Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0108-10037. The contractual start date was in December 2009. The final report began editorial review in October 2019 and was accepted for publication in October 2020. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Young et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

Context and rationale for programme

Large parts of this section have been reproduced from Godfrey et al. 1 © 2013 Godfrey et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Delirium

Delirium is a common and serious condition among older people, and is associated with distress for individuals, families and health-care staff;2 increased mortality; protracted lengths of hospital stay; lasting functional and cognitive decline; and increased requirement for long-term care placement. 3

Prevention of delirium

Prevention of delirium is, therefore, highly desirable; multicomponent prevention interventions that aim to attenuate modifiable delirium risk factors have consistently been shown to reduce incident delirium in hospitalised patients by about one-third in various inpatient specialties. 4–7 As a consequence of this evidence base, several national guidance documents have recommended that multicomponent delirium prevention interventions should be incorporated into routine care. 8–10

Modification of delirium risk factors typically requires a complex multicomponent system of care, comprising education and targeted interventions, directed at optimising hydration and nutrition, reducing environmental threats, increasing orientation to time and place, improving communicative practices, supporting/encouraging mobility, and improving pain and infection management. These interventions have been tested in different health systems, in diverse settings (medical, surgical, intensive care units and care homes), employing varied modes of delivery, including the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP). 6,11–14

The Hospital Elder Life Program

The HELP is an existing, successful, standardised and manualised North American multicomponent delirium prevention system of care, which uses a skilled interdisciplinary team assisted by trained volunteers and multicomponent targeted intervention protocols. 11,12,15 The HELP was initially developed and evaluated in the USA > 15 years ago as a novel system of care to prevent delirium among medical patients admitted to hospital for unscheduled care. Effectiveness was demonstrated in a well-conducted, non-randomised, proof-of-concept, explanatory trial involving > 850 patients. 12 The effect size for delirium prevention was estimated as 40% reduction (number needed to treat = 20). Although there have been single-site randomised controlled trials and pragmatic trials of the HELP,13,16 there have not been any multisite randomised trials. Qualitative and observational studies in subsequent dissemination sites have reported factors critical for successful implementation:15,17

-

effective clinical leadership

-

ability and willingness to adapt the original HELP protocols to local hospital circumstances and constraints

-

ability to obtain longer-term resources and funding

-

senior management support.

Approximately half of the sites that express interest in the HELP do not go on to implement the programme. 17 The two most common reasons for non-adoption are lack of senior management support (53%) and perception of high start-up costs (41%). 17 Recruitment of volunteers to the programme has not emerged as a critical limiting factor, suggesting a willingness of volunteers to engage with the programme. 18

The original version of the HELP that was evaluated is referred to in the literature as the Elder Life Program and specifically focused on delirium prevention. Subsequently, the programme was widened and the scope of the intervention extended to encompass areas of good practice including protocols for discharge planning, dementia care and optimising hospital length of stay. The resulting delirium prevention system of care and additional good practice protocols became the HELP system of care. The HELP has been widely disseminated to > 200 hospitals in the USA, Canada and internationally. The HELP provides a skilled interdisciplinary team assisted by trained volunteers to implement standardised protocols targeted at six delirium risk factors: orientation, therapeutic activities, mobilisation, optimising vision and hearing, hydration, and sleep enhancement. The core interdisciplinary team facilitates system change and programme implementation, including daily support to volunteers (Table 1).

| Inclusion criteria for the HELP | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Interventions to prevent delirium | |

| Risk factor | Preventative interventiona |

| Cognitive impairment |

|

| Sleep deprivation |

|

| Immobility |

|

| Vision impairment |

|

| Hearing impairment |

|

| Dehydration |

|

| The ‘core’ interventions to prevent delirium are supplemented by a number of clinical and educational ‘program interventions’ (e.g. staff training, nurse intervention protocols, and HELP interdisciplinary rounds) | |

Although the HELP has been consistently effective for delirium prevention, not all prevention programmes have reported a reduction in delirium incidence. 19 Although some intervention components appear more significant than others, a high degree of protocol adherence facilitates success. 20

Dissemination and embedding the programme in routine care have involved local adaptation in team composition, processes of care, procedures for patient enrolment, intervention protocols and outcome tracking. 15,17,21 Although the programme has proven cost-effective for both hospitals and nursing homes in US studies,22–26 the initial start-up costs of dedicated staff time17 may hinder adoption and sustainability in some settings. 21

Delirium prevention in the NHS

A major issue faced by the NHS in England, and acknowledged by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),8 is the lack of a delirium prevention system of care suitable for widespread national implementation.

Fundamental to our programme of work was the modification and subsequent feasibility evaluation of the HELP, the established and successful North American multicomponent delirium prevention system of care. However, the non-critical transposing of a US health system care model to NHS hospitals, which have a different organisation of care/case mix and funding, is unlikely to be successful. A thorough review and appropriate modification of the HELP should be an initial step. At the outset of the research programme, we envisaged a new, UK-specific version (i.e. HELP-UK) suitable for general use in the NHS.

Successful implementation of a multicomponent intervention is challenging: individual change is mediated not only by the availability of evidence-based guidance but also by characteristics of the intervention and the interplay of patient, social and organisational/system factors. Our aim was to understand the ‘whole system’ within which HELP-UK would be introduced, thereby enhancing the success of implementation. Our approach drew on aspects of systems theory;27 theory-based implementation;28–30 and relationships between structure, process and outcomes, defining how a service might work in context.

Aims and objectives of the research programme

The aim of the programme was to improve delirium prevention for older people admitted to NHS acute hospitals. We sought to ameliorate the large health and social care impact of delirium among older people by undertaking linked projects to investigate the feasibility, acceptability, and potential clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a delirium prevention system of care.

The objectives were to:

-

review and adapt the HELP for use in the UK health service

-

identify strategies to support the implementation of the HELP, taking into account the potential barriers to change

-

determine the optimum methods to deliver the HELP in routine care

-

conduct a feasibility study to –

-

assess the implementation and acceptability of the adapted HELP to patients and their relatives, clinicians, support staff and volunteers

-

refine the content and delivery of the intervention

-

determine preliminary estimates of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

-

gather data to inform recruitment, appropriate outcome measure selection and sample size to design a large-scale trial.

-

The programme comprised three projects:

-

Project 1: review and adapt the HELP for use in the UK and identify candidate implementation and delivery strategies.

-

Project 2: pilot study to test implementation feasibility and acceptability of a delirium prevention intervention in terms of –

-

take-up of the intervention protocols

-

impact of the intervention on staff workload

-

impact of the intervention on patient satisfaction with care

-

acceptability to patients, carers, staff and volunteers.

-

-

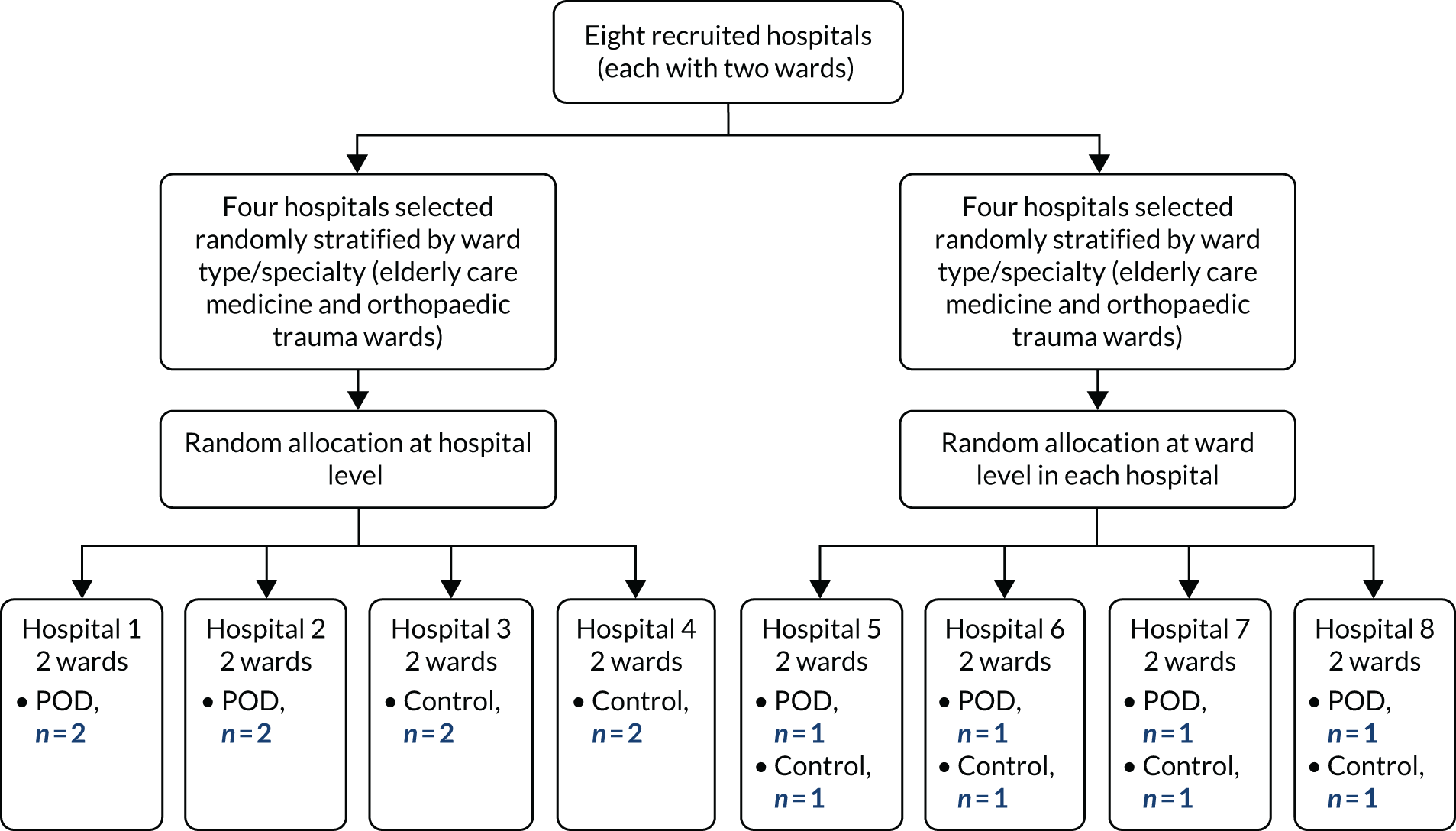

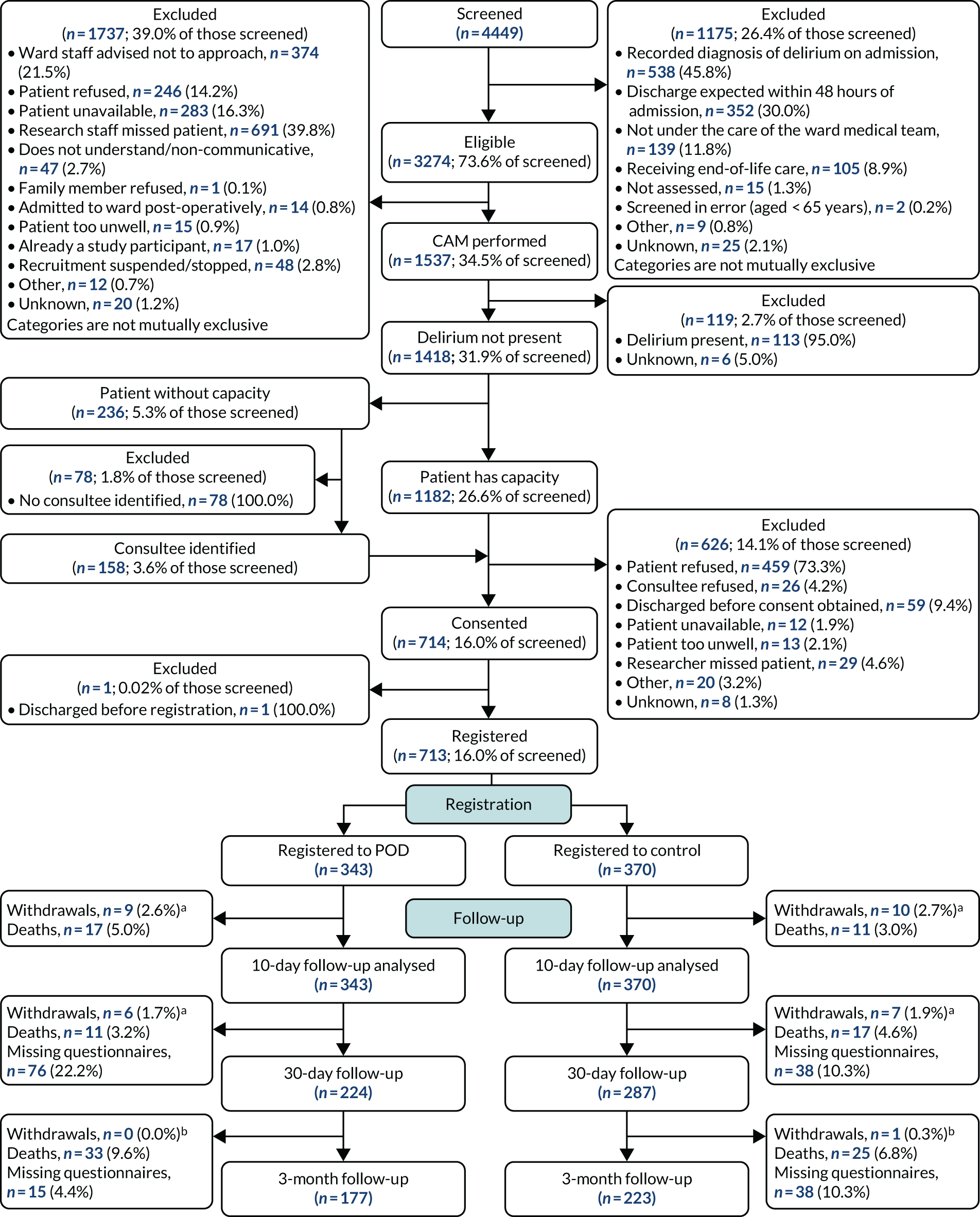

Project 3: preliminary testing of the Prevention of Delirium (POD) programme system of care.

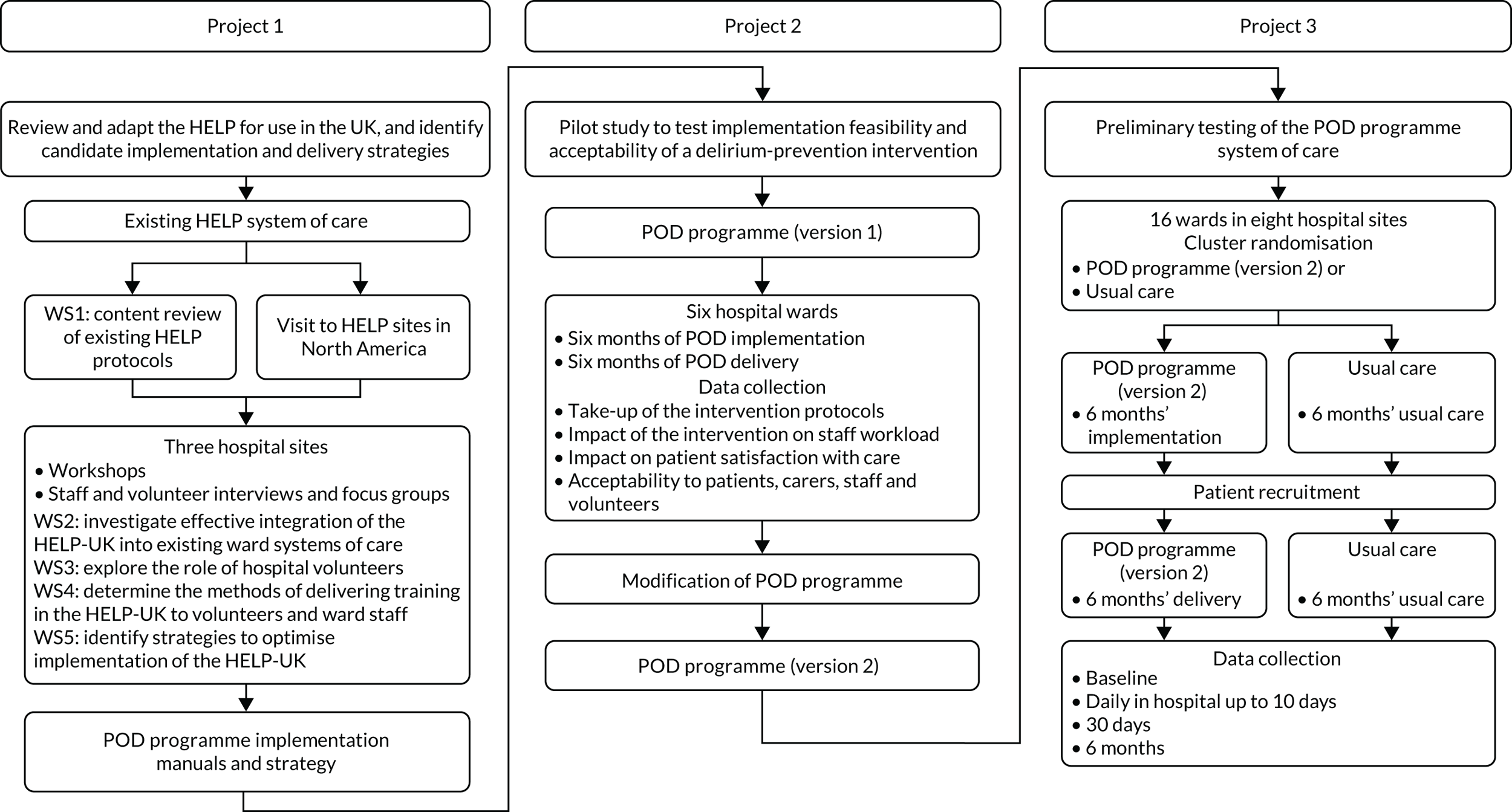

Project 1 output informed the design of the intervention, which was then tested in the preliminary pilot study (project 2). The findings of the pilot study further informed the conduct of the feasibility study (project 3) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the programme. WS, workstream.

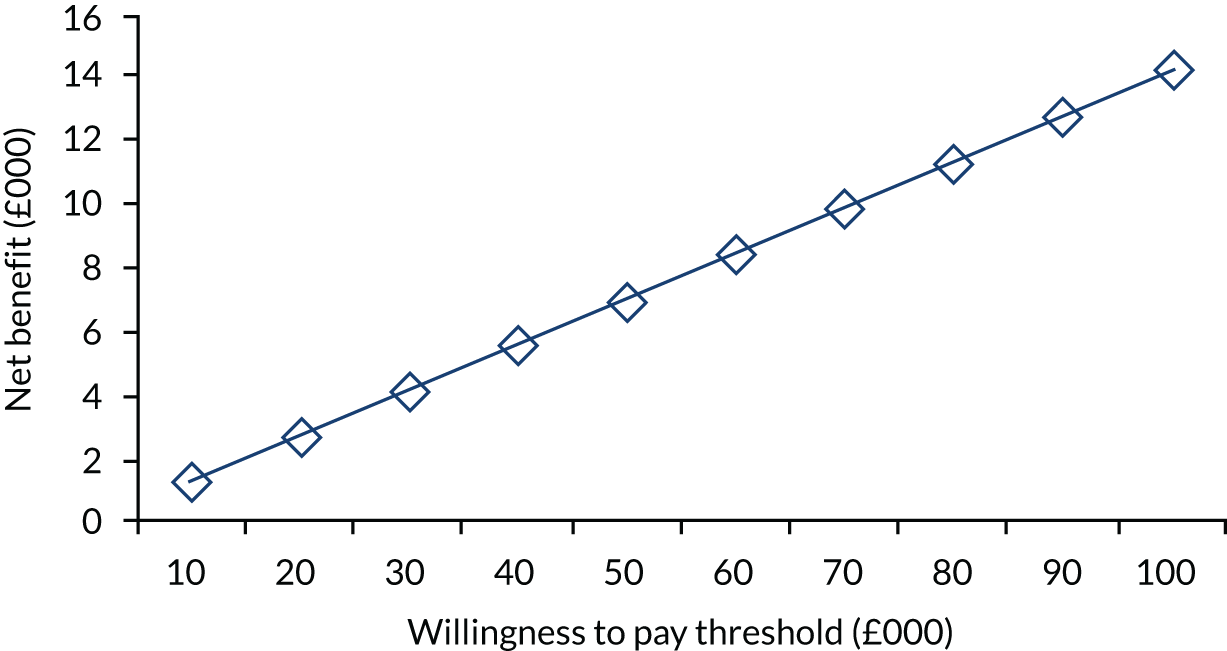

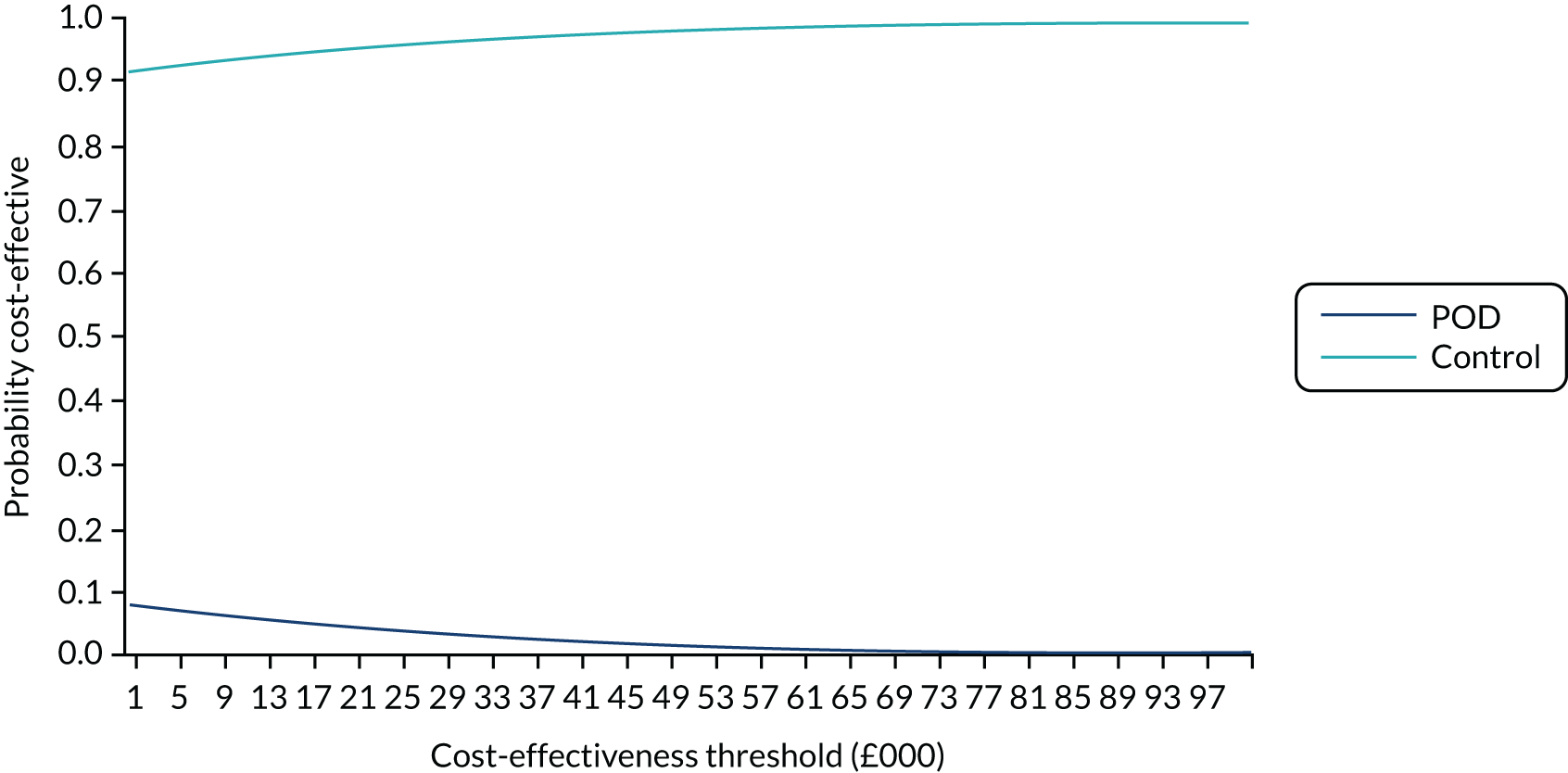

An embedded economic study assessed overall cost-effectiveness from the perspective of health and social care providers. The results of the health economic study are presented in Project 3: a multicentre, pragmatic, cluster randomised controlled feasibility study of the Prevention of Delirium programme system of care.

Project 1: review and adapt the Hospital Elder Life Program for use in the UK, and identify candidate implementation and delivery strategies

Large parts of this section have been reproduced from Godfrey et al. 1 © 2013 Godfrey et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The objectives of project 1 were to:

-

review and adapt the HELP for use in the UK (HELP-UK)

-

identify strategies to support the implementation of the HELP

-

determine the optimum methods to deliver the HELP in routine care.

Project 1 comprised five workstreams (WSs):

-

WS1: content review of the existing HELP protocols.

-

WS2: investigate effective integration of the HELP-UK into existing ward systems of care.

-

WS3: explore the role of hospital volunteers.

-

WS4: determine the methods of delivering training in the HELP-UK to volunteers and ward staff.

-

WS5: identify strategies to optimise implementation of the HELP-UK.

Workstream 1 was conducted first; then the remaining four WSs were conducted concurrently.

Methods

We planned to establish HELP-UK ‘development teams’ linked to acute hospital elderly care or orthopaedic wards. HELP-UK implementation was likely to vary depending on the clinical environment in which it was introduced. By including surgical and elderly care settings, we hoped to gain insights into a range of issues related to content and implementation, reflecting these different environments. See Report Supplementary Material 1 for the research protocol.

Site recruitment and sampling

We recruited three hospital sites in the north of England to participate in WSs 2–5 (Table 2). Purposive selection included the availability of volunteers to test out the potential for them to contribute to the delirium prevention programme, as in the HELP model. Although each hospital engaged volunteers, volunteers’ degree of active involvement with patients on the wards and the maturity of the voluntary services organisation varied considerably between sites, reflecting different approaches to how hospitals deployed volunteers, which reflects the ‘real world’.

| Variable | Hospital site | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Organisation | District general hospital | Foundation trust | Foundation trust |

| Number of beds | 480 | 400 | 650 |

| Catchment | Geographically dispersed urban and rural population | Urban, ethnically diverse population | Urban and rural population |

| Catchment population | 200,000 | 350,000 | 300,000 |

| Ward | Elderly care | Elderly care |

|

| Roles of delirium prevention development team members |

|

|

|

Following meetings by the research team with relevant managers and clinical leads in the elderly care or orthopaedic units in each of the sites, agreement to participate was secured. A delirium prevention development team, which included senior and frontline staff from elderly care and other wards with potential interest/roles in the programme, was established in each hospital. Although the focus was primarily on the ward, we were also cognisant of the effect of the wider hospital environment on ward-based delirium prevention (see Table 2). In site 2, for example, participants in the workshops included staff from the medical admissions unit, and therapists in site 1 worked across wards and the medical admissions unit. We also interviewed an accident and emergency (A&E) consultant in site 1.

Workstream 1: content review of the existing Hospital Elder Life Program protocols

For WS1, we undertook a content review of the existing HELP protocols to examine their applicability to the NHS. The research team, including delirium experts (two professors of elderly care medicine, a consultant in elderly care medicine and a consultant psychiatrist, all with a research interest in delirium), reviewed the HELP protocols, implementation process and mode of delivery (manuals, training materials), alongside the then-draft NICE delirium guidelines. 8 We additionally sought the opinion of practitioners with experience in delirium management on the HELP protocols at the European Delirium Association Meeting, held in Leeds, in 2009. We also planned to ask the Cerebral Ageing and Mental Health Special Interest Group of the British Geriatrics Society to provide an external independent review of the proposed clinical protocols before presenting them to members of the delirium prevention development teams in each hospital study site.

Visits to Hospital Elder Life Program sites

Alongside the content review of the HELP protocols, and to examine delivery of the HELP in its real-life context, the research team, as part of the research plan, undertook a visit to HELP sites in the USA and Canada in the spring of 2010. We are grateful to Professor Sharon Inouye for organising this.

The Hospital Elder Life Program materials

We encountered some unforeseen difficulties with the HELP in relation to background intellectual property rights. The HELP materials were released under signed contract agreements; this restricted the extent to which we could share and discuss the detailed content with non-HELP sites. These difficulties did not compromise our programme of work. Positive solutions were arrived at through an iterative process of discussions among the central HELP team, research team, Programme Implementation Team, Programme Management Board, and empirical work and literature review. The resultant delirium prevention model drew on the HELP protocols and principles (with permission), but extended their applicability to an NHS context.

Workstreams 2–5

-

Workstream 2: investigate effective integration of the HELP-UK into existing ward systems of care.

-

Workstream 3: explore the role of hospital volunteers.

-

Workstream 4: determine the methods of delivering training in the HELP-UK to volunteers and ward staff.

-

Workstream 5: identify strategies to optimise implementation of the HELP-UK.

Workstreams 2–5 were addressed concurrently via adoption of a participatory action research approach31 with delirium development teams. Through a sequence of practitioner workshops, interviews and ward observations, we explored models of delirium prevention and delivery. This approach provided the opportunity to examine ward practice relevant to delirium and delirium prevention in the context of current clinical and experiential knowledge, to facilitate mutual learning between relevant stakeholders, and to consider strategies for implementing a delirium system of care in the light of research evidence, current practice, and the professional and organisational factors that shaped it. This iterative, dialogic and reflexive methodology, in turn, informed the conceptual framework that guided data collection and analysis.

Workstreams 2–5: conceptual framework

We employed normalisation process theory (NPT)30,32 as a sensitising lens through which to explore knowledge and ward practices on delirium and delirium prevention. NPT focuses on microsocial processes that affect implementation of a practice (or technique) in an organisation or clinical setting. Normalisation refers to the work of individuals as they engage in activities and by which ‘it becomes routinely embedded in . . . already existing, socially patterned knowledge and practices’. 30 NPT postulates four generative mechanisms that operate individually and collectively to explicate how practices (interventions) are embedded and ‘normalised’ in routine care, namely coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring (Table 3).

| Generative mechanism | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Coherence | Individually and collectively: how the work that defines and organises a practice/intervention is understood as meaningful and invested in, in respect of the knowledge, skills, behaviours and actions required to implement it |

| Cognitive participation | How the work is perceived as something worthwhile and appropriate to commit their individual time and effort (signing up) to bring about the intended outcome |

| Collective action | How work practices and the division of labour through which these are carried out are modified or adapted to implement the change/intervention |

| Reflexive monitoring | How participants individually and collectively appraise the intervention and its benefits for participants, in relation to individual and organisational goals |

Whereas NPT has been developed as a tool for examining implementation processes and to enhance understanding of the implementation ‘gap’ between research and practice, we employed it to build a picture of how delirium and delirium prevention were understood as meaningful by acute ward staff, and how the work that staff were routinely engaged in was relevant to prevention. The aim was to facilitate systematic consideration of the barriers to incorporating, and the implementation strategies necessary to incorporate, delirium prevention within existing acute service delivery. Specifically, we were interested in how the work of staff, individually and collectively, was conducted in respect of the tasks that reduced or conversely increased iatrogenic and modifiable risk factors for delirium among those who were most vulnerable. Although the value of NPT is its focus on individual and collective practices in specific settings, we were also interested in examining the wider contextual features of settings that might affect implementation. 33,34 Thus, although new practices are introduced into organisations that vary in their history, culture, learning climate and readiness for change,35,36 organisational policies and practices are located in and are shaped by national, political, economic and health policy contexts that, in combination, will affect implementation processes and outcomes. 34

Workstreams 2–5: data collection

Data collection was undertaken by members of the research team who were not connected with the clinical teams and involved multiple qualitative methods: facilitated workshops with development teams, collection of documents/records, one-to-one interviews and focus groups with multiple stakeholders, and observation of ward practices. Informed consent was obtained from participants.

Workshops

Three workshops with the three development teams, facilitated by the researchers, were conducted, as specified in the original proposal. With the consent of team members, an additional round of workshops was held to review/refine a model of prevention relevant to the NHS. Researchers and participants worked in tandem at the workshops to:

-

explore what shaped staff knowledge (or lack of awareness) of delirium and delirium prevention

-

consider barriers to and opportunities for introducing a ward-based delirium prevention programme

-

consider which risk factors should be targeted

-

assess current practice and what would need to change to implement such a programme.

We used the HELP protocols and NICE guidelines8 to frame discussions and to examine the feasibility of involving volunteers in delirium prevention. The starting points in framing the workshop discussions were, first, the HELP model (see Table 1), specifically around the feasibility of involving volunteers in delirium prevention, and then the NICE guidelines. 8 The NICE guidelines8 provided more up-to-date and UK-specific evidence about the nature and scope of interventions to prevent delirium, albeit with little focus on how to embed practice and organisational change. Each workshop lasted ≈ 2 hours. All were audio-recorded and transcribed. The average attendance (mean) across the four workshops was as follows: site 1, 10.5; site 2, 10.5; and site 3, 7.75 (see Report Supplementary Material 2).

Interviews, ward observations and collection of documents/records

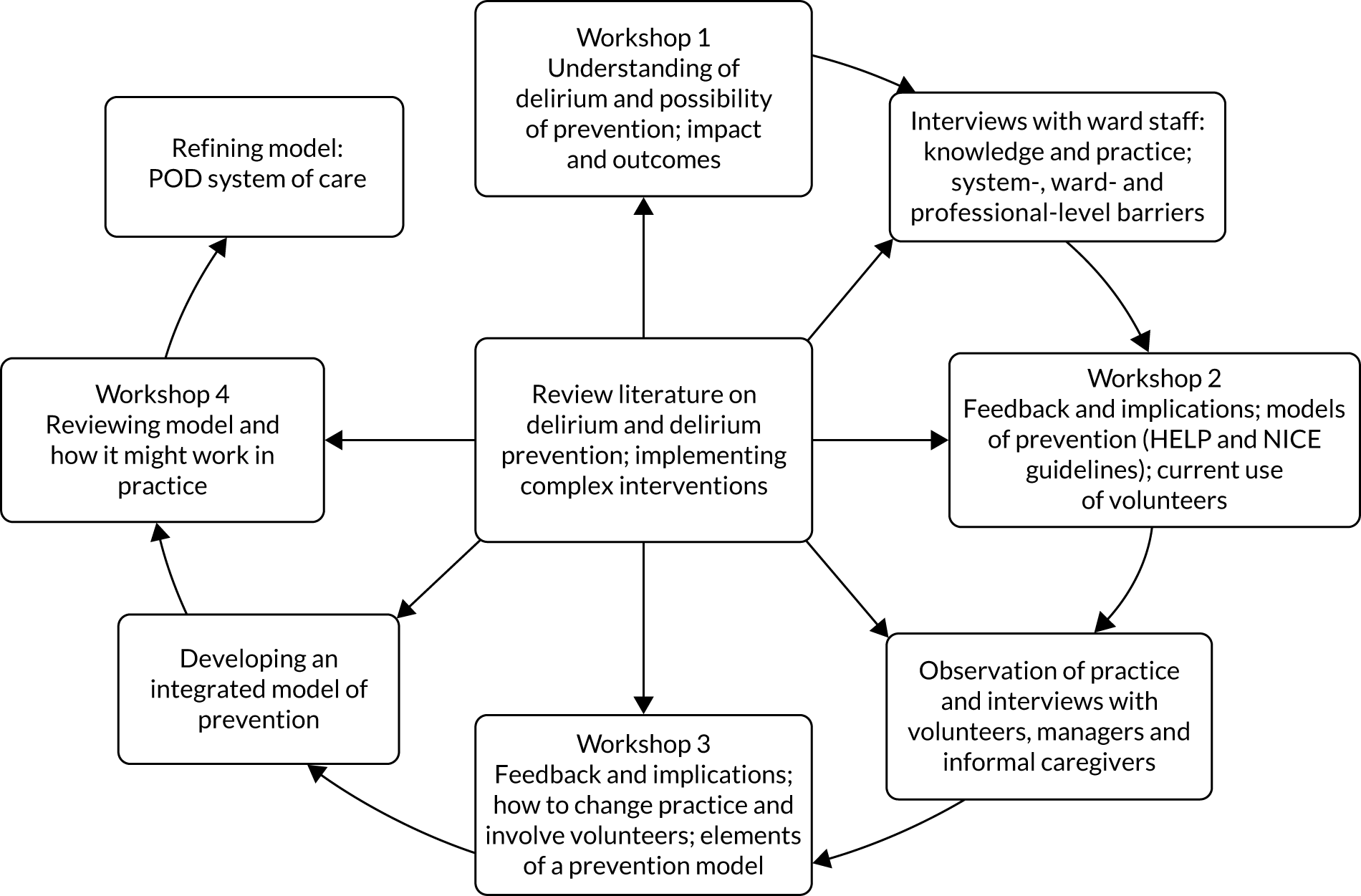

Between workshops, multiple data collection methods [qualitative interviews, ward observation and collection of documents/records (Figure 2)] were employed, using NPT30,32 as a sensitising lens to explore knowledge and ward practices on delirium and delirium prevention. Specific objectives of data collection were to:

-

garner a more detailed and nuanced picture of how delirium and delirium prevention were understood by staff (knowledge of delirium/delirium prevention)

-

explore current ward routines and staff practices pertinent to the assessment of delirium risk and the delivery of a delirium prevention programme (what was the work, how did it get done and by whom)

-

examine the nature of the patient journey from A&E to the receiving ward, and the potential for identifying the risk of delirium at each point in the journey (contextual factors affecting the work)

-

consider the current usage pattern of volunteers on the wards and the opportunities for and barriers to involving them in enhancing routine care relating to delirium prevention tasks (potential for introducing, integrating and routinising new practices).

FIGURE 2.

Qualitative research and development process for WSs 2–5.

Interviews

Interviews were conducted using topic guides with purposively selected staff and other stakeholders, chosen to obtain a range of views and experience. Twenty-nine interviews (32 individuals) were carried out with clinical staff [doctors, nurses and therapists in participating elderly care and trauma orthopaedic wards, in emergency departments (A&E) and those with a specialist/managerial role in relation to older people with dementia or delirium], voluntary services managers (VSMs) and experienced volunteers whom they identified, and caregivers who had experience of caring for a relative who had developed delirium on participating wards (see Report Supplementary Material 3).

Observations

We undertook ≈ 38 hours of observation of ward practice in the three sites at different times and on different days using ethnographic methods to expand understanding of staff routines relevant to delirium prevention in the real-life, acute ward environment (see Report Supplementary Material 4). This was supplemented by the collection of relevant documents (e.g. assessment forms, care plans, ward protocols, volunteer roles).

Workstreams 2–5: analysis

Workshop proceedings and interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and anonymised; observational notes were written up in expanded, chronological form, and all data were inputted and stored in NVivo version 9 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Analysis and data synthesis were ongoing and iterative. Each workshop involved feedback and discussion of emerging findings and implications from the empirical data, which, in turn, generated further data collection and review of evidence on implementation strategies (see Figure 2).

We used grounded theory strategies,37 such as open and focused coding and memos, constant comparison and search for negative cases, to develop categories, their constituent properties and the relationships between them. We compared and contrasted knowledge and practices relating to delirium and delirium prevention within and across wards, the professional and organisational factors that shaped them, and the consequences for service delivery. The findings and analysis led to the development of an integrated delirium prevention programme, iteratively elaborated and refined during delirium prevention development team workshops. The programme embraced intervention protocols, an implementation process and practice tools to enhance integration of delirium prevention into routine clinical practice.

Results

Workstream 1: content review of the existing Hospital Elder Life Program protocols

The content of the HELP intervention was similar to that of the NICE guidelines,8 with the important exception that the latter included additional key risk factors (pain detection and management, infection, hypoxia and nutrition). Practitioners with experience in delirium management at the European Delirium Conference 2009 broadly agreed on the appropriateness of the content of the HELP intervention protocols (see Report Supplementary Material 5). The HELP was designed to be an integrated hospital programme delivered by a skilled interdisciplinary team (geriatricians, elder-life nurse specialists and elder-life specialists), assisted by trained volunteers. An initial review suggested that this organisation and mode of delivery might prove problematic in an NHS context because of the additional staff costs to deliver the programme: 1.25 whole-time equivalent staff for 500 at-risk patients per annum, or approximately two or three new members of staff for an average-size acute hospital trust. (After initial start-up, the additional staff might be reduced to 1.25 whole-time equivalent staff for 1000–1500 at-risk patients per annum.)

We planned to present the clinical protocols to the Cerebral Ageing and Mental Health Special Interest Group of the British Geriatrics Society for an external independent review before presenting them to members of the delirium prevention development teams in each hospital study site during the first round of workshops. However, as previously mentioned, intellectual property copyright issues with the HELP prevented us from sharing the protocols outside the research team and registered sites.

Visits to Hospital Elder Life Program sites in the USA and Canada

Members of the research team visited the active HELP sites in four hospitals in the USA and Canada. We were able to discuss and witness how the HELP system of care was organised and delivered on the ground. Although presented in the literature as a protocolised intervention, it was evident from the visits that, like most complex interventions, the content and style of the HELP varied between sites. It was also apparent that a considerable infrastructure was required to support HELP delivery, for example recruitment and training of volunteers and elder-life specialist nurses. Moreover, we observed that the ward nurses, although appreciative of the HELP system of care, seemed to have little involvement in its delivery. Following the visit, the focus on adaptation of the HELP centred on the following question:

-

Is it possible to provide an effective, integrated model of delirium prevention that minimises the need for additional staffing, but that creates a therapeutic care dynamic between ward staff, volunteers and relatives? That is, does the intervention have to be delivered by an interdisciplinary team assisted by volunteers as an addition to existing ward practice (as in the HELP model), or can it be developed as a system of care that engages staff and volunteers with relatives, as appropriate, to provide a model of enhanced care?

To explore this question, we examined the literature on implementation to identify what successfully contributes to embedding new practices/interventions in routine care and we reframed the work with development teams to consider NICE guidance8 alongside the HELP protocols.

Workstream 2: investigate effective integration of the Hospital Elder Life Program-UK into existing ward systems of care

In situating the task of developing a delirium prevention system of care, we describe how delirium and the work of delirium prevention were currently understood and accomplished by staff. We draw on NPT mechanisms to organise the findings and illustrate interpretive points from our fieldnotes and interview data. We then review the evolving model of delirium prevention developed iteratively through the empirical research and participatory process with development teams. Finally, we present the integrated delirium prevention system of care (POD system of care), including the rationale, or theory of change, underpinning it.

Knowledge and awareness of delirium

Although knowledge of delirium and interest in enhancing practice to prevent it was a key motivating factor for geriatricians’ involvement in the research, awareness of delirium was more variable among other staff. Although junior doctors might be familiar with the term ‘delirium’ and knowledge-based understanding was seen to have improved among registrars specialising in the care of older people, there was less confidence that such knowledge was routinely translated into action to prevent delirium or manage it when it occurred. For nursing and therapy staff, delirium had not featured in their professional training. Among all staff, delirium and delirium prevention were not included as part of mandatory training or in-service education programmes. This was seen to reflect the low salience attached to delirium and delirium prevention in policy and practice, such that, unlike other aspects of acute care delivery such as falls and pressure sores, there were no specific protocols relating to it in any of the sites.

Nursing, therapy and care staff generally did not use the term ‘delirium’; instead, the term ‘confusion’ or ‘acute confusion’ was more typically employed, particularly on elderly care wards:

It’s just that perhaps they don’t recognise it as delirium . . . they don’t put a label on it.

Doctor

Whatever the term used, among these staff, delirium was primarily understood in its manifestation as a problem for ward management and in the disruption it caused for other patients. Thus, awareness (unprompted) was predominantly of hyperactive delirium that resulted in difficulties for staff from problematic behaviour such as aggression, agitation, shouting and wandering. There was acknowledgement that hypoactive delirium, resulting in withdrawn, lethargic behaviour, could easily be overlooked in an acute environment. Indeed, staff awareness and understanding of the experience of delirium from the perspective of patients and caregivers was prompted through presentation of the evidence by the research team, and patients’ and caregivers’ concrete accounts of specific episodes of delirium during the workshops.

How staff perceived the nature, impact and consequences of the ‘problem’ of delirium affected how they sought to manage it. Awareness of ‘acute’ or ‘temporary’ confusion was seen to result in information-seeking from family and friends to determine whether this was of long-standing duration or of recent origin:

They might have been getting worse over a few weeks so, you really need to speak to a carer or relative; quite often we ring home care as well. We ring district nurses: ‘How are they normally? How have they been? Have you noticed any change in their condition over the last few weeks?’ . . . often the consultant . . . if we haven’t done it, will ask for us to get information from home care or whatever.

Senior nurse

Ascertaining that the change was recent and that the behaviour was atypical might precipitate a search for underlying causative factors contributory to the delirium (e.g. sepsis on elderly care wards), so as to identify solutions to address them (e.g. pain relief following surgery on orthopaedic wards). The practice consequences of identifying delirium also highlighted the process whereby delirium affects treatment and extends inpatient stay. Therapists, for example, indicated that mobilisation might need to be delayed to allow patients the chance to recover sufficiently to engage in rehabilitation:

That’s very common [delirium with sepsis], now those patients who are . . . acutely ill and we feel are in that stage, we don’t always try and do anything with them in the early days because we’re aware of the fact that, say they’d come in with a UTI [urinary tract infection] that, sometimes, just having a couple of days to recuperate means that, when we intervene, then they’ll have a much more successful outcome . . . they’re the sort of patients who we might discuss with the nursing staff and they’ll say, ‘leave it today’, you know . . .

Therapist

Some staff used the terms ‘confusion’ and ‘acute confusion’ interchangeably. This imprecision in language use denoted a lack of clarity about the distinction between acute confusion and dementia. The practice consequence was that search for a cause might not be pursued:

I think a lot of the times . . . it’s probably put down more to dementia than it is to delirium . . . when, I guess, so many people who have dementia are . . . more susceptible to having delirium . . . And then [for people with dementia], I think it’s probably more put down to: ‘they’re . . . out of their own environment, they’ve had a traumatic operation, they’re just more confused’, rather than there’s perhaps another underlying issue that’s causing it . . .

Therapist

The conflation of delirium and dementia by staff was a source of heightened anxiety and perplexity among caregivers/relatives, as the suddenness of the change and the strangeness of the behaviour of their relative was not understood by staff. Aggression and/or refusal to participate in treatment could be interpreted as ‘lack of engagement’, resulting in the patient being perceived as unsuitable for rehabilitation or berated by staff for ‘inappropriate’ behaviour. The following is an illustrative example.

Mrs Patterson’s (a pseudonym) brother-in-law was admitted to hospital ‘with a very high temperature and inflammation in his leg. I’m not quite sure what diagnosis was put on it’. He was also disabled following a stroke several years previously:

When he was admitted . . . everything went . . . during the night he just screamed for my sister . . . I went down to the hospital the following morning . . . it was obvious to me something was wrong . . . he was shouting and aggressive . . . and demanding. The nurse said to me when I went on the ward: ‘Oh, I’m glad you’re here, I want to say this in front of you [looking at the brother-in-law] that you are a very difficult man and we don’t like the way you’re speaking to us and if you continue we will refuse to nurse you’ . . . I said to her that he’s not like this usually . . . The doctor later confirmed that he had delirium.

Mrs Patterson

Generally, then, variability in how delirium was understood among different groups of staff and the lack of investment at an organisational level in respect of training and education meant that, in NPT terms, delirium identification had low coherence. Delirium diagnosis was primarily effected through use of observational cues, although how these were interpreted and acted on depended on the expertise of those making the observations. Thus, management practices following on from observations reflected the skills and interests of individual professionals, rather than a collective staff and ward response.

Delirium prevention

Given the low coherence of delirium among staff groups across sites, it is hardly surprising that delirium prevention was not perceived as meaningful. Even when senior staff had initiated action to increase awareness of delirium risk (e.g. posters displaying risk factors), this did not inform assessment and care practices: ‘it’s not in the foreground of people’s minds’ (geriatrician). Interviews and observations indicated that knowledge of delirium among individual staff did not necessarily translate into specific beliefs and behaviours (cognitive participation) and the organisation of work practices geared towards prevention (collective action).

In one elderly care ward, we observed that senior nursing staff employed the term ‘delirium’ in describing specific patients, and demonstrated awareness and knowledge of both hypoactive and hyperactive delirium, as well as sensitivity to the distress caused to patients with it. The consultant geriatrician also had a particular interest in delirium. During observation of a nursing handover meeting on this ward, it was reported that just under one-fifth of current patients were characterised as having delirium. One of the patients with delirium discussed was perceived as needing considerable assistance with eating and drinking; another was referred to as having ‘hypoactive delirium’, ‘really drowsy’, not sufficiently alert to eat and drink, incontinent and ‘on IV [intravenous] fluids’. For the former patient, it was emphasised that all staff should be alerted to ensure support at mealtimes and to encourage drinking and eating. For the latter, it was agreed that she should be moved to a bed that was more visible from the nurses’ station, although this also provoked discussion about the disorientation such a move might cause. At the same meeting, several newly admitted patients were described as having symptoms that, to the observer, might portend risk of developing delirium: an 89-year-old patient who had experienced multiple urinary tract infections and been admitted following a fall, and an 80-year-old patient with a urine infection and pneumonia who had suffered a heart attack and needed oxygen. The symptoms were presented without reference to or discussion about delirium risk or any specific preventative action to be taken. This was recognised as typical practice by the development teams. Thus, even when there was shared understanding of delirium management, this did not facilitate noting and acting on risk factors before delirium had occurred (cognitive participation in NPT).

One exception to this general gap between knowledge and practice in delirium prevention was the development and implementation of a protocol on pain management post surgery for use in hip fracture patients on the trauma orthopaedic ward. This was aimed at delirium prevention. Staff remarked on how the protocol was routinely pursued, with positive outcomes as a consequence, particularly in reducing the severity and duration of delirium episodes. The ward manager attributed success to specific features of the hip fracture patient pathway: this was direct, linear and highly protocolised, with all patients diagnosed with hip fracture fast-tracked from the A&E department to the ward to undergo surgery within 24 hours. Insertion of the protocol into the pathway was viewed as an elaboration of existing practice, rather than as a major shift in how things were done. Practice change was reinforced by the perception among nursing staff that this was a relatively simple intervention with visible positive effect in a short period of time.

By contrast, the patient journey to elderly care wards across the three hospitals was more protracted and diverse. Triage systems and initial investigation in A&E to determine a differential diagnosis and whether or not admission was warranted might be followed by further observations in a short-stay assessment facility for up to 48 hours, which could be further protracted because of a shortage of acute ward beds. The chaotic nature of A&E and short-stay assessment facility environments, compounded by the multiple potential aetiologies of delirium in these settings, was viewed as contributing to delirium risk so that the scope for preventing incident delirium on acute wards could be adversely affected by the length of the patient journey into them. Even so, delirium prevention was considered to be feasible and worthwhile in the acute ward environment, although organisational factors shaping the patient journey through the hospital also needed attention as part of a strategic approach to prevention.

Current ward routines and practices

From interviews with staff and development team discussions, the acute care ward was reported as ‘busy’, often ‘chaotic’ and challenging: a picture reinforced by research observation. Explanatory, contributory factors offered by staff included patient mix and the policy and organisational imperative to achieve rapid patient throughput. Policy and service emphasis on hospital admission of those who required specialist medical and nursing expertise that could not be provided in alternative settings meant that patients were very acutely ill. Similarly, it was expected that patients would move on from acute care once medical and functional needs were met to secure ‘safe’ discharge. Patient moves within wards across all sites were also common, reflecting various organisational contingencies.

The hectic nature of ward life had the consequence that routine practice was described by staff as being primarily directed at responding to what was immediately presented, with priority given to diagnostic, observational and interdisciplinary assessment and care-planning. This picture was reinforced from observation. Thus, particularly for nursing and auxiliary staff, ward life was organised on the basis of a structured rhythm of time-sequenced care (washing, toileting), observations, diagnostic processes and treatment, punctuated by meals and visiting times, a pattern that was prone to disruption as a result of crisis events. Alongside this daily rhythm was the management of patient flow (admissions and discharges) and associated activities (negotiating with bed managers, discharge co-ordinators, social workers, relatives and community agencies), including record-keeping.

The variability and general understanding of delirium prevention among staff meant that it was not a significant driver of ward care practice. However, although delirium preventative interventions relate primarily to features of care quality, it is pertinent to consider how relevant routine care practices were accomplished, including the barriers and contextual factors that affected them.

Nutrition, fluids and sensory aids

Although nutrition and fluid intake were viewed as components of ‘basic’ care to be undertaken by ward staff, they were primarily delivered by health-care assistants (HCAs). In each site, around one-third of patients required some direct help at mealtimes. Others might need encouragement to eat, although this provision depended on staff availability and assumed lower priority. Similarly, tasks of washing and dressing, including ensuring that patients had spectacles, dentures and hearing aids, as appropriate, were mainly undertaken by HCAs. Even so, the importance that senior nursing staff attached to care tasks affected both the value attributed to them by junior nursing staff and the extent to which they pitched in to provide assistance.

Mobilisation

Mobilisation by physiotherapy staff of patients with particular needs was limited: it appeared to occur, at most, once daily, and was intended to be augmented with support and encouragement from ward staff. Patients who merely lacked confidence in getting up and walking on their own were reliant on nurses and HCAs to provide this. Similarly, local policies on prioritising therapy for those with the potential to resume independent living meant that, for example, in one site, patients admitted from nursing homes did not receive therapy. The engagement of nurses and HCAs routinely in mobilisation work in either an enhancing or a supportive role was viewed by staff as essential to sustaining mobility among patients, most of whom were of advanced age, frail and unsteady on their feet. How consistently this was done depended on factors such as the ward physical environment and other pressures.

In one site, the confined and cluttered space of the bays was a constraint on the ability of patients to move safely, and, as the distance between bed and toilet was not more than a few steps, routine mobilisation by nurses and HCAs was limited. Only therapists walked patients for longer distances along the corridor, where the wider space enabled freer and more confident movement. In another site, by contrast, the distance between the bed and toilet was some 10–20 m. Part of the ward routine included nurses and HCAs providing direct assistance to patients and/or keeping an eye out for them as they walked from bed to toilet. It was noted over an observation period how one patient progressed from being assisted with walking to managing independently with a nurse walking behind her, and then to walking on her own. Although here the physical environment was conducive to staff encouraging mobility, this practice was facilitated and reinforced by a care ethos that placed high value on all staff, including nurses, participating in such work. This is exemplified in the following episode observed in this site, but not in others. One of the nurses was with a patient as she encouraged her to stand up from being seated. As the patient made several attempts to propel herself from a sitting to a standing position, the nurse stood by continually encouraging her by showing her how to use her arms to push and move to the edge of the chair, and praising each effort until she stood up.

Orientation and communication

Features of the ward physical environment may act as constraints to ‘good’ care practice, for example inappropriately placed clocks, lack of space or infection control policies precluding personal possessions.

There was variation between individual staff and professional groups within and between sites in the extent to which they conversed with patients in the course of their work. Therapists, for example, typically introduced themselves to patients they were working with, engaging them in general, social and orienting conversation. The pattern was more diverse among nursing and care staff. In one site, there was a buzz of chatter in the bays as nurses and HCAs conversed socially with patients as they went about their daily routines of washing, dressing, medication rounds and mealtimes. The progress of individuals was remarked on and patients were complimented on efforts at walking or dressing. In another site, interaction between staff and patients seemed primarily directed on the task in hand: ‘here are your tablets’, ‘do you have any pain?’.

The hustle and bustle of ward life, particularly from early morning to mid-afternoon as described by staff, was in marked contrast to the silence and inactivity of patients once care needs and clinical observations were completed. We could discern two parallel but distinct ward rhythms: a staff rhythm marked by frenetic movement and continuous noise – buzzers, telephones and the clatter of trolleys – and a patient rhythm distinguished by a paucity of conversation and little movement. Sustained or prolonged engagement of patients by staff was absent in all sites. Development teams remarked that this was neither feasible nor valued in the context of the priority attached to moving patients quickly through the system.

Overall, some practices pertinent to delirium prevention (assistance with meals for those who needed help with eating but not for those who required encouragement) were carried out more or less consistently for some patients across all sites. Other practices (enabling support to encourage and enhance mobility among patients lacking in confidence, and personally meaningful, as opposed to task-based, communication) were accomplished more consistently in some sites than others, depending on local policies and priorities, the physical environment in which care was delivered and the existence of a care ethos that placed high value on social engagement and care. Yet other practices (spending time with patients in one-to-one conversation or engaging patients in cognitively stimulating activities) were not routinely engaged in by staff across sites, which was seen to reflect the current acute care environment. Collective action by ward staff in practices that are preventative of delirium were contingent on local policies and priorities on patient need, staffing levels, division of labour and the care culture operating. In no site were any of these explicitly linked with delirium prevention or engaged in consistently for all patients who might exhibit delirium risk factors.

Workstream 3: exploring the role of volunteers

Discussion within development teams and interviews with VSMs, volunteers and ward staff revealed considerable variability in the size and scope of the volunteering role, supervision arrangements, training and organisation of volunteers. One hospital had had a 400-strong volunteer force since its opening some four decades previously. Here, volunteers were centrally managed under the aegis of a VSM and deputy. The post holder was responsible for recruitment, organising training, deploying volunteers to some 30 different tasks/roles and providing ongoing support to them. In another hospital, by contrast, voluntary provision was fragmented and delivered through different agencies, each focusing on discrete roles and tasks. As a consequence, there was no standardised system for recruiting, inducting, training and supporting volunteers.

Although most volunteers in all sites were primarily engaged in providing practical and orientation assistance to patients and visitors, each site had a small number of volunteers, outside the chaplaincy service, which offered one-to-one befriending with patients on the wards. These volunteers spent time conversing with patients, the purpose being to reduce isolation among patients who had few visitors. They reported variable interest in what they did among ward staff, ranging from positive reinforcement of the value attached to it to indifference and hostility. Generally, staff were seen as so busy that they were unaware of volunteer input. Sustaining volunteer involvement depended on the commitment, tenacity, skills and abilities of individual volunteers and mutual support provided to each other through informal networks. One site had developed a successful programme for trained and supervised volunteers attached to specific wards to provide assistance and encouragement to patients who needed help with meals. A similar scheme at another site had been unsuccessful, which was attributed to a lack of attention as to how to engage ward staff.

Engaging volunteers in delirium prevention tasks offered a potential resource to wards and existing direct work with patients provided the building blocks to develop it. However, the ad hoc nature of the befriending role, as typically understood by staff, and the lack of clear systems for supporting volunteers, including their purposeful integration into the work of patient care, presented obstacles to realising its potential. In NPT terms, given existing models of volunteer/ward staff engagement and practices, mechanisms for creating a common sense of purpose and value attached to the volunteer role and for establishing a division of labour that was appropriate and acceptable to both volunteers and staff were necessary to create the conditions for involving volunteers in delirium prevention.

Workstream 4: determining the methods of delivering training in the Hospital Elder Life Program-UK to volunteers and ward staff, and workstream 5: identifying strategies to optimise implementation of the Hospital Elder Life Program-UK (Prevention of Delirium system of care)

Developing a model of delirium prevention

Within development teams, and through iterative feedback of empirical findings, we pursued in-depth discussion of the content of a multicomponent delirium prevention intervention and implementation process, with particular focus at the outset on the HELP mode of delivery. With regard to the intervention, there was consensus among the development teams that the NICE components and recommendations would constitute the content, as NICE extends the HELP intervention with up-to-date evidence.

One unique aspect of the HELP mode of delivery, as described previously, is the use of trained volunteers in assisting the HELP interdisciplinary team with some of the core interventions. Development teams perceived this feature of delivery as posing major practical and conceptual difficulties, thereby challenging its feasibility in an NHS context. Conceptually, although there was considerable enthusiasm for volunteer involvement, staff considered that ward practice in respect of delirium prevention activities was central to delivering consistent, quality care, such that staff needed to be actively involved in these activities. There was understanding among some senior staff that ward care practices such as nutrition, fluid intake and mobilisation were significant not only in helping to manage delirium, but in having a preventative effect on its development. These practices were also viewed as pertinent to other areas of prevention that have been targeted for action at national and local policy levels to secure care quality improvements, such as falls and pressure sores. Engaging staff in the work of delirium prevention, then, was viewed as enhancing staff awareness of and ascribing legitimacy to work that has a wide-spectrum preventative effect, with the potential to increase patient care quality overall.

Practically, the level of resource required to emulate the HELP was viewed by all of the development teams as unachievable because they believed that substantial additional staffing would be required to deliver the intervention to all patients on a typical elderly care ward. Consequently, in collaboration with the development teams, a model of delirium prevention evolved whereby the core components of prevention were assimilated into the daily routine of staff and volunteers without the need for additional staffing. This combined a practice change in the way staff went about their daily routines in respect of the 10 core components with an enhanced role for volunteers.

However, this presented two major challenges for implementation. First, there was the paucity of knowledge and understanding of delirium prevention, particularly among nursing and care staff, whose routine practices were critical in delivering preventative interventions. Second, the enthusiasm of ward staff for involving volunteers in a more focused and direct role with patients was seen to require considerable change in the way volunteers were currently deployed.

The development of such a model, therefore, required attention to both the processes and strategies for achieving practice change and the systems and mechanisms necessary to recruit, train and support volunteers to provide an enhanced and co-ordinated role in a whole-ward intervention. Such changes, moreover, had to flow directly from a knowledge and awareness of delirium prevention as worth the investment by staff individually and collectively. This represented a shift in direction from refining the HELP for an NHS context to developing a new model of delirium prevention, namely the POD system of care.

The programme we developed (the POD system of care) was the product of the interaction of the development teams’ practice knowledge, current best evidence on delirium prevention,8 and consideration of the findings of our empirical research and recent reviews of implementation theory and research. 29,30,38 The content and implementation process documented in the resultant system of care was then further tested and refined through dialogue with the development teams.

An integrated model of delirium prevention: the Prevention of Delirium system of care

The POD system of care version 1 (PODv1) was a multicomponent intervention and implementation process organised in two manuals (Table 4). The system of care aimed to integrate delirium prevention activities into routine care.

| Section | Contents |

|---|---|

| 1. Introduction | Provides the background to the programme, the theory of change underpinning it, why it is necessary, the intended objectives and the steps that need to be in place to introduce it at ward level |

| 2. Educational materials | Comprises sets of slides, vignettes and case studies to be drawn on to raise awareness of delirium and delirium prevention and to create readiness for the introduction of the programme alongside involvement of ward staff |

| 3. Preparation for change | Sets out a detailed implementation process, mechanisms and activities for planning the work, engaging staff, executing change, and reflecting and evaluating progress and outcomes preparatory to delivery |

| 4. Implementation manual | Designed to record in detail, after completion of section 3, how each of the interventions will be implemented in routine care on the ward. This is a bespoke document, with systems and division of labour adapted to local contexts, albeit addressing common functions |

| 5. Involving volunteers | Specifies the detailed work involved in engaging volunteers alongside ward staff in implementing the integrated delirium prevention programme, one set of tasks that constitute part of section 3. It is aimed at guiding the POD action group through those issues relating to volunteers that require discussion and decisions, for example providing examples of volunteer role descriptions |

| 6. Audit and model tools | Provides a range of tools that may be helpful to draw on in implementing and reviewing the outcomes of practice change |

The Prevention of Delirium system of care interventions

The POD system of care interventions comprise actions encapsulated in protocols centring on 10 targeted clinical risk factors associated with the development of delirium among vulnerable patients. 8 The risk factors were organised hierarchically into three distinct delirium prevention ‘bundles’, according to a number of factors, including the level of expertise needed for their implementation; the bundles also provide a framework for ward staff to identify what should be done and by whom, taking into account local policies and practices:

-

Actions that might typically be carried out as part of existing medical/nursing roles (assessing and managing pain, medication management, hypoxia and infection management).

-

Actions that, depending on the level of patient need, might require skilled therapy/nursing and care input, at one end of the continuum, to, at the other end, assistance provided by volunteers with appropriate competencies (e.g. mobilisation, mealtime assistance).

-

Actions that offered scope for volunteers to enhance care practices while stimulating practice change towards providing holistic care to patients (engaging in social and stimulating activities for which volunteers can offer a unique contribution).

Prevention of Delirium system of care implementation process

The POD system of care implementation process incorporates systems and mechanisms aimed at introducing, embedding and sustaining the POD system of care interventions into routine ward care. It envisaged implementation as a process involving a number of steps, not just a single event. 38 These comprised (1) mobilisation of a staff action group, (2) staff (and volunteer) training, (3) review of current ward practice, (4) examination of delirium risk factors in relation to current ward practice, (5) implementation of delirium prevention practice and (6) the volunteer programme:

Staff action group

The first step involves the mobilisation of a staff action group with the legitimacy and authority to introduce the programme and develop a plan for change that included awareness-raising and delivering training, engaging ward staff and recruiting volunteers. The action group was to comprise relevant individuals, including ward manager, matron/senior practitioner and VSM, all central to co-ordinating and delivering the change, although others (up or down the organisational hierarchy) might be mobilised around specific objectives and tasks.

Training

With the action group in place, the second step in preparing for implementation comprised staff training based on an interactive approach to foster programme coherence. 39 Educational materials presented the theory of change underpinning the POD system of care interventions and facilitated consideration of current practice on identifying risk factors and preventative actions alongside practices to be implemented. Thus, materials placed the emphasis on staff reviewing what they actually did in respect of patients at risk of delirium and what systems needed to be in place to identify those at risk to direct attention to what was different with the POD system of care. It was envisaged that educational materials might be added to and refined depending on local need, recognising that there also existed local expertise and pre-existing work on delirium prevention in some sites.

Review of current practice

The third step in the preparatory work of implementation, and through which programme coherence was further generated, was the systematic review of current practices related to each of the delirium prevention interventions via staff observations and structured feedback to inform action-planning. Thus, using a set of suggested, adaptable audit tools, the action group was to facilitate the conduct of short periods of qualitative observation of ward practices and environment, the results of which would be discussed by the ward team. This was intended to both engage the wider ward team in understanding how the intervention departed from existing practice and secure participation in the programme of change (cognitive participation), thereby also positively affecting ward vision and culture. 34,40–42

Examination of risk factors in relation to ward practice

The fourth step in implementation planning involved the action group examining the interventions, one for each of the 10 clinical risk factors, with a structured approach to decision-making around allocating roles and responsibilities between staff and volunteers, informed by the audits and ward staff discussion.

Implementation of delirium prevention practices

The implementation process activities to insert the co-ordinated model into routine work practices comprised two sets of tasks. One set involved consideration of the appropriate role of volunteers in relation to specific delirium prevention interventions consistent with local policies. This prompted action on agreeing role descriptions, associated competencies necessary to undertake roles safely and confidently, and the appropriate training and support to do so. The other set concerned establishing and inserting into routine work practices systems and processes for the assessment and recording of clinical factors contributing to delirium risk, for communicating information and preventative tasks in respect of at-risk patients to staff and between staff and volunteers, for documenting interventions carried out by volunteers and staff, and for supervising and supporting volunteers at the ward level. These activities, which have been characterised elsewhere as the tasks of ‘planning, engaging, executing and reflecting and evaluating’,29 had the objective of enhancing ownership and commitment to the integrated model of change, thereby facilitating collective action and reflexive monitoring.

The volunteer programme

Simultaneous with system of care implementation planning at ward level was the recruitment of volunteers, the provision of training to support their involvement and a process of introducing them to ward staff to facilitate an integrated team approach to delivery.

The product of the planning for implementation was a bespoke POD system of care with the systems, processes and division of labour in place to achieve and sustain its execution, and that was adapted to local contexts. Even so, the principles underpinning POD and the steps in the change process to facilitate action on the intervention were standard. 33 We envisaged that this was not a static document, but would be subject to regular review and change based on progress, experience and documentation of actions and outcomes. 43,44

Sections 1–4 of PODv1 (see Table 4) were presented to the development teams in the third workshops; they considered the programme feasible to implement. The remaining sections were presented at the next round of workshops. Following this, we were in a position to prepare the final version of the full programme for pilot implementation in new sites in project 2, scheduled to start in June 2011. This was the main output and milestone for project 1 (see Table 4).

The project 1 sites showed considerable commitment to continuing their delirium prevention work; therefore, they each received a copy of the final system of care. Any subsequent implementation they chose to undertake was outside the auspices of the research team.

Summary

The work undertaken in project 1 focused on a central facet of complex interventions, that is developing the treatment components and the associated processes of implementation while locating them in an organisational setting (in this case, an acute hospital ward) that is itself complex and dynamic. 45

The work of delirium prevention as a meaningful set of practices posed difficult challenges for staff, as prevention necessitates a more complex understanding of a problem than understanding how to manage it. Engaging in preventative action requires knowledge at different levels: about risk factors that may predispose a patient to the problem, and the kinds of interventions or practices that have the potential to reduce modifiable risk. It also requires systems to identify those at risk, and the mobilisation of staff to carry out practices that contribute to risk reduction.

Building on the participatory method and empirical findings, PODv1 was developed as a collaborative approach to delirium prevention involving ward staff, volunteers and patients/relatives. It is distinct from the HELP in several respects. First, and in contrast to the HELP, no additional programme-specific staff are required. Rather, the programme was envisaged as becoming embedded into routine ward practices. This approach is also attractive from an intervention sustainability point of view. Second, by involving staff directly in delivering the system of care, it aimed to enhance a culture of care among staff on acute wards, recognising that communicating with patients and responding to their individual needs in a holistic manner are integral to promoting recovery and reducing adverse events. Third, by including volunteers alongside staff in providing that additional ‘bit of help’ (e.g. engaging with patients as individuals, providing cognitive and social stimulation or enhancing care through assistance with tasks such as feeding), there is the potential to increase the effectiveness of delirium prevention, with an additional positive impact on the well-being of patients and the more effective use of resources. Finally, although the POD system of care has well-described core content, it was intended to be delivered flexibly depending on pre-existing practices and local circumstances.

The research process described in project 1 led to the successful formulation of a draft delirium prevention system of care suitable for use in the NHS, which, although sharing the principles of the HELP, was substantially different from the original HELP model.

We were thus ready to embark on project 2 of the research programme: pilot-testing the novel delirium prevention system of care (POD) for feasibility and acceptability.

Project 2: pilot-testing of implementation feasibility and acceptability of the Prevention of Delirium system of care (version 1)

Parts of this section have been reproduced from Godfrey et al. 46 © 2013 Godfrey et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Aims and objectives

The aims and objectives of project 2 were to conduct a feasibility study to assess the implementation and acceptability of the PODv1 to patients and their relatives, clinicians, support staff and volunteers, and to refine the content and delivery of the intervention in terms of:

-

take-up of the intervention protocols

-

impact of the intervention on staff workload

-

impact on patient and carer satisfaction with care

-

acceptability to patients, carers, staff and volunteers.

Method

We undertook a before-and-after study in hospital trusts using quantitative and qualitative data collected prospectively over a 6-month baseline/implementation period and a 6-month delivery period to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the PODv1 and to refine its content and delivery.

We used a case study approach47 to collect detailed information using mixed methods. These included facilitated workshops, analysis of documentation/records, interviews and focus groups, observation, and questionnaire surveys, which provided us with data from multiple sources and from the perspectives of all potential stakeholders. This comprehensive approach to data collection was designed to facilitate identification of the adaptations required to the content, delivery, approach and context (people, systems and organisation of care) to optimise the implementation of delirium prevention.

The setting for the case study was an elderly care or orthopaedic ward in an acute hospital. The analytic lens (the case) was the work of implementing a delirium prevention system of care (i.e. PODv1) in the specific context of the care routines and practices in each ward/hospital setting. We considered three or four case studies to be practically achievable. This number would allow some cross-case comparison to take into account differences in features such as case mix, establishments and skill mix, attitudes of staff and perceived barriers to implementation.

We identified potential local sites through previous knowledge and contacts and/or interest shown in the project and recruited four elderly care wards and two orthopaedic trauma wards in four hospital trusts. In addition, a ward from project 1 independently decided to implement and deliver the POD system of care on an orthopaedic trauma ward. Although we interviewed the development lead in this site to test out the theory of change, we did not include it in the findings. Details of recruited wards are shown in Table 5.

| Descriptor | Trust | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |||

| Hospital | i | ii | iii | iv | v | |

| Number of beds | 396 | ≈ 900 | 1113 | ≈ 450 | ≈ 420 | |

| Catchment area | Town | City | City | City | Urban | |

| Catchment population | ≈ 200,000 | ≈ 500,000 | 751,480 | 213,000 | 245,000 | |

| Ward | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Specialty | Elderly care | Orthopaedics | Elderly care | Elderly care | Elderly care | Orthopaedic/fracture neck of femur |

| Number of beds | 29 | 23 | 28 | 28 | 31 | 22 |

Engaging sites

Following recruitment, workshops were held in each case study site. Participants included patient and carer representatives, hospital managers, clinical managers and VSMs, volunteers, senior clinicians, nurses and therapists (see Report Supplementary Material 6 for participants). We explained the background to the study, the purpose and content of the delirium prevention system of care and our suggested delivery methods. Participants’ views were explored to provide an initial commentary on the practicalities of implementing PODv1, to ascertain who needed to be involved and to elicit relevant contextual knowledge (e.g. work in the hospital around delirium, key stakeholders to contact).

Data collection

For a full description, see Appendix 1.

Patient description

Anonymous ward-level patient administrative system data (sex, age on admission, length of hospital stay and discharge destination) were obtained for all admissions during the implementation and delivery phases (see Report Supplementary Material 7).

Implementation planning and delivery

We undertook qualitative interviews using topic guides with staff and volunteers; informant interviews and conversations with implementation team members; observation of ward practices, multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings, implementation team discussions and volunteer training sessions; and collection of documents (e.g. assessment, care and discharge plans; information for patients and caregivers; and care pathways). In addition, we constructed a ward diary/events log to provide a contemporaneous account of the process of implementing and delivering PODv1; communication with teams; problems encountered; solutions arrived at; and contextual factors that affected implementation planning and delivery.

To facilitate shared learning between sites, we arranged a centrally located workshop. This had a secondary purpose: to apprise the research team with information about how sites perceived the implementation and delivery processes. Only wards 1 and 2 had, at this point, begun delivery; wards 3 and 4 were in the early stages of implementation planning and ward 5 had not started implementation planning (ward 6 had not been recruited) (see Report Supplementary Material 6 for participants). The proceedings were audio-recorded.

Take-up of the intervention

We examined the extent to which each ward instigated systems to embed PODv1 in current ward practice. This included:

-

the development and introduction of –

-

a system for identifying delirium risk

-

a daily delirium prevention plan

-

a volunteer care plan and a process for supporting volunteers

-

-

audits and observations undertaken to assess/review current practice pertinent to the 10 delirium risk factors.

Impact of the intervention on nurse workload [wards 1–4 and 6 (implementation only)]

We used a ‘dependency–acuity–quality’ method at the start of POD implementation and during POD delivery to gauge its impact on ward staff activity and modification of workload. 48,49 This involved ward-based structured observations by researchers of staff activities linked to patients’ dependency/acuity. Activities included direct care (face-to-face bedside care), indirect care (patient-related, but not face-to-face, activity), associated work (e.g. ‘hotel’-type duties) and personal time (e.g. meal breaks). To obtain a broad sample of nurses’ workloads, we undertook ward observations over 24 hours during six shifts (two early, two late and two night shifts).

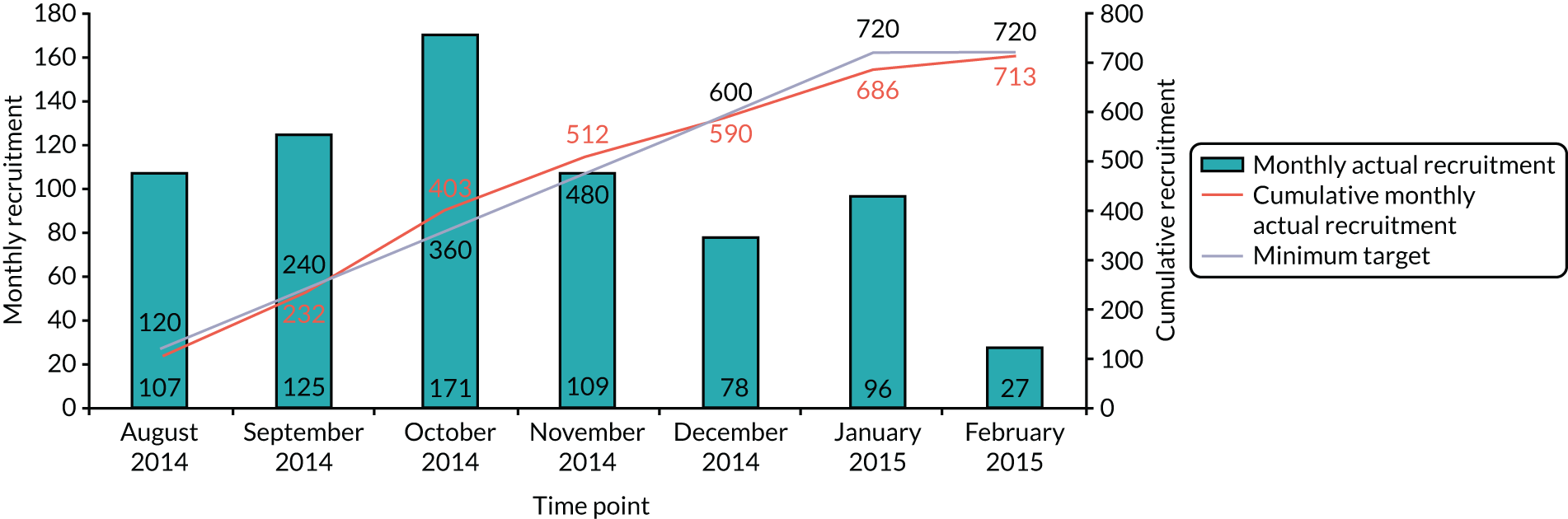

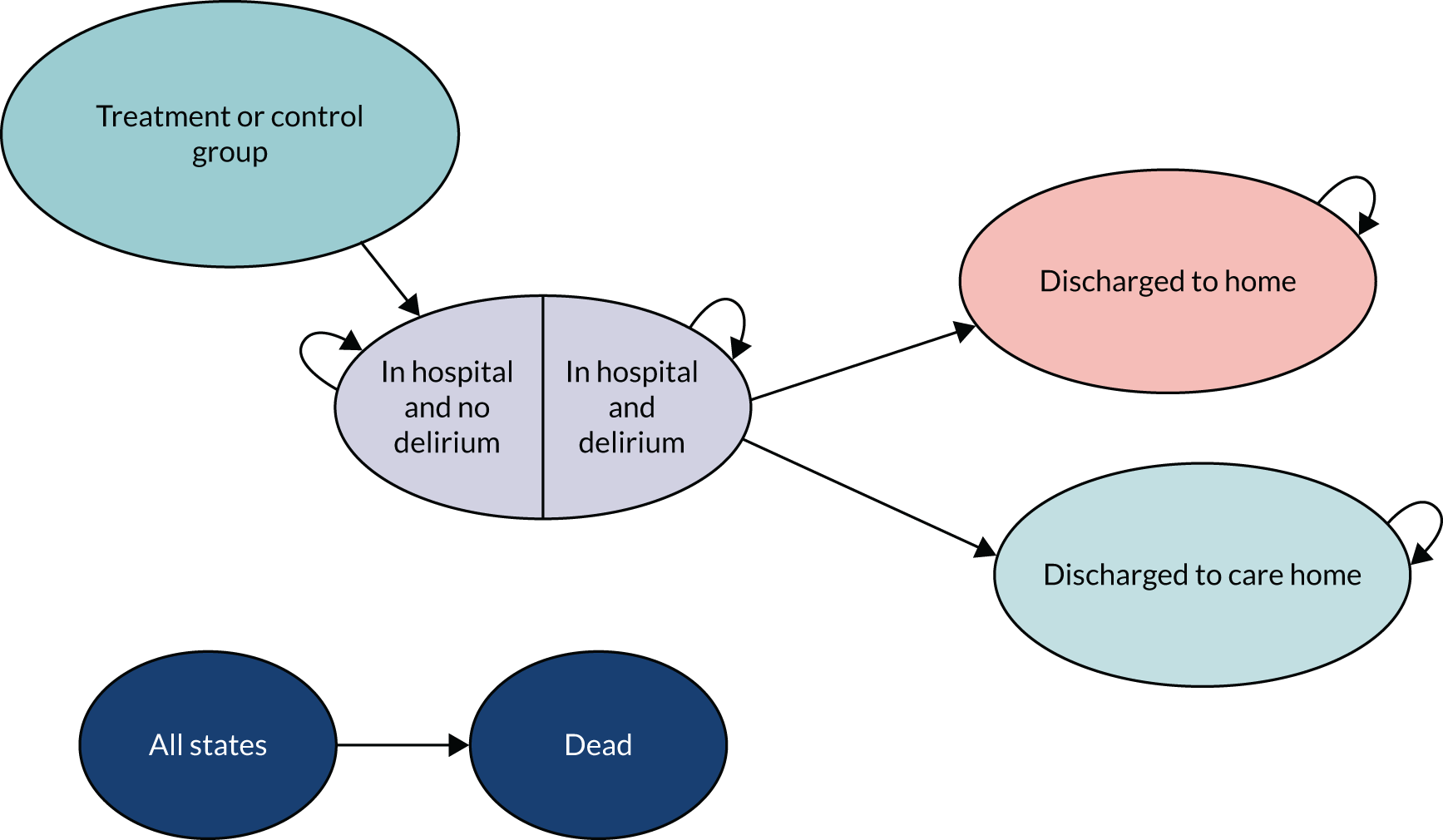

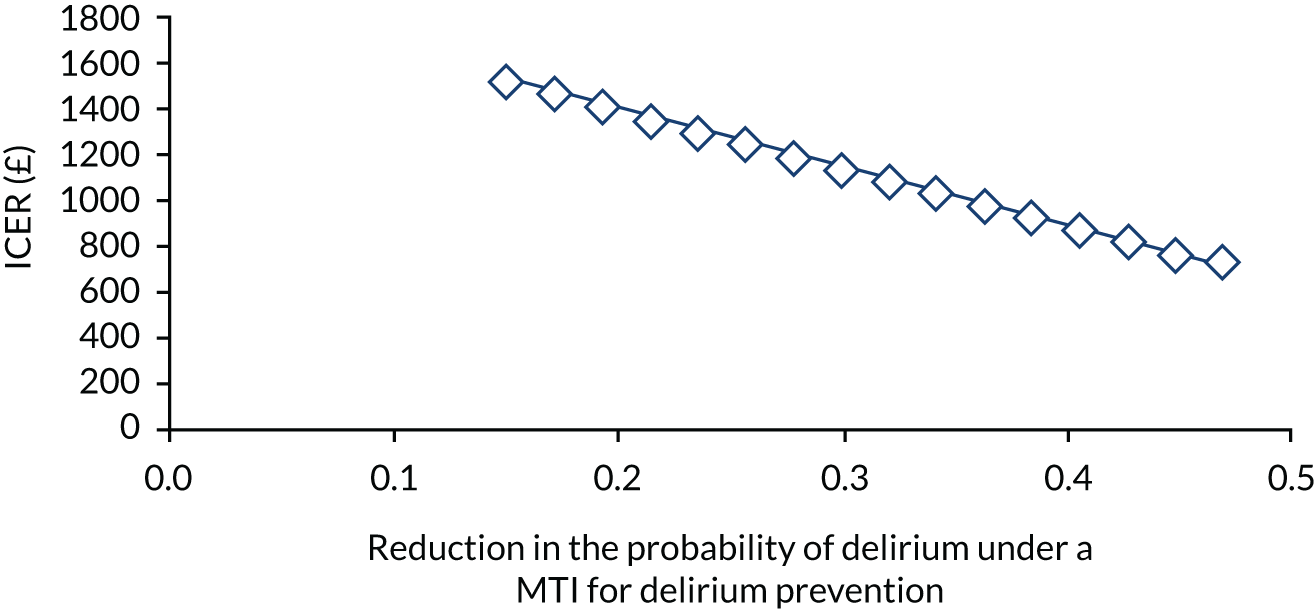

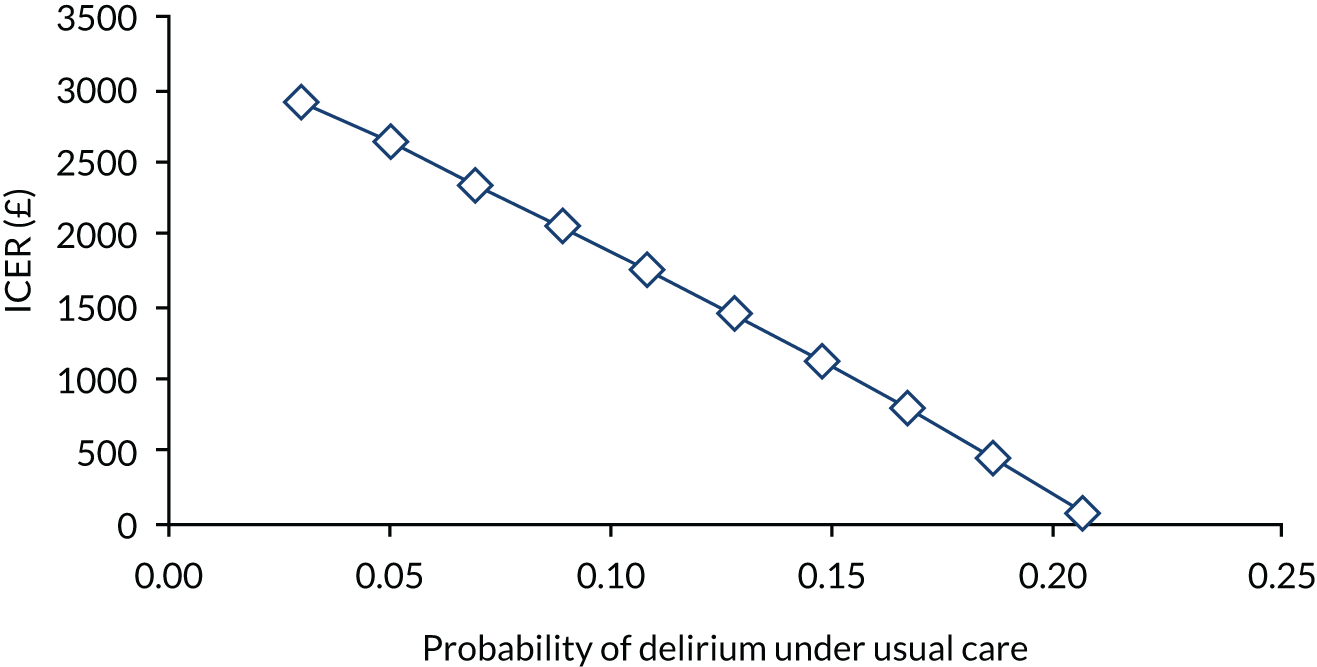

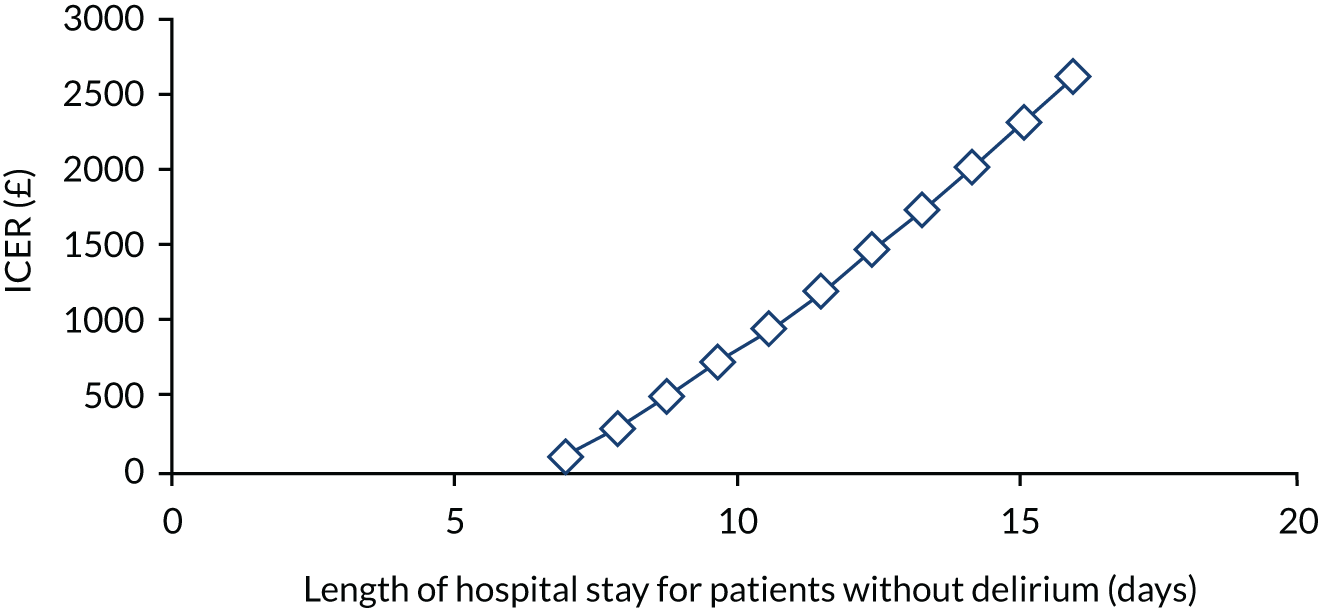

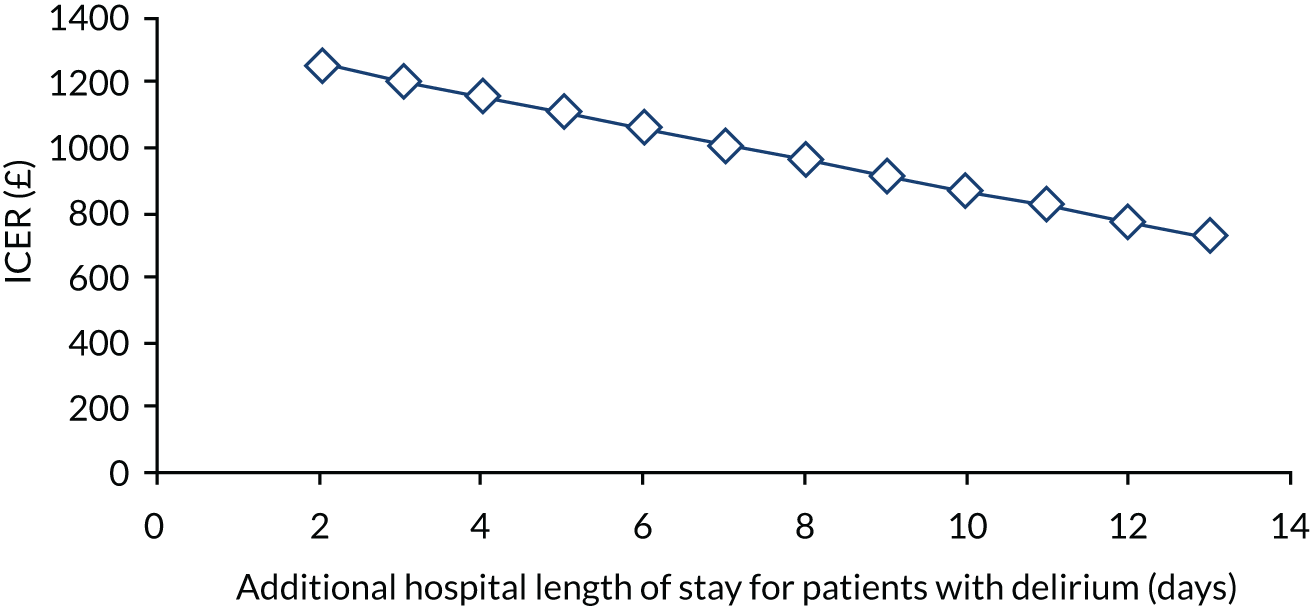

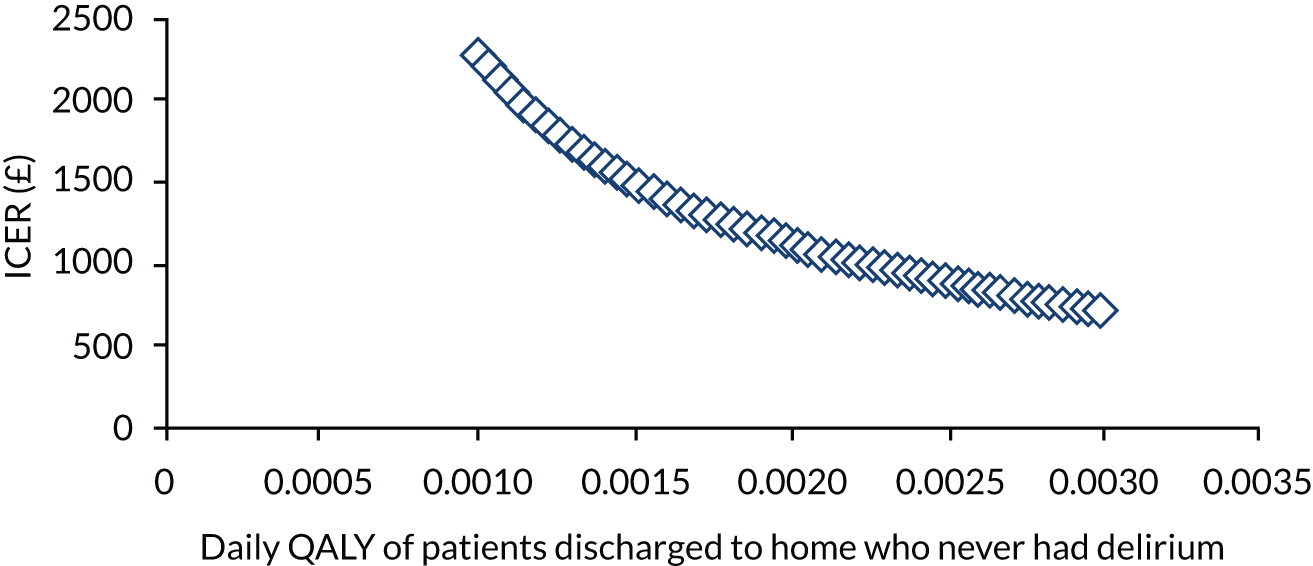

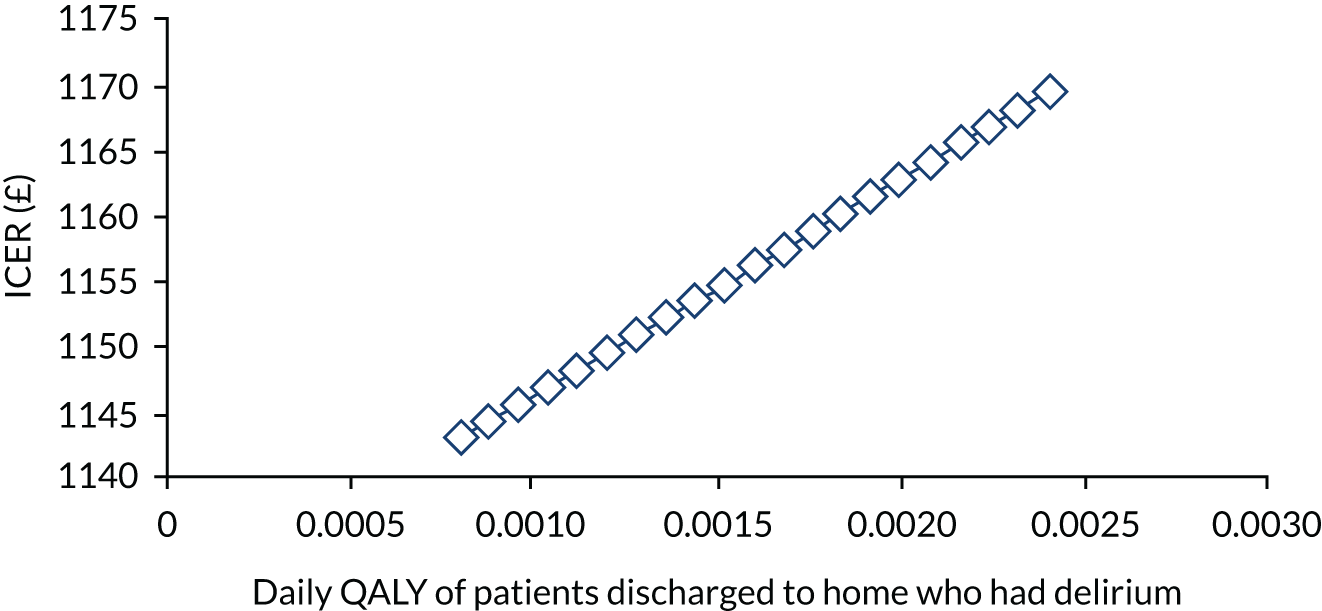

Impact on patient and carer satisfaction with care (wards 1–4 and 6)