Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 17/149/19. The contractual start date was in April 2019. The final report began editorial review in July 2021 and was accepted for publication in March 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Jepson et al. This work was produced by Jepson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Jepson et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background to the study

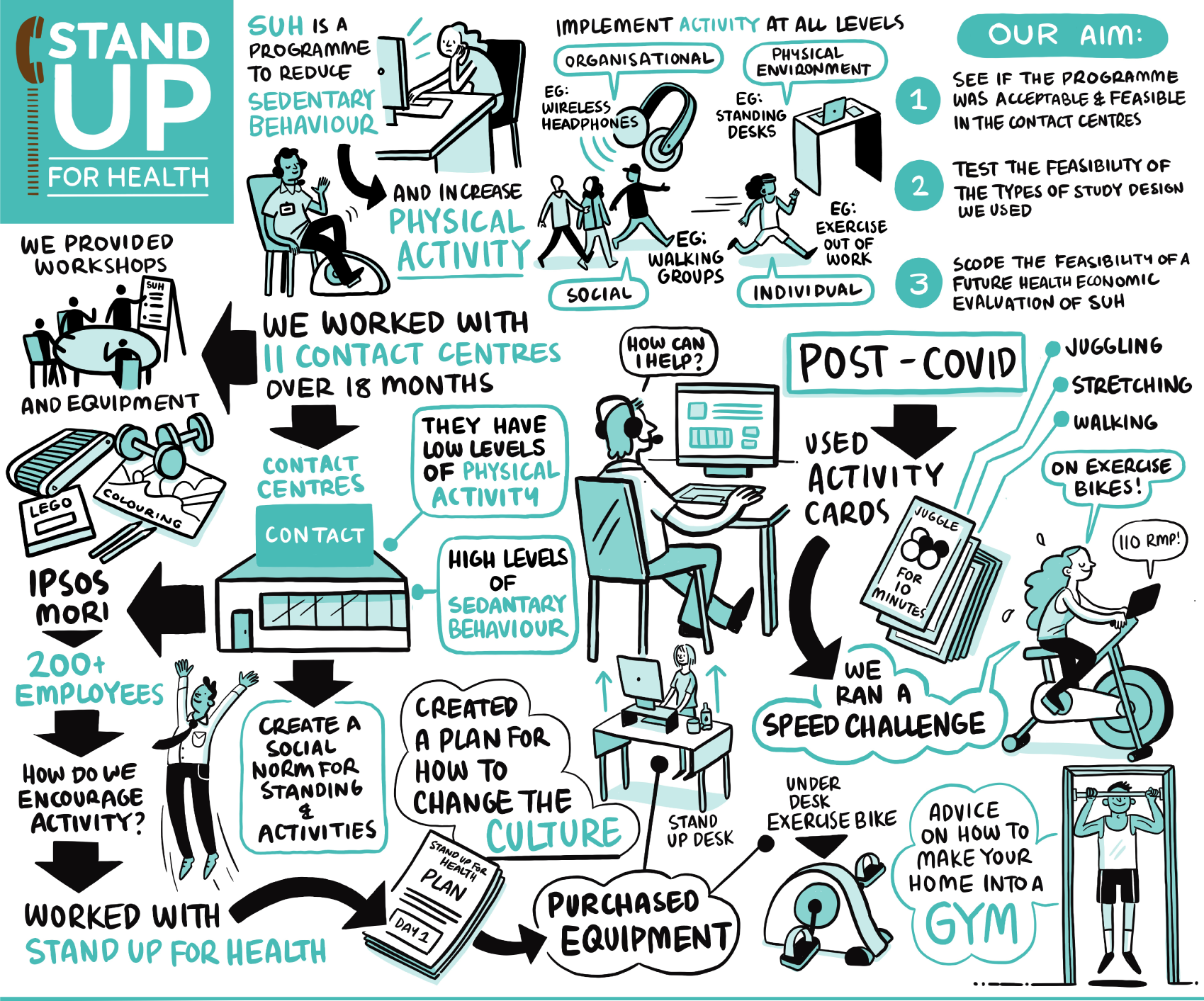

The origins of this study are in a master’s in Public Health project; it was developed by students who were taking a module on ‘Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions’. This module was developed and delivered by Ruth Jepson and members of the Scottish Collaboration for Public Health Research and Policy for the Master’s in Public Health at The University of Edinburgh, Scotland. As part of the module assessment, all students were to submit a team proposal for an intervention based on the 6 Steps in Quality Intervention Development (6SQuID) framework (this framework was developed by Ruth Jepson, Danny Wight, Erica Wimbush and Lawrence Doi). The students presented their proposal to a mock grant panel and a winning project was selected. Stand Up for Health (SUH) was the winning project in 2016. The module team believed that SUH had great potential and so decided to further develop and pilot it with members of the student team.

Ruth Jepson worked with the students to reach out to contact centres (also known as call centres) in the Edinburgh area. One contact centre, Ipsos MORI (Edinburgh, UK), responded positively and the team was able to start piloting work and developing both a theory of change and a theory of action (see Figures 2 and 4). Following this pilot, the team was able to develop this larger feasibility study. Although none of the original students is still involved directly in the project, several of them still have close links with the Scottish Collaboration for Public Health Research and Policy.

Evidence supporting the study

Sedentary behaviour as a public health problem

Sedentary behaviour is a serious occupational health hazard, which is linked with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal issues and poor mental well-being. 1–6 Earlier research studies proposed that these risks are independent of physical activity7,8 given that, conceptually, sedentary behaviour and physical activity are different,9 with each thought to pose health risks independent of each other. 5,10–12 However, more recent research shows that, although physical activity can modify the associations between health risks and sedentary behaviour,13,14 health effects of sedentary behaviour are still evident even after controlling for physical activity. 4,5,12,15 A review16 of behaviour change strategies that are used for the reduction of sedentary behaviour among adults reported that interventions that showed the most promise in reducing sitting time were those that aimed to changed sedentary behaviour rather than increase physical activity. The reduction of sedentary behaviour is, therefore, not a consequence of effectively promoting physical activity and should be recognised independently when developing interventions, guidelines and legislation.

Workplace sedentary behaviour is placing a large burden on employers and the health-care system. In office-based roles, many employees have prolonged periods of sitting, which are enforced by workplace culture and ergonomic set-up. 17 This sitting behaviour can impact on the health of office-based workers. For example, musculoskeletal issues are a leading cause of disability worldwide and one of the most common health problems for desk-based workers. 18–20 Estimates of the prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms in computer users are as high as 50%. 21 Lower back pain in particular is associated with prolonged sitting. 22

Factors associated with sedentary behaviour in workplaces

A cross-sectional study conducted among Australian adults23 found that the following were associated with higher levels of occupational sitting: being male; being younger; having higher education and income; both part-time and full-time employment; sedentary job tasks; white-collar or professional occupations; and higher body mass index (BMI). Some of these findings were corroborated by a systematic review of occupational correlates for sedentary behaviour. 24 The review identified full-time employment, working in a call centre, high level of leisure sitting time, high body weight, being older, high education and high income levels as positive correlates, and blue-collar occupations and smoking as negative correlates. 24 Political correlates (described as incentivisation, coercion and job description) that were identified included repetitive work, handling heavy loads and forceful exertion, which were found to be negatively associated with occupational sedentary behaviour. Low control or autonomy was found to have a positive association.

Qualitative studies conducted with employees and managers in a UK-based software engineering company25 and non-academic office staff at a university in Singapore26 have identified several barriers to reducing sedentary behaviour in workplaces, including workplace social and cultural norms (sitting is perceived to be a reflection of productivity by themselves and others, whereas standing is seen as disturbing others), work pressures (pressure to deliver work), the nature of the job requiring more sitting (e.g. working with computers) and physical environment and office infrastructure (small office spaces, no adjustable workstations and lack of facilities).

Contact centres as a setting for public health interventions

There are over 6200 contact centres in the UK, employing 734,000 agents,27 which is roughly 1 in 25 of the UK workforce. Scotland and the North East of England are home to some of the largest contact centres in Europe. Workplaces are often considered as homogeneous, but there are wide variations in worker demographics, the amount of worker autonomy, salaries, the environment and culture.

The call handlers (the highest proportion of contact centre staff) earn an average salary of £16,319 per year, compared with the national average of £26,500, which puts them in the bottom third of earners. 28 An industry report that collected data from 208 contact centre managers and directors using a structured questionnaire reported that turnover rates are high in UK contact centres, with an average attrition rate of 20% reported in 2020. 29 Short-term absence rates are also high, with 5.7% of agent workdays being lost to short-term sickness and unauthorised absences. 29 Career progression is limited, and a lack of promotion and development opportunities has been reported as the second greatest cause of employee attrition. 29

Contact centres and health

Contact centres are currently one of the most sedentary working environments, with higher levels of sedentary behaviour than other office-based work. 24,30 Studies have reported that contact centre staff spend 75–83% of their workday sitting. 30,31 The technology in contact centres prevents staff from regularly leaving their desk and many call handlers often report that work environments are stressful owing to low workplace autonomy, strict supervision of individual performance and commission-based salary systems. 32 Several international studies33,34 show that as many as 60–65% of contact centre employees experience musculoskeletal issues, and a study in the UK35 noted that one in four employees at a contact centre experienced upper body musculoskeletal issues.

A recent study32 found that a common factor for sedentary behaviour shared by contact centre agents, team leaders and senior staff was a considerable lack of knowledge and awareness of sedentary behaviour as a risk factor for poor health. In addition, there was a low level of knowledge among staff of guidelines and recommendations relating to sedentary behaviour and physical activity in the workplace, and therefore there is often no reflection of these guidelines and recommendations in organisational policies. 32,36

Contact centres and organisational drivers

Many organisations representing the contact centre industry are highly constrained by profit-based drivers, cost minimisation and economic outcomes based on productivity and high-quantity customer enquiry resolution. 37 Several contact centres adopt ‘mass production models’ to minimise cost and maximise output, resulting in mechanisation and standardisation of work methods, and reduced employee training and autonomy. 37 The work is such that employees do not engage with other team members and can be isolating, and employees may view themselves as replaceable. 37 These factors can also often influence organisational investment into workplace health initiatives; fears of cost-ineffective programmes and reduced productivity rates are commonly presented by senior team leaders within private contact centres. 32

Contact centre agents have voiced concerns over job security and performance monitoring, and a desire for increased autonomy over their working practices, as influential factors for their motivation to participate in strategies to reduce sedentary behaviour in the workplace. 32 However, organisational pressures to maintain high levels of productivity and meet targets frequently work against organisational investment into health and physical activity programmes within some contact centres. This is often due to perceptions that these activities will reduce the agents’ call-making time and lead to productivity losses. 38 One study reported that leaders and senior staff had ‘identified a conflict between promoting productivity and targets to call agents, while encouraging them to move more and sit less’. 32

Workplace intervention research to reduce sedentary behaviour

Over the last 5–10 years, there have been several systematic reviews of workplace interventions to increase physical activity and reduce sedentary behaviour. 24,39–41 Most recently, a systematic review of environmental interventions in workplaces (e.g. sit-to-stand desks)40 found evidence of significant reductions in sedentary behaviour in 14 out of 15 studies. This review found that multicomponent interventions that targeted more than one level of the socioecological framework, were most effective. In 2016, another systematic review41 assessed the effectiveness of white-collar workplace interventions to reduce sedentary time; it similarly found that multicomponent interventions had the greatest effect. Both reviews40,41 identified a need to assess whether policy-based measures or organisational change could further increase effectiveness. One study42 assessed the effect of sit–stand desks and ergonomic awareness on reducing sedentary behaviour in 15 Swedish contact centres and found that working at a sit–stand desk was associated with a slightly greater reduction in sitting time than sitting at a non-sit–stand desk. Regular interruptions to sitting time during the workday have previously been found to significantly reduce discomfort in the lower back and fatigue levels in overweight and obese office workers, without affecting productivity. 43 Another study44 found that the use of standing desks led to significant reductions in upper back and neck pain in office workers. A recent study45 exploring barriers to participation suggested that ‘barriers occurred at multiple levels of influence, and support the use of ecological or multilevel models to help guide future programme design/delivery’. 45

Multicomponent workplace interventions

Given the specified need to address cultural and organisational factors affecting workplace behaviour, we developed and piloted SUH (the intervention in this report). There are a limited number of other similar interventions and the evidence is still sparse, with only one UK-based study, which is ongoing. This UK-based study is funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) programme46 and is currently examining the effectiveness of the Stand More AT Work (SMArT Work) and life intervention aimed at reducing sitting time of office workers. Although this intervention is similar to our intervention in some respects, SUH specifically considers aspects of organisational change, targets contact centres and takes a systems-based approach. 47 This takes into account the complexity of the context, resources and assets of specific contact centres. The Stand Up Victoria study in Australia48,49 also had a multicomponent intervention. However, height-adjustable workstations were a main part of the intervention. Although we envisaged that some contact centres would take up this option, we recognised that not all contact centres have the resources, or desire, to implement them. A third study in Perth, Australia,50 used a similar participatory approach to SUH but had no theoretical basis and was assessed at only a 12-week time point.

Sedentary behaviour research in contact centres in the UK

Research on sedentary behaviour in contact centres is sparse and no reviews were identified on this topic. Two relevant primary studies are discussed here. 32,51 The first study32 is a qualitative study exploring factors that influence contact centre agents’ physical activity and sedentary behaviour in the workplace. The study conducted interviews with contact centre agents, team leaders and senior staff, and reported that agents said that several factors influenced their motivation to increase physical activity and reduce sitting time, including continuous performance monitoring, concerns over job security and a desire for increased autonomy in the workplace. As mentioned in Contact centres and organisational drivers, the study noted the conflict reported by team leaders and senior staff relating to productivity and promoting more movement and sitting less.

Another study51 used a mixed-methods approach to explore the acceptability and feasibility of a multicomponent intervention that targeted physical activity and prolonged sitting in contact centres. The study reported that contact centre agents perceived that the study assessments were acceptable and education sessions, height-adjustable workstations and e-mails were seen to be the most effective components. This intervention is also based on the socioecological model and is similar to the SUH programme. Although the intervention51 has several merits, SUH has a greater emphasis on organisational factors and takes an adaptive and flexible approach, taking into account the contexts and systems of each contact centre.

Relevant policy and practice

Policy regarding sedentary behaviour is insufficient considering the evidence of its associated risks. A recent study reviewed current national and international occupational safety and health policy documents (e.g. guidelines, legislation and codes of practice) for their relevance to occupational sedentary behaviour. 36 The review found that many workplaces and jurisdictions had legal frameworks that established a duty of care for occupational health, but discovered that no occupational health and safety authority had a policy specifically targeting occupational sedentary behaviour. Although some existing policies have aspects relevant to sedentary behaviour in the workplace, the authors identified a need to address the emergent hazard of excessive occupational sedentary behaviour by developing specific policies for this issue. They also highlight a need to support workplace-based initiatives that aim to minimise sedentary behaviour and the associated risks.

A number of awards exist across the UK that are designed to recognise and encourage efforts made by organisations to improve health and well-being in the workplace. These include the North East Better Health at Work Award52 in England and the Healthy Working Lives award53 in Scotland. Although these awards have several categories for health promotion that can mitigate some of the negative outcomes of excessive sitting time, reducing sedentary behaviour as a specific outcome is not acknowledged.

Importance of this research

Current UK workplace legislation means that many members of staff in contact centres receive remedial ergonomic support as a mitigation measure to reduce existing musculoskeletal issues only after a chronic or musculoskeletal condition has been diagnosed. 54 However, current practices, compounded by workplace culture, inhibit initiatives that encourage contact centre staff to reduce sitting time. 55 Taking into account the lack of policies from authoritative bodies that are specific to sedentary behaviour, mean that it is important for workplaces to proactively develop their own organisational policies that include, and promote, opportunities for reducing occupational sitting time. 36 Given that contact centres are among the most sedentary workplaces,30 and that employees report higher levels of stress and depression than other desk-based work,56 it is key that preventative approaches are implemented in contact centres.

This work is currently needed to ensure that healthier working policies are distributed equitably across all workplaces, not just those that have more worker autonomy and better working conditions. Creating healthier contact centre environments may be more difficult than in other workplace settings, which is why such an intervention is necessary. In addition, building the capacity to develop and measure workplace-based interventions for health in contact centres is vital for developing a stronger business case to encourage and enhance organisational uptake and buy-in.

Overall research aims and objectives

Aim 1: to test the acceptability and feasibility of implementing the SUH intervention in contact centres.

The research questions for aim 1 were:

-

What is the acceptability, feasibility and utilisation of the various components of the intervention in a range of contact centres?

-

Does the programme theory and process of implementing the intervention work as intended?

-

Does the programme theory/intervention need to be adapted and if so, in what ways?

-

Are there differences in delivery of the intervention between different contact centres? If so, what are the reasons for these?

Aim 2: to assess the feasibility of using a cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) study design.

The research questions for aim 2 were:

-

Is the study design (cluster RCT) feasible for a confirmatory trial of an intervention to reduce sedentary behaviour in staff working in contact centres?

-

How many clusters and participants per cluster are required for a confirmatory trial?

-

What is the recruitment rate of participants in each cluster and how many are lost to follow-up (e.g. owing to staff turnover)?

-

Are the range of study procedures (e.g. recruitment strategies and outcome measurement tools) feasible for a future confirmatory trial?

-

Are there differences in aspects of study procedures (e.g. uptake) between different contact centres? If so, what are the reasons for these?

-

What are the preliminary estimates of the variability of primary (reduction of sedentary behaviour in the workplace) and secondary outcomes within and between contact centres?

Aim 3: to scope the feasibility of a future health economic evaluation of SUH.

The research question for aim 3 was:

-

Is it feasible to provide estimates of the cost-efficiency of SUH from (1) an NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective and (2) an employer’s perspective?

Development of the Stand Up for Health programme theory

This study used a theory-based approach to evaluation. Programme theory is ‘an explicit theory or model of how an intervention, such as a project, a program, a strategy, an initiative, or a policy, contributes to a chain of intermediate results and finally to the intended or observed outcomes’. 57 Proponents of this approach argue that evaluation should not be driven by methods (as all have their strengths and weaknesses) but instead, that theories should be made explicit and the evaluation steps (and design) be built around them by elaborating on assumptions, revealing causal chains and engaging all concerned stakeholders. To develop the programme theory, we also had to consider the systems in which the SUH intervention was being implemented. The 6SQuID framework was used to develop the SUH intervention with members of staff at a contact centre using co-production methods supplemented by other data. The programme theory was developed through a comprehensive literature review and qualitative work in a pilot contact centre using the six steps in quality intervention development (6SQuID) framework. 58 The adoption of an intervention development framework is critical to understand and address the causal factors and to ensure that the programme is tailored to the needs of the centres. 6SQuID is an innovative and collaborative framework, which allows for the development of interventions that are acceptable and sustainable to the target population. It has, to date, been used to develop a range of interventions, including a family-based intervention to facilitate HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) testing,59 a kinship care intervention60 and an alcohol brief intervention in symptomatic breast clinics. 61 The framework consists of six steps:

-

step 1 – defining the problem

-

step 2 – identifying modifiable and non-modifiable causal factors

-

step 3 – defining the theory of change

-

step 4 – defining the theory of action

-

step 5 – testing and refining the intervention

-

step 6 – collecting evidence of effectiveness to justify evaluation and implementation.

In addition to these six steps, the 6SQuID process incorporates three key points to consider when following the framework. The first is to maintain stakeholder involvement throughout the entire process to encourage ownership of the problem and the solution. This is recognised as being crucial to developing acceptable and sustainable interventions. 58 The second key point is to acknowledge the system within which the intervention is being developed. All interventions take place within a system that operates in a certain way, which can impact on the success of the intervention. 58 In this study, the overarching system is the workplace, which has complex layers of written and unwritten rules and policies, fixed resources and often rigid cultures. Contact centres have particularly rigid policies, and failure to develop an intervention to take account of the systems will probably result in inadequate implementation, leading to failure of the intervention. The third key point is the consideration of the evaluation phase from the outset of development. The means by which an intervention will be evaluated should be considered during early phases of intervention development to ensure that the process and intended outcomes are measured accurately and robustly.

As an adaptive intervention, the fidelity of the SUH intervention is to the theories of change rather than being prescriptive about activities that catalyse change. 62 To ensure transferability, it takes into account the specific system (the contact centre, how it organises its work and how SUH will fit into the organisational and cultural systems) and context (e.g. layout of the centre, work-time flexibility, budget and resources available). In addition, it includes all employees from the start of development, with the aim of creating a social norm of standing more at work. By gaining insight from contact centre staff about their specific needs, this approach is more likely to lead to a sustainable and effective intervention. 58

6SQuID step 1: defining and understanding the problem and its causes

The first step of developing an intervention is to understand the problems and their causes. Step 1 creates the foundation for a successful intervention and involves fully understanding the problem that an intervention is trying to address and developing an understanding of the contributing factors to the problem. From the literature review and the stakeholder consultations (with the pilot centre, Ipsos MORI) we collectively defined the problem as the high level of sedentary behaviour (sitting time) during working hours in contact centres.

Through the literature review and focus groups with 34 participants, four themes emerged and were grouped into four levels by the researchers: individual, social/community, structural environment and organisational (Table 1). 62

| Level | Factors contributing to sedentary behaviour |

|---|---|

| Individual |

|

| Social |

|

| Environmental |

|

| Organisational |

|

6SQuID step 2: identifying which factors can be modified

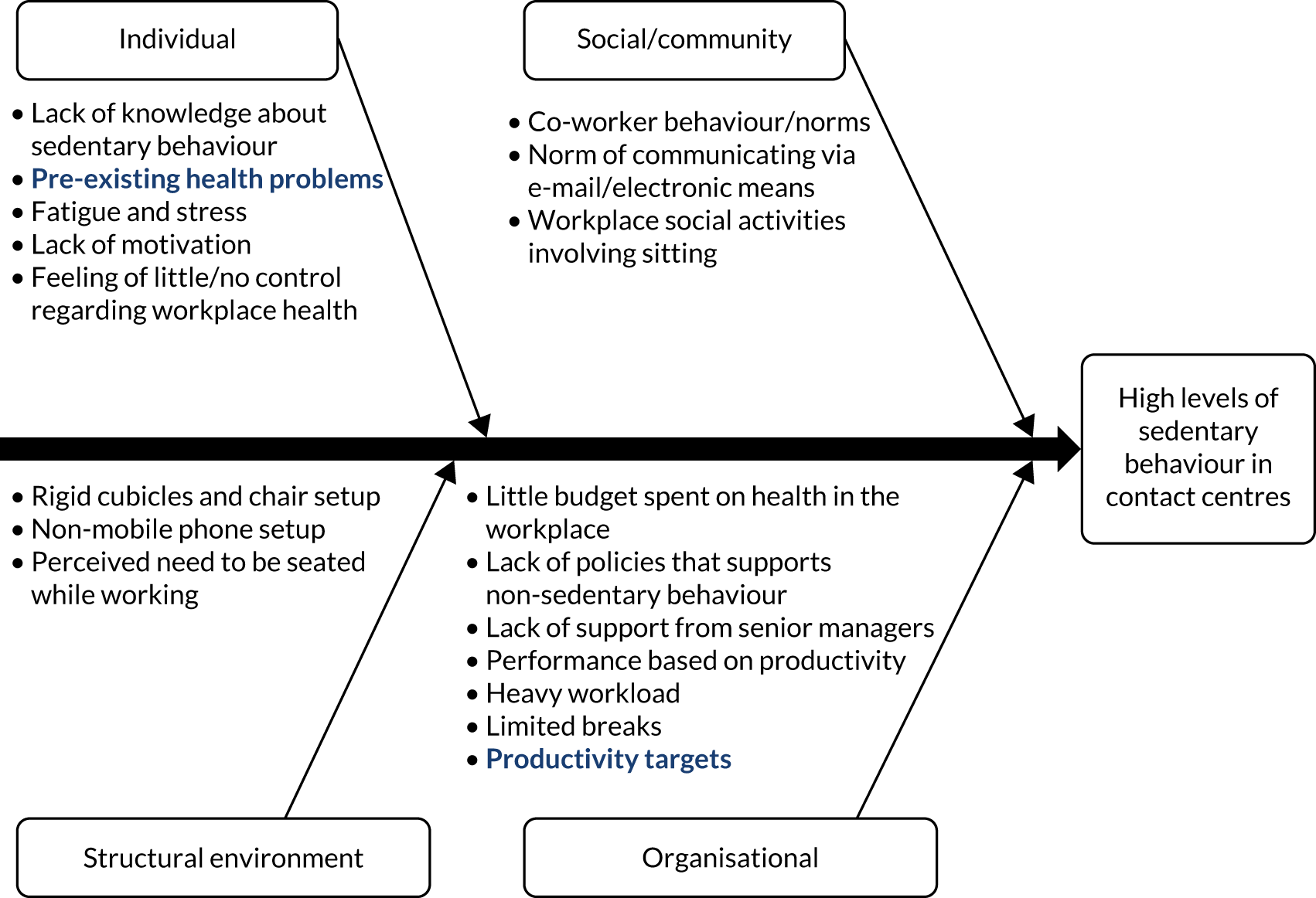

Modifiable factors with the greatest scope for change were considered to identify which specific factors should be targeted through intervention activities. These are described in the fishbone diagram (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Fishbone diagram identifying the modifiable and non-modifiable factors. Black text, potentially modifiable factors; navy text, non-modifiable/hard-to-modify factors.

6SQuID step 3: deciding on the mechanisms of change (theory of change)

The intervention was based on two main theories: social cognitive theory63 and the social ecological model. 64 The intervention also aimed to create a sense of ownership to increase the likelihood of longer-term sustainability. 58 Although social cognitive theory addresses many personal determinants and socioenvironmental factors, the social ecological model takes the proposed multifaceted approach one step further to consider the intervention at not only the individual and interpersonal levels, but also the organisational, environmental and group levels, and takes into account the interactions between each of these. 65 By targeting multiple levels of the workplace, SUH aimed to foster an atmosphere that creates a social norm within the office community of sitting and standing within the workplace. The social ecological model justifies and predicts that SUH’s multifaceted approach will be effective, acceptable, feasible and sustainable. We also took a systems-based approach, by recognising that the implementation and sustainability of the intervention is dependent on how adaptive the contact centre system is to change.

Developing a theory of change involved developing intervention activities to target each modifiable factor leading to sedentary behaviour. This step details how each modifiable factor identified in step 2 could be addressed at each level of the contact centre by designing specific activities informed by the focus groups, literature review and workshop data. The literature review identified a number of systematic reviews of workplace interventions to increase physical activity and reduce sedentary behaviour. 17,24,39,40 Most recently, a systematic review of environmental interventions in workplaces (e.g. sit-to-stand desks)40 found evidence of significant reductions in sedentary behaviour in 14 out of 15 studies. This review found that multicomponent interventions that targeted more than one level of the socioecological framework were most effective. In 2016, another systematic review assessed the effectiveness of white-collar workplace interventions to reduce sedentary time. 41 It also found that multicomponent interventions had the greatest effect. Both reviews identified a need to assess whether policy-based measures or organisational changes could further increase effectiveness. SUH is designed to have organisational change as a key component of the intervention. A recent UK study funded by the NIHR PHR programme found that the SMArT Work intervention was effective in reducing sitting time of office workers within an NHS workforce using height-adjustable workstations, self-monitoring tools and behaviour change techniques. 46,66

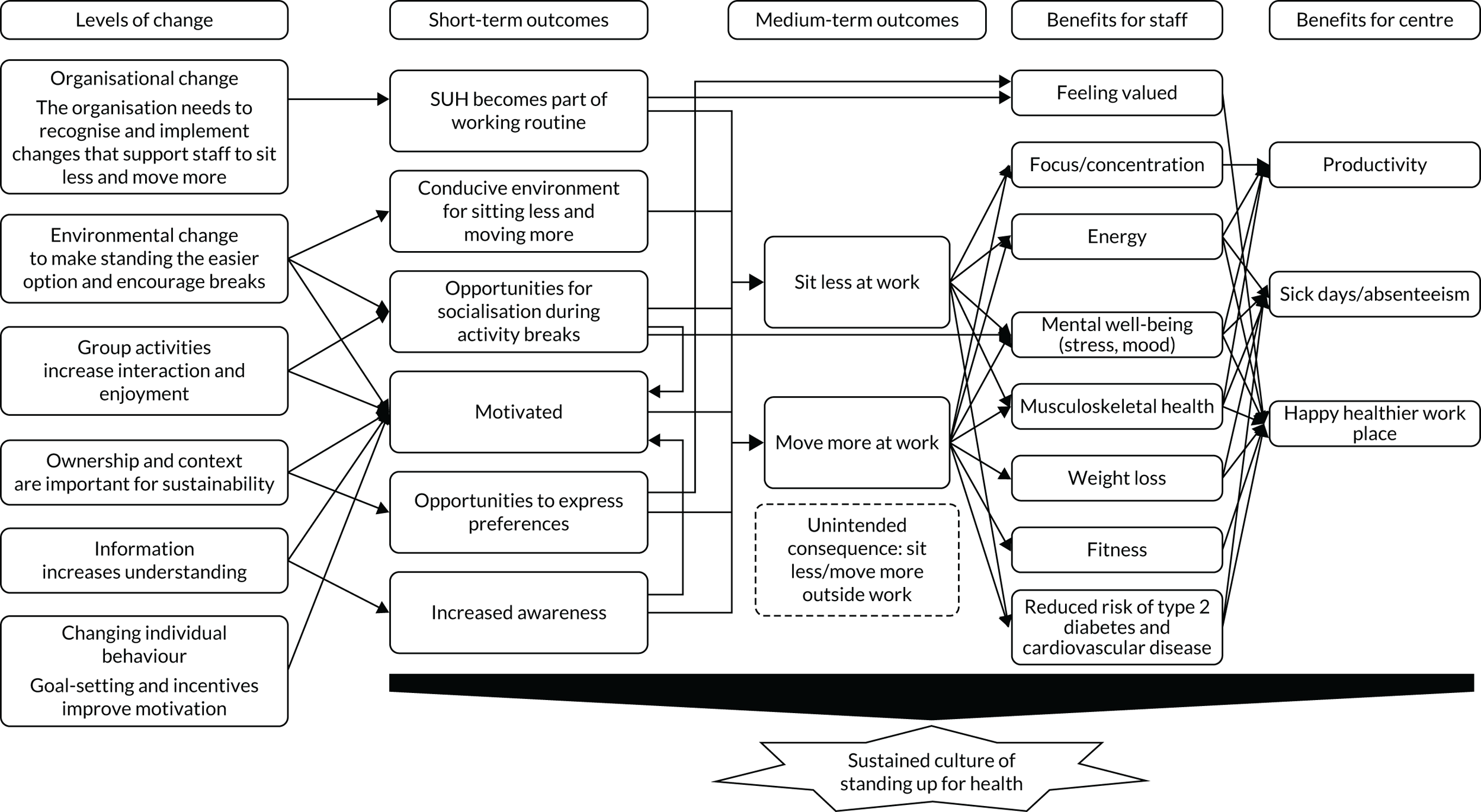

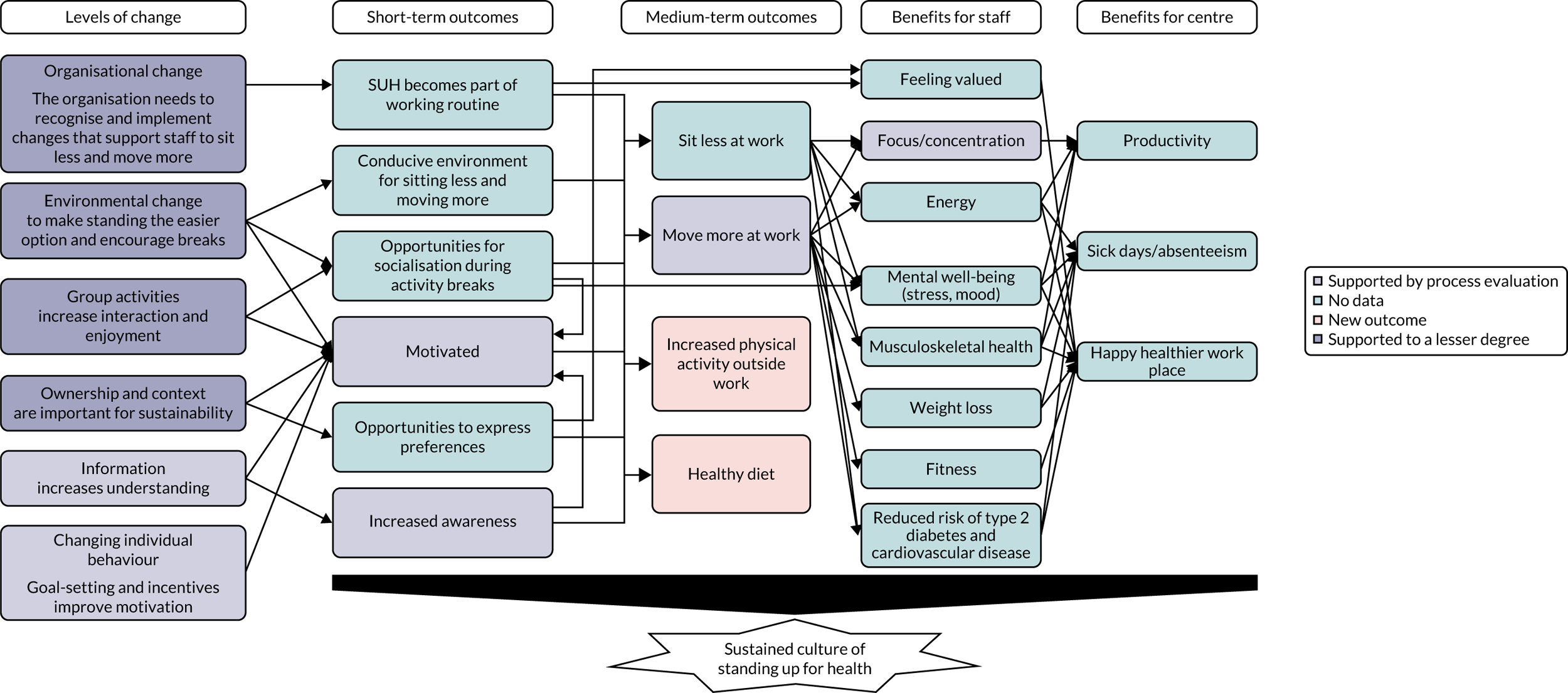

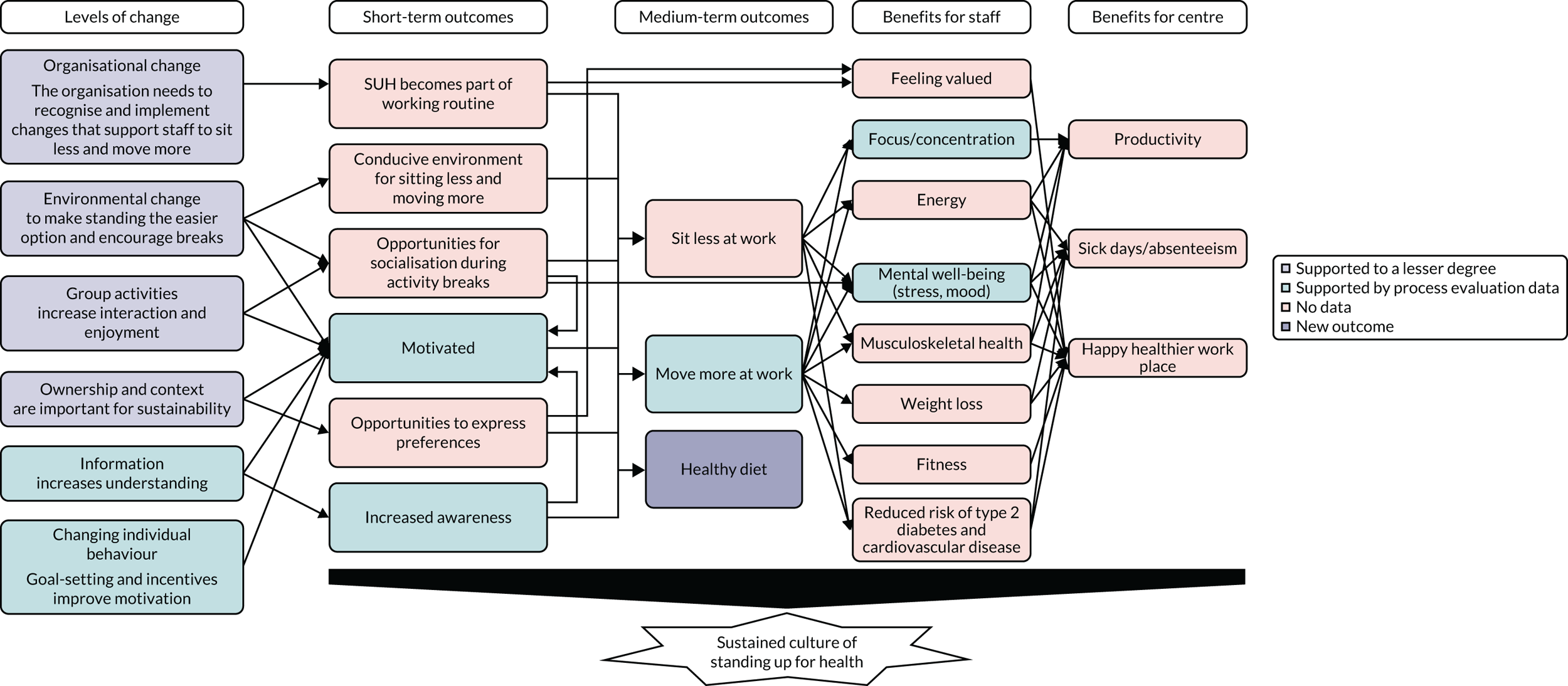

We found no reviews of interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour specifically in contact centres. The use of sit–stand desks and ergonomic awareness, as well as multicomponent workplace interventions, are effective in increasing physical activity and decreasing sedentary behaviour in contact centres. 42,51 The programme theory that we developed is outlined in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

The SUH programme: theory of change.

6SQuID step 4: clarifying how the mechanisms of change will be delivered (theory of action)

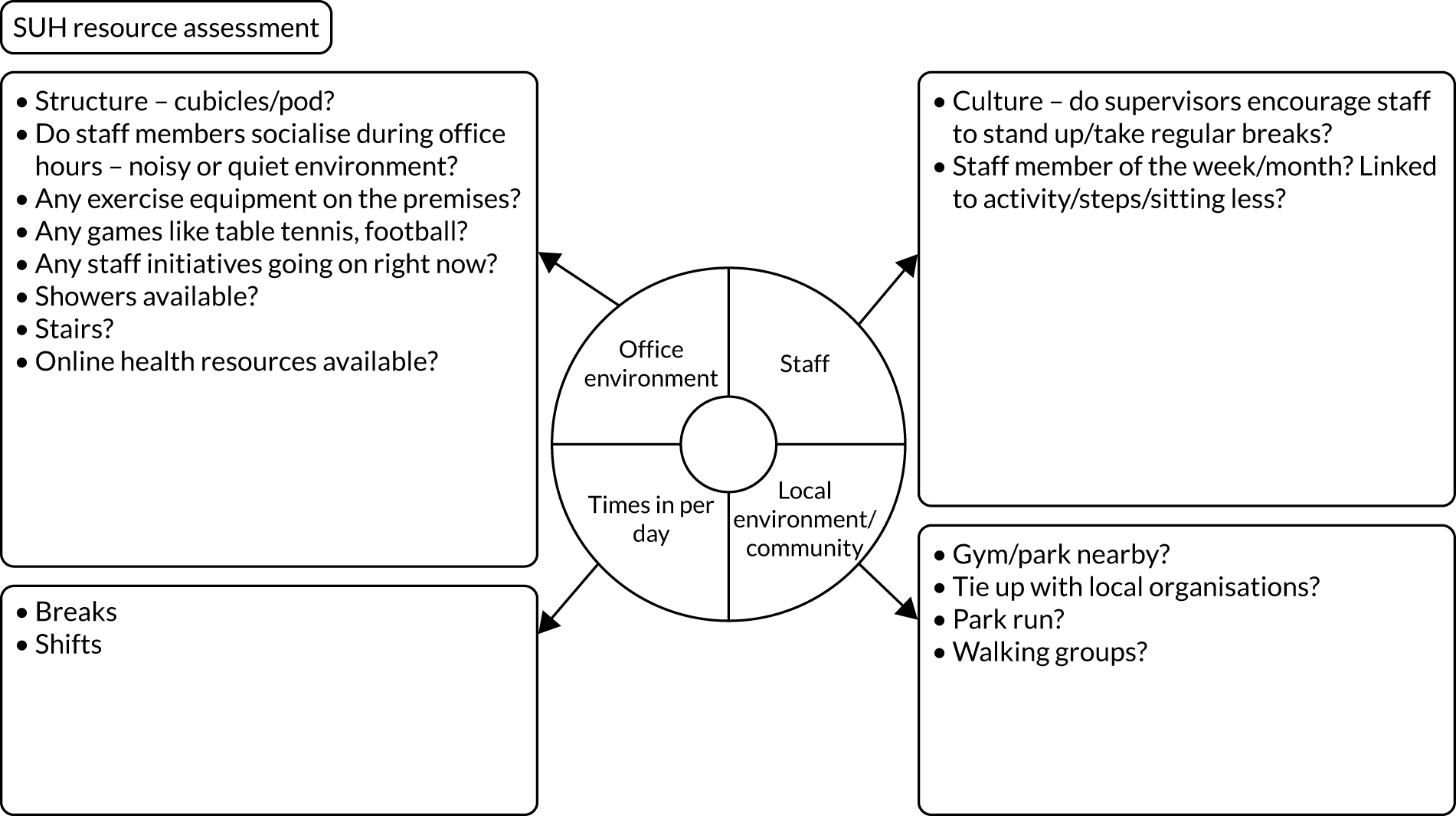

After defining the theories of change, the researchers identified the necessary resources available for implementation of the activities (Figure 3) and illustrated the programme theory in a logic model to demonstrate how intervention activities would lead to intended outcomes (Figure 4). Inputs and resources were identified through focus groups and informal discussions with management. During this phase, a workshop was held at the test contact centre to introduce staff to examples of intervention activities and equipment for the workplace. The workshop activities were developed based on feedback from staff in the focus groups. Staff were asked to contribute their own ideas and prioritise the ideas for intervention activities/workplace equipment that they wanted to try out. The research team fed back the results to the SUH implementation group; the SUH implementation group then decided on the final intervention activities to be implemented. There was at least one activity from each theory of change and the activity took account of the resources, assets (e.g. local spaces, existing equipment and spare spaces) and budget available. Once the specific intervention activities were chosen, the team worked with the contact centres to decide on an action plan for delivery and implementation of the activities (who, what, when and where).

FIGURE 3.

The SUH programme: resource assessment.

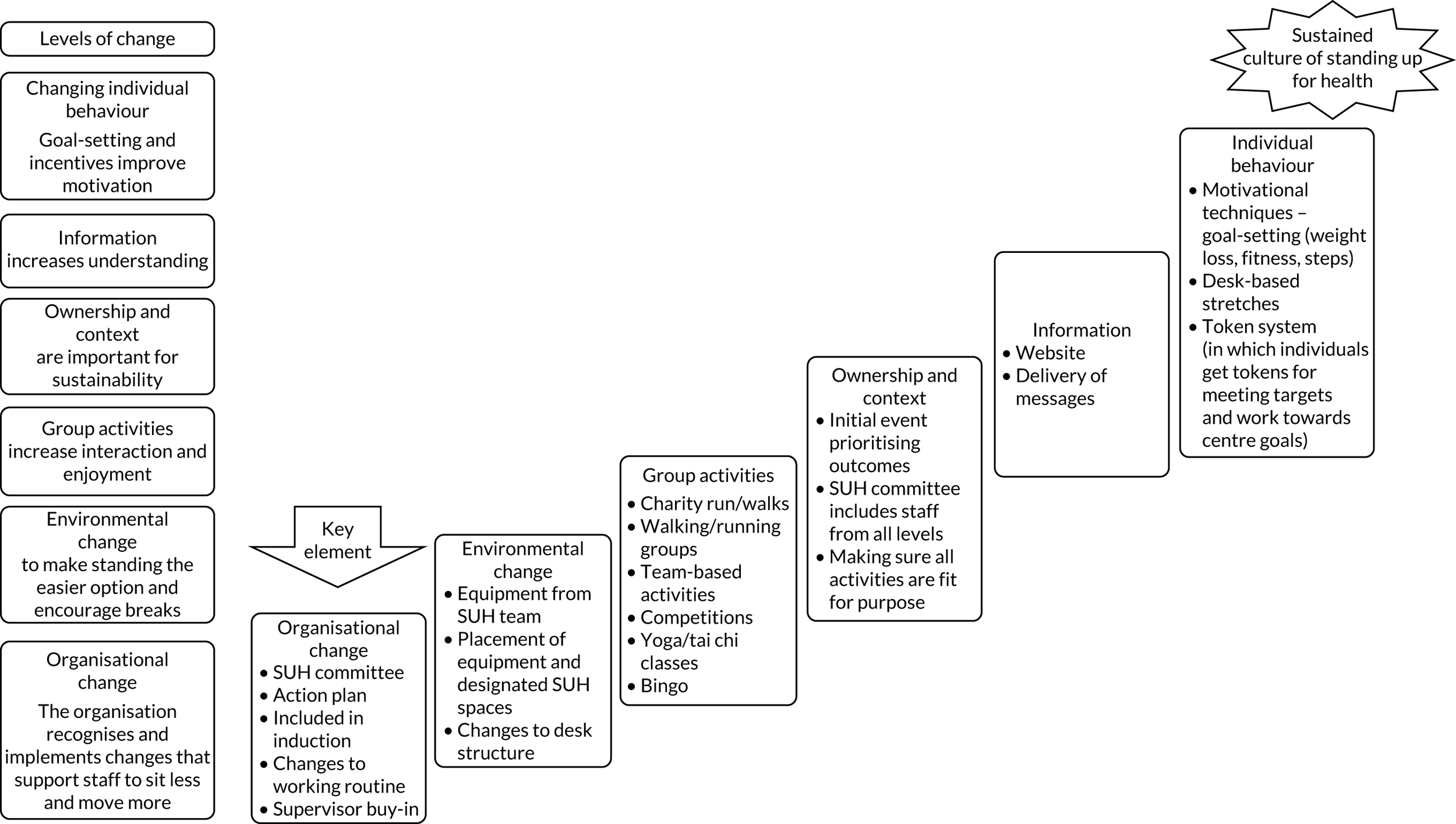

FIGURE 4.

The SUH programme: theory of action.

6SQuID step 5: testing and adapting the intervention

Contact centre staff in the pilot centre were assisted and guided by the researchers during two wellness committee meetings to establish and set goals for the programme. Continuous feedback was gathered from staff throughout the duration of the intervention so that the delivery of activities could be adapted as necessary. The intervention that was initially developed in Ipsos MORI continues to be implemented (although with a reduced emphasis owing to COVID-19) nearly 3 years after it started. The contact centre has reported that 25% of staff now use standing desks (an increase from almost none). There are a number of different activities going on at any one time and the call centre staff are constantly thinking of new activities to implement. The contact centre also asked to ‘bolt on’ a mental health component: the research team worked with them to implement mindful activities that either were standing up interventions (e.g. jigsaw puzzles on a stand-up desk) or encouraged them to leave their desk and be mindful [e.g. Lego® (Billund, Denmark) and knitting].

The final step of 6SQuID is to collect sufficient evidence of effectiveness to justify rigorous evaluation and implementation. This is the evaluation that is described in this report. However, as mentioned previously in Development of the Stand Up for Health programme theory, although the theory of change remains constant, an adaptive intervention needs to respond to contextual issues. Therefore, each centre was aided in developing a section of activities to meet its needs. Table 2 outlines which of the steps were undertaken prior to, and as part of, this study.

| Step | Pre-evaluation developmental steps | Steps undertaken in this study |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: defining the problem | Yes | No |

| Step 2: identifying modifiable and non-modifiable causal factors | Yes | No |

| Step 3: defining the theory of change | Yes | No |

| Step 4: defining the theory of action | Yes, for the Ipsos MORI site | Yes, each centre developed its own theory of action |

| Step 5: testing and refining the intervention | Yes, for the Ipsos MORI site | Yes, some centres needed to test and refine some activities |

| Step 6: collecting evidence of effectiveness to justify evaluation and implementation | No | Yes |

Developing theories of action for the contact centres in this study

6SQUiD steps 4 and 5 formed the basis of the tailored intervention for each contact centre. The hypothesised theories of change (step 3) remain constant, but the theories of action are specific to each contact centre. The first step of the intervention included a ‘workshop’ that took place at a contact centre in which staff could test, suggest and vote for various activities that they wanted to try. The staff also described the environment, location, existing equipment and other assets that were then used to plan the activities. The SUH research team provided some small pieces of equipment for centres to try out before any investment was made. Although the number of activities was not limited, we worked with the contact centres to implement at least one activity from each theory of change (see Figure 2). These activities were used to create an action plan to be implemented over several weeks. A SUH committee, made up of all levels of contact centre staff, was created to support activity implementation. At the end of the intervention period, the researchers ran a second workshop to understand which activities had worked (step 4 of 6SQuID). Further prioritisation and choosing of future activities was then undertaken. All equipment and activities were risk assessed and details of how to use the equipment/undertake the activities were provided. A website was developed with useful resources, and opportunities for the contact centres to blog/share their experiences and create a community of SUH contact centres.

Developing the programme activities: pre lockdown

To enable the activities to fit within the systemic, cultural and environmental constraints of individual contact centres, we used the following methods to develop and implement activities for the SUH programmes during the pre-lockdown period.

Workshops to co-produce the list of activities to be delivered

The SUH team conducted two workshops as part of the programme. In the initial workshop, staff tried out various equipment and activities. The staff also participated in the prioritisation exercise, in which they used stickers to express their preferences for individual, social and environmental activities. The SUH team also lent several pieces of equipment (e.g. exercise bike, stepper, twisting disks, mini table tennis and mini golf) to the centres, keeping in mind environmental factors and staff preferences. In addition, an office wellness company (Sit–Stand.Com®; Coalville, UK) provided desk risers to centres at no cost. The SUH team had a discussion with centre stakeholders regarding the best style of desk riser for their contact centre, and the following were then shipped to the centres by Sit–Stand.Com:

-

centre 2 – Yo-Yo Desk Slim 80 cm (× 2) and Yo-Yo Desk Mini (× 1)

-

centre 3 – Yo-Yo Desk 90 cm (× 2) and Yo-Yo Desk 120 cm (× 2)

-

centre 7 – Yo-Yo Desk Slim 80 cm (× 3)

-

centre 9 – Yo-Yo Desk Slim 80 cm (× 2) and Yo-Yo Desk Mini (× 1)

-

centre 10 – Yo-Yo Desk Slim 80 cm (× 2) and Yo-Yo Mat Medium (× 2)

-

centre 11 – Yo-Yo Desk Slim 80 cm (× 2).

The SUH team worked with contact centre managers to understand context (e.g. centre layout, work-time flexibility and shift patterns) and resource availability (budget, space, online material, equipment and staff members with physical activity or other expertise). They used a resource assessment template to map out the assets and resources for the centre.

The team came back to the centre for workshop 2 after 3 months, at which they spoke to the staff about activities that had been implemented, likes and dislikes, and suggestions to ensure staff involvement and ownership.

Stand Up for Health committee

It was recommended that a SUH committee, consisting of staff members from teams across the participating centre, be set up. The committee was an important element of the programme and was responsible for procuring and generating ideas for activities from staff and aiding implementation of the intervention.

Action plan

After the initial workshop, the SUH team worked with the centre stakeholder to develop an action plan specific to the centre (for an example action plan, see Report Supplementary Material 1). The SUH team encouraged the adoption of at least one activity from each level of the theory of change (Table 3). A ‘SMART’ (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound) approach was adopted to enhance success of implementation. The second workshop helped to refine the action plan.

| Theory of change | Example of activitiesa |

|---|---|

| Organisational | SUH implementation group (made up of all levels of staff; this is the only obligatory activity); management-led action plans; inclusion of non-sedentary behaviour as part of organisational strategies and goals; inclusion of non-sedentary behaviour activities for staff into roles and responsibilities (e.g. for supervisors); inclusion of ‘standing’ time into the working day |

| Environmental | Equipment: standing desks or a standing desk team area, bicycle desks, other equipment in communal places. Repurposing or changing the environment: standing communal areas with mindful/enjoyable activities, such as jigsaws or knitting, or a darts board; moving printers further away; exercise spaces; boards on walls to draw on |

| Social/cultural | Group activities in work time, such as 5 minutes of stretching per hour; group goal-setting; exercise classes before or after shifts; competitions between workspaces or teams; workplace challenges; rewards for standing more/being more physically active; educational prompts |

| Individual behaviour | Individual goal-setting, active travel to and from work, lunchtime walks; apps; links to local groups and activities |

Duration of the intervention

The duration of the intervention was defined as the period that the centres took to develop their preferred activities for each theory of change, prepare an action plan for sustained engagement and test out some of the activities. This process took around 3 months but was dependent on the contact centres and COVID-19.

Scalability and translation

This intervention is designed to be scalable and transferable into other contact centre settings in the UK and internationally. It is also transferable to other workplace settings. The reason why we have not specified activities (or fidelity to particular activities) is to allow for flexibility, scalability and transferability to different contexts. We recognise that some contact centres will have more resources and assets than others, which is why we have suggested a range of activities that can all activate the theory of change. Given that the theories of change are the most adaptive aspects of the intervention, the intervention is adaptive to all contact centres, and it is designed so that contact centres can implement it at little or no cost.

Protocol amendments in the context of COVID-19

Study aims and research questions

All of the original aims remained the same (see Overall research aims and objectives), but we added an additional aim: aim 4 – consider previous aims under the context of COVID-19.

All of the research questions also remained the same, but we included some additional ones to take account of the impact of COVID-19.

The research questions for aim 1 were:

-

Can SUH be adapted for those working remotely?

-

What is the acceptability and feasibility of this mode of delivery?

The research questions for aim 2 were:

-

Is it feasible to adopt an online format and does this affect the use of a stepped-wedge study design?

-

Does the mode of delivery impact on the feasibility of the study design (online vs. face-to-face delivery)?

Impact of COVID-19: changes to data collection

All scheduled workshops and data collection until January 2020 were completed as planned. The research team did not make any in-person visits after this time. The SUH team had planned 13 additional visits from March 2020 to June 2020, all of which were cancelled. The team shifted to remote collection of data, including interviews, focus groups and questionnaires.

It is important to note that the normal routine in centres was disrupted and, hence, any follow-up data collected may have been biased. Outcomes such as mental health, work engagement and sitting behaviour are likely to have been influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic and may not accurately capture intervention effects. Given this, we still administered the questionnaire when it was easy to do so and endeavoured not to increase burden for centres.

Posting activPAL™ devices (PAL Technologies Ltd, Glasgow, UK) to the centres was considered as an option. However, this was not feasible because researchers needed to be present to explain attachment and filling of logbooks. There would also be high risk of loss of the devices.

Impact of COVID-19: changes to intervention activities and delivery

From workshops to personalised activity plans

We were not able to go to the centres during lockdown to conduct the workshops. Instead, we conducted one-on-one virtual consults with up to 30 staff per centre to capture the varied working arrangements and unique barriers. We spent approximately 20 minutes with each staff member and asked specific questions about barriers to and facilitators of sedentary behaviour and physical activity at the various levels (environmental, social and individual). We reviewed the information and got back to them individually with tailored recommendations for their specific situation. We developed a personalised activity plan with recommendations and resources for each staff member. We then pulled all of the recommendations and resources generated from the consults and created a document(s), which was shared with all staff members at the centre.

Social activities

The SUH team organised a step count challenge to encourage staff to sit less, move more and generate social interaction. The challenge was conducted over 6 weeks, and staff made a virtual trip from Land’s End to John O’Groats. Staff formed teams of five and submitted the weekly steps for their team on the SUH website.

Equipment

The SUH team sent some pieces of equipment (e.g. balance board, balance ball chair, mini table tennis and twisting discs) to centre 7 for the benefit of staff who were working onsite.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

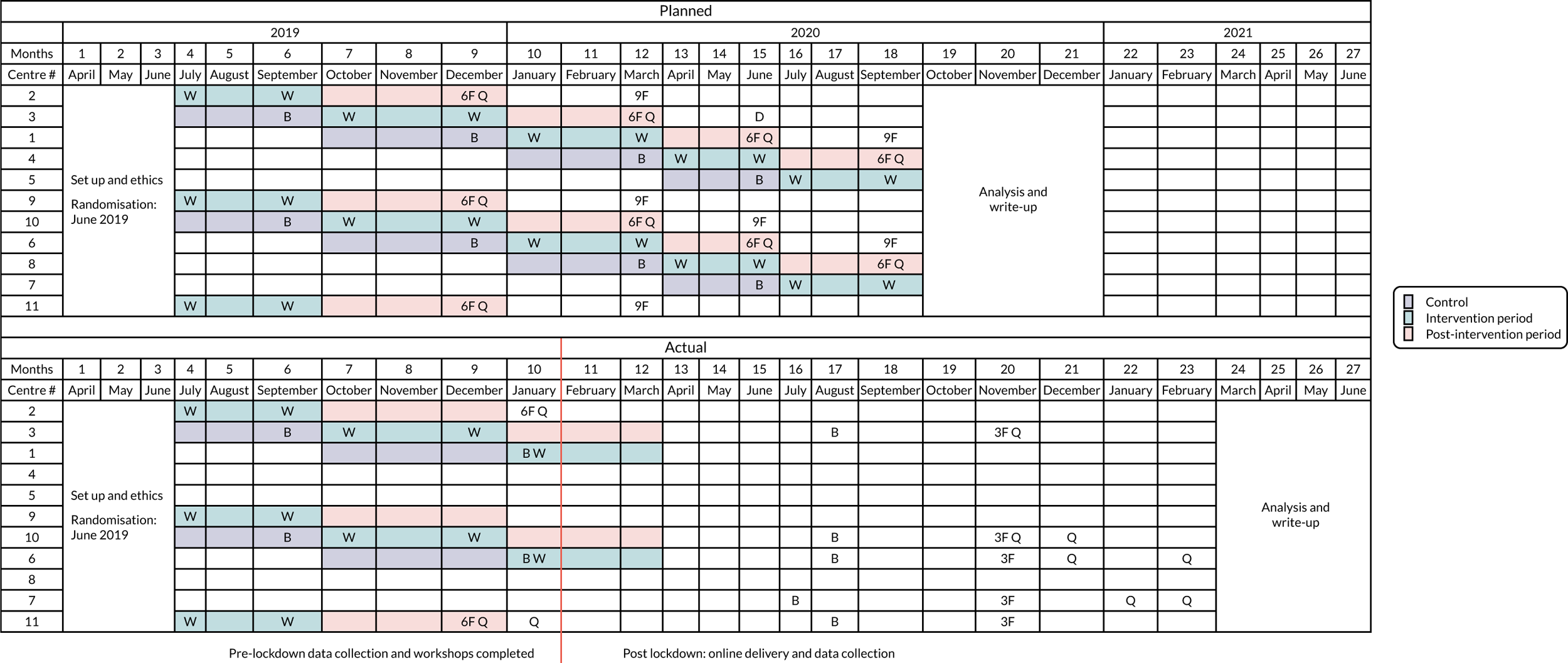

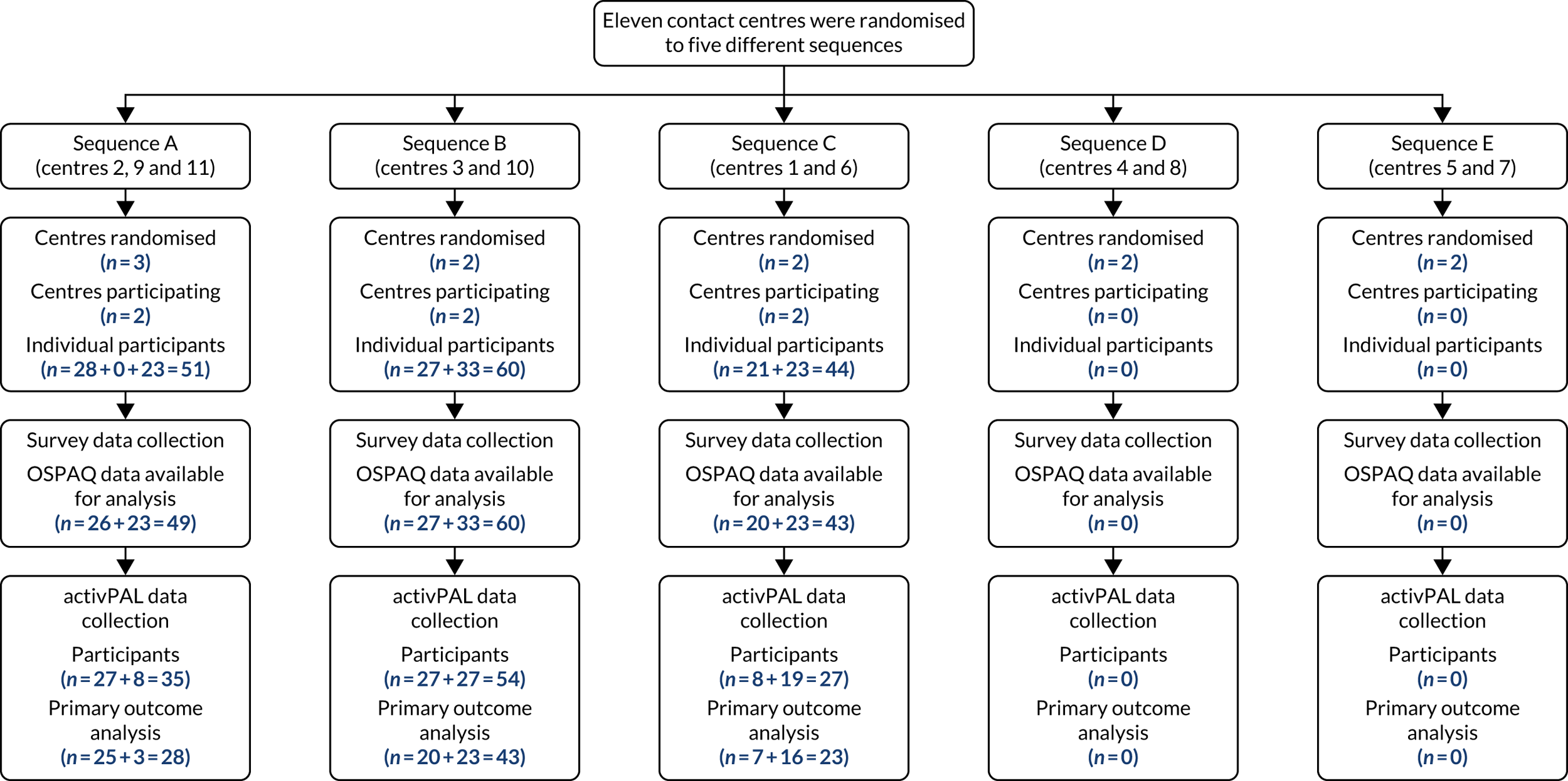

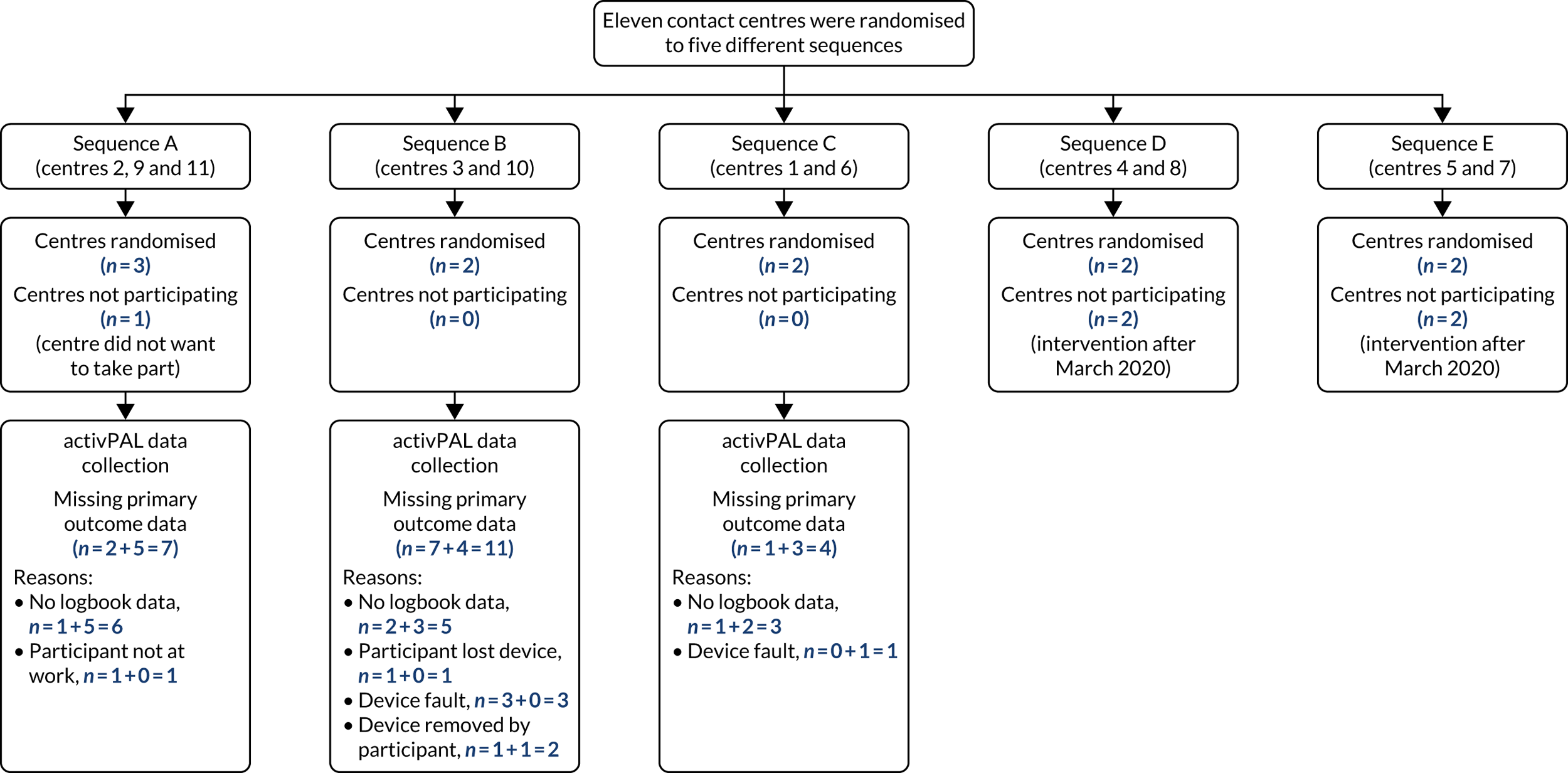

This was a feasibility study with a cluster RCT design (to address aim 2), combined with a process evaluation (to address aim 1) and an economic component (to address aim 3). Given that the intervention was implemented in a workplace, it was not possible to randomise at the individual level; therefore, a cluster RCT was the only option. We explored the relative advantages and disadvantages of the stepped-wedge and the cluster parallel-group designs as the two most appropriate options. After much discussion, we decided on a staircase stepped-wedge trial design (Figure 5). Full details of the methods and rationale for the design are provided in the paper published by our team. 67

FIGURE 5.

The SUH programme cluster trial design: planned and actual. B, baseline data collection; 3F, 3-month follow-up; 6F, 6-month follow-up; Q, qualitative data collection; W, workshop.

Our study design is unusual because it is not a standard stepped-wedge design (it has lots of incomplete sections), but it is also not a standard waiting list control design because there are many cross-sectional comparisons, which may not always be present in a waiting list control design. Similar designs are increasingly being used in evaluation research and involve random and sequential crossover of clusters from control to intervention until all clusters are exposed. 68 It can be considered as an extension of the parallel-cluster trial with a baseline period. Such a design makes it possible to achieve a phased introduction of the intervention. It combines pragmatism with a robust design, and the way that the study is conducted has much in common with the parallel-cluster trial. Such designs are likely to be appropriate (1) when evaluating an intervention that will be implemented irrespective of evidence for effectiveness and (2) when it will be logistically implausible to roll out the intervention simultaneously to all clusters. 69 This is an important consideration, given the significant cost of loaning equipment to a large number of individuals; we also would not be able to collect activPAL data on half of the anticipated sample at one time point. This design allows us to have a smaller number of individuals at each baseline assessment point, in turn meaning that a smaller number of activPAL devices, equipment and other resources would be required.

Although there continues to be debate over the design and its limitations (e.g. Kotz et al. 70), some of which are valid, evaluations of public health interventions often have to be pragmatic and consider the stakeholders and context of the intervention involved (in this instance, the contact centres). We argue that we need a pragmatic option for a number of reasons. First, it could potentially cause delays in the evaluation process if we waited until all contact centres were at the same stage of readiness for implementation. A structural/location/organisation change in one contact centre could delay the process. Second, it would be more costly and resource intensive to implement the intervention and collect baseline data in all the contact centres at a single time point. We have hired two researchers, but the spread of locations in Scotland and the North East of England would make implementation and data collection difficult and increase the potential for failure. Last, we have observed that contact centres want to implement the intervention when they hear about it and it is unlikely to cause any harm. It has been implemented in one contact centre for over 1 year and only positive benefits have been reported. Journals, such as Trials71 and Lancet Global Health,72 are publishing the results of such designs.

Setting

The trial took place in contact (or call) centres run by the public sector (e.g. the NHS), private sector (e.g. banks or businesses) or third sector organisations (charities and not-for-profit organisations).

Study population

Given that this was a cluster RCT, contact centres rather than the staff employed in the contact centres (e.g. managers, supervisors and call handlers) were recruited. All staff in those contact centres had the opportunity to participate in the intervention. For the evaluation components, staff had the option of taking part on an opt-in basis.

Recruitment

Our original aim was to recruit 10 contact centres with more than 100 employees in Scotland and/or the North East of England. The target was to recruit 10 contact centres by month 3 of the project. A total of 11 contact centres were recruited by this time, two of which had under 100 employees (72 and 33 employees, respectively). We decided to include these two smaller centres in the place of one larger centre because both were very enthusiastic and we wanted to start randomisation as soon as possible.

All staff who had been working in the contact centres were invited (via e-mail through their contact centre, posters within the centre and in-person visits to the centre by the SUH research team) to be involved in the evaluation of the intervention. Staff who were interested in participating were sent an information sheet and consent form. It was made clear that participation or non-participation would not affect terms of their employment.

Retention

The average annual turnover (attrition) of contact centre staff is around 24%, compared with 15% in other industries. This high rate of attrition has implications for the retention and follow-up of participants. The high turnover is partly because of contact centres employing a large number of students and people looking for short-term work. Although this is a problem for the evaluation, it may be conducive to the overall success of the intervention, which has the potential to impact on a range of people, enabling them to engage with health-promoting activities that may encourage the development of lifelong habits. One of the aims of this study was to determine the retention rates for a future study. We intended to use a number of strategies to increase retention into the evaluation (as opposed to the intervention):

-

Staff were incentivised (with a £5–10 gift voucher) to complete baseline and outcome data assessments.

-

If staff left the contact centre, we would explore what methods were possible for follow-up (e.g. post, e-mail and telephone) and evaluate the most effective method.

-

We were to record data on the length of time employed in the contact centres. These data would help us determine whether or not turnover is higher at the beginning of the employment period (which could impact on retention rates).

Randomisation

Randomisation occurred in month 3 of the study. The unit of randomisation was contact centres. A computer-generated block randomisation algorithm was used to randomly allocate each contact centre to start the intervention at one of five time points, 3 months apart. Randomisation of contact centres to sequences was conducted in May 2019, using stratification by centre size (≤ 500 vs. > 500 employees). Stratification by centre size ensured that the combined centre size was approximately balanced across time points. Randomisation in this way allowed us to introduce the intervention to each site in an unbiased way, unrelated to time or the particular circumstances of each site. It also aimed to ensure that there was approximate balance, on average, across all of the intervention start times in terms of participant or contact centre characteristics. Allocation concealment and centres were not informed of exactly when they were to start the intervention until close to the intervention visit, was used as far as possible.

A complete list of the contact centres that agreed to take part in the study was compiled by Divya Sivaramakrishnan and Jillian Manner. The contact centres were numbered 1 to 11, in fixed order, and this list was signed and dated by Divya Sivaramakrishnan and Jillian Manner. Randomisation was then conducted in May 2019 by Richard Parker, who was fully blinded to the names of the contact centres and who generated a list of centre numbers showing the sequences that each centre should be allocated to (see Figure 5).

Control/comparator group

All sites received no intervention for between 3 and 12 months after the start of the study, as a waiting list control. Sites then received the intervention in accordance with the schedule set out in Figure 5.

Steps to minimise bias

Allocation

Allocation to trial groups was carried out by the statistician after recruitment, who was blind to the contact centre identity.

Contamination

Although it is possible that staff may move between contact centres allocated to different trial groups, we anticipated that this would have little impact. We did, however, attempt to evaluate the extent to which this occurs. To our knowledge, this did not occur during the study.

Sampling and sample size

We anticipated that all employees at a site were likely to take part in some or all of the intervention activities. However, employees also had the option of taking part in the research evaluation component. The sample size refers to the number of people taking part in the research evaluation (not those taking part in intervention activities). The sample size and target difference are the same as another similar study73 that proposed a sample size of 160 participants per group to detect a reduction in workplace sedentary behaviour of 45 minutes per day. Given that we aimed to have six control and post-intervention cross-sectional comparisons (see Figure 5), the target sample size was 160/6, which equals ≈ 27 participants per contact centre per data collection period. We anticipated that 10 contact centres would be recruited, so we aimed to recruit at least 270 employees to take part in the research evaluation. An aim of this feasibility study was to test sample size assumptions and produce a more accurate sample size calculation for a future study. We also aimed to recruit 6–8 individuals per contact centre for the qualitative data collection (60–80 individuals in total).

Ethics/regulatory approvals

The study was conducted in line with Medical Research Council and the Economic and Social Research Council ethics framework. Ethics approval was obtained from the School of Health in Social Sciences ethics committee, University of Edinburgh (ref STAFF142).

Informed consent

Although the employees did not have to provide informed consent to take part in the intervention activities, they had to provide informed consent to take part in the research evaluation (both the quantitative and the qualitative components). We provided them with information sheets and consent forms. It was made clear that participation or non-participation in the research would not affect employees’ work contracts or roles.

Confidentiality, anonymisation and data storage

Questionnaire data were collected anonymously using numerical identification codes in a locked cabinet or stored electronically on Qualtrics (Qualtrics International Inc., London, UK). Interviews and focus groups were recorded using encrypted digital devices, or recorded using Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA) or Microsoft Teams (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Audio and video files were sent to an authorised transcription service using a secure file transfer link, transcribed and then anonymised by the study team. All data were stored on password-protected university-networked computers. A separate database of participant names and unique identification numbers was stored securely and in a separate location to the study data. In reporting the results of the qualitative data and process evaluation, care was taken to avoid the identification of participants through quotations.

The specific methods for each aim of the study and the results are presented in the subsequent chapters.

Data management and research governance

The project was sponsored by the University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, and was funded by the NIHR. The trial was registered as ISRCTN11580369. Ruth Jepson (principal investigator) was responsible for ensuring that the study was carried out with strict adherence to the principles of good governance. We established a Study Steering Committee, which met once face to face and fed back via e-mail during the pandemic. The Study Steering Committee comprised researchers, experts on workplace health and staff (at different levels) from contact centres.

Patient and public involvement

Public involvement (in this case, contact centre staff) is at the heart of this intervention. Contact centre staff at all levels were encouraged to work with us to develop activities that worked for them, and they were encouraged to take ownership of both the problem and the solution. We have successfully tested the intervention in a single contact centre; staff from that contact centre were on the Study Steering Committee and also worked with us to develop content for the study’s website and social media accounts.

Chapter 3 Process evaluation: methods and results

Background

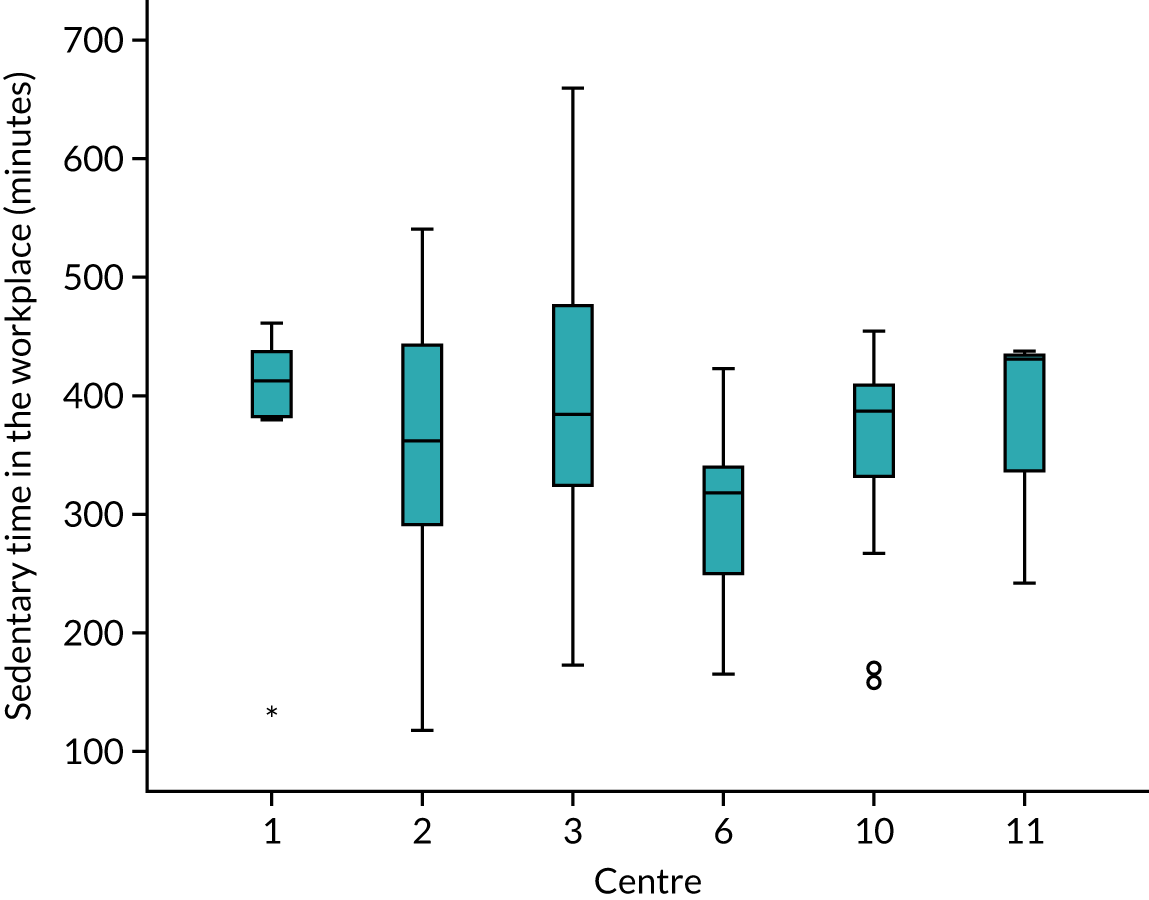

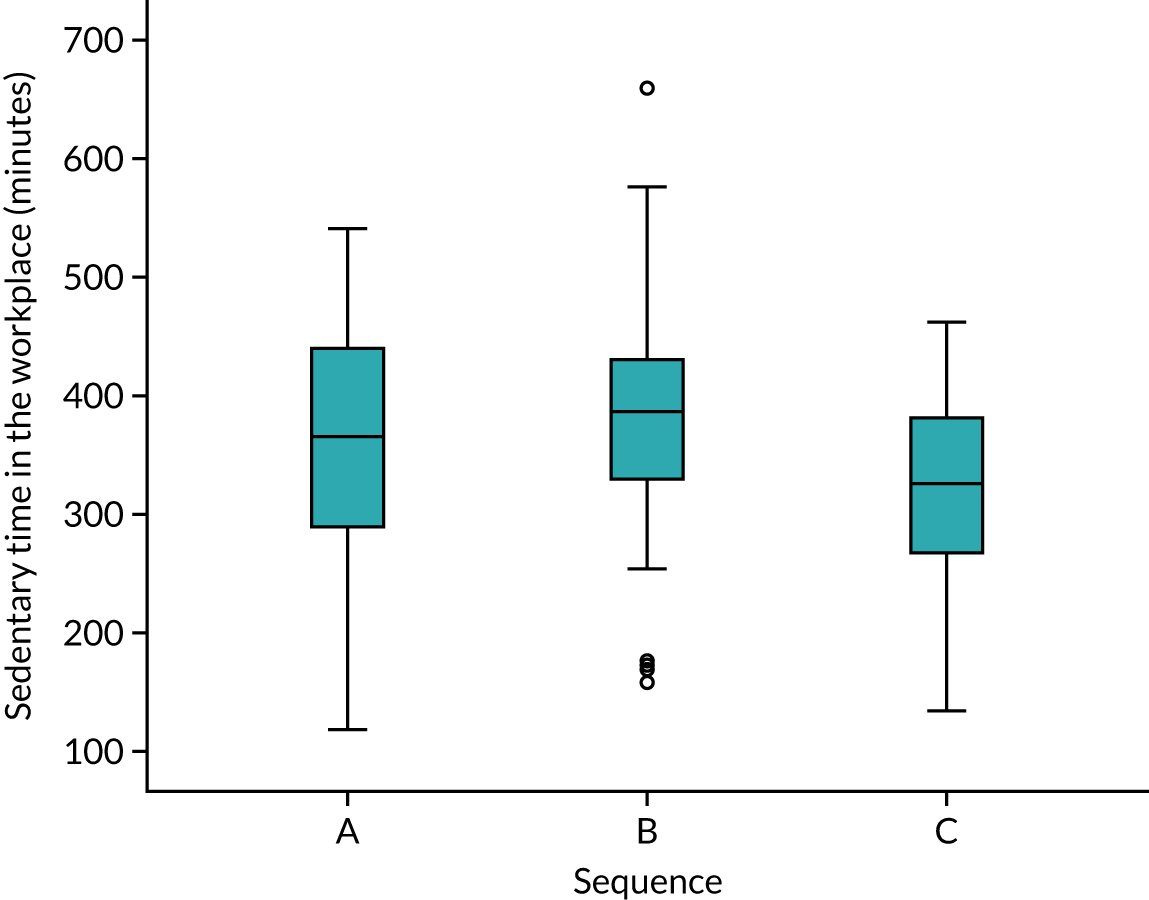

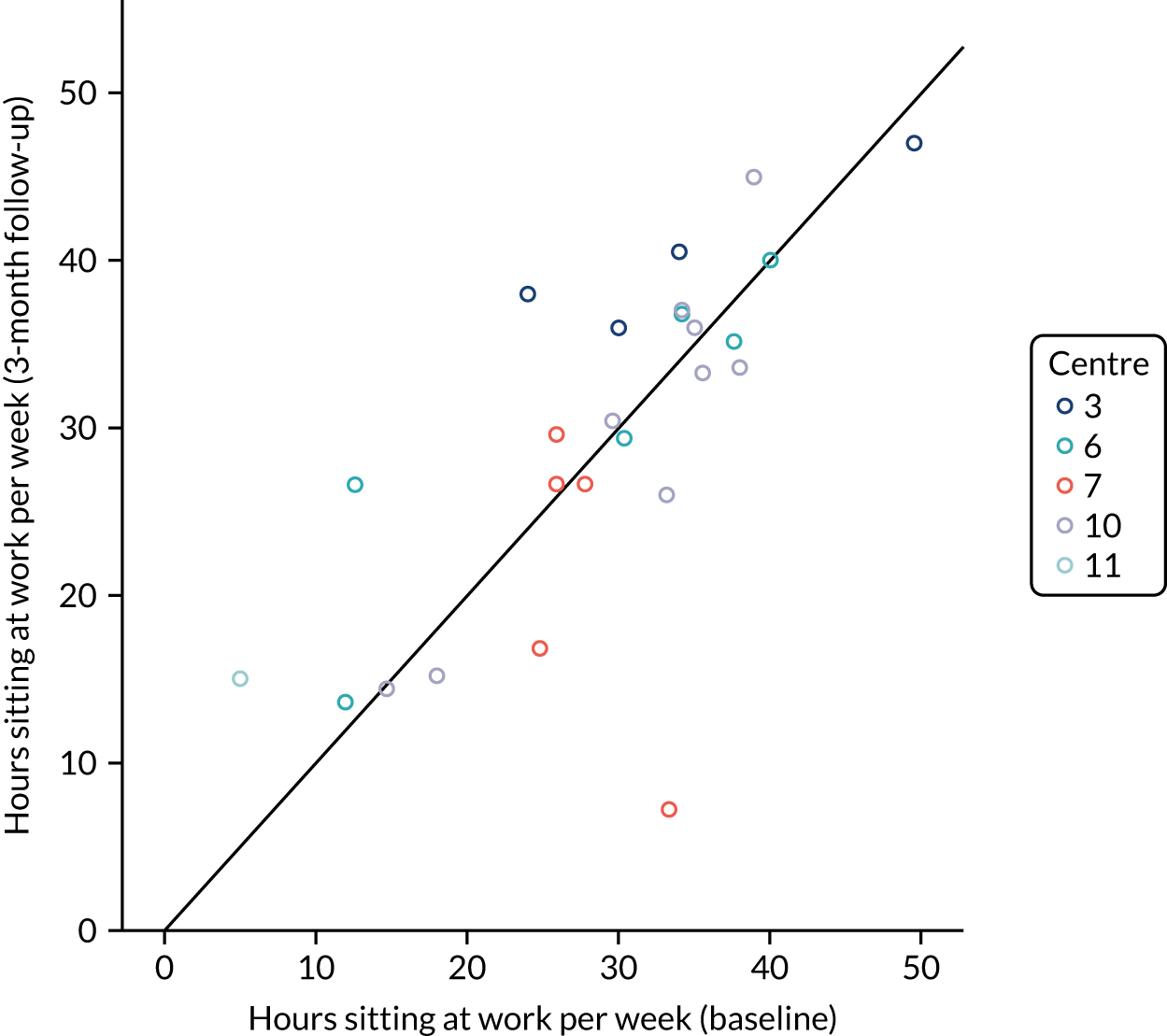

Stand Up for Health is a multicentre feasibility study. The study employs a cluster-randomised stepped-wedge design, and aims to assess the feasibility of intervention delivery and data collection methods, as well as procure preliminary estimates of effectiveness. The primary outcome was the activPAL device-measured sedentary time in the workplace, measured over 7 continuous days. This will subsequently be referred to as the primary outcome for the remainder of this report. 67 Secondary measures include subjective measures of workplace sedentary time, total sedentary time, physical activity, mental well-being, work engagement and musculoskeletal health. This component is referred to as the feasibility outcome evaluation study in this report.

Randomised controlled trials have traditionally focused on outcome evaluation, and the underlying processes and reasons why the intervention was or was not effective are not always properly understood. 74 To address these aspects, a process evaluation was carried out. Process evaluation refers to activities relating to intervention implementation, acceptance and reach. 75 It aims to understand the influence of contextual factors, explain discrepancies between expected and observed outcomes, and clarify causal mechanisms. 76 Within this study, the process evaluation sought to gather views and experiences of the SUH intervention activities and implementation processes with a view to refining the theories of change and overall programme theory. It examined whether or not the SUH activities worked as intended, the reasons why they did or did not work, and assessed any unintended consequences of the intervention. The process evaluation also aimed to provide insight into the feasibility of the study design and procedures.

Objectives

The process evaluation aimed to:

-

gather views and experiences of the SUH intervention activities and implementation processes

-

understand whether or not SUH activities worked as intended and investigate any unintended consequences of the intervention

-

explore differences in delivery of the intervention, differences between different contact centres and the reasons for these differences

-

assess the feasibility of the range of study procedures (e.g. recruitment strategies and outcome measurement tools) and understand differences between centres.

Methods

The process evaluation predominantly utilised qualitative methods substantiated with quantitative indicators from data collected over the course of the study. The overall SUH study had three aims, and the process evaluation addressed the first two aims:

-

acceptability and feasibility of the SUH intervention

-

feasibility of study design and procedures.

Acceptability and feasibility of the Stand Up for Health intervention

RE-AIM framework

RE-AIM (reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance) was the main framework adopted for the process evaluation to assess acceptability and feasibility of the SUH intervention. RE-AIM was developed to include reach and representativeness of participants and settings within the evaluation framework, with a focus on external validity. 77,78 The framework aims to improve assessment and reporting on five dimensions:77–79

-

Reach – the proportion of the target population that participated in the intervention. This is also defined as the reach (absolute number/proportion) and representativeness of individuals willing to participate in the intervention.

-

Effectiveness – success rate if implemented as in guidelines, defined as positive outcomes minus negative outcomes.

-

Adoption – proportion of settings, practices and plans that will adopt the intervention. This is the extent to which those targeted to deliver the intervention are participating, and can be measured as the percentage of providers participating in the programme.

-

Implementation – extent to which the intervention is implemented as intended in the real world. This also includes agents’ fidelity to the various elements of the protocol and the time and cost of the intervention.

-

Maintenance – extent to which a programme is sustained over time.

The RE-AIM dimensions were adapted for this process evaluation so that they were meaningful and captured essential and beneficial information. The reach dimension explored whether or not the intervention was available to everyone within each contact centre and if there were sectors of the organisation that did not have the opportunity to participate. The appeal and acceptance of the programme was also captured under the reach section. The effectiveness element included a qualitative exploration of the perceived benefits and consequences of the programme among staff and stakeholders. Given that this was a feasibility study, adoption (the percentage of contact centres that participated in the SUH programme) has limited relevance. Here, the proportion of centres that participated out of those that were targeted was assessed. The implementation element examined the activities implemented by the contact centres. Plans to continue implementation of the intervention were included within the maintenance element. The RE-AIM elements were explored mainly through qualitative methods. In addition, activity preferences among staff were captured using questionnaires, and these data were analysed and presented under the reach section to further understand programme appeal. The adoption element included a quantitative indicator showing the number of centres that participated compared with those that were recruited.

Programme theory and theory of change

The SUH intervention is an adaptive programme that does not prescribe specific activities to allow for flexibility, scalability and transferability. Programme implementation could vary between centres, with each choosing different activities within the organisational, environmental, social and individual levels. Hence, this process evaluation did not aim to assess fidelity to specific activities or consistency of delivery across sites. 79 Instead, it focused on whether or not the theories of change operated as intended. The process evaluation aimed to verify the programme’s theory of change and refine and adapt the change processes if required. This aspect is considered to be part of the implementation section of RE-AIM in this report. Organisational, environmental, social and individual factors were explored during the focus groups and interviews. We also aimed to discern underlying processes, such as increased motivation, ownership and increased awareness, as well as unintended consequences (both positive and negative).

Feasibility of using study design and procedures

The feasibility of using a cluster-randomised controlled design was evaluated using qualitative methods along with quantitative indicators. This component of the process evaluation is not considered under the RE-AIM framework. The range of study procedures evaluated, and methods of analyses, were as follows:

-

Recruitment and randomisation of contact centres and dropout– researchers’ reflections on completion of recruitment and randomisation of contact centres, including quantitative indicators on actual, compared with planned, recruitment and randomisation figures. Reasons for centre dropouts were explored using data from exit questionnaires completed by two centres.

-

Recruitment of participants and dropout – (1) quantitative indicators on actual, compared with planned, recruitment numbers and data on dropouts; (2) qualitative data on recruitment procedures through focus groups and interviews with staff and stakeholders; and (3) statistical analysis of reasons for participant dropout.

-

Data collection procedures and tools – assessed using qualitative data through focus groups and interviews with staff and stakeholders. Data from activPAL logbooks pertaining to detachment of the activPAL device and reasons for detachment are presented in this report, along with data on the number of activPAL devices issued and returned, and questionnaires completed.

A summary of the framework and measurement for the process evaluation is presented in Table 4.

| Dimension | Elements | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptability and feasibility of the SUH intervention | ||

| Pre lockdown | ||

| Reach |

|

|

| Effectiveness | Perceived benefits |

|

| Adoption |

|

|

| Implementation |

|

|

| Post lockdown | ||

| Reach |

|

|

| Effectiveness |

|

|

| Implementation |

|

|

| Maintenance |

|

|

| Feasibility of study design and procedures | ||

| Pre lockdown | ||

| Recruitment and randomisation of contact centres |

|

|

| Participant recruitment and dropout |

|

|

| Data collection procedures |

|

|

| Post lockdown | ||

| Participant recruitment and dropout |

|

|

| Data collection procedures |

|

|

Formats and time points for qualitative component

Focus groups and interviews were conducted with staff members from five centres. In addition, one individual interview was conducted with key stakeholders (primary centre co-ordinator) from six centres. The focus groups and interviews were scheduled to be conducted approximately 6 months after the start of the intervention. We were able to conduct the focus groups and interviews for centres 2 and 11 as per this schedule. However, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, we conducted the qualitative sessions for centres 3, 6, 7 and 10 approximately 3 months after the delivery of the post-lockdown intervention (see Figure 5).

Face-to-face focus groups were conducted with staff and telephone interviews were conducted with stakeholders from centres 2 and 11. Virtual focus groups and interviews were conducted using Microsoft Teams with staff and stakeholders from centres 3, 6, 7 and 11.

Participants and recruitment for qualitative component

Ethics approval for the qualitative component was procured from the School of Health in Social Sciences Ethics Committee (University of Edinburgh). Convenience sampling was used to recruit staff members for the focus groups and interviews. Stakeholders organised the session for face-to-face focus groups in centres 2 and 11, and arranged for staff to be off the telephones and attend the group discussion. Information sheets were circulated in advance and provided on the day (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Staff then provided written consent before participating (see Report Supplementary Material 3).

For the virtual focus group in centre 11, the SUH team co-ordinated with the stakeholder who organised the session at a convenient date and time. It was difficult to organise a virtual focus group in centres 6 and 7. In centre 6, the SUH team used Doodle poll (Doodle AG, Zurich, Switzerland; www.doodle.com) to set up interviews with staff. In centre 7, the SUH team procured the names of available and interested staff and co-ordinated with them to arrange interviews. Staff were sent an online information sheet and consent form (on Qualtrics) in advance of the session and provided electronic consent before participating.

The SUH team co-ordinated with centre stakeholders to find a suitable date and time to conduct the interview sessions. The information sheet and consent forms were sent to stakeholders from centres 2 and 6 before the call, and participants provided consent and returned the forms before the interviews. Stakeholders from centres 3, 6, 7 and 10 were sent an online information sheet and consent form prior to interviews, and provided electronic consent before the session.

Instrumentation for qualitative component

Topic guides for the focus group discussions and interviews were developed by Divya Sivaramakrishnan, Jillian Manner, Graham Baker and Ruth Jepson, based on the process evaluation framework, and covered topics relating to (1) the acceptability and feasibility of the SUH intervention, and (2) the feasibility of using the study design and procedures. These were then reviewed by the other SUH team members and further refined based on their comments. The topic guides for the post-lockdown focus groups and interviews were developed through amendment of the pre-lockdown guides. The post-lockdown guides included questions pertaining to post-lockdown activities (consults, activity plan and step count challenge). Topic guides are presented as supplementary material (see Report Supplementary Material 4).

Qualitative analysis

All focus group discussions had a moderator and co-moderator. The face-to-face focus groups and telephone interviews were recorded using an audio-recorder. The online sessions were recorded using the record function on Microsoft Teams. Data were transcribed verbatim by a transcription agency.

An initial coding framework was developed by Divya Sivaramakrishnan, Jillian Manner and Graham Baker based on the RE-AIM process evaluation framework (see Table 4). Five transcripts were coded by both Divya Sivaramakrishnan and Jillian Manner (two pre-lockdown staff focus groups, two pre-lockdown stakeholder interviews and one post-lockdown staff interview). The other transcripts were coded by one researcher (DS/JM). Graham Baker and Richard Parker acted as critical friends, who discussed the themes and subthemes with Divya Sivaramakrishnan and Jillian Manner; clarified and offered interpretation; and provided insights and suggestions to refine the themes. Transcripts were coded deductively based on the coding framework, with a deductive approach to capture themes within the broad framework. Thematic analysis was used to generate themes and subthemes following a six-step process. 80 Differences between centres within each theme were examined during analysis. A computer software package (NVivo version 11; QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to code the transcripts and manage the thematic structure.

Other sources of data

activPAL experience

In addition to data from focus groups and interviews on experiences with the activPAL device, data from activPAL logbooks are also presented in this chapter. All staff that wore the activPAL device were requested to complete logbooks to capture work and sleep times. One section of the logbooks captured data on whether or not the activPAL device was detached and the reason for detachment, and whether or not it was reattached. These responses were summarised and converted to percentages. An open-ended question captured additional comments and issues relating to wearing the activPAL device. Responses to this section were analysed along with the qualitative data.

Activity preferences

As a part of the outcome analysis, staff completed a questionnaire relating to the outcome measures. The pre-lockdown questionnaire asked staff how often (number of days per week, ranging from ‘did not participate’ to ‘participated daily’) they had participated in five activities over the last 6 months (use of desk-based equipment, use of non-desk-based equipment, mindfulness activities, group activities and individual activities). The post-lockdown questionnaire asked participants if they participated (yes, no, not sure) in nine activities (step count challenge, virtual social activities with an active component, goal-setting, desktop stretches, exercise videos and apps, mindfulness activities, other individual activities, using the SUH website, environmental changes). The activity preferences of staff members were captured within the post-intervention questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 5 for the pre-lockdown questionnaire and Report Supplementary Material 6 for the post-lockdown questionnaire). Responses were summarised using Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and presented as percentages.

Exit questionnaires

Two centres that dropped out (centres 5 and 8) completed an exit questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed by Divya Sivaramakrishnan and Jillian Manner, who also summarised and discussed the responses to the questionnaire. The responses were reported as a part of the section on recruitment and randomisation of centres.

Researcher’s reflections

Throughout the recruitment and data collection process, Divya Sivaramakrishnan and Jillian Manner regularly discussed concerns and issues and aspects of the process that were (or were not) working. These were noted in a shared Microsoft Word document (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and the reflections were used as a part of the qualitative analysis to substantiate themes and provide additional, deeper insights.

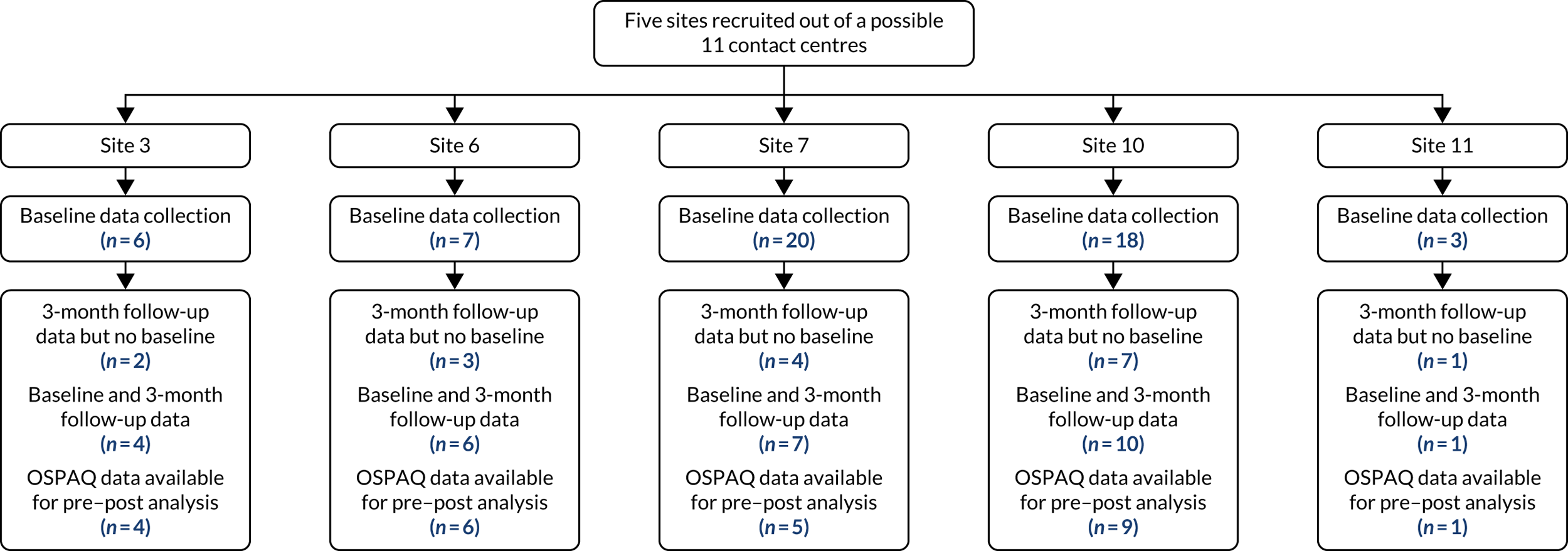

Participant dropout

The SUH team considered individuals who participated in pre-lockdown data collection, but not post-lockdown data collection, as well as those who provided baseline measurements but not follow-up measurements (3 months later) in the post-lockdown phase. We also asked stakeholders the reasons for participant dropout (e.g. left the company, moved to a different part of the company, were unavailable, did not want to participate, technological barriers, did not receive communication, I don’t know, other – elaborate). Centres 3, 6, 10 and 11 were included in the pre-lockdown analysis and the following binary variables were considered: left company, moved job and lost to follow-up. A multiple logistic regression model was fitted to each of the three binary outcomes. The multiple logistic regression model had the following explanatory variables (all entering the model as fixed effects): contact centre, sex, part-time working, age and how long the participant had worked for the contact centre. Centres 3, 6, 7, 10 and 11 were included in the post-lockdown analysis. A multiple logistic regression model was fitted to the ‘lost to follow-up’ variable, adjusting for contact centre, sex, part-time working, age and how long the participant had worked for the contact centre.

Reporting

The process evaluation framework (see Table 4) was used for reporting and the results are organised under two main sections: (1) acceptability and feasibility of the SUH intervention and (2) feasibility of the study design and procedures. Within these two sections, pre- and post-lockdown results are examined separately.

Results

Centre characteristics

Contact centre locations were London, Durham, Tyneside (Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Gateshead, South Shields and Jarrow), Sunderland and Edinburgh. The number of staff members in the centres ranged from 33 to 2000, with an average of 559 staff members.

Participant characteristics

In total, 33 staff and stakeholders from six centres participated in the process evaluation focus groups and interviews. Specifically, four focus groups (centre 2: eight participants; centre 6: two participants; centre 10: six participants; centre 11: six participants) and three interviews (centre 7: two interviews; centre 6: one interview) were conducted with staff members. Interviews were conducted with stakeholders from all six centres (eight participants).

Acceptability and feasibility of the Stand Up for Health intervention: pre-lockdown results

Reach: programme significance and appeal

The majority of staff described participating in the pre-lockdown SUH intervention as a positive experience overall. The intervention was well received and was enjoyable for individuals and teams:

I honestly think it was a really positive experience. I think, for some people, it made a difference. It really kind of . . . it changed the way they worked . . . as an employer, giving our staff the opportunity to work differently, is fantastically positive. You can’t force people to do it, but the fact that we’re able to give them the opportunity to work differently, to move around and, you know, to look after themselves and keep well, while they’re working, I think, is fantastic. I think it’s just been brilliant.

Centre 10, stakeholder

Staff and stakeholders emphasised the importance of the SUH programme for contact centres to improve physical, mental, emotional and social well-being. It was felt that SUH was a particularly significant and unique programme because it brought attention to the lack of movement in the sedentary contact centre environment, and encouraged movement in this environment. Stakeholders reported that the SUH programme helped them look after their staff better. Staff associated SUH with health in the workplace and regarded it as a means of improving their mental and physical health and well-being (specifically, musculoskeletal issues and mental health). Staff felt that SUH helped them to manage stress and cope with stressful calls. Encouraging teamwork and uplifting team spirt was another aspect of SUH that was valued by staff and stakeholders.

Stand Up for Health led some staff to think about their general health and well-being, as a first step to making lifestyle changes. Several centres noticed a morale boost in the workplace during this period and described SUH as providing fun, excitement and novelty in the office: