Notes

Article history paragraph text

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/11/02. The contractual start date was in June 2010. The draft report began editorial review in January 2012 and was accepted for publication in September 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

DAL has received an investigator-initiated educational grant from Bayer Healthcare and honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer HealthCare, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi-aventis and Pfizer. In addition, DAL is a panellist on the ninth edition of the American College of Chest Physicians guidelines on antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. DAF has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi-aventis, and AstraZeneca

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Lane et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the underlying health problem

Atrial fibrillation (AF), the most common abnormality of the heart's rhythm (cardiac arrhythmia) seen in clinical practice,1 is characterised by unco-ordinated and rapid beating of the upper chambers of the heart (atria). 2

Owing to the irregularity in the beating of the heart, the flow of blood is affected and there is an increased risk of formation of blood clots in the atria. If these clots are subsequently displaced, they can travel in the blood to other parts of the body and may block blood vessels, thereby disrupting blood flow, leading to an embolism. The most common site of embolism in patients with AF is the brain, resulting in a stroke. Patients with AF have an increased risk of stroke compared with individuals without AF. 3 AF is responsible for 15% of all strokes and one-quarter of strokes in people aged > 80 years. 4 Furthermore, AF confers a 1.5- and 1.9-fold increased risk of mortality in men and women, respectively,5 and is associated with elevated risk of developing heart failure (HF)2 and impairment of quality of life. 6,7

Incidence/prevalence

Atrial fibrillation is the most common cardiac arrhythmia in clinical practice1,8,9 and the prevalence increases markedly with older age, from 0.5% at 40–50 years to 5% in those aged ≥ 65 years and almost 10% in people aged ≥ 80 years. 10,11 AF is slightly more prevalent in men than in women. 8–10 The lifetime risk of developing AF aged ≥ 40 years is approximately one in four. 8,9

The Screening for Atrial Fibrillation in the Elderly (SAFE) study,12 a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of systematic screening (targeted and total population screening) compared with routine practice for the detection of AF in people aged ≥ 65 years in the UK involving 15,000 patients, revealed that the prevalence of AF was 7.2%, with a higher prevalence evident in men (7.8%) and those aged ≥ 75 years (10.3%). The incidence of AF ranged from 1.04% to 1.64% per year. The incidence and prevalence of AF are increasing and are projected to rise exponentially as the population ages and the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors increases. 10

Impact of the health problem

The major complication of AF is stroke. AF is associated with a fivefold increased risk of stroke compared with age- and sex-matched patients in sinus rhythm,3 and doubles the risk of stroke after adjustment for other risk factors. 1 In addition, when a stroke occurs in a patient with AF it is more severe, more likely to recur, and more likely to result in death or disability than strokes in patients without AF. 13–15 Further, stroke survivors with AF face persistent neurological deficits and permanent disability, having a significant negative impact on their quality of life and increasing the burden of care for their family and the health services. 16

Information from The Office of Health Economics17 demonstrates the huge economic burden of AF to the NHS. In 2008, patients with AF accounted for 5.7 million bed-days, at a cost to the NHS of £1873M. In addition, other inpatient costs accounted for an extra £124M and outpatient costs (such as electrocardiography, monitoring anticoagulant treatment and post-discharge attendance) a further £205M. However, this figure does not take into account the significant societal costs, days of work lost, informal care, and the impact of AF on the patient and his or her family. The cost of AF appears to have increased dramatically since the turn of the century, given that a previous study estimated that the direct cost of AF to the NHS in 2000 was £45M, equivalent to 0.97% of total NHS expenditure. 18

Risk of stroke

The risk of stroke among patients with AF is heterogeneous, with risk dependent on associated comorbidities. The Stroke Risk in Atrial Fibrillation Working Group19 conducted a systematic review to identify independent predictors of stroke in patients with AF and found that a previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) was consistently and independently associated with an augmented risk of a subsequent stroke, conferring a 2.5-fold increased risk. Increasing age also independently predicted stroke risk, with a 1.5-fold greater risk with each decade of life. In addition, a history of hypertension or elevated systolic blood pressure (> 160 mmHg) and diabetes mellitus doubled the stroke risk. Half of the studies that examined sex as a risk factor for stroke demonstrated that women had a 1.6-fold greater risk than men. 19 A history of HF and coronary artery disease (CAD) were not identified as independent risk factors for stroke by this systematic review, although systolic dysfunction (evidenced by echocardiography) was found to be a risk factor. 19 The risk of stroke in patients with AF is significantly reduced with anticoagulation therapy,20–23 and antiplatelet treatment also decreases the risk of stroke compared with placebo. 20

Current service provision

Antithrombotic management of atrial fibrillation

The management of AF consists of a rate and/or rhythm control strategy in combination with antithrombotic therapy (ATT). The aim of the former is to control the heart rate without attempting to restore the heart's normal rhythm (sinus rhythm), whereas the latter attempts to re-establish and maintain sinus rhythm. Regardless of which strategy is implemented, all patients should be assessed for individual stroke risk and receive appropriate ATT. Clinical guidelines2,24 recommend oral anticoagulant for patients who are at high risk of stroke, and either oral anticoagulation or antiplatelet(s) for those deemed to be at intermediate risk, although the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines2 prefer oral anticoagulation over antiplatelet(s) therapy in this group. Among those patients who are at low risk of stroke (those < 65 years of age with no stroke risk factors), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)24 recommends antiplatelet therapy (APT), whereas the ESC guidelines2 recommend APT or no treatment, with a preference for no therapy. 2,24

In order to determine the most appropriate ATT for each patient, his or her individual risk of stroke should be assessed. The main risk factors for stroke among patients with AF are described above (see Risk of stroke), but include previous stroke or TIA, age ≥ 65 years, HF, hypertension and diabetes mellitus, which together constitute the widely used stroke risk assessment tool, the CHADS2 (Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥ 75 years, Diabetes mellitus, and prior Stroke or TIA or thromboembolism) score,25 although there are numerous other stroke risk stratification schemas available19 (Table 1).

| Risk stratification scheme, year | Risk | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Moderate | Low | |

| AFI, 199426 | Previous stroke/TIA, hypertension, diabetes mellitus | Aged ≥ 65 years with no other risk factors | Aged < 65 years |

| SPAF Investigators, 199927 | Previous stroke/TIA, women aged > 75 years, men aged > 75 years with hypertension | Hypertension, diabetes mellitus | No risk factors |

| CHADS2, 2001 (classic)28 | Score of 3–6 | Score of 1–2 | Score of 0 |

| CHADS2, 2001 (revised)25 | Score of 2–6 | Score of 1 | Score of 0 |

| Framingham study, 200329 | Score of 16–31 | Score of 8–15 | Score of 0–7 |

| NICE guidelines, 200624 | Previous stroke/TIA/TE, aged ≥ 75 years with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or vascular disease, clinical evidence of valve disease, HF, of LV dysfunction on echocardiography | Aged < 75 years with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or vascular disease | Aged < 65 years with no moderate- or high-risk factors |

| Aged ≥ 65 years with no high risk factors | |||

| ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines, 20061 | Previous stroke/TIA/TE, or: | Aged ≥ 75 years, or hypertension, or HF, or LVEF ≤ 35%, or diabetes mellitus | No risk factors |

| or ≥ 2 moderate risk factors: age ≥ 75 years, hypertension, HF, LVEF ≤ 35%, diabetes mellitus | |||

| Eighth ACCP guidelines, 200830 | Previous stroke/TIA/TE, or: | Aged > 75 years, or hypertension, or moderately or severely impaired LVEF and/or HF, or diabetes mellitus | No risk factors |

| Two or more moderate risk factors: aged ≥ 75 years, hypertension, moderately or severely impaired LVEF and/or HF, or diabetes mellitus | |||

| CHA2DS2-VASc, 201031 | Score of ≥ 2 | Score of 1 | No risk factors |

| ESC guidelines, 20102 | Previous stroke/TIA/SE or aged ≥ 75 years, or: | Score of 1 | No risk factors |

| Two or more ‘clinically relevant non-major’ risk factors: HF or LVEF ≤ 40%, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, vascular disease,a aged 65–74 years, female sex | |||

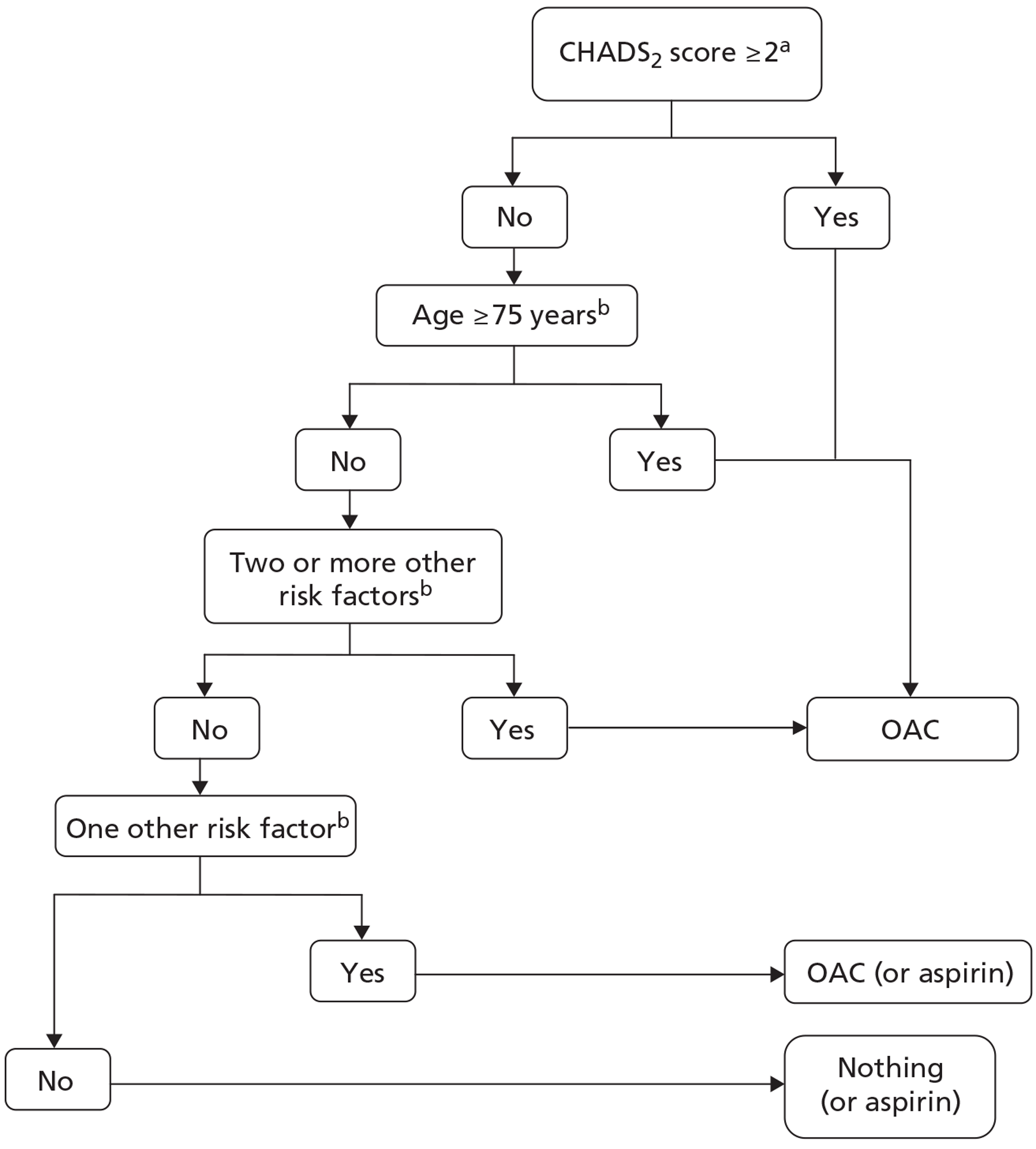

In the UK, the NICE guidelines24 currently recommend aspirin 75–300 mg daily (unless contraindicated) for patients aged < 65 years with no moderate- or high-risk factors and who, thus, are deemed to be at low risk (≤ 1% annual risk) of stroke. For patients at moderate risk (4% annual risk), namely those aged < 75 years with hypertension, diabetes mellitus or vascular disease (CAD or peripheral artery disease) and those ≥ 65 years without any high-risk factors, NICE24 suggests anticoagulation or aspirin. Among patients at high risk (12% annual risk) of stroke, i.e. those with a previous stroke/TIA or thromboembolism (TE), clinical evidence of valve disease, HF, or impaired left ventricular (LV) function on echocardiography, or aged ≥ 75 years with hypertension, diabetes mellitus or vascular disease, NICE24 recommends anticoagulation with warfarin. The ESC guidelines2 have adopted a risk factor-based approach to determine appropriate thromboprophylaxis (Figure 1 and Table 1) and these guidelines have superseded the NICE recommendations in clinical practice in the UK. 2

FIGURE 1.

Clinical flow chart for the use of ATT in patients with AF. Redrawn from the ESC guidelines. 2 a, Congestive HF, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, diabetes mellitus (1 point for each), stroke/TIA/TE (2 points); b, other clinically relevant non-major risk factors: age 65–74 years, female sex, vascular disease.

In patients with AF who have no risk factors for stroke, the ESC guidelines2 recommend either aspirin 75–325 mg daily or no ATT, with a preference for no treatment over aspirin. 2 For those with one ‘clinically relevant non-major’ risk factor [HF or left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 40%, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, vascular disease, age 65–74 years, female sex], the ESC advises that oral anticoagulation or aspirin (75–325 mg) should be administered, with an oral anticoagulant (OAC) preferred over aspirin. Among those patients with one ‘major’ (previous stroke/TIA/TE or aged ≥ 75 years) or two or more ‘clinically relevant non-major’ risk factors, a OAC is recommended. Where a OAC is recommended, this includes adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) or one of the new anticoagulant drugs (see Description of technology under assessment).

In addition, CAD is also increasing in prevalence as a consequence of the improvements in survival due to advances in medical therapy and the ageing population. 30 Between 30% and 40% of patients with AF have concomitant CAD,11 and some of these patients may also require percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stent implantation. Patients with AF and CAD are at increased risk of both stroke and further coronary events. An increasingly common management problem arises when faced with an anticoagulated patient with AF who presents with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or those who require PCI with stent implantation. 32

Current guidelines for antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation patients with acute coronary syndrome or undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention or stenting

The joint American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/ESC 2006 guidelines on the management of AF recommend that following PCI or revascularisation surgery in patients with AF, low-dose aspirin (< 100 mg/day) and/or clopidogrel (75 mg/day) may be given concurrently with anticoagulation to prevent myocardial ischaemic events,1 although it is acknowledged that these strategies have not been thoroughly evaluated and are associated with an increased risk of bleeding. The 2006 ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines also suggest that clopidogrel should be given for a minimum of 1 month after implantation of a bare-metal stent, ≥ 3 months for a sirolimus (CYPHER™, Cordis)-eluting coronary stent-P020026, ≥ 6 months for a paclitaxel (ION™, Boston Scientific)-eluting coronary stent system-P100023, and ≥ 12 months in selected patients, following which warfarin may be continued as monotherapy in the absence of a subsequent coronary event. 1 Broadly similar recommendations are made in the eighth ACCP guidelines,33 which suggest that a low dose of aspirin (< 100 mg per day) or clopidogrel (75 mg per day) may be given with anticoagulation, although the risk of bleeding may be increased, particularly in elderly patients. The UK NICE guidelines24 do not address this topic, although acknowledging that adding aspirin to warfarin increases bleeding, and that it is a matter for individual assessment of the risk–benefit ratio in prescribing aspirin plus warfarin in patients with associated CAD.

Furthermore, all of the published guidelines do not address the issue of a presentation with ACS (where PCI is often performed) and bleeding risk. Given the need to balance stroke prevention, recurrent cardiac ischaemia and/or stent thrombosis, two more recent consensus documents,34,35 based on systematic reviews of patients on OAC undergoing PCI and stenting, advocate initial triple therapy (with OAC, aspirin and clopidogrel) in such patients, and the use of bare-metal stents (owing to the need for prolonged multiple-drug ATT with drug-eluting stents). However, triple ATT is associated with a higher risk of major bleeding and this risk must be considered before treatment initiation. 34,36 Therefore, the ESC Working Group on Thrombosis consensus guidelines35 recommend limiting triple ATT to 2–4 weeks in patients who are at high risk of haemorrhage (Table 2).

| Haemorrhagic risk | Clinical setting | Stent implanted | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low or intermediate | Elective | Bare metal |

|

| Elective | Drug eluting |

|

|

| ACS | Bare metal/drug eluting |

|

|

| High | Elective | Bare metalc |

|

| ACS | Bare metalc |

|

Description of technology under assessment

Anticoagulant therapy (ACT) is recommended for patients with AF who are at high risk of stroke. The main type of ACT used for patients with AF is a vitamin K antagonist (VKA), most commonly warfarin, to maintain a therapeutic international normalised ratio (INR) value of 2.0–3.0. Other classes of anticoagulants include heparins (low-molecular-weight heparins), hirudins, and, more recently, the novel anticoagulant drugs, direct oral thrombin inhibitors (ximelagatran and dabigatran), and factor Xa inhibitors [idraparinux, apixaban (Eliquis®, Bristol-Myers Squibb), rivaroxaban (Xarelto®, Bayer) and endoxaban] (Table 3). APT is also used for stroke thromboprophylaxis in patients with AF. Antiplatelet agents currently used include aspirin (non-proprietary; typically), clopidogrel (Plavix®, Sanofi-aventis), ticlopidine, dipyridamole (Persantin®, Boehringer Ingelheim) and triflusal (Table 3).

| Anticoagulants | Antiplatelet agents |

|---|---|

VKAs

|

|

| Heparins | |

|

|

| Hirudins | |

|

|

| Direct oral thrombin inhibitors | |

|

|

| Factor Xa inhibitors | |

|

Anticoagulation, antiplatelet or combined therapy in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation

Among patients with AF, there is evidence that thromboprophylaxis with warfarin reduces the risk of TE (by 64%) compared with placebo or aspirin (by 39%). 20 Aspirin reduces the risk of TE in patients with AF by 22% compared with placebo. 20

However, it is currently unclear whether or not there is any additional benefit in adding APT to ACT in high-risk patients with AF in terms of reduction in vascular events, including stroke.

The available data from individual studies are conflicting, apart from the consistent message that combining APT with oral anticoagulation increases the risk of major bleeding. There is currently no definitive answer to the question of whether or not combination anticoagulant and antiplatelet (mono- and dual-antiplatelet) therapy is beneficial in patients with AF and concomitant CAD/vascular disease, and those undergoing PCI and stent implantation. The available evidence from observational cohort studies and registry analyses suggests a reduction in TEs with combination and triple therapy, given for a short duration, in patients with AF and concomitant CAD/vascular disease with stent implantation. However, the risk reduction in TEs is offset by an increased risk of major bleeding. 35

The aim of the current study is therefore to identify the benefits of adding APT in a subgroup of high-risk patients with AF who are receiving ACT, in whom this can be justified in terms of the balance of reducing vascular events without increasing bleeding.

Chapter 2 Methods

Aim

To determine if the addition of APT to ACT is beneficial compared with ACT alone in patients with AF who are considered to be at high risk of TEs.

Objective

To undertake a systematic review of studies comparing ACT alone with ACT in combination with APT in patients with AF.

Definitions

The Background chapter describes AF. For the purposes of this review, the definition of AF used was that determined by the authors of studies.

The Background chapter describes ACT and APT used to treat AF. For the purposes of this review, no limits were placed on the type of therapies that could be chosen as being anticoagulant or antiplatelet agents.

High-risk patients of special interest include patients with AF with previous myocardial infarction (MI) or ACS, those undergoing PCI and stent implantation, those with diabetes mellitus, and those with a CHADS2 score of ≥ 2. However, no restrictions were placed on the determinants of high risk.

Relevant study designs

Given the likely paucity of directly relevant RCTs, the steering group for this project was consulted at an early stage about whether or not evidence from a wider selection of study designs should be reviewed. The steering group decided that this should be the case.

Review methods

Standard systematic review methodology was used, consisting of searches to identify available literature, sifting and the application of specific criteria to identify relevant studies, assessment of the quality of these studies, and the extraction and synthesis of relevant data from them. The review was guided by a protocol that was prepared a priori (see Appendix 1) and externally reviewed prior to use.

Search strategies

The following resources were searched for relevant studies:

-

Bibliographic databases: The Cochrane Library [Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)] 2010 Issue 3; MEDLINE (Ovid) 1950 to September week 1 2010; MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations from inception to 27 September 2010; and EMBASE (Ovid) 1980 to September 2010. Searches were based on index and text words that encompassed the population: atrial fibrillation and the interventions; combined anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy.

-

Ongoing trials were sought in ClinicalTrials.gov, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network Portfolio, Current Controlled Trials (CCT) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP).

-

Reference lists from identified systematic reviews were checked.

-

Citations of relevant studies were examined.

-

Further information was sought from clinical experts.

All study types were sought. Searches were not limited by language or date and were carried out during September 2010 by an information specialist.

Search strategies used in the bibliographic databases can be found in Appendix 2.

Scoping searches were undertaken to identify completed and ongoing systematic reviews from the following resources: The Cochrane Library [Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database, CENTRAL and NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED)], Aggressive Research Intelligence Facility (ARIF) database of reviews, HTAi portal, MEDLINE (Ovid) 1950 onwards and EMBASE (Ovid) 1980 onwards. The systematic reviews were used to check if there were additional relevant studies.

Study selection

All records identified in the searches were imported into a Reference Manager database (Reference Manager v.11, Thomson ResearchSoft, San Francisco, CA, USA). Duplicate entries were allowed to be removed by the inbuilt feature in Reference Manager and also removed when encountered by reviewers.

Owing to the number of retrieved records and the complexity of the publications, a three-stage process was used to select the studies for review.

Stage 1

The aim was to exclude obviously irrelevant records. The titles of all records were scanned by one reviewer and the record retained if it was about an article/study that met ANY of the following criteria:

-

any AF study

-

any stroke study

-

any study with a group of patients on ACT, APT or both.

Study design or publication type was not an exclusion criterion for this stage.

Stage 2

Based on the title and abstract where available, records were retained if they were about an article/study that adhered to all of the following criteria:

-

any AF population receiving ACT, APT, or both

-

indicated effectiveness data were reported.

Study design or publication type was not an exclusion criterion for this stage.

In the first instance, this stage was undertaken by two reviewers independently; however, it became clear that complexity of the information in the records and particularly absence of detail were leading to far from ideal agreement between the two reviewers (Cohen's kappa coefficient = 0.51). For this reason all records for which discord occurred were screened independently by two further reviewers and any disagreements at this level were resolved by discussion.

All articles progressing through to this stage were obtained in hard copy.

Stage 3

The hard copies were assessed for inclusion in the review against the following criteria. All criteria had to be met to warrant inclusion.

-

Study design RCTs, non-randomised comparisons, cohort studies, case series or registries, longitudinal studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and conference abstracts published after 2008.

-

Population Patients with AF, aged ≥ 18 years. Publications were included, even if a subgroup of patients in the study conformed to this criterion.

-

Intervention Publications were included only if there was a subgroup of, or complete cohort of, patients on combined ACT and APT. Publications in which the INR of ACT was not specified were also included.

-

Comparator ACT alone or ACT plus placebo.

-

Outcomes All-cause mortality and/or at least one vascular event(s) [non-fatal and fatal ischaemic stroke, TIA, systemic embolism (SE)] SE (pulmonary/peripheral arterial embolism), MI, in-stent thrombosis, vascular death, bleeding (major, non-major, minor), reported for both intervention and comparator groups.

If any of the following criteria were met, then the article was excluded:

-

Study design: All case studies, bridging therapy studies with heparin, rationale or study design papers, ecological studies, case–control studies, cross-sectional studies (surveys), conference abstracts published before 2008, commentaries, and letters or communications were excluded.

-

Population: Articles that specified a population as having a CHADS2 score of < 2 or stroke patients with AF for whom outcomes were retrieved retrospectively, or a population with valve replacement or mechanical heart valves. If CHADS2 scoring or any other stroke risk scoring was not specified, then this was not a reason to exclude an article.

Part-translation of articles not fully published in the English language was obtained to facilitate selection.

The criteria were applied by two reviewers independently and disagreements were resolved by discussion and with the involvement of a third reviewer if required. The reason(s) for the exclusion of articles were recorded.

Where there was more than one unique article from a single study the articles were grouped together for reviewing purposes.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses that met the inclusion criteria were not reviewed but were utilised to identify further articles. Articles identified in this way were entered in to the Reference Manager database and subjected to the same selection process outlined above.

Data extraction

Data were extracted into a standard form in Microsoft Excel 2007 v.12 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) from the main and supporting publications (where relevant) of all included primary studies by one reviewer. A second reviewer checked the accuracy of extracted information. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by referral to a third reviewer if necessary.

Information regarding study design (including intervention/comparators) and characteristics of study participants was extracted. This included antithrombotic regimens used [anticoagulant ± antiplatelet(s) or placebo], type of ATT used and dose, target INR values used, indication for ATT (e.g. AF ± ACS or stent implantation), study setting (country), study design, sample size, patient inclusion and exclusion criteria, patient characteristics (e.g. age, sex, type and duration of AF, anticoagulant naive or experienced), comparability of patients between different arms (for RCTs and non-randomised trials), primary outcome measures, secondary outcome measures, length of follow-up, statistical methods used, effect sizes and uncertainty.

Data on the following outcomes were sought from included studies.

Primary outcome measures

Vascular event – stroke (non-fatal and fatal ischaemic), TIA, SE (pulmonary embolism, peripheral arterial embolism), MI, in-stent thrombosis and vascular death (from any of the aforementioned vascular events).

Secondary outcome measures

All-cause mortality and bleeding (major bleeding events, clinically relevant non-major bleeding events, minor bleeding), health-related quality of life, major adverse events (composite of all-cause mortality, non-fatal MI and stroke), revascularisation procedures (e.g. PCI, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, embolectomy) and percentage of time in therapeutic INR range.

Definitions of these outcomes as used in each study were also extracted where reported.

Data for any outcomes other than those listed above were also extracted if it was considered relevant to this report.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed by one reviewer. A second reviewer checked the accuracy of extracted information. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by referral to a third reviewer if necessary.

The methodological quality of RCTs was assessed in terms of the randomisation process, allocation concealment (adequate, unclear, inadequate or not used), degree of blinding, particularly of the outcome assessors, and patient attrition rate, using the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias assessment tool. 37

The quality assessment of studies undertaking non-randomised comparisons was undertaken using the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD)'s checklist for cohort studies. 38 Information on the following was captured: method of outcome measurement, blinding of assessors, whether or not outcome definitions were clearly explained, and which parts of the study were prospective. In addition, the following topic-specific data that were considered relevant to the quality of the studies were assessed: ‘Were the indications for use of APT given?’ and ‘Was it clear whether patients were on APT at the start or commenced such therapy during the observation period?’

Data from randomised studies that were obtained from non-randomised comparisons were classed and treated as non-randomised data. For example, when data from a subset of patients in two or more arms of a RCT were combined to compare with data from another subset of patients obtained from these or other arms of the same study.

From non-randomised comparisons the potential for confounding by indication was ever present; whereby APT was added to ACT, based on clinical judgement of a potential risk of adverse outcomes in some patients if such therapy was not given. Conversely, in those without such perceived risk APT may not have been given. Thus, the patients receiving anticoagulation alone would differ from those receiving the combined therapy, and thus any comparison between the two would be confounded.

Data analysis/synthesis

Outcomes of interest

Selected outcomes of interest were specified in the review protocol, based, in part, on the briefing document produced by the NIHR. These were as shown below.

Primary outcome measures

-

Vascular events:

-

non-fatal and fatal ischaemic stroke

-

TIA

-

SE (pulmonary embolism, peripheral arterial embolism)

-

MI

-

in-stent thrombosis

-

vascular death (from any of the above mentioned vascular events).

-

Secondary outcome measures

-

All-cause mortality.

-

Bleeding:

-

major bleeding events

-

clinically relevant non-major bleeding events

-

minor bleeding.

-

-

Health-related quality of life.

-

Major adverse events.

-

Revascularisation procedures.

-

Percentage of time within therapeutic INR range (where available).

Although definitions of these outcomes could have been described rigidly for this review (such as using the definitions of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis39) it was decided to retain and record the definitions used in the original papers and to group data accordingly. Setting aside issues around non-reporting or poor reporting of definitions, for most outcomes this was fairly straightforward. However, there were instances for which judgement was required. For example, for the outcome of SE a few studies referred to TE and it was assumed from the definitions of outcomes provided by the studies that TE referred to arterial TE, not venous TE, and thus data from these studies were grouped with SE from similar studies.

For the outcomes of interest, data were not available for all.

Handling data and presentation of results

Owing to the paucity of evidence from randomised studies, data from non-randomised and/or observational designs were also included in this review. Evidence from different study designs was not combined.

The comparison of interest was between combined anticoagulation and APT and ACT alone.

For dichotomous outcomes, data from randomised studies are presented as proportions, percentages and relative risks (RRs) [± 95% confidence interval (CI)] for comparisons. RRs and 95% CIs were calculated using Review Manager (RevMan v.5.1: The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Dichotomous data from non-randomised comparisons are not presented as RRs, given the potential for confounding by indication within such studies. If continuous outcome data had been encountered, they would be represented as differences in means or means.

Where available, data were presented for the longest follow-up available in each study. Data for follow-up assessments less than this are also presented, where appropriate. In many cases only mean/median follow-up durations were reported by studies.

Studies were considered to directly compare anticoagulation plus APT with ACT alone if the anticoagulant was the same in both arms, and there were no other treatment-related differences between arms.

Different anticoagulation therapies were considered separately. Different APTs were also considered separately. As ACT can be a fixed or adjusted dose it was decided a priori on clinical advice to report these regimes separately. A priori it was decided that only the following groups could be considered as classes of intervention. VKAs were considered as a class of intervention and, thus, reported together and where possible pooling of data across the class was considered if there was sufficient methodological and clinical homogeneity between studies. Oral direct thrombin inhibitors (ODTIs) were also considered as a class of intervention. None of the APTs was considered as a class.

Although planned, pooling of results was not attempted for the assessment of effectiveness of individual technologies because of the substantial clinical and methodological heterogeneity between studies and the confounding by indication inherent in the observational studies.

Assessment of publication bias

The number of relevant studies for a given comparison was too small to allow formal assessment of publication bias.

Ongoing studies

A number of ongoing studies were identified in the searches. They were not included in the systematic review, but discussed in Chapter 4 (see Strengths and limitations, Ongoing studies) to aid updating and extension of this review.

Sensitivity and subgroup analysis

Although the number of subgroups and/or sensitivity analyses might have been possible in this report, none was undertaken owing to lack of data.

Changes to protocol

The protocol specified that, where possible, the relevant target INR for the combined ACT-plus-APT treatment arm should be 2.0–3.0 as recommended by ESC guidelines. 2 However, it was felt that this criterion might be too restrictive or the range not reported. Therefore, this criterion was relaxed to allow inclusion of studies with either a different target range or an unspecified target INR range.

It was intended and specified in the protocol that an individual participant data (IPD) meta-analysis would be performed to specifically address the effect of APT added to ACT compared with ACT alone on (1) time to first vascular event; (2) time to first major haemorrhage or clinically relevant bleed; (3) death; and (4) time within therapeutic INR range. Predefined subgroup analyses were to be developed to possibly include the following: (1) stent type (bare metal vs drug eluting); (2) warfarin-naive subjects compared with warfarin-experienced subjects; (3) short- and long-term outcomes; (4) patients with diabetes mellitus; and (5) a CHADS2 score of ≥ 2 and < 2. Data were to be requested either in electronic or paper from triallists and subjected to consistency checks.

However, there was a paucity of evidence from the included studies for many of these analyses, and where some data were available it was clear that the methodological heterogeneity between studies, and the clinical heterogeneity within and between studies, was against such analyses. It was therefore agreed with the NIHR not to perform the IPD analysis (for further explanation, see Chapter 4, Strengths and limitations).

An additional stage of study selection was added (Stage 2 is described above – see Study Selection) because of the high yield of relevant studies from the preceding stages. In this new stage, selection criteria were based on those determined a priori for the whole review and thus unbiased. This new selection stage came before obtaining full copies of articles and the application of all of the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the review.

Reporting findings

In the following sections based on clinical input, the findings of the review are structured by outcome (and subcategories of outcome where relevant) and then for each outcome by intervention–comparison (including division by whether ACT was by adjusted or fixed dosing), with further subdivision by risk attributed to the populations where relevant. Data from randomised comparisons are the primary evidence presented with supplementary information given from pooled analyses and/or non-randomised comparisons where this information adds to that from the randomised comparisons (i.e. longer follow-up). However, caution is applied with the use of non-randomised data given that the findings are highly likely to be confounded by indication. A summary section is provided where the findings are presented by intervention and comparator, and then for each of these the data for the review outcomes are presented. Presenting the data in both ways allows access to information depending on whether the perspective required is that of the outcomes or the comparisons.

Chapter 3 Results

Quantity and quality of research available

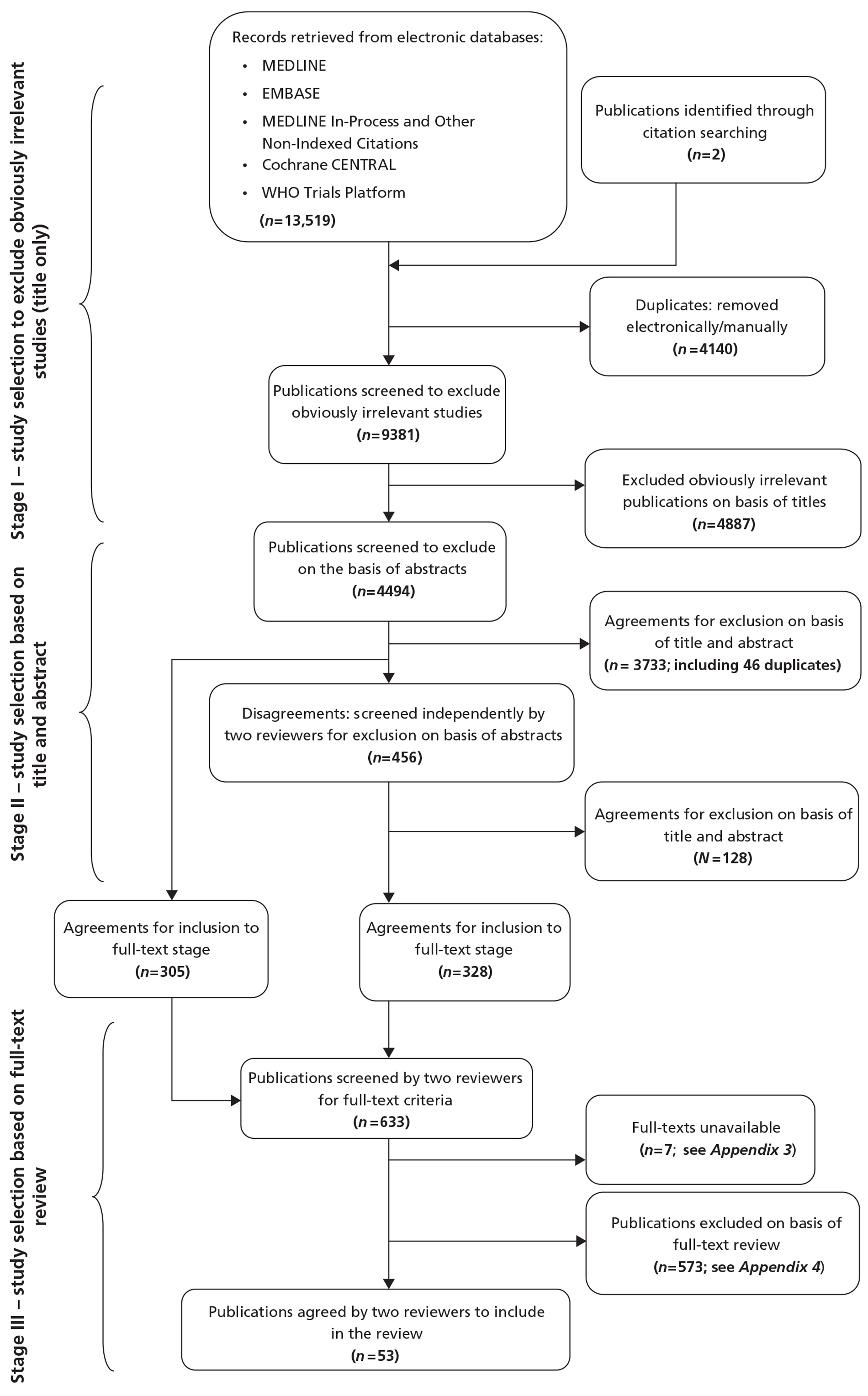

Figure 2 illustrates the study selection stages. The combined bibliographic database search yielded 13,519 citations. After the removal of records for non-relevant articles and duplicate entries, full texts of 633 potentially relevant articles were sought. The authors of 12 studies were contacted, as copies of the study reports were difficult to obtain. Seven of these were still unobtainable after this procedure. Details of these studies are presented in Appendix 3. The 626 full articles were assessed against the criteria for inclusion in the review by two reviewers independently. A total of 53 publications met the criteria (see Figure 2). A list of excluded publications along with reason(s) for their exclusion can be found in Appendix 4.

FIGURE 2.

Study selection.

No ongoing studies comparing combined ACT plus APT with ACT alone were identified in the searches. In the discussion chapter (see Chapter 4), there is a section on the pre-defined subgroup analysis of the ongoing or recently completed Phase III clinical trials identified by the steering committee.

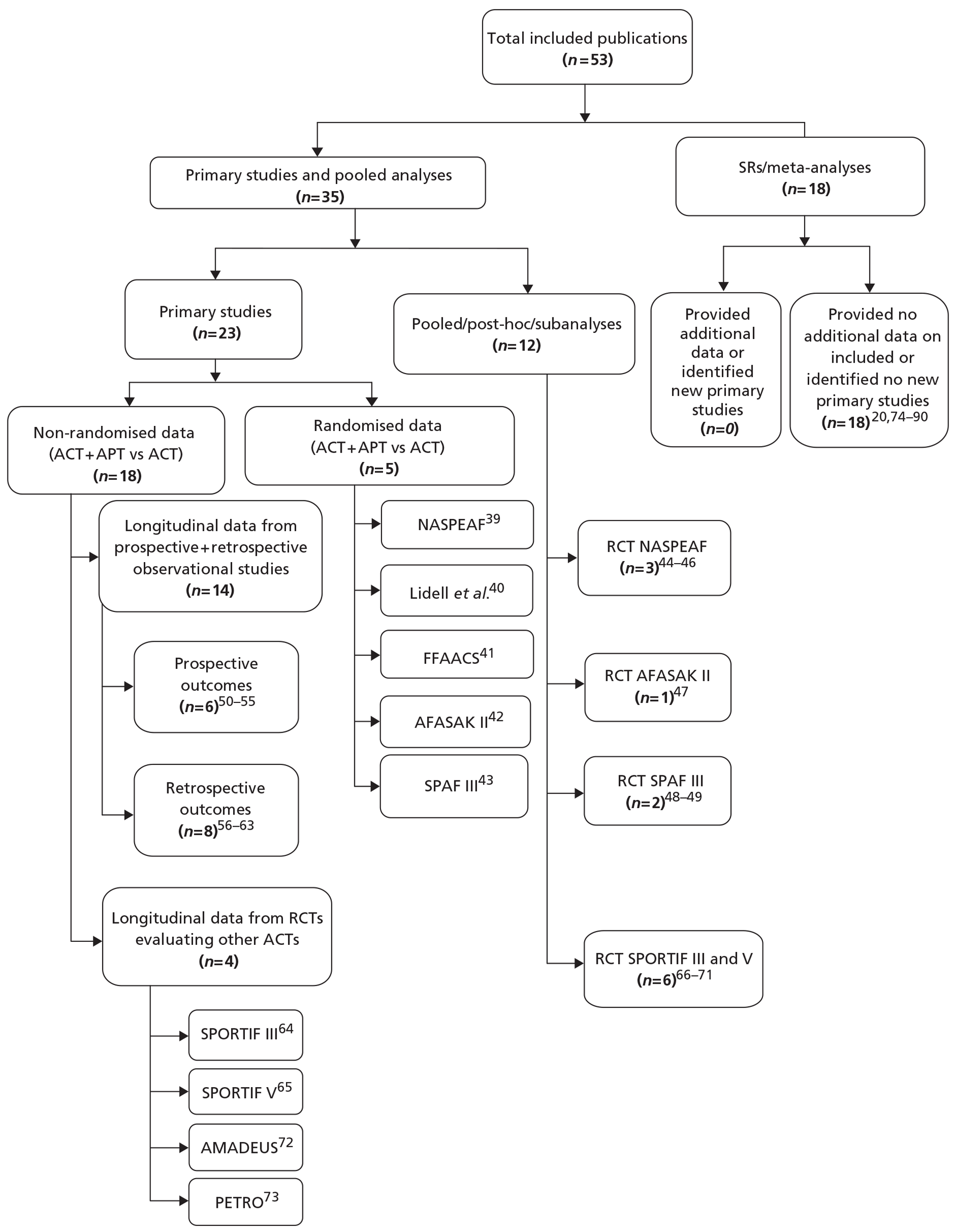

Characteristics of included studies

Of the 53 included publications (Figure 3),20,39–90 18 were reports of systematic reviews or meta-analyses20,74–90 which added no further data to the remaining 35 articles (see Figure 2 and Appendix 5). 39–73 Of the latter, five articles39–43 each reported randomised controlled studies between ACT plus APT and ACT alone. Three of these RCTs were supported by post hoc, subgroup or pooled analyses reported in a further six articles. 44–49 The characteristics of these studies and their quality assessment are reported in Tables 4 and 5, respectively, and in Appendix 6.

FIGURE 3.

Included studies. AFASAK II, Second Copenhagen Atrial Fibrillation, ASpirin and Anticoagulation Study; AMADEUS, Comparison of fixed-dose idraparinux with conventional anticoagulation by dose-adjusted oral vitamin K antagonist therapy for prevention of thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation; FFAACS, Fluindione, Fibrillation Auriculaire, Aspirin et Contraste Spontané study; NASPEAF, NAtional Study for Prevention of Embolism in Atrial Fibrillation; PETRO, dabigatran with or without concomitant aspirin compared with warfarin alone in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation study; SPAF III, Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation III study; SPORTIF, Stroke Prevention using an ORal Thrombin Inhibitor in atrial Fibrillation.

| Author, date (name of trial), location, no. of centres | Study duration (mean), randomisation design, no. of patients randomised | Intervention (ACT + APT), no. of patients | Comparator (ACT only or ACT + placebo), no. of patients | Inclusion criteria; stroke risk | Age (years): mean (SD, range), % male |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aPérez-Gómez et al., 2004 (RCT – NASPEAF), multicentre39 | 33 months, parallel, open label, n = 1209 | Adjusted-dose acenocoumarol (INR 1.25–2.0) + triflusal (600 mg), n = 222 (intermediate risk) | Adjusted-dose acenocoumarol (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 237 | Age ≥ 18 years; high risk of strokeb or intermediate risk of strokec | 68.6;d 45.6 |

| Adjusted-dose acenocoumarol (INR 1.4–2.4) + triflusal (600 mg), n = 223 (high risk) | |||||

| Lidell et al., 2003, Sweden, four centres40 | 22 days, parallel, double blind, placebo controlled, n = 43 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + clopidogrel (75 mg); n = 20 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + placebo, n = 23 | Age 35–75 years, NVAF, receiving warfarin for ≥ 2 months; no stroke risk factors reported | 66.6;d 81.4 |

| Lechat et al., 2001, (RCT – FFAACS), France, multicentre41 | 0.84 years, parallel, double blind, placebo controlled, n = 157 | Fluindione (INR 2.0–2.6) + aspirin (100 mg), n = 76 | Fluindione (INR 2.0–2.6) + placebo, n = 81 | NVAF; high risk of strokee | 73.7;d 50 |

| fGullov et al., 1998, (RCT – AFASAK II), Denmark, single centre42 | 42 months, parallel, open label, n = 677 | Fixed-dose warfarin (1.25 mg) + aspirin (300 mg); n = 171 | Fixed-dose warfarin (1.25 mg/day), n = 167 | Age ≥ 18 years with chronic NVAF; no stroke risk factors reported | 76.5 (6.9, 44–89), 60 |

| Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 170 | |||||

| gStroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators, 1996 (RCT – SPAF III), USA and Canada, 20 sites43 | 1.1 years, parallel, open label, n = 1044 | Fixed-dose warfarin (INR 1.2–1.5) + aspirin (325 mg), n = 521 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 523 | Age ≥ 18 years with NVAF, eligible 30 days from occurrence of stroke/TIA; high risk of strokeh | 72 (9); 61 |

| Author, date (name of the trial) duration (mean) | Truly random allocation and sequence generation, method | Adequate allocation concealment | Blinding | Use of ITT | Dropouts and withdrawals, n (%) | Percentage on ACT before study | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aPérez-Gómez et al., 2004 (RCT – NASPEAF), 33 months39 | Yes, computer generated, centrally administered | Nob | Yesc | No | Withdrawals, 18.3%; lost to follow-up, 50 (4.14) | NR | Withdrawals resulted in switch over from combined treatment to ACT in 56 patients |

| Lidell et al., 2003, 22 days40 | Not clear, NR | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Withdrawals and lost to follow-up, 0 | NR | Arbitrary sample size used |

| Lechat et al., 2001 (RCT – FAACS), 0.84 years41 | Yes, centrally performed randomisation through fax transmission of the inclusion form | Yes | Yesc | No | Withdrawals,30; deaths, 6; lost to follow-up, 0 | 85 | Small sample size; premature termination of trial due to low event rate and recruitment rate |

| dGullov et al., 1998, (RCT – AFASAK II), 42 months42 | Yes, computerised randomisation | Nob | Yesc | Yes | Withdrawals, 112 (16.5%); dropout, 58 (8.6) | 0 | Premature termination after publication of SPAF III43 results |

| eStroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators, 1996 (RCT – SPAF III), 1.1 years43 | Yes, stratified by study centre and sequence could not be previewed | Nob | Not clearf | Yes | Withdrawals, 72 (6.9%); lost to follow-up: 0 | 56 | Multiple laboratories with reagents of varying sensitivities used for INR measurements; trial terminated in interim analysis (after mean follow-up of 1.1 years) as adjusted-dose warfarin was found superior to combined therapy; diabetes mellitus not considered as one of the stroke risk factors |

The remaining 24 articles50–73 consisted of 18 primary studies reporting non-randomised comparisons for the therapies of interest. Of these, 14 studies50–63 (in 14 articles) reported data from observational designs, both prospective50–55 and retrospective56–63 in nature. The remaining four studies in 10 articles64–73 were originally designed to assess the effectiveness of an anticoagulant without additional APT. However, these were included because they reported data on a subgroup of patients treated with combined anticoagulant plus APT. The characteristics of these studies and their quality assessment are reported in Tables 6 and 7, respectively.

| Author, date; study source; location; no. of centres | Study duration mean (SD, range); prospective/retrospective; no. of patients | ACT (INR or dose) + APT (dose), no. of patients | ACT only (INR or dose), no. of patients | Inclusion criteria; stroke risk | Age (years): mean (SD, range), percentage males |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hansen et al., 2010; registry; Denmark; nationwide registries63 | 3.3 (2.6) years; retrospective; n = 118,606 | Warfarina + aspirin,a 18,345 Warfarina + clopidogrel,a 1430 Warfarina + aspirina + clopidogrel,an = 1261 | Warfarin,an = 50,919 | Age ≥ 30 years, surviving first-time hospitalisation for primary or secondary diagnosis of AF, discharge prescription of warfarin, aspirin, clopidogrel | 73.7 (12.3); 52.4 |

| Stroke risk NR | |||||

| bBover et al. 2009 to n = 574; 4.2 years54 | 4.92 years; prospective; n = 574 | Acenocoumarol (INR 1.9–2.5) + triflusal (600 mg), n = 155 | Acenocoumarol (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 265 | Patients who had undergone at least 12 months of follow-up | 68.6; 45.6 |

| Acenocoumarol (INR 1.9–2.5) + triflusal (300 mg), n = 120 | |||||

| Acenocoumarol (INR 1.9–2.5) + aspirin (100 mg), n = 34 | |||||

| Lopes et al., 2009; cohort of RCT – APEX AMI; USA, Europe, Australia, NZ and Canada; 296 sites50 | 90 days; prospective; n = 276 | Warfarina + aspirina + clopidogrel,an = 37 | Warfarin,an = 59 | Age ≥ 18 years | 52–81 |

| Stroke risk highc | |||||

| Abdelhafiz and Wheeldon, 2008; anticoagulation clinic referrals; UK; one hospital51 | 19 (8.1, 1–31) months; prospective; n = 402 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirin,an = 8 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 394 | New NVAF patients referred by GP | 72.3; 55.72 |

| Stroke risks NR | |||||

| Amadeus Investigators, 2008, cohort of RCT – AMADEUS; Australia, Canada, Denmark France, Italy, New Zealand, Poland, Netherlands, UK and the USA; 165 centres72 | 311 days; prospective; n = 4576 | Idraparinux or adjusted-dose VKAd (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirin (≤ 100 mg), n = 971 | Idraparinux (2.5 mg), n = 2283; adjusted-dose VKAd (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 2293 | NVAF and indication for long-term anticoagulation ≥ 1 stroke risk factore | 70.1 (9.1); 66.5 |

| Ezekowitz et al., 2007; cohort of RCT – PETRO; Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the USA; 53 centres73 | 12 weeks, prospective; n = 502 | Dabigatran (50 mg b.i.d.) + aspirin (81 mg), n = 21 | Dabigatran (50 mg), n = 105 | Documented AF + CAD ≥ 1 stroke risk criteriaf | 70 (8.3); 81.9 |

| Dabigatran (50 mg b.i.d.) + aspirin (325 mg), n = 27 | Dabigatran (150 mg), n = 166 | ||||

| Dabigatran (150 mg b.i.d.) + aspirin (81 mg), n = 36 | Dabigatran (300 mg), n = 161 | ||||

| Dabigatran (150 mg b.i.d.) + aspirin (325 mg), n = 33 | |||||

| Dabigatran (300 mg b.i.d.) + aspirin (81 mg), n = 34 | |||||

| Dabigatran (300 mg b.i.d.) + aspirin (325 mg), n = 30 | |||||

| Suzuki et al., 2007; database of cardiovascular clinic; Japan; one centre56 | 1 year, retrospective; n = 667 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 1.6–2.6) + aspirin,an = 210 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 1.6–2.6), n = 457 | NVAF patients on warfarin Stroke risks NR | 68.4 (10.6); 66.6 |

| Burton et al., 2006; patient records from GPs; Scotland; 27 practices57 | 42 months; retrospective; n = 601 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirin,an = 18 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 309 | Patients with persistent AF | 77; 51.1 |

| Stroke risks NR | |||||

| Stenestrand et al., 2005; registry; Sweden; 72 hospitals58 | 1–8 years; retrospective; n = 5616 | OACa,g + aspirin,an = 479 | OAC,a,gn = 1369 | AF on the discharge ECG and AMI as final diagnosis; stroke risk highh | 77.7; 62.43 |

| SPORTIF V investigators, 2005; cohort of RCT – SPORTIF V; USA, Canada; 409 sites65 | 20 months (5.1, 0–31); prospective; n = 3992 | Ximelagatran (36 mg b.i.d.) + aspirin (< 100 mg), unclear | Ximelagatran (36 mg b.i.d.), n = 1960 | Persistent or paroxysmal NVAF patients; high riske | 72 (9.1); 69 |

| Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirin (≤ 100 mg), unclear | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 1962 | ||||

| SPORTIF III Investigators, 2003; cohort of RCT – SPORTIF III cohort; Europe, Asia, Australasia; 259 hospitals64 | 17.4 (4.1) months; prospective; n = 3407 | Ximelagatran (36 mg b.i.d.) + aspirin (< 100 mg), unclear | Ximelagatran (36 mg b.i.d.), n = 1704 | Persistent or paroxysmal NVAF; high riske | 70 (9); 69.1 |

| Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirin (≤ 100 mg), unclear | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 1703 | ||||

| Teitelbaum et al., 2008; pooled SPORTIF III and V cohort on warfarin; Asia, EU, Australasia, Canada and the USA; 409 sites and 259 hospitals66 | 16.6 (6.3) months; prospective; n = 7329 | Ximelagatran (36 mg b.i.d.) + aspirin (< 100 mg), unclear | Ximelagatran (36 mg b.i.d.), 3664 | Persistent or paroxysmal NVAF; high riske | |

| Warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirin (≤ 100 mg), unclear | Warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), 3665 | ||||

| Akins et al., 2007; pooled data RCTs – SPORTIF III and V; Asia, EU, Australasia, Canada and the USA; 409 sites and 259 hospitals67 | 16.6 (6.3) months; prospective; n = 1539 | Ximelagatran (36 mg b.i.d.) + aspirin (≤ 100 mg), n = 157 | Ximelagatran (36 mg b.i.d.), n = 629 | Persistent or paroxysmal NVAF | NR |

| Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirin (≤ 100 mg), n = 186 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 567 | Patients with prior stroke | |||

| White et al., 2007; pooled SPORTIF III and V of cohort on Warfarin, Asia, EU, Australasia, Canada and the USA; 409 sites and 259 hospitals68 | 16.6 (6.3) months; prospective; n = 3587 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirin (≤ 100 mg), n = 475 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (2.0–3.0), n = 3112 | Persistent or paroxysmal NVAF high riske | NR |

| Halperin, 2005; post hoc analysis RCT – SPORTIF III; Europe, Asia and Australasia; 259 hospitals71 | 17.4 (4.1) months; prospective; n = 3407 | Ximelagatran (36 mg b.i.d.) + aspirin (< 100 mg), n = 337 | Ximelagatran (36 mg b.i.d.), n = 1367 | Persistent or paroxysmal NVAF high riske | 70 (9); 69.1 |

| Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirin (≤ 100 mg), n = 290 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 1413 | ||||

| Flaker et al., 2006; pooled data RCT – SPORTIF III and V; Asia, EU, Australasia, Canada and the USA; 409 sites and 259 hospitals69 | 16.6 (6.3) months; prospective; n = 7304i | Ximelagatran (36 mg b.i.d.) + aspirin(≤ 100 mg), n = 531 | Ximelagatran (36 mg b.i.d.), n = 3120 | Persistent or paroxysmal NVAF high riska | NR |

| Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirin (≤ 100 mg), n = 481 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 3172 | ||||

| Douketis et al., 2006; pooled data RCT-SPORTIF III and V; Asia, EU, Australasia, Canada and the USA; 409 sites and 259 hospitals70 | 16.6 (6.3) months; prospective; n = 7329 | Ximelagatran (36 mg b.i.d.) + aspirin (< 100 mg), unclear | Ximelagatran (36 mg b.i.d.), n = 3664 | Persistent or paroxysmal NVAF high riske | NR |

| Warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirin (≤ 100 mg), unclear | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 3665 | ||||

| Johnson et al., 2005; hospital records; Australia; four hospitals59 | 28 months; retrospective; n = 228 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + APT,a,g NR | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 228 | Age ≥ 76 years, warfarin at admission and discharge diagnosis of AF | 81.1 (76–94); 41.7 |

| Stroke risk NR | |||||

| Blich et al., 2004; primary physician clinics; Israel; 23 clinics61 | 7.2 (5.2, 2–40) years; retrospective; n = 506 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirin (100 mg), NR | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), NR | Chronic or recurrent paroxysmal NVAF (> 48 hour duration) diagnosed ≥ 2 yearsStroke risk NR | 75.7 (8.08, 35–100); 55.7 |

| Shireman et al., 2004, database of inpatients discharged from acute-care hospitals; USA; countrywide60 | 90 days or 180 days; retrospective; n = 10,093 | Warfarin a + aspirin/clopidogrel/ticlopidine/dual APT,an = 1962 | Warfarin,an = 8131 | Age ≥ 65 yearsWarfarin on discharge; AF diagnosis on discharge | 77.2; 49.6 |

| Stroke risk NR | |||||

| Klein et al., 2003; cohort of RCT – ACUTE; international sites; 7062 | 8 weeks; prospective; n = 1222 | Warfarin/heparin (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirin,an = 560 | Warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 444 | Age > 18 years, AF of > 2 days' duration, candidates for cardioversion, patients with atrial flutter who have a history of AF | 65.1; 66.67 |

| Heparin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 524 | |||||

| Warfarin + heparin adjusted dose (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 249 | Stroke risk NR | ||||

| Hart et al., 2000; cohort of SPAF III; USA and Canada; 20 sites55 | 2 years; prospective; n = 2012 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 1.2–1.5) + aspirin (325 mg/day), n = 81 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 91 | High risk of strokej | 69 (10); 72 |

| Toda et al., 1998; hospitalised patients; Japan; one hospital52 | 7.2 (5.1, 1–23) years; retrospective; n = 288 | Warfarina + APT,a,gn = 30 | Warfarin alone,an = 10 | Chronic or paroxysmal NVAF; stroke risk NR | 54.6 (13.3, 8–82); 59.0 |

| Albers et al., 1996; hospitalised patient records; USA; six hospitals53 | NR; retrospective, n = 309 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirina at admission, n = 9 | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) on admission, n = 62 | AF documented on admission or during hospitalization | 71.6 (12.7); 51 |

| Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) + aspirina at discharge, n = 22 | Warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) at discharge, n = 83 | Stroke risk NR |

| Study, total no., mean follow-up (SD) | Method of outcome measurement | Blinding of assessors | Outcome definitions clearly explained? | Indications of APT in the study | Time of APT employment | Which parts of the study were prospective?a | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hansen et al., 2010, n = 118,606, 3.3 (2.6) years63 | Events identified from registry through ICD-10 coded diagnosesb | Yes | Yes | Physician's discretion | Unclear | All stages retrospective | Previous warfarin/aspirin/clopidogrel treatment: 12.8%/16.7%/1.0%, respectively |

| Bover et al., 2009, n = 574, 4.2 years54 | Hospital follow-up and INR measurement in laboratories | No | Yes | Physician's discretion or patient preference | During follow-up | All stages prospective | 70% of patients recruited from NASPEAF cohort; patients on combined therapy reported at a higher risk of strokec |

| Lopes et al., 2009, n = 276, 90 days50 | Telephone contact at 30 and 90 days | Unclear | Yes | NR | At discharge | All stages prospective | Analysis of patients enrolled in another trial91 to compare outcomes in patients with new-onset AF vs those diagnosed with AF at discharge |

| Abdelhafiz and Wheeldon, 2008, n = 402, 19 months51 | Telephone interview every 4–6 weeks with medical notes review | Yes | Yes | Physician's discretion and presence of IHD | NR | All stages prospective | |

| Amadeus Investigators, 2008, n = 4576, 339 days72 | Follow-up at week 1, 2, 6, 13 and every 3 months thereafter, or when event occurred | Yes | Yes | Physician's discretion | Unclear | All stages prospective | Trial stopped after randomisation because of excessive bleeding in patients on idraparinux; 76% of patients reported on VKA before entry into trial |

| Ezekowitz et al., 2007 (RCT – PETRO), n = 502, 22 weeks73 | Outpatient follow-up at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks after randomisation (to dabigatran or warfarin) | Yes | Yes | NR | During the study | All stages prospective | After entry of approximately half of the patients, the requirement for CAD was removed to facilitate recruitment; all patients treated with VKA for ≥ 8 weeks prior to inclusion |

| Suzuki et al., 2007, n = 667, 1 year56 | Database review | Yes | Yes | Other cardiovascular diseases | Unclear | All stages retrospective | Study conducted on Japanese AF patients attending a hospital for cardiovascular diseases |

| Burton et al., 2006, n = 601, 42 months57 | Record review and patient contact through letters | Yes | Yes | Physician's discretion | Any time during follow-up | All stages retrospective | |

| Stenestrand et al., 2005, n = 5616, 1–8 years58 | Review of hospital records | Yes | No | Physician's discretion | At discharge | All stages retrospective | Name of OAC not specified in the study, 18% on ACT before admission |

| Flaker et al., 2006; n = 7304, 16.6 months69 | Stroke assessment every 6 months and after an event | Yes | Yes | Age ≥ 65 years with CAD with or without diabetes mellitus | Unclear | All stages prospective | Significant baseline differences in those receiving ACT + APT and ACT alone; 73.4% received anticoagulation and 20.7% were taking aspirin prior to study entry |

| Johnson et al., 2005, n = 228, 28 months59 | Patient contacted on telephone and questionnaires when event occurredd | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | All prospective | 44.3% on warfarin (n = 101/228) for varying lengths of time before their index admission |

| Blich et al., 2004, n = 506, 7.2 years61 | Review of patient records and interview with patient's GP | Yes | No | Physician's discretion | At diagnosis, during follow-up, or before TE event | All stages retrospective | 26.9% of patients receiving warfarin at diagnosis, 6.5% were young or had no stroke risk factors |

| Shireman et al., 2004, n = 10,093, 180 days60 | Review of Medicare hospital claims for events with ICD-9-CM coding | Yes | Yes | Presence of CHD | After discharge | All stages retrospective | |

| Klein et al., 2003, RCT – ACUTE cohort, n = 1222, 8 weeks62 | Weekly INR testing and TEE at 4 weeks | Unclear | Yes | NR | At enrolment | All stages prospective | No. of patients on ACT or ACT + APT not reported |

| No indication if patients took aspirin throughout the study period | |||||||

| Hart et al., 2000, n = 2012, 2 years55 | Clinic follow-up every 3–6 months | unclear | Yes | Randomisede | During follow-up | All stages prospective | Incomplete information on only a few patients on combined therapy and ACT alone reported from authors of the randomised study43 |

| Toda et al., 1998; n = 288, 7.2 years52 | Review of patient records, or patient questionnaires, supplemented with GP contact | Yes | Yes | Physician's discretion | At baseline and before event | Outcome assessment | Study conducted on hospitalised Japanese patients with AF aged 8–82 years |

| Cranial CT scan and/or angiography used to assess outcomes | |||||||

| Albers et al.,1996; n = 30953 | Chart reviews performed by HCPs in consultation with physician | Yes | No | Physician's discretion | Admission and discharge | Outcome assessment – prospective | 18% had no risk factors for stroke and 44% had contraindications for ACT on admission |

| 23.6% took warfarin before admission | |||||||

| 77% white population |

Of the included studies, three RCTs40,42,43 and 14 other studies reporting non-randomised comparisons summarised data for warfarin therapy in different regimes plus an APT compared with warfarin. 50–53,55–57,59–65 One RCT39 and one non-randomised study54 reported data on acenocoumarol (Sinthrome®, Alliance) plus an APT compared with acenocoumarol alone. The remaining one RCT41 reported data on fluindione plus aspirin compared with fluindione plus placebo. 41 One study72 reporting non-randomised comparisons used idraparinux, and one used dabigatran (Pradaxa®, Boehringer Ingelheim) as anticoagulant agent,73 whereas two studies64,65 reported data on ximelagatran plus warfarin compared with ximelagatran alone. Doses of APT varied between studies.

Of the included RCTs, three39,42,43 used therapies in an open-label fashion, whereas this information was not clear in one. 40 Assessors were blinded in three39,41,42 out of five RCTs,39–43 and intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was undertaken in three studies. 40,42,43 However, two of these studies were terminated prematurely. 41,42 The sample size varied from 43 to 1209 participants in the RCTs,39,40 with variable periods of follow-up (22 days40 to 42 months42).

Of the studies reporting non-randomised comparisons, six were retrospective,56–58,60–63 and the time of APT use varied between the studies. The majority of these studies consisted of a retrospective review of medical records where prior knowledge of allocation of therapy was not possible. 50–53,56–61,63 However, all but five studies50,55,59,62,73 clearly reported the criteria by which APT was used in the study. Of note is the study by Ezekowitz et al. 73 [PETRO (Dabigatran with or without concomitant aspirin compared with warfarin alone in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation)], in which it was difficult to identify if APT was used at random or indicated in a subgroup. For this reason, the study is classified as a non-randomised comparison of ACT plus APT and ACT only.

Between-study differences

The subsequent sections will report the event rates for each outcome. Methodological heterogeneity exists between the included studies that may explain any differences in the event rates reported. Rather than repeat these methodological differences for each and every outcome of interest, the reader will be referred to the following discussion of these differences. Where specific differences in the methodology between the included studies are apparent, which are important to highlight and/or only pertinent to that particular outcome, these differences will be specified under that outcome.

The differences in the event rates reported by the included studies may reflect differences in the population risk profile, with some studies including high-risk AF populations (three RCTS39,41,43 and seven non-randomised comparisons50,55,58,64,65,72,73) and/or intermediate-risk patients with AF (one RCT39), whereas other studies did not report the risk profile of included patients (two RCTs40,42) and 11 other non-randomised comparisons. 51–54,56,57,59–63

The sample size also varied considerably between included studies, from 43 participants in one RCT40 to 118,606 in a large non-randomised comparison. 63 As a result of the overall sample size, the number of patients receiving combined ACT and APT and the comparator also varied considerably, with only 34 patients receiving the combination therapy in Bover et al. ,54 between 21 and 36 patients receiving the various permutations of ACT plus APT in the PETRO study,73 and 76 patients receiving combination therapy and 81 receiving ACT alone in the FFAACS (Fluindione, Fibrillation Auriculaire, Aspirin et Contraste Spontané) trial,41 which will have influenced the reported event rates for each outcome.

Further, the included studies comprise both randomised and non-randomised data. Among non-randomised comparisons there is the potential for confounding by indication with the use of APT, as this was often given at the discretion of the treating physician, with patients at high risk of a vascular event and/or those less likely to bleed receiving combination therapy. Indeed, Bover et al. 54 reported that the patients receiving combined therapy were at a higher risk of stroke than those who were administered adjusted-dose acenocoumarol (INR 2.0–3.0) alone. Moreover, the number of patients with previous experience of an anticoagulant agent or APT in each study may also affect the event rate, for example patients who can tolerate either ACT or APT will continue on such therapy and therefore may be less likely to bleed on treatment than those who experience a bleed and therefore discontinue such therapy – ‘ATT survivor’.

The included studies also compared different types of anticoagulant and APT in various permutations, which makes comparison of event rates across studies using different interventions and comparators difficult. Studies compared a VKA, either warfarin,40,42,43,50–53,55–57,63–65,72 acenocoumarol,39,54 or fluindione41 in combination with either aspirin41–43,50,51,53–58,60–65,72,73 or other antiplatelet agents, such as triflusal,39,54 clopidogrel,40,63 or dual APT of aspirin plus clopidogrel. 63 Furthermore, two other studies compared an ODTI (anticoagulant) – either ximelagatran64,65 or dabigatran73 – in combination with aspirin (in different doses) or alone.

Among those studies comparing VKAs plus aspirin to a VKA alone,39–43,50–54,54–57,59–65,67,69,72 different VKA regimes were used in the combination therapy arm, either fixed dose (1.25 mg42) or adjusted dose to maintain a target INR range [e.g. INR 1.2–1.5,43 INR 2.0–3.0,40,64,65 INR 1.9–2.5,54 INR 2.0–2.6,41 INR 1.4–2.4 (high risk) and INR 1.25–2.0 (intermediate risk)39]. Of the included RCTs, therapies were administered in either an open-label42,43 or in a double-blind fashion. 41 In addition, the APT also varied (aspirin, triflusal, clopidogrel, and aspirin plus clopidogrel). In the studies reporting randomised comparisons, aspirin was utilised in different doses (300 mg,42 325 mg43 and 100 mg41), and also in non-randomised comparisons (≤ 100 mg,64,65,72 100 mg,61 81 or 325 mg73 and dose not specified in others51,53,56–58,62). Similarly, other antiplatelets were used in different doses such as triflusal (600 mg,39 600 mg and 300 mg54), clopidogrel (75 mg:40 dose not specified63) and dual APT of aspirin plus clopidogrel (dose not specified50,63), which makes direct comparison between studies difficult.

In addition, some randomised studies used the same target INR range in both the intervention and comparator arm (RCTs40,41 besides non-randomised comparisons54,51,53, 56,57,59,61,62,64,65,72), whereas others did not (RCTs39,42,43 and non-randomised comparisons54,55), again making difficult the direct comparison between the intervention and comparator arms within the studies. However, the majority of studies did use the standard therapeutic INR target of 2.0–3.0 in the comparator arm40,41,51,53–55,57,59,61,62,64,65,72 whereas others did not, although only four studies39,40,43,54 reported time in therapeutic range (TTR).

There were also differences across studies in the definitions of the outcomes of interest used and these differences are discussed, where relevant, under each outcome.

Furthermore, the considerable variation in the length of follow-up (e.g. 22 days40 to 4.92 years54) in each of the included studies may have influenced event rates. The combination of a short duration of follow-up for outcomes that are not particularly common together with a small sample size may have resulted in studies being underpowered. Of note the AFASAK II study (Second Copenhagen Atrial Fibrillation, Aspirin and Anticoagulation Study)42 was prematurely terminated when results of the SAAF III (Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation) trial,43 demonstrating the superiority of adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) alone, over combination of adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 1.2–2.5) and aspirin 325 mg in preventing stroke or SE, were published. Further, the FFAACS study41 was also terminated early due to poor recruitment. It should also be noted, that Bover et al. 54 was a non-randomised comparison that followed up of a proportion of the patients enrolled in the NASPEAF (National Study for Prevention of Embolism in Atrial Fibrillation) study39 (although it is not clear how many patients from NASPEAF were included in Bover et al. , within each arm of the latter study), with addition of newly recruited participants, over a longer period of time.

Moreover, the temporal changes in the management of AF over the last 20 years may have influenced the event rate reported in studies enrolling patients in the early 1990s (AFASAK II42 and SPAF III43) compared with those from 2000 onwards. 39,40,41,54,63,64,65,73

Outcomes

Not all of the studies measured or reported information for the primary and secondary outcomes of the review.

Table 8 details the outcomes reported in each study. Not surprisingly, bleeding, stroke and/or mortality-related outcomes were the most frequently reported. The time in therapeutic INR range was infrequently measured. To some extent this might be due to the nature of the anticoagulant agents used in some studies and thus the absence of a need for this outcome. Patient quality of life, in-stent thrombosis and revascularisation procedures were not reported in any of the studies.

| Author, year (name of study) | Outcomes | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome measures | Secondary outcome measures | ||||||||||||

| Stroke–anya | TIA | SE | Stroke + SEa | AMI | In-stent thrombosis | Death – vascular | Death – all cause | Bleeding | Quality of life | Adverse eventsb | Revascularisation procedures (e.g. PCI) | Percentage time in INR range | |

| Randomised comparisonsc | |||||||||||||

| Pérez-Gómez et al., 2004 (RCT – NASPEAF)39 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Pérez-Gómez et al., 2007 (RCT – NASPEAF)44 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pérez-Gómez et al., 2006 (RCT – NASPEAF)45 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Pérez-Gómez et al., 2006 (RCT – NASPEAF)46 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Lidell et al., 2003,40 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Lechat et al., 2001 (RCT – FFAACS)41 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Gullov et al., 1998, (RCT – AFASAK II)42 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Gullov et al., 1999, (RCT – AFASAK II review)47 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| SPAF investigators, 1996, (RCT – SPAF III)43 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Hart et al., 2000 (SPAF I, II, III pooled)48 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Blackshear et al., 1999 (RCT – SPAF-III)49 | |||||||||||||

| Non-randomised comparisons | |||||||||||||

| dHansen et al., 201063 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| d,eBover et al., 200954 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Lopes et al., 200950 | ? | ||||||||||||

| Abdelhafiz and Wheeldon, 200851 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Amadeus Investigators, 200872 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| dEzekowitz et al., 2007 (RCT – PETRO)73 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Suzuki et al., 200756 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Burton et al., 200657 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Stenestrand et al., 200558 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| SPORTIF V investigators, 200565 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| SPORTIF III Investigators, 200364 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Teitelbaum et al., 200866 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| d Akins et al., 2007 6 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| White HD et al., 2007 68 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Halperin, 2005 71 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| dFlaker et al., 200669 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Douketis et al., 200670 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Johnson et al., 200559 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Blich et al., 200461 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Shireman et al., 200460 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Klein et al., 200362 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| fHart et al., 200055 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Toda et al., 199852 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Albers et al., 199653 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

Methodological issues

Twenty-three studies in 35 articles39–73 reported the outcomes of interest for combined anticoagulant plus APT compared with ACT alone in patients with AF. Of these, 5 studies in 11 articles39–49 reported randomised comparisons, whereas 18 studies in 24 articles50–73 reported non-randomised comparisons. The characteristics of these studies have been reported previously in Tables 4 and 6.

Not all of the included studies provided non-randomised data that added information to the robust randomised data. Data were extracted from these studies, but not reported in this review. Reasons for non-inclusion of study data from such studies have been reported in Appendix 7. A few studies did not report the number of events50,56,62,68,70,72 or did not clearly report the number of participants in each therapy group,57,58,61,64,65 whereas a few other publications reported duplicate data from included primary studies. 44–47,49,71 A few studies reported non-randomised data that did not add any new information to the data available from other studies, either because of a very small sample size51 or because they did not specify the name of the APT in the combination anticoagulation plus antiplatelet arm. 52,59 Other studies that furnished complete and tangible data were included.

An example of such studies are the Stroke Prevention using an ORal Thrombin Inhibitor in atrial Fibrillation (SPORTIF) studies. 64–71 The original articles of SPORTIF III64 and SPORTIF V65 did not specify the number of events and number of participants in the interventions of interest (anticoagulant plus antiplatelet and anticoagulant alone). Six articles66–71 reported pooled post hoc analyses of these two studies. 64,65 Of these, two pooled analyses, by White et al. ,68 and Douketis et al. ,70 did not report data on the number of events or the number of participants for either intervention group; however, this information was reported in pooled analyses by Flaker et al. 69 and Akins et al. 67 Two other publications66,71 reported data for stroke, or stroke and bleeding outcomes, which were also reported in pooled analyses. 67,69 Flaker et al. 69 reported data on bleeding, mortality, stroke, and combined stroke and SE events, with detailed information on the number of events and participants in the SPORTIF cohorts. Therefore, this pooled analysis was reported in the review. Akins et al. 67 furnished data for bleeding, stroke and SE events specifically for patients with previous embolic events in the SPORTIF trials. Therefore, this study consisting of a population who were at a high risk of stroke was reported in the review.

Primary outcomes of the review

Outcome 1: stroke

Thirteen articles yielded outcome data for stroke. 42–45,47–50,54,55,63,66,69 Of these, three studies in seven articles42–45,47–49 reported randomised comparisons. The findings of these are reported in Table 9. The remaining five articles50,54,55,63,66,69 reported non-randomised comparisons, of which four were primary studies,50,54,55,63 and two were secondary analyses66,69 of the SPORTIF III and SPORTIF V studies. Table 10 presents the findings of these studies.

| Author, year, study name | Stroke risk, follow-up (mean) | ACT + APT, n | No. of events/participants in ACT + APT arm (%) | ACT (alone or ACT + placebo), n | No. of events/total participants in ACT arm (%) | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aPérez-Gómez et al., 2004, RCT – NASPEAF 39 | High risk,b 2.95 years | Adjusted-dose acenocoumarol (1.4–2.4) + triflusal (600 mg), n = 223 | Non-fatal: 6/223 (2.7) | Adjusted-dose acenocoumarol (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 247 | Non-fatal: 6/247 (2.4) | 1.11 (0.36 to 3.38) |

| Intermediate risk,c 2.6 yearsd | Adjusted-dose acenocoumarol (1.25–2.0) + triflusal (600 mg), n = 222 | Non-fatal: 3/222 (1.4) | Adjusted-dose acenocoumarol (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 232 | Non-fatal: 3/232 (1.3) | 1.05 (0.21 to 5.12) | |

| eGullov et al., 1998 RCT – AFASAK II42 | Risk NR, 3.5 years | Fixed-dose warfarin (1.25 mg) + aspirin (300 mg), n = 171 | All: 11/171 (6.4) | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 170 | All: 10/170 (5.9) | 1.09 (0.48 to 2.51) |

| Non-infarct: 3/171 (1.8) | Non-infarct: 3/170 (1.8) | 0.99 (0.20 to 4.86) | ||||

| Minor: 4/171 (2.3) | Minor: 0/170 (0) | 8.95 (0.49 to 164.92) | ||||

| Disabling: 4/171 (2.3) | Disabling: 3/170 (1.8) | 1.33 (0.30 to 5.83) | ||||

| Fatal: 0/171 (0) | Fatal: 0/170 (0) | Not estimable | ||||

| Haemorrhagic: 0/171 (0) | Haemorrhagic: 1/170 (0.6) | 0.33 (0.01 to 8.08) | ||||

| Ischaemic: 8/171 (4.7) | Ischaemic: 3/170 (1.8) | 2.65 (0.72 to 9.82) | ||||

| Non disabling: 3/171 (1.8) | Non-disabling: 4/170 (2.4) | 0.75 (0.17 to 3.28) | ||||

| Fixed-dose warfarin (1.25 mg), n = 167 | All: 13/167 (7.8) | 0.83 (0.38 to 1.79) | ||||

| Non infarct: 6/167 (3.6) | 0.49 (0.12 to 1.92) | |||||

| Minor: 3/167 (1.8) | 1.30 (0.30 to 5.73) | |||||

| Disabling: 2/167 (1.2) | 1.95 (0.36 to 10.52) | |||||

| Fatal: 2/167 (1.2) | 0.20 (0.01 to 4.04) | |||||

| Haemorrhagic: 0/167 (0) | Not estimable | |||||

| Ischaemic: 5/167 (2.9) | 1.56 (0.52 to 4.68) | |||||

| Non-disabling: 4/167 (2.4) | 0.73 (0.17 to 3.22) | |||||

| fSPAF investigators to 1996 RCT – SPAF43 | High risk,g 1.1 years | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 1.2–1.5) + aspirin (325 mg), n = 521 | Disabling:d 31/521 (5.9) | Adjusted-dose warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0), n = 523 | Disabling:d 10/523 (1.9) | 2.83 (1.44 to 5.57) |

| Ischaemic: 43/521 (8.3) | Ischaemic: 11/523 (2.1) | 3.92 (2.05 to 7.52) | ||||

| Ischaemic – fatal: 5/521 (0.9) | Ischaemic – fatal: 1/523 (0.2) | 5.02 (0.59 to 42.81) |