Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/142/04. The contractual start date was in April 2016. The draft report began editorial review in January 2022 and was accepted for publication in May 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Lois et al. This work was produced by Lois et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Lois et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

People with diabetes are at risk of experiencing permanent sight loss because of complications of diabetic retinopathy, including diabetic macular oedema (DMO), proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), and macular ischaemia. 1

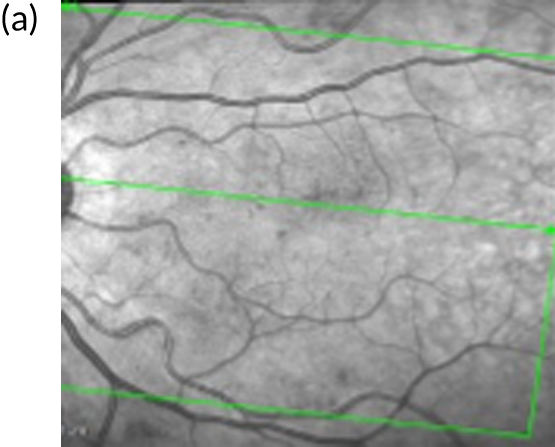

In DMO (Figure 1) fluid, and at times blood and lipid (fat), leaks from the retinal blood vessels, damaged by the chronically high glucose environment and its consequences, and builds up in the centre of the retina, the macula, the area responsible for central vision. As a result, the macular function is compromised, and the person’s sight is reduced.

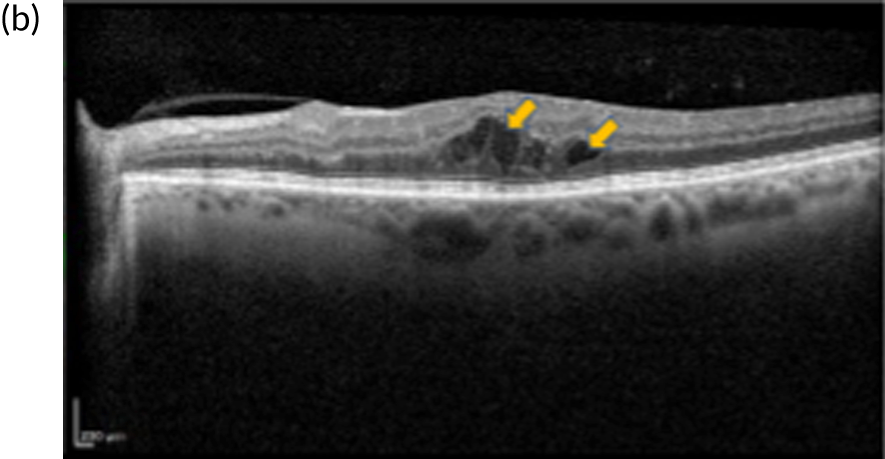

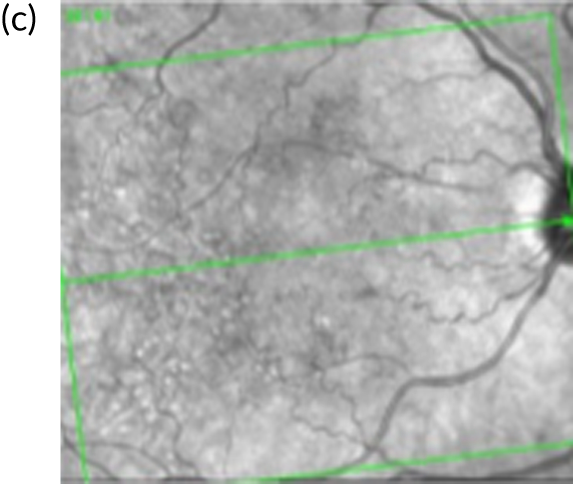

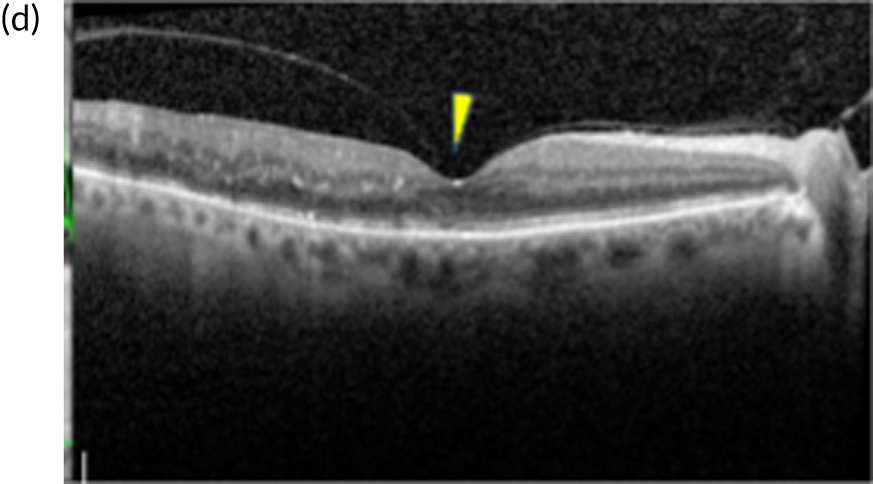

FIGURE 1.

Infrared and optical coherence tomography (OCT) images of patients with and without diabetic macular oedema (DMO). (a) Infrared image and (b) optical coherence tomography (OCT) scan of the macula (left eye) of a patient with DMO. Fluid is observed as areas or reduced reflectance (arrows) on the OCT scan. For comparison, (c) infrared image and (d) OCT scan of the macula (right eye) of another patient in whom DMO cleared following treatment. The normal depression at the centre of the macula (fovea) is present (arrowhead).

Currently, depending on the amount of fluid present [this can be measured using a diagnostic technology called optical coherence tomography (OCT) (Figures 1b and 1d)], different treatment options are recommended for patients with DMO. If the amount of fluid is considerable [i.e. people with a central retinal subfield thickness (CRT), as measured with OCT, of ≥ 400 µm], the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends treatment with intravitreal eye injections of drugs; this is known as anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy. 2,3 Anti-VEGF therapy is required monthly during the first year of treatment for most patients and at less frequent intervals thereafter, until the fluid clears. If the amount of fluid in DMO is less severe (a CRT of < 400 µm on OCT) macular laser treatment is recommended by NICE as the treatment of choice as, for this group, macular laser is as clinically effective as anti-VEGF therapy but less costly. 1,2,4 Macular laser is applied in a single session with topical anaesthetic drops; injections of local anaesthetic are not required as it causes no discomfort/pain to patients. The topical anaesthesia is used as to apply the laser, a viewing contact lens needs to be placed on the surface of the eye, so an appropriately magnified and sharp view of the macula is obtained to perform the treatment. Laser sessions may need to be repeated every 3–4 months until the fluid clears.

The first randomised clinical trial (RCT) that showed a benefit of laser treatment for people with diabetes and macular oedema was the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS). 5 The ETDRS demonstrated that macular laser reduced the risk of visual loss (≥ 3 ETDRS line loss) by 50% at 3 years in patients with what was defined as clinically significant diabetic macular oedema (CSMO). 5 The definition of CSMO was based on the presence of the following characteristics on clinical examination (slit-lamp biomicroscopy): (1) thickening of the retina at or within 500 µm from the centre of the macula, (2) hard exudation at or within 500 µm from the centre of the macula provided that it was associated with adjacent retinal thickening or (3) thickening of the retina of the size of the optic nerve head or larger within one disc diameter from the centre of the macula. In the ETDRS only 3% of patients had improvement in vision of ≥ 15 letters, but 85% of eyes included in the study had excellent vision at baseline (Snellen equivalent ≥ 20/40) which may have accounted for the limited visual improvement observed. More recent RCTs on laser treatment for centre-involving DMO showed laser can indeed improve vision, with improvements of ≥ 10 ETDRS letters observed in 32% of eyes at 2 years and in 44% of eyes at 3 years. 6,7

It is important to note that centre-involving DMO may not necessarily mean CSMO. In regards to this, trials conducted comparing anti-VEGF therapy with macular laser included people with centre-involving DMO. Centre-involving DMO is defined based on OCT findings. The natural history of centre-involving DMO diagnosed by OCT is less clear than that of CSMO.

Macular laser is also used in patients with DMO who do not fully respond to anti-VEGF therapy. In a randomised trial comparing different anti-VEGF drugs to treat centre-involving DMO, 41–64% of eyes receiving anti-VEGF therapy required macular laser by 2 years following treatment initiation to control the disease. 8

In the ETDRS study,5 laser treatment was undertaken using a continuous wave laser. This laser [referred to as ‘threshold’ laser, and here, throughout this report, as standard threshold macular laser (SL)] produces a visible burn in the retina and is considered the ‘standard’ manner in which to perform macular laser. The laser energy when using this SL is predominantly absorbed by one of the layers of the retina, the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and converted into heat. Although the mechanism of action of macular laser is not completely understood, it is believed that it has its effect, at least partly, by acting on still viable RPE cells around the area of the burn. Given that heat spreads by conduction, there could be damage to the retinal layers overlying the RPE, including photoreceptor cells (i.e. the cones and rods which are the visual cells of the retina). SL can ‘burn’ the retina and, if applied to the centre of the fovea (the centre of the macula, which is the area of the retina that provides maximal central vision) could cause marked central sight loss. Therefore, this form of laser requires considerable expertise by the clinician administering it as the fovea may not be easily identifiable when thickened by DMO. Ideally, as advised by the ETDRS,5 a fundus fluorescein angiogram (FFA) would be performed to identify areas of leakage that should be aimed at by the laser treatment. However, clinicians may opt to use SL to treat areas of macular thickening as observed on OCT. 6,7 Side effects of SL, besides the potential burning of the fovea as explained above, could include paracentral scotomas (areas of loss of sight around the centre) which can potentially affect driving ability, colour vision deficits and formation of scarring over or under the retina (i.e. epiretinal membrane/subretinal fibrosis, respectively). If strong laser is applied close to the centre of the macula, the size of the ‘burn’ (i.e. the area where retinal cells are lost) could expand over time and, even if initially the centre is not affected, central loss of vision could occur over time.

Macular laser treatment can also be delivered using what is called ‘subthreshold’ micropulse laser (SML). In SML, a series of repetitive, very short pulses of laser are delivered, with each pulse of active ‘on’ laser separated by a long ‘off’ time. This ‘off’ time allows for cooling of the retina, preventing the development of a ‘burn’ and, thus, leaving the RPE and overlying neurosensory retina, including photoreceptors, intact. It is believed SML acts by directly stimulating the RPE. As there is no destruction of the retina, this treatment could be applied to larger areas of the retina (not only those with ‘leaking’ blood vessels or thickened by DMO) in a standardised fashion and repeated as many times as needed.

Although the lack of a ‘burn’ in the retina would appear to be of clear advantage, the absence of clinically objective changes in the retina following SML has led to some clinicians/researchers being sceptical of SML having equally beneficial effects as SL. Earlier studies, however, including small RCTs, have shown comparable or superior results using SML. Lavinsky et al. 9 showed superiority regarding improvement in vision and reduction in CRT at 12 months following high-density SML in a three-arm trial that included 123 participants with CSMO (n = 42 and n = 39 randomised to high-density and low-density SML, respectively; and n = 42 to SL). Similarly, in a smaller RCT which included 62 eyes from 50 patients with centre-involving CSMO (32 eyes received SML and 30 eyes received SL) Vujosevic et al. 10 found no statistically significant differences in vision or CRT between laser groups, but a statistically significant increased retinal sensitivity (i.e. better retinal function) on microperimetry testing following SML. Other trials by Figueira et al. (n = 53 patients with CSMO according to the ETDRS definition),11 Venkatesh et al. 12 (n = 33 patients with CSMO), Kumar et al. 13 (n = 20 patients with CSMO according to ETDRS criteria) and Laursen et al. 14 (n = 16 patients with CSMO), with follow-up of 18 weeks and 8, 12 and 5 months, respectively, found no statistically significant differences in vision and CRT between both types of laser. A more recent RCT by Xie et al. 15 which included 84 patients (99 eyes) receiving standard argon laser (n = 49 eyes) or SML (n = 50 eyes) also found comparable results between laser groups.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis by Chen et al. ,16 which included all but one (Kumar et al. 13) of the RCTs mentioned above, and based on data from 398 eyes (203 eyes in the SML group and 195 in the SL group), SML was found to be statistically significantly superior to SL in terms of mean change of best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) at 3, 9 and 12 months following treatment, with no statistically significant difference in change in CRT. The largest difference in BCVA between laser arms was observed at 12 months (0.1 log-MAR) favouring SML, but this seemed to be due to the effect of one trial (Lavinsky et al. 9), and to the high-density arm of this trial; the difference would not be considered, in any case, clinically important (0.1 log-MAR, equivalent to 5 ETDRS letters).

Qaio et al. 17 subsequently published another systematic review comparing SML laser with SL, which included seven RCTs, all six included in Chen et al. ’s review16 and, in addition, the study by Kumar et al. ,13 with a total of 467 eyes from 379 participants. The primary outcomes were change in BCVA and CRT. Secondary outcomes included contrast sensitivity and retinal damage; neither quality of life nor cost-effectiveness of the treatments were evaluated. Meta-analysis found no statistically significant differences in outcomes at any time point (longest follow-up was 12 months). There was comparable preservation of contrast sensitivity with SML with less retinal damage. The review authors concluded that SML was as good as SL but caused less retinal damage.

The results of the review by Qiao et al. 17 differ somewhat from those of Chen et al. 16 owing to the choice of arm and outcome from the RCT conducted by Lavinsky et al. 9 The review by Qiao et al. 17 reported mean BCVA at 12 months with three trials, Figueira et al.,11 Lavinsky et al.,9 and Vujosevic et al.,10 whereas the review by Chen et al. 16 reported change from baseline with only two trials at 12 months, Lavinsky et al. 9 and Vujosevic et al. 10 The Lavinsky et al. 9 RCT had two SML arms, one with normal and another with high-density SML treatment, and reported better results with the latter. The Chen et al. 16 meta-analysis used only the high-density arm whereas the Qiao et al. 17 meta-analysis used only the normal density arm. Their different conclusions were due to the Lavinsky et al. trial,9 deemed to give a significant result in Chen et al. 16 (based on change from baseline) but not in Qiao et al. 17 (based on mean BCVA at 12 months).

A Bayesian network meta-analysis by Wu et al. 18 found no significant difference in mean change in BCVA and CRT between SL and SML. A 2018 Cochrane systematic review19 and meta-analysis by Jorge et al. concluded SML may be as effective as SL, but the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) assessment was of low certainty.

All conducted meta-analyses were limited by the inherent limitations of the available RCTs, including the short follow-up (longest follow-up of 12 months). Furthermore, it is unclear what the proportion of participants with a CRT of < 400 µm was in the RCTs included, which based on NICE guidelines would be the participants most likely to respond to macular laser. 1,2,4

Recently (and thus not included in any of the systematic reviews mentioned above) a small (68 participants, 34 in each group), very short-term (4 months) RCT by Fazel et al. 20 compared SML with SL in people with CSMO and with a CRT of less than 450 µm. Changes in CRT were statistically significantly higher in the SML group than the SL group. Changes in macular volume and visual acuity were only significant in the SML group but not in the SL group.

In summary, published data suggest that SML is comparable, and potentially even superior, to SL, but stronger evidence is required. None of the trials conducted comparing SML and SL included patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) or the cost-effectiveness of the treatments. Furthermore, outcomes were measured, at the longest, at 12 months. Given the lack of destruction of retinal tissue, SML can be given to larger areas of the macula and repeated as needed, potentially indefinitely. SML may allow for a more standardised delivery of treatment (e.g. using set grids that cover the entire macula), which could, in turn, minimise variability in the quality of treatment delivered, with successful delivery being less dependent on the surgeon’s skills. The lack of deleterious effects when used over the fovea21 makes SML very safe (i.e. sight loss as a result of an inadvertent foveal burn is obviated), potentially facilitating training on its application to junior ophthalmologists and ophthalmic-allied non-medical staff. This would be highly advantageous considering the major problems with capacity currently faced in ophthalmic clinics throughout the world.

On this basis, the DIAMONDS (DIAbetic Macular Oedema aNd Diode Subthreshold micropulse laser) trial was designed as a non-inferiority trial of the efficacy of SML when compared with SL, although the trial was also powered to test equivalence and superiority (if this were to exist). We chose central vision as the primary outcome, as this is very important to people with diabetes and DMO, and set the non-inferiority margin at 5 ETDRS letters (equivalence margin as ± 5 ETDRS letters), as visual changes of this size should not be clinically relevant to patients and could even be due to test/re-test variability.

Chapter 2 Clinical trial methods

Parts of this chapter are adapted or reproduced from Lois et al. 22 and Costa et al. 23 These are Open Access articles distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original texts.

Aims

The DIAMONDS trial aimed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SML when compared with SL for the treatment of patients with centre-involving DMO with a CRT on spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) of < 400 µm.

Primary objective

The primary objective of the trial was to determine whether or not SML is non-inferior (or equivalent) to SL at improving or preserving vision 24 months after treatment in patients with centre-involving DMO with a CRT of < 400 µm. The non-inferiority margin was set at 5 ETDRS letters (and the equivalence margin at ± 5 ETDRS letters), as a difference of this size is not considered to be clinically relevant and could even be due to test/re-test variability. 2,3,8,24–26

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives of the trial were to determine whether or not SML is superior to SL at improving or preserving binocular vision and visual field; reducing or clearing DMO; allowing treated patients to achieve driving standards; and improving their health- and vision-related quality of life 24 months after treatment. The relative cost-effectiveness of SML when compared with SL was also evaluated, as well as the side effects of these treatments, the number of laser treatments required and the need for additional treatments (other than laser).

Trial design

The protocol for the DIAMONDS trial was published in February 2019. 22 The DIAMONDS trial was a pragmatic, multicentre, allocation-concealed, non-inferiority, randomised, double-masked (participants and outcome assessors), prospective clinical trial set within specialist hospital eye services (HES) (n = 16) in the UK.

Patient eligibility and recruitment

Potential participants were identified at each of the participating sites through electronic databases, through referrals to HES or while in the clinic. Patients identified through electronic databases or referrals were approached by telephone or invitation letter. Verbal and written information about the study was given to potential participants. Informed consent was obtained from patients willing to take part in the trial and they were subsequently recruited. Patients identified while in the clinic were verbally informed about the study and given a patient information leaflet. They were given time to think about their participation and ask questions. If they wished to be enrolled on the same day, they were recruited into the trial following informed consent. If they wanted more time to think about their potential participation, a further visit was organised and, if they were willing to participate at this visit, they were recruited.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for the trial were centre-involving DMO, as determined by slit-lamp biomicroscopy and SD-OCT, in one or both eyes, with either (1) a CRT of > 300 µm but < 400 µm in the central subfield (central 1 mm) owing to DMO as determined by SD-OCT, or (2) a CRT of < 300 µm provided that intraretinal and/or subretinal fluid was present in the central subfield (central 1 mm) owing to DMO.

The following conditions also had to be met:

-

visual acuity of > 24 Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) letters (Snellen equivalent > 20/320)

-

amenable to laser treatment, as judged by the treating ophthalmologist

-

aged ≥ 18 years.

Exclusion criteria

A patient’s eyes were not eligible for the study if their macular oedema was owing to causes other than DMO or if their eyes met the following criteria:

-

ineligible for macular laser, as judged by the treating ophthalmologist

-

DMO with a CRT of ≥ 400 µm

-

active PDR requiring treatment

-

received intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy within the previous 2 months

-

received macular laser treatment within the previous 12 months

-

received intravitreal injection of steroids

-

cataract surgery within the previous 6 weeks

-

panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) within the previous 3 months.

In addition, patients who were otherwise eligible were not included in the study if they met the following criteria:

-

on pioglitazone (Actos®, Takeda UK Ltd.), and the drug could not be stopped 3 months before joining the trial and for its entire duration (because this drug could be responsible for the presence of macular oedema)

-

chronic renal failure requiring dialysis or kidney transplant

-

any other condition that in the opinion of the investigator would preclude participation in the study (such as unstable medical status or severe disease that would make it difficult for the patient to complete the study)

-

very poor glycaemic control that required their starting intensive therapy within the previous 3 months

-

using an investigational drug.

If both eyes were eligible, both eyes would receive the same type of laser but one was designated as the ‘study eye’. This was the eye with the best BCVA at randomisation or, if vision was the same in both eyes, the eye with the lesser CRT.

If the fellow eye was not eligible, baseline data and information on whether or not participants developed DMO or PDR in this eye during the study and about treatments administered to it were recorded in the patient’s case report form (CRF) at months 12 and 24 to determine any possible effects of these events on outcomes.

The DIAMONDS trial participants were similar to those enrolled in the original ETDRS5 in that, like those enrolled in ETDRS, they had mild to moderate non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy and had a visual acuity of 20/200 or better. As mentioned above, ETDRS was the first trial demonstrating the clinical effectiveness of macular laser for the treatment of DMO. However, unlike in ETDRS, DIAMONDS trial participants did not necessarily have to have CSMO to be enrolled, as per ETDRS definition, and they could have only centre-involving DMO as determined using SD-OCT, a technology not available at the time ETDRS was conducted. This follows standard clinical practice.

Ethics approval and consent

The protocol for the DIAMONDS trial22 was approved by the Office for Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland (ORECNI) (15/NI/0197). A Clinical Trial Authorisation (CTA) was obtained from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) (32485/0029/001–0001). The trial was registered with the European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials (EudraCT) database (2015-001940-12), in the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) register (ISRCTN16962255), and at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03690050).

Informed consent

Informed consent to participate in the study was sought from potentially eligible participants by the ophthalmologist or a designee at each participating site. The treating ophthalmologist also obtained informed consent before carrying out the allocated laser procedure.

Participant withdrawal

Participants could withdraw from the study at any time without prejudice. In the event of consent withdrawal, patients were to be asked for their permission to use the data already collected. If this permission was declined, then any collected data on that patient would not be used in the trial analysis. Withdrawal of consent was recorded on the patient’s CRF.

Interventions

Patients were randomised to one of two groups: (1) 577 nm SML or (2) SL [e.g. argon, frequency-doubled neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) 532 nm laser]. Application of the allocated laser was in accordance with the processes described in Micropulse laser and Standard laser. Information on laser type, parameters used and time spent applying the treatment was recorded in the patient’s CRF. In participants with both eyes eligible and included in the trial, both study eye and fellow eye received the same type of laser (i.e. the type randomly allocated).

Micropulse laser

Subthreshold micropulse laser was delivered using a 577 nm optically pumped diode laser (IQ 577™ laser system; IRIDEX Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA). The IRIDEX Corporation laser system was used as IRIDEX was, at the time the trial was designed and initiated, the only manufacturer that produced a 577 nm wavelength laser that could have potential benefits when compared with other available wavelengths, including lack of absorption by the macular pigment, very good absorption by melanin and good penetration through lens opacities. SML was applied confluently to the macular area, using three 7 × 7 spot grids above and below the fovea (500 µm from its centre) and one 7x7 spot grid at each side (temporal and nasal) of the fovea (500 µm from its centre). In addition, treatment was also applied to areas of thickening located outside this central area. Firstly, a threshold was set by titrating the power of the laser upwards, starting from 50 mW, in 10 mW increments, in an area where oedema was present, around > 2 disc diameters from the foveal centre (if possible), and until a barely visible tissue reaction was seen. If a reaction was evident with 50 mW, the power was not increased. Then, the laser was switched to the micropulse mode with the power of the laser set at x4 the threshold identified (e.g. if a barely visible reaction was seen at 50 mW, then micropulse laser was applied with a 200mW power). SML was then undertaken using a spot size of 200 µm, duty cycle of 5%, and ‘on’ duration of 200 ms (composed of multiple 0.1 ms of ‘on’ pulses, with 1.9 ms of ‘off’ time in between ‘on’ pulses). A standard operating procedure (SOP) for SML was prepared for the trial (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Standard laser

For patients allocated to SL, the laser was applied to areas of thickened retina, macular non-perfusion (away from and non-contiguous with the perifoveal capillaries) and leaking microaneurysms, in accordance with the ETDRS and the Royal College of Ophthalmologists guidelines. 5,27 FFA and SD-OCT were used to identify areas of non-perfusion and leakage (FFA) and thickening (SD-OCT) before treatment, at the discretion of the treating ophthalmologist. Treatment was applied to obtain a mild grey–white burn evident beneath leaking microaneurysms and in other areas of leakage or non-perfusion not affecting the perifoveal capillaries based on FFA, if FFA had been obtained, or to cover areas of thickening if treatment was given based on OCT findings, or both. The treatment was intended to spare the central 500 µm and the area within 500 µm from the optic nerve head. A standard operating procedure (SOP) for SL was prepared and used in the trial (see Report Supplementary Material 2).

The SL treatment in the DIAMONDS trial was performed using a modified ETDRS technique. In the ETDRS, argon laser was used, whereas in the DIAMONDS trial other types of lasers were allowed, given that argon laser is no longer widely available. The technique and parameters used for SL treatment in the DIAMONDS trial is representative of the technique used in other macular laser trials6,7 and that used in standard clinical practice.

Retreatment

Where necessary, retreatments were carried out with the same laser allocated by randomisation. When retreating, treatment of areas within 300–500 µm from the centre of the fovea was allowed. Details of retreatments were recorded in the patient’s CRF.

Rescue treatment

Where necessary, rescue treatment, with anti-VEGF therapy or steroids, as appropriate based on judgement by the treating ophthalmologist, was allowed in both treatment groups if the CRT increased to ≥ 400 µm at any point during the patient’s follow-up or if a loss of ≥ 10 ETDRS letters occurred in relation to DMO. The type and date of any rescue treatment was recorded in the patient’s CRF.

Participating sites and experience

Sixteen NHS HES sites participated in the recruitment, management and follow-up of DIAMONDS trial participants. All treating ophthalmologists had extensive experience in diabetic retinopathy and DMO as well as in delivering laser treatment for DMO. The participating sites were: Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast Health & Social Care Trust; Bristol Eye Hospital, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust; Frimley Park Hospital NHS Foundation Trust; Hinchingbrooke Hospital, North West Anglia NHS Trust; King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust; Manchester Royal Eye Hospital, Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust; Newcastle Eye Centre, Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Sunderland Eye Infirmary, South Tyneside and Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust; Bradford Royal Infirmary, Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust; James Cook University Hospital, South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Hull and East Yorkshire Hospital, Hull and East Yorkshire NHS Trust; Stoke Mandeville Hospital, Buckinghamshire NHS Trust; and Hillingdon Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Randomisation and masking

Randomisation

Following informed consent, eligible participants were randomised 1:1 to receive either SML or SL using a minimisation algorithm within the automated randomisation system Sealed Envelope (Sealed Envelope Ltd, London, UK; URL: www.sealedenvelope.com), with the allocation concealed to the ophthalmologist randomising the patient until the patient had joined the trial. The local ophthalmologist used this automated system to ensure post-randomisation masking of allocation to the outcome assessors. Although most patients received their allocated therapy at the baseline visit, it was acceptable for it to be performed at a later visit within two weeks of the baseline visit. If there was a longer interval between the baseline visit and the laser treatment, eligibility was re-confirmed before treatment.

The randomisation system used minimisation to balance allocation of patients across intervention groups for the following prognostic factors: centre, distance BCVA at presentation [≥ 69 ETDRS letters (Snellen equivalent of ≥ 20/40; log-MAR ≥ 0.3); 24–68 ETDRS letters (Snellen equivalent ≤ 20/50; log-MAR 0.4–1.2)] and previous administration of anti-VEGF therapy or macular laser in the study eye. A random element was used in the minimisation to provide a probability of 0.85 for assigning to the treatment group that minimised imbalance.

Masking

The DIAMONDS trial was a pragmatic RCT so that its results would be applicable immediately in an NHS setting once the trial was completed. For this reason, ophthalmologists undertaking laser treatments for DMO at each of the participating centres delivered the treatment for the trial and, thus, were not masked to the laser used. However, participants and outcome assessors (e.g. optometrists measuring visual function; photographers, technicians and nurses obtaining OCT images; and ophthalmic technicians obtaining visual fields) were all masked to treatment allocation. Patients were not informed before, during or after the laser treatment about which laser was used and remained masked until the trial ended. Similarly, investigators obtaining outcome measures had access to the CRF booklet only (and not to the notes of the patients) and this booklet did not contain information about the type of laser the patient had been allocated to or received (this information was held in a locked cabinet/locked room by the treating ophthalmologists).

Patient assessments

Patients were assessed during the study according to the schedule of assessments shown in Table 1.

| Trial procedures and assessments | Baselinea | Months post randomisationa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 | 24 | ||

| Informed consent | ✓ | ||||||

| Medical history | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Blood test: HbA1cb | ✓ | ||||||

| BCVA in study eye and fellow eye | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Binocular distance vision | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Humphrey 10–2 visual field in study eye | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Esterman binocular visual field | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| SD-OCT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| NEI-VFQ-25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| VisQoL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Randomisation | ✓ | ||||||

| Subthreshold micropulse laser/standard lasera,c | ✓ d | ||||||

| Adverse events | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Participants’ BCVA was measured in both eyes using ETDRS visual acuity charts at 4 m at baseline and at months 4, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24. BCVA was obtained following refraction at baseline and at 12 and 24 months by optometrists masked to treatment allocation. At all other visits, BCVA could be obtained by other masked staff using the most recently obtained refraction. Binocular BCVA was obtained to give an indication of the person’s vision ‘in real life’, using both eyes (i.e. with both eyes opened simultaneously). It was obtained by masked optometrists using the ETDRS visual acuity charts at 4 m at baseline and at 12 and 24 months. A refraction protocol was followed by the optometrists to obtain BCVA. ETDRS visual acuity scores were recorded for study and fellow eyes in the patient’s CRF at each study visit.

Testing of the 10–2 Humphrey visual field was performed in the study eye (and the fellow eye if this was included in the trial) by a visual field technician masked to the allocated treatment at baseline at 12 and 24 months. An Esterman binocular visual field (to determine the patient’s ability to fulfil driving standards) was obtained at the same time points. Visual fields eligible for analysis had to achieve pre-defined reliability criteria (false positives < 15%). If the visual fields were not reliable, they were repeated. The mean deviation (MD) value for the 10–2 Humphrey visual fields and the number of points seen and missed for the Esterman binocular visual fields were recorded in the patient’s CRF.

Participants’ CRT, as determined using SD-OCT, was obtained in both eyes at baseline and at months 4, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24. SD-OCT was obtained by technicians, photographers or nurses, as per standard clinical practice at each of the participating centres, who were masked to the treatment allocation. The measure of thickness at the central 1 mm (i.e. CRT) was recorded in the patient’s CRF and used for analysis. Total and maximal macular volume were also recorded in the CRF. Presence or absence of intraretinal or subretinal fluid was determined in a masked fashion at the 24-month follow-up visit by masked readers at the Central Administrative Research Facility (CARF) at Queen’s University Belfast. Images sent to CARF were anonymised. The Heidelberg Spectralis SD-OCT (Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) was used to obtain the CRT measurements for each participant at baseline and at each follow-up visit, unless for any reason, this was not possible.

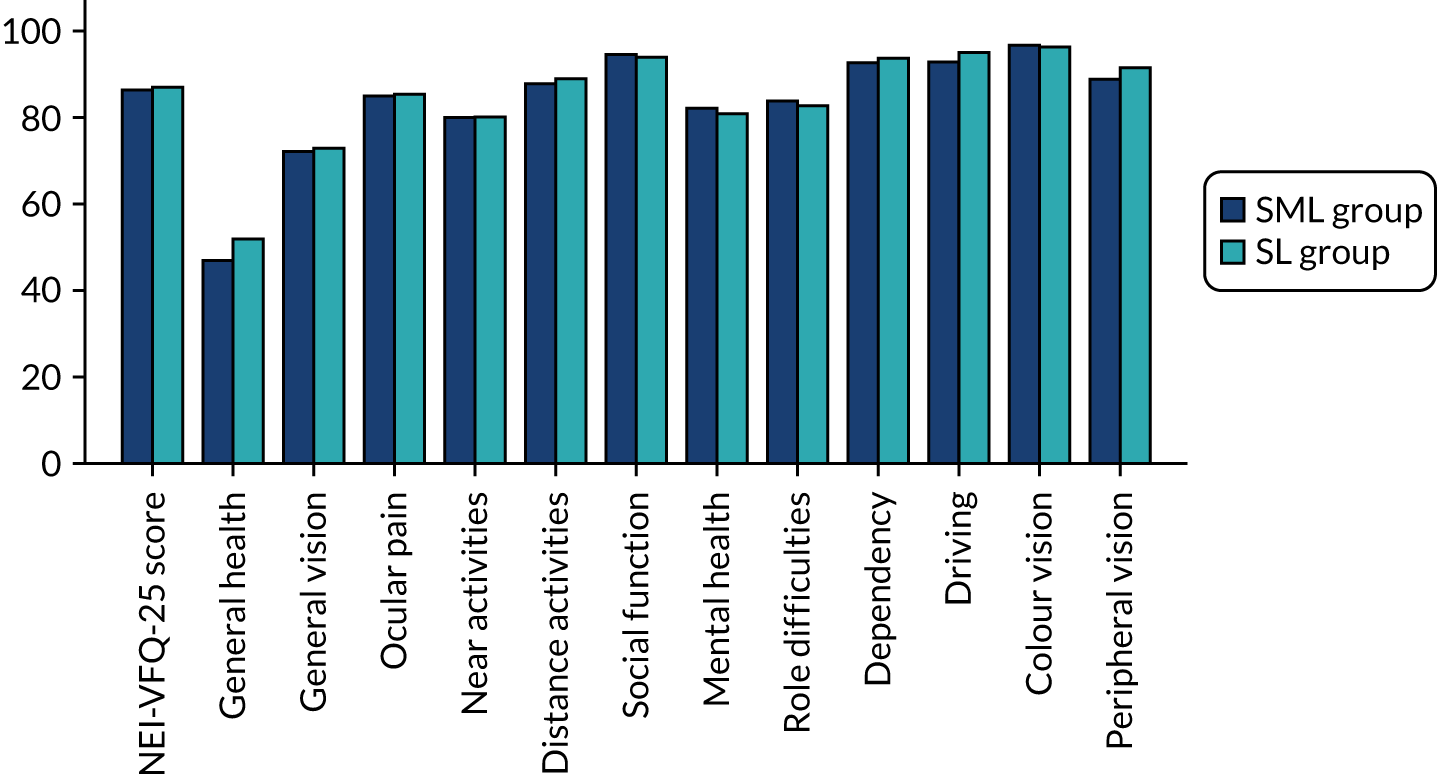

Two vision-related quality of life tools, the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire – 25 (NEI-VFQ-25) and the Vision and Quality of Life Index (VisQol), were used in the DIAMONDS trial, in addition to a generic preference-based health-related quality of life measure to generate utility data [the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)]. Questionnaires were self-completed by patients at baseline and at 12 and 24 months. Baseline questionnaires were completed before the first session of laser treatment.

Participants were followed up at 4-month intervals following laser treatment for a total of seven visits. Additional visits (interim visits) took place, if required. To maximise retention, the DIAMONDS trial was designed as a pragmatic trial, with the 4-monthly visits being akin to those in usual, routine care. In most visits, with the exception of those at baseline and at 12 and 24 months, the tests were the same as those done in routine care (i.e. a measure of visual acuity and SD-OCT scans). Consent was also obtained from the participants to allow for an evaluation of longer-term patient outcomes (at 5 years), which would be subject to a future funding application.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the difference between treatment groups in the mean change in BCVA in the study eye from baseline to month 24.

The secondary outcomes comprised the following:

-

mean change in binocular BCVA from baseline to month 24

-

mean change in CRT in the study eye, as determined by SD-OCT, from baseline to month 24

-

mean change in the MD of the Humphrey 10–2 visual field in the study eye from baseline to month 24

-

change in the percentage of people meeting driving standards from baseline to month 24

-

mean change in EQ-5D-5L, NEI-VFQ-25 and VisQoL scores from baseline to month 24

-

cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained

-

adverse effects

-

number of laser treatments carried out

-

additional treatments required (other than laser).

Data collection and management

Case report forms were used to collect data for each participant in the DIAMONDS trial. On-site monitoring visits during the trial checked the accuracy of entries on CRFs against the source documents and adherence to the protocol and procedures, the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use – Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) guidelines, and regulatory requirements. Monitoring visits were undertaken by a monitor from the Northern Ireland Clinical Trials Unit (NICTU). To ensure accurate, complete and reliable data were collected, the chief investigator and the NICTU provided training to site staff through investigator meetings and site initiation visits.

Data quality

The chief investigator and the NICTU provided training to unit staff on trial processes and procedures including CRF completion and data collection. Monitoring during the trial included adherence to the protocol, trial-specific procedures and good clinical practice. Within the NICTU, the clinical data management process was governed by SOPs, which ensured standardisation and adherence to International Conference of Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines and regulatory requirements.

Data quality control checks were carried out by a data manager following the NICTU SOP. Data validation was implemented and discrepancy reports were generated following data entry to identify discrepancies such as out-of-range values, inconsistencies or protocol deviations based on data validation checks. Changes to data were recorded and fully auditable. Data errors were documented and corrective actions implemented.

A Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) and a Trial Steering Committee (TSC) were convened for the DIAMONDS trial, the former to carry out reviews of the accumulating data at regular intervals during the study, to ensure the safety of participants and the latter to monitor the progress of the trial, among other tasks.

Adverse events

The safety of the treatment was assessed at each visit by noting any complications during or after laser treatment, including self-reported visual disturbances, and an ETDRS visual acuity loss of ≥ 10 letters and ≥ 15 letters occurring from visit to visit. Patients were asked specifically about reduced colour vision, presence of paracentral scotomas or distortion (‘waviness’ of straight lines) at each visit and responses were recorded in the appropriate CRF. Although serious adverse events (SAEs) related to the study procedures were unlikely to occur as a result of any of the study procedures (see below), all SAEs were recorded on the patient’s CRF and the sponsor and the Research Ethics Committee were informed of these. The DMEC was also provided with information on all SAEs on a routine basis.

As the DIAMONDS trial did not investigate medicinal products, adverse event reporting followed the Health Research Authority guidelines on safety reporting in non-Clinical Trials of Investigational Medicinal Products (non-CTIMP) studies. Adverse events (AEs) and SAEs were recorded on the patient’s CRF and the information was updated with the date and time of resolution or confirmation that the event was due to the participant’s illness when this information became available.

An AE was defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a participant in a research study, including occurrences which were not necessarily caused by or related to the study. AEs relating to pre-existing underlying diseases were not recorded in the DIAMONDS trial.

A SAE was defined as an untoward occurrence that met one or more of the following criteria:

-

resulted in death

-

was life-threatening

-

required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

consisted of a congenital anomaly or birth defect

-

was otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator.

Hospitalisation was defined as an inpatient admission regardless of length of stay, even if the hospitalisation was a precautionary measure for continued observation. Hospitalisations for a pre-existing condition, including elective procedures, did not constitute a SAE.

Anticipated adverse events due to laser treatment

The following were listed in the protocol22 as potential AEs in the DIAMONDS trial:

-

foveal burn

-

central/paracentral scotomas

-

epiretinal membrane formation

-

choroidal neovascularisation related to the laser

-

self-reported reduced colour vision

-

self-reported metamorphopsia.

Statistical methods for effectiveness analyses

Pre-trial power calculation

The DIAMONDS trial was powered to demonstrate not only non-inferiority but also equivalence of SML compared with SL with respect to the primary outcome (i.e. mean change in BCVA in the study eye between baseline and month 24). This was because, based on the existing knowledge when the trial was designed, it was possible that no differences could be found in the primary outcome but that differences could exist in other important secondary outcomes, such as PROMs. The DIAMONDS trial was also sufficiently powered to determine superiority of one laser over the other, if this were to exist.

Based on a mean of 0.08 log-MAR [standard deviation (SD) 0.23 log-MAR] for BCVA change from baseline for the standard care laser9 and a permitted maximum difference of 0.1 log-MAR (± 5 ETDRS letters) between groups, we estimated that the DIAMONDS trial would require 113 randomised participants per group, at 90% power and 0.05 level of significance. Allowing for up to a 15% dropout rate during the 24 months of follow-up, as observed in other randomised trials on DMO with outcomes determined at 24 months,28,29 the recruitment target was set at 266 patients.

A permitted maximal difference of 5 ETDRS letters between groups was chosen as the non-inferiority margin (± 5 ETDRS letters for equivalence) because a difference of this size or less is not considered clinically relevant or meaningful to patients. 2,3,8,24–26

In addition, 24-month data for 113 participants per group would also be sufficient to detect a mean difference between lasers of 37.7 µm in CRT (based on a SD of 86.810 µm) and of 6.55 in NEI-VFQ-25 scores (based on a SD of 15.1 score as per Tranos et al. 30). These are important secondary outcomes and such differences in CRT and NEI-VFQ-25 scores have been shown to be clinically relevant. 31,32

Analysis principles

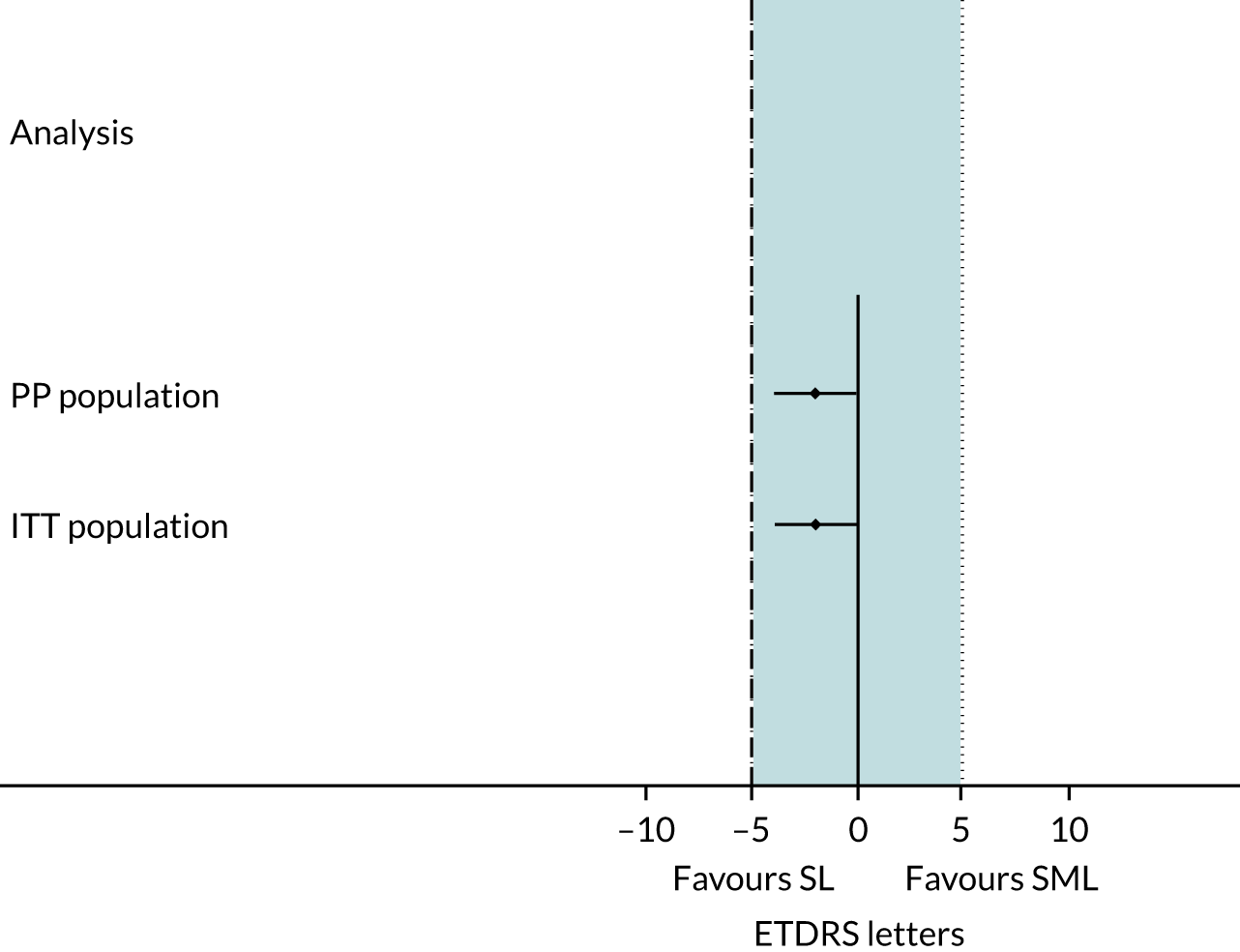

The DIAMONDS trial was designed with sufficient power to detect not only non-inferiority but also equivalence of SML when compared with SL and the primary statistical analysis was per protocol (PP), but an intention-to treat (ITT) analysis was also undertaken. ITT is recommended for superiority trials but, for non-inferiority or equivalence trials, a PP analysis is preferred because ITT increases the risk of a type I error for such trials. The main analyses were as pre-specified in the protocol, but some additional post hoc analyses were also undertaken (these are detailed in Post hoc analyses).

The difference between lasers for change in BCVA [with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)] from baseline to month 24 (primary end point) was compared with the permitted maximum difference of 5 ETDRS letters (0.1 log-MAR). SML would be deemed non-inferior to SL if the lower limit of the 95% CI of the treatment difference was above this non-inferiority margin. If the 95% CI of the treatment difference was wholly within both the upper and lower margins of the permitted maximum difference (± 5 ETDRS letters), then SML would be deemed to be equivalent to SL.

Change in BCVA from baseline to month 24 was compared between the two intervention groups using an independent two-sample t-test with a secondary analysis using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model adjusted for baseline BCVA score, baseline CRT and minimisation factors/covariates comprising centre; distance BCVA at baseline of ≥ 69 ETDRS letters (Snellen equivalent of ≥ 20/40; log-MAR ≥ 0.3) or 24–68 ETDRS letters (Snellen equivalent ≤ 20/50; log-MAR 0.4–1.2); previous use of anti-VEGF therapies in the study eye; and previous use of macular laser in the study eye.

The primary analysis was based on data from the study eye only. When performing a secondary analysis on the subset of participants with both eyes eligible and treated, study eye was included as a random effect within the mixed model. The principal analysis was based on available case data with no imputation of missing values. Intention-to-treat analyses were used for all secondary outcomes because the aim was to assess superiority for these outcomes.

Side effects of laser treatment and use of additional treatments (e.g. steroids or anti-VEGF therapy) were analysed using logistic regression models with adjustment for the minimisation covariates. Analyses of secondary measures of visual function and anatomical outcomes (MD of the 10–2 visual field test, CRT and macular volume) and number of treatments required were undertaken using linear regression models adjusted for baseline BCVA score and minimisation variables. Analysis of ‘driving ability’ (i.e. meeting standards for driving) was undertaken using a logistic regression model adjusted for baseline BCVA and the minimisation variables. The number of AEs, adverse reactions (ARs), SAEs, serious adverse reactions (SARs) and suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs), and the number and percentage of participants experiencing these events are reported. The chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test if appropriate) and proportion test were used to check if incidences of AEs differed between intervention groups. Relative risks with 95% CIs are reported. Baseline characteristics, follow-up measurements and safety data are presented using appropriate descriptive summary measures depending on the scale of measurement and distribution.

Statistical diagnostic methods were used to check for violations of the model assumptions.

Statistical significance was based on two-sided tests, with p < 0.05 taken as the criterion for statistical significance and with no adjustment for multiple testing.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were undertaken to assess the impact of missing data by imputing extreme values (lowest and highest) and last observation carried forward; the impact of including patients who were not treatment naive (i.e. excluding those who have had previous laser treatment for DMO in the study eye or previous anti-VEGF therapy for DMO or PDR in the study eye); and the impact of using month-24 data that were collected outside of ± 14 days of the due date.

Subgroup analyses

We conducted pre-specified subgroup analyses of the primary outcome based on clinical rationale. These subgroups were centre; distance BCVA at baseline of ≥ 69 ETDRS letters (Snellen equivalent of ≥ 20/40; log-MAR ≥ 0.3) or 24–68 ETDRS letters (Snellen equivalent ≤ 20/50; log-MAR 0.4–1.2); previous administration of anti-VEGF therapy; and previous use of macular laser in the study eye. These analyses were carried out by including the corresponding interaction term in the regression model and 99% CI.

We also conducted analyses to identify whether or not any group of participants was at high risk of poor outcomes. High-risk participants were defined as participants with a baseline glycated haemoglobin type A1c (HbA1c) value of ≥ 53 mmol/mol (≥ 7%). These were analysed in exploratory subgroup analyses.

Primary analysis

The primary analysis was performed on the mean change in BCVA in the study eye from baseline to month 24 and comprised the following: mean change in BCVA by intervention group (with SDs); difference in means with 95% CI; p-value from independent two-sample t-test; and secondary analysis using ANCOVA adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables. The non inferiority (and equivalence) margin was compared against the 95% CI for both PP and ITT analyses.

Secondary analyses

The secondary analyses, and how they were reported, were as follows:

-

Mean change in binocular BCVA from baseline to month 24 – mean (SD) by intervention group, difference in means with 95% CI and p-value from linear regression adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables

-

mean change in CRT as determined by SD-OCT, from baseline to month 24 – mean (SD) by intervention group, difference in means with 95% CI and p-value from linear regression adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables

-

mean change in the MD of the Humphrey 10–2 visual field from baseline to month 24 – mean with SD by intervention group, difference in means with 95% CI and p-value from linear regression adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables

-

change in the percentage of participants meeting driving standards from baseline to month 24 – number and percentage of participants meeting driving standards by intervention group, odds ratio with 95% CI and p-value from logistic regression adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables

-

number of participants experiencing side effects from baseline to month 24 – number and percentage of participants by intervention group, odds ratio with 95% CI and p-value from logistic regression adjusted for minimisation variables

-

number of laser treatments used in the study eye from baseline to month 24 – mean with SD by intervention group, difference in means with 95% CI and p-value from linear regression adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables

-

number of participants receiving at least one additional treatment (other than laser) from baseline to month 24 – number and percentage of participants by intervention group, odds ratio with 95% CI and p-value from logistic regression adjusted for minimisation variables.

Additional analyses specified in the statistical analysis but not in the published protocol

Additional analyses specified in the statistical analysis but not in the published protocol, and how they were reported, were as follows:

-

mean change in BCVA in the study eye from baseline to month 12 – mean with SD by intervention group, difference in means with 95% CI and p-value from ANCOVA adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables

-

mean change in binocular BCVA from baseline to month 12 – mean with SD by intervention group, difference in means with 95% CI and p-value from linear regression adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables

-

mean change in CRT, as determined by SD-OCT, from baseline to month 12 – mean with SD by intervention group, difference in means with 95% CI and p-value from linear regression adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables

-

mean change in the MD of the Humphrey 10–2 visual field from baseline to month 12 – mean with SD by intervention group, difference in means with 95% CI and p-value from linear regression adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables

-

change in the percentage of people meeting driving standards from baseline to month 12 – number and percentage of participants meeting driving standards by intervention group, odds ratio with 95% CI and p-value from logistic regression adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables

-

number of participants experiencing side effects from baseline to month 12 – number and percentage of participants by intervention group, odds ratio with 95% CI and p-value from logistic regression adjusted for minimisation variables

-

number of laser treatments used in study eye from baseline to month 12 – mean with SD by intervention group, difference in means with 95% CI and p-value from linear regression adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables

-

number of participants with at least one additional treatment (other than laser) from baseline to month 12 – number and percentage of participants by intervention group, odds ratio with 95% CI and p-value from logistic regression adjusted for minimisation variables

-

number of steroid injections as additional treatments from baseline to month 12 and from baseline to month 24 – mean with SD by intervention group, difference in means with 95% CI and p-value from linear regression adjusted for minimisation variables

-

number of participants with at least one steroid injection from baseline to month 12 and from baseline to month 24 – number and percentage of participants by intervention group, odds ratio with 95% CI and p-value from logistic regression adjusted for minimisation variables

-

number of anti-VEGF treatments as additional treatments from baseline to month 12 and from baseline to month 24 – mean with SD by intervention group, difference in means with 95% CI and p-value from linear regression adjusted for minimisation variables; and as number and percentage of participants by category (≤ 4, 5–10 and > 10)

-

number of participants with at least one anti-VEGF treatment as additional treatment from baseline to month 12 and from baseline to month 24 – number and percentage of participants by intervention group, odds ratio with 95% CI and p-value from logistic regression adjusted for minimisation variables

-

number of participants receiving rescue treatments from baseline to month 12 and from baseline to month 24 – number and percentage of participants by intervention group, odds ratio with 95% CI and p-value from logistic regression adjusted for minimisation variables

-

number of participants satisfying rescue criteria from baseline to month 12 and from baseline to month 24 – number and percentage of participants by intervention group, odds ratio with 95% CI and p-value from logistic regression adjusted for adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables

-

number of participants experiencing a loss of 10 or more ETDRS letters between baseline and month 24 – number and percentage of participants by intervention group, odds ratio with 95% CI and p-value from logistic regression adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables.

Post hoc analyses

Post hoc analyses, and how they were reported, were as follows:

-

mean change in macular volume from baseline to month 24: mean with SD by intervention group, difference in means with 95% CI and p-value from linear regression adjusted for baseline BCVA and minimisation variables

-

number of participants experiencing a loss of 5 or more ETDRS letters from baseline to month 24

-

number of participants experiencing an increase in BCVA or a BCVA loss not greater than 5 ETDRS letters from the baseline value to month 24

-

number of participants satisfying rescue criteria at least once at any time from baseline to month 24

-

number of participants satisfying rescue criteria at least once and receiving rescue treatment at any time from baseline to month 24

-

number of participants satisfying rescue criteria at least once and not receiving rescue treatment at any time from baseline to month 24

-

number of participants who did not satisfy rescue criteria at all from baseline to month 24

-

number of participants who did not satisfy rescue criteria at all but received rescue treatment from baseline to month 24.

Health economics methods

Overview

The main objective of the health economics evaluation was to conduct a short-term (baseline to 2 years’ follow-up) within-trial analysis comparing the cost-effectiveness of SML with SL in patients with DMO fulfilling the DIAMONDS trial eligibility criteria. To achieve this, a systematic comparison of the costs of resource inputs used by participants in the two treatment groups and the consequences associated with the interventions was conducted. The primary analysis adopted an NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective. The economic evaluation took the form of a cost–utility analysis, expressed in terms of incremental cost per QALY gained. Costs and outcomes beyond the first year of follow-up were discounted at 3.5% in line with the NICE reference case. 33

For the health economics analysis, we adopted an ITT approach as reported in the health economics analysis plan. ITT requires that study participants are analysed according to their treatment assignment regardless of actual treatment received. This is the approach preferred by NICE for cost-effectiveness analyses as stated in their methods guide. 33 We report the results for the per-protocol analysis in a sensitivity analysis.

Measuring resource use and costs

Data were collected on resource use and costs associated with delivery of laser treatment (direct intervention costs) and broader health service resource use during the 24 months of follow-up. All costs were expressed in Great British pounds and valued in 2019–20 prices. Where appropriate, costs were inflated to 2019–20 prices using the NHS Cost Inflation Index. 34

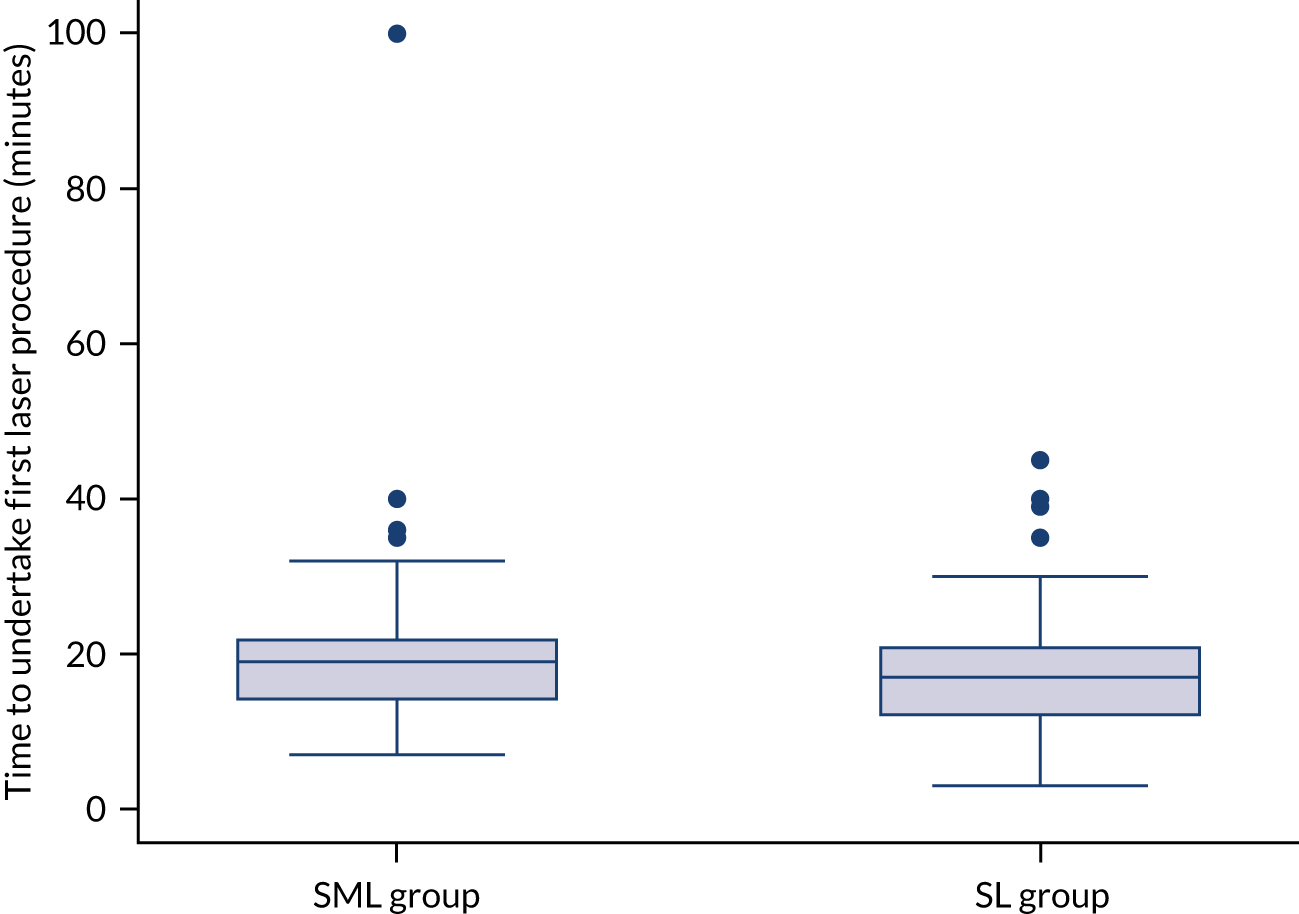

Direct intervention costs

Direct intervention costs were costs associated with the delivery of laser treatment. These included staff costs and equipment costs (i.e. costs of laser machines) (see Appendix 1, Table 22 and Table 23). Unit costs for staff were obtained from the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2020 compendium34 and were multiplied by the time it took to perform specified procedures for each participant. The time it took to undertake various procedures was recorded on the DIAMONDS trial CRFs and comprised: (1) the time it took imaging technicians to obtain FFA and SD-OCT scans to guide laser treatment and (2) the time taken by consultants and associate specialists to perform the laser procedure, as well as the time invested in counselling the patient. Costs of laser machines were obtained directly from manufacturers. An annual equivalent cost of equipment was obtained by annuitising the capital costs of the item over its useful life span, applying a discount rate of 3.5% per annum. We derived a per-patient cost of equipment (including annual maintenance costs) by assuming that the machine will be used to perform laser procedures on 3000 patients per year (Professor Noemi Lois, Queen’s University Belfast, 2021, personal communication).

Measuring and valuing resource use

Resource use data were captured on trial CRFs at scheduled clinic visits over the 24-month follow-up period, at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24 months. On-site monitoring visits during the trial ensured the accuracy of entries in the CRF. The CRFs captured details related to the eye condition of inpatient and day case admissions, outpatient attendances, other tests or investigations, medication use including anti-VEGF therapy/steroids or other rescue treatments, and laser retreatments.

Resource inputs were valued by attaching unit costs derived from national compendia in accordance with NICE’s Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisal. 33 The key databases for deriving unit cost data included the Department of Health and Social Care’s Reference Costs 2018–19 schedules,35 the PSSRU’s Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2019 compendium34 and volume 80 of the British National Formulary. 36 Appendix 1, Table 22 gives a summary of the unit cost values and data sources for broader resource use categories identified within the follow-up questionnaires.

The following assumptions were made in costing outpatient attendances. Where an outpatient attendance was reported but no procedure undertaken, the average unit cost of an outpatient ophthalmology visit was used; this varied between £80 and £101 per consultation depending on whether the consultation was ‘non-consultant’ or ‘consultant-led’. We used data captured on trial CRFs documenting the grade of professional that attended to the patient to select the most appropriate unit costs. For example, if a consultant attended to the patient, then the consultant-led unit cost was applied. Where a procedure(s) was undertaken as part of the visit, the relevant Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) code was derived using the HRG4 + Reference Costs Grouper Software (NHS Digital, Leeds, UK). High-cost drugs (specifically anti-VEGF therapy) were separately costed as these are considered an unbundled HRG. We also costed steroid rescue treatment. Costing of laser retreatments followed the same approach as costing for the index (first-session) laser procedure.

Summary statistics were generated for resource use variables by treatment allocation and assessment point. Mean resource use and cost values were compared between groups using two-sample t-tests. Differences between groups, along with 95% CIs, were estimated using non-parametric bootstrap estimates (10,000 replications).

Health outcomes

The primary outcome of the within-trial economic evaluation is the QALY, as recommended in the NICE reference case. 33 The QALY is a measure that combines quantity and quality of life lived into a single metric, with one QALY equating to 1 year of full health. QALY estimates are generated from combining length (survival) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) data from participants for the period covering the trial time horizon through an area under the curve (AUC) approach using a linear extrapolation. 37 Since AUC estimates are predicted to correlate with baseline scores (and thus potential baseline imbalances), AUC estimates were adjusted for baseline scores within regression analyses. HRQoL was converted into health-state utilities indexed at 0 and 1, where 0 represents death and 1 represents full health. Patients who died during the study were subsequently scored 0 at later scheduled follow-up visits for both cost and HRQoL scores and were included as observed data.

To calculate QALYs, it is imperative to obtain health state values for participants within the trial. The HRQoL of trial participants was assessed at baseline and at 12 and 24 months’ post randomisation using the EQ-5D-5L instrument. The EQ-5D-5L consists of the descriptive system and the visual analogue scale. The descriptive system includes five questions addressing mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression, with each dimension assessed at five levels from no problems to extreme problems. Responses to the EQ-5D-5L instrument were converted into health utility scores using the EQ-5D-5L Crosswalk Index Value Calculator currently recommended by NICE, which maps the EQ-5D-5L descriptive system data onto the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) valuation set. 38 A detailed description of the mapping methodology is provided in the study by van Hout et al. 38

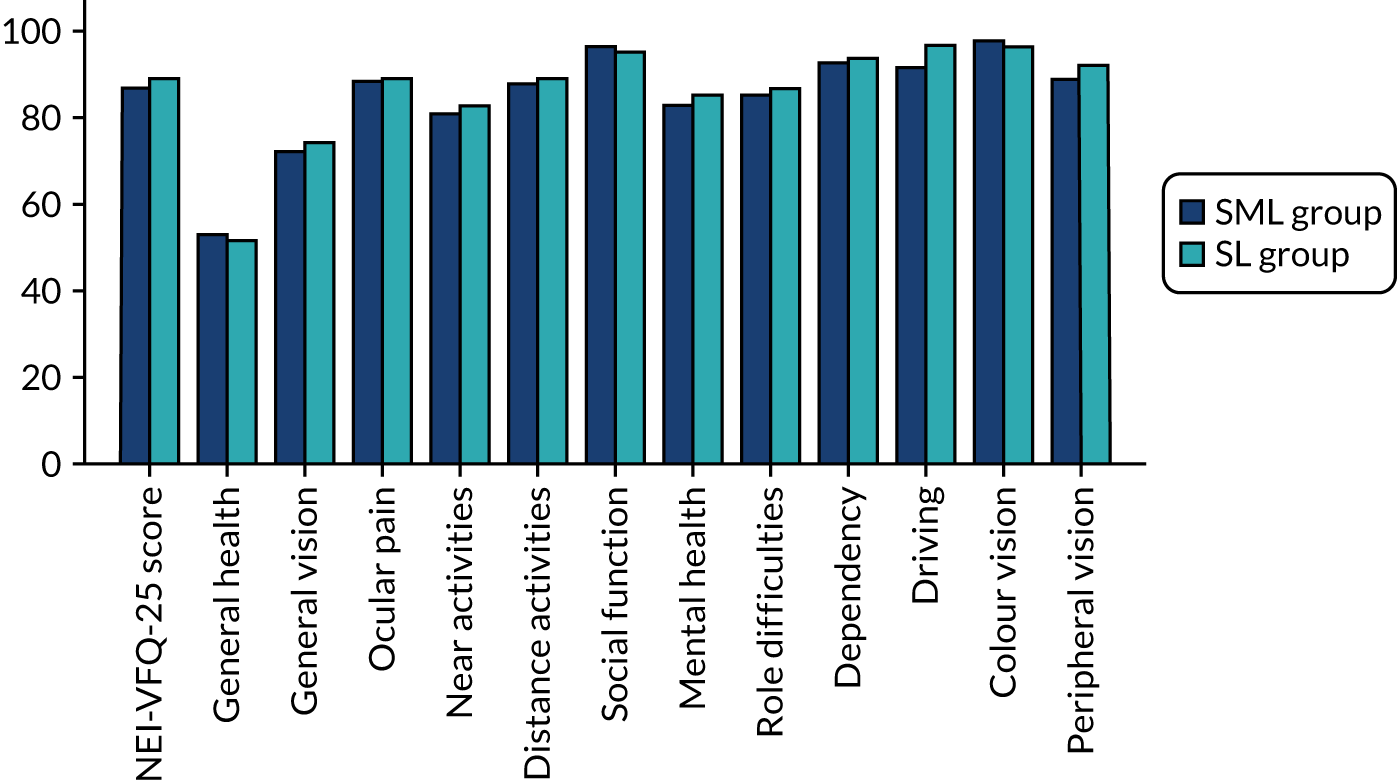

Health-related quality of life was also assessed by determining the vision-related quality of life using two vision specific measures: the NEI-VFQ-25 and the VisQoL. 39–41 The NEI-VFQ-25 is a vision-specific patient-reported quality of life tool. This validated questionnaire has been used widely to evaluate visual outcomes in patients with eye diseases, including diabetic retinopathy. In addition to eliciting information about general health and vision, it specifically addresses difficulty with near vision, distance vision, driving and the effect of light conditions on vision, providing a comprehensive evaluation of vision-related quality of life. The NEI-VFQ-25 scoring is done in two-stages: (1) each item is scored on a scale of 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest), where a higher score represents better functioning; and (2) items within each subscale are averaged together (11 subscales in total for the NEI-VFQ-25). To obtain the combined score for the questionnaire, the average of the subscales (excluding the general health rating question) is undertaken. Averaging across the subscales scores, rather than individual items, gives equal weight to each subscale.

The VisQol questionnaire is shorter than the NEI-VFQ-25 with only six attributes: physical well-being, independence, social well-being, self-actualisation, planning and organisation. However, it has not been widely validated. The utilities for VisQoL were developed using a time trade-off exercise in people who were visually impaired including patients with age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma. 41

The health utility values and QALYs accrued over the 24-month follow-up period were summarised by treatment group and assessment point and presented as means and associated standard errors (SEs). Between-group differences were compared using the two-sample t-test, in a similar way to the descriptive analyses of resource inputs and costs.

Handling of missing data

Multiple imputation by chained equations was used to predict missing health status (utility) scores and costs based on the assumption that data were missing at random (MAR). The MAR assumption was tested through a series of logistic regression analyses comparing participants’ characteristics for those with and without missing end-point data. Imputation was achieved using predictive mean matching, which has the advantage of preserving non–linear relationships and correlations between variables within the data. 42 Twenty imputed data sets were generated and used to inform the base-case analyses. Parameter estimates were pooled across the 20 imputed data sets using Rubin’s rules to account for between- and within-imputation components of variance terms associated with parameter estimates. 43 Imputed and observed values were compared to establish that imputation did not introduce bias into subsequent estimation.

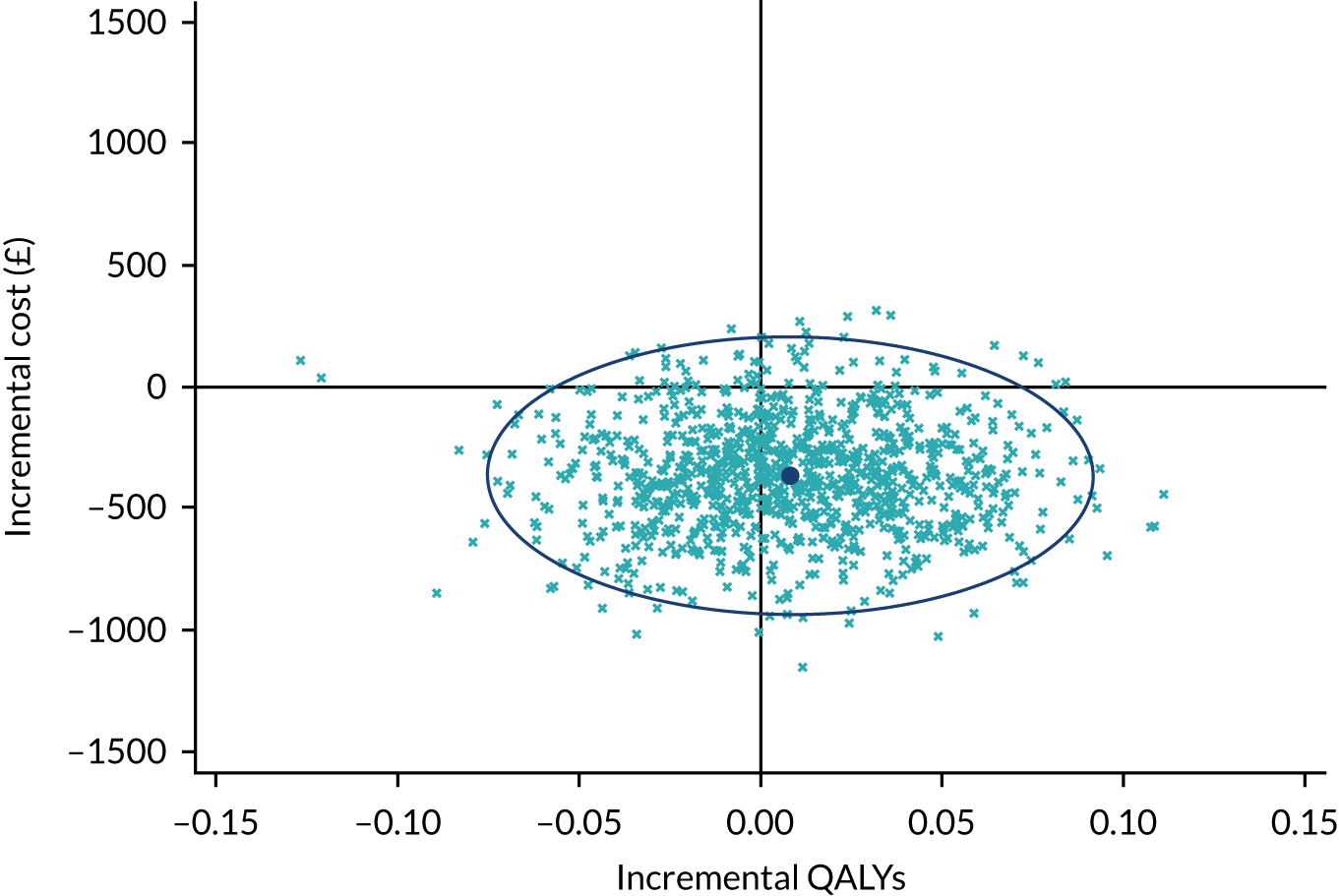

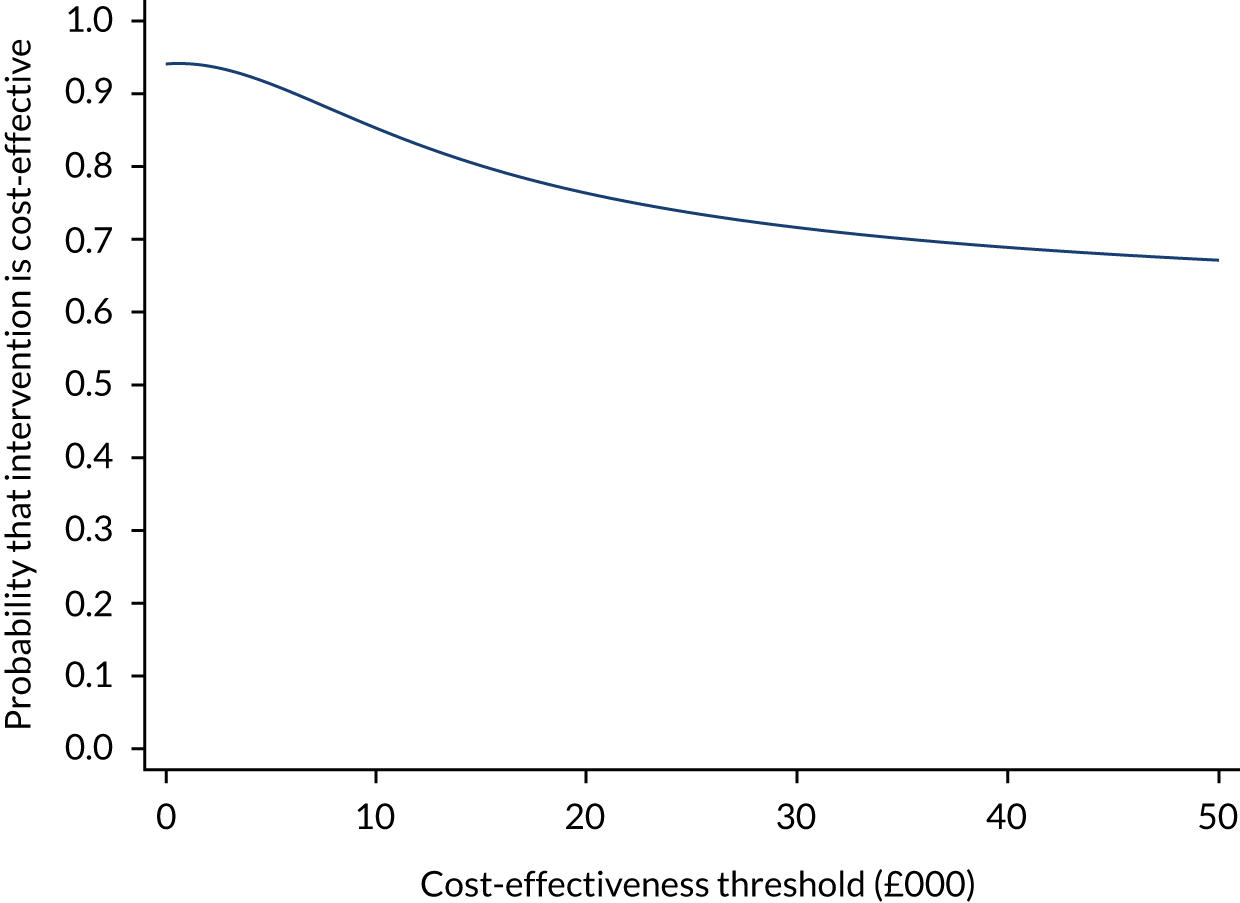

Cost-effectiveness analysis

The base-case cost-effectiveness analysis was performed using an ITT approach. Mean incremental costs and QALYs were estimated using seemingly unrelated regression methods that account for the correlation between costs and outcomes. The seemingly unrelated regression adjusted for the following covariates: baseline utilities, baseline body mass index (BMI), baseline BCVA, patient-reported previous use of anti-VEGF therapy at baseline and previous use of macular laser. The joint distributions of costs and outcomes were generated using non-parametric bootstrap methods and used to populate the cost-effectiveness plane. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for SML compared with SL was calculated by dividing the between-group difference in adjusted mean total costs by the between-group difference in adjusted mean QALYs. Mean ICER values were compared against cost-effectiveness threshold values ranging between £15,000 and £30,000 per QALY gained, in line with NICE guidance. 33 The cost-effectiveness thresholds provide an indication of society’s willingness to pay for an additional QALY; lower ICER values than the threshold could be considered cost-effective for use in the UK NHS. The incremental net monetary benefit (NMB) of switching from SL to SML was calculated for cost-effectiveness thresholds ranging from £15,000 to £30,000 per QALY gained. NMB is calculated as the net benefit of an intervention (expressed in monetary terms) considering all costs associated with the intervention. A positive incremental NMB, suggests that, on average, SML is cost-effective compared with SL at the given cost-effectiveness threshold. In that case, the cost to derive the benefit is less than the maximum amount that the decision-maker would be willing to pay for this benefit. 44

Trial management

The chief investigator had overall responsibility for the conduct of the DIAMONDS trial. The chief investigator and NICTU undertook trial management including clinical trial applications (Ethics and Research Governance), site initiation and training, monitoring, analysis and reporting. The trial co-ordinator was responsible on a day-to-day basis for overseeing and co-ordinating the work of the multi-disciplinary trial team and was the main contact between the trial team and other parties. Before the DIAMONDS trial started, site training ensured that all relevant essential documents and trial supplies were in place and that site staff were fully aware of the study protocol and procedures. The following trial committees were established.

Trial Management Group

The Trial Management Group (TMG) was chaired by the chief investigator and included representation from the NICTU and other investigators or collaborators involved in the study. The TMG had responsibility for the day-to-day operational management of the DIAMONDS trial and met monthly throughout the trial to discuss and monitor its progress.

Trial Steering Committee

The conduct of DIAMONDS was overseen by a TSC, on behalf of the sponsor and funder. The TSC comprised an independent chair, additional independent members (including a patient representative) and members of the trial team (including the chief investigator). TSC meetings were arranged so that they coincided with meetings of the DMEC, to allow members in both committees to discuss issues and recommendations raised by the DMEC.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

The DMEC was responsible for safeguarding the interests of participants in the DIAMONDS trial. The DMEC monitored the main outcome measures including safety and efficacy. The DMEC comprised two clinicians and a statistician who were independent of the trial.

DIAMONDS patient and public involvement group

At the very early stages of the DIAMONDS trial conception, a DIAMONDS patient and public involvement (PPI) group was established. The DIAMONDS PPI group contributed to the trial design, including the selection of outcomes, preparation of patient-related materials for the trial, recruitment strategies, interpretation of trial results and preparation of the Plain English summary.

Sponsor

The Belfast Health and Social Care Trust (BHSCT) was the sponsor for the DIAMONDS trial.

Reporting

The reporting of the DIAMONDS trial follows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines45 and guidelines on reporting for equivalence and non-inferiority trials. 46

Changes in trial methodology since trial conception

There were no changes made in the design, outcomes or conductance of the DIAMONDS trial after trial commencement.

Chapter 3 Clinical effectiveness

Participating sites and characteristics of DIAMONDS trial participants

Table 2 lists the 16 participating sites, the date when they were opened to recruitment and the total number of participants screened and recruited at each site.

| Site code | Site name | Date site opened | Total screened | Total recruited |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Belfast Health and Social Care Trust | 18 January 2017 | 44 | 38 |

| 02 | Bristol Eye Hospital | 19 April 2017 | 23 | 19 |

| 03 | Frimley Park Hospital | 28 February 2017 | 49 | 42 |

| 04 | Hinchingbrooke Hospital | 20 July 2017 | 12 | 12 |

| 05 | London King’s College Hospital | 03 April 2017 | 32 | 29 |

| 06 | Manchester Royal Eye Hospital | 22 March 2017 | 25 | 12 |

| 07 | Moorfields Eye Hospital | 22 February 2017 | 27 | 20 |

| 08 | Newcastle Eye Centre | 12 April 2017 | 16 | 15 |

| 09 | John Radcliffe Hospital (Oxford) | 04 April 2017 | 12 | 6 |

| 10 | Sheffield Royal Hallamshire Hospital | 28 February 2017 | 14 | 10 |

| 11 | Sunderland Eye Infirmary | 24 February 2017 | 30 | 21 |

| 12 | Bradford Hospital | 18 October 2017 | 12 | 10 |

| 13 | James Cook Hospital (South Tees) | 13 October 2017 | 20 | 16 |

| 14 | Hull & East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust | 17 August 2018 | 11 | 8 |

| 15 | Stoke Mandeville Hospital | 05 September 2018 | 2 | 1 |

| 16 | Hillingdon Hospital | 14 September 2018 | 7 | 7 |

Participants

Participant flow

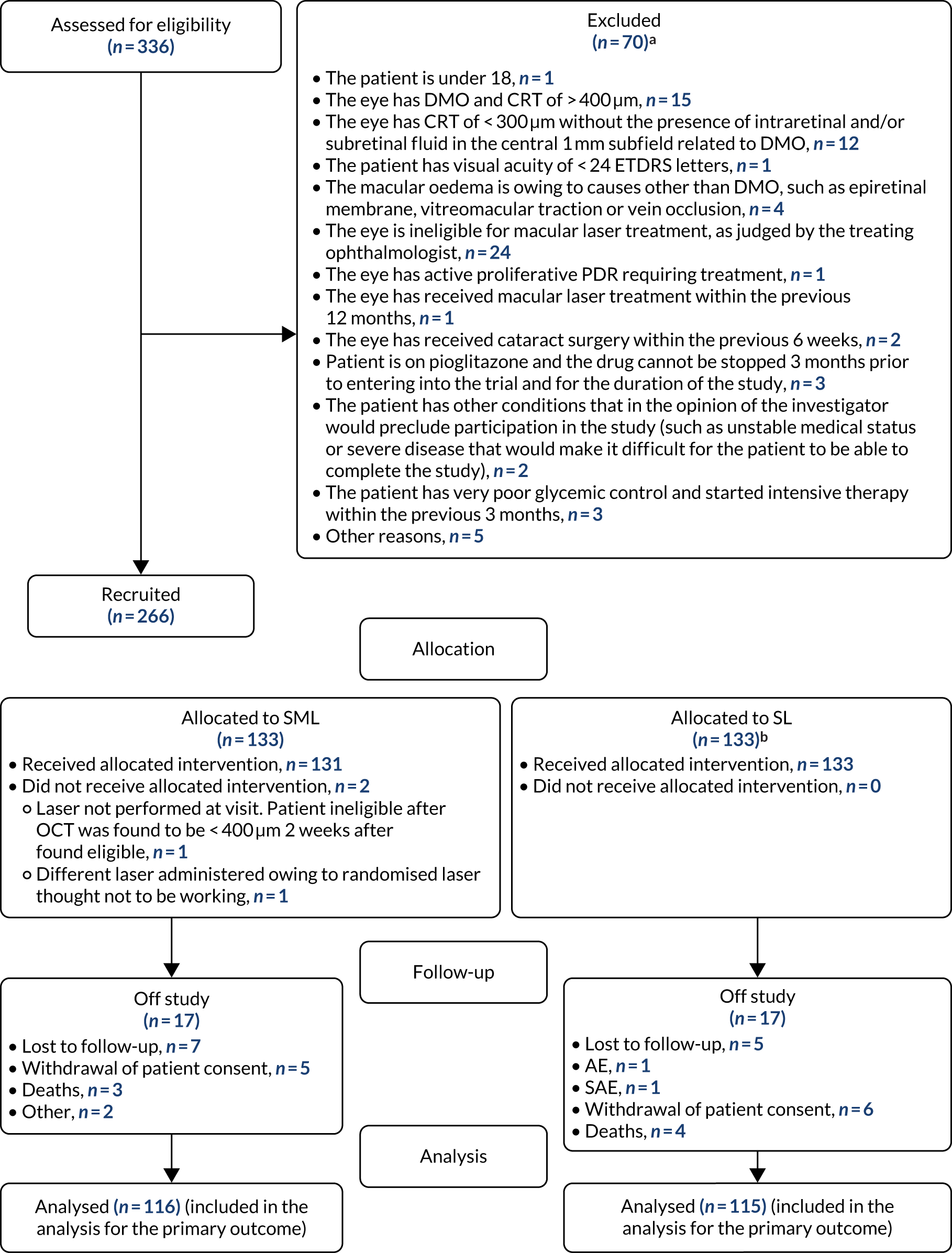

The CONSORT flow diagram in Figure 2 details the flow of patients through the DIAMONDS trial.

FIGURE 2.

Participant flow in the DIAMONDS trial. a, Total number of reasons can be greater than number of patients excluded as patients can have multiple exclusion reasons; b, n = 1 patient withdrew permission for their data to be used and will not be included in any analysis going forward. Reproduced with permission from Lois et al. 47 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure above includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

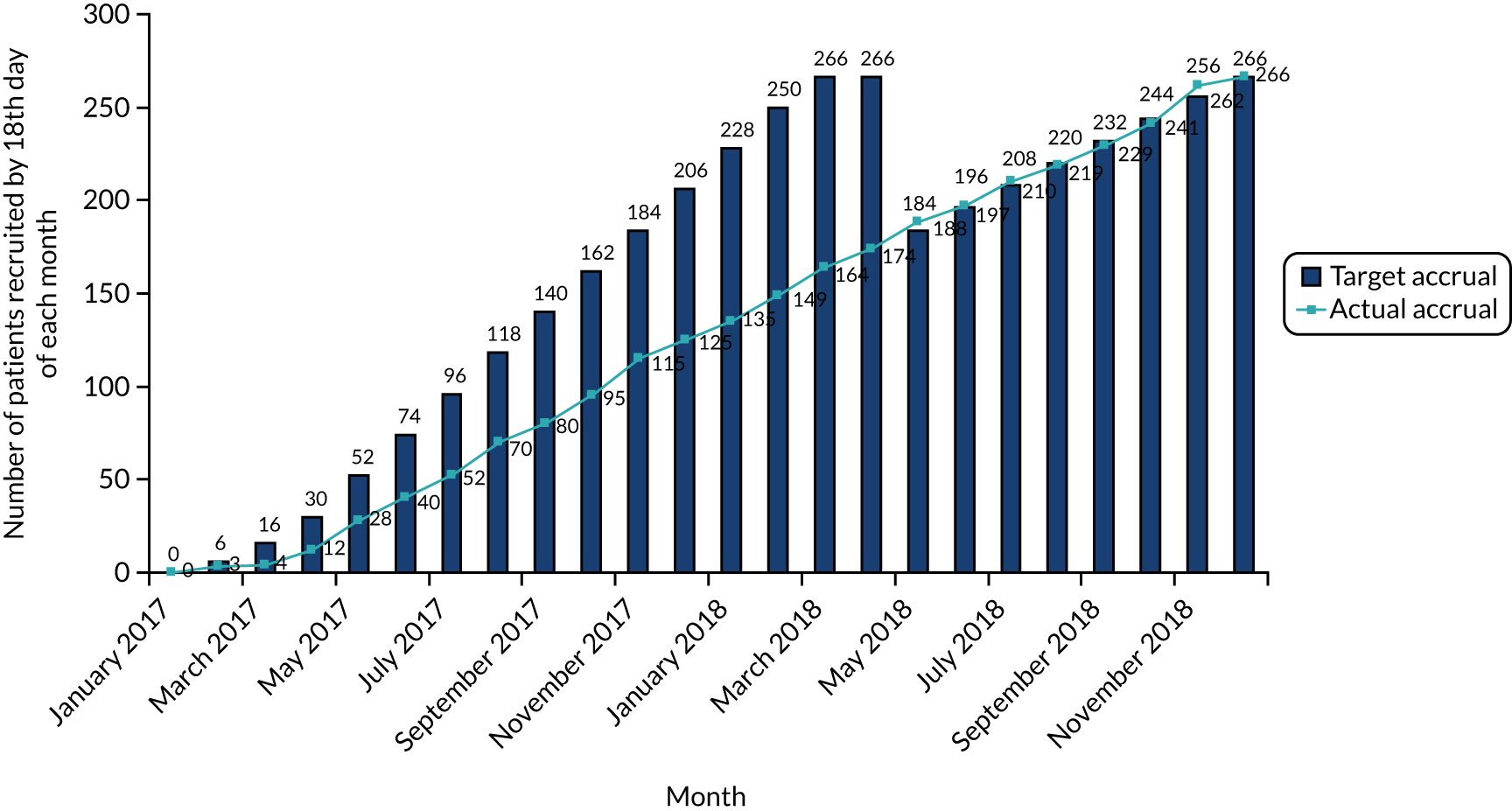

Patient recruitment took place between 18 January 2017 and 20 November 2018. A total of 336 participants were assessed for eligibility and 266 (79%) of those assessed as eligible agreed to join the trial and were randomised (intervention, n = 133; control, n = 133). One participant withdrew consent for their data to be used and was excluded from all analyses. The first month 24 follow-up visit was conducted on 25 January 2019 and the final month 24 follow-up visit was conducted on 22 December 2020. Recruitment was initially due to be completed by April 2018 but, at that time, the recruitment of participants had not been completed. An extension was subsequently approved to extend this timeline until December 2018; recruitment was then completed. The cumulative patient recruitment against the anticipated pre-trial sample size is shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Patient recruitment.

Patient baseline characteristics

Patient baseline characteristics were broadly similar across intervention groups (Table 3).

| Baseline characteristics at trial entry | Treatment group | Total, N = 265 (100.0%)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SML, N = 133 (50.2%) | SL, N = 132 (49.8%) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 91 (68.4) | 95 (72.0) | 186 (70.2) |

| Female | 42 (31.6) | 37 (28.0) | 79 (29.8) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 61.9 (10.1) | 62.6 (10.4) | 62.2 (10.3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 105 (79.0) | 100 (75.8) | 205 (77.4) |

| Asian | 15 (11.3) | 15 (11.4) | 30 (11.3) |

| Black (African) | 12 (9.0) | 14 (10.6) | 26 (9.8) |

| Other | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.5) | 3 (1.1) |

| Middle East | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Black (African American) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Diabetes | |||

| Type 1, n (%) | 20 (15.0) | 18 (13.6) | 38 (14.3) |

| Duration of type 1 (years), mean (SD) | 28.8 (12.9) | 23.6 (9.0) | 26.4 (11.4) |

| Type 2, n (%) | 113 (85.0) | 113 (85.6) | 226 (85.3) |

| Duration of type 2 (years), mean (SD) | 16.0 (8.4) [n = 112] | 15.3 (6.7) [n = 112] | 15.7 (7.6) [n = 224] |

| Other, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Duration of other (years), mean (SD) | – | 14.3 (–) | 14.3 (–) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current smoker, n (%) | 10 (7.5) | 7 (5.3) | 17 (6.4) |

| Number of years smoked (current smoker), mean (SD) | 27.9 (15.1) | 38.7 (7.9) | 32.4 (13.5) |

| Past smoker, n (%) | 50 (37.6) | 46 (34.9) | 96 (36.2) |

| Number of years smoked (past smoker), mean (SD) | 16.5 (12.8) [n = 47] | 19.1 (13.2) [n = 46] | 17.8 (13.0) [n = 93] |

| Never smoked, n (%) | 73 (54.9) | 79 (59.9) | 152 (57.4) |

| DMO diagnosis (study eye) | |||

| Present, n (%) | 133 (100.0) | 132 (100.0) | 265 (100.0) |

| Mean (SD) duration of diagnosis (years) | 3.0 (5.8) | 2.1 (2.6) | 2.5 (4.5) |

| Absent, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| DMO diagnosis (non-study eye) | |||

| Present, n (%) | 93 (69.9) | 82 (62.1) | 175 (66.0) |

| Duration of diagnosis (years), mean (SD) | 4.1 (6.7) | 2.9 (3.2) | 3.5 (5.3) |

| Absent, n (%) | 40 (30.1) | 50 (37.9) | 90 (34.0) |

| Previous DMO laser treatment (study eye) | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 32 (24.1) | 32 (24.2) | 64 (24.2) |

| No, n (%) | 101 (75.9) | 100 (75.8) | 201 (75.9) |

| Number of previous DMO laser sessions, median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) [n = 30] | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) [n = 62] |

| Time since last DMO laser session (years), mean (SD) | 4.7 (6.6) [n = 30] | 3.7 (2.1) | 4.2 (4.8) [n = 62] |

| Previous DMO laser treatment (non-study eye) | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 39 (29.3) | 33 (25.0) | 72 (27.2) |

| No, n (%) | 94 (70.7) | 99 (75.0) | 193 (72.8) |

| Number of previous DMO laser sessions, median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) [n = 37] | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) [n = 70] |

| Time since last DMO laser session (years), mean (SD) | 5.3 (6.7) [n = 37] | 4.4 (3.1) [n = 32] | 4.9 (5.3) [n = 69] |

| Previous anti-VEGF therapies (study eye), n (%) | |||

| Bevacizumab (Avastin®, Roche): yes | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) |

| Bevacizumab: no | 132 (99.3) | 131 (99.2) | 263 (99.3) |

| Ranibizumab (Lucentis®, Roche): yes | 14 (10.5) | 11 (8.3) | 25 (9.4) |

| Ranibizumab: no | 119 (89.5) | 121 (91.7) | 240 (90.6) |

| Aflibercept (Eylea®, Bayer): yes | 9 (6.8) | 5 (3.8) | 14 (5.3) |