Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0610-10066. The contractual start date was in October 2012. The final report began editorial review in July 2019 and was accepted for publication in February 2021. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Scott et al. This work was produced by Scott et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Scott et al.

SYNOPSIS

The synopsis provides a narrative account of the main results from the programme. The results are reported in nine separate sections. They are preceded by this introductory section and followed by a final section that outlines key conclusions and recommendations for further research, making eleven sections in total.

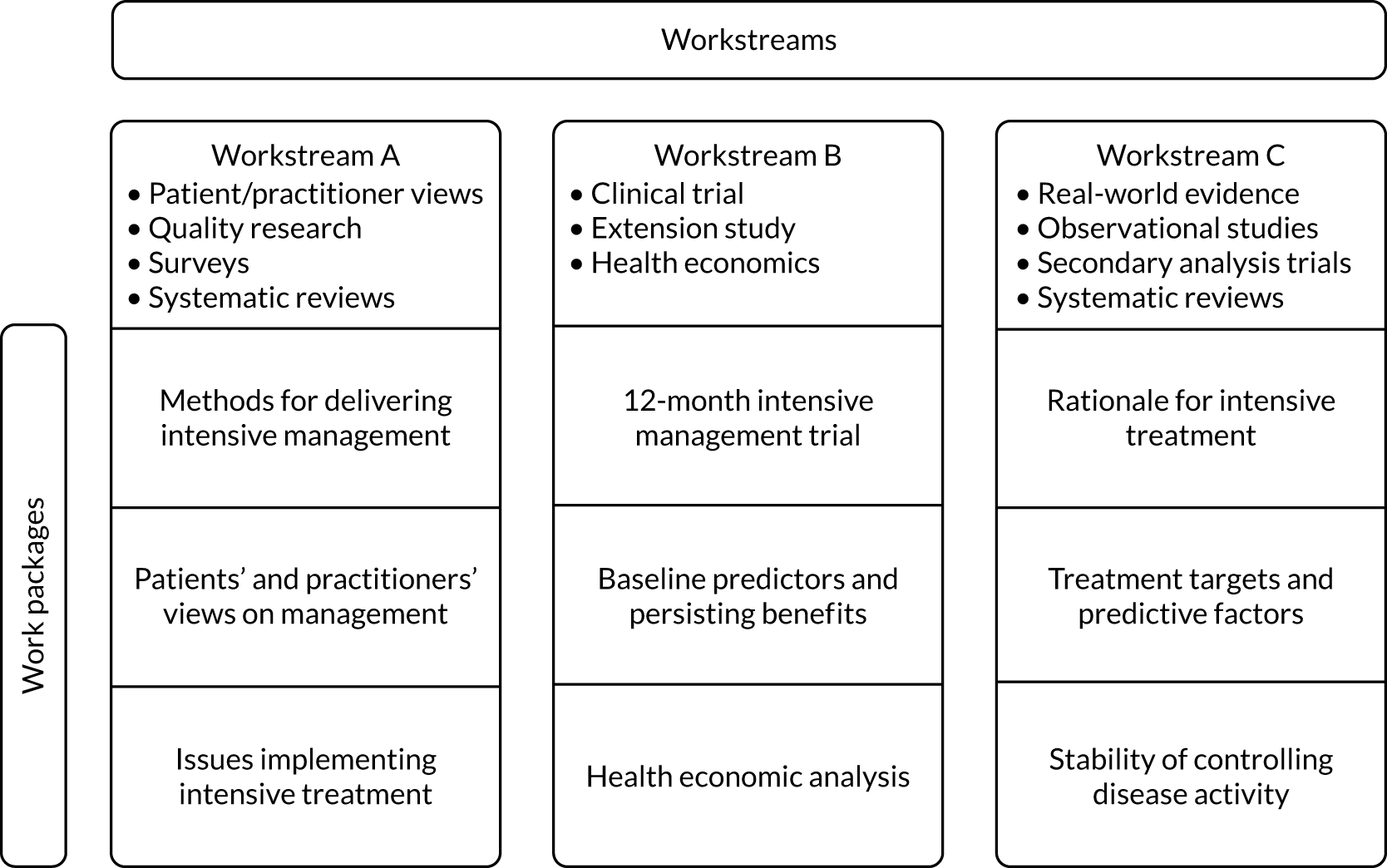

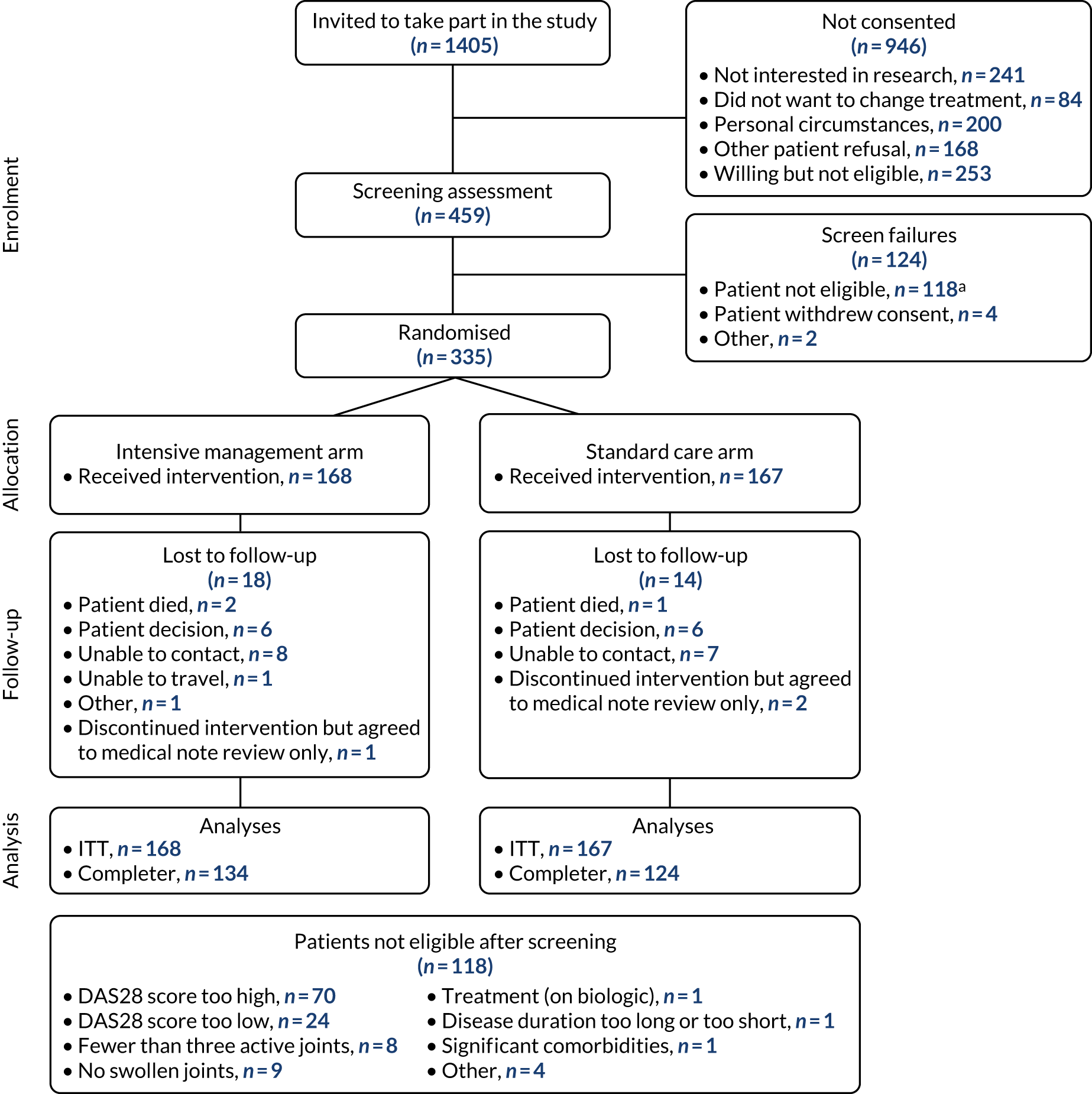

The research was undertaken across three workstreams. They were characterised by their dominant research approaches. Workstream A focused on patients’ perspectives, workstream B was built around the TITRATE (Treatment Intensities and Targets in Rheumatoid Arthritis ThErapy) clinical trial and workstream C concentrated on analysing existing evidence from real-world observational studies and published clinical trials. Each of three workstreams continued throughout the duration of the programme. Labelling these workstreams A–C was for convenience and it does not imply any particular order.

Each workstream was subdivided into three different work packages. They all comprised one large or several small studies that formed a distinct cluster. Each of these nine work packages is described in a separate section. The inter-relationship between the workstreams and work packages is outlined in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Research design pathway.

The research findings could be ordered in several different ways in this synopsis and none is necessarily best. We have chosen to present them in a chronological order because we consider such an approach is most practical. Therefore, we have reported research on longstanding observational studies and completed trials first, followed by research on developing the intervention used in the TITRATE trial, then the trial results and, finally, research related to the findings in the trial. This order cuts across the different workstreams.

The nine research sections in the synopsis comprise:

-

the rationale for intensive management

-

treatment targets and predictive factors for intensive management

-

delivering intensive management

-

the TITRATE trial

-

a health economic evaluation of the TITRATE trial

-

response predictors and response persistence in the TITRATE trial

-

stability of disease control and impact on disability

-

patients’ and practitioners’ views

-

implementing intensive management.

Each of these results sections have similar substructures. These consist of aims, methods, key findings, limitations and relation to overall programme.

For most sections, detailed accounts of the patients and methods are provided in the appendices. This is because the sections are overviews of published papers and papers about to be submitted. This approach is the simplest way to make the information available to readers. However, details about patients and methods for the TITRATE trial itself, the health economic analysis of the TITRATE trial and secondary analyses of the trial are given in the main text. This is because these parts of the programme are standalone studies in which the methods and results are best considered together.

Patient and public involvement

The whole programme involved extensive patient and public involvement (PPI) and two patients are co-authors of the report. Three sections (i.e. Delivering intensive management, Patients’ and practitioners’ views and Implementing intensive management) involved extensive PPI. Patients also contributed to the trial protocol. The involvement of patients is summarised in the individual sections. The general approach is given in Patient and public involvement.

Introduction

Programme theme

The TITRATE programme studied the impact of intensive management for patients with moderately active rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Current management goals in patients with RA include minimising disease activity, decreasing physical disability and improving health-related quality of life. There is considerable evidence that, in patients with active RA, intensive management helps achieve these goals. However, many patients with RA have moderate disease activity, which falls between active disease and remission. The TITRATE programme assessed the benefits of intensively managing these patients with moderate RA disease.

Key features of rheumatoid arthritis

Overview

Rheumatoid arthritis is an immunologically driven long-term condition. Its key features are persistent synovitis of the joints, systemic inflammation and autoantibodies, such as rheumatoid factor. 1–3 RA affects 0.5–1% of adults in high-income countries, although there is considerable variation between countries and populations. 4–6 It particularly involves women and older adults. Its annual incidence is 5–50 per 100,000 people. 6–8 Uncontrolled active RA results in substantial physical disability and poor quality of life,9,10 which are often associated with loss of work and high medical and social costs. 11–13

Management

Rheumatoid arthritis is usually managed in the UK by multidisciplinary teams that comprise rheumatologists, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and other health-care professionals. The multidisciplinary teams provide education, medication, psychological support, exercise and joint protection. There is substantial variability in the nature of these teams,14 and the evidence supporting the different approaches they use also varies. 15,16 Surgical intervention may be required for end-stage joint damage. 17

Treatment focuses on the control of joint inflammation and the prevention of disease progression using disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). 18 These reduce synovitis and systemic inflammation in the short term and physical disability and erosive progression in the long term. DMARDs can be categorised into several groups. We have classified them as conventional DMARDs, biologics and new orally acting Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors. Together with short-term steroids, they are the key drug treatments for RA.

Methotrexate is the dominant conventional DMARD. 19–21 Other currently prescribed conventional DMARDs include sulfasalazine, leflunomide and hydroxychloroquine. Some patients are treated by combining two or more conventional DMARDs. Such intensive combination treatment is constrained by concerns about adverse event risks. 22,23

Biologics are used when RA is not controlled by conventional DMARDs. 24–28 They include the tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) rituximab, abatacept and tocilizumab. All biologics are highly effective in reducing joint inflammation. They are usually combined with methotrexate or another conventional DMARD to increase efficacy and reduce the formation of blocking antibodies that could reduce their efficacy. Their use is limited by their high costs, although the advent of biosimilars is likely to reduce their costs. 29 Despite often achieving substantial reductions in disease activity, biologics are not curative. New oral drugs for RA, the JAK inhibitors, have a similar position to biologics in the treatment paradigm. 30

Steroids (glucocorticoids) are used in the short term to reduce joint inflammation. However, their long-term use is not recommended because of their side effects. 31 RA patients also receive various symptomatic treatments, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics. 32,33 These are not usually given to control the disease process.

Clinical guidelines

There are many clinical guidelines for RA, including English guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which outline its overall management. 34 High-cost treatments, such as the biologics, have specific NICE Health Technology Appraisals that recommend when they should be used. 35 The various guidelines have not resolved how best to manage patients with moderately active RA.

NHS importance

Patient load

The long-term management of RA dominates specialist rheumatology services. The 2016 national audit of early arthritis enrolled > 5000 patients, most of whom had RA. Inflammatory arthritis accounts for 40–60% of rheumatology follow-up visits. English Hospital Episode Statistics data show that there were more than 1,300,000 rheumatology outpatient follow-ups in 2017/18,38 and it is likely that a substantial proportion of these would have been for RA, potentially in the region of 300,000–600,000 outpatient follow-ups. The 2009 report from the National Audit Office estimated that 580,000 English adults had RA, with 26,000 new diagnoses each year. 39

Costs

Rheumatoid arthritis has substantial financial impacts for the NHS and the whole UK. The National Audit Office estimated that NHS costs were £560M per year and work-related disability costs were another £1800M per year. 39 Most costs are incurred by patients with high disability levels. Early intensive management targeted at remission should reduce future disability and, therefore, decrease costs. Biologic drug costs, which currently exceed £1B per year, continue to increase. 40

Need for research

The 2009 NICE guidance41 identified several unresolved questions that have been directly addressed in the TITRATE programme. Crucial issues included (1) the optimal management of patients with moderate disease activity, (2) the impact of enhancing remission rates on reducing future disability and (3) the role of self-management and the support patients need to use it.

Although more clinical guidelines have been published since 2009, including updated NICE guidance,41 and much new research has been undertaken, these questions remain important and unresolved.

Key prior research

Pathogenic heterogeneity

Rheumatoid arthritis may not be one disease. Instead, it may represent a final common pathway for several inflammatory joint diseases that vary by antibody profiles and clinical features. 42–45 Consequently, individualised management strategies are needed.

Effective treatments strategies

Both conventional DMARDs and biologics are effective treatments in active RA. However, there are uncertainties about their benefits and costs. In particular, there is debate about the relative value of combinations of conventional DMARDs compared with biologics. 46–49

Intensive management

Strategy trials have shown that combining treatments, such as conventional DMARDs, short-term steroids and, in some trials, biologics, optimise clinical outcomes. 37,50,51 Such strategy trials justify adopting treat-to-target approaches. However, there are uncertainties about the impact of intensive management on established RA patients with moderate disease activity.

Aim and objectives

Aim

The overall aim of the TITRATE programme was to assess the evidence that outcomes improve in patients with established RA who have moderate disease activity when they receive intensive management.

Objectives

There were three objectives. These were to:

-

define how to deliver intensive therapy to patients with moderate established RA

-

establish the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of intensive therapy in treatment of moderate established RA in a clinical trial

-

evaluate existing evidence supporting such intensive management in observational studies and completed trials.

Each of these objectives was studied in one of the workstreams. The first, second and third objectives were studied in workstreams A, B and C, respectively.

Rationale for intensive managements

The studies in this section place the TITRATE programme into perspective using observational studies, secondary analyses of completed trials and systematic reviews. The studies assessed changes in the outcomes and intensities of RA management in routine clinical care over the last two decades, the strength of existing evidence for the clinical effectiveness of intensive management in RA and supportive evidence for using intensive management strategies in moderate RA.

Aims

Research studies with four inter-related aims are included in this section. These aims comprised analysing temporal changes in treatment, the perspectives in RA management guidelines, the evidence base for intensive management and observational evidence supporting intensive management for moderate RA. Four parts of the research have been published. 52–55

Changes in rheumatoid arthritis management and outcomes

Rheumatoid arthritis management and outcomes continually evolve, and there is considerable evidence that RA is becoming better controlled or less severe. 56–66 We therefore examined changes in disease activity, disability and treatment intensities in observational studies in routine practice settings in recent years. We examined changes in erosive progression in a systematic review of long-term observational studies52 that measured this outcome. We had to take this approach for erosive progression because X-ray damage is not quantified in routine practice.

Clinical management guidelines

Expert guidance about managing RA also evolves. 67,68 We therefore systematically reviewed published clinical guidelines on RA management to identify current recommendations on disease assessments and intensive management (both of which are crucial for the TITRATE strategy).

Trial evidence supporting intensive management

The evidence base for intensive management of RA is also expanding. 69 We therefore undertook two systematic reviews in the area. The first systematic review focused on remissions with all intensive managements and the second systematic review assessed the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treat-to-target strategies.

Clinical evidence for treating moderately active rheumatoid arthritis intensively

The TITRATE programme reflects two concepts. First, patients with moderate RA and persisting disease activity are likely to have substantial ongoing disability, and observational evidence supports this perspective. 17 Second, if patients with moderate disease activity subsequently achieve remission, then they will have less disability, but there is little definitive evidence for this perspective. We evaluated both assumptions by analysing an observational study and two trials. Our aim was to ensure that evidence existed in favour of treating moderate RA intensively.

Methods

Observational studies

One observational study combined four cross-sectional surveys undertaken in two adjacent specialist units from 1996 to 2014 (three surveys had previously been published70–72). The studies each enrolled 189–520 patients (see Appendix 1, Table 27, for details of these patients). Overall, 1324 patients were studied. The patients in each survey were similar: 76–80% were female, their mean age was 58–60 years and their mean disease duration was 9–10 years. No particular treatment strategy was followed.

The other observational study was a longitudinal cohort study established in 2005 at Guy’s Hospital (London, UK). It involved most of the RA patients who were managed in another specialist centre until 2015. The study enrolled 1693 patients. Seventy-five per cent of the patients were female and their mean age was 55 years and mean disease duration was 11 years at entry to study (details of these patients are given in Appendix 1, Table 28). Patients were managed intensively using a treat-to-target approach. The longitudinal observational study included 752 patients, who were followed over ≥ 3 years.

Clinical trials

The CARDERA (Combination Anti-Rheumatic Drugs in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis) trial, which lasted 24 months, enrolled 467 patients, and complete end-point data were available in 379 patients. 73 The TACIT (Tumour Necrosis Factor Inhibitors Against Combination Intensive Therapy) trial, which lasted 12 months, enrolled 208 patients, and complete end-point data were available in 179 patients. 74 Details of these patients are given in Appendix 1, Table 31.

Clinical assessments

We assessed disease activity using the Disease Activity Score for 28 joints based on the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR)75 and disability using the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ). 76 Further details are given in Appendix 2.

Systematic reviews

Four systematic reviews assessed:

-

erosive progression in long-term observational studies

-

clinical guidelines for managing RA

-

intensive managements and remission

-

the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treat-to-target strategies.

Full details of these systematic reviews are given in the supplementary online material, including PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagrams (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Figure 1), and details of the included studies (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 1–5).

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed descriptively using means, standard deviations (SDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). The longitudinal observational study used mixed models to examine the changes in DAS28-ESR over time.

The systematic review of erosive damage used Larsen77 and Sharp–van der Heijde scores78 to estimate annual rates of change in a linear regression model. The systematic review of intensive management and remissions used meta-analysis with RevMan 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) to report relative risks in random-effects models,79 using Cochrane’s chi-squared test to assess between-study heterogeneity and quantify I2 statistics. 80 The other systematic reviews were descriptive and further details are given in Appendix 3.

Key findings

Clinical studies of changes in disease activity and disability

Both observational studies showed that there have been considerable reductions in disease activity levels and increases in treatment intensities over the last two decades.

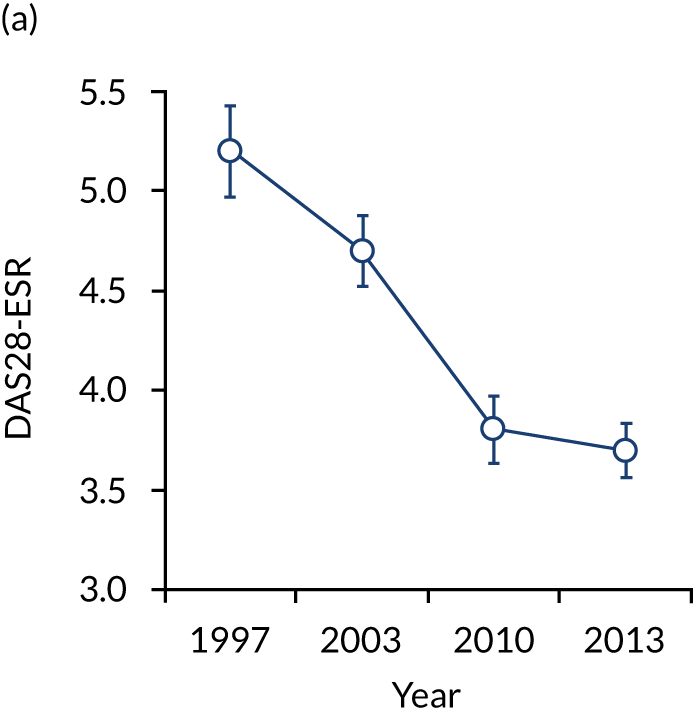

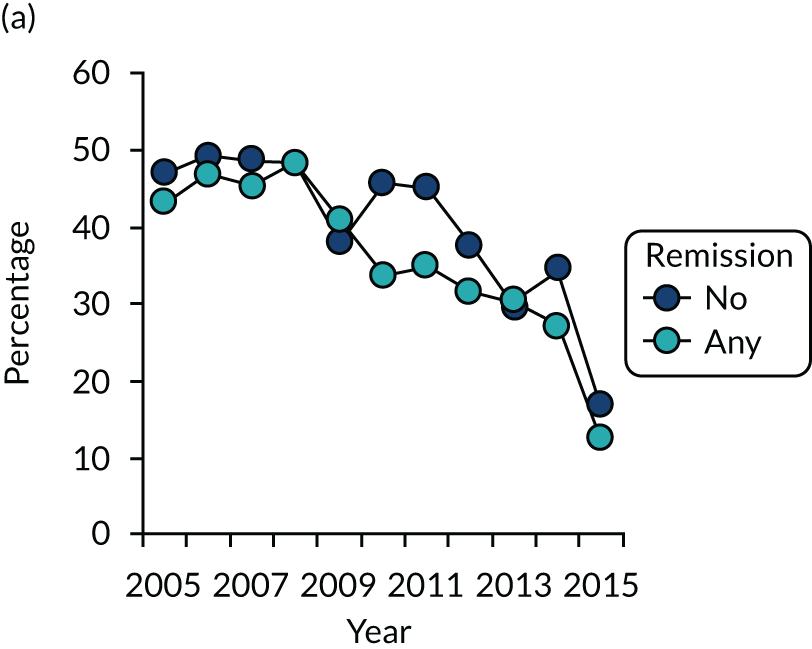

The first observational study, involving four cross-sectional surveys between 1996–7 and 2012–14, showed substantial decreases in mean DAS28-ESR scores (Figure 2). In 1996/7, mean DAS28-ESR scores were 5.2 (95% CI 5.0 to 5.4) and they decreased to 3.7 (95% CI 3.6 to 3.8) by 2012/14. DAS28-ESR remissions increased from 8% to 28%. The main treatment change was increased biologics use. None was used before 2000, but by 2012/14 biologics were used in 32% patients. Despite reductions in disease activity and increases in biologics use, disability levels were stable. In 1996/7, mean HAQ score was 1.30 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.52), and in 2012/14 it was 1.32 (95% CI 1.25 to 1.39).

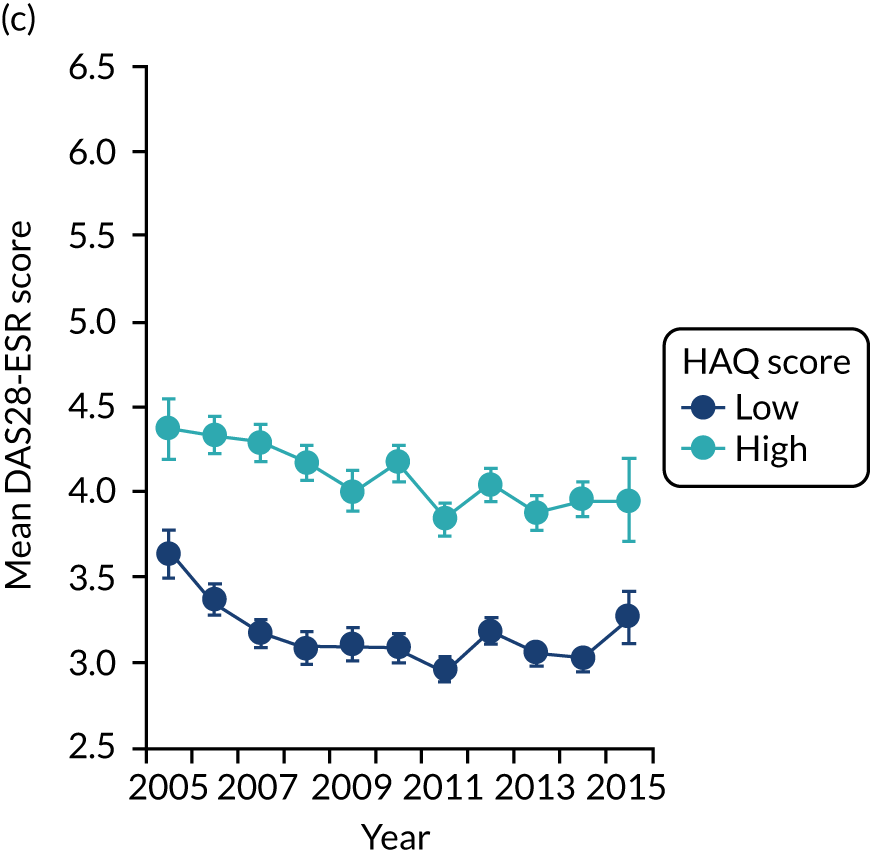

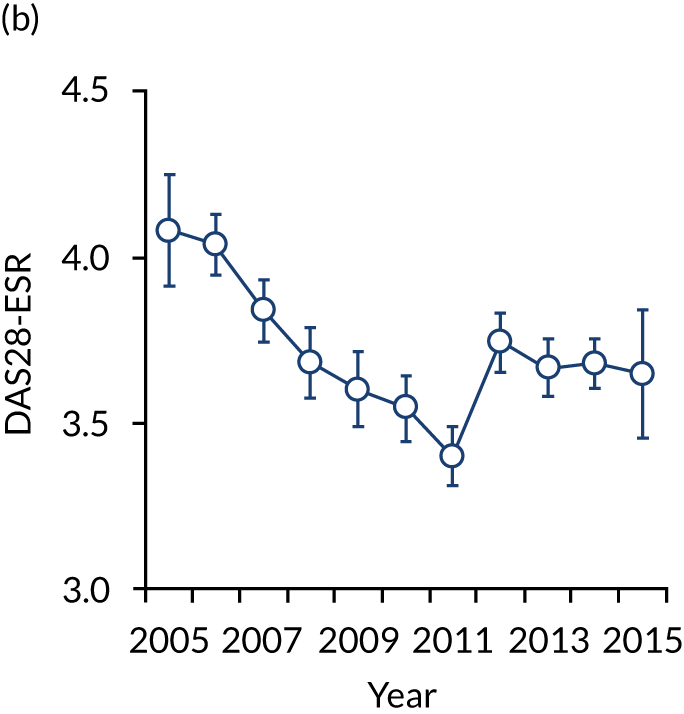

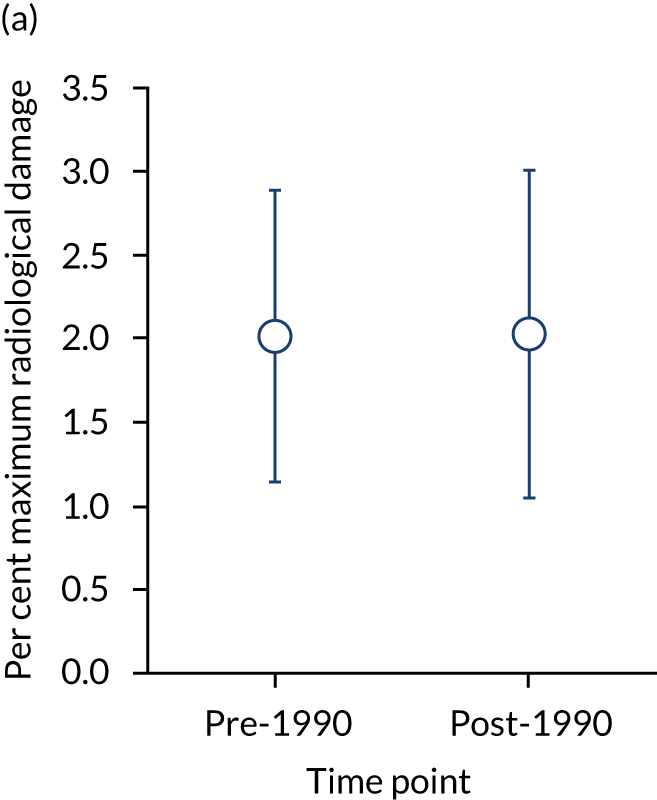

FIGURE 2.

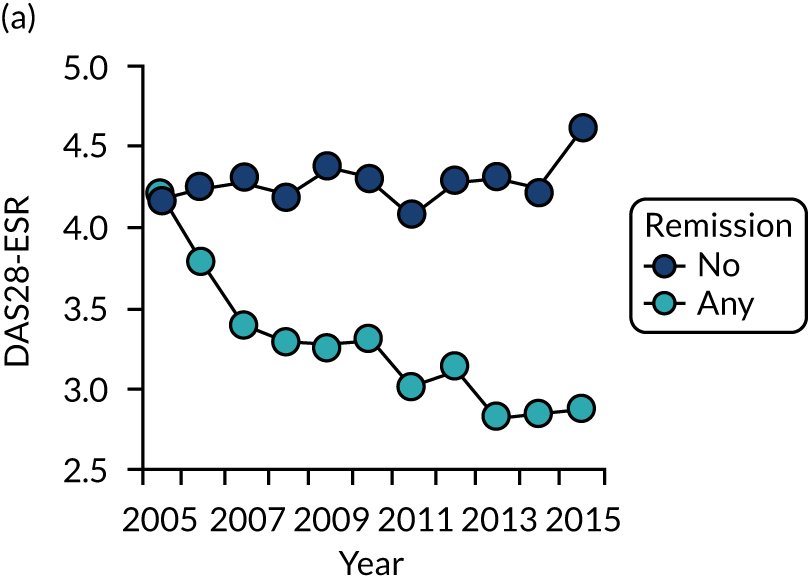

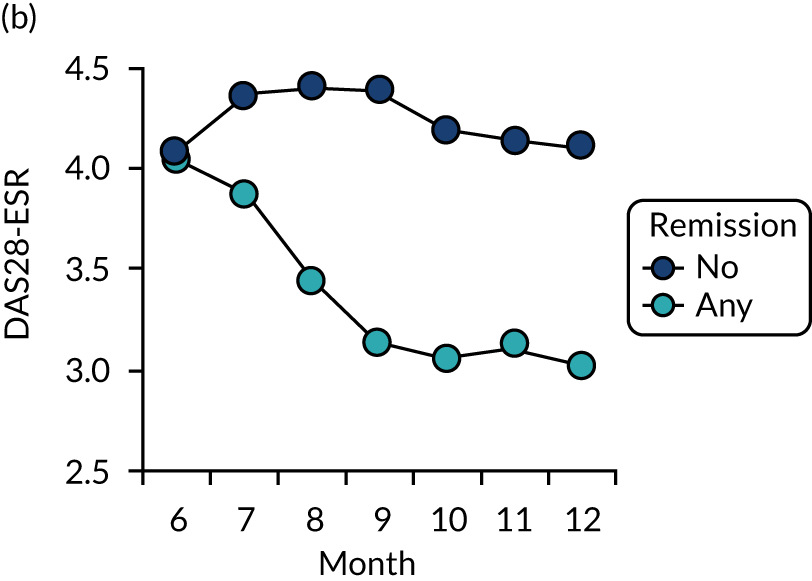

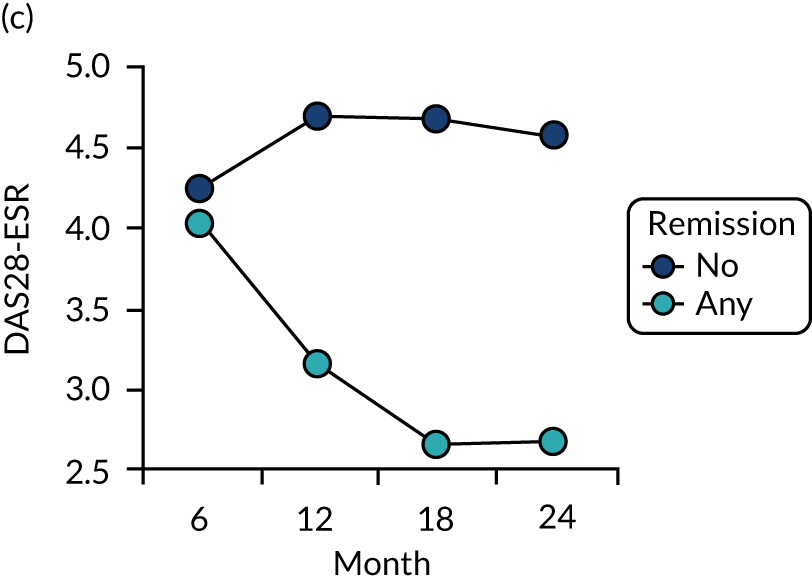

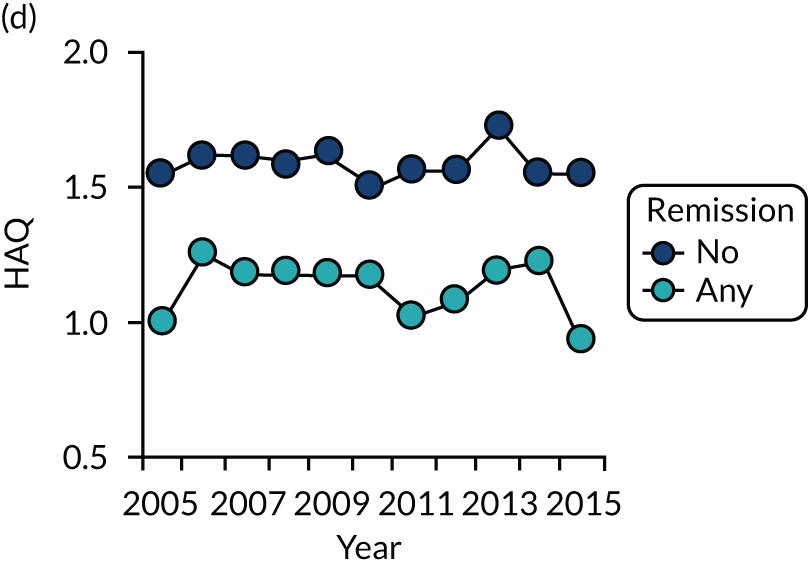

Changes in DAS28-ESR over time. (a) Cross-sectional surveys; and (b) longitudinal study.

The second observational study, which comprised a longitudinal cohort study from 2005 to 2015, also showed that mean DAS28-ESR scores had decreased (see Figure 2). In 2005, the mean DAS28-ESR score was 4.1 (95% CI 3.9 to 4.3), and by 2015 it was 3.6 (95% CI 3.3 to 3.8). DAS28-ESR remissions increased from 18% to 27%. The main treatment change was increased biologics use. Biologics were prescribed for 19% of patients in 2005 and 42% of patients in 2015. The mean HAQ scores fell from 1.38 (95% CI 1.26 to 1.50) in 2005 to 1.19 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.34) in 2015.

Systematic review of changes in the progression of erosive damage

We identified 28 studies reporting RA radiological progression, and 10 studies, reported in nine papers,81–89 had sufficient data for meta-analysis. These 10 studies recruited patients from 1965 to 2000 and followed them for 5–20 years. Of 1121 patients, 73 had baseline radiological data. Five of the studies recruited from 1965 to 198981–85 and the other five studies recruited from 1990 to 2000. 85–89

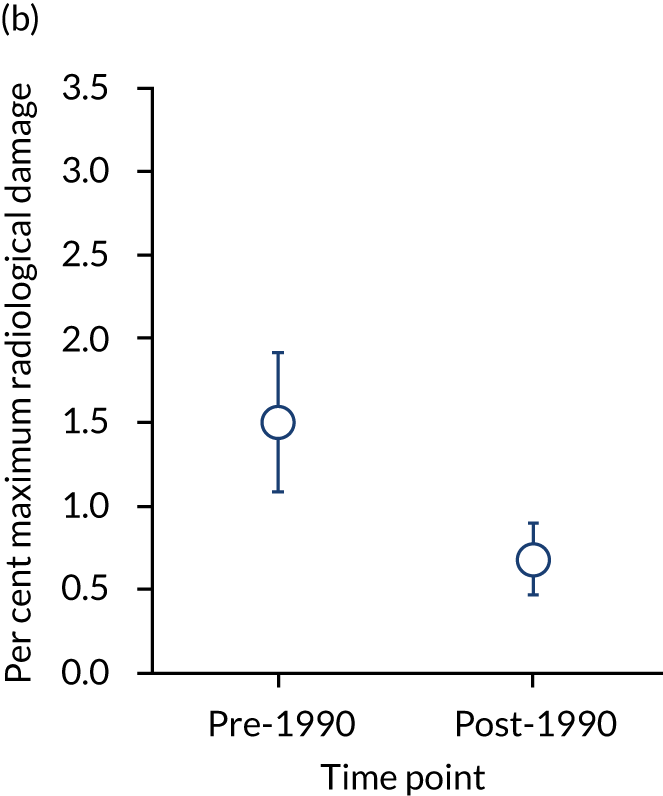

Baseline radiographic scores were similar in pre- and post-1990 studies (with a mean maximum damage of 2.01% and 2.03%, respectively). The annual rate of erosive change was higher in pre-1990 studies (mean 1.50%, 95% CI 1.08% to 1.92%) than in post-1990 studies (mean 0.68%, 95% CI 0.47% to 0.90%) and the difference was significant (p < 0.05) after adjusting for scoring methods. These changes are summarised in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Initial damage and annual rate of damage in pre- and post-1990 cohorts. Means and 95% CIs are shown. (a) Initial; and (b) annual progression.

Systematic review of clinical management guidelines

We identified 22 guidelines36,90–110 (three were for early RA,99,105,107 one for established RA98 and 18 for all disease durations36,90–97,100–104,106,108–110). They were compiled by rheumatologists with variable patient involvement and contributions from nurses, allied health professionals and other experts. All guidelines dealt with drug therapies (11 guidelines covered diagnosis and 13 guidelines covered non-drug treatments).

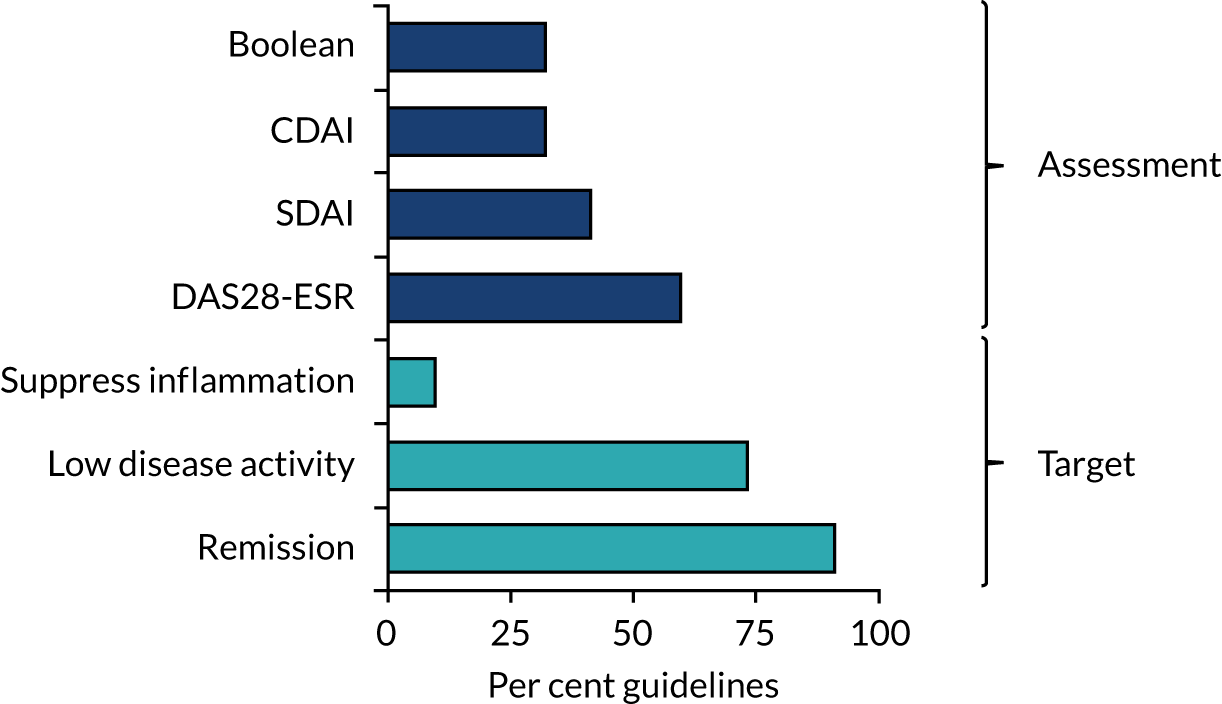

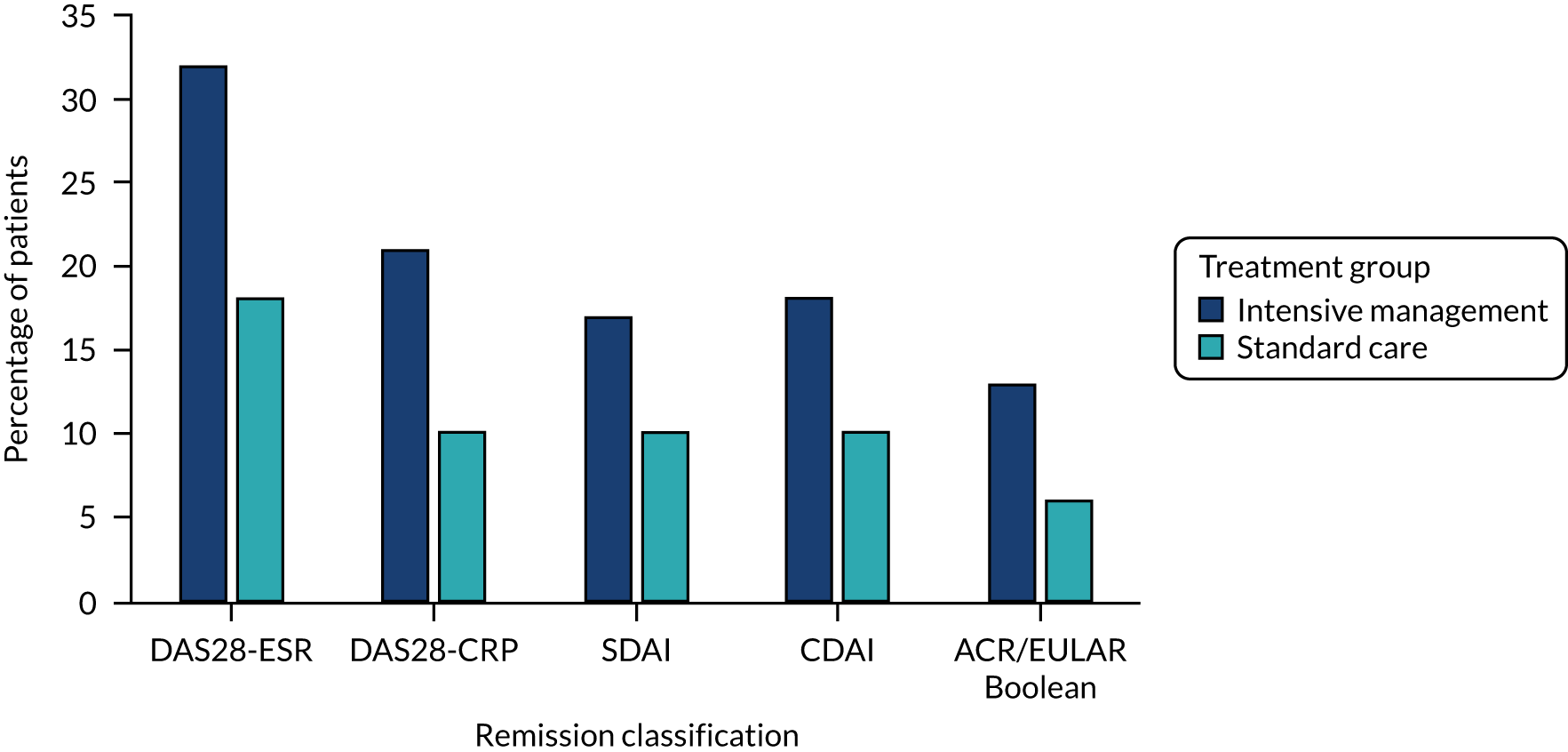

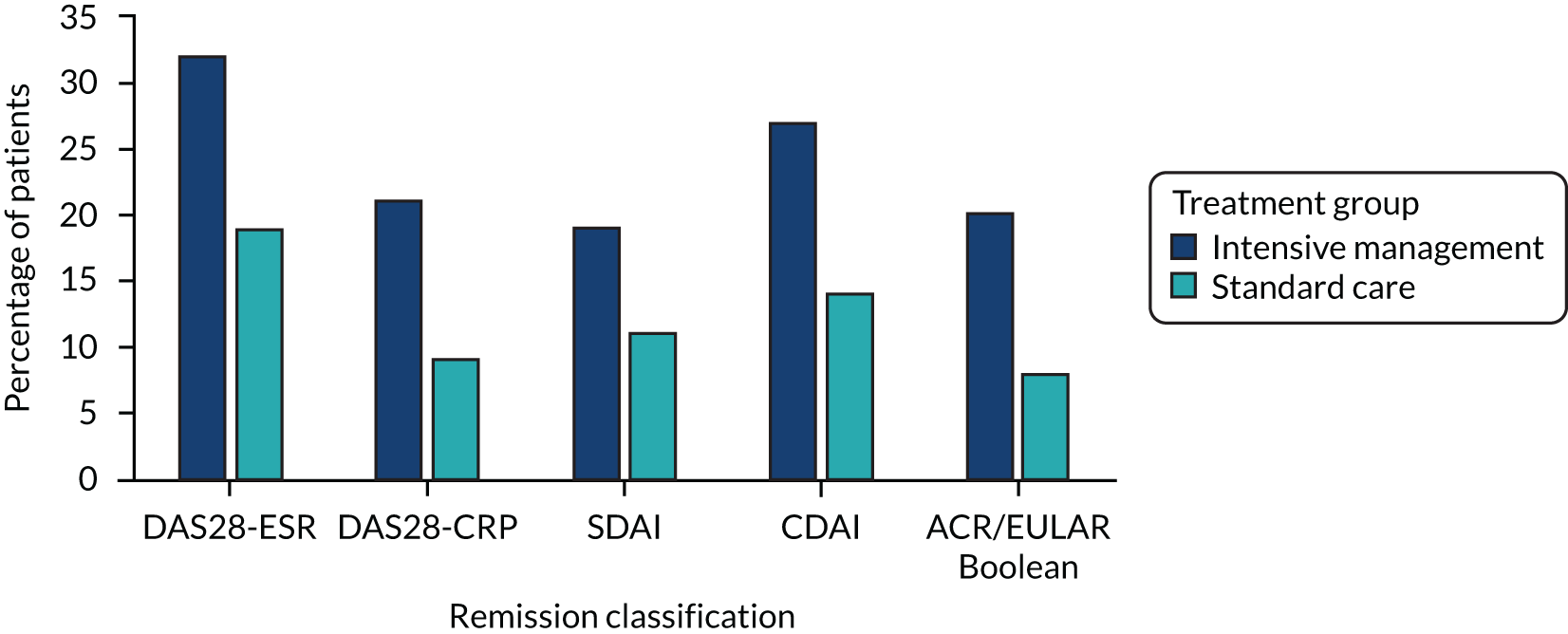

Twenty guidelines36,90–98,100–105,107–110 recommended remission as the treatment target, and 16 guidelines36,90–97,102–104,107–110 recommended low disease activity as an alternative. Two guidelines98,106 recommended suppressing joint inflammation without defining what it implies. These recommendations are summarised in Figure 4. Remission was defined in various ways. DAS28-ESR remission was recommended in 13 guidelines,90,92–95,97,101,102,104,107–110 Simple Disease Activity Index (SDAI) in nine guidelines,36,92,95–97,102–104,108 Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) in seven guidelines92,95,97,102,104,108,109 and American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) Boolean in seven guidelines. 36,92,95,97,103,104,109 Six guidelines did not recommend any specific remission criteria. 91,96,98–100,105,106

FIGURE 4.

Remission assessments and treatment targets in RA guidelines.

All guidelines36,90–110 recommend treating active RA. There was less unanimity about treating moderately active disease. Thirteen guidelines91,92,94–97,100,102–105,107,108 included definite recommendations about treating moderate disease, four guidelines36,90,101,109 gave implied guidance about treating moderate disease by indicating what treatment policies were needed until patients achieved remission and five guidelines93,98,99,106,110 made no recommendations.

Systematic review of trials of remissions with intensive management

We identified 53 trials reporting remissions. 74,111–162 Forty-eight trials111–132,134–139,142,143,145–162 were superiority trials in which an intensive management strategy was compared with a less intensive strategy, six trials74,128,133,140,141,144 were head-to-head trials comparing combination DMARDs with biologic treatments and one trial was in both groups. 128

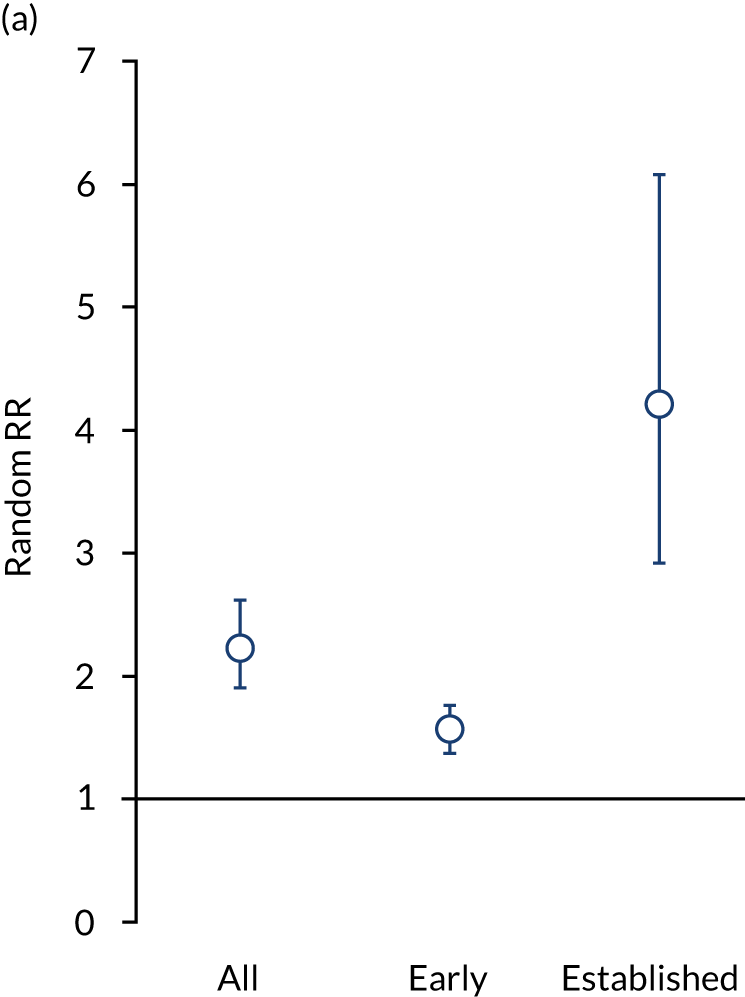

In superiority studies, 3013 of 11,259 patients achieved remission with intensive management, compared with 1211 of 8493 control patients. Meta-analysis of the 53 comparisons showed a significant benefit for intensive management [risk ratio (RR) 2.23, 95% CI 1.90 to 2.61]. Intensive management increased remissions in early RA (23 comparisons; RR 1.5, 95% CI 1.38 to 1.76) and established RA (29 comparisons; RR 4.21, 95% CI 2.92 to 6.07). All intensive strategies (i.e. combination DMARDs, biologics, and JAK inhibitors) increased remissions. These effects are shown in Figure 5.

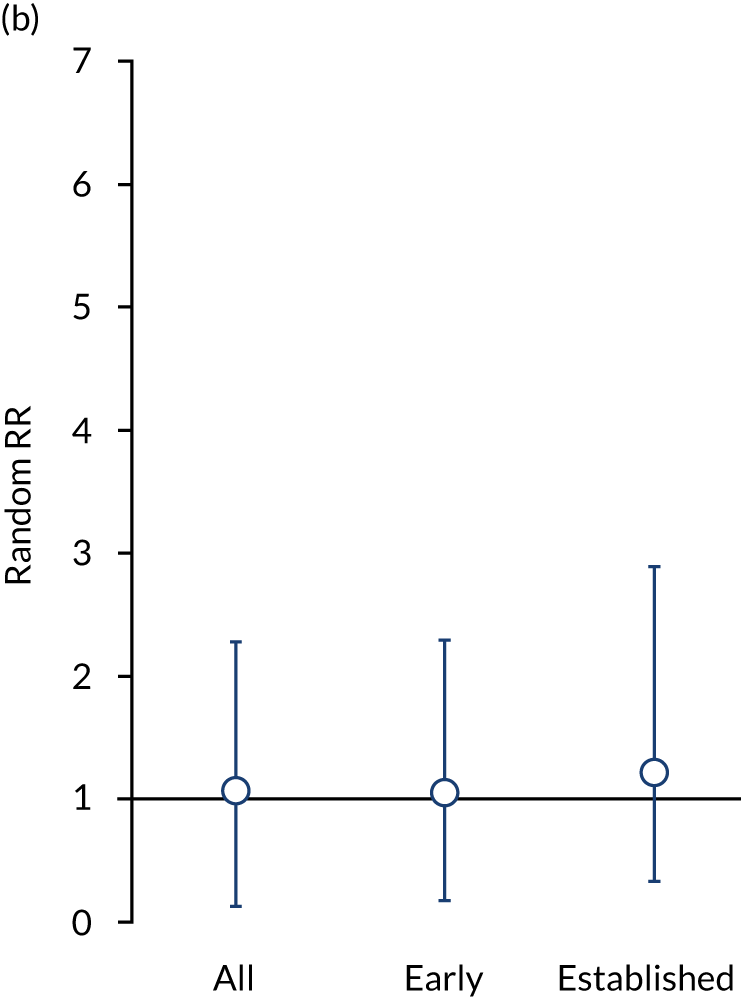

FIGURE 5.

Effectiveness in superiority and head-to-head trials assessed by random RRs. (a) Superiority trials; and (b) head-to-head trials.

In the six head-to-head trials,74,128,133,140,141,144 317 of 787 patients achieved remission with biologics, compared with 229 of 671 patients receiving combination DMARD therapies. There was no difference between treatment strategies (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.21). These effects are shown in Figure 5.

Remission frequencies differed in early and established RA. In early RA, 49% of patients had remissions with intensive management compared with 34% of control patients (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.24). In established RA, 19% patients had remissions with intensive management compared with 6% of control patients (RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.68).

Systematic review of trials supporting using treat to target

We identified 41 papers49,113,128,129,141,148,153,155,163–195 reporting 16 relevant trials. Six trials129,158,171,179,186,190 compared treat to target with usual care, six trials49,113,128,177,183,185 compared different treatment protocols, two trials141,172 compared different treatment targets and two trials153,160 had other comparisons of conventional with intensive therapy. As the trials were too heterogeneous for meta-analysis, we undertook a narrative analysis. Details of the impact of treat-to-target strategies on remission in studies with controls receiving conventional treatment is shown in Table 1.

| Trial | Disease duration | Standard care | Intensive management | Relative risk (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Patients, n | Remission, n (%) | Treatment | Patients, n | Remission, n (%) | |||

| STREAM158 | < 1 year | Conventional | 40 | 19 (49) | Intensive | 42 | 27 (66) | 1.35 (0.88 to 2.01) |

| T-4 study186 | 1 year | Routine | 62 | 13 (21) | DAS28-ESR/MMP3 driven | 61 | 34 (56) | 2.66 (1.34 to 4.78) |

| Optimisation of adalimumab179 | Established | Routine care | 109 | 17 (16) | DAS28-ESR target | 100 | 38 (38) | 2.44 (1.44 to 4.24) |

| TICORA129 | 2 years | Routine | 55 | 9 (16) | Intensive | 55 | 36 (65) | 4.00 (2.15 to 8.02) |

| CAMERA160 | < 1 year | Conventional | 148 | 55 (37) | Intensive | 151 | 76 (50) | 1.35 (1.03 to 1.79) |

| BROSG153 | 13 years | Symptomatic | 233 | 23 (14) | Intensive | 233 | 34 (20) | 1.48 (0.87 to 2.52) |

| BeSt128 | < 1 year | Monotherapy | 126 | 36 (29) | Prednisone combination | 133 | 44 (33) | 1.16 (0.79 to 1.72) |

| Infliximab (Remicade®; Centocor Biotech Inc., Horsham, PA, USA) combination | 128 | 45 (36) | 1.23 (0.84 to 1.92) | |||||

| FIN-RACo177 | < 1 year | Single drug | 100 | 18 (18) | Combination treatment | 99 | 36 (37) | 2.02 (1.21 to 3.47) |

| U-Act-Early113 | < 1 year | Methotrexate | 108 | 48 (44) | Tocilizumab (Actemra®; Roche, Basel, Switzerland)/methotrexate | 106 | 91 (86) | 1.92 (1.56 to 2.31) |

Four of six trials comparing treat to target with usual care reported remissions and all found more remissions with intensive management. Differences were clinically and statistically significant in three trials,129,179,186 but the differences were considered meaningful in the STREAM (Strategies in Early Arthritis Management) trial. 158 Two trials171,190 comparing treat to target with usual care reported only low disease activity states. One trial171 found a significant difference and the other trial190 did not.

The six trials49,113,128,177,183,185 that compared treatment protocols all reported remissions. Two trials113,177 included conventionally treated controls and found significantly more remissions with intensive managements. Five49,128,183,185 of these trials compared different intensive management regimens and found no significant differences in remissions between regimens. One of these trials [Behandel–Strategieën (BeSt)128] included a conventionally treated group that had fewer remissions, although the difference was not significant.

Two trials141,172 compared targets in patients receiving different intensive management regimens. Both trials141,172 found no significant difference between groups. Finally, two trials153,160 that did not fit into the previous categories had conventionally treated controls and reported more remissions with intensive managements. The difference was significant in one trial,160 but not in the other. 153

Twelve trials reported harms. Deaths were reported in seven trials. 49,113,128,129,141,183,186 There were no deaths in three trials and 11 deaths in the other four trials (three deaths in two standard care arms and eight deaths in 10 intensive management arms). Serious adverse events were reported in eight trials. 49,113,128,141,158,177,185,186 Overall, 11% patients had a serious event (12% of patients receiving intensive management and 9% of patients receiving standard care).

Two studies129,153 reported cost-effectiveness. In one study,129 treat to target dominated usual care and in the other study153 step-up combination treatments were cost-effective. In 5 of the 16 studies158,172,179,183,185 included in the clinical effectiveness review, no cost-effectiveness conclusion could be reached, and in one study49 no conclusion could be drawn in the case of patients designated as low risk. In the remaining 10 studies,113,128,129,141,153,160,171,177,186,190 and among patients identified as high risk in one study,49 cost-effectiveness was inferred. In most cases, treat to target is likely to be cost-effective, except where biological treatment in early disease is used initially. No conclusions could be drawn for established RA, as there were too few studies to assess benefit.

Clinical studies of treating moderately active rheumatoid arthritis intensively

The impact of achieving remission on subsequent disease activity and disability, particularly in moderate disease patients, was studied in 752 patients in a longitudinal observational study followed for ≥ 3 years and in secondary analyses of early and established RA trials.

The frequency of moderately active disease at baseline in the 752 patients in the observational study and at 6 months in the 558 patients in the trials was substantial. It varied from 39% to 45% of patients (Table 2). In all three studies, moderate disease patients were the largest group in terms of disease activity levels. The mean end-point DAS28-ESR scores in these patients after 1–3 years’ follow-up varied between 3.5 and 4.2, and their end-point mean HAQ scores varied between 1.3 and 1.5.

| Activity status | Observational study | Established RA trial (TACIT trial74) | Early RA trial (CARDERA trial73) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Final DAS28-ESR, mean (95% CI) | Final HAQ, mean (95% CI) | n (%) | Final DAS28-ESR, mean (95% CI) | Final HAQ, mean (95% CI) | n (%) | Final DAS28-ESR, mean (95% CI) | Final HAQ, mean (95% CI) | |

| Initial/6 months: all patients | |||||||||

| Remission | 179 (24) | 2.4 (2.3 to 2.6) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.9) | 24 (13) | 2.6 (1.9 to 3.2) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.5) | 74 (20) | 2.9 (2.5 to 3.2) | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.8) |

| Low | 101 (13) | 3.0 (2.8 to 3.3) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) | 20 (11) | 3.3 (2.7 to 3.8) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7) | 37 (10) | 3.4 (3.0 to 3.8) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.1) |

| Moderate | 322 (43) | 3.5 (3.4 to 3.7) | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.5) | 69 (39) | 3.8 (3.5 to 4.1) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 169 (45) | 4.2 (4.0 to 4.4) | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.4) |

| High | 150 (20) | 4.1 (3.9 to 4.4) | 1.7 (1.6 to 1.8) | 66 (37) | 4.8 (4.4 to 5.2) | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) | 99 (26) | 5.2 (5.0 to 5.5) | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.8) |

| Subsequent | |||||||||

| Never | 167 (52) | 4.3 (4.1 to 4.4) | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.8) | 46 (67) | 4.2 (4.0 to 4.5) | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) | 138 (82) | 4.6 (4.4 to 4.8) | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.5) |

| Any | 155 (48) | 2.8 (2.6 to 2.9) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 23 (33) | 2.9 (2.3 to 3.4) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7) | 31 (18) | 2.7 (2.2 to 3.2) | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) |

| Significance | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | NS | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

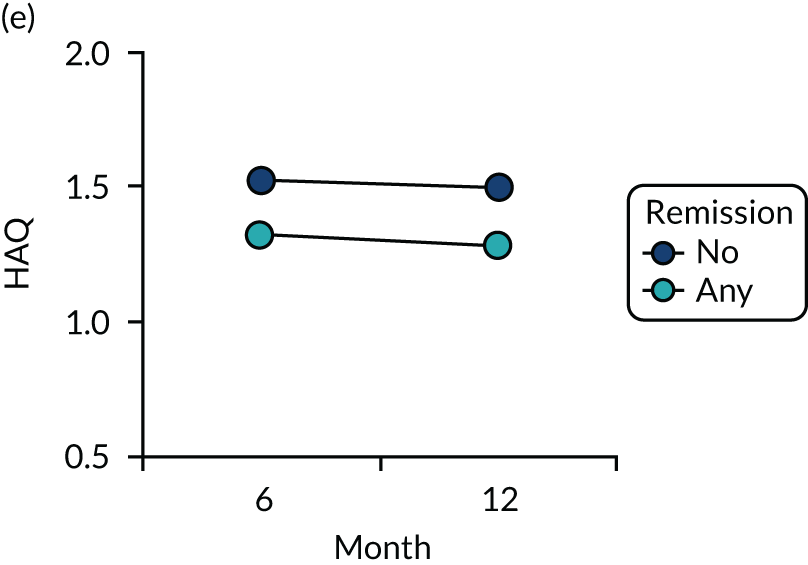

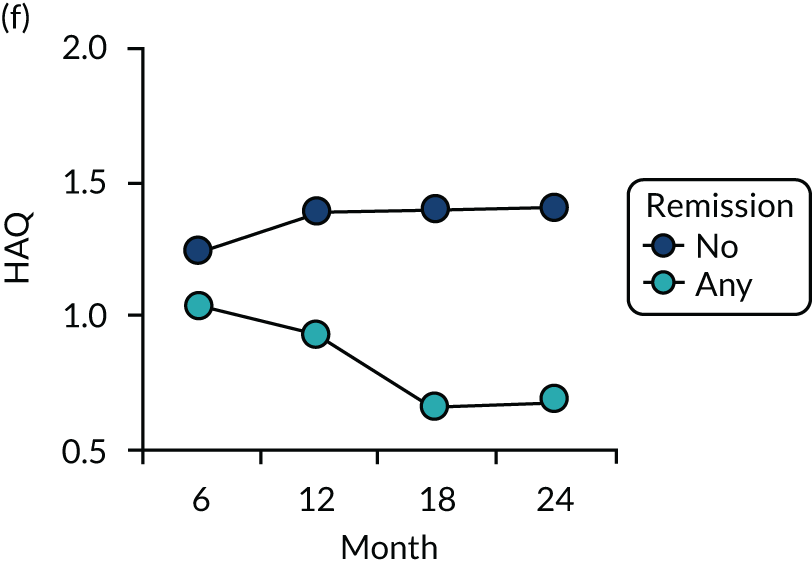

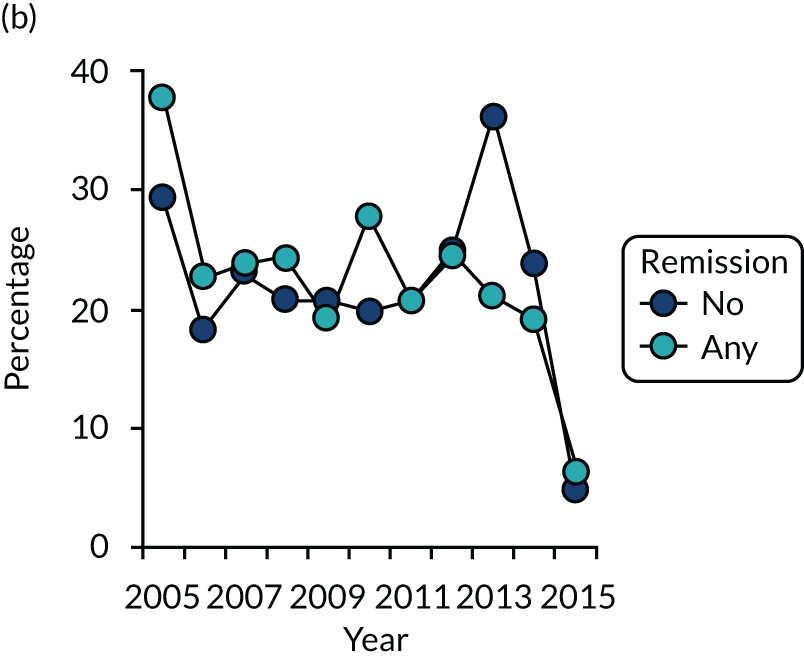

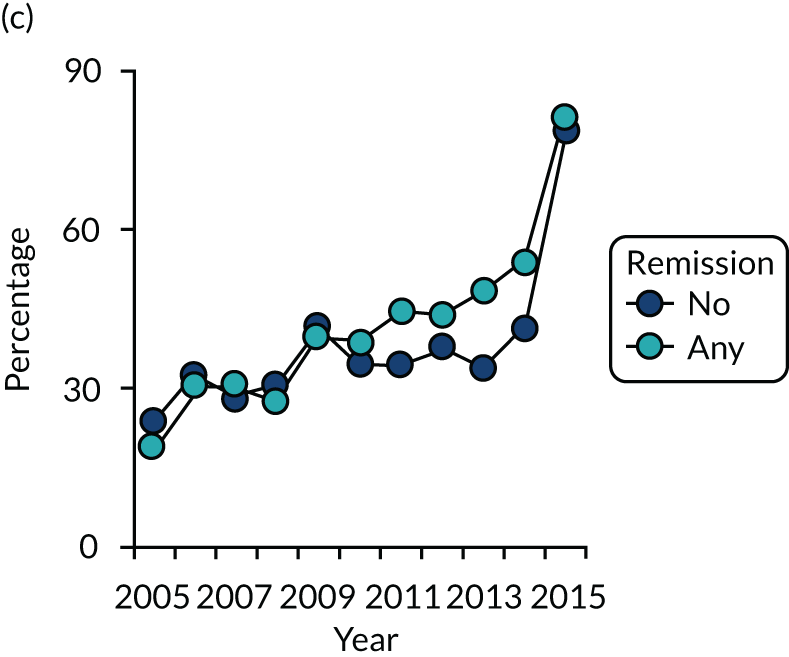

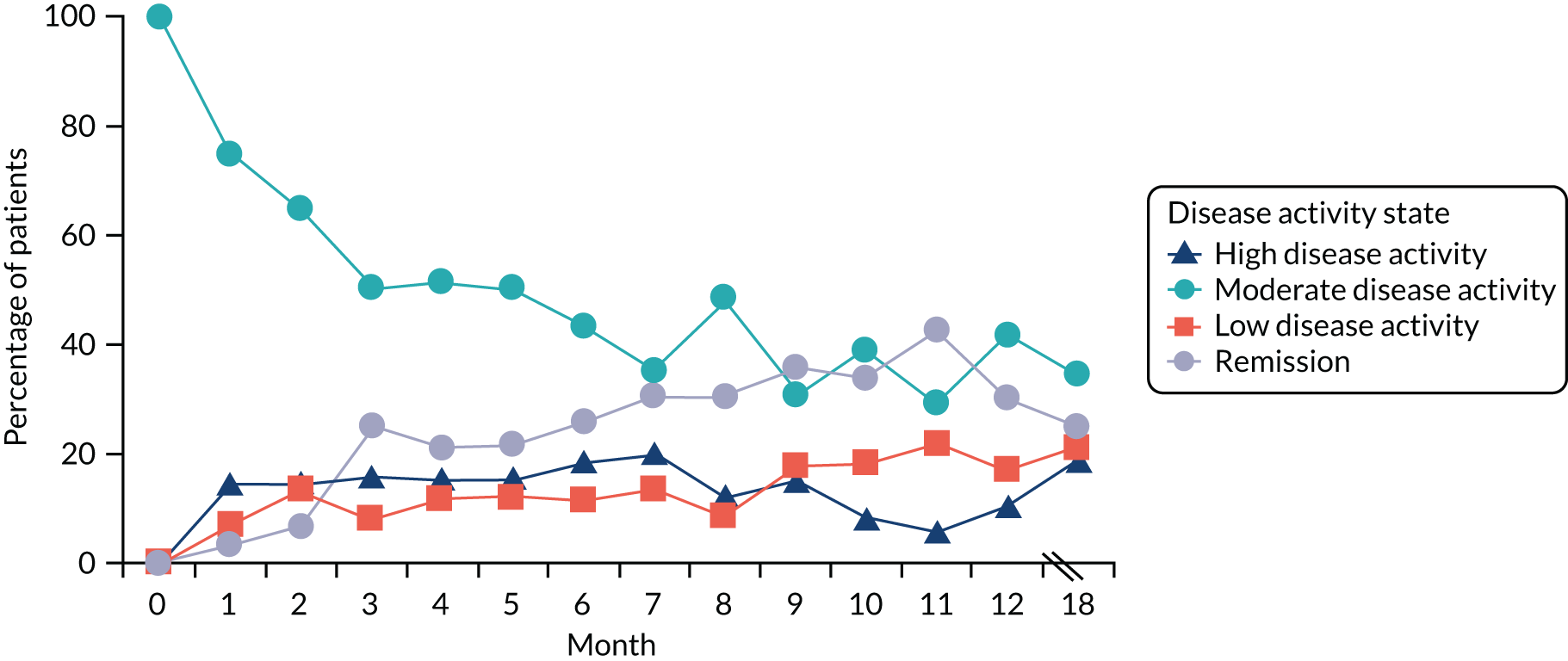

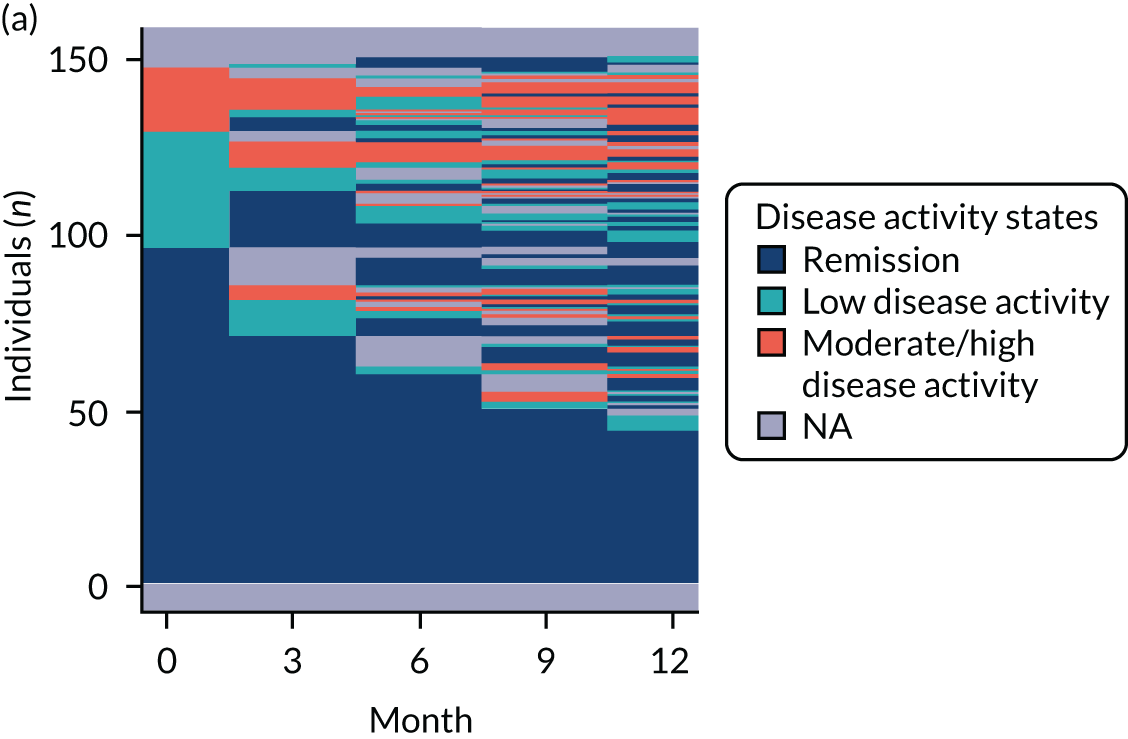

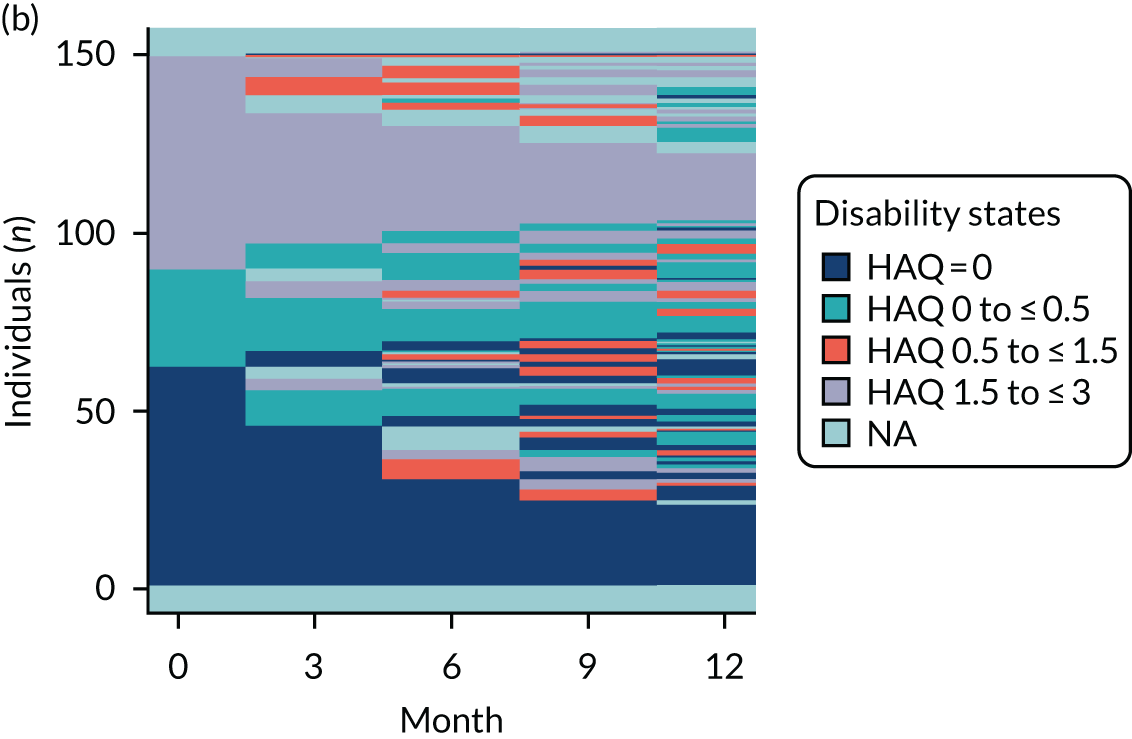

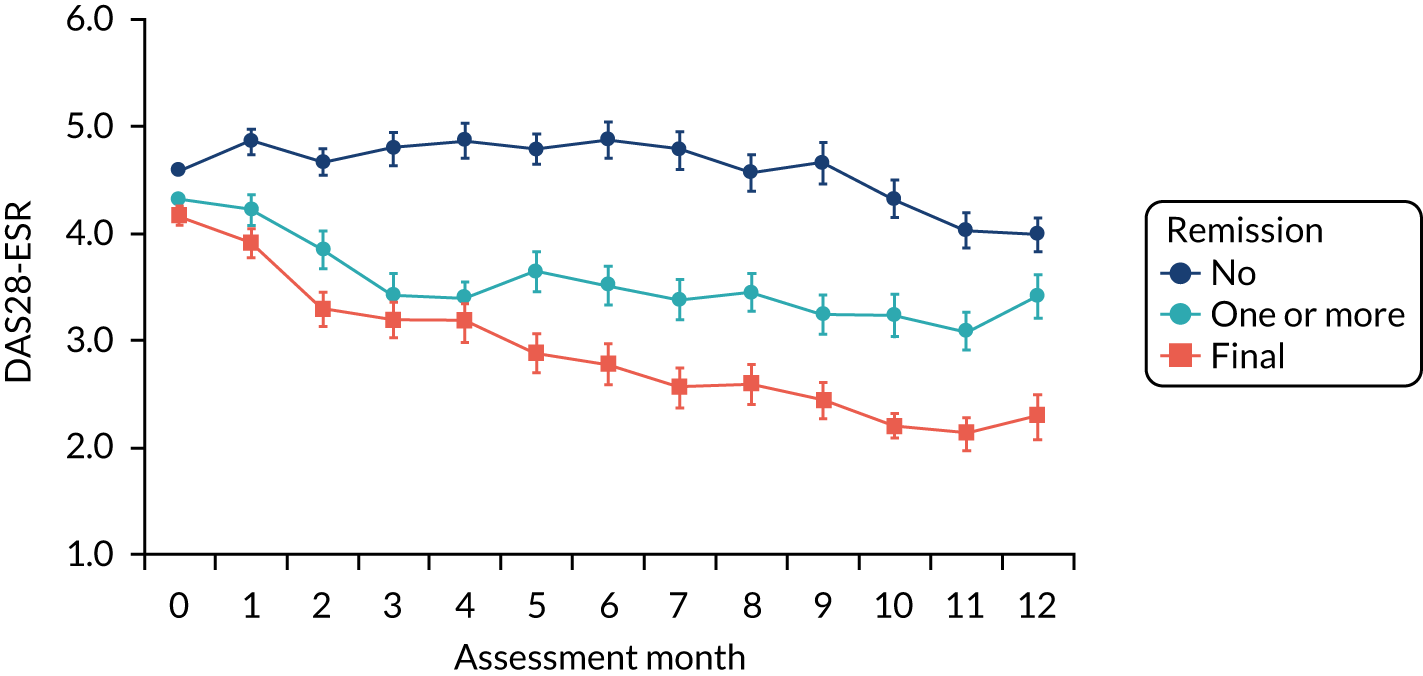

Dividing patients with initial/6-month moderate RA into those who subsequently had one or more DAS28-ESR remissions and those who did not (Figure 6) shows two things. First, those patients who achieved one or more remissions had lower subsequent mean DAS28-ESR scores than patients who did not. Second, mean HAQ scores were lower in patients who achieved one or more remissions.

Evaluating these changes in detail (see Table 2) showed that 18–48% of patients with initial/6-month moderate disease achieved one or more episodes of remission during the period of follow-up. The patients with one or more remissions had significantly lower end-point mean DAS28-ESR scores in all studies and significantly lower end-point mean HAQ scores in two studies (i.e. the observational study and the CARDERA trial73). In the other study (i.e. the TACIT trial74), end-point mean HAQ scores were lower in patients who achieved one or more remissions, but the difference was not significant. In patients with initially moderate disease, treatment intensities were comparable in patients with and without subsequent remissions (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Changes in DMARD and biologic prescribing in patients with initial moderate disease activity in the observational study. Patients are divided by whether they had one or more remissions during follow-up. (a) DMARD monotherapy; (b) DMARD combination; and (c) biologics.

Limitations

The studies in this section were limited by the types of patients studied, their assessment of benefits and risks and the type of intensive management that was used.

Patients studied

It is likely that patient inclusion and follow-up strategies in observational studies have changed over time. In particular, patients with milder disease may have attended more frequently in recent years. Such changes in patient care could explain some or all of the reductions in disease activity we observed. It is also possible that the clinical phenotype of RA has evolved, with milder disease increasing in frequency. However, a recent analysis of English early RA patients since 1990 does not suggest that there have been major changes in RA clinical phenotypes. 196

Assessing benefits and risks

The assessment of remission and the duration of treatment varied in the trials of intensive management in the systematic review. This variation created unavoidable complexities when combining data from studies. When there are many studies, as occurred in the comparison of all intensive managements, combining heterogeneous data appears reasonable. However, when there are few studies, as occurred in comparisons of treat-to-target strategies, it is best avoided.

Evidence about the benefits of intensive management are almost entirely based on clinician-defined outcomes, such as changes in disease activity (e.g. remissions, reductions in disability and erosive damage). The extent to which patients consider intensive management to be beneficial is largely unknown. Patients can have different perspectives to clinicians. 197–199

One final and important issue is that we did not assess the potential of intensive management to harm patients in detail. In routine practice settings, it is particularly difficult to assess harms because they are not reported in any organised way. Nevertheless, we found no evidence of intensive management substantially increasing adverse events. Published systematic reviews of intensive management, predominantly using biological treatments, have also not found any substantial increases in adverse events with more intensive treatment regimens. 23,200,201

Treatments

There is no internationally agreed definition of what constitutes intensive management in RA. The numbers and types of treatments used, the time frames over which they are increased and the frequencies at which patients are assessed vary across studies. The absence of definite agreement makes it difficult to compare the benefits of intensive management.

Relation to overall programme

The intention in this section was to place the TITRATE programme in perspective. The various studies highlighted what is accepted and where there are continuing uncertainties.

Generally agreed areas

There is extensive evidence that intensive management in RA patients increases the frequency of remissions. One consequence has been that the use of intensive management is supported in all clinical guidelines. Another consequence has been that, over the last two decades, the intensity of treatment has increased in routine practice settings. This change has been reported in other settings. 67,202–204 Associated with the increased use of intensive managements have been reductions in overall disease activity levels and increases in the frequency of remissions. These findings have also been reported by others. 57,60 In addition, erosive progression has lessened substantially for an even longer period, and this is most likely a consequence of increased treatment intensity together with earlier diagnosis and treatment, although it remains a relevant outcome measure. This finding has also been identified in other studies and reviews. 59,205

Continuing uncertainties

There is considerable support from expert opinion in clinical guidelines for treating moderate RA intensively. We also found, in our analysis of observational data and trials, that remissions are associated with overall reductions in disease activity levels in patients with moderate disease activity. Although there is some evidence that reducing disease activity improves disability in patients with moderate RA, our results were not conclusive and further work is needed to resolve this important question.

It is also not possible to be certain that achieving remission in patients with moderate RA in our observational study and in secondary analyses of completed clinical trials was a result of the intensity of their treatment. This uncertainty can be resolved only in a prospective clinical trial that directly tests this hypothesis.

Treatment targets and predictive factors

The studies in this section evaluated RA treatment targets and simple outcome predictors using observational studies and secondary analyses of clinical trials. The studies addressed some aspects of the complex problem of what to measure when assessing RA patients.

Aims

Research studies with two overarching aims are included in this section. These aims comprised (1) defining optimal treatment targets and (2) identifying simple response predictors. They addressed the complex problem of what to measure when assessing RA patients. Optimising treatment targets and response predictors are important for interpreting the results of the TITRATE programme and implementing its findings in clinical care. Five parts of the research have been published. 206–210

Treatment targets

Targets must balance the ideal with the practical. Stringent targets may deliver optimal outcomes in some individuals, but achieve fewer overall benefits than more readily achievable targets. The TITRATE programme adopted DAS28-ESR remission as its primary target because it is the most widely used composite remission assessment. There is also extensive evidence that achieving DAS28-ESR remission optimises health-related quality of life and function and minimises radiological damage. 211–215 Sustained remission over time is particularly important because it is associated with better outcomes than remission at a single time point. 216,217 We collected components of other composite measures to compare their value as targets during intensive management.

In this section, we evaluated four aspects of treatment targets: (1) comparisons of sustained remission (persistent remission after 6 months’ treatment) and point DAS28-ESR remission and low disease activity, (2) the impact of lesser improvements in DAS28-ESR, (3) limitations of DAS28-ESR in comparison to other composite assessments and (4) associations of DAS28-ESR components with health-related quality of life.

We focused on these aspects of treatment targets, as they are important and we had access to relevant observational and trial data. We could not examine all indices, as some of the necessary data are not collected in routine care settings or our published trials. As C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and physicians’ global assessments are not usually measured in routine practice in England, we could not study the SDAI. 218

Simple baseline outcome predictors

Using baseline measures to predict clinical outcomes may help routine practice. We therefore assessed the value of simple four-point scores, HAQ scores alone and mental health status.

We selected these areas on the basis of what was practical and likely to be used in clinical practice. There was a case to assess rheumatoid factor and subtypes and other autoantibodies in predicting RA outcomes,81,219,220 but these were not used in the observational studies and trials that we could access.

Methods

Observational studies

We further studied the observational longitudinal cohort study established in 2005 at Guy’s Hospital. The study focused on 752 patients followed over ≥ 3 years. Details of these patients are given in Appendix 1, Table 28. We also studied 155 early RA patients who completed 12 months’ follow-up with clinical data at 0, 6 and 12 months in an observational study [Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Network (ERAN)]. Details of these patients are given in Appendix 1. We selected these studies because they involved patients treated in recent years. More historical studies were not used because patients received far less intensive management.

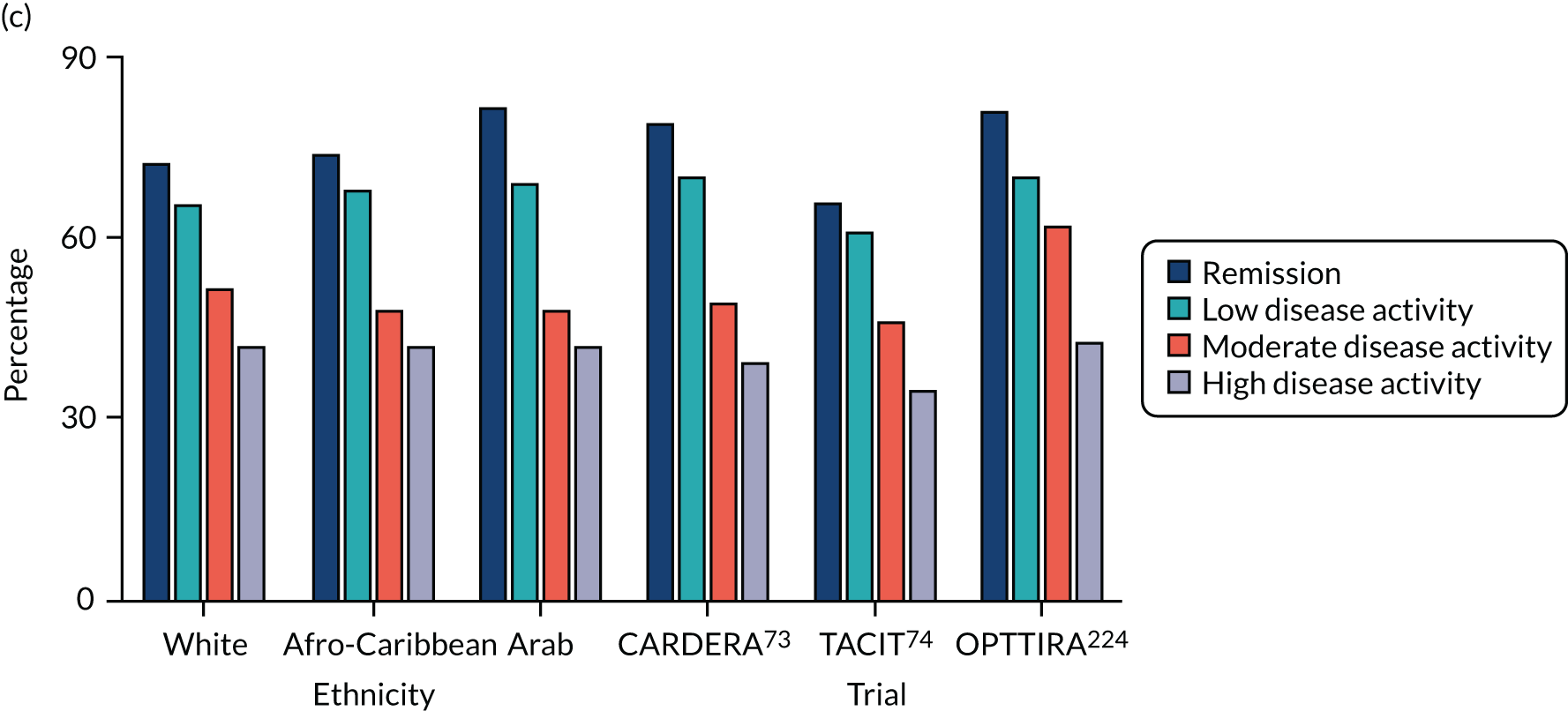

We also evaluated a compilation of single time point observational studies of outpatients with RA. 72,221–223 The patients included 747 European white RA patients, 197 black African/Caribbean British patients and 430 Arab patients seen in rheumatology clinics in Saudi Arabia. No specific treatment policies were followed in these patients. Details of these patients are given in Appendix 1, Table 29.

Clinical trials

We further evaluated the 379 patients completing the 24-month CARDERA trial73 and the 179 patients completing the TACIT trial. 74 We also evaluated patients with established RA in the OPTTIRA (Optimizing Treatment with Tumour Necrosis Factor Inhibitors In Rheumatoid Arthritis) trial. 224 The OPTTIRA trial, which lasted 6 months, enrolled 103 patients, and complete end-point data were available in 97 patients. Details of these patients are given in Appendix 1, Table 31.

Clinical assessments

We assessed disease activity using DAS28-ESR, CDAI and Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3), disability using the HAQ, and health-related quality of life using EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36). 225–230

Further details are given in Appendix 2.

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed descriptively using means, SDs and 95% CIs or medians and IQRs for non-normally distributed data. Other tests included chi-squared tests, assessments of sensitivity and specificity, t-tests, regression analyses, Spearman’s correlations and multiple linear regression methods. Further details are given in Appendix 3.

Key findings

Treatment targets: DAS28-ESR and disability

The relationships between remission and low disease activity with disability and quality of life were studied in early and established RA trials and an observational cohort. In these patients, both sustained remission and sustained low disease activity were relatively uncommon. Between 5% and 9% of patients had sustained remissions and 9–16% of patients had sustained low disease activity. More patients had remission and low disease activity at single time points. Between 35% and 58% of patients had an episode of remission and between 49% and 74% of patients had an episode of low disease activity.

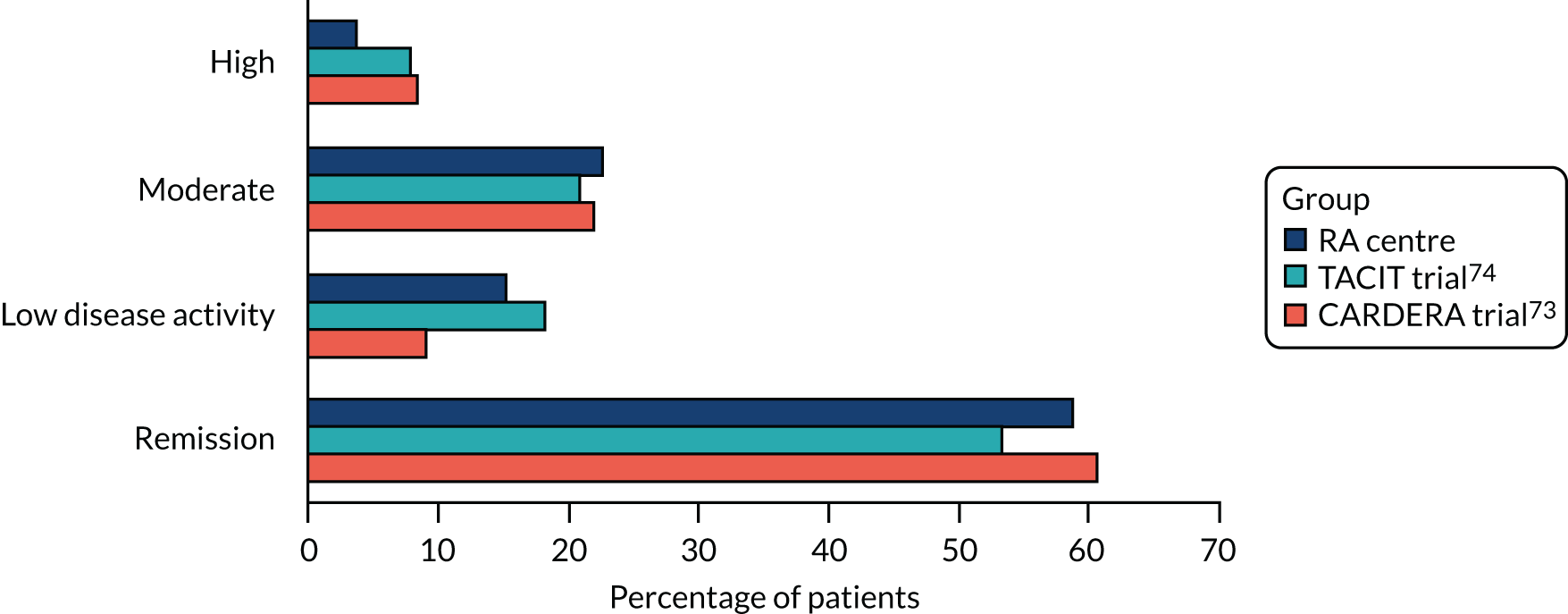

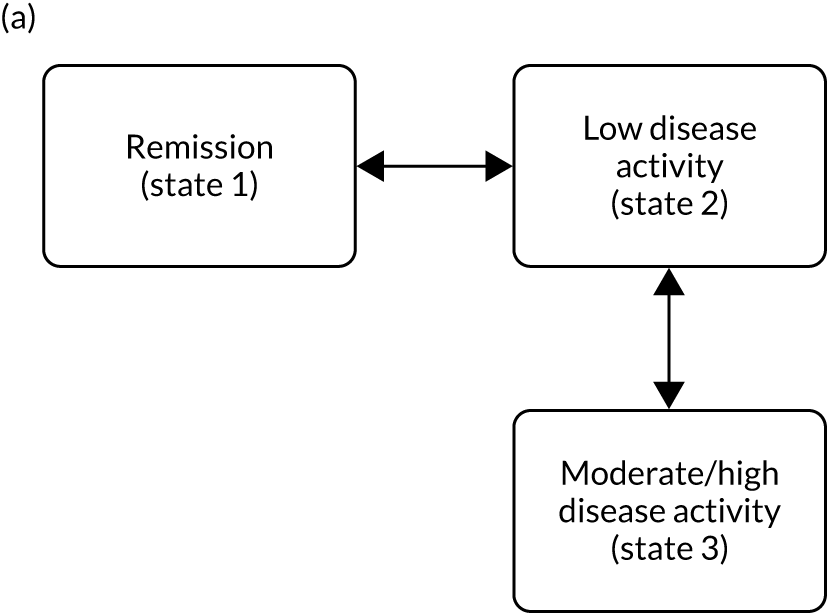

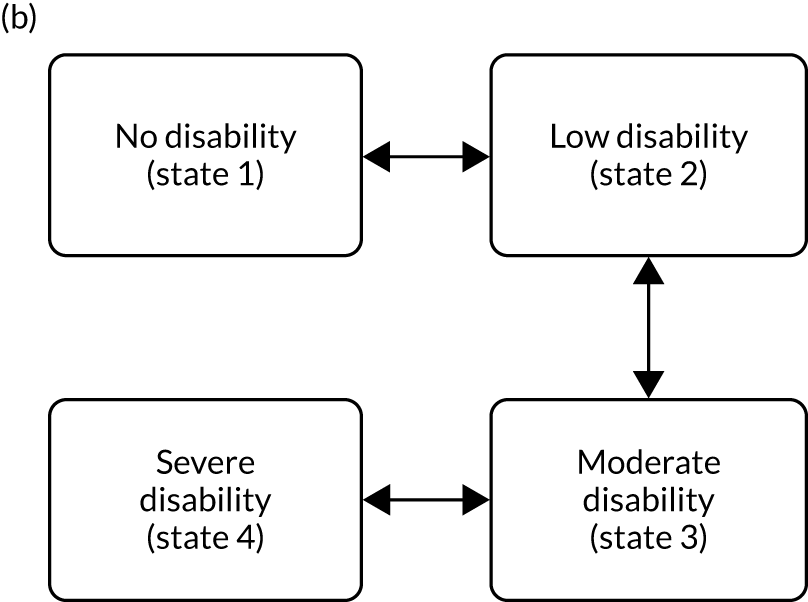

Disease Activity Score for 28 joints based on ESR scores varied substantially after patients had achieved an episode of remission. End-point DAS28-ESR scores (at 12 and 24 months in TACIT and CARDERA trials,73,74 and at final assessment in the observational study) in patients achieving an episode of remission showed that 53–61% of patients were still in remission, 9–18% of patients had low disease activity, 21–22% of patients had moderate disease activity and 4–8% of patients had high disease activity. These findings are shown in Figure 8.

FIGURE 8.

End-point DAS28-ESR category after attaining point remission.

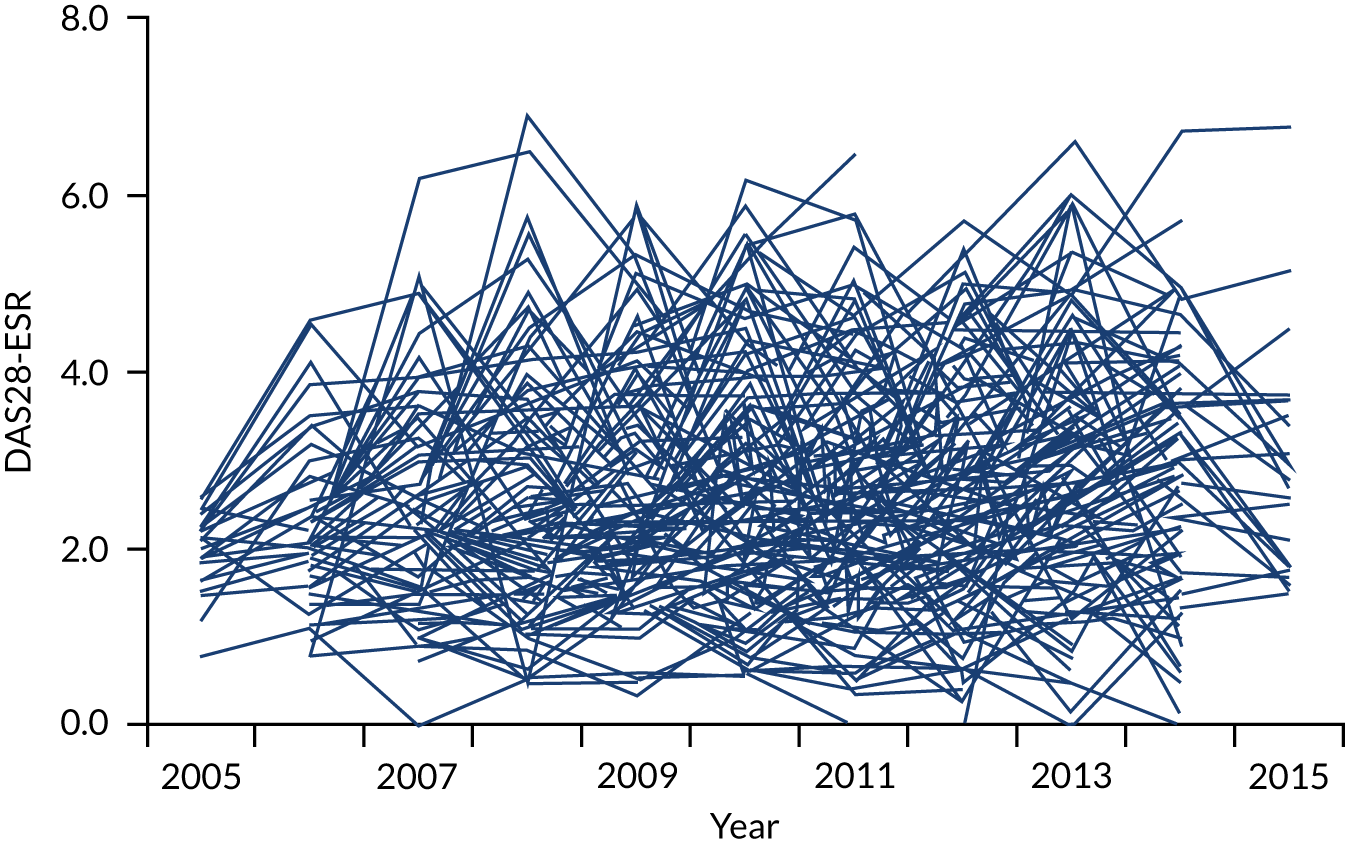

Individual patients showed marked levels of variation in their subsequent DAS28-ESR scores following attaining remission. The extent of this within-individual variability was similar across all three cohorts. Figure 9 shows DAS28-ESR scores for all patients following attaining remission in the longitudinal observations study in patients with at least five subsequent DAS28-ESR measures.

FIGURE 9.

Within-individual variability in DAS28-ESR scores after remission for patients in the longitudinal observational study. DAS28-ESR scores for each individual patient following an episode of remission are plotted, provided there were at least five subsequent DAS28-ESR measures. Reprinted from Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, Volume 49, Scott IC, Ibrahim F, Panayi G, Cope AP, Garrood T, Vincent A, et al. The frequency of remission and low disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and their ability to identify people with low disability and normal quality of life, pp. 20–6, Copyright 2019, with permission from Elsevier. 210

Sustained and point remissions had varying impacts on end-point low disability and normal EQ-5D scores (Table 3). Sustained remissions were most specific for low disability (97–98%) and normal EQ-5D (93–97%), but lacked sensitivity (low disability: 19–29%; normal EQ-5D: 19–36%). Point remission gave a better balance between sensitivity and specificity (low disability: specificity 50–78% and sensitivity 68–89%; normal EQ-5D: specificity 42–72% and sensitivity 70–93%).

| Group | Remission/LDA status | Patients | Mean end-point DAS28 (95% CI) | End-point HAQ | End-point EQ-5D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAQ ≤ 0.5 | Specificity | Sensitivity | Normal EQ-5D | Specificity | Sensitivity | ||||

| CARDERA trial73 (n = 379) | Sustained remission | 26 (7%) | 1.80 (1.61 to 1.99) | 19/91 | 98% | 21% | 16/60 | 97% | 27% |

| Point remission | 132 (35%) | 2.81 (2.57 to 3.04) | 68/91 | 78% | 75% | 42/60 | 72% | 70% | |

| End-point remission | 80 (21%) | 1.92 (1.80 to 2.03) | 48/91 | 91% | 51% | 35/60 | 86% | 58% | |

| Sustained LDA/remission | 45 (12%) | 2.02 (1.84 to 2.19) | 33/91 | 96% | 36% | 26/60 | 94% | 33% | |

| Point LDA/remission | 187 (49%) | 3.09 (2.89 to 3.28) | 79/91 | 63% | 87% | 52/60 | 58% | 87% | |

| End-point LDA/remission | 114 (30%) | 2.20 (2.09 to 2.32) | 62/91 | 82% | 68% | 46/60 | 79% | 77% | |

| TACIT trial74 (n = 192) | Sustained remission | 10 (5%) | 1.66 (1.32 to 2.00) | 6/31 | 97% | 19% | 4/17 | 96% | 19% |

| Point remission | 80 (42%) | 2.81 (2.53 to 3.10) | 19/31 | 63% | 68% | 13/17 | 62% | 77% | |

| End-point remission | 41 (22%) | 1.92 (1.77 to 2.08) | 17/31 | 85% | 55% | 10/16 | 82% | 59% | |

| Sustained LDA/remission | 17 (9%) | 1.75 (1.50 to 2.00) | 8/31 | 94% | 26% | 6/17 | 94% | 35% | |

| Point LDA/remission | 119 (62%) | 3.18 (2.94 to 3.43) | 29/31 | 44% | 94% | 17/17 | 41% | 100% | |

| End-point LDA/remission | 66 (35%) | 2.29 (2.14 to 2.44) | 23/31 | 72% | 74% | 13/17 | 69% | 81% | |

| RA centre (n = 752) | Sustained remission | 67 (9%) | 1.56 (1.46 to 1.67) | 52/180 | 97% | 29% | 21/59 | 93% | 36% |

| Point remission | 437 (58%) | 2.83 (2.75 to 2.91) | 160/180 | 50% | 89% | 55/59 | 42% | 93% | |

| End-point remission | 167 (22%) | 1.98 (1.90 to 2.05) | 106/180 | 87% | 57% | 37/59 | 78% | 52% | |

| Sustained LDA/remission | 120 (16%) | 1.91 (1.81 to 2.01) | 73/180 | 92% | 41% | 24/59 | 86% | 41% | |

| Point LDA/remission | 560 (74%) | 3.07 (2.99 to 3.14) | 174/180 | 31% | 97% | 57/59 | 25% | 97% | |

| End-point LDA/remission | 310 (41%) | 2.41 (2.34 to 2.48) | 142/180 | 70% | 79% | 50/59 | 62% | 85% | |

Attaining sustained low disease activity was also highly specific for low disability (92–96%) and normal EQ-5D (86–94%), but lacked sensitivity (low disability: 26–41%; normal EQ-5D: 33–41%). Low disease activity at any point was highly sensitive (low disability: sensitivity 87–97%; normal EQ-5D: sensitivity 87–100%), but had only moderate specificity (low disability: specificity 31–63%; normal EQ-5D: specificity 25–58%).

Treatment targets: optimal responses in DAS28-ESR scores

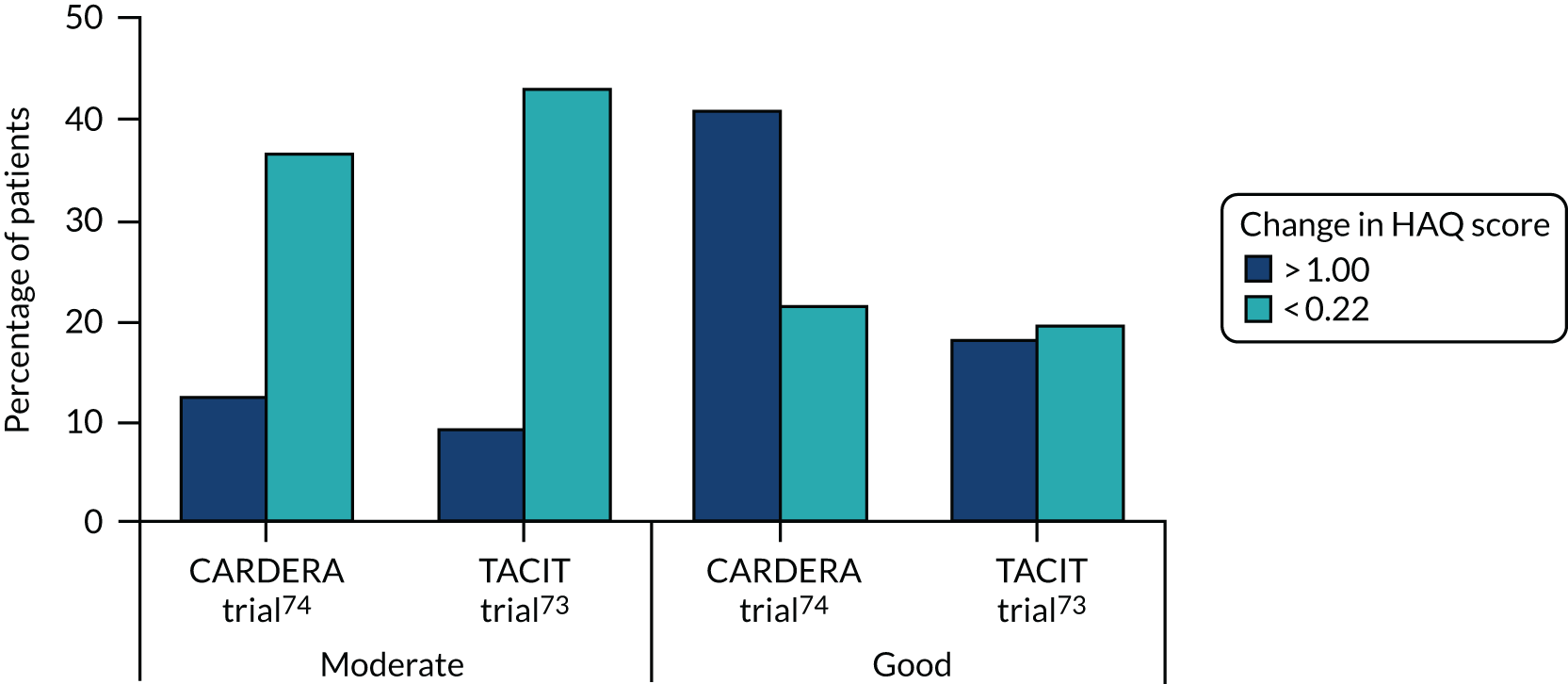

An alternative way of assessing the inter-relationship between DAS28-ESR scores, disability and quality of life was examining the impact of EULAR responses in clinical trial settings. This approach was taken in another study208 that evaluated the impacts of moderate and good EULAR responses on changes in HAQ scores at the end points of early and established RA trials.

Moderate EULAR responders’ mean HAQ scores decreased by 0.39 and 0.33 in the CARDERA and TACIT trials, respectively. 73,74 In contrast, EULAR good responders had reductions of 0.88 and 0.64, respectively. In both trials, the difference between moderate and good responders exceeded the minimum clinically important difference for HAQ scores (0.22). The differences in mean reductions of 0.49 and 0.30 between moderate and good responders were significant (p < 0.01, unpaired t-test).

There were similar findings for EQ-5D scores. In moderate EULAR responders, EQ-5D scores increased by 0.18 and 0.15. In good EULAR responders, EQ-5D scores increased by 0.30 in both trials. The differences (0.12 and 0.15) between moderate and good responders also exceeded the minimum clinically important difference, which is generally considered to be 0.07, and were significant (p < 0.01, unpaired t test).

In addition, the frequencies of large and minimal improvements in disability and quality of life were assessed in these patients (Figure 10). With HAQ scores between 41% and 18%, good EULAR responders had large decreases in HAQ score (> 1.00) in early and established RA. However, only 13% and 9% of moderate EULAR responders had such reductions. By contrast, only 21% and 20% of good EULAR responders had minimal changes in HAQ score (> 0.22), compared with 37% and 43% of moderate EULAR responders.

FIGURE 10.

Changes in HAQ score in moderate and good EULAR responders. In early and established RA trials (CARDERA trial73 and TACIT trial,74 respectively). Shows per cent of patients with substantial (> 1.00) and minimal changes (< 0.22). Adapted with permission from Mian et al. 208 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Treatment targets: DAS28-ESR and alternative assessments

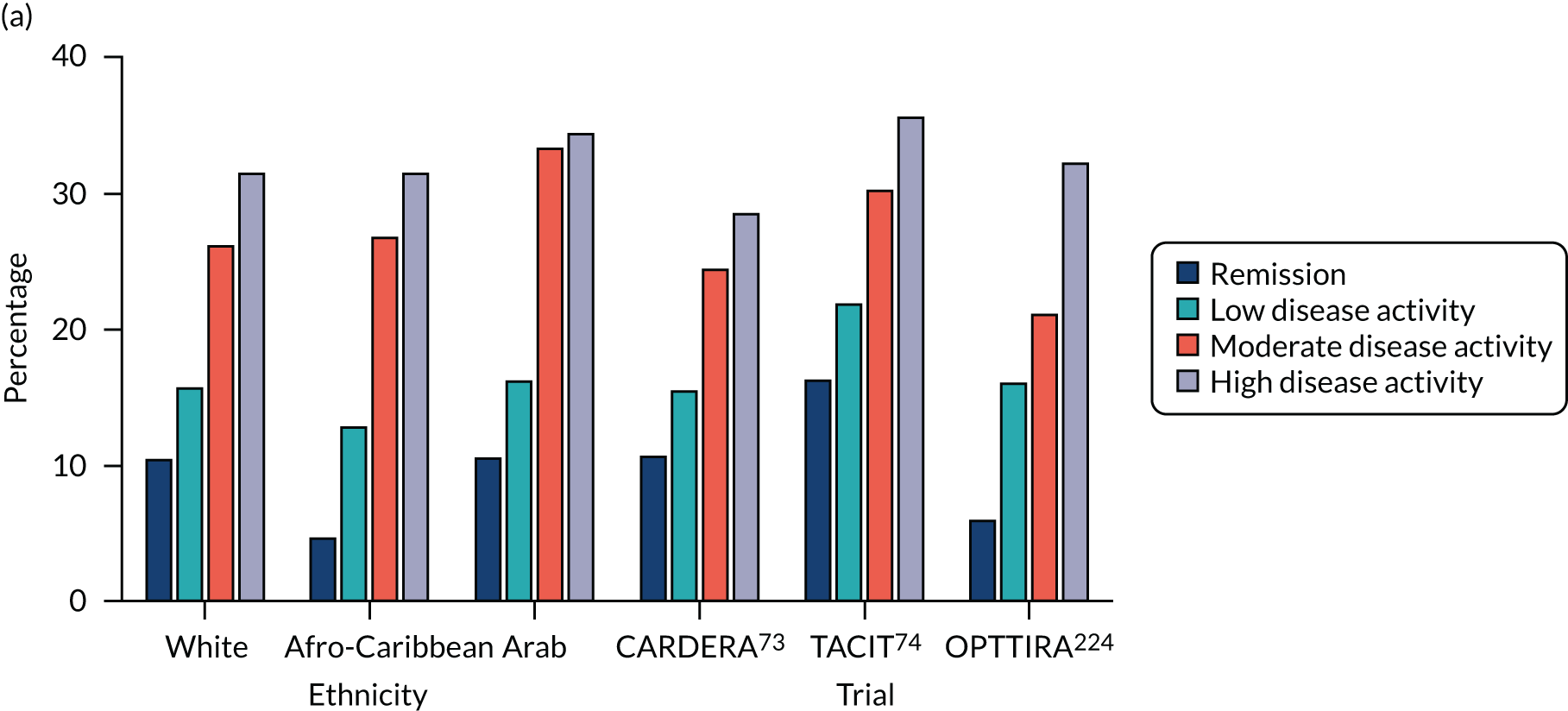

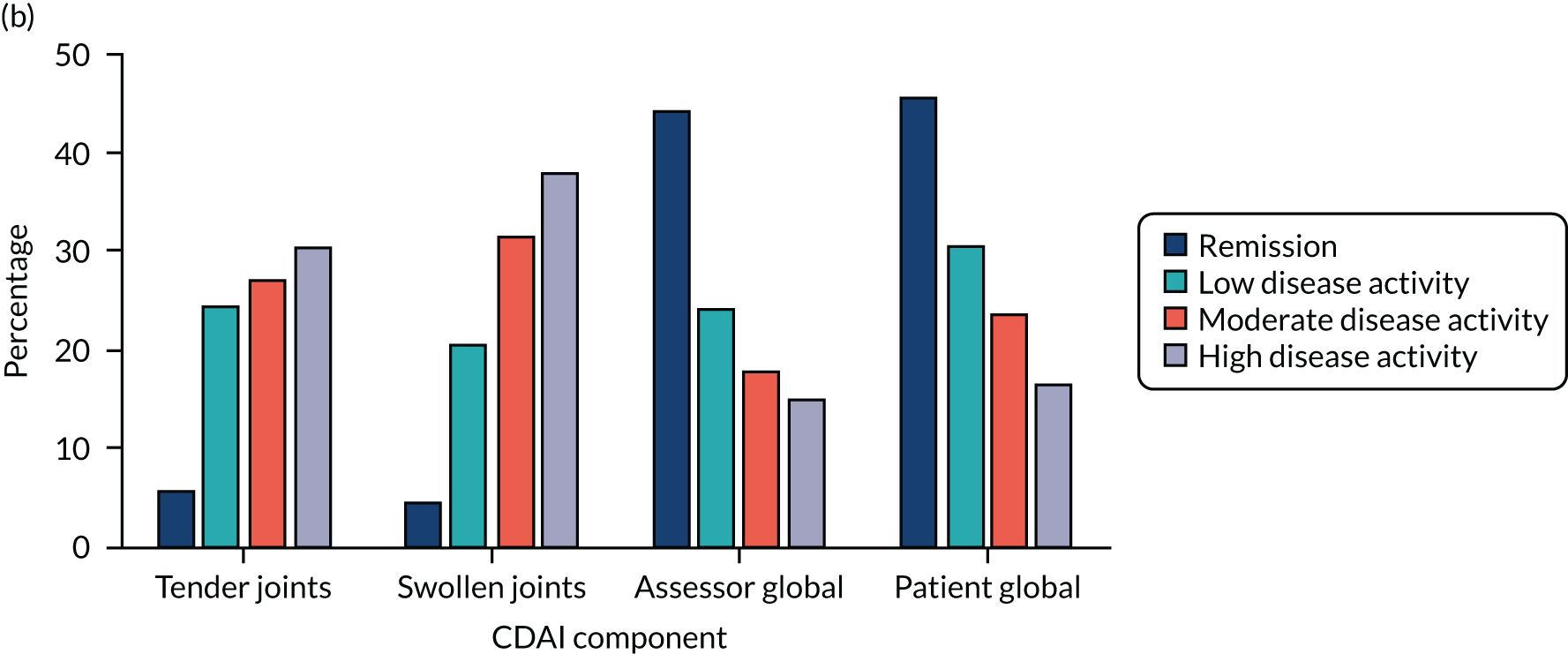

The inter-relationships between the four components of DAS28-ESR scores were assessed over the four disease activity levels: (1) remission, (2) low disease activity, (3) moderate disease activity and (4) high disease activity. Initially, these inter-relationships were assessed in an observational study of 747 European white patients. This analysis showed that ESRs contributed most to mean DAS28-ESR scores at all activity levels. However, their contribution was greatest in remission, when ESRs accounted for 70% of DAS28-ESR scores. The contribution of ESR decreased to 40% of DAS28-ESR scores in active disease. In contrast, the contributions of tender joint count to overall DAS28-ESR scores declined as DAS28-ESR fell. Swollen joint counts and patient global assessments showed small stable contributions to DAS28-ESR scores over all disease activity levels.

These findings were replicated in two further observational studies of 197 black African/Caribbean British patients223 and 430 Arab patients. 222 They were also replicated in three clinical trials (i.e. CARDERA,73 TACIT74 and OPTTIRA224) that involved 97–369 patients. Figure 11 shows the contributions of ESR and tender joint counts to DAS28-ESR disease activity levels in all six of these observational studies and trials.

FIGURE 11.

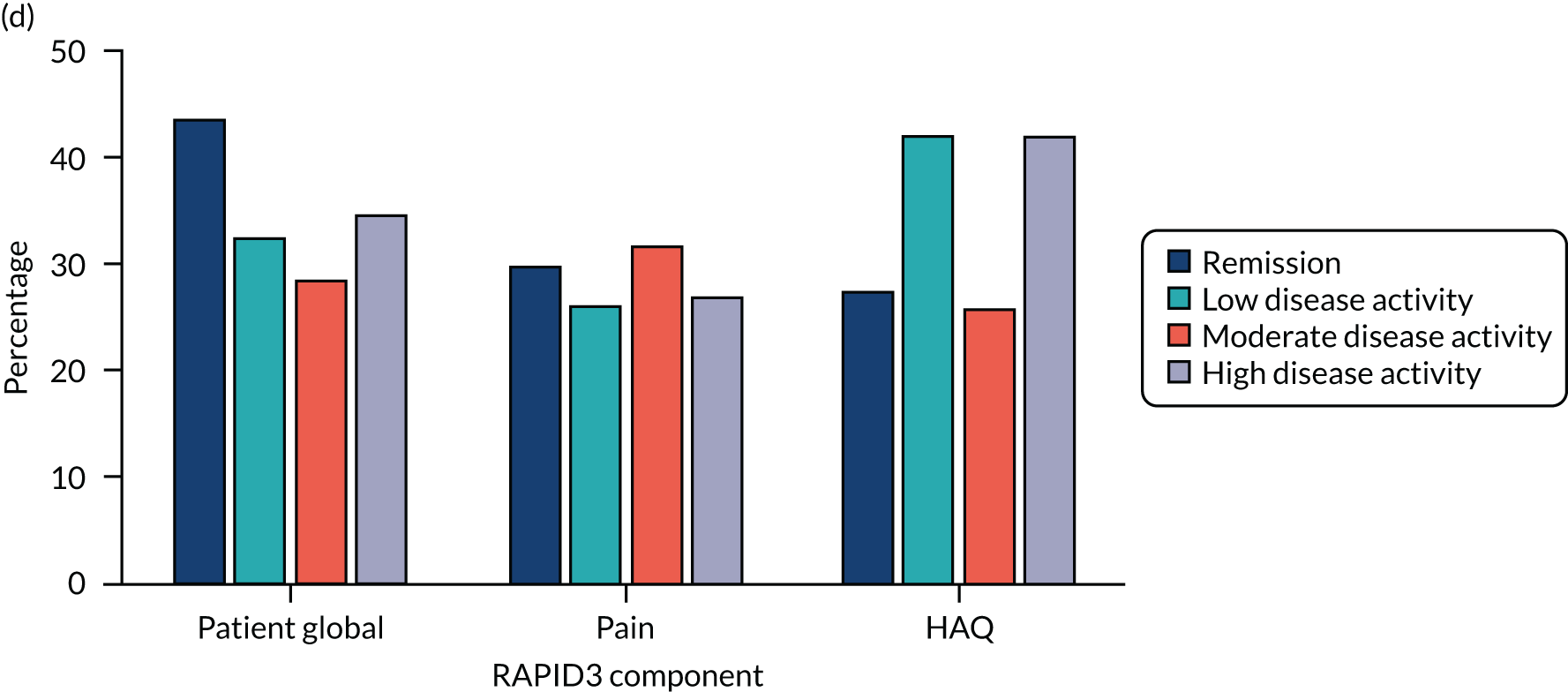

Contributions of different components to activity scores in different states of disease activity. Tender joints and ESR in DAS28 in data from six studies72–74,221–224 and components CDAI and RAPID3 in data from the CARDERA trial. 73 (a) DAS28 tender joints; (b) CDAI all components; (c) DAS28-ESR; and (d) RAPID3 all components.

Two other composite scores – CDAI and RAPID3 – were studied in a comparative manner in one early RA trial (i.e. the CARDERA trial73). These alternative composite scores showed different patterns of variation across disease activity levels, which is also shown in Figure 11. With the CDAI, patient and assessor global assessments dominated in remission and swollen and tender joint counts dominated in active disease. With RAPID3, patient global score, pain score and HAQ score made relatively stable contributions to the overall score across all activity levels.

Treatment targets: DAS28-ESR and health-related quality of life

The association between different components of the DAS28-ESR and health-related quality of life was assessed using the SF-36. The inter-relationships were evaluated in clinical trials of 672 patients with early and established RA.

Linear regression models, which included all four DAS28-ESR components, examined the relationships to SF-36 physical component score (PCS) and mental component score (MCS). The regression models were adjusted for treatment, age, sex and disease duration. The regression models found significant correlations between patient global scores and both SF-36 summary scores in early and established RA (Table 4). Other components of DAS28-ESR had significant correlations in early RA patients, but did not have significant correlations in established RA patients.

| SF-36 | Early RA trial | Established RA trial | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardised β (SE) | p-value | Standardised β (SE) | p-value | |

| PCS | ||||

| Swollen joint count | −0.19 (0.05) | < 0.001 | −0.06 (0.08) | 0.412 |

| Tender joint count | 0.00 (0.05) | 0.977 | −0.08 (0.09) | 0.370 |

| ESR | −0.08 (0.04) | 0.036 | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.676 |

| Patient global assessment | −0.45 (0.05) | < 0.001 | −0.36 (0.08) | < 0.001 |

| MCS | ||||

| Swollen joint count | −0.12 (0.06) | 0.029 | 0.05 (0.08) | 0.527 |

| Tender joint count | 0.15 (0.05) | 0.003 | −0.16 (0.09) | 0.080 |

| ESR | −0.12 (0.04) | 0.008 | 0.00 (0.07) | 0.974 |

| Patient global assessment | −0.43 (0.05) | < 0.001 | −0.33 (0.08) | < 0.001 |

Predictive factors: simple four-point scores

The first approach to predicting RA outcomes involved developing and testing a simple predictive score using data that are regularly collected in routine care settings. It focused on predicting persisting active RA. The score was developed in an observational study (ERAN),206 using 155 early RA patients who completed 12 months’ follow-up and had clinical data at 0, 6 and 12 months. Regression modelling identified three main predictors for persisting active disease: (1) tender joint counts, (2) HAQ scores and (3) ESR. Each of these predictors was then dichotomised (six or more tender joint counts, HAQ score of ≥ 1.0 and an ESR of ≥ 20 mm/hour) to give a four-point score. This index predicted persisting active disease (i.e. a DAS28-ESR score of > 3.2) at 6 and 12 months during follow-up in ERAN.

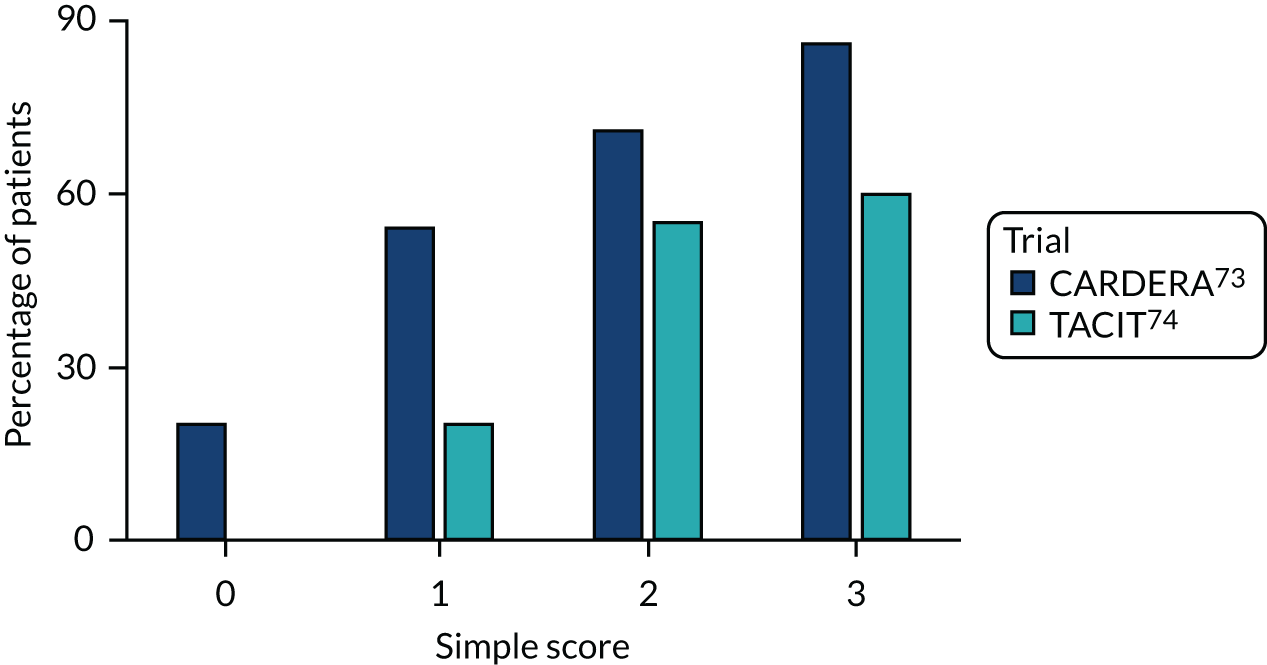

The value of this four-point score was then assessed in clinical trials in 558 patients with early and established RA. In the early RA trial, only 20% of patients with no predictors had persistent active disease, whereas 80% of patients with all three predictors had persistent active disease (Figure 12). This relationship was significant (p < 0.01). There was a similar relationship in the established RA trial, although this was weaker because none of the patients in the established RA trial had no initial predictive factors. In these patients, 20% of patients with one predictive factor had persistent active disease, compared with 60% of patients with all three predictors (p = 0.05).

FIGURE 12.

Simplified predictors of persistently active disease in trial patients.

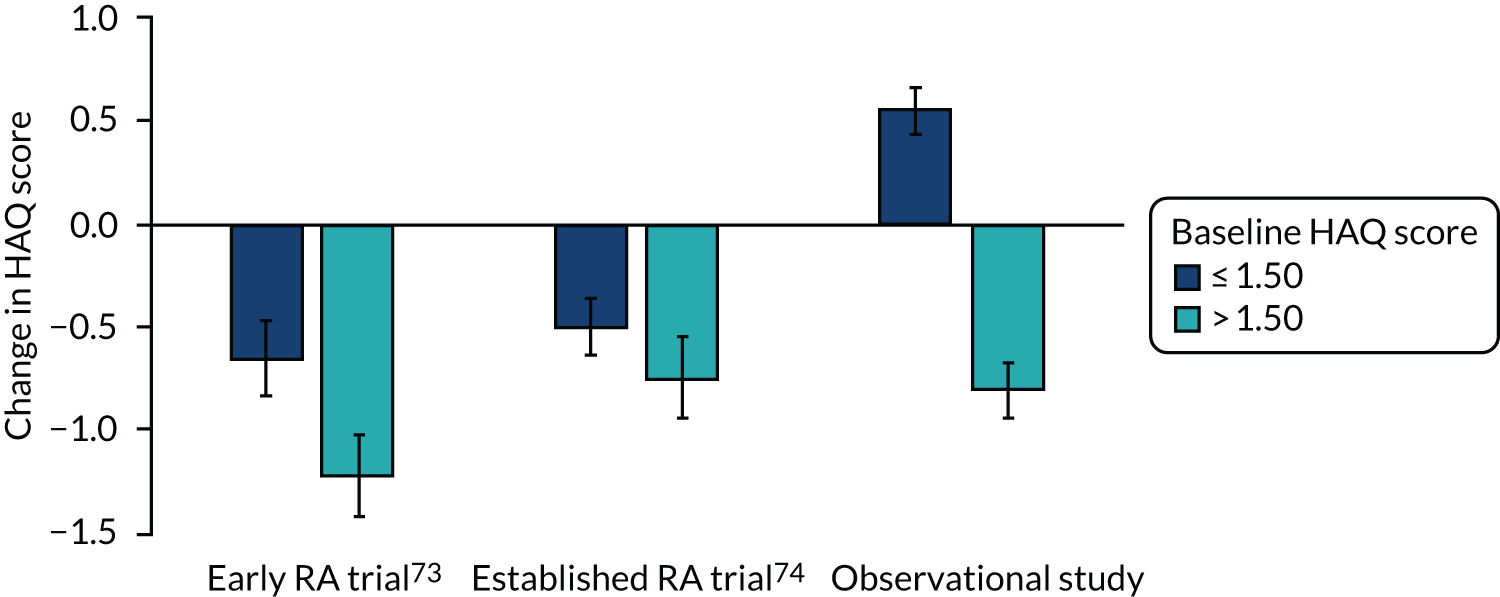

Predictive factors: high baseline Health Assessment Questionnaire score as an outcome predictor

A second approach to predicting outcomes used initial HAQ scores alone. The value of baseline HAQ scores in predicting outcomes was assessed in 558 patients in early and established RA trials73,74 and 752 patients followed over ≥ 3 years in the observational study.

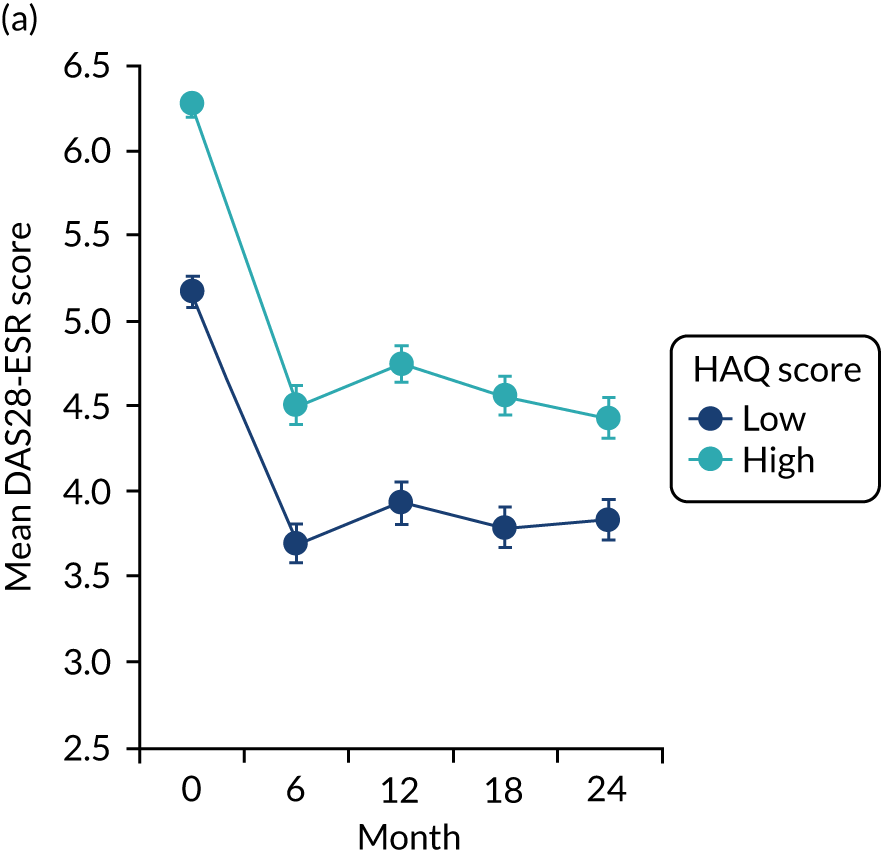

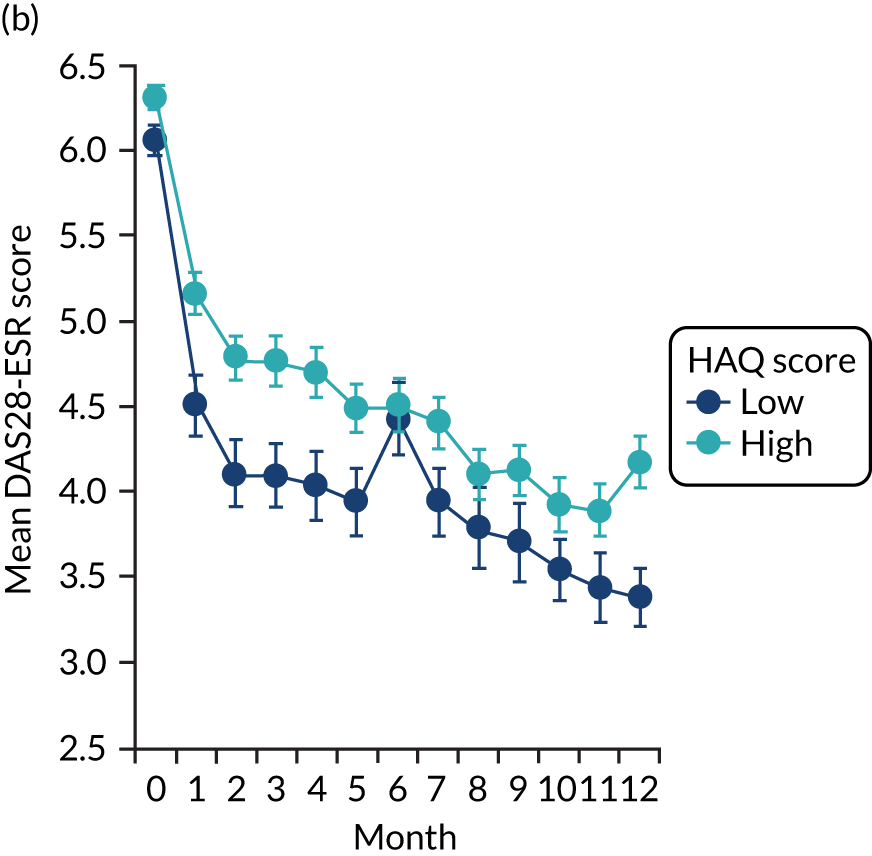

In both trials,73,74 patients with low baseline HAQ scores (≤ 1.50) had significantly more good EULAR responses (both p = 0.013) and significantly lower final mean DAS28-ESR scores (both p > 0.001) than patients with high baseline HAQ scores (> 1.50). These differences are shown in Figure 13. In the observational study, patients with low baseline HAQ scores had significantly lower overall mean DAS28-ESR scores (p < 0.001). In both trials, patients with high initial HAQ scores (> 1.50) had the largest end-point decreases in HAQ score if they achieved good EULAR responses. The observational study showed the same pattern.

FIGURE 13.

Initial high and low HAQ scores and changes in HAQ score in EULAR good responders. Mean and standard errors are shown.

Sequential changes in DAS28-ESR scores in both trials73,74 and the observational study showed that patients with low baseline HAQ scores had lower mean DAS28-ESR scores at all subsequent follow-up time points (Figure 14). The pattern of response was similar in all three groups, although the difference in DAS28-ESR scores attributed to baseline HAQ was larger in the early RA trial73 than in the established RA trial. 74

The relationship between baseline HAQ scores, subsequent remissions during treatment and changes in HAQ scores with treatment are shown in Table 5. The analysis shows two main things. First, patients with high baseline HAQ scores had significantly fewer remissions. Second, when remissions occurred, especially several remissions, the changes in HAQ scores were greatest in patients with high baseline HAQ.

| Study | Initial HAQ score | Remissions | HAQ score (95% CI) | Difference in HAQ score (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | ||||

| CARDERA trial73 | ≤ 1.50 | None | 1.01 (0.93 to 1.09) | 1.04 (0.92 to 1.16) | 0.03 (0.09 to 0.15) |

| One | 0.92 (0.75 to 1.08) | 0.72 (0.53 to 0.92) | –0.19 (–0.46 to 0.08) | ||

| Two or more | 0.93 (0.81 to 1.05) | 0.37 (0.24 to 0.50) | –0.56 (–0.71 to –0.40) | ||

| > 1.50 | None | 2.14 (2.08 to 2.19) | 1.04 (0.71 to 1.36) | –0.89 (–1.28 to –0.51) | |

| One | 1.93 (1.80 to 2.06) | 1.04 (0.71 to 1.36) | –0.89 (–1.28 to –0.51) | ||

| Two or more | 2.03 (1.90 to 2.16) | 0.65 (0.40 to 0.89) | –1.38 (–1.62 to –1.14) | ||

| TACIT trial74 | ≤ 1.50 | None | 1.18 (1.07 to 1.29) | 0.94 (0.74 to 1.15) | –0.24 (–0.44 to –0.03) |

| One | 0.97 (0.76 to 1.18) | 0.28 (0.01 to 0.55) | –0.69 (–1.11 to –0.27) | ||

| Two or more | 0.93 (0.73 to 1.12) | 0.53 (0.33 to 0.74) | –0.39 (–0.56 to –0.22) | ||

| > 1.50 | None | 2.25 (2.18 to 2.33) | 2.00 (1.88 to 2.12) | –0.26 (–0.35 to –0.16) | |

| One | 2.22 (2.07 to 2.38) | 1.79 (1.50 to 2.09) | –0.43 (–0.63 to –0.23) | ||

| Two or more | 2.07 (1.95 to 2.19) | 1.30 (1.07 to 1.54) | –0.77 (–1.00 to –0.54) | ||

| Observational study | ≤ 1.50 | None | 0.87 (0.78 to 0.97) | 1.29 (1.16 to 1.42) | 0.42 (0.27 to 0.56) |

| One | 0.83 (0.70 to 0.96) | 1.09 (0.92 to 1.26) | 0.25 (0.06 to 0.44) | ||

| Two or more | 0.73 (0.62 to 0.84) | 0.67 (0.51 to 0.83) | –0.06 (–0.22 to 0.09) | ||

| > 1.50 | None | 2.16 (2.10 to 2.22) | 2.11 (2.01 to 2.20) | –0.04 (–0.13 to 0.04) | |

| One | 2.09 (1.97 to 2.21) | 1.92 (1.72 to 2.13) | –0.17 (–0.40 to 0.07) | ||

| Two or more | 2.08 (1.95 to 2.22) | 1.49 (1.24 to 1.75) | –0.59 (–0.81 to –0.36) | ||

Predictive factors: anxiety and depression

The final approach to predicting outcomes assessed the impact of anxiety and depression using EQ-5D, which were related to outcomes in 379 patients in an early RA trial73 using linear regression models.

In unadjusted regression models, patients with moderate and high levels of depression and anxiety at baseline had higher HAQ and DAS28-ESR scores over time and at the trial end point. After adjusting for age, sex, disease duration, time, treatment type, baseline HAQ and DAS28-ESR scores and rheumatoid factor status, there were no longer between-group differences for HAQ score (Table 6). However, there continued to be a significant relationship between high levels of depression and anxiety at baseline and higher end-point DAS28-ESR scores.

| Model | Primary outcomes | Secondary outcomes: DAS-28 components | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAQ | DAS-28 | SJC | ESR | PGA | TJC | |||||||||||||

| Post-treatment mean differences (SE) | Standardized mean differences | p-value | Post-treatment mean differences (SE) | Standardized mean differences | p-value | Post-treatment mean differences (SE) | Standardized mean differences | p-value | Post-treatment mean differences (SE) | Standardized mean differences | p-value | Post-treatment mean differences (SE) | Standardized mean differences | p-value | Post-treatment mean differences (SE) | Standardized mean differences | p-value | |

| Unadjusted | ||||||||||||||||||

| No depression/anxiety | ||||||||||||||||||

| Moderate depression/anxiety | 0.31 (0.07) | 0.44 | < 0.001 | 0.47 (0.15) | 0.34 | < 0.01 | 0.07 (0.08) | 0.10 | 0.33 | 0.06 (0.09) | 0.08 | 0.50 | 8.00 (2.24) | 0.37 | < 0.001 | 0.16 (0.09) | 0.18 | 0.10 |

| Extreme baseline depression/anxiety | 0.72 (0.15) | 1.01 | < 0.001 | 1.20 (0.30) | 0.86 | < 0.001 | 0.13 (0.15) | 0.19 | 0.38 | 0.18 (0.17) | 0.23 | 0.31 | 18.81 (4.56) | 0.87 | < 0.001 | 0.61 (0.18) | 0.70 | < 0.001 |

| Adjusteda | ||||||||||||||||||

| No depression/anxiety | ||||||||||||||||||

| Moderate depression/anxiety | 0.04 (0.06) | 0.06 | 0.45 | 0.10 (0.14) | 0.07 | 0.49 | −0.01 (0.08) | −0.01 | 0.95 | −0.04 (0.07) | −0.05 | 0.57 | 2.81 (2.19) | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.05 (0.09) | 0.06 | 0.59 |

| Extreme baseline depression/anxiety | 0.21 (0.12) | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.59 (0.29) | 0.42 | 0.04 | 0.06 (0.15) | 0.09 | 0.68 | 0.07 (0.15) | 0.09 | 0.64 | 8.72 (4.54) | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.38 (0.17) | 0.44 | 0.02 |

At the trial end point, 80 (21%) patients had remissions (i.e. DAS-28 scores < 2.6). Patients with moderate levels of depression and anxiety at baseline had fewer clinical remissions than patients with no depression and anxiety at baseline [odds ratio (OR) 0.50, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.88; p = 0.02]. Patients with high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms at baseline also had reduced odds of reaching remission; however, this comparison was not significant (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.25 to 2.33; p = 0.64). This is likely to reflect the small number of patients with extreme symptoms at baseline (n = 24), reducing the power to find a significant effect because of an imprecise estimate.

Limitations

Studies in this section were limited because they involved secondary analyses of previously collected data, omitted rheumatoid factor when predicting outcomes and enrolled patients using different classification criteria for RA compared with the TITRATE trial.

Secondary analyses of existing data

Most studies in this section were post hoc analyses of existing data. They did not address prespecified hypotheses. As a consequence, caution is needed interpreting their significance.

Rheumatoid factor and other autoantibodies

The prognostic studies did not consider the impact of rheumatoid factor isotypes or anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies. These are recognised response predictors that, together with smoking status, are linked to rheumatoid factor positivity. 231–234 However, as autoantibodies are measured in many different ways across centres, it is impractical to use them in current clinical practice studies. Smoking status is also not usually recorded in routine clinical practice.

Diagnostic criteria and intensive management strategies

Rheumatoid arthritis patients in all studies assessed were enrolled before the introduction of new diagnostic criteria for the classification of RA. There is evidence that these new criteria change the patients classified as having RA, particularly patients with seronegative disease. 45,235–238 The TITRATE trial uses the most recent criteria and it would have been a mistake not to do so. This change makes it difficult to relate historical findings exactly to new data.

The trials studied did not involve the same intensive management strategies used in the TITRATE programme and the impact of changing treatment in patients who did not achieve sustained remissions was not examined. These are general limitations with all trials involving intensive management strategies. 239–244

Relation to overall programme

Our findings in this section focused on the impact of different durations of remission, the effect of alternative remission assessments and the role of simple outcome predictors.

Duration of DAS28-ESR remission

We found that achieving sustained DAS28-ESR remission gave the greatest chance of minimising disability and maximising health-related quality of life; however, this was uncommon, reflecting international experience with sustained remission. 217,245–249 More patients benefited when the treatment target was to achieve DAS28-ESR remission at any time during follow-up.

End-point remission and low disease activity were both reasonable targets.

Other assessments of remission

Disease Activity Score for 28 joints based on ESR scores were dominated by the ESR at low levels and in remission. Other composite disease activity assessments, such as CDAI and RAPID3, show different patterns in their components as disease activity changes. However, there was no reason to favour one composite index over another. These findings reflect the ongoing debate about how best to use composite indices in assessing RA disease activity. 250–254 We also found that patient global assessment, a component of most composite measures, was most closely associated with patient-assessed health-related quality of life. Several other recent reports255–257 have highlighted the importance of patient global assessments in RA.

Simple outcome predictors

Poor outcomes were predicted by several simple baseline measures, including a simple four-point predictive score, initial HAQ score and the presence of anxiety and depression. The situation with the HAQ was complex, as the largest improvements with treatment were seen in patients who had high initial HAQ scores and then showed substantial clinical improvements and achieved remission. Other research has highlighted the relevance of baseline HAQ score258–261 and depression262–265 in predicting RA outcomes.

Delivering intensive management

The studies in this section helped establish how best to provide intensive management to patients and evaluated patients’ expectations and identified practical approaches for delivering care. This part of the research had considerable PPI.

Aims

Research studies with four related aims are included in this section. These aims comprised assessment of patients’ expectations, development of a patient handbook and clinician training manual, and design of supportive material, including a training course for rheumatology practitioners. There was considerable PPI in this part of the research. Four of these papers have been published. 266–269

The overall objective of workstream A was patient-led development and implementation of an experimental intensive management strategy for patients with RA with moderate disease activity. The qualitative research was pragmatic and specific in its nature, namely to examine the acceptability, development and evaluation of the intensive management intervention. A more phenomenological approach would have provided richer data, but such a perspective would have been unsuitable for the aims and objectives of the work package.

Qualitative study of patient expectations

We explored the views and expectations of patients with moderately active RA and their carers about intensive management strategies. Several previous reports have examined the views of patients with more active RA. 270–272

Patient handbook

We developed a patient handbook to support patients who received intensive management, and this reflects growing recognition of the importance of the involvement and shared decision-making of patients in their disease management. 273–277 Patients helped to identify relevant information and ensured that its content was acceptable and accessible.

Clinician training manual

We developed a training manual to support clinicians to deliver intensive management. During the development of the manual, we systematically reviewed the evidence for psychological approaches, in general, and motivational interviewing (MI) to incorporate psychological approaches to support patients receiving intensive management. Psychological interventions are likely to be beneficial as adjunctive treatments for pain, fatigue and psychological distress in RA. 278 Health-care professionals can be trained to deliver psychological interventions to support patients with common long-term disorders,279 and MI fits this niche. 280,281

Motivational interviewing was identified as a candidate psychological technique because the trial research questions focused on treat-to-target approaches. Stopping, starting and changing medications and doses is a behaviour. Therefore, the intervention required a behavioural approach to support discussions about medication, which could lead to assessment of motivation for behaviour change in routine care by specialist nurses. The clinical and research expertise of Jackie Sturt, the academic lead for the psychological intervention component, identified the potential of MI to deliver the required behavioural changes around medication changes. Researchers undertook a review of the evidence to understand whether or not MI had been used experimentally in RA and the ways in which MI had been used in long-term condition self-care behaviours in general. The wealth of evidence in many long-term conditions and the absence of evidence in RA confirmed our decision to use MI. We considered it a good fit from both the clinical and theoretical perspectives. In addition, we noted that there was no existing evidence base for its use in this population.

Other developmental activities

Two other developments did not require primary research: (1) to devise treatment plans to capture patients’ views about their treatments and (2) the development of training courses for clinicians to deliver intensive management.

Methods

Qualitative studies of patient expectations

Focus groups and one-to-one interviews were conducted with nine patients with RA and five carers from four rheumatology clinics in three London hospitals. Two non-English-speaking patients were included and were assisted by a professional translator. The groups and interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and assessed using a framework analysis approach. 282 Details of the patients and carers are shown in Appendix 1, Table 32.

Audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were analysed by the researcher (LP). A second rater (HL) appraised the emergent themes from the transcripts and consensus between both researchers was reached. The transcripts were analysed using a framework analysis approach. 283 The process of framework analysis involves a series of stages: (1) familiarisation, (2) identification of a thematic framework, (3) indexing, (4) charting and (5) mapping and interpretation.

A combined inductive–deductive approach was taken, as the study had some specific issues to explore; however, it still allowed space to discover participants’ views and concerns. The codes were based on an iterative process that incorporated both the research question and line-by-line analysis of two patient and two carer transcripts. The remaining data were indexed in a systematic way in accordance with the thematic framework. Where new codes were identified, previously indexed interview transcripts were re-read to ensure that all relevant data were coded. 283,284

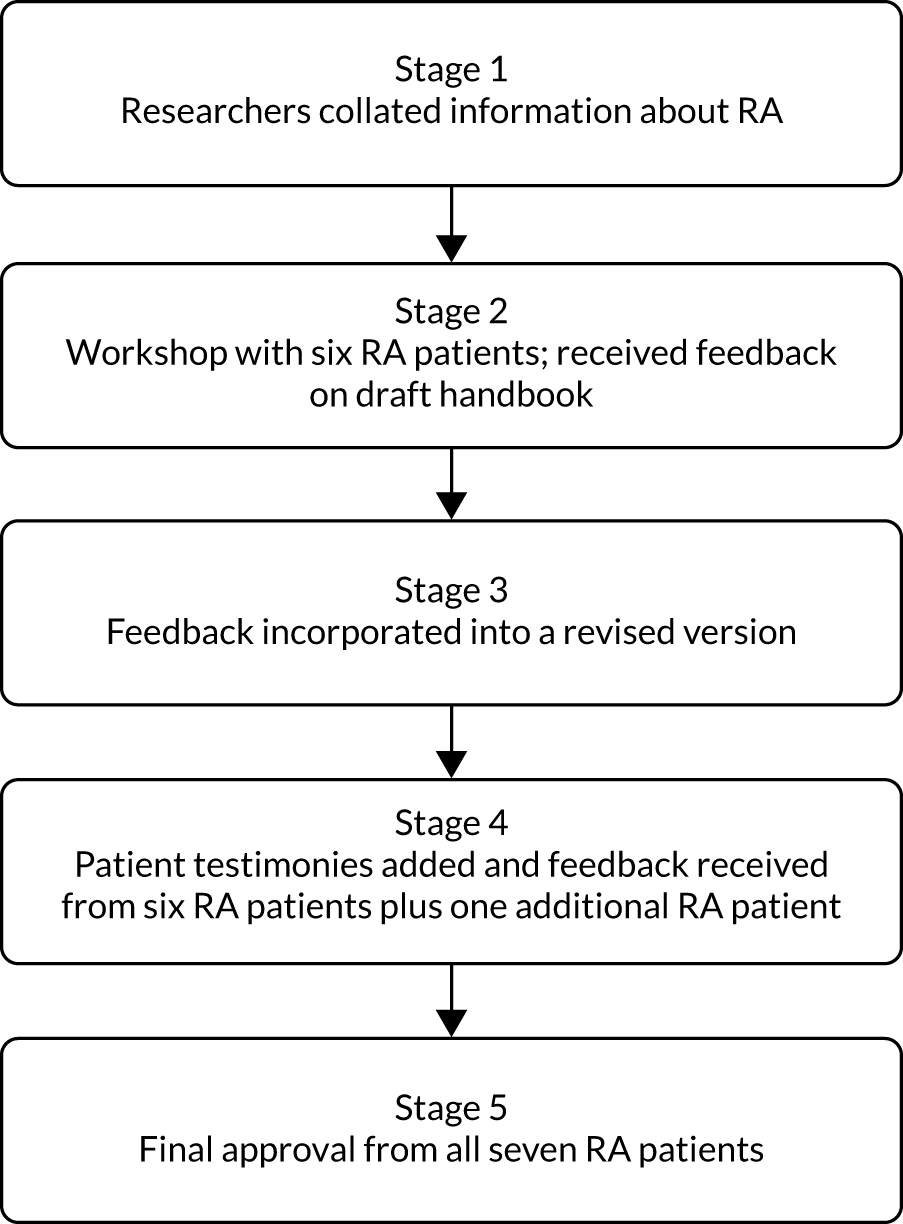

Patient workshop

Handbook development was facilitated by an audio-recorded workshop that involved six patients, with another patient giving more feedback via e-mail. None had substantial prior knowledge of intensive management. The workshop transcript was analysed using thematic content analysis. 285

Systematic reviews

Two systematic reviews were undertaken, searching MEDLINE and other databases using predefined terms. The first assessed systematic reviews of psychological interventions in RA. The second assessed MI in musculoskeletal diseases. Full details of these systematic reviews are given in Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2, including a PRISMA flow diagram (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Figure 5) and details of the included studies (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 6–8).

Key findings

Patients’ and carers’ views and expectations

Patients’ and carers’ views about intensive management spanned several themes and are shown in Tables 7 and 8. One theme was treatment expectations (i.e. patients want to have improved physical symptoms, reduced pain, increased mobility and greater independence). A second theme was increased medication. Patients had varying views about taking more medication, subject to the stability and benefits of their current treatment regimens. Most patients did not receive drug combinations that fully controlled their RA and they were willing to try more intensive managements, despite concerns about potential side effects. Intensive management involved more frequent clinic appointments, but these were generally acceptable to patients and carers.

| Physical Outcomes | |

|---|---|

| Reduce pain | Maybe my general pain in my body will be reduced by this treatment . . . I have got constant pain in my body(Patient 9, male, 46 years) |

| Improve mobility | Since 2006, I have to keep walking with my stick and if I don’t do that, sometimes I fall. Imagine if one day I could put it away . . . I see some people when they do the intensive management that happens to them(Patient 1, female, 52 years) |

| Stabilise RA | So as long as it (the RA) don’t get any worse . . . doesn’t spread to other parts of the body and you can contain it, then I think that’s fair enough . . . If it’s stabilised, that’s as good as it’s going to get(Carer 3, male, 71 years) |

| Reduce fatigue | Well I would like to be a bit more active, because I do get fatigue quite a lot(Patient 2, female, 62 years) |

| Increased Independence | |

| Rely less on family | . . . if you have got a wonderful family like I have got who . . . I could sit about and do nothing all day. Because they would say ‘I’ll do it, Mum you can’t do it, I’ll do it’. So a bit more independence is what I would like(Patient 4, female, 62 years) |

| Engage in more activities | It’s so frustrating; because there are things I want to do and I can’t . . . I can’t lift a kettle up if it’s too full(Patient 6, female, 64 years)I think if something could help her [patient] get that lifestyle back, where she could still do her own bits. She used to be a chef, so her not being able to cook, I think is one of the hardest things for her(Carer 1, female, 26 years) |

| Increased Medication | |

|---|---|

| Positive views | Yes, [I would try intensive management] anything that could be positive, because if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work, we go and try another one [treatment](Patient 1, female, 52 years) |

| Negative views | Well at the moment we’re [carer and patient] doing fine . . . having had one very bad flare up about three years ago [patient], I should hate for that to happen again and I’ll be very apprehensive in changing the medication now. working, it’s balanced. Everything is nice and stable(Carer 3, male, 71 years) |

| Monthly Appointments | |

| Positive views | I wouldn’t mind . . . I would like to be able to sit down with someone, someone break down what these numbers mean from her [Mother’s] blood test . . . I just feel that if someone saw her [Mother] a bit more frequently the medication could be changed as soon as it [RA] gets worse(Carer 1, female, 26 years) |

| Negative views | How would I feel about it [attending monthly appointments]? Well, personally [hesitates] it would be a pain wouldn’t it really going up there [to the clinic] once a month? I know that sounds really ungrateful and I don’t mean that . . . what I mean is perhaps it [monthly appointments] might be a bit too much(Patient 4, female, 62 years) |

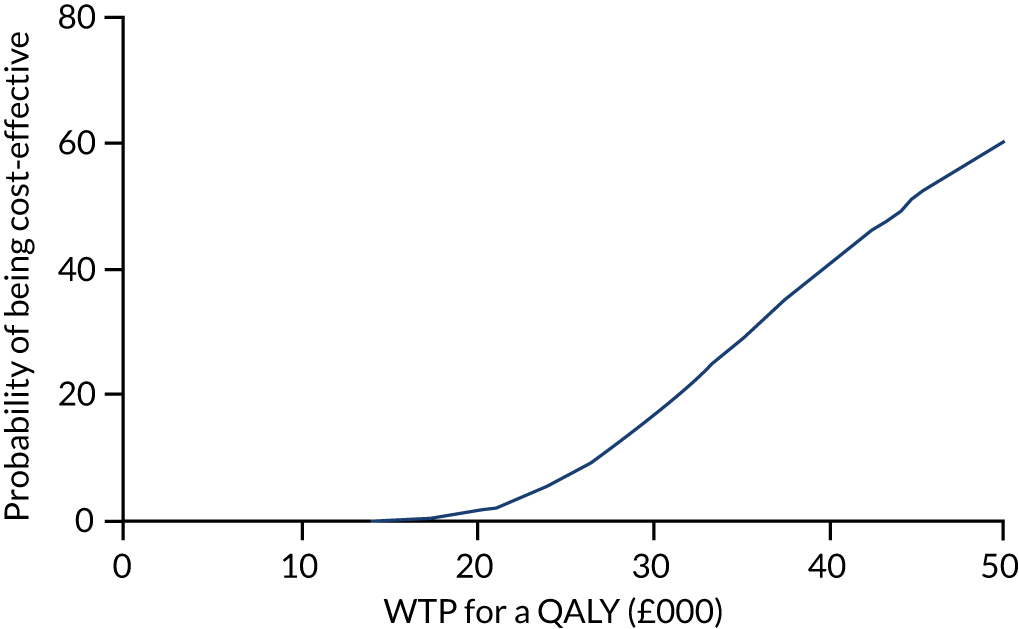

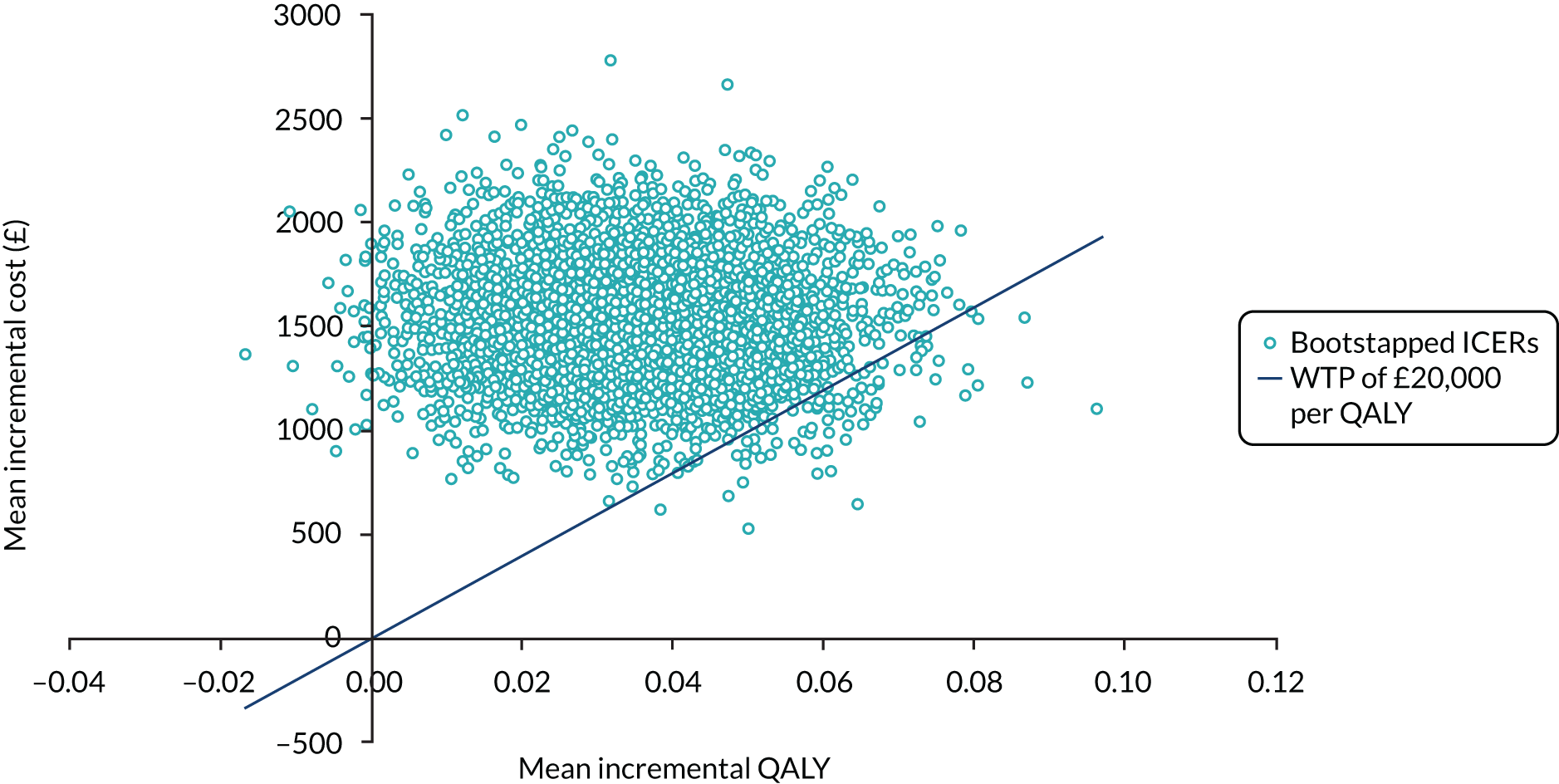

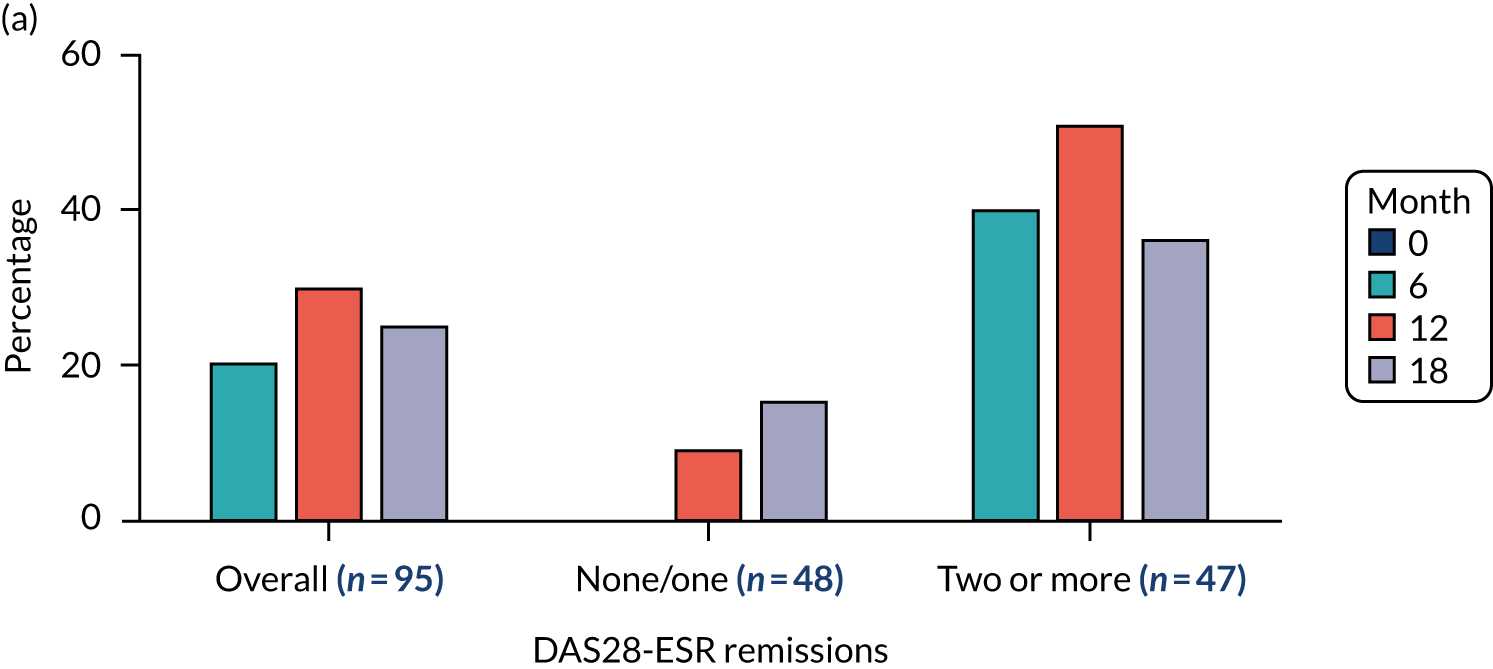

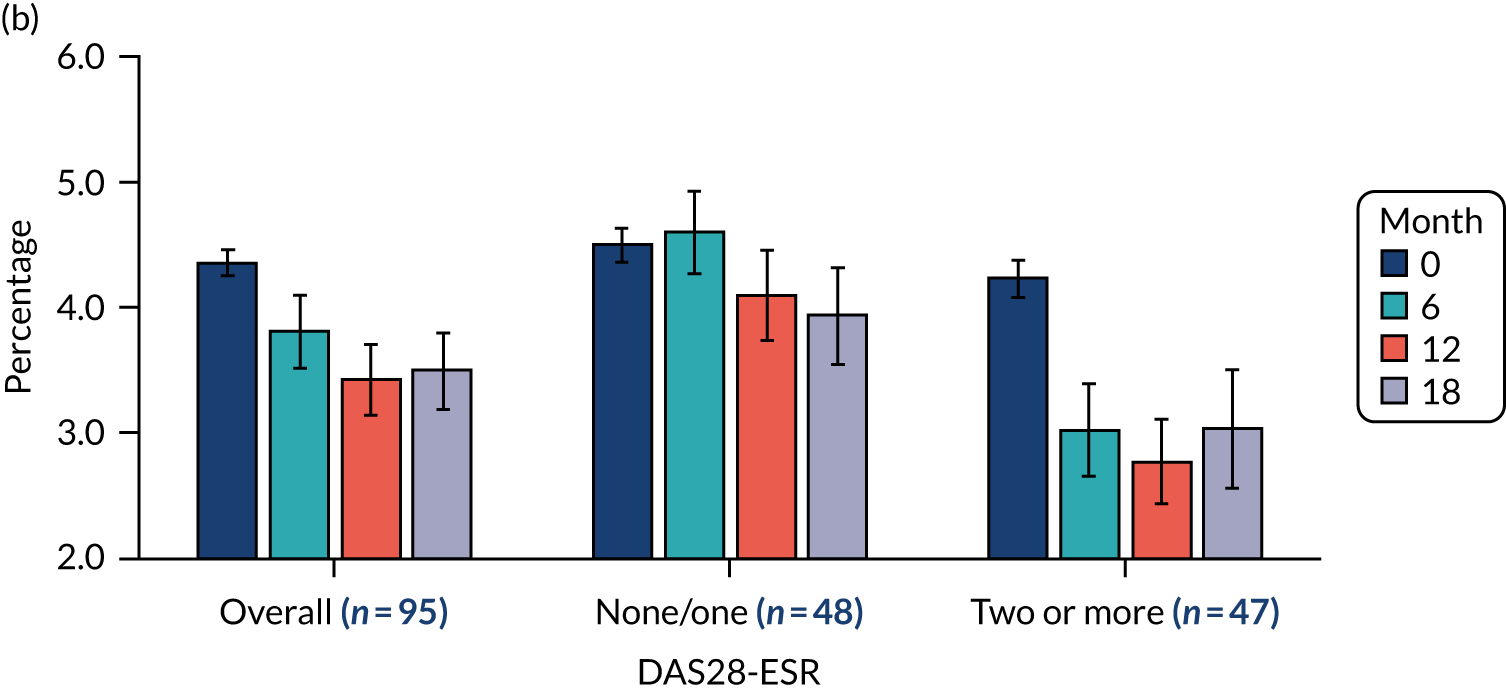

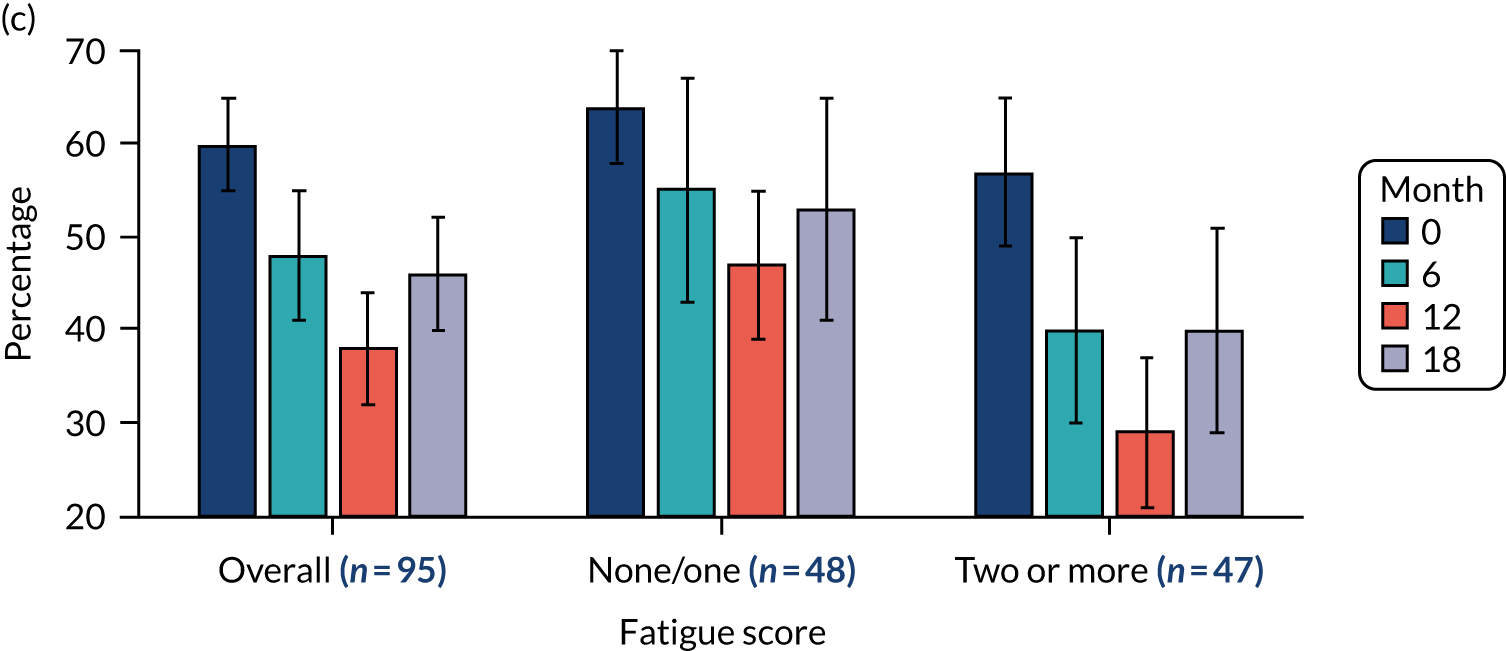

Tables 7 and 8 provide both positive and negative views, reflecting variation in participant responses. The findings identified that there was variation depending on individual circumstances.