Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR127655. The contractual start date was in March 2019. The final report began editorial review in November 2020 and was accepted for publication in May 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Corrections

-

This article was corrected in March 2022. See Turner J, Knowles E, Simpson R, Sampson F, Dixon S, Long S, et al. Corrigendum: Impact of NHS 111 Online on the NHS 111 telephone service and urgent care system: a mixed-methods study. Health Serv Deliv Res 2022;9(21):148–149. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr09210-c202203

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Turner et al. This work was produced by Turner et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Turner et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

Demand for emergency and urgent care

Emergency and urgent care is provided by a range of services, including emergency services (999 ambulance service, emergency departments), urgent-care services [general practitioner (GP) out of hours, minor injury units, walk-in centres, urgent care treatment centres, NHS 111] and in-hours general practice (requests for same-day appointments and telephone advice). There is widespread concern about rising demand for urgent and emergency care services. In England, national statistics show that in March 2015 there were 1.76 million first attendances at emergency departments (including minor injury units and walk-in centres), 543,172 ambulance responses to 999 calls and 1.08 million calls answered by the NHS 111 telephone service. Four years later, in March 2019, these figures had risen to 2.17 million, 730,000 and 1.32 million, respectively,1 and NHS England estimates that each year there are 85 million same-day urgent care contacts with primary care. 2 These demand increases are not wholly explained by population increases or an ageing population. 3

With demand rising year on year and increasing difficulties in recruiting and retaining a sustainable workforce,4 it is questionable if emergency and urgent care services have the capacity to deal with future demand increases. There are also concerns that some of this demand is a result of clinically unnecessary service use, for example where people choose a higher-acuity service level than is clinically necessary5,6 and could be diverted to lower-level care. Developing and improving the delivery of emergency and urgent care has been a key policy issue for a number of years. In 2013, the NHS England Urgent and Emergency Care Review7 was published, which set out to address ongoing concerns about the increasing and potentially unsustainable pressure faced by emergency and urgent care services. Underpinning the review was the premise that care should be provided ‘as close to home’ as possible by helping people with urgent care needs to get the right advice, in the right place, first time. This emphasis has continued, with emergency and urgent care provision identified as one of the four areas for further development in the 2017 NHS Five Year Forward Plan. This includes an explicit commitment to the introduction of an online version of NHS 111 to help people navigate access to urgent care. 8

Developing remote access to emergency and urgent care

Over the last two decades, a number of different organisational interventions have been implemented in England to attempt to manage demand for emergency and urgent care services. A cornerstone has been the introduction of telephone advice and triage via NHS Direct, subsequently replaced by NHS 111. This is a telephone service to provide clinical assessment and direct people with non-urgent or low-acuity non-emergency health problems to the most appropriate service, or to provide self-care advice for their clinical need. Despite these services’ apparent success in terms of receiving large call volumes, they have had little impact on reducing the demand for emergency services. 9 NHS England data show that, in 2017/18, NHS 111 answered 14,995,168 calls, an average of 46,082 per day, and this is expected to continue increasing. The outcomes of these calls were that 21% had ambulances despatched or were recommended to attend an emergency department (ED), 60.7% were recommended to attend primary care, 4.6% were recommended to attend another service and 14% were given information or self-care advice. 1 The Five Year Forward View8 policy has prompted significant efforts to further enhance the NHS 111 service by increasing the clinical assessment capacity and supporting more integration with other services. It also highlighted the potential for some lower-urgency calls to be handled through online services, which may relieve some of the pressure on the telephone service by diverting some activity, make more efficient use of the workforce, support demand management and reduce costs. An online service also fits with the broader aspirations of exploiting technological innovations to improve health-care delivery and offer alternative access systems in a world where digital solutions have transformed the way people live. This has been done successfully with the introduction of smartphone application (app)-based services to help people manage specific conditions such as diabetes. 10 More broadly, with service provision, as it is currently delivered, reaching saturation, it has been suggested that strategies to reduce patient health-seeking behaviours and increase self-management should be a focus for the NHS. 11

In response to this policy, four pilot online NHS 111 services were introduced in different geographical areas across England in 2017. A useful description of these services is provided in a recent discussion,12 but, briefly, they comprise online and app-based platforms that provide symptom checkers and advice on what users should do next, either self-care or contact another service. Early results from the pilot study reported that NHS 111 Online uptake across all pilots varied between 2% and 15%, but on average was approximately 6%. However, it was hoped that uptake would increase over time to a similar level to that reached in a similar Australian service, where calls to the equivalent telephone triage service decreased by 33% 3 years after the service was introduced. 13

During 2018, the service rapidly expanded to cover the whole of England. In addition, a decision was taken to use only one of the original four platforms across the country. This is the online application developed from the NHS Pathways clinical assessment system used by the NHS 111 telephone service. The service can be accessed via a web-based application or the NHS app and allows users to work through a set of symptom-based questions. It then provides advice on what service to access themselves, options for further telephone assessment with NHS 111 clinicians, out-of-hours GP or other services, appointments with services or self-care advice.

Need for evaluation research

The principles behind introducing an online service as an access point to urgent care in the NHS are based on an expectation that it can make access easier, direct people to appropriate levels of care and divert some activity away from the NHS 111 telephone service and, hence, slow increases in demand for that service.

However, there is also a risk that this new system may increase overall demand, duplicate health-care contacts, change the pattern of service use through differences in triage outcomes, remove some of the ‘gatekeeping’ that the telephone service provides, or provide unsafe advice. The uptake of an online service may be influenced by a lack of consideration of the many and varied reasons why patients chose particular services, including access to primary care; perceived urgency, anxiety and the value of reassurance from emergency-based services; views of family, friends or health-care professionals; convenience; and the perceived need for ambulance or hospital care, treatment or investigations. 14

A recent systematic review of digital and online symptom checkers for urgent health problems undertaken by the University of Sheffield found little evidence to suggest that digital and online symptom checkers are harmful to patient safety, but this may be because this outcome was reported by small, short-term studies only. 15 Deficiencies have been reported in the diagnostic and triage capabilities of symptom checker algorithms that would potentially be used in a digital 111 platform. 16 The systematic review identified that research is needed to investigate the pathways followed by patients using a digital 111 service and to identify whether or not the overall number and level of contacts with the health system can be reduced without the quality and safety of patient care being affected. 15

This research has been designed to meet a clear need set out by NHS England to evaluate and establish the current and future potential impact of an online service on the existing NHS 111 telephone service and wider urgent care system. There is a commitment to providing a national NHS 111 Online service, but robust evidence is needed to inform future plans about what the online offering should look like, and the likely impact on service use and associated costs, and to identify any potential unintended consequences that need to be addressed as the service continues to develop.

Conceptual framework

To our knowledge, there is no established and agreed theoretical framework that underpins the delivery of urgent care, but we have used three conceptual approaches to guide and interpret this research:

-

Our recent extensive evidence review of models for delivering urgent care3 found a clear consensus that evaluation research concerned with the provision of urgent care services needs to take an emergency and urgent care system-wide perspective, rather than focus on a single service. This research uses an emergency and urgent care system model.

-

The provision of an online NHS 111 service is one element of the broader NHS England emergency and urgent care strategy set out in the 2013 Urgent and Emergency Care Review7 and is relevant to the principles set out in that review of providing access to care that is ‘right first time’, providing better support for people to self-care and providing more care closer to home in local communities. More specifically, enhancing the NHS 111 service by improving integration with other services to provide efficient patient care pathways, increasing clinical assessment and adding an online access gateway are critical to the concepts set out in the NHS England Next Steps on the Five Year Forward View8 to help manage demand for urgent care. A key objective to achieving this is the development of online triage services that enable patients with urgent health-care problems to enter their symptoms and receive tailored advice or a call back from a health-care professional. Conceptually, therefore, the population of potential users of NHS 111 Online is expected to be similar to that of those who currently use the NHS 111 telephone service. More broadly, the addition of an online NHS 111 service fits with the NHS Digital Technology strategy to harness the potential of digital technology in ways that can empower and support people to take control of their health and care. 8 The call for this research is embedded in a very clear policy need, and these underlying urgent care policy principles have been used to frame the questions and design of this study and will be used to support the interpretation of the findings.

-

NHS 111, whether a telephone or an online service, provides a point of access for people who have health problems that they perceive to be urgent. The operating model of using a symptom-based approach to assessment assumes an immediate need and uncertainty about what to do rather than simply seeking information about available services. This demand for and use of urgent care services is driven by the health-seeking behaviours of a population, but these have been poorly understood. This issue has been addressed in two recent National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded studies on sense-making strategies and help-seeking behaviours associated with use of urgent care16 and a population study on the drivers of the demand for urgent care. 17 These studies were unpublished when this study was being designed but the researchers were available to help with the interpretation of this study’s findings.

Aims and objectives

The primary aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of providing an NHS 111 Online service to access urgent health-care advice and signposting to services on the telephone-based NHS 111 service. The secondary aim is to explore the potential effects on the wider urgent care system and the implications of providing a national NHS 111 Online service. The objectives are to:

-

update and summarise the evidence on digital and telephone-based services for accessing urgent care, building on existing systematic and rapid evidence reviews

-

measure the impact of the NHS 111 Online system on contacts with the NHS 111 telephone service, and estimate the effects on other services in the emergency and urgent care system and on NHS 111 services in the future

-

explore and compare in detail the characteristics of users of the NHS 111 Online service and the NHS 111 telephone service, service processes, patient care pathways and user experience and satisfaction

-

assess the practical issues associated with the implementation of the new service and the workforce implications of any changes to the overall NHS 111 telephone service and, specifically, the impact on clinical assessment teams

-

estimate the cost–consequences of implementing an NHS 111 Online service for the overall costs of the combined online and telephone 111 services and model the potential cost effects for the emergency and urgent care system.

Chapter 2 Overview of the study

Study design

The overall design is an observational mixed-methods study using a set of discrete but inter-related work packages (WPs) to address the broad range of issues identified in the objectives. The findings of the WPs were integrated during the study to provide information for the economic analysis and at the end of the study to provide a broad picture of the overall impact on services and the people who use them and to assess the potential implications for the future provision of NHS 111.

The five WPs and corresponding chapters are as follows:

-

WP1 – an update of two systematic reviews to assess the current evidence about telephone and digital access services to urgent care (see Chapter 3).

-

WP2 – the use of routine activity data to (1) explore the characteristics of people who use each type of service and whether this results in different types of advice or direction from other services, (2) measure if the introduction of an online service has diverted some activity in the telephone service and other urgent care services and (3) use the trends from this analysis to predict potential future use (see Chapters 4 and 5).

-

WP3 – a survey of telephone and online NHS 111 service users to establish what services people actually use, and compliance with advice and satisfaction, and patient interviews to look in more detail at whether people using the online service find it accessible, useable and valuable (see Chapters 6 and 7).

-

WP4 – interviews with a range of staff and other stakeholders to explore whether or not the online service has had any effect on the telephone service in terms of response to telephone calls, clinical assessment services and staff recruitment and retention (see Chapter 8).

-

WP5 – a cost–consequences analysis to measure the economic impact of introducing an online service on the telephone service and wider emergency and urgent care system (see Chapter 9).

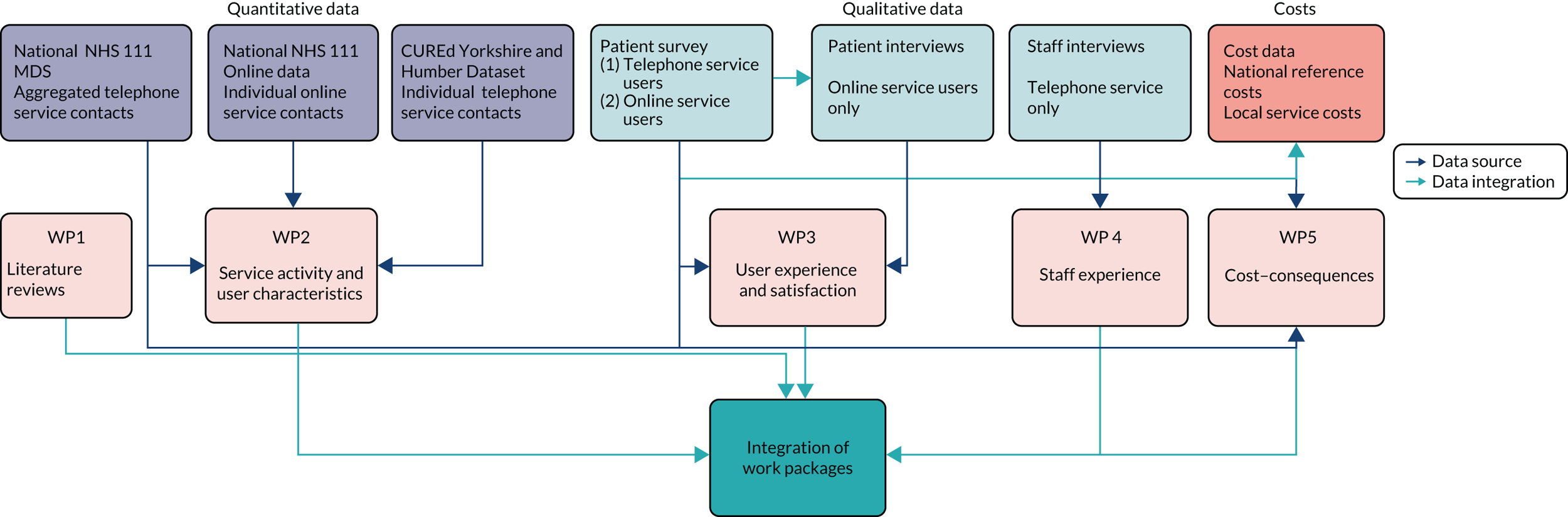

Unlike some mixed-methods studies, the short timescales of this project meant that the quantitative and qualitative components had to be conducted simultaneously. Most of the integration took place at the end of the study; however, there were two earlier integration points. First, in WP3, early interim results from the survey of NHS 111 Online users helped with framing the questions for the user interviews. Second, the results of the surveys of both NHS 111 telephone and online services were used to inform the cost–consequences analysis in WP5. Figure 1 provides an overview of the data sources used for each WP and where integration occurred.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of data sources and WPs. CUREd, Centre for Emergency & Urgent Care.

Changes from the original proposal

-

The introduction of an NHS 111 Online service is a significant policy issue, and there was a requirement for this research to be completed within a short time frame (16 months). In our proposal, we stressed that meeting this would be contingent on obtaining the routine, patient-level data collected by the NHS 111 telephone and online services that were needed to explore changes in activity and user characteristics early in the project. Data for the online service are collected centrally, as the online service is a single service. Data for the telephone service are collected both at the local service level and centrally by the NHS Pathways service. Our preference was to use the single source of NHS Pathways to avoid making multiple data requests of individual sites. Unfortunately, this proved difficult. Extensive discussions took place over several months about whether the anonymised data could be shared directly or whether these needed to be requested via the NHS Digital Data Access Request Service (DARS). This was eventually resolved for the online service, and patient-level data were supplied, but this was not the case for the telephone service data, which necessitated access via the DARS. However, NHS Pathways data are not a data asset held by the DARS, and so these data need to be migrated before an application can be made. At this point, we were already 9 months into the project. Data migration, the DARS application process and then a minimum wait of 3 months for supply would have added at least 6 months to the project. Given that this research was commissioned to address an urgent policy issue, we made a pragmatic decision not to pursue this further and instead used the publicly available data available from the NHS 111 minimum data set (MDS). This provided sufficient data on call volumes and dispositions to allow the time series analyses to be undertaken. However, these data are aggregated, not patient level, and, consequently, we were unable to complete some intended analyses. Principally, this meant we could not make the detailed comparisons of the characteristics of the NHS 111 telephone and online populations that we had planned. This was mitigated to some extent by using historical data we already hold, but it limited what we were able to explore. The MDS data are also collected by broad areas, so we had to change some of our intended study sites. The changes are described in Chapters 3 and 4.

-

In our proposal we intended to identify four of our study sites as case studies where we would combine the findings from the different WPs and compare different models of service delivery, for example by service provider type for the telephone service or by geographical type (urban vs. rural). However, we were able to recruit only two sites to undertake the user survey for the telephone service. This, combined with the changes to sites needed for the quantitative analyses described above, meant that we had insufficient complete sites to be able to use a case study approach.

-

The planned economic evaluation comprised two parts: a cost–consequences analysis and scenario analyses. The second item depended on the data mining of patient-level records, which was not possible for the telephone user population, and delays in obtaining data left minimal time for the economic work. We therefore focused on completing the cost–consequences analysis.

Public involvement

There was a very short time period during which we could consult the public about this research opportunity. However, we are fortunate that we have access to the Sheffield Emergency Care Forum (SECF), a public involvement group with whom we have a well-established and excellent working relationship. They identified a co-applicant for us (DF), who reviewed and commented on our proposal and helped to construct the lay summary. The research team also met with a small group of four SECF members to discuss the planned research and the relevance to the general public of a new access point for urgent care. This helped us focus our research questions and design.

Once the study started, we gave a presentation about the research to the full SECF group and provided them with a link to the online service so that they could try it themselves before the meeting. This provided valuable feedback about the usefulness of the service for different age groups and the issues we needed to consider when developing the questions for the user surveys and interviews, with a particular emphasis on the accessibility and usability of the online platforms.

Daniel Fall was a member of the project management group and had a liaison role with the SECF throughout the study to provide input into the development of topic guides for the qualitative research with service users and questions to be added to existing user surveys. He also contributed to writing the lay summary for the ethics application and the plain English summary for this report.

A member of a second public involvement group – the Deepend cluster, a public involvement group supporting GPs in the most deprived areas of Sheffield – was a member of the Study Steering Committee, providing feedback on emerging findings and contributing to writing the report’s plain English summary.

We will continue to work with the public involvement groups to develop our dissemination strategy and to consider how to disseminate the work to the general population, as well as to develop lay summaries for dissemination.

Patient involvement members were paid for their contribution to the project.

Ethics

Ethics approval for the interview-based work with service users and stakeholders was granted by North West Haydock Research Ethics Committee (reference 19.NW/0361). The University of Sheffield Research Ethics Committee granted ethics approval for the telephone and online NHS 111 user surveys (reference 030991) and the secondary use of routine data (reference 031640).

Study Steering Committee

A Study Steering Committee provided oversight of the research. The Study Steering Committee was chaired by Dr Alison Porter (Swansea University) and comprised members representing service providers, clinical commissioners, primary care, public health, NHS 111 Online development, NHS Digital and public involvement. NHS Digital provided additional technical input. The Study Steering Committee met three times during the study.

Study setting and intervention

The NHS 111 service

The NHS 111 service has been in operation since 2010, with the core function of providing a free-to-use telephone access service for people with urgent health-care problems that is available 24 hours per day, 365 days of the year. The service provides health information and an assessment service, which uses the NHS Pathways system to ask callers a series of questions about their problem and then direct them to an appropriate service using a local Directory of Services (DoS), provide telephone clinical advice or provide self-care advice. The initial assessment is conducted by a non-clinical call adviser and, where appropriate, the call can be passed on for further assessment by a clinician (usually a nurse).

As it has developed, the NHS 111 service has grown to include a secondary function of providing a single point of access for urgent care services, including out-of-hours services, to create a fully integrated urgent care access, clinical advice and treatment service. Integrated urgent care services have access to a wide range of general and specialist clinicians. They offer advice to health professionals in the community and to the ambulance service, manage patients over the telephone who have called NHS 111 and, in some cases, provide appointment booking services and face-to-face management of patients in treatment centres, the patient’s residence or another location, if required. Although a national service, NHS 111 is commissioned by Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) using a variety of providers, including ambulance services, social enterprise organisations and commercial organisations. The geographical footprint of providers is very variable, ranging from large regional services covering multiple CCGs to small areas of two or three CCGs. The range and scope of integration with other services also varies by area and by commissioning arrangements.

The introduction of the NHS 111 Online service has essentially added another arm to the NHS 111 service by providing an alternative access point for people who need information and advice about what to do when they have an urgent health problem.

How does NHS 111 Online work?

The NHS 111 Online service has been designed so that people can get medical help or advice using a smartphone, laptop or other digital device. Users of the service can ask questions about their symptoms, get advice about what to do and where to go and, if needed, get further advice from a nurse, doctor or other trained health professional. The service can be accessed via a website (https://111.nhs.uk/) or the NHS App (https://digital.nhs.uk/services/nhs-app) for smartphones and tablet devices.

The online version of NHS 111 uses an adapted version of NHS Pathways to replicate the questions that are asked by the health advisers in the NHS 111 telephone service.

The implementation of the NHS 111 Online service has occurred in three phases:

-

Phase 1 – people accessing the service can answer questions about their health problem and the results direct them to the appropriate service using the local DoS.

-

Phase 2 – in addition to advice on appropriate service, users can, where needed, book a clinical call-back from the telephone NHS 111 service or integrated urgent care provider.

-

Phase 3 – in addition to 1 and 2 above, users can receive a call back from services such as out-of-hours GPs, dentists, urgent treatment centres and other services, where the technology links have been put in place to accept referrals from the online service.

There are some differences between the online process and the telephone process. These are described in Table 1.

| NHS 111 Online | NHS 111 telephone | Site differences |

|---|---|---|

| The home screen welcomes the user and asks them to enter their postcode |

After dialling 111, the caller is asked to press 9 to confirm that they wish to continue. When the service is busy, a recorded message informs the caller that the online service is available for people over the age of 17 years and asks whether they wish to be sent a link Otherwise, the caller is transferred to the local 111 service. Depending on area, an interactive voice response may allow them to select different options for particular problems, which direct them to specialist clinicians or external services. All other calls are connected to an NHS 111 health adviser |

Interactive voice response options differ by site. Can include:

|

|

The user is directed to the emergency rule-out page (module 0) and asked to confirm that they do not have any of six symptoms which could indicate a life-threatening condition. If they cannot rule out these six symptoms, the user is told to call 999 immediately and triage ends If continuing, the user is asked to enter their age and sex. If they are asking about a person under the age of 5 years, or if they cannot confirm the sex or that the person they are asking about has a gender identity other than male or female, they are told to call NHS 111 |

A health adviser asks the caller for some basic personal details and to confirm that they do not have any of six symptoms that could indicate a life-threatening condition. If they cannot rule out all of these symptoms, the call is transferred for a 999 ambulance response Callers in some areas are transferred to a clinical adviser at this point if they are calling about a person under 5 years or over a particular age |

|

| The user enters an initial symptom. They then work through the questions and can move backwards and forwards through the answers until they reach a disposition | The caller is asked about an initial symptom and the health adviser will work through questions until a disposition is reached | |

| For 999 dispositions, the user is asked to call 999 | For 999 dispositions, the call is transferred to 999 | Some 999 dispositions are assessed by a clinician (revalidation) before transfer |

| For ED or other urgent care treatment services dispositions, users are advised to attend and a list of available services in their area is provided | For ED or other urgent care treatment services dispositions, users are advised to attend and a list of available services in their area is provided | Some ED dispositions are assessed by a clinician (revalidation) before the caller is given this advice |

| If the disposition suggests that the user needs to speak to an NHS 111 clinical advisor, then they are offered a call back and are asked to enter their telephone number, and the date of birth, current location and home address of the person they are asking about. These details are transferred to the local NHS 111 telephone service and added to the clinical advisor call queue | If the disposition suggests that clinical advice in needed, the caller is transferred to a clinical adviser, or asked to wait for a call back | Availability of specialist clinical advisers differs between sites (e.g. mental health, dental, palliative care) |

| If the disposition suggests that the user needs to speak to primary care or other service, they are advised to contact primary care themselves. In some areas, a call back with a primary care clinician or other service can be offered | If the disposition suggests that the user needs to speak to primary care or other service, they are advised to contact primary care themselves. In some areas, a call back with a primary care clinician or other service can be offered | Availability of call-back booking with other services differ between sites |

| If the disposition suggests a service where direct booking is available, the user is asked to enter personal details so that the direct booking can be arranged | If the disposition suggests a service where direct booking is available, the call handler/clinician will arrange a direct booking | Services available for booking differ between sites |

| For other dispositions, users are advised to contact other services (dentist, pharmacy, optician). Where available, the contact details of local services are provided | For other dispositions, users are advised to contact other services (dentist, pharmacy, optician). Where available, the contact details of local services are provided | |

| If no service is needed, users are provided with self-care advice | If no service is needed, users are provided with self-care advice |

As with the telephone service, NHS 111 Online is a national service, but the outputs of a user’s interaction with the central NHS Pathways assessment system are customised and linked to the provider of the telephone and integrated urgent care service in their postcode area. So, for example, if a user is advised to go to an emergency department or other service, a list of local available services and opening hours is provided. If a call back with a clinician is booked, then this is passed to the NHS 111 service that covers their area.

Some early adopters of the NHS 111 Online service implemented the three phases sequentially, but areas that went live later implemented a full phase 3 service from the outset. The service was available nationally from December 2018. We spoke to nine NHS 111 provider sites, which identified the following main features of the set-up and implementation phases:

-

Setting up and testing technical links for Personal Demographics Service matching. When a user of the NHS 111 Online service enters their details (date of birth, full home address, home telephone and emergency telephone number) for a call back, a Personal Demographics Service look-up automatically identifies the patient’s GP practice and NHS number. If a full match is found, this populates a document that is sent into a call queue at the NHS 111 service so that the clinical adviser has access to the patient’s details. If a full match is not found, the patient is allocated an individual patient identification number for the NHS 111 call. When the clinical advisor calls back, they clarify personal details in order to find the full match. Rates of automatic Personal Demographics Service matching vary between sites.

-

DoS profiling so that the NHS Pathways disposition at the end of the NHS 111 triage session maps to the right service from which direct referrals (for call backs or appointments) can be made. The ability to make direct referrals to other services differs by site, depending on the local services available, but can include dental services, urgent treatment centres and GP out-of-hours services. The correct technical links (electronic transfer and e-mail requests) were also put in place. The range of services to which online users can be referred is likely to increase as the integrated urgent care hubs expand and incorporate more specialist services, such as mental health, end-of-life care and pharmacy.

-

The process of project set-up and commissioning of the online service appeared to be relatively straightforward, particularly for the later sites, which described how some of the teething problems had been resolved by earlier sites. Project set-up phases were short, with the most resource-intensive work reported to be developing, testing and re-testing the DoS to ensure that all pathways ended in the correct dispositions. The technical links for referrals were tested robustly to make sure that they worked correctly.

-

Sites reported having a clear plan of the actions required to set up the online service and clear instructions of responsibilities set out by NHS Digital. Discussions between providers and commissioners were uncomplicated, although some site leads reported that commissioners were concerned that the introduction of the online service may lead to increased demand. Site leads reported that detailed descriptions for dealing with clinical governance and clear guidance were provided by NHS England, which helped to oversee the robust testing phase.

-

The pilot phase and early roll-out of the NHS 111 Online service involved significant work in adapting and testing NHS Pathways questions to make them as user-friendly as possible. The tone and language of questions were adapted to maximise how easy these would be for the general public to understand. The question development process aimed to ensure that there was as accurate a match as possible between the wording of the online questions and the scripted questions read out by the call advisers on the telephone service.

-

The work required to implement the online NHS 111 service was absorbed into existing job roles and none of the site leads reported needing any additional resources or staffing to get the sites up and running. Some site leads expressed concerns about potential future cost implications if call volumes increase as use of the online service exapands due to the increased length of clinical adviser time for online NHS 111 users.

Study services

In our original plan, we identified nine NHS 111 provider sites to include in our study: four sites that had implemented early (from 2017) and five that had implemented later. The nine sites were chosen to represent a range of size of coverage, geographies (urban and rural areas) and provider types. As described earlier, the need to change one of our main data sources meant that we were unable to use this specific set of sites for the main time series analyses. We have still included some of these sites in other WPs, but these vary. The sites used are described in the methods section of each relevant chapter.

Chapter 3 Rapid update of the evidence base on telephone and online urgent care access services

Introduction

This section addresses objective 1. In recent years, this research team have conducted a number of related systematic and rapid evidence reviews in the topic areas. In 2012, as part of our earlier evaluation of NHS 111 telephone service pilot sites, we published a systematic review of the evidence on appropriateness of and compliance with telephone triage advice. 18 In 2015 the NIHR Rapid Evidence Review Centre based in ScHARR (School of Health and Related Research), University of Sheffield, published a review of models for urgent care. 3 This included a comprehensive analysis of the evidence on telephone triage services.

Most recently the NIHR Rapid Evidence Review Centre conducted a systematic review of digital and online symptom checkers and health assessment/triage services for urgent care. 15 We have therefore already synthesised the related evidence in detail. Given this is a time limited study we have updated these reviews utilising the existing search and review strategies (e.g. inclusion and exclusion criteria) used for these reviews to identify relevant new evidence from the cut-off point of the earlier studies. The purpose is not to create new reviews but to assess whether or not there is recent evidence that changes the overall findings and conclusions of the earlier reviews and which might influence the interpretation of this study.

Methods

Database search strategies

Telephone triage

For telephone triage, the 2012 and 2015 reviews used a similar search strategy but the 2012 version was broader, so, for completeness, we have replicated the search used for this review. The search used a combination of free-text and medical subject headings (MeSH), including telephone, triage or consultation, NHS Direct, telephone triage, call centre triage, advanced nursing, appropriate, under-referral, safe, decision-making, technology transfer, general practice, teleconsultation, telepathology, video conferencing, virtual reality, video consultation and epidemiology.

The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (via Ovid SP), EMBASE (via Ovid), the Cochrane Library (via Wiley Online Library), Web of Science (via the Web of Knowledge) and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCOhost). Searches were limited by publication date from 1 July 2010 to 28 March 2019.

All search results were downloaded into EndNote X9 [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA].

Inclusion criteria

-

Empirical data from patient-based studies.

-

Requests for emergency/urgent care.

-

Telephone triage/advice/consultations.

-

Report relevant outcomes: accuracy, compliance, appropriateness, safety, impact on other services, patient satisfaction.

-

Written in English.

Exclusion criteria

-

Descriptive studies with no assessment of outcome.

-

Telephone services for single conditions.

-

Telephone services for non-urgent advice.

-

Opinion pieces and editorials.

-

Non-English-language papers.

-

Conference abstracts.

Digital and online symptom checkers

The search strategy used in our recent systematic review15 was replicated. Search terms included symptom checker(s); self-diagnosis; self-triage; online, web based, electronic, digital, app; online diagnosis; web based triage; and electronic triage.

The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (via Ovid SP), EMBASE (via Ovid), the Cochrane Library (via Wiley Online Library), and CINAHL (via EBSCOhost). Searches were limited by publication date from 1 January 2018 to 22 May 2020.

Inclusion criteria

-

Systems providing information to address urgent health problems.

-

Any online digital service designed to assess symptoms, provide health advice and direct patients to appropriate services.

-

Report relevant outcomes: accuracy, compliance, appropriateness, safety, impact on other services, costs, patient satisfaction.

-

Written in English.

Exclusion criteria

-

Descriptive studies with no assessment of outcome.

-

Systems for single conditions or information only (no direction to care services).

-

Opinion pieces and editorials.

-

Non-English-language papers.

-

Studies from low-/middle-income countries.

Review process

The same process was used for both reviews. Titles and abstracts of references identified from database searches were scrutinised by one member of the research team and assessed for relevance using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A randomly generated 10% sample of studies from the database searches was double sifted by another member of the study team. A single reviewer assessed full papers of potential inclusions, with a 10% random sample assessed by a second reviewer. Studies where there was uncertainty were agreed by consensus by the two reviewers.

Data extraction was carried out directly into summary tables, rather than using detailed data extraction forms. We used a simple broad template to summarise the key characteristics from each included paper, including the study design used; the population and setting; the main purpose and objectives, including the outcomes measured; and the key findings and conclusions. A formal quality assessment of inclusions was not carried out.

Findings were synthesised in a narrative summary that included commentary on the quality of the included studies. The main focus was on identifying any key new evidence that changed or strengthened the conclusions of the previous reviews.

Results

Telephone triage

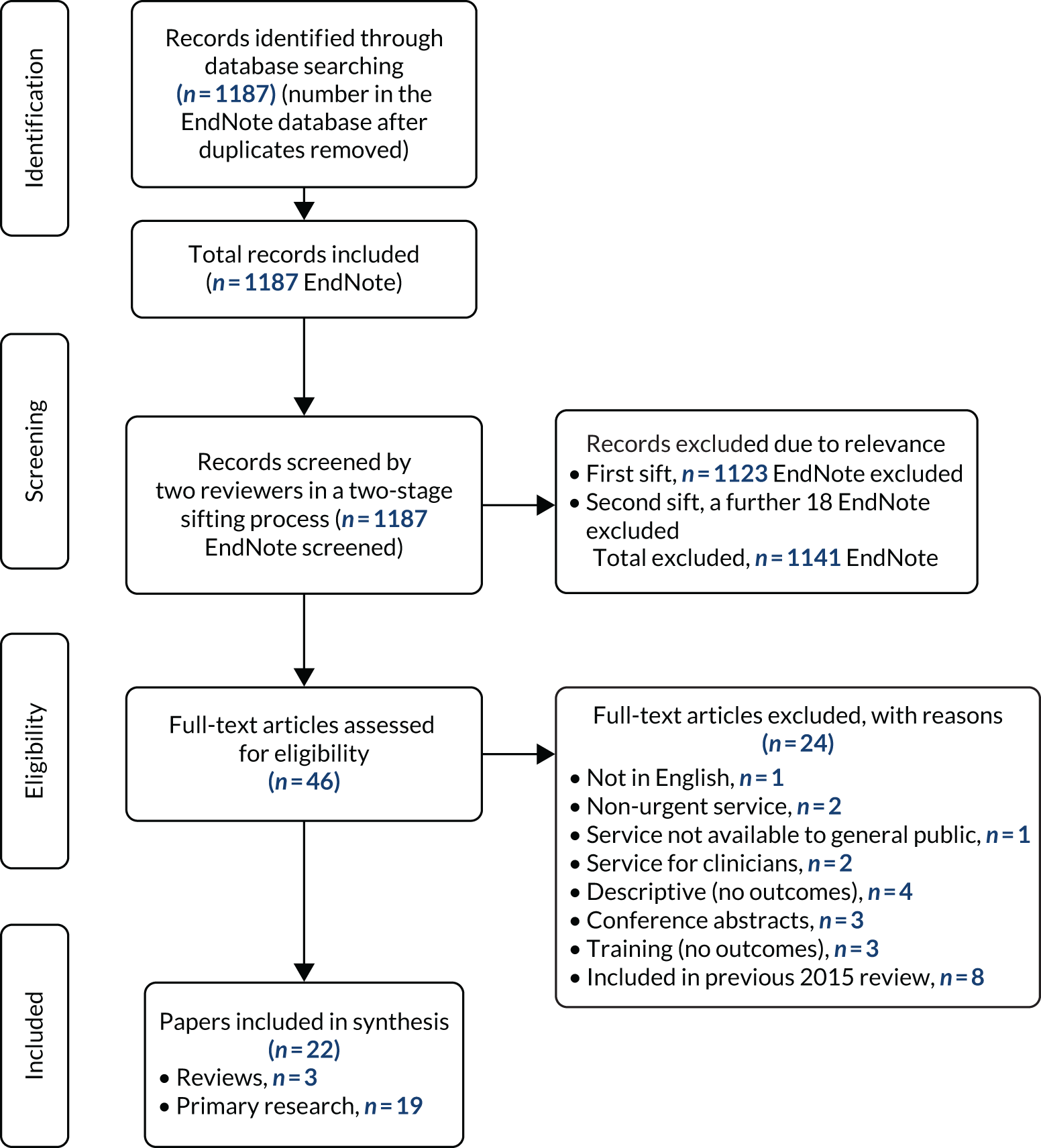

The results of the review sifting process are given in Figure 2. Among 46 full-text reviews, 22 papers were included for data extraction and narrative summary. Eight papers were duplicates included in our previous 2015 review and were not considered again. There were three review papers. Of the 19 inclusions presenting primary evidence, four (21%) each were from the UK and Australia, two (10.5%) were from the USA and nine (47.5%) were from the rest of Europe. By broad study design type, there were six (31.6%) observational studies, four (21%) mixed-methods studies, three (15.8%) survey studies, two (10.5%) each of cohort and qualitative studies and one (5.8%) each of modelling and uncontrolled before-and-after designs. The majority of studies were conducted in an urgent care setting (13/19, 68.4%), four (21%) were conducted in primary care and one each was conducted in an emergency department and an emergency medical services setting. A description of each of these 19 studies is provided in Appendix 1, Table 26.

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA flow diagram for telephone triage.

Summary of findings

Of the three review articles identified, one19 was a review of 10 existing systematic reviews about telephone triage in urgent care settings. Seven of these systematic reviews were included in our own 2015 review. 3 As a result, the conclusions about the same broad themes concurred with our earlier work; that is, there is variation in the measured estimates of appropriateness of triage decisions depending on the definition used. Compliance with advice is variable and higher for emergency care (ED) or self-care than for primary care; patient satisfaction is generally high; overall decisions tend to be safe but higher risk for more serious conditions; and there is some evidence of impact on service utilisation, but this is mainly for primary care. Evidence is weak about the impact of telephone triage on access and costs, showing potential for only modest savings. One review20 focused specifically on telephone secondary triage of low-urgency ambulance (emergency medical services) emergency calls. Findings have been consistent that this process can divert suitable calls away from an ambulance response, although this rate varies from 52% to 83% depending on the setting and call type. The process has also been found to be safe, with very low reports of adverse events, high levels of patient satisfaction and the potential for cost savings through the reduction of unnecessary hospital admissions. The final review paper21 examined the evidence on the safety of triage decisions made by clinical and non-clinical assessors. It found that nurses had higher levels of appropriate referral rates (91%) than non-clinicians (82%) and were most likely to be cost-effective, although different triage systems were used. The authors compared nurses with non-clinical emergency medical dispatchers and concluded that the latter group were less effective clinical decision-makers, but the authors also acknowledged that this might not have been a useful comparison as the two groups perform different functions.

The 19 primary research studies identified addressed key outcomes relevant to telephone triage.

Compliance

Two papers from Australia22,23 examined compliance with nurse telephone triage decisions. One reported compliance rates of 68.6% for ED, 64.6% for clinician consultation and 77.5% for self-care22 and another reported a similar rate for ED (66.5%). 23 Both studies found similar rates of self-referral to ED against advice of 7%22 and 6.2%. 23 Another study24 found that 22% of callers who intended to go to ED did not follow GP telephone advice. One study25 of low-urgency emergency medical services calls found that patients were more likely to follow advice provided by telephone triage (95%) than that provided by a paramedic on-scene treat-and-refer scheme. Several papers examined caller characteristics and the relationship to compliance and found that calls made out of hours, from patients in disadvantaged areas, by another person on the patient’s behalf and by people with an intention to attend ED are associated with lower compliance. 22 Callers living in remote or rural areas are less likely to comply with advice to attend ED. 22,23 The level of care advised, the extent to which advice agreed with the caller’s prior intention, care option availability and perceptions of risk also have an effect, with compliance seven times higher if the highest level of care is advised. 26 One paper27 investigated the effect of English-language proficiency and found that those with limited proficiency were less likely (60.9%) to follow advice than those who were proficient (69.4%) and were more likely to have a higher level of care disposition.

Appropriateness

A UK study28 used GPs to review ED dispositions in a nurse-led telephone triage service and found 73% would have been given an alternative disposition to lower-level care. A Danish study29 in an out-of-hours primary care telephone triage service examined calls from people referred for a face-to-face consultation and estimated that 84% were relevant but 12% could have been managed over the telephone. Two papers30,31 explored the use of caller self-reported degree of worry to help in the decision-making process and found that a high degree of worry was associated with symptom duration of > 24 hours,30,31 more serious illness30 and an increased likelihood of needing a face-to-face disposition. 31

Safety

Only one paper32 explored safety and the rate of potential adverse events from undertriage by examining telephone triage cases which resulted in a subsequent emergency ambulance call and hospital admission, and found the rate to be small, at 0.04% of all calls. These calls resulted from inadequate communication and non-normative symptom description. One other paper33 compared nurse telephone triage, hospital clinicians and GP assessment of ED walk-in patients and found low congruence between the three types of assessment and a risk to health of 0.65%, although the sample size, of 208, was small. One interesting development is emerging research about the effects of the work environment and clinical and non-clinical call advisor performance. A study by Turnbull et al. 34 explored the management of risk by NHS 111 non-clinical call handlers and found that a substantial part of the handlers’ work involves the management of risk, in terms of both assessing patients safely and balancing this with allocating scare resources. The study highlighted that, although technologies have been introduced to support risk, risk has not been removed but has been redistributed to create a new task of ‘making technology work’. Another qualitative study35 of nurses from telephone triage call centres found that most found that the work was rewarding and enabled them to use their clinical skills. However, it was also cognitively demanding, and a lack of support from the workplace and other health-care professionals had a negative impact on the nurses’ ability to do their jobs effectively.

Patient satisfaction

Existing evidence has shown a consistently high rate of satisfaction among users of telephone triage services, and this persists in two papers25,36 that report ≥ 80% of patients being satisfied or very satisfied. More interesting is new evidence that examines reasons for variation in satisfaction with different patient characteristics or types of advice. One study in a primary care out-of-hours service found that satisfaction was significantly lower among patients who had received a treatment centre consultation than among those who had received a telephone consultation. Call answering delays, waiting for call backs and shorter consultations were also associated with lower satisfaction. 37 Two Swedish studies38,39 examined satisfaction with nurse telephone advice. One found that callers who expected a higher level of care and/or did not agree with the disposition were less satisfied than those who did agree. 38 The former were also more likely to self-refer to another service within 3 days. The other found that younger callers and those receiving a self-care disposition were significantly less satisfied than other callers and that reassurance had the most effect on increasing satisfaction. 39

Impact on other services

There is limited new evidence about the impact on other services. One study24 showed that telephone triage produced a small reduction (3.6%) in ED attendance compared with callers’ original intention. A comparison of two types of out-of-hours primary care telephone triage showed a reduction in utilisation of a GP emergency service of 17.8–58.3%, depending on the service configuration. 40 A modelling study using nurse telephone triage advice and patient self-reported subsequent service use concluded that, overall, a triage service reduced health-care utilisation, except where a patient’s original intended action had been to attend the ED and the nurse’s advice was self-care. 26 Only two studies considered costs. A Swedish study estimated an overall health service cost saving of 3.3% for actual action compared with intended action after telephone triage and 12.7% if all nurse advice dispositions were followed. 26 A smaller study28 of ED disposition review by GPs estimated a potential cost saving to EDs of £52,528 compared with GP employment costs of £41,416. However, the impact would be limited, as only 11% of telephone triage calls have an ED disposition.

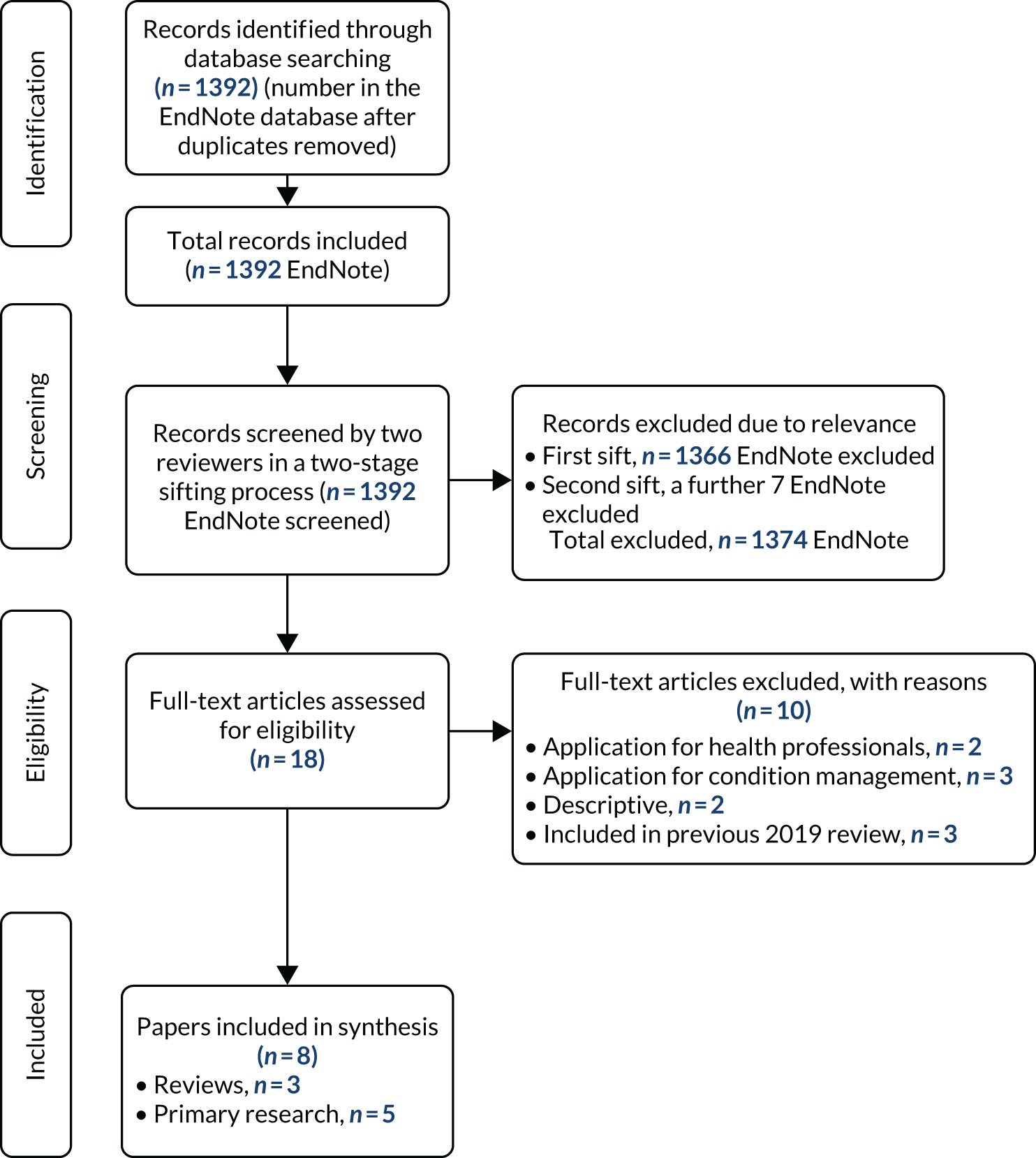

Digital and online symptom checkers

The results of the review sifting process are given in Figure 3. Among 18 full-text reviews, eight papers were included for data extraction and narrative summary. Three were review papers and five presented primary evidence: one each from Hong Kong and Australia and three from the USA. A description of each of these eight studies is provided in Appendix 2, Table 27.

FIGURE 3.

The PRISMA flow diagram for online and digital symptom checkers.

Of the three review papers, one was a systematic review of digital interventions for parents of ill children to enable decision-making for self-limiting infections. Three studies were included, with two triage services reporting sensitivity of 84% and 93% when compared with nurse triage decision for ED intervention and none of the studies demonstrating a reduction in the use of urgent care services. 41 A scoping review42 of self-diagnosing digital platforms synthesised 19 inclusions, although more than half were conceptual or opinion articles, with primary research representing specific conditions rather than urgent care. The authors identified significant research gaps in the use of digital interventions and the complexity in the number of applications and diseases considered, and that more research is needed to understand user experience. The third systematic review43 focused on digital triage for primary care problems and synthesised the same evidence included in our review,15 and concluded that evidence is limited, with more evaluation needed.

Three of the primary research papers were simulation studies using patient records to create vignettes to test symptom checker applications. One study tested five symptom checkers for hepatitis C and HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection and found that they had poor diagnostic accuracy; only 20% of infections were identified at the first diagnosis and 55% of the checkers did not identify either infection at all, with substantial variation between applications. A correct emergency care triage decision was more accurate for hepatitis C (59.7%) than for HIV (35.6%). 44 A study using case records of ED patients compared the accuracy of two symptom checkers with the ED triage category and found accuracy of 74% and 50%. Sensitivity for emergency cases was 70% and 45%, with low negative predictive values (43% and 24%), leading to the conclusion that the symptom checkers were not a suitable alternative to ED triage. 45 A study in Australia46 investigated the performance of 36 public access diagnostic and triage symptom checkers using medical condition vignettes. Diagnostic symptom checkers listed the correct diagnosis first in 36% of cases (range 12–61%) and in the top 10 in 58% of cases. Triage applications provided the correct advice for 49% of tests and were more accurate for emergency and urgent care advice (63% and 56%, respectively) than for non-urgent or self-care (30% and 40%, respectively). The authors concluded that the quality of symptom checkers was variable and that triage applications were generally risk averse, often recommending higher levels of care than were needed. 46

An experimental study47 comparing the accuracy of three symptom checkers for cough in an outpatient setting found that their diagnostic accuracy was poor when compared with physician assessment reference standard, with a 26.2% difference in correct diagnoses. A recent paper48 described the rapid introduction of a digital self-triage and scheduling tool for COVID-19 integrated into a primary care system. Users enter their information, and people who are asymptomatic receive information and advice is provided, whereas people who are symptomatic are triaged to four categories from emergency care to self-care and, where needed, directed to appointment scheduling or a telephone hotline. In the first 16 days of use, the tool’s sensitivity in detecting the need for emergency-level care was 87.5%, and there were early indications of reductions in unnecessary face-to-face visits, telephone calls and messages. 48

Summary

For telephone triage, there is a substantial existing body of evidence that has been synthesised in numerous systematic reviews. Most of the new evidence identified in this exercise has confirmed earlier findings; that is, that compliance and appropriateness are variable depending on service and setting, patient satisfaction tends to be high and little attention has been directed at issues around impact on access. A conclusion of our previous systematic review18 was that more investigation was needed into the association between appropriateness of a decision and subsequent compliance and satisfaction. The most valuable and relevant new evidence is from research that has started to investigate the more complex patient and system factors that can explain variation and behaviours. There is an emerging theme about the important relationships between caller expectations, intended action, attitudes to risk, agreement with triage decision and subsequent satisfaction and utilisation of services,26,27,38,39 together with environmental factors such as rurality and deprivation,22,23 all of which need to be considered as part of service design. There are interesting developments about how patient-reported characteristics, such as degree of worry, might be incorporated into triage questioning31,40 and about the effect of language proficiency. 27 There is also important new evidence that has started to consider workforce factors, such as managing risk and demand, and the subsequent impact on safety and performance for telephone triage services. 34. 35

For digital symptom checkers and triage tools, the updated evidence review has confirmed our own recent findings, which are that the evidence on patient safety is weak, diagnostic accuracy is variable between systems but generally low, and algorithm-based triage tends to be more risk averse than that of health professionals. There is also very limited evidence on patients’ compliance with online triage advice. The reporting of the rapid development of a digital self-triage tool for COVID-1948 illustrates how the advantages of digital development – speed, remote working, scale and reach – can be exploited in response to a health emergency and provides an example of how digital technologies can be used in the future.

Chapter 4 Time series analysis of NHS 111 telephone and online contact outcomes

Introduction

The introduction of NHS 111 Online has added a new access point for urgent care. One of the intended policy expectations is that the new service will divert some activity from the NHS 111 telephone service and direct more people with less urgent problems away from emergency care services. 2 This chapter addresses objective 2 of the evaluation. The aim of this work package was to use NHS 111 telephone call and online contact data to determine whether or not the NHS 111 Online service has had an effect on the number of calls to the NHS 111 telephone service and its impact on other emergency and urgent care services.

Methods

Data collection

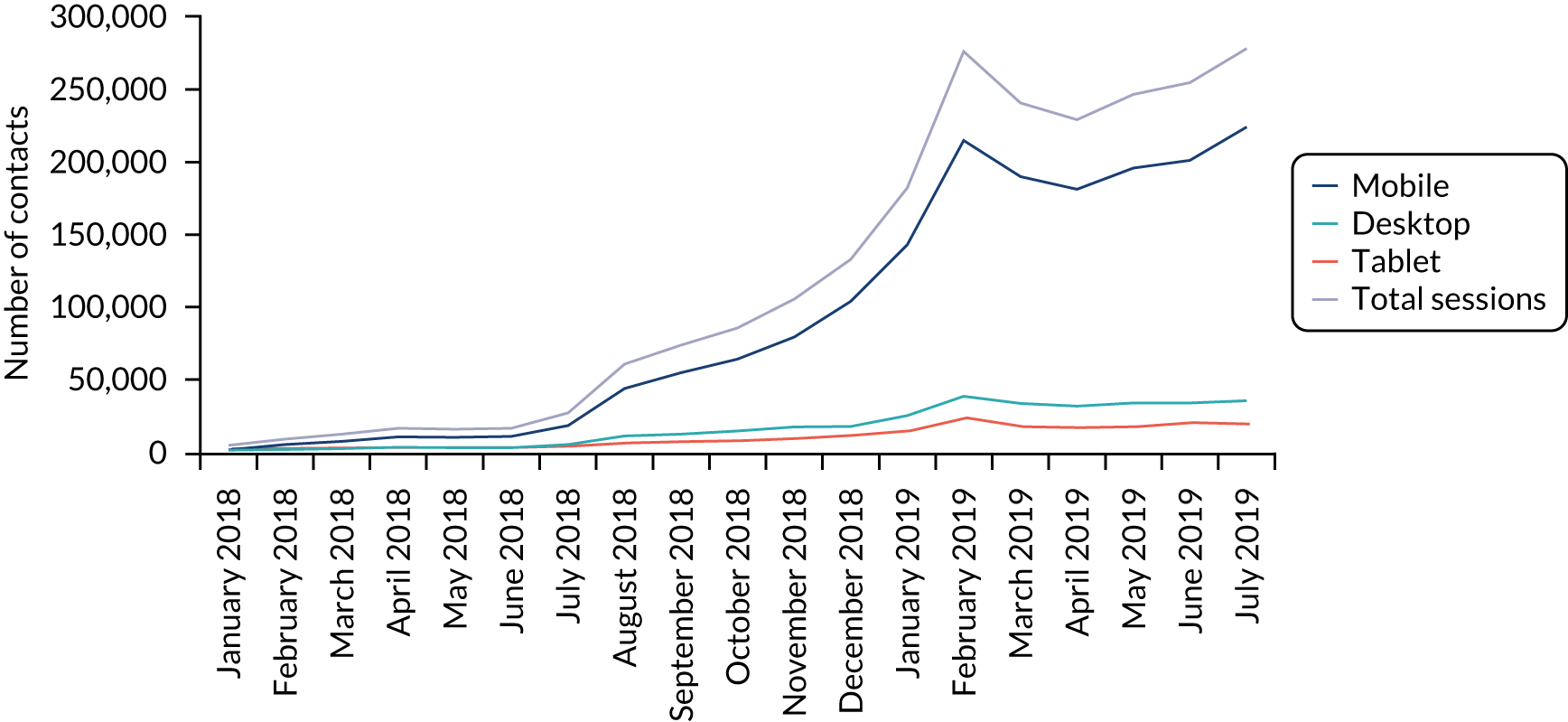

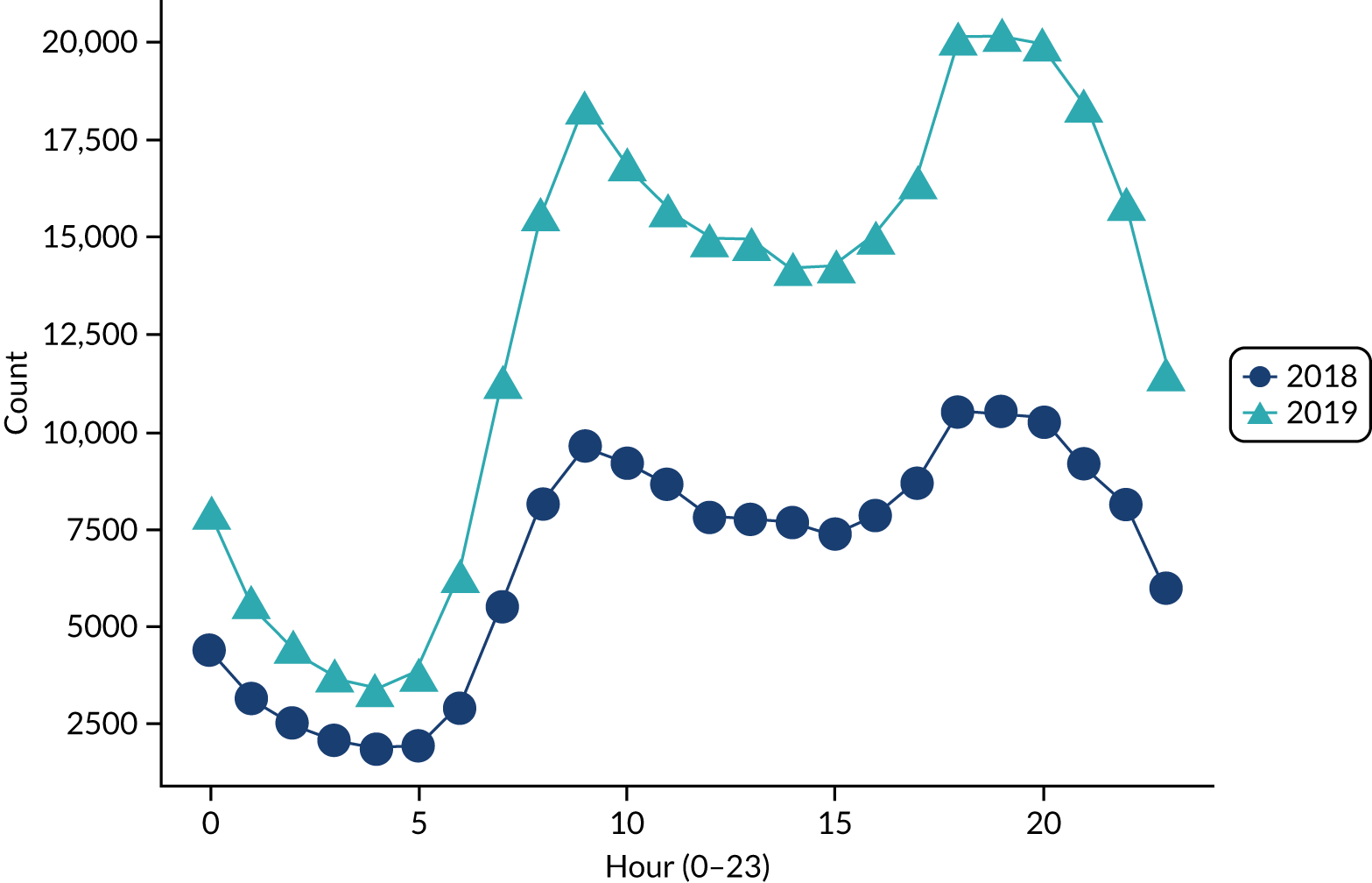

Data on NHS 111 calls and online contacts were collected between October 2010 and December 2019 and between January 2018 and December 2019, respectively. The NHS 111 calls data were obtained from the NHS 111 Minimum Data Set, Time Series, to December 2019 and accessed online (URL: www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/nhs-111-minimum-data-set/nhs-111-minimum-data-set-2019-20/) in January 2020. 49 The NHS 111 Online data were provided by NHS Digital. Call data provided monthly counts at the NHS 111 area code level, whereas online provided daily, individual-level data. As call data were at a summary level only, analyses of both data sets were conducted at this level. Both data sets provided variables for all calls and contacts; triaged calls and contacts; calls and contacts passed for clinical advice; and the final disposition for the call/contact as the advice about which service to contact or attend, or where no service was needed.

The call data were made up of 71 NHS 111 area codes and the online data were classified by both Sustainability and Transformation Partnership (STP) and CCG areas, which were mapped to 38 of the NHS 111 area codes. For historical call data, some of the older codes have been merged into newer area codes. These 38 area codes were the potential sites for our analysis. However, because of the way the NHS 111 telephone service is commissioned, geographical coverage of different service providers means that either the area codes can be made up of multiple STPs or some STPs can be split over two area codes. Because the NHS 111 Online service was introduced at STP level, this meant that not all online area codes could be included, as some STPs had different start dates. In addition, for the interrupted time series analysis, 1 full year of NHS 111 Online data were required; therefore, any area codes where the online service had not been operating for at least 1 year were removed. For consistency, the call data were capped at 2 years prior to the introduction of the NHS 111 Online service, so each area code had a minimum of 36 months of data. This meant that there were 18 area codes remaining for the analysis; however, these areas are spread across the country and represent a range of geographical, service size and provider types, so we are confident that they are a reasonable representation. It was unfortunate that the area where the NHS 111 Online service was first introduced (Yorkshire and the Humber) and, therefore, had the longest post-implementation time could not be used. This is because the NHS 111 telephone call data are reported for Yorkshire and the Humber as a single area, but there are 22 CCGs and the NHS 111 Online service became live at different times in these CCGs, meaning that we could not account for the time point of change in the interrupted time series models. A list of the 18 sites included is provided in Appendix 3, Table 28.

Outcomes measured

The primary outcome was the impact of introducing the NHS 111 Online service on the number of triaged calls to the original NHS 111 call service. Triaged calls are those where a call advisor assesses the call using NHS Pathways and excludes calls that, for example, just provide health information with no assessment.

The secondary outcomes were to explore the impact of NHS 111 Online on the total number of calls, the number of clinical call backs and the effect on the relative proportions of final dispositions and hence on other related services.

These primary and secondary outcomes can be split into those which affect the NHS 111 telephone service only and those that have an impact on the wider NHS system.

NHS 111 telephone service only:

-

triaged calls

-

total calls answered – including non-triaged calls for health information, and those where the caller terminates before triage

-

clinical call backs – calls referred to clinical advisors for further assessment.

Wider NHS system:

-

emergency ambulance referrals or advice to contact 999

-

advice to attend an emergency department or other urgent care treatment facility

-

advice to contact primary care

-

advice to contact with community service

-

advice to attend another service

-

no recommendations to attend any service and self-care advice.

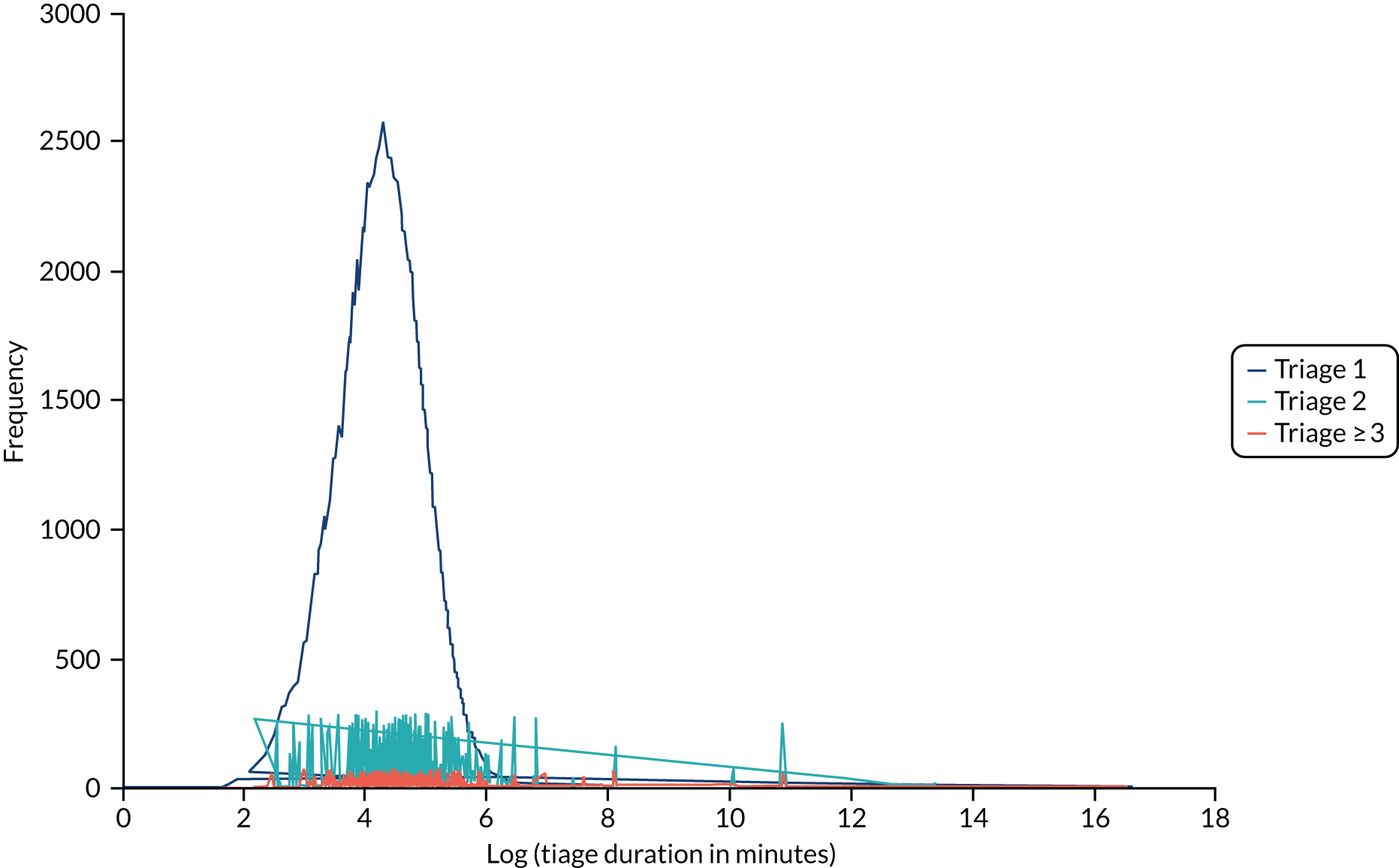

For calls to the telephone service, there is a specific data variable recording the number of calls passed for and receiving a clinical assessment. This is less clear for the NHS 111 Online data, as clinical call-backs are managed outside the online platform. The online data provided two data variables, a clinical call back variable (offered and sent or offered and failed to send) and the final disposition (advice) code (DX code) at the end of the questioning. There were 11 DX codes for ‘speak to a clinician from our service immediately’ as the final disposition. If a patient had both a clinical call back variable and a relevant DX code, they were assigned as having a clinical call back. The online clinical call backs were added to the telephone call clinical call backs as the outcome for this analysis.

The secondary outcomes, which look at the impact on the wider NHS system, were created in a similar way to the clinical call back outcome. The outcome was made up of a combination of the dispositions (DX codes) from both the call and the online data. For example, the outcome of all ambulance referrals is made up of all the ambulance dispositions in the call data plus all the ambulance dispositions to call 999 in the online data.

Statistical analysis

All analysis was conducted using R, version 3.6.3 (R Core Team, 2020; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Interrupted time series

To model whether or not the introduction of the NHS 111 Online service has had an impact on the monthly number of calls, an interrupted time series was used. However, unlike with conventional interrupted time series, a dose–response model was used. This means that instead of the number of calls being modelled as a function of the time after the launch of the online service, it was modelled as a function of the number of online contacts that month. The dose–response model provides an estimate of the reduction or increase in the number of telephone calls per online contact. The model also included some systematic components: an underlying time trend, a step change for when NHS 111 Online was introduced and ‘fixed’ seasonal effects (four levels: December–February, March–May, June–August and September–November).

As each area code had different start dates for the introduction of NHS 111 Online, each was modelled separately and a meta-analysis was used to determine the overall effect (see Meta-analysis). Given that there were 18 different area codes and a range of outcomes to model, we decided to use the same model for each site and outcome, but different models were used as a sensitivity analysis.

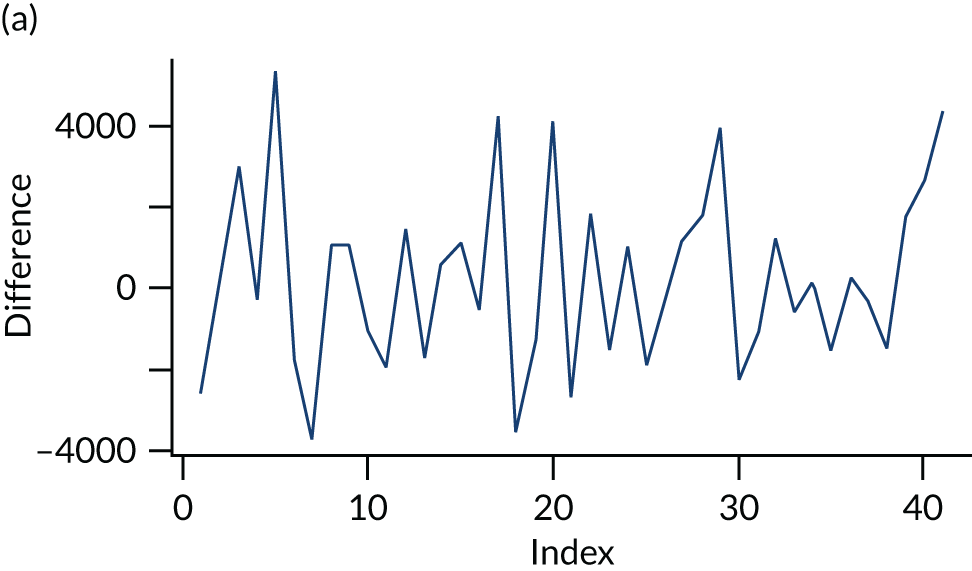

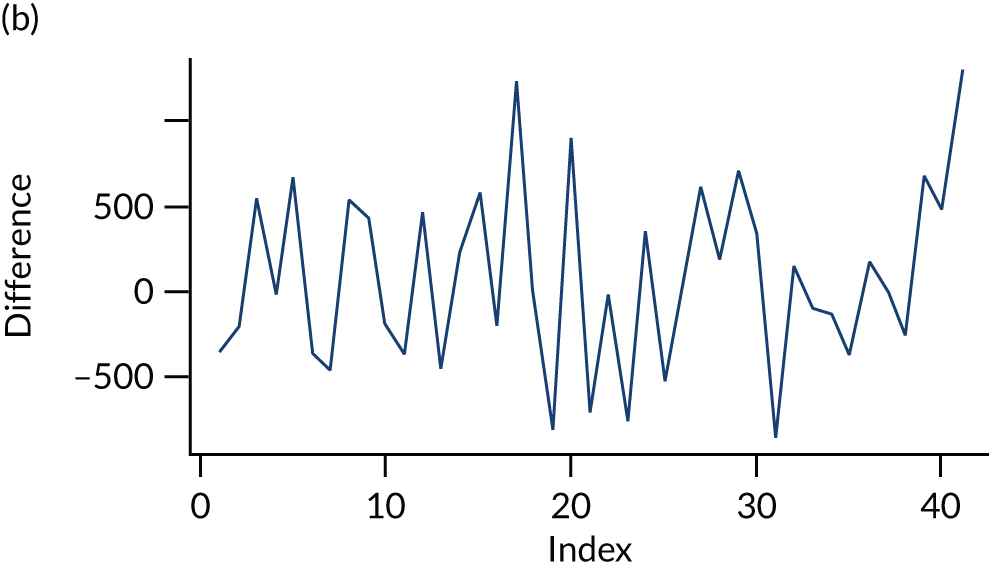

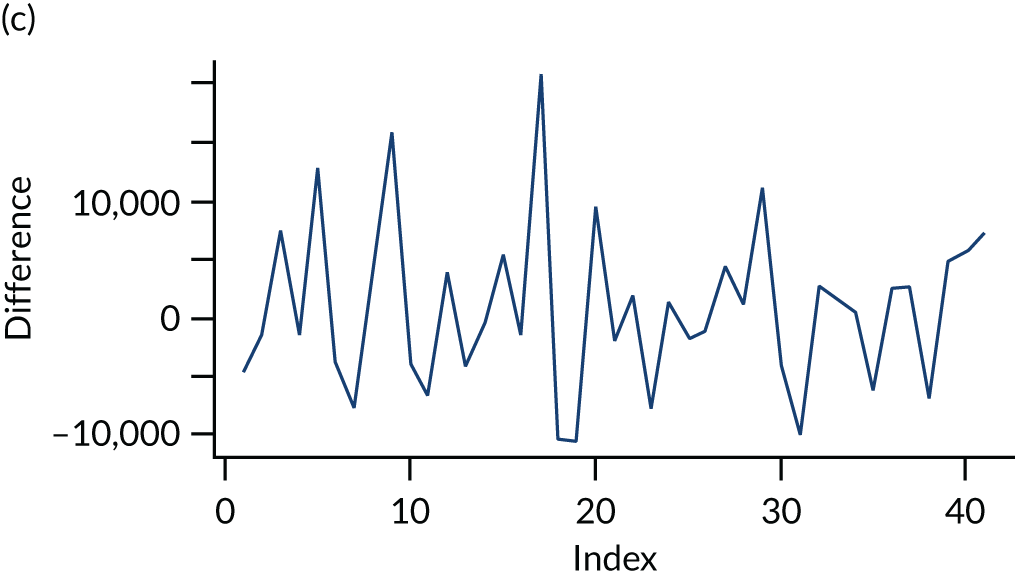

To determine which model to use, four area codes were chosen independently by two statisticians (RS and RJ) to test the models. Both statisticians chose the same four sites (Hertfordshire, Milton Keynes, North East and Nottinghamshire) as these represented areas with large to small numbers of calls. The models tested were Poisson or negative binomial, and whether or not the model was autoregressive (AR) was also examined.

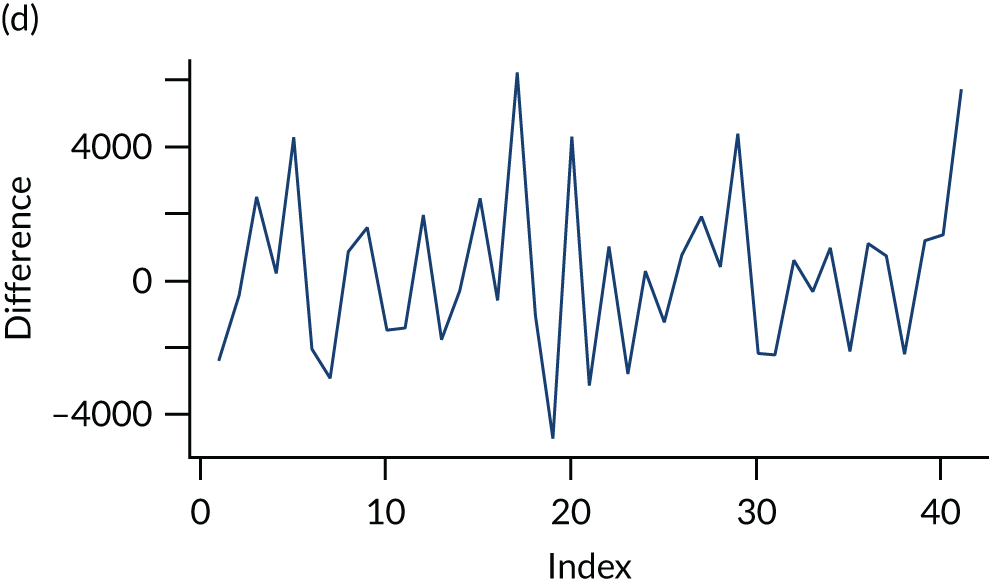

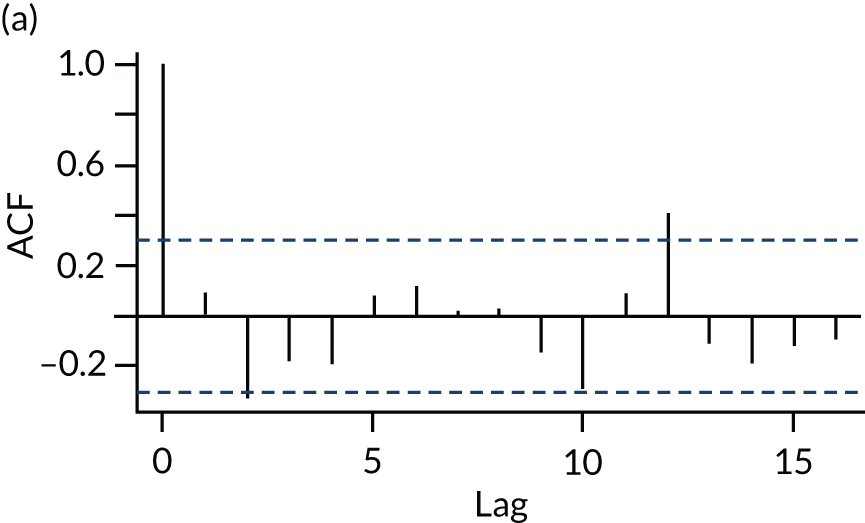

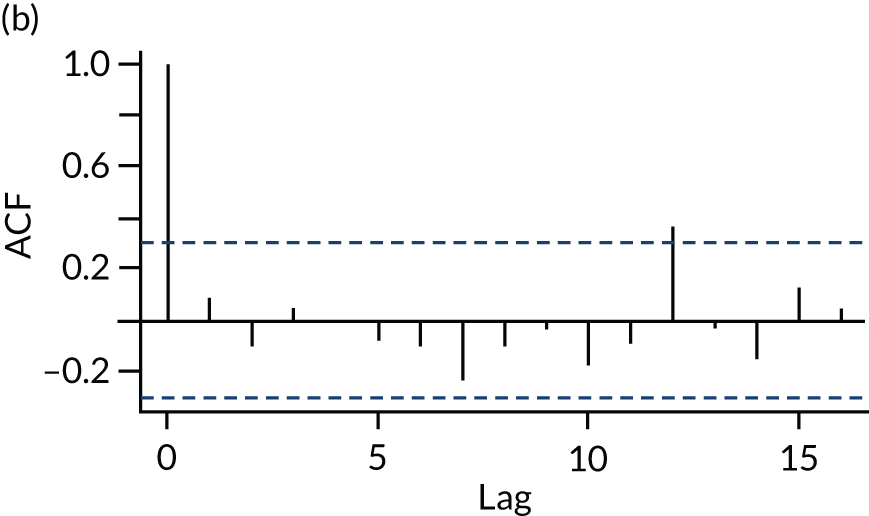

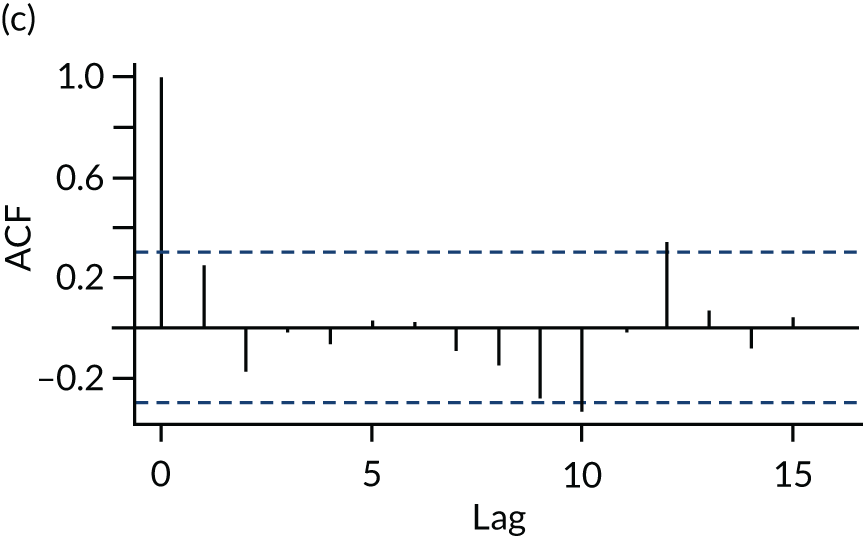

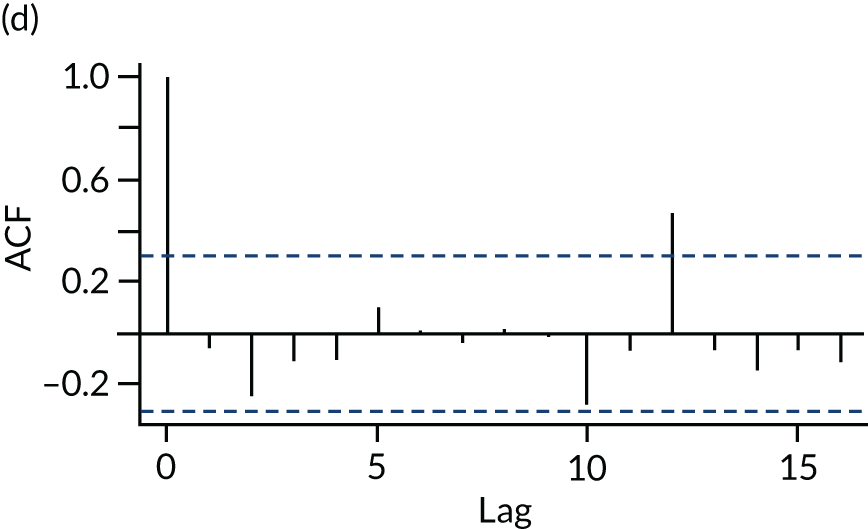

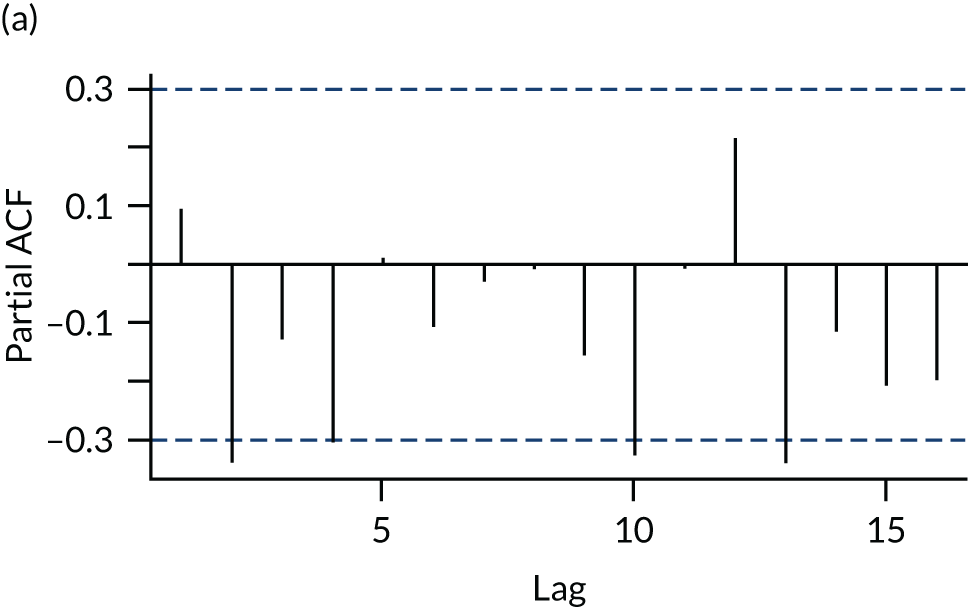

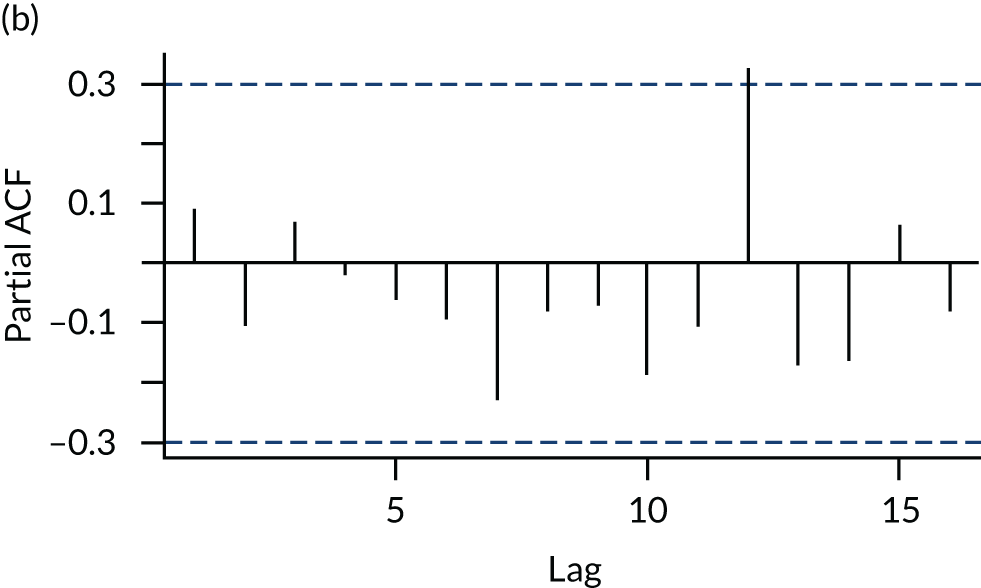

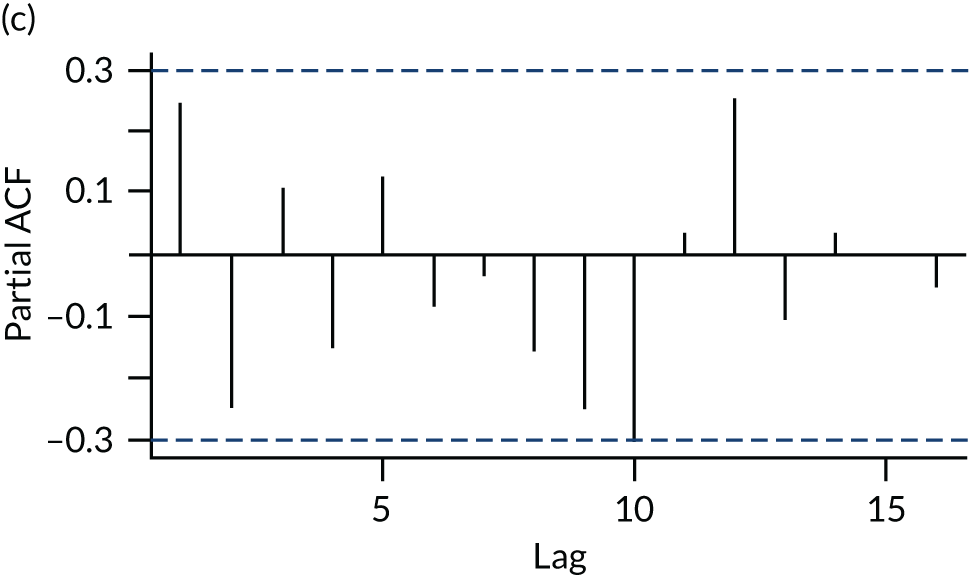

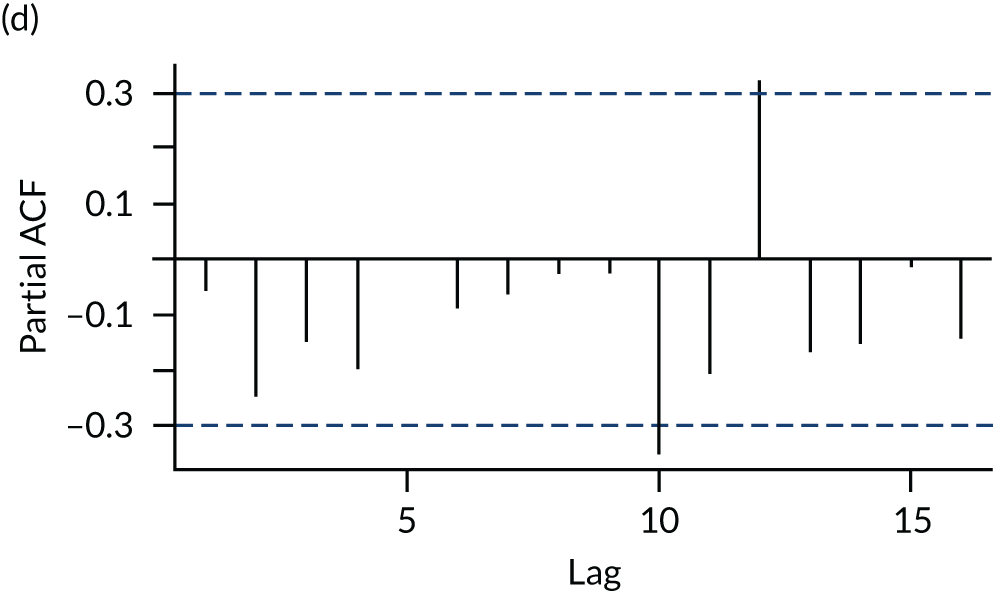

To determine whether an AR model was appropriate, the primary outcome was differenced to remove the general upwards trend (see Appendix 3, Figure 19) and the autocorrelation function and partial autocorrelation function plots were investigated. It was agreed for all four models that an AR model was not needed but there may be some seasonality. Seasonality would be accounted for with the season variable which was prespecified to be included in the model.

As the primary outcome variable was the number of triaged calls to 111 each month, these are count data, so either a Poisson or a negative binomial model was considered. After fitting both the Poisson and the negative binomial models, the model output for the Poisson model showed that the data were overdispersed. Given this, the negative binomial model was chosen over the Poisson model. The autocorrelation function and partial autocorrelation function plots were investigated again and it was confirmed that an AR model was not needed (see Appendix 3, Figures 20 and 21).

The final model used for the analysis was:

where the outcome is the number of calls to the NHS 111 telephone service each month, time is a linear variable 0, 1, 2, . . ., dose is the number of NHS 111 Online contacts for each month, step is a binary variable that is coded 0 before the introduction of NHS 111 Online and 1 afterwards, and season is a fixed variable that represents the four seasons in the year.

For sensitivity analyses, an AR(1) model and a non-linear model with a non-linear term for time were used.

Both of these sensitivity models were applied to all sites and outcomes. The Isle of Wight was one of the 18 area codes included in the analysis. Owing to the size of the Isle of Wight, with small call volumes and an atypical urgent care service configuration, we have included a further sensitivity analysis from which we have excluded the Isle of Wight.

All three of these models included a log-link function. For the linear and non-linear negative binomial model, the glm.nb function of the Modern Applied Statistics with S (MASS) package was used. 50 For the AR model the tsglm function of the tscount package was used. 51

Meta-analysis

For each of the outcomes, the dose from the individual area analyses were summarised using forest plots with estimates displayed as the incidence rate ratio per 1000 online contacts. The results from each area were combined to estimate the average effect of introducing the online service on each outcome using a random-effects meta-analysis. 52 The between-area variance, τ2, was estimated using the DerSimonian–Laird method53 and heterogeneity was evaluated using the I2-statistic. 54 The overall estimate for each outcome and a 95% confidence is reported along with a p-value. Meta-analysis was conducted using the metagen function of the meta library. 55

Meta-analysis was repeated for all sensitivity analyses and the overall estimate and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each model was displayed on a forest plot for comparison.

Results

Primary outcome (triaged calls)

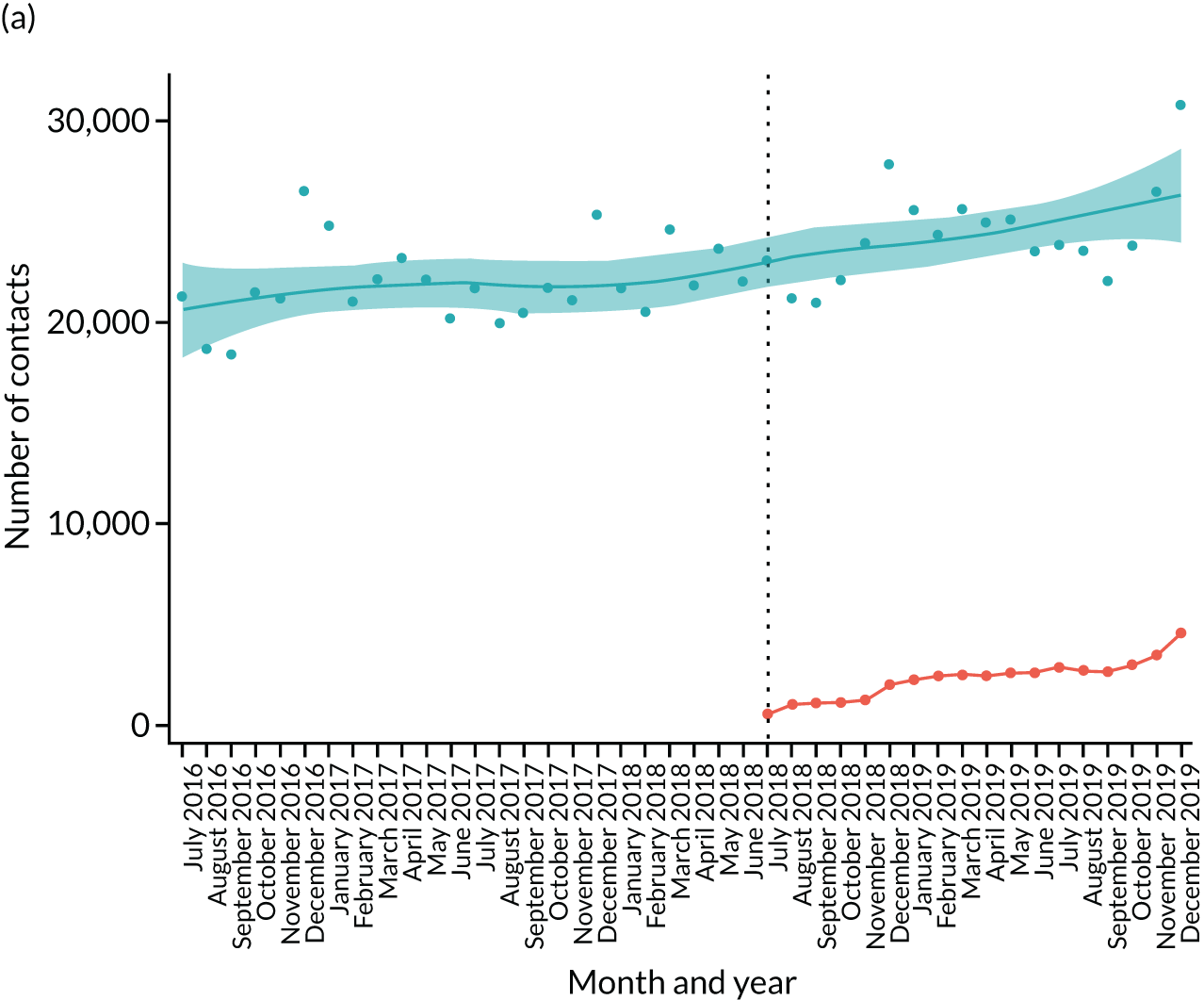

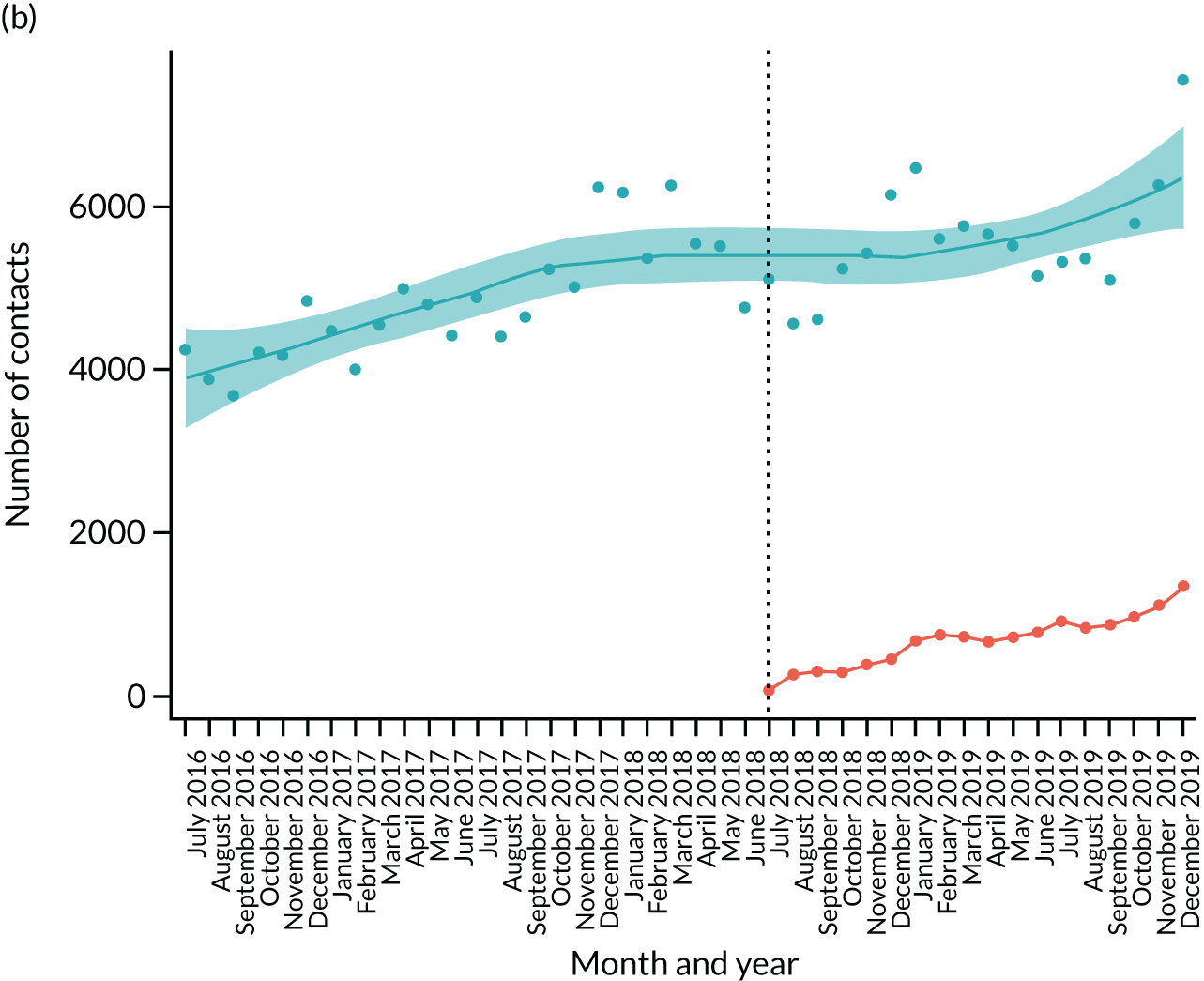

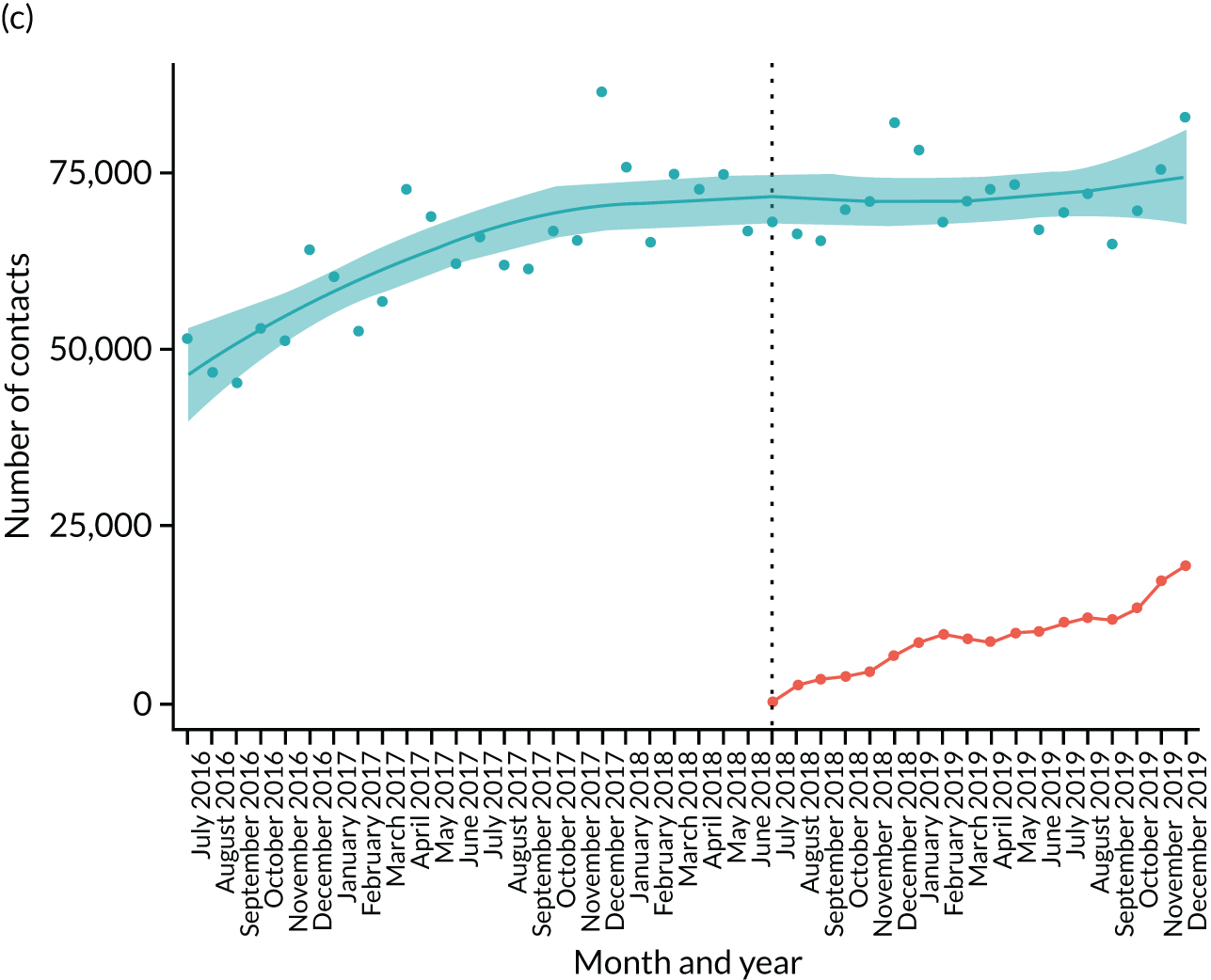

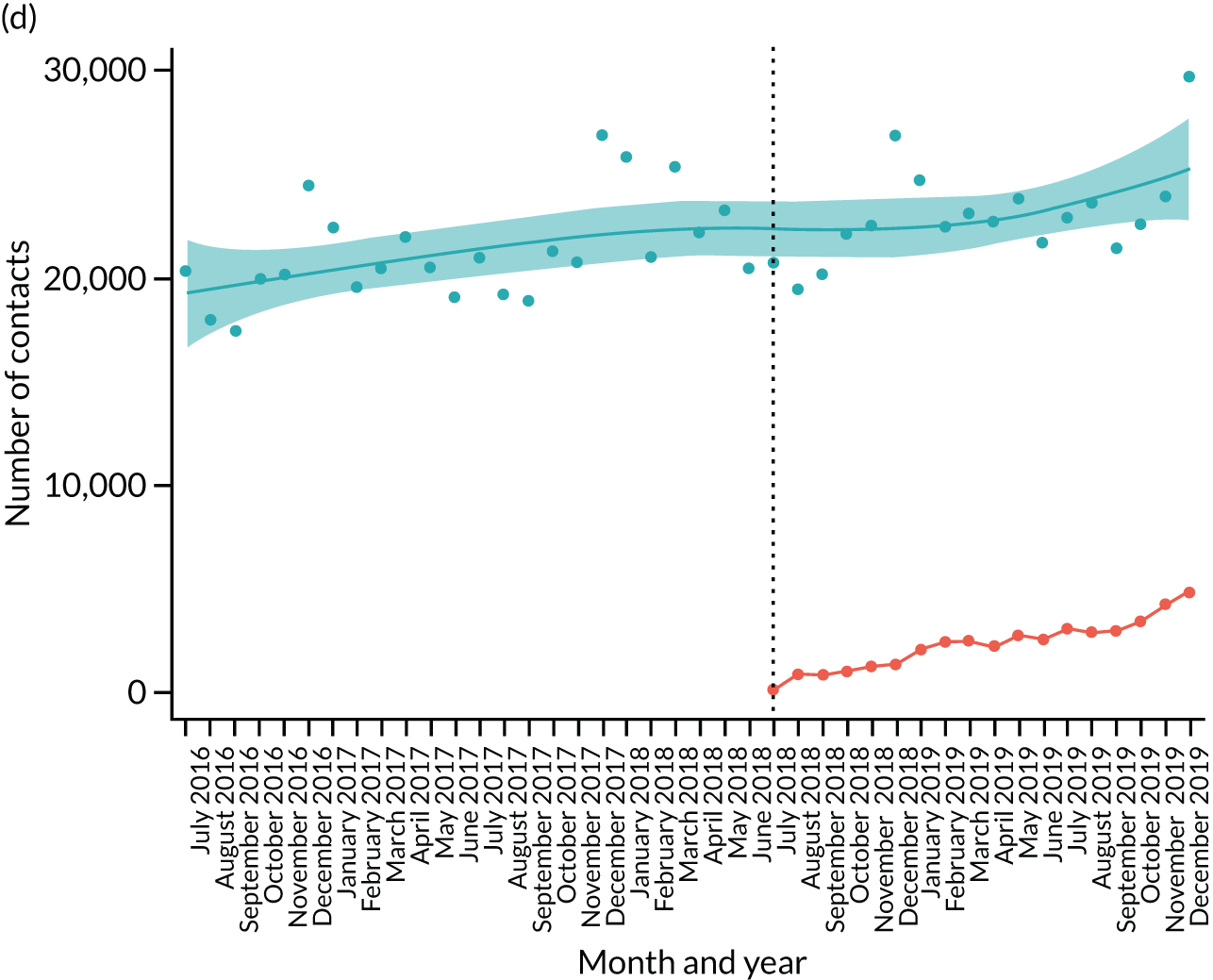

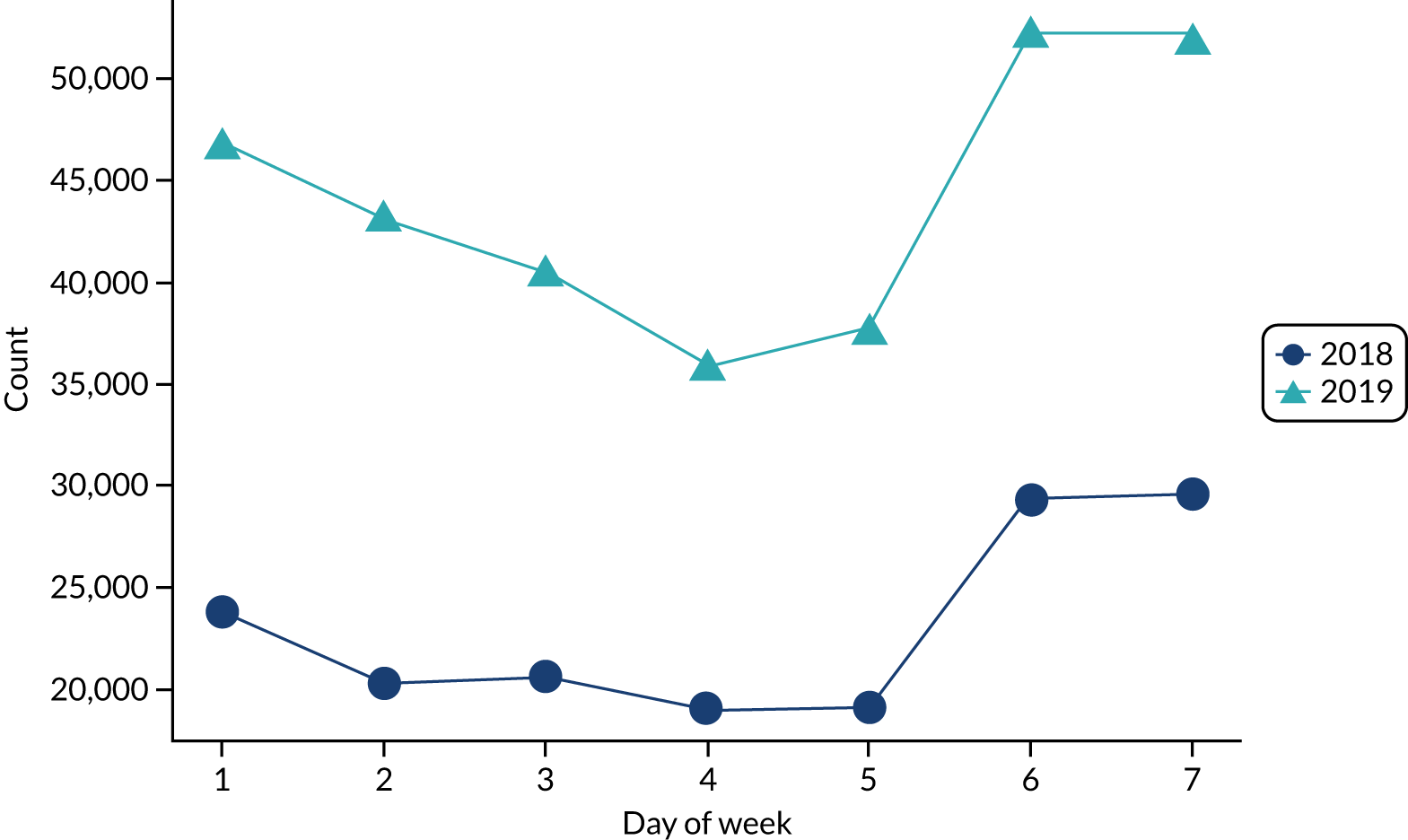

The primary outcome for the analysis was the number of triaged NHS 111 calls. Triaged calls are all the calls that were triaged which excludes both calls which were abandoned and those not triaged. Figure 4 presents LOESS (locally estimated scatterplot smoothing) plots for the four area codes in which the model was chosen.

FIGURE 4.

The LOESS plots of the number of triaged calls and online contacts for the four test area codes. Blue, triaged NHS 111 calls; orange, online NHS 111 contacts. (a) Hertfordshire; (b) Milton Keynes; (c) North East; and (d) Nottinghamshire.

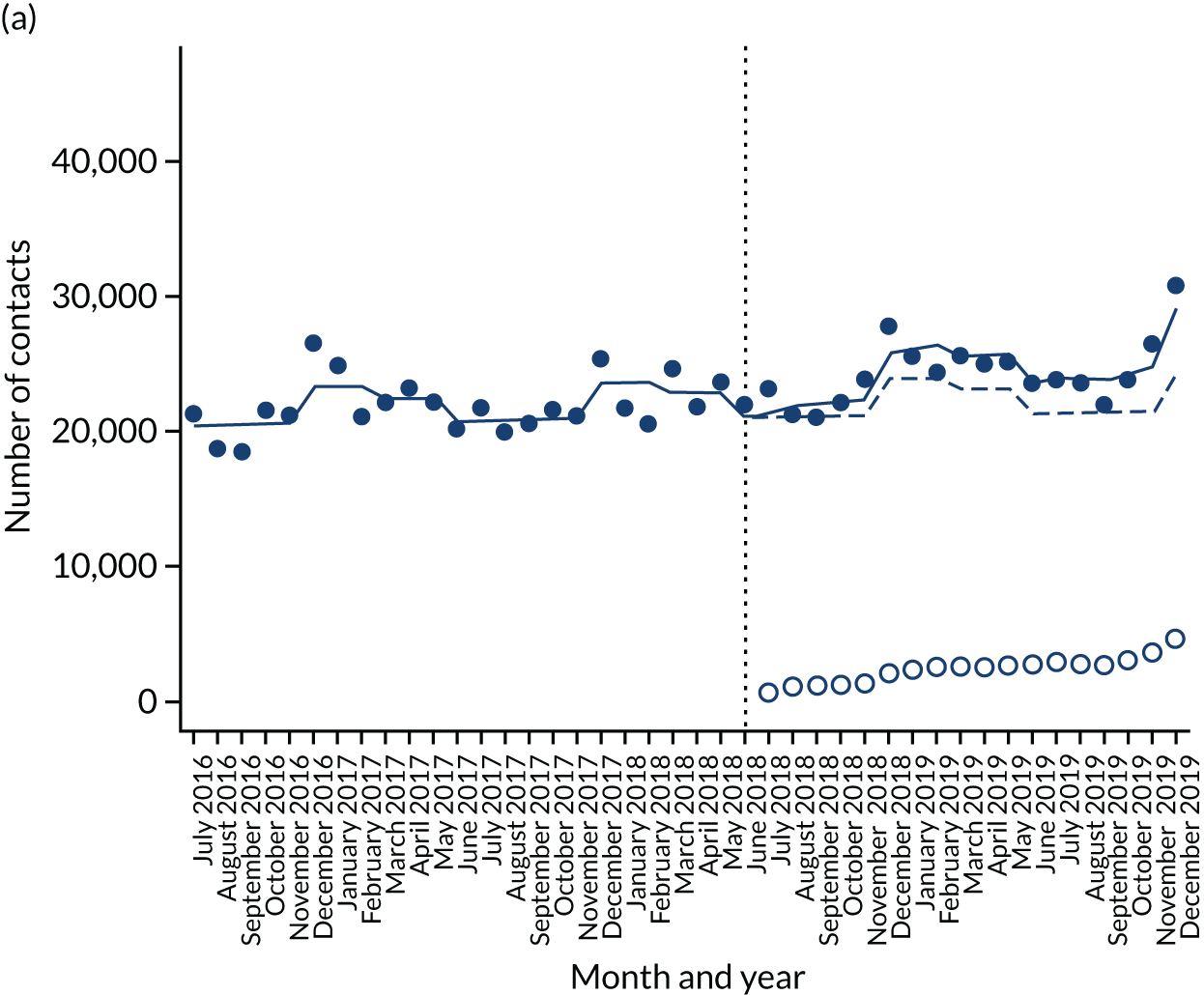

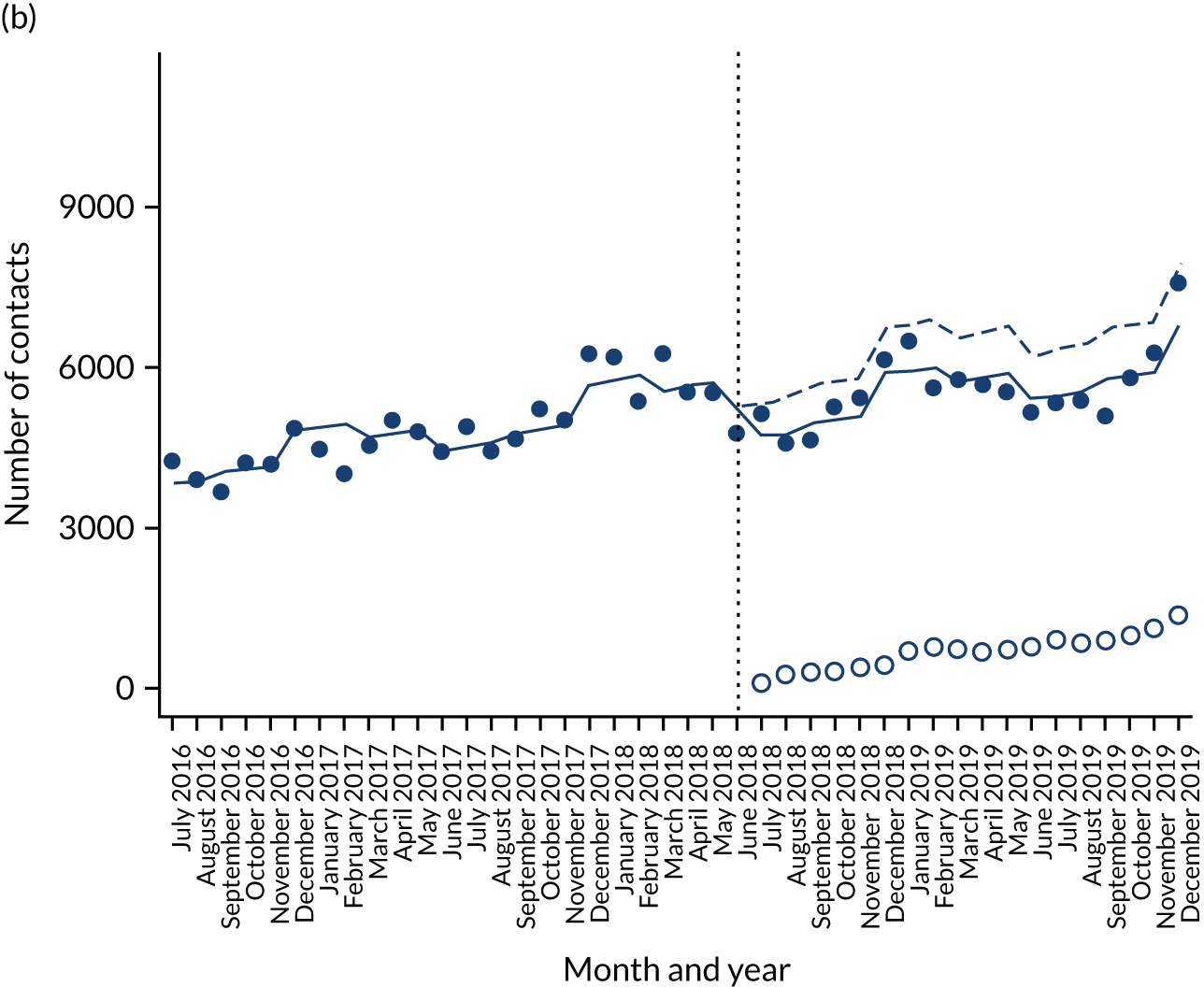

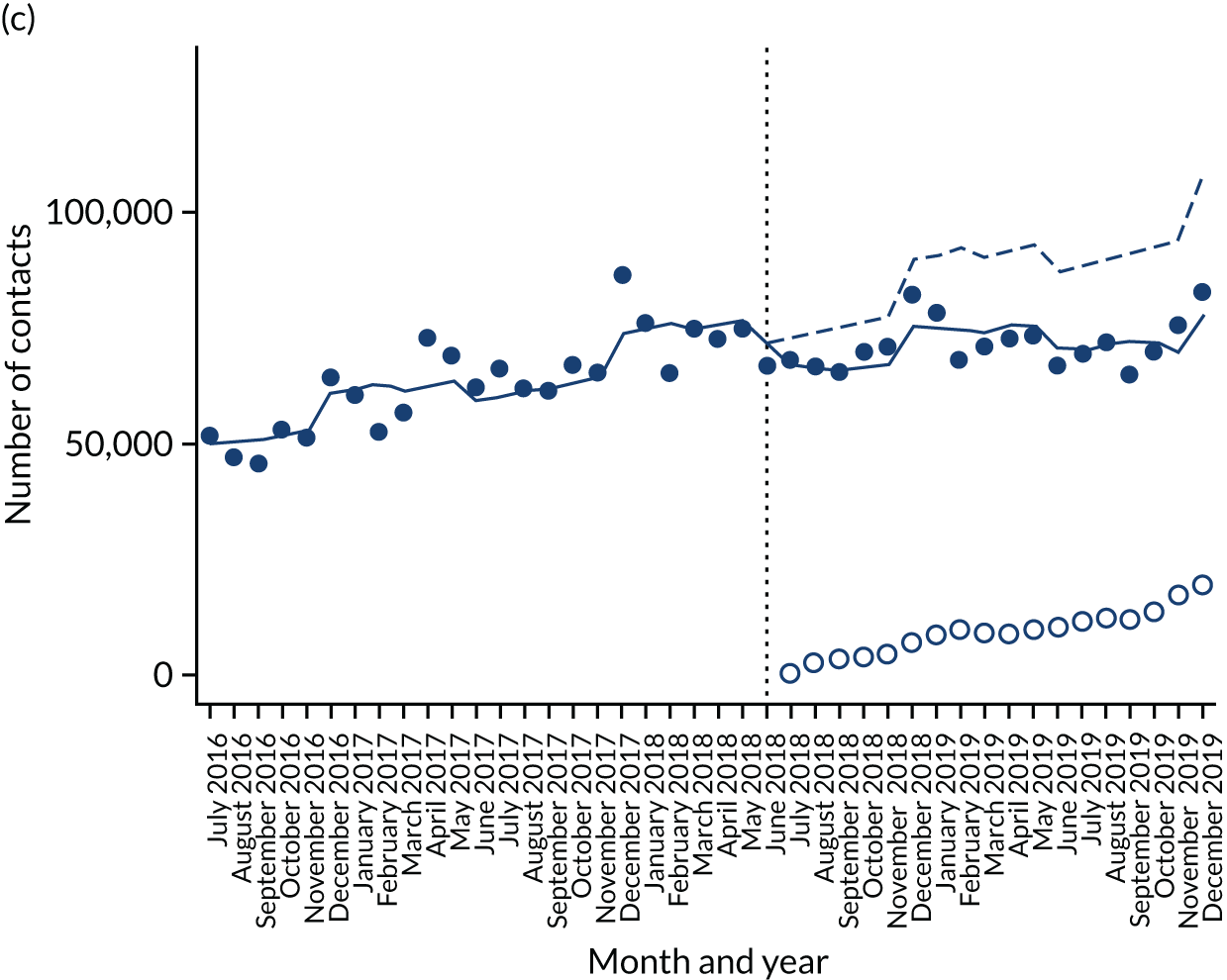

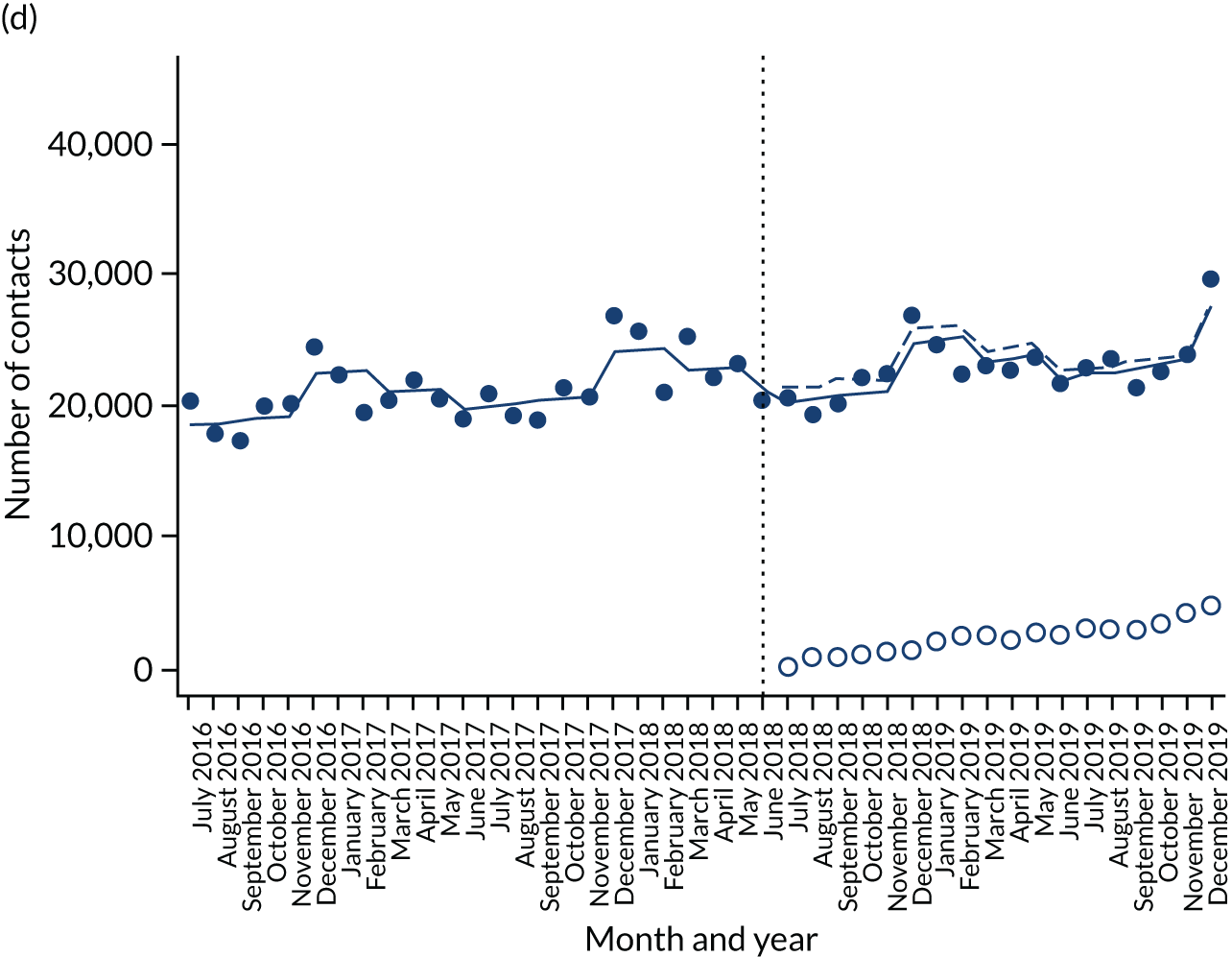

Figure 5 presents the interrupted time series model for the four area codes for the primary analysis method [linear negative binomial with no AR(1)].

FIGURE 5.

The interrupted time series plots for the four test sites. Solid blue line, interrupted time series model; dashed blue line, null model (no intervention); solid dots, triaged NHS 111 calls; hollow dots, online NHS 111 contacts. (a) Hertfordshire; (b) Milton Keynes; (c) North East; and (d) Nottinghamshire.

Meta-analysis

Below are the meta-analysis results of triaged 111 NHS calls for the primary analysis method for each site and then for each sensitivity analysis overall.

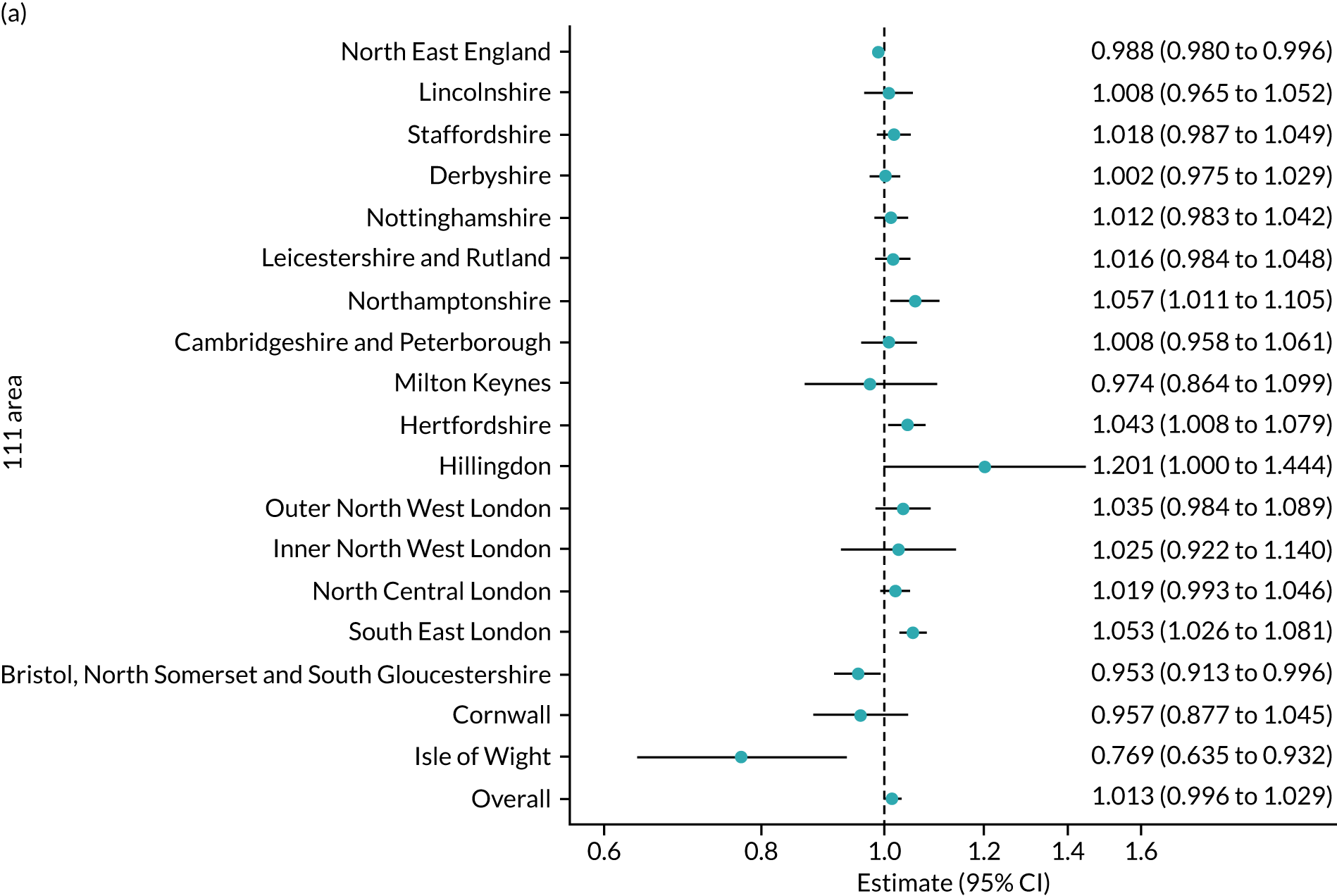

Negative binomial generalised linear model

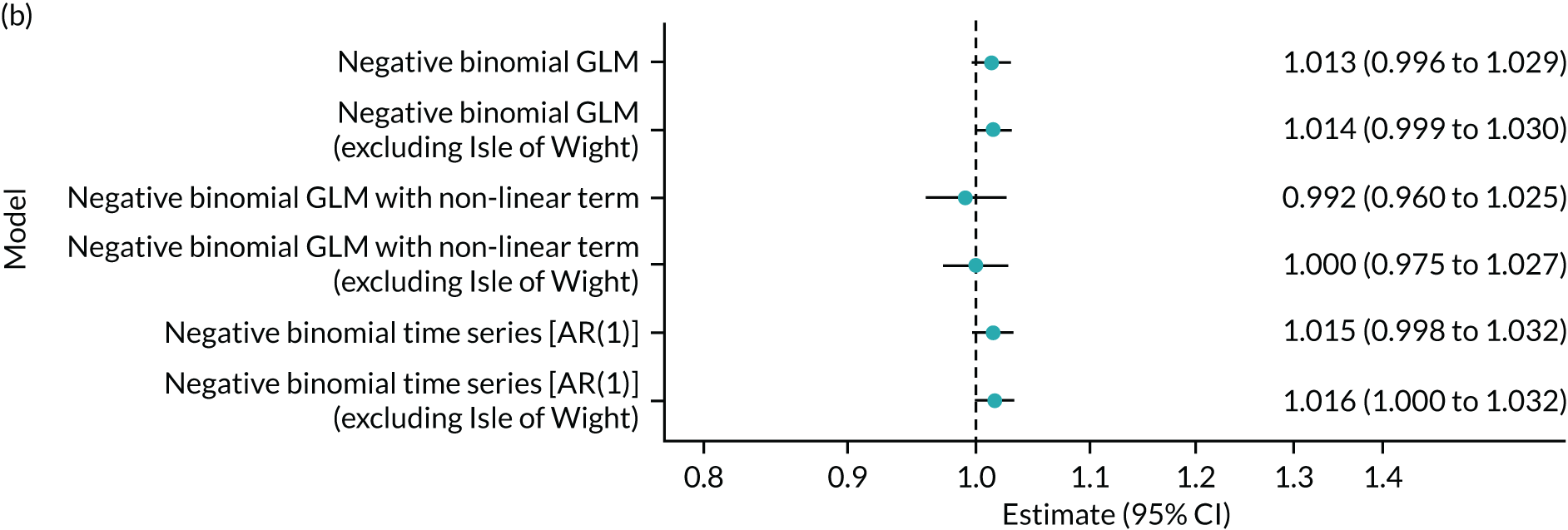

Figure 6a shows the forest plot of results for the primary analysis. The x-axis shows the incidence rate ratio per 1000 online contacts. The overall incidence rate ratio per 1000 online contacts is 1.013 (95% CI 0.996 to 1.029; p = 0.127). This means that, on average, for every 1000 online contacts, the number of calls to the NHS 111 telephone service that are triaged has increased by 1.3% (95% CI –0.4% to 2.9%). However, this result is not statistically significant.

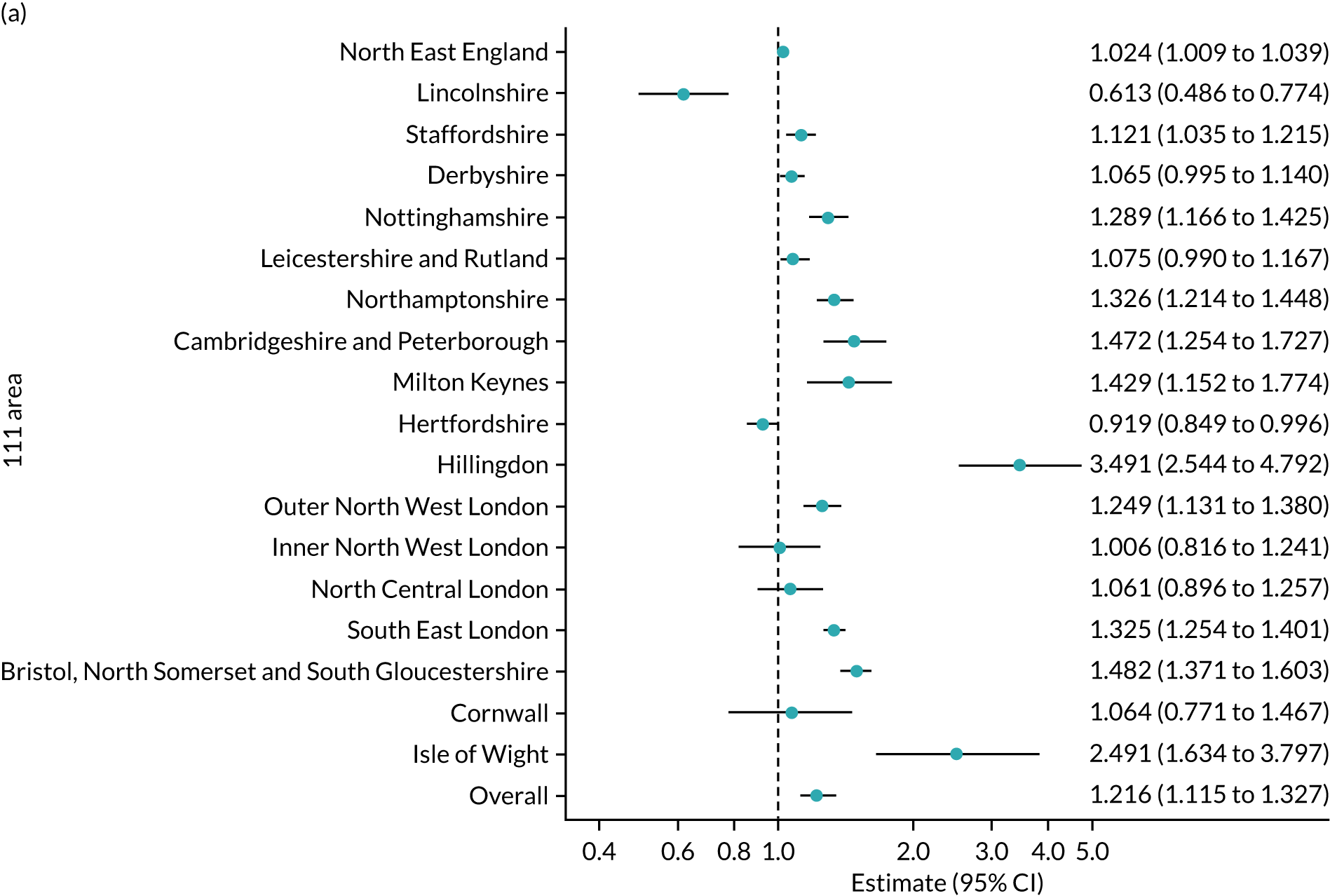

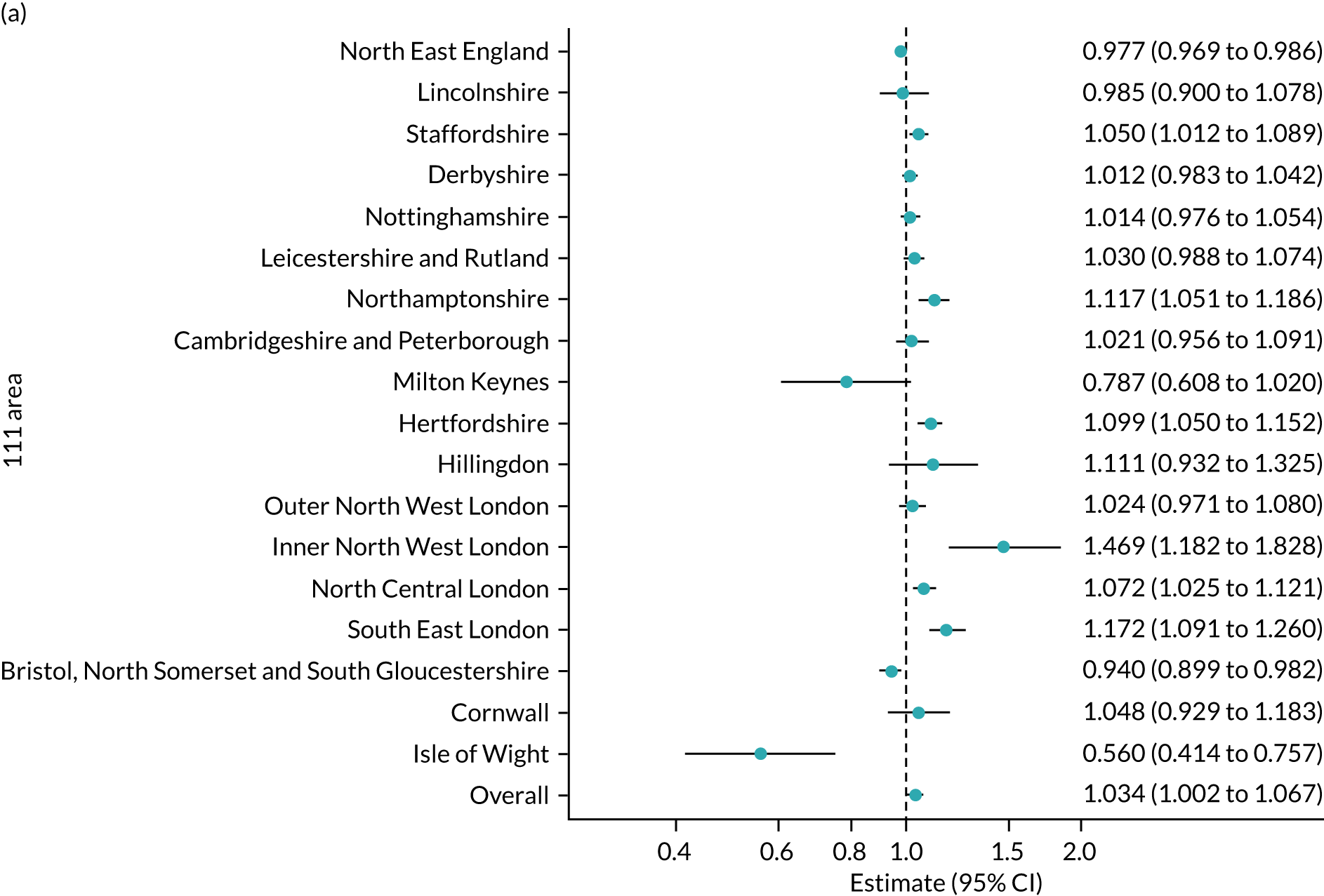

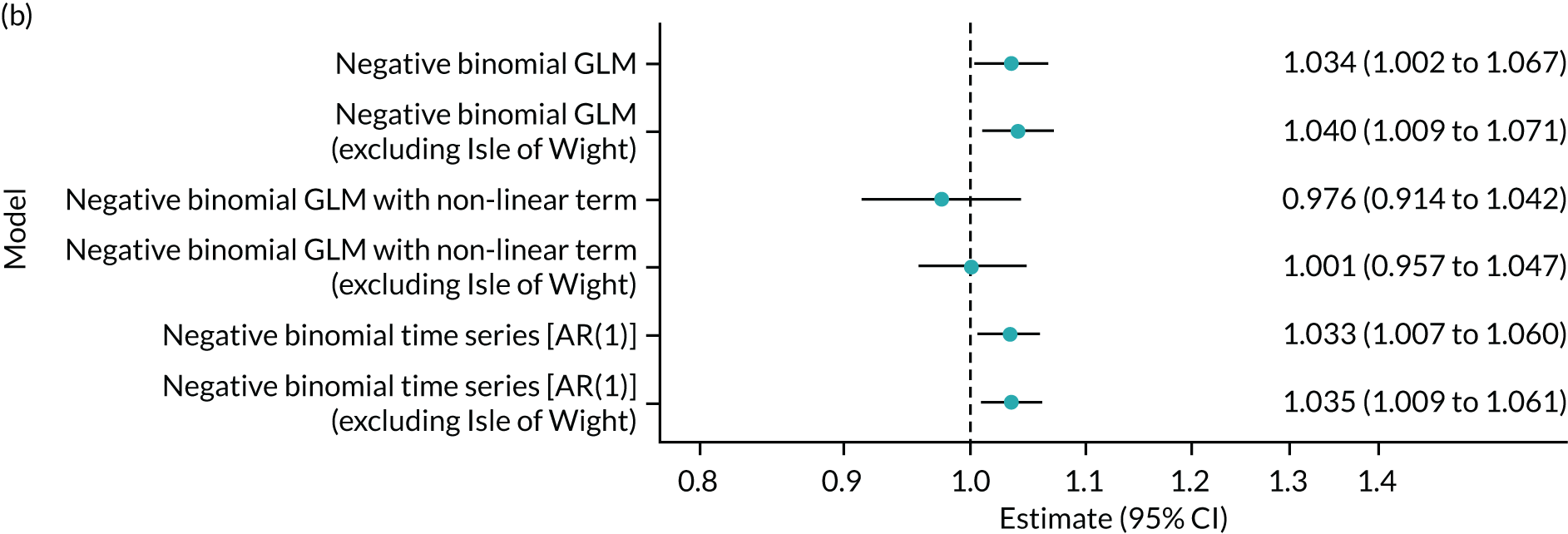

FIGURE 6.

Forest plots showing the effect of introducing the NHS 111 Online service on the number of triaged calls to the NHS 111 telephone service. (a) Estimated effects for individual areas and the overall average effect from the primary analysis (negative binomial GLM), heterogeneity I2 = 71.5% (95% CI 54.1% to 82.3%); and (b) average effects from the primary analysis and sensitivity analyses. Estimates are incident rate ratios per 1000 online contacts. GLM, generalised linear model.

Figure 6b shows the forest plot of the main analysis method and various sensitivity analyses. Excluding the Isle of Wight has little effect on the estimate. Including a non-linear term for time increases the standard error and lowers the estimates, but the overall conclusion remains the same. The AR(1) model provides similar incidence rate estimates and CIs.

Secondary outcomes

Total calls

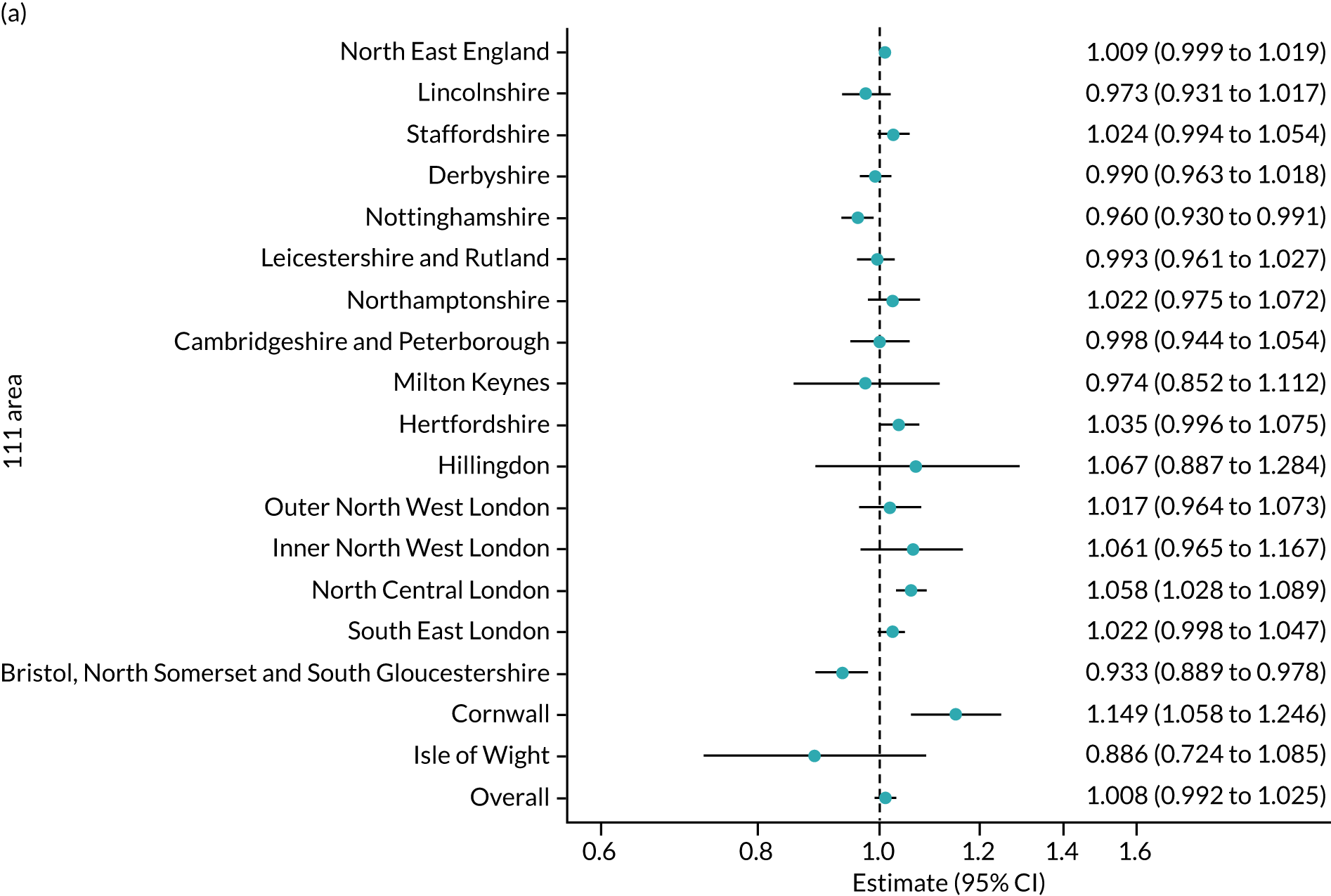

Total calls is all calls offered to NHS 111, reflecting how many people attempted to contact the service. Figure 7a shows the forest plot of total calls for all area codes for the primary analysis method. The x-axis is showing the incidence rate ratio per 1000 online contacts. The overall incidence rate ratio per 1000 online contacts is 1.008 (95% CI 0.992 to 1.025; p = 0.313). This means that, on average, for every 1000 online contacts, the number of calls to NHS 111 has increased by 0.8% (95% CI –0.8% to 2.5%). However, this result is not significant.

FIGURE 7.

Forest plots showing the effect of introducing the NHS 111 Online service on the total number of calls to the NHS 111 telephone service. (a) Estimated effects for individual areas and the overall average effect from the primary analysis (negative binomial GLM), heterogeneity I2 = 68.0% (95% CI 47.7% to 80.4%); and (b) average effects from the primary analysis and sensitivity analyses. Estimates are incident rate ratios per 1000 online contacts. GLM, generalised linear model.

Figure 7b shows the forest plot of the main analysis method and various sensitivity analyses. Excluding the Isle of Wight has little effect on the estimate. Including a non-linear term for time increases the standard error and decreases the incidence rate ratio; there is now a 3–4% decrease in calls per 1000 online contacts, but the overall conclusion remains the same. The AR(1) model provides similar incidence rate estimates and CIs.

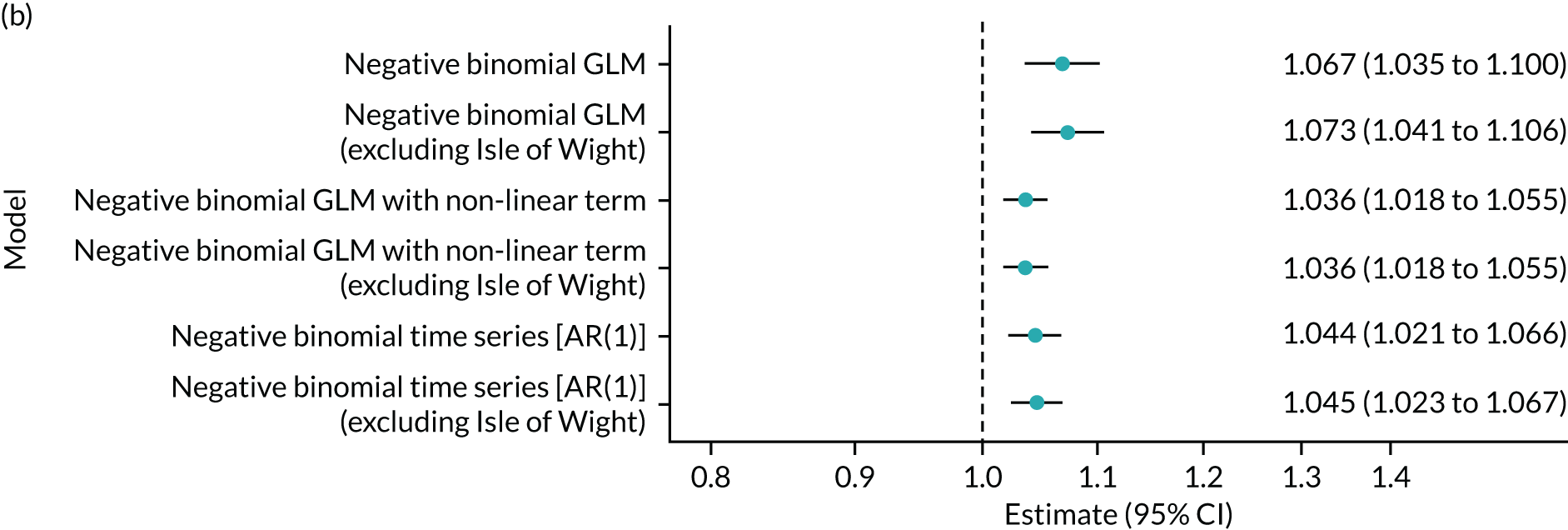

Clinical calls

Clinical calls are calls or online contacts that resulted in a disposition of call back from a clinical adviser. For the telephone data, the number of actual clinical assessments is recorded. For the online data, the disposition reflects a request for a call back but not whether or not this call back actually took place.

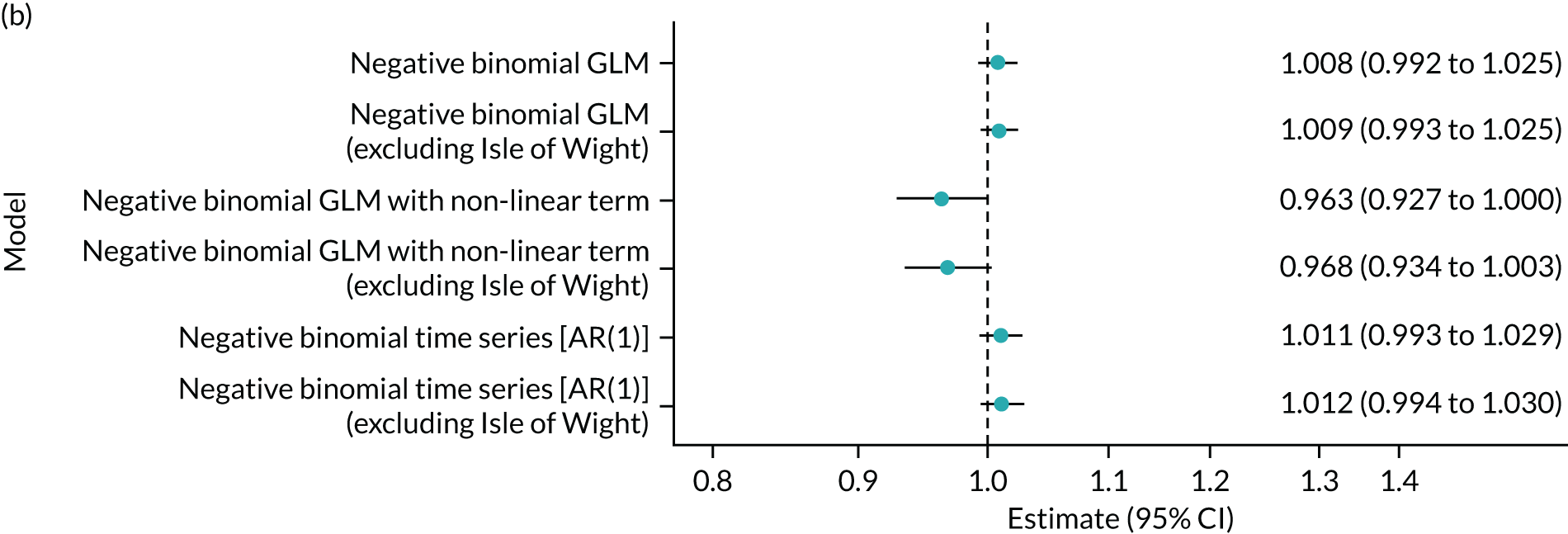

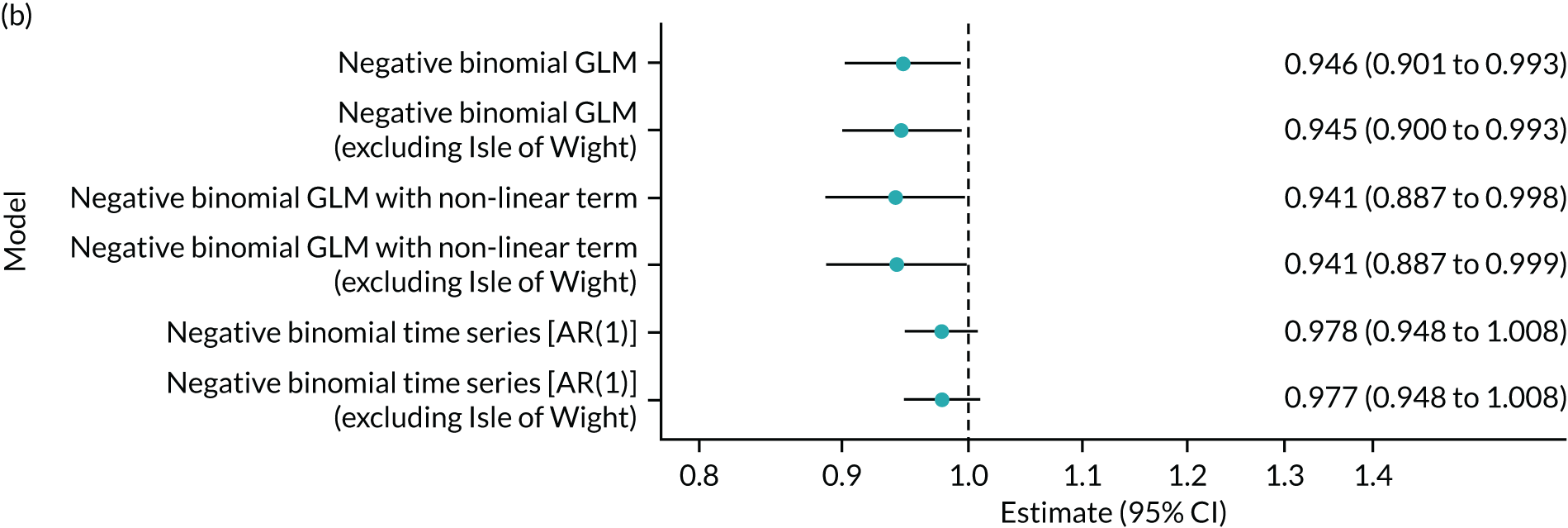

Figure 8a shows the forest plot of clinical calls for all area codes for the primary analysis method. The x-axis shows the incidence rate ratio per 1000 online contacts. The overall incidence rate ratio per 1000 online contacts is 0.946 (95% CI 0.901 to 0.993; p = 0.025). This means that, on average, for every 1000 online contacts, the number of clinical call backs decreases by 5.4% (95% CI –9.9% to –0.7%). This result is considered a statistically significant effect, suggesting that, on average, the online 111 service has caused a reduction in the number of NHS 111 contacts (calls and online) that result in a clinical call back.

FIGURE 8.

Forest plots showing the effect of introducing the NHS 111 Online service on the total number of call backs or requests for call backs from a clinical advisor. (a) Estimated effects for individual areas and the overall average effect from the primary analysis (negative binomial GLM), heterogeneity I2 = 94.5% (95% CI 92.7% to 95.9%); and (b) average effects from the primary analysis and sensitivity analyses. Estimates are incident rate ratios per 1000 online contacts. GLM, generalised linear model.

Figure 8b shows the forest plot of the main analysis method and various sensitivity analyses. Again, excluding the Isle of Wight has little effect on the estimate. The non-linear model also has little effect on the estimate and CIs. The AR(1) model provides slightly smaller incidence rate estimates but the result is no longer statistically significant (p = 0.148).

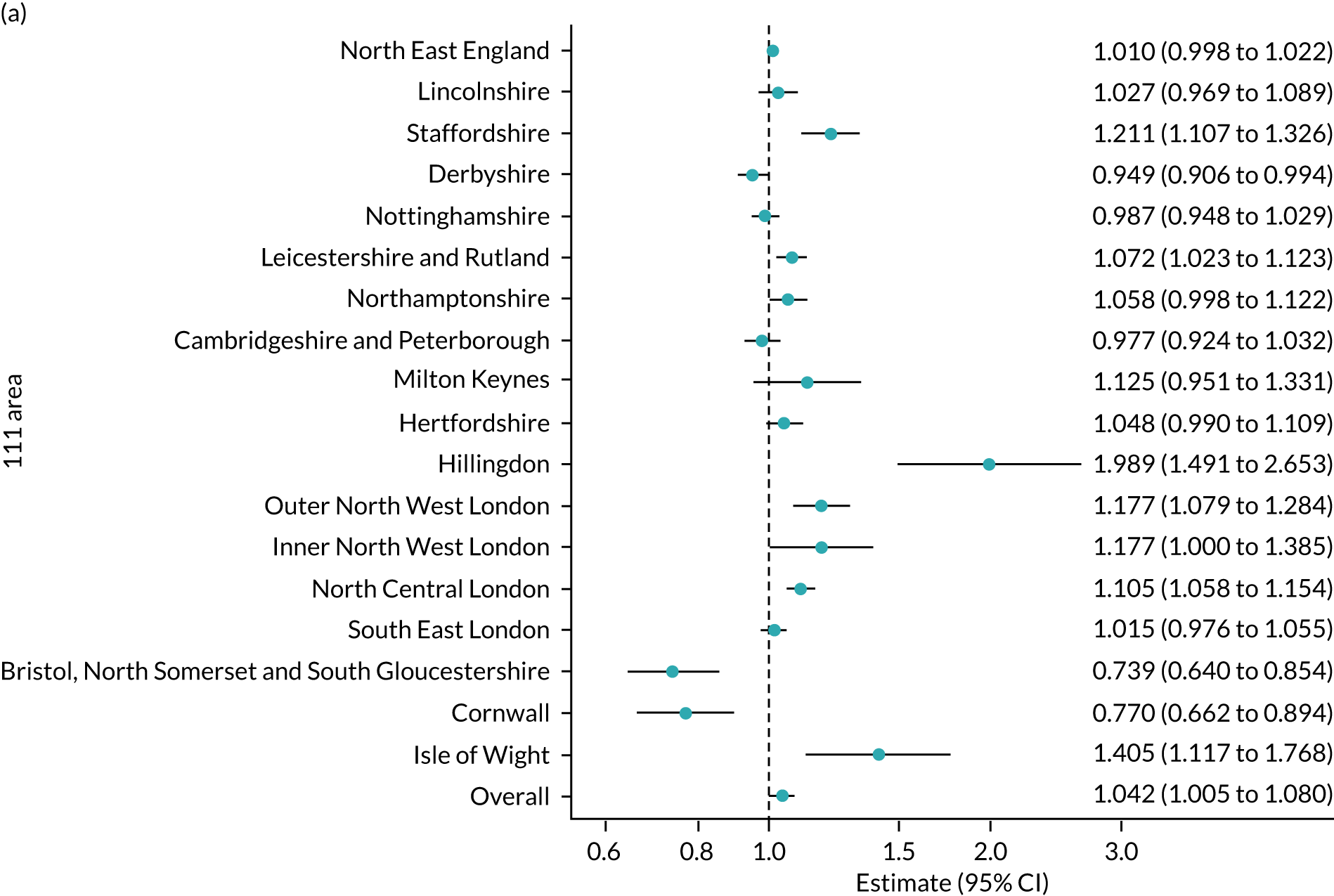

Ambulance dispositions

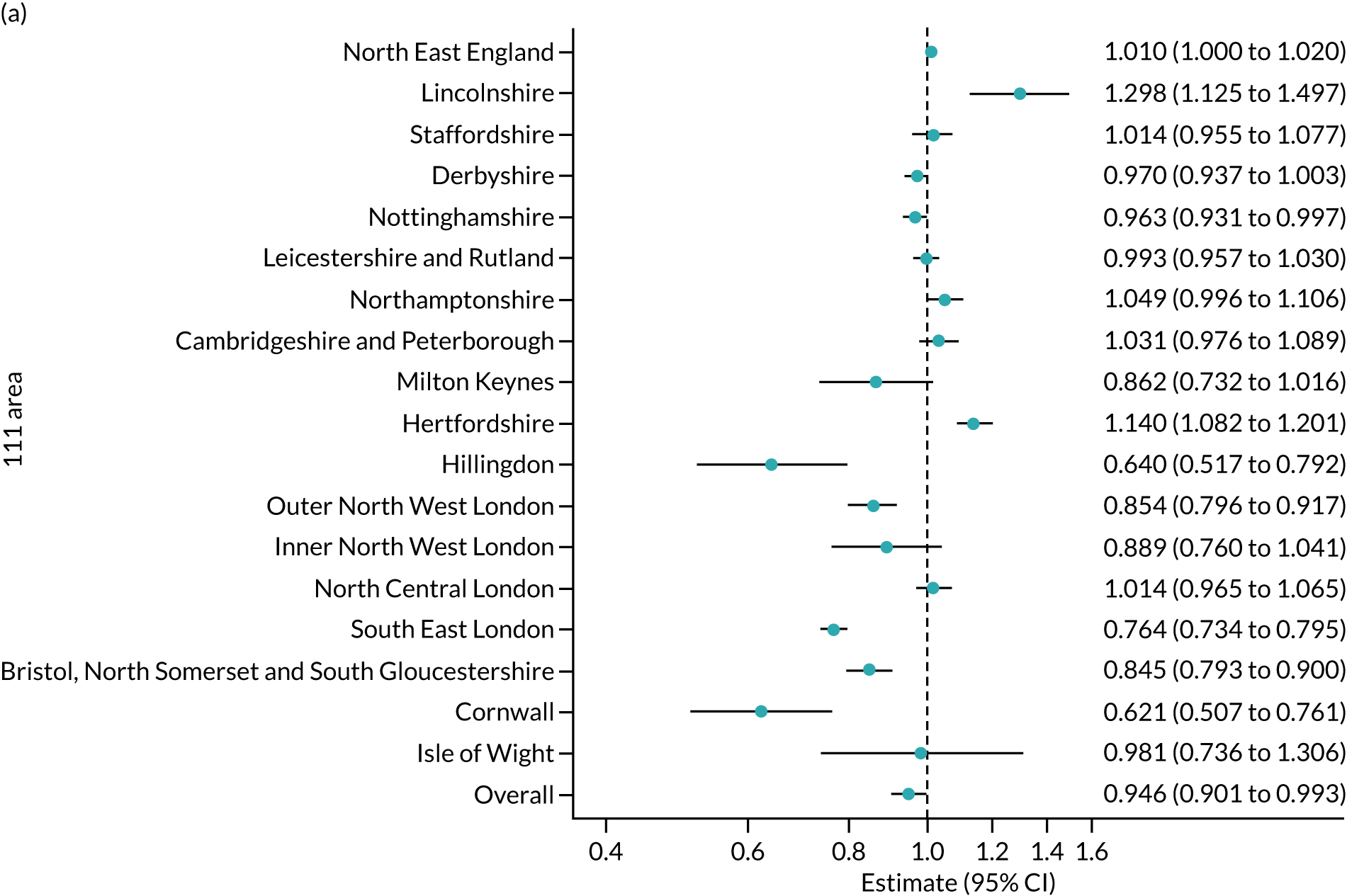

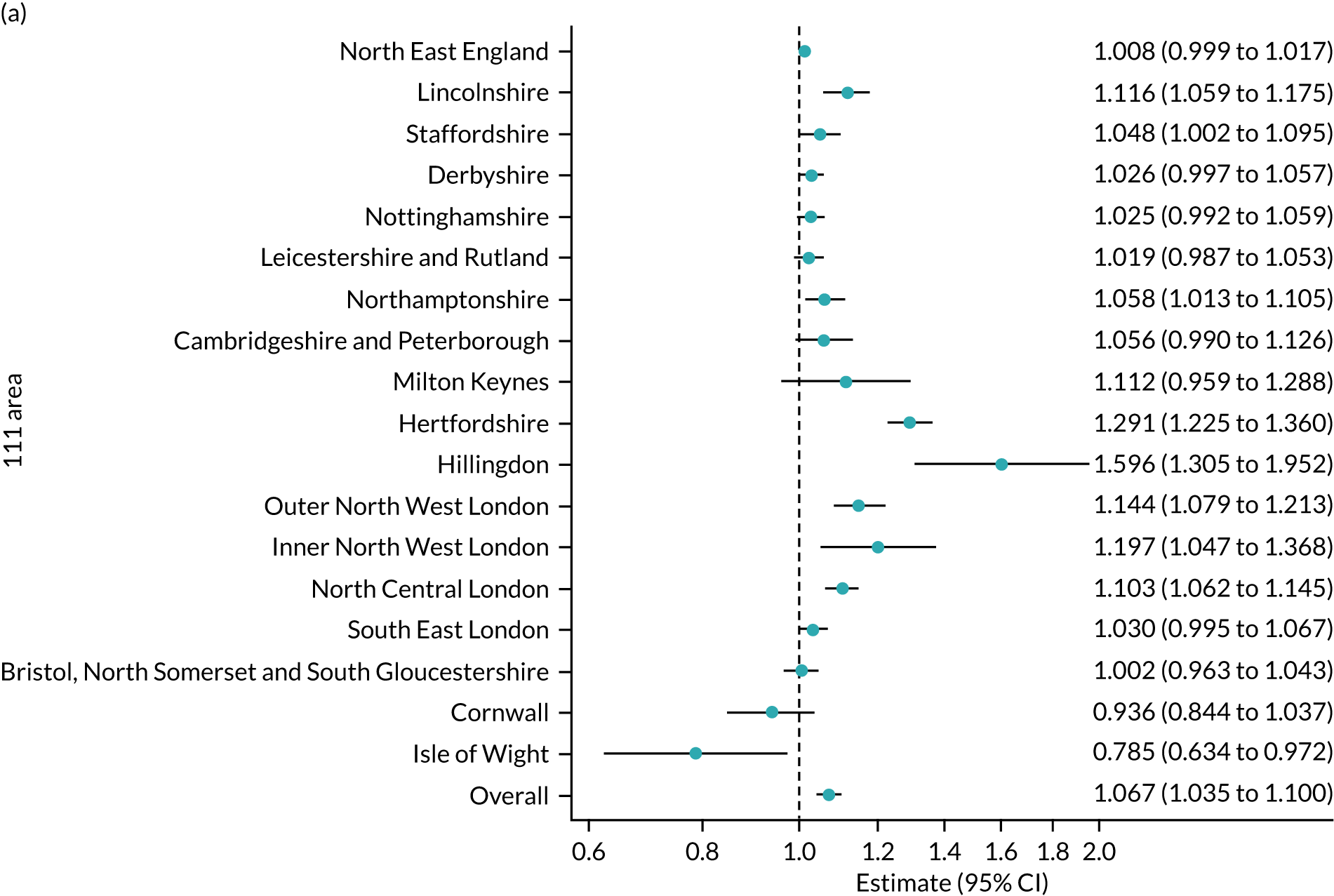

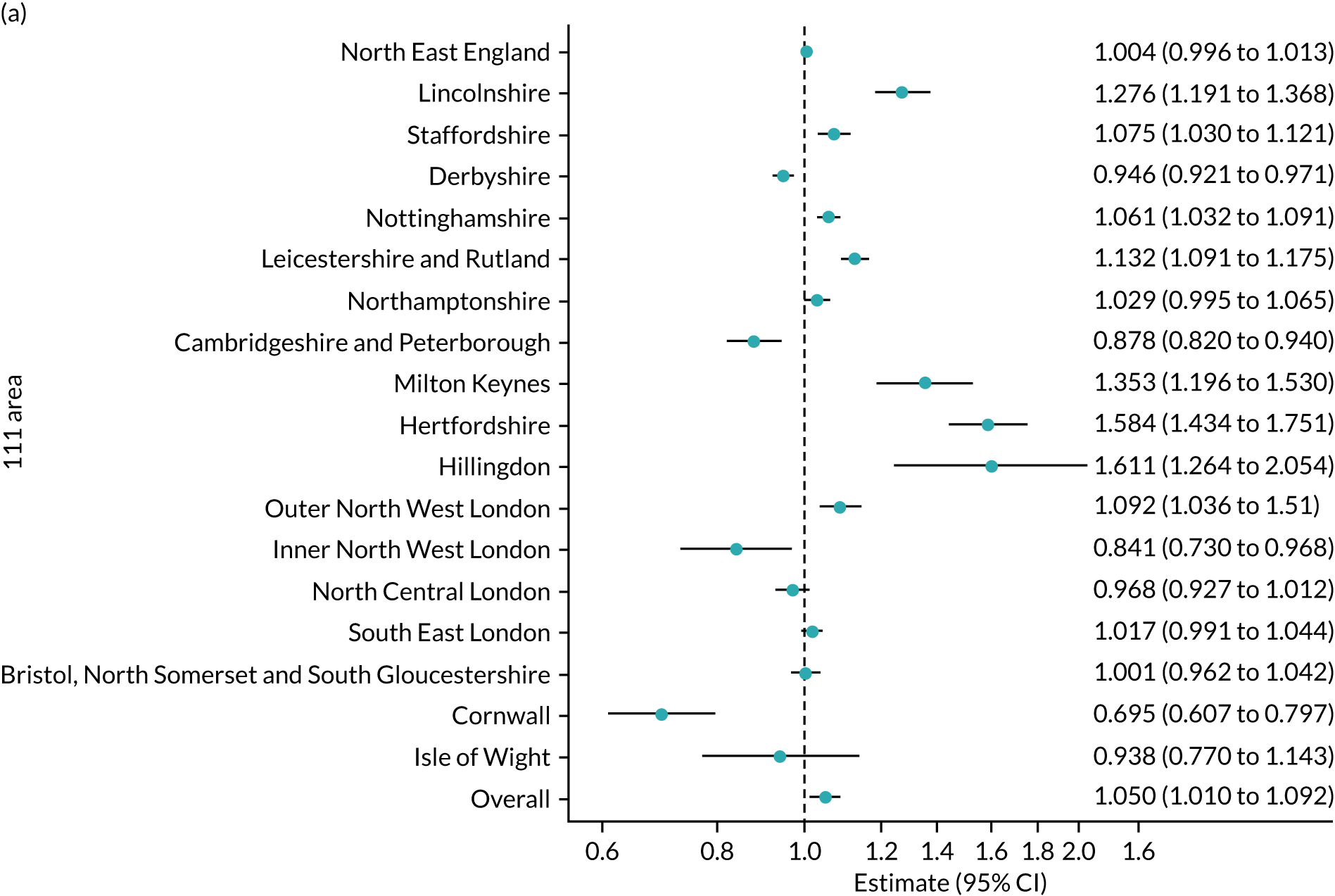

One disposition at the end of an NHS 111 contact is to recommend an emergency ambulance response. Within the telephone service, this is facilitated by NHS 111 sending the request directly to the local ambulance service. For NHS 111 Online contacts the disposition advice is to call 999. The outcome for this analysis is the number of ambulance dispositions for both NHS 111 calls and NHS 111 Online. Figure 9a shows the forest plot of clinical calls for all area codes for the primary analysis method. The x-axis shows the incidence rate ratio per 1000 online contacts. The overall incidence rate ratio per 1000 online contacts is 1.067 (95% CI 1.035 to 1.100; p < 0.001). This means that, on average, for every 1000 online contacts, the number of ambulance dispatches potentially increases by 6.7% (95% CI 3.5% to 10.0%) if all online contacts follow this advice. This result is considered a statistically significant effect, suggesting that, on average, the online 111 service has the potential to result in an increase in the number of ambulance dispatches overall.

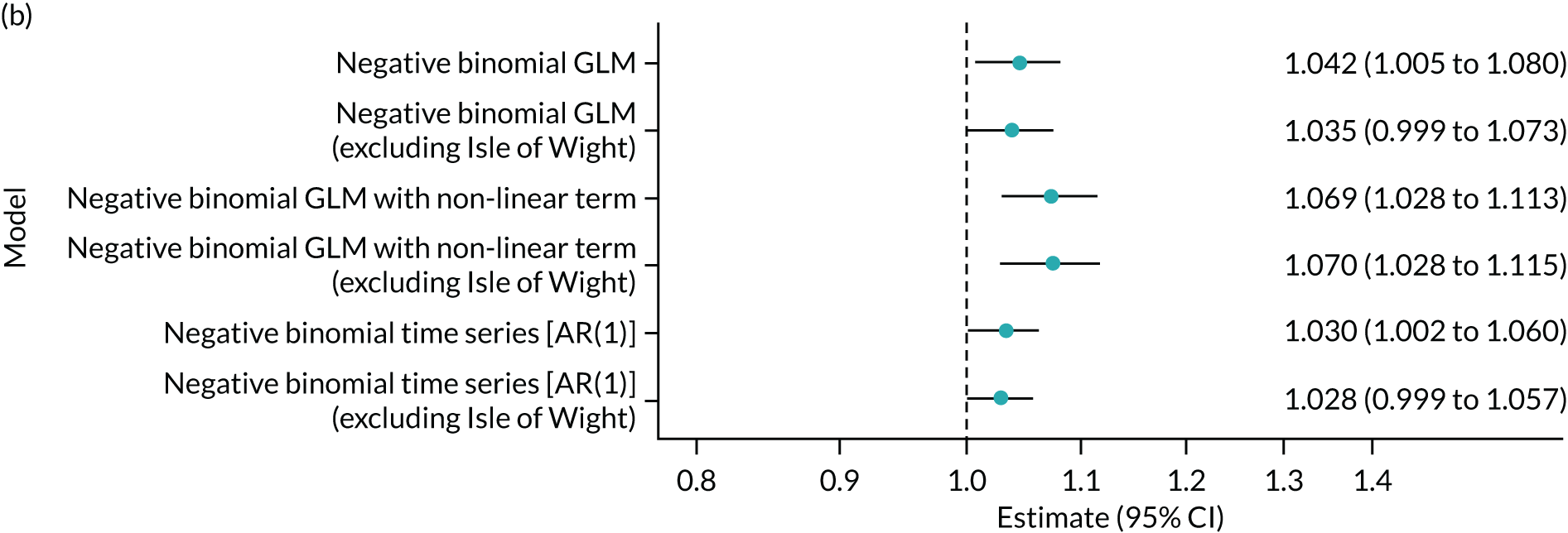

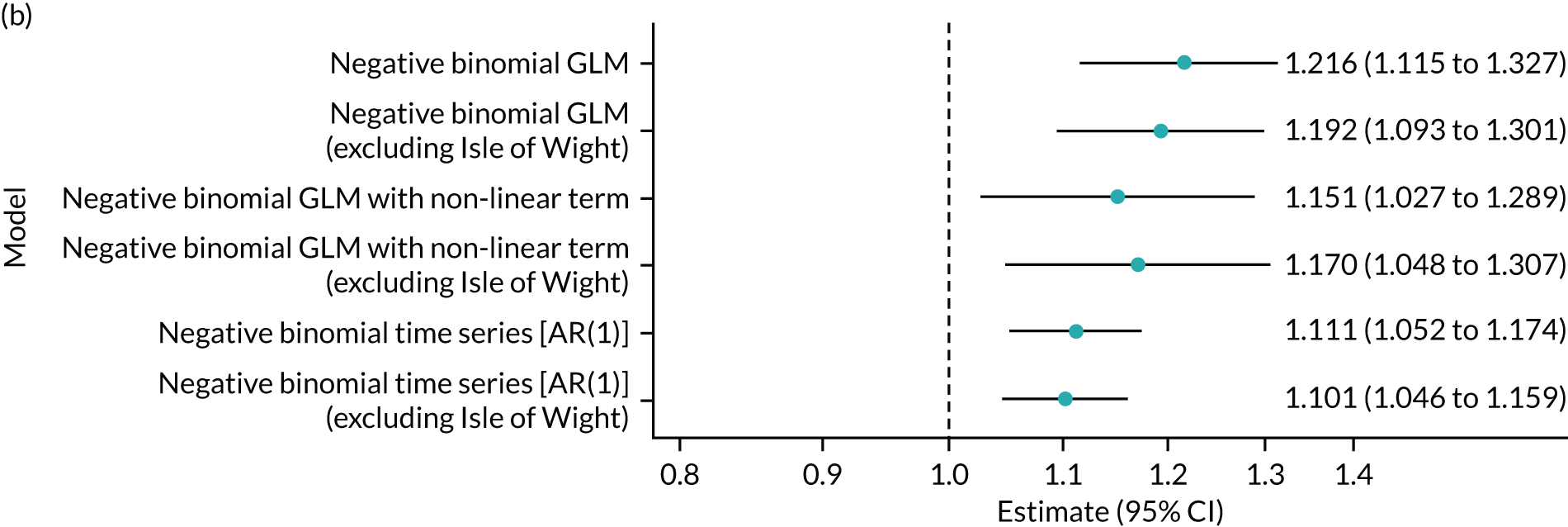

FIGURE 9.

Forest plots showing the effect of introducing the NHS 111 Online service on the number of ambulance dispositions. (a) Estimated effects for individual areas and the overall average effect from the primary analysis (negative binomial GLM), heterogeneity I2 = 89.8% (95% CI 85.4% to 92.8%); and (b) average effects from the primary analysis and sensitivity analyses. Estimates are incident rate ratios per 1000 online contacts. GLM, generalised linear model.

Figure 9b shows the forest plot of the main analysis method and various sensitivity analyses. Again, excluding the Isle of Wight has little effect on the estimate. The non-linear model also has little effect on the estimate and CIs; the estimates have decreased slightly, and this is similar for the AR(1) model.

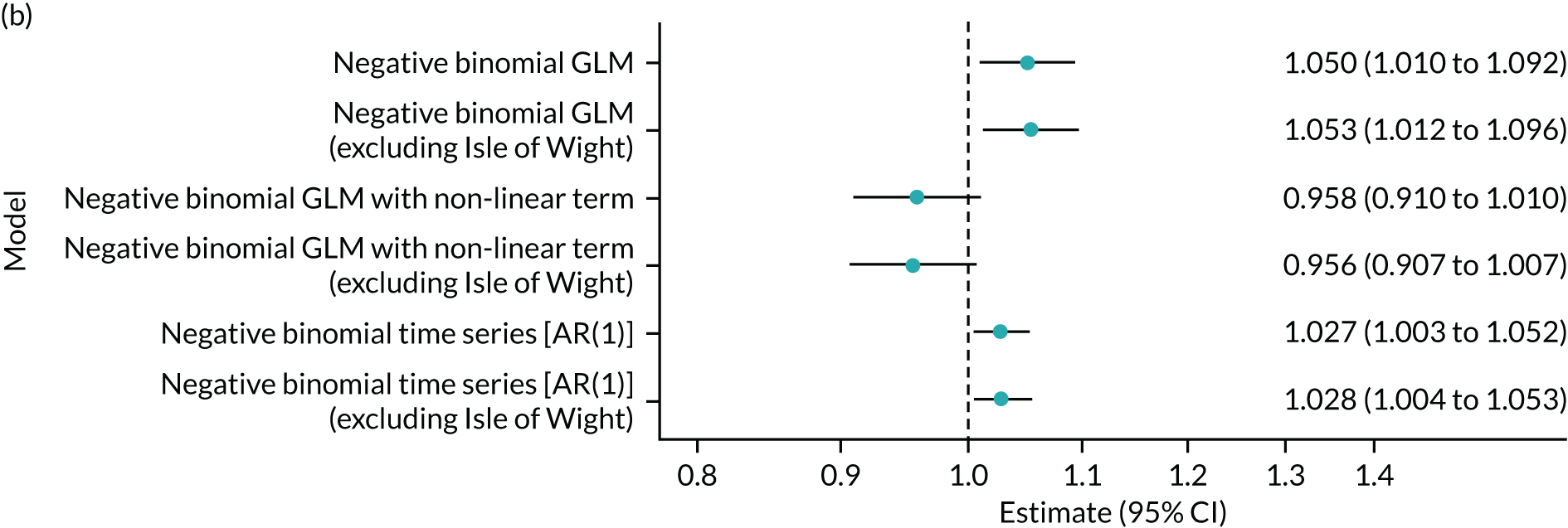

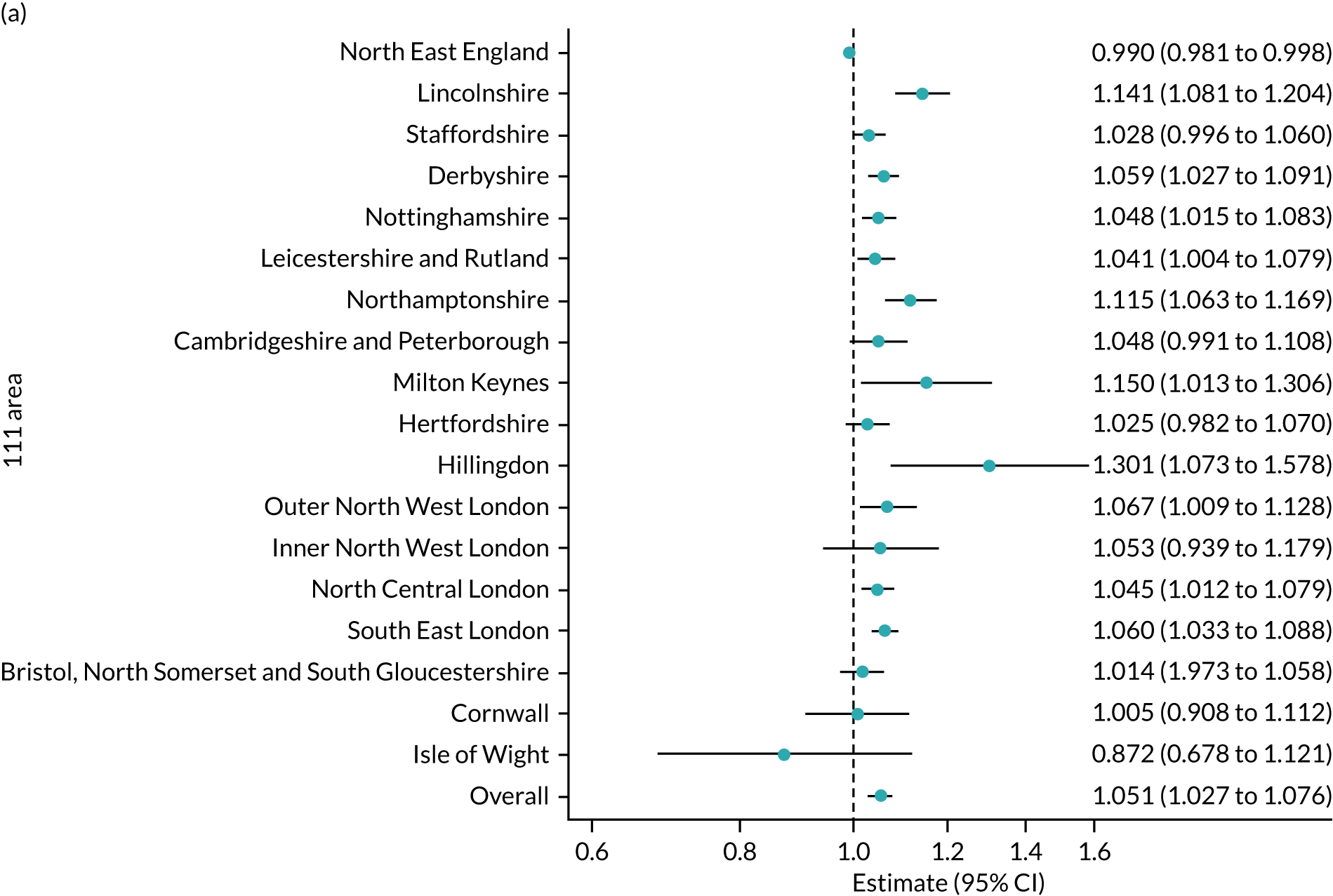

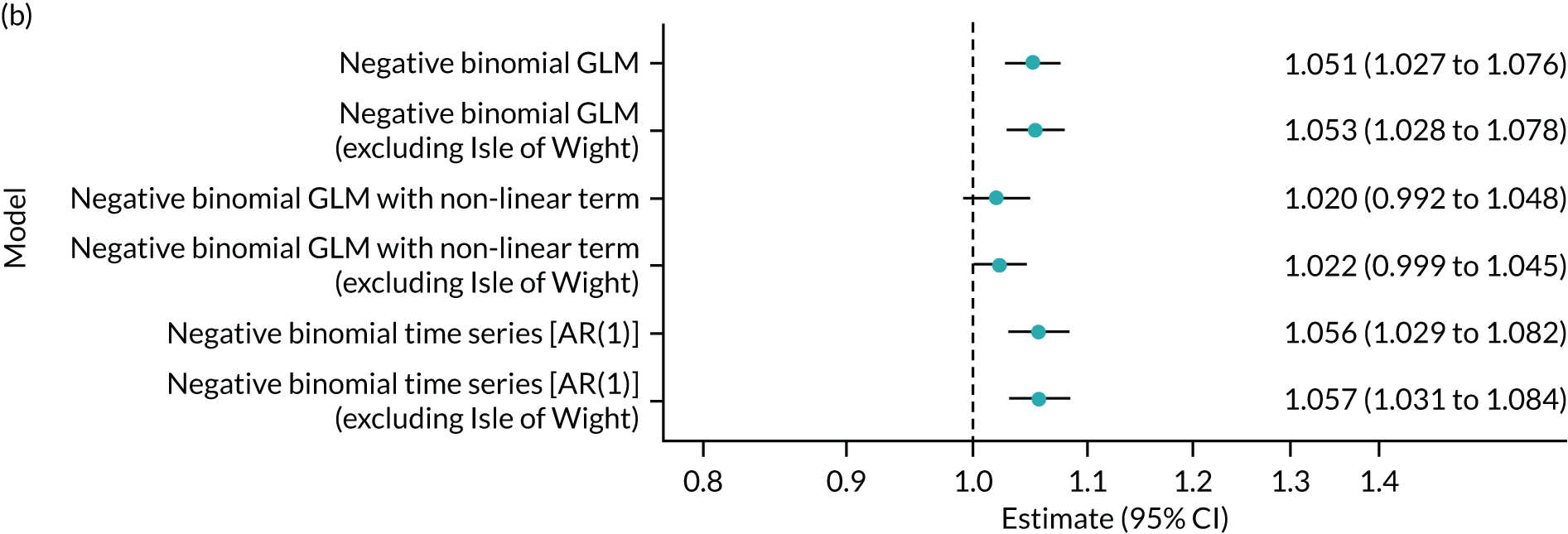

Emergency department dispositions