Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/167/01. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The draft report began editorial review in May 2019 and was accepted for publication in December 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Athimalaipet V Ramanan has received speaker fees/honoraria/consulting fees from Abbvie Inc. (North Chicago, IL, USA), Union Chimique Belge (Brussels, Belgium), Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA), Novartis (Basel, Switzerland), Roche Holding AG (Basel, Switzerland) and Bristol-Myers Squibb (New York, NY, USA). Paula R Williamson reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme outside the submitted work and involvement with a clinical trials unit funded by NIHR.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Jones et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

In the UK, juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common inflammatory disorder in childhood, affecting 10 : 100,000 children and young people (CYP) each year, with a population prevalence of around 1 : 1000. 1 JIA is a set of related disorders, all including chronic arthritis, with or without other, extra-articular, features, and with no other associated diagnoses, such as infection or other autoimmune multisystem disorders. It is difficult to assess arthritis in JIA, as active arthritis causes several symptoms or clinical signs. Pain in the joint is not always present in active JIA and can also be caused by many non-inflammatory conditions. Signs of arthritis can include joint swelling, tenderness, warmth and restriction of movement, and can be seen in varying degrees and combinations. However, some joints, such as spinal joints and the hips, are enclosed in bone or deeply hidden from direct touch, making it impossible to feel tenderness and swelling in these joints. Similarly, restriction of movement can be due to both acute inflammation and later joint damage.

The natural untreated outcomes of JIA are serious and disabling, but with modern treatment regimens, including biologic drugs, the prognosis has improved dramatically. However, there is no sustainably effective treatment or cure and some patients, and some individual joints, are still relatively resistant to treatment with available drugs. In addition, the ability to withdraw treatment fully without subsequent flare is possible in only about one-third of cases. 2,3

For these reasons, arthritis activity is measured using a combination of clinical variables known as a core outcome set (COS). These are variously composed of the Physician’s Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PGA), the number of active joints (both swollen and/or tender), the number of joints with limited movement, physical functional ability [measured with the validated Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (CHAQ)], self- and parent-reported disease activity [measured by the Patient/Parent Assessment of Global Assessment (Pa/PtGA)] and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). These can be combined into the American College of Rheumatology Paediatric (ACR Pedi) responses4 or the Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (JADAS). 5 The ACR Pedi responses define relative symptom improvement and include the ACR Pedi 30%, the ACR Pedi 50%, the ACR Pedi 70% and the ACR Pedi 90%. To achieve the ACR Pedi 30%, the patient must exhibit improvement from baseline of at least 30% in three of any six variables in the COS, with no more than one of the remaining variables worsening by > 30%. ACR Pedi 50%, ACR Pedi 70% and ACR Pedi 90% improvement criteria are defined in the same way, but require improvements of 50%, 70% and 90%, respectively. These improvement measures have been used in clinical trials, but the considerable complexity of calculating improvement makes use of these measures difficult in real-time clinical practice. 6

Activity can also be measured by the JADAS using 71 joints, 27 joints or a maximum score of the first 10 active joints. The score is the summation of the active joint count, the PGA and the Pa/PtGA, with the ESR. 5 More recently, the clinical Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (cJADAS), without ESR, has been shown to be accurate and is simpler to score, and can be assigned in clinic at each visit. 6

The Childhood Arthritis Prospective Study (CAPS) (www.caps-childhoodarthritisprospectivestudy.co.uk; accessed 5 June 2020) is the largest incident cohort study of JIA worldwide, studying the management and outcome of JIA, and has delivered one publication on the health economics of treating arthritis7 among many clinical publications from the cohort. This health economic study found that the costs of clinician time are partly a reflection of the unpredictable nature of the inflammatory response and the clinical flares of arthritis, and the need for urgent reviews and treatment intensification.

Corticosteroids (CSs) have been used in the treatment of JIA since the 1950s. 8 It is well known that CSs can transform disease activity in JIA and that the majority of JIA patients receive CSs during their care. 9 However, the widespread clinical practice of using high-dose CSs for a limited period, to downgrade the inflammatory response with the aim of inducing initial remission, is not evidence based. CSs have been used in the treatment of JIA both at initial presentation and at subsequent disease flares, and they are also sometimes used to maintain long-term disease remission. 7 The intention of clinicians is generally to spare the long-term use of CSs, although actual practice differs, as demonstrated by the CAPS disease cohort data,7 and, in reality, CSs are still a very common treatment in JIA.

Minimising the perpetuation of chronic disease and the prevention of long-term damage from inflammatory presentations and disease flares in JIA are associated with treatment inductions, which cause early and complete remission. 10 Although disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), especially methotrexate (MTX), are well established in the treatment of JIA, they are slow to act if used alone. This can leave the inflammatory process essentially unchecked for the 6–12 weeks11 that are required for MTX to work, with associated morbidity and amplification of the inflammatory response from under treatment. Biologic drugs may be highly effective in inducing remission in early disease, but there are no guidelines that include immediate use of these agents at diagnosis or as intermittent-pulsed treatments to control flares. This is because of a combination of the cost of the biologic drugs and the possible long-term, as yet unknown, safety issues. The reasonable reserving of biologic drugs to second-line treatment is well established in JIA. In adult rheumatoid arthritis (RA), treatment with additional disease-modifying agents, or increased doses of existing drugs added at frequent clinic review until remission is established, is known as treating to target. However, all such regimens include the use of CSs. 12–15 Increasingly, UK and international centres treating JIA are also adopting this treat-to target approach. 16

Routes of corticosteroid administration

Corticosteroids are currently administered by four routes: (1) orally, (2) by intravenous (IV) infusion, (3) by intramuscular (IM) injection or (4) by intra-articular injection; however, the only informative evidence base of effectiveness and efficacy in JIA is for intra-articular CS injections (IACIs). However, the above routes, either alone or in combination, are widely used on the basis that the initial systemic CS treatments suppress the severity of the inflammatory response and reduce the number of active joints that will eventually require IACIs. Many patients receive CSs by more than one route in a single flare, but there is no robust evidence base to guide the decision as to which route or dose to use.

In theory, and in clinical practice, there is no reason to use different routes of administration of CSs in new or flaring patients or in patients with different JIA disease subtypes. The fact that IACIs are widely used is, in part, because the oligoarticular subtype of JIA, in which four or fewer joints are involved, is the most common subtype. The more localised nature of the arthritis lends itself to IACIs, and it is thought that localised treatment may be associated with fewer systemic CS side effects and be more effective in suppressing local inflammation. However, there have been no comparative trials to test this hypothesis. In addition, disease flares, irrespective of subtype, may also be limited to a few joints at any time, making IACIs an attractive initial treatment in this case also.

The CAPS17 treatment data is invaluable for its real-world prospective information on the use of CS in JIA. Six UK centres recruited a total of 1477 new patients with JIA, of whom 759 were followed up for 3 years. Among this group, 340 (45%) received oral, IM or IV CSs. However, very few patients were treated with IM injections (n = 8) compared with oral CSs (n = 265), IV CSs (n = 191) or IACIs (n = 603) (noting that some patients received treatment by more than one route) (Professor Wendy Thomson, Deputy Director Arthritis Research UK Centre for Genetics and Genomics, University of Manchester, 2017, personal communication).

From discussions with physicians in specialty groups and international study groups we know that routes and doses of CSs in clinical practice are based on physician preference. For example, individual physicians may administer high-dose methylprednisolone IV infusions for 1–3 consecutive days on 1 or 2 consecutive weeks. Patients may then be changed to oral CSs, or IACIs may be used to treat individual joints that remain active. By contrast, in adult RA, treatment flares are often treated with IM injections of CSs. 18 In paediatric practice, some centres use the IM route only infrequently, but the reasons for this are not clear. Clinicians who use this route anecdotally describe good treatment responses and excellent patient acceptability, but the extent of such practice is currently not known. It is possible that the IM route is considered too painful for use in children, but this has not been formally studied. On the other hand, the IM route could provide better long-term remission, and is potentially the cheapest route with the lowest CS adverse event burden, but this has not been studied in JIA. Given these uncertainties, this study addresses the acceptability of including the IM injection modality in a final trial protocol.

We believe that it is important to understand why and how clinicians and patients together choose to use or, even more importantly, to reject different modalities of CS treatment in JIA. Given that there is no firm evidence base for CS use, that some CS delivery methods may be more costly or difficult to use than others and that CS doses vary greatly, it appears that the factors influencing choice may be linked to individual practice and experience, as well as to the availability of treatment facilities. However, there are pros and cons in terms of delivery experience, as well as risks and benefits for each type of treatment, and without an evidence base on efficacy and duration of effect of each modality it is not possible to make this a fully informed decision. Even if simple non-inferiority of one route of CS administration were demonstrated, other factors, such as acceptability, speed of delivery, cost of treatment and duration of effect, could justify the choice of an alternative route.

Intra-articular corticosteroid injections are also frequently used to control individual joint disease in patients with active JIA, with single or multiple injections being administered in a single treatment session, but the extent to which CS administered by this method is functioning as a de facto CS depot, affecting distant joints as well as acting directly on the injected joints, is not known. The IM injection depot route is considered to work in exactly this way. In some patients, multiple IACIs are administered repeatedly without the use of additional DMARDs. Upwards of 20 joints are injected at one time in some JIA patients. 19 IACIs are sometimes administered with conscious sedation (inhaled nitrous oxide), but multiple injections need to administered in theatre under general anaesthetic (GA), often with radiographic or ultrasound guidance. In some centres with poor availability of theatre space, this can lead to a long waiting list for treatment.

It is not known whether the best route to achieve long-term remission is the direct intra-articular route, which can be used in any inflamed joint, or IV infusion of a larger ‘pulse’ dose (rapidly effective but possibly with a shorter duration of action). Oral administration of a moderate dose may result in a smoother CS profile, but it is not known if the response is complete or if this route results in more long-term side effects (as the cumulative dose is nearly always higher). On the other hand, the high-dose IV infusion can produce immediate systemic side effects that may be more severe than those associated with lower-dose oral CSs. IM injection is intended to provide a slow-release depot of CS. IM injection, in contrast to IACI does not necessitate direct joint needling and as a result does not increase the volume/pressure of the joint cavity or lead to subcutaneous fat atrophy. In this study we elicited the views of patients and parents on these different delivery routes and investigated real-world data on the choice of the CS-dosing regimen used in different delivery routes.

It is not known if some subtypes of JIA respond better to some routes of administration than to others, or if the duration of action of CSs, in terms of suppression of inflammation, differs between routes. There is no evidence regarding the relative side effect profile associated with each route, considering the balance of the harmful effects of inflammation on the health of the joint and the well-being of the patients. This is especially pertinent given the evidence of the impact of JIA on general well-being. 20

Standardisation of JIA treatment could reduce the time taken to achieve disease control, which would in turn reduce the time to induction of remission. As is to be expected given the lack of an evidence base, JIA treatment rates and the choice of CS treatment regimen vary greatly. Consensus guidelines for the treatment of JIA are being produced by the European Union (EU)-funded Single Hub and Access point for paediatric Rheumatology in Europe (SHARE)21 but do not include the CS regimens to be used. The variability in CS regimens causes confusion and complicates analyses of outcome data from other studies, such as the biologic drug long-term safety registry studies (for example Kearsley-Fleet et al. ). 22

To our knowledge, there have been no studies of patient preference in the choice of CS administration route. There have not been any head-to-head studies of different routes of CS administration in induction regimens to assess non-inferiority in terms of efficacy, patient acceptability, pharmacokinetic (PK)/pharmacodynamic (PD) variables, overall CS burden and the frequency of CS-related side effects. In this study we asked patients, their families and health-care professionals (HCPs) about their experiences of treatment with the various modalities and their views on a possible drug trial.

Undertaking a definitive randomised controlled trial (RCT) is inherently costly. Therefore, undertaking a definitive study in an area where national practice is so varied, where stakeholder acceptability is unknown and without an agreed primary outcome poses a significant and unnecessary risk. Designing a trial to explore different routes of CS administration in patients with JIA is complicated by a number of factors, including differences in JIA subtype, differences in joints affected, whether initially or during flares, differences in disease severity, the wide variety of treatment choices and uncertainty regarding the willingness of units or patients to embark on a trial of well-established treatments. This study provides much needed information that will help to guide the design of any future such trial.

The Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme Commissioning Board concluded that a well-run feasibility study of CS induction in JIA is needed to justify a definitive trial. For example, the number of patients in each group may prove to be too small to justify a full trial and the number of treatment combinations and JIA subtypes must be clearly rationalised, something that we achieved using a consensus process.

To our knowledge, there have been no previous studies of patient preference in the choice of CS administration routes. Nor to our knowledge have there been any head-to-head studies of different routes of CS administration in induction regimens to assess non-inferiority in terms of efficacy, patient acceptability, PK/PD variables, overall CS burden and the frequency of CS-related side effects. In this study we asked patients, their families and HCPs about their experiences of treatment with the various modalities and their views on a possible drug trial.

Compliance with Health Technology Assessment commissioned brief

The HTA commissioned brief arose from the important clinical question ‘What is the best initial treatment to induce remission of JIA and which treatment should be used to manage significant disease flares?’.

A literature search and horizon scan for this application found only four interventional studies of CSs in JIA, all relating to IACI, only two of which were RCTs. 23,24 We identified no interventional studies and only 13 observational studies of other forms of CS treatment, with two prospective studies23,24 examining the current management of JIA, including oral CSs. Damage in JIA is the result of joint erosions that lead to cartilage loss and bony eburnation with resultant pain, functional disability and an increased need for early joint replacement. 25 Disorders of local bone growth and restriction of overall growth in height are frequent in inadequately controlled disease. 26,27 CSs would be used as part of most treatment to target or treatment regimens with tight control of inflammation in adults who have RA; however, in a relatively recent evidence summary it was concluded that there is a ‘near complete lack of published evidence’ for the use of systemic glucocorticoids in JIA. 28 In addition, Dueckers et al. 29 state that ‘there are no controlled trials and no standardised therapeutic regimens for the use of systemic glucocorticoids’. It is well known and widely reported that CSs are used frequently to induce remission of JIA. 30 Most clinical trials of therapeutic agents in JIA,, such as biologic drugs, have attempted to control for CS effect by controlling the allowed changes in CS dosing. However, no trials have directly compared the different CS induction regimens while controlling for other DMARDs and/or biologic agents.

Both patient/family treatment acceptability and physician decision-making processes play a large part in the choice of route of CS administration in JIA. A RCT comparing the different routes of CS administration is unlikely to succeed unless the reasons behind treatment decisions are understood and patients are willing to be randomised to different administration routes. There is a paucity of robust data to aid the decision as to which of the most commonly used CS regimens should be chosen as the comparator arm.

Safety, clinical and cost-effectiveness of corticosteroids in juvenile idiopathic arthritis

High-dose CSs and CSs given for protracted periods result in significant adverse drug reactions (ADRs), including:

-

reduction in growth in height

-

weight gain

-

facial puffiness

-

striae

-

acne

-

behavioural issues

-

sleep alteration

-

immunosuppression

-

increased blood pressure

-

hirsutism

-

propensity to diabetes

-

cardiovascular complications

-

osteoporosis.

Subcutaneous fat atrophy occurs in approximately 8% of individuals who receive CSs by intra-articular injection,31 but rates of ADRs associated with other routes of CS administration are not known. It is essential to optimise the CS dosage to maximise the benefit while minimising cumulative dose-related ADRs. However, the brief of this feasibility study did not encompass the collection of ADR rates; therefore, this is an issue to be discussed before carrying out a full trial. However, we know from consumer groups in the UK, including the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Studies Group (CSG) in paediatric rheumatology, that the issue of CS side effects is one of the top research priorities of CYP with JIA, as well as their parents and carers (personal communication). There are currently still no validated methods for scoring the severity of CS-related ADRs in inflammatory disease, and this is a factor that must be included in a future full trial proposal. There has been no systematic data collection of ADRs associated with different routes of treatment; however, this is an important part of the risk–benefit ratio needed to make clinical choices about treatment.

Corticosteroids have a significant effect on halting the radiological progression of rheumatoid arthritis. There are still large differences in doses, health-care costs and patient burden between the different CS treatment regimens across the UK. There are no studies involving head-to-head comparisons of CS treatment while controlling for other treatment modalities, such as DMARDs or biologic agents, although CSs are frequent concurrent medications in clinical trials in JIA.

Available evidence for the effectiveness of corticosteroids in juvenile idiopathic arthritis

-

A Cochrane review included 15 RCTs (1414 patients receiving CSs in the first 2 years of treatment). 32 A small RCT in 22 patients with systemic-onset JIA found that IV infusion of methylprednisolone in combination with low-dose oral prednisolone produced a better response than with oral prednisolone alone. 33

-

Data from a study of the treatment of JIA with IACI demonstrated that, when administered by intra-articular injection, triamcinolone hexacetonide (TH) was superior to triamcinolone acetonide (TA), with a longer duration of action and a lower relapse rate. 34

-

A British Society of Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology (BSPAR)-led audit of CS use in 2006 received data from three out of 12 tertiary paediatric rheumatology referral centres that were approached and two out of seven district general hospitals with paediatric rheumatology clinics that were approached. The results showed that, among 86 patients with all JIA subtypes receiving CSs in the previous 2 years, 68 (79%) were treated with IACIs and nine (10%) received oral CSs alone. Only one patient (1%) received IV CSs and two (2%) received only IM CSs, with the remaining 25 patients (29%) receiving CSs by a combination of delivery routes. In all 39 treatment episodes of IV infusion of methylprednisolone the doses used were uniform. Three patients (3%) received different doses and types of IM CSs. However, with such a low unit response rate (26%) to this audit, the results are not generalisable. The low response rate to the audit also highlights difficulties with busy units supporting clinical studies, something that this feasibility study sought to address.

It is possible that the long-term concurrent use of DMARDs or very expensive biologic drugs could be reduced or avoided in some patients by using instead repeated short courses of systemic CSs or multiple and repeated IACIs, but this has not been studied. The advent of DMARD and biologic treatment has led to an impression of a reduced role for CSs in JIA, but available databases such as CAPS show that CSs are still commonly used in JIA. The annual cost of the average biologic drug was > £10,000 in 2010,35 although the costs of most biologics used in JIA are now significantly lower owing to the availability of biosimilars. However, if even a few patients were prevented from requiring biologic treatment by satisfactory suppression of inflammation from timely CS doses with or without cheaper DMARDs, then the health-economic effect of evidence-based CS use could be marked.

Patient and public engagement/involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) has been an integral component of this study since conception. Preliminary PPI commenced prior to the study application, when PPI contributors ranked the study question as a key priority for young people and their families as part of the NIHR Clinical Research Network (NIHR CRN): Children/Versus Arthritis (Chesterfield, UK) Paediatric Rheumatology CSG problem/population, intervention/indicator, comparison, outcome (PICO) prioritisation exercise. In addition, young person and parent-led prioritisation exercises revealed that any CS treatment, the uncertainty of treatment scheduling/outcomes and treatment side effects were all major concerns for young people with JIA and their parents/carers.

During the study outline application process, discussions regarding the planning of the study were undertaken with the study co-applicant (SS), who is a young adult living with childhood-onset JIA and who subsequently helped to lead PPI in the overall study. The study co-applicant (SS) was involved in the submission of the outline application, and in the response to reviewers and the submission of the study application, which was subsequently approved and funded. SS was also involved in the management and oversight of the study, as a member of the study management group (SMG), while an external PPI contributor (CT), who is also a young person living with childhood-onset JIA, was identified to sit on the study steering committee (SSC). An external PPI co-ordinator (HB) was identified as an individual to support the study co-applicant in undertaking PPI activities as part of the study. PPI contributors were also provided with continuous professional development certificates after their attendance at the consensus meetings, to document their contributions.

The chief investigator (EMB) and study co-ordinator (GN) acted as mentors and liaison individuals for PPI contributors, although a positive working relationship was established between PPI contributors and other academic/clinical members of the study team, enabling an open, honest and transparent working relationship that was built on equality and respect to follow. Enabling PPI contributors to feel valued as part of a research team is integral to successful partnerships built on these qualities. PPI contributors were embedded within existing networks, such as the CSG, and so were able to liaise between external PPI contributors with an interest in the study.

Our PPI contributors provided valuable input into the design and conduct of the study across the different phases, including the literature review, qualitative study, consensus process and feasibility study. They were also involved in the submission process by seeking ethics approval for the study and by providing specific comments on topics relevant to young people and parents/carers taking part in the study. Specific activities that were related to the study design and conduct included the design of advertisement leaflets for young people, parents/carers and HCPs; reviewing participant information sheets; reviewing assent/consent forms; and the identification and refinement of potential outcome measures for inclusion, including outcome descriptions. PPI contributors also facilitated recruitment of participants to the study, as well as facilitating the identification of PPI members to take part in the consensus process.

Our PPI contributors were heavily involved in the consensus process, including consensus meetings that were held in July 2017 and December 2018. Simon R Stones and Heather Baguley co-delivered several of the presentations and sessions at both meetings and acted as named individuals for other PPI contributors in attendance. PPI contributors were also encouraged and supported by academic/clinical members of the study team to document the consensus meeting process and to contribute to the preparation of reports and dissemination of findings from the meeting(s).

In addition, PPI contributors were involved in advising on data analysis, for example in discussions about emergent themes from the literature review and the qualitative phase of the study. They were also heavily involved in the preparation and dissemination of study findings, including the co-authorship of conference abstracts and manuscripts, and the subsequent preparation and delivery of findings, such as conference posters. Simon R Stones also led the writing of conference abstracts and a manuscript about the first consensus meeting, seeking input from academic/clinical members of the team. PPI contributors also suggested conferences that would be suitable for presentation of the study findings and led on the translation of scientific findings into accessible plain language summaries, available to those who took part in the study, as well as to young people and parents/carers more broadly. This included the dissemination of findings on social media and among peer networks.

Finally, PPI contributors were involved in the writing of this report. This section was prepared by Simon R Stones and Chapter 6 was co-authored by Simon R Stones. Simon R Stones also reviewed all chapters of the report during the review process by the entire study team.

Important outputs of this feasibility study

Many RCTs find recruitment difficult if clinical teams are not involved in the development of study protocols and, therefore, are not committed to the study through the ownership of the study questions and the need for evidence. The design of this feasibility study was planned to maximise HCP ‘buy-in’ to a final RCT by adapting the protocol and outcome measure choice following the literature review, extensive surveys, qualitative interviews and structured survey and stakeholder consensus process of opinions and refining agreements in areas of difference. 36

A head-to-head RCT of different CS regimens is the eventual goal. However, because of the difficulties in achieving such a study, a detailed feasibility study was required to discover whether or not such a RCT is acceptable and achievable, and whether or not the results will be meaningful.

Irrespective of whether not the findings of this feasibility study suggest that a future full trial is possible, this study also generated significant outputs of value and impact to the wider national and international research community and to NIHR, in terms of, for example, the joint consumer and HCP choice of primary outcome, the treatment preferences and a wider UK paediatric rheumatology unit engagement with research by the active participation with the research question and protocol development.

Aims and objectives

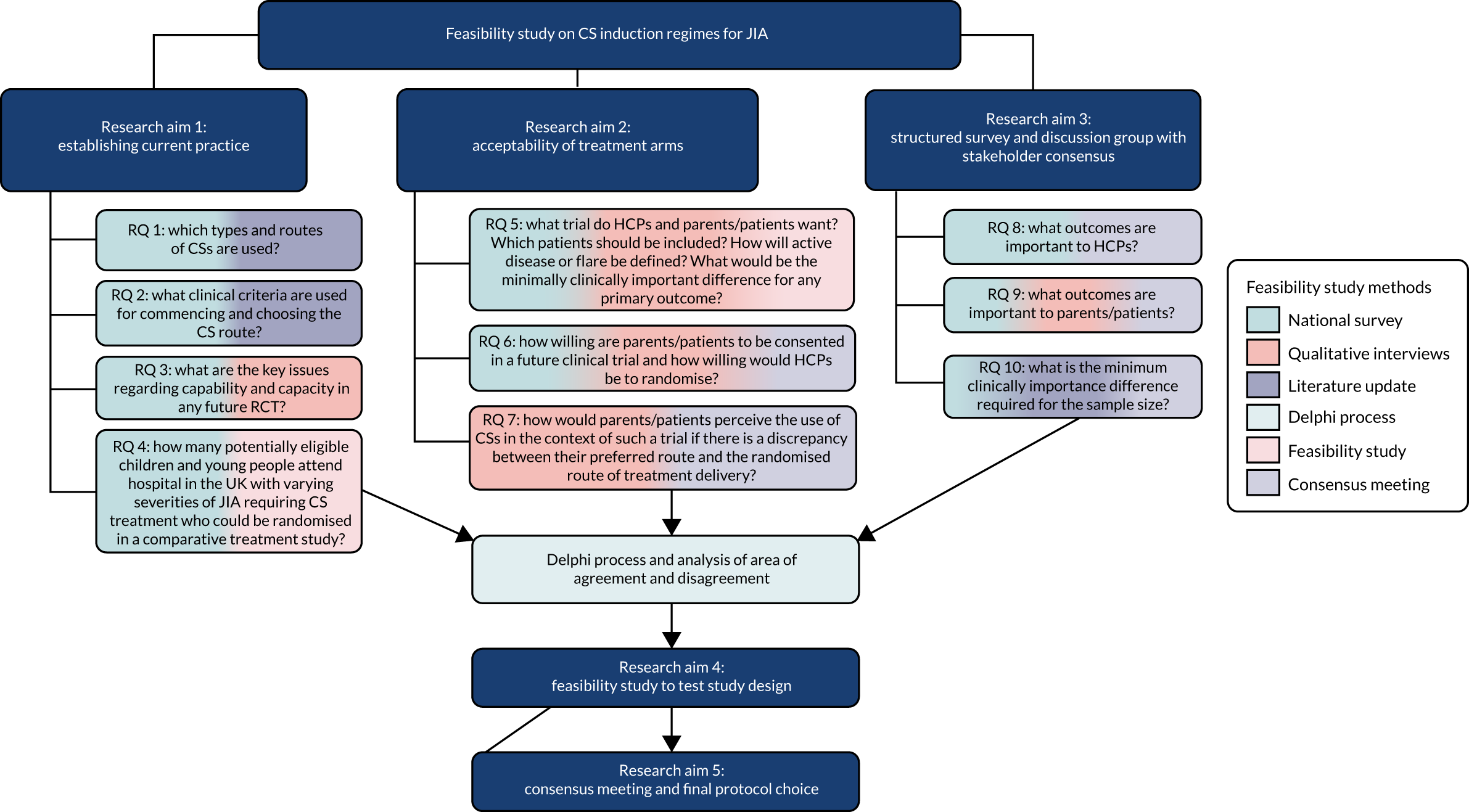

We identified specific study aims with objective research questions underpinning each aim. There is currently a lack of consensus as to which regimen of CS induction should be used in children with various disease subtypes and severities of JIA.

Overall aim

The overall aim was to establish the feasibility and acceptability of conducting a RCT to evaluate the safety and efficacy of different CS regimens. We proposed a mixed-methods study with engagement of stakeholders [HCPs, patients and parents (PPI)] fundamental to each phase of the process.

The study delivered a review of published literature on CS outcomes in JIA; a prospective study of the actual number of JIA patients treated with CS (including doses and routes of administration); HCP- and PPI-informed (where possible) choice of control, intervention and outcome for a proposed RCT; and a prospective evaluation of change in chosen primary outcome over 12 weeks. Willingness to randomise (HCP) and willingness to participate (patients and parents) were estimated.

The overall feasibility study comprised several phases:

-

A review of the literature identifying candidate outcomes to be evaluated as a consensus primary outcome for a RCT.

-

An exploratory phase providing quantitative and qualitative information on current practice informing potential regimens to be tested –

-

A national e-survey of HCPs’ and UK paediatric rheumatology units’ current practice in CSs use to be used to define the treatment arms of a RCT and to identify the most common treatment to be used as the control arm of a future RCT. The survey asked about factors influencing choice of regimen, for example individual and unit treatment protocols, and experiences of response; outcomes measured and recording of ADRs, and factors influencing HCP choice of route of administration.

-

Qualitative interviews with patients and parents with a specific focus on acceptability of a full RCT of CS regimens, to allow in-depth discussion of views and experience of factors influencing individual treatment choice (including administration route) and willingness to be randomised.

-

-

A national survey and consensus process refining the primary outcome measure of induction of response for a proposed RCT.

-

A consensus stakeholder meeting – finalising key parameters, including inclusion/exclusion criteria, primary outcome, minimally important clinical difference and treatment arms.

-

An observational prospective feasibility study – identifying patients nationally with agreed eligibility criteria receiving current/proposed treatment arms with observational data on consensus primary outcome collected at baseline and after CS treatment and at 12 weeks, to inform estimate of sample size for a future RCT.

-

An overall feasibility study report – providing summary of key parameters to enable decision to be made by the HTA Commissioning Board on feasibility of a future RCT.

Research aim 1

The first aim was to establish the current practice for CS use in treating JIA in the UK. In particular, we aimed to obtain a snapshot of the numbers of patients with JIA of different degrees of severity who were attending hospital and requiring CS treatment, as well as the unit HCPs’ capacity to deliver a RCT.

Objective research questions (RQs):

-

RQ 1 – what types, routes and doses of CSs are used and in which JIA patients?

-

RQ 2 – what clinical criteria are used for commencing CSs and choosing the route of CS administration?

-

RQ 3 – what are the key issues/concerns with regard to capacity and capability in the conduct of a future RCT?

-

RQ 4 – how many potentially eligible CYP with JIA of different degrees of severity attending hospital in the UK require CS treatment and could be randomised in a comparative treatment study?

To fulfil the commissioning brief, this report will characterise current practice and inform an estimate of eligible patients for a future RCT.

Research aim 2

The second research aim was to determine the control, intervention and patient group(s) for a future RCT and to establish HCPs’ willingness to randomise and the likely consent rate.

Objective RQs:

-

RQ 5 – what characteristics would HCPs and parents/patients want to see included in a future RCT of CSs in JIA? Which patients should be included/excluded? What would be the most appropriate control group in a future trial? How would active disease or a disease flare be defined?

-

RQ 6 – how willing would patients/parents be to consent to be randomised in a future clinical trial and how willing would HCPs be to randomise?

-

RQ 7 – how would patients’/parents’ preference for mode of CS delivery influence their willingness to participate in a future RCT?

To fulfil the commissioning brief, this report will identify the clinician- and patient-directed control and intervention for a RCT and inform randomisation and consent rates in a RCT.

Research aim 3

The third research aim was to choose the primary outcome for use in a future clinical trial of CSs in JIA.

Objective RQs:

-

RQ 8 – what primary outcome is important to HCPs?

-

RQ 9 – what primary outcome is important to parents/patients?

-

RQ 10 – what would a minimally important clinical difference be for any potential primary outcome?

To fulfil the commissioning brief, this report will identify the primary outcome.

Research aim 4

The fourth research aim was to conduct a prospective observational study of newly diagnosed patients with JIA who fulfil the proposed inclusion/exclusion criteria and who naturalistically receive the proposed control or treatment arms, and to observe change and variance in the proposed consensus primary outcome over a 12-week period to inform the precision of the sample size calculation.

To fulfil the commissioning brief, this report will inform the sample size estimate for the RCT and characterise further the estimate of eligible patients for the RCT.

Research aim 5

The fifth research aim was to develop a report for the HTA programme on the feasibility for a definitive study defining the design, control and intervention arms, with recommendations to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, primary outcome, sample size based on the primary outcome and subtypes of JIA to be included.

Research methodology

This mixed-methods study included:

-

A national structured survey on current treatment practice in JIA was carried out among stakeholders, including HCPs (paediatric rheumatologists, paediatricians with a specialist interest in rheumatology, adolescent rheumatologists with expertise in JIA and specialist nurses in paediatric rheumatology), combined with the results from the unit screening log. The survey asked about –

-

Current practice including criteria for starting CSs, the proportion of patients with JIA receiving CSs, the timing of reviews, dosing criteria with any systemic CS reduction regimens, as well as the number receiving more than one CS modality.

-

Capability including the proportion of Good Clinical Practice-trained nursing/medical staff, out-of-hours consultant/research nurse and clinical nurse specialist cover, number of available day-case facilities for in-hospital CS delivery by the IM injection, IV infusion and IACI routes (e.g. occupancy, staffing ratios).

-

Acceptability, in broad terms, of a RCT on the use of each of the four CS delivery methods in different JIA subtypes and patient age groups. This component also assessed the barriers perceived by HCPs (identified using an online survey) to accepting a treatment regimen as a trial arm when this is not part of the current treatment choice for the team.

-

-

Determining the choice of primary outcome and CS treatment regimen for the future clinical trial in JIA through:

-

Review of the literature, review of the latest revision of the European Medicines Agency guideline on JIA trial design, review of the outcomes of the SHARE conclusions.

-

Stakeholder consultation through –

-

– A survey and stakeholder consensus process, including parents, patients and HCPs, to achieve consensus on the primary outcome, inclusion/exclusion criteria and treatment modalities.

-

– A stakeholder meeting [using formal consensus techniques including the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) scoring] to present and discuss the findings from the structured survey on the parameters of the proposed trial. A joint HCP and consumer/PPI consensus meeting to determine the primary outcome measure, acceptability of the CS routes and the treatment decisions around choice of CS induction regimen and aspects of the feasibility trial design including type and timing of intervention and barriers to recruitment.

-

-

A qualitative study of patient/parent views and experiences of the use of CSs and of a future trial involving randomisation between delivery routes. Patients (≥ 8 years) and parents were sampled from the co-applicant centres where one or more of the delivery routes were used.

-

-

An observational prospective feasibility study was conducted. This collected primary outcome and treatment data on newly diagnosed, or flaring, JIA patients receiving CS treatments. The study focused on the JIA disease subtype, the doses and routes given and on data relevant to the primary outcome at baseline and at 6 weeks and 12 weeks post commencement of the CS therapy, with assessment of a priori definitions of remission, from changes in primary outcome measure over the 12-week study period. The number of newly treated or flaring patients with CSs in each JIA subtype was determined to allow for reliable power calculations to be made for a potential future randomised trial.

-

Preparation of a project report has included the basic consideration of whether or not a definitive trial is truly feasible based on defining the appropriate eligibility, sample size, primary outcome and choice of CS interventions and the route for the control arm, based on 1–3 above. In addition, the willingness of HCPs to consider enrolling patients into such a trial, and for patients to be enrolled, was a central factor in defining whether or not a formal trial could succeed. Unit buy-in and clinician enthusiasm for such a study was also explored in combination with practical questions such as study set-up times and times for site regulatory approvals at participating NHS trusts.

Chapter 2 Literature review on the use of corticosteroids in juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Introduction

The ultimate goals in managing JIA are to prevent or control joint damage, to prevent loss of function and to decrease pain. JIA is a chronic disease that is characterised by periods of remission and flare. Treatment is aimed at inducing rapid remission while minimising toxicity from medications, in the hope of inducing a permanent remission.

The standardised outcome measures used during the management of patients with JIA are of importance for both clinical care and research. To date, to our knowledge there have been no controlled trials on the use of intra-articular (IA) CSs versus systemic agents in children with JIA. To our knowledge, there are also no controlled trials on the dosage and route of systemic CSs (oral vs. IV). Outcome measures used in clinical trials in JIA to date have used the ACR Pedi responses,4 but these are hard to calculate in clinical practice.

Aim and objectives

Our aim was to undertake a literature review on the use of CSs in children with JIA. Our objectives were to identify whether or not there is a standardised use of CSs published in the literature and also to identify the outcome measures used in these JIA studies. This activity was a crucial part of the method to determine an agreed outcome measure(s) for the planned prospective feasibility study SIRJIA (Study of the Induction of Remission in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis).

For the purpose of this review, we included the articles published in English from 2000 to May 2016. We searched in the databases CINAHL, the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, MEDLINE, the Turning Research into Practice (TRIP) database, International Clinical Trials Registry, UK NIHR CRN study Portfolio and the Australian clinical trials register.

Methods

We carried out a literature search in the above databases for articles published from 2000 until May 2016 in English, using the following PICO format:

-

patient, population – CYP with JIA

-

intervention – treatment with CSs

-

comparison – not applicable

-

outcome – remission, reduction in disease activity, JIA core outcomes and JADAS.

We also gathered information from the referenced articles with the intention of obtaining as much evidence as possible from the literature regarding the use of CSs in JIA, and the outcome measures used.

A further literature search in MEDLINE and EMBASE was carried out by the clinical librarian to include on any additional studies published from 2016 to 2018. As the literature review was not systematic, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) or its extensions do not necessarily apply.

Results

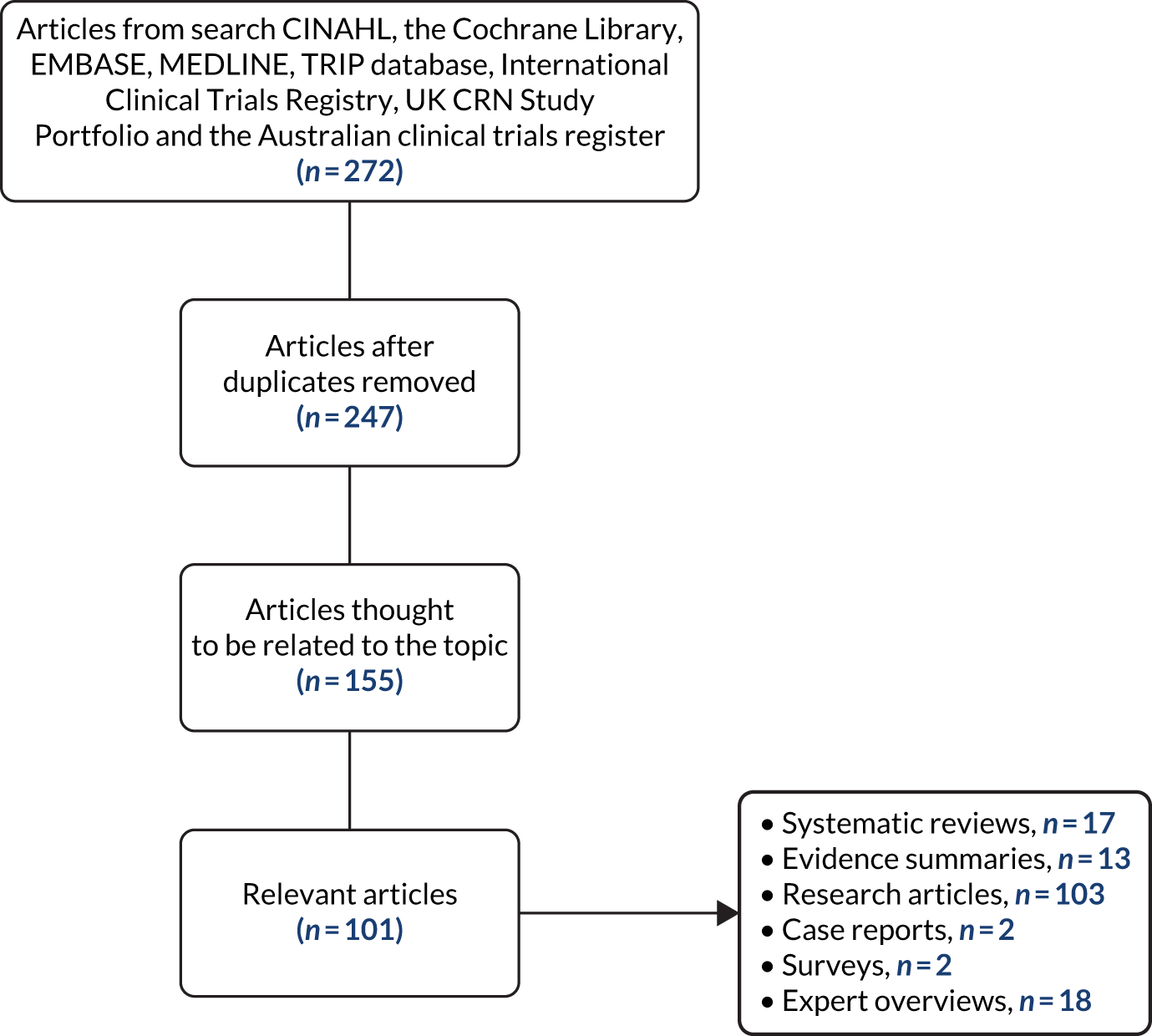

The combined electronic searches identified 272 records from eight databases, of which 25 records were removed after accounting for duplicates, leaving 247 records for further consideration. The titles and abstracts of the remaining records were screened for eligibility using the PICO screening tool, and 101 full-text papers were found to be potentially eligible for inclusion. The abstract and methodology sections of these articles were further analysed, and subsequently 54 articles contributed to the results outlined in this paper. In addition, references from the original articles, including expert opinions and review articles, were also included in the results despite being published prior to the study period (systematic reviews, n = 17; evidence summaries, n = 13; research articles, n = 103; case reports, n = 2; surveys, n = 2; expert overviews, n = 18).

The flow chart in Figure 1 illustrates the study selection process.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the literature review.

Synthesis of evidence

Intra-articular corticosteroids

The use of IACIs for the treatment of inflammatory arthritis in adults was initially reported by Hollander et al. in 1951. 37 The use of IACIs in children was first noted anecdotally in 1979,38 and the first prospective evaluation of IACIs in the management of chronic arthritis in children was reported by Allen et al. in 1986. 39 In that prospective study, 53 knees were injected in 40 children with chronic arthritis and responses were evaluated at 6, 12 and 24 months for good clinical response, relapse and time to relapse. All knees responded well to treatment, with 36.7% relapse. IACIs appeared to be a safe and effective treatment option for the management of JIA, particularly the management of oligoarticular JIA. 40,41 IACIs are an effective way to control disease activity and to induce resolution of synovitis, decrease the presence of joint and limb deformities, improve function, provide pain relief and serve as an adjunct to the longer-term, first-line DMARD therapy, MTX. Various technical aspects, different formulations of CSs, duration of disease at treatment, concomitant use of other medications and disease severity might impact the efficacy of IACIs, although conclusive data that elucidate these factors are scarce. 42

A systematic review to evaluate the advantages of administering CSs during arthrocentesis for temporomandibular disorders, including JIA, found no significant differences in the clinical outcomes observed between the CS injection group and the control groups (which were injected with normal saline, physiological salt water or Ringer’s lactate). 43

Ravelli et al. 44 conducted a multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label trial that compared the effects of IACIs with IACIs plus oral MTX (15 mg/m2, maximum 20 mg). The CS used was TH (for shoulder, elbow, wrist, knee and tibiotalar joints) or methylprednisolone acetate (for subtalar and tarsal joints). The trial reported that concomitant administration of oral MTX did not augment the effect of IACI therapy.

Comparative effects of different corticosteroids in intra-articular injections

A double-blinded study of adults with rheumatoid arthritis of the knee found that intra-articular injection of TH resulted in significantly greater initial and more lasting improvement in joint inflammation than prednisolone t-butyl acetate or methylprednisolone acetate. 45 In the first double-blinded comparison of CS preparations reported in children, TH was found to be superior to betamethasone in reducing knee swelling and stiffness in children with oligoarticular JIA. 46 Honkanen et al. 47 compared the effect of IACIs in the knee in 45 children with JIA who were administered 1.5 mg/kg methylprednisolone acetate and 34 children injected with 0.7 mg/kg TH, and found a significantly higher remission rate (p < 0.005) in the TH group. Zulian et al. 48 found TH to be superior to TA, even when the TA dose was doubled from 2 mg/kg to a maximum of 80 mg. The joints in patients injected with TA relapsed first in 53.8% of the joints injected, compared with only six (15.4%) of the joints injected with TH. Eberhard et al. ,49 who carried out a retrospective study of 227 joints, reported a longer time to relapse with TH than with TA, with the mean time to relapse being 10.14 ± 0.49 months and 7.75 ± 0.49 months in the TH group and the TA group, respectively. The updated literature search identified a report of TA use in recent practice in India owing to the easier availability of the drug. 50

The duration of response to IACI is dependent on the actual CS used, with less soluble preparations providing a longer duration of response. The greater efficacy of TH in IACI can probably be explained by its PD properties: it is less soluble and absorbed more slowly than TA; thus synovial levels are maintained for longer and systemic corticoid levels are reduced. 51 As a result of this study, TH has been recognised among paediatric rheumatologists as the medication of choice for IA administration of CYP with JIA.

Dosage regimen for intra-articular corticosteroids

The dosage regimen for TH currently used by the majority of UK paediatric rheumatologists is 1 mg/kg for large joints (i.e. knees, hips and shoulders) and 0.5 mg/kg for medium-sized joints (i.e. ankles, wrists and elbows). 52 There is more variability in the smaller joints in the hands, where methylprednisolone acetate is recommended. 52 In addition, TH is recommended for the hands and feet at 1–2 mg per joint for metacarpophalangeals/metatarsophalangeals and 0.6–1 mg per joint for proximal interphalangeals. 52

Paediatric rheumatologists frequently administer multiple IACIs in a single episode of treatment of JIA, while simultaneously initiating therapy with a DMARD and/or biologic/biosimilar agents. This strategy, the so-called ‘bridge’ effect, is regarded as an alternative to systemic CSs. The aim is to induce prompt remission of synovitis, that is to achieve a quick control of inflammatory symptoms, while awaiting the full therapeutic effect of a DMARD or biologic/biosimilar medication. 53

Use of systemic corticosteroids

Systemic CSs, that is CSs administered orally or by IV infusion or IM injection, are used in the treatment of children with acute severe arthritis, both around the time of presentation and during disease flare. Systemic CSs have been used mainly for the treatment of children with polyarticular or systemic JIA. However, to date, there are no standardised protocols or guidelines and no RCTs comparing the effect of various forms and dosages of systemic CSs to treat children with systemic JIA. It is important to note that the choice of CS in systemic JIA is likely to be influenced by the tendency for this type of JIA to be complicated by potentially life-threatening macrophage activation syndrome.

Michels54 published the results of a survey conducted among paediatric rheumatologists from North America, Israel, Australia and Europe. The survey, utilising a standardised questionnaire, elicited rheumatologists’ personal definitions of low-dose, long-term CS treatment of JIA. The results obtained from 99 respondents revealed that paediatric rheumatologists’ definitions of low-dose, long-term CS therapy varies within a wide range. The dosage that was still considered low was 0.26 ± 0.14 mg/kg/day prednisolone (minimum–maximum, 0.04–0.5 mg/kg/day). Reported dosages were higher in northern Europe (0.29 ± 0.12 mg/kg/day; n = 9), western Europe (0.42 ± 0.14 mg/kg/day; n = 7), southern Europe (0.30 ± 0.14 mg/kg/day; n = 9), eastern Europe (0.25 ± 0.14 mg/kg/day; n = 6) and North America (0.33 ± 0.17 mg/kg/day; n = 16) than in central Europe (0.19 ± 0.09 mg/kg/day; n = 43).

The ReACCh-Out study55 was a multicentre, prospective, inception cohort study of CYP with JIA who were diagnosed within 12 months before enrolment. Prospective data were collected at enrolment, 6-monthly for 2 years and then annually. Initial data published in 2010 showed that oral prednisolone was used most often in CYP with systemic JIA and rheumatoid factor (RF)-positive polyarticular JIA. 23 The probability of instituting systemic CSs within 6 months of diagnosis was 79% and 61% in systemic JIA and RF-positive polyarticular JIA, respectively. 55 The literature includes a case report of an adolescent with systemic JIA that responded to oral CSs56 and a report of CS-dependent refractory systemic JIA. 57 The reports do not include the details of all the dosing regimens used.

The Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) developed standardised consensus treatment plans (CTPs) for systemic JIA with the goal of comparing their effectiveness (in achieving clinically inactive disease) using data collected for the CARRA registry. 58 The physicians chose the actual CTPs for each of their patients with systemic JIA and an electronic survey was sent to voting members of CARRA regarding CTP choice for CYP with new-onset systemic JIA in whom treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) monotherapy had failed. Respondents were asked to select one or more of the following CTPs for each clinical case scenario: (a) systemic CSs only, (b) MTX (with or without CSs), (c) anti-interleukin 1 (IL-1) therapy (with or without CSs) or (d) anti-IL-6 therapy (with or without CSs). Respondents could choose more than one CTP if factors such as insurance limitations or family preference might affect treatment. The results showed significant variability in systemic JIA treatment approaches, no clear standard of care among CARRA members58 and widespread use of MTX and CSs. MTX use increased with more arthritis features. However, MTX and CSs are frequently used, regardless of presenting disease features. Overall, concurrent CS use was indicated by the majority of respondents across all CTPs.

In a prospective cohort study (TREAT) of 85 children with polyarticular JIA, patients were randomised blindly to MTX, etanercept or rapidly tapered prednisolone and assessed for clinically inactive disease (CID) over 1 year of treatment. 59 Patients starting on methylprednisolone acetate achieved CID earlier, and had more study days in CID, than those starting MTX, but the differences were not significantly different.

Uveitis is the one of the most severe complications of JIA. There are studies60,61 reporting the use of systemic CSs for severe uveitis associated with JIA, and these were included in this literature review, as uveitis may be an indication for CSs in JIA in the absence of any specific joint indication. It was felt that evidence for the use of systemic CSs to treat uveitis could usefully supplement the evidence regarding response to different modalities of treatment as either arthritis or uveitis could be the indication for CS treatment at different times and convergence of treatment plans could be helpful. However, the evidence base of use of systemic CSs in uveitis is also limited. Marvillet et al. 60 conducted a retrospective analysis of records of 70 children with JIA. Severe ocular involvement necessitated systemic CS therapy in 29 (42.0%) patients. 60 Among immunomodulating agents, MTX and cyclosporine were used in 41 patients and tumour necrosis factor α antagonists were used in 15 patients. Twelve patients (17.4%) achieved complete resolution of uveitis, whereas 14 (20.3%) experienced a relapsing course and in 23 (33.3%) uveitis became chronic, with relapses as soon as the treatment was decreased and 21 (30.4%) had a severe course. Nouair et al. 61 reported use of CSs in 41% of patients in a retrospective analysis of children with non-infectious uveitis who were followed between 2004 and 2013.

With regard to IV infusion of CSs in JIA, the literature search revealed little of note apart from a single case report of a patient with systemic JIA57 in whom a methylprednisolone succinate pulse of 1 g for 2 days was followed by a maintenance dose of prednisolone of 1.3 mg/kg/day.

The literature review revealed a lack of standardised dosing regimens for either induction or maintenance therapy and no evidence of tapering doses of CSs.

In the STIVEA trial,62 adult patients with very early inflammatory polyarthritis (4–10 weeks’ duration) were randomised to receive three IM injections of 80 mg of either methylprednisolone acetate or placebo, administered at weekly intervals. 62 Assessments were carried out monthly for the first 6 months after the first injection, with a final 6-month review at 12 months after the first injection. Patients in the placebo group (76%) were more likely to need DMARDs during the first 6 months of the trial than patients in the CS group (61%) [adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 2.11, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.16 to 3.85; p = 0.015). Disease activity did not differ between the two groups at 12 months. After 12 months, arthritis had resolved without the need for DMARDs in 9.9% (11/111) of patients in the placebo group and in 19.8% (22/111) of patients in the CS-treated group (adjusted OR = 0.42, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.99; p = 0.048). We found no RCTs of the use of IM CSs in children with JIA.

Corticosteroid side effects

There is a paucity of studies in the literature to guide practitioners in counselling CYP about the anticipated weight changes and side effects following CS initiation in JIA.

In a prospective study63 that examined CS-related changes in body mass index among CYP with rheumatic diseases, the median starting CS dosage was 1.3 mg/kg/day prednisone equivalents. However, the study participants included those with other rheumatological diagnoses and only 38% of the study participants had a diagnosis of JIA.

Cleary et al. 40 reported that it is likely that multiple IACIs (10 or more joints, including large joints) result in sufficient systemic absorption of CS to produce a Cushingoid appearance. The clinical features of Cushing’s syndrome can include a moon-shaped face, centripetal adiposity, supraclavicular fat pad accumulation, bruising, striae and proximal myopathy, but adverse effects can also be subclinical or overlap with those of other medical conditions. There is an increased risk of developing diabetes or hypertension and a predisposition to opportunistic infections. 57 Huppertz and Pfüller64 reported transient suppression of cortisol release detected by a low morning peak value of salivary cortisol. No adverse events were recorded secondary to this transient adrenal suppression.

There is a case report of severe acneiform rashes in two adolescents with JIA following bilateral knee IACI of TH. 65

Valta et al. 66 reported a prospective study evaluating bone health and growth in 62 CYP with JIA. No correlation was found between the bone mineral density and the disease characteristics or cumulative CS dose. 66 This study showed low prevalence of osteoporosis and normal growth in CYP with JIA. However, the study population was small and this question warrants larger controlled trials.

Outcome measures used in juvenile idiopathic arthritis studies

We analysed outcome measures used in studies that were identified by our literature review. The most widely used primary outcome measures that were identified were the number of active and restricted joints, the number of flares, medications, ESR, JIA core outcome variables, CHAQ, visual analogue scale (VAS), Pa/PtGA and PGA and clinical remission (based on clinical examination, ACR Pedi 30 or ACR Pedi 70).

Esbjörnsson and colleagues measured gait dynamics using three-dimensional gait analysis and foot-related disability using the Juvenile Arthritis Foot disability Index in their study of the effect of IACIs on foot and walking function. 67 In the BSPAR etanercept study,68 JADAS, ACR, Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score, 71-joint count (JADAS-71), ACR Pedi 90 and minimal disease activity at 1 year were measured.

There is limited literature regarding the use of outcome measures in systemic JIA specifically. The main outcomes used are clinical inactivity with no arthritis, no fever, rash, serositis and generalised lymphadenopathy. In studies specifically of temporomandibular joint arthritis, jaw pain or dysfunction, maximal incisal opening distance and magnetic resonance imaging-detected inflammation have been used as outcome measures. The Disease Activity Score-28 was used in one study. Other measures identified include duration of morning stiffness, knee joint circumference and knee joint flexion in degrees.

There was no evidence of any PPI involvement in the choice of outcome measures used in any of these studies.

Limitations

Our review was a scoping review of literature on the use of CSs rather than a systematic analysis. Articles in languages other than English were not included in the study.

Discussion

There is good evidence for the use of IACIs in CYP with JIA, leading to grade A recommendations for use. There is reasonable evidence supporting the efficacy of systemic CSs in CYP with systemic JIA, polyarticular JIA and JIA-associated uveitis; however, the optimal mode of administration remains unclear. In children with polyarticular JIA, IACIs are more often used as a bridging therapy while waiting for the disease to show a complete response to DMARD agents and biologic therapy.

No standardised dosing regimen for either induction or maintenance therapy, or any defined tapering dose of CS, is available in the literature. It appears that there is widespread variation in the use of CSs among different clinical settings and centres. There is very little evidence regarding CS treatment regimens and, in particular, there is no good evidence of the relative efficacy and tolerability of oral and IV modes of CS administration.

It is of note that this review is limited to published clinical trials, as would be expected when attempting to establish evidence-based practice. However, one cannot ignore the fact that, historically, in the field of clinical medicine, reasons for favouring certain methods of treatment over others may be educated by individual experiences. These experiences contribute to herd opinions among HCPs. Patient preferences may change with time, and knowledge of the pathogenesis and evolution of a chronic disease may lead to a different treatment focus at different times. A good example of this is macrophage activation syndrome, which is now diagnosed much more frequently in the systemic JIA subset because awareness has increased. CS treatments are now more intensive in an attempt to prevent the high mortality rate associated with this disorder.

There is a clear and pressing need for future studies comparing the efficacy, toxicity and tolerability of different CS treatment regimens (multiple IACIs, oral and systemic routes of administration). The length of follow-up of a future RCT needs to consider both short-term efficacy and longer-term outcomes, such as future flare rate, as demonstrated by several of the reviewed studies.

Chapter 3 Families’ views on a proposed randomised controlled trial of corticosteroid induction regimen in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: qualitative study

Some excerpts in this chapter are adapted from Sherratt et al. 69 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

The number of RCTs being initiated for JIA is increasing. 70 Recruitment of patients is crucial to the success of such trials; poor recruitment can inflate costs,71 result in underpowered trials and lead to potentially effective interventions being abandoned or their introduction delayed. 72 Approximately 45% of multicentre trials in the UK do not achieve their original recruitment target, which often results in costly recruitment extensions. 73

Patient recruitment can be especially challenging in paediatric studies and in relatively uncommon conditions, such as JIA. 74,75 Compared with trials in adult rheumatology, informed consent can be more complex in paediatric studies owing to the need to involve both child and parents in enrolment decisions. 76 In addition, some treatments may be poorly tolerated by younger children,77 leading to high drop-out rates. Innovative trial methodology and involving families in the design of JIA trials have the potential to speed up the trajectory towards making evidence-based treatments available to young patients. 78,79

Increasingly, researchers are also using qualitative methods to explore the feasibility of trials from the perspective of patients and to proactively identify and address problems that may undermine a future trial. 80,81 Early-stage feasibility studies without a randomised component, such as the one we report here, are a distinct subtype of feasibility study. These are often used to resolve fundamental questions, such as which treatments to compare or uncertainties about the ‘in principle’ acceptability of a trial to patients and recruiters before committing resources to a pilot or full randomised trial.

Although studies involving CYP are advocated in the literature,82,83 we are aware of only one early-stage feasibility study84 that qualitatively accessed the perspectives of both parents and CYP to inform the design and conduct of a trial. This recent study focused on the experiences of CYP with acute osteomyelitis or septic arthritis, whereas the current study explores the perspectives of CYP with JIA. As JIA is a long-term condition, CYP with JIA may find trial participation especially challenging as a result of the high level of burden of their condition,82 which often requires patients to attend for frequent blood tests and reviews, or as a result of their previous treatment experiences. This study aims to shed light on such issues.

This chapter explores what an early-phase qualitative feasibility study that involves interviews with both parents and CYP can tell us about the viability of a proposed JIA trial to investigate CS induction therapy regimens.

Aims and objectives

The overarching project had several aims and objectives, as detailed elsewhere. In particular, the qualitative study aimed to address aspects of research aims 2 and 3:

-

research aim 2 – to determine the control, intervention and patient group(s) for a future RCT and to establish HCPs’ willingness to randomise and the likely consent rate

-

research aim 3 – to choose the primary outcome for use in a future clinical trial of CSs in JIA.

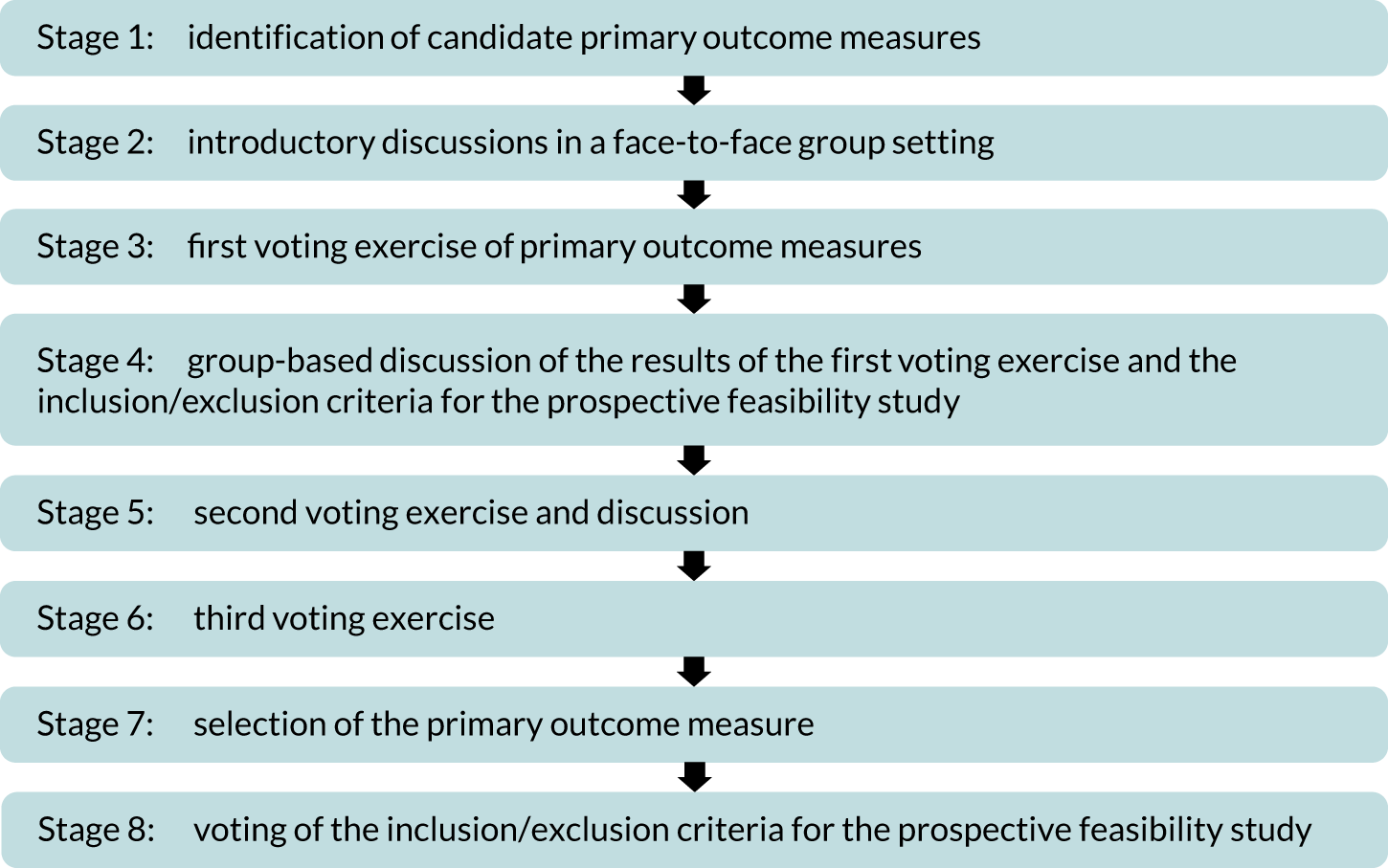

Specifically, the aims of the qualitative study (see Appendix 1, Figure 4) included:

-

establishing the characteristics that parents and patients would want to see included in a future RCT on CSs in JIA

-

exploring how willing patients and parents are to consent to be randomised in a future RCT

-

exploring whether or not patients’ and parents’ preferences for mode of CS delivery influence their willingness to participate in a future RCT

-

establishing which treatment outcomes are most important to parents and patients with JIA to inform the selection of a primary outcome for use in a future RCT.

Methods

Qualitative research methods

We adopted a qualitative approach involving semistructured interviews. Qualitative research provides in-depth insights into participants’ experiences and perspectives. Such studies are typically characterised by smaller sample sizes but many rich data. 83 More specifically, qualitative research has been used to identify and address key uncertainties in planning and designing proposed trials. 80 Semistructured interviews are well suited to exploring the patients’ perceptions of complex and sensitive issues,85 as they enable families to raise matters of importance to them and enable interviewers to inform families about trials and to clarify any misunderstandings.

A Research Ethics Committee (REC) in the north-east of England (the North East – Newcastle and North Tyneside 2) approved this study (16/NE/0047).

Participant selection

Clinicians from four paediatric and adolescent rheumatology centres in the UK approached the families of CYP who met the eligibility criteria (Box 1), briefly described the study and requested verbal permission for a researcher to contact them. CYP were required to have a confirmed diagnosis of JIA in line with current guidance. 86,87 Frances C Sherratt and Louise Roper, both experienced in qualitative research in health settings, conducted the interviews after seeking informed consent from parents and assent or consent from CYP. Interviews took place from August 2016 to March 2017 and were audio-recorded and transcribed. The research team monitored sampling characteristics to ensure that the sample was inclusive of patients of varying ages, time since diagnosis/flare and CS delivery route experience. Sampling for interviews ceased when data saturation was reached, that is when further interviews were no longer contributing new information. 88

-

CYP were aged ≤ 16 years.

-

CYP had received a clinical diagnosis of JIA in line with current practice. 86,87

-

CYP had recent experience (≤ 12 months) of at least one out of four CS regimens: (1) oral prednisolone (tablets), (2) IV methylprednisolone, (3) IACIs (triamcinolone hexacatonide) or (4) IM depot methylprednisolone.

Interview protocol

Semistructured, topic-guided interviews with CYP and parents covered the topics identified in Box 2 (see Report Supplementary Material 1 for an example of the topic guide for parent interviews). These interviews were conversational to allow participants to raise and reflect on matters of concern to them. Although we interviewed all parents regardless of their child’s age, only children who were aged ≥ 8 years were interviewed. We developed separate topic guides for parents, children (8–12 years) and young people (13–16 years) and adapted these throughout the study, guided by the ongoing analysis. We also developed stimulus materials to facilitate the interviews, including a video, a flow chart that illustrated the proposed trial and prompt cards that detailed potential benefits and side effects of the four CS delivery routes (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Consultant paediatric rheumatologists advised on the development of the prompt cards. These cards listed key points about the delivery routes that the rheumatologists perceived as important. The cards were designed to facilitate discussion in the interviews, rather than to provide an exhaustive list of benefits and side effects of the delivery routes.

In brief, the proposed trial was described to participants as comparing four CS delivery routes (hereon referred to as treatments): (1) oral prednisolone (referred to herein as tablets), (2) intravenous methylprednisolone (IV), (3) triamcinolone hexacatonide intra-articular CS injection(s) (IACIs) and (4) IM depot methylprednisolone. These four treatments are widely used in clinical practice to treat JIA, although the only informative evidence base of effectiveness and efficacy is for IACIs. 40,89 Referring to the prompt cards, the interviewer described the four delivery routes to families, including the process of delivery (e.g. duration) and the potential pros and cons. Although a trial could help to establish which of the treatments is most effective in treating JIA, the feasibility of such a trial is uncertain.

-

Patient’s initial symptoms

-

Receiving a diagnosis and initial treatments offered

-

Decision-making and experiences of initial treatments

-

CS delivery routes

-

Experiences of delivery routes (good and bad points)

-

Perceptions of delivery routes (good and bad points)

-

Delivery route preferences based on experiences and perceptions

-

Experienced/anticipated treatment outcomes

-

Description of proposed RCT

-

Understanding of RCT

-

Acceptability of randomisation

-

Willingness to participate

-

Other factors that might influence willingness to participate

-

Providing further information on pros and cons of delivery routes

-

Treatment acceptability

Qualitative analysis

We drew on the framework method,83 an approach to the thematic analysis of qualitative of data,90 and used NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to assist with data indexing and coding. Frances C Sherratt, Louise Roper and Bridget Young initially read a selection of transcripts and discussed the developing analysis. Frances C Sherratt and Louise Roper double-coded approximately 10% of transcripts, discussing divergences and their resolution, leading to the development of a preliminary coding framework. The remaining transcripts were coded by either Frances C Sherratt or Louise Roper, and further data analysis meetings were organised involving the research team (BY, LR, and FS) throughout the course of analysis to discuss convergences and divergences, identify quotes for report writing and agree when data saturation had been reached.

In quantitative research, numbers contribute to the persuasive ‘power’ of the findings, whereas in qualitative research, the words of participants are essential to enable the reader to judge whether or not the research team’s interpretations of the data are grounded in the experience of the participants. 91 The research team discussed and selected participant quotes for this report to illuminate and substantiate the researchers’ synopsis of the themes identified through systematic data analysis. 92,93 A draft report of the analysis that contained extensive data extracts was circulated to the wider study team. This enabled investigator triangulation helping to ‘test’ and refine the analysis. Participants were sent a summary of the study findings.

Results

Participants

All 26 eligible families, who were identified by clinicians, agreed to researcher contact. Of these, nine (35%) could not subsequently be contacted and two (8%) declined trial participation. Twenty-eight participants from 15 families completed or attempted an interview (58% response rate), comprising nine patients and 19 parents (Table 1). In one of the 28 interviews, we were unable to sufficiently engage the interest of one of the patients (C8_8–10y) in discussing the concepts that we wished to explore. As no meaningful data were obtained, this patient’s interview was not transcribed or analysed, although their parents’ interview was. Another patient’s interview (C11_8–10y) was unusually short (6 minutes) because the family had limited time available, but the patient’s mother was also interviewed and both interviews were analysed. Excluding the outlier interview (C11_8–10y), interviews lasted from 23 to 76 minutes (median 43 minutes, interquartile range 35–54 minutes).

| Family number | Parent interviewed | CYP age (years) | CYPs’ JIA status (reported by clinician) | Treatments experienced by the child/young persona | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral tablets | IV infusion | IM injection | IACI | ||||

| 1b | Mother and father | 11–13 | Flare | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2 | Mother | 5–7 | Flare | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3b | Mother | 14–16 | Flare | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 4c | Mother and father | 1–4, 5–7 | Diagnosis, flare | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 5 | Mother | 1–4 | Diagnosis | ✓ | |||

| 6 | Mother | 5–7 | Diagnosis | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 7 | Mother and father | 1–4 | Diagnosis | ✓ | |||

| 8b | Mother and father | 8–10 | Flare | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 9b | Mother | 11–13 | Diagnosis | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 10b | Mother | 14–16 | Flare | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 11b | Mother | 8–10 | Flare | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 12b | Mother | 11–13 | Diagnosis | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 13b | Mother | 14–16 | Flare | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 14b | Mother | 14–16 | Flare | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 15 | Father | 14–16 | Flare | ✓ | ✓ | ||

Participants were interviewed in their homes (n = 9), in a private setting in the paediatric rheumatology clinic (n = 4), in the parent’s workplace (n = 1) or by telephone (n = 1). Of the nine CYP, two were interviewed jointly with one parent and seven were interviewed separately. Of 19 parents, 14 were interviewed separately and five were interviewed with their child present, including the two noted above and three parents whose children were ≤ 7 years and ineligible for interview.