Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 14/183/02. The contractual start date was in September 2016. The final report began editorial review in September 2021 and was accepted for publication in April 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Coulton et al. This work was produced by Coulton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Coulton et al.

Chapter 1 Structure of the report and background to the research

Structure of the report

The study assessed the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a multicomponent psychosocial intervention [i.e. the RISKIT-Criminal Justice System (RISKIT-CJS) intervention], compared with treatment as usual (TAU), in reducing substance use for adolescent substance users who were involved in the criminal justice system (CJS). The trial protocol has been published previously. 1 The RISKIT-CJS randomised controlled trial (RCT) was a two-armed, mixed-methods, prospective, pragmatic, individually RCT in young people aged 13–17 years (inclusive). The trial was carried out across four geographical areas of England (i.e. North East, North West, South East and London) and involved a baseline assessment and follow-ups at months 6 and 12, with month 12 designated as the primary outcome point. The study included an integrated qualitative component that evaluated young people’s and stakeholders’ views on the acceptability and suitability of the intervention, in addition to exploring the process of change associated with the intervention. All participants were eligible to receive any TAU available in their area. Participants in the intervention group received a multicomponent intervention that comprised a single one-to-one motivational interview, followed by two half-day group sessions and a final one-to-one motivational session. Interventions were provided by specifically trained youth workers with experience of working with young people with substance misuse issues.

Research questions

The study built on the Medical Research Council guidelines Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions. 2 We conducted research to explore the theoretical validity of the intervention and synthesised this theoretical approach with the current evidence base and with the views of potential participants to model an appropriate intervention approach. We tested the feasibility of implementing the intervention in the target population and refined the intervention and its delivery as a result of that feasibility study. We conducted an appropriately designed pilot study to explore potential effectiveness on the key parameters and from this found evidence of potential effect in reducing substance use and risk-taking behaviour, as well as high levels of satisfaction and engagement. The next step was to conduct a rigorous evaluation to address key outcomes in a way that provides valid scientifically rigorous evidence and is useful to those engaged with this population and commissioners of services. To this end, we have conducted a full multicentre RCT of the RISKIT-CJS intervention compared with TAU, with an embedded qualitative component, to explore the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing substance use and improving mental well-being. The RCT is acceptable to participants and is economically viable to deliver.

Chapters of the report

This report is structured as seven chapters that detail the design, management and outcomes of the main trial. The report starts by providing an overview of the existing evidence and outlines the key literature that informed the design of the trial. Following this, a chapter is dedicated to each core component of the trial. Chapter 2 addresses the design of the intervention and the outcomes used to assess clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Chapter 3 reports the results of the statistical analysis, presenting the findings of the primary and secondary outcomes and exploring baseline and process factors that may have an impact on the outcomes observed. Chapter 4 details the design, methods and results of the economic aspects of the study. Chapter 5 provides the design and outcomes of the integrated qualitative aspects of the study. Chapter 6 provides a discussion on the results and, finally, Chapter 7 provides the key conclusions of the study and recommendations for future research.

Research ethics

The study was granted ethics approval by the University of Kent Social Research Ethics Committee (reference SRCEA169) in December 2016. The University of Kent acted as sponsor of the research and the trial was registered as ISRCTN77037777.

Changes to the original study protocol

The original protocol was published in 20171 and the current protocol is revision 4. Since the application, a number of modifications were made with the agreement of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the funder. First, our original target population was adolescents aged 13–17 years (inclusive) who were actively managed by a youth offending team (YOT) and who scored ≥ 2 on the ASSET tool3 for substance use, indicating that substance use was associated with their criminal activity. Since the original application was submitted, the Youth Justice Board (YJB) has implemented a number of strategies to reduce the number of young people engaged with the CJS. These strategies have included taking a youth-first approach to offending, diverting out of the CJS for early offenders and focusing on education rather than punishment. These strategies have resulted in a large reduction in the number of young people managed by YOTs. Consequently, we sought, and received, permission to extend our recruitment to include young people who had been diverted from the CJS, that is, young people who had committed an offence involving substance use and had been referred for assessment by a substance misuse team (SMT) and young people educated in pupil referral units (PRUs) who had been involved with the CJS and actively used substances.

Second, in our original sample size calculation, we aimed to detect an effect size of 0.3, with 80% power and an alpha of 0.05, using a two-sided test and allowing for a 30% attrition at month 12. We expected there to be sufficient consenting participants in each YOT to allow allocation to be conducted in the ratio of 2 : 1, control to RISKIT-CJS intervention, respectively. This would maximise the cost-efficiency of the trial. However, as the study progressed, it became apparent that the numbers recruited per YOT were not sufficient to create appropriate-sized groups for the RISKIT-CJS intervention and permission was sought, and received, from the TSC to switch from a 2 : 1 allocation ratio to a 1 : 1 allocation ratio. This reduced the overall sample required from 567 to 502. To adjust any analysis by the impact of this change, an outcome identifying whether a participant was recruited under the 2 : 1 or 1 : 1 scenario was included as a secondary analysis.

Third, to reduce participant burden and to employ the most scientifically rigorous outcome assessment, we made some changes to the outcome measures collected between the original application and the latest version of the protocol. In our original application, we proposed to assess emotional regulation and behaviour using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. 4 Recent research suggests5 a high level of correlation between the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and our proposed measure of well-being, that is, the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS). 6 As WEMWBS has more established psychometric properties, particularly sensitivity to change, we reduced participant burden by assessing only WEMWBS. In our original application, we planned on assessing motivational stage of change using the Readiness to Change Questionnaire – Treatment Version. 7 During the implementation stage of the study, concerns were raised about the validity of this instrument for adolescents and for substances other than alcohol. As a consequence we replaced the Readiness to Change Questionnaire – Treatment Version with a brief assessment of motivation to change designed for multiple substances and validated in an adolescent population [i.e. the Stages Of Change Readiness And Treatment Eagerness Scale – 7 Dimensions (SOCRATES-7DS)8,9]. All changes were discussed with, and approved by, the TSC.

Fourth, in our original application, we aimed to collect and analyse criminal justice outcomes, including arrests, charges and convictions in the 12 months prior to and 12 months after randomisation. We planned on deriving these outcomes from the Police National Computer at the end of the final follow-up period. Initial approaches to the Home Office were denied because of a major information technology infrastructure upgrade, and approaches to the Criminal Records Office were denied because the research was considered beyond its scope. We finally had agreement to source the data through the Ministry of Justice and we sought ethics approval in September 2019. Unfortunately, as the COVID-19 pandemic progressed, all non-essential access to data and data safe havens was denied and access to these data has not been possible at the time of submission. Consequently, we have not included analysis addressing recidivism and we have excluded criminal involvement from our wider public sector economic analysis.

Research management

The Trial Management Group (TMG) was responsible for ensuring the appropriate, effective and timely implementation of the trial. The TMG usually met once per month, depending on the needs of the trial, and comprised the chief investigator, trial co-ordinator, researchers working on the trial, co-applicants and representatives of the service delivering the intervention. A TSC was appointed to provide an independent overview of the trial conduct and represent the interests of the funders. The TSC subsumed the role of Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee. The TSC met annually throughout the study and its remit included measuring progress against agreed milestones in terms of recruitment and retention, adherence to the protocol, participant safety and reviewing of adverse events, and considering emerging evidence pertinent to the key research questions. Written terms of reference were agreed and used by the TMG and TSC (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Research governance

The study complied with the requirements of the General Data Protection Regulations 201610 and the Freedom of Information Act 2000. 11 The trial was managed and conducted in accordance with the Medical Research Council’s guidelines on good clinical practice in clinical trials,12 which includes national and international regulations on the ethics involvement of participants in clinical research (including the Declaration of Helsinki 2013). All data were encrypted at the point of collection and held in a secure environment, with participants’ information identified using a unique identification number. Any personally identifiable information was stored separate from outcome and process data and was accessible only to those who needed to access the information. All research staff were employed by academic institutions and had enhanced Disclosure and Barring Service clearance. In addition, all research staff were governed by the conditions of service of the employing institution.

Background

Adolescence as a critical developmental stage

Adolescence is a critical developmental stage when young people make behavioural and lifestyle choices that have the potential to affect their health and well-being into adulthood. Although risk-taking is important for healthy psychological development for many, inappropriate risk-taking is significantly associated with health and social harms during adolescence, and these harms can persist well into adulthood. 13 Young people are much more vulnerable than adults to the adverse effects of substance use because of a range of physical and psychological factors that often interact and because of the differential impact of substances on the developing brain. 14–16 In addition to an increased risk of accidents and injury,17 substance use in adolescence is also associated with poor educational performance and exclusion from education. Over the academic year 2015–16, almost 10% of permanent school exclusions in state secondary schools were because of alcohol and substance use. 18 In the longer term, substance use is also associated with an increased prevalence of non-communicable diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular disease and gastrointestinal disorders. 19,20

Prevalence of substance use among young people in the UK

The number of young people who consume alcohol is declining, although those who do drink tend to drink more. In 2018, 54% of youths aged 14 years and 69% of youths aged 15 years consumed alcohol, with 23% having consumed alcohol in the past week. 21 The mean weekly alcohol consumption for males at age 14 years was 5 units and for those aged 15 it was 7 units, where one unit equals 10 ml or 8 g of pure ethanol. For females, the mean weekly alcohol consumption was 5.5 units and 5 units, respectively. Six per cent of youths aged 14 years and 11% of youths aged 15 years reported having used cannabis in last month. In addition, 2% of 14-year-olds and 4% of 15-year-olds reported having used a class A substance at least once. 21

Young people in the criminal justice system

Although the relationship between criminal activity and substance use is complex, there is clear evidence that the prevalence of substance use is far higher in the youth offending population than in the general youth population. Data derived from the YOT AssetPlus3 indicate that most (76%) young people in the CJS use substances and 72% have a mental health need.

Data from the Juvenile Cohort Study22 show that 32% of young offenders score ≥ 2 on the ASSET tool for substance use, indicating that substance use is at least, in part, a reason for them associating in criminal activity, and 12% of young offenders score ≥ 3. Substance use is defined as the use of alcohol, traditional illicit substances or legal highs, as well as inappropriate use of prescribed medication. Although the relationship between substance use and criminal activity is complex, it is clearly a major issue in the youth offending population.

In the CJS, substance use and offending are related to other forms of disinhibitory behaviour, such as aggression and risk-taking. Young people involved in the CJS are a particularly vulnerable group, with a greater propensity to take risks that are likely to have a long-term impact on their future health and well-being. This is because young offenders often lead chaotic lives and face complex problems, including substance use, unsuitable accommodation and emotional or mental health issues. 23 Literacy levels among young people involved in the CJS are unacceptably low, and the vast majority of young people involved in the CJS have, in the past, been excluded from school. 24 As a result of the above risk factors, the list of negative consequences that result from substance use by young people is extensive and includes physical, psychological and social problems in both the short and the long term. In 2020, the number of young people receiving education in a PRU was just over 15,000,25 of whom 10% had been excluded from mainstream education because of substance use. Being excluded from school and educated in a PRU increases the propensity for young people to engage in criminal activity and 23% of new entrants to the CJS are educated in a PRU. 26

Young people who offend often experience a range of complex multiple risks and vulnerabilities, including neglect and abuse,27 substance use and related problems,28 and exclusion from school. 29 Research has shown that young people who offend are more likely to experience a range of inequalities in later life, for example worse physical health,28 early pregnancy in females,30 and higher rates of tobacco use and drug and alcohol dependence,29,31,32 reduced employment opportunities and economic hardship. 33 Indeed, there is widespread agreement that young people who offend are at an increased risk of health and social problems, making them one of the most vulnerable populations in the UK. 34 Furthermore, the UK has one of the highest youth custody populations in western Europe. 35 Epidemiological studies have shown that, in common with other vulnerable groups of young people, such as the homeless and those in care, young offenders are a hard-to-reach group from a health needs perspective, accessing physical and mental health services only in times of crisis, and that accessing these services is often associated with involvement with other agencies. 32,36,37

The Youth Justice System in England and Wales works to prevent offending and re-offending by those aged < 18 years. The latest available data indicate that there were 19,000 arrests of young people in 2019, which is an 82% drop from 2009. 38 Boys accounted for 83% of these arrests, and the average age of offenders was 15.3 years. Over the same period, there were 11,000 first-time entrants, that is, those receiving first reprimand or warning of community conviction, to the Youth Justice System, which is a reduction of 84% since 2009. 38 It is estimated that 38.5% of new offenders go on to re-offend after serving their initial sentence. 38

The ASSET tool is a standardised assessment tool that was developed within the CJS in England and Wales. The ASSET tool aims to identify the underlying causes of a young person’s offending behaviour to plan appropriate interventions. 3 The ASSET tool is often used on multiple occasions to help measure change in young offenders’ health and social needs and the risk of re-offending over time, and has been used with all young offenders in England and Wales since 2000. The ASSET tool examines 12 dynamic risk factors: (1) living arrangements, (2) family and personal relationships, (3) education, (4) neighbourhood, (5) lifestyle, (6) substance use, (7) physical health, (8) emotional health, (9) perception of self and others, (10) thinking and behaviour, (11) attitudes to offending and (12) motivation to change. The severity of each domain is rated on a scale of 0–4, with 0 being the least severe and 4 being the most severe, and a score of ≥ 2 is indicative that the domain contributes to the individual’s offending behaviour. 3

Previous research

To date, systematic reviews of interventions for substance-using offenders in CJS environments have not identified a clear evidence-based intervention strategy,39–41 but they have highlighted the paucity of good-quality research in the area and a lack of UK-based studies, with no scientifically rigorous studies focusing on young offenders. A recent meta-analysis of 22 studies42 synthesised the evidence regarding the use of motivational interventions for adolescents (aged 12–20 years) who engage in substance use. The results showed that, compared with TAU, the use of motivational interventions reduces the number of heavy alcohol use days by 0.7 days per month [95% confidence interval (CI) –1.6 to –0.02 days], substance use days by 1.1 days per month (95% CI –2.2 to –0.3 days), and overall substance-related problems by a standardised net mean difference of 0.5 (95% CI –1.0 to 0).

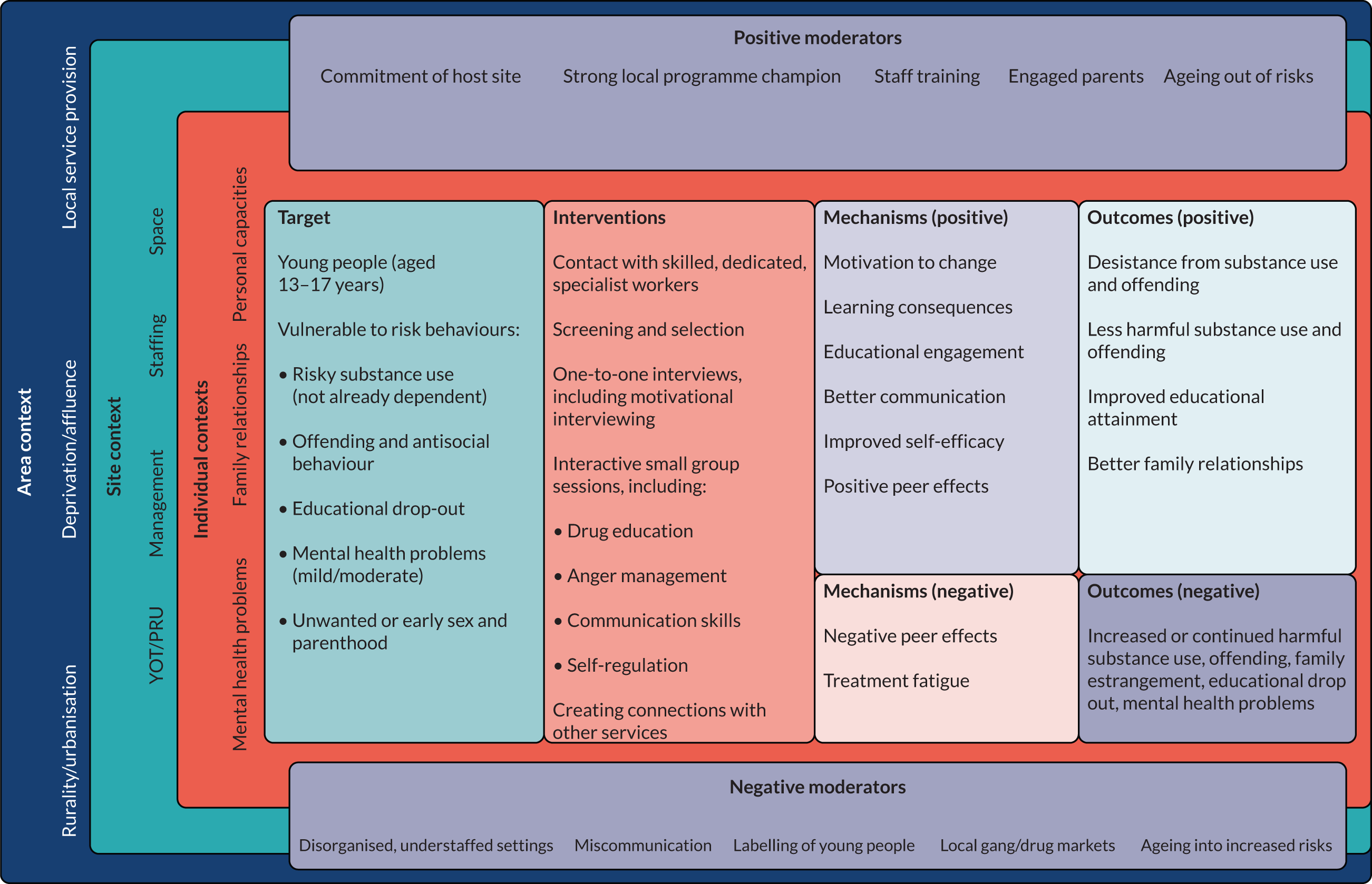

Developing and evaluating the RISKIT multicomponent intervention

The development of the RISKIT multicomponent intervention43 was based on two streams of work: (1) a participatory consultation with young people and (2) a review of the current research evidence. The theoretical perspective was informed by the social development model. 44–46 This approach suggests that the distal influences of socioeconomic status, biology, normative regulation and discipline are mediated through proximal influences on behaviour, which are identified as perceived opportunities for poor antisocial behaviour and perceived rewards for this behaviour. The social development model marries the ecological context of young people’s behaviour to an explanation of how this ecology influences their behaviour. It suggests that, even in the absence of a structural change to their health ecology, the provision of socioemotional and cognitive skills can help young people prevent or reduce risk-taking behaviour and suggests that the building of bonds with organisations promoting prosocial learning and opportunities is important in the reduction of risk-taking. The model provides a coherent and empirically validated approach that suggests that intervention approaches should be multicomponent and encompass knowledge and education, cognitive and learning skills, self-efficacy and motivation.

The participatory consultation was adapted from participatory action research47,48 and was carried out with a number of groups of young people. The aim of the exercise was to establish, with young people, what they perceived as risk-taking behaviour, why they took risks, the consequences of taking risks and how they perceived the problems could be addressed. The main themes in terms of risk-taking behaviour centred around criminal activity, substance use and sexual activity, and these activities were considered as being linked. The participants thought that prevention programmes that focused on the negative outcomes of risk failed to appreciate that risk-taking can be positive and can lead to positive outcomes, an issue highlighted by other research exploring the processes associated with risk-taking. 45,49 The young people identified the need for education regarding risks and consequences, but particularly highlighted the preference for interventions that provided skills and strategies to manage risk and the opportunity to discuss these skills with peers and to learn how to implement them. Interestingly, parental influences were not considered critical to any intervention, and many young people considered parental involvement to be inappropriate and unacceptable. The primary focus for the young people was not on eradication of risk-taking, but rather a focus on how risk could be reduced and how the negative consequences could be minimised.

Our second stream of work focused on the current evidence base that could inform the development of a multicomponent intervention. We consulted a number of existing reviews and research studies50–55 and found that, although there is a growing body of research in the field, there is a paucity of rigorously evaluated interventions, with the majority of research arising from the USA, with limited applicability to the UK. Of importance was what has been proven not to work, and this includes focusing on negative aspects of risk and abstinence from risk-taking behaviours. Promising intervention approaches include motivational interviewing and cognitive and socioemotional life skills training. In addition, there is emerging recognition of the importance of providing interventions in a structured manner and, with the young people’s preference for peer group interventions, the importance of managing the potentially negative effects of labelling and peer influence.

A synthesis of the participatory group views, the theoretical underpinnings and a review of the evidence was undertaken, and the RISKIT intervention model was developed as an approach that focuses on those who are vulnerable to the negative consequences of their risk-taking behaviour. The RISKIT intervention combines individual motivational interviewing sessions to target motivation and behaviour change with eight group-orientated life skills sessions that cover a variety of areas, including identifying and managing risk, communication skills, assertiveness training, anger management, preparing for behaviour change and sexual health. In addition, the group sessions focus on identifying resources within the community that could be of benefit for the young people and provide opportunities to access these resources.

An initial feasibility study was undertaken followed by a larger quasi-experimental study43 in which the RISKIT intervention was delivered across schools in Kent to 226 adolescents who were identified as engaging in excessive risk behaviour. Consent rates in the eligible population were high (80%), with almost all adolescents attending at least part of the intervention and 74% of adolescents attending all the intervention sessions. Follow-up rates were high, with 82% of adolescents being followed up at 6 months. At this point, 32% of the intervention group had reduced their risk-taking behaviour to a point where it was of no further concern and significant improvements were observed in terms of number of days abstinent from alcohol and other substances, indicating a positive effect on this domain. Participant views were positive, with high levels of engagement and satisfaction, and a general view that the intervention had been useful in developing new skills, was informative and could lead to changes in behaviour. Delivery of the model was sustainable, but required the input of specialist, rather than generic, staff, and a full economic evaluation of cost-effectiveness was not undertaken. The most recent outcomes for the RISKIT intervention, delivered in school settings over 2014 and 2015, indicated a 92.9% completion rate for those youths identified as being eligible, a 37.8% reduction in any alcohol consumption, a 24.6% reduction in using other substances and, for those who continued using illicit drugs, a reduction of 27.2% in drug-using days. In addition, improvements were observed in terms of mental health and well-being. Further to our pilot study, the RISKIT intervention was tested for feasibility in both custodial and community CJSs, with high levels of satisfaction on the part of the participants. A recent study in the community setting,56 commissioned by Kent Police as an element of their diversionary strategy, targeting young offenders committing a drug-related offence (n = 175), suggested that consent and engagement was high, with 90% of young offenders consenting, 100% of young offenders attending at least one session and 95% of young offenders attending all sessions. Further analysis at 6 months post intervention indicated a 50% reduction in re-offending rates, that is, a significantly greater reduction than that observed in a similar population who received youth justice interventions only. As part of this work, we adapted the intervention in terms of delivery by providing it over two half-day sessions over consecutive weeks on weekends, rather than the 8-weekly 1-hour sessions provided in the school-based study. 1

Aims

Our aim was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the RISKIT-CJS intervention, compared with TAU, in reducing substance use for adolescents engaged with the CJS.

Primary objective

-

To conduct a prospective pragmatic RCT to evaluate the effectiveness of the RISKIT-CJS intervention, compared with TAU, for substance-using adolescents involved in the CJS.

Secondary objectives

-

To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the intervention compared with TAU.

-

To explore participants’ and criminal justice staff’s experience of the intervention and the acceptability of the methods employed.

-

To assess the fidelity with which the intervention was conducted and to explore the role of fidelity, therapeutic alliance and baseline psychological factors on the outcomes observed.

-

If the intervention was shown to be effective within the parameters set, to develop a protocol for dissemination and integration of the intervention in current practice.

Outcomes and measurements

Validated and reliable tools were used to capture the primary and secondary outcomes.

Primary outcome

Our primary outcome measure was per cent days abstinent (PDA) from substance use in the 28 days prior to the 12-month follow-up and this was measured using the Timeline Followback 28 (TLFB28),57 which is a valid and reliable tool for assessing the quantity and frequency of substance use over time periods ranging from 1 to 365 days. The outcome has been validated for use in adolescent populations58 and recent pilot work has indicated high levels of agreement between the shorter, 28-day, and longer, 90-day, reference period.

Secondary outcomes

In addition to PDA, the TLFB28 allows for the derivation of a number of secondary outcomes over the period, including quantity and type of substances consumed. The TLFB28 is completed by a trained member of research staff and takes approximately 20 minutes. The outcome was measured at baseline and at 6 and 12 months. Mental health and well-being was assessed using the WEMWBS. The WEMWBS is a 14-item self-completed scale that addresses different aspects of eudemonic and hedonic mental health and well-being. The scale has established valid reliable psychometric properties in adolescent populations5 and is sensitive to change. 59 The WEMWBS instrument is highly correlated with other measures of psychological health and well-being, including the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the General Health Questionnaire. The WEMWBS was administered at baseline and then again at 6 and 12 months.

Motivational state and readiness to change substance use behaviour was measured using SOCRATES-7DS. The using SOCRATES-7DS contains 20 items and has four items for each stage of precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action and maintenance. When an individual item is missing, then this results in a missing score for the relevant domain of behaviour change.

The Brief Situational Confidence Questionnaire (BSCQ) was used to assess self-efficacy. 60 The BSCQ comprises eight visual analogue scales to record confidence (on a scale of 0–100) in resisting the temptation to use drugs in a variety of situations.

Health-related quality of life was measured using the KIDSCREEN-10 Index. 61 This unidimensional measure represents a global score incorporating elements of physical and psychological well-being, autonomy and parent relations, peer and social support, and school environment. The KIDSCREEN-10 Index comprises 10 items rated on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, which are summed to give a total score. In addition, the KIDSCREEN-10 Index includes an overall self-reported assessment of general health (i.e. poor, fair, good, very good or excellent). The total score for the 10 items is calculated when there are no missing values for any individual item.

Process outcomes

Therapeutic alliance was measured at the end of the intervention using the Therapeutic Alliance Scale for Children: Youth version (TASC-r). 62 The TASC-r distinguishes between the affective bond and client–therapist collaboration. Items are rated on a scale from 1 (not true) to 4 (very much true) and are summed to give a total score. When fewer than four items are missing, the total is estimated using mean substitution for missing values.

All individual motivational interventions were recorded and a random sample of 20% (stratified by region, age and therapist) were selected and assessed by independent raters using the Behaviour Change Counselling Index (BECCI)63 to assess fidelity and quality. Overall scores were calculated by summing the checklist item scores and by dividing by the number of items to give a mean score. Mean substitution was used when an item on the checklist was not applicable.

Attendance at each of steps 1 to 4 of the intervention was recorded for each participant. Each interventionist delivering the RISKIT-CJS intervention was assigned a unique identifier and this was recorded for each step of the intervention for each individual.

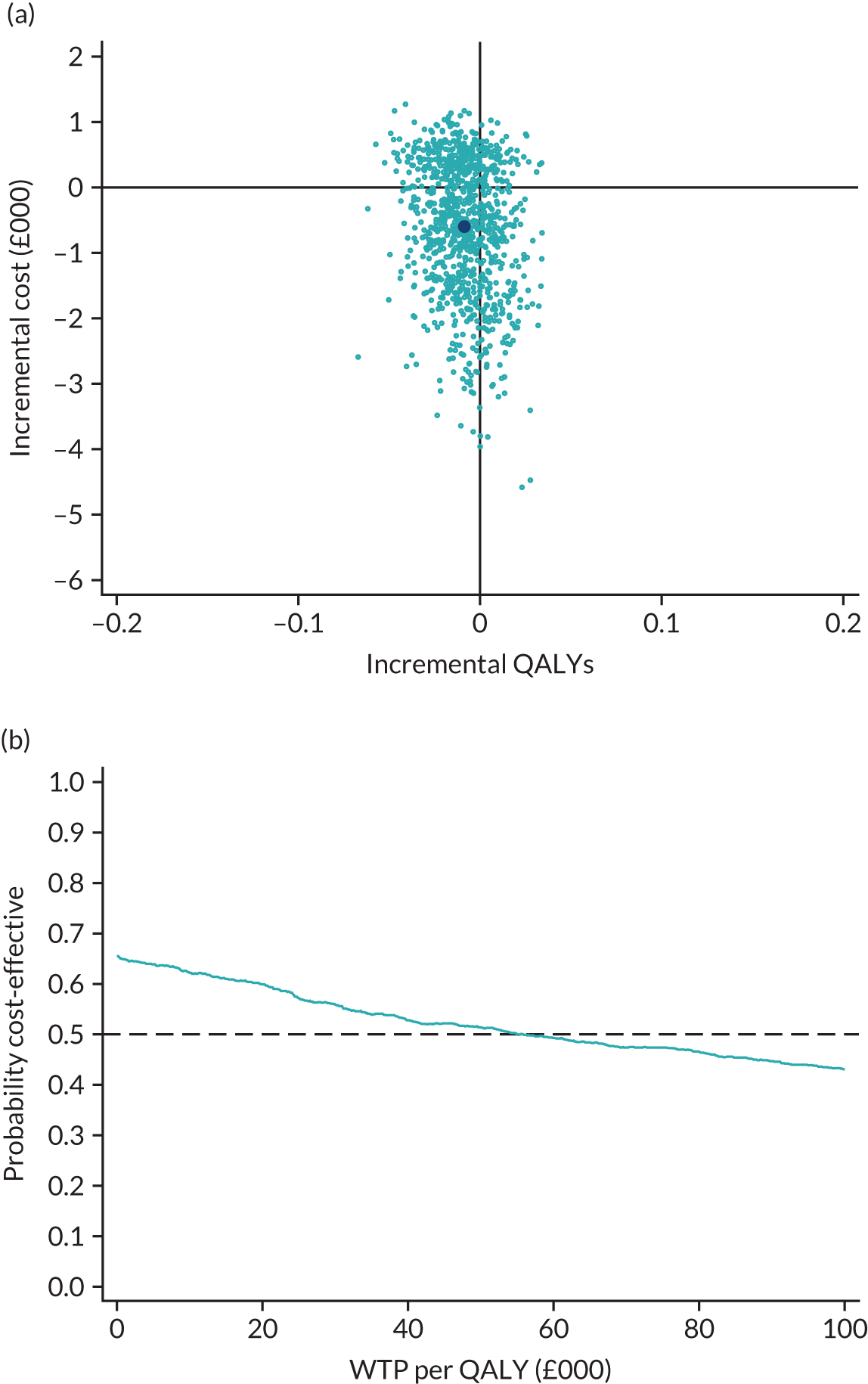

Economic outcomes

The economic outcome measures addressed the costs of delivering the interventions, changes in health utility in the 12 months after randomisation and the costs associated with participants in the 12 months after randomisation. Costs associated with delivering the intervention were derived using a micro-costing approach, accounting for the actual costs, including associated training, facilities and overheads, and management costs. Health utility was assessed using the self-completed EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), and the Child Health Utility – 9 dimensions (CHU-9D),64 which were assessed at baseline and at 6 and 12 months. Service utilisation on the part of the participant was assessed using a specifically designed Client Receipt Service Inventory65 previously used with the adolescent population. Service use was assessed from a wide public sector perspective, encompassing health and social care, criminal justice, education and employment service utilisation.

Qualitative outcomes

Twelve RISKIT-CJS groups were purposefully selected according to geographical region and group dynamics, and a group discussion was conducted at the end of step 3 of the intervention, that is, the last group session attended. The group discussions were facilitated by experienced qualitative researchers, trained in both qualitative methods and the participatory rapid appraisal approach. 66 The researchers had experience of the RISKIT-CJS intervention but had not been part of the session delivery, enabling young people a space to share both positive and negative responses. Two researchers joined the selected groups at the close of the last group session and this created a distinction between the role of the researchers and interventionists. The approach employed was a participatory rapid appraisal66 to elicit in-depth exploration of the acceptability and perceived effectiveness of the programme and of the different elements within it.

To explore the RISKIT-CJS intervention from the perspective of the practitioners, 23 semistructured telephone interviews were conducted 2 weeks after the final motivational interviewing intervention. The semistructured interviews and field notes maintained by interventionists were used to explore a number of key objectives, feasibility, acceptability and perceived effectiveness of the programme.

Telephone interviews were carried out with a purposively selected sample of practitioners, including staff working in YOTs, PRUs and SMTs, who were involved with RISKIT-CJS programme and were chosen according to their profession and region. The aim was to explore the impact of the RISKIT-CJS intervention from the perspective of the YOT staff who worked with the target population. It was proposed that there would be 24 semistructured telephone interviews with staff across the participating teams and that these should be conducted 4 weeks after the final step 4 of the motivational interviewing intervention.

Chapter 2 Trial process and delivery of the intervention

Introduction

All young people recruited into the trial, regardless of the arm they were allocated to, continued to receive TAU, as was delivered in the setting and location they were recruited from.

Patient and participant involvement

Young people played a critical role in the co-production of the RISKIT intervention. The trial processes and materials were reviewed by a young person’s advisory group. A young person was invited to attend the TMG and trial TSC meetings and provide input on the ongoing trial progress. As part of the qualitative work, we asked young people for their views on the interpretation of the trial results.

Describing treatment as usual

During the study, it was apparent that TAU varied across settings and locations and, bearing in mind that youths with severe substance use or youths subject to an order related to their substance use were excluded from participation, in many centres no intervention was offered specifically to address substance use. In the YOT setting, some participants were able to access structured psychoeducation, delivered either individually by a youth worker or as part of a small group. The general topics included exploring peer pressure, consequential thinking and making choices, victim awareness, alcohol awareness, substance use and the law, and substance use and health. In addition, some YOTs used community resolution and community payback to enable offenders to reflect on the impact of their offences on others. In general, it was observed that participants tended not to engage with psychoeducation or community interventions unless they had been dictated by a court order. In the PRU settings, all schools provided personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) education and although there are no prescriptive guidelines of what constitutes PSHE it usually covers alcohol and substance use. Although PSHE varies from school to school, it tends to cover risks associated with substance use, provision of information leaflets and videos, advice delivered by teachers and external speakers, and information for parents. In addition to PSHE, PRUs offered a number of different approaches for social, emotional and behavioural support, sometimes in response to a specific recommendation in an education health and care plan and sometimes across the whole school. Often these approaches were evidence informed rather than evidence based, and included Lego® (The Lego Group, Billund, Denmark) therapy, gardening, equine therapy, positive mentoring and mindfulness.

Those participants recruited from SMTs received the most standardised form of TAU, and this involved a medical assessment to identify any additional clinical needs, single-session brief interventions based on a motivational interviewing approach and individual sessions addressing anxiety management and behavioural triggers for substance use.

As the TAU varied by setting, we adjusted our analysis to take account of these variations.

Trial processes

Study setting and population

Young people aged 13–17 years (inclusive) were targeted. Young people were recruited from a mixture of YOTs, PRUs and SMTs between September 2017 and June 2020. Recruitment was conducted in four geographical areas of England (i.e. North East, South East, London and North West).

In the YOTs, all young people are routinely screened using the ASSET tool, and research staff approached any young person who scored ≥ 2 on the substance use domain, indicating a relationship between criminal behaviour and substance use. In PRUs, school staff identified potential participants who were subsequently assessed by research staff to ensure that they had been involved with CJS and were engaged in substance use. The SMT cohort included young people who had recently come to the attention of the police for being involved in criminal activity and who were also found to be in possession of illegal substances. As part of a scheme to divert these young people from criminal justice services, they were referred to a young person’s SMT for assessment and, when necessary, intervention.

Eligibility checks were conducted by a researcher trained in the process and who had previously worked with adolescent populations. Young people who were eligible were provided with detailed trial information (see Report Supplementary Material 2) both verbally and in writing and were asked to consider participating. It was made clear that a participant could withdraw from the intervention or the trial completely at any stage and withdrawing would have no effect on any intervention they would receive as TAU. All young people, irrespective of eligibility and consent, were recompensed for their time with a £10 voucher. If a participant was willing to consent, then the researcher decided whether or not the young person aged ≥ 16 years met the criteria for being Gillick competent and, if they were, then consent was taken. For young people aged < 16 years and young people aged ≥ 16 years and considered not to be Gillick competent, assent was taken from the young person and formal consent taken by contacting the primary caregiver, who was provided with a copy of the trial information sheet. The young person was asked to consent both to the trial and for access to offence records held on the Police National Computer. After consent had been taken, the researcher conducted the TLFB28 on paper. The young person completed the rest of the baseline assessment on a tablet device using specifically designed software. The researcher was available to aid any young person who had difficulty in understanding the questions. After the completion of the baseline assessment, randomisation was conducted automatically through the tablet device and the young person was informed of their allocation. Once sufficient numbers of young people had been allocated to the intervention to form a group, usually six or more, but not exceeding eight, then the list of group members was reviewed by staff within centres to identify any potential risks, such as a lone female in a dominant male group, group members known to be engaged in violent conflict or associated with different gangs and very vulnerable participants. If any risks did arise, then the young person was considered for another group at the same setting. If no other group was available, then the young person received the individual components of the intervention. Follow-up was conducted as close to the 6- and 12-month follow-up as possible. Young people had a choice in how they were followed up: in person with a researcher, by telephone with a researcher or by completing a paper-based questionnaire by e-mail or post. Once follow-up was completed at 6 and 12 months, participants were recompensed for their time with a £10 voucher at both time points. This both recognised the contribution the participant made to the research and was designed to reduce attrition over time. 67

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To maximise the generalisability of the trial population, inclusion and exclusion criteria were kept to a minimum. Participants were included if they were aged 13–17 years (inclusive), if they had recently engaged in substance use and had been involved in the CJS, and if they were engaged in a participating YOT, PRU or SMT.

Participants were excluded if the severity of their substance use was such that a referral to specialist services for detoxification was required, if the severity of criminal involvement was such that the young person was likely to be incarcerated during the intervention or follow-up period, or if the young person was currently on a court-mandated order with alcohol or substance use abstinence as a prerequisite.

Randomisation

Randomisation was conducted at the level of the participant by an independent secure randomisation service, using random permuted blocks of random length. Strings developed independently were encrypted and stored, with the tablet devices and allocation revealed only when a participant had been judged eligible, provided written consent and completed the baseline assessment. Copies of the strings for audit and quality assurance purposes were held in an encrypted database by an organisation not associated with the research. Randomisation was stratified by site, sex and age group [i.e. 13–15 years (inclusive) vs. 16–17 years (inclusive)].

Staff identified to deliver the RISKIT-CJS intervention

We worked in collaboration with youth substance misuse services provided by Addaction, now renamed We Are With You (London, UK). Staff delivering the interventions were paid, experienced youth workers and youth substance misuse workers who had been trained and accredited, and had experience of delivering motivational interviewing. Many of the staff had experience of delivering the schools version of the RISKIT intervention, which is similar to the RISKIT-CJS intervention but is delivered for 1 hour per week over an 8-week period.

RISKIT-CJS intervention training and support

Staff were invited to participate in a 2-day training course as part of their continuous professional development. In addition to providing an overview of their roles and responsibilities relating to the trial, the 2-day course explored the theoretical underpinning of the RISKIT-CJS intervention, detailing delivery of each programme element, including managing group dynamics, managing ambivalence, identifying risks and safeguarding. Staff engaged in written coursework and role play, and had an opportunity to conduct motivational interviews and manage groups while being observed by an experienced senior practitioner. Only when a staff member had been deemed competent by the senior practitioner were they allowed to deliver the RISKIT-CJS intervention. Intervention delivery was monitored on an ongoing basis by senior staff who observed practice in individual and group sessions, providing ongoing guidance and supervision.

The RISKIT-CJS intervention

The RISKIT-CJS intervention was based on a similar individual and group intervention developed in collaboration with young people and delivered in school settings. 43 The intervention delivered in the trial consisted of four distinct steps. The first step, delivered immediately after randomisation, was an individual face-to-face session with a trained interventionist, lasting approximately 40 minutes. This session used techniques associated with motivational interviewing to discuss substance use, to explore the role substance use plays in risk-taking behaviour or emotional dysregulation, to explore and support behaviour change, and to enhance motivation to engage with the intervention. Step 2 was a group session delivered about 1 week after step 1. The group session, delivered over half a day at a convenient location for the participants, employed a group cognitive–behavioural therapy approach, employing group discussion and interactive whiteboards. The aim of the session was to provide both psychoeducation and skills development, encompassing understanding substance use and associated harms, understanding triggers to substance use, developing strategies for harm minimisation and reducing consequential risks, exploring techniques to divert or distract from substance use, and exploring substance use and sexual health risks. The actual topics and depth covered were decided at the beginning of the session to meet the needs of the group. Step 3 occurred usually 1 week after step 2 and took a similar group approach, but with a greater emphasis on skill development. Topics included communication strategies and assertiveness training, managing anger and anxiety, mindfulness and planning for the future. Two interventionists covered each group, with one interventionist delivering the content and the other encouraging engagement within the group. Step 4 was conducted about 1 week after step 3 and comprised a 40-minute face-to-face session conducted in a mutually convenient location. This session, using a similar motivational interviewing approach as step 1, explored outstanding barriers to change, managing expectancy and enhancing self-efficacy. In addition, each step 4 intervention was tailored individually to consolidate what had been learned from the group sessions and to explore opportunities to engage in local services and provision to encourage pro-social behaviour. Participants were not paid to attend any of the sessions, although they were reimbursed for any travel expenses and provided with refreshments.

Assessing intervention fidelity

Intervention fidelity relates to the extent to which an intervention is true to the underlying therapeutic theory. Researchers need to be able to determine whether or not the intervention is delivered as intended and, although complete manualisation of an intervention goes against many therapeutic principles, it is important to be able to assess the content of an intervention. High-fidelity delivery of an intervention makes it more appropriate to draw causal conclusions regarding any intervention and effect observed; it also makes any intervention easier to replicate in practice. In addition to keeping a log of what subjects were covered in the group sessions, interventionists sought the consent of young people to audio-record their individual sessions. From the sessions recorded, a 20% random sample was drawn, stratified by sessions (1 or 4), interventionist and site. These sessions were listened to by two independent raters. The raters scored the sessions using BECCI,68 that is, a tool specifically designed to measure the micro-skills of behaviour change counselling and motivational interviewing.

The BECCI focusses on the interventionist’s consulting behaviour and attitude rather than a self-report. Scores are provided on a scale of 0–4 (where 0 = not at all, 1 = minimally, 2 = to some extent, 3 = a good deal and 4 = a great extent). Ratings consider 15 domains of practitioner skill and are completed in accordance with the rater manual. Two raters considered each recording and made decisions regarding the overall score. When significant deviation regarding the allocated rating occurred, the two raters listened to the recording together and came to a consensus on the score. Ratings were incorporated into the assessment of fidelity reported in Chapter 3.

Chapter 3 Trial methods and results

Trial summary

The RISKIT-CJS RCT was a mixed-methods, prospective, pragmatic RCT with individual allocation, combining both quantitative and qualitative evidence. The trial was conducted across four geographical areas in England (i.e. South East, South London, North East and North West), covering a diverse socioeconomic and ethnic population. The study evaluated the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the RISKIT-CJS intervention in addition to TAU, compared with TAU only, on substance use 12 months after randomisation.

Inclusion criteria

Young people were included if they were aged 13–17 years (inclusive), if they had recently engaged in substance use and had been involved in the CJS, and if they were engaged in a participating YOT, PRU or SMT. In addition, young people had to be willing and able to provide consent.

Exclusion criteria

Young people were excluded if the severity of their substance use was such that a referral to specialist services for detoxification was required, if the severity of their criminal involvement was such that the young person was likely to be incarcerated during the intervention or follow-up period or if the young person was currently on a court-mandated order with alcohol or substance use abstinence as a prerequisite.

Sample size and power calculation

We aimed to recruit 500 participants over a 19-month period, with the aim of assessing at least 350 of these participants at the 12-month assessment point. We estimated a loss to follow-up at the primary end point (i.e. 12 months post randomisation) of 30%. Our sample was designed to identify a clinically important effect size difference of 0.3 in the primary outcome measure (i.e. PDA from all substances), with an alpha of 0.05 and power at 80%, using a two-sided test.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome measure was PDA from all illicit substances (including alcohol) in the 28 days prior to the 12-month follow-up, and this was derived using TLFB28 method.

Secondary outcomes derived from TLFB28 were PDA for all illicit substances excluding alcohol and PDA for 11 types of illicit substance use: (1) alcohol, (2) cannabinoids/marijuana, (3) cocaine/crack, (4) amphetamine-type stimulants, (5) opiates, (6) prescribed opioid substitution, (7) MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine)/ecstasy, (8) prescription medication, (9) inhalants, (10) hallucinogens and (11) novel psychoactive substances.

Mental health and well-being was measured using the WEMWBS. The WEMWBS total score was derived by summing the individual items score. When more than three individual item scores were missing, the total score was assumed to be missing. When fewer than three items were missing, the total score was estimated using mean substitution for missing values.

Readiness to change was measured using SOCRATES-7DS. The SOCRATES-7DS contains 20 items, with four items for each stage of precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action and maintenance. When an individual item was missing, then this resulted in a missing score for the relevant domain of behaviour change.

The BSCQ was used to assess self-efficacy. The BSCQ comprises eight visual analogue scales to record confidence (on a scale of 0–100) in resisting the temptation to use drugs in a variety of situations.

Health-related quality of life was measured using the KIDSCREEN-10 Index. This unidimensional measure presents a global score incorporating elements of physical and psychological well-being, autonomy and parent relations, peer and social support, and school environment. The KIDSCREEN-10 Index comprises 10 items rated on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, which are summed to give a total score. The KIDSCREEN-10 Index also includes an overall self-reported assessment of general health (i.e. poor, fair, good, very good or excellent). The total score of the 10 items was calculated when there were no missing values for individual items.

Primary and secondary outcomes were measured at baseline and at 6 and 12 months.

Therapeutic alliance was measured at the end of the intervention using the TASC-r. The TASC-r distinguishes between the affective bond (i.e. the extent to which the therapist is an ally) and client–therapist collaboration on therapeutic tasks and goals (i.e. the extent to which it is difficult to work with the therapist on solving problems). Twelve items are rated on a Likert scale from 1 (not true) to 4 (very much true) and summed to give a total score. When more than three individual item scores were missing, then the total score was assumed to be missing. When fewer than three items were missing, then the total score was estimated using mean substitution for missing values.

All individual motivational interventions were recorded when consent to record had been granted. A random sample of 20% of recordings (stratified by region, age and therapist) was selected and assessed by independent raters using BECCI63 to assess fidelity and quality. Overall scores were calculated by summing the checklist item scores and by dividing by the number of items to give a mean score. Mean substitution was used when an item on the checklist was not applicable.

To assess how well the blind was maintained, researchers conducting follow-up assessments completed a five-point scale to record their confidence in treatment allocation.

Attendance at each of steps 1–4 of the intervention was recorded for each participant. Each interventionist delivering the RISKIT-CJS intervention was assigned a unique identifier, and this was recorded for each step of the intervention for each individual.

Statistical analysis plan

Two data sets were created for the statistical analysis. The primary analysis was based on the analysis by treatment allocated (ATA) data set. The secondary analyses examined treatment effects under different scenarios for compliance with allocation/treatment, including complier-average causal effect (CACE) and per protocol (PP). The definition of compliance with allocation for this trial was (1) participants attending at least one individual session and at least one group session are considered ‘compliers’ in the active treatment group (Table 1, cell A) and (2) participants in the control group who did not receive any intervention (see Table 1, cell D). All non-compliers in the treatment group were regarded as being ‘contaminated’ because they received the control condition. For the control group, there is no option for control participants to access the intervention and so there cannot be non-compliance (see Table 1, cell C).

| Treatment allocated | Treatment received | |

|---|---|---|

| RISKIT-CJS intervention | Control | |

| RISKIT-CJS intervention | A. Treatment complier: one individual session and one group session | B. Treatment non-complier: only individual or group attended; no sessions attended |

| Control | C. Control non-complier: n/a | D. Control complier: control group participant |

Analysis by treatment allocated

The data set contains all available data for participants who were randomised, regardless of whether or not they complied with allocation. This includes participants who were withdrawn from the trial post randomisation. These analyses are a lower-bound estimate of treatment effects, as they represent the effect of offering a programme, rather than the effect of actually receiving that programme.

Complier-average causal effect

We assessed treatment effects in the presence of non-compliance, with compliance measured at the individual level and including all those allocated as part of the trial. Our approach for assessing treatment effects under non-compliance was to use the instrumental variables framework. 69 The benefit of using an instrumental variables approach is that randomisation is maintained in the analysis, which is crucial for estimating unbiased treatment effects. 70 CACE weights the ATA treatment effect by the proportion of compliers:

If the proportion compliant is 1.0 (i.e. perfect compliance), then the CACE estimate is the same as the ATA estimate, but otherwise the impact of this approach is to increase the magnitude of the treatment effect.

Complier-average causal effect uses a two-stage least squares approach. The stage 1 model uses treatment received (T) as the outcome, with random allocation (Z) as the independent variable:

Based on the stage 1 model, we then calculate predicted values of treatment received (T^) for use in stage 2. The stage 2 model predicts the substantive outcome (Y, e.g. days abstinent) using the predicted values of treatment received (T^) based on the stage 1 model:

The CACE analysis was conducted using a two-stage least squares estimation with the ivregress command in Stata® version 16.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A linear regression modelling approach was used for PDA and WEMWBS score.

Per-protocol data set

The PP data set contains all data for participants who complete the trial as planned without any major protocol violations or exclusions. PP analyses essentially drop those individuals who have not strictly complied with their allocated treatment, that is, both those who only partially complied with their allocated treatment and those who did not receive their allocated treatment. This means that PP represents a likely ‘best case scenario’ for treatment effect estimation.

Missing data

The proportion of missing data and patterns of missingness were examined for the primary and secondary outcomes. Levels of missing data are reported along with any systematic occurrences of missing data observed in the data sets. When outcomes were derived scores, individual item scores were checked for systematic missingness by comparing the proportion of missing values by age (< 16 years or ≥ 16 years), sex, service type (i.e. YOT, PRU or SMT) and allocated group.

To avoid loss of efficiency, it was planned to impute missing outcome values (both primary and secondary WEMWBS score) using multiple imputation, if the proportion of missing data was > 5% and < 40%. 71 Multiple imputation methods perform less well when the number of missing data is substantial (i.e. if > 40% of the primary outcome data are missing in the primary analysis, then the assumptions are less plausible).

For PDA all substances and WEMWBS score, the percentage of data missing at 12 months was 45% and 55%, respectively, and, consequently, multiple imputation was performed as a sensitivity analysis only and not as part of the main analysis.

We explored the mechanism of missing data to establish whether the data could be considered missing completely at random or missing at random (MAR). For each allocated arm, and overall, participants were grouped based on the time they were lost to follow-up or withdrew, and means/medians at baseline and each time point were examined to assess whether there were systematic differences between those who dropped out at specific time points and those who remained in the study.

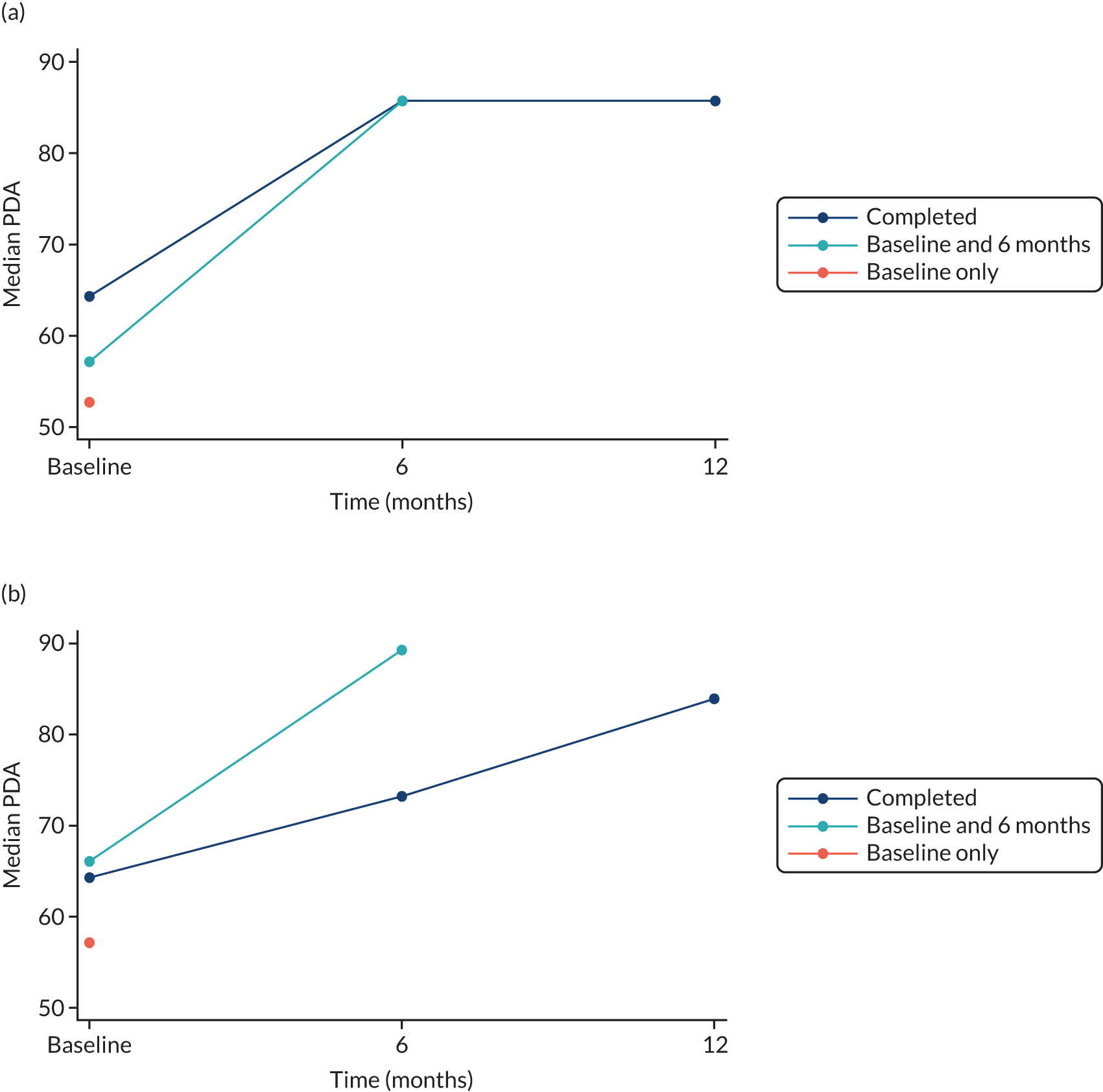

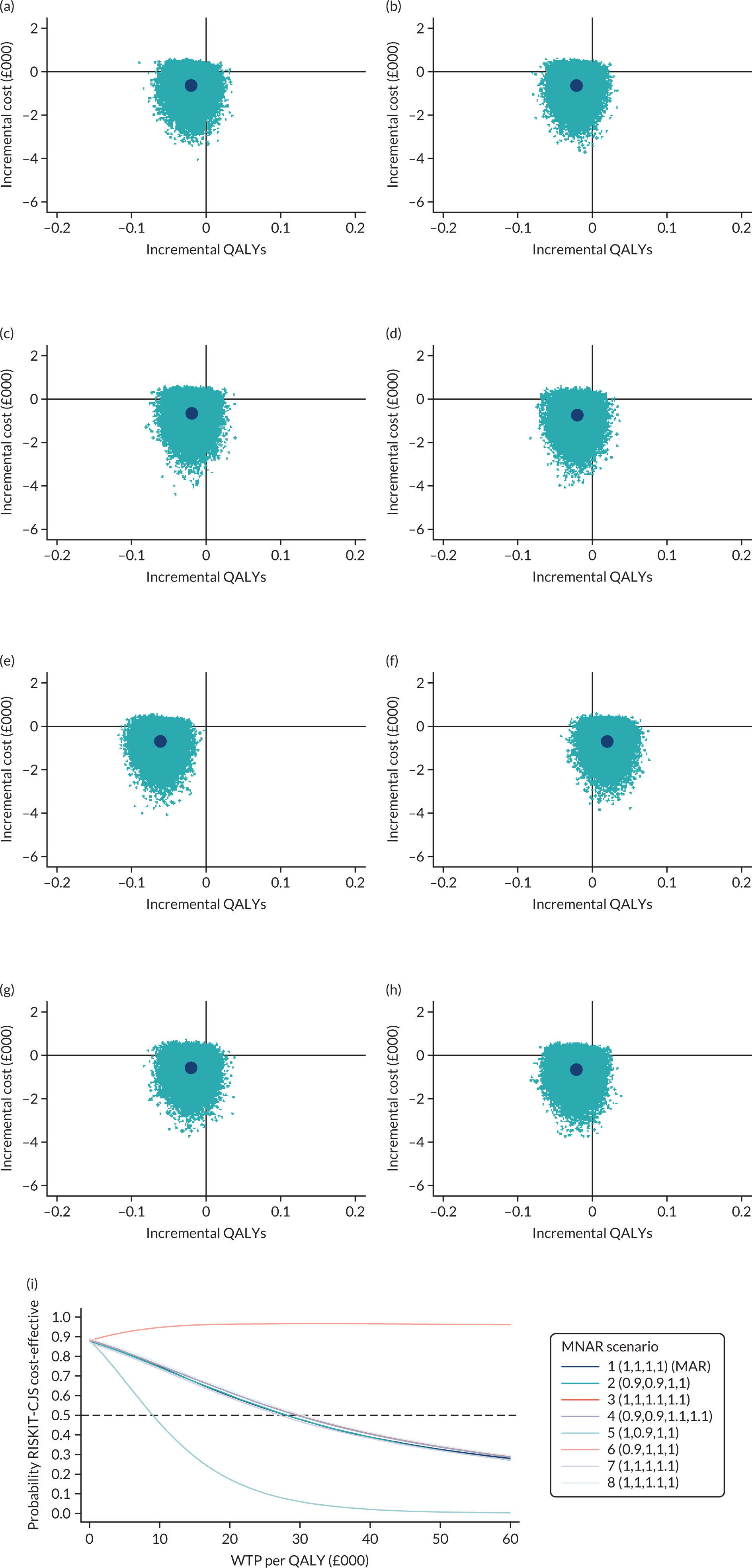

Figure 1 shows that the median PDA at baseline was lower for participants with only baseline data than for participants who remained in the study, and this was the same in both arms. Compared with participants with complete data at 12 months, participants with only baseline and 6-month data had a greater increase in median PDA at 6 months in both arms, although the number of participants in this group was smaller. These data suggest that the assumption of MAR may not be plausible.

FIGURE 1.

Median PDA all substances by allocated arm. (a) RISKIT-CJS intervention; and (b) control.

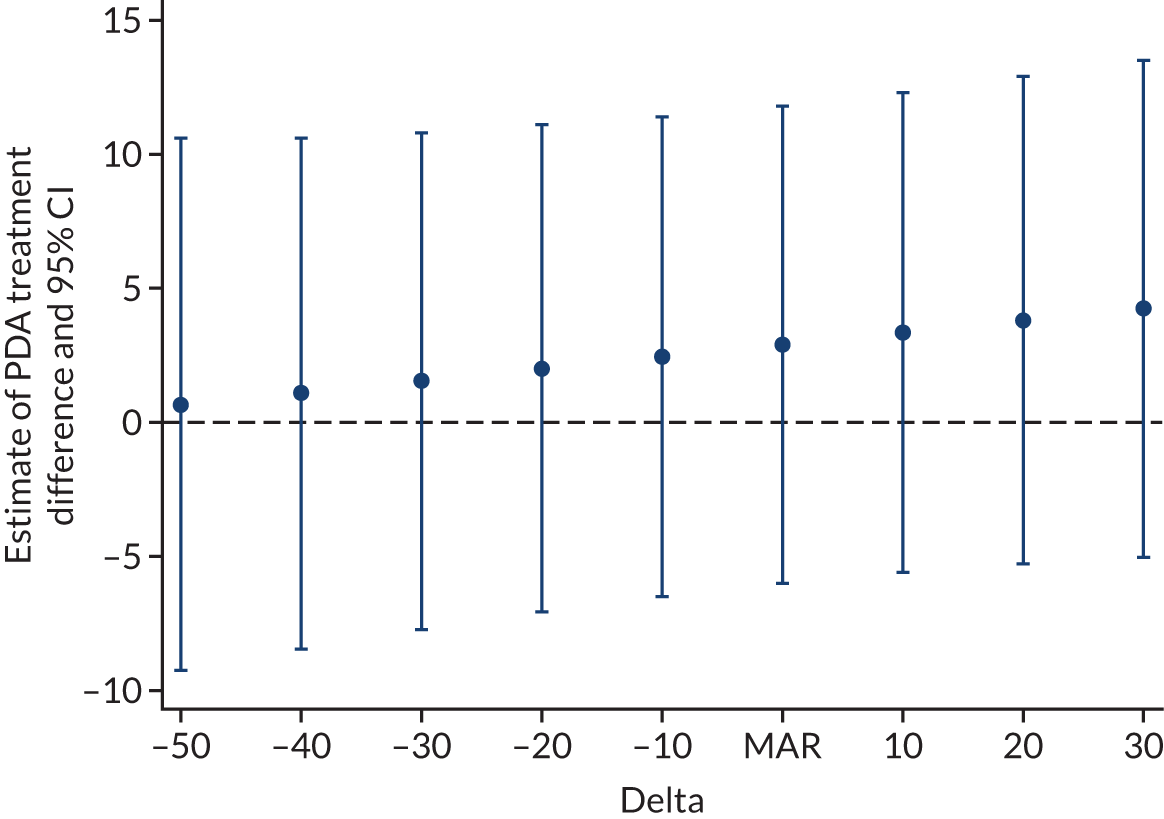

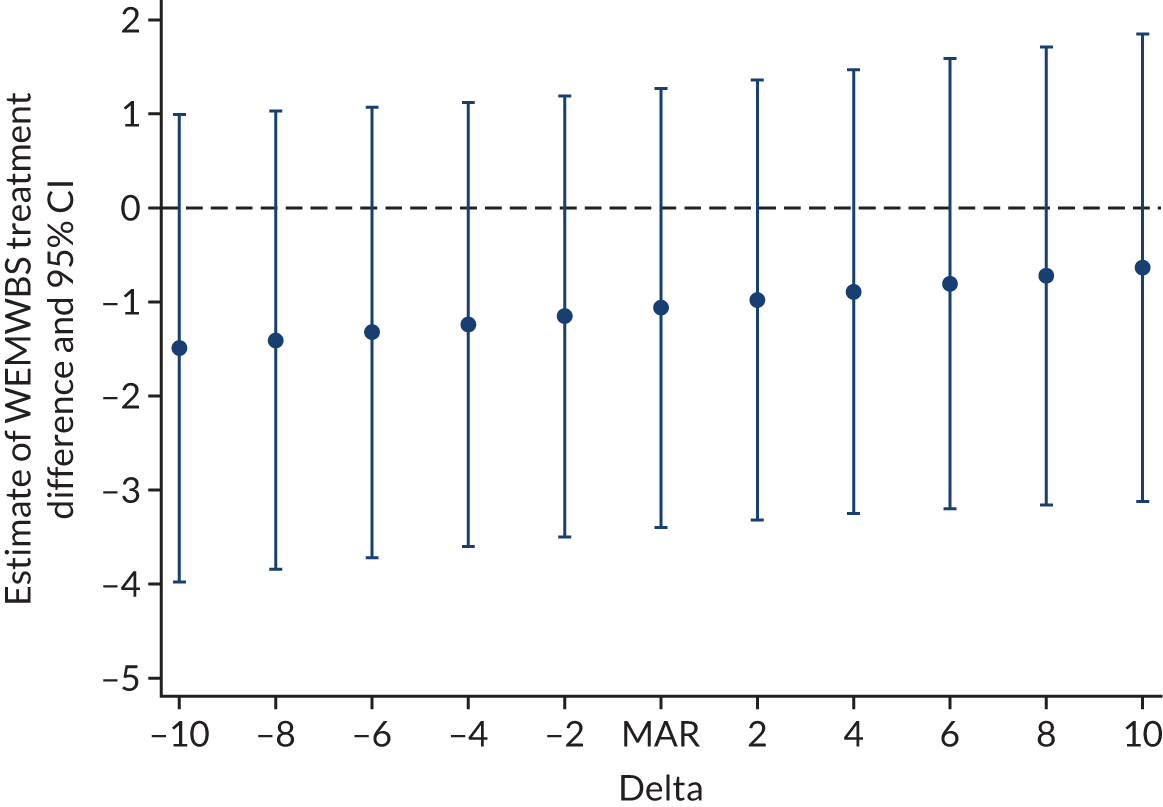

A sensitivity analysis was performed using a pattern mixture approach and multiple imputation to compare the sensitivity of conclusions with varying assumptions about the missing value mechanism. It is possible that participants who failed to attend their follow-ups differed from those who did attend (e.g. had fewer days abstinent and, therefore, would have lower PDA than if they had attended the follow-up, or vice versa). This would mean that the data were missing not at random (MNAR) and would represent a departure from the MAR assumption. The sensitivity of the primary analysis results to departures from the MAR assumption were explored using a pattern mixture model, implemented using the rctmiss command in Stata. 72,73

Deviation from the statistical analysis plan

Plots of the primary outcome, by dropout time, to assess the missing value mechanism suggested that missing values are not MAR. In addition, the planned analysis to compare the sensitivity of conclusions with varying assumptions about the missing data uses multiple imputation, which is less tenable given the high proportion of missing values. These analyses were completed as a sensitivity analysis, and two additional approaches were used and reported as secondary analyses. The first approach used last observation carried forward (LOCF) for each individual to estimate the 12-month data value when data at 6 months were measured. The second approach, when the 6-month data were missing, used a combination of LOCF and baseline observation carried forward (BOCF), and this method assumes that individuals remain at the same level as their last measurement after they are lost to follow-up or leave the study.

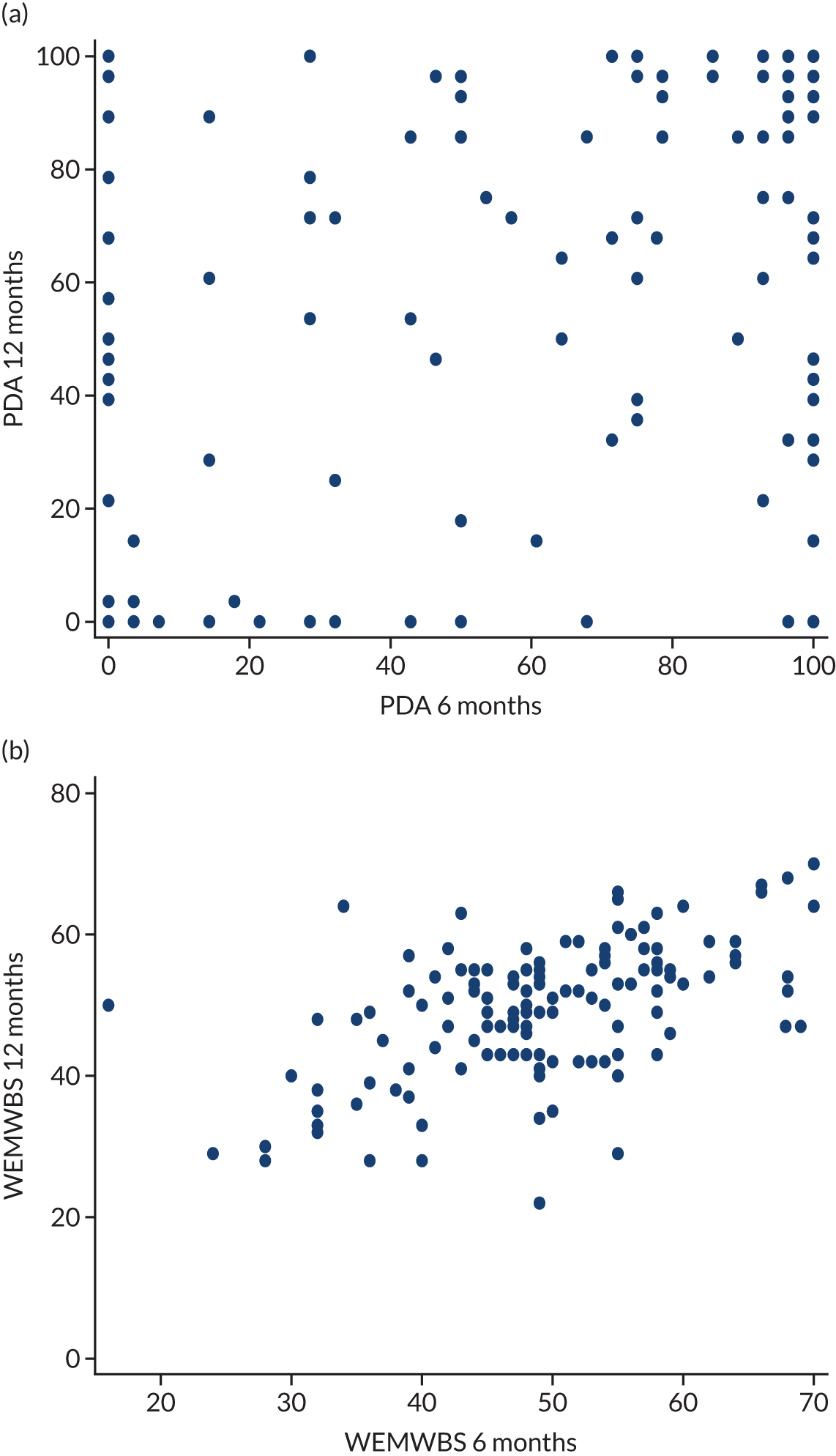

Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated for the primary outcome to estimate the strength of association between time points (i.e. baseline, 6 months and 12 months) and scatterplots were also produced.

Methods

Analysis and results are presented in accordance with CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines. All statistical analysis was conducted using Stata/IC.

The primary analysis was based on the ATA data set, which contains all available data for participants who were randomised, regardless of whether or not they complied with allocation.

Diagnostic tests and plots to assess the assumptions of normality for PDA were performed prior to analysis. There were significant departures from normality and an alternative model was implemented, as specified in the statistical analysis plan, to allow for the fractional nature of the primary outcome response. A fractional linear logistic model74 was fitted, assuming that the variance in response was proportional to a binomial distribution and using the logit link function to maintain bounds between 0 and 1. Fixed effects were included for allocated arm, service type (i.e. YOT, PRU and SMT), age (< 16 years and ≥ 16 years) and sex. The outcome was adjusted for baseline by including the baseline measure as a covariate. Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) between the RISKIT-CJS intervention and control group, with accompanying 95% CIs.

The secondary outcome of WEMWBS score was analysed using analysis of covariance to compare the mean response across treatment arms, with fixed effects for treatment arm, service type (i.e. YOT, PRU and SMT), age (< 16 years and ≥ 16 years) and sex. The outcome was adjusted for baseline by including the baseline measure as a covariate. Results are presented as mean differences between the RISKIT-CJS intervention and control group, with accompanying 95% CIs.

Secondary analysis was performed for the PP data set and using the CACE approach for the primary outcome and WEMWBS score. The primary outcome and WEMWBS score at the 6-month follow-up were also analysed.

Stepwise regression analysis was performed to model the relationship between pre-randomisation factors and observed outcomes at 12 months, separately for the primary outcome and WEMWBS score. Interaction terms with treatment arm were included in the analysis, and a significance level of 0.1 was used to determine which factors were added and removed from the regression model. Pre-randomisation factors included in this analysis included demographic data (i.e. sex and social class measured using the Index of Multiple Deprivation by postcode), readiness to change (i.e. the SOCRATES-7DS) and self-efficacy measures (i.e. the BSCQ). This analysis was augmented by an additional analysis that included participants in the RISKIT-CJS intervention arm only, for the primary outcome and WEMWBS score and using the same pre-randomisation factors, but also including process measures of adherence, therapeutic alliance (i.e. the TASC-r) and interventionist.

Other secondary outcomes and outcomes derived from TLFB28 and demographic data were summarised to compare allocated arms. Means and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated for continuous normally distributed variables, medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for non-normally distributed variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables.

A description of TAU at each site was collected and is presented as part of the analysis.

Change in allocation ratio

At the start of the trial, the randomisation allocation ratio was 2 : 1, with one-third of participants receiving the RISKIT-CJS intervention. During the trial, it was agreed to change the allocation ratio to 1 : 1. However, for an interim period, the allocation ratio was 1 : 2, with twice as many participants receiving the RISKIT-CJS intervention as the control, until there was an equal number of participants in the control and intervention groups, when the allocation ratio was switched to 1 : 1 for the remainder of the trial.

An additional analysis was performed for the primary outcome and WEMWBS score to take account of any bias incurred from the change in allocation ratio during the trial. 75 An individual patient data meta-analysis approach was taken to analyse the data, using the one-stage approach. 76 The data were analysed using the statistical model specified previously for the main analysis. A fixed effect for allocation ratio group was added to the model, with interactions of allocation ratio group with treatment group and covariates. This one-stage individual patient data model was used to estimate differences between treatment groups and 95% CIs for each allocation ratio group and overall.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were performed using a pattern mixture approach and multiple imputation to compare the sensitivity of conclusions with varying assumptions about the missing value mechanism. The pattern mixture model works by including a sensitivity parameter, quantifying the departure from the MAR assumption. For example, if it is expected that participants who were lost to follow-up after the baseline visit, on average, have a difference of 20% in PDA at 12 months compared with participants who remained in the study, then the sensitivity parameter would be equal to 20.

The pattern mixture model is used to obtain an estimate of the treatment effect given this level of departure from the MAR assumption. Graphs of the adjusted mean difference in PDA and WEMWBS score between treatment groups for varying values of the sensitivity parameter are reported. Analysis was performed assuming that the value of the sensitivity parameter was equal in both groups (i.e. missing data were equally informative in both groups).

Safety data

Serious adverse events and partial compliance because of safeguarding concerns are summarised by type and treatment arm. Safeguarding concerns occur when a young person is withdrawn from a group session, but not an individual session, because there are concerns of iatrogenic effects of participation.

Results

Box and whisker plots and summary statistics are reported in Report Supplementary Material 3, Figures 1–26, for all the primary and secondary outcomes.

Of those participants allocated to the intervention, 214 (87%) received the initial motivational interview, 98 (40%) attended the first group session and 74 (30%) attended the second group session and the second motivational interview. Table 2 provides an overview of these figures.

| Intervention step | RISKIT-CJS intervention (N = 246), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Motivational interviewing session 1 | 214 (87) |

| Group session 1 | 98 (40) |

| Group session 2 | 74 (30) |

| Motivational interviewing session 2 | 74 (30) |

| Compliera | 104 (42) |

| PPb | 47 (19) |

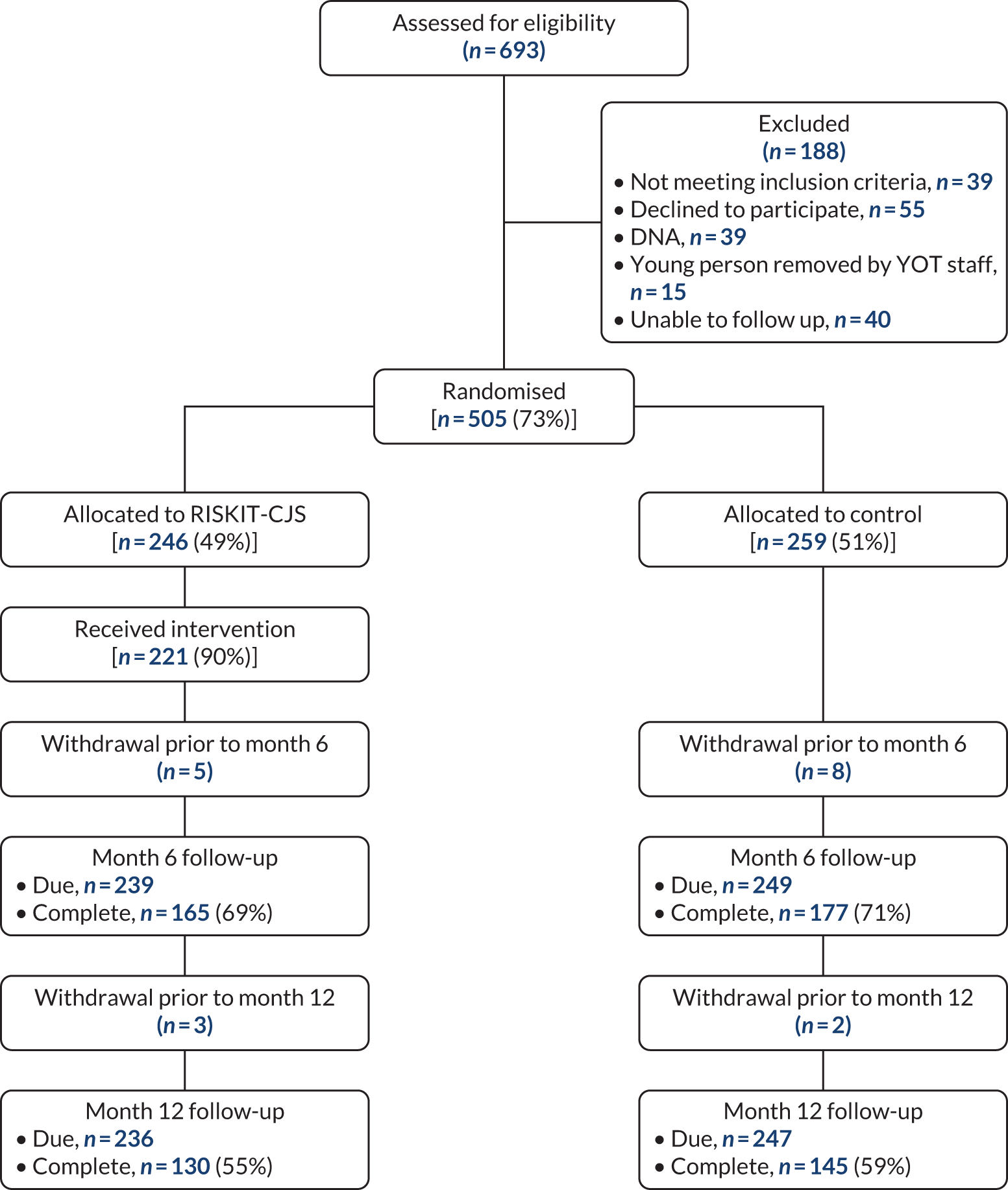

A full CONSORT diagram is provided in Figure 2. There were 505 participants at baseline, with 191 (37.8%) participants recruited from YOTs, 262 (51.9%) participants recruited from PRUs and 52 (10.3%) participants recruited from SMTs. The mean age of participants was similar for both arms (15.2 years vs. 15.3 years for the RISKIT-CJS intervention and the control, respectively) and the proportion of participants younger than 16 years overall was 58.8%. There were fewer female participants than male participants, with 24.6% female participants overall. Table 3 contains a summary of demographic variables at baseline and Table 4 contains details on the main substances consumed.

FIGURE 2.

The RISKIT-CJS CONSORT diagram. DNA, did not attend.

| Demographic information | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| RISKIT-CJS intervention (n = 246, 48.7%) | Control (n = 259, 51.3%) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 15.2 (1.13) | 15.3 (1.15) |

| Aged < 16 years, n (%) | 149 (60.6) | 148 (57.1) |

| Male, n (%) | 181 (73.6) | 200 (77.2) |

| Service type, n (%) | ||

| YOT | 83 (33.7) | 108 (41.7) |

| PRU | 135 (54.9) | 127 (49.0) |

| SMT | 28 (11.4) | 24 (9.3) |

| Main substance consumed | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| RISKIT-CJS intervention (N = 243), n (%) | Control (N = 256), n (%) | |

| Alcohol | 143 (58.8) | 160 (62.5) |

| Cannabinoids/marijuana | 185 (76.1) | 196 (76.6) |

| Cocaine/crack | 19 (7.8) | 19 (7.4) |

| Amphetamine-type stimulants | 4 (1.6) | 3 (1.2) |

| Opioid analgesics | 6 (2.5) | 2 (0.8) |

| Prescribed OST | 0 | 0 |

| MDMA/ecstasy | 24 (9.9) | 25 (9.8) |

| Prescription medication | 7 (2.9) | 3 (1.2) |

| Inhalants | 5 (2.0) | 5 (2.0) |

| Hallucinogens | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) |

| Novel psychoactive | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

The proportion of missing data and patterns of missingness were examined for the primary and secondary outcomes. The majority of participants who were lost to follow-up or withdrew from the study dropped out after the baseline visit and before 6 months, and this was the same for both treatment arms. The proportion of missing data for the primary outcome at 12 months was similar for both treatment arms (47.6% and 43.6% for the RISKIT-CJS intervention and the control, respectively) (Tables 5 and 6).

| Loss and withdrawal by time point | Treatment group | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RISKIT-CJS intervention | Control | ||

| Lost to follow-up, n | |||

| 6 months | 74 | 72 | 146 |

| 12 months | 32 | 30 | 62 |

| Withdrew, n | |||

| 6 months | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| 12 months | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Dropouts, n | 114 | 112 | 226 |

| Allocated, n | 246 | 259 | 505 |

| Dropout rate, % | 46.3 | 43.2 | 44.8 |

| Outcome | Number (%) of missing values | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | |

| PDA all substances | |||

| RISKIT-CJS intervention (n = 246) | 3 (1.22) | 115 (46.7) | 117 (47.6) |

| Control (n = 259) | 3 (1.16) | 125 (48.3) | 113 (43.6) |

| Overall (n = 505) | 6 (1.19) | 240 (47.5) | 230 (45.5) |

| WEMWBS | |||

| RISKIT-CJS intervention (n = 246) | 0 (0) | 151 (61.4) | 140 (56.9) |

| Control (n = 259) | 2 (0.772) | 158 (61.0) | 139 (53.7) |

| Overall (n = 505) | 2 (0.396) | 309 (61.2) | 279 (55.2) |

A greater proportion of males than females dropped out of the study, and primary outcome data at 12 months were recorded for 66.1% of female participants, but only 50.7% of male participants. There were more participants lost to follow-up from YOTs and SMTs than from PRUs. Primary outcome data at 12 months were available for 47.6% of participants from YOTs and 26.9% of participants from SMTs compared with 64.9% of participants from PRUs. Similar patterns were observed for WEMWBS score.

Tables 7 and 8 summarise baseline data by arm. There is no evidence of differences at baseline between treatments, supporting balance between the treatment arms and successful implementation of the randomisation procedure.

| Outcome | RISKIT-CJS intervention | Control | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 25% percentile | 75% percentile | n | Median | 25% percentile | 75% percentile | n | |

| PDA | ||||||||

| All substances | 60.7 | 7.14 | 89.3 | 243 | 61.8 | 3.57 | 85.7 | 256 |

| Substances alone | 64.3 | 7.14 | 96.4 | 243 | 64.3 | 3.57 | 96.4 | 256 |

| Alcohol alone | 96.4 | 89.3 | 100 | 243 | 96.4 | 89.3 | 100 | 256 |

| Cannabinoids/marijuana | 67.9 | 10.7 | 96.4 | 243 | 67.9 | 7.14 | 96.4 | 256 |

| Cocaine/crack | 100 | 100 | 100 | 243 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 256 |

| Amphetamine-type stimulants | 100 | 100 | 100 | 243 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 256 |

| Opioid analgesics | 100 | 100 | 100 | 243 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 256 |

| Prescribed OST | 100 | 100 | 100 | 243 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 256 |

| MDMA/ecstasy | 100 | 100 | 100 | 243 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 256 |

| Prescription medication | 100 | 100 | 100 | 243 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 256 |

| Inhalants | 100 | 100 | 100 | 243 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 256 |

| Hallucinogens | 100 | 100 | 100 | 243 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 256 |

| Novel psychoactives | 100 | 100 | 100 | 243 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 256 |

| BSCQ | ||||||||

| Unpleasant emotions | 30.5 | 1 | 70 | 246 | 49 | 10 | 93 | 259 |

| Physical discomfort | 50 | 10 | 100 | 246 | 50 | 3 | 100 | 259 |

| Pleasant emotions | 46.5 | 2 | 75 | 246 | 32 | 0 | 70 | 259 |

| Testing control over alcohol/drugs | 50 | 0 | 100 | 246 | 50 | 0 | 100 | 259 |

| Urges and temptations | 48 | 0 | 83 | 246 | 48 | 0 | 90 | 259 |

| Conflict with others | 50 | 10 | 100 | 246 | 50 | 3 | 100 | 259 |

| Social pressure to use | 51.5 | 11 | 100 | 246 | 55 | 6 | 100 | 259 |

| Pleasant time with others | 23.5 | 0 | 60 | 246 | 26 | 0 | 70 | 259 |

| Outcome | RISKIT-CJS intervention | Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | |

| WEMWBS | 48.3 | 9.67 | 246 | 48.4 | 8.80 | 257 |

| SOCRATES-7DS | ||||||

| Pre contemplation | 13.1 | 2.67 | 243 | 14.0 | 2.61 | 254 |

| Contemplation | 9.64 | 3.70 | 243 | 9.16 | 3.53 | 254 |

| Preparation | 8.29 | 3.47 | 243 | 7.74 | 3.29 | 254 |

| Action | 12.4 | 4.26 | 241 | 11.5 | 4.53 | 253 |

| Maintenance | 11.1 | 3.99 | 241 | 10.6 | 4.23 | 252 |

| KIDSCREEN-10 Index | 31.7 | 5.30 | 237 | 31.5 | 5.25 | 248 |

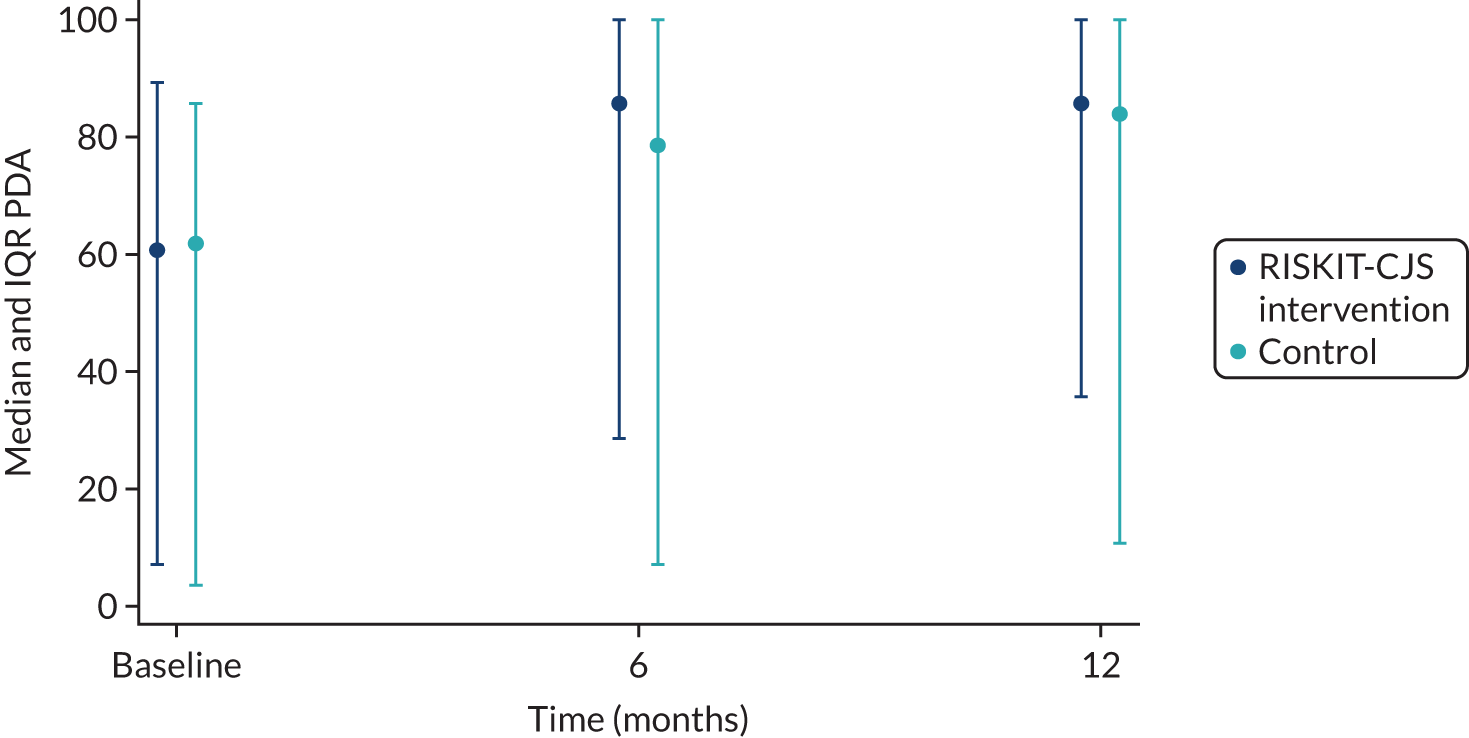

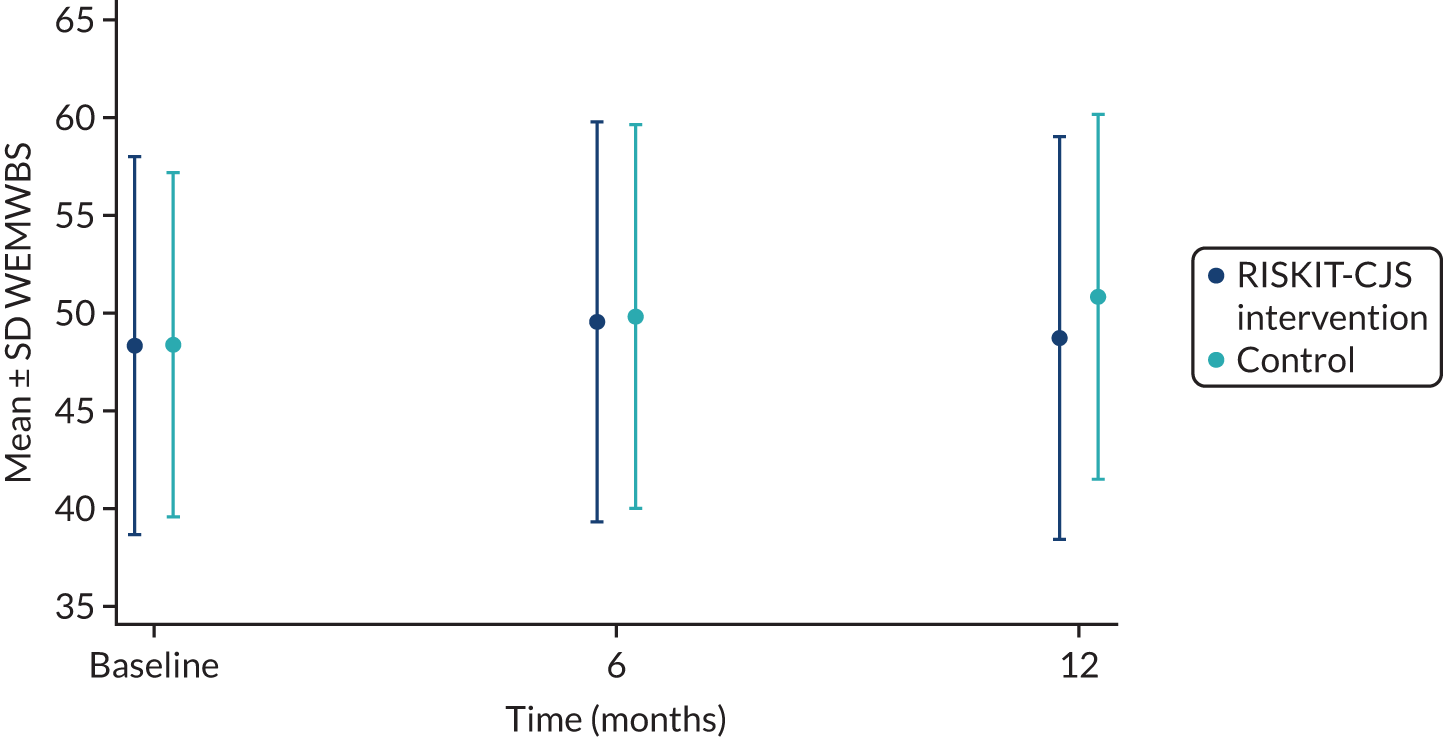

Figure 3 shows the median and IQR over time by treatment arm for the primary outcome PDA all substances. For both treatment groups, the PDA increases at 6 months compared with baseline values, and median values at 6 and 12 months appear to be similar. Figure 4 shows the mean and SD of WEMWBS over time by treatment arm, and there are no obvious differences between the RISKIT-CJS intervention and control or between times.

FIGURE 3.

Median and IQR for PDA all substances by time and allocated arm.

FIGURE 4.

Mean and SD for WEMWBS by time and allocated arm.

Tables 9 and 10 show the results from the statistical analysis of primary and secondary outcomes at 6 months and 12 months. There were no statistically significant differences between allocated arms for the primary outcome, PDA all substances, or for the secondary outcome, WEMWBS score.

| Outcome | RISKIT-CJS intervention, median | Control, median | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDA all substances | 85.7 | 83.9 | 1.14 | 0.743 to 1.76 | 0.542 |

| PDA all substances (PP) | 82.1 | 83.9 | 0.827 | 0.434 to 1.58 | 0.565 |

| PDA substances alone | 100 | 96.4 | 1.21 | 0.742 to 2.23 | |

| PDA alcohol alone | 96.4 | 100 | 1.01 | 0.625 to 1.64 | |

| PDA cannabinoids | 100 | 94.6 | 1.53 | 0.778 to 3.02 | |

| RISKIT-CJS intervention, meana | Control, meana | Treatment difference | |||

| WEMWBS | 49.3 | 50.4 | –1.10 | –3.45 to 1.25 | 0.357 |

| WEMWBS (PP) | 49.3 | 50.7 | –1.37 | –5.13 to 2.40 | 0.474 |

| KIDSCREEN-10 Index | 32.0 | 32.1 | –0.0821 | –1.60 to 1.44 |

| Outcome | RISKIT-CJS intervention, median | Control, median | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDA all substances | 85.7 | 78.6 | 1.39 | 0.900 to 2.15 | 0.137 |

| PDA all substances (PP) | 92.9 | 78.6 | 1.69 | 0.793 to 3.59 | 0.174 |

| PDA substances alone | 89.3 | 96.4 | 1.29 | 0.768 to 2.17 | |

| PDA alcohol alone | 100 | 100 | 1.31 | 0.687 to 2.50 | |