Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/114/95. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The final report began editorial review in May 2019 and was accepted for publication in December 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Glenn Robert reports that through The Point of Care Foundation in London he has previously provided advice on and training in experience-based co-design.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Jones et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction and context

Stroke care in the UK has improved radically since the launch of the National Audit Programme in 19981 and the National Stroke Strategy in 2007. 2,3 Access to specialist services, reduced length of stay and community services such as early supported discharge are now accepted as standard. However, important efficiency and process improvements such as these have not always been matched by the experience of patients, especially those with moderate to severe disability, who can spend weeks and months on an inpatient stroke unit. Persistent concerns are raised about stroke unit environments that focus on organisational priorities, which provide minimal opportunities for patients’ social, cognitive or physical activity. 4,5 Results from observational studies on stroke units since the 1980s have consistently shown that, for most of the time (> 70%), patients are inactive and very often alone. 6–8

Currently, the focus in relation to activity levels is the provision of structured rehabilitation by therapists [physiotherapists (PTs), occupational therapists (OTs) and speech and language therapists], which is audited against a national guideline that recommends that every day each patient should receive at least 45 minutes of therapy, as appropriate. 9,10 However, audits and standards have not improved the experience of patients or increased activity opportunities outside these structured rehabilitation sessions with therapists. 11,12 This is critical as when patients are bored and inactive it can have an impact on aspects of their recovery and potentially foster a feeling that ‘nothing is being done’. 7

In a recent commentary on mainstream approaches to quality improvement and the potential role of co-production, Batalden13 highlighted how professionals and patients can become increasingly frustrated by product-dominant models, which focus solely on processes, actions and outputs, and that such approaches risk neglecting relationships and outcomes that are important to patients but are less easy to measure (such as patient preferences). However, improvement work to date in acute stroke care has been highly regulated and measured through national and local audits;3 there is an opportunity now for more creative responses to the persistent problem of very low activity levels in inpatient stroke units. Co-production uses the experiences and assets of patients with stroke and their families to work together with staff to address the problem. 14,15

We aimed to evaluate (1) whether or not co-production approaches can be used to improve the accessibility and quality of therapeutic activity in acute stroke care and (2) whether or not the co-produced solutions in one stroke unit are transferable to other similar acute inpatient services.

In this introductory chapter, we briefly describe stroke and stroke care and management, setting out the policy context before providing a brief summary of the persistent concerns about rehabilitation, inactivity and improving patient experience. We then describe experience-based co-design (EBCD), our chosen co-production method for quality improvement. Our rapid evidence synthesis, conducted during the set-up of the sites 1 and 2 and for the EBCD study, is mentioned here briefly. Chapter 2 provides a description of the methods and Chapter 3 provides the results. The paper was published in 2017. 16

Stroke: the state of play

Stroke statistics: organisational issues and impact

Stroke, known in recent public communications as a ‘brain attack’, can have a devastating impact on people’s lives and equally on the lives of those who live with and care for those people. 17 The effects of stroke are wide-ranging depending on the location and extent of the brain damage, but they can include paralysis and cognitive and communication difficulties among many other problems, such as difficulty with vision, continence and fatigue. 18 Stroke continues to be the largest cause of disability in the UK, and 84% of people leaving hospital will require help with activities of daily living. 17

Stroke incidence is high; 100,000 people will experience a stroke in the UK each year. 17 Although the numbers of first stroke have fallen significantly since 1990, by 2035 the rate of people over the age of 45 years having a stroke is expected to rise by 59% and the absolute number of people living with stroke will rise by 123%. 17 Population studies show that stroke incidence is not equal across different populations; people of black African, black Caribbean or South Asian ethnicity are more likely to have a stroke at a younger age. 19 In London, black people are twice as likely as white people to have a stroke. In addition, people from more socially deprived groups are likely to experience more strokes earlier in life. 20

These UK trends are also reflected in global studies that show that the absolute numbers of people who have a stroke every year, stroke survivors and related deaths, as well as the overall global burden of stroke, are great and increasing. 21 Estimates vary depending on the population sample and data sources, but it is suggested that in the UK there are 950,000 people aged ≥ 45 years. 22 This costs the UK economy approximately £8.9B per year (5% of the NHS budget), of which £4B is spent on treatment, including organised inpatient stroke unit care. 23 This figure is set to treble by 2035. 22

Recent decades have seen significant developments in the organisation and management of stroke, particularly following the implementation of the National Stroke Strategy by the Department of Health and Social Care in 2007. 24 The role of organised stroke care is well established in significantly improving outcomes after acute stroke. 25 Most people experiencing a stroke in the UK will get early access to care provided by stroke specialist staff. Large-scale service reconfigurations such as the London and Greater Manchester models have fundamentally changed care pathways, and the average length of stay on an inpatient stroke unit is likely to be around 17 days. 26,27 Large-scale reorganisation has also seen the case mix on stroke units change; patients with mild disability are discharged earlier as a result of the expansion of early supported discharge services, while critically ill patients with more complex and severe disability are likely to require a considerably longer inpatient stay. 1

Rehabilitation, recovery and persistent concerns

The component of acute stroke care consistently highlighted as likely to improve long-term outcome is rehabilitation. This assertion is informed by research showing that early activity post stroke not only improves overall prognosis but also can reduce disability. 28 This is reflected in the following statement from the Department of Health and Social Care’s National Stroke Strategy:

Rehabilitation after stroke works. Specialist co-ordinated rehabilitation, started early after stroke and provided with sufficient intensity, reduces mortality and long-term disability.

Rehabilitation is, therefore, a major part of stroke care. Multidisciplinary stroke teams typically include doctors, nurses, social workers, therapists, dietitians and psychologists, but OTs, PTs, and speech and language therapists are recognised as the central providers of rehabilitation who aim to maximise independence and prevent further complications after a stroke. 29

The fifth edition of the National Clinical Guideline for Stroke,9 published in 2016, includes a number of key recommendations that, if followed, would have the most impact on the quality of stroke care. One of these recommendations is about the intensity of rehabilitation, and states:

Patients with stroke should accumulate at least 45 minutes of each appropriate therapy every day, at a frequency that enables them to reach their rehabilitation goals, and for as long as they are willing and capable of participating and showing measurable benefit from treatment.

Reproduced with permission. Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party, page xiv9

Similar recommendations were published in the 2013 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for stroke rehabilitation30 and updated in more recent formulations of NICE stroke rehabilitation pathways:31

Offer initially at least 45 minutes of each relevant stroke rehabilitation therapy for a minimum of 5 days per week to people who have the ability to participate, and where functional goals can be achieved. If more rehabilitation is needed at a later stage, tailor the intensity to the person’s needs at that time.

Each of the recommendations is underpinned by high-quality evidence that increasing the frequency and intensity of rehabilitation improves recovery and clinical outcomes. 32,33 This has strongly influenced the design and implementation of organisational change interventions with a focus on achieving large doses of therapy and the belief that ‘more is better’. 18,34 However, this hypothesis is built on three assumptions: first, that national stroke guideline recommendations on rehabilitation intensity are interpreted and enacted consistently by therapists; second, that therapy is available over all 7 days of an inpatient week; and, third, that rehabilitation is the responsibility of therapists alone and not that of the whole multidisciplinary team.

Measuring the performance of stroke units against agreed standards is the responsibility of the Stroke Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP). A minimum data set based on self-reported activity is collected continuously and reported quarterly, which includes performance against the rehabilitation intensity standard described above. Although the proportion of patients reported to require therapy remains constant (PT and OT, 80–85%; speech and language therapist, 50%), the median number of minutes received of the required intensity remains below the target of 45 minutes (PT and speech and language therapist, 30 minutes; OT, 40 minutes), with wide national and regional variation. Importantly, therapy is rarely a 7-day service; in 2016, SSNAP data showed that only 31% of stroke units had access to at least two types of therapy 7 days per week. 35

Several authors have stated concerns about the focus on a 45-minute therapy guideline:11,12 first, the accuracy of reporting and what is being counted and, second, that direct contact time with therapists could be considerably lower. Clarke et al. 11 carried out an ethnographic case study across eight stroke units comprising > 1000 hours of non-participant observations and 433 patient-specific therapy observations and found that a considerable amount of time was spent carrying out activities relating to information exchange rather than patient-focused therapy. In another ethnographic study across three stroke units, Taylor et al. 12 found that therapists wanted to provide more therapy and felt guilty for not doing so; there was also a lack of multidisciplinary rehabilitation. Both research teams found that rehabilitation was largely the responsibility of therapists, and patients were often observed as inactive outside their designated therapy sessions. Evidence from these studies and others shows that the issue of inactivity of stroke patients on stroke units persists. Studies consistently show that often the most disabled patients are likely to spend the majority of their time inactive and disengaged. 7,36

Some attempts have been made to address the enduring issue of inactivity, but with mixed results. A study in Australia37 concluded that dose-driven interventions, including circuit class therapy and 7-days-a-week therapy, increased the amounts of therapy provided but did not increase meaningful patient activity outside therapy sessions; the researchers called for greater understanding of the drivers of activity outside therapy sessions. Trammell et al. 38 found that a programme of physical activities ‘prescribed’ in addition to structured therapy on a stroke unit was feasible, but again this was overseen and graded by therapists. Although the research team found that staff and patients reported high satisfaction, levels of expectations about activity prior to implementation were not known and the activities consisted of repetitive exercises that required supervision.

We question whether current models of ‘therapist’-focused inpatient stroke rehabilitation and reliance on ‘waiting for therapy to be delivered’ may foster dependency and inactivity and are, therefore, at odds with promoting activity and self-management in hospital and after discharge. 39,40 The irony is that a highly medicalised stroke unit can meet national quality standards but is counterproductive to promoting patients’ independent activity. Overall, evidence suggests that acute health-care environments, staff, carers and patients could do more to enable an increase in activity, which could also have the potential to expedite discharge and decrease dependency on health and social care services in the longer term. 28,40,41 We have found that although studies have identified short-term methods to increase patients’ activity, these are often driven by the perspectives of professionals, with little evidence of patient and carer involvement in the development and implementation of interventions.

We subscribed to the ideal put forward by Sir Roger Boyle, previously the National Director for Heart Disease and Stroke, ‘to make rehabilitation the basis of the patient’s day’ (p. 4; contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 42 We also recognise that there is an opportunity for patients with stroke, families and staff to work together to address the issue of inactivity. Studies thus far have emphasised the necessity to change but have not directly considered the ideas and experiences of the people that they seek to help.

Improving patient experience: acute health care

Improving patients’ experiences and putting patients at the centre of everything is a key aim of the NHS and is frequently reflected in health policy such as ‘putting patients first’, which highlighted citizen participation and empowerment as one of six characteristics of a high-quality, sustainable NHS. 43 The value of innovations, which build on patients’ rights to drive up quality of experience, is becoming more apparent. NHS England’s Five Year Forward View44 set out how the NHS must change, arguing for a more engaged relationship with patients and carers in order to promote well-being and prevent ill health. Frameworks are now available for organisations to carry out organisational assessments to evaluate how patient experience is embedded into culture and operational processes, with ‘good’ exemplified by evidence of staff and patients who have worked together to improve services. 45 To improve patients’ experiences, NHS policy-makers increasingly seek to encourage the development of new relationships between patients, carers and clinicians. These relationships are to be based on working together, in equal partnership, not only to make personal care decisions and agree care plans, but also to develop partnerships in which patients, carers and clinicians are involved in the co-design, co-commissioning and co-production of health-care services. 45,46

The NHS is a complex system, and to focus on patients’ experience when resources and workforce are under pressure is a fundamental and critical challenge. Some authors have raised concerns that ‘the picture [patient experience] is one of monitoring and compliance rather than ownership and motivation to improve this key aspect of quality’. 47 In addition, the empirical evidence for patient and public involvement is low and tends to be descriptive rather than evaluative. 48 Yet Berwick states that ‘workers and leaders can often find the best gaps that matter by listening very carefully to the people they serve’;49 similarly, Goodrich and Cornwell highlight that ‘patients’ stories and patients’ complaints remind us of the importance of seeing the person in the patient and bringing patients’ experience alive’ (© The King’s Fund; reproduced with permission under the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence, see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). 50

Co-production

We believe that engaging patients and staff in service redesign of stroke units could provide solutions that address the lack of activity outside structured therapy. Co-production methods harness the power of patients, carers and staff to make changes they know and care most about. 46,51,52 In the broadest sense, co-production means delivering public services in an equal and reciprocal relationship between professionals and people using services and their families. 53 The central idea in co-production is that people who use services are hidden resources, not drains on the system, and that no service that ignores this resource can be efficient. Advocates of co-production see it as a different way of thinking about public services, with potentially transformational consequences, as people who use services take control of defining and managing their care:

The biggest untapped resources in the health system are not doctors but users. [. . .] We need systems that allow people and patients to be recognised as producers and participants, not just receivers of systems. [. . .] At the heart of [co-production], users will play a far larger role in helping to identify needs, propose solutions, test them out and implement them, together.

Cottam and Leadbeater, p. 16.

[. . .] assessing, and evaluating the relationships and actions that contribute to the health of individuals and populations. At its core [co-production] are the interactions of patients and professionals in different roles and degrees of shared work.

Batalden13

Batalden emphasises the value of health care as a co-produced service but that the essential aspects such as utilising all forms of knowledge are often neglected. The ambition of ‘shared work’ can be misinterpreted and the importance of trustworthiness between patients, carers and staff misunderstood.

Despite the increased focus on co-production in health-care policy and improvement, no studies have reported using a co-production approach or participatory methods to improve acute stroke care. However, there are examples from across other areas of acute health care. Our first research question was ‘What is known about the efficacy and effectiveness of co-production approaches in acute health care?’. A rapid evidence synthesis published in 2017 systematically reviewed the outcomes of studies that had developed and implemented co-produced interventions in acute health-care settings. 16 The review highlighted a lack of rigorous evaluation of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of co-produced interventions in acute health care (despite the increasing adoption of co-production as a form of intervention and one that typically drew on co-design approaches). Nonetheless, the impact of what might be perceived as ‘small, mundane things’ and the range and quality of patient-focused improvements seems to have a large impact on experience. As other authors have commented, an increasing focus on the attached meanings, rhythms and time frames in a health-care service – the degree and type of ‘the doing’ – can shape services in profound ways. 54

As interest in co-production within health-care improvement grows, so do the concerns that co-production may become misused or diluted from its original aim of enhancing collaborative work to produce public goods or services with citizens playing an active role. 16,55 Co-production originated through a recognition of the role that service users play in determining the effectiveness of public services, but several authors have highlighted issues with the false impression of equality or implicit professional dominance that can emerge as relationships between service users and providers are – supposedly – reconfigured. 55,56 Approaches that prioritise the narrative and lived experiences of those who use health-care services can have the power to captivate and engage staff, helping to create conditions necessary to enable shared improvement work.

Experience-based co-design

With increasing attention to the potential for co-production and applying design thinking as a means of improving health care, participatory approaches such as EBCD have become more widespread. The ‘co’ in ‘co-design’ refers specifically to partnership, equity and shared leadership in terms of face-to-face user and provider collaboration in the co-design of services. 47,51 EBCD originated in 2005 as a participatory action research approach that explicitly drew on design theory51 and was first piloted in a head and neck cancer service at Luton and Dunstable Hospital. 57 Through a structured six-stage process, EBCD entails staff, patients and carers sharing and reflecting on their experiences of a service, working together to identify improvement priorities, devising and implementing changes, and then jointly reflecting on their achievements. An important element of the approach is that patient experiences are gathered through filmed narrative interviews, and insights from these are shared with staff in an edited ‘trigger’ film. Several years ago, an international survey of completed, ongoing and planned EBCD projects in health-care services found that at least 59 EBCD projects had been implemented in at least six countries, with at least a further 27 projects in the planning stage. 58 The number of projects appears to be growing year on year, but, to our knowledge, EBCD has not been used in acute stroke services, despite the seemingly intractable issue of inactivity and boredom and an over-reliance on system- and (narrowly defined) outcome-focused improvement.

Full details of each of the six stages in EBCD can be found in The Point of Care Foundation’s free-to-access online toolkit, which also provides lessons and feedback from staff and patients, including details of an ‘accelerated’ form of the method, which was previously developed and evaluated with funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research programme. 59,60 A general overview of the approach is provided in the study by Robert et al. 61

The EBCD cycle, which typically takes 9–12 months,51 is divided into six stages: (1) setting up the project; (2) gathering staff experiences through observational fieldwork and in-depth interviews; (3) gathering patient and carer experiences through observation and 12–15 filmed narrative-based interviews; (4) bringing staff, patients and carers together in a first co-design event to share – prompted by an edited 20- to 30-minute ‘trigger’ film of patient narratives – their experiences of a service and to identify priorities for change; (5) sustained co-design work in small groups (typically of four to six people) formed around those priorities; and (6) a celebration and review event. 47

One of the major barriers to the implementation of the approach is the time and costs involved. 16,60 Questioning whether it is always necessary – for the purposes of local quality improvement work – to generate local trigger films in the discovery phase, Locock et al. 60 tested an accelerated approach that used a national video and audio archive of films; they found that this method generated a comparable set of improvement activities. Building on this work, we first aimed to evaluate the feasibility of a full EBCD cycle and the impact of stroke patients, carers and staff co-designing and implementing interventions to increase activity in two stroke units. We then aimed to compare and contrast the impact of undertaking a full EBCD cycle in these two units with an ‘accelerated’ approach – which drew on the fieldwork and findings from the first two units – in two further units. We recognised that stroke projects addressing inactivity have focused mainly on physical activity, and for this project we used an umbrella term of ‘activity’ to be anything that patients do, however small, supervised or non-supervised, and encompassing physical, cognitive or social forms.

In summary, we believe that rehabilitation and the promotion of activity should be considered as a joint enterprise that draws continuously on both lay experience and professional expertise; this contrasts with the largely unsuccessful target- and audit-driven approaches employed to date. An EBCD cycle may provide a novel space and sufficiently flexible structure for staff, patients and families to think creatively about how post-stroke care in stroke units could be redesigned to increase activity. Central to the approach is the carefully considered development and implementation of workable solutions that can be applied and tested in routine practice through an iterative process of co-designing and prototyping. This extended type of engagement recognises the necessarily adaptive nature of stakeholder involvement, and of the gradual crafting, refinement and emergence of innovative interventions. Developing cultures of continuous rehabilitation is likely to require early and sustained involvement of the whole multidisciplinary team and some revision of their working practices, and the development of practical ways to engage and involve patients and their families.

This led us to formulate the following research questions to be explored through our empirical fieldwork in four acute stroke units in England:

-

How do patients and carers experience the use of a co-production approach and what impact does it have on the quality and intensity of independent and supervised therapeutic activity on a stroke unit?

-

How do staff from acute stroke units experience the use of a co-production approach and what improvements in independent and supervised therapeutic activities does the approach stimulate?

-

How feasible is it to adopt EBCD as a particular form of co-production for improving the quality and intensity of rehabilitation in acute stroke units?

-

What role can patients and carers have in improving implementation of National Clinical Guideline recommendations on the quality and intensity of rehabilitation in acute stroke units?

-

What are the factors and organisational processes that act as either barriers to or facilitators of successfully implementing, embedding and sustaining co-produced quality improvements in acute care settings, and how can these be addressed and enhanced?

Chapter 2 Methods: intervention development

This study involved two main aspects: (1) the ‘intervention’, consisting of ‘full and accelerated’ EBCD, to generate and implement a number of co-designed changes to increase supervised and independent activities within four stroke units, and (2) the evaluation, which was carried out pre and post implementation of the co-designed activities in each unit. For the purpose of the report, we first document the methods used in the intervention development and then present the evaluation components in Chapter 3.

Parts of this chapter are based on Clarke et al. 16 © Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2017. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The intervention: full and accelerated experience-based co-design

Settings and sampling

We set out to recruit four stroke units: two in London and two in Yorkshire. We included stroke units that met the classification of a specialised stroke service defined as ‘capable of meeting the specific health, social and vocational needs of people with stroke of all ages’ set out in section 3.2 of the 2012 National Clinical Guideline for Stroke (reproduced with permission). 62 A stroke unit is classified as either a ‘routinely admitting stroke unit’ with hyperacute stroke units and acute stroke units or a ‘non-routinely admitting stroke unit’. 63 All stroke units provide acute and rehabilitation care, but only hyperacute units admit patients within the first 72 hours post stroke and return discharge data in SSNAP. 62 We also aimed to recruit stroke units with evidence of previous participation in research so that we could ensure that the units had an interest in delivering the research planned.

Stroke units were purposively selected following discussions held with senior staff and local stroke research networks. As advised by NIHR, we aimed to include not those stroke units that were based in large teaching hospitals and already taking part in clinical trials, but those that showed a willingness and commitment to take part in a study such as CREATE (Collaborative Rehabilitation in Acute Stroke) that comprised multiple stages over at least 12 months.

The two stroke units selected for the first stage and full EBCD were based in London and Yorkshire; we refer to these stroke units as sites 1 and 2. In the second stage, stroke units taking part in accelerated EBCD were also based in London and Yorkshire (sites 3 and 4). Each of the four sites was a non-routinely admitting unit that received patients only after they had been cared for in a hyperacute unit either in the same hospital (as at sites 2 and 4) or at a nearby major stoke centre (as at sites 1 and 3). More detail about each site is provided in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of stroke beds | 24 | 24 | 26 | 26 beds (14 and 12) |

| Hospital | District general hospital with 629 beds | District general hospital with 500 beds | City-centre teaching hospital with 700 beds | District general hospital with 600 beds |

| Layout | The stroke unit is on the third floor of the hospital. It has an L-shaped layout with five bays, each containing four beds, and four single rooms. The end of one corridor connects directly to another medical ward and the nursing desk is at the end of the other corridor. Visitor and staff catering services are on the ground floor of the hospital | The stroke unit is on the third floor of the hospital. It has an L-shaped layout, a long main corridor with five bays, each containing four beds, and three side rooms off this corridor. Day room and one-bed pre-discharge flat are in the smaller L-section. Visitor and staff catering services are on the ground floor of the hospital | The stroke unit is on the ground floor of the hospital. It has a central desk and one wide corridor with two male and two female bays, each with six beds, and two single rooms at the entrance to the ward. Visitor and staff catering services are on the ground and first floors of the hospital | The stroke unit is on the second floor of the hospital. It has a circular layout around four ‘pods’ that make up the stroke service. Three pods, 7a, 7b and 7d, are rehabilitation wards and 7c is the hyperacute ward. There is access by lift to outside spaces including a small therapy garden and walkways around the main hospital site. Visitor and staff catering services are on the ground floor of the hospital |

| Shared space | No day room; no outside access | Day room used by staff as a storage and meeting area at start of study. No outside access | Day room used also by staff; access to outside garden |

Day room on 7d in use as a chair store (32 chairs) at the start of the study Day room on 7b accessible but used frequently for staff meetings |

| Visiting hours | 14.00–20.00 | 11.00–20.00 | 14.00–17.00/18.00–20.00 | 11.00–20.00 |

| Meetings | Nursing handover between the day and night staff each morning. A brief morning multidisciplinary meeting, known as the ‘whiteboard meeting’, and weekly MDT meetings to review discharge plans. MDT meetings on Tuesdays | Nursing handover between the day and night staff each morning and at 12 o’clock for the late shift. Therapists and nurses meet each Monday morning. This ‘board round’ is at 09.00; MDT meeting every Wednesday | Nursing handovers every day at 08.00. and 20.00; MDT meetings on Friday afternoon | Nursing handover between the day and night staff each morning; therapist handovers follow this Monday to Friday |

| 7-day therapy service | No | An OT and a PT work on Saturday covering the acute and rehabilitation units. On Saturdays and Sundays one stroke rehabilitation assistant is on the unit | No | No |

| Performance in last Acute Organisation Report 201664 when units were graded against 10 key indicators (see Appendix 1, Table 15) | Achieved 7 of the 10 key indicators | Achieved 4 of the 10 key indicators | Achieved 8 of the 10 key indicators | Achieved 5 of the 10 key indicators |

Each of the four sites was included in the most recent biennial SSNAP Acute Organisational Audit report,64 published in 2016, which includes site-level and national performance against 10 key indicators (see Appendix 1, Table 15). The sites also return data continuously for the SSNAP Clinical Audit, which measures performance against standards for 10 key domains reflecting processes of care provided to patients. The clinical audit includes an overall performance score for 3 months, made up of a combined total indicator score derived from the average of patient- and team-centred key performance indicators, case ascertainment and audit compliance. Performance is graded A–E, with A indicating first-class service, B indicating good or excellent in many aspects, C indicating reasonable overall – some areas need improvement, D indicating several areas need improvement and E indicating substantial improvement required.

The SSNAP Acute Organisational Audit reports and the prospective clinical audit data provide an indicator of each site’s performance at a point in time, but reporting on these data carries several caveats. First, CREATE sites 1–4 did not treat patients within 72 hours (known as the hyperacute stage) following stroke and audit data also included results from these units providing hyperacute care. Second, Acute Organisational Audit data provide a snapshot of staffing at 10.00 and 22.00 and a whole-time equivalent at each grade against national indicators and the national medians on any given day, but this is likely to vary from day to day and does not include data about the severity of disability of the patients cared for. Appendix 1, Table 15, shows an overview of SSNAP Acute Organisational Audit site-level data and performance of all participating stroke units (1–4) against the 10 key indicators.

Project governance and management

The project needed Health Research Authority approval, including an independent ethics review. In each of the four sites, a senior clinician was identified who acted as principal investigator; they negotiated site access, supported local approvals and took day-to-day responsibility for the study, including identifying potential participants.

In addition to the senior clinician, each stroke unit nominated a group of core clinical staff, which included senior nurses, therapists, dietitians and psychologists. They played a key role in EBCD by helping facilitate introductions and communications with local stakeholders such as head of estates, volunteer co-ordinators, matrons, general operation managers, and communication leads for the trust. After receiving training from The Point of Care Foundation about the six stages of EBCD, the core groups assisted the research team with communications about the stages of co-design and explained to all staff how this might advance in their own stroke units. The Point of Care Foundation training was delivered by an independent facilitator who had experience in EBCD and it was carried out before EBCD commenced with teams from across the two stroke units in stage 1 and then later with the further two stroke units in stage 2. Training consisted of a full day for sites 1 and 2 but was reduced to a half-day for sites 3 and 4 following feedback from clinical teams. Further detail of training is in Report Supplementary Material 1.

In each stroke unit, the core staff and principal investigators helped researchers by identifying patients and family members who might want to engage with co-design and inviting them to do so. Following the guidance given in the EBCD toolkit,65 patients were recruited if they had been an inpatient on the unit in the previous 3–6 months and ranged in terms of ethnic group, gender and stroke severity. We set out to recruit patients with and patients without family members and a similar number of staff.

Steps of the process (full and accelerated experience-based co-design)

We followed all six stages of EBCD at sites 1 and 2, completing the full co-design process. This enabled staff, patients and families to reflect on their experiences of the acute stroke unit, work together to identify improvement priorities and devise and implement changes, and then jointly reflect on their achievements. At sites 3 and 4 we began an ‘accelerated’ process at the joint staff and patient event, using the composite films from sites 1 and 2 to trigger discussion about priorities for co-design. EBCD in CREATE was also embedded in our mixed-methods case evaluation and we undertook pre- and post-implementation data collection that is not part of a standard EBCD approach; this comprised extended ethnographic observations, behavioural mapping and patient-reported outcome measure (PROM)/patient-reported experience measure (PREM) questionnaires.

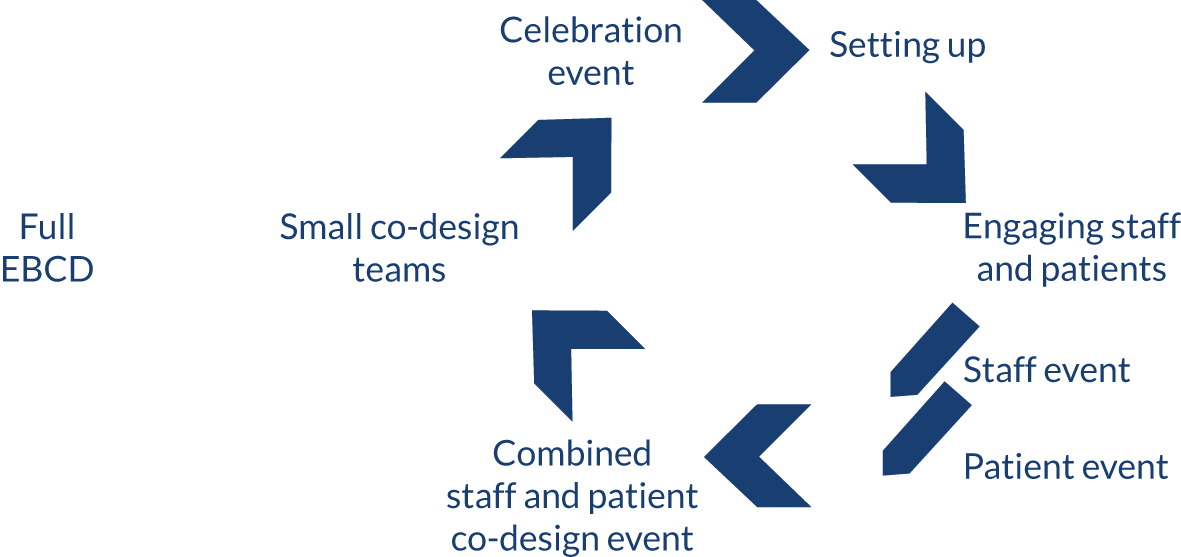

The six stages of the EBCD cycle are described as typically taking 9–12 months to complete. 51 The full EBCD cycle, contextualised to CREATE and used at sites 1 and 2, is shown in Figure 1 and described in more detail below.

FIGURE 1.

Full EBCD cycle used at sites 1 and 2.

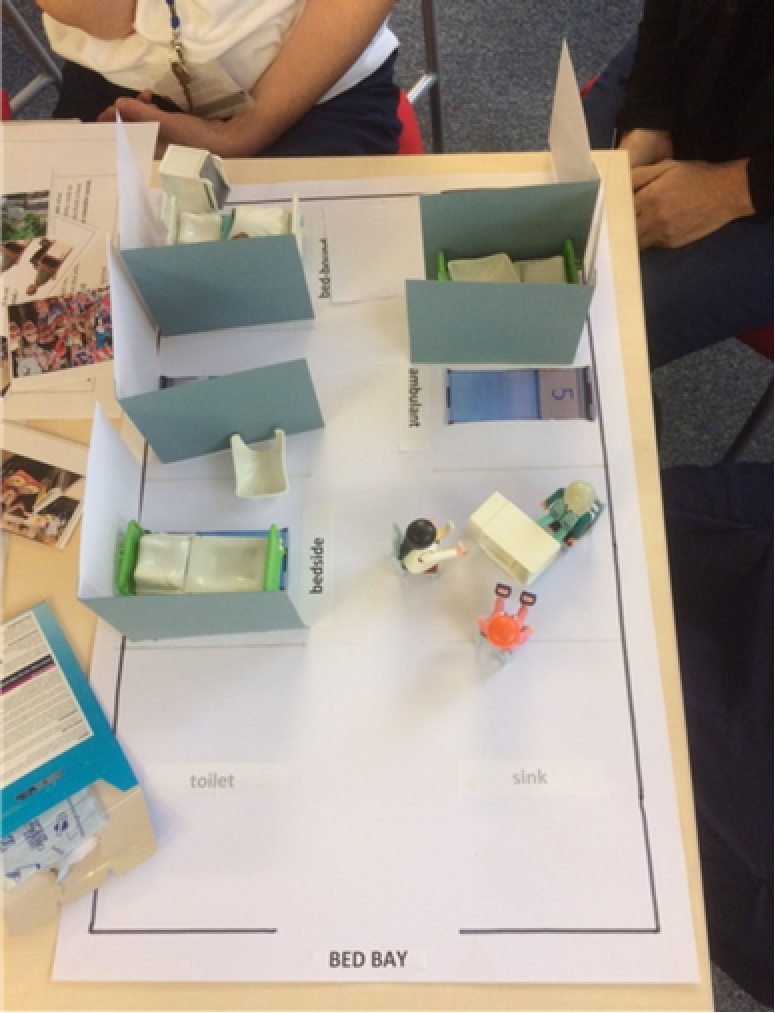

Stage 1: setting up the project

Stage 1 involved a period of stakeholder mapping with the core staff team to identify key contacts and services and/or staff who could help champion the co-design process in the trust and expedite approvals required on each unit for changes in layout, décor, or activities. We formed study oversight groups with trust leads at sites 1 and 2, meeting in person and communicating by e-mail. Core staff, together with researchers, developed posters and flyers about the project and held briefings with larger staff groups at different times during the day, for example nursing handover, goal-setting meetings with therapists and weekly multidisciplinary team meetings.

Stage 2: gathering staff experiences through observational fieldwork and in-depth interviews

In stage 2, staff were interviewed to explore their experiences of working on the stroke unit, particularly with respect to routines, structures and interactions in the team and with patients (see Table 3 for numbers of staff interviews). We also explored how ‘activity’ was perceived and what staff felt were the barriers and limitations to activity that could be addressed through co-design. Researcher-led ethnographic observations, which contributed both to EBCD and to pre-implementation evaluation data collection, were carried out at each site. Observations were carried out over a 3-week period or less and included weekday and weekends between 07.30 and 12.30, between 08.30 and 13.30 or between 15.00 and 20.00. The purpose, described in more detail in the evaluation section of this chapter, was to develop an understanding of the social and organisational processes linked to activity and the regularities and irregularities of the organisation of work and of social interaction in order to enhance our understanding of how and why stroke patients may be active or inactive during the inpatient day.

Stage 3: gathering patient and carer experiences through observation and filmed narrative-based interviews

In stage 3, patients and families were observed as part of the researcher-led ethnographic observations and staff observations described above. Patients and families were recruited for filmed narrative interviews that were edited into one composite film specific to sites 1 and 2. Most patients were filmed in their homes, with one patient choosing to be interviewed in a university building. Interviews lasted between 1 and 2 hours, during which time their experiences of being a patient on the stroke unit were explored. Some patients chose to be interviewed with their family member or on occasion separately for practical reasons. Family members reflected on their experiences of visiting and supporting their relative during the admission. The interviews explored routines and structures that either helped or hindered activity; interviewers encouraged patients to reflect on their activity during a usual day and across the whole week, including weekends. The composite films were produced for sites 1 and 2 and comprised nine patients and three family members (site 1) and seven patients and four family members (site 2).

Stage 4: bringing staff, patients and carers together at separate and joint events

In stage 4, the interview and observational data from stages 2 and 3 were summarised to draw out key themes and help orientate discussions towards priorities for change. The composite films comprised a narrative of patients’ and family members’ reflections and experiences of being on the stroke unit and several touch points. The duration of the composite film was 20 minutes and 24 minutes for sites 1 and 2, respectively.

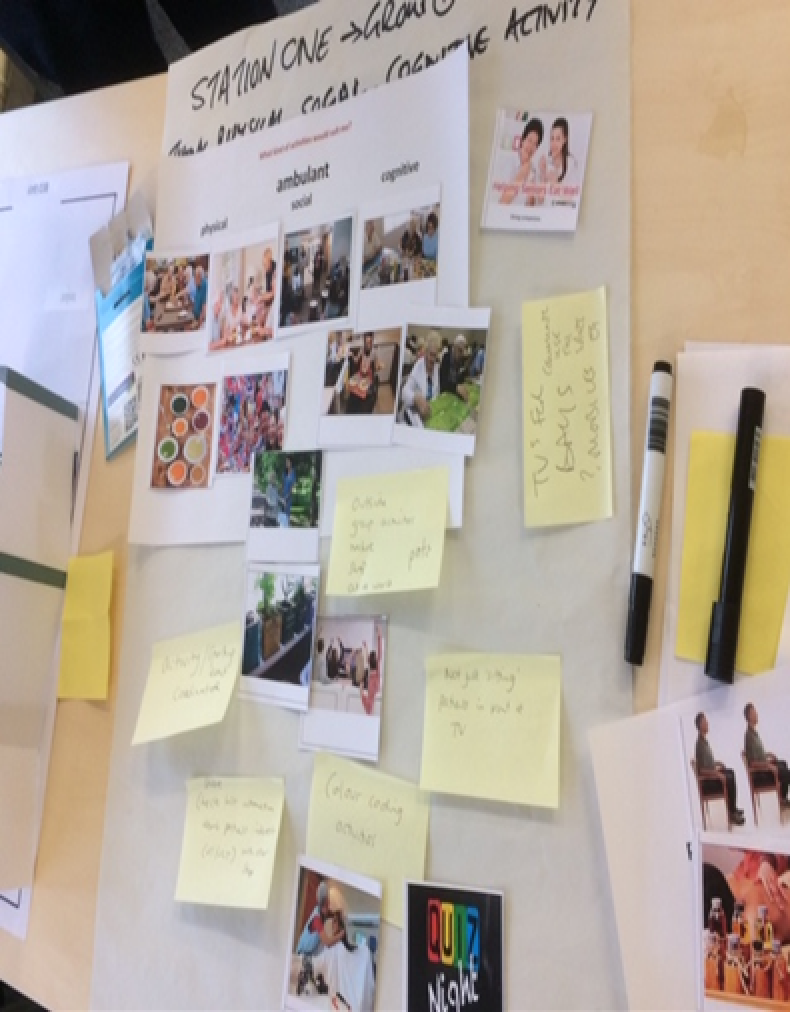

Patient events

Through a staged process of facilitation and discussion, following guidance and methods suggested by trainers from The Point of Care Foundation, patients and families viewed the composite film and explored their ideas for change. These methods included an icebreaker exercise and working in small groups to brainstorm ideas and emotions after viewing the film. Emotional mapping was used to rank and prioritise ideas for change from most to least important and to refine the final list to be shared with staff at the joint event.

Staff events

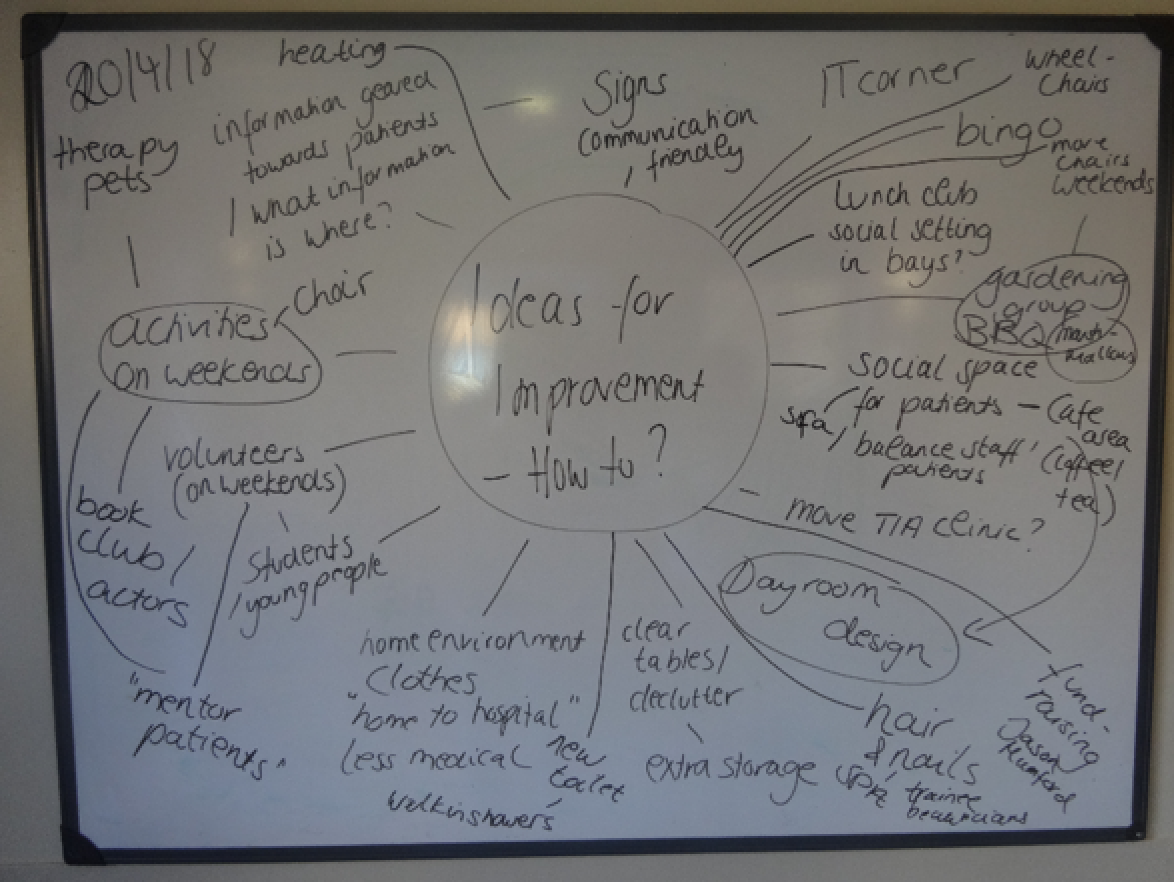

The staff events were structured in a similar way to the patient events but without the use of a composite trigger film. Discussion and ideas were generated following the research team’s presentation of observational data and staff interviews. Through a staged process of facilitation and emotional mapping exercises, they explored ideas about areas for change, and generated a list of ideas and priorities as a group to present to patients and families at the joint event.

Joint events

Patients and staff then came together for a joint event. The numbers of attendees at each event are shown in Table 2. Other stakeholders from the trust, including volunteer co-ordinators and senior nursing and therapy managers, also attended these events. Attendees watched the composite film, and the staff and patient/family groups then separately presented their list of priorities. Facilitated by the researchers alongside the core team members/champions, staff, patients and families worked in small groups through a staged process of sharing and discussing what they had heard, what resonated and what they perceived as the most important priorities for change. During several stages of discussion, each small group chose their joint priorities; through stages of voting and discussion, the wider group agreed a final list. Participants then indicated which priority areas they preferred to work on and signed up for one (or more if they wished) of the co-design groups at each site.

| Site | Co-design participants (n) | Number of co-design group meetings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Carers | Staff | ||

| Site 1 | 5 | 6 | 13 | 10 |

| Site 2 | 4 | 4 | 12 | 9 |

| Site 3 | 11 | 7 | 14 | 15 |

| Site 4 | 3 | 4 | 15 | 9 |

| Total | 23 | 21 | 54 | 43 |

Stage 5: sustained co-design work in small groups formed around priorities

In stage 5, co-design groups were held over 4–5 months, with groups meeting up to five times. Co-design groups were researcher supported and co-led with clinicians, and they typically lasted 1.5–2 hours. The groups were held in accessible spaces, usually on site at the hospitals, and timed for after the midday meal to gain maximum attendance from nursing staff. Refreshments and transport for patients and families were provided if required. Each group explored the ideas within their own priority area and developed action plans; researchers made notes and shared these with all participants after each group to confirm actions. Tasks such as contacting estates or local voluntary groups were delegated and shared among the group.

Stage 6: a celebration and review event

An important part of the EBCD process is the opportunity for staff, patients, carers and researchers to come together and celebrate their involvement in developing, implementing and sustaining the co-designed changes. 51,61 Celebration events were held in both sites 1 and 2 and were attended by approximately 60 patients, staff and families. The events included presentations and informal sharing of experiences by those staff and patients involved in the co-design process, reflecting on the changes that had occurred and the lessons learnt and summarising the post-implementation data from observations and staff and patient interviews. The research team gave an overview of the progress of the CREATE project across sites and the plans for the next stage. A number of additional events enabled further dissemination of the project, including a mayoral visit and an official launch of the changes in the stroke unit at site 1, as well as more detailed feedback of the results to small groups of staff and other stakeholders.

Break point

Our original proposal aimed to have a break point between phases 2 and 3 (full and accelerated EBCD) to review the results and evaluate changes in behavioural mapping data and experiences of implementing the co-produced interventions from qualitative findings. If a positive change was found in supervised and independent therapeutic patient activity following the implementation of co-produced interventions, evidenced in either behavioural mapping data or qualitative data from post-implementation interviews and feedback events, then we would proceed to test the interventions in two further stroke units in phase 3. Subsequently, ethics approvals (see Report Supplementary Material 3) stated that we would have to submit substantial amendments detailing the range of changes in phase 2 (sites 1 and 2) that might be expected, and this approval would need to be in place before recruiting and commencing at sites 3 and 4. We were able to demonstrate to the Study Steering Group that the qualitative data indicated positive change but changes in behavioural mapping data were inconsistent. Following guidance and discussion with our Study Steering Group and NIHR manager, we had agreement to proceed to phase 3. On reflection, the use of the break point should have been defined not as ‘potentially stopping’, but rather as using the findings from phase 2 (sites 1 and 2) to plan and inform the accelerated EBCD at sites 3 and 4.

‘Accelerated’ experience-based co-design sites 3 and 4

Our research questions asked how feasible it would be to adopt EBCD as a particular form of co-production for improving the quality and intensity of rehabilitation (activity) in acute stroke units. The full EBCD carried out at sites 1 and 2 took 9–10 months. Our methods for sites 3 and 4 were informed by Locock et al. ,60 who showed that it was possible to accelerate the process using a national video and audio archive. We were keen to use the stroke-specific trigger films developed at sites 1 and 2 and contextualised at two further sites using the methods outlined below. Consequently, at sites 3 and 4 we sought to reduce the length of the process by making two distinct changes from the methods of Locock et al. 60

First, we used the trigger films already generated by stroke participants at sites 1 and 2. Although staff and patients were still interviewed as part of our pre- and post-implementation data collection, we chose not to film the interviews or edit the narratives to produce a composite film; instead, we used the trigger films from sites 1 and 2.

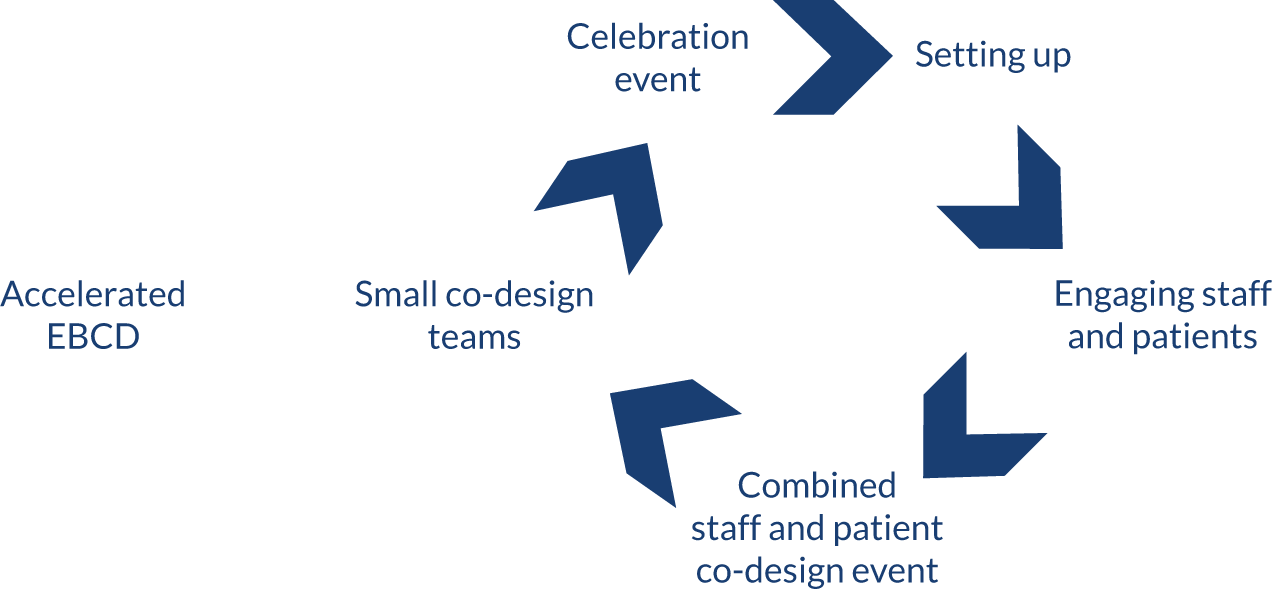

Second, we progressed straight to a joint event after site set-up, interviews and observations without holding separate staff and patient events. This meant that staff, patients and carers saw the film together for the first time but the same methods were used in the joint event to explore ideas and priorities and to develop co-design groups. A total of 82 staff, patients and families attended the joint events at sites 3 and 4, and again co-design groups were formed around agreed priorities (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Accelerated EBCD used at sites 3 and 4.

Celebratory events were held at sites 3 and 4 in a similar way as at sites 1 and 2. Staff, patient and family members gave presentations and shared experiences informally, and the research team gave a summary of the project and progress. Further dissemination and spread of project findings happened at sites 3 and 4, including a mayoral visit and official launch of the new common room at site 3, and an open day at site 4, as well as more detailed feedback of the results to small groups of staff and other stakeholders.

Chapter 3 Methods: the evaluation

Parts of this chapter are based on Clarke et al. 16 © Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2017. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Design and conceptual framework

Our evaluation used a mixed-methods, case comparison design. We conceptualised the development and implementation of the co-produced interventions as an organisational and social process involving interaction between the creators and the users of knowledge. Translating the knowledge arising from health services research into practice through the implementation of service innovations remains a key challenge in the drive to improve the quality of health care. Organisational and social processes will largely determine whether or not service improvements to patient, family and staff experiences are implemented in practice. Although frameworks have become increasingly sophisticated, the influence of context has not been fully accounted for in these models. 66

Our aim was to evaluate the feasibility and impact of patients, carers and clinicians co-producing and implementing interventions to increase supervised and independent therapeutic patient activity in acute stroke units. We were particularly interested in the processes by which co-designed improvements are implemented in particular contexts and settings, and whether or not this process could be enhanced. We aimed to study both the impact of the improvements designed to increase activity and the feasibility of using EBCD in stroke units for the first time and the experiences of staff, patients and families taking part. We used normalisation process theory (NPT) to study the implementation and assimilation of the co-produced interventions in the local context of our study settings. 67,68

The evaluation team consisted of researchers based at each site (FJ, KGW, DC and SH) who were supported by the wider project group (AM, GR, RH, CM and GC). The site researchers were responsible for all data collection. Analysis and interpretation were shared by the whole group. During phases 2 and 3, researchers were regularly present on the stroke units and attended staff meetings, handovers and training sessions to engage staff in the project and communicate with stroke unit-based clinical staff during pre and post data collection.

We used multiple data collection methods to generate quantitative and qualitative data to address the project’s research questions:

-

What is known about the efficacy and effectiveness of co-production approaches in acute health care?

-

How do patients and carers experience the use of a co-production approach and what impact does it have on quality and supervised and independent therapeutic activity on a stroke unit?

-

How do staff from acute stroke units experience the use of a co-production approach and what improvements in supervised and independent therapeutic activities does the approach stimulate?

-

How feasible is it to adopt EBCD as a particular form of co-production for improving the quality and intensity of rehabilitation in acute stroke units?

-

What role can patients and carers have in improving implementation of National Clinical Guideline recommendations on the quality and intensity of rehabilitation in acute stroke units?

-

What are the factors and organisational processes that act as either barriers to or facilitators of successfully implementing, embedding and sustaining co-produced quality improvements in acute care settings, and how can these be addressed and enhanced?

Question 1 was answered in a rapid evidence synthesis published in 2017. 16 We anticipated that the findings would inform intervention phases and highlight the gaps in existing studies that could be addressed through our project phases. The aim was to identify and appraise reported outcomes of co-production as an intervention to improve the quality of services in acute health-care settings.

There are no agreed international guidelines for designing and conducting a rapid evidence synthesis. However, there is overall agreement that the process should involve providing an overview of existing research on a defined topic area, together with a synthesis of the evidence provided by these studies to address specific review questions. Rapid evidence syntheses are typically completed in 2–6 months, which does not normally allow for all stages of traditional effectiveness reviews. The rapid evidence synthesis was conducted between January and June 2016. The search terms used were specific to the use of co-production in acute health-care settings (see Appendix 8). To keep the search focused on co-production approaches, we omitted broader search terms, including co-operative behaviour, patient participation, collaborative approach and service improvement.

Database searches were conducted for the period 1 January 2005 to 31 January 2016. Given that two more general reviews relating to co-production had been published previously,7,18 and given the CREATE study focus, we reviewed post-2005 evidence and only that reporting on studies in acute health-care settings. We completed citation tracking of five seminal papers; in addition, five experts in co-production were requested to nominate three to five seminal papers relevant to our review.

The databases searched and the inclusion and exclusion criteria are given in Appendix 8 and the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram and checklist for the rapid evidence synthesis are in Report Supplementary Material 5.

Screening

Two reviewers independently read all titles and abstracts. Differences in retain or reject decisions were discussed by the two reviewers, with the involvement of a third reviewer when consensus could not be reached. Three reviewers independently read the included full-text papers; decisions to retain or reject were made independently based on the inclusion criteria. All three reviewers then reached a consensus on retain or reject recommendations. The same three reviewers completed data extraction. The quality appraisal checklists developed by NICE for quantitative and qualitative studies were used. These address 14 areas of study quality ranging from theoretical approach to study design, data collection and analysis methods and ethics review. Two reviewers undertook data extraction and quality appraisal independently for each study. We did not exclude studies on the basis of quality appraisal, including all studies in the synthesis to inform discussion of the evidence identified. A mixed research synthesis approach was used. Studies were grouped for synthesis not by methods (i.e. qualitative and quantitative) but by findings viewed as answering the same research questions, or addressing the same aspects of a target phenomenon.

Our main evaluation focused on research questions 2–6.

Prior considerations

During project set-up and commencement, we recognised that the term ‘rehabilitation’ as used in our original application can be misleading and is often interpreted by patients as treatment delivered by a therapist. In the CREATE study we focused on supervised or independent social, cognitive and physical activity undertaken by patients and occurring outside one-to-one therapy sessions. We used an umbrella term of ‘activity’ for anything that patients do with or without help, however small, outside an individual one-to-one scheduled session of therapy. This could also include ‘clinical’ or ‘daily living’ activities, such as walking assisted/unassisted to the bathroom or getting dressed, and talking to other patients or to staff.

Of note is that the ethnographic observations and semistructured interviews conducted with patients and carers and staff pre and post completion of the EBCD cycles were used both to inform the EBCD process and as part of our evaluation. Prior to the introduction of EBCD, data generated using these methods enabled the research team to develop an understanding of what was occurring at those points in time and what activity was wanted going forward, and of staff members’, patients’ and carers’ experiences in these stroke units. Post the EBCD cycles, these data enabled the research team to develop an understanding of staff members’, patients’ and carers’ experiences of the EBCD process and their perspectives on the changes designed and implemented to increase social, cognitive and physical activity opportunities in these four stroke units. An overview of our data collection methods and whether the methods were used for evaluation, EBCD or both is provided in Table 3.

| Site | Staff interviews: EBCD and evaluation | Patient interviews: EBCD and evaluation | Carer interviews: evaluation | PROMs/PREMs: evaluation | BM: number of participants | BM: number of observations | Observations: EBCD and evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 pre | 13 | 9 | 4 | 22 | 9 | 702 | 50.2 hours |

| Site 1 post | 8 | 5 | 5 | 24 | 7 | 949 | 46.5 hours |

| Site 2 pre | 15 | 9 | 4 | 45 | 11 | 769 | 48 hours |

| Site 2 post | 7 | 6 | 2 | 26 | 10 | 528 | 44 hours |

| Site 3 pre | 6 | 9 | 3 | 28 | 12 | 945 | 49.2 hours |

| Site 3 post | 8 | 6 | 3 | 11 | 7 | 782 | 37 hours |

| Site 4 pre | 7 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 6 | 655 | 44 hours |

| Site 4 post | 12 | 5 | 3 | 11 | 6 | 701 | 46 hours |

| Total | 76 | 53 | 27 | 179 | 68 | 6031 | 364.9 hours |

Procedure and participants

The observations and the interviews were conducted with patients and carers and staff pre and post completion of the EBCD cycles. Behavioural mapping was carried out with patients who were present on the stroke unit and able to provide informed consent the day before data collection. Interviews with staff across all specialties and grades took place after observations had been completed (pre and post EBCD) in each site.

Patients’ interviews took place within 3–6 months of their discharge from the stroke unit, when enough time had passed for adaptation to life at home to have begun, but soon enough after their inpatient care episode to allow reasonably accurate recall. Family members were recruited at the same time as patients. PROMs and PREMs combined in a single questionnaire pack (see Table 3) were sent to all patients discharged from each stroke unit in the 6 months prior to data collection in the pre-EBCD period and all those cared for during the EBCD/intervention period at each site.

Sampling and recruitment

Recruitment

We aimed to recruit participants who reflected the population of stroke patients admitted and discharged from our sites, who would naturally include patients with different levels of stroke severity, gender, age and ethnicity. We also aimed to include participants who had communication and/or cognitive impairments in order to reflect the stroke population, and encouraged family members to provide support when patients were unable to complete the questionnaires or take part in interviews. Several strategies were used to estimate our target numbers for recruitment.

Based on stroke admission data across London and Yorkshire, we estimated that it would be possible to collect PROM/PREM data from an independent sample of 30 patients from each unit pre and post implementation of co-produced interventions.

Behavioural mapping data collection took place during non-consecutive days. We aimed to recruit a minimum of four and a maximum of eight patients who met the inclusion criteria and were able to provide consent on the day before the observation.

Pre implementation of EBCD cycles, we aimed to purposively recruit a sample of approximately 10–15 staff, stroke participants and family carer members (30–45 in total from each unit) to take part in interviews as part of the co-design process. Stroke participants and family members or friends (carers) were also recruited 3–6 months after discharge from the stroke unit to allow time for adaptation to life at home to begin, but sufficiently soon after their inpatient care episode to allow reasonably accurate recall.

Post implementation of EBCD cycles, we aimed to recruit a further sample of up to 10 members of staff/patients and carers in each of the four sites to participate in semistructured interviews to explore their experiences post implementation of co-designed interventions. We also aimed to carry out interviews with a sample of staff members, patients and families who took part in the co-design groups to explore their experiences of being part of the whole process. The size of the sample was also informed by reaching thematic saturation during data analysis.

Sampling technique

-

Convenience sampling was used to collect PROM/PREM data from consecutive patients and family/carer members discharged from participating stroke units over a 3- to 6-month period.

-

Purposive sampling was used for behavioural mapping to ensure that recruited participants included those with different levels of stroke severity and those with aphasia (who are often excluded from stroke research).

-

Purposive sampling was also used to recruit staff who worked on the participating stroke units. To ensure that a broad range of views were accommodated, we aimed to recruit staff from different grades and professional groups. In recruiting patients/families, we included those with experiences that varied according to the severity and range of impairment, as well as those stroke patients who may not have family members.

Data collection methods

Evaluation data collection took place pre and post implementation across all four sites. Table 3 shows the timings of data collection and the methods used:

-

Semistructured interviews with patients and carers were carried out to elicit their perceptions and recall of opportunities for and experiences of activity in the stroke units. Patients from each unit were interviewed post discharge, and (at sites 1 and 2) in the pre-implementation stage these interviews were filmed. Topic guides for all of the interviews are in Appendices 2–5.

-

Semistructured interviews with staff were carried out with staff with a range of stroke unit experience, from PTs, OTs and speech and language therapists, to nurses, doctors, psychologists, dietitians and support workers, at different grades, to elicit their perceptions of the stroke unit and the opportunities for and experiences of patient activity. In addition, staff perceptions of organisational processes that influenced activity with patients, carers and other members of the stroke team were explored, together with their views on areas in which additional supervised and independent therapeutic activity could be enhanced.

-

PROMs and PREMs were sent to more than 60 patients cared for in each unit in the 6 months pre and post implementation (and cared for during the EBCD period). These measures are postal self-completed measures previously developed, reviewed and agreed in consultation with experienced stroke clinicians in West Yorkshire as part of the Clinical Information Management System for Stroke study [a Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health and Care (CLAHRC) project]. The measures allow a carer or a family member to record responses for a patient, if necessary, and were used successfully with patients after stroke in the Clinical Information Management System for Stroke study. The PROM incorporates validated measures including the Oxford Handicap Scale, the Subjective Index of Physical and Social Outcome and the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D). The PREM was developed by Kneebone et al. 69 and is a validated tool for patient-reported experience of neurological rehabilitation.

-

Non-participant observations (ethnographic fieldwork) in each stroke unit took place pre and post implementation. An observational framework developed for use in a previous process evaluation of caregiver training70 was used to record observations of the stroke unit contexts, organisational processes, staff and patient interactions and instances of planned and unplanned activity, including noting when timetabled therapy was occurring on a one-to-one or group basis (see Appendix 6). Observations, typically of 4–5 hours each, took place across 10 days at different times of the day, evenings and at weekends in order to develop understanding of how activity may vary across a range of times and days of the week.

-

Behavioural mapping was used to record any social, cognitive or physical activity. These data were generated to establish an indication of activity levels in each unit at a given time point before and after the EBCD cycle was implemented. The data were from separate groups of patients; thus, we did not seek to compare ‘before and after’ scores for individual patients but rather we used the behavioural mapping data as a broad indicator of activity level. The approach was adapted from that successfully employed in two earlier stroke studies concerned with increasing patient activity. 28,71 Patients on the stroke unit were screened 24 hours before to determine whether or not behavioural mapping would be feasible. We aimed to recruit a minimum of four and a maximum of 10 patients who met the inclusion criteria and were able to provide consent on the day before the observation. This number was achieved across all sites (see Table 3). The patients were observed at 10-minute intervals between 08.00 and 17.00 or between 13.00 and 20.00 on 3 separate days. This allowed for up to 60 observations of each patient per day. We varied the times and days of the week for behavioural mapping to allow for possible variation in activities by day of the week. During each 10-minute interval, the data for each patient were based on an observation made by the researcher over a period of no longer than 5 seconds. The researcher observed one participant and then progressed to the next participant. The researchers positioned themselves so that they could see the participants – at the same time taking steps to be inconspicuous – and noted where they were, what they were doing and who was present in the same location as the patient. Observations began at the commencement of each 10-minute interval (i.e. 08.00, 08.10, 08.20, 08.30, etc.). The behavioural mapping protocol and recording instrument are in Appendix 7.

In our initial proposal, we anticipated accessing the SSNAP data at an individual patient level to enable us to compare patient dependency during the periods of study, a factor that can influence the activity levels achieved. We had anticipated that we could collect these data on the ward before they were uploaded to SSNAP, but we were not able to gain permission for access.

We agreed that pursuing access to the anonymised SSNAP data would prove overly time-consuming and impossible within the project time scales. This change was discussed in full by the Study Steering Committee and approved by our Health Services and Delivery Research programme manager. An additional justification for this decision was that the national case-mix data are based on the patient cohort within the first 72 hours, that is while at the first routinely admitting stroke unit. Each of the CREATE sites was non-routinely admitting and received patients repatriated from the main routinely admitting hospital linked to their unit.

Data analysis

Qualitative data analysis

We first describe the processes used to analyse the qualitative data generated from non-participant observations of staff, pre EBCD training and activity, during EBCD (i.e. of the separate patient and carer, staff meetings, joint meetings and co-design meetings) and from interviews with patients, carers and staff pre and post EBCD. The integration of these data in the EBCD evaluation and also in the linked process evaluation involved an iterative approach to analysis that focused initially on the data generated at each site and then progressed, using team half-day analysis meetings, to a comparison between sites, as described below.

Interview data video files (patients and carers at sites 1 and 2) and audio files (staff all sites and patients and carers at sites 3 and 4) were transcribed verbatim. The research fellows and research lead for each site completed an initial thematic analysis of the data at each site (London and Yorkshire) and prepared summary memos identifying the main themes and summarising the key issues related to the presence or absence of activity outside therapy, the opportunities to make changes and the attitudes towards possible changes. These summary memos were then compared and reviewed iteratively in a series of half-day face-to-face meetings (held approximately every 3 months in London or Leeds) by all four researchers, before the summaries were presented to and discussed with Study Steering Committee members.

For observational data, field notes were prepared by each researcher conducting an observation and shared among the researchers for that site. On completion of the series of observations (pre and post implementation and during EBCD activities), summary memos were developed to identify recurring themes and to compare and contrast findings from pre- and post-EBCD activities within and then between sites in London and Yorkshire. Again, these were compared and reviewed iteratively by all four researchers in a series of half-day meetings (as described above) before being shared with Study Steering Committee members. The memos included references to contextual factors considered relevant to service delivery, and to patient experiences of the EBCD process in each site. These processes were used for sites 1 and 2 and then repeated for sites 3 and 4.

Following these half-day meetings and the discussions resulting from presentations of the ongoing data analysis, the core and cross-cutting themes reported in Chapter 5 were developed and agreed by the research leads for London and Yorkshire and shared with Study Steering Committee members.

Integration of data in the experience-based co-design evaluation and process evaluation

The data used in the process evaluation were not generated separately from those used in the main evaluation of the feasibility of using full and accelerated EBCD in the four sites; rather, the same data were critically examined using NPT’s four core constructs and associated components. A data collection plan linked to NPT’s four constructs was developed prior to data collection. The purpose of the plan was to engage with the NPT constructs as data were analysed at each time point, and to identify evidence of (in the summary memos described above) examples such as staff progression from coherence to cognitive participation. This might comprise staff making sense of the EBCD approach, then thinking about what introduction of and support for increased patient activity outside planned therapy would mean for them individually and for the routine service provision currently in place. Once the EBCD activities had ceased at sites 3 and 4, the summary memos and the researcher reflections were reviewed by the research lead for the process evaluation and a draft single integrated account was constructed. This was reviewed by the research team as a whole, and the final agreed account is presented in Chapter 5. Our approach comprised both an ongoing integrative analysis of these data focused on staff and patient engagement with the EBCD process and on designing and implementing changes to promote or directly support increased activity, and a post hoc review of the full integrative data set.

Confirmability of analysis was further enhanced through a process of independent, joint and team half-day analysis and review cycles, after which the emerging analysis was discussed with the Study Steering Committee members. Credibility and transferability of the analytical approach are evident in how we have used detailed data extracts and interview quotations to support plausible explanations of the observational and interview data in terms of participants’ engagement with EBCD and the facilitators of and barriers to its introduction and use in the four sites. We incorporated researcher reflection and reflexivity in the data collection process and used these insights in the team analysis of the data.

Quantitative data analysis

Behavioural mapping

We entered all data into a SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions) (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) file and described the frequency of activity occurrence for each participant during each data collection period. This approach, used by Askim et al. ,71 included additional categories in social and cognitive activity. These data were used to generate descriptive statistics to quantify the proportion of physical, social and cognitive activity occurring for each patient during the period of observation.

Patient-reported outcome measure and patient-reported experience measure data

These data were entered into a SPSS file and reported as descriptive statistics (or frequency counts) for each item. These data provide insight into patients’ perceived functioning post stroke (PROM) and their experiences on stroke units (PREM). Some of the PREM items sought responses directly related to opportunities and resources for activity.

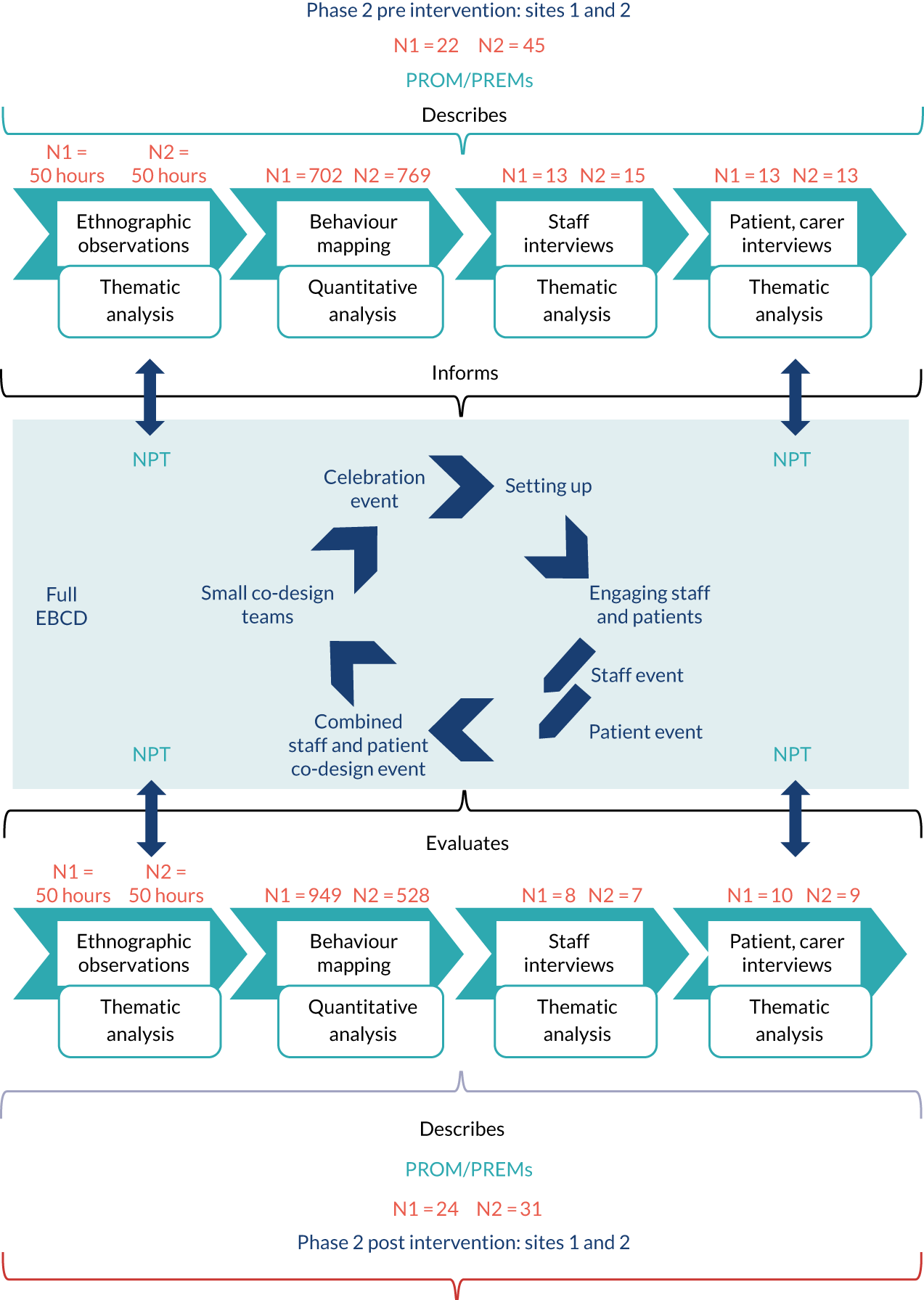

Figure 3 depicts our integrative approach to analysis across the whole data set (qualitative and quantitative) process evaluation.

FIGURE 3.

Data analysis for both the evaluation and the intervention (EBCD).

Process evaluation methods

A parallel process evaluation aimed to understand the functioning of the intervention (i.e. the co-design and generation of new activities in each stroke unit) by examining implementation, mechanisms of impact and contextual factors. Mechanisms of impact refer to the ways in which intervention activities and participants’ engagement with them trigger change in a given setting. Process evaluations contribute to understanding the impact and outcomes of complex interventions. We adopted primarily qualitative methods in the process evaluation (see below), which was informed by NPT. 72