Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/161/05. The contractual start date was in May 2017. The draft report began editorial review in December 2019 and was accepted for publication in August 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2021 Gould et al. This work was produced by Gould et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Gould et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

What is generalised anxiety disorder?

Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) is the most common anxiety disorder among older people, with estimated prevalence rates ranging from 1.2% to 11.2%. 1,2 The main symptoms that characterise GAD are excessive anxiety and worry, which the person experiences as difficult to control, as well as feelings of fear, dread and uneasiness that have occurred on more days than not for at least 6 months. Other symptoms include restlessness or feeling ‘on edge’, tiredness, irritability, muscle tension, difficulties with concentrating, difficulties with sleeping, shortness of breath, fast heartbeat, sweating and dizziness. 3 It is a condition that may persist for decades, with a mean symptom duration of 20–30 years, in older people across community, medical and mental health samples in multiple countries. 4,5

Generalised anxiety disorder in older people is associated with poorer health-related quality of life, increased disability, greater health-care utilisation, increased medication intake and functional limitations in comparison with non-anxious older people. 6–8 Comorbidity with other anxiety, mood and personality disorders is common and is associated with poorer outcomes. 6,9–12 For example, comorbid anxiety and depression is associated with more severe somatic symptoms, poorer social functioning, greater suicidal ideation and a higher likelihood of prescription of benzodiazepines, as well as poorer treatment response. 13,14 Several factors are associated with treatment-resistant anxiety, including comorbid physical and mental health conditions, noncompliance and environmental stressors. 13

How is generalised anxiety disorder currently managed in the NHS?

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines currently recommend a stepped care approach to the management of GAD. 15 Step 1 comprises identification and assessment, followed by education and active monitoring within primary care. If symptoms have not improved, then in step 2 one or more low-intensity psychological interventions, such as guided self-help based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and psychoeducational groups, are offered, again within primary care. Should symptoms persist, or if there is marked functional impairment, then pharmacotherapy [(e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) and/or high-intensity, individual psychotherapy (either CBT or applied relaxation)] are offered (step 3). Following this, if symptoms still persist, a referral to specialist mental health services (usually located within secondary care) for assessment and treatment is recommended as step 4. Suggested treatment options in step 4 include offering interventions from steps 1–3 that have been previously declined and offering combination therapy (e.g. pharmacological plus psychological therapy).

What is the evidence for the management of generalised anxiety disorder in older people?

With respect to psychological interventions, the majority of studies have examined the efficacy of CBT for GAD in older people. 8,16–26 Only a few have examined other psychological interventions such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction. 27,28 Pooled odds ratios in favour of these interventions when compared with waiting list or usual care controls have been reported, but not when compared with active controls or other forms of psychotherapy. 29

Furthermore, there is evidence of smaller treatment effect sizes among older people than among working age adults, as well as higher drop-out rates. 30–32 For example, a recent meta-analysis of CBT for GAD reported an overall effect size that was nearly double that achieved in younger people than in older people {g = 0.94 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.52 to 1.36] in working-age adults vs. g = 0.55 (95% CI 0.22 to 0.88) in older people}. 33 As the authors of this meta-analysis noted, there is clearly room for improvement in the provision of effective psychological interventions for GAD in older people.

‘Treatment-resistant’ older people, that is, older people who fail to respond adequately to first-line pharmacological and psychological interventions, are by definition less likely to respond to treatment. Although there is no agreed definition of treatment-resistant generalised anxiety disorder (TR-GAD),34 when a person with GAD fails to respond to treatment after completing the first three steps of the stepped care approach,15 GAD can be considered to be resistant to treatment. A previous systematic review35 was unable to identify any randomised controlled trial (RCT) or prospective comparative study of either pharmacological or psychological interventions for treatment-resistant anxiety in older people. Given that the older adult population is projected to increase rapidly in the next 40 years,36 and hence more people will present with TR-GAD to older adult services, identifying effective interventions for this population is clearly a priority.

One possible intervention for managing TR-GAD in older people is CBT. However, as noted above, evidence of lower efficacy of CBT for GAD in older people than in working-age adults suggests that an alternative form of psychological intervention may be required. ACT could be a particularly promising candidate for this age group, given that older people with chronic pain respond better to ACT than to CBT, whereas younger people respond better to CBT than to ACT. 37 Consequently, the present study sought to investigate whether or not ACT is an acceptable and feasible approach for potentially managing TR-GAD in older people.

What is acceptance and commitment therapy?

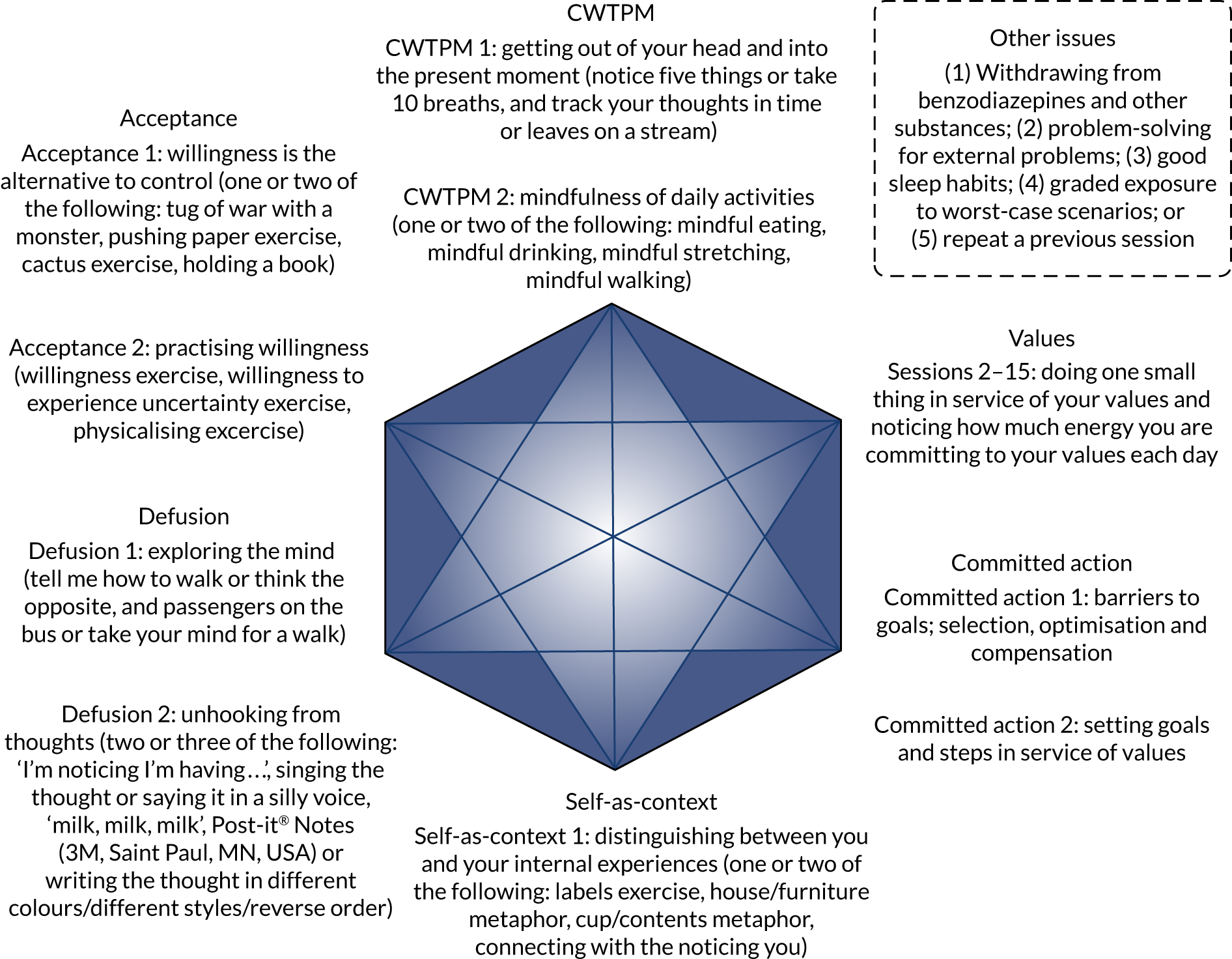

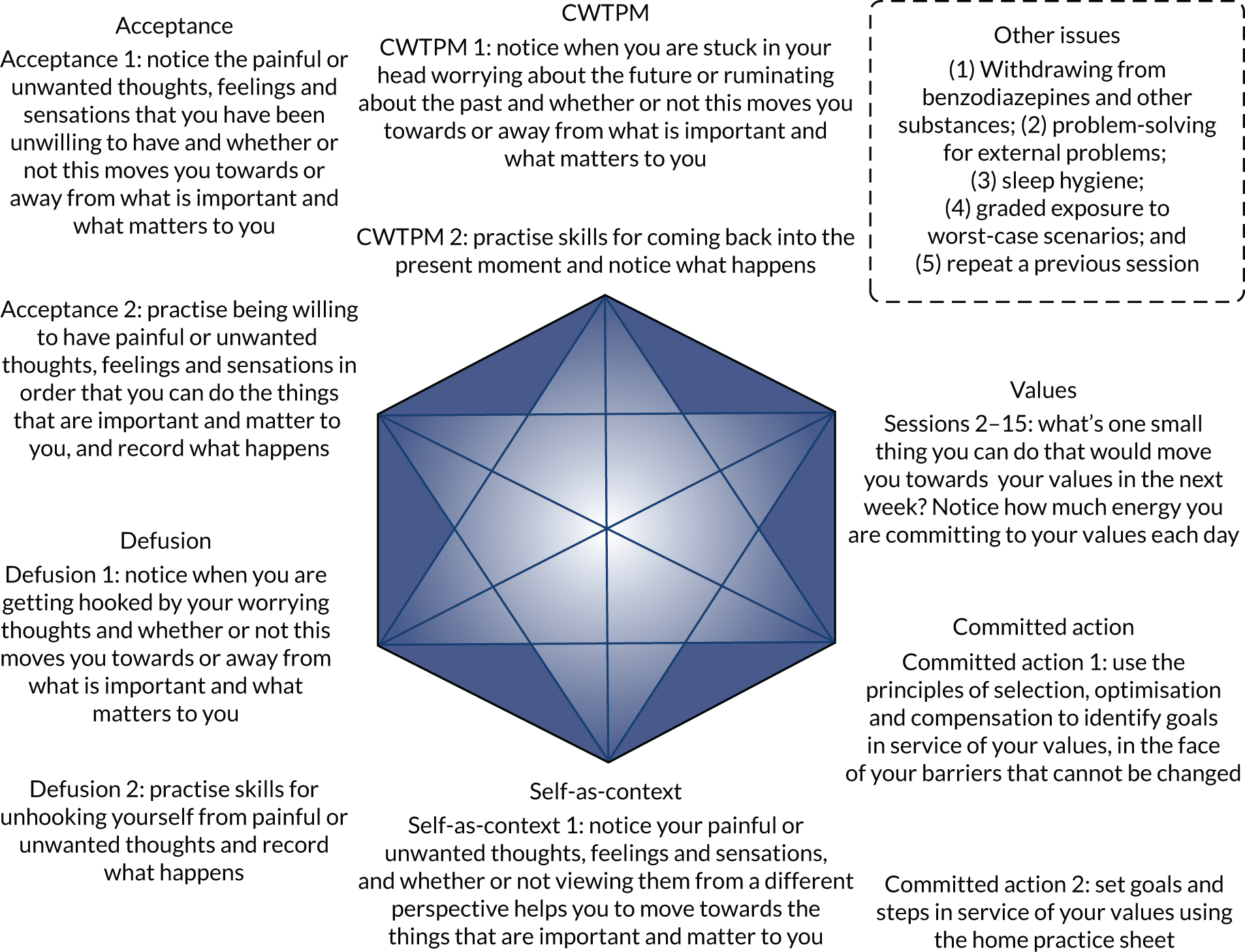

Acceptance and commitment therapy is an acceptance-based behaviour therapy38 with a strong evidence base for improving outcomes (such as functioning, quality of life and mood) in chronic pain39 and a growing evidence base in chronic disease40 and mental health contexts. 41 It aims to (1) teach people new skills for managing thoughts, feelings and sensations; (2) help them to clarify what they value and what is important and meaningful to them in their lives; and (3) identify ways in which they can best live their lives in accordance with these values alongside the thoughts, feelings and sensations they may be experiencing. It achieves this through a variety of ‘core’ acceptance, mindfulness, commitment and behaviour change processes (as shown in Table 1), with the ultimate aim of increasing ‘psychological flexibility’. Psychological flexibility is defined as ‘the ability to contact the present moment more fully as a conscious human being and to either change behaviour or persist, when doing so serves valued ends’. 42 Research has supported the applicability of these core ACT processes in a variety of clinical populations, including in older people. 43

| PIP | Description | PFP | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiential avoidance | Trying to avoid, get rid of or change the frequency or form of internal experiences (e.g. thoughts, emotions, sensations) | Acceptance | Reducing avoidance of or opening up to internal experiences (when this might be a barrier to life-enriching activity) so that one can do what matters to oneself |

| Cognitive fusion | Getting hooked by or fused with thoughts, images or memories, or acting as if they are literally true | Defusion | Reducing the degree to which one is caught up in thoughts, images or memories by stepping back from them and seeing thoughts as just thoughts |

| Dominance of past and future | Being stuck in one’s head, ruminating about the past or worrying about the future | Contact with the present moment | Reducing the amount of time one is stuck in one’s head by increasing awareness of the present moment |

| Self-as-content | Being attached to the stories that one tells about oneself, or seeing oneself as the content of one’s internal experiences | Self-as-context | Seeing oneself as distinct from the content of one’s internal experiences (e.g. thoughts, emotions, sensations) |

| Lack of clarity or loss of contact with values | Losing connection with or not knowing what really matters to oneself | Values | Knowing what really matters to oneself in one’s life (i.e. what is important and meaningful) |

| Inaction, impulsivity or avoidant persistence | Failing to act in accordance with what really matters to oneself through avoidance or inaction | Committed action | Committing to doing what really matters (i.e. engaging in personally meaningful activities that support what one values) |

Acceptance and commitment therapy can be seen as a novel alternative to traditional forms of psychotherapy such as conventional CBT. The focus of conventional CBT is on alleviating distress or symptoms by changing how one thinks and behaves in emotional situations (e.g. by challenging the validity of negative thoughts or solving problems). The phrase ‘catch it, check it, change it’, in relation to negative thoughts, captures the essence of conventional CBT. By contrast, ACT is focused on increasing personally meaningful behaviour in the presence of distress and symptoms (although distress or symptoms may improve as a by-product of therapy). The phrase ‘Accept your experiences and be present, Choose a meaningful direction for your life, and Take action’ sums up ACT. 44

What is the rationale for acceptance and commitment therapy for older people with treatment-resistant generalised anxiety disorder?

There are several reasons why ACT may be a beneficial intervention for older people with TR-GAD. First, a preliminary RCT of ACT versus CBT for GAD in older people reported improvements in worry/anxiety and depression with both interventions and higher treatment completion rates with ACT than with CBT. 27 Although these results are promising, this study was limited by its small sample size (n = 7 in the ACT condition and n = 9 in the CBT condition) and limited applicability to older people with TR-GAD in the UK (as the study did not exclusively recruit those with TR-GAD and was conducted in the USA).

Second, the approach taken to managing unwanted thoughts, emotions and sensations in ACT may be a better fit for older people with TR-GAD than the approach taken in conventional CBT. ACT aims to reduce attempts to control, eliminate or avoid unwanted thoughts, emotions and sensations and to improve function through increased engagement in valued, meaningful activities. Conventional CBT, on the other hand, aims to change or suppress emotional experiences, for example by challenging the validity of unwanted thoughts or trying to eliminate or solve problems. Such approaches may not work well with older people with TR-GAD given that multiple, comorbid chronic physical and mental health conditions and multiple losses (e.g. to one’s health, family, social network, role/identity and financial status) are common in this population. This is because issues such as these may not be amenable to being solved or eliminated, and thoughts about them may be entirely valid. Furthermore, challenging the validity of worries about future losses may be perceived negatively by older people with TR-GAD because, although excessive and unhelpful, they may have an obvious basis in reality.

Third, there is evidence that control-orientated strategies, such as trying to eliminate problems that cannot be solved, are actually detrimental to older people’s well-being. 45 This may partly explain two related findings: first, why smaller effect sizes in favour of CBT for GAD, as well as higher drop-out rates, have been reported among older people than among younger people;30,32,33 and, second, why older people with chronic pain were more likely to clinically respond to ACT than CBT, whereas younger people were more likely to respond to CBT than ACT. 37 ACT, with its focus on increasing adaptive functioning and how best to live with such difficulties and worries (as opposed to challenging, changing or trying to eliminate them), may be more appropriate in this population. Supporting this, ACT has been shown to better fit the needs of people with disabling long-term conditions46 and may be particularly helpful when distress is associated with realistic or valid thoughts. 47

Finally, ACT has been found to be as effective as CBT and applied relaxation in the treatment of GAD in working-age adults. 48–51 Furthermore, greater recovery rates and lower drop-out rates have been reported with ACT than with CBT in the management of treatment-resistant mental health problems in working-age adults. 52 Whether or not ACT is similarly effective in older people with TR-GAD is clearly worthy of further investigation.

What is the evidence for acceptance and commitment therapy in older people with treatment-resistant generalised anxiety disorder?

Although ACT has been applied to a wide range of mental and physical health conditions including anxiety, depression and chronic pain,53,54 very few studies of ACT have been conducted with older people. The majority of studies have examined ACT for chronic pain,55–58 with only a few other studies focusing on GAD,27 veterans aged ≥ 65 years with depression59 and those living in long-term care facilities. 60 Beneficial effects on symptoms of depression, anxiety and functional measures have been reported in these studies, along with high rates of attendance. For example, 100% session attendance was reported in 7 out of 7 (100%) older people with GAD27 and in 59 out of 76 (78%) older people with depression. 59 However, to our knowledge, no studies to date have examined ACT specifically for older people with TR-GAD.

Research question

At present, there is a lack of evidence to guide the management of TR-GAD in older people and indeed in working-age people. There are several compelling justifications for an alternative form of psychological intervention that sufficiently meets the needs of older people with TR-GAD. ACT shows great promise as this alternative form, but has not yet been applied to this target population. Consequently, we examined the feasibility of this approach in the current study. Specifically, we aimed to address the following research question: how feasible is a study to examine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ACT for TR-GAD in older people?

Aims and objectives

Aims

The aim of the current study was to develop an intervention based on ACT specifically for older people with TR-GAD, and to examine the feasibility and acceptability of its delivery in the NHS.

Objectives

The objectives of the current study were to:

-

develop and refine a manualised intervention in accordance with Medical Research Council (MRC) guidelines for developing and evaluating complex interventions61 and using qualitative methodological approaches

-

use qualitative interviews to explore the intervention’s acceptability and feasibility to older people with TR-GAD

-

use a nationwide survey to clarify usual care for older people with TR-GAD (information that could be used for a future substantive trial)

-

obtain quantitative and qualitative estimates of the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention and study methods in an open, uncontrolled, feasibility study

-

clarify key study design parameters for a future substantive trial of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness (e.g. the choice of comparator and outcome measures, and the number of recruitment sites based on referral/recruitment/attrition rates in the uncontrolled feasibility study).

Chapter 2 Intervention development

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Lawrence et al. 62 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

As noted in Chapter 1, guidance on managing TR-GAD in older people (and indeed in working-age people) is lacking. Developing treatment strategies that are acceptable and effective for older people with TR-GAD is therefore a high public and mental health priority, particularly in the context of population ageing. 7,35 ACT may be particularly suitable for older people with TR-GAD, who often experience comorbid chronic physical and mental health conditions and multiple losses, and for whom conventional ‘change strategies’ (e.g. changing the content of thoughts or trying to solve problems) might not be as effective.

In a small preliminary study, ACT was reported to be feasible for use with older people with GAD, as well as being effective at reducing worry. 27 However, the effects observed were substantially smaller than those reported in younger people with GAD. The authors concluded that ACT requires adaptation to ensure its relevance and acceptability to older people.

Consequently, the first phase of the current study used qualitative methods to optimise the relevance, acceptability and feasibility of ACT for older people with TR-GAD, in accordance with MRC guidelines. 61 This has been reported in Lawrence et al. 62 The objectives were to use:

-

qualitative methodological approaches to develop and refine a manualised intervention in accordance with MRC guidelines for developing and evaluating complex interventions

-

qualitative interviews to explore the intervention’s acceptability and feasibility to older people with TR-GAD.

Methods

Design

A person-centred approach was used to ground the development of the intervention in the perspectives and lives of the older people for whom it was intended. 63 Systematic, qualitative methods were used alongside patient and public involvement (PPI) to build on an ACT protocol previously piloted with a small number of older people with GAD (n = 7), but not specifically those with TR-GAD. 27 Stage 1 (intervention planning) investigated intervention preferences and priorities, relevant experiences, and barriers to and facilitators of engaging with talking therapy. Stage 2 (intervention design and development) involved formulating design objectives, and intervention features relevant to each objective, for the ACT intervention. Table 2 shows a summary of the person-based activities involved in each stage of intervention development.

| Stage of intervention development and evaluation | Person-based intervention development activities | Objective of person-based intervention development activities |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: intervention planning |

|

Qualitative interviews to elicit views on intervention preferences and priorities (including relevant previous experience and barriers to and facilitators of engaging with talking therapy in general) |

| Stage 2: intervention design, development and optimisation |

|

Consultation to agree guiding principles, comprising:

|

Participants

Older people with TR-GAD were eligible to participate in the study if they met the following eligibility criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged ≥ 65 years with a primary diagnosis of GAD as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), Axis I Disorders64 and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders. 65

-

Failed to respond to treatment in steps 1–3 of the stepped care approach for GAD.

-

Living in the community.

-

Able to provide informed, written consent.

-

Sufficient understanding of English to enable engagement in the study.

Exclusion criteria

-

Diagnosis of dementia.

-

A Standardised Mini-Mental State Examination (SMMSE)66 total score of < 25 points.

-

Other medical or psychosocial factors that could compromise full study participation, such as imminently life-limiting illness or severe sensory deficits (e.g. blindness).

Recruitment procedures

Stage 1: intervention planning

We recruited older people with TR-GAD via primary care services [i.e. general practice surgeries and Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services], secondary care services [i.e. Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs)] and self-referrals following the distribution of study posters and leaflets to local day centres and activity groups for older people. Recruitment was purposive to include older people with different living situations and lengths and severities of illness, of different sexes, across a range of age groups and from both inner-city (London) and rural (Oxfordshire) settings in order to provide access to a range of perspectives. Clinicians from primary and secondary care services identified and approached potentially eligible participants and sought verbal consent for researchers to contact them. A researcher (KK) contacted prospective participants to discuss the patient information sheet, answer questions about the study and schedule a written consent and screening appointment.

We recruited health-care professionals in primary and secondary care, including general practitioners (GPs), psychologists, psychiatrists, community psychiatric nurses and occupational therapists, via online forums and secondary care services for older people. This was to ensure that a range of experiences of working with older people with GAD who do not seem to respond adequately to treatment was obtained. We invited interested participants who had contacted the research team to participate in a 30- to 40-minute telephone interview. In addition, we approached academic clinicians from the Mental Health of Older People research group at University College London and invited them to participate in a 1-hour focus group.

Stage 2: intervention design and development

We invited the same older people with TR-GAD who completed interviews in stage 1 to participate in semistructured face-to-face interviews in stage 2. In addition, we invited older people with lived experience of TR-GAD who were part of the study’s Service User Advisory Group, and academic clinicians who were involved in the study as co-applicants/collaborators, to participate in discussions about the intervention. Finally, the academic clinicians and therapists who would be involved in delivering the intervention provided further feedback on the developed intervention.

Procedure

Stage 1: intervention planning

We conducted semistructured face-to-face interviews between July and September 2017 with 15 older people with TR-GAD who had previously been offered other psychotherapies. A sample size of 15 participants was consistent with the sample size recommended for qualitative interviews. 67 Stage 1 interviews used a topic guide flexibly to identify relevant issues specific to this population that the intervention would need to consider, including individuals’ attitudes towards their condition, its perceived impact on their lives, their experiences of medication and psychological therapies and their views on which elements of ACT interventions might be suitable or relevant for older people (see Report Supplementary Material 1). We revised the guide iteratively to allow exploration of the main concerns of participants. We conducted face-to-face interviews in participants’ homes (n = 9), the care setting in which they were recruited (n = 4) or at the lead university (n = 2) in accordance with participant preference. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim with contextual notes and reflections documented in an analytical diary.

We also conducted semistructured telephone interviews during this same period with 31 health-care professionals. In addition, a 1-hour focus group was conducted with five academic clinicians from the Mental Health of Older People research group at University College London. Again, interviews used a topic guide flexibly to explore the challenges of supporting older people with GAD and how an intervention could be more attractive, persuasive and feasible to implement (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Interviews continued until we achieved theoretical saturation of data. We recorded views and recommendations in detailed research notes.

Stage 2: intervention design and development

We developed themes relating to the specific needs, issues and challenges of people with GAD into recommendations for optimising an ACT intervention and presented these to the study’s Service User Advisory Group, which comprised five older people with lived experience of TR-GAD, for discussion. Views on the salience and feasibility of the proposed intervention components, together with discussions with eight academic clinicians involved as co-applicants/collaborators in the research, informed the guiding principles and design of the ACT intervention manual.

We conducted further semistructured face-to-face interviews with the 15 older people with TR-GAD who completed interviews in stage 1 using ‘think aloud’ techniques. 68 This is when researchers observe people using an intervention while saying their thoughts out loud. We used a topic guide flexibly to explore opinions about the developed intervention (see Report Supplementary Material 1). We mailed out a written summary of the key features of the manualised intervention to participants in advance of the interview to help elicit their views. We also asked participants to voice their thoughts during and after a sample of intervention exercises. We iteratively modified the features in the ACT intervention to improve acceptability. This was then subject to further feedback from eight academic clinicians involved in the management of the study and 15 therapists involved in the provision of ACT for the study.

Data analyses

We used the framework approach69 to facilitate analysis within and between individual cases and groups of participants. One author (KK) conducted the interviews and focus group with academic clinicians, listened to all recordings and repeatedly read the transcripts and research notes to familiarise herself with the data. We noted key issues, recurrent themes and interpretations, and discussed these in supervision and at research team meetings. Two additional authors (VL and RG), who had not analysed the other transcripts, reviewed three transcripts to help identify alternative viewpoints. We developed a descriptive theoretical framework of key beliefs about GAD, coping strategies and therapy specific to this group and considered relevant to the intervention by consensus and used this to index subsequent transcripts. Data were then charted into matrices to help map and interpret the data set as a whole; comparisons were made across themes and participants to help synthesise the findings.

Ethics

Ethics approval was granted by the London–Camberwell St Giles Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 9 May 2017 and Health Research Authority approval was granted on 12 May 2017 [Integrated Research Approval System (IRAS) identifier (ID) 214775, REC reference 17/LO/0704; see Report Supplementary Material 2].

Results

Participants

As shown in Table 3, the majority of older people with TR-GAD were recruited from secondary care services (n = 8, 53%) and self-identified as female (n = 11, 73%), were in their 70s (n = 8, 53%), were married (n = 7, 47%) and were educated to at least degree level (n = 8, 53%). All self-identified as white/white British (n = 15, 100%). The majority of health-care professionals and academic clinicians self-identified as female (n = 27, 75%) and were most commonly clinical or counselling psychologists (n = 13, 36%) or psychiatrists (n = 10, 28%) working in secondary care settings (n = 25, 84%).

| Variable | N (missing n, %) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Older people with TR-GAD (n = 15) | ||

| Sex | 15 (0, 0) | |

| Female | 11 (73) | |

| Male | 4 (27) | |

| Age (years) | 15 (0, 0) | |

| 60–69 | 5 (33) | |

| 70–79 | 8 (53) | |

| 80–89 | 2 (13) | |

| Ethnicity | 15 (0, 0) | |

| White/white British | 15 (100) | |

| Marital status | 15 (0, 0) | |

| Married | 7 (47) | |

| Divorced | 2 (13) | |

| Single | 1 (7) | |

| Co-habiting | 1 (7) | |

| Widowed | 4 (27) | |

| Education | 15 (0, 0) | |

| No qualifications | 2 (13) | |

| O level/GCE/GCSE | 3 (20) | |

| A level | 2 (13) | |

| Undergraduate degree and higher | 8 (53) | |

| Recruitment setting | 15 (0, 0) | |

| Primary care | 2 (13) | |

| Secondary care | 8 (53) | |

| Self-referral | 5 (33) | |

| Health-care professionals (n = 31) and academic clinicians (n = 5) | ||

| Sex | 36 (0, 0) | |

| Female | 27 (75) | |

| Male | 9 (25) | |

| Profession | 36 (0, 0) | |

| Clinical or counselling psychologist | 13 (36) | |

| CBT therapist | 1 (3) | |

| Occupational therapist | 4 (11) | |

| GP | 4 (11) | |

| Psychiatrist | 10 (28) | |

| Nurse | 4 (11) | |

| Service level | 35 (1, 3) | |

| Primary care | 5 (14) | |

| Secondary care | 29 (83) | |

| Tertiary care | 1 (3) | |

Key themes in stage 1

Interviews with older people and health-care professionals identified key issues, needs and challenges that would need consideration when developing the intervention. These were categorised into four key themes: (1) ‘expert in one’s own condition’, (2) ‘deep-seated coping strategies’, (3) ‘expert in therapy’ and (4) ‘support with implementation’. Subthemes within each key theme were also identified. We present data across the participant groups, with similarities and discrepancies highlighted where relevant. Sample quotations are presented in Appendix 1.

Theme 1: expert in one’s own condition

The majority of older people with GAD presented themselves as experts in their own condition, recounting deep-seated views of self, contributing factors, circumstances that triggered their anxiety and the futility of this response (see theme 1 in Appendix 1, Table 51). Many described themselves as having a propensity to worry, with anxiety being an inherent part of who they are. Worry was often intertwined with negative aspects of ageing, including pain, lack of mobility, poor health and bereavement. There was consensus among health-care professionals that physical health problems contributed to GAD, were difficult to resolve and limited older peoples’ ability to attend and concentrate in therapy sessions. Yet a large proportion of professionals were also critical of what they viewed as ‘entrenched negativity’, whereby identifying worrying as part of one’s sense of self could prevent individuals from taking ownership of their condition or assuming a role in effecting change. They suggested that this led to an over-reliance on services and, subsequently, a need to socialise older people to a therapeutic model that is fully collaborative and directed towards change. Nevertheless, health-care professionals recognised that older people had unrivalled knowledge of their condition, which was further evidenced by the detailed accounts that individuals gave of the circumstances and thoughts that triggered their anxiety, such as the health and well-being of their children, social interaction, travelling and finances. Many older people recognised that worrying was to a large extent unnecessary and, to an even greater degree, futile, yet some health-care professionals felt that older people with TR-GAD required a deeper understanding of just how unproductive these existing thinking patterns could be.

Theme 2: deep-seated coping strategies

Older people had often established deep-seated coping strategies over the course of their illness (see theme 2 in Appendix 1, Table 51). Almost all commented, often with regret, that they had come to avoid most social contact and activities, as these were a major cause of anxiety. Those who continued to meet with friends described how they circumvented particularly uncomfortable aspects of the social situation (e.g. by getting a taxi to a friend’s house to avoid public transport) or concealed their anxiety. Putting on a ‘brave face’ was a source of both pride and pain. Another common strategy was to plan for the worst by anticipating all eventualities. Two older women reflected that these efforts to exercise control over the events and people in their lives had been detrimental to their relationships. Health-care professionals acknowledged the challenge of addressing these entrenched behaviours, which were widely recognised, suggesting that they necessitated longer and more ‘intensive’ therapy.

Theme 3: expert in therapy

Participants had accumulated considerable personal experience of talking therapies, most often CBT (see theme 3 in Appendix 1, Table 51). Therapies were criticised for being ‘too academic’ and for relying on short-term courses and inexperienced therapists who lacked the life experience to truly understand their problems. One woman indicated her discomfort at reflecting on her behaviour during therapy; another reported that she found it difficult to change how she thinks at this stage in her life.

There was evident frustration among health-care professionals in primary and secondary care as they described the difficulty of engaging these older people in thinking about their anxieties. One GP suggested that years of medication had created a distance between older people with GAD and their distress, and eroded individuals’ awareness of their internal states. Older people were ambivalent about medication: most felt it had the potential to ameliorate anxiety in some cases but had side-effects and, like talking therapy, did not eliminate underlying problems. A handful of participants articulated a desire for a ‘magic pill’ that would remove their distress. Health-care professionals saw this wish for a cure as further evidence of older people’s unwillingness to assume responsibility for change themselves, leading to an over-reliance on services and an expectation that therapists should provide treatment without recognising the need for active participation on the older person’s part. Health-care professionals stressed the importance of reaching realistic, shared goals for therapy and of adopting a collaborative approach. It was striking that almost all older people highlighted the qualities of the therapist as the most important aspect of therapy. Participants indicated that empathy was a prerequisite for any therapeutic alliance, with value placed on therapists who did not make judgements but listened carefully to understand their experience.

Theme 4: support with intervention

It was widely recognised among older people that implementing relaxation techniques in their lives required practice and commitment (see theme 4 in Appendix 1, Table 51). Most were receptive to this in principle, but felt they lacked sufficient discipline in practice. Many were sceptical of the ability of talking therapies to produce a sustained benefit, but nonetheless were forthcoming in contributing suggestions to achieve this. For example, it was thought that meditation could be supported using audio tapes, videos and telephone reminders. However, input from others via weekly groups, brief follow-up contact with health-care professionals and family encouragement were considered necessary to embed this practice in their lives. Health-care professionals routinely advocated using handouts and engaging family members so that they could fully understand and support this work. There was a consensus among professionals that interventions needed to be flexible, offering a range of activities that could be practised at home with the support of handouts and, some suggested, occasional home visits.

Guiding principles in stage 2

Themes identified in stage 1 were developed into guiding principles for therapy (Table 4), in consultation with the Service User Advisory Group, and modified in response to follow-up interviews with older people with TR-GAD and via further discussion with experts (clinical academics and therapists involved in the study). Some of the key features for optimising an ACT intervention for older people with TR-GAD are described in this section. The final outputs from the process of intervention design, development and optimisation have been presented rather than incremental changes being itemised.

| Key issue | Design objectives that address each key issue | Key intervention features relevant to each design objective |

|---|---|---|

| Expert in one’s own condition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Deep-seated coping strategies |

|

|

|

|

|

| Expert in therapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Support with implementation |

|

|

Theme 1: expert in one’s own condition

Examine beliefs around ‘self as worrier’

Older people acknowledged that exploring beliefs around the view of the self as a worrier may be of benefit, including evaluating how this might help or hinder individuals from living the life they want. Clinical academics felt that the perceived inevitability of worrying in the context of age, pain, lack of mobility, poor health and bereavement should be discussed, as this could develop into a negative self-stereotype and deter individuals from attempting to change their behaviour. Similarly, older people could be helped to understand that worrying not only is futile but could also limit their activities beyond those imposed by any chronic illness or functional impairment.

Listening and respecting values and enduring concerns

Older people were unequivocal in their view that therapy must respect their lifelong knowledge and experience. All stakeholders agreed that this information can be used to personalise activities and to support therapists in using metaphors and exercises, as is typical in ACT, that are relevant and meaningful to individual service users.

Theme 2: deep-seated coping strategies

Evaluate the costs of deep-seated coping strategies

Although not raised in interviews with older people, members of the Service User Advisory Group agreed that therapy should examine the consequences of the coping behaviours that older people have developed over many years to help them control their worrying. This should include raising awareness of the costs of trying to control their worries (e.g. through avoidance behaviour), including the emotional toll of concealing anxiety and of trying to control situations, people and events. Experts felt that therapy should consider the extent to which curtailing social contact and activities had caused individuals to lose contact with the things that gave meaning to their life (i.e. their values).

Consider any useful functions of avoidance behaviour

Older people felt that it should not be assumed that all control and avoidance behaviour is problematic; older people are experts in living with their own condition and certain behaviours may serve a useful function. Clinicians subsequently supported this point.

Theme 3: expert in therapy

Communicate the goal of acceptance and commitment therapy

Older people liked the fact that ACT does not involve challenging thoughts around losses that may be realistic, and all saw the benefit of focusing on remaining resources and living life in accordance with deeply held values. Members of the Service User Advisory Group stressed that the aim of ACT should be clearly communicated and differentiated from the aim of CBT, with which older people may be more familiar; it should be stressed that the purpose of ACT is not to fix problems or change thoughts and feelings.

Helping older people to recognise and discuss thoughts and feelings

Regular mindfulness exercises were suggested by academic clinicians and endorsed by older people as a way to develop skills in recognising and describing their thoughts and their feelings. They thought that the use of concrete metaphors and experiential exercises (i.e. those using visual or physical props) could make concepts easier to understand for some, but not others, with some older people expressing a preference for ‘speaking plainly’ without the use of metaphors or props.

Working in collaboration

There was consensus among older people and clinicians that therapy should be a collaborative partnership between the therapist and the older person. Older people continued to prioritise an empathic approach and therapists expressed confidence in validating individuals’ experiences and emotions. However, members of the Service User Advisory Group acknowledged that therapists should not be expected to ‘fix’ the individual or provide solutions. Rather, individuals must be active in pursuing value-based goals.

Theme 4: support with implementation

Provide strategies and materials to support implementation

All agreed that multiple strategies should be used to help older people apply therapeutic principles in their lives. As it is common that older people experience mild age-related cognitive changes, adaptations should be made to accommodate for potential changes in memory, attention and processing speed. Older people responded positively to the following practices and suggestions: repetition of key ACT phases throughout the intervention, working at a slower pace when necessary, providing a summary of the sessions as a reminder of what has been discussed and asking the service user to discuss their understanding of weekly practice tasks in their own words, to check that what has been set by the therapist has been understood.

Work with close family and friends

Older people thought that the aim of ACT should be clearly communicated to all those involved in the health and welfare of the client at the start of therapy. Partners, family members or close friends could contribute to the account of an individual’s difficulties and help them to work through potential barriers to behavioural change. However, members of the Service User Advisory Group cautioned that many would not want to burden their children by involving them in this way.

Discussion

The findings suggest that ACT psychopathological processes can be identified in people with TR-GAD, underlining the potential suitability of using an ACT approach with this population. For example, participants appeared to have difficulty in separating themselves from the literal meaning of their thoughts (cognitive fusion), frequently telling themselves that they are worriers (self-as-content) and placing limits on their behaviour (lack of committed action). They described avoided situations that make them feel uncomfortable and attempts to try to control their thoughts and emotions (experiential avoidance). These approaches have been associated with distress in older people,70 and participants confirmed that they exert an emotional burden. As posited elsewhere,43 the goal of ACT to live life in accordance with deeply held values, despite the many challenges that may be experienced, seemed to resonate with this group; group members had experienced little success with control-orientated treatment strategies such as CBT in the past.

The findings also highlight the unique experience of older people with TR-GAD and important implications for how talking therapies and, more specifically, ACT are applied with this group. Some generic implications included ensuring that attention is given to validating and accommodating the individual’s knowledge and experience in therapy, and that therapeutic strategies are used to compensate for age-related cognitive changes. Implications specific to ACT included differentiating the aims of ACT from those of CBT and using mindfulness to support discussion of thoughts and feelings. Notably, not all older people responded positively to the use of metaphors and experiential exercises, key tools in ACT for communicating abstract concepts. This reinforces previous suggestions that these techniques must be used thoughtfully and tailored to the client’s language and life experience. 71 Participants also cautioned against assuming that all efforts to control unwanted thoughts and experiences are unhelpful. Brock et al. 71 elaborate on this point, suggesting that there may be times when avoiding certain emotional experiences is the functional thing to do and therapists should identify the role that avoidance plays in the client’s day-to-day life. The concept of workability, that is, how well a strategy is helping a person to live their life in accordance with their values, is key here.

There was a large overlap in the views of older people and health-care professionals. Notably, despite expressing optimism around the principles of ACT, both groups described feelings of hopelessness with respect to change. One of the strongest themes to emerge in the data was the idea of ‘entrenched negativity’, requiring an early focus on cognitive fusion in relation to negative attitudes about ageing and the individual’s sense of self. However, health-care professionals felt that this also necessitated a change in how older people with TR-GAD approach therapy. Positioning ACT as a collaborative partnership between clients and therapists and exploring older people’ expectations around therapy should support this. It has previously been noted that there is a risk that therapists delivering ACT will be drawn into the content of their clients’ experiences and develop a wish to eliminate clients’ suffering (Mark A Serfaty, Division of Psychiatry, University College London, 2017, personal communication). Therapists are advised to validate the experience, not the content, and to help clients reflect on how the situation could be changed (Mark A Serfaty, personal communication). The client–therapist relationship in ACT has been described as ‘strong, open, accepting, mutual, respectful and loving’,72 which is accordant with the emphasis that older people placed on therapists who are interested in understanding their experiences. It is notable that, although older people valued empathy, their comments suggested a desire for more than ‘just’ a passive listener. Finally, health-care professionals may also need to examine their own beliefs around working with older people with TR-GAD that might impede therapeutic progress. Acquiring experience of an intervention that works with older people with TR-GAD is likely to inculcate therapeutic optimism in service users and clinicians alike.

How acceptance and commitment therapy was adapted for older people with treatment-resistant generalised anxiety disorder

A description of the specific adaptations made to the ACT intervention for older people with TR-GAD is presented below. This takes into account the guiding principles identified in Table 4, as well as previous recommendations with respect to using ACT with older people. 43

Acceptance and commitment therapy assessment

Several key areas were assessed during the initial session and throughout the intervention with respect to their contribution to the development and maintenance of TR-GAD, as it is important to understand the biopsychosocial context in which a person’s difficulties are occurring. These key areas included:

-

biological factors (e.g. comorbid physical health difficulties and mild age-related cognitive difficulties)

-

psychological factors (e.g. unwanted internal experiences, loss, psychiatric comorbidity, core ACT processes)

-

sociocultural factors (e.g. financial, social, cultural and environmental factors)

-

suicidal ideation and risk of harm to self

-

substance misuse (including alcohol and illicit and prescribed drugs).

Therapists were encouraged to develop an idiosyncratic ACT case conceptualisation for each participant in sessions 1–5 so that the order in which ACT processes were chosen to be targeted was hypothesis driven in sessions 6–15.

Introduction to acceptance and commitment therapy

An introduction to ACT was provided in the first session, which included (1) what ACT is and a rationale for it, (2) the aim of ACT and its focus on change (i.e. ‘living better’ rather than ‘feeling better’), (3) an emphasis on active participation in therapy (i.e. a ‘doing therapy’ rather than a ‘talking therapy’), (4) an explanation of the importance of skills practice between sessions and (5) an emphasis on working collaboratively together ‘as a team’, highlighting willingness as a choice (i.e. the participant always gets to choose whether or not they are willing to take part in experiential exercises).

Early focus on values and committed action

Previous research with older people with GAD has suggested that it may be beneficial to adapt ACT so that there is an early focus on values and committed action. 27 Consequently, a focus on values and committed action was introduced early into the intervention (after the initial assessment) and repeatedly revisited throughout the intervention.

Focus on workability

The desire to get rid of anxiety or feel better (i.e. attachment to the emotional control agenda in ACT terms) is more likely in those with treatment-resistant anxiety disorders, particularly those who have a lifelong history of GAD and have been struggling with their symptoms for years. Therefore, there was a greater focus on workability in the intervention than may ordinarily be used to target entrenched or narrowed behavioural repertoires. This involved exploring (1) what strategies a person had been using to try and get rid of anxiety (e.g. avoidance behaviour); (2) how these had been working in the short and long term (i.e. the costs and benefits of these strategies), both in terms of anxiety and quality of life; and (3) the degree to which they were helping the person to live a rich, full and meaningful life (i.e. doing what is most important to them and being who they most want to be). This also involved validating and normalising the desire to want to get rid of anxiety or feel better, as well as the desire for a ‘magic pill’. In addition, it involved exploring the alternative to emotional control (i.e. trying to get rid of anxiety) by encouraging a willingness to experience uncomfortable thoughts and feelings to help people move towards the things that are important and matter to them. (In ACT terms, the process of discovering how control is often the problem is called ‘creative hopelessness’ or ‘workability’.)

Use of concrete metaphors and experiential exercises

Some older people may struggle to understand abstract concepts, particularly those with age-related cognitive difficulties. Consequently, care was taken to ensure that as many metaphors and experiential exercises used visual and/or physical props or physical demonstrations as possible. Examples of these are as follows:

-

acceptance – ‘tug of war’ metaphor with a rope; ‘Chinese finger trap’ metaphor with a Chinese finger trap; sticky notes exercise with sticky notes; acting out the ‘pushing paper’ exercise; cactus metaphor with a spiky ball; ‘holding a book’ metaphor with a book; acting out ‘passengers on the bus’ metaphor

-

defusion – ‘milk, milk, milk’ exercise; sing the thought/say it in a silly voice/say it very slowly and very quickly; ‘I’m noticing I’m having the thought that . . .’ exercise; write the thought in different colours, different styles and reverse order; sticky notes exercise with sticky notes; acting out ‘passengers on the bus’ metaphor; ‘take your mind for a walk’ exercise

-

contact with the present moment – mindful eating, drinking, stretching, walking, etc.; daily mindfulness (e.g. mindful showering, mindful shopping)

-

self-as-context – ‘cup and contents’ exercise with a paper cup and sachets of coffee, milk and sugar; labels exercise with actual luggage labels and stickers; house and furniture exercise with a visual handout

-

values – lifetime achievement award with the client listening to the recorded speech.

Whenever possible, therapists were encouraged to customise metaphors and experiential exercises to participants’ struggles, needs, history, own language and preferences, as suggested by others. 73

Focus on mindfulness

As we previously noted,43 some older people may experience difficulties in recognising, describing, observing or being aware of their internal states. Therefore, we introduced a mindfulness exercise at the beginning of each session, in addition to sessions dedicated to developing mindful awareness, to develop and increase skills in awareness of internal states.

Focus on cognitive fusion and self-as-content (or attachment to the conceptualised self)

Older people with TR-GAD who report lifelong issues with worrying may be strongly fused with a conceptualised sense of themselves as having ‘always been a worrier’ or of worrying as being a part of who they are (and therefore not knowing who they are without worrying). They may also demonstrate strong fusion with a conceptualised future self (e.g. ‘my health is only going to get worse and there’ll be nobody to look after me’), which, although based in reality, may interfere with value-driven behaviours. In addition, cognitive fusion with negative attitudes about ageing (e.g. ‘I am too old to exercise’, ‘feeling depressed is a normal part of ageing’) and chronic ill health or physical/cognitive impairment (e.g. ‘I can’t do anything more’, ‘I’m not the person I used to be’) may be apparent, and may also serve as an internal barrier to behavioural change. Thus, therapists helped participants to explore the workability of holding onto such self-beliefs (i.e. how well they were helping them to live a life in service of their values rather than in service of avoiding difficult thoughts, feelings, sensations). In addition, therapists helped participants to develop skills for stepping back from thoughts and for holding views about themselves lightly so that they could move towards the things that are important and matter to them and be who they want to be.

Laidlaw and Kishita’s CBT conceptual framework74 advises that cohort beliefs, and beliefs in relation to transitions in role investments (e.g. due to retirement, caring for another person or bereavement) and intergenerational linkages, should be considered when working with older people. Examples of shared generational cohort beliefs include ‘always keep a stiff upper lip’, ‘you can’t teach an old dog new tricks’ and ‘needing help is a sign of weakness’. Examples of beliefs in relation to transitions in role investments and intergenerational linkages include ‘I’m a nobody now’, ‘I’m no longer needed’ and ‘I’m a burden on my family’. Therapists were similarly advised to consider cognitive fusion with such beliefs when using ACT with older people with TR-GAD because these may pose a further internal barrier to behavioural change. In addition, therapists were advised to explore cognitive fusion in relation to seeking help, because discussing shame in seeking help has been suggested to be helpful when working psychotherapeutically with older people. 75

Use of principles of selective optimisation with compensation

Principles of selective optimisation with compensation were originally developed to aid adaptation to the challenges of ageing and have since been successfully used in ACT for chronic pain. 55,76 They involve strategies for helping people to choose the best functional domains in which to focus their resources, engage in tasks that they perform best and find ways of compensating for losses. They can be similarly applied to older people with TR-GAD to help them to participate as fully as possible in their lives in ways that are meaningful to them and to help them achieve valued goals despite the challenges of ageing. Consequently, the use of principles of selective optimisation with compensation was specifically incorporated into sessions focusing on committed action.

Examples of using principles of selective optimisation with compensation in ACT include:

-

selecting or limiting goals to those that are in service of the person’s most important values

-

selecting or limiting goals to those that are in the best domains of functioning for the person

-

adapting goals or focusing on specific aspects of a goal so that they can be more realistically achieved

-

replacing goals that are no longer achievable by identifying what it is that a person liked about the original goal

-

optimising engagement in goal-related activities (e.g. by practising or learning new skills and capitalising on a person’s strengths)

-

utilising additional resources so that goals can be achieved (e.g. asking others for help)

-

using alternative strategies, aids or tools to compensate for losses in function due to mental or physical health-related difficulties to achieve valued goals (such as memory aids and walking aids).

Compensating for age-related cognitive changes

It is important to compensate for mild age-related cognitive changes in working memory, attention and processing speed when working with older people with GAD because these have been associated with a reduced response to CBT in this population. 77 We incorporated standard therapeutic strategies that can compensate for age-related cognitive changes in the intervention, as suggested by others. 43,78 These included:

-

providing modifiable worksheets (so that they can be adapted for visual impairment) and session summaries as a reminder of the content of the sessions

-

repeating key concepts and skills in and between sessions (e.g. recapping on the previous session at the beginning of the next session)

-

asking participants to repeat home practice assignments in their own words to check their understanding of the assignments or working through an example before the session ends

-

having the flexibility to work at a slower pace when necessary

-

providing appointment reminders by automated text message reminder systems, with consent from participants.

Working with comorbidities

Physical and mental health comorbidity (e.g. depression, other anxiety disorders, personality disorders, mild cognitive deficits, physical ill-health, pain) is common in TR-GAD and is associated with poor treatment response. 13 It was emphasised to therapists that, as ACT is a transdiagnostic form of psychological therapy, comorbidities can be dealt with in the same way as TR-GAD: by targeting the ACT processes that are hypothesised to be responsible for the narrowing of the person’s behavioural repertoires.

Working with substance misuse

Substance misuse, including excessive use of prescription medication (e.g. benzodiazepines and other hypnotic drugs), over-the-counter medication (e.g. sedative antihistamines), alcohol and illicit substances (e.g. cannabis), is common in GAD. Engagement in substance misuse is typically formulated in the ACT model as a means of reducing or avoiding unwanted internal experiences (e.g. anxiety symptoms). This may interfere with therapy because a person may not be able to fully benefit from exercises aimed at helping them to increase their willingness to have anxiety symptoms (in order to do the things that are important and matter to them and be the type of person they want to be). Therefore, an ‘optional session’ was included in the intervention in which psychoeducation about substance misuse, the risks and benefits of this, and ways of reducing this during the provision of ACT (e.g. via supervised gradual withdrawal)79 could be addressed, if necessary.

Working with skills deficits

Standard CBT manuals for GAD in older people typically include sessions on problem-solving and sleep hygiene in recognition of the fact that some older people with GAD may have poor problem-solving skills, or poor sleeping habits. 21,24,80 Thus, an ‘optional session’ on problem-solving for external problems and sleep hygiene was also included in the intervention, which therapists could introduce if necessary. It was emphasised to therapists that these were ACT consistent so long as the following provisos were met: (1) problem-solving was used to address external problems but not internal problems (e.g. thoughts, feelings, sensations) and (2) sleep hygiene was focused on improving sleep habits and not reducing associated distress.

Working with families and health-care professionals

With participants’ consent, we invited partners, family members or close friends to attend the first therapy session to communicate the aim of ACT and its therapeutic stance to all involved given that it is not focused on reducing distress. They were also invited to attend sessions focused on committed action, as this can be helpful in working through potential barriers to behavioural change and helping participants to implement action plans.

One of the most challenging behavioural repertoires in GAD for partners, families, friends and health-care professionals is reassurance seeking. Repetitive questioning and requests for reassurance may take the form of repeated conversations with partners, telephone calls to family members, visits to the GP and accident and emergency (A&E) or telephone calls to emergency services. It was emphasised to therapists that this can be addressed, as with other behaviours, by examining the function of the behaviour (e.g. whether or not the function of reassurance seeking is to reduce anxiety) and its workability. Therapists were encouraged to discuss an ACT-consistent strategy for dealing with repeated reassurance seeking with all parties involved, in conjunction with the participant (and with their consent).

Use of terminology in acceptance and commitment therapy

Throughout the intervention, we emphasised to therapists the importance of ‘speaking plainly’ (i.e. using jargon-free language), using terms that participants understood and establishing participants’ preferred terms for things such as anxiety, GAD and homework.

Limitations

It is important to note that the sample of older people with TR-GAD involved in the study reported high levels of academic achievement, few would be categorised as ‘older old’ (i.e. in their 80s) and all identified themselves as white British. Health-care professionals, Service User Advisory Group members and academic clinicians were encouraged to reflect on experiences across cultural and socioeconomic groups, but it cannot be assumed that the findings of the current study apply to this broader population. Furthermore, health-care professionals and some older people advocated engaging family members so that they could fully understand and support therapy. We cannot comment on family carers' attitudes towards this because they were not included in the qualitative interviews. Telephone conversations with health-care professionals were not audio-recorded (instead, comprehensive notes were taken with key quotations recorded verbatim). However, this can be balanced against the insights gained from the large sample size and the resultant opportunities to verify and amend interpretations of the data. This study was committed to understanding and interweaving the experiences of service users and staff, consistent with experience-based co-design. 81 However, additional benefit may have been gained by bringing stakeholders together to jointly reflect on their shared experiences.

Conclusions

The aim of this study was twofold. First, the study aimed to demonstrate the value of adopting an iterative, person-centred approach to developing an intervention that is fit for purpose. We used rigorous methods, triangulating the perspectives of older people and health-care professionals and examining alternative explanations using analytical diaries, multiple coding exercises, supervision and discussions with service users and experts. Second, in describing the decisions and processes involved in developing ACT for older people with TR-GAD, the study aimed to lay the foundations for a therapeutic intervention that can be built on and replicated in future research. This was an important step forward designed to maximise the likelihood of a successful outcome if the intervention is subsequently evaluated for clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in a future substantive trial.

Chapter 3 Survey

Introduction

Little is known about the usual care that is typically offered to and received by older people with TR-GAD. Such information would be useful in clarifying the best comparator for a future substantive trial of ACT for older people with TR-GAD. Consequently, we invited older people with TR-GAD and health-care professionals to take part in a brief online survey of what constitutes ‘usual care’ in this population in phase 1 of the FACTOID (a Feasibility study of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Older people with treatment-resistant generalised anxiety Disorder) study. Although it may have been possible to gather this information from the open uncontrolled feasibility study conducted in phase 2, this information would have been relevant only to those living in London. We anticipated that there might be regional variations in usual care for TR-GAD in older people, for example because psychological therapies are easier to access in urban than rural settings. Therefore, we judged that a brief online survey would more accurately clarify what constitutes usual care in this population.

In addition to clarifying usual care, we explored the perceived helpfulness of psychological therapy and/or pharmacotherapy for TR-GAD in service users and health-care professionals. Although the very definition of TR-GAD suggests that, overall, treatments would be perceived to be helpful to a degree at best, little is actually known about this in older people with TR-GAD. Knowing what forms of treatment are perceived to be the most helpful (either previously or currently) could inform the choice of comparison condition in a future substantive trial. For example, it might suggest what form of treatment could be used as a comparison condition in a non-inferiority or superiority trial. It could also suggest what form of treatment might optimise recruitment rates in a future substantive trial.

Methods

Design

This was a cross-sectional study.

Participants

Participants were:

-

Older people aged ≥ 60 years who were experiencing or had experienced difficulties with GAD or worrying. All older people who self-identified as experiencing difficulties with worrying were invited to complete the survey, as opposed to just those who were experiencing TR-GAD, because it was thought that participants might find it difficult to identify whether or not they qualified as ‘treatment resistant’ (i.e. failed to respond after completion of steps 1–3 of the stepped-care approach for GAD).

-

Health-care professionals who work with this population of older people in primary and secondary care settings (including GPs, psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, community psychiatric nurses, occupational therapists and social workers).

Settings

Older people were recruited from the community via convenience sampling through GP practices (via local Clinical Research Networks across the UK), primary and secondary care services (IAPT services and CMHTs for older people), a mental health charity [Mind, URL: www.mind.org.uk (accessed 2 February 2021)], local community groups [University of the Third Age (U3A) groups], a service user research forum [INVOLVE, URL: www.invo.org.uk/communities/information-for-members-of-the-public/ (accessed 2 February 2021)], and online forums for older people [Fifty Plus Forum, URL: www.fiftyplusforum.co.uk (accessed 2 February 2021); Pensioners Forum, URL: www.pensionersforum.co.uk/ (accessed 2 February 2021); Senior Forums, URL: www.seniorforums.com (accessed 2 February 2021); Buzz 50, URL: www.buzz50.com (accessed 2 February 2021); Senior Chatters, URL: https://seniorchatters.co.uk (accessed 2 February 2021)]. Several other online forums for older people were approached to assist with advertising the survey but declined involvement or did not permit this [Age UK, URL: www.ageuk.org.uk/get-involved/social-groups/older-peoples-forums/ (accessed 2 February 2021); Gransnet, URL: www.gransnet.com/forums (accessed 2 February 2021); Silver Surfers, URL: www.silversurfers.com/silversurfers-forum/ (accessed 2 February 2021)].

Health-care professionals were identified through GP practices (via local Clinical Research Networks across the UK), online forums associated with occupation-specific organisations (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Royal College of Nursing, The British Psychological Society) and an online forum for those working in health and social care [Contact, Help, Advice and Information Network (CHAIN), URL: www.chain-network.org.uk (accessed 2 February 2021)]. The Royal College of Occupational Therapists was approached to assist with advertising the survey but declined involvement.

Survey

The brief online survey comprised a series of multiple-choice questions with free-text boxes that enabled provision of further information if desired. There were two versions of the survey – one for service users and one for health-care professionals – because the content of questions and terminology differed for the two groups of respondents. The survey was kept as brief as possible to maximise completion rates and took approximately 5–10 minutes to complete.

Service user version

The service user version comprised 15 questions about demographic information (e.g. age, sex, ethnicity, education), clinical information (e.g. diagnosis, duration of worrying), treatments offered previously or currently, whether or not these treatments were taken up and perceptions of the helpfulness of these treatments on a 5-point Likert scale [from 1 (not at all helpful) to 5 (extremely helpful)]. It also included a brief screening tool, the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7),82 which is routinely used in IAPT services and GP surgeries, to ascertain the severity of current difficulties with GAD. A copy of the service user survey is available as Report Supplementary Material 3.

Clinician version

As shown in Report Supplementary Material 4, the clinician version comprised 19 questions about demographic information (e.g. age, sex, ethnicity), professional information (e.g. profession, years since qualification), clinical information (e.g. the percentage of older people seen per month, the proportion of these with GAD), treatments typically offered when an older person has completed steps 1–3 of the stepped-care approach for GAD and how often, why treatments might not be offered and perceptions of the helpfulness of these treatments rated on a 5-point Likert scale [from 1 (not at all helpful) to 5 (extremely helpful)].

Procedure

We contacted a range of organisations across the UK and asked them to advertise the survey (see Settings). The survey used a web-based survey tool, Opinio, version 7 (2017) (ObjectPlanet, Inc., Oslo, Norway). A paper-based version of the survey was available on request but was not routinely distributed as originally hoped owing to resource limitations (both finances and time). A participant information sheet was provided at the beginning of the survey; if participants proceeded to complete the survey, it was assumed that they were providing their consent to participate. The survey was open for data collection from September 2017 to December 2017. The survey was piloted with our PPI group prior to data collection. All responses were anonymous.

Rural Urban Classification83 was used to categorise participants’ geographical area of residence (based on postcode or closest city/town). Areas with a population > 10,000 were categorised as urban and those with a population ≤ 10,000 were categorised as rural.

Data analyses

Responses were excluded if participants indicated that they were aged < 60 years or had ‘never experienced difficulties with long-term worrying or their nerves’. Those with current symptoms of GAD and a treatment history suggestive of TR-GAD were identified in post hoc analyses so that what constitutes usual care in this specific group of respondents could be clarified. Current symptoms of GAD were defined as a score of > 5 points on the GAD-7 and a treatment history suggestive of TR-GAD was defined as either having received at least two types of treatment (pharmacotherapy and/or psychological therapy) for worrying or having been offered at least two types of treatment (pharmacotherapy and/or psychological therapy) for worrying and having refused.

Data relating to demographic and clinical characteristics of service users and demographic and professional characteristics of health-care professionals were summarised using frequencies and percentages, and means and standard deviations (SDs) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for very skewed distributions (i.e. skewness values < –2 or > 2). 84 Perceived helpfulness of treatments was rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all helpful) to 5 (extremely helpful) and was summarised using medians and IQRs.

Parametric rather than non-parametric tests were chosen to analyse Likert scale responses, as previously recommended. 85,86 Data pertaining to the perceived helpfulness of treatments in service users and health-care professionals were analysed as follows. The perceived helpfulness of treatments in service users was examined by submitting data to an exploratory two-way (treatment × time) within-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA), with type of treatment (pharmacotherapy vs. psychological therapy vs. a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychological therapy) and time (current vs. past) as within-subjects variables. The perceived helpfulness of treatments in health-care professionals was examined by submitting data to a one-way within-subjects ANOVA, with type of treatment as a within-subjects variable. Post hoc Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons were used to examine differences between conditions, where appropriate.

Ethics

Ethics approval was granted by the London–Camberwell St Giles Research Ethics Committee on 9 May 2017, with Health Research Authority approval granted on 12 May 2017 (IRAS ID 214775; REC reference 17/LO/0704).

Results

Service users

A total of 136 service users completed the online survey. Responses were excluded for three service users (2%) who were aged < 60 years and for 11 service users (8%) who had ‘never experienced difficulties with long-term worrying or their nerves’. Therefore, we analysed data from 122 service users (90%). Post hoc analyses identified 58 service users (48%) who were considered to have current symptoms of GAD and a treatment history suggestive of TR-GAD. We report data for all service users in Appendix 2.

As shown in Table 5, the majority of service users were aged 65–74 years (n = 33, 57%). Most self-identified as female (n = 55, 95%) and white/white British (n = 54, 93%) and resided in urban areas (n = 50, 86%), mainly in the London region (n = 34, 59%). Just under half of service users had a degree or postgraduate qualification (n = 28, 48%), with only five service users (9%) reporting no educational qualifications.

| Variable | N (missing n, %) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58 (0, 0) | |

| 60–64 | 13 (22) | |

| 65–74 | 33 (57) | |

| 75–84 | 11 (19) | |

| 85–94 | 1 (2) | |

| ≥ 95 | 0 (0) | |

| Prefer not to say | 0 (0) | |

| Sex | 58 (0, 0) | |

| Male | 3 (5) | |

| Female | 55 (95) | |

| Prefer not to say | 0 (0) | |

| Ethnicity | 58 (0, 0) | |

| Asian/Asian British | 1 (2) | |

| Black/black British | 0 (0) | |

| Mixed | 1 (2) | |

| White/white British | 54 (93) | |

| Other | 2 (3) | |

| Prefer not to say | 0 (0) | |

| Age (years) left school/education | 58 (0, 0) | |

| 14–16 | 22 (38) | |

| 17–19 | 32 (55) | |

| 20–22 | 0 (0) | |

| 23–25 | 3 (5) | |

| ≥ 26 | 1 (2) | |

| Highest educational qualification | 58 (0, 0) | |

| School Leaving Certificate | 0 (0) | |

| O level/GCSE | 9 (16) | |

| Diploma | 9 (16) | |

| A level | 3 (5) | |

| Undergraduate degree | 18 (31) | |

| Master’s degree | 9 (16) | |

| PhD | 1 (2) | |

| No educational qualifications | 5 (9) | |

| Other | 4 (7) | |

| Prefer not to say | 0 (0) | |

| Geographical area | 58 (0, 0) | |

| Urban | 50 (86) | |

| Rural | 2 (3) | |

| Prefer not to say/no response | 6 (10) | |

| Region of the UK | 58 (0, 0) | |

| Englanda | 49 (84) | |

| East Midlands | 4 (7) | |

| East of England | 0 (0) | |

| London | 34 (59) | |

| North East | 0 (0) | |

| North West | 0 (0) | |

| South East | 6 (10) | |

| South West | 2 (3) | |

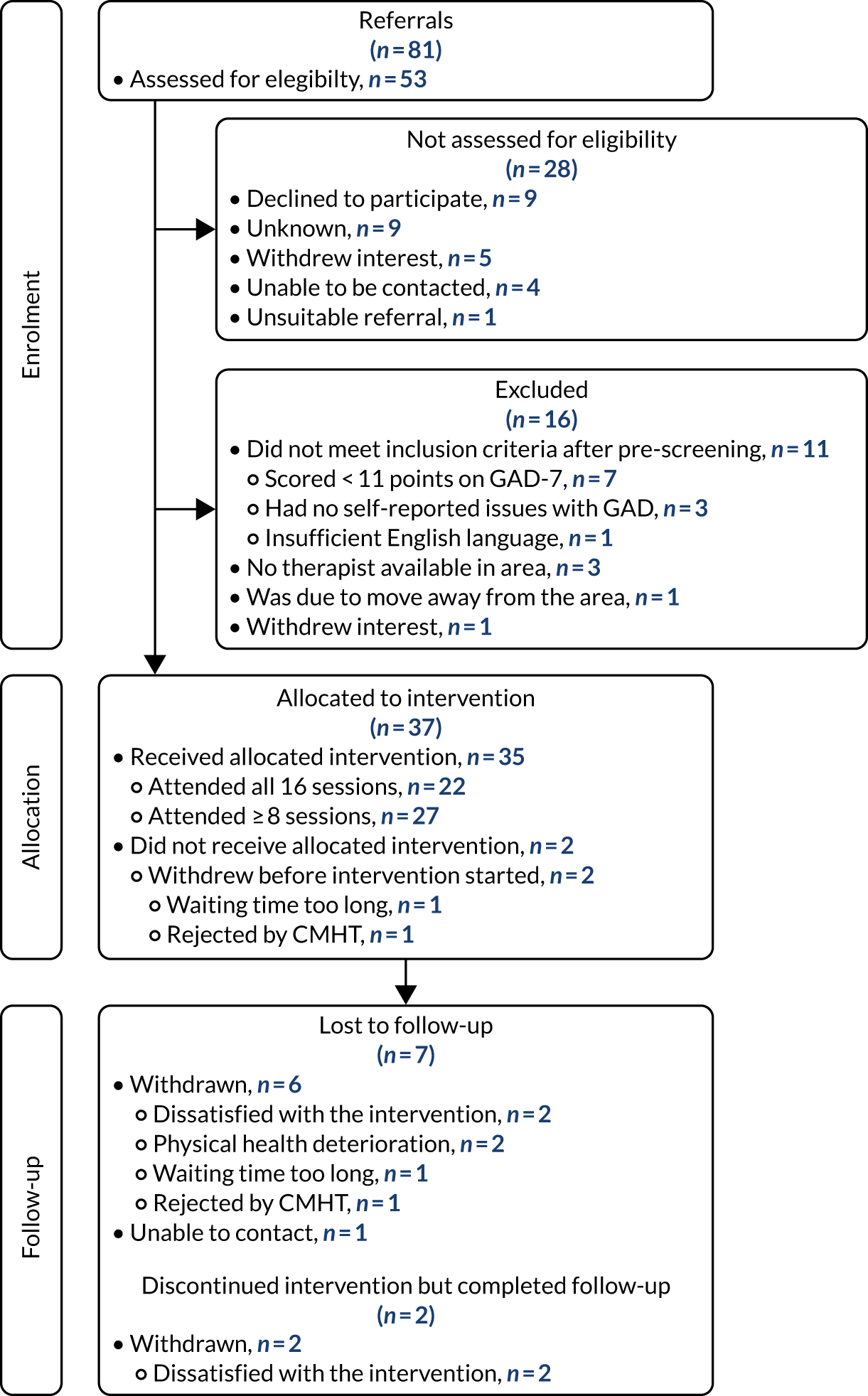

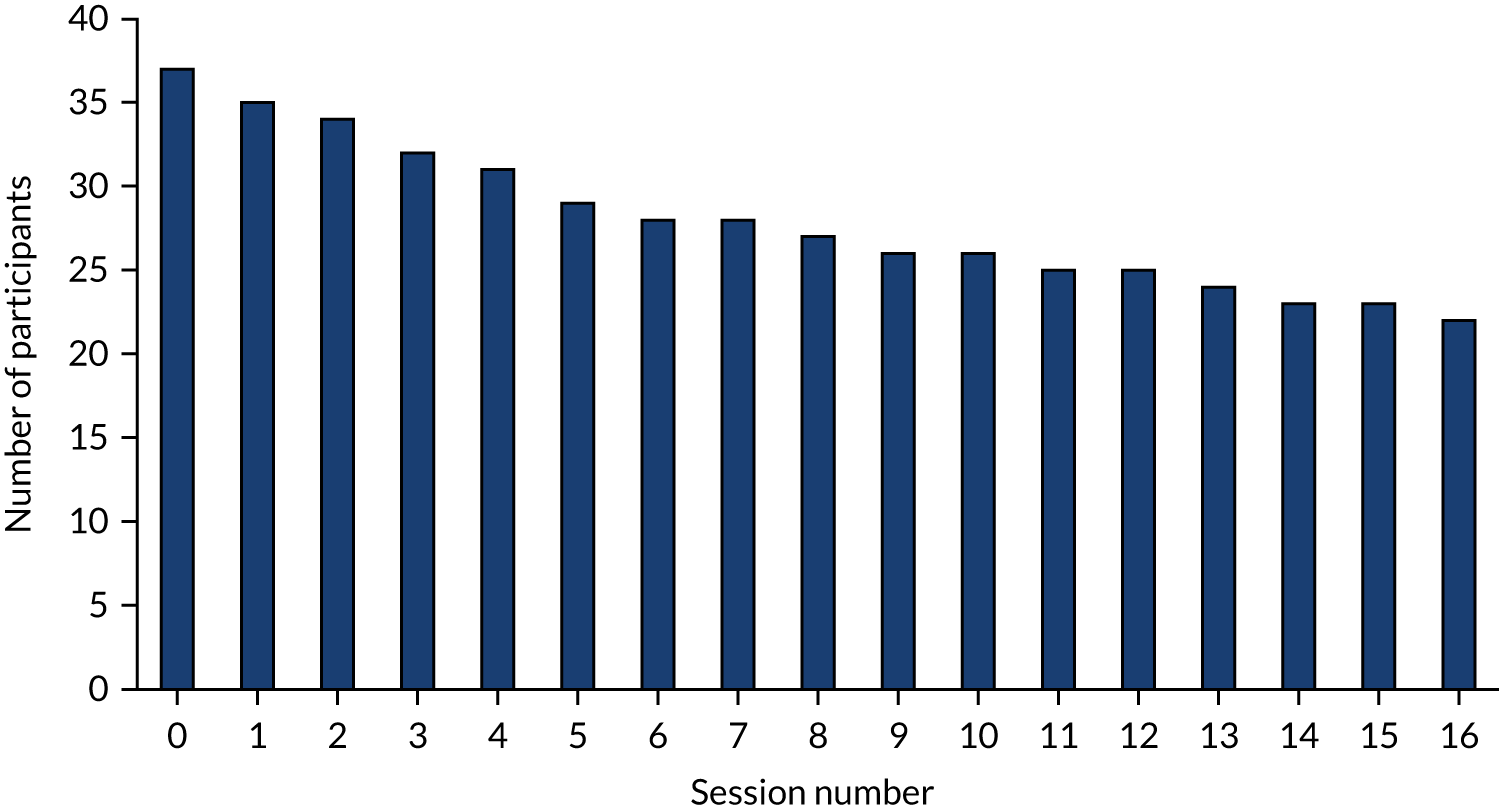

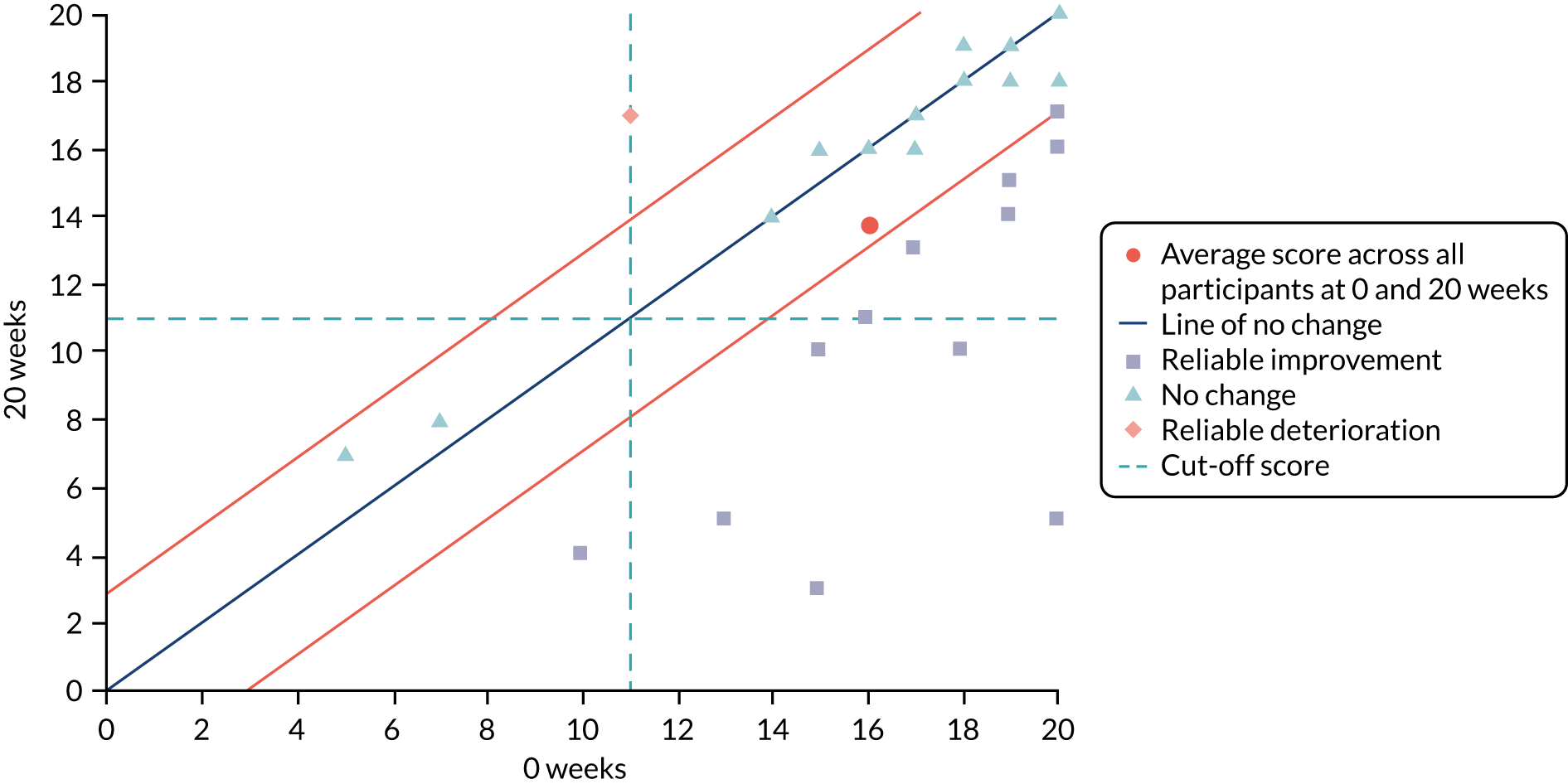

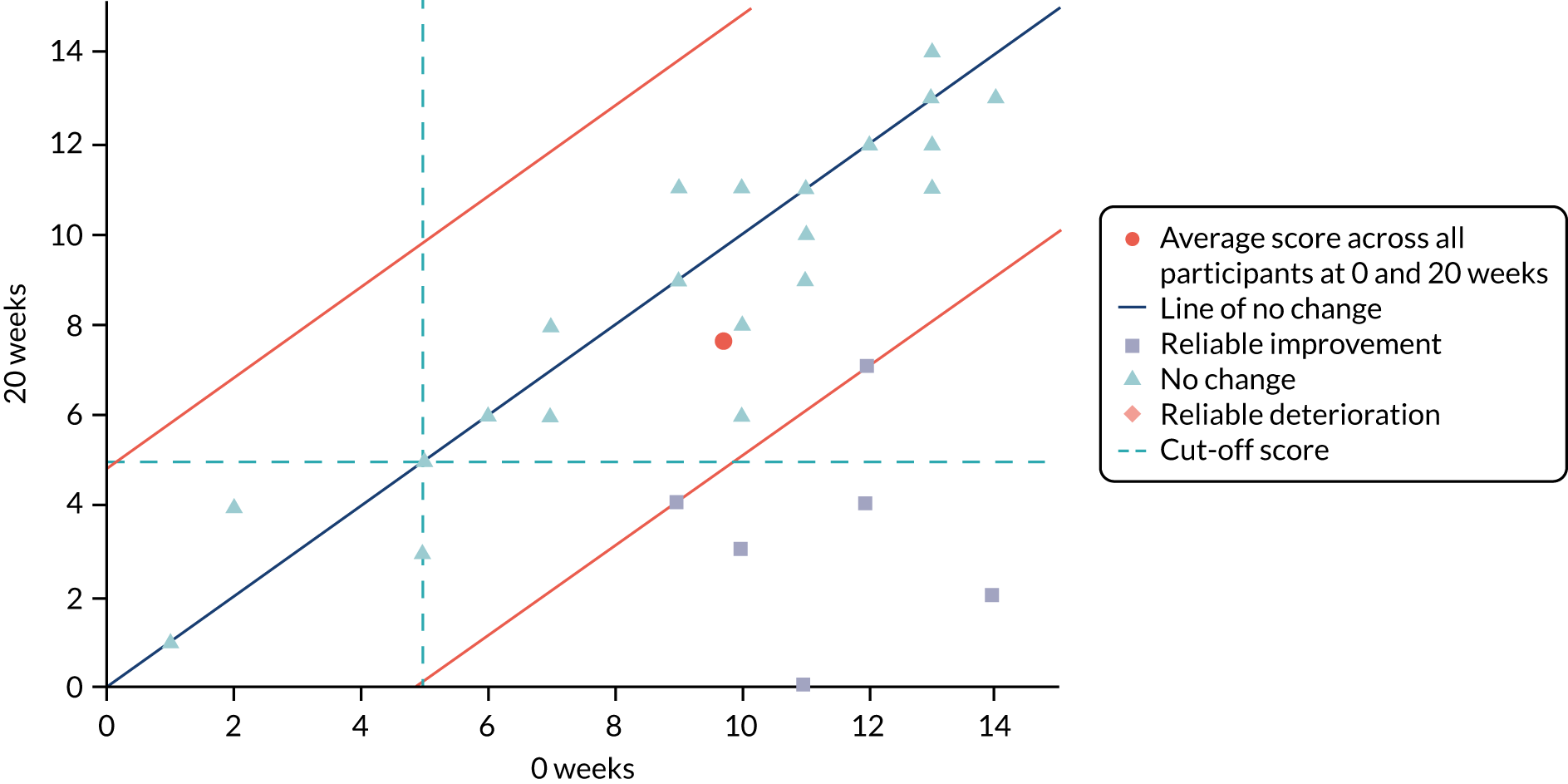

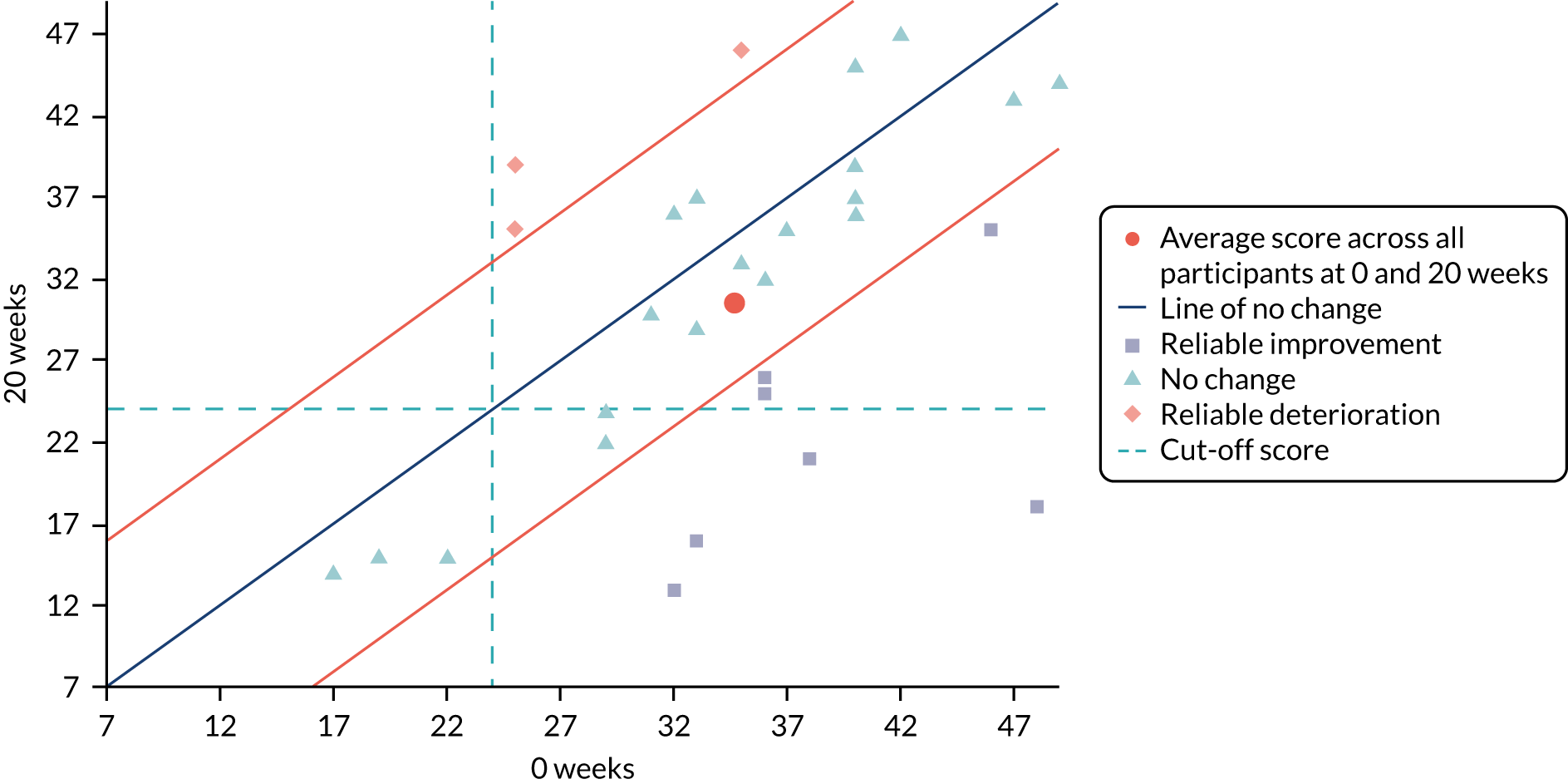

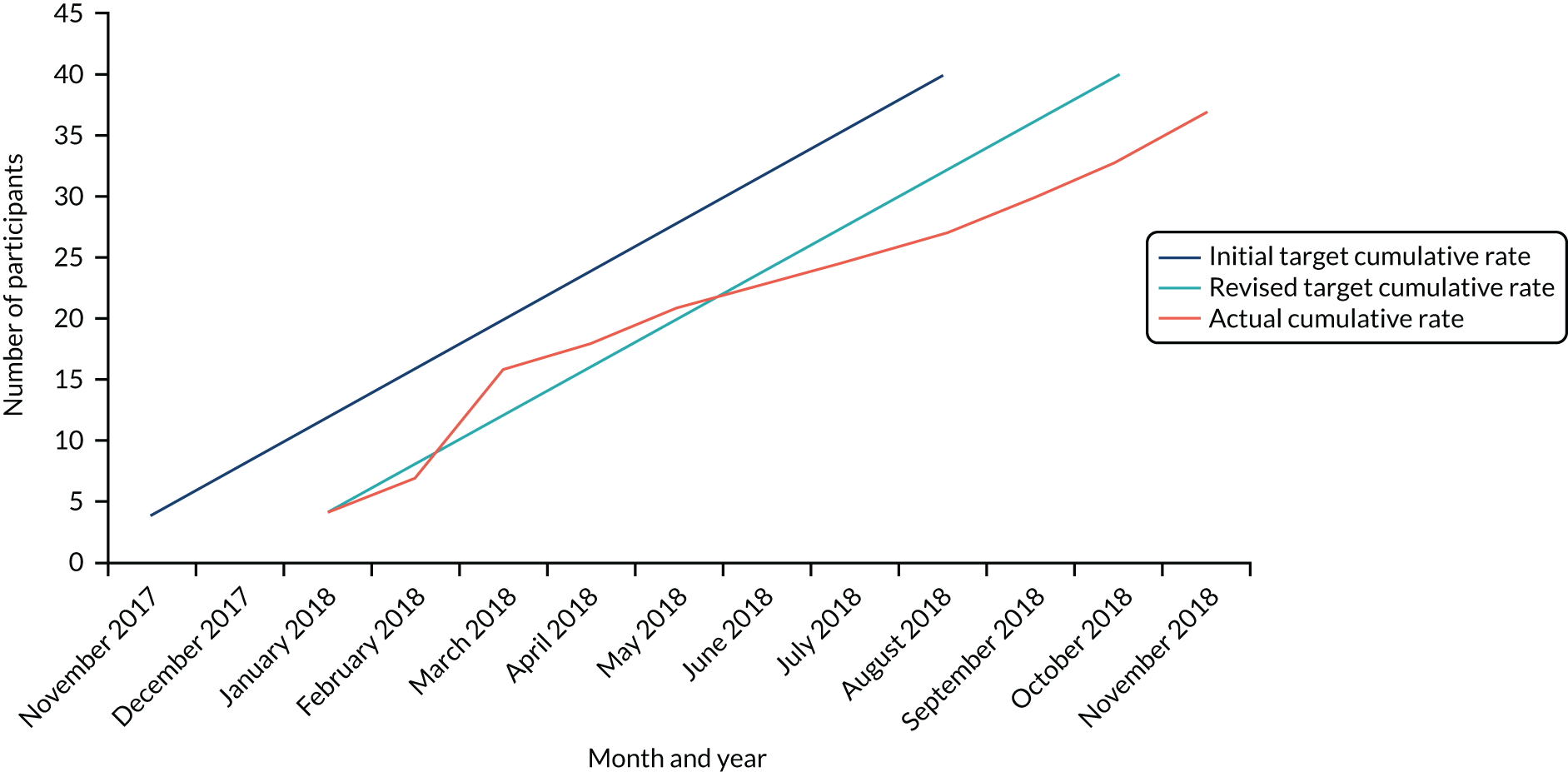

| West Midlands | 2 (3) | |