Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 15/05/28. The contractual start date was in October 2016. The final report began editorial review in December 2019 and was accepted for publication in April 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Cockayne et al. This work was produced by Cockayne et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 The authors

Chapter 1 Introduction

Material throughout the report has been reproduced from Cockayne et al. 1,2 These are Open Access articles distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Slips, trips and falls on the same level (STFL) are a major contributor to the burden of workplace injury in Great Britain (GB; refers to England, Scotland and Wales). They are the most common cause of non-fatal injury to employees, accounting for around 30% of those injuries reported to GB’s Health and Safety Executive (HSE). 3 It is estimated that there are around 100,000 non-fatal workplace injuries due to STFL every year. 4

The consequences of work-related STFL are rarely fatal, but the resulting injuries are not always trivial. Nearly 40% of the STFL injuries reported to the HSE in 2017/18 were ‘specified’ injuries,5 which means that the injury appeared on a predefined list that tends to represent the more serious workplace injuries,6 with the vast majority being fractures. 7 Fractures can sometimes have long-lasting effects, such as nerve damage, decreased strength and increased discomfort around the site of the fracture. It is estimated that, on average, a worker takes around 9 days off work if injured by a workplace STFL, which equates to nearly 1 million working days lost through STFL injuries every year. 4

Furthermore, the workforce is ageing and the employment rate for those aged ≥ 65 years has doubled over the last 20 years. 8 Older workers are more susceptible to falls and tend to sustain more serious injuries when they occur. 9,10 In the workplace, normal age-related physiological factors, such as diminished balance, vision changes and hearing loss, can contribute to increased STFL work hazards. 11 Hence, workplace STFL are an increasing concern, particularly within the context of an ageing workforce.

Slips in the workplace and the role of slip-resistant footwear

Injury-reporting systems rarely differentiate between slips, trips and other causes of falls on the same level, but it is thought that slipping is a major contributor. Courtney et al. 12 reviewed six reporting systems in the USA, the UK and Sweden, and found that just three (in the USA and Sweden) provided sufficient information to attempt to isolate the contribution of slipping to the overall burden of STFL. The authors12 suggested that slipping contributed to between 40% and 50% of STFL-related injuries.

Workplace slips and their resulting falls happen for a number of reasons. Factors that can contribute to slips in the workplace include the floor surface, the presence and characteristics of any contamination of the floor (wet or dry), the cleaning regime, the level and type of pedestrian activity, footwear choice, the working environment (e.g. lighting or noise levels) and human factors (how people interact with their working environment). 13 A multitude of factors may be present at the same time and so it is rarely just one factor that causes a specific slip incident.

In the UK, employers have a duty to assess risks (including slip risk) and, when necessary, take action to address them. This is done through a risk assessment, when the employer considers what workplace risks may lead to slip injuries and decide what suitable and effective control measures could prevent them. In many instances, straightforward measures can readily control risks (e.g. ensuring that the floor surface is kept clean and dry or by installing a floor surface that is sufficiently slip resistant when contaminated). However, when it is not practicable to prevent the floor surface becoming slippery, employers may consider the use of slip-resistant footwear.

The choice of slip-resistant footwear is important and the selection of inappropriate footwear (i.e. with poor slip resistance) could potentially add to the problem rather than provide a solution. Choosing appropriate footwear can be difficult, as there is a lack of robust testing and reliable information to help guide the decision-making process.

It has been suggested that testing footwear under more lifelike conditions will provide a more accurate assessment of the slip-resistant properties of the footwear. 14,15 In response to this, and to help guide the selection process, the HSE developed the ‘GRIP’ rating scheme. 16 This scheme utilises a test regime designed to reflect the biomechanics of walking, and categorises footwear in accordance with the level of slip resistance it provides on a smooth surface contaminated with (1) water and (2) a 75% volume per volume glycerol solution (aqueous). ‘GRIP’ star ratings, ranging from one to five stars, are assigned to the footwear soling units on the basis of the results obtained, with five stars being awarded to those with the highest level of slip resistance. The risk assessment process can help guide the employer on which star rating is required for their workplace.

Current evidence relating to the use of slip-resistant footwear

A number of publications have described studies investigating the influence of footwear on slip risk using a range of laboratory tests. The evidence suggests that the level of slip resistance provided by different types of footwear varies considerably and that the effectiveness of footwear at preventing slips and falls depends on factors such as the footwear material, the tread design, the type of contamination and the characteristics of the floor. 17–19

The HSE has developed tests to accurately assess the slip resistance of footwear and has helped to inform the footwear selected by some companies that have subsequently seen a reduction in accidents and personal liability claims. For example, one case study20 showed how the test method could be used to remove inadequate footwear from use and identified alternatives. As a consequence, the risk of workplace accidents was reduced. 20 However, these are individual, non-peer-reviewed before-and-after case studies and the findings are not in the context of a randomised controlled trial (RCT).

There is, however, some evidence to support this suggestion in studies that have measured a reduction in slips occurring in the workplace by the use of appropriate slip-resistant footwear. Bell et al. 21 evaluated a comprehensive slip, trip and fall prevention programme for hospital employees in the USA. The programme included slip-resistant footwear for certain employee subgroups, but also included many other prevention strategies, such as hazard assessments, changes to housekeeping, general awareness campaigns and flooring changes. The study suggested that the programme reduced workers’ compensation claims for slips, trips and falls by 58%, but it was not possible to disentangle the specific effect of slip-resistant footwear from the other preventative interventions. 21

An uncontrolled before-and-after study among fishermen in Denmark suggested that slip-resistant boots led to a reduction in self-reported slips, trips and falls. 22 In contrast, a cross-sectional study23 of 125 fast-food restaurant workers in the USA did not find an association between slipping and use of footwear perceived to be slip resistant. The authors suggested that the null finding could have been due to the method of classifying footwear as slip resistant (through visual inspection of the tread), possibly leading to misclassification and the potential for reverse causality (people who had experienced a slip or fall in the past being more likely to wear slip-resistant footwear).

More recently, in the USA, a prospective cohort study24 of 475 fast-food restaurant workers found that the use of slip-resistant footwear was associated with a 54% reduction in the reported rate of slipping. A case-crossover study nested within the same cohort found that rushing and walking increased the rate of slipping, but that use of slip-resistant footwear reduced the effects of rushing and walking on slip risk when on a contaminated floor. 25 Further analysis of the cohort indicated that slip-resistant shoes worn for < 6 months were marginally more effective at preventing slips than slip-resistant shoes worn for > 6 months. 26

We are aware of only one RCT27 assessing the effectiveness of slip-resistant footwear. This cluster randomised trial of food service workers from 226 school districts in the USA found that the probability of a slipping injury fell by 67% in the intervention group, who received slip-resistant footwear. By contrast, the control group (who wore slip-resistant footwear that they purchased themselves in accordance with company policy) saw a slight increase in the probability of slipping injury during the follow-up period.

Overall, there seems to be promising evidence that slip-resistant footwear can substantially reduce the burden of accidents at work, but much of this evidence has been gathered for footwear with slip-resistant properties that are ill-defined. It was therefore considered important to test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of appropriately specified slip-resistant footwear in a large pragmatic trial within a UK setting.

Trial setting

It is estimated that the health and social care sector employs 1 in 10 of the working population28 and has one of the highest numbers of non-fatal STFL compared with other industries in GB. It is estimated that every year around 14,000 workers in this industry sector are injured as a result of STFL [Health and Safety Executive. Estimated Incidence of All Self-Reported Workplace Non-Fatal Injury Resulting in a Slip, Trip or Fall on the Same Level, Sustained in Current or Most Recent Job, By Industry, for People Working in the Last 12 Months, Averaged 2014/15–2016/17 (Unpublished data). London: Labour Force Survey; 2018].

The NHS is the biggest employer in the sector and the fifth biggest employer in the world. 29 NHS sites, particularly hospitals, present challenging working environments with respect to slip risk. For example, the floor is generally smooth and not carpeted to aid regular cleaning, there are multiple sources and types of contamination, there is a relatively high level of pedestrian activity and of varied types (e.g. walking, pushing and pulling) and people frequently walk at speed, often multitasking or focused on a more critical objective than the environment around them. Many large hospital sites are a conglomeration of buildings and so people often switch between indoor and outdoor environments, and community staff are mainly offsite with no control over their surrounding environment. In such circumstances, it would seem potentially beneficial for staff to consider wearing slip-resistant footwear.

It is for these reasons that NHS staff were considered to be a good population on which to base research into the potential effectiveness of appropriately specified (in this study, 5-star, GRIP-rated) slip-resistant footwear. In addition, the NHS includes different working subpopulations (e.g. nursing staff, kitchen staff, porters and people who work in the community). This will help to generalise any research to other industries that share many of the same risk factors, such as retail, hospitality, education and manufacturing, and maximise the impact of the research. One other potential benefit of undertaking the trial within the NHS is that its staff are generally used to the research environment although it is usually patients rather than the staff who take part in research. However, it seemed likely that, for this reason, participation in this research would be higher among NHS staff than among those of other employers.

Objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective of this research was to assess whether or not the offer and provision of 5-star, GRIP-rated, slip-resistant footwear to NHS employees working in general, clinical or catering areas leads to a reduction in the incidence rate of self-reported slips.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives of this study were to:

-

undertake an internal pilot RCT to (1) check the feasibility of the study, including if it is possible to recruit, randomise and follow up 800 participants; (2) check the sample size calculation assumptions and the attrition rate; and (3) explore and address any issues regarding footwear compliance

-

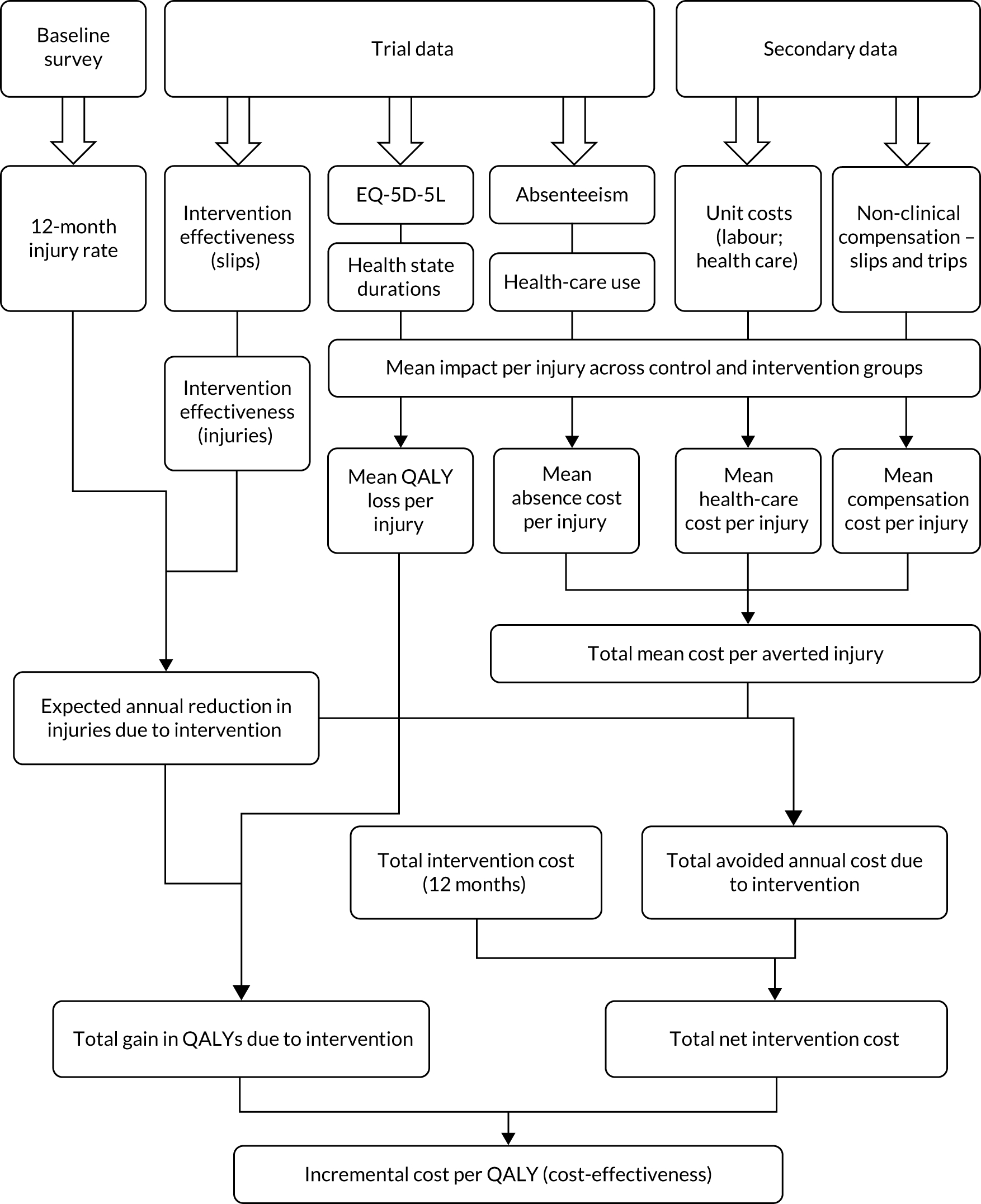

assess if the provision and use of 5-star, GRIP-rated footwear leads to a reduction in slips and is cost-effective

-

disseminate the findings of this study using the HSE, NHS trust managers and health and safety managers (in addition to publishing the results of the study in key journals and in this Public Health Research monograph).

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The Stopping Slips among Health-care Workers (SSHeW) trial was a pragmatic, two-arm, open RCT with an internal pilot trial, economic evaluation and qualitative study. Participants were randomised to either the intervention group and were offered a pair of 5-star, GRIP-rated, slip-resistant shoes to wear at work (free of charge to themselves), or to the waiting list control group and were asked to wear their usual work footwear for the trial period and offered a pair of the slip-resistant shoes at the end of their participation in the trial (free of charge to themselves). The trial included an economic evaluation (see Chapter 4) and a nested qualitative study to explore the experiences of participants in the trial (see Chapter 5). The SSHeW trial also served as a host trial for an embedded study within a trial (SWAT) to evaluate the effectiveness, on response rate, of enclosing a pen with the 14-week post-randomisation postal follow-up questionnaire.

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the University of York, Department of Health Sciences Research Governance Committee (DHSRGC), on 28 November 2016. The study was approved by the Health Research Authority (HRA) on 7 March 2017 (HRA reference number 17/HRA/0435). The HRA did not require Research Ethics Committee approval for the study, as the participants were NHS staff (as opposed to NHS patients). Approval and ‘confirmation of capacity and capability’ was obtained for each participating trust prior to commencement of the trial at that site (see Appendix 1). Substantial amendments to the protocol were submitted to the DHSRGC, the HRA and each site’s research and development office during the course of this study.

The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number registry as ISRCTN33051393. The trial protocol is published. 1

Setting

Recruitment of participants took place in seven NHS trusts in England. The participating trusts ranged from large acute hospital trusts to smaller trusts, and included district general hospitals serving local communities, a trust that provided mental health services and a community trust.

Recruitment procedure

Recruitment of participants into the study took place in multiple sites within participating NHS trusts, facilitated by members of the research and development teams, and assisted by members of the HSE team and University of York researchers in some sites. Sites used a variety of recruitment strategies to recruit participants, which were developed during the pilot phase of the study. These included holding ‘shoe shops’ (where interested staff could learn more about the study, and see and try on samples of 5-star, GRIP-rated, slip-resistant footwear) and stands promoting the trial in convenient hospital locations, such as reception foyers or the canteen, or at staff conferences or induction days. Other recruitment activities included promotion of the trial via posters, information on the staff intranet, screensavers and weekly staff bulletins. Direct staff recruitment occurred by members of the research team attending staff meetings and ward areas, particularly at shift handover time, and via word of mouth as participants discussed the trial with colleagues who then approached research staff to discuss participation.

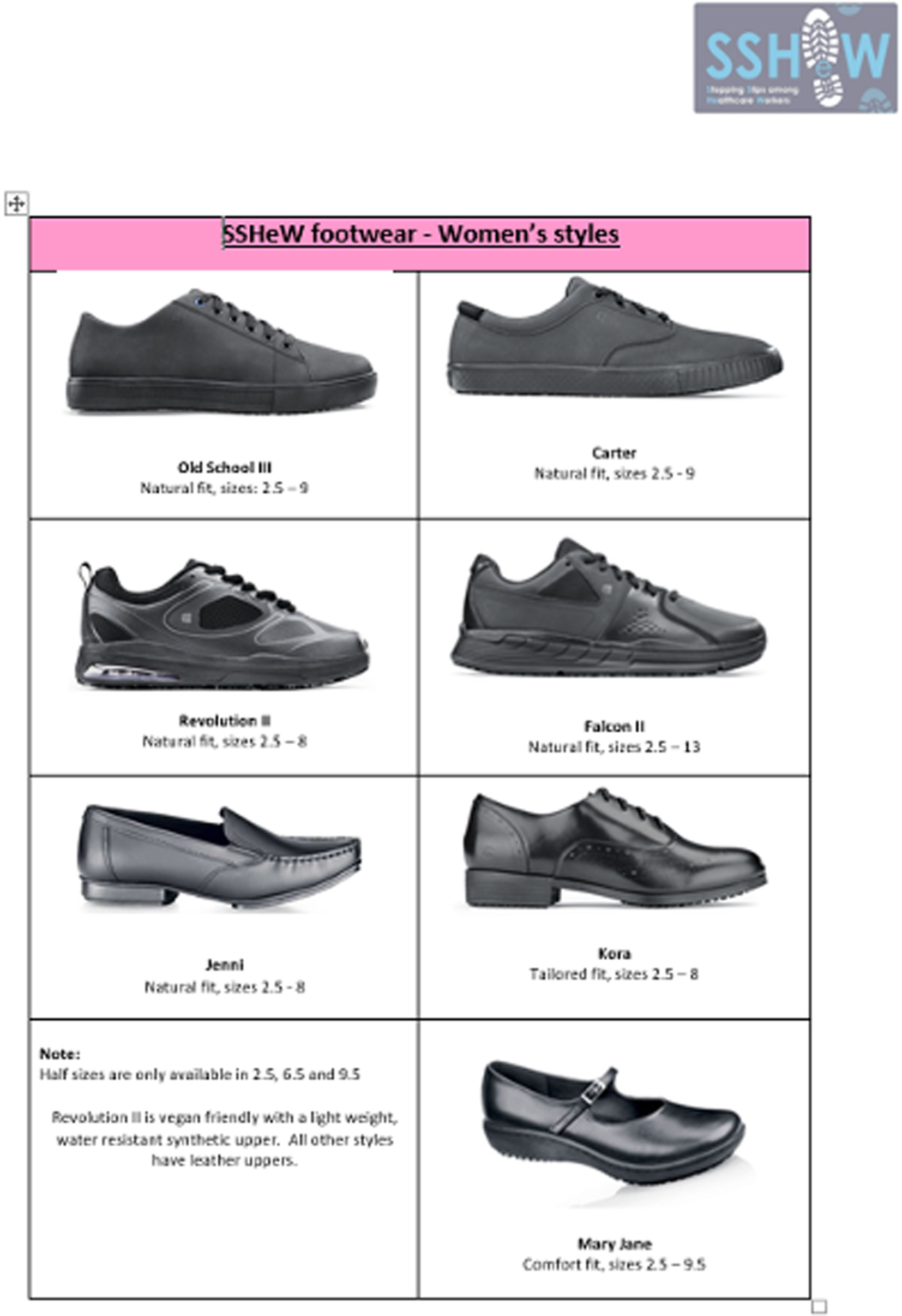

At recruitment, research staff provided information about the study and demonstrated the 5-star, GRIP-rated, slip-resistant shoes being tested in the trial. Sample styles and sizes were available for interested staff to try on. Research staff briefly assessed eligibility of interested staff by asking if they were employed by the recruiting trust, their area of work and the average number of hours they worked per week, before giving them a recruitment pack. The recruitment pack contained an invitation letter from the principal investigator at the NHS trust (see Report Supplementary Material 1), a participant information sheet, which included contact details for the research team should they have had any queries about the study (see Report Supplementary Material 2), a flier with pictures of the shoe styles being offered at the trust (see Appendix 2 for an example of this document offered at one trust), a baseline questionnaire including more detail on the eligibility criteria (see Appendix 3), a consent form (see Report Supplementary Material 3) and a prepaid envelope for returning the completed paperwork.

Consent process

Participation in the SSHeW trial was voluntary. Participants who wished to take part in the trial after receiving information about the trial from a member of the research team and/or reading the participant information sheet provided in the recruitment pack were asked to complete the consent form by initialling that they had read the items listed, and signing and dating the form.

The consent form also asked if participants were willing to take part in a telephone interview about the study (for the qualitative component of the study, further consent was obtained from the participant by post prior to undertaking a telephone interview). Participation in the SSHeW trial was not affected if the member of staff did not consent to participate in a telephone interview.

Baseline assessment

On receipt of completed written consent, researchers at the York Trials Unit (YTU) assessed the participants’ responses to the baseline questionnaires for eligibility in accordance with the following criteria.

Participant eligibility

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Employed by (named) participating NHS trust.

-

Were required to adhere to a dress code.

-

Worked in a clinical, general or catering area.

-

Worked at least 30 hours per week [80% working-time equivalent (WTE)] (reduced mid-way through the trial to 22.5 hours/week or 60% WTE).

-

Had a mobile phone and were willing to receive and send text messages for trial data collection.

Exclusion criteria

-

Not employed by the participating NHS trust.

-

Did not have a mobile phone, or were unwilling or unable to receive and send text messages.

-

Were provided with, and required to wear, protective footwear by their employer (e.g. steel toe-capped boots).

-

Were agency staff or staff with < 6 months remaining on their employment contract.

-

Worked < 60% WTE (22.5 hours/week).

-

Were predominantly office or theatre based.

Note that the eligibility criterion with respect to the number of working hours was changed from the initial requirement of working, on average, at least 80% WTE (equivalent to 30 hours/week) to working, on average, at least 60% WTE (equivalent to 22.5 hours/week) (protocol version 5.0, dated 26 April 2018 and approved 2 September 2018). This change was made to facilitate the recruitment of participants to meet the required sample size. Participating sites had saturated the eligible workforce and found that the number of hours worked was the predominant factor limiting others from taking part. The required working hours were dropped to no lower than 22.5 hours to ensure that participants were working a sufficient amount of time to (1) provide a sufficient work-related slip rate and (2) retain the ability to detect a reduction in this slip rate. It was felt that if we reduced the working hours further then we would not have been able to do this.

Participants who were assessed as being ineligible for the study were notified in writing and no further correspondence was sent. Participants who were deemed eligible were entered into the trial and sent a welcome text message that said:

Welcome to the SSHeW trial. We very much value your agreement to participate. You will shortly start to receive text messages asking about any slips you have at work. These texts will always come from this number and will begin with the word SSHeW so that you can recognise them. Thank you.

All participants who were eligible to take part were sent a copy of their signed consent form and a paper diary enabling them to record slips, falls and injuries when they occurred, and any time off work as a result (see Appendix 4). This was intended as a memory aid to help participants complete the text message responses and the 14-week questionnaire.

Pre-randomisation phase

After the welcome message was sent, all eligible participants were sent a text message each Sunday at 18.30 for 4 weeks, unless they requested that these be stopped. We chose to send text messages at this time as we anticipated that fewer participants would be at work, which would lead to higher response rates. This message read:

SSHeW trial: How many slips did you have at work between [DD/MM/20YY] and [DD/MM/20YY]? Please provide a single number (e.g. 2) or 0 if you did not slip. Thank you.

The dates were populated with the previous Monday and the current date. Those who provided a valid response (a numerical value or written number, rather than a written text response or other message, such as a symbol) to at least two of the slip data collection text messages were randomised into the trial.

It became apparent during the trial pilot phase that some eligible participants had misunderstood the trial process. Instead of providing slip data in response to their text messages, they reported not having received their trial shoes as they mistakenly thought that they needed to report slip data only once they had received their trial shoes. Therefore, the protocol was amended (substantial amendment 6, approved 20 June 2018) to allow two additional text messages to be sent to participants who had not responded to their pre-randomisation text messages, along with a reminder that they needed to reply to these messages if they wished to be included in the trial.

Randomisation

Participants who fulfilled the eligibility criteria, provided written consent to take part in the study, completed a baseline questionnaire and returned at least two of the weekly text messages providing slip data were eligible for randomisation. Participants were randomised using the YTU’s secure web-based randomisation system based on an allocation sequence generated by an independent data systems manager at the YTU. The systems manager was not involved in the recruitment of participants. Block randomisation, stratified by trust, was used with variable block sizes. Participants were randomised at a particular site in batches of 1 : 1 between the intervention and control group (depending on when sites had capacity to order and deliver footwear). The block size was equal to the number of participants to be randomised in each ‘batch’. Participants were notified of their group allocation by letter from the YTU.

Blinding of trial participants to group allocation was not possible because of the nature of the intervention. Members of the study team, including the statistician, health economist and those involved in the administration of the study, were not blinded to group allocation.

Group allocation

Intervention

Individuals allocated to the intervention arm were offered a pair of 5-star, GRIP-rated, slip-resistant shoes. The footwear was provided by a single manufacturer [Shoes For Crews (Europe) Ltd] and the cost covered by the NHS trust. A range of intervention shoes were offered as part of the trial. The shoes included a variety of styles, to suit different people and job roles, including dress shoes, casual styles and ‘trainer’-type designs. The shoes had either a water-resistant leather or synthetic mesh upper (the synthetic materials being vegan). Each individual trust reviewed the footwear available in terms of style; to offer a range of footwear representative of that already worn by staff; health and safety issues, for example potential for needlestick injuries; potential infection control issues; and cost. They then produced a list of footwear which was deemed suitable for staff at their trust to wear. All participants were asked to indicate on their baseline questionnaire, prior to randomisation, which style and size of trial shoe they would like to wear. This facilitated swift ordering of the shoes by the trust for participants subsequently randomised to the intervention group. The indicated shoes were ordered for the participant, who was then provided with instructions about how to collect their trial shoes. Further information was provided to participants about how to exchange their shoes if required. (Participants were able to exchange their shoes if they were found to be unsuitable, for example incorrect size, as long as the shoes were unworn and returned in their original box.) We had hoped that this process would facilitate shoes being available for intervention participants to collect no later than 2 weeks after randomisation; however, we know that in some sites, and at certain times, there were delays in ordering and/or delivery of the trial shoes. In addition, we know that not all intervention participants collected their shoes if they were delivered to a ‘collection point’ at the hospital, and those that did may not have done so in a timely manner. More information on receipt, and timing of receipt, of trial footwear is provided in Chapter 3, Receipt of shoes.

The shoes used in the trial had been assigned a 5-star GRIP rating from the HSE. The GRIP rating scheme was developed by the HSE to allow footwear users to identify slip-resistant footwear to help prevent slipping accidents. During GRIP-rating assessment, the soling of footwear is tested under very challenging conditions (i.e. a smooth surface contaminated first with water and then with a glycerol solution). Slip resistance of shoes is rated one to five stars on the basis of the results, with five stars being awarded to the highest performing footwear. The shoes used as the intervention in the trial had a rubber sole with an intricate tread pattern that provided higher levels of slip resistance than most other types of footwear on surfaces that are contaminated with non-clogging substances (Figure 1). This level of slip resistance is achieved by the soles providing a relatively large surface contact area, while also effectively dispersing any surface contamination. When walking surfaces are clean and dry the trial footwear would be expected to behave like any other footwear; however, their slip resistance is not compromised to the same extent as other footwear when walking on surfaces that are contaminated.

FIGURE 1.

Example of sole of intervention footwear. Photograph received and reproduced with permission from Shoes for Crews (Europe) Ltd.

Control

Participants allocated to the control arm were asked to continue to wear their usual work shoes for the 14-week trial period. They were informed that they would receive a free pair of 5-star, GRIP-rated, slip-resistant shoes at the end of the 14-week trial period, the size and style of which they indicated on their baseline questionnaire. The footwear was provided by a single manufacturer (Shoes For Crews Ltd) and the cost covered by the NHS trust. Control group participants were also sent a copy of their signed consent form and a slip diary, the same as the intervention group, at the start of their participation in the trial.

Participant follow-up

All participants in the SSHeW trial were sent weekly text messages for 14 weeks post randomisation to collect slip data (i.e. the number of slips the participant had experienced at work in the past week). As with the pre-randomisation messages, these were sent on a Sunday evening (18.30) and the wording was the same, with dates inserted relative to the past week:

SSHeW trial. How many slips did you have at work between [DD/MM/20YY] and [DD/MM/20YY]? Please provide a single number (e.g. 2) or 0 if you did not slip. Thank you.

These messages started, for all participants, the first Sunday after they were randomised, regardless of whether or not the intervention participants had received their shoes.

Non-responders did not receive reminder text messages, as there was limited time to send these because of the short time frame of 1 week before the next text message was sent. Participants were also sent a group-specific postal questionnaire at 14 weeks post randomisation to collect data on slips, falls, injuries, time off work, health-care resource use, if participants were worried about slipping and falling, how often they had worn the trial shoes while at work and if participants had any views on trial shoes (intervention group only) (see Appendices 5 and 6). Participants who did not return this questionnaire within 3 weeks were sent a postal reminder. Participants who reported a slip in their weekly text response were sent a questionnaire for further details regarding their first reported slip, including whether or not they were wearing the trial shoes when they slipped, any resultant injury, health service use and time off work. Furthermore, participants reporting an injury were sent an injury follow-up questionnaire.

Slip data collection sheet

On reporting their first slip via a weekly post-randomisation text message, participants were posted a questionnaire asking for further details about that slip, with reference to the week in which the slip occurred (see Appendix 7). This collected information about the date of the slip, whether or not the slip resulted in a fall, any consequence of the slip (such as superficial or other injury), whether or not the participant sought health-care advice and if the participant required any time off work. The questionnaire also included the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) measure. 30 A reminder letter and further copy of the questionnaire was sent to those participants who had not returned the questionnaire after 2 weeks. Initially, data were going to be collected over the telephone, rather than by post, for each slip that occurred; however, it quickly became apparent that this would place too great a burden on the participant and study team.

Injury follow-up

An injury follow-up questionnaire was sent when a trial participant reported an injury. A participant may have reported an injury via one of several means: by text message, direct telephone call or e-mail to either a member of the trial team at the YTU or a member of the research team at participating sites, reported on a returned slip data collection sheet (SDCS) or reported on the 14-week questionnaire. If the participant reported an injury between randomisation and the 14-week questionnaire, an injury questionnaire was sent asking for EQ-5D-5L data, whether or not the participant had fully recovered from the injury and the date they recovered (see Appendix 8). If the participant had not fully recovered from the injury, a further injury follow-up questionnaire was sent 1 month later. This continued until the injury was resolved, the participant no longer wished to be contacted or the trial ended. If the participant reported an injury after completion of the 14-week questionnaire then they were also sent an injury follow-up questionnaire (see Appendix 9). This questionnaire collected the same data as the injury form sent out during the trial (i.e. EQ-5D-5L scores and details of any time required off work) and also included questions asking about health-care services used for the injury after the 14-week trial period. This continued until the injury was resolved, the participant no longer wished to be contacted or the trial ended.

Compliance text message follow-up

In addition to the weekly text messages collecting data on the number of slips per week, participants in the intervention arm of the trial were sent a text message at 6, 10 and 14 weeks post randomisation to gather information about how often the participant was wearing their trial shoes:

SSHeW trial. In the past month, how often have you worn your trial shoes at work? Reply 0, 1 or 2 (0 = none of the time, 1 = some of the time, 2 = all of the time).

Wear testing

The soles of all footwear degrade over time and so it was important to have a concept of how long the slip resistance of the trial footwear lasted in a real-world setting. This information could help determine any replacement schedule, and results from this fed into the health economic analysis for the trial.

To assess the serviceable life of the intervention footwear, we asked eligible participants from three trusts who had continued to wear their trial shoes beyond the trial period to return them for assessment. Participants from the intervention group who had been in possession of the trial footwear for 6, 9 or 12 months since randomisation, and had reported wearing the footwear either all of the time or most of the time in response to the 14-week questionnaire, were contacted to establish if they had continued to wear the footwear. Those who had were then asked if they would be willing to return their trial footwear in exchange for a new pair. The exchange of footwear was co-ordinated by the participating trusts.

The soles of each pair of footwear were cleaned, rinsed and allowed to dry prior to the assessment. A visual inspection was carried out to assess the condition of the footwear and identify any defects. Each pair of footwear was inspected by one member of the HSE research team and a HSE colleague who was not involved in the study to provide layperson corroboration. The condition of the upper was rated as good, reasonable or poor, and any defects were recorded. The depth of tread was measured to determine the approximate proportion of sole area that had tread depth below the 2 mm minimum recommended by the manufacturer.

The slip resistance of the worn footwear was then tested on the HSE’s simulated slip test31 and the results compared with those generated for the same styles of footwear when new. Each pair was tested in line with the conditions set out in the HSE GRIP scheme handbook. 32

Outcomes

Primary outcome

Parts of this text have been reproduced with permission from Cockayne et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The primary outcome in this study was the incidence rate of self-reported slips, not necessarily resulting in a fall or injury, in the workplace over a 14-week period, as reported via weekly text messages. A slip was defined as ‘a loss of traction of your foot on the floor surface, which may or may not result in a fall’. A fall was defined as ‘an unexpected event in which you come to rest on the ground, floor or lower level’.

Participants were also asked on the 14-week questionnaire, ‘How many times did you slip (with or without falling) while at work in the past 14 weeks?’. Responses to this question were used when the participant did not provide any text message data.

Secondary outcomes

-

The incidence rate of falls resulting from a slip in the workplace over 14 weeks (14-week questionnaire).

-

The incidence rate of falls not resulting from a slip in the workplace over 14 weeks (14-week questionnaire).

-

Proportion of participants who reported a slip over 14 weeks (weekly slip text message and 14-week questionnaire).

-

Proportion of participants who reported a fall (whether or not resulting from a slip) over 14 weeks (14-week questionnaire and SDCS).

-

Proportion of participants who reported a fracture over 14 weeks (SDCS).

-

Time to first slip (number of days between randomisation and date of first slip, as reported via text message).

-

Time to first fall (number of days between randomisation and date of first fall, as reported on the 14-week questionnaire or SDCS).

-

Health-related utility (measured by the EQ-5D-5L) and cost-effectiveness.

Sample size

Parts of this text have been reproduced with permission from Cockayne et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

There were limited published data on which to base a sample size calculation for this trial. A prospective cohort study24 found that 49 of 422 (11.6%) workers in a restaurant setting in the USA reported at least one ‘major’ (i.e. resulting in a fall and/or injury) slip over a 12-week follow-up period. The exact number who experienced any type of slip was not reported in that study, but could reasonably be expected to be higher than this. For our sample size calculation, we required an estimate of the proportion of individuals in the control group who would experience at least one slip over a 14-week follow-up period; we conservatively assumed a proportion of 10%. We proposed to randomise 4400 participants using 1 : 1 allocation (i.e. 2200 per group) to have 90% power to show a 30% relative reduction in the proportion of participants who report at least one slip over a 14-week period (a 3-percentage-point absolute reduction from 10% to 7%), allowing for 20% attrition. This sample size would also give us 80% power to see an absolute reduction of 2 percentage points in the risk of falls, from 5.5% to 3.5%, allowing for 20% attrition. Although we based the sample size calculation on detecting a difference in proportions, the primary outcome is the incidence rate of slips over the 14 weeks and so we used a mixed-effects negative binomial regression model to compare this outcome between the two groups. As this analysis uses more information than a simple binary outcome, we expected it to still be adequately powered.

Trial completion and exit

Participants completed the trial if they completed the 14-week trial period post randomisation. Participants exited the trial if they had completed the 14-week follow-up period, had fully withdrawn from the trial (no further follow-up by text or post), were lost to follow-up or had died.

Participant change of status and participant withdrawal

Participants could withdraw from the trial at any time without giving a reason. If, however, a reason was provided, then it was recorded. If we were informed that a participant wanted to withdraw from the trial, a member of the research team would attempt to clarify to what extent they wished to withdraw (i.e. fully or partially). Participants could partially withdraw from the trial in two ways; first, by withdrawing from the intervention only, meaning that they would not wear the trial shoes but continue to provide text and questionnaire data; and, second, participants could withdraw from data collection either by declining to respond to text messages or by declining to complete the follow-up questionnaires. Data were retained for withdrawn participants unless a participant requested specifically that their data be removed. A change of circumstance form was completed by a member of the research team for any participant changing status during the trial (see Report Supplementary Material 4).

Adverse events

Adverse events (AEs) were reported by participants to the research team at the YTU via telephone or text message or by writing free-text comments in the postal questionnaires. AEs could also be reported through the local research teams at the participating sites. Details of AEs were recorded on a SSHeW AE form (see Report Supplementary Material 5). The AE reporting period started at the point when the participant gave their consent to be in the trial and ended at 14 weeks after they were randomised.

Serious AEs that were related to being in the study and were unexpected were recorded. Non-serious AEs were not recorded, unless they were related to being in the study or were related to the intervention.

A serious AE was defined as any untoward occurrence that:

-

resulted in death

-

was life-threatening

-

required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

consisted of a congenital anomaly or birth defect

-

was otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator.

Expected events

Slips and falls were not recorded as AEs in this trial, as these were recorded as trial outcomes. It was expected that some participants could experience foot problems associated with the new footwear. These could range from minor superficial problems associated with skin irritation and pressure, such as blisters or calluses, to more mechanical foot complaints, such as plantar fasciitis and tendonitis. In severe cases, when shoe styles were not suited to the participant’s foot shape, changes or exacerbation of foot structure, such as toe deformities, could be expected.

The occurrence of AEs during the trial was reported and monitored by the combined Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). The TSC and DMEC were immediately sent all serious AEs that were thought to be related to treatment.

The SSHeW internal pilot trial

An internal pilot trial was conducted during the first 6 months of the study (March–September 2017). The objectives of the pilot trial were to:

-

test and refine recruitment strategies for the study

-

check the sample size calculation assumptions by reviewing the proportion of participants in the control group who experienced a slip

-

check the attrition rate

-

explore and address any issues regarding footwear compliance.

To progress to the main SSHeW trial, the pilot phase had to meet the following criteria:

-

at least 400 participants recruited in 6 months

-

80% of participants contributing at least 50% of the requested follow-up text data (i.e. responding to 7 of the 14 weekly post-randomisation text messages)

-

90% of participants responding to at least one post-randomisation text message

-

a slip rate in the control group of at least 7%.

Data analysis

Analysis

There were two analyses: (1) a descriptive analysis of the internal pilot data and (2) a single effectiveness analysis of the trial data at the end of follow-up of all participants. All analyses were conducted in Stata v15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and followed the principles of intention to treat, with participants’ outcomes analysed in accordance with their original randomised group, irrespective of deviations based on non-compliance. Statistical tests are two-sided at the 5% significance level and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are used.

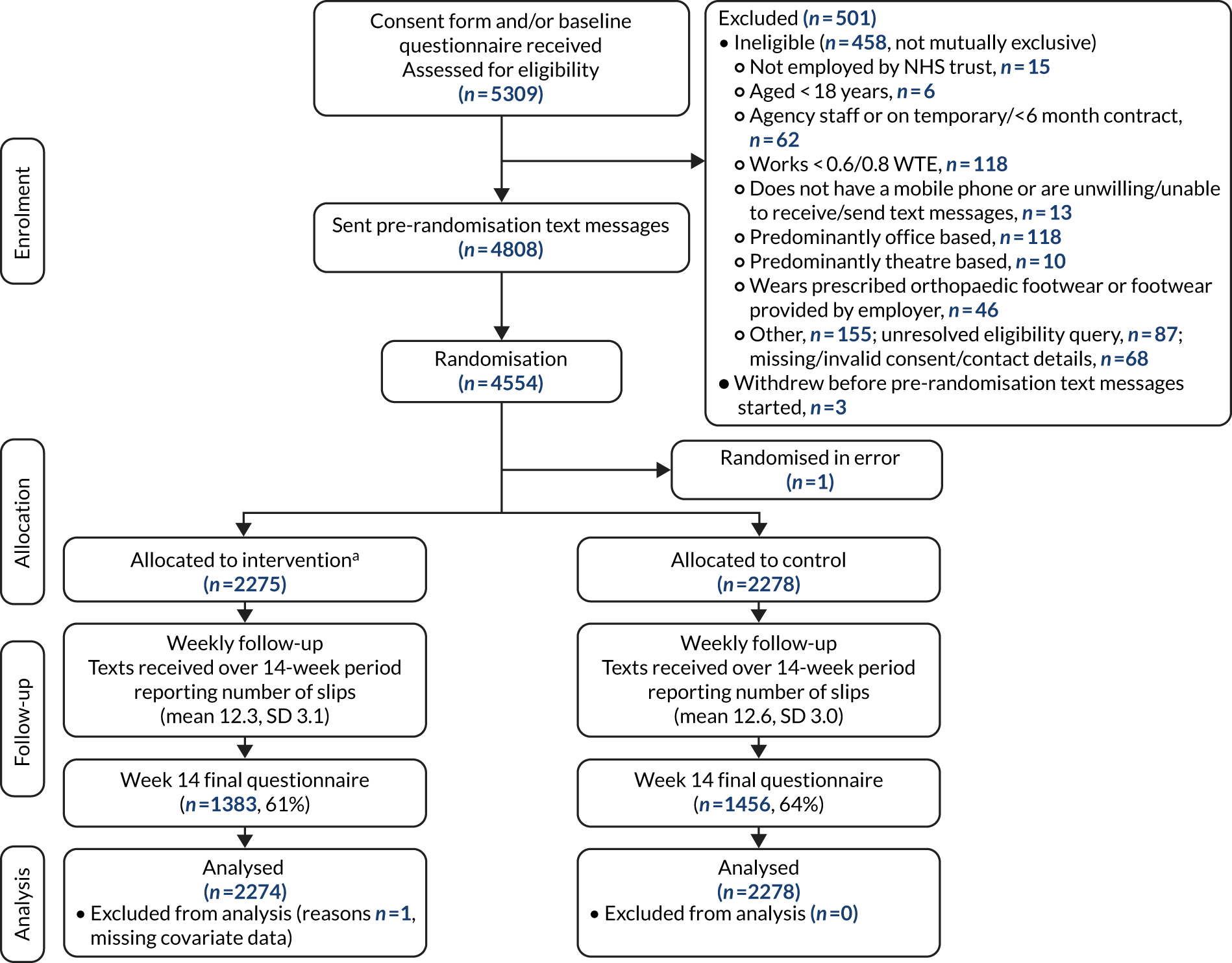

The trial is reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for parallel-group, randomised trials [URL: www.consort-statement.org/ (accessed 19 May 2020)]. The flow of participants through each stage of the trial, including reasons for non-eligibility, is presented in a CONSORT diagram (see Figure 2).

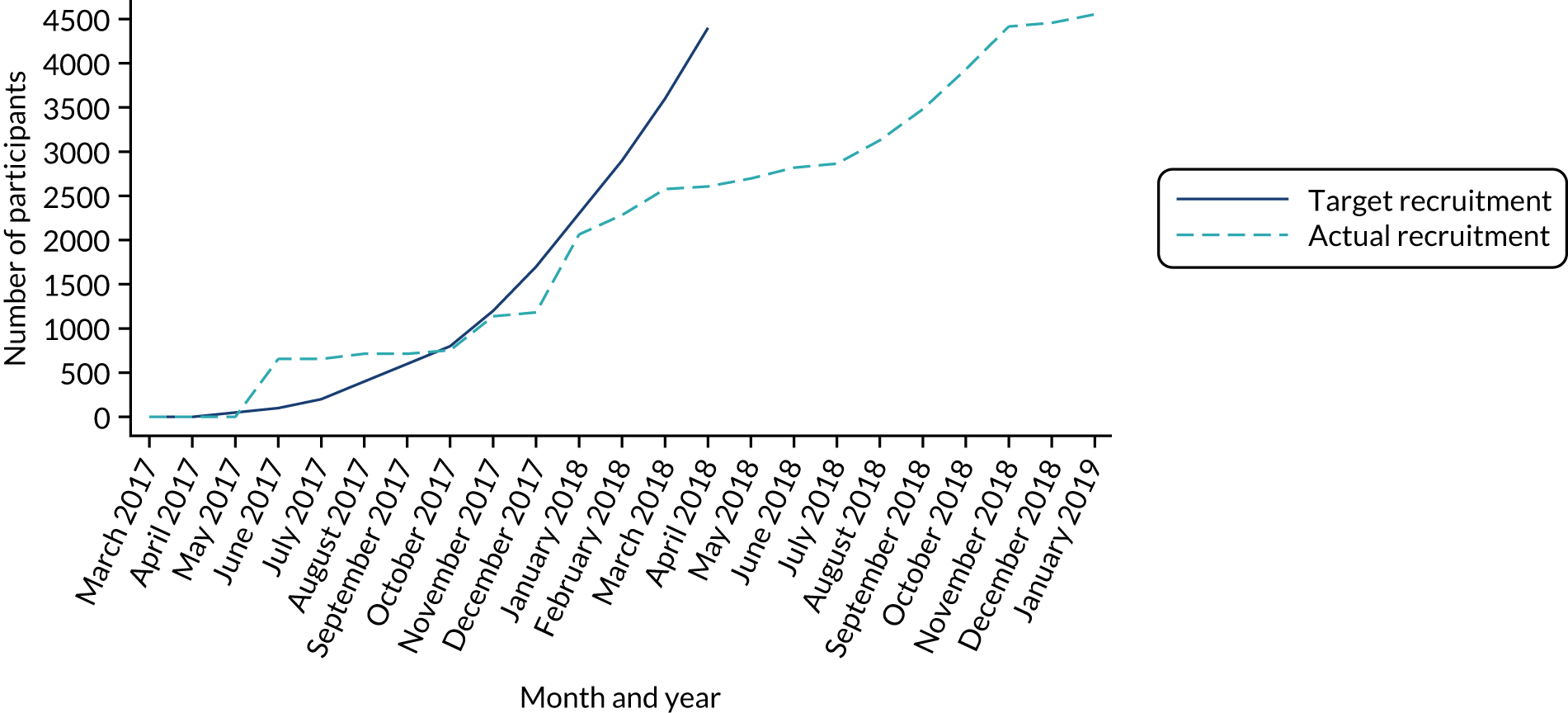

Figure 3 presents the overall recruitment by month, and the actual compared with target recruitment.

Follow-up response rates to the weekly text messages (both pre and post randomisation), the compliance text messages (for the intervention group only), SDCSs and the 14-week participant questionnaire (including time to response) are summarised overall and by treatment group when appropriate.

The number of intervention participants receiving a pair of trial shoes and the time taken from randomisation to receiving the shoes is summarised. The date provided by the participant on their 14-week questionnaire was the primary source of data for the date when shoes were received, with the date provided by the sites used, when available, if participants did not provide a date. We primarily used the participant-reported date, as the date provided by the site may be the date the shoes were delivered to the shoe collection point for the participant and not necessarily the date the participant collected the shoes, which could potentially have been significantly later.

Withdrawal

Type and timing of withdrawals are presented overall and by randomised group, with reasons when available.

Baseline data

Baseline data are summarised descriptively overall and by randomised arm. Continuous measures are reported using descriptive statistics [mean, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum and maximum], whereas categorical data are reported as counts and percentages. No formal statistical comparisons of baseline data were undertaken between the trial arms. Comparisons are made based on visual observation only.

Primary analysis

The difference in slip rate between the intervention and control groups over 14 weeks was analysed using a mixed-effect negative binomial regression model, adjusting for gender (three categories: male; female; prefer not to say or missing), age at enrolment (continuous) and job role [four categories: administration and information technology (administrator/receptionist/secretarial, ward clerk); facilities workers (catering, porter); direct patient care (doctor/consultant, qualified nurse/midwife, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, health-care assistant, pharmacist/pharmacy technician, social worker, support worker, podiatrist, other qualified staff/health-care professional); other/missing (imaging, other)], and baseline weekly slip rate ascertained from the pre-randomisation text message responses as fixed effects. Trial site was included as a random effect to account for potential clustering by recruitment site. The total number of hours that participants worked in the weeks for which they provided slip data was calculated (by multiplying the number of weeks the participant provided valid post-randomisation text message slip data by the number of hours they indicated they worked, on average, per week on the baseline questionnaire). This amount of time was accounted for in the negative binomial model (using the exposure option in Stata).

The incidence rate ratio (IRR) and associated 95% CI and p-value for the treatment effect are presented.

This analysis primarily included slip data from the weekly text message responses. When no post-randomisation responses were returned, data from the 14-week questionnaire were used for a participant, when available.

The primary analysis included all participants who had full baseline covariate data. The model could accommodate participants who did not provide a valid response to any weekly text messages or the 14-week questionnaire by considering that they reported zero slips over a negligible exposure time of 0.1 hours.

The primary analysis was checked by a second statistician (GF), who reviewed the analysis syntax, the derivation of variables required for the analysis, and the reporting and interpretation of the results.

Sensitivity analysis

Missing data

In our prespecified analysis plan, we said that if > 5% of randomised participants did not provide any slip data then, to account for possible selection bias in the primary analysis, a mixed-effect logistic regression would be run to predict non-response (no post-randomisation slip text message responses or 14-week questionnaire received), including all baseline variables collected prior to randomisation and trial site as a random effect. The primary analysis would then have been repeated including as covariates all variables found to be significantly predictive of non-response, to determine if this affected the parameter estimates. However, as < 5% of randomised participants did not provide slip data, this analysis was not performed.

Intervention compliance

Information on how often participants reported wearing their shoes, as recorded for the intervention group in the compliance text messages at 6, 10 and 14 weeks post randomisation and on the 14-week questionnaire, are summarised. Differences between responses provided via the different methods are discussed.

Complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis to assess the impact of non-compliance on treatment estimates was undertaken. CACE analysis allows an unbiased treatment estimate of, in this case, the IRR of slips between the two groups in the presence of non-compliance with the shoes to be obtained. It is less prone to biased estimates than the more commonly used approaches of per-protocol or ‘on-treatment’ analysis, as it preserves the original randomisation. A two-stage instrumental variable approach was used, with randomised group as the instrumental variable.

The difficulty with this type of analysis is precisely how ‘compliance with the intervention’ is defined and quantified. This requires identifying a measure of how well a participant followed the intended elements of the intervention that can be applied to all participants. In this scenario, the intervention was the offer and provision of the trial slip-resistant footwear within the follow-up period. ‘Compliance’ was therefore defined, initially, in two very simplistic ways in separate compliance analyses, receiving the trial shoes:

-

during the first 7 weeks of the follow-up period

-

within the 14-week follow-up period.

However, these analyses do not account for how often the shoes were actually worn. A third and more complex definition of exposure to the trial shoes was therefore defined based on receiving the shoes and the responses to the 6-, 10- and 14-week compliance text messages (and response to the compliance question on the 14-week questionnaire when compliance text responses were missing):

-

A score between 0 and 12 was calculated based on the number of weeks the participant had the shoes, assigning a score of 0 for each week that, according to the participants, the shoes were worn ‘none of the time’, a score of 0.5 for each week the shoes were worn for ‘some of the time’ and a score of 1 for each week the shoes were worn ‘all of the time’ (this analysis allows for 2 weeks immediately after randomisation for participants to receive their shoes).

The CACE analysis was repeated using this continuous ‘compliance score’.

Subgroup analysis

We considered whether or not the intervention effect differed by gender and area of work by repeating the primary analysis and by including the factor and an interaction term between the factor and group allocation in the model. Area of work was categorised as areas with higher risk of spillages or contamination (food preparation areas, clinical rooms/areas, wards, indoor hospital grounds/corridors, theatres, laboratories) and areas with lower risk (community, pharmacy, office, podiatry).

Secondary analysis

All secondary outcomes and other important collected data (including data from the SDCSs) are summarised descriptively overall and by trial arm.

The IRR of falls (both resulting and not resulting from a slip) over 14 weeks was analysed in the same way as described for the primary outcome of slips (not including the exposure option in the model as the follow-up is time fixed).

The following outcomes were analysed using mixed-effects logistic regression, adjusting for the same fixed-effect covariates as the primary analysis, with NHS trust as a random effect. The first outcome was the proportion of participants who slipped at least once over 14 weeks (two separate analyses: one according to weekly slip text message data or 14-week questionnaire if no text message data were provided, and one using only 14-week questionnaire data), and the second was the proportion of participants who fell at least once during the 14 weeks. The number of participants who reported a fracture was very small and so no formal analyses of this outcome were undertaken (see Chapter 4). Odds ratios (ORs) and their associated 95% CIs are provided.

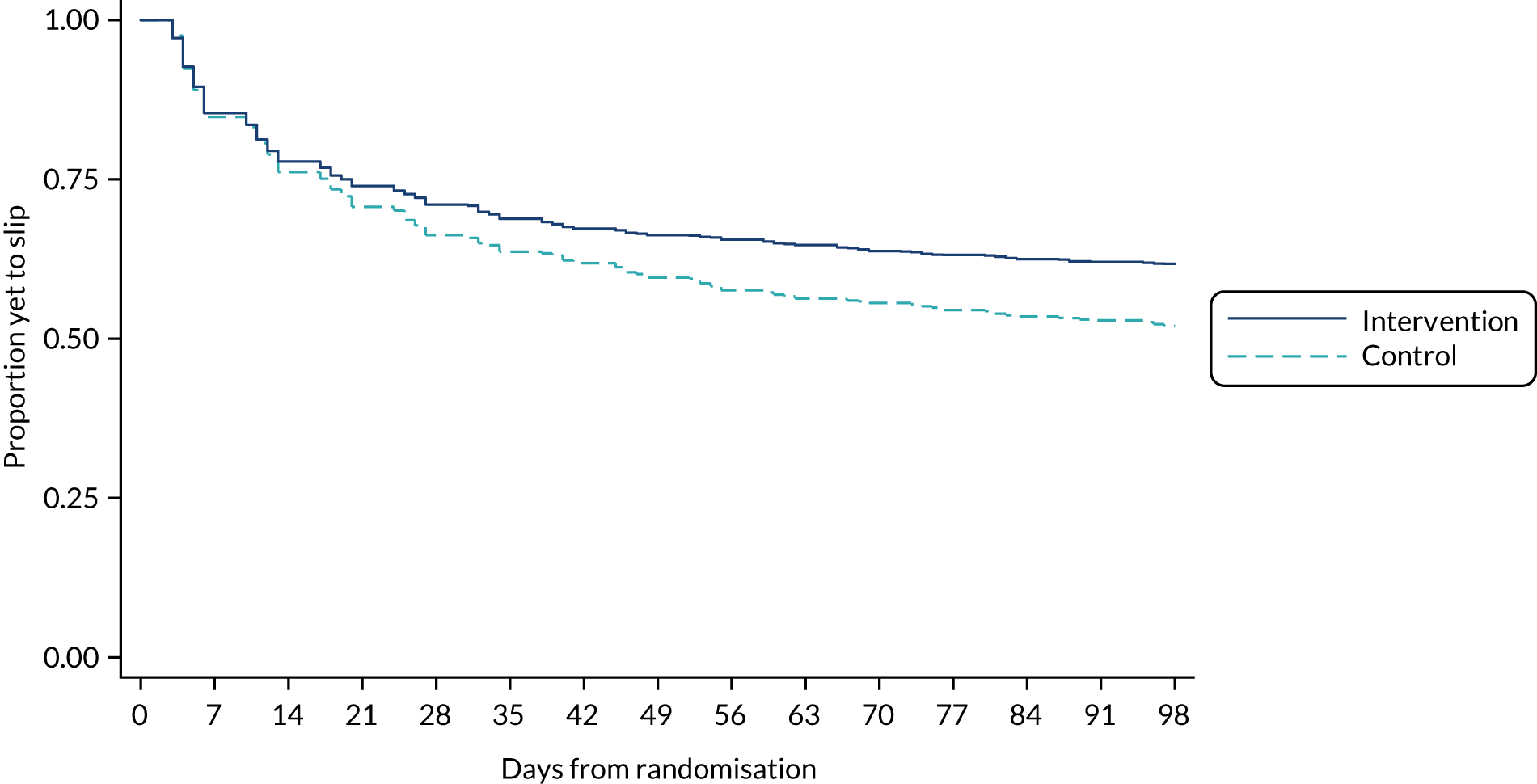

Time to first slip and the time to first fall were calculated. Participants who did not report a slip were treated as censored at their date of trial exit (completion of follow-up or withdrawal). The proportion of participants yet to experience a slip is summarised by a Kaplan–Meier survival curve for each group. Time to first slip was analysed using Cox proportional hazards regression with shared centre frailty and adjusting for the same covariates as in the primary analysis model. Hazard ratios (HRs) and their associated 95% CIs are provided. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated using Schoenfeld residuals. Time to first fall was not analysed via a Cox proportional hazards regression model for two reasons: (1) relatively few falls were reported and (2) the date of the fall was poorly reported for any falls that were reported.

Adverse events

Adverse events are summarised descriptively by treatment arm.

Patient and public involvement in research

The SSHeW trial was informed by the involvement of NHS staff from diverse roles. These included nurses, health-care assistants, radiographers, physiotherapists, catering staff, and maintenance and housekeeping staff of different ages (age range 20–71 years) and genders. The study design was discussed with ward managers at their ward management task and finish group meeting and among NHS staff. The staff provided feedback about the rationale for the trial, the range of shoe styles to be offered in the trial, the use of text messages to collect data, the use of a slip diary and the length of the follow-up period. We had originally planned to follow-up participants for 12 months. However, the patient and public involvement (PPI) group felt that 12 months was too onerous and that participants would not provide outcome data for this length of time. We therefore reduced this to 3 months (12 weeks), but added an additional 2 weeks to allow for the ordering and delivery of shoes. During the trial, further views on the footwear, footwear buying habits and testing of staff’s usual shoes to determine slip resistance took place. In total, 30 pairs of shoes were tested.

Changes to the trial protocol

Minor changes to the trial protocol were submitted during the trial. These are listed in Appendix 10.

Study within a trial: pen substudy

To add to the body of evidence relating to making trial processes more efficient, a SWAT33 was conducted. The aim of this SWAT was to evaluate the effectiveness of enclosing a YTU, University of York pen with the 14-week postal questionnaire, on the response rates to the questionnaire.

Participants in the SSHeW trial who were to receive their 14-week questionnaire were randomised using simple randomisation in the ratio of 1 : 1 (receive a pen or not receive a pen). Generation of the allocation sequence was conducted by the trial statistician, who was not involved with sending the questionnaires.

The pen substudy was embedded into the trial part-way through recruitment. All participants in the main trial who were to be sent their 14-week questionnaire between 4 July 2018 and 12 February 2019 were included in this SWAT (unless they had withdrawn from follow-up). Participants in the main trial who had already been sent their 14-week questionnaire before the SWAT was introduced were excluded. No pens were included with questionnaires sent after 12 February 2019.

The primary outcome measure for the pen substudy was the proportion of participants in each group who returned the questionnaire. Secondary outcome measures included length of time taken to respond to the questionnaire, number of items completed and whether or not a reminder notice to return the questionnaire was required. As is usual with an embedded trial, no formal power calculation was undertaken, as the sample size was constrained by the number of participants to be sent the 14-week questionnaire. Binary data were compared using logistic regression, time to response by a Cox proportional hazards model and number of items completed by a linear regression model. All models were adjusted for the main trial allocation.

Chapter 3 Effectiveness results

Pilot phase

The findings from the pilot phase of the trial evaluating the progression criteria are presented in Table 1. As all of the progression criteria were met, the trial continued seamlessly.

| Criterion | Evaluation | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Recruit at least 400 participants in 6 months (March–September 2017) | 714 participants recruited and randomised | Fulfilled |

| 80% of the participants will provide a valid response to at least 50% of the follow-up text data (i.e. 7 of the 14 weekly post-randomisation text messages) | 335 participants sent all 14 of their post-randomisation text messages, of whom 302 (90%) provided a valid response to at least 50% (n = 7) of messages | Fulfilled |

| 90% of the participants will respond to at least one post-randomisation text | 714 participants sent at least one post-randomisation text message (minimum five messages sent), of whom 707 (99%) responded to at least one message | Fulfilled |

| The slip rate in the control group will be at least 7% | Considering the post-randomisation text message responses from all participants in the control group (n = 357), regardless of the length of time they had been in the trial, 137 participants reported at least one slip (38%, 90% CI 34% to 43%). Across the 168 participants who had completed the trial (i.e. sent all 14 post-randomisation text messages) 53 (32%) reported at least one slip (90% CI 26% to 38%) | Fulfilled |

Recruitment

Participants were enrolled into the SSHeW trial from seven NHS trusts in England: (1) Cheshire and Wirral Partnership NHS Trust (CWP), (2) Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, (3) York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, (4) Lancashire Care NHS Foundation Trust, (5) Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, (6) Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust and (7) University Hospitals of Derby and Burton NHS Foundation Trust. York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust was split into two geographical locations. Theses were considered as two distinct populations (Scarborough and Bridlington areas, and York and Malton areas) and formed eight trial sites. A total of 8524 recruitment packs were estimated to have been handed out in the eight sites between March 2017 and November 2018 (Figure 2), with follow-up occurring until June 2019. Varying numbers of recruitment packs were sent to the sites from YTU to be handed out to potential participants, depending on the size of the site and its capacity. The number of unused packs was reported to the YTU at the end of the trial. The number of packs handed out was estimated at 8524 by subtracting the number reported unused from the number originally sent to the site, on the assumption that the rest were distributed (CWP, n = 2029; Leeds, n = 1686; York, n = 642; Scarborough, n = 775; Lancashire, n = 1251; Nottingham, n = 1240; Harrogate, n = 401; and Derby, n = 500).

FIGURE 2.

A CONSORT flow diagram of participants in the SSHeW trial. a, n = 1930 (85%) received trial shoes within the 14-week trial follow-up. Reproduced with permission from Cockayne et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

A completed baseline form was received at YTU from 5309 (62.3%) potential participants, of whom 498 (9.4%) were ineligible. Reasons for ineligibility were not mutually exclusive. One of the most common reasons was not working enough hours, on average, per week. Initially, the inclusion criteria specified that potential participants had to work, on average, at least 80% WTE (30 hours/week, assuming 37.5 working hours/week as full time). When it was observed that this was a predominant reason for ineligibility, it was, with the agreement of the TSC, DMEC and the funder, decided to lower this to 60% WTE (22.5 hours/week).

A total of 4811 participants were eligible to be sent the pre-randomisation text messages. Three participants withdrew before these text messages were started (one participant moved out of the trust, one participant was discovered to be a duplicate and one participant had an issue with their mobile telephone number that was never resolved), and 254 participants did not provide a valid response to at least two text messages. Therefore, 4554 participants were randomised (a slight increase of 154 participants on the 4400 planned). One participant was discovered to be ineligible after randomisation and so was immediately withdrawn (their data are not included in summaries of randomised participants). The flow of participants is illustrated in a CONSORT diagram (see Figure 2).

Pre-randomisation text message response rates

A total of 4808 participants were deemed eligible for the trial and were sent at least one pre-randomisation text message. Participants could request that the text messages be stopped at any time and so not all were sent at least four messages. Send and response rates to the initial four text messages were all > 86% (Table 2). A total of 4605 (95.8%) participants responded to at least one text message. A total of 260 participants were sent a fifth text (108 replied, 41.5%) and 245 were sent a sixth text (103 replied, 42.0%). Overall, 87 of 245 (36%) replied to both messages.

| Week | n received/N sent (%) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 4222/4808 (87.8) |

| 2 | 4256/4806 (88.6) |

| 3 | 3716/4249 (87.5) |

| 4 | 3044/3524 (86.4) |

| 5 | 108/260 (41.5) |

| 6 | 103/245 (42.0) |

All but one of the 4555 participants who replied to at least two pre-randomisation text messages (either two of the first four messages, or both the fifth and sixth messages) were randomised into the trial (one participant withdrew prior to randomisation).

Randomisation

Our required sample size was 4400 participants, which we aimed to achieve by the end of April 2018. However, recruitment was slightly slower than anticipated and we agreed with the trial sponsor, funder and HRA to extend recruitment to late 2018 to meet the target.

The first participants were randomised on 1 June 2017 and the last on 10 January 2019. Over this 20-month period, 4554 participants were randomised into the trial (2276 to the intervention group and 2278 to the control group); however, one participant (intervention group) was randomised in error, so their data have not been used post randomisation. A median of 529 (range 299–1014) participants were recruited from each site. Figure 3 presents the target compared with actual recruitment.

FIGURE 3.

Target vs. actual participant recruitment.

Baseline data

Baseline data are presented by randomised group and overall in Tables 3–6. One participant, allocated to the intervention group, withdrew shortly after they were randomised and requested that all their data be removed; they are included in the denominators in Tables 3–6, but all their data are missing.

| Characteristic | Intervention group (N = 2275) | Control group (N = 2278) | Total (N = 4553) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 42.7 (11.5) | 42.7 (11.3) | 42.7 (11.4) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 44.0 (19.0, 74.0) | 44.0 (18.0, 71.0) | 44.0 (18.0, 74.0) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 325 (14.3) | 355 (15.6) | 680 (14.9) |

| Female | 1948 (85.6) | 1921 (84.3) | 3869 (85.0) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) |

| Missing | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 27.0 (5.5) | 27.0 (5.2) | 27.0 (5.3) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 25.9 (14.4, 56.5) | 26.3 (16.1, 54.2) | 26.1 (14.4, 56.5) |

| Education after school leaving age, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 1839 (80.8) | 1844 (80.9) | 3683 (80.9) |

| No | 421 (18.5) | 423 (18.6) | 844 (18.5) |

| Missing | 15 (0.7) | 11 (0.5) | 26 (0.6) |

| Degree/equivalent professional qualification, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 1512 (66.5) | 1522 (66.8) | 3034 (66.6) |

| No | 747 (32.8) | 741 (32.5) | 1488 (32.7) |

| Missing | 16 (0.7) | 15 (0.7) | 31 (0.7) |

| Ethnic group, n (%) | |||

| White/white British | 2008 (88.3) | 1982 (87.0) | 3990 (87.6) |

| Asian/Asian British | 154 (6.8) | 176 (7.7) | 330 (7.2) |

| Black/black British | 84 (3.7) | 82 (3.6) | 166 (3.6) |

| Mixed/multiple | 24 (1.1) | 28 (1.2) | 52 (1.1) |

| Other | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) |

| Missing | 3 (0.1) | 7 (0.3) | 10 (0.2) |

| Average number of hours worked per week | |||

| Mean (SD) | 35.8 (4.3) | 35.8 (4.5) | 35.8 (4.4) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 37.5 (22.5, 63.0) | 37.5 (15.0, 62.0) | 37.5 (15.0, 63.0) |

| Job characteristic | Intervention group (N = 2275) | Control group (N = 2278) | Total (N = 4553) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Job type, n (%) | |||

| Qualified nurse/midwife | 952 (41.8) | 985 (43.2) | 1937 (42.5) |

| Support worker | 286 (12.6) | 276 (12.1) | 562 (12.3) |

| Health-care assistant | 272 (12.0) | 246 (10.8) | 518 (11.4) |

| Other qualified staff/health-care professional | 150 (6.6) | 163 (7.2) | 313 (6.9) |

| Domestic services | 115 (5.1) | 110 (4.8) | 225 (4.9) |

| Administrator/receptionist/secretarial | 78 (3.4) | 100 (4.4) | 178 (3.9) |

| Occupational therapist | 65 (2.9) | 65 (2.9) | 130 (2.9) |

| Imaging staff | 64 (2.8) | 53 (2.3) | 117 (2.6) |

| Physiotherapist | 68 (3.0) | 36 (1.6) | 104 (2.3) |

| Pharmacist/pharmacy technician | 50 (2.2) | 53 (2.3) | 103 (2.3) |

| Ward clerk | 44 (1.9) | 49 (2.2) | 93 (2.0) |

| Doctor/consultant | 38 (1.7) | 42 (1.8) | 80 (1.8) |

| Catering staff | 29 (1.3) | 38 (1.7) | 67 (1.5) |

| Phlebotomist | 13 (0.6) | 17 (0.7) | 30 (0.7) |

| Podiatrist | 16 (0.7) | 9 (0.4) | 25 (0.5) |

| Laboratory staff | 7 (0.3) | 10 (0.4) | 17 (0.4) |

| Facilities | 9 (0.4) | 6 (0.3) | 15 (0.3) |

| Social worker | 6 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) | 10 (0.2) |

| Porter | 3 (0.1) | 5 (0.2) | 8 (0.2) |

| Other | 9 (0.4) | 11 (0.5) | 20 (0.4) |

| Missing | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| Areas worked in, n (%)a | |||

| Ward | 1261 (55.4) | 1199 (52.6) | 2460 (54.0) |

| Clinical room/area | 722 (31.7) | 755 (33.1) | 1477 (32.4) |

| Community | 260 (11.4) | 268 (11.8) | 528 (11.6) |

| Indoor hospital grounds/corridors | 160 (7.0) | 183 (8.0) | 343 (7.5) |

| Office | 91 (4.0) | 113 (5.0) | 204 (4.5) |

| Food preparation/serving area | 77 (3.4) | 87 (3.8) | 164 (3.6) |

| Pharmacy | 40 (1.8) | 49 (2.2) | 89 (2.0) |

| Laboratory | 21 (0.9) | 47 (2.1) | 68 (1.5) |

| Theatre | 9 (0.4) | 14 (0.6) | 23 (0.5) |

| Podiatry | 10 (0.4) | 8 (0.4) | 18 (0.4) |

| Required to work in the community, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 552 (24.3) | 554 (24.3) | 1106 (24.3) |

| No | 1688 (74.2) | 1689 (74.1) | 3377 (74.2) |

| Missing | 35 (1.5) | 35 (1.5) | 70 (1.5) |

| Time spent on feet at work, n (%) | |||

| Most of the time | 1843 (81.0) | 1829 (80.3) | 3672 (80.7) |

| Some of the time | 385 (16.9) | 400 (17.6) | 785 (17.2) |

| A little of the time | 11 (0.5) | 18 (0.8) | 29 (0.6) |

| Missing | 36 (1.6) | 31 (1.4) | 67 (1.5) |

| Slips and falls in past 12 months | Intervention group (N = 2275) | Control group (N = 2278) | Total (N = 4553) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have you had slip at work?, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 850 (37.4) | 885 (38.8) | 1735 (38.1) |

| No | 1318 (57.9) | 1297 (56.9) | 2615 (57.4) |

| Do not know | 101 (4.4) | 91 (4.0) | 192 (4.2) |

| Missing | 6 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) | 11 (0.2) |

| If yes, how many? | |||

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 2 (1, 400) | 2 (1, 300) | 2 (1, 400) |

| Have you suffered injury from any of these slips?, n (%) | 96 (11.3) | 89 (10.1) | 185 (10.7) |

| Have you had a fall at work?, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 188 (8.3) | 192 (8.4) | 380 (8.3) |

| No | 2039 (89.6) | 2040 (89.6) | 4079 (89.6) |

| Do not know | 29 (1.3) | 31 (1.4) | 60 (1.3) |

| Missing | 19 (0.8) | 15 (0.7) | 34 (0.7) |

| If yes, how many? | |||

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 1 (1, 52) | 1 (1, 20) | 1 (1, 52) |

| Have you suffered injury from any of these falls?, n (%) | 69 (36.9) | 74 (39.5) | 144 (38.2) |

| How often do you worry about slipping or falling in the workplace?, n (%) | |||

| All of the time | 57 (2.5) | 63 (2.8) | 120 (2.6) |

| Most of the time | 149 (6.5) | 121 (5.3) | 270 (5.9) |

| Some of the time | 734 (32.3) | 746 (32.7) | 1480 (32.5) |

| A little of the time | 798 (35.1) | 818 (35.9) | 1616 (35.5) |

| None of the time | 454 (20.0) | 461 (20.2) | 915 (20.1) |

| Missing | 83 (3.6) | 69 (3.0) | 152 (3.3) |

| Footwear | Intervention group (N = 2275) | Control group (N = 2278) | Total (N = 4553) |

|---|---|---|---|

| How many months do your usual work shoes last before they need replacing? | |||

| Median (IQR) | 12 (6–12) | 12 (6–12) | 12 (6–12) |

| Normally buy your work shoes from, n (%)a | |||

| High street store | 2113 (92.9) | 2091 (91.8) | 4204 (92.3) |

| Online specialist shop/catalogue | 194 (8.5) | 225 (9.9) | 419 (9.2) |

| Brand of shoe usually worn at work, n (%)a | |||

| General high street brand | 1893 (83.2) | 1888 (82.9) | 3781 (83.0) |

| General sports shop brand | 400 (17.6) | 402 (17.6) | 802 (17.6) |

| Any/various/depends on cost | 15 (0.7) | 23 (1.0) | 38 (0.8) |

| Shoes for Crews Ltd | 10 (0.4) | 13 (0.6) | 23 (0.5) |

| Magnum (Portsmouth, UK) | 9 (0.4) | 8 (0.4) | 17 (0.4) |

| Other safety/uniform shoe brand | 3 (0.1) | 7 (0.3) | 10 (0.2) |

| Alexandra (Bristol, UK) | 6 (0.3) | 3 (0.1) | 9 (0.2) |

| J&M Medical (Sunderland, UK) | 3 (0.1) | 6 (0.3) | 9 (0.2) |

| Other | 39 (1.7) | 41 (1.8) | 80 (1.8) |

| Style of shoes normally worn at work, n (%)a | |||

| Trainers | 671 (29.5) | 661 (29.0) | 1332 (29.2) |

| Pumps | 357 (15.7) | 361 (15.8) | 718 (15.8) |

| Work/safety boots | 39 (1.7) | 47 (2.1) | 86 (1.9) |

| Clogs | 82 (3.6) | 100 (4.4) | 182 (4.0) |

| Heeled shoes/boots | 90 (4.0) | 119 (5.2) | 209 (4.6) |

| Flat shoes/boots | 1115 (49.0) | 1098 (48.2) | 2213 (48.6) |

| Casual/dress shoe or boot | 404 (17.8) | 404 (17.7) | 808 (17.7) |

| Other | 81 (3.6) | 79 (3.5) | 160 (3.5) |

| Does your usual style of shoe have a secure fastening over the top of foot (e.g. laces or velcro strap)? n (%) | |||

| Yes | 1309 (57.5) | 1308 (57.4) | 2617 (57.5) |

| No | 932 (41.0) | 943 (41.4) | 1875 (41.2) |

| Missing | 34 (1.5) | 27 (1.2) | 61 (1.3) |

The recruited participants were predominantly female (n = 3869, 85.0%) and the average age was 42.7 (range 18–74) years. Participants worked a median of 37.5 hours per week and qualified nurse or midwife was the most represented job role (n = 1937, 42.5%). One participant who reported working 15 hours per week (less than the required amount) was randomised in error into the trial. Options to manage this participant were discussed with the TSC and DMEC and it was agreed that this participant should be retained in the trial and their data included in the analyses (as the impact of this one participant would be negligible).

Just over one-third of participants reported experiencing a slip at work in the previous 12 months (median of two slips), of whom 11% had suffered an injury as a result of one of these slips.

Via the pre-randomisation slip text messages, a total of 3891 slips were reported (2035 from participants who were subsequently randomised to the intervention group and 1856 from participants subsequently randomised to the control group). Both groups provided pre-randomisation text message slip data for an average of 3.4 (SD 0.8, median 4, range 2–4) weeks. Overall, 1627 (35.3%) participants (of the 4605 participants who responded to at least one text) reported at least one slip in the pre-randomisation text messages. The average number of reported slips was 0.89 (SD 2.00, median 0, range 0–22) in the intervention group and 0.81 (SD 1.76, median 0, range 0–26) in the control group. The baseline slip rate was calculated as the average weekly number of slips: 0.27 (SD 0.59, median 0, range 0–7) in the intervention group and 0.24 (SD 0.51, median 0, range 0–6.5) in the control group.

The treatment groups, as randomised, appear to be comparable on all measured baseline data.

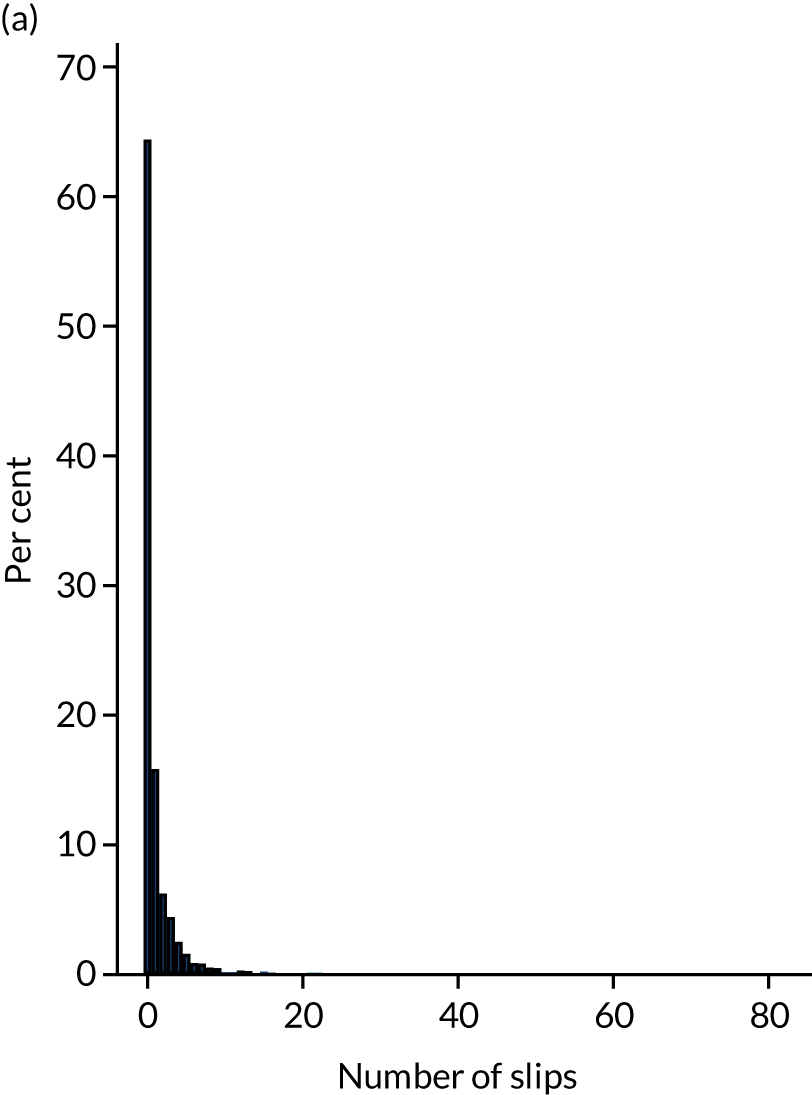

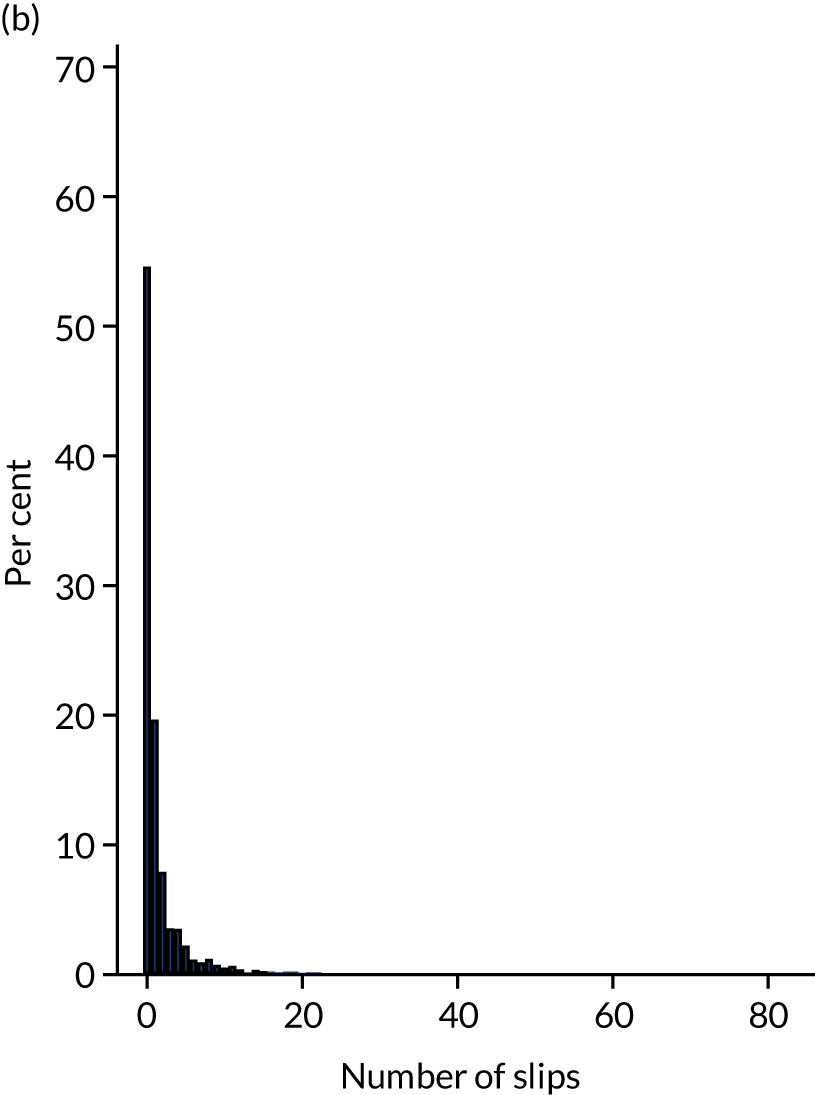

Post-randomisation text message response rates

Following randomisation, participants were sent up to 14 weekly slip text messages. At any time, participants could request not to be sent any further messages. Response rates to the post-randomisation text messages are presented in Table 7 by group allocation. Of the 4553 participants sent at least one post-randomisation text message, a valid response to at least one message was received from 4494 (98.7%). Participants in the intervention group responded to an average of 12.3 (SD 3.1, median 14) text messages and participants in the control group to an average of 12.6 (SD 3.0, median 14) text messages.

| Week post randomisation | Intervention group (n = 2275), n received/N sent (%) | Control group (n = 2278), n received/N sent (%) | Total (n = 4553), n received/N sent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2109/2275 (92.7) | 2112/2278 (92.7) | 4221/4553 (92.7) |

| 2 | 2117/2272 (93.2) | 2101/2278 (92.2) | 4218/4550 (92.7) |

| 3 | 2079/2270 (91.6) | 2094/2278 (91.9) | 4173/4548 (91.8) |

| 4 | 2052/2269 (90.4) | 2075/2276 (91.2) | 4127/4545 (90.8) |

| 5 | 2063/2267 (91.0) | 2068/2275 (90.9) | 4131/4542 (91.0) |

| 6 | 2033/2265 (89.8) | 2047/2272 (90.1) | 4080/4537 (89.9) |

| 7 | 1967/2265 (86.8) | 2055/2271 (90.5) | 4022/4536 (88.7) |

| 8 | 1963/2261 (86.8) | 2028/2271 (89.3) | 3991/4532 (88.1) |

| 9 | 1962/2261 (86.8) | 2034/2271 (89.6) | 3996/4532 (88.2) |

| 10 | 1936/2259 (85.7) | 2012/2271 (88.6) | 3948/4530 (87.2) |

| 11 | 1948/2259 (86.2) | 1996/2271 (87.9) | 3944/4530 (87.1) |

| 12 | 1926/2256 (85.4) | 1988/2271 (87.5) | 3914/4527 (86.5) |

| 13 | 1921/2255 (85.2) | 1996/2271 (87.9) | 3917/4526 (86.5) |

| 14 | 1924/2253 (85.4) | 1985/2269 (87.5) | 3909/4522 (86.4) |

Withdrawals