Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 13/90/16. The contractual start date was in April 2015. The final report began editorial review in December 2017 and was accepted for publication in April 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rona Campbell is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research Funding Board and is a NIHR Senior Investigator. Russell Jago is a member of the NIHR Public Health Research Board. William Hollingworth is a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Sebire et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Physical activity among girls

Physical activity (PA) in adulthood is associated with a reduced risk of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes mellitus and all-cause mortality. 1 Being physically active in childhood has been associated with lower levels of cholesterol and blood lipids and favourable blood pressure and body composition. 2 Sedentary behaviour in children and adolescents has been associated with adiposity3 and insulin resistance,4 both markers of metabolic syndrome. 5 PA is also associated with adolescent mental health and well-being, including improved self-esteem,6 self-image,7 lower levels of stress8 and academic performance. 9 Despite the benefits, girls are less active than boys at all ages,10–12 the age-related decline in girls’ PA levels (7% per year) being greater and occurring at younger ages than for boys (5% per year). 13 A recent study reported that 68% of girls aged 15 years in the UK accumulated less than the recommended minimum of 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per day. 14 As PA tracks moderately from adolescence into adulthood,15 increasing PA levels, especially among girls, is important.

Several psychosocial factors underpin girls’ PA including enjoyment, perceived competence, self-efficacy and physical self-perceptions. 16 Findings from qualitative studies suggest that changes to friendship groups, peer support, perceived competence, competing priorities, self-presentational concerns and ‘sporty’ gender stereotypes experienced during the transition from primary to secondary school may contribute to the observed decline in girls’ PA. 17–19 PA interventions aimed at young girls have produced small positive effects, the effect being larger for interventions that targeted girls only (vs. those that targeted girls and boys) and that used multifaceted designs and educational content. 20 The promotion of young people’s health in schools is a public health priority,21 it is easier to recruit through schools, and school-based interventions can have broad reach over time. However, a recent meta-analysis22 of school-based interventions, which used objective measures of PA in adolescents, found weak evidence for small effects (a standardised mean difference of 0.02 for total activity and 0.24 for MVPA). These interventions comprised traditional top-down strategies including activity breaks in class, health education/information provision, extra physical education (PE) lessons and pedometer-based self-monitoring.

The Physical Activity 4 Everyone multicomponent school-based intervention in Australia23 increased adolescents’ MVPA by 7 minutes [95% confidence interval (CI) 2.7 to 11.4 minutes; p = 0.002] at 2 years of follow-up compared with controls. However, the intervention was more effective in boys (10-minute increase) than in girls (4-minute increase), resource heavy (e.g. providing an expert health and PE teacher to each school 1 day per week) and expensive (£227 per student, £33 per minute of MVPA). 24 To achieve a population-level increase in girls’ activity, more cost-effective and scalable approaches are needed. The evidence suggests that, by focusing school-based interventions on top-down provision of education and short-term structured PA,25 the potential power of peers to influence girls’ activity has been underutilised. New creative ideas are needed that take advantage of the complexity of the system surrounding girls’ PA, such as their peer groups.

Peers and physical activity

A 2012 systematic review26 identified six ways in which peers can influence PA: peer social support, presence of peers during PA, peer norms (one study), friendship quality, peer affiliation to certain groups and peer victimisation (i.e. being the subject of aggressive behaviour). Consistent positive associations were found between peer support, the presence of peers, peer norms, friendship quality and adolescent PA levels. 26 Social network research supports this, showing that adolescents have friends with similar PA levels and behaviours to themselves and that adolescents may moderate their PA behaviour over time to be more like that of their friends’. 27 Both systematic reviews support the view that peer-led interventions are a possible avenue to increasing adolescent PA. There is a need to capitalise on existing peer processes in schools by promoting peer support and enhancing peer communication skills, specifically among girls. 26

Peer-led health interventions

Peer-led interventions have targeted several health behaviours in young people including asthma, smoking, alcohol consumption and drug use, water versus sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, PA and sedentary behaviour. 28–31 The majority were delivered in secondary schools and trained peer leaders to formally educate younger peers using information provision and skill development. 32 Eight interventions were effective in changing a behavioural outcome, with three changing psychological mediators and the effects of two being less clear. A recent high-quality cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT),33 conducted in English secondary schools, of an intervention in which Year 9 students mentored Year 7 students in formal one-to-one meetings for 6 weeks did not increase the PA of Year 7 students (measured by accelerometery). Studies of peer-led PA interventions are limited by a lack of high-quality trial interventions. They do not consistently utilise behaviour change theory and peer-led intervention mechanisms limited to older students supporting younger students, and using formal methods (e.g. leading educational classes), which are time limited and intensive.

An alternative approach is to train peer supporters (PSs) to informally diffuse health promotion messages among their trusted peers. This is based on the diffusion of innovations (DOI) theory34 that conceptualises how ideas, beliefs or behaviours are informally communicated through members of a social system. The DOI approach was adopted in ASSIST (A Stop Smoking In Schools Trial), which included a process,35 economic36 and outcome28 evaluation.

To informally diffuse messages about the importance of not smoking for 10 weeks, ASSIST aimed to reduce smoking rates in secondary school-aged students and trained 15% of Year 8 students, who were identified by their year group peers as influential. The cluster RCT28 involved 10,730 12- to 13-year-olds in 59 schools across England and Wales. The training content aimed at increasing knowledge of smoking and its effects, to improve participants’ communication, negotiating, decision-making, empathy and group work skills.

ASSIST was effective in achieving a sustained reduction in the uptake of smoking 2 years after baseline. Students who received the intervention were less likely than those in the control condition to be smokers immediately after the intervention [odds ratio (OR) 0.75, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.01] and at 1 year (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.99) and 2 years of follow-up (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.01). 28,34 The economic evaluation of ASSIST showed that the intervention could be delivered at a ‘modest’ cost {mean total cost £5662 [standard deviation (SD) £1226] or £32 per student}. PS recruitment targets were met37 and attrition was low, with 87% of children (i.e. 816 out of 942 children) who were invited to be a PS being trained and carrying out their role. Attendance at follow-up sessions was high (> 86%). 38 Trainers noted that the training could be improved if the delivery pair had different delivery styles, expertise and experience. 37 PSs focused on their friends within their year group and tried to influence people they thought they could persuade not to take up the habit (as opposed to those already smoking). 38 Teachers believed that Year 8 was a suitable time for an intervention such as ASSIST to take place, as there are no examinations and the project complemented broader teaching (encouraging responsibility and promoting transferable skills). 39 These findings indicate that peer-led DOI-informed interventions can be effective in changing adolescent health behaviours.

The Activity and Healthy Eating in ADolescence (AHEAD) study40 tested the feasibility of the ASSIST model for preventing obesity in adolescents. The project was piloted and refined in one school before a feasibility study was conducted in six schools. The results showed that, although it was feasible to implement AHEAD, PSs found it hard to learn about both PA and healthy eating in appropriate detail to confidently support their peers. The intervention was resource and labour intensive and was, subsequently, relatively expensive. The AHEAD study was well received by participants, but ultimately showed no evidence of promise. 40 Learning from both ASSIST and the AHEAD study has informed the refinement of the Peer-Led physical Activity iNtervention for Adolescent girls (PLAN-A) intervention.

Theoretical background of the Peer-Led physical Activity iNtervention for Adolescent girls

Interventions that target theoretical mechanisms of behaviour change are likely to be more effective than those that do not. 41 However, few peer-led PA interventions explictly incorporate principles of commonly used behaviour change theories. 30 The present study combines two complementary theories: DOI34 and self-determination theory (SDT). 42 As a cornerstone of the study, DOI provides a framework for harnessing the influential capacities of change agents (e.g. Year 8 girls identified as opinion leaders by their peers) who can informally diffuse messages about being active among their peers and, in turn, influence changes in beliefs/attitudes that can change behaviours.

Self-determination theory concerns the personal and social conditions needed to foster high-quality and sustainable motivation for behaviours. Within SDT it is hypothesised that autonomous motivation for PA (based on authentic choices, inherent satisfaction or personal value) is associated with positive behavioural, affective and cognitive outcomes, whereas controlled motivation (based on guilt or compliance with others’ demands) undermines these outcomes. 43 Autonomous motivation is supported by the degree to which the social environment satisfies (and individuals perceive the satisfaction of) three psychological needs: autonomy, competence and relatedness. SDT has been applied extensively to research aimed at understanding motivation for PA among children and adolescents19,44,45 and used to guide PA interventions,46 including a peer-led PA intervention for older adults. 47

Research has identified positive associations between autonomous motivation and PA among secondary school-aged children48 and children’s positive affect, challenge-seeking48 and quality of life. 49 Furthermore, autonomous motivation is positively associated with psychological need satisfaction (i.e. greater perceptions of autonomy, competence and relatedness). 45,50 SDT is well suited to a peer-to-peer intervention because peers can create a social climate that can either undermine or facilitate their peers’ interest in, and levels of, PA. 30 They can also create health and affiliation motives, perceptions of competence, connectedness and social support and realistic choices and options of how to be physically active. 17,19 Further details of how SDT was incorporated into PLAN-A are shown in Chapter 2.

Overview of the Peer-Led physical Activity iNtervention for Adolescent girls

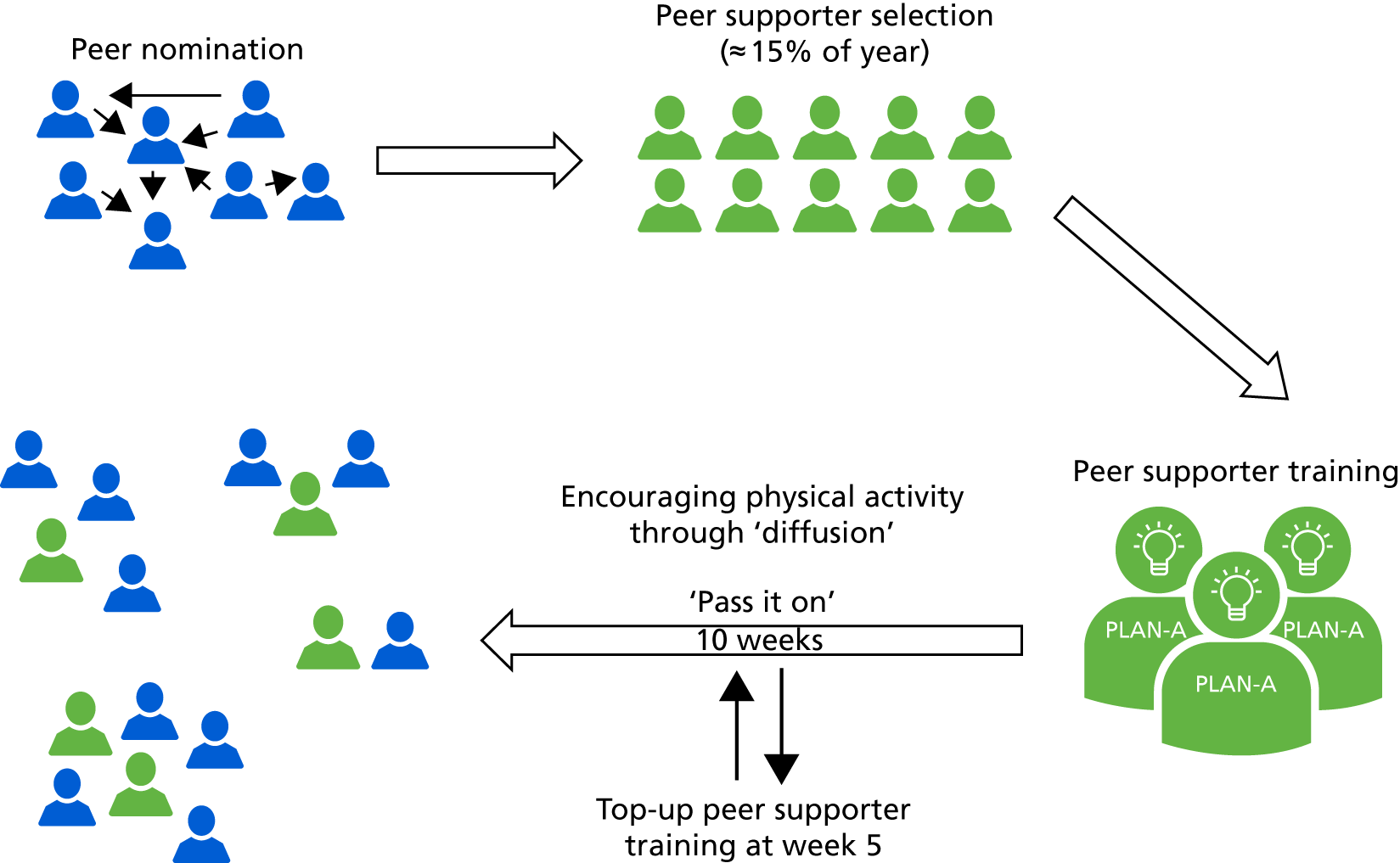

The ASSIST intervention model formed a template for PLAN-A (Figure 1). This was refined prior to piloting and feasibility testing. PSs were identified by Year 8 girls who nominated those they perceived to be influential in their school year. The highest scoring 18% were invited to be a PS, with the aim of ensuring that ≥ 15% became PSs. PSs attended a 2-day training course (plus a top-up day at week 5) to develop the skills, knowledge and confidence to promote PA among their peers. It should be noted that the ASSIST approach is to conduct four 1-hour in-school top-up training sessions with PS during the intervention period. However, feedback from stakeholders at the Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer)’s IMPACT (a not-for-profit company, with expertise in translation and impact of evidence-based public health and owners of ASSIST) and from teachers who had run ASSIST suggested that these sessions were poorly attended and lacked focus. As such, in PLAN-A these were replaced with a single day-long top-up day at week 5 of the intervention. External trainers, who had attended a 3-day training programme, delivered the PS training. The PS training was informed by phase 1 findings, was interactive and addressed issues central to girls’ PA. As previously discussed, the content was grounded in SDT. On completion of the training, PSs returned to school and informally promoted messages about increasing PA among their peers for 10 weeks. For details about the final intervention see Chapter 2, Description of the final intervention elements.

FIGURE 1.

The PLAN-A model.

Study aims and objectives

The study comprised two phases: phase 1, refinement and piloting and phase 2, a feasibility study.

Phase 1 objectives

-

Adapt and refine the ASSIST intervention to develop a PS training programme that focuses on promoting PA among Year 8 girls.

-

Develop an intervention logic model to refine in the feasibility trial.

Phase 2 objectives

-

Estimate the recruitment rate of PSs and non-PSs (NPSs), and monitor attendance at the PS training.

-

Qualitatively examine the acceptability of the intervention to students, trainers, schools and parents, and identify necessary refinements.

-

Report accelerometer and questionnaire data provision rates, examine data quality and explore the implications of missing accelerometer data in terms of how these data might be imputed in a definitive trial.

-

Estimate the potential effect of the intervention on daily accelerometer-derived MVPA and secondary PA-related and psychological variables immediately after the intervention (T1) and at 12 months after baseline (T2).

-

Estimate the school-related intraclass correlation (ICC) for daily MVPA.

-

Estimate the sample size for an adequately powered definitive trial evaluation.

-

Identify and test the feasibility of collecting the data needed to cost the intervention and conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis in a definitive trial.

-

Qualitatively examine parental views regarding allowing their child’s data to be used for data linkage with academic records kept by the National Pupil Database (NPD). Examine the completeness of data required to link participant data to educational attainment (via the NPD).

Progression criteria

The following criteria were established during protocol development and were used to inform on whether or not or how to proceed to a definitive trial:

-

Can we recruit trainers?

-

Is it feasible to implement the intervention in secondary schools?

-

Were the training and materials for the trainers and PSs acceptable?

-

Was the intervention acceptable to schools?

-

Were trial design and methods acceptable?

-

Does the intervention show evidence of promise to positively influence the proposed primary outcome (i.e. weekday MVPA)?

-

Indications of affordability and cost-effectiveness for local authorities.

-

Is there a positive view about data linkage from stakeholders involved (parents, schools, data custodians)? (See Chapter 3, Protocol amendments.)

Evidence of promise for weekday MVPA was a priori stated in the original trial protocol (version 1) as: ‘95% confidence intervals around the point estimate of the difference in means between trial arms on daily minutes in MVPA to include approximately 10-minute difference’.

Chapter 2 Phase 1: formative research and pilot study

Formative research

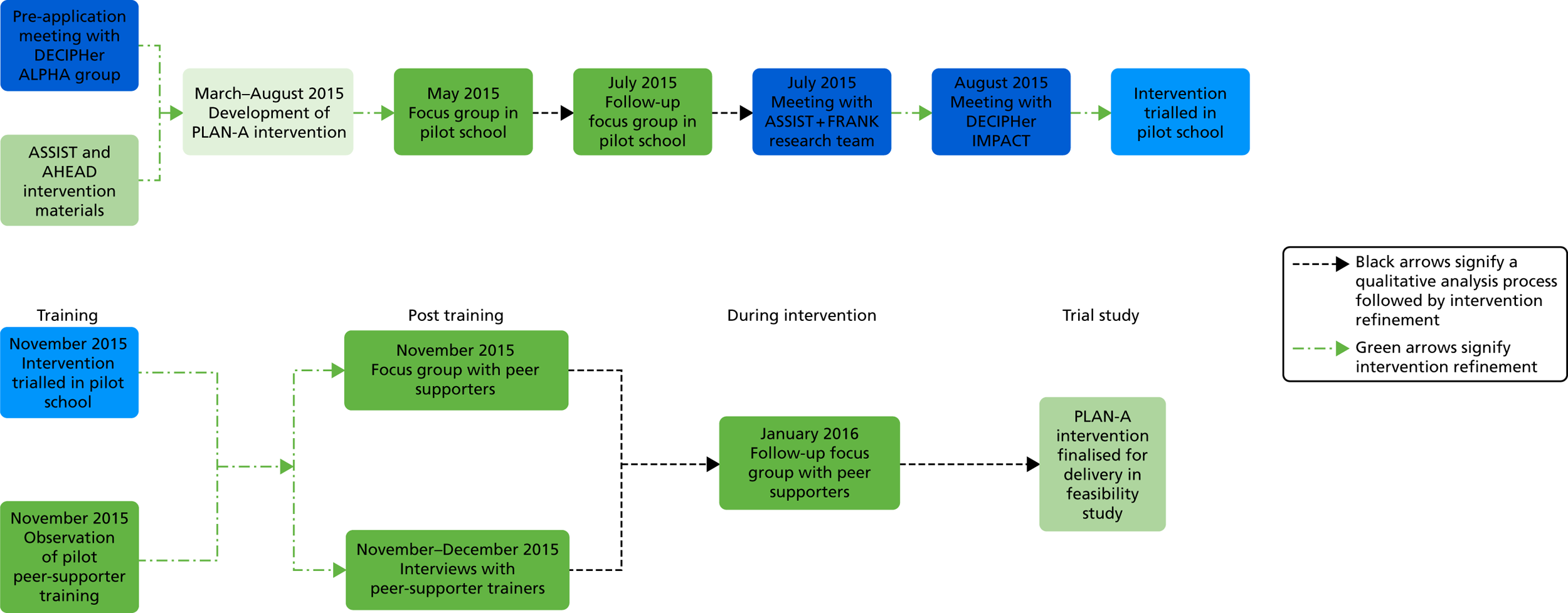

Formative research was conducted in 2015. The sequencing of phase 1 is shown in Figure 2; it comprised:

-

a focus group with the DECIPHer Advice Leading to Public Health Advancement (ALPHA) group (a research advisory group of young people) and an interview with a local secondary school teacher

-

a series of iterative focus groups with Year 8 girls in the pilot study school

-

sharing of practice and experience with the ASSIST+ FRANK51 team

-

a review of the proposed intervention by the chief operating officer of IMPACT.

FIGURE 2.

Sequence of phase 1 intervention refinement and piloting focus group with the DECIPHer ALPHA group.

The pilot study was granted ethics approval from the School for Policy Studies, University of Bristol (SPSREC14–15.A10) and was sponsored by the University of Bristol.

A semistructured focus group was conducted with six adolescent girls (aged 13–16 years) from the DECIPHer ALPHA public and patient involvement (PPI) group. A female PE teacher from a local secondary school was also interviewed. The focus group and interview were audio-recorded and the data were analysed using deductive thematic analysis using the question topics as a guide. 52 Table 1 shows the themes, summarised findings and the implications for the intervention design.

| Question topic | Findings | Implications for PLAN-A design |

|---|---|---|

| PS concept | Concept clear. Peers powerful in trends and PAa | Concept clear to Year 8 girlsa |

| Peer mentoring used in schoolsb | Schools open to peer mentoringa | |

| Supportive of 10-week intervention durationb | ||

| How to encourage PSs to participate | Sell the benefits (e.g. CV, certificates)a | Explore other benefits in phase 1 focus groupsa |

| Use videos from the pilot in recruitmenta | ||

| Refer to long-term benefitsa | Consider using videos of PSs from pilota | |

| Sign of kudos as nominated by peersb | ||

| PS training content and logistics | Off-site training and young adult female trainersa | Trainers and locationa |

| Consensus for girls only interventiona | ||

| Focus on health and not appearancea | Explore salient health messagesa | |

| Provide information on local PA opportunitiesa | ||

| Focus on PA primary–secondary transitionb | Identify local PA opportunitiesa | |

| Balance theory and practical learningb | ||

| PA terminology and how PA fits into the life of adolescents | Avoid complex terms, just talk normallya | Simplify termsa |

| Relate activity to Year 8 everyday lifea | Design activities to relate to Year 8 livesa | |

| Identify times for incidental PA (active travel)a | Peer education on incidental PAa | |

| Explore a day in the life of a Year 8 for PAa | ||

| Diffusing messages to peers | Peer supporting and compromise, not pressurea | Focus training on peers supporting, not ‘instructing’, and negotiation skillsa |

| Frame messages in Year 8 terms (e.g. ‘what are you doing tonight?’) to encourage PAa | ||

| Using social media | Support for Twitter (www.twitter.com; Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), Instagram (www.instagram.com; Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) (‘active selfies’) and Facebook page (www.facebook.com; Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA). Better than textinga,b | Integrate social mediaa |

| Research team–peer and peer–peer idea-sharinga | Facilitate photo-sharinga |

Recruitment and description of the pilot study school

One pilot school was identified by Wiltshire Council to be above the median of the Pupil Premium (i.e. relatively more deprived) and which would give a robust early test of the intervention. Recruitment materials were sent to the head teacher, who then delegated responsibility to a school contact (assistant leader in learning in PE). A school study agreement form was completed. The school (N = 1086, students; n = 70, Year 8 girls) was located in a medium-sized town. The school was given £500 as a thank you for participating.

Iterative focus groups: round 1

Methods

Two semistructured focus groups (n = 16 participants, eight per group; duration 61–66 minutes) were conducted by two facilitators in May 2015 to explore girls’ views on PA barriers, PS recruitment, logistics and content of PS training and use of social media. Focus groups were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis52 to generate themes pertaining to intervention design and refinement. All participants provided informed consent and were given a £5 voucher in recognition of their time.

Results

Findings are presented under two themes (Recruitment materials and Intervention content) alongside mapping in which the girls’ views were included in the intervention design.

Recruitment materials

Both focus groups suggested that PLAN-A recruitment materials should highlight how their participation in the project would (1) help their peers; (2) improve their own (and PS) skills and knowledge; and (3) increase their potential to influence their peers and have their voice heard. These themes should be reflected on the PLAN-A website and a video would be a good method of communication for girls their age. Both focus groups recommended that recruitment materials provided an insight into the PA training activities. Certificates, endorsements in records of achievement and/or PLAN-A-branded clothing were not viewed as suitable incentives to participate.

Intervention content

Well-being and feeling good about oneself were seen as key facilitators. Time constraints, lack of confidence, competence and being seen by boys when exercising were barriers.

The characteristics of a good PS included confidence, good communication and leadership skills and an ability to encourage others. Girls wanted confirmation at the point of peer nomination that the peers whom they nominate do not need to be their friends. The characteristics that participants thought the trainers should have included patience, fun, having good knowledge about PA and being genuine in their relationship with the girls.

Both groups recommended that games should not be too childish and suggested focusing on topics such as making PA fun, how to fit PA into their day, how much PA to do and how to be a PS. Participants also suggested including role-play, reaction test games and parachute games.

Participants’ concerns about being a PS included peers not listening or disagreeing with what they said, not knowing what to say, being judged and teased.

These findings were used to refine the intervention content, including draft recruitment materials, PS training timetable and study logos, that were then further explored from the user’s perspective in the second round of focus groups.

Iterative focus groups: round 2

Methods

Participants were the same girls who had participated in round 1. A topic guide was developed to explore girls’ preferences for the study logo, feedback on recruitment materials, the PS training timetable, how best to communicate with PSs (e.g. using e-mails), how to make training fun and engaging, and dealing with potential bullying. Focus groups were between 40 and 42 minutes in duration, they were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically, as in round 1. Participants were each given a £5 voucher.

Results

The findings are similarly organised into Recruitment materials and Intervention content themes.

Recruitment materials

Suggested revisions to the recruitment materials included having less text and more pictures, emphasising the fun side and benefits of the training, giving further details of what the PS training would entail and reiterating that PSs did not have to be good at sport. Participants selected a favourite logo and guided the colour and the tag line ‘peer-power active girls’.

Intervention content

Incorporating yoga was a considered a good idea, but the word ‘yoga’ may be off-putting to some. Key points for creating a fun atmosphere included a non-serious environment, playing music at times and preventing individuals from dominating discussions.

Participants suggested bean bag games and further creative tasks, such as poster-making. Although participants from both groups thought the term ‘energiser’ was appropriate for activities to refresh the group, one group suggested the term ‘circle time’ was childish. Participants had concerns about PSs receiving support via e-mail, including being e-mailed by ‘strangers’.

Participants were asked about receiving e-mails to remind them of the PS role. Platforms such as Facebook were popular but pupils reported that its use was not permitted within school, thus preventing a school-based project from endorsing its use. The idea of contact via short messaging service (SMS) text was not raised by the students, but was supported when prompted. However, some participants raised concerns about sharing their personal mobile number with the research team and being contacted by ‘strangers’ (i.e. members of the PLAN-A team/trainers). Students also demonstrated inconsistent use of school e-mail, with some not using it and others checking it only in information technology lessons. A common theme for e-mail and social media contact was that participants did not want to be contacted too frequently (e.g. every few weeks was suggested as suitable).

Summary

Phase 1 resulted in the co-production of the draft PLAN-A, which was taken forward to pilot testing. The ASSIST intervention framework was successfully blended with the views and preferences of the user group. A description of how these findings were incorporated in to the final intervention is presented in Appendix 1.

Pilot study

Aims and objectives

The objective of the pilot study was to test the student recruitment approach and rehearse the peer nomination and PS selection processes, train the trainers and test the PS training (see Chapter 2, Description of the final intervention elements for details). In evaluating the delivery and receipt of the pilot intervention to identify refinements, the process evaluation methods were also piloted.

Methods

School and participant recruitment

Recruitment of the pilot school is presented in Recruitment and description of the pilot study school. A recruitment briefing was given to all Year 8 girls (N = 70; a new Year 8 cohort not involved in the formative work) to introduce PLAN-A and explain the role of the pilot school. Students were invited to ask questions and received parent and child information packs (distributed to absent girls by the school contact). Parents signed an opt-out form if they did not wish their child to participate. Parents of PSs provided written informed consent for their daughters to attend the training and PSs provided assent.

Peer supporter nomination, selection and recruitment

All consenting students completed a peer nomination questionnaire. The analysis of peer nomination questionnaires and the selection of PSs was carried out in accordance with the PLAN-A peer nomination standard operating procedure (SOP). This mirrored the ASSIST process: the 18% of students who received the most nominations were selected, with the aim of 15% of the year group being trained as PSs. Commensurate with ASSIST protocols, in which the cut-off point of 18% included multiple students, all of these students were invited to be a PS. Students who were selected to be a PS were invited to a meeting held within school that outlined what the nomination meant, the PS role and training. Students were provided with written information for themselves and their parents and were asked to provide written assent and parent consent to participate as a PS.

Trainer recruitment

A list of trainers was generated through local contacts and searches of sports development, youth work and health promotion organisations near to the pilot school. Two trainers were recruited to deliver the pilot PS training. In line with ASSIST28 and the AHEAD study,40 trainers were recruited to have between them a combination of subject (PA/health promotion) expertise and experience in teaching or leading groups of adolescents (e.g. theatre and/or youth work experience). Both trainers met informally with the principal investigator and project manager, who explained the study and informally assessed the trainers’ fit with the role.

Pilot train the trainers course

The two trainers received a 3-day training course, covering all aspects of the study (see Description of final intervention elements for a full description of the course). The training was provided by three study staff (MJE, KB and JM).

Pilot peer supporter training

The 2-day PS training was piloted in a venue close to the school site (see Description of final intervention elements). Following the training, PSs were asked to support their peers in school, as instructed in the training, for 5 weeks. This time was deemed sufficient for the girls to experience the PS role and to identify any challenges associated with it. Given the short time frame between the pilot study and the delivery of the intervention in the feasibility study, the top-up PS training was not included in the pilot.

Quantitative measures

Participant recruitment and retention

The number and percentage of participants who opted out of the study was recorded in addition to the number of girls attending peer nomination, the number of girls invited to be a PS and the percentage of girls who consented.

Peer supporter training attendance and adverse events

Trainers recorded the attendance of girls at each day of the PS training and reasons for absence. Trainers recorded adverse events and reported them to the research team.

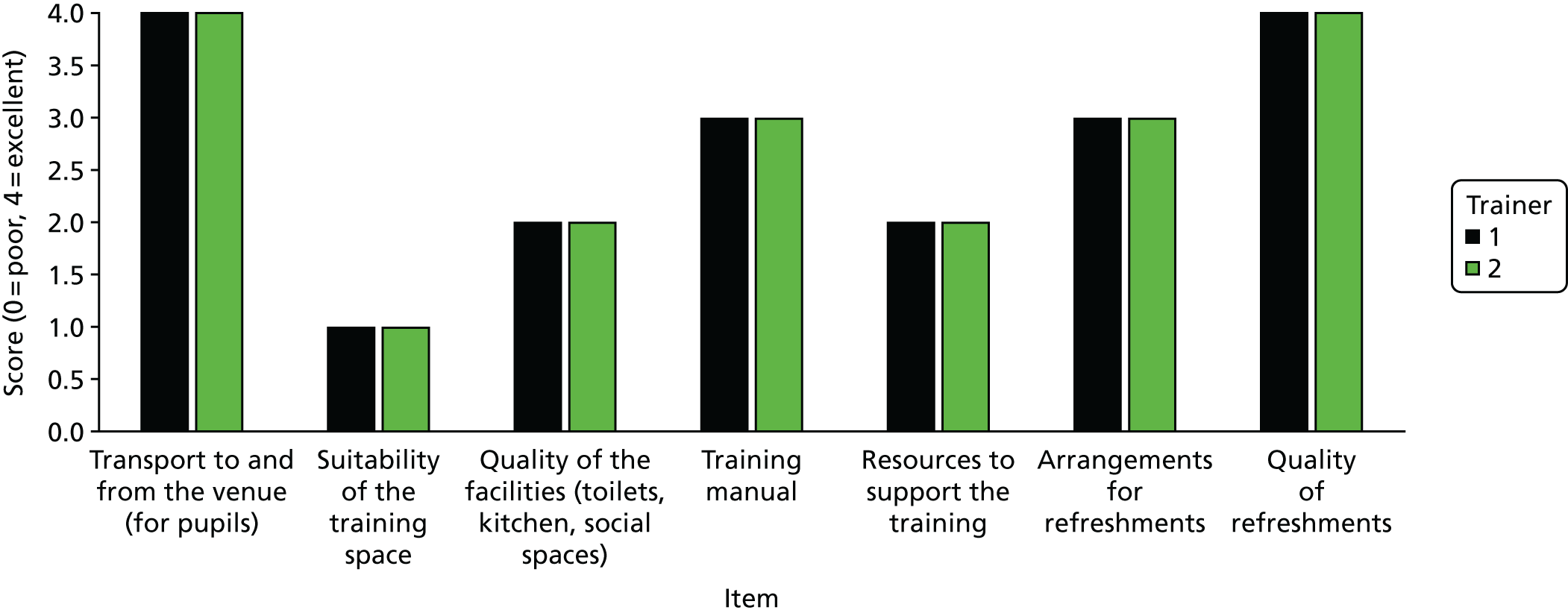

Trainer questionnaire

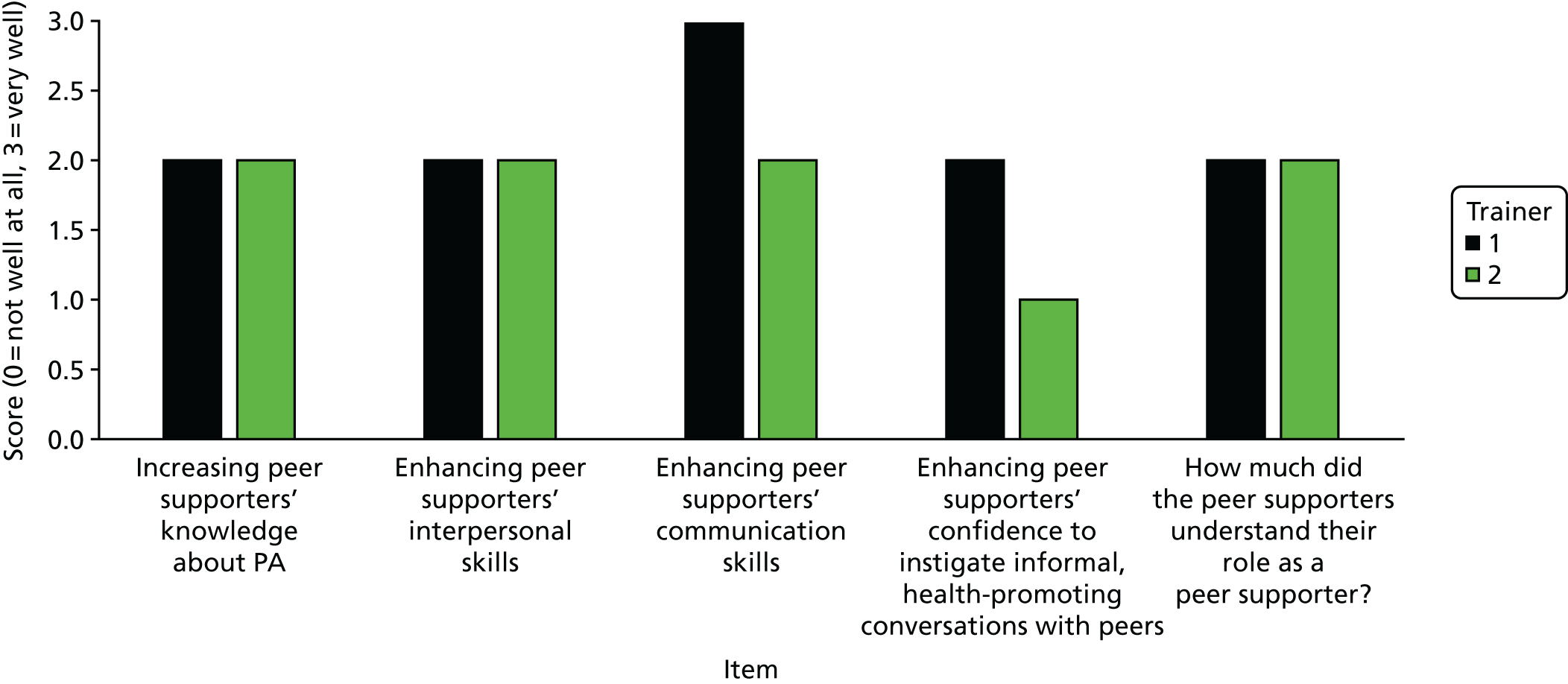

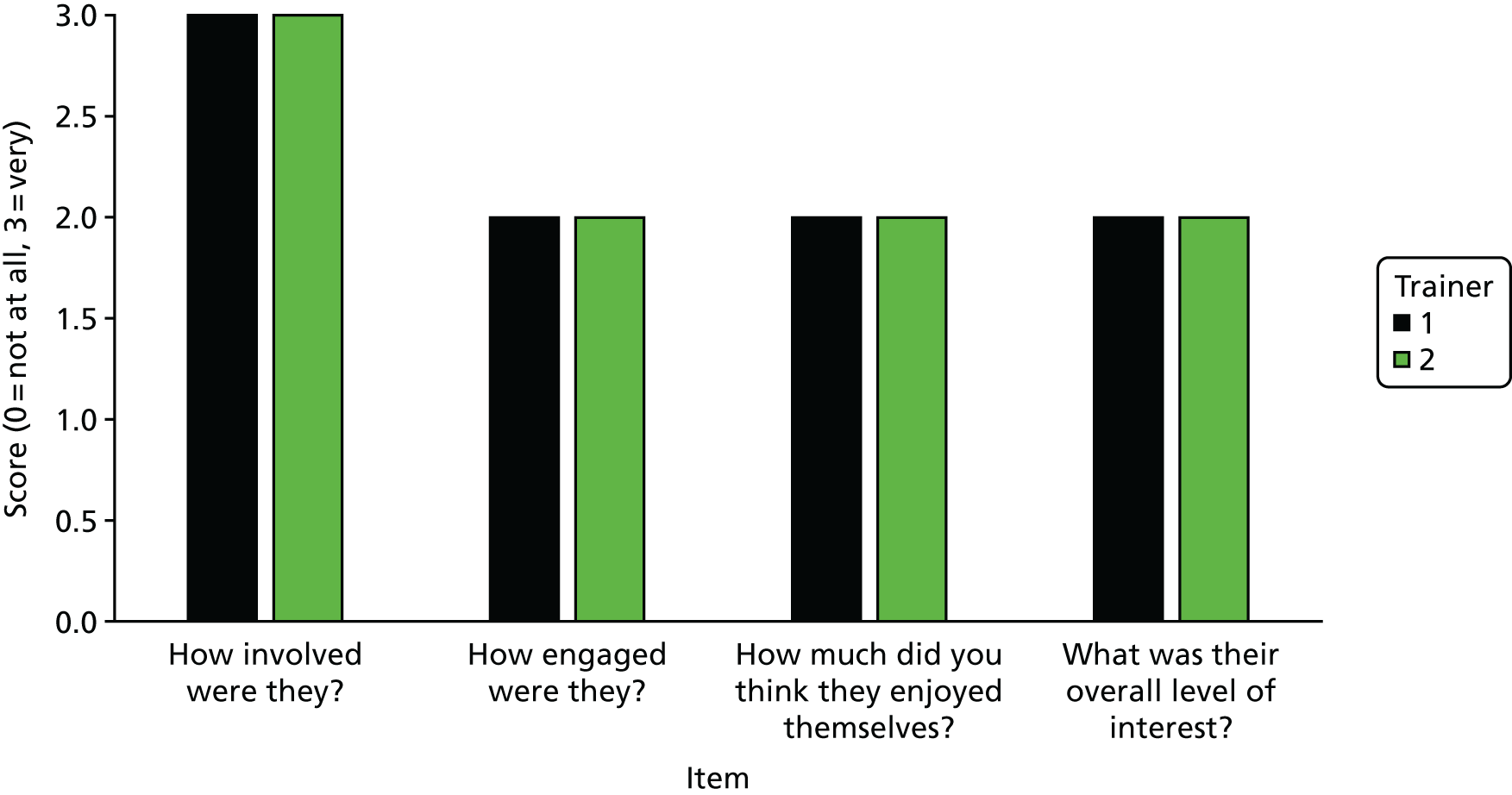

Trainers completed an evaluation questionnaire following delivery of the PS training (see Appendix 2). The measures were adapted from a similar questionnaire used in the AHEAD study. 40 Achievement of PS training objectives was assessed through trainers’ perceptions that the training achieved key objectives of increasing PS knowledge, interpersonal skills, communication skills and confidence to be a PS using a four-point scale (0 = ‘not well at all’ to 3 = ‘very well’). Perception of the PS response to training was measured using four items (engagement, involvement, enjoyment and interest) and scored from 0 (‘not at all’) to 3 (‘very’). The training arrangements (e.g. suitability of training space) were rated on a five-point scale (0 = ‘poor’ to 4 = ‘excellent’).

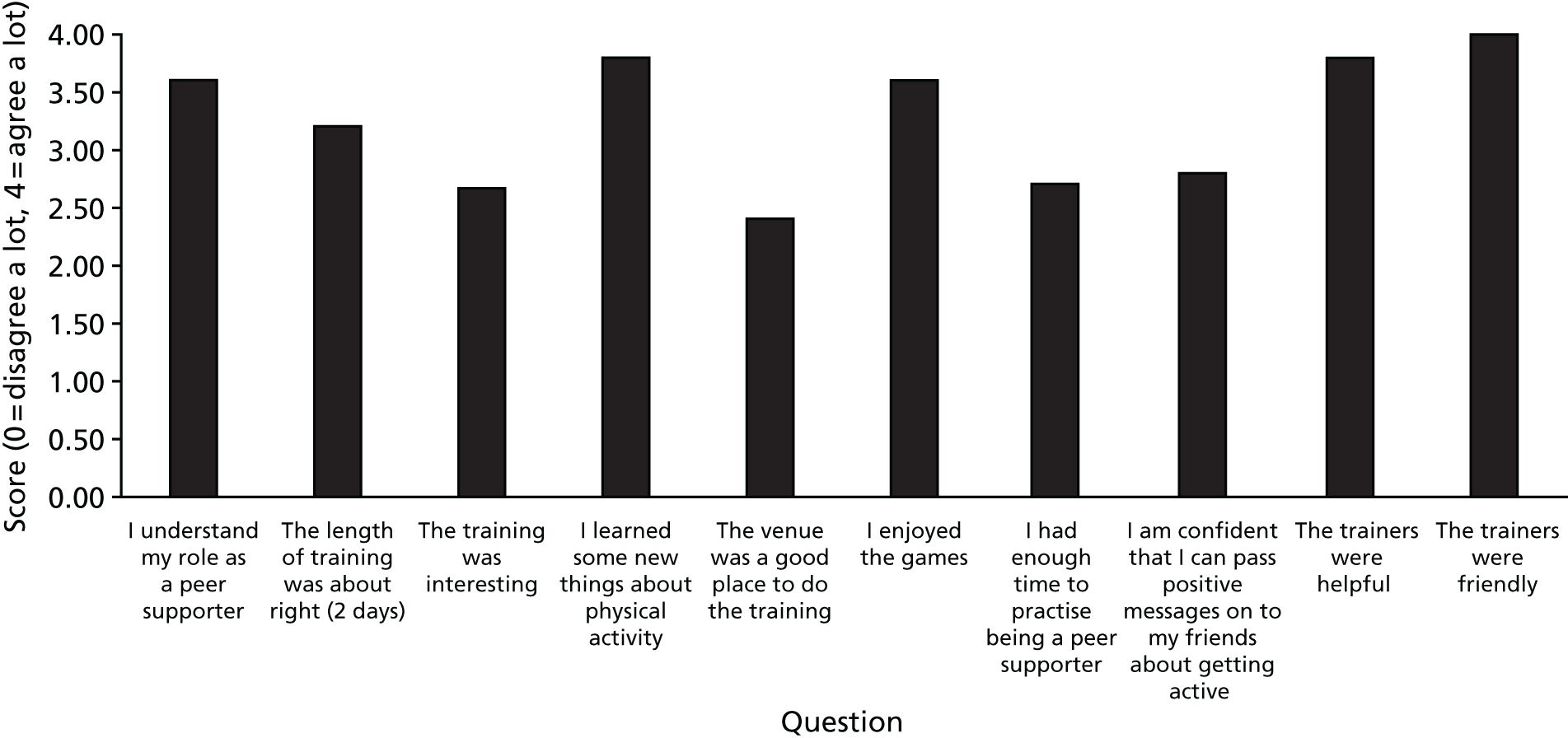

Peer supporter questionnaire

Peer supporters completed an evaluation questionnaire at the end of the training (see Appendix 3) that assessed enjoyment, views on training content and logistics and perceived trainer autonomy support. Enjoyment of the training was rated using a five-point scale (1 = ‘not at all’ to 5 = ‘a lot’) and open text responses. Ten items assessed PSs’ views on the content and logistics of the training (e.g. ‘I understand my role as a PS’, ‘the length of the training was about right’) using a scale ranging from 0 (‘disagree a lot’) to 4 (‘agree a lot’). The Sport Climate Questionnaire53 measured PSs’ perceptions that trainers were autonomy supportive with five items (e.g. the PLAN-A trainers provided me with choices and options) anchored by responses ranging from 0 (‘disagree a lot’) to 4 (‘agree a lot’). The mean of the five items was derived to produce an autonomy support score for each training pair.

Observation of the pilot peer supporter training

A researcher who worked on the AHEAD study, and was familiar with the PS training approach, observed the PS training to assess fidelity. An observation form (see Appendix 4) was developed to record the timing of training components and to record whether or not individual activity objectives were met (0 = objective fulfilled ‘not at all’ to 3 = objective fulfilled ‘lots’). PS engagement was estimated from 0 (‘not at all’) to 3 (‘very’) for each activity. Notes documenting the extent to which trainers’ delivery style was need-supportive, elements that worked and those that did not were made.

Qualitative measures

Peer supporter focus groups

Focus groups with PSs (n = 10) were conducted at two time points: (1) the day after the second day of PS training (‘post training’) and (2) approximately 5 weeks after training (‘during intervention’). At both time points, PSs were divided into two groups of five. The post-training focus group guide focused on identifying improvements and participants’ experiences of the training and views on trainers. The during-intervention focus group guide examined the girls’ experiences of being a PS, feelings of preparedness, what actions they had taken, what had/had not worked and what their Year 8 peers thought of their role. Focus groups ranged from 25 to 30 minutes in duration.

Trainer interviews

Both trainers were interviewed separately (interview lengths were 63 and 52 minutes) by Kathryn Banfield. The trainer interview guide considered both the train the trainers workshop and the delivery of the PS training, including the content and logistics of training, what worked/what did not, potential changes and how to engage the PSs. Interviews and focus groups were recorded using an encrypted digital recorder (Olympus DS-3500; Olympus, KeyMed House, Southend-on-Sea, UK), then transcribed verbatim and anonymised.

Quantitative analysis

Quantitative data were analysed descriptively using means and SDs for each trainer or number and per cent of participants, as appropriate. Data from open-ended questions on the PS evaluation forms (e.g. ‘to make the training better you could . . .’) were reduced to qualitatively similar categories and a frequency count was derived.

Qualitative analysis

The framework method54 was used to produce a matrix for constant comparison to synthesise the data from the PSs and the trainers. This method facilitates the combination of inductive and deductive analysis. Data were analysed using the following steps:

-

Kathryn Banfield, Mark J Edwards and Joe Matthews read and re-read each transcript and listened to audio-recordings to become familiar with and write initial impressions of the data.

-

Initial codes for each informant group were created. For the purposes of deductive analysis, predefined codes were broad (Table 2). In addition, codes were inductively developed by the three researchers independently. To ensure consistency and agreement, each researcher independently coded the same transcript from each informant group.

-

The three researchers discussed the codes and agreed a refined set of codes that could be applied to the remaining transcript(s). An analytical framework was developed for PSs and trainers.

-

Each framework was applied to the remaining transcripts by the three researchers (KB, MJE and JM) using NVivo (version 10; QSR International, Warrington, UK). Each researcher applied the framework to a different set of transcripts (trainer, post-training and during-intervention focus groups) and this was cross-checked by another researcher to ensure consistency and agreement of coding. New codes that emerged were discussed and amendments were made to each framework.

-

Coded data were charted into a framework matrix in NVivo to summarise the data for PSs and trainers by category, including representative quotations.

-

Codes were interpreted and themes generated through frequent meetings to review the coding matrix. The three researchers (KB, MJE and JM) agreed on illustrative quotations.

The frameworks were triangulated between informant groups to assess convergence.

| Code | Informant group | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment/initial involvement | Trainer and PS | How the participant(s) became involved, thoughts on the recruitment process and reasons for involvement |

| Training the trainers | Trainer | Thoughts on the logistics of the training (venue, length and resources) and the content |

| PS training logistics | Trainer and PS | Views on the training venue, timings, length and catering for the training |

| PS training content | Trainer and PS | What was enjoyed and what was not, activities or elements of the training that worked and did not work. Any improvements to the content or adaptations made to activities |

| Delivering the PS training | Trainers | Experience of delivering the training to the girls, how prepared they felt and difficulties they had |

| Impact of the PS training | Trainer and PS | Evidence of how the training helped the girls become PSs or how it has developed their skills |

| Views on trainers | PSs | What the trainers were like and their delivery style |

| Impact on other girls in Year 8 | PSs | What PSs have done to encourage other girls to be active and whether or not they were successful |

| Support for PSs | PSs | Whether or not the PSs helped each other, whether or not they needed help and how the study can encourage them to peer support |

| Need support | Trainer and PS | Evidence of trainers providing autonomy support by providing positive feedback, offering choice, setting out clear expectations and being empathetic. It also includes evidence of genuine interest in the girls’ lives and nurturing individual interests |

Qualitative notes collected by the observer were used as a reference point for intervention refinements only. Formal analysis was not conducted. The qualitative and quantitative findings were blended to provide a rich mixed-methods evaluation.

Results

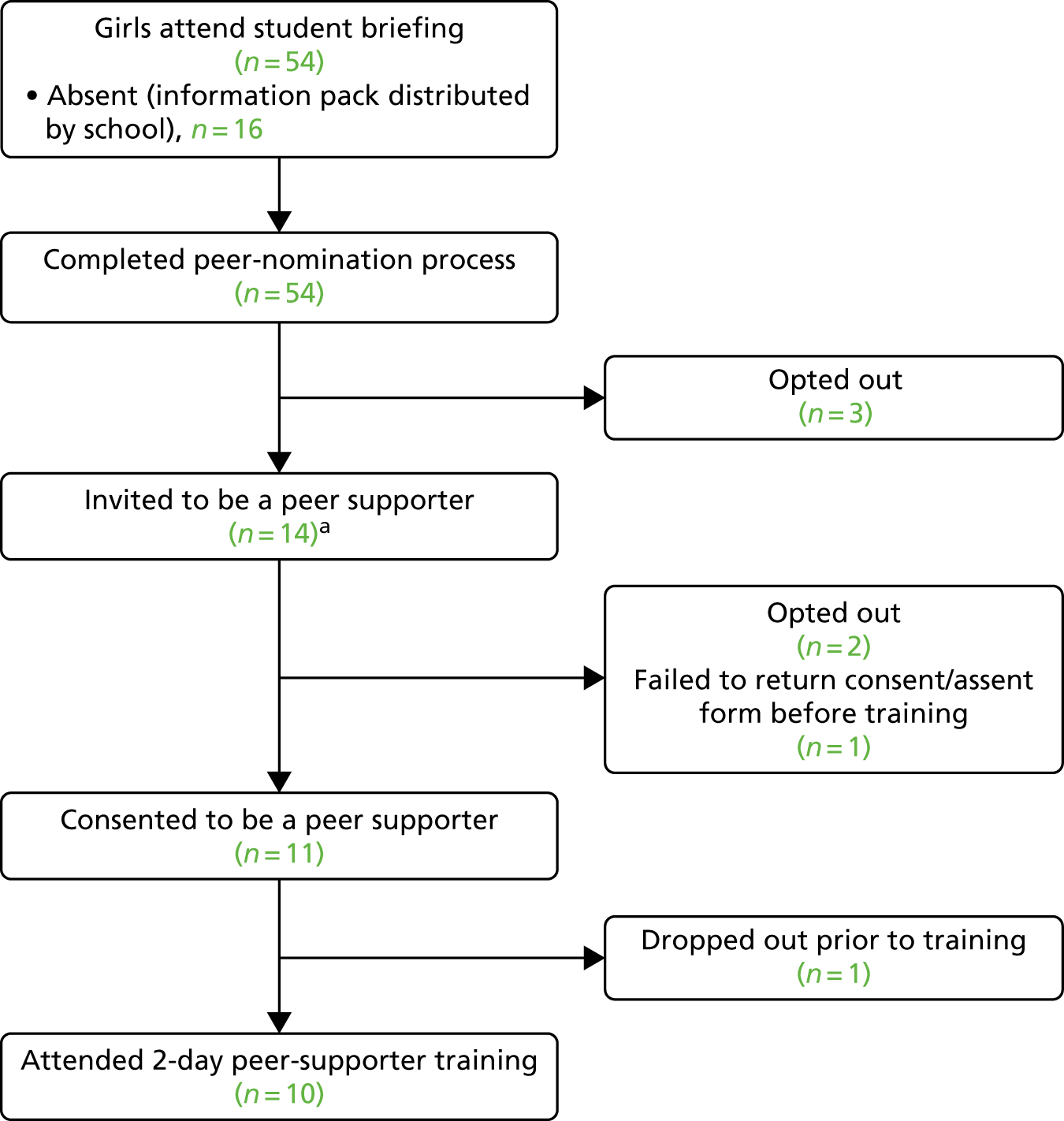

Participant recruitment, peer nomination, peer supporter selection and recruitment

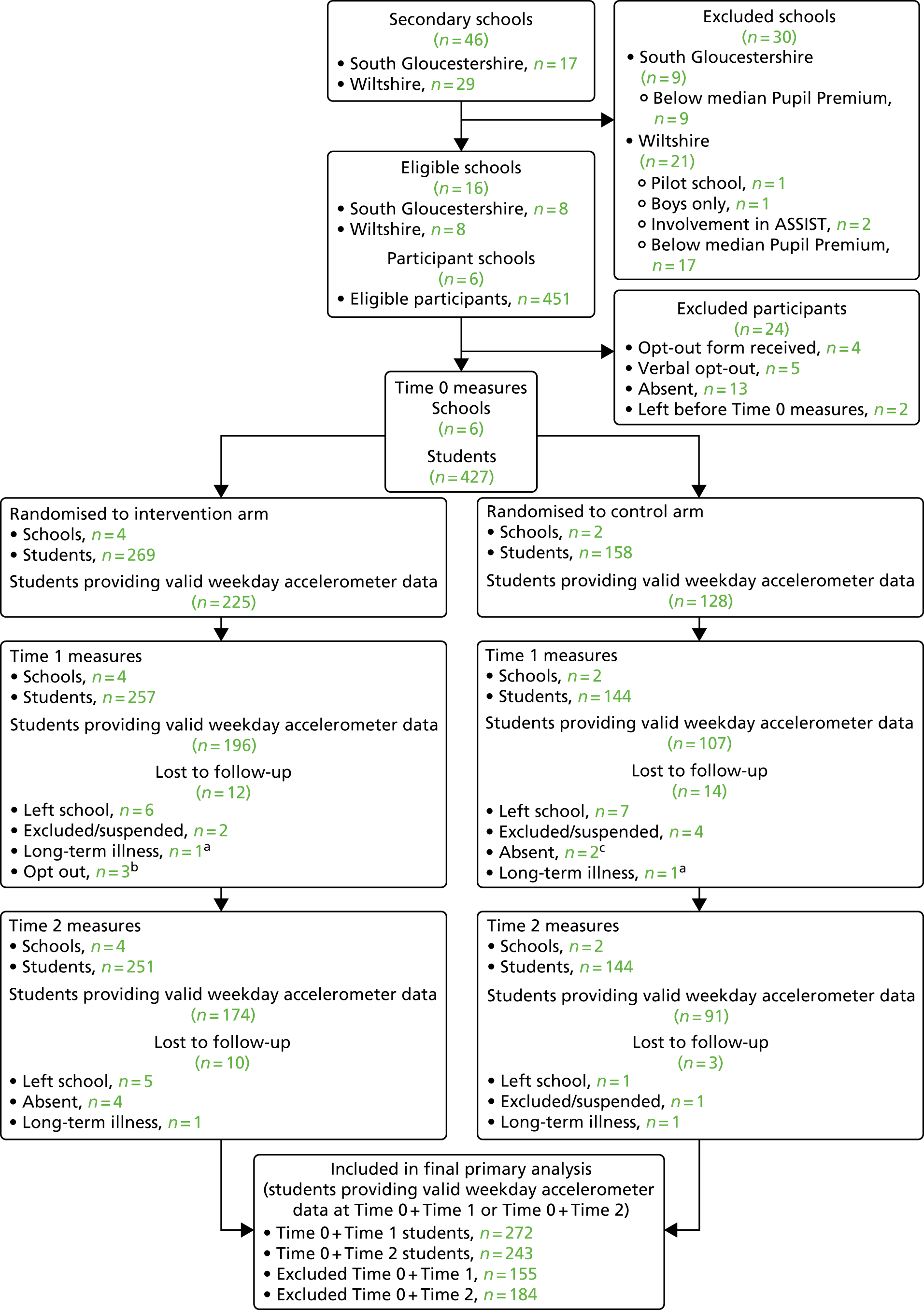

Participant recruitment flow is summarised in Figure 3. Of the 70 Year 8 girls, 54 (77%) attended the study briefing. Three (4%) study opt-out forms were returned. A total of 54 girls completed the peer nomination questionnaire, and the two researchers who led this process were satisfied that no amendments were required. The PS selection process was successful and 14 girls (20%) were invited to be a PS, all of whom attended the briefing meeting. The meeting was well received and 11 girls (16%) provided assent and parent consent to participate in the training.

FIGURE 3.

Flow diagram of PS recruitment in the pilot study. a, Number of Year 8 girls invited to PS meeting was > 18% as, in accordance with the ASSIST protocol, any student with an equal number of nominations as the final nominee was also invited to the training.

When PSs reflected on the peer nomination process they commented that the majority of PSs were from the same friendship group (many from the netball team) and believed that most of their friends were physically active:

. . . a lot of the people chosen are from the same friend group anyway, so there’s a lot of different people in the school who won’t have any friends that will have been voted for . . .

Post-training focus group 1

One participant suggested that rewording the peer nomination form to refer to ‘their closest friends’ could increase the diversity nominations across friendship groups:

I think maybe if you’d got everybody to write down, I don’t know, their five closest friends, then you could have a person from every friendship group.

Post-training focus group 1

Reasons PSs gave for wanting to be a PS included wanting ‘to help me help more people’ and personal skill development:

. . . you could benefit a lot of skills, not just for use in school but for when you get older for your jobs and stuff like that.

Post-training focus group 1

One participant took part because she thought the course would be focused on playing sports:

I thought it was to do with sports, to be honest.

Post-training focus group 2

During the PS meeting, participants suggested that they would prefer to wear PE kit, which the school contact agreed with. For the feasibility study, a decision was taken to recommend that the girls wear comfortable, casual clothing so as to (1) highlight that the training is not a sports event, (2) avoid the potential negative connotations of PE or PE kit for some PSs and (3) separate the PLAN-A training from school.

Recruitment of trainers

Two female trainers were recruited and, as planned, shared a mixture of expertise in delivering PA/sports coaching to young people, and in theatre and youth work settings.

Train the trainers

Overall, the training was delivered according to plan with little deviation from the schedule. Key feedback from the trainers was to provide more active, hands-on activities early in the training, before agreeing the group rules.

Intervention materials

All training and intervention materials, including the session plans and trainers’ guide, were seen as useful and clear. One trainer felt that the session plans presented too much information for use in the training (see Chapter 2, Peer supporter training, Logistics and resources).

Structure and venue

Trainers felt that there was insufficient training time for them to understand the content of the activities and allow them to ‘sink in’ (Trainer 1) and that the training was carried out too far ahead of the PS training delivery. Both trainers suggested lengthening the training to allow more time to practise each activity rather than just talk through them. The venue was considered satisfactory, but too small:

I think you could have done more learning by practise, by doing, because then you actually fully understand what the exercise is and how it works and what you’re trying to get from it.

Trainer 1

The training was well received, with clear information delivered with sufficient depth. Trainer 2 felt that there could have been more detail on the background of the project that they could disseminate to PSs:

If you went through it [background information] a little bit more, I think when we then said it to the girls I think it might have flowed a lot better rather than just saying, ‘OK, that’s that.’ It might have been nice to go in depth.

Trainer 2

Feelings of preparedness

Both trainers felt insufficiently prepared to deliver the PS training based on the train the trainers event alone. One trainer revisited the content in their own time, the other wanted to but did not have time:

There maybe needs to be another couple of hours added on, to maybe 2 top-up days, just to really go through it . . . I don’t think I was prepared enough in terms of knowing each activity off by heart.

Trainer 2

In response to this, the week before delivery of the PS training, a half-day meeting was held to allow trainers to prepare. The trainers found the extra meeting useful and the timing, structure and content of the 3-day train the trainers event was revised in light of these findings.

Peer supporter training

Attendance

Attendance was 91% (n = 10) at both training days; one girl did not attend because of a disagreement with another PS outside the PLAN-A training.

Logistics and resources

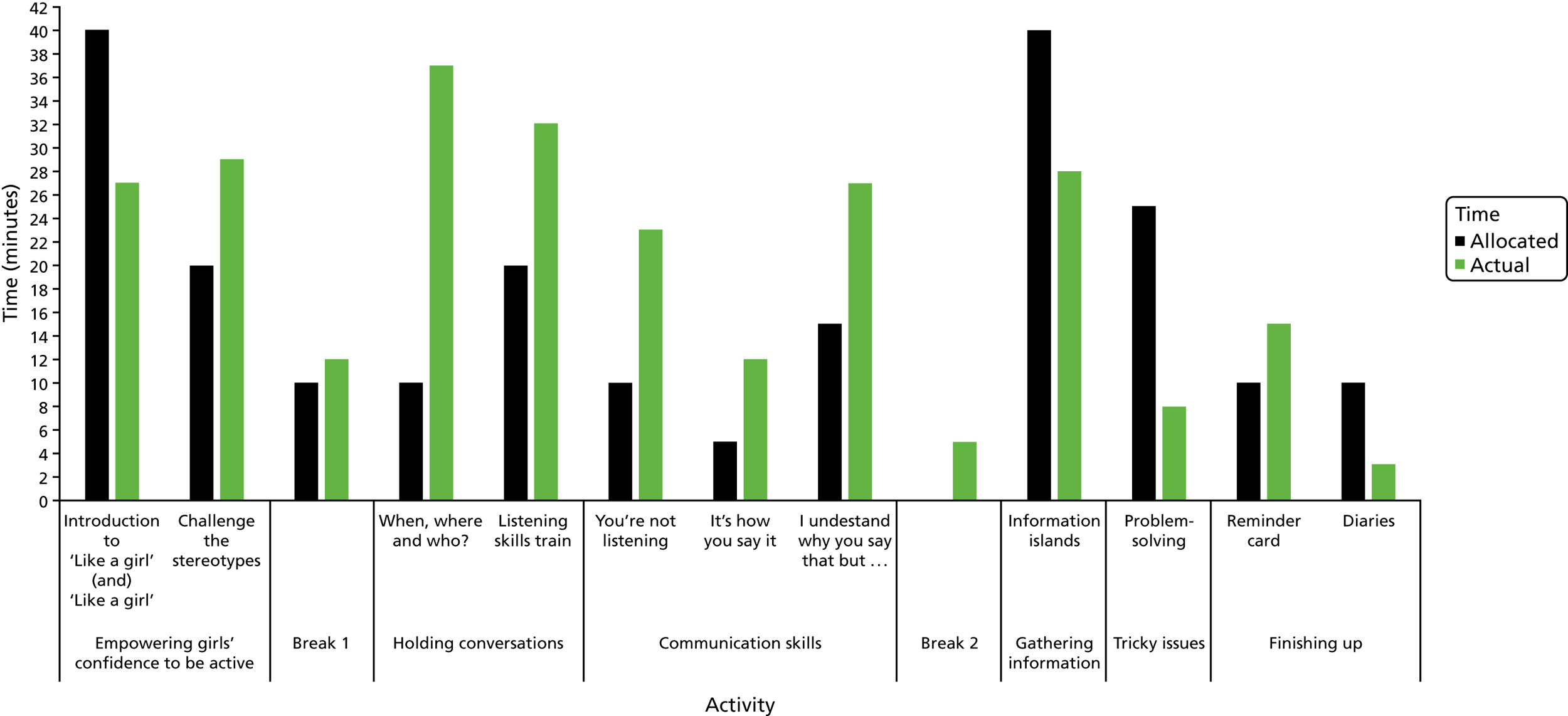

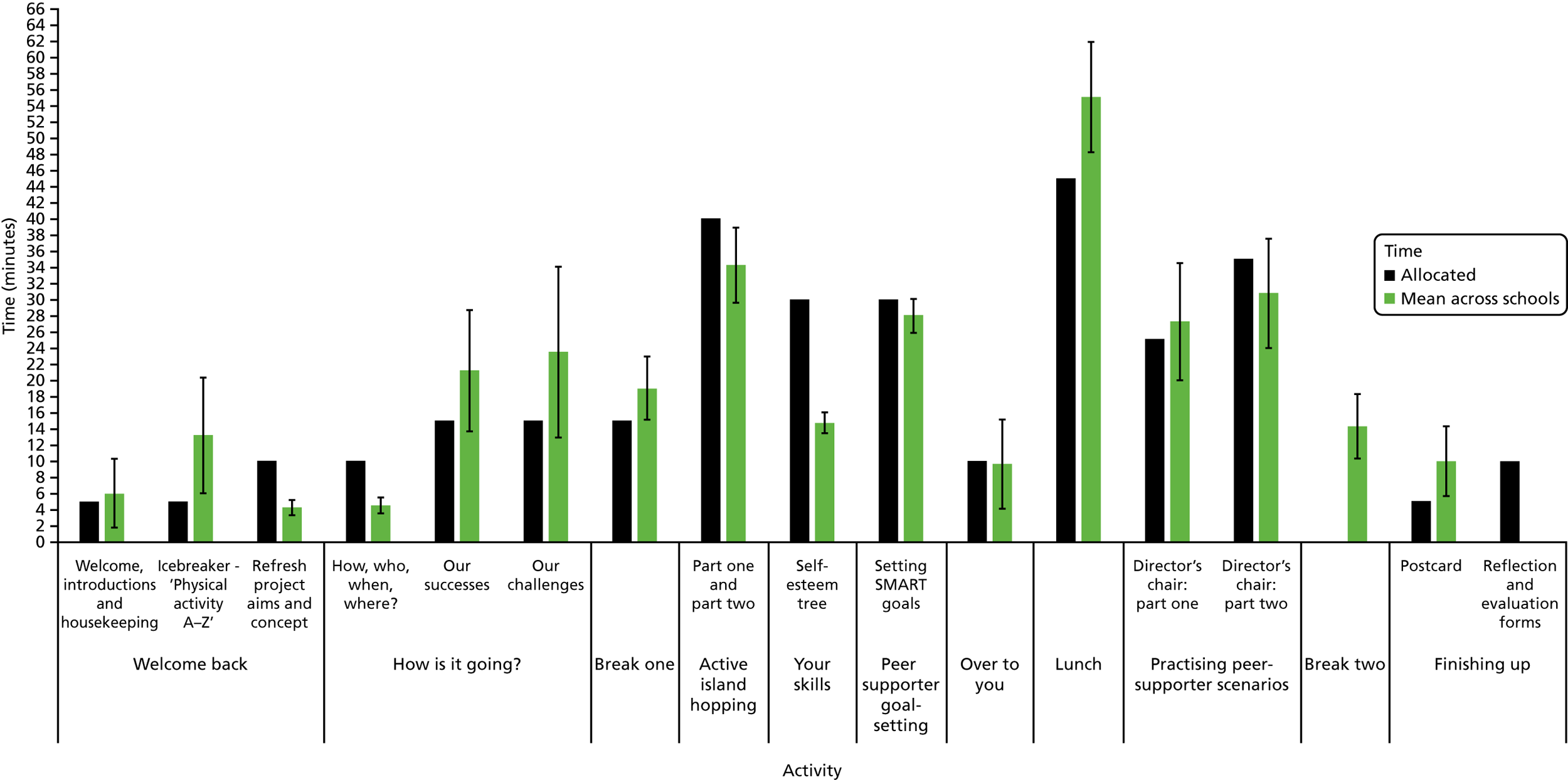

The PS training space and venue were rated ‘adequate’ by both trainers (Figure 4) and PSs (see Figure 7). This was largely because of its small size and lack of break-out space. This led to an environment in which it was difficult to concentrate. The observer also felt that the layout of the room (including a lack of tables) led to a very informal learning environment. Trainers and PSs rated the refreshments for the training highly (see Figures 4 and 7).

FIGURE 4.

Trainer ratings of PS training arrangements.

The training manual and resources were considered to be ‘very good’ and ‘good’, respectively, by the trainers (see Figure 4). Trainers agreed that the session plans were helpful and clear, but suggested condensing the quantity of information to make delivery easier:

There’s too much going on on the page . . . I don’t think you can take that in and use that as a thing to use in the classroom, for me.

Trainer 1

As a result, cue cards were developed that allowed the trainers to write their own notes about each activity to use in the PS training.

The girls found the PS booklets to be a helpful prompt of key information and good to show others what they did. They suggested that the booklet should be used more for reference by PSs rather than using it to write in during the training:

If you were to forget something, then you have a booklet to look back on. I feel maybe instead of copying it down you could have it written on the board and already written in the booklet.

Post-training focus group 2

The PSs felt that the PS diaries were a good idea; however, during the intervention the girls reported not using them because they forgot about them or did not want to record conversations:

I just don’t need it. I just can’t be bothered with it.

During-intervention focus group 2

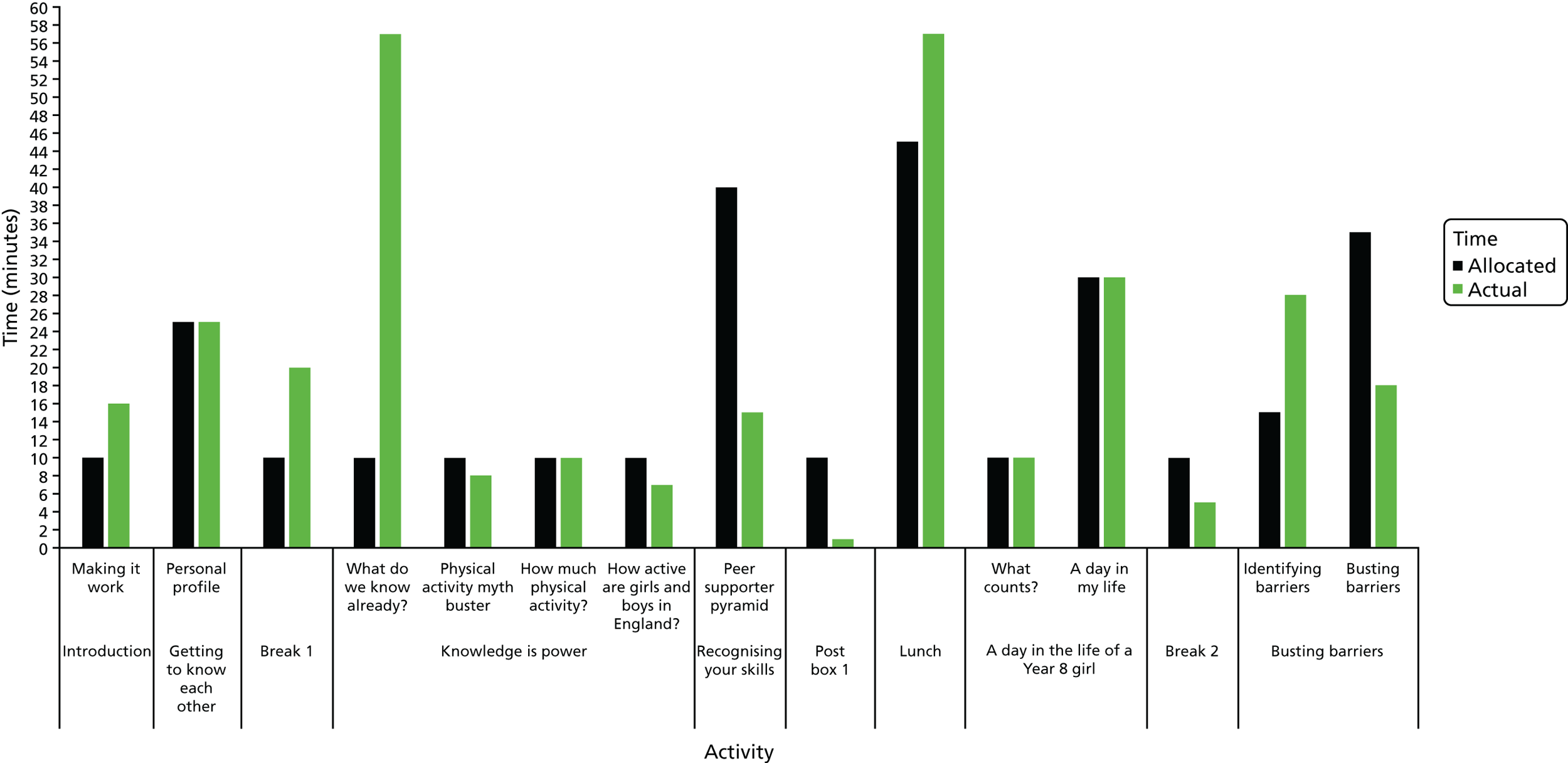

Fidelity to the session plans

Given the time constraints, on day 1 two activities were not delivered: the ‘thought shower: why be active?’ (10 minutes in duration) and ‘post box’ (10 minutes in duration) activities. On day 2, the ‘relaxation activity’ (5 minutes in duration) was excluded.

The allocated time and observed delivery time for each activity are shown in Appendix 5. On day 1, three out of nine activities before lunch took more time than allocated to deliver (e.g. ‘what do we know already?’). Lunch was slightly longer than scheduled, which resulted in activities after lunch being excluded or shortened. On day 2, activities before and immediately after lunch were an average of 12 minutes longer than scheduled, again leading to activities in the afternoon being given less time. Qualitative findings supported the observations: trainers felt that there was too much content to deliver and a lack of time for discussion. As a result, both trainers suggested that the training should be extended and more time should be added for discussion:

It’s too much in 2 days . . . I think it would have been nice to spread it over 3 days if you keep the activities, have a bit longer for each of them.

Trainer 2

The observer recorded that trainers added in active games to energise girls when necessary. Despite intending to benefit the girls, these contributed to the drift from the schedule. In addition, the observer noted that trainers could have shortened some sessions that were longer than intended:

Too long was given for discussions amongst small groups/activities . . . The girls would then talk about ‘off task’ things . . . time could have been used better.

Observation note

The extent to which PS training objectives were met is reported in Table 3. For timetabled sessions that comprised more than one distinct activity, the mean objective fulfilment is reported. Seven activities (41.18%) across both days were not rated. The mean rating for activities was 3.00, suggesting that objectives were achieved. However, fulfilment of objectives was lower (1.00) for activities at the end of day 2.

| Day | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| Activity | Fulfilment, mean (SD) | Activity | Fulfilment, mean (SD) |

| Introduction | 3.00 (–) | Empowering girls’ confidence | 3.00 (0.00) |

| Getting to know each other | 3.00 (–) | Holding conversations | 3.00 (0.00) |

| Knowledge is power | 2.67 (0.58) | Communication skills | 3.00 (–) |

| Recognising your skills | 3.00 (–) | Gathering information | 3.00 (–) |

| A day in the life of a Year 8 | 3.00 (0.00) | Tricky issues | 1.00 (–) |

| Busting barriers | 3.00 (–) | Finishing up | 1.00 (–) |

| Day average | 2.89 (0.33) | Day average | 2.50 (0.93) |

| Average objective fulfilment | 2.71 (0.69) | ||

Both trainers felt they successfully enhanced PSs’ knowledge about PA, communication skills, interpersonal skills and understanding of their PS role (Figure 5). The objective to enhance PSs’ confidence to spread informal messages among their peers was not met well (1.5 ± 0.71); this supports PSs’ reported low confidence in this area (see Peer supporters’ experience of training).

FIGURE 5.

Trainer-rated achievement of pilot PS training objectives.

The qualitative data gave insight into why some objectives were not achieved fully, including losing focus because of activities over-running (and other activities being rushed), omitting key activities and trainers not being clear on general group rules:

When it came to the core message of it and becoming a PS, I think we did not do enough because we physically did not have enough time.

Trainer 2

Peer supporters’ experience of training

Peer supporters’ engagement with training was high on day 1 and slightly less so on day 2 (Table 4). A need to maintain engagement in the ‘communication skills’ and ‘finishing up’ activities was identified.

| Day | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| Activity section | Engagement, mean (SD) | Activity section | Engagement, mean (SD) |

| Introduction | 3.00 (–) | Empowering girls’ confidence | 3.00 (0.00) |

| Getting to know each other | 3.00 (–) | Holding conversations | 3.00 (0.00) |

| Knowledge is power | 3.00 (0.00) | Communication skills | 2.00 (0.00) |

| Recognising your skills | 3.00 (–) | Gathering information | 3.00 (–) |

| A day in the life of a Year 8 | 3.00 (0.00) | Tricky issues | 3.00 (–) |

| Busting barriers | 3.00 (–) | Finishing up | 2.00 (–) |

| Day average | 3.00 (0.00) | Day average | 2.67 (0.50) |

| Average engagement | 2.83 ± 0.38 | ||

Figure 6 shows that the trainers felt the PSs were very involved throughout the training. They perceived the PSs to be somewhat engaged and interested. PSs wanted to discuss topics and ask questions throughout:

Every time we did something they wanted to talk about it. They were quite chatty and so they wanted to talk about things.

Trainer 1

That was quite good because you had to debate your point. That was quite good.

Post-training focus group 1

FIGURE 6.

Trainers’ ratings of PSs’ responses to the pilot training.

Girls were particularly engaged in activities that they could relate to and that involved being active:

It worked well because the video is so powerful. It was a ‘visual’ and some of them probably can relate to that . . . that’s why, because they can relate to those questions.

Trainer 2

However, although most activities were rated as highly engaging, there was evidence of some boredom, fatigue and distraction because of the ineffective timings of activities (i.e. rushing activities at the end of day 2), overuse of writing rather than more physical tasks and a disagreement between PSs on day 2:

Some silly[ness], some look bored [afternoon] day 2? Lethargic.

Observation notes

Some became distracted or I saw it in their face. OK, they might be looking but I could see they’re still not there.

Trainer 2

I just think there could have been more activities. . . . We probably learn more by doing stuff than writing because I think we get a bit bored writing.

Post-training focus group 1

Enjoyment over the 2-day training was moderate to high and was marginally higher on day 2 (3.80 ± 0.79) than on day 1 (3.30 ± 0.68). Open-ended responses revealed that all girls enjoyed the ‘listening train’ activity most and 60% felt they were good at role-play tasks. Activities that were more active and involved discussion and debate were also enjoyed, which supported trainers’ perceived drivers of engagement (see above):

I liked the big discussion we had about fitness between boys and girls and self-confidence. I liked that big debate.

Post-training focus group 2

Peer supporters believed that the training helped them understand their role; they enjoyed the games and learnt something new (Figure 7). Eighty per cent reported five different facts they learnt about PA in free text. The PSs felt prepared to support their friends by enhancing their knowledge, confidence and ability to empathise with others:

It does actually work, that you feel like you can go out and talk to people about it. It’s not just something that you do and then you forget about it.

Post-training focus group 1

Like, if one of your friends has an insecurity, you know how to understand them and how to talk to them about it.

Post-training focus group 1

FIGURE 7.

Peer supporter ratings of pilot training content.

Trainers expressed concerns about the PSs’ ability to be realistic about how to peer support. This was also reflected in observation notes that questioned how empowered the girls were to make changes at school. Similarly, 60% of PSs suggested that more time could be devoted to practising being a PS, which would further enhance their confidence to be a PS (see Figure 7). Some PSs were unsure of how to use the facts they had learnt or how to start a conversation with their peers:

It feels like if we have all these facts – like, you can’t just casually slip a fact into, like, a conversation that you’re having with someone.

During-intervention focus group 2

Peer supporters thought that including more activities that focus on building confidence would improve the training:

Like with the confidence, we didn’t go a lot over how to be confident.

Yeah, because that’s like a major thing. If you’re going to help someone else you need to be confident in yourself as well.

Post-training focus group 1

Need-supportiveness of trainers and perceptions of need-support

On average, PSs reported relatively high levels of trainer autonomy support (3.42 ± 0.47; range 2.80–4.00) and thought that trainers were helpful (3.80 ± 0.42) and friendly (4.00 ± 0.00). Similarly, the observation documented that the trainers circulated among the girls, interacted with them and helped them with their tasks. The girls respected the trainers, commenting that they were different from teachers, made the training fun, were trusted, not boring and ‘understood us more than actual teachers’:

If you said something to them, you really felt you could trust them. They were just very friendly and stuff.

Post-training focus group 2

Autonomy support

Trainers provided autonomy by giving PSs choice within a structure of clear instructions and the opportunity to lead discussions and express their opinions:

They gave us lots of choices. They kind of said what to do but then they were giving you choices of how to do it, which was better than everybody saying, ‘you’ve got to do it like this’.

Post-training focus group 1

Trainers empathised with the PSs, and when the training required concentration or when engagement was low, they responded by incorporating elements that they felt the girls enjoyed:

In the lunchtimes, they were desperate to move. We were getting the tennis balls out and [Trainer 2] got some tunes on and was getting them dancing.

Trainer 1

Trainers frequently provided competence-based feedback, praising the girls’ efforts. Trainers circulated around the group asking questions and they provided help when needed. Both trainers reinforced the girls’ understanding of activities and provided them with the skills to become a PS, in particular ensuring that the girls were realistic about their role:

We talked a lot about being realistic. You’ve got to be realistic, so it’s not saying, ‘Right, let’s go for a 2-hour run.’ ‘Oh, but I don’t like running.’ Where do you go from there? ‘I want to watch TV.’ ‘Let’s go for a half-hour walk and then come and watch TV.’ So it’s that compromise . . .

Trainer 1

Trainers explicitly tried to help the PSs understand their role and spent time empowering the girls’ confidence to be a PS:

I think if they feel confident and empowered then they can go off and do anything. And I know that was quite a big part of the course, and I think we spent a lot of time doing that and I hope and think that went in.

Trainer 1

PSs, competence may have been undermined when the trainers rushed activities. Sometimes the PSs felt confused, and trainer 2 felt that some core messages were missed because of time constraints:

When it actually came to the core message of it and becoming a PS, I think we didn’t do enough of because we physically didn’t have enough time.

Trainer 2

Both trainers endeavoured to, and were successful in, forming trusting relations with the PSs within the short training window. Trainers valued the PSs’ opinions, empathised with them and were interested in them as individuals. The PSs described the trainers as ‘friends’ and felt that the trainers understood them:

They [the trainers] related well to the girls and their delivery style supported SDT. Connections between the girls and with trainers [are] clear.

Observation notes

They were trusting. If you said something to them, you really felt you could trust them. They were just very friendly and stuff.

Post-training focus group 2

I could see they’re still not there [engaged], and when they sat down is when I suggested different ideas as a group, because I know when I was that age I was a really, really shy girl so I wouldn’t want to say anything.

Trainer 2

Experience of being a peer supporter

What girls did to peer support

The PSs reported engaging in little peer-supporting activity. Efforts to peer support included suggesting active travel and leading by example:

We went to the gym last year just before the end of term, and, we kind of spoke to everyone about it, like a few of our friends. And then they invited a few of their friends to go.

During-intervention focus group 1

One of my friends, we were, coming back from town or something. She was like, ‘Oh, no, I’ll get my mum to pick us up.’ I was like, ‘Why can’t we walk, to get some exercise?’

During-intervention focus group 2

PSs felt that they encouraged their peers to walk more or go to the gym:

And [girl name] and [girl name] house are, like, an hour away from each other, and we walked, like, all the way.

During-intervention focus group 2

There were a number of instances of PSs talking to family or non-female Year 8 peers:

I had a conversation with this year seven, who was in my tutor [group].

During-intervention focus group 1

Challenges of being a peer supporter

The main challenges and reasons many girls did little peer supporting was that they lacked confidence in approaching peers and encouraging them to be active, particularly peers whom they did not know:

A bit awkward if I just went up to someone and told their friends. It would be a bit weird to just come up to her in person.

During-intervention focus group 1

Despite the PS training dedicating sessions to the when, where and how of starting conversations and overcoming challenges, a barrier to PS activity was knowing how and when to start a conversation. Participants suggested including more activities in the training to support this:

You might have told us, like, how to start the conversation or something. Because, in a conversation, we don’t really – it doesn’t really bring it up that much.

During-intervention focus group 2

Participants also reported that many of their friends are already active:

Most of the girls in our class are already really active, so it’s kind of not really.

During-intervention focus group 2

Perceived impact of the Peer-Led physical Activity iNtervention for Adolescent girls

The main impact that PSs perceived their role to have was improving their confidence and increasing their PA:

But it’s got me a lot more active, and it’s boosted my confidence a lot.

During-intervention focus group 1

The NPS Year 8 girls appeared to be aware of PLAN-A and were interested in it; however, PSs felt that it would be beneficial to have posters or to do a presentation to the rest of the year to raise awareness and help make their role easier:

I think more like getting all the girls together and talking about it, so, like, having like a presentation about what we’ve done because then all the girls will be in the room and nothing to be ashamed of.

During-intervention focus group 1

Ancillary accelerometer study

In addition to testing the intervention design, data collection methods were also tested with the pilot school. Year 8 girls from the pilot school were asked to wear either waist or wrist accelerometers, or both, for a short period; their thoughts about these different methods were qualitatively assessed to inform data collection for the feasibility trial (see Appendix 6).

Implications of phase 1 findings on the Peer-Led physical Activity iNtervention for Adolescent girls

The formative research carried out in phase 1 facilitated a user-centred refinement of the ASSIST intervention to form PLAN-A. The pilot study allowed the school, student and PS recruitment methods to be tested and refined. In addition, the peer nomination activity, train the trainers and PS training were delivered, rehearsed and critiqued. The key implications of the formative work and pilot study for the design of these intervention components are presented in Appendix 1.

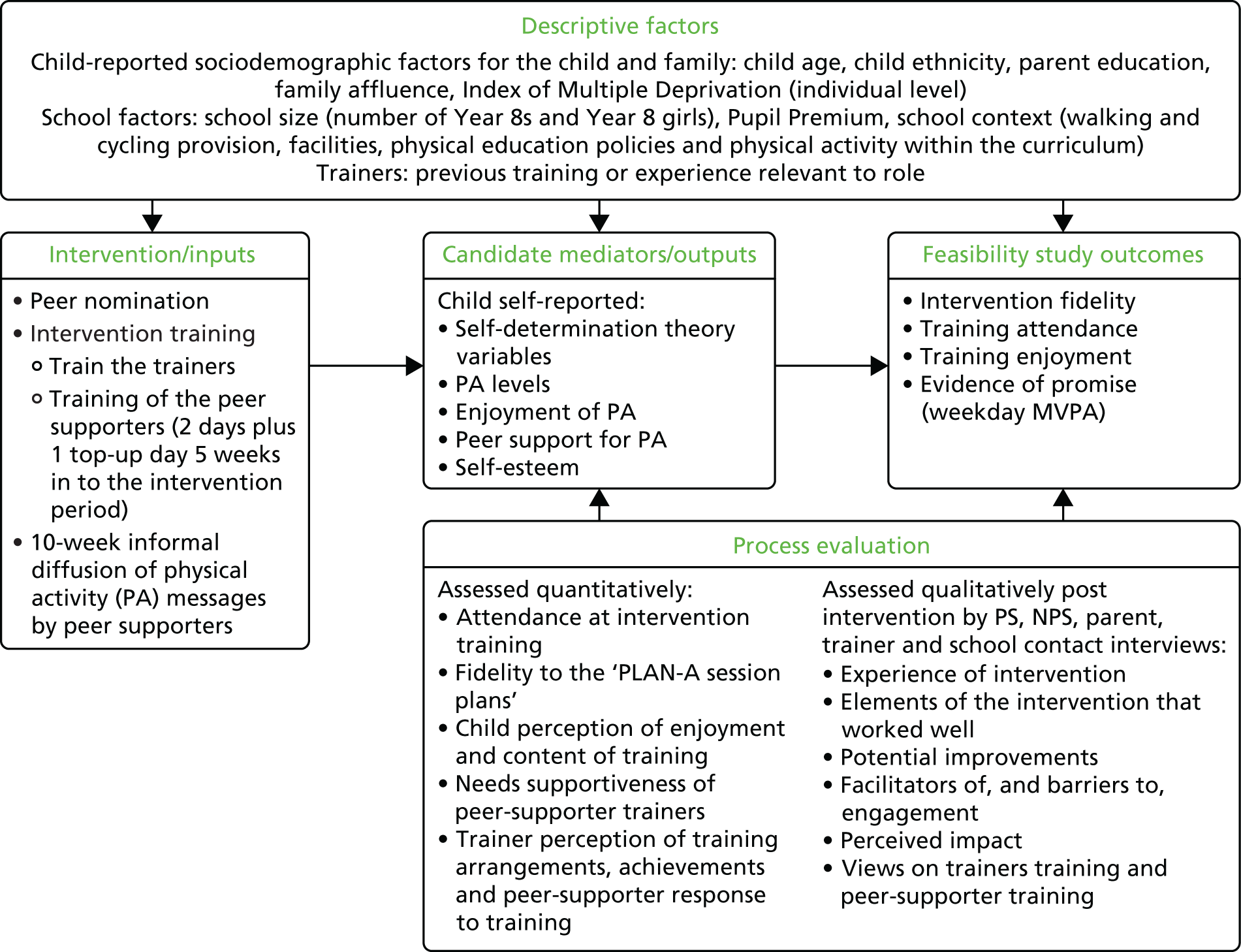

Description of final intervention elements

Figure 8 depicts the PLAN-A project logic model, including the process evaluation approaches taken to assess outputs and outcomes in addition to school context. The resources and elements of the intervention that were tested in phase 2 are presented in Table 5.

FIGURE 8.

The PLAN-A logic model.

| Intervention element | Description | Materials/resources needed |

|---|---|---|

| Peer nomination and selection | Peer nomination instructions read to all participating Year 8 girls, who then complete the peer nomination questionnaire | Peer nomination questionnaires and pens. Register, including list of girls who have opted out |

| Peer nomination analysis | Analyse the peer nomination questionnaires to determine which Year 8 girls will be invited to be a PS | Completed peer nomination forms, register and PLAN-A SOP for peer nomination analysis |

| PS meeting | Briefing for girls who have been nominated to be a PS. Explain the nomination and describe the PS role. Include time to answer questions | Student and parent information sheet, student assent form and parent consent form |

| Train the trainers 3-day workshop | 3-day training event, delivered by two PLAN-A staff, for the PS trainers. Training includes the theoretical underpinnings of PLAN-A, intervention content and time to practise delivery of the PS training activities. As delivery of the PS training is in pairs, the training provided opportunities for trainers to plan their delivery | Train the trainers Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) presentation manager slides, 3-day training schedule and for each trainer a ‘trainers’ guide’ and ‘PLAN-A session plans’. A PLAN-A resources pack for each trainer pair that will be used to deliver the PS training (see below). In addition, an information leaflet detailing the logistics of each session |

|

||

| PLAN-A session plans (PS training): details on the objectives, resources, time required, how to set-up and deliver each activity across all 3 PS training days. Sections about how to use the manual and additional information (i.e. FAQs) | ||

| PS training (initial 2 days) | A 2-day training event for PSs that takes place within usual school hours. Preferably delivered at a venue off the school site, with catering and transport arranged by study staff. A staff member from the school will chaperone the PSs to the training and be available if any behaviour issues arise. Two trainers lead the PSs through PLAN-A material and prepare them for the role of a PS | PLAN-A resources pack used to deliver the training, including the PS booklet and diary (see below) |

|

||

| PS booklet and diary: a booklet including information about PLAN-A and the role of a PS, including tips, information and worksheets about activities from the training. A diary also forms part of this booklet, including useful links, tips and reminders about how to be a PS | ||

| PS training (top-up day) | A mid-intervention (approximately 5 weeks after the initial training) training day to refresh PSs on the aims and importance of their role and extend their knowledge of PA and being a PS. An opportunity to discuss any barriers to, or issues faced in, their role so far. Preferably use the same pair of trainers that delivered the initial 2-day training to maintain rapport | PLAN-A resources pack used to deliver the top-up training (see above) |

Self determination theory was used to inform the delivery and content of the PS training (Table 6). In terms of delivery, trainers were trained to facilitate the PS training in ways that support autonomy (e.g. empowerment to support peers and provide choice), competence (e.g. confidence in how to be an effective PS and support one’s peers’ competence to be active) and belonging (e.g. supportive network of PSs and being a trusted friend to one’s peers). The PS training was designed to encourage PSs to recognise and promote autonomous rather than controlled motivation for PA (focusing on health, challenge-seeking and social affiliation reasons rather than appearance and peer pressure), to support their peers’ needs for autonomy, competence and belonging and use autonomy-supportive language when diffusing PA messages (e.g. ‘I’m going to walk to school, will you come with me?’ versus ‘you need to do more activity so you do not get fat’).

| Training session/activity/tasks | Behaviour change technique56 | Behavioural mediators |

|---|---|---|

| PA content | ||

| PA knowledge: examining pre-existing knowledge, exploring PA myths, interactive tasks to find out what counts as PA, PA recommendations and levels of PA in adolescent girls |

|

Knowledge and competence |

| Fitting PA in: PSs analyse ‘A day in their life’, identify existing PA and sedentary time and places and means by which to add in PA. Working with others to support them to identify how to fit PA into daily life and practical activities to reduce sedentary time in a range of situations |

|

Autonomy, competence and relatedness |

| Busting barriers: identification and discussion of barriers adolescent girls face to being active. Problem-solving tasks to ‘bust’ the barriers |

|

Autonomy, competence and relatedness |

| Confidence and competence: watching a short video about girls’ PA stereotypes, discussing beliefs in groups and empowering through focusing on self-esteem and past success |

|

Autonomy, competence, relatedness and self-esteem |

| Goal-setting: learning how to set ‘SMART goals’ and planning two PS/activity goals |

|

Autonomy and competence |

| PS content | ||

| Identifying personal PS attributes: self-reflection on personal skills and interests which may make them a good PS |

|

Competence and self-esteem |

| Identifying PS skills: group work to develop a list and then pyramid of the most important PS skills |

|

Competence and autonomy |

| When, where, who: activity to identify the timing, situations and social circumstances in which to give peer support |

|

Competence and relatedness |

| Listening skills: interactive games to highlight key skills related to listening to peers about being active |

|

Competence and relatedness |

| Communication skills: written and practical role-play activities building awareness of communication skills and practising their use |

|

Competence and relatedness |

| PS role-play: reinforcement of key PA information/learning and combination with simple role-plays using sentence starters (e.g. ‘I was at this training the other day . . .’) |

|

Autonomy, competence and relatedness |

Template for intervention description and replication checklist

Table 7 summarises PLAN-A in accordance with the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist. 57

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Name | PLAN-A |

| 2. Why? | The primary aim of this study was to assess the feasibility of the PLAN-A peer-led intervention designed to increase the PA levels of adolescent girls. The aims of the feasibility study were to estimate recruitment, retention and attendance rates and examine the acceptability of the intervention to schools, trainers, PSs, NPSs and parents. The study also sought to test the feasibility of data collection and assess data provision rates, as well as examine the intervention’s effect on accelerometer-derived MVPA. An additional aim was to estimate school-related ICC for daily MVPA and sample size for a definitive trial |

| The MVPA levels of girls are lower than boys throughout childhood and adolescence, and they decline at a steeper rate. As girls become older, it is thought that this decline can be contributed to not only changes in their social context (friendship groups/peer support), but the perception of significant barriers to PA that begin to emerge. Research suggests that there is an urgent need for effective PA interventions for girls, and harnessing peer influence may be the answer | |

| Peers, through peer support, PA co-participation and creating positive peer norms for PA, can play a central role in adolescent girls’ PA. Social network research has also revealed that children within the same friendship group tend to have similar activity levels and may alter their activity levels to match their friends | |

| Utilising ‘peer power’ in an intervention alone may not be enough to see positive changes in PA behaviour. PLAN-A is based on the fundamental framework for using such influential change agents (PSs), DOI theory, as well as SDT, which aims to foster autonomous motivation for PA by satisfying autonomy, competence and social belonging among the girls. PLAN-A has the potential, therefore, to positively influence girls’ PA behaviour and motivation to be active | |

| 3. What? (Materials) | Training (train the trainers) was provided for the trainers hired to deliver the PS training. The training took place over the course of 3 consecutive days. Content covered the concept and principles behind PLAN-A, the theoretical underpinnings of the intervention, how to deliver the training to uphold these (particularly when in a challenging environment) and a rehearsal of all the activities that formed the PS training. Slides were used to support delivery |

| Each trainer was provided with a ‘trainers’ guide’ introducing PLAN-A (including its rationale and aims), detailing SDT principles, their role as a trainer, any practicalities or logistics, how to use the ‘session plans’ and a run through of the train the trainer training days | |

| The ‘PLAN-A session plans’ comprised a complete guide to all the activities to be delivered during the 2-day and top-up day PS training. The manual gave exact details of each activity, as well as resources needed, how to prepare and objectives for each activity | |

| Each PS received a PS booklet combined with a diary. Each trainer pair received a resource pack containing worksheets and materials to help deliver the training, as well as any technical equipment needed | |

| The booklet contained supporting materials and answers to various activities held within the training. The diary provided the PSs with an opportunity to record and reflect on the conversations they may have had with peers | |

| 4. What? (Procedures) | Recruitment letters were sent to secondary schools in the South Gloucestershire and Wiltshire council areas. Once schools expressed interest, a meeting was held between the PLAN-A project manager and the school contact for further discussion and to obtain a signed study agreement form. A student recruitment briefing was then held for all Year 8 girls in which they were told about PLAN-A and given information packs for themselves and their parents. Parents signed an opt-out form if they did not wish their daughter to take part |

| Peer nomination and data collection were held in all schools. Schools were then randomly assigned to intervention (n = 4) or control (n = 2) groups and were made aware of their allocation post-T0 data collection. This gave the schools and study team sufficient time to organise the PS training. Peer nomination analysis was completed for each intervention school | |

| A PS meeting was held with all the nominated PSs from each intervention school. This covered details about the role of a PS and the logistics and content of the PS training. PSs were given information packs for themselves and their parents. PSs had to return a signed parent consent and student assent form in order to attend the PS training | |

| All PSs received an initial 2-day PS training, delivered by two trainers. Half way through the intervention period they received a top-up day training session. The training gave the PSs the skills, knowledge and confidence to fulfil the role of a PS. Once training was complete, PSs returned to school and spread informal messages encouraging their peers to be active | |

| A process evaluation, using quantitative and qualitative methods, was conducted throughout the study to identify areas of success and required improvement. It also examined the acceptability of the intervention and its design, as well as assessing mechanisms of impact. PSs training attendance was recorded by trainers, and observations of each trainer pair on the 2-day and top-up day training were carried out to assess intervention fidelity, logistics and PS engagement. PSs and trainers completed a post-2-day and post-top-up day training evaluation form. PSs reported on enjoyment, knowledge gained, concerns about being a PS and perceived trainer autonomy support. Trainers reported on fulfilment of objectives, logistics and perceived student engagement. Semistructured interviews and focus groups were conducted with trainers, PSs, parents of PSs, school contacts and NPSs to gain feedback about the successes and any issues with the intervention. A school context audit was completed to assess level of PA provision, school policies to support PA and attitude towards PA | |

| 5. Who provided? | Female trainers with a background in delivering PA programmes, working with young people or in theatre were recruited to the study to deliver the PS training |

| A total of five trainers delivered the intervention; one trainer was unable to deliver any top-up day training and, therefore, another trainer took her place. All trainers completed a 3-day train the trainers programme approximately 1 week before delivery. Instructors were paid to attend the train the trainers programme and for each PS training they delivered | |

| 6. How? | PS training was provided to the top ≈ 18% of girls nominated to be a PS of each school (range in number of PSs at each school: 11–17) and delivered by two trainers. PSs then returned to school and informally diffused messages about PA to their friends |

| 7. Where? | PS training was delivered during the school day in the four intervention schools. Schools were located in South Gloucestershire and Wiltshire. The 2-day and top-up day sessions were delivered off the school site, usually in a town/local hall. PS training for one school was held within school grounds because the school was unable to release a staff member to attend the training |

| 8. When and how much? | Intervention schools received the initial 2-day PS training in February 2016 and received the top-up day midway through the intervention period in April 2016 (this was conducted in term time). The training days ran from ≈ 9:00 to 15.00 to reflect the usual school day. The intervention was 10 weeks; however, PSs were encouraged to peer support for as long as they felt necessary and, therefore, there was no defined period |

| 9. Tailoring | All trainers received the same training and resources for delivery and were encouraged to deliver the PS training in an autonomy-supportive style consistent with SDT. PSs from all schools received the same training, but delivered by different trainers, and sessions were observed for intervention fidelity |

| 10. Modifications | No modifications were made to the intervention |