Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 11/3002/11. The contractual start date was in February 2014. The final report began editorial review in August 2019 and was accepted for publication in May 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Personal dedication

Our work aims to improve the life chances of babies. All babies are precious. Their wonderful potential, their joy and their sorrows can sometimes get lost when quantified statistically. It is often our personal knowledge that brings meaning to such numbers. I dedicate this report to my own grand-daughter, Luna Alice Atkins, who left us this year aged only three days old. She will forever remain precious to us and her life will always have meaning. Michael Robling, 2020

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Robling et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from the published protocol paper by Lugg-Widger et al. 1 © Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2017. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Summary

The Building Blocks: 2–6 years (BB:2–6) study has followed up the cohort of mothers originally recruited to the Building Blocks (BB) trial of the Family Nurse Partnership (FNP) in England, BB: 0–2 years (BB:0–2). Using routine data drawn from across public sector providers to augment trial data, the study offers a unique opportunity to evaluate the medium-term outcomes of the FNP as a preventative intervention to reduce child maltreatment in England. This chapter provides an introduction to the principal clinical domain addressed by the BB:2–6 study; presents previous research on the specialist home-visiting programme both in the UK and internationally; and provides a rationale and description for the current study aims and objectives.

Maltreatment

Maltreatment involves acts of omission (neglect) or commission (abuse), often by caregivers who either threaten to risk, risk or actually cause harm to a child. 2 Abuse may be physical, emotional or sexual. Neglect represents persistent failure to meet a child’s basic physical or psychological needs, often resulting in serious impairment of the child’s health or development. 2 Neglect may involve failing to do any of the following: protect a child from physical and emotional harm or danger, ensure adequate supervision or ensure access to appropriate medical care. In the financial year ending 31 March 2018 in England, there were 655,630 referrals to children’s social care (CSC) services (relating to 581,280 children, an average of 1.13 referrals per child), 406,770 children were starting an episode of need (an overall rate of 341.0 per 10,000) and 53,790 children became subject to a child protection plan. 3 A child protection plan is a plan drawn up by the local authority detailing how the child can be supported. The most common reason for a child to become subject to a child protection plan was neglect (48.0%), followed by emotional abuse (35.1%). 3

In the UK, preventing maltreatment is an important focus of government concern. The Children Act 19894 specifies agencies’ responsibilities to co-operate in the interests of vulnerable children, for children in need (section 17) and children suffering or likely to suffer from significant harm (section 47). A child in need (CIN) is defined as a child who is unlikely to achieve or maintain a reasonable level of health or development, a child whose health and development is likely to be significantly or further impaired without the provision of services, or a child who is disabled. 4 Local authority provisions may include supervision of activities; financial help; and/or provision of family accommodation, respite or home help, in addition to advice and guidance from social workers.

Specialist home visiting: the Family Nurse Partnership

There has been an increasing emphasis on the primary prevention of child maltreatment, including interventions directed at general populations and those targeting high-risk groups. The US Department of Health and Human Services’ Home Visiting Evidence and Effectiveness review5 maintains an ongoing assessment of evidence on home visiting as a preventative intervention. One such preventative home-visiting approach to reducing maltreatment is the FNP programme [developed in the USA as the Nurse–Family Partnership (NFP)], with three overarching goals: to improve birth outcomes; to improve child health and development, including reducing maltreatment; and to promote the economic self-sufficiency of mothers. 6 The programme aims to promote sensitive and competent caregiving and to reduce maltreatment through activities such as education about child development, modelling sensitive parent–child interaction, and guidance on accessing appropriate child care. The NFP is one of three preventative programmes shown to be effective in preventing maltreatment;7 in the USA, it is delivered in 42 states (plus the US Virgin Islands). 8 In three US trials (in Elmira, NY; Memphis, TN; and Denver, CO),9–11 the NFP has demonstrated improvements in prenatal health behaviours and birth outcomes; improvements in sensitive child care; reductions in child injuries, abuse and neglect; improvements in maternal life course (e.g. greater workforce participation); and improvements in child and adolescent functioning. The NFP has shown greatest impact on those at greater risk, and, although there is no net saving for married women or those of higher socioeconomic status, for low-income and unmarried mothers, the cost of the programme was recovered by a child’s fourth birthday.

In the first US trial,9 in the subgroup of poor unmarried teenage mothers, by the age of 2 years, there was verified abuse/neglect in 19% of control children, compared with 4% in the NFP group, and for the NFP group a 56% relative reduction in emergency department attendance for injuries and ingestions during the second year of life compared with the control group. Among the subgroup of children (56 families) with a state-verified report of maltreatment by age 4 years, the NFP group of children exhibited fewer risks for harm than the control group (e.g. fewer attendances for injuries/ingestions, safer home environment). 12 In the 15 years after birth, mothers as perpetrators of abuse were less common in the NFP arm than in the control arm (log incidence of 0.29 vs. 0.54, respectively; p < 0.001), an effect even greater for the most vulnerable subgroup: mothers of low socioeconomic status who were unmarried (log incidence of 0.11, compared with 0.53 for the control arm; p < 0.001). 13 Although the beneficial impact on state-verified first-time reports of maltreatment is generally experienced after age 5 years, the difference is seen earlier (age 3 years) for the most vulnerable subgroup of poor unmarried mothers of the NFP trials.

Common to other home-visiting programmes, the NFP aims to address several related child and maternal outcomes, and a key objective is to promote child development and school readiness. This can be supported by programme elements such as educating parents about child development, promoting positive parent–child interactions and linking families to additional specialist support. US trials of the NFP found improvements in mathematics (among mothers with low resource) and mental processing (whole sample and low resource) at age 6 years, and in reading and mathematics at ages 9 and 12 years. 14,15 Language skills were also improved at 34 and 48 months for children of mothers with low resource. 16,17

Family–Nurse Partnership and the Building Blocks trial

The NFP was adapted for the UK prior to implementation as the FNP and was introduced in England in 2007. Adaptations included rebranding professionals as family nurses, changing the programme name to the FNP, ‘anglicisation’ of programme surface structure (e.g. materials handed out to clients), and the addition of an eligibility criterion emphasising maternal age as a principal indicator of need. 18,19 An implementation evaluation reported progress in the delivery of the programme in 10 test sites. 20 The differing pattern of service provision and sociocultural context meant that the relative costs and benefits of the programme needed to be replicated in England before widespread implementation could be recommended. This was an explicit licensing requirement of the programme, and the stimulus for the BB:0–2 trial (ISRCTN23019866) of the FNP. We evaluated the short-term impact of the FNP (up to age 2 years) when added to usually available supportive services, compared with usual support alone. 21

Assessed against the FNP fidelity criteria, the programme was considered to have been adequately delivered in the trial and to have been delivered as would be expected when rolled out as an NHS service. 22 We found no differences in the two maternal primary outcomes: biomarker-calibrated self-reported tobacco use by the mother at late pregnancy and the proportion of women with a second pregnancy within 24 months post partum. Likewise, no differences were found in the two child primary outcomes: birthweight of the baby and emergency attendances and hospital admissions for the child within 24 months post partum. 22 We observed some differences in secondary child development outcomes, including maternally reported language development at age 2 years and the rate of safeguarding events reported in primary care records.

Despite the lack of benefit for some key outcomes that had been found in earlier trials of the programme and which had been prioritised by the original funding call, longer-term evaluation was considered essential for three reasons. First, previous evaluations had demonstrated benefit over the longer term (e.g. up to 15 years of age)23 for outcomes such as school readiness, attainment and antisocial behaviour. Second, for maltreatment outcomes, the pattern of benefit would be expected to become increasingly evident after age 4 years. 9 Third, the suggestion of benefit for clinically important child development outcomes, such as language, warranted tracking to determine if maternally reported differences at age 2 years would give rise to objective outcomes when children reach school.

Although the BB:0–2 trial commenced in 2008 at 18 sites and reported to the funder in 2015, the programme was concurrently rolled out across England. Up to 132 sites offered the programme, and by its 10th anniversary, in 2017, 30,000 babies had been born to families supported by the FNP, and 950 FNP nurses had been trained to deliver the programme. 24

Other evaluations of the Nurse–Family Partnership

In a Dutch trial of the NFP (the VoorZorg trial),25–27 the intervention was offered to women with multiple risk factors (e.g. psychological, health, economic, social). VoorZorg found that the NFP reduced rates of smoking in late pregnancy and increased rates of breastfeeding at 6 months post birth. 25,26 Programme impact on maltreatment was assessed at 3 years using Child Protective Services reports, with lower rates found for children in the intervention arm. 25 A trial assessing the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of group FNP in England to reduce risk factors for maltreatment found no differences for child abuse potential and parent–infant interaction at 12 months. 20 Pro Kind is a German adaptation of the NFP; it was trialled between 2006 and 2012 with 755 first-time mothers. 28 A current study to evaluate the medium-term impact of Pro Kind (to age 7 years) will assess maltreatment by parental self-report and also assess child development and school achievement. 29 Another UK-based evaluation of the FNP in Scotland using routinely collected data will assess maltreatment and is due to report in 2021. 30 Appendix 1, Table 25, summarises the outcomes relevant to BB:2–6 that the NFP9–11 and VoorZorg25–27 trials evaluated.

Justification/rationale for the study

This study aimed to provide evidence for the medium-term effectiveness and costs of one of the most promising early-intervention programmes for reducing the risk of child maltreatment in a targeted vulnerable population. This would inform policy about whether or not to continue implementing a programme for which there is limited existing UK evidence for effectiveness. Although we generated evidence related to short-term effects in the BB:0–2 trial (i.e. up to the point when families graduate from the programme before or at their first child’s second birthday), the recognised potential programme benefits (in particular for child maltreatment) have largely been demonstrated only in the longer term. This study presented a unique opportunity to extend learning from the trial by using the existing outcome data in combination with newly arising routinely recorded data.

Research aims and objectives

Given the evidence from both US and Dutch trials of programme benefit for families arising in the 4-year period following the NFP graduation, we aimed to determine the medium-term impact of the FNP on child maltreatment outcomes and key indicators of neglect (e.g. injuries and ingestions), child development and educational outcomes, and other hypothesised programme impacts measurable through routine data.

Primary objective

The primary objective was to determine the effectiveness of the FNP programme in reducing objectively measured maltreatment outcomes when compared with usually provided health and social care alone. Using a multimethod multisource approach, main outcomes included CIN status, child protection registration and referral to social care.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives were to:

-

determine the effectiveness of the FNP programme in reducing maltreatment when assessed using associated measures of injuries and ingestions, hospital did-not-attend (DNA) rates and immunisation rates

-

determine the impact of the FNP programme on medium-term outcomes, most notably subsequent pregnancies, school readiness and educational outcomes

-

explore the impact of theoretical moderators of programme effect, including domestic abuse and baseline maternal characteristics

-

determine the costs and consequences of the FNP programme over the full period of available follow-up (i.e. data from the BB:0–2 trial22 and this follow-up study, BB:2–6).

This report continues with a description of the study methods. A substantive pilot phase was undertaken to establish the feasibility of the study design; this is reported in Chapter 3. Both the study protocol1 and the results of the feasibility study31 are already published, various material has been reproduced from these publications and are cited as appropriate for transparency and to provide some additional information. The original study title referred to ‘long-term’ follow-up. However, to reflect the extended duration of follow-up for the US trials of the NFP and contemporary evaluations of NFP-derived home visiting in Germany, we have updated this to reflect a medium-term follow-up. Study findings are then presented in Chapters 4–6, followed by a description of the public involvement activity that was undertaken in the course of delivering the study (see Chapter 7). Chapter 8 summarises our key findings, sets the work in broader research and policy context and provides recommendations for further work.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from the published protocol paper by Lugg-Widger et al. 1 © Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2017. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Research objectives

In the BB:2–6 study, we used existing trial cohort data linked to routinely collected national data sets to assess the medium-term impact of the FNP on objective measures and indicators of child maltreatment outcomes; child health, development and educational outcomes; and other programme-relevant outcomes.

Study design

The data-linkage study generated a linked anonymised database hosted by a data safe haven. We followed up participant mothers and children from BB:0–2 for a further 5 years using routine data only. Health, education and social care data from a range of routine public sector sources were retrieved and linked to existing trial cohort data on an individual level. This enabled children and mothers to be followed until the child reached Key Stage 1 (KS1), the 2 years of schooling when pupils are aged between 5 and 7 years. Participants were recruited to the BB:0–2 trial between June 2009 and July 2010; therefore, the follow-up for all participants was completed in May 2018, when the youngest children completed their KS1 assessment. A summary of the data sources is provided in Appendix 2, Table 26.

Study participants

In the BB:0–2 trial, we recruited nulliparous women aged ≤ 19 years, living in one of 18 local authority FNP catchment areas, who were at < 25 weeks’ gestation, who were able to provide consent and who could engage with the FNP in English. 21 Women expecting multiple births and those with a previous pregnancy ending in miscarriage, stillbirth or termination were eligible. Women planning to have their child adopted or to move outside the FNP catchment area for > 3 months were not eligible. Women and their first child (or twins, if relevant) who were not mandatorily withdrawn from the BB:0–2 trial (e.g. owing to miscarriage, stillbirth, infant death or adoption), or who did not electively withdraw (including their consent for use of their data) were eligible to be included in BB:2–6 study.

The BB:0–2 trial intervention

Experimental intervention

The FNP is an intensive programme of home visits for women expecting their first baby. In this trial, specially trained FNP nurses delivered the programme from early pregnancy until the child was 2 years old. It comprised a maximum of 64 scheduled visits (14 during pregnancy, 28 during infancy and 22 during toddlerhood), covering content domains of personal and environmental health, life course development, maternal role, family and friends, and access to health and social services. 32

Control

Although participants in both study arms received usually provided health and social care services for pregnancy and new mothers, participants in the control arm received these services alone. These services included maternity care and care provided by health visitors. 32

Outcomes

The study follows the multimethod multisource approach to maltreatment research, which considers an outcome continuum from child maltreatment to family wellness. 33,34 As we have access to routine data, which are a record of professionally determined outcomes, our data are primarily objective (in that we are not using parent-reported proxy outcomes). 35 Although professional decision-making will involve subjective assessment, our distinction is between assessments that are established by professionals and those directly involving parents. We have also distinguished between objective measures of maltreatment assessed in the CSC and associated measures of maltreatment assessed in health care. Although a primary outcome is identified, interpretation will collectively assess evidence for maltreatment.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was CIN status recorded at any time during the follow-up period [sourced from the National Pupil Database (NPD)]. CIN status refers to a child who is unlikely to achieve or maintain a reasonable level of health or development, or a child whose health and development is likely to be significantly or further impaired without provision of services, or a child who is disabled. CIN is a legally defined and professionally determined measure of need, which is reported via the NPD. In most cases, children are assessed as in need because of maltreatment, followed by other reasons such as family dysfunction and acute family distress.

Secondary outcomes

The outcome domains and secondary outcomes are described here. A full listing is provided in Appendix 2, Table 27.

Objective measures of maltreatment

The objective measures of maltreatment used were referral to social services (overall, child protection referral, CIN referral), child protection registration, CIN categorisation, looked-after status (mother, child), all sourced from the NPD.

Associated measures of maltreatment

The associated measures of maltreatment used were recorded injuries and ingestions, and DNA rates for hospital appointments, both sourced from NHS Digital. We aimed to obtain General Practice Extraction Service data and examine immunisations rates, but these data were not available to researchers.

Maternal outcome

The maternal outcome measured was subsequent pregnancies (sourced from NHS Digital and abortions data).

Child health, developmental and educational outcomes

The child health, developmental and educational outcomes assessed were special educational needs (SEN), early educational and school attendance, and assessments [Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) and KS1], all sourced from the NPD. The data fields informing the disability outcome were not available from the NPD or NHS Digital for the years requested.

Costs

Health and social care resource use costs were calculated. The latter were to be sourced via education records, but were not available with sufficient detail for meaningful costings to be derived.

Data sets and data providers

The BB:0–2 trial

Data collected for the initial trial were used in the present study. 21,22 A baseline home assessment was conducted on trial entry using a computer-assisted personal interview. Follow-up was by a computer-assisted telephone interview at 34–36 weeks’ gestation and at 6, 12 and 18 months post natal. A final home-based personal interview was conducted at 2 years after birth. Several routinely collected data sets were accessed and data were obtained from the following sources: maternity records (medical and obstetric history items, antenatal attendances and maternal and neonatal outcomes), primary care notes for each mother-and-child dyad (consultations, immunisations, pregnancies, safeguarding), abortion data from the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) abortion statistics team and immunisation data via Cover of Vaccination Evaluated Rapidly programme contacts.

NHS Digital

The Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data sets hold records on hospital admissions, outpatient and accident and emergency (A&E) episodes. Data can be requested from NHS Digital (formerly known as the Health and Social Care Information Centre),36 the executive non-departmental public body established under the Health and Social Care Act 2012. 37 These data were requested for mothers and children on recruitment to the BB:0–2 trial. A further request for data was made for the BB:2–6 study, in which mothers’ and children’s data were sought for follow-up. For the BB:2–6 study, all available records belonging to cohort members (mothers and children) were obtained from study entry of the mother, which occurred between June 2009 and July 2010, until the date the child turned 6 years of age. The data requested included diagnoses, procedures, duration of episode and external causes of injuries coded according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), codes. 38 NHS Digital has responsibility for collecting these data from across the health and social care system to allow NHS hospitals to be paid for the care they deliver. At the end of the financial year (March), a final data set is collated. This data set is cleaned and validated before being available for research at the end of each year (December). NHS Digital also provide access to data from the Personal Demographics Service (PDS), which is the national electronic database of NHS patient details. 39 This service can be used to update participant demographic details (e.g. name, NHS number, address, date of birth) when there is a legal basis to do so.

Office for National Statistics

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) collects information on cause of death from civil registration records. Mortality data can be accessed through NHS Digital and supplied as a linked file with the HES data. For registered deaths, the underlying cause of death is derived from the sequence of conditions leading directly to the death, and is recorded on the death certificate. Deaths are subsequently coded in line with the ICD-10. Maternal or child death was captured as an outcome. In December 2018, a lawful basis was established that enabled NHS Digital to collect mortality data directly from the ONS and release it as health data, in accordance with the Health and Social Care Act 2012. 36,37 At this point, ONS mortality data held by the study became civil registration mortality data (a data set controlled by NHS Digital). This report will continue to refer to mortality data as ONS data, as they were at the time of data receipt.

Department for Education

The Department for Education (DfE) holds information on pupils throughout the different phases of education. Records are sourced from publicly funded schools, local authorities and awarding bodies, and are held in the NPD, which is a collection of linked data sets. The data sets are available on various aspects of education (e.g. school census data, absence data and school attainment) and social care (e.g. the CIN census). 40 Data sets are collated throughout the year and are available at set time points annually; these time points differ across the data sets available to request.

Social care data

Social care data from local authorities are available through the NPD via two data sets: CIN and child looked after (CLA). The CIN census captures individual-level information on children referred to and assessed by CSC services within each 12-month period. CLA data are collected in the SSDA903 return: an annual statutory data collection for all local authorities. When a child is referred to English local authority children’s services, it is first recorded as a contact. Contacts are not submitted to the CIN census. If a case provisionally meets the threshold for support, it is passed on to the assessment team as a referral. All children who are referred to CSC for a social care assessment are in the CIN census, even if they are later assessed as ‘not in need’. The children in the CLA data set are, then, a subset of the children in the CIN census who are looked after by local authorities in England. Any child in the cohort who was in either of these data sets was identified, up to the age of 6 years. Mothers who were < 18 years at the time of participation in the BB:0–2 trial would also be identified in these data sets if present in any of the data sets requested. Children in medium-term foster placements or adopted within the 6-year study period could be linked up to the date of adoption. The primary outcome was sourced from the CIN data set.

The NPD carry out the matching to the CIN and CLA data sets by a two-step process. These data sets do not hold any identifiable data except for Unique Pupil Number (UPN). Therefore, to identify individuals in the CIN and CLA data sets, participants are first matched to the other NPD data sets. Their UPN is then identified and used to match again to the CIN and CLA data sets. This means that it was possible to identify records in the CLA and CIN data sets only once the children appeared in a school-level data set.

Education data

Education data are available through the NPD via a number of data sets, and contribute to the secondary outcomes for the BB:2–6 study.

The pupil-level annual school census (PLASC) and early years census (EYC) return data on maintained schools (funding and oversight is through the local authority), which represent the majority of schools, academies (funding and oversight is from the DfE), City Technology Colleges, maintained and non-maintained special schools, and hospital special schools. Schools that are entirely privately funded and home education are not included in the data; this represents 7% of English students,41 but is likely to include few/none of the trial participants. The data requested included the number of hours attended, early educational development, eligibility for free school meals and SEN provision type. All available records belonging to cohort members (children) were obtained until the date the child turned 6 years of age.

The EYFS is a statutory framework set by the DfE that sets the standards for the development, learning and care of children from birth to age 5 years. The EYFS profile assessment is carried out in the final term of the year in which a child reaches 5 years of age. It is based on ongoing observation and assessment in three prime areas of learning (communication and language; physical development; and personal, social and emotional development) and four specific areas of learning (literacy, mathematics, understanding the world, and creating and thinking critically). There are 17 early-learning goals linked to one of these areas of learning, and a child is judged on whether they are meeting the level of development expected at the end of the reception year (‘expected’), exceeding this level (‘exceeding’) or not yet reaching this level (‘emerging’). 42

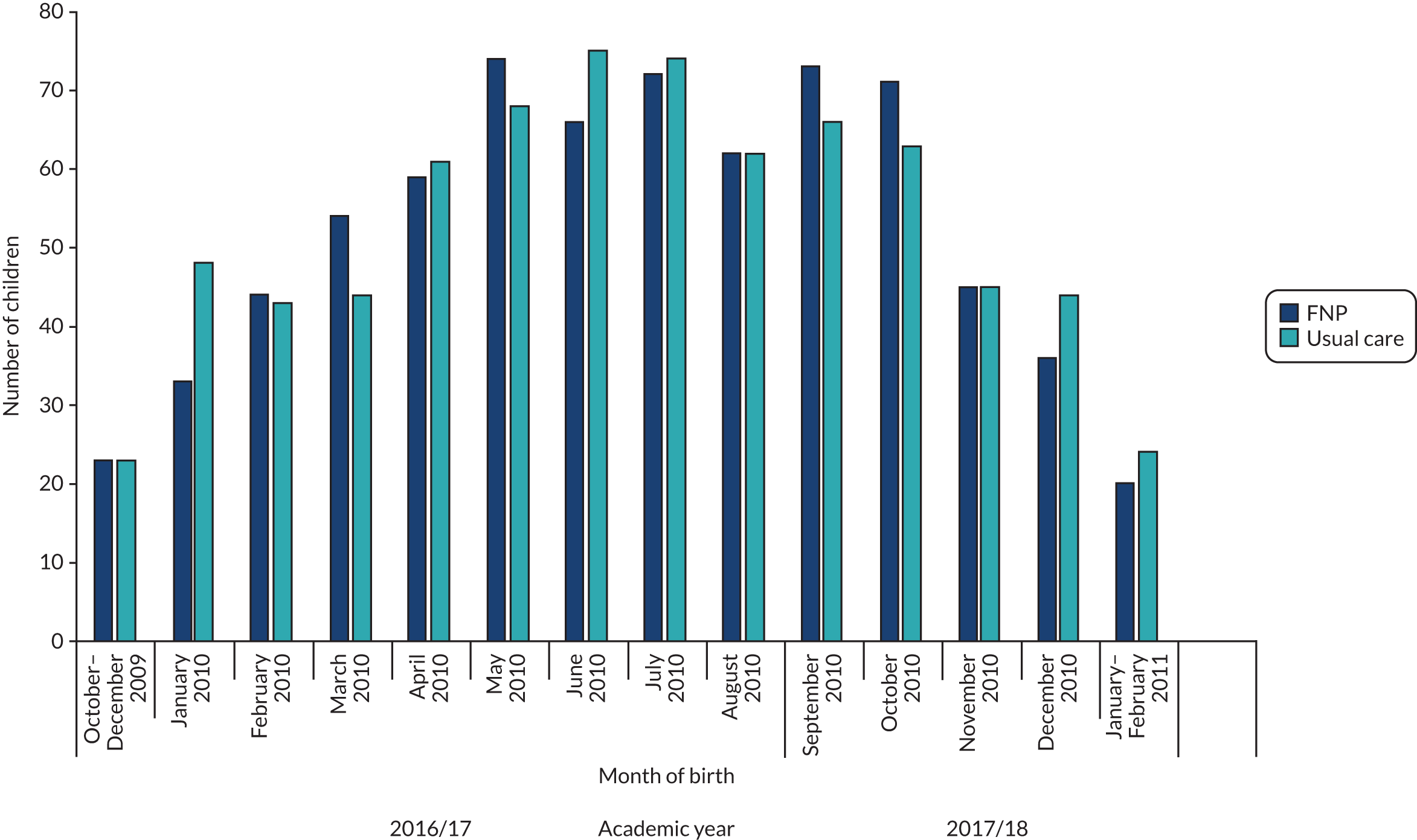

Key Stage 1 is an assessment made by the teacher according to the national assessment framework for children aged 6 or 7 years in the May of that academic year. KS1 tests cover English reading, English grammar, punctuation and spelling (‘writing’), mathematics and science. Pupils are assessed against the standards provided in the framework. For reading, writing and mathematics, pupils can achieve one of three levels (1, lower than expected; 2, the expected level; and 3, greater depth of knowledge). For science, pupils can achieve either level 1 or level 2 only. Between the academic years 2016/17 and 2017/18, the Standards and Testing Agency introduced a revised teacher assessment framework in English writing. 43

Key Stage 1 data were received in two tranches from the NPD: first, for children assessed in the 2016/17 academic year (received in May 2018), and, second, for the younger children, who were assessed in 2017/18 (received May 2019). Reading, mathematics and science are examined for the whole cohort for children over both academic years.

Department of Health and Social Care

The DHSC is responsible for receiving and monitoring the returns of abortion notifications (HSA4 form) as required by the Abortion Act 1967. 44 Registered medical practitioners are legally required to notify the Chief Medical Officer of every abortion performed in England and Wales. With approval from the Chief Medical Officer, data can be accessed for scientific research. 45

Data for 1532 study participants were supplied to the DHSC with a unique participant identifier and their dates of birth and postcodes. Five were not submitted because they had no postcode. Matching was conducted on data for 2009–16, but data for 2012 were not available for matching because the date of birth was not stored (only age). Following the recommendations given by the DHSC, we used data on mothers for whom a match was found on exact date of birth and postcode (matching criterion 1). Matching criteria 2 and 3 [match found for exact date of birth and (1) postcode minus the last two letters and (2) postcode minus the last three digits, respectively] have an increased risk of false-positive matches, compared with criterion 1; therefore, matching criterion 1 is likely to be the most robust method for matching.

Dissent model

Recruitment/dissent

Participants previously consented to enter into the BB:0–2 trial and provided self-report and access to their routine records for the period up to 2 years post partum. To obtain an unbiased estimate of the effect of the FNP on medium-term objective and associated maltreatment outcomes, we sought section 251 support of the National Health Service Act 200646 approval from the Health Research Authority’s (HRA’s) Confidentiality Advisory Group (CAG) to pass identifiable participant data legally held by Cardiff University to the data providers to link to routine data. This did not require further consent from participants, but instead used an opt-out/dissent model.

Justification of dissent approach

Developing the opt-out approach was necessary because of (1) the child protection focus of the study and the consequent sensitivity and impracticality in asking directly for consent, (2) participant mobility and relative difficulty in maintaining ongoing direct access, (3) the likely introduction of non-ascertainment bias on sample representativeness – resulting in a non-random sample, and (4) the likely cost and logistical requirements of securing even modest levels of additional consent.

Methods of notifying participants

We discussed the issue of dissent and fair processing with the HRA CAG, and subsequently attempted to contact all mothers recruited to the original BB:0–2 trial to inform them that follow-up using anonymised records would be undertaken.

We updated details of participants’ residential addresses using the most recent address registered with their general practitioner (GP). When available, we used mobile phone numbers and e-mail addresses collected during the trial to send short message service (SMS) messages and e-mails to participants. We used all three modes of contact over a 2-day period and we provided participants with a 2-month window in which to contact the project team to discuss the project and opt out if they wished. We created a website with the same information where we encouraged participants to contact the project team if they wished.

We worked with a group of care-experienced young people (CASCADE Voices),47 who advised on the layout, wording and tone of a letter to be sent to all participants. A key consideration was to communicate the focus of this follow-on study in a sensitive manner. The final version of the letter was approved by both an NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC) and the CAG as part of overall governance approval for the study. The letter contained information about the trial and the follow-on study, and a flow chart for what to do if women wished to discuss the project and/or opt out (see Appendix 12).

We recorded women notifying us of their dissent as ‘opted out’ and removed them from all project data sets for this follow-up work and from identifiable data sets to be sent to data providers. They were not included in any of the data sets or analyses for this follow-on study.

Tracing

Two tracing exercises were undertaken to update the contact details of the mothers and children to ensure that (1) participants were contacted about the opportunity to opt out using their most recent address, (2) participants were not contacted if there had been a death (mother or child), (3) participants who had withdrawn prior to the birth of their child remained eligible (there had been a birth) and (4) the identifiers used provided the best opportunity for matching.

We used the NHS tracing system provided by NHS Shared Services Partnership to update the BB:0–2 trial cohorts’ contact details prior to contacting them to offer them the opportunity to opt out of becoming BB:2–6 study participants. On receipt of data from NHS Shared Services Partnership, there were a number of details that remained uncertain/in contradiction with what was previously held. These were then sent to the NHS Digital PDS for manual tracing. For example, differing NHS numbers or sex of a child were felt to be worth further investigation.

For the electively withdrawn trial participants, it was not always clear if the pregnancy had ended in a live birth or how many children had been born. Therefore, in an attempt to identify births including twins, the PDS investigated, via the mothers’ record, to identify presence and number of births at the time of the BB:0–2 trial. The REC and CAG provided approval for this via a substantial amendment.

Data access and storage

Data were requested in two stages: (1) for the pilot phase as part of the feasibility work and (2) the main data request. When the study started in 2014, the children were only 3 years of age, thus providing the opportunity for the pilot phase to ensure that we could access the data, link the records and address the primary and secondary outcomes using the data received. 31 Data were requested in autumn 2014 for data from NHS Digital and the NPD and then again in summer 2017 for the main extract. Data were requested from the Abortion Statistics Team in autumn 2017. The identifiers used to match the BB:2–6 study participants to each data provider are shown in Appendix 2, Table 28.

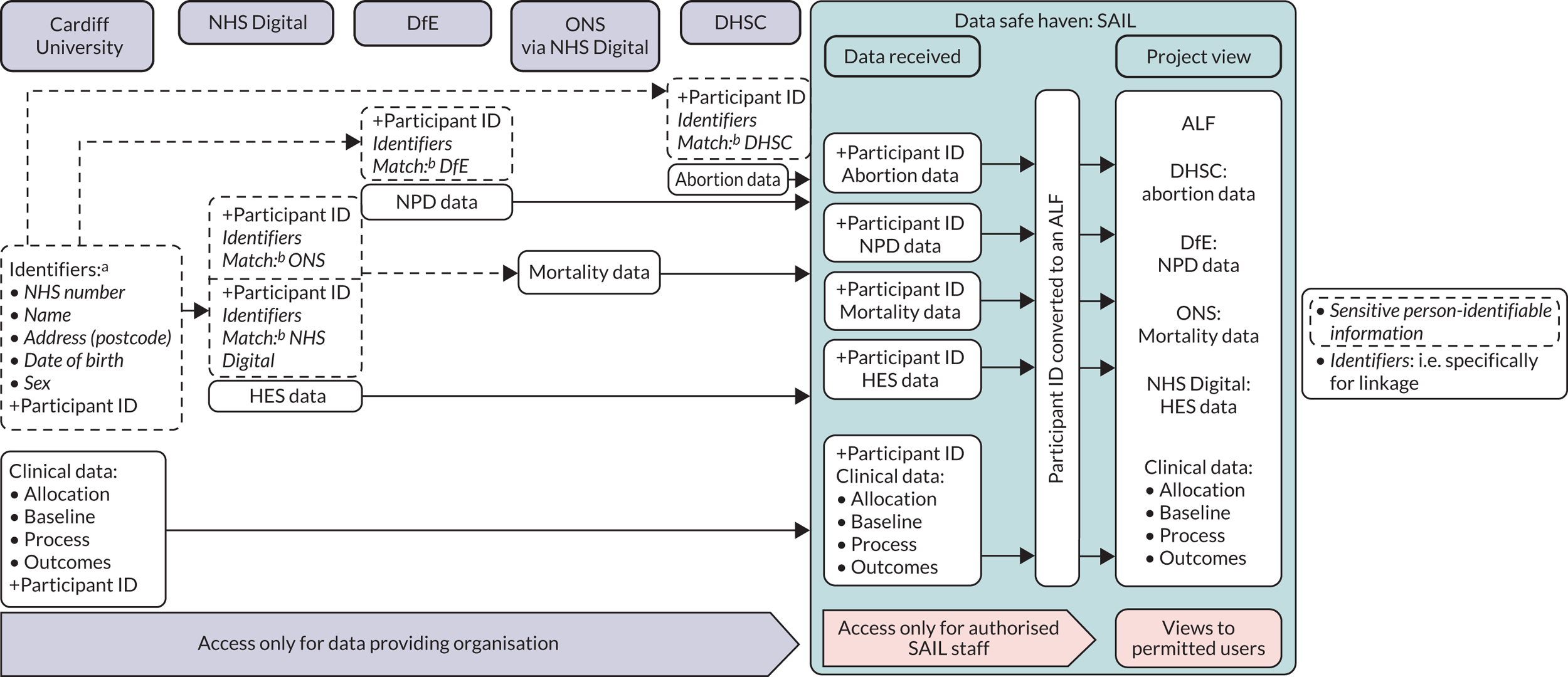

We used a data safe haven, the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) databank, to receive all data sent from data providers, replace the participant identifier with a new anonymous linking field (ALF) and store the corresponding identifier in a separate encrypted password-protected file. 48 All data held in SAIL must not be identifiable; therefore, the study team went through a de-identification and standardisation process to ensure that all variables (e.g. date of birth) were amended to be non-disclosive (e.g. week of birth) or removed from the data set prior to sending. Figure 1 depicts the data flow between data providers and the data safe haven. Participants are not identifiable to the study team, or to the SAIL analyst, but incoming data sets from all data providers could be linked at the individual level using the ALF. The study team have controlled remote access to these data, thus ensuring the security of the pseudonymised database. 49 All data cleaning and analyses were carried out via the remote portal by the study data manager(s), statistician and health economist.

FIGURE 1.

Final model of data flow, storage and access used in BB:2–6. a, De-identification and standardisation applied (e.g. date of birth to week of birth). b, Data providers confirm matching of BB/NHS Digital/ONS/DfE/DHSC IDs. ID, identifier.

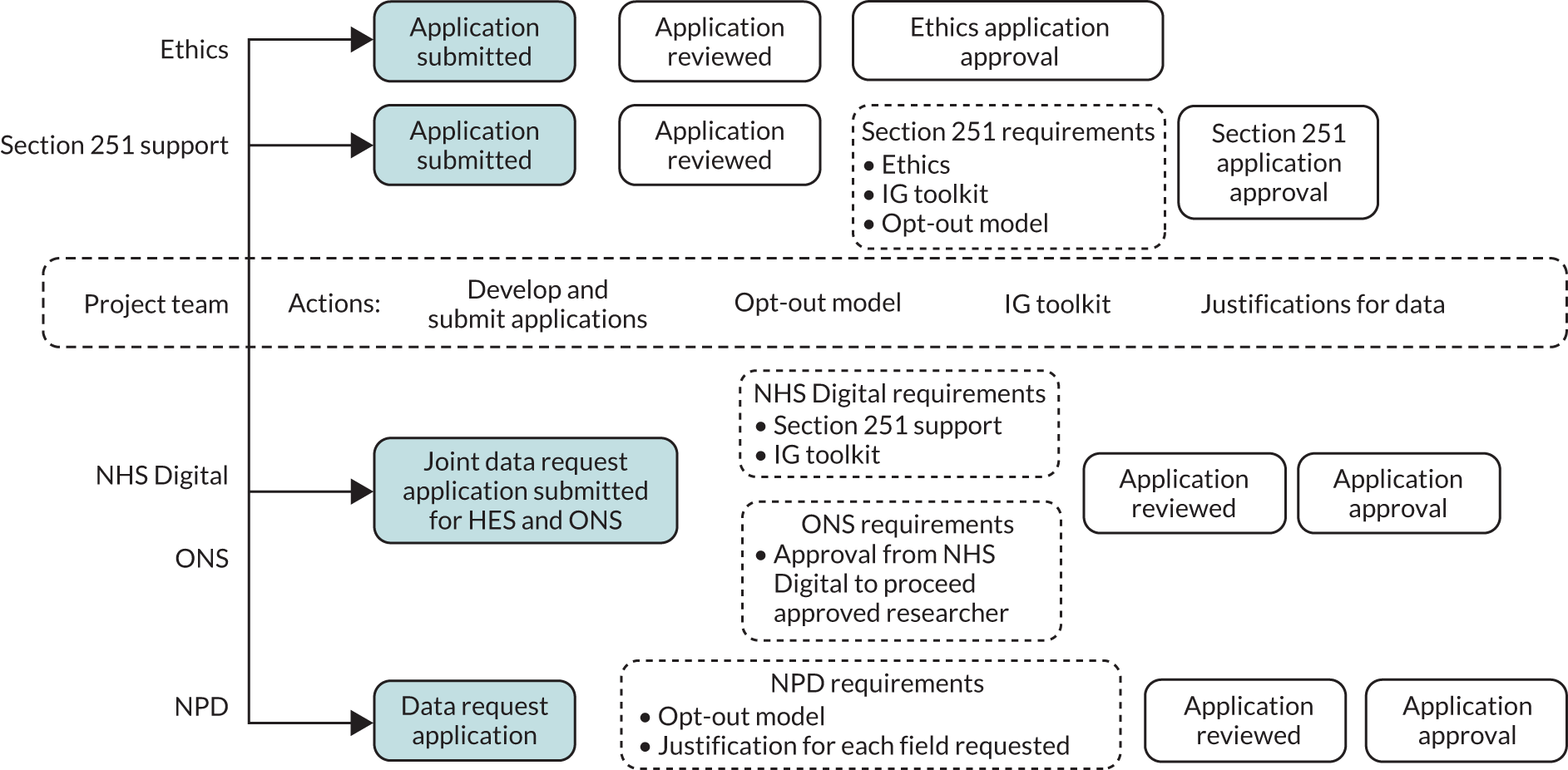

Governance

Following REC approval (reference number 14/WA10062) and section 251 support (CAG number 10-08(b)/2014), we could submit data request applications to the DfE, NHS Digital and the DHSC. To satisfy the requirements of the section 251 support and NHS Digital contract, the (then) information governance toolkit self-assessment50 (commissioned by the DHSC for NHS Digital to develop and maintain) was required. This is now known as the Data Security and Protection Toolkit. This organisation-level assessment provides reassurance of satisfactory information governance within the host research organisation. Both the section 251 support and the Data Security and Protection Toolkit are assessed and renewed on an annual basis. The opt-out model was also required to satisfy the section 251 support, as well as the DfE assessment of compliance with principle 1 of the Data Protection Act 1998. 51 Governance and data provider requirements prior to application approval are shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Governance and data provider requirements prior to application approval. IG, information governance. The shading represents the starting point for each activity. The dotted-line boxes indicate the project team roles.

Statistical analysis

Sample size justification

The sample size was fixed according to the available trial cohort. Nevertheless, here we present the number of children required to observe clinically relevant differences and how that compares with the numbers we were able to link and follow up in the study.

Primary outcome (child-in-need status at any point between birth and 6 years of age)

For CIN status, available UK data on rates are not specific to the age range of interest, but the rate per 10,000 general population aged 5–9 years is 4.6% (calculated as an average rate of local authorities that the sites in the BB:0–2 trial covered). 52 The rate of CIN status would be expected to be greater in the specific study sample; therefore, we have assumed a rate of 8%. We hypothesised that the FNP would reduce the occurrence of CIN status in the first 6 years and assumed a difference of 4% as being important. To detect a difference of 4% (4% vs. 8%) we would require 602 children in each arm (1204 in total), using 80% power and a two-sided 5% alpha level. The BB:0–2 trial recruited 1645 women, with 1562 available for follow-up (i.e. excluding those subject to a mandatory withdrawal). Follow-up through medical records assuming 10% loss in tracking and linkage would result in 1405 participants, thus providing sufficient data to assess the primary outcome.

A key secondary maltreatment outcome is referral to CSC. Data from the FNP implementation evaluation (n = 1304 women) show an observed referral rate of children (in the period up to a child’s second birthday) of 8.2%. 53 A sample of 1319 for analysis will provide 90% power at the two-sided 2.5% alpha level to detect a difference between the two groups of 6.3% (14.5% to 8.2%) in the proportion having a referral to CSC. This represents a conservative estimate, as further referrals to CSC will be observed in the remaining 4-year period.

Randomisation

We had already randomised women in the BB:0–2 trial. In doing so, we applied individual minimisation using gestation at recruitment (< 16 weeks/≥ 16 weeks), smoking status at recruitment (smoker/non-smoker) and preferred language for data collection (English/non-English), and stratification by study site. We achieved balance across trial arms on these and other maternal characteristics. We acknowledge that there are possible threats to the balance of baseline characteristics and potential confounders by loss of participants through linkage to routine data in Chapter 4.

Participant population for analysis

We sent identifiers for the BB:2–6 trial cohort to the data providers. The population on which analysis was conducted were those participants whose identifiers could be sent, linked and data released by the data providers. This does not include participants whose individual data can be used but cannot be matched because of:

-

Incorrect linking fields.

-

Other exclusions from health or education, for example private or home schooling (would not appear in any NPD data sets).

-

Any national opt-outs. Patients in England are able to opt out of their personal confidential information being shared by NHS Digital for purposes other than their own direct care. National opt-outs apply to health data (NHS Digital) only and do not apply to that held by the NPD. They were previously referred to as type 2 opt-outs. 54

Therefore, the study populations for analysis (mother and child) depended on which data provider and outcome the data were coming from. For example, for the primary outcome of CIN status, the denominator would be all children who were matched to and appearing in any of the NPD data sets requested. We expected that all children by the age of 6 years would be registered with a primary school or alternative provision, so would be linked to the PLASC and alternative provision data sets. If they were not in PLASC/alternative provision data sets, but appeared in another data set (e.g. CIN), then we concluded that they were in the study population but, for some reason, were missing from the PLASC/alternative provision data set (e.g. home or privately schooled). Similarly for NHS Digital data, for any health data outcome, the denominator would be all participants who have their identifiers matched to any of the HES data sets (inpatients, outpatients, A&E). We expected each mother and child to have had at least one hospital admission event (birth of baby/being born, respectively), and so each participant should have appeared in the inpatient data.

For some outcomes, the maximum age of the child at assessment was strictly fixed by their chronological age (e.g. we included all health-care events such as inpatient and outpatient episodes for the child up to the day before their sixth birthday). For other outcomes, the maximum age varied according to the actual date of assessment within an annual cycle of assessment (e.g. EYFS profile and KS1), meaning that, at KS1, children could be either 6 or 7 years of age. Finally, maximum ages could be determined by data provider annual reporting census periods (e.g. formal reporting for CIN ran up to 31 March each year), which meant that, for the final year of data available to the study, the maximum age (of children) at which a child could have an event reported would depend on their date of birth (see Appendix 2, Table 29).

Missing data

Appendix 2, Table 29, shows each outcome and how we defined denominators, numerators and missing data considerations. Children who were not included in any of the NPD data sets were classed as missing. If a participant did not appear in an outcome data set (e.g. CLA or CIN data set), then we assumed that they did not have that event (rather than missing). We conducted all primary and secondary comparative analyses on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis with complete-case population (those who have complete follow-up data). This modified ITT population consisted of all randomised participants in the groups they were randomised to in the BB:0–2 trial, regardless of the intervention they actually received.

We defined loss to follow-up in this study as a child death or an adoption, both of which we were able to determine. We excluded children from analyses of binary outcomes when a child had no event, and when follow-up was incomplete. With time-to-event analyses, children were censored at these loss to follow-up events.

Pooling of investigational sites

In the original BB:0–2 trial, randomisation was stratified by the 18 research sites and adjusted for in the analysis by including site as a random effect in all models.

Withdrawals

We excluded from all analyses individuals who had been mandatorily withdrawn from the BB:0–2 trial. We included participants who elected to withdraw from the BB:0–2 trial if they had not removed consent to further use of their data. During the first tracing exercise, we identified any mothers and/or children who had died between the trial ending and the point at which we updated their records. Mothers who had died (or whose child had died) were excluded. Any mothers who registered to opt out of the BB:2–6 study were removed along with their child(ren).

Small numbers

Small numbers were handled according to SAIL rules, whereby any cell counts of < 5 were suppressed and reported as < 5. We handled the presentation of abortion data in accordance with the data-sharing agreement with the DHSC, whereby counts of < 9 are suppressed (including 0).

Descriptive analysis

Baseline data

We quantified potential bias in the followed-up BB:0–2 trial sample by examining group differences (BB:0–2 vs. BB:2–6 participants) in baseline maternal, birth and baby demographics, and clinical and questionnaire data. For all BB:2–6 participants (mother and children) eligible and linked to data providers’ data, we used appropriate descriptive summaries of baseline maternal, birth and baby demographics, and clinical and questionnaire data, presented by trial arm. We used descriptive statistics [n (%), mean (standard deviation) and median (interquartile range)] to summarise baseline variables and identified any marked imbalance between the study arms. We did not formally test between-arm differences for any variables at baseline.

The participant population varied depending on which data provider was examined (NHS Digital/NPD), and so we examined baseline data for each population/data source combination. To assess potential bias, we compared those mothers and children who were successfully linked to NPD/NHS Digital data with the population of all participants in the BB:0-2 trial.

In addition, we assessed the characteristics of children not in any school data set, but who appeared in either health or social care data sets, to examine if they were different or at higher risk of adverse outcomes.

Main analytical approach

We conducted all analyses on a modified ITT basis and placed due emphasis on confidence intervals (CIs) for the between-arm comparisons. First, we examined binary outcomes in twins, to examine the correlation between them. If outcomes tended to always apply to both twins (e.g. in maltreatment data, we would expect both children to be under child protection), then we aimed to reduce the multilevel nature of the data (children within mother) to one child, as opposed to adjusting for twins. We used three-level multilevel modelling to allow for clustering of effect within a site and family nurse, whereby both were fitted as random effects. When there was little impact of clustering at the family nurse level, we aimed to present the results from the two-level model (site and participant). We used the Akaike information criterion to select the best-fitting model. We present all parameter estimates alongside a 95% CI and p-value. We adjusted for variables used in minimisations such as smoking status, gestational age and language.

Primary outcome

In the primary comparative analysis, we examined whether the firstborn (‘BB:0–2 child’) child had ever been referred to social services and classed as a CIN at any point between birth and 6 years of age. There is no flag in the data set to identify whether or not a child is in need after they have been referred to social services. Therefore, CIN was defined (as per DfE methodology)55 as all children referred to social services, excluding cases for which:

-

the referral is flagged as being a referral resulting in no further action

-

the only activity recorded is an assessment, and the case was closed after assessment with no further action.

As the outcome is binary (CIN or not), we used logistic multilevel modelling to investigate differences in the proportion defined as in need between the trial arms (FNP compared with usual care). We present the resulting estimate as an odds ratio (OR).

Secondary analyses of primary outcome

For children classed as in need, we calculated the interval between birth and the date (age) that the child was classed as in need for the first time (based on referral date). We examined group differences for this interval using Cox multilevel regression analysis to calculate hazard ratios for referral, together with 95% CIs. We censored those who were not ever classed as in need by 6 years of age; those who died in this period were censored at date of death.

We examined the number of distinct CIN referrals using multilevel Poisson regression modelling appropriate for count data. When distribution of events displayed signs of overdispersion (greater variance than might be expected in a Poisson distribution), then a negative binomial model was used (or a zero-inflated model if there was an excess of zero events). We present results as the (adjusted) incidence rate ratio (IRR) in the FNP arm, compared with the usual care arm.

Sensitivity analyses on primary outcome

The BB:0–2 trial sample is well characterised (in terms of demographic and clinical data recorded at baseline), and there are detailed records on programme fidelity. We explored:

-

Adjustment for any hypothesised confounders of outcomes at baseline.

-

How variation in adherence to programme fidelity (e.g. dosage) was associated with outcome variation. The efficacy of FNP visits on the primary outcome was estimated in a way that preserved randomisation using complier-average causal effect (CACE) modelling by fitting a structural mean model. As in the original BB:0–2 trial, we defined adherence as the total number of valid FNP visits that a woman received between programme enrolment and the child’s second birthday (covering pregnancy, infancy and toddlerhood). A valid visit was defined in the BB:0–2 trial (using FNP criteria) as the first visit on any calendar date of at least 15 minutes’ duration with the client present and recorded on the FNP information system form UK001 as having been completed.

-

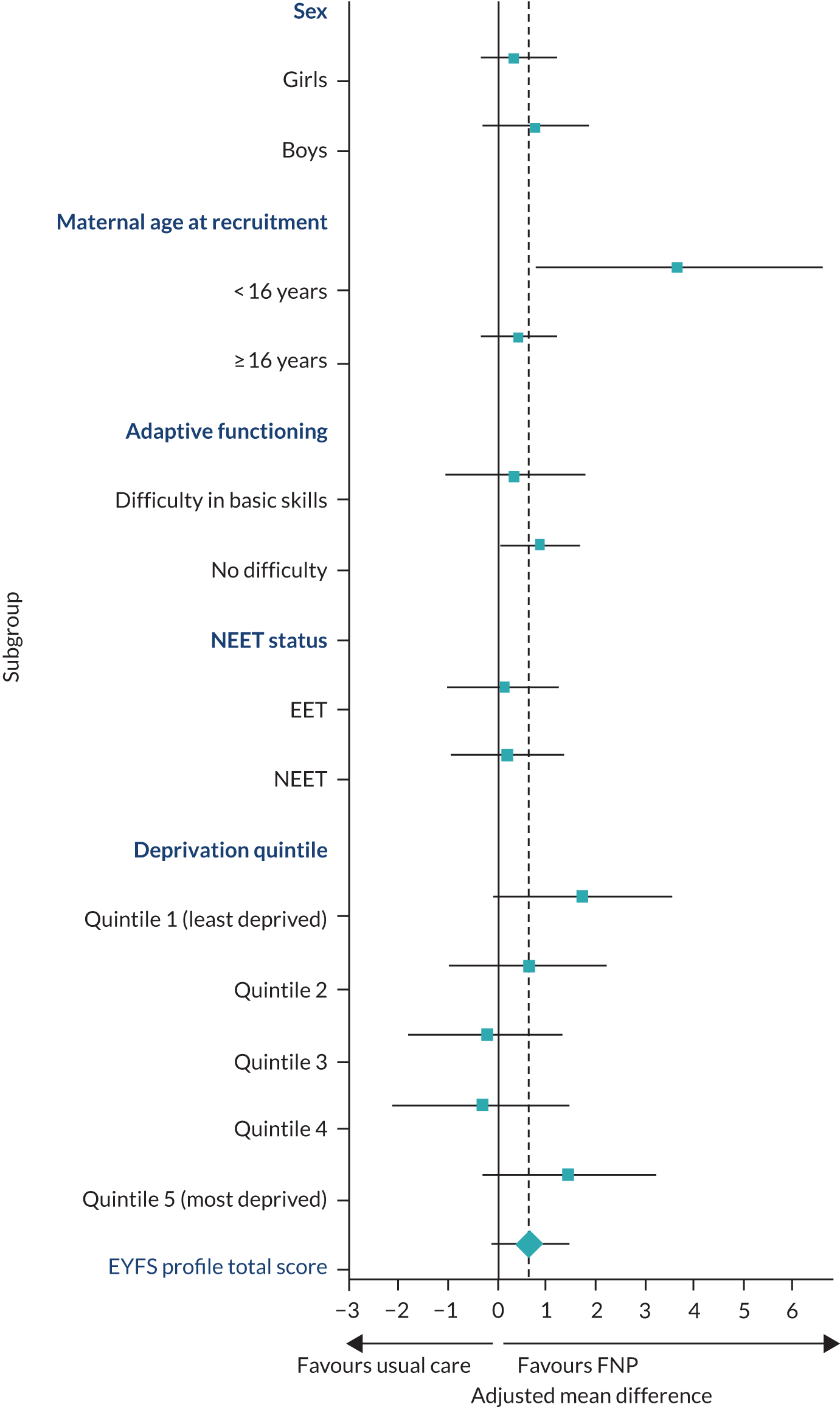

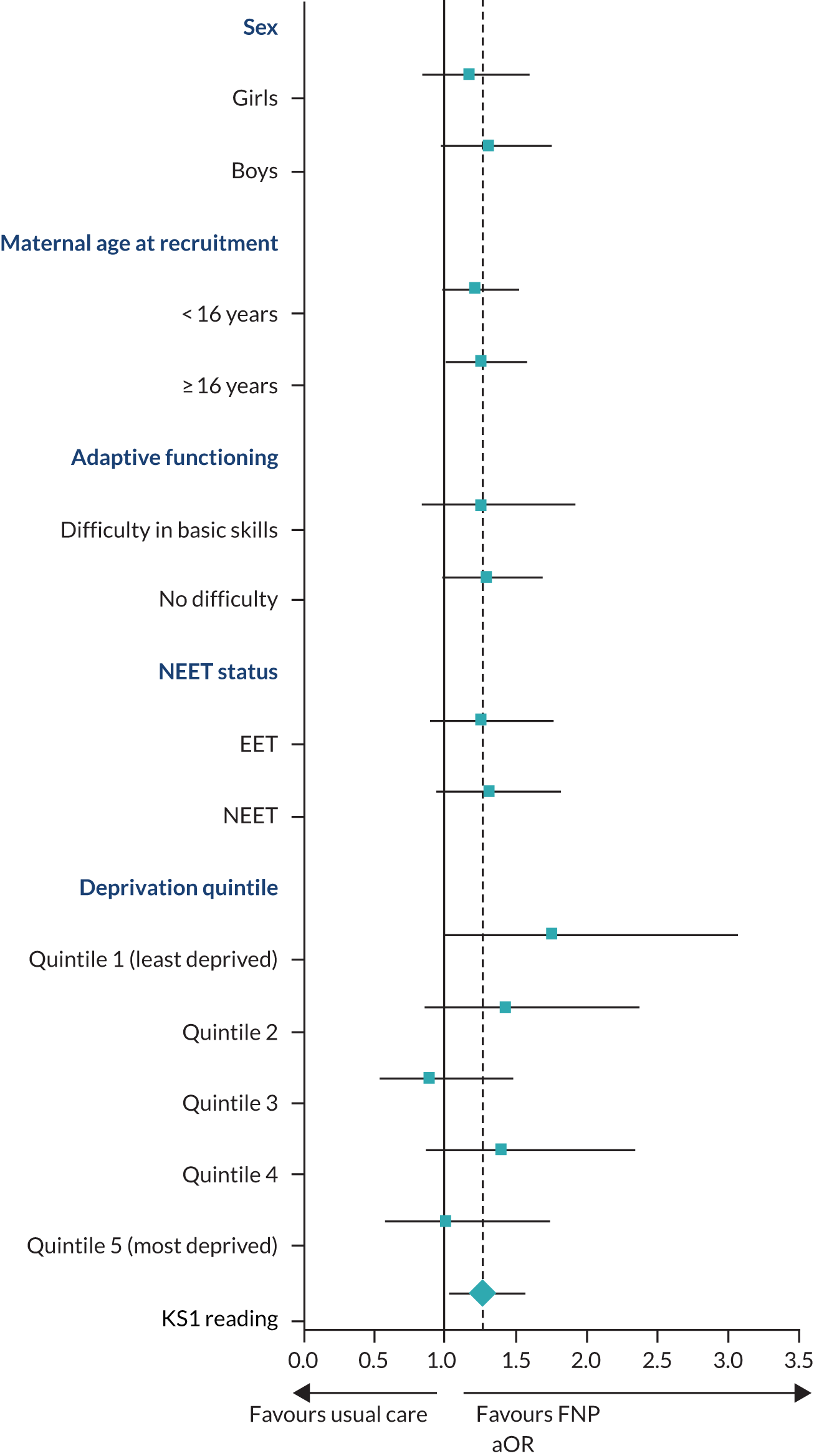

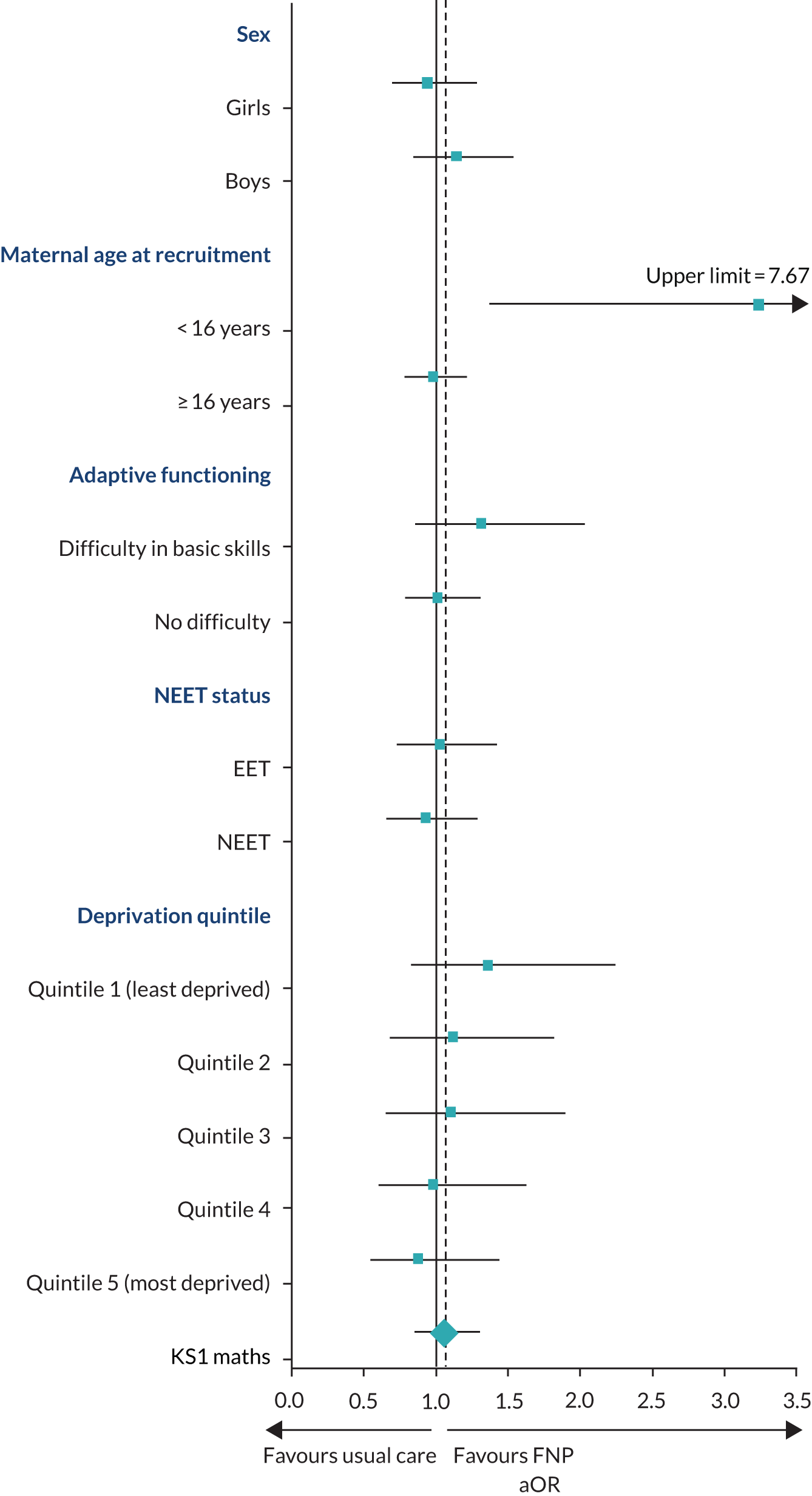

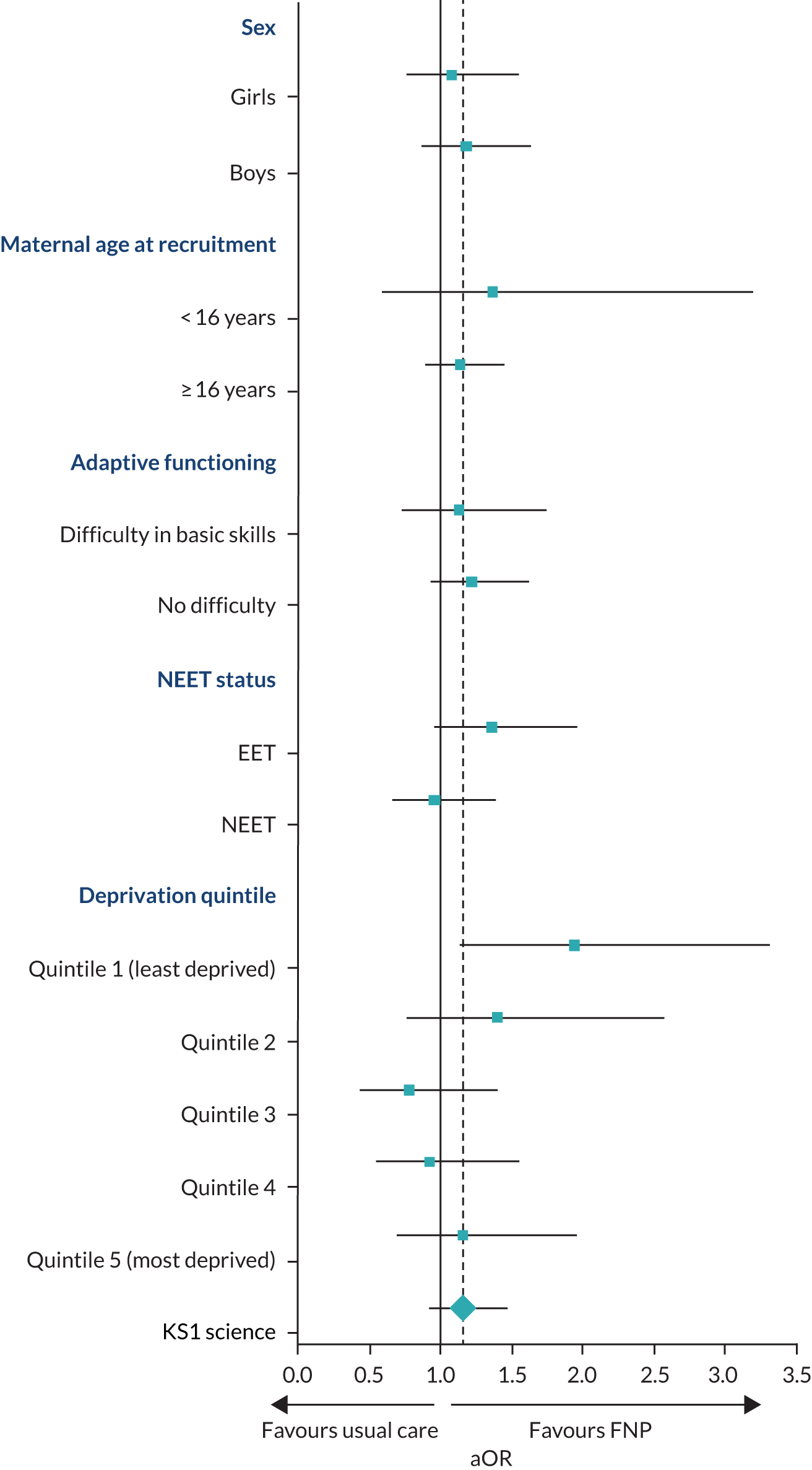

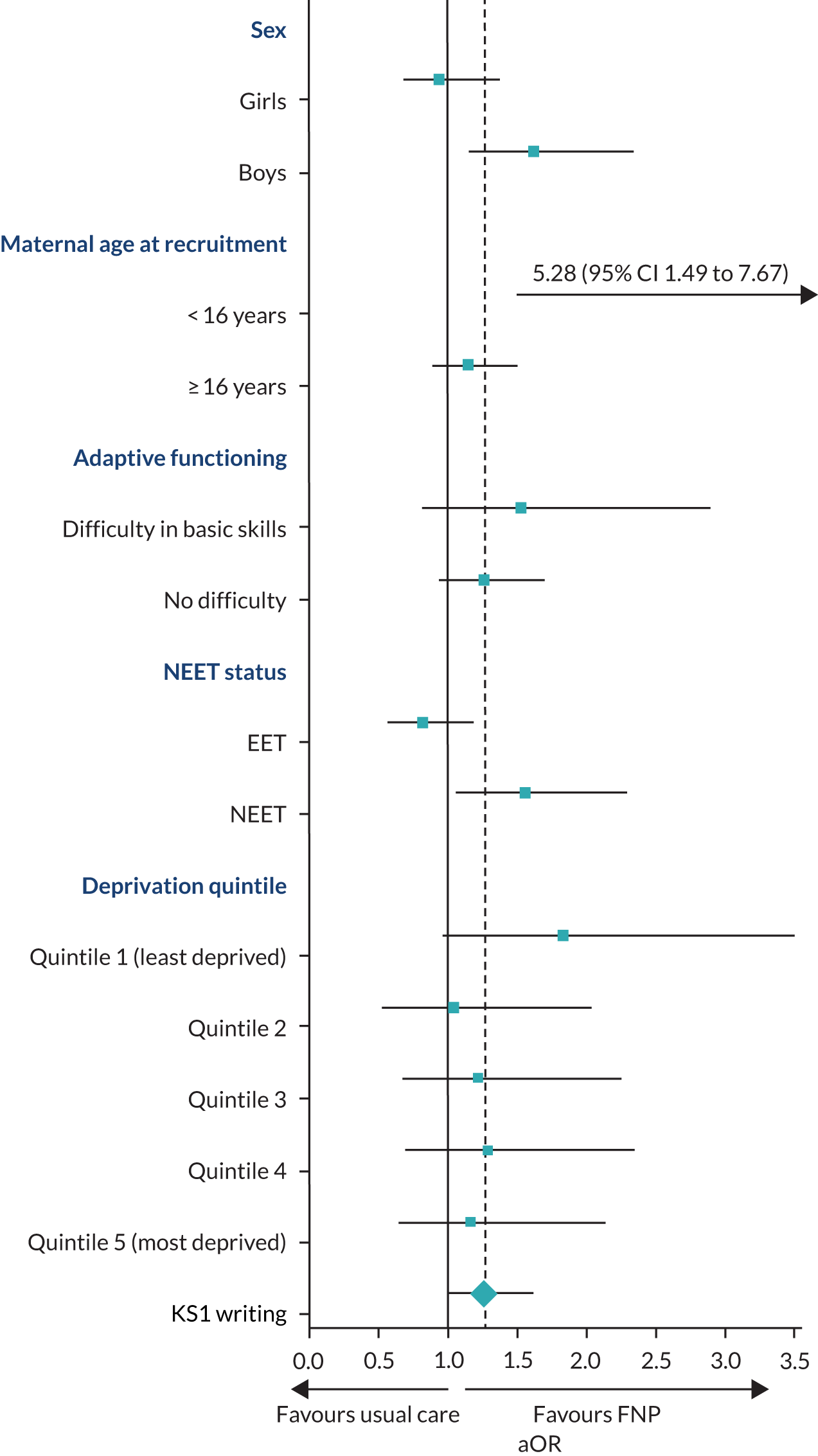

The role of potential moderators and mediators of programme effect by extensions to the primary outcome model including predictive factors (main effects) and interaction terms. Pre-planned subgroup analysis is an investigation of whether or not any between-arm effects differ according to characteristics measured at baseline. Results are presented as the p-value for the interaction coefficients. We prioritised the following variables as a priori subgroup analyses on the primary outcome:

-

Maternal deprivation.

-

Not in employment, education or training (NEET) (applicable only to women aged > 16 years at baseline).

-

Maternal age at recruitment.

-

Sex of child as a possible effect moderator. This extends what was specified in the published protocol paper,1 but was included in the updated a priori statistical analysis plan.

-

We also explored the role of mothers’ care status (ever/never been placed in care) and the duration of maternal care as a potential moderator of programme effect. We also aimed to explore the role of potential mediators of programme effect, such as duration of maternal care and domestic abuse self-reported at 24 months. We conducted these subgroup analyses by the inclusion of appropriate interaction terms in the regression models. Results are presented as the p-value for the interaction coefficients. We also aimed to explore the role of potential moderators of programme effect, such as domestic violence self-reported at 24 months.

Secondary outcomes

Although the study was powered to examine a 4% difference in CIN status, we undertook secondary analyses to assess group differences in referral rates to social services and maltreatment profiles. We examined levels of concern by looking at the extent of action taken (e.g. category of abuse, subjected to a child protection conference and plan).

Objective measures of maltreatment

For binary outcomes [referral to social services, child protection plan (CPP), looked-after status of child] we used logistic multilevel modelling to investigate differences in proportions between the trial arms (FNP compared with usual care), with estimates presented as ORs. For categorical variables (CIN categorisation of primary need, CPP categorisation of abuse, legal status of child looked after), we examined group differences by multinomial regression and presented results as ORs. We also described the source of the referrals. The number of CIN referrals, the total period of care as a CIN (days) or a looked-after child (months) were examined using Poisson multilevel regression modelling appropriate for count data. When distribution of events displayed signs of overdispersion (greater variance than might be expected in a Poisson distribution), then a negative binomial model was used (or a zero-inflated model if there was an excess of zero events). Results are presented as IRRs in the FNP arm, compared with the usual care arm. Numbers and cause of death are descriptively presented when numbers are not disclosive.

Surveillance bias in detection of maltreatment during a child’s infancy and toddlerhood was assessed by examining subsequent reporting. The duration between birth and the date of first referral to social services was calculated and group differences examined using Cox regression analysis to calculate hazard ratios for referral, together with 95% CIs. Surveillance bias is most likely to occur during the intervention phase (i.e. FNP clients being in closer contact with health professionals up to the point of their graduation from the programme), although improved handover to other services at 2 years may lead to higher identification in the following year. Severity based on the primary need of the referral will also be compared between the two groups.

Associated measures of maltreatment

We examined the number of children who were not taken to at least one hospital outpatient appointment (DNAs) using a logistic regression model. We took a similar approach to analysis in the BB:0–2 trial: assessing injuries and ingestions occurring as emergency attendances in A&E, and admissions to hospital (see Appendix 2, Tables 30 and 31). We used logistic multilevel modelling to analyse the associated outcomes (e.g. proportion of children with at least one injury and ingestion by age 6 years); these events were grouped and described together and by data source. We analysed the number of admissions per child using Poisson or, when skewed, alternatives such as negative binomial or a zero-inflated model. Results are reported as IRRs. We also describe the length of hospital stay for children experiencing injuries and ingestions.

Maternal outcomes

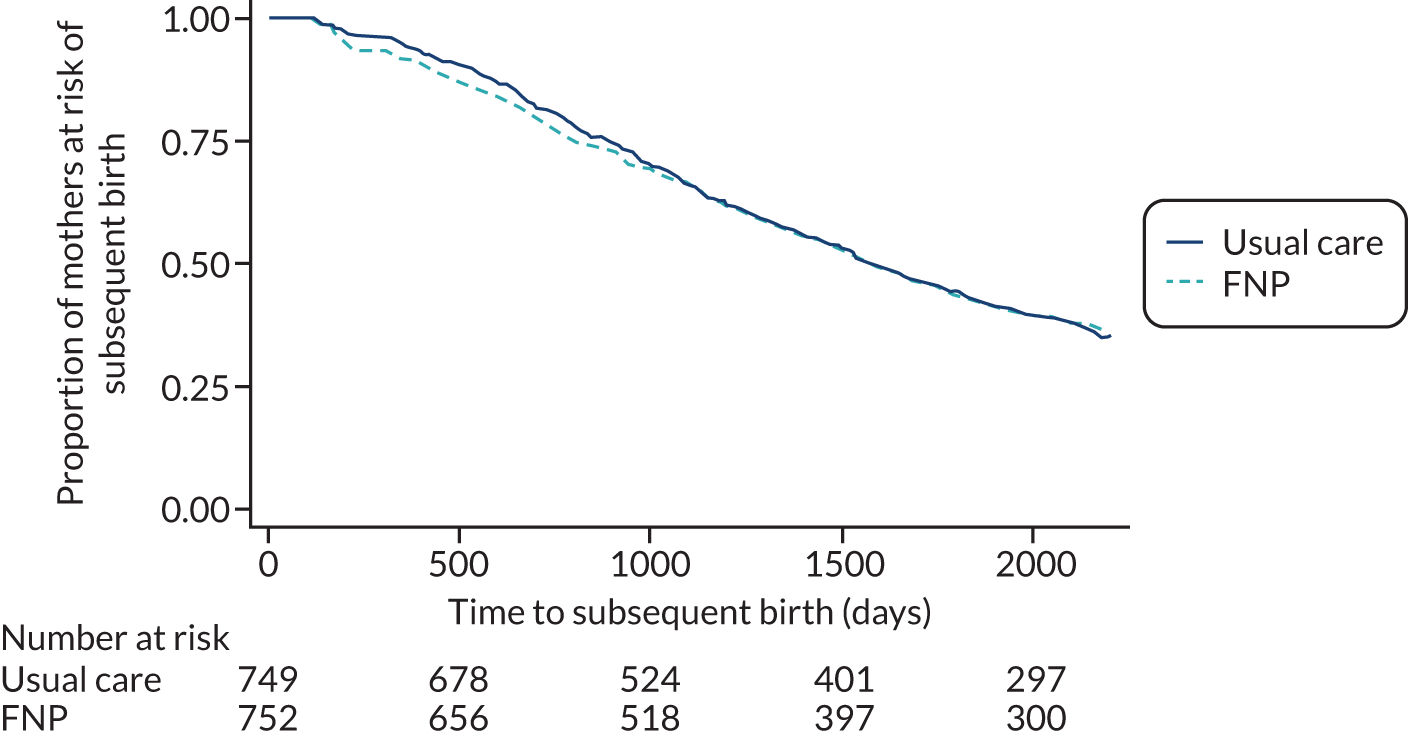

We used a similar approach to the BB:0–2 trial by combining the following data sources: inpatients, outpatients, abortions (0–6 years post birth of the BB:0–2 child) to identify any pregnancy or related attendances/admissions that were not associated with the BB:0–2 trial. For outpatients, attendances of pregnancy were identified using codes for obstetric and midwifery as a main or treatment specialty. For the admissions data (inpatients), episodes of pregnancy, registrable births, abortions and miscarriage were identified using the coding list in Appendix 2, Table 32. For both these data sources, the same cut-off point of 100 days post birth of first baby to assume a new pregnancy was used, as in the BB:0–2 trial, but the admissions in the 29- to 100-day period were checked for abortions or miscarriages in the early pregnancy period. We assessed group differences in the proportion of women with at least one subsequent pregnancy recorded in inpatient/outpatient/abortion data using a logistic regression model. Results are reported as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) alongside 95% CIs. The number of births was described using a Poisson model, if suitable. If data were sparse, then a multinomial regression model was used and categories such as none, one, two and three-plus subsequent births were used. We examined the time to the first subsequent registered birth (interbirth interval) and analysed this data using a Cox regression model with hazard ratios alongside 95% CIs.

Child health, developmental and educational outcomes

Special educational needs (binary), early-education attendance (binary), type of day care [Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted)-registered private, voluntary or independent (PVI) provider/pupils registered at school], early-years assessment (using the EYFS profile, an indicator of school readiness), school attendance and KS1 attainment were all sourced solely from the NPD. For binary outcomes (SEN, early-education attendance, school attendance and KS1 attainments), we used logistic multilevel modelling to investigate differences between trial arms in the proportion of children with or without these outcomes. Estimates were presented as aORs, alongside 95% CIs and p-values.

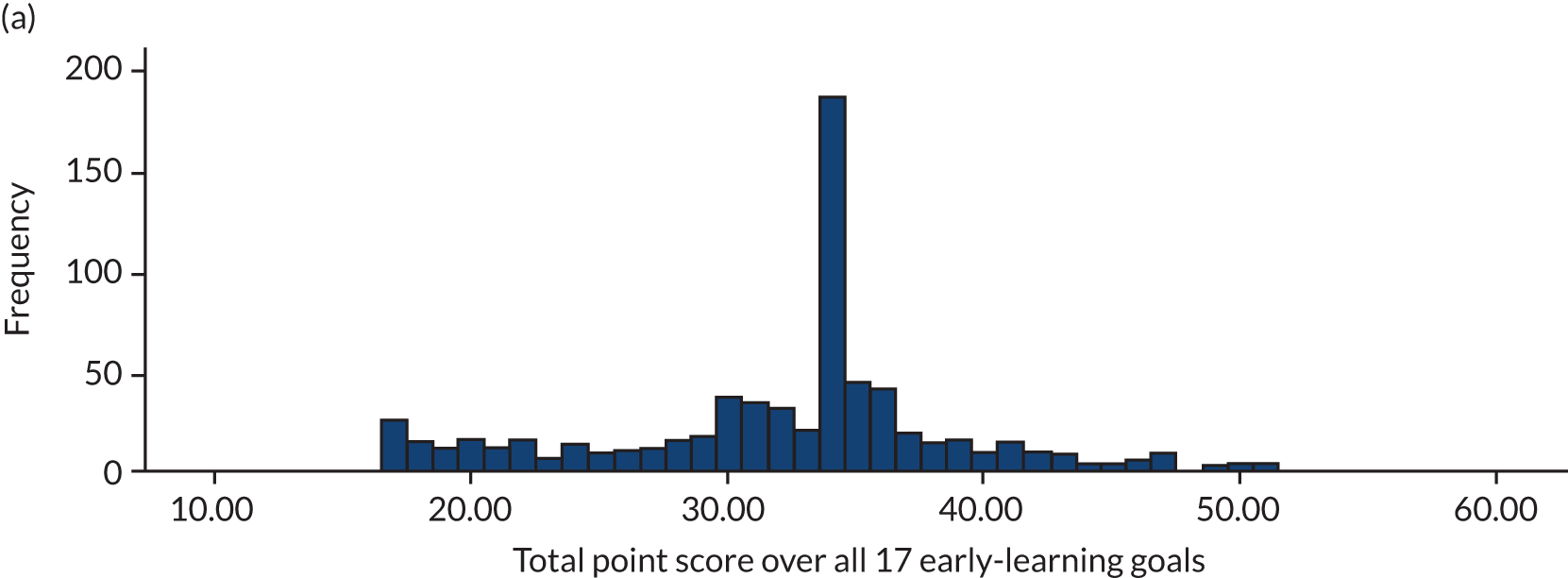

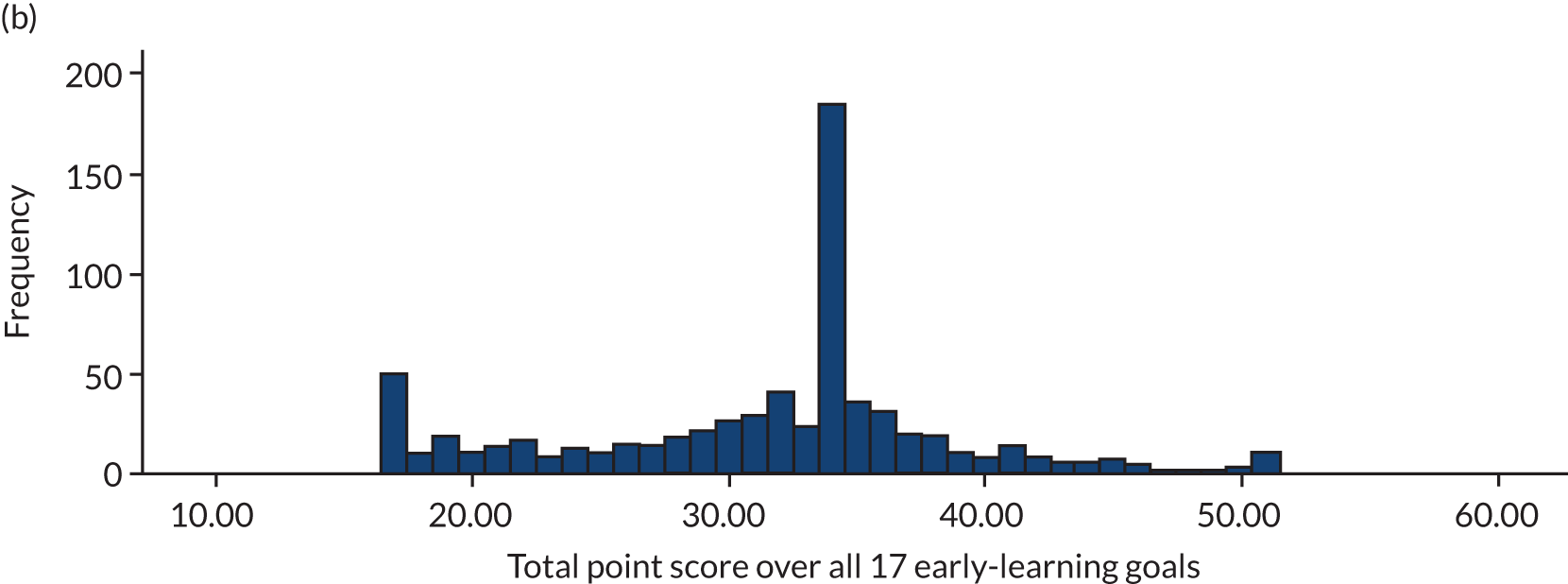

The early-years assessment (EYFS profile) was examined by the following outcomes: (1) the proportion of children achieving a good level of development (GLD) [i.e. achieving at least the expected level (2+)] in all five areas of learning, (2) the proportion of children achieving at least the expected level in all 17 early-learning goals (score of 2+) and (3) the average total point score (over all 17 early-learning goals) (scores can range from 17 to 51). For the early-years total point scores, a linear multilevel regression was run and residuals of the fitted model (kernel density, histograms, qnorm, pnorm) were examined to assess linearity. We examined differences in scores between trial arms, and estimates are presented using adjusted mean differences plus 95% CIs. School attendance was defined by overall absence rate (overall absence sessions/total number of sessions). When possible, these were broken down into unauthorised (e.g. holidays/arrived in school after registration closed) and authorised sessions (illness/medical or dental appointments).

Key Stage 1 attainment was examined using the proportion of children achieving at least the expected level (2+) in reading, writing, mathematics and overall science, and the proportion of children achieving lower than expected (level 1), the expected level (level 2) and a greater depth of knowledge (level 3) in reading, writing, mathematics and science.

Sensitivity analyses of secondary outcomes

We undertook sensitivity analyses (CACEs, imputation for missing subgroups) on the following secondary outcomes:

-

early-years assessment (EYFS profile total score)

-

KS1 assessment (achieving at least the expected level in each subject)

-

referral to social services.

Exploratory analysis

-

We included the following variables for subgroup examination in exploratory analyses: self-efficacy score,58 subjective (personal and family) social status,59 and social support and networks (i.e. the Medical Outcomes Study survey60). These data were sourced from the original BB:0–2 trial data set. A composite index of risk (based on these and other variables in the data set), which predicts subgroups that may particularly benefit from the FNP, was also constructed.

-

We planned to use a state-transition model using Markov chains to assess the probabilities of moving from one stage marker (state) to another. A Markov chain is an iterative process whereby subjects are assumed to stay in one cycle for a certain time and then make a transition to another cycle. The Markov chain contained the following states –

-

referred to social services

-

child identified as in need

-

CPP

-

CLA

-

placement.

The transition probabilities (the probability of the various state changes) in the model were derived from the data and compared between groups, if numbers allowed. The model also included children who leave and then re-enter the system, if numbers allowed.

-

-

Because a more robust measurement of mothers’ experiences in care was determined using the NPD data, this subgroup (of care-experienced women) was also to be examined for the BB:0–2 trial outcomes (i.e. smoking in pregnancy and birthweight). We also explored the BB:0–2 trial baseline characteristics to see which were associated with ever being in care.

Economic analysis

A health economics analysis was undertaken using the routinely collected data available from the BB:2–6 study.

The evaluation consisted of:

-

a description of the resource use and costs associated with the FNP during the BB:2–6 study

-

a cost–consequences analysis (CCA) of the FNP based on the outcomes reported in the BB:2–6 study

-

a summary of the total known health-care costs of the FNP over the full 6-year follow-up period, by summarising the costs associated with the FNP.

Summary of the BB:0–2 trial health economic evaluation

The BB:0–2 trial included a comprehensive economic evaluation, with a cost–utility analysis [incremental cost per maternal quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gain] presented as the primary analysis, and a CCA presented as an alternative economic approach. 32,61 The analysis showed that there were marginal gains in maternal QALYs, but that these gains cost an extra £1992.89, on average, per person, and that there was a low probability of the FNP being cost-effective. The CCA reported that health-related costs were lower for women in the FNP arm, but non-health-related costs were higher.

Health economic methods in the BB:2–6 study

Prior to commencement of the analysis, a health economic analysis plan was produced, reviewed by the study team and incorporated into the statistical analysis plan. The analysis plan reflected several practical challenges in presenting a health economic analysis that could reflect the impact of the FNP over the full BB:0–2 and BB:2–6 time horizons. These challenges are summarised in the following paragraphs.

The BB:2–6 study captured secondary health-care data (A&E, hospital inpatient and hospital outpatient data) through HES, but not primary health-care/community resource use (e.g. visits to the GP, nurse, health visitor, counsellor), as captured in the BB:0–2 trial. In the BB:0–2 trial, additional consideration was given to non-health-care resource items such as social assistance, temporary education, educational attendance, child care and other services. In the BB:2–6 study data sets, the large variety of possible non-health-care resource interactions (e.g. who the child saw, how often they saw them, where the visits took place, how long for), and the limited data on such resources, meant that these could not be adequately translated into costs.

As a result, the perspective utilised in the BB:2–6 health economics analysis would be constrained to available costs from secondary health care.

In the BB:0–2 trial, resource use (health and non-health) and costs for each mother were included, alongside subsequent resource use and costs to their child, using published unit costs. In the BB:2–6 study, the available health-care costs to the mother were analysed and presented separately to those of the child.

Unlike the BB:0–2 trial, health-utility data (captured by measures such as the EuroQol-5 Dimensions) were not available; therefore, a cost–utility analysis for the BB:2–6 study could not be conducted.

It was recognised that the potential benefits of the FNP did not apply to only one system (i.e. health care), but cut across a range of public sector agencies (such as social care and education), and beyond to individuals, families and society. As a result, the outcomes of interest go beyond health outcomes – as reflected by the primary and secondary outcomes of interest in the BB:2–6 study.

A CCA was chosen as the most meaningful method to use, given the data available. This enabled the evaluation of available health-care resource use and cost data associated with the FNP over the follow-up period covered in the BB:2–6 study, and enabled comparison with the range of primary and secondary outcomes, in order to extend the original economic analysis reported in the BB:0–2 trial in a practical and informative way.

Perspective and time horizon of the BB:2–6 study

The costs of the FNP during the BB:2–6 study were considered from a secondary health-care provider (UK NHS) perspective. Costs were collected for mothers and children separately. The time horizon reflected the BB:2–6 study follow-up period (i.e. 4 years). The data used to inform the economic analysis were obtained from the linkage methods (see Data sets and data providers). The remainder of this chapter describes the additional steps for the economic analysis.

Resource use and costs included

Hospital Episode Statistics data sets

The HES data warehouse was used as the primary source of data comprising inpatient, outpatient and A&E attendance data sets. Similar principles to those used in the BB:0–2 trial were employed, when possible, to enable consistency in the costing methods between studies. Each data set was processed through the relevant section (Admitted Patient Care, Non-Admitted Consultations or Emergency Medicine) of the NHS Digital Reference Cost grouper to generate Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) codes for each activity record. The relevant annual grouper (e.g. 2009/10) was used, dependent on the discharge date of the activity record. Once the records were coded, they were then matched, using this HRG code, to the appropriate annual NHS Reference Costs. Inpatient data were costed split on whether patients underwent elective or emergency admissions, whereas A&E data were split on whether patients were discharged or admitted. Resource use was valued in Great British pounds at 2010 prices (baseline date).

The HES data-cleaning rules were used to check variables created by HES to identify possible errors. Several records, in each of the data sets, were unable to be coded, because either they did not have enough required data points or they had unrecognised codes. Once processed, if these data were uncoded, and therefore uncosted, average costs were imputed. Imputed costs used the average cost of all coded and costed attendances, of that particular type, for the year of that attendance. For example, an uncoded emergency hospital admission in the 2011/12 year would have had an average cost imputed from all of the coded and costed emergency hospital admissions for the year 2011/12. All data sets were checked to identify and remove duplicate records prior to analysis.

Outcomes

The primary and secondary outcomes reported (see Appendix 2, Table 27) were the same as the main study outcomes: CIN status, referral to social services, child protection registration, looked-after status, SEN, school attendance, early-years assessment, DNA rates for outpatient appointments, and recorded injuries and ingestions.

Cost–consequences analysis

A CCA was undertaken for the BB:2–6 study. A CCA is a form of economic evaluation in which the range of costs and outcomes (consequences) are reported without aggregation or weighting. 62 This allows the reader to assess the disaggregated costs and outcomes and to form their own opinion as to their relevance and importance to their own decision-making context. 63 The analysis follows a descriptive approach, which presents effectiveness results (primary and secondary outcomes) separately to that of the costs. The CCA approach is recommended for complex interventions that look to observe a broad range of effects, which are difficult to measure in a single common unit. 63,64 In essence, the reporting of a CCA takes the form of a balance sheet and helps to give a straightforward, but richer, set of information on costs and outcomes for decision-makers. 65

It should also be noted that there are limitations associated with CCAs that must be borne in mind when interpreting their results. They provide no guidance in relation to cost-effectiveness, they have limited generalisability and they are open to selective, non-transparent decision-making based on the results that best fit a decision-maker’s agenda. 63 Overall, a CCA allows for the consideration of a broader range of potential benefits when determining whether the FNP represents good value.

Analysis

Missing data

Data can be missing from routine health records. This occurs when individuals are missing a component of data. Theoretically, every study participant will have HES inpatient data from the birth; these might be missing in the data set or the individual may have a type 2 opt-out (see Participant population for analysis). It has been assumed that the absence of data for the inpatient, outpatient and A&E data sets means that no resource has been utilised.

Resource use and costs

A descriptive analysis of the resource use and costs associated with mother and child in the period covered by the BB:2–6 study was presented separately in the first instance, with means, medians and ranges presented for the FNP and usual-care arms.

Given that there was a focus on child maltreatment in the BB:2–6 study, health-care resource use for children was also separated by whether or not it was related to an injury or ingestion. Therefore, results were displayed in three categories: all resource use, all resource use excluding injuries and ingestions, and injuries and ingestions’ resource use.

Incremental mean differences in costs for each disaggregated cost category (e.g. secondary care admissions) were reported.

The costs across each disaggregated category were added to the relevant cost category in the BB:0–2 trial and a similar descriptive analysis was undertaken to present an illustration of the costs associated with the FNP, compared with usual care, across the full period of cohort follow-up (see Appendix 10).

Discounting

Health-care resource use occurred over multiple years. Therefore, once processed and costed, health-care costs were discounted back from the year of event to baseline (2009/10) on an annual basis at 3.5% to adjust for inflation.

Cost–consequences analysis

The costs and outcomes were summarised in a cost–consequences table(s) to report the disaggregated health-care resource costs for the FNP arm, compared with those for the usual-care arm, for mother and child over the BB:2–6 follow-up period and to report cumulative costs over the full period of cohort follow-up, tabulated against the outcomes.

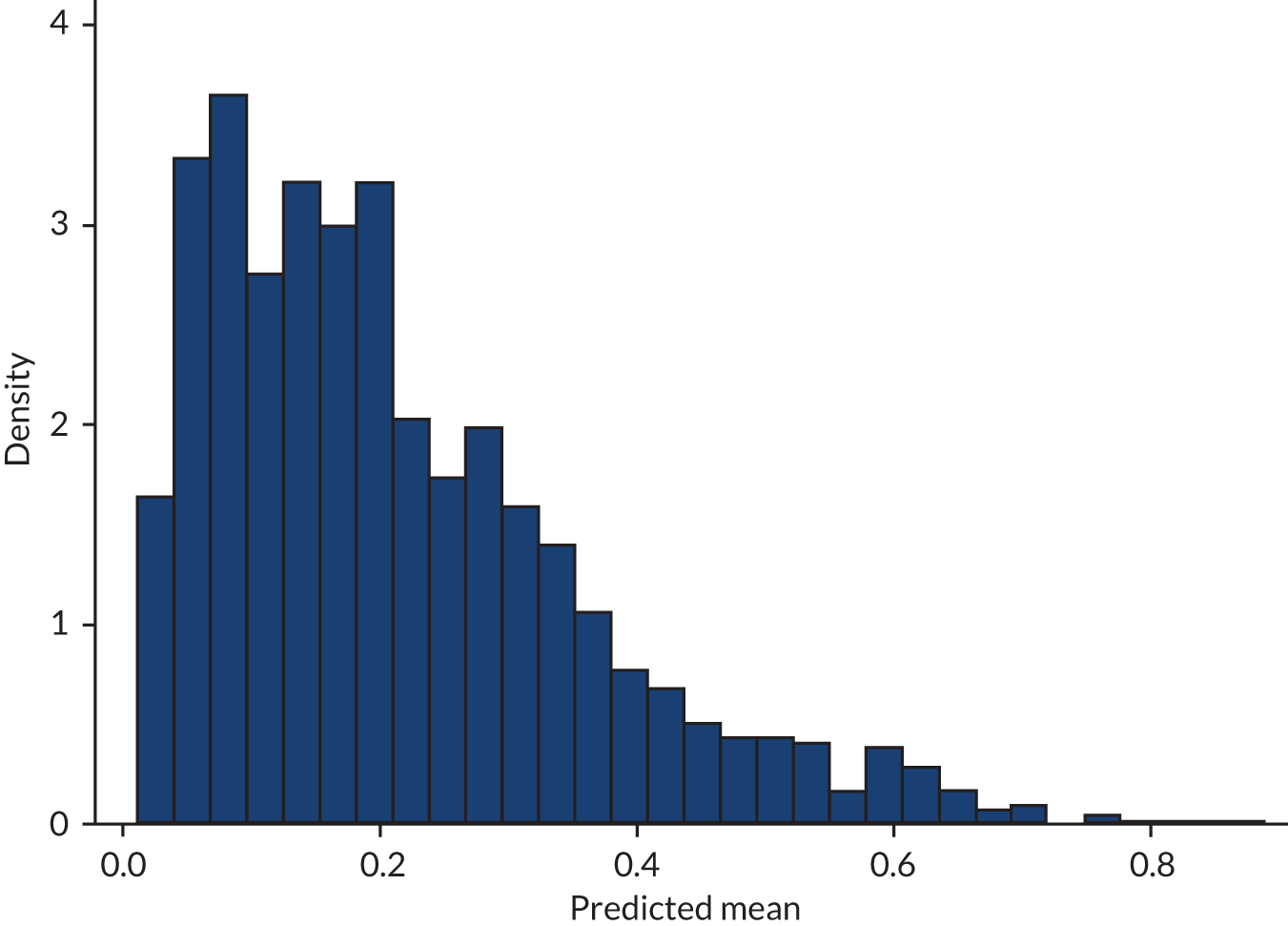

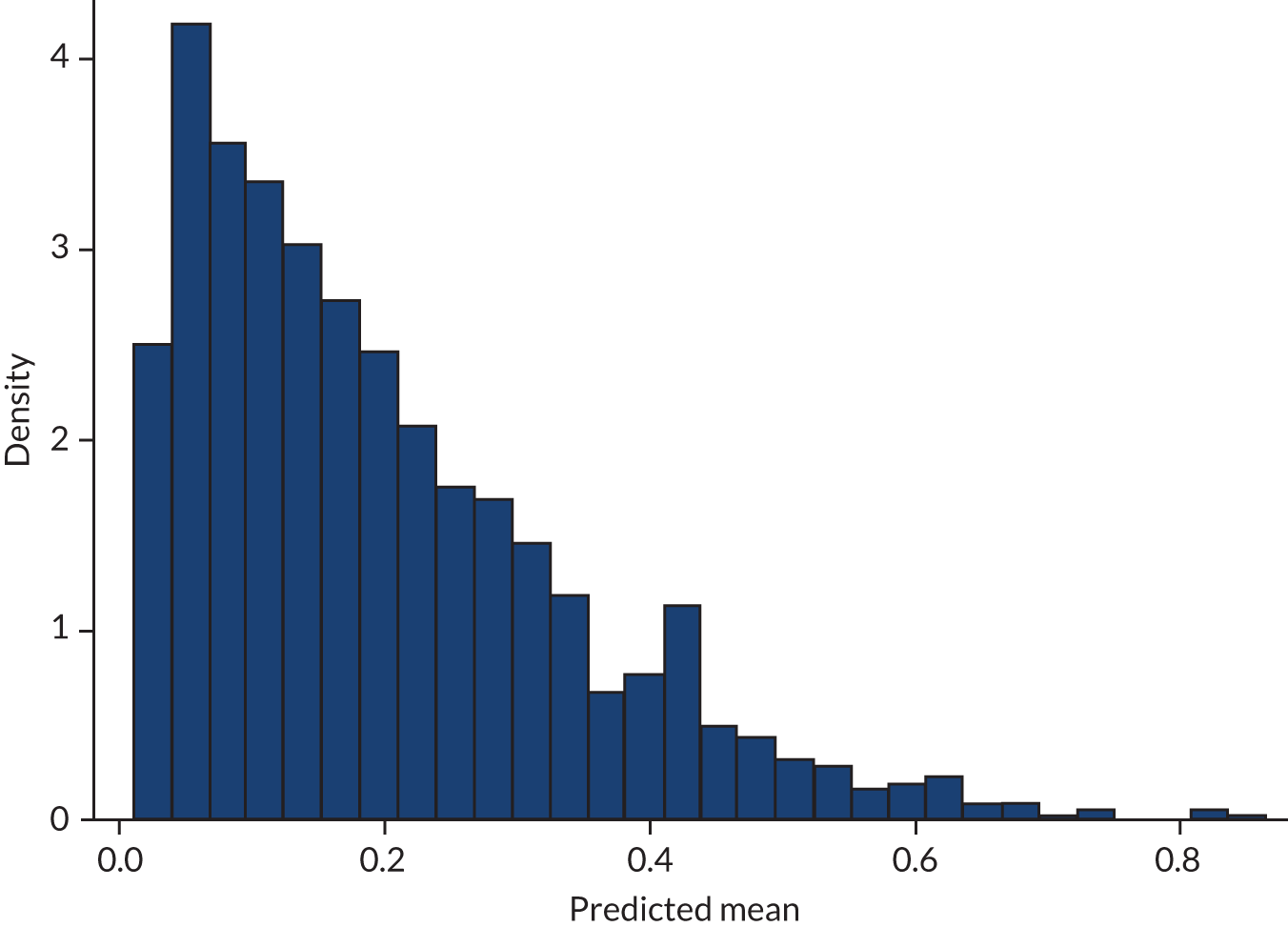

Distributions of health-care resource use and cost were tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normality. As all variables were skewed (i.e. not normally distributed), the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test was used to test the difference between the usual care and FNP arms.

Subgroup analysis

No subgroup analysis was undertaken.

Chapter 3 Pilot study

This chapter describes the work conducted in the pilot phase of the BB:2–6 study. The primary purpose of the pilot phase was to demonstrate the feasibility of using the routine data-linkage model to answer the research objectives and planned analysis. This phase, therefore, provided an opportunity to assess the model of data linkage being constructed, to provide reassurance that the final extract and analysis could progress effectively and as efficiently as possible and to make changes where required. Although not all data that we aimed to collect in the main study were being sought at this point, the study design was not expected to change significantly. Therefore, we regarded this phase as a pilot study (a small-scale version of a future study), rather than a more generic feasibility study. 66

Content in this chapter has been reproduced from the published feasibility study paper by Lugg-Widger et al. 31 © Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article). This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Aims/objectives

The aims of the pilot phase were (1) to establish and verify the governance, regulatory and logistical arrangements for linking data sets and (2) to prepare and assess the suitability of data for answering the research objectives and planned analysis.

Objectives

The key objectives of the pilot phase were to:

-

obtain data from the two primary data providers for the study

-

establish acceptable levels of record linkage

-

establish adequate data quality.

Methods

Obtaining data from data providers

We requested data from NHS Digital and the DfE (NPD) for a proportion of the BB:2–6 sample. For NHS Digital, this included data from trial entry of the first mother (June 2009) to 31 March 2015. Local authority safeguarding data, accessed via the modular NPD data sets, were requested to 31 March 2014, and education data were requested from the NPD to other end points in 2014. Appendix 3, Table 33, summarises the time periods requested for each data set. Data sets are released annually, but at different points throughout the year, by both NHS Digital and the NPD; therefore, the data were requested to allow the greatest number of years possible at the time of request.

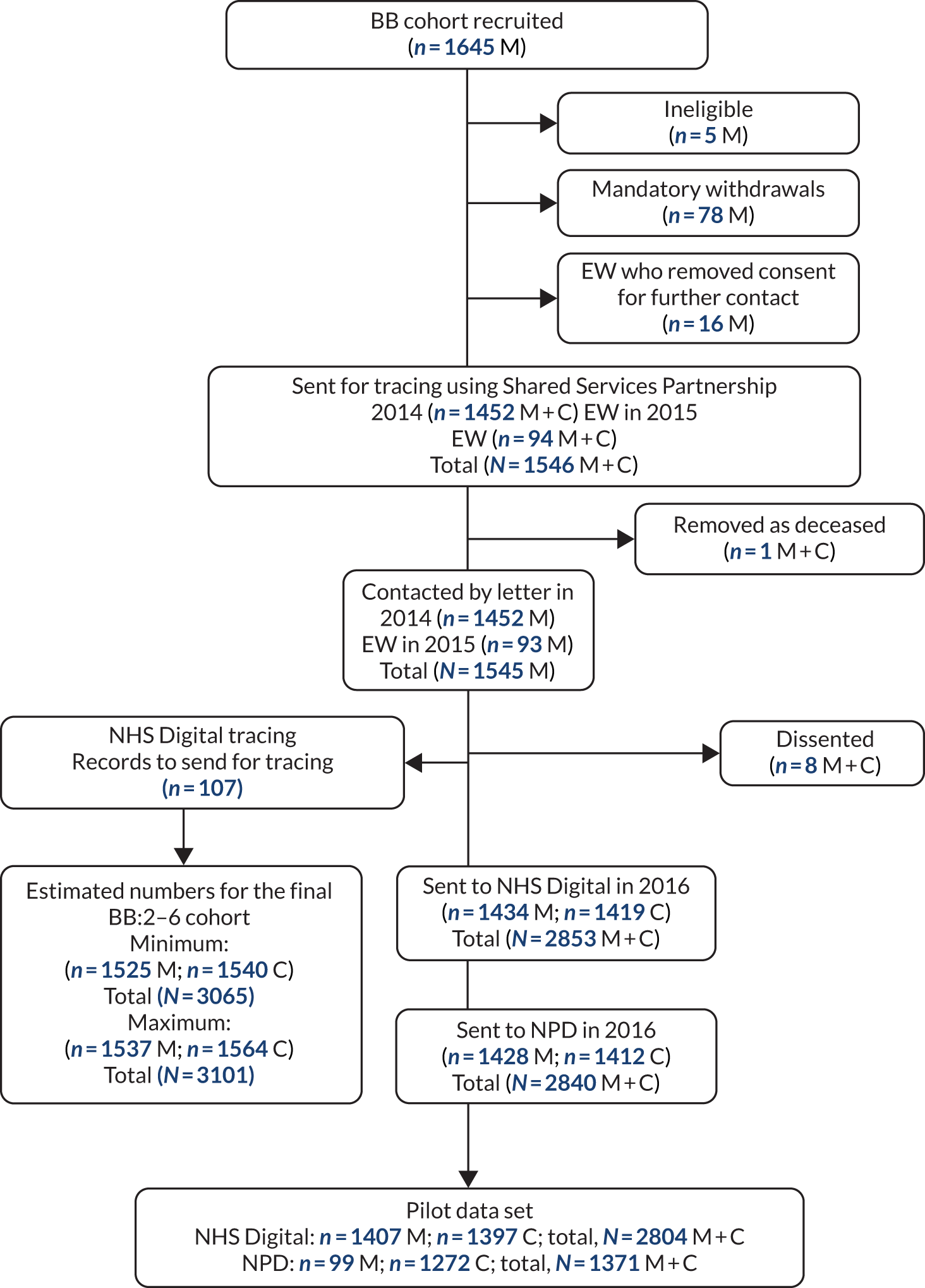

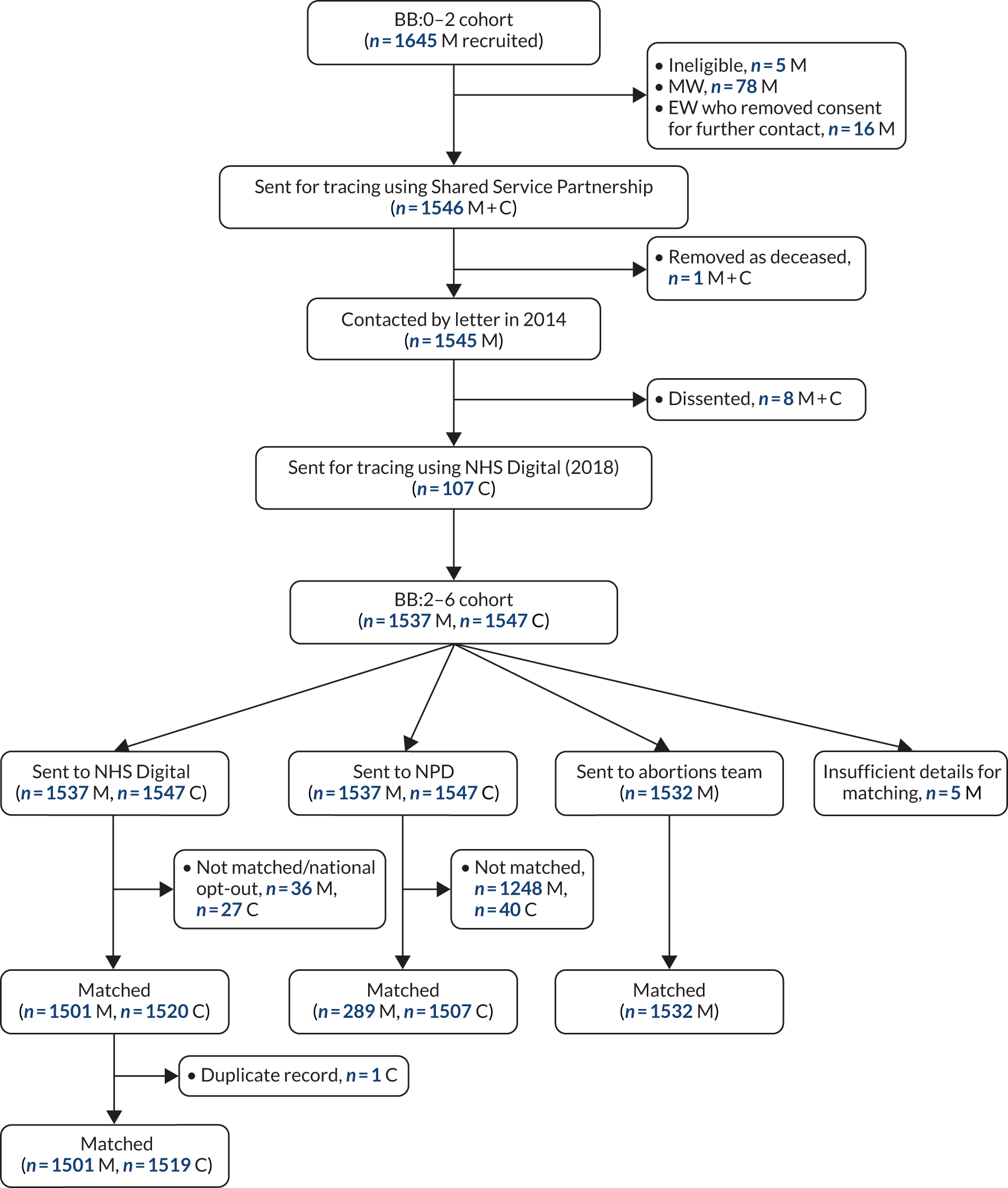

We did not include participants electively withdrawn from the BB:0–2 trial in the pilot cohort sent for matching, as further tracing was ongoing at the time of data transfer. In addition, we did not send a small number of the main cohort for matching for the same reason (i.e. tracing indicated a different date of birth or sex, which needed further investigation). Figure 3 outlines participants’ progress through the trial processes, including the numbers of participants involved at each stage. It also includes the estimations of sample numbers at the time pending the tracing.

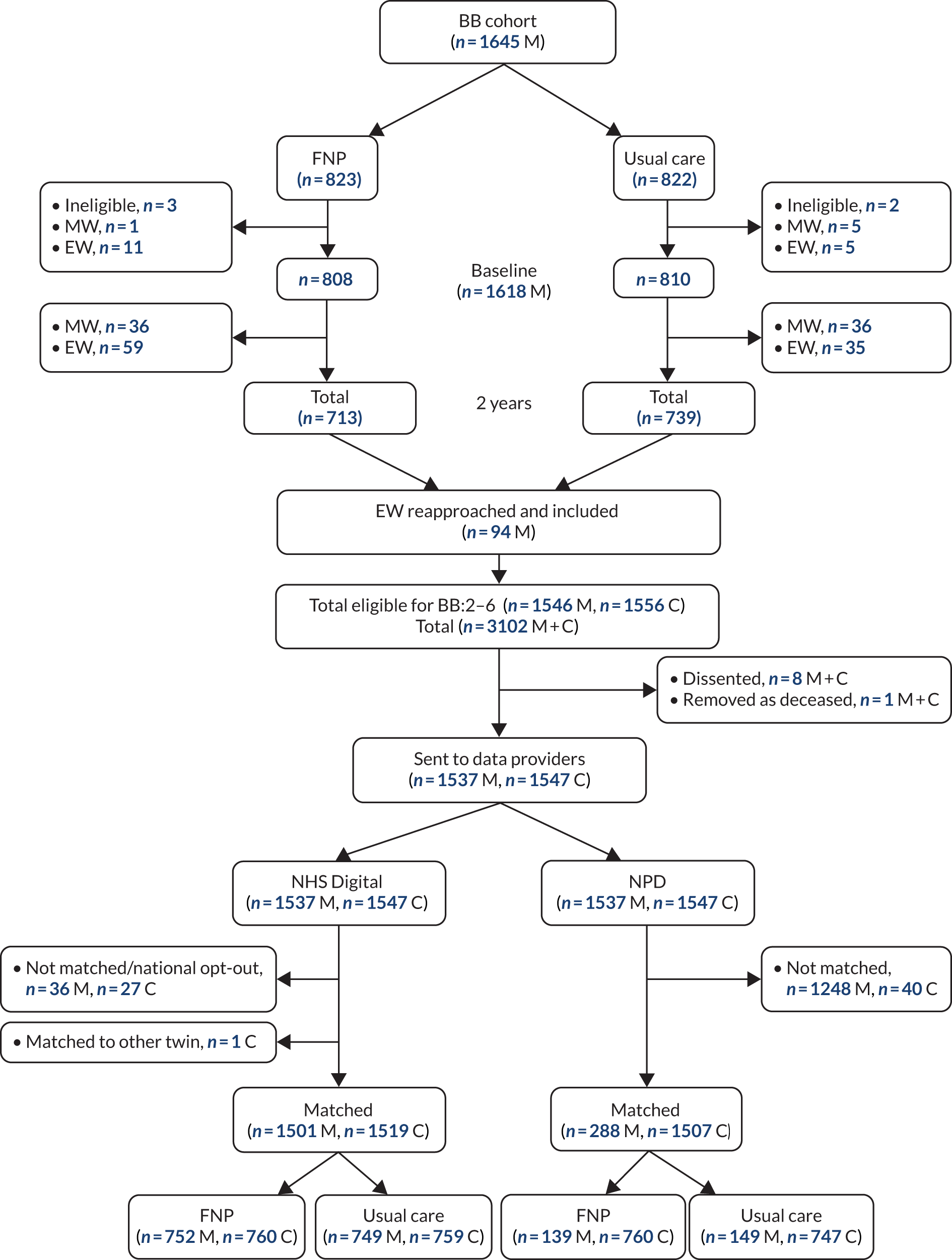

FIGURE 3.

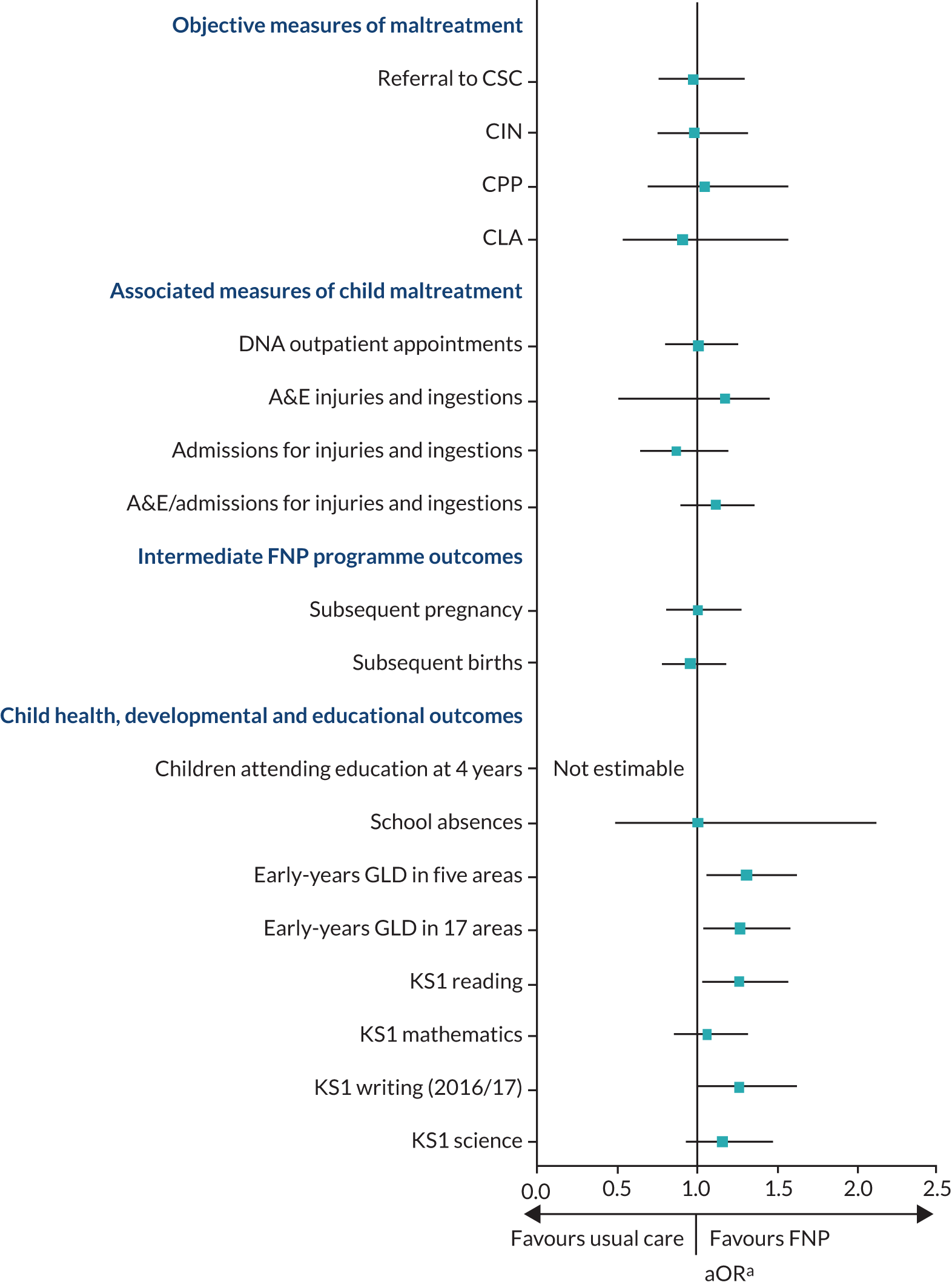

Participant flow diagram showing numbers of mothers and children sent for matching and successfully linked in the pilot and main study phases. C, children; EW, elective withdrawals; M, mothers.