Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 15/102/04. The contractual start date was in November 2016. The draft manuscript began editorial review in April 2023 and was accepted for publication in May 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Dias et al. This work was produced by Dias et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Dias et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Dupuytren’s contracture

Dupuytren’s contracture (DC) is a fibro-proliferative disease, characterised by the excessive accumulation of connective tissue in the hand. 1,2 The connective tissue organises into cords which shorten, causing the finger to bend. This condition interferes with hand function and dexterity over time as the affected individual loses the ability to straighten one or more affected fingers. It can have a multifaceted, detrimental effect on quality of life. Individuals living with DC need to adapt to or avoid certain daily activities, and experience embarrassment and anxiety regarding contracture recurrence. 3–5

About 2–2.5 million UK adults are affected, with greater prevalence in males aged over 50 years old, and of northern European descent. 6–8 Smoking and occupations that involve manual labour or forceful stretching of the fascia are associated with increased risk of developing DC. 6

Dupuytren’s contracture is first detected as firm nodules in the palm. These nodules can generate cords which span from the palm to the fingers. When this cord crosses the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint and/or proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint and gradually shortens, the finger is pulled in towards the palm (see Appendix 1, Figure 31). 2,9 The cord contracts over a period of months or years. The most widely used method to establish the severity of this contracture is measurement of the affected joints in both extension (total active extension and passive extension deficit) and flexion (total active flexion), using a goniometer. 10 Medical treatment is usually offered following this, given the cord is mostly irreversible. 2

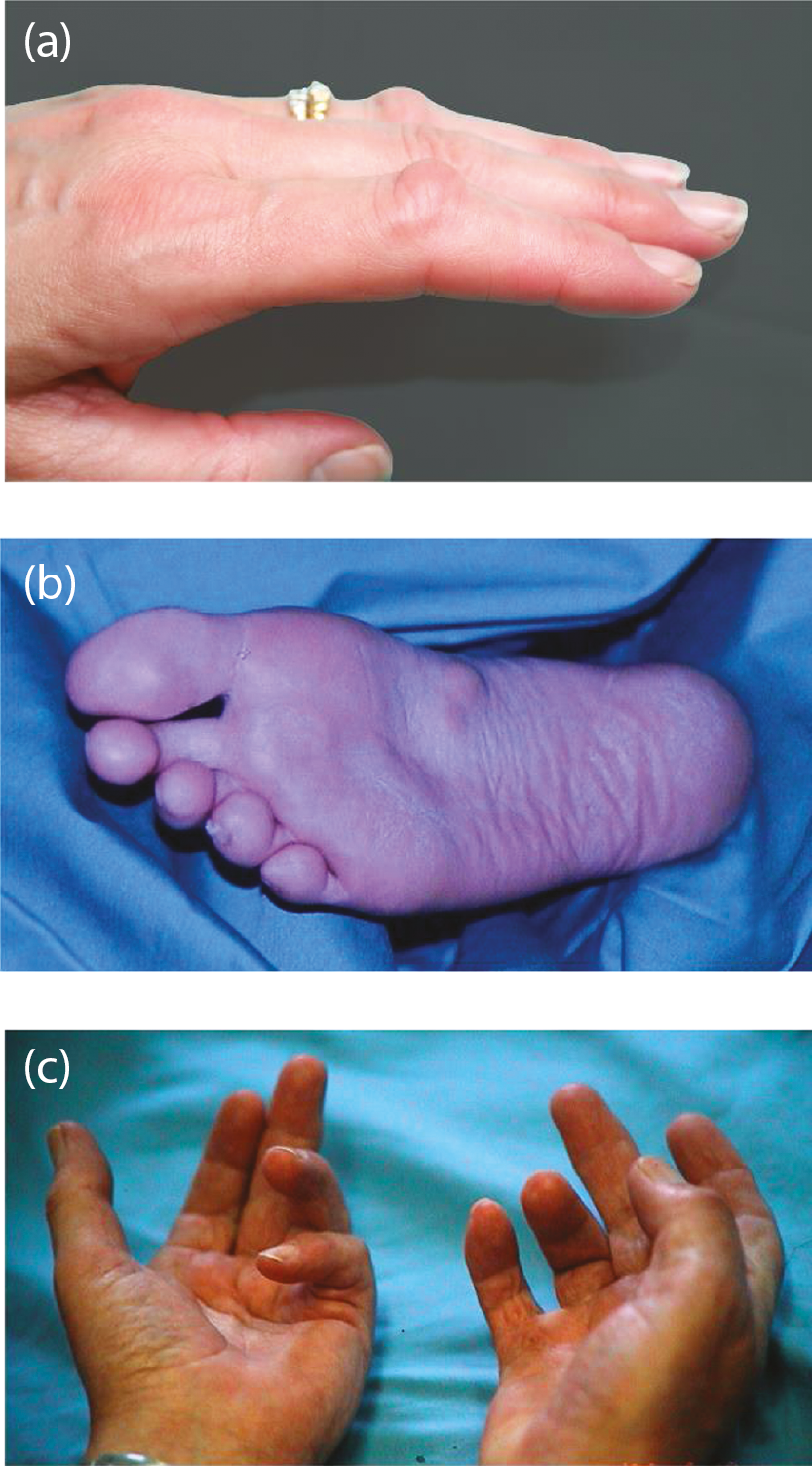

There is no cure for Dupuytren’s disease, even if the associated skin is radically excised and replaced with a graft, and so the cord can recur. Recurrence has been defined as a change in extension deficit of 6 degrees between 3 and 6 months after treatment or 20 degrees between 3 months and 1 year after correction of the contracture, again assessed using goniometric measurement. 11,12 The rate of recurrence depends on treatment given and certain risk factors. These include occurrence of DC before the age of 50, male gender, presence of Ledderhose disease (see Appendix 1, Figure 32), contractures in both hands (see Appendix 1, Figure 32) and a family history of Dupytren’s. 13–17

Treatments

A comprehensive range of options are used to treat DC, including surgical, pharmacological, and radiotherapy. Physical therapies such as splinting, massage, and ultrasound have no evidence of efficacy. Radiotherapy, which impairs the cells that create the contracting fibrous tissue,18 is occasionally used to manage early-stage DC or as concomitant therapy to other surgical or pharmacological interventions for more aggressive disease. 18

Surgical and pharmacological interventions, such as limited fasciectomy surgery (LF), collagenase injection, and percutaneous needle fasciotomy (PNF) aim to remove, break, or dissolve fibrous tissue of the cord to correct or improve the joint contracture. 2,9 The relative benefits and risks of each of these interventions relate to differences in recovery time, number and severity of treatment complications, and DC recurrence. However, current data on risks and benefits is derived from low-quality, non-randomised studies largely. 19

Surgical correction

Surgical correction for DC involves excision of the cord(s). There are four levels of surgical correction: the least invasive is fasciotomy; followed by very limited or segmental fasciectomy; next is LF; and the most invasive is dermo-fasciectomy. 9 The type of surgery recommended to a patient depends on disease severity. Fasciotomy or very LF is recommended for cases where the cord is discrete and usually causing only MCP contracture. Dermo-fasciectomy is normally reserved for patients with a high risk of recurrence as it has a higher risk of complications. 9,20 If the contracture is very severe and cannot be corrected by fasciectomy, the only way to improve hand function may be to fuse the contracted joint or amputate the affected digit. 2

Limited fasciectomy is the most frequently used method for correction of DC in the UK and Europe. 21,22 It is estimated that about 73% of patients see a full correction immediately following LF. However, 6% of patients will experience moderate complications, such as numbness, reduced movement, or stiffness, swelling or nerve injury. Recurrence after 2–3 years occurs in approximately 12% of patients, rising at 5 years to approximately 21–32% of patients. 23,24 Recurrence is reported to be more likely if the PIP joint was treated than the MCP joint or where severe contractures are present in both joints. 25,26

Collagenase injection

Collagenase Clostridium histolyticum (CCH) is an enzyme that weakens a Dupuytren’s cord by breaking down collagen. It is injected directly into the cord and after a few days the weakened cord can be snapped (by manipulation) to straighten the contracted joint. 27 The benefit of collagenase treatment is potential quicker recovery time as compared to LF. Also, it can be delivered in clinic, rather than in an operating theatre, thus reducing cost. 27–29

It is estimated that about 53% of patients have full correction immediately following injection and manipulation. Approximately 2% of patients will experience moderate complications, such as numbness, reduced movement, or stiffness, swelling, or nerve injury. Tendon or sheath rupture after injection is possible but rare. Recurrence after 2–3 years occurs in approximately 38% of patients, rising to 51% of patients within 5 years of treatment. 11,30,31 Recurrence is more likely if the PIP joint was treated than the MCP joint. 31

Collagenase was withdrawn from the market, except in the USA, for commercial reasons on 29 February 2020. 28 There were no safety concerns, as the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) confirmed that stocks already available within the UK could continue to be used for the same indication. At the time of writing, there was no information on whether the supplier would reinstate supply to Europe.

Percutaneous needle fasciotomy

A needle aponeurotomy, also called percutaneous needle fasciotomy, is a technique that uses a needle to puncture or cut a section of the cord at multiple points to weaken it. The weakened cord is then snapped so that the finger can straighten. 32 This is an outpatient procedure with a short recovery period. 32 However, there are drawbacks. Firstly, this method is less suitable for PIP joints as these are more difficult to treat and there is greater risk of damage to digital nerves9,32 and tendons. Secondly, the recurrence rate is high at between 74% and 85% after 5 years. 23,24 This method is typically reserved for patients with MCP contractures of < 20°. 21 It is less effective than LF at correcting contractures. 33

Percutaneous needle fasciotomy was not assessed within the Dupuytren's interventions surgery versus collagenase (DISC) trial, the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of PNF compared to LF is currently being undertaken in a separate National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)-funded study (HAND-2: https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN12525655), following an earlier feasibility study. 34

Rationale

The DISC trial was designed in response to a NIHR commissioned call to compare the most common form of surgery for moderate DC to collagenase. Collagenase has several benefits compared to LF, including a shorter recovery35 and no dependency on theatre space, therefore reducing waiting lists. 27 Additionally, collagenase may be beneficial in terms of cost to the NHS. According to UK Hospital Episode Statistics data, collagenase injection costs about £1287 per patient, compared to £4807 for LF. However, the overall cost-effectiveness, considering the efficacy and need for subsequent intervention to treat recurrence, remains unknown. We also do not know patients’ experiences and preferences for these treatments. The DISC trial aims to answer these important questions.

The clinical impact of the results of this study is high. If the trial identifies that collagenase is not inferior to LF in terms of efficacy and patient experience, and is less expensive, this will make it the preferred treatment for the NHS and for Dupuytren’s patients (subject to the return of collagenase to the European market). Conversely, if collagenase proves to be inferior to LF, this information can be used to protect patients from a procedure which is less effective and potentially save the NHS money by reducing the number of subsequent treatments needed for recurrence.

Current evidence

The quality of currently published evidence on the efficacy of collagenase compared to LF is low. Collagenase is suspected to be more cost-effective; however, the evidence is limited to small retrospective studies. 35,36 A meta-analysis of cohort studies found that the short-term efficacy was similar between the two treatments, although collagenase had a four times greater risk of minor complications. 37 There is no information available from completed randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 35,36 One ongoing RCT, the DupuytrEn Treatment EffeCtiveness Trial, aims to compare effectiveness of LF, collagenase and PNF, including follow-up for recurrence up to 10 years after treatment. 38 Another RCT looking specifically at collagenase treatment and LF secondary to recurrence is also ongoing. 39

Research objectives

The primary objective was to determine whether collagenase injection is not inferior to LF in the treatment of DC, as determined by patient-reported hand function 1 year after treatment.

The secondary objectives were to:

-

investigate contracture recurrence at 1 and 2 years after treatment

-

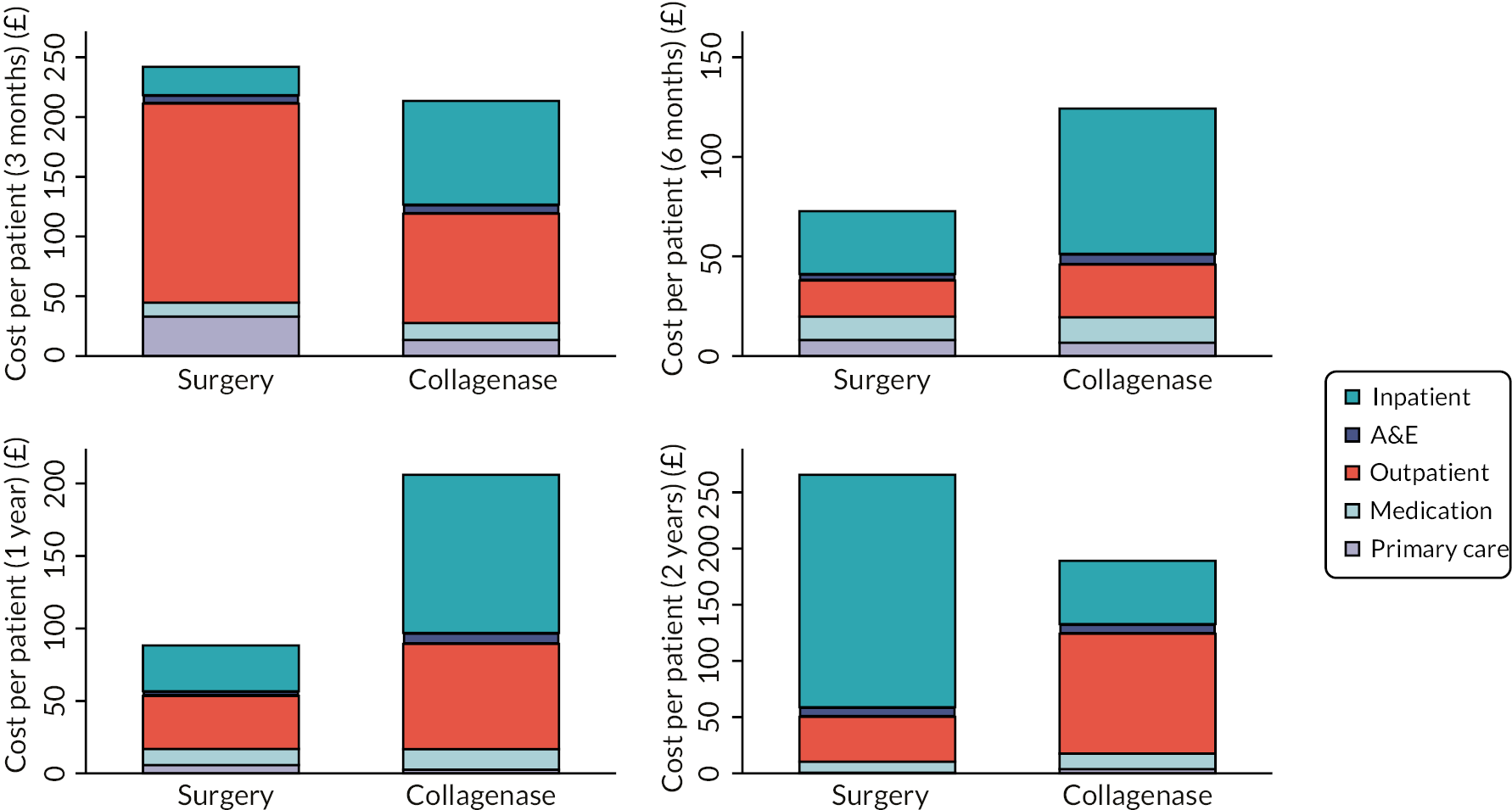

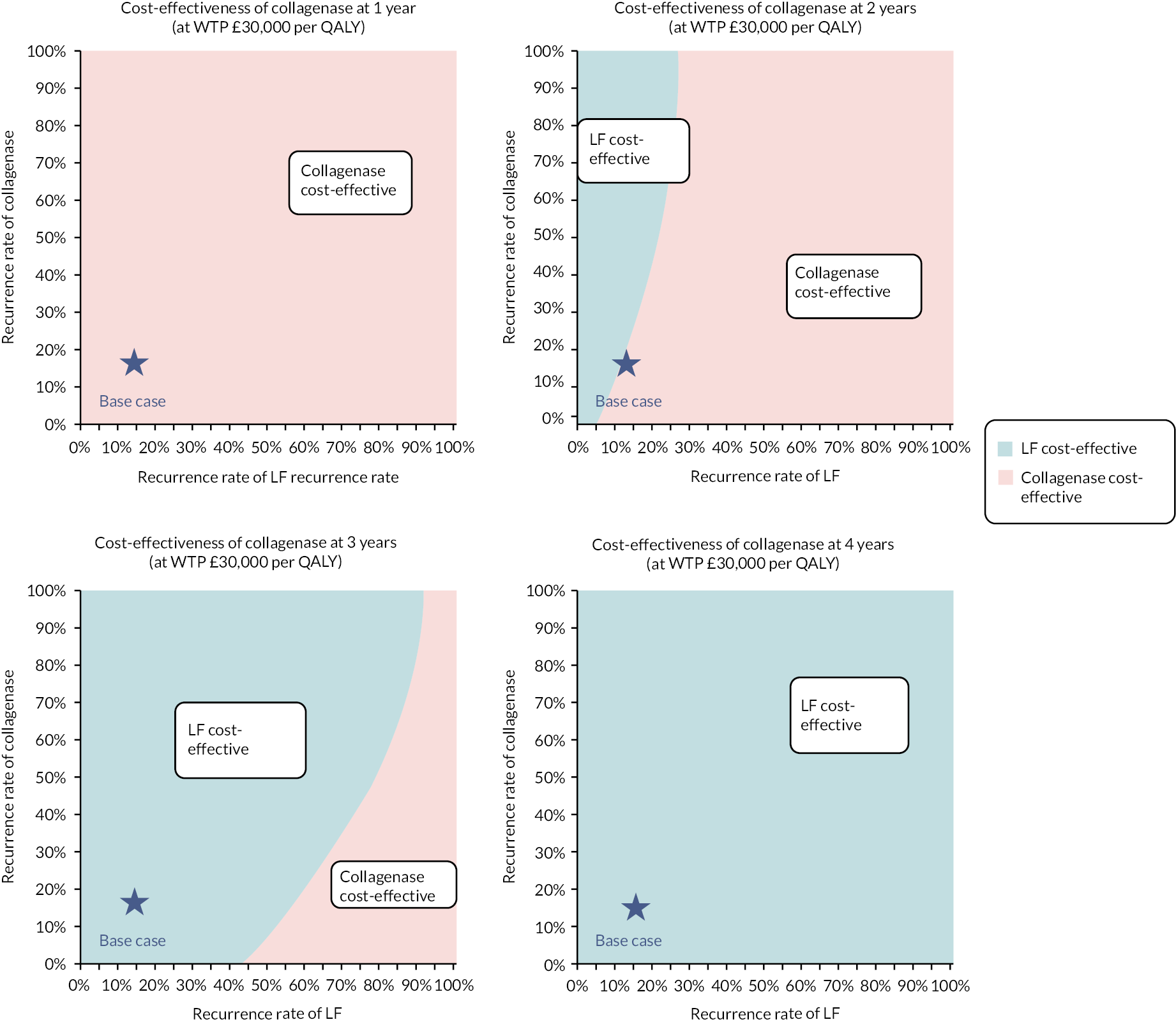

investigate the cost-effectiveness [from the NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspectives] of collagenase injections compared to LF at 1 and 2 years after treatment

-

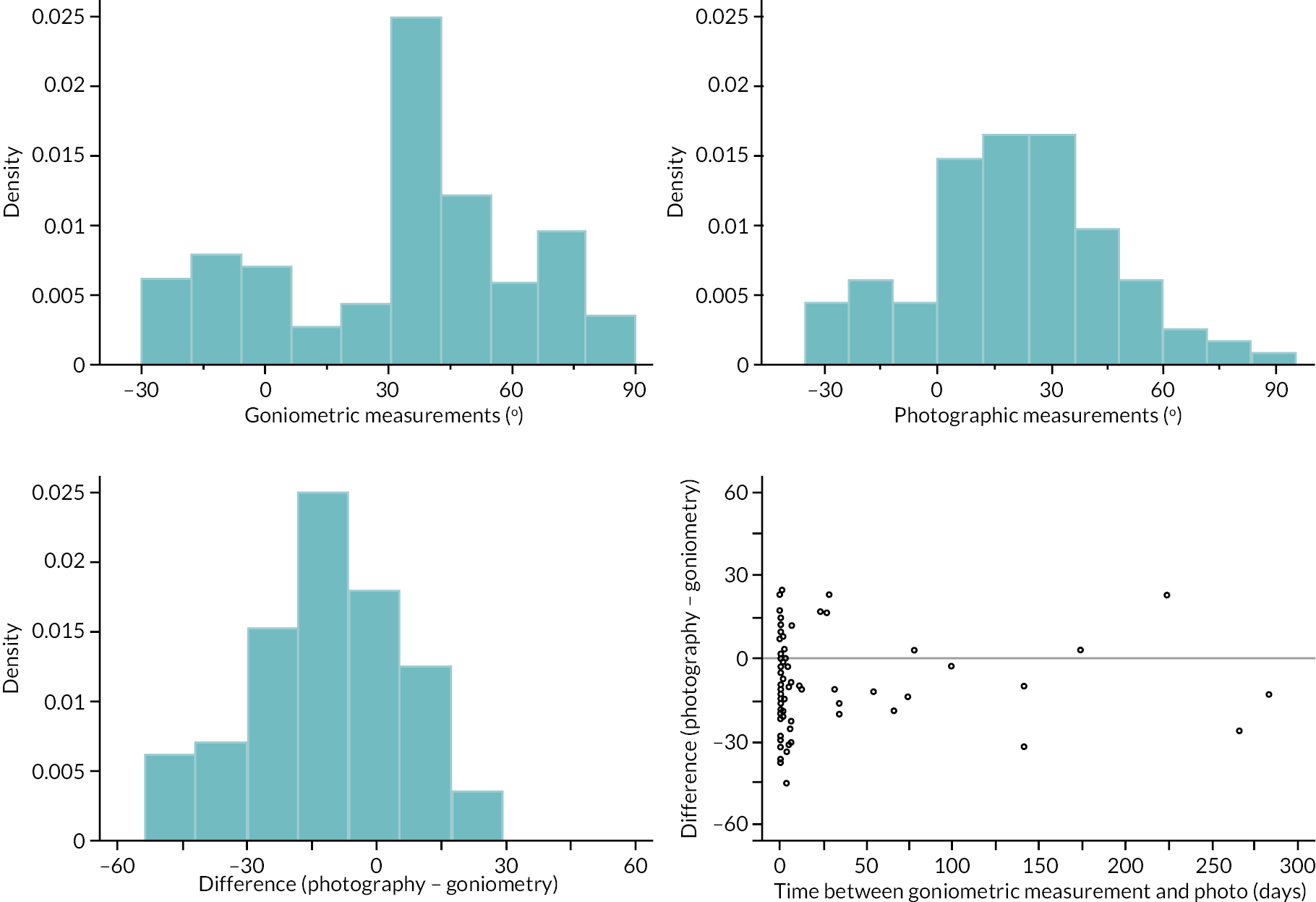

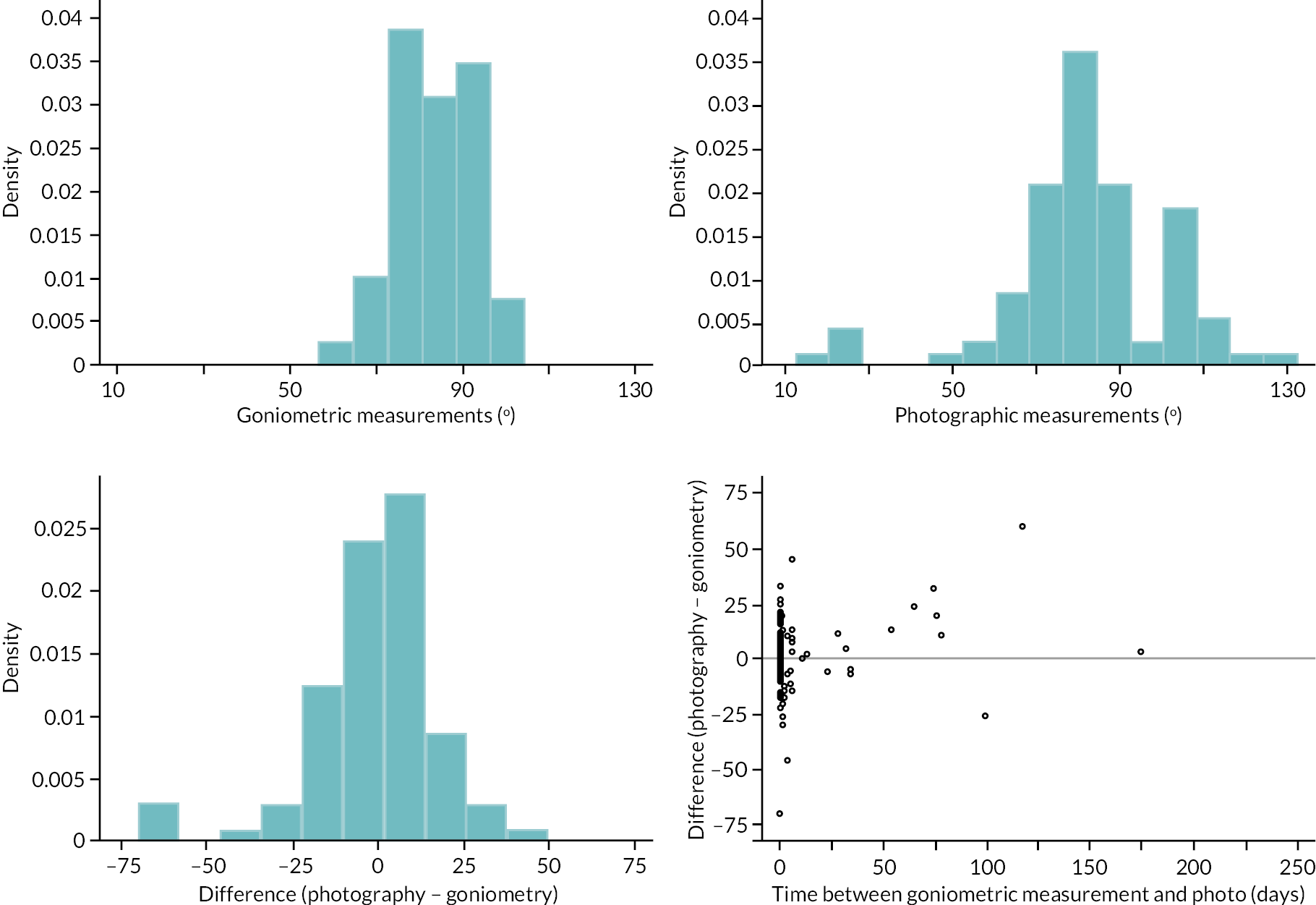

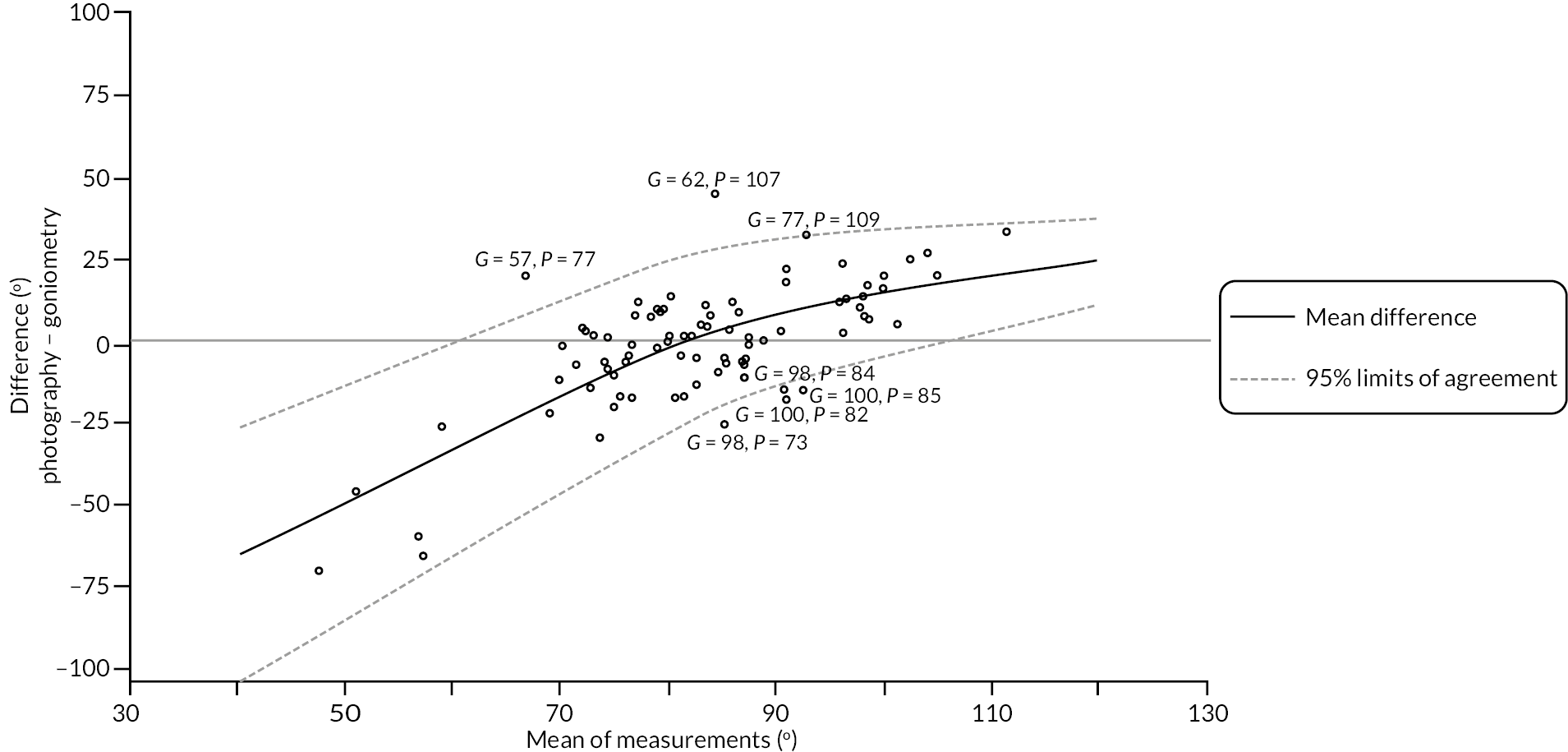

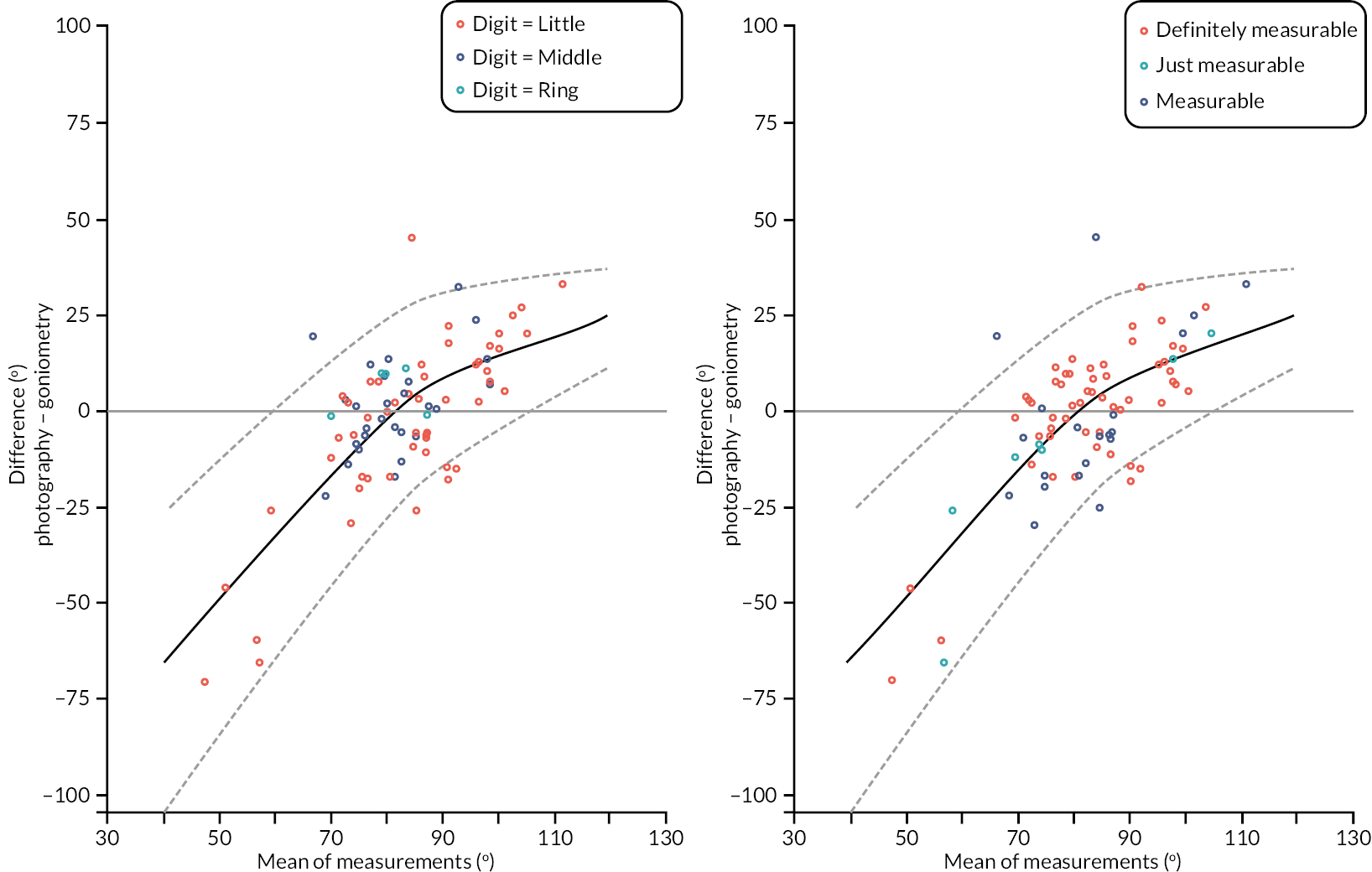

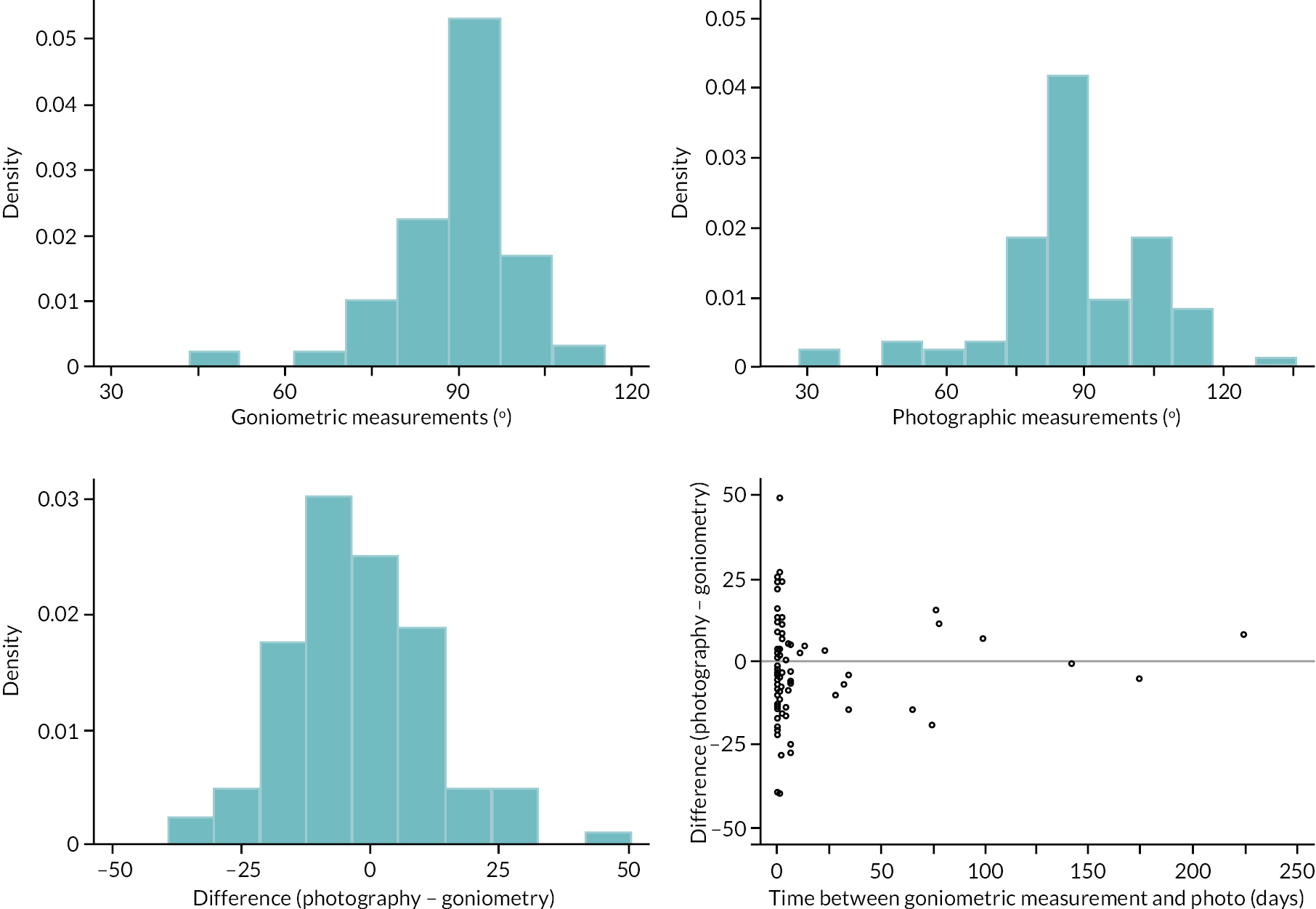

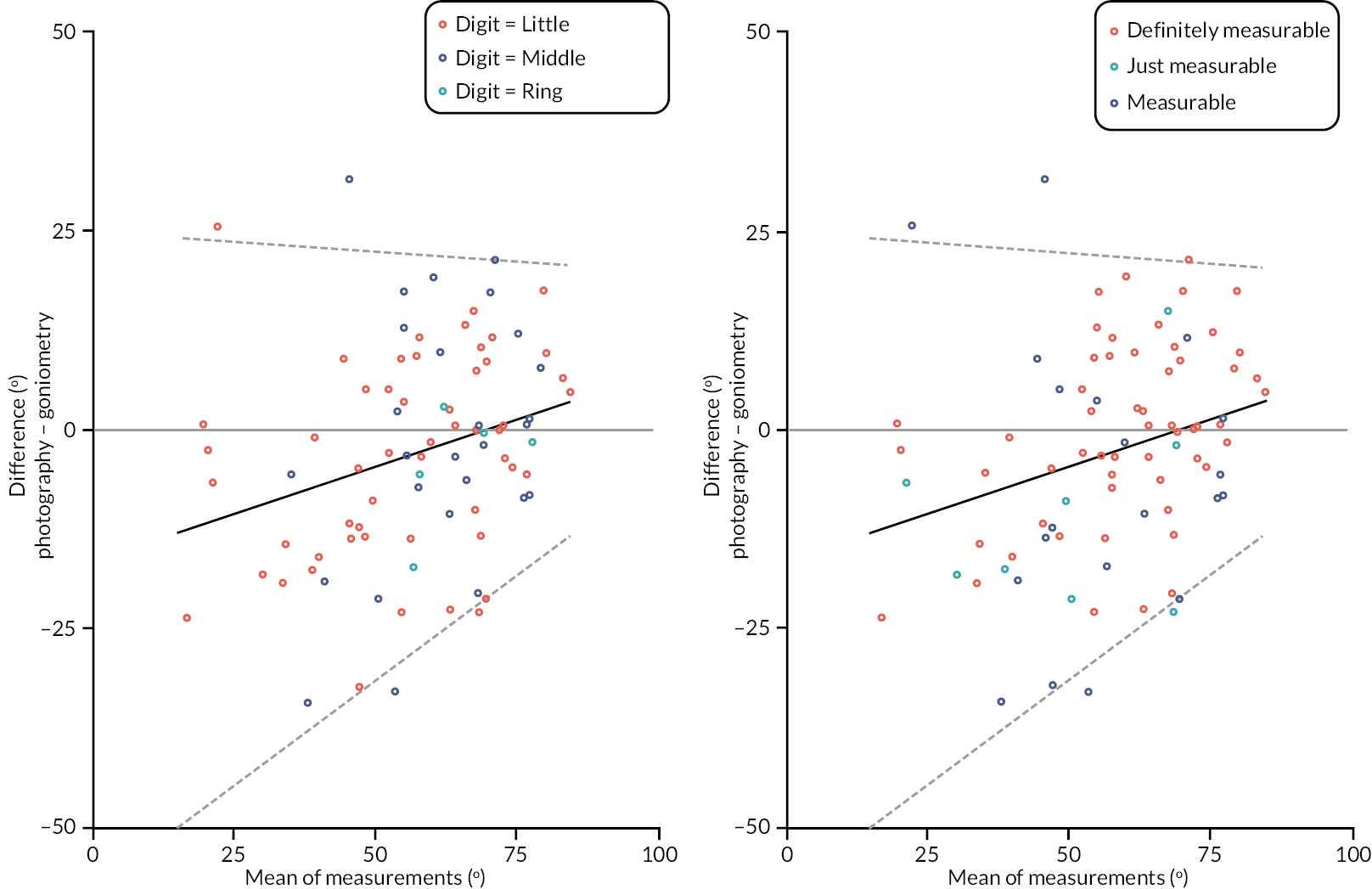

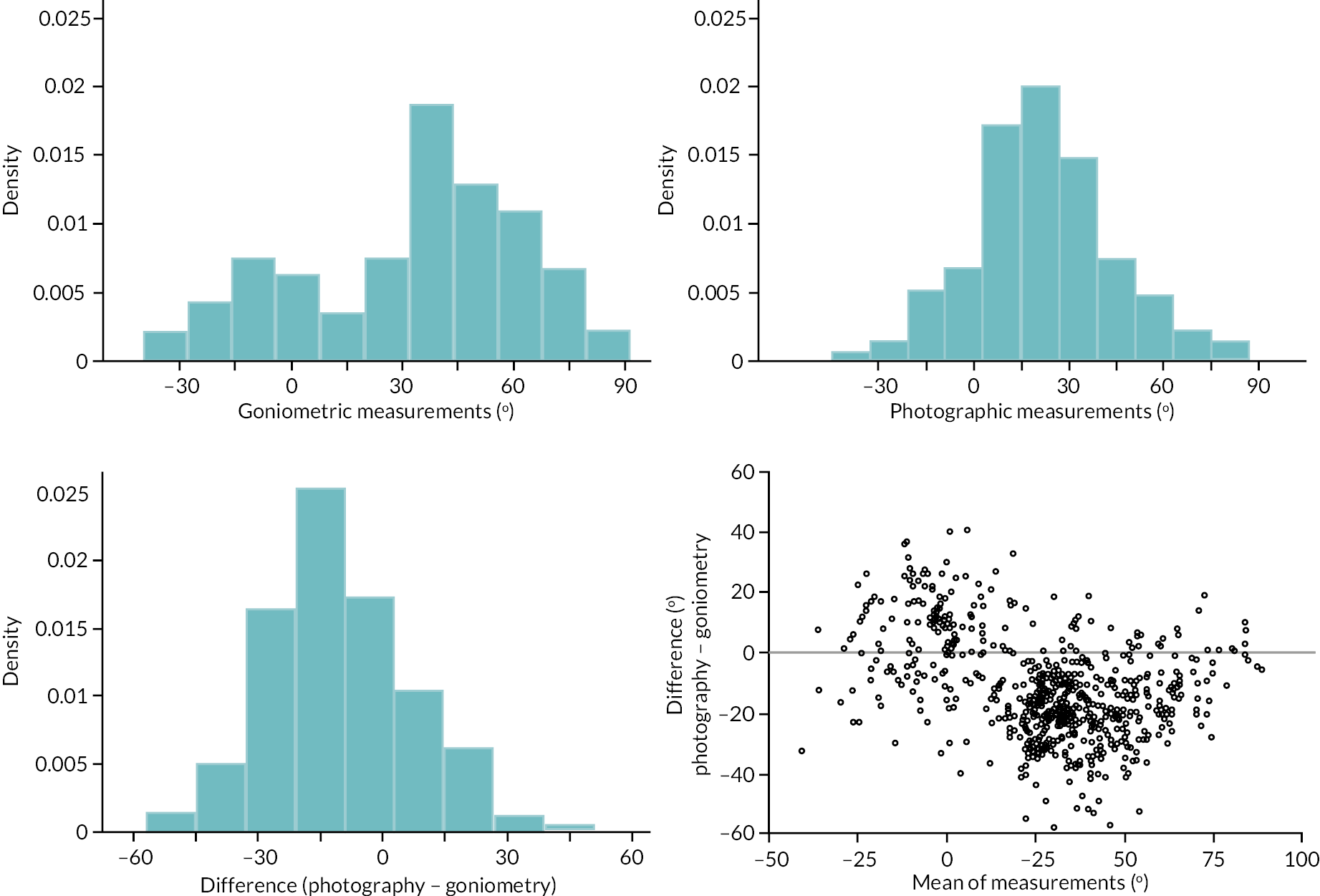

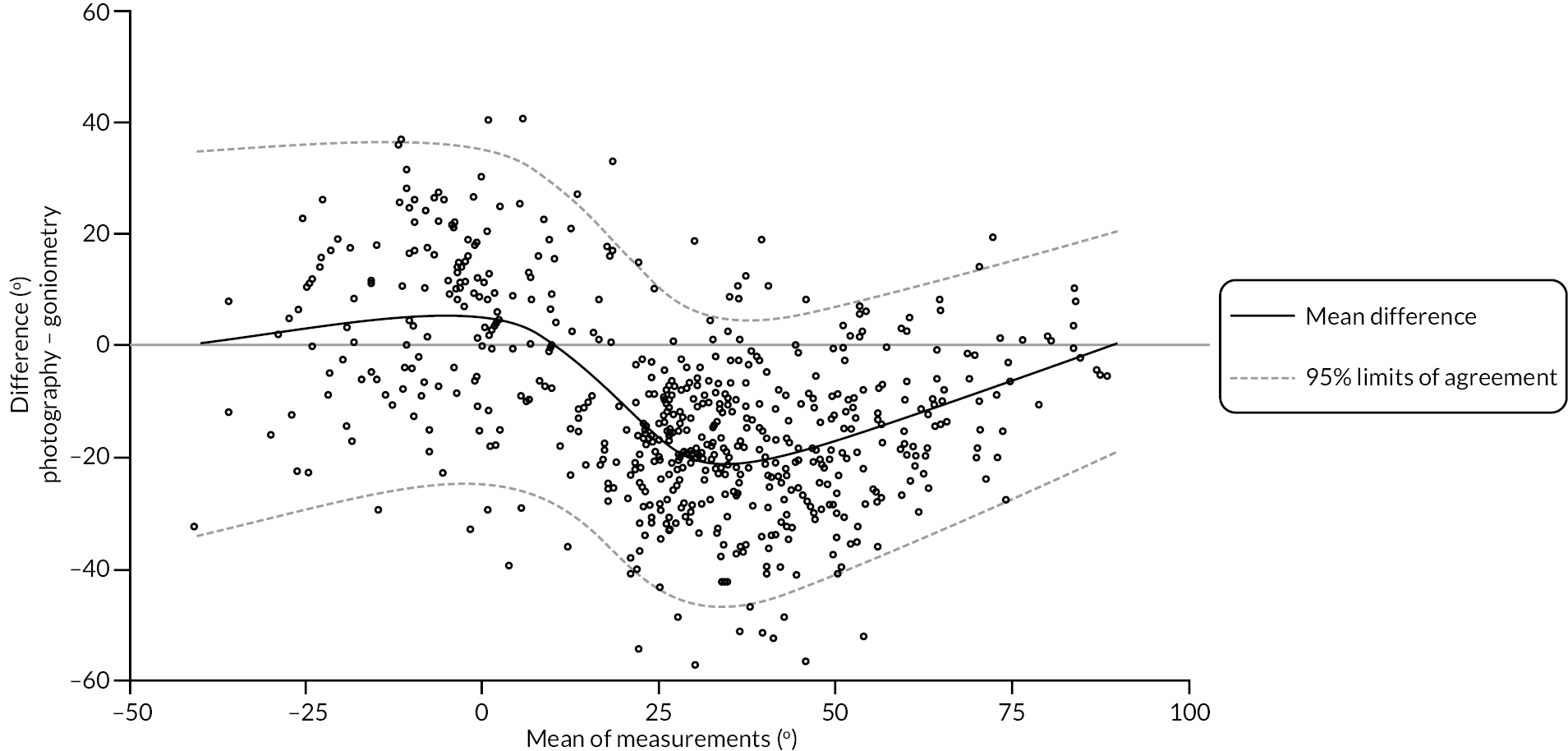

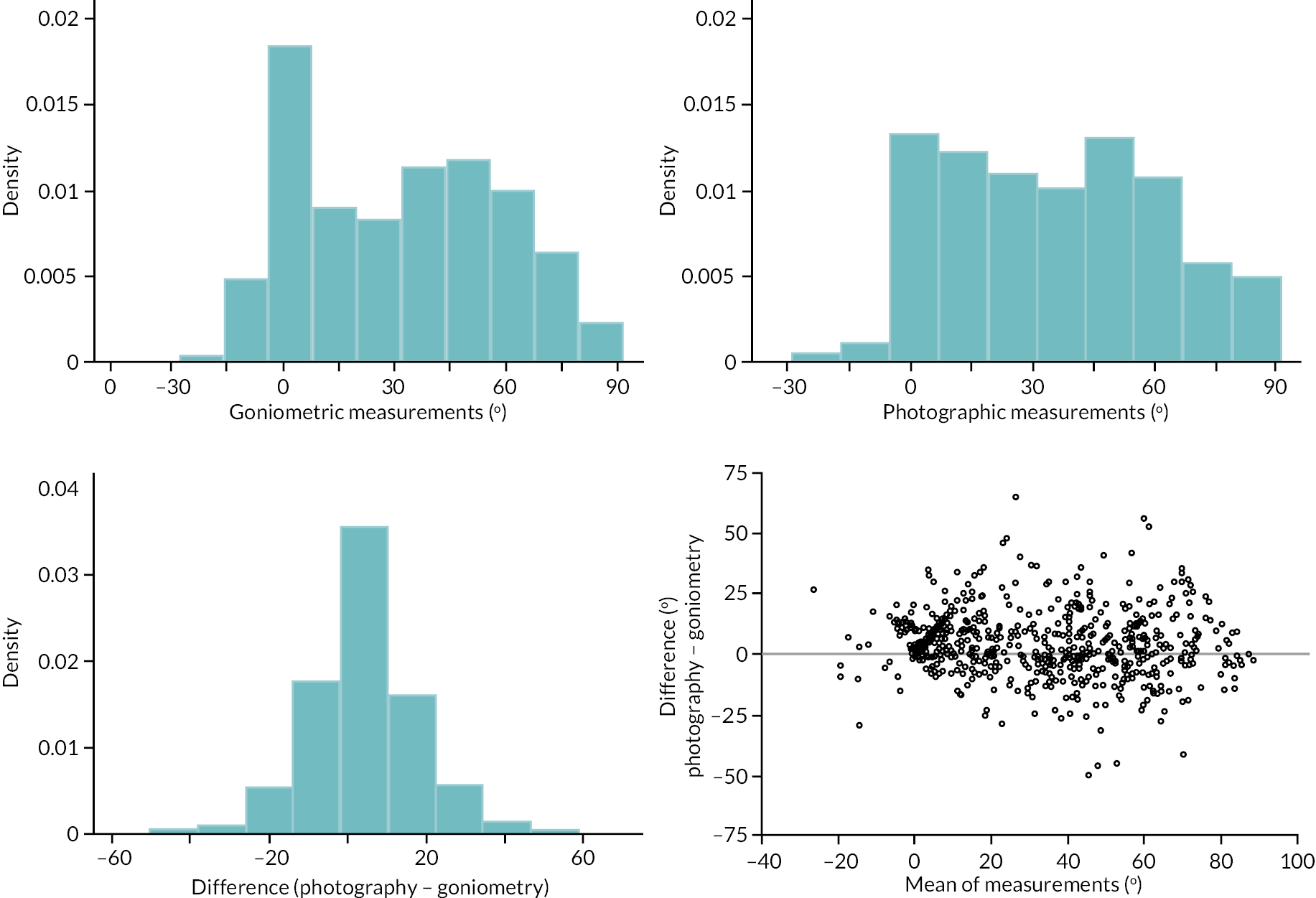

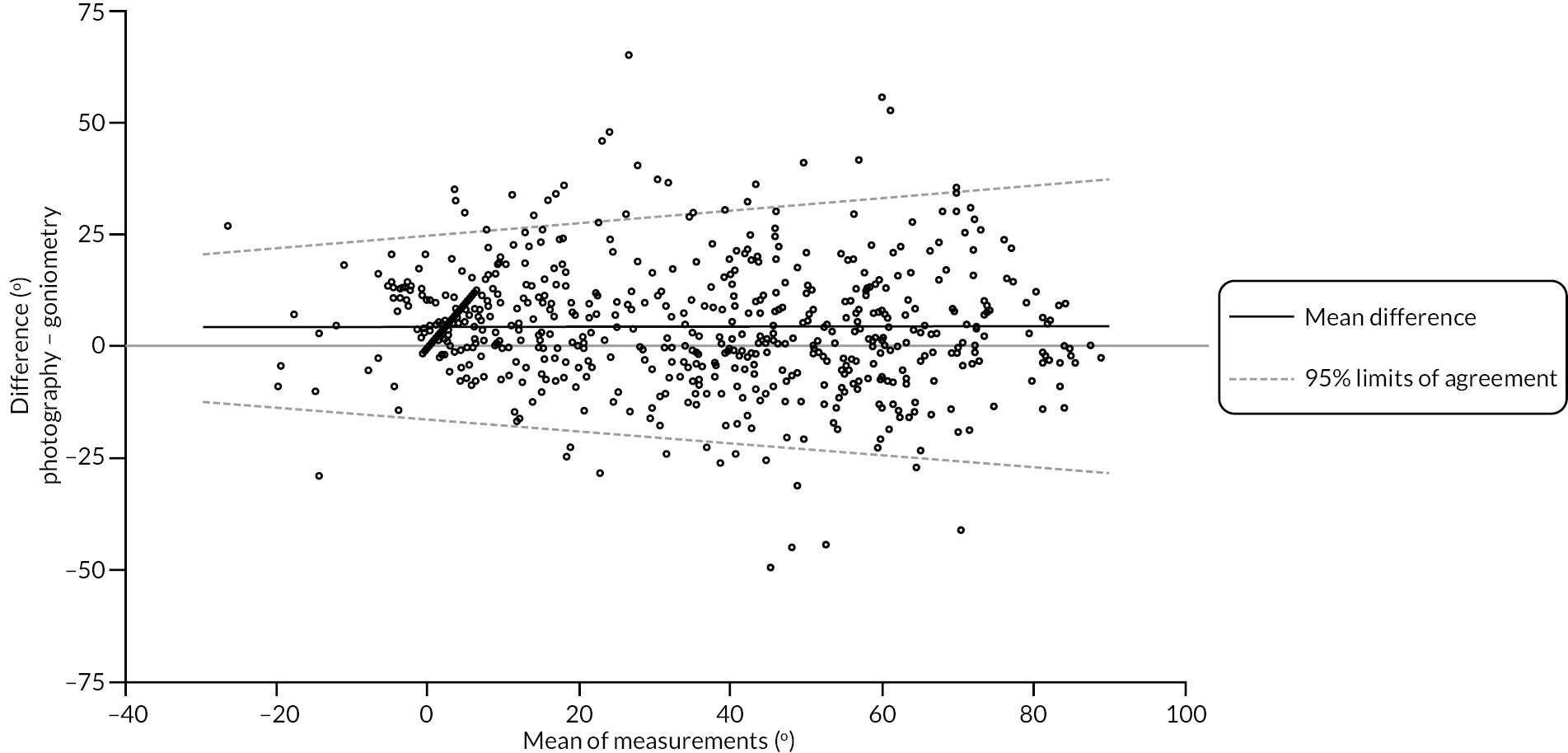

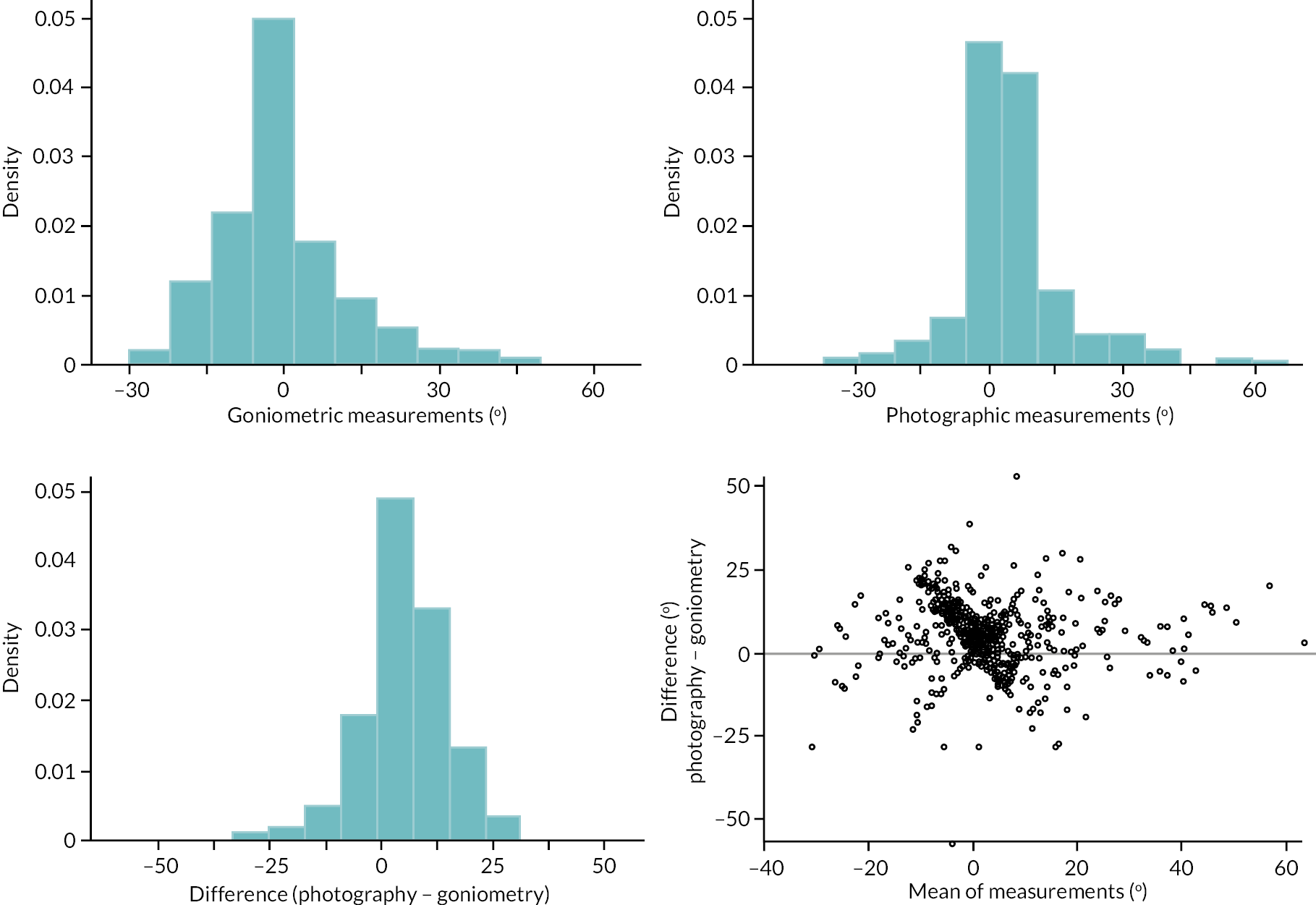

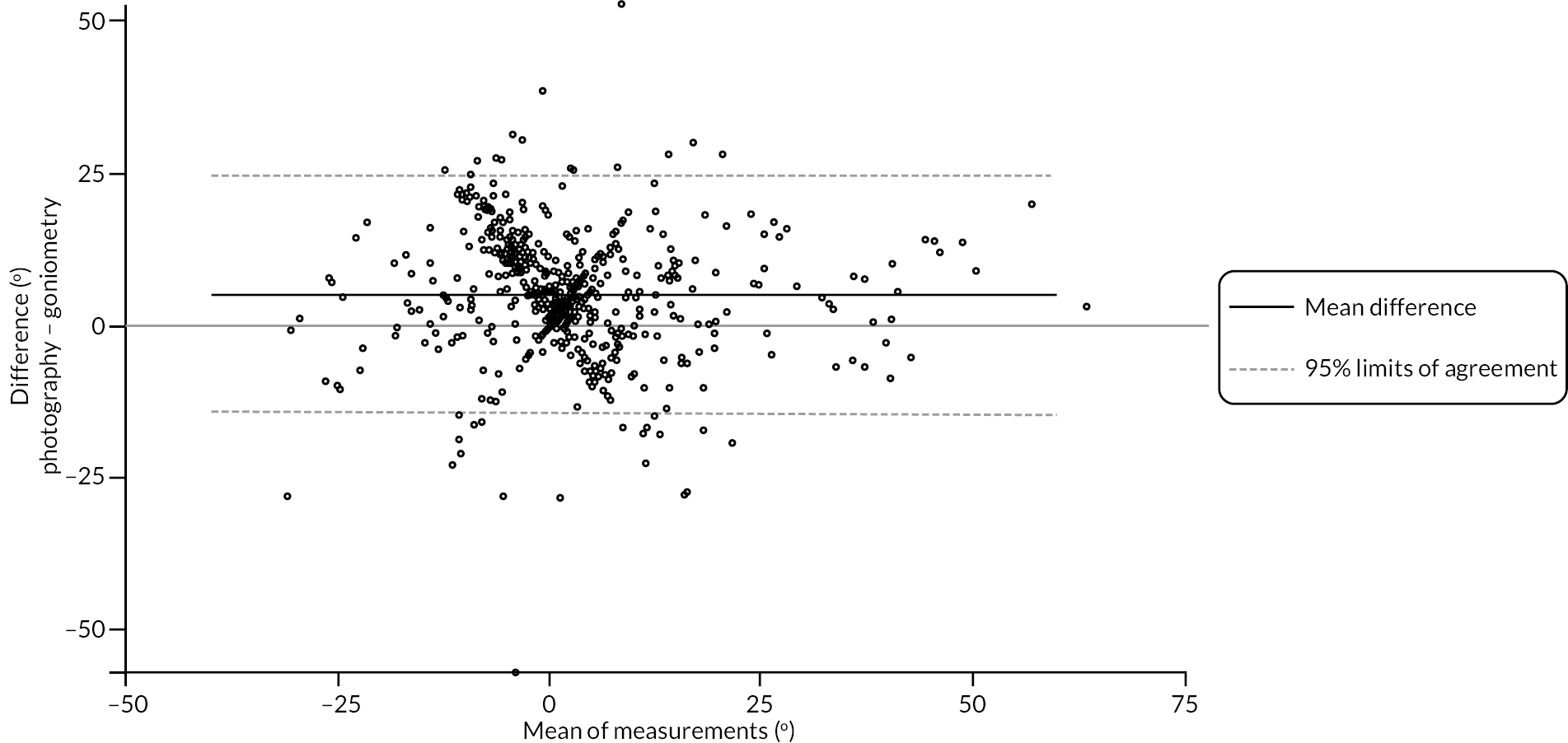

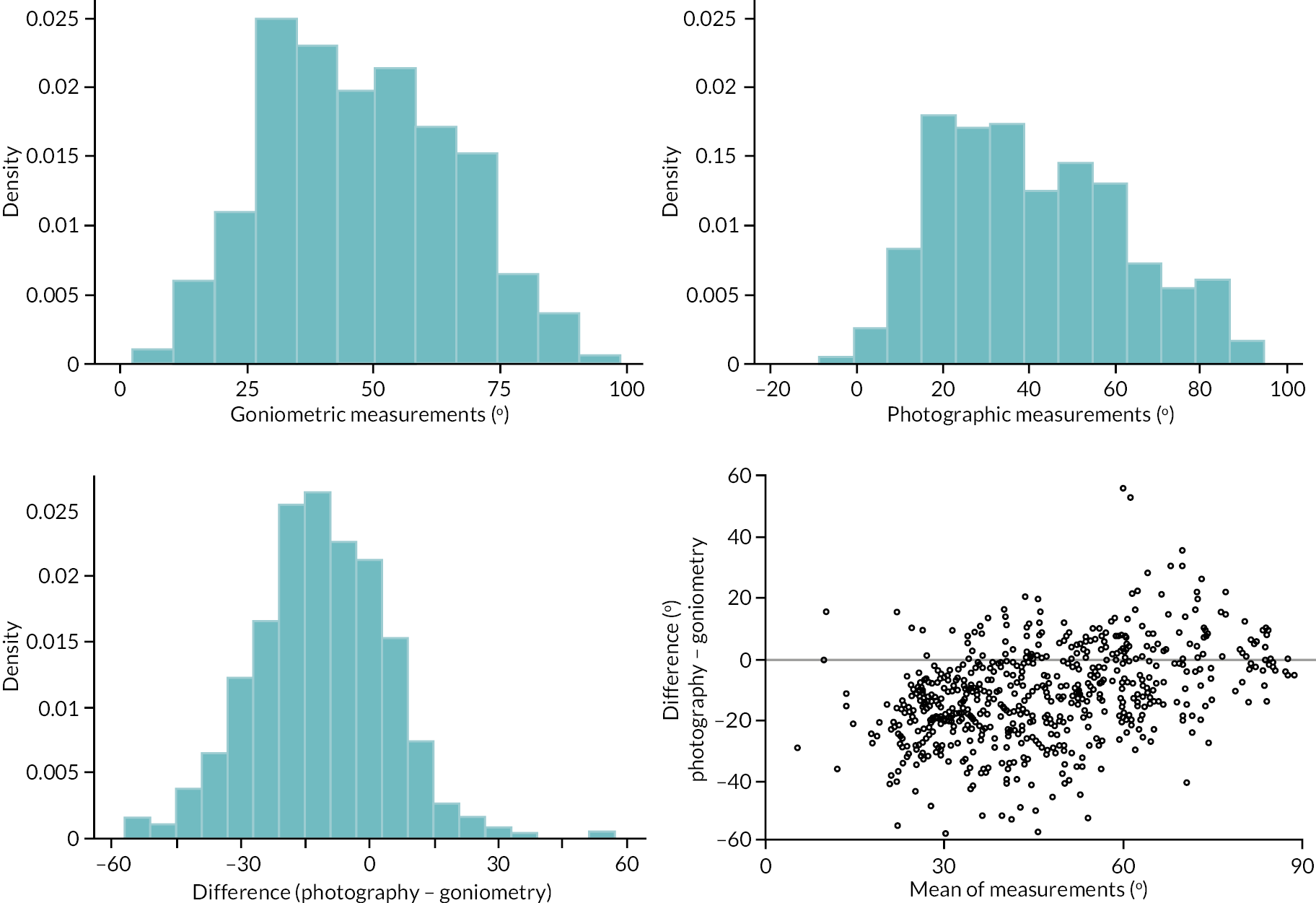

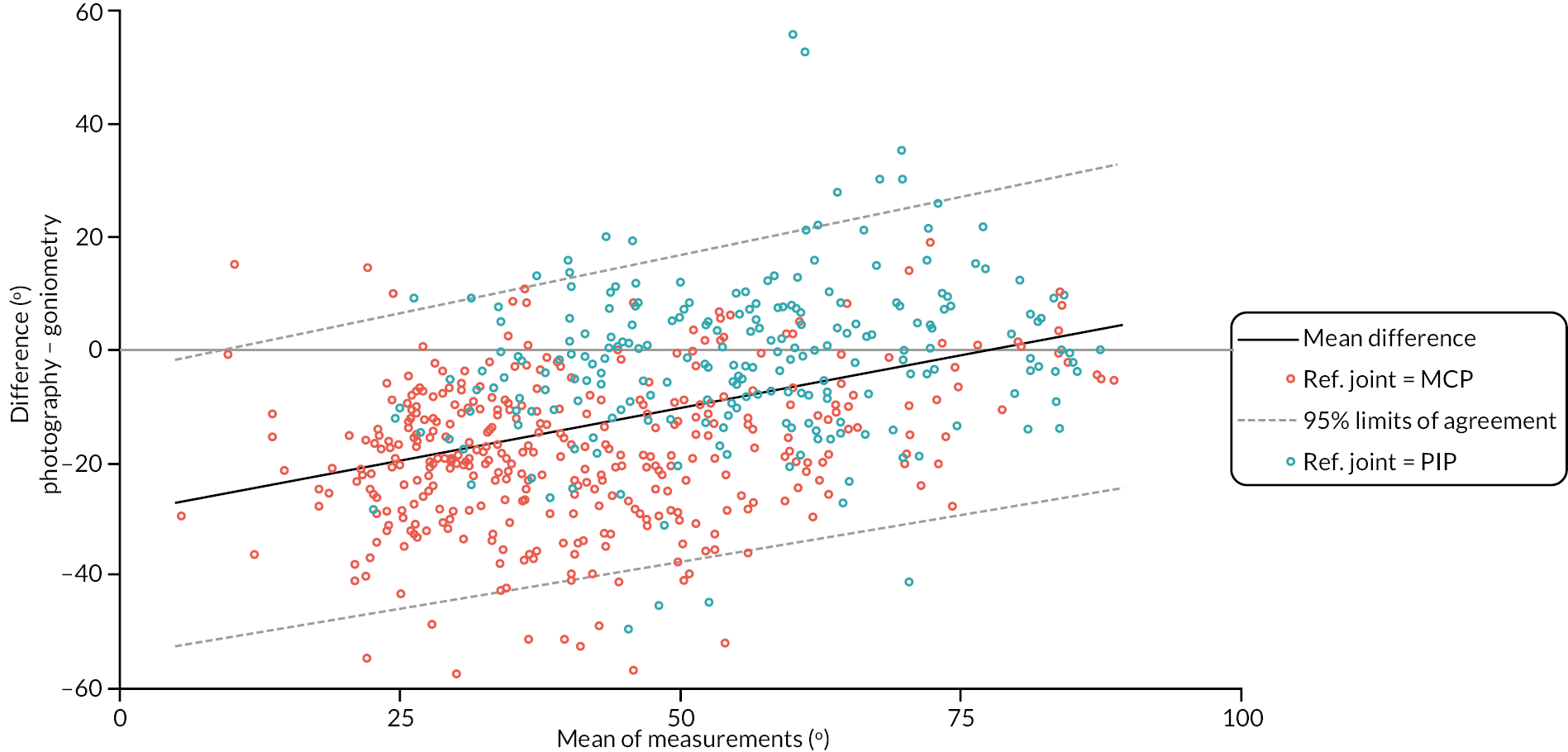

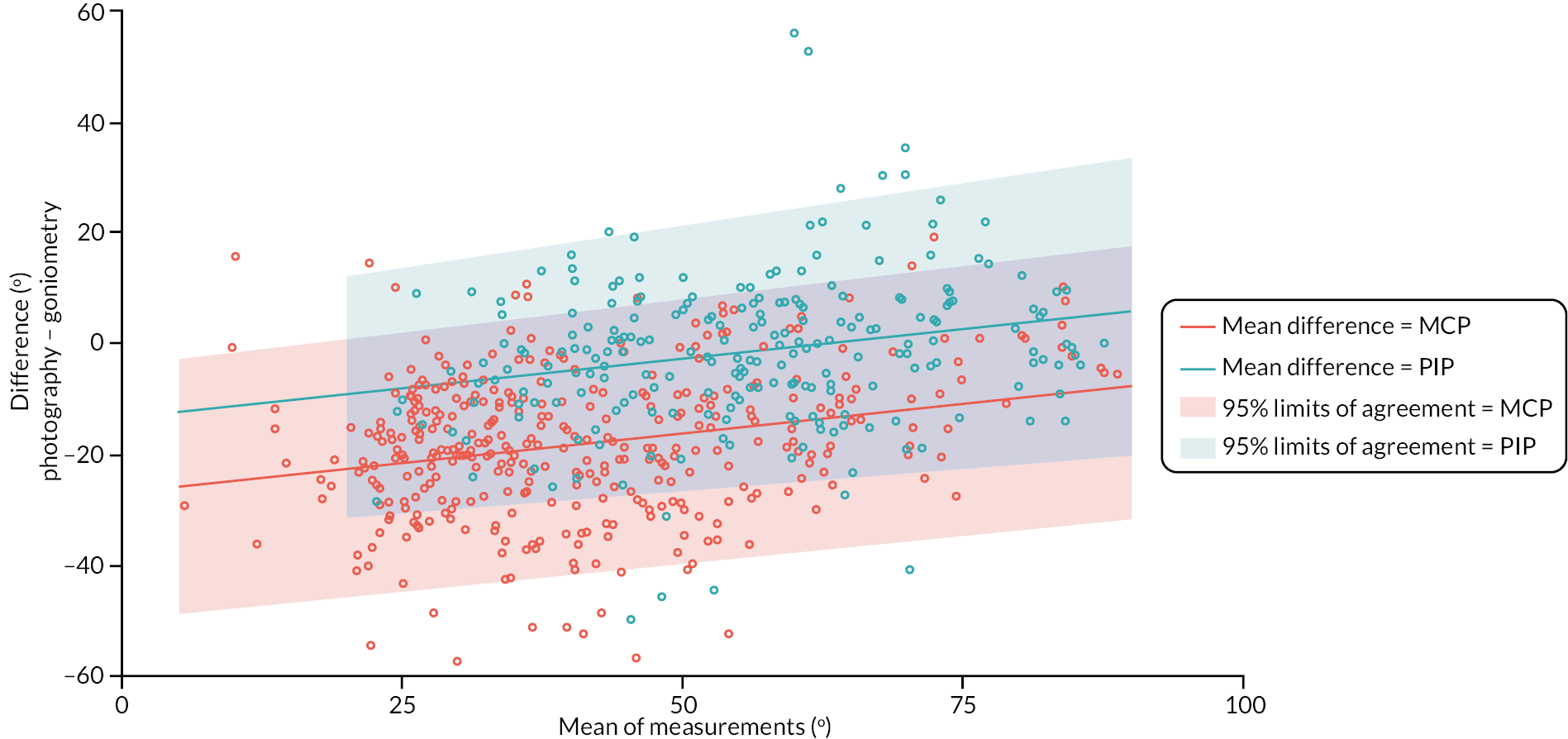

investigate if active extension and flexion measurements obtained from photographs taken remotely by patients are comparable to goniometric measurements taken by a medical professional (photography substudy)

-

explore patient’s views on collagenase injections compared to LF related to their experiences and preferences (qualitative substudy).

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

This chapter describes the trial design and methods used to address the aforementioned clinical effectiveness. The trial protocol has been published. 40

Trial design

The DISC trial was a multicentre, parallel-group, pragmatic, individually randomised controlled non-inferiority trial comparing collagenase injection and manipulation versus LF for the correction of DC of the hand in adult patients referred to hospital care in the UK. The trial included a cost-effectiveness evaluation (see Chapter 4), a qualitative substudy (see Chapter 5), and a photography substudy (see Appendix 2), the methods for which are detailed in their respective chapters, along with an internal pilot study during the first 6 months of recruitment (see Chapter 3).

Minor methodological changes were made following trial commencement in consultation with and approval from the independent oversight committees, the funder, sponsor, Research Ethics Committee (REC), and Health Research Authority, and where applicable from the UK Competent Authority – MHRA (see Appendix 3, Tables 61–63). The final trial methods are described below.

Participants

Patients with DC meeting the trial inclusion/exclusion criteria were identified from clinician referral letters, surgery, and general practitioner (GP) lists and reviews of patients attending orthopaedic, plastic surgery, or musculoskeletal clinics. Patients identified in private practice could be approached if transferred to NHS facilities for treatment.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible if they met the following criteria (and none of the exclusion criteria):

-

Male or female and aged 18 years or over.

-

Presence of discrete, palpable, contracted cord involving the MCP and/or PIP joint of a finger.

-

Degree of contracture ≥ 30 degrees in either joint that is patient cannot put the palm of the hand flat on a table (Hueston’s tabletop test).

-

Able to identify a predominant cord for treatment, which would not require more than one collagenase injection as treatment to the joint.

-

Appropriate for LF surgery and collagenase injection for DC [i.e. cords suitable for collagenase injection and LF and not requiring skin grafting or PNF (e.g. discrete MCP joint cords in elderly)].

-

Willing and able to give informed consent for participation in the study.

Exclusion criteria

-

Severe contractures of the MCP and/or PIP joint (Tubiana Grade 4 – total extension deficit > 135 degrees). 41

-

History of previous treatment for DC (e.g. surgery, collagenase injection or needle fasciectomy) to the study reference digit.

-

History of any other pre-existing disorder of the hand causing significant restriction of movement and/or pain and affecting hand function, for example, post-traumatic stiffness, stiffness due to other causes, infection or arthritis.

-

Non-English-speaking because of the need to complete multiple questionnaires which have not been validated in multiple languages.

-

Resident in a location where attendance for follow-up at one of the recruiting centres would not be possible.

-

Contraindicated for use of collagenase including:

-

Hypersensitivity to: collagenase, sucrose, ketorolac trometamol, hydrochloric acid, calcium chloride dehydrate, and sodium chloride.

-

-

Diagnosis of a coagulation disorder.

-

Any other significant disease or disorder (including autoimmune disorders) which, in the opinion of the investigator, may put the participant at risk because of participation in the study, or may influence the result of the study, or the participant’s ability to participate in the study.

-

Participation in another research study involving an investigational product in the past 12 weeks.

-

Female participants who were pregnant or breastfeeding.

Setting

The trial recruited from 31 secondary-care hand units in NHS hospitals in the UK. One further site agreed to participate in the study but was unable to open to recruitment. The British Society for Surgery of the Hand (BSSH) helped to identify study sites. Details of participating sites are provided in the results section in relation to recruitment.

Interventions

The study required participants to be scheduled for collagenase injection or LF within 18 weeks of randomisation (recommended referral to treatment time). Where possible, sites were encouraged to complete treatment within 12 weeks of randomisation.

Separate cords could be treated (injection or LF) at the same treatment visit. However, a reference joint was identified prior to randomisation, with follow-up assessments (e.g. for recurrence) based primarily on the reference cord. The type, concentration and volume of anaesthetic used during treatment was determined by the clinical team at treating sites. Treatments were delivered by trained professionals familiar with relevant procedures. Details of the participants’ treatment were collected within the relevant case report forms (CRFs) (see Report Supplementary Material 16).

Collagenase Clostridium histolyticum (intervention)

Collagenase was supplied through routine hospital stocks at participating study sites and stored in accordance with the current approved summary of product characteristics (SmPC) for CCH. 28 The investigator used a trial prescription to request this medication from the local site pharmacy department. Once selected for use with a study participant, the intervention was handled as an investigational medicinal product (IMP).

For treatment, either 0.25 ml (MCP joint) or 0.20 ml (PIP joint) of reconstituted solution (0.58 mg CCH) was injected as three aliquots at set anatomical points in accordance with the current approved SmPC. 28 After an interval of 1–7 days, the participant returned to clinic and, under local anaesthetic, the cord was snapped correcting the contracture. This extended period for manipulation, was approved by the MHRA.

When the DISC trial commenced, collagenase was manufactured by Auxilium and marketed by Sobi, in Sweden. However, marketing authorisation for collagenase use within Europe was withdrawn in March 2020 by the parent company (Endo) for commercial reasons. 28 The DISC trial team worked extensively with Sobi to facilitate availability of sufficient vials to enable completion of the study to the contracted target. These efforts were driven by a clear steer by clinicians [site principal investigators (PIs) and co-applicants] that results of this study would have an important bearing on treatment options offered to patients. These efforts were reviewed and supported by the funder (NIHR) and DISC trial oversight committees.

Most treatments were delivered in the same NHS hospital where participants were recruited. However, in a small number of cases treatment occurred elsewhere, in line with local and national guidance and treatment pathways during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, in line with UK government guidance on non-emergency operations and COVID-19 ‘Green Patient Pathways’, a small number of participants were treated at other UK sites (NHS or private). 42 In addition, to maximise recruitment and treatment following marketing authorisation withdrawal, where supplies at the recruiting site were depleted, if necessary participants could be referred onto other trial sites for collagenase treatment subject to local NHS pathways and approval.

Limited fasciectomy (control)

Under anaesthesia, the diseased fascia, nodule and cord, or a part of it, are removed to correct the joint contracture. 25,43 Following LF, as determined by clinical need, the skin was left to heal by secondary intention, closed directly, closed with a Z-plasty, or using a full thickness skin graft.

Following LF, participants were reviewed at a routine wound check appointment.

Concomitant and care following the trial

Further assessment, interventions and treatments, including collagenase injections, and prescribing of concomitant medications were determined by clinical need and were recorded in follow-up CRFs (see Report Supplementary Material 17). Following completion of study follow-up, participants returned to the care of their treating healthcare professional for any re-intervention if required.

Outcomes

The data collection schedule for the study is detailed in Table 1. All outcomes are as originally proposed; no changes were made to outcomes after the trial commenced.

| Procedures | Baseline | Treatment delivery | Week 2 after treatment | Week 6 after treatment | 3 months after treatment | 6 months after treatment | 1 years after treatment | 2 years after treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informed consent | x | |||||||

| Demographics | x | |||||||

| Condition history | x | |||||||

| Compliance | x | |||||||

| Joint measurements (goniometry) | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Diathesis indicators | x | |||||||

| Comorbidity index | x | |||||||

| Clinical assessment of cords | x | |||||||

| Treatment delivered | x | |||||||

| Concomitant medications | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Hand photographs | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Patient Evaluation Measure (PEM) | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Unité Rhumatologique des Affections de la Main (URAM) scale | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire | x | x | x | |||||

| EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Further treatments (further care and/or re-intervention) and complications | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Resource use | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Adverse event assessments | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

Data collection time points were fixed to the date of treatment as opposed to randomisation.

Details of the scoring procedures for included outcomes are given in the Statistical Analysis Plan (available at: www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN18254597) and in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Primary outcome

The primary end point was the score obtained for the 11 items in part 2 of the Patient Evaluation Measure (PEM) 44 at 1 year after treatment (0–100, with higher scores indicating worse outcome).

The PEM is a validated 19-item patient-reported outcome measure comprised of three parts: Part 1 – treatment (5 items), part 2 – hand health profile (11 items) and part 3 – overall assessment (3 items). The score for part 2 (hand health profile) was used as the primary outcome, with the scores for part 1 (treatment) and parts 2 and 3 combined (hand health profile and overall assessment) serving as secondary outcomes The PEM was collected at baseline, just prior to treatment delivery and at 3 and 6 months, and 1 and 2 years (see Report Supplementary Materials 18 and 19).

The inclusion of a patient-reported primary outcome was stipulated by the NIHR commissioned funding call. The PEM was chosen as the primary end point as opposed to other validated measurement tools for the hand, given this can fully capture changes in a patient’s hand health after treatment. The other validated measures were included as secondary outcomes. 45 The primary outcome time point was set as 1 year after treatment to ensure that any associated complications had subsided sufficiently prior to outcome assessment.

Secondary outcomes

Both patient-reported and clinical outcomes were included as secondary outcomes. Patient representatives specifically noted the importance of a return to function as soon as possible following treatment and given the limited available evidence comparing recurrence rates following collagenase injection and LF, relevant measures for each were included and prioritised to allow treatment effectiveness in the context of these key elements to be assessed.

Unité Rhumatologique des Affections de la Main patient-rated outcome measure

The Unité Rhumatologique des Affections de la Main (URAM) was included as a validated, nine-item, six-interval disease-specific disability scale, with higher scores indicating greater difficulty. 46 This outcome was collected at baseline and at 3 and 6 months, and 1 and 2 years.

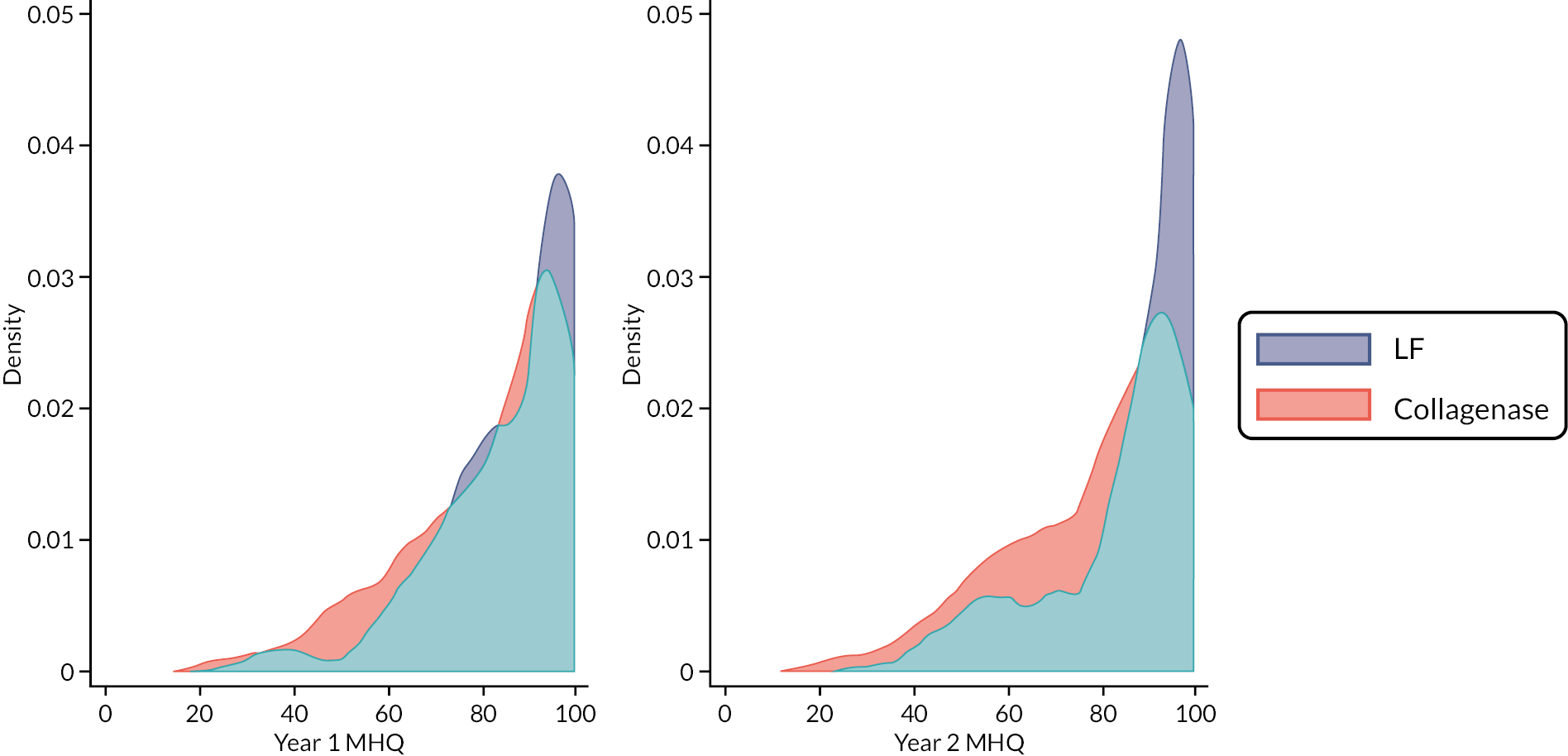

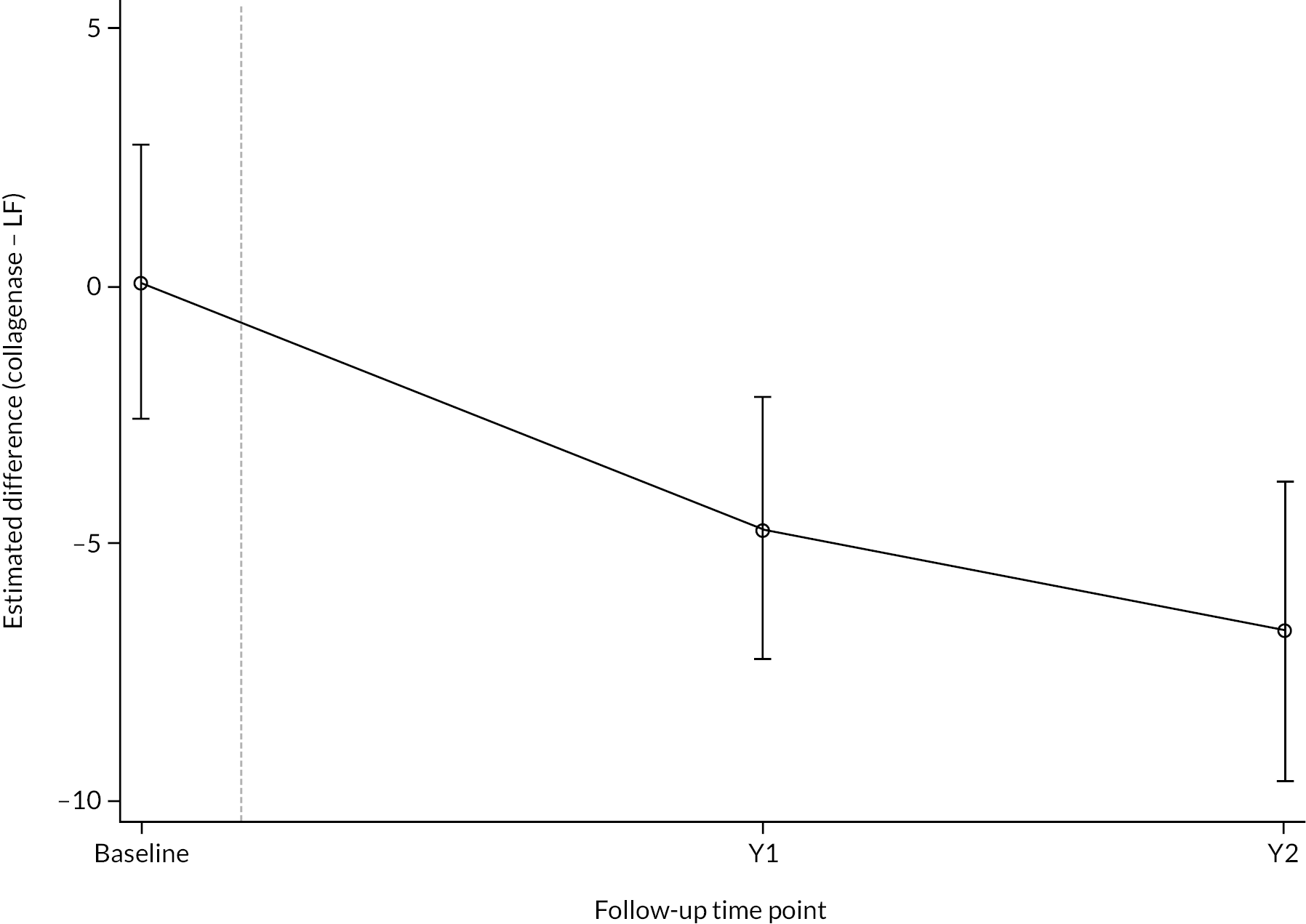

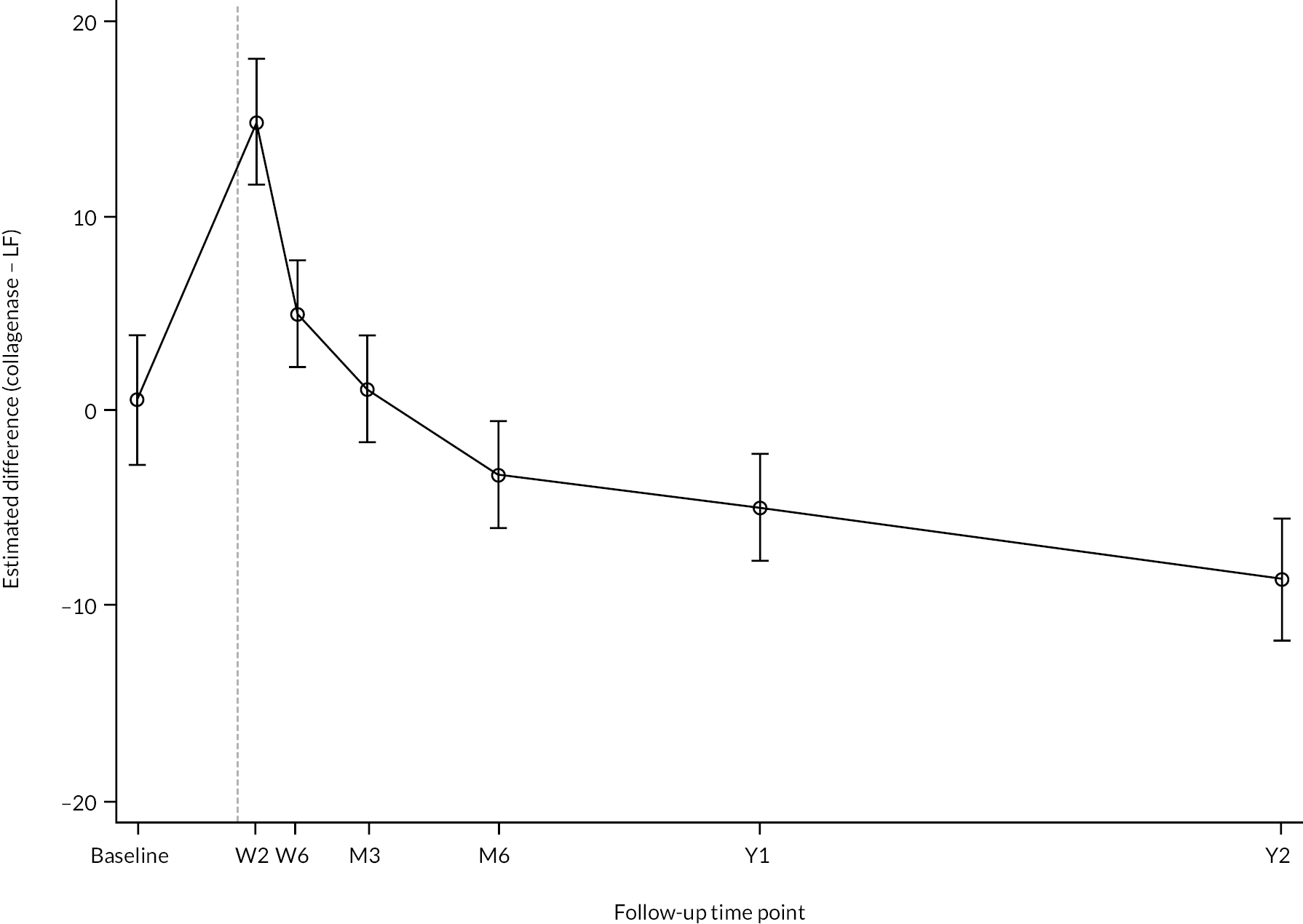

Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire

The Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire (MHQ), validated for use in this patient group, assesses each hand individually via 63 questions across 6 domains (overall hand function; activities of daily living; work performance; pain; aesthetics; and patient satisfaction with hand function). 47,48 The function and pain domains refer to patient symptoms while work and activities of daily living refer to disability and handicap. Higher scores indicate better overall functioning and satisfaction. This outcome was collected at baseline and at 1 and 2 years.

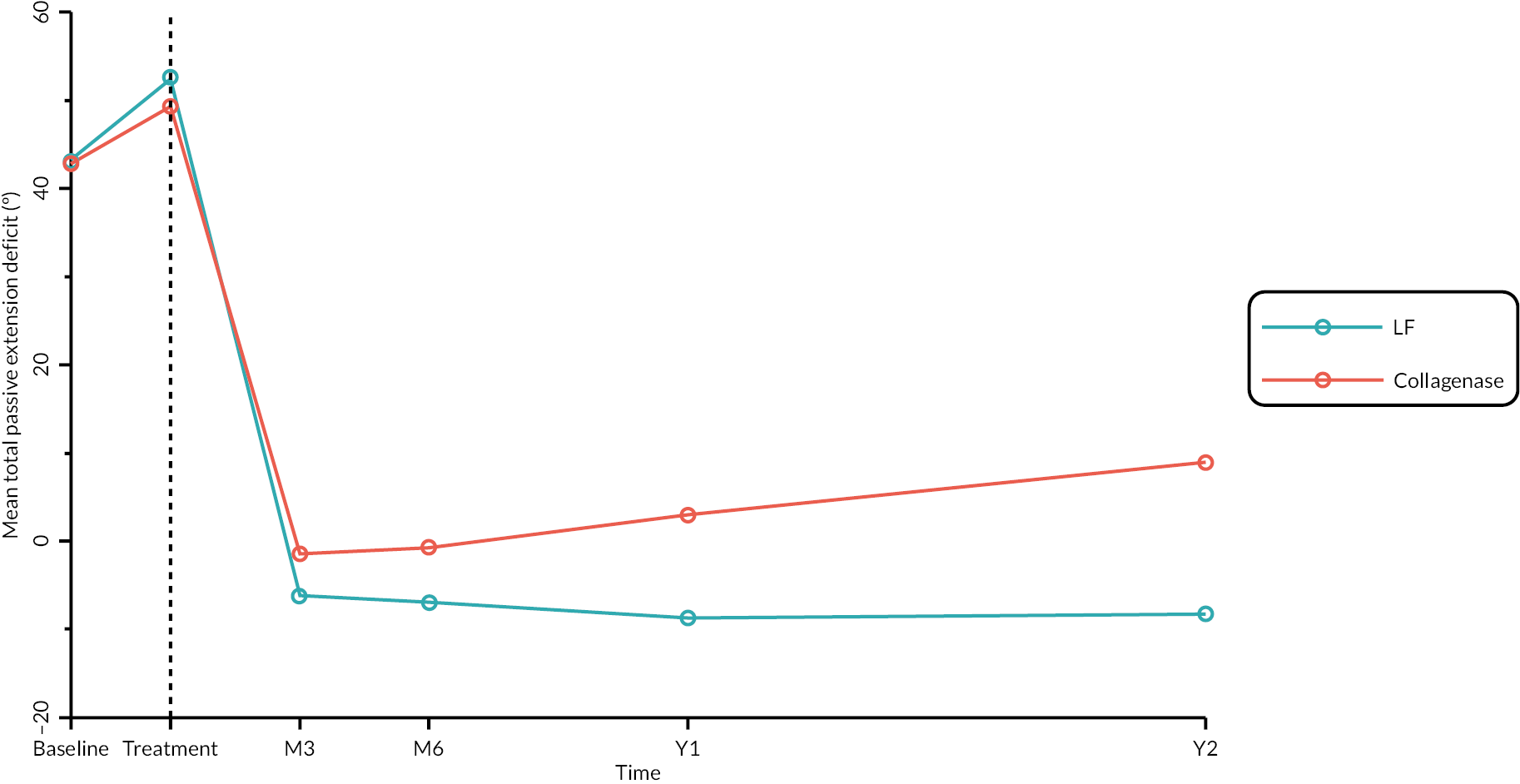

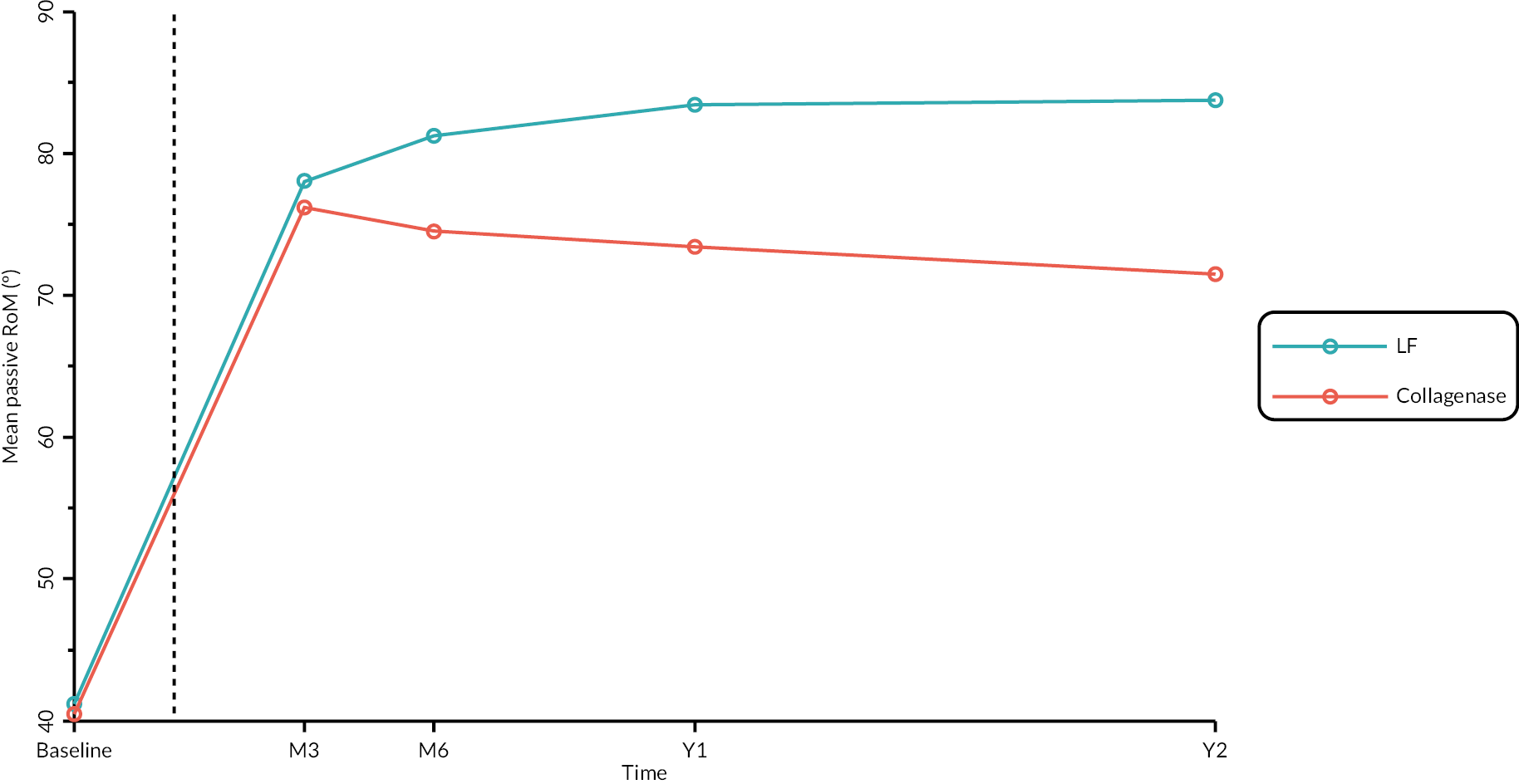

Objective measures (recurrence, extension deficit and total active movement)

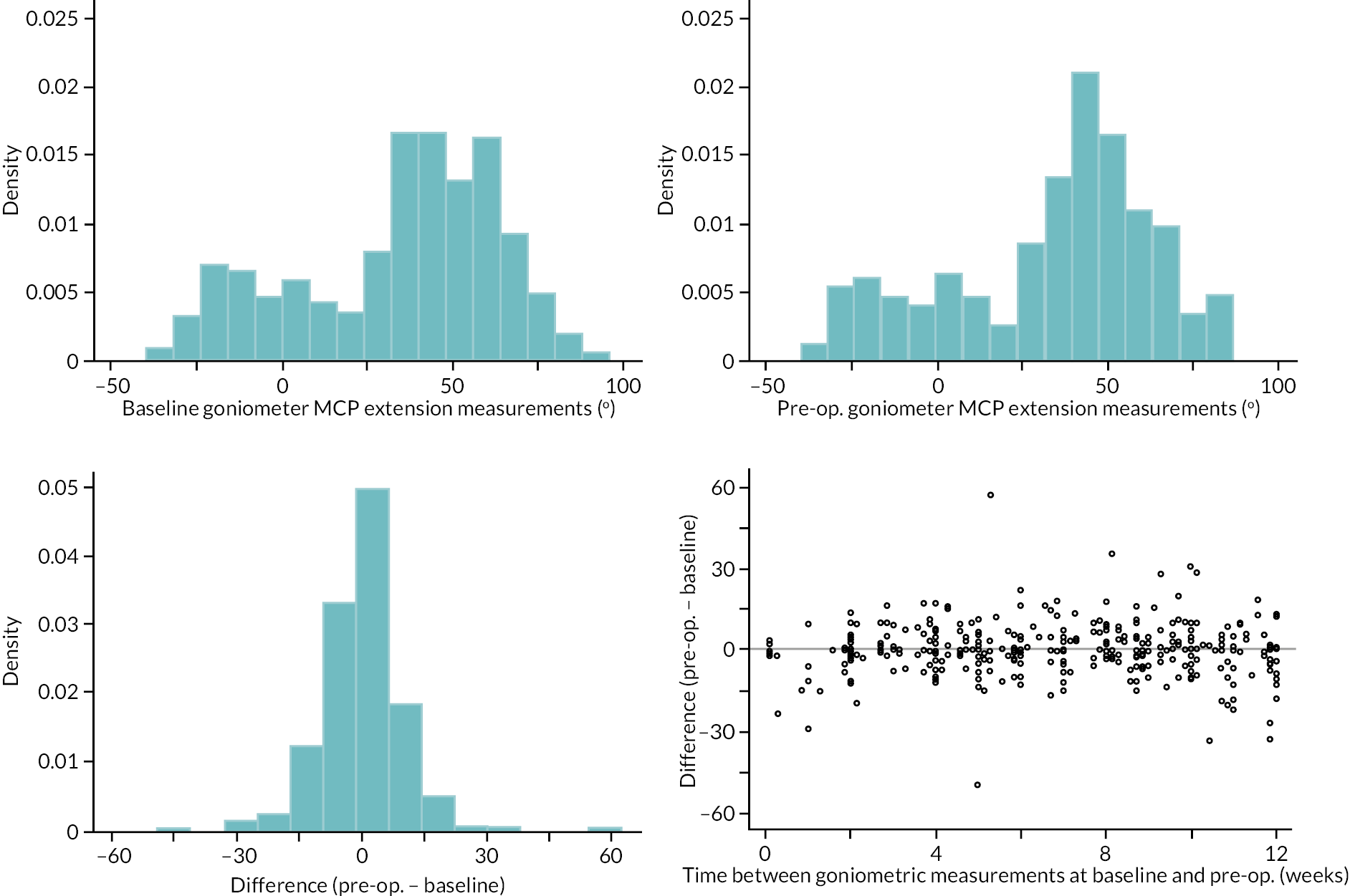

Goniometric measurements of the joints of the reference digit were taken at baseline, immediately prior to treatment delivery and at 3 and 6 months, and 1 and 2 years by qualified NHS practitioners. At baseline and the time points after treatment, sites were asked to provide three repeated goniometric measurements of the active extension, passive extension, and flexion of the joints of the reference digit (i.e. 18 measurements at each time point if the reference digit was the thumb, and 27 measurements if the reference digit was not the thumb). The arithmetic means of the three repeated measurements were used for analysis. At treatment delivery, sites were asked to provide a single goniometric measurement of active and passive extension for each joint of the reference digit (i.e. four measurements in total if the reference digit was the thumb, and six measurements if the reference digit was not the thumb).

These goniometric measurements were used to derive several outcomes: recurrence, passive and active range of movement (RoM), and passive and active extension deficit and stiffness (maximal flexion). For the study, recurrence was defined as a change in extension deficit (as measured by passive extension) of 6 degrees between 3 and 6 months, or 20 degrees from 3 months to 1 year after treatment12,29 at the reference joint. At each time point, RoM for each joint was calculated as the difference between the mean total active flexion measurement and the mean total active extension or extension deficit measurement.

A study-specific manual for performing joint measurements was provided (see Report Supplementary Material 2) and goniometers were required to meet pre-specified criteria (permits measurement of up to 30 degrees of hyperextension; measures flexion to 120 degrees; measures in at least 2-degree increments), to ensure that assessments were standardised.

In addition to goniometric measurements, photographs of the participant’s reference hand (extension, flexion, and anterior-posterior views) were taken. A study-specific manual was used to standardise the images (see Report Supplementary Material 3). If willing, participants also took and returned a photograph of their hand. A study-specific procedure and video were provided to participants to assist with standardisation of these images (see Report Supplementary Materials 4 and 5). The photographs afforded the opportunity for further quality assurance of joint measurements. Clinical members of the team used these images to undertake validation measurements using OsiriX software (Geneva, Switzerland).

Further treatment

All relevant treatment required for the participants’ DC were collected and documented at each follow-up assessment.

Ongoing hand therapy and/or physiotherapy appointments to treat chronic regional pain syndrome, stiffness, swelling or scar problems were referred to as further care. Participants who underwent more than six outpatient follow-up visits for hand therapy and/or physiotherapy had the details of these appointments reviewed on an individual basis to determine whether this extended duration of therapy should be considered further care or routine care.

For the purposes of this report, if participants underwent further collagenase injection, LF, dermo-fasciectomy or PNF to the reference digit at any point during follow-up, then this was counted as further intervention for contracture correction and deemed re-intervention.

Complications

Complications relating to the intervention and control treatments were recorded. Expected complications for the collagenase group are listed in the SmPC. 28 Complications which were expected for the LF group are listed later in Chapter 2 in relation to adverse events (AE).

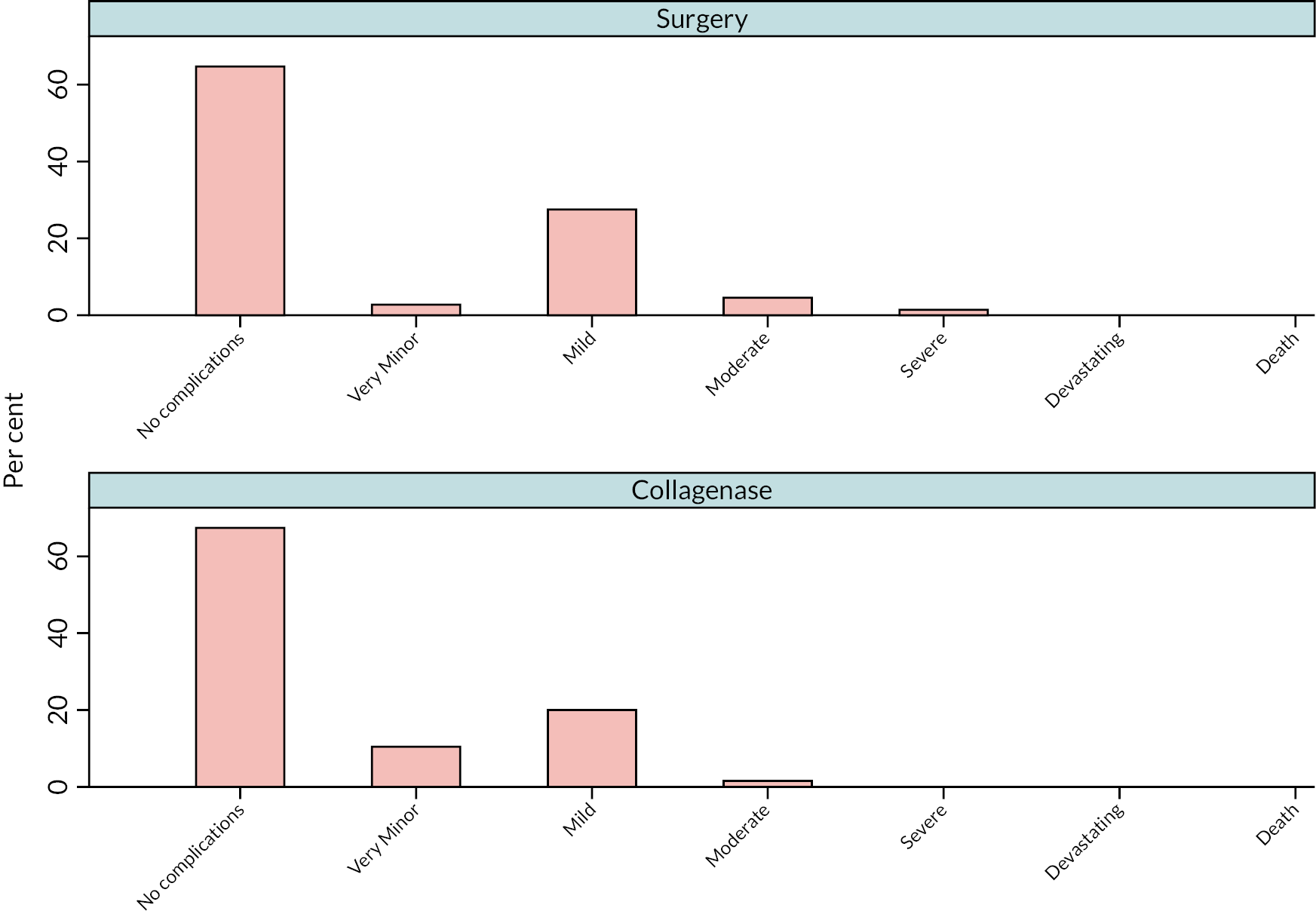

Complications were reviewed and graded on their severity using an 8-level ordinal classification system from 0 (no complications) to 8 (death). Two clinical observers independently completed grading, with conflicts in grading resolved through discussion.

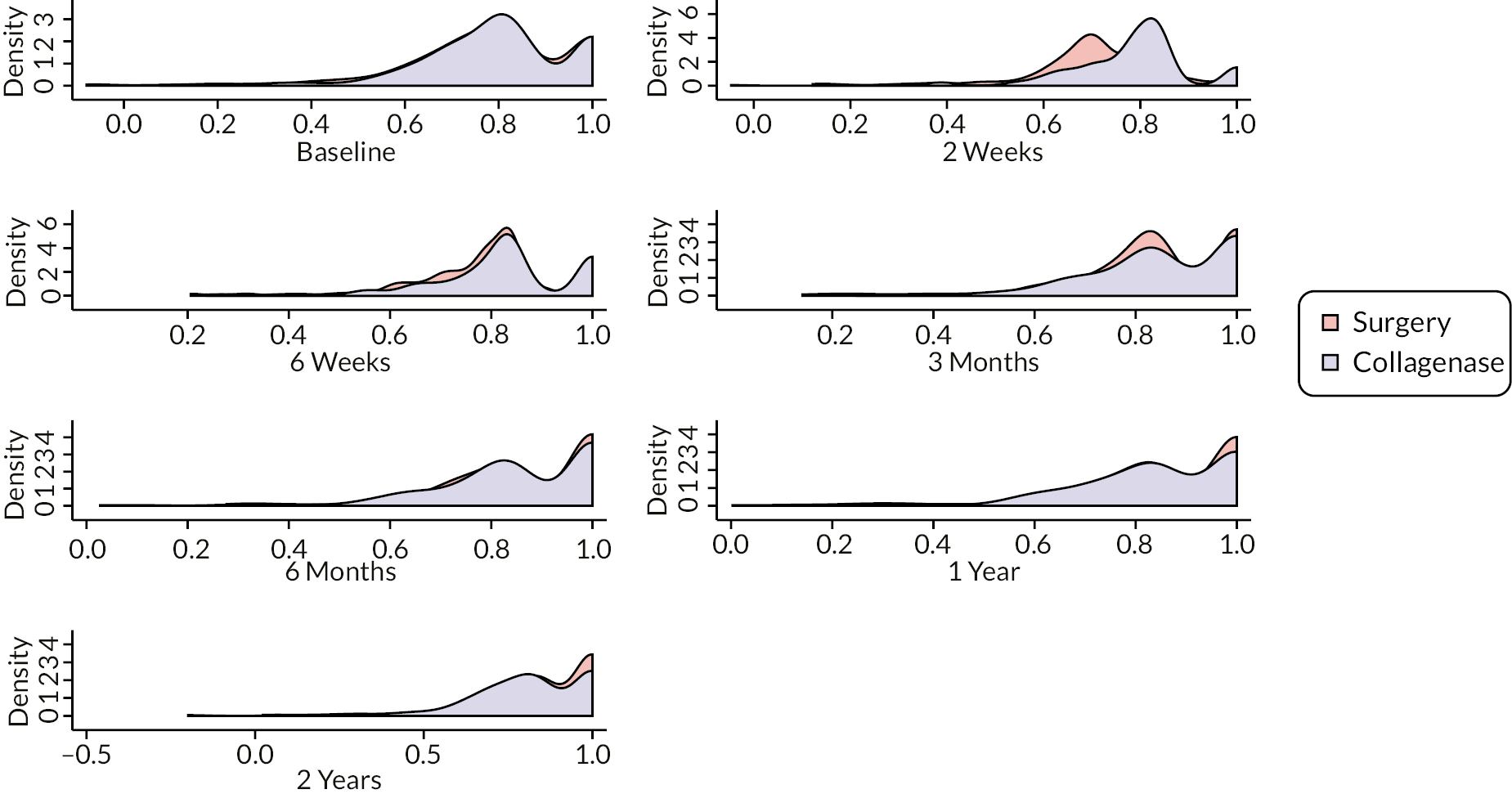

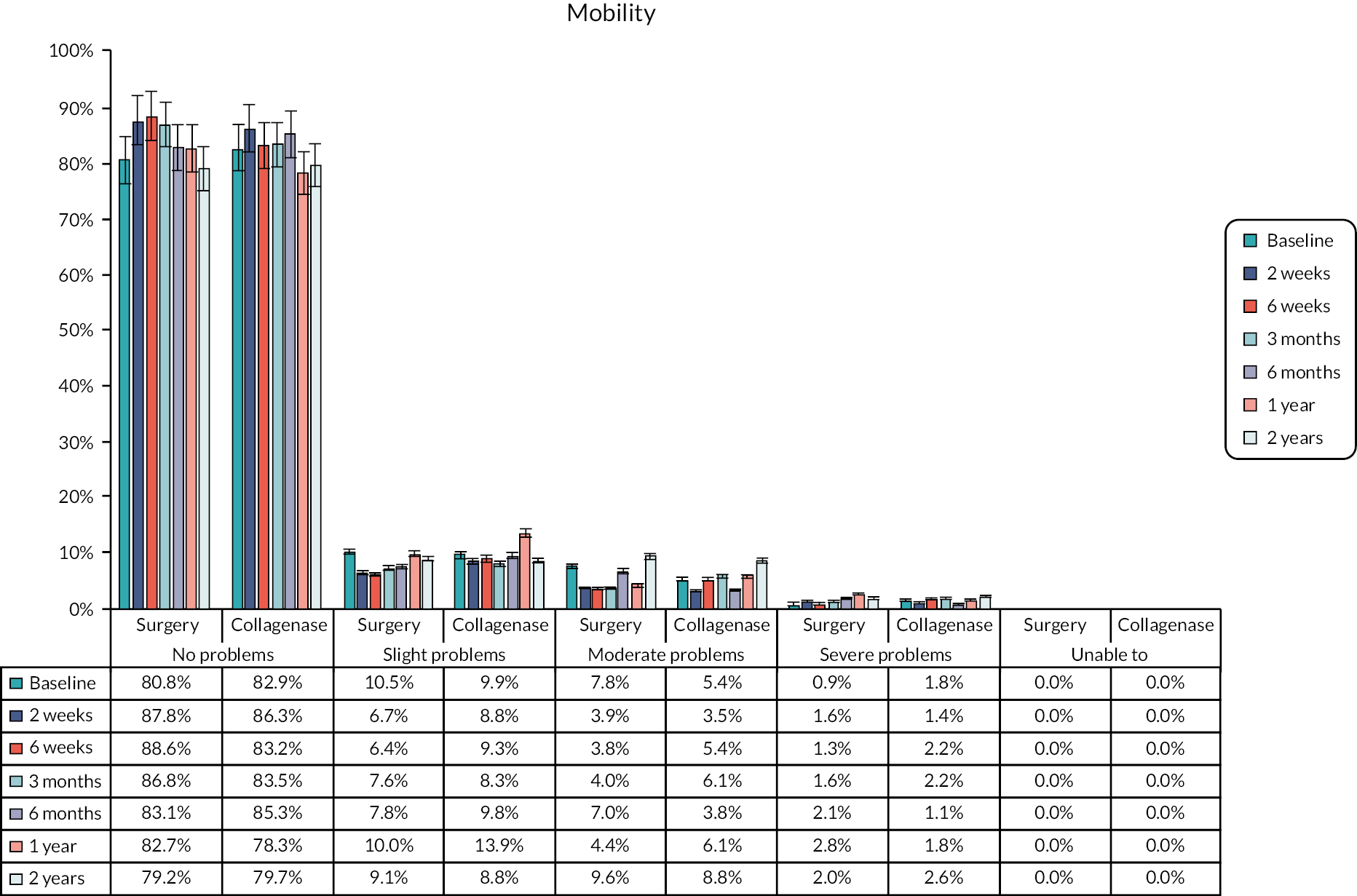

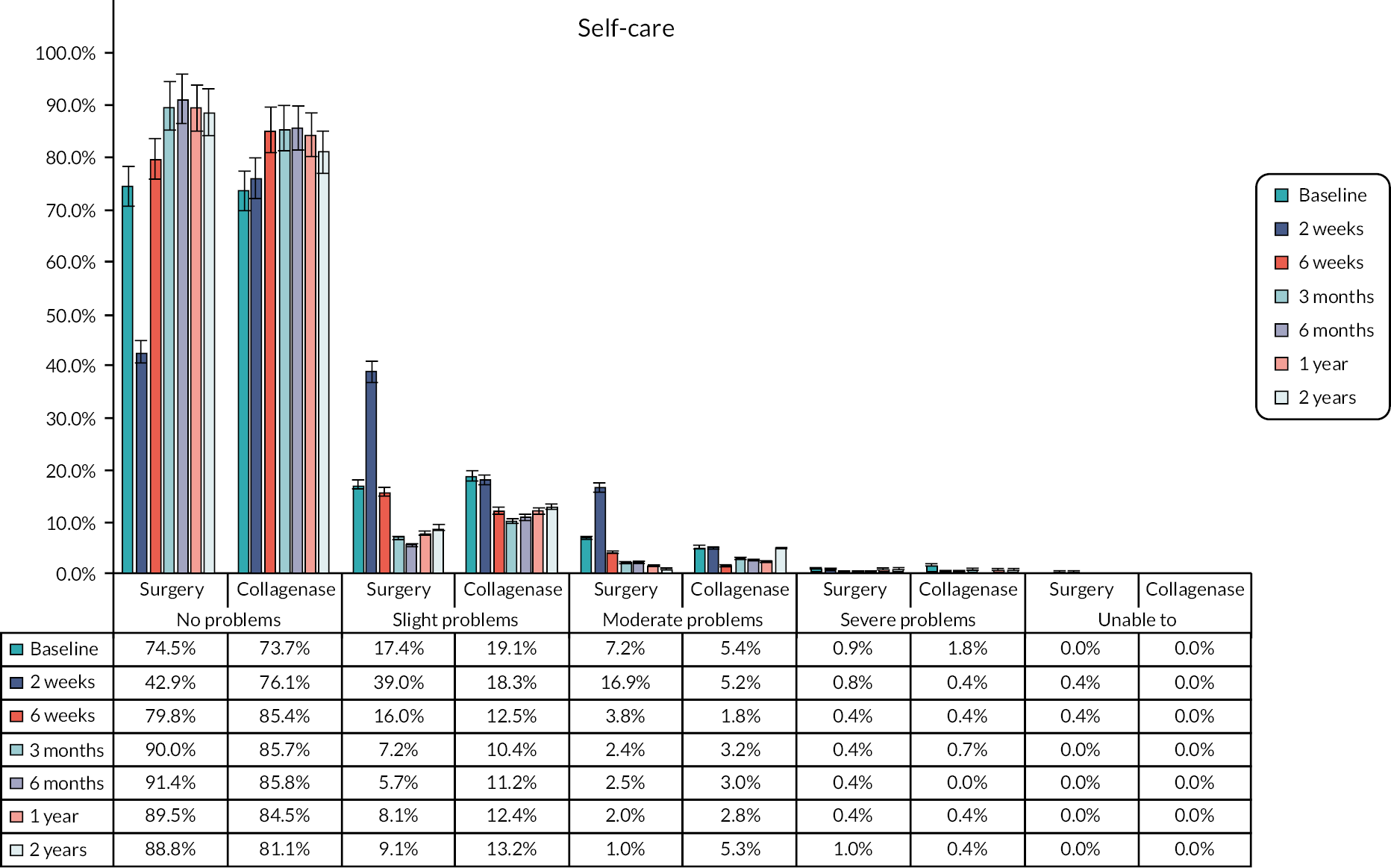

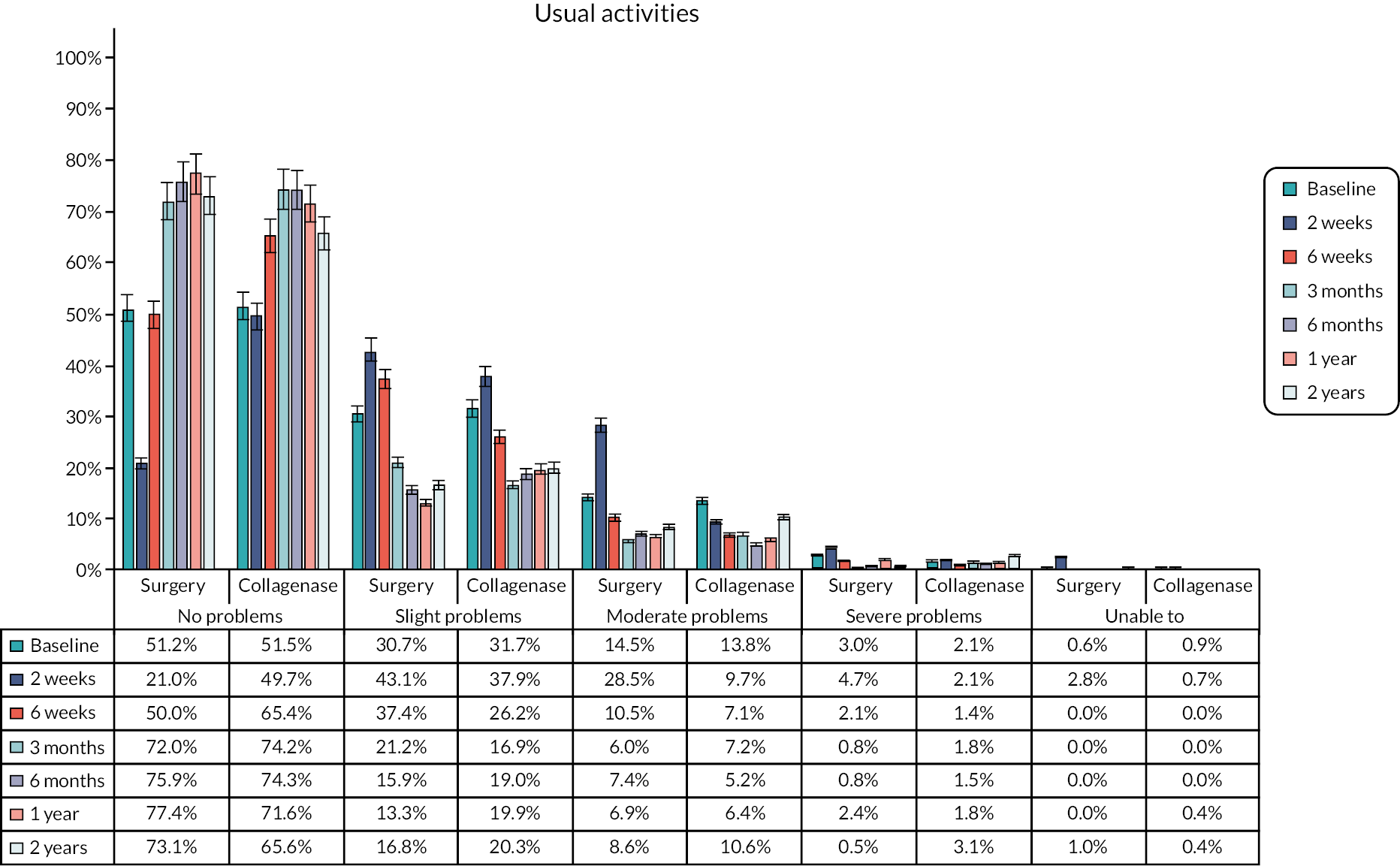

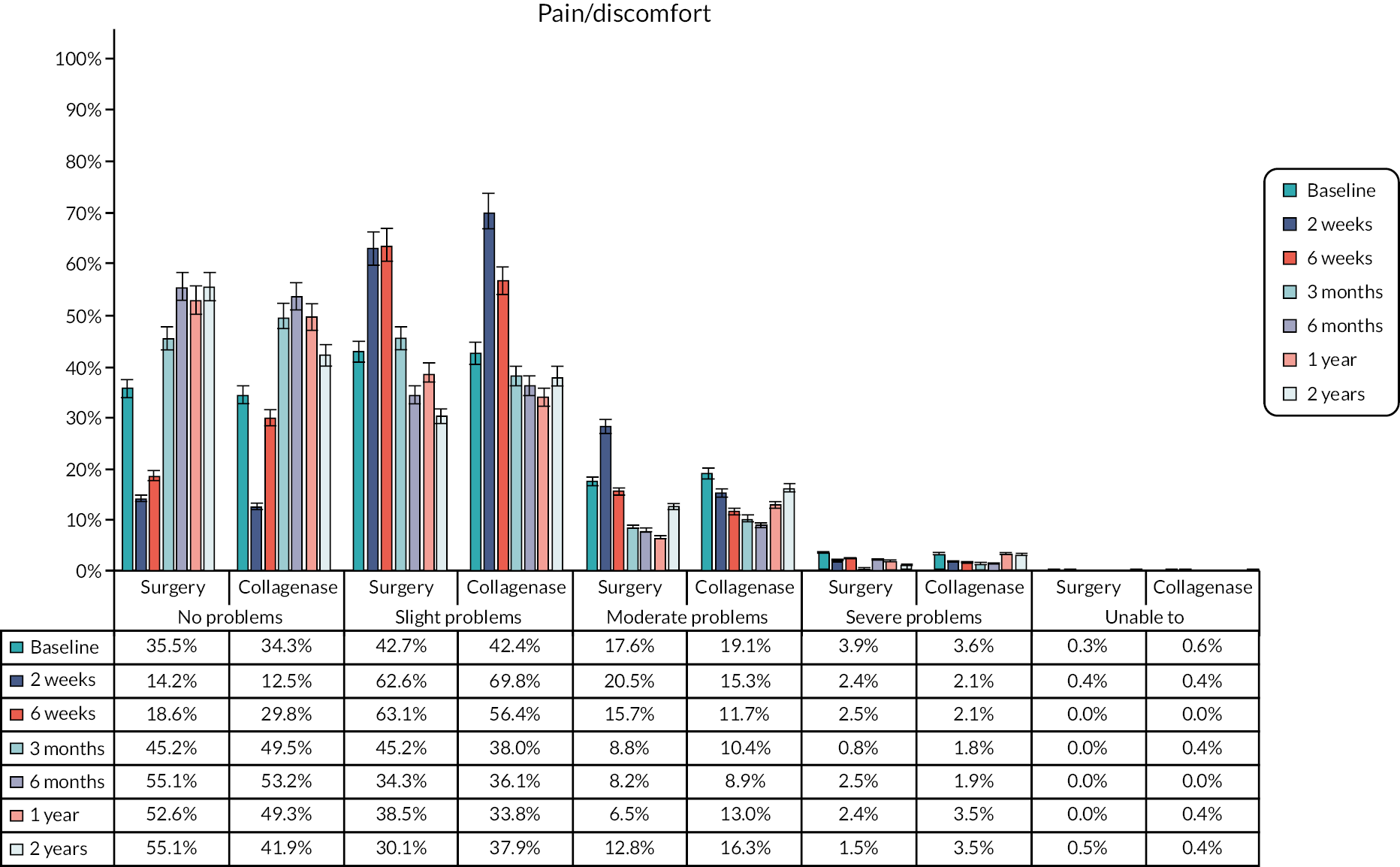

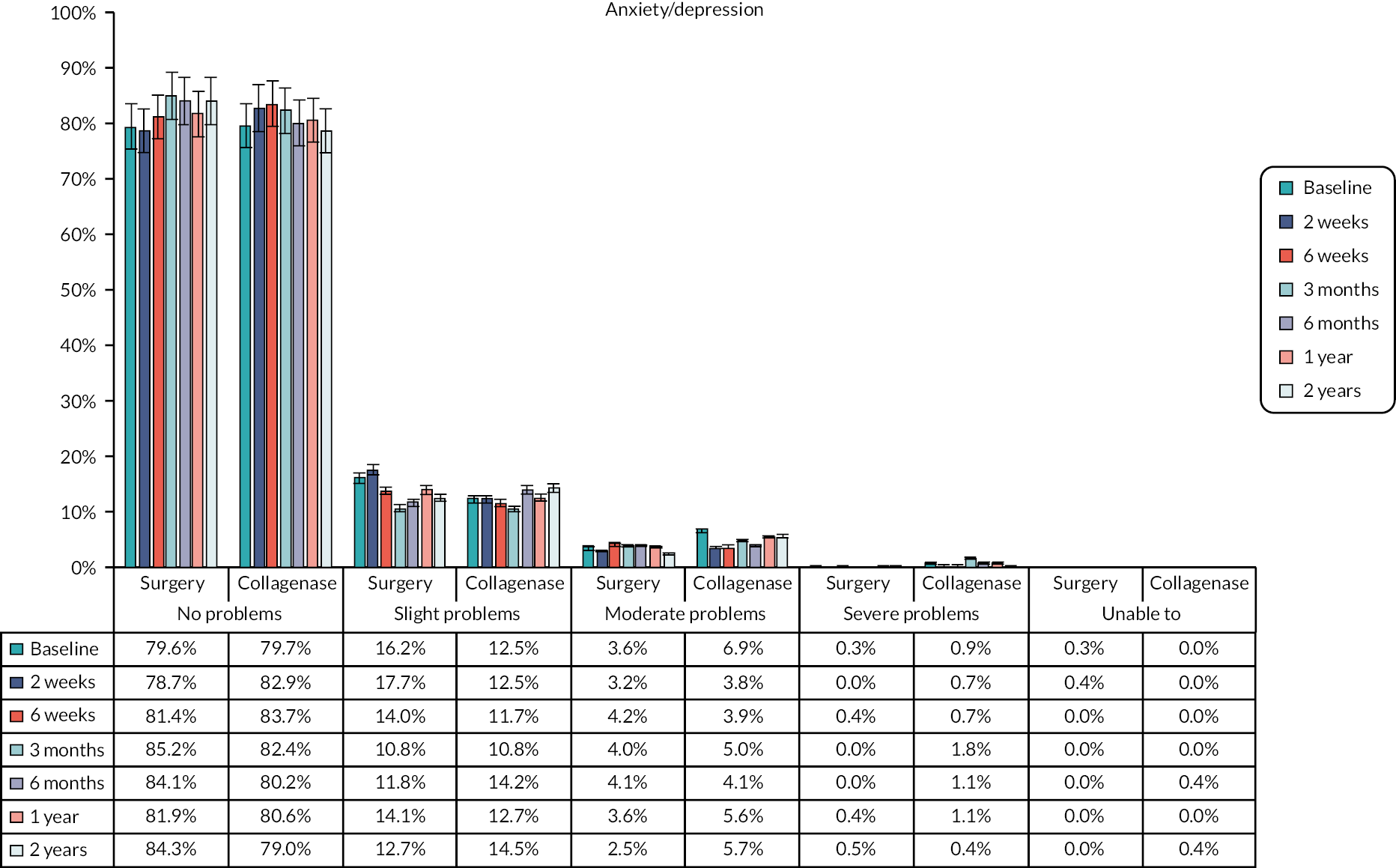

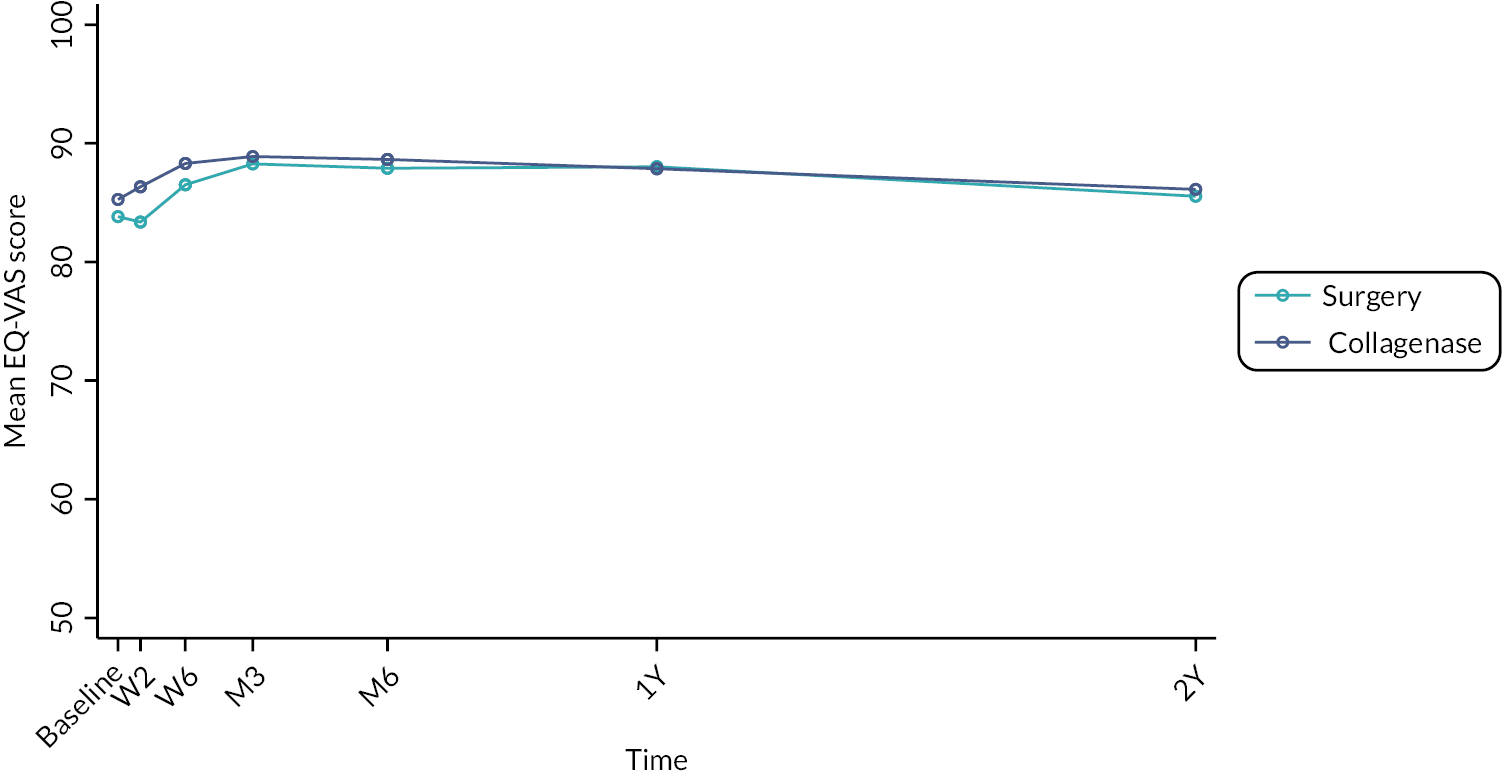

EuroQol

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)49 assesses 5 dimensions of health (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) on 5 severity levels (no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and unable/extreme problems). A visual analogue scale (VAS) from 100 (best imaginable health) to 0 (worst imaginable health),49 also records participants’ overall evaluation of their health.

This validated, generic, patient-reported health status measure was included to enable assessment of health-related utility and quality-of-life outcomes as required for the cost-effectiveness evaluation (see Chapter 4).

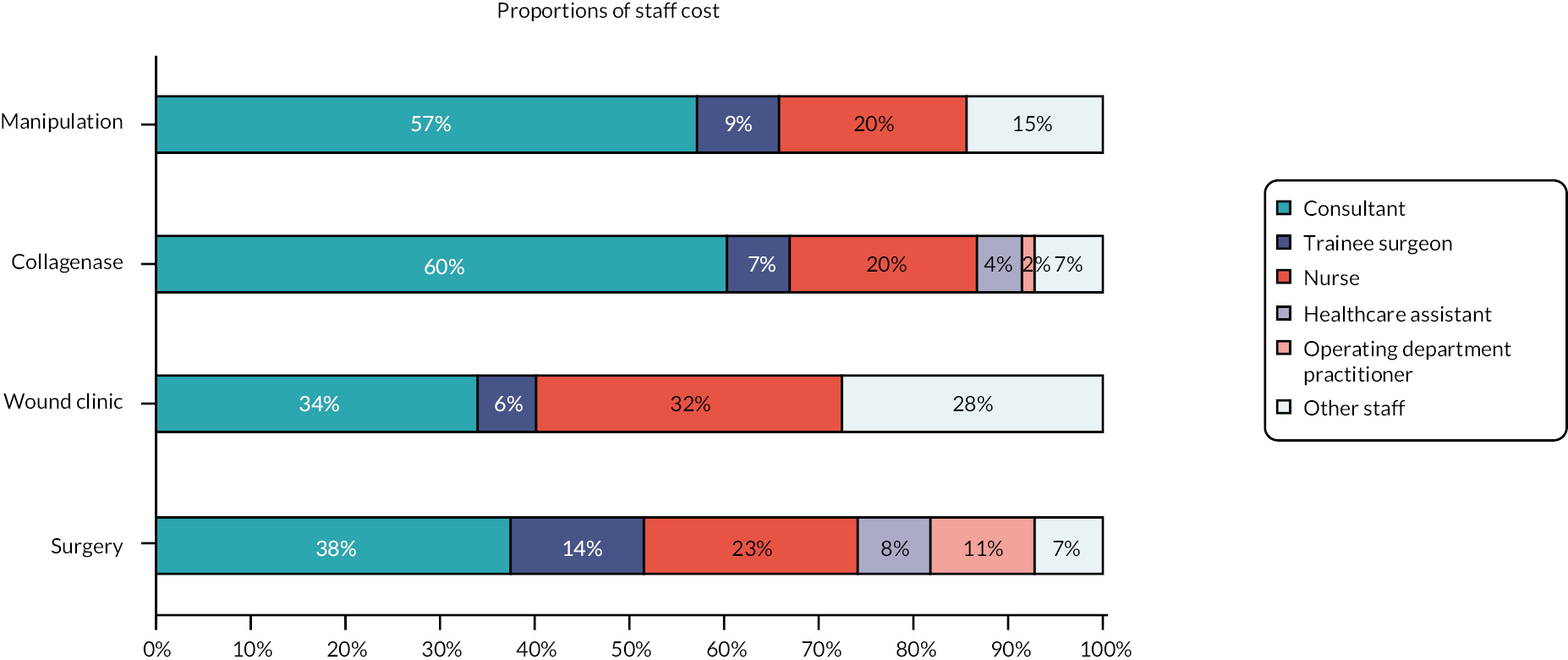

Resource use

Resource use data were collected from hospital records and through participant self-report and documented in study-specific forms. Data collected included health resource use [treatment delivery, inpatient episodes, outpatient visits, emergency hospital admissions, and primary care visits (e.g. GP, nurse and physiotherapy)] in addition to return-to-work and out- of-pocket expenses. Resources were utilised for the cost-effectiveness evaluation detailed in Chapter 4.

Time to recovery of function

Time to recovery of function was assessed using a Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE) measure,50 a single-question, patient-reported measure, which assesses patient hand functionality. This outcome was collected at baseline, 2 and 6 weeks (see Report Supplementary Material 20), 3 and 6 months, and 1 and 2 years.

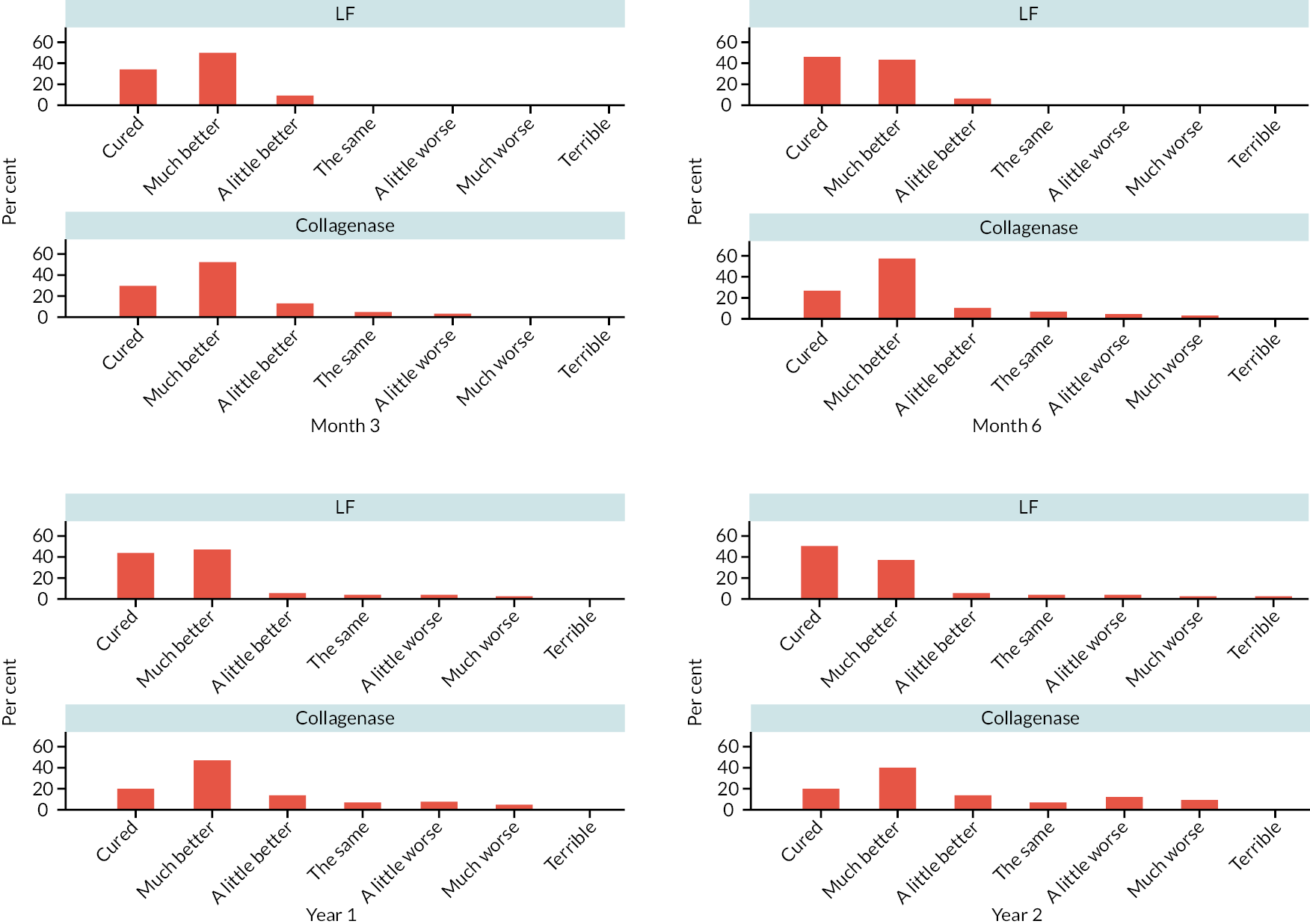

Overall hand assessment

At 3 and 6 months, and 1 and 2 years, participants were asked a single global question about the problems they experienced with the hand that was treated compared with the problems they experienced prior to treatment. Responses were given on a seven-item ordered scale from terrible to cured.

Sample size

The primary outcome for DISC was the score (0–100) obtained for the 11 items in part 2 of the PEM at 1 year. There were no planned interim analyses for the trial or stopping guidelines, hence the sample size calculation was based on the number of participants required for a single test of the difference (δ = collagnase – surgery) in expected PEM score at 1 year using all available follow-up data.

Previous survey data collected from a representative sample of 880 patients with DC suggested a population standard deviation (SD) of about 22 points for part 2 PEM scores. 51 Using methods of predictive value against an anchor question for functional improvement, we estimate that a 6-point difference on the PEM at 1 year represents the threshold at which treatment differences become important, and which would represent an appropriate non-inferiority margin.

Assuming a non-inferiority margin of 6 points and a SD of 22 points, an effective sample size of 568 participants (284 per arm) was required to obtain 90% power for 1-sided independent samples t-test of size 2.5%, of H0:δ≥6 versus H1:δ<6, ignoring any precision gained by conditioning on informative baseline covariates. Assuming 20% attrition at the 1-year follow-up, the total target sample size was 710.

Recruitment

Potential participants were identified using:

-

clinician referrals

-

surgery and clinic lists

-

allied clinics and centres (e.g. musculoskeletal and physiotherapy clinics, musculoskeletal triage centres)

-

private practice

-

GP settings.

The central trial team also worked with the British Dupuytren’s Society, which publicised the study to its members through newsletters and social media. Interested individuals contacted the trial team for more information and were informed of the nearest recruiting site to request referral by their GP if appropriate.

A delegated clinician at the recruiting hospital assessed potential participants and confirmed eligibility before completing the study eligibility CRF (see Report Supplementary Material 6).

Eligible patients were then approached, provided with an information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 7) and infographic (see Report Supplementary Material 8), and were given the opportunity to ask questions about the study. If willing to participate, a suitably qualified, experienced, and delegated research nurse or clinician obtained informed consent (see Report Supplementary Material 9), following which baseline CRFs (participant and investigator) were completed (see Report Supplementary Materials 10 and 11).

Patients who consented to participate in the main DISC trial were also eligible to participate in the photography and/or qualitative substudies. Separate consent forms were completed for these substudies (see Chapter 5, Appendix 2, and Report Supplementary Materials 12 and 13).

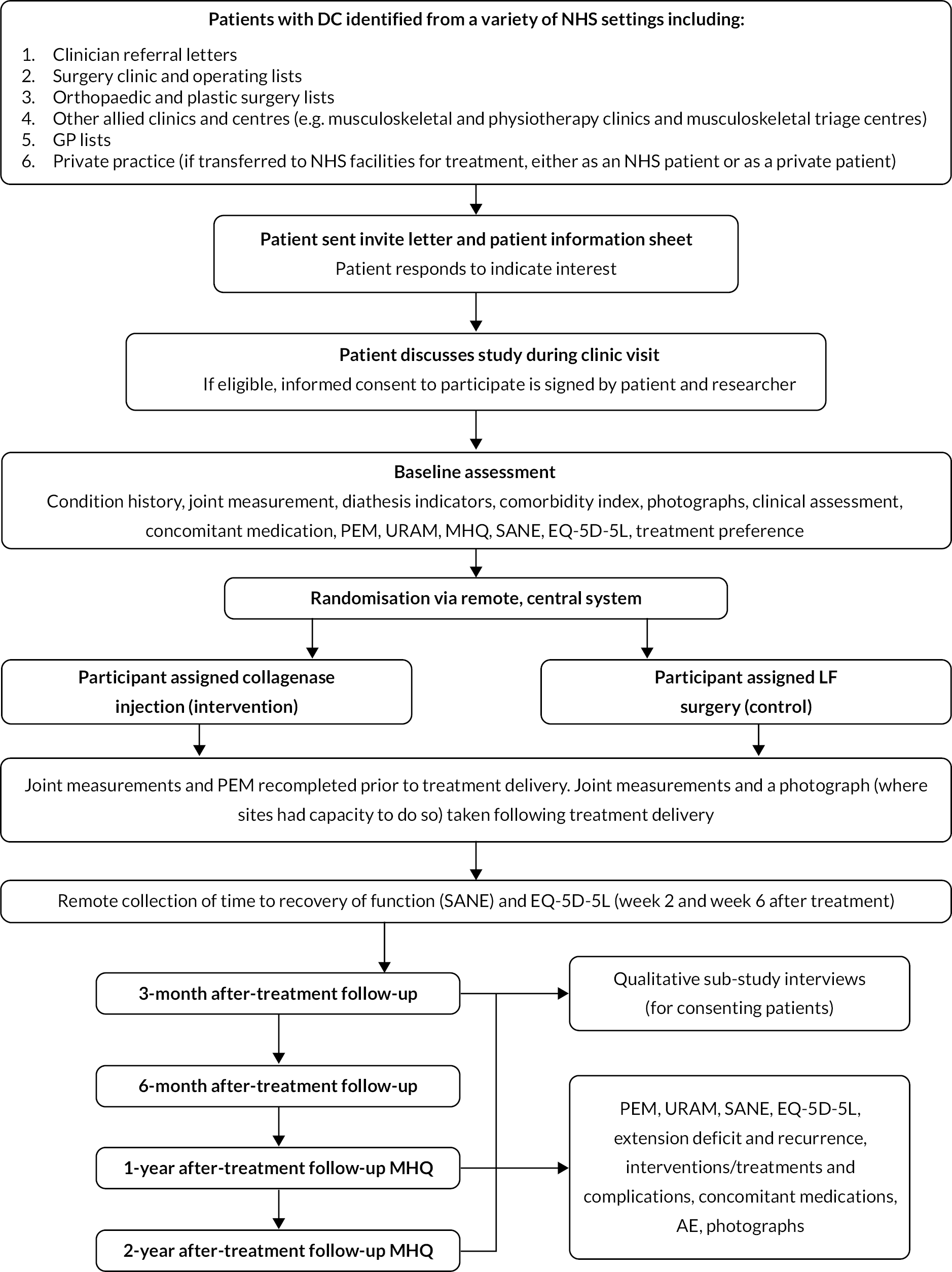

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, in the later stages of the study, clinic visits could be completed by video appointment if required and patients were provided with guidance on using the relevant software prior to the appointment to facilitate this. Where a video appointment was completed for baseline, the consent form was required to be signed by both the participant and the delegated clinician prior to treatment delivery. Figure 1 shows participant recruitment and follow-up.

Strategies for achieving adequate participant recruitment included seeking advice from our patient focus group and completion of recruitment evaluation interviews with site teams. Trial training and discussions in relation to key study elements were implemented through face-to-face meetings with site PIs at BSSH conferences and routine site investigator meetings.

Training was provided to research teams through a site initiation visit (SIV) and a trial manual was also provided to ensure adherence to trial processes. Ongoing support and guidance were provided to staff as required (e.g. when new staff join or replace existing site staff) with clinical guidance from the chief investigator when necessary.

Participant timeline

Randomisation

Participants were randomly allocated 1 : 1 to one of the two study arms (collagenase injection or LF) using blocked randomisation, with randomly varying block sizes (four or six allocations) and stratification by the designated reference joint (MCP or PIP). The randomisation sequence was amended, with effect from 21 January 2020, to include stratification by centre to account for the limited availability of collagenase following marketing authorisation withdrawal. The study statistician, independent of participating NHS hospitals, generated the randomisation sequence.

To ensure adequate allocation concealment for the study, randomisation was carried out, following completion of baseline assessments, via the internet using a secure, central service hosted by Sealed Envelope Ltd (London, UK). This centralised system recorded information to identify all potential participants and to confirm their eligibility to avoid inappropriate entry of participants into the trial.

Blinding

Given the pragmatic nature of the trial, and the surgical and injection interventions used, it was not possible to blind clinicians or participants to study allocation. It was also not possible to blind the analysing statistician to trial allocation due to the way in which data were collected. To mitigate any impact of this, a statistical analysis plan (available at: www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN18254597) pre-specified all analyses and any changes made to the data set prior to analysis were documented appropriately.

Statistical methods

Internal pilot phase analysis

An internal 6-month pilot study was conducted at the start of the recruitment period to check the initial assumptions about recruitment and feasibility of the trial. A summary of the data were provided to the independent Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC – described later in Chapter 2), which reviewed the pilot data and made a recommendation to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC – described later in Chapter 2) and Trial Management Group (TMG) to recommend any changes required to the study team and the funding body.

The success of the internal pilot phase was based on the following objectives:

-

To set up 6 pilot sites, with a target to recruit 48 participants from these sites

-

To ensure that set-up of a further nine sites (inclusive of pilot sites) had been completed

-

To monitor closely operational aspects of the trial, including training, eligibility and time to consent, study activity, and participant adherence.

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow diagram.

Findings from the internal pilot study are detailed in Internal pilot.

Statistical methods

A detailed analysis plan was written and agreed with the DMEC prior to completion of recruitment. Brief details of the analyses undertaken are given below (please refer to the analysis plan available at www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN18254597 for further details), and any deviations from the planned analyses are detailed and justified below. All analyses were undertaken at the end of the follow-up period using all available data; hence no stopping rules or associated adjustments for multiplicity were required. All analyses included all participants with data available for the relevant outcome in the groups that they were allocated to, except for the imputed data analyses that included all randomised participants. Analyses were conducted using Stata/SE v17.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Baseline data were summarised by allocation and overall, both as-randomised and as-analysed. The as-randomised set comprised all randomised participants, excluding any ineligible patients randomised in error. The as-analysed set comprised all participants included in the primary analysis (i.e. all participants with primary outcome data available for at least one time point after treatment).

For all outcomes/time points, continuous outcome data were summarised in terms of the non-missing sample size, mean, SD, median, interquartile range and range, and categorical data in terms of frequencies and proportions. A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram was used to summarise participant flow and data completeness. 52

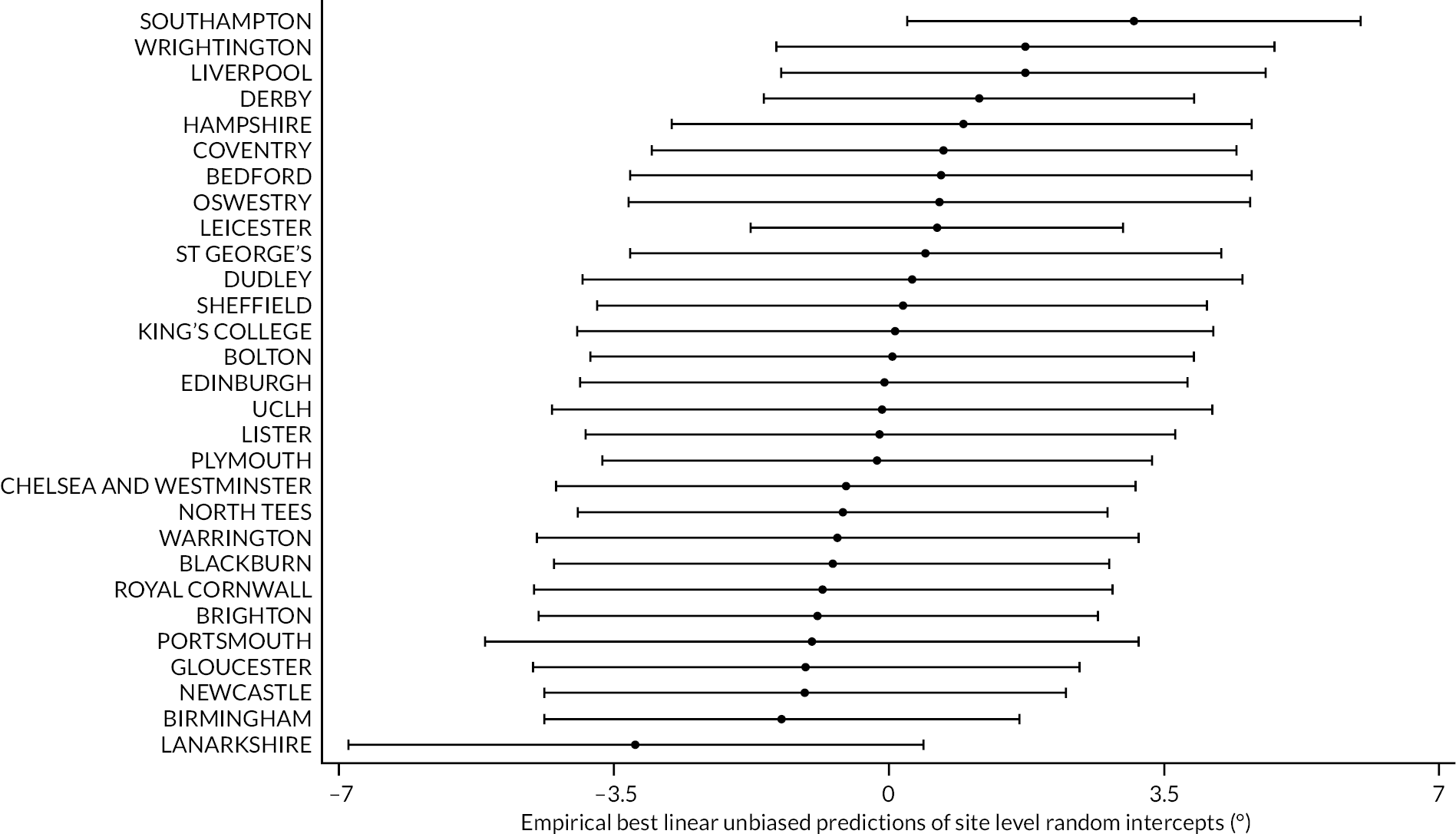

Primary analysis

All participants with at least one PEM Hand Health Questionnaire measurement after treatment were included in the primary analysis. A covariance pattern model, with all PEM measurements taken after treatment included as outcomes, was used to estimate the group differences (collagenase – LF) in expected PEM score at each time point after treatment. Treatment groups, time points, and their interactions were included as fixed effects. This model also included fixed effects for study reference joint (the stratification factor) and baseline PEM score (modelled via a single linear term) and a random intercept for study recruitment site. The correlation between the repeated measurements was accounted for using an unstructured covariance matrix. This model was fitted using restricted maximum likelihood, with the Kenward‒Roger method53 used to calculate degrees of freedom for the interval estimates and statistical tests reported. The null hypothesis that collagenase is inferior to LF was rejected if the upper bound of the two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference (collagenase – LF) in expected score for the primary end point (PEM at 1 year) was less than the non-inferiority margin of 6 points.

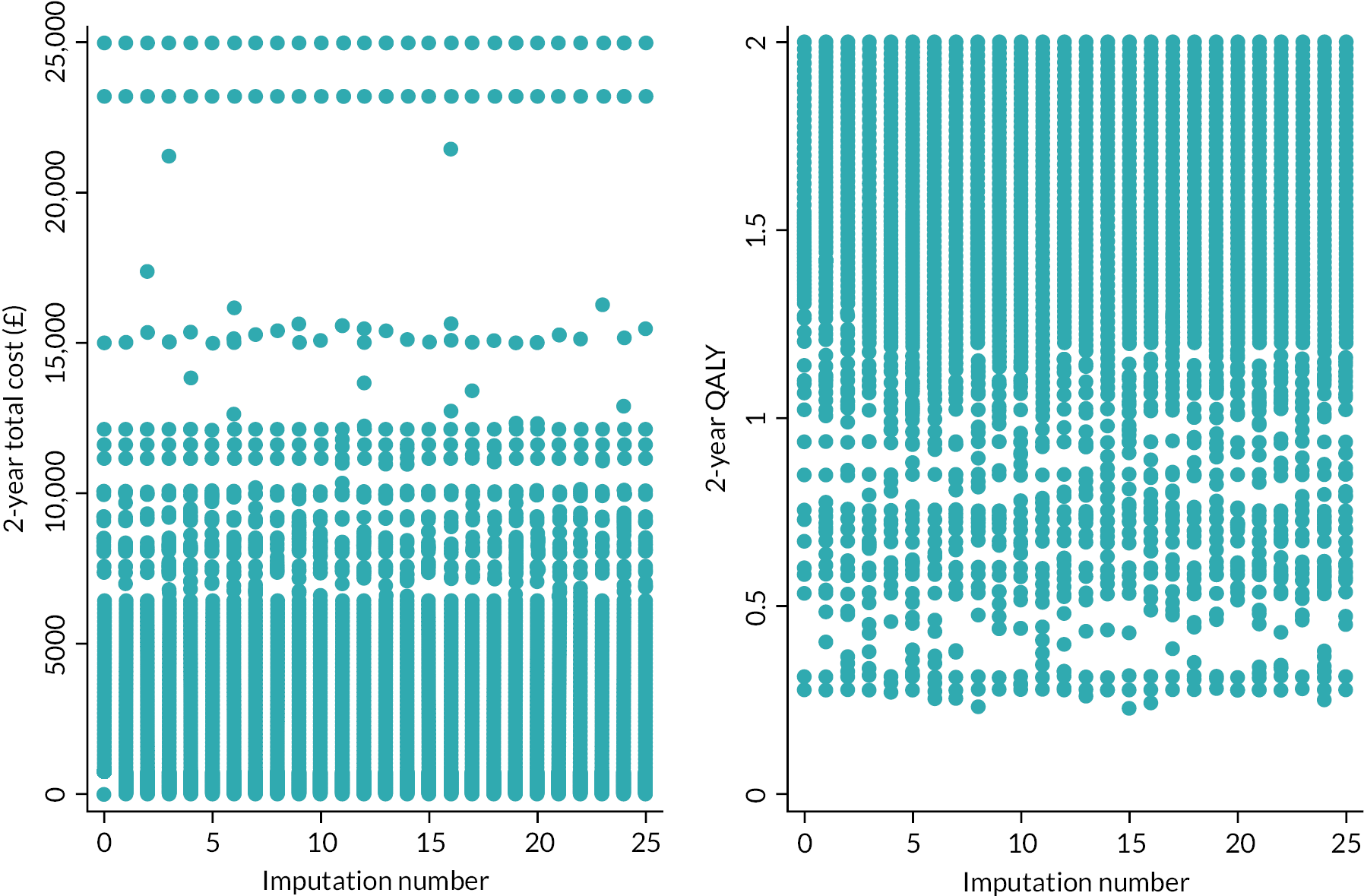

Further analyses of primary outcome

The primary analysis assumed missing outcome data were missing at random (MAR) conditional on the baseline covariates and non-missing outcomes included in the primary analysis model. Multiple imputation (MI) was used to obtain treatment effect estimates (at each time point) under a slightly weaker MAR assumption, by imputing missing outcomes conditional on additional relevant pre- and post-randomisation variables. The sensitivity of the results of the primary analysis to various systematic departures from MAR54 was explored, using a delta-based sensitivity analysis implemented via a pattern mixture model. We also undertook further sensitivity analyses to investigate the robustness of the results of the primary analysis to differential delays in time to receipt of treatment across groups, and departures from the planned timing of follow-up assessments.

Treatment compliance was reported descriptively, and an instrumental variable estimator (with random allocation as the instrument) used to estimate the complier-average causal effect (CACE; i.e. the average causal effect of collagenase compared to LF within the ‘complier’ principal stratum).

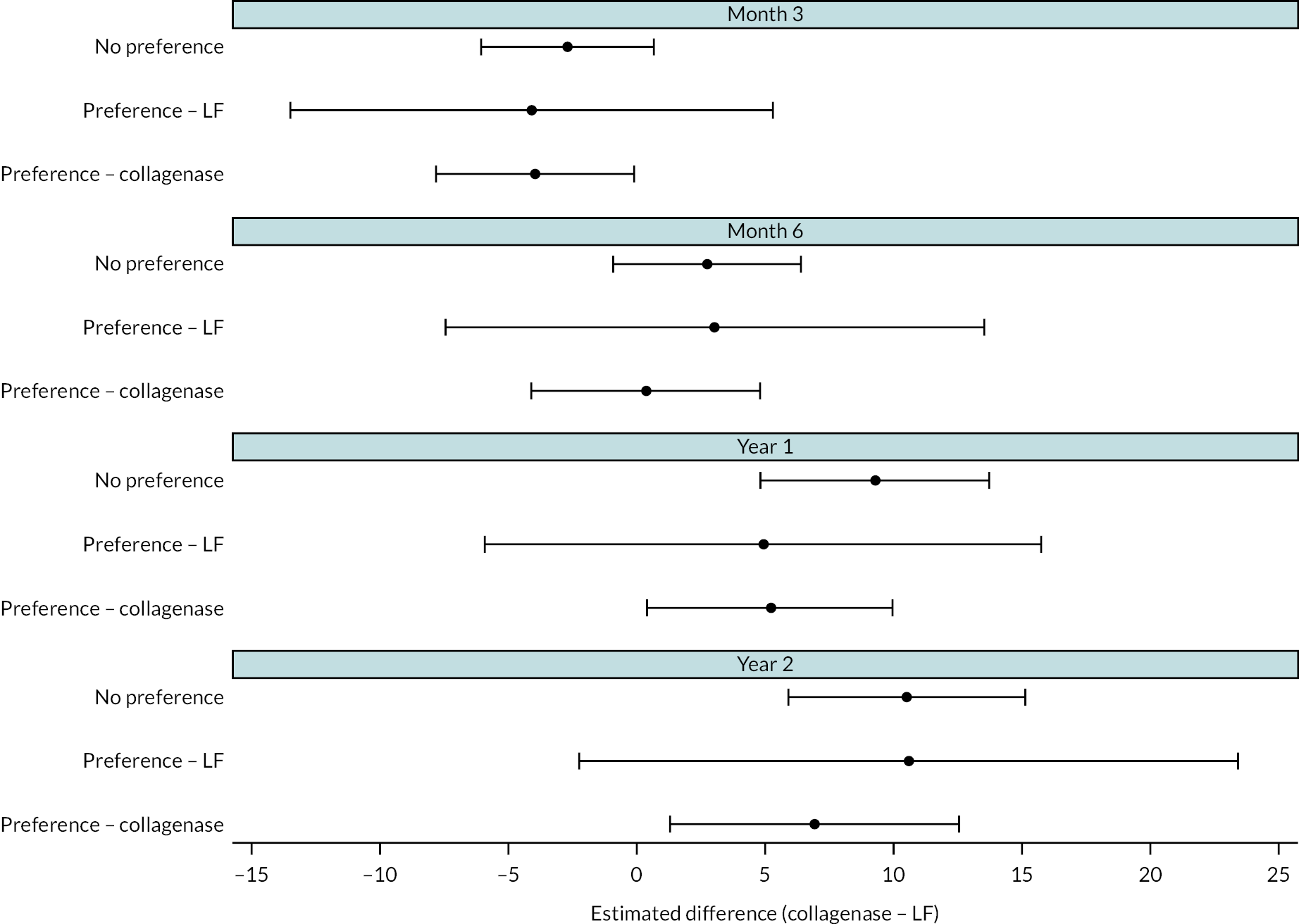

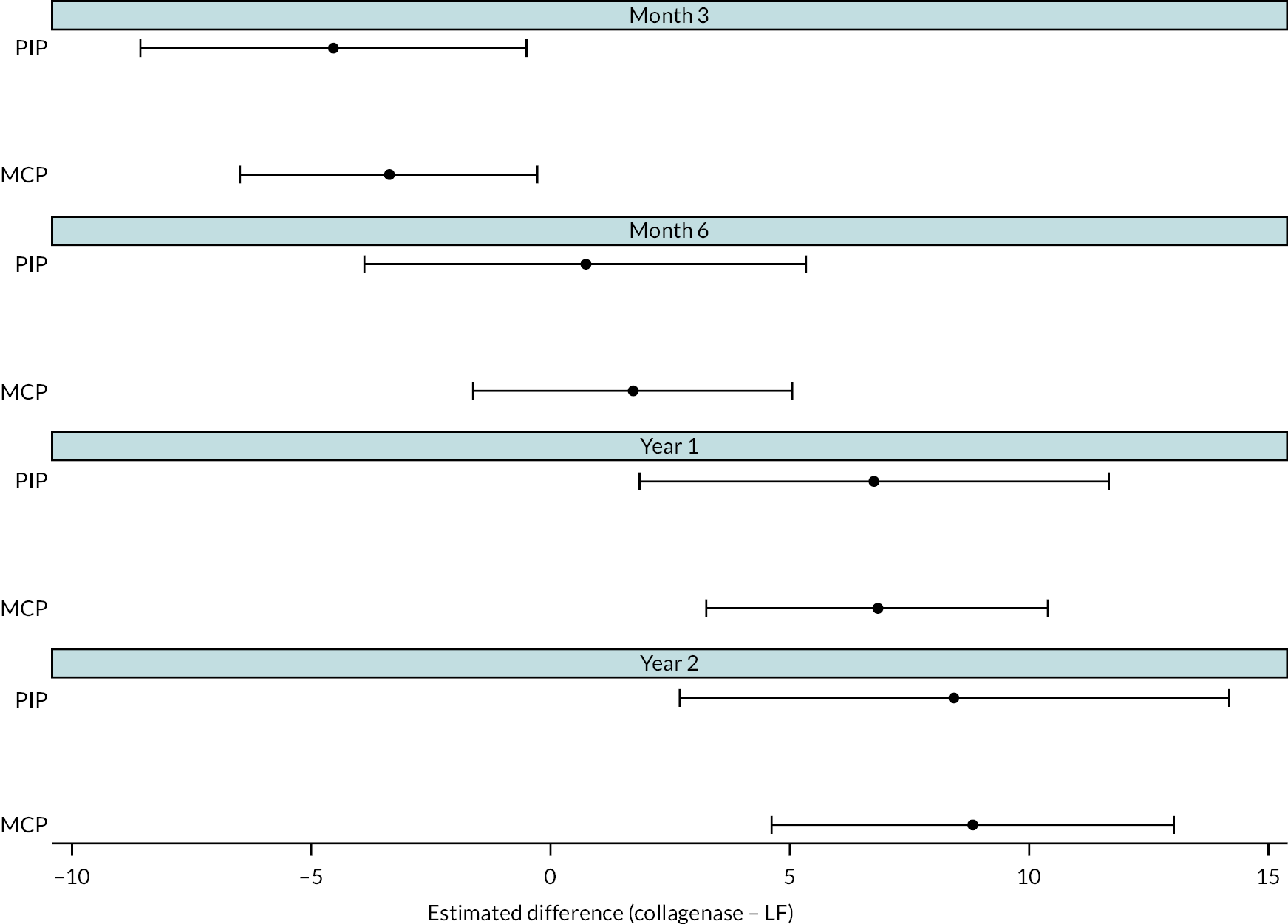

We undertook two subgroup analyses to investigate heterogeneity of treatment effects across subgroups defined by baseline characteristics, one planned and one post hoc. The planned subgroup analysis investigated treatment effect heterogeneity associated with baseline treatment preference (preferred collagenase, preferred LF or no preference). The post hoc subgroup analysis investigated treatment effect heterogeneity associated with designated study reference joint (MCP or PIP).

Secondary outcomes

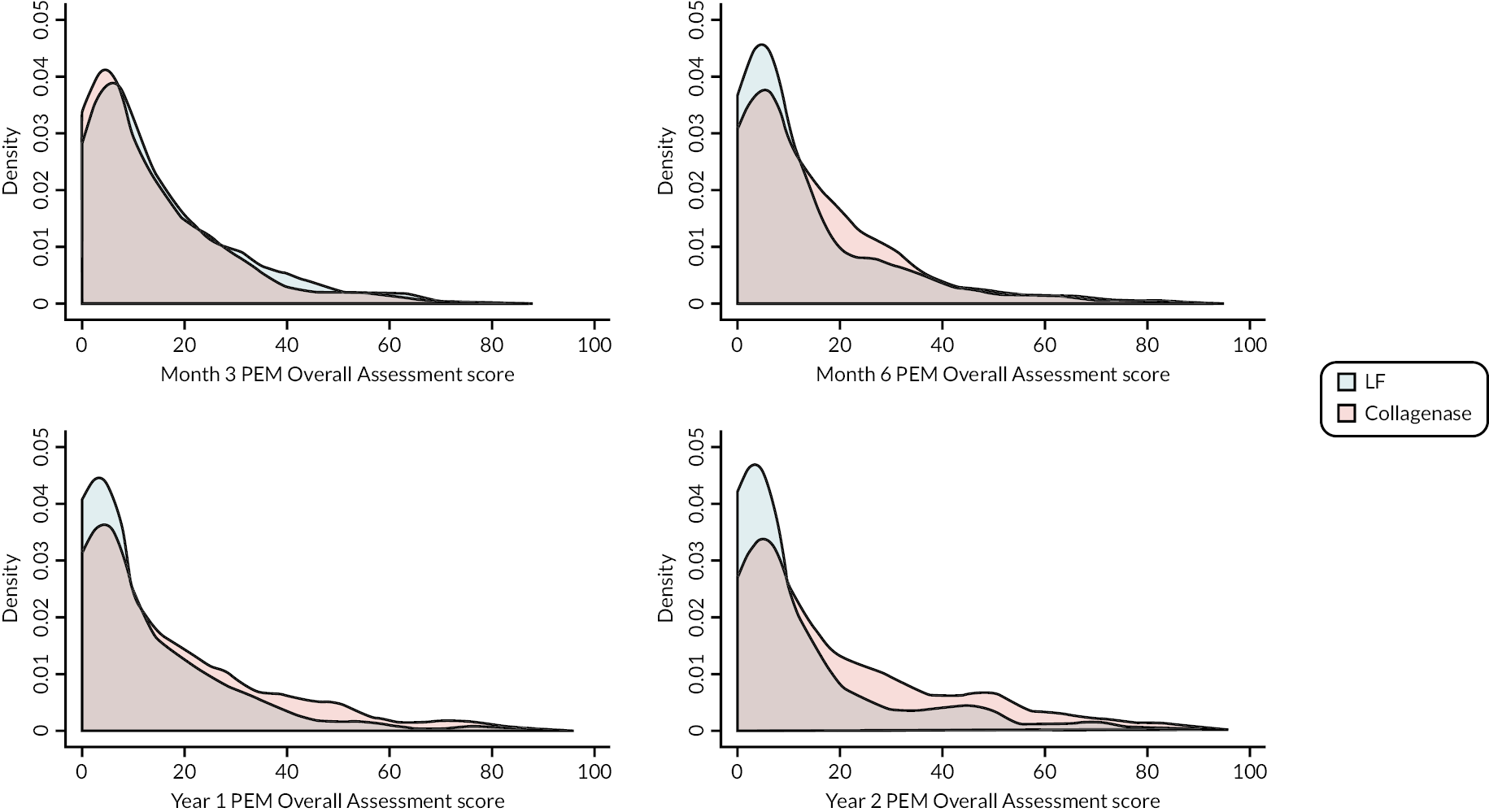

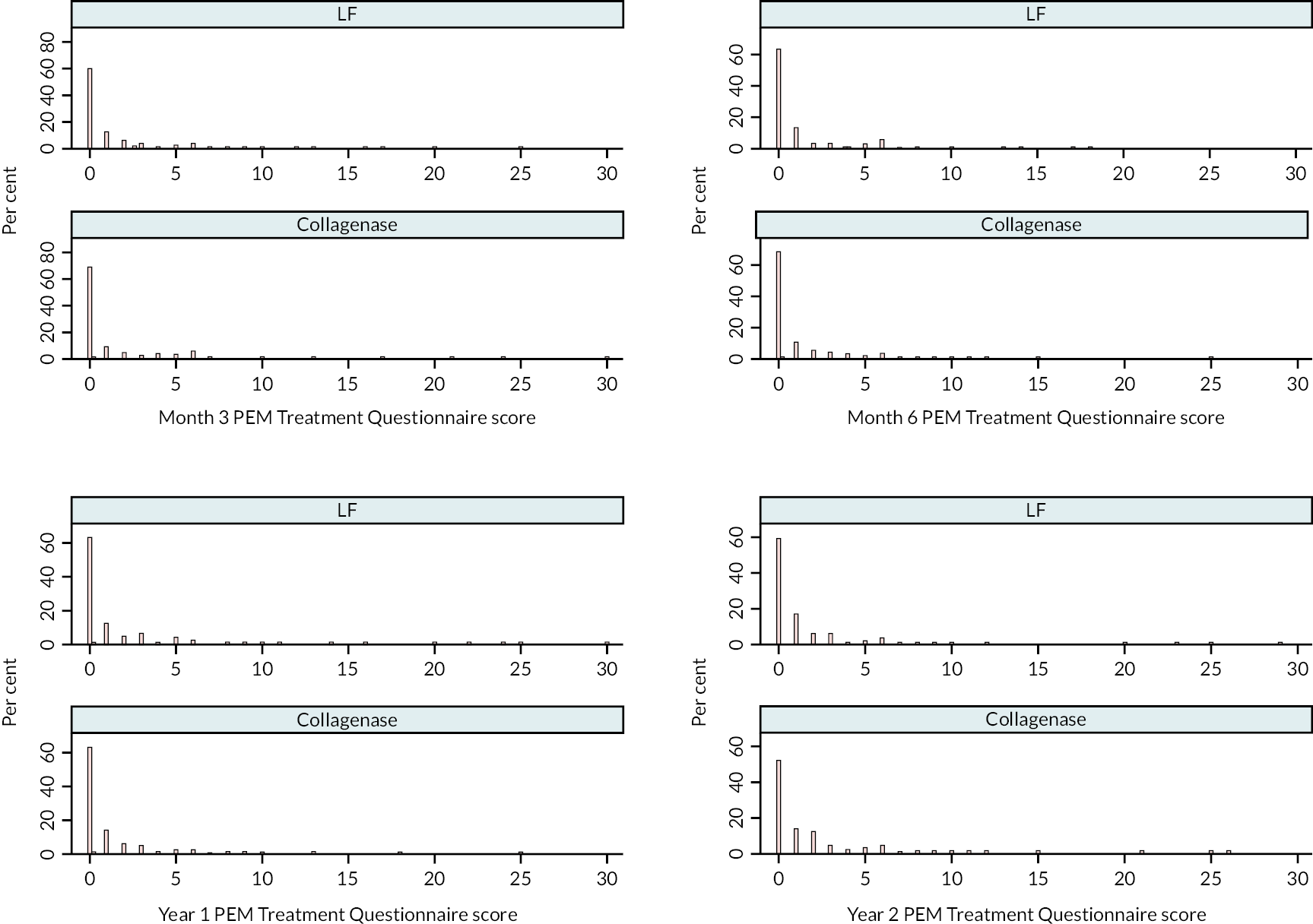

Covariance pattern models like those used for the primary analysis were used to analyse continuous secondary outcomes (e.g. URAM, MHQ, SANE, and active/passive extension deficit and RoM), except for the PEM Overall Assessment and Treatment Questionnaire score, which were reported descriptively.

Appropriate binary or original logistic regression models were used to analyse the categorical outcomes (e.g. recurrence, re-intervention, further care, overall hand assessment, and severity of reported treatment complications). A partial proportional odds model was used to analyse the complication outcome, with the effects of allocation unconstrained across levels of the outcome and effects of all other predictors constrained to be equal across the levels of outcome.

A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to estimate the relative hazard of further treatment (further care and/or re-intervention) to the reference digit and obtain estimates of the absolute differences in risk of further treatment by 2 years conditional on representative patterns of the baseline covariates. As non-inferiority margins were not pre-specified for most of the secondary outcomes [except for recurrence for which an absolute risk difference (RD) of 10% was used], the secondary analyses focused primarily on interval estimation, as opposed to hypothesis testing under either a non-inferiority or superiority framework.

Data management

Data collection, case report form processing and data checks

A comprehensive data management plan was generated at the outset of the trial to document details of the data processing.

Receipt of completed CRFs at the United Kingdom Clinical Research Collaboration-registered University of York Trials Unit (YTU) were recorded in a bespoke research data management system.

Data from completed CRFs were entered using an automated, electronic system (Teleform, Waterloo, Canada) in accordance with the licence held by the YTU. Computerised data cleaning checks and validation rules were applied to review for completion and accuracy of key variables required for the statistical analysis, check for discrepancies, and ensure consistency of the data.

Where discrepancies were identified, these were raised with the local research teams and changes made in accordance with good clinical practice (GCP).

An electronic audit trail system was maintained to track all database data changes and regular backups of the electronic data were also performed.

Promoting participant retention and follow-up completion

Participants received £40 following completion of each of the 1- and 2-year participant outcome questionnaires given this has found to have an effect in improving participant retention and questionnaire response rates. 55,56

Participants were also sent a study newsletter 4 weeks before the 1-year time point to maintain trial engagement and to encourage attendance at the 1-year study visit. This was accompanied by a cover letter from the study chief investigator to thank them for their continued contribution to the study.

Trial sites were contacted by the YTU to ensure that visits for the 1-year primary outcome time point were arranged accordingly. Where a visit could not be arranged within 4 weeks of the visit due date, a postal questionnaire was sent to the participant. If there was still no response after a further 4 weeks, the participants were telephoned to collect their data.

Pressures on the NHS due to the COVID-19 pandemic and associated national restrictions and guidelines had significant implications on research. Cancelling/delaying of clinic appointments, patient concerns about COVID-19 risk and attending hospital, and NHS research capacity strains meant that remote data collection methods were implemented on DISC to ensure that follow-up data could be collected during this time. 57 Remote methods were used to collect site-reported (telephone or video consultations) and participant-reported (postal or telephone questionnaires) data. At sites where COVID-19 burden meant that research nurses were redeployed, follow-ups were temporarily supported by the YTU.

Two nested, randomised retention studies within a trial were undertaken to ascertain effectiveness of retention strategies: one evaluated the effectiveness of a thank you card, the other the effectiveness of a festive greetings card (implemented December 2019). Details of these studies will be reported separately.

Discontinuation or withdrawals of participants

Trial participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time. In addition, the investigator could discontinue a participant from the study at any time if they considered it necessary for any reason. The reason for withdrawal was recorded in the relevant CRF (see Report Supplementary Material 14).

Participants who requested to withdraw during a study visit were asked if they were willing to complete the questionnaires prior to withdrawal. Where a participant requested to withdraw fully outside of a scheduled study visit, no further follow-up questionnaires were completed.

Unless the participant specifically withdrew consent for their data to be stored, all data collected from them continued to be stored as per the original participant consent. At a participant’s request, their data collected up to the point of withdrawal could however be withdrawn from the trial and would not be used in the final analysis.

Where participants requested remote follow-up (i.e. follow-up without clinic visits), the research nurse contacted the participant at each visit time point to complete a safety assessment (AE reporting).

Confidentiality and data protection

The DISC trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, relevant regulations, International Council for Harmonisation Guidelines for GCP, the Data Protection Act 2018, and the General Data Protection Regulations in place during the trial.

To ensure participant confidentiality, participants and associated data were identified by initials and a unique four-digit participant ID number.

All documents were stored securely, accessible only by delegated trial staff and authorised personnel.

For the photography substudy, photographs of participants’ hands were anonymised prior to electronic transfer between sites, the YTU and the University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust. Similar processes were also used for the qualitative substudy. Details on confidentiality for these components are available in Chapter 5 and Appendix 2.

In accordance with applicable regulations, authorised persons could review data at any time during the study to verify that the study was being carried out correctly. However, this was not required during the study.

All study documentation will be retained in accordance with UK law, following which data will be disposed of securely.

Adverse event management

Serious adverse events (SAEs) were defined in accordance with the standardised criteria for SAE. 58 Both SAE and non-serious adverse events (NSAE) were defined as any untoward medical occurrence related to either the affected digit or hand, or to the study medication or procedure (intervention or control). Adverse reactions (ARs) were a response to any dose of medicinal product (intervention) where a causal relationship was at least a reasonable possibility. Any AR, where the nature or severity was not consistent with the applicable product information was a suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction (SUSAR).

For the purposes of reporting, specific reasons for hospitalisation were deemed to not be a SAE within the DISC trial, and instead were reported as NSAE.

These included hospitalisation for:

-

A procedure required by the protocol

-

A routine procedure followed by the centre (e.g. stent removal after LF)

-

A pre-existing condition that had not worsened

-

Routine treatment or monitoring of the studied indication not associated with any deterioration in condition

-

Treatment, which was elective or pre-planned, for a pre-existing condition not associated with any deterioration in condition, for example, a pre-planned hip replacement operation which does not lead to further complications

-

Treatment on an emergency, outpatient basis for an event not fulfilling any of the definitions of serious.

Expected AE (SAE and NSAE) were derived from the SmPC for the intervention. 28 For the control group, expected AE (as detailed in Table 2) were agreed by consensus prior to the study commencing.

| Amputation | Scar pain |

|---|---|

| Arterial injury | Scar-related complications (including hypertrophy) |

| Bleeding | Stiffness |

| Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) | Swelling |

| Delayed healing | Tendon injury |

| Infection | Edge necrosis |

| Instability | Carpal tunnel syndrome (starting within 6 weeks of LF) |

| Nerve injury | Other – tenosynovitis (starting within 6 weeks of LF) |

| Pain | Other – trigger finger (starting within 6 weeks of LF) |

| Paraesthesia (including dysaesthesia, burning and hyperaesthesia) |

In accordance with the SmPC,28 any pregnancy occurring during the clinical study, and the outcome of the pregnancy, was recorded and followed up for congenital abnormality or birth defect. In line with routine practice, the local research nurse or clinician questioned participants about their pregnancy status throughout the trial.

Adverse event reporting

Information regarding event description, onset and end date, relationship to study medication, and action taken were recorded on study-specific reporting forms (see Report Supplementary Material 21–23). NSAE were required to be reported within 5 days and SAE within 24 hours of being made aware of the event.

Events related to the study medication or procedures were followed up until resolution or the event was considered stable. Related events which resulted in participant withdrawal from the study were followed until a satisfactory resolution was achieved.

The relationship of SAEs/NSAEs to the study medication was assessed by a medically qualified investigator. For SAEs event details, causality and expectedness were reviewed by the chief investigator or other delegated medic.

Should any event have been deemed to be a SUSAR, then these would have been reported to the MHRA and REC within 7 days for fatal or life-threatening SUSARs, and 15 days for all other SUSARs.

All events were routinely reported to the TSC, DMEC and sponsor. Annually throughout the trial, a Developmental Safety Update Report was submitted to the MHRA and REC, detailing patient safety considerations.

Ethics approval and monitoring/governance

The DISC trial was approved by the Yorkshire and Humber – Leeds West REC on 22 May 2017 (Reference: 17/YH/0120). The study was also approved by the MHRA on 21 April 2017 (Reference: 21275/0293/001-0001). NHS permission was given by each participating site prior to study activity commencing locally. Any amendments to the study were approved by the REC, MHRA and sites prior to implementation.

The study was prospectively registered with the ISRCTN (Reference: ISRCTN18254597; Registered 11 April 2017) and with European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials (Reference: 2016-004251-76; Registered: 21 October 2016).

Trial Management Group

The TMG met quarterly to oversee the management of the trial. The group included the chief investigator, co-investigators, and members of the YTU and the Academic Team of Musculoskeletal Surgery (AToMS) responsible for the day-to-day management of the study. A representative of the sponsor also attended when available.

The TMG meetings monitored the progress of the DISC trial in relation to recruitment (e.g. enrolment, consent, and eligibility), allocation to study groups, adherence of the trial interventions to the protocol, retention of trial participants, monitoring of (S)AEs and reasons for participant withdrawal.

Trial Steering Committee

An independent TSC was appointed by the funding body (NIHR) to provide overall supervision of the trial and to advise on its continuation. Meetings were held on a bi-annual basis during the study. The TSC comprised two independent members (one clinician and one methodologist) and a patient and public representative. Membership is detailed in the Additional information section.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

An independent DMEC was appointed by the funding body (NIHR) to monitor trial data in respect of any ethical or safety reasons why the trial should not continue. Access to unblinded data to facilitate this review was provided if required.

Meetings were held on a bi-annual basis during the study. The DMEC comprised three independent members (two clinicians, one statistician) and a patient and public representative. Membership is detailed in the Additional information section.

Site monitoring

In accordance with regulatory approvals, regular monitoring was required for the DISC trial, and a monitoring plan was prepared accordingly.

A combination of onsite and remote SIVs, including comprehensive study training, were conducted prior to study activity commencing at each site. During onsite visits, the pharmacy department storage facilities were reviewed. Where visits were completed remotely, the pharmacy team provided confirmation of temperature monitoring arrangements and imaging of storage arrangements (if the IMP was to be held outside of the main site pharmacy).

An initial on-site monitoring visit was completed with all sites (except one due to COVID-19 restrictions) following recruitment of three participants, or once 8–12 weeks had elapsed since the study opened to recruitment at the site. Scheduling was amended once three participants had been recruited and treated or at 18 weeks after recruitment activity commencing (with an interim review at 8–12 weeks) to enable a review of pharmacy activity at the visit. Source data verification (about 20% of CRF data), a review of AE, pharmacy processes and accountability, and the investigator site file were completed.

A second monitoring visit was completed remotely using self-completed checklists to confirm investigator site file maintenance and provision of relevant information in participants’ medical records.

Centralised monitoring included CRF completion checks (with a specific focus on the confirmation of eligibility CRF) and a 100% check of consent.

Study closure was completed remotely using a close-out checklist to confirm investigator site file contents and documentation in participants’ medical records.

Chapter 3 Results

Internal pilot

The internal pilot phase was originally due to run for 6 months but ran for 11 months (1 May 2017 and 31 March 2018).

At the end of the internal pilot, eight recruiting sites opened to recruitment with a further three sites in advanced set-up (i.e. SIV completed) and eight sites in the early stages of set-up. The mean time from SIV to recruitment green light was 75 days, with the mean time to first participant recruited being 55 days after green light.

During the internal pilot, 52 participants were recruited and randomised to DISC, which equated to an average of 1.5 participants per site per month.

The internal pilot enabled assessment of additional secondary feasibility objectives in relation to site training and engagement, documentation, participant ineligibility and non-consent reasons, and adherence to treatment. The information collected during this time informed changes to the study during the main trial phase as required.

Recruitment and retention

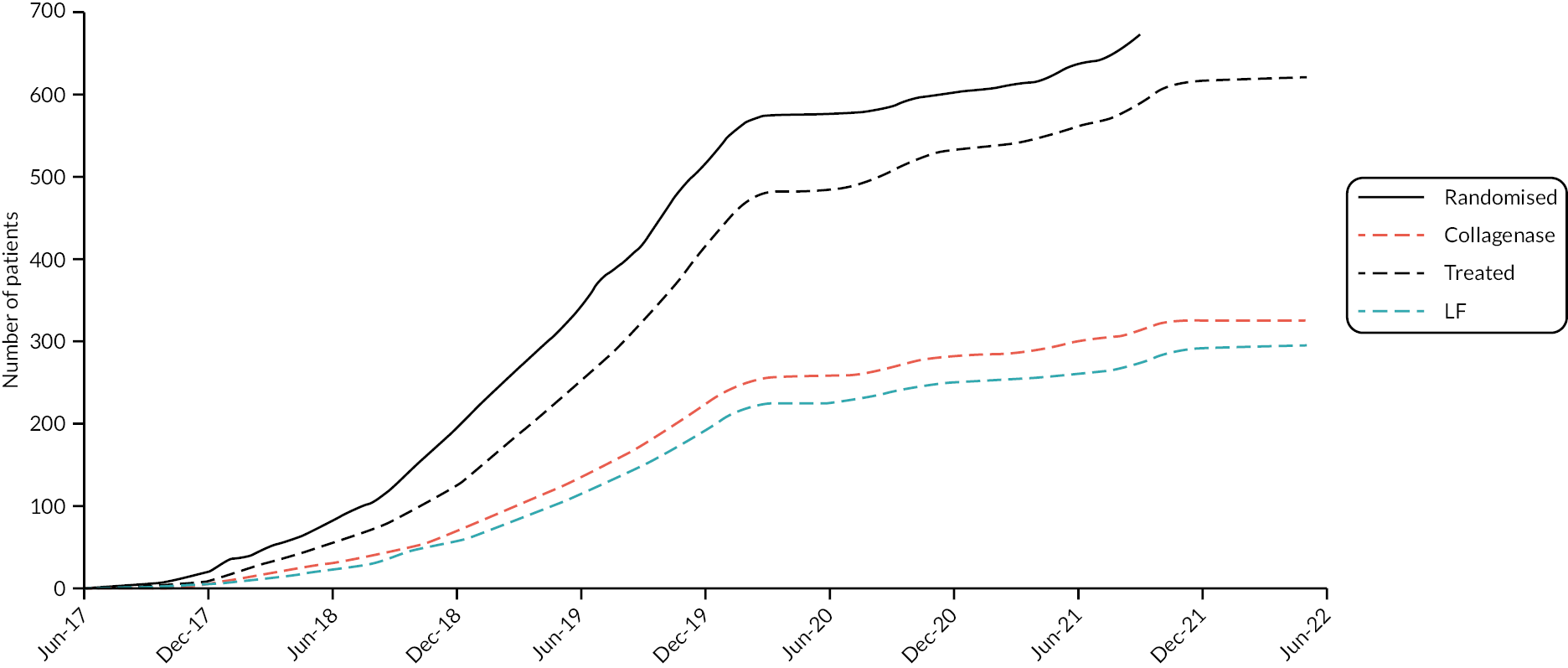

Between 31 July 2017 and 28 September 2021, a total of 1269 patients were screened for inclusion in the DISC trial, of which 540 patients were deemed to be ineligible and 57 were eligible but non-consenting. Detailed reasons for ineligibility and non-consent are provided in Appendix 4, Tables 64 and 65. This resulted in 672 participants (94.6% of the target of 710) being randomised into the DISC trial (336 to each group). The planned target of 710 was to account for 20% attrition. The actual required number of valid end points needed for a well-powered study was 568, which was achieved. Recruitment stopped in September 2021 given follow-up for the primary outcome would not have been possible within the funded period. Recruitment progress and trial treatment delivery over time are illustrated in Appendix 4, Figure 73 and Table 66

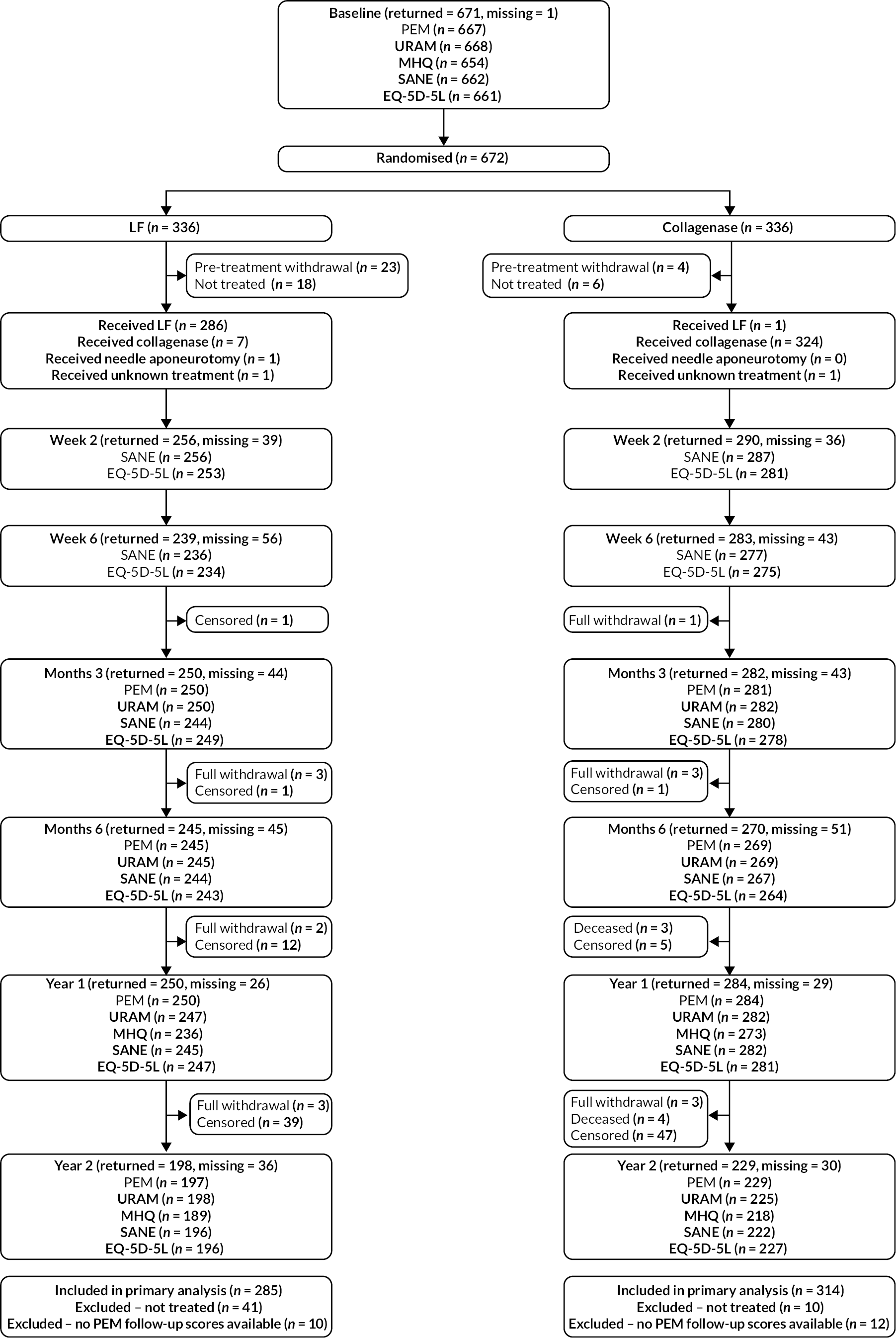

As shown in Figures 2 and 3, a significantly larger proportion of the participants in the LF group did not receive treatment as part of the trial, compared with the collagenase group (12.2% LF vs. 3.0% collagenase). Detailed reasons for pre-treatment withdrawals are provided in Appendix 4, Table 67. This discrepancy in treatment delivery explains the imbalance in the number of follow-ups expected and completed subsequently, although the proportion of treated participants that were followed up is similar across groups at all time points.

FIGURE 2.

Participant completed data flow diagram (‘censored’ means that the trial follow-up period finished prior to the subsequent follow-up time points being due/completed).

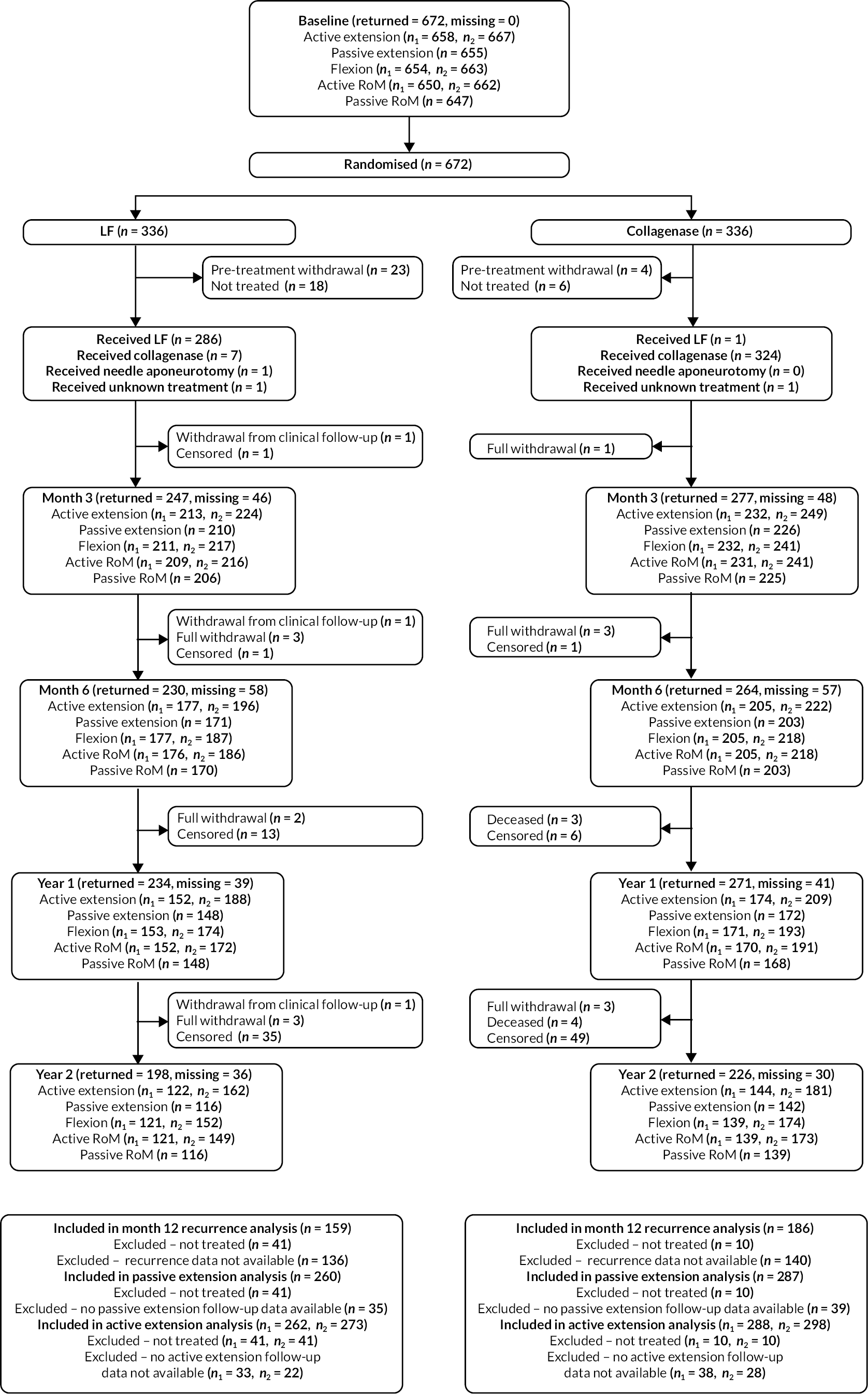

FIGURE 3.

Investigator/clinician completed follow-up data (‘censored’ means that the trial follow-up period finished prior to the subsequent time points being due/completed). For active extension and flexion measurements, n1 denotes the number of participants with the relevant measurement available (for the reference joint) based on data collected using goniometry only, and n2 denotes the number of participants with the relevant measurement available based on data collected using goniometry and photography.

Baseline data

Of the 672 participants randomised, 672 (100%) had an investigator-completed baseline CRF and 671 (99.9%) had a participant-completed baseline CRF available for analysis. This CRF data is summarised (by allocation) for both the randomised population, and the population included in the primary analysis in Tables 3–7. Baseline data by allocation for the population excluded from the primary analysis (i.e. those that were not treated, or were treated but had no available follow-up primary outcome data – see Appendix 5, Tables 68–72).

| Randomised (N = 672) |

Included in primary analysis (N = 599) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF N = 336 |

Collagenase N = 336 |

LF N = 285 |

Collagenase N = 314 |

|

| Age (years) | ||||

| N | 336 | 336 | 285 | 314 |

| Mean (SD) | 66.5 (9.2) | 66.4 (8.8) | 66.4 (8.9) | 66.2 (8.9) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 66.9 (61.3, 72.8) | 67.4 (61.0, 72.7) | 66.8 (61.7, 72.6) | 66.8 (60.3, 72.6) |

| Minimum, maximum | 31.1, 89.0 | 38.6, 89.1 | 31.1, 87.2 | 38.6, 89.1 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 263 (78.3) | 270 (80.4) | 219 (76.8) | 256 (81.5) |

| Female | 73 (21.7) | 66 (19.6) | 66 (23.2) | 58 (18.5) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 333 (99.1) | 332 (98.8) | 283 (99.3) | 310 (98.7) |

| Mixed race | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Asian/Asian British | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||

| Never | 159 (47.3) | 143 (42.6) | 137 (48.1) | 136 (43.3) |

| Current | 37 (11.0) | 39 (11.6) | 31 (10.9) | 38 (12.1) |

| Previous | 137 (40.8) | 152 (45.2) | 115 (40.4) | 138 (43.9) |

| Missing | 3 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.6) |

| Drinks alcohol, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 285 (84.8) | 282 (83.9) | 247 (86.7) | 263 (83.8) |

| No | 46 (13.7) | 52 (15.5) | 34 (11.9) | 49 (15.6) |

| Missing | 5 (1.5) | 2 (0.6) | 4 (1.4) | 2 (0.6) |

| Randomised (N = 672) |

Included in primary analysis (N = 599) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF N = 336 |

Collagenase N = 336 |

LF N = 285 |

Collagenase N = 314 |

|

| Age of onset (years) | ||||

| N | 262 | 277 | 232 | 266 |

| Mean (SD) | 55.9 (12.4) | 57.2 (11.1) | 55.9 (12.3) | 57.3 (10.9) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 57.0 (49.0, 64.0) | 58.0 (50.0, 65.0) | 57.0 (49.5, 64.0) | 58.0 (50.0, 65.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | 2.0, 85.0 | 18.0, 82.0 | 2.0, 85.0 | 18.0, 82.0 |

| History of bilateral disease, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 170 (50.6) | 174 (51.8) | 140 (49.1) | 163 (51.9) |

| No | 151 (44.9) | 151 (44.9) | 130 (45.6) | 141 (44.9) |

| Missing | 15 (4.5) | 11 (3.3) | 15 (5.3) | 10 (3.2) |

| Received LF previously, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 84 (25.0) | 79 (23.5) | 71 (24.9) | 74 (23.6) |

| No | 250 (74.4) | 252 (75.0) | 212 (74.4) | 235 (74.8) |

| Missing | 2 (0.6) | 5 (1.5) | 2 (0.7) | 5 (1.6) |

| Received collagenase injection previously, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 13 (3.9) | 16 (4.8) | 10 (3.5) | 15 (4.8) |

| No | 321 (95.5) | 317 (94.3) | 273 (95.8) | 297 (94.6) |

| Missing | 2 (0.6) | 3 (0.9) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.6) |

| Known family history of DC, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 126 (37.5) | 112 (33.3) | 107 (37.5) | 107 (34.1) |

| No | 209 (62.2) | 221 (65.8) | 177 (62.1) | 204 (65.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.0) |

| History of Garrods pads, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 54 (16.1) | 43 (12.8) | 50 (17.5) | 41 (13.1) |

| No | 224 (66.7) | 238 (70.8) | 182 (63.9) | 221 (70.4) |

| Missing | 58 (17.3) | 55 (16.4) | 53 (18.6) | 52 (16.6) |

| History of Peyronie’s disease, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 11 (3.3) | 14 (4.2) | 7 (2.5) | 14 (4.5) |

| No | 208 (61.9) | 212 (63.1) | 172 (60.4) | 199 (63.4) |

| Not applicable | 73 (21.7) | 66 (19.6) | 66 (23.2) | 58 (18.5) |

| Missing | 44 (13.1) | 44 (13.1) | 40 (14.0) | 43 (13.7) |

| History of Ledderhose disease, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 24 (7.1) | 18 (5.4) | 19 (6.7) | 16 (5.1) |

| No | 251 (74.7) | 262 (78.0) | 211 (74.0) | 245 (78.0) |

| Missing | 61 (18.2) | 56 (16.7) | 55 (19.3) | 53 (16.9) |

| Randomised (N = 672) |

Included in primary analysis (N = 599) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF N = 336 |

Collagenase N = 336 |

LF N = 285 |

Collagenase N = 314 |

|

| Hands currently affected, n (%) | ||||

| Left only | 105 (31.3) | 114 (33.9) | 87 (30.5) | 109 (34.7) |

| Right only | 119 (35.4) | 113 (33.6) | 107 (37.5) | 104 (33.1) |

| Both | 112 (33.3) | 109 (32.4) | 91 (31.9) | 101 (32.2) |

| Dominant hand currently affected, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 232 (69.0) | 227 (67.6) | 197 (69.1) | 210 (66.9) |

| No | 104 (31.0) | 109 (32.4) | 88 (30.9) | 104 (33.1) |

| Study reference digit, n (%) | ||||

| Thumb | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) |

| Index | 4 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Middle | 24 (7.1) | 17 (5.1) | 15 (5.3) | 15 (4.8) |

| Ring | 109 (32.4) | 111 (33.0) | 91 (31.9) | 105 (33.4) |

| Little | 198 (58.9) | 207 (61.6) | 174 (61.1) | 193 (61.5) |

| Study reference joint, n (%) | ||||

| MCP | 207 (61.6) | 221 (65.8) | 172 (60.4) | 204 (65.0) |

| PIP | 129 (38.4) | 115 (34.2) | 113 (39.6) | 110 (35.0) |

| Study reference digit/joint on dominant hand, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 180 (53.6) | 175 (52.1) | 154 (54.0) | 160 (51.0) |

| No | 156 (46.4) | 161 (47.9) | 131 (46.0) | 154 (49.0) |

| Number of digits affected (total), n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 166 (49.4) | 177 (52.7) | 147 (51.6) | 165 (52.5) |

| 2 | 94 (28.0) | 101 (30.1) | 76 (26.7) | 95 (30.3) |

| 3 | 36 (10.7) | 36 (10.7) | 33 (11.6) | 35 (11.1) |

| 4 | 25 (7.4) | 14 (4.2) | 19 (6.7) | 12 (3.8) |

| 5 | 8 (2.4) | 4 (1.2) | 6 (2.1) | 3 (1.0) |

| 6 | 4 (1.2) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.6) |

| 7 | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) |

| 8 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) |

| Number of digits affected (reference hand), n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 231 (68.8) | 245 (72.9) | 201 (70.5) | 227 (72.3) |

| 2 | 73 (21.7) | 78 (23.2) | 59 (20.7) | 75 (23.9) |

| 3 | 27 (8.0) | 9 (2.7) | 24 (8.4) | 8 (2.5) |

| 4 | 5 (1.5) | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.0) |

| 5 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Number of joints affected (total), n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 110 (32.7) | 120 (35.7) | 96 (33.7) | 114 (36.3) |

| 2 | 108 (32.1) | 108 (32.1) | 91 (31.9) | 99 (31.5) |

| 3 | 47 (14.0) | 54 (16.1) | 39 (13.7) | 52 (16.6) |

| 4 | 32 (9.5) | 27 (8.0) | 29 (10.2) | 24 (7.6) |

| 5 | 14 (4.2) | 12 (3.6) | 11 (3.9) | 11 (3.5) |

| 6 | 8 (2.4) | 6 (1.8) | 7 (2.5) | 6 (1.9) |

| 7 | 9 (2.7) | 2 (0.6) | 6 (2.1) | 2 (0.6) |

| 8 | 5 (1.5) | 4 (1.2) | 4 (1.4) | 3 (1.0) |

| 9 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.6) |

| 10 | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| 11 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 12 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Number of joints affected (reference hand), n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 149 (44.3) | 161 (47.9) | 127 (44.6) | 150 (47.8) |

| 2 | 118 (35.1) | 123 (36.6) | 101 (35.4) | 116 (36.9) |

| 3 | 36 (10.7) | 27 (8.0) | 30 (10.5) | 27 (8.6) |

| 4 | 19 (5.7) | 20 (6.0) | 18 (6.3) | 16 (5.1) |

| 5 | 10 (3.0) | 2 (0.6) | 7 (2.5) | 2 (0.6) |

| 6 | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.6) |

| 7 | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 8 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 9 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Randomised (N = 672) |

Included in primary analysis (N = 599) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF N = 336 |

Collagenase N = 336 |

LF N = 285 |

Collagenase N = 314 |

|

| Active extension deficit of reference joint (°), goniometry only | ||||

| N | 329 | 329 | 279 | 307 |

| Mean (SD) | 52.5 (15.2) | 51.8 (16.4) | 52.9 (15.4) | 51.8 (16.6) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 51.7 (40.0, 63.3) | 50.7 (39.3, 63.3) | 51.7 (40.0, 64.0) | 50.7 (39.3, 63.3) |

| Minimum, maximum | 11.7, 91.3 | 2.3, 90.7 | 11.7, 91.3 | 2.3, 90.7 |

| Active extension deficit of reference joint (°), goniometry and photography | ||||

| N | 333 | 334 | 282 | 312 |

| Mean (SD) | 52.3 (15.4) | 51.5 (16.7) | 52.7 (15.6) | 51.5 (16.8) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 51.7 (40.0, 62.7) | 50.7 (39.0, 63.3) | 51.7 (40.0, 63.3) | 50.7 (39.3, 63.3) |

| Minimum, maximum | 10.0, 91.3 | 2.3, 90.7 | 10.0, 91.3 | 2.3, 90.7 |

| Passive extension deficit of reference joint (°) | ||||

| N | 327 | 328 | 278 | 306 |

| Mean (SD) | 45.9 (16.4) | 45.8 (17.3) | 46.1 (16.9) | 45.7 (17.4) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 44.7 (34.0, 58.0) | 45.3 (32.0, 58.7) | 44.7 (34.0, 59.3) | 45.3 (32.0, 58.7) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0.0, 90.0 | −10.0, 84.7 | 0.0, 90.0 | −10.0, 84.7 |

| Flexion of reference joint (°), goniometry only | ||||

| N | 328 | 326 | 279 | 305 |

| Mean (SD) | 87.2 (10.5) | 86.2 (11.2) | 87.3 (10.8) | 86.3 (11.3) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 88.0 (80.7, 93.3) | 87.5 (80.7, 92.0) | 88.0 (80.7, 94.0) | 88.0 (80.7, 92.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | 31.3, 113.3 | 10.0, 130.0 | 31.3, 113.3 | 10.0, 130.0 |

| Flexion of reference joint (°), goniometry and photography | ||||

| N | 331 | 332 | 282 | 310 |

| Mean (SD) | 87.1 (10.4) | 86.2 (11.3) | 87.2 (10.8) | 86.4 (11.4) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 88.0 (80.7, 93.3) | 87.3 (80.7, 92.0) | 88.0 (81.0, 94.0) | 87.8 (80.7, 92.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | 31.3, 113.3 | 10.0, 130.0 | 31.3, 113.3 | 10.0, 130.0 |

| Active RoM of reference joint (°), goniometry only | ||||

| N | 326 | 324 | 277 | 303 |

| Mean (SD) | 34.7 (15.6) | 34.6 (15.3) | 34.5 (15.7) | 34.6 (15.5) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 34.0 (23.3, 46.0) | 34.7 (22.7, 46.0) | 34.0 (22.7, 45.3) | 34.7 (22.7, 46.3) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0.0, 86.0 | 0.0, 79.3 | 0.0, 86.0 | 0.0, 79.3 |

| Active RoM of reference joint (°), goniometry and photography | ||||

| N | 330 | 332 | 281 | 310 |

| Mean (SD) | 34.7 (15.8) | 34.6 (15.7) | 34.6 (15.9) | 34.8 (15.7) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 34.0 (23.3, 46.0) | 34.7 (22.7, 46.2) | 34.0 (22.7, 45.3) | 34.7 (22.7, 46.7) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0.0, 86.0 | −12.3, 79.3 | 0.0, 86.0 | 0.0, 79.3 |

| Passive RoM of reference joint (°) | ||||

| N | 324 | 323 | 276 | 302 |

| Mean (SD) | 41.2 (17.0) | 40.5 (16.9) | 41.2 (17.3) | 40.6 (17.1) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 41.8 (29.0, 52.7) | 40.7 (28.0, 51.3) | 41.3 (29.0, 52.8) | 41.0 (28.0, 52.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | 3.3, 90.0 | 0.0, 92.7 | 3.3, 90.0 | 0.0, 92.7 |

| Total active extension deficit of reference digit (°), goniometry only | ||||

| N | 314 | 314 | 267 | 294 |

| Mean (SD) | 64.3 (31.4) | 62.5 (31.8) | 65.0 (30.9) | 61.9 (31.6) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 59.3 (40.0, 87.0) | 56.8 (40.7, 80.7) | 59.7 (40.0, 88.7) | 56.7 (40.0, 80.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | 4.7, 151.7 | 0.0, 160.0 | 4.7, 151.7 | 0.0, 160.0 |

| Total active extension deficit of reference digit (°), goniometry and photography | ||||

| N | 326 | 330 | 278 | 310 |

| Mean (SD) | 64.0 (31.1) | 62.6 (31.9) | 64.8 (30.7) | 62.0 (31.7) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 59.3 (40.0, 86.3) | 56.8 (40.0, 80.7) | 59.4 (40.0, 87.3) | 56.7 (40.0, 80.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | 4.7, 151.7 | 0.0, 160.0 | 4.7, 151.7 | 0.0, 160.0 |

| Total passive extension deficit of reference digit (°) | ||||

| N | 308 | 308 | 262 | 287 |

| Mean (SD) | 43.1 (36.3) | 42.8 (35.7) | 43.6 (36.2) | 41.7 (35.6) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 37.7 (18.8, 63.7) | 39.3 (20.0, 64.7) | 37.3 (20.0, 64.0) | 38.7 (18.7, 63.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | −91.7, 175.0 | −65.0, 144.0 | −91.7, 175.0 | −65.0, 144.0 |

| Randomised (N = 672) |

Included in primary analysis (N = 599) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF N = 336 |

Collagenase N = 336 |

LF N = 285 |

Collagenase N = 314 |

|

| PEM Hand Health Questionnairea | ||||

| N | 333 | 334 | 283 | 312 |

| Mean (SD) | 34.1 (19.7) | 34.2 (20.2) | 33.9 (19.7) | 33.8 (19.8) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 31.8 (18.2, 48.5) | 31.8 (18.2, 47.0) | 31.8 (18.2, 48.5) | 31.8 (18.2, 45.5) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0.0, 87.9 | 0.0, 93.9 | 0.0, 86.4 | 0.0, 93.9 |

| URAM total scoreb | ||||

| N | 335 | 333 | 284 | 311 |

| Mean (SD) | 17.2 (9.5) | 17.0 (9.3) | 16.9 (9.4) | 16.9 (9.2) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 16.9 (10.0, 24.0) | 16.0 (10.0, 23.0) | 16.4 (10.0, 23.0) | 15.8 (10.0, 23.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0.0, 43.0 | 0.0, 44.0 | 0.0, 43.0 | 0.0, 44.0 |

| MHQ total scorec | ||||

| N | 328 | 326 | 279 | 306 |

| Mean (SD) | 67.5 (17.7) | 67.6 (17.1) | 68.1 (17.3) | 67.8 (17.0) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 70.4 (55.2, 81.1) | 70.1 (56.4, 81.1) | 70.7 (55.3, 81.8) | 70.5 (56.5, 81.4) |

| Minimum, maximum | 21.3, 100.0 | 15.5, 99.0 | 23.1, 100.0 | 15.5, 99.0 |

| SANE scored | ||||

| N | 328 | 334 | 278 | 312 |

| Mean (SD) | 61.6 (21.7) | 62.0 (21.8) | 62.0 (21.4) | 62.2 (21.6) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 65.0 (49.0, 80.0) | 65.0 (49.0, 80.0) | 65.0 (50.0, 80.0) | 65.0 (49.5, 80.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | 10.0, 100.0 | 0.0, 100.0 | 10.0, 100.0 | 0.0, 100.0 |

| EuroQol-5 Dimensions – general health VAS e | ||||

| N | 331 | 335 | 281 | 313 |

| Mean (SD) | 83.8 (15.4) | 85.3 (14.8) | 84.2 (14.7) | 85.6 (14.7) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 90.0 (80.0, 95.0) | 90.0 (80.0, 95.0) | 90.0 (80.0, 95.0) | 90.0 (80.0, 95.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | 5.0, 100.0 | 5.0, 100.0 | 5.0, 100.0 | 5.0, 100.0 |

| Treatment preference | ||||

| Collagenase injection | 134 (39.9) | 148 (44.0) | 108 (37.9) | 135 (43.0) |

| Surgical intervention | 29 (8.6) | 18 (5.4) | 25 (8.8) | 16 (5.1) |

| No preference | 168 (50.0) | 164 (48.8) | 148 (51.9) | 158 (50.3) |

| Missing | 5 (1.5) | 6 (1.8) | 4 (1.4) | 5 (1.6) |

The groups as randomised were similar at baseline with regard to the demographic (Table 3) and clinical variables collected (Tables 4 and 5), measurements of the designated reference joint/digit (Table 6), and the baseline scores for the various patient-reported outcomes (Table 7).

The measures of location/scale, and frequencies/proportions observed across both groups for the randomised population, appear similar to those observed for the subset of participants that are included in the primary analysis.

Treatment delivery

Of the 672 participants randomised, 621 received treatment as part of the trial (see Table 8). Notably more participants allocated to collagenase received treatment (97%) than participants allocated to LF (88%). This is partly driven by the differences in pre-treatment withdrawals (6.8% LF group vs. 1.2% collagenase group), and partly by delays leading to treatment not being delivered by the end of the scheduled follow-up period (5.4% LF group vs. 1.8% collagenase group). The differences in pre-treatment withdrawals (see Appendix 4, Table 67) are likely to be at least partly explained by treatment preferences at baseline, with about 86% of the participants that reported a treatment preference for collagenase (see Table 7). The overall preference for collagenase treatment (from those expressing a baseline treatment preference) may also explain the higher number of crossovers in/from the LF group (2.1% vs. 0.3% in the collagenase group). However, the overall number of treatment crossovers was small relative to the number of participants treated and is unlikely to have materially affected the clinical effectiveness results.

| LF N = 336 |

Collagenase N = 336 |

Total N = 672 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment received, n (%) | |||

| LF | 286 (85.1) | 1 (0.3) | 287 (42.7) |

| Collagenase | 7 (2.1) | 324 (96.4) | 331 (49.3) |

| Needle aponeurotomy | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Unknown treatment received | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

| Withdrew prior to treatment | 23 (6.8) | 4 (1.2) | 27 (4.0) |

| Did not receive treatment | 18 (5.4) | 6 (1.8) | 24 (3.6) |

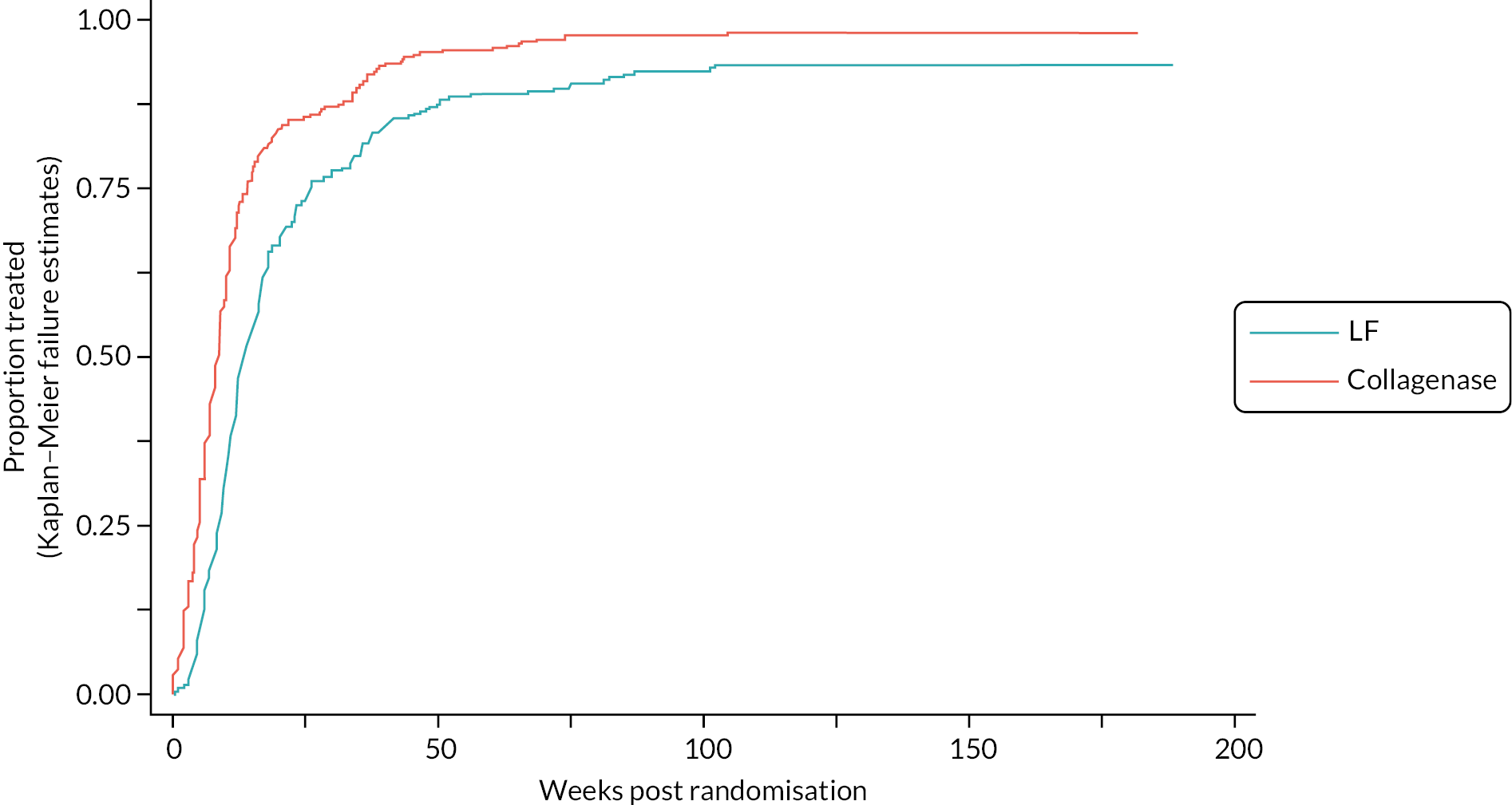

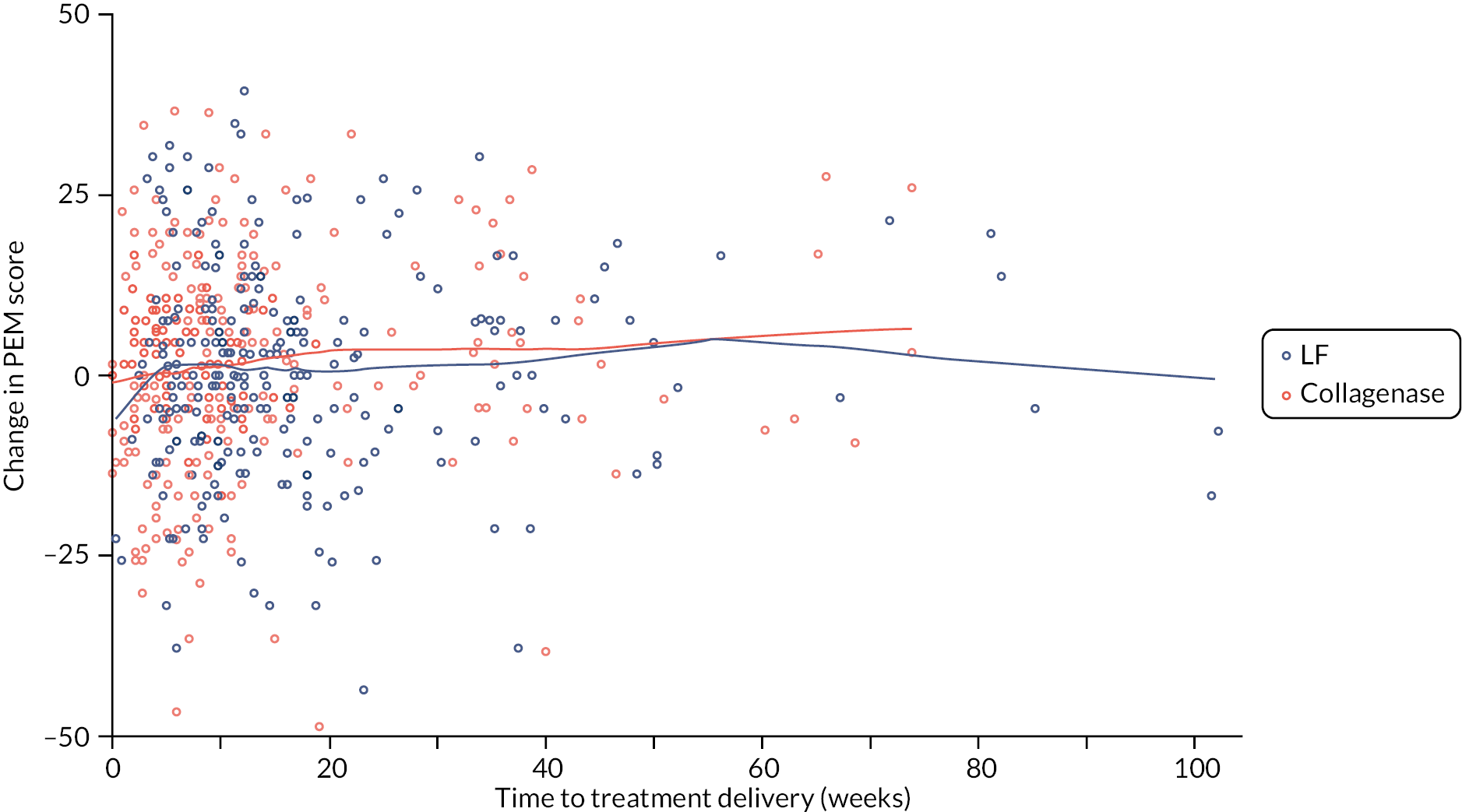

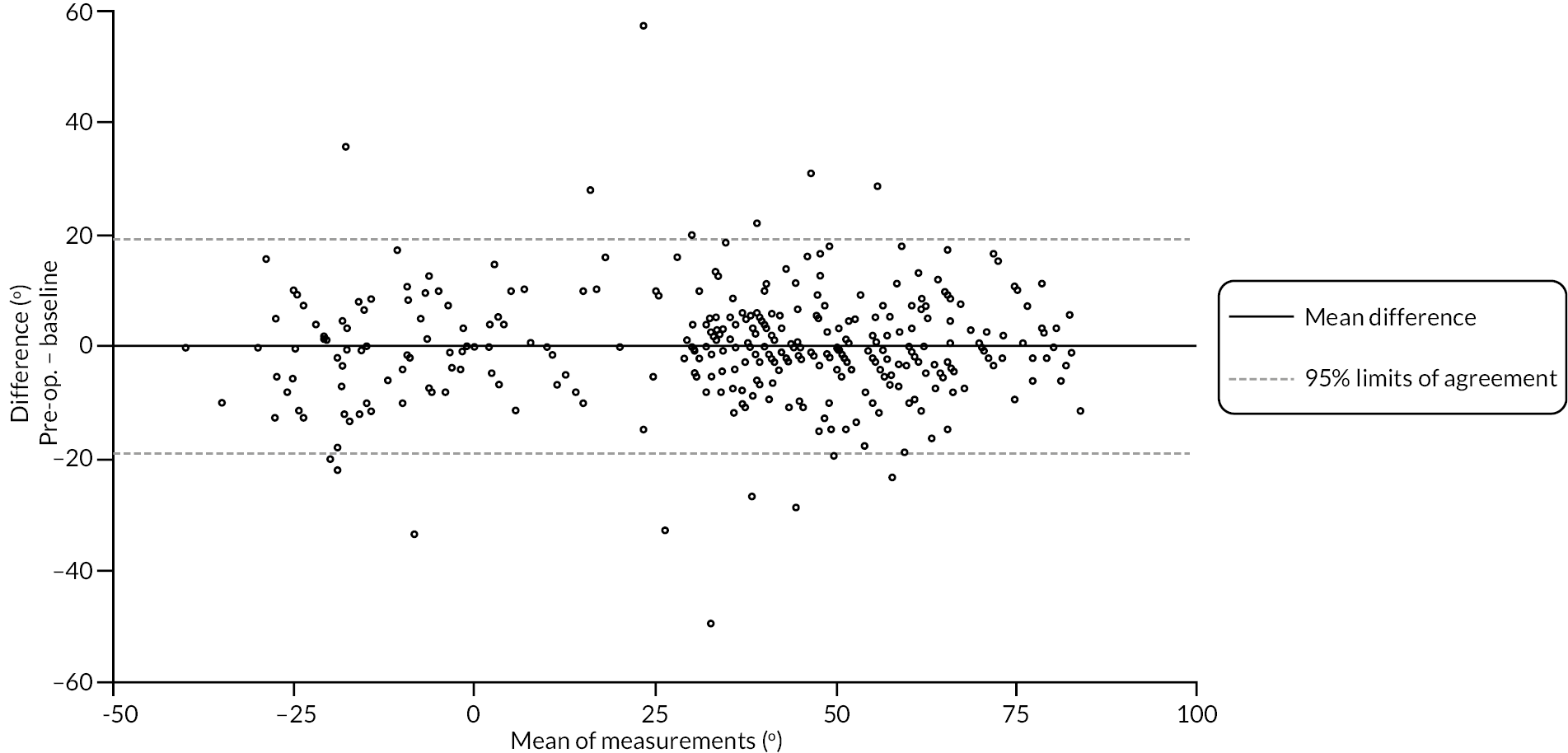

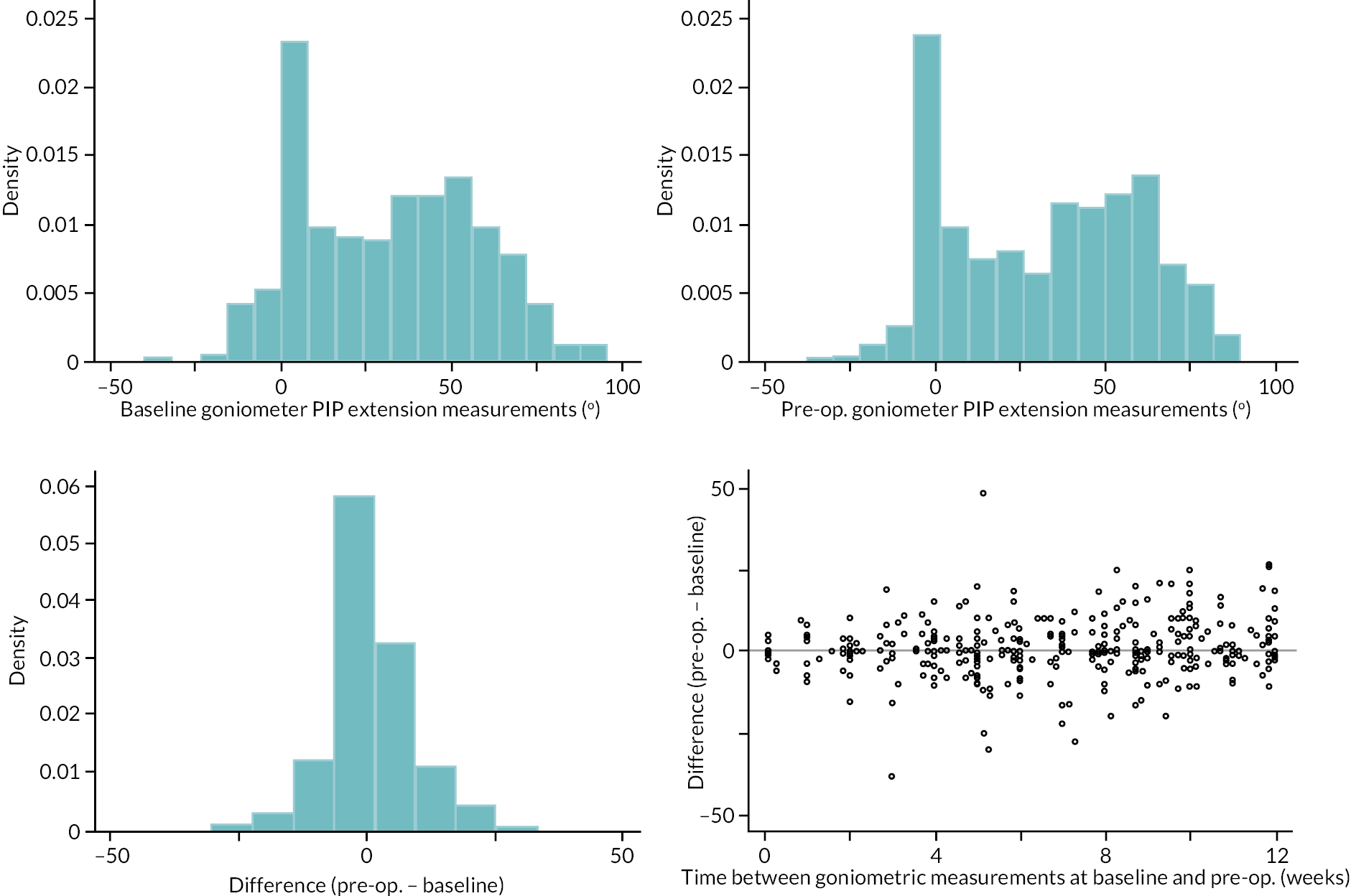

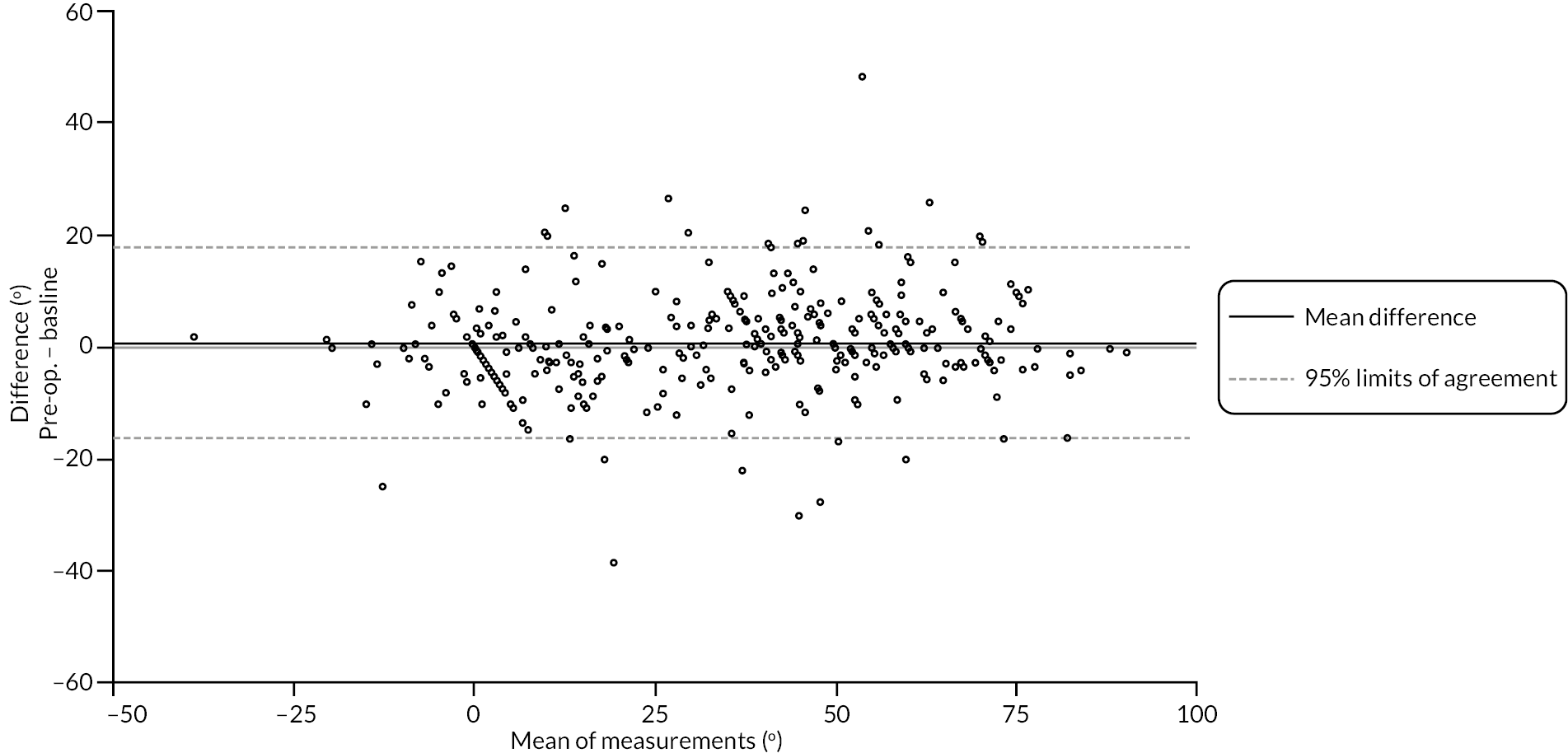

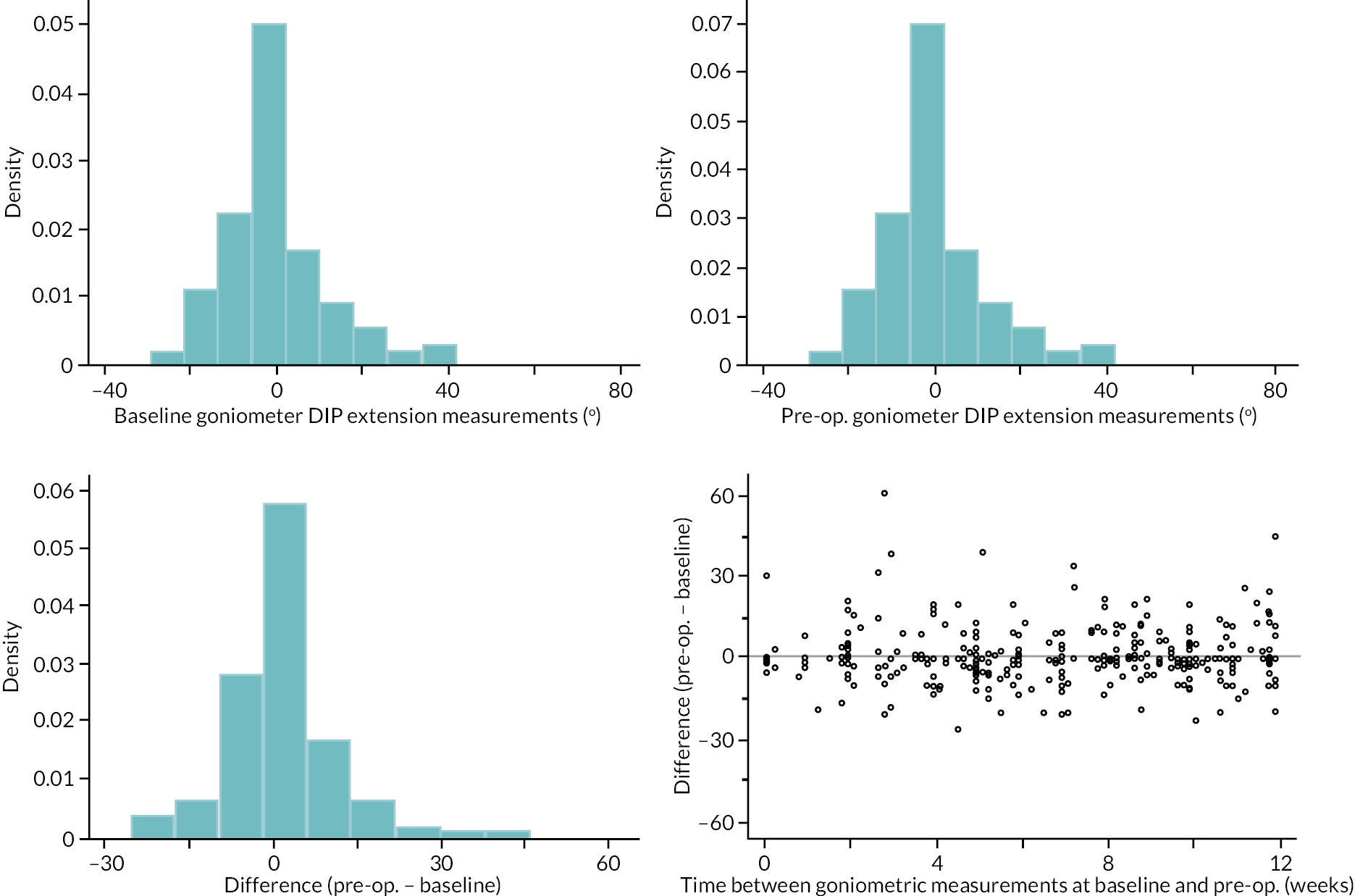

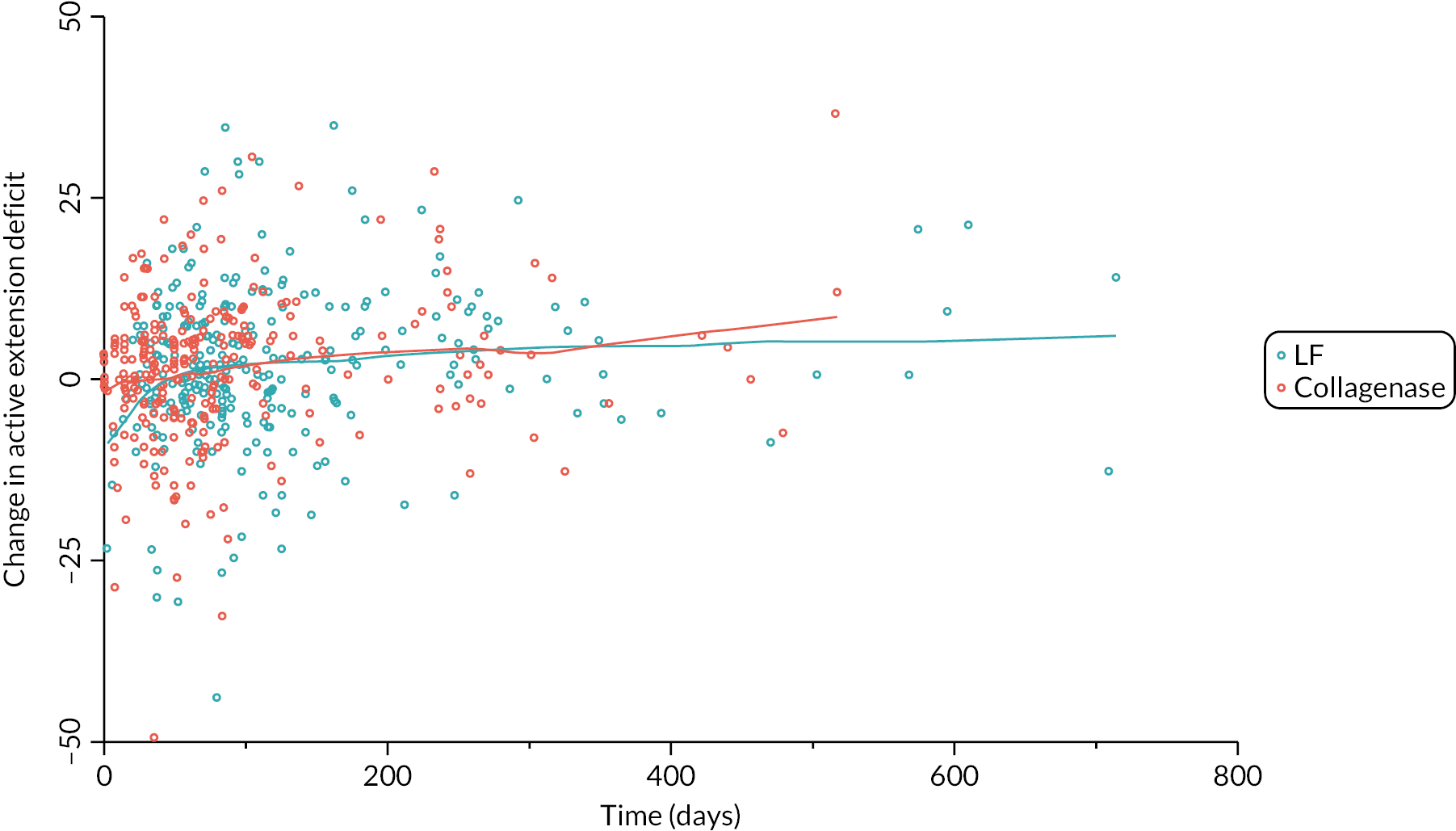

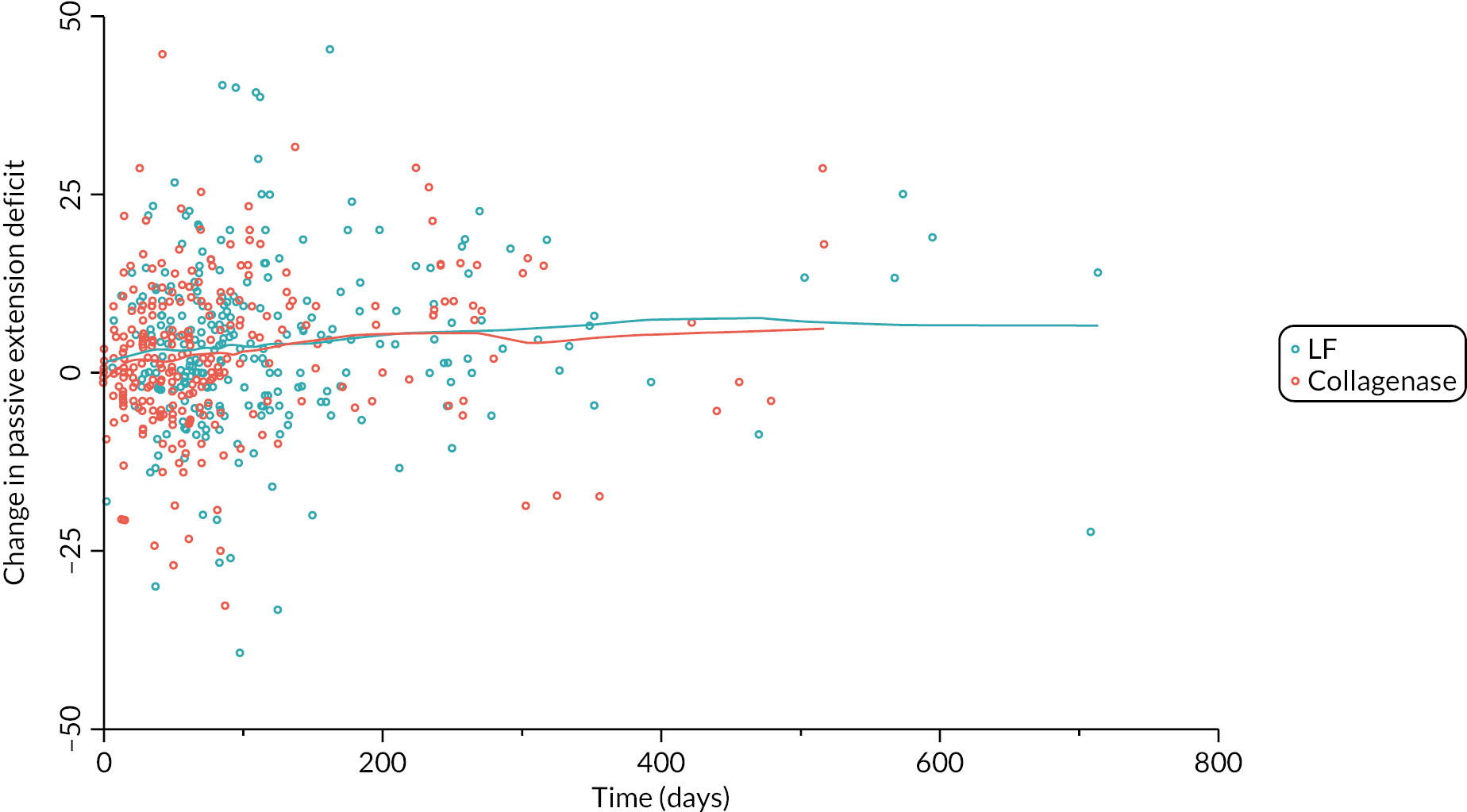

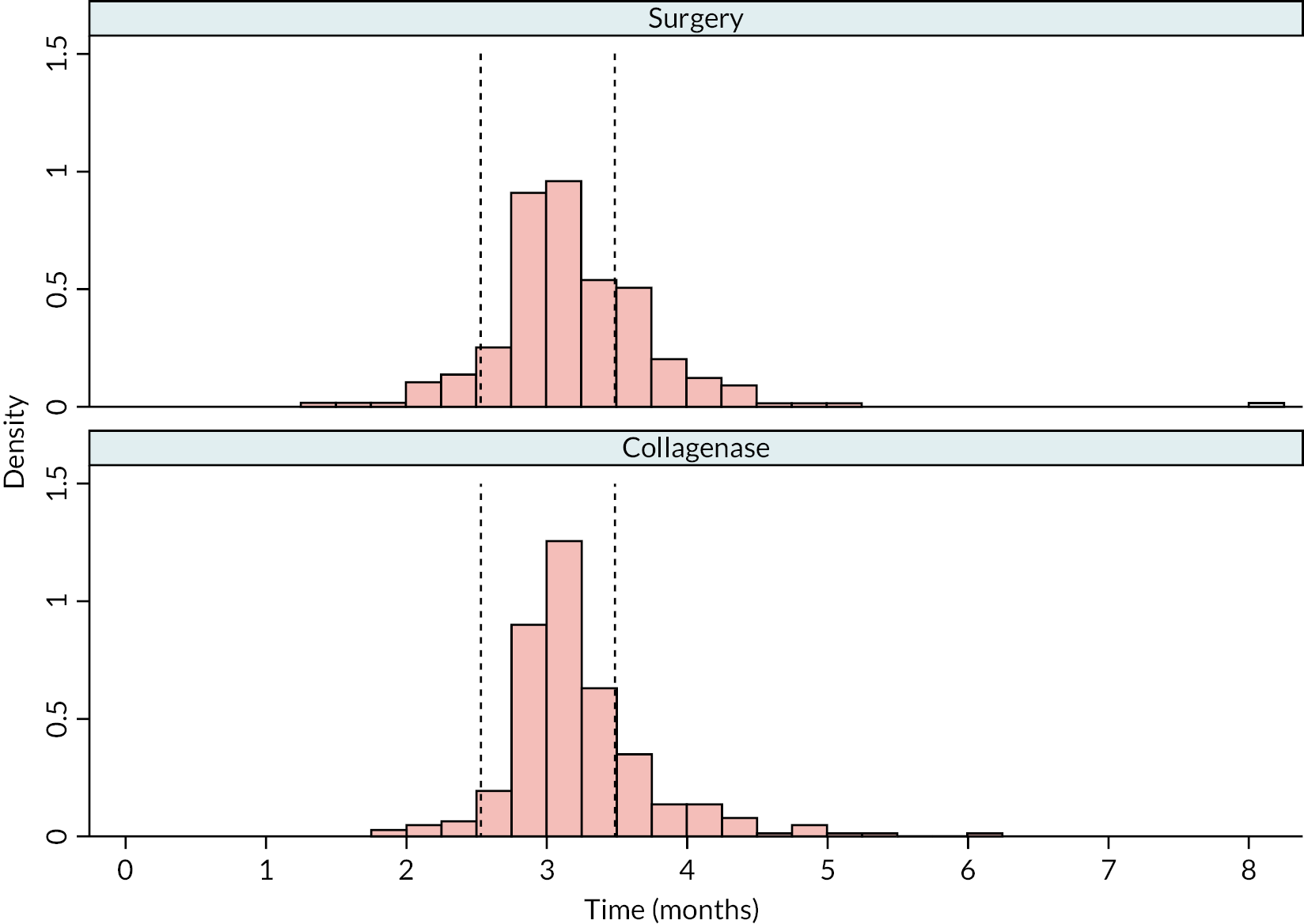

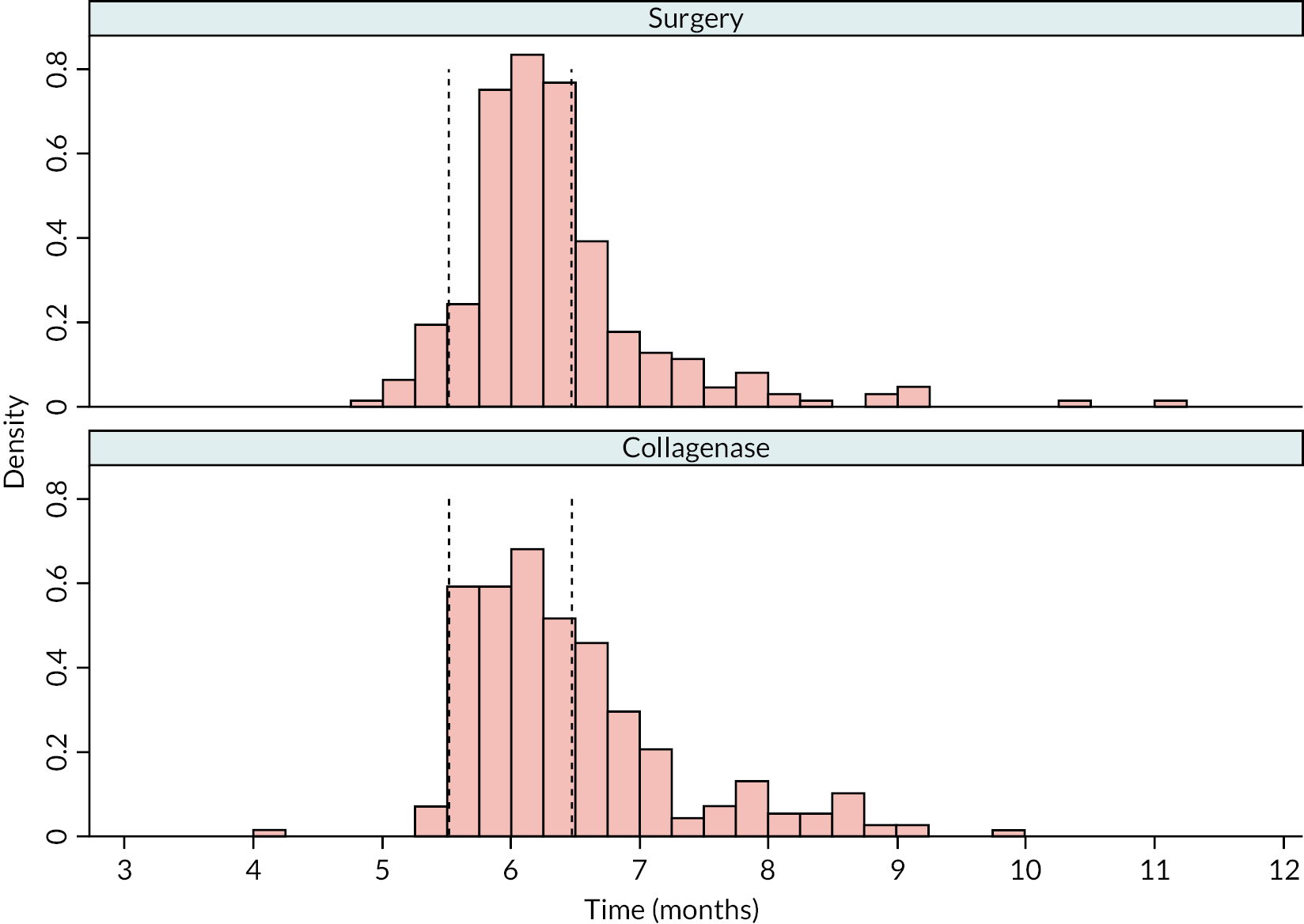

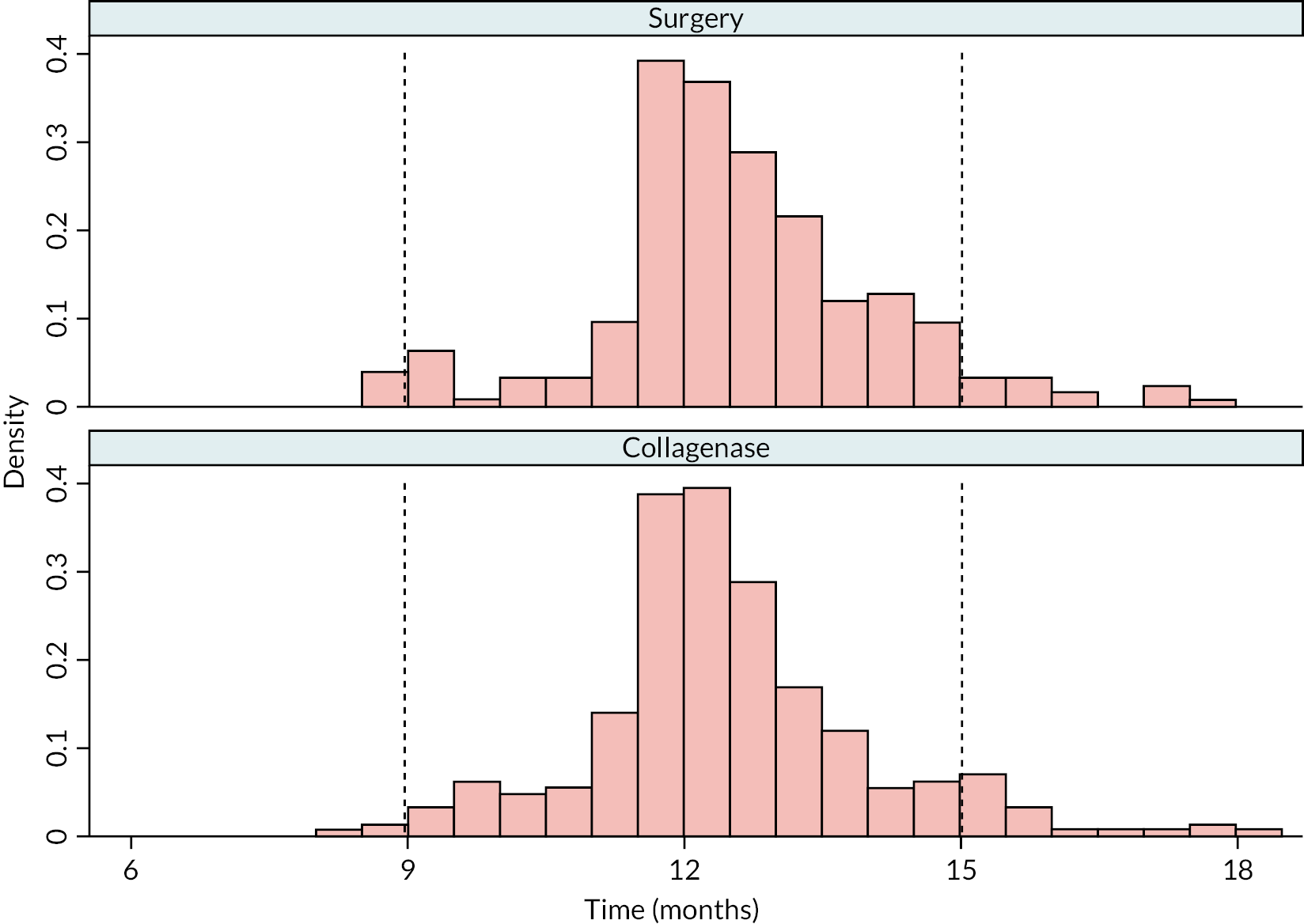

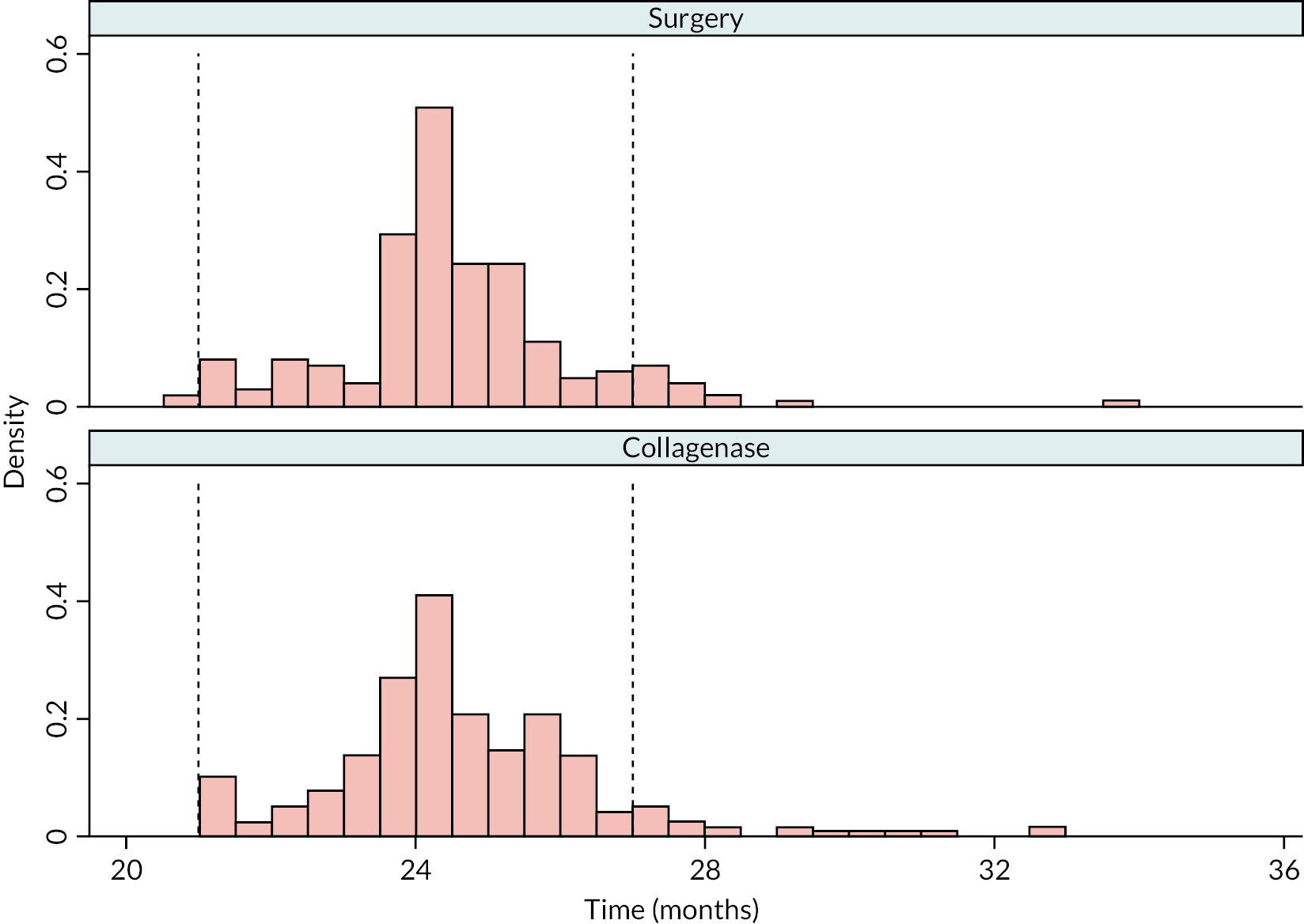

Table 9 and Figure 4 illustrate the large degree of variation in time to treatment delivery within groups, but also show systematic differences between groups. On average, participants allocated to LF received treatment 4–8 weeks later than participants allocated to collagenase. Given the slow nature of the disease, this difference is unlikely to have resulted in material differences between groups in severity of disease/contracture at the point of treatment delivery. This is consistent with the figures in Table 10, and patterns of change illustrated in Figure 5, with further details available in Appendix 5, Figures 74 and 75. While there was a slight worsening of contracture (as measured by PEM and active/passive extension deficit measurements) between baseline and treatment delivery, there is little evidence that the extent of this deterioration differed by group.

| LF N = 295 |

Collagenase N = 326 |

Total N = 621 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Time between randomisation and treatment delivery (weeks) | |||

| N | 295 | 326 | 621 |

| Mean (SD) | 17.7 (16.5) | 12.1 (13.7) | 14.7 (15.3) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 12.1 (8.3, 20.4) | 8.0 (4.6, 12.6) | 10.0 (5.9, 16.7) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0.3, 102.0 | 0.0, 104.4 | 0.0, 104.4 |

FIGURE 4.

Time (weeks) elapsed between randomisation and treatment delivery (Kaplan–Meier failure estimates).

| LF N = 295 |

Collagenase N = 326 |

Total N = 621 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Increase in PEM Hand Health Questionnaireascore between baseline and treatment | |||

| N | 271 | 321 | 592 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.0 (14.4) | 1.5 (13.5) | 1.3 (13.9) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.5 (−8.3, 8.0) | 1.5 (−6.1, 9.1) | 1.5 (−6.1, 9.1) |

| Minimum, maximumb | −43.5, 46.0 | −48.5, 36.7 | −48.5, 46.0 |

| Increase in active extension deficit (°) between baseline and treatment | |||

| N | 279 | 316 | 595 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.7 (10.7) | 1.2 (9.4) | 1.5 (10.0) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.3 (−3.3, 8.0) | 0.7 (−2.7, 5.7) | 0.7 (−3.3, 6.7) |

| Minimum, maximumb | −43.8, 35.0 | −49.3, 36.7 | −49.3, 36.7 |

| Increase in passive extension deficit (°) between baseline and treatment | |||

| N | 260 | 304 | 564 |

| Mean (SD) | 3.9 (11.7) | 2.7 (10.0) | 3.3 (10.8) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 3.5 (−2.0, 10.0) | 2.0 (−2.7, 9.3) | 2.2 (−2.3, 9.3) |

| Minimum, maximumb | −39.3, 45.3 | −32.7, 44.7 | −39.3, 45.3 |

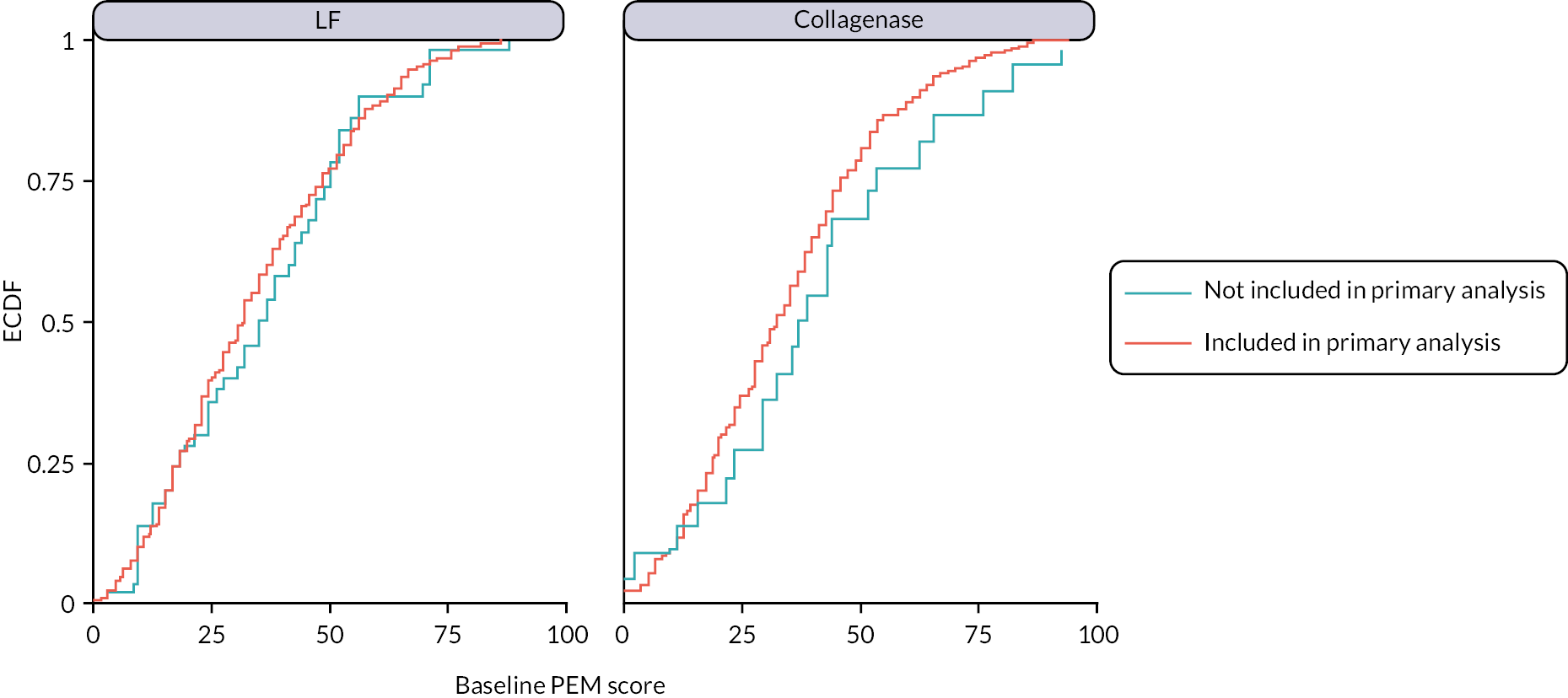

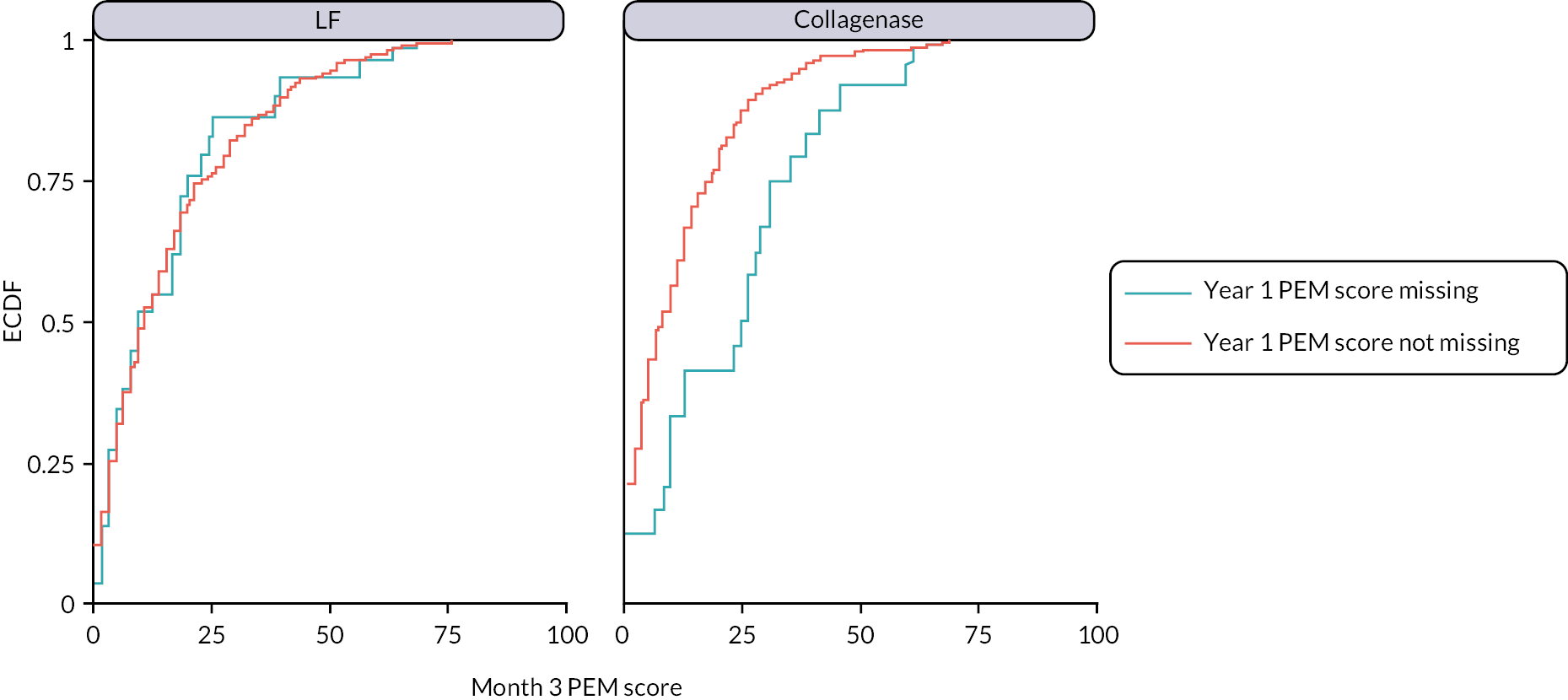

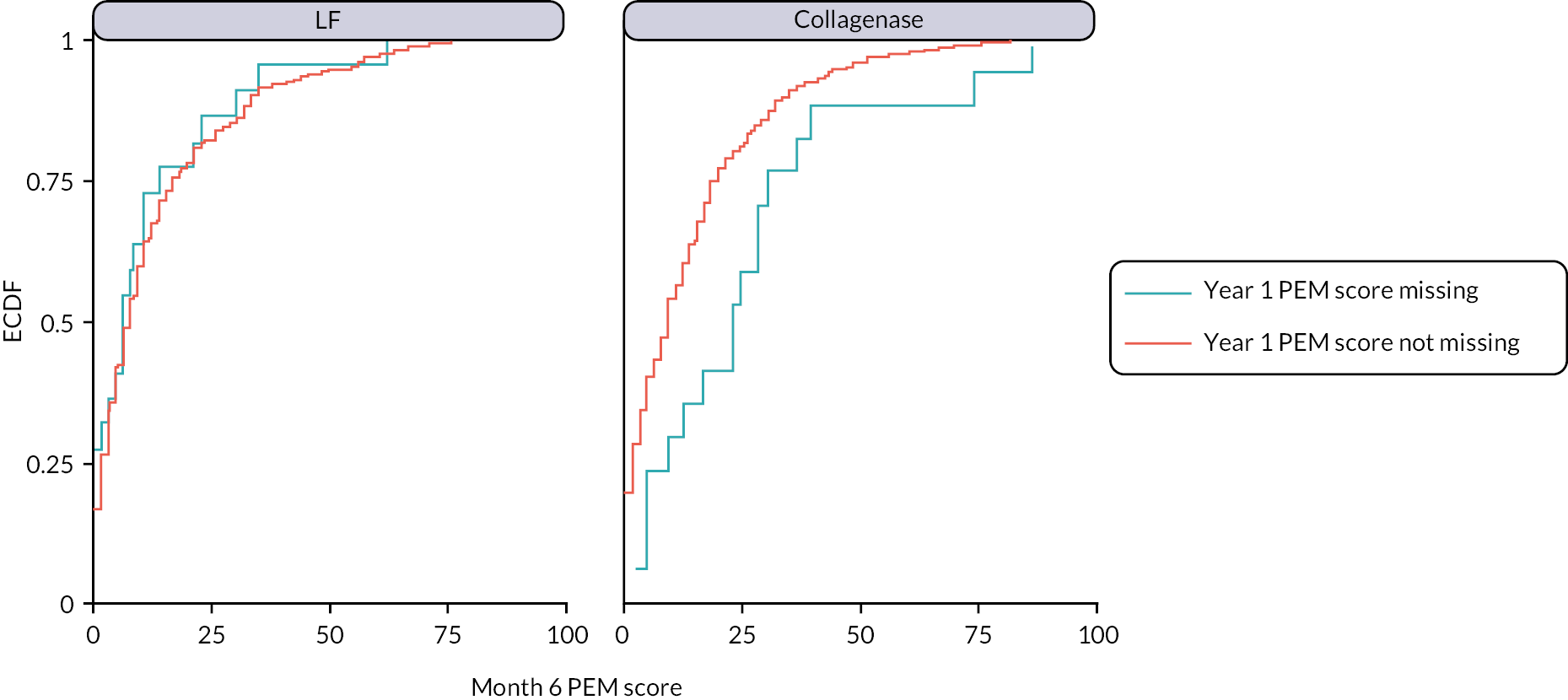

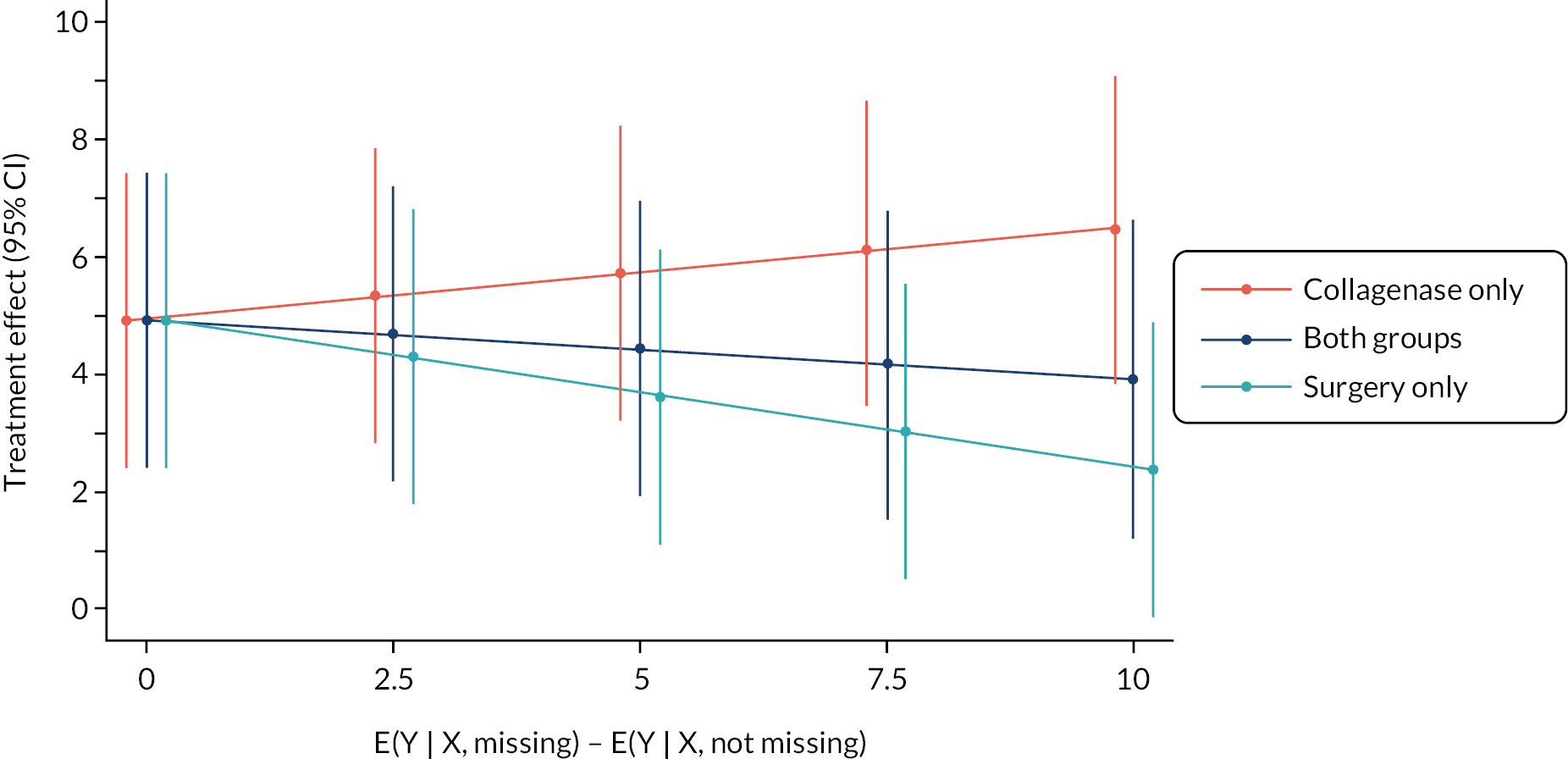

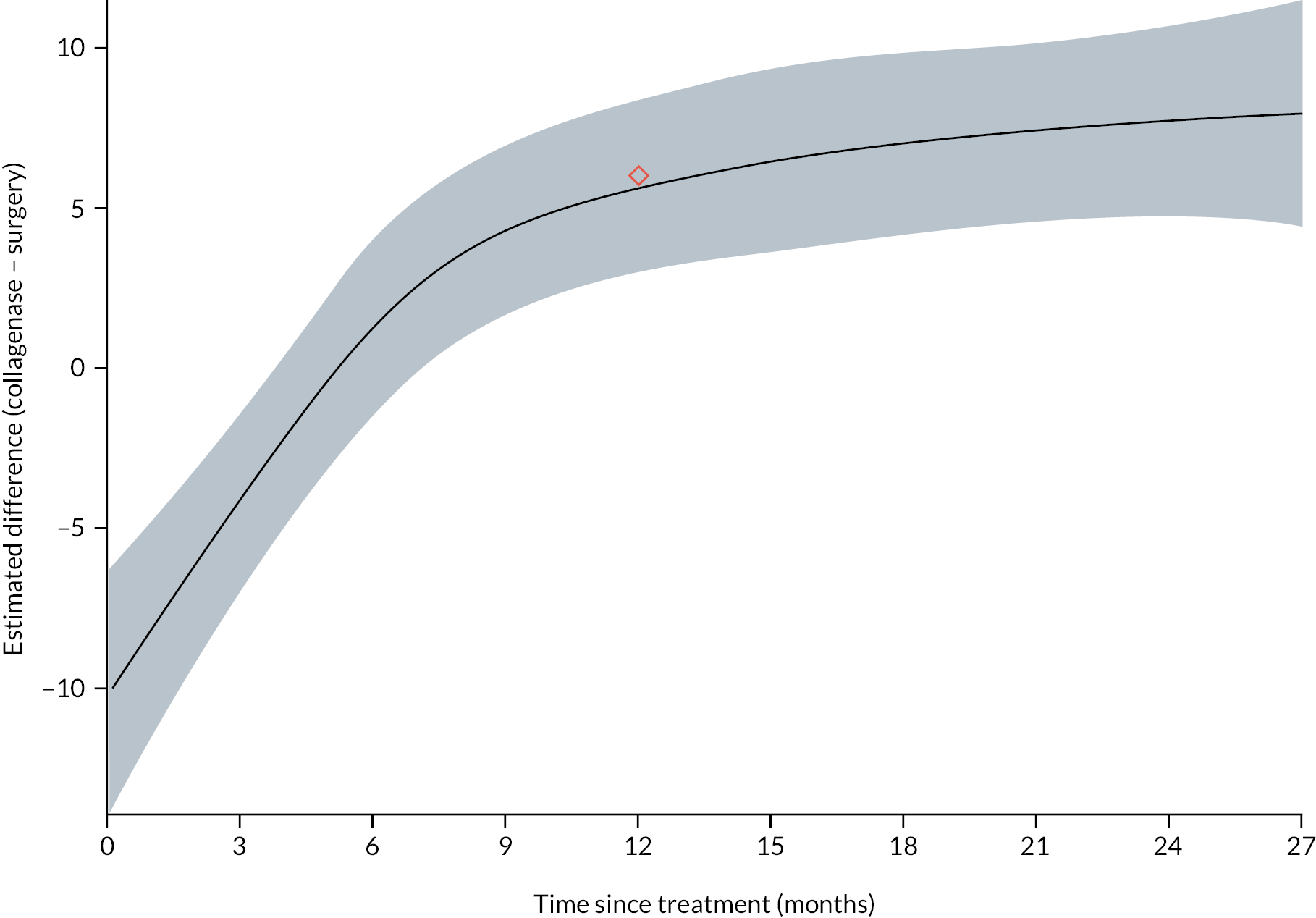

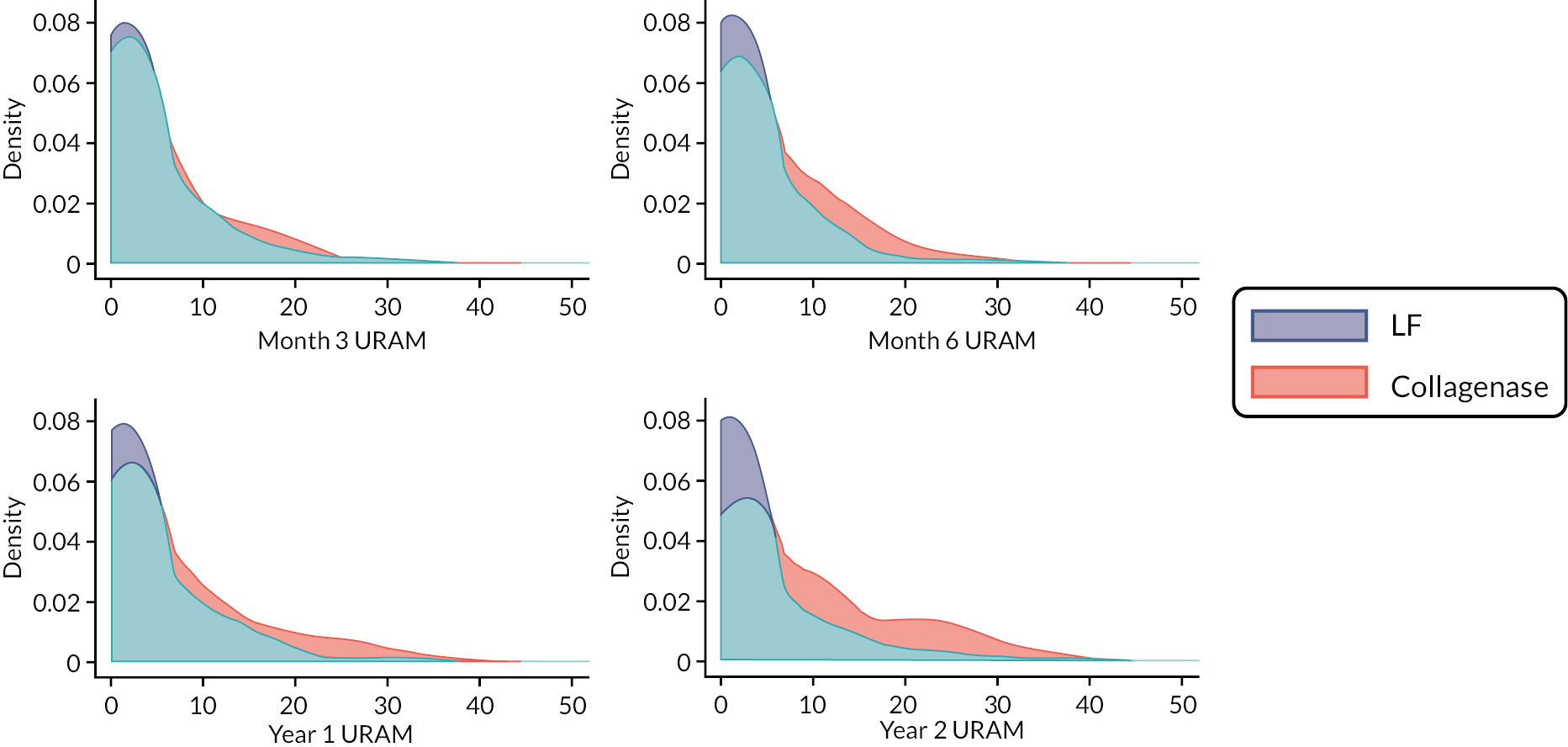

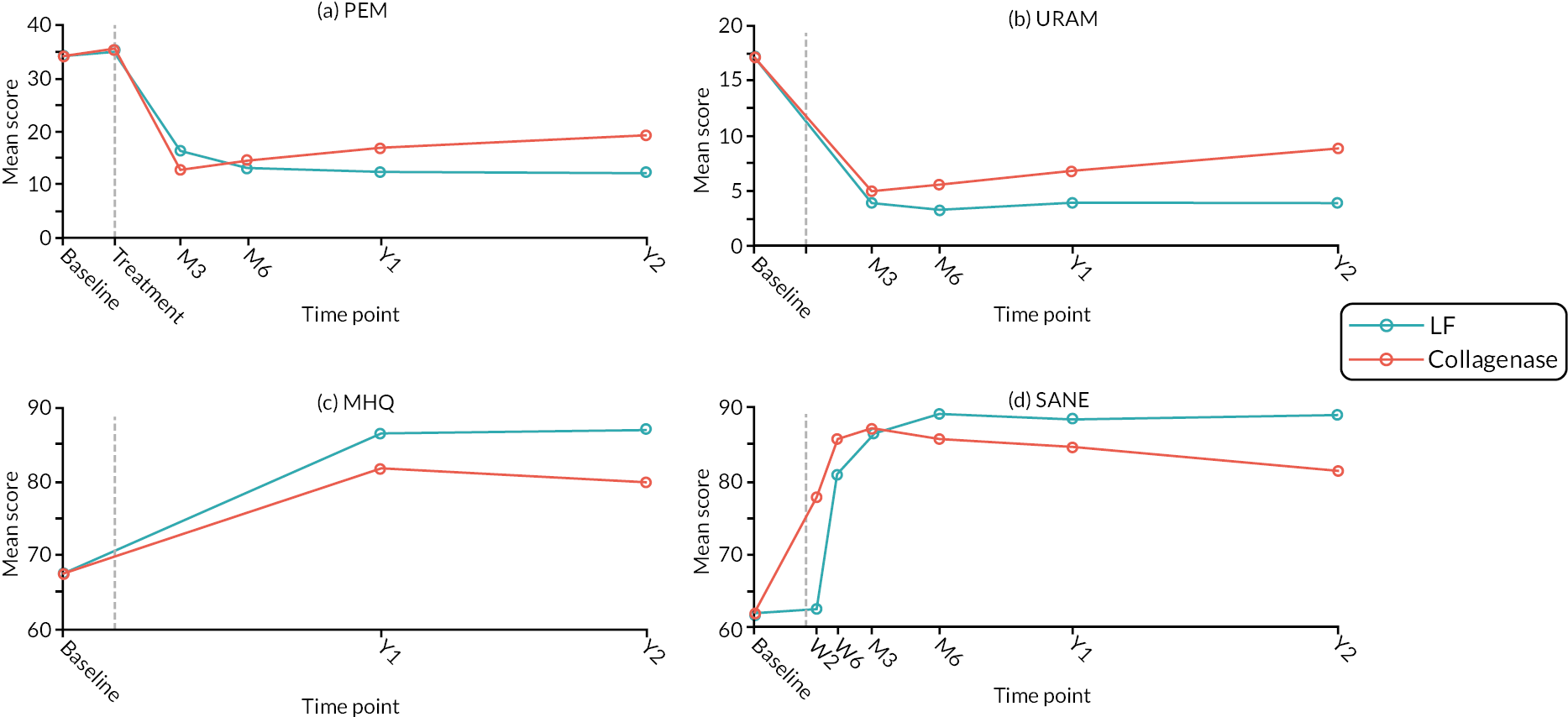

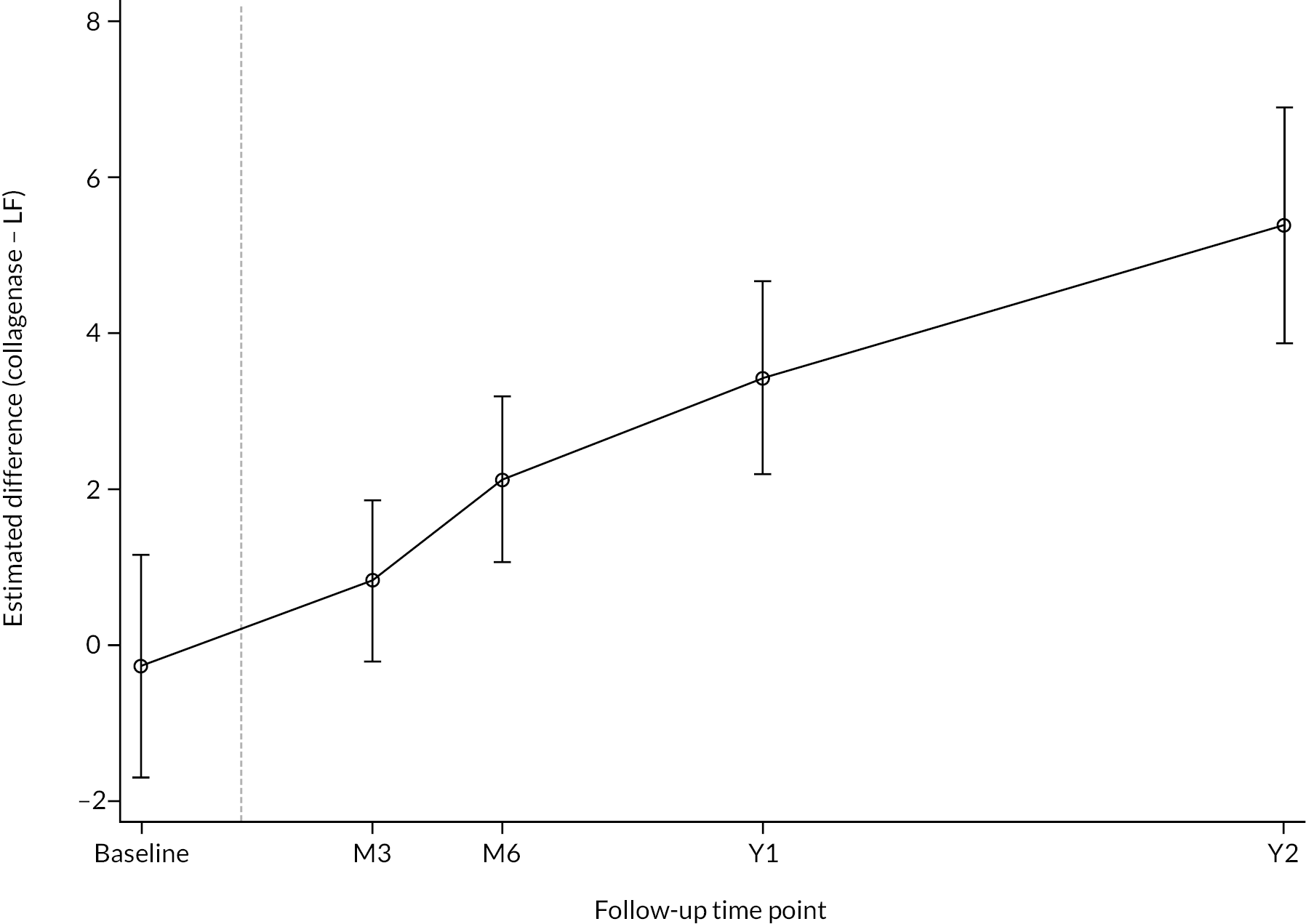

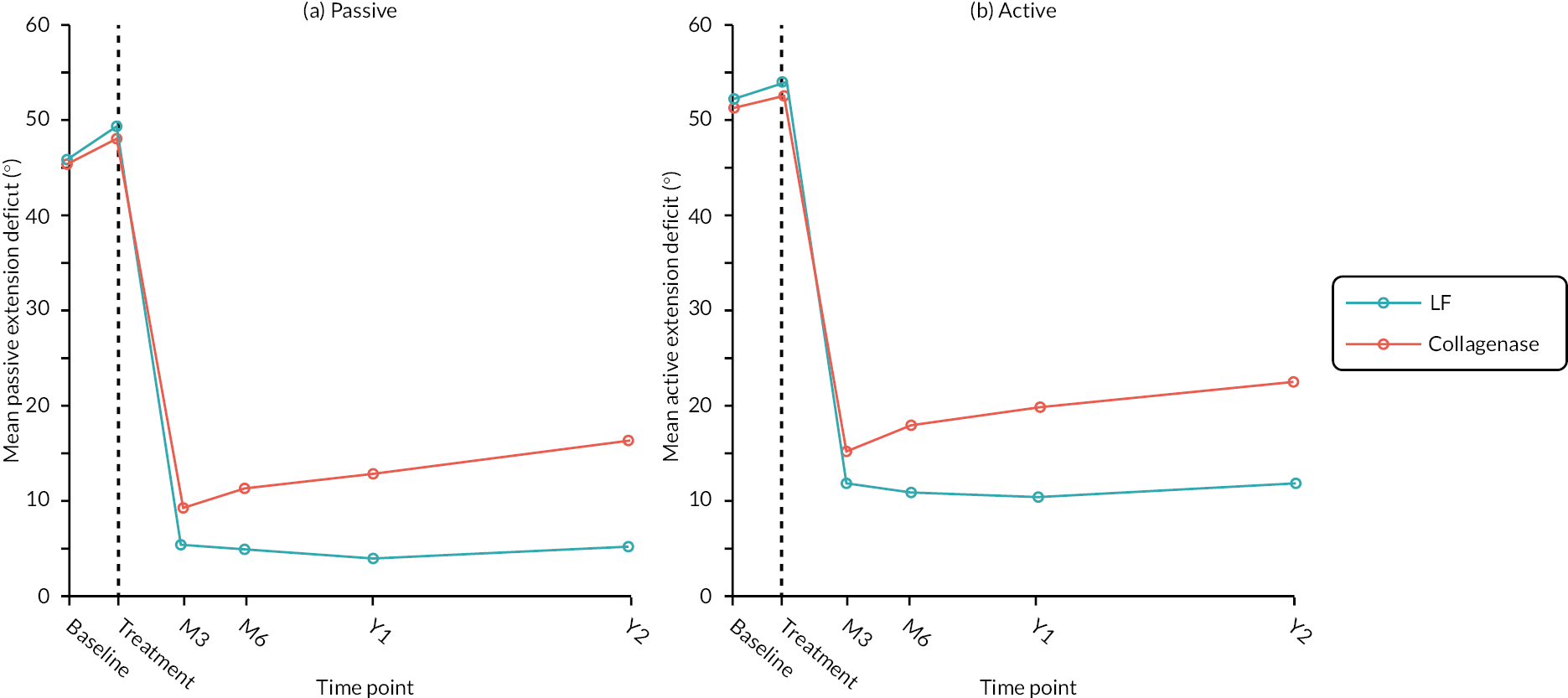

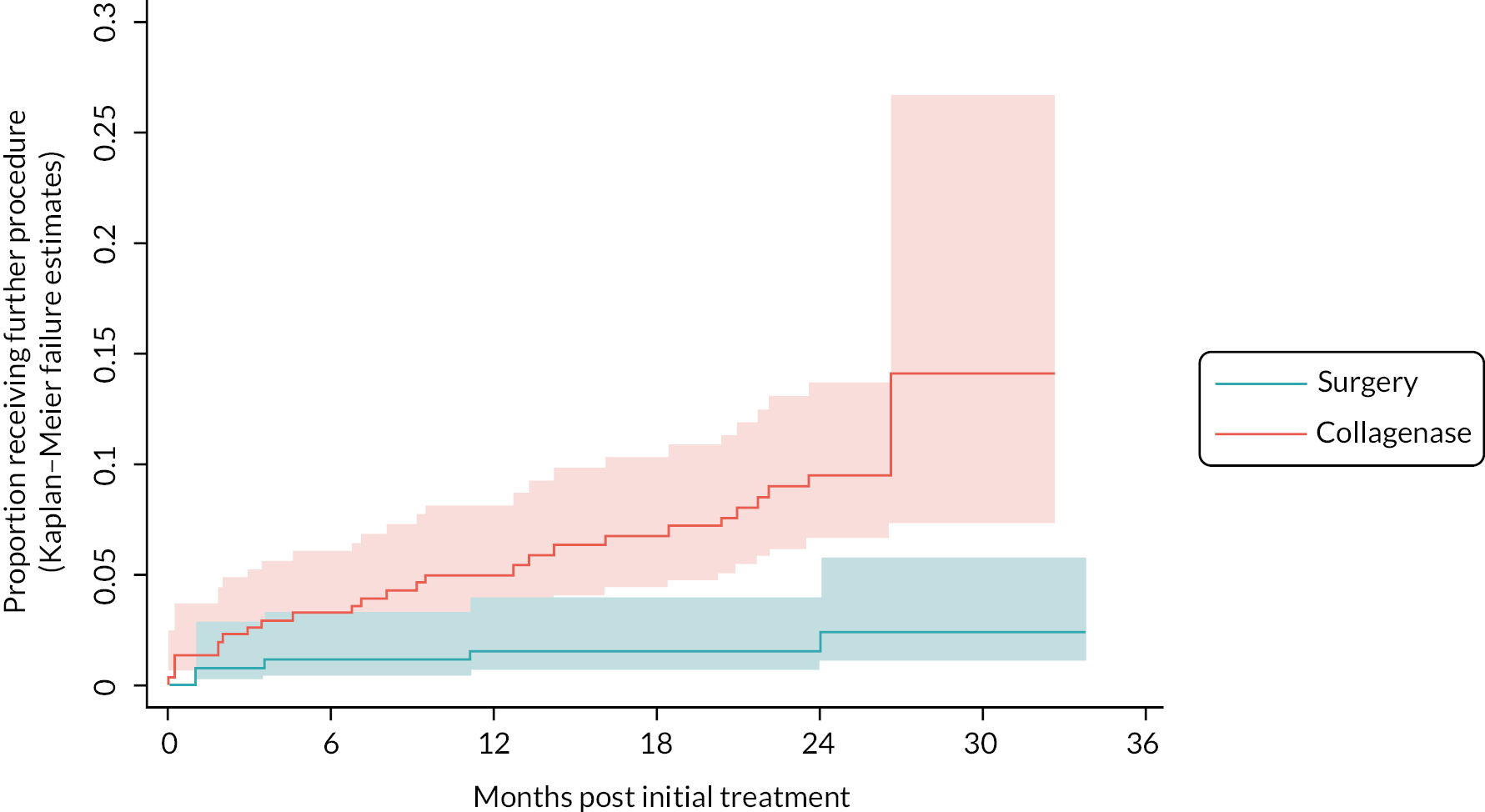

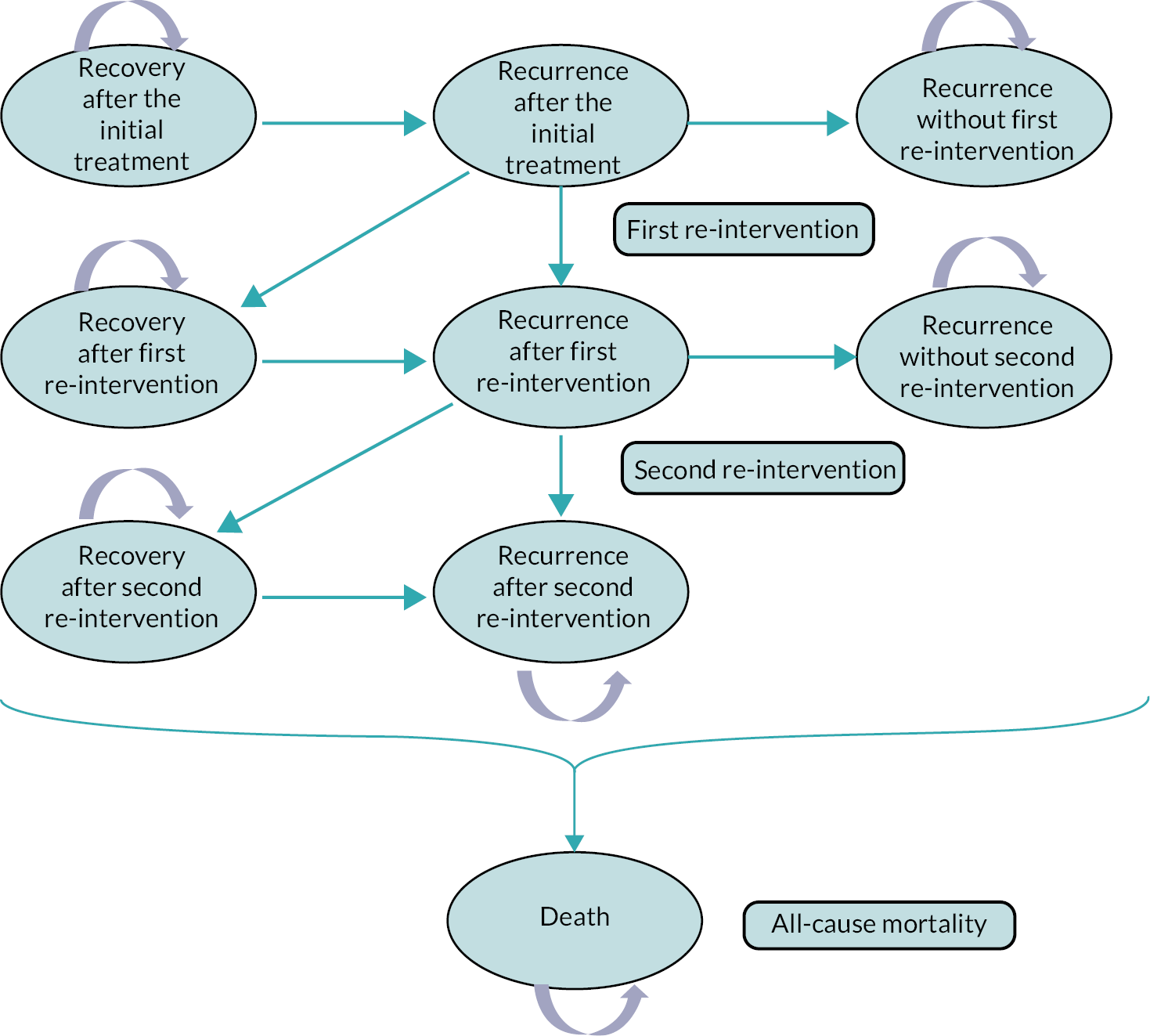

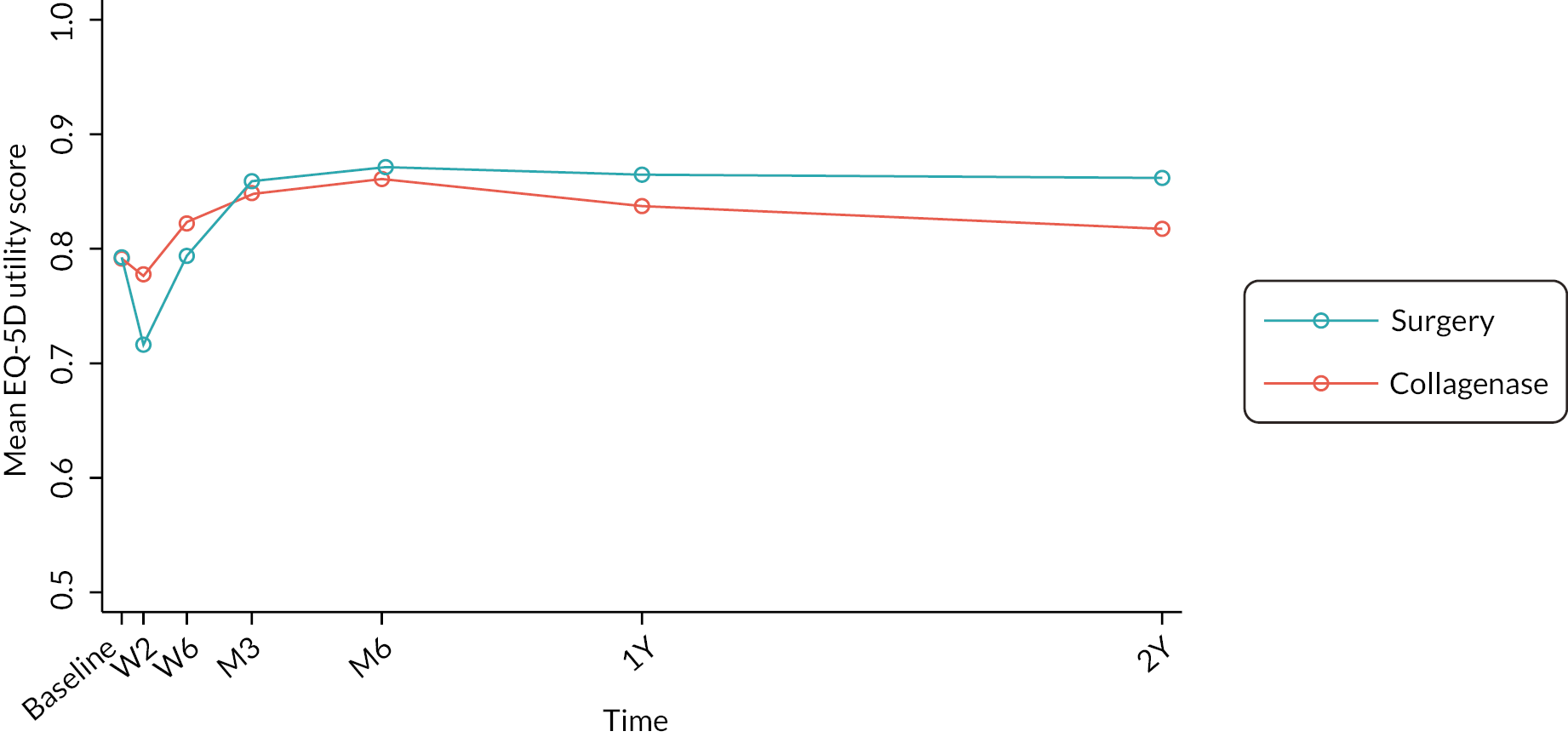

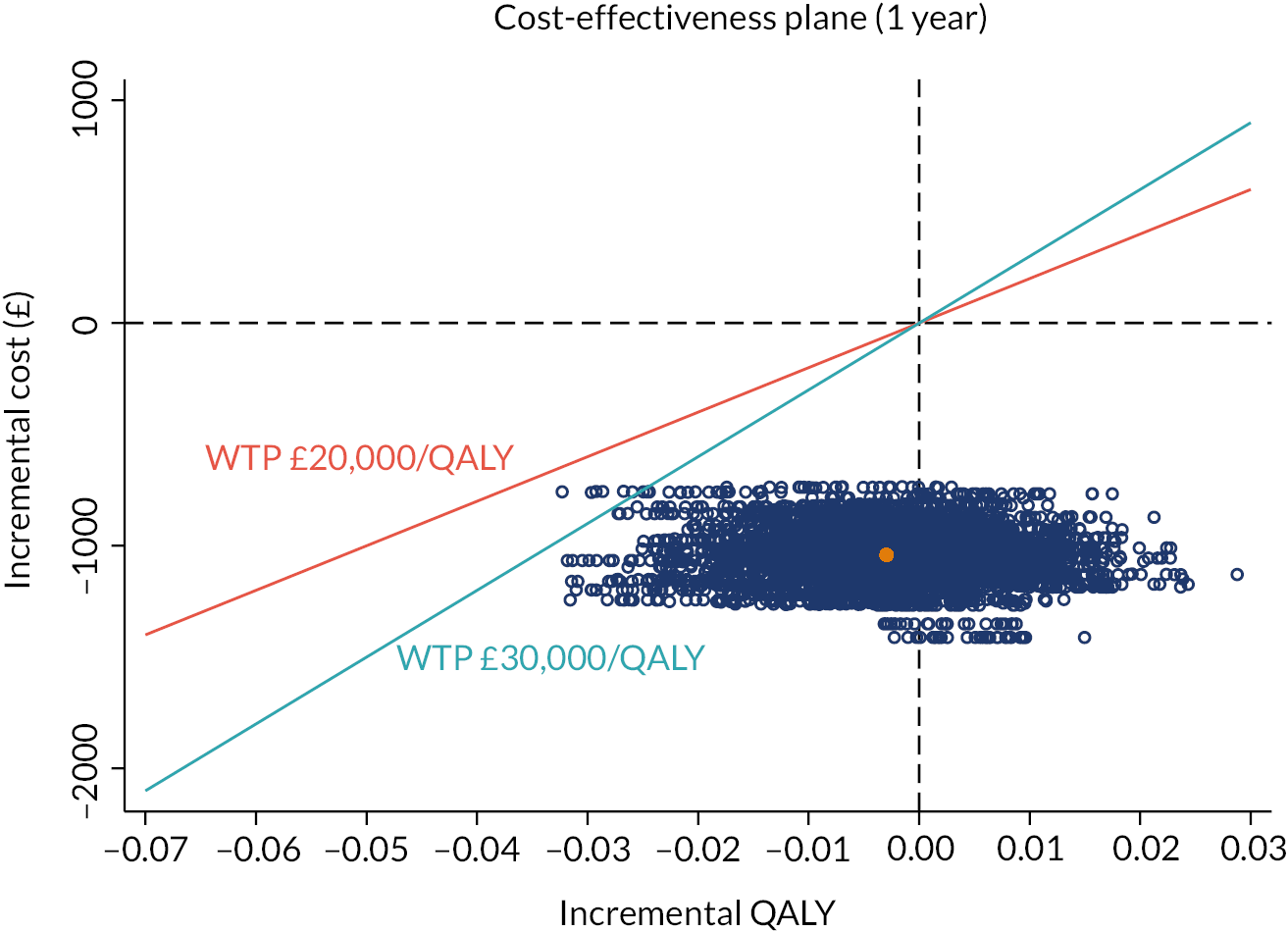

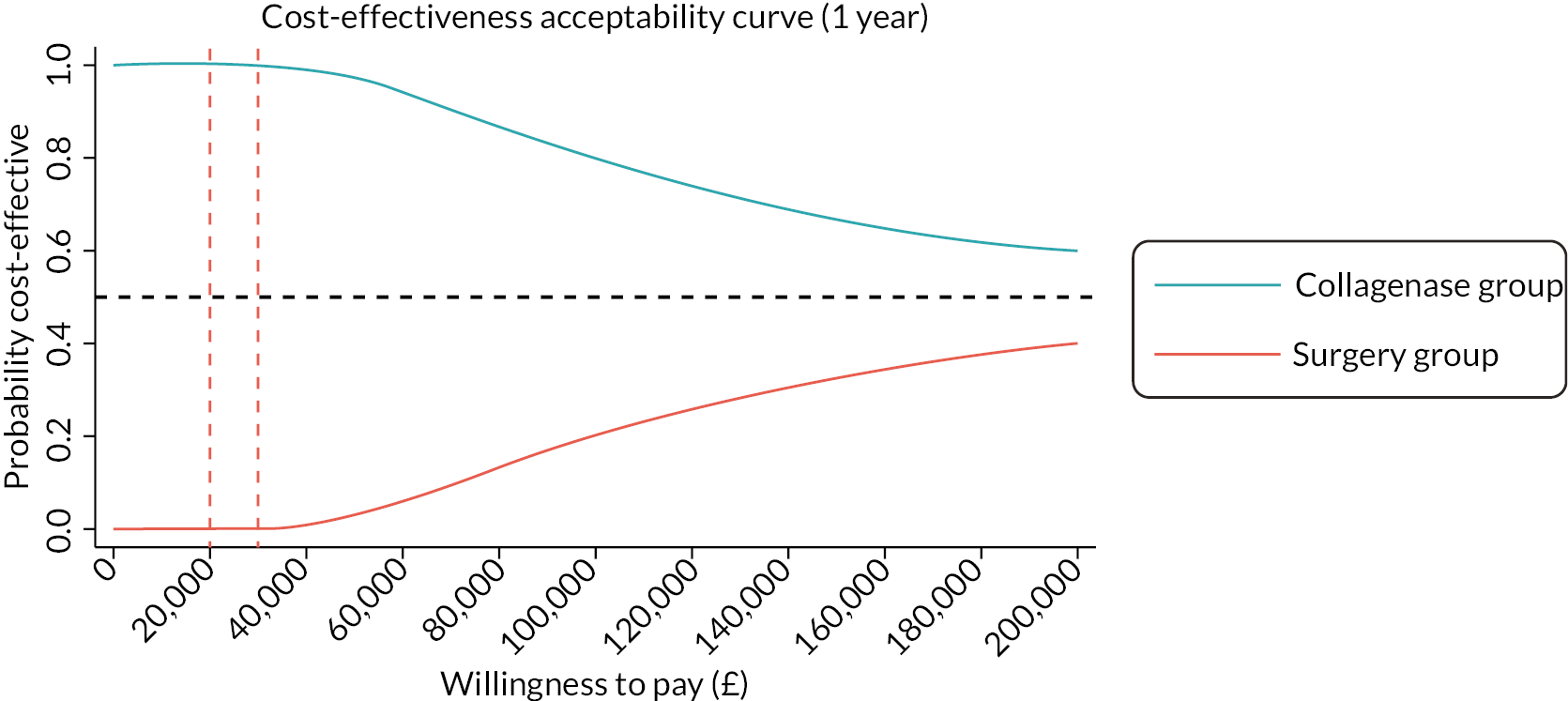

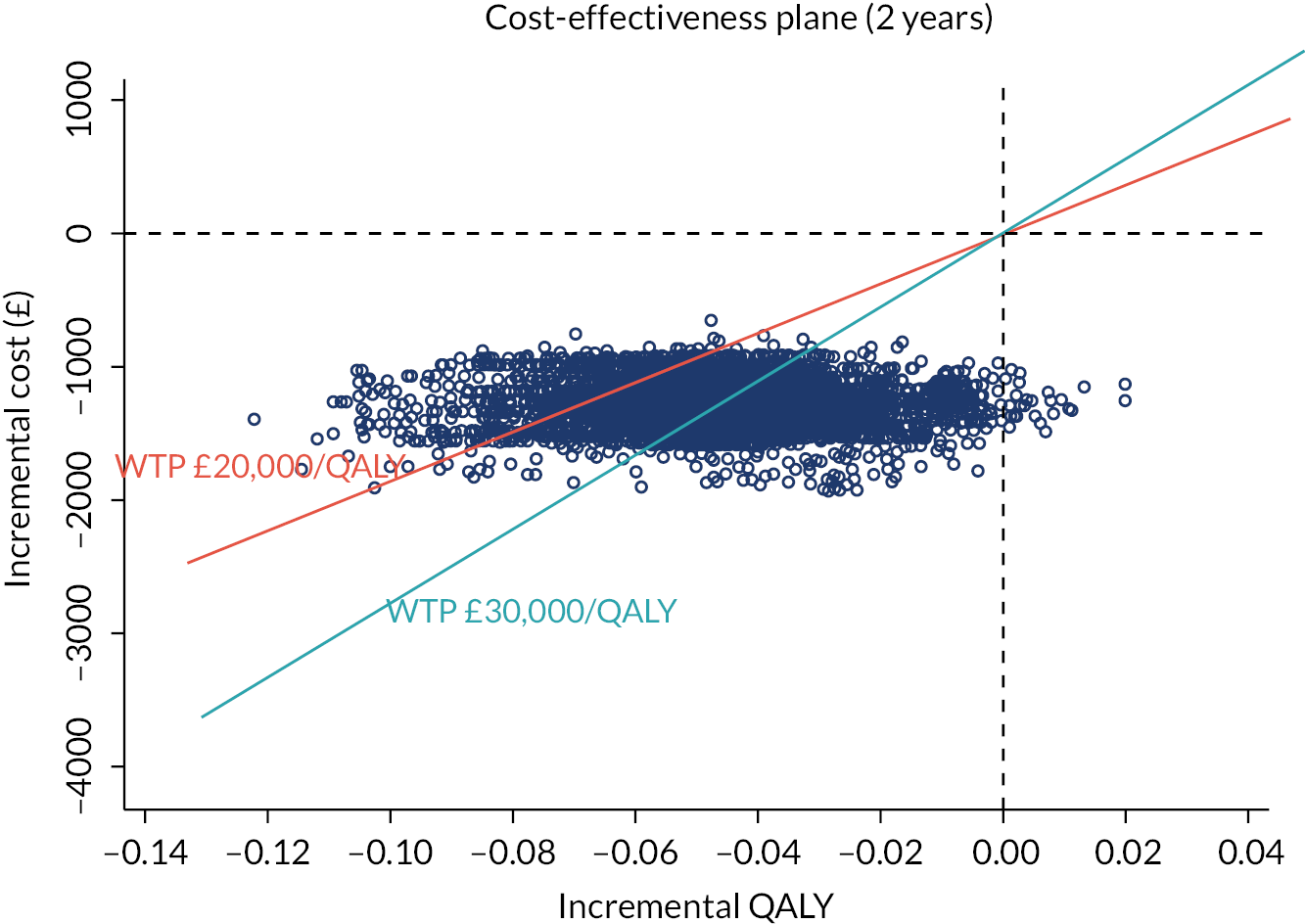

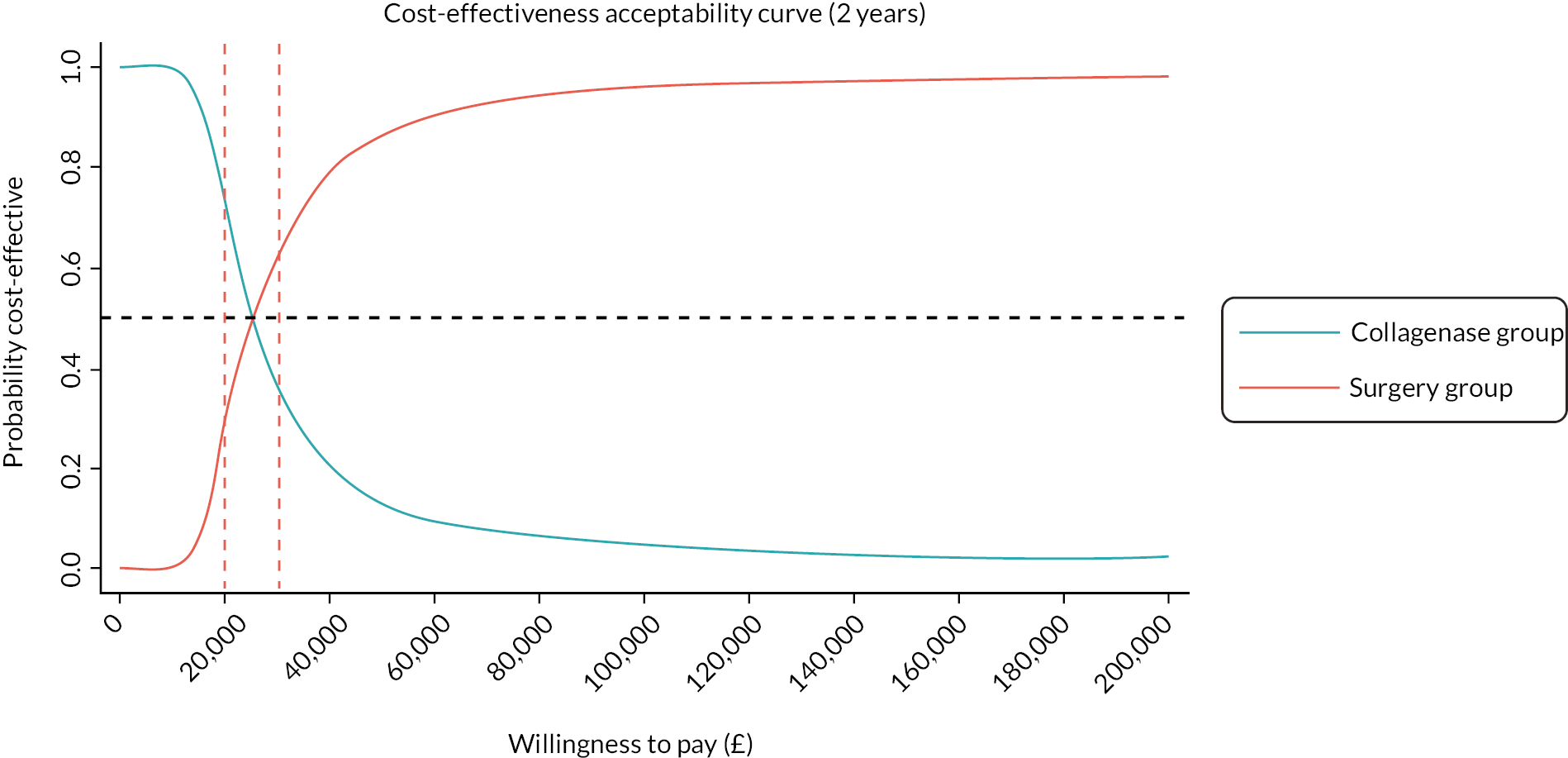

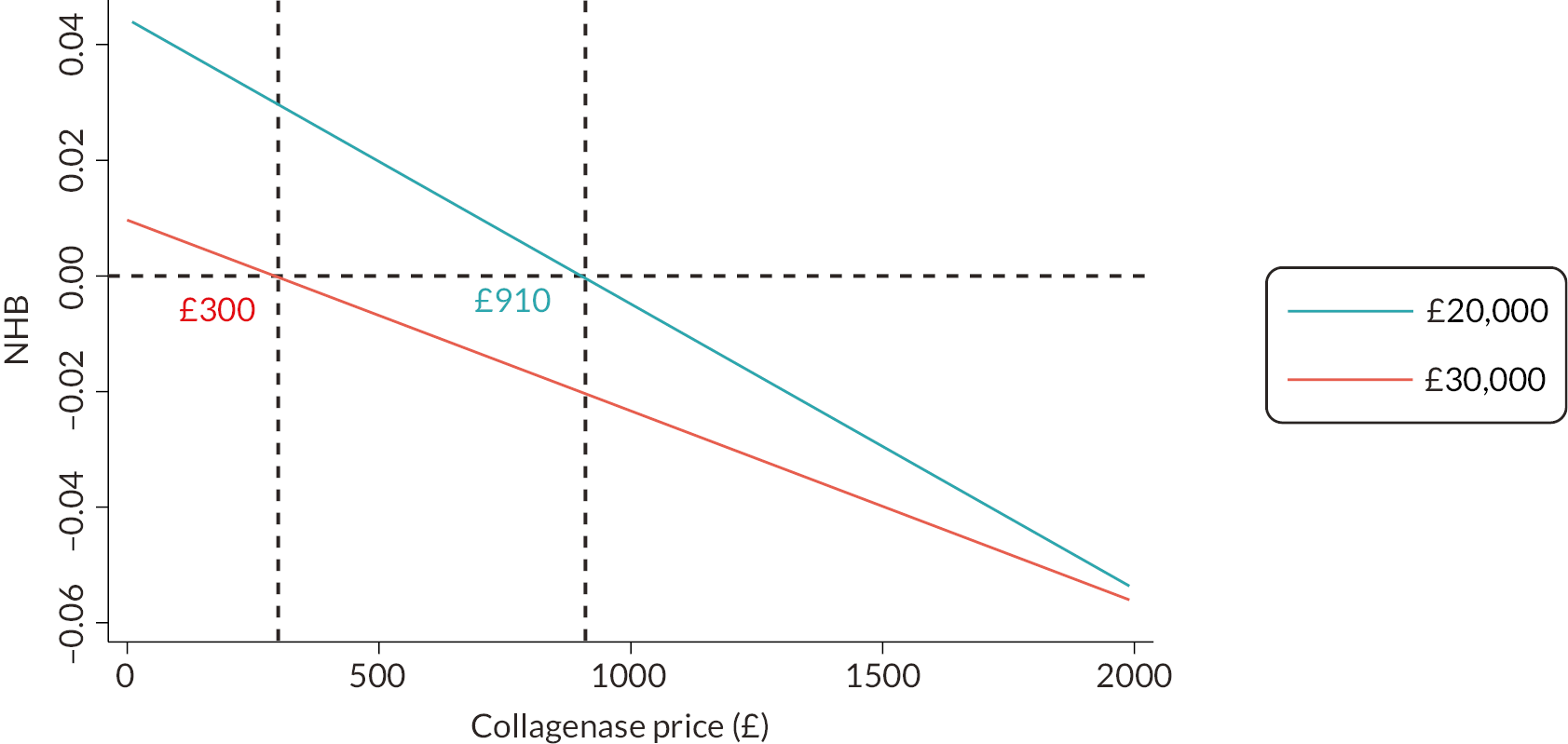

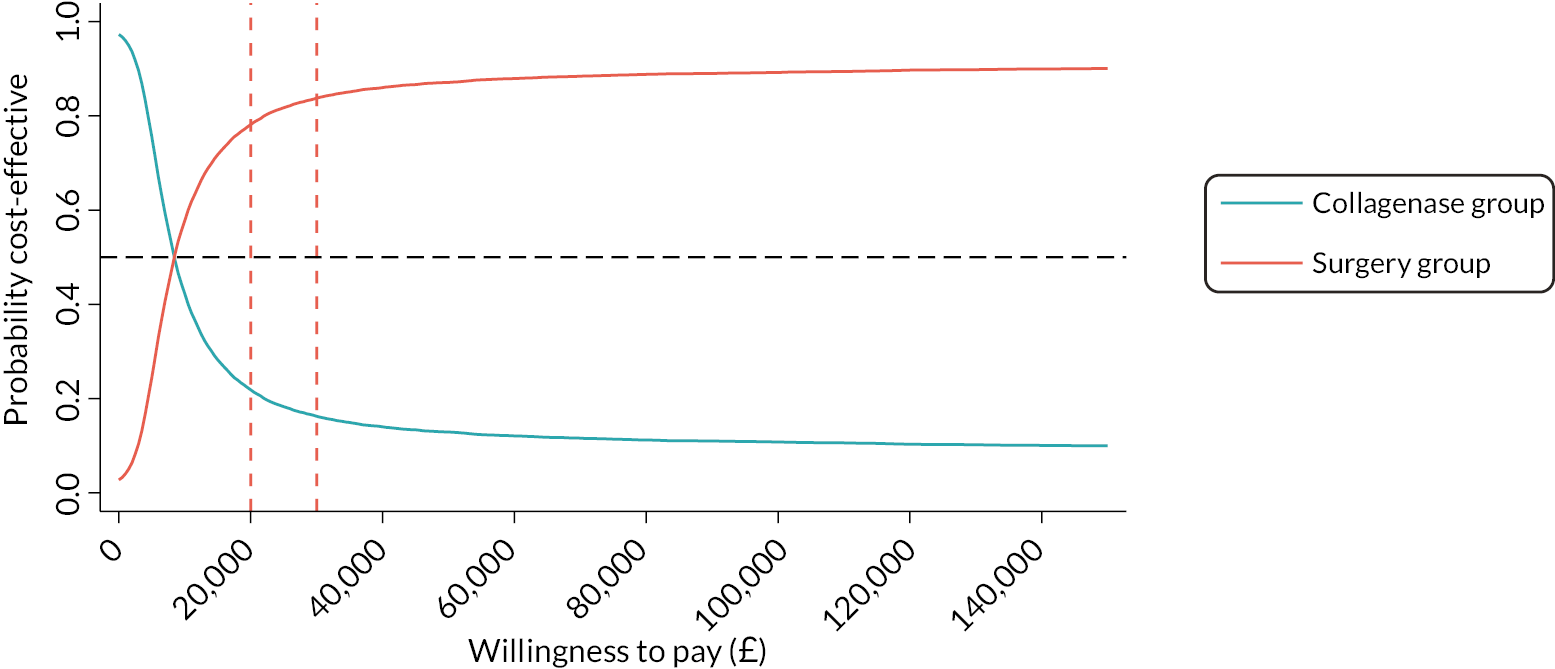

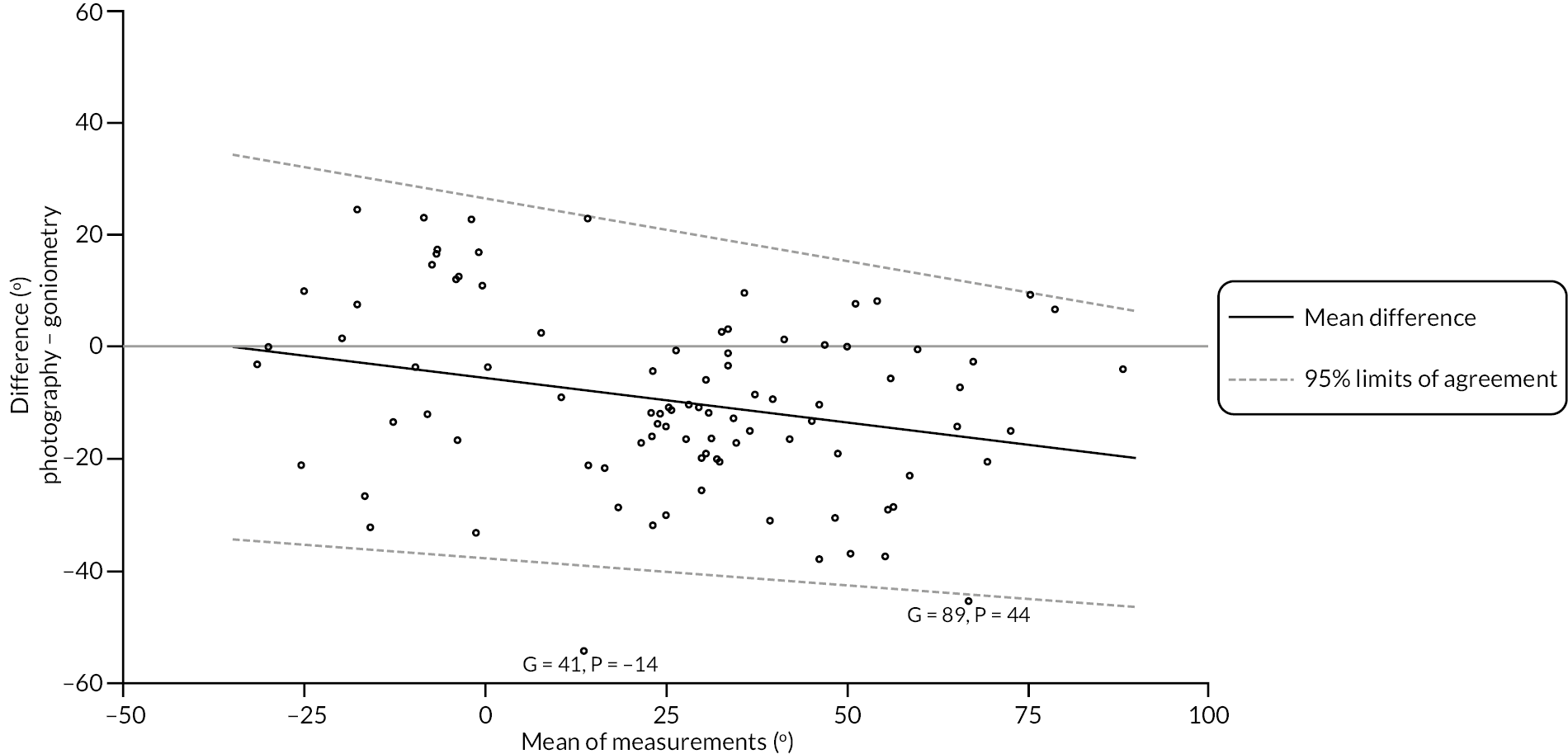

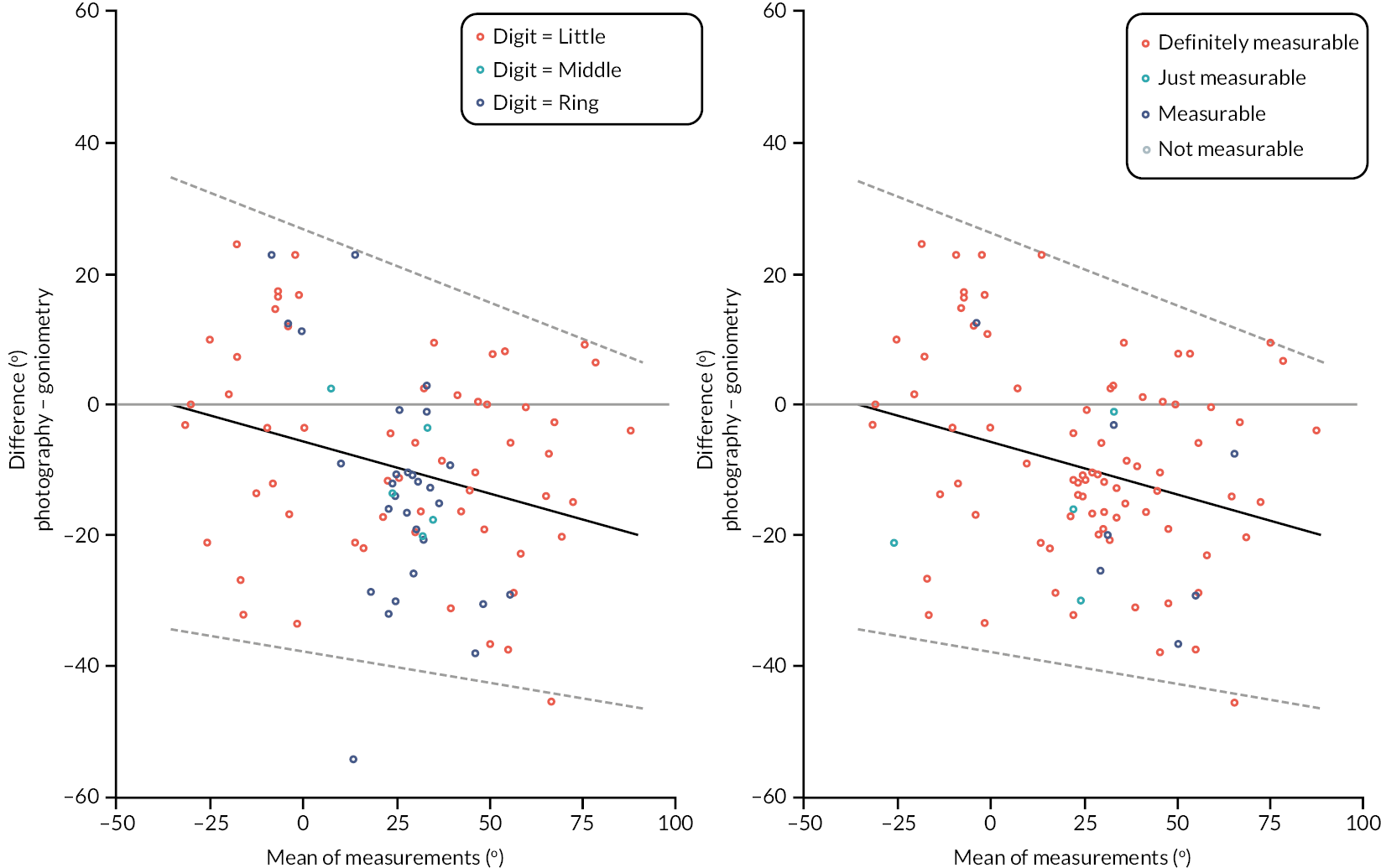

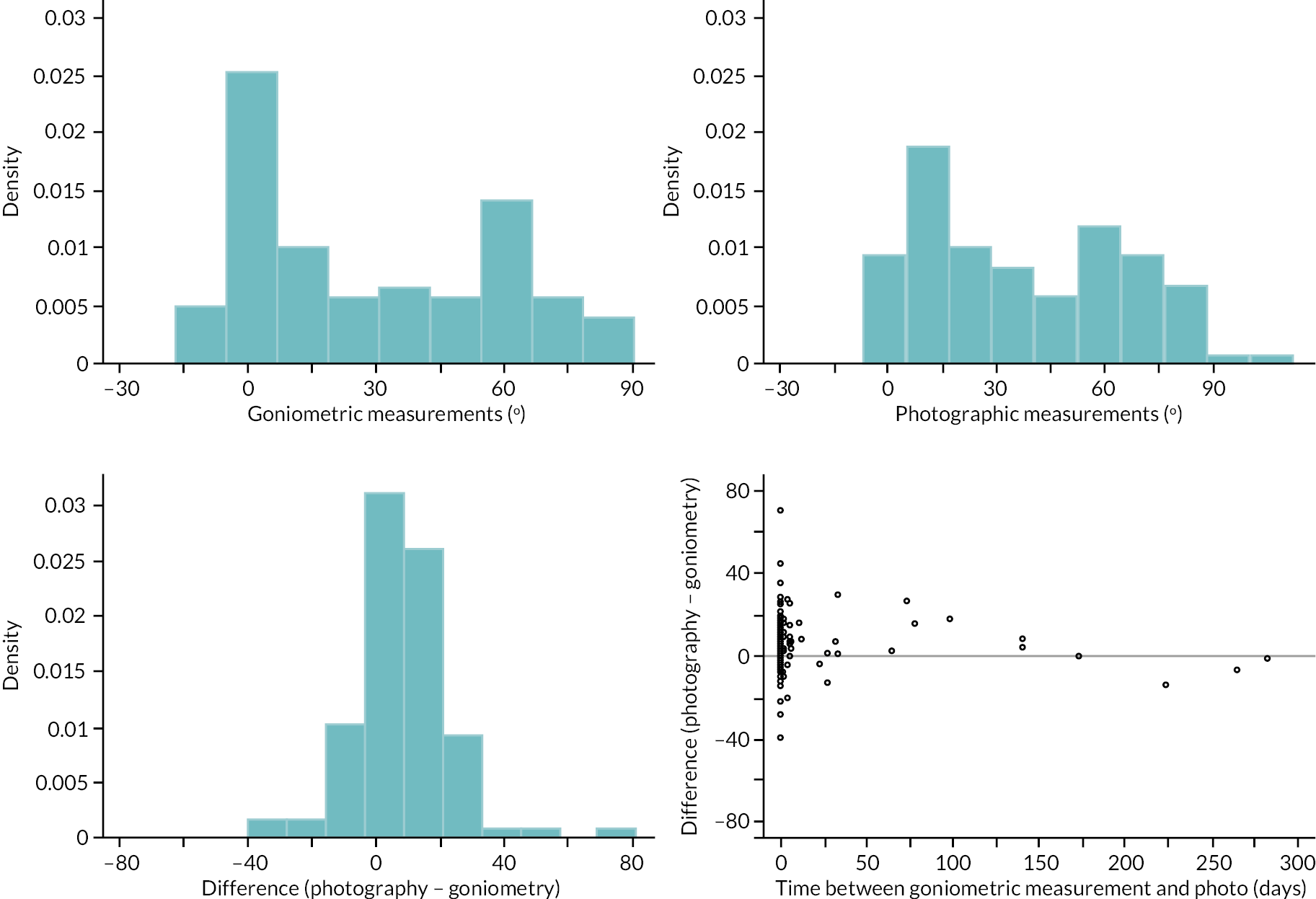

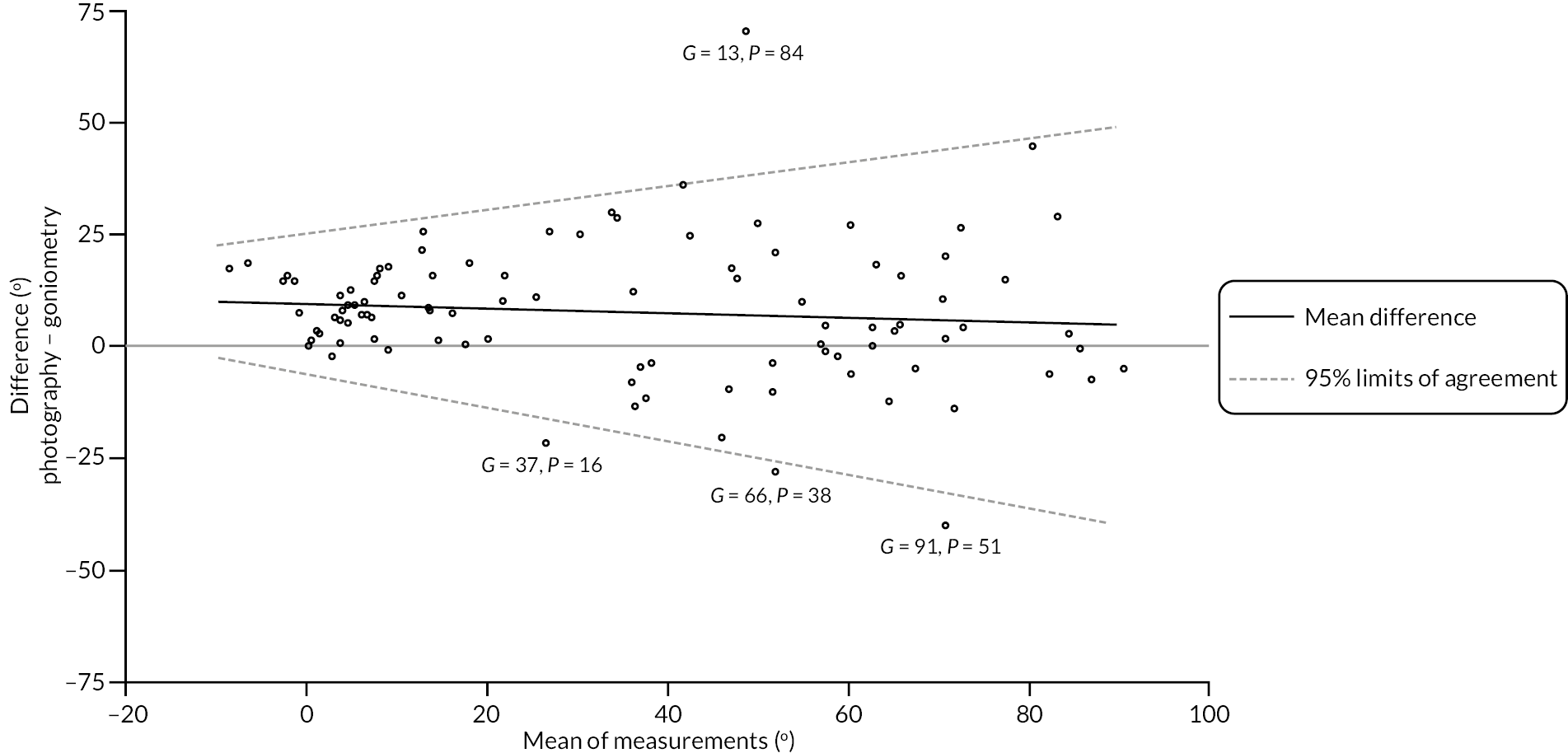

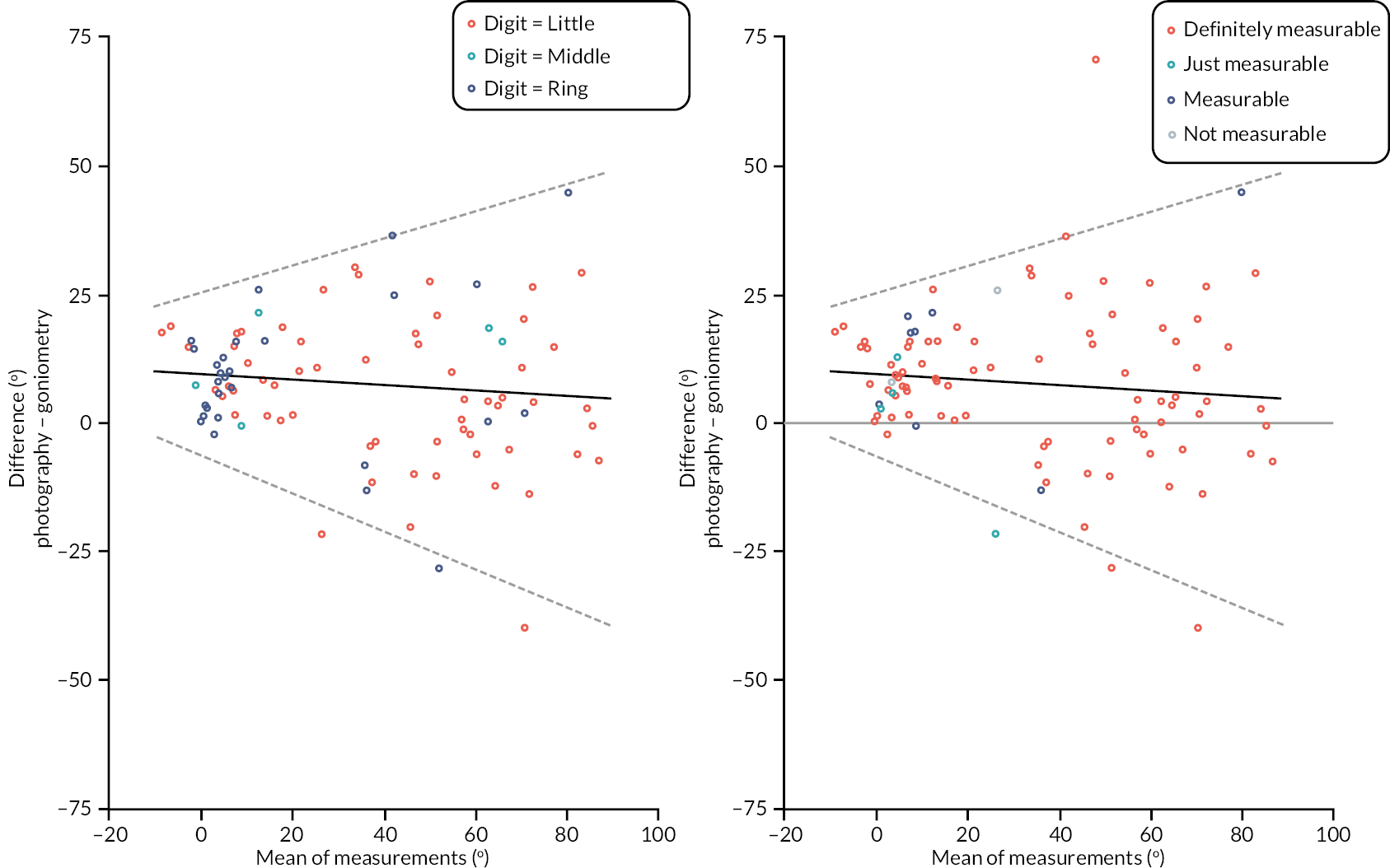

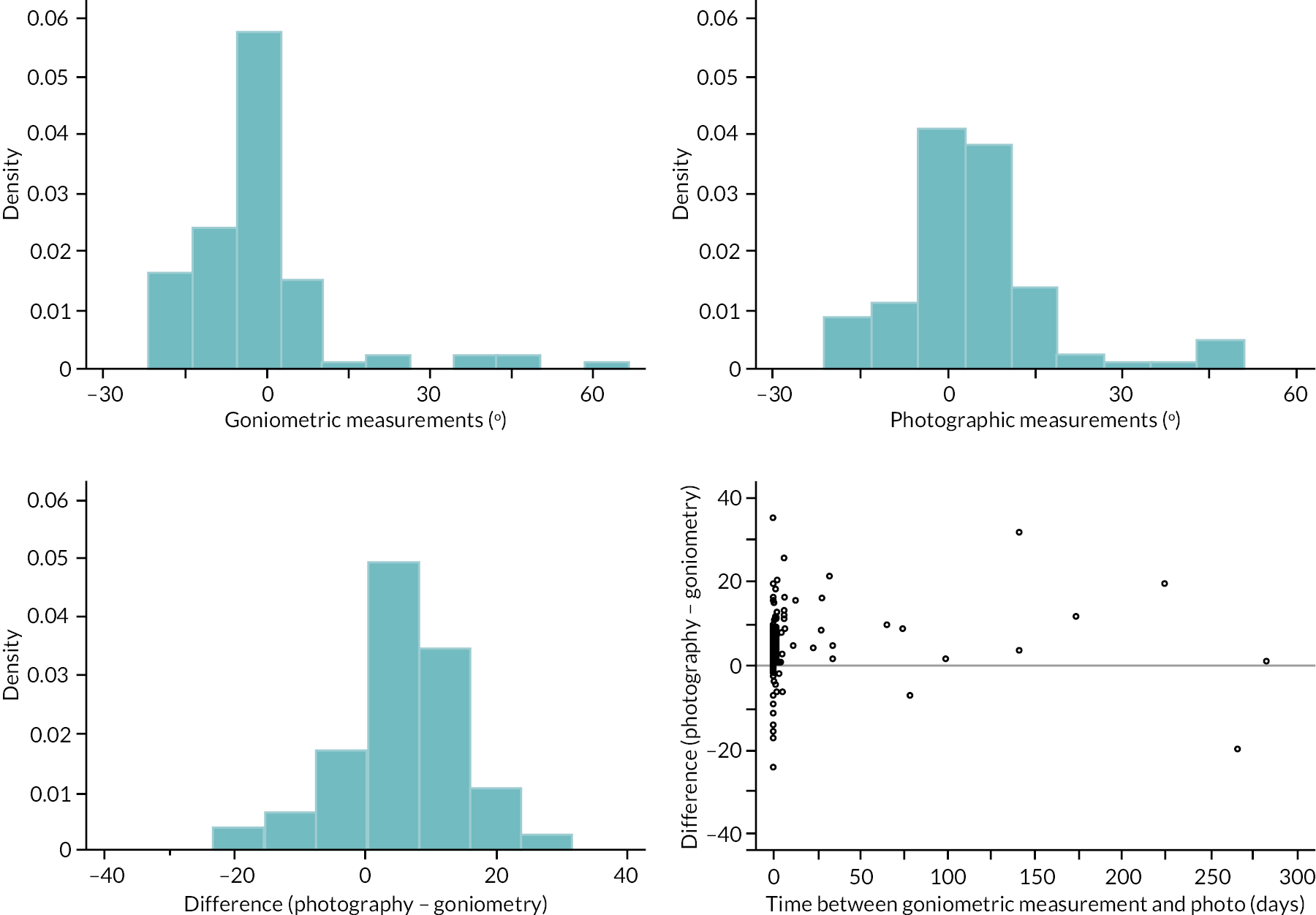

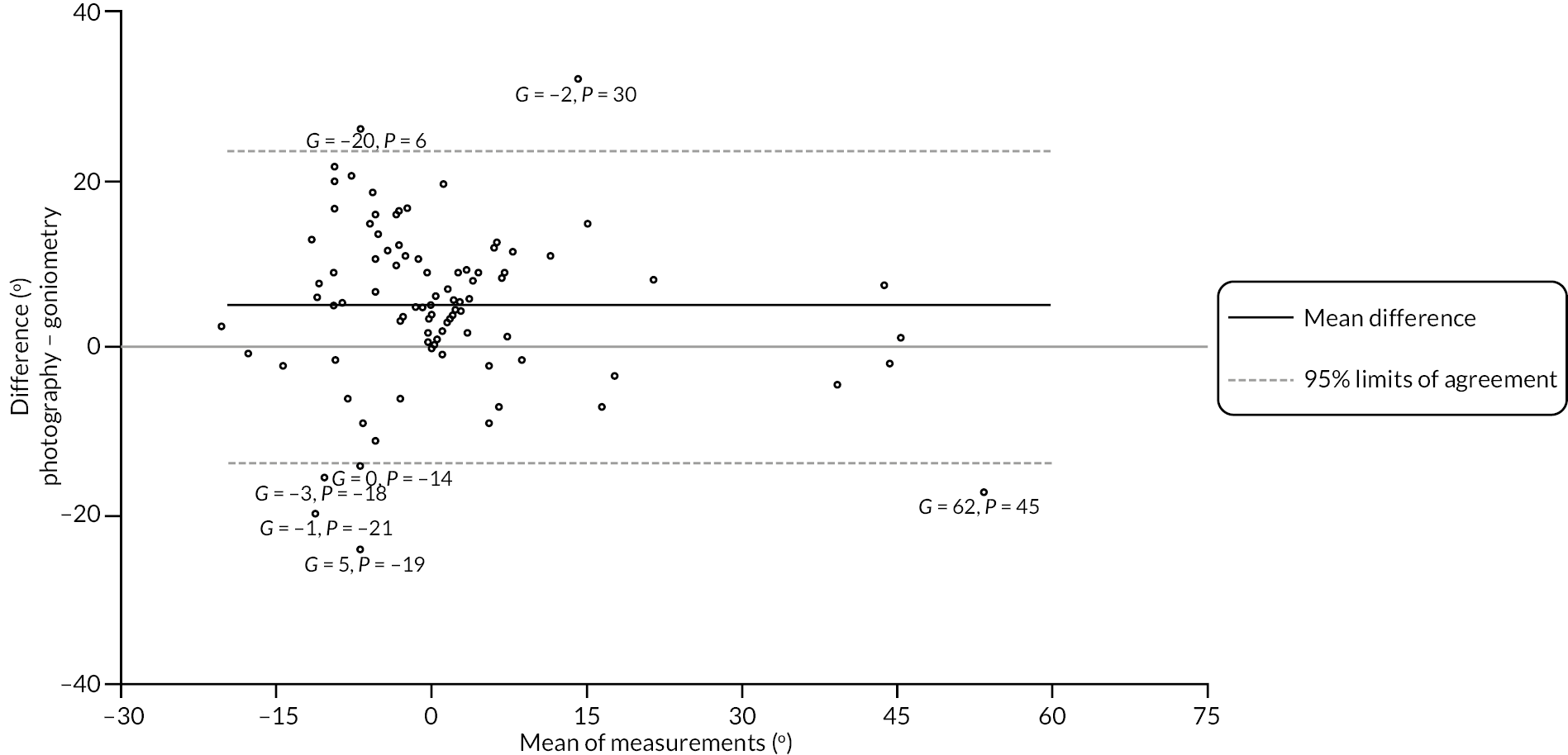

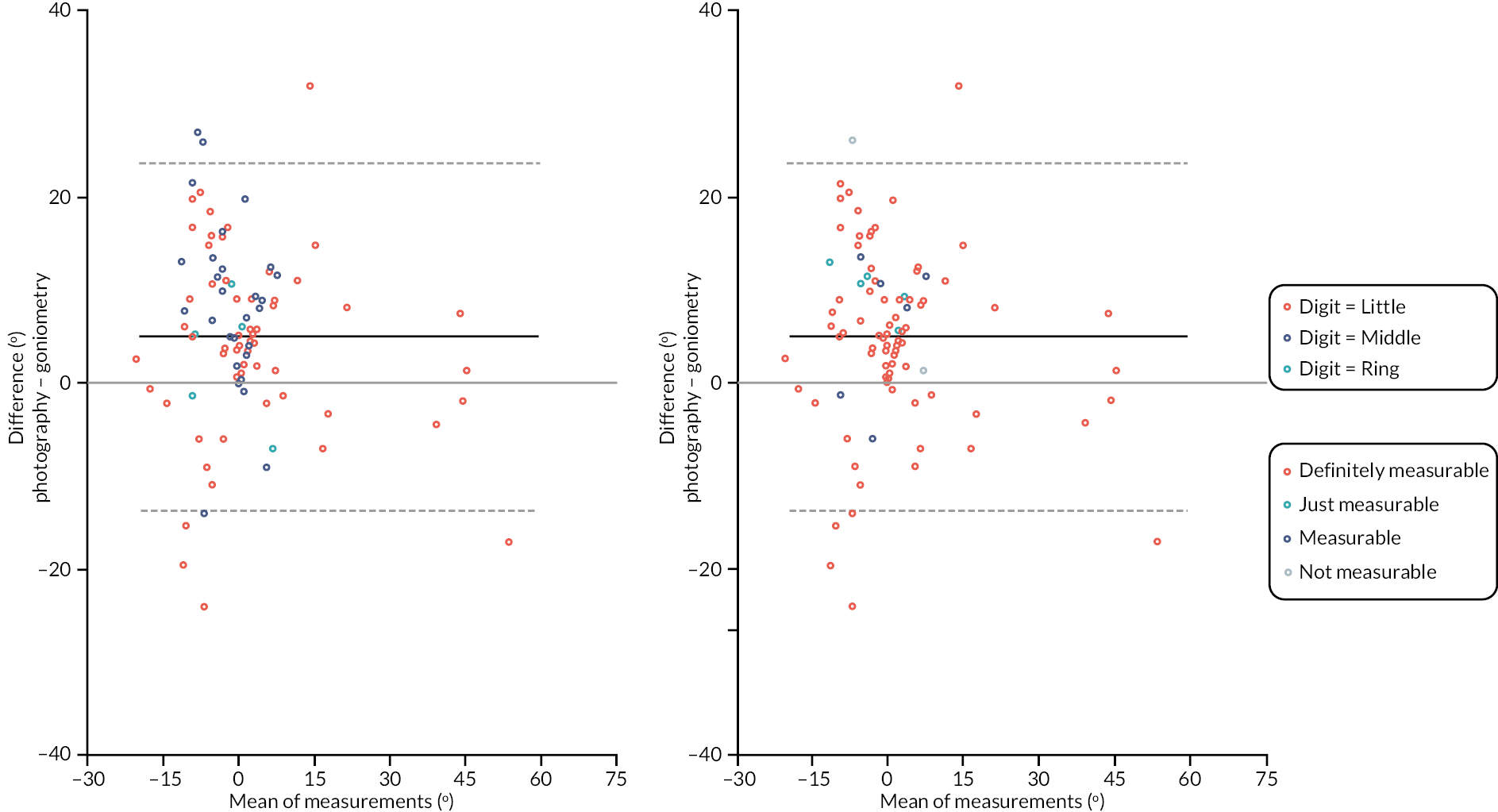

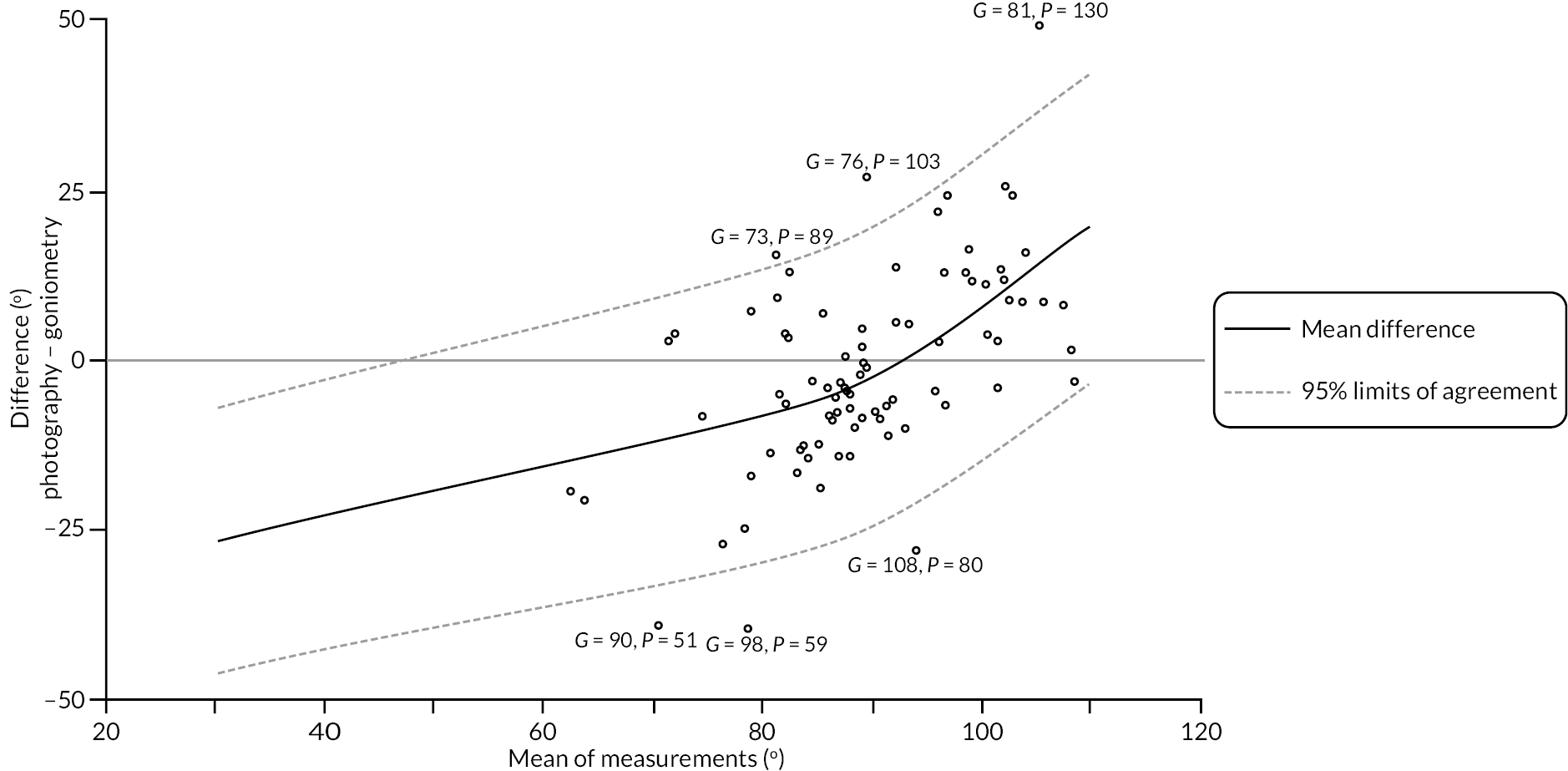

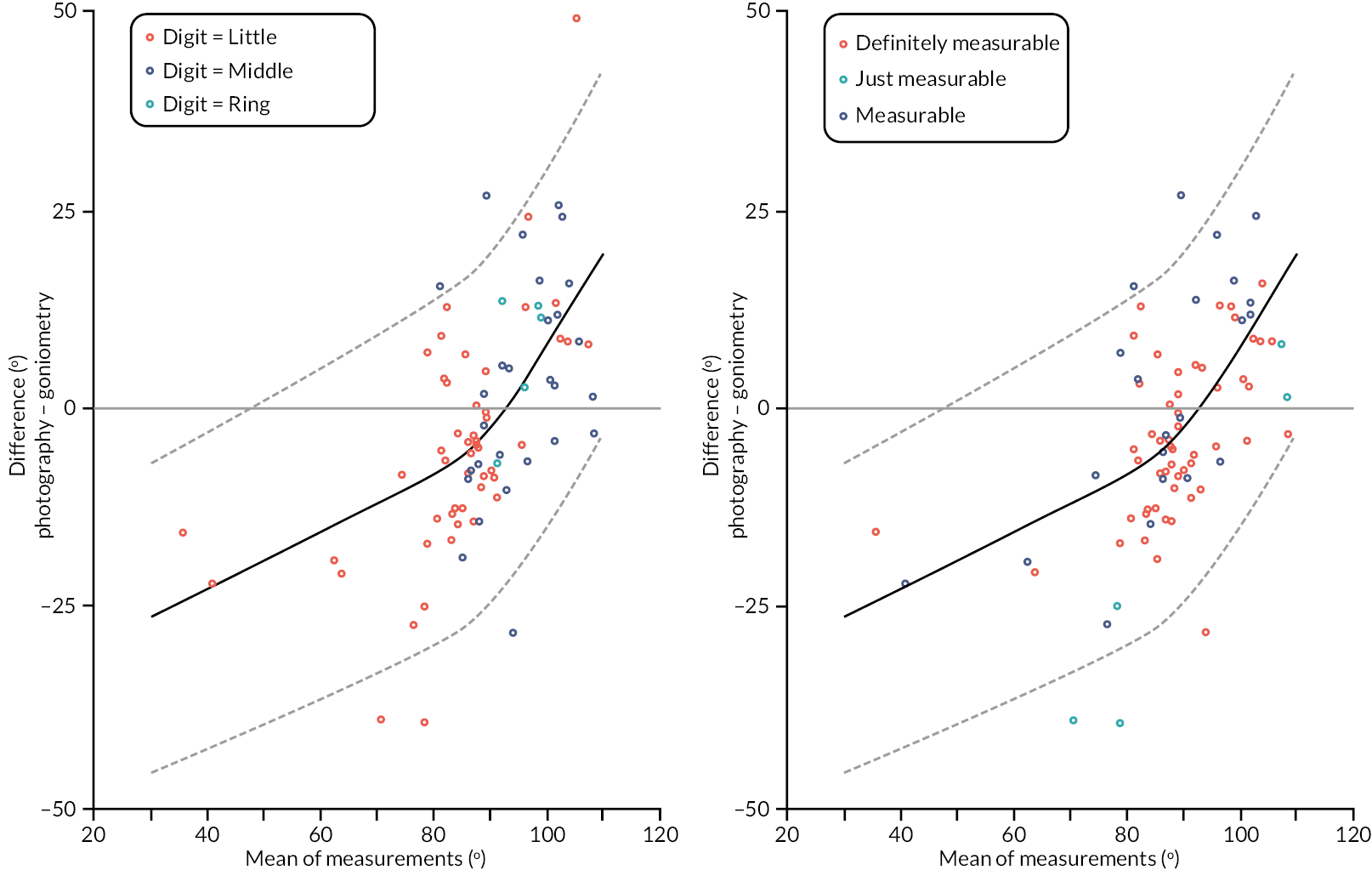

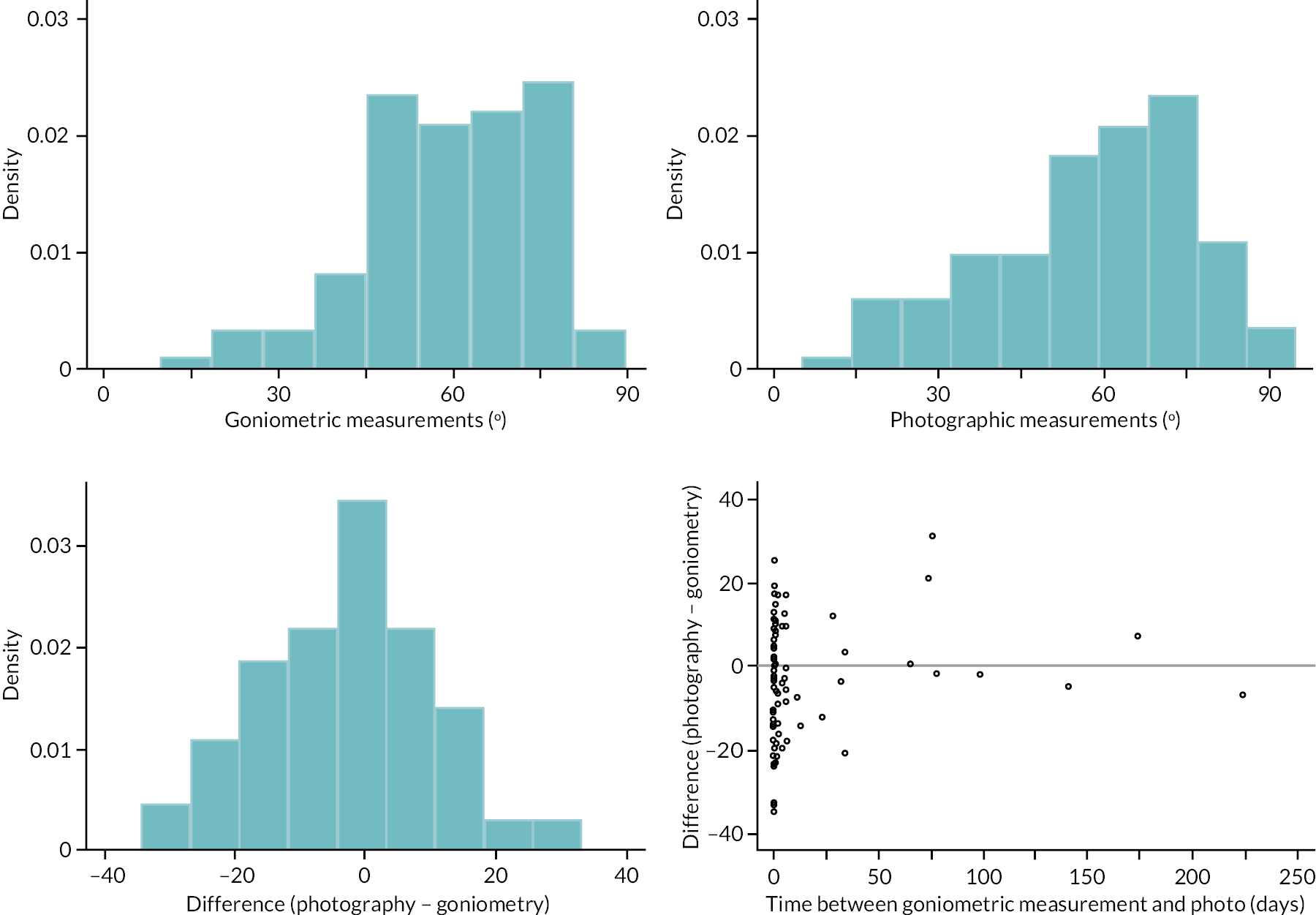

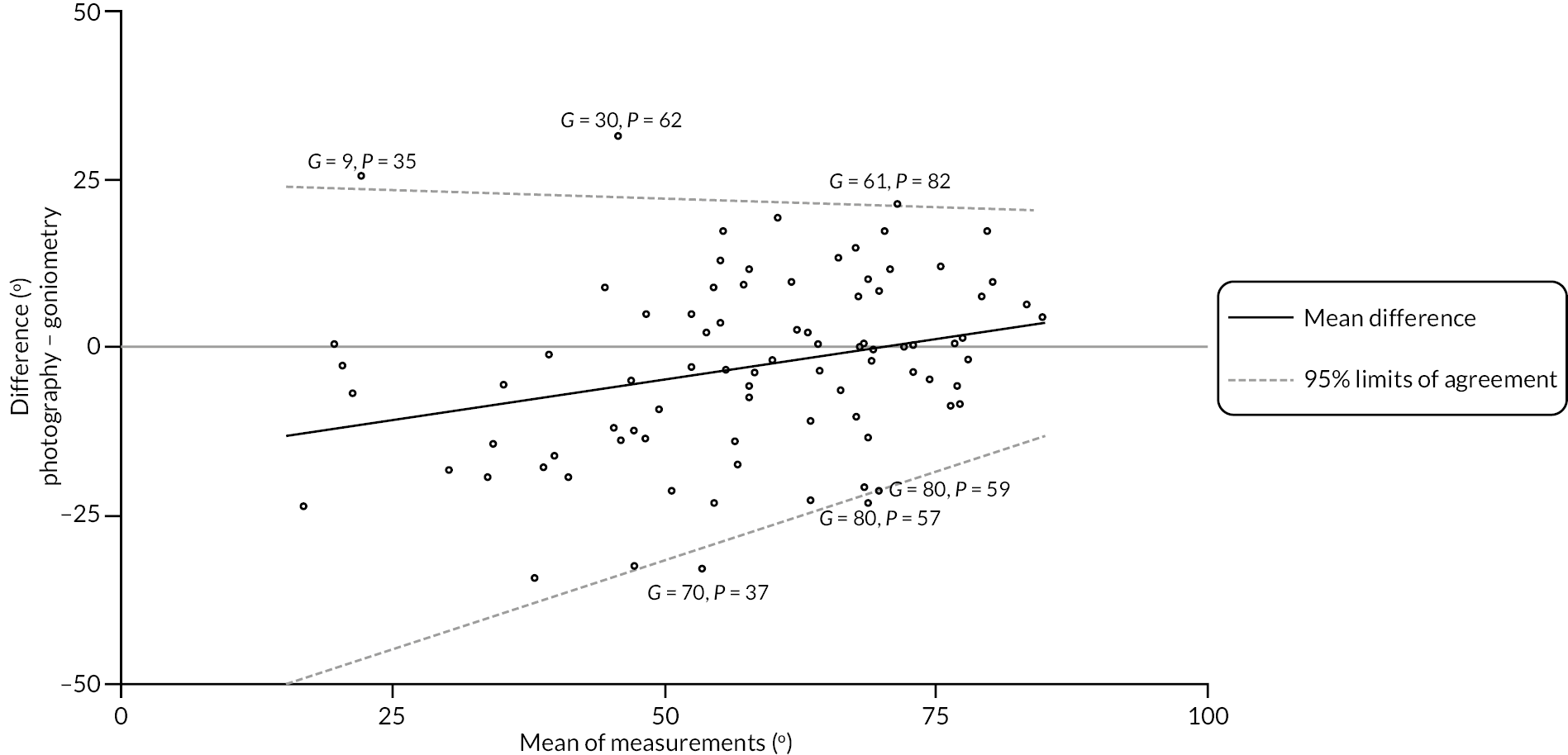

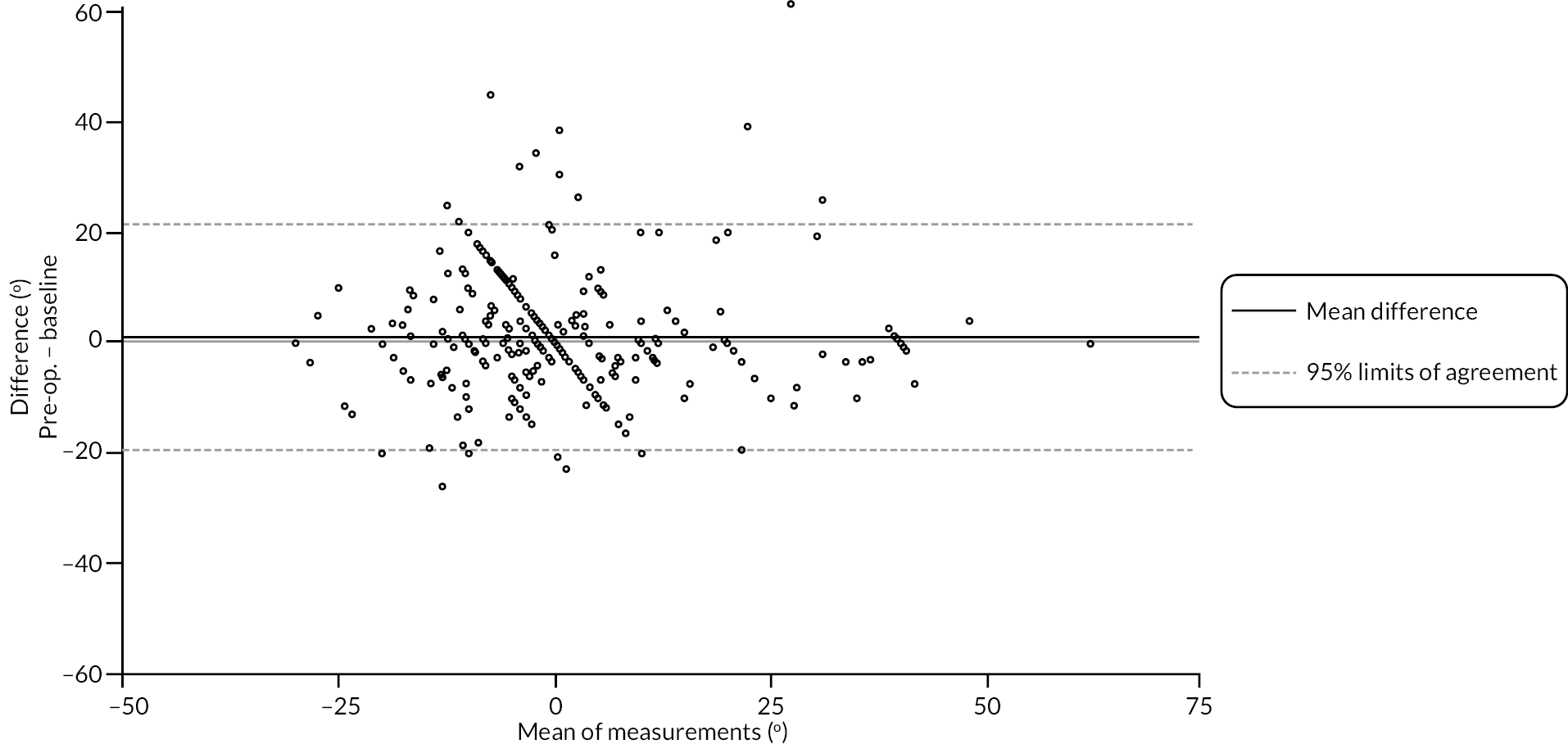

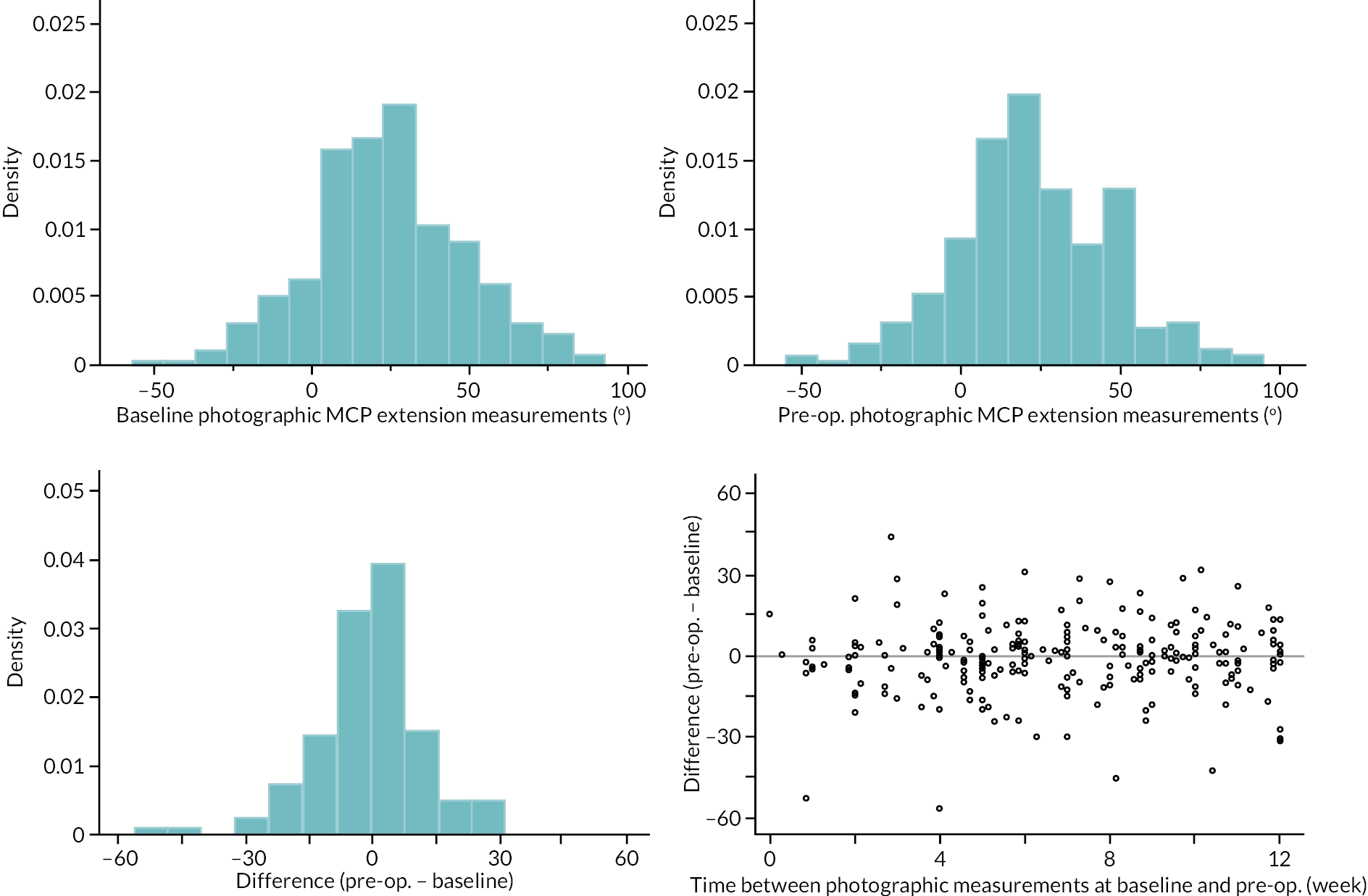

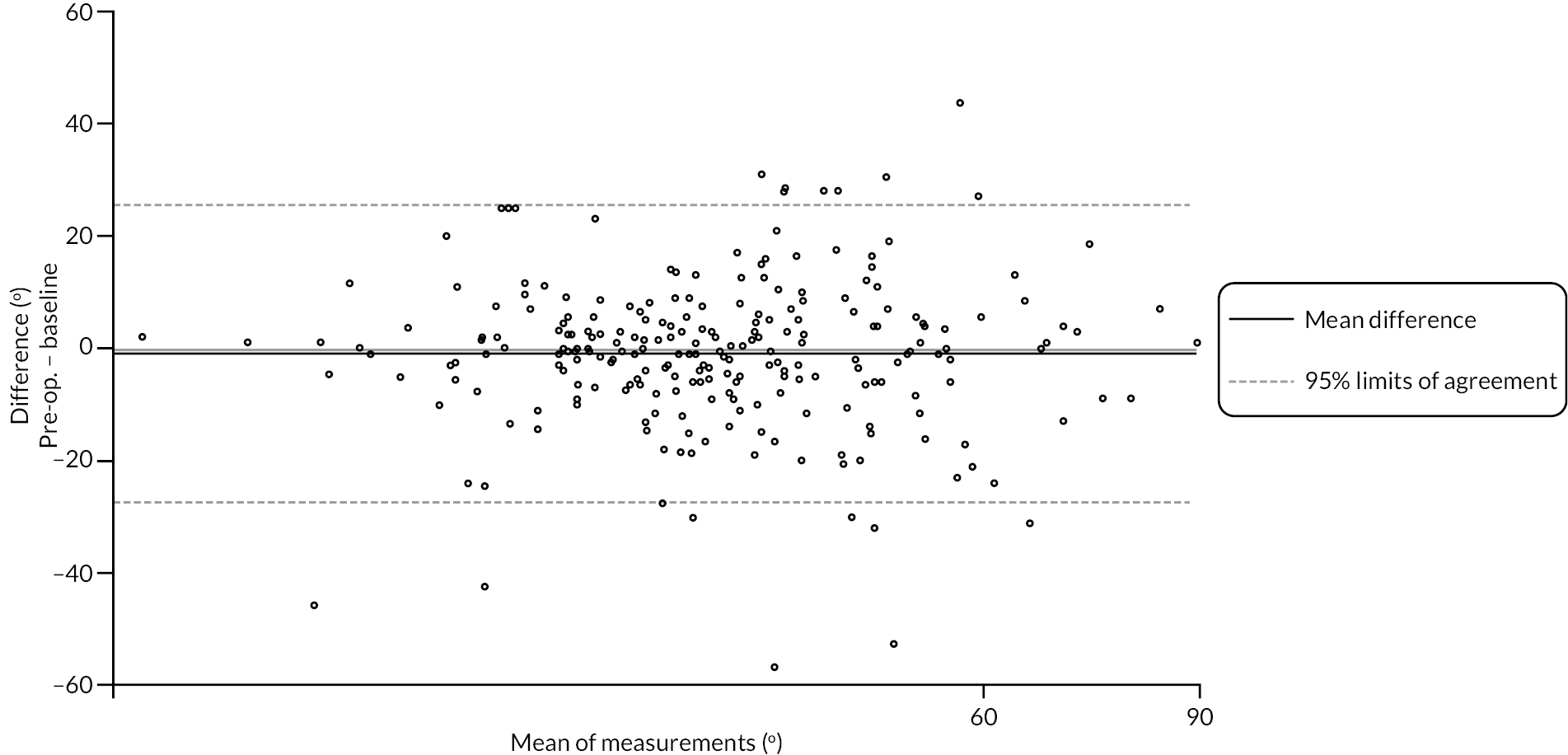

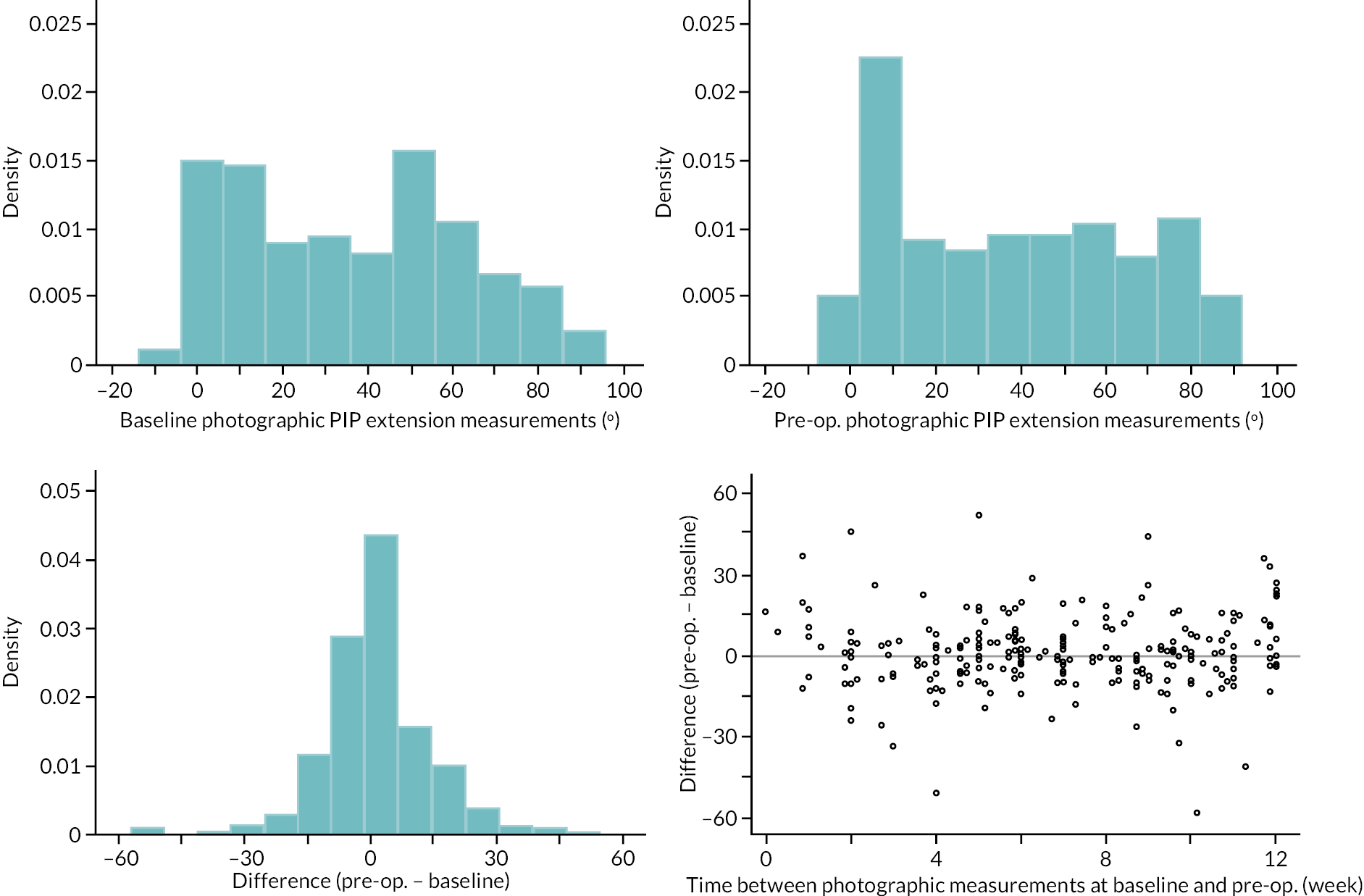

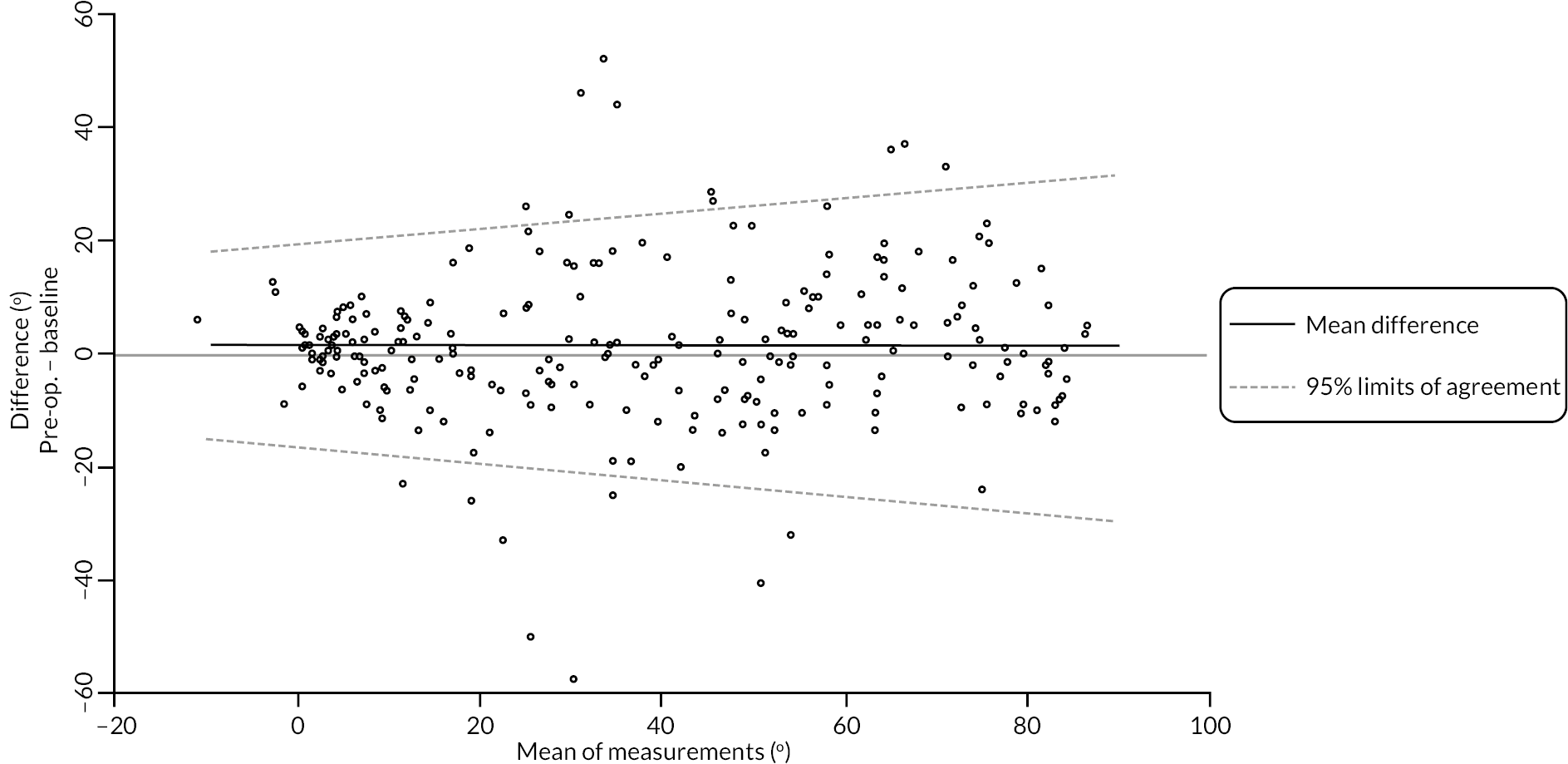

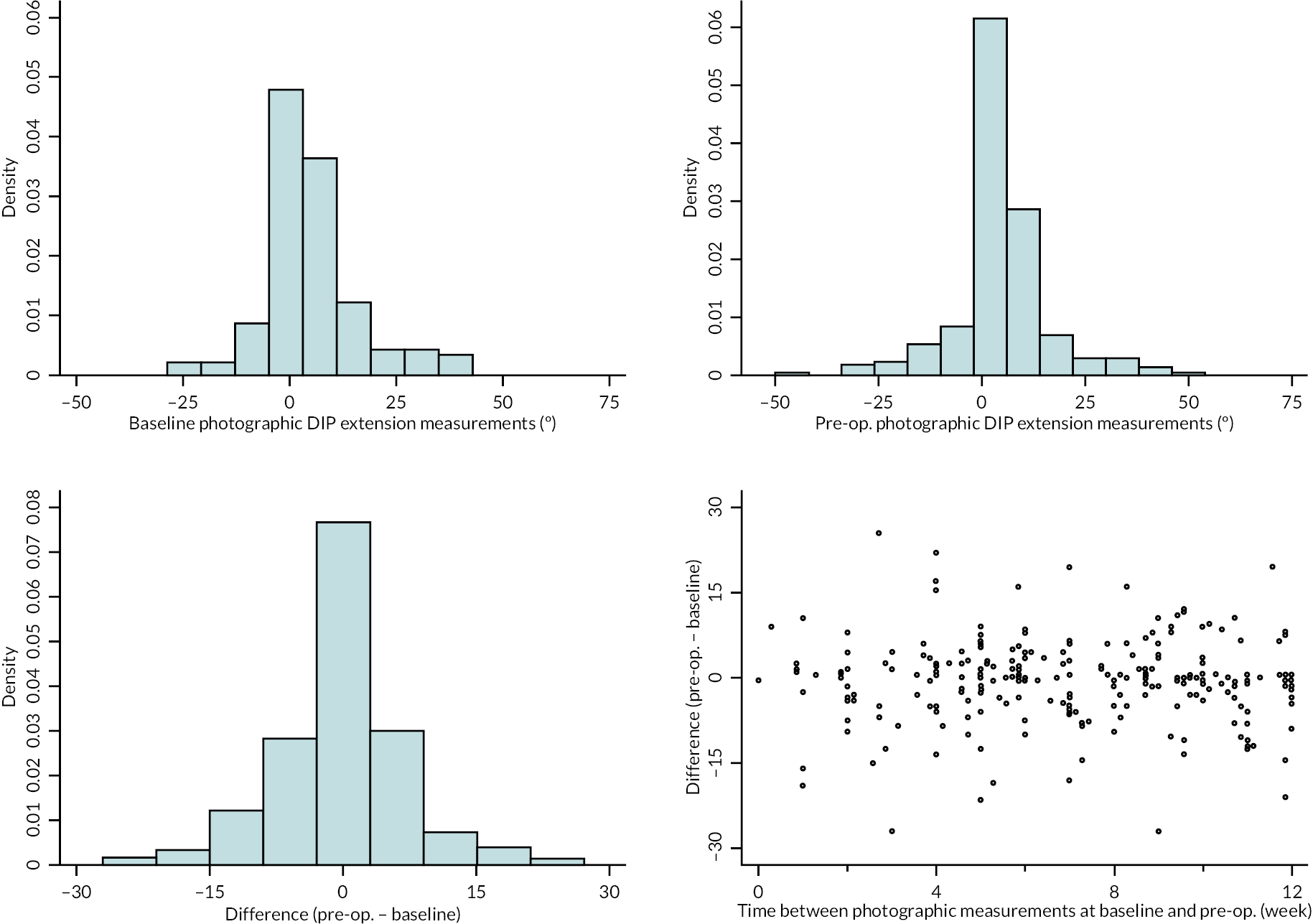

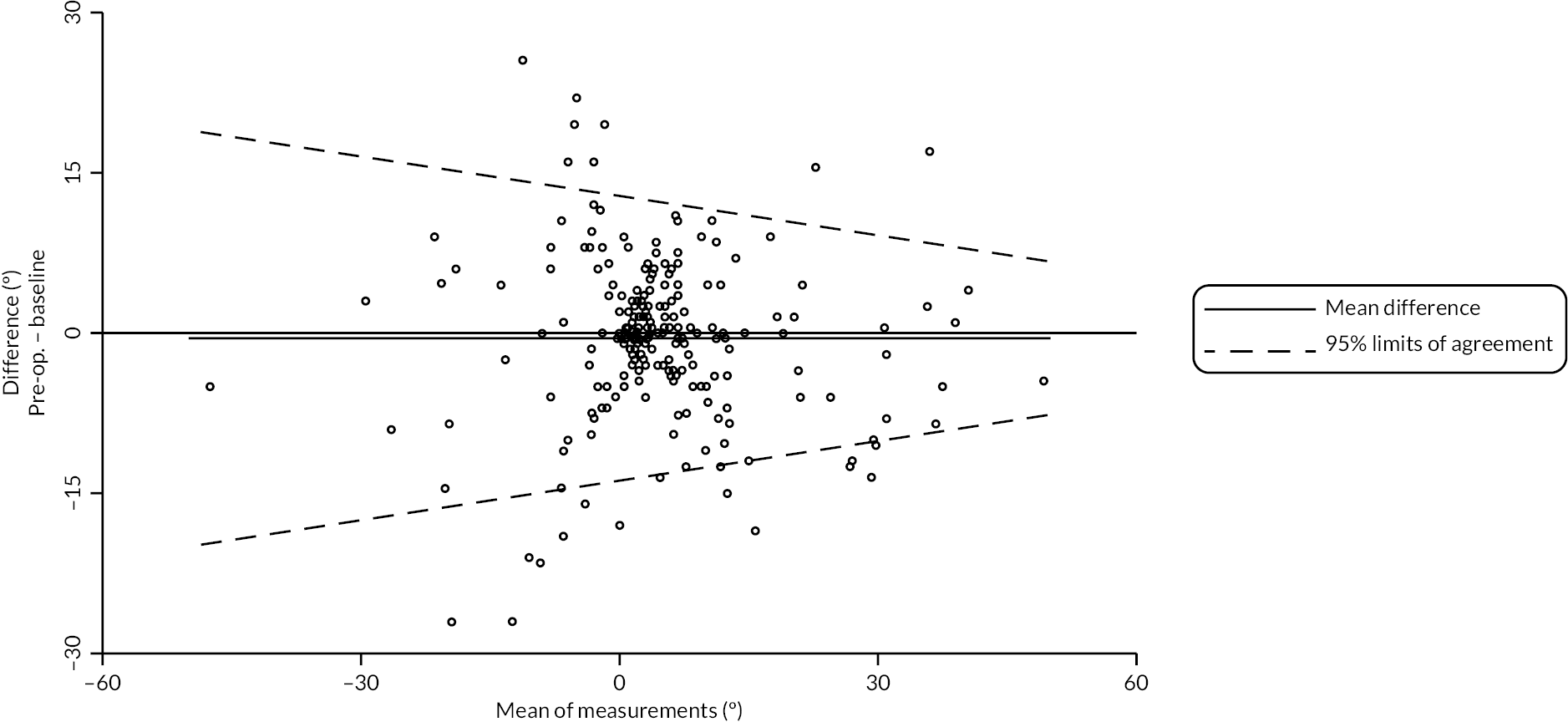

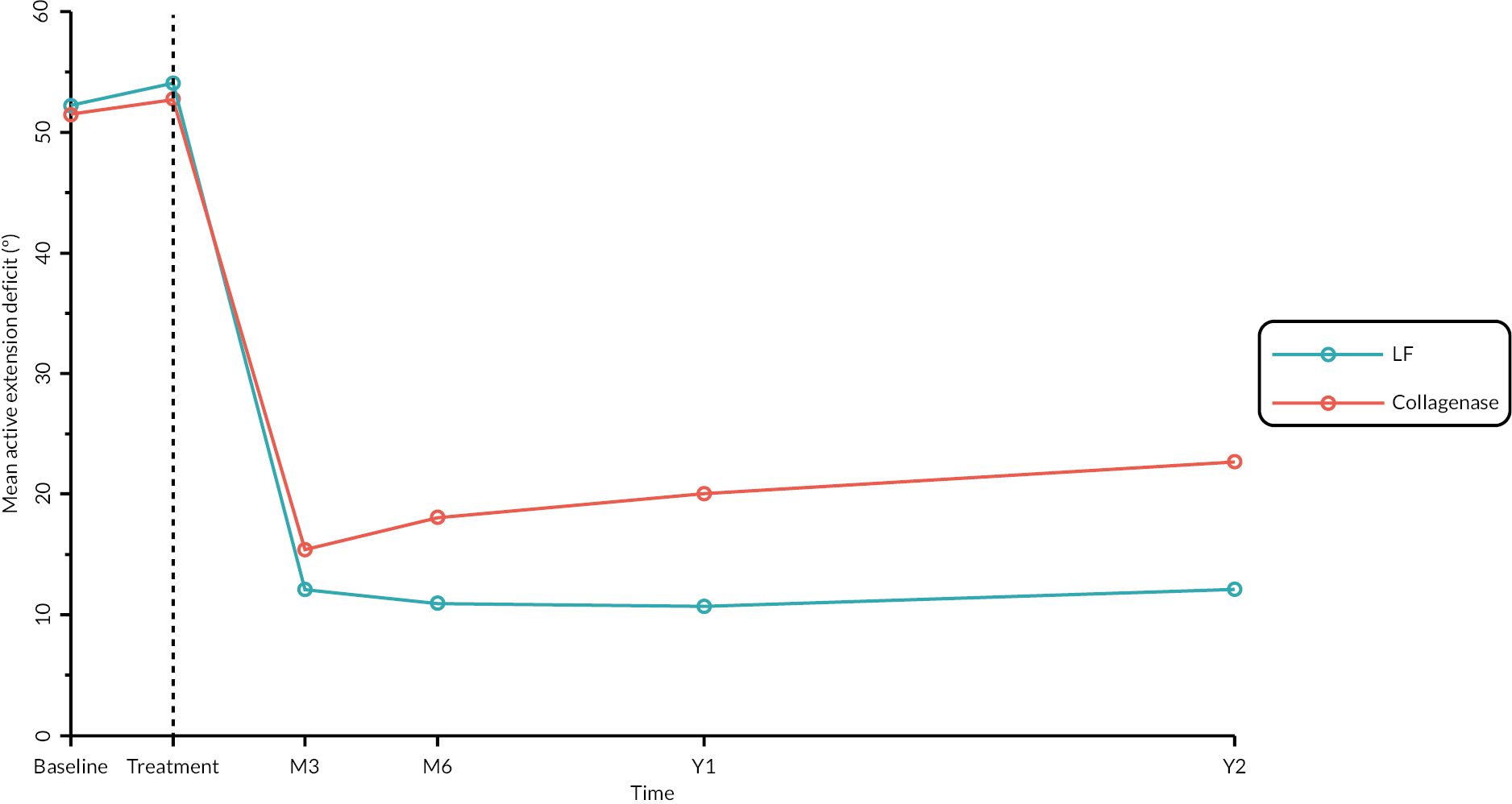

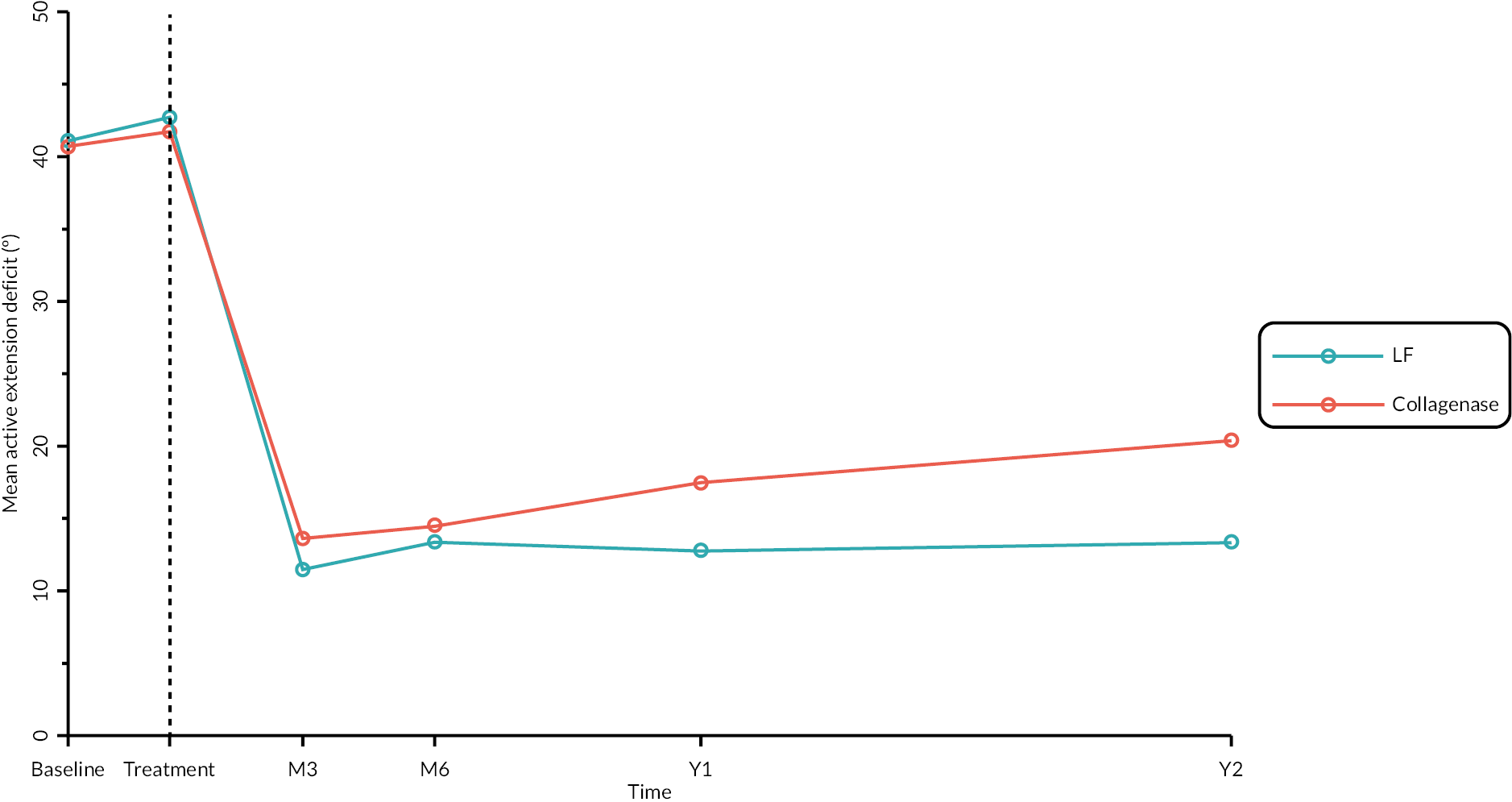

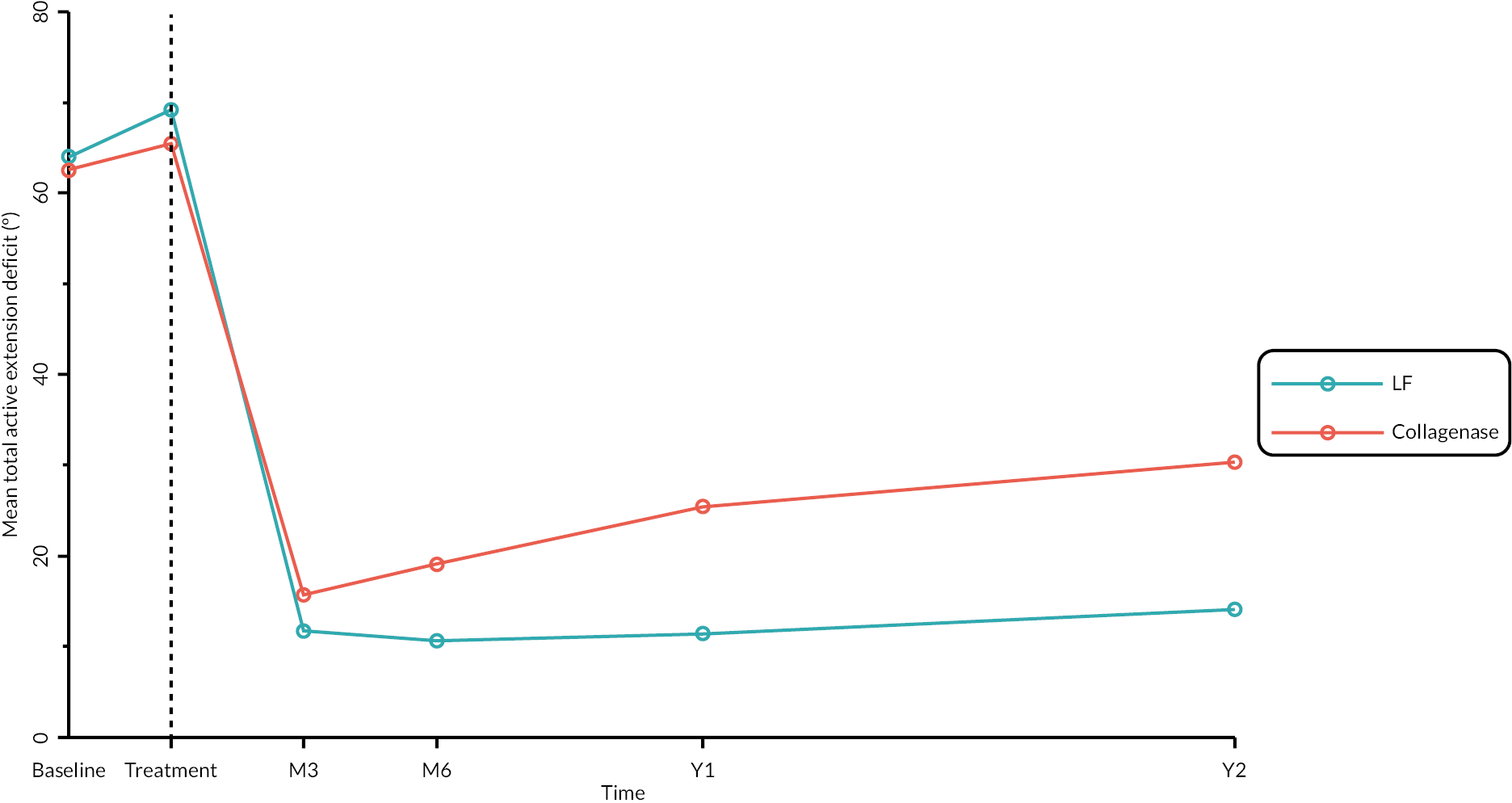

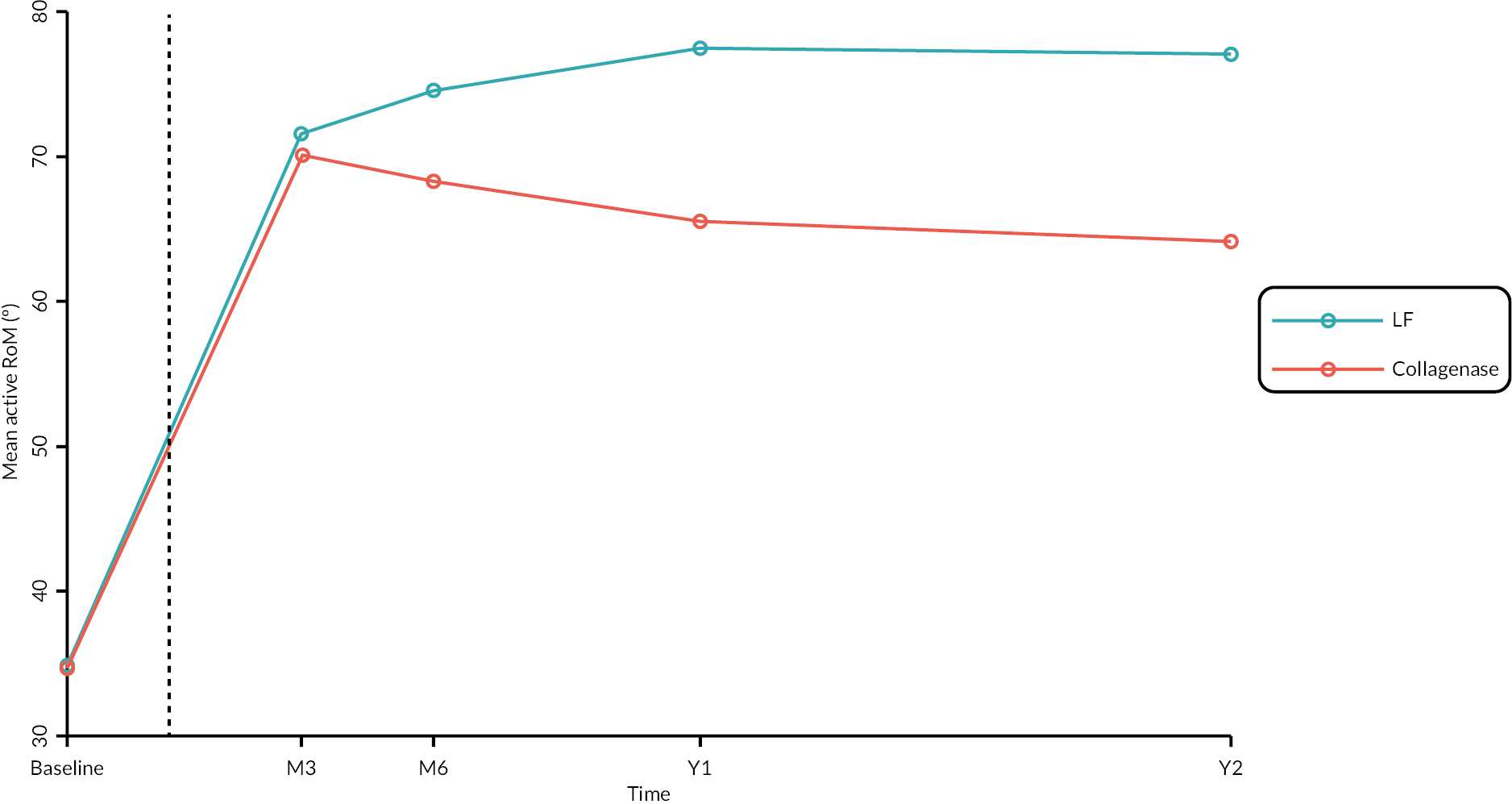

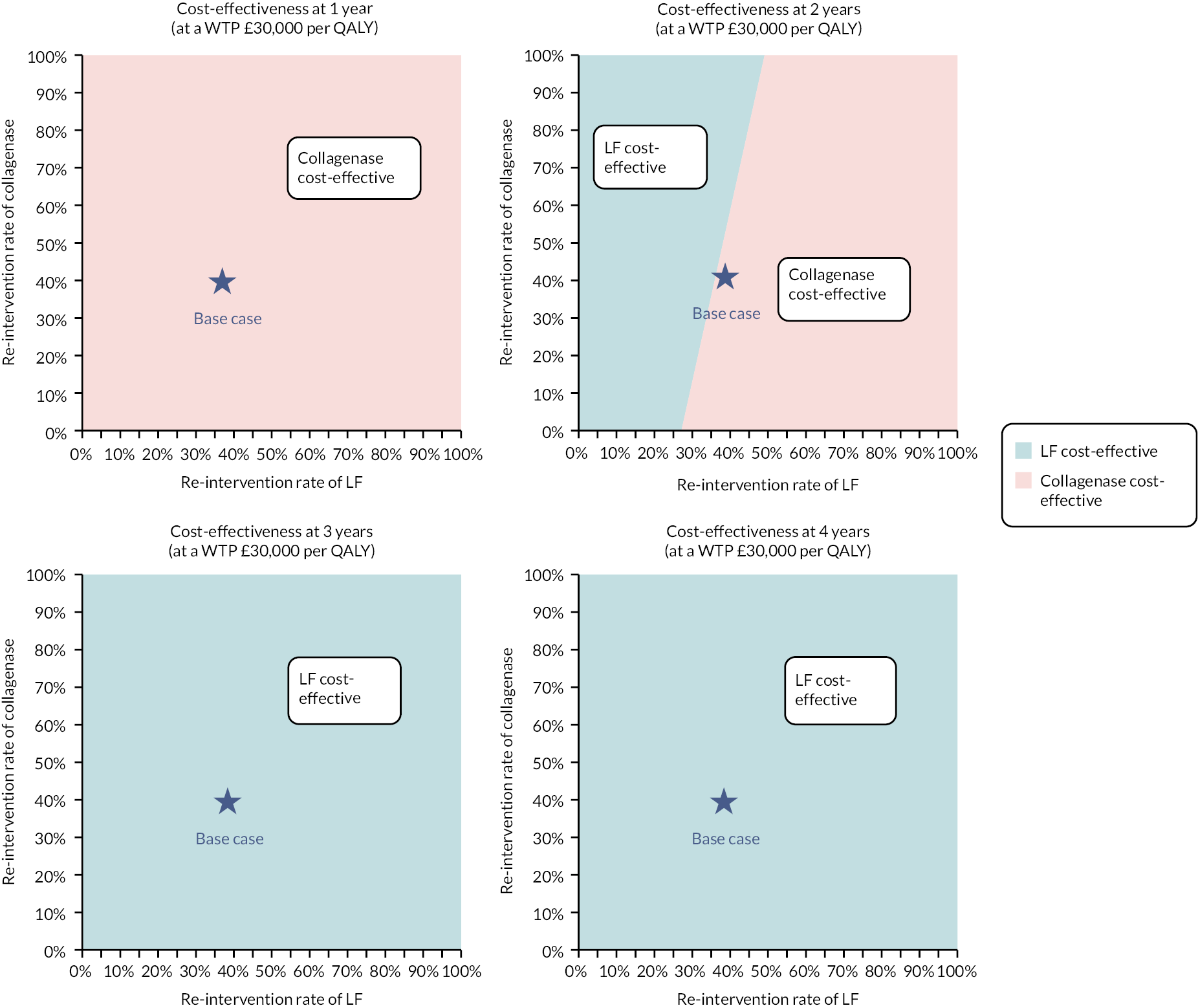

FIGURE 5.