Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 09/3001/09. The contractual start date was in March 2010. The final report began editorial review in January 2012 and was accepted for publication in January 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors:

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Crombie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Structure of the report

Introduction

This study assessed the feasibility of a randomised controlled trial to determine the impact of a novel intervention delivered by text message on drinking behaviour among disadvantaged young to middle-aged men. This was achieved by carrying out all of the stages of a pragmatic randomised controlled trial, with a particular focus on how well each stage was conducted. The aim of this close scrutiny was to identify whether or not a full trial would succeed and what improvements could be made to the conduct and likely effectiveness of the trial. The study was conducted in three phases.

Phase 1 comprised six focus groups to develop the recruitment strategy, to optimise the design of the text messages and images and to determine the most acceptable sequence for their delivery. Five focus groups were conducted with men and one focus group with women. The focus groups explored drinking behaviour and attitudes and beliefs about drinking, its benefits and harms. The findings from this phase were also used to help develop the intervention.

Phase 2 involved the planned recruitment of 60 participants who were randomised to receive either the alcohol intervention or general health promotion messages. This phase was conducted in a series of distinct steps. As the target group was disadvantaged young to middle-aged men, recruitment to the study was given careful attention. The intervention was a series of interactive text messages and images designed using messaging theory, social cognition models, motivational interviewing (MI) and systematic reviews of interventions to tackle alcohol problems. The intervention was delivered to mobile telephones using a programmed computer system. Participants were followed up for 3 months to assess retention, willingness to respond to text messages and to complete the final assessment of drinking behaviour. The aim of this assessment was to determine whether or not the outcomes could be readily measured on the participants. Although the feasibility study was not powered to detect changes in drinking behaviour, it could give an indication of whether or not the intervention might be effective in a full trial.

Phase 3 involved interviews with 20 participants to assess the acceptability of the intervention, the impact it had on their willingness to moderate their drinking and factors that might limit their ability to drink less. The aim was to assess the acceptability of all aspects of the study and to identify opportunities to improve the intervention.

The chapters of the report

This report is laid out as a series of 12 chapters which provide a forensic analysis of the design, conduct and outcome of the feasibility study. Chapter 2 begins with an outline of the research objectives of the feasibility study. Chapter 3 identifies the motivation for the study and then explores the main design challenges which needed to be addressed. This is followed by eight chapters which provide a description of the series of interlinked substudies which were conducted to meet the aims of the feasibility study. Each chapter is self-contained, comprising an introduction, methods and results sections, together with a discussion which summarises the main findings and assesses their significance in the light of previous research. This approach is appropriate because each substudy had a distinct purpose and a specific set of methods. Combining methods or discussion sections into single chapters would lose the close relationship between methods, results and discussion which is essential for a full forensic evaluation. The individual substudies are:

-

Chapter 4 , Understanding drinking motives and behaviours

-

Chapter 5 , Developing the text messages

-

Chapter 6 , Recruitment strategies

-

Chapter 7 , Randomisation and baseline characteristics

-

Chapter 8 , Retention strategy

-

Chapter 9 , Outcome assessment

-

Chapter 10 , Process evaluation

-

Chapter 11 , Post-trial assessment.

Chapter 12, Summary and conclusions, has three linked aims. It presents a concise synthesis of the main findings from the whole feasibility study, together with their implications for future research. It then assesses the extent to which the feasibility study met its aims. Finally, it makes recommendations for modifications to the protocol which will improve the conduct and outcome of the proposed full trial.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

Introduction

The overall objective of this feasibility study was to develop and test the feasibility of an intervention delivered by text messages to reduce the frequency of heavy drinking among young to middle-aged disadvantaged men. This involved conducting all the stages of a randomised controlled trial. The intervention has been developed from brief interventions that have been successful when delivered face to face, but is delivered by a series of text messages and images. This provides a method for reaching large numbers of people at low cost. If the development and feasibility testing are successful, the intervention will be tested in a full-scale randomised controlled trial in a further study for which new funding will be sought.

Research questions of the full-scale trial of the novel intervention

Prior to the feasibility study it was thought that the research questions for the full trial would focus on the effectiveness of the intervention, and on the behavioural antecedents of reduced heavy drinking. Specifically it would investigate whether or not a brief intervention delivered by mobile telephone could:

-

reduce the frequency of heavy drinking by disadvantaged men

-

increase awareness of the harms of excessive drinking

-

increase intentions to avoid becoming drunk

-

increase self-efficacy for refusing drinks.

These questions were to be reassessed in the light of the findings of this feasibility study.

Research questions of the feasibility study

The feasibility study was concerned with the practical issues of recruitment and intervention development and delivery. Successful completion of all these stages is a prerequisite for a full trial of a complex intervention to reduce the frequency of heavy drinking among young to middle-aged disadvantaged men. The specific questions were:

-

What are the best ways to recruit and retain disadvantaged men in a study aimed at reducing the frequency of heavy drinking?

-

What is the type of content and timing of the delivery of a series of text messages and images that is most likely to engage young to middle-aged men?

-

Is the intervention likely to be an acceptable way to influence the frequency of heavy drinking?

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for all aspects of the study was obtained from the East of Scotland Research Ethics Service (reference number 09/S1401/78).

User group representatives

Two men, one a reformed heavy drinker, the other a continuing heavy drinker, were recruited to the Research Group. They attended steering group meetings, where they shared their views on drinking cultures, and the attitudes, beliefs and experiences of drinkers. They were the first to raise two important issues: the prevalence of very heavy binge drinking and the fact that many drinkers in the target age range, 25–44 years, will have suffered, or know someone who has suffered, serious harm from alcohol. They also advised on the construction of the intervention text messages and stressed the importance of phrasing texts in appropriate language. This helped ensure that the interventions were acceptable and the outcomes were relevant and measurable.

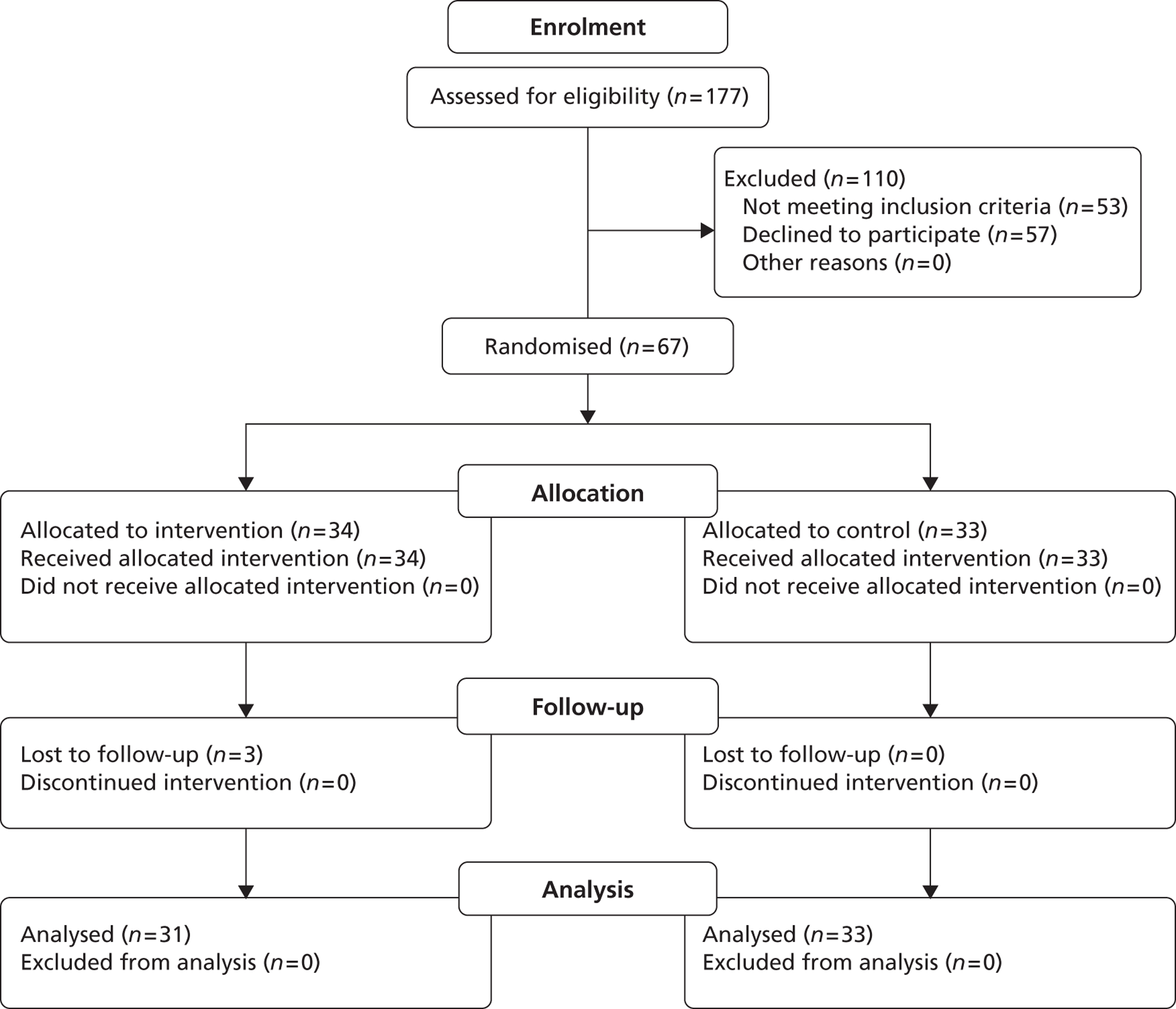

Protocol amendments

The intended sample size was exceeded (67 participants instead of 60). This occurred in recruitment of participants through primary care. Invitation letters were sent out in batches and all men who were eligible and willing to take part were included in the study. Recruitment from the final batches of letters led to more men being recruited than intended.

The intervention was modified in the light of findings from the focus groups. MI was added because it provided a convenient technique for presenting components of the intervention. The transtheoretical model (TTM) was added to the intervention design because it offered a logical framework for designing and sequencing of messages. This approach was appropriate because it was anticipated that most participants would be in the pre-contemplation stage.

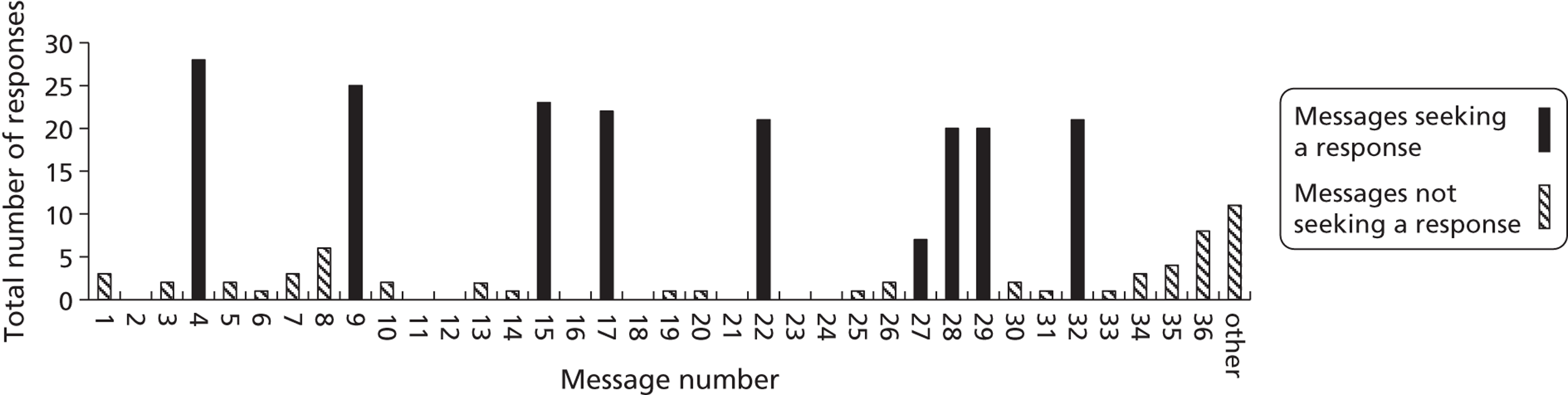

The number of text messages which was sent was increased from the proposed 28 to 36 for two reasons: (1) texts were inserted which asked participants to respond to specific questions that probed key components of the behaviour change strategy; and (2) some messages were sent in pairs, with the second one sent a few minutes after the first. These devices promoted increased thinking time, a technique used in MI.

The protocol proposed that a post-trial evaluation be conducted to identify ways to improve the study. This was expanded to include an extensive process evaluation of the fidelity of delivery of the intervention. It also assessed the extent of engagement of the study participants with the main behaviour change components of the intervention. The aim of these evaluations was to provide a series of detailed recommendations to improve the acceptability and impact of the intervention.

Chapter 3 Introduction

The morbidity and mortality caused by alcohol are a major public health challenge. The prevalence of alcohol misuse and its cost to society has risen substantially over the last 20 years. 1 It is currently estimated at more than £55B per year in England1 and more than £3.5B per year in Scotland. 2 These costs occur through lost productivity, increased health-care and other public sector costs, and through crime and social disruption. In 2009–10, there were over 1 million hospital admissions in England for alcohol-related conditions. 3 These figures included 177,400 admissions for mental and behavioural disorders and 43,100 for liver disease which were solely due to alcohol. A total of 6584 deaths were due to alcohol, of which two-thirds were due to liver disease. The cost of alcohol to the NHS in England is £2.7B (at 2006–7 prices). The major costs of alcohol to society come from social disruption, crime and costs to the economy. Alcohol was associated with more than 500,000 crimes in England in 2006–7. It was a contributory factor in up to 1 million assaults and 125,000 instances of domestic violence. 4 Some 17 million working days are lost each year because of drinking.

Alcohol-related harms are not evenly distributed in the population. People who are socially disadvantaged are at a substantially higher risk of developing alcohol-related diseases. 5,6 Tackling the culture of drinking among this group in order to prevent alcohol-related problems in later life is a priority for research. This introduction reviews the main issues to be addressed for the design and delivery of a brief alcohol intervention to disadvantaged young to middle-aged men.

Alcohol and brief interventions

Extensive evidence shows that brief interventions delivered in health-care settings are effective in reducing alcohol consumption. 7–10 These interventions were developed for middle-aged and older men attending health care. However, the group who binge drink most frequently are young to middle-aged disadvantaged men. 11 Existing brief intervention studies mainly recruit through health-care settings. However, men aged 25–44 years are seldom in contact with health services. They will therefore not be reached by current initiatives to tackle excessive drinking delivered through health-care settings, so alternative approaches are needed. Targeting this group would lead to reductions in heavy drinking before chronic health harms develop. It would also prevent the accidents, violence, social disruption and criminal activities associated with episodes of heavy drinking. This group may be receptive to brief interventions; one recent survey reported that among current drinkers, 32% of men aged 25–44 years felt the need to cut down on their drinking. 11 Thus, there is a need to develop brief interventions which are appropriate for disadvantaged young men.

Brief interventions are commonly based on models from social psychology, such as the theory of planned behaviour (TPB). 12 Many of the interventions use MI,13,14 a person-centred technique which encourages individuals to identify possible inconsistencies between what they do (get drunk) and what they want to achieve (socialise, find a partner). Recent reviews have identified theoretical constructs and specific behaviour change techniques which should form part of behaviour change interventions. 15,16

A further requirement for brief interventions is to reach large numbers of individuals. Traditional face-to-face interventions are limited in the numbers of individuals they can reach. 17 Over 8 million people in England have an alcohol misuse disorder. 18 In England, 26% of men aged 25–44 years exceed the recommended limit of 21 units per week. 3 In Scotland, over 30% of men aged 25–44 years binge drink each week. 11 Given the scale of current problems there is a pressing need for interventions which can be delivered to large numbers of individuals at low cost.

Intervention delivery by mobile telephone

The mobile telephone is an attractive method to deliver interventions to large numbers of people at very low cost. This approach is well suited to young to middle-aged men because their ownership of mobile telephones is high. Text messaging has been used to modify adverse health behaviours19,20 and to increase health-care uptake. 21,22 Recent systematic reviews suggest that brief interventions by mobile telephone are beneficial. 23,24 However, none of the primary studies to date has addressed alcohol and none were directed at disadvantaged men.

Delivering a brief intervention by mobile telephone text messages faces the challenge that the texts are limited to 160 characters (including spaces and punctuation). The challenge for this study was to incorporate the components of behaviour change theory and specific behaviour change techniques in a series of text messages which would be effective with disadvantaged men. Unfortunately, little can be learned from previous text message intervention studies as few of them have been based explicitly on theories of behaviour change. 16

Behaviour change interventions and disadvantaged people

Two recent extensive reviews provide a consistent and deeply worrying assessment of the current situation on social disadvantage. 25,26 Health behaviour varies substantially by socioeconomic status, with disadvantaged individuals being more likely to have adverse health behaviours and to suffer poorer health outcomes. 25 There is a marked social class variation in the uptake of preventive services, with the most disadvantaged being the least likely to take them up. Few intervention studies have addressed the impact of interventions on socially disadvantaged groups. There is some evidence that disadvantaged individuals are harder to recruit and retain in research studies. Available studies on behaviour change are often of poor methodological quality. Most evidence is available from studies of smoking cessation, which show that success rates are lower in individuals from disadvantaged areas. Nonetheless, there is evidence that interventions can be effective in disadvantaged individuals. The recent reviews concluded that there is an urgent need for high-quality studies of interventions targeted at groups of low socioeconomic status.

Recruitment

Participation rates in research studies have been falling over the last 30 years. 27,28 Several studies have found that many trials struggle to recruit their intended sample sizes. 29,30 There is now considerable interest in strategies to increase recruitment rates. 31,32 As people from deprived areas are more difficult to recruit to research studies,33–35 the recruitment strategy for trials targeting this group needs to be designed with particular care. Relying solely on recruitment through health care, the traditional method for trials of brief interventions,8,9,36 may not succeed as the target group is healthy and seldom in contact with health services. Thus, alternative recruitment strategies may be needed.

Respondent-driven sampling (RDS) was developed to survey hard-to-reach groups, particularly those who engage in stigmatised or illegal behaviours. 37,38 RDS was designed to overcome the limitations of other techniques such as snowball sampling and key informant sampling. The technique assumes that the target population is distributed through a number of socially networked groups, making it suitable for a group behaviour such as drinking. It has been extensively and successfully used with injecting drug users and groups at high risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection. 39

The need for the feasibility study

The intervention used in this project has multiple components and thus is a complex intervention. The Medical Research Council framework for complex interventions recommends that the feasibility of all aspects of the trial be piloted and that the causal mechanism by which the intervention will work be tested in advance of a formal trial. 40 The methods of recruitment to the trial and the retention of participants should also be piloted. This feasibility study was designed to test all components of a full trial from recruitment to outcome measurement. Finally, the potential effectiveness of the intervention would be assessed through an extensive process evaluation.

Chapter 4 Understanding drinking motives and behaviours

Introduction

There is a pressing need for an intervention to tackle harmful drinking in disadvantaged young to middle-aged men which can be rolled out nationally. Although it might be possible to translate existing brief interventions9 for delivery by text message, this would be problematic for two important reasons. The drinking motives, attitudes and beliefs of disadvantaged young to middle-aged men have not been well studied, and may differ from those of men in general. The proposed delivery medium, mobile telephone text message, is markedly different from face-to-face interventions and may not lend itself to the same intervention techniques.

The aim of this phase of the study was to explore these issues to ensure the optimal content for a brief intervention which would exact the greatest behavioural change. Several questions were investigated. To what extent are drinking motives in young to middle-aged disadvantaged men similar to those presumed in brief interventions? Specifically, is drinking influenced by positive alcohol expectancies, social norms and refusal self-efficacy? How are the harms of alcohol perceived and how might these best be used to motivate behaviour change? Could drinking be influenced by other, as yet unknown, factors? How could appropriate interventions be tailored to be delivered by mobile telephone to this target group? What style and content of text message might be effective in reducing the frequency of binge drinking?

Methods

The exploratory nature of the research questions, coupled with a need to identify the breadth of views and experience rather than their frequency, suggested that a qualitative method was most appropriate. 41,42 This phase of the study comprised five focus groups with disadvantaged men and one with female partners of heavy-drinking disadvantaged men. This chapter presents only the findings relevant to the drinking motives, attitudes and beliefs of disadvantaged young to middle-aged men. Two further sets of findings from this phase are presented separately in Chapter 5. These are the results from the women's focus group and the men's views on a draft set of text messages.

Sampling

In accordance with best practice for qualitative research we sought to implement a maximum variation sampling strategy which would achieve diversity in key variables for which views and experience around alcohol would likely differ. 43 Research elsewhere has suggested that the profile of drinking behaviours varies by age; consequently, within our age group (25–44 years) we sought to ensure individuals were represented in both the 25–35 years and 36–44 years age bands. In addition, we sought to include a number of individuals who may be aged between 44 and 60 years in order to obtain their views on past behaviour (with the experience of hindsight).

Recruitment

We purposively sampled from a variety of social venues likely to represent the target group of interest to the study. Venues included Saturday amateur football league clubs, public houses, an employment training centre and a further education college (Table 1). Systematic reviews have shown that the provision of monetary incentives can significantly increase recruitment to research studies. 44,45 Consequently, men agreeing to take part were given a £10 gift voucher and travel expenses. They found the experience rewarding because a prestigious organisation (the university) was interested in their lives and believed what they had to say was valuable. Many said it was therefore something they could share with pride in their social network.

| FG | Social network | Venue of FG | No. and age range of participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| FG 1 | Saturday amateur football league clubs | Pub | Five participants aged 27–33 years |

| FG 2 | Unemployed training centre | Training centre | Five participants aged 38–57 years |

| FG 3 | Unemployed training centre | Training centre | Seven participants aged 28–43 years |

| FG 4 | ‘Back to work’ training group | Further education college | Six participants aged 21–55 years |

| FG 5 | Criminal Justice Services | Criminal Justice Office | Five participants aged 37–52 years |

Thus, 28 men aged 21–57 years living in areas of high deprivation were recruited to the study. Deprivation was measured using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD),46 which is similar to the English Index of Multiple Deprivation. Individual-level socioeconomic position was also assessed from brief questionnaires on current socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. Summary characteristics of participants are shown in Table 2.

| Variable | Participants (N = 28) |

|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 37.5 |

| Sex | Male, n = 28 |

| Marital status | Married/living with partner, n = 9 |

| Single, n = 19 | |

| Education (highest level) | Secondary education, n = 19 |

| Diploma (vocational qualification), n = 7 | |

| University degree, n = 2 | |

| Employment status | Employed, n = 4 |

| Unemployed, n = 24 | |

| House type | Owned, n = 3 |

| Rented, n = 25 |

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected using a focus group approach. It was clear that much drinking reflected a social practice influenced in part through group norms and sets of social expectancies. Consequently, enabling men to talk as a group would enable identification of these expectancies, attitudes and values. 47 A topic guide was constructed based on a background search of relevant literature in the area. However, conversations were not limited to these areas. All participants were informed of the confidential nature of the research. All groups were audio-recorded and transcribed. Analysis was conducted by three members of the research team (JC, DWF and BW) using the framework approach. 48 Pseudonyms have been used in direct quotations to protect participant identity.

Results

The majority of the older men in the study believed that their drinking behaviours, motives and desire to change were significantly different from when they were younger. Explanations for current drinking patterns, and the way these change over time, appear rooted in shifts in three interacting conceptual areas: private purpose, social roles and concrete experience. At the heart of this shift is what might be termed the ‘mature drinker’ role. This consists of a set of social expectations stemming from recognition of the person's wider social roles and responsibilities (employee, husband/partner, parent), abilities (self-discipline/control, ability to tolerate alcohol, judge limits and resist social pressure) and life experiences to date.

Private purpose and social roles

Our findings suggest that alcohol consumption behaviours vary in accordance with two parallel drivers: private purpose and public role. Private purpose refers to an individual's personal reasons for and against particular forms of alcohol consumption. While these purposes may sometimes be made public, they are generally tacit. Public role highlights the social role of alcohol in many individuals' lives. As with any role it brings a set of social expectations and duties which must be followed if sanctions are to be avoided. Private purpose may be seen to be a driver of private drinking, while social drinking may be influenced by both private purpose and social role.

Private purpose

All participants clearly identified a range of benefits from alcohol consumption. Predominant among these were reward, relaxation and release. Most men regarded alcohol as having a range of sensory benefits leading to an inherent enjoyment of the experience.

I think just enjoying it. I think as I've got older I just go out to actually have a pint. . . it's actually enjoying it, enjoying a pint of [name of Irish stout], enjoying the ale. You know going into the supermarket and buying the two bottles and thinking right, I might have one of those this week. . . Just enjoying the actual drink for the taste of it and yeah.

Jim, aged 31 years

The positive experiential nature of alcohol meant that it was frequently used as a personal reward. There was a sense that they had earned and therefore deserved the experience. However, although this would suggest that there may be social rules indicating when alcohol was legitimate, i.e. deserved (and thus conversely when it was not), we could not find instances in the data when alcohol was not consumed because it was seen as not deserved. This suggests that drinking as a reward may not so much determine whether or not drinking takes place but rather how one feels about it; the ‘well-deserved drink’ may convey greater satisfaction and pleasure simply because it feels deserved and symbolises an individual's achievements.

Social, but also for me at home it's sometimes a reward. Like if you've had a shit day or you've been working non-stop, it's sometimes good to like have a drink at the end of the night and it's not because you even want one it's because you feel like you deserve something.

Eddie, aged 33 years

A related but slightly different motive for alcohol consumption among this age group was relaxation.

Normally when I drink it's because I feel good about myself. And that way, I could relax at the end of the week, have a drink, knowing that the family is all as it should be. I'd have a drink, not to celebrate, but to relax.

Harry, aged 50 years

However, alcohol-related relaxation was rarely, if ever, associated with alcohol alone; instead, relaxation related to a number of what might be termed ‘alcohol plus’ scripts (i.e. groups of associated behaviours that combine to provide relaxation). Key ingredients in these scripts included alcohol itself, a core activity (watching television, playing pool, darts) and company (existing friends or meeting new people). Location was frequently cited but on closer examination this appeared to be predominantly as a means to access and facilitate these ingredients.

The concept of relaxation suggested a motive that could be engaged in by almost anyone; it represented the pursuit of something positive as much as the removal of anything negative. However, for some men alcohol consumption was sometimes motivated by the latter rather than the former. In these cases alcohol served for some as an emotional release, which would distract or take the edge off perceived problems. It therefore came to be seen by men as an established coping device for stressful times, a means of achieving ‘freedom from’, even if it did not permanently solve, the problem.

You're not worried about money at the end of the night. You're just worried about getting legless and just forgetting about all your problems.

Brian, aged 31 years

I find it a good release. . . I'll just go out and have a laugh and maybe take my head away from things that are going on at the time.

Simon, aged 27 years

Social roles

While some older men used alcohol as a form of release and thus a way of achieving ‘freedom from’ (the stresses and problems of everyday life), for many more it was seen also as a means of achieving ‘freedom to’ – it facilitated the achievement of personal attributes and fulfilling public social roles that they otherwise would not have had the self-confidence to attempt: ‘it can help people, shy people actually come out of their shell, ken.’

However, all quotes relating to this were notable in that they referred to their view of other people's reliance on alcohol to achieve this, or to their own but in earlier years. Using alcohol to improve social confidence and fulfil other social roles and identities was therefore either less important for older men, or was something they were reluctant to admit to personally.

In addition to enhancing one's ability to achieve a valued social identify and fulfil a public role, it became apparent that the social nature of drinking in the pub environment was in fact a social role characterised by a set of expectations, duties and potential sanctions (Box 1). These included expectations to drink alcohol (rather than soft drinks) and to pay one's fair share of rounds. There was evidence of significant disapproval of individuals not conforming, giving rise to a felt pressure to conform and drink.

I know a lot of people that go out, just to have a drink, to look for women, ken what I mean. A lot of the guys that are sober couldn’t chat a woman up unless they’ve had something inside them

Martyn, aged 38 years

I’d say I would probably drink more while I was in the pub, but I probably drink more often at home . . . Whereas when you’re at home, you’re kind of, you’re not as going hell for leather because you’re sitting having a quiet drink rather than having a social piss-up so to speak

Simon, aged 27 years

The drinking role

Expectation to drink alcohol

I’ve been in a pub for a glass of orange. I couldn’t sit all day and do that

Martyn, aged 38 years

Well I’m going to have to say never on that one. That’s how it was. Never. If you go out, pub’s there, that’s it. You have a pint. There’s no way I could ever have walked into a pub and just ordered a coke

Arran, focus group 2

Duty to pay your share of rounds

If we’re in the pub we’re on the rounds, so everybody has pretty much the same amount to drink

Bob, aged 31 years

And if you’re the fastest drinker, you’re buying rounds and you don’t want to see anybody with an empty glass so as soon as someone finishes, the person goes ‘it’s your round’

Simon, aged 27 years

I find that every time I go in the pub it’ll be like ‘what you having mate’ and then that’s me in that round

Simon, aged 27 years

Sanctions and disapproval for transgression

You get the odd people maybe say ‘oh, you lightweight’ or stuff like that

John, aged 27 years

Certain people go out and spend their money and then have to end up borrowing off their pals so they can keep going, you know what I mean. They do it all the time. I get it all the time. ‘You’ve got money with you ‘cos I’ve spent mine.’ It’s always the same people

Fred, aged 34 years

Shifting purpose and role – the importance of age

Participants frequently generated a narrative looking back to earlier times in their lives; in addition, they sometimes compared their own motives, experiences and behaviours to other contemporary younger drinkers. Through these comparisons it became clear that they perceived a very significant shift in both the social role expectations and duties, and the private purpose motives for drinking. Consequently, there was a move towards what might be termed the ‘mature drinker’. Indeed, these were sufficiently consistent as to suggest that there may broader agreement on the existence of younger and mature drinker roles. This shift is shown in Table 3.

| Drinking motive | Age → | |

|---|---|---|

| The young drinker | The ‘mature’ drinker | |

| Private purpose | Freedom to:

|

Freedom from:

|

| Social role | Expectation:

|

Similar expectation:

|

Increased expectation regarding:

|

||

There was a general view that older drinkers were less likely to be drinking in order to get drunk and more likely to drink for general relaxation, social company, reward and as a means of escaping from daily pressures. In addition, older drinkers saw themselves as more able to know their limits and more likely to be able to ‘hold’ their drink. Some felt that they had more money to drink now that they were older while others found that finance was a major obstacle. Consequently, these drivers meant that more mature drinkers might well consume greater volumes of alcohol but be drunk less frequently.

Although these issues suggested that greater quantities of alcohol might frequently be consumed, there were multiple examples of explanations of changes in drinking behaviour rooted in the adoption of multiple new social roles which competed and were sometimes incompatible with their past drinking behaviours. These provided a new and perhaps wider ‘perspective’ on the role and impact of alcohol in their lives:

Yeah because maybe if you're seeing a lassie, you’ll maybe get a bottle of wine and a DVD or have a glass of wine with my tea most nights or a couple of beers maybe watching the Champions League. You've got a different perspective on drink because you’re older.

Simon, aged 27 years

A commonly reported shift was with regard to their obligations within family roles and relationships. This included both partners and children:

But you do, even like when kids come on the scene, if you’ve got your partner, you split up, you get your bairn one week, you get the bairn weekends. That changes yourself as well. That’s like me, I get [inaudible] every weekend, so I don’t go out. I go out every Wednesday, that’s when I got out.

Fred, aged 34 years

More frequently expressed were their current identities and obligations as employees. When they were younger such responsibilities were not of concern, but now they constrained what the men could do:

With my job and responsibilities, I can’t just go out, I’m not working in a warehouse like I was when I was 18 where you can just do what you want the next day, it doesn’t matter. But now, during the week, it just can’t happen, with my job the next day, I just couldn’t function properly.

Jim, aged 31 years

There was recognition that the adoption of these wider life roles and responsibilities were appropriate and to be expected as part of the process of becoming more mature. They were not expressed in pejorative forms and there was little sense of nostalgia about what they were losing in terms of past drinking behaviour. Consequently, even among those older men who were still drinking significantly there was a willingness to publicly express their intention to change as these new roles emerged for them:

Well I don’t want to be, my ideal at some point would be to settle down and have some sort of family unit that my focus was on them, and go for the occasional night out with the boys and the odd couple of pints. But certainly not drink socially the way we drink now and I wouldn’t want to be drinking to that extent when I get older. I’m not saying I might, what I want and what will happen might be two different things but certainly, for the picture of where I want my life to go I don’t want to be still having the nights out the way I have them just now in say 5–10 years’ time. I would rather want my focus to be somewhere more important.

Simon, aged 27 years

Awareness of consequences and the importance of concrete personal experience over abstract risk

High levels of alcohol consumption among the older men do not appear to be rooted in a lack of awareness of the consequences of drink. There was ample evidence, and graphic examples, of the consequences including hangovers, significant financial cost, changed character, poor health and violence with its associated implications.

Underpinning many of the consequences was recognition that during the drinking process their usual selves, with their typical motives, intentions, values and self-discipline diminish, culminating with a complete disappearance and a lack of awareness or memory of anything that occurred:

Your judgement could be all wrong.

Martyn, aged 38 years

You forget a lot, you don’t ken what you’ve done. You lose your identity as well because you don’t know what you’ve done.

Derek, aged 28 years

Yeah me, I have. Quite a few years ago. I was out with a mate, a friend of mine and ended up having quite a few drinks and the next thing I knew I woke up in hospital.

Jeff, aged 40 years

I woke up in Orkney Street in Govan and I thought ‘How did I get here?’

Brian, aged 31 years

Consequently, while alcohol had been described as facilitating the achievement of social roles and valued personal identity in their earlier years through improved social confidence (‘freedom to’), alcohol now frequently proved to be an obstacle to achieving such an identity (partly because that valued identity had changed as new domestic, work and even the mature drinker role had been adopted). Ultimately, it was seen to change one's character and desired behaviours:

I think it hampers your personality on all points, and that’s not always a good thing. I mean, you can say things you regret or those feelings that have been sitting on your mind or your boss, maybe you shouldn’t say something if you’re at a work night out, or a girl, that you’d maybe regret the next day, when you've left a text or a comment on a social network site or anything. And you’re like, this seemed like a good idea at the time. . . [laughter]

Tony, aged 28 years

My dad said to me at one point, he says, I always know when you’re back on the drink or drugs, you’re an obnoxious little shit.

Ross, aged 37 years

. . . she just says ‘I don’t like you when you drink, I don’t like your attitude and the way you are.’ She says I get quite aggressive.

Jim, aged 31 years

The most common seemingly powerful consequences of alcohol consumption for participants were in relation to aggression and physical violence. Many participants knew of others who had been in trouble with the police (including assault and murder), while others had personal experience:

Yeah. I’ve been arrested and put in the cells overnight and stuff like that. I’ve been in quite a few fights because of it, so.

Ben, aged 38 years

When I used to drink, if I drank whisky, it just made me drowsy. I’d get a heavy hangover and I’d probably start fighting with somebody.

Graeme, aged 43 years

Although there was widespread awareness of a range of negative consequences from alcohol consumption, it was interesting to note that explanations for changes in participants' drinking were rooted in past personal experience of these issues rather than knowledge of their more abstract existence and risk. The most important of these appeared to be the impact on the person's children, although multiple causes were often seen to combine.

The main reason for me is one, no more criminal record. Two, I’ve got two children that I haven’t seen for two years now. And obviously the money as well. And health. My brother’s only 40 and he drinks and he had a stroke last year, so that’s a bit worrying when you’ve got heart problems in the family as well, so I thought, I’ll stop as well, so.

Ben, aged 38 years

Other reported triggers to changing included the financial impact, e.g. falling behind in paying bills, and personal health events. Although most examples related to the individual's own personal experience of a substantive problem, a few individuals did indicate that it was the observed experience of a close friend or relative which had prompted their change in drinking. In earlier discussions regarding consequences of excessive drinking, participants frequently reported the consequences that they had observed in other people; however, observations only appeared to motivate actual reported change in the participant when it was someone close to them. This suggested that in some instances vicarious experience may prompt change, or at least intentions to change consumption patterns.

Discussion

Men reported a significant change in their drinking motives from when they were younger. This stemmed from a shift in the private purpose and social roles facilitated by alcohol use. Alcohol was now predominantly used as a form of reward, relaxation and release from life pressures. Patterns of consumption were also influenced by obligations to a range of competing social roles including parent, partner and employee that had not been extant when younger. Knowledge of the negative experiences of alcohol was detailed and widespread. However, reported changes in behaviour appeared rooted in concrete personal or vicarious experience of these issues rather than more abstract risk.

The importance of the ‘mature drinker’ role

Our data suggest that contemporary society may have a particular set of expectations and beliefs about the more ‘mature drinker’: someone who can tolerate greater amounts of alcohol without becoming drunk, has greater self-discipline, is more likely to be able to resist social pressures to drink, and drinks as a means of reward, relaxation and release. The existence of such a set of social expectancies is perhaps evident in the way society may interpret public drunkenness by a teenager or person in their early 20s differently compared with a man in his 40s. The existence of the ‘mature drinker’ role and the individual's desire to conform/live up to the identity it affords may prove useful in both behavioural interventions and those employing more social marketing approaches. 49,50

The development of competing social roles and identities as an explanation for changes in drinking behaviour with age

Our findings also show that reasons for alcohol consumption among older disadvantaged men differ from their younger counterparts. Therefore, brief interventions to tackle the problem must incorporate different approaches. The literature suggests the perceived benefits of alcohol (alcohol expectancies) for young people include mood enhancement and enjoyment, stress relief and escapism, easier socialising and social success, and conformity with peers. 51,52 Thus, three different types of drinkers have been identified: enhancement drinkers, social drinkers and coping drinkers. 53 Although similar benefits were stressed by the older men in this study, there was a clear shift in emphasis away from the use of alcohol as a means of achieving valued social identities, social confidence and group membership (‘freedom to’), towards a greater value attached to the use of alcohol as reward, relaxation and release (‘freedom from’). Such changes were clearly rooted in changes in social identities and roles acquired as men grew older. They became employees, partners and fathers – roles and responsibilities which had the potential to constrain alcohol consumption, or at least excessive drinking. The existence of these competing roles as a constraint may provide a means through which potential behavioural interventions may operate. The power of social roles to influence behaviour comes from the potential social sanctions applied when expectations and duties associated with those roles are not fulfilled (e.g. failing to be a good employee, partner or parent). 54 Consequently, the psychological concept of ‘subjective norm’ (an individual's perception of social normative pressures, or relevant others' beliefs that he or she should or should not perform such behaviour55) may be helpful in future behavioural interventions for this population.

Studies have shown that peer pressure is a significant factor in the level of alcohol consumption among young people. 56 Low levels of drinking refusal self-efficacy have been found to increase the acquisition and maintenance of binge drinking. 57 However, the adult version of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ) has no scale to measure peer (conformity) motives, because it assumes the influence of peer pressure declines with age. 53 Although this, to a large extent, is true, our findings suggest the influence of peers and social networks on the older cohort may be more complex and subtle than first assumed. Although some men felt that their friends were more accepting of their decisions to slow their drinking down, other men still felt pressure from their peers to consume large amounts of alcohol. In the second context it was the behaviour – the consumption of alcohol – that signified membership of the group and gave the men a sense of belonging. The men's refusal self-efficacy therefore largely depended on whether the group was predominantly defined by its drinking behaviour or another organising factor. A brief intervention might therefore highlight that the men have a choice about the different social networks they are accessing, and that this choice will affect the amount of alcohol they consume and ultimately their health and well-being.

Alcohol and role incompatibilities: the potential of ‘developing discrepancy’

Drinking was a component of many rituals that were deeply satisfying to the older men in the study, and which reinforced the pleasure because of this association. Yet many of the benefits the men identified were not compatible with being very drunk. This presents an opportunity to highlight the inconsistency between an individual's drinking habits and the intended aims of drinking. Thus, brief interventions could highlight the mismatch between being drunk, and success in socialising, working, ‘doing good turns’ and feeling good about oneself. The utilisation of such discrepancies is at the centre of MI, suggesting that this approach may be effective, or at least a contributory approach, to behavioural strategies in this area. Indeed, the efficacy of MI in addressing drinking behaviours has demonstrated success in meta-analyses,58 and the feasibility of implementing it through brief intervention formats has been shown. 59

Concrete personal or vicarious experience as a trigger for behaviour change

Young people tend to believe that they will not come to harm, and that drinking will have few negative consequences. 51 Thus, they are unlikely to modify dangerous drinking habits because they do not perceive themselves as being susceptible to harm. On the contrary, such beliefs are associated with increased levels of consumption. 60 However, in marked contrast, the older men in our study believed they were susceptible to (or had actually experienced) the health and social consequences of excessive alcohol consumption. The most frequently cited negative consequences were the risk of injury or criminal record (through aggression and violence); serious illness (such as liver disease or stroke); family disruption and separation; and financial drain. Critically, a minority believed that any health damage was irreversible and therefore saw little point in reducing alcohol consumption.

However, although acknowledgement of the existence of these dangers was widespread, it appeared only to be those who had experienced them personally (or vicariously through a very close family member or friend) who reported them as a driver to behaviour change. This finding is unsurprising given both behavioural theory and empirical research elsewhere that suggests that beliefs that are less abstract and experientially more concrete are more likely to result in behaviour change. 61,62 Consequently, any intervention needs not only to present the true risks of alcohol, but wherever possible to ensure that this is expressed in non-abstract and more direct or even concrete/experiential terms. This may include anything from the use of graphics over abstract text, through to reminding people of key past negative personal experiences of alcohol and its impact on others. Although some participants were sceptical regarding the use of images in interventions, this centred primarily on the potential ambiguity of meanings within images compared with clear text. This is clearly important. Indeed, issues of what is now termed ‘visual literacy’ are well acknowledged and must be taken into consideration when designing any images. 63 Where such personal experiences do not exist then utilising those of close family, friends or even well-known and liked public figures may prompt similar results through vicarious experience. The potential of vicarious experience has been little studied but empirical evidence in other behavioural contexts suggests there may be potential for its use. 64 The potential of concrete personal experience as a motivator also raises questions regarding whether or not coinciding the timing of the delivery of the intervention to a point soon after any such experience may significantly improve its effectiveness. Certainly, concepts such as ‘triggers to action’65 and, more recently, the idea of the ‘teachable moment’66,67 would support this.

Conclusion

Interventions to reduce alcohol consumption among young to middle-aged men from disadvantaged backgrounds should acknowledge different motives for drinking and reducing consumption. The onset of wider competing social roles and reminding individuals of concrete personal negative experiences may be productive. Brief interventions need to reduce the frequency of heavy drinking among young to middle-aged disadvantaged men and increase their intentions to avoid becoming drunk. Our study suggests that this may be achieved through interventions which:

-

(a) highlight the discrepancy between being drunk and desired success in socialising; family, work and community relationships and roles; and feeling good about oneself

-

(b) show how behavioural change can heal the body, family and social relationships, and conserve (and enhance) financial resources

-

(c) are expressed through concrete experiential form, act as reminders of past personal negative experience of alcohol, or are timed to be delivered soon after such an experience

-

(d) promote success in achieving aspects of the ‘mature drinker’ role

-

(e) suggest men have a choice about the different social networks they can access, and that this choice will affect the amount of alcohol they consume.

Chapter 5 Developing the text messages

Introduction

The challenge in this study was to develop a brief intervention which could be delivered by text messages and images to a mobile telephone. A limitation of previous studies on text messages is the lack of a theoretical basis for the interventions. 23 This study adopted a systematic, transparent approach to message development. This began with reviews of the literature on empirical studies of brief alcohol interventions, text message interventions and behaviour change theories. The brief alcohol interventions identified the main design features required and identified some of the main design challenges to be solved. The text message studies identified many techniques for message design. A review of the literature on psychological models of behaviour change identified constructs which could form components of text messages for the intervention. A review of communication theory identified the best ways to render these components into text messages. A preliminary set of messages was prepared and tested in focus groups. The revised set of messages was then systematically checked against reviews of successful behaviour change techniques. This chapter describes these processes and the resulting set of theory-based text messages used in the intervention. The chapter also describes the design decisions for the control messages and the set of messages that were prepared.

Design features of published alcohol brief interventions

Brief interventions based on psychological theories have been developed to tackle alcohol-related problems. There is extensive evidence that brief interventions are effective. 7–10 Brief interventions are conventionally delivered face to face by a health-care professional such as a general practitioner (GP), nurse, psychiatrist, psychologist, alcohol worker or trained counsellor. The consultation can vary in length from 1 to 50 minutes, with patients receiving from one to seven sessions. Total duration of intervention may range from 10 to 175 minutes. The control groups generally receive much less contact, up to a maximum of 10 minutes.

The content of the intervention varies substantially across studies. 9 Early studies usually employed at least two techniques (raising awareness of the problem and giving advice about change) with the aim of increasing motivation to change. Other techniques, including emphasis on personal responsibility, provision of a menu of change options and enhancement of self-efficacy, were quickly added. 68 In addition, the intervention can be supported by an information leaflet, a self-help manual, a diary to record alcohol consumption, drinking goals and suggestions for alternatives to alcohol. A recent systematic review9 concluded that such interventions are derived from social cognition theories and can include the following elements: feedback on alcohol use, clarification of low-risk drinking, benefits of reducing consumption, harms of excessive consumption, motivational enhancement, coping strategies and a plan for reduced consumption. The systematic review confirms the finding from previous reviews that these interventions are effective, reducing total consumption by an average of 38 g of alcohol per week, 12.4% of baseline consumption.

Design features of published text message studies

Text messaging has been used to modify adverse health behaviours19,20 and to increase health-care uptake. 21,22 Delivering interventions through text messages to young to middle-aged men is attractive because ownership of mobile telephones is high in this group. Recent systematic reviews have shown that text messages can successfully change behaviour. 23,24,69 However, few of the primary papers described the behaviour change theories on which the intervention was based, although some studies mentioned the use of motivational messages. 23,24,69 Interactivity was an important feature of most interventions, commonly achieved by using text messages which requested responses.

Most of the primary text message studies which focused on improving the clinical care of patients provided feedback of test results, tailored advice, goal-specific prompts and direct contact with health-care professionals. 23,24,69 Studies trying to promote healthy behaviours provided advice, support and solutions for potential barriers to behaviour change. Many studies used supplementary material such as e-mails, websites, booklets and diaries. Interventions designed to change health behaviour relied mainly on the text messages, although a few provided access to other sources of support.

The number of texts and the frequency at which they were sent varied substantially between studies. One review paper23 commented that the frequency of sending texts depended on the target behaviour. Most studies had a predefined programme for message sending, although a few allowed participants to set their own frequency. The control groups generally received little attention with few, if any, text messages being sent.

Almost all studies tailored messages to the target individuals. Two studies which did not tailor messages experienced high attrition rates. 23 Tailoring could involve the use of first name or nickname, age-, gender- and culture-specific messages, current health status or behavioural preferences. A potential weakness of current studies is that most repeat some of the messages during the course of intervention delivery. Reinforcing the content of a message could be beneficial, but using the same words to do so could decrease the impact of the text. Furthermore, few studies use informal language. This is in marked contrast to the conventional texts which frequently dispense with the niceties of grammar and make regular use of abbreviations. 70 A formal style could result in less attention being paid to the messages.

Behaviour change theories

The theory of planned behaviour

The TPB has been widely used to predict intentions and behaviour. 12,71 It states that intention is the proximal determinant of behaviour and that the three main influencers of intention are attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control. 72 Attitudes are determined by beliefs about the desirable and undesired consequences of a behaviour, which lead to an overall evaluation of the behaviour. Subjective norms are the beliefs about the views of significant others (approval or disapproval). Perceived behaviour control was initially regarded as the extent to which internal factors, such as skills, and external factors influenced the individual's perceived control over the behaviour. More recently, perceived behavioural control has been subdivided into two factors:73 self-efficacy, that is, confidence in one's ability to perform the behaviour and the extent to which carrying out the behaviour is easy or difficult; and perceived control, perceptions of control over the behaviour and the extent to which the performance of the behaviour is within the individual's control. 74

Binge drinking has been extensively studied using the TPB,72,73,75 with implications for interventions to change behaviour. As attitude is a strong predictor of intention, focusing on the negative consequences of binge drinking has great promise. 75 Negative consequences are often described as negative alcohol expectancies and include hangover, vomiting, aggression and accidents. 76 These negative expectancies could be portrayed in text messages, encouraging participants towards preventive strategies. Subjective norms are another target to facilitate behaviour change. Although difficult to change at a population level, it would be possible to increase the salience of the views of significant others (parents, partners, close family) to encourage more moderate drinking. To ensure the significant other holds a more moderate view of drinking, the text message would need to direct the participant to those who would be pleased with a reduced consumption. Increasing drinking refusal self-efficacy is another promising approach. 77 Finally, the intervention could try to reinforce both self-efficacy and perceived behavioural control. Self-efficacy could be bolstered by acknowledging that change is difficult, while supporting continued effort for even modest improvements.

Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing was developed from clinical experience in the treatment of problem drinkers. 13 Recent meta-analyses have shown that it is an effective technique for treating problem behaviours. 36,58 It is a style of counselling that promotes behaviour change by helping individuals to decide for themselves that they wish to change. 13 Although it is directional, in that it seeks a specific behaviour change, MI avoids confrontation, or coercive approaches to behaviour change. 14 These are thought to make individuals defensive, increasing resistance to change. Instead MI empathises with individuals, recognising the legitimacy of their viewpoint while encouraging them to identify personal advantages of changing behaviour. Two further techniques are crucial to this approach. The first is to identify discrepancy between what the individual wants from a behaviour and the adverse outcomes which sometimes occur. For example, when drinking most people want to have fun and socialise, whereas if they become very drunk, arguments, violence or even physical collapse can prevent achieving the desired goals. MI encourages the individual to identify and describe this discrepancy for themselves, leading to a personal choice to change. That the individual, rather than the counsellor, identifies the need for change is seen as crucial to MI. 58

A second technique is to promote self-efficacy, an individual's belief in his or her ability to change behaviour. This can be done by encouraging individuals to make positive statements to reframe thinking about a behaviour. 78 Statements from the counsellor which affirm that behaviour change is difficult and that the individual should persevere under difficult circumstances can also promote self-efficacy. Another approach is to ask what would be the best outcome if behaviour were to change.

Motivational interviewing is traditionally delivered face to face,36 but it provides an attractive style for the design of the text messages. It suggests that approaches that emphasise autonomy, empathy and self-efficacy and avoid authority and adversarial content might be more effective and more acceptable. The emphasis on empathy would minimise any perception of the intrusiveness of the messages. This could occur with messages which were unsolicited and from an unknown source. The techniques of encouraging individuals to pursue discrepancies in their drinking behaviour, combined with improving self-efficacy also identify important content for the messages. Two other techniques of MI, avoid argument and roll with resistance, were deemed inappropriate for a text message intervention.

The approach of MI emphasises that advice giving should be avoided. This conflicts with the design of many brief interventions, particularly when delivered by health professionals, in which advice giving and an implicit appeal to professional authority are key ingredients of the behaviour change strategy. 9,68,79 Given the nature of the target group, healthy disadvantaged young men with few concerns about their drinking, avoidance of advice giving seemed the better choice. This view was supported by the focus group study, which showed the text messages offering tips to reduce drinking were unpopular.

The transtheoretical model

The TTM was developed in the 1970s as a synthesis of therapeutic approaches to behaviour change into a comprehensive model of change. 80 It has been used to explore change in drinking behaviour among individuals with alcohol problems. 81,82 It identifies a series of stages of readiness to change: from pre-contemplation (not thinking about cutting down), to contemplation, to preparation to change, to active behaviour change. 83 Motivation is seen as central to behaviour change84 at all stages of change. The model is driven by processes specific to each particular stage. These include: validating lack of readiness to change, encouraging re-evaluation of current behaviour, encouraging self-exploration not action, explaining and personalising risks, evaluating pros and cons of change, promoting new positive outcome expectations, helping identify and remove obstacles, helping patients identify social support and bolstering self-efficacy. 85

Reviews of behaviour change theories

Some recent reviews of theories of behaviour change have been concerned with giving guidance for the construction of interventions to change behaviour. One study identified, from a range of theories, a set of 12 theoretical constructs which explained behaviour. 86 A further study linked theoretical constructs to specific behaviour change techniques. 16 Another approach was to review the techniques commonly used in behaviour change studies, identifying those with theoretical support. 15 This led to a set of 26 defined techniques linked to specific theories. Finally, an evaluation of alcohol education leaflets identified 48 categories of message. 87 This was reduced to a set of 29 categories of message which target cognitive antecedents of drinking. Together these studies provided explicit descriptions of theory-based behaviour change techniques. These helped inspire the creation of text messages and provided a checklist against which the intervention messages could be compared to ensure that important techniques were not omitted. As expected,15 not all the techniques were appropriate for the target group or for delivery by text message. However, as the authors of the reviews suggested, identification of these techniques greatly aids the development of behaviour change interventions.

Communication theory

The design of the text messages was based on current communication theory. This draws attention to the series of steps from message receipt to behaviour change. To be effective a message must be attended to, comprehended, processed, accepted and acted on. 88 Communication theory identifies four features of a message which affect the likelihood of behaviour change: the source (i.e. credibility) of the message, its style and content, the nature of the recipient and the context (the circumstances in which the message is received). Each of these features affects the impact of the message on behaviour change. 89,90 The nature of the message comprises many facets, including its length, content (number of arguments), language and style (such as use of images). Important design features are the personal relevance of the message89 and whether the arguments are gain-framed (emphasising the benefits of moderate drinking) or loss-framed;91 gain-framed messages are much more persuasive in altering behaviour. Items can also be included to maintain interest (such as interesting and unexpected statements).

Conclusions from the literature review

The literature identified a series of key issues that had to be resolved:

-

What should be the style and tone of the messages?

-

Which harms of alcohol should be mentioned and how should these be displayed?

-

Which psychological models and behaviour change techniques are most appropriate for the target group and for delivery by mobile telephone?

-

Which components of the psychological models should be conveyed in the text messages?

-

In what sequence should the messages be sent?

-

How often should the messages be sent and at what times of day?

-

How could guidance to reduce consumption be given without patronising or preaching?

-

What should the balance be between serious and more whimsical messages?

-

Should the text messages be supplemented by other materials?

-

How many text messages should the control group receive?

Constructing a logical sequence of messages

The theories of communication and behaviour change, together with the reports of previous intervention studies, identify many key components for the intervention and important design features to take into account. However, they do not specify the sequence in which the components should be arranged to achieve maximum effect. Intuitively, a plausible sequence would be to review harms of current drinking, explore the benefits of moderated drinking then promote intentions to change behaviour. However, it would be preferable to have a theoretical justification of the sequence.

A second problem is that, although many drinkers are content with their current pattern of consumption, some wish to reduce their consumption. 11 This raises the question of whether or not different sets of messages should be sent to different types of drinkers. Brief interventions delivered face to face can establish how individuals view their alcohol consumption and whether or not they are thinking about reducing their consumption. A skilled counsellor can select the relevant components of the intervention and weave them into a coherent behaviour change strategy. This is more difficult with an automated text delivery system. It would be possible to screen each individual at baseline and, by clever programming, create a customised set of messages. However, this would increase the cost of the system if it was rolled out nationally as staff would be required to conduct screening interviews. As potential for national roll-out was a key requirement of the intervention, the need for simplicity meant that all participants would be given the same set of messages.

The TTM85 provided a convenient solution to the problem of presenting the messages in a logical order which is suitable for all drinkers. The texts were arranged in the sequence pre-contemplation (prompt re-evaluation of current behaviour), contemplation (focus on reasons for change), preparation (identify and overcome barriers to change) and action (promote self-efficacy, goal setting). One benefit of this model and the sequence of text messages is that it will be suitable for individuals irrespective of their stage of change at enrolment to the study. For example, those in the preparation stage will view the pre-contemplation messages as reinforcing their decision to do something about their drinking. Clearly this would not work if the messages were tedious or repetitive. A feature of this approach is that it encourages integration of behaviour change strategies from other theoretical models. Thus, the text messages make extensive use of the components of other theories of behaviour change.

Design decisions

Short Message Service (SMS) text messages can be no more than 160 characters in length. This meant that complex constructs from the psychological models had to be conveyed concisely. Mobile telephones can also send images through Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS) messages. At the time of the design of the intervention texts, not all mobile telephones could receive MMS images. However, given the speed of advance of mobile telephone technology it was concluded that, by the time the intervention was suitable for national roll-out, all telephones would support MMS messages.

Basis for the intervention

The intervention was to comprise a series of interactive text messages and images using communication theory,88,91,92 social cognition models,93 the TTM80 and the components of effective brief interventions for alcohol described by systematic reviews of interventions to tackle alcohol problems. 8–10 The text messages were all mapped to behaviour change models and techniques. A few examples will help clarify this mapping process:

-

Raising awareness of harms: ‘1 in 20 deaths a year in Scotland are caused by alcohol! Don't be the 1!’

-

Subjective norm: ‘Can U think of someone who'd be happy if U made a change! What would U hear them say?’

-

Drinking refusal self-efficacy: ‘Drinking too much can spoil a good night out & make U regret the things U did! Self-control = more fun!’

-

Outcome expectancy: ‘Some people change for the worse when they're incredibly drunk. Think of the benefits of taking it a wee bit easier.’

-

Goal setting: ‘Set yourself a goal & try to avoid alcohol on weekdays (Monday–Thursday). Give it a go!’

Credible source

The University of Dundee provided a credible source for the research project. The university logo was printed on all letters sent and appeared in the first text messages of the intervention. Thus, the introductory text used the university identity to welcome participants to the study. ‘Welcome, Dave! U are 1 of 60 men chosen by Dundee University for this important study on alcohol use’. This text had the additional benefits of making the men feel valued and building rapport.

Style and tone of the messages

The messages employed a simple, non-academic, friendly and non-confrontational language. Some messages contained quotes from the focus groups, suitably anonymised. The style of the messages changed across the intervention. The first text was a friendly welcome to the study using the participant's name, and the following texts were supportive, establishing rapport and making the men feel valued. However, the texts then became progressively more serious with the final messages emphasising the importance of behaviour change. The final text thanked the men for participating in the study.

The personal pronoun ‘you’ was used throughout, as it increases personal relevance and the processing of message arguments. 94 An early decision was to construct messages according to the conventions of texting, and to use the language of the target group. For example, the letter ‘u’ was used in place of ‘you’ and capitalised as ‘U’ to make it stand out. The abbreviated forms ‘it's’, ‘don't’, ‘I'll’ and ‘they're’ were used to create informality, but had the additional benefit of saving characters.

Unlike previous studies,23 no messages were repeated. Furthermore, the type and content of the messages was varied from day to day to maintain interest. Some messages were included because they might not be expected. For example, one text introduced a little-known side effect of heavy drinking, that it can cause ‘man boobs’ (male breasts).

Humour

Humour is thought to increase attention to messages, to increase their persuasiveness and to make them more memorable. 95,96 Humour was primarily used during the first 2 weeks of the study to engage the interest of the participants and build rapport with them. The jokes were designed to have sufficient appeal to be the kind you would want to show to your friends. Sharing texts would reinforce the impact of the message, increasing its salience and enlisting peer support for the study. As the target group was young to middle-aged men the humour had to be grounded in popular culture and included references to drunkenness and to sexual activity.

Tailoring of text messages

Tailoring is an essential feature of text messages. First name, or preferred name, was used for the first two and last two text messages of the intervention. Many messages reflected the drinking culture of the men which had been identified in focus groups, including drinking episodes with unfortunate consequences. The focus groups also provided examples of telling phrases which were used (anonymously) in the text messages. For example, one text used the expression of regret the day after a drinking session: ‘Many a weekend I've thought if I'd just went home at 8–9 p.m., I wouldn't be sitting here now feeling like a bag of shite’. When used, these quotes were attributed to individuals. To preserve anonymity individual names were replaced by the five most popular names given to babies born in Scotland in 1975; this was the mid-point of the years of birth of the study participants, 1966–85.

Gain-framing of messages

Conveying the adverse consequences of heavy drinking will help motivate participants to reduce their consumption. However, there is clear evidence that gain-framed messages are more effective than loss-framed ones. 91,97 To avoid loss-framing the messages about harms were frequently extended to conclude with the benefit of avoidance behaviour. For example, a text on the high death rate from alcohol was extended to wish the participant a long and healthy life. Similarly, the text on the high cost of alcohol was turned round to conclude with the amount that could be saved by cutting consumption.

Images

Images can enhance the coherence of the message (i.e. more clearly demonstrate how cause and effect are linked) by making behaviours and their consequences appear less abstract and more concrete. They can also help extend the narrative being developed, a particular benefit for short text messages. Images are often more memorable than verbal- or text-based messages. 98,99 In short, images can influence attitudes100,101 and intentions, thus increasing the likelihood of behaviour change.

Seventeen images, selected to be bright and colourful, were sent as MMS messages. They were designed to develop and extend the narrative and to make concrete the many harms of alcohol: impotence, vomiting, violence, crime, liver cirrhosis and death. For example, the way in which alcohol can make a peaceable individual aggressive was illustrated with a popular cartoon character, the Incredible Hulk™ (Marvel). The image of a jail was thought to be a powerful adjunct to a text conveying the risk of crime associated with heavy drinking. To ease the harshness of the message, a cartoon of the Monopoly™ (Hasbro) ‘Go to Jail’ character was used.

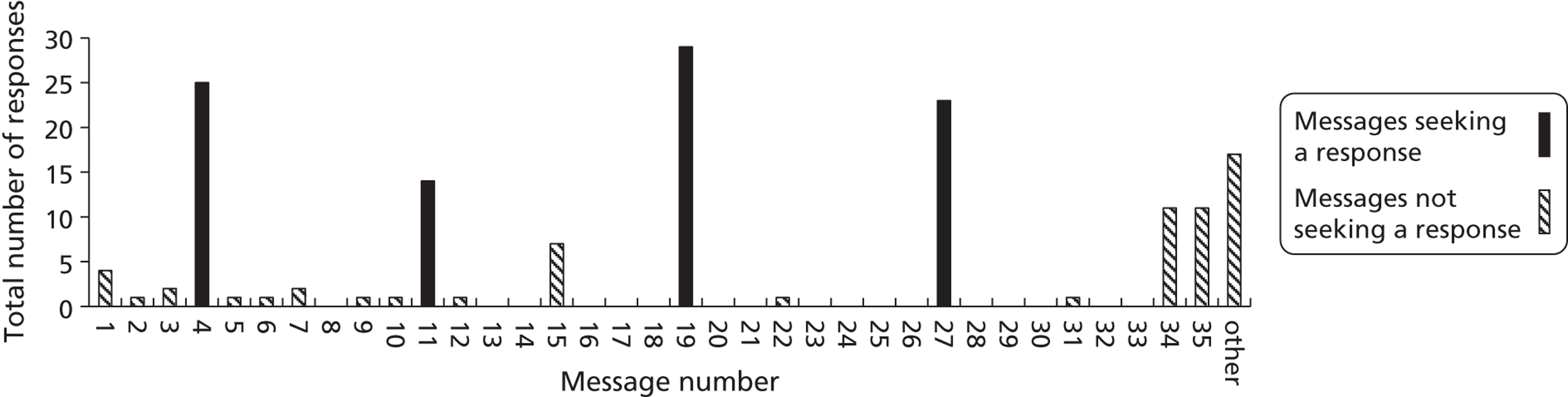

Paired messages