Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1128. The contractual start date was in September 2007. The final report began editorial review February 2013 and was accepted for publication in November 2013. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust received additional funding for the submitted work from The Stroke Association. AF received funding from the NIHR Stroke Research Network and The Stroke Association for activities outside of the submitted work. Funding was provided by a Stroke Association Junior Research Fellowship for NA to undertake a PhD - a realist evaluation of the LoTS care trial. JRTF 2009/03.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Forster et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

There are over 900,000 people in England who have had a stroke, of whom 300,000 live with moderate to severe disability. 1 As such, stroke generates considerable health and social care costs. Costs are estimated at £7B a year, which includes £2.8B in direct costs to the NHS, £2.4B in informal care costs and £1.8B in income lost to productivity and disability. 1 Unplanned general practitioner (GP) visits and hospital readmissions generate an economic burden to the NHS and cause stress and discomfort to the patient. Previously viewed in a nihilistic way, stroke care is now characterised by a more dynamic and positive approach supported by the development of stroke medicine as a clinical specialty, rigorous reviews of services and production of evidence-based guidelines. 2 Although successful preventative measures (e.g. carotid endarterectomy) and drug interventions (e.g. thrombolysis) have been identified, they are appropriate for only a minority of stroke patients, and rehabilitation remains the cornerstone of treatment for many.

The recommended stroke care pathway in the first weeks after stroke is becoming established. Well-described service components include neurovascular clinics, stroke units and early supported discharge schemes. Despite these service developments, approximately one-third of stroke survivors are left with some physical impairment,3,4 one-third of stroke survivors are depressed,5 inactivity is common, participation levels are low6 and health-related quality of life deteriorates post stroke. 7

Community-based observational studies over three decades have left little doubt about the daily struggle for stroke survivors and their families as they come to terms with the longer-term consequences of a stroke illness. 8–10 Many stroke survivors require assistance from informal carers, often family members, for activities of daily living, including bathing, dressing and toileting. 11,12 This burden of care has an important effect on carers’ physical and psychosocial well-being,13,14 with up to 48% of carers reporting health problems, two-thirds reporting a decline in their social life and high self-reported levels of strain. 14

In recognition of the pressing need for a ‘comprehensive revolution’ in stroke care the National Stroke Strategy (NSS) was produced in 2007. 15 This included an emphasis on longer-term stroke care.

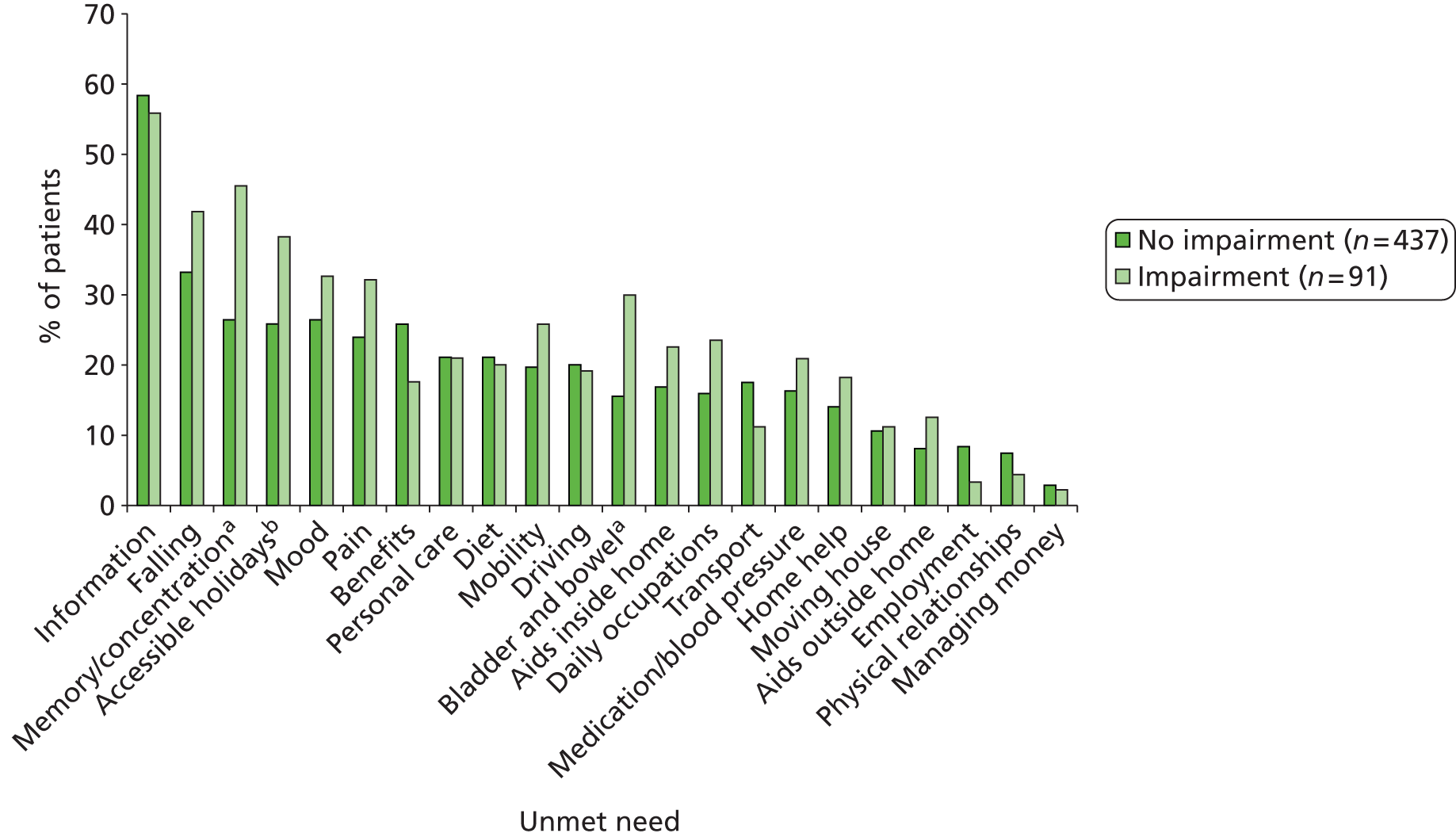

Despite this recognition of the importance of longer-term stroke care, surveys undertaken demonstrate that current service responses are not appropriately developed as stroke survivors have a range of unmet needs 1–5 years after stroke. In one study including 1251 participants,4 half reported some unmet needs. These related to information provision (54%) mobility problems (25%), falls (21%), incontinence (21%), pain (15%) and fatigue (43%).

The National Service Framework for Older People16 and the NSS15 emphasised the need for post-discharge support, in particular the need for ‘good-quality, appropriate, tailored and flexible rehabilitation’ (p. 35). 16 Previous service models for post-stroke care have been associated with equivocal,17–21 and sometimes adverse, outcomes. 20 There was a requirement therefore for innovative models of care to be developed, more closely tailored to the expressed needs of patients and their carers, and embedded in local stroke services. 8,22 A primary care orientation to assess, support and co-ordinate services might be more helpful in minimising longer-term stroke morbidity.

To address this we developed (through previously funded work; see Appendix 1) a systematic approach (termed a system of care) to longer-term stroke care based on the expressed needs of patients and carers23–25 and a monitoring tool to identify longer-term unmet needs after stroke. The twofold aim of the current programme was to enhance the care of stroke survivors and their carers in the first year after stroke and to gain insights into the process of adjustment.

Development of the system of care

Previously no systematic approach has been developed for routine monitoring, problem identification and co-ordination of services to assist stroke patients and their families as they continue to recover from their stroke and make life adjustments to its consequences. The system of care is based on a systematic review and synthesis of the available qualitative literature reporting interviews with stroke patients and carers in which longer-term stroke-related issues were discussed. Approximately 500 patients and 180 carers had participated in the 23 studies included in the review. 25 The review identified 203 patient- and carer-centred problems, which were clustered into five domains (hospital experience, transfer of care, communication and information, service provision and social and emotional difficulties) encompassing 12 main problem areas. A complementary review of 27 quantitative stroke surveys including 6000 patients and 3000 carers assessed the prevalence of these problem areas. 24 A further two prevalent problem areas (falls and sexual problems) were identified. To confirm content validity, our emerging findings were checked and refined by stroke patients and carers in individual interviews and in focus groups, leading to the addition of two more problem areas. 26 This approach has ensured that the proposed new service model is targeted at the most common stroke-related problems of central importance to stroke patients and their carers. The final 16 problem areas were transfer of care, communication and information, medicines and general health, pain, mobility/falls, personal hygiene and dressing, shopping and meal preparation, house and home, cognition, driving and general transport, finances and benefits, continence, sexual functioning, patient mood, patient social needs (and employability) and carer social and emotional needs.

Validated assessment tools (e.g. The Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly27 and EASY-Care28) were appraised to map relevant questions to the identified problem areas. A number of questions required modification to ensure that they accurately reflected the stroke-specific problem areas identified in the reviews. Additionally, some problem areas were not represented by the assessment tools and thus assessment questions were developed by the research team. From this process, patient and carer action plans were devised consisting of 15 questions (patient) and 12 questions (carer) representing the problem areas identified and an additional question to capture ‘other’ stroke-related problems.

Creation of problem-specific reference guides

Having identified the key problem areas and operationalised them through appropriate assessment questions, a range of literature, both within and beyond stroke, was reviewed to identify effective evidenced-based service interventions. The 16 problem-specific reference guides (relating to the 15 patient questions plus one carer-specific question) contain educational text with supporting assessment/treatment algorithms and checklists. The algorithms guide problem-solving as many apparently straightforward problems become multilayered on closer examination. For example, the activity of shopping might be impeded by physical barriers (mobility, lack of suitable transport), cognitive problems (poor comprehension, short-term memory loss) or psychological problems (fear, embarrassment). The final stage in this development phase was to obtain feedback from a range of local community and primary care professionals. This involved presenting and discussing the model during two workshops. Feedback from the workshops enabled us to frame our model into a product that was considered acceptable to primary care professionals. The resulting system of care is presented in a manual.

Manual presentation

Evidence on the implementation of clinical guidelines suggests that presentation can influence uptake into practice. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)29 details five key principles – language and style, bulleted lists, tables and figures, abbreviations and algorithms – and these were used to structure the components of the system of care. The aim of these principles is to make the information clear, accessible to non-specialists, unambiguous, succinct and guiding, but not prescriptive.

The resulting manual comprises patient- and carer-structured assessments representing the identified problem areas linked to, a reference guide and treatment algorithm; patient and carer goal and action plans; a directory of service information; and a selection of validated assessment scales for specific areas such as depression30 and cognitive impairment,31 included as appendices. Thus, we have created a manualised system for longer-term stroke care that is comprehensive (encompasses all areas of potential concern to patient and carer) but individualised (patient-specific action plans constructed).

Clinical implementation

The next stage in the development of the system for longer-term stroke care was to identify means of clinical implementation. Our previous work has identified a need for a service embedded in the community, where staff would have a greater awareness of locally available services. 22 Other work has identified that nurse-delivered interventions have been effective. 32 A survey of local district nurses demonstrated that nurses had relevant insights and skills but would appreciate additional training. 33

The National Service Framework for Older People16 identified a new role of ‘stroke care co-ordinator’ (SCC) to provide advice, arrange reassessment when necessary and co-ordinate long-term support. But who should be involved and how this role might be fulfilled are ill-defined. Through national presentations of our work, through links with the Stroke Association and through the National Stroke Nursing Forum, we were aware that a number of centres were developing SCC roles. To explore this further we undertook a national survey of all UK stroke services. For the purposes of this survey, a SCC was defined as ‘a qualified health professional in regular contact with stroke patients in the community, co-ordinating care inputs on their behalf’.

Pilot work: feasibility of the system for longer-term stroke care

Pilot work was conducted to investigate the practical implementation and feasibility of the proposed system of care. 23 A training programme was provided to community-based staff recruited to use the system of care in clinical practice. In total, 47 stroke patients and 21 carers were assessed using the new system of care. Analysis of care plans, 3 months after the initial assessment, indicated that the process was successful in picking up patient and carer problems. Of 219 problems, 75% had been resolved 3 months after assessment. Patient and carer participants thought that the review process would be more valuable if conducted sooner after hospital discharge (undertaken 8 months after stroke in the pilot study). We were able to demonstrate that a systematic assessment approach incorporated in a disease-specific manual is feasible to implement and was successful in identifying problems and triggering interventions.

Objectives

Projects 1 and 2 of the programme grant described here continue this work:

-

project 1 – an update of the evidence-based treatment algorithms using a structured protocol for searching and assessing the available literature (see Chapter 2)

-

project 2 – a cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) of the system of care as delivered by SCCs, evaluating its impact on patients’ and carers’ psychological and physical outcomes and its cost-effectiveness (see Chapter 3).

Since this programme grant was awarded in 2007, there have been considerable changes in stroke service provision across the UK. Our system of care is very much in keeping with current developments. Similar approaches have been developed, for example the Greater Manchester Stroke Assessment Tool (GM-SAT) for 6-month reviews. 34 This indicates that our thinking is feasible, practical and appropriate for ongoing service development.

Assessment of unmet needs after stroke

In interlinked work we had undertaken preliminary development of a tool to assess and monitor patient longer-term unmet needs after stroke [the Longer-term Unmet Needs after Stroke (LUNS) tool].

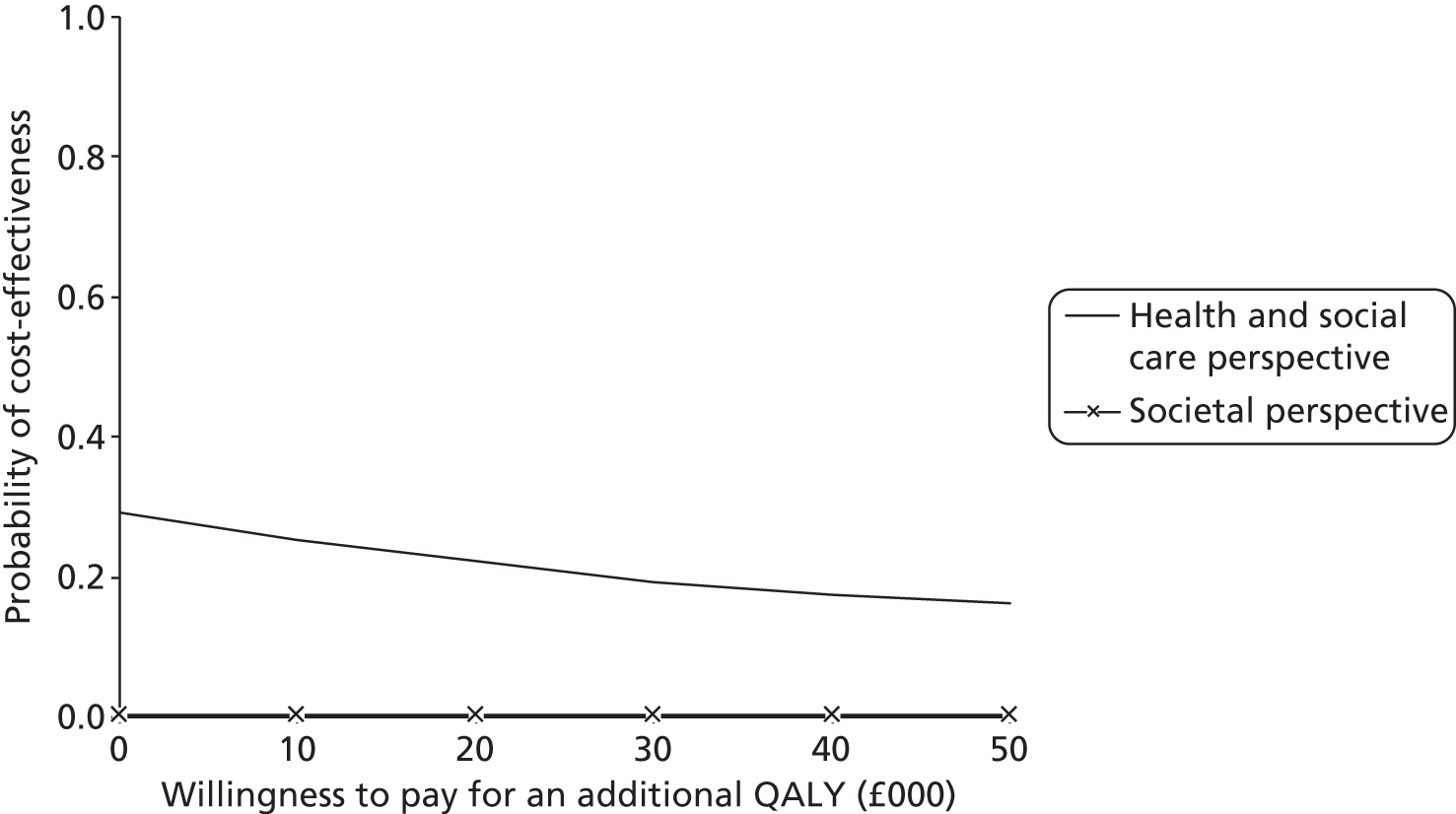

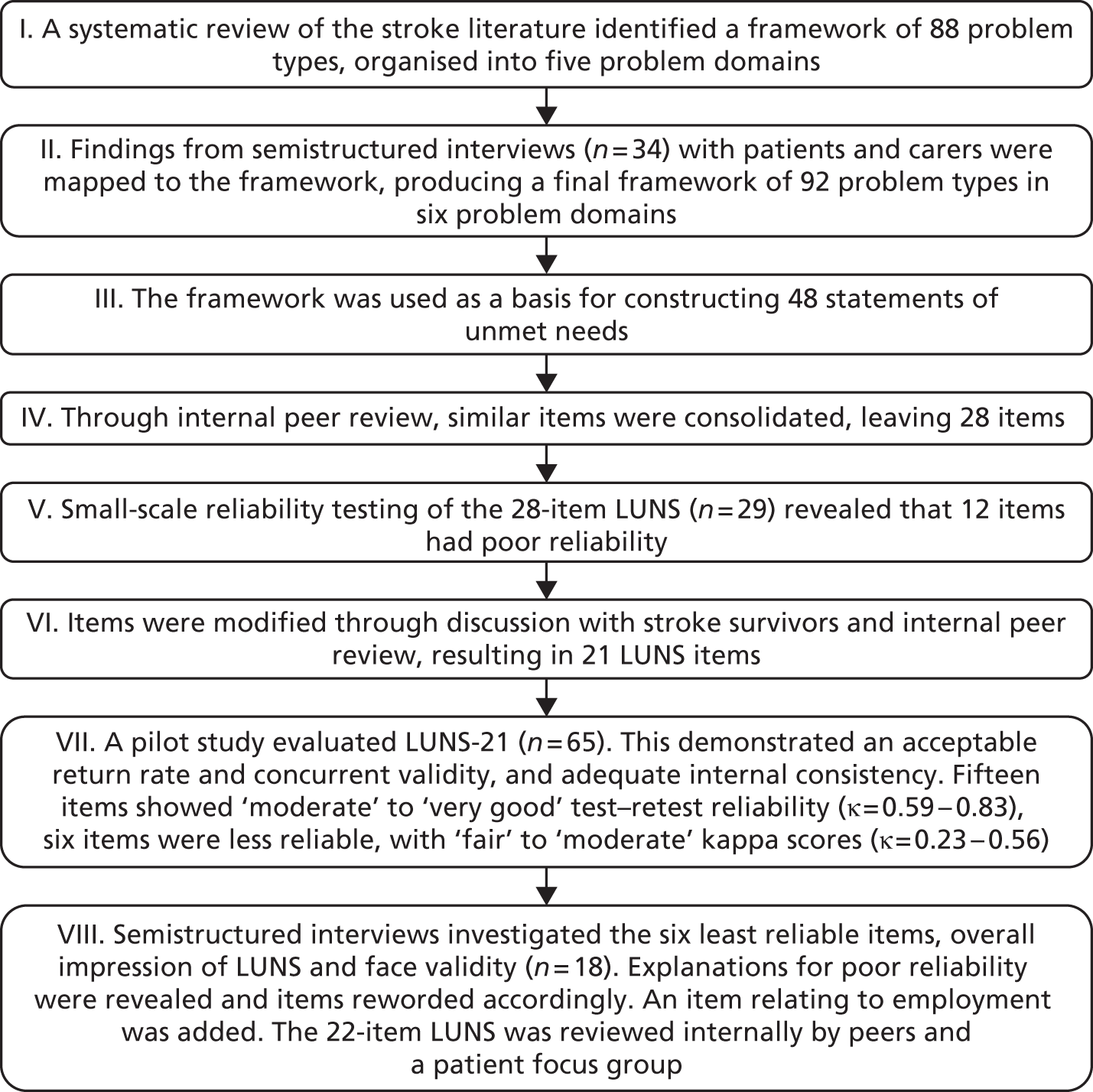

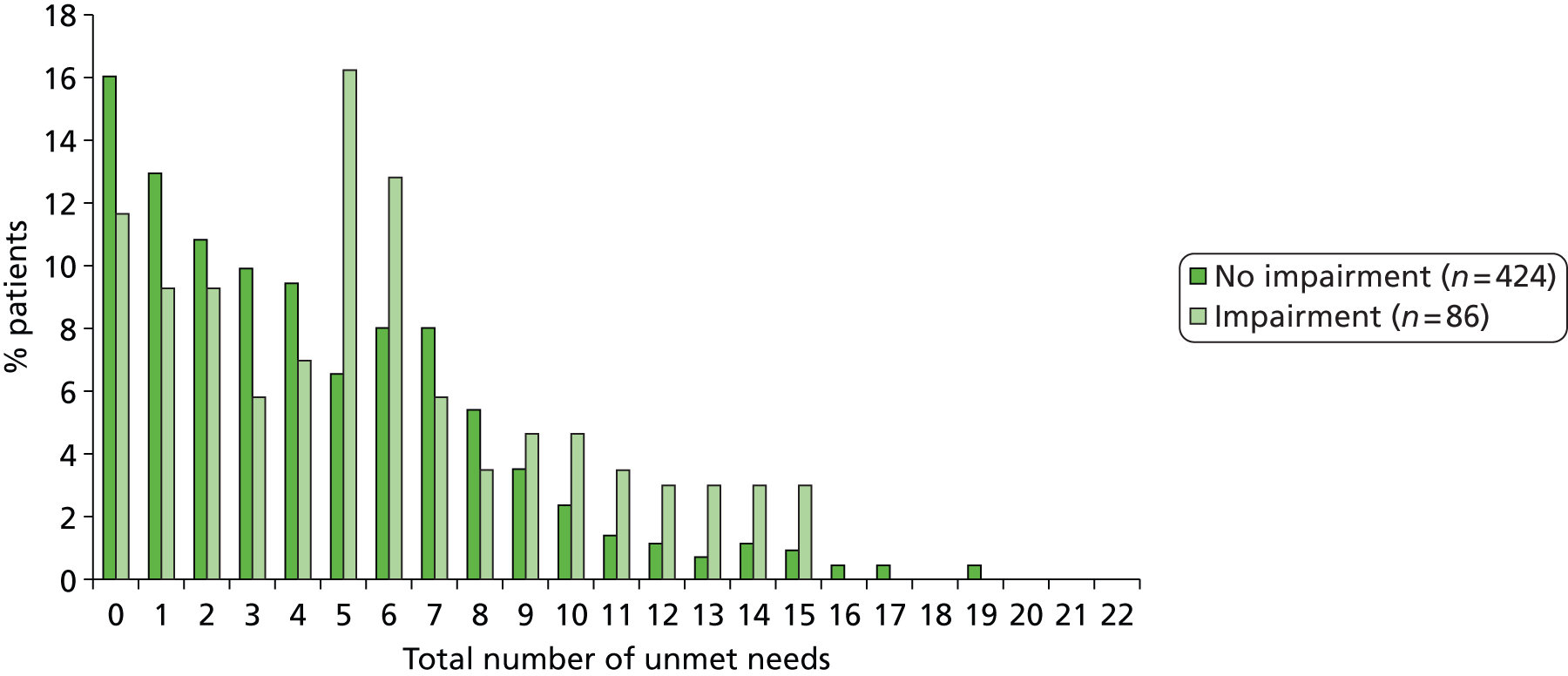

We, and others, have demonstrated that the problems faced by stroke patients and their families in the longer term encompass physical, social and mental well-being. 4,24,25 There is no currently available measure that provides a ‘good fit’ across all of these outcome domains in the special context of longer-term stroke care. The common compromise in research, in which greater insights are required, is to use a basket of measures, all addressing different components of the stroke experience, or to create and use one larger outcome tool (e.g. the Stroke Impact Scale35). In clinical practice such approaches are impractical, expensive and time-consuming and there is a need for a short, easy to complete monitoring tool. We developed a comprehensive monitoring tool to measure unmet needs in stroke patients by converting the assessment questions (based on patient- and carer-identified problems) contained in our proposed system of care into statements of need. Preliminary psychometric testing was undertaken. The draft, 28-item version of the measure, was reviewed by experts in the field and refined in collaboration with our Consumer Research Advisory Group (CRAG), which contributed to various aspects of the measure, including layout, presentation and wording of questions. The monitoring tool therefore has face and content validity. We have undertaken preliminary work (through existing funding) to investigate the reliability of the measure. Patients (n = 29) were assessed with the measure in their home on two occasions, approximately 1 week apart. Statistical analysis demonstrated poor reliability for 12 questions and, in the light of this, further work was undertaken with the CRAG, members of other local stroke groups and stroke physicians. All aspects of the measure, including layout, presentation and wording of questions, were reviewed. The number of items was reduced from 28 to 21 and the questions were grouped according to whether they addressed informational needs or practical needs.

Objectives

Project 3 in this programme continues this work:

-

further development and psychometric testing of a measure to assess and monitor patient longer-term met/unmet stroke-related needs (the LUNS questionnaire) (see Chapter 4).

Identification of needs after stroke has become increasingly topical during the implementation of this programme grant. The Stroke Association commissioned a survey of post-stroke unmet needs and co-applicants of this grant (Forster and Young) contributed to the development of this survey,4 which included some questions from the LUNS tool.

‘Failure to thrive’ patients

A complementary approach to the described projects is to work with patients and their families to gain a greater understanding of the mechanisms of adjustment to stroke. It is reported in the literature, and often cited anecdotally, that many patients with good physical recovery are paradoxically socially inactive; however there is little information on the prevalence or cause of poor social recovery.

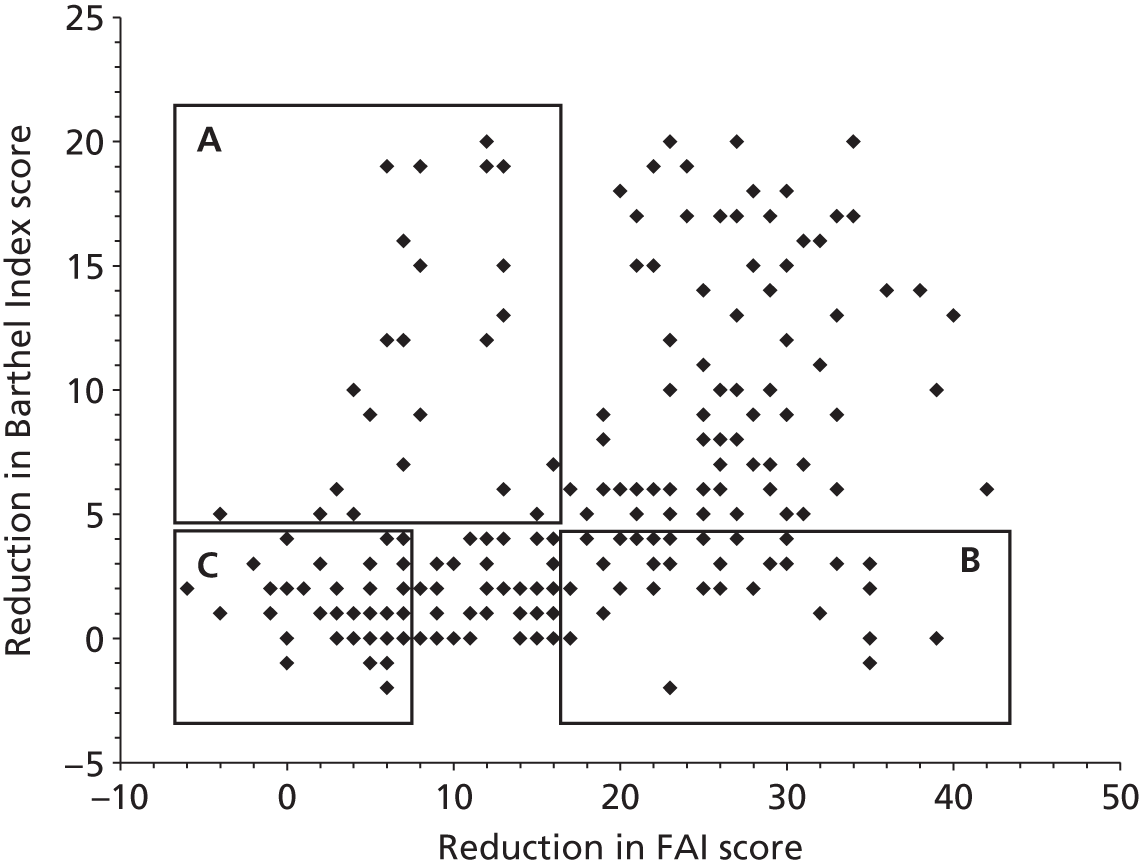

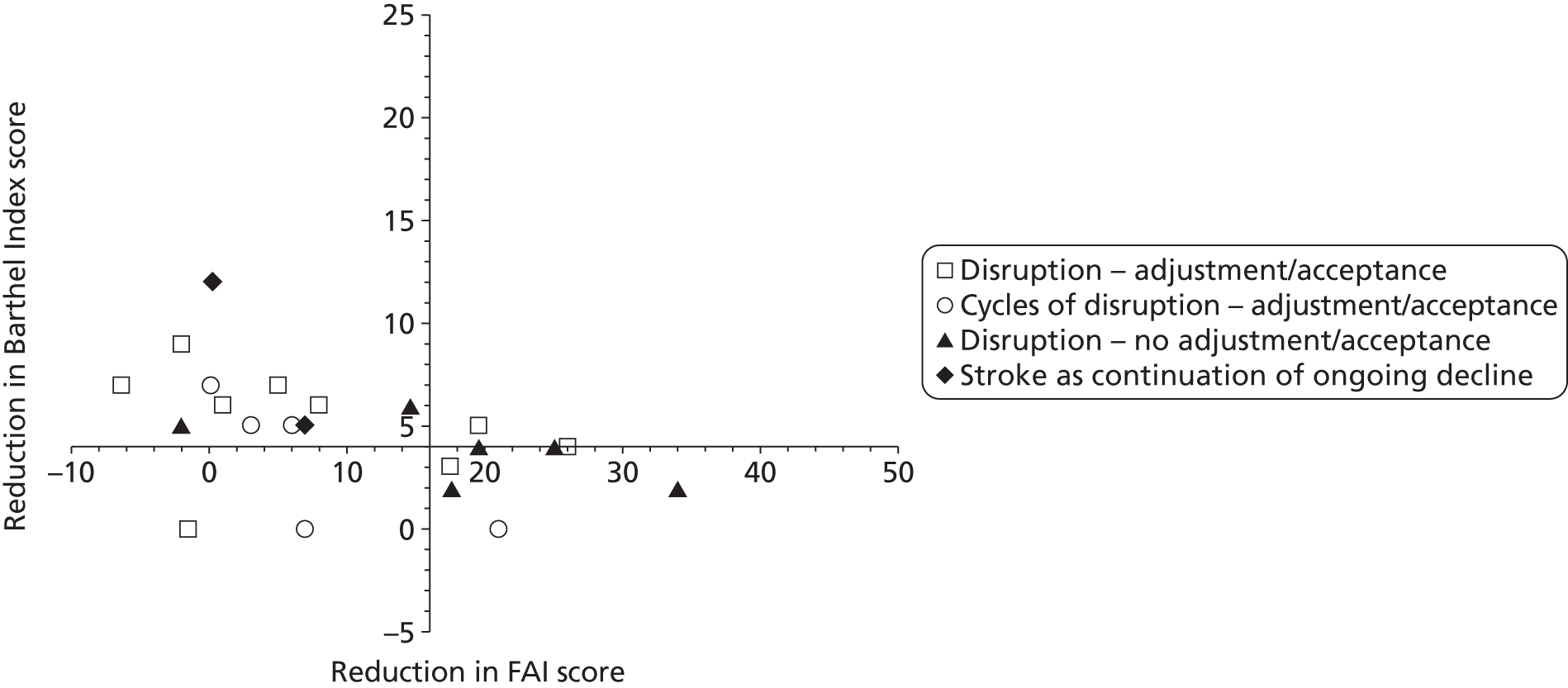

We were fortunate to have a number of data sets available to us from previous community stroke studies,18,36,37 on which we undertook some exploratory analysis. By comparing Barthel Index38 scores at various time points with social activity scores [measured by the Frenchay Activities Index (FAI)39] we have been able to identify statistically a small subgroup of patients who do not do as well as we would expect, that is, they are more socially restricted than would be expected for their level of disability. To investigate why there is such a variation in social recovery for patients with good physical recovery, this subgroup was investigated further. Unsurprisingly, previous activity level, age and living in institutional care were all related to poor social activity at 12 months after stroke, even when physical recovery is good. A review of a number of our previous data sets indicates that approximately 10% of the patients in each of the samples had ‘unexplained’ poorer outcomes (i.e. more socially restricted than expected for their level of disabilty but not explained by age or living in institutional care or pre-stroke activity). Although this group of patients is small, it is possible that they have attributes that have impeded their recovery that are present to a lesser extent in the wider stroke population and therefore have been difficult to detect. A specific study of this smaller group may therefore provide insights of relevance to the wider stroke population and thereby inform future service development.

Objectives

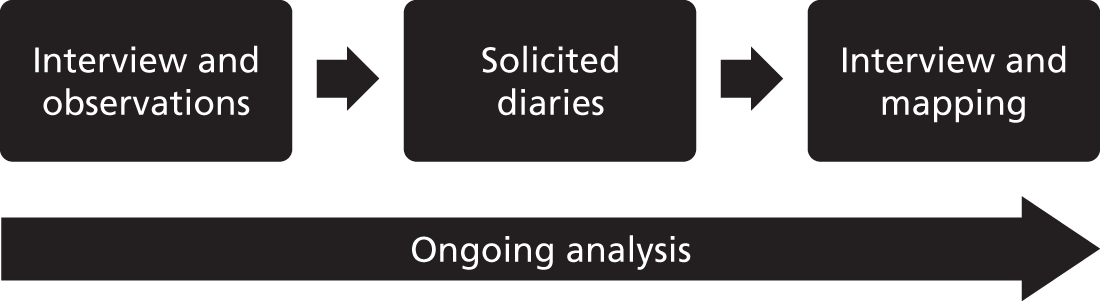

Project 4 undertook further exploratory work:

-

identify factors contributing to patients’ poor adjustment after stroke through a qualitative and quantitative case–control study nested in the randomised trial (see Chapter 5) [it was clarified during the review of the grant application that the design is not in fact a nested case–control study but rather a qualitative substudy (with purposive sampling based on the quantitative trial data)].

Programme management

This programme grant has been undertaken and completed by a committed team of co-applicants. The management structure is summarised in Appendix 2. During implementation one of the co-applicants (Val Steele) retired and another (Joanna Powell) left clinical practice. The update of the system of care (project 1) and further development of the LUNS tool (first part of project 3) were completed before the system of care trial (project 2), which then ran until the end of the programme grant; the LUNS tool was included in the trial outcome measures. Psychometric evaluation of the LUNS tool (second part of project 3) was carried out in parallel with project 2. Exploration of poor adjustment (project 4) was carried out in parallel with the 12-month follow-up in project 2.

Clinical engagement

Clinical engagement has been sustained throughout the programme through:

-

Yorkshire Stroke Research Network (YSRN) therapy meetings – held three times a year and open to all allied health professionals in Yorkshire

-

the attendance of the chief investigator at the quarterly Clinical Stroke Network meetings, where research progress is reported as a regular agenda item

-

the ongoing contact of the chief investigator, clinical lead for the YSRN, with all local stroke services and robust links with national colleagues.

Patient and public involvement

Terry Brady (co-applicant and stroke survivor) has been involved at all stages of programme development. He is a member of the CRAG, which has met bimonthly throughout the duration of the programme. The CRAG has been provided with regular updates on the progress of the programme and has contributed at all stages.

Terry Brady is also on the organising committee for the annual consumer conference, which is hosted by the YSRN and attracts over 70 stroke survivors and their carers each year. Updates on ongoing research are provided at the conference and this includes progress reports on this programme of research. In addition, advice and guidance were sought on specific components of the research through ‘round table’ discussions, for example outcome assessment for the cluster trial and layout of the outcome assessment booklet (project 2); considerable input into the development of the LUNS tool, both content and layout (project 3); and contribution to the adjustment after stroke study and consideration of the results (project 4).

Colleagues in the CRAG have become experienced in the review of stroke research. One of our members, Mick Speed, is now a member of the Stroke Association research panel.

Collaborations

Professors Anne Forster and John Young were members of the Stroke Association UK Stroke Survivor Needs Survey study team and this survey included some of the questions from the LUNS questionnaire.

Chapter 2 Project 1: update of the system of care documentation

Abstract

Background

Our purposely developed system of care was framed around patient- and carer-identified problems. To support treatment delivery a manual was created that included algorithms to assist SCCs in clarifying problems and directing patients to treatment options. To ensure that all of the treatment algorithms were up to date and evidence based, they were rigorously reviewed and updated.

Methods

In collaboration with information specialists at the University of Leeds, a hierarchical, comprehensive structured protocol for identifying evidence in each of the 16 problem areas was developed. This protocol included identifying relevant stroke- and problem-specific guidelines; meta-analyses and systematic reviews; and, if necessary, individual RCTs. Two researchers independently reviewed all outputs. Guidelines, reviews and papers identified for inclusion were assessed for quality using standard tools. Drafted treatment algorithms were peer reviewed by external experts.

Results

Over 71,000 articles were identified by the initial searches. Robust guidelines were identified for three problem areas; for one problem area, information provision, we are the authors of the Cochrane review, which we updated. For the 12 remaining problem areas detailed searches were implemented. Following the review procedure algorithms were updated in accordance with the identified evidence and, following external peer review, they were incorporated into the system of care manual. Presentation of the manual was informed by expert opinion and feedback from clinical colleagues.

Conclusion

The system of care manual was created using robust methods to ensure that advice and guidance provided were up to date and evidence based.

Introduction

The system of care was formulated around the post-stroke problems identified by patients and their carers. These were translated into a series of assessment questions to elicit the problems and to enable the SCC to work with each patient and his or her carer to develop goals and action plans. Goal setting is considered an essential part of clinical rehabilitation,40 and there has been growing emphasis on the need for interventions with patients to be goal orientated. Our intent was that the system of care would more appropriately address patient unmet needs. Documentation involved with the delivery of this system of care included:

-

the care plan: assessment questions (formulated around problem areas) and goal and action planner

-

the manual: providing information about the problem area (reference guide) linked to an evidence-based treatment algorithm and other supporting material

-

national and local service information.

All required refining and updating before the planned trial to evaluate the system of care (see Chapter 3).

The care plan

The care plan included questions addressing all problem areas supported by additional prompts. It also included goal and action planners for the patient/carer, which aimed to encourage and support shared decision-making about goals and the prioritisation of goals according to patient (carer) preference and joint problem-solving approaches. The layout and presentation of the assessment questions for patients and their carers were initially reviewed by the study management group (SMG) and clinical colleagues. The care plan was further refined by SCCs taking part in the trial, before the start of the trial (see Chapter 3, Intervention arm: system of care).

Part of the care plan is shown in Appendix 3.

The manual

The manual associated with our system of care was created in 2003. The manual included introductory text, reference guides with associated detailed treatment algorithms, which are centred around the patient- and carer-identified problems, and general advice on patient assessment. On commencement of the programme grant the manual needed updating to ensure that it remained a relevant and reliable resource.

Methods

Updating the manual

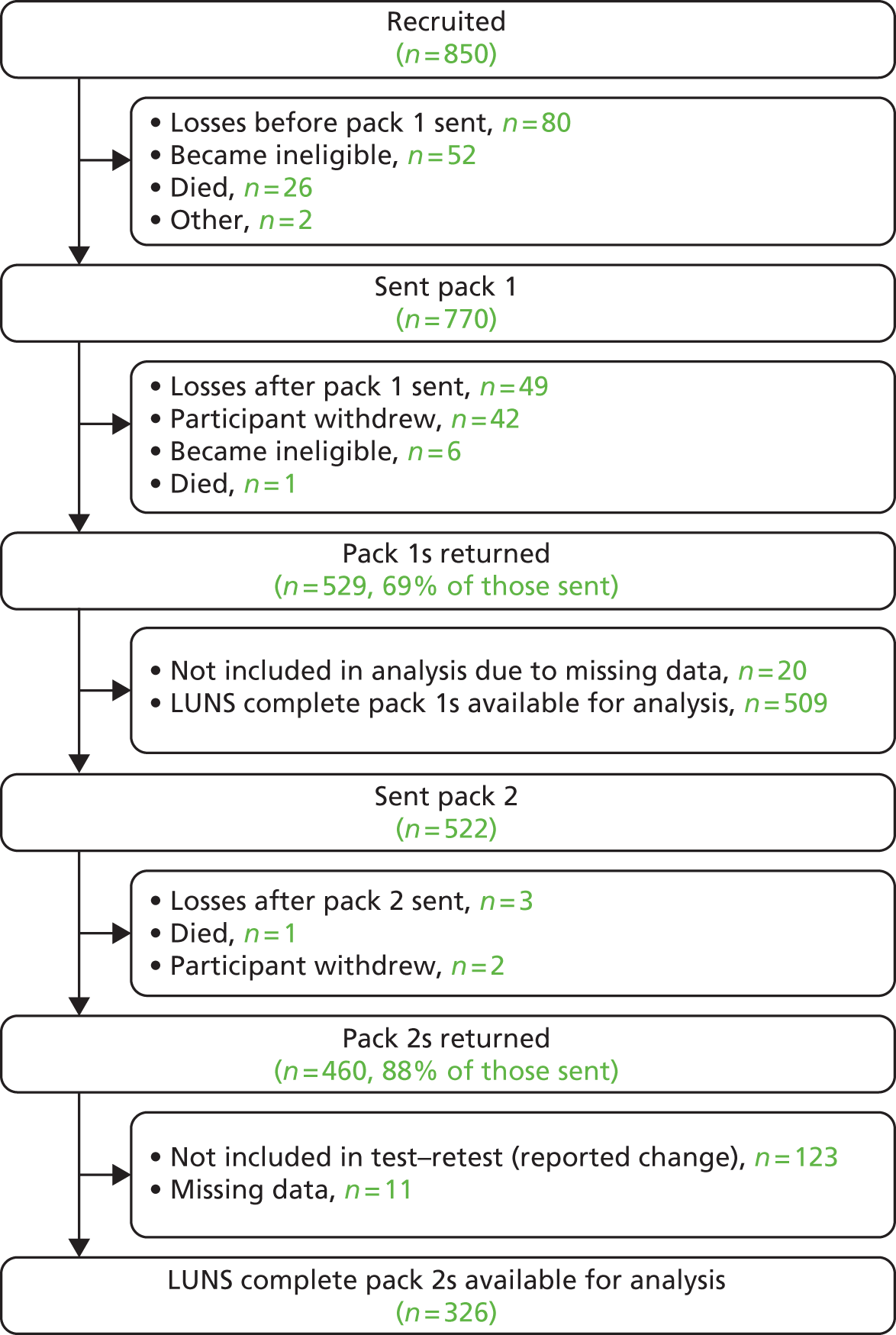

To ensure that all of the treatment algorithms were up to date and evidence based, in collaboration with information specialists at the University of Leeds, a hierarchical, comprehensive, structured protocol for identifying evidence in each problem area was developed (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Protocol for identifying evidence-based interventions for stroke problem areas. AGREE, Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation; AMED, Applied and Complementary Medicine Database; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; HTA, Health Technology Assessment; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.

The reference guides linked to treatment algorithms addressed the following problem areas:

-

transfer of care

-

communication and information

-

medicines and general health

-

pain

-

mobility/falls

-

personal hygiene and dressing

-

shopping and meal preparation

-

house and home

-

cognition

-

driving and general transport

-

finances and benefits

-

continence

-

sexual functioning

-

patient mood

-

patient social needs (and employability)

-

carer social and emotional needs.

The protocol started (stage 1) with searches to identify all potentially relevant evidence-based stroke guidelines (e.g. the National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke2,41). This progressed to the identification of guidelines for problem areas of relevance to stroke but that were not necessarily stroke specific (stage 2) and the identification of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (stage 3). If it was considered that the problem area had not been adequately addressed (e.g. through the availability of national guidelines) then a comprehensive electronic search strategy was developed and implemented to identify all RCTs of effective interventions evaluated for stroke and for other diseases with similar experiences to those of stroke (stage 4).

The search strategy was developed iteratively. Each problem area was discussed between the researchers (A Forster, J Murray and R Breen) and the information specialists and consensus agreement was reached about scope (e.g. age limits, key words, databases to be searched). When available, guidance on search terms was taken from existing reviews (e.g. the Cochrane review on the prevention and treatment of urinary incontinence after stroke in adults42). Example search strategies for pain for MEDLINE and EMBASE are provided in Appendix 4 and other search strategies are available on request from the authors. All searches were restricted to the English language only, with a date restriction from 1995 onwards, and included appropriate methodological filters for guidelines, consensus statements, systematic and other reviews and RCTs. The information specialists then conducted initial searches with the results reviewed by J Murray and A Forster to verify that appropriate titles were being identified. Following further amendments as necessary, the full search was undertaken, with the results downloaded into EndNote (version 5; Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). All searches were undertaken in MEDLINE, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Evidence-based Medicine Reviews, PsycINFO and EMBASE. A member of the research team was designated as lead reviewer for each problem area.

The overall purpose was not to develop guidelines but to identify and present the evidence in a format that will aid the clinical application of the structured assessment system, triggering appropriate, evidenced-based interventions. These interventions had to be relevant to SCC practices; therefore, for example, in medicines management the focus was on knowledge rather than the SCC being an active prescriber of drugs. Similarly, when considering the problem area of mobility, interventions that require specialist equipment (such as a treadmill) were not considered as the SCC would refer to a physiotherapist for such specialist treatment.

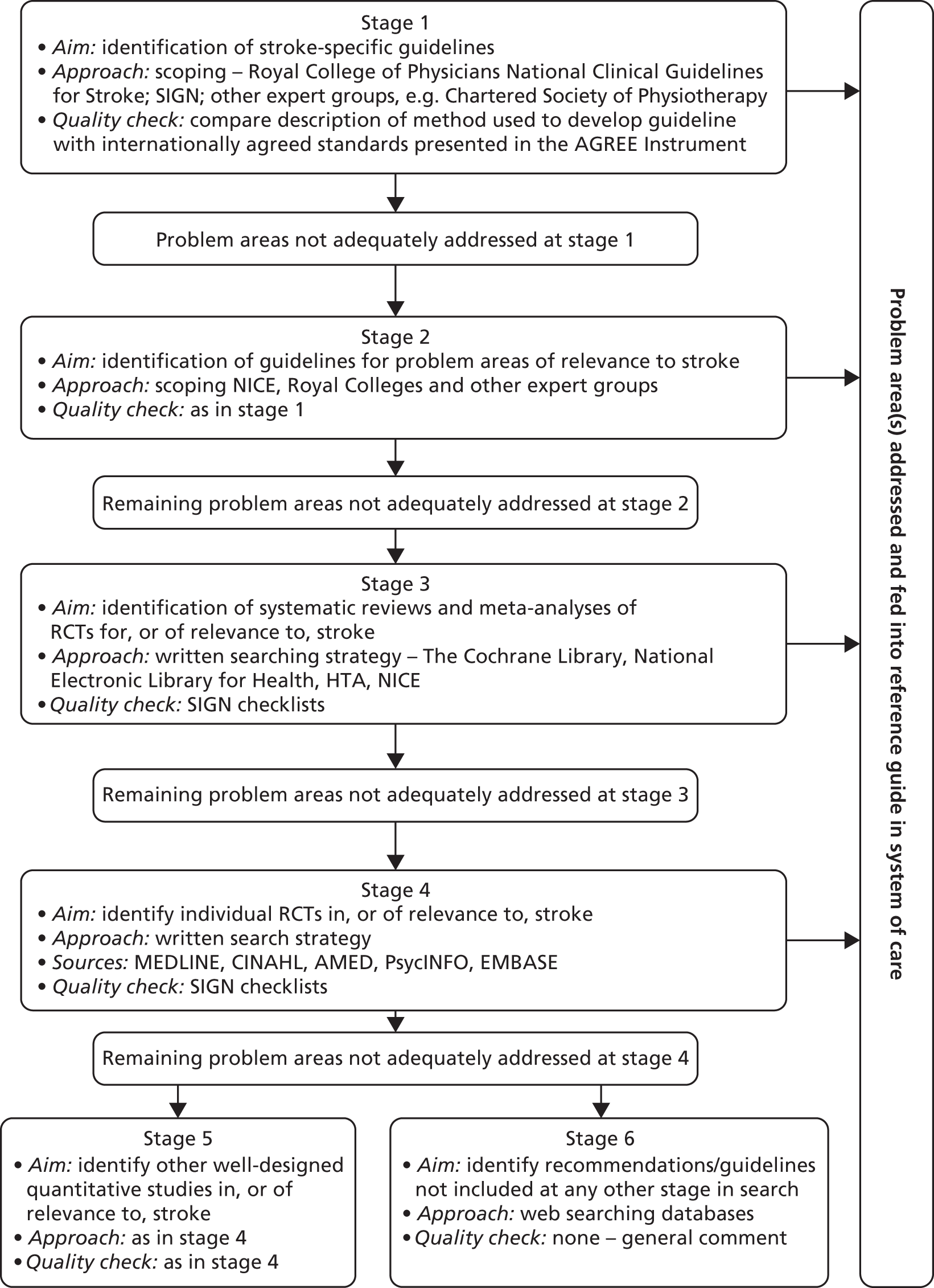

The outputs from stages 1–3 were initially reviewed by one researcher (J Murray) and presented and discussed at regular SMG meetings (monthly then moving to fortnightly). For stage 4 (Figure 2), initial screening of the titles was conducted in two phases: the first reviewer carried out an initial screen to eliminate any obviously irrelevant papers and then the second reviewer screened all remaining papers. The abstracts/full papers were then considered by two reviewers independently using a standard proforma. A third reviewer was required when there was a conflicting opinion or both reviewers were unsure about study inclusion. Following discussions a consensus of studies for inclusion was reached.

FIGURE 2.

Written search strategy used in stage 4.

Quality assessment

The quality of the guidelines was assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) Instrument (see www.agreetrust.org/about-the-agree-enterprise/agree-research-teams/agree-collaboration/). Quantitative studies were assessed using quality checklists developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (see www.sign.ac.uk).

Synthesis of papers

Evidence identified through the structured protocol was presented to the SMG by the lead reviewer for each problem area. The evidence (identified guidelines/studies, etc.) was used to inform development of the reference guide (supporting text) and treatment algorithm. Existing algorithms were reviewed and amended as necessary. A synthesis of study results through meta-analysis was not undertaken. Drafts of the reference guides and algorithms for each problem area were discussed and reviewed in SMG meetings.

Once agreement on content was reached by the SMG, the reference guides were then sent out for peer review to topic experts in the UK and their feedback was incorporated into the updated reference guides.

Presentation of the manual

Concurrent with content development, advice was sought regarding presentation, to facilitate ease of use. This was sought through a review of the relevant literature and from the Medical Illustration Department of Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. In addition, the SMG considered what components were essential for delivery of the system of care.

The Cochrane review of information provision for stroke patients and carers

The Cochrane review of information provision for patients and their carers after stroke has been updated twice during the programme. The systematic review was conducted using The Cochrane Collaboration-recommended methodology for undertaking systematic reviews of RCTs and full details of the methods and outcomes have been published. 43–45

Studies were included if there was random assignment of participants (patients with a clinical diagnosis of stroke and/or their identified carers) to intervention groups (one of which involved the provision of information and/or education) and to a control group. In addition, studies using a matched pairs design and studies in which strict randomisation procedures were not adopted were also considered for inclusion.

We excluded trials in which information giving was only one component of a more complex rehabilitation intervention, for example family support worker trials (e.g. Forster and Young18 and Dennis et al. 20), which are the subject of a separate Cochrane review. 46

The primary outcomes used to assess the effectiveness of information provision were patient and carer knowledge about stroke and stroke services, and impact on health, especially mood. Secondary outcomes were activities of daily living; handicap; social activities; perceived health status; quality of life; satisfaction with information; hospital admissions, service contacts or health professional contacts; compliance with treatment/rehabilitation; death and/or institutionalisation; and cost to health and social services.

Relevant trials were identified in the Cochrane Stroke Group Specialised Trials Register. Additional intervention-based search strategies were developed for the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL/CCTR, formerly Cochrane Controlled Trials Register), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, ISI Citation Index, ISI Web of Science Service, ASLIB Index to Theses, Dissertation Abstracts International, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts and PsychLIT/PsycINFO. We also searched registers of trials in progress and bibliographies of retrieved papers, articles and books.

Results

Updating the manual

Following a review of all problem areas it was agreed that each category of problem should be subjected to a separate search, with the approach and range of the search varying according to the problem. Broadly three approaches to the search strategy were undertaken:

-

an inclusive general search of the problem area

-

the search was restricted to ‘stroke’

-

the search was restricted to stroke and other similar long-term conditions, which we termed a ‘chronic illness filter’.

A summary of the search methods used is presented in Table 1.

| Reference guide | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| Transfer of care | It was felt that a full literature search of this area was outwith the scope of this model. A systematic review and guideline were available |

| Communication and information | A Cochrane review on information provision was conducted as part of this programme (see an update of the Cochrane review on information provision for stroke patients and carers44,45) |

| Medicines and general health | The National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke2 had comprehensively covered this problem type |

| Pain | Stroke-specific search, specifically including shoulder pain and neuropathic pain |

| Mobility/falls | Mobility: stroke/exercise guidelines; excluded equipment-related therapy (treadmills/robots) as SCCs would not deliver this treatment Falls: stroke-specific search – for general falls a Cochrane review is available47 |

| Driving and general transport | Search combined because of considerable overlap. General search then limited using terms (stroke, traumatic brain injury, disabled persons, chronic disease) supported by text word searches for physical disabilities |

| Continence | General search: aware that a Cochrane review of urinary incontinence is available42 |

| Sexual functioning | General search then limited to stroke, chronic heart disease, traumatic brain injury, disabled persons |

| Shopping and meal preparation | Problem areas combined. General search excluding anorexia/bulimia/children, then limited to stroke, traumatic brain injury, disabled persons, chronic disease and text word searches for physical disabilities |

| House and home | General search (excluding children) |

| Finances and benefits | General search |

| Personal hygiene and dressing | General search then limited using chronic illness filter |

| Cognition | Search terms tailored based on existing Cochrane reviews;48–50 additional search for compensation devices, e.g. aids/devices to compensate for memory loss |

| Patient mood | A recent systematic review and guidelines were available51 |

| Patient social needs (and employability search) | General search |

| Carer social and emotional needs | General search followed by stroke-specific search |

Over 71,000 titles were indentified by the individual searches, details are provided in Table 2. In total, 12 problem types required a review of evidence-based interventions from stage 3 (see Figure 1). Two problem areas, shopping and meal preparation and house and home, were addressed by a combined search and one problem area, patient social needs (and employability), was addressed by two separate searches.

| Reference guide | Guidelines/reviews/RCTs identified | Number of papers after first review | Number of papers after final review | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer of care | – | – | – | |

| Communication and information | – | – | – | |

| Medicines and general health | – | – | – | |

| Pain | 215 guidelines, 1619 reviews, 1565 RCTs | 190 | 7 | |

| Mobility/falls | 193 guidelines, 141 reviews, 109 RCTs | 17 | 8 | |

| Driving and general transport | 131 guidelines, 364 reviews, 1028 RCTs | 49 | 49 | |

| Continence | 867 guidelines, 5793 reviews, 12,139 RCTs | Guidelines sufficient | Guidelines sufficient | |

| Sexual functioning | Not recorded | 243 | 21 | |

| Shopping and meal preparation | } | 313 guidelines, 1377 reviews, 4213 RCTs | 40 | 16 |

| House and home | ||||

| Finances and benefits | 640 guidelines, 1296 reviews, 4101 RCTs | 80 | 10 | |

| Personal hygiene and dressing | 195 guidelines, 742 reviews, 830 RCTs | 43 | 17 | |

| Cognition | Not recorded | 83 | 13 | |

| Patient mood | – | – | – | |

| Patient social needs (and employability) | 94 guidelines, 489 reviews, 1757 RCTs | 209 (395) | 25 (21) | |

| Carer social and emotional needs | 3483 general, 485 stroke | 420 | 52 | |

Identified guidelines and papers were subject to appropriate quality assessment. Relevant evidence-based interventions from guidelines and studies found to be of high quality were then used to update treatment algorithms. Each was drafted by a lead reviewer and then reviewed by the SMG before external review. Final versions were further revised and formatted for inclusion in the manual.

The completed reference guides and treatment algorithms with supporting text are included in the manual; an example (for pain) is provided in Appendix 5.

Manual content and layout

In discussion with clinical colleagues and colleagues from the Medical Illustration Department of Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, presentation of the manual was agreed. Introductory text was finalised and advice and guidance on use of the manual were provided. Each reference guide has a number of sections (‘The problem’, ‘The evidence’ and ‘Addressing the problem’) followed by the algorithm. A frequency table was also provided for each of the problem areas (e.g. 88% of stroke patients have a fear of falling), to provide insight for SCCs and also assist them in informing/reassuring the patient. A list of screening tools that might be of use was included in the manual, with the tool reviewed to ensure that there were no copyright issues. All documentation was reviewed by members of the SMG before being finalised.

The essential components of the system of care were considered by the SMG. These were described as principles and were included in the manual. They were as follows:

-

patient-centred comprehensive coverage of problems identified as important by patients and carers

-

all assessment questions asked

-

follow-up on actions and review goals.

In addition, national information about services available for patients after stroke was collated, with the intention that this would be used alongside information about local services.

Review of the evidence

Updating these treatment algorithms provided an opportunity to review evidence gaps. Available evidence was reviewed for each problem area. The results were tabulated and summarised to include available evidence and recommendations (if available) made in the Evidence-Based Review of Stroke Rehabilitation (see www.ebrsr.com), a relevant Cochrane review, Royal College of Physicians (RCP) guidelines,2 Australian guidelines52 or Canadian guidelines53 or identified through searches undertaken for the manual update. We also highlighted when a relevant RCT was ongoing. The resulting output is 85 pages long. Although the work was completed, we did not promote it as we were mindful that NICE was developing stroke rehabilitation guidelines (issued June 2013)54 that could replicate the work and the RCP was similarly updating its guidelines (issued September 2012). 55

The Cochrane review of information provision for stroke patients and their carers

For the first update44 we identified 228 abstracts, of which 63 studies were potentially relevant to the review. In total, 17 studies, involving 1773 patients and 1058 carers, were included (published 2009).

For the most recent update45 we reviewed 28,110 titles including 134 full papers, resulting in the inclusion of four additional studies. The current review includes 21 trials from seven countries involving 2289 patients and 1290 carer participants.

Meta-analyses of reported outcomes showed a significant effect in favour of the intervention on patient knowledge, carer knowledge and patient satisfaction with information provision. There was also an effect on patient depression; however, the reduction was small and may not be clinically relevant. There was no effect on the number of cases of anxiety or depression or on patient mortality. Qualitative analyses found no strong evidence in favour of the intervention for other outcomes relevant to stroke recovery, including independence, participation in social activities, service use or modification of health-related behaviours.

Post hoc subgroup analyses demonstrated that, when information was provided in a format that more actively involved patients and carers, for example by offering repeated opportunities to ask questions, it had more effect on patient mood than information provided on one occasion only. However, as we saw no effect on the dichotomous end points of anxiety or depression (number of cases), the effects may be small. The specific component of the active information provision that may provide beneficial effects requires further investigation. There was no evidence that active information provision strategies were effective for other outcomes.

Discussion

The content and delivery of the developed system of care were comprehensively reviewed. Reviewing the literature for evidence-based treatment options focusing on patient-identified problems is a novel approach. This work focused on handicap rather than impairments and intended to create a more patient-centred service.

We took expert advice and guidance in the development of the treatment algorithms, using recognised methods to review the literature, and involved external peer review. The work was rigorous and comprehensive. However, some topic areas, for example house and home, are huge and may not be addressed in the more medical, impairment-focused literature. However detailed our searching, we may have missed some pertinent literature in less mainstream journals.

Information provision is reported as the most common unmet need and we undertook and published the Cochrane review relating to information provision for stroke patients twice during this programme. 43,45

Chapter 3 Project 2: cluster randomised controlled trial to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a system of longer-term stroke care

Abstract

Trial design

A pragmatic, multicentre, cluster RCT compared a new system of care with usual practice delivered by SCCs.

Methods

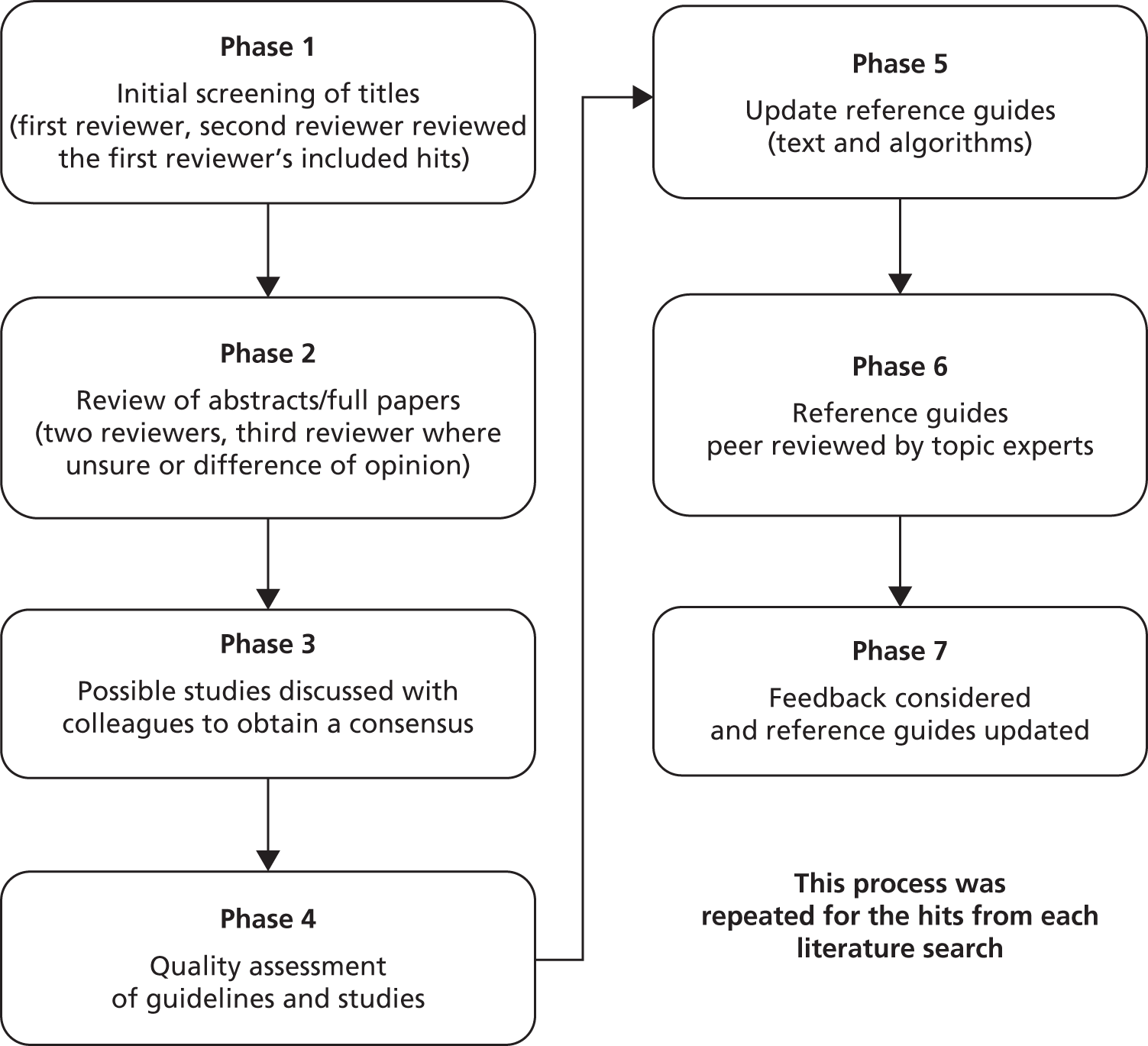

Stroke services were randomised to the intervention or the control. Patients with new stroke living at home post stroke and referred to a SCC, and their informal carers, were eligible for recruitment before their first SCC assessment. The primary objective was to determine whether the intervention improved patient psychological outcomes (General Health Questionnaire-12, GHQ-12) at 6 months; secondary objectives included further functional outcomes for patients, carer outcomes (if registered) and cost-effectiveness. Follow-up was through self-completed postal questionnaires at 6 and 12 months after registration.

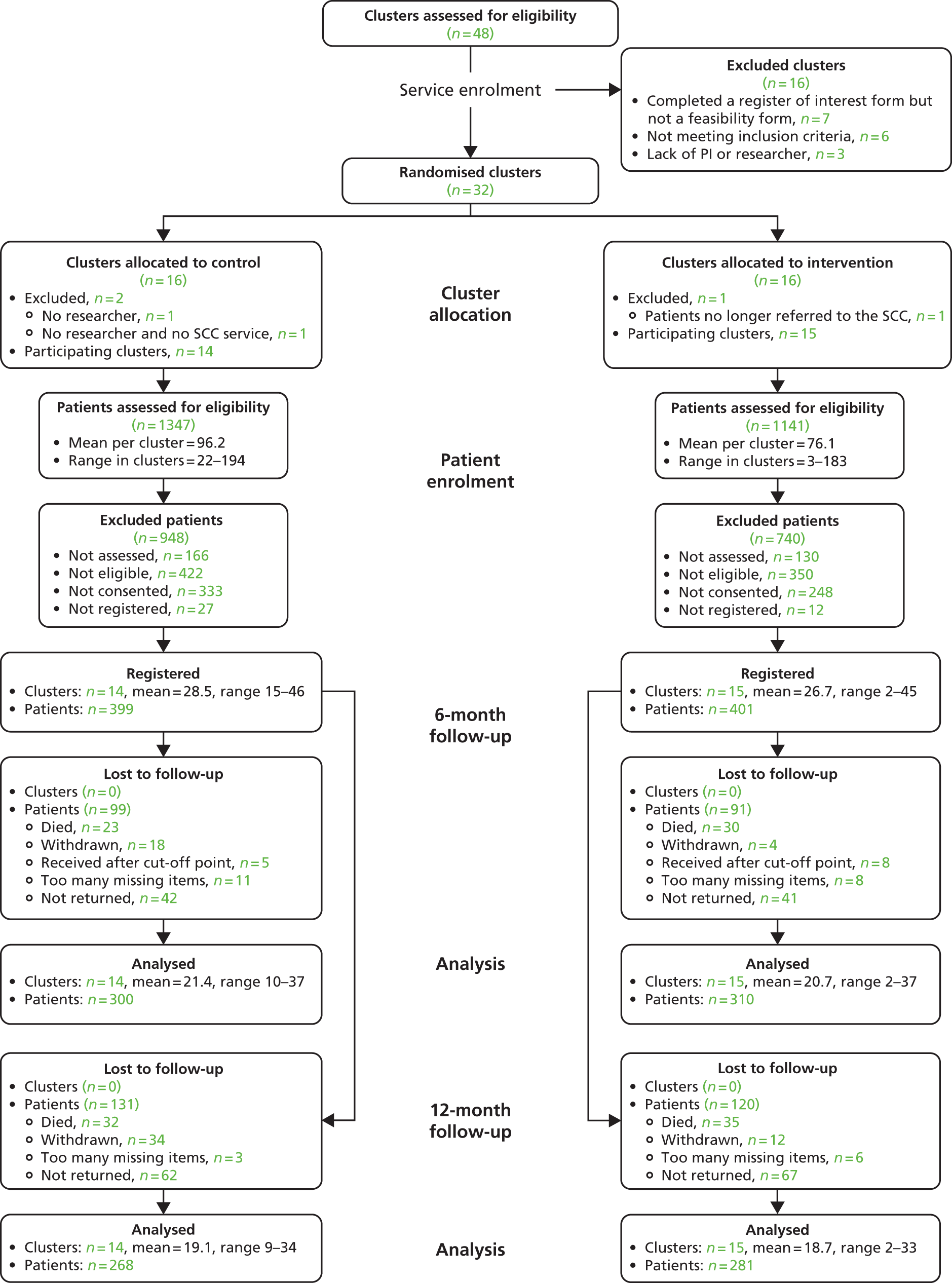

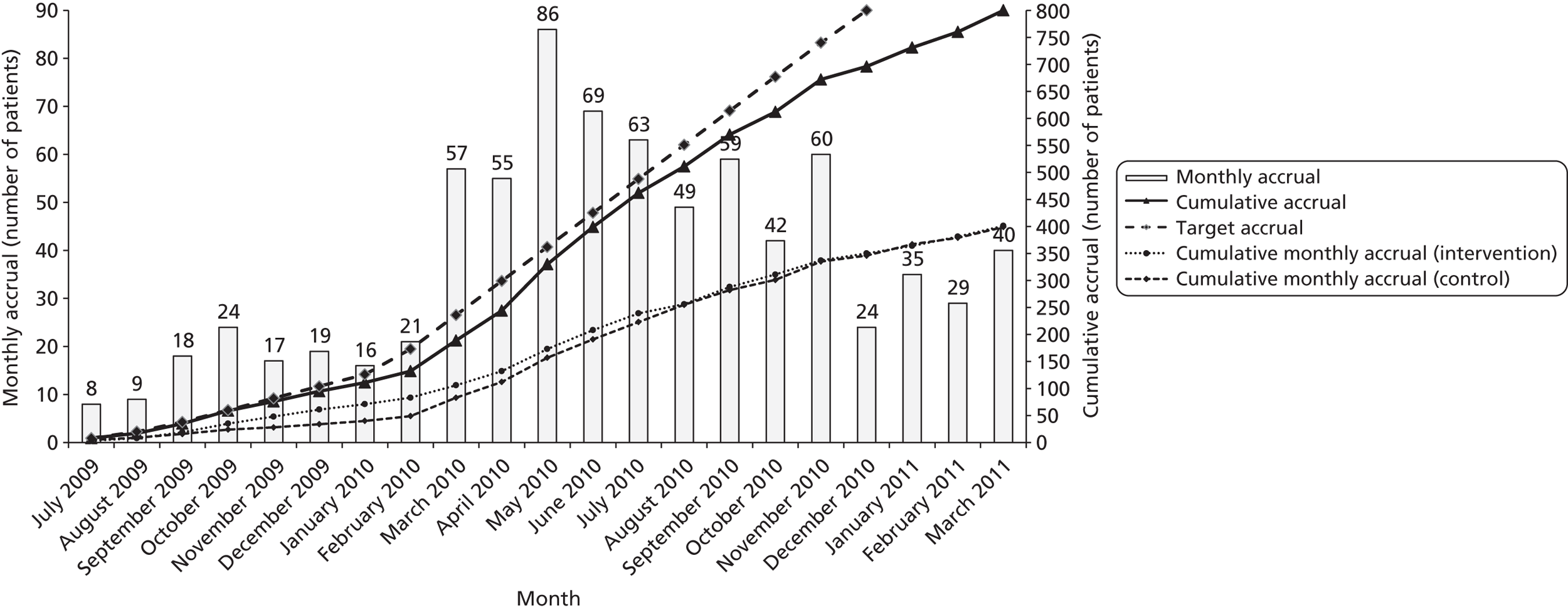

Results

In total, 32 randomised stroke services (29 participated), including 800 patients (399 control, 401 intervention) and 208 carers (100 control, 108 intervention), were recruited. In intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis the adjusted difference in patient GHQ-12 mean scores at 6 months was −0.6 points [95% confidence interval (CI) −1.8 to 0.7 points; p = 0.394], indicating no evidence of a statistically significant difference between treatment arms; analyses of secondary end points and of the per-protocol population resulted in the same conclusion. The intervention involved no additional SCC time. Quality-adjusted life-years and total health and social care costs at 6 months, 12 months and over 1 year were similar between arms. Societal costs were higher for the intervention arm (+£1163 at 6 months, 95% CI £56 to £3271).

Conclusions

This robust trial demonstrated no benefit for clinical effectiveness or cost-effectiveness outcomes for the system of care compared with usual SCC practice.

Trial registration

This trial was registered as ISRCTN67932305.

Introduction

Background

The diversity of longer-term problems experienced by stroke patients and their carers has long been recognised,56 but they remain poorly addressed by existing services. 57 There are persuasive arguments that a community-based orientation to post-stroke care delivered by primary care in the patient’s local community, to assess, support and co-ordinate relevant services, might be more helpful in minimising longer-term stroke morbidity. 22,58

To address this we have developed an evidence-based system of care that aims to meet the longer-term needs of stroke survivors and their carers living at home in the community. The system of care incorporates structured assessment focused on patient- and carer-centred problems and associated evidenced-based treatment algorithms.

We aimed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of the system of care when delivered by SCCs compared with usual practice in a cluster RCT [Longer-Term Stroke care (LoTS care) trial]. The methodology for the trial was informed by our survey of 39 SCCs. 59 The survey, undertaken in 2006, revealed that approximately 40% of SCCs reviewed the patient within 1 week of discharge from hospital. Most SCCs (n = 27) saw patients more than twice after discharge from hospital, but the number of contact visits was often dependent on patient need (as opposed to defined time points). The majority of SCCs appeared to refer on to other services for carer assessments.

Objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective of the trial was to determine whether the system of care improved psychological outcomes for stroke patients living at home.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives were to:

-

determine whether the provision of the system of care improved functional outcomes for stroke patients living at home

-

determine whether the provision of the system of care improved psychological and functional outcomes for carers of stroke patients living at home

-

assess whether the system of care was cost-effective based on patient outcomes from both health/social care and societal perspectives.

Methods

A summary of the protocol has been published. 60 The study was approved by Leeds West and Scotland A Research Ethics Committees.

Trial design

The trial has been designed as a pragmatic, multicentre, cluster RCT. The unit of randomisation was at the level of the stroke service, with SCCs (single practitioners or part of a community-based team) randomised to deliver the new system of care to all patients (and their carers, if appropriate) or to continue to deliver current practice as determined through local SCC policy and practices. Follow-up was through postal questionnaires at 6 and 12 months after recruitment.

A prospective cluster RCT design was used to reduce between-group contamination. The training component of the intervention was designed to impact on the skills, knowledge and clinical practice of SCCs and therefore the risk of contamination would be high if randomisation was at the individual patient level. If a service had more than one SCC it was likely that the SCCs would meet on a regular basis and work as a team, sharing caseloads. For these reasons the unit of randomisation was at the level of the service.

The system of care was evaluated as a whole to avoid a type III error,61 in which deconstruction of the component parts of a complex intervention may result in the loss of benefits of the interactions between components.

We recognised that the intervention may be effective on a number of domains. We therefore chose a range of outcome measures. The primary outcome measure was the General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12),62 to reflect patient mood, which would be influenced by a range of service inputs (including overall co-ordination of care). We aimed to capture psychosocial outcomes rather than just physical abilities as reflected in activities of daily living. The GHQ-12 has been used in previous stroke research and is sensitive to change.

Eligibility

Stroke services

The trial evaluated a complex intervention delivered to patients by a SCC within a stroke service; therefore, eligibility criteria were applied at three levels – the stroke service, the stroke unit and the SCC.

A stroke service encompasses primary and secondary care over a defined geographical area within the UK. As treatment in a stroke unit is the recommended care pathway for all patients after stroke,16,63 a stroke service was considered for inclusion in the trial only if it included a stroke unit that fulfilled the RCP’s41 definition of a stroke unit, that is, it fulfilled four out of the five following criteria:

-

it had a consultant physician with responsibility for stroke

-

it had formal links with patient and carer organisations

-

it had multidisciplinary meetings at least weekly to plan patient care

-

it provided information to patients about stroke

-

it provided continuing education programmes for staff.

A SCC was eligible if he or she fulfilled the following criteria:

-

is a registered health-care professional with documented experience in stroke care

-

undertakes a community-based/liaison or co-ordinating role for stroke patients (i.e. providing care for patients living in the community after discharge from hospital)

-

is in contact with patients and co-ordinates a range of longer-term care inputs on their and their carers’ behalf (e.g. signposting, carrying out assessments)

-

works within a stroke service as above.

If SCCs worked as a team and shared caseloads then they were classed as one ‘stroke service’ for the purpose of the trial randomisation. A SCC was classified as working in a team if he or she attended regular (i.e. weekly/fortnightly) community multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings.

Participants

In keeping with the pragmatic trial design, the patient eligibility criteria were broad to be inclusive of a clinically meaningful variety of stroke pathology and severity affecting patients and reflecting current clinical practice.

Patients were eligible for the trial if they:

-

had a confirmed primary diagnosis of new stroke

-

were referred to a SCC on discharge home from hospital or within 6 weeks of stroke and were still waiting for their first home or outpatient SCC assessment

-

were able to provide written informed consent or consultee declaration.

Patients were excluded from the trial only if:

-

they had a planned permanent admission to, or were already resident in, a nursing or residential care home

-

their main requirement was palliative care

-

they had been previously registered to the trial.

Patients involved in other Stroke Research Network (SRN)-adopted studies could be recruited into this trial unless they were first recruited into another study that was considered to overlap, as listed in the excluded studies list [Assessing Communication Therapy in the North West (ActNoW), LUNS, Oxford Vascular Study (OXVASC), Surgical Trial in Lobar Intracerebral Haemorrhage (STICH) II and Training Caregivers After Stroke (TRACS)].

Recruitment of carers was optional. Carers were eligible for the trial if:

-

they were identified by the patient as the main informal carer who provides the patient with practical support a minimum of once per week.

Carers were excluded from the trial if their patient did not consent to the trial.

Randomisation

Randomisation was undertaken by the University of Leeds Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU). Stroke services were randomised on a 1 : 1 basis to either the intervention group or the control group. A detailed overview of the stroke services was obtained before randomisation to inform stratification.

Randomisation was stratified by the quality of the stroke unit [National Stroke Audit (NSA) score based on 2006 data64], the annual number of referrals, whether SCCs work alone or within a community-based MDT and the Strategic Health Authority (SHA). When a SCC received referrals from more than one stroke unit, a weighted average of the NSA scores reflecting referral rates was used.

A method of obtaining a balanced design from the covariates available at the start of the trial, as proposed by Carter and Hood,65 was used. This method uses an imbalance measure to compare the extent to which all possible designs balance important covariates between the arms of the trial and then randomly selects one member from the class of designs that achieves maximum balance. The advantage of the method is that it allows randomisation in multiple phases, conditioning on previous allocations. Because of the complexities of the current research approvals process, which created variable time delays (see Appendix 6), the services were randomised in two phases.

Blinding

As this was a cluster trial, all patients within the services randomised to the intervention received the new system of care and all patients within the services randomised to the control received usual care.

Recruitment of trial participants was by members of the independent reseach team and the SCCs were unaware which of their patients had consented to participate. Members of the research team were blinded to whether they were recruiting within an intervention service or a control service. This trial design has the advantage of reducing the potential for selection bias from differential recruitment, inherent if the SCCs were responsible for patient identification, and it minimises altering of SCCs’ clinical activity for trial participants.

Interventions

All patients received the services of a SCC in a community stroke service. SCCs within the intervention arm provided care according to the new system of care. Control SCCs continued with usual practice.

Control arm

Patients who received care from the control SCCs received current community-based care as determined by local policy and practices.

Intervention arm: system of care

The development and description of the system of care is provided in Chapter 1 and Appendix 1. For implementation in the trial, the system of care comprised the following components:

-

A care plan containing a structured assessment (assessment questions linked to reference guides in the manual) and a goal and action planner for each contact (patients and carers) (see Appendix 3). In discussion with the SCCs it was agreed that the assessment documentation should incorporate the patient details that they collected in delivery of their service, the intent being to create a single care plan that would replace currently used patient records, thus facilitating it becoming embedded in their service. The care plan was piloted by the SCCs (between the two training days; see below) before the final version was produced.

-

An optional checklist detailing the content of the assessment to be given to patients before the SCC visit.

-

A manual containing reference guides with evidence-based treatment algorithms, a frequency table of longer-term problems after stroke, a service directory and recommended assessment scales.

-

National information about services available for patients after stroke was collated and provided to the SCCs at the first training day. Each SCC was given a large box file including leaflets of relevant services (e.g. Disabled Holiday Directory, Age Concern). The SCCs were asked to further develop a resource inventory of local services.

Training in the delivery of the system of care was provided for each of the SCC services randomised to the intervention before commencement of patient recruitment. Training was delivered through two centrally based Royal College of Nursing-accredited training days approximately 1 month apart and was supported by detailed documentation and a purposely produced CD. The first training day included details of the system of care [from the Academic Unit of Elderly Care and Rehabilitation (AUECR) research team, involved in its development, and clinicians involved in the pilot work], guidance on problem-solving techniques and the principles of the intervention, as described below:

-

patient centred (comprehensive coverage of problems identified by patients and carers)

-

provide assessment areas (checklist) before assessment whenever possible

-

ask all assessment questions

-

keep accurate records

-

problem-solving approach with collaborative goal setting

-

follow up on actions

-

review goals

-

non-prescriptive – individual creativity

-

according to local services/resources

-

within patient’s own environment whenever possible

-

timing/duration of intervention (according to national recommendations)

-

cut-off time (problem-solving approach leads to reduced problems over time)

-

flexible approach to carer assessment.

The SCCs then used the system of care with several patients in their service before the second training day, which reviewed the use of the system of care and problem solving and in addition provided training in specific areas such as pain and benefits. After the second training day SCCs began to use the system of care for all patients referred to their service. Recruitment was not opened until all parties were satisfied that the system of care was being delivered. This was assessed during site set-up visits at which a sample of care plans was reviewed to ensure that all assessment questions were asked and that identified problems were being addressed in the goal and action planner.

Documentation of interventions

Before randomisation, all SCC services completed a survey and a semistructured interview; these were used both to assess eligibility and inform stratification and to describe the services and the nature of their interactions with patients. Changes in service set-up and SCC practice were captured by semistructured interviews midway through recruitment and after the end of the 12-month follow-up and by a second survey after the end of follow-up. The second survey also requested estimates of typical SCC input times, to be used in the economic analysis. Interviews that took place during recruitment were designed and performed so that they did not influence SCC practice.

After randomisation, control SCCs were asked to complete time logs for all patients, documenting the number and duration of contacts and the time spent co-ordinating actions, note writing and discussing patients in MDT meetings. Time logs were collected for trial patients after the end of the 12-month follow-up so as not to unblind SCCs to trial patients during follow-up. Once trained in use of the system of care, intervention SCCs were asked to use the care plan for all contacts with all patients (and carers if carer assessments were performed). After the end of the 12-month follow-up, equivalent data to those contained in the time logs and additional information on the use of the structured assessment and goal and action planner were collected for trial patients by transcribing the appropriate information from the care plans at site. This was carried out by two researchers from AUECR who were familiar with the intervention, to ensure consistency.

Assessments

Recruitment

The trial reflected usual referral pathways of patients to SCCs, determined during site set-up visits, involving the SCCs and the hospital-based clinical team and clinical research team. Patients were referred to SCCs in three main ways: by in-hospital referral (the majority of patients), by referral post discharge or by referral of patients not admitted to local hospitals. The recruitment process was facilitated by close liaison between the clinical research team and the clinical team, but patients were recruited by independent members of the clinical research team.

Anonymous screening data (demographic data and modified Rankin Scale score66) were collected for all patients referred to a participating SCC. Written informed consent for baseline and follow-up assessments was obtained from patients and carers (if appropriate) before any trial-specific procedures were carried out. In the event that a patient lacked the capacity to consent, the patient’s family member, carer or friend was asked to act as the consultee and provide a consultee declaration.

The clinical research team collected baseline demographic data, which included assessment of cognition [six-item Cognitive Impairment Test (6CIT)],67 language ability, pre-stroke disability (Barthel Index)38,68 and the six factors from the Edinburgh stroke case mix adjuster. 69

Patients and carers completed the baseline questionnaires predominantly before discharge from hospital. Patients completed the GHQ-12,62 the FAI,39 the Barthel Index (post-stroke disability), the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)70–72 and the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI). 73–75 Carers completed the GHQ-12.

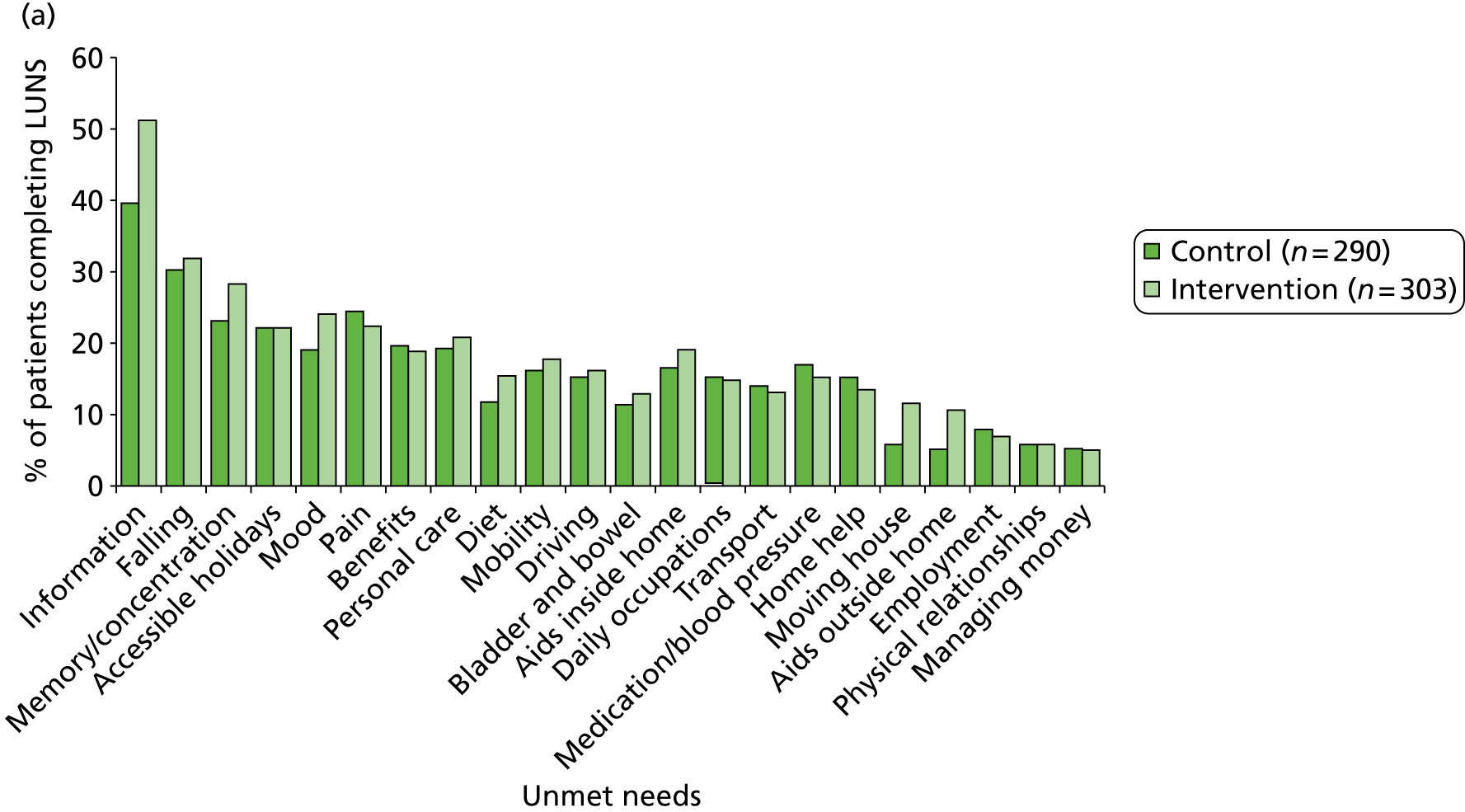

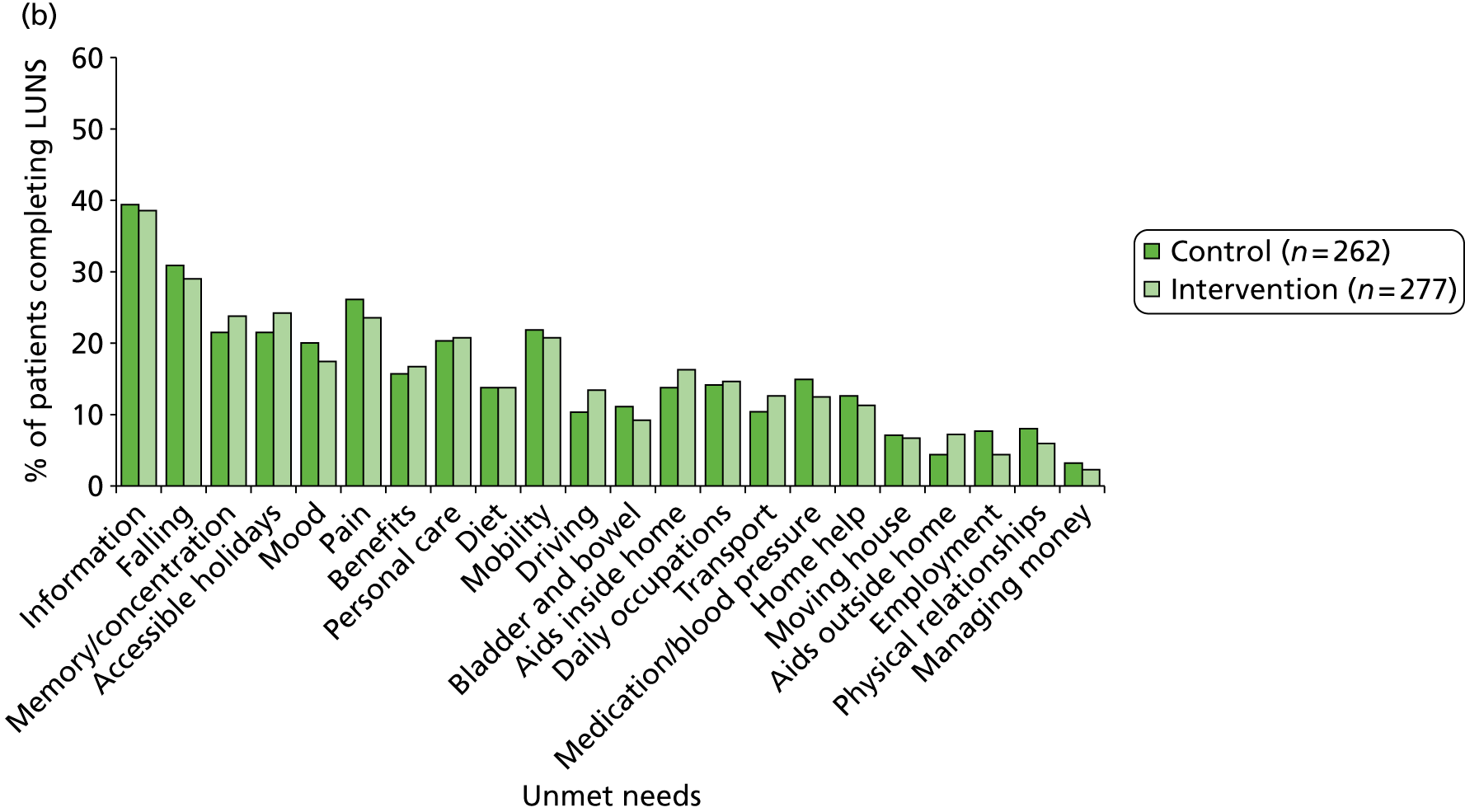

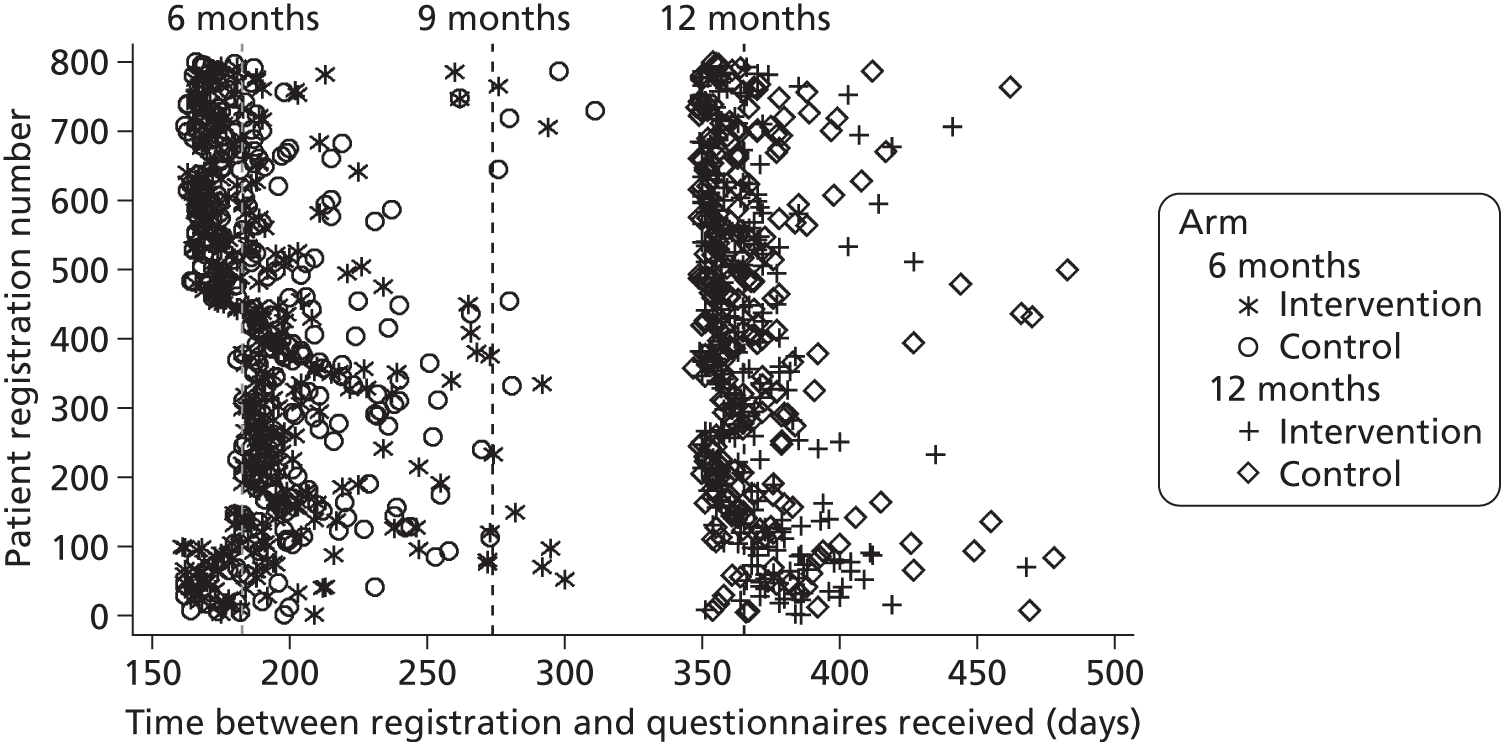

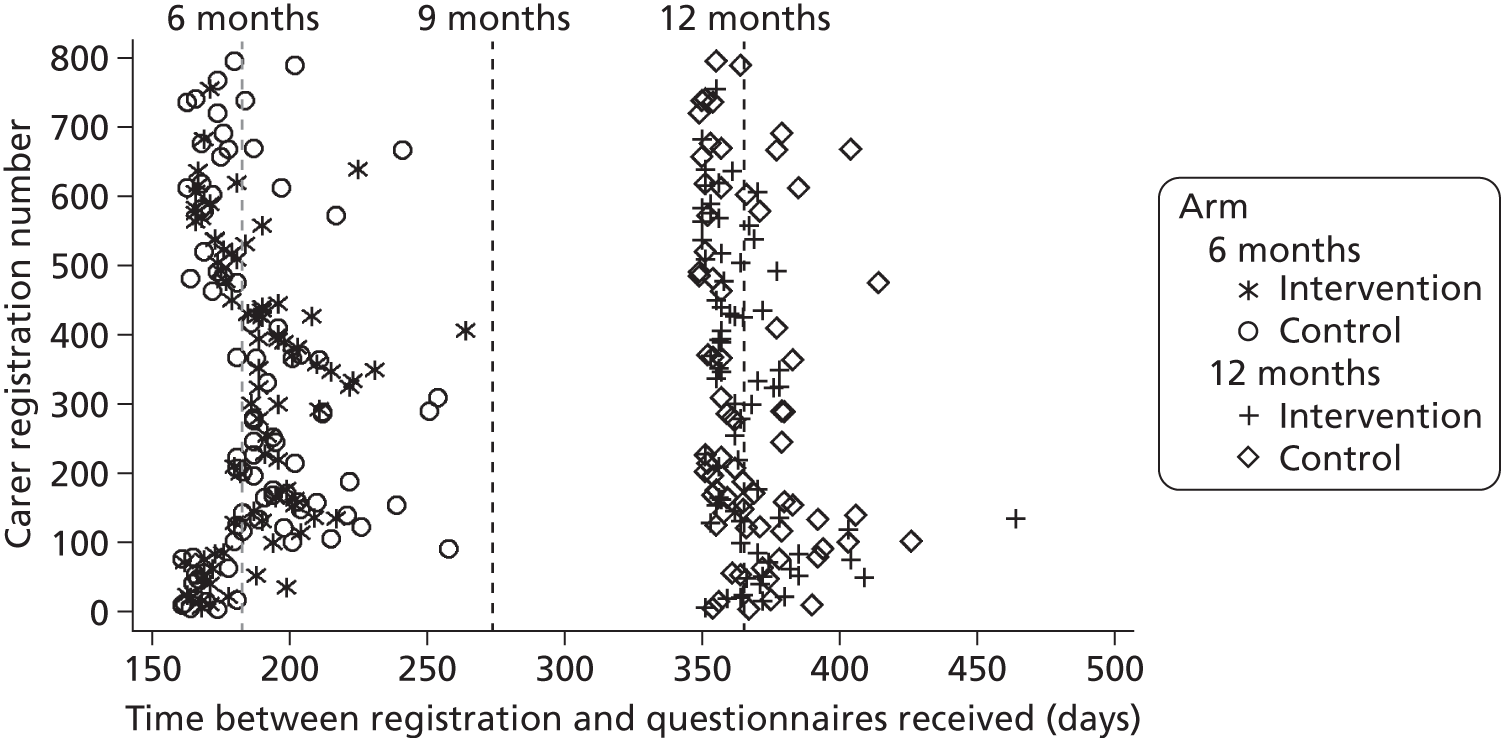

Follow-up

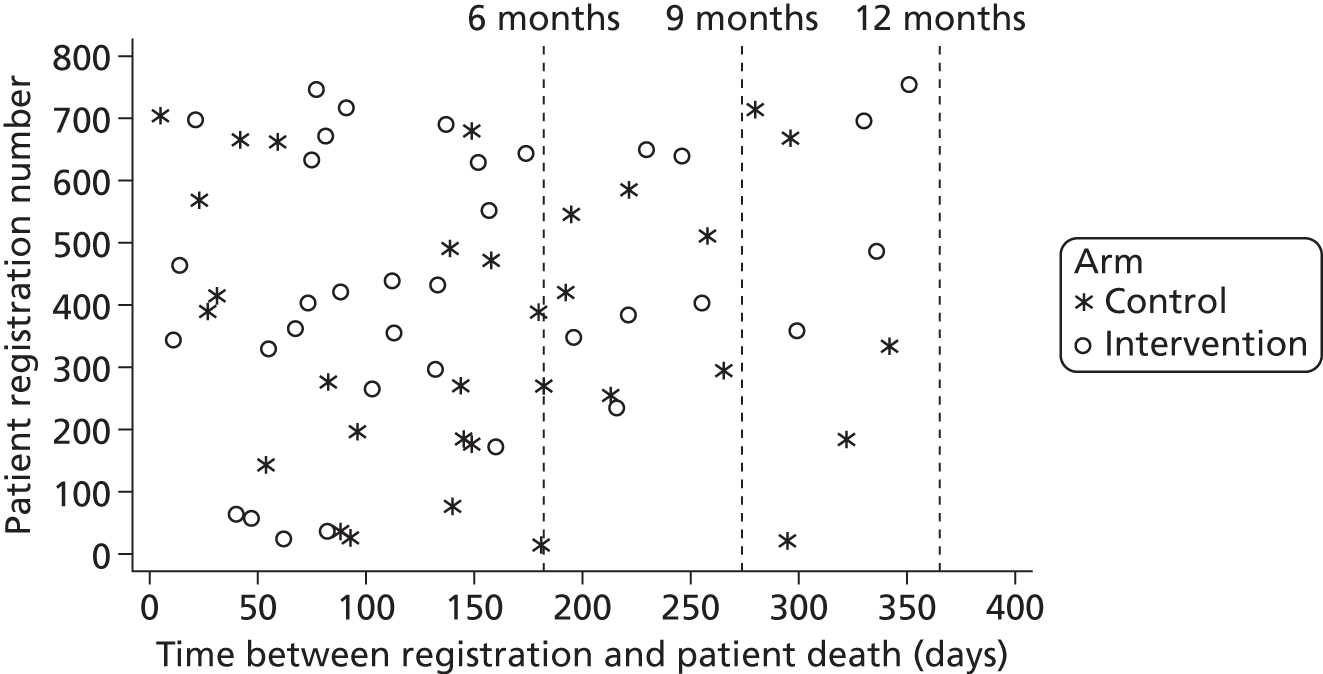

Patients and carers were followed up by the CTRU using postal questionnaires at 6 and 12 months post recruitment. These included the questionnaires completed at baseline and in addition the LUNS questionnaire (see Chapter 4) for patients and the Caregiver Burden Scale (CBS)76 for carers. This was supported by postal and telephone reminders if questionnaires were not returned within 2 weeks. If necessary (following postal and telephone reminders), patients were contacted by telephone to complete the primary outcome measure (GHQ-12)62 at 6 months and at 12 months if no 6-month data had been obtained. The clinical research team recorded deaths, emergency outpatient treatment and hospital admissions at 6 and 12 months.

Questionnaire scoring

-

The GHQ-12 is measure of current mental health. It is a 12-item scale with a total score ranging from 0 to 36; higher scores are indicative of greater psychological distress.

-

Modified Rankin Scale – 0, no symptoms; 1, no significant disability; 2, slight disability; 3, moderate disability; 4, moderately severe disability; 5, severe disability.

-

The Barthel Index is a measure of daily functioning, specifically the activities of daily living and mobility. The total score ranges from 0 to 20, with lower scores indicating increased disability. Barthel Index (categorical):77 independent 20, mild disability 15–19, moderate disability 10–14, severe disability 0–9.

-

6CIT – the total score ranges from 0 to 28; a score of ≤ 7 indicates normal cognitive function whereas a score of > 7 indicates cognitive impairment.

-

The Edinburgh stroke case mix adjuster predicts the probability of survival free of dependency at 6 months.

-

The EQ-5D is a five-item scale able to identify 243 unique health states. The EQ-5D index varies from –0.59 for the worst possible health status to 1.0 for perfect health, with 0 on the scale representing the state of being dead.

-

The CBS is a 22-item scale measuring subjective burden score, with higher scores indicating greater carer distress. Each domain has a possible score of 1–4, with the overall score ranging from 22 to 88.

-

The FAI is a measure of instrumental activities of daily living for use with patients recovering from stroke. It is a 15-item scale with the total score ranging from 0 to 45; a low score is indicative of a low level of activity.

-

The LUNS questionnaire is a monitoring tool that has been developed to assess unmet needs consisting of 22 items, with a ‘yes’ response indicating unmet need.

The CSRI measures use of health, social care and informal resources (see Resource use data).

Outcomes

In common with other stroke rehabilitation trials78,79 the primary outcome point was at 6 months, with the final follow-up at 12 months to assess whether any intervention effect was sustained.

Primary outcome

The primary end point was the psychological outcome for stroke patients living at home as measured by the patient-reported GHQ-12 at 6 months after recruitment.

Secondary outcomes

Patients

The following patient-reported secondary outcomes were measured at 6 and 12 months after recruitment: social activity (FAI), disability (Barthel Index), health state (EQ-5D), unmet stroke-related needs (LUNS questionnaire; see Chapter 4), death, hospital readmission and institutionalisation. In addition, the psychological outcome for patients was measured using the GHQ-12 at 12 months after recruitment.

Carers

Secondary outcomes also included the following carer end points: carer self-reported GHQ-12 and CBS scores, death and institutionalisation, all measured at 6 and 12 months after recruitment.

Sample size

Initial sample size calculations, based on the primary outcome measure, GHQ-12 at 6 months, indicated that recruitment of 800 patients from 40 services would provide 90% power at the 5% significance level to detect a clinically relevant difference of 2.5 GHQ-12 points [standard deviation (SD) 7 points], as defined in the Trial of Occupational Therapy and Leisure (TOTAL). 78 This sample size accounted for loss to follow-up and clustering; the inflation factor of 1.95 was derived from a maximum cluster size of 20 and an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of no greater than 0.05. 80,81 The TOTAL study achieved an 80% response rate to postal questionnaires at 6 months and a 71% response rate at 12 months. We therefore estimated the maximum loss to follow-up at 6 months as 25%. Losses to follow-up are likely to increase over time78 and the interpretation and credibility of results are difficult if losses exceed 30%. Therefore, follow-up was limited to 12 months post recruitment and the primary outcome was defined as 6 months, when there will be a higher follow-up rate.

The SCCs indicated that they were likely to receive two or three new referrals per week, of which one or two were likely to consent to inclusion in the trial. The initial aim was to recruit 40 SCC services; if 40 services recruited an average of 20 patients, this would result in the required number of patients (800) and the trial having 90% power to detect the clinically relevant difference (2.5 GHQ-12 points). Overall, 32 services were randomised, each with the aim of recruiting 25 patients, providing a power of 88%. To minimise unequal recruitment, the maximum number of patients per service was capped at 45, maintaining 85% power.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were based on the ITT population. All statistical testing was performed at a two-sided 5% significance level.

The ITT population was defined as all patients registered for active follow-up regardless of non-compliance with the intervention. All patients within a stroke service were analysed according to the intervention that that stroke service was randomised to. The ITT population was used for both primary and secondary analyses.

Per-protocol analysis was also undertaken in which major protocol violators or patients not receiving care from a SCC were excluded from the ITT population. The following groups of patients were excluded from the per-protocol population:

-

non-eligible patients

-

patients registered but then not referred to the SCC

-

patients referred to the SCC at baseline but who were not known to the SCC as a referred patient

-

patients not receiving any care from the SCC for the following reasons: patient declined the SCC service, the SCC was unable to contact the patient and the patient was registered but died before the first SCC assessment.

As the trial was a cluster RCT, outcome measures at follow-up were compared between the intervention group and the control group using a two-level multilevel model, with patients nested within stroke services.

Both primary analysis and secondary analysis involved a two-level linear model. The models were adjusted for the patient-level covariates (level 1) [baseline Barthel Index score (pre and post stroke); gender; age; living circumstances (living alone vs. living with carer); stroke severity, reflected by speech and language impairment (normal/impaired) and baseline 6CIT score (normal/impaired), and patient baseline score for the outcome measure] and the following stroke unit-level covariates (level 2): quality of stroke unit (NSA score), referral rate and SCCs working alone compared with working within a community MDT.

Two-level linear models for analyses of carer outcomes were adjusted for carer covariates (level 1) (carer baseline score for the outcome measure, gender, carer education, patient baseline Barthel Index score) and stroke unit covariates (level 2) [quality of stroke unit (NSA score), referral rate and SCCs working alone vs. working within a community MDT].

No interim analyses were undertaken.

All losses to follow-up because of death, dropouts and loss of contact are fully reported.

Details of patient deaths and hospital readmissions, carer deaths, any serious adverse events and related and unexpected serious adverse events are reported for each treatment group.

Sensitivity analyses to examine the robustness of the conclusion of the primary analysis were employed. Each of these analyses was compared with the primary analysis separately. The following sensitivity analyses were performed:

-

Including patients who died – patients who died were assumed to have a GHQ-12 score of 36 (worst possible outcome).

-

Only including patients returning postal questionnaires at 6 months; patients who provided primary outcome data by telephone were excluded.

-

Repeating analysis without proxy responses (the proxy response was when the whole questionnaire was completed on the patient’s behalf without consulting him or her) to assess the impact of proxy responses on the analysis of the primary end point.

-

Using data collected at 12 months for patients who did not send their questionnaires back at 6 months.

-

Accounting for all participants in the ITT population assuming data missing at random using multiple imputation. Information based on Edinburgh stroke case mix adjuster, clinical classification of stroke, patient status in terms of response compared with non-response (alive, died, too poorly) and prespecified model covariates was used to impute the missing outcomes. The analysis with imputed values was repeated using the same model as the model in the primary analysis.

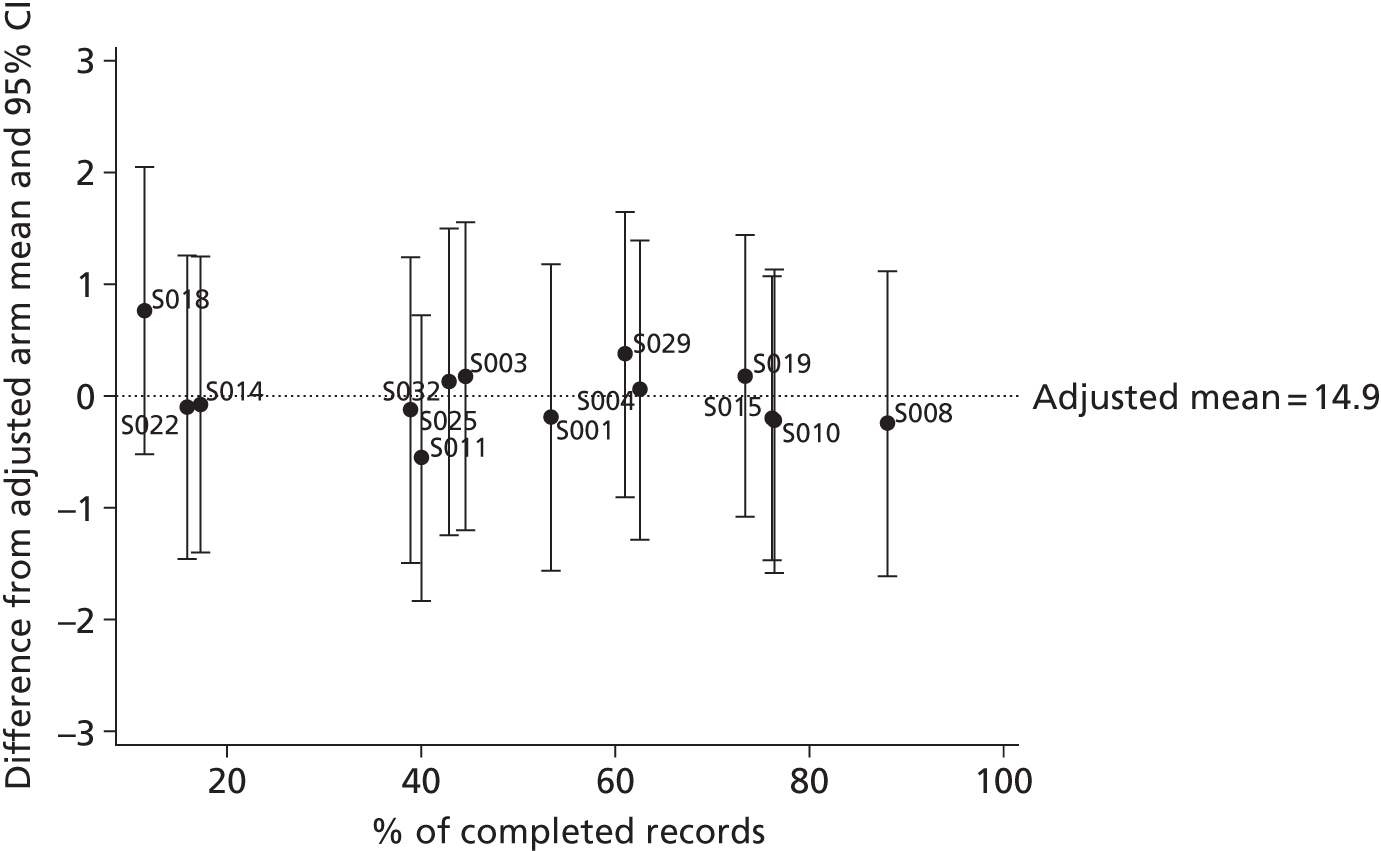

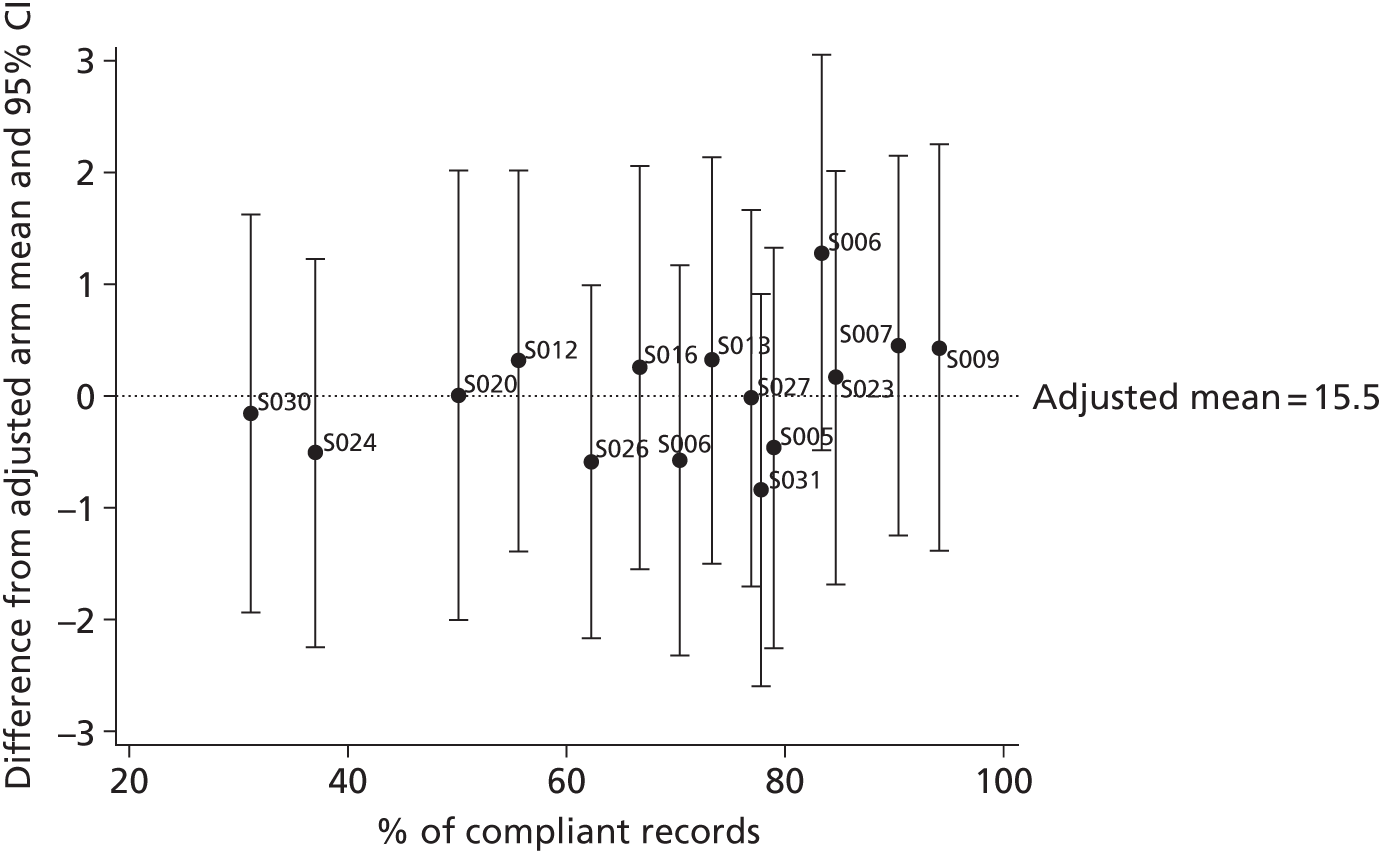

The relationship between the adjusted primary outcome and compliance with care plans and completion of time logs was explored graphically.

Economic evaluation

Study question

Is SCC care under the new system of care cost-effective compared with SCC care according to usual practice, from either a health and social care perspective or a societal perspective?

Selection of alternatives

The economic evaluation was embedded within the trial and incorporated the same comparators (system of care vs. usual care) as for the outcome evaluation and the same overall design (same sample size, participants, randomisation, recruitment, etc.).

Form of evaluation

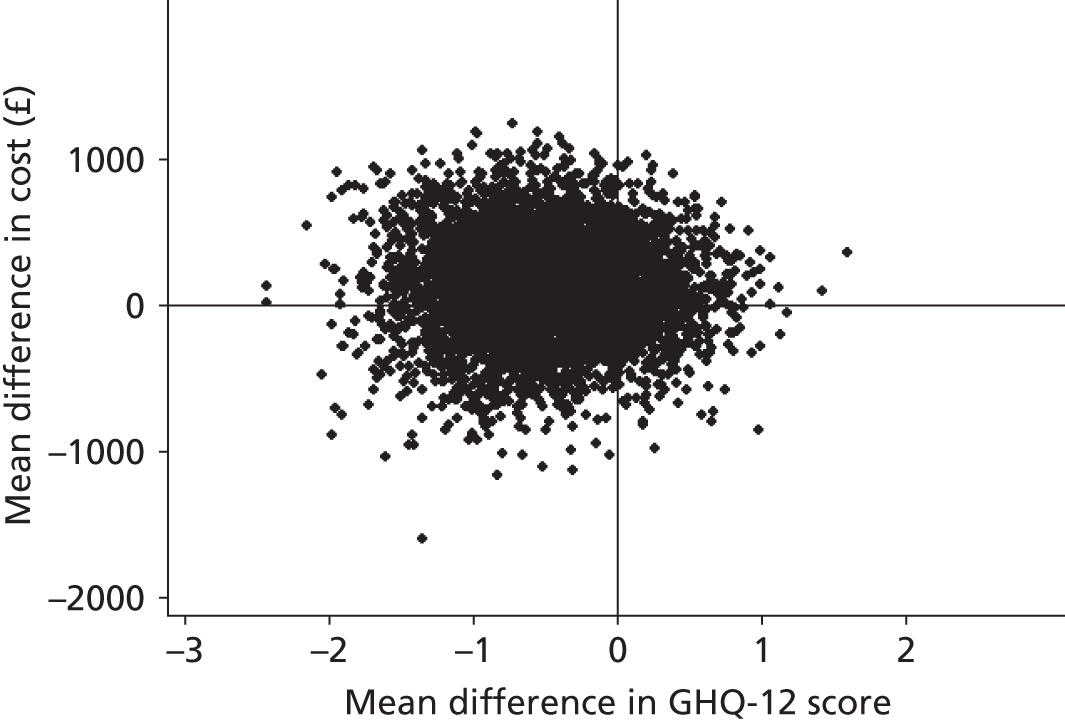

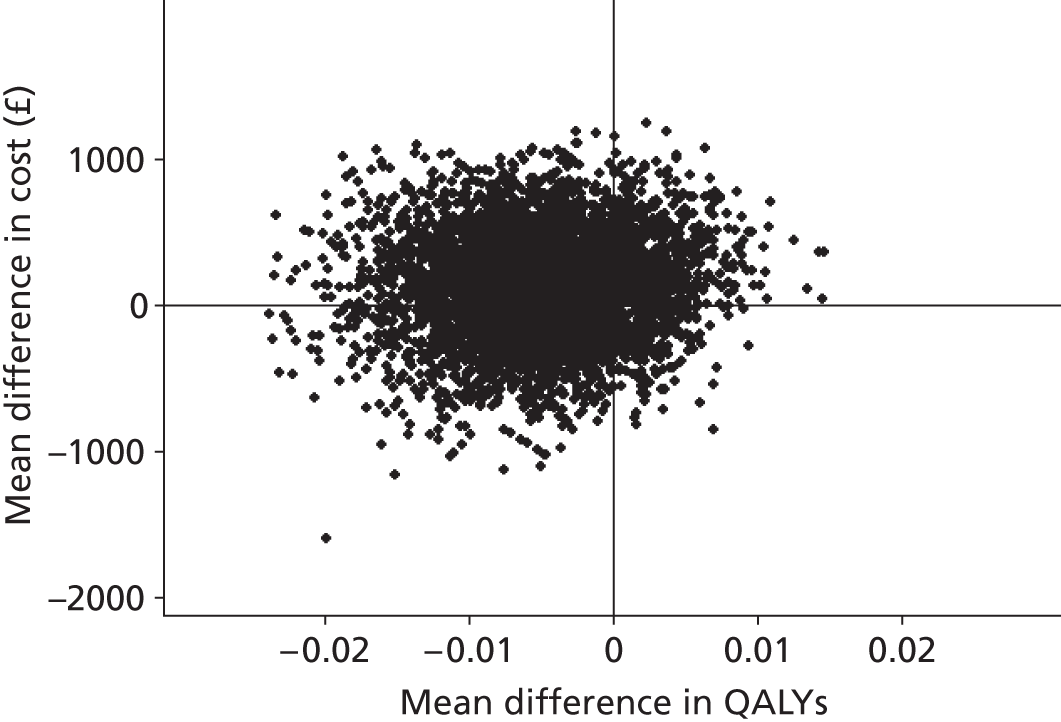

The economic evaluation was based on individual-level data collected within the trial. It assessed cost-effectiveness based on the GHQ-12 and cost–utility based on quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) derived from the EQ-5D.

Time horizon

In keeping with the outcome evaluation, the primary end point for the economic evaluation was 6 months. We also explored findings at 12 months and over 1 year to determine whether any advantages were sustained in the longer term. The 1-year costs were estimated as the sum of the costs from the 6-month and 12-month assessments and were linked with (1) GHQ-12 values at 12 months and (2) the sum of the QALYs from the 6-month and 12-month assessments.

Effectiveness data

The GHQ-12 scores were measured as described earlier. For the estimation of QALYs, health states were measured using the EQ-5D at baseline, 6 months and 12 months. Utility weights from a UK general population survey82 were attached to these. QALYs were estimated using linear interpolation to calculate the area under the QALY curve as follows:

Resource use data

Individual-level data on use of health and social care resources and informal care were collected using a CSRI specifically adapted for this study from versions used successfully in previous large stroke rehabilitation trials. 73–75 It was administered retrospectively as a self-complete questionnaire alongside other measures, predominantly in hospital for the baseline assessment (which measured the previous 3 months) and as a postal questionnaire at 6 months and 12 months (each of which measured the previous 6 months).

We also prospectively measured the duration of SCC inputs (of both a contact and a non-contact nature) at the individual patient level in both the intervention group and the control group. In the intervention group, these inputs were measured as part of the care plan. In the control group, staff recorded equivalent inputs into a specifically designed time log. Staff were also asked to report their pay band to enable costs to be estimated by staff level.

We further conducted a general survey of SCCs at all services to gather information about typical inputs (e.g. typical duration of a patient assessment, typical duration spent discussing a patient in a MDT meeting) across all of their patients, not just trial participants, to obtain service-relevant imputation values in the event of missing trial data for trial participants because of non-completed/partially completed or misplaced care plans or time logs.

Unit costs

Unit cost estimates, their sources and any assumptions made for their estimation are detailed in Appendix 7 and summarised in Table 3. Unit costs were standardised at 2010/11 levels and national estimates were used when possible to represent the geographical spread of the sites and facilitate the generalisability of the results.

| Category | Unit | Unit cost (£, 2010/11) |

|---|---|---|

| Residential care home stay | Night | 75 |

| Nursing home stay | Night | 76 |

| Inpatient services | Bed-day | Range 315–1213 |

| Day hospital/day case services | Activity | Range 230–1190 |

| Outpatient services | Visit | Range 3–772 |

| Primary care/community-based services | Contact/hour/item | Range 9–152 |

| Value of caregiver time – average wage | Hour | 15 |

| Value of caregiver time – leisure time | Hour | 5 |

| SCC | Hour | Range 19–78 |

| Stroke MDT meeting | Hour | 284 |

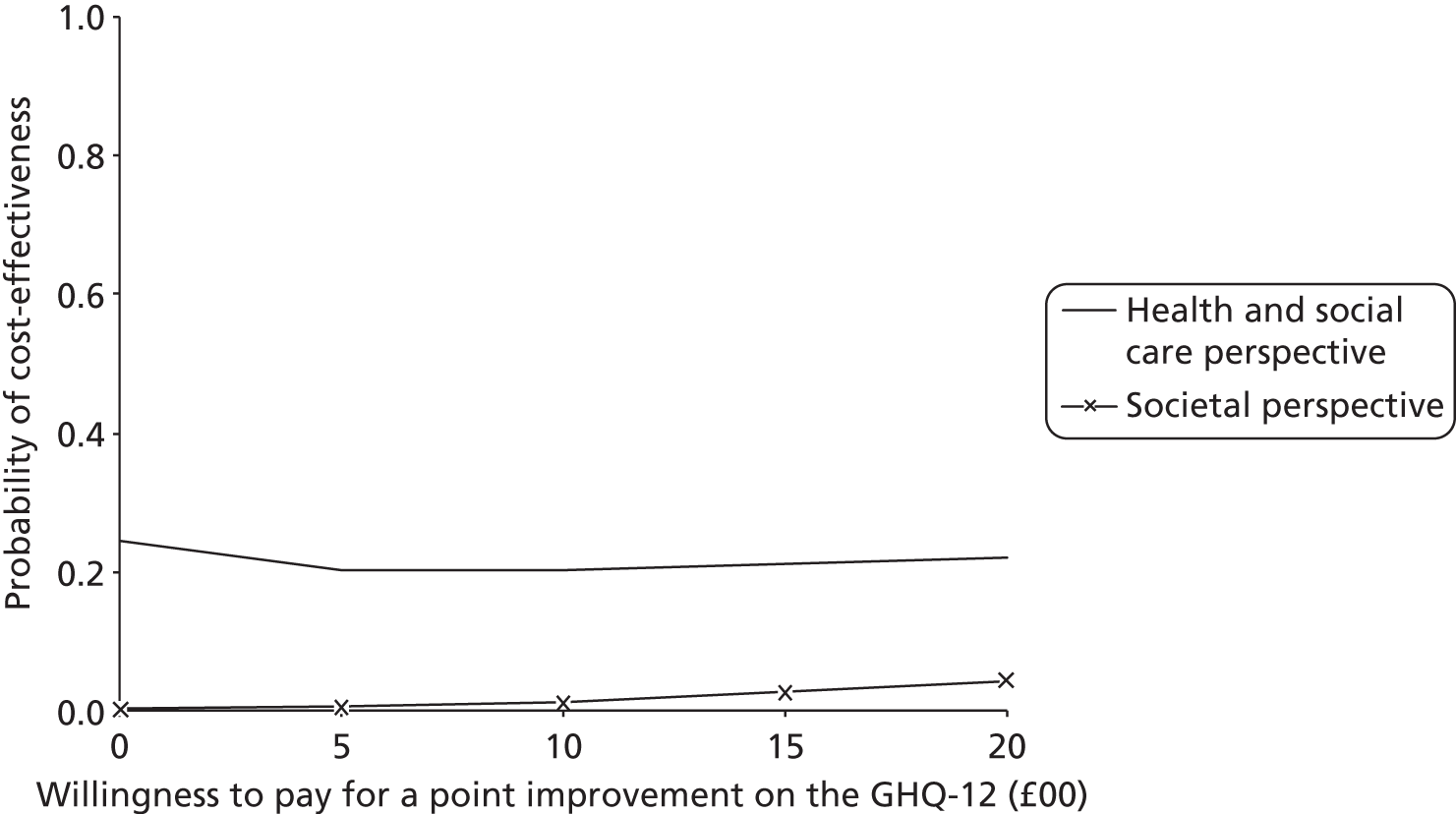

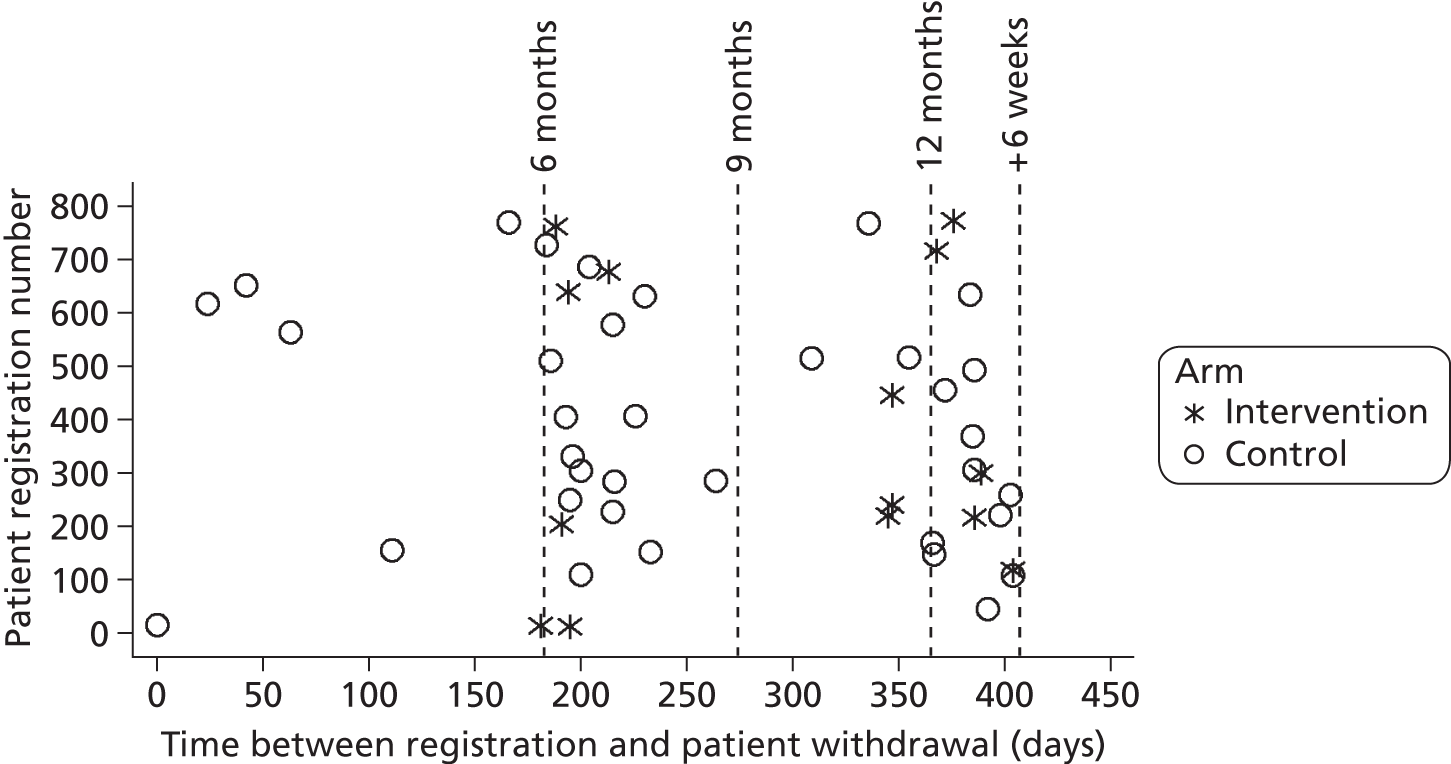

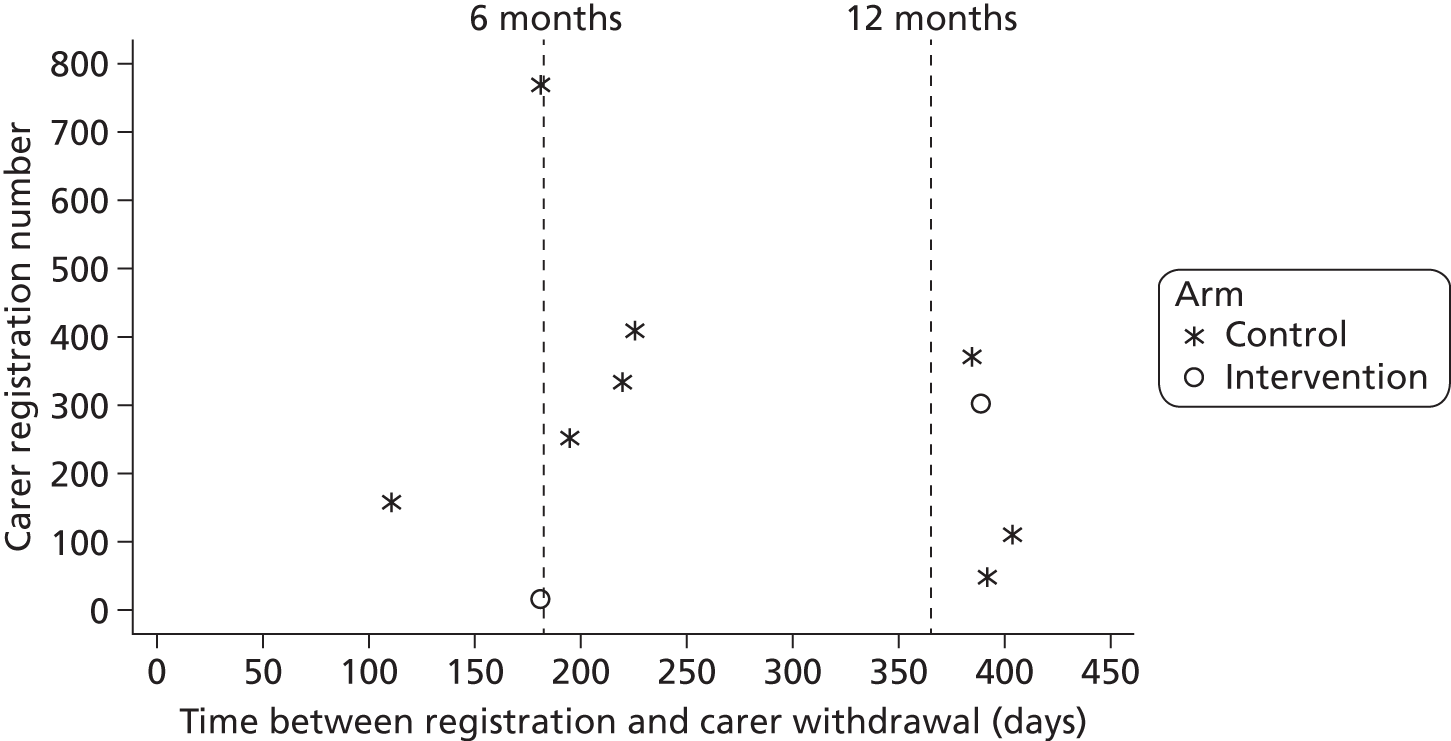

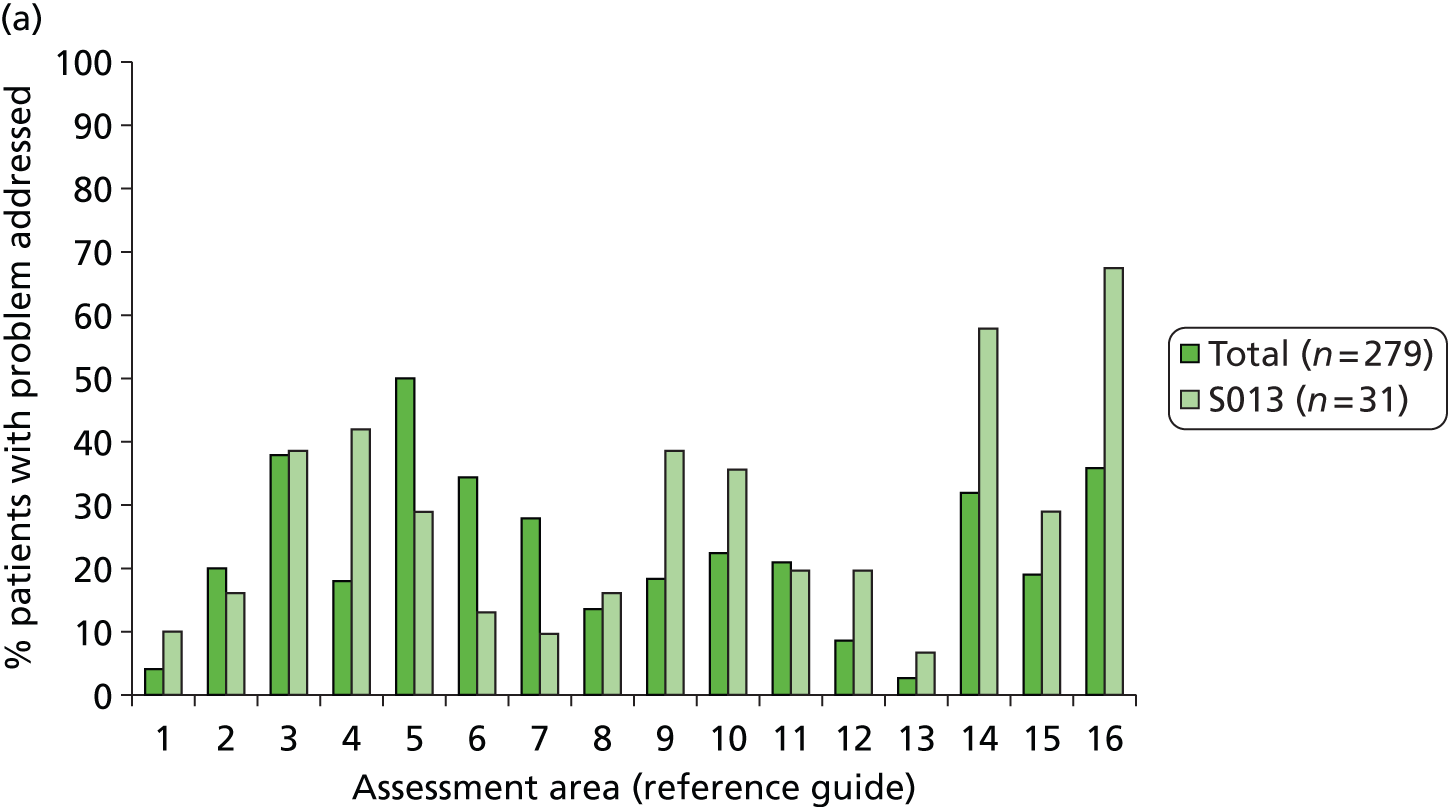

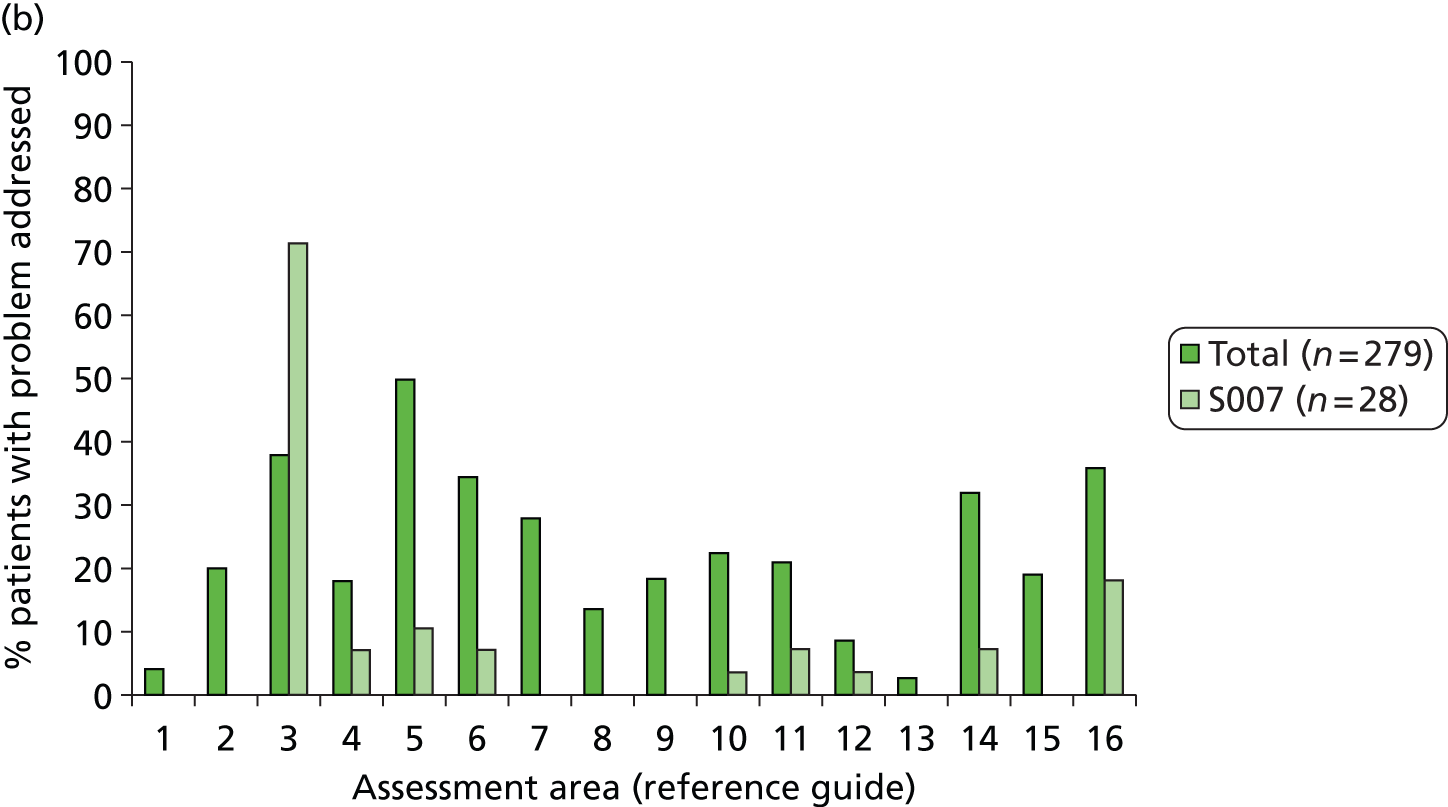

Hospital admission costs were estimated by mapping participant-reported specialty or reason for the admission to Healthcare Resource Groups (HRGs) and then applying weighted average non-elective long-stay bed-day costs for each of those HRGs (or across HRGs when multiple specialties were reported for one admission). An average cost across all HRGs was applied when specialty and reason were missing or could not be readily allocated to a specific HRG. Outpatient costs were estimated using the same approach.