Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/157/34. The contractual start date was in June 2015. The final report began editorial review in March 2018 and was accepted for publication in August 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jeremy Dawson is a board member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Service and Delivery Research programme. Amanda Forrest is a board member of Sheffield Clinical Commissioning Group.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Dawson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Introduction

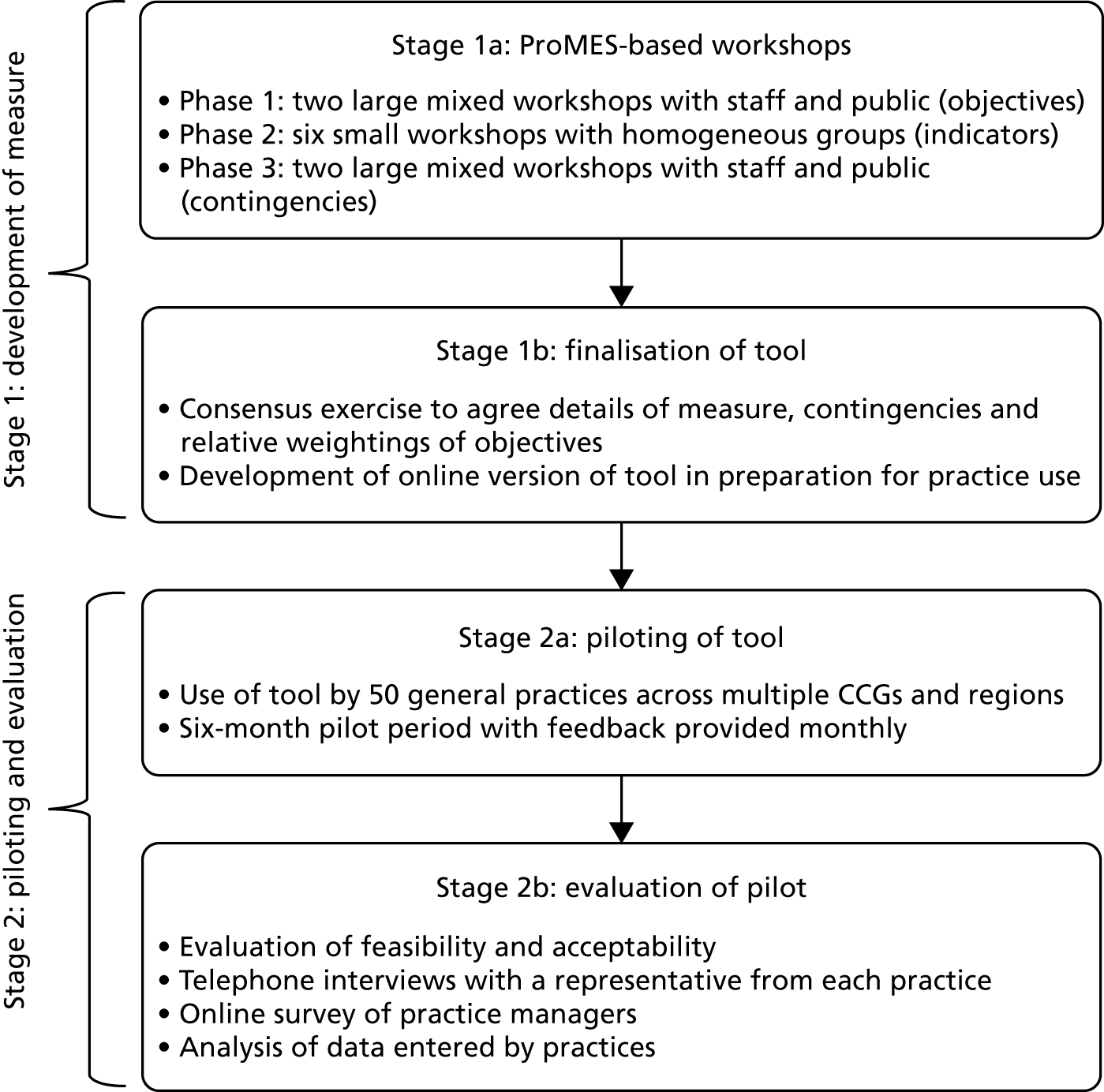

This report describes a study aimed at designing a measure of productivity for general practices providing NHS services in England. It uses a two-stage process of developing a measure [using the Productivity Measurement and Enhancement System (ProMES)] and then testing and evaluating the measure’s use in a range of general practices. In this chapter, the context for the measure is introduced, including the role of general practice and what measures are currently available, and then the study aims and objectives are outlined.

The context of general practice in England

Since the formation of the NHS in 1948, general practitioners (GPs) have always existed on the periphery of the main NHS structure, in the sense that the majority are not employed directly by NHS organisations, but are either independent contractors, being partners in small businesses (general practices) that receive payments for providing NHS services, or employed by such practices. General practices are a key element of the provision of primary care, which can be defined as the first point of contact for health care for most people, mainly provided by GPs, but also by community pharmacists, opticians and dentists. 1 GPs do not work in isolation, but generally in multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) comprising nurses, allied health professionals and other clinical and administrative staff. Critically, GPs often act as the gatekeeper to other NHS services, and provide key links to other parts of the health and social care system.

Each general practice has a list of patients for whom it provides primary medical services, including (but not limited to) patient-led consultations with GPs, practice nurses and other clinical staff; prescriptions; treatment for certain ailments; referrals to specialists; screening and immunisations; management of long-term conditions; and health promotion. The variety and scope of tasks undertaken by general practices is huge, and in recent times there has been greater encouragement towards integrated care, and to prevention rather than cure. 2 The nature of the employment relationship, however, in addition to the variety and complexity of the task performed by GPs in providing primary care, means that even defining productivity and effectiveness, let alone collecting data to measure such concepts, is far from straightforward.

Since 2004, there have been two major changes in the management of primary care provision in England that have had significant implications for both the role of the general practice and the data available. First, in 2004, new GP contracts were introduced: the General Medical Services (GMS) contract, used by ≈60% of practices, and the Personal Medical Services (PMS) contract, used by ≈40% of practices. 3 The funding methods are not straightforward, but depend on a combination of core payments for delivering essential services to registered patients, and various additional payments for meeting particular targets and delivering enhanced services (which may be commissioned locally). In particular, a major route for determining extra payments is the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), which will be discussed in greater detail in Overview of measurement of productivity and effectiveness in general practice.

The other significant recent change is the Health and Social Care Act 2012,4 which led to the creation of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs). These replaced the primary care trusts that had previously been responsible for commissioning services for patients as well as providing some community-based care. CCGs were designed to be led by clinicians, principally GPs operating within the relevant geographical area, who would have the best idea of the health needs of the local population. The manner in which CCGs are led by GPs, and the extent of external assistance, varies substantially from one CCG to another, and in some CCGs a far greater proportion of GPs will play an active role in the CCG than in others. 5 At the same time, many general practices have sought to improve efficiency and manage demand better by developing networks or federations including multiple practices. These would typically share some services, but, again, the extent and formality of this arrangement will vary from one network to another. Some practices are owned by a parent company; typically, such companies will employ GPs and other staff working within their practices.

The role of general practice within the NHS is paramount. It has been estimated that ≈90% of NHS contacts take place in general practice. 3 As of December 2017, there are 6601 general practices on either GMS or PMS contracts within England, covering over 58 million registered patients. There are a total of 41,817 GPs, with a full-time equivalent (FTE) of 33,782 GPs. One year previously, these numbers were 41,589 GPs and 34,126 FTE GPs. As of March 2017, there were 132,430 other staff employed by general practices (90,984 FTE), including 22,737 nurses (15,528 FTE), 17,585 other clinicians involved in direct patient care (11,413 FTE), 11,147 practice managers or management partners (9784 FTE) and 81,258 other administrative and non-clinical staff (54,259 FTE). 6–8

At the same time, general practice is facing unprecedented challenges. 9 The number of people aged ≥ 65 years is increasing sharply in all areas of the country, and the number of people with long-term conditions, most which are managed within general practice, is increasing. The number of consultations in general practice between 2010/11 and 2014/15 grew by over 15%, whereas funding has remained relatively stable, placing practices under massively increasing pressure. In conjunction with a workforce that is failing to keep up with rising demand, this suggests that an emphasis on productivity, efficiency and effectiveness is needed. 10 The General Practice Forward View,11 discussed more fully in the next section, provides some processes setting out how this may be achieved. Improving access in order to improve outcomes for some patient groups is a priority and new data from the British Social Attitudes survey12 published in February 2018 has shown that public satisfaction with the services provided by GPs is at its lowest level since the survey began in 1983. 13,14

Overview of measurement of productivity and effectiveness in general practice

Productivity and effectiveness are terms that are used in myriad ways. A classical definition of productivity is simply the ratio of outputs to inputs, and is often defined in simple financial terms. However, in health care this definition is not sufficient – the simple measurement of financial outputs does not usually take account of the quality of care delivered. Productivity in health care should measure ‘how much health for the pound, not how many events for the pound’. 15 Therefore, a definition often used within health is ‘the ratio of outputs to inputs, adjusted for quality’. 16 (Reproduced from Appleby et al. 16 © The King’s Fund 2010. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license, which permits others to copy and redistribute the work, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). However, the nature of this adjustment is a matter of debate: it is not generally possible to assess the financial effects of quality directly, as to do this would require assessment of the services’ marginal contributions to social welfare,17 and identifying and isolating these contributions would be difficult if not impossible (although, in principle, identifying the financial inputs should be easier).

Although attempts have been made to measure quality-adjusted outputs directly (e.g. Dawson et al. 18 and Castelli et al. 19), these have tended to focus on secondary care, and do not generally account for the wide range of potential data, but instead rely on routinely collected outcome data. Quality can refer to a mixture of things, including health outcomes, safety and patient experience. Here, it is argued that, particularly for primary care, the full extent of quality cannot be measured without taking into account a broader set of indicators, for example the views of patients. 20

Given the importance of primary care and general practice within the NHS more widely, it is perhaps surprising that there have not been more attempts to provide a more specific definition and measurement of productivity – or other forms of performance, such as effectiveness – that can be applied at the practice level. There have, however, been various attempts to capture the performance of general practice for other, more specific, purposes.

The widest-known current method for assessing general practice outputs is the QOF. This sets payments to practices based on their activity against a number of indicators across two principal domains. Practices report on their performance on these indicators in accordance with clearly defined criteria; each indicator has a different weighting, so that the total QOF score is composed of a weighted sum of all the indicators together. Specifically, in 2017/18, there were 63 clinical indicators (across 19 specific clinical conditions or groupings of condition) and 12 public health indicators. 21

Despite the growing demands of a larger population, more older people and more people with multiple chronic conditions requiring management in primary care, the share of NHS spending on general practice has fallen in recent years. There are plans to redress this problem, and in April 2016 NHS England announced a 5-year plan to increase investment in general practice. 11 The funds allocated to each practice each year include a global sum calculated to adjust for workloads and features of the patient population (age, morbidity, mortality, population turnover), and pay for performance elements made up of the QOF and enhanced services, some of which may be determined locally. On the basis of these payment streams, in 2014–15 practices received a median of £105.79 (interquartile range £96.35–121.38) per patient. In recent work,22 however, it has been shown that population factors related to health needs were, overall, poor predictors of variations in adjusted total practice payments and in the payment component designed to compensate for workload.

The precise content has varied from year to year. Notably, all of the ‘quality and productivity’ indicators and the one ‘patient experience’ indicator from earlier years were discontinued from 2014/15 onwards, giving the impression that only clinical outcomes, rather than other areas of effectiveness and patient experience, are being prioritised. QOF has been criticised for many reasons, including being arbitrary in its setting of targets, being influenced by contractual negotiations, being subject to regular changes and creating tensions between patient-centred consulting and management. 23,24 These arguments will be expanded in the next section, which reviews the literature on the topic. Other output measures, such as those used by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), likewise do not cover all activity or focus on a different level (e.g. the NHS Outcomes Framework, which focuses on the CCG level). 25

The importance of primary care quality is further indicated by the fact that the Care Quality Commission (CQC) now inspects general practices, including out-of-hours (OOH) services. These inspections ask the key questions about whether or not services are safe, effective, caring, responsive and well led. This brings together quality and safety, but does not directly address productivity, and leads to a broad-brush rating at one of four levels between ‘inadequate’ and ‘outstanding’. 26

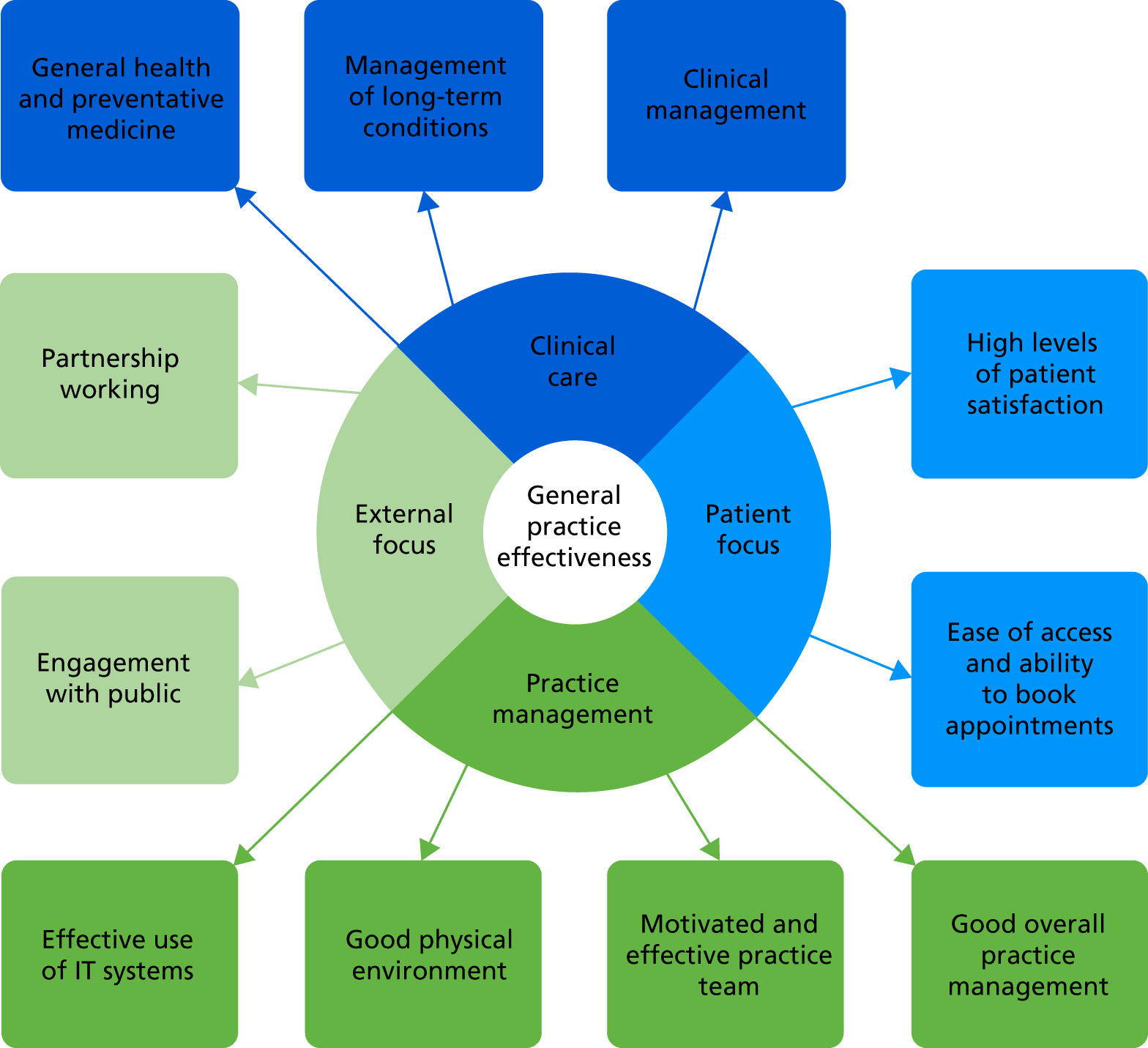

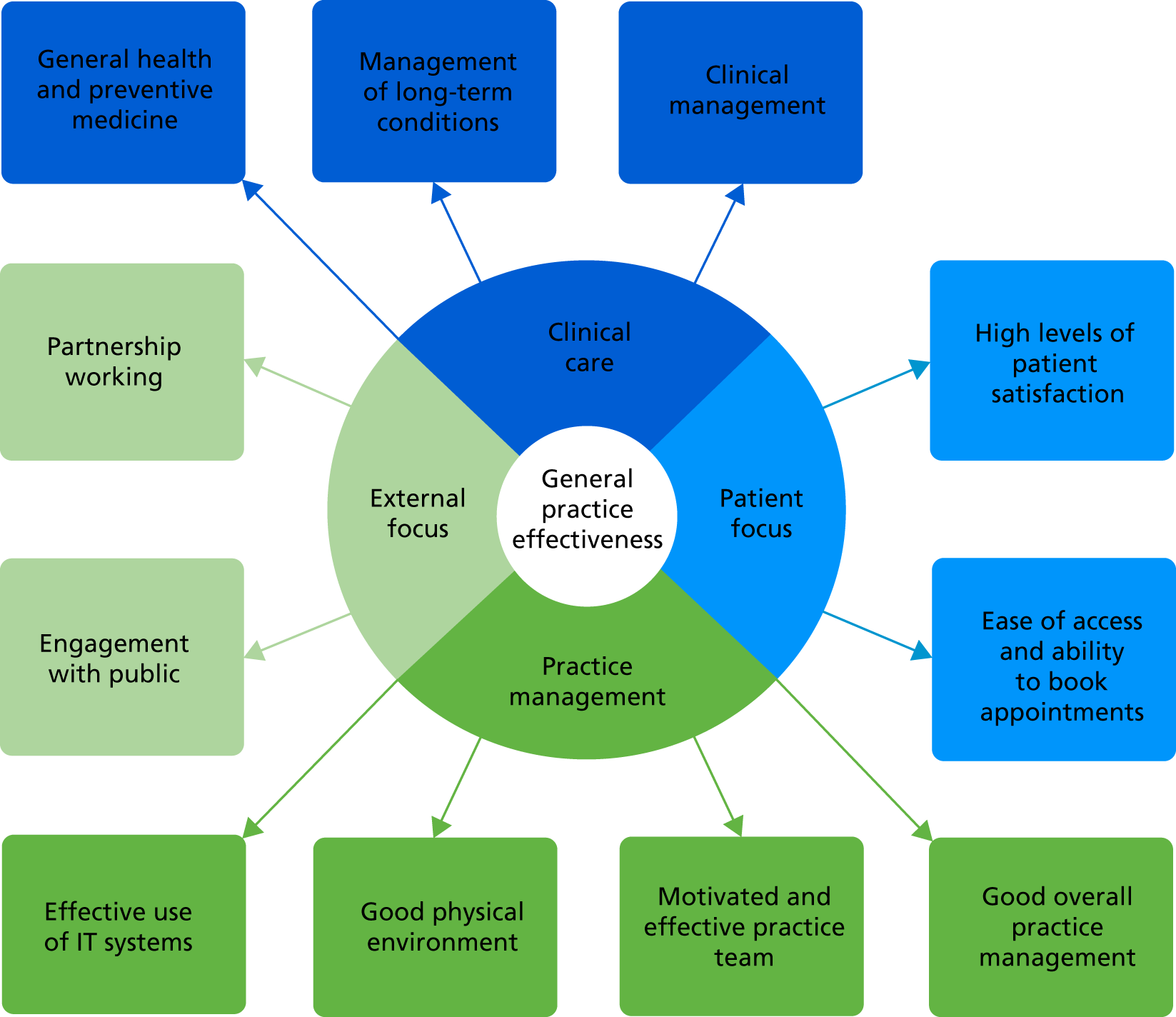

Any comprehensive measure of general practice productivity or effectiveness would, however, need to consider the wide range of outcomes from primary care, including elements relating to public health and health improvement. In order to capture the range of outcomes, but also the differing importance of them, a model is needed that addresses both of these factors. The model used in this study does this. This approach, explored in greater depth in the following section, provides a method of capturing a range of different objectives and assigning them different weights, and is driven by the users on the ground: in this case, general practice staff and patients. 27

Performance measurement: literature review

Overall performance measurement

The measurement of performance in health care has long been a contentious issue. The pressures of competing priorities mean that there is often no consensus over the definition of what constitutes high-quality performance. 28 In health systems that operate for profit, profitability of a unit may provide one suitable measure of performance; however, in the NHS and other systems that do not operate on a for-profit basis, the measurement of financial performance is both more complex and less appropriate.

To capture overall performance in health care (whether of a single organisation or the system as a whole), a range of different indicators is undoubtedly necessary. Often these will take the form of a ‘balanced scorecard’ – a set of measures designed to capture all the main areas of performance. For example, areas covered may include indicators relating to patient health, mortality, safety, patient satisfaction and the extent to which targets are met. The precise types of measures will depend on the context and nature of the units being studied; however, there should certainly be alignment between the objectives of the unit and the measurements used. 29,30

Productivity is a particularly difficult area of performance measurement. It is always a challenge for health-care providers and administrators to be able to produce as much as possible with the resources available. In the NHS, for example, the Wanless report31 identified that in future years the NHS would need to be able to make better use of its resources in order to maintain the same level of service – and that was at a time of relative prosperity and growth in the NHS. In times of relative austerity and uncertainty, the necessity becomes even greater.

A classical definition of productivity is simply the ratio of outputs to inputs, and is often defined in simple financial terms. However, in health care this definition is not sufficient: the simple measurement of financial outputs does not usually take account of the quality of care delivered. The most common definition used in health care is the ratio of outputs to inputs, adjusted for quality.

Although attempts have been made to measure quality-adjusted outputs directly, these have tended to focus on secondary care, and do not generally account for the wide range of potential data, but instead prefer routinely collected outcome data. 18,19 Quality can refer to a mixture of things, including health outcomes, safety and patient experience. It seems evident that, particularly for primary care, the full extent of quality cannot be measured without taking into account the views of patients. 20

Performance measurement in primary care

Primary care in general (and general practice in particular) covers a huge range of activity, with practitioners needing a wide enough scope of knowledge to be able to deal with all presenting problems, whether these are dealt with directly within the primary care setting or referred on to secondary care or other services. 2,32 Some models of overall primary care effectiveness do exist, although they do not focus on productivity, and are not geared towards the NHS situation in particular. However, the dimensions identified by Kringos et al. 33 in particular (i.e. primary care processes determined by access in addition to continuity, co-ordination and comprehensiveness of care, and outcomes determined by quality of care, efficiency of care and equity in health) give a useful benchmark for comparison.

The role of the GP within this setting is key to its success, and the nature of the consultation between GP and patient has itself been the subject of much scrutiny, particularly with regard to its potential to explore broader health concerns than that initially presented by the patient. For example, Stott and Davis34 presented a four-point framework to help GPs achieve greater breadth in consultations, covering management of presenting problems, modification of help-seeking behaviour, management of continuing problems and opportunistic health promotion. By engaging in all four of these aspects, rather than merely dealing with the primary issue, GPs can seek to improve general health and avoid future concerns. Mehay35 went further than this, describing 15 separate models of doctor–patient consultation, and Pawlikowska et al. 36 undertook an analysis of a variety of consultation types. Although they36 did not advocate any one particular model, their analysis suggested some key themes including establishing a rapport, appropriate questioning style, active listening, empathy, summarising, reflection, appropriate language, silence, responding to cues, patient’s ideas, concerns and expectations, sharing information, social and psychological context, clinical examination, partnership, honesty, safety netting/follow-up and housekeeping. In particular, Pawlikowska et al. 36 concluded that excellent communication skills alone are not enough. In general, GPs also have a key role in managing patients’ uncertainty, and act as a key operator at the boundary between different agencies. 37

With this in mind, the measurement of performance in general practice needs to embrace this complexity and reflect the broad activity undertaken by GPs and other practice staff, including the work of practice nurses and other clinicians working under the umbrella of the general practice; however, this is far from straightforward. One attempt to do so is the provision of profiles of general practices by Public Health England. However, these include only certain areas of performance and are updated infrequently. A 2015 review38 conducted by the Health Foundation examined indicators that were then in use in the NHS. Although there were a multiplicity of sources of indicators available, the over-riding conclusion was that the accessibility of these indicators was poor, particularly from the patients’ perspective. Considering that the rationale for publication of indicators may include improvement, patient choice/voice, and accountability, it recommended that a single web location be developed to provide access to these indicators (rather than relying on very different web sources, such as NHS Choices, CQC ratings, MyNHS, Public Health England and NHS Digital), but, even then, there would be significant areas of performance that were not covered by reliable indicators. The review also suggested that composite indicators should not be developed and gave six reasons for this: (1) aggregation masks aspects of quality of care, (2) it was suggested that a composite index would provide little value over and above the CQC ratings, (3) patients and service users are not a homogeneous group, (4) any selection and weighting of indicators would be highly contentious, (5) the number of robust indicators available is extremely small and not comprehensive and (6) there would not be enough detail for professionals to pinpoint areas for improvement. 38

Some of these arguments are more persuasive than others. It is certainly true that aggregation can mask specific aspects of care, but this does not imply that overall performance is not a meaningful concept. In particular, if an overall performance index can be developed that also allows examination of specific areas within it, it could service both needs. We disagree that no value can be added to the CQC ratings with other composite indicators; as discussed later in this section, CQC inspections (leading to ratings) are made too infrequently and do not offer the detail that could be given by a more comprehensive index. It is also true that patients and service users are a very varied group, and any attempt to measure overall performance of a practice should not imply that the performance is the same for all groups. The contentious nature of the choice of indicators, particularly in the light of the small number of robust indicators, is a critical issue. This suggests that any specific choice of indicators might favour one type of practice over another. The difficulty of balance in performance measurement is something discussed by multiple authors. 39–41 For this reason, any overall performance index may not be so useful as a direct comparison between practices, but instead as a longitudinal tracker within practices – more as an improvement tool than a performance management tool.

Baker and England42 have presented a framework covering many of these outcomes: both final outcomes (including mortality, morbidity, disease episodes, quality of life, adverse incidents, equity, patient satisfaction, costs and time off work/school) and intermediate outcomes (e.g. clinical outcomes, such as immunisation/screening, health behaviours, resource utilisation and patient experience, and practitioner-related outcomes, such as work satisfaction). For each outcome (or type of outcome) there is both a degree of importance of the outcome to the overall perception of effectiveness, and a degree of influence that the general practice can have over it. For example, mortality is a very important final outcome, and, although primary care can influence mortality, the influence is small, with the characteristics of patients being very much the most powerful predictors of mortality rates. On the other hand, patient satisfaction with care is increasingly seen as an important outcome, and the delivery of primary care will certainly influence it much more directly.

One of the greatest challenges for general practice is in the effective allocation of resources. A 2017 study by Watson et al. 43 used a value-based health-care framework to propose how resources can be allocated more effectively. As well as quality, safety, efficiency and cost-effectiveness, it includes optimality (balancing of improvements in health against cost of improvement). Optimality requires evidence and shared decision-making with individual patients. The authors argue that primary care has an essential role in delivering optimality and, therefore, value. However, they also point to the lack of readiness currently within the primary care system: ‘primary care measurement systems need to be developed to generate data that can assist with the identification of optimality’. 43 Of interest, among its suggestions for things to do more/less of, it suggests fewer health checks and fewer unnecessary appointments. It does, however, recommend more social prescribing, more patient self-care, better integration of services and a higher overall allocation of resources into primary care.

This is closely tied to the area of efficiency, which has had its own section of literature within health care generally and primary care in particular. Of particular note here is the work using data envelopment analysis, which uses multidimensional geometric methods to compare the inputs and outputs of a unit and to establish a comparative index of efficiency. In particular, Pelone et al. 44–46 have undertaken to do this in different primary care settings. However, this method is simply one of using other indicators to create a composite measure of efficiency (or productivity); it does not calculate a specific index, but instead depends on the comparability of units. Therefore, the choice of appropriate indicators is still of paramount importance.

The nature of primary care means that a certain number of clinical and patient activity indicators are inevitable, and these should cover as many of the major conditions and patient types as possible, including public health priorities. However, there are other, more general areas that also need to be considered. One of these is patient safety. However, patient safety within primary care is not something that is measured in any standard form. Lydon et al. 47 conducted a systematic review of measurement tools for the proactive assessment of patient safety in general practice. Of the 56 studies identified by this systematic review, 34 used surveys/interviews, 14 used a form of patient chart audit and 7 used practice assessment checklists; there were a handful of other tools that were not repeated across studies. Nothing was discovered that was either commonplace or appropriately sophisticated. Similarly, Hatoun et al. 48 undertook a systematic review of patient safety measures in adult primary care. They found 21 articles, including a total of 182 safety measures, and classified these into six dimensions: (1) medication management, (2) sentinel events, (3) care co-ordination, (4) procedures and treatment, (5) laboratory testing and monitoring and (6) facility structures/resources. However, the types of measures were not dissimilar to those found by Lydon et al. 47 An earlier review by Ricci-Cabello et al. 49 undertook a similar exercise and reached similar conclusions (albeit on a smaller scale). Therefore, the inclusion of patient safety within a broader index will pose a significant challenge.

It also seems important, following on from the Baker and England42 and Dixon et al. 38 frameworks, that the experience of the patient is given a key place within any overall index. Patient satisfaction and experience measures are commonplace in health care, but are used to a different extent in different scenarios; in the NHS, routine data collection is common, with the annual GP patient survey and all practices using a (minimal) Friends and Family Test (FFT) on an ongoing basis, as well as gathering qualitative feedback via patient reference groups (PRGs). Moreover, the advent of technology has started to change how these data are collected. A recent National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research study examined patient survey scores in detail, aiming to understand the data and how general practices respond to low scores, looked at some specifics [e.g. black and minority ethnic (BME) patient scores and OOH care] and carried out a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of an intervention to improve patient experience. This intervention involved real-time feedback via a touchscreen on exit; encouragement of patients boosted response rates hugely. The major conclusions were that a variety of feedback mechanisms should be used, and certainly not reliance on postal surveys. In addition to satisfaction with the care provided, access is a key issue for patients, but it is increasingly under pressure. 50

Overall, a wide variety of measures of performance have been used in general practice settings (both in the NHS and elsewhere), and these continue to evolve without there yet being much in the way of definitive best practice. However, it is important to consider next what is currently used in the NHS at a national stakeholder level, and to determine in what ways these do and do not satisfy the needs of practices, patients and other stakeholders.

General practice performance in the NHS

As with much of the NHS, there has been significant emphasis on measuring performance in primary care, even though this is sometimes less straightforward than for other parts of the service (such as the acute sector). Since the introduction of the GMS and PMS contracts for general practice in 2004, the main vehicle for measuring the performance of practices, and for determining at least part of the payments due to practices, has been the QOF.

Under the QOF, each practice needs to submit data annually as evidence of how they are meeting various targets. Detailed rules are provided about how each score should be calculated, with most being derived directly from clinical information systems. For example, one of the indicators under the area ‘secondary prevention of coronary heart disease (CHD)’ is the percentage of patients with CHD in whom the last blood pressure reading (measured in the preceding 12 months) was ≤ 150/90 mmHg. This percentage, which can be extracted using a specific query from the practice’s clinical system, is worth up to 17 points (out of a possible 45 points for the domain, or 558 QOF points in total) and is maximised when the percentage is between 53% and 93%. The sum for all 77 indicators (across 25 areas in two domains) is calculated for a practice and this is converted to a payment made to the practice as part of their overall funding. Thus, the financial incentive for practices to perform well on QOF is strong.

In one sense, therefore, this already provides an overall index of performance for a practice. However, the content of the QOF indicators is a matter of some contention. Table 1 summarises the domains, areas and indicators in use in the NHS year 2017/18, although this detail has changed somewhat over the years. Originally, the QOF indicators were developed by the Department of Health and Social Care, with a total of 146 indicators across four domains: clinical, organisational, patient experience and additional services. Since 2009, the changes made to the QOF have been the responsibility of NICE. As with much of NICE’s work, this was supposed to ensure that decisions were based on a strong evidence base. However, within general practice this is not always straightforward, and the evidence (or lack of evidence) underlying changes to QOF scores has been criticised as relying too much on expert opinion. 52

| QOF area | Number of indicators | Points available |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical domain | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 | 29 |

| Secondary prevention of CHD | 4 | 35 |

| Heart failure | 4 | 29 |

| Hypertension | 2 | 26 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 3 | 6 |

| Stoke and transient ischaemic heart attack | 5 | 15 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 | 85 |

| Asthma | 4 | 45 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 6 | 35 |

| Dementia | 3 | 50 |

| Depression | 1 | 10 |

| Mental health | 7 | 26 |

| Cancer | 2 | 11 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1 | 6 |

| Epilepsy | 1 | 1 |

| Learning disability | 1 | 4 |

| Osteoporosis: secondary prevention of fragility fractures | 3 | 9 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 | 6 |

| Palliative care | 2 | 6 |

| Public health domain | ||

| Cardiovascular disease: primary prevention | 1 | 10 |

| Blood pressure | 1 | 15 |

| Obesity | 1 | 8 |

| Smoking | 4 | 64 |

| Cervical screening | 3 | 20 |

| Contraception | 2 | 7 |

| Total | 77 | 558 |

In particular, there have been major changes to the structure of the QOF. Of the initial four domains, the clinical domain has been substantially expanded, but the organisational and patient-experience domains have been removed, principally because of a lack of good-quality data in these areas, rather than because of a perceived lack of importance. This, therefore, represents a significant weakness within the current QOF; it is often perceived as being imbalanced (either in terms of what is perceived as most important or in terms of the actual work of general practices). 53 In addition, and probably less controversially, the additional services domain has been subsumed within a broader public health domain.

Even more contentious, however, is the effectiveness of the QOF as an index and its usefulness as a methodology. This has attracted a substantial level of research and comment in recent years. Forbes et al. 54 undertook a review of research examining the effects of the QOF. They found that the introduction of the QOF was associated with a modest slowing of both the increase in emergency admissions and the increase in consultations in severe mental illness, and modest improvements in diabetes mellitus care. However, there was no clear evidence of causality. Furthermore, there was no evidence of any effect on mortality, on integration or co-ordination of care, on holistic care, self-care or patient experience. The work of this research team in the field of CHD confirms the lack of evidence of an effect on mortality and offers a potential explanation in that the QOF has concentrated clinical attention on the management of patients with diagnosed conditions instead of a population approach to primary care that actively identifies patients with undiagnosed conditions. 55 Specifically, levels of detection of hypertension predict premature mortality, greater detection being associated with lower mortality, whereas QOF indicators did not predict mortality. 56

Marshall and Roland57 argued that the QOF is highly divisive and has become increasingly unpopular with GPs. Using financial incentives has diverted focus from the interpersonal elements that are important in consultations, and care for single diseases has been prioritised over holistic care. Their review57 of observational studies suggested that there had been modest improvements in some areas and a small decrease in emergency admissions in the incentivised areas, but no overall effect on patient mortality. Counterbalancing the limited evidence of improvements is a rising administrative workload associated with the QOF. They conclude that although the QOF may have had some benefits, it has failed to achieve what was intended in terms of driving improvements in health. 57 In a similar vein, Ryan et al. 58 performed a longitudinal population study on data from 1994 to 2010 using a difference-in-difference analysis, studying mortality in areas that had been prioritised by the QOF. They found that the introduction of the QOF was not associated with any improvement in mortality, either in specific conditions or overall. This is perhaps unsurprising given the marginal link between general practice and mortality overall.

Thorne10 revealed that health inequalities had not been reduced by the introduction of the QOF. Ashworth and Gulliford59 used findings from QOF-based research to argue that an increase in funding for general practice was needed, and that a salaried GP workforce could assist in improving the situation.

Ruscitto et al. 60 studied the issue of payments for individual diseases by modelling possible scenarios in which comorbidities attracted different payments. They found that, although there were substantial differences in the resulting payments, the existing system favours more deprived areas, because of the higher number of patients with multiple morbidities, which therefore attracts multiple payments. Kontopantelis et al. 61 examined a different problematic area within the QOF: that of exemptions (patients who could be excluded from QOF calculations). They found that, across 644 practices, there was evidence that the odds of exemption increased with age, deprivation and multimorbidity. At the same time, exempted patients were more likely to die in the following year. Thus, combining these findings with those of Ruscitto et al. ,60 it appears that the QOF system may favour practices in more deprived areas, but not necessarily to the benefit of the patients in those areas. The fidelity of QOF reporting has also been called into question: Martin et al. 62 uncovered differences in the monitoring of physical health conditions for patients with major mental illness.

Overall, the research into the effects of the QOF is somewhat inconclusive. There is certainly little clear evidence that it is effective in improving population health, and yet there is substantial evidence about unintended consequences. Combined with the concerns about the coverage of the QOF (in particular its current lack of any patient experience, access or organisational indicators), the research points to a system that is, at best, imperfect and, at worst, a wasteful exercise. Indeed, even Simon Stevens, Chief Executive of NHS England, stated in October 2016 that the usefulness of QOF was nearing its end, and would be phased out in new GP contracts. 63 However, as yet, there have been no firm plans announced about how QOF will be replaced or altered in future years.

Given that the QOF cannot be relied on to measure the effectiveness of practices, it is unsurprising that national bodies, particularly regulators, have turned to different measures. In 2014, the CQC embarked on a series of in-depth inspections of general practices. Inspections are conducted by independent teams that always include a GP, as well as various other people, often including an ‘expert by experience’ (patient/service user). As of May 2017, on the most recent inspection, 86% of practices were rated as ‘good’ and 4% as ‘outstanding’; 8% were rated as ‘requires improvement’ and 2% as ‘inadequate’.

Within this overall rating, however, there are five dimensions rated: safe, effective, caring, responsive to people’s needs and well led. Six different population groups are considered separately: older people; people with long-term conditions; families, children and young people; working-age people; people whose circumstances make them vulnerable; and people experiencing poor mental health. Safety is the main concern: on this dimension, 13% of practices were rated as ‘requires improvement’ and 2% as ‘inadequate’ (although this is a substantial improvement from the first inspection, when these figures were 27% and 6%, respectively). Often, these failings were found to stem from poor systems, processes or governance. 9

Although CQC inspections may be viewed as broader than QOF (especially given the focus on safety, more holistic care, and good leadership), they cannot provide regular feedback to (or about) practice teams, as in normal circumstances there would be multiple years between inspections. Practices wanting more regular feedback therefore require other tools. Examples of these have been provided by the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP), which introduced a suite of quality improvement (QI) tools. In particular, it described a QI ‘wheel’ for general practice. The hub of the wheel represents context and culture in QI. The inner wheel comprises QI tools (diagnosis, planning and testing, implementing and embedding, sustaining and spreading), and the supporting rings represent patient involvement, engagement and improvement science. However, although tools for diagnosis are suggested, and other techniques such as plan, do, study, act (PDSA) cycles, run charts and statistical process control charts are discussed, the implementation is largely left to practices’ own priorities, and some of the outer aspects of the wheel are less well developed. 64

However, practices are not operating in a vacuum. Efforts to ameliorate the continually increasing pressures on the NHS in general, and general practice in particular, create specific difficulties. The 2014 NHS Five Year Forward View65 presented a vision for the NHS that required a transformation in the way services are delivered, and primary care is a key aspect of this. 65–67 The evolving sustainability and transformation partnerships (STPs) (formerly known as sustainability and transformation plans) for each of 44 localities in England, and the forthcoming integrated care systems (ICSs) that will be formed from these, are an effort to create more efficient, integrated, patient-focused services that respond to the needs of a particular local population, and, unsurprisingly, most place general practice at their heart. 68 Health Education England has produced a report69 on developing the skill mix of primary care teams and allowing GPs to concentrate on more complex clinical problems. Ongoing reforms mean that practices need to be more productive, serving increasing numbers of patients with more complex health needs while making better use of resources; therefore, efficiencies are needed across the service, and the General Practice Forward View11 presented a vision of how this would be achieved, with five major elements:

-

Increasing investment – accelerating funding of primary care by investing an additional £2.4B per year, representing a 14% real-terms increase on 2015/16 levels by 2020/21.

-

Increasing the workforce – expanding and supporting GPs and wider primary care staffing, with plans to double the rate of growth of the medical workforce, leading to an overall net growth of 5000 GPs by 2020; this would also require additional international recruitment.

-

Reducing workload – lowering practice burdens and releasing staff time.

-

Improving practice infrastructure – developing primary care estate and investing in better technology [including an increase of > 18% in allocations to CCGs for provision of information technology (IT) services/technology for general practice].

-

Improving care design – providing a major programme of improvement support to practices (including greater integration and, in particular, involvement in ICSs).

The extent to which these objectives are achievable is unclear; in particular, the increase in workforce is not currently supported by increases in training, and the specific approaches to increasing the number of GPs are ambitious. Reform in other areas, such as expanding the roles of pharmacists, will need careful examination also. Because of this, greater attention is needed towards initiatives to increase efficiency and lower waste. In some regions, groups of practices have joined together as federations – effectively acting as one organisation, but still providing care across the same locations. 63 In other areas, looser networks have been formed. A report published by the NHS Alliance in 2015, Making Time in General Practice,70 identified 10 high-impact actions that practices could take to improve the time available for care. These are summarised as follows:

-

Active signposting – provides patients with a first point of contact who directs them to the most appropriate source of help. Web- and app-based portals can provide self-help and self-management resources as well as signposting to the most appropriate professional.

-

New consultation types – introduce new communication methods for some consultations, such as telephone and e-mail, improving continuity and convenience for the patient and reducing clinical contact time.

-

Reduce did not attends (DNAs) – maximise the use of appointment slots and improve continuity by reducing DNAs. Changes may include redesigning the appointment system, encouraging patients to write appointment cards themselves, issuing appointment reminders by text message and making it quick for patients to cancel or rearrange an appointment.

-

Develop the team – broaden the workforce in order to reduce demand for GP time and connect the patient directly with the most appropriate professional.

-

Productive work flows – introduce new ways of working that enable staff to work smarter, not harder.

-

Personal productivity – support staff to develop their personal resilience and learn specific skills that enable them to work in the most efficient way possible.

-

Partnership working – create partnerships and collaborations with other practices and providers in the local health and social care system.

-

Social prescribing – use referral and signposting to non-medical services in the community that increase wellbeing and independence.

-

Support self-care – take every opportunity to support people to play a greater role in their own health and care with methods of signposting patients to sources of information, advice and support in the community.

-

Develop QI expertise – develop a specialist team of facilitators to support service redesign and continuous QI.

However, most of these are entirely unrelated to what is captured by the QOF and, although some overlap with CQC inspection domains (particularly the ‘well-led’ domain), it seems appropriate that any overall effort to capture the effectiveness and/or productivity of general practices should include the areas mentioned in these 10 high-impact actions.

Overall, therefore, there is much room for improvement in the measurement of performance in general practice. One of the principal objectives of this study was to rectify this, which the research team have attempted to do using a specific method of measure development, ProMES. 27 In the following section, the literature on this method is reviewed.

Productivity Measurement and Enhancement System

The ProMES was initially developed in the 1980s as a way to enable teams or work units to identify the factors that contribute to their productivity (or effectiveness), and to track this productivity over time, with feedback creating the motivation to improve. 71 It involves four stages:

-

Develop objectives (called ‘products’ in the original terminology): things that the unit (in this case, the general practice) is expected to do or produce. These would normally be determined by a series of meetings between members of the unit. Typically, between three and six objectives might be identified, although this can vary depending on the type of work the unit does (this number was expected to be greater for general practices).

-

Develop indicators of the objectives: a way of measuring how well the unit is doing on each particular objective. These are developed by the same personnel who identify the objectives, and involve thinking of ways of identifying the extent to which the unit was doing well on a particular objective, by either using existing data or collecting new data. Each objective would have at least one indicator, but may have more than one.

-

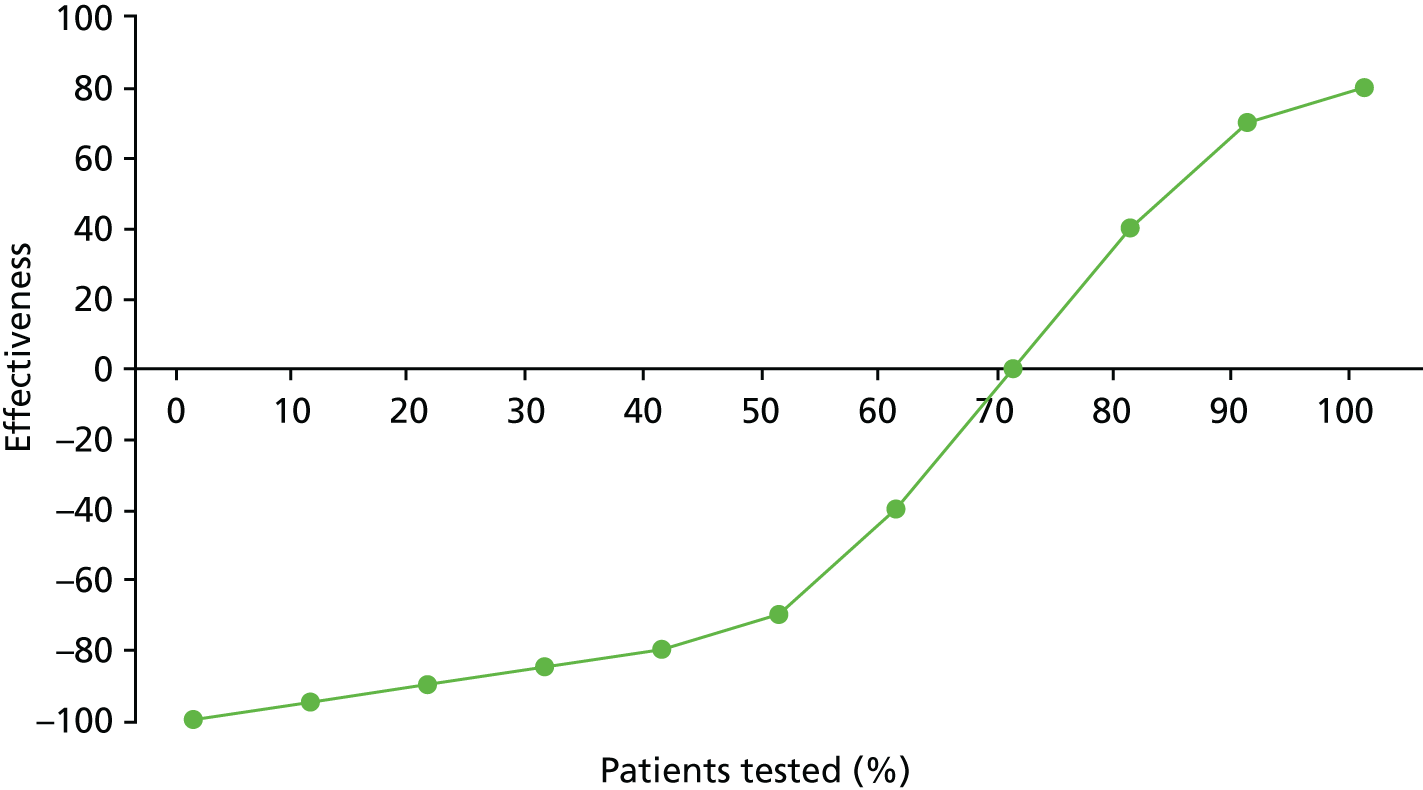

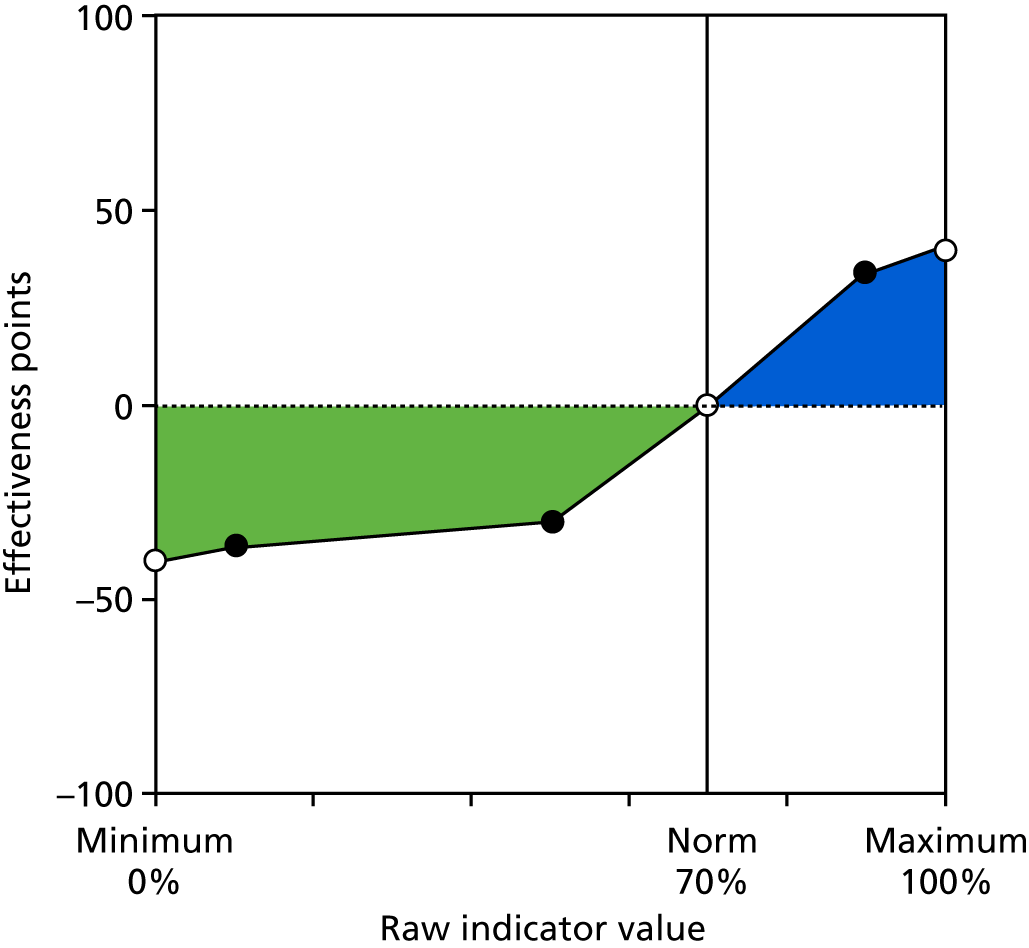

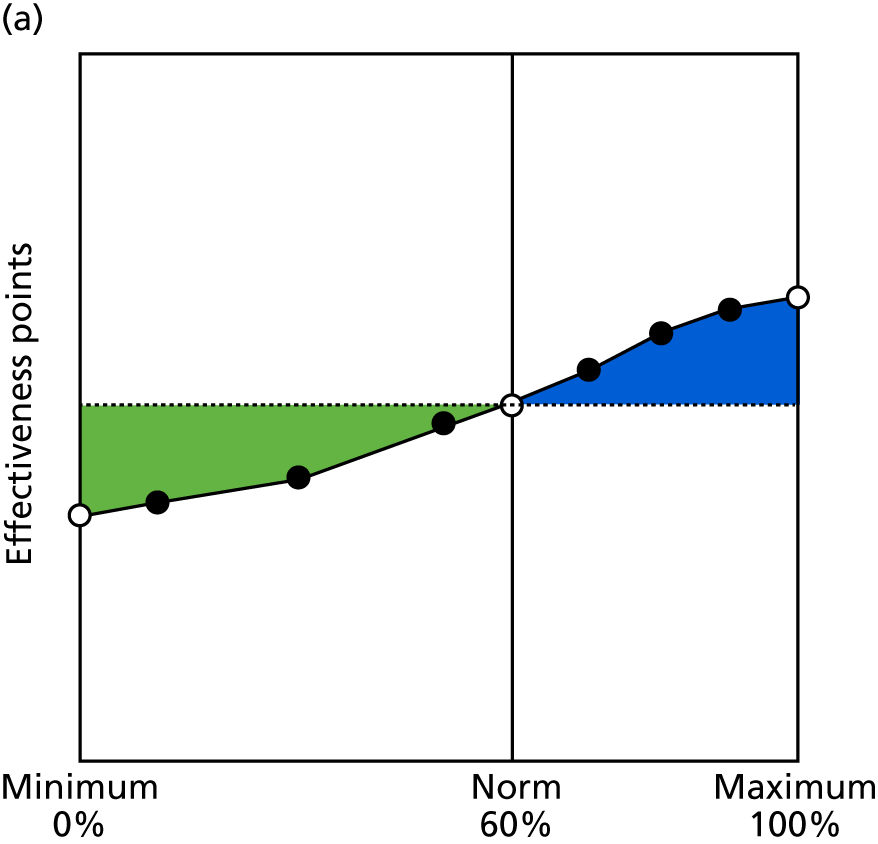

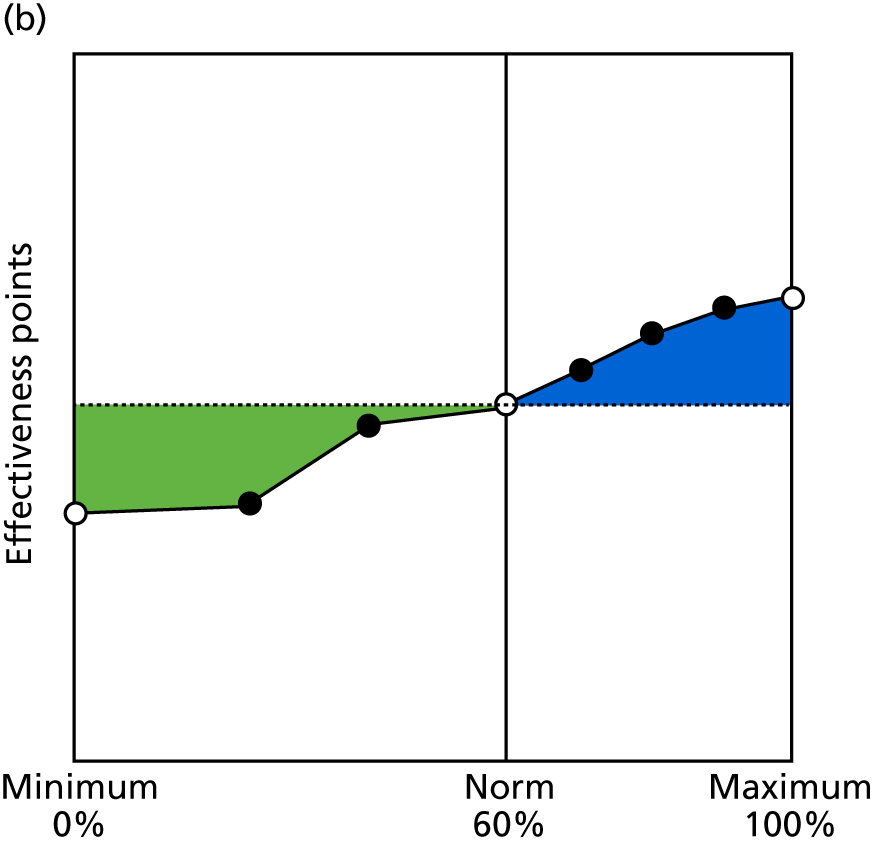

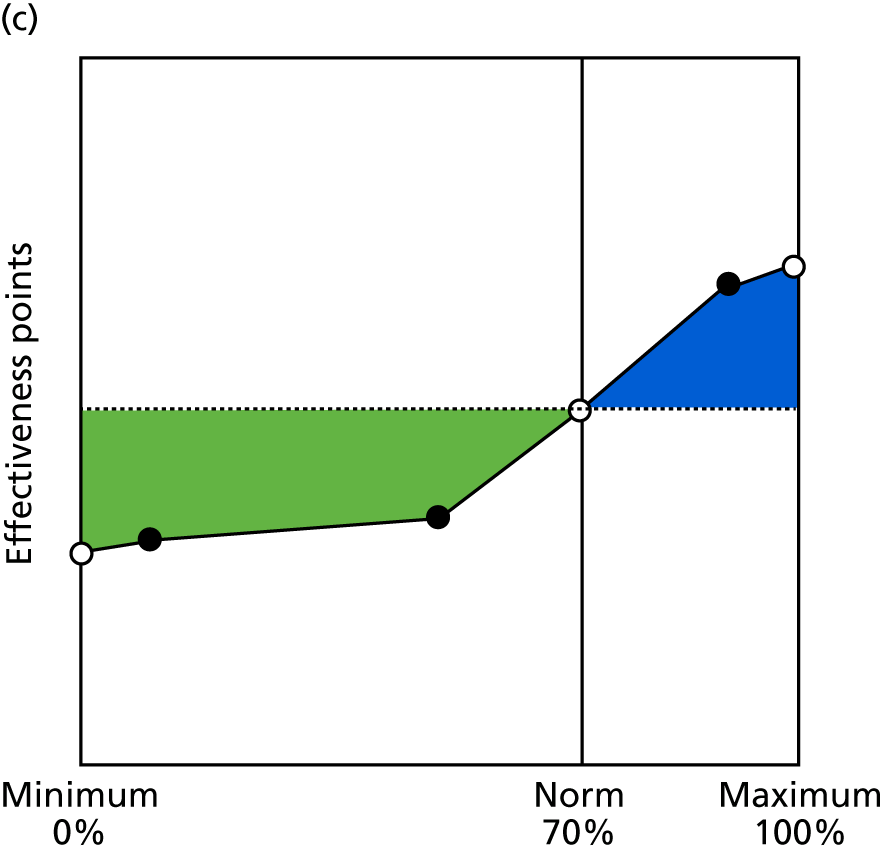

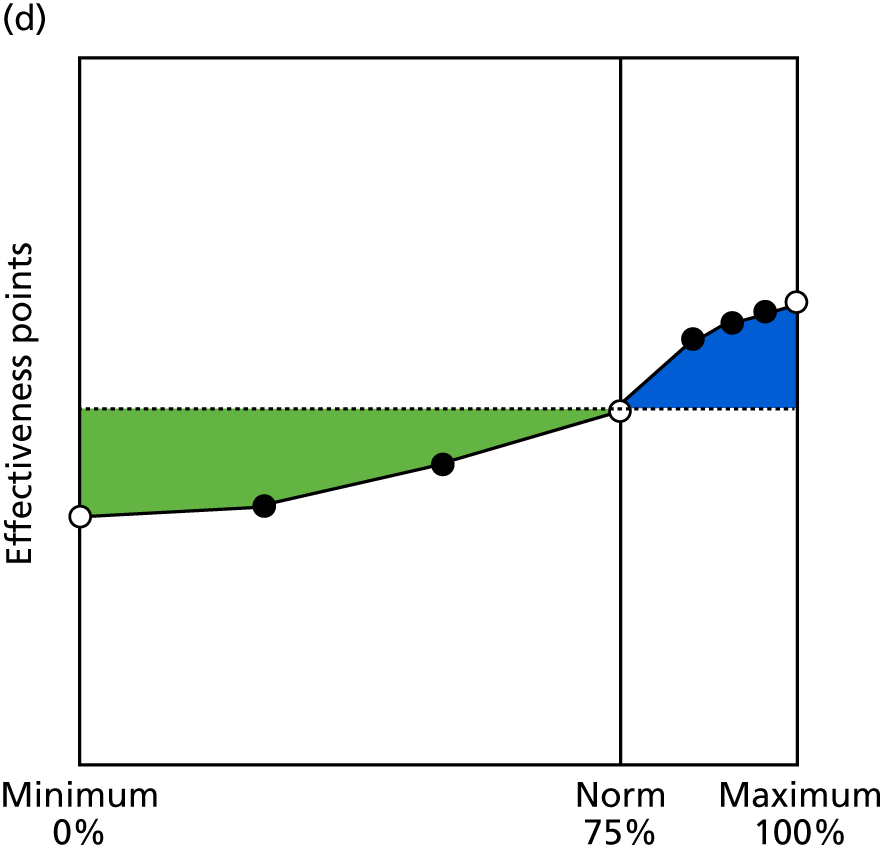

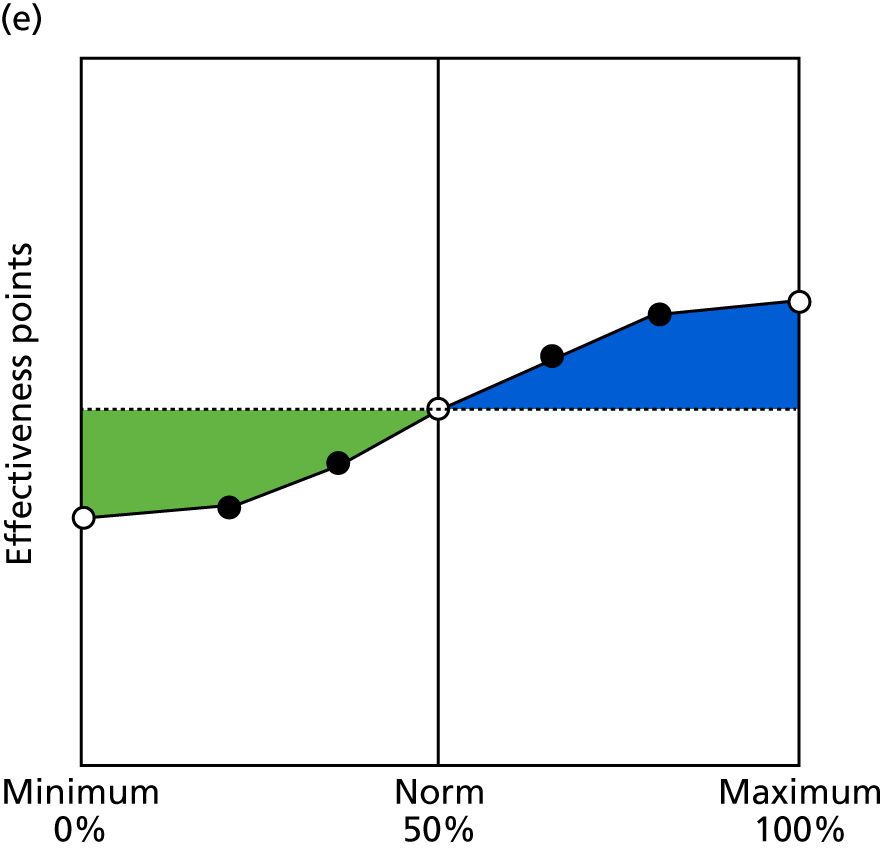

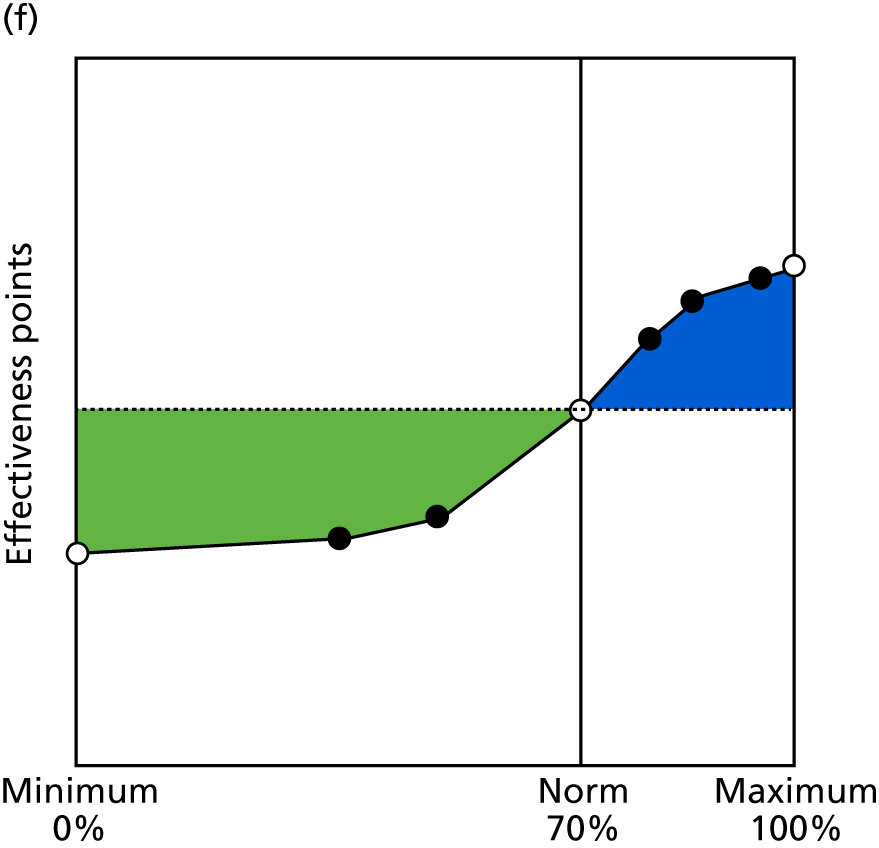

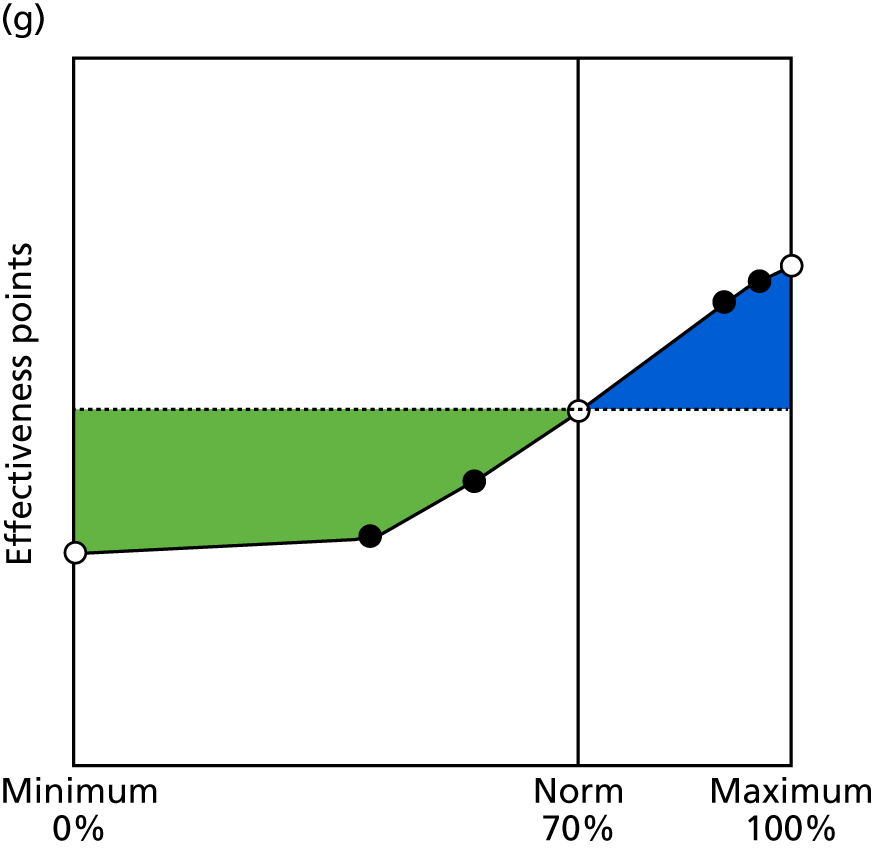

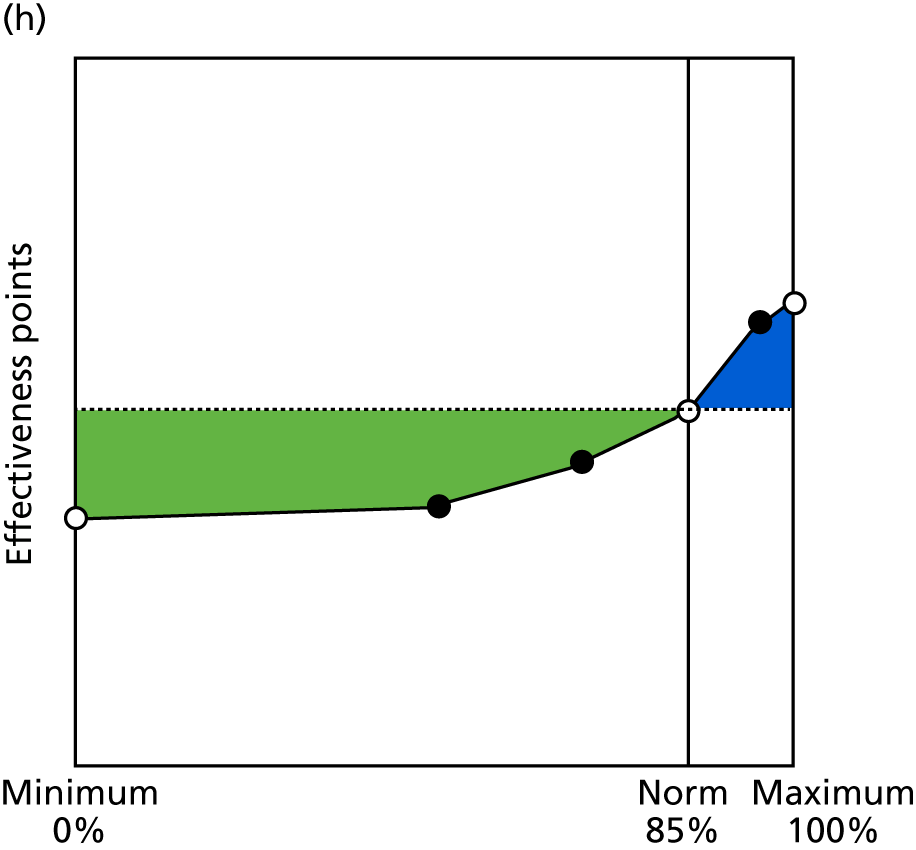

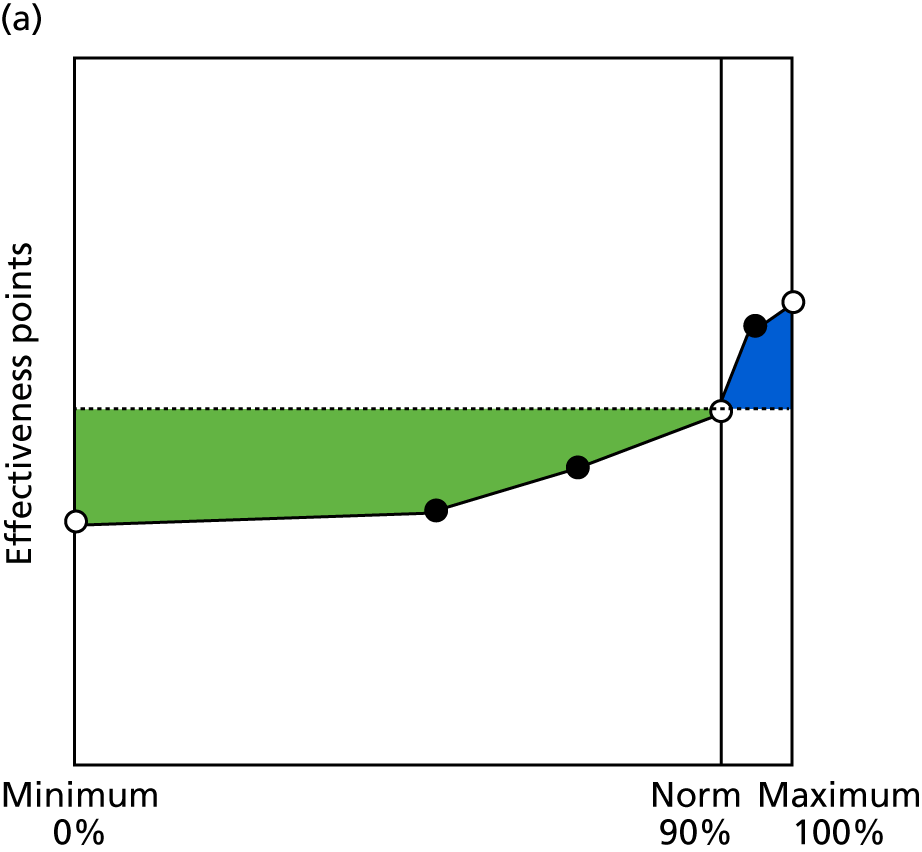

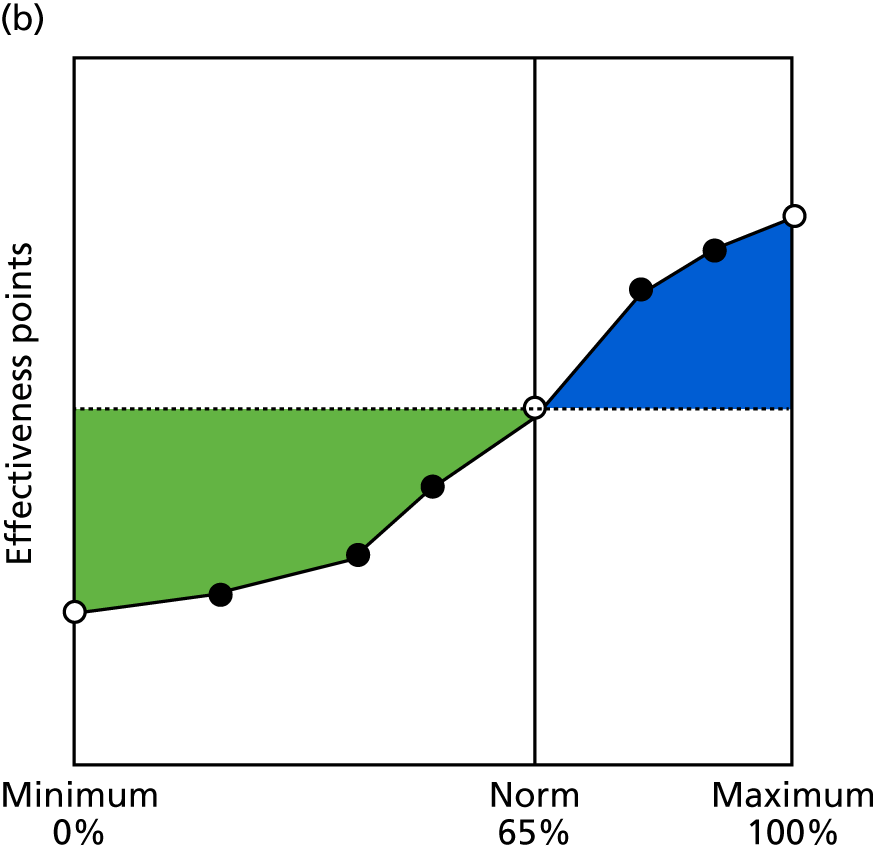

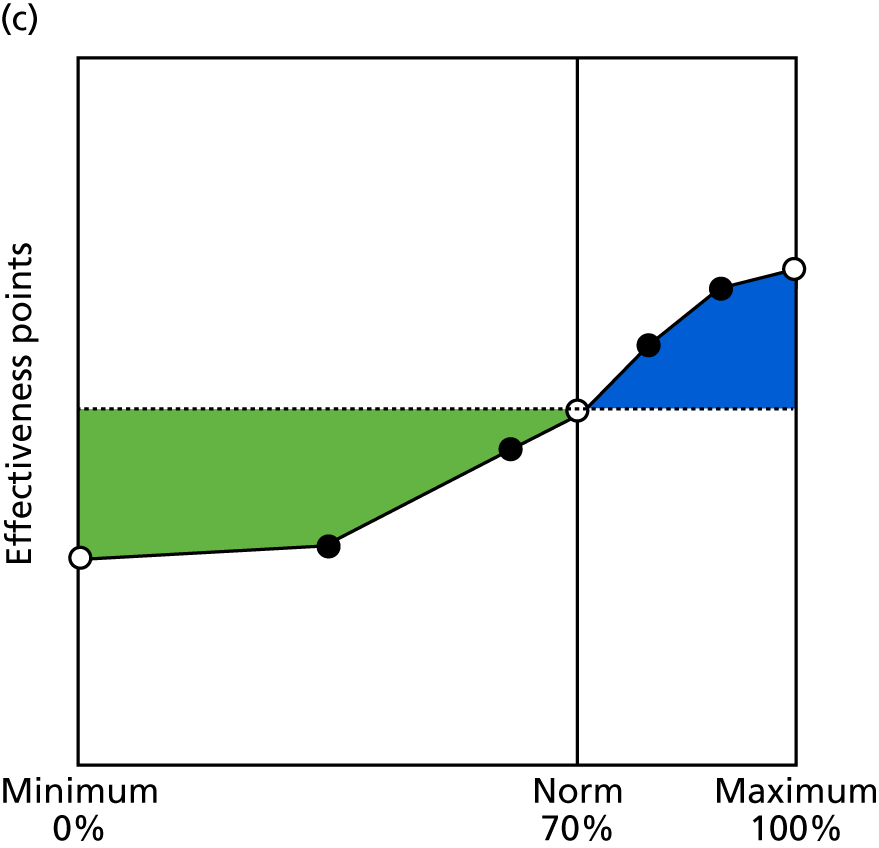

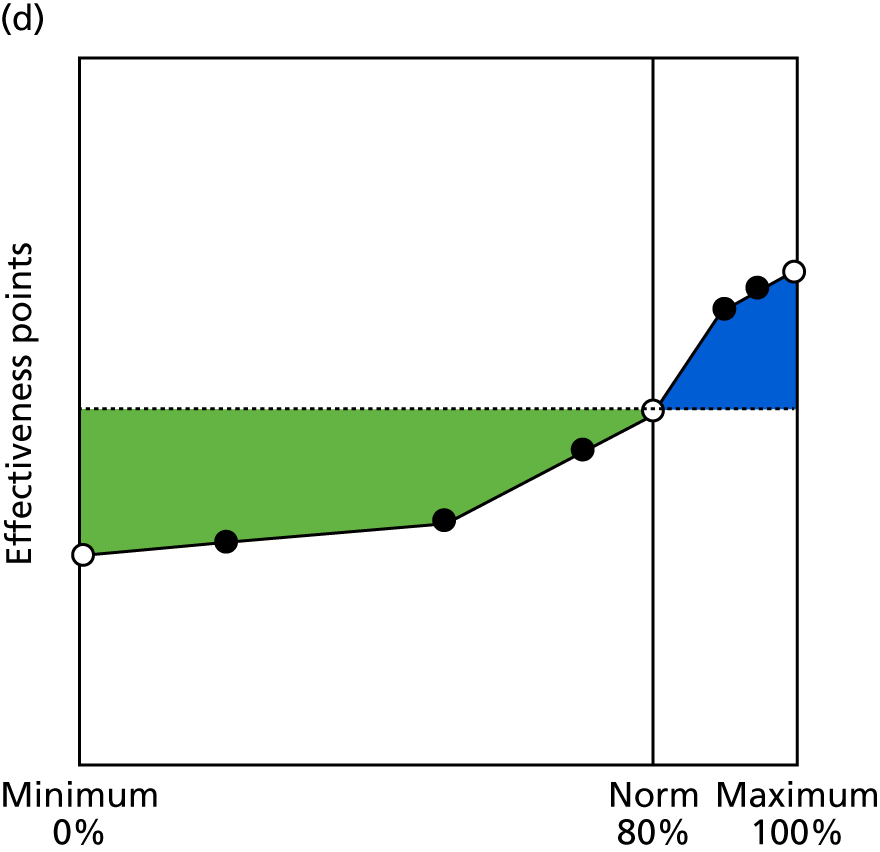

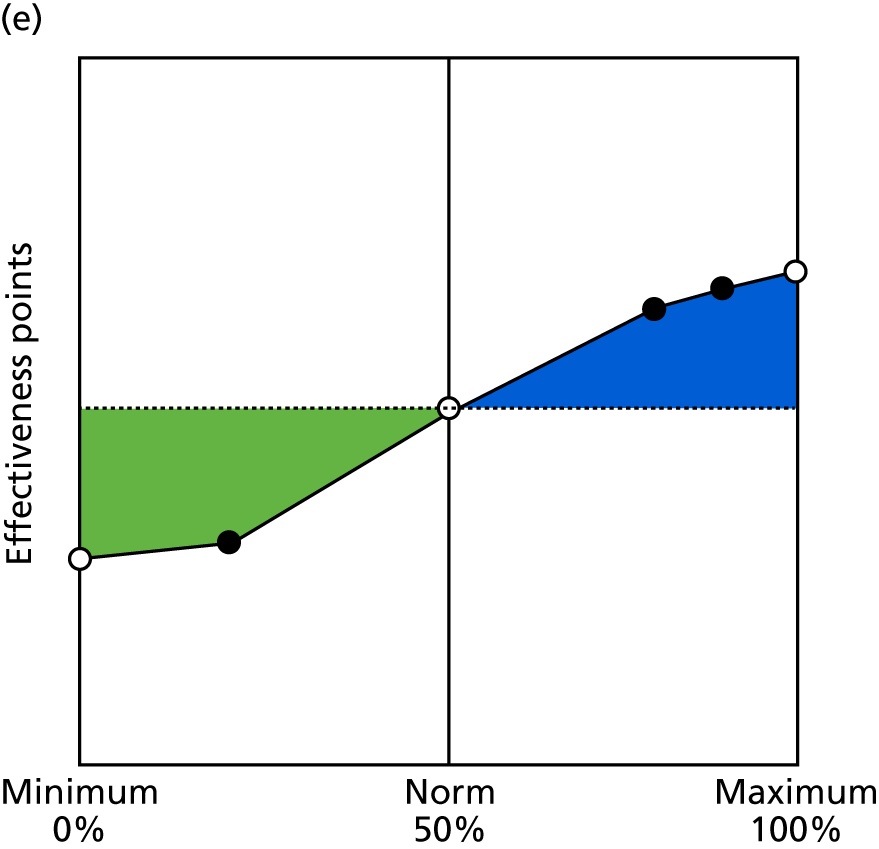

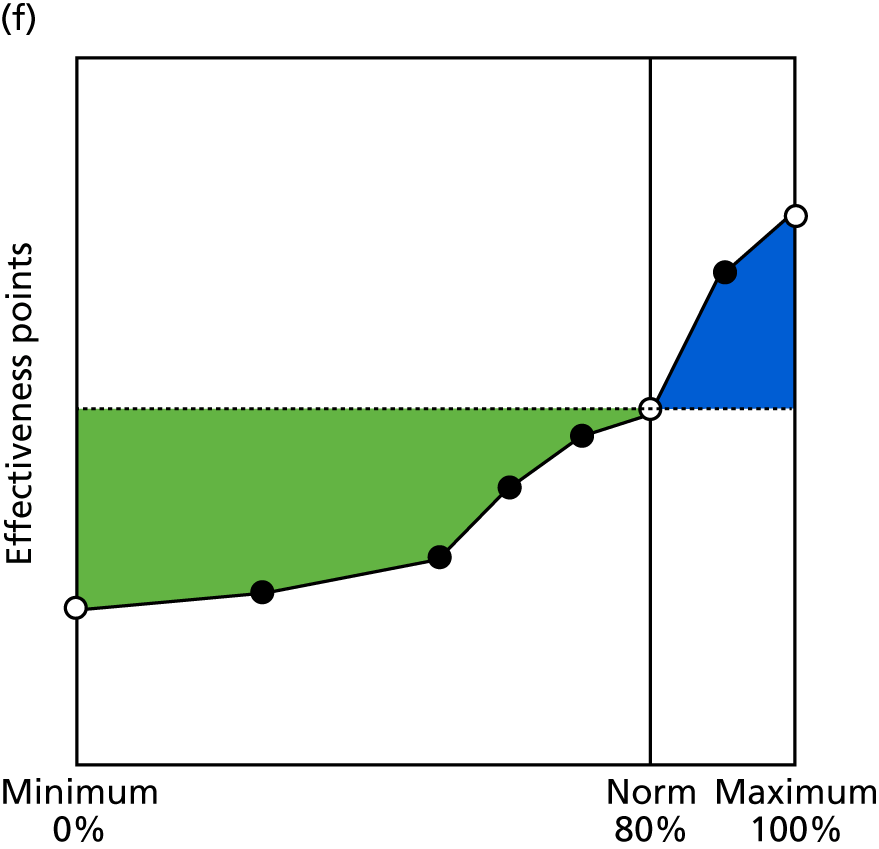

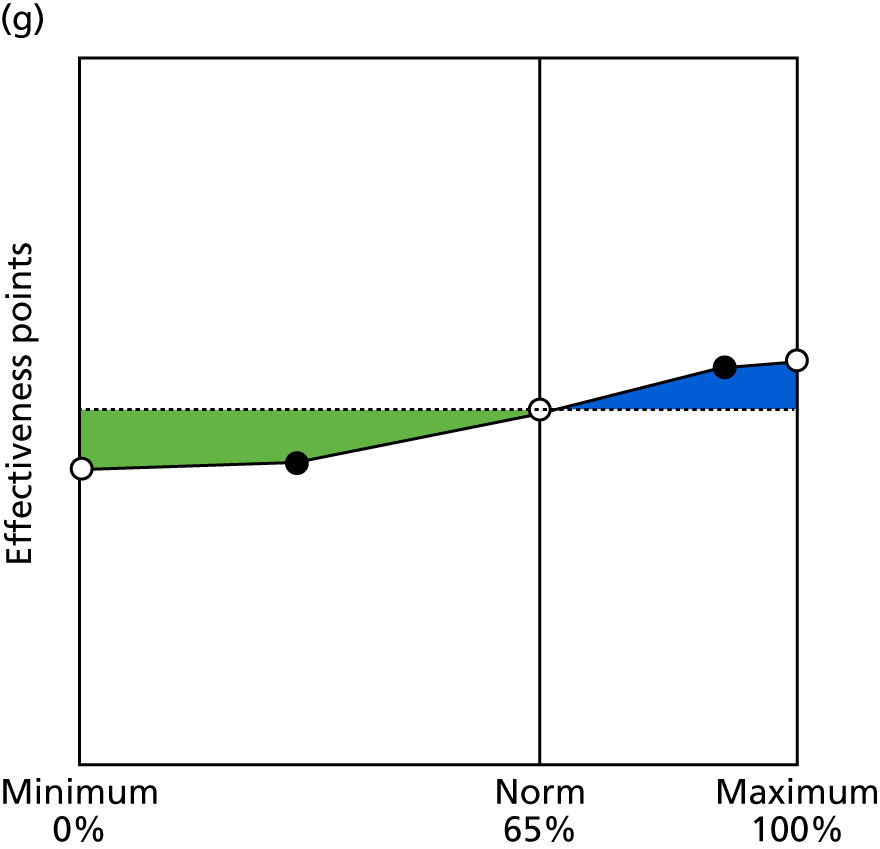

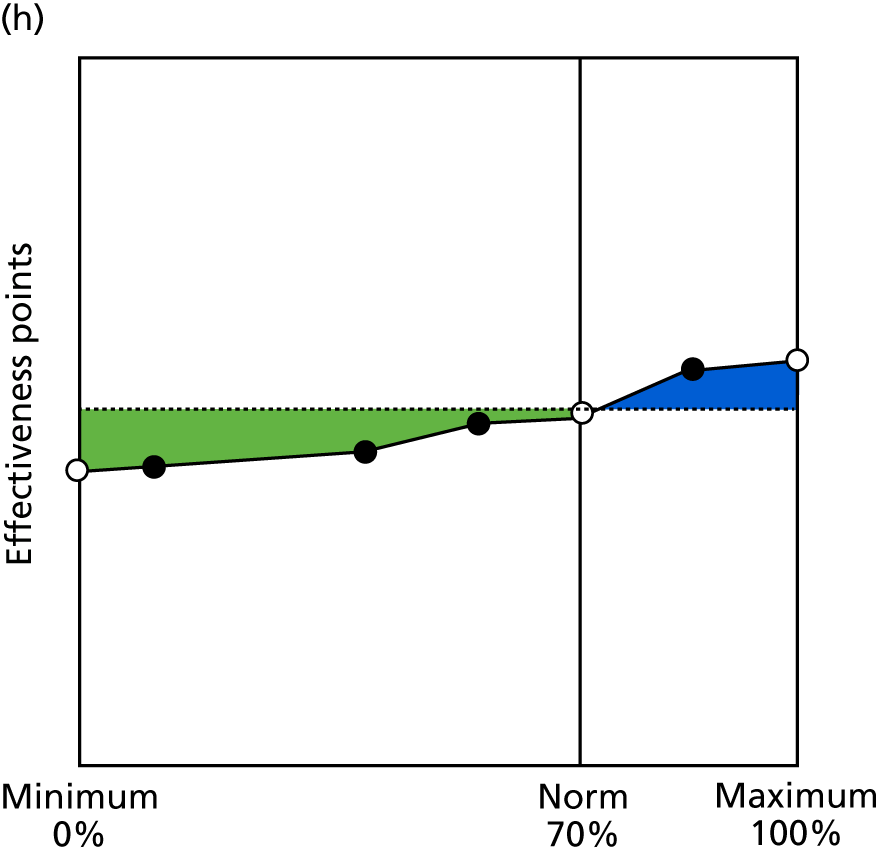

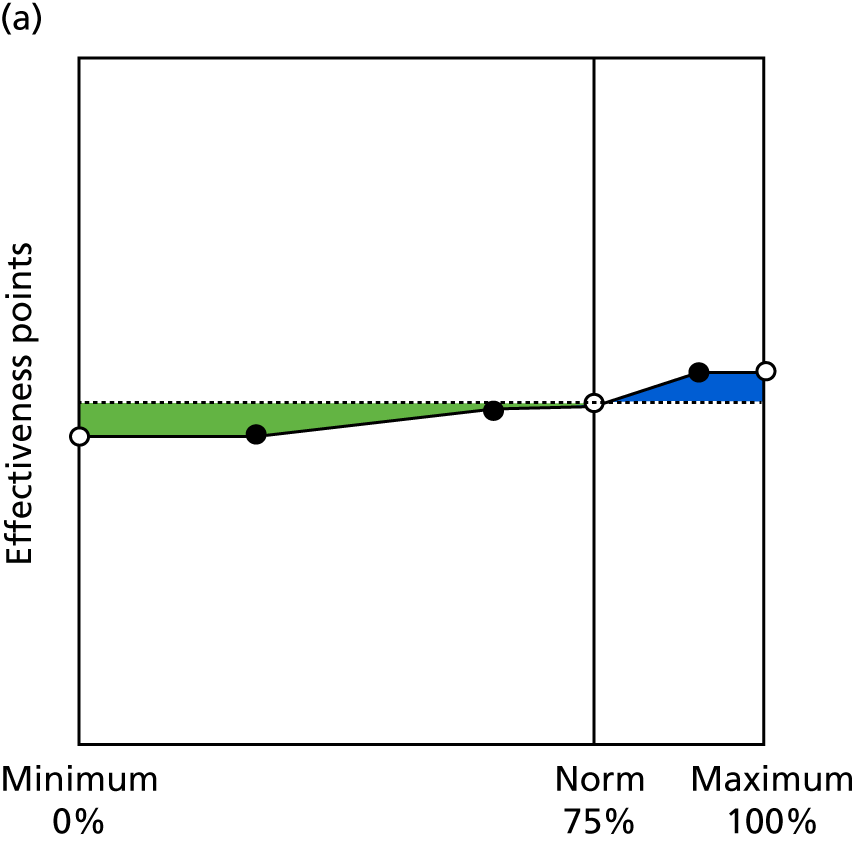

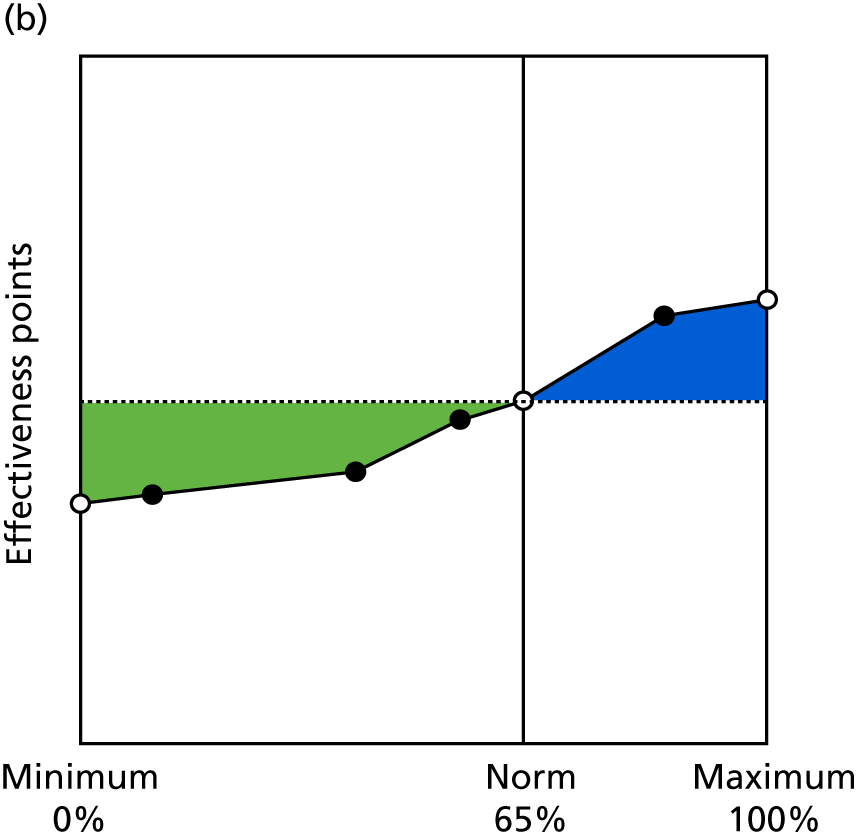

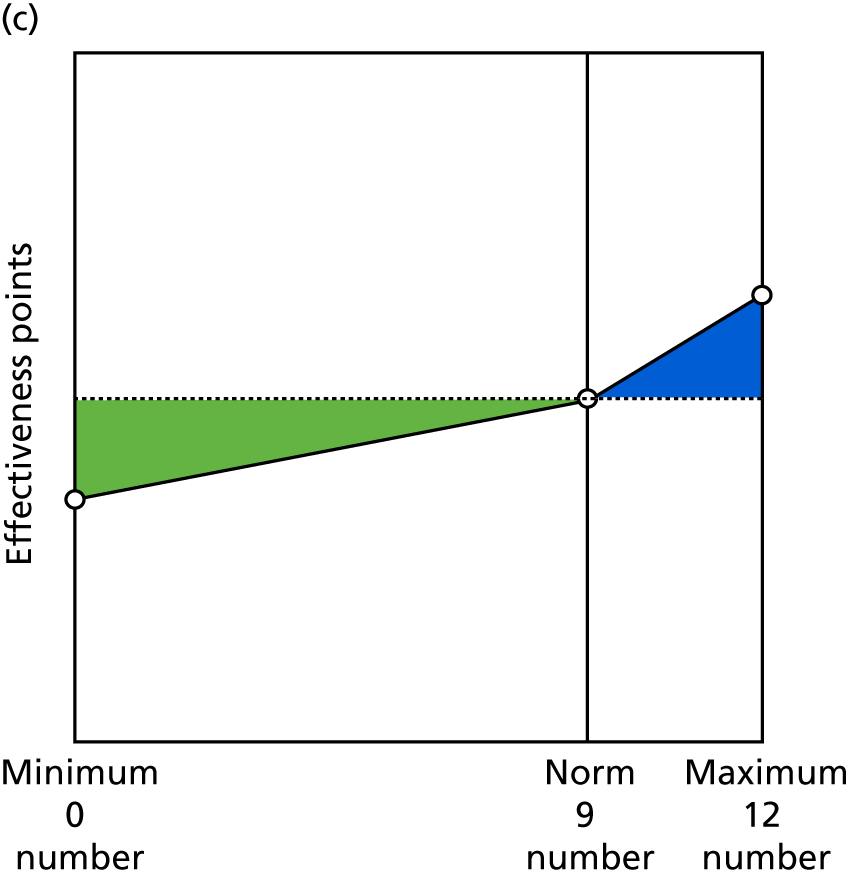

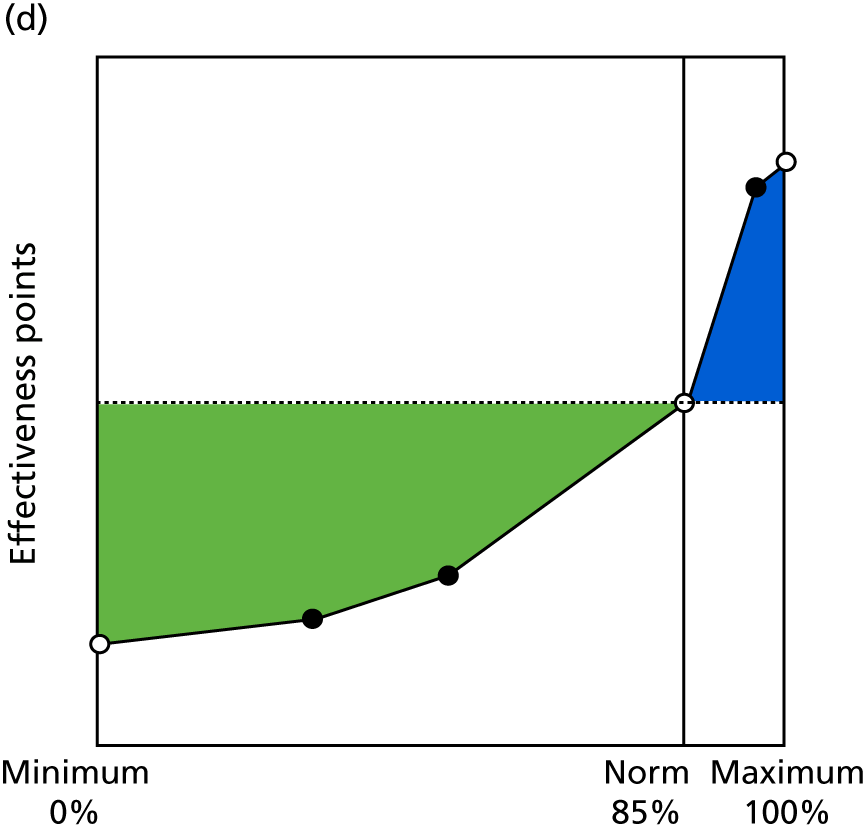

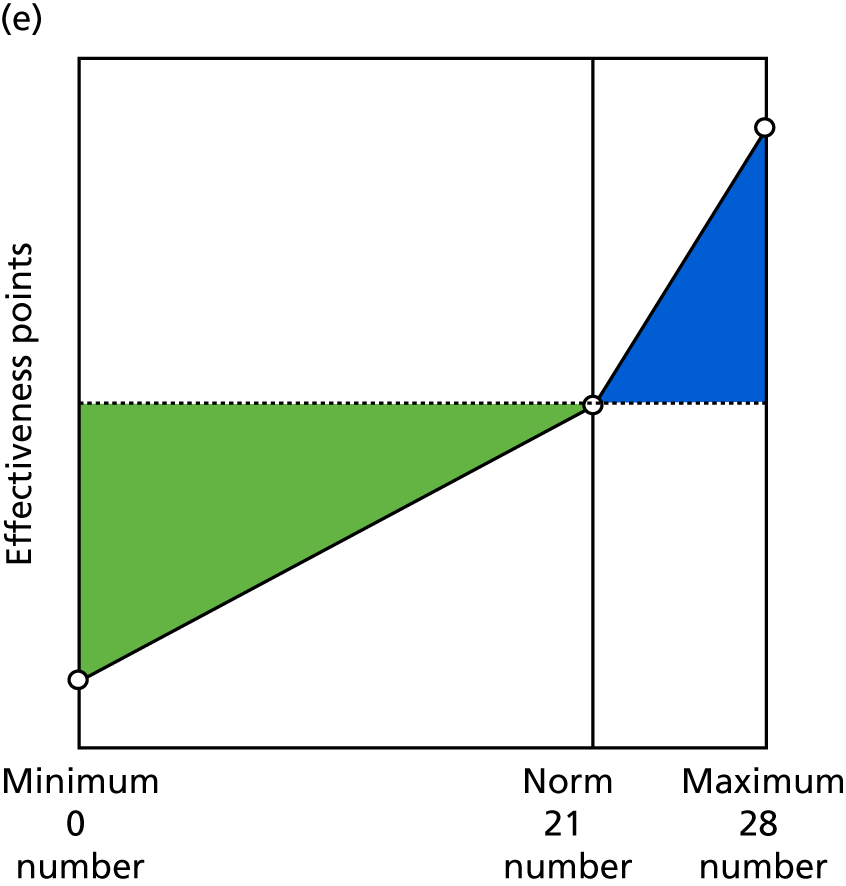

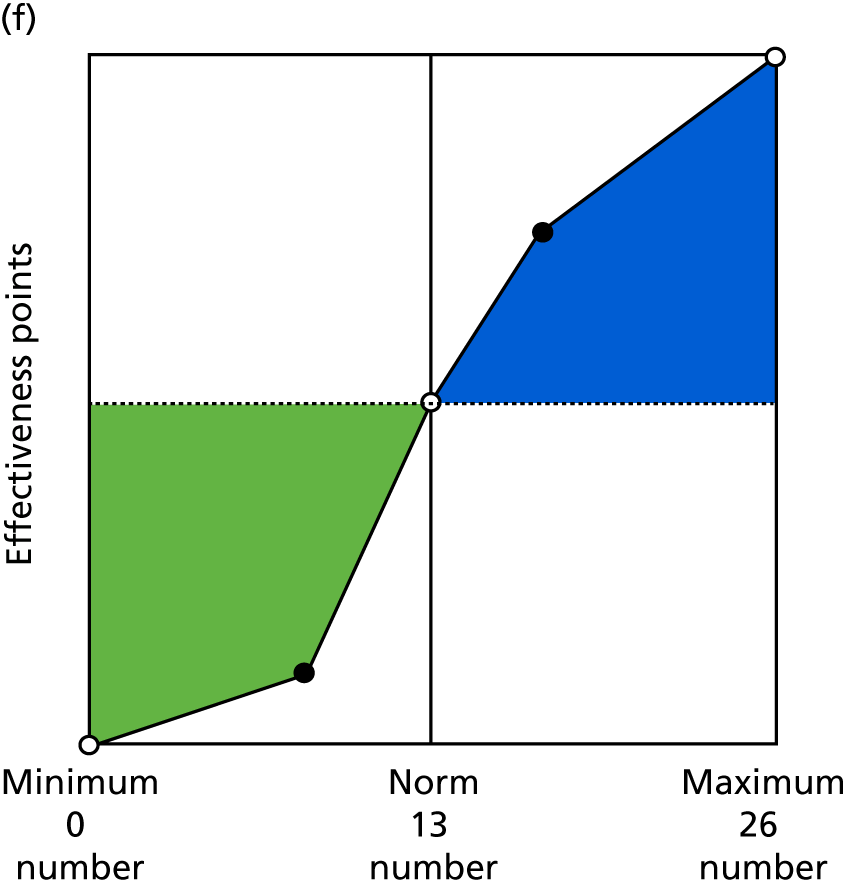

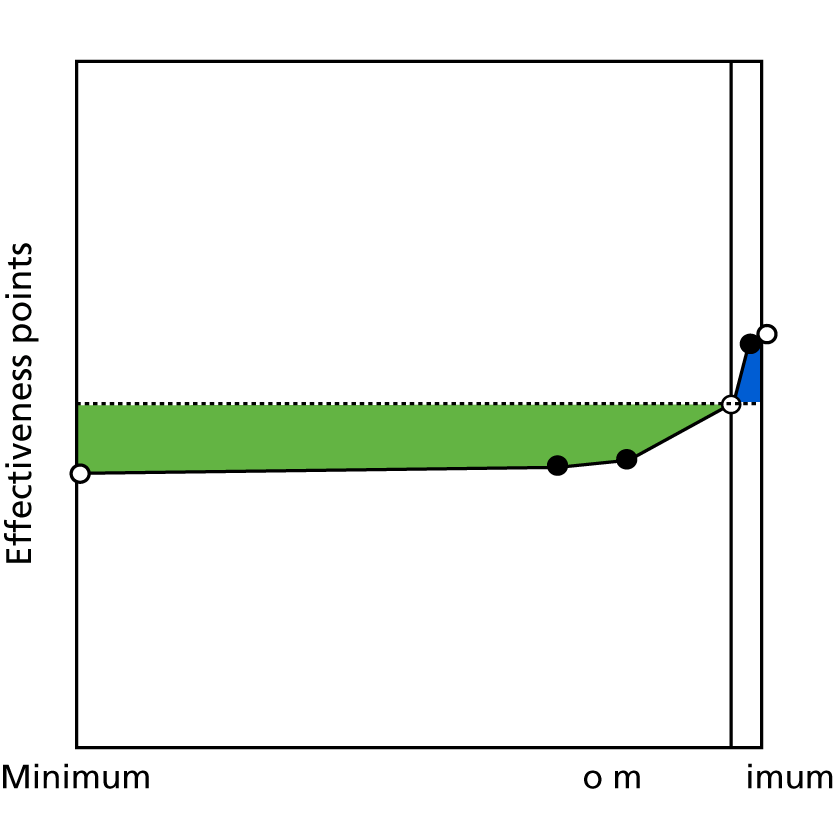

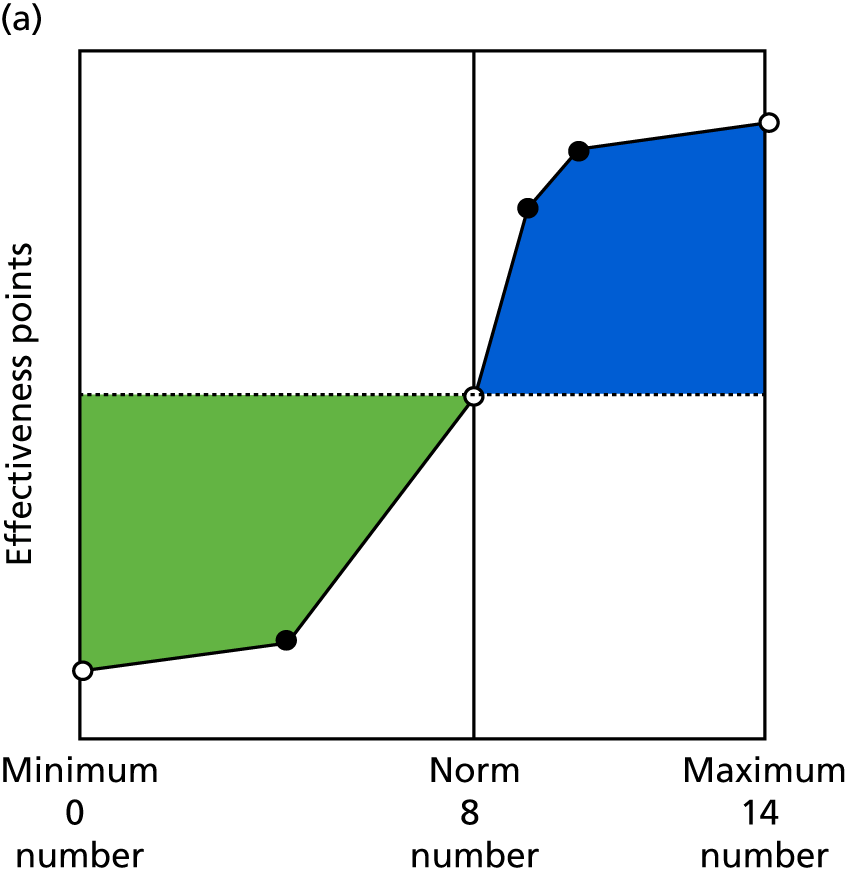

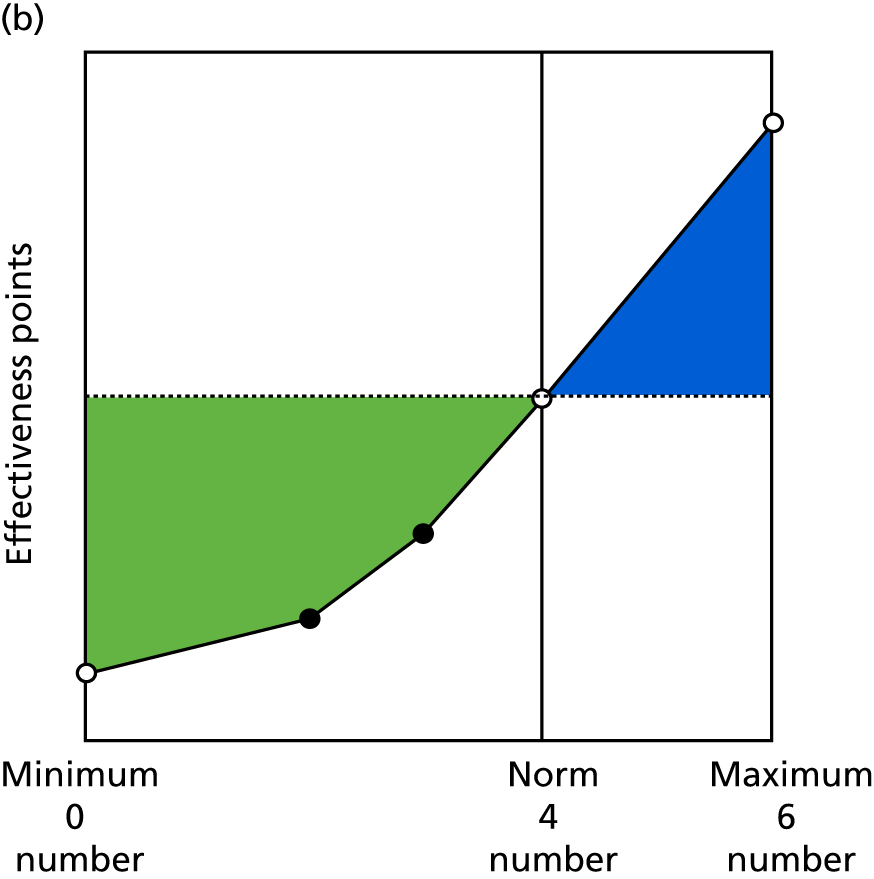

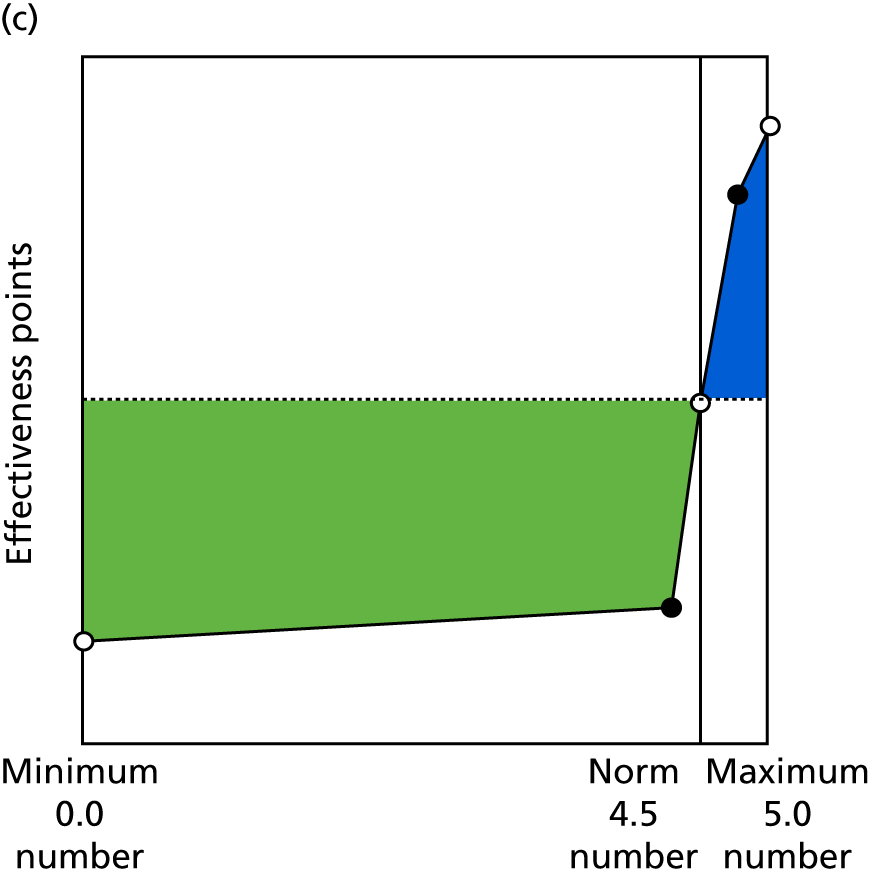

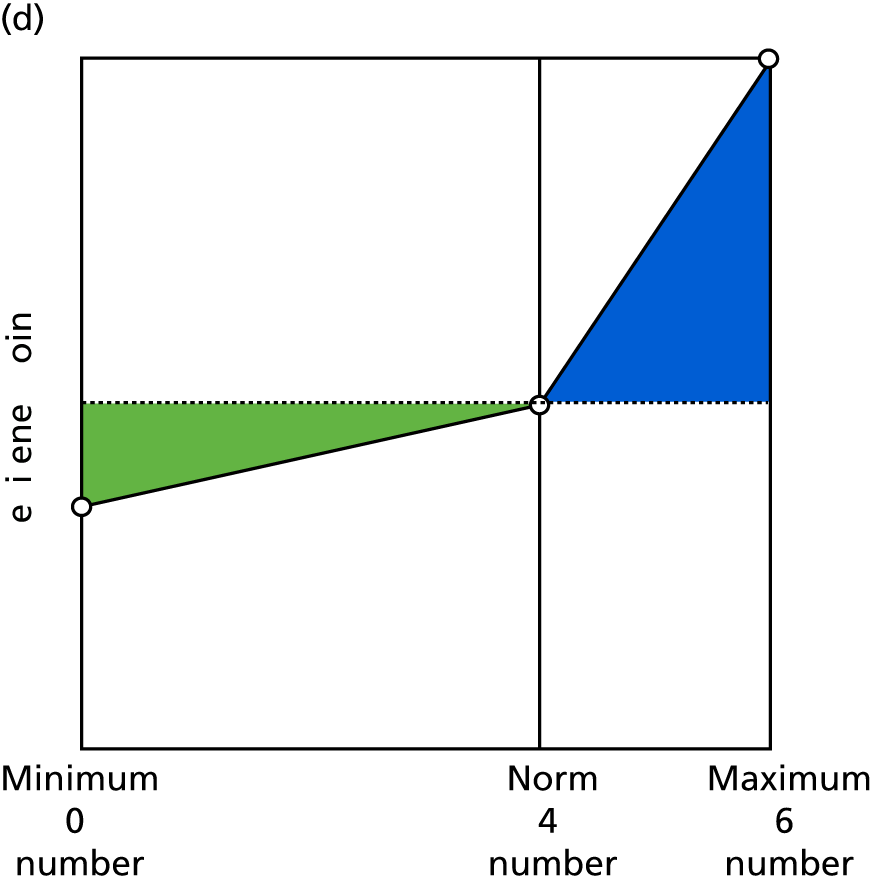

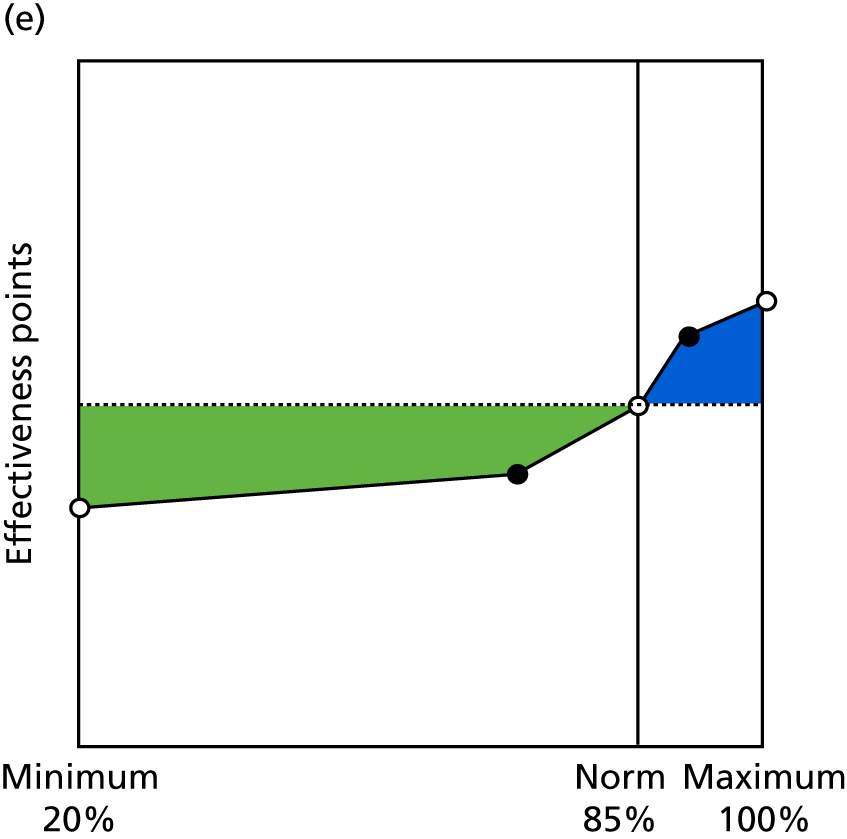

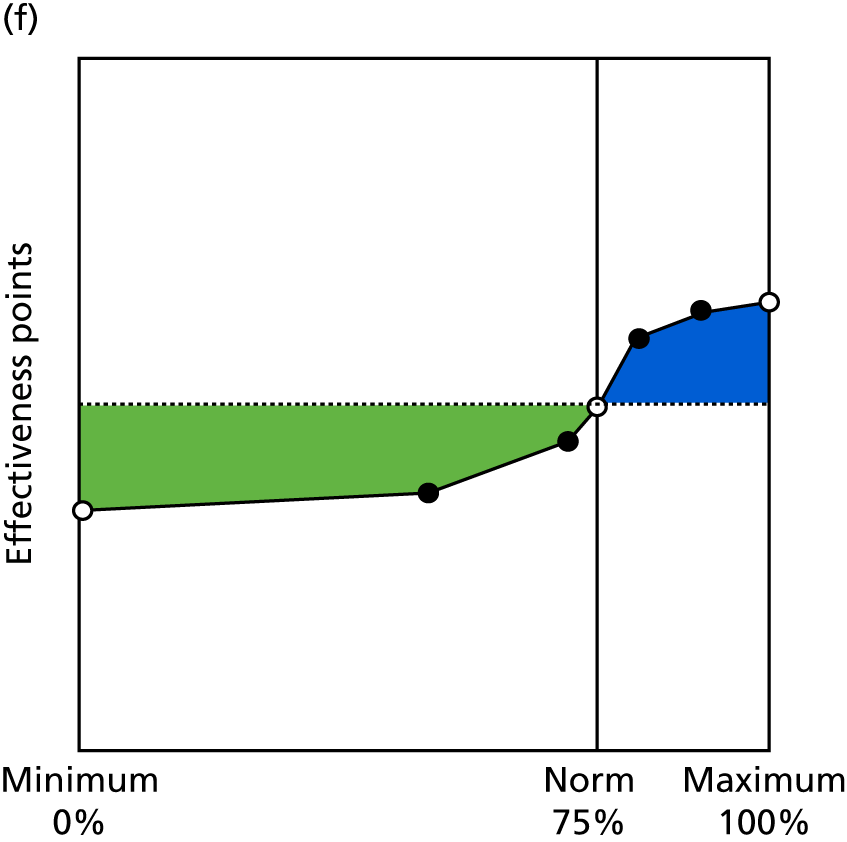

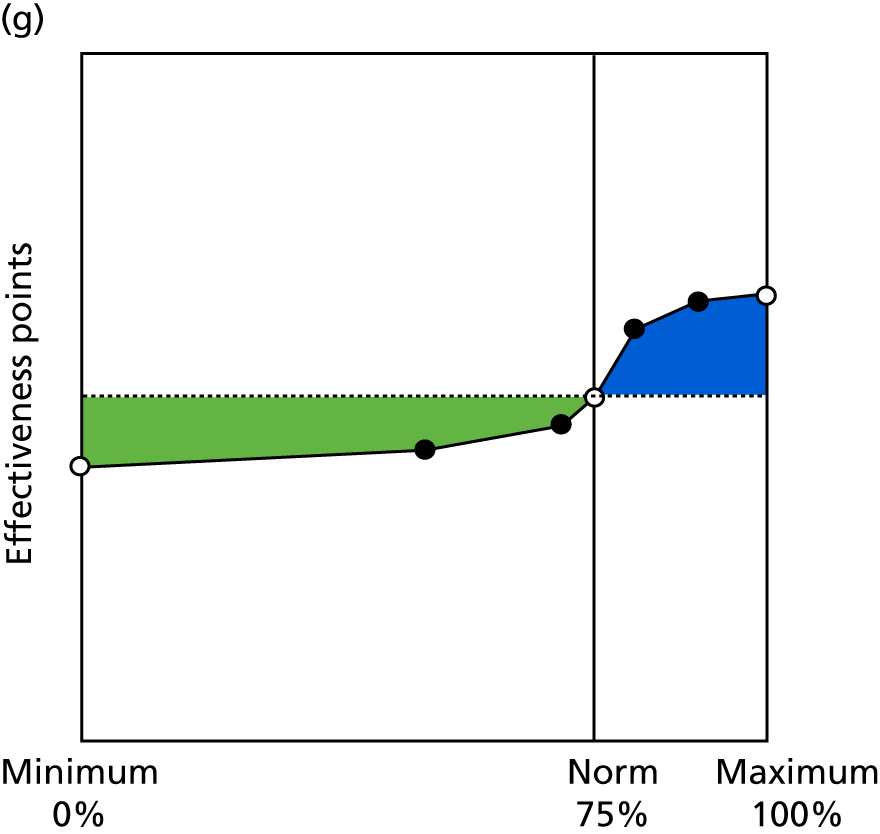

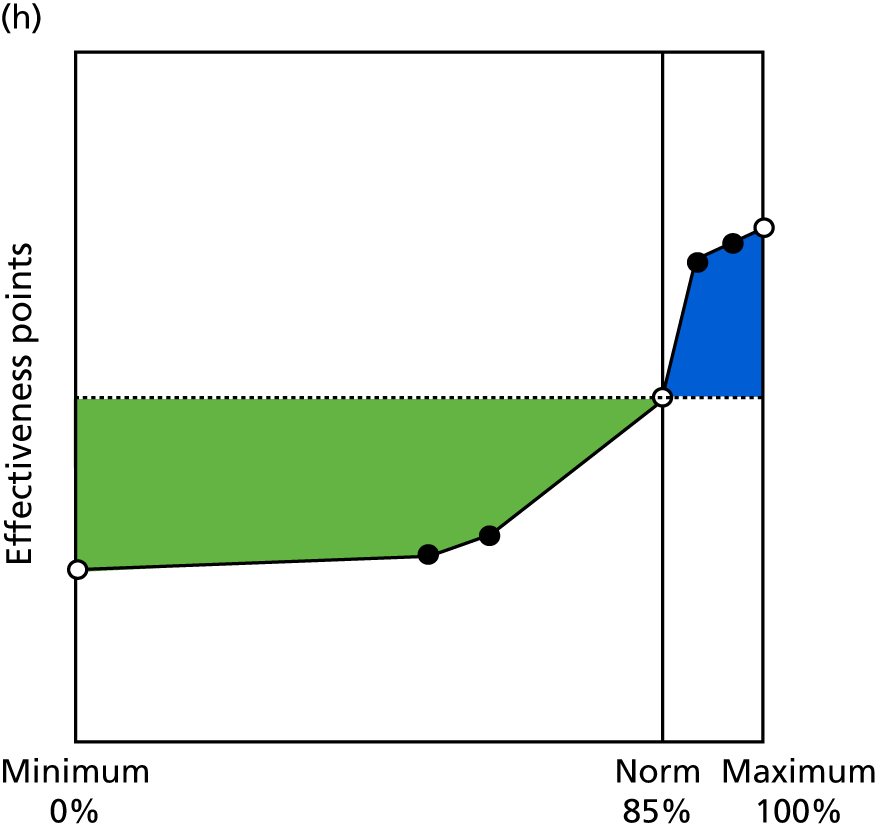

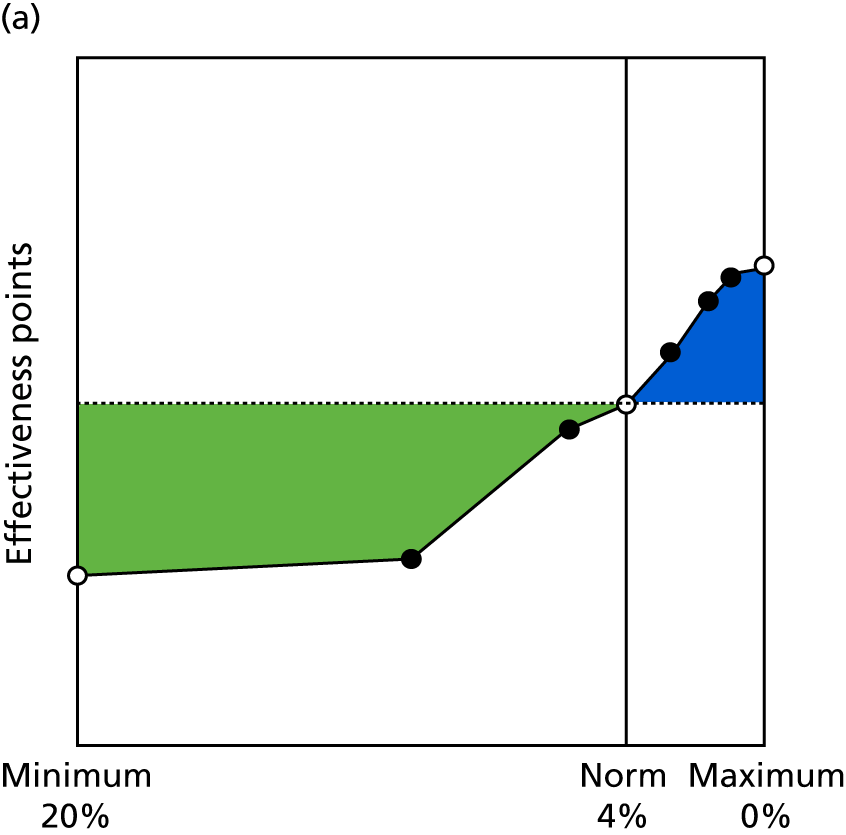

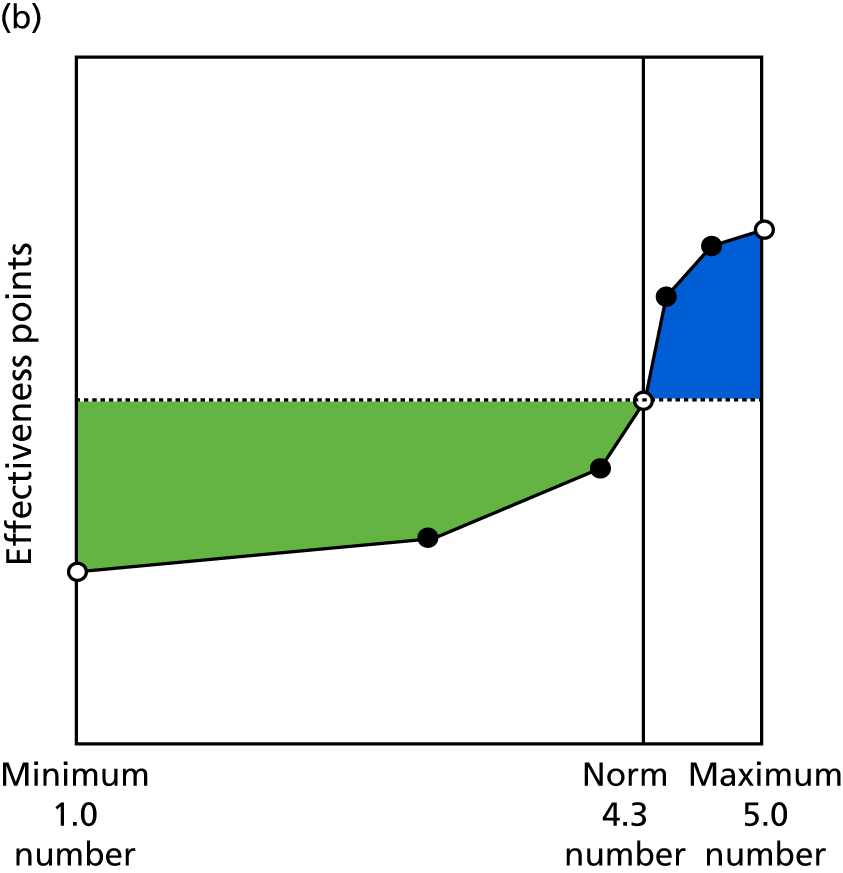

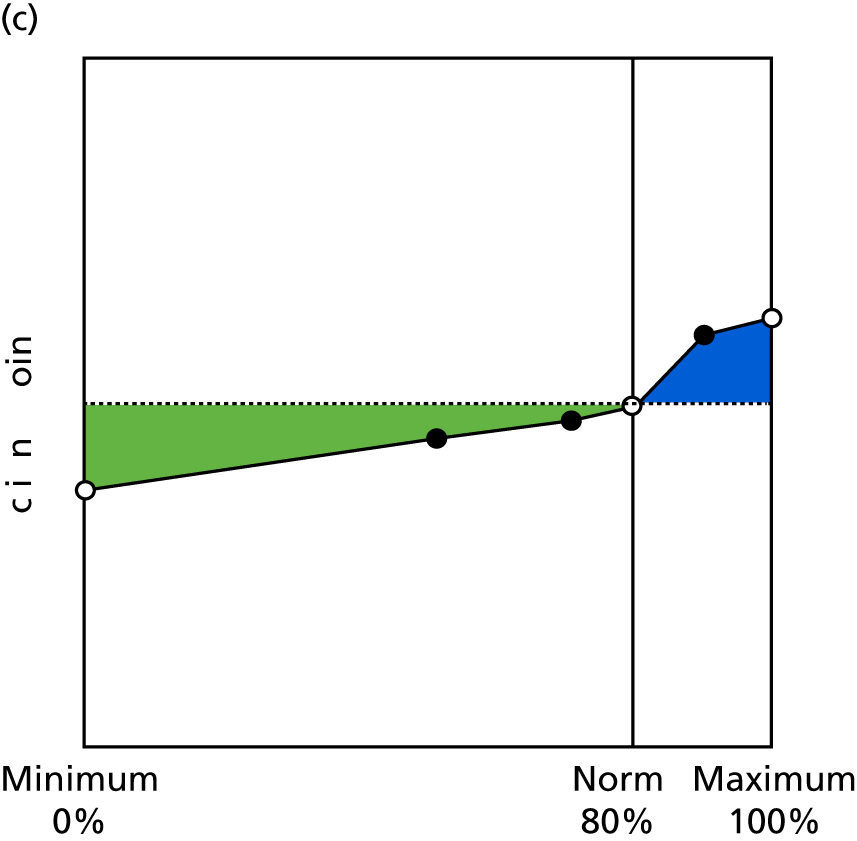

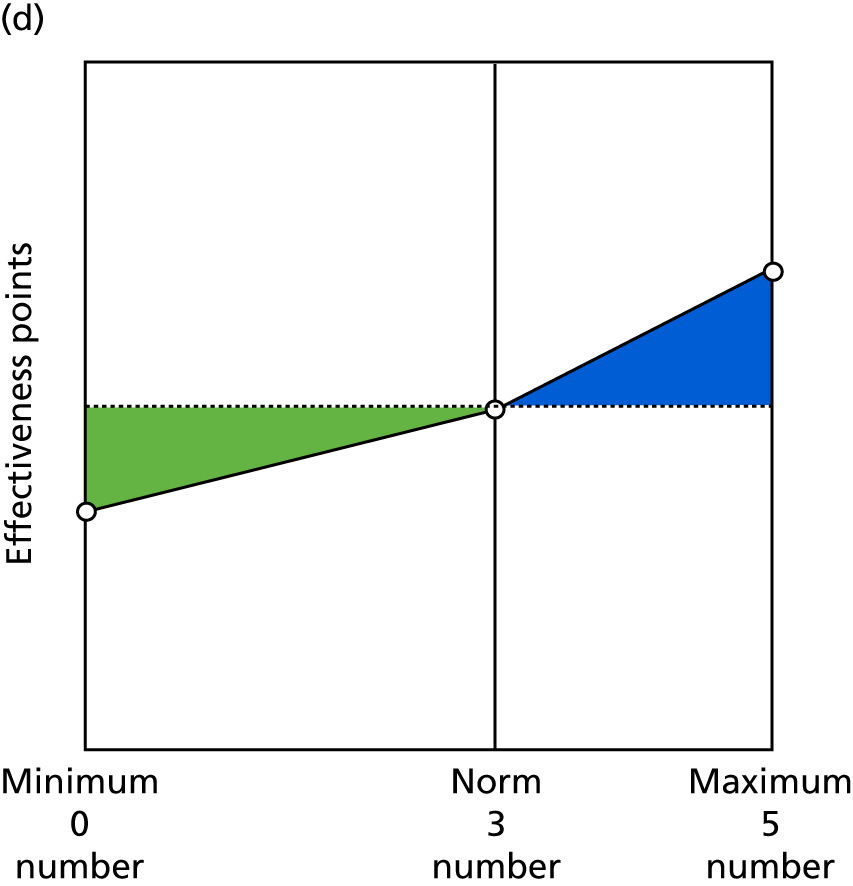

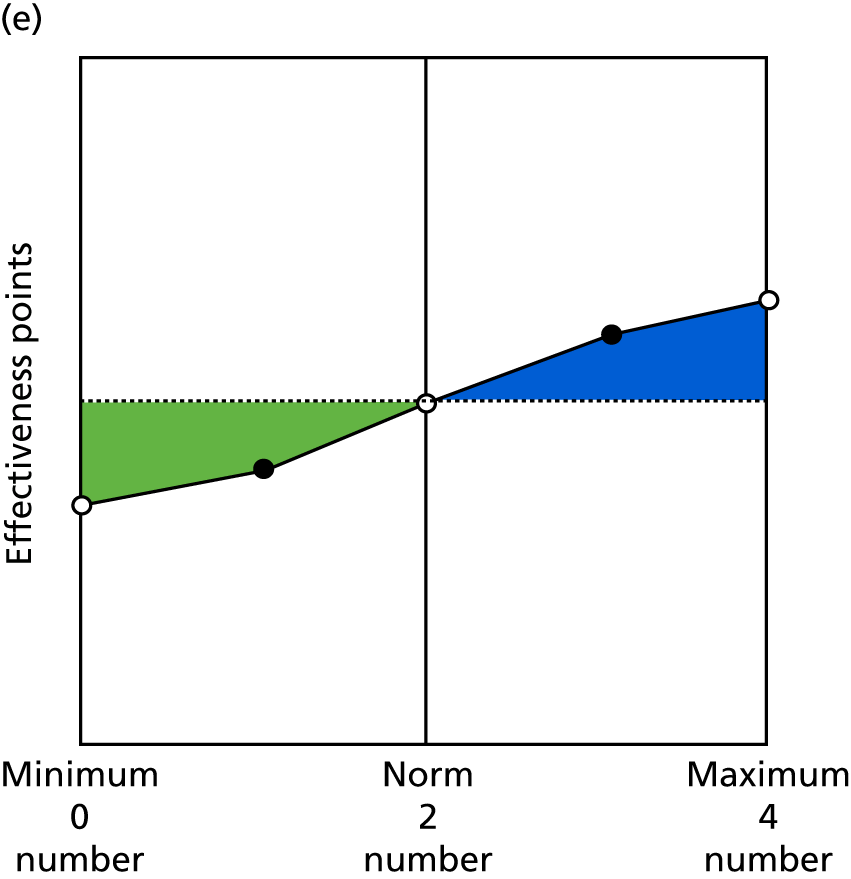

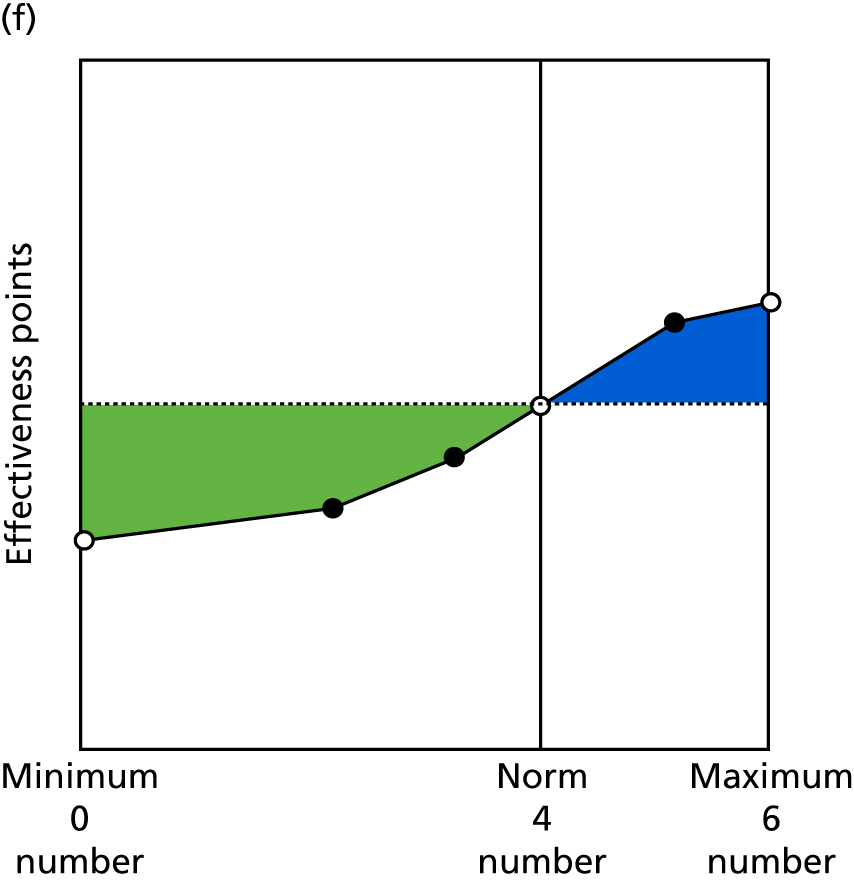

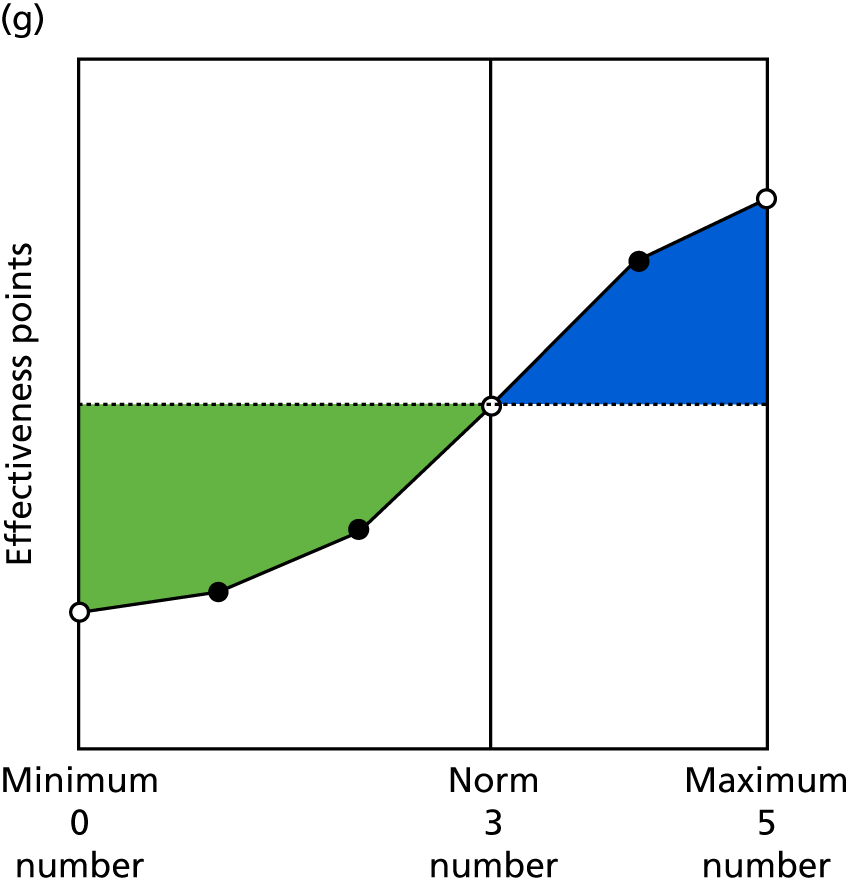

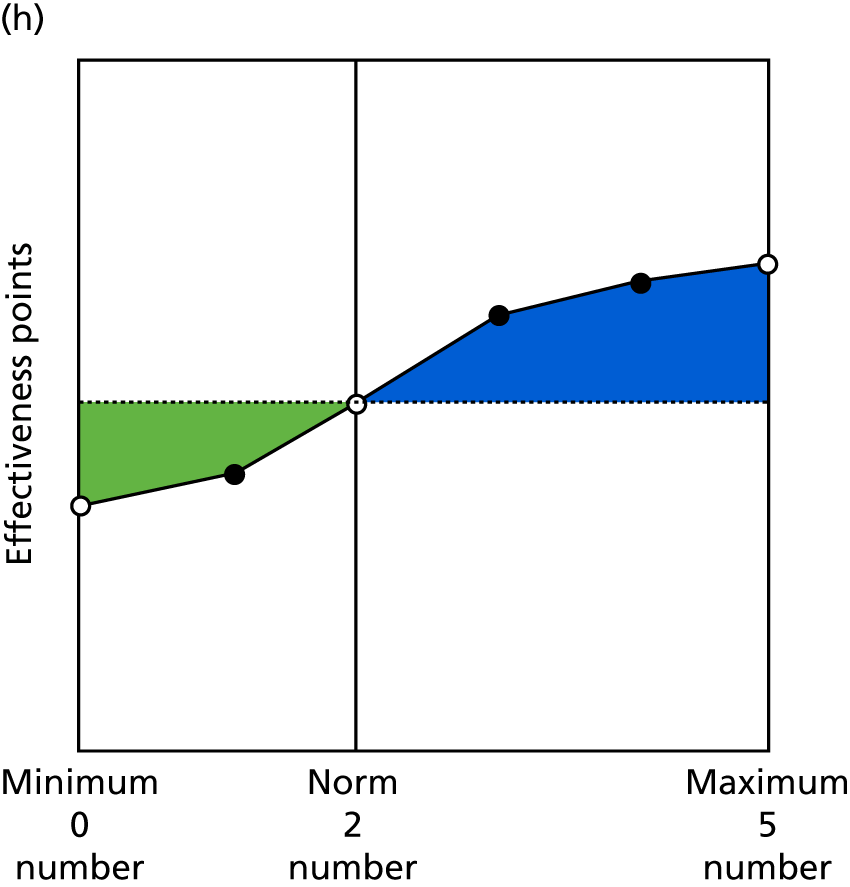

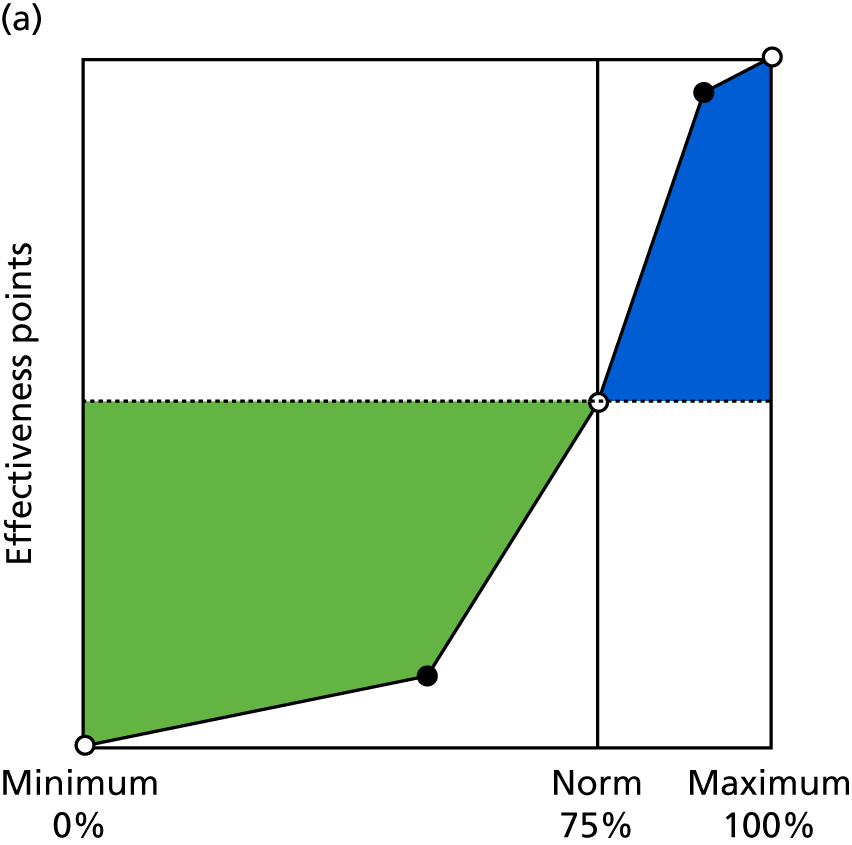

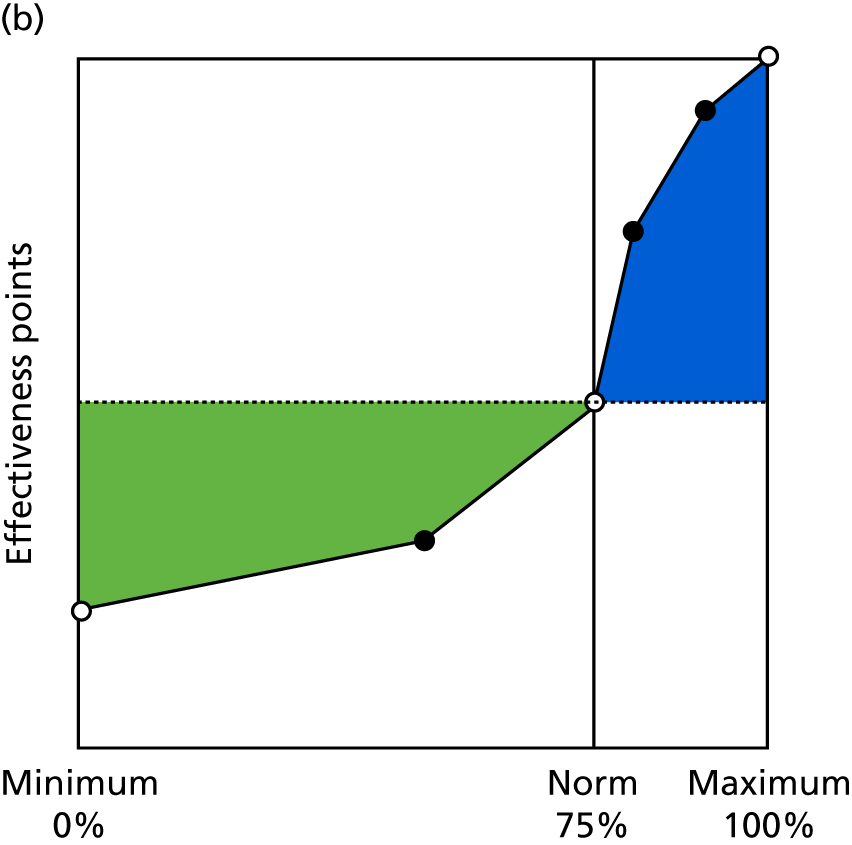

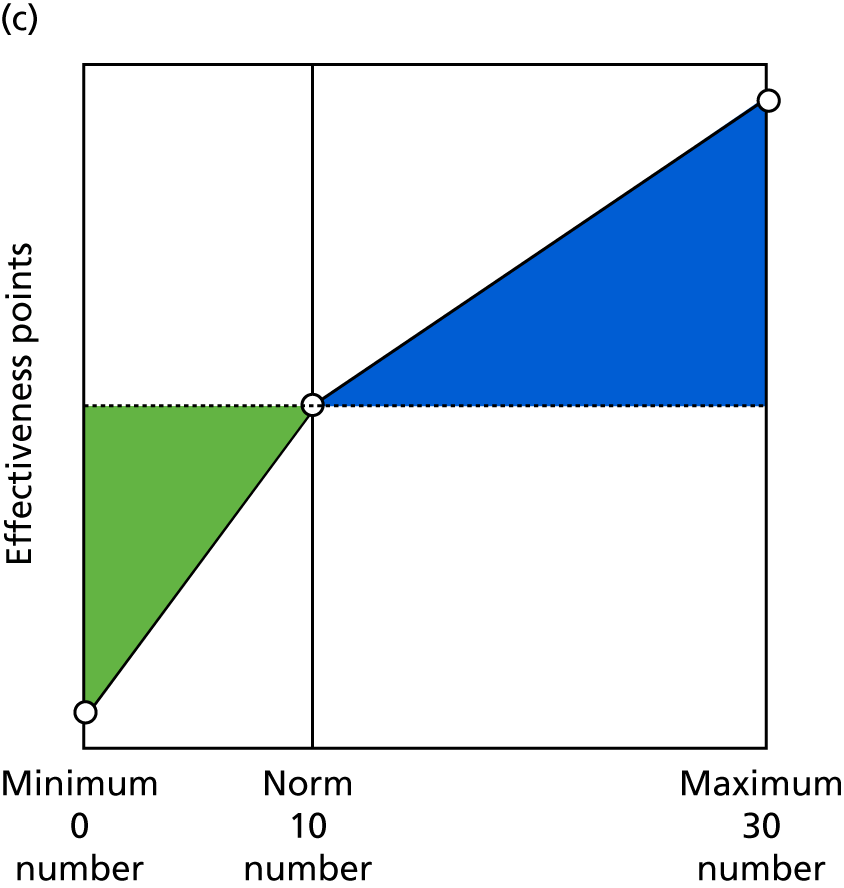

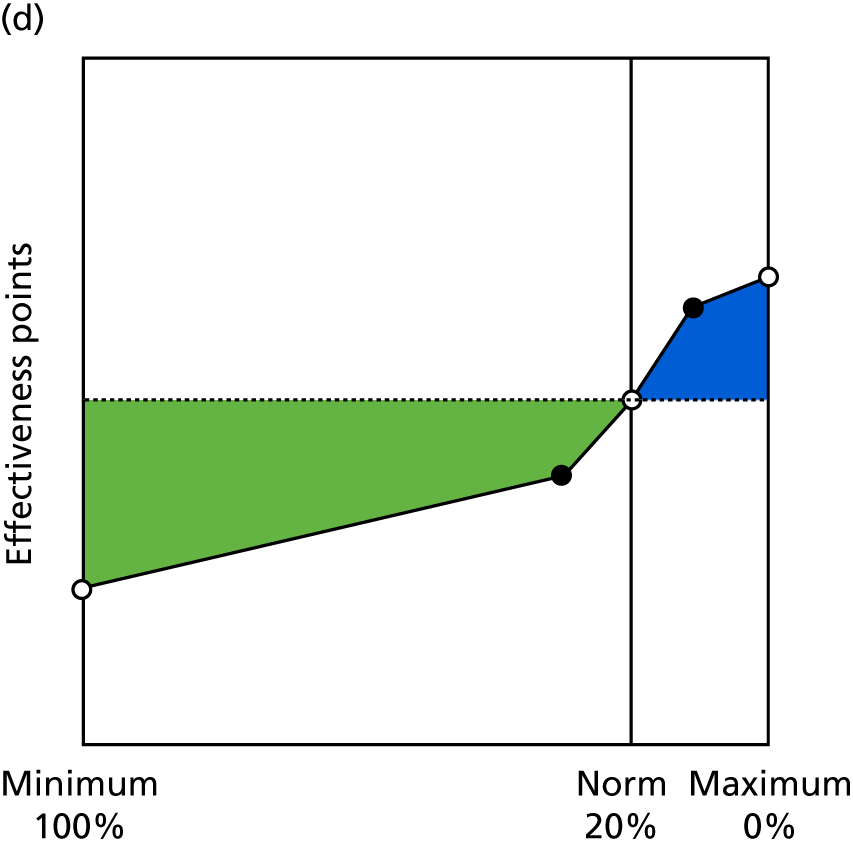

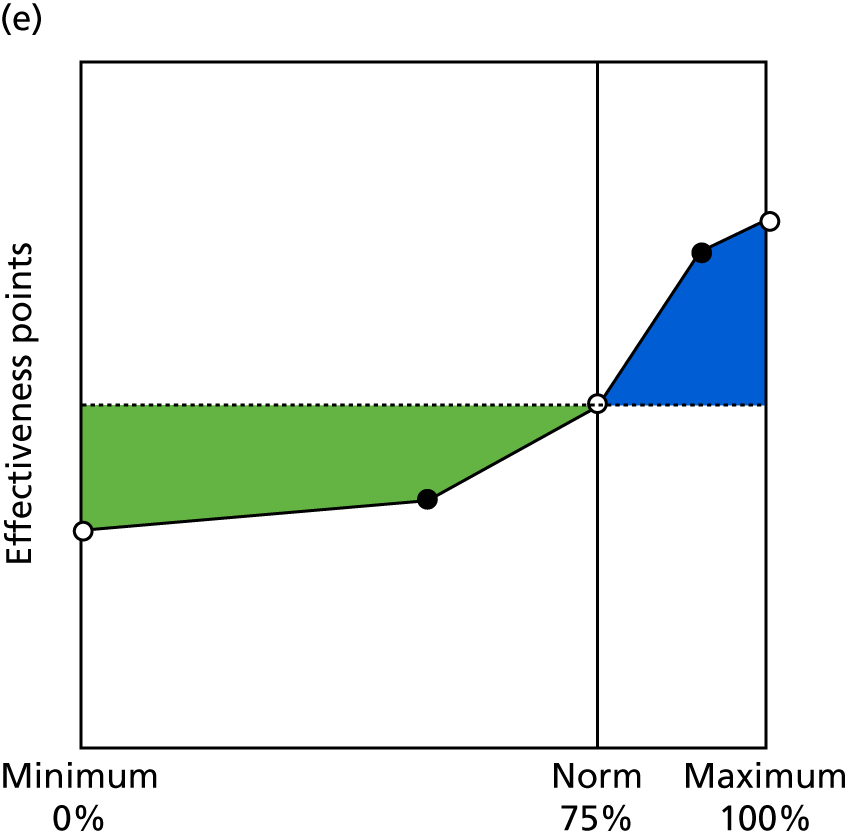

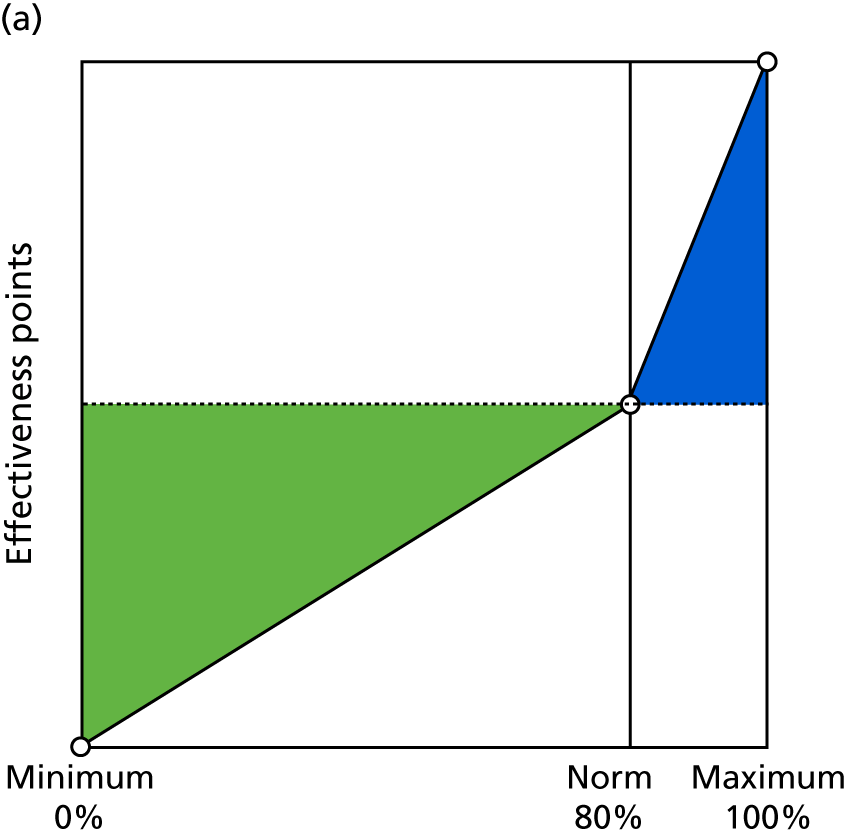

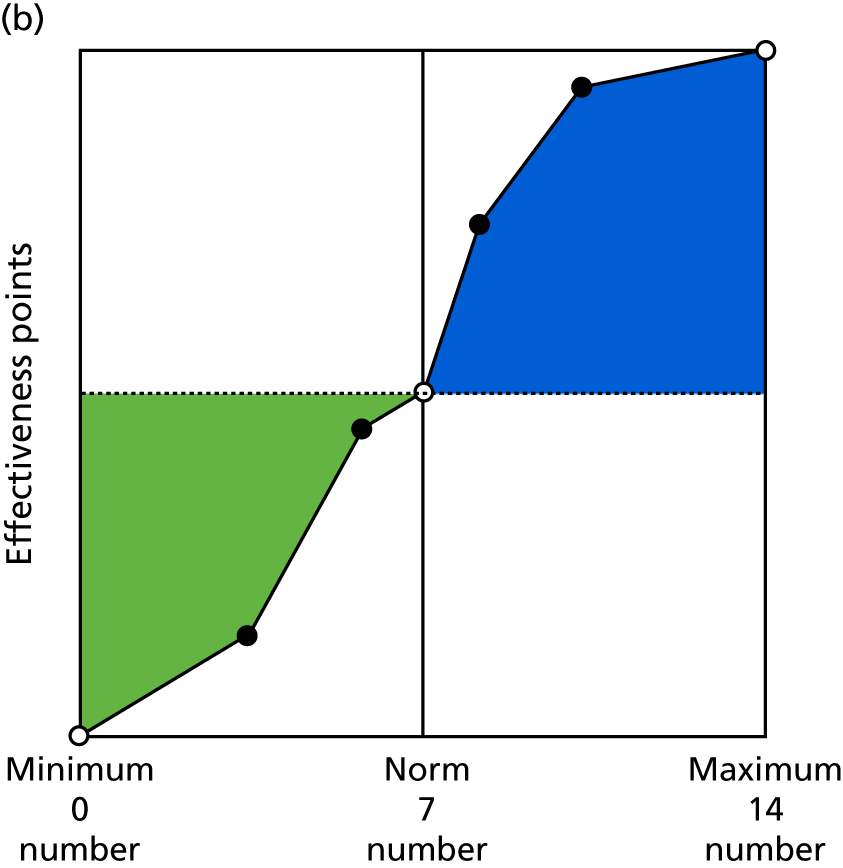

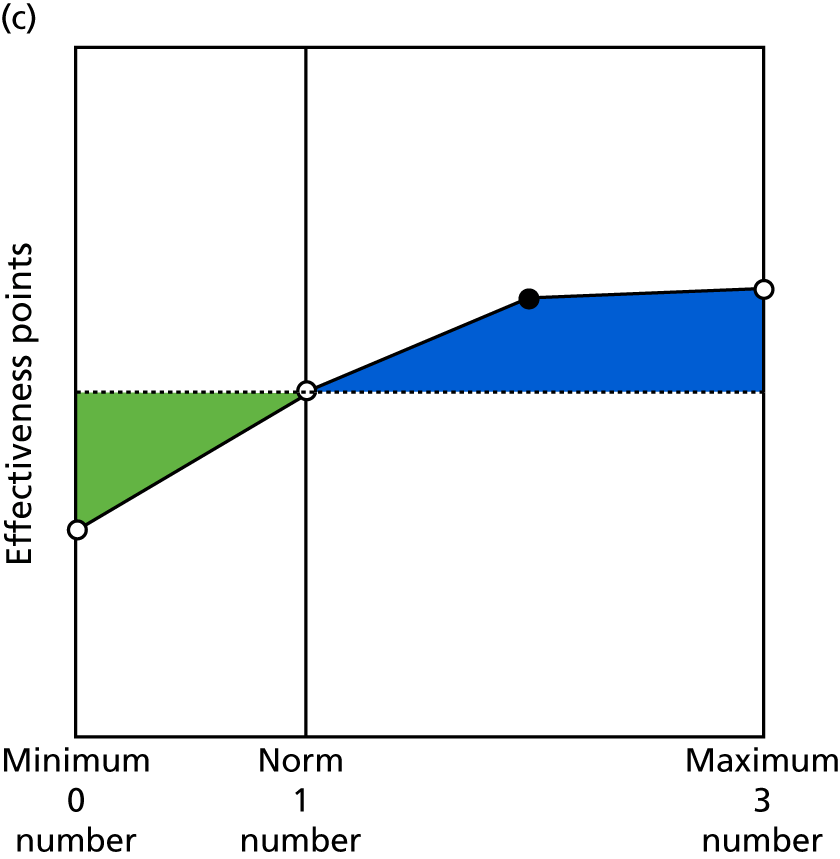

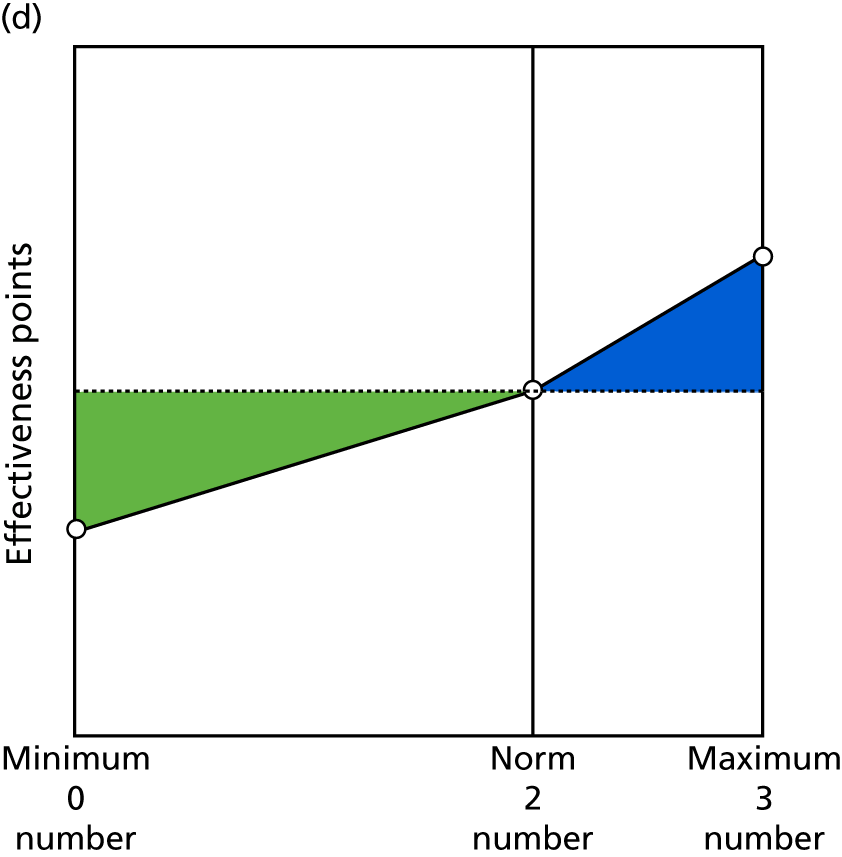

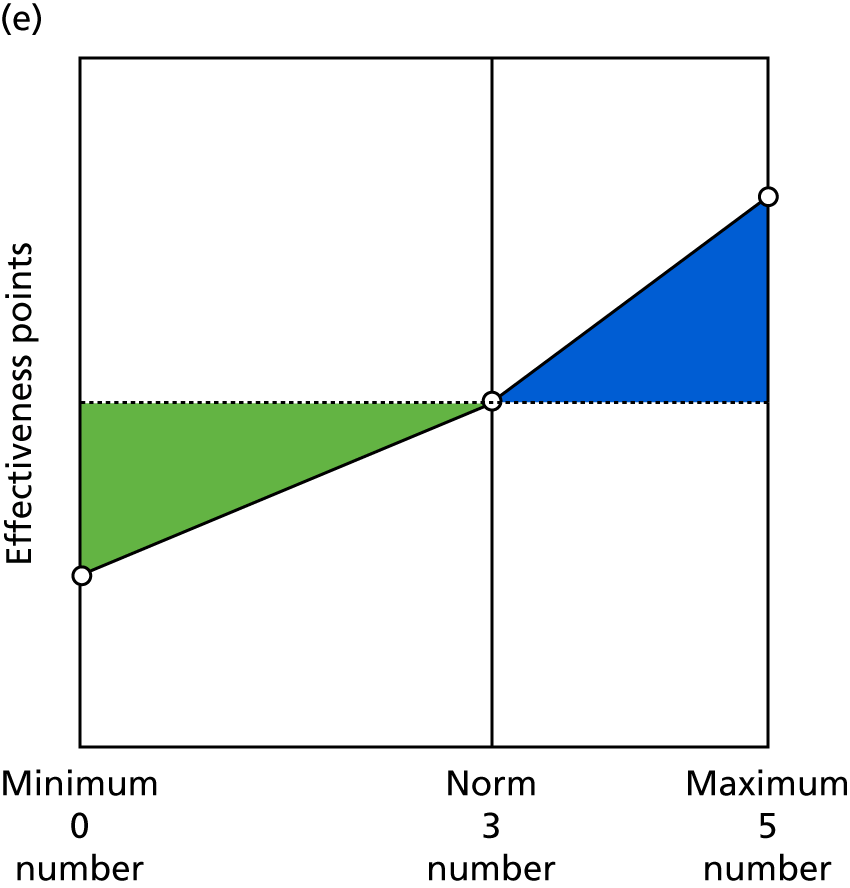

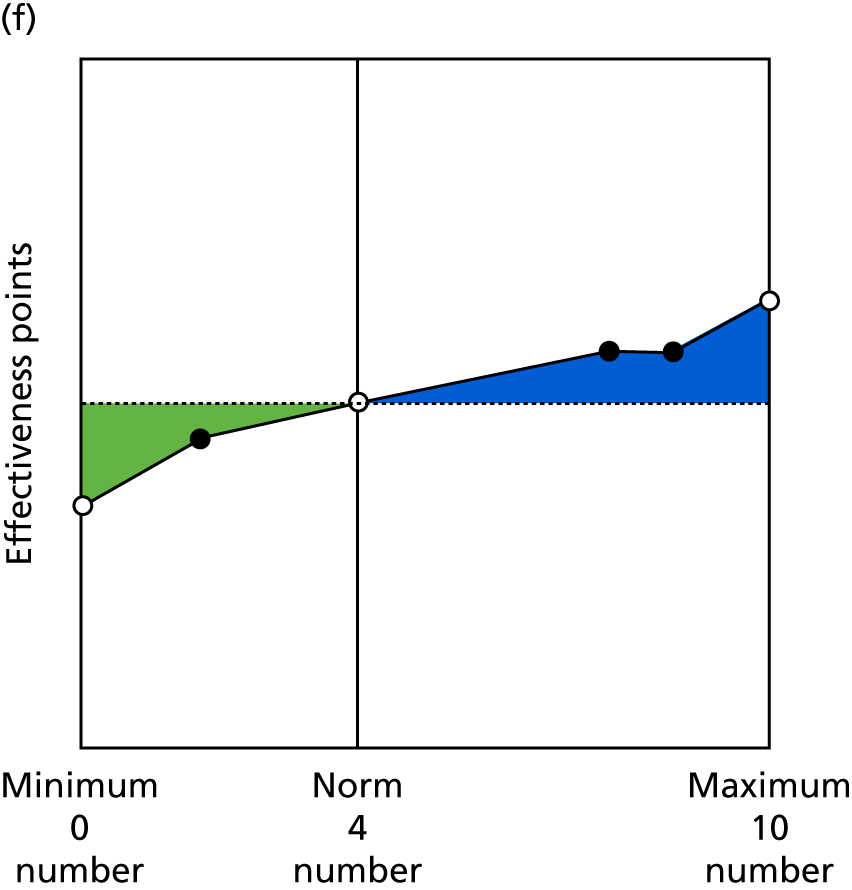

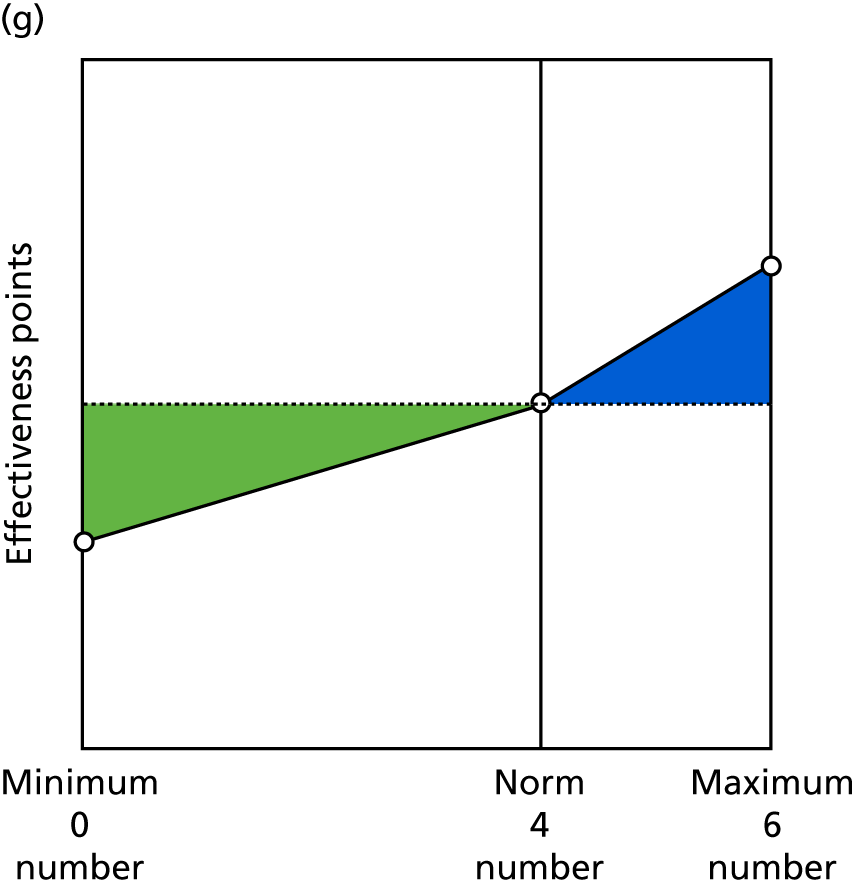

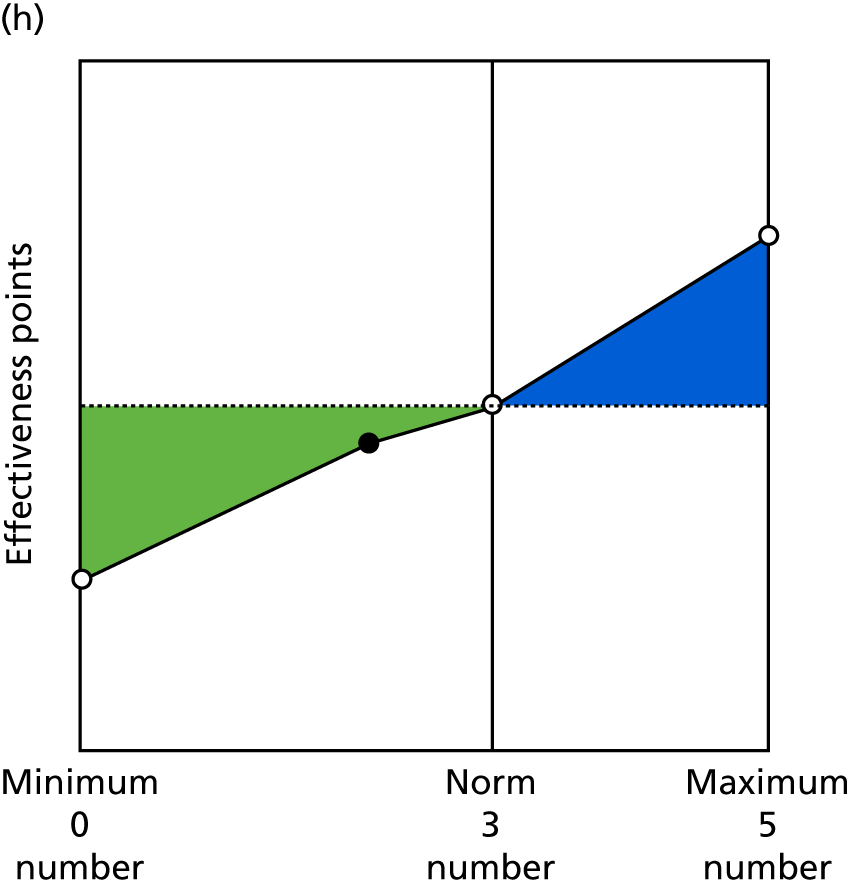

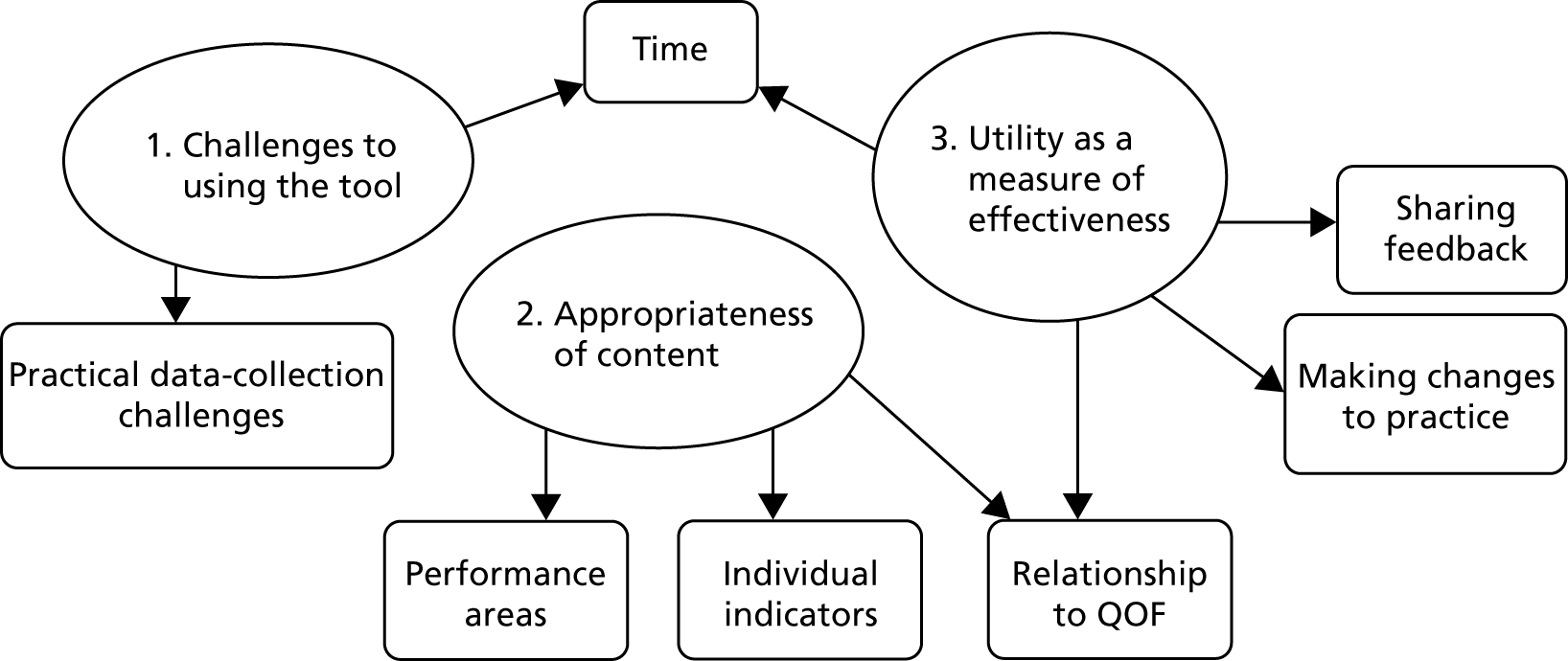

Identify contingencies: a method of weighting the different objectives. For each indicator, the contingency is a way of converting the actual value of the indicator into a score used for the overall productivity measure, in other words, saying just how good or bad particular values would be. These are set with a value of zero at the ‘neutral’ point, with maximum and minimum values of up to ±100 for the most important indicators, or proportionally less for less important indicators. These can be non-linear and asymmetrical (so that small changes can mean more at one point of the scale than at others). The setting of contingencies is also done as a collaborative effort between different unit members, although not necessarily the same ones as those who set the objectives and indicators. An example of a contingency is shown in Figure 1.

-

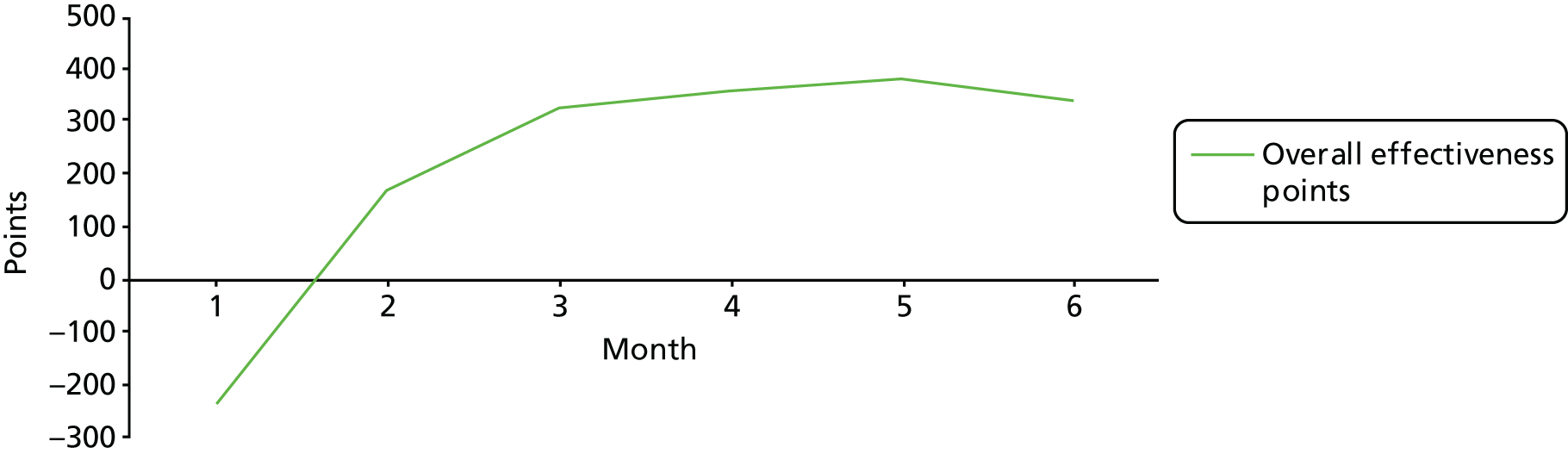

Finally, the system runs by collecting the indicator data over a designated period of time (e.g. 1 month), with an effectiveness score being calculated for each indicator at the end of that period, converted via the relevant contingency. These can then be summed to give an overall effectiveness score.

FIGURE 1.

Example of a ProMES contingency.

This comprises the measurement part of the process. The score produced is alternatively referred to as a productivity score and an effectiveness score. The underlying framework for ProMES somewhat conflates these two concepts, as its definition of productivity involves both effectiveness and efficiency,27 rather than being a ratio-based measure of productivity, as has been defined more clearly elsewhere in the literature and described earlier in this chapter. Therefore, this is referred to hereafter as the effectiveness score.

The overall effectiveness score, as well as individual indicator effectiveness scores, are then fed back to unit members, leading to the enhancement part of the process: based on the theory of feedback and motivation, the knowledge of not only the unit’s overall effectiveness, but effectiveness on different objectives, creates a motivation to improve effectiveness. 72 This has been shown to work with ProMES on many occasions: a meta-analysis73 of 83 field studies using ProMES found that there was a large and statistically significant improvement in performance following the beginning of ProMES feedback, with an average improvement of 1.16 standard deviations (SDs) – although Bly74 showed that this depends on the type of effect size used, by any estimate it was still a standardised score of > 1 – this represents a large effect by any standard metrics, and certainly larger than most organisational interventions. Other review articles72–77 have concluded that ProMES has been more successful in Europe than in the USA, that favourable attitudes towards productivity improvement are associated with faster improvements, and that higher-quality feedback was also associated with faster improvements.

The popularity of ProMES shows no sign of abating, with recent discussion demonstrating how it can be used effectively. 78,79 Within the specific field of primary care, one study is using ProMES in patient-aligned care teams, created from former primary care clinics. 80

The original ProMES methodology is designed to undertake this process with one team or work unit only. However, with the objective of developing an effectiveness measure that can apply to multiple teams, this specific method does not work. Therefore, some previous studies have adapted the methodology for use in multiple teams, in which representative members are brought together to undertake stages 1 to 3 of the ProMES approach, as described above. Large-scale adaptations have been used before in the NHS. 81–83 Most relevant to the current study is West et al. ,82 who used 10 workshops across three phases (one for each stage of the ProMES approach) to develop a measure of effectiveness for Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs). The first and last stages brought together care professionals and service users in four large workshops (two per stage), whereas the second stage involved six smaller homogeneous workshops to develop indicators. This was found to be a successful method in generating consensus between two potentially different groups of participants, and the final measure had good face validity for all involved. 82

Research aims and objectives

Following all of the background and literature described in this chapter, the main aim of this study was to develop and evaluate a measure of productivity (a ratio of quality-adjusted effectiveness to inputs) that can be applied across all typical general practices in England, and that may result in improvements in practice, leading to better patient outcomes.

Specifically, the objectives were to:

-

develop a standardised, comprehensive measure of general practice productivity via a series of workshops with primary care providers and patients, based on the ProMES methodology

-

test the feasibility and acceptability of the measure by piloting its use in 50 general practices over a 6-month period

-

evaluate the success of this pilot, leading to recommendations about the wider use of the measure across primary health care in consultation with key stakeholders at local and national level.

The methods for doing this are described in Chapter 3. First, however, the literature linking features of general practices with outcomes is examined.

Chapter 2 Factors affecting performance in general practice: a mapping review

In this chapter, a mapping review, conducted during the study, is presented of empirical research into features and processes within the control of practices, and the methods used to evaluate their effect on productivity, quality or effectiveness. A mapping review is a specific type of systematic literature review that uses a systematic search to identify key literature about a specific question, and then produces an evidence map to show what is known and what is not known about that topic. It does not provide as much depth of analysis as a full systematic review.

Aims of the review and review question

The first aim of the mapping review was to describe the current picture of empirical research measuring productivity, quality and effectiveness of general practice. The second aim was to understand how the research compares features and processes that general practices can adapt with outcomes related to productivity, quality or effectiveness.

A mapping review can be performed with or without the use of a question framework; however, its use can aid locating the correct terms for search. The sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation, research type (SPIDER) framework has been used in previous systematic mapping reviews and is suitable for mixed methods. 84–86 Table 2 shows the research question formulated with the SPIDER framework.

| Study characteristic | Scope of included studies |

|---|---|

| Sample | General practices in countries of relevance to the UK |

| Phenomenon of interest | Features, processes or interventions that are controlled at the level of an individual practice |

| Design | Any |

| Evaluation | The productivity, quality or effectiveness of health care provided by the practice |

| Research type | Empirical research. Quantitative and qualitative |

| Other | English language only |

Methods

Defining the map parameters

A mapping review is typically used for broad questions; therefore, an important first step to ensure that the topic and definitions are matched to the available resources is to define the map parameters.

The map parameters used were set using the methods outlined in the Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) guidance. 87 These involved (1) discussion of the review topic between members of the research team, (2) pre-map scoping of the literature, (3) operationalising the parameters into inclusion and exclusion criteria and (4) developing a search strategy. These steps were used iteratively so that, with each process, the findings were used to make suitable changes to parameters.

Scoping searches were conducted using MEDLINE. Initially, these consisted of free-text terms, then corresponding terms were found using a search engine for medical subject headings (MeSHs). Numbers of hits for these searches were recorded and titles scanned to check their relevance.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed and trialled with title and abstract screening on the results from scoping searches. This was also used to check the search terms were retrieving studies pertinent to the review question. In early searches, this was done by simply asking whether or not the paper fitted with the broad review question. Reasons why papers did not fit the review question were recorded and these recordings were used to make a more comprehensive list for inclusion and exclusion criteria. The screening was conducted by one author, but another author also screened a random 10% sample of the articles to assess inter-rater agreement.

This process was iterated three times before the relevant search terms and eligibility criteria were finalised. Finally, an information specialist was consulted to maximise the sensitivity of the search strategy while maintaining a manageable volume of hits.

Search strategy

Databases searched were MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Emerald Insight. No date range was specified (i.e. it was unlimited) and the final search was conducted on 1 August 2017. These databases were chosen as research in the fields of medicine, nursing and management was considered relevant.

Full searches were carried out in August 2017. The full list of terms can be found in Appendix 1. The agreed search strategy used thesaurus and free-text entries with Boolean logic, combining terms relating to the general practice setting, practice-level phenomena, and quality, effectiveness or productivity. Search terms were added with the Boolean phrase ‘NOT’ to exclude phenomena relating to policy or QOF, as these would be beyond the scope of the review. Searches were limited to English-language articles.

Reference tracking was performed on included studies identified through database searching. Hand-searching was used on the most recent issues of a select range of journals, to capture any relevant articles that may not yet have entered the database records. These were the British Journal of General Practice, the Canadian Family Physician, the New Zealand Family Physician, the Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care and the Australian Family Physician.

As the review was focused on mapping the empirical evidence, grey literature searching was limited and focused on finding the referenced empirical evidence. This consisted of searching the NHS network for materials related to the 10 high-impact actions and compiling these,88 and tracking the references of the main report70 for these actions.

Study selection

The inclusion and exclusion criteria that were finalised after scoping searches are given in Table 3, alongside the justification for the parameters set.

| Study characteristic | Inclusion | Exclusion | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | General practice: staff or service users | Other primary care services, including dental surgeries, optometry, community pharmacies, A&E direct access services, walk-in centres and minor injuries units | The sample criteria are deliberately wide, as the GP effectiveness tool considers how the practice works for the whole practice population |

| High-income countries, similar to the UK | Hospital-based services | Specialist services and other forms of primary services are beyond the scope of this review | |

| Secondary and tertiary care | |||

| Low- or middle-income countries | In order to maintain relevance to UK general practice, low- or middle-income countries were excluded because they face different resource issues | ||

| US based | US system significantly different from the UK system | ||

| Phenomenon of interest | Practice-level adaptations in features or processes related to management, organisation and clinical care | Features controlled at a level higher than the practice itself including policy and funding changes | The tool is designed to help practices evaluate where resources should be allocated, so any interventions or exposures should be controlled at the level of the GP practice |

| Features a practice could not feasibly adapt such as geographic location or socioeconomic deprivation of practice population | |||

| Interventions or features relating to general practice staffing, including doctors, nurses, practice managers and reception staff | Interventions or features of care specific to single clinical group, for example substance-misuse patients or diabetics | The aim is to identify research into areas concentrated on the general practice service as a whole, so initiatives specific to a single condition or therapies for individuals are not considered here | |

| Interventions randomised at an individual level, not practice level | |||

| Academic programmes for training the individual professional, for example students or trainee GPs | This would be a high-level phenomenon and not of interest in this review | ||

| Design | Systematic reviews and meta-analyses | Protocols | A mapping review is deliberately wide in the included designs of studies to gain an understanding of the scope and form of current research on the topic |

| RCTs | Non-systematic reviews | ||

| Cohort studies | Editorials | ||

| Case–control studies | Letters | The review is focused on empirical evidence | |

| Observational studies | |||

| Ecological studies | |||

| Evaluation | Measures of quality, effectiveness or productivity of services for the practice population | Not evaluating productivity, quality or effectiveness of the practice | The criteria are deliberately wide, as the scope of the question is wide and there are a multitude of methods of evaluating quality, effectiveness or productivity |

| Evaluation of academic training programmes | The evaluation of large-scale vocational training programmes are not of interest | ||

| Evaluation of change management; a measure of how well an intervention has been implemented as opposed to its impact | Change management evaluation would not reflect the quality, effectiveness or productivity of a practice | ||

| Research type | Quantitative research | Non-empirical research | Scope set wide owing to the methods of the mapping review. Empirical research |

| Qualitative research | |||

| Other | English language | Not English language | As a result of the scope and resources of the review |

Titles and abstracts were screened using the eligibility criteria. A random sample of 10% of those excluded at this stage were checked by a different member of the research team to ensure consistent application of the exclusion criteria. Full papers of those not yet excluded were then assessed for eligibility and reasons for excluding papers were provided.

Data extraction

A formalised data extraction form was used, which can be found in Appendix 2. This was designed using the examples given by James et al. 86 and following guidance provided for mapping reviews by the SCIE. 87 As the aim of a mapping review is to provide a description of the current body of research, and not to evaluate the results, data extraction focuses on metadata, such as methods, sample characteristics and country of study. Brief data regarding the results were extracted and quality assessment was recorded so that this could be taken into account when performing data synthesis. 86,87

Quality assessment

Commonly, the hierarchy of evidence scale alone is used to describe the level of quality of studies within mapping reviews. However, this is considered a rudimentary form of assessment in which study designs vary (e.g. a mixture of observational and experimental designs) in accordance with the phenomenon of interest or a broad-based question is applied. Although not an essential component of a systematic mapping review, use of a quality assessment tool helps provide a more detailed description of the validity of the current research body on the review topic. For this reason, criteria created by Kmet et al. 89 were used. These were first designed for a systematic review with a broad question, for assessing internal validity of diverse study designs. There are two checklists in the criteria: one for quantitative studies and one for qualitative studies. The criteria can be found as part of the data extraction form in Appendix 2. For each item, studies are given a score from 0–2 depending on whether or not the study answers the criterion (no, partial or yes). As there are a variable number of questions that apply to a given study, the total score is turned into a percentage of the maximum score from all of the applicable questions. This can then be used to compare the quality with that of other included studies. 86,89

Data synthesis

The generic data were summarised into a table of studies, including year of publication, country of study, design and methods, population of interest and sample size. Studies were then synthesised into a map, to demonstrate the current areas of research into the review topic.

The methods of evaluation were classified as concerning productivity, quality or effectiveness. As there is considerable crossover in terminology, three broad definitions were used to group outcomes as assessing effectiveness, quality or productivity. Productivity referred to any studies assessing how the practice was performing with consideration of resources (either monetary or human). Studies were ascribed as studying quality if they assessed standards of practice in terms of safety, adherence to best practice guidelines, or patient experience. Effectiveness was said to be assessed when measures of how a service was functioning (provision of care processes or achievement of outcomes) were used. The methods of evaluation were then summarised in accordance with whether they were processes, or intermediate or final outcomes as described by Baker and England. 42

Studies were grouped by the phenomena they investigated. These were grouped in accordance with their relationship to infrastructure, personnel or governance, and any patterns in topics that emerged were considered. A narrative overview of the findings in each of these areas was presented briefly, but with the caution that conclusion on effects could not be drawn.

Results

Search results

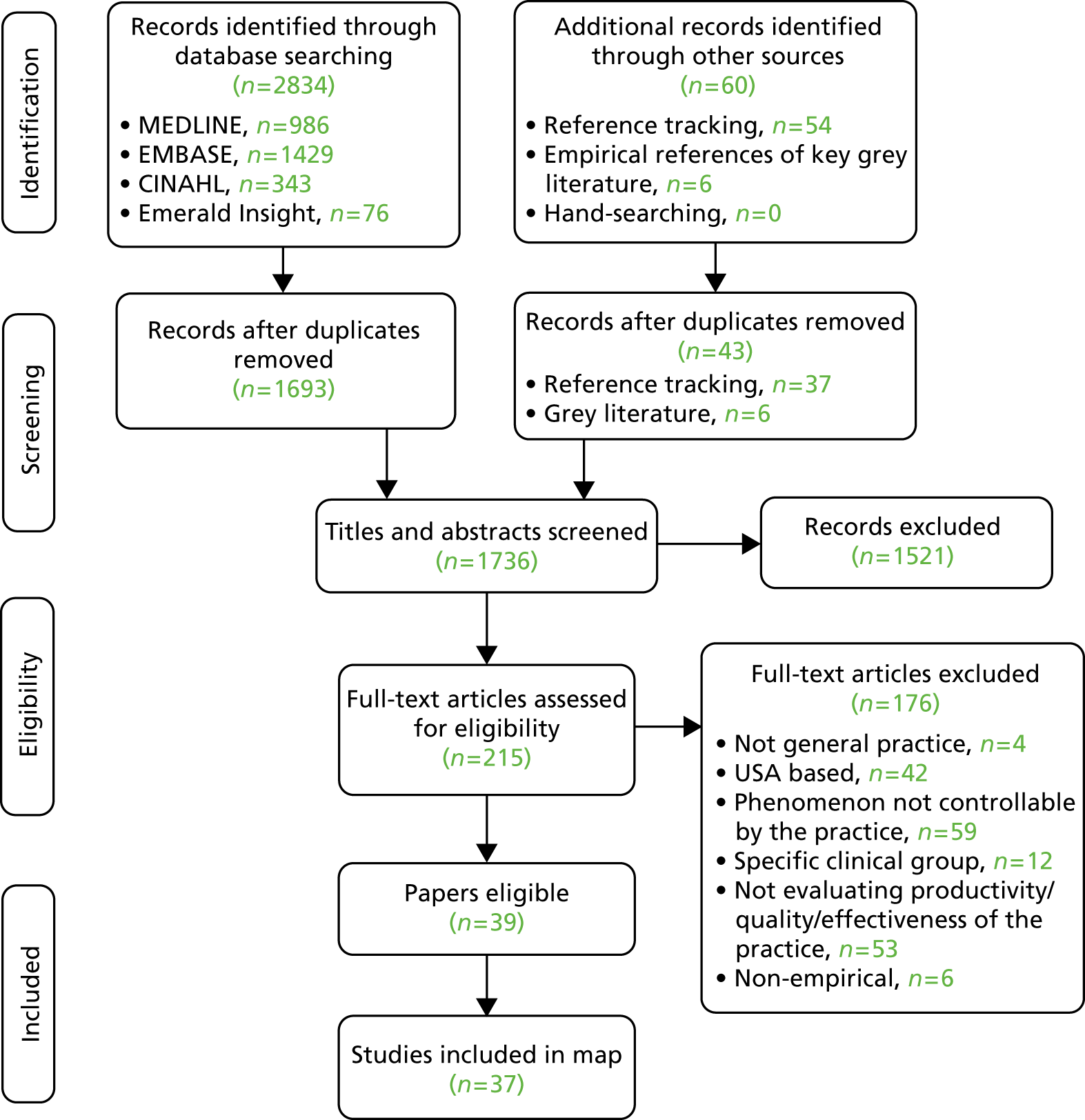

Figure 2 depicts the results from the search strategy using a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram. Initially, database searches returned 2834 results. Once duplicates were removed, 1693 results were identified from database searches. A further 37 studies were identified using reference tracking, once duplicates were removed. Searching of the grey literature identified six relevant empirical titles. A total of 1736 records were screened at title and abstract level and 1521 were excluded at this stage. There were 215 full texts assessed for their eligibility. Of these, 39 papers met the criteria for inclusion in the systematic map, referring to 37 distinct studies. 90–128 The primary reasons for excluding the 176 studies are given in the PRISMA flow diagram (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA flow diagram. (See text for explanation of papers that were eligible, but are not included in the map.)

In two cases, multiple papers referred to samples from the same study. Bower et al. 95 and Campbell et al. 96 report results from a mutual sample using the same independent variables, with Bower et al. 95 reporting an additional outcome: team effectiveness. Ludt et al. 117 and Petek and Mlakar. 120 both drew data from the European Practice Assessment of Cardiovascular risk management (EPA-Cardio) study, considering the same dependent and independent variables. In both cases, the more recent papers (2013117 and 2016120) were included in the map, as they reported in more detail. Klemenc-Ketis et al. 114 also drew data from the EPA-Cardio study, but examined a different population (those with established disease and healthy participants, in addition to those with a high cardiovascular risk), and reported on a different dependent variable (patient satisfaction). Therefore, it has been considered as a separate study.

Study designs

The characteristics of the included studies can be found in Appendix 3. The majority (n = 15) were based in the UK, with others being set in Canada (n = 6), Australia (n = 4), New Zealand (n = 3) and Europe (the Netherlands, n = 5; Slovenia, n = 2; multiple countries, n = 2). Publication dates ranged from 1978 to 2017.

A quantitative design was used by 26 studies,90–95,97,98,103,106–110,112–114,116,117,119–122,124–126,128 four studies used a qualitative design102,105,115,127 and five studies used mixed methods. 99–101,118,123

Two systematic reviews were included: Goh and Eccles104 focused on primary studies of any design, whereas Irwin et al. 111 used tertiary synthesis – reviewing systematic reviews. The individual systematic reviews in this tertiary synthesis were not considered as separate entities as they assessed interventions tailored for specific clinical groups or drew from populations wider than just primary care. However, at a tertiary level, this review drew together areas of QI that were highly relevant to this project and so justified inclusion.

Of those using quantitative data, the majority (n = 19) were cross-sectional. Three studies used a retrospective cohort design98,112,120 and four used experimental designs (one non-RCT,110 two RCTs113 and one pre- and post-intervention study97). This was anticipated, as the features and processes of interest were not likely to be pragmatic topics for RCTs or longitudinal assessment.

Of the qualitative studies, Grant et al. 105 and Swinglehurst et al. 127 used an ethnographic approach involving observations of practice, whereas Fisher et al. 102 and Lawton et al. 115 used face-to-face or telephone interviews.

Mixed-method designs were used for two studies examining a cross-section of general practice,99,101 and three studies100,118,123 in which phenomena were studied longitudinally, with the implementation of a change in practice being evaluated.

Quality assessment

The quality assessment scores for the studies can be found in Appendix 3. The checklist did not translate well for use when assessing systematic reviews so was not applied to Goh and Eccles104 or Irwin et al. 111 As quality assessment is not a requirement of a mapping review, this was considered an acceptable decision.

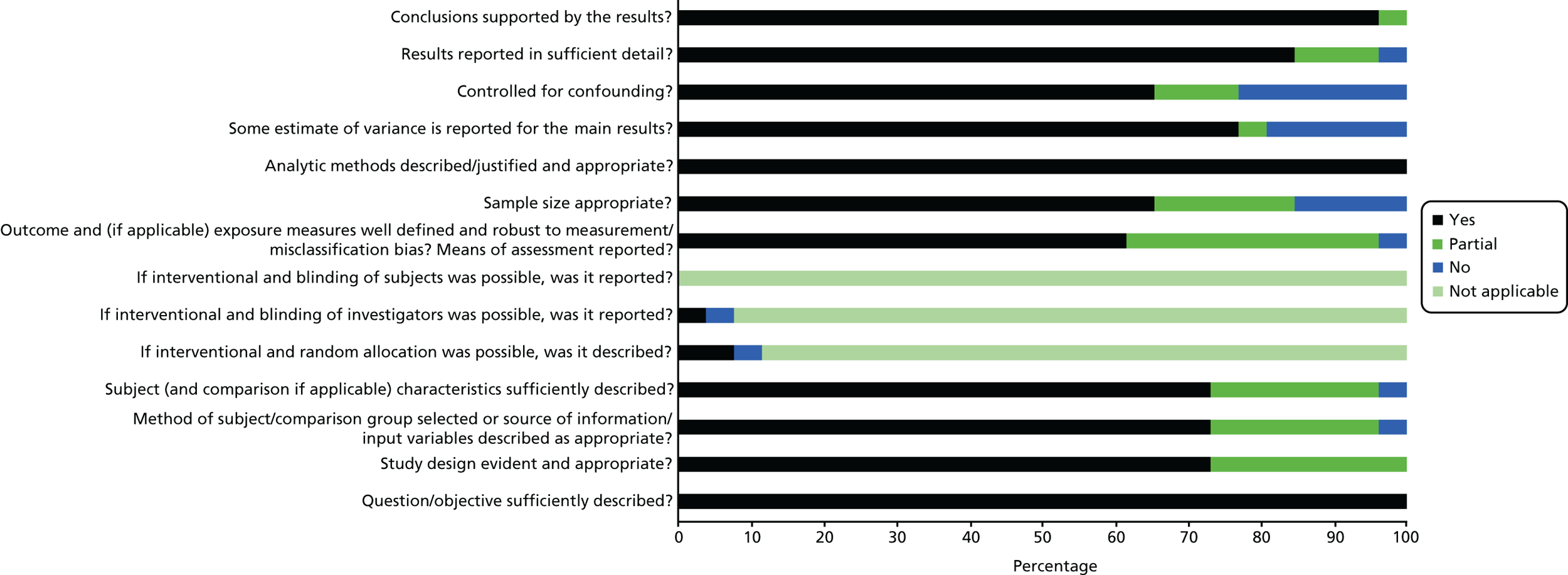

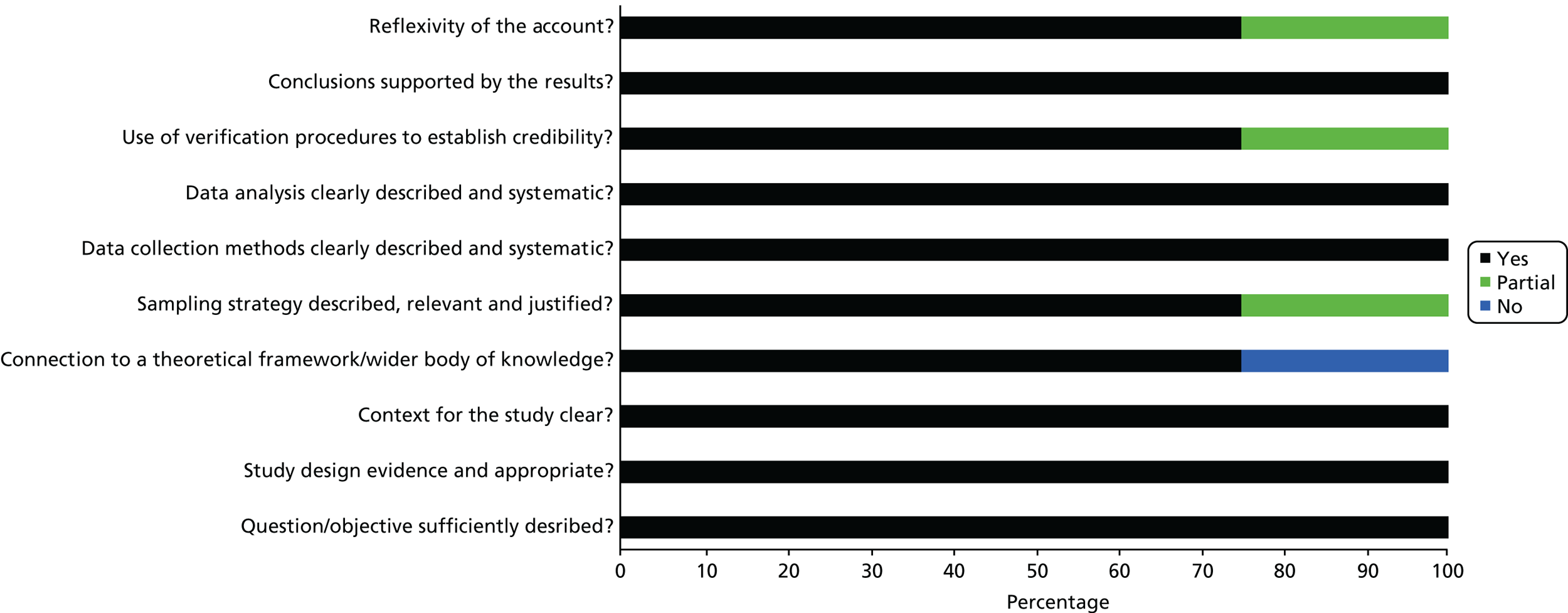

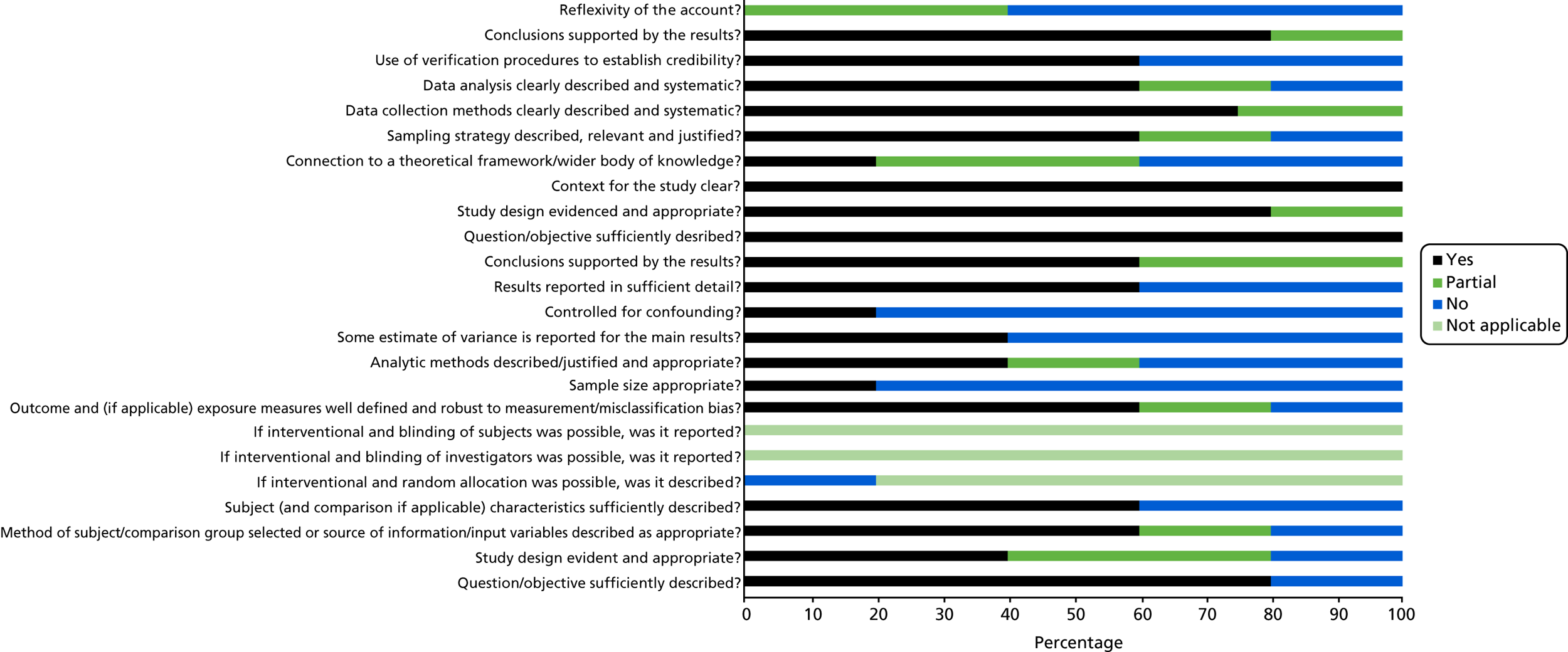

Scores for the remaining 35 studies ranged from 45% to 100%, of which 26 scored ≥ 75%. This suggests that, overall, the quality of the studies was quite high. See Appendix 3, Figures 17–19, for the areas in which the studies scored yes, no or partial on the quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies.

Of 26 quantitative studies, 22 scored ≥ 75%. Areas in which studies scored well were the research question and aims, methods of analysis, results reporting and conclusions drawn. Areas in which quality was particularly poor were in the measurement of outcomes and exposures, controlling for confounding variables and sample size. All four qualitative studies scored > 75%. Each study lost points on a different component of quality, with all studies performing well on the question/objectives, design, context, data collection methods and analysis. Of those using mixed methods, none of the studies scored > 75%. They tended to score poorly on questions relating to the quantitative elements, especially regarding sample size and controlling for confounders, and on the reflexivity of the account, suggesting that the blending of the two methodologies was not, on the whole, sufficient.

Data synthesis: study mapping

Appendix 4 provides a summary of the phenomena adaptable by general practices that were investigated in the included studies. The methods used to evaluate their impact on practice outcomes are also summarised as effectiveness, quality or productivity, along with references to the corroborating papers. Appendix 4 represents all practice-adaptable features identified in the studies, regardless of results.

Means of evaluating productivity, quality and effectiveness

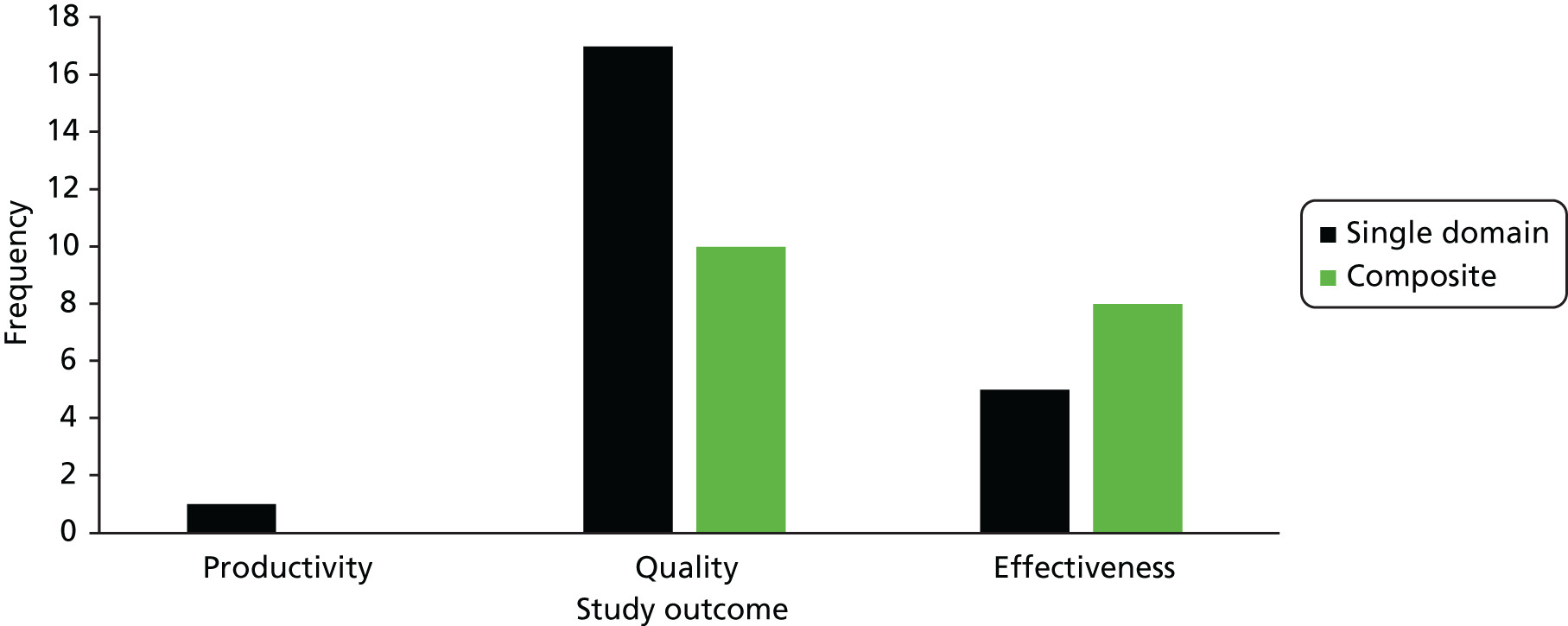

Figure 3 demonstrates the number of studies identified as relating to effectiveness, quality or productivity, and, of those, the number of studies that covered a single aspect of these outcomes compared with the number using a composite of objectives. As some studies used outcomes that were classified as effectiveness and quality, the sum of the bars in the graph is > 37. Of note is the fact that only Fisher et al. 102 identified an outcome related to productivity, and this was qualitatively evaluated. Most studies assessed a single objective relating to quality (n = 17), whereas five studies assessed a single objective relating to the effectiveness of a practice. Twelve studies measured effectiveness and/or productivity using multiple objectives. The review by Goh and Eccles104 was also concerned with both effectiveness or quality from multiple domains, whereas the review by Irwin et al. 111 examined quality in three categories: process improvement, physiological markers and other patient outcomes.

FIGURE 3.

Classification of study outcomes.

Features and processes adaptable at practice level

The independent variables studied that a practice could adapt are discussed in Infrastructure and Personnel. Beyond the remit of the study were many variables relating to features that a practice could not feasibly adapt. One grey area that emerged was the size of the practice. A variety of methods to measure this was used in the papers, but there was often overlap with features that the practice could not feasibly adapt, such as the size of the practice population. Although potentially relevant, these measures were excluded from the map as it was felt that selection bias could occur when dividing the measures into those that a practice could adapt and those that were not adaptable.

Infrastructure

In investigating characteristics of general practice, studies touched on four adaptable areas relating to infrastructure: (1) the physical environment, (2) use of IT systems, (3) the organisation of appointments, patient lists and access, and (4) the provision of clinical services and resources. Physical environment was investigated in two studies. 99,103 Desborough et al. 99 qualitatively identified adequate rooms as a facilitator of practice nurse consultations’ impact on patient satisfaction and enablement. Gaal et al. ,103 on the other hand, assessed staff perceptions of their working environment and found that the only dimension of quality outcomes that was associated with perceptions of working environment was building safety.

A practice’s use of IT systems was a phenomenon researched in seven studies98,102,109,114,117,124,127 and the review of systematic reviews,111 with varying evidence of use. Investigating its use generally, Harris et al. 109 found no significant impact on patients’ ability to access same- or next-day appointments, although it was associated with after-hours access. IT use in electronic prescribing was assessed in the tertiary review,111 in two qualitative studies102,127 and in a cross-sectional study. 114 Irwin et al. 111 found evidence of its effect for QI using intermediate outcomes (drug dosage), but not final outcomes (mortality). Fisher et al. 102 qualitatively identified IT systems as useful for reducing workload, and ethnographic observations by Swinglehurst et al. 127 identified an improvement in the quality and safety of prescribing practices. On the other hand, Klemenc-Ketis et al. 114 found IT use in medication review had a negative association with patient satisfaction. IT use in prevention services was assessed by de Koning et al. ,98 who found a non-statistically significant reduction in the odds of suboptimal stroke care quality. The use of electronic patient records was not found to be a significant variable for the quality of cardiovascular prevention117 or chronic disease management. 124

Nine studies90,93,95,100,102,107,125,128,129 considered the infrastructure surrounding appointments. Longer appointments were identified in a focus group as a facilitator of more effective chronic care management and patient self-care. 101 In two cross-sectional studies, allotting more time for appointments was associated with the quality of chronic illness care: for Beaulieu et al. ,90 this was only seen for practices providing very long (i.e. > 30 minutes) appointments for emergencies or follow-up, whereas Bower et al. 95 found significant associations for 10-minute appointments over shorter (i.e. 7.5- or 5-minute) intervals. Use of personal or pooled list systems was studied by Baker and Streatfield,93 personal lists being significantly associated with higher patient satisfaction and experience of care (accessibility and availability). The use of telephones in relation to appointments or advice had a variable influence. Qualitatively, Fisher et al. 102 found mixed opinions on whether telephone triage and appointments were facilitators of or barriers to productivity, whereas Smits et al. 125 found that availability of telephone appointments showed no significant association with use of OOH care. Of a variety of variables related to telephone access measured in this study, only average telephone waiting times were associated with use of OOH care, an indicator of unmet need. 125 Access to telephone lines 24 hours per day was also found to have a small but statistically significant effect on patient experience of care. 107 The same study was the only one to investigate evening and weekend access and found a very weak influence of walk-in availability only on patient experience of care. 107 Thomas et al. 128 similarly looked at consultation by appointment and found that walk-in availability decreased the odds of patient movement to another practice, which was used as a marker of patient dissatisfaction. 128 Appointment access was also considered by Dixon et al. ,100 who looked at the correlations between implementing on-the-day booking and access, and found that, on average, the time to the third available appointment decreased. However, in the study’s100 qualitative exploration, stakeholders raised concerns about the effectiveness of new advanced-access appointment systems for patients with chronic illness and had variable views on their effect on staff. 100