Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/115/29. The contractual start date was in May 2016. The draft report began editorial review in September 2020 and was accepted for publication in May 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Logan et al. This work was produced by Logan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Logan et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction: why this study was needed

Material throughout the report has been adapted with permission from the trial protocol. 1

Why are falls important?

A fall can have a devastating impact on a person, their family and their carers, and can place demand on health and social care resources. Falls are common, with one-third of those aged > 65 years and half of those aged > 80 years falling at least once per year. 2 Ageing societies pose challenges for health and social care systems. The UK has an ageing population; there are nearly 12 million people ≥ 65 years, of whom 5.4 million are aged ≥ 75 years, 1.6 million are aged ≥ 85 years, over 500,000 are aged ≥ 90 years and 14,430 are centenarians. 3 Falls are the most common cause of emergency hospital admissions for older people. 4 In 2017/18, there were around 218,000 emergency hospital admissions related to falls among patients aged ≥ 65 years, with around 149,000 (68%) of these patients aged ≥ 80 years. 5

Consequences of a fall

Falls can cause injury, distress, pain, reduced mobility, loss of confidence or independence, and a fear of falling, leading to reduced levels of activity in daily life and increased mortality. 2 In 2017, 5048 people aged ≥ 65 years died from having a fall, equating to 14 people every day. 4 Hip fracture is the most common serious injury following a fall, and it is estimated that around one-quarter of people who are aged > 65 years and fracture their hip will consequently require long-term care in a care home. Hip fractures are the leading cause of accidental death. 6 Older adults with frailty are less able to cope and recover from accidents, physical illness or other stressful events, including falls. People living in care homes are more frail than community-based populations and their care needs merit specific attention. 7 Delivering comprehensive, consistent and structured enhanced support to those in care homes will ensure that their needs continue to be identified and met proactively. 8

Prevention and management of falls

The National Falls Prevention Coordination Group’s falls and fractures consensus statement advocates a whole-system approach to the prevention of falls that includes risk factor reduction across the life-course, case finding and risk assessment, strength and balance exercise programmes, healthy homes, high-risk care environments, fracture liaison services, and collaborative care for severe injury. 9 Identification of those at risk of falls; assessment of contributory risk factors for falling; and interventions to reverse, reduce or modify those risk factors are recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 10 However, these recommendations are based on people living in their own homes who have capacity to listen and react to health professional’s advice; they were not written for care home staff or residents.

Falls in care homes

Approximately 421,000 older people were living in UK care homes in 2016–17. 11 Two levels of care accommodation are available, depending on the level of care required. These are personal care and 24-hour support (provided by care homes without nursing, sometimes called residential homes), and additional on-site nursing (provided by care homes with nursing, sometimes called nursing homes). Some homes provide both levels of care (dual-registered homes). Care homes both with and without nursing match the international consensus definition of a nursing home. 12 Around 5500 different providers in the UK operate 11,300 care homes for the elderly, with 95% of beds provided by the independent sector (both for-profit and charitable providers). 13

The majority of older people living in care homes are aged > 85 years; live with cognitive impairment, multimorbidity and limited mobility; and take multiple medications. 7 The rate and risk of falls for residents of care homes is high, with falls being three times more common in care home residents than in older people living in their own homes, and those falling in care homes being 10 times more likely to suffer a serious injury. 14 One in five people living in care homes will die within a year of suffering an injurious fall. 15 Falls may often occur as a symptom of underlying frailty and illness. 16 Falls may engender feelings of anxiety in care home staff, and fear of litigation and complaints, which may have an impact on care staff’s willingness to encourage residents to be physically active. 17

Multiple diverse factors can contribute to the increased risk of falls in care home residents, including frailty, the presence of long-term conditions, physical inactivity, taking multiple medications and the unfamiliarity of the surroundings. The interaction of factors that contribute to an individual’s risk of falling is unique to them; therefore, interventions to reduce falls risk must be individualised and meaningful for individuals. Protocols used to perform risk assessments for falls in hospitals and care homes vary in quality, do not necessarily trigger individually tailored interventions to reduce risk factors and, in some cases, seek only to stratify risk. 18

A number of interventions have been applied to reduce falls in care homes, including multifactorial approaches. However, a Cochrane review found the evidence to be of low quality and inconclusive regarding effective strategies to reduce both falls rates and falls risk. 19

Implementing health-care interventions in care homes

The NICE falls guidelines and quality standards10 do not explicitly provide guidance for care home residents. Instead, care home staff and clinicians are relied on to apply research evidence from hospital in-patient and community falls trials. Interventions are often difficult to implement within a care home and it is unclear whether or not interventions can lead to cultural change that becomes embedded in care home practices so that effects are sustained or even increase after the intervention. 20

Improving the lives and health of older people living in care homes is a major UK government priority and is embedded in the NHS Long Term Plan. 21 The Enabling Research In Care Homes (ENRICH) initiative brings together care home staff, residents and researchers to facilitate the design and delivery of research in care homes. Increasingly, research has looked at providing care home staff with training in an aspect of care from experts, with the aim of increasing carers’ knowledge and expertise in caring for older people with frailty. A recurrent observation has been the need to adapt existing approaches to improvement and implementation to take account of and empower care home staff and organisations. 22 In addition, there is evidence that a number of care home-specific issues affect how ready care homes are to engage with external organisations regarding change. 23 Where care home staff and NHS professionals are required to work together, there is evidence that outcomes will be better if specific activities that encourage shared working between care home staff and visiting health-care professionals are integrated into care delivery. 24

Falls are often a consequence of undiagnosed and untreated underlying health conditions, frailty and environmental factors, including the way that care is structured. Approaches to falls prevention are therefore likely to be multiagency collaborations between care home staff and external health-care providers. Taking into account the lessons learned about effective partnership working and implementation science, adoption of early co-design and strong stakeholder involvement in the planning and design of the intervention and study was essential to create a falls prevention programme that was pragmatic and suitable to subsequent adoption, while also maximising the external validity of the study. The Medical Research Council’s framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions25 provided a framework for the development of our falls prevention programme, feasibility study and multicentre trial. The framework highlights the need to understand the context for delivery of a complex intervention, which is even more relevant in care homes as they pose a distinct challenge for the introduction of complex interventions: they vary in size, funding, workforce and culture, and house vulnerable individuals with far-reaching health and social care needs.

The feasibility study [Falls in Care Homes (FiCH)], which laid the foundation for the current Falls prevention in Care Homes (FinCH) trial, found that an effective falls prevention programme would have to use language that care home staff could understand and identify with, explain the rationale for falls prevention in ways that aligned with care home organisational priorities, and be conducted in a way that allowed for care home schedules and care regimes. 26

The GtACH programme

Our intervention, the Guide to Action for falls prevention in Care Homes (GtACH) programme,27,28 was developed to reduce falls rates by supporting care home staff to identify risk factors for falling that are pertinent for an individual and take action to reduce those risks. It was co-produced by a group of care home staff, clinicians, researchers, public, voluntary and social care organisations and includes care home staff training, support and documentation. Care home staff are trained to implement the programme in their home by an NHS falls lead over 1 hour in small groups. The NHS falls lead is a nurse, physiotherapist or occupational therapist who has specialist training, skills and knowledge in falls prevention and bone health. The homes are asked to identify a falls champion to help maintain implementation. When the GtACH programme is implemented, homes are given a copy of the GtACH manual and are supplied with the GtACH tool. The latter is a paper form, comprising an assessment component (a checklist of falls risk factors) and care planning section supported by suggested actions linked to each fall risk factor (see Appendix 1). After training, it takes an average of 20 minutes to complete the GtACH tool for each resident. Initial proof of concept work29 and a subsequent feasibility randomised controlled trial (RCT), FiCH, showed that the GtACH programme was implementable and changed staff behaviour in line with gold standard practice. 26

Limitations of previous studies

A Cochrane review published in 2018,19 which looked at the effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals, found that the majority of trials were at high risk of bias in one or more domains, mostly relating to lack of blinding. With few exceptions, the quality of evidence for individual interventions in either setting was generally rated as low or very low. Risk of fracture and adverse events (AEs) were generally poorly reported and, where reported, the evidence was of very low quality. The authors concluded that there was a need for further research and, in particular, large RCTs in care facilities to inform practice in falls prevention.

Justification for current trial

The Cochrane review in 201819 concluded that further research to strengthen the evidence for multifactorial interventions for falls reduction in care homes was required as there were some individual trials that showed potentially important reductions in the rate of falls. The authors noted that a key feature of these multifactorial interventions was the individualised nature of the interventions delivered. The review stated:

[t]his implies that further research with emphasis on an individualised, standardised approach to delivery of interventions with consistent description and application within further trials is warranted, including as a clear description of existing falls prevention practices in the control arm of any trials and the interaction of the intervention arm of the trial with usual care. A mixed methods approach may be necessary to achieve this.

Reproduced with permission from Cameron et al. 19 Copyright © 2020 The Authors. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. on behalf of The Cochrane Collaboration. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Research aims

The aims of the trial were to:

-

determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the GtACH programme compared with usual care

-

complete a process evaluation to provide insight into the implementation of the GtACH programme and to contextualise trial findings.

Chapter 2 Trial design, including interventions

This chapter describes the trial as originally designed and the interventions. It is a summary of the full protocol,1 with the methods of analysis for the economic evaluation and results presented in Chapter 4. The methods and analysis for the process evaluation are presented in Chapter 5.

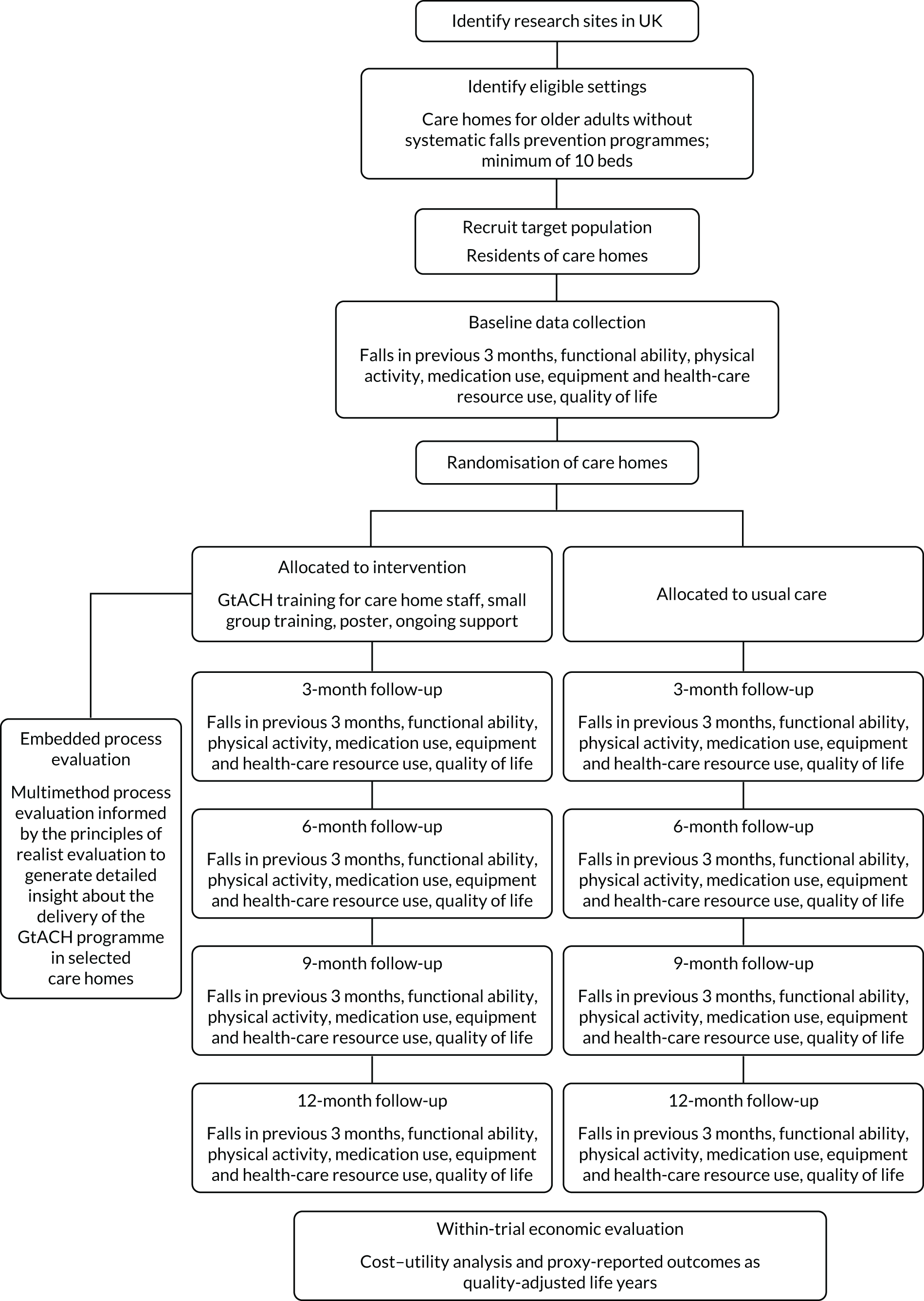

Trial design

The FinCH trial was a pragmatic, multicentre, cluster parallel 1 : 1 RCT to evaluate the GtACH programme compared with usual care (an absence of a systematic and co-ordinated falls prevention process) in UK care homes for older people. The allocation was at the care home level. A flow diagram of the trial design is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the trial design.

Care homes and residents took part in the study. The primary RCT health outcome was falls rates in the 90-day period between 91 and 180 days post randomisation. Secondary outcomes were collected at baseline and at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months post randomisation.

Trial population

The trial population was care homes (with and without nursing) registered with the care home regulator [the Care Quality Commission (CQC)] in England.

Eligibility criteria: care homes

Inclusion criteria:

-

long-stay care home with old age and or dementia registration

-

≥ 10 potentially eligible residents

-

falls routinely recorded in residents’ personal records and on incident sheets

-

written agreement of care home manager to comply with the protocol and identify a care home falls champion if allocated to the GtACH arm.

Exclusion criteria:

-

participated in GtACH pilot/feasibility studies

-

exclusively provided care for those with learning difficulties or substance dependency

-

contracts with health or social providers were under suspension, or were under investigation by the regulator of care homes (the CQC) or special measures at time of recruitment

-

a significant proportion of beds taken up by health-service commissioned intermediate-care services

-

existing systematic falls prevention programme.

Eligibility criteria: residents

Inclusion criteria:

-

all long-term care home residents.

Exclusion criteria:

-

residents receiving end-of-life care.

Identification of care homes and consent of care home managers

Research assistants at each site identified care homes through examining the CQC website, presenting the study at the ENRICH research network events and liaising with Clinical Research Network (CRN) staff who had experience of conducting research in care homes. Care home managers were telephoned and/or sent a letter inviting them to participate. If they responded to the invitation, the researcher posted details of the study to the care home and an appointment was made to visit the home. A researcher then visited the care home to confirm eligibility at least 24 hours later to allow adequate time for the manager to digest the written study information. Questions and an opportunity to clarify their involvement were encouraged at the visit and, if willing, informed consent from the care home manager was obtained. All care homes invited to participate in the research were offered an incentive of £200. Control homes were given this at the start of the study. Intervention homes were given £100 at the start of the study and a further £100 once the training was complete. The homes were asked to send an invoice to the University of Nottingham.

Screening, recruitment and identification of participants

Once the care home manager agreed to participation in the study, care home staff distributed (within the care home) or posted study invitation letters and participant information sheets (PISs) or consultee information sheets to residents, relatives and/or personal consultees (PCs). After a 2-week window, details of those who confirmed that they were happy to take part were provided to the researcher, who then arranged to meet with the resident (and their consultee, if appropriate) at a mutually agreeable time to provide further information about the study and obtain consent. This took place prior to randomisation of the care home.

Resident recruitment and consent procedures

All residents consented to participate or a consultee agreed to their participation. For residents who were unable to provide consent, the researcher used a short ‘picture’ version of the PIS to explain the study to the resident in the presence of their consultee.

A recommendation by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) to change the definition of ‘fall’ on the PIS was implemented so that the control arm and GtACH arm were given the same definition.

The researcher confirmed eligibility, assessed capacity and fully explained the study to the resident, relative and/or PC. Before being enrolled in the study, informed written consent was obtained in accordance with Research Ethics Committee (REC) guidance and good clinical practice (GCP). When a consultee was required, the consultee signed a declaration if they believed that the participant would have wished to take part in the study had they had the mental capacity to state their preference. Residents who did not have capacity and whose relatives did not respond to the invitation letter within 2 weeks were also able to be enrolled in the study, as the care home manager acted as consultee in these instances. Baseline data were collected by the researcher after consent or consultee agreement was given.

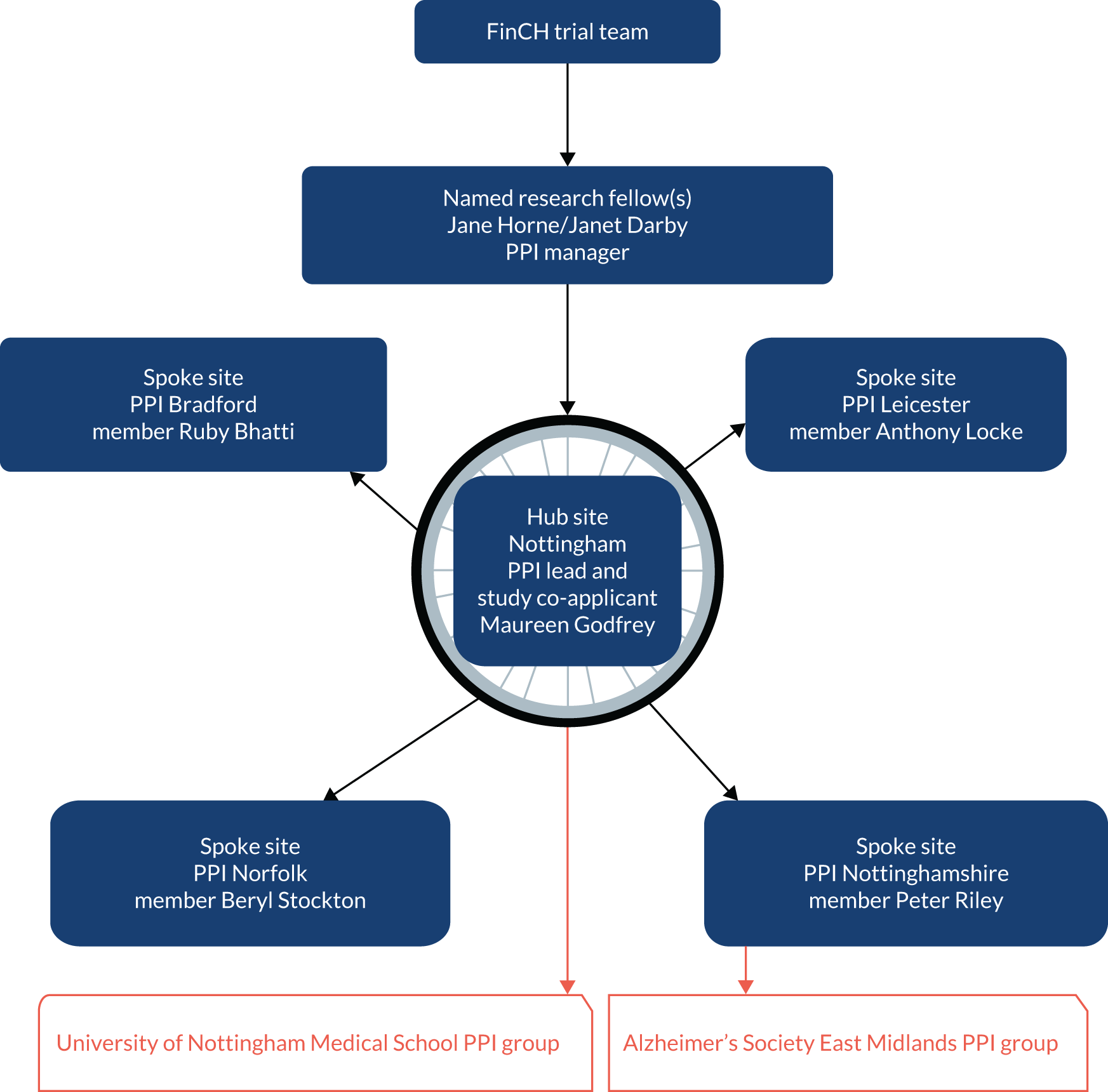

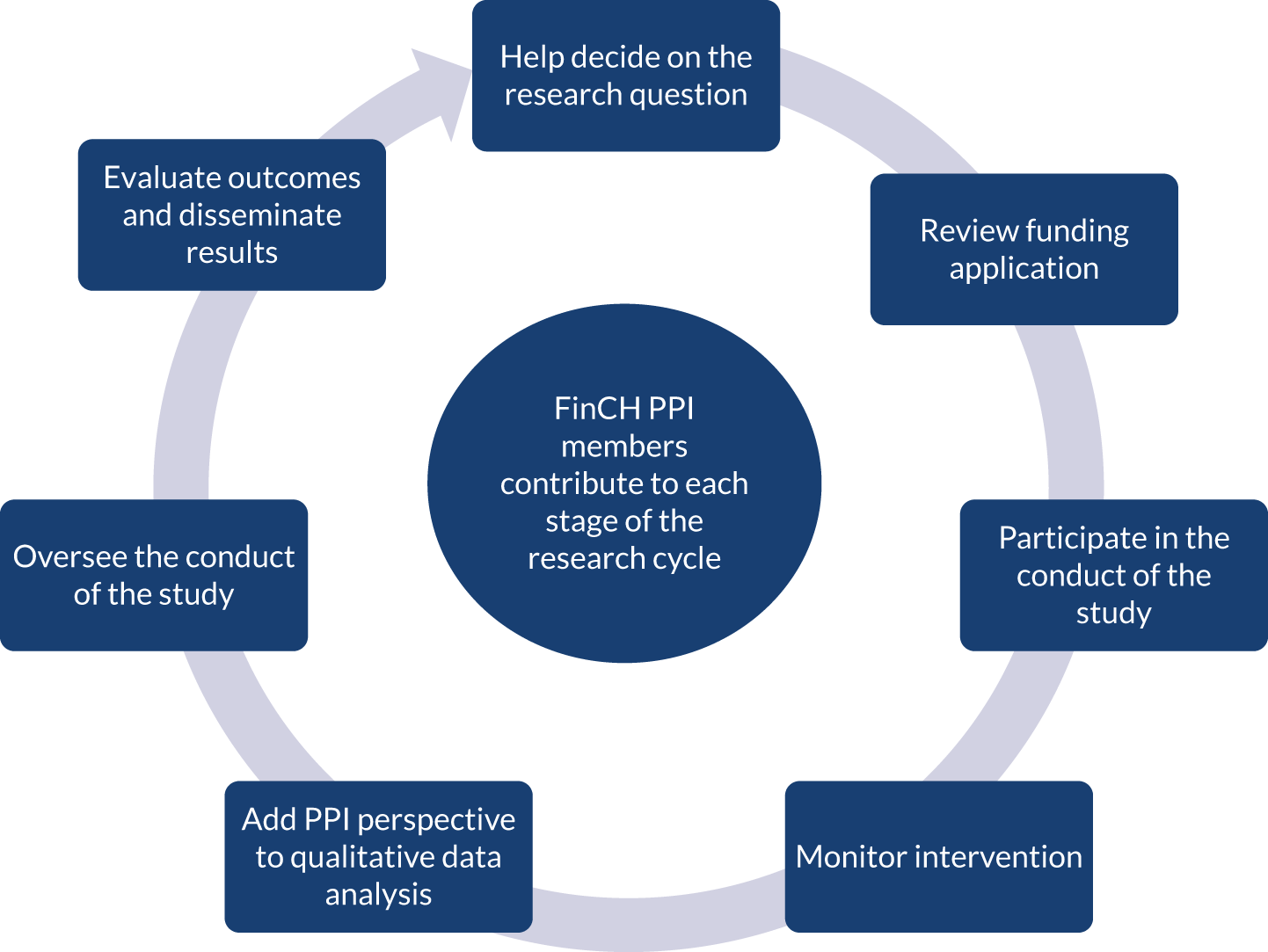

The process of contacting PCs for residents who did not have capacity was identified as the main barrier to recruitment. An amendment was sought, with patient and public involvement (PPI), for a cover letter to be sent to residents’ PCs summarising the research and indicating that if a response from the consultee was not received within 2 weeks of receipt of the letter, a care home manager would act as nominated consultee on the resident’s behalf. The amendment was approved by the REC in June 2017 and implemented in July 2017.

Interventions

The GtACH programme

The GtACH programme is summarised using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist30 and can be obtained from the authors.

Rationale

The relatively untrained nature of care home staff, the complex nature of falls risk factors in care home residents and the need for multiple interventions to address multiple risk factors require a systematic home-wide programme, including staff education and support in the use of risk assessment and decision support tools.

Materials

-

GtACH training slides: these were used by the NHS falls lead to train care home staff in each intervention home.

-

The GtACH reference manual: given to care home staff to support implementation of the GtACH paper screening and assessment tool. It included a master copy of the paper tool, information about the study, a copy of the training session slides, falls information (including a definition of a fall, why falls are important and causes of falls), instructions on how to complete the GtACH paper screening and assessment tool, a falls incident analysis template, a medication and falls chart and information on how to obtain further expert advice or support from the local falls expert.

-

The GtACH paper screening and assessment tool comprised 33 items related to falls risk factors grouped into four domains: falls history, medical history, movement/environment and personal needs. The presence of risk factors prompts up to 30 individual staff actions (see Appendix 1).

-

Attendance certificate: given to care home staff at the end of training.

-

The GtACH poster: an A4 poster given to care homes to display in the home to act as a reminder to implement the GtACH programme in the home.

Procedures

-

Care home staff training was provided by the local NHS falls lead, lasted 1 hour per session and included the purpose of the study, purpose of the training, prevalence of falls in care homes, the GtACH programme’s history, and how to complete and where to file completed forms. It emphasised consistent delivery and referenced the materials listed above, in particular the GtACH reference manual. Case studies and role play were used. The NHS falls lead was a registered nurse, physiotherapist or occupational therapist who was trained and specialised in falls prevention and bone health. As it was not feasible for all care home staff to attend a single training session, repeated training sessions were offered according to care home staff availability.

-

A care home falls champion, whose role was raising awareness and liaising between staff and the NHS falls lead, was identified in each care home.

-

Trained staff were asked to complete the GtACH screening and assessment tool with every resident within 2 weeks of the training, in private, and involve family, friends and other care home staff as appropriate. Completed GtACH documentation was to be placed in the resident’s care records and it was expected to contribute to the care plan for each resident. Reassessment was expected if the resident developed a new health condition or fall, or every 3–6 months.

The training period for care homes was extended from 2 weeks to 4 weeks (post randomisation) to enable fall leads time to train very large homes (≥ 50 staff members).

Control intervention

The intervention in the homes randomised to the control arm was usual care. The materials and procedures described in the intervention were not used and no systematic falls prevention approach was applied.

Strategies to reduce contamination

Health-care trials of complex interventions are at risk of contamination bias as the interventions often involve multiple components, multiple stakeholders and a range of organisations that interact with the context in which they are delivered. FinCH was a complex rehabilitation trial for which the intervention and trial procedures involved interactions between clinicians, care homes, residents, researchers and wider stakeholders (e.g. commissioners and private organisations). These interactions could lead to a change in behaviour and, potentially, a change in usual care, even in the control settings where exposure to the intervention is intended to be prohibited. In the design and conduct of the FinCH trial, the following strategies were used to reduce the potential for contamination:31

-

Research staff at the set-up meetings explained the importance of continuing with usual care for the control arm to act as a comparator.

-

NHS falls leads in the sites were asked to sign a confidentiality agreement to state that they would not share the GtACH reference manual.

-

Data on the number of care home staff leaving and starting at each home were collected.

-

The GtACH reference manual was not published prior to study completion.

-

The content of the intervention was not described in detail when the study team were invited to present the ongoing trial information at conferences and high-profile impact events.

-

The study team spoke to commissioners to explain the trial timelines and confirm that all control care homes would be offered the intervention at the end of the trial.

-

All control care homes were offered the intervention at the end of the trial.

-

Therapists and nurses in the sites were given training in RCT design and ethics considerations to help them understand the issues.

Strategies to reduce bias

We aimed to minimise the risk of falls recording and ascertainment bias by care home staff through our eligibility criterion that homes were required to have a falls recording process in place to routinely record falls in residents’ personal records and on incident sheets. The GtACH programme did not include a falls recording system.

We aimed to reduce bias arising from research staff collecting outcome data by ensuring that they were not involved in and were independent of care delivery in any of the study care homes.

Further steps were:

-

All research assistants (RAs) collecting outcome data were blind to allocation of the homes.

-

When unblinding occurred, we asked the RAs to report this on an unblinding form, localised by site and collated by Norwich Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU). When site staff were available, RAs/CRN staff did not continue data collection at care homes for which they had been unblinded to trial allocation.

-

Data were collected from care home records using a standardised data collection form, and data were checked by a second researcher if there were concerns over the content of handwritten notes.

-

When possible, CRN staff collected data, as they were better trained and less emotive about the results.

-

Data were inputted into the research trial database (REDCap)32,33 by data entry technicians unrelated to the study where site capacity allowed. NCTU monitored data quality throughout the trial, reporting to sites on a weekly basis so that there was more of a chance that researchers could find the source data in the care homes to check.

Baseline and outcome measures and assessment

The following characteristics of care homes were collected:

-

number of staff in caring role

-

number of beds in care home

-

number of residents

-

falls monitoring processes.

Baseline data collected

Primary outcome

The primary RCT outcome was the rate of falls per participant in the 90-day period between 91 and 180 days post randomisation, with data collected from care home records and incident forms. The primary outcome for the economic analysis was the cost per fall prevented (cost-effectiveness) and the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) (cost utility).

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were assessed at 90, 180, 270 and 360 post randomisation:

-

Falls were assessed by a researcher examining residents’ care home records for routinely collected data at each time point. Incident report forms were also examined. The date, time and source of the information for each fall was recorded on the participant’s case report form (CRF).

-

Fall injuries were assessed by a researcher using residents’ care home records, and through liaison with care home staff to source the data. A yes/no response to the ‘sustaining an injury’ question was recorded on the CRF at the same time point by the researcher. Any details of medical assistance and source of the information was collected and added to the CRF.

-

Medication administration records – consent was sought to allow clarification of medication data from general practitioner (GP) records where necessary.

-

Days in hospital were obtained from NHS Digital data.

-

Fractures per participant were collected using NHS Digital data.

-

Personal activities of daily living (ADL) were assessed using the Barthel ADL Index34 completed by care home staff and collected by the researcher.

-

Resident knowledge, skills and confidence (activation) were assessed using the Physical Activity and Mobility in Residential Care (PAM-RC)35 (completed by care home staff and collected by the researcher.

-

Quality of life (QoL) was assessed using the validated questionnaires Dementia Quality of Life utility version-5 dimensions (DEMQOL-U-5D)36 and EuroQol-5 dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)37 completed by the resident, and the proxy measures Dementia Quality of Life Utility version, proxy complete-4 dimensions (DEMQOL-P-U-4D)38 and EuroQol-5 dimensions, five-level version, proxy complete (EQ-5D-5L-P)37 completed by care home staff. Participants were offered help to complete the QoL questionnaires by the researcher, if necessary. Dual recording of these data were undertaken to ensure that baseline data were captured in the event of a resident losing mental capacity.

-

Death was recorded using care home records.

Economic data

-

Secondary care resource use was identified from electronic records held by NHS Digital.

-

Provision of equipment to an individual resident and the item, date purchased and description of item obtained was identified from the resident’s care home records and care home staff’s knowledge.

-

Medication administration records: consent was sought to allow clarification of medication data from GP records where necessary.

-

Community health-care provision was identified from care home records.

-

Resources used to deliver the intervention (training, staff time and materials) were measured by recording the number of training sessions delivered, the number and names of staff at each training session, and the cost of the manual and printed materials.

-

Secondary care resource data were obtained from NHS Digital data.

Ethics and regulatory issues

The trial was not initiated until after the protocol, informed consent forms and PISs received approval/favourable opinion from the REC and the NHS Research and Development department. Approval was received from the NHS Health Research Authority and NHS sites. (Yorkshire and the Humber – Bradford Leeds REC, 11/04/2016, reference 16/YH/0111).

The NCTU governed the trial, monitored data collection, and completed data checking and data cleaning.

The trial was conducted in accordance with the ethics principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki, 1996;39 the principles of GCP, and the Department of Health and Social Care Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care, 2005. 40

The trial was registered as Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN34353836 with protocol V6 14 November 2017.

Sample size

The sample size was based on the primary RCT outcome of falls rate during the 90-day period between 91 and 180 days post randomisation. The original total sample size estimate was for 1308 residents to be recruited from 66 care homes (33 in each arm). This assumed a falls rate of 2.5 falls per year (0.625 falls in 3 months) in the control arm,41 80% power and a two-sided significance level of 5%, resulting in the need to recruit 189 residents per arm to detect a 33% reduction in falls rate in the GtACH arm. A reduction rate of 33% was chosen as this was the rate achieved by community-based falls prevention interventions16 and therefore deemed clinically significant. The sample size calculation was based on information obtained from a previous care home study that had a falls rate of 15 falls per year,26 but only recruited those residents who had fallen recently. The adjustment for clustering assumed an average cluster size of 20 residents42 and an intracluster coefficient of 0.1,42 giving a sample size of 549 residents per arm. Incorporating a further 16% into the sample size to account for potential attrition gave a total sample size of 1308 residents (654 in the GtACH arm and 654 in the control arm).

During recruitment it became apparent that the average number of residents per cluster was slightly smaller than expected (19 residents) and the size of the clusters was variable (coefficient of variation 0.5). Based on this new information, the design effect for the revised sample size calculation increased from 2.9 to 3.275, leading to a total sample size of 1474 residents after the adjustment for 16% attrition rate. This led to a need to recruit 39 care homes per arm. Across all sites, it was anticipated that the rate of recruitment was five or six care homes, each with 18–19 residents.

Randomisation and blinding

Care homes were randomised on a 1 : 1 basis to one of two parallel arms: the GtACH programme or control (usual care). Participants, care home staff, site NHS falls leads and RAs undertaking the process evaluation at the care homes were not blinded to allocation.

Randomisation of homes to trial arms occurred after all participants had given consent and all baseline data had been collected. The RA who gathered the baseline information notified the local site NHS falls lead when the care home was ready to be randomised. The NHS falls lead used a remote, internet-based randomisation system to obtain the allocation for each home and informed the falls champion within the care home of the allocated GtACH arm.

Randomisation was based on a bespoke, computer-generated, pseudo-random code using variable block randomisation within strata [site, care home type (nursing/residential/dual registration)] provided by the NCTU via a secure web-based randomisation service.

The sequence of treatment allocations was concealed from the study statistician until all interventions had been assigned and recruitment, data collection and all other study-related assessments were complete.

The Trial Management Group (TMG) and the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) were unblinded to the intervention. The chief investigators and principal investigators (PIs) had direct contact with the randomised care homes, although not with the participants.

The RAs at the sites, participating residents and staff informants were blind to allocation at recruitment and for baseline data collection because participants were recruited prior to care home randomisation. RAs collecting outcome data were not informed of allocation (occasions of unblinding were recorded). NHS Digital data were extracted blind to allocation.

Interim analyses required to populate recruitment and data monitoring for harm reports for the DMC were conducted on unblinded data by the NCTU.

Assessment of compliance

Care home records for all care homes randomised to the intervention were reviewed by the NHS falls lead during the first 3 months post randomisation to GtACH training and during the implementation period to consider broad compliance with the GtACH programme. As part of this evaluation, evidence was sought that the GtACH manual was accessible, the GtACH poster was displayed, and the GtACH paperwork was attached to care records. The number of care home staff who attended the GtACH programme training was recorded as a proportion of the total number of available staff. Compliance with the intervention was also evaluated as part of the process evaluation. We did not record the number of GtACH forms completed in the homes.

Withdrawal of participants

Residents were able to withdraw from the trial at their own request, their consultee’s request or at the discretion of the investigator. The participants were assured that withdrawal would not affect their future care. Participants and consultees, when appropriate, were made aware (through the information sheet and consent form) that should they withdraw, the data collected up to the date of withdrawal could not be erased and may still be used in the final analysis. Care home managers were able to withdraw support for the trial at their own request or at the discretion of the investigator (residents were also withdrawn following care home manager withdrawal of consent).

Adverse event reporting

Data on AEs (serious and non-serious) were not collected in this study.

This was a low-risk intervention. No specific risks, untoward incidents or AEs were reported during the feasibility work. The GtACH tool recommends that actions are taken but does not stipulate what these actions are, other than to recommend referral to health professionals as appropriate. If residents became distressed during the GtACH assessment or when intervention actions were completed, the process was halted, and the event was recorded and closely monitored until resolution, stabilisation or until it was shown that the study intervention was not the cause. The participant had the right to decline any intervention at any time.

Gentle exercises were 1 out of the 30 activities included in the action checklist. If gentle exercises were recommended after the assessment, staff in the care home were advised to refer the resident to a physiotherapist so that a programme of exercise could be put in place. It was possible that participants may have suffered an injury that they would not have had if they had not taken part in the exercise. These were recorded and monitored by the falls champion in the care home. If there was any concern, the falls champion referred to the NHS falls lead for advice. If required, the exercises were stopped.

Falls rates were monitored for harm and reported to the DMC and TSC every 3 months after they were collected. The DMC and TSC had the ability to recommend changes to the study protocol if falls rates were substantially higher than expected. The DMC reviewed unblinded safety data, including reported falls frequencies, at least yearly. These were provided by the NCTU via secure e-mail.

As the GtACH programme is copyrighted by the University of Nottingham, the University of Nottingham was responsible for any issues that arose because of the design of the intervention, training given to care home staff or any issues with the programme itself. However, in respect of the use of the GtACH programme in care homes, the care home was responsible if the programme as a whole was incorrectly used. Care home managers were asked to confirm that they had indemnity for this and, if the indemnity did not include research, they were asked to seek indemnity from their insurance providers, making clear that all individual components of the GtACH programme were currently being used in routine care but in a consistent or structured manner.

The GtACH assessments and or actions were stopped if the participant showed evidence of distress. This was documented in one participant, but the participant was not withdrawn from the study.

Data handling and record keeping

All trial staff and investigators endeavoured to protect the rights of the trial’s participants to privacy and informed consent, and adhered to the Data Protection Act 1998. 43 The CRF collected the minimum required information for the purposes of the trial only. CRFs were held securely in a locked room, or locked cupboard or cabinet. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools32,33 hosted at the University of East Anglia. REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data capture, (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures, (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages and (4) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources. Access to the information was limited to the trial staff and investigators, and relevant regulatory authorities. Data held on computers, including the trial database, were held securely and password protected. All data were stored on a secure dedicated web server. Access was restricted by user identifiers and passwords (encrypted using a one-way encryption method). Information about the trial in participants’ care home records was treated confidentially in the same way as all other confidential medical information. Electronic data were backed up every 24 hours to both local and remote media in an encrypted format.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were undertaken on an intention-to-treat basis in which care homes were analysed in the arm to which they were allocated regardless of their compliance with the intervention. The progress of care homes and residents through the phases of the trial from the screening and enrolment of care homes to the analysis of the outcome data has been summarised in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram (see Figure 6). Those who died between care home randomisation and the 3-month follow-up data collection were regarded as having been exposed to the intervention (GtACH/control) and recorded as lost to follow-up at the time of death.

Data were analysed according to a prespecified statistical analysis plan (SAP) that was finalised prior to the start of the analysis. Full details of all analyses are provided in the SAP (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Analyses were based on available case data. Two-sided tests were used to test statistical significance at the 5% level. The analysis was carried out using standard statistical software, either Stata/MP® version 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), SAS® (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) or R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Baseline characteristics of care homes and residents as well as outcome measures at baseline and each follow-up time point were summarised by treatment arm using descriptive statistics. The baseline falls rate was expressed as the number of falls per 1000 resident-days for each arm.

The primary outcome, the rate of falls per participating resident during the 90-day period between 91 and 180 days post randomisation, was expressed as the number of falls per 1000 participating resident-days for each arm. This period was chosen to give time for the intervention to be implemented after training, while acknowledging that people in care homes have short life expectancies. The secondary outcomes, rate of falls occurring during the 90-day period between 181 and 270 days post randomisation, and the 90-day period between 271 and 360 days post randomisation were calculated and reported in the same way as for the primary outcome.

The number of falls per resident was compared between arms using a random-effects/hierarchical two-level Poisson model with resident at level one and care home at level two, with length of residence in care home as an offset. The primary analysis adjusted for type of care home (residential, nursing, dual registration) and site.

Two additional models were fitted to assess the robustness of the model. In addition to adjusting for care home type and site, we adjusted for (1) baseline falls rate during the 3 months before the baseline assessment and (2) baseline falls rate and other variables that were thought to be associated with falling.

The falls rates during the 3-month periods prior to the 9- and 12-month follow-up were analysed and presented in the same way as for the primary outcome variable. For other secondary outcomes, arms were compared using multilevel regression analysis for continuous outcomes and multilevel logistic regression for binary outcomes. Regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were presented.

Compliance with the intervention was calculated as the percentage of care-giving staff in each care home trained to use the GtACH screening and assessment tool. We calculated this as:

The percentage adherence was calculated and presented for each care home in the GtACH arm. The average adherence for all intervention care homes has also been presented.

Site support

The RAs supported the recruitment, data collection, data entry and data cleaning at each site. Delivery models included a combination of National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) CRN delivery staff, NHS research staff, NHS research therapists and academics employed by higher education institutions. RAs received training in trial processes by the NCTU. A RA network was developed to support RAs who were geographically dispersed across the 10 sites. This was led by a RA based in the same site as the chief investigator.

Monthly teleconferences were held to discuss challenges and share good practice, with any ongoing issues raised at the monthly trial management meetings. The format, content and evolution of the network was directed by the RAs. The peer support of the group allowed open discussion of challenges in a supportive environment. The primary foci of discussions were clarification of recruitment and data collection processes, identification of common barriers to recruitment through PCs, and sharing of methods to engage and sustain relationships with care homes. Face-to-face investigator meetings were held for all FinCH trial team members, including the RAs, PPI members and the teams delivering the interventions. Two meetings were held throughout the trial:

-

May 2017 (16 RAs, 4 PPI members and 10 therapists attended), which included training in the recruitment of older adults lacking capacity, open discussions on good practice and the opportunity to feed back challenges and solutions to the senior research team.

-

July 2018 (23 RAs attended), which included training in abstract and poster design, data quality and awards for sites related to recruitment outcomes.

Chapter 3 Randomised controlled trial results

Recruitment

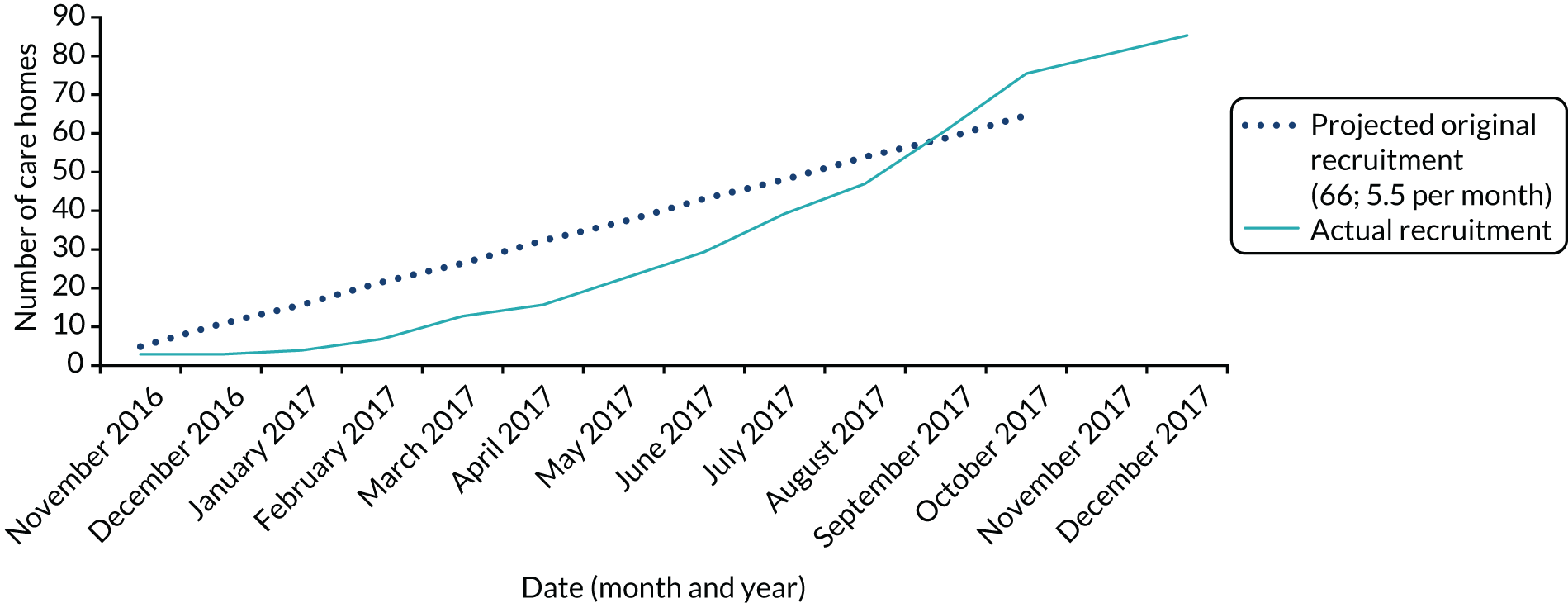

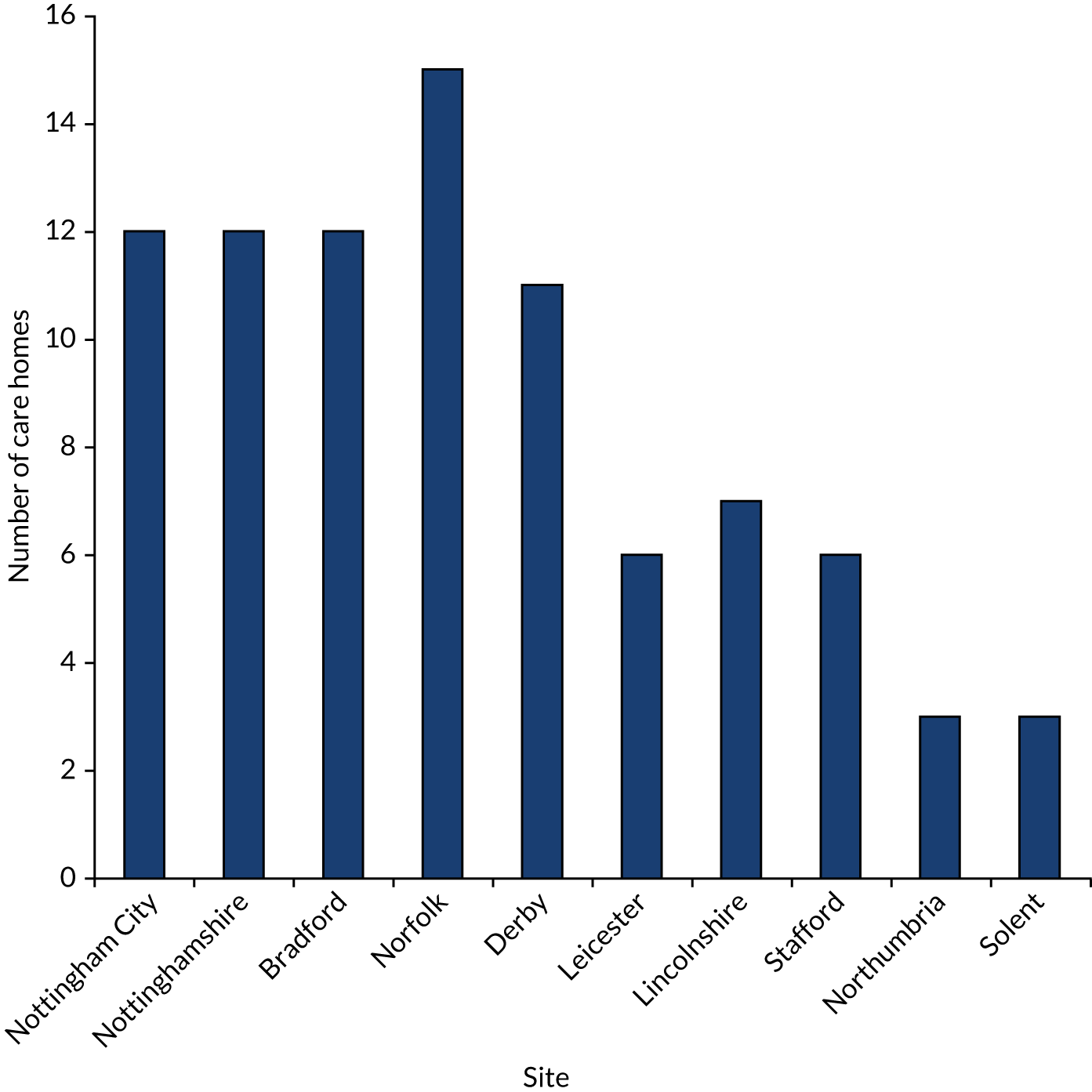

Recruitment to the FinCH trial opened on 1 November 2016. The first care home was recruited on 16 November 2016 and the first resident was consented on 23 November 2016. In total, 10 sites were recruited to the FinCH trial (Table 1). The last care home was recruited on 29 December 2017 and the last resident was recruited on 31 January 2018; all care homes were randomised by 31 January 2018.

| Site | Date recruitment started | Total care homes recruited (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Nottingham City | 16 November 2016 | 12 |

| Nottinghamshire | 21 November 2016 | 12 |

| Bradford | 2 February 2017 | 12 |

| Norfolk | 1 March 2017 | 15 |

| Derby | 7 March 2017 | 11 |

| Leicester | 24 April 2017 | 6 |

| Lincolnshire | 7 June 2017 | 7 |

| Stafford | 24 July 2017 | 6 |

| Northumbria | 2 August 2017 | 3 |

| Solent | 3 October 2017 | 3 |

| Total | 87 |

In total, 87 care homes were recruited; 84 of these care homes were randomised to either the GtACH programme or usual care (Figure 2). Over-recruitment was permitted to allow care homes that were actively engaged in the recruitment of residents by 29 December 2017 to continue through to randomisation by 31 January 2018.

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment of care homes.

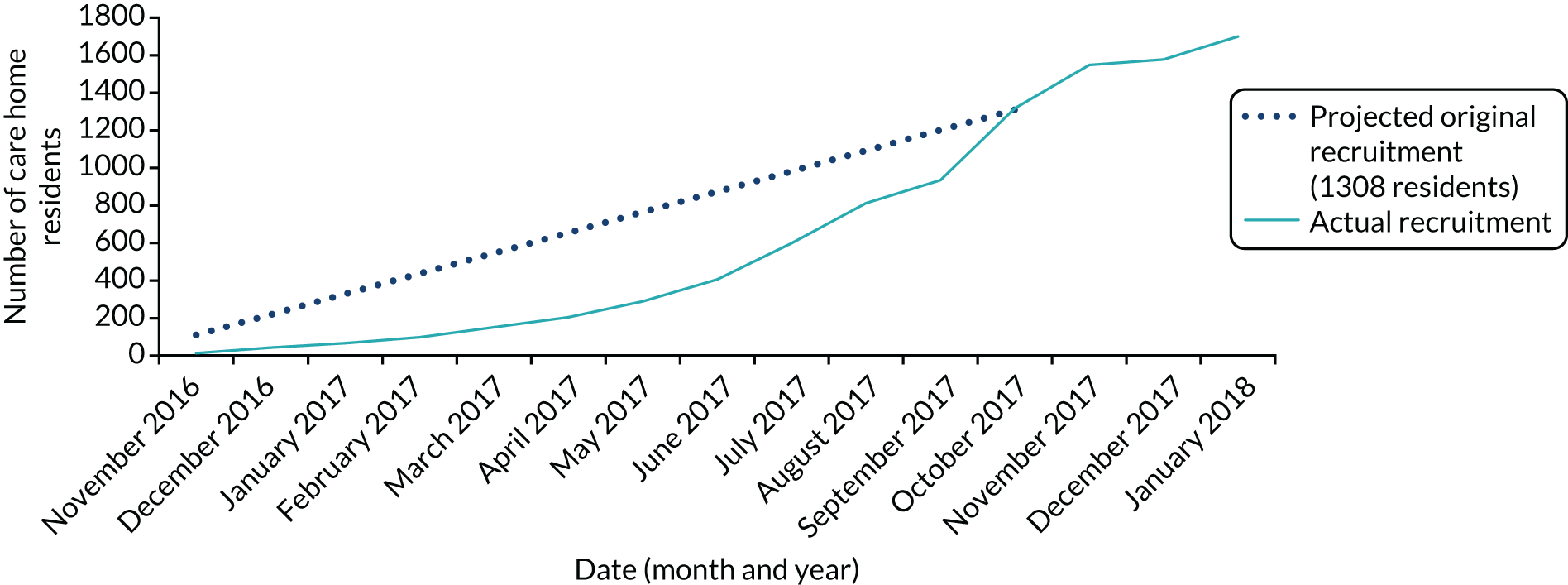

In the same period, a total of 1698 residents were recruited; again, this was higher than the adjusted target of 1482 individuals (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Recruitment of residents.

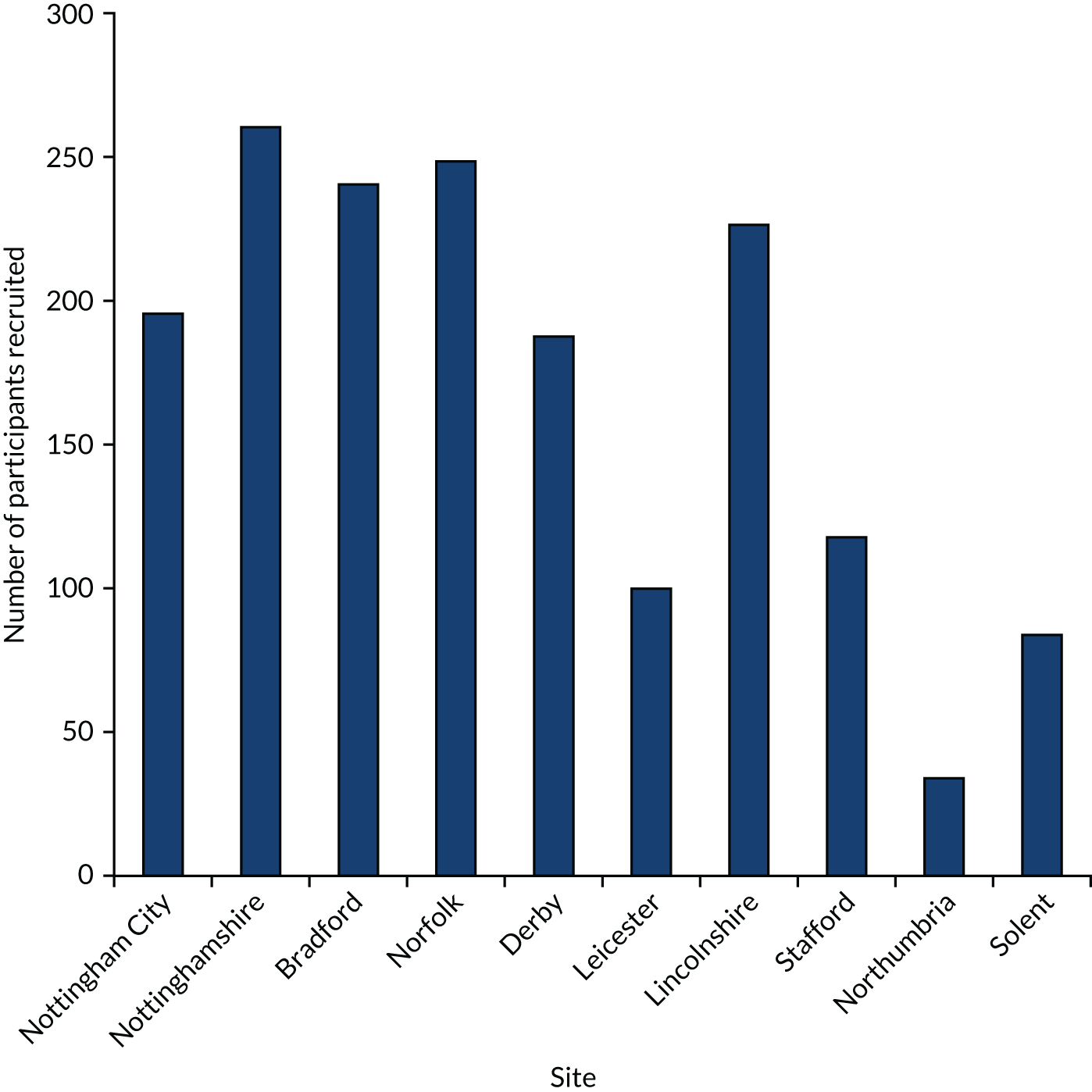

Figure 4 shows care home recruitment and resident recruitment by site. An average of 50% of residents from the participating care homes were consented and there was an average of 19.5 participants per care home. There was an average of 45 days between care home consent and randomisation. Figure 5 shows care home recruitment by site.

FIGURE 4.

Care home recruitment by site.

FIGURE 5.

Care home resident recruitment by site.

The CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 6) shows trial screening and recruitment to completion, as well as follow-up loss and completion. During the study there were 490 deaths, of which 459 occurred following care home randomisation. A total of 63 participants moved out of the study care home, 60 of these following randomisation. A total of 24 participants were residents in a care home that withdrew from the trial and a further eight participants were residents in a care home that was closed following a CQC inspection. Primary outcome data (falls occurring between 90 and 180 days after randomisation of the care home) were available for 1342 residents.

FIGURE 6.

The CONSORT flow diagram of the flow through the trial. The CONSORT flow diagram indicates the flow through the trial from the perspective of the availability of primary outcome variable data (falls). Availability of secondary outcome data, including QoL questionnaires is detailed in Secondary outcome analysis. a, Would not provide a falls champion (n = 24), had falls prevention in place (n = 13), had participated in FinCH feasibility trial (n = 4), home exclusively to learning disability/substance misuse (n = 3), in special measures (n = 1), did not wish to participate (no reason given) (n = 10). b, Wished to participate but did not have time (n = 1), initially indicated willingness but then stopped communicating with researcher (n = 8), initially indicated willingness but adopted a local falls intervention prior to consent (n = 3), wished to participate but were not recruited (no reason given) (n = 7).

Intervention adherence

Intervention adherence was defined as the percentage of care-giving staff trained to use the GtACH programme. Table 2 shows intervention adherence for each care home randomised to the GtACH arm. Average adherence to the training per care home was 71% (70% per site; minimum 17%, maximum 130%). A total of 14 (36%) care homes achieved adherence of ≥ 80%.

| Site | Number of care-giving staff at time of care home recruitment | Number (%) of care-giving staff trained to use the GtACH programme |

|---|---|---|

| Lincolnshire | ||

| 01/01 | 75 | 67 (89.3) |

| 01/07 | 48 | 38 (79.2) |

| Total | 123 | 105 (85.3) |

| Derby | ||

| 02/01 | 40 | 26 (65.0) |

| 02/03 | 16 | 16 (100.0) |

| 02/07 | 41 | 29 (70.7) |

| 02/08 | 32 | 20 (62.5) |

| 02/09 | 18 | 11 (61.1) |

| 02/11 | 24 | 19 (79.2) |

| Total | 171 | 121 (70.8) |

| Northumbria | ||

| 03/02 | 27 | 22 (81.5) |

| 03/03 | 33 | 43 (130.3)a |

| Total | 60 | 65 (108.3) |

| Leicester | ||

| 04/01 | 37 | 18 (48.6) |

| 04/02 | 54 | 42 (77.8) |

| Total | 91 | 60 (65.9) |

| Stafford | ||

| 05/02 | 16 | 9 (56.3) |

| 05/03 | 59 | 25 (42.4) |

| 05/06 | 66 | 11 (16.7) |

| Total | 141 | 45 (31.9) |

| Norwich | ||

| 06/02 | 55 | 40 (72.7) |

| 06/05 | 30 | 24 (80.0) |

| 06/07 | 36 | 30 (83.3) |

| 06/09 | 39 | 30 (76.9) |

| 06/12 | 38 | 30 (78.9) |

| 06/13 | 22 | 18 (81.8) |

| 06/15 | 18 | 10 (55.6) |

| Total | 238 | 182 (76.5) |

| Nottingham City | ||

| 07/01 | 25 | 22 (88.0) |

| 07/03 | 39 | 24 (61.5) |

| 07/04 | 45 | 30 (66.7) |

| 07/05 | 48 | 22 (45.8) |

| 07/08 | 16 | 19 (118.8)a |

| 07/11 | 12 | 10 (83.3) |

| Total | 185 | 127 (68.6) |

| Nottinghamshire | ||

| 08/03 | 59 | 47 (79.7) |

| 08/04 | 67 | 51 (76.1) |

| 08/06 | 23 | 22 (95.7) |

| 08/10 | 22 | 12 (54.5) |

| 08/11 | 49 | 37 (75.5) |

| Total | 220 | 169 (76.8) |

| Bradford | ||

| 09/01 | 26 | 10 (38.5) |

| 09/06b | 38 | 17 (44.7) |

| 09/08 | 53 | 43 (81.1) |

| 09/09 | 50 | 40 (80.0) |

| 09/10 | 33 | 29 (87.9) |

| 09/11 | 62 | 38 (61.3) |

| Total | 262 | 177 (67.6) |

| Solent | ||

| No care homes allocated to intervention | ||

| All | ||

| Overall compliance | 1491 | 1051 (70.5) |

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of care homes

The characteristics of the 84 randomised care homes are given in Table 3. Overall, just under half of the homes had dual registration (nursing and residential), 96% were reported by the care home owner to be privately owned, and the average number of staff per care home was 43. Care homes were fairly well balanced between the two arms in size and registration, although homes in the control arm reported a larger number of care-giving staff.

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 84) | GtACH (N = 39) | Control (N = 45) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of care homes by site, n (%) | |||

| Lincolnshire | 7 (8) | 2 (5) | 5 (11) |

| Derby | 10 (12) | 6 (15) | 4 (9) |

| Northumbria | 3 (4) | 2 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Leicester | 5 (6) | 2 (5) | 3 (7) |

| Stafford | 5 (6) | 3 (8) | 2 (4) |

| Norwich | 15 (18) | 7 (18) | 8 (18) |

| Nottingham City | 12 (14) | 6 (15) | 6 (13) |

| Nottinghamshire | 12 (14) | 5 (13) | 7 (16) |

| Bradford | 12 (14) | 6 (15) | 6 (13) |

| Solent | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 3 (7) |

| Number of care homes by type, n (%) | |||

| Nursing | 11 (13) | 5 (13) | 6 (13) |

| Residential | 34 (40) | 16 (41) | 18 (40) |

| Dual registration | 39 (46) | 18 (46) | 21 (47) |

| Number of care homes by ownership | |||

| Charity, n (%) | 3 (4) | 2 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Private, n (%) | 81 (96) | 37 (95) | 44 (98) |

| Total number of care-giving staff | 3609 | 1491 | 2118 |

| Mean (SD) care-giving staff per home | 42.9 (41.0) | 38.2 (16.4) | 47.1 (53.8) |

| Total number of beds | 4112 | 1912 | 2200 |

| Mean (SD) beds per home | 49.0 (25.1) | 49.0 (21.3) | 48.9 (28.2) |

| Total number of residents | 3561 | 1672 | 1889 |

| Mean (SD) residents per home | 42.4 (21.9) | 42.9 (19.4) | 42.0 (24.1) |

Baseline characteristics of participants

Table 4 shows the characteristics of the 1657 trial participants. Overall, the average age was 85 years and the majority of residents were female. The median time spent in the care home at baseline was just under 19 months. Just under one-third of residents experienced one or more falls in the 3 months prior to randomisation (baseline period). Resident characteristics were reasonably well balanced between arms.

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 1657) | GtACH (N = 775) | Control (N = 882) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at consent to FinCH trial (years), mean (SD) | 85.04 (9.28) | 86.03 (8.64) | 84.16 (9.74) |

| Male, n (%) | 532 (32.1) | 231 (29.8) | 301 (34.1) |

| Consent, n (%) | |||

| Resident | 387 (23.4) | 186 (24.0) | 201 (22.8) |

| Consultee | 1270 (76.6) | 589 (76.0) | 681 (77.2) |

| Time in care home (months), median (IQR) | 18.6 (8.3–36.4) | 18.8 (8.1–36.5) | 18.1 (8.6–35.8) |

| Recorded diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Dementia | 1109 (67.0) | 506 (65.4) | 603 (68.4) |

| Diabetes | 320 (19.3) | 150 (19.4) | 170 (19.3) |

| Stroke | 262 (15.8) | 118 (15.2) | 144 (16.3) |

| Coronary heart disease | 234 (14.1) | 100 (12.9) | 134 (15.2) |

| Number of falls during period 3 months prior to baseline data collection, n (%) | |||

| None | 1138 (68.8) | 546 (70.6) | 592 (67.1) |

| 1 | 299 (18.1) | 134 (173) | 165 (18.7) |

| 2 | 92 (5.6) | 42 (5.4) | 50 (5.7) |

| 3 | 55 (3.3) | 26 (3.4) | 29 (3.3) |

| 4 | 25 (1.5) | 10 (1.3) | 15 (1.7) |

| 5 | 6 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.5) |

| 6 | 8 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) | 6 (0.7) |

| 7 | 5 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) |

| 8 | 5 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.5) |

| 9 | 9 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) | 7 (0.8) |

| 10 | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) |

| 11 | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) |

| 12 | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| 13 | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) |

| 15 | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| 16 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| 20 | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| 31 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Number of falls per person during period 3 months prior to baseline data collection | |||

| No falls, n (%) | 1138 (68.8) | 546 (70.6) | 592 (67.1) |

| 1–5 falls, n (%) | 477 (28.8) | 214 (27.7) | 263 (29.8) |

| 6–10 falls, n (%) | 29 (1.8) | 8 (1.0) | 21 (2.4) |

| 11–15 falls, n (%) | 8 (0.5) | 4 (0.5) | 4 (0.5) |

| ≥ 16 falls, n (%) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) |

| Mean (SD) number of falls per person during the 3 months prior to baseline data collection | 0.71 (1.82) | 0.61 (1.57) | 0.79 (2.02) |

| Number of medications in the 3 months prior to baseline data collection, n (%) | |||

| None | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| One to three | 56 (3.4) | 26 (3.4) | 30 (3.4) |

| Four or more | 1601 (96.6) | 749 (96.6) | 852 (96.6) |

| Physical activity (PAM-RC) score at baseline, mean (SD) | 8.61 (6.09) | 8.57 (5.95) | 8.66 (6.21) |

| ADL (Barthel) score at baseline, mean (SD) | 8.57 (6.05) | 8.86 (6.12) | 8.30 (5.99) |

| DEMQOL at baseline | 0.82 (0.16) | 0.83 (0.16) | 0.81 (0.16) |

| DEMQOL-P at baseline | 0.74 (0.12) | 0.74 (0.12) | 0.74 (0.12) |

| EQ-5D-5L self-completion at baseline | 0.49 (0.36) | 0.52 (0.36) | 0.46 (0.35) |

| EQ-5D-5L proxy at baseline | 0.35 (0.37) | 0.36 (0.37) | 0.34 (0.36) |

Unblinding rates

The RAs responsible for recruiting care homes, consenting patients and carers, and collecting care home and patient-level outcome data were to remain blinded to the home allocation. In some instances, the RAs became unblinded, typically being unblinded by the care home manager.

Unblinding occurred in 26 out of the 84 participating care homes when the RA entered the care home 3 months after randomisation to collect the primary outcome measure and 3-month data. Of these 26 homes, 16 were GtACH care homes and 10 were control care homes.

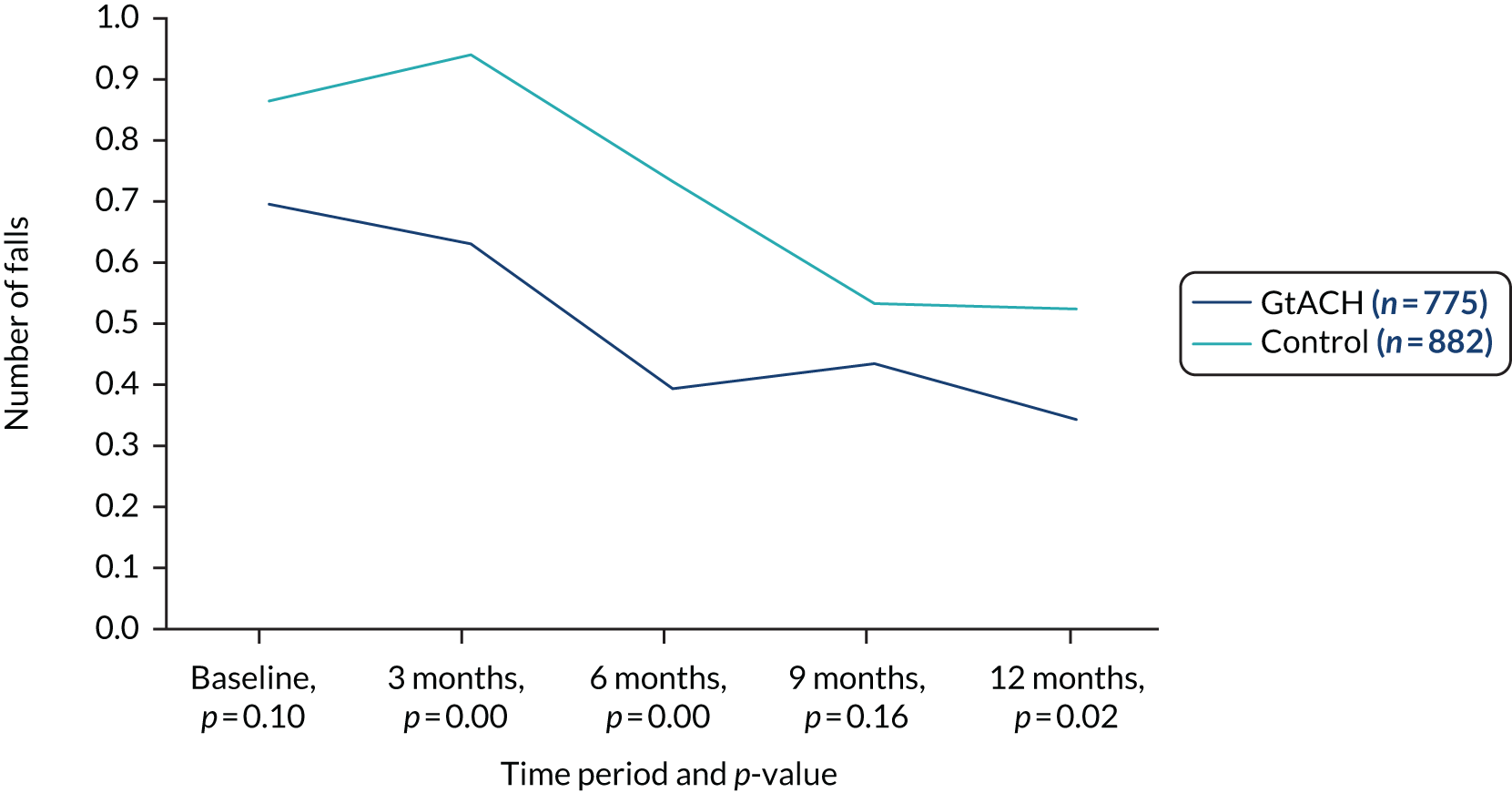

Primary outcome: falls between 90 and 180 days

A negative binomial regression model [generalised estimating equation (GEE)] showed that the falls rate in the GtACH arm was reduced compared with that in the control arm in both the unadjusted and the adjusted analyses. Over the period of the primary outcome assessment (a 90-day period between 91 and 180 days after randomisation), the falls rate was 6.0 per 1000 residents in the GtACH arm and 10.4 per 1000 residents in the control arm (Table 5). Results of other approaches to the analysis of the primary outcome may be seen in Appendix 2, Tables 22–26.

| Time point | GtACH | Control | Unadjusted | Adjusted for baseline falls | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At risk, n | Falls, n (SD) | Falls rate, n (SD) | At risk, n | Falls, n (SD) | Falls rate, n (SD) | IRR (95% CI) | p-value | IRR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Pre randomisationa | 773 | 0.61 (1.57) | 6.97 (17.67) | 882 | 0.79 (2.02) | 9.48 (24.14) | ||||

| 0–90 days | 708 | 0.55 (1.36) | 6.93 (20.56) | 826 | 0.88 (2.37) | 10.24 (27.26) | 0.6 (0.49 to 0.73) | < 0.001 | 0.74 (0.60 to 0.92) | 0.006 |

| 91–180 days | 630 | 0.49 (1.13) | 6.04 (14.02) | 712 | 0.89 (2.60) | 10.38 (29.52) | 0.57 (0.45 to 0.71) | < 0.001 | 0.63 (0.52 to 0.78) | < 0.001 |

| 181–270 days | 547 | 0.60 (1.29) | 7.28 (16.67) | 633 | 0.73 (1.85) | 9.21 (28.77) | 0.85 (0.69 to 1.05) | 0.128 | 0.91 (0.74 to 1.12) | 0.369 |

| 271–360 days | 502 | 0.55 (1.14) | 6.22 (12.88) | 573 | 0.79 (2.37) | 9.22 (27.36) | 0.79 (0.60 to 1.03) | 0.078 | 0.93 (0.71 to 1.22) | 0.614 |

Secondary outcome analysis

Falls rates and fallers over other periods

There was a significant reduction in falls rates in the GtACH arm in the 0- to 90-day period, but there was no significant difference between the arm’s falls rates for either of the 3-month follow-up periods between 6 and 9 months or between 9 and 12 months (Table 5).

There was no difference in the proportion of residents who fell on one or more occasion (i.e. “fallers”) during any of the outcome time periods (Table 6).

| Time point | GtACH | Control | Unadjusted | Adjusted for baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At risk (N) | Fell, n (%) | At risk (N) | Fell, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Pre randomisationa | 773 | 227 (29.4) | 882 | 290 (32.9) | ||||

| 0–90 days | 708 | 194 (27.4) | 826 | 266 (32.2) | 0.7 (0.50 to 1.00) | 0.048 | 0.75 (0.53 to 1.05) | 0.09 |

| 91–180 days | 630 | 167 (26.5) | 712 | 216 (30.3) | 0.76 (0.56 to 1.03) | 0.078 | 0.81 (0.60 to 1.10) | 0.179 |

| 181–270 days | 547 | 165 (30.2) | 633 | 187 (29.5) | 1.00 (0.73 to 1.37) | 0.986 | 1.06 (0.78 to 1.45) | 0.697 |

| 271–360 days | 502 | 147 (29.3) | 573 | 175 (30.5) | 0.88 (0.60 to 1.29) | 0.516 | 0.94 (0.65 to 1.37) | 0.752 |

Activities of daily living: Barthel Index

There was no difference in the 20-point Barthel (ADL) Index scores between the arms at any of the time points considered (Table 7).

| Time point | GtACH | Control | Unadjusted | Adjusted for baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | p-value | Mean difference (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Pre randomisationa | 768 | 8.86 (6.12) | 854 | 8.30 (5.99) | ||||

| 0–90 days | 643 | 8.24 (6.12) | 726 | 7.87 (5.94) | 0.08 (–0.96 to 1.13) | 0.874 | –0.03 (–0.69 to 0.64) | 0.937 |

| 91–180 days | 584 | 8.12 (6.05) | 648 | 7.54 (5.86) | 0.16 (–0.89 to 1.20) | 0.766 | –0.02 (–0.48 to 0.43) | 0.924 |

| 181–270 days | 514 | 8.52 (6.17) | 576 | 7.18 (5.98) | 0.90 (–0.29 to 2.10) | 0.138 | 0.46 (–0.10 to 1.01) | 0.11 |

| 271–360 days | 447 | 8.11 (6.20) | 519 | 6.86 (5.92) | 0.82 (–0.32 to 1.96) | 0.159 | 0.44 (–0.26 to 1.15) | 0.214 |

Physical activity and mobility: Physical Activity and Mobility in Residential Care

There was no difference in the PAM-RC scores between the arms at any of the time points considered (Table 8).

| Time point | GtACH | Control | Unadjusted | Adjusted for baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | p-value | Mean difference (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Pre randomisationa | 773 | 8.57 (5.95) | 878 | 8.66 (6.21) | ||||

| 0–90 days | 652 | 7.99 (6.01) | 736 | 8.16 (5.98) | –0.41 (–1.51 to 0.69) | 0.468 | –0.1 (–0.55 to 0.35) | 0.662 |

| 91–180 days | 578 | 8.11 (6.05) | 633 | 7.74 (6.08) | 0.07 (–1.04 to 1.17) | 0.908 | 0.23 (–0.28 to 0.75) | 0.376 |

| 181–270 days | 491 | 8.13 (5.98) | 576 | 7.59 (6.12) | 0.32 (–0.90 to 1.54) | 0.61 | 0.43 (–0.24 to 1.10) | 0.209 |

| 271–360 days | 439 | 7.96 (5.63) | 520 | 7.19 (6.03) | 0.45 (–0.57 to 1.47) | 0.39 | 0.49 (–0.16 to 1.14) | 0.141 |

Inpatient days in hospital

There was no difference in inpatient hospital days between the arms at either baseline to 6 months post randomisation or at 6 to 12 months post randomisation using a GEE approach (Table 9). A Poisson regression of these data (see Appendix 3, Table 27) yielded similar results.

| Time point | GtACH | Control | Unadjusted | Adjusted for baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | p-value | Mean difference (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Pre randomisationa | 773 | 0.46 (2.62) | 877 | 0.60 (2.69) | ||||

| 0–180 days | 697 | 1.54 (5.36) | 793 | 1.61 (4.85) | 0.91 (0.64 to 1.28) | 0.588 | 0.94 (0.67 to 1.32) | 0.725 |

| 181–360 days | 532 | 1.08 (4.04) | 620 | 1.58 (6.03) | 0.66 (0.40 to 1.08) | 0.101 | 0.63 (0.38 to 1.06) | 0.081 |

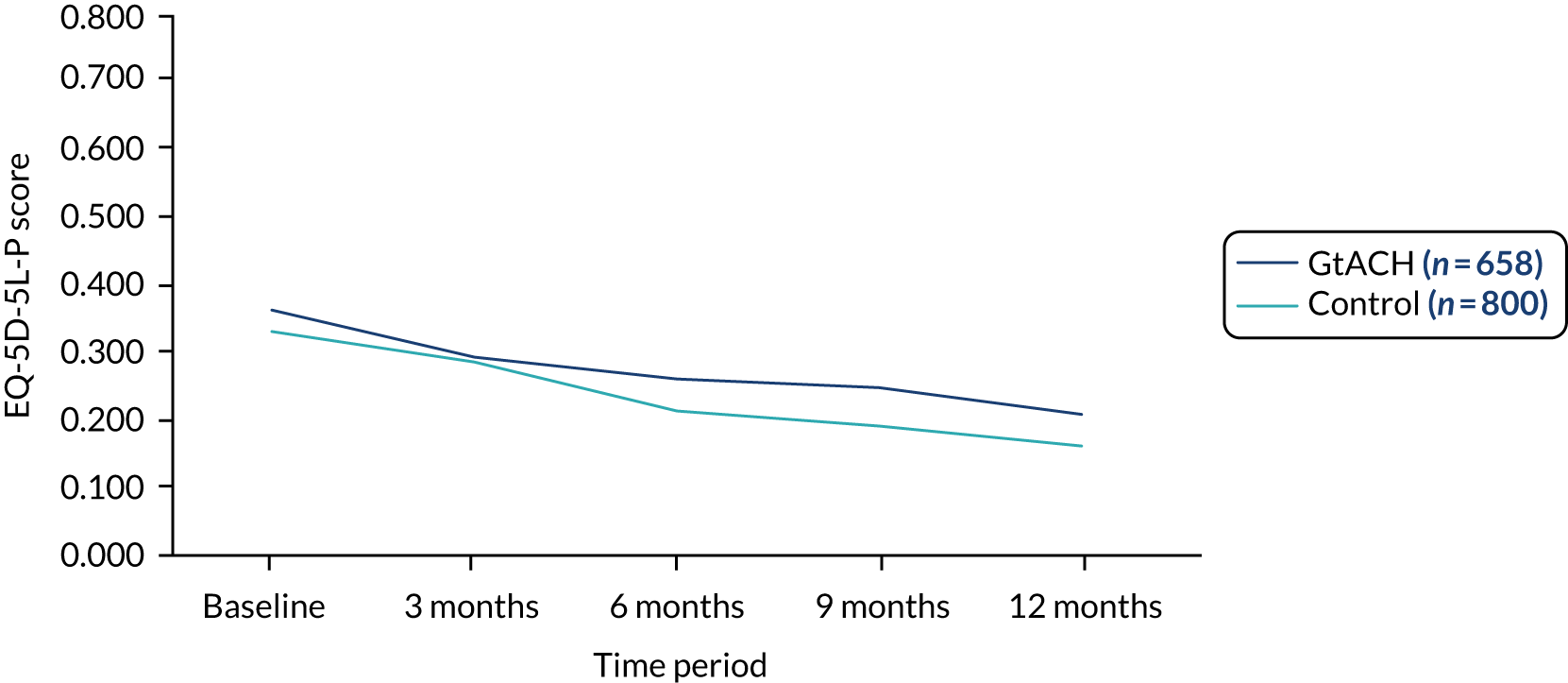

Quality of life

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version, proxy complete

There was no difference in the EQ-5D-5L-P scores between the arms at any of the time points considered (Table 10).

| Time point | GtACH | Control | Unadjusted | Adjusted for baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | p-value | Mean difference (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Pre randomisationa | 766 | 0.36 (0.37) | 878 | 0.34 (0.36) | ||||

| 0–90 days | 728 | 0.30 (0.38) | 802 | 0.30 (0.36) | –0.01 (–0.08 to 0.06) | 0.851 | 0 (–0.05 to 0.04) | 0.854 |

| 91–180 days | 717 | 0.26 (0.36) | 817 | 0.22 (0.34) | 0.02 (–0.05 to 0.08) | 0.588 | 0.02 (–0.03 to 0.07) | 0.483 |

| 181–270 days | 693 | 0.25 (0.36) | 823 | 0.20 (0.33) | 0.03 (–0.03 to 0.10) | 0.288 | 0.04 (–0.01 to 0.08) | 0.083 |

| 271–360 days | 674 | 0.21 (0.32) | 809 | 0.16 (0.31) | 0.04 (–0.01 to 0.08) | 0.105 | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.07) | 0.083 |

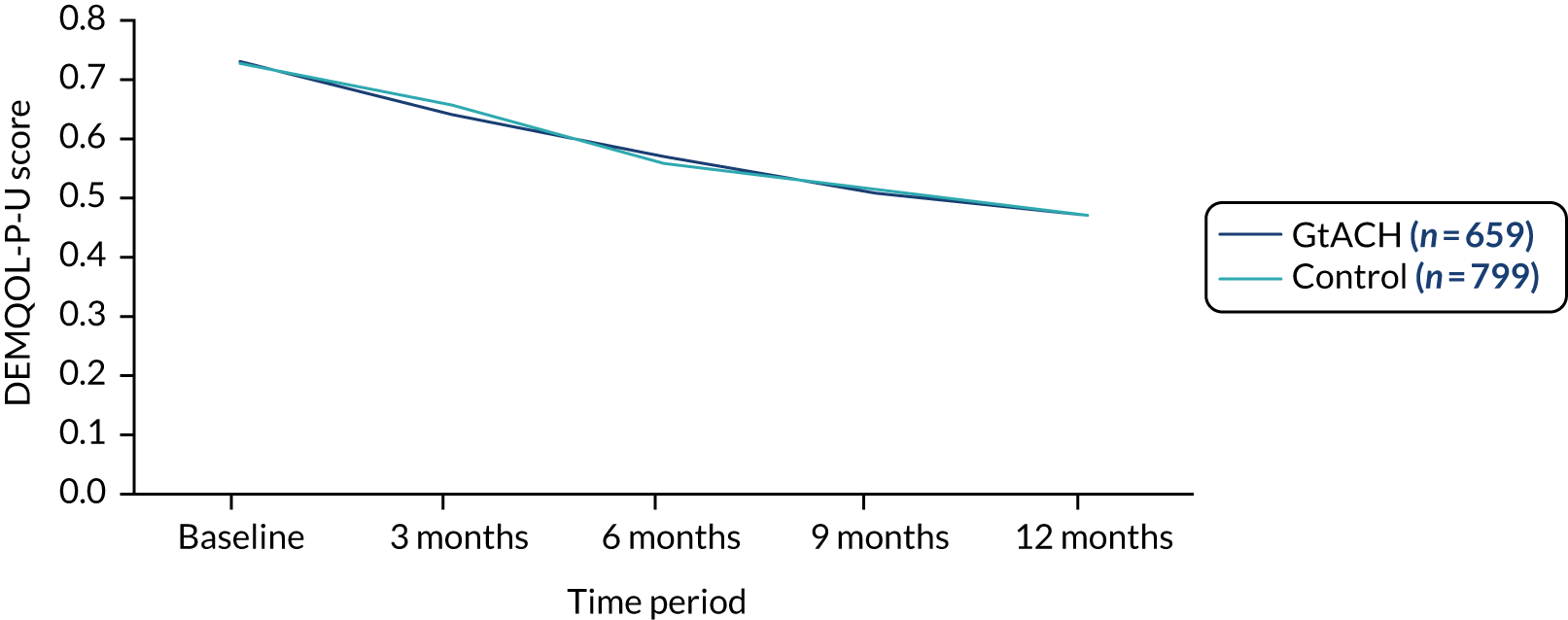

Dementia Quality of Life Utility version, proxy complete

There was no difference in Dementia Quality of Life Utility version, proxy complete (DEMQOL-P-U), scores between the arms at any of the time points considered (Table 11).

| Time point | GtACH | Control | Unadjusted | Adjusted for baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | p-value | Mean difference (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Pre randomisationa | 764 | 0.74 (0.12) | 877 | 0.74 (0.12) | ||||

| 0–90 days | 716 | 0.66 (0.25) | 807 | 0.67 (0.23) | –0.02 (–0.05 to 0.02) | 0.355 | –0.02 (–0.05 to 0.02) | 0.315 |

| 91–180 days | 698 | 0.59 (0.31) | 805 | 0.57 (0.31) | 0.02 (–0.04 to 0.08) | 0.511 | 0.02 (–0.04 to 0.07) | 0.565 |

| 181–270 days | 694 | 0.52 (0.34) | 807 | 0.52 (0.35) | 0.00 (–0.07 to 0.07) | 0.977 | –0.01 (–0.07 to 0.05) | 0.85 |

| 271–360 days | 673 | 0.48 (0.36) | 809 | 0.47 (0.36) | –0.01 (–0.07 to 0.06) | 0.868 | –0.01 (–0.07 to 0.05) | 0.779 |

Deaths

There was no difference between the arms in the number of deaths occurring at any time during the trial (Table 12).

| GtACH | Control | Unadjusted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Deaths | n | Deaths | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Overall deaths | 775 | 233 (30.1%) | 882 | 281 (31.9%) | 0.93 (0.73 to 1.20) | 0.576 |

Fractures

There was no difference between the arms in the number of hip fractures, wrist fractures or any fractures occurring between baseline and 6 months. There was a significantly lower rate of fractures between 6 and 12 months (Table 13); however, note that the actual numbers were small and there was no corresponding reduction in falls rates over this period. A list of fractures included in these analyses is provided in Appendix 4.

| Time point | Fracture | Arm, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Number | GtACH | Control | |||

| Baseline to 180 days | Hip | 0 | 758 (97.8) | 867 (98.3) | ||

| 1 | 12 (1.5) | 8 (0.9) | 1.4 (0.67 to 2.96) | 0.371 | ||

| 2 | 5 (0.6) | 7 (0.8) | ||||

| Wrist | 0 | 772 (99.6) | 880 (99.8) | |||

| 1 | 3 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) | 1.63 (0.26 to 10.2) | 0.603 | ||

| Any | 0 | 742 (95.7) | 850 (96.4) | |||

| 1 | 22 (2.8) | 17 (1.9) | 1.19 (0.70 to 2.01) | 0.527 | ||

| 2 | 10 (1.3) | 12 (1.4) | ||||

| 3 | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | ||||

| 4 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | ||||

| 181–360 days | Hip | 0 | 591 (98.5) | 662 (96.6) | ||

| 1 | 9 (1.5) | 23 (3.4) | 0.38 (0.17 to 0.85) | 0.019 | ||

| Wrist | 0 | 600 (100.0) | 685 (100.0) | NA | NA | |

| Any | 0 | 591 (98.5) | 659 (96.2) | |||

| 1 | 7 (1.2) | 11 (1.6) | 0.34 (0.15 to 0.75) | 0.007 | ||

| 2 | 2 (0.3) | 15 (2.2) | ||||

Changes to the analysis plan during the trial

Although we had specified that multiple imputation (MI) would be used to account for missing data, this was not undertaken because the primary reason for missing data was that the patient had died. However, we did collect and analyse the falls data until the date of death. We have presented medians and interquartile ranges for time spent in the care home, rather than means and standard deviations (SDs), because of the skewed distribution of these data.

Chapter 4 Economic evaluation

Overview

The aim of this chapter is to report the within-trial economic evaluation undertaken to estimate the cost-effectiveness of delivering the GtACH programme in care homes from an NHS and personal social services (PSS) perspective. The primary analysis was a cost–utility analysis and presents proxy-reported outcomes as QALYs. A cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) based on cost per falls averted was also conducted so that the GtACH programme can be directly compared with other interventions aimed at reducing falls.

Methods

The health economics analysis plan (HEAP) was written and approved by the TMG prior to the data being locked. The HEAP is available as Report Supplementary Material 3.

Measuring resource use and estimating costs

In line with NICE guidelines,44 we estimated costs from a health and PSS perspective. This included the cost of implementing the GtACH programme, any health resource use (primary care, secondary care, medications and ADL equipment) and social services received as part of routine care.

GtACH programme resource use and costs

The specific technology under investigation was the GtACH programme, which was delivered to care home residents by trained and supported care home staff. 26–28 The GtACH programme is a systematic falls risk assessment and action process, co-designed by care home and NHS staff, and based on NICE clinical guidelines. 44

The GtACH programme was delivered by care home staff who had received training from NHS falls leads. NHS falls leads were health-care professionals (generally occupational therapists or physiotherapists) recruited in each location to provide on-site training for care home staff.

The GtACH programme costs included the senior trial team training the NHS falls leads, NHS falls leads then delivering GtACH training sessions to care home staff, care home staff delivering the GtACH programme to residents, and support provided by the falls prevention leads in the first 3 months of delivery. Specific training details were recorded by the NHS falls leads at each care home. Additional costs of the delivery and receipt of GtACH training included travel time and consumables, but we excluded the cost of developing the tool itself, as this had been developed previously and was considered a sunk cost. 26

We assumed that, in the base case, every resident was assessed using the GtACH tool once, as this was reflective of observations by the process evaluation team. The estimated time required for the GtACH programme was 30 minutes, based on observations from process evaluation and discussion with the senior trial team.

The per-protocol delivery of the GtACH programme would be for the tool to be used after every fall. We surmised that, given staffing pressures, the maximum number of repeat GtACH programmes each care home could provide would be one per month. Therefore, in sensitivity analysis, we included the cost of up to 11 extra intervention sessions (after the initial session in month 1) that would take place for an individual experiencing any falls in the previous 30 days, continuing to trial end.

To calculate the total cost of staff time, an hourly wage was estimated for a typical NHS falls lead and care home staff based on Agenda for Change wage rates45 (see Appendix 5, Table 28). The training costs and costs of delivering the GtACH programme were calculated for each care home and then divided among the residents recruited in that care home to produce an estimated cost per resident.

Usual-care resource use and costs

The comparator to the intervention was usual care, where usual care was defined as the absence of a systematic and co-ordinated falls prevention process. The control care homes had the option to receive the GtACH training at the end of the trial, but the cost of this has not been included as this occurred after the trial follow-up period.

Health and social services resource use

To estimate the cost of primary care, community health, and social services visits, data on resource use incurred during the previous 3 months were extracted from care home residents’ care plans by study RAs at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months post randomisation. Baseline resource use (90 days pre randomisation) data were also collected to control for prior health resource use in analyses because past resource use may predict future costs. A copy of the health resource use questionnaires used as part of the CRF are provided in Report Supplementary Material 2. For secondary care [inpatient stays, accident and emergency (A&E), and outpatient attendances], we requested linked data from NHS Digital, receiving one data transfer covering the entire trial after the trial had closed.

Unit costs, in 2017/18 Great British pounds (the most recent year available at the time of analysis), were applied based on annually published national sources including the National Schedule of Reference Costs46 and the Personal Social Services Research Unit’s Unit Costs of Health and Social Care. 45

Medication costs

Researchers collected data on all medications recorded in care home records as ongoing at baseline or as being taken in the preceding 90 days. At each subsequent quarterly data collection point, researchers reported whether the medications were stopped or new medications were started. Medications were mapped to the Prescription Cost Analysis47 (price year 2017/18) to apply unit costs for each individual preparation used, assuming one item was prescribed per month during the period a resident was recorded as using the medication.

Equipment costs

Residents use of any equipment to help them cope with a health problem was recorded. Items deemed to be shared among residents (for instance stair lift or hoists) were not costed. For larger ADL equipment (for instance wheelchairs or profile beds), costs were annuitised to reflect the expected lifespan of the piece of equipment (assuming an expected lifespan of 5 years). 48 Unit costs were derived from NRS Healthcare (Coalville, UK) where possible49 (see Appendix 5, Table 29).

Secondary care costs

Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data were requested from NHS Digital for all inpatient stays, outpatient attendances and A&E attendances for all residents for the period they were in the trial. Costs were applied by mapping the HES-provided Health Research Group code to the NHS National Tariff, using 2017/18 prices regardless of activity date. These costs were provided in the HES data received from NHS digital. Further details on costing HES data are reported in Report Supplementary Material 4, and unit costs and sources are reported in Appendix 5, Table 28.

The mean costs per resident in the GtACH arm and per resident in the control arm were estimated by summing intervention costs and wider NHS and PSS costs, and then dividing by the number of residents in the trial arm.

Outcomes

The main outcome measure in the economic evaluation was QALYs accrued for the resident over the 12 months’ follow-up period as valued using the DEMQOL-P-U and EQ-5D-5L proxy. For both instruments, responses were obtained from proxies (care home staff) at baseline and 3-monthly intervals. Responses were converted into a utility using published UK tariff values; for the DEMQOL-P-U this was the valuation sets published by Mulhern et al. 38 and Rowen et al. ,50 and for the EQ-5D-5L-P this was in line with current recommendations51 to use the ‘cross-walk’ valuation set published by van Hout et al. 52 in 2012. These utilities represent residents’ overall health-related quality of life (HRQoL) at single time points. These utilities were employed to generate QALYs using linear interpolation and area under the curve analysis with baseline adjustment, adjusted for age at randomisation and sex. 53 If residents died, their utility value (and costs) were assumed to be zero from the subsequent assessment point and their data were retained in the analyses.

If residents had sufficient mental capacity they were also asked to complete the EQ-5D-5L and Dementia Quality of Life Utility version (DEMQOL-U) (while also having these measures captured by proxy respondents). This secondary analysis was important because of uncertainties regarding how best to capture health utilities in this population. 38,50,54

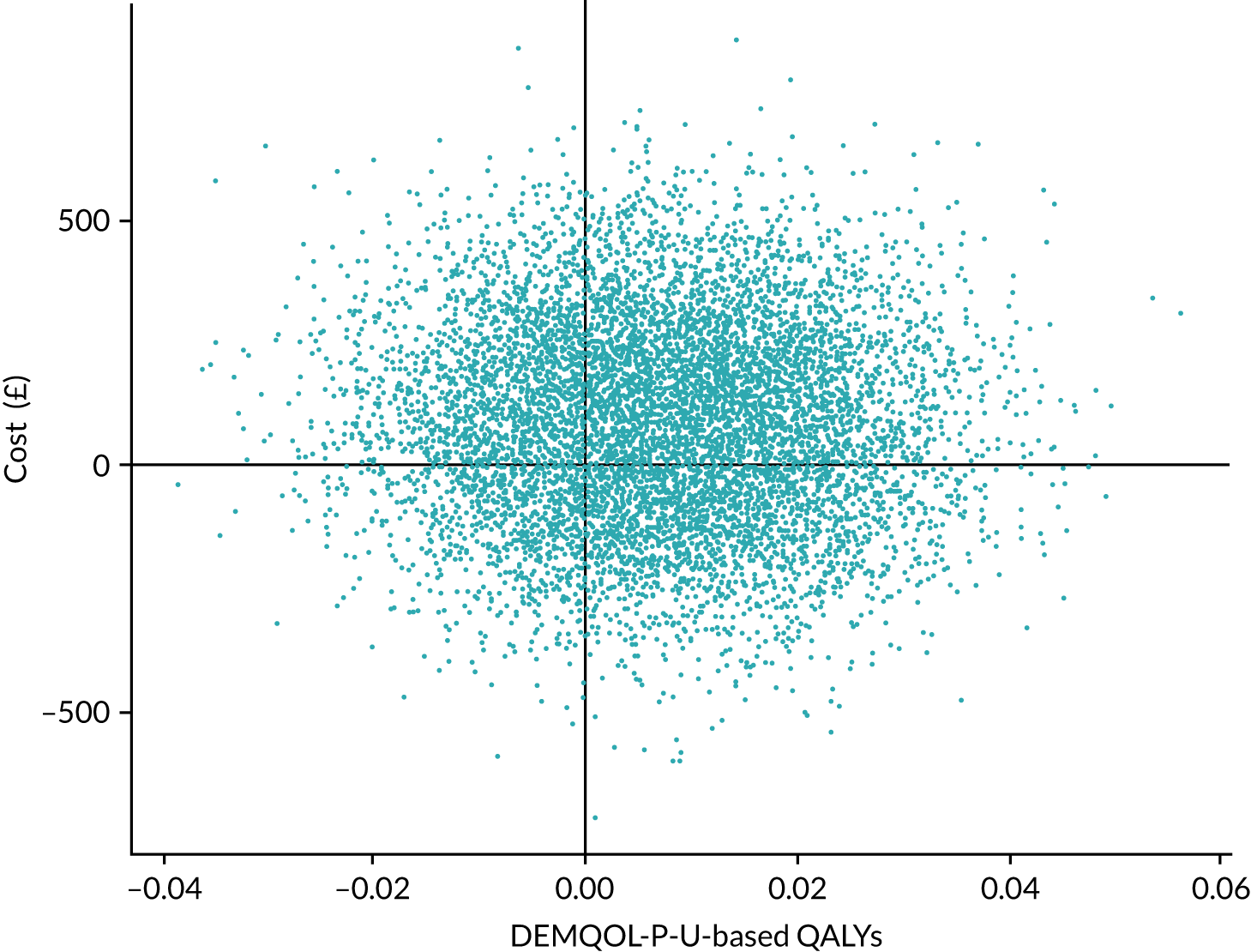

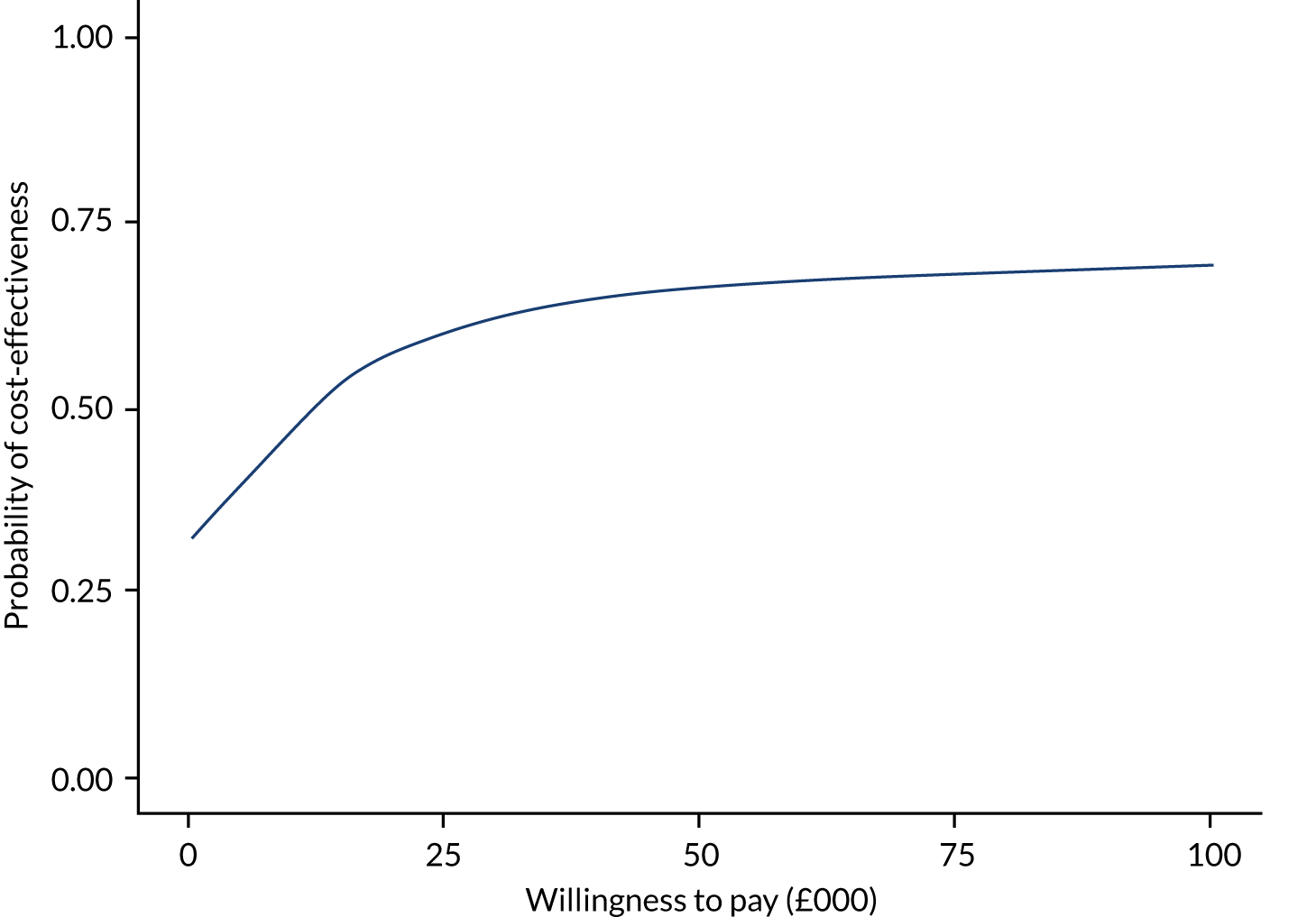

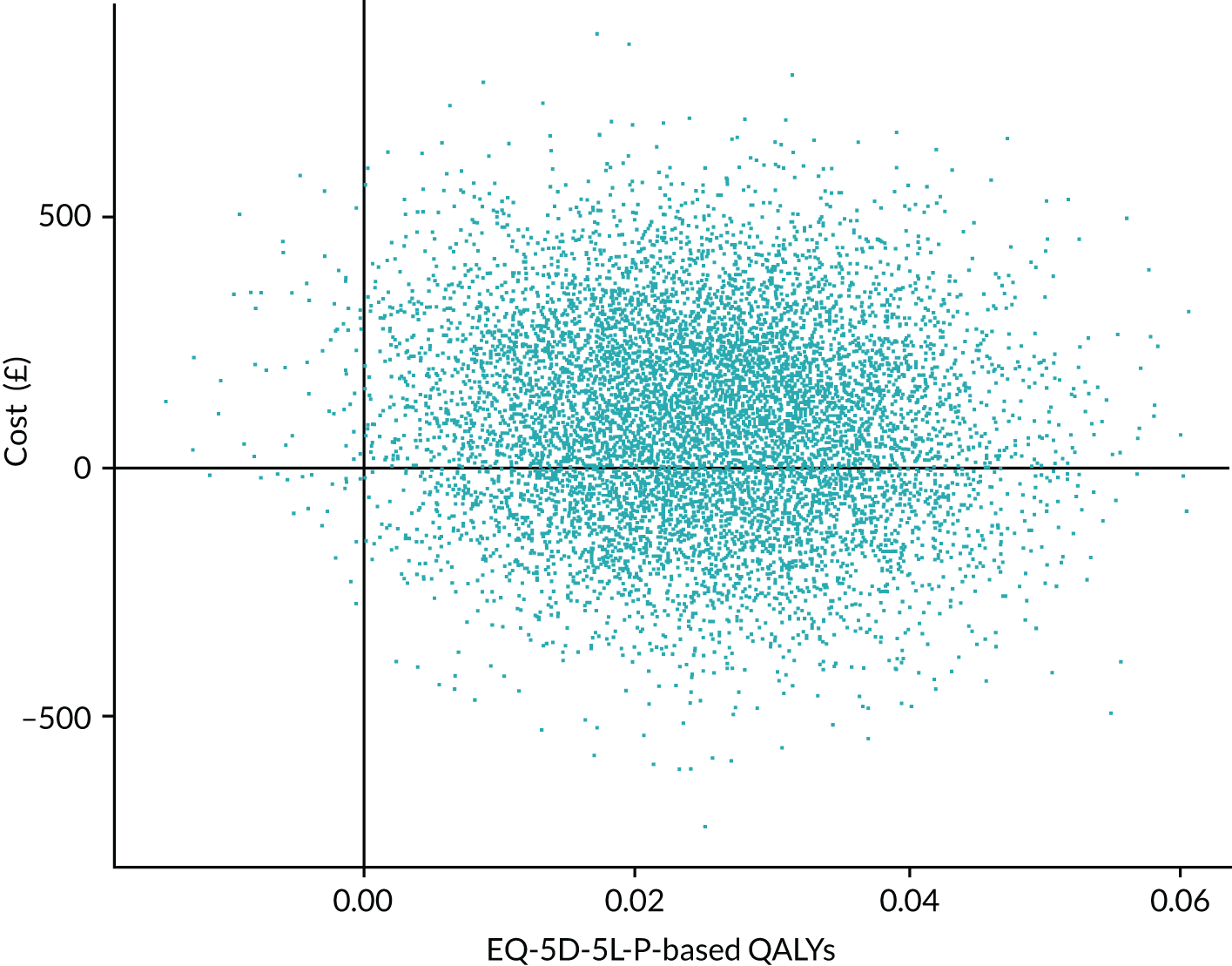

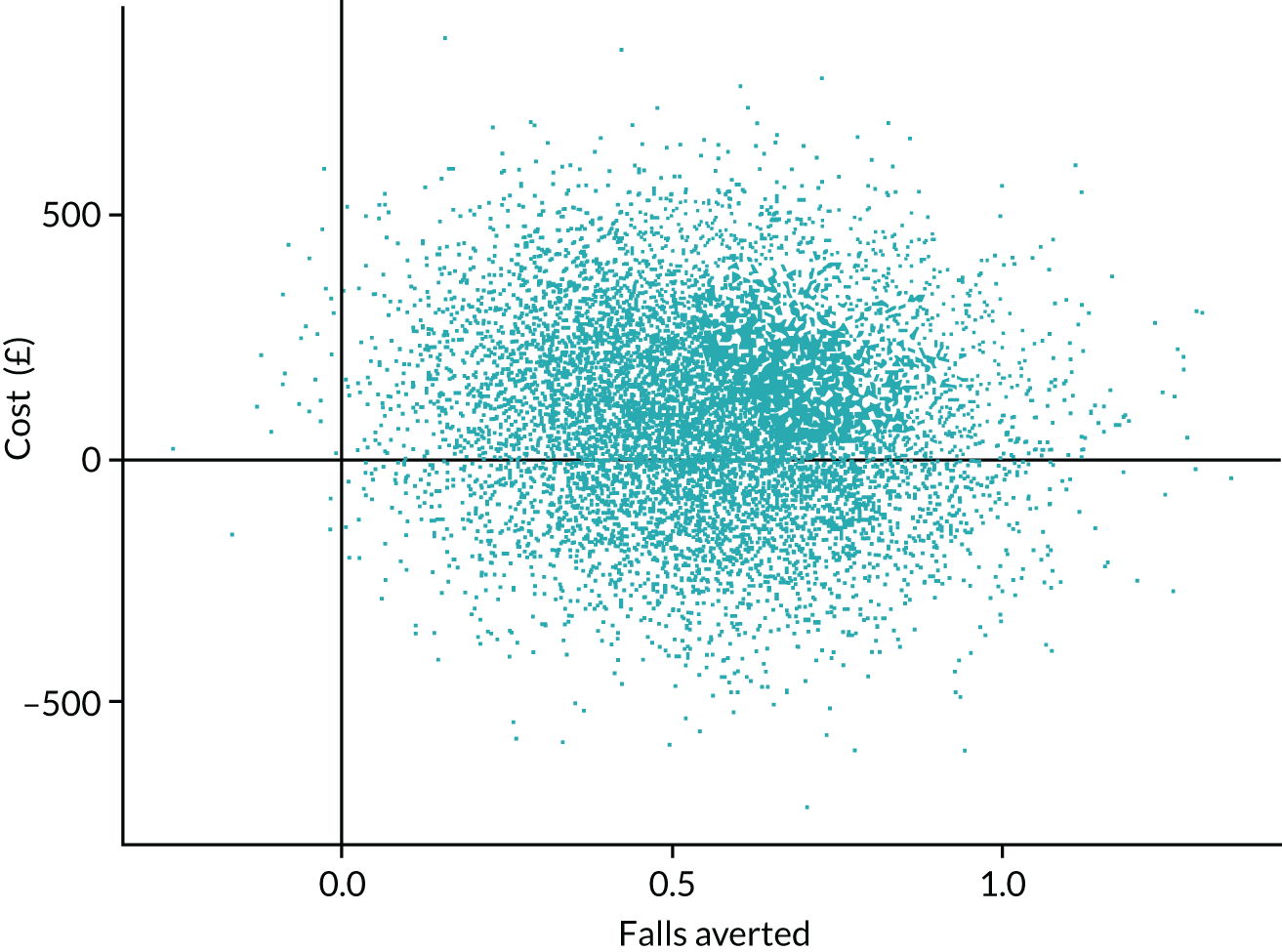

Economics analysis

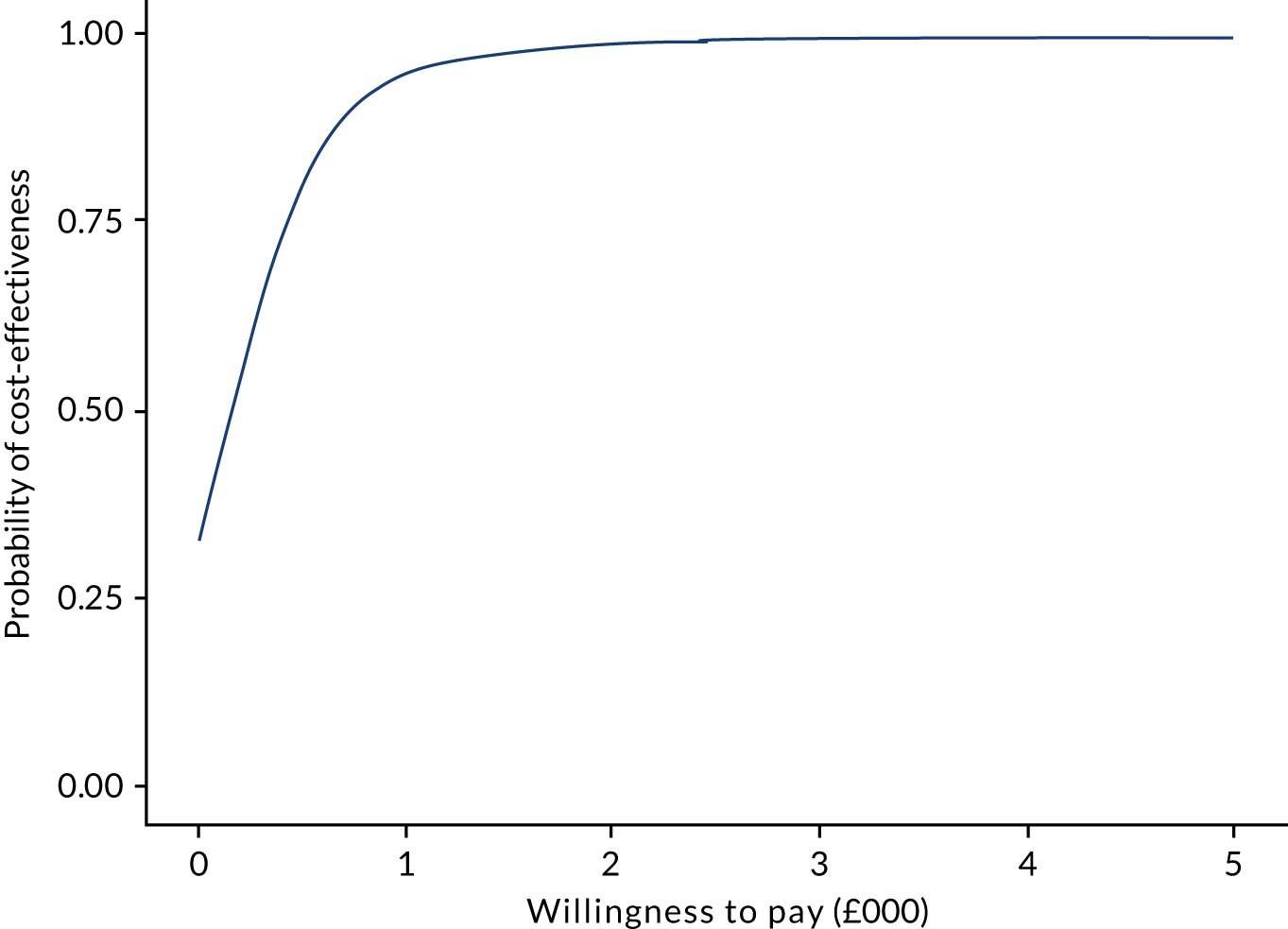

The primary economic analysis was a within-trial cost–utility analysis comparing the GtACH intervention with usual care without a systematic and co-ordinated falls prevention process in place, with outcomes expressed in QALYs. As the clinical analyses used falls rates as the primary end point, a secondary CEA based on difference in falls rates over 12 months was also conducted. Analysis was undertaken based on the intention-to-treat principle, including all randomised residents with data available. As follow-up did not continue past 12 months, discounting of costs or outcomes was not undertaken.