Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 09/3005/09. The contractual start date was in April 2011. The final report began editorial review in November 2016 and was accepted for publication in June 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

At the time of the study, Steven Cummins and Charlotte Clark were both members of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research Programme Funding Board. Steven Cummins was also funded by a NIHR Senior Research Fellowship.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Cummins et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Health follows a social gradient, with those further up the socioeconomic scale experiencing better health. 1,2 In the UK, health inequalities have persisted over the past two decades, with the mortality gap between the most advantaged and disadvantaged groups standing at around 8 years. 3 Policies and interventions that tackle the wider socioeconomic and environmental determinants of poor health have been promoted by UK governments as important components of strategies to improve health and well-being, and to reduce health inequalities. 2,4 In recent years, large-scale programmes that tackle entrenched social and environmental deprivation through improvements in living conditions have become an increasing feature of the policy landscape. Such interventions have usually taken the form of large-scale urban regeneration and neighbourhood renewal programmes that have good potential to tackle health inequalities as they directly influence the wider social, economic and environmental determinants of physical and mental health. 5 Between 1980 and 2004 spending on such schemes in the UK was thought to have reached £11B. 6 In more recent years many of these schemes have been area based, and have thus involved the targeting of places that are considered to be in the greatest social and economic need. Such initiatives target areas of multiple deprivation and commonly comprise investment in schemes that might affect the key socioeconomic and environmental determinants of health, for example employment, housing, education, income and welfare. Much of this occurs through infrastructural improvements to the built environment such as new or upgraded transport links, the provision and upgrading of retail space, the creation of new green space, parks and public areas, and improvements in housing. General improvements in aesthetics and safety via neighbourhood redesign through lighting, furniture, public art, pedestrian zones and the amelioration of environmental stressors such as graffiti, litter and noise are also common components of regeneration programmes.

Despite continuing large-scale public investment, recent systematic reviews identify a dearth of evidence of the effectiveness of urban regeneration programmes in improving health and well-being, and alleviating health inequalities. 6–8 The evidence that does exist is weak with mixed findings. In the UK, studies investigating the health impacts of urban regeneration are rare and highly variable in terms of study quality and reported outcomes, and exist primarily in the grey literature. Although some studies with health indicators have reported improvements (e.g. mortality rates),9 previous research also suggests the possibility of negative effects. 10 Evaluations have tended to focus on socioeconomic outcomes (such as impacts on employment, education, income and housing quality) and have often neglected to assess effects on health outcomes. These evaluations of socioeconomic impacts have also been mixed, with the reporting of both positive and negative effects on socioeconomic factors, making it difficult to speculate as to the direction and nature of plausible indirect impacts on health. 10–12 Most studies are also focused on adults: evaluations of the impact of urban regeneration on young people and their families represent an important gap in the evidence, as adolescence may be a critical period for the emergence of health inequalities in later life.

Previous research therefore suggests that even though urban regeneration programmes have the potential to affect population health there is limited evidence to support this. Overall, the literature is clear: robust evaluations of the impact of urban regeneration programmes on the social determinants of health, and on health and behaviours, have rarely been undertaken and the evidence that does exist is of generally mixed quality. There has been little work on how impacts vary across population subgroups. Recently, there has been increasing demand from public health policy-makers, as well as practitioners, in urban planning for evidence that provides guidance to help ‘design-in’ health-promoting features of the urban environment, allowing them to maximise the health impact of new built infrastructure development. This might include design features that favour public and active modes of transport over the private motor car; increasing accessibility to resources that promote physical activity and well-being, such as green space, facilities for physical activity and more opportunities for leisure-time walking and cycling. The present study has therefore been designed to provide robust, longitudinal evidence on whether or not the large urban regeneration catalysed by the London 2012 Olympics has resulted in improvements in physical activity and psychological well-being.

The London 2012 Olympics as a catalyst for large-scale urban regeneration in east London

Hosting the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games provided an opportunity to establish a quasi-experimental study of the effects of urban regeneration associated with the 2012 Olympics on physical activity and psychological well-being, as well as a wider range of health outcomes and behaviours. The components of the Olympic-related regeneration programme delivered in east London are common to the majority of urban regeneration programmes elsewhere (e.g. improvements in facilities, services, housing and built infrastructure). This presents an opportunity for wider learning around about the range and nature of positive and negative impacts on health and an exploration of the causal pathways between urban regeneration and health by linking specific individual components of regeneration to changes in specific outcomes and behaviours. Urban regeneration under investigation in this study is focused on east London, specifically the London boroughs of Hackney, Tower Hamlets, Newham, and Barking and Dagenham.

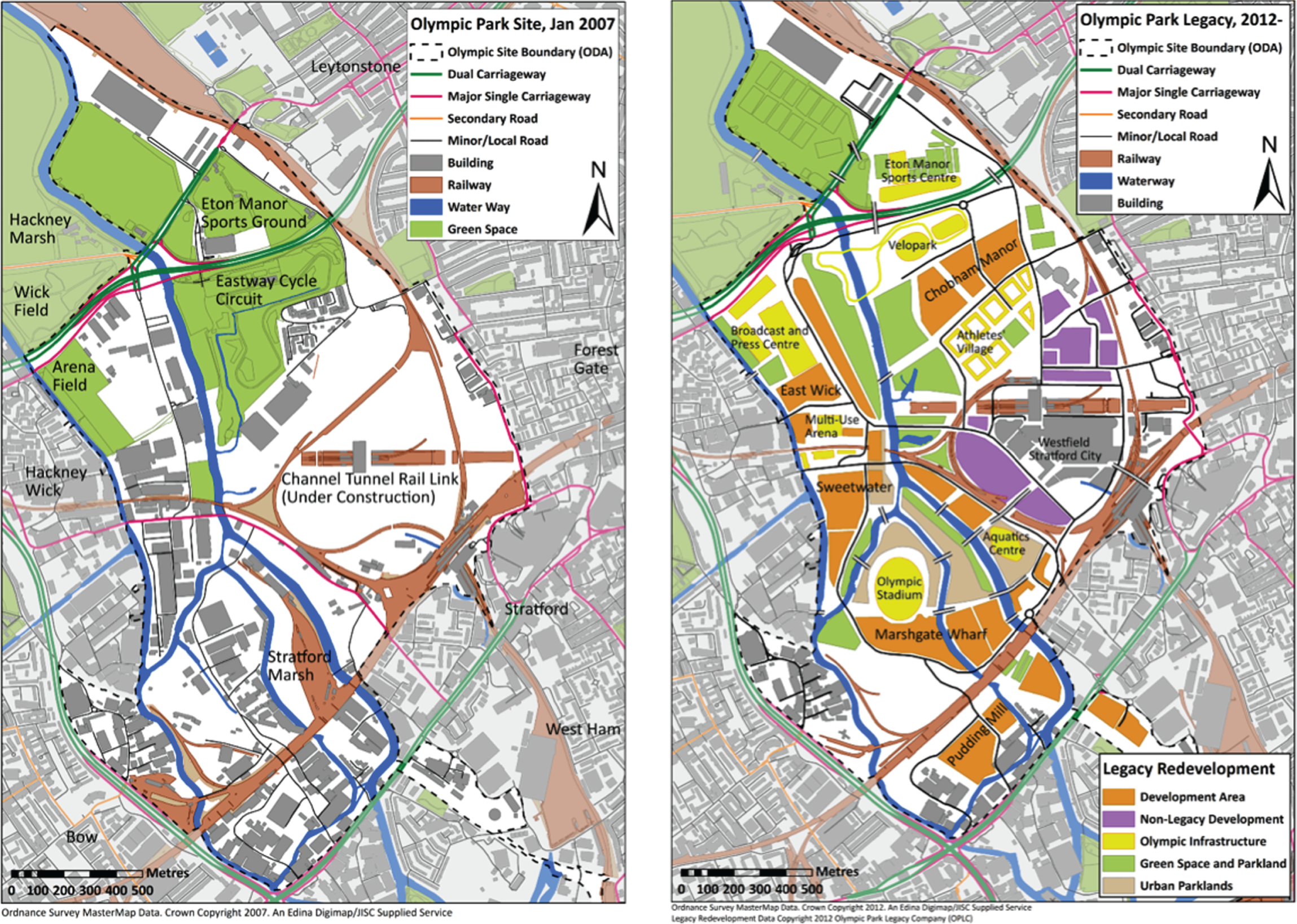

The east London boroughs included in this study comprise an ethnically diverse population of approximately 1.1 million people. This area is also relatively disadvantaged, with some of the most deprived neighbourhoods in the UK within its borders. The bid to host the London 2012 Games was centred on creating the first ‘Legacy Games’ and was predicated on leaving a lasting legacy for the residents of east London through improvements to infrastructure and housing, stimulating economic development and aiming to ‘inspire a generation’ to be more physically active. In the context of this study regeneration primarily consisted of the construction of services, infrastructure and facilities supporting the Olympic Park and Stratford City developments during late 2011 and 2012, plus the early legacy phases that were delivered from 2013. These developments covered an area of 7000 acres in the London Borough of Newham. The Legacy Masterplan13 outlines provision for a total of 2.9 million ft2 of retail and leisure space, 1.3 million ft2 of hotel space, a 6.6-million-ft2 commercial district, and 180,000 ft2 of new and refurbished community spaces. Regeneration components that are the focus of this study comprise ‘sustainable’ transport networks (rail and active travel corridors); new and refurbished civic spaces, parks and green areas; improvements in accessibility to services and facilities of communities on the fringe of the regeneration sites; and development of retail, business and community facilities. The main physical regeneration activities are summarised in Table 1.

| Date | Area | Main components |

|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | Stratford City Development | Retail and leisure centre comprising 579,120 m2 of retail space (including Westfield Stratford City), 152,400 m2 of office and business space, new civic and public space |

| 2012–14 | Olympic Park | The Olympic Park consists of 2,460,000 m2 of regenerated land that consists of new green spaces and parkland, public space and play areas, world class sports venues (main stadium, aquatics centre, velodrome, BMX and mountain bike tracks, road cycle route) and associated facilities, and improved physical connectivity and accessibility to the Olympic Park from surrounding areas (foot and cycle paths, bridges, waterways, road and rail links). New housing associated with the former Athletes Village (East Village) |

| 2012–14 | Olympic Fringe | Area surrounding the Olympic Park will receive 900,000 m2 of improved green/civic space and improved connectivity to the main Olympic Park |

The London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games took place over a 6-week period from 27 July to 9 September 2012, with the park site closed for several years prior to these dates. After the completion of the Games, the Olympic Park entered legacy mode and was closed for refurbishment. It reopened to the public in phases between July 2013 and April 2014. A full timeline can be found here: https://web.archive.org/web/20161015003425/http://queenelizabetholympicpark.co.uk/our-story/transforming-east-london/timeline (accessed 13 September 2018).

Our study was therefore designed to answer a set of specific questions that linked elements of environment change related to urban regeneration in east London to changes in physical activity behaviour and psychological well-being to generate generalisable evidence on how the modification of urban environments might affect these health outcomes.

Primary research questions

The aim of this study, the Olympic Regeneration in East London (ORiEL) study, was to address the following primary research question:

-

What is the impact of urban regeneration on the social determinants of health (employment), health behaviours (physical activity) and health outcomes (mental health and well-being) of adolescents and their parents/carers?

We also aimed to answer the following secondary research questions:

-

How are any socioeconomic and health impacts distributed by age, sex and ethnicity?

-

What are the effects of specific components of the regeneration programme on physical activity and psychological well-being?

-

Are any socioeconomic and health impacts sustained over time?

It was not possible to investigate effects on a range of secondary outcomes (such as diet and obesity) within the time frame of the current grant. Further analyses of ORiEL data focusing on these areas are ongoing and we anticipate that findings will be published over the next 2 years.

This report

The report presented here is an original summary of a large body of ongoing research, some of which has been published, submitted or prepared for publication in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Given the space available, we have focused our report on the main findings of interest. As a consequence, the report is primarily focused on findings related to the adolescent cohort. Findings related to parents/carers are briefly described, but are limited in nature and scope, as we found few statistically significant associations with our primary outcomes of interest in cross-sectional, longitudinal and repeat cross-sectional analyses.

The work presented here is therefore a summary and further details on the study methods and the findings can be found in already published work. Further work will emerge from the data generated by the study. This work, when possible, is referenced in the text and is available from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Research Online website: http://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/ (accessed 13 September 2018).

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter describes the research design and methods employed to evaluate the impact of Olympic-led urban regeneration on young people and their families. Here we describe the overall design of the study, respondent recruitment, fieldwork and data collection, the operationalisation of key variables and the general approach employed to analyse quantitative and qualitative data.

The content of this chapter updates previously published material contained in the protocol for the ORiEL study, published immediately before the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. For further details of the published study protocol, see Smith et al. 14

Research design

The ORiEL study is underpinned by a multilevel socioecological conceptual framework recognising that both individual and environmental risk factors are important for health. The implication is that action to improve health requires a focus not only on individual lifestyle and socioeconomic factors but also on the local environmental resources and opportunities available to those individuals. 15,16

Our main aim was to assess the impact of a multicomponent urban regeneration programme linked to the 2012 Olympic Games on the social determinants of health (employment), health behaviours (physical activity) and health outcomes (mental health and well-being) of adolescents and their parents or carers. The study was originally conceived as a natural quasi-experimental study of a school-based cohort of adolescents and their parents/carer, living within four east London boroughs (Hackney, Tower Hamlets, Newham and Barking and Dagenham), with a further in-depth qualitative study of a subsample of families enrolled in the cohort.

The overall study comprises two main elements:

-

A longitudinal controlled quasi-experimental quantitative study examining changes in health behaviour and health outcomes in a cohort of adolescent school pupils aged 11–12 at baseline, and their parents or primary carers (parent/carer). Residents in the intervention area (Newham) receiving urban regeneration were compared with those who live in comparison areas (Hackney, Tower Hamlets, and Barking and Dagenham) not receiving urban regeneration of this magnitude. Adolescent and parent/carer survey data were collected in three waves in intervention and comparison areas: wave 1 (baseline pre intervention, 2012), wave 2 (6 months post intervention, 2013) and wave 3 (18 months post intervention, 2014).

-

An in-depth longitudinal qualitative study of family experiences of, and attitudes towards regeneration in the intervention area and influences on socioeconomic status, health behaviours and health outcomes. The initial investigation comprised a subgroup of approximately 20 families at baseline that reflected the diversity of the survey sample. The qualitative study sample was drawn from wave 1 participants and was repeated at wave 2.

Study setting

The study took place in four London boroughs: Newham (intervention site), Barking and Dagenham, Tower Hamlets and Hackney (comparison sites). The boroughs have an estimated combined population of around 1.1 million residents17 and are significantly more disadvantaged than the London average. 18 For example, between 2011 and 2012 unemployment rates were 7.0% (compared with 5.1% in London),19 the incidence of violent crime was 22.0 offences per 1000 population per year (compared with 18.8 offences per 1000 population per year in London)20 and the proportion of the population with no educational qualifications was 22.0% (compared with 17.6% in London). 21 This setting was suitable for research of this type as area-based urban regeneration programmes that influence the socioeconomic and environmental determinants of health may be particularly beneficial for relatively disadvantaged communities with degraded infrastructure. 8

Methods: quantitative study

Sampling strategy

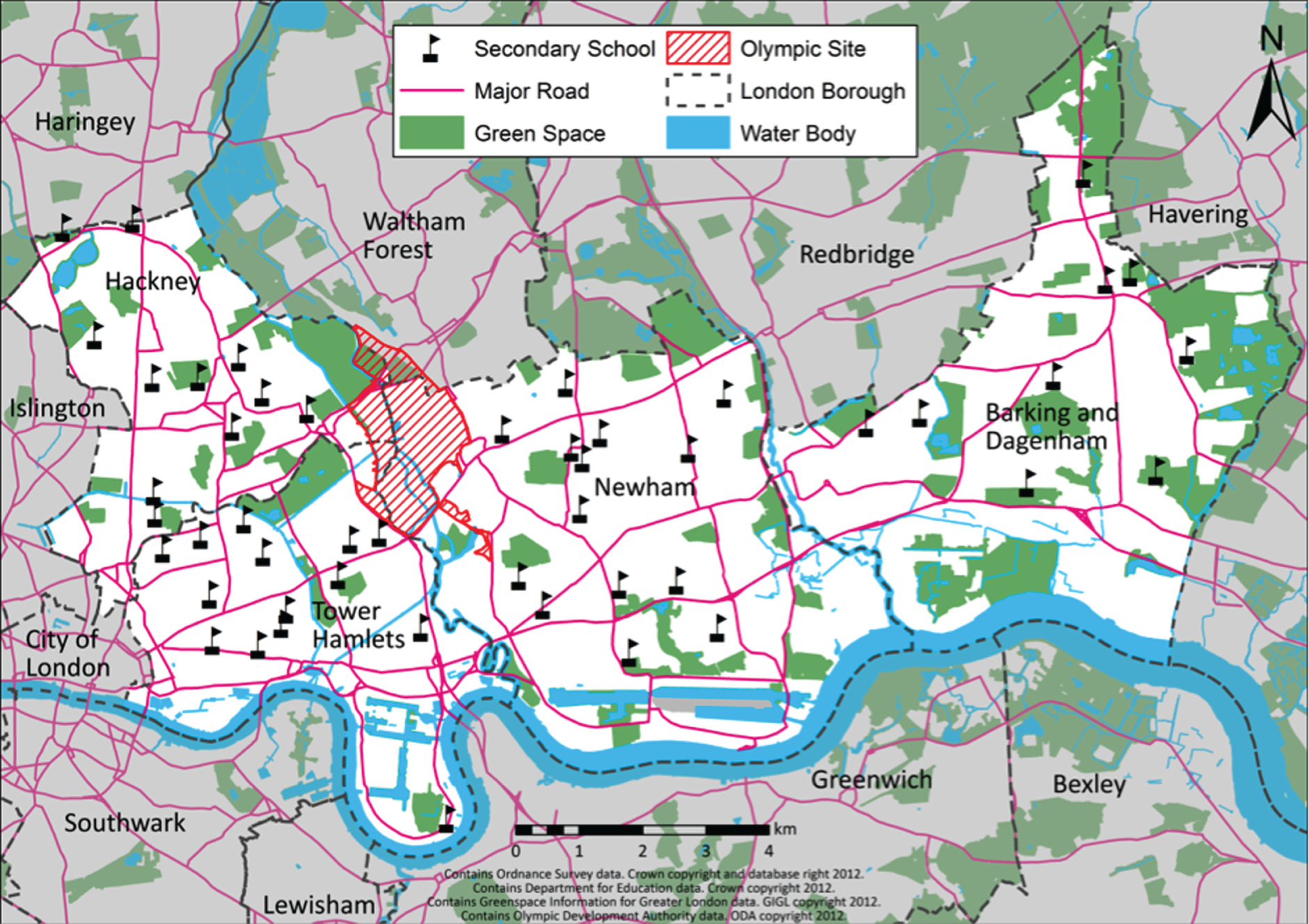

Participants at baseline were pupils aged 11–12 years (school year 7) who attended randomly selected state schools in the intervention and comparison boroughs, and their parents/carers. Schools were selected using simple randomisation within each borough, with refusals replaced by eligible schools from the same borough. Included adolescents were those with sufficient cognitive and language skills to complete a paper-based questionnaire, including those who required some assistance to do so. Special-needs schools, pupil referral units and independent schools were excluded. The total number of eligible schools in each borough was as follows: Newham, n = 14; Tower Hamlets, n = 14; Hackney, n = 11; and Barking and Dagenham, n = 9. The geographical location of these east London boroughs, and the schools’ position within them relative to the Olympic Park area, is shown on the map in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Map showing the location of eligible schools adjacent to the Olympic Park in the London boroughs of Newham, Tower Hamlets, Hackney, and Barking and Dagenham. Map contains Ordnance Survey data, Crown copyright and database right 2012; Department for Education data, Crown copyright 2012; Greenspace Information for Greater London data, GIGL copyright 2012; and Olympic Development Authority data, ODA copyright 2012. Reproduced with permission from Smith et al. 14 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Study power

The study is powered to detect differences in our primary outcome measures of employment, mental well-being and physical activity. In the only high-quality controlled prospective study of neighbourhood change with related outcomes to those proposed here (the Moving to Opportunity study), the proportion of people employed increased by 13% among minority groups,22 and mental well-being scores, on a range of scales, improved by 8–33% for adults, and up to 25% for children. 23

On the basis of this, a plausible conservative minimum change in our primary outcomes (employment, mental well-being and physical activity) would be 8%. Given the finite number of schools available in the intervention area (n = 14) compared with comparison areas (n = 34), we assumed a 1 : 3 ratio for the number of participants in intervention and comparison arms, respectively.

A total sample size of 712 adolescents and 712 parents/carers at wave 3 was therefore, required to detect a difference of 8% with 80% power at a significance level of 5%. To take account of clustering by school, we assumed an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.02 (as our primary outcome is health related we expect a smaller ICC than that usually seen for measures such as educational attainment, which will be more highly school related). This results in a design effect of 2.48 with a total required sample size at second follow-up (wave 3) of 1766 adolescents (24 schools and 74 per school) and 1766 parents/carers. Our achieved adolescent sample size therefore has 80% power to detect the minimum difference of 8%, at the 5% significance level.

Recruitment

Adolescent survey

Participants were recruited through secondary schools in two ways: (1) school-based enrolment of adolescents aged 11–12 years in year 7, and (2) recruitment of parents/carers through the surveyed adolescents. Schools were incentivised by a single donation of £1000 paid after completion of the baseline survey.

Adolescent recruitment began by asking the borough-level administrators (local education authorities/learning trusts) to encourage schools to participate. This approach has been previously successful in recruiting primary schools, albeit outside London. 24 However, all four boroughs suggested that we contact schools directly. A letter of invitation was sent to school principals (and members of their senior leadership team), followed by a telephone call. This resulted in the recruitment of 10 schools. The remaining schools were recruited from an e-mail campaign targeting heads of year and subject leaders who might find the ORiEL project of academic interest to their students (e.g. physical education, geography, sociology). Overall, 42 of the 48 eligible schools were approached to recruit the final 25 schools needed. The most common reason for schools refusing was ‘research fatigue’. This suggests that personal preferences of organising staff were a cause of refusal rather than pupil characteristics. Further details can be found in Smith et al. 14

Respondents were recruited from six schools in each of the London boroughs of Newham, Hackney, and Barking and Dagenham and from seven schools in Tower Hamlets (Table 2). The cross-sectional baseline survey respondents comprised 3095 adolescents in year 7 of secondary school (aged 11–12 years) who completed a paper-based questionnaire during the 6 months (January to July 2012) prior to the start of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. To maximise the sample, the whole school year was surveyed in seven schools that had relatively small year groups. The remaining 18 larger schools provided an allocation of mixed-ability adolescents selected on the basis of school timetabling. Adolescents were followed up at approximately 6 months (January to July 2013) and 18 months (January to July 2014) post intervention. Schools were surveyed as close to the same month of each year, when possible, in order to minimise seasonality effects. The cross-sectional sample was larger at follow-up than at baseline owing to a deliberate oversampling strategy. This was a logistical requirement given that the cohort members became dispersed over time to many different classes across the school timetables at first follow-up (year 8).

| School | Wave cross-section | Wave 1/2/3 cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Newham | ||||

| 1 | 163 | 155 | 152 | 108 |

| 2 | 126 | 158 | 151 | 93 |

| 3 | 136 | 145 | 147 | 98 |

| 4 | 209 | 229 | 228 | 145 |

| 5 | 112 | 103 | 91 | 81 |

| 6 | 147 | 145 | 155 | 103 |

| Mean | 149 | 156 | 154 | 105 |

| Total | 893 | 935 | 924 | 628 |

| Hackney | ||||

| 7 | 156 | 158 | 138 | 112 |

| 8 | 95 | 98 | 86 | 74 |

| 9 | 100 | 105 | 96 | 81 |

| 10 | 124 | 126 | 129 | 99 |

| 11 | 111 | 104 | 103 | 84 |

| 12 | 143 | 168 | 174 | 103 |

| Mean | 122 | 127 | 121 | 92 |

| Total | 729 | 759 | 726 | 553 |

| Tower Hamlets | ||||

| 13 | 105 | 115 | 105 | 85 |

| 14 | 95 | 95 | 89 | 73 |

| 15 | 104 | 103 | 101 | 77 |

| 16 | 116 | 130 | 146 | 85 |

| 17 | 121 | 120 | 105 | 85 |

| 18 | 127 | 120 | 113 | 90 |

| 19 | 135 | 136 | 118 | 89 |

| Mean | 115 | 117 | 111 | 83 |

| Total | 803 | 819 | 777 | 582 |

| Barking and Dagenham | ||||

| 20 | 130 | 133 | 87 | 77 |

| 21 | 105 | 111 | 86 | 73 |

| 22 | 100 | 110 | 108 | 87 |

| 23 | 113 | 112 | 115 | 99 |

| 24 | 112 | 105 | 101 | 80 |

| 25 | 103 | 129 | 117 | 75 |

| Mean | 111 | 117 | 102 | 82 |

| Total | 663 | 700 | 614 | 491 |

| Overall mean | 124 | 129 | 123 | 90 |

| Total | 3088 | 3213 | 3041 | 2254 |

The final sample featured single- and mixed-sex schools and drew on the largest and smallest schools in the four boroughs, which were affiliated to a range of religious denominations.

Table 3 compares the sociodemographic profile of the ORiEL sample at baseline with census data. The sociodemographic characteristics of the ORiEL baseline sample were broadly similar to the equivalent population observed by the 2011 census, with some exceptions. The ORiEL sample was slightly under-represented in terms of female respondents and Bangladeshi and white UK respondents; this ethnic difference contrasted with an ORiEL over-sample of white other and mixed white ethnic groups. The high proportion of white other groups included recent migrants from European Union states and will have contributed significantly to the higher than expected numbers of participants born overseas. Overall, the baseline response rate was 87% and the study sample (n = 3095 in school year 7) can be estimated at approximately 25% of the entire age group attending state schools in the catchment areas (n = 12,136 in school year 6).

| Variable | ORiEL study sample at 2012 baseline, n (%) | 2011 Census in ORiEL catchment area, n (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| Genderb | ||

| Male | 1756 (56.6) | 6205 (51.1) |

| Female | 1347 (44.4) | 5938 (48.9) |

| Ethnic groupc | ||

| White: UK | 598 (19.5) | 13,328 (24.0) |

| White: other | 399 (13.0) | 4454 (7.4) |

| White: mixed | 380 (12.4) | 4648 (7.7) |

| Asian: Indian | 108 (3.5) | 2846 (4.2) |

| Asian: Pakistani | 130 (4.2) | 2888 (4.1) |

| Asian: Bangladeshi | 508 (16.6) | 12,976 (22.4) |

| Asian: other | 27 (0.9) | 1943 (3.0) |

| Black: Caribbean | 147 (4.8) | 2772 (4.6) |

| Black: African | 364 (11.9) | 8666 (14.3) |

| Black: other | 242 (7.9) | 2511 (4.2) |

| Other | 163 (5.3) | 2392 (4.0) |

| Nativityc | ||

| Born overseas | 628 (20.7) | 26,697 (12.2) |

| Boroughb | ||

| Newham | 895 (28.8) | 3967 (32.7) |

| Tower Hamlets | 807 (26.0) | 2771 (22.8) |

| Barking and Dagenham | 670 (21.6) | 2559 (21.1) |

| Hackney | 733 (23.6) | 2839 (23.4) |

| Economic activityd | ||

| Both unemployed | 279 (10.4) | 23,536 (11.7) |

| One parent/carer employed | 941 (35.07) | 67,187 (33.4) |

| Both parents/carers employed | 1054 (39.28) | 61,638 (30.6) |

| Lone parent/carer employed | 235 (8.76) | 23,145 (11.5) |

| Lone parent/carer unemployed | 174 (6.49) | 25,917 (12.9) |

Parent/carer survey

The recruitment of parents/carers was carried out under contract with an external market research agency using face-to-face interviewer-administered questionnaires. Owing to data protection legislation, schools were unable to supply the home addresses of parents/carers of children enrolled in the study. We therefore asked adolescents to volunteer their home address during the completion of their questionnaires and this information was then passed on to the market research organisation for recruitment. Parents/carers received a letter of invitation to participate along with an incentive of an automatic entry into a prize draw in which five people would win £100. The overall response rate was 60%, a high response rate for east London, which has been historically difficult to enumerate. 25 However, the achieved sample size of the baseline cross-section was a considerably smaller than the adolescent sample because invitations to participate could be sent only to homes with a valid address provided by the adolescent during the survey session (Table 4). We were also obliged under the terms of the Market Research Society guidelines to ask all adult participants whether or not they would be willing to participate in the follow-up interview. Consequently, 37% of respondents opted out of the potential follow-up cohort at baseline. Because of the loss to follow-up, the study protocol was amended for follow-up data collection. The modified parent/carer survey adopted a repeat cross-sectional design, although a nested cohort was retained at each wave of data collection. This approach was agreed with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) as an appropriate compromise.

| Borough | Wave | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Newham | |||

| Total | 389 | 365 | 343 |

| Hackney | |||

| Total | 253 | 193 | 257 |

| Tower Hamlets | |||

| Total | 286 | 246 | 234 |

| Barking and Dagenham | |||

| Total | 317 | 219 | 161 |

| Total | 1245 | 1023 | 995 |

Data collection

Adolescent questionnaire

A paper-based questionnaire, based on validated tools and instruments listed below, was administered to assess individual and household sociodemographic characteristics, mental health and well-being, and physical activity of participating adolescents. Core questionnaire items are outlined below.

Socioeconomic circumstances

Household socioeconomic circumstances were measured using the Revised Family Affluence Scale (FAS II),26 whether or not adolescents were receiving means-tested free school meals and whether or not parents/carers were in employment. FAS II is a four-item questionnaire that has been validated in adolescents cross-nationally26 and is predictive of physical activity, self-reported health and mental well-being, and dietary outcomes. 27 However, we did not use the FAS II in our subsequent analyses owing to a very poor reliability of the scale (Cronbach’s alpha ≤ 0.4). Instead we used receipt of free school meals as our main measure of socioeconomic circumstance.

Mental health and social support

Well-being, mental health and social support were assessed using three self-completed scales. The first of these is the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS), a scale for assessing positive mental health/subjective well-being. 28 It has 14 positively worded item scales with five response categories (ranging from ‘none of the time’ to ‘all of the time’) and covers most aspects of positive mental health (positive thoughts and feelings), including both hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives. The total score ranges from 14 (lowest level of well-being) to 70 (highest level of well-being) and is reported as a mean value. The scale has been validated in adolescents29 and cross-culturally within Pakistani and Chinese subgroups. 30

Second, the Moods and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ)31 is a 32-item questionnaire for depressive symptoms based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Third Edition (Revised)32 (DSM-III-R) criteria for depression. The 13-item short form Moods and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ), based on the discriminating ability between the depressed and non-depressed, was completed by each adolescent. Each item is rated on a three-point scale: ‘true’, ‘sometimes true’, and ‘not true’, with respect to the events of the past 2 weeks. Scores range between 0 (lowest risk of depressive symptoms) and 26 (highest risk) and the variable was dichotomised with a total score of eight or more indicating clinically relevant depressive symptoms. 31 This scale was used in the previous Research with East London Adolescents: Community Health Survey (RELACHS) study33–35 of east London adolescents.

Third, the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) is a reliable and validated 12-item instrument designed to assess perceptions about support from family, friends and a significant other. 36 It is rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from ‘very strongly agree’ to ‘very strongly disagree’. The scale has a high construct and discriminant validity and high test–retest reliability (α = 0.92). 36 Summed scores for each domain and the overall total score were split into tertiles because of a skewed positive distribution.

Physical activity and sedentary behaviour

Physical activity and sedentary behaviour were assessed using the self-completed Youth Physical Activity Questionnaire (Y-PAQ). 37 This instrument was developed by the Medical Research Council (MRC) Epidemiology Unit in Cambridge. The validated questionnaire assesses accumulated time spent physically active and taking part in sedentary behaviours. 38 Estimates of total physical activity are comparable with previous population-based studies in a similar age group in Britain and other European countries. 39 A standard procedure was used to clean the Y-PAQ data and to account for extreme cases of overestimation of time and frequency of physical activity. The procedure sets outliers to a maximum value derived from validation studies and flags the value for the analyst.

Secondary outcomes and exposures

A range of sociodemographic, health-related and environmental variables were also collected. Participants were asked about their age, gender, home address and postcode, ethnicity (based on a question adapted from the 2011 Census for England and Wales),40 religion,41 cultural identity,42 country of birth, self-reported health,43 any long-term illnesses41,44 or mobility problems,44 smoking,45 drinking45 and dietary behaviours,46 parental interest in schooling,39,47 life events41,48 and education or employment expectations on reaching age. 41,47 The height and weight of participants were measured by the study team (Seca 899 scale, Seca 217 stadiometer, Seca Ltd, Birmingham, UK), with the exception of those individuals who declined to be measured or for whom an accurate reading was not possible, for example wheelchair users. These data were used to calculate body mass index (BMI) (taking age into account). Potential outliers for height and weight were noted during the measurement process and so confirm true cases of extreme values. Perceptions of the local cycling and walking environment were assessed using relevant items adapted from the Assessing Levels of Physical Activity and Fitness (ALPHA) environmental questionnaire. 48,49 Fifteen items were rated on a five-point scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) with an additional item asking participants to rate in minutes how near they live to a range of neighbourhood resources. Finally, attitudes to the Olympic and Paralympic Games were investigated using an adapted version of the Department for Education’s questionnaire for evaluating schools’ engagement with the Games via the national Get Set initiative. 50 Questions examined excitement about the Games prior to the event and also frequency of use of the Olympic Park at follow-up. Adolescent questionnaires can be found in Appendices 1–3.

Parent/carer questionnaire

The content of the parent/carer questionnaire was similar to that of the adolescent questionnaire. The three primary outcomes (employment, mental health, and physical activity and behaviour) were identical but used instruments adapted for face-to-face adult interviews.

Primary outcome: employment

Parental/carer employment status was assessed using the standardised questions posed at the 2011 census for England and Wales. 40 Individual occupations were coded to SOC (Standard Occupational Classifications) 2010, which were further coded to the standard National Statistics Socioeconomic Classification System (NS-SEC). 51

Primary outcome: mental health

In addition to the WEMWBS assessment of positive well-being, parents/carers completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). This is a validated 14-item questionnaire that detects depression and anxiety,52 with each item rated on a four-point scale with respect to the last week. Finally, experiences of job strain have been reported using a validated questionnaire assessing psychosocial job demands, decision latitude and social support at work. 53 Job characteristics are indicative of the quality of employment as well as being directly associated with mental health and cardiovascular outcomes. 54

Primary outcome: physical activity

Physical activities and behaviours were measured using the Recent Physical Activity Questionnaire (R-PAQ). The scale, developed by the MRC Epidemiology Unit at Cambridge University, describes the extent of physical activity around the house and travel to work patterns and determines recreational physical activity energy expenditure over the previous 4 weeks. This instrument has demonstrated validity for ranking individuals according to their time spent on vigorous-intensity activity and overall energy expenditure. 55

Secondary outcomes and exposures

Parent/carers’ sociodemographic factors included age, gender, relationship with the surveyed adolescent, ethnicity, religion, and their country of birth and that of their parents/carers. Socioeconomic indicators vary in their importance and meaning across the ethnic groups predominant in this east London sample. 56,57 Therefore, socioeconomic circumstances were captured using a battery of questions to assess the level of material deprivation, benefit receipts, financial difficulties and household living conditions. 58

A summary measure of physical and mental health was measured by the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12). 59 This is a shorter version of the Short Form-36 health questionnaire designed for use in clinical practice and research, health policy evaluations and general population surveys. 60 The SF-12 generated a mental component and physical component summary score and has been validated cross-culturally. 61 Adults additionally reported any specific physical or mental-health conditions from a list provided and described patterns of alcohol consumption, smoking and eating habits.

Neighbourhood perceptions were assessed by scales developed within the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). 62 The six-item scale describes perceived aesthetic quality of the area, walkability of the environment, the availability of healthy foods, and levels of safety, violence and social cohesion within the neighbourhood.

Experiences and perceptions of discrimination were investigated by a seven-item questionnaire adapted from the Ethnic Minority Psychiatric Illness Rates in the Community (EMPIRIC) survey. 63,64

Respondents were asked a series of questions examining the extent of their participation and general attitudes towards the Olympic and Paralympic Games in 2012, adapted from wave 4 of the Understanding Society UK longitudinal study. 65 These questions distinguished between active participation, such as spectating, volunteering or being in paid employment at the Games, and passive engagement, namely watching events on television, listening on the radio or reading about them at home.

Fieldwork

Study protocols were drafted that detailed standard procedures in the preparation of fieldwork materials and duties and regulations during the in-school data collection. These quality management systems were implemented to ensure that all fieldworkers were trained to the same level and shared the same knowledge of the questionnaire. This helped to minimise the potential response bias introduced if fieldworkers provided differing levels of assistance or information to adolescents completing their questionnaire.

A pilot study was conducted on a subsample within a participating school to determine the appropriate length of the adolescent questionnaire, identify language or comprehension difficulties with the use of standard scales, and refine elements of the survey protocol focused on school and parental/carer consent, and adolescent assent. The questionnaire was designed so that the primary research outcomes were completed early in the schedule to ensure higher response rates, with secondary outcomes completed towards the end of the questionnaire, when there was a greater risk of non-response. For the main study at baseline, school-based data collection commenced in January 2012 and finished 3 weeks before the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, which were held on 27 July 2012.

Consent

One week prior to survey, the school provided each adolescent with an age-appropriate study information sheet and a study information sheet to take home to their parent/carer. The letter presented the opportunity for parents/carers to actively opt the adolescent out of the study at any time. Parental consent was therefore passively obtained if the opt-out form was not returned by the adolescent.

During the survey visit the questionnaire was explained orally prior to completion; all adolescents additionally provided active written assent prior to completing the survey, and all adolescents were reminded that they were free to withdraw at any time without consequence. Immediately following survey completion all students were provided with a copy of their assent form and a duplicate of the age-appropriate information sheet. They were invited to contact the ORiEL study team if they had further questions.

Written consent from the school Principal or authorised member of the school’s senior leadership team was obtained before fieldwork began in their school.

Response rates

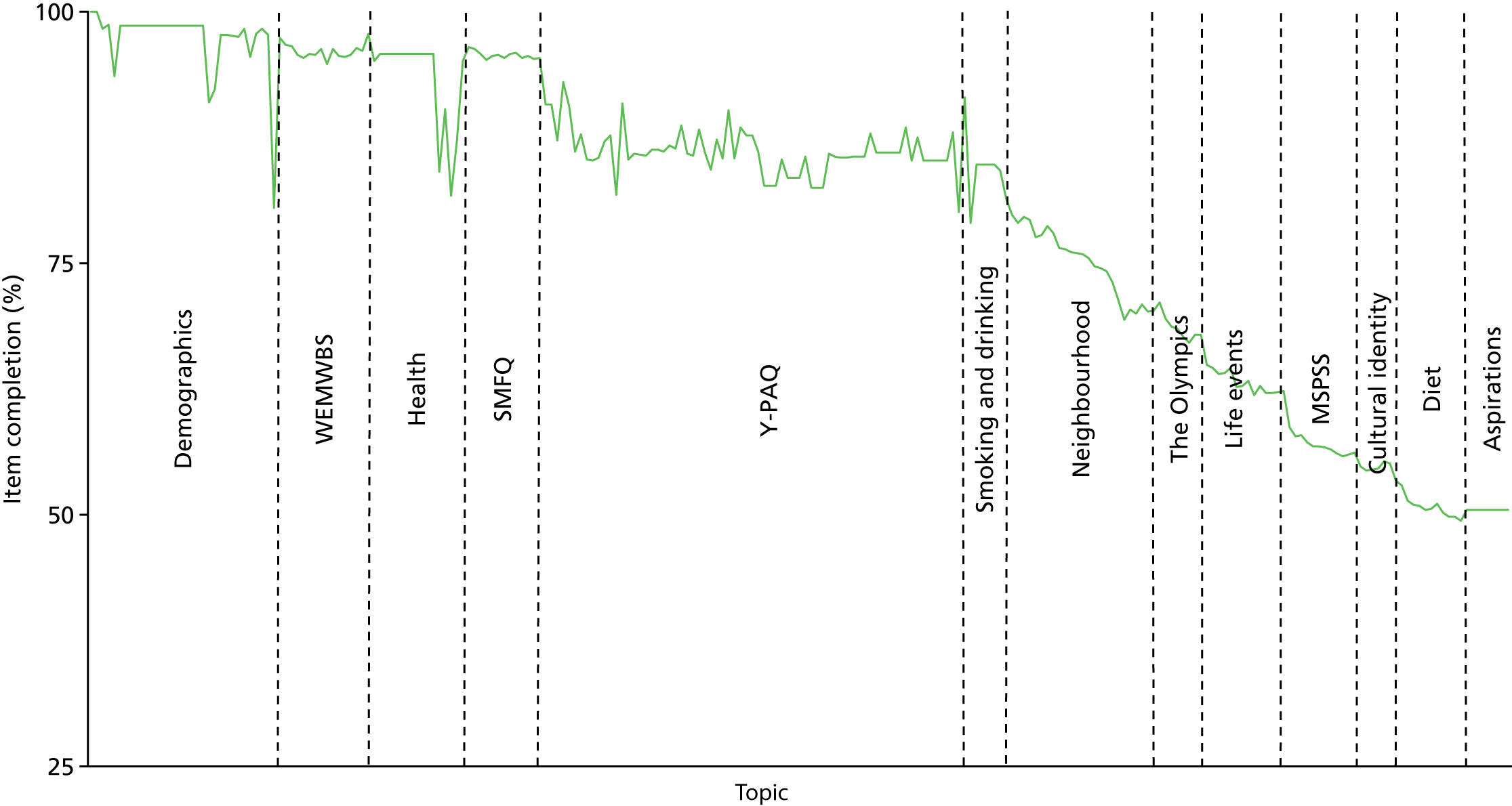

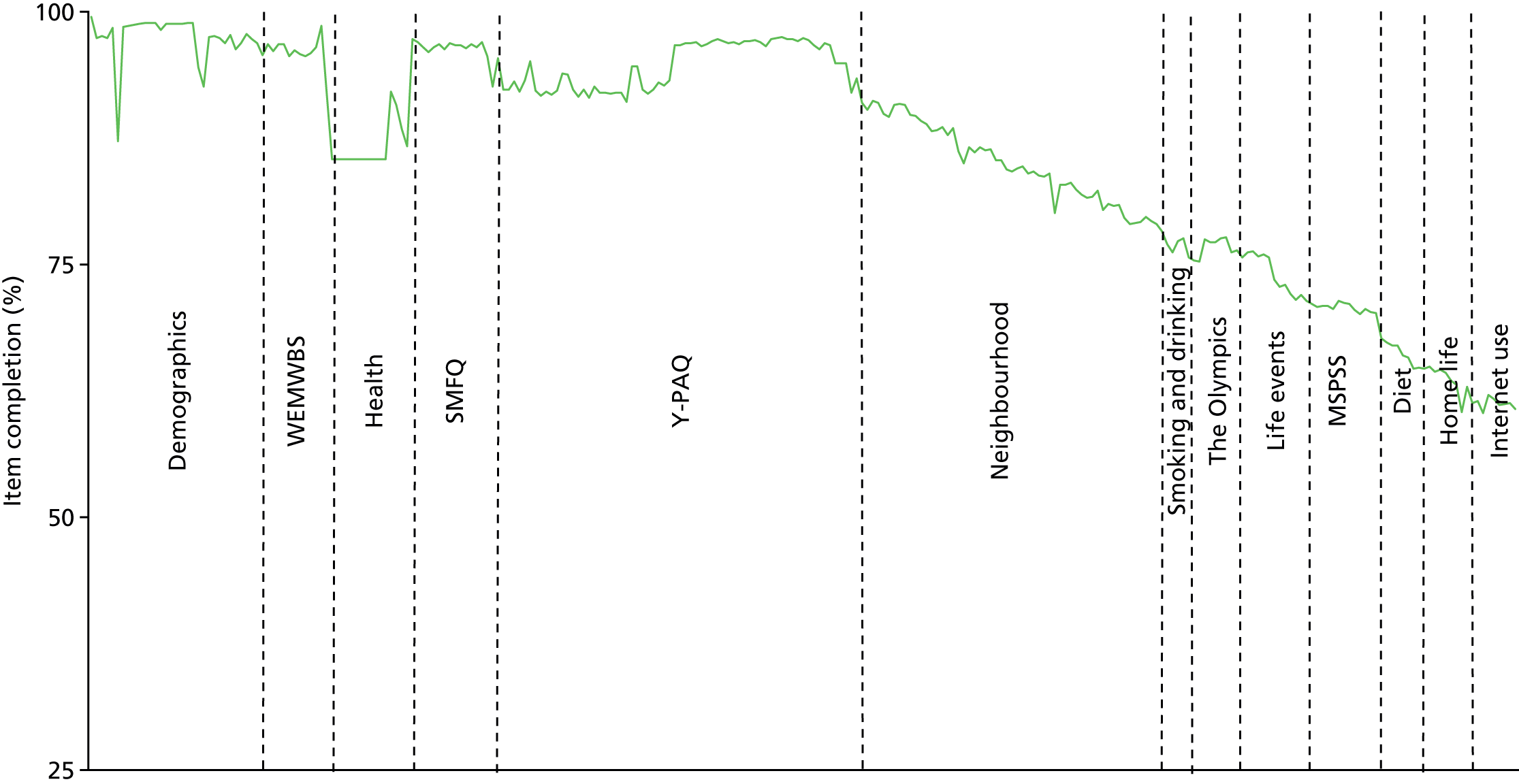

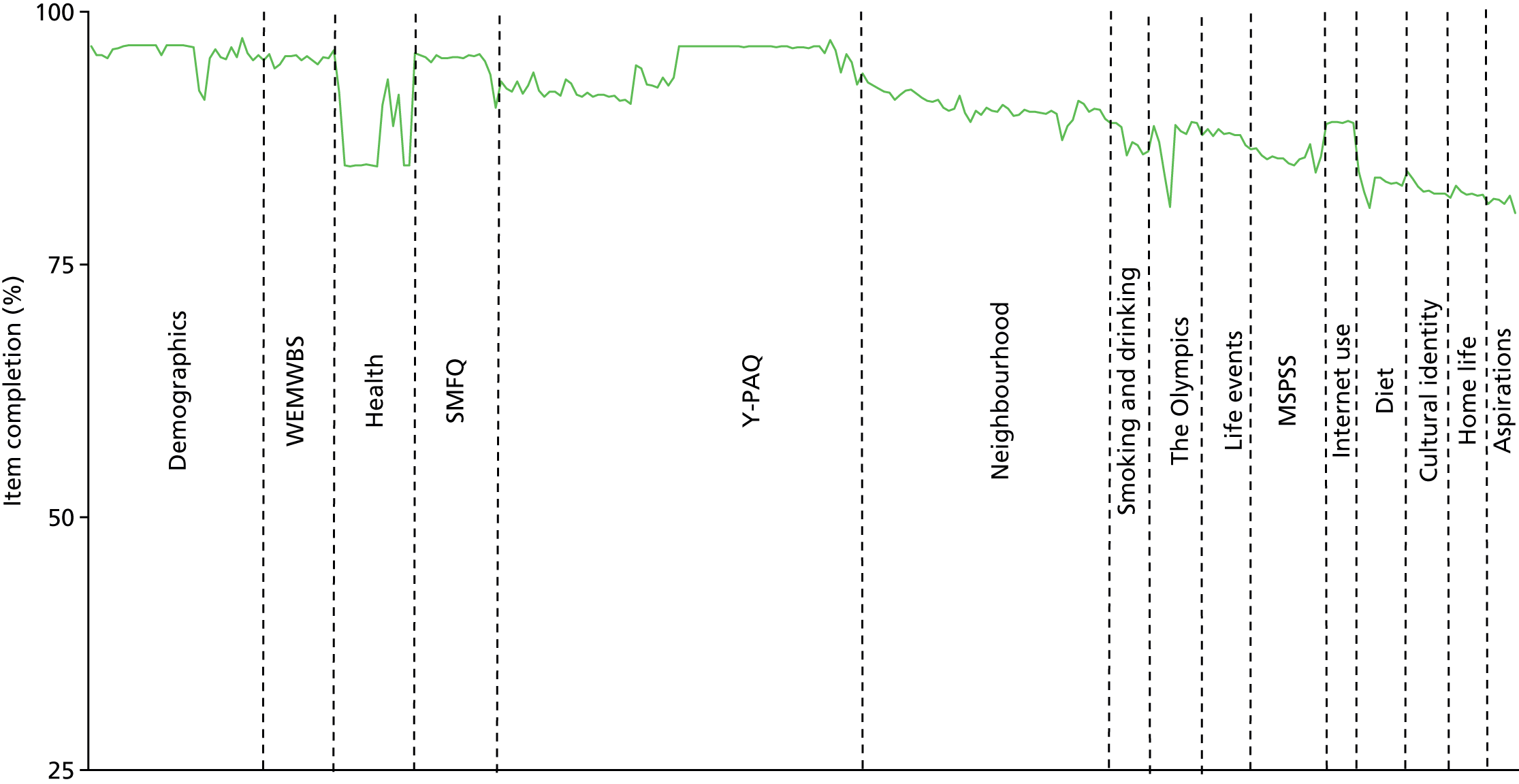

Survey completion was defined as answering the final battery of questions. Any adolescent respondent who had a record of ‘non-compliance’ – either because the student was a random box ticker or it was obvious that the questionnaire was not being taken seriously – was removed from the database. This amounted to 18 individuals at wave 1, 15 individuals at wave 2 and 48 individuals at wave 3. Figures 2–4 show the percentage of respondents completing each item on the questionnaire at each wave, in which the x-axis represents the proportion of the questionnaire designated to each topic.

FIGURE 2.

The ORiEL baseline adolescent questionnaire: item completion by topic.

FIGURE 3.

The first ORiEL follow-up (wave 2) adolescent questionnaire: item completion by topic.

FIGURE 4.

The second ORiEL follow-up (wave 3) adolescent questionnaire: item completion by topic.

Full questionnaire completion at baseline was 50%, rising to 60% at first follow-up, increasing further still to 80% at second follow-up. Reasons for non-completion include unexpectedly short or interrupted questionnaire sessions; random sampling of streamed lower ability groups; higher levels of special educational needs; and lower than anticipated levels of literacy or English-language skills.

In order to invite parents/carers to participate in the study, we asked each adolescent participant for their home address. Overall, 88.8% of participants provided a valid home address at baseline. Addresses at first and second follow-up were derived by reconciling previous addresses with new details contained in the more recent follow-up questionnaires. This yielded addresses for 88.1% of participants at the first follow-up and for 86.7% at the second follow-up.

Parents/carers were also sent a letter of invitation describing the study’s aims and requesting participation in a doorstep interview. Those who did not wish to participate were asked to e-mail or ring the telephone number provided. If parents/carers did not opt out within 2 weeks of receiving the invitation, they were included in the doorstep interview schedule. Up to seven attempts to gain an interview were made before the participant was classified as a non-responder. Parents/carers were given the opportunity to refuse participation when first contacted by the market research fieldworkers and at any point during or after completion of the interview. Interviews were anonymised and parents/carers were linked to the relevant child.

Parent/carer interviews started in April 2012 and were completed by 27 July 2012. A market research agency administered the 35-minute face-to-face computer-assisted personal interview to consenting parents/carers and interviews were carried out at the parent/carer’s home address. To overcome any potential language problems, the parent/carer survey was translated into two of the most common non-English languages within the local community, namely Urdu and Bengali. Interviewers with particular language skills were allocated to specific participants, when required. All interviews were completed and had no missing data. The response rates were 60% at baseline, 51% at wave 2 and 57% at wave 3.

Data processing

Survey data entry was performed by an external agency with extensive experience in generating data files for longitudinal cohort studies. Variable names and coding structures were devised by the ORiEL research team and were implemented by the data entry contractor. Questionnaire data were double-punched and cleaned using range, consistency and logic checks. In a limited number of cases, the data were manually cleaned by ORiEL research staff when it was unclear to the third party what the correct coding should be.

Participants were allocated a unique identifier to allow us to track cohort members across waves while continuing to anonymise questionnaires. Adolescent and parent/carer names and addresses were stored separately from each other on encrypted USB drives. These were accessible by a single data custodian and were linked only temporarily by a unique identification number to produce lists of participants who were eligible for follow-up.

Environmental exposures and spatial data

Urban regeneration programmes related to the London 2012 Olympics were hypothesised to modify the built environment characteristics relevant to health either directly or indirectly. We therefore assessed whether or not environmental factors might be associated with health outcomes and behaviours at baseline and whether or not exposure to these environmental risks changed over the duration of our study.

All environmental and spatial data were obtained from a range of providers including local authority registers for food and alcohol, Transport for London, Ordnance Survey (OS) MasterMap, GiGL (Greenspace Information for Greater London) and Sport England. For further details, including information on the sourcing of all environmental data used within the study, see Appendix 4.

All data were cleaned and de-duplicated. A 10% random sample of environmental data for the food and alcohol establishments was selected and validated against Google StreetView.

We used ArcGIS, a geographical information system (GIS),66 to compute exposure to environmental risks. We identified five domains of environmental exposures that were relevant to the study:

-

the food environment

-

the alcohol environment

-

green space

-

sporting and recreation facilities

-

walkability.

In this report, owing to limitations of space, we focus our analyses on the main environmental exposures of interest that were hypothesised to be relevant to our primary outcomes and were most likely to change over the course of the study: green space and sporting and recreation facilities (see Chapter 4).

Environmental exposures: metric construction

In this study we use three distinct approaches to characterising environmental exposures: (1) proximity-based measures, (2) density-based measures and (3) ‘egocentric’ measures. A description of these is provided below.

Proximity-based measures

Proximity to the nearest environmental resource is estimated according to the shortest path distance in metres on the road network. The road network is given by the OS survey MasterMap Integrated Transport Network. The resolution of the distance, in all but a small number of cases, is address-point to address-point. For an aggregate of environmental resource types, the minimum distance for those types represents the shortest distance to a member of that aggregate class. Metric creation used the Esri ArcGIS version 10.3 network (Esri, Redlands, CA, USA) analyst extension.

Proximity measures were created for food establishments, premises selling alcohol, green spaces (access points), and sports and recreation facilities.

Density-based measures

An adaptive kernel density estimation (aKDE) approach is used to compute density surfaces covering the study area for which comprehensive point location data have been collected. The aKDE is carried out in the R package (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) sparr (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/sparr/sparr.pdf); map outputs have a cell size of 25 m, and intensity values indicate the estimated relative density of a given environmental resource type per km2 for the area covered by a given cell.

We used aKDE, as opposed to the standard fixed-bandwidth kernel density estimation, owing to the highly clustered nature of observations within the various environmental resource data sets. A fixed bandwidth approach would probably produce unsatisfactory results, over-smoothing areas with high resource numbers and under-smoothing areas with low numbers, resulting in a density surface that inadequately captures variation in density. An adaptive approach better preserves the locally varying densities across the study area.

The aKDE method computes a density based upon a Gaussian (normal) kernel, and employs adaptive smoothing on the basis of a ‘pilot bandwidth’. Fitting a locally adaptive kernel is an optimisation problem; the use of a pilot bandwidth simply acts to help limit the size of the bandwidth to within realistic bounds. The pilot bandwidth is first calculated in sparr using leave-one-out least-squares cross-validation (LSCV). In practice, this method can be unreliable for computing fixed bandwidths and has a tendency towards conservative estimates that over-smooth spatial data. However, as pilot bandwidth inputs for aKDE, they are effective at narrowing the search space so that a density surface can be computed in a reasonable time.

Density-based measures better represent the local availability of environmental resources than do proximity-based measures, although the two are closely related. Density-based measures incorporate the combined effect of all nearby resources, whereas proximity-based measures generally restrict investigation to the nearest resource, or the nearest k resources.

A density value representing environmental resources of different types per km2 was calculated for each respondent, and for each environmental resource type. Density values were summed within environmental themes (e.g. food environment, alcohol environment) in order to provide a density for a chosen aggregate of resource types within that environment theme.

Metric creation used the ESRI’s ArcGIS version 10.3 spatial analyst extension, and R version 3.0.2 with sparr 0.3–4, and spatstat 1.36–0. 67

Density-based measures were created for food establishments, premises selling alcohol, and sports and recreation facilities. Density-based measures could not be created for green-space access as it is not possible to compute a kernel density value for polygon data.

Egocentric measures

An egocentric residential neighbourhood is created for each study respondent based on an 800-m road network buffer, using the same reference data as the proximity-based measure. This distance is widely used in epidemiological literature as representing the 10-minute walking distance of an average person, and is therefore said to represent the likely extent of the immediate residential neighbourhood. 68

Using respondent home address, we computed a set of bespoke neighbourhood buffers for each ORiEL respondent. We counted the occurrences of each environmental resource that fell within each buffer to measure how many resources an individual can reach for a given egocentric neighbourhood. When green space is concerned, we count the number of access points for distinct green spaces that are contained within each egocentric neighbourhood (e.g. parks), avoiding the repeated count of the same green space if an individual can access more than one entrance point.

Egocentric neighbourhoods also underlie the creation of the walkability index. All the components of walkability are captured subject to the 800-m network buffer. We used the egocentric neighbourhood as a ‘cookie cutter’ in order to compute the denominators for each walkability component as follows:

-

Residential density is computed as the count of domestic addresses as a ratio of the area of residential building footprints within each egocentric 800-m neighbourhood.

-

Intersection density is computed as the count of junctions connected to three or more edges (loosely, streets) as a ratio of the kilometres of road within each egocentric 800-m neighbourhood.

-

Land use mix is computed using the normalised Shannon entropy formula69 for each egocentric neighbourhood, which effectively measures the evenness with which the three categories are distributed within the 800-m buffer. Residential, office and commercial land uses are computed as proportions of combined land use based on the building footprint area of buildings belonging to each category. Assigning building footprints to office, commercial or residential usage is done using the National Land Use Database classification implemented in the OS MasterMap AddressLayer 2 data.

Metric creation used the ESRI’s ArcGIS version 10.3 network, including the network analyst extension.

Egocentric measures were created for food establishments, premises selling alcohol, green spaces (access points to green spaces), sports and recreation facilities, and walkability.

Further details of analyses can be found in the relevant results chapters.

General approach to analysis

Many different quantitative analyses are summarised in this report. Further details on specific analyses can be found in the relevant chapters or in previously published papers. These are signposted in the text. Our overall approach was to use regression modelling to estimate associations between our dependent and independent variables, adjusting for hypothesised confounders. We employed a range of approaches including linear, logistic and multilevel regression depending on the data structure and outcomes under investigation. Some models were stratified by a priori effect modifiers, a key example being gender for analyses with physical activity as the main outcome. Multiple imputation was used to impute missing data (see the methods sections in each specific results chapter for further details) for the adolescent data set. There were no missing data in the parent or carer data set.

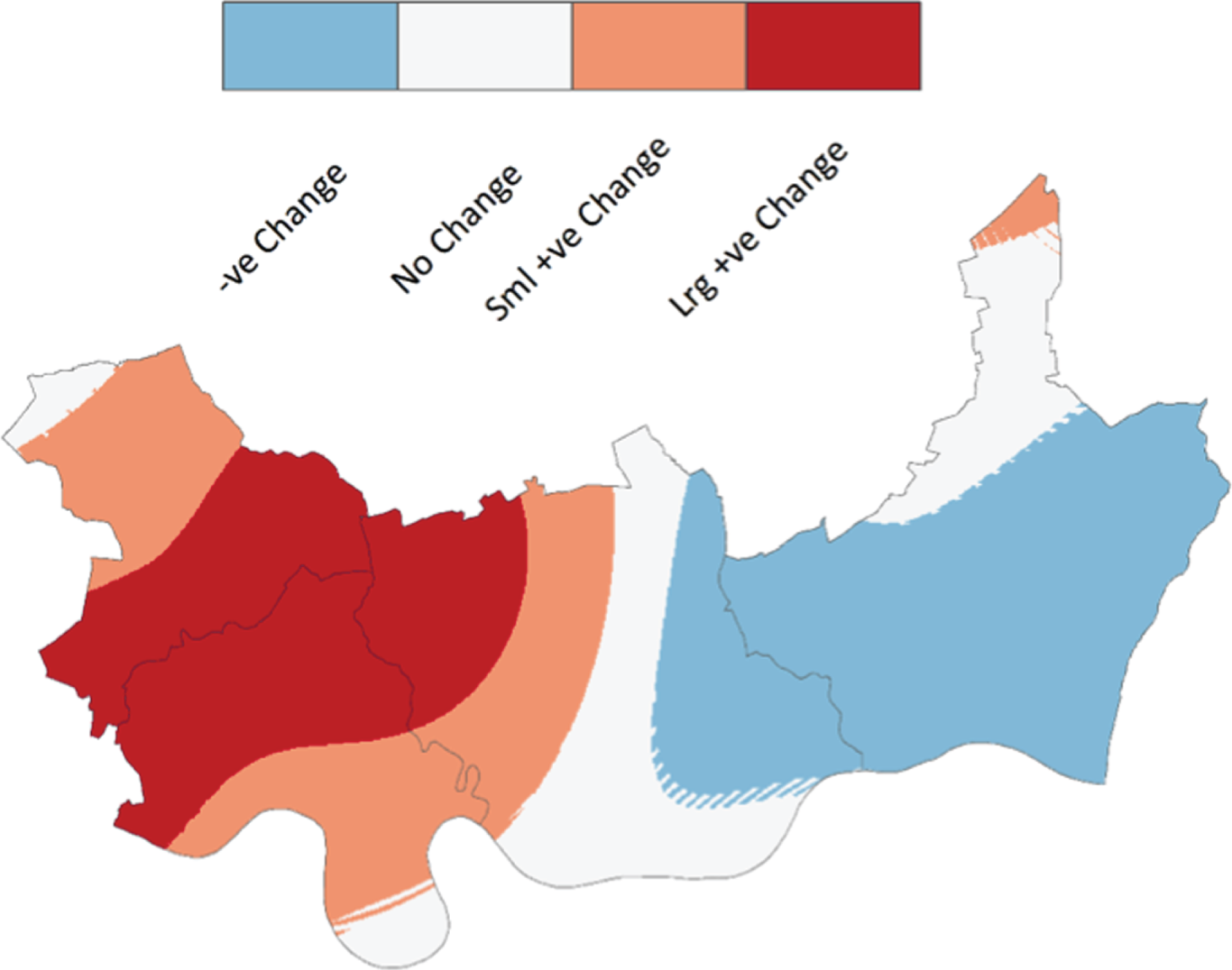

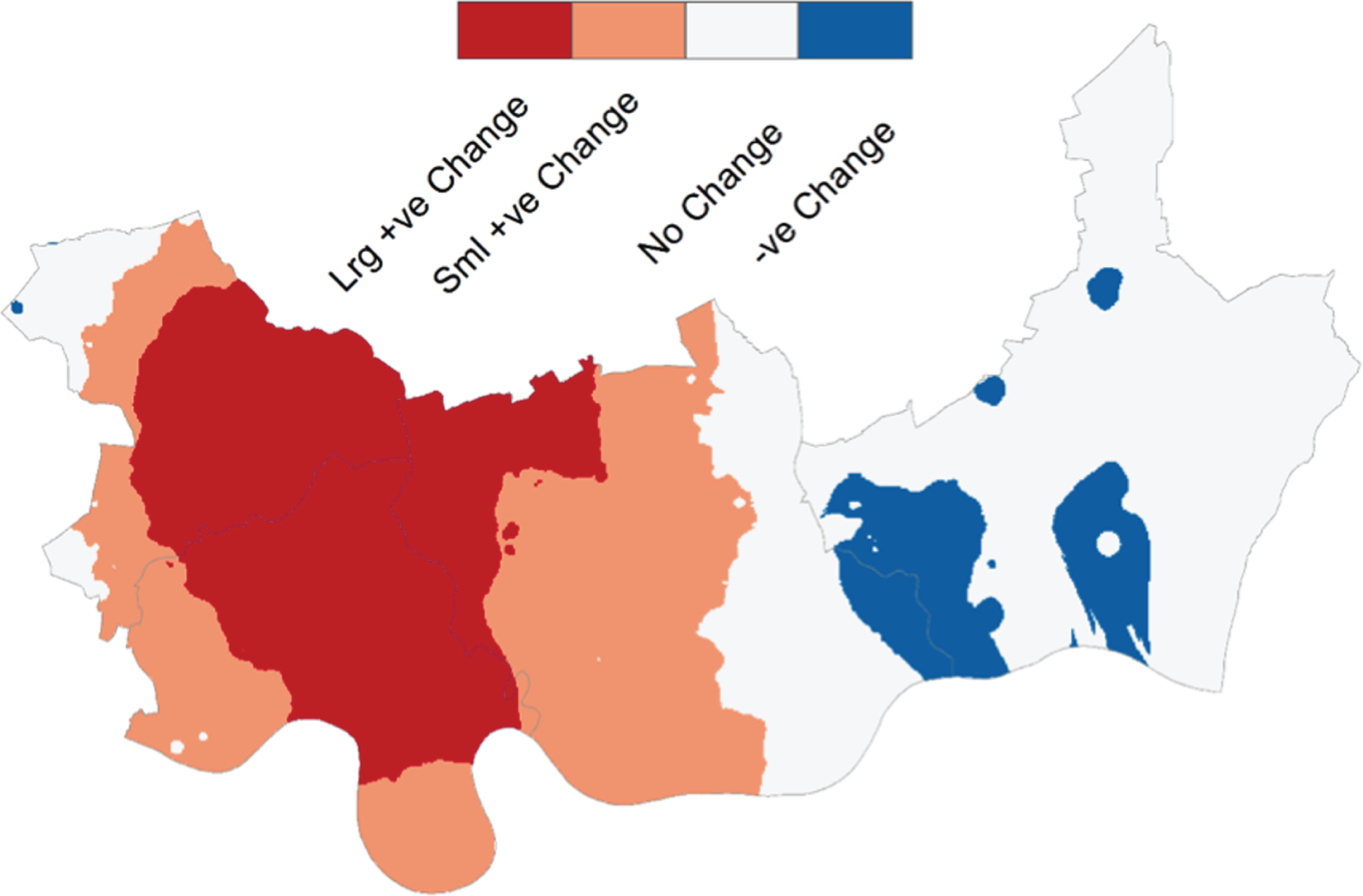

Intervention and comparison groups

Participants residing within Newham at baseline and subsequent waves of the study were considered to have received a greater ‘dose’ of urban regeneration. Participants residing in Barking and Dagenham, Hackney and Tower Hamlets at baseline and subsequent waves of the study were considered not to have received urban regeneration (or not such a strong dose of regeneration) and, therefore, formed the comparison group.

At baseline, participants were asked to give consent to be followed up even if they moved during the lifetime of the study. Pupils who moved to attend a different school already participating in the ORiEL study were followed up at their new school when possible. When pupils moved outside the study schools, these were no longer followed up as the administration cost involved was considered too high given the relatively small numbers involved. Very few participants moved schools across the waves, so an intent-to-treat (ITT) approach was taken for the analyses, based on the following approach. All participants are analysed as if they had remained living in the same borough that they lived in at baseline for subsequent waves.

This therefore involved analysis of the change in well-being, mental health and physical activity before the Olympics, 6 months after the Olympics and 18 months after the Olympics for Newham, compared with Tower Hamlets, Barking and Dagenham, and Hackney, using all those who took part at baseline. Some individuals may have moved boroughs during the project, swapping from control to intervention school, from intervention to control school, from one control school to another, or from one intervention school to another. More simply, they may have dropped out or moved out of the area completely. The ITT approach does not take into account any movement between schools or drop out after baseline. ITT is the typical approach taken in randomised controlled trials, based on the argument that it preserves randomisation. Alongside ITT, other sensitivity analyses were conducted and compared.

Attrition and missing data

Participant non-response was present in individual questionnaire items and by wave, introducing attrition. Attrition was explored through missing data patterns and logistic regression, investigating predictors of missingness by wave. Missingness by wave was not found to be associated with any predictors and supported the assumption that attrition followed a missing completely at random (MCAR) mechanism. With a MCAR mechanism we were able to create a non-biased cohort of adolescents present at all three waves.

For each analysis, the missing data mechanism was explored for individual questionnaire items. We found no violations against the assumption that the missing data mechanism is missing at random (MAR). Data were imputed using multiple imputation to gain statistical power, and sensitivity analysis was explored to check if inferences were robust to the MAR assumption. The imputation methodology used in each analysis is described in more detail in each of the results chapters.

Weighting

Design weights have been derived to address over- or under-sampling of specific cases or for disproportionate stratification and sample clustering. These weights are used when we want the sample under investigation to be representative of the population. Design weights are used in analyses in which clustering is considered a nuisance to be controlled for. When clustering or area effects are a point of interest, then a hierarchical multilevel model has been used to estimate these effects. Non-response weights for the data sets are not necessary; rather, we have adjusted our models for a range of covariates known to predict non-response such as age, gender and ethnicity.

Methods: qualitative study

The qualitative component of the ORiEL study aimed to examine local perceptions and experiences of the Olympic event and associated regeneration. This primarily consisted of an in-depth longitudinal qualitative study of family experiences and perceptions of the London 2012 Games and associated regeneration in Newham, the main Olympic borough. This entailed two waves of qualitative data collection, with the first period of fieldwork commencing immediately after the Games (2012) and the second wave a year later (2013). Here we describe data collection and our overall approach to analysis.

Recruitment and sampling

The qualitative sample comprised both a family sample and an adolescent sample. At wave 1 a total of 66 participants took part (Table 5). At wave 2 this fell to 40.

| Participants | Characteristic | Number of participants |

|---|---|---|

| Adult core participants (20 in total) | Sex | |

| Male | 8 | |

| Female | 12 | |

| Age (years) | ||

| Range | 20–55 | |

| Median | 40.5 | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White British | 5 | |

| White other | 3 | |

| Black African | 4 | |

| Black British | 1 | |

| Indian | 1 | |

| Pakistani | 1 | |

| Bangladeshi | 1 | |

| Asian British | 2 | |

| Asian other | 1 | |

| Mixed | 1 | |

|

Those also in attendance at family narrative interviews (1) young people (19 in total) |

Sex | |

| Male | 10 | |

| Female | 9 | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 12 | 10 | |

| 13 | 6 | |

| 15 | 2 | |

| 16 | 1 | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White British | 4 | |

| Black African | 3 | |

| Black British | 1 | |

| Indian | 2 | |

| Pakistani | 1 | |

| Bangladeshi | 1 | |

| Asian British | 2 | |

| Asian other | 2 | |

| Mixed | 3 | |

| (2) adults (1 in total) | Sex | |

| Female | 1 | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 45 | 1 | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Asian other | 1 | |

| Adolescent core participants (26 in total) | Sex | |

| Male | 12 | |

| Female | 14 | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 12 | 13 | |

| 13 | 7 | |

| 14 | 4 | |

| 15 | 2 | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White British | 8 | |

| White other | 6 | |

| Black African | 3 | |

| Black British | 1 | |

| Indian | 2 | |

| Pakistani | 2 | |

| Asian British | 2 | |

| Mixed | 2 | |

Family sample

Participants were recruited via the parent/carer quantitative survey. We wrote to all survey participants who had indicated that they were willing to be contacted again with a view to participating in further research. These letters were followed up with a telephone call inviting them to participate in the qualitative study. In total, 130 people were contacted in this way, of whom 20 made themselves available for interview at wave 1. We asked that these core participants invite other members of their household to participate in interviews as they saw fit. In all, an additional 19 young people and one spouse also took part. At wave 2 this fell to 15 core participants and an additional 13 of their family members.

Adolescent sample

In total, 26 adolescent core participants (12 boys and 14 girls) were recruited from three participating schools at wave 1 (two in Newham and a pilot in a neighbouring borough). School contacts, who served as gatekeepers for qualitative recruitment, were each asked to select up to nine students from their year 8 and 9 cohorts to participate in a half-day video focus group workshop. At wave 2 the pilot school dropped out and a total of 12 adolescents participated in the focus group workshops.

Data collection

Data were collected in three phases, with the same data collection activities used at both waves:

-

family narrative interviews with the family sample

-

go-along interviews with a subset of the family sample

-

school video focus group workshops with the adolescent sample.

Family narrative interviews

A family narrative interview was conducted with each of the families. The typical format for this was an interview with a parent/carer (core participant recruited from the adult survey) and their children. However, adult participants often invited other family members to participate, and sometimes the other family members decided themselves to join in. Two of the adult participants wanted to be interviewed alone without any other family members present. At wave 1, participants were asked to provide a narrative account of their experience of the Games and whether or not they felt that it affected them personally. The interview then moved on to focus on what had changed in their local area and daily life, and how they perceived their neighbourhood. At wave 2, we asked the families to revisit their original narratives and update us on events between waves. These interviews provided insight into how the Games were experienced as a spectacle in their own right and how participants positioned the Games and regeneration in relation to their own lives, trajectories and local areas.

Go-along interviews

A go-along interview is a mixture of observation and interview concentrated around a particular site, journey or activity. 70 The researcher can accompany the participant(s) on a routine journey or activity to a specific place or request that the participant give them a ‘tour’ of part of their familial environment. In this way the interviews can provide direct experience of the natural habitats of informants, and access to their practices and perceptions as they unfold in real time and space. 71 The accounts and narratives made by all participants in the preceding family interviews (described above) were extended in the go-along interviews with the aim of understanding how participants experienced these sites and how they related them to their own lives and practices.

School video focus group workshops

Half-day workshops were organised with three participating schools. Focus groups were used because these interviews generate rich information within a social context in which interaction between participants can reveal cultural values and group norms that may not arise in individual interviews. 72 The first half of the sessions was a focus group interview on participants’ perceptions and experiences of the Games and of their local neighbourhoods, followed by small group work in which students were split into groups and given the task of interviewing each other about aspects of neighbourhood experience arising from the focus group discussion. Safety and crime was a popular choice of topic for participants. The sessions were video recorded so that they could be viewed by these participants at the next wave of data collection and serve as a prompt for reflection and discussion. At wave 2 we showed the participants clips from wave 1 and asked them to update us and reflect on their contributions to the previous wave.

Ethics and informed consent

All parent/carer core participants (family sample) were provided with a study information sheet, a consent form, and a verbal explanation of what would happen to their data and of their right to withdraw at any time. It was also explained to them that other members of the household could participate in the narrative family interviews and go-along interviews at their discretion. In the case of the video focus group workshops, contact teachers were given opt-out parental/carer consent forms and information sheets to send out to the parents/carers of those adolescents they selected to participate. At the outset of the workshop sessions, separate consent forms and information sheets were distributed to deal with both the interview data and the video footage. It was explained to participants that their data would be anonymised and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. We also provided contact details should the participants wish to ask further questions of the research team. Full ethics approval for the qualitative study was obtained from the Queen Mary Research Ethics Committee.

Data analysis

Transcripts were analysed verbatim and were used to facilitate a narrative analysis of the whole data set for each sample (family and adolescent). Narrative approaches are particularly useful for understanding lived experiences of health because they examine how social conditions are perceived and handled and, thereby, how they constrain the freedom of individuals to act in such ways that these conditions could be transformed or avoided. 73 By analysing the data in this way, the researchers can examine how individuals interpret biographical experiences, and broader social trends and events, such as the Olympic Games, and how they position themselves in relation to them. It is the interpretation expressed by the participant that is important, namely how they explain their circumstances and account for their behaviours and perceptions, and how they construct narratives in analytically persuasive ways. 73

NVivo 9 (QSR International UK, Daresbury, Cheshire, UK) software was used to facilitate a qualitative longitudinal analysis of the data set. The aim of the analysis was to investigate the lived experiences of the social determinants of health and how these may have changed in the year after the Olympic Games. In order to understand the causal processes by which social conditions (such as housing) shape health, it is necessary to examine both how social conditions are perceived and how they constrain the freedom of individuals to act in such ways that these conditions could be transformed or avoided. 73 Data from all elements of the qualitative work were combined for analysis. As a result, the qualitative data set was large and multimodal, comprising a total of 632 pages of transcribed interviews, 38 pages of field notes and 211 minutes of video-recording. The stages of the analysis were as follows:

-

thematic coding of the whole data set

-

identification of narrative episodes and the production of a list of core narratives for comparison across waves

-

identifying and describing the progression and sequencing of themes into narrative sense-making within these episodes

-

tracking the changes and continuities of the conceptual categories and substantive content of personal narratives between waves

-

examining the way in which individuals deploy wider cultural discourses within their personal narratives74 and draw upon shared meanings. 74

Feedback for participants

For both arms of the study newsletters were produced annually to inform participants and schools of the emerging findings of the study. In addition, we volunteered to undertake masterclasses on social research methods for schools with a sixth form and produced certificates for schools that recognised their participation in the study.

Ethics approval

Overall, the study operated to the highest ethics standards and the study gained approval from the Queen Mary University of London Ethics Committee (QMREC2011/40), the Association of Directors of Children’s Services (RGE110927) and the London Boroughs Research Governance Framework (CERGF113).

Chapter 3 Social patterning of health and well-being in the ORiEL study

In the previous chapter we described the general methodological approach to this study and the data collected. In this chapter, we describe the patterning of our key primary health and well-being outcomes, for both adolescents and their parents/carers, with the aim of exploring and describing social inequalities in health in these groups within our baseline data. To do this, and for reasons of space, we focused on two key sets of outcomes: (1) the social patterning of physical activity and mental health for adolescents, and (2) the social patterning of employment for parents and carers.

Individual sociodemographic factors and perceptions of the environment as determinants of inequalities in adolescent physical and psychological health

In this section we describe the social patterning of health and well-being in the baseline survey of adolescents in the study. We explore associations between demographic, socioeconomic and environmental factors and physical/sedentary activity, physical health and psychological well-being. Full results can be found in Smith et al. 75

Methods

Results from the cross-sectional baseline survey are presented here and come from 3105 adolescents in year 7 of secondary school (aged 11–12 years) who completed a paper-based questionnaire during the 6 months (January to July 2012) prior to the start of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Outcome measures

As described in Chapter 2, validated instruments were deployed to assess a range of health outcomes. The main items of interest for this analysis were mental well-being, depression, physical activity and sedentary behaviour, self-rated health and long-term illness or disability. These were operationalised as described in the following sections.

Mental well-being

Mental well-being was assessed using the WEMWBS. 28 This is a positively worded 14-point scale with five response categories capturing eudaimonic and hedonic perspectives of positive mental health. The total score ranges from 14 (lowest well-being) to 70 (highest well-being) and is reported as a mean value within groups. It has been validated in adolescents29 and cross-culturally,30 and was introduced as a core module to the nationally representative Health Survey for England in 2010. 43

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were investigated using the SMFQ. 31 This is a validated 13-item short form of the 32-item MFQ scored on a three-point scale of ‘true’, ‘sometimes true’ or ‘not true’. Scores range between 0 and 26, with total score of 8 or more indicating depressive symptoms.

Physical activity and sedentary behaviour

This was estimated using the self-reported Y-PAQ. 39 This questionnaire assesses the accumulated time spent physically active or sedentary, respectively, over the previous 7 days outside school. The total time spent physically active in recreational games and sports outside school was derived. Conversely, the total time involved in sedentary activities, including screen time, was also estimated for outside school. Individuals reporting > 75 hours of total activity per week (outside school) were excluded from the analysis because of probable over-reporting of time.

Self-rated health

Participants were asked to rate their own health in general and responses were dichotomised to fair/poor/very poor as opposed to good/very good. 44

Long-term illness or disability

Long-term illness or disability was defined as a health problem that has troubled the participant over a period of time, or that is likely to affect the participant over a period of time. 45 Examples included asthma, anaemia, eczema, type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, hearing and eyesight problems, and chronic fatigue syndrome.

Individual demographic, social and environmental factors

The distribution of health outcomes described above was explored across a range of individual demographic and household socioeconomic indicators as well as by individual perceptions of the local environment. These were are described in the following sections.

Demographic indicators

These included borough of residence, gender, ethnicity and whether or not the respondent was born in the UK. Self-reported ethnicity used the wording and adapted categories of the England and Wales census 2011. 40 These sample-specific and age-appropriate categories were derived via extensive piloting to capture the characteristics of the highly ethnically diverse sample in east London. The analysis includes the seven largest groups in the study, namely white UK, white mixed (‘white UK and any other background’), Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, black Caribbean and black African. All other ethnic minority groups collapsed to the other category for analysis by health outcome.

Socioeconomic indicators

Adolescents were asked whether or not their parents/carers ‘had a job’ to determine if both parents/carers were not in paid employment (unemployed), if one parent was not in paid employment (one employed), if both were in paid employment (both employed) or if they were cared for by a lone parent carer in paid employment (lone parent employed) or a lone parent carer who was not employed (lone parent unemployed). Household socioeconomic circumstances were quantified by the FAS. 26 This four-item scale has been validated in young people cross-nationally26 and is predictive of physical activity and self-reported general and mental health. Adolescents were additionally asked whether or not they were in receipt of means-tested free school meals.

Perceptions of the environment

Adolescents were asked for their perception of their local neighbourhood, defined as the area they could walk to within 15 minutes from their house, using selected domains from an adapted and age-appropriate ALPHA questionnaire. 49 Statements about perceptions of neighbourhood safety, aesthetics and walkability/cycleability were rated on a four-point scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) with an additional domain asking how near in minutes participants lived to a range of businesses or services. Owing to a positively skewed distribution of the summed scores, all four domains were split into tertiles representing a relatively positive, mixed or negative perception of each environmental characteristic.

Statistical analysis

Analyses presented here were completed using Stata 13.1 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA). There are four stages to the analysis. The first stage uses the total sample available for each outcome to estimate the unadjusted mean mental well-being total score, mean total time spent in physical/sedentary activity, and the proportion self-reporting fair/(very) poor general health, long-term illness and depressive symptoms for all participating adolescents across the range of demographic, socioeconomic and environmental indicators. An unpaired t-test (for mean outcomes) or logistic regression (for binary outcomes) was used to test for significant differences between subcategories of covariates. The second stage repeated this analysis using a complete-case sample for each outcome. In the third stage, the prevalence of each outcome was then fully adjusted for all demographic, socioeconomic and environmental factors using a complete-case mixed-effects linear regression and a logistical (logit) regression model to account for clustering at the school level. Likelihood ratio tests were used to assess whether or not the variance for each outcome was attributable to the clustering effect within schools. Finally, the relationship between all health outcomes was examined using mixed-effects logistic and linear regression to account for clustering, adjusted for gender, country of birth, ethnicity, borough, parental carer employment, family affluence and all neighbourhood characteristics.

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics of the ORiEL baseline sample were broadly similar to a cohort of similar ages observed at the most recent 2011 census with some exceptions (see Table 3 for a description). Overall, the response rate was 87% (n = 3105 in school year 7). The archived study sample can be estimated at approximately 25% of the entire age group attending state schools in the catchment areas (n = 12,136 in school year 6).