Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 14/182/14. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The final report began editorial review in April 2019 and was accepted for publication in January 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Mitchell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and rationale

Against a backdrop of changing sexual repertoires, young people report higher levels of unsafe sex and higher rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) than any other age group. 1,2 Early intervention is required to prevent risks converting to poor lifetime sexual health, and schools are particularly well placed to facilitate these interventions. 3 Young people who cite school as their main source of information about sex are less likely to report unsafe sex and previous STI diagnosis. 4 The proportion of people citing school as their main source is increasing,5 but the content and quality of provision of sex education in UK schools is variable. 6 Over two-thirds of young people report inadequate knowledge when they first felt ready for sex,5 suggesting significant room for improved delivery of school-based sex education.

Young people are susceptible to powerful social influences that could enhance or undermine school-based sex education. These include norms and values that are transmitted both offline and online via peer networks. With respect to the latter, social media can increase social connectedness, strengthen social identity and facilitate access to health information, but it also adds risk of exposure to harmful messages, social pressures and bullying. 7

Against this background, we sought to develop and assess a novel school-based intervention that addresses limitations of existing peer-led sex education, while unlocking the potential of peer influence and social media.

Sexual health of young people

Almost one in six young people (aged 16–24 years) report unsafe sex, defined as at least two partners with whom no condom was used in the past year. This is higher than in any other age group. 8 In England in 2015, 15- to 24-year-olds accounted for 62% of heterosexual people diagnosed with chlamydia, 52% of heterosexual people diagnosed with gonorrhoea, 51% of heterosexual people diagnosed with genital warts and 41% of heterosexual people diagnosed with genital herpes. The diagnostic rate of chlamydia was 824 per 100,000 in males aged 15–19 years and 2436 per 100,000 females of the same age. 9 In Scotland, 65% of all diagnoses of chlamydia are among young people aged < 25 years; and among women, 75% of diagnoses were in those < 25 years. 9 There has been a significant shift in young people’s sexual repertoires over recent decades. The proportion of young people (aged 16–24 years) in the UK reporting all three types of intercourse (oral, vaginal and anal) rose from 10% in 1990 to 20% (females) and 25% (males) in 2012, primarily reflecting an increase in those experiencing oral and anal sex. 1

A narrow focus on risk avoidance ignores key inter-relationships between risk and other aspects of sexual health and well-being. Young people’s sexual behaviour is influenced by social factors, including gender stereotypes, peer pressure and social expectations. 10 It is therefore important to look beyond the biological markers of sexual health and focus on outcomes that are more meaningful to young people, such as the quality of sexual relationships, in particular the reduction of sexual violence (including discrimination) and improved sexual experience. 11 Positive romantic relationships are associated with both good physical health and good mental health, and supportive social networks, lending support to the notion of synergistic benefits between these aspects of young people’s lives. 12 There are calls to place greater emphasis on sexual enjoyment to reduce sexual risks (e.g. promoting the pleasurable use of condoms). 13

Reframing adolescent sexual health as a positive developmental process offers a focus on outcomes that may be more meaningful to young people. 14 Sexual health interventions should consider both risk taking and risk reduction, and how pleasure (as an underpinning mechanism) can account for both. Ideally, intervention development should be driven by sexual health policies that promote positive sexual health and well-being, in addition to reducing risks. 13

Sexual health policy in the UK

All four countries in the UK have sexual health strategies that emphasise the importance of prevention and treatment of sexual health problems among young people. A central focus is to develop and reinforce positive cultural norms, openness, respect and responsibility as key drivers of improving sexual health. 15–18

These strategies also indicate the need to implement digital platforms to improve access to sexual health resources and services, including social media for sexual health promotion. 16 School-based sex education is compulsory in England and Wales, but not in Scotland and Northern Ireland. All UK policies focus on developing sexual health knowledge and attitudes in relation to biological outcomes (e.g. STIs and pregnancy). All UK policies include the emotional, social and relational aspects of sexual health.

In addition, Scotland has The Curriculum for Excellence, which seeks to build an educational environment in which young people can become successful learners, confident individuals, responsible citizens and effective contributors to society. 19 The emphasis is on more rounded development, which values personal and social growth in addition to academic achievement, including benchmarks to evaluate sexual health promotion. This fits into the Scottish Government’s broader policy for child and family support and development known as Getting it Right for Every Child20 and a national resource titled Relationships, Sexual Health and Parenthood for use in a range of educational settings. 21

Sexual health interventions: evidence of effectiveness

School-based interventions

Most sexual health interventions for young people are school based, as this setting facilitates access to the widest range of young people in terms of socioeconomic background and vulnerability to poor sexual health. Schools provide a major context for social development22 and are ideally placed to challenge unhealthy and inequitable norms underpinning sexual risk behaviours. 23 For interventions attempting to diffuse change through social networks, schools provide a ‘captive audience’ and naturally occurring friendship groups. 24

School-based interventions tend to comprise one or both of:

-

sexual health education and training to improve knowledge, exploring emotions and sexual norms, developing sexual negotiation skills and self-efficacy, and making informed choices3,25

-

providing access to sexual health services either in or out of school, including condoms or access to other forms of contraception (e.g. hormone-based medication). 26–29

Evidence from older systematic reviews suggests that school-based sex education has an effect on sexual health knowledge and attitudes, but only some programmes delay sexual behaviour and increase condom use. 3 Shepherd et al. 25 are cautious about the impact of such programmes in bringing about behavioural change, acknowledging that significant changes in sexual health knowledge and self-efficacy (e.g. knowing how to use a condom) are more common.

More recent systematic reviews suggest that combining education with contraceptives or access to sexual health services may be more effective. For example, Oringanje et al. 27 found that providing education alongside contraceptives increases condom use and may reduce unintended pregnancies. Interventions that combine education with interactive techniques to improve condom use, teaching how to negotiate sex and providing a range of contraceptives can lead to an increase in knowledge and effective use of contraceptives, delay sexual initiation and improve condom use. 28 Owen et al. 26 found that school-linked sexual health services did not encourage sex or risk-taking, and may at best reduce chlamydia infection (males only) and pregnancy; however, the evidence is based on a small number of mainly US studies of variable quality. Studies rarely show an impact on biological markers, such as human immunodeficiency virus, herpes and syphilis, partly because these are relatively rare outcomes and require extremely large samples to detect an effect. 29

A number of contextual factors affect these outcomes. A review of process data from trials30 suggests two key influences: (1) fidelity, influenced by the extent to which the school has a supportive culture, a flexible administration, and enthusiasm and expertise among those delivering the sexual health content; and (2) acceptability and engagement, influenced by enthusiasm, credibility and expertise of intervention providers, and relevance and enjoyment to young people. Another systematic review31 noted the diversity in approaches of effective interventions, suggesting that a range of mechanisms exist.

Peer interventions

Peer education is a method of disseminating knowledge, values or achieving behaviour change through a social network, delivered by someone of a similar age and standing in that network. 32 The theoretical appeal of peer involvement lies in its potential to reinforce positive values and beliefs, thereby strengthening social norms that might influence sexual behaviour. 33,34 The key mechanisms include role-modelling,35 a shared identity between the peer workers and their peer group, and the ability of the peer workers to influence their networks. 32 There is a range of peer-led roles and approaches, including educator or assistant educator,35 peer supporter (PS) and, occasionally, peer leader. 32

Evidence from systematic reviews on the evaluations of peer sexual health interventions for young people demonstrates a weak effect on sexual attitudes, knowledge and intentions, and ‘unconvincing’ evidence for the impact on sexual behaviour. 32,35,36 Methodologically, reviews have highlighted a paucity of peer-based sexual health interventions for young people that are evaluated using randomised control trials. 32

Two notable studies in the UK33,34 engaged peer educators to replace teaching staff, at least in part; however, in the other studies peer educators assisted teachers. Across peer-led interventions, the dominant model is one of a peer educator (teacher) rather than peers as supporters of positive norms and behaviour. 32–36 Involving youth peers as ‘influencers’ within their sexual networks has been under-researched in the field of sexual health. 36 In a review of peer interventions aimed at addressing a range of health and social issues, Harden et al. 37 identified five studies that compared the effectiveness of peer leaders with teachers in delivering the same intervention. In one sexual health evaluation from the USA, peer leaders were found to be generally more effective than teachers. More specifically, peer leaders are thought to be more effective at establishing conservative (non-risky) norms, but less effective than adults at imparting factual information and getting students involved in classroom activities. 34 A formal teaching role may undermine credibility with peers38 and may be less effective than informal social support work. 39

Participation rates in peer interventions vary and further research is required to optimise the most appropriate level of peer participation, which should consider the level of social ease experienced by peer workers, establish how participation affects peer networks and include theoretically informed outcome measures. 32,35,36

How peer educators are chosen and their reputation among peers is important. 32,33 Most studies rely on self-selection or teacher selection, but both these strategies may result in educators who are not particularly credible and find it difficult to reach high-risk students. 40 The Students Together Against Negative Decisions (STAND) study used peer nomination and diffusion of innovation theory in a youth-focused sexual health intervention in schools. 41 Peer leads delivered an education-based programme to ‘opinion leaders’, who were then asked to engage with their networks (although not via social media). Awareness of the STAND study intervention was high. The intervention was effective at improving knowledge and behaviour among those trained, but had mixed success in diffusing risk reduction practices to other non-trained students. 41

Digital media interventions

Digital media offer inspiration for rethinking sexual health promotion. 42 There has been an exponential increase in the use of digital media by young people in the last decade, including social networking, mobile applications (apps), video sharing, podcasts, online games and video or photo communications. 43 Most (95%) young people in the UK use social networking sites at least once per week, most commonly Instagram (URL: www.instagram.com; Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), Snapchat (URL: www.snapchat.com; Snap Inc., Santa Monica, CA, USA) and Facebook (URL: www.facebook.com; Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA). 7 Technologies such as smartphones give unprecedented mobile access to the internet. 44 New internet-based platforms, including social media, offer greater opportunity for more interactive communication, possibly at the point of health-related decision-making. Digital media can deliver interventions conveniently and anonymously to young people using personalised information. 45

In theory, digital media offers the potential to deliver sexual health messages to those who are already making use of these technologies and are confident in using them. 46 Recent systematic reviews on the impact of digital media on young people found that it can improve sexual health knowledge (of STIs and emergency contraceptives) and self-efficacy (condom use and STI testing), and reduce sexual risk behaviour, but there has been no demonstrated impact on biological outcomes. 42,47–50

The popularity of social networking sites among young people render these as obvious candidates for sexual health promotion, although those in the health and research communities have been slow in using this approach. 51 A review of early interventions indicated that these sites were mainly used to heighten awareness of online sexual health programmes. 52 Few studies have examined the impact of social networking sites on the sexual health of young people. One cluster randomised controlled trial53 found that a peer-led community-based Facebook intervention called ‘Just/Us’ increased condom use over a 2-month period, although the effect diminished by 6 months. Another pilot study54 reported a potential increase in condom use and reduction in chlamydia infection.

Recommendations from systematic reviews highlight the need to involve young people in the design of digital interventions, the importance of using theory to inform intervention development and the importance of using stronger research designs,42,50 including research in the use of social media for sexual health promotion. 45 Few digital media programs provide tailored advice and none assesses social network interventions in school settings. 42,47,48 On a pragmatic level, findings from the evaluation of the FaceSpace project highlight the importance of securing sufficient resources for developing social network platforms and maintaining a high profile, reach and engagement with young people. 55,56

Summary and scientific rationale

It is over 10 years since Kirby et al. 3 published their seminal review of sex education in schools, and the substantial growth in evidence since then suggests that school interventions have a consistent effect on sexual health knowledge and attitudes, but less so on sexual risk behaviours. A key question, therefore, is how to enhance these effects.

Digital media offer an exciting opportunity to work with young people through their networks using social media platforms. Few digital media programs provide tailored advice and, to our knowledge, none has assessed social network interventions in school settings to tackle sexual health. 42,47,48

Peer interventions could be combined with online social networking sites to enhance effects. The weight of evidence on the effectiveness of peer interventions suggests a similar or weaker pattern to that of traditional school-based interventions. 32,35,36 Four important issues are often overlooked: (1) how peer educators are recruited,30,32 (2) the nature of their influence,36 (3) their position within their network20,40 and (4) the need to establish outcomes that are theoretically informed. 32,35,36 These are issues we sought to address in this study.

The intervention in the current study [Sexually Transmitted infections And Sexual Health (STASH)] builds on a peer-led smoking prevention intervention [A Stop Smoking In Schools Trial (ASSIST)], which recruited and trained ‘influential’ students (aged 12 or 13 years) as PSs in schools to spread and sustain non-smoking norms through informal interactions with peers. 40 A cluster randomised control trial57 found that smoking was reduced over a 2-year period. The intervention is recommended by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)58 and is now disseminated under licence in hundreds of schools, in over 30 areas in England, Wales, Scotland and France (see Chapter 2, Developing a theory-informed young people’s sexual health intervention).

ASSIST is based on diffusion of innovation theory, which explains how new ideas are adopted across social networks. 59 Instrumental to this is the influence of early adopters (peer leaders), who seek to bring about change in others. Critically, the peers are tasked with changing (or reinforcing positive) norms and competence. ASSIST also draws on implementation theory (IT), which includes normalisation process theory60 and accounts for how, and to what extent, interventions are embedded in the existing school environment.

Following the Medical Research Council (MRC)’s guidance on the development and evaluation of complex interventions,61 there are five key reasons why a feasibility study is required here. First, our proposed intervention is novel in that it comprises elements that have not been combined in previous sexual health interventions for young people, namely setting (secondary schools) and method of delivery (influential peer leaders, social networking and social media). Second, there are a number of design challenges and uncertainties specific to our proposed approach (detailed in Chapter 2). Third, we need to better understand the extent to which the intervention works as intended, including the facilitators of and barriers to implementation. Fourth, there is the need to establish a theoretical understanding of the mechanisms that may lead to improved sexual health for young people and thereby identify the most appropriate intermediate and outcome variables for a trial. Finally, given the lack of controlled trials and drawing from guidance regarding the best use of resources,61 we need to consider the resource and methodological implications of conducting a large trial, including the feasibility of an economic analysis.

In conclusion, given the popularity of social media platforms among young people and their potential to access and influence social networks, this is an opportune time to integrate these with peer-based approaches in a closed social system, such as a school. Theoretically, these may act synergistically to develop and strengthen cultural values, thereby supporting social norms that influence sexual behaviour.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this study is to develop and test the feasibility and acceptability of a school-based intervention delivered by PSs (the STASH study) to reduce transmission of STIs and improve the sexual health of secondary school students aged 14–16 years in the UK.

The objectives of the study are to:

-

finalise the design of a school-based STI prevention intervention, in which influential PSs use online social networks and face-to-face interactions to influence norms, knowledge, competence and behaviour, and promote the use of sexual health services

-

assess the recruitment and retention of PSs, as well as feasibility and acceptability of the intervention among PSs, participants and key stakeholders

-

assess the fidelity and reach of intervention delivery by trainers and PSs, including barriers to and facilitators of successful implementation

-

refine and test the programme theory and theoretical basis of the intervention

-

enhance understanding of the potential of social media, when used by influential peers, to diffuse norm change and facilitate social support for healthy sexual behaviour

-

determine key trial design parameters for a possible future large-scale trial, including recruitment, retention rates and strategies, outcome measures, intracluster correlation (ICC) and sample size

-

determine the key components of a future cost-effectiveness analysis and test data collection methods

-

establish whether or not pre-set progression criteria are met and if a larger-scale trial is warranted.

Chapter 2 Developing the STASH intervention

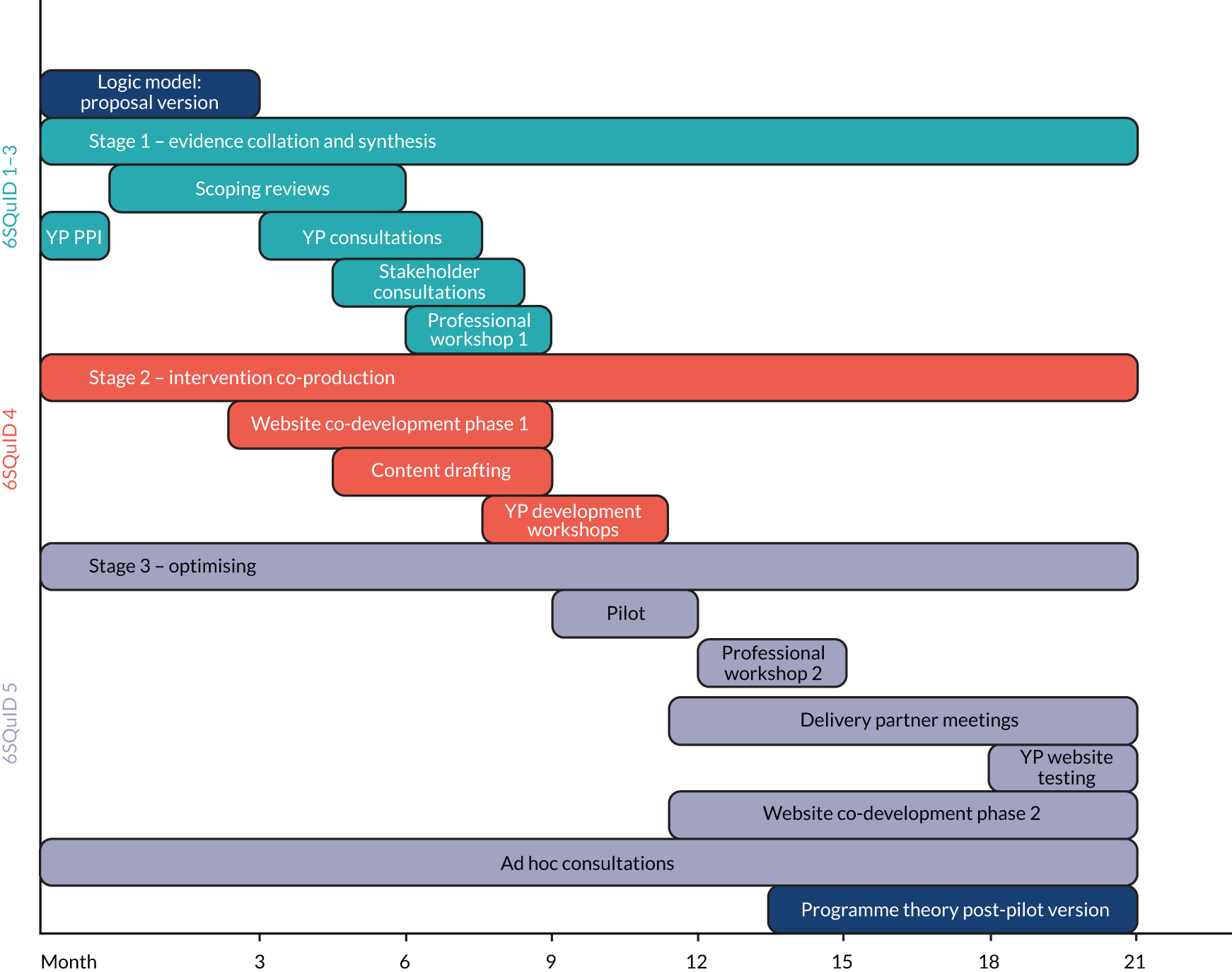

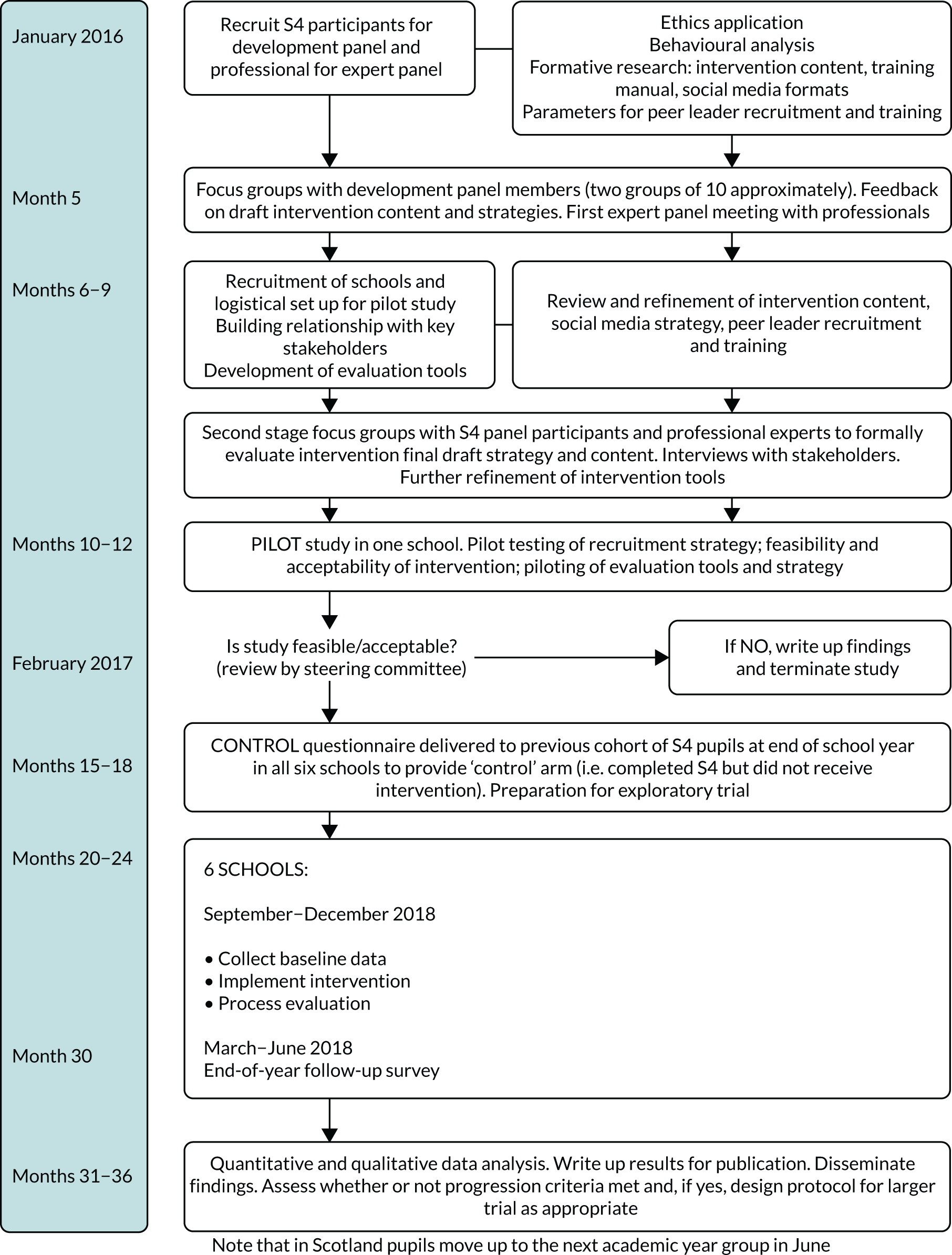

This chapter describes how the intervention developed from the initial plan set out in the funding proposal, to the intervention as delivered in the feasibility study. It details methods (including a pilot) and explains how we integrated our learning from three development stages – (1) evidence collation and synthesis, (2) co-production and (3) optimisation – into design decisions. The intervention development process is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The STASH study intervention development process (by 6SQuID component). 6SQuID, Six Steps in Quality Intervention Development; PPI, patient and public involvement; YP, young person.

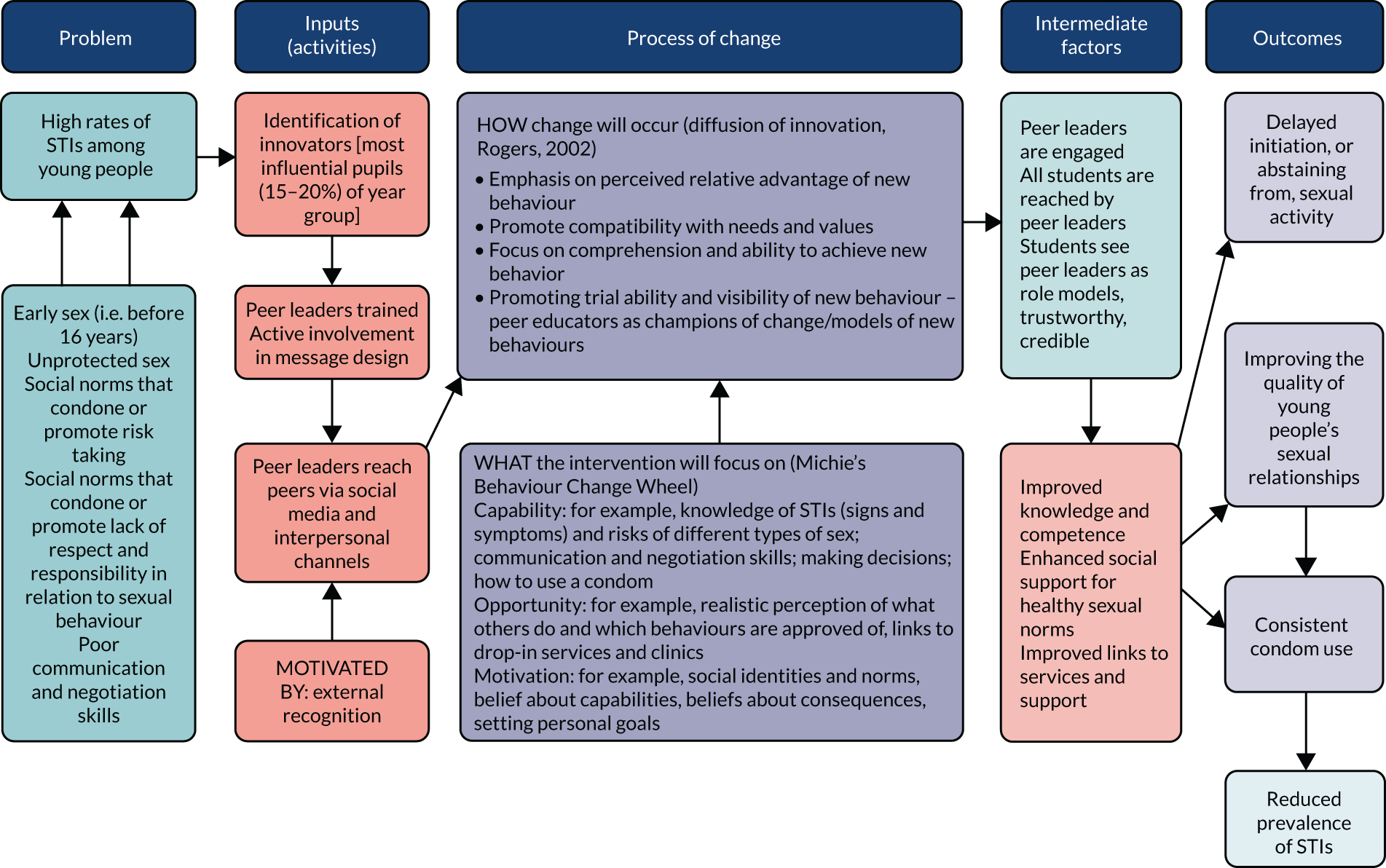

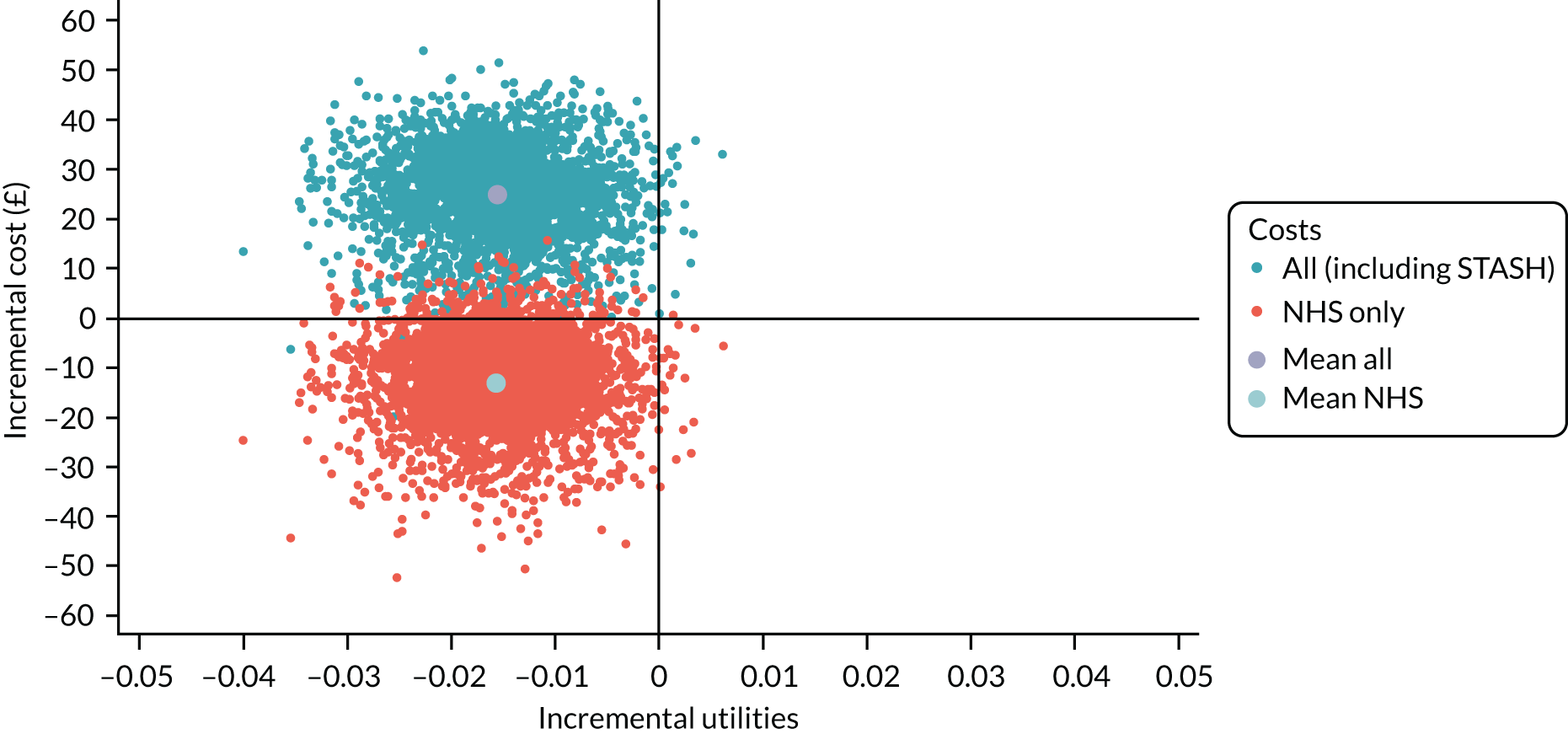

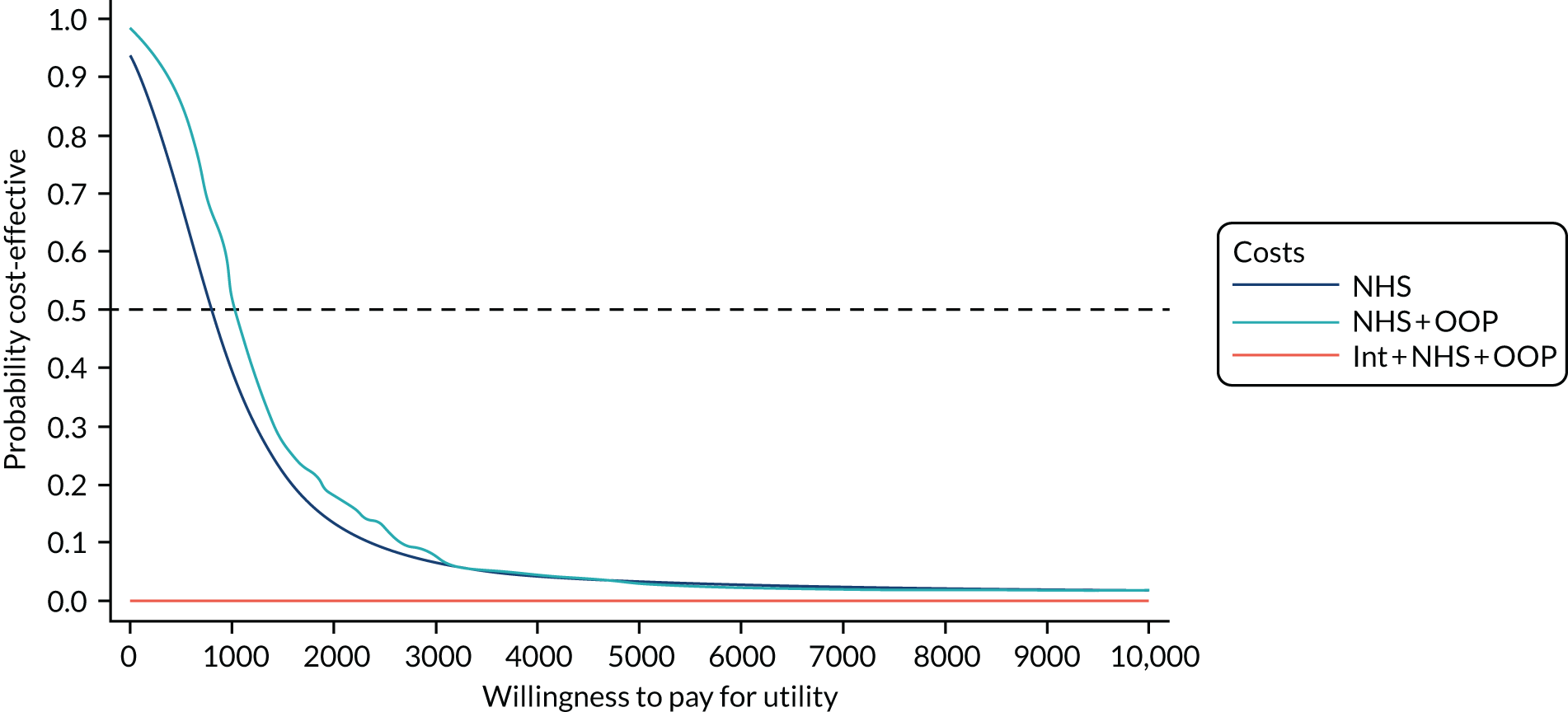

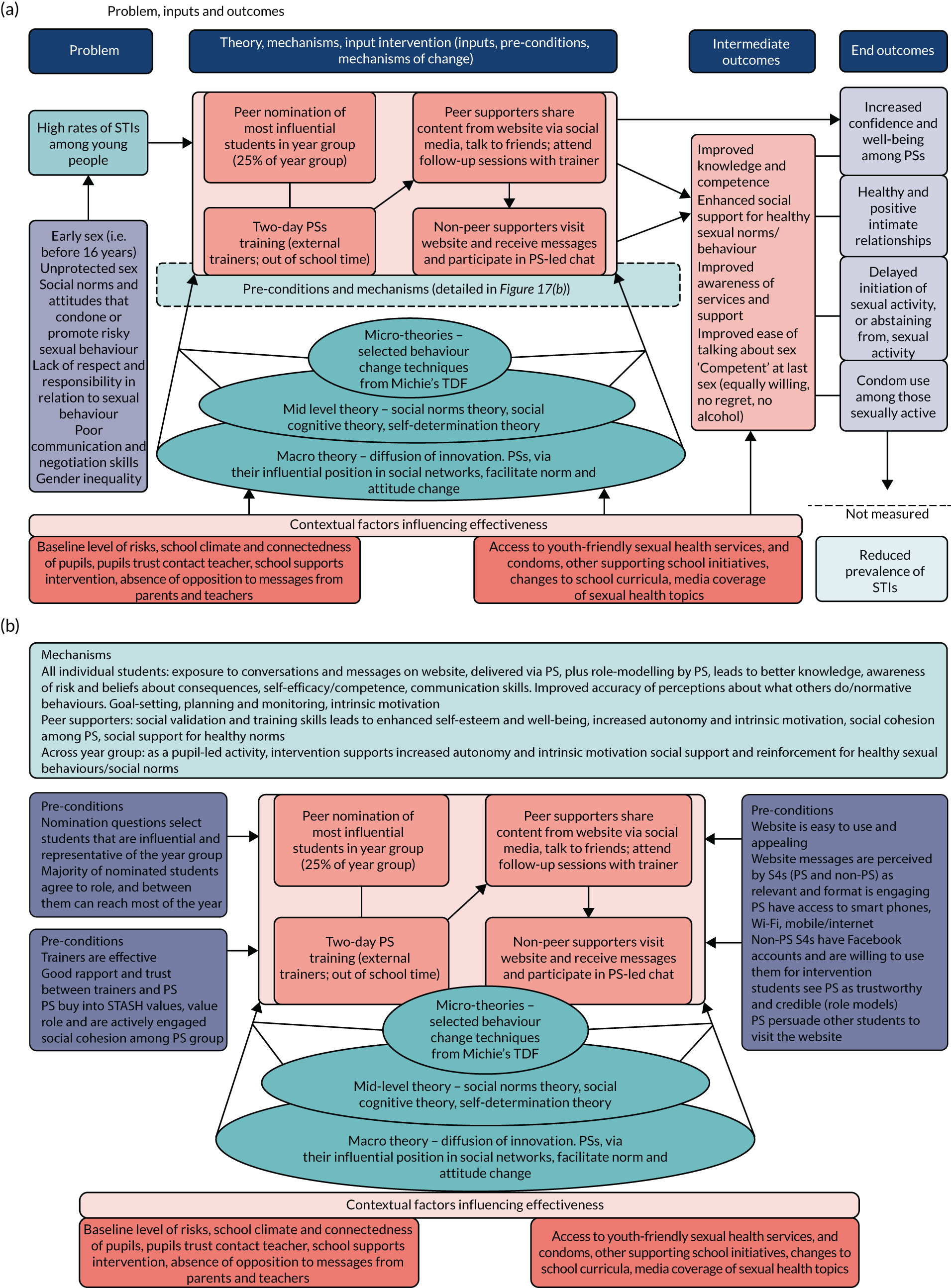

Background

Our starting point was the proposal version of the STASH study logic model (Figure 2). This offers a visual representation of the problem (as conceived), inputs (intervention components that were expected to bring about change), process by which change would occur, intermediate factors and expected end outcomes. This was subsequently developed into a full programme theory that, in addition to theorising the mechanisms of change, hypothesised the conditions under which they would operate effectively. The post-pilot version of the programme theory (see Figure 4) guided the evaluation and identified important contextual factors that might shape outcomes and effects.

FIGURE 2.

The STASH study logic model: proposal stage. Reproduced from Forsyth et al. 62 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Developing a theory-informed young people’s sexual health intervention

Development work is essential to tailor theoretically grounded programmes to the needs of the target population. 63–65 The STASH study aimed to adapt what was known to work in a successful existing public health intervention to a new problem and context. The planned intervention drew on theories and mechanisms that were effective in ASSIST40 (see Chapter 1), while targeting an older age group (14–16 instead of 12–13 years) and focusing on STI prevention instead of smoking. Therefore, although ASSIST offered a theoretical starting point, the appropriateness of intervention components needed to be reviewed and revised accordingly. We anticipated that these differences would require significant adaptations to the ASSIST content and mode of delivery. Crucially, we also set out to explore how we might harness the potential of social media as a mechanism to communicate messages and, in doing so, modernise ASSIST.

Key intervention components brought forward from ASSIST

We began with the overarching mechanisms of ASSIST:

-

Recruitment and training of ‘influential’ students (PSs) to spread and sustain positive norms through informal interactions with peers. Grounded in diffusion of innovation theory59 and recruitment of ‘early adopters’,66 ASSIST found that recruiting 15% of the year group was effective in the context of smoking prevention. 67

-

Use of professional trainers to train PSs to increase intervention efficacy and credibility, reduce burden on schools and ultimately increase potential for scalability and widespread adoption.

We intended to use the following components from ASSIST.

Nomination

Identify the most influential students in secondary 4 (S4) by blinded peer nomination.

Recruitment

From this influential group, recruit a percentage of the entire year group to act as PSs.

Training

A 2-day PS training programme, delivered by a third-sector organisation in school time, at an external venue, covering PS role, skills and responsibilities, and knowledge building.

Peer supporter-delivered activities

A period in which trained PSs carry out intervention activities.

Trainer-led activities

Follow-up sessions delivered during the PS activity period.

Participant acknowledgement

Peer supporters receive formal recognition for their role.

Our development work followed MRC guidance61 on the development and evaluation of complex interventions, which acknowledges that intervention development is often not linear and may have several phases. We focused on exploring the evidence base and identified relevant theory and pilot work to address ‘key uncertainties’. 61 In the STASH study, ‘key uncertainties’ were the feasibility of a PS approach in a sexual health context, the older age group (compared with ASSIST) and use of social media as a forum for interaction.

We also followed the Six Steps in Quality Intervention Development (6SQuID) framework, which sets out ‘practical, logical, evidence-based ways to maximise effectiveness’. 68 These six steps are:

-

define and understand the problem and its causes

-

identify which causal or contextual factors are malleable and have the greatest scope for change (and who would benefit most)

-

decide on mechanism(s) of change to be utilised

-

clarify how these will be delivered

-

test and refine on a small scale

-

collect sufficient evidence of effectiveness to justify rigorous evaluation/implementation.

We detail the STASH study development stages in line with 6SQuID stages 1 and 2 (grouped here as ‘evidence collation and synthesis’), stages 3 and 4 (grouped here as ‘co-production’) and stage 5 (grouped here as ‘optimising the intervention’). Stage 6 is addressed in Chapters 5–7. We included Michie’s Behaviour Change Wheel/Theoretical Domains Framework in the preliminary logic model69,70 and referred to it in designing the STASH study website and training materials, but found it less applicable to determining macro-level mechanisms of change, as these were, to a large extent, determined by the ASSIST intervention.

Intervention development aims and objectives

The overall aims of the development stage were to finalise the intervention design and refine and test the initial logic model. The broad objectives were to:

-

fully articulate the problem [i.e. young people’s sexual behaviour and risk of STI transmission (6SQuID stage 1)]

-

explore and clarify causal and contextual factors relating to young people’s sexual behaviour and identify those most amenable to change (6SQuID stages 2–4)

-

identify contextual factors that might shape implementation (6SQuID stages 2–4)

-

establish how the STASH study might bring about change in young people’s sexual behaviour (6SQuID stage 3)

-

identify intervention content, including existing high-quality resources (6SQuID stage 3)

-

refine programme theory (overall 6SQuID aims).

Intervention development process

Each stage in this iterative process – and its constituent activities, objectives and methods – is outlined, followed by a synthesis of findings (see Synthesising and operationalising development process findings).

Stage 1: evidence collation and synthesis – 6SQuID steps 1–3 (months 0–9)

The objective of stage 1 was to collate and synthesise evidence to inform key intervention content, establish the most effective delivery format and develop the most appropriate theoretical framework to guide this. We explored necessary adaptations to ASSIST, including a shift to social media as an alternative mechanism for delivering content. Key findings and recommendations derived from each activity are outlined in Appendix 1.

Review of the evidence base: ‘scoping’ literature review

This review examined academic literature for evidence to identify drivers of target behaviours, effective components of school- and digital media-based interventions, and behaviour change theories relevant to young people and sexual health.

Following relevant guidance,71 targeted scoping searches of high-level literature were conducted, including systematic reviews of interventions [peer education, social media, school-based sex and relationships education (SRE)]; review, discussion or state-of-evidence articles (key drivers of risk, facilitators of safer practices and well-being, and issues in young people’s sexual behaviour); and behaviour change theories relevant to young people’s sexual health and well-being.

Search inclusion criteria were:

-

age range 12–19 years (to include age groups encompassing target group)

-

English as the publication language

-

a publication date post 1990

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)/high-income countries.

We excluded studies that were published before 1990, were not in English, focused primarily on primary school or post-statutory education-aged children or were based in non-OECD countries.

Searches used combinations of controlled vocabulary and free text (e.g. title/abstract = ‘adolescent’ and ‘condom use’). We undertook targeted searches of the following databases: Child Development & Adolescent Studies, EMBASE, POPLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed and Web of Science. We also reviewed pertinent theoretical literature on complex interventions and behaviour change, beginning with diffusion of innovation theory (the basis of ASSIST). 59 Targeted manual searches also included reviewing article reference lists, reviews of subsequent publications citing key papers and papers identified through the expertise of the Trial Management Group (TMG).

Reviews of resources and materials: relevant grey literature, sex and relationships education/practitioner resources, digital media sources, potential social/digital media platforms

We collated high-quality SRE resource exemplars (websites, resource packs). We sought to identify key features, examine theoretical grounding, if available, and identify potential content relevant to the STASH study. Grey literature and relevant web resources were identified opportunistically via professional networks of the TMG and by non-systematic and targeted online searches. We identified policy and guidance documents focused on SRE delivery in the UK. Resources were categorised by source, type and quality, and key points summarised. We assessed quality of youth-oriented sexual health web resources [including information sites, YouTube videos (URL: www.youtube.com; YouTube, LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA) and vloggers/influencers], rating them according to relevance to the STASH study, content quality, design quality (appeal to young people) and apparent authority or legitimacy.

Finally, we reviewed candidate social media platforms for user demographics, functionality, appeal and regulatory information. Platforms [e.g. Instagram, WhatsApp (URL: www.whatsapp.com; Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), Snapchat and Facebook] were appraised for age restrictions, message-sharing functions (including traceability over time, images, audio, video and ability to interface with a website), private group messaging options and whether or not posted content could be visible to the research team to enable evaluation (feasibility).

Consultations (patient and public involvement): young people’s consultation groups

Consultations explored the target group’s attitudes to and use of social media, and views on the proposed intervention format.

Pre-pilot consultations with young people built on earlier consultations at the pre-proposal stage (16 participants aged 14–19 years in central Scotland). In the first development stage, we conducted three group interviews (20 participants in total) with young people outside the intervention area. Two group interviews were school based and the third was with a community centre-based youth group (conducted at a community centre). We identified each via the Project Executive Group (PEG) and sought to ensure a range of socioeconomic backgrounds [two schools serving populations from mixed Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) quintiles and a youth group located in an area of high relative deprivation]. Discussions were facilitated by the research team (KRM, CP and RF) and audio-recorded. A semistructured topic guide (see Report Supplementary Material 1) asked for views on classroom SRE (including gaps) and key perceived influences on young people’s sexual behaviour and attitudes. We also asked about preferences in relation to proposed intervention format, including what would engage and motivate PSs. We also explored views on the use of social media to spread messages. Discussions were summarised and reviewed for key themes, commonalities and differences, including comparison with the pre-proposal young people data.

Other stakeholder consultations

Consultation activities were designed to explore local constraints on and facilitators of implementation (including concerns) and stakeholder perspectives on young people’s sexual health, SRE and social media use.

We conducted semistructured interviews with four teachers at two secondary schools considering participation in the feasibility trial. Participants were members of school senior management teams, with some involvement in guidance and SRE. A topic guide (see Report Supplementary Material 1) explored factors emerging from the reviews, primarily relating to views on young people’s sexual health and behaviour, young people’s social media use, SRE delivery in their school (topics addressed, effectiveness) and the planned intervention (including suggested improvements and practical advice). Interviews were transcribed, summarised and reviewed for key themes and learning.

We also met with two relevant quality improvement officers/child protection leads in participating local authorities and with each participating school’s senior management team to further explore the above issues. An additional meeting was held with one school to address concerns around the intervention model. Notes from meetings were reviewed for key learning and integrated with the teacher interview findings.

Development workshop with relevant professionals (sexual health and health promotion specialists, peer educators, youth workers, academics)

The first of two ‘professional’ workshops explored and established key messages to underpin intervention format and content, and likely mechanisms of change. Participants (n = 16) were identified via the TMG’s and PEG’s professional networks and knowledge of the local health and education services landscape. In the workshop, small group discussions focused on key issues emerging from literature reviews (e.g. barriers to and facilitators of positive sexual health and relationships for young people) and how to address these in the STASH study, potential behaviour change mechanisms, function and format of the intervention, and potential challenges for PSs.

In Appendix 1, we outline key findings from each review and consultation, and recommendations for intervention design. How these were actioned is detailed in Synthesising and operationalising development process findings.

Stage 2: intervention co-production – 6SQuID step 4 (months 1–9)

Stage 2 addressed 6SQuID step 4 and aimed to develop and refine proposed intervention format and content, guided by learning from stage 1.

First phase website co-development with Antbits development consultancy

Co-production with web development consultancy Antbits (Cambridge, UK) aimed to develop an interactive website and content management system to provide mobile-optimised access and desktop functionality, and multilevel access for use by PSs (level 1) and by trainers and the research team (level 2). In multiple teleconferences with Antbits, the team explored design options and potential for presentation of curated sexual health content (sexual health information, web links, videos, etc.).

Drafting intervention content

An iterative drafting process aimed to generate a set of content for both the STASH study website and PS training and follow-up sessions, organised by topic (e.g. around relationships, consent, STIs), which would constitute a comprehensive resource. Drafts were led by KRM and built on a synthesis of evidence gathered in stage 1, guided by relevant behaviour change theories identified in the reviews. Topics and content were discussed and agreed at development ‘away days’. Draft content was reviewed by an expert SRE educator to refine focus, tone and language.

Young people’s development workshops

KRM and CP revisited the two school-based groups to gauge opinions on draft website content. Following a loose topic guide (see Report Supplementary Material 1), participants reviewed drafts (via tablet and smartboard) and gave views on visual appeal and ease of use, topics and messages, language, acceptability of external links, information gaps and general acceptability. During the sessions, five students took part in brief cognitive interviews to test selected questionnaire items. Workshops were conducted in school time, lasted approximately 1.5 hours and were audio-recorded, with notes written up and reviewed for key learning.

Stage 3: intervention optimisation – 6SQuID step 5 (months 10–21)

The overarching aim of stage 3 was to pilot the intervention in one school and to use learning from the pilot to refine the intervention. Guided by 6SQuID step 5, this stage consisted of six phases, described as follows.

Intervention pilot

The pilot school was selected from among those expressing interest in participation. It was chosen as typical of schools in the locality (regarding size and relative deprivation), and because the senior management team were supportive of the STASH study. The intervention was implemented over 9 weeks, comprising peer nomination, recruitment meeting, PS training and five follow-up sessions. Of 163 students in the year group, 31 (19%) were invited to recruitment, having received the highest number of nominations. Of these students, 19 (61% of those invited, 12% of year group) were trained and 14–17 attended follow-up sessions (attendance varying weekly). No students explicitly withdrew from the PS role, so all 19 students were considered ‘completers’ and awarded a certificate.

The purpose of the pilot was to test and refine the intervention on a small scale. We undertook a process evaluation primarily to identify what did or did not work (and why), and to identify potential improvements in anticipation of the feasibility study. The eight data collection strands were:

-

semistructured interviews with a convenience sample of intervention participants (14 PSs and three S4 friends of PSs who had some engagement with the STASH study)

-

semistructured observation of the PS training

-

PS evaluation of training via a one-page evaluation form (n = 17)

-

trainer feedback sessions (at the close of training days) and in-depth interviews with all three trainers (at the end of pilot)

-

PS online questionnaire (n = 14)

-

semistructured interviews with three teachers (including the STASH study contact teacher and two other teachers with guidance responsibilities and some awareness of the STASH study)

-

Facebook monitoring data (group membership, number of messages sent)

-

project monitoring log (participation numbers, key contextual information, e.g. school interactions, contemporaneous events).

The pilot enabled us to test the data collection tools and analytical approach. The latter was guided by an analytic framework designed to explore fidelity, acceptability, reach, recruitment and retention, context and perceived impact, and to capture any emergent and unanticipated issues. All pilot data were assessed for common themes using an approach informed by the framework method. 72,73 Data from across the data collection strands were collated by the above categories and reviewed in a matrix for commonalities, differences and key learning for the next stage of the study. We also piloted the baseline and follow-up questionnaires.

Second professional workshop

Those attending the first professional workshop were invited back to a second workshop to discuss key findings from stages 1 and 2, particularly the pilot results. Small group discussions focused on how to improve the STASH study website and message-sharing process, on intervention reach and impact, and on PS training and follow-ups. Meeting notes were reviewed for key learning points.

Intervention development meetings

Intervention development meetings consisted of four ‘away days’ with the researchers and delivery partners (West Lothian Drug and Alcohol Service and Fast Forward). Sessions focused primarily on optimising website messages and training content, including the trainer manual, slides and materials (such as games and activities). Detailed notes were taken by the research team and content drafts revised in the course of discussion.

Second phase website co-development

Following handover of the content management system from Antbits, the second phase of website development was led by the research team. Supported by Antbits and the MRC/Chief Scientist Office (CSO) Social and Public Health Sciences Unit in-house graphic designer, the research team worked to streamline and simplify content and structure, and improve visual appeal, primarily via the creation of bespoke infographics.

Website testing with young people

We conducted group interviews with two youth groups: one face to face with an established young people’s action research group (Young Edinburgh Action) and one online using Facebook Messenger (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) with a pre-existing friendship group identified through the professional networks of the research team. Groups comprised six (all female) and seven (four female, three male) participants, respectively. Participants were slightly older than the target group (aged 16–17 years), to enable reflection on what information and format they would have preferred at age 14–15 years. Groups discussed relevance, credibility and relatability of newly created content. The face-to-face group was audio-recorded and notes were taken from the audio, whereas the online group generated a transcript of the online discussion. Each was reviewed for key revisions.

Ad hoc consultation meetings (across months 0–21)

A series of meetings were held with school contact teachers, head teachers (HTs) and deputy head teachers (DHTs) at schools considering participation in the trial (two or three per school), academic colleagues, intervention development partners, professional panel participants and local NHS young people’s sexual health specialists. In addition, discussions held in regular PEG, TMG and Trial Steering Committee (TSC) meetings contributed significantly to intervention optimisation.

Synthesising and operationalising development process findings

The following section synthesises findings from across all development activities, showing how these shaped the final intervention. Findings are organised by intervention component (see Key intervention components brought forward from ASSIST). Appendix 1 details specific recommendations from each activity. The synthesis begins with a brief summary of higher-level decisions made regarding the theory underpinning the intervention.

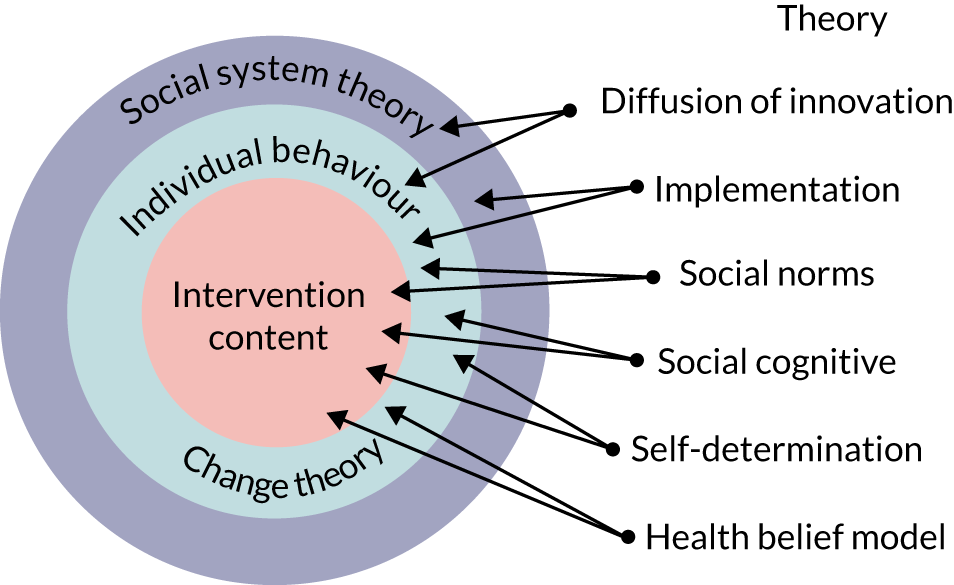

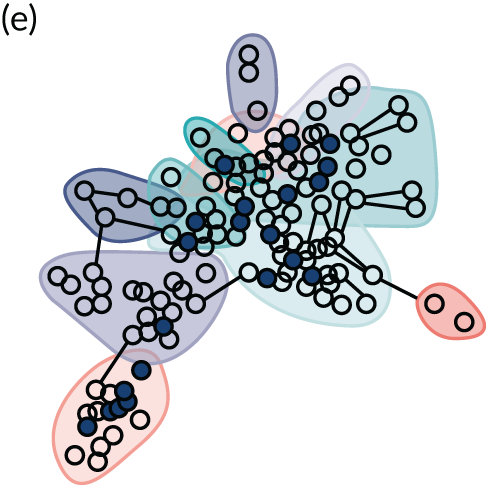

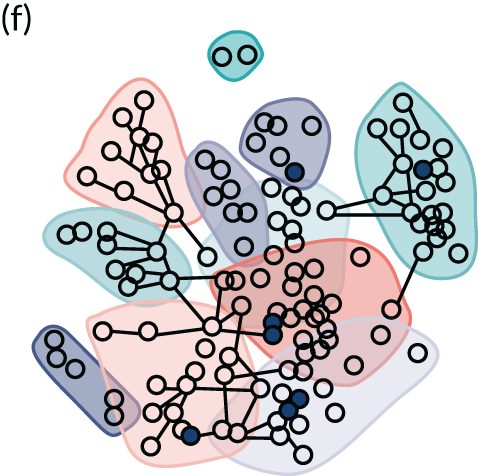

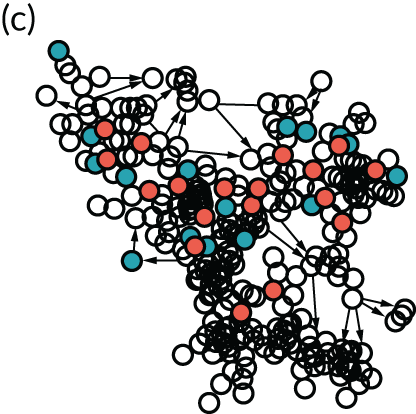

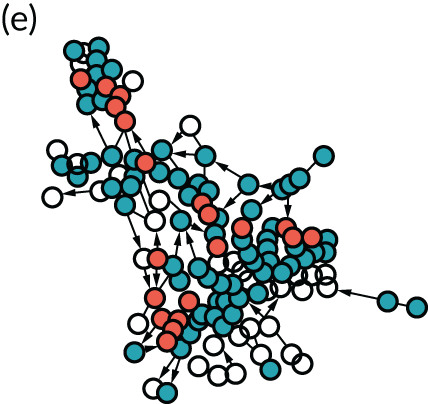

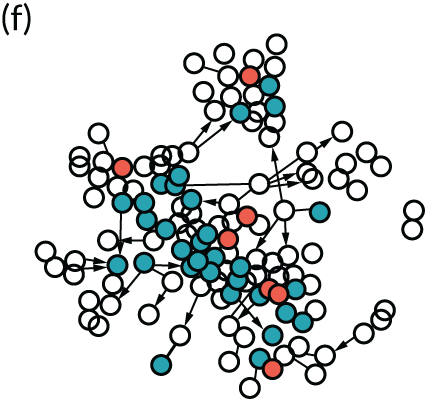

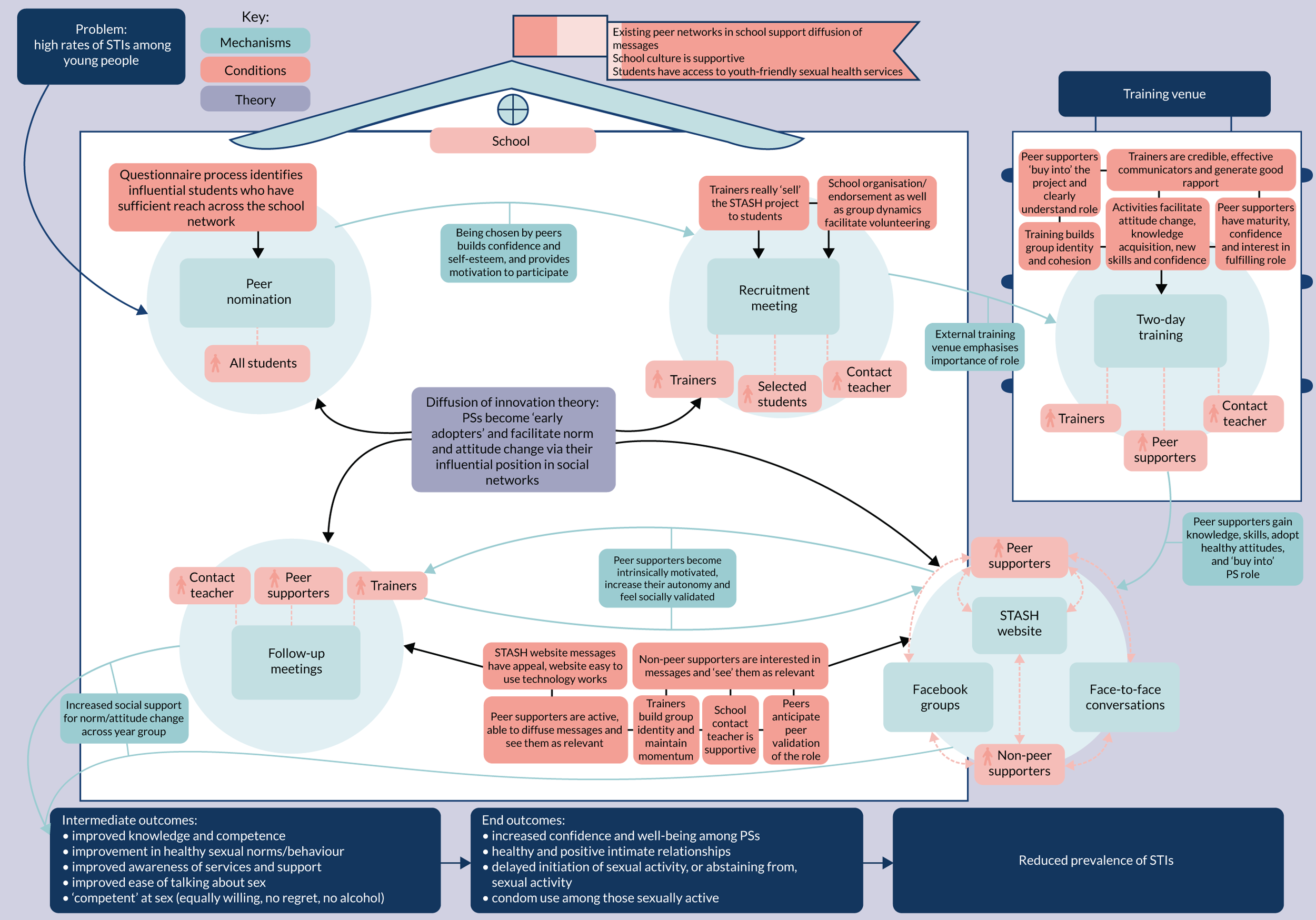

Developing the STASH study programme theory

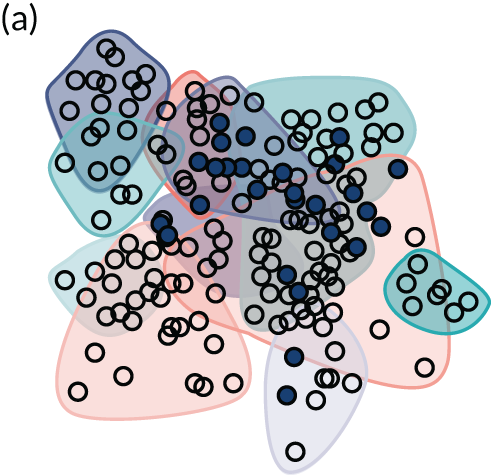

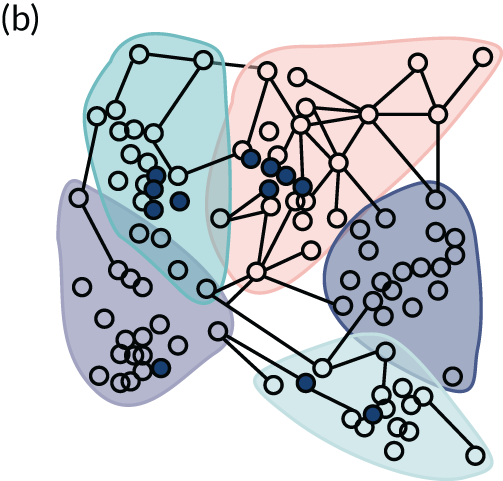

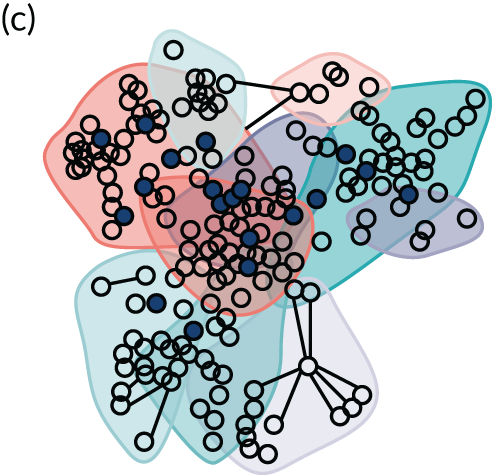

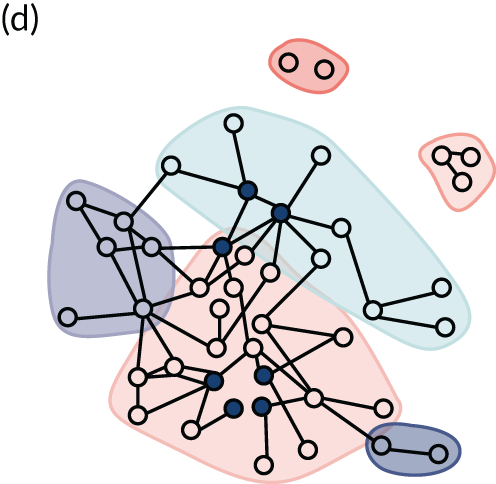

We conceptualised and used relevant theories at three levels (Figure 3): (1) the social system level (macro theory), (2) the individual level (mid-level theory) and (3) the behaviour level (micro theory). We identified, via literature review, mid-level theories relevant to young people’s sexual health and behaviour. This review, together with stakeholder consultations, informed the choice of behaviour change techniques and training, and website content. We developed our programme theory in line with what we already knew about mechanisms of change in ASSIST and adapted these for the sexual health context.

FIGURE 3.

Use of theory in the STASH study.

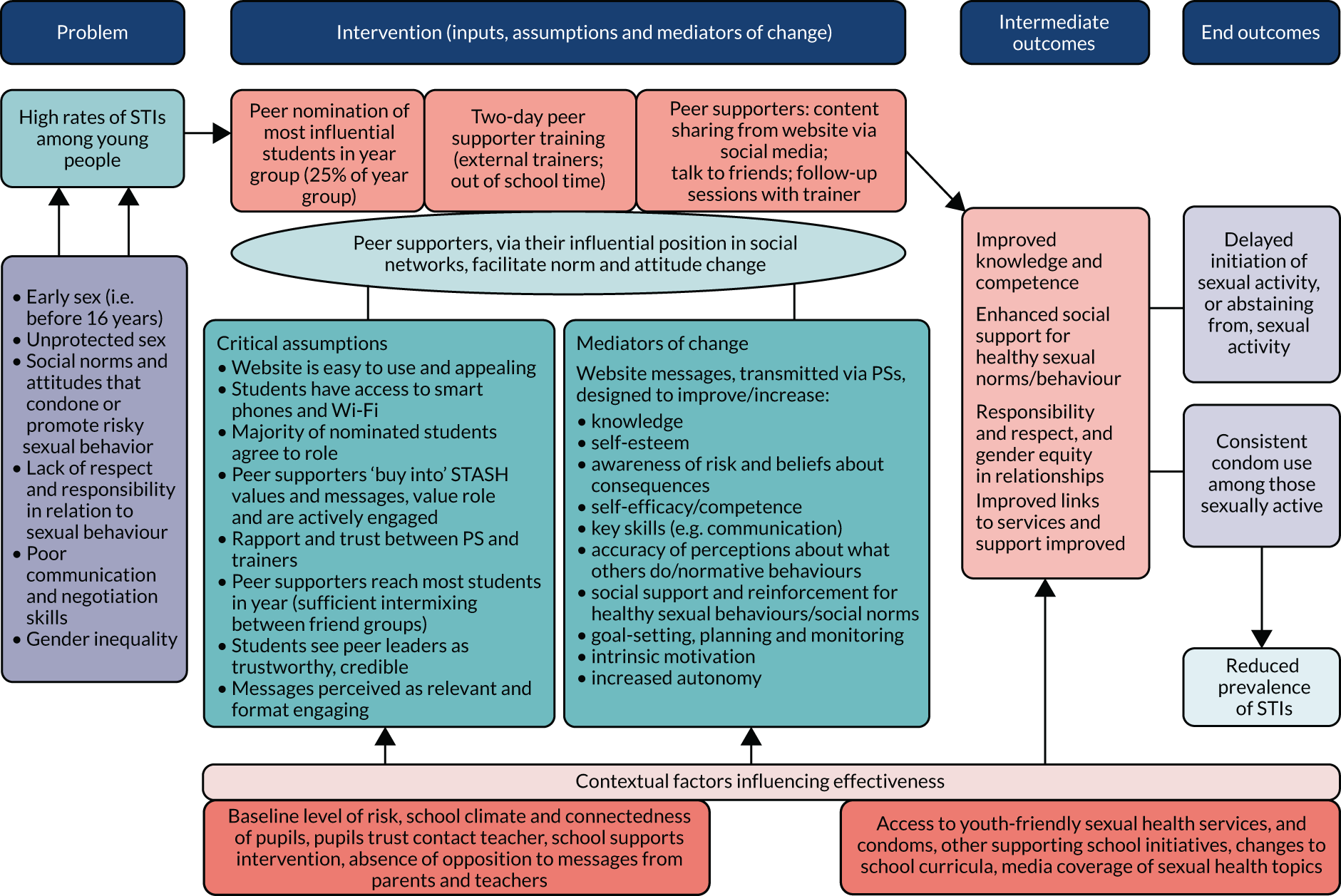

A detailed description of the theories and how we used them is given in Appendix 1 (see Table 19). Following the literature review, we excluded the least relevant of any overlapping theories and applied those most relevant at three levels (see Figure 3): (1) the social system of the intervention, (2) individual behaviour change and (3) specifics of intervention content. Together, these theories describe potential mechanisms for change that might be expected to occur as a result of the intervention. 74 Having explored their relevance and utility in the pilot, we integrated these into the revised programme theory (Figure 4) and feasibility trial.

FIGURE 4.

The STASH study programme theory: pre pilot.

Guided by these theories and our consultations (see Synthesising and operationalising development process findings), we established that it would be crucial to prioritise skills development (particularly communication), encourage and support active participation and responsibility-taking (within the intervention and with regard to sexual behaviour), boost intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy, provide SRE information relevant to young people and tailor the intervention to the needs of the target group.

Synthesis and actions relating to key intervention components

Nomination and recruitment

Motivating schools

Our development activities and literature30,65,75 reviews established that school buy-in would be key to successful implementation. ASSIST highlighted that use of external trainers is a key means of limiting school burden and enhancing intervention workability. Our grey literature review and expert consultations identified that helping schools meet national policy requirements would be a strong motivator. This related particularly to the Scottish Government’s Curriculum for Excellence,19 Getting it Right for Every Child20 policy and the National Health and Wellbeing Outcomes. 76 Our schools brochure, therefore, explicitly outlined how the STASH study could help schools meet relevant indicators, particularly around enhancing students’ confidence and sense of responsibility, and addressing stigmatising attitudes.

Peer nomination process

Our consultations with young people and professionals affirmed learning from ASSIST, suggesting that peer nomination (as opposed to teacher or self-selection) would identify the most ‘credible’ or ‘trustworthy’ students40 and that schools should not be allowed to shape the list of peer-nominated students. This was stipulated in the guidance provided to schools.

The ASSIST study also found that to obtain the 15% ‘critical mass’ required for effective diffusion of innovation throughout the year group, 17.5% of nominated students should be invited to recruitment. However, our consultations suggested, and the pilot confirmed, that the sensitive topic and older cohort would require a tougher sell. In the pilot, inviting 31 nominees (19% of year group) resulted in only 19 (12% of year) being trained. To enhance the likelihood of reaching the 15% ‘critical mass’, we increased the proportion of nominees invited to recruitment to 25%. The pilot and young people consultations identified that emphasising potential curriculum vitae (CV) benefits, time with friends, and the sense of responsibility and satisfaction at being nominated, might also enhance uptake.

Discussions on peer recruitment at professional workshops and TMG meetings mooted whether or not the older cohort and sensitive topic might necessitate alternative recruitment questions to those used in ASSIST. The TMG therefore designed four new nomination questions (see The STASH study intervention design for the feasibility trial) and piloted those alongside existing ASSIST questions. Learning from the pilot also highlighted the importance of practical considerations – such as allowing plenty of time for circulation and return of parent and carer consent forms – to avoid losing some potential recruits.

Peer supporter training

Intervention content

Most development activities fed into decisions about training and website content. The literature reviewed suggested that young people’s sexual health knowledge tends to converge around risk, STIs and contraception, and that current gaps in SRE include communication, consent, pornography, sexual pleasure and online literacy. 6,77 Stakeholder consultation highlighted that current SRE packages are outdated and lack information on contemporary issues, such as consent and coercion, a view echoed in the young people consultations. Young people also expressed a desire for relatable experiential information and, echoing the literature, suggested that the use of humour78 and interactive components would enhance training and online content. In collaboration with the trainers, we integrated each of these considerations into content design.

The online resource review identified a vast array of training activities and websites aimed at young people, of varying relevance to the STASH study. Selection from among these was based on the extent to which resources linked to our key content-guiding theories (e.g. sought to change perception of social norms, boost self-efficacy and support new behaviours) (see Appendix 1), as well as their likely appeal to young people and their potential for interactive learning. Several shortlisted resources were tested with young people in the development phase. Among these were two key videos that conveyed experiential information and behaviour modelling. [‘Ryan and Natalie’ uses a gently comedic approach to illustrate a young couple navigating their first sexual encounter [URL: www.truetube.co.uk/film/screwball (accessed 4 August 2020)], whereas ‘Tea and Consent’ [URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZwvrxVavnQ (accessed 4 August 2020)], developed for Thames Valley Police, also uses humour and a tea metaphor to explain sexual consent.] We identified Hannah Witton as an important ‘influencer’ [URL: https://hannahwitton.com (accessed 4 May 2020)] and that the BISH (best in sexual health) website had strong appeal to young people [URL: www.bishuk.com (accessed 4 May 2020)].

Some activity types were excluded or reduced post pilot. Role-plays, in particular, were used more selectively in the feasibility study, following observation of PS discomfort in performing these during the pilot training.

Values

Our theoretical grounding suggested that a clear set of values should be conveyed to participants, so that they could judge congruence with their own priorities and understandings. 60 We therefore included an overview of ‘STASH study values’ within the PS training. These values drew on the literature, policy and stakeholder consultations. Foremost among these were aims to address negative gender norms,23,79 to take a broadly ‘sex-positive’ rather than risk-focused approach and to draw on a rights-based discourse of sexual health. 80 A rights-based approach was familiar to students and teachers from the current Scottish curriculum.

Peer supporter role

Theory-guiding development, expert consultations and findings from the pilot similarly highlighted the necessity of clearly articulated role expectations for PSs. From pilot to feasibility trial, the role was refined and distilled to four key components: (1) give information, (2) influence attitudes, (3) promote the STASH study website and (4) signpost friends to trusted adults or sexual health services. These components were revisited repeatedly throughout training. Beyond these, the other key feature of the PS role was to establish and post in a secret Facebook group.

During the development stage, concerns were raised by professional workshop participants and education stakeholders about whether or not the role required too much of students. Fears coalesced around whether PSs would have the requisite maturity to handle potentially inappropriate responses from peers (including online ridicule) and whether or not they could appropriately manage potentially sensitive disclosures, including those raising safeguarding or child protection issues. To signal the responsibility inherent in the role, PSs were asked to sign a ‘STASH study charter’ on completion of the training. This reiterated role expectations and the STASH study values. The training included a session on recognising and handling sensitive disclosures, with emphasis on swift referral to an appropriate adult if anything gave cause for concern. We emphasised that PSs should not offer any sort of counselling beyond what would typically happen in their everyday friendships (see Chapter 3, Assessment of harms).

Discussion of the PS role, supported by the literature, foregrounded the importance of building generic skills of communication and listening, essential to the PS role. 81 We therefore kept the ASSIST format of building generic PS skills on training day 2, including several activities adapted from ASSIST.

Training activity format

Close consideration was given to the most effective format for all training activities, whether newly designed or drawn from ASSIST. Adaptations and revisions drew primarily on observational data from the pilot training and intervention delivery partner meetings, in which the training format was finalised. It was agreed that activities should prioritise smaller group work – which process evaluation data suggested was more effective – and that fewer topics should be covered, but in more depth (with remaining topics moved to the follow-up sessions). Based on these same sources, it was decided that use of the website and Facebook groups should be more fully integrated into the training (to improve PSs’ familiarity and confidence with content and process). It was also decided that information and skills training should be integrated across both days, rather than allocated 1 day each.

Peer supporter-led activities

Using social media

The use of social media in the STASH study was novel and, therefore, a key focus of the development stage. Our review of platforms, stakeholder consultations (patient and public involvement) and design decisions, suggested the following priorities for functionality: appeal to young people; provide options to post web links, images and/or text; provide an option to create private, invite-only groups; ease of viewing messages and message stability; potential for monitoring; and potential for interface with a website. This ruled out popular platforms such as Snapchat (messages disappear, primarily images) and Twitter (messages likely to be lost in traffic, primarily appeals to older users) (URL: www.twitter.com; Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA). Instagram (primarily visual) at the time had no option for private groups or for a bespoke application programming interface (API) to link to the STASH study website. We ruled out WhatsApp, on the basis that this would necessitate participants sharing mobile telephone numbers with fellow group members. We also ruled out school-linked platforms [such as Glow (URL: https://glowconnect.org.uk/)], which might limit credibility and perceived student ownership of the project. Ultimately, Facebook was identified as the only platform to meet all priorities. Although not the most popular choice for the target group, consultations did suggest that the platform was widely used and that young people would be willing to utilise it for the STASH study. A priority emphasised by young people throughout the consultations was privacy and control over who would see their posts, and the ‘secret’ group functionality of Facebook addressed this particularly well.

The reviewed literature suggested that the best use of a digital platform in this context would be one that drew on dynamic and interactive components. We therefore created sharable content for the STASH study website, which participants were able to post and comment on in Facebook groups, and adapt if desired.

The STASH study website

The first website iteration required PSs to log in with individual passwords. However, pilot data suggested that this created an unnecessary barrier, should technical issues arise (e.g. forgotten password). We also subsequently realised that opening the website to all students could allow PSs to direct friends to visit for themselves. The final version, therefore, required only a school-wide password (circulated by PSs). An additional login for PSs, via a bespoke API (created by Antbits), allowed PSs to post messages directly to their Facebook groups. Website accessibility was thus increased, while maintaining a degree of security that limited contamination beyond S4 at participating schools. We reiterated at training that PSs should give the STASH study password to friends in S4 at their school only, and they were provided with STASH study cards indicating the web address to facilitate this.

Based on the pilot and professional workshop findings, the website was significantly streamlined for the feasibility trial stage. Key revisions included removal of subsections for different activity types, replacing textual messages with more visually appealing bespoke infographics and memes, reducing external links (participants tended not to click on these) and dropping conversation prompts (which were minimally engaged with). The TMG proposed ‘gamifying’ the online component of the STASH study as a means of boosting interactivity, engagement and motivation, but ultimately dropped this idea, prioritising simplicity over desirable ‘add-ons’. Instead, it was agreed that PSs could be motivated in a ‘low-tech’ way by offering a ‘PS of the week’ prize at follow-up. We also considered a search function and ‘escape’ button (allowing students to quickly close the site); however, given the significant work required to refine basic functionality, these additions were not possible within our resources.

Participants in website testing groups were positive about the revised website, particularly with the inclusion of humorous memes and brightly coloured visuals.

The final version of the STASH study website [URL: www.stashtrial.org.uk (accessed 4 May 2020)] was organised under eight topics:

-

What’s STASH all about?

-

Is my relationship good?

-

What’s normal?

-

Am I ready for sex?

-

What’s consent?

-

How do I avoid risk?

-

Are pics and porn OK?

-

How do I feel good about myself?

Each topic had a website page, comprising an overview and a series of easily sharable messages (text, memes, infographics, embedded videos, external links; see Appendix 2 for examples) and a list of support sources.

School support and intervention profile

The pilot process evaluation echoed the existing literature in highlighting that school leadership support and contact teacher amenability to the intervention were key preconditions for successful implementation. Learning from ASSIST suggested that the contact teacher should attend PS training. Although invited, the pilot contact teacher (a DHT) was able to attend for only a brief portion of the training and instead sent a pupil support staff member. This led the TMG to reflect on whether or not a less senior member of staff would be more suited to the contact teacher role. The pilot findings also generated TMG discussions about how we might increase awareness of the STASH study across the entire staff body and led to suggestions such as highlighting the STASH study at staff meetings. Post-pilot student and teacher interviews indicated that the profile of the STASH study across the school was low. The TMG discussed and agreed that at the training PSs (and the teacher present) should agree how best to ‘announce’ the STASH study to their wider year group. Following the suggestion of one PS, STASH study PS badges were provided to PSs to identify them as such.

Trainer-led activities

Adaptations from ASSIST

The ASSIST study used pro forma diaries to track PS activity and, although these helped prompt PSs, the process evaluation found that entries were sometimes fabricated or omitted and did not offer an accurate activity record. 82 In the STASH study, the trainers and research team were able to monitor Facebook activity directly and a decision was made to capture face-to-face conversations via reports to trainers at weekly follow-ups, rather than via the more cumbersome and potentially less reliable diary method (although the conversations remained self-reported).

Previous research suggested that ‘booster’ sessions enhance intervention effectiveness. 65 The pilot confirmed that, as with ASSIST, regular follow-ups provided an acceptable means of ‘checking in’, troubleshooting and encouraging PSs. We extended this model by adding interactive learning activities to these sessions. This was done to supplement the training (as it was not possible to cover all relevant topics therein) and to maintain interest and momentum. Given the complexity of the issues and behaviours the STASH study sought to address, we added one further follow-up session for the feasibility stage, giving a total of five, plus a sixth session to conduct evaluation activities (PS questionnaire, group interviews).

To meet the concerns of teachers and child protection officers consulted regarding online bullying and sensitive online disclosures, we stipulated that a trainer (via a generic STASH study trainer account) should be a member of all PS groups. Pilot data suggested that this was acceptable to PSs, offering additional reassurance and opportunity to contact trainers with queries between follow-ups.

Peer supporter acknowledgement

During all intervention development stages, there was much discussion about how best to motivate PSs, as this was known to be essential. 60,81,83 Informed by ASSIST, and by feedback from students and professionals, we opted to provide formal academic recognition with a University of Glasgow certificate, in addition to a £10 voucher on completion of the PS questionnaire. PSs were also given the opportunity to bank time spent on the STASH study towards attainment of a Saltire Award (Scottish Volunteer Award scheme for 12- to 25-year-olds). 84 On a week-to-week basis, commitment was rewarded by a ‘PS of the week’ prize (a STASH study highlighter).

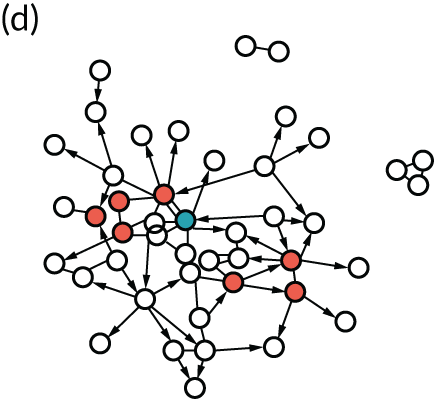

Revisiting the STASH study programme theory

As a result of the development work, we were able to more clearly articulate the critical assumptions underlying the intervention, the potential mediating factors and key contextual factors. The pre-pilot programme theory is shown in Figure 4.

The STASH study intervention design for the feasibility trial

Following development, refinement and optimisation, and ahead of the feasibility study, the final design of the STASH trial was determined as follows.

Peer nomination

All students in S4 (aged 14–16 years) are asked to complete a peer nomination questionnaire. Each school is given a different combination of nomination questions. Three are the same as those used in ASSIST:

-

Who do you respect in S4 at your school?

-

Who are good leaders in sports or other group activities in S4 at your school?

-

Who do you look up to in S4 at your school?’

Four questions are newly designed for the STASH study:

-

With whom in S4 would you feel comfortable to talk about something personal or sensitive?

-

Who in S4 is good at encouraging and persuading others to do things?

-

Whose opinion do you trust and value most in S4 at your school?

-

Who in S4 is confident at talking to people outside their friendship group?

The 25% of young people receiving most nominations, stratified by gender, are invited to a recruitment meeting.

Peer supporter recruitment

A meeting is held with nominees in each school, in which trainers explain the intervention purpose, the PS role and answer questions. The aim is to recruit 15% of the year group to participate in PS training. If recruitment attendance is poor or role uptake low (or skewed significantly towards one gender), a second recruitment meeting is held.

Two-day peer supporter training

A 2-day PS training session is held in school time, at an external venue, facilitated by Fast Forward and West Lothian Drug and Alcohol Service. The training is intended to equip PSs with the knowledge, skills and confidence required for the role; build motivation and enthusiasm for the role; generate trust and rapport within the PS group and among PSs and trainers; build sexual health knowledge and skills; improve understanding of risks and consequences; build self-esteem and self-efficacy; reinforce social support for healthy sexual norms; and boost intrinsic motivation and autonomy. PSs are required to sign a code of conduct during training and agree a plan to ‘announce’ the project to their year group.

Peer support work

The period in which PSs are active varies between schools: 5 weeks in three schools and 10 weeks in three schools.

Activities

Peer supporters are to establish ‘secret’ Facebook groups (invitation only groups with the highest privacy setting), comprising friends and the STASH study trainer. PSs are encouraged to post messages from the STASH study website to this group and to initiate face-to-face conversations centred on the STASH study messages. They are asked to alert friends to the STASH study website and to local support sources. To ensure maximum reach, PSs use STASH study cards to advertise a non-sharing version of the STASH study website, particularly to students who do not use Facebook. PSs are supported by a trainer for the duration of this period, as well as by an appointed contact teacher. As far as possible, PSs are encouraged to engage with intervention resources flexibly; for instance, they can choose which messages and links to share, and have the option of editing messages into their own words.

Trainer-led activities include moderation of group discussions and monitoring posts, supporting the PSs and facilitating follow-up meetings (weekly or fortnightly) with all PSs for the intervention duration.

Acknowledgement

Peer supporters who fulfil the requirements of the role would be provided with University of Glasgow certificates and, if they complete the online questionnaire, a £10 gift voucher. Schools may also support PSs towards attainment of an accredited Saltire Award.

Chapter 3 Study methods

This chapter describes the methods for the feasibility trial. The study objectives are described in Chapter 1, Aims and objectives. The development of the STASH study intervention (including methods of the development stage) can be found in Chapter 2. A full description of the post-pilot intervention can be found in Chapter 2, The STASH study intervention design for the feasibility trial.

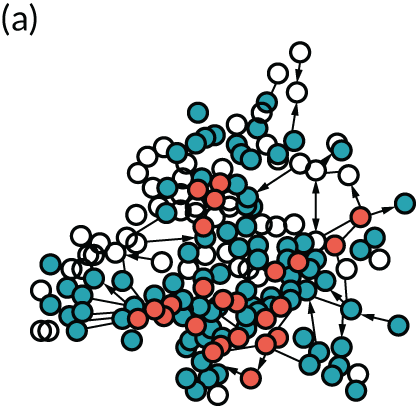

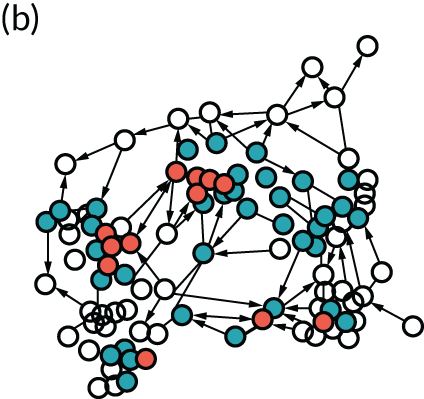

In this chapter we describe the overall study design, and present the progression criteria regarding the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention and evaluation methods (the primary outcome for the trial). We then describe the process evaluation [including social network analysis (SNA)], piloting of outcome measures and economic evaluation. Within each of these sections, we describe the aims, methods, measures and analysis.

Study design and setting

The STASH study was a non-randomised feasibility study conducted with students in six mixed-sex, state-funded secondary schools in Lothian, Scotland, during the 2017/18 academic year (August 2017 to June 2018).

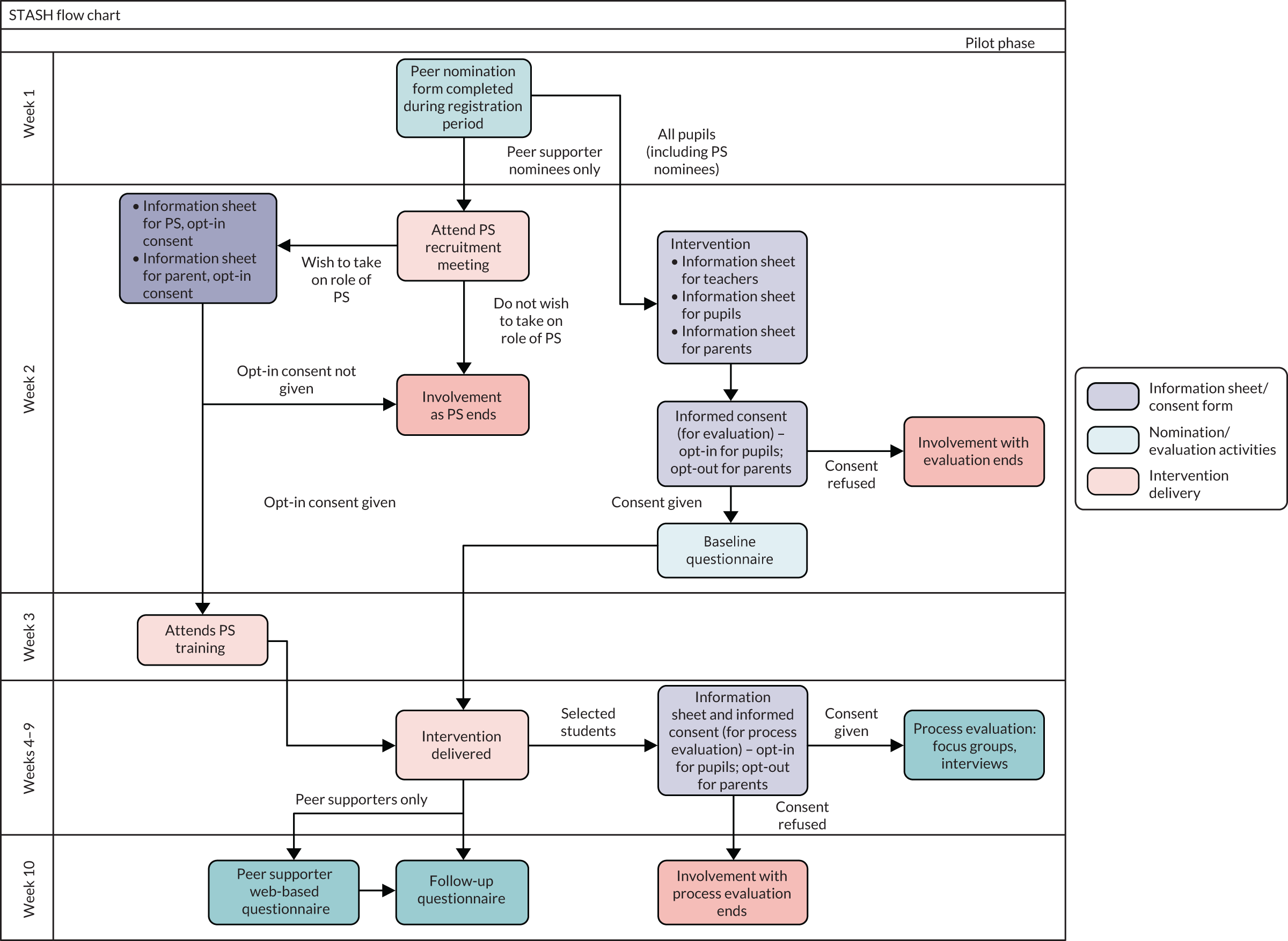

All six study schools received the intervention and provided both intervention and control data. The latter were provided by students in the year above the intervention group and were collected prior to the delivery of the intervention. These were then compared with data from the intervention year group collected 1 year later. Control and intervention participants were therefore the same age when they completed the control and follow-up questionnaire, respectively, but the intervention year group had received the intervention and the control group had not. A flow chart for the study is shown in Figure 5 and a flow chart for participant involvement in the intervention and evaluation is shown in Figure 6.

FIGURE 5.

The STASH study flow chart. Reproduced from the STASH protocol, Forsyth et al. 62 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

FIGURE 6.

Movement of participants through intervention and evaluation.

Participants

Participants were year 4 students (aged 14–16 years) in secondary schools meeting the study inclusion criteria. (In Scotland, secondary school education begins at age 11 years and comprises 6 years, with compulsory education ending after 4 years.)

Intervention participants were students in S4 during the academic year (2017/18) when the STASH study was delivered. Control participants were in S4 in the previous academic year (2016/17).

Inclusion criteria

Secondary 4 students (aged 14–16 years) in state-funded schools who had received, or were receiving, teacher-led sex education, regardless of their sexual experience or individual level of risk, were eligible to participate.

Exclusion criteria

Students attending private or independent schools or state schools not currently delivering comprehensive sex education were ineligible.

The STASH study was designed to augment rather than replace usual sex education. Therefore, to participate, schools had to be already providing SRE. At the time of study, most Lothian schools were delivering a version of the Sexual Health and Relationships Education (SHARE) package85 as part of their personal and social education curriculum. Faith schools were included in the invitation to participate, but none took up the offer.

Sample size

As a feasibility study, the STASH study was not designed to identify an estimate of effect and thus a standard power calculation was not appropriate. We anticipated that 1400 participants would be sufficient to allow qualitative and quantitative progression criteria to be assessed and provide information on key parameters for the design of a future trial, and that a cluster of six schools would enable us to generate an estimate – albeit imprecise – of ICC, when combined with a range of ICC estimates from published evaluations of similar interventions, using the model outlined by Turner et al. 86 The average year size for West Lothian is 160 students and, allowing for a non-response rate of 15% due to student absence, we estimated a sample size across six schools of approximately 700 intervention participants and 700 control participants. We thus aimed to recruit six schools.

Selection and recruitment of schools

Schools in the study area were introduced to the STASH study by management staff at West Lothian and South West Edinburgh education authorities. The research team followed up these introductions by e-mail and visited those expressing interest. All interested schools received a STASH study brochure outlining project steps, roles and responsibilities. HTs and DHTs agreed to participate on behalf of the school and usually handed on responsibility for the STASH study to a contact teacher (typically someone with responsibility for personal and social education, physical education or pastoral care). A senior staff member was asked to sign a research agreement, after which point the school was considered formally recruited into the study.

At the end of the evaluation activity, schools received £500 compensation for any disruption caused by the intervention or evaluation activities and an extra £500 to cover backfill costs for teachers to attend sessions such as the STASH study training.

Criteria for progression to a full trial

The main aim of the feasibility trial was to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention and evaluation methods to PSs, the target group and stakeholders. The primary study outcome was whether or not the study met progression criteria regarding the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention and evaluation methods.

The criteria, outlined in Table 1 were discussed within the TMG and agreed via discussion with the TSC after the pilot and before the main feasibility stage. The results reported in Chapters 5–7 are focused on ascertaining whether or not these criteria were met, as well as contextualising the broader experience of the trial in relation to the criteria and study objectives. There was some debate within the TMG around criterion 1. The figure of 60% (for role uptake among nominated students) was set based on learning from ASSIST67 and in view of the need to ensure that PSs had reach or influence across their social networks. However, it was acknowledged that with an older year group in a public examination year and a more sensitive intervention topic, it would be harder to recruit PSs in the STASH trial than in ASSIST. The question of whether or not 60% was still required in an intervention engaging social media as well as face-to-face interaction was also raised. These issues are discussed in Chapters 5 and 6 and revisited in Chapter 9.

| Number/chapter | Target | Assessed by | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green | Amber | Red | ||

| 1 | Acceptability of role/feasibility | Was it feasible to recruit PSs? | ||

| Chapter 5 | In each of four schools, 60% of nominated students are recruited and complete the training | 50%, in each of four schools | Amber target achieved in fewer than four schools | Attendance monitoring at recruitment meetings and training (monitoring log) |

| 2a | Reach/feasibility | Were PSs able to carry out the role? | ||

| Chapter 6 | In each of four schools 60% of PSs complete the training, send three or more messages/have three or more conversations and attend two or more follow-up meetings | 50%, in each of four schools | Amber target achieved in fewer than four schools | PS questionnaire administered at last follow-up session; project monitoring log; PS activity log |

| 2b | Acceptability | Was the STASH study acceptable to PSs? | ||

| Chapter 5 | In each of four schools 60% of PSs report that they ‘liked’ the role | 45%, in each of four schools | Amber target achieved in fewer than four schools | PS questionnaire: ‘I liked being a PS’ (five-point Likert scale) |

| 3a | Acceptability | Was the STASH study acceptable to the wider target group? | ||

| Chapter 5 | In each of four schools, 60% of students who are exposed to the STASH study agree that the intervention was acceptable | 50%, in each of four schools | Amber target achieved in fewer than four schools | Follow-up questionnaire: ‘The way the STASH project was run was acceptable’/‘The information given in the STASH study was acceptable’ (five-point Likert scale) |

| 3b | Acceptability | Was the STASH study acceptable to participating schools? | ||

| Chapter 5 | No major acceptability issues raised | One or two major issues | Major acceptability issues | Teacher interviews at end of intervention |

| 3c | Acceptability | Was the STASH study acceptable to parents? | ||

| Chapter 5 | Less than 15% of PSs report that their parents/carers were unhappy about them being a PS | Less than 20% | Amber target not met | PS questionnaire (‘My parents/carers were happy that I was a PS’); teacher interviews; PS interviews |

| 4 | Acceptability of evaluation/feasibility | Were the evaluation methods acceptable and feasible? | ||