Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/115/48. The contractual start date was in May 2016. The draft report began editorial review in November 2020 and was accepted for publication in July 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Duffy et al. This work was produced by Duffy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Duffy et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Description of the health problem

Depression is a leading cause of disability, with more than 300 million people having depressive illness worldwide. 1 According to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), depression is defined as a state of mental health that can be characterised by symptoms of low mood, loss of interest or pleasure, tearfulness, feelings of guilt or low self-worth, social withdrawal, disturbed sleep or appetite, poor concentration, tiredness and diminished activity. 2

Owing to difficulties in distinguishing between clinically significant and ‘normal’ mood changes, it is now generally accepted that depressive symptoms are a continuum of severity. 3 The severity of depressive illness can range from mild to severe. Even mild to moderate depression can impair people’s ability to function and cope with daily life. The diagnosis of depression is based not only on severity of symptoms but also on their duration and the degree of social and functional impairment. Depression is no longer thought of as a time-limited disorder with complete recovery after 4–6 months of treatment; it is now accepted that depression is often chronic (lasting for ≥ 2 years) or recurrent. Although it has been accepted that depression exists as a continuum, researchers and clinicians still use terms such as episode, relapse and chronicity to guide the diagnosis, and to inform and monitor treatment.

Treatment options for depression

People with depressive symptoms are mainly treated in primary care, and antidepressants are usually the first-line treatment; they are used to treat acute depressive symptoms and for maintenance treatment, that is to prevent relapse once an individual has recovered. The number of prescriptions for antidepressant medication has risen dramatically in high-income countries in recent decades, largely because of an increase in the number of patients receiving long-term treatment. 4,5 Psychological treatments, such as cognitive–behavioural therapy, are also effective treatments for depression, including for those who have not responded to antidepressants. 6

Economic consequences of depression

Depression not only causes marked emotional distress and interferes with daily function for the individual, but also has substantial negative social and financial impact on the wider community. 7 Every year, it has been estimated that depression reduces England’s national income (gross national product) by over 4% (approximately £80M). This reduction results from increased unemployment, a larger number of sick days and reduced productivity. It is also accompanied by increased welfare expenditure. 8,9

Current evidence on the effectiveness of maintenance treatment

A substantial proportion of the burden of depression arises from relapses, recurrence and chronicity. However, in contrast to the large number of drug trials in acute depression,10 there are relatively few studies assessing antidepressant efficacy in preventing relapse of depression during maintenance treatment. A number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses11–14 report a reduced risk of relapse rate in patients receiving antidepressant medication by between 50% and 70% compared with patients receiving placebo. The constituent studies had several limitations. These studies recruited patients from secondary care during an acute depressive episode, treated the patients with an open-label antidepressant and reported that only those who met criteria for recovery were eligible for randomisation to either remain on double-blind antidepressant or switch to placebo. Most studies were conducted during the 1980s or early 1990s in secondary care by pharmaceutical companies for regulatory purposes, using tricyclic antidepressants that are no longer widely used for depression. Most studies had either short (≤ 2 months) or intermediate (3–5 months) pre-randomisation treatment. It is difficult to generalise these findings to people currently receiving antidepressants in primary care, many of whom have been on maintenance treatment for some years. 15,16 Studies of the effectiveness of maintenance treatment for patients receiving antidepressants for longer than 8 months are rare and have several limitations. 17–19 All were very small (n < 20 participants in total) and had a poor follow-up rate.

NICE guidance on the treatment and management of depression in adults20 recommends that patients who have recovered from an episode of depression should stay on their antidepressant medication for at least 6 months after remission. The guidelines also suggest that the medication should be continued for 2 years after remission in those ‘at risk of relapse’; the risk is defined as ‘two or more episodes, residual symptoms or severe or prolonged episodes’ (© NICE 2010. Depression: Management of Depression in Primary and Secondary Care. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg23. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication). 20 However, there is no evidence that these proposed factors (number of episodes, residual symptoms and severity of previous episodes) affected the difference between antidepressant and placebo maintenance treatment. 13 NICE recommends that antidepressant maintenance treatments should continue to be used for 2 years for those at risk of relapse; however, NICE also recognise the uncertainty about the benefit of long-term maintenance treatment and recommend further research into its psychological and pharmacological effects.

At present, there is little evidence to support the use of long-term maintenance antidepressant treatment, despite its widespread use. Given the costs of treatment and medical supervision, the side effects of the medication and patients’ wish to be medication free, it is important to investigate this question further.

Health economic considerations are discussed and presented in Chapter 4.

Current evidence on withdrawal symptoms

There is also uncertainty about the frequency and severity of withdrawal symptoms after antidepressants are discontinued. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials are required to provide robust evidence on withdrawal symptoms. A recent systematic review of such trials found evidence of withdrawal symptoms after antidepressant discontinuation, but the studies were too heterogeneous to establish the frequency, severity and timing of withdrawal effects. Almost all of these trials were rated as being of low quality because of the high risk of selection bias, attrition and incomplete outcome data. 21 Withdrawal symptoms are an important risk to evaluate when considering stopping maintenance treatment. They raise an important clinical question of the benefits of antidepressants compared with the possible risks.

Aim and objectives

The ANTLER trial was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) as part of its Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme. The overall aim of the ANTLER trial was to answer the following research question: ‘What is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in UK primary care of continuing on long-term maintenance antidepressants compared with a placebo in preventing relapse of depression in those who have taken antidepressants for more than 9 months and who are now well enough to consider stopping maintenance treatment?’.

The trial was pragmatic, embedded in primary care and had broad inclusion criteria to increase the generalisability to the population currently receiving maintenance antidepressants.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

The ANTLER trial was a Phase IV, double-blind, pragmatic, multisite, individually randomised parallel-group controlled trial that was funded by the NIHR HTA programme. We recruited primary care patients who were taking one of four of the most commonly used antidepressant medications. At the point of recruitment, the patients were well enough to consider stopping their medication. Participants were recruited from primary care practices in four UK sites: London, Bristol, Southampton and York.

The trial compared maintenance treatment with antidepressant (citalopram 20 mg, sertraline 100 mg, fluoxetine 20 mg or mirtazapine 30 mg) treatment by replacing the medication with an identical placebo after a tapering period. We chose these antidepressant doses because they are the most common for long-term maintenance treatment in UK primary care and they simplified the manufacture of placebo and the conduct of the trial. In addition, there is no evidence that higher doses increase effectiveness. 22 The trial intervention was for 52 weeks and the participants were followed up at 6, 12, 26, 39 and 52 weeks.

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval was obtained from the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) committee, East of England – Cambridge South (reference 16/EE/0032) and the Health Research Authority. A number of subsequent communications were sent to both the NRES and the Health Research Authority either seeking approval for substantial amendments or informing committees of minor changes. Clinical trial authorisation was given by Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. The trial sponsor was University College London.

The ANTLER trial was registered on the Current Controlled Trials International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry (ISRCTN15969819; 21 September 2015) and also received a EudraCT number (2015-004210-26). As part of the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Co-ordinating Centre research portfolio, the trial was adopted and listed on the portfolio.

Participants

The trial recruited patients from 150 general practices across four research sites (London, Bristol, Southampton and York). Table 1 provides a summary of the main characteristics of the participating practices.

| Characteristic | Category | Per cent of category (n = 150) |

|---|---|---|

| Centre | Bristol | 20 |

| London | 55 | |

| York | 10 | |

| Southampton | 15 | |

| Geographical locationa | Urban | 85 |

| Rural | 15 | |

| List sizeb | 1–4999 | 5 |

| 5000–9999 | 27 | |

| 10,000–14,999 | 33 | |

| ≥ 15,000 | 35 | |

| Number of GPs employed | 0–5 | 24 |

| 6–10 | 51 | |

| 11–15 | 19 | |

| ≥ 16 | 6 | |

| Number of randomised participants | 0–4 | 76 |

| 5–10 | 19 | |

| 11–15 | 5 | |

| Index of Multiple Deprivationc | 1–10 | 22 |

| 11–20 | 43 | |

| 21–30 | 26 | |

| ≥ 31 | 9 |

Inclusion criteria

Patients were considered for inclusion if they:

-

Had had at least two episodes of depression (because participants find it difficult to remember previous episodes and depressive symptoms are on a continuum, we used a pragmatic approach and considered those who had been treated for over 2 years as having two episodes).

-

Were aged 18–74 years (we excluded older people because different assessments for depression are used in the older age groups).

-

Had been taking antidepressants for ≥ 9 months and were taking citalopram 20 mg, sertraline 100 mg, fluoxetine 20 mg or mirtazapine 30 mg.

-

Had satisfactory adherence to medication – the ANTLER trial used a five-item self-report measure of compliance, as adapted for the MIR23 and CoBalT trials. 6 Given the relatively long half-life of antidepressant medication, individuals who had forgotten to take 1 or 2 days’ worth of medication were excluded, and this was established with an extra question: ‘Did you forget to take 2 days of your medication in a row?’. Therefore, the criteria defined people as adherent if they (1) scored zero on the first four questions, (2) scored 1 and said ‘no’ to the extra question or (3) scored 2 because of ‘forget’ and ‘careless’ questions and said ‘no’ to the extra question.

-

Were considering stopping their antidepressant medication.

Comparison of the age and gender of the participants who were invited with those who participated can be found in Report Supplementary Material 11.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they:

-

met internationally agreed (ICD-10) criteria for a depressive illness

-

had bipolar disorder, psychotic illness, dementia, alcohol or substance dependence or a terminal illness

-

were unable to complete self-administered questionnaires in English

-

had contraindications to any of the prescribed medication

-

were pregnant or intended to get pregnant with the next 12 months

-

were using monoamine oxidase inhibitors

-

had allergies to placebo excipients

-

were enrolled in another clinical trial of an investigational medicinal product.

The screening questionnaire is in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Recruitment

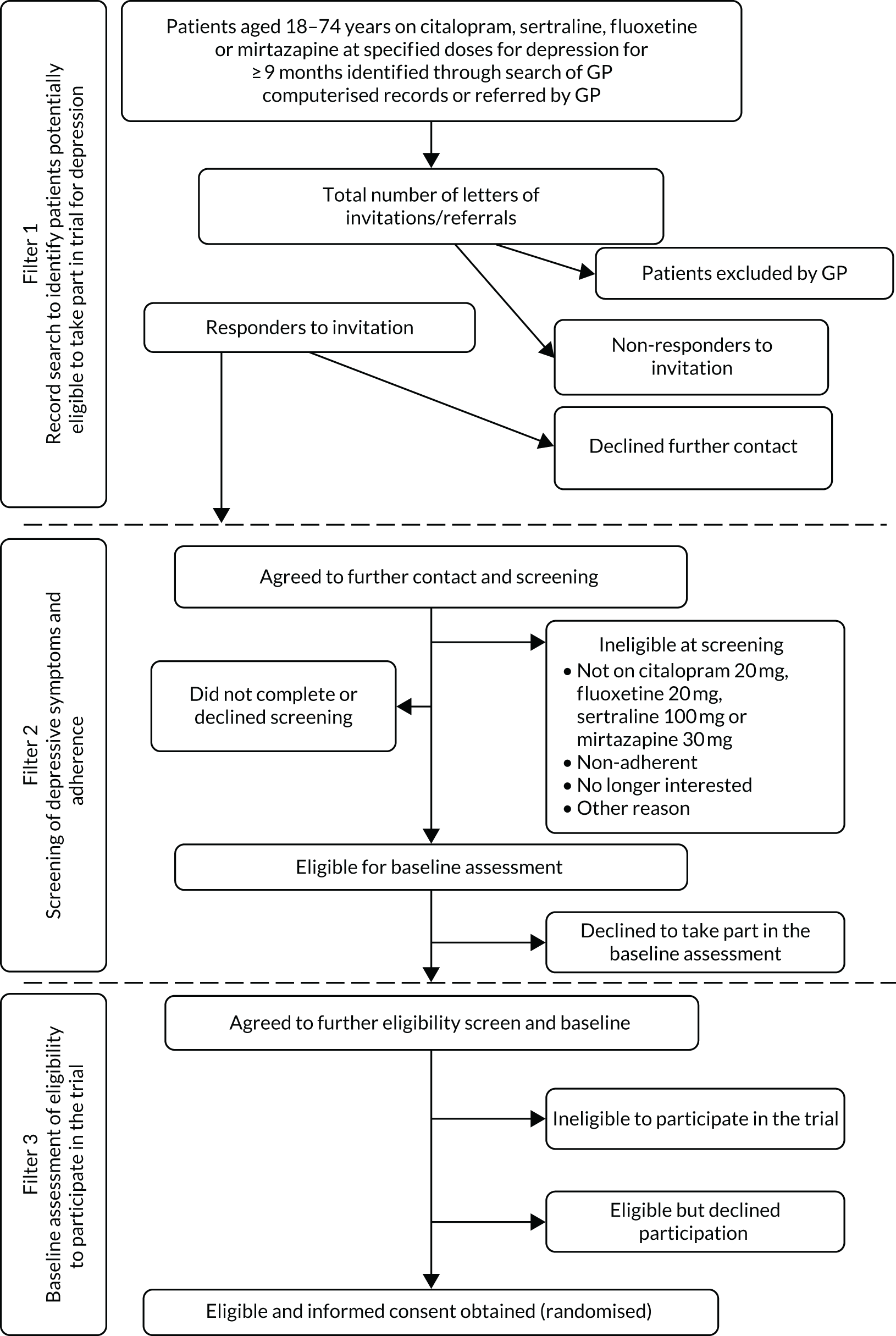

Recruitment started in March 2017. Within 2 years, 478 participants were recruited from general practices across our four research centres using two methods: record search and in-consultation recruitment. Figure 1 outlines a detailed flow chart of the stages of recruitment.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart outlining the stages of recruitment.

Record search method

General practitioner (GP) electronic patient records were searched to identify potential participants. These individuals were sent an initial letter and the patient information sheet by the GP surgery, followed by a reminder invitation letter if there was no response. Those patients who replied positively to the invitation letter were reviewed by their GP, who informed the local research team on inclusion/exclusion criteria from the patients’ medical notes. The GP could also decide that the person was unsuitable to take part in the trial on any other grounds.

In-consultation recruitment method

General practitioners could introduce the trial to suitable patients at a consultation, give them the patient information sheet to read at home and ask for their permission for release of their contact details to the local trial team. The information was sent by secure nhs.net e-mail or fax to the trial team.

Intervention

Choice of medication

The objective of the ANTLER trial was to provide a valid and generalisable estimate of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of long-term maintenance treatment with antidepressants in UK primary care. The trial population was patients who were taking long-term maintenance treatment but who were well enough to consider stopping their antidepressant medication. The intervention that was studied by the ANTLER trial was taking patients off their antidepressant medication rather than starting antidepressant medication.

The choice of medication was guided by the pragmatics of recruitment and carrying out the trial. The ANTLER trial medication was citalopram 20 mg, sertraline 100 mg, fluoxetine 20 mg and mirtazapine 30 mg. We selected these doses because they are the most commonly prescribed doses in primary care (Professor Irene Petersen, University College London, 2013, personal communication; based on The Health Improvement Network electronic health records data). At the time of developing the ANTLER trial protocol in 2013, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were the most commonly prescribed medication, followed by citalopram (32% of antidepressant prescriptions in England after excluding amitriptyline, which is mainly used to manage pain and sleep), sertraline (15%) and fluoxetine (14%). Mirtazapine accounted for 13% of prescriptions in England in 2013. Mirtazapine is a different type of antidepressant, a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant; however, the net effect of its action is similar to that of SSRIs, to increase serotonergic transmission.

Together, these medications account for about 75% of all long-term antidepressant prescriptions in England (Professor Irene Petersen, personal communication), and all are licensed for the treatment of depression. According to recent data from openprescribing.net,24 these are still the four most commonly prescribed antidepressants.

We excluded escitalopram because it is not widely used in primary care, paroxetine because prescription rates are dropping and it leads to more marked withdrawal symptoms, and venlafaxine because it also causes withdrawal symptoms and most clinical guidelines recommend it as second-line treatment only. We, therefore, recruited patients taking maintenance treatment with citalopram, sertraline, fluoxetine or mirtazapine. These medications account for the vast majority of all antidepressant prescriptions.

Treatment of participants

At baseline, participants were taking citalopram 20 mg, sertraline 100 mg, fluoxetine 20 mg or mirtazapine 30 mg. They were randomised either to remain on their current medication (maintenance group) or to discontinue medication after a tapering period. In the first month, those in the discontinuation group took their usual medication at half of the dose (citalopram 10 mg, sertraline 50 mg or mirtazapine 15 mg). In the second month, they took either half the dose of their usual medication or placebo, on alternate days. From the third month to the end of the trial, they took only the placebo. As fluoxetine is not available as a 10-mg capsule, in the first month those taking fluoxetine at baseline who were allocated to the discontinuation group alternated between a 20-mg capsule and the placebo. During the second month and subsequent months, they took the placebo because fluoxetine has a long half-life.

The active medication was encapsulated and the placebo was an identical capsule filled with an inert excipient. All capsules exactly matched in dimensions and appearance, so that allocation concealment and blinding were maintained.

Subsequent assessments

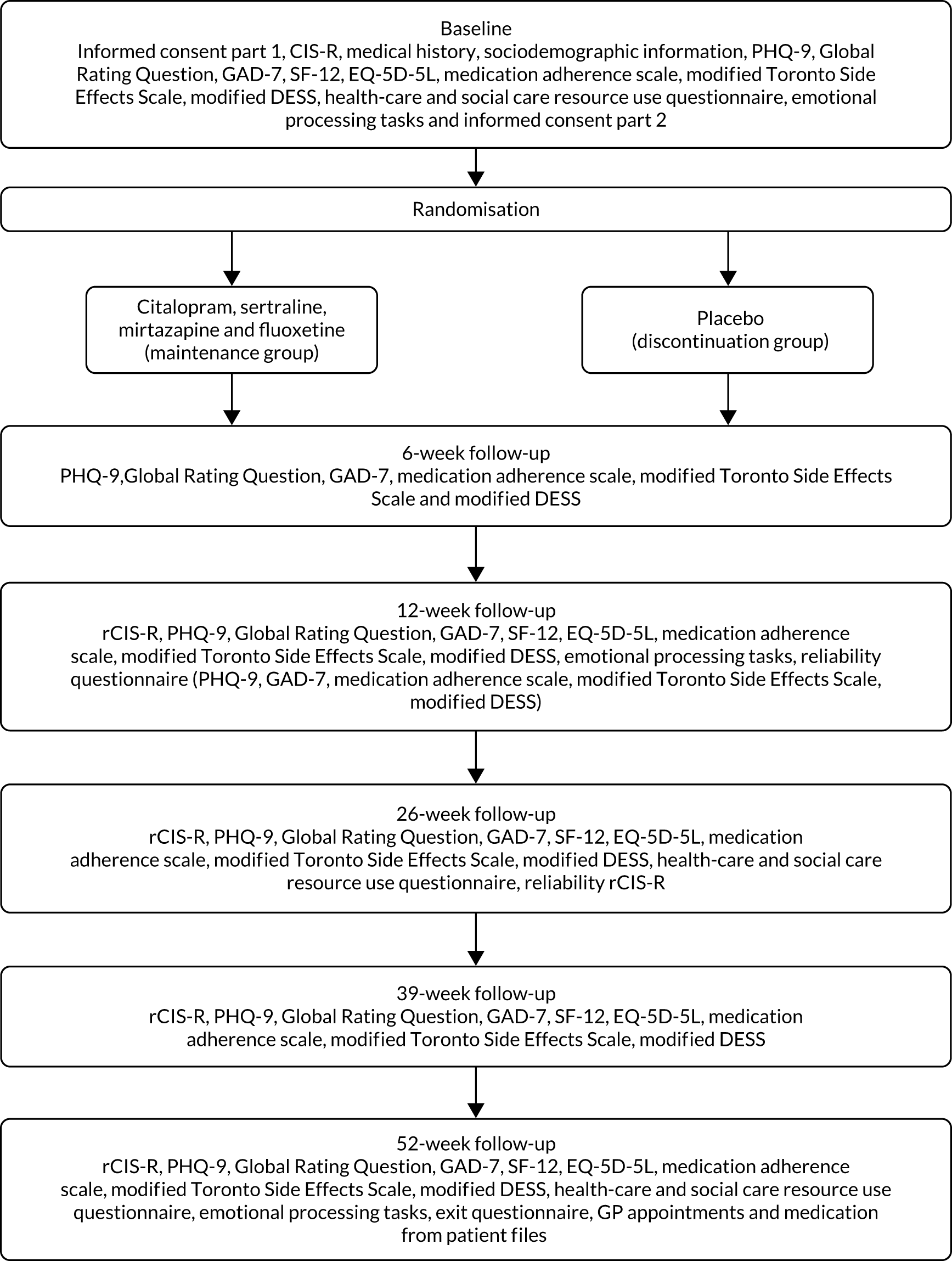

The follow-up assessments were carried out at 6, 12, 26, 39 and 52 weeks after randomisation. Participants were invited to follow-up appointments unless they had withdrawn from the trial. Participants were followed up even if they stopped taking the trial medication. The follow-up appointments took place at the participant’s home, their general practice or university premises. Figure 2 describes the baseline and follow-up assessments. The baseline questionnaire can be found in Report Supplementary Material 2. The 6-week follow-up questionnaire can be found in Report Supplementary Material 3. The 12-, 26-, 39- and 52-week follow-up questionnaire can be found in Report Supplementary Material 4. The exit questionnaire can be found in Report Supplementary Material 7.

FIGURE 2.

Schedule of assessments. DESS, Discontinuation-Emergent Signs and Symptoms; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version; GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items; SF-12, Short Form questionnaire-12 items.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The time in weeks to the beginning of the first episode of depression after randomisation (we call relapse) was measured using the rCIS-R, which is based on the CIS-R,25 which asks about the previous 12 weeks at all follow-up points, except at 6 weeks. Only the five sections (i.e. depression, depressive ideas, concentration, sleep and fatigue) that are used for a depression diagnosis were asked, along with questions that asked about symptoms. Further questions were asked to determine the time to the nearest week when the score was ≥ 2. The rCIS-R and the precise description of relapse are described further in Reliability of the retrospective Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised.

Secondary outcomes

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9). 26,27 This is a nine-item questionnaire. Each item has four responses that range from not at all (0) to nearly every day (3). The score from each item is added to give a total that ranges from 0 to 27. If there are one or two items missing from a participant’s questionnaire, the items are replaced by the mean of the items present. If there are more than two items missing, the questionnaire is considered missing for that participant.

Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) questionnaire. 28 This is a seven-item questionnaire. Each item has four possible responses that range from not at all (0) to nearly every day (3). The score from each item is added to give a total that ranges from 0 to 21. If there are one or two items missing from a participant’s questionnaire, the items are replaced by the mean of the items present. If there are more than two items missing, the questionnaire is considered missing for that participant.

The adverse effects of antidepressants were measured using a modified Toronto Side Effects Scale. 29,30 This is a 13-item measure for males and females and an open-ended item to report any other side effects. Following a consultation with patient groups, we included a question on electric sensations in the brain (brain zaps); this resulted in a 15-item scale. For each item, the scale asks how often the side effect has been present in the past 2 weeks: never, on several days, on more than half of the days or nearly every day. Scores from each item are added to give an overall score between 13 and 52.

Health-related quality of life was measured using the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12). 31 The physical and mental component scores were analysed separately.

Withdrawal symptoms were based on Rosenbaum et al. ;32 participants are asked about the 15 most common symptoms of depression, and a score ranging from 0 to 15 is calculated by summing the number of ‘new symptom[s]’ and the number of ‘old symptom[s] but worse’.

To measure the time to stopping trial medication, the exact date on which the trial medication was stopped is recorded for those who stopped early. For those who completed their course of medication, the date is the date of the last interview or the date that they took the last dose of trial medication, whichever was later.

For the Global Rating Question, participants were asked at baseline and at each subsequent follow-up point, ‘Compared to when we last saw you, how have your moods and feelings changed?’. The possible responses were ‘I feel a lot better’, ‘I feel slightly better’, ‘I feel about the same’, ‘I feel slightly worse’ and ‘I feel a lot worse’. 33 We created a dichotomous variable: feeling worse (1) and feeling the same or better (0).

We also examined the test–retest reliability of the PHQ-9, GAD-7, rCIS-R, adverse effects, withdrawal symptoms and adherence questionnaires by asking participants to complete again these questionnaires at one of the follow-up appointments. We included the results of the test–retest reliability of the rCIS-R in Reliability of the retrospective Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised.

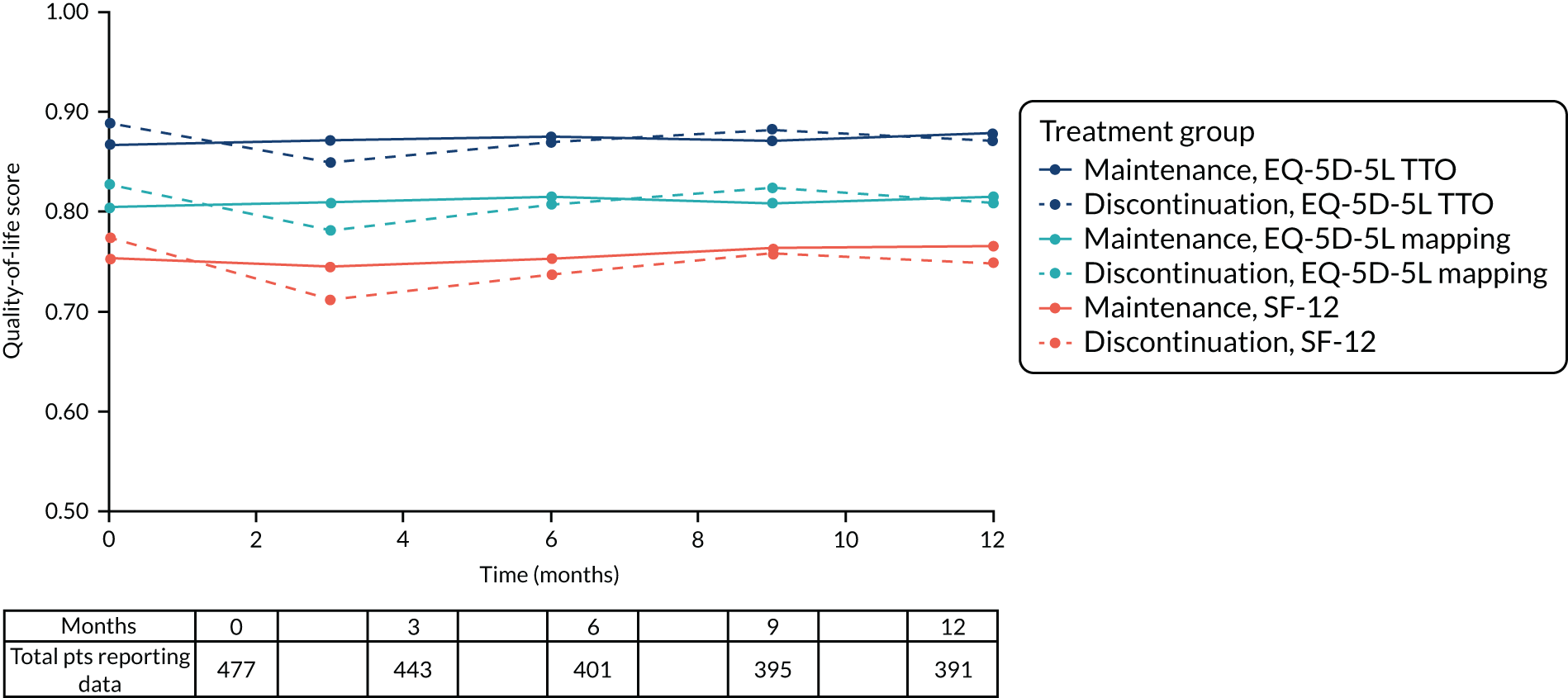

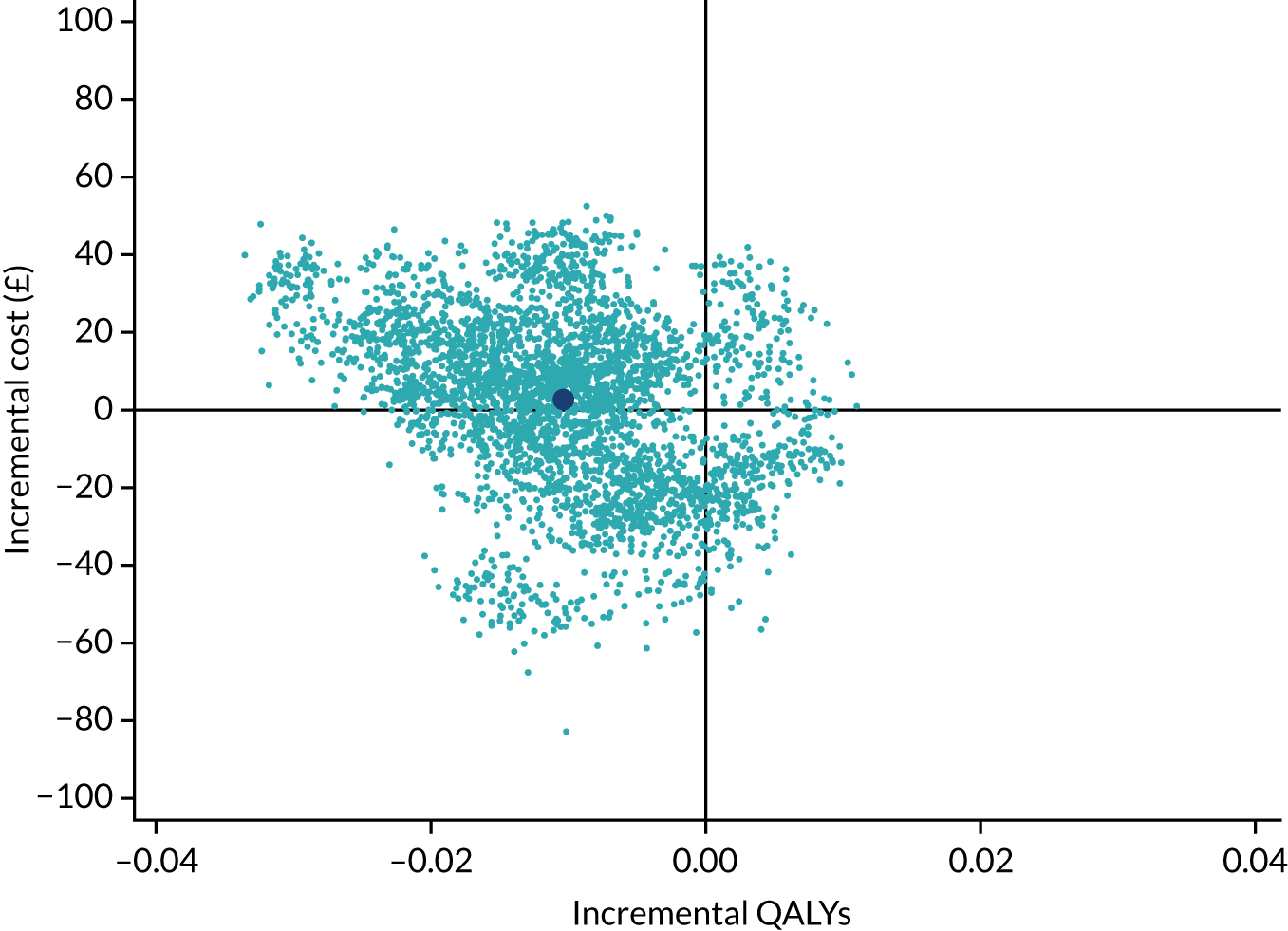

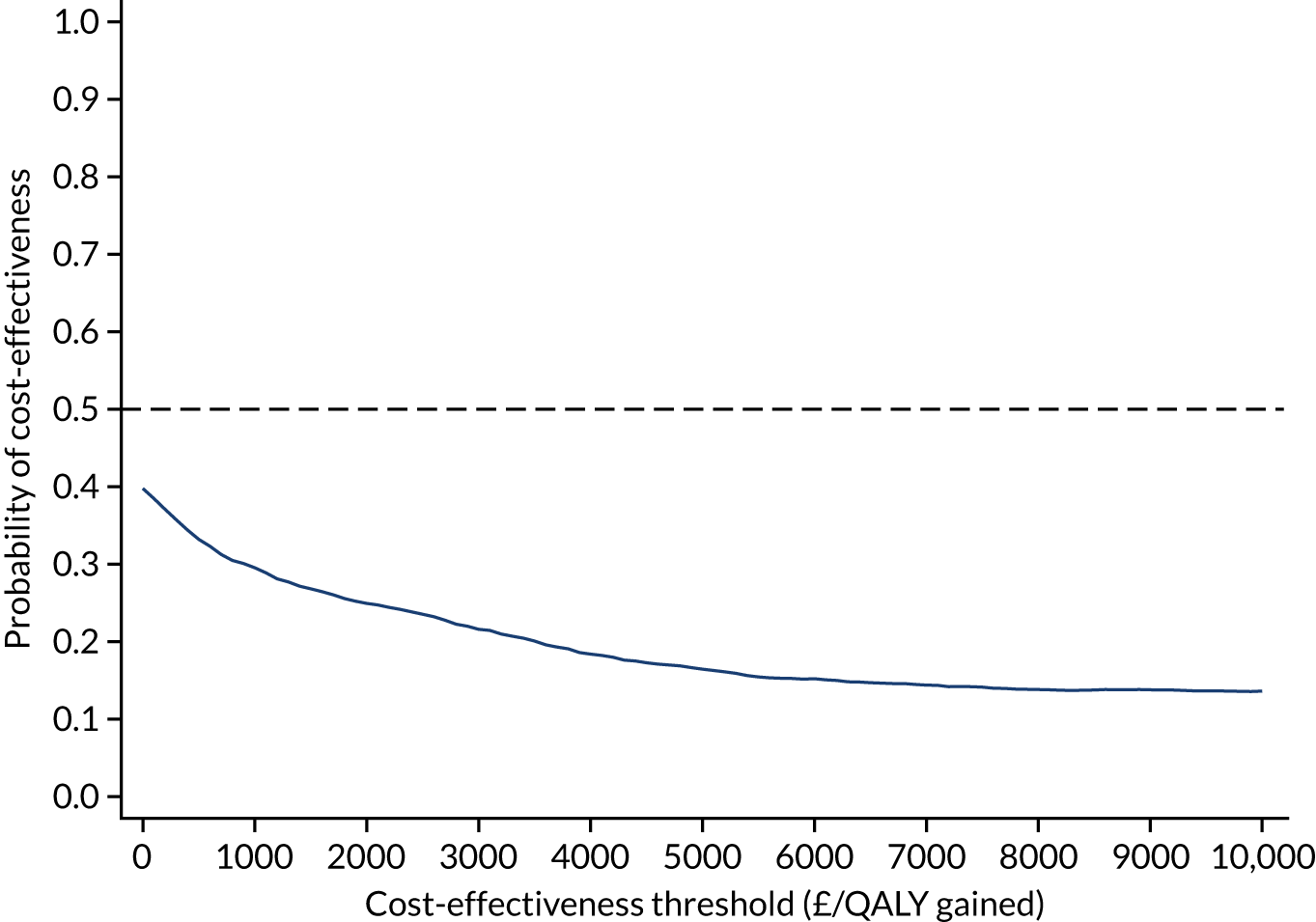

The measures used in the economic evaluation are discussed in Chapter 4.

Mechanistic outcomes

The mechanistic outcomes are not reported in the report or in the main trial paper that reports the clinical outcomes; they will be reported in separate paper(s). 34 However, we provide their description below.

Face recognition task

In this task, prototypical ‘happy’ and ‘sad’ composite images are generated from 20 individual male faces showing a happy facial expression and the same individuals showing a sad expression from the Karolinska emotional face set (CD ROM available from Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychology section, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm), using established techniques. 35 These are used as the end points of a linear morph sequence, which consists of 15 images that change in displayed emotion incrementally from unambiguously ‘happy’, through ambiguity, to unambiguously ‘sad’.

The procedure comprises 45 trials, with each stimulus in the sequence presented three times. Images are presented sequentially, in a random order, for 150 ms. Stimuli are preceded by a fixation cross, presented for a random duration ranging from 1500 to 2500 ms. Following presentation, a 250-ms backward mask of visual noise prevents processing of afterimages. Participants are prompted to judge whether the face was ‘happy’ or ‘sad’. As responses change monotonically from one emotion to the other, this allows the calculation of a balance point: the continuum frame at which participants shifted from perceiving primarily happiness to perceiving primarily sadness.

Word recall task

The word recall task36 tests the memory of socially rewarding and socially critical information. The participant is presented with 20 likeable (e.g. cheerful and honest) and 20 dislikeable (e.g. untidy and hostile) personality characteristic words on a laptop screen in a random order for 500 ms. Words are matched according to length, usage frequency and meaningfulness, and they differ at each time point. After each word, participants indicate whether they would ‘like’ or ‘dislike’ to hear someone describing them in this way by pressing a key on the keyboard. At the end of the task, participants are asked to recall as many words as possible in 2 minutes. This is a surprise recall task (at baseline) to test incidental memory. The number of positive and negative words accurately recalled (i.e. hits) and the number of false responses (i.e. intrusions) are also recorded.

Go/no-go task

In the go/no-go task,37 each trial includes three events: the presentation of a fractal image, the presentation of a target and the presentation of a probabilistic outcome. At the beginning of each trial, one of four possible fractal images is presented on a computer screen, which indicates whether the best choice in a subsequent target detection task is a go (pressing a key on the keyboard) or a no-go (withholding a response to the target). The fractal also indicates the valence of any outcome dependent on the participant’s behaviour (reward/no reward or punishment/no punishment). The meaning of the fractal images (go to win, no-go to win, go to avoid punishment, no-go to avoid punishment) is randomised across the participants, and participants have to learn these by trial and error. Participants are informed that the correct choice for each fractal image is either a go (button press) or a no-go (withhold button press). Actions are required in response to a target circle that follows the fractal image. After a brief delay, the outcome is presented (an upwards arrow indicates a win, a downwards arrow indicates a loss and a horizontal bar indicates the absence of a win or a loss). In go to win trials, a button press is rewarded. In go to avoid punishment, a button press avoids punishment. In no-go to win, withholding a button press is rewarded. In no-go to avoid losing trials, withholding a button press avoids punishment. The task consists of a total of 240 trials (60 trials per condition). The participant could win between £1 and £10.

Table 2 lists the schedule of assessments used in the trial.

| Time point | Trial period | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | Baseline | Post allocation | Close-out | |||||

| –t 1 | 0 | 6 weeks | 12 weeks | 26 weeks | 39 weeks | 52 weeks | After 52 weeks | |

| Enrolment | ||||||||

| Eligibility screen | ✗ | |||||||

| Informed consent | ✗ | |||||||

| Eligibility determination | ✗ | |||||||

| Randomisation | ✗ | |||||||

| Intervention | ||||||||

| Sertraline, citalopram, fluoxetine or mirtazapine | ||||||||

| Matching placebo | ||||||||

| Assessments | ||||||||

| Medical history | ✗ | |||||||

| Sociodemographic information | ✗ | |||||||

| CIS-R | ✗ | |||||||

| rCIS-R | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| PHQ-9 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| GAD-7 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| EQ-5D-5L | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| SF-12 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Toronto Side Effects Scale (modified) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Medication adherence | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| DESS scale (modified) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Global Rating Question | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Placebo/active question | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Pill count | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Emotional processing | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Health-care and social care resource use | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| GP appointments and medication | ✗ | |||||||

Sample size

The sample size estimation was based on the evidence from systematic reviews available when the trial was designed. The reduction in the odds of relapse in an active group compared with a placebo group was estimated to be 70% in a systematic review by Geddes et al. ,11 65% by Kaymaz et al. 13 and Glue et al. 12 and 50% by NICE. 20 Between 15% and 22% of those taking the active drug relapsed in 12 months. To detect the difference between relapse rates of 15% (maintenance group) and 30% (discontinuation group) (hazard ratio 0.46), or between relapse rates of 20% (maintenance group) and 35% (discontinuation group) (hazard ratio 0.52), we estimated that the required sample sizes were 333 and 383 participants, respectively, for 90% power at the 5% significance level. Allowing for 20% attrition, we therefore proposed to recruit 479 participants. 38 Analyses are expressed with the discontinuation group as reference, equating to a hazard ratio of 1.92 for the power calculation.

Randomisation and blinding

Following completion of the baseline assessment, eligible participants who consented were randomised using the automated randomisation service provided by Sealed Envelope (London, UK; https://sealedenvelope.com). The randomisation was minimised by the four study centres, the four medications and the severity of depressive symptoms at baseline (two categories measured using the CIS-R). The dispensing pharmacy (University Hospitals Bristol Pharmacy) was informed of the randomised allocation and posted the medication by recorded delivery to either the participant’s home or the GP surgery at 8-week intervals. Trial participants, clinicians and all members of the research team were blinded to the trial treatment allocation. Statisticians analysed the data blind to allocation. Health economists were aware of the allocation so that they could cost the trial medications. Participants were free to withdraw from the medication at any time.

Together with trial medication, participants were posted a contact card so that any treating clinician could be unblinded to treatment allocation in case of a medical emergency (emergency unblinding) or to enable treatment decisions (early unblinding). If unblinding was required, a formal request by a clinician was made to the trial pharmacy (through the 24-hour contact number provided on the contact card) that had a list of the participants’ treatment allocations. The treating physician managed the medical emergency as appropriate on receipt of the treatment allocation.

The researcher recorded any breaking of the code and the reasons for doing so in the unblinding log. When possible, members of the research team remained blinded. Those participants who did not require emergency or early unblinding were unblinded on completion of the trial (routine unblinding). This information was provided to their GP by the pharmacy; the participant was encouraged to see their GP to discuss any further treatment during that consultation. The trial team remained blind to this information.

Statistical methods

Primary outcome and secondary analysis

The statistical analysis plan was agreed in advance with the Trial Steering Committee and the independent Data Monitoring Committee (uploaded to https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10089782/; accessed 27 September 2021) and includes the health economics analysis plan. All statistical analyses were complete case and conducted using intention to treat. That is, data were analysed in the groups that they were randomised to regardless of whether or not participants maintained the allocation that they were randomised to throughout the trial.

The time to depression relapse was analysed using exact Cox proportional hazards modelling. The start date was the date of baseline data collection, and the end date was the date of relapse, date of withdrawal from the trial or date of final follow-up. Participants were asked to identify the number of weeks since the previous assessment that their symptoms began to estimate the date of onset of their relapse. If participants withdrew from the trial and did not provide further data, they were censored at the date of last data collection. The primary model adjusted for the participant’s CIS-R depressive symptom score. Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome included adjusting for the minimisation variables (centre in four categories and antidepressant in four categories, depressive symptoms above or below the median in two categories), using best- and worst-case scenarios for the 10 participants who were not included in the primary analysis. For the best- and worst-case scenarios, those in the maintenance group with missing primary outcome data were censored at the date of last follow-up or withdrawal (good outcome, no relapse) and for those in the discontinuation group with missing primary outcome data, relapse on the day before last follow-up or withdrawal (bad outcome, relapse).

The scales [PHQ-9, GAD-7, SF-12, Toronto Side Effects Scale and modified Discontinuation-Emergent Signs and Symptoms (DESS)] were analysed as if continuous. These secondary outcomes were analysed at each time point separately using mixed-effects linear regression, with two observations per participant: the baseline value and the value from the follow-up point. For these analyses, there was a fixed effect parameter for time and a parameter that was coded as follows: 1 for discontinuation group at follow up and 0 for maintenance group at both times and for discontinuation group at baseline. 39 These outcomes were also analysed using available data from all time points in a similar way to the analysis at each time point. The Global Rating Question was analysed using logistic regression at each time point. The time to stopping trial medication was analysed using exact Cox proportional hazards modelling. The start was taken as the latest of receiving trial medication, the date that the participant reported starting the medication or the date of randomisation. The end date was the earliest of the reported date that participants reported stopping taking trial medication or their final follow-up date. The main model included the randomisation variable and the participant’s depression CIS-R score. A sensitivity analysis also included the minimisation variables.

For secondary outcomes and time points, we conducted sensitivity analyses that included predictors of missingness identified using univariable logistic regression. For this, the outcomes were whether or not the measure was missing at each time point separately. Baseline variables were considered as possible predictors of missingness. Those that were statistically significant for each outcome and time point were adjusted for using models similar to the main secondary outcome models. For the models including data from all time points, all of the baseline predictors of missingness for the given outcome were included in the model. A predictors of missingness analysis was not carried out on the outcome of time to stopping the ANTLER trial medication given that we had data on whether or not all participants had stopped taking the ANTLER trial medication.

Subgroup analyses were conducted for the outcomes of time to relapse, PHQ-9, GAD-7 and the Global Rating Question. We conducted interactions between the treatment group and the antidepressant medication (dropping mirtazapine because of small numbers), baseline CIS-R depression and anxiety scores, number of previous episodes of depression (dichotomised at two compared with three or more) and the age at which the participant became aware of depression as a continuous measure. The p-value for the interaction is reported. In addition, we carried out analyses for each subgroup separately and the coefficient or odds ratio for the treatment group is reported. For this analysis, the age at which the participant became aware of depression was dichotomised at the median. Similar models to the main analyses were used for the subgroup analyses. These were carried out at each time point for PHQ-9, GAD-7 and the Global Rating Question. We also conducted a post hoc analysis, which was requested by a reviewer, to investigate whether or not withdrawal symptoms in the discontinuation compared with the maintenance group differed by antidepressant class.

There were no interim analyses and no predetermined stopping rules.

Reliability of the retrospective Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised

We assessed the onset of a depressive episode and called this assessment rCIS-R and conducted a test–retest reliability study of rCIS-R. The study was nested within the ANTLER trial. The ANTLER trial participants were asked to complete the rCIS-R twice: at the beginning of one of the face-to-face follow-up appointments and at the end of the same appointment.

Why we needed a new measure to assess relapse

One of the methodological challenges of measuring relapse in depression studies has been a lack of clarity in defining relapse and how to differentiate relapse from recurrence. Frank et al. 40 attempted to define the course of depressive illness by defining the use of terms, such as response, remission, recovery, relapse and recurrence, and offering conceptualisation and operational criteria for each term. However, Frank et al. 40 did not provide the time scale to recovery, leaving uncertainty on when the distinction should apply. Rush et al. 41 elaborated further on the distinctions between the terms and proposed defining remission in terms of minimal symptoms over a 3-week duration and defining recovery as having at least 4 months of remission. However, to ensure that the occurrence of recovery has been accurately determined, frequent (i.e. every 2 weeks) assessments must be carried out to detect the return of the index episode. Such an approach is perhaps impractical in clinical practice. The ‘minimal symptoms’ definition is dependent on the measure used, producing arbitrary definitions. Given that depression is no longer seen as a time-limited disorder with episodes lasting around 4–6 months with full recovery, but is rather thought of as a ‘relapsing–remitting’ continuum with debilitating symptoms occurring between acute episodes,42 we believe that studies assessing the benefit of long-term maintenance treatment need to measure the appearance of any depressive episode and that the proposed distinction between relapse and recurrence is less important. We, therefore, use the term relapse in this report to refer to any new episode of depressive symptoms.

Another issue with assessing relapse is the variety of scales used in medical research. A considerable effort has been put into research of acute treatment; by contrast, there have been relatively few studies investigating long-term maintenance treatments (see Chapter 1, Current evidence on the effectiveness of maintenance treatment). To measure relapse, most studies used clinical rating scales, such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression43 or the Montgomery and Äsberg Depression Rating Scale,44 at frequent intervals, typically fortnightly. Such scales are prone to observer bias because they are administered by a clinician and measure current symptoms. Self-completed questionnaires, such as the Beck Depression Inventory45 and PHQ-9,26 are often used in research in addition to rating scales by clinicians. Although they eliminate observer bias, they can be regarded as crude and might miss some symptoms and/or their intensity owing to patients interpreting the questions in different ways. 46 They also assess the current symptoms and do not determine the time to relapse.

Fully structured interviews have also been used in research on relapse; they can be administered by lay interviewers, can eliminate observer bias and, therefore, are much more economical. An example is the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). 47 However, the CIDI has over 280 symptom questions that are accompanied by ‘probe’ questions to assess severity, which makes the interview extremely long, up to 3 hours, and often unacceptable for participants. In addition, the rigid rules of administration and the use of complex flow charts may lead to mistakes by the interviewer in either presenting questions or interpreting participants’ responses. 48 The Structured Clinical Interview Disorder (SCID)49 is semistructured, so interviewers need more extensive training in its use, is lengthy (taking between 2 and 6 hours to administer) and requires judgements to be made about the presence of symptoms, thus incurring the risk of introducing observer bias. Although the inter-rater reliability study50 of SCID on 151 participants produced fair agreement on the depression scale, the use of audio tapes in this study could have improved the reliability because both raters had access to the same verbal information, but the second rater did not have non-verbal information and any interviewer-related measurement error would not have been included.

A simpler structured interview that is considerably shorter and assesses the symptoms in the last 12 weeks would be a better option to accurately assess the symptoms.

The aim of the reliability study

The aim of this study was to assess the test–retest reliability of the rCIS-R. We developed a simple measure that can be used to diagnose the reappearance of depressive symptoms after recovery. The rCIS-R is a new assessment that is based on the CIS-R,25 a validated measure that has been widely used by researchers to assess the severity and duration of depression; however, the CIS-R asks about symptoms in the last 7 days. Therefore, we adapted it to assess the symptoms in the last 12 weeks in a fully structured format, that, to our knowledge, has not been carried out for other existing measures.

The measure

The rCIS-R was designed as a self-administered computerised questionnaire and asked about the previous 12 weeks at each follow-up point: 12, 26, 39 and 52 weeks. Only five sections (i.e. depressive mood, depressive ideas, concentration, sleep and fatigue) that are used for a depression diagnosis are asked, along with questions asking about the duration of the symptoms and the intensity of symptoms during the worst week, and questions establishing the start of the symptom(s) in the last 12 weeks. The rCIS-R begins with the two overarching mandatory questions for the depressive mood and depressive ideas sections. To progress further, the participant is required either to answer ‘yes’ to the first mandatory depression question, ‘Almost everyone becomes low in mood or depressed at times. Has there been a time in the past three months when you had a spell of feeling sad, miserable or depressed?’, or to answer ‘no’ to the second mandatory question, ‘In the past three months, have you been able to enjoy or take an interest in things as much as you usually do?’. If the participant’s answers indicate that they have experienced either low mood or anhedonia in the last 12 weeks, they are asked about the duration to establish that symptoms have been present for ≥ 2 weeks and the time when they started feeling depressed. If the symptom(s) have been present for ≥ 2 weeks, the participant is considered to be positive for that symptom and is asked 10 additional questions covering depressive symptoms during the worst week (e.g. feeling low for prolonged periods, unresponsiveness of mood, loss of sexual interest, restlessness, decreased cognitive function, feeling of guilt, lower self-esteem, hopelessness, feeling life is not worth living and suicidal thoughts).

The other three sections of the rCIS-R (i.e. concentration, sleep and fatigue) are similar in structure and they also start with mandatory question(s). If the participant’s answer to the mandatory question(s) indicates that they have not experienced such symptoms, the extra questions relating to the severity of the symptom are not asked and the participant skips to the mandatory question in the next section of the rCIS-R. If the participant’s answer indicates that they have experienced the symptom, they are considered positive for that section and further questions about their experience during the worst week are also asked. It is possible to score a maximum of 3 on the concentration and fatigue sections and 4 on the sleep section.

Box 1 shows the concentration section as an example of a section from the rCIS-R. The first two questions are the mandatory questions and if the answer is ‘yes’ to at least one, the other three questions are asked.

Has there been a period of time in the PAST THREE MONTHS, when you had problems in concentrating on what you were doing?

Has there been a period of time in the PAST THREE MONTHS, when you noticed any problems with forgetting things?

During the worst WEEK in the past three months:

1. Could you concentrate on all of the following without your mind wandering?

• A whole TV programme

• A newspaper article

• Talking to someone

1. Yes, I could concentrate on all of them

2. No, I couldn’t concentrate on at least one of these things

2. Did problems with your concentration STOP you from getting on with things you used to do or would like to do?

1. No

2. Yes

3. Did you forget anything important?

1. No

2. Yes, I did forget something important

The assessment takes approximately 5 minutes to complete; however, if the participant does not have any symptoms, it takes as little as 2 minutes.

Testing the algorithm

A relapse of depression was defined as experiencing two or more depressive symptoms from any of the five sections during the worst week in the past 3 months (this must include at least one of the two overarching mandatory questions on depressive mood or anhedonia for ≥ 2 weeks) on the rCIS-R.

We also defined relapse in line with ICD-10 criteria and investigated the number of participants experiencing four or more depressive symptoms. In addition to defining a binary outcome of relapse, rCIS-R generates a total score for the depressive episode that occurred in the previous 12 weeks. Each section generates a maximum score between 3 and 6; higher scores indicate more symptoms and the total score can range from 0 to 21.

In September 2018, before the statistical analysis plan was finalised, we looked at some preliminary data from the 12-week follow-up. Data were available for 157 ANTLER trial participants and we used this subset to test the algorithm. Using the above definition for relapse, 29 participants (18%) were identified as having relapsed in depression by their 12-week follow-up appointment. We also explored if the number of relapses changed if the algorithm included more symptoms, so we tested the following algorithms:

-

participant experienced either low mood or anhedonia for ≥ 2 weeks in the past 3 months and was positive on two of any of the five sections (depressive mood, depressive thoughts, fatigue, concentration or sleep)

-

participant experienced either low mood or anhedonia for ≥ 2 weeks in the past 3 months and was positive on three of any of the five sections (depressive mood, depressive thoughts, fatigue, concentration or sleep)

-

participant experienced either low mood or anhedonia for ≥ 2 weeks in the past 3 months and was positive on four of any of the five sections (depressive mood, depressive thoughts, fatigue, concentration or sleep).

The first two algorithms generated the same number of cases as the original algorithm (29 cases). However, the last algorithm generated 25 cases. We concluded that a score of ≥ 2 on the five sections of depression (including at least one of the two mandatory questions) accurately identifies participants who have relapsed and, therefore, we adopted this case definition as our primary outcome.

Analysis

The level of agreement between the first and the second completion of the rCIS-R was assessed using kappa (quadratic weighted and unweighted) statistics. Quadratic weighted and unweighted kappa produced very similar results. Given that weighted kappa provides a ratio-scale degree of disagreement to each cell of the κ × κ table, making weighted kappa suitable as a measure of agreement. The test–retest reliability was also assessed by using a Bland–Altman plot. 51 We also calculated the intraclass correlation coefficient using a single-measurement, absolute agreement, two-way mixed-effects model.

Results of the reliability study of the retrospective Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised

Of 478 participants who were recruited to the trial, 396 completed the rCIS-R twice. Two participants completed the rCIS-R at the 12-week follow-up appointment, 335 participants at 26 weeks, 42 participants at 39 weeks and 17 participants at 52 weeks. There were 106 male participants, the mean age was 55 years (SD 6 years) and 6% of the participants reported being from an ethnic minority group. The full description of the reliability study sample characteristics compared with the trial sample is in Table 3.

| Characteristic | Reliability study sample | Trial sample |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 55 (6) | 54 (6) |

| Male, n/N (%) | 106/396 (27) | 128/478 (27) |

| Ethnicity, n/N (%) | ||

| White | 373/396 (94) | 449/473 (95) |

| Not white | 23/396 (6) | 25/473 (5) |

| Highest educational qualification, n/N (%) | ||

| Degree/higher degree | 146/396 (37) | 179/472 (38) |

| Diploma/A Levels or equivalent | 127/396 (32) | 148/472 (31) |

| GCSE or equivalent/other/none | 123/396 (31) | 145/472 (31) |

| Site, n/N (%) | ||

| London | 170/396 (43) | 199/478 (42) |

| Bristol | 80/396 (20) | 102/478 (21) |

| Southampton | 84/396 (21) | 96/478 (20) |

| York | 62/396 (16) | 81/478 (17) |

| Antidepressant, n/N (%) | ||

| Sertraline | 62/396 (16) | 78/478 (16) |

| Citalopram | 183/396 (46) | 223/478 (47) |

| Fluoxetine | 135/396 (34) | 160/478 (33) |

| Mirtazapine | 16/396 (4) | 17/478 (4) |

| CIS-R score at baseline, mean (SD) | 5.0 (4.8) | 5.1 (4.8) |

| PHQ-9 score at baseline, mean (SD) | 3.8 (3.6) | 3.8 (3.5) |

| Age first became aware of having depression (years), mean (SD) | 32 (5) | 32 (15) |

The Cohen’s kappa for relapse in depression was 0.84 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.71 to 0.97], which indicates excellent agreement between the first and the second completions of the rCIS-R (Tables 4 and 5). The level of agreement of the individual sections of the rCIS-R was also excellent (see Table 4). The agreement of the time of depression relapse was also assessed: both agreement of month κ = 0.84 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.97) and agreement of week κ = 0.87 (95% CI 0.74 to 1.00) of reappearance of depression.

| Frequency present at the first completion (%) | Weighted Cohen’s kappa (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Relapse | 20 | 0.84 (0.71 to 0.97) |

| Symptoms | ||

| Depression or depressive mood | 54 | 0.87 (0.77 to 0.97) |

| Depressive thoughts | 50 | 0.87 (0.77 to 0.87) |

| Fatigue | 56 | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.95) |

| Concentration | 25 | 0.81 (0.72 to 0.91) |

| Sleep | 52 | 0. 91 (0.82 to 1.00) |

| Relapsed on the second completion | Relapse on the completion (n) | Total (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did not relapse | Relapsed | ||

| Did not relapse | 301 | 18 | 319 |

| Relapsed | 15 | 62 | 77 |

| Total | 316 | 80 | 396 |

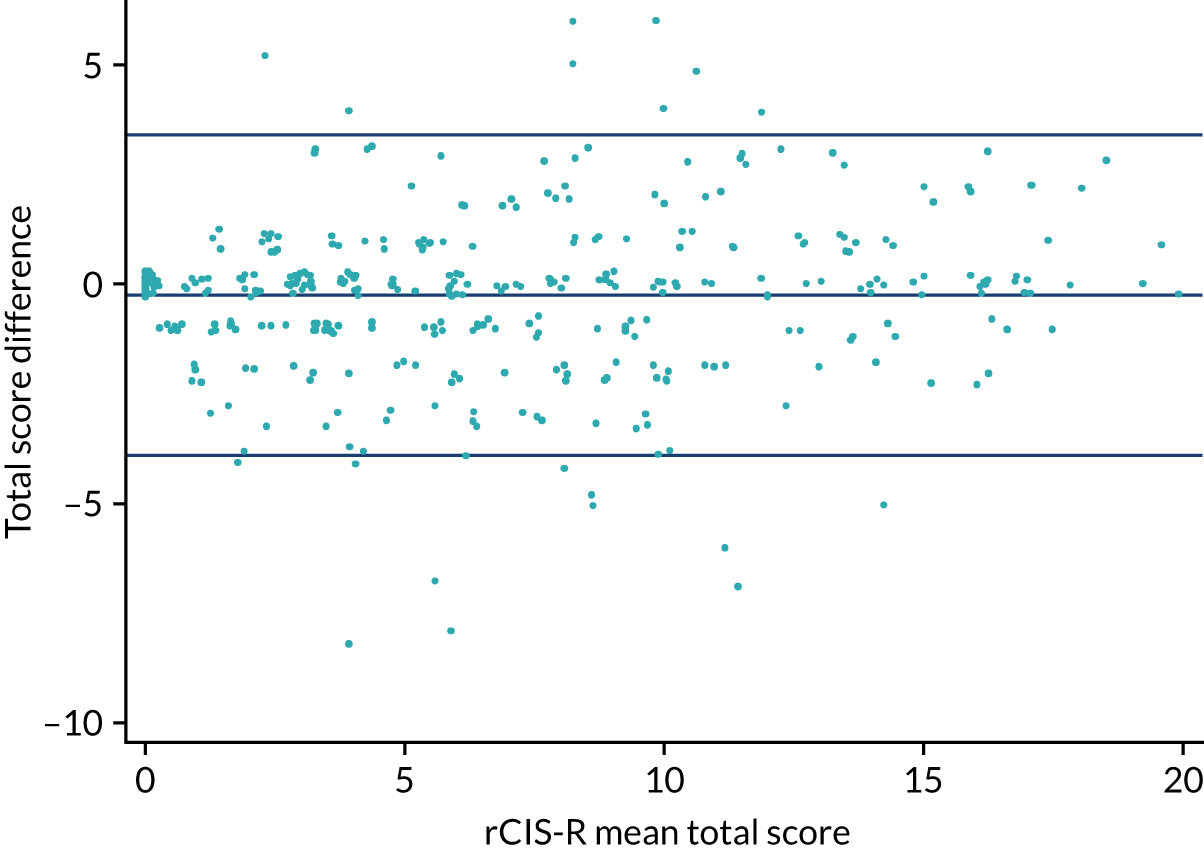

The mean score for the first completion of the rCIS-R was 6.67 (SD 5.06) and the mean score for the second completion was 6.41 (SD 5.25). The percentage of participants meeting the relapse criteria at the first completion was 20% (n = 80) and at the second completion was 19% (n = 77). The mean total score difference was –0.25 (95% CI –0.43 to –0.07).

The Bland–Altman plot (Figure 3) shows the agreement between the first and the second completion of the rCIS-R. The intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.94 (95% CI 0.92 to 0.95).

FIGURE 3.

Difference in the total rCIS-R score against the mean total score.

We also looked at defining relapse in line with ICD-10 criteria: 18% of participants relapsed according to the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for depression at the first (n = 72) and second (n = 70) completions. Cohen’s kappa for relapse of depression according to ICD-10 criteria was 0.74 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.84).

Public and patient involvement

Paul Lanham, our public and patient involvement (PPI) representative, is a co-applicant of the proposal and has been involved in all stages of the trial for almost 5 years. He is a former chairperson (1988–93) and director (1986–2009) of Depression Alliance [now merged with Mind (London, UK)] and provided input to previous studies on depression funded by the HTA programme (TREAD,52 CoBalT6 and PREVENT53).

In the development of the proposal, Paul Lanham was supportive of examination of the effectiveness of maintenance medication and wrote ‘From a user point of view this strikes me as being vitally important and I am delighted to be involved in it; I am sure that others (especially sufferers and GPs) will also welcome it and gain a great deal from its results’ (reproduced with permission from Paul Lanham, London, May 2014, personal communication). Paul is currently on maintenance antidepressants himself and added ‘I mistrust terms like “remission”, “well”, “normal” etc. People ask me if Citalopram helps; the answer is that I have no idea of what I would be like without it so I cannot judge. This [study] will hopefully determine whether such drugs are a help or not. It would be really valuable to know the answer to this through the study’ (reproduced with permission from Paul Lanham, personal communication). Paul was a co-applicant on the HTA proposal and a co-author on the final report.

During the trial, Paul Lanham was a member of the Trial Steering Group and the Trial Management Group, but he decided once the trial was established that his contribution was not required. In 2017, we recruited another PPI member, Lucy Carr, who was a former participant in a NIHR-funded trial, PANDA. 33 She was an independent member of the Trial Steering Committee and contributed, along with Paul Lanham, to the design and content of the study documentation, including patient information sheets and self-harm protocols.

In addition, we enlisted the support of the North London Service Users Research Forum (SURF). North London SURF was co-founded in 2007 by service users and clinical academic psychiatrists at University College London to provide meaningful consultation on research. It has 12 members who have mental health problems. Since 2007, it has been consulted on over 100 projects, and North London SURF members have also been invited to join steering/management groups on many of these. As a result, the group is very experienced and confident about the advice and input that it provides; members’ comments on the trial paperwork have been invaluable. The letter templates, patient information sheets and questionnaires were amended to reflect the North London SURF feedback. We also consulted on the protocol concerning self-harm or risk of self-harm, which was used if patients reported this in the course of the trial.

We also contacted Luke Montagu, who has experienced withdrawal symptoms from antidepressants and is a well-known activist in this area. Luke Montagu, along with others with lived experience, helped us modify the DESS scale measure of withdrawal symptoms. We shortened the scale (from 42 to 15 items) to improve its acceptability and selected the most commonly found items using published literature and a survey of Luke Montagu’s contacts. After consulting with the group, we included a question on electric sensations in the brain (brain zaps), apparently a very common, disabling symptom that has been poorly understood and not included in previous scales. Close involvement of the PPI for the duration of the trial has been invaluable for its success from the set-up stage onwards, shaping the study through to the discussion on the interpretation of results. We plan to carry on using the services users’ involvement in the design, documentation and analysis of any future studies.

Chapter 3 Results

Flow of participants in the trial

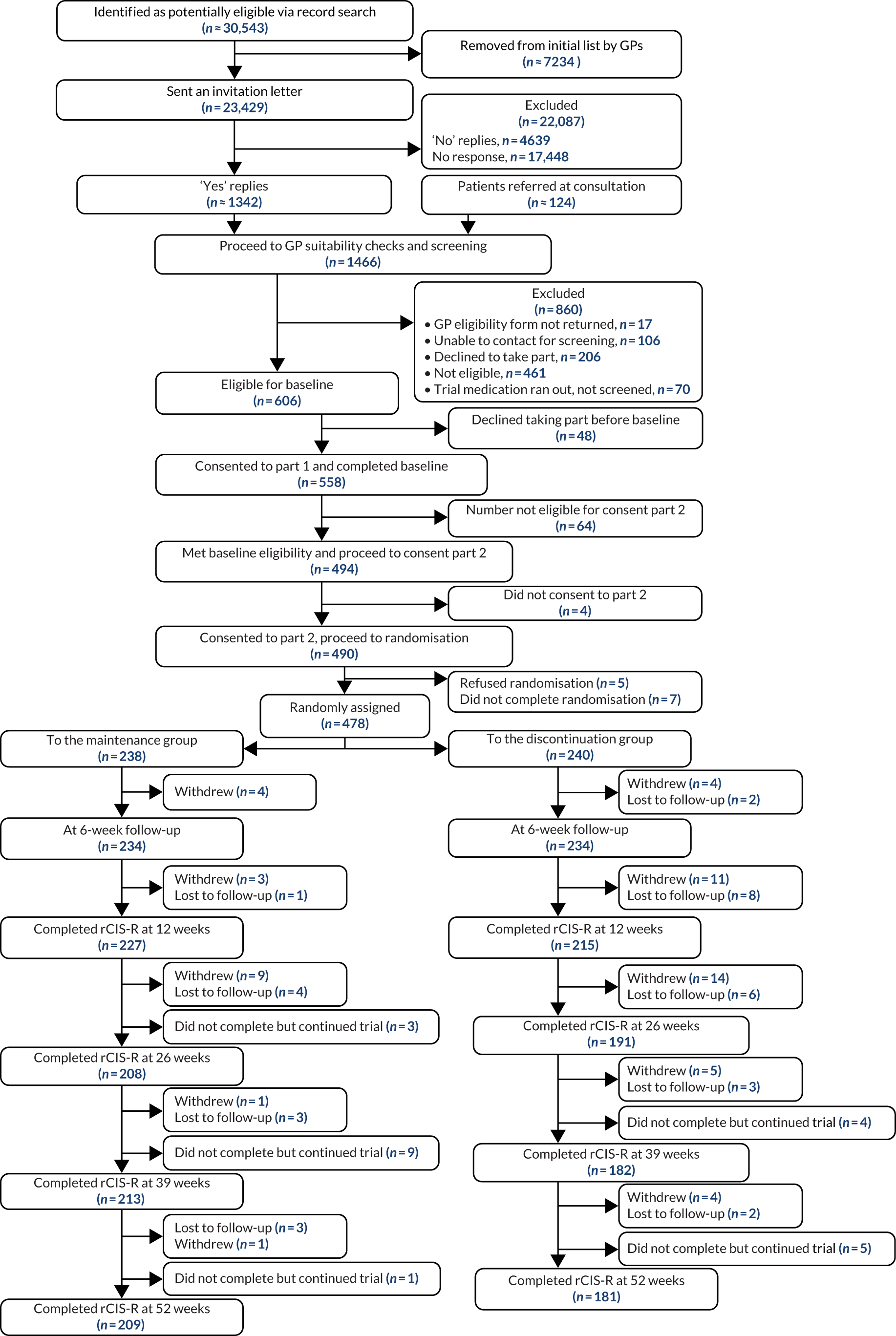

Recruitment began on 9 March 2017 and the last participant was randomised on 1 March 2019. The flow of participants through the trial is shown in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram (Figure 4). The GP record search identified 23,429 potentially eligible patients, who were sent an invitation letter. Another 124 potentially eligible patients were referred during GP consultation, resulting in 1466 patients wanting to take part. Of these patients, 606 were eligible. A total of 478 participants were randomised: 238 to the maintenance group and 240 to the discontinuation group. All of the participants provided data on whether or not they relapsed; however, 10 participants (maintenance group, n = 6; discontinuation group, n = 4) did not provide data on timing of relapse, so could not be included in the analysis of the primary outcome.

FIGURE 4.

The CONSORT flow diagram for the ANTLER trial.

Baseline comparability

The baseline characteristics of the sample overall and by treatment group are shown in Table 6. The treatment groups were well balanced at baseline, with just over one-quarter of male participants and a mean age of 54 years (SD 13 years) in the maintenance group and 55 years (SD 12 years) in the discontinuation group. Just over 40% of participants were recruited from London, 20% from each of Bristol and Southampton, and 17% from York. Under half of the participants were taking citalopram, one-third fluoxetine, one-sixth sertraline and < 5% mirtazapine. Almost three-quarters of the participants had taken antidepressants for more than 3 years, with over one-third taking them for ≥ 6 years. The mean age at becoming aware of having depression was 33 years (SD 16 years) in the maintenance group and 32 years (SD 14 years) in the discontinuation group. The median time between randomisation and taking the trial medication was 9 days (interquartile range 6–13 days) in the maintenance group and 8 days (interquartile range 6–13 days) in the discontinuation group.

| Characteristic | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| Maintenance | Discontinuation | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 54 (13) | 55 (12) |

| Male, n/N (%) | 70/238 (29) | 59/240 (25) |

| Ethnicity, n/N (%) | ||

| White | 221/238 (93) | 228/235 (97) |

| Not white | 17/238 (7) | 7/235 (3) |

| Marital status, n/N (%) | ||

| Married | 146/238 (61) | 161/240 (67) |

| Single | 35/238 (15) | 26/240 (11) |

| Separated or divorced | 39/238 (16) | 33/240 (14) |

| Widowed | 18/238 (8) | 20/240 (8) |

| Employment status, n/N (%) | ||

| Employed | 140/238 (59) | 152/240 (63) |

| Retired | 71/238 (30) | 68/240 (28) |

| Other | 27/238 (11) | 20/240 (8) |

| Site, n/N (%) | ||

| London | 101/238 (42) | 98/240 (41) |

| Bristol | 48/238 (20) | 54/240 (23) |

| Southampton | 48/238 (20) | 48/240 (20) |

| York | 41/238 (17) | 40/240 (17) |

| Antidepressant, n/N (%) | ||

| Sertraline | 41/238 (17) | 37/240 (15) |

| Citalopram | 111/238 (47) | 112/240 (47) |

| Fluoxetine | 77/238 (32) | 83/240 (35) |

| Mirtazapine | 9/238 (4) | 8/240 (3) |

| CIS-R above the median,a n/N (%) | 116/237 (49) | 110/240 (46) |

| Age first became aware of having depression (years), mean (SD) | 33 (16) | 32 (14) |

| Three or more previous episodes of depression, n/N (%) | 224/238 (94) | 219/239 (92) |

| Time taking antidepressants, n/N (%)a,b | ||

| 9 months to < 1 year | 12/238 (5) | 18/239 (8) |

| 1 to 2 years | 56/238 (24) | 53/239 (22) |

| 3 to 5 years | 81/238 (34) | 79/239 (33) |

| 6 to 10 years | 48/238 (20) | 48/239 (20) |

| ≥ 11 years | 41/238 (17) | 41/239 (17) |

| Courses of antidepressants in the past, n/N (%) | ||

| 0 | 102/238 (43) | 92/239 (38) |

| 1 | 40/238 (17) | 39/239 (16) |

| ≥ 2 | 96/238 (40) | 108/239 (45) |

| Taking other psychotropic medication, n/N (%) | ||

| Diazepam or lorazepam | 3/238 (1) | 3/240 (1) |

| Zopiclone or zolpidem | 5/238 (2) | 2/240 (0.8) |

| Using psychotherapy, n/N (%) | 24/237 (10) | 18/239 (8) |

| PHQ-9, mean (SD)c | 3.9 (3.5) | 3.8 (3.6) |

| GAD-7, mean (SD)d | 3.2 (3.1) | 2.8 (3.0) |

| SF-12 physical, mean (SD)e | 48 (11) | 50 (9) |

| SF-12 mental, mean (SD)e | 47 (9) | 48 (9) |

| Modified Toronto Side Effects Scale, mean (SD)f | 4.2 (2.7) | 3.7 (2.7) |

| At least one symptom on the Toronto Side Effects Scale, n/N (%) | 217/235 (92) | 218/239 (91) |

| Number of new or worsening symptoms using modified DESS scale, mean (SD)g | 1.0 (1.4) | 0.6 (1.0) |

| At least one new or worsening symptom using modified DESS scale, n/N (%)g | 118/238 (50) | 95/240 (40) |

| Mood worse than 2 weeks ago, n/N (%) | 13/237 (5) | 9/239 (4) |

Primary outcome

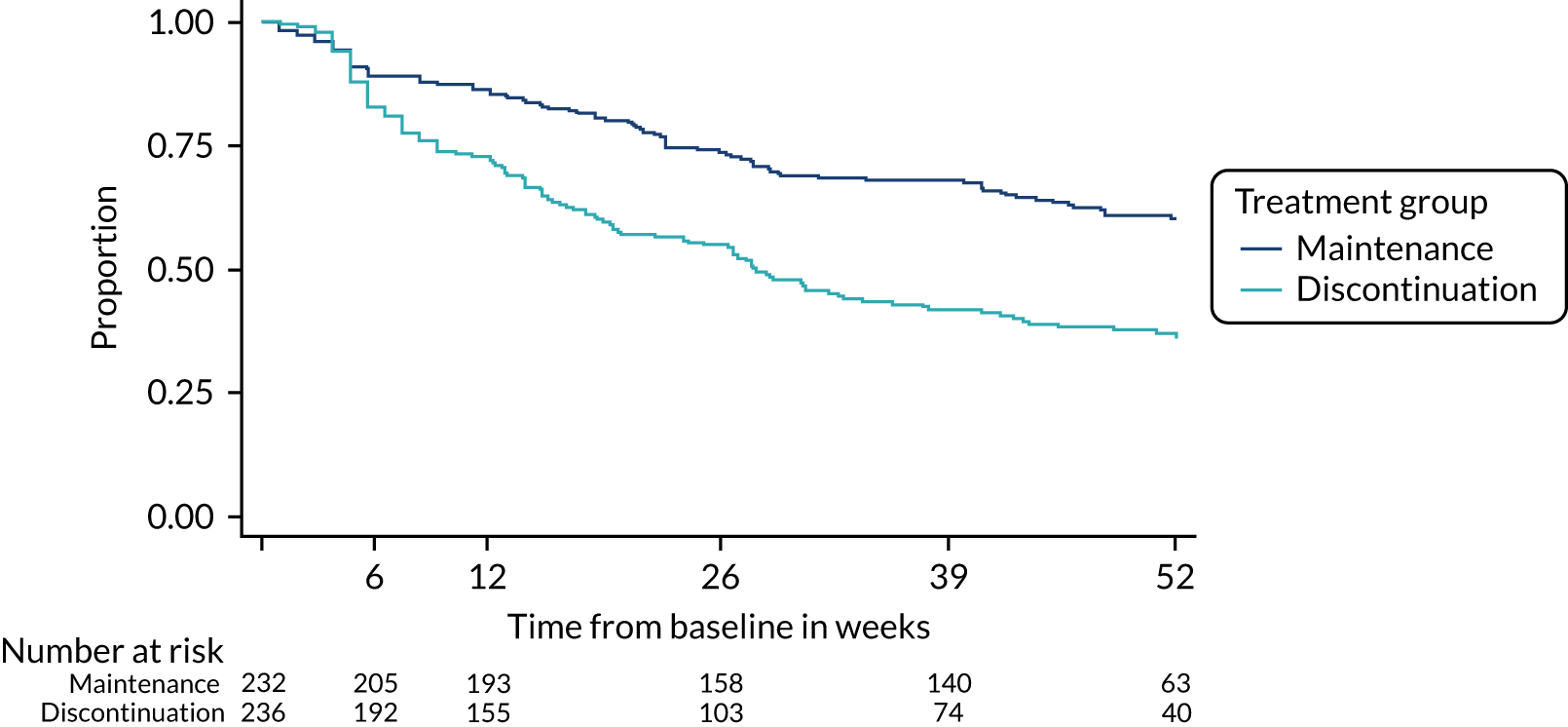

The time to relapse was shorter in participants who discontinued antidepressants than in those who stayed on maintenance treatment [hazard ratio (HR) 2.06, 95% CI 1.56 to 2.70; p < 0.0001] (Table 7 and Figure 5). This result was unaltered after sensitivity analyses.

Overall, relapse was experienced by 39% (n = 92/238) (95% CI 32% to 45%) of participants in the maintenance group and 56% (n = 135/240) (95% CI 50% to 63%) of participants in the discontinuation group by the end of the trial (52 weeks). Relapses according to treatment group are shown in the tree diagrams (see Report Supplementary Material 9).

| Outcome | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Time to first depression relapse (N = 468) | 2.06 (1.56 to 2.70) |

| Time to first depression relapse, including minimisation variables (N = 468)a | 2.07 (1.57 to 2.72) |

| Time to first depression relapse, good outcome in control and bad outcome in intervention (N = 478)b | 2.12 (1.61 to 2.78) |

FIGURE 5.

Kaplan–Meier plot for the primary outcome. From N Engl J Med, Lewis G, Marston L, Duffy L, Freemantle N, Gilbody S, Hunter R, et al. , Maintenance or discontinuation of antidepressants in primary care, vol. 385, pp. 1275–67. 34 Copyright © 2021 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission.

Secondary outcomes

The PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores were higher (worse) in the discontinuation group than in the maintenance group at 12 and 26 weeks, the highest of which for both was at 12 weeks (PHQ-9: coefficient 2.16, 95% CI 1.47 to 2.84; GAD-7: coefficient 2.40, 95% CI 1.81 to 2.99).

The number of withdrawal symptoms reported was higher in the discontinuation group than in the maintenance group at 6, 12, 26 and 39 weeks, with the difference largest at 12 weeks (coefficient 1.87, 95% CI 1.46 to 2.28).

Participants in the discontinuation group had lower (worse) SF-12 mental health-related quality-of-life scores at 12, 26 and 39 weeks, with the difference largest at 12 weeks (coefficient –4.86, 95% CI –6.44 to –3.29). At 12 weeks, in the discontinuation group, the odds of feeling worse, determined using the Global Rating Question, was more than twice that (odds ratio 2.88, 95% CI 1.90 to 4.38) in the maintenance group (Table 8).

| Outcome | Treatment group | Estimate (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintenance | Discontinuation | ||

| PHQ-9 (coefficient),a mean (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 3.9 (3.5) | 3.8 (3.6) | |

| 6 weeks (n = 478) | 4.1 (3.8) | 4.4 (4.0) | 0.30 (–0.26 to 0.87) |

| 12 weeks (n = 477) | 4.1 (3.8) | 6.3 (5.1) | 2.16 (1.47 to 2.84) |

| 26 weeks (n = 477) | 4.2 (3.7) | 5.0 (4.6) | 0.72 (0.02 to 1.42) |

| 39 weeks (n = 477) | 3.8 (3.9) | 4.4 (4.2) | 0.55 (–0.14 to 1.24) |

| 52 weeks (n = 477) | 3.7 (3.7) | 4.0 (4.5) | 0.38 (–0.32 to 1.07) |

| Over all time points (n = 478) | 0.84 (0.38 to 1.29) | ||

| GAD-7 (coefficient),b mean (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 3.2 (3.1) | 2.8 (3.0) | |

| 6 weeks (n = 478) | 3.2 (3.6) | 3.6 (3.7) | 0.50 (–0.03 to 1.03) |

| 12 weeks (n = 477) | 3.1 (3.3) | 5.3 (4.6) | 2.40 (1.81 to 2.99) |

| 26 weeks (n = 477) | 3.4 (3.8) | 4.1 (4.4) | 0.79 (0.13 to 1.45) |

| 39 weeks (n = 477) | 2.9 (3.5) | 3.8 (4.1) | 0.99 (0.36 to 1.62) |

| 52 weeks (n = 477) | 3.0 (3.7) | 3.1 (3.0) | 0.27 (–0.36 to 0.89) |

| Over all time points (n = 478) | 1.00 (0.58 to 1.42) | ||

| Modified Toronto Side Effects Scale (coefficient),c mean (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 4.2 (2.7) | 3.7 (2.7) | |

| 6 weeks (n = 478) | 3.7 (2.7) | 4.0 (2.8) | 0.53 (0.13 to 0.92) |

| 12 weeks (n = 477) | 4.2 (2.9) | 4.6 (3.0) | 0.68 (0.25 to 1.11) |

| 26 weeks (n = 477) | 4.0 (2.6) | 3.9 (2.8) | 0.20 (–0.26 to 0.66) |

| 39 weeks (n = 476) | 3.8 (2.5) | 3.7 (2.6) | 0.16 (–0.30 to 0.62) |

| 52 weeks (n = 475) | 3.7 (2.6) | 3.5 (2.8) | 0.04 (–0.41 to 0.49) |

| Over all time points (n = 478) | 0.36 (0.06 to 0.65) | ||

| Number of new or worsening symptoms using modified DESS scale (coefficient),d mean (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 1.0 (1.4) | 0.6 (1.0) | |

| 6 weeks (n = 478) | 1.1 (2.0) | 1.5 (2.5) | 0.51 (0.17 to 0.84) |

| 12 weeks (n = 478) | 1.3 (2.4) | 3.1 (3.5) | 1.87 (1.46 to 2.28) |

| 26 weeks (n = 478) | 1.4 (2.3) | 1.9 (2.9) | 0.50 (0.12 to 0.89) |

| 39 weeks (n = 478) | 0.8 (1.6) | 1.7 (2.7) | 0.94 (0.60 to 1.28) |

| 52 weeks (n = 478) | 0.8 (1.8) | 1.1 (2.5) | 0.32 (–0.02 to 0.65) |

| Over all time points (n = 478) | 0.86 (0.62 to 1.11) | ||

| SF-12 physical (coefficient),e mean (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 48 (11) | 50 (9) | |

| 12 weeks (n = 476) | 48 (10) | 50 (9) | 0.44 (–0.91 to 1.78) |

| 26 weeks (n = 476) | 48 (10) | 49 (10) | 0.15 (–1.33 to 1.62) |

| 39 weeks (n = 476) | 48 (11) | 51 (10) | 1.49 (–0.06 to 3.04) |

| 52 weeks (n = 476) | 49 (10) | 49 (11) | –0.59 (–2.09 to 0.92) |

| Over all time points (n = 476) | 0.44 (–0.60 to 1.48) | ||

| SF-12 mental (coefficient),e mean (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 47 (9) | 48 (9) | |

| 12 weeks (n = 476) | 46 (10) | 41 (11) | –4.86 (–6.44 to –3.29) |

| 26 weeks (n = 476) | 46 (11) | 44 (11) | –2.56 (–4.35 to –0.77) |

| 39 weeks (n = 476) | 48 (10) | 45 (11) | –3.07 (–4.84 to –1.31) |

| 52 weeks (n = 476) | 47 (10) | 46 (11) | –1.59 (–3.43 to 0.25) |

| Over all time points (n = 476) | –3.02 (–4.23 to –1.81) | ||

| Global Rating Question (OR), n/N (%) | |||

| Baseline (N = 476) | |||

| Feeling the same or better | 224/237 (95) | 230/239 (96) | |

| Feeling worse | 13/237 (5) | 9/239 (4) | |

| 6 weeks (N = 446) | |||

| Feeling the same or better | 182/223 (82) | 182/223 (82) | 1.00 |

| Feeling worse | 41/223 (18) | 41/223 (18) | 1.00 (0.62 to 1.61) |

| 12 weeks (N = 444) | |||

| Feeling the same or better | 180/228 (79) | 122/216 (56) | 1.00 |

| Feeling worse | 48/228 (21) | 94/216 (44) | 2.88 (1.90 to 4.38) |

| 26 weeks (N = 403) | |||

| Feeling the same or better | 164/210 (78) | 151/193 (78) | 1.00 |

| Feeling worse | 46/210 (22) | 42/193 (22) | 0.99 (0.62 to 1.59) |

| 39 weeks (N = 396) | |||

| Feeling the same or better | 185/212 (87) | 153/184 (83) | 1.00 |

| Feeling worse | 27/212 (13) | 31/184 (17) | 1.39 (0.79 to 2.43) |

| 52 weeks (N = 391) | |||

| Feeling the same or better | 181/210 (86) | 154/181 (85) | 1.00 |

| Feeling worse | 29/210 (14) | 27/181 (15) | 1.09 (0.62 to 1.93) |

| Time to stopping trial medication (HR) (N = 477) | 2.28 (1.68 to 3.08) | ||

| Time to stopping trial medication including minimisation variables (HR) (N = 477) | 2.39 (1.76 to 3.24) | ||

Missing data

The results of the predictors of missingness analysis are in Report Supplementary Material 12. We conducted sensitivity analyses that included predictors of missingness for continuous secondary outcomes. Results for all outcomes were similar to the main analyses (see Table 8) when including predictors of missingness in the models (Table 9).

| Outcome | Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| PHQ-9 (coefficient)a | |

| 6 weeks | 0.31 (–0.25 to 0.88) |

| 12 weeks | |

| 26 weeks | 0.80 (0.05 to 1.56) |

| 39 weeks | 0.64 (–0.05 to 1.33) |

| 52 weeks | 0.38 (–0.32 to 1.08) |

| Over all time points | 1.02 (0.65 to 1.39) |

| GAD-7 (coefficient)b | |

| 6 weeks | 0.50 (–0.03 to 1.03) |

| 12 weeks | |

| 26 weeks | 1.13 (0.42 to 1.85) |

| 39 weeks | 1.03 (0.41 to 1.67) |

| 52 weeks | 0.28 (–0.34 to 0.91) |

| Over all time points | 1.19 (0.74 to 1.64) |

| Toronto Side Effects Scale (coefficient)c | |

| 6 weeks | 0.54 (0.16 to 0.92) |

| 12 weeks | |

| 26 weeks | 0.25 (–0.28 to 0.77) |

| 39 weeks | 0.21 (–0.24 to 0.66) |

| 52 weeks | 0.09 (–0.34 to 0.53) |

| Over all time points | 0.47 (0.16 to 0.77) |

| Modified DESS scale new or worsening symptoms (coefficient)d | |

| 6 weeks | 0.51 (0.18 to 0.84) |

| 12 weeks | |

| 26 weeks | 0.53 (0.12 to 0.95) |

| 39 weeks | 0.95 (0.61 to 1.29) |

| 52 weeks | 0.31 (–0.02 to 0.65) |

| Over all time points | 0.96 (0.70 to 1.22) |

| SF-12 physical (coefficient)e | |

| 12 weeks | |

| 26 weeks | 0.16 (–1.46 to 1.77) |

| 39 weeks | 1.65 (0.11 to 3.19) |

| 52 weeks | –0.44 (–1.94 to 1.05) |

| Over all time points | 0.27 (–0.84 to 1.37) |

| SF-12 mental (coefficient)e | |

| 12 weeks | |

| 26 weeks | –2.91 (–4.78 to –1.04) |

| 39 weeks | –3.05 (–4.80 to –1.30) |

| 52 weeks | –1.68 (–3.51 to 0.15) |

| Over all time points | –3.13 (–4.39 to 1.88) |

| Global Rating Question: feeling worse (OR) | |

| 6 weeks | 1.03 (0.63 to 1.66) |

| 12 weeks | |

| 26 weeks | 1.08 (0.63 to 1.85) |

| 39 weeks | 1.39 (0.79 to 2.43) |

| 52 weeks | 1.12 (0.63 to 1.98) |

Adherence to trial medication

A larger percentage of participants in the placebo than maintenance group stopped taking their trial medication before the end of the trial (48% vs. 30%; HR 2.26, 95% CI 1.67 to 3.07). By 52 weeks, 39% (95% CI 32% to 45%) of participants in the discontinuation group and 20% (95% CI 15% to 25%) in the maintenance group had stopped taking trial medication and had returned to an antidepressant prescribed by their GP.

Subgroup analyses

For the subgroup analyses for the primary and secondary outcomes, there was no evidence of any differences according to the number of previous episodes of depression dichotomised at two compared with three or more or types of antidepressant. The most consistent evidence that we found supported a larger difference between groups in those who were younger at onset. For example, the p-value for interaction between age and PHQ-9 at 12 weeks was 0.0001. Among participants who were older at the onset of depression, those in the discontinuation group were less likely to relapse, although this finding was not statistically significant (p = 0.0553) (Tables 10–13).

| Subgroup | HR (95% CI) | p-value for interaction |

|---|---|---|

| Sertraline | 2.41 (1.20 to 4.82) | 0.6010 |

| Citalopram | 2.14 (1.44 to 3.18) | |

| Fluoxetine | 1.70 (1.05 to 2.76) | |

| CIS-R depression score below the mediana | 2.34 (1.56 to 3.52) | 0.4252 |

| CIS-R depression score above the mediana | 1.80 (1.24 to 2.61) | |

| CIS-R anxiety score below the medianb | 2.08 (1.49 to 2.89) | 0.9893 |

| CIS-R anxiety score above the medianb | 1.95 (1.20 to 3.18) | |

| Two previous episodes of depression | 0.96 (0.26 to 3.62) | 0.2132 |

| Three or more previous episodes of depression | 2.15 (1.63 to 2.85) | |

| Age at onset of depression below the medianc | 2.66 (1.84 to 3.85) | 0.0313 |

| Age at onset of depression above the medianc | 1.43 (0.94 to 2.16) |

| Subgroup | Coefficient (95% CI) | p-value for interaction |

|---|---|---|

| 6 weeks | ||

| Sertraline | 0.74 (–0.76 to 2.25) | 0.5279 |

| Citalopram | 0.56 (–0.28 to 1.41) | |

| Fluoxetine | –0.10 (–1.00 to 0.80) | |

| CIS-R depression score below the medianb | 0.29 (–0.23 to 0.81) | 0.0649 |

| CIS-R depression score above the medianb | 0.45 (–0.50 to 1.40) | |

| CIS-R anxiety score below the medianc | 0.49 (–0.09 to 1.07) | 0.0233 |

| CIS-R anxiety score above the medianc | 0.01 (–1.19 to 1.21) | |

| Two previous episodes of depression | 1.23 (–0.21 to 2.67) | 0.9420 |

| Three or more previous episodes of depression | 0.27 (–0.32 to 0.87) | |

| Age when became aware of depression below mediand | 0.52 (–0.30 to 1.34) | 0.0631 |

| Age when became aware of depression above mediand | 0.06 (–0.71 to 0.83) | |

| 12 weeks | ||

| Sertraline | 4.74 (2.93 to 6.55) | 0.0351 |

| Citalopram | 1.61 (0.67 to 2.55) | |

| Fluoxetine | 1.73 (0.60 to 2.86) | |

| CIS-R depression score below the medianb | 2.25 (1.45 to 3.04) | 0.0204 |

| CIS-R depression score above the medianb | 2.16 (1.14 to 3.17) | |

| CIS-R anxiety score below the medianc | 2.05 (1.29 to 2.81) | 0.1288 |

| CIS-R anxiety score above the medianc | 2.49 (1.19 to 3.80) | |

| Two previous episodes of depression | 1.69 (0.06 to 3.31) | 0.4567 |

| Three or more previous episodes of depression | 2.22 (1.50 to 2.95) | |

| Age when became aware of depression below the mediand | 3.01 (2.02 to 3.99) | 0.0001 |

| Age when became aware of depression above the mediand | 1.14 (0.23 to 2.06) | |

| 26 weeks | ||

| Sertraline | 3.73 (1.84 to 5.61) | 0.0029 |

| Citalopram | 0.61 (–0.42 to 1.65) | |

| Fluoxetine | –0.41 (–1.48 to 0.67) | |

| CIS-R depression score below the medianb | 0.79 (–0.05 to 1.63) | 0.0002 |

| CIS-R depression score above the medianb | 0.66 (–0.33 to 1.64) | |

| CIS-R anxiety score below the medianc | 1.09 (0.31 to 1.87) | 0.0005 |

| CIS-R anxiety score above the medianc | 0.06 (–1.22 to 1.33) | |

| Two previous episodes of depression | 0.57 (–0.84 to 1.98) | 0.7258 |

| Three or more previous episodes of depression | 0.79 (0.05 to 1.52) | |

| Age when became aware of depression below the mediand | 1.34 (0.35 to 2.34) | 0.0423 |

| Age when became aware of depression above the mediand | 0.07 (–0.88 to 1.03) | |

| 39 weeks | ||

| Sertraline | 1.23 (–0.57 to 3.03) | 0.4909 |

| Citalopram | 0.47 (–0.55 to 1.48) | |

| Fluoxetine | 0.02 (–1.09 to 1.14) | |

| CIS-R depression score below the medianb | 0.33 (–0.44 to 1.10) | 0.0044 |

| CIS-R depression score above the medianb | 0.82 (–0.20 to 1.85) | |

| CIS-R anxiety score below the medianc | 0.45 (–0.30 to 1.21) | 0.1390 |

| CIS-R anxiety score above the medianc | 0.92 (–0.41 to 2.24) | |

| Two previous episodes of depression | –1.70 (–2.90 to –0.49) | 0.1743 |

| Three or more previous episodes of depression | 0.77 (0.04 to 1.50) | |

| Age when became aware of depression below the mediand | 1.06 (0.13 to 2.00) | 0.1984 |

| Age when became aware of depression above the mediand | 0.01 (–1.01 to 1.03) | |

| 52 weeks | ||

| Sertraline | 1.72 (–0.10 to 3.54) | 0.5997 |

| Citalopram | –0.04 (–1.07 to 0.99) | |

| Fluoxetine | –0.01 (–1.07 to 1.05) | |

| CIS-R depression score below the medianb | 0.13 (–0.69 to 0.95) | 0.0036 |

| CIS-R depression score above the medianb | 0.67 (–0.34 to 1.67) | |

| CIS-R anxiety score below the medianc | 0.48 (–0.30 to 1.26) | 0.0032 |

| CIS-R anxiety score above the medianc | 0.22 (–1.09 to 1.52) | |

| Two previous episodes of depression | –0.89 (–2.53 to 0.75) | 0.6074 |

| Three or more previous episodes of depression | 0.48 (–0.26 to 1.22) | |

| Age when became aware of depression below the mediand | 0.28 (–0.65 to 1.21) | 0.9822 |

| Age when became aware of depression above the mediand | 0.42 (–0.63 to 1.48) | |

| All time points | ||

| Sertraline | 2.26 (0.97 to 3.55) | 0.0319 |

| Citalopram | 0.72 (0.07 to 1.37) | |

| Fluoxetine | 0.22 (–0.48 to 0.93) | |

| CIS-R depression score below the medianb | 0.74 (0.21 to 1.27) | 0.0092 |

| CIS-R depression score above the medianb | 1.00 (0.34 to 1.67) | |

| CIS-R anxiety score below the medianc | 0.88 (0.37 to 1.40) | 0.0192 |

| CIS-R anxiety score above the medianc | 0.84 (–0.01 to 1.70) | |