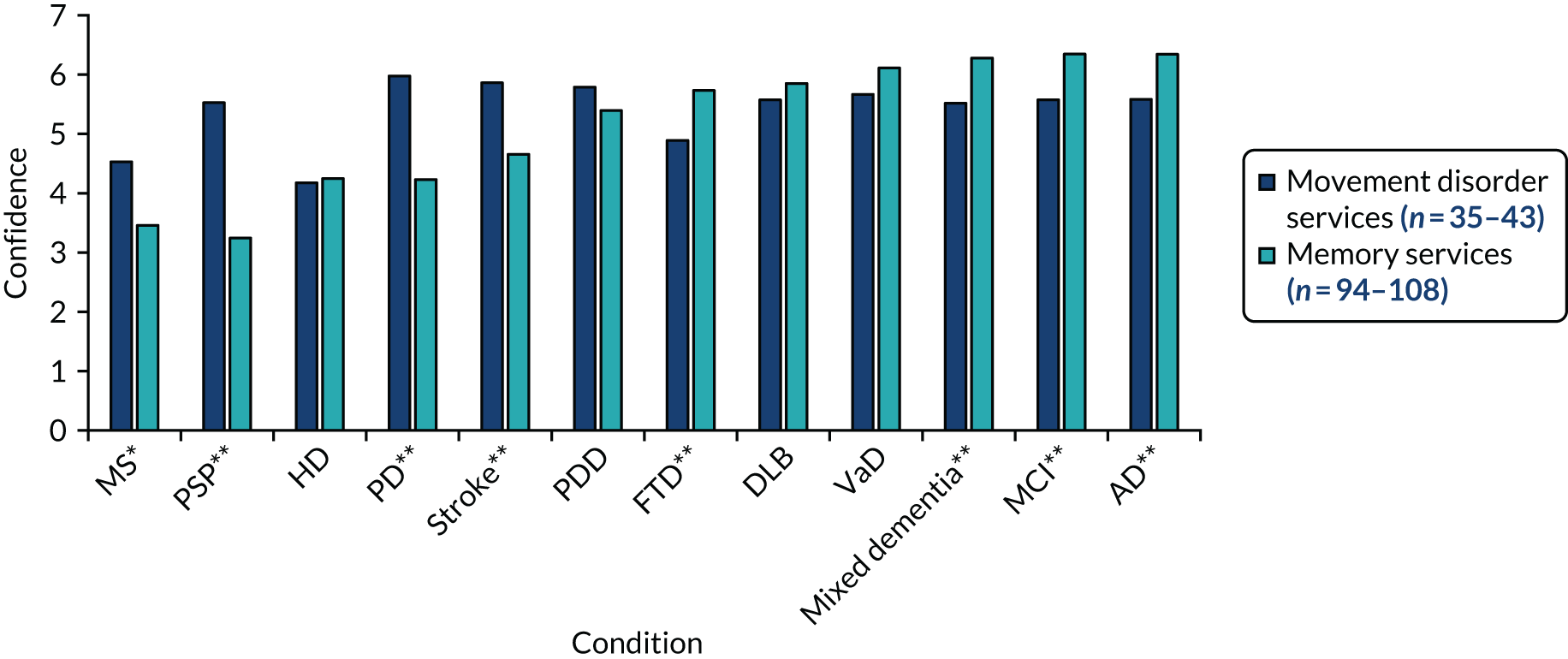

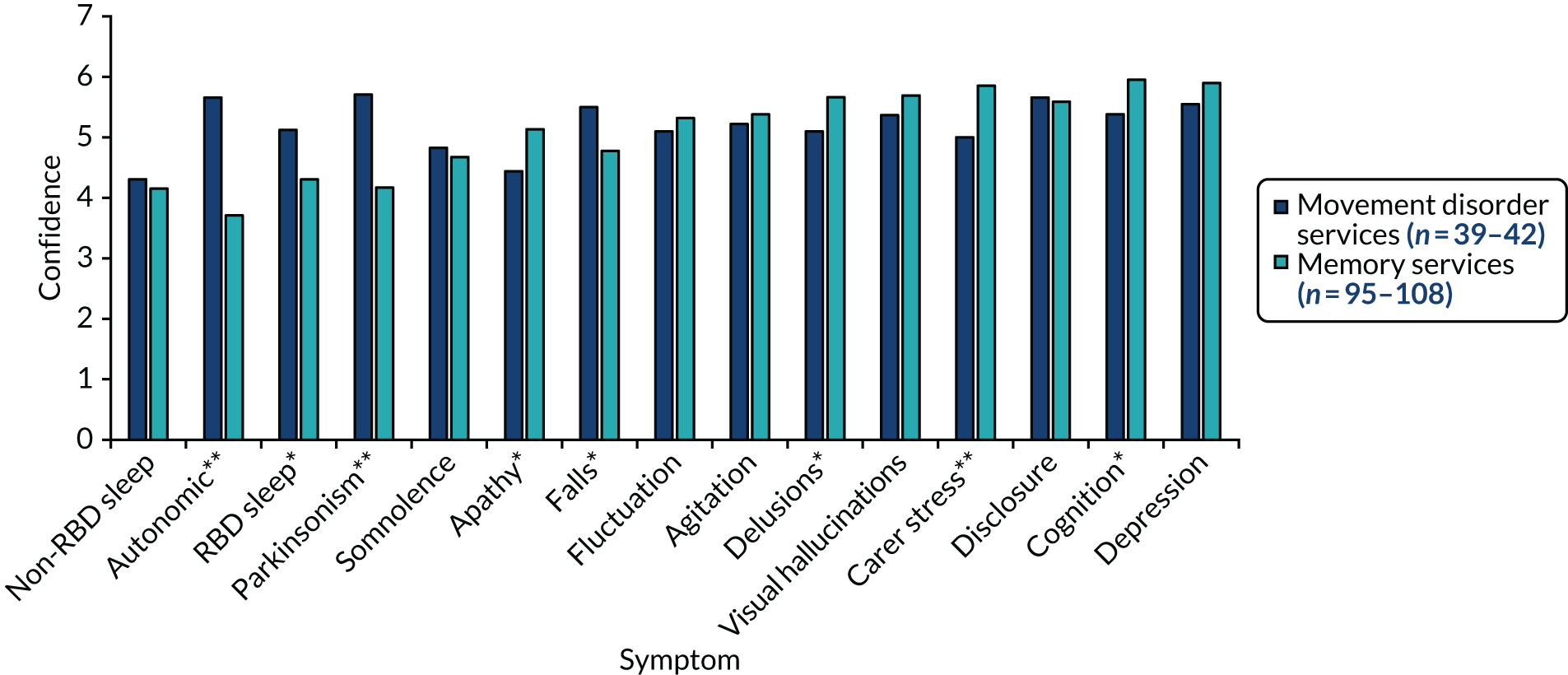

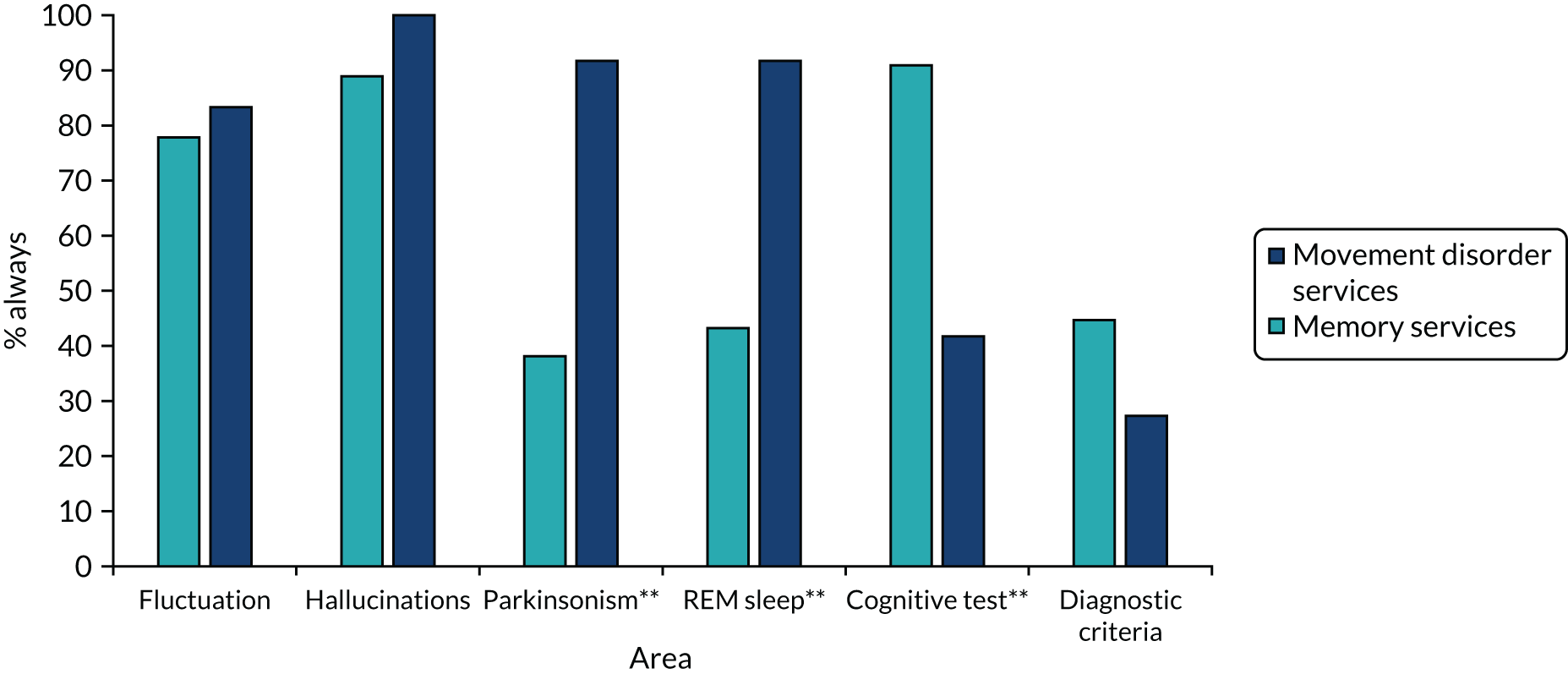

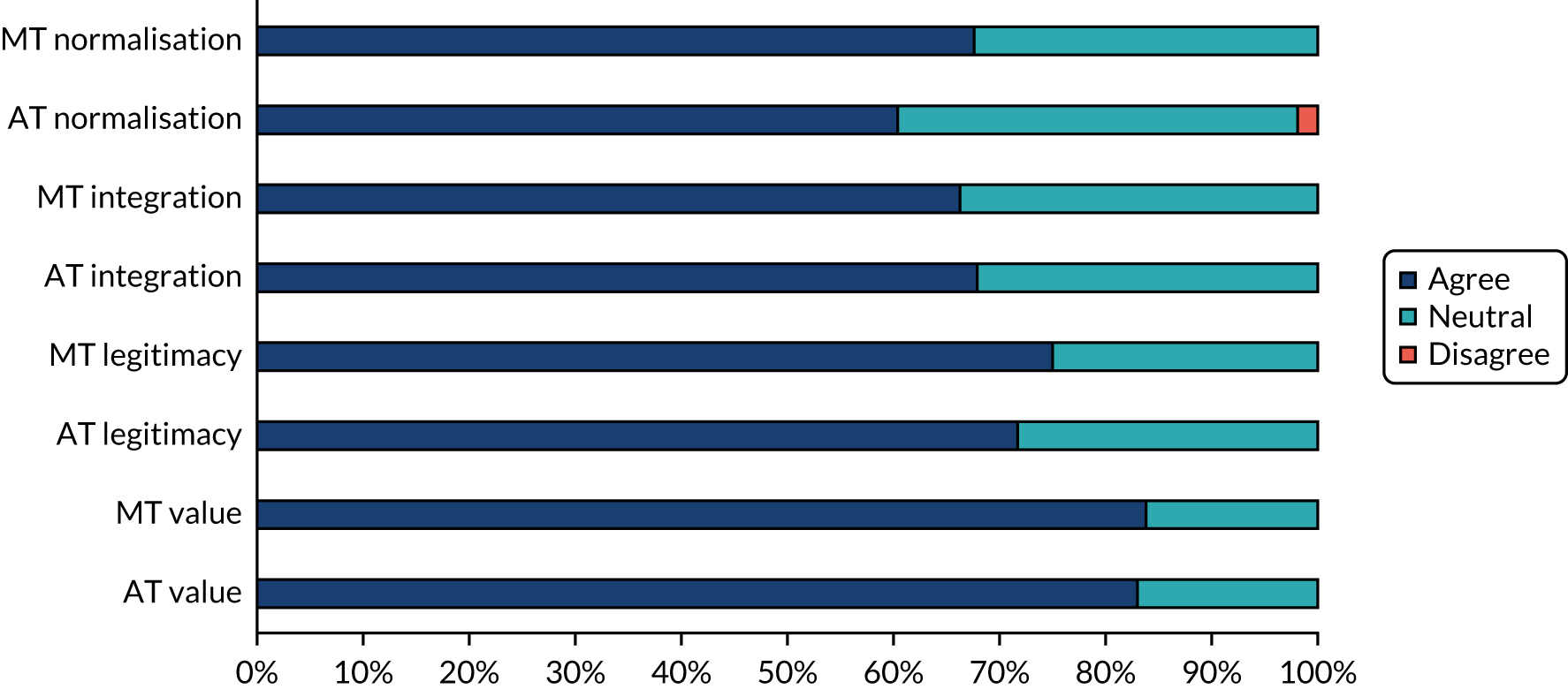

We used ethnographic methods, including semistructured interviews, focus groups and observations of clinical practice, throughout WP5. Structured questionnaires were used to collect information on current practice, confidence in diagnosing and managing LBD, and (in WP5.3) views on the assessment and management toolkits (Table 5).

| WP | Methods | Participants |

|---|---|---|

| WP5.1: understanding current practice | Clinician questionnaire (T0) | 146/336 completed questionnaires |

| Clinician interviews | 20 | |

| Clinician focus groups | Two (16 participants) | |

| Observation of routine practice |

17 clinical sessions (44 patients and 36 carers) Three clinical discussions (eight patients and eight carers) Two multidisciplinary team meetings (five patients and two carers) |

|

| WP5.2: acceptability of assessment and management toolkits | Clinician interviews | 60 (across whole study) |

| Observation of acceptability of toolkits in feasibility study | 0 | |

| Interviews with patients and carers with whom the toolkits had been used |

Six patients Four carers |

|

| WP5.3: implementation of assessment and management toolkits | Clinician questionnaires (T1 towards the start of WP5 and T2 after the pilot trial) |

60/124 completed T1 questionnaires 52/140 completed T2 questionnaires |

| Clinician interviews | 40 (including nine from the feasibility study) | |

| Clinician focus groups | Five (32 participants) | |

| Observation of routine practice | 25 clinical sessions | |

| Interviews with patients and carers were only planned in the event of any indication of the toolkits having had an impact on consultations | None |

Participants

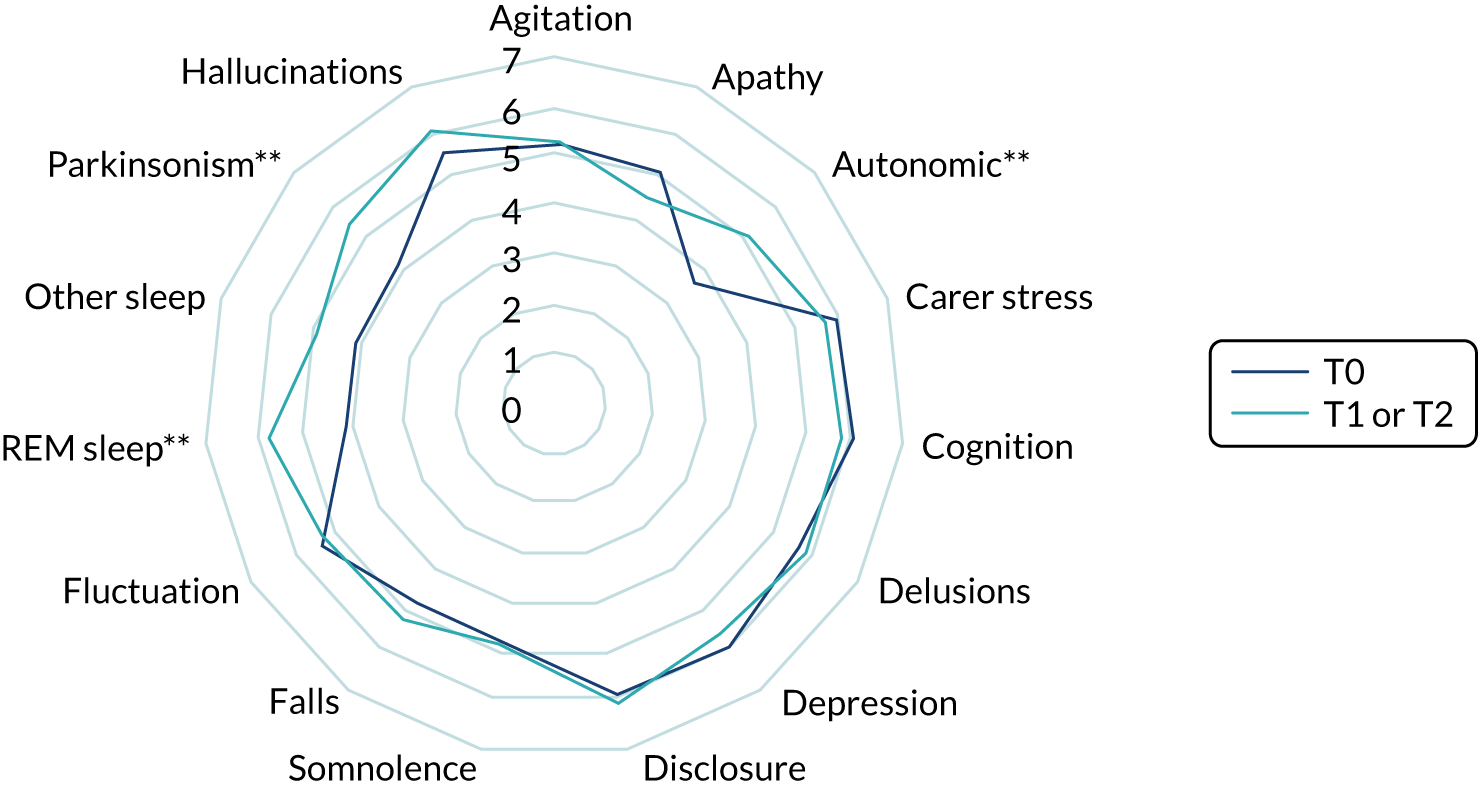

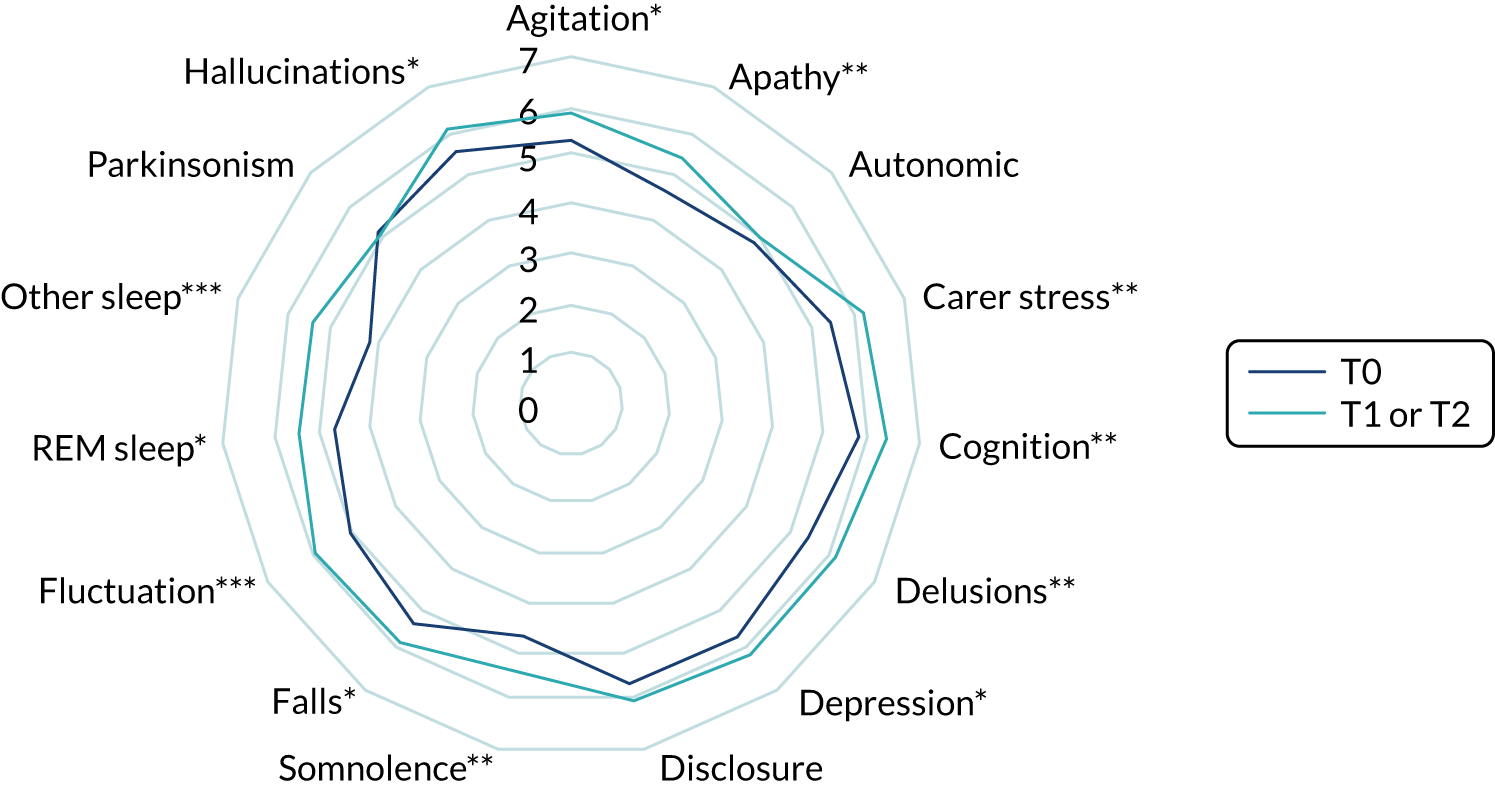

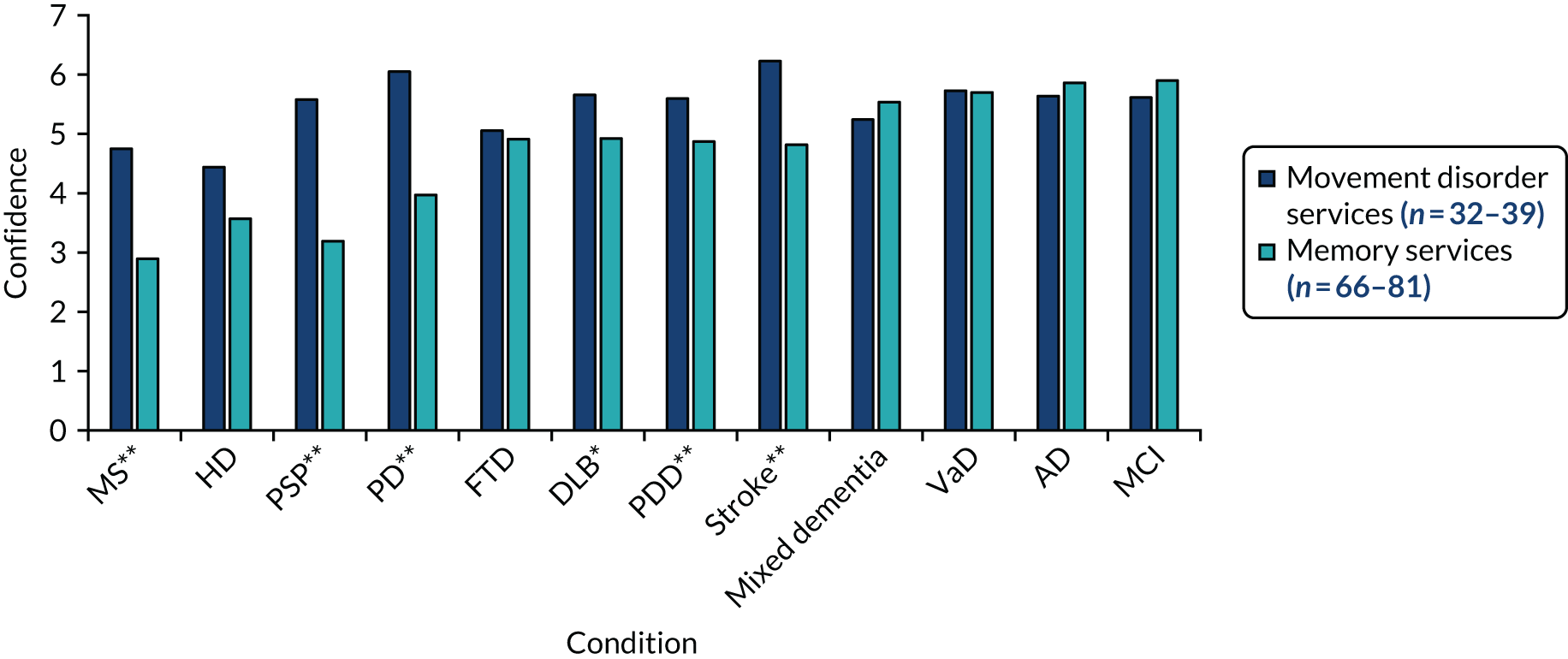

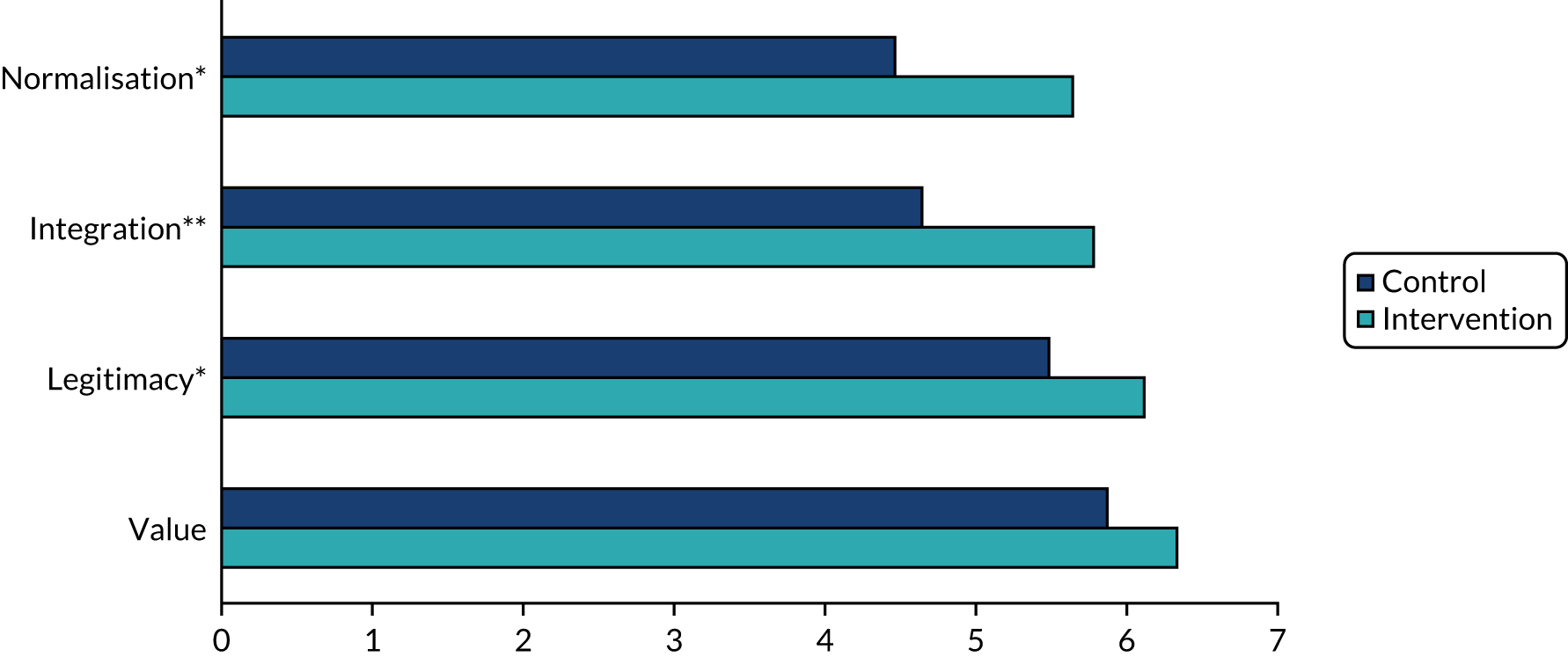

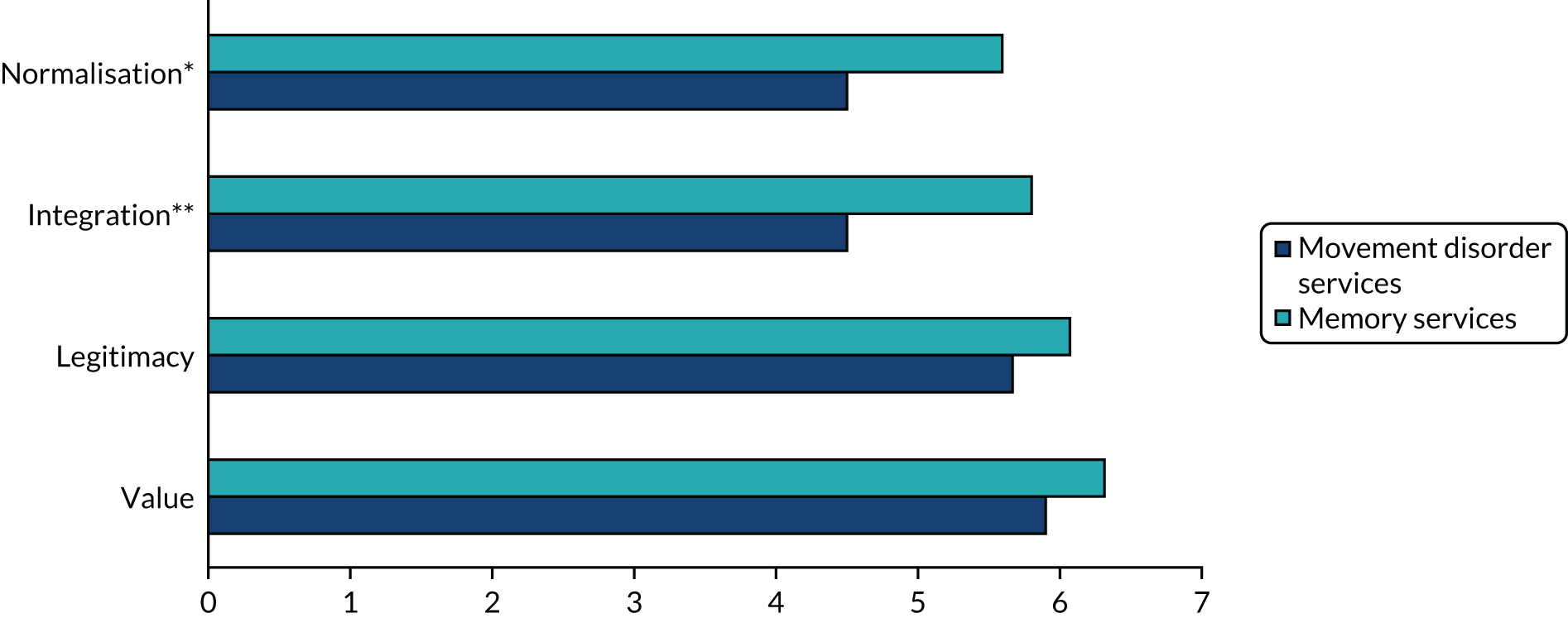

Participants included clinicians working in memory and movement disorder services (including geriatricians and/or neurologists) and patients attending participating services together with any companions (hereafter ‘carers’). We aimed to recruit maximum variation samples throughout (with the exception of WP5.2 where we recruited all available participants). Relevant clinician characteristics were professional background (doctors, nurses, allied health professionals), specialty (e.g. geriatrics, neurology, old age psychiatry), geographical location (East Anglia, North East) and, in WP5.3, study arm (control, intervention). Only 22 services took part in WP5.3. The remaining service involved in WP4 dropped out prior to the start of WP5.3.