Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-1210-12017. The contractual start date was in May 2013. The final report began editorial review in August 2018 and was accepted for publication in September 2020. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Forster et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

Parts of this report have also been reproduced from Forster et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY NC) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Context and rationale for the programme

Over the past century, there has been a shift in the demographics of the world’s population. 2 There has been a particular expansion of the ≥ 85 years age group (i.e. the oldest old), and this trend is likely to continue as longevity in later life improves. 3 In the UK, the number of individuals belonging to this age group is expected to more than double between 2014 and 2034 to 3.2 million. 4

Although population ageing should be celebrated as one of humanity’s major achievements, the fact that increases in life expectancy are typically mirrored by extended periods of morbidity and disability cannot be overlooked. 5 Many disabling conditions, including cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal diseases, and mental and neurological disorders, are age-related. 5 Moreover, the incidence of multimorbidity increases sharply with age. 6,7 As a result, many older adults will experience complex and interacting health needs, and will ultimately require some form of support in their later years. 2 Although policy and service developments have emphasised alternatives to long-term care,8 recent estimates suggest that around one in four older people will spend some time in a care home (CH) in their last year of life. 9 Evidently, the need for such care will persist. 10

Residents of CHs are among the frailest individuals in the population, distinguishable from community-dwelling older adults of the same age because of their physical disability, multimorbidity, dependency on others and cognitive impairment. 11 For these individuals, their dependency and functional impairments will probably compound health difficulties by directly affecting their physical and psychological health, and will reduce opportunities to participate in social activities. Social isolation, in turn, has a negative impact on mood and self-esteem, which can then further adversely affect physical health. 12 Furthermore, the increasing health requirements of this expanding client group places considerable burden on the NHS. 11 Still, frailty may be considered a dynamic process; although it is likely that residents become frailer and are at higher risk of worsening disability, falls and admission to hospital, this deterioration is not immutable and there is scope to intervene. 13 Accordingly, it is important to explore factors that may help slow the progression in functional decline and also maintain or improve quality of life.

One factor known to have a positive impact on the ageing process and to contribute to the maintenance of health with rising age is physical activity (PA),14 defined here as a complex and multidimensional behaviour that involves skeletal muscle contraction and results in increased energy expenditure. 15 There is now a considerable body of evidence concerning the health and social benefits of engaging in PA for older adults. 16–18 With respect to CH residents specifically, engagement in PA has been shown to have favourable effects in terms of physical function19–21 and social engagement. 22 Nonetheless, a prominent finding from research conducted in a CH setting is that residents engage in very little PA and spend the majority of their time sedentary (a separate, albeit related, construct to PA, characterised by minimal movement and very low levels of energy expenditure). 23–25 This is particularly concerning as there is growing evidence (some of which postdates our programme) of the detrimental effect sedentary behaviour may have, independently of engagement in PA, on a number of parameters related to health,26 including cardiovascular risk,27 physical function28,29 and quality of life. 30,31 For CH residents in particular, substantial levels of sedentary behaviour may lead to increased incidence of pressure sores, contractures, cardiovascular deconditioning, urinary infections and loss of independence. 32

In the light of this evidence, we surmised that, for older adults residing in CHs, a recommendation to encourage engagement in PA and reduce sedentary time would be well placed. This is supported by the recent guidance for interpreting the UK PA guidelines,33 which states that frail older adults should strive to engage in some PA every day and minimise the amount of time they spend being sedentary for extended periods. Encouragingly, a Cochrane review34 addressing rehabilitation in long-term care facilities demonstrated that strategies to enhance PA can be implemented in CHs with reported benefits. However, many of the interventions evaluated were dependent on external resources (e.g. therapists) and gains were not sustained. 34

We reviewed the evidence for ways to increase PA in residents that may be of benefit. As part of programme development work, we also undertook observations and conducted interviews with staff and residents in two CHs to inform our understanding of current levels of PA and what might work in practice.

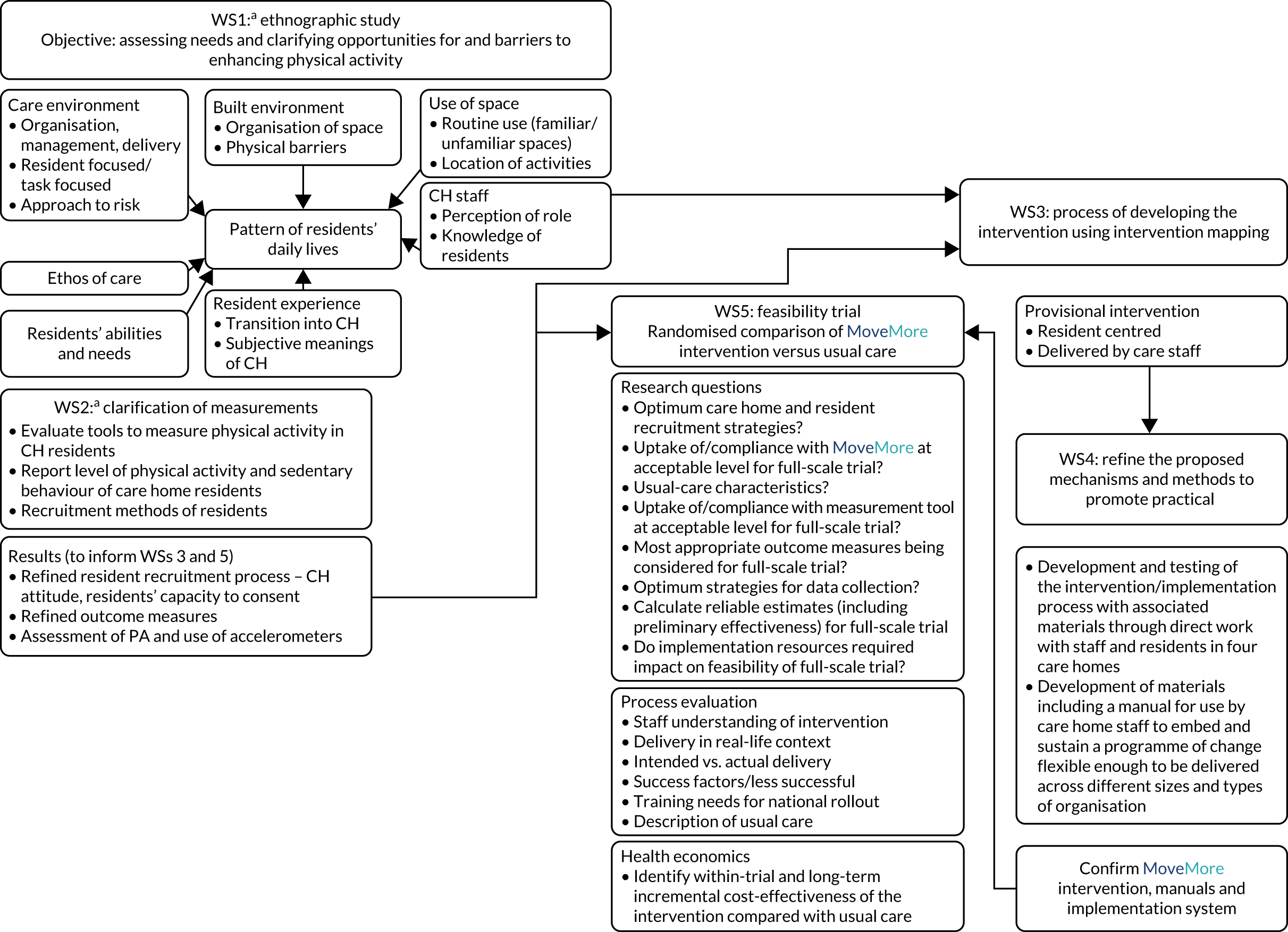

We have undertaken a research programme, delivered through five workstreams (WSs), in which we worked with CH staff and residents to develop and preliminarily test strategies to enhance PA in the daily life routines of CH residents to improve their physical, psychological and social well-being (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Inter-relationship between the different WSs of the programme. a, WSs 1 and 2 were undertaken simultaneously.

Workstream 1: needs assessment and clarifying opportunities for and barriers to enhancing routine physical activity

Aims and objectives

The aim was to explore the potential for developing and delivering an intervention to increase PA in the daily life routines of CH residents, with the objective of assessing needs and clarifying opportunities for and barriers to PA.

Methods for data collection

This WS was implemented in accordance with the grant proposal and employed a mixed-methods research design in four CHs. The WS included three interlinked components:

-

ethnographic work (observations)

-

qualitative interviews with residents, relatives and friends (when appropriate) in each home

-

qualitative interviews with staff in each home.

See the protocol in Report Supplementary Material 1 for details of the data collection methods.

Data were anonymised; names are pseudonyms.

Sampling strategy

Four nursing and residential CHs, differing in size, setting and ownership, were purposively selected in the Bradford area and recruited to participate in WS1 and WS2: Bourneville CH, Eden Park CH, Hebble House and Rowntree Nursing Home.

All four CHs offered residential care (one specialised in dementia care); in addition, two offered nursing care. One was run by the local authority and three were run by private or family companies (one by a national company and one by a large international company). Sizes ranged from 20 to 55 beds. One CH was situated in the inner city; the others were in semi-urban, semi-rural or rural locations. See Appendix 2, Table 14, for full details of the CHs.

Ethnographic work (observations)

An ethnographic approach was adopted to understand how daily life is organised in relation to the resident profile and the physical and social environment within which care is delivered. This combined observation and informant interviewing in a naturalistic setting. Ethnographic work enabled us to further our understanding of potential linkages between CH culture, staff practices and residents’ engagement with different kinds of social and physical activities. A conceptual framework and methods for recording observations had been refined during our previous Programme Development Grant (PDG) work. 35

It was planned for researchers to spend 2 days per week in each home over 4 months. Observations were to include day, evening and weekend periods, to encompass different types of activities at different time points, as well as to facilitate contact with families and friends. 36,37

In the course of the observations, the researcher engaged in informal interviewing/conversation with both residents and staff. We looked to combine these informal interviews with formal interviews (see Qualitative interviews with residents and relatives). Observations, recorded in contemporaneous fieldnotes, focused on events, activities, interactions and conversations with residents, staff and relatives. A chronological fieldwork journal combined descriptive materials with reflective accounts of the meaning of what was observed, as well as hunches and working hypotheses. These included the researcher’s impressions and reactions to the observations.

Observations undertaken during the PDG work identified several emerging categories or preliminary hypotheses. These were explored further through more focused observation.

Particular emphasis was placed on what was typical, as well as what was idiosyncratic, within and between homes, and what distinguished homes that were more or less resident centred in their culture and care practices.

Qualitative interviews with residents and relatives

Formal, semistructured qualitative interviews were undertaken with a sample of residents, their relatives and friends in the four homes. The topic guide allowed for flexibility by allowing researchers to draw on their observations to inform the interviews and to ensure that they were as inclusive as possible. Interviews were conducted, when possible, in quiet private areas, were audio-recorded and were transcribed verbatim.

The aim of the interviews was to clarify the findings from the ethnographic work and to examine options, preferences and choice of (physical) activities, assessing needs as well as opportunities and barriers to their introduction.

Qualitative interviews with staff

A purposively varied sample of staff from each home was selected for interview. We drew on our observational data to identify individuals who played a significant role in the life of the home, including those who may have had experience/knowledge of potential barriers to increasing PA and those who may have been drivers of or barriers to change.

The interviews encompassed knowledge, perspectives and attitudes towards enhancing activities; exploring opportunities for and barriers to active interventions, including perceived benefits and risks; and the contexts in which they might work for residents with different abilities and preferences. In interviews with managers from each home, we additionally explored the current provision of social and exercise opportunities, facilities and the resources available. We also examined and discussed their routine data collection and recording systems.

All researchers were familiar with CH environments, owing to previous research conducted by the team. In addition, all researchers spent a period of time conducting orientation visits to the CHs to familiarise themselves with the care environments of the participating homes.

Data analysis

A modified grounded theory approach to data analysis (using NVivo, version 8, QSR International, Warrington, UK) was employed, using the method of constant comparison38 and iterative engagement with the research literature. The observations were analysed to identify actual and potential opportunities for enhancing activities, and possible opportunities for change.

Themes were identified and coded, and categories were developed. We examined within- and across-group similarities and differences, with a focus on exploring what shaped perceptions and behaviour, and opportunities for and barriers to, PA. The findings from all research participants shed light on those mechanisms or triggers in different care contexts that facilitated a shift in care practices and resident motivation to optimise opportunities for increasing PA/reducing sedentary behaviour in both activities of daily living (ADL) and leisure spaces. Further details are available in Hawkins et al. 39 (2018).

Data collected

Ethnographic observations

Ethnographic observations and ethnographic conversations40,41 were conducted by researchers in communal spaces, as planned, on approximately 2 days per week over approximately 4 months in each home; > 100 observations were undertaken between December 2012 and October 2013. Each session of observation took approximately 4 hours (with some flexibility at the discretion of the researcher, however, for them to sufficiently capture a variety of activities taking place in the CHs). Each researcher was allocated a particular CH (or CHs) in which to conduct their observations, as is standard practice in ethnographic work. Detailed fieldnotes were produced to capture the observations.

Interviews

Towards the end of the period of observation, 55 qualitative interviews were undertaken across the four participating CHs with staff members (n = 22), residents (n = 16) and relatives (n = 17).

Key findings

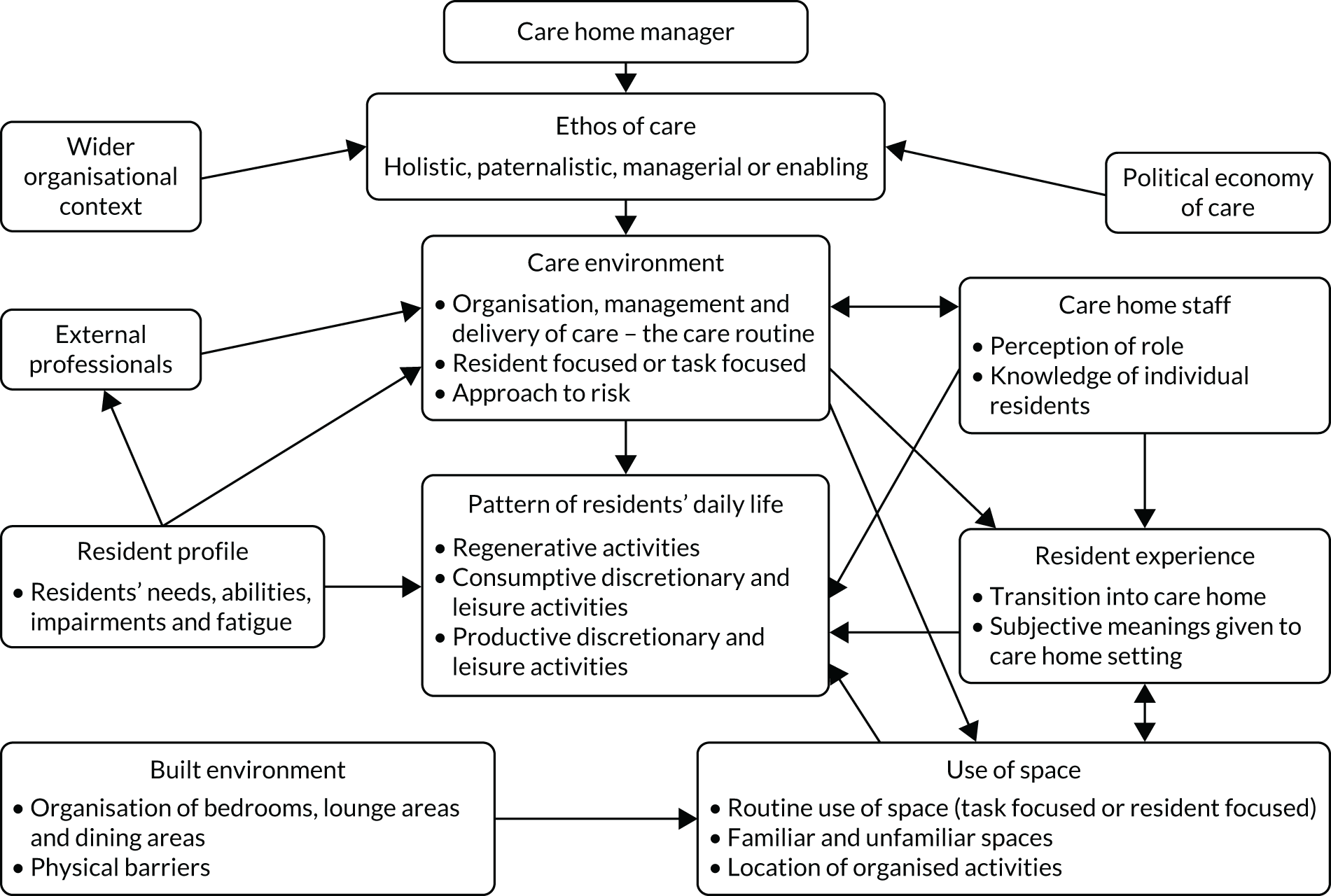

A number of interacting factors and social processes shaped and sustained the patterns of residents’ daily life and the routinisation of movement in the CH settings (Figure 2). These included the:

-

ethos of care

-

organisation, management and delivery of care

-

individual environment

-

physical environment

-

routine of residents’ daily life.

FIGURE 2.

Illustrative summary of the factors and social processes that shape and sustain the pattern of residents’ daily life.

For a rich description of daily life and an in-depth exploration of the findings, see Appendix 1.

This ethnographic work enabled an understanding of the PA undertaken by CH residents in the context of daily routine life. It also allowed for an understanding of ways in which greater PA may be facilitated and provided an indication of the kinds of culturally specific changes that would be required to bring about such developments, given the characteristics of residents’ physical and mental health, as well as the processes by which health and social care services are delivered. A number of barriers to and opportunities for enhancing movement became apparent during the study.

In the organisation, management and delivery of care, the ethos of care shaped opportunities for occupation, PA and movement. If the CH adopted a more enabling or holistic care ethos, this often resulted in greater opportunities for residents to move. The tension between risk management and the promotion of independence, and how this was managed at an organisational level and at the point of care delivery, also had implications for residents’ daily routine, as did whether a resident- or task-focused approach to the delivery of care was facilitated and encouraged. In particular, how care assistants went about monitoring, curtailing and enabling residents’ movement, and whether or not care staff perceived their role to include spending time engaging with residents socially and in activities, was important.

The ability of the management team to translate the often abstract, espoused values of care into tangible care practices and to communicate such practices to care staff was important to residents’ routine movement. It was through the process of translation and communication that decisions were made regarding what was workable and acceptable in practice.

In addition, it was important that senior staff valued any practices arising from these decisions and that any trade-offs potentially arising were acknowledged (e.g. increased time needed for care tasks to enable residents to move more). It seemed especially important to be able to translate abstract values into care practices that promote independence, alongside resolving how these can work in practice, something potentially problematic for vulnerable adults and older people in the context of health and social care. 42,43

The role of formal and informal staff training and supervision in ensuring a consistent approach to care practice and allowing space for reflection and problem-solving is important. Supervision, leadership style, knowledge, skills and a solution-focused approach have been highlighted as important in relation to good-quality care practice in CHs. 44,45

The individual and physical environments were important. The routine use of space was an important factor in the residents’ ADL; how physical space was organised, whether there was a task-based or resident-focused approach to how residents use spaces/where they spent time, whether or not residents were enabled to move around space, and how residents expected each other to behave in semipublic spaces shaped their conduct in such settings.

Another factor was the residents’ familiarity and comfort with the CH space. Moving around the home and/or participating in activities were facilitated by the familiarity of the space, familiar faces and companionship, engaging occupation and activities, and encouragement, reassurance and support from care staff.

The meaning given to the CH setting by residents was also important: the transition of residents into the CH setting, their expectations of the CH and how they were supported to adapt to living in the CH setting shaped their routine. The subjective meanings residents attributed to the setting also shaped how they occupied themselves and moved around the CH.

In the CH daily routine, residents’ daily life created barriers and opportunities. For example, whether or not residents’ participation in occupation and PA was encouraged in a manner that demonstrated knowledge of residents’ abilities, likes or dislikes; whether or not activities were personally meaningful, familiar or had some connection to the life history of the group of residents; and the role that residents were enabled and supported to adopt (and whether that was an active or a passive role), in particular, opportunities for increasing residents’ involvement in domestic-type tasks.

We took steps to ensure the rigour of our data collection and analysis, including keeping detailed fieldwork notes and memos, purposively sampling participants for in-depth observation and interviews, regularly meeting with the research team and study management group, and undertaking collaborative analysis.

Limitation

We were permitted to conduct observations in the communal areas of the CHs only; therefore, we did not directly observe patterns of movement occurring in private spaces (e.g. residents’ bedrooms). However, by supplementing observation data with qualitative interviews, we attempted to address this gap, but we acknowledge that our analysis may have been limited.

Relationship with other parts of the programme

This WS, which encompassed a needs assessment and clarified the opportunities for and barriers to enhancing the PA of CH residents, forms a key component of the intervention mapping (IM) framework [see Workstream 3: development of an intervention to enhance physical activity, and appropriate methods of implementation (e.g. training materials) through a process of intervention mapping], which underpinned intervention development.

Organisational structures and processes are known to shape care practices in CHs. However, the relationship between those structures and practices is nuanced and dynamic. 45 By exploring the structures and processes in-depth, we have highlighted how the management processes, staff training and supervision, and care planning processes shape residents’ movement in care settings. Understanding how organisational factors shape routine movement among residents will inform the development of embedded and sustainable interventions that aim to enhance PA and reduce sedentary behaviour in CH settings.

Workstream 2: clarification of measurements

Aims

The primary aims of WS2 were to review the methods of data collection at the levels of the residents and CHs and to evaluate the methods and tools to measure PA in this population to inform outcome assessment. A secondary aim was to review and assess the method of recruiting CH residents to a research study. The intent was to inform the processes for the feasibility trial in WS5.

Methods/design

The study was divided into two phases:

-

Phase 1 – to explore the methods and content of routinely collecting data in CHs and to explore the appropriateness of different questionnaire assessments of physical function and mobility in a CH population.

-

Phase 2 – to explore different methods of measuring PA and sedentary behaviour in older CH residents. Phase 2 comprised three parts:

-

an observational study to assess the criterion validity of estimates of PA and sedentary time derived from hip- and wrist-worn accelerometers in largely inactive CH residents

-

the feasibility of assessing the PA and sedentary behaviour of CH residents over an extended period using the ActiGraph (ActiGraph, LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA) accelerometer

-

evaluation of the Assessment of Physical Activity in Frail Older People (APAFOP) questionnaire. 46

-

Recruitment of care homes

Care homes were purposively selected for both WS1 and WS2 (see Workstream 1: needs assessment and clarifying opportunities for and barriers to enhancing routine physical activity).

Recruitment of residents

We undertook a range of activities in the CHs to enhance recruitment, including attending staff and residents’ meetings, hosting a coffee morning to meet relatives/friends of residents and attending ‘open days’ in the home(s). All residents were screened for eligibility. Residents were excluded if they were acutely unwell, bedbound, receiving end-of-life care or if, in the opinion of the CH manager, they may have found the research distressing.

Recruitment procedures

For a full description of recruitment procedures, see the WS2 protocol in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Residents were approached for participation in the study by a research assistant if, in the opinion of the CH manager, the residents had the mental capacity to consent. Capacity to consent was confirmed by the researcher. Signed and dated consent (or witnessed verbal consent, if necessary) was obtained from residents wishing to participate. Personal consultees (PCs) of residents without capacity to consent were approached by letter about participation in the study. A consultee declaration form was provided for response. Nominated consultees were not used in this WS.

Methods for data collection and data analysis

For a full description of the methods for data collection and analysis, see the study protocol in Report Supplementary Material 1, and the WS2 report in Appendix 2, Data collection and Data analysis.

Data were assessed for normality; analyses varied depending on the data collected. Parametric and non-parametric statistics were employed, depending on the distribution of the data.

For ease of reference, we present the results of CH recruitment, resident recruitment and participant characteristics, before describing details of each phase of the study.

Care home and resident recruitment, and participant characteristics

Care home recruitment

As reported in Workstream 1: needs assessment and clarifying opportunities for and barriers to enhancing routine physical activity, four CHs were selected to participate in WSs 1 and 2. An additional two CHs were recruited in November 2013 for WS2 to assess the appropriateness of PA measures, as resident recruitment was lower than anticipated in the four CHs originally recruited. See Appendix 2, Table 14, for details of the CHs.

Resident recruitment

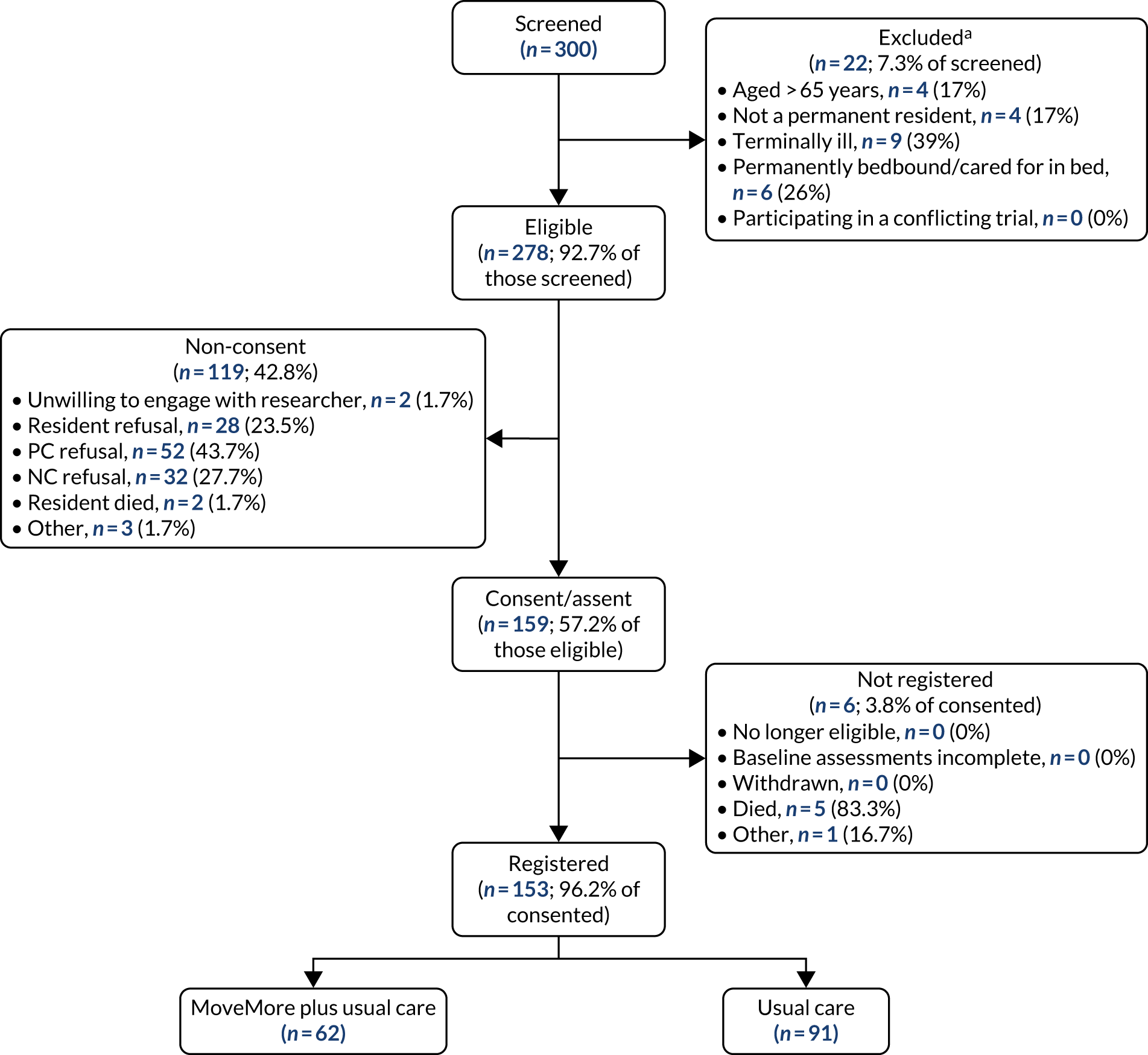

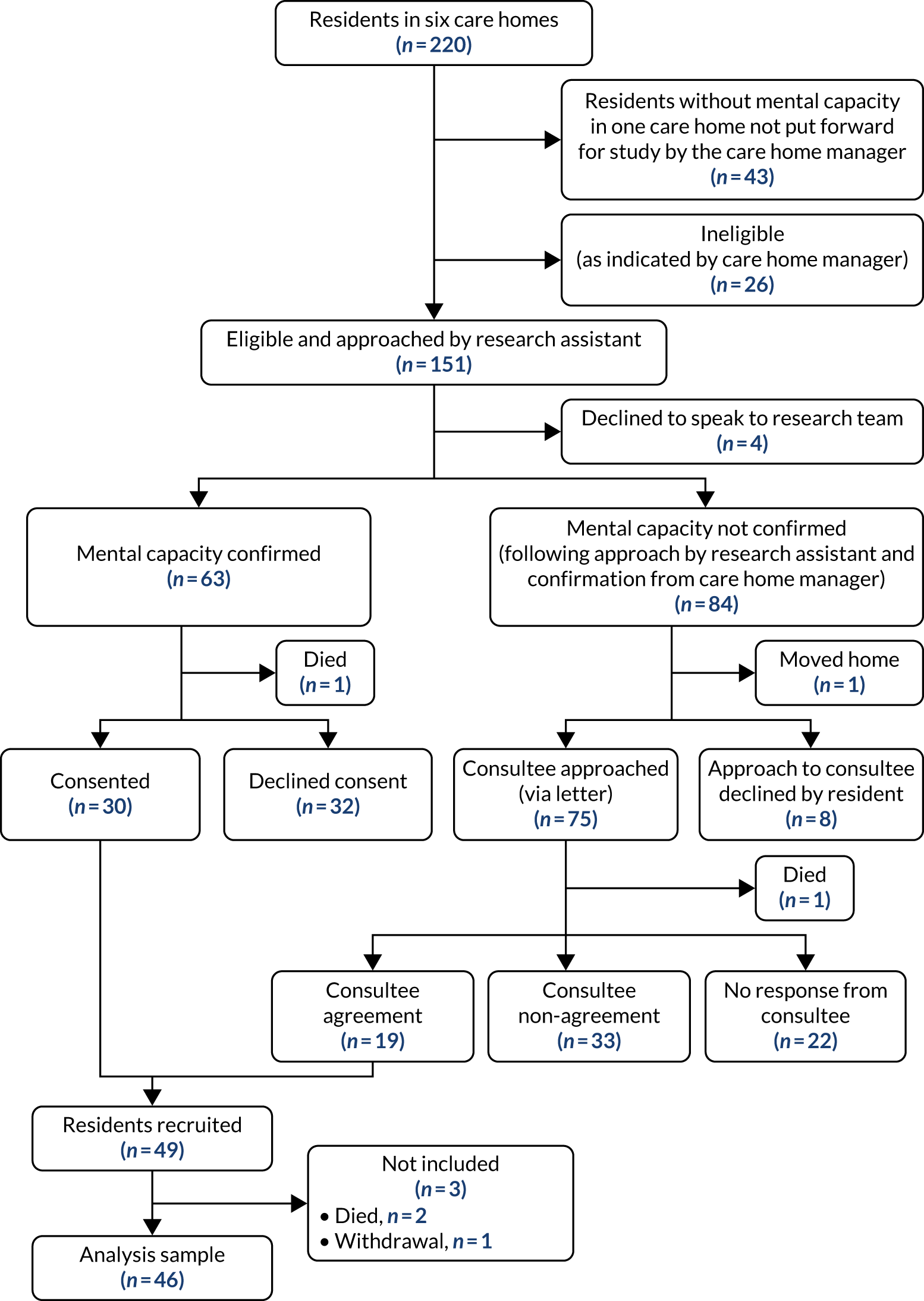

Of the 220 residents across the six CHs, 151 (69%) were eligible. Of these, 49 (32%) residents consented or had PC declaration, and 46 participated in the study (two residents died and one resident withdrew consent before/during data collection) (see Appendix 2, Recruitment of participants).

Participant characteristics

Sixty-seven per cent of participants were female; 55% were aged ≥ 85 years. Participants had resided in the CH for a median of 15 months. More than 40% had a diagnosis of dementia; more than one-third had fallen in the previous 6 months (see Appendix 2, Participant characteristics).

Phase 1: methods of routinely collecting data, and function and mobility questionnaires

Methods

The research team collected personal health data for residents participating in the study and explored the feasibility of using a range of tools designed to assess mobility and other outcomes. Specifically, these tools were as follows:

-

cognitive impairment – Six-item Cognitive Impairment Test (6-CIT)47

-

physical function –

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe outcomes. Participants were grouped according to age (< and ≥ 85 years), sex (male/female), functional walking ability (non-ambulatory, low ability, medium ability, high ability) and function (BI score of ≤ 11: dependence in ADL; BI score of ≥ 12: independence in ADL). 51 Differences between groups were examined using independent t-tests or Mann–Whitney U-tests. Alpha was accepted as a p-value of < 0.05.

Phase 2: assessment of physical activity and sedentary behaviour

Methods

The aim of this phase was to explore the feasibility of different methods of measuring PA and sedentary behaviour in older CH residents.

Part 1: observation of physical activity

The aims were to:

-

use the observations of residents’ activities as a reference to compare with the data captured by accelerometers to assess the validity of using accelerometers in a frail, elderly and largely inactive population

-

identify whether hip- or wrist-worn accelerometers were the most accurate in recording activities that CH residents typically engage in.

The ActiGraph GT3X and GT3X+ (ActiGraph, LLC) models, previously chosen in the PDG work,35 were used. Accelerometers are a direct and valid assessment of PA. At the suggestion of a reviewer, we also investigated the feasibility of a newer accelerometer, the GeneActiv (Activinsights Ltd, Kimbolton, UK).

Residents who had been recruited to WS2 were approached and asked if they would be prepared to participate in the observational study. Residents were invited to wear a hip- or wrist-worn accelerometer over a 2-hour ‘free-living’ period while being observed by the researcher.

The researcher used a predetermined list of activities to systematically record what the observed residents were doing every 15 seconds over the monitoring period. The list of activities included both PA and sedentary behaviours believed to be typical of CH residents.

Part 2: utilisation of accelerometers to assess physical activity over extended periods

The aims were to:

-

investigate both the feasibility of using accelerometers and the appropriateness of the wear criteria of at least 8 hours per day on at least 4 days52,53 in this population

-

describe the levels of PA and sedentary behaviour.

All recruited residents in the participating CHs were invited to wear a hip- or wrist-worn accelerometer for a period of up to 10 days while they continued with their usual routine. For all residents, it was required that a daily log of the time the accelerometer was put on and removed (i.e. wear time) was kept for the duration of the monitoring period. Staff were asked to assist by completing the log when residents were not able to complete it themselves. However, on collecting the first accelerometers, it became apparent that activity logs were not being completed. This, coupled with the largely sedentary profile of participants’ behaviour, made distinguishing actual wear time from non-wear time difficult. Consequently, as the study progressed, a more pragmatic approach was instituted:

-

Residents were asked to wear the accelerometers for as long as they were comfortable doing so. Sometimes this was taken on a day-by-day basis, with continuous support from the researcher (in assisting with administering the accelerometers and completing the activity logs during frequent visits to the home).

-

Accelerometers were collected once it was indicated that there was 5–7 days of data (not necessarily consecutive), or when residents indicated that they no longer wanted to wear the monitor.

Analysis

Observational study of physical activity

Raw activity count data were downloaded and reintegrated into 15-second epochs using appropriate ActiLife software 6.8.0 (ActiGraph, LLC) to allow for comparison with the observational pro forma data. Accelerometer data and observational data were categorised as either PA or sedentary behaviour. The agreement between the categorisation of PA and sedentary behaviour derived from the observational data and that derived from the accelerometer data was evaluated. Specifically, sensitivity, predictive value (PV), overall agreement and the kappa statistic were calculated.

Feasibility study: utilisation of accelerometers to assess physical activity over extended periods

Raw activity count data collected by the accelerometers were downloaded and reintegrated into 60-second epochs prior to analysis. Daily wear time of the accelerometers was determined, and the time spent engaged in, and the number and duration of ‘bouts’ of, PA and sedentary behaviour were calculated.

Part 3: the Assessment of Physical Activity in Frail Older People

The APAFOP is a PA questionnaire purposely developed for and tested for reliability with older people with and without cognitive impairment. 46 It is based on considerable development work, including a systematic review54 and robust psychometric testing. It is administered verbally by a researcher; the interviewee is asked to recall activities undertaken in the previous 24 hours, with a focus on ADL, making it potentially suitable for our work. 55 Although direct assessment of movement is not possible using this instrument, time spent in PA of differing metabolic-equivalent categories can be calculated. The instrument thus offers a more global assessment of habitual PA, which might have generic value for CHs once the efficacy of the whole-home intervention has been established. We explored content and face validity with CH residents.

Key findings

For a full description of the findings, see Appendix 2, Results.

Resident recruitment and participation

In anticipation of subsequently developing a ‘whole-home’ intervention, an inclusive approach to resident recruitment was adopted, with few exclusion criteria. In spite of this, only 49 (22.3%) of the 220 residents in the participating CHs were recruited: a lower rate than our provisional estimate of 80 recruited residents (20 per CH).

Over half of eligible residents did not have mental capacity confirmed by researchers. PC agreement was therefore sought for 75 residents (eight residents declined the approach to their PC). Twenty-two (29.3%) of the 75 PCs did not respond. Nominated consultees (NCs) were not used in the study because one of the CH managers objected to this approach, resulting in a loss of potential residents for recruitment. This influenced our approach to the feasibility trial in WS5, for which we adopted a number of strategies to enhance recruitment. This included:

-

encouraging CH managers to speak to as many relatives as possible in person about the study, prior to sending out information

-

ensuring that the research team was approachable and available, should relatives have any queries

-

attending resident/relative meetings and meetings for staff to increase awareness of the research

-

offering reassurance to CH managers regarding the process of consulting a NC.

Phase 1: outcome measures

The 6-CIT was attempted by 36 (78.3%) of the 46 residents participating in the study. Of these, five residents were able to complete the scale only partially. Twenty-two participants scored ≥ 8 points, indicating significant cognitive impairment. The measure provided indications of the level of cognitive impairment of the resident population. A review of alternative measures did not identify any that were more appropriate. We therefore included the 6-CIT in the data collection for the main trial.

The BI, the PAM-RC and functional walking ability were completed in conjunction with CH staff for all participants. There were only small differences between mobility assessment scores according to age and sex. According to the functional walking ability questionnaire, 12 (26.1%) residents were categorised as non-ambulatory, three (6.5%) were categorised as having a low level of ability, 12 (26.1%) were categorised as having a medium level of ability and 19 (41.3%) were categorised as having a high level of ability.

Staff reported that completing the BI, the PAM-RC and functional walking ability questionnaire was not onerous; this was reflected in the high completion rates. Proxy completion of the BI has been recommended as more valid than self-completion in older and cognitively impaired populations. 56 The PAM-RC is a relatively new scale, with little evidence yet for its use in research. However, it has face validity for this population and has been reported to have excellent test–retest reliability, internal consistency and good construct validity (Dr Julie Whitney, personal communication). The functional walking ability questionnaire was based on the FAC. 50 For this study, it was felt that the functional walking ability questionnaire was more accessible for CH staff. However, going forward to the feasibility trial in WS5, it was decided to use the full FAC to allow comparability with existing research.

Phase 2: assessment of physical activity

Part 1: observation of physical activity during a 2-hour ‘free-living’ period

Twelve observations of nine residents wearing accelerometers on the hip (n = 7), wrist (n = 4) or both hip and wrist (n = 1) were completed. Unfortunately, owing to a malfunction of the monitors, data for two of the accelerometers worn on the wrist were not available. A total of 19 hours and 45 minutes of resident activity data (mean 1 hour and 48 minutes per participant) were available for analysis.

Sensitivity for sedentary time and PV for PA time were higher for the hip counts than for the wrist counts (Table 1). Conversely, the sensitivity for PA time and PV for sedentary behaviour were higher for the wrist counts than for the hip counts. Overall agreement was better for the hip data than for those collected by the wrist-worn accelerometer. The kappa statistic indicated that the agreement for hip counts was moderate (0.47), whereas the agreement for the wrist counts was slight (0.08). 57

| Metric assessed | Accelerometer | |

|---|---|---|

| Hip (n = 8) | Wrist (n = 3) | |

| Sensitivity | ||

| PA time (%) | 42.22 | 64.63 |

| Sedentary time (%) | 96.93 | 63.25 |

| PV | ||

| PA time (%) | 75.57 | 10.29 |

| Sedentary time (%) | 88.18 | 96.48 |

| Overall agreement (%) | 86.56 | 62.92 |

| Kappa statistic | 0.47 | 0.08 |

Although the sensitivity for PA and the PV for sedentary behaviour was higher for the wrist than for the hip counts, all of the other measures used to assess criterion validity suggested that the hip counts were superior to the wrist counts. Indeed, both the overall agreement and the kappa statistic indicated that the classification agreement was considerably better when using the hip counts than when using the wrist counts. Thus, despite the suggestion that a wrist-worn accelerometer may provide more valid estimates of PA and sedentary behaviour than those derived from a hip-worn monitor in older CH residents, the results suggest that the hip remains the preferred wear location when using accelerometers in this population. However, these results must be treated with some caution because of the limited sample size.

Part 2: feasibility study – utilisation of accelerometers to assess physical activity over extended periods

Accelerometer wear time

Extended wear of accelerometers by residents was high: 41 (89.1%) of the 46 recruited residents undertook extended wear of an accelerometer. Thirty (73.2%) wore the accelerometer on the hip, 10 (24.4%) wore the accelerometer on the wrist and one resident was asked to wear a commercially available device so that we could explore the data collected by this device. Unfortunately, there are no published cut-off points validated in older adults for wrist monitor wear; thus, the data for wrist accelerometers were not subsequently analysed. In addition, the outcomes of the commercially available device were based on distance moved; therefore, we decided that these data were unlikely to be sufficiently accurate for our purposes in this population.

Twenty-two (73.3%) of the 30 residents wearing a hip accelerometer had valid data (≥ 8 hours on ≥ 4 days of the week) and wore the accelerometers for a mean of 6 days (range 4–9 days). The mean wear time per day was 12 hours 24 minutes [standard deviation (SD) 2 hours 36 minutes] (Table 2).

| CH | Resident data sets (n) | Daily wear time, mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 5 | 12 h 33 min (2 h 34 min) |

| 3 | 1 | 15 h 50 min (2 h 7 min) |

| 4 | 2 | 11 h 31 min (2 h 28 min) |

| 5 | 10 | 11 h 40 min (2 h 11 min) |

| 6 | 4 | 13 h 14 min (2 h 36 min) |

| Total | 22 | 12 h 24 min (2 h 36 min) |

The proportion of residents meeting the criteria for valid wear time (73.3%) was lower than that found in the development work (84.8%). This may, however, be attributed to differences in participant characteristics, for example inclusion of those deemed to lack capacity in this study. Enabling residents with cognitive impairment to wear monitors may have required greater support from staff; this may not have been prioritised by staff, given their heavy workloads. Furthermore, over half of the potential participants (10/19, 52.6%) in the development work declined to take part in the study because they did not wish to wear an accelerometer for an extended time (5 days were needed for data to be considered valid). It may have been that those who did wear an accelerometer were not representative of a CH population.

Compared with more recent studies conducted in long-term care settings that have employed similar criteria to define valid wear time, a similar or greater proportion of residents in the current study had valid data. 23,58,59

Activity logs

Correct identification of accelerometer wear time is imperative to ensure that accelerometer data are interpreted and analysed correctly. 60 Although different methods of identifying accelerometer non-wear are used in the literature, automated algorithms and activity logs are the most common. However, both methods present limitations. Automated algorithms have not been developed with this population specifically, and, on examination of the first sets of data collected, it was apparent that sedentary time may be mistakenly categorised as non-wear time, thus underestimating wear time and incorrectly categorising sedentary time as non-wear time. Consequently, although it was acknowledged that completion of activity logs may be viewed as burdensome, much emphasis was placed on attempting to collect accurate information about accelerometer wear using an activity log.

Accordingly, activity logs were administered in a way in which the CH managers felt would result in the greatest success. Nevertheless, completion was poor and appeared onerous for staff, even after they were asked principally to record the times of administration and removal of the monitor, and advised that recording reasons for removal were optional.

Eight (19.5%) of the activity logs were fully completed for the time accelerometers were in the residents’ possession, 20 (48.8%) were partially completed and 13 (31.7%) were not completed at all. Only three (10.7%) of the logs were completed by residents; 12 (42.9%) were completed by CH staff with the assistance of the researcher and 13 (46.4%) were completed by the reseacher alone.

Given the importance of collecting accurate wear time information in this population, the activity log was amended. The amended activity log, in addition to strategies proposed to encourage completion, was to be trialled and further refined, if necessary, in WS4 prior to their use in WS5, the feasibility trial.

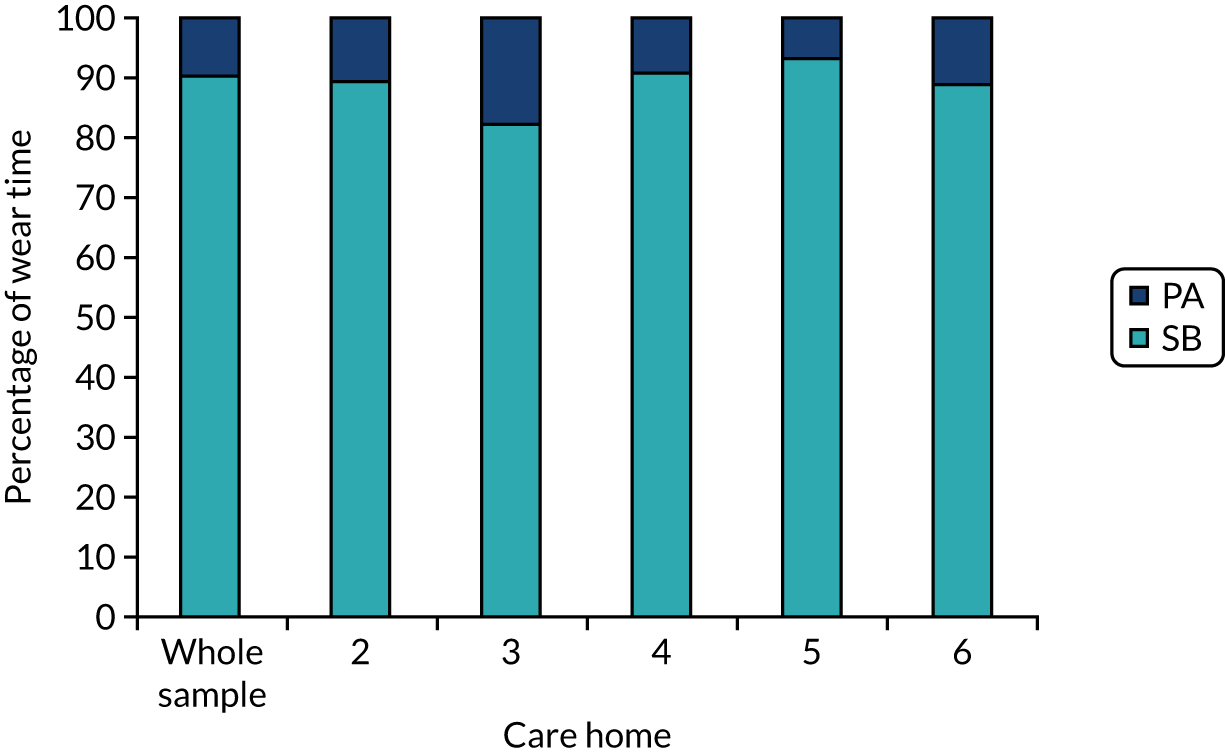

Levels of physical activity and sedentary behaviour

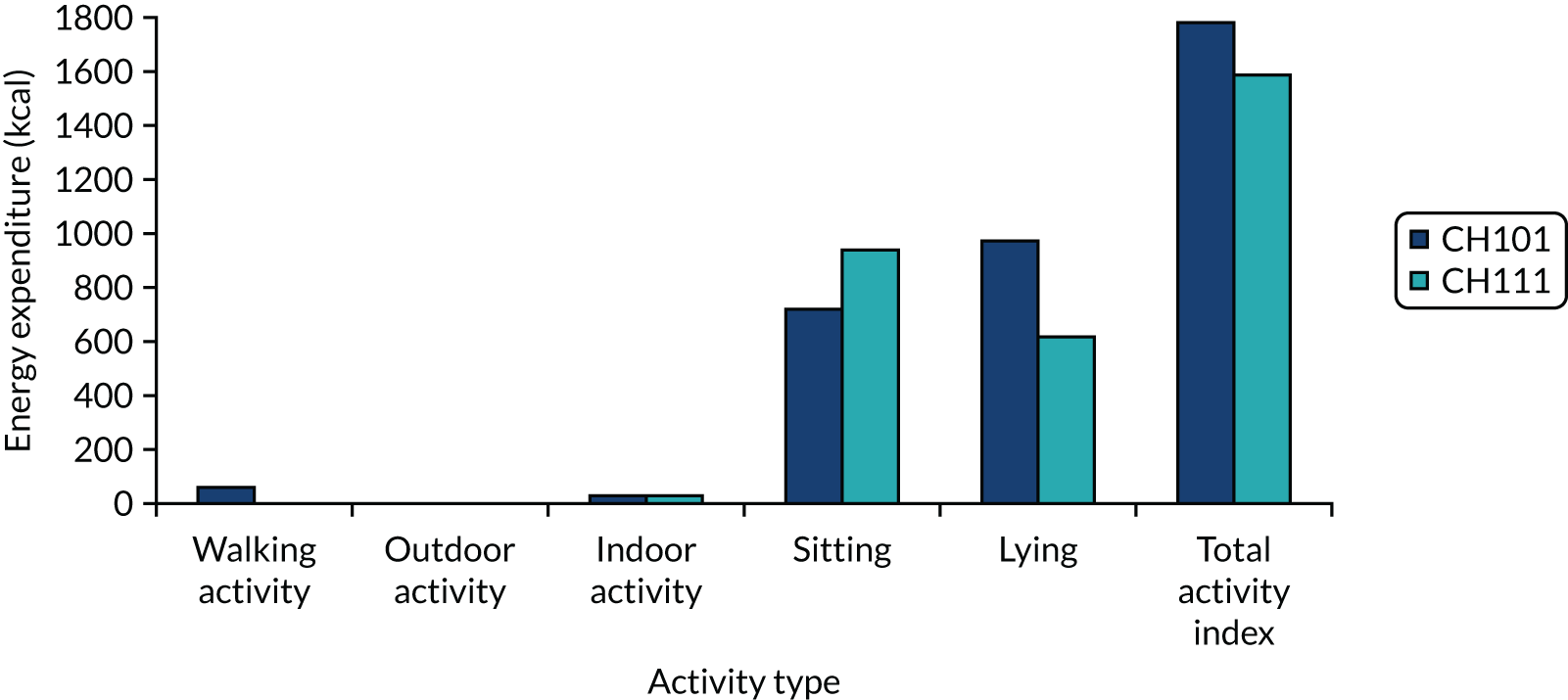

Mean daily time spent in engaging in PA was 1 hour 13 minutes (SD 1 hour 8 minutes) (Table 3), which equated to 9.5% (SD 8.3%) of accelerometer wear time (Figure 3).

| CH | Data sets (n) | Time, mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary | Low-intensity PA | Light-intensity PA | Moderate- to vigorous-intensity PA | Combined total PA categories | ||

| 2 | 5 | 11 h 17 min (3 h 1 min) | 1 h 12 min (1 h 00 min) | 0 h 4 min (0 h 5 min) | Negligible (–) | 1 h 16 min (1 h 3 min) |

| 3 | 1 | 13 h 0 min (1 h 51 min) | 2 h 38 min (0 h 54 min) | 0 h 12 min (0 h 7 min) | Negligible (–) | 2 h 50 min (0 h 59 min) |

| 4 | 2 | 10 h 24 min (2 h 13 min) | 1 h 0 min (0 h 43 min) | 0 h 6 min (0 h 7 min) | 0 h 1 min (0 h 1 min) | 1 h 7 min (0 h 50 min) |

| 5 | 10 | 10 h 54 min (2 h 7 min) | 0 h 41 min (0 h 37 min) | 0 h 5 min (0 h 8 min) | 0 h 1 min (0 h 2 min) | 0 h 46 min (0 h 44 min) |

| 6 | 4 | 11 h 33 min (1 h 50 min) | 1 h 36 min (1 h 30 min) | 0 h 5 min (0 h 5 min) | Negligible (–) | 1 h 41 min (1 h 31 min) |

| Total | 22 | 11 h 11 min (2 h 21 min) | 1 h 7 min (1 h 04 min) | 0 h 5 min (0 h 7 min) | 0 h 1 min (0 h 1 min) | 1 h 13 min (1 h 8 min) |

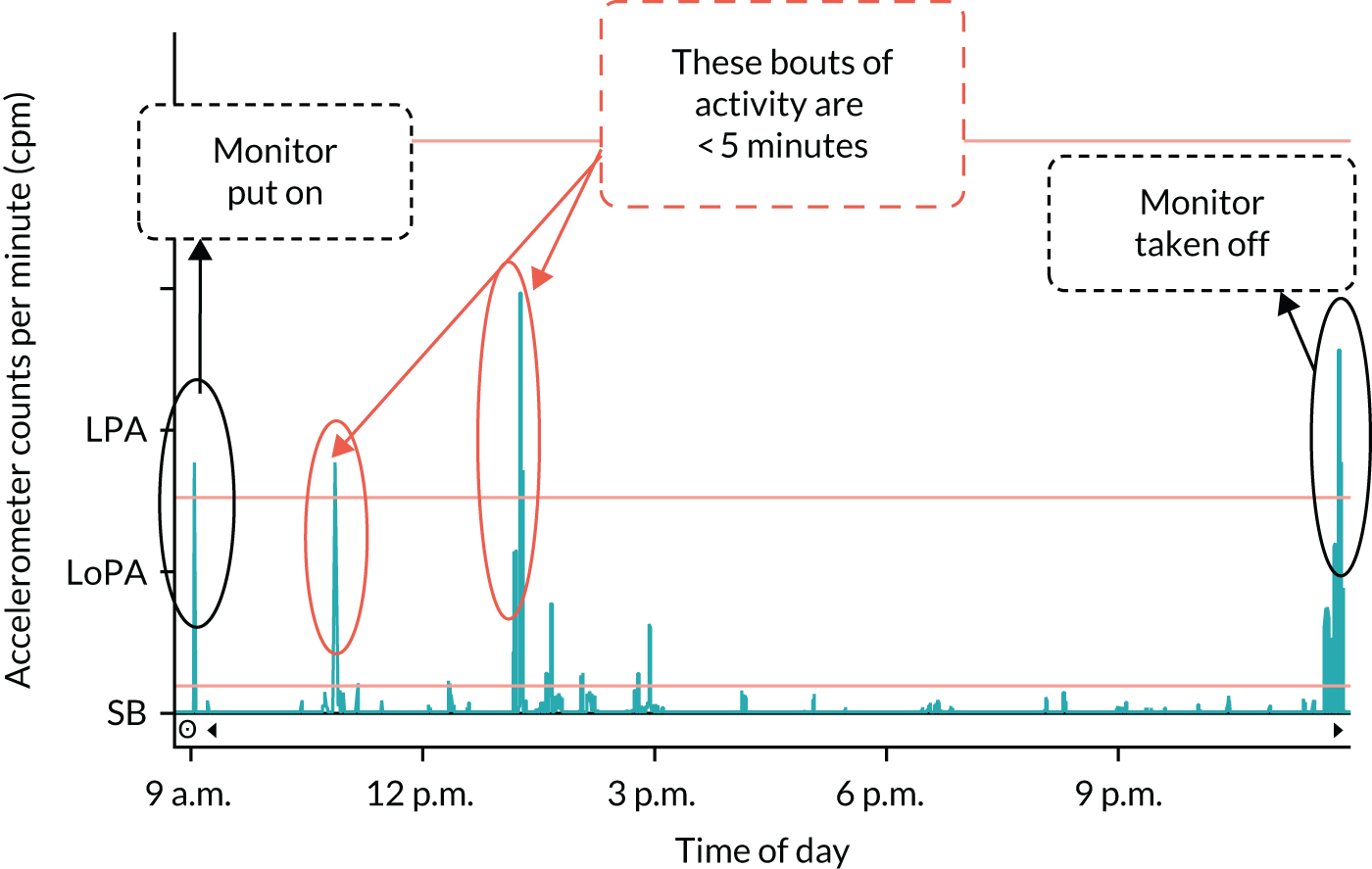

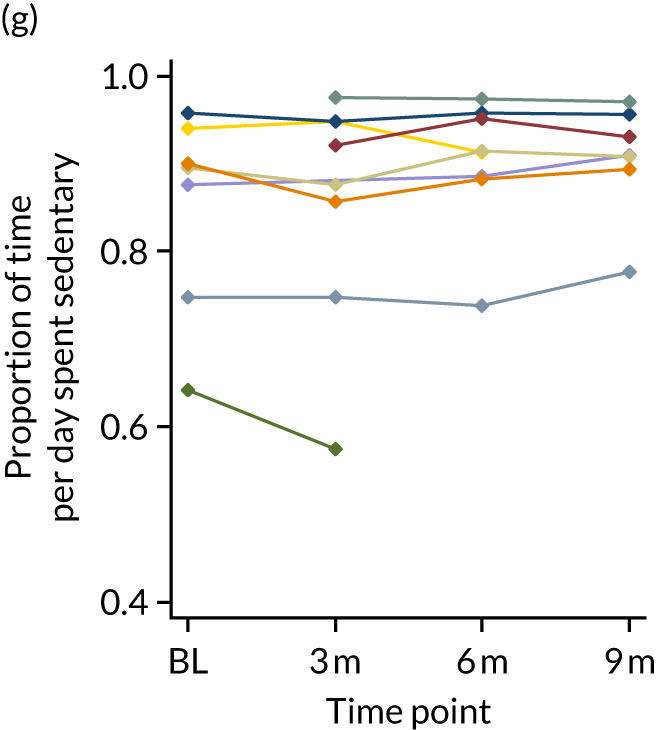

FIGURE 3.

Proportion of daily wear time spent sedentary and in combined low, light and moderate to vigorous PA levels in each individual CH and, on average, across all CHs (n = 22). SB, sedentary behaviour.

The majority of the time spent in PA was spent in low-intensity PA [1 hour 7 minutes (SD 1 hour 4 minutes); 8.7% (SD 7.7%) of wear time].

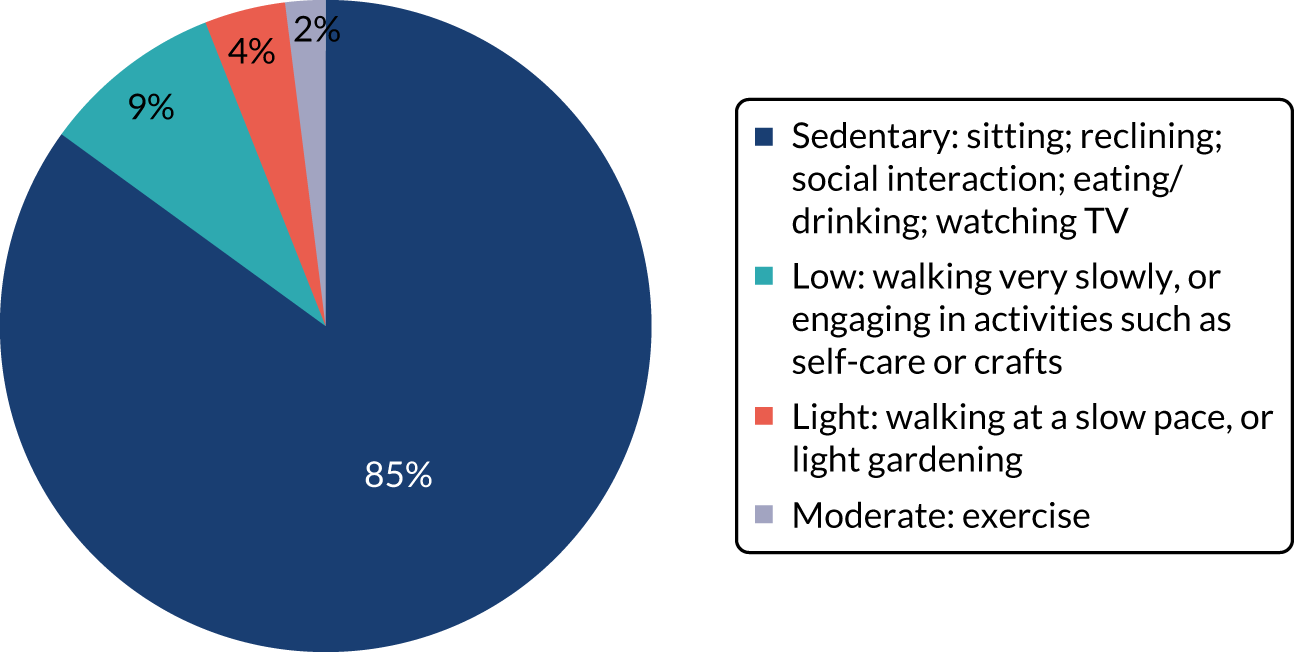

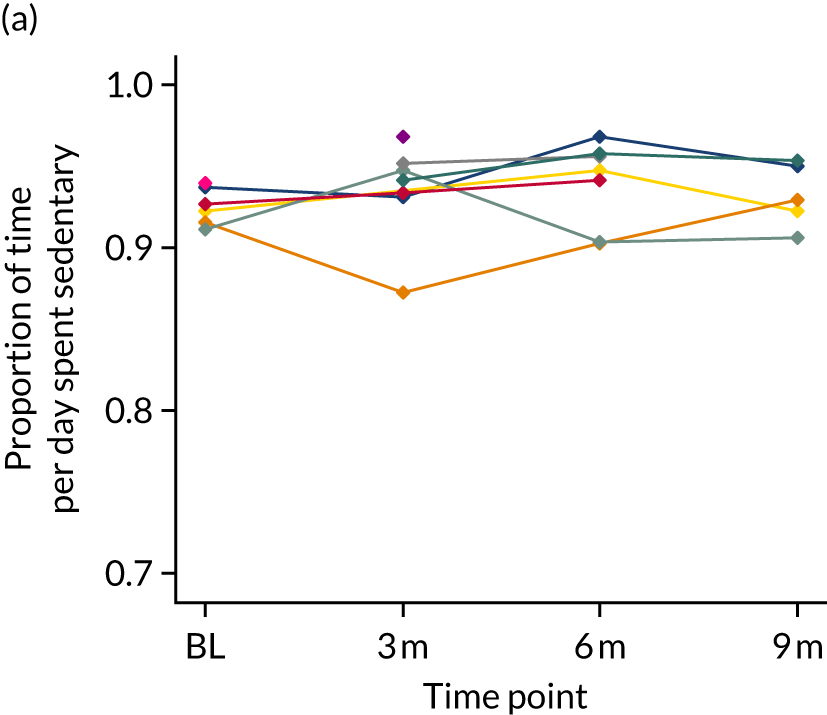

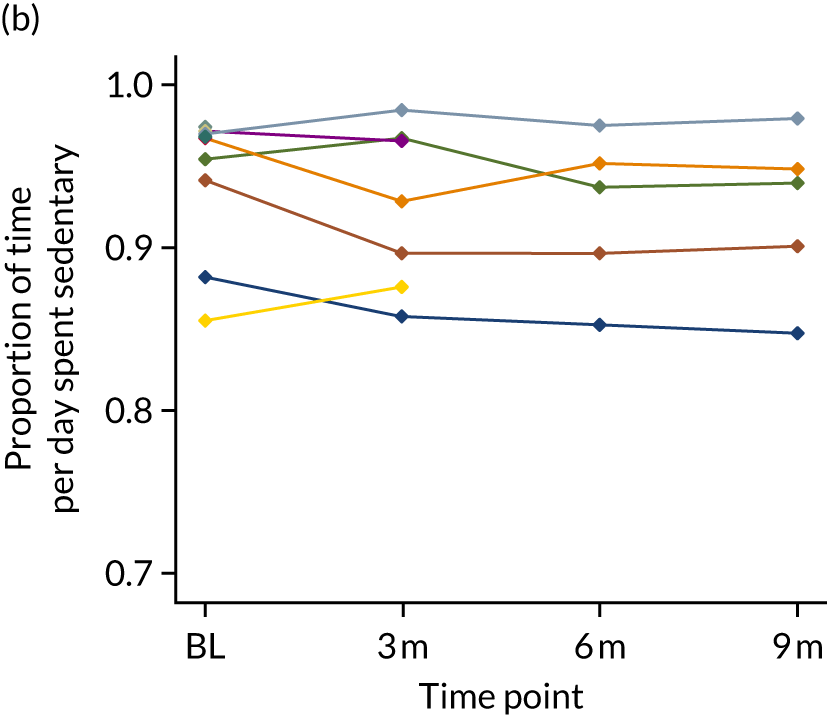

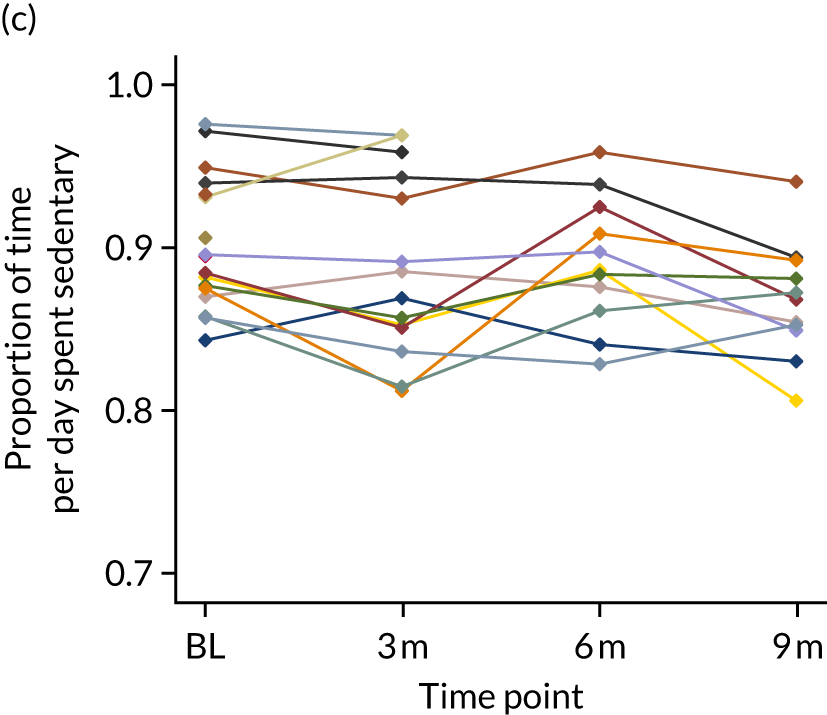

Patterns of physical activity and sedentary behaviour

Residents spent the majority of their time engaging in sedentary behaviours, and the little PA they did engage in was predominantly of low intensity (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

The proportion of accelerometer wear time residents (n = 22) spent engaging in PA of differing intensities and in sedentary behaviour.

Two typical patterns of activity were apparent among residents:

-

Residents spent the majority of their time sedentary; the little PA engaged in was associated with self-care activities (getting out of bed and dressed in the morning and getting ready for bed in the evening) (Figure 5).

-

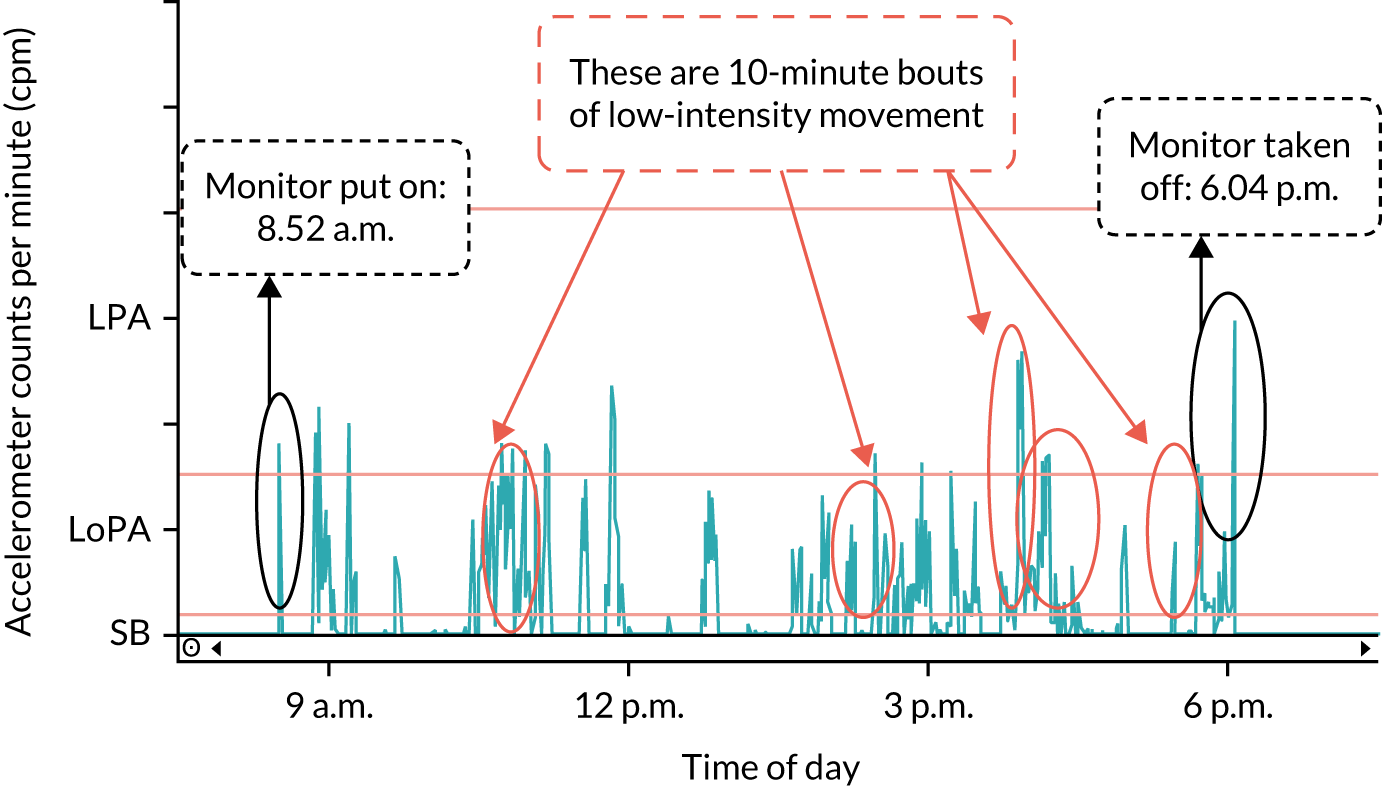

Residents engaged in more PA throughout the day and actually managed to accumulate continuous ‘bouts’ of low-intensity PA. Based on observational data, the main form of regular movement observed in all the CHs generally involved accessing the toilet or moving to a different location for meals/organised activities (Figure 6).

FIGURE 5.

The PA level of a resident in CH5 throughout the day, as demonstrated by accelerometer cpm: pattern of activity type 1. This resident was a 72-year-old male who was categorised as non-ambulatory (functional walking ability score = 0) and dependent in ADL (BI score = 7). cpm, counts per minute; LPA, light physical activity; LoPA, low physical activity; SB, sedentary behaviour.

FIGURE 6.

The PA level of a resident in CH5 throughout the day, as demonstrated by accelerometer cpm: pattern of activity type 2. This resident was a 74-year-old female who was categorised as able to ambulate independently (functional walking ability score = 3) and independent in ADL (BI score = 15). cpm, counts per minute; LPA, light physical activity; LoPA, low physical activity; SB, sedentary behaviour.

Initially, it would appear, therefore, that the conclusions from the initial development work still hold, namely that there are two key opportunities to increase PA in CH residents:

-

break up long sedentary periods with activity

-

increase the duration of bouts of PA towards a goal of 10-minute bouts of low to light activity and, finally, to an accumulation of 20–30 minutes of low to light PA on 5 days per week, as per guidance for interpreting the UK physical activity guidelines for frailer older people. 33

In addition, we have identified that there is opportunity to increase bouts of low-intensity activity.

Part 3: the Assessment of Physical Activity in Frail Older People

Unfortunately, the manual to implement the APAFOP46 was not available initially. After receiving it, we had concerns about the feasibility of administering the APAFOP and its validity in a population with high levels of cognitive impairment. We therefore decided to undertake a small feasibility assessment of the use of the APAFOP. The APAFOP was trialled in two purposively selected residents in one CH who had relatively strong capacity. Although administering the APAFOP was relatively straightforward with residents deemed to have capacity, questionnaire assessment of PA is unlikely to be feasible in residents with more severe cognitive impairment, as there would be issues relating to recall. Little walking or activities of any form were recorded. Both residents spent the majority of their time engaged in typically sedentary activities (sitting or lying). The sensitivity to change of the APAFOP in a population of CH residents was also questioned. Our observational work suggests that CH residents spend a considerable proportion of their time sedentary and the little PA they do engage in encompasses activities such as ADLs, which are unlikely to increase energy expenditure substantially. Thus, in the light of these limitations and following discussion among the applicant team, the APAFOP was considered to be unsuitable for our purpose.

Relationship with other parts of the programme

We optimised recruitment procedures going forward to subsequent WSs, including approaching appropriate NCs when there was no response from PCs.

We concluded that the 6-CIT, the BI, the PAM-RC and the FAC were suitable and feasible measures of physical function/mobility in this CH population.

The hip remains the preferred wear location when using accelerometers in this population group, and was used in subsequent WSs.

In the light of this, a more structured approach to the accelerometer data collection procedures was proposed for use in future WSs.

Accelerometers were to be administered more systematically (i.e. in batches) whenever possible, and the level of support for CH staff when assisting with accelerometers would be increased. This included a member from the research team visiting or telephoning the CH periodically (the frequency of visits/contacts based on perceived need) over the measurement period. In addition, it was decided to produce and provide a list of participants wearing an accelerometer and ‘reminder posters’ for CH staff to display prominently in the CH. The activity log was also amended in an attempt to make it less burdensome to complete and to ensure that accurate information around wear time was recorded.

Workstream 3: development of an intervention to enhance physical activity and appropriate methods of implementation (e.g. training materials) through a process of intervention mapping

Background: context and theoretical framework

Work undertaken in WSs 1 and 2 demonstrated that CH residents undertake little PA and spend many hours sedentary (see Figure 4). Activities organised in CHs are often not necessarily in line with residents’ wishes, setting up a cycle of low participation, reduction in activities organised and dissatisfaction for both staff and residents. Our work identified unmet needs and barriers to increasing PA, and indicated that there are opportunities to enhance residents’ movement within the daily routines of CHs.

Early WSs had highlighted the importance of PA for not only physical health, but also more general well-being. Encouraging residents to be more active could deliver benefits in terms of physical and psychological health and quality of life, as well as providing potential cost savings in health and social care. We identified a need for simple, practical strategies that could be used by care staff to increase residents’ movement throughout the day, without adding to existing workload, and for an effective implementation plan, which can be adapted to different types of CHs.

Given the number of different providers of CHs, the varied and multifactorial needs of residents, and the effect of a lack of PA/too much sedentary behaviour on health-related quality of life, interventions designed to address the needs of residents are likely to be complex and to involve multilevel strategies to produce system and individual changes that will improve outcomes. We undertook development and implementation of this complex intervention, in the context of the Medical Research Council’s framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions,61 guided by IM. 62 IM offers a systematic approach to the development of health interventions that target individual behaviour and environmental and organisational changes. Using this approach ensured that components of our intervention were based on research evidence, were shaped by expressed views of residents, relatives and staff, and were tailored to the CH environment.

The intent was to design an intervention to be delivered by CH staff that was sufficiently flexible to facilitate the participation of individuals with the range of physical and mental health care needs that form the population of CHs.

Aims

The aim was to develop an intervention to enhance the PA of residents in CHs and to develop appropriate methods of implementation (e.g. training materials) through a process of IM.

Method: intervention mapping

We used the IM framework62 to provide a systematic framework for identifying the components of an evidence-based complex intervention to enhance routine PA in residents of CHs for older people.

Advisory group

A stakeholder advisory group was convened to provide guidance through the IM process, especially in relation to the feasibility of this complex intervention in terms of successful implementation and acceptability to residents and staff. The advisory group consisted of CH managers/owners, activity co-ordinators who were also care assistants and residents, lay members, a physiotherapist and members of the research team. This group met on a regular basis (four meetings of all members, interspersed with six internal, small group meetings) to discuss specific issues with and through the IM structured process, and to consider changes that needed to happen to integrate PA (increased movement) and decrease sedentary behaviour in CH culture, systems and daily routines.

Intervention mapping

The IM protocol is a stepwise method to develop interventions systematically using relevant theory and evidence. 62 It enables specific behavioural change objectives to be targeted and decisions to be made regarding how to achieve changes, using behaviour change strategies that are most likely to effect the desired outcomes.

The IM process involved a number of defined steps. 62 We implemented the first four steps in the development of our intervention:

-

needs assessment

-

definition of the performance objectives, selection of behavioural determinants and definition of matrices of change objectives

-

selection of methods and behaviour change strategies

-

translation of these into an actual intervention programme.

These steps guided the schedule for the advisory group meetings (see Report Supplementary Material 2).

Needs assessment (workstream 1)

The intervention development process began in WS1, with a needs assessment undertaken through ethnographic work in four CHs (see Workstream 1: needs assessment and clarifying opportunities for and barriers to enhancing routine physical activity). This work provided insights into daily life in CHs (see Figure 2).

A number of consistent themes emerged from the needs assessment that guided the process of IM (see Figure 2):

-

The ethos of care shaped the opportunities for occupation, activity and movement.

-

If the CH adopted a more enabling or holistic approach to care, this often resulted in greater opportunities for movement.

-

-

The approach taken to risk had implications for daily routine.

-

How the tension between protecting residents from harm and promoting their independence was managed had implications for residents, including whether or not they were enabled to move around the home.

-

-

The care assistant role.

-

If care staff perceived interacting with and engaging residents in occupation to be an important part of their role, this led to greater opportunities for movement.

-

-

Residents’ experiences of the CH setting shaped their daily routine.

-

Residents attributed meanings to the setting and had different expectations of CH life

-

Residents’ daily routines were distinct if they established meaningful and active roles in the CH.

-

We also consulted the literature, which provided information about good practice and barriers to and facilitators of behaviour change.

Identification of outcomes, performance objectives and selection of determinants

Identification of outcomes and performance objectives

The target outcome was to enhance the PA levels of residents in CHs by embedding increased movement into the daily routine care of the home. The starting point for this was to produce an initial list of opportunities for and barriers to movement for residents in CHs using information collected from the ethnographic observations and interviews (see Appendix 3). To achieve our overall outcome, a number of subobjectives were identified; such objectives included increasing participation in ADL, making better use of time between meals and making more use of outdoor space.

The subobjectives were formally developed into a list of proximal performance objectives in consultation with the advisory group. The list of performance objectives targeted manager(s)/organisation, staff and residents (see Appendix 4). This list was essentially a checklist of ‘what needs to happen’ to achieve the target outcome: that ‘each resident can achieve their potential for movement (for the benefit of physical health and well-being)?’. Each performance objective was informed by our previous work and was refined and validated by the advisory group through an iterative process, involving constant comparison to existing CH practices and initiatives, regularly considering the feasibility of the objective. In parallel with the meetings of the advisory group of key stakeholders, we also convened an internal group of researchers who moved the agenda forward outside these meetings. This included referring to a comprehensive review of associated literature, referring to outcomes from previous studies, and consulting current toolkits and national recommendations related to increasing PA in CHs.

Selection of determinants

The next step in the IM process was to identify the theoretical methods and practical steps required to achieve each of the performance objectives. This involved the identification of ‘change objectives’ through the mapping of each of the performance objectives onto a set of theoretical determinants. We drew on Michie et al. ’s63 framework, consisting of 11 theoretical domains pertaining to determinants of behaviour change. Determinants are personal and external factors that may influence outcomes, and include the following.

List 1: explanatory determinants

-

Knowledge.

-

Environmental context and resources.

-

Motivation and goals (intention).

-

Beliefs about capabilities (self-efficacy).

-

Emotion.

-

Social influences (norms).

-

Skills.

-

Beliefs about consequences (anticipated outcomes).

-

Action-planning.

-

Memory, attention and decision processes.

-

Social and professional role and identity.

The result of this step of the IM process consisted of a matrix of cells that included the intersection of proximal performance objectives (rows of the table) with specified determinants (columns of the table) (see Appendix 5). From the intersecting cells, a statement or a learning or change objective was identified that would support the achievement of the proximal performance objective. This was achieved by scrutinising each performance objective individually to identify what barriers were associated with achieving each desired outcome. Our change objectives outlined specific challenges that staff, residents and relatives face in increasing regular movement, and the objectives could be clearly mapped to psychological determinants of behaviour (e.g. ‘intention’, ‘social influences’ and ‘skills’). For example, one of the determinants selected to be targeted in the intervention was knowledge. This was in recognition of the fact that baseline level of knowledge about what PA is, in the context of increasing everyday movement, rather than structured PA in exercise classes, and how staff might engage residents in increasing movement a little every day, was necessary.

Selection of strategies for behaviour change, incorporating suggestions from the advisory group

Following the above process and informed by previous work, appropriate theoretical methods were selected and translated into ideas for practical strategies. This involved identifying appropriate theoretical intervention techniques for each of the change objectives, and then considering how these would be delivered in practice. We used the described theoretical framework as a supporting process, which enabled suggested strategies to be operationalised. As an initial guide, we used the explanatory determinant list (see List 1: explanatory determinants) to select and combine behaviour change techniques (BCTs) and methods to achieve behaviour changes that were indicated to be effective. Here we drew on BCTs that had been mapped onto each of the 11 behavioural determinants, based on empirically supported theory. 63

The advisory group was purposely convened to lead us in the processes of selecting practical strategies and developing, refining and prioritising the techniques for each performance objective. (An example of how the concepts were presented to the advisory group is outlined in Report Supplementary Material 3.) The views of the group and our prior knowledge from the ethnographic work were invaluable in providing examples from existing practice. The practical strategies that we identified included provisional methods for implementation, some of which were appropriate to be applied at the level of the individual and some at the level of the home. The suggested practical applications, mapped to determinants, change objectives, performance objectives and BCTs, were then refined based on further discussion within the internal intervention group.

Developing and organising programme components and materials

The fourth step in the process involved designing and organising the programme to be implemented. We did this by broadly following Bartholomew et al. ’s62 recommendations of using the results of the needs assessment (step 1) and the theoretical and practical strategies from the targeted users (step 2) to design and organise the programme. In this case, this involved discussing and assessing the practical strategies for acceptability with members of the advisory group, and taking suggestions from these stakeholders for implementation of the intervention. We then grouped the emergent strategies into four key themes focusing on:

-

improving knowledge about movement and changing beliefs about consequences

-

finding out what residents want to do to move more

-

supporting staff to enable residents to move more

-

amending the environment to encourage PA.

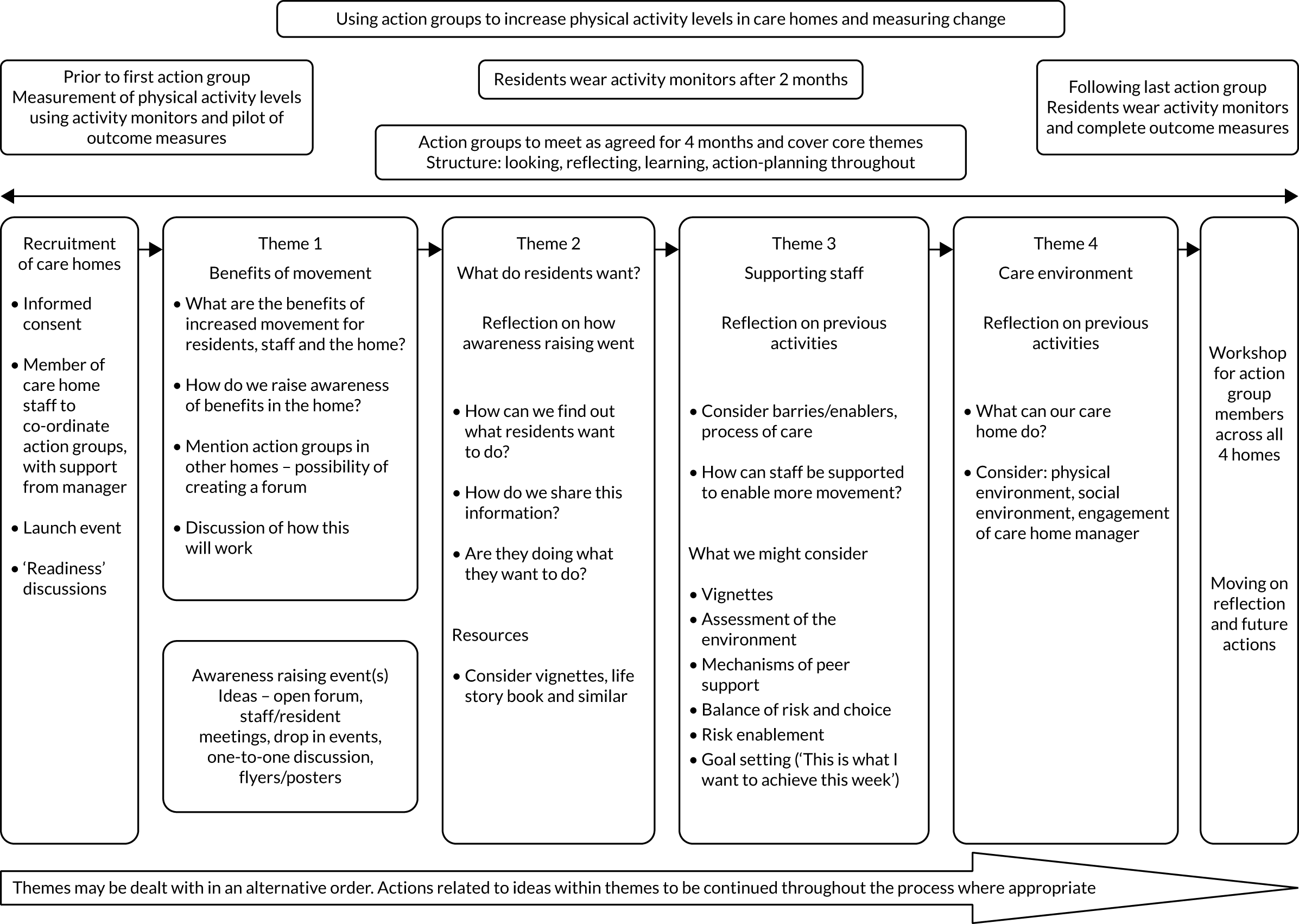

This formed the basis for a schematic guide outlining suggested areas of change that might promote more regular routine daily movement for residents (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Schematic guide to action groups.

Toolkits

In parallel with the advisory group meetings, we reviewed existing resources that had recently been produced relating to PA in CHs. We found that examples of practical strategies provided by the group were closely aligned with some existing resources (notably, resources produced by The Royal College of Occupational Therapists64 and The British Heart Foundation33). These resources (an ‘ideas bank’) were selected and collated based on decisions as to which change objective(s) would be addressed by the existing materials and what BCT(s) the existing materials represented (see Report Supplementary Materials 4 and 5). This ensured that all practical applications were based on sound theoretical methods. As a result, we produced a resource pack of selected materials, which was organised into the four themes.

Implementation would take the form of a stepwise process through supportive workshops to introduce and then embed the intervention into routine care delivery.

Delivery would be enhanced by a team of key stakeholders at the home (staff, relatives and residents), initially supported by researchers and professionals. Change would be implemented by the team using a cyclical process whereby goals would be developed from observations in the CH by stakeholders, and then progress would be reviewed.

Thus, a provisional intervention was developed. This consisted of the schematic guide focused on the four key themes and planned implementation through engagement of key stakeholders at the CH, with supportive workshops and a comprehensive set of resources (an ideas bank).

Key points

We successfully engaged with the stakeholder group and, through this, we developed a provisional intervention.

In creating the provisional intervention, we used a systematic and collaborative approach, guided by principles of IM. The IM process was useful as a planning template to incorporate our evidence base derived from previous research, theoretical components, practical strategies and other input from the advisory group. In this process, we established a need for better resources and implementation guidance in relation to increasing residents’ movement in CHs.

We have identified a number of specific enabling and limiting factors that we encountered in using IM to develop a complex intervention.

Strengths

Intervention mapping facilitated precision in determining which behaviours should be targeted and which change objectives (actions) were required to achieve the performance objectives and desired outcome (enhancing movement of residents in CHs). We found the early assessment of needs and involvement of relevant stakeholders in the intervention development process critical to developing the intervention. A number of strategies for behaviour change were intrinsically incorporated into various components of our intervention, based on the behavioural determinants identified in the IM process.

Limitations

Maintaining the focus of the advisory group was challenging, as the group was quick to suggest strategies and solutions without considering underlying determinants. This meant that the IM process did not always follow a linear format and the research team worked flexibly to capture all outputs.

Workstream 4: engaging care home staff and residents in intervention development and refinement of the intervention pack

Aims and objectives

The aims and objectives of this WS were to gain insight into the progress of the intervention implementation process (through implementation of action groups) by undertaking observations of meetings and daily life in the homes.

We also undertook additional related work to optimise the selection of outcome measures. This is reported in Appendix 6.

Methods

For a full description of the methods, see the protocol in Report Supplementary Material 6. The methods included the capture of action group activity and non-participant observations in CHs. Normalisation process theory (NPT) informed the refinement of strategies that were developed for implementation in CH routines.

Selection of homes

For a full description of recruitment procedures, see the study protocol in Report Supplementary Material 6. Briefly, four CHs in the Yorkshire area (different from those in previous WSs and the development work) were purposively selected.

The CHs varied in size from 19- to 96-bed facilities. One of the homes was designed to support residents with dementia and another (the largest home) had two of three units designated as specialist dementia resource. The homes varied in terms of their management/ownership: three were managed as part of large national private provider organisations and one was owned by a small local provider.

Action groups

Participative action-planning approach (action groups)

Action groups were established in each of the four homes, consisting of manager(s), care staff, residents, relatives/friends and a member of the research team, who acted as a facilitator. Twenty-nine individuals consented to participate in the action groups (nine residents, 18 staff and two relatives/friends of residents). We recognised that residents with the cognitive ability and willingness to participate may not be representative of the client group in that home; therefore, we sought innovative ways to involve the wider resident group.

Having developed a prototype for how an intervention might be delivered and a preliminary outline of issues that should be addressed (see Figure 7), an action research cycle of service improvement was employed to develop the intervention and engage staff and residents directly in the process of how to make change happen. 65

The action groups aimed to follow the provisional intervention developed in WS3. The purpose was to create a dialogue between researchers and these stakeholders about implementation strategies to increase PA/reduce sedentary time of residents, to try these strategies with staff and residents, and to review barriers to and opportunities for implementation in the real-life context of CHs that varied in terms of their resident profile and care environment.

Information about the importance of movement and some of our initial ideas were presented by a member of the research team and discussed with the group. Each action group was tasked with considering the current pattern of movement of residents, both in respect of the routines of daily living and during the leisure periods, and with exploring ways, through action plans, of increasing the PA/movement undertaken by residents in their CHs. At each action group meeting, progress in achieving action plans was reviewed through input/dialogue between members of the group. Barriers and solutions were identified, changes/refinements were made, depending on the progress achieved, and new action plans were developed to take the process of change forward through successive improvement cycles. The researchers also fed the group relevant data pertinent to contributing to the service improvement process. This included examples from observation, ‘ideas’ from the resource pack and emerging data systematically collected on the process of action-planning and the effects on staff and residents. In this way, we built up an ‘ideas bank’ of ‘what works, how and for whom’ in the real-life context of the home.

The proceedings of the action groups were, with participants’ permission, recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. Researchers also carried out observation of the process of implementation as it proceeded and contributed to the action cycle. Ethnographic observation and informant conversations between action group meetings built up a picture of the CH environment and the possibilities for change, and examined how and in what ways the strategies that were tried out affected residents.

Results of participative action-planning approach (action groups)

Action groups were successfully convened in all four homes, but sustaining engagement in the intervention implementation process as planned was challenging. The researchers successfully maintained engagement with the CHs, recorded group activities and collated observational data, as planned.

However, within the homes, there were practical difficulties in sustaining the action groups and maintaining interest in implementing change. These barriers included organisational turmoil, high rates of staff turnover, time constraints and a lack of senior management interest in supporting the process. On occasion, there were tensions between group members: between care staff and managers, between residents and care staff, and between researchers and care staff.

Challenge: there appeared to be a gap between our explanation of what the research was about and CH managers hearing what the study involved. The concept of increasing movement both at the level of daily life routines and in the leisure spaces appeared difficult for those working in the homes to understand; instead, movement was perceived of more in terms of PA/physical exercise.

Response: to ensure that, in the feasibility trial, the engagement in the study is not a one-off agreement but a sustained process of negotiation and to be very explicit about the focus of the research.

Challenge: on an organisational level, the difficulties of implementing change in CHs were highlighted. These included rapid unexpected changes of staff (and, in once case, ownership of the home), staff perceptions of the distinctive role of the activity co-ordinator and the work generated by Care Quality Commission (CQC) inspections.

Response: to consider what would support and drive the intervention and to ensure that implementation is sustained.

Response: it became clear in this WS that a more detailed implementation plan was required to optimise embedding the intervention in the CHs. Consideration was given to whether or not the intervention should be more prescriptive. This would not, however, take account of the very different circumstances and contexts of each CH, a key feature of the research in all of the CHs in the programme thus far. However, we did consider that there was an important difference between a more explicit process of implementation (what should happen and when in terms of making change) and the content of the changes, which should be home specific.

Response: training (interactive structured workshops, advice from experts, demonstration of strategies) could be incorporated into the implementation plan.

Challenge: a significant issue that emerged in three of the homes was the lack of engagement from care staff in activities around movement, as care staff perceived their role as primarily about the delivery of care. There appeared to be a divide between ‘care’ and ‘activities’, whereby movement is conceived of as part of ‘activities’ and is the realm of the staff charged with responsibility for ‘activities’ (i.e. the activity co-ordinator). This divide was perceived as a more active antagonism between some care staff and the activity co-ordinator in one of the CHs.

Response: to reconsider if we had clearly expressed in the presentation of the programme/intervention that the work of increasing movement embraces all staff. The materials and implementation process were amended to ensure that this key concept was fully captured.

Challenge: in two CHs, difficulties in knowing when to ‘push’ residents were expressed. Residents’ choices should be respected, so if they chose to remain in their rooms/have meals in their rooms this choice should be respected. There was also a lack of knowledge about how far to push residents, given their ill health.

Response: an experienced CH physiotherapist assisted with implementation of the intervention in the feasibility trial, specifically by providing a short introduction on the importance of movement.

Challenge: in the individual homes, some staff in the action groups were able to recognise that residents were sedentary, but in other homes there was a reluctance to acknowledge that any change could be achieved and staff were quite defensive. There was a perception from managers and carers that they were doing all they could to promote movement when they have enough time to do so.

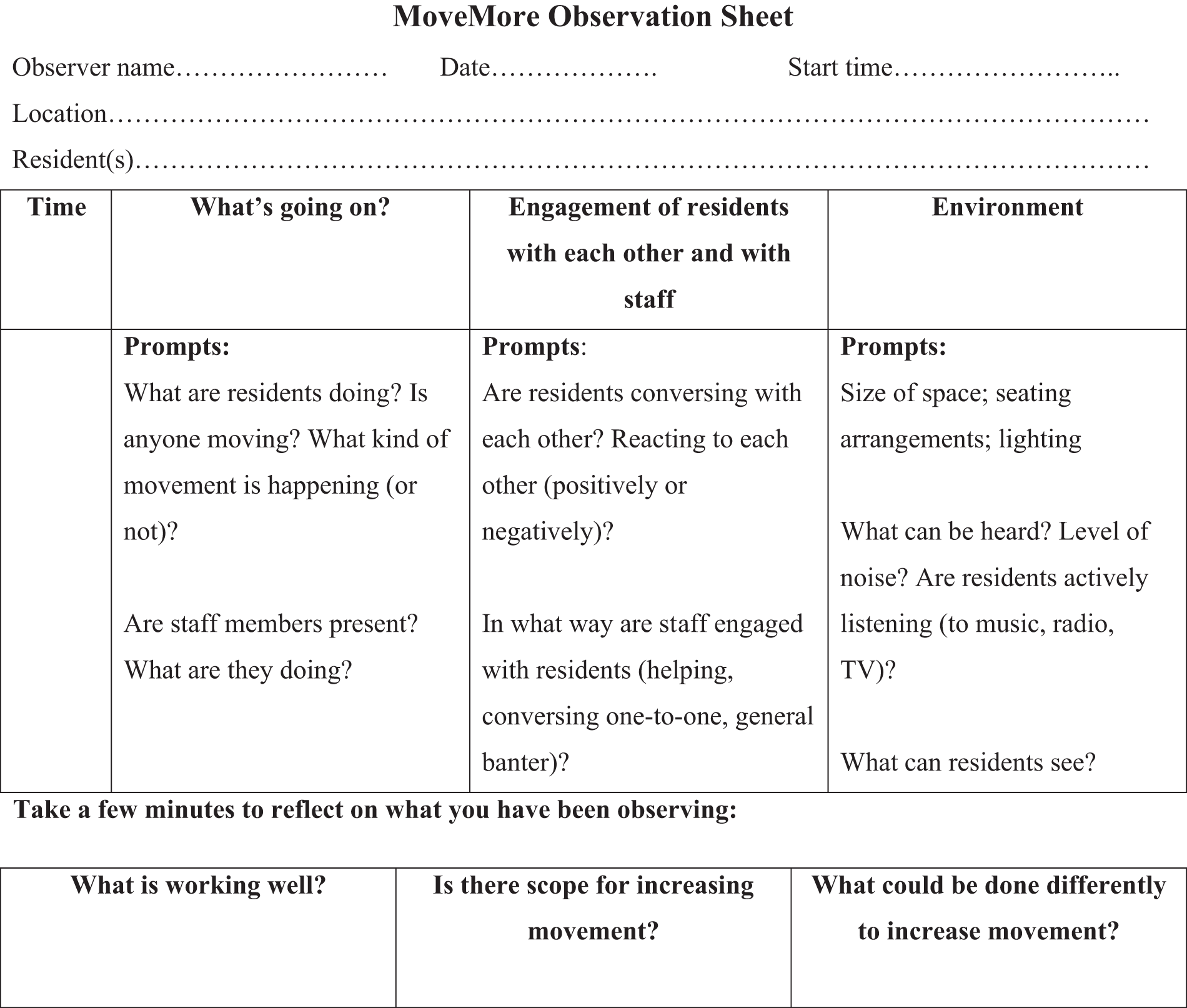

Response: an important factor in engaging staff in a programme of change is to encourage them to take a close look at/reflect on what they currently do. In their CH, are residents encouraged to move? All residents? Some residents? In what aspects of CH life (self-care, walking about, organised leisure activities)? What works well? What does not work? And for whom? Staff need to be convinced that, in the context of their ‘home’, what is involved is more than what they currently do, and the value of the change is worth the work involved in making it happen. Difficulty in getting staff to recognise the potential of increasing PA prompted the further development of a short observational tool that staff were encouraged to complete. This enabled them to explore current practice and consider what might be done to effect change.

Supporting staff to take a step back enables them to have a different perspective, challenging taken-for-granted ideas and practices. The observational tool was designed to combine simple, short observation with critical appraisal (what actually happens), and follow quickly to actions. For example, staff members might spend 10 minutes observing, at a particular time of the day, particular residents and particular activities (personal care and daily life routines, moving about, individual and collective leisure activities). They could then more proactively engage in identifying problems/barriers and consider whether or not and how the activities are modifiable.

Facilitators: action groups and the ongoing engagement with the CHs during this WS provided a great opportunity to gain insight into staff perspectives. This enabled us to establish what modifications were needed in the content and delivery to improve the implementation and acceptability of the intervention and embed it into practice, as well as establishing what works, for whom, in what contexts.

The action groups were successful in identifying a number of actions, including rearranging chairs in communal areas to facilitate interaction, incorporating short walks into care routines and encouraging residents to participate in domestic tasks. Interventions for individual residents were undertaken and music was used to prompt PA/movement.

Response: These ideas were incorporated into the ‘ideas’ bank of the intervention.

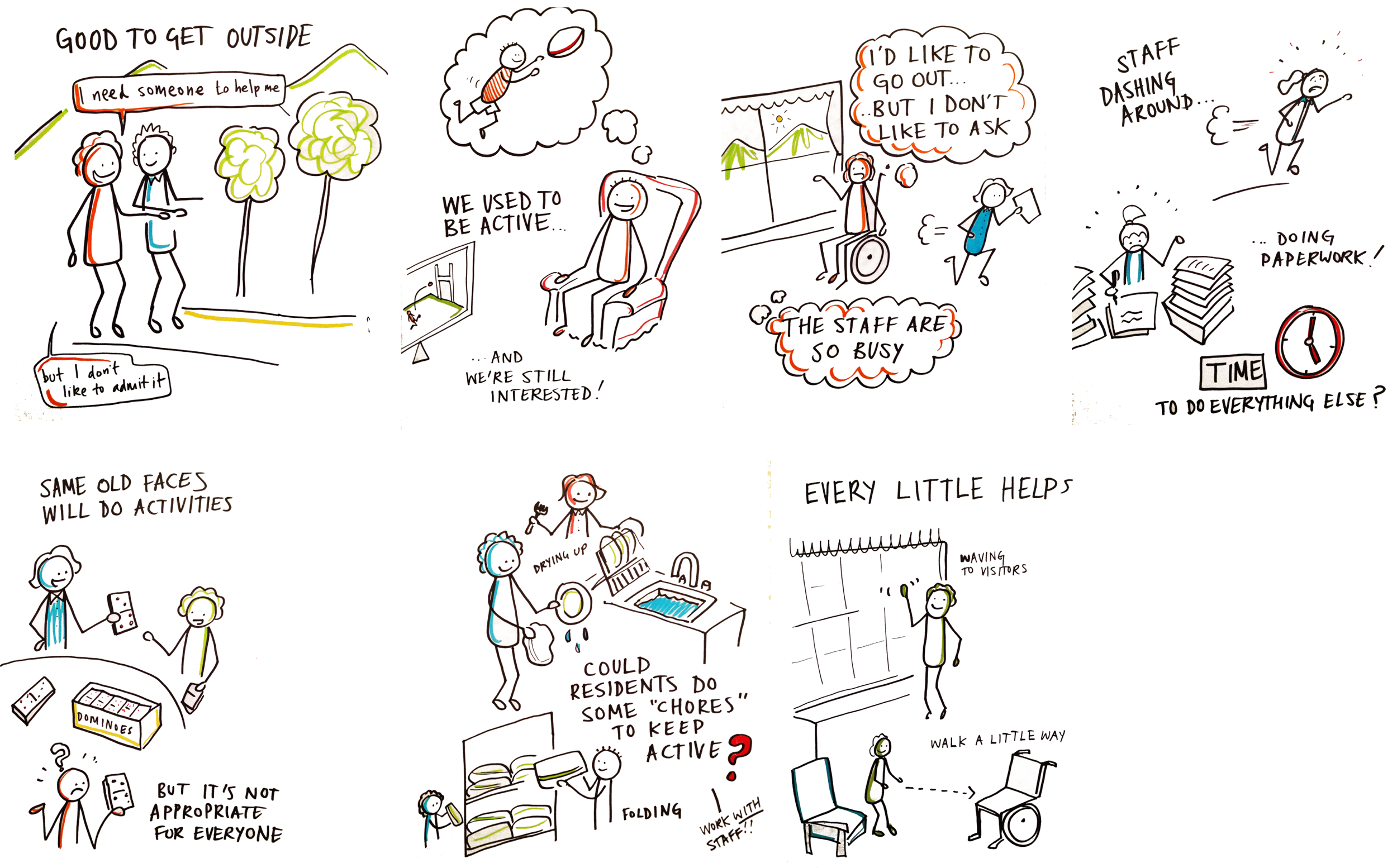

Success: engagement with a local artist was particularly successful. Residents described their daily life to the artist and he depicted this in drawings (Figure 8). This succeeded in engaging residents with communication difficulties (e.g. from dementia, stroke) and stimulated lively discussion. The immediate outputs were displayed in the CHs and served as prompts to increase movement of residents and staff. The input of the artist became an integral component of the intervention.

FIGURE 8.

Artist’s drawings. Pictures developed through ‘movement’ discussions with staff and residents, facilitated by a researcher and in collaboration with a local artist, Tom Bailey, at one of the Workstream 4 homes.

Accessible summaries of the key findings were produced and fed back to staff and residents in each home (see examples in Report Supplementary Materials 7 and 8).

Through this careful iterative work (led by co-applicant Mary Godfrey), we successfully produced a defined intervention to be implemented to enhance the PA of residents in CHs, which was still focused on the four key themes identified [see Workstream 3: development of an intervention to enhance physical activity and appropriate methods of implementation (e.g. training materials) through a process of intervention mapping].

Key findings

Finalised intervention

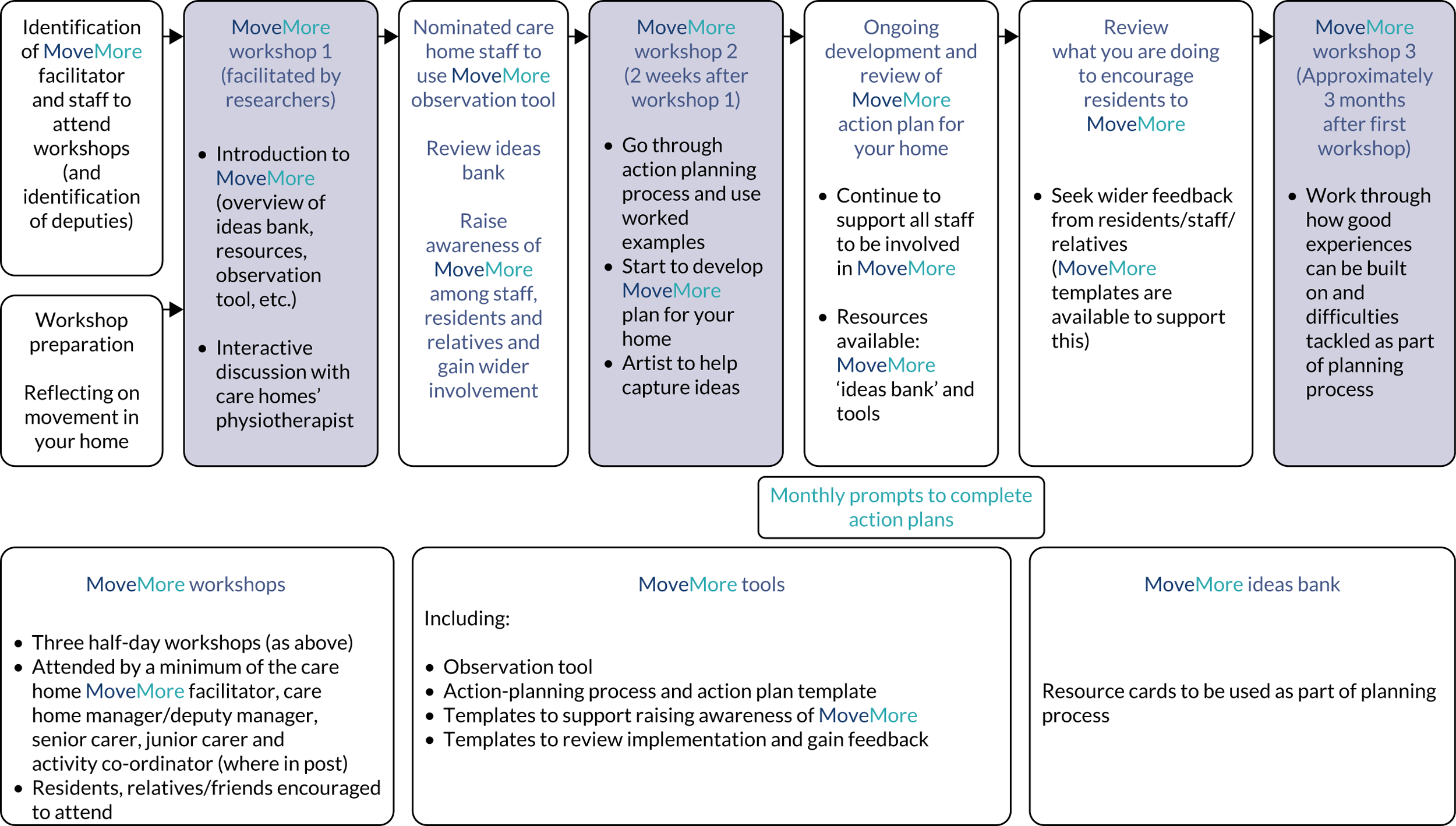

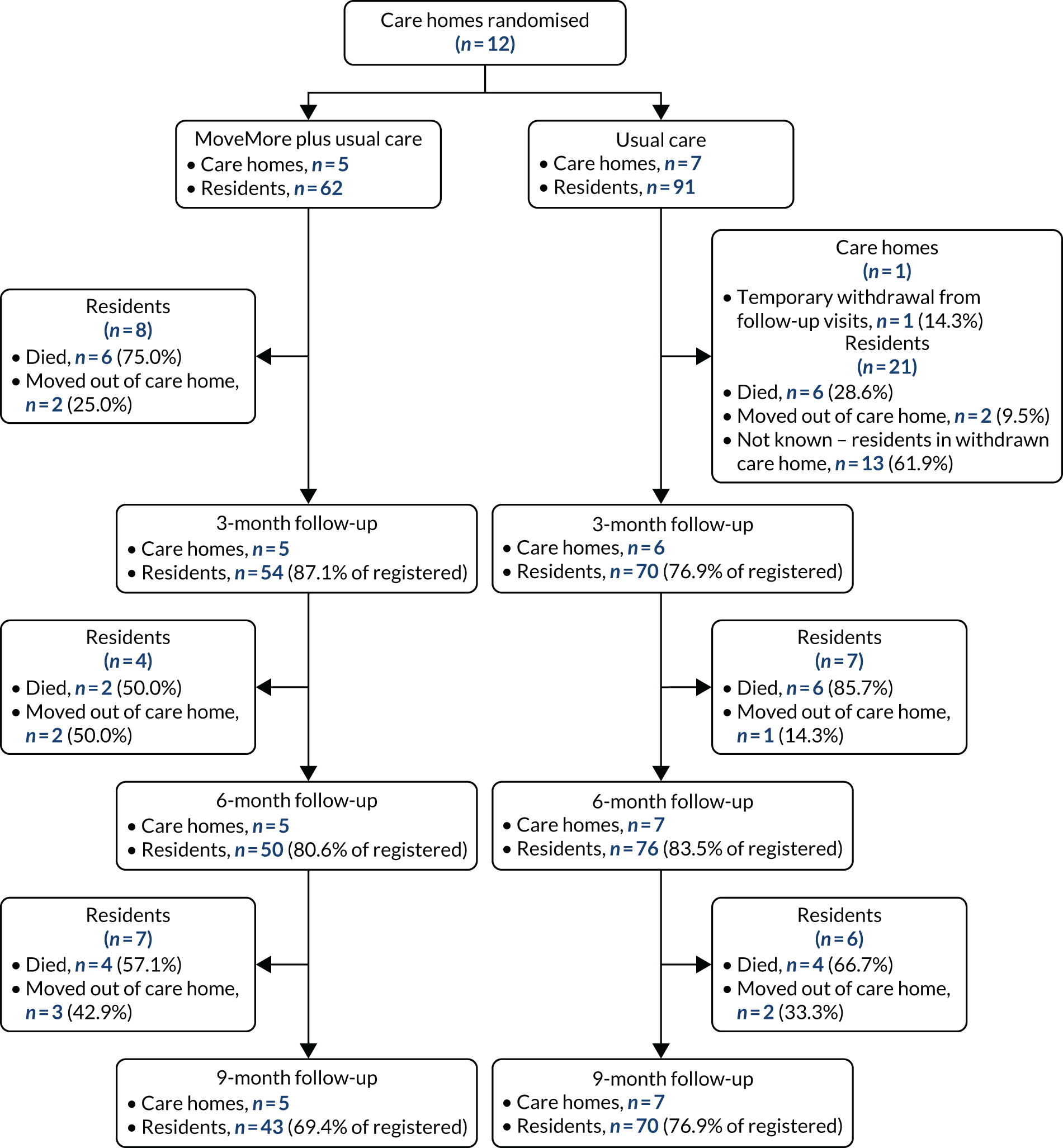

The primary outcome of this WS and the previous WS was a finalised intervention called MoveMore. MoveMore consists of an intervention folder (manual) and supporting resources.