Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 14/67/14. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The final report began editorial review in January 2019 and was accepted for publication in August 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Amanda Avery, alongside her academic position at the University of Nottingham, also holds a consultancy position at Slimming World® (Alfreton, UK). Neither Amanda Avery nor Slimming World had access to trial data or was involved in data collection or analyses of the trial.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Bick et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

On discharge from maternity care at around 6 to 8 weeks postnatally, two-thirds of women weigh more than their pre-pregnancy weight. 1 Women who start their next pregnancy with an overweight or obese body mass index (BMI) score have a higher risk of adverse outcomes for themselves and/or for their infants. Failure to manage postnatal weight is linked to poor health behaviours including smoking, dietary choices, lack of regular exercise and failure to breastfeed. 2–4 In the UK around half of all pregnant women have overweight or obese BMI scores, with concerns increasing about women who develop excessive gestational weight gain (EGWG) as defined using Institute of Medicine (IoM) criteria from the USA:5 > 18 kg if pre-pregnancy BMI score was < 18.5 kg/m2; > 16 kg if pre-pregnancy BMI score was 18.50–24.99 kg/m2; > 11.5 kg if pre-pregnancy BMI score was 25.00–29.99 kg/m2; and > 9 kg if pre-pregnancy BMI score was ≥ 30 kg/m2. There are currently no equivalent guidelines for the UK population. Evidence of potential use of the IoM criteria for women in the UK was considered by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in 2014 to consider the need for an update to the 2010 NICE guidance on weight management before, during and after pregnancy. 6 A decision was taken not to revise recommendations owing to lack of evidence from a UK population, and it remains an area where urgent further research is needed.

Failure to lose weight within 6 months of giving birth is an important predictor of future weight gain and obesity. 7 This is a major public health issue, as postpartum weight retention contributes to long-term obesity, hypertension, diabetes and degenerative joint disease. 8 Evidence from the UK shows that a significantly greater proportion of women from areas of high deprivation have weight management problems,9 and a large cohort study in the USA found that excessive pregnancy weight gain and failure to lose weight postnatally was highly prevalent among young, ethnic minority women with low incomes. 10 The impacts of poor weight management are not confined to the woman; their infants are at risk of a high BMI score and blood pressure in childhood and young adulthood. 4 The complexity of supporting and treating individuals who have overweight or obese BMI scores remains a challenge. 11 There is a clear need for a clinically effective and cost-effective postnatal weight management intervention in UK settings, but a lack of evidence to support what this should include,12 when an intervention should be offered or how best to recruit women. 7 There is evidence in general population studies that commercial organisations may be of more benefit than NHS providers to support individuals to manage their weight. 13

Weight management interventions during pregnancy

Recent trials of diet and weight management interventions during pregnancy, some of which included postnatal outcomes, have measured the impact on risk of gestational diabetes, having a large-for-gestational-age infant and caesarean birth,14–17 but there is limited evidence of clinical effectiveness. 18 In the UK, NICE public health guidance for weight management before, during and after pregnancy6 recommended that dieting and weight loss during pregnancy should be avoided owing to concerns about their impact on neonatal outcomes, although an Australian study found no evidence of harm. 19 A UK-based multicentre trial of a behavioural intervention during pregnancy based on changing diet to foods with a lower glycaemic index and increasing physical activity aimed to reduce the risk of gestational diabetes and birth of large-for-gestational-age infants. 20 Women who had a BMI score of ≥ 30 kg/m2 were recruited between 15 and 19 weeks’ gestation and followed for up to 6 months postnatally to assess if the intervention led to sustained dietary and physical activity change. A total of 1555 women with a mean BMI score of 36.3 kg/m2 [standard deviation (SD) 4.8 kg/m2] were recruited: 772 were randomly assigned to standard antenatal care and 783 were randomly assigned to the behavioural intervention. No difference was found in rate of gestational diabetes or incidence of large-for-gestational-age babies. Gestational diabetes was reported in 172 (26%) women in the standard care arm compared with 160 (25%) women in the intervention arm [risk ratio (RR) 0.96, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.79 to 1.16; p = 0.68]. A total of 61 (8%) out of 751 babies in the standard care arm were large for gestational age compared with 71 (9%) out of 761 babies in the intervention arm (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.59; p = 0.40). A recent meta-analysis of individual participant data on over 12,000 women from 36 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of diet and physical activity interventions on gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes21 found less weight gain in the intervention arm than in the control arm (mean difference –0.70 kg, 95% CI –0.92 to –0.48 kg; 33 studies, 9320 women); this effect was observed regardless of a woman’s parity, BMI score, ethnicity or pre-existing medical condition. There were no statistically significant reductions in maternal and infant composite outcomes or differential intervention effects for gestational weight.

The UK-based Healthy Eating and Lifestyle in Pregnancy (HELP) cluster RCT aimed to assess if a theory-based intervention during pregnancy for pregnant women with obesity could reduce women’s BMI score at 12 months postnatally by equipping women with knowledge and skills to make healthier choices for themselves and their unborn infants. 17 The women allocated to the intervention were offered a weekly 1.5-hour weight management group that combined expertise from Slimming World® (Alfreton, UK) with clinical advice and supervision from NHS midwives until 6 weeks postnatally. Secondary outcomes included weight gain in pregnancy, impact on diet, level of physical activity, mental health, social support, breastfeeding, and cost-effectiveness. Trial results have not yet been published.

Postnatal-only interventions

Findings from studies that have evaluated postnatal weight management interventions are equivocal. A Cochrane systematic review of diet and/or exercise for weight reduction in women after childbirth,22 in which 12 trials contributed data on 910 women to outcome analysis, found that women who exercised did not lose significantly more weight than women in usual-care arms (two trials, n = 53, mean difference –0.10 kg, 95% CI –1.90 to 1.71 kg) but women who took part in a diet (one trial, n = 45, mean difference –1.70 kg, 95% CI –2.08 to –0.132 kg) or a diet plus exercise programme (seven trials, n = 573, mean difference –1.93 kg, 95% CI –2.96 to –0.89 kg) lost significantly more weight than women in usual-care arms. Trials were included of women with obesity, overweight or who gained excessive weight in pregnancy, with trial recruitment taking place from 3 weeks to 24 months postpartum and interventions duration ranging from 10 to 24 weeks postnatally. Interventions were often delivered as a ‘package’, for example walking for a set time each day, social support and healthy cooking sessions. Only one trial was from the UK. Despite considerable heterogeneity owing to differences in the type or duration of the intervention and differences in the participants’ characteristics, the authors suggested that diet and exercise together rather than diet alone could help women to lose weight after giving birth because the former could improve their cardiovascular fitness level and preserve fat-free mass.

A systematic review on interventions to reduce postpartum weight retention across all BMI categories was carried out by van der Pligt et al. 7 Studies were selected for inclusion if postpartum weight was a primary outcome and diet and/or exercise and/or weight monitoring were intervention components. Women were recruited from 4 weeks to 12 months postpartum. Interventions were administered from 11 days to 9 months postpartum and included counselling, individualised physical activity plans, healthy eating groups and clinic visits. Of 11 studies selected for inclusion, 10 were RCTs and none were from the UK. Seven reported a decrease in postpartum weight retention, six of which included diet and physical activity delivered by health professionals. No study considered cost-effectiveness, with wide heterogeneity in approaches to how interventions were administered. Nevertheless, findings suggested that postnatal weight loss was achievable, although the best setting, approach to delivery, intervention duration and recruitment approach were unclear. Of note is that intervention retention rates in the majority of studies were high (> 80%).

A small RCT from Sweden23 of a dietitian-led postnatal intervention that targeted women 6 to 15 weeks postnatally with self-reported BMI scores of > 27 kg/m2 randomised 110 women to a diet behaviour modification arm or to a control arm the members of which were offered a healthy eating booklet. The intervention comprised a structured 12-week diet plan, supported by a dietitian, based on the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations and self-weighing three or more times per week. Outcomes included weight change after 12 weeks and at 1 year postpartum. At 12 weeks, median weight change in the intervention arm was –6.1 kg (range –8.4 to –3.2 kg) compared with –1.6 kg (range –3.5 to –0.4 kg) in the control arm (p < 0.001). Differences in weight loss were maintained at the 1-year follow-up, with high follow-up in both trial arms.

Evidence that weight management in a postpartum lifestyle intervention could impact on other health behaviours, including smoking cessation, was considered in a systematic review by Hoedjes et al. 24 Of 17 included studies, eight assessed effects on weight loss and nine on smoking cessation and relapse prevention. Of the weight loss studies, five reported significant effects of combined diet and exercise. Two of the four studies that assessed smoking relapse prevention found no evidence of effect. Four studies included interventions for both smoking prevention and prevention of relapse. One study found increased abstinence (5.9% vs. 2.7%, respectively) and reduced smoking relapse (45% vs. 55%, respectively) at 6 months’ follow-up in the intervention arm compared with the control arm, but effects were not sustained at 12 months. Compared with the control arm, one study reported significant effects on smoking cessation and smoking relapse prevention at 6 months and one study found a small benefit on smoking cessation, but not smoking relapse, at 6 months. One study found no evidence of differences between arms at 3 months’ follow-up. Although the authors recommended that existing postpartum lifestyle interventions could achieve weight loss, smoking cessation or prevent smoking relapse, caution was needed. There was wide variability in study methods, details of who completed study selection and data extraction were not provided and study quality was not assessed.

Evidence from weight management interventions in general population studies

Previous UK RCTs have assessed the clinical effectiveness of weight management programmes in primary care settings. 13 In one trial, 740 women and men who had obesity or overweight and a comorbid disorder were recruited from one primary care NHS trust that served a diverse population. Interventions of interest included weight management programmes of 12 weeks’ duration, including those provided by Slimming World, Weight Watchers (WW International, Inc, New York, NY, USA), Rosemary Online© (Digital Wellbeing Limited, Steyning, UK), group-based dietetics-led programmes and general-practice-led or pharmacy-led one-to-one counselling. Participants selected which programme they attended, with those in comparator groups offered 12 vouchers to access a local leisure centre free of charge. Weight loss at programme end was the primary outcome, with secondary outcomes including self-reported physical activity and weight loss at 1 year. Data for follow-up were available on 658 (88.9%) participants at programme end and 522 (70.5%) participants at 1 year.

All programmes achieved significant weight loss from baseline to programme end and all except general practice and pharmacy provision had better weight loss at 1 year than the control arm. The commercial weight programmes achieved better weight loss at programme end (mean difference 2.3 kg, range 1.3–3.4 kg) and were cheaper by ≈£40 per person than the primary care services. Cost data included costs of provider’s service, searches in general practice and sending letters of invitation. The lack of process evaluation coupled with the control arm receiving a different intervention (rather than standard care), which could have diluted the impact, limited the ‘learning’ from this trial. Nevertheless, it provided useful feedback on other potential benefits of commercial weight management programmes, including the positive impact of group dynamics and attending fleixibly timed and widely available weight management groups. The lack of appropriate training and time available to clinicians tasked with providing weight management advice could limit their potential role. 13

A more recent RCT25 considered the clinical effectiveness of an internet-based behavioural intervention with regular face-to-face or remote support from primary care health clinicians compared with brief advice. Individuals registered with general practices who had a BMI score of ≥ 30 kg/m2 (or ≥ 28 kg/m2 with risk factors) were recruited by postal invitation. Positive Online Weight Reduction (POWeR+) was a 24-session online weight management intervention completed over 6 months. Individuals were randomly allocated to the control intervention (n = 279), which comprised brief online information that encouraged swapping to healthier foods and increasing intake of fruit and vegetables plus 6-monthly nurse weighing, POWeR+ supplemented by face-to-face nurse support (POWeR+F) (up to seven contacts) (n = 269) or POWeR+ supplemented by remote nurse support (POWeR+R) (up to five e-mails or brief telephone calls) (n = 270). The primary outcome was average weight reduction over 12 months. A total of 818 eligible individuals were randomised. Weight change, averaged over 12 months, was documented in 666 participants (81%; control, n = 227; POWeR+F, n = 221; POWeR+R, n = 218). The control arm maintained nearly 3 kg of weight loss per person. Compared with the control arm, the estimated additional weight reduction with POWeR+F was 1.5 kg (95% CI 0.6 to 2.4 kg; p = 0.001) and with POWeR+R was 1.3 kg (95% CI 0.34 to 2.2 kg; p = 0.007).

By 12 months, mean weight loss was not statistically significantly different between arms, but 20.8% of control participants, 29.2% of POWeR+F participants (RR 1.56, 95% CI 0.96 to 2.51; p = 0.070) and 32.4% of POWeR+R participants (RR 1.82, 95% CI 1.31 to 2.74; p = 0.004) maintained a clinically significant 5% weight reduction. Maintenance of weight loss after 1 year was unknown and few (19/54) health-care staff participated in follow-up interviews. As this was an older (mean age 53 years) general population sample that included men and women, implications of the findings for women who have recently given birth are unknown.

Rationale

There is increased recognition of the importance of postnatal care as an opportunity to implement interventions to improve women’s shorter- and longer-term health, including weight management for women with high BMI scores. Evidence is accruing of the longer-term consequences on outcomes of future pregnancies and the health of their children if women with obesity or overweight at antenatal ‘booking’, or who gain excessive gestational weight, do not manage their weight. Prior to undertaking a definitive RCT of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, evidence was needed to see if such a trial could be undertaken. Evidence was needed of whether or not women who have recently given birth would be prepared to enter a trial of weight management, when would be an appropriate time to intervene to optimise postnatal weight management, the appropriate content of a pragmatic and accessible intervention for postnatal women in an inner-city area, if an intervention could have an impact on other positive health behaviours, and outcomes likely to be of most importance in a future trial.

Use of a commercial weight management programme

In line with the remit of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) programme, which funds research ‘to generate evidence to inform delivery of non NHS interventions intended to improve the health of the public and reduce inequalities in health’, a non-NHS intervention had to be considered. 26

Following discussion with local women who had used different weight management approaches (including online resources), academic colleagues with expertise in evidence of use of commercial weight management programmes, evidence from UK general population studies13 and review of the content of the dietary and other advice offered by commercial programmes appropriate for the needs of postnatal women, Slimming World was considered to be the most appropriate intervention for several reasons. At the time of the funding application, there was some evidence that commercial weight management interventions were likely to be of more benefit than programmes provided by the NHS. 13 Indeed, work with a local patient and public involvement (PPI) group of women who had BMI scores of ≥ 25 kg/m2 to inform the original application highlighted that women did not want to attend NHS groups and felt that it was important that weight management support was offered in a peer-group setting where they had the opportunity to meet other people (and not necessarily only new mums).

Slimming World was the only commercial organisation that offered tailored support for postnatal women, including those who are breastfeeding. It has a flexible weight management and healthy eating programme, which includes a range of different food types, suitable for nursing mothers, including adequate calcium and fibre intake. Groups are standardised, and at the time of trial commencement there were over 12,000 groups available run by consultants who lived in the local area and would be aware of cultural and dietary influences. Each consultant undertakes evidence-influenced training in dietary aspects of weight management, physical activity and dietary change, and Slimming World implement rigorous quality control procedures and monitoring of group provision undertaken by the providers. If the feasibility trial achieved its aims, this meant that it would be possible to run as a multicentre trial, knowing that the intervention would be standardised and accessible to women across all settings. One issue was that Slimming World, as a commercial organisation, charges a range of fees to attend groups, determined by whether the individual is a new or an ongoing member, with a standard weekly fee of £4.95 (as of 1 December 2018). 27 To support the Supporting Women with postnAtal weight maNagement (SWAN) trial, Slimming World agreed to waive the fees for women allocated to the intervention. They also agreed that women in the control arm would be offered the chance to commence groups with fees waived for the first 12 weeks.

Chapter 2 Methods

Aim of the SWAN feasibility trial

This was a single-centre feasibility trial, the primary objective of which was to assess the feasibility of conducting a future definitive RCT to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lifestyle information and access to commercial weight management sessions for 12 weeks in relation to achieving and maintaining long-term postnatal weight management and positive lifestyle behaviour in women at risk of poor weight management in an ethnically diverse inner-city population.

This objective was supported and supplemented by the following secondary objectives:

-

assess recruitment/time to recruitment and retention

-

estimate the impact of lifestyle information and postnatal access to commercial weight management sessions on maternal weight change from first antenatal visit to 12 months postnatally

-

explore the influence of lifestyle information and postnatal access to commercial weight management sessions on secondary outcomes at 6 and 12 months, including weight management, diet, physical activity, breastfeeding, smoking cessation, alcohol consumption, physical and mental health, infant health, sleep patterns, body image, self-esteem and patient health-related quality of life

-

assess the acceptability of the intervention and trial procedures

-

assess resource impacts across different agencies likely to be of relevance and identify data appropriate for economic evaluation in a definitive RCT based on assessment of quality and completeness of economic data generated, a preliminary within-trial cost–utility analysis and review of evidence

-

decide if criteria to inform progression to a definitive RCT are met.

The methods for the main trial (to meet objectives 1–3) are described first, followed by the process evaluation (objective 4) and the health economic evaluation (objective 5).

Trial design

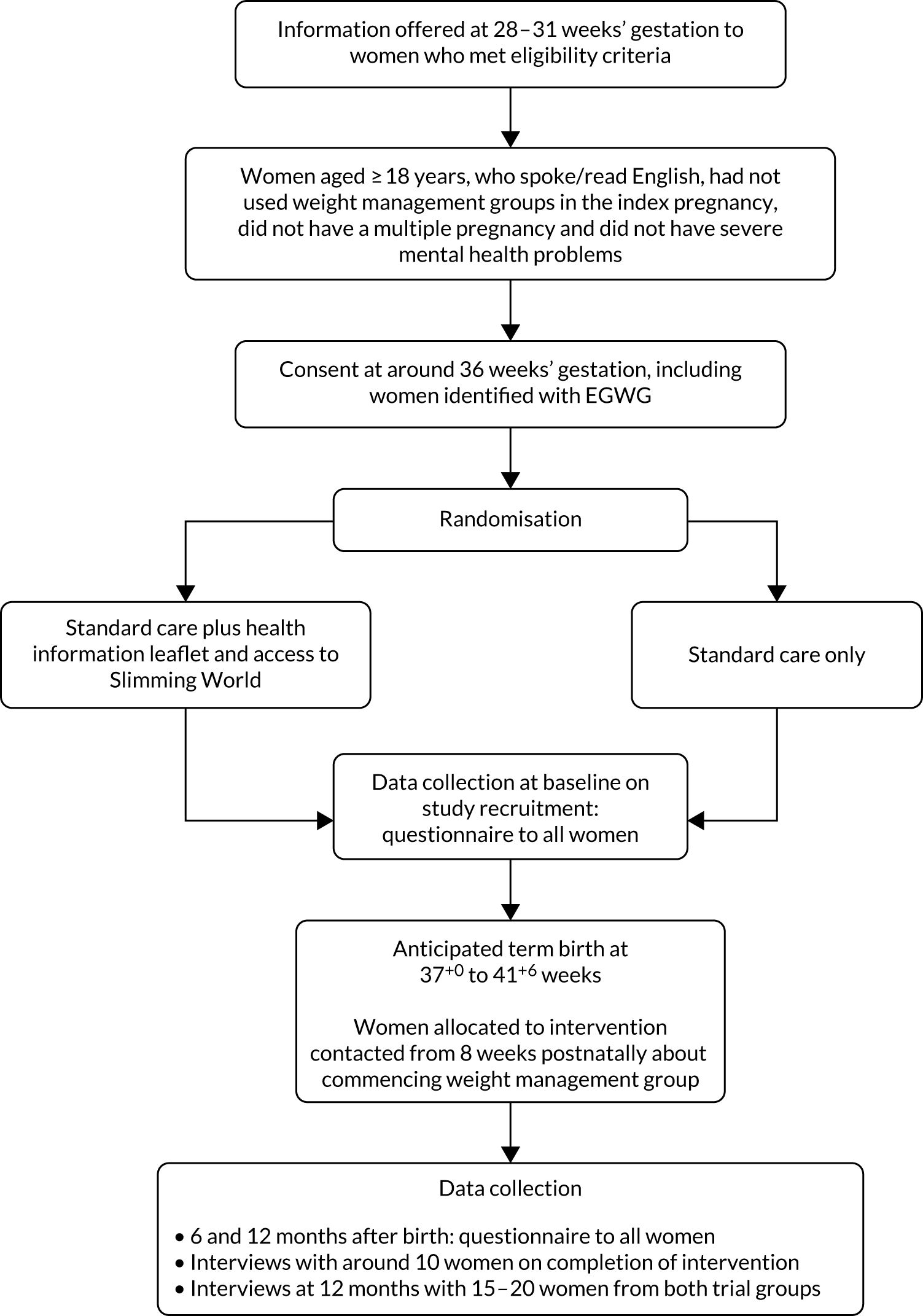

The SWAN trial was a single-centre, individually randomised feasibility trial that incorporated an integral mixed-methods process evaluation in line with Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance for developing complex interventions. 28 It had a target recruitment of 190 women who had a BMI score of ≥ 25 kg/m2 at antenatal booking or women who had a normal BMI score at antenatal booking but gained excessive gestational weight at 36 weeks’ gestation. It was a two-arm trial, with one arm allocated to receive standard care plus a lifestyle information leaflet and access to a commercial weight management group, commencing from 8–16 weeks postnatally, or standard care only (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Trial flow diagram.

Participant eligibility

The following inclusion criteria were applied throughout participant recruitment.

Inclusion criteria

Women eligible to participate were those aged ≥ 18 years who could speak and read English, were expecting a single baby and had not accessed weight management groups in the index pregnancy.

Women who booked for their pregnancy care at the trial site were eligible to be randomised to the feasibility trial if they met the following criteria:

-

were aged ≥ 18 years

-

had sufficient understanding of spoken and written English

-

had no current diagnosis of major psychiatric disorder documented

-

had no known abnormality detected in the fetus

-

were not involved in another postnatal study (to reduce ‘burden’ of research participation)

-

had no identified medical complications (e.g. cardiac disease, type 1 diabetes)

-

had no identified eating disorders

-

had not undergone previous surgery for weight management.

Exclusion criteria

Women who did not fulfil all of the inclusion criteria were not included in the trial.

Sample population

All women who met the inclusion criteria were considered eligible to participate in the trial.

Trial setting

One NHS maternity unit in an inner-city area in the south of England. The unit provides maternity care to women living in one of the most densely populated boroughs in the UK, with high proportions of people of black African and black Caribbean ethnicity, some of the most disadvantaged populations in the UK and high levels of mobility and migration. 29 When trial funding was awarded (in 2015), 54% of the postnatal population of women who gave birth at the trial site were of white British ethnicity, 36% were women of black African or black Caribbean ethnicity and 3% were of South Asian ethnicity. In 2017, when trial recruitment was in progress, of over 7000 births at the trial site ≈50% of women were of white ethnicity, 34% were of black ethnicity and around 5% were of South Asian ethnicity. Of the women who booked for their maternity care at the unit in 2017, 15% had BMI scores classed as obese and 25% had BMI scores classed as overweight. There were lower rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 6–8 weeks among women of black Caribbean ethnicity and women of mixed Caribbean ethnicity, and around 3% of women reported that they smoked during pregnancy.

Information for women and obtaining informed consent

We used two approaches to inform women about the trial. The first was for women who had BMI scores of ≥ 25 kg/m2, who were identified from their antenatal booking information for the index pregnancy on the maternity administration system. At approximately 26 weeks of pregnancy, all identified women in this group were sent a trial letter (see Report Supplementary Material 1) that briefly explained the trial aims and advised women that a research midwife would be in contact to explain the trial further. The letter also explained how the woman could contact the team if she did not want to receive further information. Two weeks after sending the letter, the research midwife contacted women who did not ask to be removed from the contact list to explain the trial in more detail.

The second approach was for women who had a normal BMI score at antenatal booking but gained excessive weight during pregnancy as assessed against IoM criteria. 5 Women were offered the opportunity to self-refer or were referred by their midwife or obstetrician to the research midwives; posters and postcards placed at the trial site advertised the trial. Women who were interested were asked to contact the research midwives to arrange to be weighed at around 36 weeks’ gestation (or at their next nearest antenatal appointment) as routine weighing is not recommended in current NHS maternity care. 6 As women in the normal BMI score group did not respond to this approach after 3 months of recruitment, the protocol was revised and ethics approval obtained to send opt-out letters, similar to those being used for women who had a BMI score of ≥ 25 kg/m2 at antenatal booking, during the final 2 months of the planned recruitment period (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Letters were then sent to the women with normal BMI scores at antenatal booking at around 32–34 weeks’ gestation of pregnancy.

All women identified using these approaches were offered a patient information sheet (PIS) by the research midwives prior to seeking their written informed consent at around 36 weeks’ gestation (see Report Supplementary Material 3). If, after reading the PIS, women were willing to participate in the trial, informed consent was obtained. The PIS made it clear that women were free to withdraw from the trial at any time for any reason without prejudice to their future care and were under no obligation to give a reason for withdrawing from the trial. Women interested in participating were met by the research midwives at the trial site (in the obstetric unit or a community clinic) to obtain consent and complete the baseline questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 4). Consent was obtained by the research midwife with delegated authority from the principal investigator at the trial site. Consent comprised a dated signature from the woman and a dated signature from the research midwife. A copy of the signed informed consent document was given to the woman, a copy retained in the woman’s medical records and a copy retained in the trial site file.

Intervention arm

Women were allocated to receive standard care (see Control group), plus a positive lifestyle information leaflet (see Report Supplementary Material 5) at around 36 weeks of pregnancy on recruitment to the trial and access to 12 commercial weight management sessions provided by Slimming World, which they could commence at any time between 8 and 16 weeks after giving birth. Women could choose which group they attended, the day, date and time of attendance and when they commenced groups to fit in with their postnatal recovery, lifestyle and family demands. They were able to take their babies with them to the groups, an important consideration for any postnatal intervention.

Joining the commercial weight management group

As the intervention was to commence 8 to 16 weeks postnatally, it was important that women were reminded about the trial offer. Processes for commencing the commercial weight management intervention included a ‘welcome’ leaflet from Slimming World about joining sessions, which was given to all women allocated to the intervention arm, a ‘congratulations’ text from the research midwives on notification of the birth of the baby and reminder texts sent by the research midwives from 6 to 8 weeks postnatally about joining Slimming World. From 8 to 16 weeks postnatally the women were asked to call Slimming World member services to speak to a consultant who could register the woman, advise her where her nearest groups were located, the venues and dates/times of groups and the name of the local consultant running the group. Following this first call, if a woman was not yet ready to join (e.g. if she felt unwell), she was asked to call Slimming World member services again when she felt ready. At this call, women were asked to provide their height and current weight.

All women were given a Slimming World trial identifier (ID), which was used to ‘track’ the woman through each group she attended, including her weight as taken at each group session. This also enabled women to be tracked who attended groups beyond the trial offer and the extent to which women moved between different groups. In line with all members of Slimming World, women had a ‘swipe card’ that included their free access to up to 12 group sessions and their recorded weekly weight information and date, time and group attended. This approach also meant that women were treated as a ‘regular’ Slimming World attendee, with no potential to be identified as receiving the offer as part of a research trial.

Content of the commercial weight management group

The content of Slimming World group programmes is underpinned by behaviour change models and groups that are homogeneous with respect to content and delivery. 30 Behaviour change techniques are supported by social cognitive theory, with a focus on motivation and self-efficacy for weight management and reducing relapse from the programme. Key techniques include goal-setting, self-monitoring, social support and positive reinforcement. 31,32 Consultants receive standardised training overseen by Slimming World dietitians and nutritionists, which includes motivation to support positive lifestyle changes to manage weight, nutrition and food facts and information on the role of exercise and activity in health and weight management. Consultants repeat training every 2 years to remain up to date with the latest evidence and attend a local programme of safeguarding training approved by the NHS. Groups follow a standard format, starting with a weigh-in for members and an introduction to the programme for new members, followed by a whole-group discussion that includes discussion of group member’s experiences of weight management to help change habits and share healthy swaps (i.e. healthy alternatives to common food choices) and recipe ideas. Sessions can include basic cooking skills, taking cost, cultural preferences and time constraints into account. A food optimising system encourages adherence to healthy eating, and physical activity encouragement includes facilitation of behaviour change, redefining what ‘activity’ can include. The diet includes a combination of different food types: ≈80% combined from fruit, vegetables, carbohydrates and protein; a smaller proportion of calcium and fibre-rich foods; and an allowance for foods high in fat or sugar. Other than limiting the intake of high-fat or high-sugar foods, Slimming World does not promote a ‘restrictive’ diet.

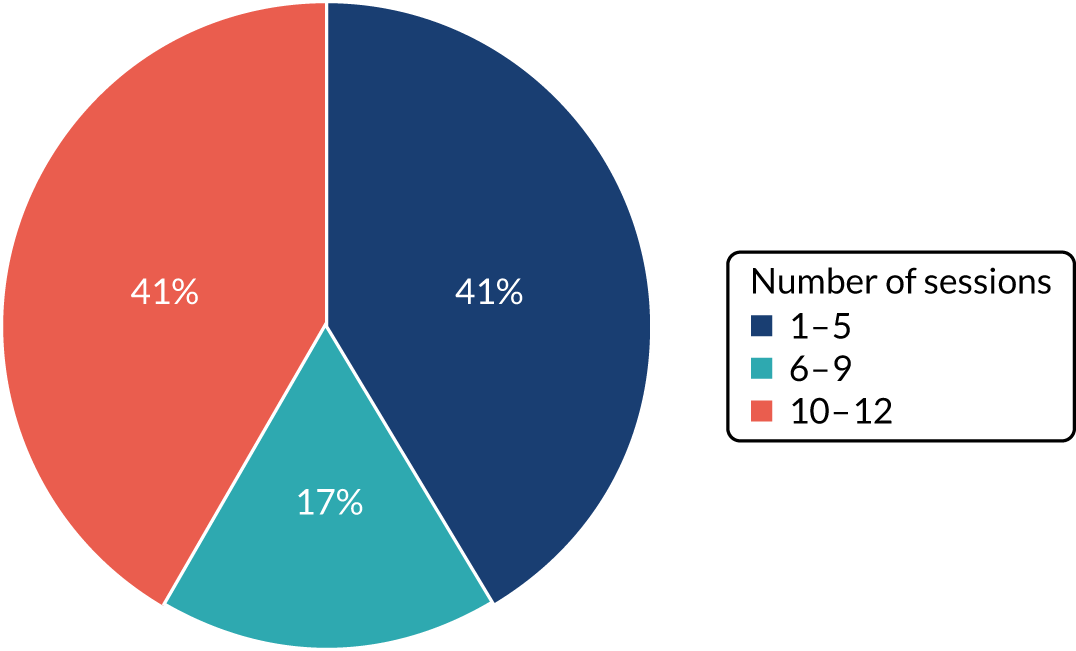

Women allocated to the intervention were offered (with fees waived) the standard membership, namely attendance for 12 sessions run over 14 consecutive weeks to allow 2 ‘holiday’ weeks within the 12-session offer. Slimming World guidance is that, to achieve a 5% loss in weight from baseline (a difference considered to improve health outcomes), individuals need to attend at least 10 out of the 12 group sessions. Attendance was considered in the process evaluation in terms of whether women ‘attended’ for a whole group session or only attended a group session to be weighed, and if women attended ≥ 10 sessions, six to nine sessions, one to five sessions or no sessions at all. On completion of the 12-session offer, women could continue to attend weekly sessions, but Slimming World standard fees would apply.

Lifestyle information leaflet

As postnatal health planning should start in pregnancy,33 an evidence-based positive lifestyle leaflet reflecting current NICE public health guidance for women on breastfeeding, diet, smoking cessation/prevention of relapse, reducing alcohol and managing sleep11,33 was offered following recruitment and allocation to the intervention at 36 weeks’ gestation (see Report Supplementary Material 5). The leaflet was developed with the trial Expert PPI Group and written to comply with Plain English Campaign guidance,34 using pictures and tick/cross messages to enable women of all reading abilities to understand the content. Local women we consulted when developing the trial highlighted that this information was not routinely offered to women, despite recommendations that it should be. 6,33 The research midwives were asked to go through the leaflet with the woman and discuss the content with an emphasis on why the information could support women to adopt practices likely to be of benefit to their own health and the health of their infants.

Control group

Women allocated to standard care received standard NHS maternity care for 8 weeks postnatally prior to discharge from maternity care. This could include, for example, routine midwifery and health visitor contacts for infant-feeding assessment, monitoring of recovery from the birth, commencement of the infant immunisation programme, routine assessment as part of the Healthy Child Programme, parenting interventions and other contacts with the family as determined by need. A routine contact with their general practitioner (GP) at around 6–8 weeks postnatally is usually offered. On completion of trial follow-up at 12 months, women allocated to the control arm were able to take up the same Slimming World offer as the intervention arm, namely access to 12 group sessions over a 14-week period with fees waived.

Monitoring of adherence to allocation

Monitoring of adherence to allocation was used to inform feasibility in terms of whether or not women allocated to the intervention arm would attend a commercial weight management group after giving birth and, if so, how many attended the full programme (attended ≥ 10 sessions). Data were provided by Slimming World on women’s initial and ongoing adherence to the group programme, which included weekly data on women’s attendance at groups, if they stayed with the same group or changed groups (which women could do, in line with any ‘standard’ Slimming World member) and their weekly weight. Data on women in the trial who attended groups were sent in a password-protected Microsoft Excel © (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) file on a weekly basis to the trial team. In addition, all women allocated to the intervention arm were sent a copy of a ‘log’ (see Report Supplementary Material 6) that they were asked to complete regarding attendance and duration of attendance at each session (e.g. whether they just went to get weighed or also stayed for the group session) as these data are not collected by Slimming World. On completion of the offer, they were asked to return the log to the trial office using a pre-paid postage envelope.

Standardisation of the weight management groups that women attended was overseen by Slimming World. To capture data on women’s experiences of adherence to allocation, women allocated to the intervention arm were asked in the follow-up questionnaires (see Report Supplementary Material 7 and 8) if they did or did not attend any groups, what informed their decision, how many groups they attended, if they stayed for each session in full or left after being weighed (which takes place at the start of each group meeting), if they found groups helpful and if they continued to attend groups after the 12-session offer. These issues were further explored with women who were interviewed immediately post intervention and again at 12 months post birth.

In follow-up questionnaires women in both trial arms were asked what other support they had accessed to help them manage their postnatal weight, and women allocated to the control arm were specifically asked about the timing of their access to additional support (to further inform the timing of commencement feasibility issue), and if they had joined Slimming World, to enable any potential contamination between trial arms to be assessed.

Randomisation

Randomisation and allocation were carried out using the InferMed MACRO (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) web-based data entry system hosted by King’s College London Clinical Trials Unit (www.ctu.co.uk; accessed 25 November 2019). Women were registered on the InferMed MACRO (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) web-based data entry system by the research midwife prior to randomisation to allocate each a unique trial patient identifier number (PIN). The research midwife accessed the system and, using the PIN, initials and date of birth, requested randomisation. E-mail confirmations were automatically generated. The unit of randomisation was individual participant, allocated in a ratio of 1 : 1 to intervention and control. Use of a web-based system protected against allocation bias as neither the women nor the research midwives were aware of the randomisation sequence or codes. Selection bias was minimised by ensuring that all women eligible and recruited had equal opportunity of being allocated to each trial arm. Use of intention to treat (ITT) analysis limited attrition and analytical bias. It was not possible to ‘blind’ the research midwife or women to allocation, but those responsible for analyses were blinded to allocation.

Trial feasibility objectives

The aims of the quantitative evaluation were to meet objectives 1, 2, 3 and 5. These objectives included:

-

recruitment/time to recruitment and retention

-

impact of lifestyle

-

information and postnatal access to commercial weight management groups on maternal weight change from first antenatal (booking) visit to 12 months postnatally

-

influence of lifestyle information and postnatal access to commercial weight management groups on secondary outcomes at 6 and 12 months

-

resource utilisation and costs outcomes.

Proposed primary outcome

The proposed primary outcome for subsequent study was difference between trial groups in weight 12 months postnatally, expressed as percentage weight change and weight loss from the woman’s antenatal booking weight. This outcome was supported by the trial Expert PPI Group, who considered that this would be viewed positively by women, as it did not suggest that they should reach their pre-pregnancy weight.

Secondary outcomes

Data using the following measures were collected at baseline (36 weeks’ gestation) and 6 and 12 months following birth (see Report Supplementary Material 4, 7 and 8). Selection of measures enabled hypothesised shorter- and longer-term outcomes that could result from a postnatal weight management intervention to be assessed. Further information on the measures and why measures were selected for use in the trial are included in Chapter 5.

-

Dietary intake: the Dietary Instrument for Nutritional Education (DINE) (University of Oxford, Oxford, UK);35 questions on soft drinks intake were developed for the trial.

-

Physical activity: the International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form (IPAQ-SF). 36

-

Mental health: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). 37

-

Breastfeeding intent, uptake and duration: questions developed for the trial.

-

Sleep patterns: questions developed for the trial.

-

Smoking: smoking status/cigarette dependence. 38

-

Alcohol consumption: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. 39

-

Self-esteem: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. 40

-

Infant health: questions developed for the trial.

-

Impact on body image. 41

-

Resource utilisation and costs outcome measures: the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), and the Adult Service Use Schedule (AD-SUS). 42

Data collection schedule

Information at trial entry, including eligibility and relevant maternal and obstetric characteristics (antenatal booking BMI score, parity, age, ethnicity and deprivation score), was obtained from each woman’s maternity records and entered into the trial database. A baseline questionnaire that included the measures described in Secondary outcomes was completed by women at their recruitment appointment at 36 weeks’ gestation. Following the birth, data were obtained from women’s maternity records on mode of birth, infant outcomes (gestation and infant birthweight) and duration of inpatient postnatal stay. At 6 and 12 months, women were invited to meet with the research midwives at the trial maternity unit, or arrange an appointment for the research midwife to see them at home, to be weighed (women were asked to remove their shoes) and to complete, during the appointment, a self-administered questionnaire that included the same measures as included in the baseline questionnaire, with the addition of questions on body image, infant health, use of NHS primary and secondary health-care services by the woman and/or her infant and use of weight management support interventions. Women who opted for an appointment at the trial unit were sent an off-peak travel card to cover costs of attending the two appointments. If women were unable to attend an appointment for whatever reason, they could complete the questionnaire and return it to the trial office by post. In these cases, women were asked to weigh themselves (after removing their shoes) and record their current weight in the questionnaire. In terms of acceptability of trial procedures, completion rates of measures included in the questionnaires at each time point were also considered.

An overview of time points at which trial data were collected is presented in Table 1.

| Data collection | During pregnancy | Immediately after birth | Intervention-only group | 6 months | 12 months | Completion of data collection instrument |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility screen | ✓ | Completed by research midwife from assessment of women’s maternity records | ||||

| Contact sheet at 28 weeks’ gestation | ✓ | Completed by research midwife following telephone call with women | ||||

| Baseline health measures: recruited women only | ✓ | Self-administered questionnaire completed by women | ||||

| Women’s and infants’ labour and birth data | ✓ | Completed by research midwife on all women who consented to participate | ||||

| Health questionnaire | ✓ | Self-administered questionnaire completed by all trial women | ||||

| Log book of weight management session attendance | ✓ | Self-administered and completed by women in the intervention arm | ||||

| Interviews with women allocated to the intervention arm | ✓ | Completed by researcher from SWAN trial team | ||||

| Health questionnaire | ✓ | Self-administered questionnaire completed by all trial women | ||||

| Weight measurement | ✓ | ✓ | Research midwife follow-up appointment/document in self-administered questionnaire; all trial women | |||

| Interviews with women from both trial arms | ✓ | Completed by researcher from SWAN trial team |

Sample size

The proposed sample size was 190 women. This was to allow a 30% loss to follow-up to ensure that we achieve the required sample size of 130 women. The trial was designed to establish the rates at which women could be recruited and retained in a future definitive RCT and estimate critical parameters with necessary precision to inform sample size requirements. In particular, we required estimates of the SD and design effect for the proposed primary end point, allowing for clustering by intervention arm. A total of 130 women would enable estimates of the required sample size for any given clinically important difference to within 30% of the true value. Based on published data,13,30 the mean percentage weight change following a Slimming World programme of 12 weekly groups is –5.5% (SD 3.3%). Assuming that these numbers are typical, 65 women in each group (130 in all) would be required to detect a difference of 2% between active and control arms with 90% power. At the time of submitting the funding application (in 2014), of the ≈6600 women who gave birth at the reference maternity unit over 12 months, 40% had a BMI score of ≥ 25 kg/m2, 15% of whom had a BMI score in the obese range (≥ 30 kg/m2). Data on women with EGWG were not routinely collated. Potentially 55 women booking each week would meet obese/overweight BMI score inclusion criteria. Recruiting seven to eight women each week over an 8-month (32-week) period was considered sufficient to achieve the desired sample size to meet the aims of this feasibility trial.

Trial process evaluation objectives

The process evaluation met objective 4 of the feasibility trial. The aims of the process evaluation were to assess:

-

the acceptability of the intervention and how the intervention was experienced by women, including views on timing of commencement

-

the likely variation in groups attended by women (day/time; whether or not women changed groups/consultant)

-

timing and sources of additional weight management support, including risk of contamination

-

the acceptability of trial processes and procedures.

Trial feasibility objectives reflected MRC guidelines for process evaluation of complex interventions43 with some important exceptions owing to the nature of the trial and intervention proposed. The purpose was not to evaluate the intervention itself as Slimming World weight management groups are a ‘standardised’ intervention, with robust mechanisms to ensure intervention fidelity. Owing to the robust in-built quality assurance and evidence base for the intervention, process evaluation was not designed to answer some standard questions seen in complex evaluations regarding the generalisability of the intervention to other contexts/settings, to provide assurance that implementation/delivery of the intervention has been consistent across trial sites, or to determine mechanisms of impact. This trial reflected a pragmatic trial approach, evaluating the impact of the intervention in the hands of many, where women can choose which group to attend and can switch groups if they like, exactly as they could if they were a ‘standard’ self-referred member of the commercial weight management group.

The acceptability of the intervention and trial procedures was evaluated through brief questions included in the 6- and 12-month questionnaires and through semistructured interviews with women allocated to the intervention arm at 6 months (on completion of the commercial weight management offer) and at 12 months with all women. The probable variation in groups attended by women was assessed using data provided by Slimming World on the groups attended by women (each session attended had a ‘group’ and ‘consultant’ code, and group codes had information regarding the day of the week and timing of the group), and the timing and sources of additional weight management support was assessed through questions in the 6- and 12-month questionnaires.

Postnatal questionnaires at 6 and 12 months

The content relevant to the process evaluation was included in the final section of the questionnaires (see Report Supplementary Material 4, 7 and 8). This comprised seven or eight questions (intervention arm at 6 and 12 months, respectively) or five questions (control arm); some were quantitative (binary/categorical questions) and some were free-text/open questions. The questions were the same at both time points (although at 6 months the option was given to women allocated to the intervention arm to answer that they were part-way through the commercial weight management intervention).

For women allocated to the intervention arm, the questions included a section about attendance at the commercial weight management groups, asking if they attended any sessions and, if so, how old their baby was when they attended their first group; how many sessions they had attended in total; and if they stayed for the whole-group session or just went to get weighed. Two free-text questions asked women to add an explanation regarding why they left sessions without staying for the whole session (if relevant) and how useful they found the commercial weight management sessions. Women who had not attended any sessions were asked to explain why they chose not to attend.

All women (women allocated to the intervention arm and women allocated to the control arm) were asked if they had sought any support to help manage their weight since having their baby. If they responded ‘yes’, they were asked to indicate the type of support (categorical question) and to comment on how useful they had found the support. Women allocated to the control arm were specifically asked whether or not they had joined Slimming World and were also asked about the ‘timing’ at which they sought the support (how many months postnatally).

Interviews

Interviews were conducted with 13 women allocated to the intervention arm immediately post intervention (approximately 6 to 8 months post birth) and with nine women allocated to the intervention arm (six of whom had participated in 6-month interviews) and eight women allocated to the control arm at 12 months post birth.

Diversity of the sample was considered to be more important than the number of interviews (in line with guidance about qualitative research in feasibility RCTs44), particularly as analysis regarding the acceptability of the intervention and trial procedures would also involve integration of analysis of the textual data from completed questionnaires. For these reasons we estimated that interviews with 14–20 women allocated to the intervention arm across the two time points and 8–12 women allocated to the control arm would be sufficient.

Purposive criteria for selecting women to be invited for interview immediately post intervention aimed to capture diversity in the sample in relation to attendance at the commercial weight management sessions (including women who attended ≥ 10 sessions and those who attended fewer or none at all), weight change and ethnicity.

For the interviews at the end of the trial (12 months postnatally), the same criteria were applied for women allocated to the intervention arm (including some women interviewed at 6 months to provide a longitudinal sample) and women allocated to the control arm, aiming to include diversity in relation to weight change and ethnicity. Interview topic guides are included in Report Supplementary Material 9.

Procedure

Women who met the purposive criteria were identified by the research midwives and given or sent a separate trial PIS to consider their participation in the trial (see Report Supplementary Material 10 and 11). If a women was willing to participate, written informed consent was taken by the research midwives and her contact details were confirmed and given to the researcher conducting the interviews (VB). The researcher contacted each participant to arrange a mutually convenient time for the interview, all of which were conducted over the telephone (although face-to-face options were offered). The opportunity to ask questions was provided ahead of the interview and consent was reconfirmed verbally at the start of interviews.

Interviews immediately post intervention explored motivations for participating in the trial and experiences of participating in the intervention (and also of using the lifestyle leaflet). Interviews with both groups at the end of the trial (at 12 months postnatally) were used to explore trial processes and experiences of participating, including reasons for taking part/dropping out, recruitment and randomisation (expectations/understanding of the trial and its aims), views on outcome measures, attendance for weighing appointments as part of trial follow-up and lifestyle behaviours. They were also used to explore knowledge of weight management and the role of diet and exercise in this.

For women allocated to the intervention arm, weekly data on number of weight management groups attended were obtained from Slimming World. For each woman allocated to the intervention arm, this included weekly data on their attendance, including a code for the group, for the consultant and the woman’s weight. These data enabled analysis of variability in groups attended by women and analysis of whether they stayed with the same group or changed groups (which women were free to do, in line with other Slimming World members) and of their weight change over the intervention period. It also provided information on whether women continued to attend beyond the trial period. The interviews lasted ≈45 minutes and were digitally recorded with participants’ permission.

Governance

Ethics arrangements

Favourable ethics approval for the trial was granted by the Health Research Authority (HRA) London – Camberwell St Giles Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 2 September 2016 (reference number 16/LO/1422) and HRA approval was received on 11 October 2016. Approval was obtained from the research and development department of the participating hospital. Table 2 provides details of the substantial amendments to the protocol approved by the REC. The research and development office was notified of all amendments after REC approval was received.

| Amendment | Date (version of protocol, if revised; revision date) | Description of main items in the request for approval |

|---|---|---|

| Substantial amendment 1 | 19 April 2017 (5; 29 January 2017) |

Revision to wording of postcard for recruiting women who had normal BMI scores at antenatal booking but gained excessive gestational weight. Letter about the trial to be sent to women with normal BMI scores at antenatal booking Provision of a log book for women who attended the commercial weight management groups to complete after each group meeting to provide information on whether they stayed for the whole group session or left after being weighed Revised questions about attendance at weight management groups in the 6- and 12-month questionnaires (control and intervention arms) |

| Non-substantial amendment 1 | 15 May 2017 (6) | To extend period of participant recruitment from 6 to 8 months; to focus on recruitment of women with EGWG |

| Substantial amendment 2 | 4 January 2018 (7; 13 August 2017) | It was originally planned to collate data to consider probable variation in characteristics of the commercial weight management groups in relation to both characteristics of the groups (date/time of day, size of group) and characteristics of group members [proportion of members who reached their target weight, demographics of group members (age, sex, postcode)]. Further discussions with Slimming World highlighted that these data were not routinely collected and they would not support data collection specifically for the feasibility trial |

| Non-substantial amendment 2 | 16 March 2018 | Request for a trial end date extension to 30 November 2018 following approval from the funder (NIHR) |

Trial governance

Trial Steering Committee

The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) included an independent chairperson, three independent professional members (a professor of midwifery, a statistician and a researcher with expertise of studies in obesity and weight management) and a patient representative. Non-independent members included the chief investigator. Membership of the committee was approved by the NIHR PHR Committee. The TSC agreed a charter at the first meeting, which was informed by MRC guidance for Clinical Trials Units. 45 The TSC met four times, with the final meeting held to discuss trial findings and TSC views and recommendations with respect to progressing to a definitive RCT. As this was not a Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product, an independent data monitoring committee was not required to oversee the safety of participants in the trial and the TSC took overall responsibility for the conduct of the trial.

Serious adverse event reporting

Although no serious adverse events (SAEs) were anticipated, it was possible that these could have occurred and a system for reporting these promptly was required. All SAEs occurring during the trial observed by the investigator or reported by the participant, whether or not attributed to the trial, would be reported on the data collection form. SAEs considered to be related to the trial by the investigator would have been followed up until resolution or the event was considered stable. All related SAEs that resulted in a participant’s withdrawal from the trial, or were present at the end of the trial, would have been followed up until a satisfactory resolution occurred. No SAEs were reported.

Data handling, checking, cleaning and processing

Data collection forms, including baseline and 6- and 12-month questionnaires completed by women and consent forms for trial participation and participating in a trial interview, were returned to the trial office and date stamped. Data files received via password-protected e-mails from Slimming World were stored electronically on designated password-protected trial computers. All data were entered by the research midwives onto a bespoke trial database set up by MedSciNet (https://medscinet.com; accessed 6 November 2019). MedSciNet ran validation checks for missing data and inconsistencies in data capture. Validation errors were queried with the research midwives and chief investigator. Any errors on the women’s questionnaires were not queried with the women.

Patient and public involvement

When the commissioned call for this research was launched, we worked with a group of local women who were previously participants in a NIHR Health Technology Assessment-funded pregnancy weight management trial. 20 Based on these women’s advice and experience of weight management support during pregnancy, it was clear that a non-NHS peer-supported intervention that was flexible and to which babies could be taken was perceived as more appropriate than an NHS-provided intervention. It was also apparent from these women’s feedback that we needed to initially assess whether or not this trial could be undertaken. We advertised for local women who had given birth at the trial site and had experienced weight management issues around the time of pregnancy to join the trial Expert PPI Group to inform all stages of the work. Four women came forward to join us.

When the research team was assembled, we invited the National Childbirth Trust (NCT) (www.nct.org.uk; accessed 6 November 2019) to work with the team and included funding for a dedicated research post at the NCT to take the lead for planned qualitative work. The NCT were also asked to provide ongoing support for an ‘expert’ group of local women who would meet alongside the Core Project Team (CPT). Sarah McMullen, Head of Research at NCT, joined as a co-applicant, and her colleague Vanita Bhavnani was employed on behalf of the trial to arrange and conduct trial interviews and provide ongoing support for the trial Expert PPI Group. Both Sarah McMullen and Vanita Bhavnani and the trial Expert PPI Group commented on the intervention lifestyle behaviour information leaflet, PISs and women’s questionnaires and were involved in all stages of trial development, including the drafting and writing of this report and plans for dissemination activities.

Chapter 3 Analysis plan

The main analysis is considered (in relation to objectives 1–3) in this chapter and in Chapters 4 and 5, followed by the analysis for the process evaluation (objective 4) (see Chapter 6) and the health economic analysis (objective 5) (see Chapter 7). Implications for a future definitive RCT (objective 6) are then described (see Chapter 9).

A data analysis plan (see Appendix 2) was written and approved by the TSC at the commencement of trial recruitment and prior to commencing trial analysis.

Losses to the trial post randomisation were defined as women for whom:

-

valid consent was not obtained

-

consent to use their data was withdrawn.

Women were able to specify whether or not data collected up to the point of withdrawal could be used. If a woman’s response was ‘no’, she would be categorised as excluded post randomisation; if a woman’s response was ‘yes’ (i.e. data collected up to the point of withdrawal could be used), data would be reported as ‘missing’ for all subsequent outcomes. Numbers of exclusions are reported by randomised treatment group.

For the primary analysis, women were analysed in the arms to which they were randomly allocated. Outcomes of women allocated to the intervention were compared with those who were allocated to receive standard care only. The unit of analysis for all outcomes was the woman.

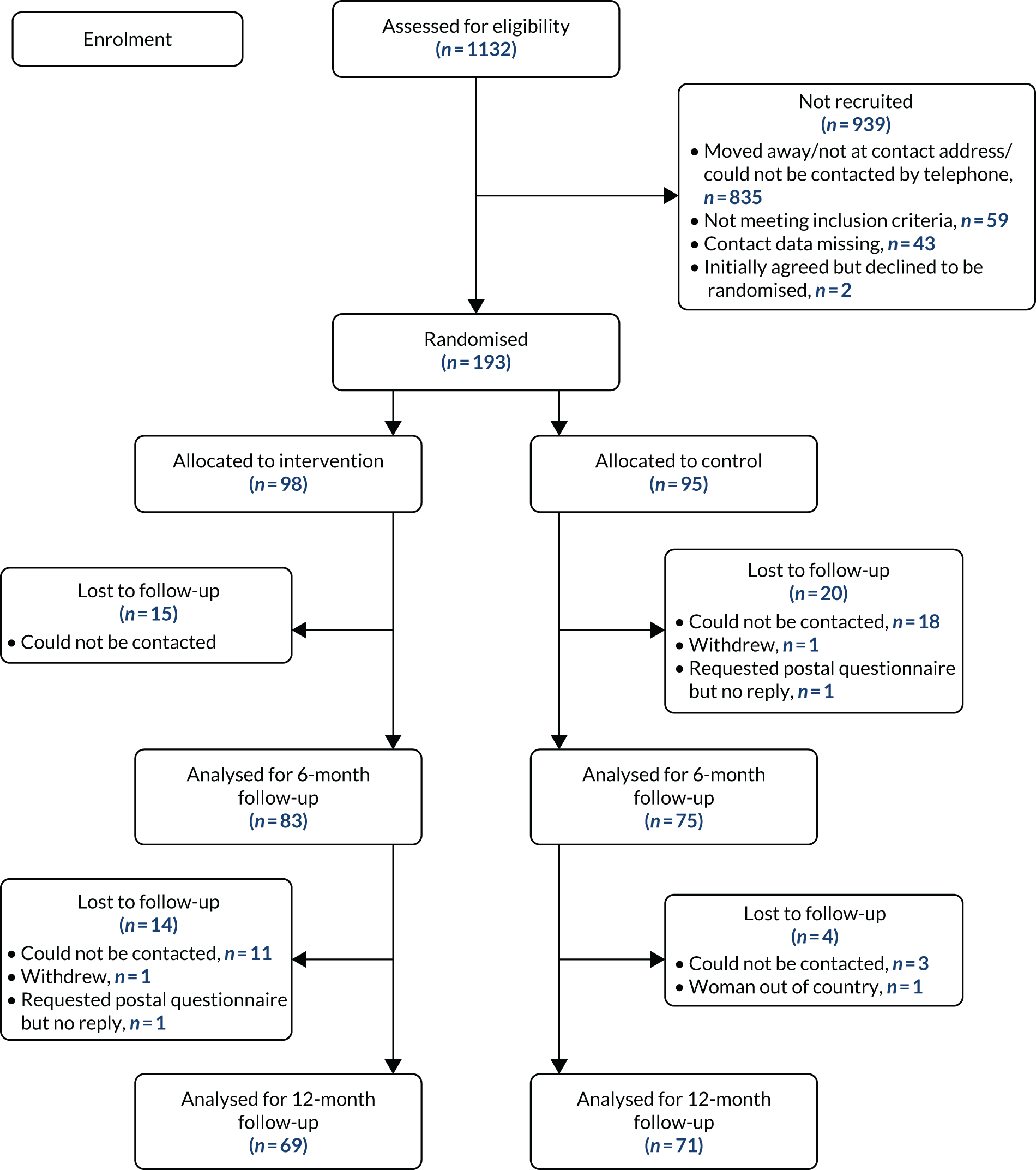

Descriptive analysis

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram (see Figure 3) shows the flow of participants through each stage of the trial. The number of women analysed for primary assessment is also reported, as are numbers for the 12-month follow-up, including number of women lost to follow-up. Only two women withdrew: one from the control arm at 6-month follow-up and one from the intervention arm at 12-month follow-up. Neither woman asked for her data to be withdrawn. The total number of eligible women who were approached but declined participation is also reported.

Recruitment was assessed as the number of women randomised per month from the trial centre, with 95% CIs derived from the Poisson distribution. Retention was assessed as the proportion of women randomised who provided complete analysable data for primary assessment. Linear regression was used for the primary end point and other continuous measures. Where data were available, adjustment was made for corresponding measurements made pre randomisation using the Bulk Centile Calculator version 6.2 (Gestation Network, Perinatal Institute, Birmingham; www.gestation.net). Binary regression with a log link was used to assess RRs for all binary (yes/no) outcomes, adjusting for the most important potential confounders: maternal BMI score, ethnicity and parity. Following the most recent CONSORT guidelines and additional recommendations,46 risk differences were also estimated.

Significance tests were carried out to test only for differences in drop-out rates between trial arms and for estimates of treatment effects. No formal interim analysis was planned because the results of this feasibility trial were to be used to decide if a definitive trial could be undertaken.

Reduction of weight by 5% and 10% were analysed as binary variables, with RRs and risk differences presented. Maintenance of EGWG was defined as a BMI score at 12 months postpartum > 1 kg/m2 above estimated pre-pregnancy weight. Baseline measurements of aspects of healthy lifestyle and health as assessed by questionnaire at 6 and 12 months were used in the analysis as a covariate. 46

We also planned to undertake pre-planned subgroup analysis of the primary end point in women of different antenatal booking BMI categories [overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2), obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) and normal (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2)] at antenatal booking who gained EGWG when weighed at 36 weeks. Interaction tests were used to determine if the treatment effect varied by subgroup.

Per-protocol analysis

To explore if women who received the intervention as intended (e.g. attended ≥ 10 weight management sessions) were more likely to have greater weight loss at 12 months postnatally than women attending < 10 groups or women in the control arm, we conducted per-protocol analyses to assess if there was a ‘dose effect’ on this outcome. We also assessed if women who did not attend 6- or 12-month follow-up appointments with the research midwives to be weighed but recorded and documented their own weight in postal questionnaires had different weight change than women who attended appointments.

Statistical software

Stata® version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all quantitative analyses.

Reliability

Data on women’s eligibility to participate, including their antenatal booking BMI score, were obtained from the woman’s maternity records, with primary end-point data (maternal weight at 12 months) obtained when women attended pre-arranged contacts with the research midwives or returned self-administered questionnaires with their self-recorded weight. Data recorded on women’s weight at each session attended were provided to the researchers for all women at weekly intervals until 12 months postnatally to enable assessment of sustainability and how long women continued to attend sessions.

Protocol violations and deviations

Failure to comply fully with the final trial protocol as approved by the REC or research department, such as non-compliance with the protocol resulting from error, fraud or misconduct, is deemed to be a protocol violation. A protocol deviation is a departure from the final trial protocol as approved by the REC. There was one protocol deviation: one woman in the control arm was offered information in error on how to join Slimming World at 6 months, rather than at 12 months, when she should have been offered the information.

Trial process evaluation

Data from questionnaire responses and interviews were first analysed separately before being integrated to answer the research questions and meet the aims of this part of the trial.

The analysis of interview data and of the free-text responses in the questionnaires was underpinned by the capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour (COM-B) framework for understanding behaviour and behaviour change. 47 The model proposes that for someone to engage in a particular behaviour they must be physically and psychologically ‘capable’ of performing the behaviour, have the social and physical ‘opportunity’ to carry out the behaviour and be ‘motivated’ (by both reflective and automatic mechanisms that activate or inhibit behaviour) to carry out the behaviour. The COM-B framework is proposed as a simple starting point to understand behaviour because it is comprehensive, parsimonious and applicable to all behaviours.

Questionnaire analysis

Quantitative responses from the questionnaires were analysed descriptively. Free-text questions were read in full by two members of the research team, who independently noted key themes. The thematic framework was agreed and text was coded and labelled according to the three dimensions of the COM-B framework. Data were then examined using frameworks to compare patterns between different groups of women and their responses in relation to capability, motivation and opportunity (e.g. comparing women who attended different ‘doses’ of sessions).

Interview analysis

All interviews (intervention and control) were transcribed verbatim. First, transcripts were read and re-read to ensure familiarisation with the data. Second, interview data were organised and coded using the COM-B framework, initially by two researchers independently (CT and VB). Coding was compared and discussed before all data were coded. As the elements of the COM-B framework are inter-related (not mutually exclusive), data often fit several of the dimensions and, therefore, multiple codes were applied where appropriate. Coding of the remainder of the data (by VB) continued independently and a summary of all coded data was presented in a framework matrix.

Two members of the research team (CT and VB) reviewed and discussed the coded summary data in the frameworks and compared data with and between women to identify themes and patterns in and between different women, including comparisons according to the number of sessions (fewer than six, six to nine or ≥ 10 sessions) they attended. Comparisons were also made on the basis of weight change between antenatal booking weight and weight at 6 and 12 months. This enabled the identification of key factors influencing engagement with the intervention and behaviour change. Similarly, researchers compared the coded summary data and identified themes and patterns from interviews with control arm women in relation to weight loss or gain at 6 and 12 months to allow for comparison with women allocated to the intervention arm. An example framework is provided in Appendix 1.

Integration of process data from questionnaires and interviews

Questionnaire data were coded to indicate if the women also participated in interviews so that ‘double counting’ could be avoided. Themes were compared across both samples. The final thematic framework applied to both sets of data. Interview and questionnaire data are presented according to theme, with attention paid to instances where one of the data sets expanded on or contradicted the other data set (or if one data set was ‘silent’). This was the case sometimes for the questionnaire thematic data set owing to the specific nature of the questions asked.

Trial health economic analysis

The economic analysis to meet objective 5 was carried out principally from an NHS payer and provider perspective, although some service items included in the cost analysis (e.g. smoking cessation services, social worker and housing worker contacts) are paid for through local government authority budgets. The weight management programme evaluated in the feasibility trial was delivered by a private for-profit organisation and is paid for privately by those who enrol, but trial participants were offered free access. The standard costs include a one-off enrolment fee plus a weekly attendance fee. Costs of enrolment were included in the cost-effectiveness analysis on the basis that any future commissioning of the programme would potentially be paid for through either NHS or local authority commissioning budgets.

Service contacts

Service contact data were collected using an adapted version of the AD-SUS42 used to evaluate antenatal psychological interventions for women with mental health problems. 48 The SWAN version of the AD-SUS asked trial participants to self-report the number of contacts made with a prespecified list of community-based health and social care services, hospital outpatient services, accident and emergency (A&E) departments and number of admissions to hospital. An open-ended question also allowed for service contacts not covered by the prespecified services list to be recorded. The AD-SUS was initially administered as part of the baseline questionnaire in which women were asked to report service contacts over the period of their pregnancy to date of recruitment at 36 weeks’ gestation. This covered use of community- and hospital-based antenatal services and non-pregnancy-related service contacts. The AD-SUS was then administered as part of the 6- and 12-month follow-up questionnaires in which participants were asked to report service contacts over the previous 6 months, including contact with services for both mother and infant (see Report Supplementary Material 4, 7 and 8). To measure and cost medical resources allocated to birth, data on the mode of birth for each trial participant were extracted from women’s maternity records provided by the participating NHS trust.

Unit costs

Unit cost data required for costing community- and hospital-based service contacts (including admissions to hospital) and mode of birth were extracted from the publications NHS Reference Costs 2016/1749 and Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2017. 50 To cost contact with the weight management programme for women in the intervention arm of the feasibility trial, an enrolment cost of £49.50 quoted by the service provider (Slimming World) was applied, covering registration to the programme plus 12 weeks of programme involvement irrespective of number of sessions attended. This was assumed to be charge per participant, which would be levied on a service commissioning body if a weight management programme of the type evaluated were to be subsidised by the NHS or through a local authority public health budget. All unit costs were reported and applied to service contact data at 2017 price levels.

Quality of life measurement

Quality of life data pertinent to estimating within-trial intervention impact on quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and cost-effectiveness at 12-month follow-up were collected using the EQ-5D-5L instrument51 administered as part of the baseline, 6- and 12-month questionnaires (see Appendix 4, Table 29).

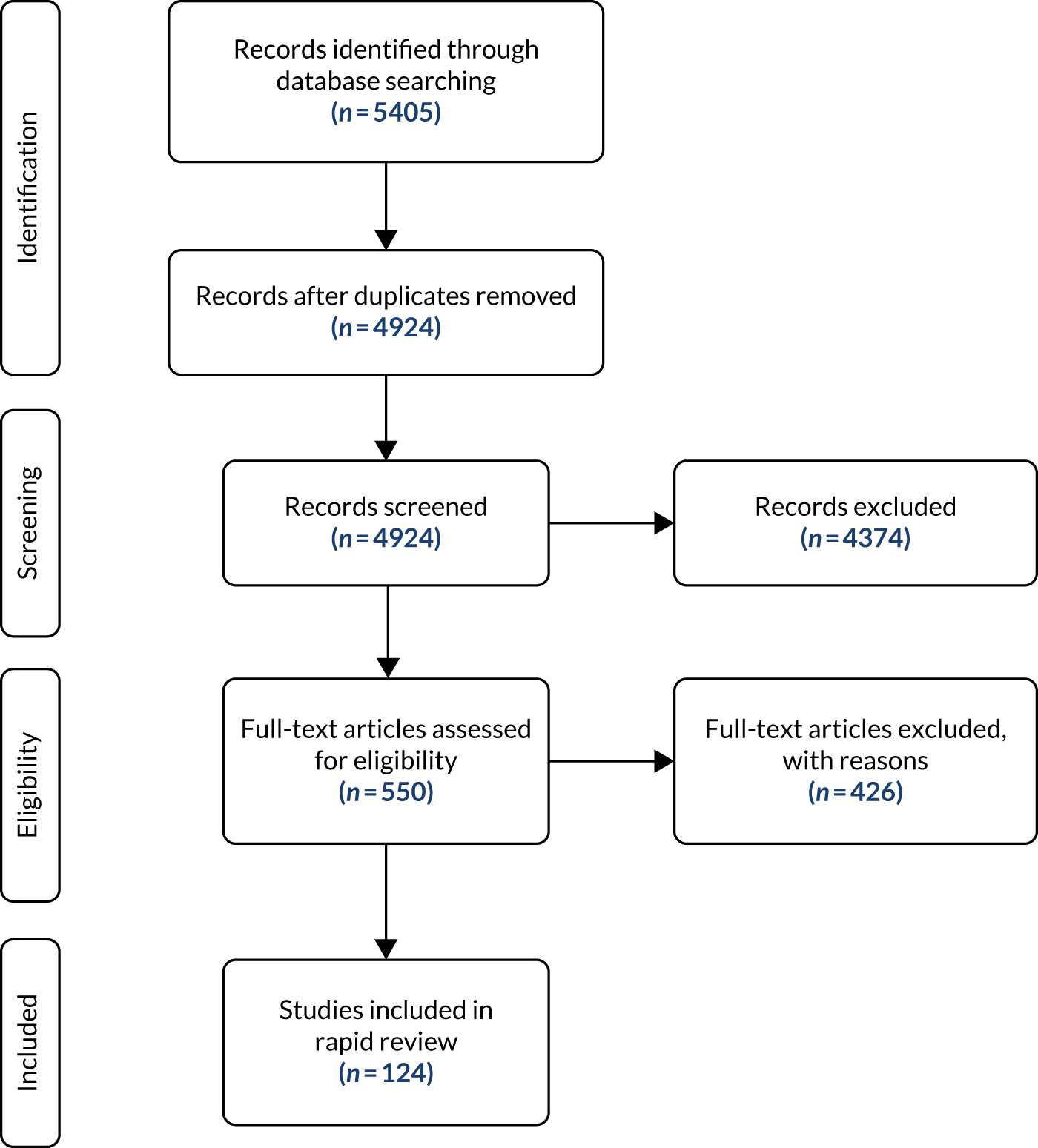

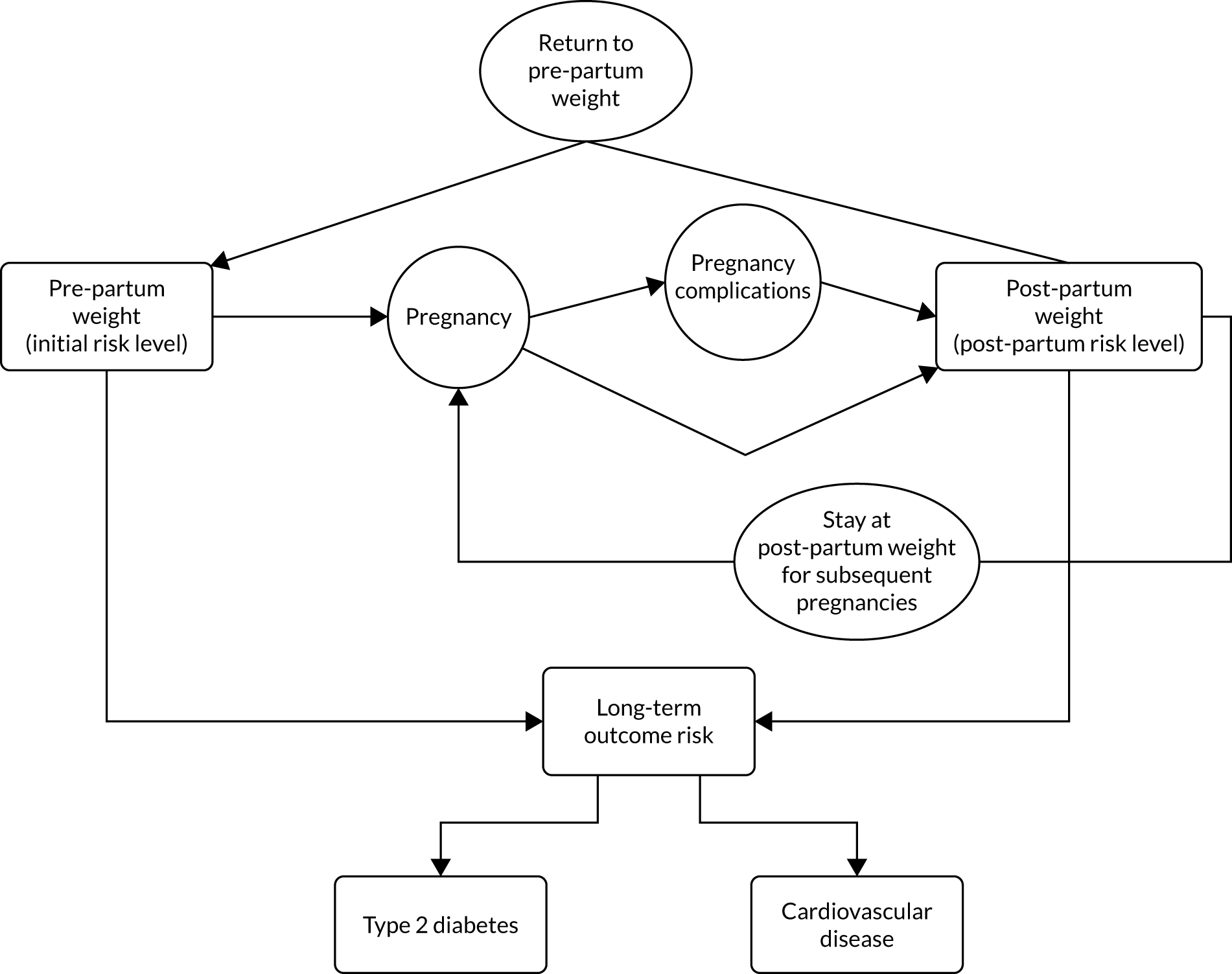

Modelling out-of-trial programme impacts

An overview of the available evidence required to support economic modelling of the out-of-trial cost and QALY impacts of improved postnatal weight management as part of a larger definitive trial was undertaken to inform general recommendations as to how this work might proceed. Capturing longer-term impacts of postnatal weight management is likely to be complex, requiring economic modelling of one form or another. A broad assessment into the probable feasibility of modelling longer-term impacts as part of a definitive trial was completed, including the plausible time scales over which these impacts might be assessed. A rapid evidence review of the type of evidence required to develop and parameterise an economic model of this type was completed, full details of which are presented in Chapter 7.

Integration of main feasibility trial and process evaluation findings

Following the completion of the main feasibility analyses and process evaluation, we carefully examined the findings from both sources to inform the overarching aim of determining whether or not it is feasible to conduct a definitive RCT to determine clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lifestyle information and access to the commercial weight management groups for 12 weeks to support women in an ethnically diverse inner-city population to achieve and maintain postnatal weight management and positive lifestyle behaviour.

We integrated the findings by ‘following threads’ backwards and forwards from the quantitative findings to the qualitative/mixed-methods process findings (and vice versa) to identify aspects of the findings that corroborated each other, conflicted with each other and where one source was ‘silent’. 52 For example, we examined how both data sets informed us about the relationship between the intervention and weight loss, and analysis of the qualitative data led to us conducting further analysis of the quantitative data (a per-protocol analysis to test for a dose-response effect). We followed the methods described by Moffat et al. 53 to explore the potential reasons for any conflict or ‘silence’ in relation to findings that were not concordant. This included considering the following: (1) treating the methods as fundamentally different, (2) exploring the methodological rigour of each component, (3) exploring data set comparability, (4) using additional data and making further comparisons, (5) exploring whether or not the intervention worked as expected and (6) exploring whether or not the outcomes of the quantitative and qualitative components match.

Chapter 4 Trial conduct

Important feasibility outcomes included whether or not we were able to recruit women during pregnancy to a weight management trial commencing postnatally, whether or not it was possible to recruit to the required sample size within time allocated, and whether or not we could retain sufficient women to 12 months postnatally.

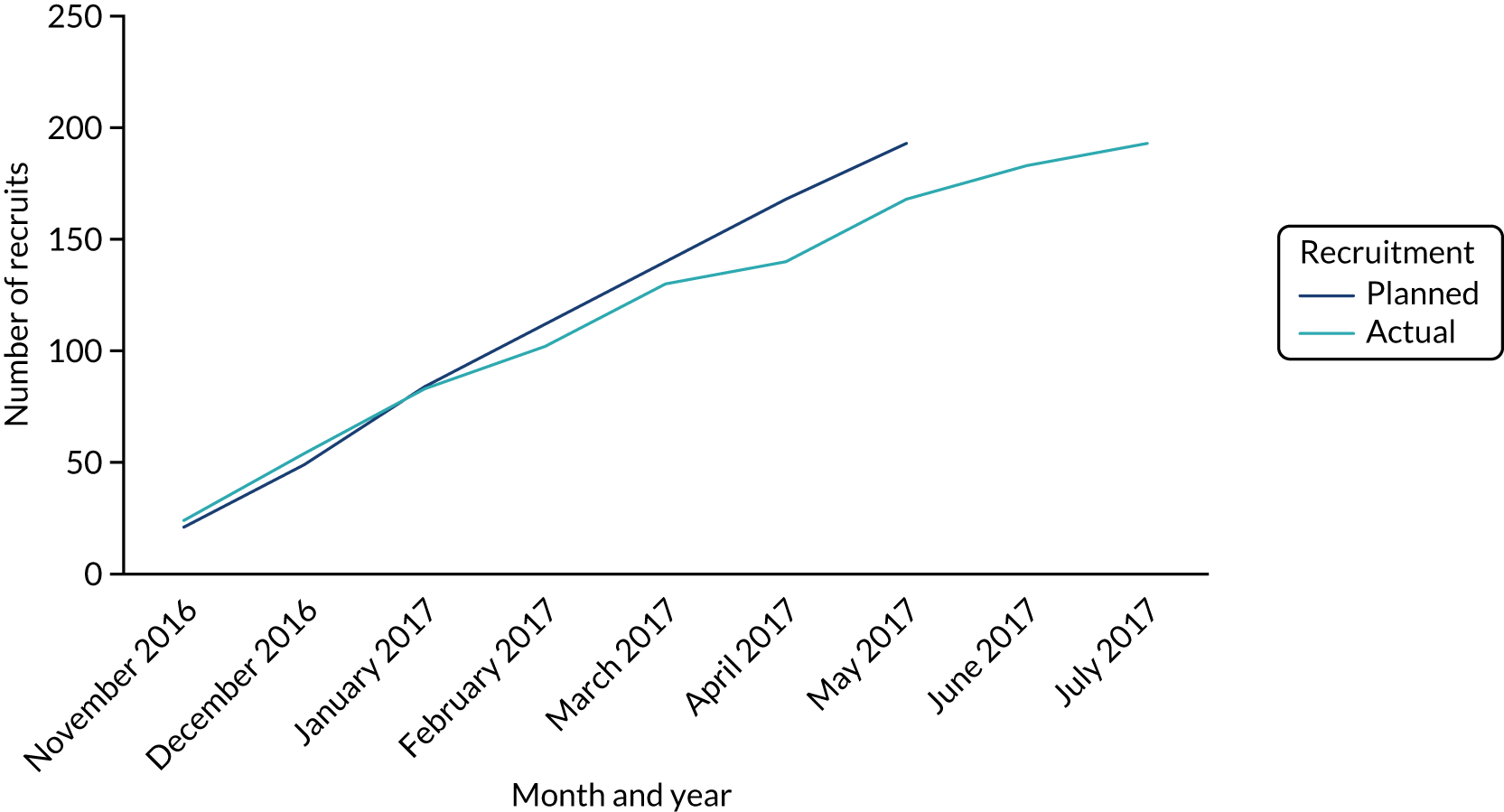

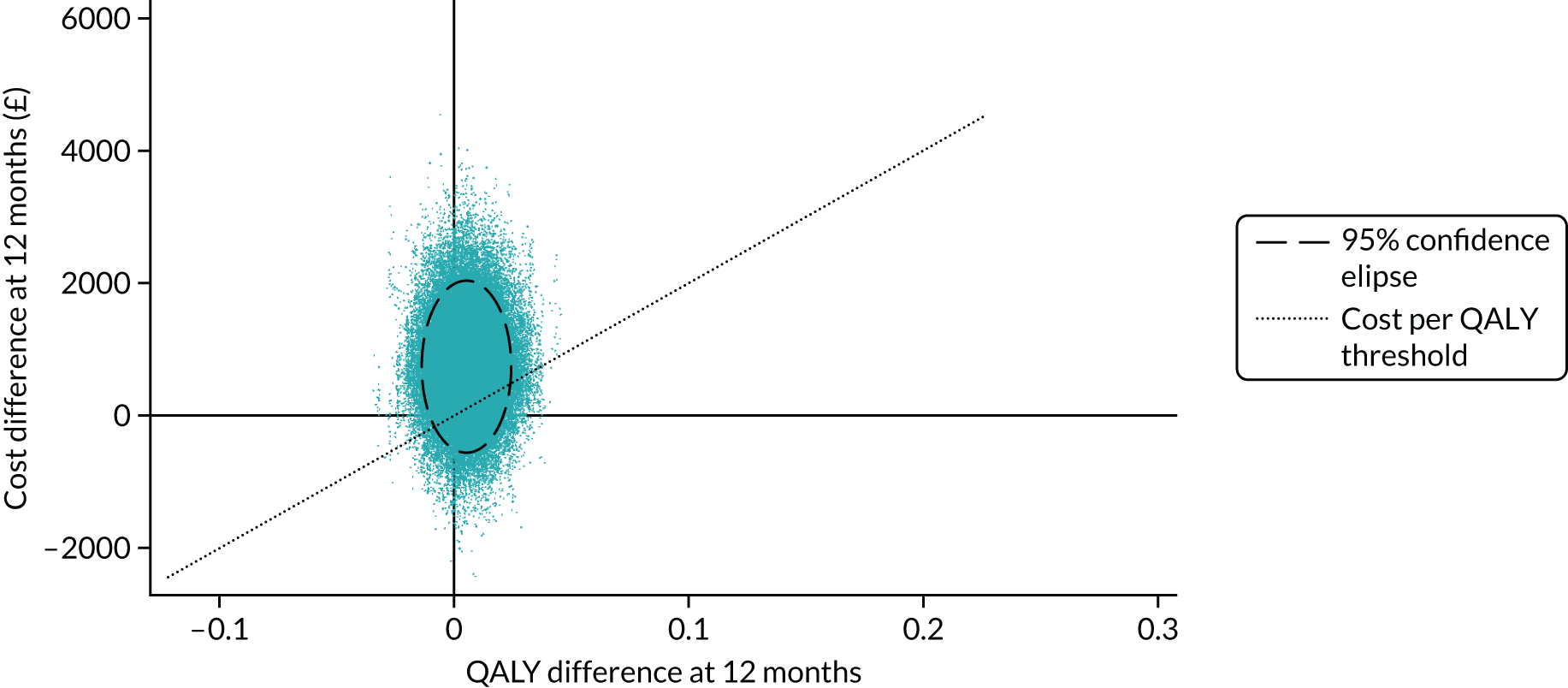

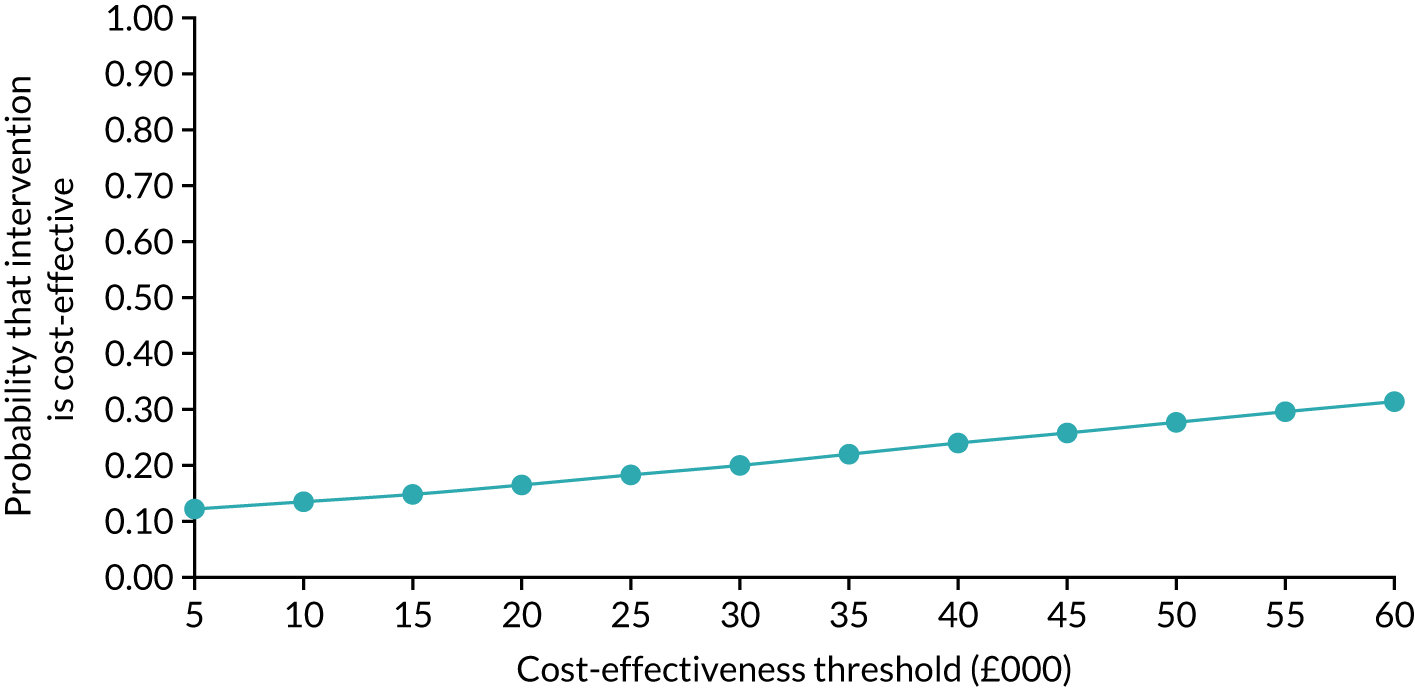

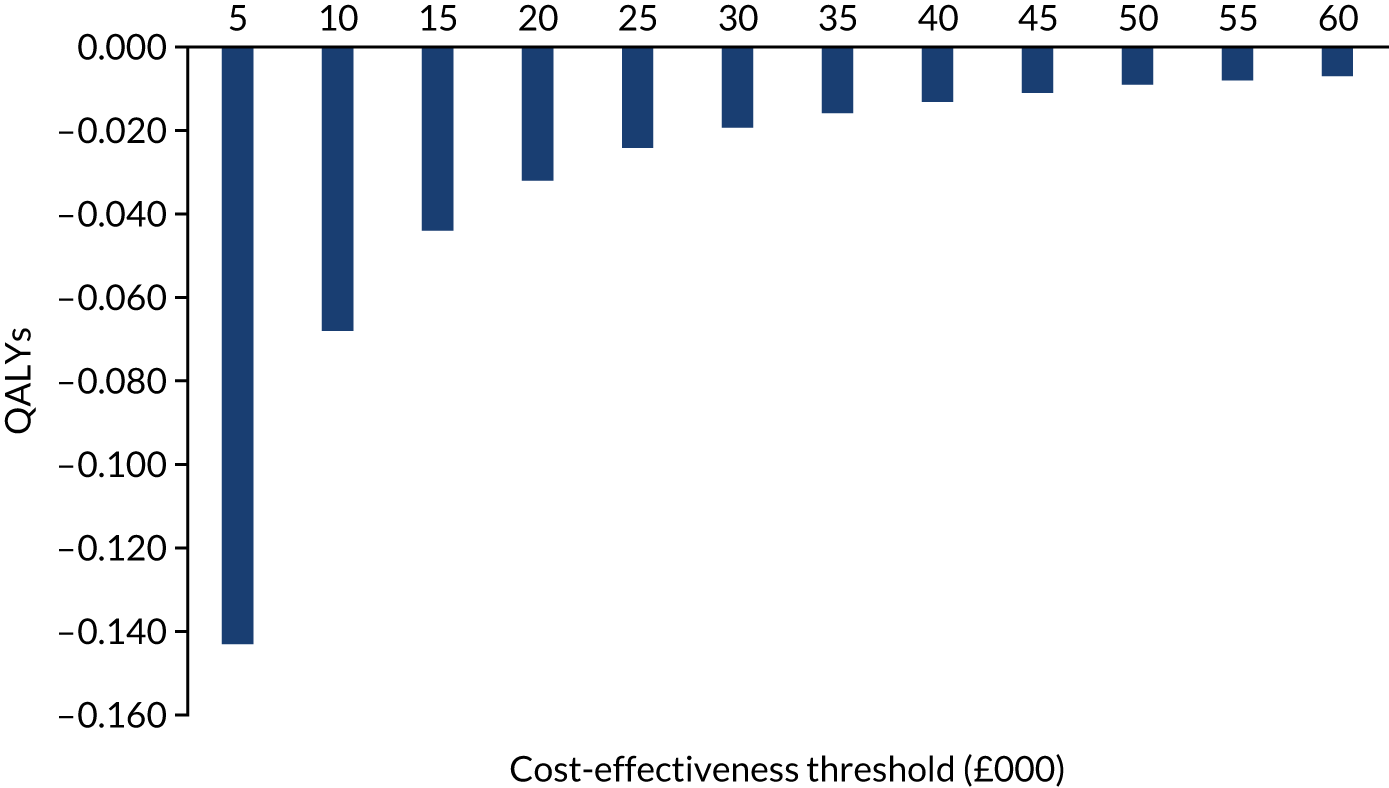

Recruitment