Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as award number NIHR129113. The contractual start date was in April 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in October 2022 and was accepted for publication in March 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Evans et al. This work was produced by Evans et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Evans et al.

Chapter 1 Background

About this chapter

In this chapter, we present the context of the CHIMES review, outlining the problem being addressed, the rationale for the review and how it responds to gaps in the extent evidence base, and the review’s aim and research questions (RQs).

Care-experienced, looked-after and in care: key concepts and definitions

Care-experienced children and young people represent a diverse population. There is extensive variation in nomenclature internationally. 1 Historically, in the UK, individuals who have been in care have been defined as ‘looked after’. However, recently there has been a move away from this term, as it has the potential to perpetuate some of the reported stigma associated with being in care. 2 For example, the practice of looked after child reviews, or the common acronym of LAC, might have negative connotations of ‘lack’ or ‘lacking’. As such, it is increasingly common to use terms such as ‘children looked after’, with some third-sector organisations indicating that young people prefer the term ‘in care’. 3 In light of these considerations, in the CHIMES review, we use the term ‘care-experienced’.

Care-experienced children or young people can include those who have resided in kinship care, foster care, or residential care. 4 In some cases, they might also remain at home with a supervision requirement order. Centrally, there is formalised statutory involvement, usually resulting in the transferral of parental rights. Care experience can include those who are currently in care but can extend to include care leavers. Again, this group is largely defined by their continued rights to statutory provision. For example, in Germany, individuals from a range of care placements are entitled to legal assistance until 21 years of age, whereas in England they are entitled to relevant services up to 25 years. 4 In the CHIMES review, we classify care-experienced young people as those aged up to 25 years.

Most recent data for 2021 report that 88,115 children and young people are registered as being in statutory, local authority care in England and Wales. 5,6 This reflects a continued trend in the growth of the ‘looked-after’ population, despite fewer placement commencements as a consequence of COVID-19 lockdown measures. 5,6

Mental health and well-being among care-experienced children and young people

The mental health and well-being of care-experienced populations remains a significant public health and social care concern. 7 Almost 50% of individuals involved in the child welfare system have a diagnosable mental health condition,8 and they are nearly five times as likely to have at least one psychiatric diagnosis compared with the general population. 9 Care-experienced individuals are at an elevated risk of poor subjective well-being,10 and are more than four times as likely as their peers to attempt suicide. 11

Poor mental health potentiates the risk of a range of adverse outcomes across the life course. This includes limited physical health, increased criminality, lower levels of educational engagement and attainment, and lower rates of employment. 12–14 A 2020 UK longitudinal study reported that individuals with a history of foster and/or residential care had excess mortality in adulthood due to increased risk of self-harm, accidents and other mental health and behavioural disorders. 15

Mental health problems can also incur significant health and social care costs, often due to the associated risk of placement instability and breakdown. 16–18 This is a notable challenge given the context of increasing financial pressure on the social care system in the UK, with reports of increased demand, reduced budgets and rising unit costs. 19

Prioritising the mental health and well-being of care-experienced children and young people: current policies, interventions and research

There is a clear need to prioritise mental health and well-being provision for care-experienced children and young people. The UK policy context has demonstrated a strong commitment in this area, with the Department for Education and Department of Health and Social Care’s joint statutory guidance on the promotion of health and well-being for care-experienced children mandating that local authorities ensure the provision of timely and adequate care. 20 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendations have indicated the need to enhance intervention across a range of domains, particularly in regard to relationship-based support, training for carers, introduction of a therapeutic approach to working practices and the immediate availability of specialist support for individuals awaiting access to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). 21

There are, however, potential barriers to improving the availability and quality of interventions. For example, with regard to access to mental health services, there are often reported incidents of failure to identify need, overly stringent eligibility thresholds and withholding of care where there is not a stable placement. 22 There are also concerns about the lack of support for carers’ own well-being, arising from the stress associated with parenting children with complex mental health and behavioural needs. 23

Intervention research to support policy and guidance recommendations has generally been limited, with NICE guidance previously stating that the UK evidence base does not adequately serve this population. 21 However, while there continues to be a lack of intervention research conducted in the UK, there is a wealth of interventions evaluated internationally. These can be preventative or treatment based. They operate across a range of socioecological domains, often targeting the skills of children and young people;24–26 interpersonal relationships with peers, carers and other adults;27–31 the ethos and culture of social care teams (e.g. adoption of trauma-informed practices);32–34 and the availability of wraparound community and mental health services provided by child welfare systems. 35

Given the emergent evidence base for intervention in the UK context, which contrasts to a relatively large (if equivocal) evidence base internationally, there is a clear need to explore the potential transportability of international approaches to this context. To this end, there is scope for systematic reviews that synthesise evidence on the effectiveness of interventions, while also exploring the contexts in which they are evaluated. Such work would help researchers and policymakers to understand the extent to which the evidence base for interventions is transferrable beyond their immediate implementation and evaluation context.

Limitations of the evidence base: the need for a complex system informed systematic review

To date, there have been a number of systematic reviews offering syntheses of the international evidence base for mental health and well-being interventions targeting the care-experienced population. 36–50 This includes a 2021 NICE review of interventions to promote physical, mental and emotional health and well-being of care-experienced children, young people and care leavers. 51 The review informed specific NICE guideline recommendations to consider the implementation of interventions within the UK context. 21

There are limitations with existing reviews, both in terms of methodology and focus, which together provide a rationale for the current CHIMES study. Reviews have often been restricted to specific intervention packages (e.g. treatment foster care, TFC),37,52 intervention outcomes (e.g. externalising behaviours)43,44 or population subgroups and care placement types (e.g. foster care). 24,37,39,43,48,53 Reviews within the UK context have predominantly been non-systematic literature reviews that do not use a robust methodology. 36

Of central importance is that reviews tend to focus on the synthesis of outcomes, with only rudimentary treatment of intervention theory, context or process data. Equally, where comprehensive syntheses of evidence reporting barriers and facilitators to intervention implementation have been conducted, they have not been fully integrated with outcome data to understand and explain variations in effectiveness. 51,54 As a result, they offer limited insight as to whether the international evidence base might be applied to the UK context.

In response to these limitations, we sought to conduct an integrative review, drawing together theory, context, process, outcome and economic data, to understand which interventions are effective in which contexts and why. This is supported by recent advances in complex-systems thinking in systematic reviews,55,56 which operate on the assumption that interventions are system disruptions and so their effectiveness is contingent on the system in which they are implemented. 57–59

This approach is further justified by recommendations from methodological guidance related to intervention development and evaluation,60,61 notably recent updated Medical Research Council guidance. 62 These frameworks and models emphasise the need to prioritise intervention theory and understand the mechanisms through which interventions operate and interact with contextual conditions, as the activation of relevant causal pathways is inherent to an intervention’s success. There is also a focus on process evaluation to explore how context factors inform facilitators and inhibitors of implementation and structure how diverse stakeholders interact with interventions. 63

More recent developments in methodological guidance have considered intervention adaptation and the potential transferability of interventions across contexts. Frameworks and recommendations, including the ADAPT guidance,64 indicate the need to understand similarities and differences between contexts before evidence-based interventions are transported, to ensure that necessary adaptations are made in relation to local needs.

The importance of attending to contextual specificities, such as international variations in social and healthcare systems, is apparent from the example of Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (MTFC) and Multi-System Therapy (MST), which demonstrate the complexities in replicating the positive effects of US-originated interventions in Sweden. 65 MST was not effective when replicated in the new context, as it was essentially equal to usual care, whereas MTFC demonstrated impact, as it combined components that are common in usual care in Sweden but are rarely delivered as an integrated suite of provision.

Review aims and research questions

The CHIMES review is a complex-systems informed, multimethod systematic review that aimed to synthesise extant international evidence on interventions addressing the mental health and well-being of care-experienced children and young people and consider the potential applicability of this evidence base in the UK context.

This research aim was addressed through the following RQs:

-

What are the types, theories and outcomes tested in mental health and well-being interventions for care-experienced children and young people?

-

What are the effects (including inequities and harms) and economic effects of interventions?

-

How do contextual characteristics shape implementation factors, and what are key enablers and inhibitors of implementation?

-

What is the acceptability of interventions to target populations?

-

Can and how might intervention types, theories, components and outcomes be related in an overarching system-based programme theory?

-

Drawing on the findings from RQ1 to RQ5, what do stakeholders think is the most feasible and acceptable intervention in the UK that could progress to further outcome or implementation evaluation?

Summary

In this chapter, we have considered the context for the CHIMES review and its aim to address limitations with the extant evidence base. The next chapter reports the methodology of the review.

Chapter 2 Methodology

About this chapter

In this chapter, we outline the methodology used in the CHIMES review. The methods were a priori defined in the protocol. 66 Amendments to the protocol are listed in Appendix 1. To date, there are no recommended reporting checklists for complex-systems-informed, multimethod systematic reviews. As such, we report the review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist. 67 Method-specific syntheses are reported in accordance with relevant checklists in associated publications: the evidence map68 is reported with reference to the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews69 and the process evaluation synthesis is reported with reference to the ‘Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research’ statement. 70 Stakeholder engagement is reported in accordance with the short form Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public version 2 (GRIPP2). 71

Review design, research questions and work packages

The CHIMES review aimed to synthesise extant international evidence on interventions addressing the mental health and well-being of care-experienced children and young people. The RQs are presented in the previous chapter.

The review process was conducted in three phases. First, we constructed an evidence map charting key evidence gaps and clusters (RQ1). From here, with input from stakeholder consultation, we refined and confirmed the parameters of the review. Second, we conducted a systematic review with method-level syntheses (RQ2–4). Third, these method-level syntheses were integrated into a review-level synthesis (RQ5), which was the basis of further stakeholder consultation (RQ6). This work mapped on to five interrelated work packages (WPs):

-

WP0: study co-ordination and dissemination (RQ1–6)

-

WP1: searches, extraction and appraisal (RQ1–4)

-

WP2: intervention theories, context, implementation and acceptability (RQ1, RQ3, RQ4)

-

WP3: intervention effects (RQ2)

-

WP4: modelling of intervention theory (RQ5)

-

WP5: stakeholder consultation (RQ6)

The remainder of this chapter is structured to present the methodology linked to each of these WPs.

Work package 0: study co-ordination and dissemination (research questions 1–6)

The first WP co-ordinated the review, overseeing governance and protocol compliance, risk monitoring, stakeholder collaboration, output management and impact activities. It had a specific remit for ensuring the integration of subsequent WPs. While published after the commencement of the CHIMES review, the study co-ordination was supported by the TRANSFER Approach framework,72 which is a seven-stage model to encourage partnership between review teams and stakeholders to consider systematically and transparently the factors that impact the transferability of systematic review findings to a specified context.

CHIMES collaboration partnership: establishing review need and relevance

The review was a formal collaboration between Cardiff University, University of Bangor, University of Exeter and the Fostering Network in Wales. Our collaboration initially addressed stage one of the TRANSFER framework,72 which is to establish the need for a review. Meetings between the review team and the Fostering Network in Wales (2018–9) identified a paucity of evidence-based interventions supporting the mental health and well-being of care-experienced children and young people in Wales, despite an evident need. The application to the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) funding panel for the CHIMES review was a product of these initial meetings.

Project advisory group

The review was overseen by a project advisory group, which comprised two academics, two policy and practice professionals and two foster carers. The advisory group convened at four key time points during the study:

-

On completion of the initial mapping of the research evidence to confirm the parameters of the review (month 6).

-

On completion of the process evaluation synthesis to reflect on the findings and undertake an initial exploration of how they might support the interpretation of the outcome evaluation synthesis (month 12).

-

To consider the content and structure of final stakeholder consultations (month 22).

-

To reflect on the review and explore opportunities for future intervention research (month 28).

Stakeholder consultations

We conducted stakeholder consultations in two phases. The first phase, undertaken within the first 12 months of the review, was to refine the review parameters after the evidence-mapping stage. The first phase included identifying key context factors in the UK social care system that should be prioritised in the conduct of the review, which is prescribed by stages 2 and 3 of the TRANSFER model. 72 The second phase, undertaken in the last 6 months of the review, was to interpret and reflect upon the review findings (WP5).

A summary of the three consultations undertaken during phase one is presented in Table 1. The first consultation was conducted with CASCADE Voices, a young people’s advisory research group comprising care-experienced individuals up to the age of 25 years. As the group was facilitated by a third-party organisation, we did not have specific details on the age or care history of participating members. Key discussion points confirmed that the synthesis needed to focus on the priority outcomes of well-being and suicide-related outcomes. It further identified key context factors in the UK that should be attended to and foregrounded as part of the process evaluation synthesis, notably around system identities and resources.

| Stakeholders | Structure of consultations | Summary of consultations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Priority intervention types and outcomes | Key context factors | ||

| CASCADE Voices (28 May 2020) | Online consultation facilitated by the CASCADE Engagement Manager at Cardiff University; 8 young people aged up to 25 years | Need to prioritise positive constructs of well-being (e.g. self-care, resilience, self-worth) and suicide-related outcomes. Lack of structural-level interventions currently being implemented in UK | System identities: UK has a deficit model of care-experienced young people, with negative perception that poor mental health is simply attention seeking. As a result, there may be a lack of system support for implementing mental health and well-being promotion interventions |

| System resources: UK has long waiting lists and lack of resources for children and young people’s mental health. Funding mental health interventions may not be feasible | |||

| The Fostering Network in Wales Young Person Forum (17 February 2021) | Online consultation facilitated by the Fostering Network in Wales; 7 young people aged 16–26 years | Need to prioritise positive constructs of well-being and suicide-related outcomes | System culture: perception that US social care system more punitive than UK making it ‘frightening’ and ‘abusive’. May reduce young people’s receptiveness to engage with interventions developed in the US care system |

| System resources: perception that US has stronger emphasis on removing children from the family than the UK so have more resources to support out-of-home care. UK less likely to resource interventions to support foster carers | |||

| All-Wales Fostering Team Managers Forum (25 March 2021) | Online consultation facilitated by the Fostering Network in Wales; 17 foster carer managers | Need to prioritise well-being | System identities: concern about UK foster carers’ dual identity as parent and professional, and difficulty of balancing the role if having to deliver specialist trauma-informed approaches. May compromise perceived safety of care placement where young person is receiving a mental health intervention from a carer who is also a ‘parent’, potentially leading to increased breakdown in placements |

| System resources: concern about the availability and level of carer skill to deliver mental health and well-being intervention in the UK. International interventions that target foster carers may not be feasible in UK as suitable carers not funded and available. Lack of system support for carers, which may make it harmful if delivering mental health support ‘out of work’ hours | |||

A further two consultations were planned at this time but, as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, these consultations were delayed until January–February 2021. One consultation was hosted with the Fostering Network in Wales Young Person Forum, which is a group of care-experienced young people who provide advice and guidance to the charity on their programmes of work. A second consultation was conducted with the All-Wales Fostering Team Managers Forum, which is also facilitated by the Fostering Network in Wales. The forum comprises a range of local authority and independent foster-care providers working in Wales. While these consultations were hosted as the review was in progress, they did help to confirm the scope and focus. They also extended and refined the key context factors to be explored.

It should be noted that, in our consultation with the Young Person Forum, young people queried why the review was considering the transportability of interventions across contexts, questioning why interventions were not being developed to meet the specific needs of care-experienced children and young people in the UK.

Convergent synthesis design

The review adopted a convergent synthesis design. 73,74 This approach entailed data from method-specific WPs being extracted, analysed and synthesised in a complementary manner, before being harmonised and integrated into an overarching review-level synthesis. RQs were designed to be complementary and contingent, where achieving a comprehensive answer to one question was dependent on the answers to other questions. Furthermore, when conducting the review, we (1) had the same members of the research team work on both the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative data; (2) screened all study types simultaneously and by the same members of the research team, storing data in EPPI-Reviewer version 4 (EPPI Centre, Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education, London, UK) to ensure ease of sharing of study data across syntheses and (3) used method specific appraisal tools that have been combined in previous reviews due to providing epistemological flexibility or consonance.

Work package 1: searches, extraction and appraisal (research questions 1–4)

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion parameters for the review are reported in accordance with the PICOS (population, intervention, comparison, outcomes and study) framework.

Types of participants

Intervention participants could be care-experienced children and young people or their proximal relationships, organisations and communities. For participating children and young people, they had to be aged ≤ 25 years. The upper limit of 25 years was selected as in the UK care leavers are eligible for statutory local authority support until this age. They could be currently placed in care, transitioning out of care or have previous care experience. The amount of time in care was not restricted. Care could include in-home and out-of-home care (foster care, residential care and formal kinship care). Care had to specify statutory involvement. For participating families, organisations and communities, they could be any individual or group. These could include but were not limited to carer, birth family, teacher or social worker. The following populations were excluded: general population, children in need, individuals at the edge of care, care without statutory involvement (e.g. informal kinship care), adoption, or unaccompanied asylum seekers and refugees.

Intervention

We defined interventions broadly, conceiving them as any attempt to disrupt existing system practices. They could be monocomponent or multicomponent and could operate across any of the following socioecological domains: intrapersonal, interpersonal, organisational, community and policy. Interventions could focus on prevention and/or management/reduction of symptomatology. Interventions did not necessarily have to be termed ‘mental health’ interventions; they could be interventions addressing education, social care, criminal justice or housing, provided that they included a relevant mental health outcome. There were no a priori criteria for implementation (i.e. delivery setting, delivery mode, delivery agent). Pharmacological interventions were excluded.

Comparator

For outcome evaluations, a comparator was required and could include treatment as usual, other active treatment or no specified treatment.

Outcomes

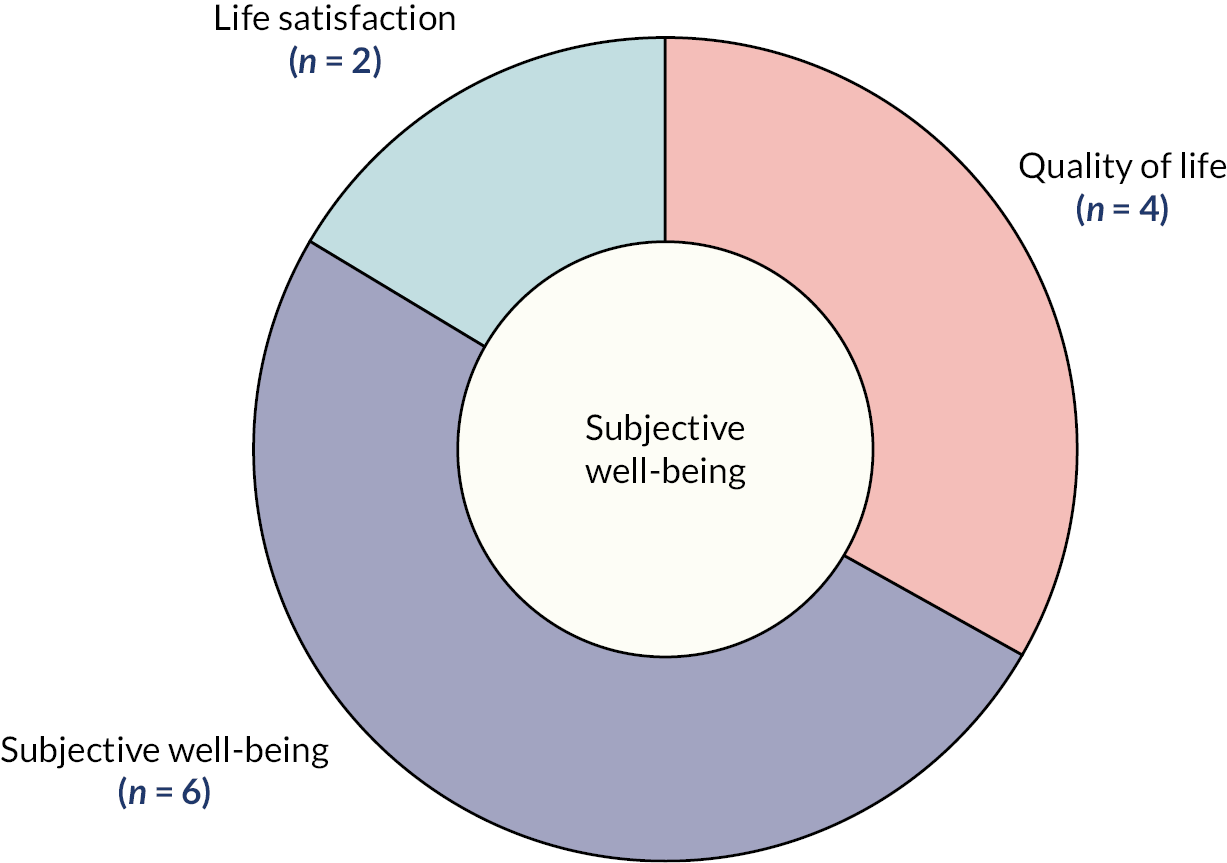

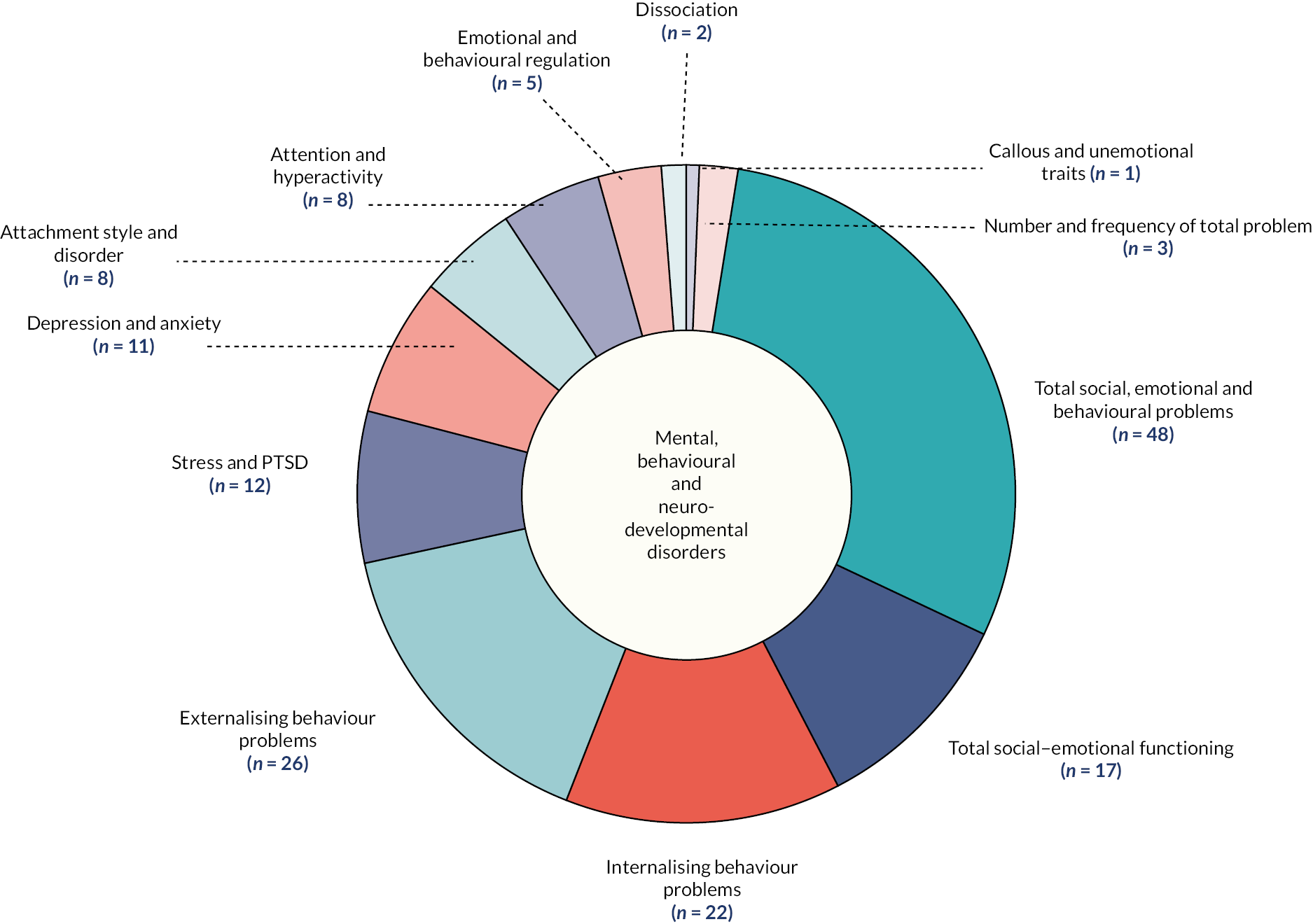

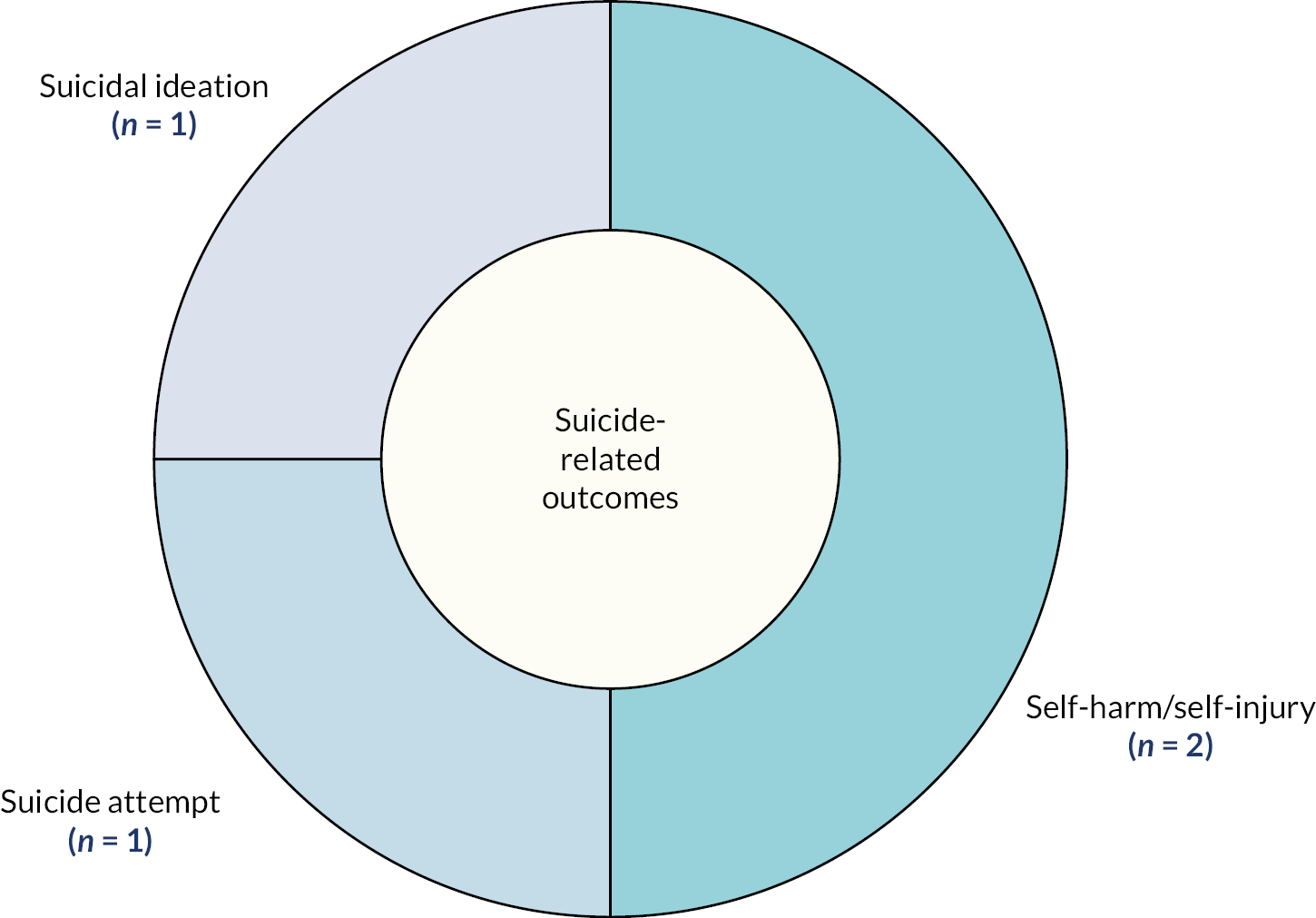

There were three domains of eligible outcomes, with interventions having to target one of these outcomes as a primary of secondary outcome:

-

Subjective well-being (eudaimonia and hedonia), life satisfaction and quality of life

-

Mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders as specified by the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Edition (ICD-11). The specific disorders were: neurodevelopmental; schizophrenia/primary psychotic; catatonia; mood; anxiety/fear-related; obsessive–compulsive disorder; stress; dissociation; feeding/eating; elimination; impulse control; disruptive/dissocial; personality; paraphilic; factitious; neurocognitive; mental/behavioural associated with pregnancy/childbirth

-

Self-harm; suicidal ideation; suicide

We made protocol amendments to outcomes at the stage of mapping study reports. First, quality of life was included as an explicit outcome. Second, the mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental category was inductively classified into a set of subdomains that reflected the measurement domains and assessment tools reported in studies. These domains were: total social, emotional and behavioural problems; social–emotional functioning difficulties; internalising behaviour problems; externalising behaviour problems; depression; anxiety; stress and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); attention and hyperactivity; attachment; psychosis. These domains are presented in more detail in the outcome synthesis reported in Chapter 4.

Outcome measures could be dichotomous, categorical or continuous. Domains of outcomes could be ascertained through clinical assessment, self-report or report by another informant (e.g. teacher). Outcomes had to be reported at the level of the child or young person. The following outcomes were excluded: substance misuse/substance use disorder; euthanasia or assisted suicide; accidental death (e.g. accidental overdose); biomedical markers of potential mental health problems (e.g. cortisol as an indicator of stress related disorder).

Study design

Different study designs were eligible according to the RQ being addressed:

-

Programme theory: described intended theory or mechanisms of effect. Could include mediation analysis or logic model.

-

Outcome evaluation: (individual/cluster) randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-experimental study designs (difference in difference; non-equivalent control groups). We excluded post measurement only or pre/post measurement in intervention group only.

-

Process evaluation: all qualitative and quantitative study designs. Included studies had to empirically report on implementation, relevant contextual influences and/or acceptability.

-

Economic evaluation: economic evaluations had to relate costs to benefits. They could report cost-minimisation, cost-effectiveness, cost–utility or cost–benefit analysis. They could be model or trial based. Decision-analytic models capturing intervention impacts on mental health and well-being were eligible.

Countries

Countries were limited to higher income countries as classified by the World Bank.

Information sources

We identified study reports from five information sources: (1) electronic bibliographic databases; (2) websites; (3) expert recommendations; (4) screening of relevant systematic reviews and (5) citation tracking of included study reports.

Databases

We searched 16 electronic bibliographic databases, covering a range of research disciplines, in May–June 2020 and again in April–May 2022. These databases were identified by the review team based on experiences of conducting related reviews.

The bibliographic databases were:

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts

-

British Education Index

-

Child Development and Adolescent Studies

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

-

Education Resources Information Center

-

EMBASE

-

Health Management Information Consortium

-

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences

-

MEDLINE (including MEDLINE in Process and MEDLINE ePub)

-

PsycInfo

-

Scopus

-

Social Policy and Practice

-

Sociological Abstracts (including Social Services Abstracts)

-

Web of Science (Social Sciences Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index Social Science and Humanities, Emerging Sources Citation Index).

Websites

We searched 22 websites of relevant social and healthcare organisations in May–June 2020 and again in April–May 2022. Again, these were identified by the review team based on their substantive and methodological expertise, combined with their experience of related systematic reviews:

-

Action for Children

-

Barnardo’s

-

Care Leavers’ Association

-

Catch-22

-

Child Poverty Action Group

-

Children’s Commissioner for four UK nations

-

Children’s Society

-

Department for Education

-

Early Intervention Foundation

-

Joseph Rowntree Foundation

-

Mental Health Foundation

-

Mind

-

National Children’s Bureau

-

Nurtureuk

-

Rees Centre

-

Samaritans

-

Spring Consortium

-

Thomas Coram Foundation

-

Young Minds.

Expert recommendation

We identified a total of 32 subject experts and 17 third-sector organisations. They were contacted via e-mail, inviting them to indicate any grey literature, unpublished research or ongoing studies of relevance.

Screening of relevant systematic reviews

We identified relevant systematic reviews to unpick and retrieve potential study reports for inclusion. Reviews were identified at the protocol development stage and through the searches of electronic bibliographic databases.

Citation tracking

We conducted forward and backward citation tracking of included study reports. To maximise resource efficiency, citation tracking prioritised identifying clusters of theory, context and process evaluations linked to included interventions to strengthen understanding of effects. We also placed an emphasis on citation tracking of evaluations conducted in the UK, as one of the central aims of the review was to consider the evidence base in relation to this context and initial searches revealed the predominance of study reports from the USA.

Search strategy

For bibliographic databases, we developed and tested a search strategy in OVID MEDLINE (see Appendix 2). It was adapted to the functionality of each bibliographic database. Search terms were clustered around the areas of: children; social care; mental health; well-being; study design. Where appropriate, subject headings were included in the search strategy. Searches were limited in date from 1990 to coincide with the ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child,75 which prescribes comprehensive social and healthcare provision for children internationally and started the proliferation of intervention in this area. No further limits were used within the search.

For websites, the search strategy depended on the functionality of the platform. Search terms focused on children and young people in care, mental health and well-being. These terms were searched through the website search function or Google advanced search, and in the absence of this functionality website pages and publication lists were screened for relevant study reports.

Selection process

We uploaded retrieved study reports to the EPPI-Centre’s specialist online review software EPPI-Reviewer version 4.0 for storage and management. The software stores the bibliographic details of each study report, including the abstract. For citations that progress to full text screening, the software enables the upload of related electronic documents.

We conducted screening of retrieved study reports in three stages. First, retrievals from electronic bibliographic databases and websites were screened to identify clearly irrelevant retrievals by checking the record title (e.g. animal testing of pharmacological treatment). To note, while the search strategy was designed for specificity and sensitivity, it did retrieve a large evidence base on older people’s social care. This stage was conducted by one member of the review team. Retrievals identified as clearly irrelevant were checked by a second reviewer. Where there was a conflict in decisions, the study report was marked as clearly relevant and progressed to the next stage of screening. Study reports identified through the other additional information sources were not assessed for relevance.

Second, we screened the title and abstracts of retrievals from almost all information sources independently and in duplicate. Where there was a conflict on exclusion, the study report progressed to the next stage of screening. At this stage, there was a 5% rate of conflict in decision-making. Expert recommendations were not screened at this stage as responses provided study reports specific to the review remit and generally needed consideration at full text in the first instance.

Third, we screened the full text of study reports from all information sources independently and in duplicate. Where there was a conflict, a decision was made through recourse to a third member of the research team. At this stage, there was a 13% rate of conflict, reflecting some of the complexities in deciding if the population (e.g. care-experienced or children in need) or outcome (e.g. self-esteem) was eligible for the review.

An inclusion criteria proforma guided the selection process (see Report Supplementary Material 1). The review protocol specified that the proforma would be tested and calibrated by two reviewers screening the title and abstracts of the same 50 references. Owing to the size and brevity of the available literature, we increased this to 117 references, which was more than 1% of the retrievals from the electronic bibliographic database and website searches. Three members of the review team test screened the sample, with each retrieval being screened by two reviewers. There was a 10% conflict rate. Discussion among the review team indicated that the inclusion criteria were clear, but that we needed to ensure familiarity with the agreed criteria. For example, this included the countries (e.g. higher income countries) that were eligible for the review. The inclusion criteria proforma was regularly reviewed, with any clarifications reported in an update to the review protocol.

Economic evaluation searches and study identification

While we conducted the aforementioned searches and selection, we progressed with searches for economic evaluations by unpicking a recent relevant review of economic evaluations of children and young people’s social care interventions conducted by authors of the CHIMES review. 76

The 20 study reports included in the economic evaluation review were assessed against the CHIMES review’s inclusion criteria. We screened titles and abstracts independently and in duplicate. Eighteen progressed to screening at full text. None were assessed to be eligible for the present review. Reasons for exclusion were: wrong population (n = 14); wrong outcome (n = 3); evaluation report could no longer be accessed (n = 1).

The original review had run searches until 2018. Using the review’s search strategy, we reran searches from 2018 to May 2020. This retrieved 3411 additional citations. Following de-duplication, we screened 1636 retrievals at title and abstract, with 42 progressing to full text screening. No study reports were identified as eligible. Reasons for exclusion were: wrong publication type (n = 4); wrong outcome (n = 3); wrong population (n = 33). Two study reports could not be accessed. Economic evaluations were also searched for in the main CHIMES review searches.

Evidence map, relationship between study designs and method-level syntheses

Following the identification of eligible study reports, we constructed an evidence map. From here, we assessed which study reports would be included in method specific syntheses.

To be included in the description of programme theories, interventions had to have an associated outcome evaluation.

For process evaluations, we constructed a classification which identified evaluations as either ‘conceptually and/or empirically thin’ or ‘conceptually and/or empirically rich’. Thin process evaluations had to have an associated outcome evaluation to be included. They often formed part of a mixed-method study report anddid not have a dedicated description of method. They also lacked transferrable data or interpretations that could help to understand the context of intervention implementation and acceptability more broadly. Rich process evaluations were included as stand-alone study reports in the process synthesis, regardless of whether there was a linked included outcome evaluation, as they provided potentially generalisable contextual insight into how interventions might interact with complex system characteristics.

To support classification of thin and rich process evaluations, we drew upon an existing review’s classification system for the sampling of qualitative research to develop an assessment tool77,78 (Table 2).

| CHIMES classification of process evaluations | Score | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptually and/or empirically rich | 4 | Empirical: a large amount and depth of qualitative data AND conceptual: substantial interpretation by the authors and consideration of the transferability of data |

| 3 | Empirical: a large amount and depth of qualitative data OR conceptual: substantial interpretation by the authors and consideration of the transferability of data | |

| Conceptually and/or empirically thin | 2 | Empirical: a small amount of qualitative data, often from a limited number of participants OR conceptual: lack of interpretation by authors, with data presented fairly descriptively, potentially using an analytical approach (e.g. simple thematic analysis) that does not facilitate theoretical insights |

| 1 | Empirical: a small amount of qualitative data, often from a limited number of participants AND conceptual: lack of interpretation by authors, with data presented fairly descriptively, potentially using an analytical approach (e.g. simple thematic analysis) that does not facilitate theoretical insights |

Owing to the scale of the review, we made an a priori decision that we would only include interventions targeting the intrapersonal and interpersonal level in the outcome synthesis if they were evaluated with a RCT study design. For interventions operating at the organisational, community and policy level (which were identified as priority areas but are typically less amenable to RCT study designs), we included all eligible evaluation study designs (e.g. RCT and non-RCT) in the outcome synthesis.

Economic evaluations did not have to have an associated outcome evaluation.

Data extraction and data items

Data extraction process

We developed and calibrated a standardised data extraction form in EPPI-Reviewer 4, with extraction items being converted into a coding tree that included selectable a priori defined items and free-text coding. The coding tree had different sets of codes for each RQ and study design. For each study design, two to three study reports were used to develop and calibrate the extraction form. Once confirmed, we coded a minimum of 10% of study reports independently and in duplicate. The remainder of the study reports were coded by one reviewer and checked for accuracy by a second reviewer. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Review mapping, intervention characteristics and programme theory

In the first instance, we coded all eligible study reports as part of the evidence map. We extracted the following data items: country; publication date; intervention type according to socioecological domain; target population; intervention name; evidence type; study design; intervention outcome domains. As part of the convergent synthesis design, this mapping also served to structure the analysis undertaken as part of the subsequent process evaluation and outcome synthesis (e.g. grouping of outcomes for meta-analysis).

Intervention characteristics were coded in accordance with the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist for intervention development. 79 We extracted intervention rationale, material provided to participants, procedures and activities, delivery agent, mode of delivery, location of delivery, period of delivery and dose, plan for personalisation or adaptation and modifications undertaken. These items were parent codes, with child codes being inductively coded from the study reports. In practice, descriptions of interventions provided limited detail.

For study reports presenting a programme theory, data extraction was guided by tools used in other reviews80 (see Report Supplementary Material 2). We extracted method or process for developing the theory, name of theory, discipline of theory, socioecological domain of theory, description of theory and how the theory is articulated (e.g. a logic model). These items were parent codes, with child codes being inductively developed from the study reports.

Process evaluation extraction tool

We used different extraction tools with thin and rich process evaluations. For thin-process evaluations, which included quantitative and mixed method data, we used generic codes for context, implementation and acceptability (see Report Supplementary Material 3). For rich-process evaluations, data extraction was informed by the context and implementation of complex interventions (CICI) framework to emphasise the prominence of context in the review81 (see Report Supplementary Material 3). We extracted: study characteristics; context, which was classified according to the CICI domains of epidemiological, sociocultural, political, legal, ethical, geographical and socioeconomic; implementation, which was classified according to the CICI domains of implementation theory/strategy, implementation agents and implementation outcomes (including reach, receipt and fidelity); and acceptability, which was coded according to participants, implementers, funders and other stakeholders. These items were parent codes, with child codes inductively developed from study reports. We extracted data from the results sections of studies, but also authors’ narratives and interpretations.

Outcome evaluation extraction tool

For outcome evaluations, both randomised and non-randomised study designs had the same parent codes for data extraction. These were: study design; population; study arms and duration; analysis; effectiveness outcomes; mediators; moderators. For each type of study design, the child codes were tailored. Under the study design parent code for RCTs, we extracted method of recruitment, method of randomisation, unit of randomisation, cluster randomisation, blinding, allocation sequence, allocation concealment, total sample size and power calculation (see Report Supplementary Material 4). For non-RCTs, owing to the diversity of study designs, generic child codes were included: study design, method of recruitment and total sample size (see Report Supplementary Material 5).

Equity harms extraction tool

We extracted equity harms from study reports that included moderator analysis or interaction effects. Harms were initially categorised according to the PROGRESS-Plus for equity harms:82 place; race/ethnicity; occupation; gender/sex; religion; education; socioeconomic status; social capital; discriminated characteristics; relationship features; time-dependent relationships. Subdomains were inductively coded from study reports. We extracted PROGRESS-Plus domain, equity subdomain, absolute effects and relative effects.

Economic evaluation extraction tool

For economic evaluations, data were intended to be extracted according to the Drummond checklist,83 with key data items being direct and indirect costs, perspective, structural and empirical inputs, time horizon and cost-effectiveness.

Missing data

Where data were incomplete or information (e.g. outcome measurements or primary data to calculate effect size) was missing and the data could not be located, we recorded it as missing and considered it in the risk of bias (RoB) assessment.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment process

We appraised the quality of each study report independently by two reviewers. Quality appraisal was undertaken in EPPI-Reviewer 4.

Programme theory quality appraisal tool

We appraised programme theory study reports using a tailored appraisal tool developed for a previous systematic review with a theory synthesis81 (see Report Supplementary Material 2). While the review focused on mapping intervention theories, quality appraisal was useful in considering the strength of intervention’s associated theories and the extent to which they could help inform future intervention development and adaptation. The quality domains assessed were: clarity: clarity of construct definition; clarity: clear pathway from inputs to outcomes; plausibility and feasibility: theorised pathways are plausible; plausibility and feasibility: empirical evidence in support of theory; testability: evidence of empirical testing of theory; ownership: theory developed with children and young people; ownership: theory developed with parents, carers, social care professionals and other stakeholders; generalisability: theory presented as general; generalisability: theory describes its application to different contexts; and generalisability.

We adapted the appraisal tool to meet the needs of the CHIMES review by including two ownership domains, whereas the original version included one. This was due to our awareness of extant research and practice, where the voices of care-experienced children and young people are rarely privileged. As such we wanted to have a clear assessment of the extent to which they were engaged in intervention development. Domains were rated according to a binary assessment of yes or no.

Process evaluation appraisal tool

We appraised qualitative data within rich process evaluations using a tool developed in a previous systematic review84 (see Report Supplementary Material 3). We made a global assessment of overall reliability/trustworthiness and overall trustworthiness. Rigour domains included: steps taken to increase rigour in sampling; steps taken to increase rigour in data collection; steps taken to increase rigour in the analysis of data; findings grounded in/supported by the data. Usefulness domains included: breadth and depth of study; study privileges the perspectives and experiences of children and young people; study privileges the perspectives and experiences of parents, carers, social care professionals and other stakeholders. Domains were rated as high, medium, low or unclear.

Randomised controlled trials appraisal tool

We appraised outcome evaluations that were conducted using a RCT study design using the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomised trials (RoB 2)85 (see Report Supplementary Material 4). The quality domains assessed were: bias arising from the randomisation process; bias due to deviations from intended interventions; bias due to missing outcome data; bias in measurement of the outcome; and bias in selection of the reported result. Each domain has a number of signalling questions to inform assessment, which can be assessed as yes, probably yes, probably no, no, and no information. We judged the domains according to low RoB, some concerns and high RoB.

Non-randomised intervention studies appraisal tool

We appraised outcome evaluations using a non-randomised study design, or quasi-experimental design (QED), with the Cochrane Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I)85 (see Report Supplementary Material 5). The quality domains assessed were: bias due to confounding; bias in selection of participants into the study; bias in the classification of interventions; bias due to deviations from the intended intervention; bias due to missing data; bias in measurement of outcomes; bias in the selection of the reported result. We judged the domains according to low risk, moderate risk, serious risk, critical risk and no information.

Economic evaluation appraisal tool

We did not formally assess economic evaluations with a quality appraisal tool, but the one retrieved partial evaluation was considered in relation to the items of the Drummond checklist,83 which covers the reporting of study design, data collection and analysis and interpretation of results.

Data synthesis

Mapping of evidence, intervention characteristics and theories

We used scoping review methods and systematic mapping guidance to support the mapping of the evidence base86–88 (Figure 1). Following the coding of study reports, we constructed numerical and narrative summaries of evidence clusters and gaps, accompanied by descriptive tables and infographics. For details on intervention characteristics, a narrative summary described the interventions in detail, with an accompanying table presenting a summary of extractable data according to the TIDieR framework. For the subset of interventions reporting on intervention theory, these were narratively summarised according to the socioecological domains in which the theories operated and accompanied by a summary table.

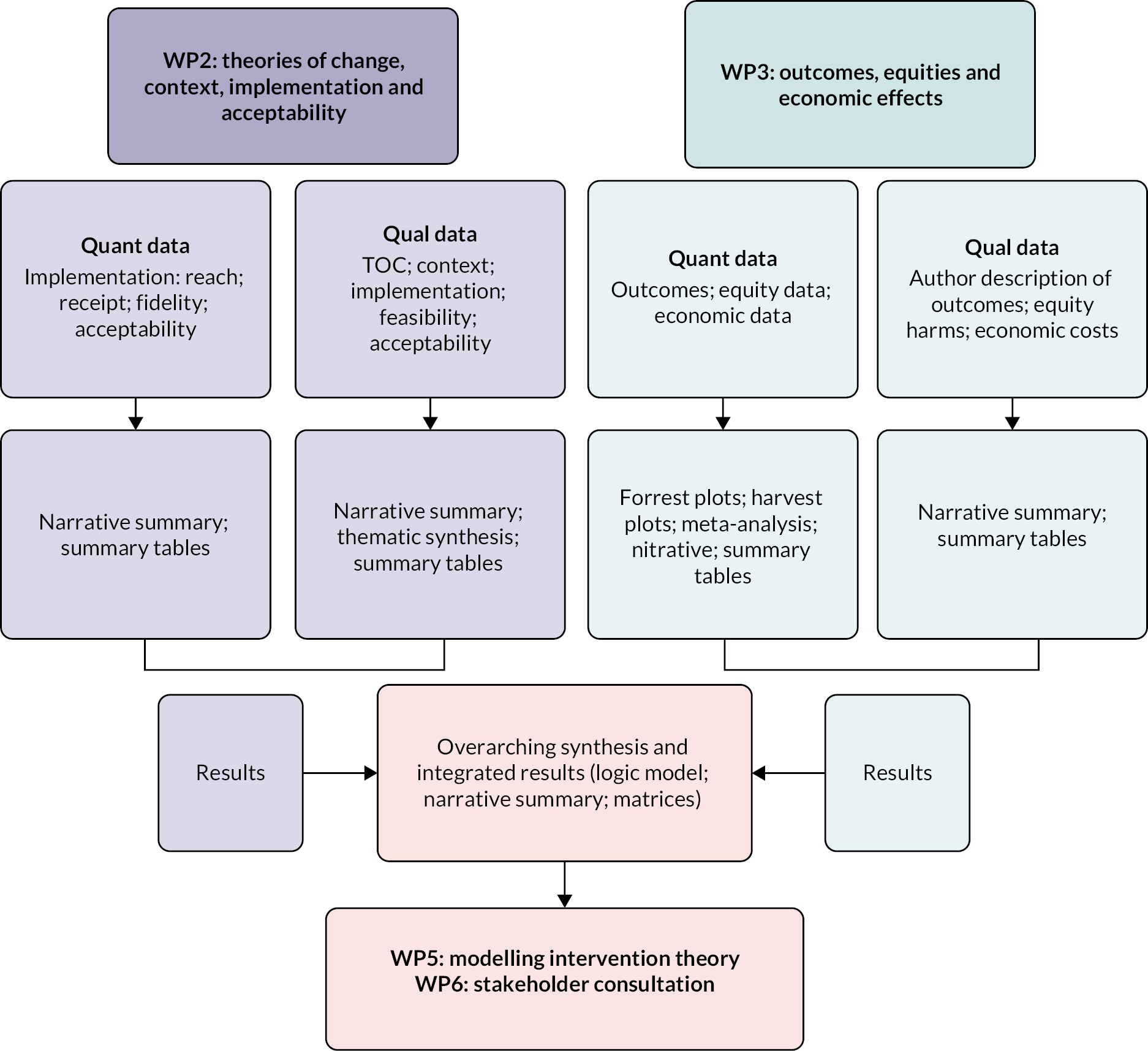

FIGURE 1.

Results-based convergent synthesis design.

Process evaluation synthesis

For thin-process evaluations, we constructed a narrative summary for the main domains of context, implementation and acceptability. This was accompanied by a summary table. For rich-process evaluations, we drew upon the principles of framework analysis and thematic analysis. 89–91 Analysis commenced with familiarisation of evaluations to become sensitised to within study and between study differences. We then developed a conceptual framework that integrated elements of process evaluations that might support explanation of intervention functioning: context, implementation and acceptability. Context and implementation were defined in reference to the CICI framework. 81 Study reports were then identified and coded according to this conceptual framework. Ten per cent were done independently and in duplicate, with the remainder coded and checked by one reviewer and verified by a second. The next stage was the charting of the coded, with study reports grouped according to context and how it related to implementation and acceptability. These categories formed the basis of initial themes or ‘context factors’ that went beyond the CICI framework and were more closely aligned with the data. The final stage was mapping and interpretation, which entailed transforming the initial themes into analytical themes, and generating new interpretive insights. For example, we transformed an initial theme related to the lack of time into a richer theme of ‘intervention burden’. This extended to include the cognitive, time and emotional burden linked to intervention delivery and engagement. The initial phase of stakeholder consultation supported this transformation. We presented the synthesis narratively, with a summary table reporting study report characteristics and the key context factors presented at the individual-study level.

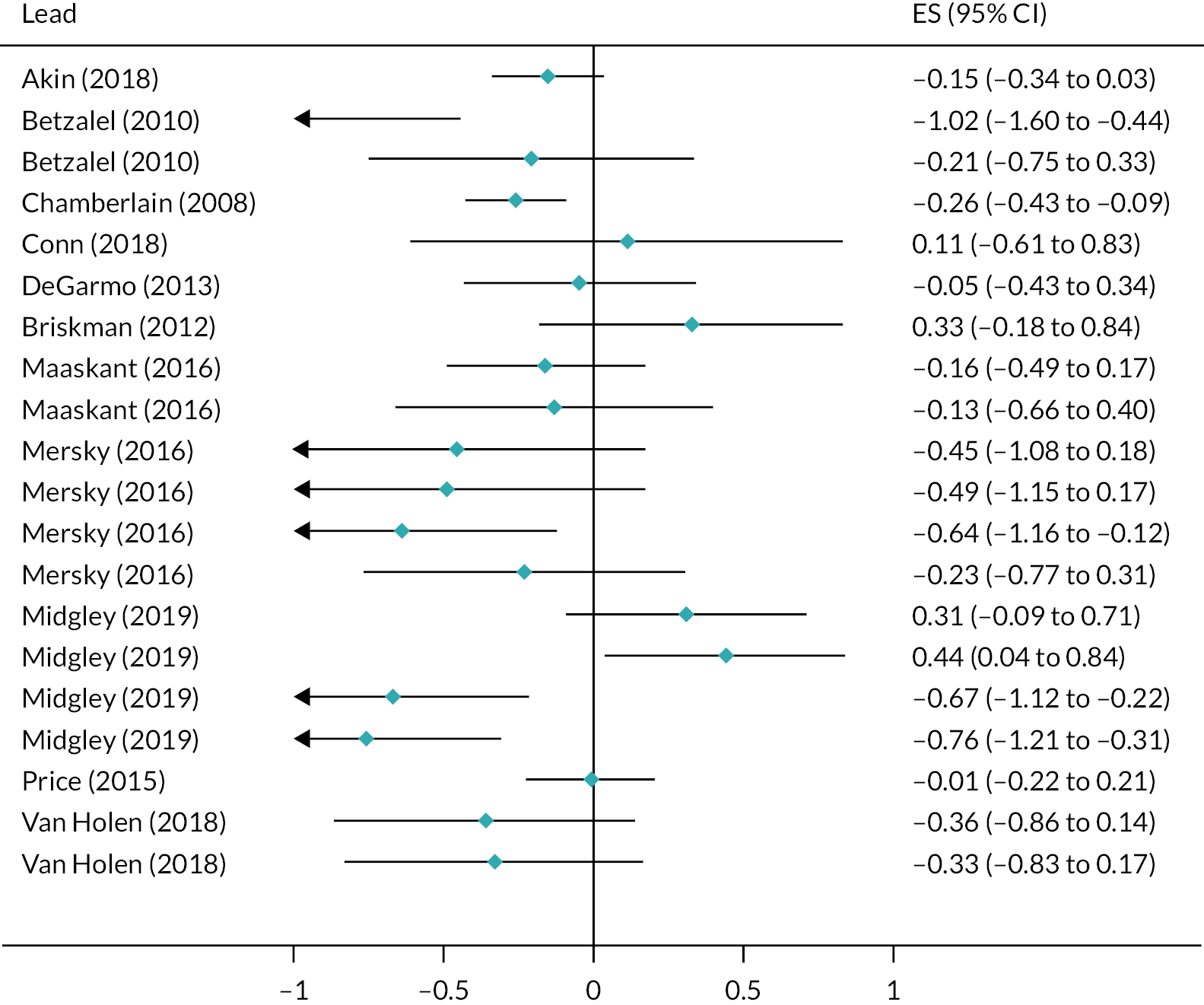

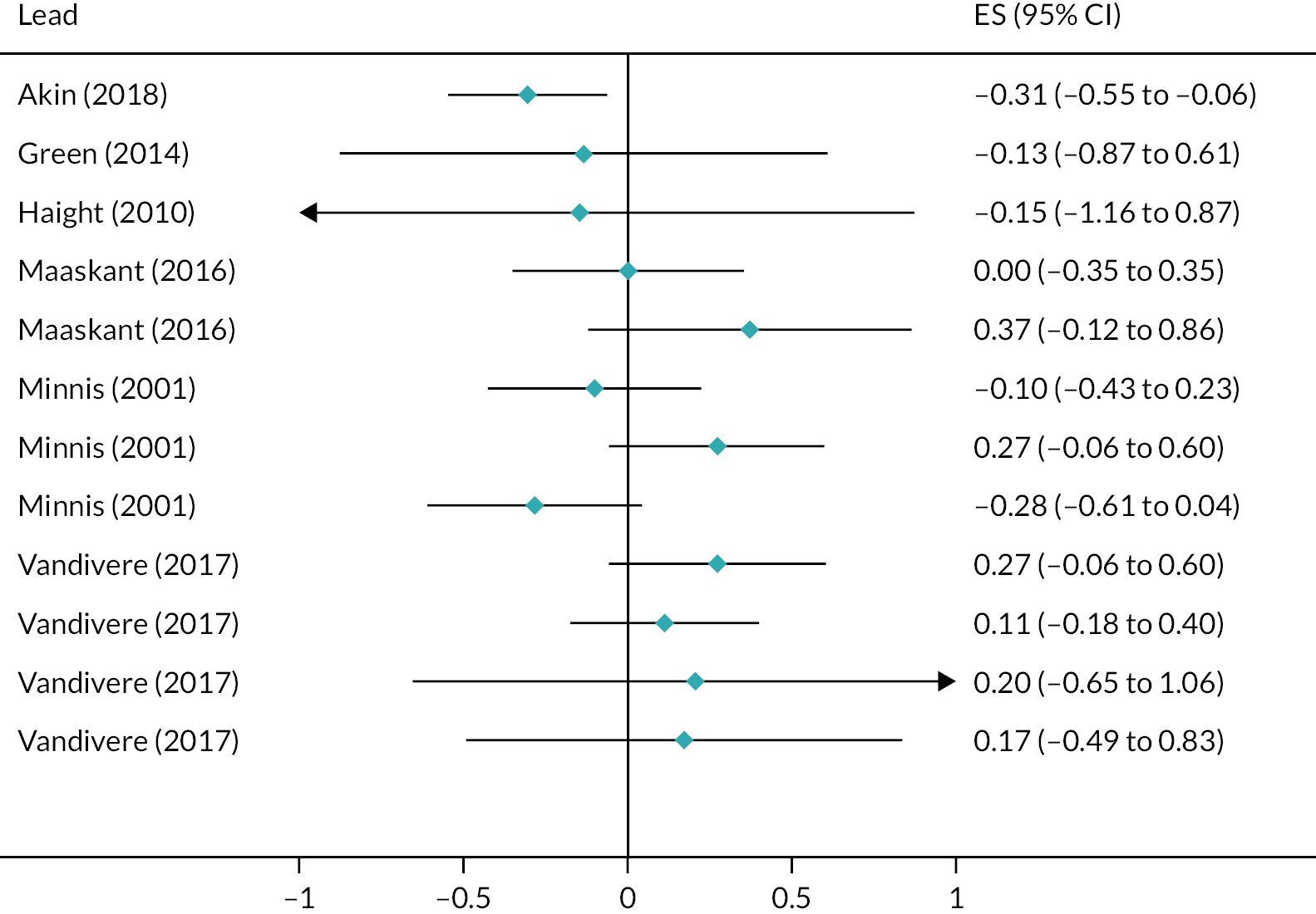

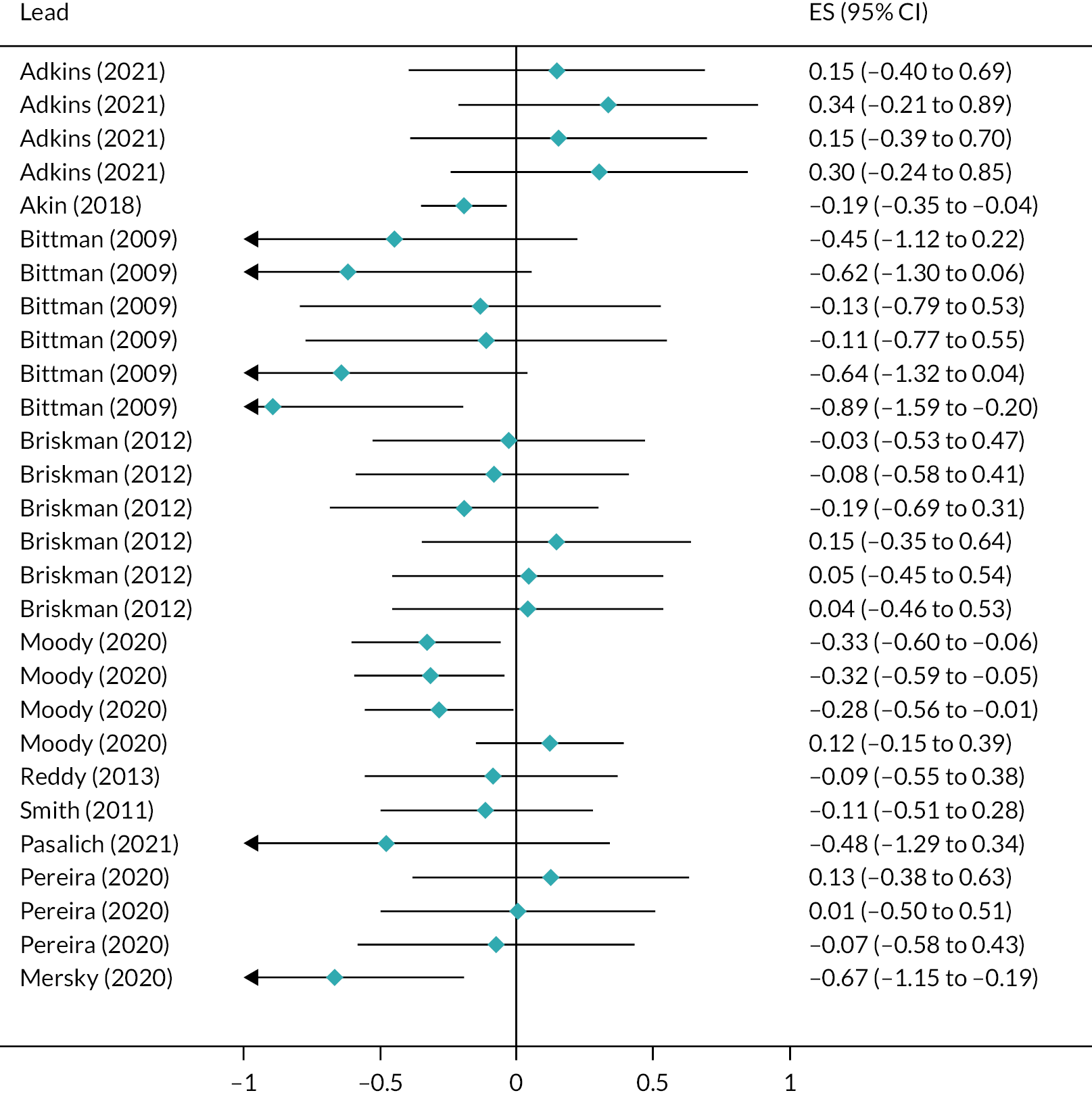

Outcome evaluation synthesis

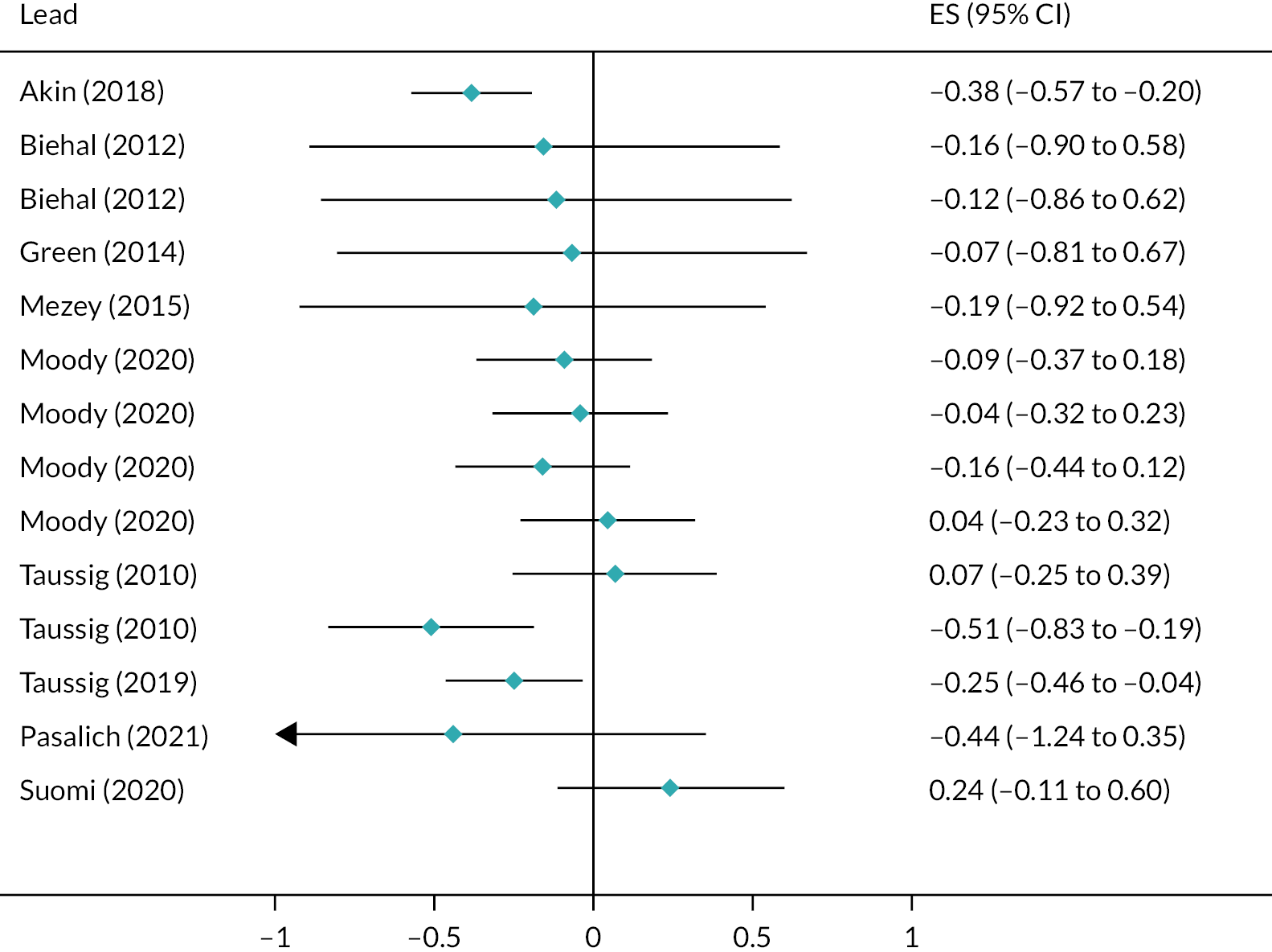

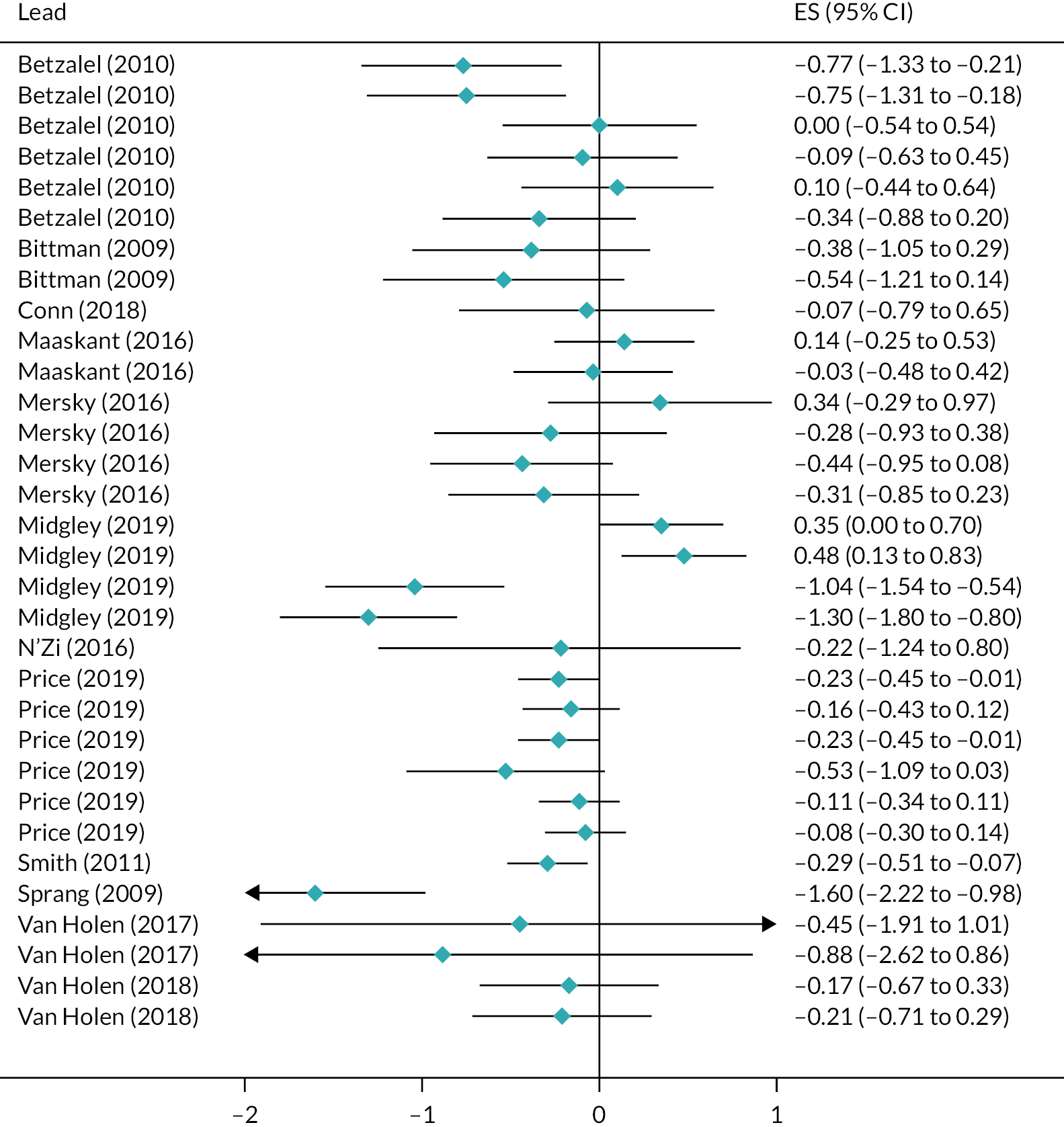

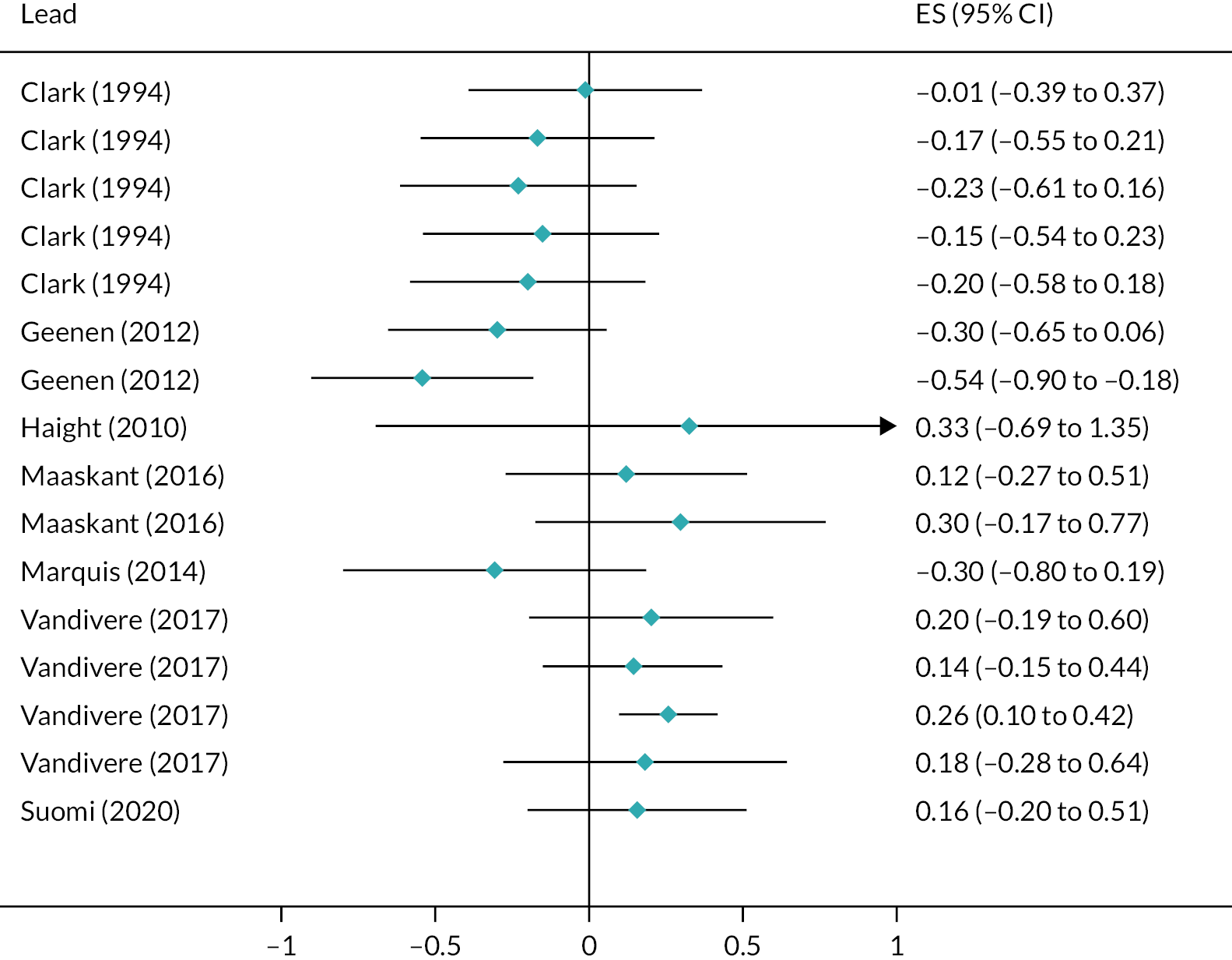

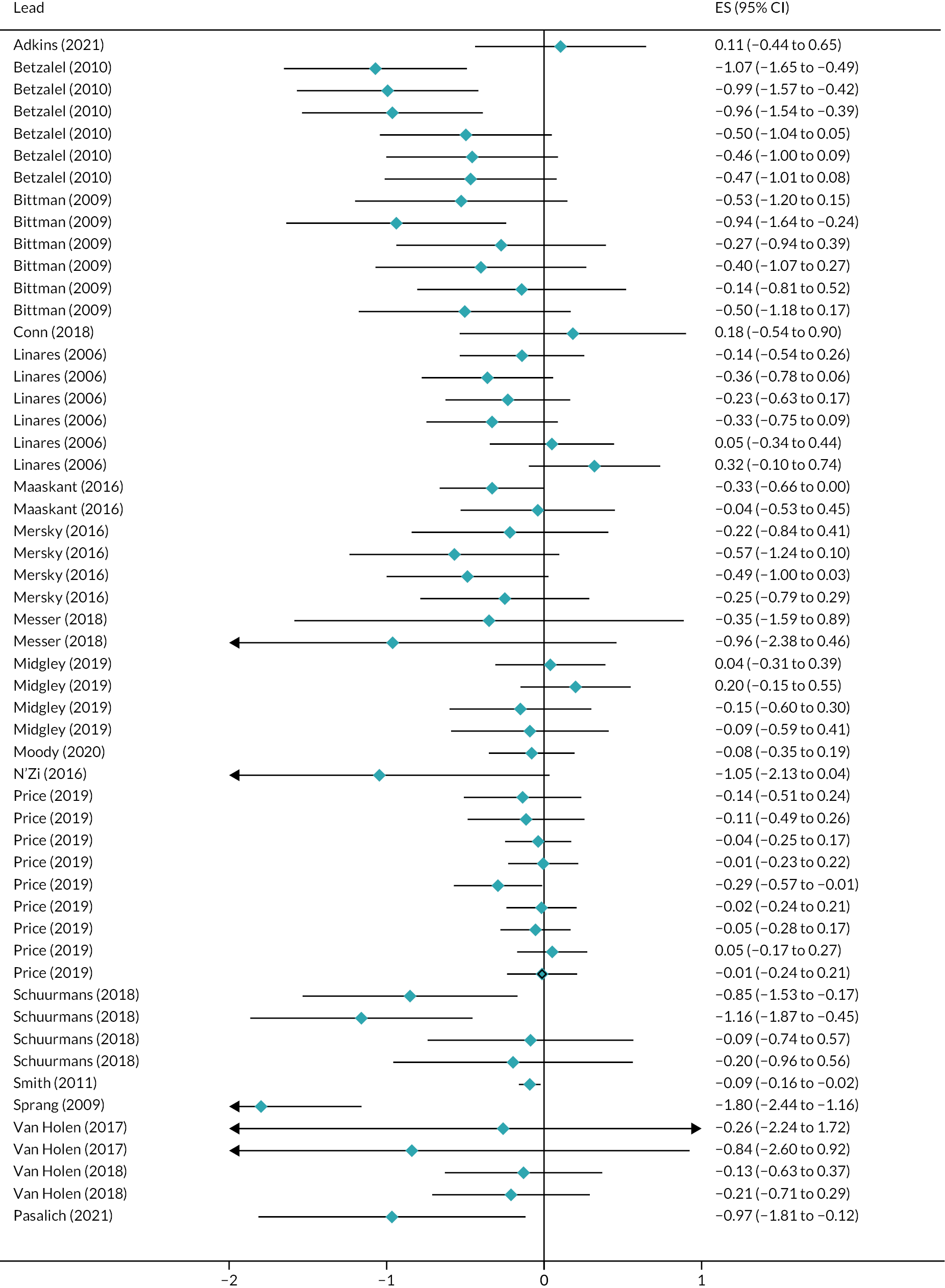

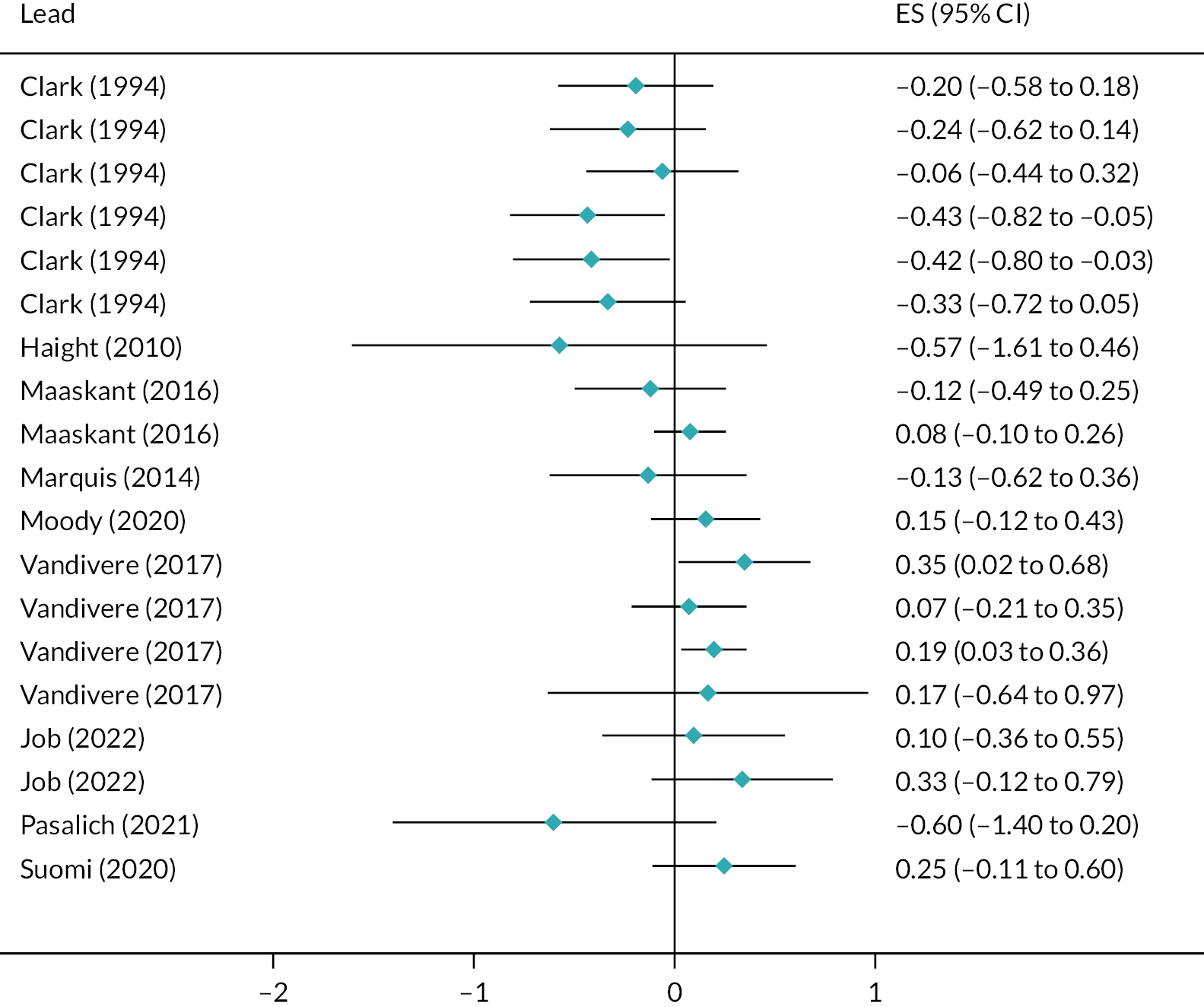

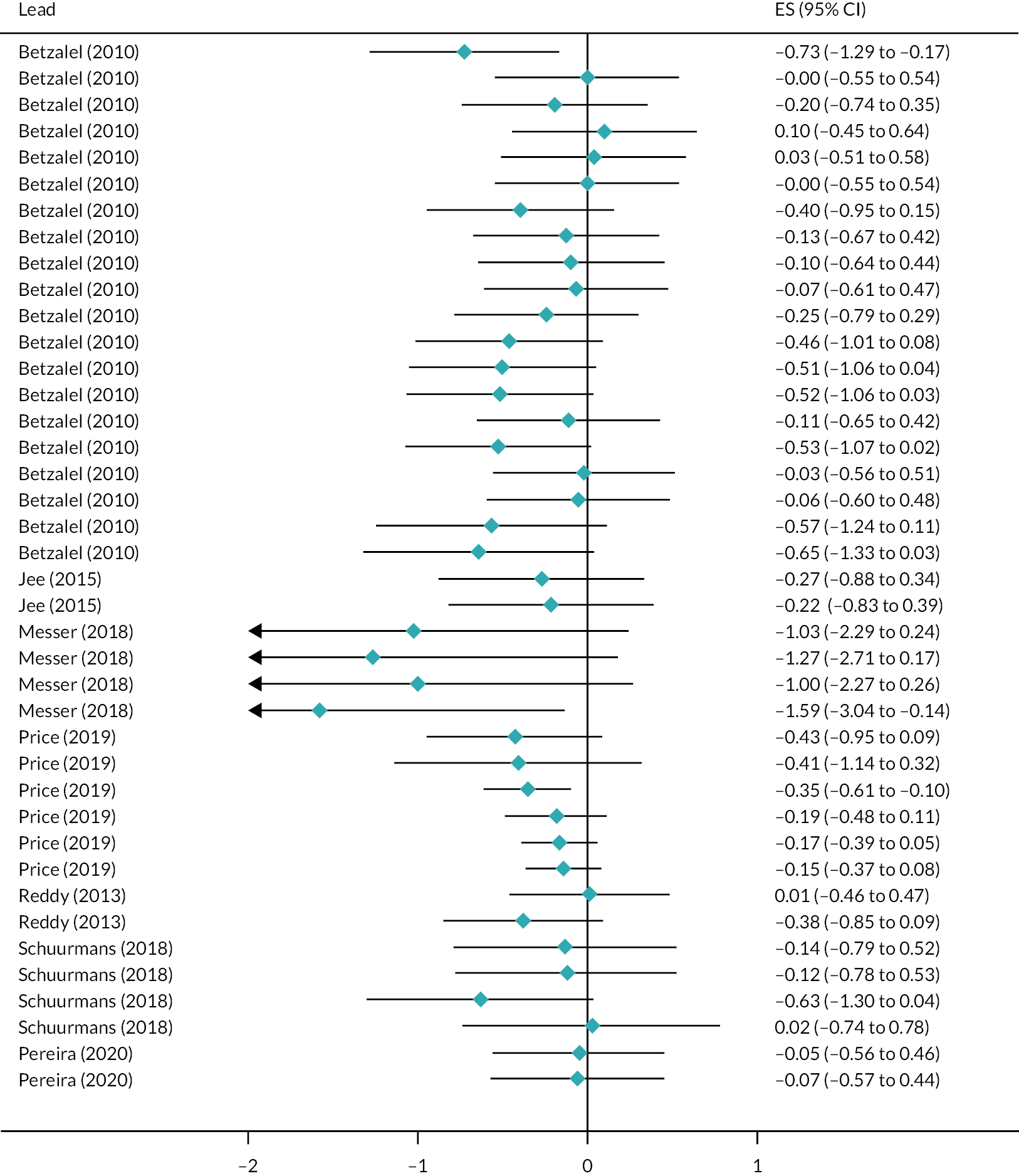

We constructed a narrative summary and descriptive tables to present the results of outcome evaluations. We conducted meta-analyses for outcome categories evaluated by RCT study designs, relating to mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders as specified by ICD-11. There was not an adequate number of studies to conduct meta-analyses for the outcome domains of subjective well-being or suicide-related outcomes. Owing to the small number of eligible non-randomised evaluations, these were also not synthesised through meta-analysis.

For the meta-analysis, we extracted effect estimates for the subdomains of mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders from study reports. Where appropriate, outcomes were converted to odds ratios using logistic transformation for pooling. Estimates from cluster randomised trials were checked for unit of analysis issues and, where necessary, an inflation factor was applied to the standard error of effect estimates. Where intracluster correlation coefficients (ICC) were not available and effect estimates had not been adjusted for clustering, we imputed an ICC using the average of estimates for specific outcomes from ‘most similar’ intervention evaluations.

We undertook robust variance estimation meta-analyses according to intervention outcome and time point, considering up to 6 months from baseline as short-term outcomes, and outcomes measured between 7 months and 2 years as long term. Robust variance estimation meta-analysis is a method that permits the inclusion of more than one effect estimate per study in a meta-analysis; this is in contrast to standard meta-analysis models that assume independence between individual effect estimates. It is common in meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for outcome evaluations to present multiple relevant effect estimates per outcome (e.g. multiple estimates of child behavioural problems). This method permitted use of all relevant information from included studies. Within each meta-analysis, we examined heterogeneity using a combination of Cochran’s Q, τ2 and I2. Where heterogeneity was substantial (I2 > 50%), we scrutinised included studies to hypothesise and explore the reasons for this.

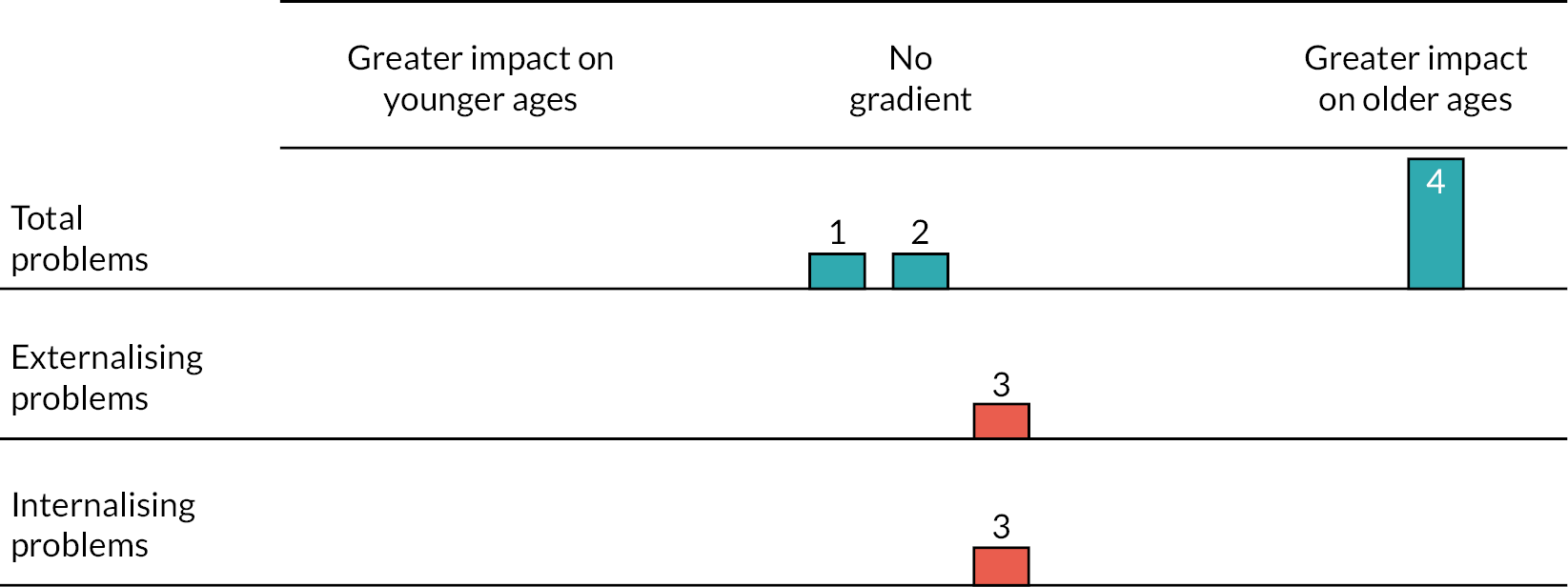

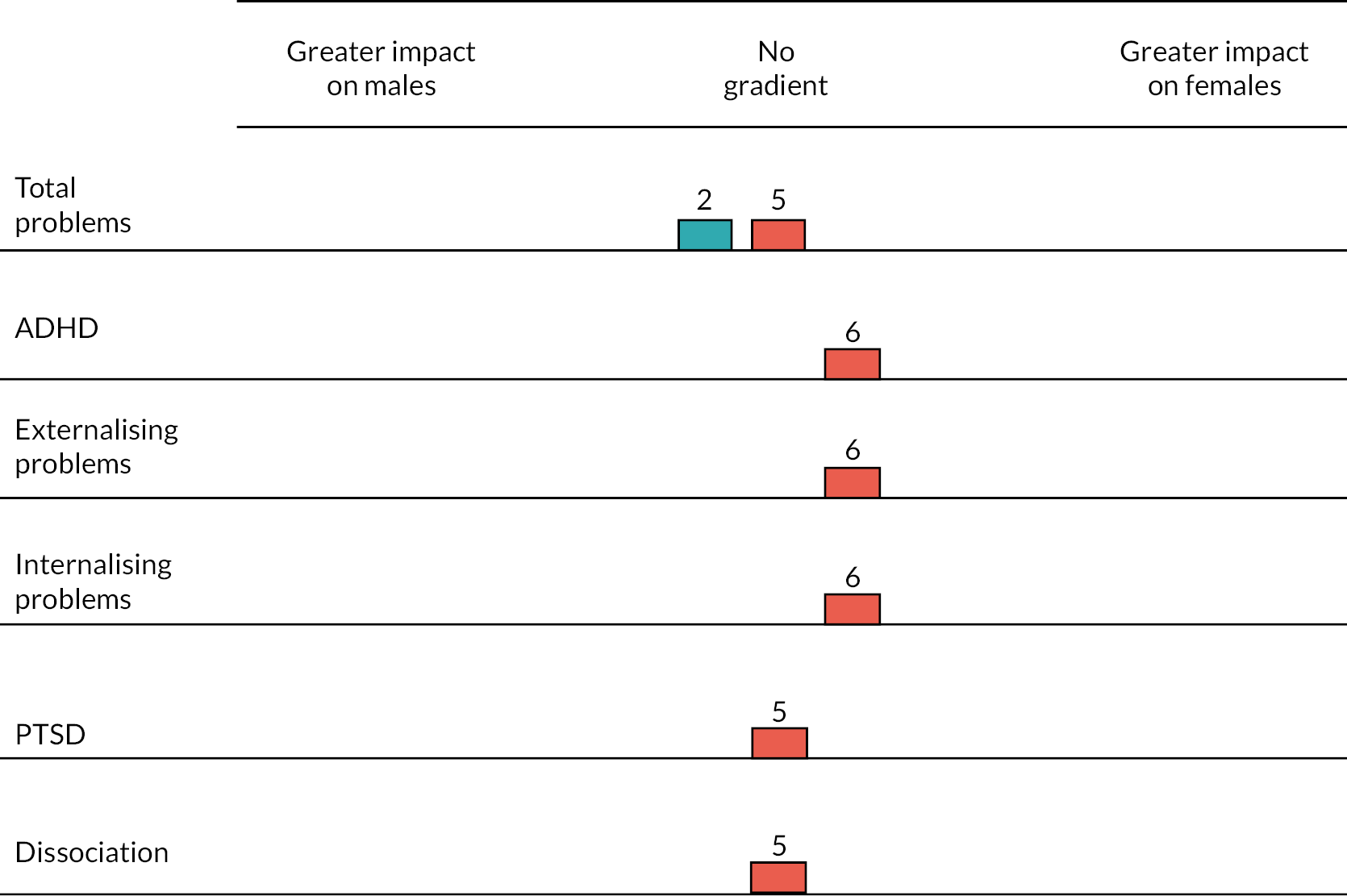

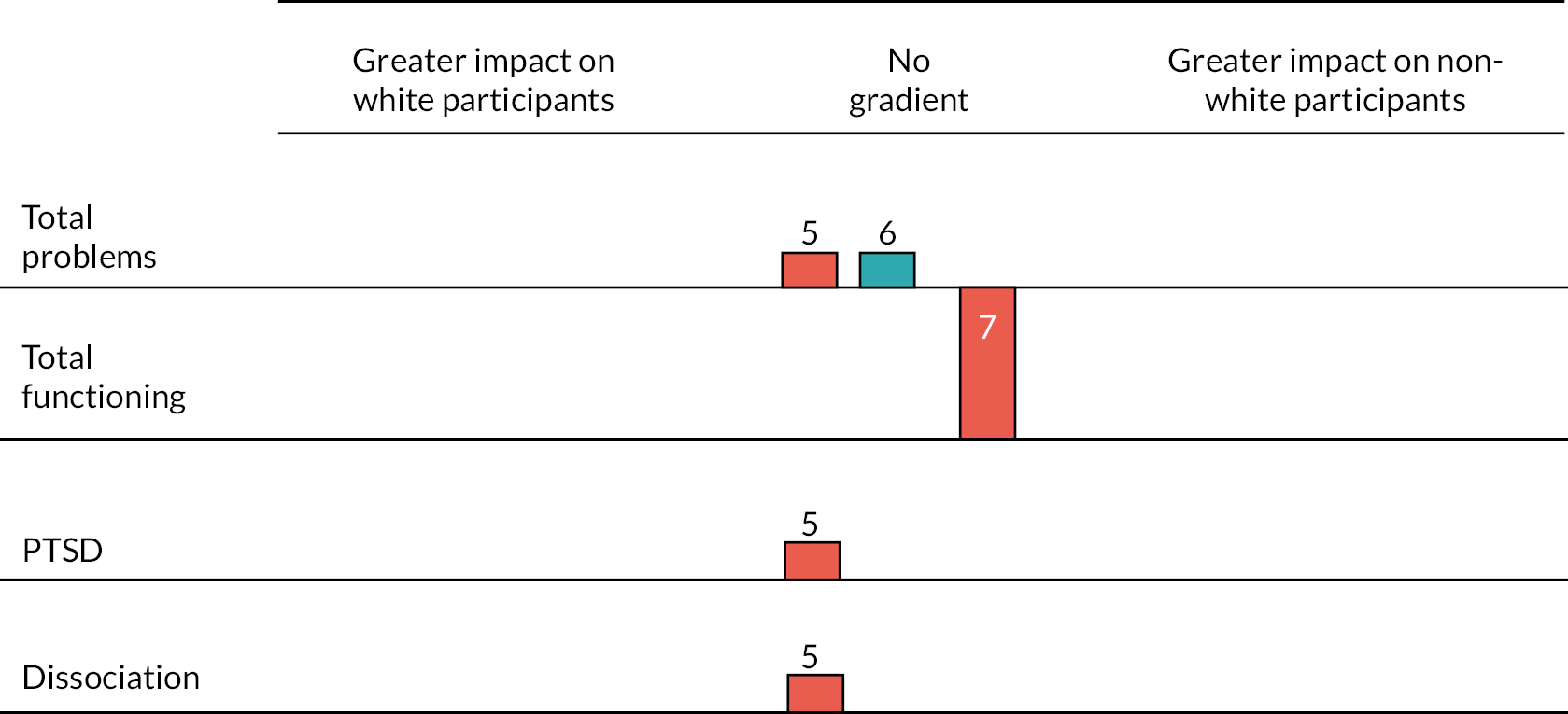

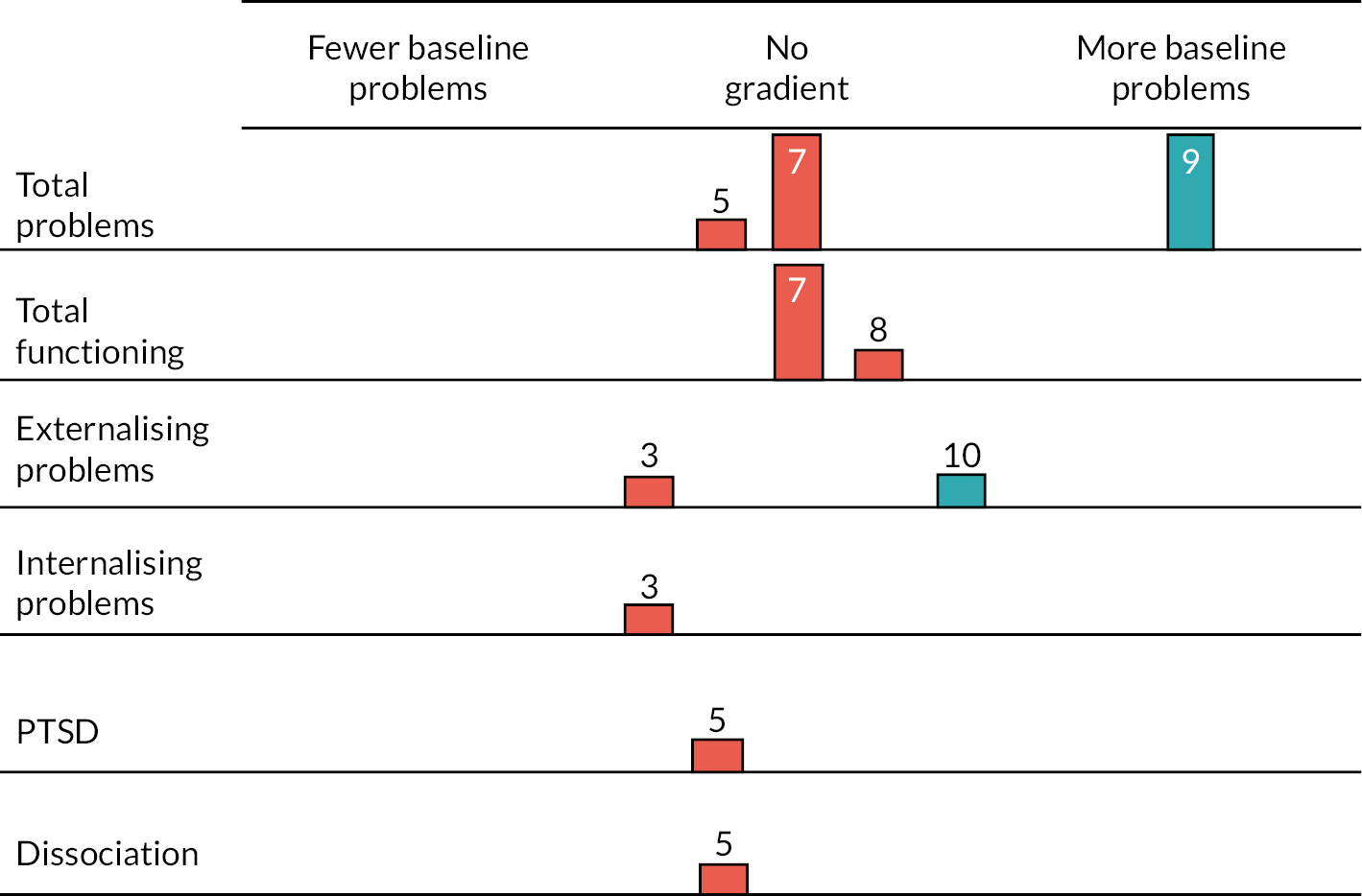

Equity harms synthesis

We produced a narrative overview and summary table of equity harms. We intended to construct harvest plots for the three key outcome domains of the review: (1) subjective well-being; (2) mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders and (3) suicide-related outcomes. Owing to the number of study reports presenting moderator analysis or interaction effects, harvest plots could only be generated for mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders.

Economic evaluation synthesis

Only one partial economic evaluation was identified, and we summarised this in narrative form.

Method-level syntheses integration and review-level synthesis

As reported, we used a results-based convergent synthesis design,73,74 which supported the integration of method-level syntheses to construct a review-level synthesis (see Figure 1). There were two key mechanisms through which we integrated the method-level syntheses. First, the synthesis of thin and rich process evaluations was integrated with outcome data to explain intervention effectiveness and variations in effects. 92 In alignment with stages 4 and 5 of the TRANSFER model,72 which focuses on assessing the relevance of international review evidence to the local context, integration paid attention to the context in which outcome and process syntheses were conducted and the implication for intervention in the UK moving forward.

Second, we constructed two integrative matrices, which were adapted from an approach used in a 2017 Cochrane review. 93 This was conducted as part of WP6. The first of these 2 × 2 matrices mapped interventions and their evidence base by stakeholder (both in process evaluations and consultations) preferences in regard to intervention theories and types. This was intended to establish whether current interventions are relevant and responsive to needs within the UK context. The second of these 2 × 2 matrices mapped intervention outcomes by stakeholders’ priority outcomes to assess if interventions are targeting desired effects.

Assessment of certainty

For the assessment of the certainty of the evidence base, we used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE)94,95 and GRADE Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual)96 tools. This supported the convergent synthesis design and maps to stage 6 of the TRANSFER framework. 72

We applied the GRADE tool to evidence of effectiveness from randomised and non-RCTs. 95,97 Certainty was assessed for short- and long-term outcome subdomains relating to subjective well-being, mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders and suicide-related outcomes. This was done for the RCTs that assessed intrapersonal, interpersonal, organisational, community and policy-level interventions. It was conducted for non-randomised evaluations of organisational, community and policy-level interventions.

For both randomised and non-randomised studies, we conducted an assessment to decide if an individual study was biased or unbiased for each outcome, which was largely derived from the quality appraisals. RCTs had a baseline rate of high certainty and non-randomised studies a low certainty rating. As per GRADE guidance, the certainty assessment per outcome was then determined by prespecified criteria. Certainty was rated down according to RoB, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness and publication bias. Certainty was rated up for large magnitude of effect, dose–response gradient and residual confounded would decrease the magnitude of effect (where this is an effect). The certainty of the evidence was assessed according to very low, low, moderate and high. Where there were serious concerns about the evidence, it was downgraded by + 1 points, and where there were very serious concerns, it was downgraded by + 2 points. Where there were reasons to upgrade the evidence, it was upgraded by + 1 point if there was sufficient reasoning and by + 2 points if there was strong reasoning.

We used the GRADE-CERQual96 tool to assess the certainty of evidence from rich process evaluation studies, with six statements being generated. Each statement was assessed across four components: methodological limitations; coherence; adequacy; and relevance. Each evidence statement was rated as high in the first instance and was rated down if there were concerns about each component. From here, an overall CERQual assessment of confidence in the evidence was made, with an accompanying explanation. Confidence in the evidence was rated as high, moderate, low or very low.

Work package 4: modelling of intervention theory (research question 5)

Drawing upon the integrated data from WP2 and WP3, we identified evidence-based interventions and, where reported, associated theories that could potentially address the CHIMES review outcomes. As per the protocol, the aim was to generate an overarching candidate intervention and theory to share as part of stakeholder consultations for WP5. This was to be accompanied with a narrative description and logic model. However, as the review indicated a range of interventions with a largely mixed evidence base and a lack of reported programme theories, we felt that they could not be integrated into a single approach and modelled without further consultation from stakeholders. As such, we decided to share descriptions of individual evidence-based interventions from across the socioecological domains for stakeholders to discuss.

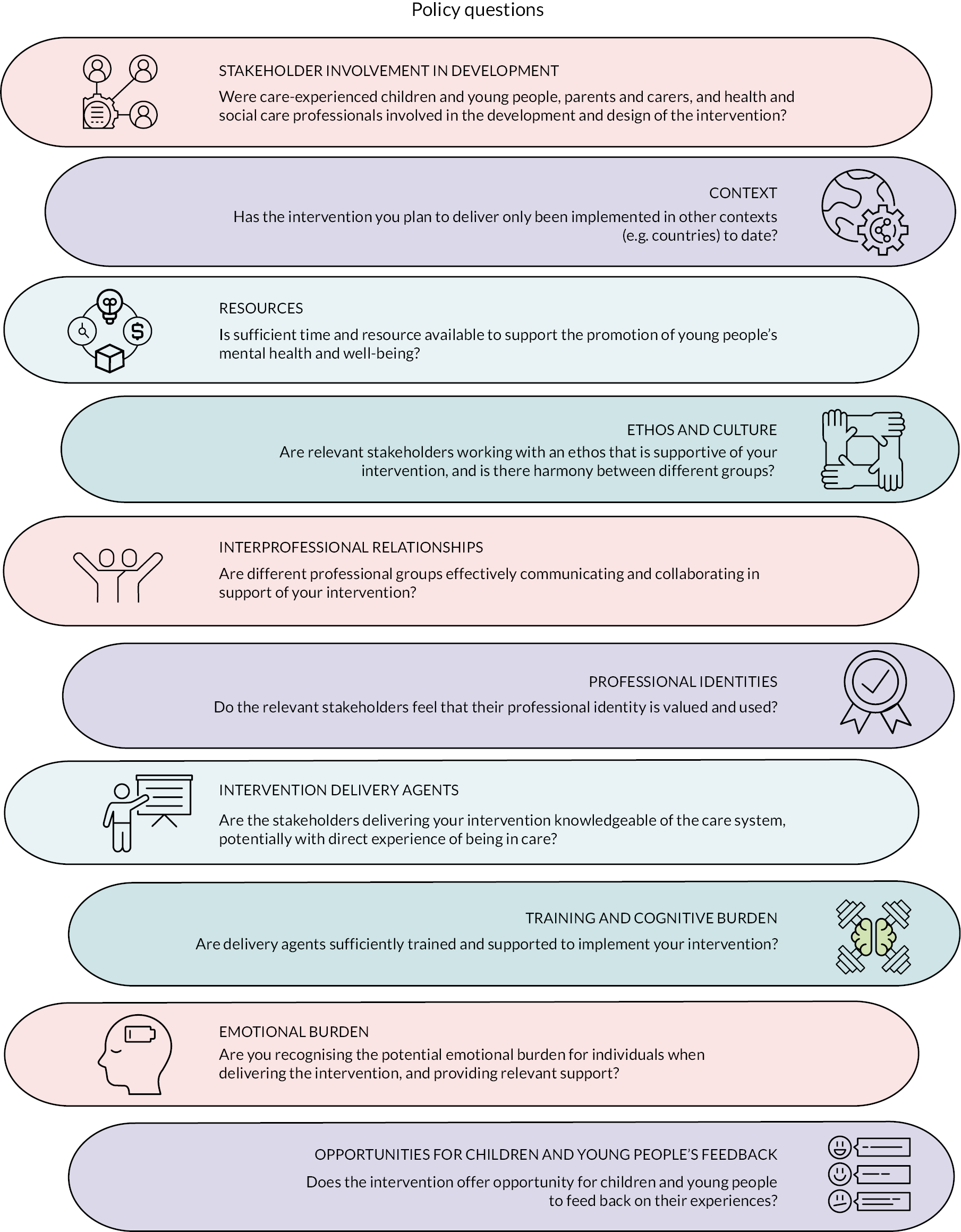

Work package 5: stakeholder consultation and intervention prioritisation (research question 6)

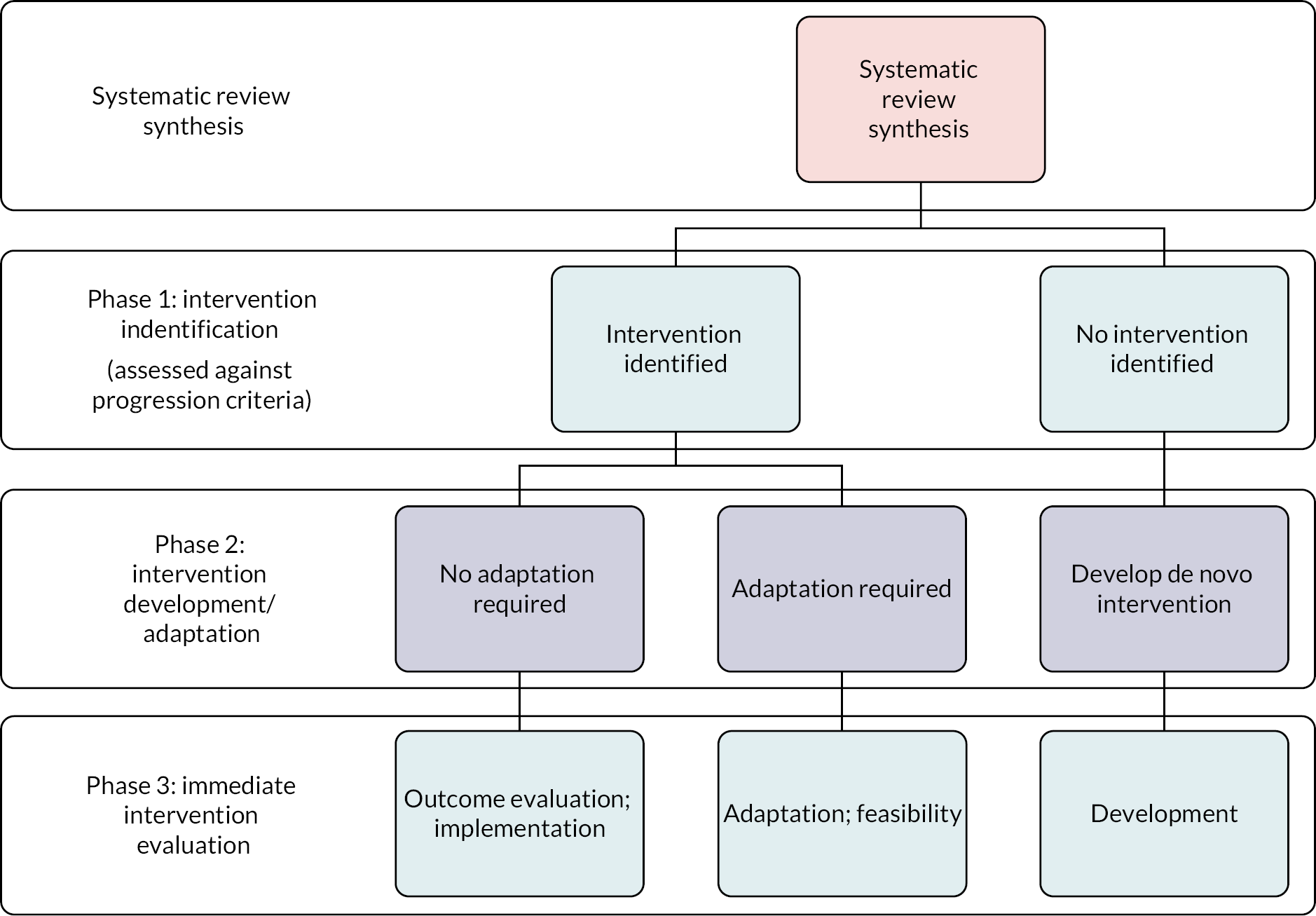

The final stage of the review involved seven stakeholder consultations to consider the applicability of the review evidence base to the UK context, and identify a potential intervention for further development, adaptation and evaluation. This WP responds to the last stage, stage 7 of the TRANSFER model, which recommends discussing the transferability of review findings with stakeholders. 72 The membership of the stakeholder consultations, the structure of events, and the key discussion points are reported in Chapter 6. As part of the consultations, we conducted three phases of assessment, as outlined in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Intervention prioritisation for development, adaptation and evaluation in UK context.

Phase 1: intervention identification

We asked stakeholders to assess the potential candidate evidence-based intervention theories and types identified from the review against the following progression criteria: (1) acceptability; (2) potential effectiveness and (3) feasibility (particularly feasibility of implementing an intervention in the UK context). To support this process, consultations considered the key context factors identified from earlier consultations and the process evaluation synthesis.

Phase 2: intervention development and adaptation

The next stage was to identify an intervention to take forward for future development, adaptation and evaluation. Stakeholders in this phase of consultation, combined with the discussion from earlier consultations, generally felt that the interventions identified in the evidence base were not exactly relevant to the UK context. As such, much of the emphasis of discussion was on the potential for de novo intervention development. To support this, we considered any additional context factors that would need to be taken account of, preferable intervention theories and associated components, and priority outcomes. Following the consultations, we cross-referenced this discussion with the review evidence base to check if there were interventions that may not necessarily have established evidence of effectiveness, but enacted the preferred theories, used suggested components and targeted priority outcomes. This was considered as part of the 2 × 2 integrative matrices on priority intervention types, theories and outcomes.

Phase 3: intervention evaluation

The final phase was considered by the research team and focused on recommendations for future research, considering potential intervention development and evaluation in accordance with Medical Research Council’s guidance. 98

Ethical considerations

Cardiff University School of Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (REC) considered the CHIMES review to assess whether ethical approval was required from the REC. The REC requested to consider the review in two discrete parts: (1) desk-based review (WP1–4) and (2) consultations to support the identification of an intervention for the UK context (WP5). The REC agreed that neither of the two stages of work required ethical approval. This was largely due to consultations not involving the generation of individual-level participant data, meaning that individual names were not recorded and only summary notes of discussion were taken. We did undertake steps to ensure the safety and well-being of participants engaged in stakeholder consultations. One of the primary reasons for using pre-existing groups for young people and carers (e.g. CASCADE) was that there was a clear infrastructure available to participants after consultation in the event that they required follow-on support.

Summary

In this chapter, we have reported the methodology for the CHIMES review. The next chapter presents the results of the searches, the associated PRIMSA flow diagram and the results of the mapping phase of the study.

Chapter 3 Mapping interventions

About this chapter

In this chapter, we report the mapping of interventions and associated study reports included in the CHIMES review. It addresses the following RQ:

-

What are the types, theories and outcomes tested in mental health and well-being interventions for care-experienced children and young people?

As indicated in the methodology, construction of the evidence map served two functions. First, it supported mapping of key evidence clusters and gaps, with the identification of paucities in certain types of intervention research offering direction to strengthen the evidence base moving forward. Second, given the potential size of the review, it facilitated refinement and confirmation of the scope of the subsequent method-level syntheses.

In this chapter, we first present the results of the searches. We then detail the characteristics of included interventions and study reports, mapping the types of evidence retrieved for each RQ, the rates of report, geographical location, types of interventions, intervention characteristics, programme theories and intervention outcomes. We further summarise key intervention clusters and gaps and the confirmed scope of the systematic review.

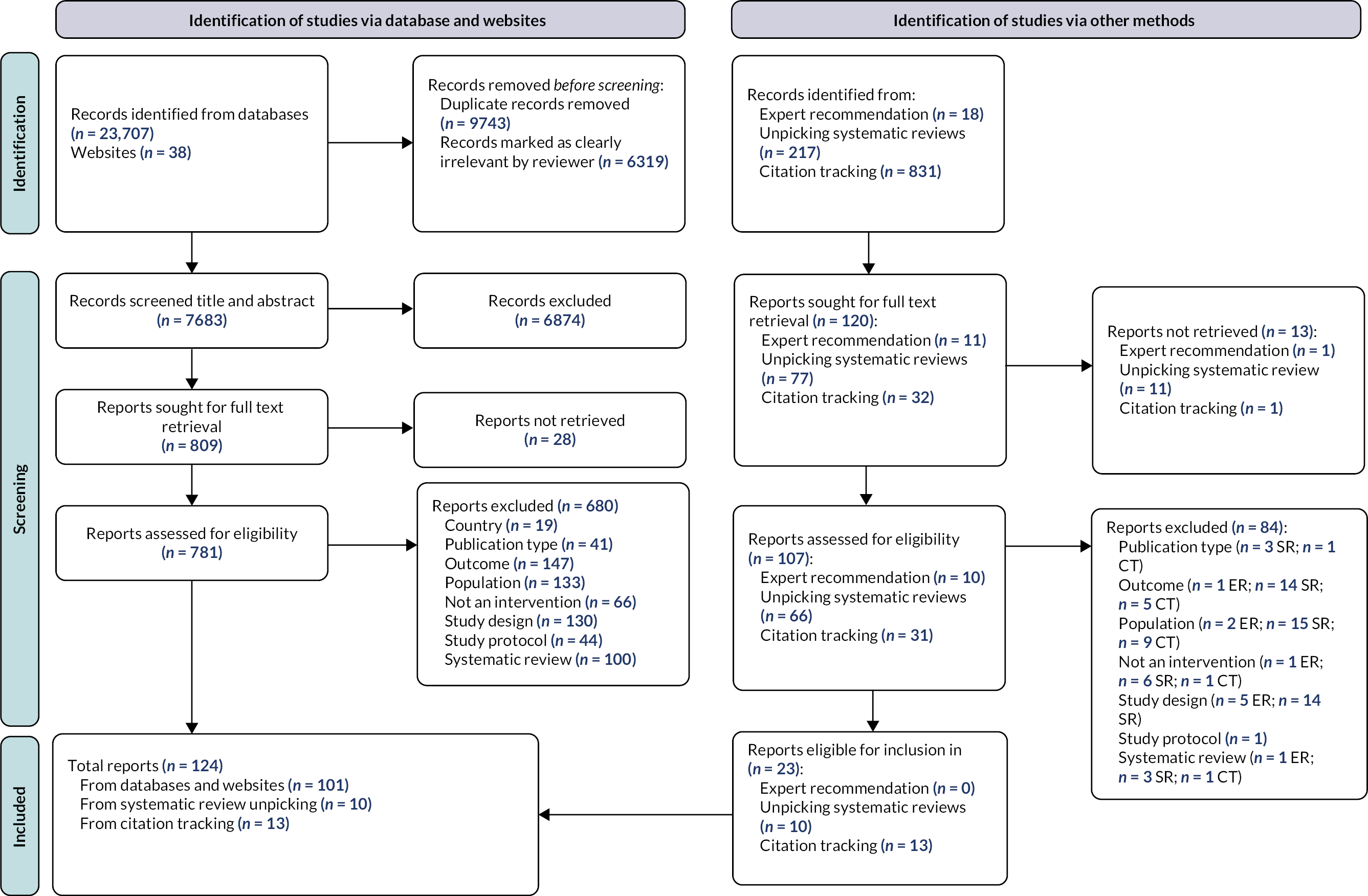

Search results and study report inclusion

The process of study report retrieval and the number of reports identified through each data source is reported in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 3). In total, 124 unique study reports were included in the review, linked to 64 interventions. Of these, 101 were from databases and websites, 10 were from the unpicking of systematic reviews and 13 were from citation tracking.

FIGURE 3.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram. CT, citation tracking; ER, expert recommendation; SR, systematic review.

Study characteristics

Types of evidence

All 124 reports, linked to 64 interventions, were eligible as part of the evidence map. We have included these in the present chapter (RQ1). Study reports presented theory, process, outcome and economic evaluations. We classified study types by evaluation design to support understanding of whether current evaluation practice in this area is conducted in accordance with methodological guidance on intervention development and evaluation, which recommends the integration of these four evaluation types;98,99 24 reports provided an explanation of interventions’ programme theory (RQ1);25,27,28,30,100–119 50 process evaluations, both conceptually rich and thin, provided data on context, implementation and acceptability (RQ3; RQ4). 27,34,108,114,118,120–164 There were 86 outcome evaluations, using a RCT or non-randomised study design (RQ2). 26,27,29,31,33–35,100,103,108,109,111,113–118,122,128,130,131,134,135,140,142,143,147,148,151,157–160,162,163,165–212 There was one partial economic evaluation (RQ2). 213 The study reports according to each evidence type are presented in Report Supplementary Material 6.

Rates of report

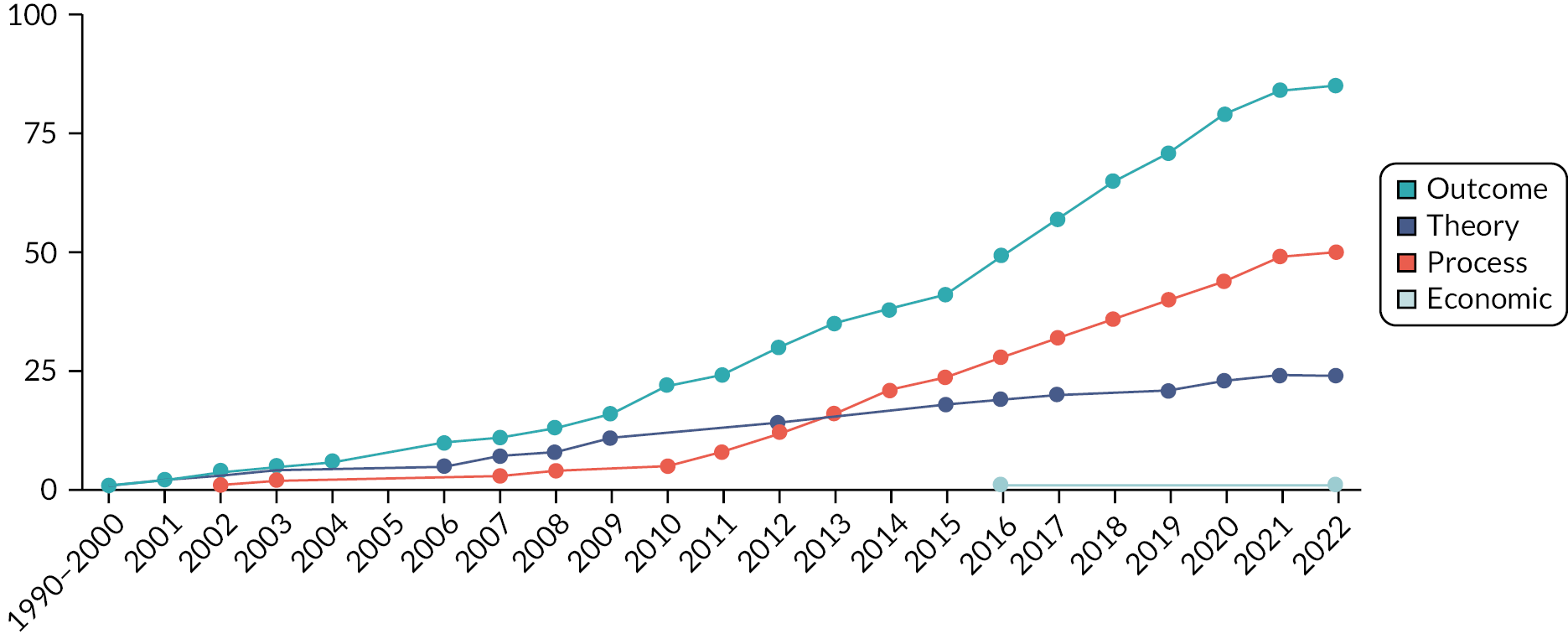

The 124 study reports were published between 1990 and 2022. Only two reports were published between 1990 and 2000. 105,170 Reports were published by subsequent years as follows: 1 in 2001;178 3 in 2002;106,109,148 3 in 2003;30,126,202 1 in 2004;188 5 in 2006;101,171,174,203,205 2 in 2007;108,112 3 in 2008;117,127,192 6 in 2009;28,107,110,169,184,206 6 in 2010;26,131,168,172,197,211 4 in 2011;136,146,160,183 7 in 2012;100,102,114,122,134,159,201 8 in 2013;35,103,111,125,133,142,153,187 7 in 2014;31,120,124,129,141,158,176 5 in 2015;25,27,135,164,182 12 in 2016;104,144,150,151,163,177,180,181,189,191,194,213 11 in 2017;34,113,121,149,152,173,175,186,190,198,204 10 in 2018;33,128,132,143,145,166,185,193,199,200 8 in 2019;29,116,123,140,147,161,167,207 11 in 2020;157 and 8 in 2021115,130,137,139,155,162,165,210 and 1 in 2022. 157 Figure 4 reports the number of study reports published by year according to the review RQ and evidence type. Study reports are double counted where they report evidence according to more than one RQ. There were no significant increases in reporting on programme theory. In contrast, there was a growing number of intervention evaluations using RCT and non-randomised evaluation designs and an expansion in the use of process evaluation.

FIGURE 4.

Cumulative rate of report and evidence type.

Geographical location

We specified that study reports had to be located in higher income countries as the review was primarily concerned with intervention transportability to the UK context. In total, the study reports were from 12 countries, with one report being conducted across both the USA and UK. 102 A significant majority of reports were from the USA (n = 77). 25,26,28–30,33–35,101–108,110–112,115–117,119,123–125,127–129,131,132,135,137,141,142,145–147,152,156,158–161,164–167,169–172,174,177,180–184,186–192,194,197,199–202,205–207,210–212 The remainder were from UK (n = 22);27,31,102,109,118,120–122,126,130,133,134,136,139,140,149–151,154,155,178,179,213 the Netherlands (n = 6);143,163,173,175,193,203 Belgium (n = 3);113,114,185 Australia (n = 3);153,162,209 Portugal (n = 3);144,204,208 Canada (n = 2);148,176 Ireland (n = 2);138,196 Israel (n = 2);100,168 Germany (n = 1);157 Spain (n = 1)198 and Sweden (n = 1). 195

Types of interventions

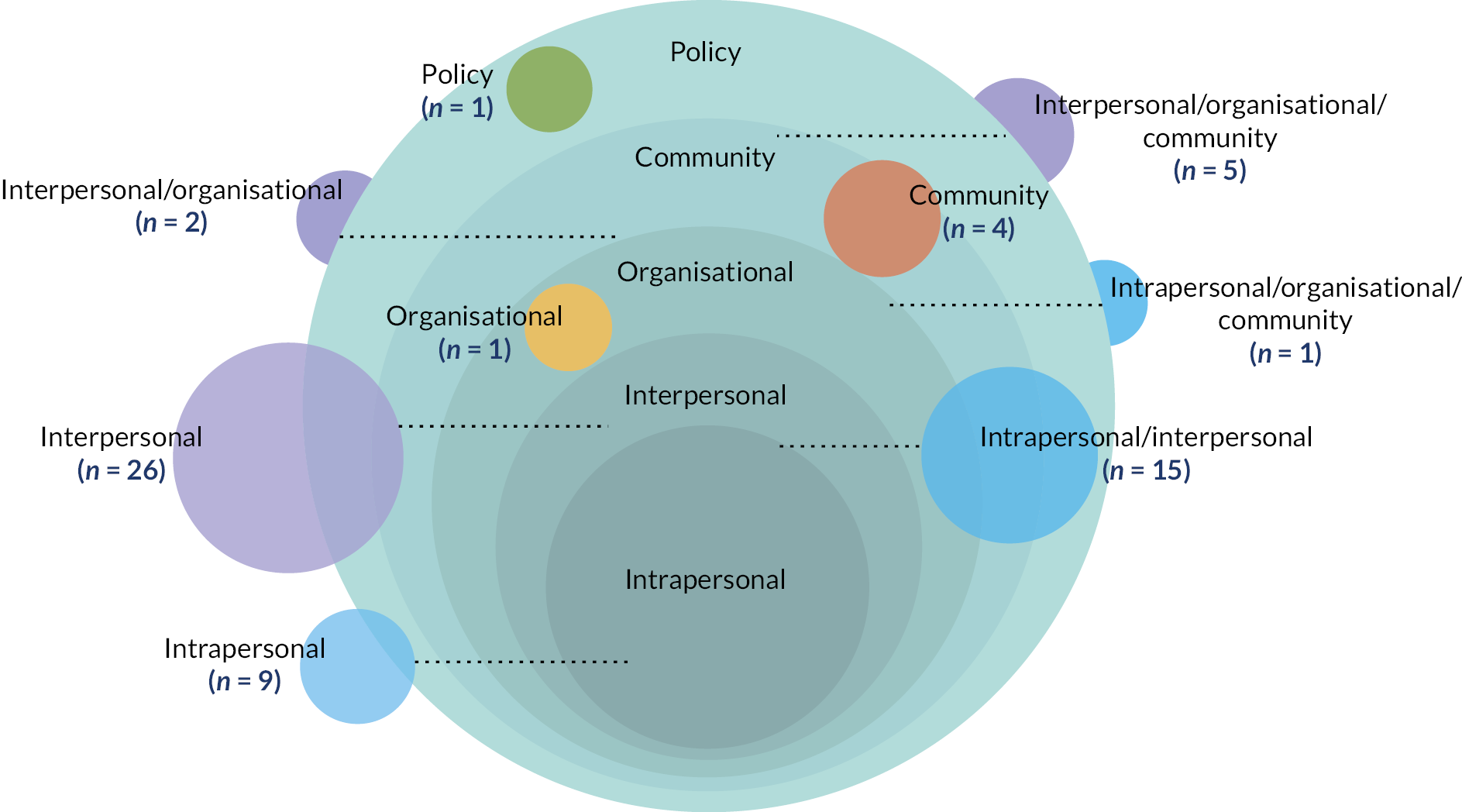

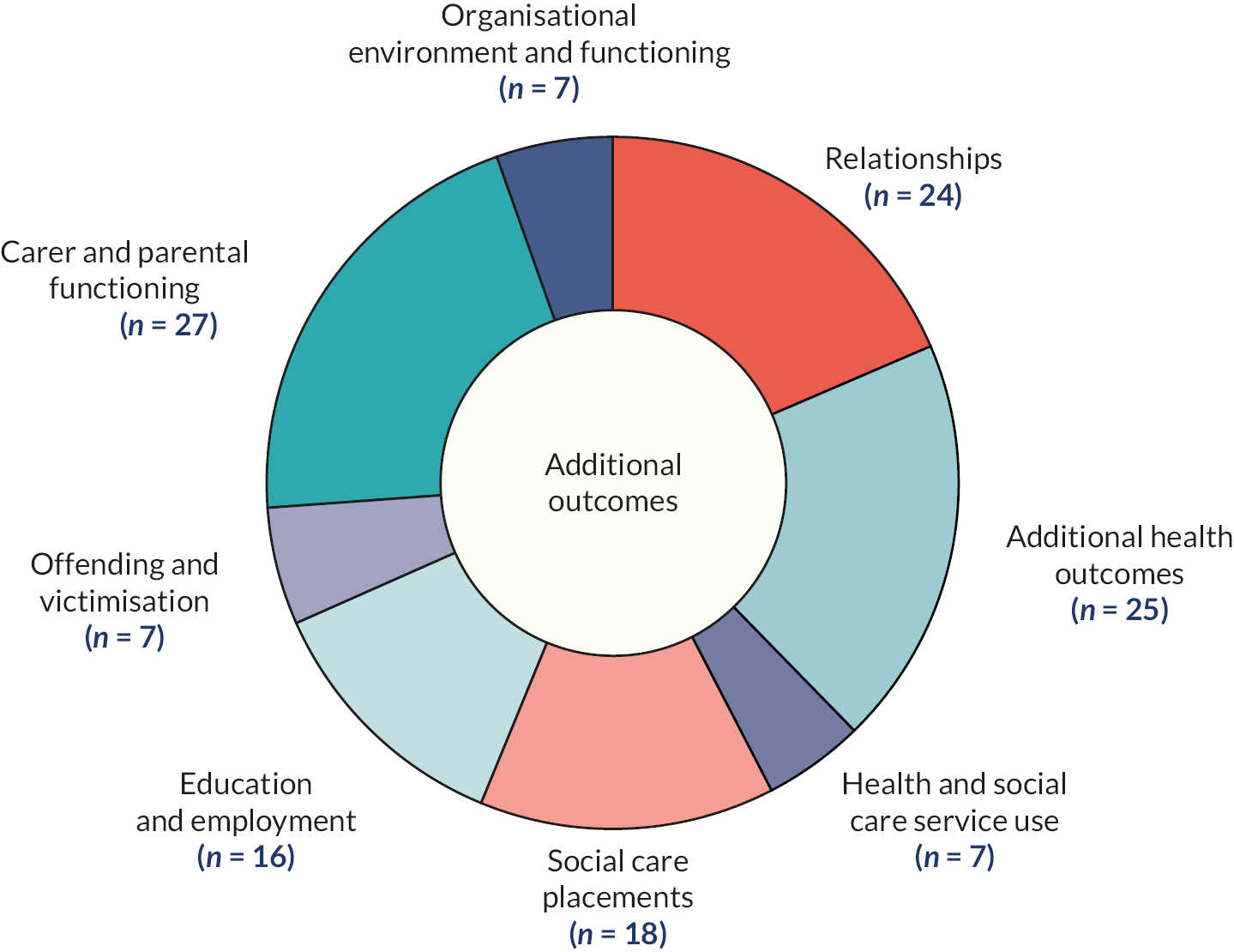

We classified types of interventions according to the socioecological domain or domains in which they operated (see Report Supplementary Material 6). The range of interventions are described in Figure 5. As indicated in Chapter 2, this was undertaken to respond to the review’s focus on the contextual contingency of intervention effects; we operated on the assumption that interventions working at different socioecological levels may interact differentially with the system depending on the area in which they are implemented. Classification of socioecological domain was informed by the theoretical basis of interventions, where this information was available. However, as the majority of interventions did not present a clear theory, we also considered information on the population and setting that was targeted by intervention activities (e.g. a skills curriculum directly engaging children and young people).

FIGURE 5.

Overview of intervention type by socioecological domain.

Nine interventions, with nine study reports, operated at the intrapersonal level, primarily targeting children and young people;120,135,142,143,151,168,200,202,204 15 interventions, with 24 study reports, targeted both the intrapersonal and interpersonal domain. 25,26,100,105,111,112,115,116,118,129,131,147,154,155,158,159,169,176,188,195,198,203,206,208 These interventions largely combined skill and knowledge development for children and young people, with curricula and coaching to support the carer–child relationship. 105 One intervention targeted the intrapersonal, organisational and community domains. 170

A total of 26 interventions, with 47 study reports, targeted the interpersonal domain, primarily focused on the relationship between care-experienced young people and their peers, carers and parents or other significant adults. 27,33,103,108,109,113,114,123,128,130,133,134,138,140,145,146,148,156,157,160,162,163,165–167,174,175,178–181,183,185,186,192,194,196,204,205,207,209,210,212 Two interventions, with 2 study reports, operated at the interpersonal and organisation level;132,139 5 interventions, with 32 study reports, targeted the interpersonal, organisational and community domains. 28–31,101,102,105–107,110,117,121,122,124,125,127,136,137,141,149,150,152,153,161,164,172,173,182,189,201,213

One intervention, with two study reports, targeted the organisational domain, focusing on organisational culture. 119,191 Four interventions, with four study reports, targeted community mental health and well-being provision. 34,35,126,187 One intervention, with four study reports, operated at the policy level, and focused on the comparison of different placement types that might be prioritised and funded. 190,193,197,199

Intervention characteristics

We mapped interventions against the TIDieR framework to describe their characteristics. 214 Owing to limits in the ways that interventions were reported in the literature, not all domains of the framework could be comprehensively addressed, particularly in relation to plans for adaptation and subsequent modifications. As such, domains with extractable data are discussed presently. Interventions are presented according to the primary socioecological domains in which they operated. Further description of included interventions is presented in Report Supplementary Material 6.

Intrapersonal intervention characteristics

The nine interventions classified as operating primarily at the intrapersonal level tended to focus on developing the skills, knowledge and resilience of children and young people. Cognitive and affective bibliotherapy comprises eight sessions with young people in residential care, exploring written texts as a departure point for discussing emotions. 168 Cognitively based compassion training is a 6-week, foster care-based cognitive training programme that delivers twice weekly sessions to teach competency in loving kindness, empathy and compassion. 142 One intervention provides additional therapeutic support, namely individual and rehabilitative strategies, to children and young people in intensive TFC. 200 The Sanctuary Model (Sanctuary Institute, New York, NY, USA) delivers 12 weekly psychoeducational group curricula to children and young people in residential care, with these groups also supporting trauma recovery. 202 Staff provide ongoing technical assistance and consultation, in addition to twice daily community meetings in the placement to teach young people awareness about the importance of proximal relationships.

Two cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) informed interventions were delivered through online and virtual modalities. One computer game intervention for young people in residential care entails playing the computer game The Sims: Life Stories (or ‘electronic dolls house’), to identify and model emotions, with parallel emotion regulation skill coaching by a social worker. 120 Meanwhile, Dojo Biofeedback is a game that teaches young people in residential care CBT-based relaxation techniques through a series of tutorials and mini-games. 143

Two interventions emphasised mindfulness practice. One is a 20-week Kundalini yoga programme delivered in residential settings, which addresses posture, breathing and mindfulness techniques. 151 The second is a mindfulness curriculum for children and young people in foster and kinship care, which includes guest speakers, arts and crafts activities, yoga instruction, playing music and open time to socialise. 135 Finally, Opportunities Box is a 6-week programme focusing on promoting career ability, adaptability and decision-making for institutionalised youth with a history of care. 204

Fifteen interventions operated at both the intrapersonal and interpersonal level, often combining individual development with group-based curricula and relationship-based components. Acceptance and commitment therapy for children in residential care comprises group-based psychoeducational curricula including experiential exercises, role plays and illustrations to develop psychological flexibility. 195 One intervention for children and young people in care tests a range of treatments that includes behavioural management by online care workers, psychodynamic treatment, structured boundaries and relationships, and adventurous learning that models self-supportive, adaptive behaviours. 203 Derived from MTFC, early-intervention foster care intends to provide parenting coaching and group support to foster carers to encourage placement permanency. 105 This is combined with behavioural specialist services and weekly therapy playgroup sessions for children.

Two interventions explicitly drew on a range of creative and leisure activities to support children and young people’s skills development and relationships. HealthRHYTHMS Drumming Protocol is a weekly group session for young people to non-verbally express themselves through music, before progressing to verbal and written forms of communication. 169 Wave by Wave is a 3-hour weekly psychoeducational programme for young people in foster care, which includes the physical activity of surfing to reduce the potential stigma of receiving mental health support. 208

Two interventions had a focus on animal-based therapy. Equine-facilitated psychotherapy (EEP) provides 7 months of weekly sessions with a horse for young people in residential care, with the aim of building a therapeutic alliance, developing adaptability and providing a healing experience. 100 Animal-assisted psychotherapy for children in foster care includes individual and small-group sessions with animals during an overnight visit to a farm. 198