Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 14/52/15. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The final report began editorial review in January 2018 and was accepted for publication in September 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Chris Bonell and Rona Campbell are members of the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research Funding Board. Rona Campbell is a scientific advisor to the Decipher Impact Ltd (Bristol, UK), a non-profit company.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Tancred et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Bonell et al. 1 Contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

Description of the problem

This review focuses on substance use (i.e. alcohol consumption, smoking and drug use) and violence because these are important, intercorrelated outcomes that are addressed by interventions sharing common theories of change. 2–5 Alcohol has been suggested to be the most harmful substance in the UK. 6 Treating alcohol-related diseases costs the NHS in England an estimated £3.5B annually. 7 The total annual societal costs of alcohol use in England are estimated at £21B. 8 Alcohol-related harms are strongly stratified by socioeconomic status (SES). 9 Early initiation of alcohol use and excessive drinking are linked to later heavy drinking, alcohol-related harms10,11 and poor health. 12 Alcohol use among young people is associated with truancy, exclusion and poor attainment, as well as unsafe sexual behaviour, unintended pregnancies, youth offending, accidents/injuries and violence. 13

Preventing young people from taking up smoking is another key public health objective with 80,000 deaths due to smoking each year. 14 In 2005–6, smoking cost the NHS £5.2B and wider costs amounted to £96B. 15,16 A total of 40% of smokers start smoking in secondary school17 and early initiation is associated with heavier and more enduring smoking and greater mortality. 18,19 Smoking among young people is a major source of health inequalities. 17

Among UK 15- to 16-year-olds, 25% have used cannabis and 9% have used other illicit drugs. 18 Early initiation and frequent use of ‘soft’ drugs may be a potential pathway to more problematic drug use in later life. 20 Drugs such as cannabis and ecstasy are associated with an increased risk of mental health problems, particularly among frequent users. 20–23 Young people’s drug use is also associated with accidental injury, self-harm, suicide24–26 and other ‘problem’ behaviours. 27–30

The other primary outcome of the review is violence. The prevalence, harms and costs of violence among young people mean that addressing this is a public health priority. 31,32 One UK study found that 10% of young people aged 11–12 years reported carrying a weapon and 8% admitted to attacking someone with intent to hurt them seriously. 33 By the age of 15–16 years, 24% of students reported that they have carried a weapon and 19% of students reported attacking someone with the intention to hurt them seriously. 33 There are also links between aggression and antisocial behaviours in youth and violent crime in adulthood. 34,35 As well as leading to further health inequalities, the economic costs to society of youth aggression, bullying and violence are high. For example, the total cost of crime attributable to conduct problems in childhood has been estimated at about £60B per year in England and Wales. 36

In the UK, many schools are reducing the provision of lessons that address health37–39 because schools now increasingly focus on narrow attainment targets and school inspections have only a limited focus on schools’ promotion of student health and personal development. 40 In addition, in England, personal, social and health education (PSHE) is not a statutory subject. 39

Description of the intervention

Existing systematic reviews suggest that school curriculum-based health interventions can reduce alcohol consumption,41 smoking,42 drug use43 and violence,44–46 but these are increasingly difficult to deliver within constrained school timetables. In this context, many schools integrate health education with academic learning. 47 Such interventions may either teach health education within other mainstream school subjects or provide specific health education lessons (ones that are also providing teaching that covers academic, as well as health, knowledge and skills). Even without the marginalisation of PSHE, this approach may be more effective because it could allow for increased curriculum teaching time,47,48 it may be less prone to student resistance to health messages,4 and it may enable synergy and reinforcements between sessions provided in different subjects. 2 On the other hand, integration may lead to a delivery of the intervention by staff unqualified or unwilling to address health, or to a delivery of the intervention with only a cursory treatment of health topics. Existing UK interventions use a range of innovative approaches to integrate health and academic education,49,50 but have not been informed by existing theory or evidence. For example, the British Heart Foundation’s ‘Money to Burn’49 and the Ariel Trust’s ‘Plastered’50 interventions incorporate education about the respective risks of smoking and drinking into mathematics lessons. Money to Burn includes activities such as calculating how much a smoker would typically spend on cigarettes per day, per week or per year, and Plastered includes activities such as calculating units of alcohol consumed and presenting statistics on attitudes to alcohol as a basis for whole-class discussions about the harmful consequences of alcohol consumption.

The UK can learn from theory and evidence being generated in other countries. For example, the Reading, Writing, Respect and Resolution (4Rs)3,51–57 intervention aims to integrate the learning of social and emotional skills with literacy skills for children in US elementary schools to reduce violence and antisocial behaviour. Lessons use a discussion of children’s literature as a basis for education about managing emotions and negotiating disagreements non-violently. A randomised controlled trial (RCT) reported a significant reduction in aggression and improved academic attainment. 3,51,52

In terms of theorised mechanisms, such interventions may either fully integrate health and academic education, so that the same learning activities address health and academic learning objectives together, or partially integrate health and academic education, so that separate learning activities aim to address health and academic learning objectives within one overall package. Such interventions could address substance use or violence by developing social and emotional skills, such as self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy and communication,58 healthier social support or norms among students,3,51,52 knowledge of the costs49 and consequences50 of substance use, media literacy skills to critique tobacco and alcohol advertising, and modifying students’ social norms about substance use. 2,4,49,59,60 This category of intervention is likely to involve theories of change that are distinctive from conventional health education because such interventions aim to integrate health promotion into academic learning, and may aim to promote developmental cascades involving the interplay of cognitive and non-cognitive skills. 3,61 Effects on substance use and violence are likely to be synergistic because each predisposes the other and has common risk factors. 5

Rationale for the current study

No systematic review has examined theory or empirical evidence concerning interventions integrating health and academic education. The reviews cited above,41–46 some of which are now quite old, are focused on school-based interventions, but the interventions included in the reviews are overwhelmingly those delivered in specific PSHE lessons or their international equivalents. Some of these reviews do include some interventions that integrate health and academic education, but they omit important studies and do not specifically analyse or draw conclusions about the effects of this category of intervention. Furthermore, these reviews have not synthesised evidence on intervention theories of change or process evaluations and have not considered components or mechanisms and, thus, cannot provide information about the intended mechanisms or the feasibility and acceptability of interventions, or their transferability to the UK.

These are important gaps to investigate because of the marginalisation of health education in the UK and the potential advantages of interventions integrating health and academic education (as well as the risk that these interventions might actually be less effective than conventional discrete health education), and the distinctive approaches and theories of change of this category of interventions. There is thus a good rationale for a new systematic review focused on this category of interventions. This review focuses on substance use (i.e. alcohol consumption, smoking and drug use) and violence because our scoping searches and logic model (see appendices 1 and 2 of the protocol1) suggest that these interventions have the most potential in reducing the risk of these behaviours. Substance use and violence are closely intertwined,5 and the theories of change underlying interventions addressing these outcomes appear to be similar. As explained in Appendix 1, which lists deviations from the protocol,1 we originally intended to consider interventions that weaved health education into any existing academic lesson other than biology. However, we subsequently decided to include any interventions that integrated health and academic education regardless of whether the lessons in which they occurred were existing, timetabled academic lessons or new health lessons but with an academic component, and we decided against the exclusion of biology as an academic subject used to deliver health and well-being information. These modifications were made because it is the integration of health and academic education that is the focus of this review rather than the place in the school timetable in which this education occurs. This modification also gave our review greater international utility, as the division between health education and other lessons that exists in the UK is not as clear in many other countries (e.g. the USA). In the USA, health education is very commonly delivered in social studies lessons, which is an academic subject but in which there is often no integration of health and academic education.

Review aim and objectives

To search systematically for, appraise the quality of and synthesise evidence on curriculum interventions that integrate health and academic education in schools to prevent substance use and violence. These aims have been addressed by focusing on the following objectives:

-

to conduct electronic and other searches

-

to screen found references and reports for inclusion in the review

-

to extract data from, and assess the quality of, included studies

-

to develop a typology of interventions and synthesise theories of change and process evaluations

-

to consult with policy/practice and youth stakeholders on the typology and theory/process synthesis to inform amendments and plans for synthesis outcome data

-

to synthesise outcome evaluation data and undertake meta-regression and/or qualitative comparative analyses

-

to draw on these syntheses to draft a report addressing our research questions

-

to consult with policy/practice and youth stakeholders on the draft report to inform amendments and dissemination.

Review questions

The following questions were addressed:

-

What types of curriculum interventions that integrate health and academic education in schools and address substance use and violence have been evaluated?

-

What theories of change inform these interventions and what do these suggest about their potential mechanisms and effects?

-

What characteristics of interventions, deliverers, participants and school contexts facilitate or limit successful implementation and receipt of such interventions, and what are the implications of these for delivery in the UK?

-

How effective are such interventions in reducing alcohol consumption, smoking, drug use and violence, and increasing academic attainment when compared with usual treatment, no treatment or other interventions, and does this vary according to students’ sociodemographic characteristics?

-

What characteristics of interventions, deliverers, school contexts and students appear to moderate or are necessary and sufficient for the effectiveness of such interventions?

Chapter 2 Review methods

About this chapter

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Bonell et al. 1 Contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted from Bonell et al. 62 Contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

This section outlines the methods used in this systematic review, which were described a priori in the research protocol. 1 The study is also registered with the PROSPERO registry of systematic reviews (reference number CRD42015026464) and is available from www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPEROFILES/26464_PROTOCOL_20160011.pdf (accessed 9 September 2018). Although there are no existing checklists for a complex, multimethod review such as the one undertaken, we have adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidance63 and the PRISMA checklist can be found in Appendix 2.

Design

The project is a multimethod systematic review of known existing research. This chapter describes the review methods. Chapter 3 describes the flow of studies through the review as well as the characteristics of included studies (addressing research question 1), study reports and interventions. This is followed by four chapters presenting our various syntheses.

-

A thematic synthesis of the literature describing the theories of change of interventions included in this review (addressing research question 2).

-

A thematic synthesis of process evaluations exploring what factors facilitate or limit successful implementation and receipt (addressing research question 3).

-

A narrative synthesis and meta-analysis of the effects of interventions on substance use and violence outcomes (addressing research question 4). The evidence reviewed did not enable us to examine how effects varied according to students’ sociodemographic characteristics.

-

An analysis of intervention components assessing key features of interventions integrating academic and health education (this reports a post hoc analyses not included in the original protocol1).

The evidence reviewed did not allow us to examine research question 5, concerning what characteristics of interventions, deliverers, school contexts and students appear to moderate or are necessary and sufficient for the effectiveness of such interventions. Chapter 7 of this report draws on all the component syntheses to develop overall conclusions.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

The criteria and definitions used for considering which studies to include in this review are outlined below. These inclusion criteria were operationalised into exclusion criteria to inform the screening of found studies (see inclusion and exclusion criteria in the protocol1). The results of this screening process are detailed in Chapter 4.

Types of participant

Studies were included where the majority of participants were children and young people aged 4–18 years attending schools. Interventions that targeted specific subpopulations defined in terms of health outcomes, such as autistic children, children with learning disabilities or children with known behavioural problems, were excluded. This is a clarification of the original protocol,1 which was not explicit about including only studies addressing general student populations (see Appendix 1). The rationale is that theories of change for interventions targeting subpopulations defined by specific health outcomes will differ from those addressing a general student population, and so would introduce inappropriate heterogeneity into the review.

Types of intervention

School-based health curriculum interventions integrating health and academic education targeting young people aged 4–18 years were included. Academic education was defined as education in specific academic subjects, such as literacy, numeracy or study skills. It did not include education on social conduct in the classroom, relationships with peers or staff, attitudes to education, school or teachers or aspirations and life goals. Study reports needed to state explicitly that the intervention aimed to integrate health and academic education. To have been included, integration could have taken the form of either health education being fully integrated with academic education, so that the same activities address learning in each domain (i.e. the earlier example where education on smoking and alcohol was woven into existing timetabled mathematics lessons), or partial integration, when interventions combine activities separately addressing health and academic learning within one overall package (e.g. a social and emotional skills curriculum aiming to prevent violence that also included sessions aiming to improve literacy or study skills). We originally intended to exclude interventions integrating health education with biology but decided against this because it would have been an arbitrary exclusion (see Appendix 1). Interventions could be delivered by teachers or other school staff, such as teaching assistants, but could also be delivered by external providers, for example from the health, voluntary or youth service sectors. Our definition excluded interventions that were delivered in mainstream subject lessons but did not aim to integrate health and academic education, trained teachers in classroom management without student curriculum components or were delivered exclusively outside classrooms.

Types of outcome

Studies that addressed one or more of the following primary review outcomes were included: smoking (e.g. salivary cotinine, carbon monoxide levels, self-reported use of cigarettes), alcohol use (e.g. self-reported alcohol consumption via questionnaires or diaries), legal or illegal drug use (e.g. self-reported drug use) and violence [self-reported violence perpetration (e.g. carried a weapon, got into a fight) or victimisation].

Types of outcome were informed by existing systematic reviews focused on substance use and violence among young people. 41–46 The outcome measures of these reviews could have drawn on dichotomous or continuous variables and self-report or observational data, they could have used measures of frequency (e.g. monthly, weekly or daily), the number of episodes of use or an index constructed from multiple measures. Alcohol measures could have examined alcohol consumption or problem drinking. Drug outcomes could have examined drugs in general or specific illicit drugs, including drug convictions. Measures of violent and aggressive behaviour could have examined the perpetration or victimisation of violence, including convictions for violent crime. Of note is that we included some outcomes that were a composite, such as items examining physical violence alongside non-physical (e.g. verbal or emotional) violence, but excluded other composite outcomes, such as physical violence alongside other items examining non-violent behaviours (e.g. damage to property). The section on the synthesis of outcome evaluations (see Chapter 6) describes how measures were combined.

Although not an inclusion criterion, we also assessed academic attainment as a secondary outcome [e.g. student standardised academic test scores, intelligence quotient (IQ) tests or other validated scales and school academic performance].

Types of studies

To address research question 1, we have presented a summary of all included studies, regardless of evaluation type, in Chapter 3. To address research question 3, we included studies reporting on process evaluations this included studies reporting on the planning, delivery, receipt or causal pathways of interventions using quantitative and/or qualitative data. These studies could have reported exclusively on process evaluations or on process alongside outcome data. To address research question 4, we included studies reporting on outcome evaluations using RCTs allocating schools, classes or individuals. Control participants could have been students, classes or schools allocated randomly to a control group in which no or usual school health and academic education was delivered or to a control group that included another ‘active’ intervention. To address research question 2, we drew on included process and outcome evaluations as defined above, which also included descriptions of intervention theories of change or logic models. To address research question 5, we aimed to draw on syntheses of all of the above study types.

Date

Studies were not restricted by date of research or publication.

Language

No language restrictions were placed on searches. Studies were not excluded based on language.

Search strategy

Database search strategy

Search terms

A sensitive search strategy was developed and tested by an experienced information scientist (CS). Test searches were undertaken in PsycINFO in order to further refine the search. Definitive searches were run between 18 November and 22 December 2015. Key search terms were determined by the review question and the inclusion criteria and were developed and tested against reports already known to the research team. The search strategy involved developing strings of terms and synonyms to reflect three core concepts in the review:

-

health education curricula (e.g. violence, smoking, drugs or alcohol education)

-

integration with academic learning (e.g. integration within mathematics or literacy teaching)

-

population and setting (e.g. primary and secondary school-aged children).

These concepts were combined in searches as follows: concept 1 and concept 2 and concept 3.

It was identified that relevant research is described with very diverse terminology, and that a broad range of search terms would be needed to identify relevant literature. Thus, a range of free-text and database-controlled vocabularies was used. The free-text searches were used across all databases and the search strategies were adapted within each database to incorporate database-specific controlled terms. Full details of the search strings used for each database can be found in Appendix 3.

Databases

The following 19 electronic bibliographic databases were searched from inception to between 18 November and 22 December 2015, with the precise date of the search varying between databases (see Appendix 3). These databases were selected to draw on research literature from the fields of education, economics, social sciences and health and health behaviour. The list of databases that were originally intended to be searched was amended (see Appendix 1) on the advice, informed by initial pilot searches, of the information scientist (CS):

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) via ProQuest

-

Australian Educational Index via ProQuest

-

BiblioMap (database of health promotion research) via Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre)

-

British Educational Index via EBSCOhost

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials via The Cochrane Library

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews via The Cochrane Library

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects via The Cochrane Library

-

Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews via EPPI-Centre

-

Dissertation Abstracts (UK theses, all dates; global theses 2010–15) via ProQuest

-

Econlit via EBSCOhost

-

Educational Research Index Citations via EBSCOhost

-

Health Technology Assessment Database via The Cochrane Library

-

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences via ProQuest

-

MEDLINE via Ovid

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database

-

PsycINFO via OVID

-

Social Policy and Practice Including Child Data & Social Care Online via OVID

-

Social Science Citation Index via Web of Knowledge

-

Trials Register of Promoting Health Interventions via EPPI-Centre.

Other search sources

The following 32 websites were also searched to identify relevant studies:

-

Cambridge Journals [URL: www.cambridge.org/core/ (accessed 12 January 2016)]

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Smoking & Tobacco Use [URL: www.cdc.gov/tobacco/index.htm (accessed 12 January 2016)]

-

Child and Adolescent Research Unit [URL: www.cahru.org/ (accessed 12 January 2016)]

-

Childhoods Today [URL: www.childhoodstoday.org/ (accessed 12 January 2016)]

-

Children in Scotland [URL: https://childreninscotland.org.uk (accessed 12 January 2016)]

-

Children in Wales [URL: www.childreninwales.org.uk/ (accessed 12 January 2016)]

-

Community Research and Development Information Service [URL: https://cordis.europa.eu/home_en.html (accessed 14 January 2016)]

-

Database of Educational Research (EPPI-Centre) [URL: https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/webdatabases/SearchIntro.aspx (accessed 14 January 2016)]

-

Drug and Alcohol Findings Effectiveness Bank [URL: https://findings.org.uk/ (accessed 14 January 2016)]

-

Google [URL: www.google.com (accessed 14 January 2016)]

-

Google Scholar [URL: www.scholar.google.com (accessed 14 January 2016)]

-

Government of Wales [URL: http://gov.wales/?lang=en (accessed 18 January 2016)]

-

Government of Scotland [URL: www.gov.scot/ (accessed 18 January 2016)]

-

Joseph Rowntree Foundation [URL: www.jrf.org.uk/ (accessed 18 January 2016)]

-

National Criminal Justice Reference Service [URL: www.ncjrs.gov/ (accessed 18 January 2016)]

-

National Society of the Prevention of Cruelty to Children [URL: www.nspcc.org.uk/ (accessed 18 January 2016)]

-

National Youth Agency [URL: https://nya.org.uk/ (accessed 18 January 2016)]

-

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio [URL: www.nihr.ac.uk/research-and-impact/nihr-clinical-research-network-portfolio/ (accessed 19 January 2016)]

-

Northern Ireland Executive [URL: www.northernireland.gov.uk/ (accessed 19 January 2016)]

-

OpenGrey [URL: www.opengrey.eu/ (accessed 19 January 2016)]

-

Personal Social Services Research Unit [URL: www.pssru.ac.uk/ (accessed 19 January 2016)]

-

Project Cork [URL: www.dartmouth.edu/∼cork/ (accessed 21 January 2016)]

-

University College of London Institute of Education Digital Education Resource Archive [URL: http://libguides.ioe.ac.uk/dera (accessed 21 January 2016)]

-

University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign [URL: http://illinois.edu/ (accessed 21 January 2016)]

-

US Centre for Substance Abuse Prevention [URL: www.samhsa.gov/accessed (accessed 21 January 2016)]

-

Social Issues Research Centre [URL: www.sirc.org/accessed (accessed 21 January 2016)]

-

The Campbell Library [URL: www.campbellcollaboration.org/library.html (accessed 21 January 2016)]

-

The Children’s Society [URL: www.childrenssociety.org.uk/ (accessed 21 January 2016)]

-

The Open Library [URL: https://openlibrary.org/ (accessed 22 January 2016)]

-

The Schools and Students’ Health Education Unit Archive [URL: http://sheu.org.uk/ (accessed 22 January 2016)]

-

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform [URL: www.who.int/ictrp/en/ (accessed 23 January 2016)]

-

Young Minds: Child & Adolescent Mental Health [URL: https://youngminds.org.uk (accessed 21 January 2016)].

Several of the above websites were not included in the original protocol1 but were added to the list later on (see Appendix 1).

Dependent on the functionality of each website’s interface, searches were undertaken using Google’s (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) function to search a website, using the following search: ‘(drugs OR alcohol OR smoking OR violence OR bullying OR weapons) AND (primary school OR secondary school OR elementary school OR junior high OR high school) AND (lessons OR curriculum OR classes OR classroom OR health education OR health literacy OR health promotion)’. Websites were searched using the Google site function to enable more advanced search functioning than is typically possible using the search within each website. This search function enables all relevant webpages under a specific domain to be searched at the same time. Furthermore, results are returned within Google, which enables easy numeration of references found. For websites that are databases themselves (e.g. EPPI-Centre Database of Educational Research, NIHR Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio, OpenGrey, University College of London Institute of Education Digital Education Resource Archive and The Open Library) the following search was used: ‘(drugs OR alcohol OR smoking OR bullying OR violence) AND (primary school OR elementary school OR high school OR secondary school) AND (curriculum OR integration OR lessons OR education)’. All webpages were then explored for their relevance and included if they met our inclusion criteria.

Subject experts in the field who were known to us a priori were contacted to identify possible studies for inclusion, including unpublished or ongoing research. See Appendix 4 for the experts contacted, a template of the e-mail sent to them and the included studies found via this search method. The reference lists of all included studies were searched for further relevant studies. The protocol stated that we would hand-search journals when these were not indexed on databases to be searched, but that published included study reports found only via reference checking. 1 No such studies were found and so no hand-searches were conducted.

Update searches

We noted that all reports of outcome evaluations were retrieved from a combination of Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and PsycINFO searches. Given the date of our original searches, we reran tailored versions of our original search strategy in both of these databases to search for outcome evaluations. Searches for outcome evaluations relating to substance use were undertaken on 14 May 2018, and searches for outcome evaluations relating to violence were undertaken on 28 February 2018. Findings from these searches were subject to the same study selection, data extraction and synthesis methods as findings from the main searches.

Information management

All citations identified by our searches were uploaded and managed during the review process using the EPPI-Centre’s specialist online review software, EPPI Reviewer version 4.0 (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre, University of London, London, UK). This software records the bibliographic details of each study, where studies were found and how, reasons for their inclusion or exclusion, descriptive and quality assessment codes, text about each included study and the data used and produced during synthesis. The software also enabled us to store and track electronic documents [e.g. portable document files (PDFs)].

Study selection

An exclusion criteria worksheet was prepared, informed by our inclusion criteria (see above) and with guidance notes. For the screening of references identified from electronic databases, this was piloted by four reviewers (CB, TT, GMT and AF) who screened 50 references in pairs on title and abstracts. Pilot screening results were discussed by pairs of reviewers involved in screening to ensure consistency in applying the criteria. This process was invaluable because, despite being guided by clear inclusion criteria, decisions about whether or not an intervention aimed to integrate health and academic education were not always easy. The definition of integration in terms of full and partial integration of health and academic education was also helpful in making clear decisions about which studies to include or exclude. A 90% agreement rate was required before proceeding to screening by single reviewers, with each reviewer screening discrete subsets of the full set of references. Full reports were obtained for those references judged as meeting our inclusion criteria based on title and abstract, or for which there was insufficient information from the title and abstract to judge inclusion or exclusion. These reports were then screened to determine inclusion. The reviewers piloted the procedure by screening full reports and working in pairs screening 50 reports each and discussing any differences in opinion. A 90% agreement rate was required before proceeding to independent screening of the full set of references. The principal investigator (CB) reviewed all studies identified as potentially includable in the review as a final check to determine inclusion, identify which review question they answered and group multiple reports from the same study. Citations identified from websites were screened online based on their title, title and abstract or full text, when available. Potentially includable studies were cross-referenced with the electronic searches imported to EPPI-Reviewer to identify any unique references. As is customary with searching of this type, only the included references, not the excluded ones, were recorded.

Data extraction

Tools

Data were extracted using coding tools developed for the review components relating to each review question (see Appendices 6–8). Each tool drew on and supplemented the codes used in the EPPI-Centre classification system for health promotion and public health research. 62 For studies describing a theory of change,3 we extracted data on the description of the theory of change, rationale for integrating health and academic education, links to other theories and how the theory differs from others included in the study. For process and outcome evaluations, we extracted data using a modified version of an existing tool,62 including items on study location, intervention/component description, description of integration, intervention development, timing of the intervention and evaluation, target population description, provider and provider organisation characteristics, research questions or hypotheses, timing of the evaluation, sampling methods and sample size at baseline and follow-up, sociodemographic characteristics of participants at baseline and any follow-ups, and data collection and analysis. After piloting and refinement, two reviewers working independently extracted study reports before meeting to agree on coding. For studies reporting on outcome evaluations, we also extracted data on research design, the nature of the control group(s), the unit of allocation, the generation and concealment of the allocation, blinding, baseline equivalences between control and intervention groups, the adjustment/control of clustering and confounding, the use of intention-to-treat analyses, outcome measures and the evidence of reliability and validity, and effect sizes overall and by age, sex, SES, and ethnic subgroup.

Data extraction process

Data extraction tools were piloted on five studies (two theory reports, two process evaluations and one outcome evaluation). Reviewers met to compare extraction and identify any differences that might inform refinements of the coding tools or how these were applied. All study reports were then extracted by two reviewers working independently in parallel, before meeting to discuss and agree on their coding to ensure quality and consistency in their interpretations.

Missing data

When additional data were needed to calculate effect sizes, we contacted the authors for the relevant information. If authors did not provide the relevant information, we used the best approximation available, generally by using other information from within the same study (see Appendix 8 for a template of the e-mail sent to authors to obtain additional data).

Quality assessment

Quality assessment process

The quality of each study was independently assessed by two reviewers with differences in opinion resolved by discussion, without the need for recourse to a third reviewer, except for reports of theory. For theory reports, there were frequent differences of opinion. Discussion between the reviewers concluded that these differences were inevitable and could not be addressed through consultation with a third reviewer. Despite our best efforts in developing quality criteria informed by previous research (see Quality assessment tool for theory studies), some criteria could not be applied to make objective judgements. As a result, for theories of change we decided to report each reviewer’s independent judgements (see Appendix 9).

Quality assessment tool for theory studies

The quality of studies reporting on theory was assessed using a tool adapted from a previous review64 informed by other recent work on theory synthesis. 65 Quality was assessed in terms of:

-

clarity

-

constructs defined

-

clear pathways from intervention inputs to outcomes

-

-

plausibility/feasibility

-

theory is logical with plausible pathways from intervention inputs to behaviour change

-

theory is supported by existing empirical evidence

-

-

testability

-

evidence of empirical testing of theory

-

-

ownership

-

theory has been developed with practitioners

-

theory has been developed with community members

-

-

generalisability

-

theory is presented as generally applicable to different contexts

-

theory describes how it is applicable to different contexts

-

authors present empirical evidence of the generalisability of the theory.

-

Quality assessment tool for process evaluations

Process evaluations were assessed using the standard Critical Appraisal Skills Programme and EPPI-Centre tools66 developed to assess qualitative studies and assess the rigour of whether or not the sampling strategy was indicated, the data collection methods were indicated (including any statements around increasing the rigour of data collection), the methods of data analysis were indicated (including any statements around efforts made to improve reliability of findings and reduce bias) and the extent to which the study findings were grounded in the data, privileged the perspectives of youth participants and the breadth and depth of findings. The tool was used in this review to assess process evaluations regardless of whether these drew on qualitative or quantitative data, because the criteria were judged applicable to both. A final step in quality assessment was to assign studies two types of ‘weight of evidence’. First, reviewers assigned a weight (i.e. low, medium or high) to rate the reliability or trustworthiness of the findings (i.e. the extent to which the methods employed were rigorous/could minimise bias and error in the findings). Second, reviewers assigned an additional weight (i.e. low, medium or high) to rate the usefulness of the findings for shedding light on factors relating to the review questions. Guidance was given to reviewers to help them reach an assessment on each criterion and the final weight of evidence. To be judged as highly reliable, studies needed to have taken steps to ensure rigour in at least three of the first four criteria. Studies were judged as medium when scoring only two out of the first four criteria and low when scoring only one or none out of the first four criteria. To achieve a rating of ‘high’ on usefulness, studies needed to be judged to have privileged the perspectives of participants and to present findings that achieved both breadth and depth. Studies that were rated as ‘medium’ on usefulness only partially met this criteria, and ‘low’ rated studies were judged to have sufficient but limited findings. Quality was used to determine the qualitative weight given to findings in our synthesis, with none of the themes represented solely by studies judged as low on both dimensions.

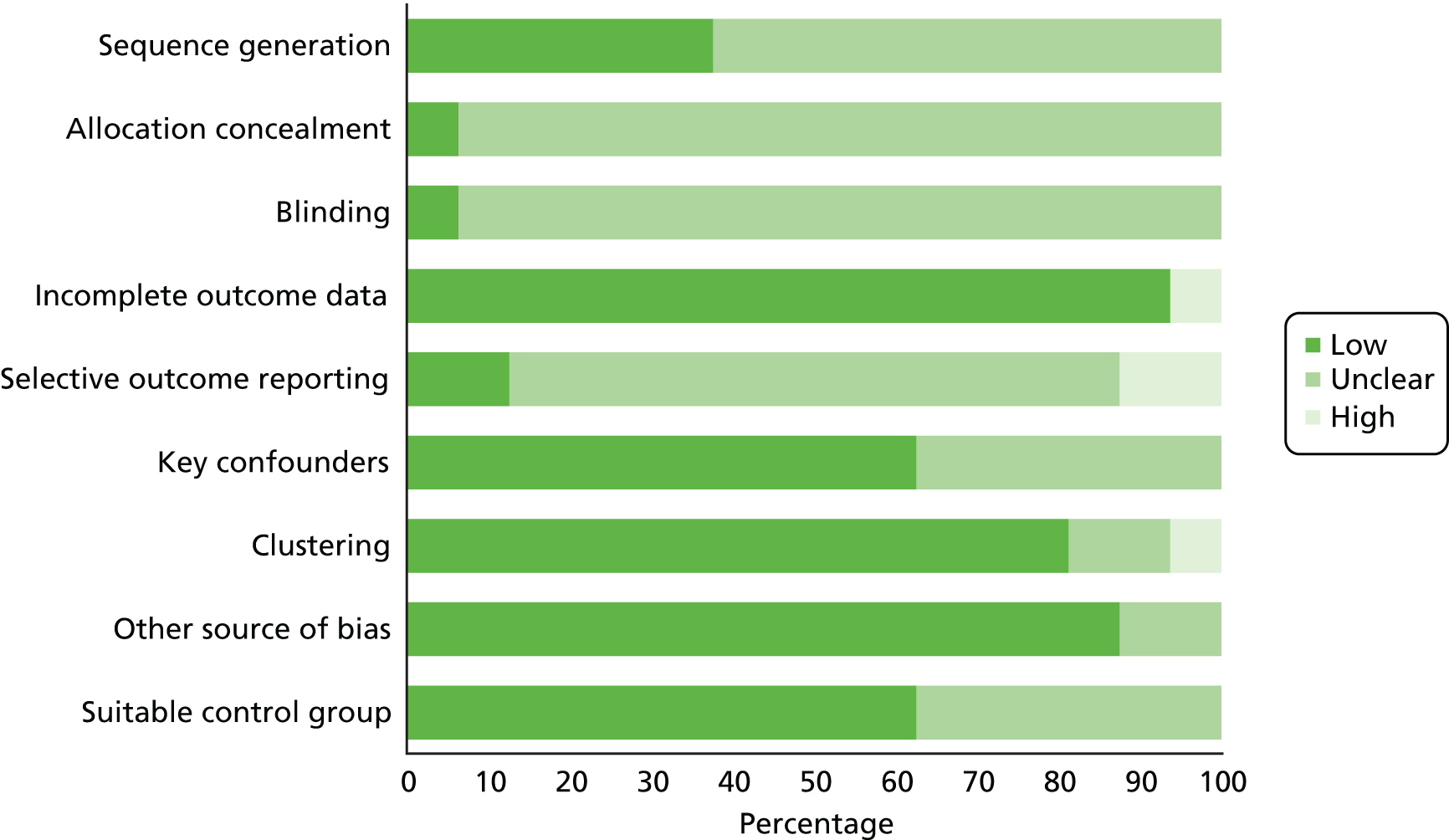

Quality assessment tool for outcome evaluations

Outcome evaluations were assessed for risk of bias using the tool modified from the questions suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 67 For each study, two reviewers independently judged the likelihood of bias in seven domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (of participants, providers or outcome assessors), completeness of outcome data, whether or not clustering was accounted for, other sources of bias and the suitability of the control group. Each study was subsequently allocated a score of ‘high risk’, ‘low risk’ or ‘unclear risk’ within each domain. We used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) approach as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions67 to present the quality of evidence (see Table 3). The downgrading of the quality of a body of evidence for a specific outcome was based on five factors: limitations of the study, indirectness of the evidence, inconsistency of results, imprecision of results and publication bias. The GRADE approach specifies four levels of quality (i.e. high, moderate, low and very low).

Synthesis of results

Intervention descriptions

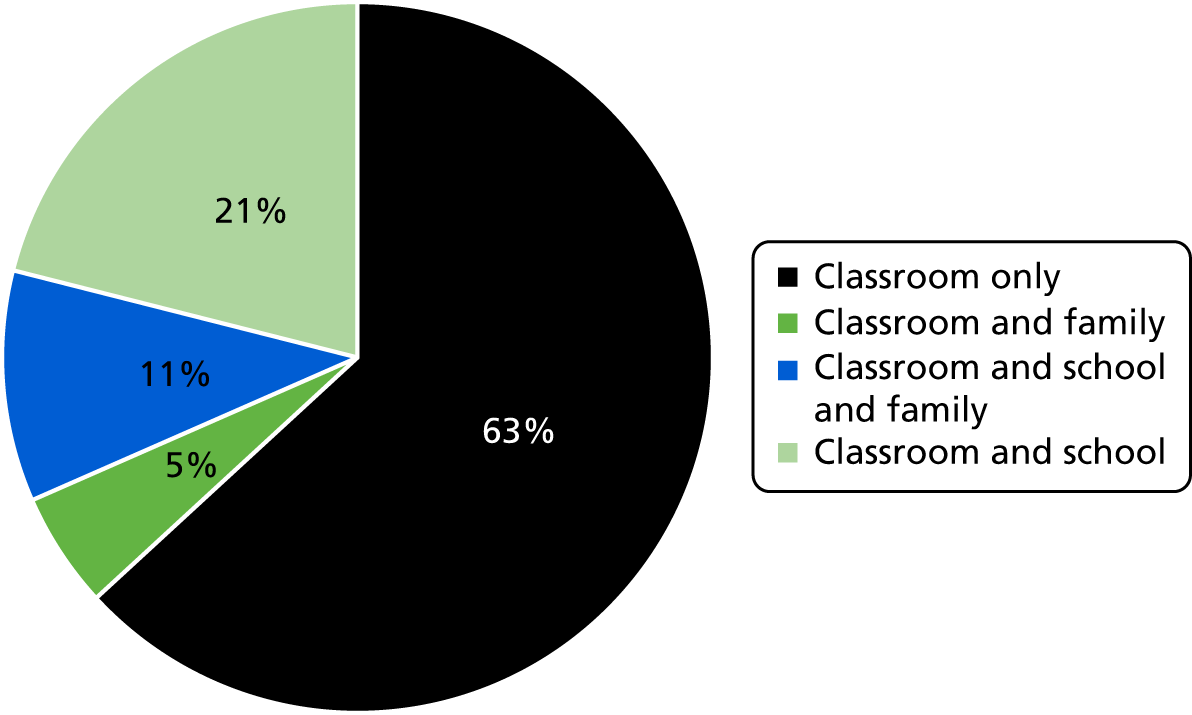

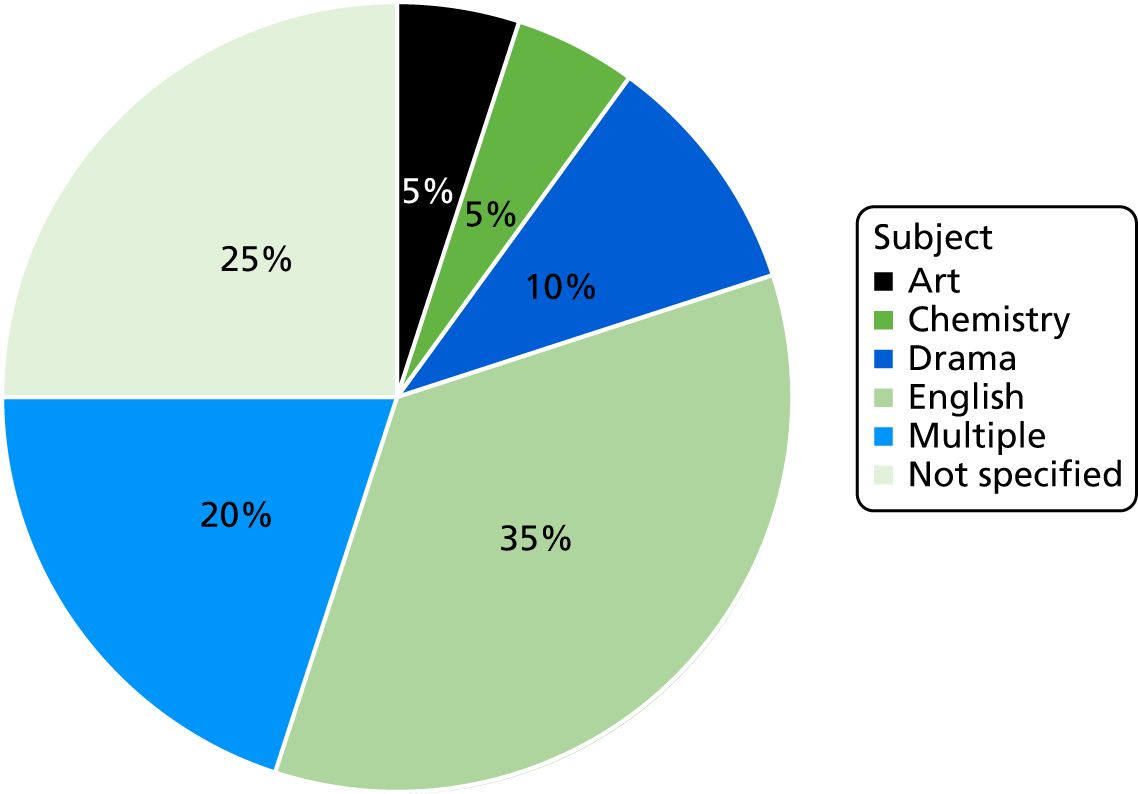

We first produced a basic descriptive categorisation of interventions based on a narrative review of intervention descriptions in all study reports in order to report on their targeted school level, providers, components, the subject within which the intervention is delivered and the extent of integration of health and academic education.

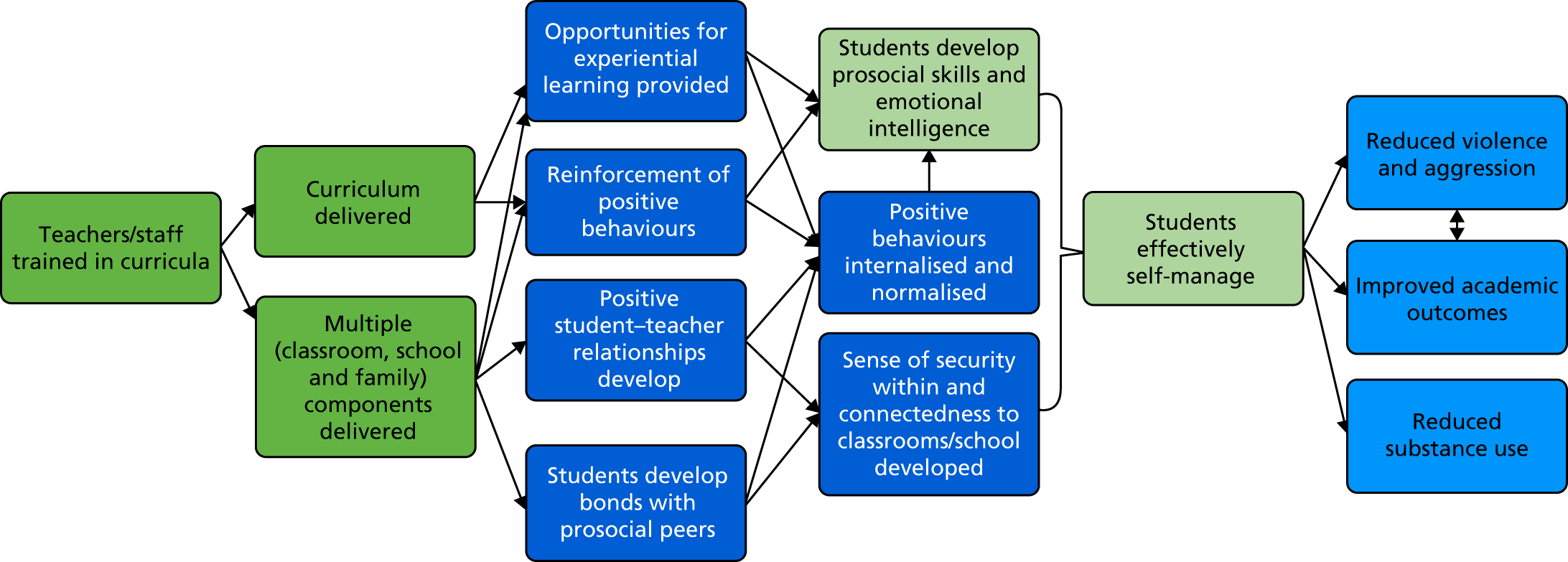

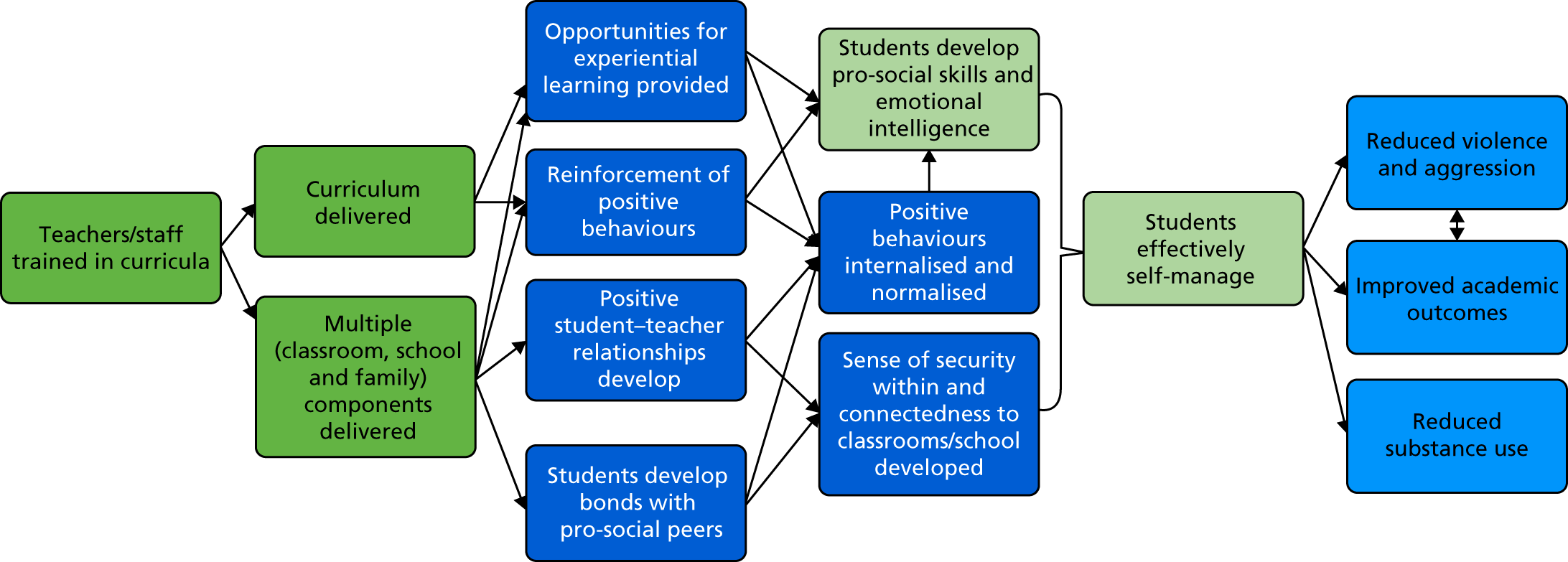

Theories of change

We then synthesised theories of change. There is a growing literature on synthesising theories of change of interventions. Methods of theory synthesis tend to draw on methodological approaches to synthesising empirical qualitative data (or ‘qualitative synthesis’). 68 Methods of qualitative synthesis, in turn, draw on methods of primary qualitative data analysis. 69 Broadly, common principles and practices apply to different approaches to qualitative analysis and synthesis, including data immersion, an emphasis on depth, iterative coding, triangulation among multiple researchers, and the purposive inclusion of ‘deviant’ cases in the analysis.

There are several examples of systematic reviews and syntheses of theories of change within the public health literature. 70 There are challenges when applying methods used to synthesise empirical qualitative data, which are generally context specific, to the synthesis of theory, which is generally abstracted from context. 71 However, we considered that synthesis could be achieved by treating theory data as primary data in itself. We considered that synthesising theories of change for interventions that have similar premises and similar stated outcomes could also be conducted through meta-ethnography. 71,72

For the theory synthesis reported here, we noted that two levels of analysis would be possible and useful. First, it was possible to synthesise theories of change for each individual intervention included in the review. These may have been reported on only once or by multiple authors and across multiple reports. Second, it was possible to synthesise theories across all interventions to explore points of reciprocal resonance, refutation and/or complementarity potentially leading to the development of a line of argument ‘representing different stages along the same causal pathway’. 73 This led us to employ a mix of methods: line-by-line coding and thematic synthesis69 for the ‘within intervention’ theories, and meta-ethnography for the ‘across-intervention’ theories. Specific methods are detailed below.

For the thematic synthesis of individual intervention theories, two reviewers first read and reread two reports deemed by two reviewers to be of high quality (i.e. having quality scores > 50%) (see Appendix 9), by different authors and focused on the same intervention. Line-by-line codes were applied and memos were written to identify and explain the content of the description of theory. Codes were then grouped, organised into frameworks and exchanged and compared between the reviewers to develop an overall set of codes (see Appendix 10 for an example of this). This set of codes was then applied to any other study reports for the intervention in question, keeping track of and comparing any modification with the coding framework made as a result of the coding of subsequent reports. Having judged that this piloted process was appropriate, it was then repeated for each intervention.

In this way, we synthesised theories for each individual intervention. Thematic synthesis identified commonalities, differences of emphasis and contradictions within the single or multiple reports for each individual intervention theory of change, drawing on the coding described above. 3 Any apparent inconsistencies were resolved by discussion. A third reviewer helped achieve reconciliation when necessary. When only one report described the theory of change for an intervention, that was taken to represent the theory of change for that intervention. This process enabled us to develop summaries of the theories of change for each intervention, describing intervention inputs, mechanisms of change, underlying assumptions, and proximal and distal outcomes. These individual theories of change were undertaken as a preliminary step, prior to undertaking an across-intervention synthesis, and are not presented in this report.

For meta-ethnography across intervention theories, we used a meta-ethnographic approach to synthesise across individual intervention theories of change to develop an overarching theory of change for the overall category of interventions that integrate health and academic education to prevent substance use and violence (see Appendix 11). We determined that meta-ethnography was an appropriate method for this synthesis given it is commonly applied to synthesising areas of literature that are diverse yet share commonalities, as we judged was the case with the included theories of change for interventions integrating health and academic education. 68

In this approach we considered the key concepts extracted during the coding exercise as our primary data, treating these concepts as ‘first-order constructs’. 74 These were considered first-order constructs because they represented the authors’ key theoretical concepts, and so were distinctive from authorial points within an empirical study report, which are rightly regarded as second-order constructs. 70,75 We then generated second-order concepts that were our interpretations of authors’ views. 71,72,76 Finally, we developed third-order constructs through a process of reciprocal translation (a dynamic, iterative process during which concepts from each of the previous syntheses were ‘translated’ into one another). We then adapted an approach from Britten et al. ’s76 worked example of meta-ethnography to build up the line of argument of the overall synthesis of the theory of change for the interventions included in our systematic review.

Developing a line of argument was challenging because intervention theories in many cases described similar notions but offered limited explanations for key concepts and assumptions. In developing our third-order constructs and overarching synthesis, it was helpful to use an existing theoretical framework to identify commonalities across what initially might have appeared to be a set of disparate concepts. Informed by the notion of ‘boundary erosion’ proposed by Markham and Aveyard77 as a key mechanism by which schools may promote student health, we integrated concepts arising from the individual syntheses into a set of third-order constructs and so developed an overall line of argument. A few themes did not initially fit with the concept of boundary erosion as presented by Markham and Aveyard. 77 This stimulated us to refine and expand the concept of boundary erosion so that it could encompass these apparently divergent themes. These are presented alongside our line of argument synthesis in Appendix 11, Table 14.

Process evaluations

Process evaluations reported qualitative, quantitative or mixed results. Process evaluations were synthesised qualitatively using thematic synthesis methods68,78 applied to both qualitative and quantitative results. Although some quantitative studies did examine correlates of implementation, these findings were too heterogeneous to meta-analyse statistically. Instead, textual reports of quantitative results were subject to thematic synthesis after first checking that they were consistent with the quantitative data presented in study reports.

Thematic synthesis proceeded via the following process: studies were first read and reread by two reviewers and the two reviewers then carried out line-by-line coding of process data, drawing inductive codes from the process data itself (see Appendix 12 for a coding template for all process studies). Coding focused on textual reports that included verbatim qualitative data excerpts and author interpretations of these.

Reviewers wrote analytic memos throughout to describe emerging ‘meta-themes’. Each reviewer developed an emerging coding structure of hierarchically arranged codes applied in the course of the analysis. The two reviewers then compared their coding to agree on a common structure that formed the basis for the synthesis. This approach to coding was first piloted on two studies before proceeding, without modification, to the remainder of the reports. As the overall analysis was developed, the reviewers referred to tables summarising the methodological quality of each study to ensure that the synthesis reflected study quality.

Outcome evaluations

We undertook both narrative and meta-analytic syntheses of the results of outcome evaluations. Our narrative synthesis included both end-point measurements and trajectory estimates. Many evaluations compare participants on differences in change over time, but meta-analytic methods have not yet been developed for these models. Thus, we narratively synthesised trajectory evidence from interventions separately.

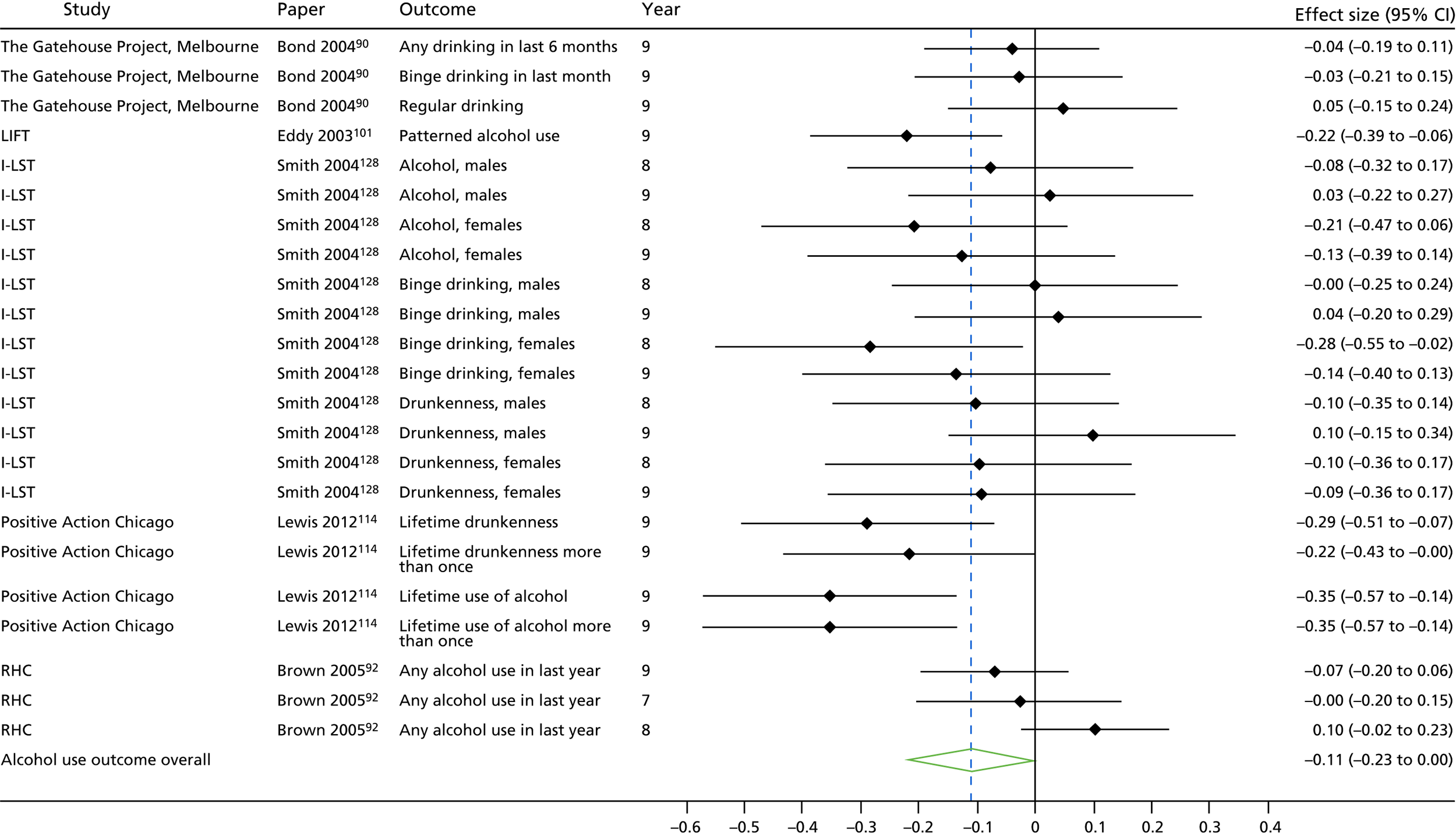

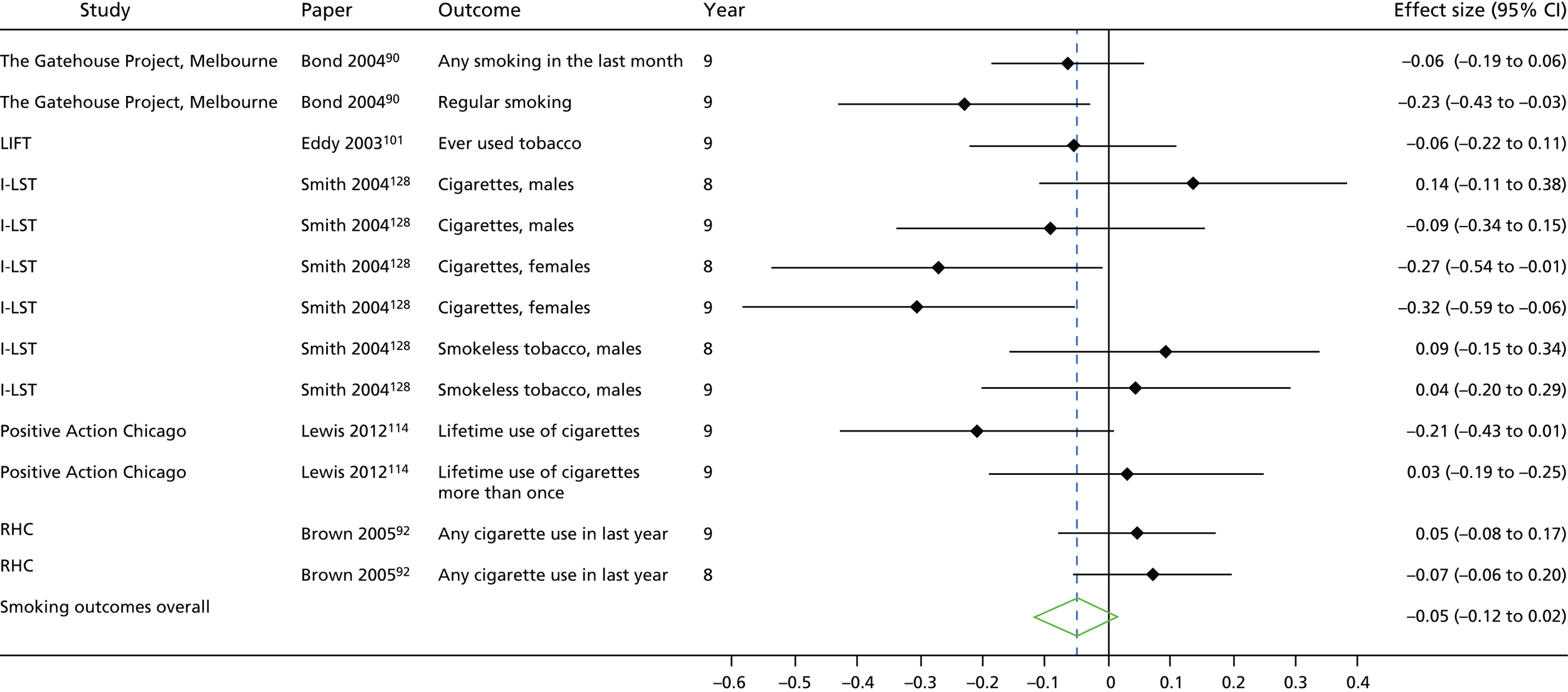

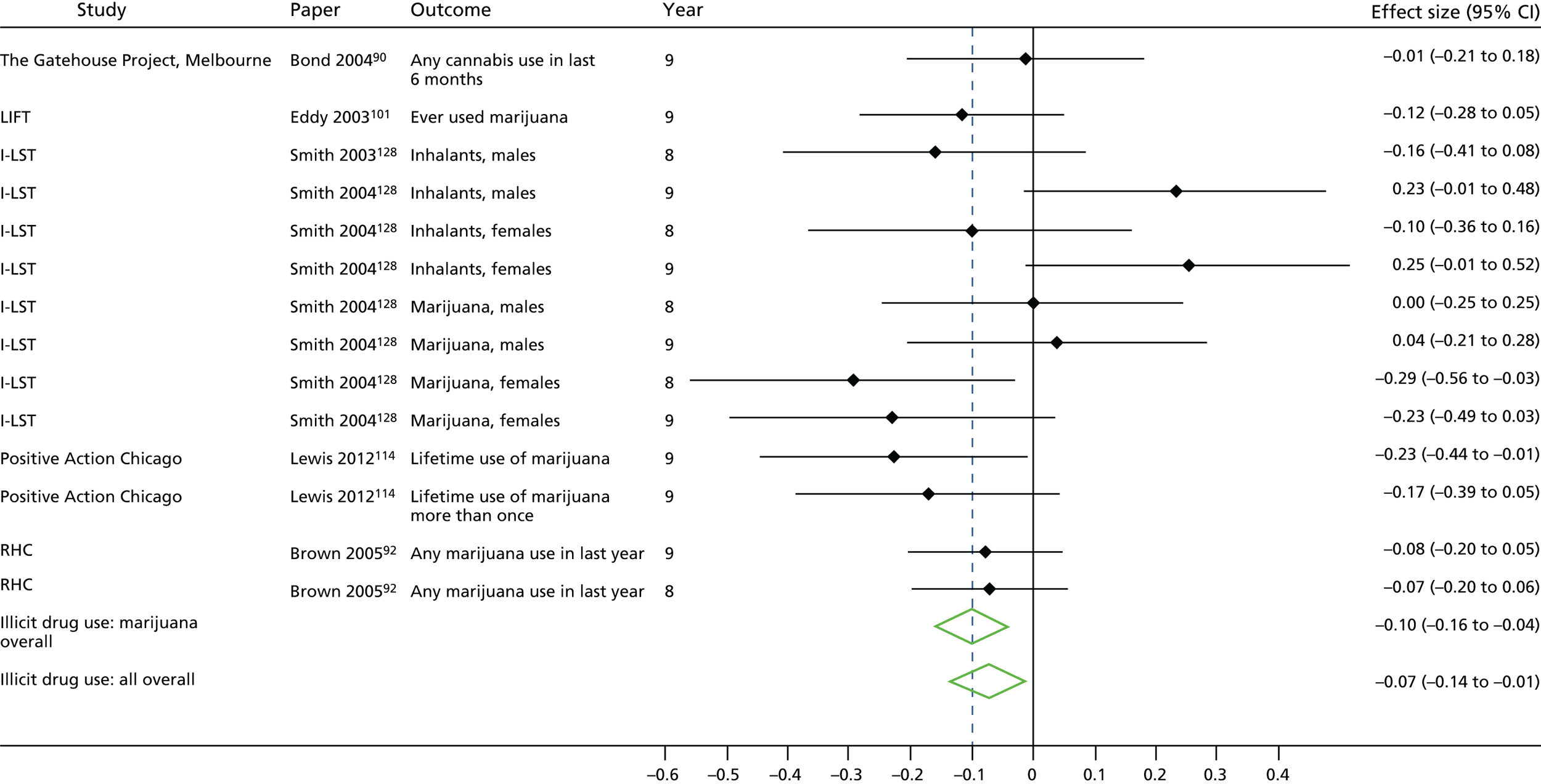

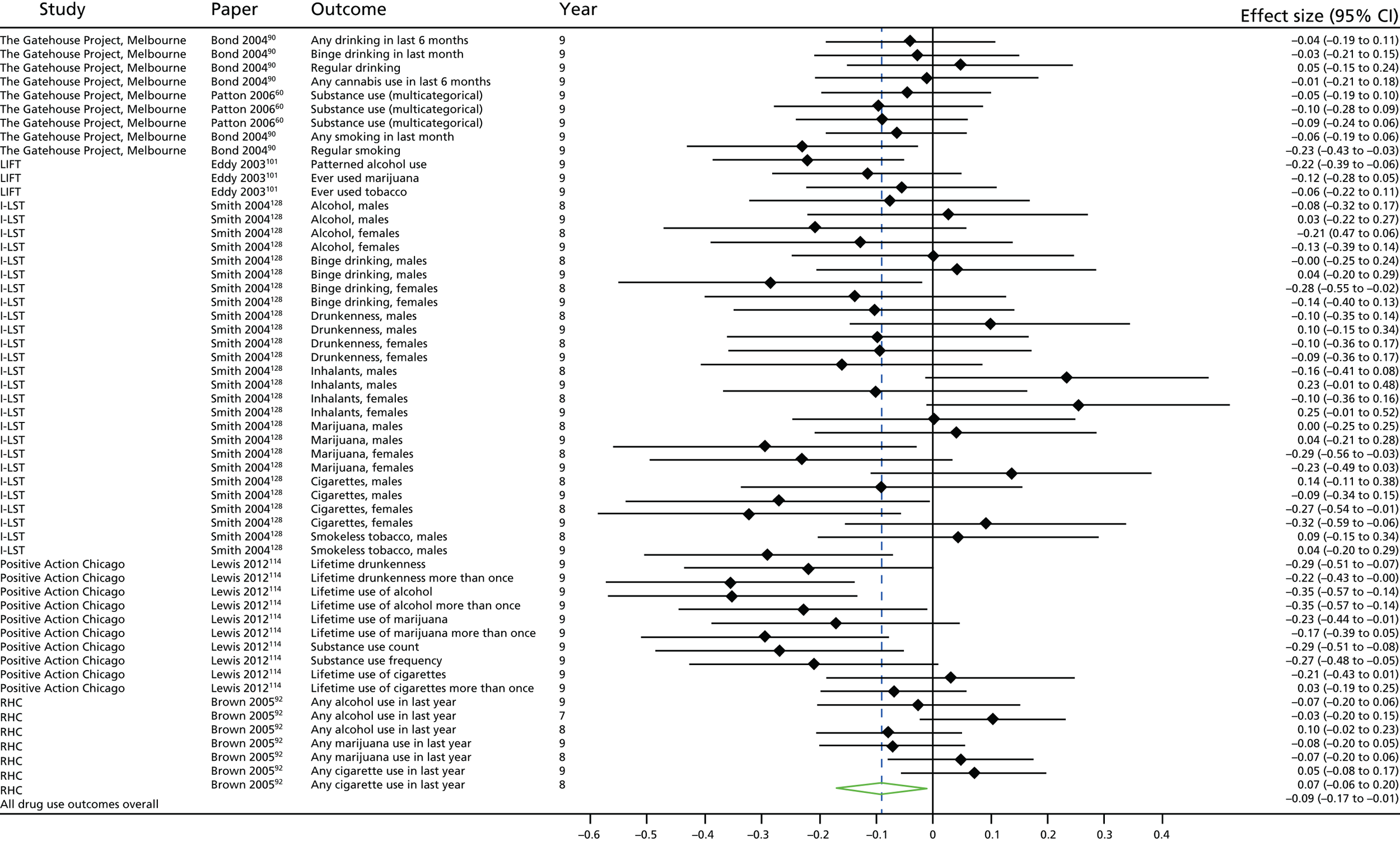

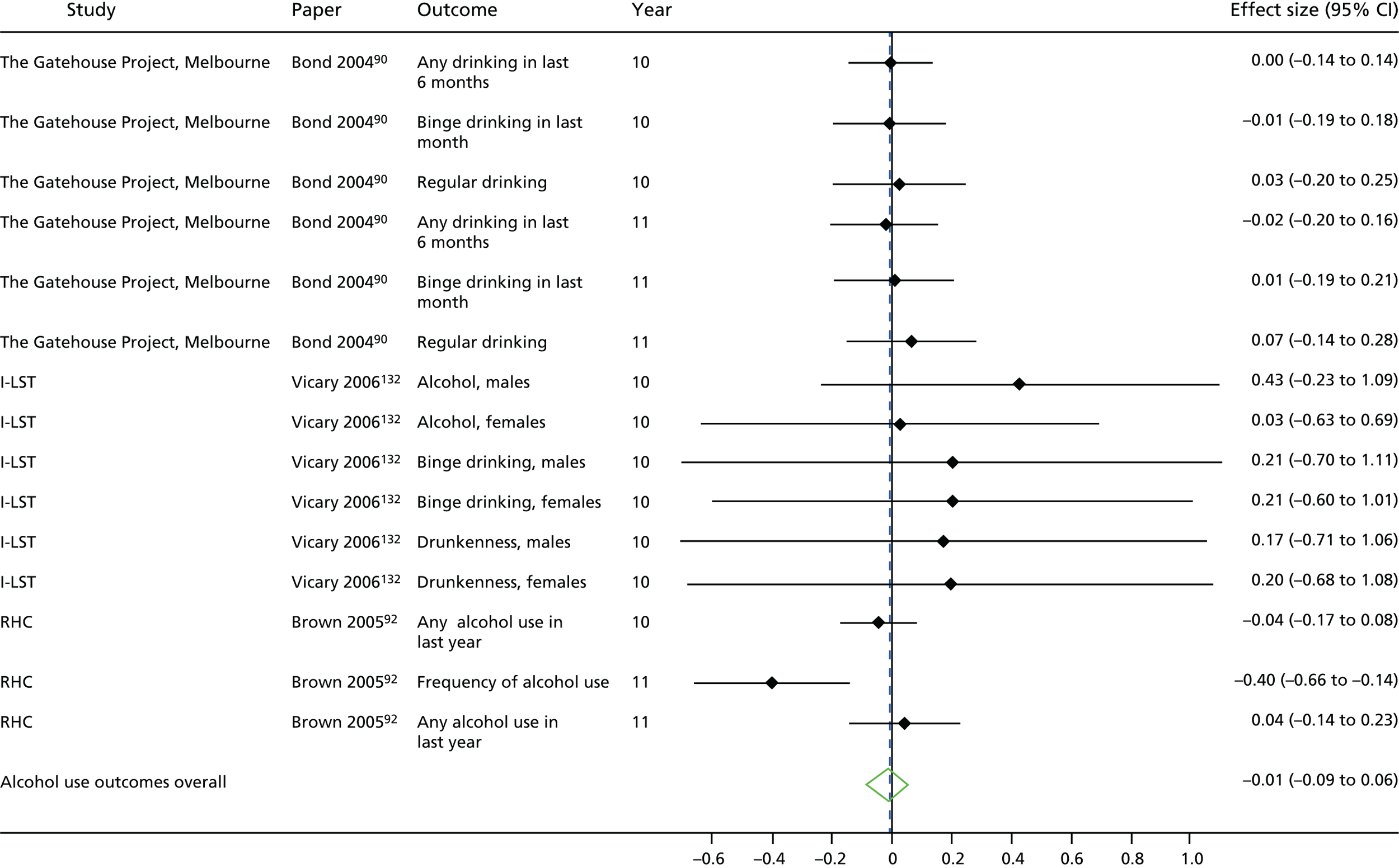

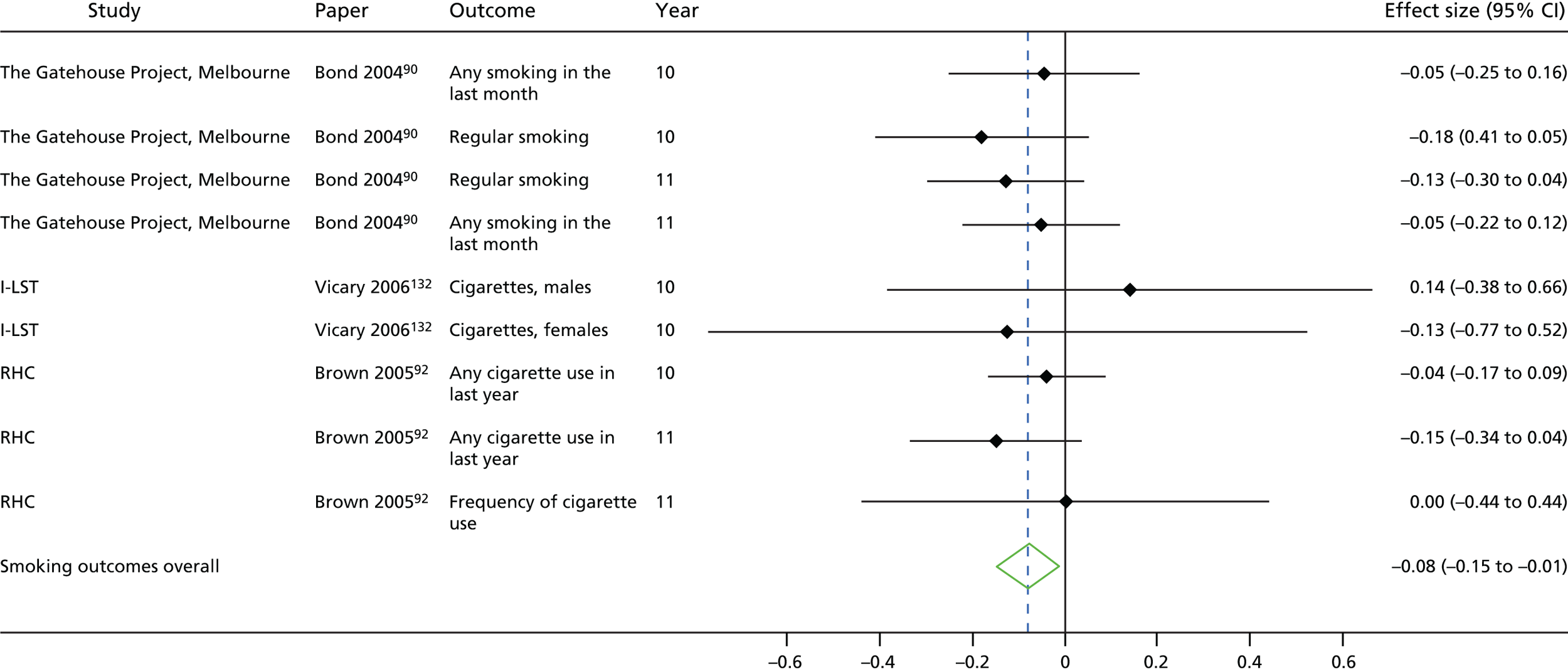

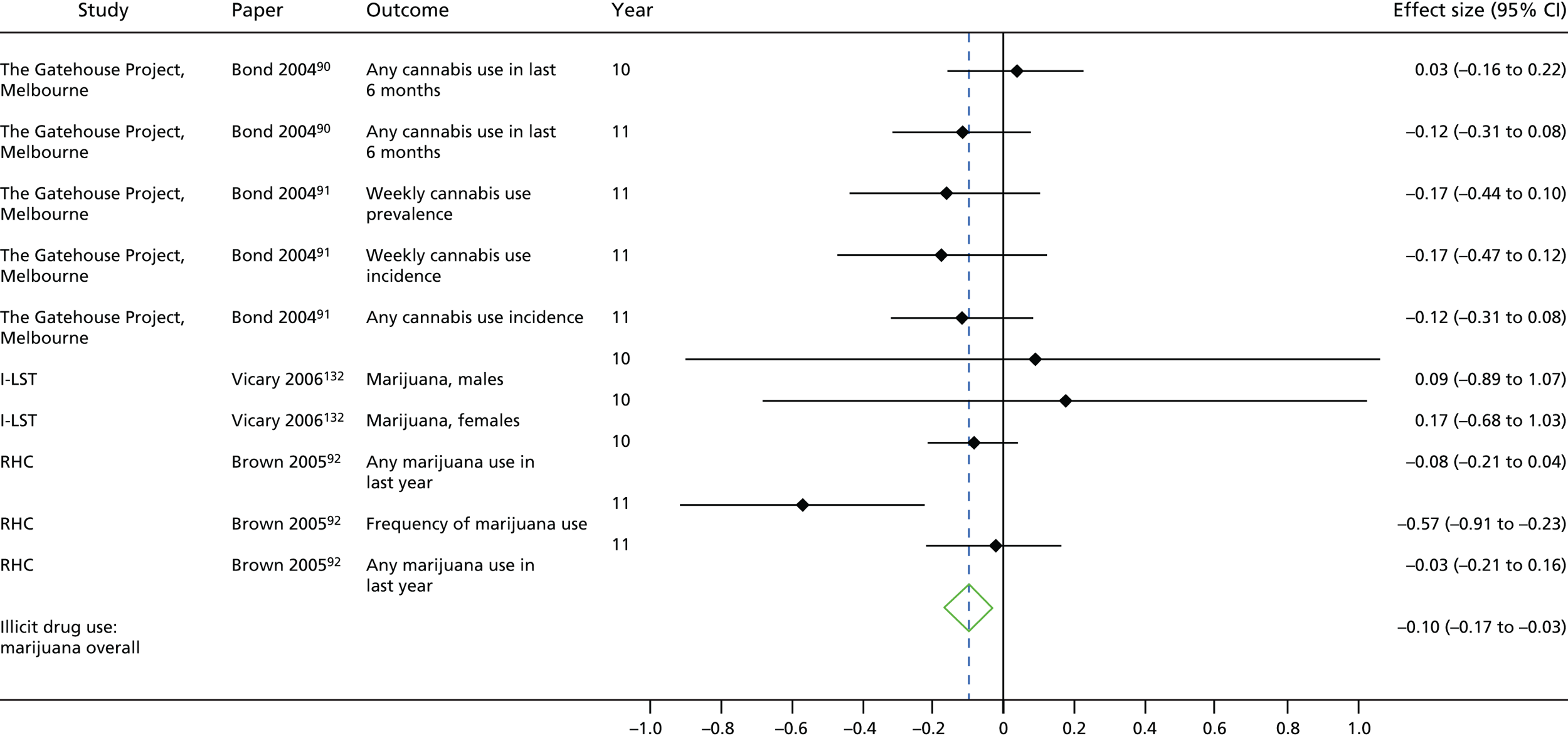

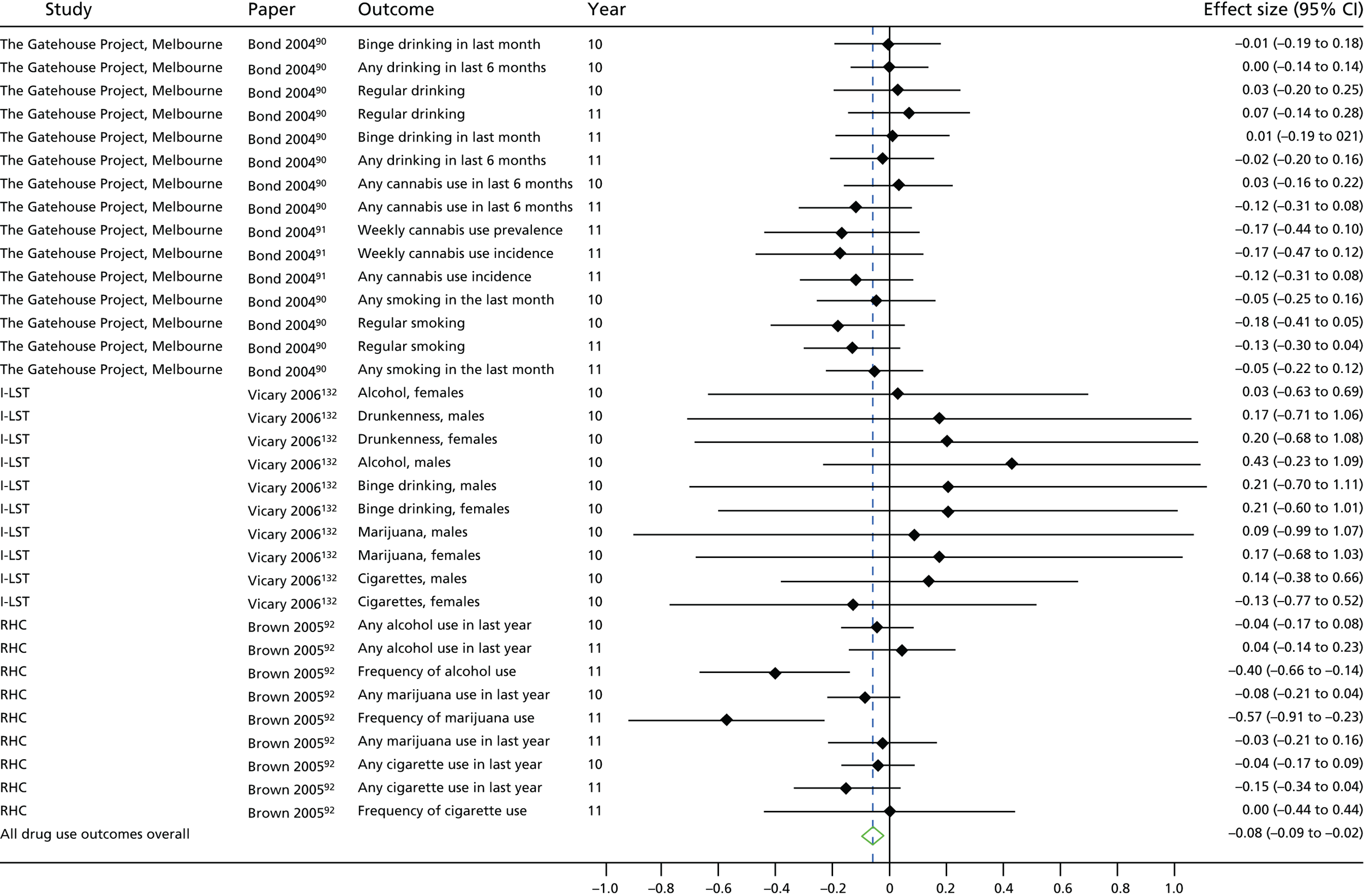

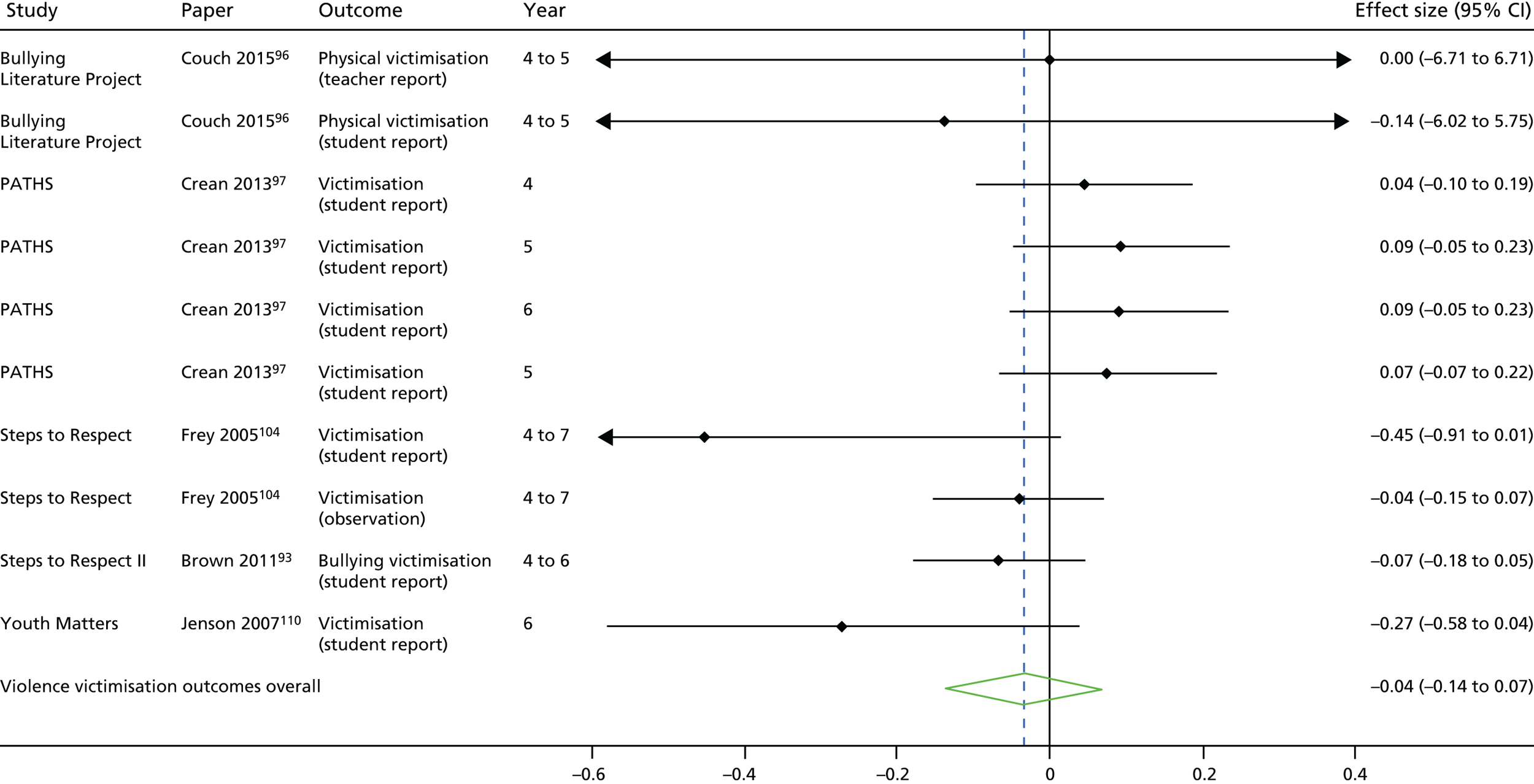

Effect sizes from included study reports concerning substance use (i.e. smoking, alcohol or drugs) or violence, as defined in the protocol,1 were extracted into a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet and converted into standardised mean differences (MDs) (Cohen’s d) using all available information as presented for each study. Because all evaluations were cluster randomised trials, some baseline imbalance on individual participant characteristics was likely. Thus, we used effect estimates adjusted for covariates when these were presented alongside unadjusted estimates. In interpreting the results of meta-analyses, we followed the standard rule for the interpretation of Cohen’s d: 0.2 is a small effect, 0.5 is a medium effect and 0.8 is a large effect. Negative effect sizes indicate a positive effect (e.g. a reduction in substance use).

Because of the variation in reporting across studies, some degree of data transformation and imputation was necessary (see Appendix 13). Odds ratios (ORs) were converted to standardised MDs assuming the logistic transformation. When appropriate, we used the test statistic values from t-tests and F-tests to estimate the standardised MD. Clustering was accounted for when possible and necessary, using information provided in the evaluation and through contact with authors.

Most studies reported several substance use and violence outcomes at several measurement time points. As indicated in the protocol,1 we used multilevel meta-analysis as set out by Cheung79 and Van den Noortgate et al. 80 with random effects at both the outcome and study level. Multilevel meta-analysis accounts for dependencies between outcomes from the same study by partitioning the variance (τ2) between outcomes into a within-study and a between-study level. The final effect size estimate includes all of the information that the multiple effect size estimates contribute while correcting for the non-independence of multiple effect size estimates from each study.

A standard three-level model was used, with level one being the ‘hypothetical’ participants who contributed to the effect sizes, level two being the within-study outcome-specific effect size estimates with sampling error and level three being the between-study level. Because several evaluations were reported as multiple papers, the between-study level does not reflect clustering by paper but rather by evaluation.

We aimed to estimate several different models. Because interventions are often measured at several time points in the developmental trajectory, we created a ‘matrix’ of key stage (KS) (Table 1) against type of outcome. We then meta-analysed findings within each cell of the matrix when appropriate (e.g. substance use for students in KS3). We set out to estimate models for substance use, violence perpetration and violence victimisation. Within substance use, we considered omnibus outcomes (e.g. count of substances used, any substance use), alcohol outcomes, smoking outcomes and illicit drug use outcomes separately, and then as a combined model to examine the global impact of these interventions on substance use.

| KS | Years included |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1–2 |

| 2 | 3–6 |

| 3 | 7–9 |

| 4 | 10–11 |

| 5 | Sixth form (years 12–13) |

For each model, we estimated an overall effect size expressed as a standardised MD with a 95% confidence interval (CI). We estimated I2 at the study level using the variance components implied by the multilevel model. Interpretation of I2 at the level of the study is most comparable to the interpretation of I2 in ‘standard’ meta-analyses that include one effect size per study.

We intended to estimate meta-regression models to examine how intervention effects varied by participant SES, sex and ethnicity, to examine how intervention effects varied by area deprivation and in order to test hypotheses on other moderators of effects. These other hypotheses were derived from the syntheses of theory and process evaluations, and consultations with young people and policy/practitioner stakeholders. However, such analyses were not possible because of the absence of meaningful heterogeneity in effects between studies as well as the lack of consistency of reporting of subgroup effects within studies. We also intended to run a qualitative comparative analysis to examine the causal combinations of conditions that predict intervention effectiveness. However, this was not possible because of the generally poor description of interventions. We also did not find sufficient studies (≥ 10 per outcome) to draw funnel plots to assess the presence of possible publication bias. Full details of these methods may be found in our protocol. 1

Note on terms used in the synthesis of outcome evaluations

Included interventions were conducted in a diversity of settings. For the sake of clarity, we used intervention descriptions to map when interventions were implemented in children’s educational progression to the UK system (i.e. years 1 to 13). Because included evaluations often tested multiyear interventions, we generally describe points of follow-up in terms of when measurements occurred relative to the start of the intervention. For example, a measurement taken in the first summer term after an intervention’s start would be described as ‘at the end of the first intervention year’, and a measurement taken at the start of the school year following the initiation of the intervention would be described as ‘at the start of the second intervention year’. For each set of outcomes synthesised, we present a schematic depicting when interventions were implemented and when outcome measurements were presented in evaluations.

User involvement

We conducted two sets of one-to-one consultations to reflect on our findings with young people and with policy and practice stakeholders. Individual consultation was used instead of group meetings because of the impossibility of finding a date when all could attend a meeting. The first set of consultations was conducted from December 2016 to June 2017. As per the protocol,1 we aimed to discuss the validity of our typology of interventions and synthesis of process evaluations and identify the feasibility and acceptability of such interventions in the UK. Our original intention was to then use these discussions to determine which specific interventions should be included in a secondary analysis of outcome data focused on interventions most relevant for the UK. However, it was clear from our typology of interventions and synthesis of process evaluations, as well as from consultation with stakeholders, that it was not possible to identify a discrete subset of interventions that were relevant to the UK. All interventions were potentially relevant to the UK with adaptation. The adaptations required would concern the detail of the intervention materials rather than the overall intervention approaches and theories of change.

Stakeholders’ views were sought about the potential feasibility and acceptance of integrated academic and health education within the UK (see Appendix 14). We asked the following general questions:

-

Could this type of intervention be delivered within the UK?

-

If so, which intervention characteristics (e.g. delivered within primary or secondary schools, delivered within specific academic classes, integration being ‘full’ or ‘partial’, intervention being facilitated by teachers, etc.) would be the most appropriate?

-

Do you think schools would be receptive to this type of intervention in the UK?

-

What factors would enable or inhibit these types of interventions in the UK?

In addition, based on some preliminary findings from the review, as well as on the review team’s previous experiences, we explored the following hypotheses with stakeholders:

-

Interventions of this sort will, in general, be more feasible in primary rather than secondary schools because the timetable is more flexible and the emphasis is on core skills (e.g. literacy) that such interventions often address.

-

Interventions will be more feasible when they target an academic subject that is part of the national curriculum for students of that year group.

-

Interventions that aim to integrate health with academic subjects that not all schools or students will study will have much less reach (e.g. drama).

-

Interventions that focus on students beyond year 9 will be less attractive to schools because they will be perceived as reducing curriculum time for exam preparation.

-

Interventions that aim to fully integrate health into existing academic education will be more feasible than those which provide discrete new curricula that include separate health and academic components.

-

Interventions that are to be delivered in regular, timetabled health education lessons (e.g. PSHE) will be less feasible because many schools, especially at the secondary phase, do not run such lessons.

-

Interventions that include the whole school alongside classroom elements will be feasible in principle but the more complex the school-level components are the less likely it is that they will be implemented with fidelity.

-

Intervention components that aim to reach out to parents will generally not be well delivered, especially at the secondary level.

-

Interventions that require teachers to attend training away from school for > 1–2 days will not be feasible because schools will be reluctant to release teachers for this amount of time.

The second round of consultations occurred in September/October 2017, with the aim of reviewing the validity and usefulness of our syntheses to inform how our research outputs are structured and disseminated. Participants were given a summary of study findings (see Appendix 14), inclusive of outcome evaluation synthesis results. Furthermore, we discussed stakeholder views around next steps in terms of knowledge translation, replication studies and the creation of new interventions.

Consultations involved the following adult policy stakeholders: the Ariel Trust (Paul Ainsworth), Mentor UK (Michael O’Toole), Public Health Wales (Mary Charles), the School Health Research Network (Joan Roberts), Public Health England (Claire Robson), the PSHE Association (Jonathan Baggaley), the Association for Young People’s Health (Ann Hagell and Emma Rigby), London Fields Primary School (Sindee Bass), St. Saviour’s Church of England Junior School (Nick Bonell), Barnhill Community High School (Greig Pilkington) and Newstead Wood School (Jonathan Lewis).

Young people were consulted via the Advice Leading to Public Health Advancement (ALPHA) young people’s public health research advisory group based in the Centre for Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer) for Public Health Improvement, a collaboration between the universities of Cardiff, Bristol and Swansea. Ten young people were consulted, half of whom were female and half of whom were male, and the age range was from 14 to 18 years.

Ethics arrangements

This project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of University College of London Institute of Education (ethics approval reference number REC 746). The project complied with the Social Research Association’s Ethical Guidelines81 and guidance from the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement. 82

Chapter 3 Included studies

About this chapter

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted from Bonell et al. 62 Contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

This chapter reports the results of our systematic search and screening process, and gives a brief overview of the included studies, study reports and interventions. It categorises interventions in order to address research question 1.

Results of the search

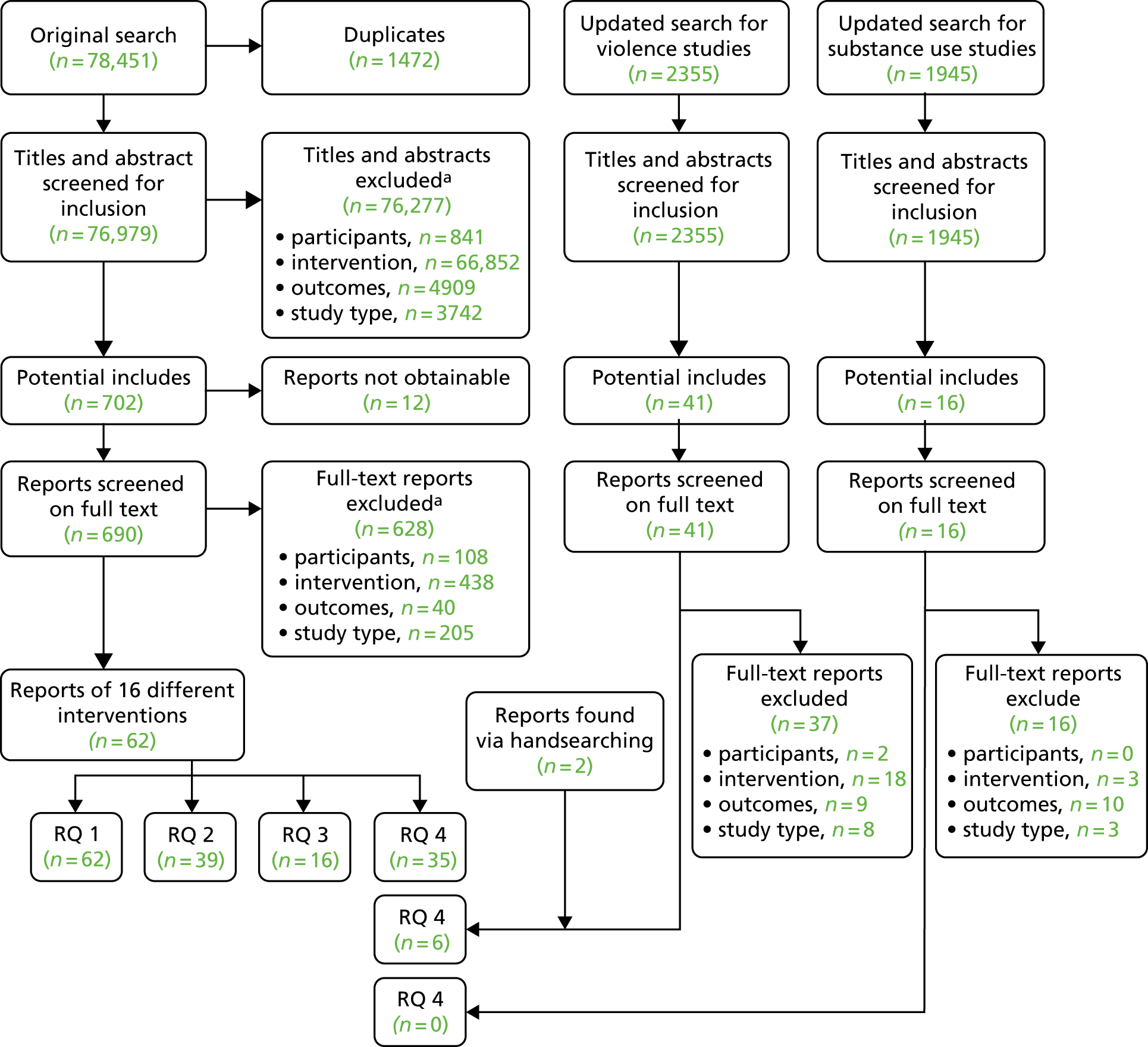

A total of 78,451 references were identified from the searches. Of these, 1472 (2%) references were identified as duplicates. The remaining 76,979 references were screened on title and abstract and, of these, 76,277 (99%) were excluded using the criteria listed in the protocol. 1

When piloting the process for screening on title and abstract, initial screening agreements between reviewers were consistently < 90% on whether or not a study should be excluded. Agreement was lower on the question of which particular criterion should be cited in excluding a particular reference, varying from 28% to 62% among six different pairs of reviewers. Discussion between reviewers established that this reflected the multiple criteria that could be used to exclude many studies and, therefore, a somewhat arbitrary choice of which particular criterion to cite in each case. Given that agreements were < 90% on whether to exclude or not, we moved to a system of one reviewer independently screening each reference, as set out in our protocol. 1

Of the 702 references that were not excluded after screening on title and abstract, we were able to obtain the full-text reports of 690 (98%) references, the remainder not being accessible online or through interlibrary loans. Piloting the application of the same exclusion criteria used at the title and abstract screening stage on the full reports, screening between two pairs of reviewers also reached < 90% agreement on whether or not a study should be excluded, and so an individual reviewer (TT) moved to independent screening of documents, consulting with the principal investigator (CB), when necessary. CB made a final check of all the studies included. This procedure led to a further 628 studies being excluded at this stage in the review screening process.

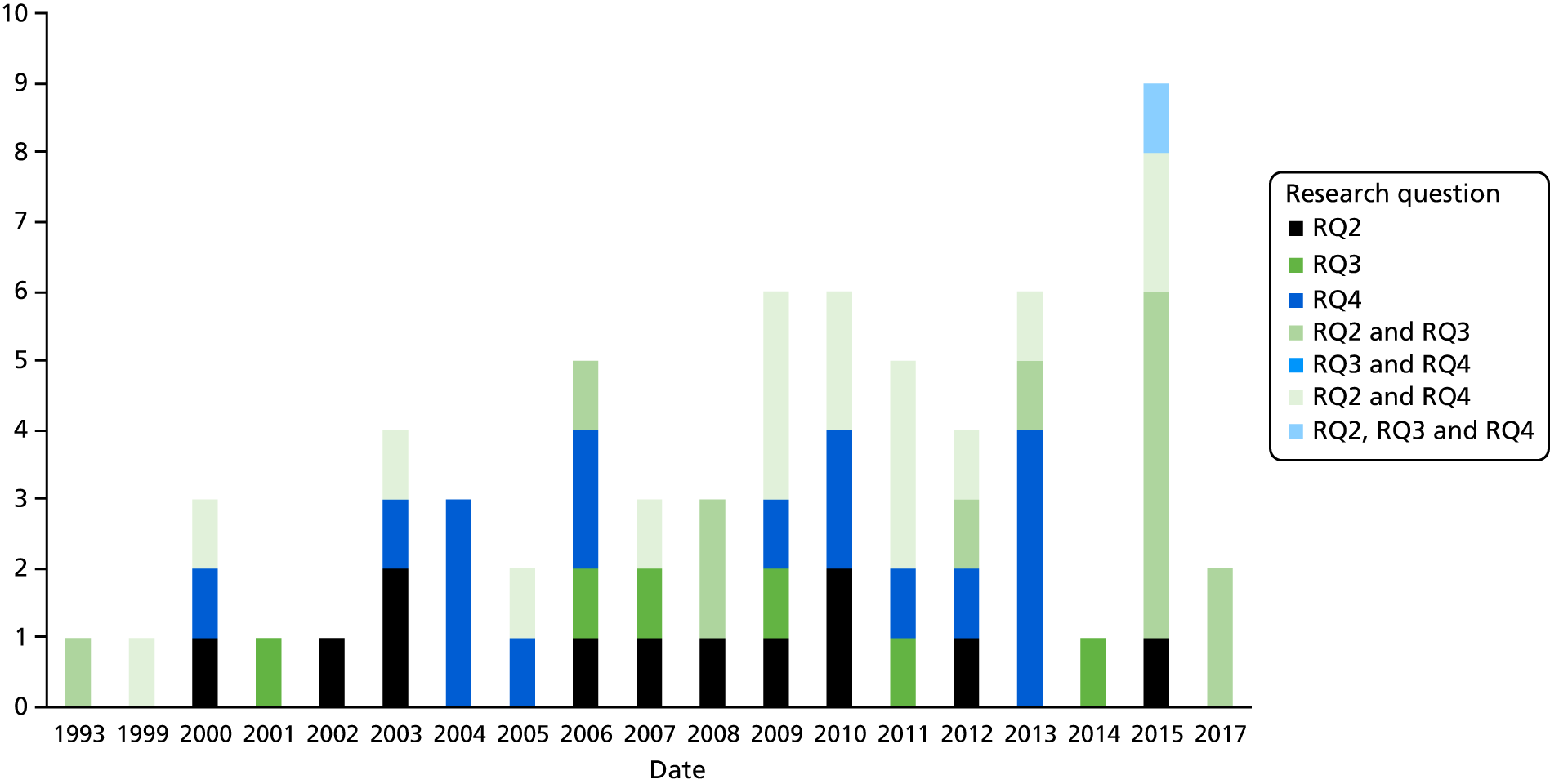

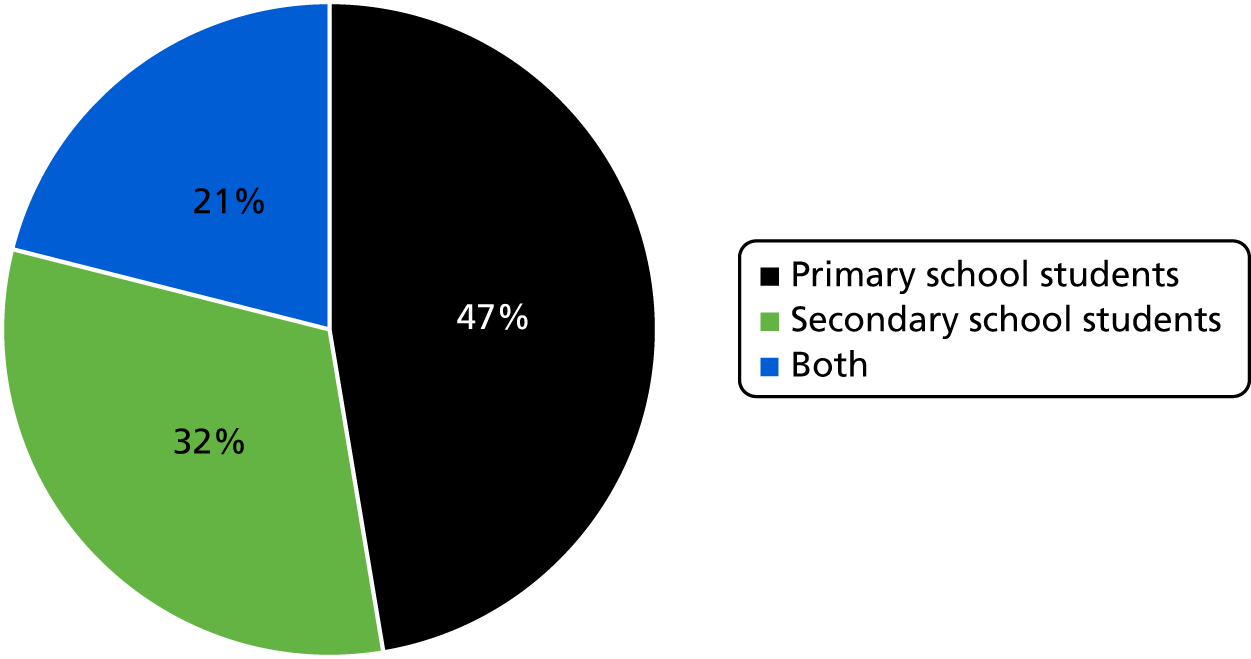

The remaining 62 reports3,51–57,60,83–135 deemed eligible for inclusion in the review were coded according to the review question they answered. Sixteen distinct interventions were examined by studies included in the review. Only three interventions had only one report,108,133,135 and 13 interventions were described in the remaining 59 reports. 3,51–57,60,83–107,109–132,134 Furthermore, 27 study reports provided answers to more than one review question. 3,52,53,57,84,86–88,92–98,100,103,107,108,110,113,118,125,127,133–135 In presenting the number of studies and study reports, we have not double-counted those that address more than one of our review questions. When appropriate, we clarify whether a study or report addressed more than one of our review questions. Figure 1 summarises the flow of references, reports and studies through the review, providing a breakdown of the exclusion criteria at both title and abstract and full document stages and the number of studies included in each synthesis. Table 2 provides an overview of the interventions included in this review that were subject to process or outcome evaluation.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of studies in the review: main searches. RQ, research question. a, Note that these do not sum to 628 references, as some studies were excluded based on more than one criterion.

| Interventions examined in the review | Included theory studies (author, year) | Included process evaluations (author, date, location) | Included outcome evaluations (author, year, location) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4Rs |

Aber et al. , 201153 Brown et al. , 201054 Flay et al. , 200955 Jones et al. , 200856 Jones et al. , 201052 Jones et al. , 20113 Sung, 201557 |

Sung, 201557 (New York, NY, USA) |

Aber et al. , 201153 (New York, NY, USA) Jones et al. , 201052 (New York, NY, USA) Jones et al. , 201051 (New York, NY, USA) Jones et al. , 20113 (New York, NY, USA) |

| Bullying Literature Project |

Couch, 201596 Wang et al. , 2015134 |

None |

Couch, 201596 (California, CA, USA) Wang et al. , 2015134 (California, CA, USA) |

| Bullying Literature Project–Moral Disengagement | None | None | Wang et al., 2017136 |

| DRACON | Malm and Löfgren, 2007119 | O’Toole and Burton, 2005120 (Brisbane, QLD, Australia) | None |

| English Classes (no name) | Holcomb and Denk, 1993108 | Holcomb and Denk, 1993108 (Houston, TX, USA) | None |

| Hashish and Marijuana | Zoller and Weiss, 1981135 | Zoller and Weiss, 1981135 (Haifa, Israel) | None |

| I-LST | Bechtel et al., 200684 | Bechtel et al., 200684 (Pennsylvania, PA, USA) |

Smith et al. , 2004128 (Pennsylvania, PA, USA) Vicary et al. , 2006132 (Pennsylvania, PA, USA) |

| KAT | Segrott et al., 2015127 |

Rothwell and Segrott, 2011126 (Wales, UK) Segrott et al. , 2015127 (Wales, UK) |

Segrott et al., 2015127 (Wales, UK) |

| Learning to Read in a Healing Classroom | None | None |

Torrente et al. , 2015137 Aber et al. , 2017138 |

| LIFT |

DeGarmo et al. , 200998 Eddy et al. , 2000100 Eddy et al., 201599 Reid et al. , 1999125 Reid and Eddy, 2002124 |

None |

DeGarmo et al. , 200998 (Oregon, OR, USA) Eddy et al. , 2000100 (Oregon, OR, USA) Eddy et al. , 2003101 (Oregon, OR, USA) Reid et al. ,1999125 (Oregon, OR, USA) Stoolmiller et al. , 2000131 (Oregon, OR, USA) |

| Peaceful Panels | Wales, 2013133 | Wales, 2013133 (Athens, GA, USA) | None |

| Positive Action |

Beets et al. , 200886 Beets et al. , 200987 Flay, 200955 Flay and Allred, 2010102 Lewis, 2012113 Malloy et al. , 2015118 |

Beets, 200785 (Hawaii, HI, USA) Beets et al. , 200886 (Hawaii, HI, USA) Malloy et al. , 2015118 (Chicago, IL, USA) |

Bavarian et al. , 201383 (Chicago, IL, USA) Beets et al. , 200987 (Hawaii, HI, USA) Lewis, 2012113 (Chicago, IL, USA) Lewis et al. , 2012114 (Chicago, IL, USA) Lewis et al. , 2013115 (Chicago, IL, USA) Li et al. , 2011116 (Chicago, IL, USA) Snyder et al. , 2010129 (HI, USA) Snyder et al. , 2013130 (HI, USA) |

| PATHS |

Crean and Johnson, 201397 Flay et al. , 200955 Greenberg and Kusché, 2006106 Kusché and Greenberg, 2012112 |

Ransford et al., 2009123 (Pennsylvania, PA, USA) | Crean and Johnson, 201397 (USA) |

| RHC |

Brown et al. , 200592 Catalano et al. , 200395 |

None |

Brown et al. , 200592 (Seattle, WA, USA) Catalano et al. , 200395 (Seattle, WA, USA) |

| Roots of Empathy |

Cain and Carnellor, 200894 Gordon, 2003105 Hanson, 2012107 |

Cain and Carnellor, 200894 (WA, Australia) Hanson, 2012107 (Isle of Man and Western Canada) |

None |

| Second Step | None | None |

Espelage et al. , 2013139 Espelage et al. , 2015140 Espelage et al. , 2015141 |

| Steps to Respect |

Brown et al. , 201193 Frey et al. , 2009103 |

Low et al., 2014117 (California, CA, USA) |

Brown et al. , 201193 (CA, USA) Frey et al. , 2005104 (Pacific Northwest, USA) Frey et al. , 2009103 (Pacific Northwest, USA) |

| The Gatehouse Project |

Bond and Butler, 201088 Patton et al. , 2000122 Patton et al. , 2003121 |

Bond et al., 200189 |

Bond et al. , 200491 (Melbourne, VIC, Australia) Bond et al. , 200490 (Melbourne, VIC, Australia) Bond and Butler, 201088 (Melbourne, VIC, Australia) Patton et al. , 200660 (Melbourne, VIC, Australia) |

| Youth Matters | Jenson and Dieterich, 2007110 | None |

Jenson and Dieterich, 2007110 (Denver, CO, USA) Jenson et al. , 2010111 (Denver, CO, USA) Jenson et al. , 2013109 (Denver, CO, USA) |

Updated searches for violence outcomes found a total of 2355 records, of which 41 were screened at full text. Six records relating to three evaluations were included. Updated searches for substance use outcomes found a total of 1945 records, of which 16 were screened at full text. No records were included from this update.

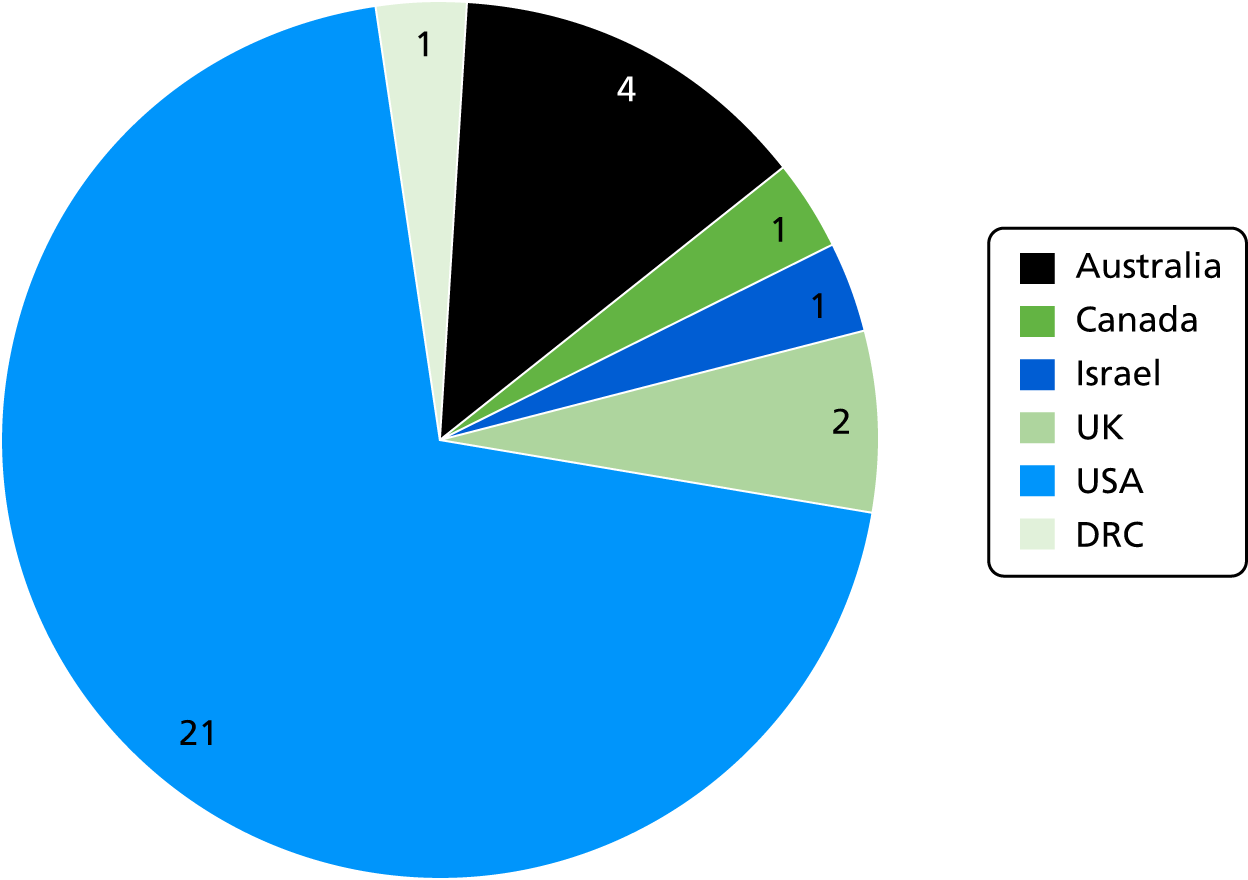

Interventions evaluated

Overall, 19 interventions were studied in 68 reports,3,51–57,60,83–137,139–141 of which one55 reported findings about three separate interventions. The 19 interventions and the corresponding reports for each are summarised below according to the research question that the study helped to answer. These are summarised as ‘included theory studies’ that helped to answer research question 2, ‘included process evaluations’ that helped to answer research question 3 and ‘included outcome evaluations’ that helped to answer research question 4. All reports helped to answer research question 1. See Appendix 15 for a listing of all included reports by the research question they answer.

The 4Rs programme aimed to integrate social–emotional learning and conflict resolution with lessons in literacy centred on children’s books. 3,51–53 One of the driving ideas behind this intervention was to ‘reintroduce’ social–emotional learning to the curriculum in the face of crowding out by more explicitly academic lessons. The intervention is designed to be implemented school-wide in the US equivalent of years 1–6, but the evaluation cohort was enrolled in year 4. The intervention, which was extensively manualised, was implemented by classroom teachers and supported by intensive introductory training (25 hours in duration) and ongoing coaching and classroom observation. In each year of the intervention, the course materials were divided into seven units, with 21–35 lessons across the units and a benchmark of one lesson delivered per week. 3 In each unit, students were introduced to a children’s book, and teachers then followed-up each book with between three and five social–emotional learning lessons. The intervention was underpinned by both ‘multilevel program theory’ and ‘developmental cascades theory’;53 that is, 4Rs is designed to address multiple levels of social relationships and is expected first to affect ‘proximal’ outcomes, such as hostile attribution biases, to be followed by improvements in more ‘distal’ outcomes, such as reduced aggression.

The Bullying Literature Project96,134 aimed to prevent bullying in the USA-equivalent of years 4 and 5 via integrating lessons on how to cope with bullying and how to intervene in peers’ bullying behaviours with children’s literature. The intervention was conducted over five sessions of between 35 and 45 minutes each in one school term and implemented by school psychologists (i.e. not classroom teachers). The Bullying Literature Project, which was underpinned by social learning theory, was based on combining instructional elements with role playing and modelling the positive behaviours demonstrated by characters in the chosen texts. 96,134 The interventionists read the lesson’s story to children and then engaged them in activities, including role plays and writing. The intervention developers noted that by giving students the opportunity to practice new skills and observe how peers react to bullying scenarios, students could also learn to reduce their own bullying behaviours. In addition to classroom lessons, data collected on students’ reported bullying experiences and behaviours were presented to both students and school staff, and parents were informed of the intervention and provided with a list of suggested readings and strategies to reinforce learning from the intervention.

A second iteration of this intervention, the Bullying Literature Project–Moral Disengagement,136 included additional content relating to moral disengagement and sought to teach students how to intervene as bystanders rather than ‘walking away’ from others’ bullying behaviours.

The goals of DRAma = CONflict (DRACON)119,120 are to use drama to develop cognitive understanding of conflict and bullying, to empower students to manage their own conflict both personally and within the broader school community. DRACON is delivered to students in primary and secondary schools (ages 7–16 years). Conflict literacy is taught through ‘enhanced forum theatre’ and other drama techniques. The peer learning classes taught by the students are typically not delivered in drama classes but in other classes (e.g. English) because of the perceived opportunities in the curriculum to discuss conflict and bullying. Health and academic education are said to be integrated by conflict literacy being taught through ‘enhanced forum theatre’ and other drama techniques. It is unclear from the study report, but it appears that there are nine cycles, each of which runs for 8 weeks with two 100-minute classes per week within the school year. Cycle two onwards has the aim of combining drama and peer teaching by older classes with their younger peers. These classes also aim to develop group communication, familiarity, and empathy. The DRACON project’s theory of change119,120 is informed by Coleman’s model of adolescent development,142 Kolb’s modes and characteristics of experiential learning143 and Winslade and Monk’s approaches to peer mediation. 144

The English Classes108 intervention targets students in the USA-equivalent of years 9 and 10 in the UK (aged 13–15 years). Teachers are trained and, working in pairs, develop integrated health/English material, with a specific emphasis on the prevention of drug and alcohol use. It is unclear from the study report, but it seems that the intervention is expected to be delivered in (potentially) every English class, with health lessons integrated whenever appropriate. Health topics are infused into English classes. English was chosen because it was felt to be the subject during which non-traditional concepts could be discussed and because it is taken by all students. No details on the timing and ‘dose’ of the intervention are provided. The theoretical basis of the English Classes intervention is vague but is described as being informed by learning theory145 and the notion of the impact of integrated subject matter. 146

The goal of the Hashish and Marijuana programme135 that is delivered to students in Israeli upper high school (aged 17–18 years) is to develop scientific knowledge of hashish and marijuana and to strengthen students’ problem-solving and decision-making skills. Lessons about hashish and marijuana are delivered through lectures in chemistry classes and complemented by group work, class discussions, independent study, projects, games, field trips and any other curricula additions that develop social and decision-making skills. The intervention is entirely integrated into chemistry classes, where lessons around hashish and marijuana take place, teaching the students about the chemical aspects of the drugs. Behaviour change is also addressed through more participatory teaching methods. No information on ‘dose’ and no theoretical basis are provided for the Hashish and Marijuana intervention. 135