Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 17/50/01. The contractual start date was in July 2018. The final report began editorial review in March 2021 and was accepted for publication in October 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Jago et al. This work was produced by Jago et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Jago et al.

Chapter 1 Background and introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Willis et al. 1 and Jago et al. 2 These are Open Access articles distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Girls’ physical activity during adolescence

Physical activity during adolescence is associated favourably with body composition, blood pressure, cholesterol and blood lipid levels,3 as well as with higher well-being, self-esteem4 and academic performance. 5 There is moderate evidence that physical activity tracks through adolescence and into adulthood,6–8 and physical activity in adulthood is strongly associated with reduced risk of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and all-cause mortality. 9

On average, children and adolescents do not meet the current international guidance of 1 hour of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per day. 10 Girls are less physically active than boys at all ages, but especially in adolescence [difference in daily MVPA 17 minutes, 95% confidence interval (CI) 16 to 18 minutes], and are more sedentary (difference in sedentary time 22 minutes, 95% CI 19 to 25 minutes). 10 Thus, there is a need to support girls to be more physically active.

Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for girls

Increasing physical activity among girls has been identified as a public health priority,11 and a number of studies have attempted to help girls to be more active. However, systematic review evidence suggests that interventions have been only minimally effective at increasing physical activity among young people12 and, specifically, among girls. 13–15

In their meta-analysis of the effect of school-based interventions on objectively measured physical activity, Borde et al. 12 pooled data from 12 studies (two with boys only and two with girls only) and found that the effect on both overall physical activity (standardised mean difference 0.02, 95% CI −0.13 to 0.18) and MVPA (standardised mean difference 0.24, 95% CI −0.08 to 0.56) was small and non-significant. Common components of the reviewed interventions included traditional top-down strategies, such as increasing active breaks, providing health education and information, running extra lessons and distributing pedometers for self-monitoring. The authors reported that studies with higher compliance with accelerometer protocols yielded stronger positive effects. 12 A similar review and meta-analysis looking at school-based interventions targeting only girls concluded that, to date, interventions have recorded a very small effect on adolescent girls’ physical activity levels (k = 16, g = 0.07; p = 0.05); nonetheless, it also concluded that multicomponent interventions showed more promise, and interventions underpinned by theory may be more effective. 14 This is aligned with findings from an earlier review that found that multicomponent interventions were more effective at increasing physical activity; however, the findings also differed in that atheoretical interventions of higher quality yielded more positive outcomes than those of lower quality that were underpinned by theory,13 identifying the importance of trial quality on results.

A narrative review of 15 interventions (10 of which were school based) aimed at changing objectively measured health outcomes (i.e. physical activity, body mass index, body fat percentage) in adolescent girls15 identified little evidence that interventions increased objectively assessed physical activity. The authors also highlighted that the impact of the studies may have been limited by attendance rates to the interventions, as well as compliance with accelerometer measurement of physical activity. 15 Collectively, this evidence suggests that interventions to increase physical activity levels in adolescent girls, whether school based or not, are minimally effective, at best, and are potentially limited by methodological issues, such as the measurement of physical activity, intervention design and dose, or a combination of these factors.

Correlates of girls’ physical activity

Factors known to be associated with physical activity in adolescent girls are increased enjoyment, increased perceived competence, higher self-efficacy and higher socioeconomic position (SEP). 16 There is also some evidence that adolescents from lower socioeconomic groups engage in lower levels of physical activity,17 which may, in part, be explained by less favourable psychosocial determinants of physical activity. 18 Furthermore, a scoping review exploring gender norms in relation to physical activity and nutrition concluded that lifestyle components are greatly affected by feminine ideals through complex negotiations, perceptions, body-centred discourse and societal influences. 19 Similarly, changes to friendship groups, social/peer support, perceived competence, competing priorities, body-centred issues (e.g. weight status and menstruation) and ‘sporty’ gender stereotypes encountered during adolescence are factors that may contribute to the decline in girls’ physical activity. 20–23

Peers and physical activity

Peers play a central role in adolescents’ physical activity through peer support, co-participation, peer norms, friendship quality, peer affiliation and peer victimisation. 24,25 Qualitative studies among adolescent girls have shown that co-participation in physical activity with peers is an important motivating factor,23 and that a shared interest in physical activity with friends is associated with higher levels of motivation to be active, as well as greater enjoyment of being active. 26 Social network research has shown that adolescents have similar physical activity levels to their close friends, and they may adapt their physical activity behaviour over time to be more like that of their friends. 27,28 Peer-led interventions, therefore, have the potential to increase adolescents’ physical activity. There is a need to develop effective physical activity interventions, especially among girls, that capitalise on existing peer processes in schools by promoting peer support and enhancing peer communication skills. 24

Peer-led health interventions

Peer-led approaches have been used in attempts to change a range of health behaviours among young people, including tobacco, alcohol and drug use,29 nutrition education, water consumption30,31 and sexual health. 32 A small number of studies have attempted to use peer influence to change physical activity and sedentary behaviours;33 however, more recently, studies using a peer-led approach to target physical activity in young people have increased. A recent scoping review of peer-led physical activity interventions highlighted several approaches to increasing physical activity; however, the results are mixed in terms of their effectiveness, with no clear indication of specific approaches or intervention factors affecting impact. 34

The authors of this review note that many approaches use young people to deliver adult agendas. For instance, most peer-led health interventions to date have been delivered in secondary education settings; through information provision and skill development, these interventions also trained peer leaders to educate other pupils by teaching sections of the curriculum (that would otherwise be taught by adults) through buddy learning or by leading new physical activity initiatives and supporting teacher-led activities. 34,35 However, using a different approach, young people in the role of peer leader could take more control over the intervention that they delivered, which may have enhanced their credibility among their peers, in contrast to delivering a clearly adult agenda. 34,36

An alternative peer-led approach, based on diffusion of innovations theory (DOI),36 is to provide training to young people that empowers them with the information and skills to diffuse health promotion messages to their peers through informal means. DOI explains how ideas, beliefs or behaviours can be informally communicated through members of a social system in ways that are authentic to their peer group, an approach that was adopted in the effective and nationally disseminated ASSIST (A Stop Smoking in Schools Trial). 37 The findings from ASSIST demonstrated that informal school-based peer-led interventions can be effective in changing smoking behaviour. 37

Theoretical underpinning

Evidence of the influence of theory on the effectiveness of health behaviour interventions is, generally, mixed, although robust analysis of interventions, based on theories for which there are sufficient data to analyse (e.g. social cognitive theory and transtheoretical model), show that their use is unlikely to increase intervention effectiveness. 38 Overall, the evidence is restricted in several ways; notably, there is a lack of studies with a robust theoretical basis (especially a limited use of theory during intervention development), limited use of a range of theories, inadequate mapping of behaviour change techniques to theory in interventions and scant use of theory to select participants or tailor the intervention.

Conversely, theory that is used with clarity and focus, and that is well matched to the intervention design and target group (including to select participants) and underpinned by a logic model highlighting mediating mechanisms, with clear mapping of behaviour change techniques to theoretical mediators, can provide an important element of intervention design, delivery and evaluation. Using theory effectively will also contribute higher-quality theory-based interventions that can advance research into the effectiveness of the use of theory.

Few peer-led physical activity interventions integrate theoretical principles in their design or delivery. 33,34 The present trial combines two complementary theories: DOI and self-determination theory (SDT). DOI was used to inform the intervention design and the selection of key participants (i.e. peer supporters as agents of change). SDT was used to inform the content (i.e. the ‘what’ and the ‘how’) of the intervention, including behaviour change techniques to proposed mediators between the intervention (i.e. peer support) and the outcome (i.e. physical activity).

Diffusion of information uses pre-existing social systems, such as friendship networks, to diffuse information and influence behaviour. 39 Therefore, it provides a framework for harnessing the influential capacities of change agents in social networks, who can informally diffuse positive health messages to their peers. The relevance of DOI for interventions targeting adolescent girls is clear because of the role that peers play in influencing drivers of physical activity. 23,24,26

Self-determination theory40 is concerned with the personal and social conditions required to foster high-quality and sustainable motivation, and has been used extensively to understand young people’s motivation to be physically active,22,41,42 as well as to guide interventions. 43–45 SDT argues that autonomous motivation (i.e. motivation based on choice and personal value or inherent satisfaction) is associated with more positive behavioural and psychological outcomes than controlled motivation (i.e. motivation driven by external factors, such as meeting others’ expectations or guilt). Evidence points to consistent positive associations between autonomous versus controlled motivation and physical activity in children, adolescents and adults alike. 41,42,46–49 Autonomous motivation is associated with perceptions of autonomy, competence and social belonging;42,50 therefore, it is supported by social environments and interactions (e.g. interactions with peers) that satisfy these three psychological needs. SDT is, therefore, fitting for a peer-led intervention, as peers can create a social climate that either facilitates or undermines girls’ interest in,33 enjoyment of and motivation for physical activity;23,26 perceptions of competence; social support; and choice of how to be active. 20,22

Summary of formative work

The Peer-Led physical Activity iNtervention for Adolescent girls (PLAN-A) intervention design was informed by extensive formative, pilot and feasibility research, including iterative qualitative research conducted to adapt the ASSIST37 peer-led smoking intervention model to target physical activity, as well as an intervention pilot51 and a cluster-randomised feasibility trial. 52 The feasibility trial was conducted in six UK secondary schools (four intervention and two control) with girls in Year 8 of the UK education system (i.e. girls aged 12–13 years), and included a health economics assessment and a comprehensive mixed-methods process evaluation. 51–53

The intervention consisted of three stages:

-

Girls anonymously nominated the peers they felt were well suited to being a peer supporter (the peer nomination process).

-

The 18% of girls who were most frequently nominated in each school were invited to attend 3 days of specialist peer supporter training to provide them with skills and information.

-

The trained peer supporters then informally influenced the physical activity of their close peers using a range of supportive techniques over a 10-week diffusion period.

The intervention design was based on DOI, and SDT was layered into the delivery, resources and content of the peer supporter training. Pupils’ physical activity was measured at baseline, immediately after the 10-week diffusion period and then approximately 5 months after the intervention period. 53

The results showed that the intervention was deliverable, acceptable and affordable. There was evidence of promise at the 5-month follow-up time point, at which time there was a 6.1-minute difference in weekday MVPA favouring the intervention arm, after adjustment (95% CI 1.4 to 10.8 minutes). In addition, mean sedentary time per day was 23 minutes lower (95% CI –43.7 to –2.8 minutes) in the intervention arm than in the control arm at the same time point. 51 The economic evaluation demonstrated that the programme has potential for cost-effective delivery from a public-sector perspective. The mean cost of intervention delivery equated to £37 per Year 8 girl and £6 per additional minute of weekday MVPA,45 comparing favourably with other multicomponent physical activity interventions in adolescents. 54 The mixed-methods process evaluation identified key refinements for the intervention delivery and content, including increasing participatory learning, focusing more on how to start conversations with peers and providing more support to overcome challenges to giving peer support. 55

Rationale for the current trial

Physical activity during childhood is positively associated with physical and psychological health. Physical activity declines with age and, by adolescence, few girls are sufficiently active. School-based interventions have had limited success and novel interventions are needed to mitigate girls’ lack of participation in physical activity. The power of peer influence presents a natural and sustainable intervention opportunity that has received little attention in high-quality research to date. Having followed the Medical Research Council framework for the development of complex interventions56 and made revisions to intervention content informed by robust feasibility work, the aim of this definitive trial was to test whether or not the PLAN-A intervention can increase adolescent girls’ physical activity and be cost-effective.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Willis et al. 1 and Jago et al. 2 These are Open Access articles distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Research aims

The four research aims of this trial were to determine the:

-

effectiveness of PLAN-A in increasing the objectively assessed (i.e. accelerometer-derived) mean weekday minutes of MVPA among Year 9 girls (i.e. 13–14 years old) 5–6 months after the end of a 10-week intervention

-

effectiveness of PLAN-A in improving the following secondary outcomes among Year 9 girls 5–6 months after the end of a 10-week intervention –

-

mean weekend minutes of MVPA

-

mean weekday minutes of sedentary time (accelerometer-derived)

-

mean weekend minutes of sedentary time (accelerometer-derived)

-

self-esteem (self-reported)57

-

-

extent to which any effects of the intervention on primary or secondary outcomes are mediated by autonomous and controlled motivation towards physical activity and perceptions of autonomy, competence and relatedness/peer support in physical activity

-

cost-effectiveness of PLAN-A from a public-sector perspective.

Trial design

The trial was a two-arm, school-based, cluster-randomised controlled trial to compare the PLAN-A intervention with a usual-practice control. The trial included a mixed-methods process evaluation and a health economics evaluation. The method and results are reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidance,58 the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist,59 the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist60 and the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement checklist. 61 The trial was registered with the International Standard Registered Clinical/social sTudy Number (reference ISRCTN14539759) on 31 May 2018.

Protocol amendments

The original trial protocol (version 1.0) was submitted to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) on 31 May 2018. Version 1.1 was submitted on 28 January 2019 with one minor change, and version 1.2 was submitted on 10 April 2019 with further changes. These revisions are detailed in Table 1.

| Change made to version | Description of amendment | Submitted |

|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | Page 8: clarification of the randomisation process | Submitted to NIHR on 28 January 2019 in version 1.1 |

| 1.1 | Page 12: sample size. The lead trial statistician updated the text to correct an inconsistency in the sample size calculation and justify the decision to include 20 schools based on pragmatic power calculations. These changes were agreed with the TSC | Submitted to NIHR on 10 April 2019 in version 1.2 |

| 1.1 | Page 13: data analysis. The lead trial statistician updated text to reflect pre-specified subgroup analyses proposed and agreed in the TSC meeting dated 15 March 2019, and to explain the conditions under which a per-protocol secondary analysis would be performed. These changes were agreed with the TSC | Submitted to NIHR on 10 April 2019 in version 1.2 |

| 1.1 | Page 13: economic analysis. The lead trial health economist updated text to align with the statistical inclusion of prespecified subgroups and use of imputation in sensitivity analyses. They also further detailed how quality-of-life measures would be analysed and how extrapolation of results may be performed if the trial was effective. All changes were approved by the TSC | Submitted to NIHR on 10 April 2019 in version 1.2 |

Methods

Ethics

This trial was granted ethics approval by the School for Policy Studies Ethics and Research Committee at the University of Bristol (Bristol, UK; reference SPSREC17–18.C22) on 24 May 2018. The trial was funded by NIHR Public Health Research Programme (PHR) (project number 17/50/01). The intervention costs were funded by lottery funding from Sport England (London, UK). The University of Bristol acted as the trial sponsor (sponsorship number 2898). The occurrence of any adverse events during the project was recorded and reported to the chairperson of the School for Policy Studies Ethics and Research Committee and the chairperson of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

Sampling and participants

State-funded secondary schools located in south-west England with girls in Year 9 were invited to take part. Special education and independent schools were excluded. Priority was given to schools whose local pupil premium indicator was above the median (i.e. those that were more deprived) by inviting them to participate first. Schools were required to sign a trial agreement form to take part. All Year 9 girls were eligible to participate; therefore, the trial aimed to recruit all Year 9 girls in each of the 20 participating schools. Research staff members gave a standardised recruitment briefing to Year 9 girls in attendance on that day in each school to explain the purpose of the trial, the intervention, randomisation and the data collection process. The girls were given the opportunity to ask questions and were informed that they could withdraw their participation. Each girl was given a written information pack for herself and her parents, which also contained a pupil consent and parent opt-out form. Participation in the trial was contingent on providing a signed pupil consent form. Parents could opt their daughter out of the trial by providing a completed opt-out form.

Sample size

The trial was designed to achieve 90% power for the primary outcome of weekday MVPA at follow-up and was informed by the results of the feasibility trial conducted in a slightly younger cohort of girls. 51 Based on those results, the sample size calculation assumed a fixed cluster (i.e. school) size of 70 girls, an intracluster correlation coefficient of weekday MVPA of 0.01, standard deviation (SD) of 20 minutes and coefficient of variation in cluster size of 0.22. The sample size calculation allowed for 30% of girls not providing primary outcome data and the alpha was set to 5%. Informed by the feasibility trial,52 which observed a between-group difference in weekday MVPA of 6.1 minutes, we estimated that we would need 20 schools (equating to 1400 students) to detect a difference of 6 minutes in weekday MVPA with 90% power under the assumptions outlined above. Given the inherent uncertainty in many of these assumptions, two reserve schools were recruited to mitigate school withdrawal prior to completion of baseline measures.

Data collection

The PLAN-A feasibility trial52 found that including a measurement point at the end of the 10-week intervention period increased participant burden and did not allow sufficient time for behavioural changes to take root, thus showing nothing. Therefore, to maximise the possibility of observing an intervention effect and simultaneously reducing participant burden, data were collected from Year 9 girls in all schools at just two time points: baseline [time 0 (T0); October 2018 to February 2019] and at 5–6 months post intervention, approximately 12 months post baseline [time 1 (T1)]:

-

school level –

-

T0:

-

county/region

-

total number of pupils

-

total number of Year 9 pupils

-

total number of Year 9 girls

-

proportion of pupils taking free school meals

-

-

T1:

-

school-context measures

-

-

-

participant level –

-

T0:

-

accelerometer data for 7 days

-

psychosocial questionnaire (on tablet device)

-

KIDSCREEN-10 score (on tablet device)

-

EuroQol 5-Dimensions, Youth version (EQ-5D-Y), score (on tablet device)

-

demographics and family affluence (on tablet device)

-

home postcode (on paper)

-

-

T1:

-

accelerometer data for 7 days

-

psychosocial questionnaire (on tablet device)

-

KIDSCREEN-10 score (on tablet device)

-

EQ-5D-Y score (on tablet device)

-

date of birth (on paper).

-

-

All questionnaire measures at T0 and T1 were collected using a Samsung® Galaxy Tab A 10.1 (Samsung Electronics Limited, Surrey, UK) device and Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap®) software (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA). 62 All demographic data were self-reported and collected using the Samsung device or reported to research staff at T0 (i.e. home postcode) or T1 (i.e. date of birth). Process evaluation measures were completed during the project at each intervention school (i.e. at observations and evaluations of training between March 2019 and June 2019) and post intervention (i.e. during qualitative work between June 2019 and July 2019). At both time points, participants who completed data collection were given a £10 shopping voucher in appreciation of their contributions to the trial. Following completion of the T1 data collection, all participating schools received £500 for taking part in PLAN-A and were provided with a summary report of the findings.

Physical activity and sedentary time

To assess physical activity levels, participants wore an ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometer (ActiGraph, LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA) during waking hours for 7 days at both time points. Participants were asked to remove the accelerometer when sleeping, showering/bathing or participating in water or contact sports. The devices were set to record data at 30 Hz and raw data were accumulated into 10-second epochs using ActiLife 6 (ActiGraph LLC).

Measures

The specific measures used for variable generation are detailed in Table 2.

| Variable | How it was assessed |

|---|---|

| Age at baseline | Age at baseline was calculated from the self-reported date of birth and date of baseline measurement |

| Ethnicity | Ethnic background was self-reported by selecting one of 13 descriptions, based on the UK Census |

| SEP | The participant’s SEP was estimated using the following parameters:

|

| Mean accelerometer-determined minutes of MVPA on weekdays | Physical activity was assessed using ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometers, which are small devices that record bodily acceleration and have been used and validated among young people.65 Participants were asked to wear an accelerometer for 7 days at T0 and T1. Periods of ≥ 60 minutes of zero counts were recorded as ‘non-wear’ and removed. Participants were included in analysis if they provided ≥ 2 valid days (i.e. 500 minutes of data between 05.00 and 23.59). Mean minutes of daily MVPA were estimated using the Evenson66 cut-off point of ≥ 2296 CPM, which is the most accurate threshold for adolescents67 |

| Mean weekend minutes of MVPA | This was calculated as above, but across Saturday and Sunday at T0 and T1. Participant data were included in weekend analyses if they provided valid data for one or more weekend day |

| Mean weekday minutes of sedentary time | Sedentary time was calculated as for MVPA but using a cut-off point of ≤ 100 CPM66 at T0 and T1 |

| Mean weekend minutes of sedentary time | This was calculated as the mean weekday minutes of sedentary time, but across Saturday and Sunday at T0 and T1 |

| Self-esteem | Self-esteem was derived from the Self-Description Questionnaire II,57 issued at T0 and T1. The questionnaire contains four positively worded (e.g. ‘Most things I do, I do well’) and five negatively worded (e.g. ‘I don’t have much to be proud of’) items. Pupils rated how ‘true’ or ‘false’ each description was for them using a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘False – not like me at all’) to 6 (‘True – very much like me’). A mean item score was then calculated |

| Physical activity motivation (autonomous and controlled) | Pupils completed a 19-item version of the Behavioural Regulations in Exercise Questionnaire 2,68 assessing (1) intrinsic motivation (four items, e.g. ‘I value the benefits of exercise’), (2) identified motivation (four items, e.g. ‘I am physically active because it’s fun’), (3) introjected motivation (three items, e.g. ‘I feel guilty when I’m not physically active’), (4) external motivation (four items, e.g. ‘I am physically active because other people say I should be’) and (5) amotivation (four items, e.g. ‘I think being physically active is a waste of time’). Pupils indicated their agreement with each statement using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘Not true for me’) to 4 (‘Very true for me’). Composite autonomous (i.e. the mean of intrinsic and identified) and controlled (i.e. the mean of introjected and external) were then calculated |

| Physical activity psychological need satisfaction | Pupils’ perceptions of autonomy (six items, e.g. ‘I feel I’m active because I want to be’), competence (six items, e.g. ‘I am pretty skilled at different physical activities’) and relatedness (five items, e.g. ‘I feel understood’) were assessed using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘Not at all true’) to 7 (‘Very true’)46,69 at T0 and T1. Participants rated how ‘like them’ each statement was. Item means for each need variable were then calculated |

| Physical activity self-efficacy | Eight items were used to assess participants’ self-efficacy to be physically active in different situations (e.g. ‘I can be physically active most days after school’) at T0 and T1.70 Pupils indicated their endorsement of each statement by giving one of three responses (‘No’, ‘Not sure’ or ‘Yes’). A mean item score was then calculated |

| Physical activity social support |

Six items assessing social support from friends for physical activity were taken from a broader questionnaire measuring factors associated with physical activity in adolescents71 at T0 and T1. Pupils read the stem ‘Thinking about your close friendship group how often do they do the following’ and rated each item (e.g. ‘Invite you to engage in physical activity with them’) using a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘Never’) to 3 (‘Always’). Items cover social support in the form of encouragement, involvement, co-participation, talking about physical activity and giving positive comments. A mean of the items was then calculated Pupils were asked two questions to assess their perceptions that others in their year (1) spoke to them about physical activity (‘Has anyone in your year group talked with you recently about physical activity?’, response options: ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Not sure’) and (2) whether or not they felt it helped them be more active (‘Did talking to anyone in your year help you to be more active?’, response options: ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Not sure’, ‘N/A’) |

| Peer norms for physical activity | The six-item Social Support Scale72 was used to measure three factors of peer-based social support at T0 and T1. Prevalence of friends’ physical activity was assessed with two items (e.g. ‘How many of your close friends would you say are physically active?’), scored using a four-point scale (0 = ‘None’ to 3 = ‘All’). Perceived importance placed on physical activity by peers was measured using two items (e.g. ‘How important do you think it is to your close friends to be physically active?’), scored using a three-point scale (0 = ‘Not important at all’ to 2 = ‘Very important’). Peer acceptance of the participant’s level of physical activity was assessed using two items (e.g. ‘My friends encourage me to be physically active’), scored using a four-point scale (0 = ‘Disagree a lot’ to 3 = ‘Agree a lot’). A mean item score was then calculated for prevalence, importance and acceptance |

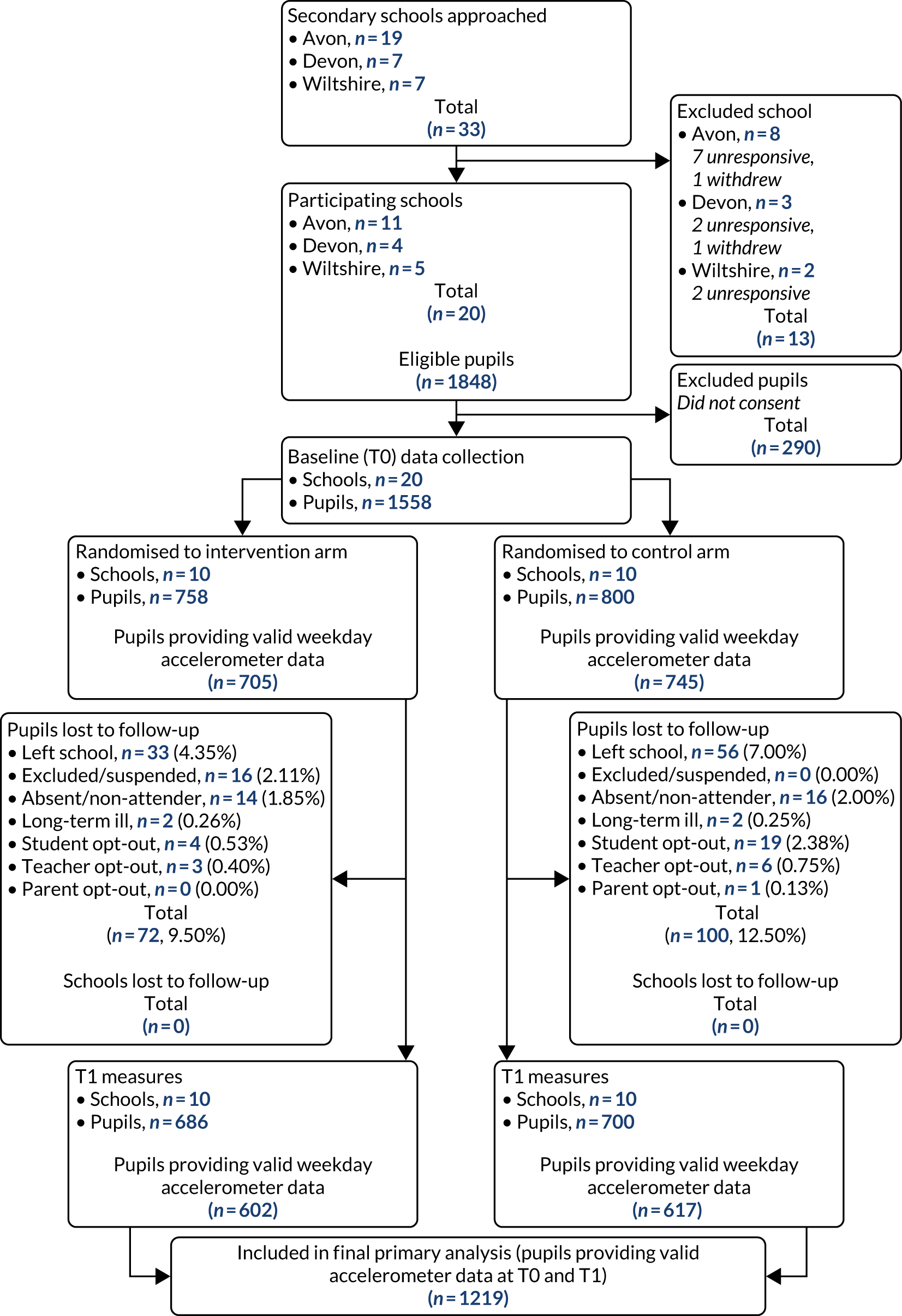

Randomisation

The school was the unit of randomisation. Following the completion of T0 data collection, schools were randomised to the control (n = 10) or intervention (n = 10) arm, stratified by county (Avon, Devon or Wiltshire) and the England Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score for the lower-layer super output area in which the school was located (dichotomised as less than the median of sampled schools in the county versus greater than or equal to that median) to ensure balance in each stratum. Schools were allocated, using a computer-generated algorithm, to either the control or intervention arm by a member of the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration (BRTC) who was blinded to the school identity and worked separately to the fieldwork team. Also blinded to the allocation were the lead statistician and all other team members, other than the trial manager, research associate and fieldworkers.

Intervention

The intervention design was adapted from the ASSIST model37 and comprised four components: peer nomination, train the trainers, peer supporter training and a 10-week diffusion period. The intervention components and theoretical enactment that were developed and tested in the feasibility trial have been described in detail elsewhere. 52

Refinements to the intervention

Prior to the intervention, members of the trial team made refinements to both the train-the-trainers and peer supporter training materials that were used in the feasibility trial,52 using feedback from the feasibility trainers and peer supporters (Table 3). In addition, patient and public involvement focus groups were conducted with adolescent girls between September 2018 and November 2018, exploring issues around menstruation and being physically active, the perceived and real barriers, and strategies to overcome them. The findings of these focus groups73 were woven through new intervention content during intervention refinement.

| Area of refinement | Objective of changes | Details of change |

|---|---|---|

| Train the trainers | Reinforce the principles of SDT to further trainer understanding | Additional time was added to the top-up training day to reinforce SDT |

| Peer supporter training | ||

| Logistics | Improve training venues and equipment | Venues were required to have suitable outdoor spaces, and a wider variety of equipment for peer supporters was made available |

| Structure | Improve peer supporter concentration and understanding of key message of why you should be active | Activities were reordered to promote understanding of concepts, followed by practical reinforcement |

| Material and resources |

Improve the use of the peer supporter booklet Make group size more visible to the trainers |

When to use the peer supporter booklet was highlighted in the session plan manual and a space for notes was added to the booklet Activity descriptions were simplified |

| Training content |

Reinforcing the peer supporter role Increase knowledge about being active during menstruation Allow peer supporters to feel comfortable about their role Make top-up day less repetitive Improve peer supporter engagement and enjoyment of activities Help peer supporters overcome challenges Promote peer supporter teambuilding and teamwork Make the activities easier for the peer supporters to understand |

A new, shorter activity was added Several activities were adapted to include menstruation The top-up day introduction game was adapted The ‘how, who, when, where’ activity was removed A number of the activities were made more active Activities were more focused on problem-solving Games that promoted teamwork were added to the training The terminology in the activities was simplified |

| Individual activities |

Make the concept of goal setting easier to understand for the peer supporters Improve the explanation of tasks Provide a more realistic approach to problem-solving |

Active games were added to these activities, in addition to promoting variety in answers given More guidance was provided along with activities being simplified Redundant statements were replaced with more relevant examples |

Peer nomination

To identify those girls who were influential within their year and, therefore, whom to invite to become peer supporters, all girls in Year 9 in each participating school were asked to complete a peer nomination questionnaire at the same time as the baseline measures. This questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 1) asked the girls to anonymously nominate up to five girls whom they respected, trusted, listened to and looked up to. The highest scoring 18% of the girls who were nominated were invited to become a peer supporter in the schools randomised to the intervention arm (with the aim of ≥ 15% agreeing to take on the role). Following feedback from the feasibility trial,52 in schools where the year group was split and the two halves shared no curriculum time, this process was conducted separately in each half to ensure fair representation of peer supporter nominations across the year group.

The nominated girls attended a briefing and were provided with an information pack for themselves and their parents, which outlined the training and their role as a peer supporter. The girls were required to provide both parental and pupil informed consent if they wished to attend the training. The girls who did not opt-in to the data collection aspect of the trial were still eligible to opt in as a peer supporter. The peer supporter and parent consent rates were recorded by the field team. Any nominated peer supporters who opted out, either before the training began or during, were asked to fill in a form at T1 to provide a reason. This was voluntary and all of the girls understood that this was optional. The reasons for non-consent were reported descriptively.

Train the trainers

Female trainers were recruited via advertisement through local authority health improvement teams and recruited as freelancers to deliver the peer supporter training component of the intervention. Trainers from the feasibility trial who had expressed interest in continued involvement were also contacted. Those expressing an interest were screened by the trial manager for availability and suitability (i.e. a background in physical activity or coaching, experience working with young people and being good communicators). Seven trainers were appointed in total, including a ‘lead trainer’, who was an experienced PLAN-A trainer from the feasibility trial with extensive teaching experience. All appointed trainers had at least a master’s degree in a physical activity research discipline plus coaching experience, or > 5 years’ practical experience in youth work.

All trainers were required to attend a training course (i.e. train the trainers) to prepare them for delivery. This course was delivered over 3 days, mimicking the peer supporter training. It was held in a studio space at the University of Bristol. To closely replicate an intervention model that would be used in a community setting, the train-the-trainers course was led by two trainers: the lead trainer and a member of the research team, who had been extensively involved in the development and refinement of the intervention. The lead trainer met with the research team beforehand for half a day to prepare. The train-the-trainers course was dedicated to the aims and design of PLAN-A, their role as a trainer, how the activities and the trainer’s delivery style aligned with DOI and SDT, and working with challenging young people. There was also a chance for the trainers to choose how they spent the last hour of the training on each day, whether this involved going over activities on their own or with a trainer they were partnered with, or leading activities themselves.

Each trainer was provided with resources to aid them in delivering the peer supporter training, including a ‘trainers’ guide’ that contained information about the principles behind PLAN-A and its concept, PLAN-A’s approach to motivation and the underpinning theories, the practicalities and logistics of delivery, and more detailed reasoning behind each of the activities. They were also provided with a ‘session plan booklet’ that detailed how to deliver each activity, the resources needed and the key messages/objectives to achieve. All resources are described in detail elsewhere. 52 In addition, trainers were provided with a resource pack for each school delivery.

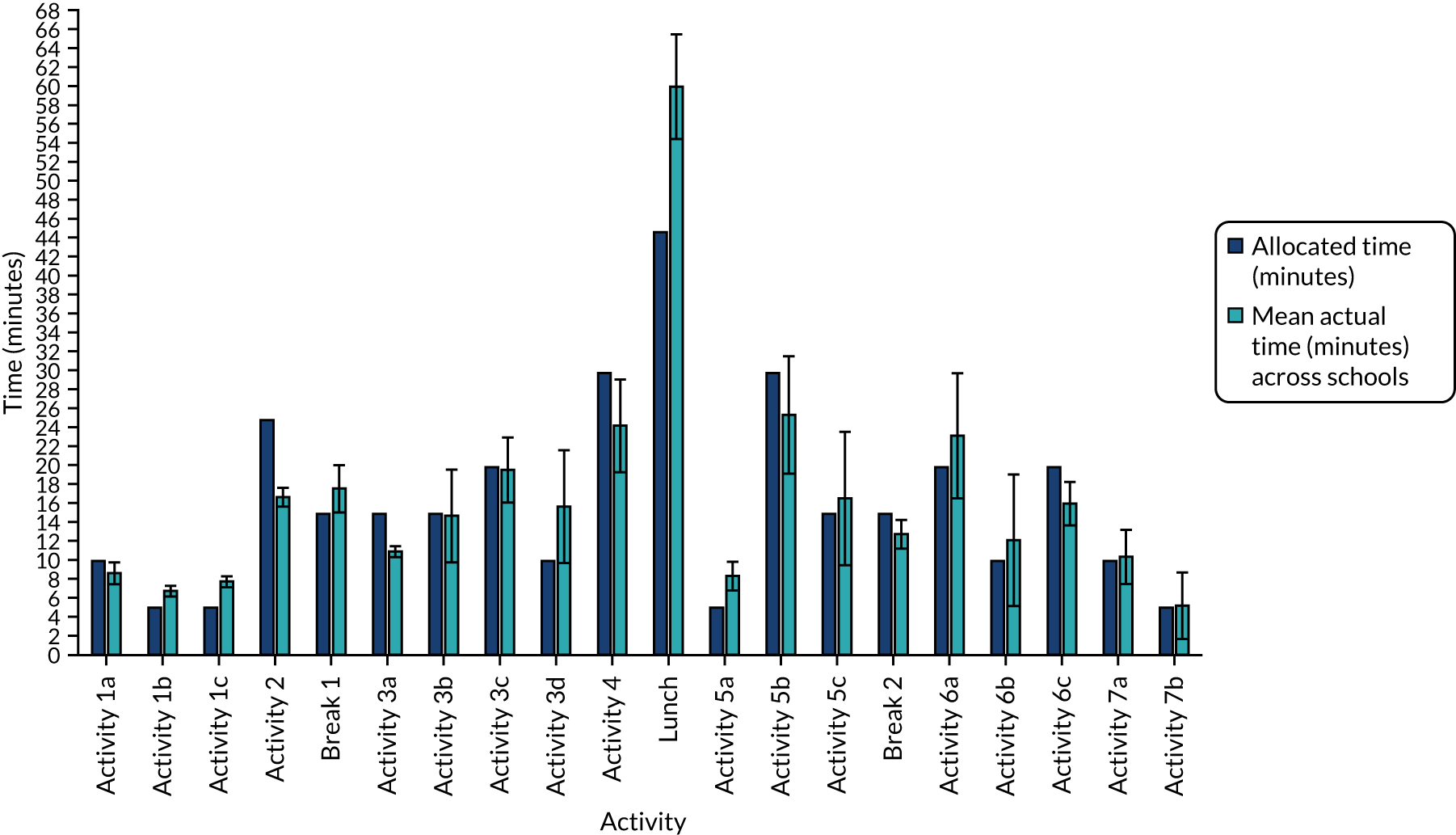

Peer supporter training

All consenting peer supporters attended a 3-day training session as a school group, which was led by two trainers; the training comprised an initial 2 days of training, followed by a top-up training day 5 weeks later. Where possible, the training sessions were held at suitable venues away from school (on-site training was an option when schools were unable to provide a chaperone to attend the training and if they could offer a suitable space; schools, n = 2). To minimise school staff burden, a member of the trial team arranged venue bookings and refreshments and co-ordinated travel (if necessary) with each school. Based on the experience in the feasibility trial,52 venues needed to have ample floor space (e.g. to accommodate group games and activities), chairs, space and power to project slides, bathroom facilities, and, preferably, a food preparation area and safe outside space to use for breaks.

The training sessions had two themes. The first involved increasing the peer supporter’s knowledge around physical activity and addressed how to fit in activity, what counts as being active, the barriers to physical activity for Year 9 girls and the importance of being physically active. The second theme involved developing and improving peer supporters’ communication skills; content included how to start conversations about being active, methods of peer support and recognising opportunities to encourage, support and motivate peers to be active. The purpose of the top-up day was to provide a refresher on core topics, to discuss actions that peer supporters had taken to support their peers and to tackle any challenges that they may have faced.

Each peer supporter was provided with a ‘peer supporter booklet’ that contained worksheets used in the peer supporter training and resources to support the peer supporters outside the training. The booklet also contained a diary that offered the peer supporters the option to record conversations that they had started or support that they had provided to encourage their peers to be active. To promote continued peer support, each peer supporter wrote herself a postcard with personal motivation reminders at the end of the training that the trial team posted back to them 2 weeks after the training finished.

The training content was developed and refined to be interactive, engaging the girls both mentally and physically (see Table 3). The intervention framework was based on DOI, allowing the resources, content and delivery to harness the potential of peer influence, as well as uphold the key principles of SDT. It was designed to nurture the peer supporters’ autonomy, belonging and competence for physical activity and peer support. The framework also helped the peer supporters to promote autonomous, rather than controlled, motivation for physical activity among their peers.

The 10-week diffusion period

Once the peer supporters completed the training, their role was to support and encourage physical activity among their close peers for a period of 10 weeks. The training encompassed multiple methods of providing support, including holding conversations about being active, co-participation and providing opportunities to be active. As the intervention was based around an informal, peer-led approach, the peer supporters were encouraged to carry out their role in a way that they felt comfortable with and was most effective, taking into consideration their peers’ needs, preferences and confidence.

Control group provision

The eligible participants of the control schools participated in both data collection and peer nomination at T0. A total of 10 schools were randomly assigned to the control condition. These schools continued with normal practice [normal physical education (PE) provision and physical activity opportunities during teaching and co-curricular activities], before completing T1 data collection.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using Stata® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), version 15.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of schools and pupils were compared between arms by reporting relevant summary statistics to identify any potentially influential imbalance. The baseline characteristics were summarised using means and SDs, medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), or numbers and percentages, depending on the nature of the data and its respective distribution. Where the baseline characteristics of the groups differed by > 10% or half a SD, the effect of this variable on the outcome was investigated in sensitivity analyses.

Analysis of intervention effect

Two-tailed tests were used, with effect estimates, 95% CIs and p-values presented. No adjustment for multiple testing took place. Analyses using regression models adjusted for stratification variables, as well as the baseline values of the outcome studied. The primary approach for analysis was on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis, defined as analysing participants as randomised.

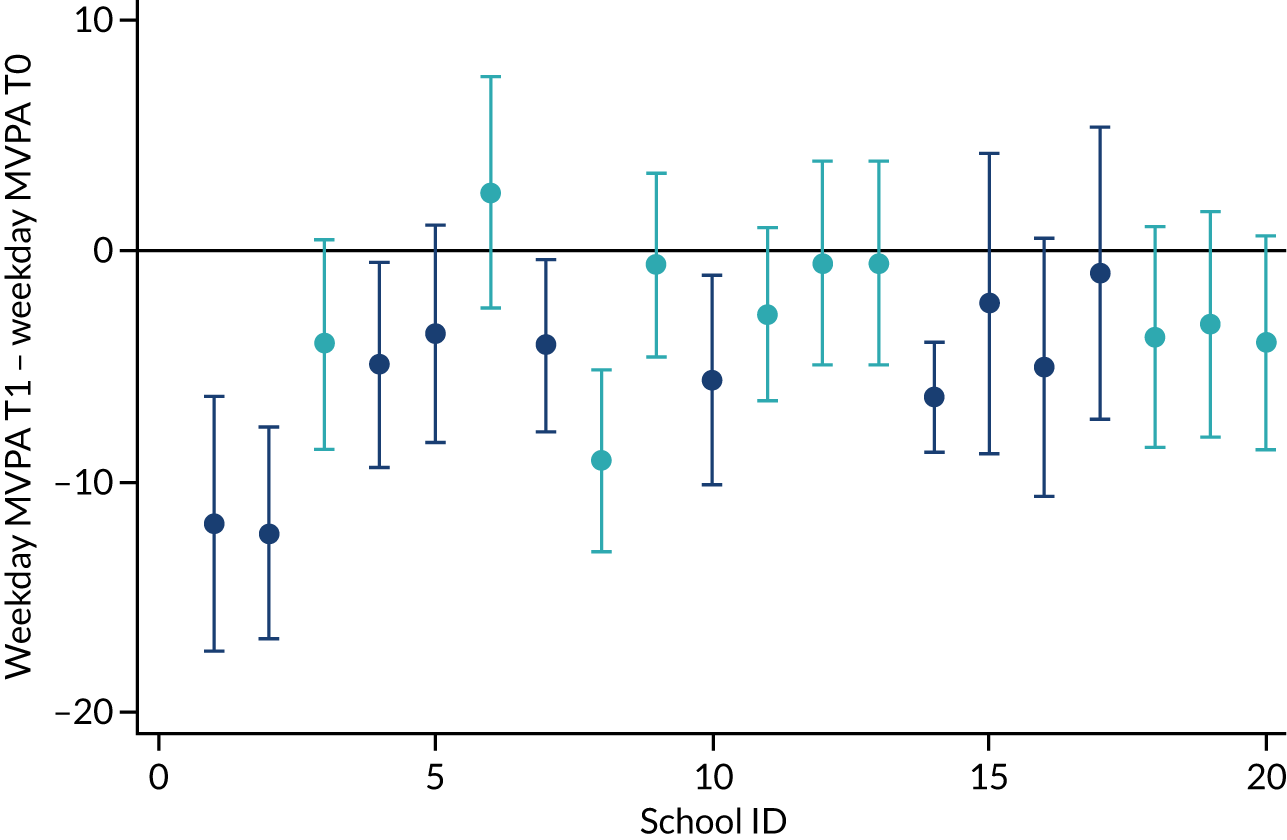

The primary outcome was the accelerometer-determined minutes of MVPA on weekdays collected at T1. This was described in each group using means and SDs. Comparisons between arms used a multivariable, mixed-effects, linear regression model to allow for clustering within schools, adjusting for baseline MVPA scores (i.e. random school effects to account for clustering), and the number of valid days of accelerometer data and randomisation variables.

Secondary outcomes consisted of mean weekend and weekday minutes of sedentary time, mean weekend minutes of MVPA and self-esteem. These were continuous measures and were analysed using the same modelling approach as that used for the primary outcome.

Sensitivity analyses

Exploratory sensitivity analyses that were part of the pre-agreed statistical analysis plan,74 which was approved by the TSC prior to any analyses being conducted, were presented alongside the primary analysis to assess the sensitivity of the primary analysis to the following conditions:

-

Imbalance between groups. Where imbalance between the arms was evident at baseline, the primary analysis was repeated, adjusting for the variables showing an imbalance.

-

Missing outcome data. Patterns of missing MVPA data were explored and missing values were imputed by using the MI command in Stata to perform multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE). Analyses using imputed data were compared with the primary analysis.

-

Month of data measurement (i.e. seasonal bias). The primary analysis was repeated, adjusting for the month of the year in which the MVPA measurements were taken.

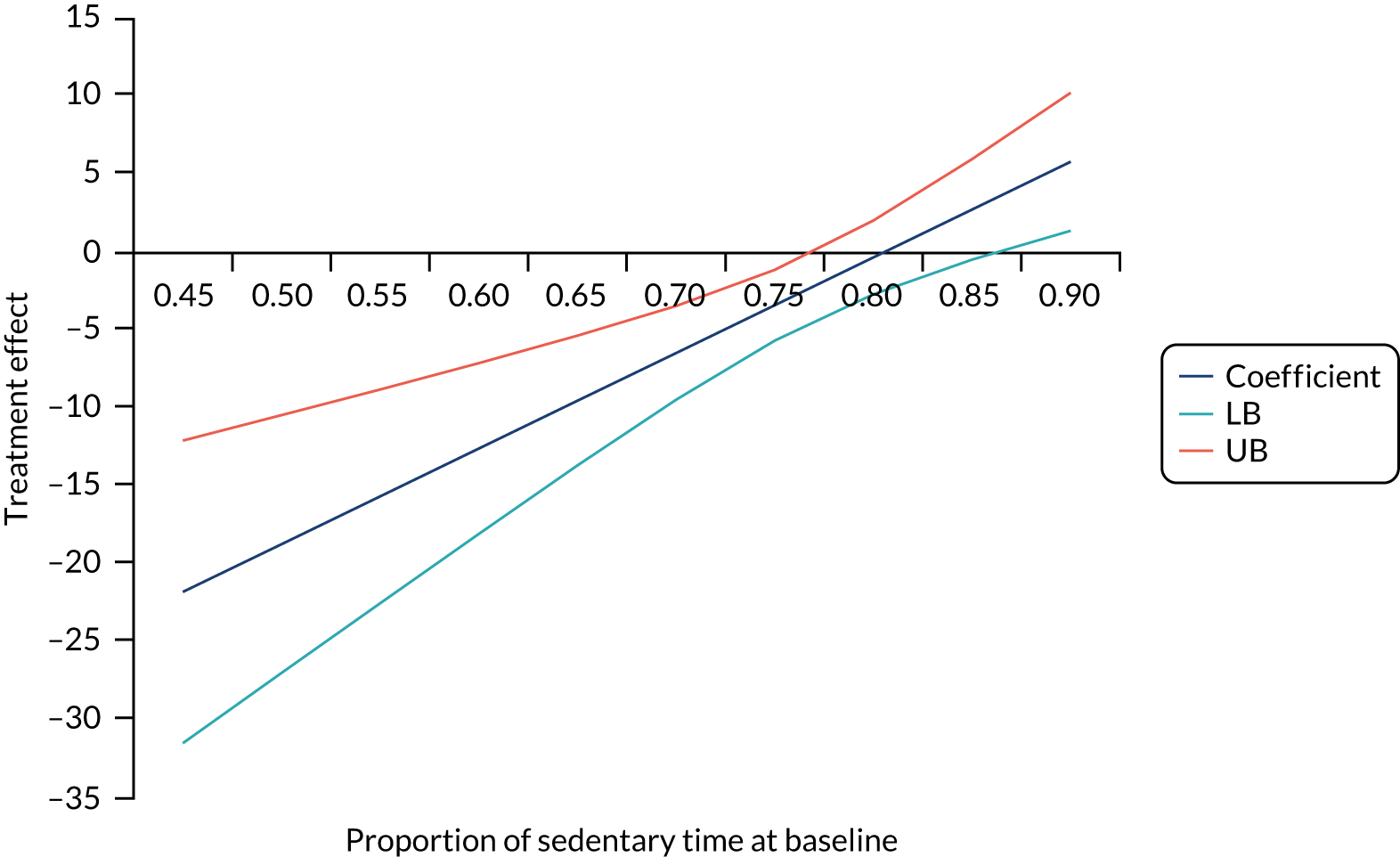

Subgroup analyses

Pre-agreed subgroup analyses were performed to estimate whether or not the intervention was differentially effective in subgroups of SEP, nominated peer supporters (peer supporters vs. non-peer supporters) and the proportion of sedentary time at baseline. This involved including interaction terms between the arms and moderator (i.e. SEP, peer supporter training or proportion of sedentary time at baseline) in the primary analysis models and using the likelihood ratio test for hypothesis testing.

As the trial was not powered to detect effectiveness in subgroups, these analyses were treated as exploratory and interpreted with caution.

Mediation analysis

Mediation analysis was conducted to explore whether or not any effect of the intervention was mediated by self-determined physical activity autonomous motivation,68 autonomy,46 competence69 or relatedness. 46 The MEDEFF command in Stata was used to estimate the causal mechanisms. Mediators were treated as continuously measured variables and described using the mean scores, stratified by arm.

Compliance and missing data

The following criteria have been used in previous studies. 75 Accelerometer compliance was calculated at each time point using the number of valid days of accelerometer data provided by each girl enrolled in the trial at that time. For participants to be considered compliant, valid accelerometer data for at least two weekdays were required. At each time point, the number and percentage of girls enrolled in the trial who provided questionnaire data were used to calculate questionnaire compliance. Rates of provision of accelerometer data (missing, invalid and valid) and questionnaire data (missing and not missing) were recorded for T0 and T1. Data were classified as missing when the valid wear time condition was not achieved or if an accelerometer was not returned. (See Table 12 for details of data provision at each time point.)

Process evaluation methods

The process evaluation for the definitive trial used a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods to examine the intervention delivery and how implementation and the resulting impact on participants were connected. Specifically, this examined the:

-

intervention implementation and fidelity

-

receipt of the intervention by pupils (peer supporters and non-peer supporters)

-

potential sustainability of the intervention and roll-out, if effectiveness was demonstrated in analyses of the primary and secondary outcomes.

We also assessed school context using physical and social environment audit tools76,77 that were piloted in the feasibility trial55 and then adapted. Data collection was carried out by the trial team with informant groups that included peer supporters, non-peer supporters, peer supporter trainers, school contacts and external stakeholders (e.g. public health commissioners).

Measures

The process evaluation measures with pupils, trainers and teachers were conducted during or straight after the intervention period in each intervention school (March–July 2019).

Peer supporter training attendance

Peer supporters’ attendance at all three of the training days was recorded by the trainers, along with reasons for absences, if known, using attendance registers. Trainers were also asked to record any adverse events that occurred.

Fidelity to PLAN-A session plans

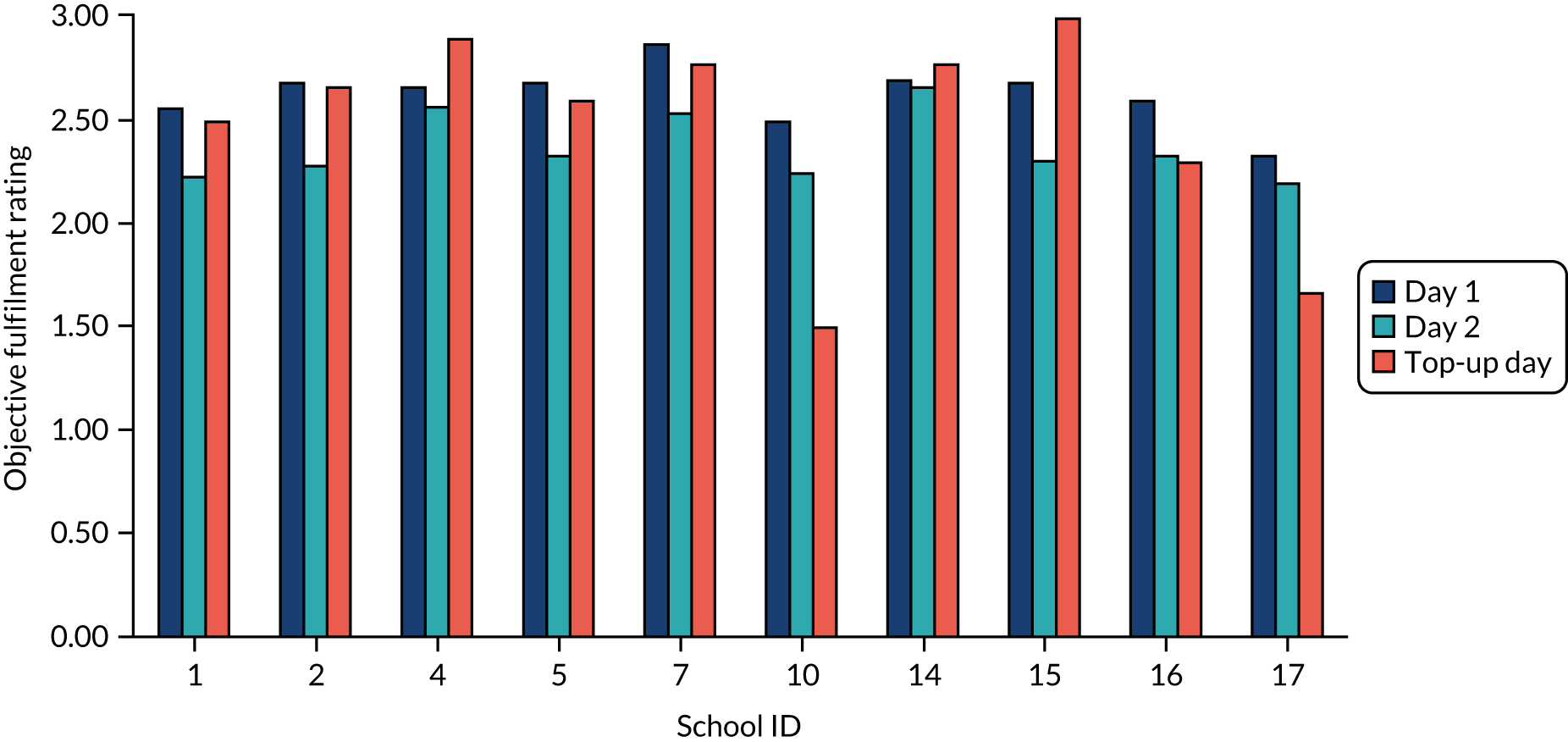

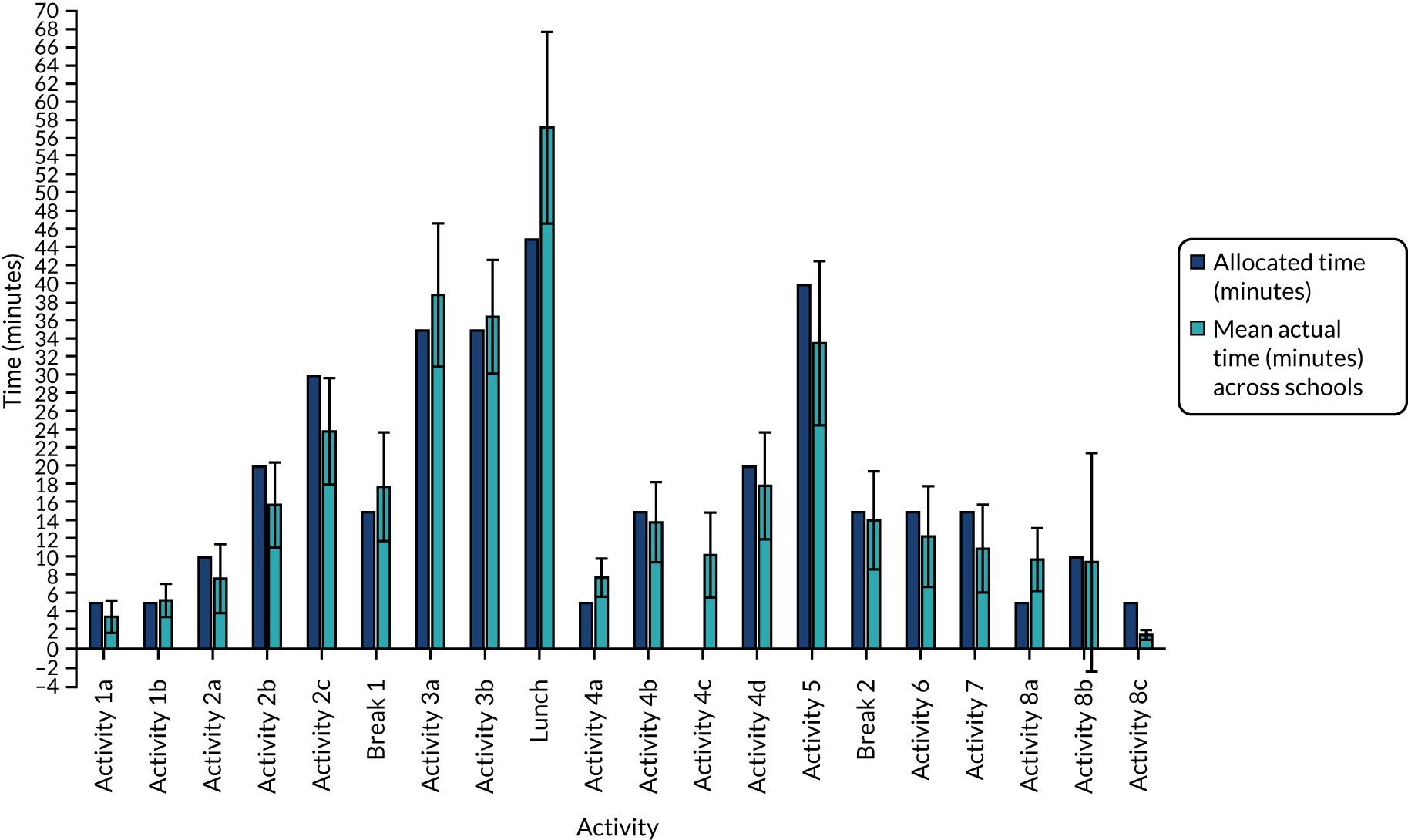

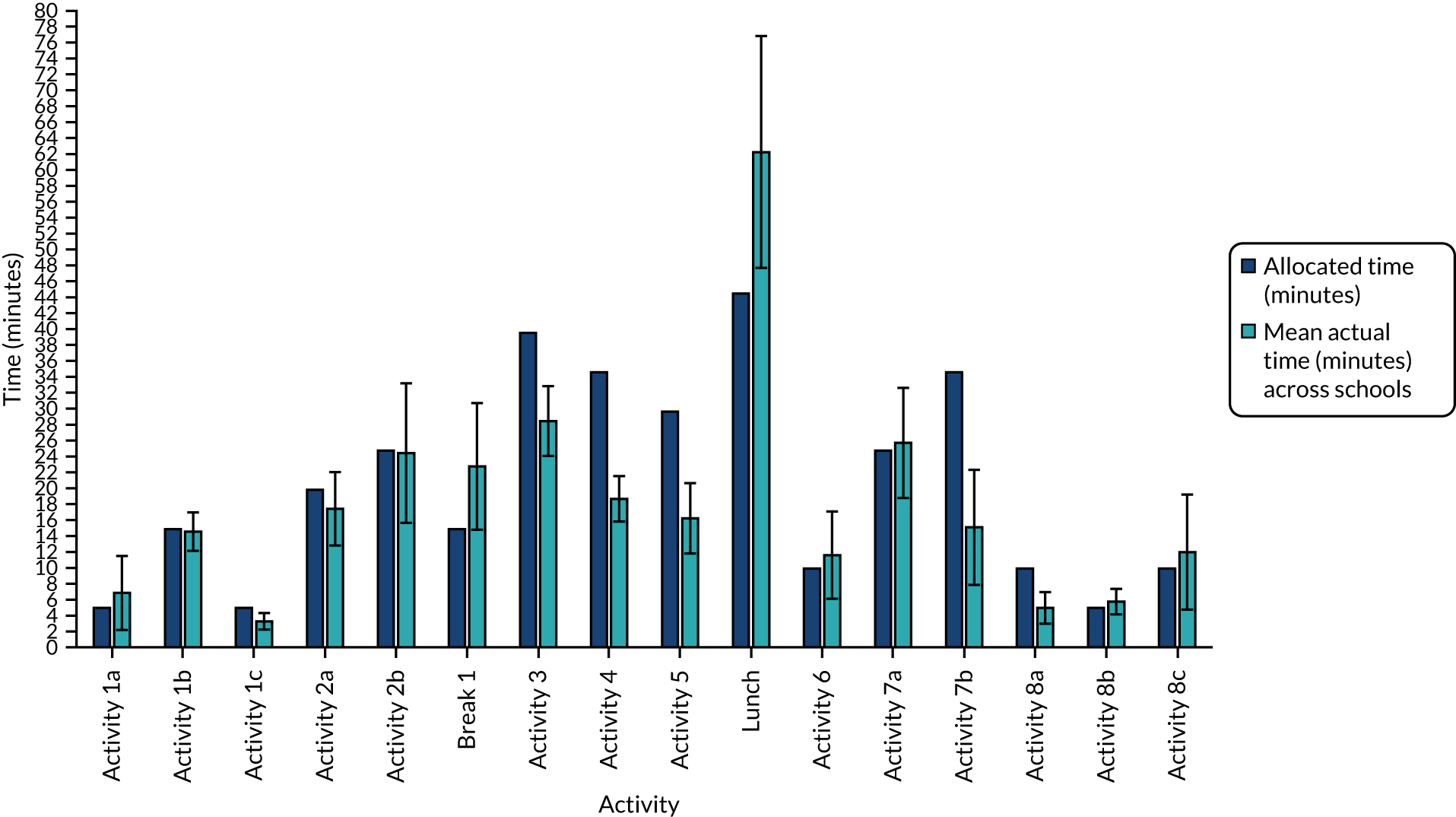

Direct observation of the intervention sessions in each school was conducted by a member of the trial team using an observation form (see Report Supplementary Material 2) and a copy of the ‘session plan manual’ for reference. For each activity, the observer recorded whether any activities were missed or changed, how engaged the pupils were, and whether or not the learning objectives for each activity were achieved (scale ranging from 0, objective fulfilled ‘not at all’, to 3, objective fulfilled ‘mostly/all’). Fulfilment of activity objectives and pupil engagement were reported by school for each activity section using means and SDs. The observing researcher also commented on what did and did not work during the activity, potential improvements, things affecting delivery and the extent to which it supported the three needs underpinning SDT: autonomy, relatedness and competence. These qualitative data were analysed thematically to compare delivery between schools.

Trainers’ experience of the peer supporter training

Trainers completed an evaluation form after delivery of day 2 and the top-up day training (see Report Supplementary Material 3), assessing the suitability of training arrangements (ratings ranged from 0, ‘poor’, to 4, ‘excellent’, and included statements related to the resources provided to aid delivery of the training, refreshments and quality of the training facility); achievement of the training objectives (ratings ranged from 0, ‘not well at all’, to 3, ‘very well’, for statements related to how successful they felt the training was in achieving key objectives, e.g. increasing peer supporter knowledge or communication skills) and how well the peer supporters responded to training (ratings ranged from 0, ‘not at all’, to 3, ‘very’, for four items covering engagement, involvement, enjoyment and interest of peer supporters). Means and SDs were computed to describe data by school and trainer.

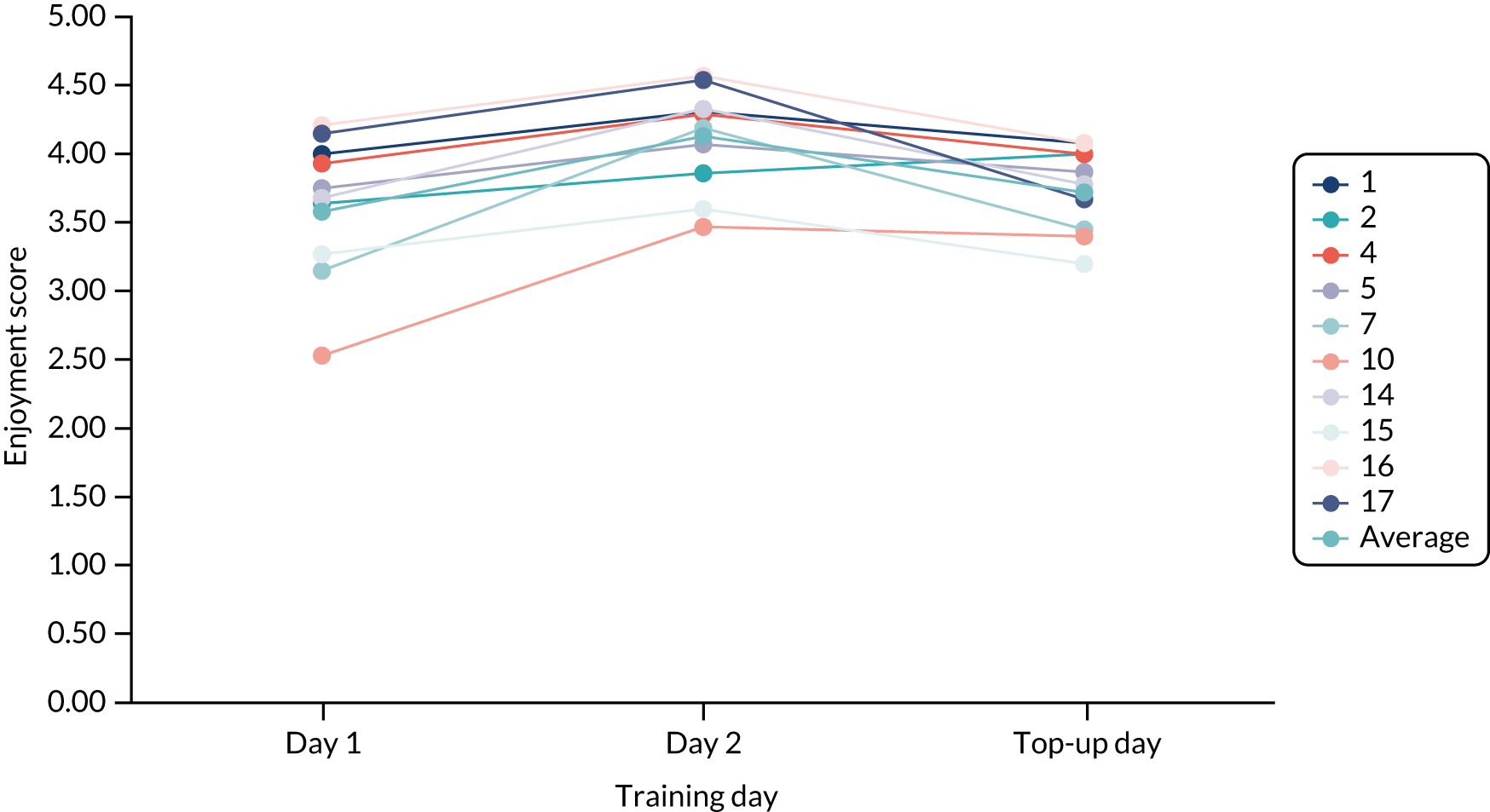

Participants’ experience of the peer supporter training

Peer supporters completed an evaluation form after completing day 2 and the top-up day of the training (see Report Supplementary Material 4), assessing enjoyment, content and logistics. Enjoyment of the training sessions was measured on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating ‘not at all’ and 5 being ‘a lot’. Statements pertaining to training content, logistics and concept understanding (e.g. ‘I understand my role as a peer supporter’ and ‘the length of the training was about right’) were rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 0, ‘disagree a lot’, to 4, ‘agree a lot’. For all schools, means, SDs and ranges were reported by question. The evaluation form also included qualitative items asking about what they had learned, what they enjoyed most, what they needed for them to be more confident peer supporters and suggested improvements for the training.

Fidelity to self-determination theory in the delivery of the peer supporter training

Peer supporters’ perceptions of autonomy support provided by the trainers during the training was measured using a six-item measure (the Sport Climate Questionnaire46), previously used in a PE setting, that was nested in the evaluation questionnaire administered after the training days. Peer supporters were asked to rate how much they agreed with statements related to how supportive the trainers were of their needs, ranging from 0 (‘disagree a lot’) to 4 (‘agree a lot’). The mean of the six items was derived to produce a needs-support score. The means and SDs were reported by school. Cronbach’s alpha estimates of internal consistency were reported for training days 1 and 2 (combined) and the top-up day.

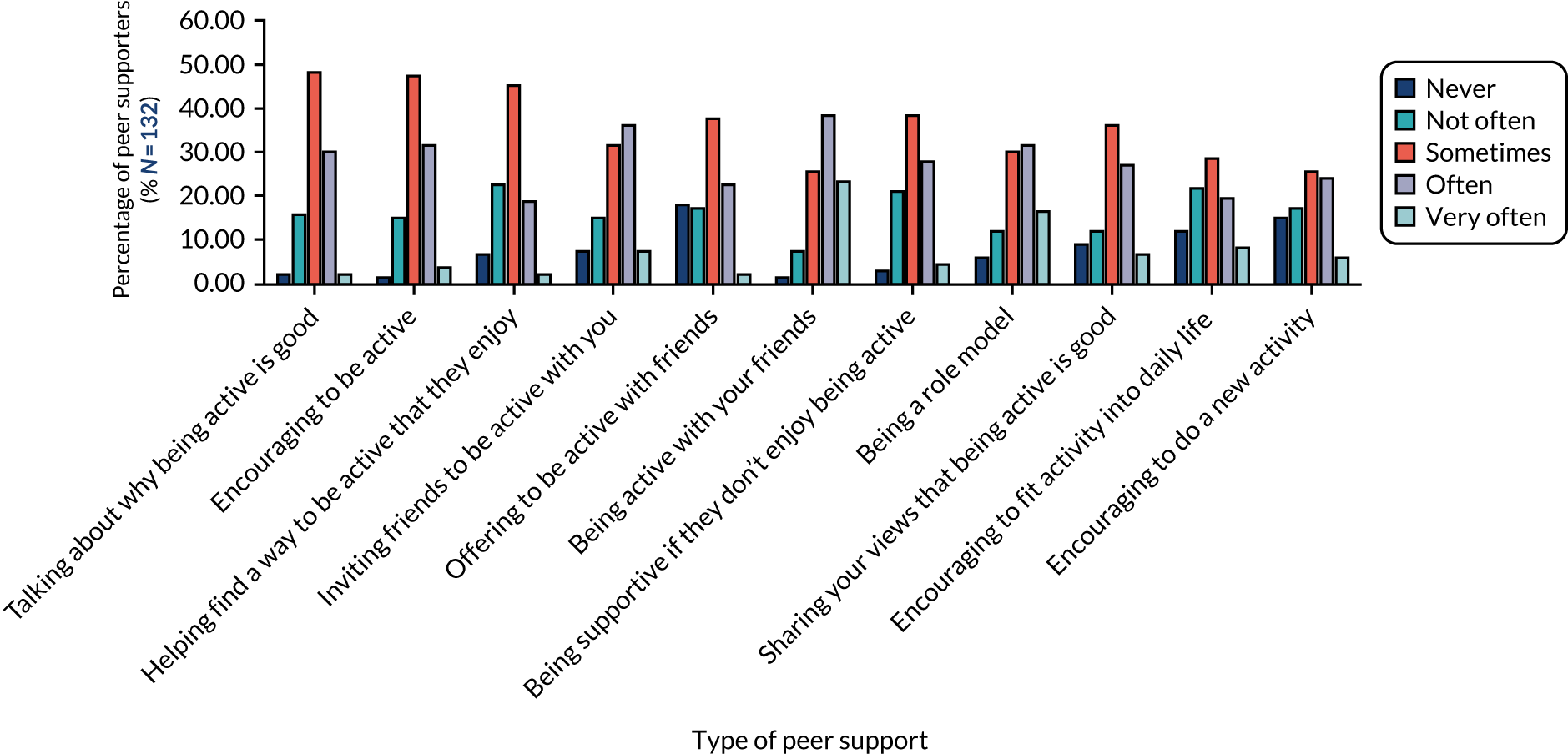

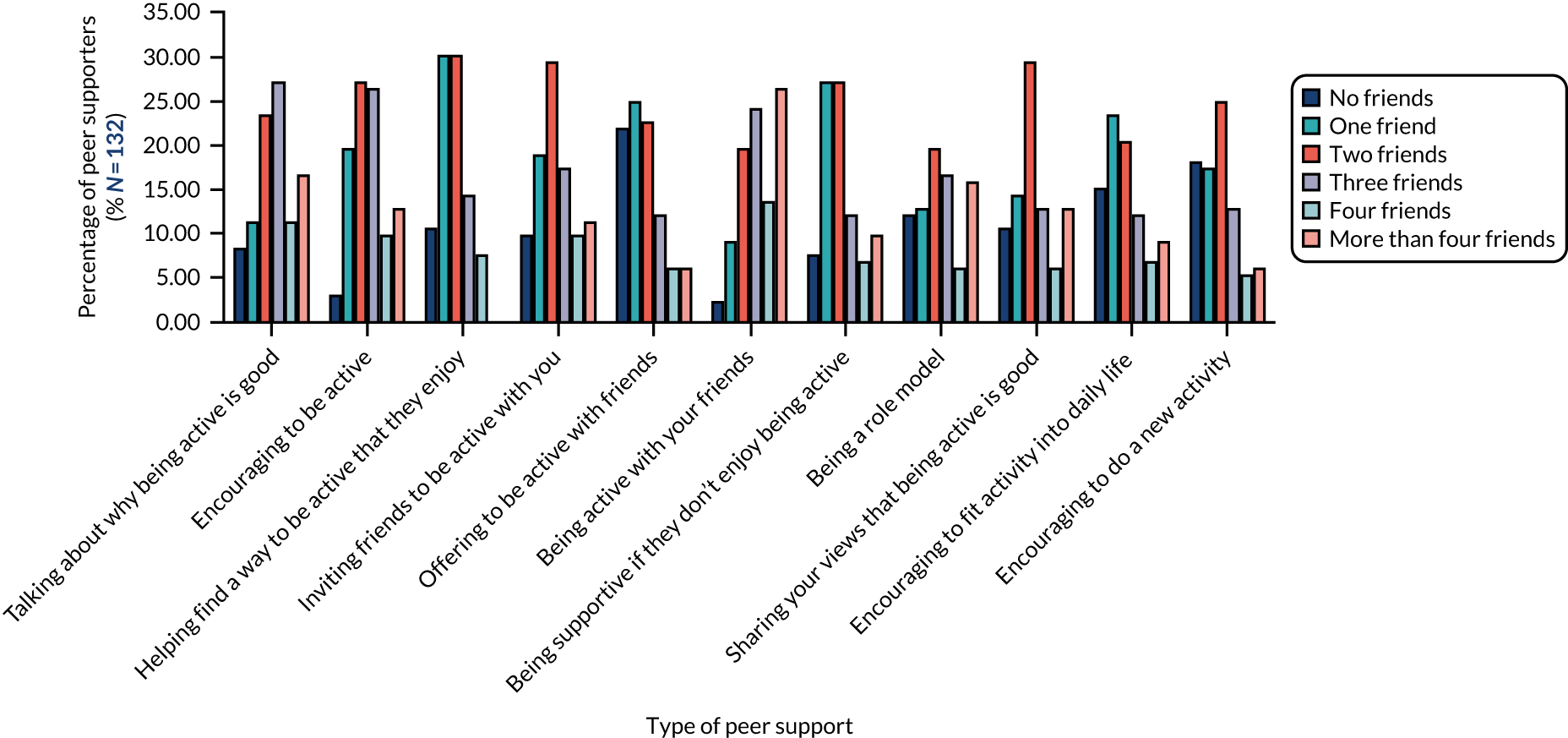

Intervention fidelity

Peer supporters were asked to complete a questionnaire at the top-up day and, again, at the end of the 10-week diffusion period (see Report Supplementary Material 5); this was a self-reported record of the peer support undertaken. Ratings for how often different types of support were given ranged from 0, ‘never’, to 4, ‘very often’, and options for how many friends they gave that type of support to ranged from ‘0’ to ‘> 4’. Qualitative examples of peer-supporting behaviour provided in free-text space on the questionnaire were analysed qualitatively and triangulated with focus group data, as described below.

Interviews and focus groups

At the end of the 10-week diffusion period, members of the research team conducted focus groups and interviews with all informant groups (i.e. peer supporters, non-peer supporters, peer supporter trainers and school contacts). Interviews with public-sector stakeholders (e.g. public health commissioners) were conducted later, once the trial results were known.

Participants were invited to take part in a focus group or interview through information letters. All informants were required to provide informed consent to take part in the qualitative process measures. Focus groups and interviews were recorded using an encrypted digital recorder and audio recordings were transcribed verbatim. Transcribed data were anonymised before the analysis.

Separate interview guides were developed for each informant group. All interview and focus group topic guides were developed by Byron Tibbitts (PLAN-A trial manager, male) and Kathryn Willis (research associate, female), in consultation with Russell Jago (PLAN-A principal investigator) and Simon J Sebire (PLAN-A co-investigator). Interviews were conducted in private with one of three research team members [BT (male), KW (female) or TR (male)], who were all trained in qualitative data collection and analysis. Focus groups were conducted by two members of the research team in tandem, with one leading and the other supporting. Field notes were made by the supporting researcher. A prior rapport had been struck between the researchers conducting the interviews and the trainers and respondents in intervention schools through exposure to one another during intervention delivery and data collection phases.

At the start of each interview or focus group, the researcher (BT, KW or TR) outlined the purpose of the interview/group and disclosed their role in the project. The first interviews and focus groups served to pilot the topic guides, which were subsequently discussed and refined by the research team.

Peer supporter focus groups

One focus group was conducted at each intervention school between June 2019 and July 2019 (duration range 32–62 minutes). Six participants were chosen at random from the group of peer supporters using a random-number generator. The joint foci of the focus group guide were the peer supporter training and their experience of being a peer supporter (see Report Supplementary Material 7). Topics included recruitment, training logistics, training content, perceptions of the trainers and their delivery style, and experiences of and challenges to peer supporting.

Non-peer supporter focus groups

One focus group was conducted at each intervention school between June 2019 and July 2019 (duration range 17–40 minutes). Six participants were selected purposively from the non-peer supporter group to include girls across the range of baseline MVPA (i.e. random sampling within MVPA tertiles). The topic guide (see Report Supplementary Material 8) addressed general attitudes among their year group towards physical activity and the associated barriers; perceptions of the recruitment and data collection process; awareness of the intervention; and the perceived impact of the intervention on attitudes or behaviours within their year group and, specifically, on the peer supporters.

Trainer interviews

Face-to-face semistructured interviews were conducted with each trainer, including the lead trainer, between July 2019 and September 2019 (trainers, n = 7; duration range 53–83 minutes), after they had finished delivery in their final school. Interviews took place in a setting of the respondent’s choosing. The interview guide (see Report Supplementary Material 9) considered the training that they had received to carry out their role, as well as the peer supporter training that they delivered in schools. Topics included intervention content, logistics and support, what did and did not work, challenges to delivery and potential improvements that could be made to the intervention.

School contact interviews

The primary liaison for the research team at each intervention school (i.e. the school contact) was interviewed, either face to face or by telephone, after the intervention had been delivered (school contacts, n = 10; duration range 31–52 minutes). The school contact interview guide (see Report Supplementary Material 10) addressed their involvement in the project and the logistics of liaising with the trial team, with the aim of identifying any potential improvements to how the intervention could be implemented in schools.

Public-sector stakeholder interviews

Telephone interviews were conducted with 19 public-sector stakeholders (duration range 30–61 minutes), such as public health commissioners, school and regional sports partnership leads, advanced public health practitioners, education officers and agents from national governing bodies that promote physical activity in schools. Participants were sampled purposively using the following criteria: the person was employed in the public or private sector, and their professional role directly involved the implementation of physical activity-promoting initiatives with young people and/or working with schools to do so.

In order for the questions to be tailored to maximise the utility of the information received, the interviews were conducted between October 2020 and January 2021, after the trial outcomes were known. The interview topic guide (see Report Supplementary Material 11) sought to elicit stakeholders’ experience-driven perspectives on factors that influence the effectiveness of physical activity interventions in school settings, and the direction that research should take to support improvements in intervention adoption and impact. After 19 interviews, the three researchers agreed that no novel insights were emerging from transcripts and additional data would not add meaningful information power, so data collection ceased.

School context

Various quantitative and qualitative data were collected to establish school context and the potential effects on the implementation or efficacy of the intervention. Details of school size and pupil premium were provided by the school contact or school reception to establish pupil demographics. In addition, PLAN-A researchers made narrative records of school ‘social environment’ after data collection visits to reflect the experience of engaging with the school, the key contact(s), the pupils and any other factors that may have had an impact on implementation.

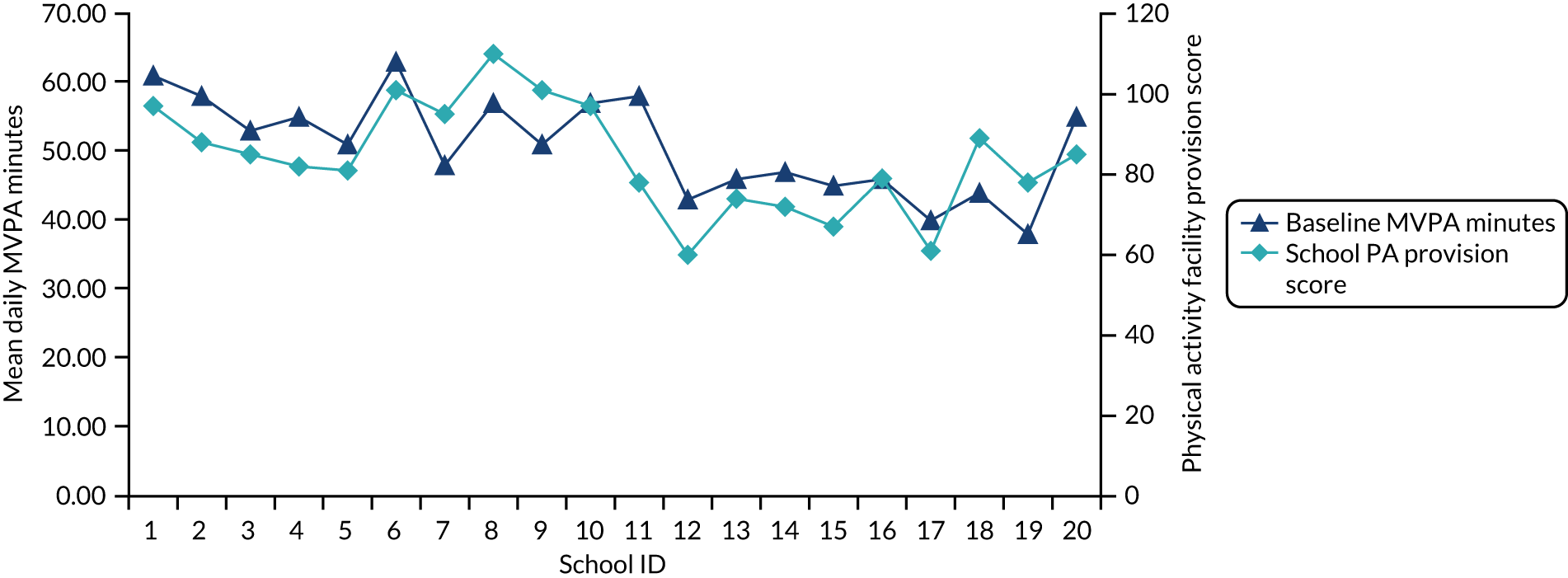

To explore any differences between schools in the physical activity environment, a quantitative school context audit (see Report Supplementary Material 6), which addressed similar constructs to those in Jones et al. ’s76 validated tool and was developed further in the PLAN-A feasibility trial52 and another school project,78 enabled members of the trial team to collect information on school-level physical activity provisions. Items in the adapted audit tool assessed the presence (i.e. count) and quality (graded on a five-point quality scale) of different physical activity facilities (e.g. courts, pitches, hard-surface playgrounds).

A second part of the school context measure asked school contacts to provide details on school policies regarding physical activity and the integration of physical activity throughout the curriculum. 77 To further explore school-level differences in physical activity provision that may affect the primary outcome of the trial, we asked all 20 school contacts to report termly on any change in physical activity provision or other lifestyle interventions in the school that were available to the girls in the trial.

School physical activity context scoring

Parts of this section have been reproduced with permission from Jago et al. 75 © Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Jago et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

One school environment audit was completed per school at the T1 measurement time point, except for school 13 (which was split across two sites), for which one audit was completed for each site. Scoring was adapted from Jones et al. ,76 and was refined in the PLAN-A feasibility trial52 and another school project. 75 Each school was given a ‘school physical activity suitability’ score, which is a sum of the scores from the ‘cycling provision’, ‘walking provision’, ‘sports and play provision’ and ‘design of school grounds’. Where an item occurred in more than one section of the tool, it was included only once in the physical activity suitability score to avoid replication (i.e. the items in the walking provision set are already included under cycling provision, so the scores for these items were counted only once). In addition, each school was scored on ‘other facility provision’ (which included items such as benches, drinking fountains and wildlife garden provision) and ‘aesthetics’. The aesthetics items were scored out of five for ‘abundance/agreement’ and included positive features (e.g. trees, planted beds, art) and negative features (e.g. dog faeces, ambient noise, litter) that may contribute to an overall climate that is more or less enjoyable to spend time in while being active. Where a facility (i.e. marked pedestrian crossing) is marked as present, scores were weighted as yes = 1 and no = 0. If the quantity of facilities was provided, scores were weighted relative to the mean number of facilities across all schools:

-

0 = none was recorded

-

1 = the number was between 1 and the mean plus 1 SD

-

2 = the number was greater than the mean plus 1 SD.

In the case where the mean plus 1 SD equalled < 1:

-

0 = none was recorded

-

1 = up to the mean plus 1 SD (or 1, whichever is greater)

-

2 = > 1.

The mean quality scores for physical activity facilities and the mean abundance/agreement scores for environment aesthetics were reported by school. Items assessing individual school physical activity policies and physical activity throughout the curriculum were reported descriptively. Each school received a ‘policy’ score (maximum score = 13) and ‘curriculum’ score (maximum score = 8).

Qualitative analysis

Parts of this section have been reproduced with permission from Jago et al. 75 © Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Jago et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

To synthesise the wide range of qualitative data collected, the framework method79 was used, as it produces a matrix of the data (from different participant groups) that allows comparison. The framework method also allows a combined approach to the analysis, enabling themes to emerge inductively from participant accounts and for specific issues to be explored deductively. Data were analysed using the following steps:

-

Researchers from the trial team thoroughly read and re-read each transcript, and listened back to audio recordings to become familiar with the data set. Initial impressions of the data were recorded to inform code development.

-

Initial codes were identified inductively by each researcher; these were refined as subsequent transcripts were analysed. For the deductive analyses, broad predefined codes for each informant group (see Appendix 1) were applied, with the primary purpose of categorising relevant information, which was to be further interrogated to elicit more refined codes and interpretations. Specifically, for questions relating to the central tenets of SDT,40 predefined codes were used to examine whether or not the intervention supported autonomous motivation among the participants and the three needs-support constructs:

-

autonomy: feelings of choice

-

relatedness: a feeling of connection between participants and with the instructor

-

competence.

-

-

An analytical framework that could be applied to all transcripts was agreed and developed to fit each informant group to avoid losing any key data using the following process:

-

Three researchers (KW, TR and BT) independently read and analysed the same two transcripts from each informant group, and then met, discussed and created draft frameworks for each.

-

A fourth researcher (SS) read the transcripts from each informant group alongside the draft frameworks and provided feedback.

-

Kathryn Willis, Byron Tibbitts and Tom Reid met to discuss and refine draft frameworks.

-

-

Three researchers (KW, BT, TR) then applied each framework to the remaining transcripts (with some level of double coding) using NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK), version 11. New, emerging codes were discussed between researchers and each framework was adjusted accordingly.

-

A framework matrix was then used to map all coded data by informant group, summarising the data by category and including descriptive quotations. Summarising techniques were compared to ensure consistency within the research team.

-

Frequent meetings were held between the researchers to review the matrix-enabled data analysis and theme generation. During this process, illustrative quotations to demonstrate the nature of each theme were agreed.

-

The level of convergence was evaluated by triangulating the frameworks and comparing the set of codes for each informant group.

To optimise the credibility and transparency of the research, the qualitative analysis was reported in accordance with the COREQ checklist. 59

Economic evaluation

Overview and aims

The aim of the economic evaluation was to determine the cost-effectiveness of PLAN-A.

The primary questions most relevant to the economic analysis were:

-

What is the estimated resource use and cost associated with the peer supporter training and PLAN-A intervention?

-

What is the mean cost of the PLAN-A intervention per school and per Year 9 girl?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness, in terms of (a) cost per unit increase in weekday MVPA and (b) cost per pupil achieving a 5-minute increase (which is considered a clinically important difference)80 in weekday MVPA, of the PLAN-A intervention in adolescent girls?

-

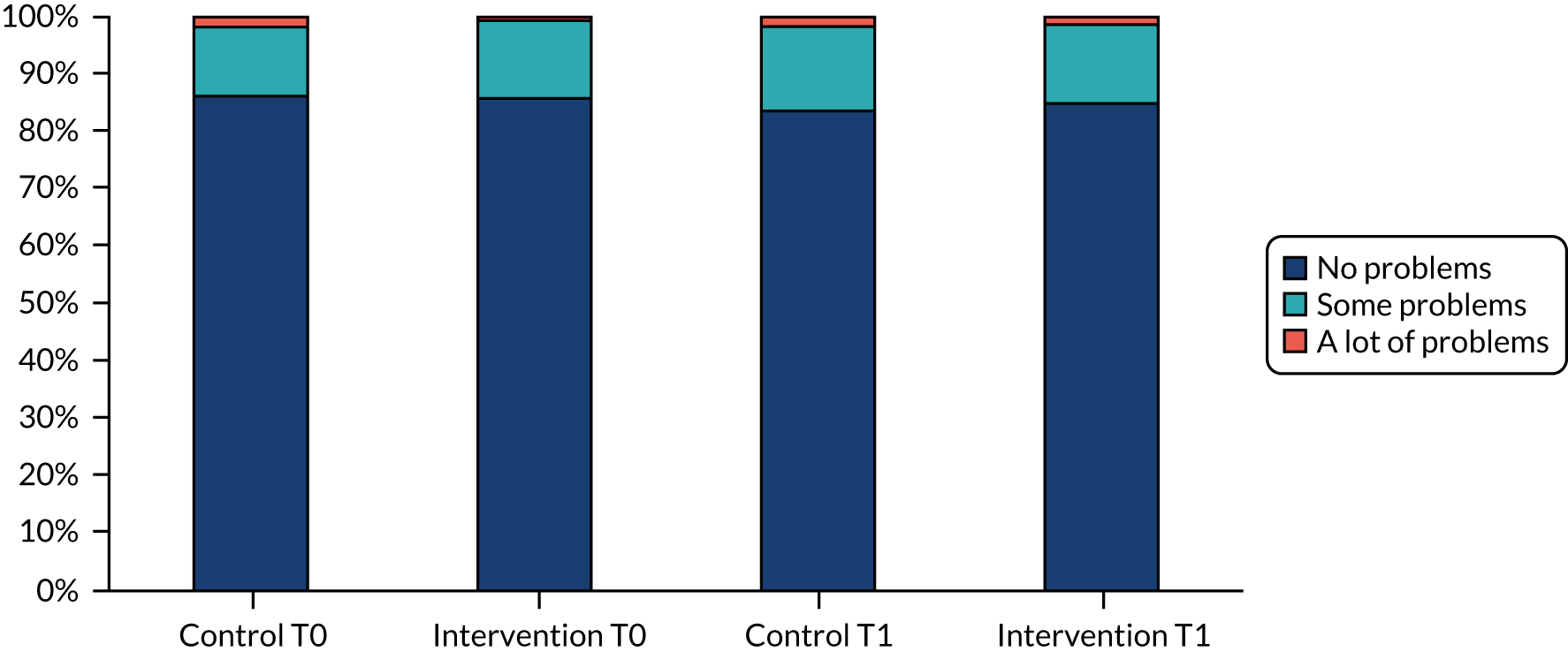

What is the effect of the PLAN-A intervention on health-related quality of life (HRQoL), measured using the EQ-5D-Y and KIDSCREEN-10?

-

What is the effect of the PLAN-A intervention in terms of the mapped Child Health Utility Instrument, nine dimensions (CHU-9D), utility scores (as derived from the KIDSCREEN-10)?

-

What is the cost–utility, in terms of cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), of the PLAN-A intervention? (This was an exploratory analysis using mapped CHU-9D scores.)

Furthermore, if there is evidence of promise that PLAN-A improves MVPA at T1, what is the potential longer-term cost-effectiveness of the intervention? (For our analysis, we consider that there is evidence of promise if the point estimate of weekday MVPA is positive and the 95% CI includes the possibility of a meaningful, i.e. 5 minutes of weekday MVPA, positive intervention effect.) The within-trial economic analysis was performed using individual participant-level data on physical activity and quality of life, and school-level data on intervention costs from the PLAN-A trial. The within-trial analysis reports results 5–6 months after the end of the PLAN-A intervention and 12 months after baseline (T0). Therefore, the economic time horizon corresponds to 1 year.

Methods for costing intervention resource

To estimate a mean cost per school and per Year 9 girl, the set-up and delivery of the PLAN-A intervention in intervention schools was costed. The resources used for other physical activity initiatives, used as part of the normal curriculum, in intervention and control schools were not measured. This assumed that the PLAN-A intervention was additional to normal practice (i.e. ‘physical activity education as usual’) and that schools did not adjust their physical activity initiatives to compensate for being allocated or not being allocated to the PLAN-A intervention. The costs were collected from a public-sector perspective, using the cost year 2019, in Great British pounds (£).

The main components of resource use were school staff, trainer (including lead trainer) and pupil time, travel and materials, venue hire and administration. In the trial, some intervention activities were supported by members of the research team and the trainers were employed by the research trial. To approximate the ‘real-world’ costs for if the intervention were scaled up to all local schools, we assumed that all intervention-related tasks would be conducted by trainers and that the trainers would be employed by local authorities. In brief, resources were logged using staff time logs [which documented the role of the school staff member/trainer, the activity, the purpose and the time spent on the activity (recorded in minutes)], expense claims (i.e. mileage/travel claims) and invoices (i.e. venue, refreshment and material costs). Where possible, resource use records were completed at the time of set-up/delivery events (i.e. the train-the-trainers, peer nomination and peer supporter events). Table 4 provides an overview of the resource captured as part of intervention cost. The intervention costs exclude the cost of intervention development during the feasibility trial. We assumed that this was a ‘sunk cost’ that would not be relevant to other schools and local authorities that were considering providing training and delivering the PLAN-A intervention in the future, if PLAN-A were to become standard practice.

| Resources measured (how collected) | Source of data | Resource units |

|---|---|---|

| Train the trainers | ||

| Lead trainer and trainers’ time | Staff timesheet | Hours per trainer |

| Venue hire | Invoice | £/venue |

| Refreshments | Invoice | £/event/day |

| Travel costs | Travel expense claim | Miles, parking charges (where applicable) |

| Peer nomination with pupils | ||

| Trial staff timea | Peer nomination log | Hours/trainer |

| Travel costs | Travel expense claim | Miles |

| Pupil time | Peer nomination log | Hours |

| PLAN-A intervention consumables | ||

| Printing and other consumables (including resource kits for peer supporter training) | Invoices and PLAN-A trial budget database | £ per resource kit and additional £ per school for any disposable itemsb |

| PLAN-A intervention administration (non-face to face) | ||

| Trial staff timea | Research staff time log | Hours/trainer |

| Peer supporter intervention delivery in schools | ||

| Trainer time | Intervention delivery log | Hours/trainer |

| School staff time | School staff time log | Hours per teacher/leadership teacher/teaching support staff |

| Venue hire | Invoice | £/venue |

| Refreshment | Invoice | £/event/day |

| Travel costs | Travel expense claim | Miles, parking charges (where applicable) |

Salary band information was used to calculate school staff costs using the national teaching union main pay scale81 (Table 5). The unit cost per hour for school staff considered was calculated based on 195 contractual days for a teacher (in line with the National Association of Schoolmasters Union of Women Teachers, the teaching union for the UK)81 and ‘in-school’ hours. This includes salary on-costs (i.e. pension and national insurance). Because the logs also identified who in the school was involved with delivering the PLAN-A intervention (e.g. qualified teacher, teaching administrator or teacher with leadership responsibilities), we estimated the national average rate of pay for that role to determine the cost. The unit cost for trainers also included salary on-costs and was based on the published local government pay scale82 and assumed working days/hours for local government employees. Staff costs were calculated by multiplying the units of staff time (i.e. hours) by the appropriate unit cost for each staff member.

| Cost item | Unit cost (£)a | Source of unit cost, price year 2019 |

|---|---|---|

| Staff costs | ||

| Lead trainer | 30/hour | Based on reimbursement within trial (assumes lead trainer is self-employed) |

| Assistant lead trainer (research associate in PLAN-A trial) | 13.51/hour | Assumption that, post implementation, this work could be undertaken by a local government trainer or equivalent role |

| Trainer | 13.51/hour | Sports coach,b based on local government pay scale:87 £26,345, inclusive of pay and NI |

| PE/health education teacher | 22.76/houra | Based on mid-point (m4) on main school pay scale:82£33,288, inclusive of pay and NI |

| Head or senior teacher with leadership responsibilities | 58.35/houra | Based on national leadership and head teacher’s pay scale, 2019. Head Group 4, Spine L27: £85,338, inclusive of NI and pension contributions |

| Non-qualified teaching support staffc | 16.55/houra | Based on salary of £24,201, inclusive of pension and NI |

| Other resource costs | ||

| Travel costs (e.g. car, motoring cost) | 0.45/mile | Expense claims mileage (local government-approved rate) |

| Venue hire | Variable | Receipt of trial expenses |

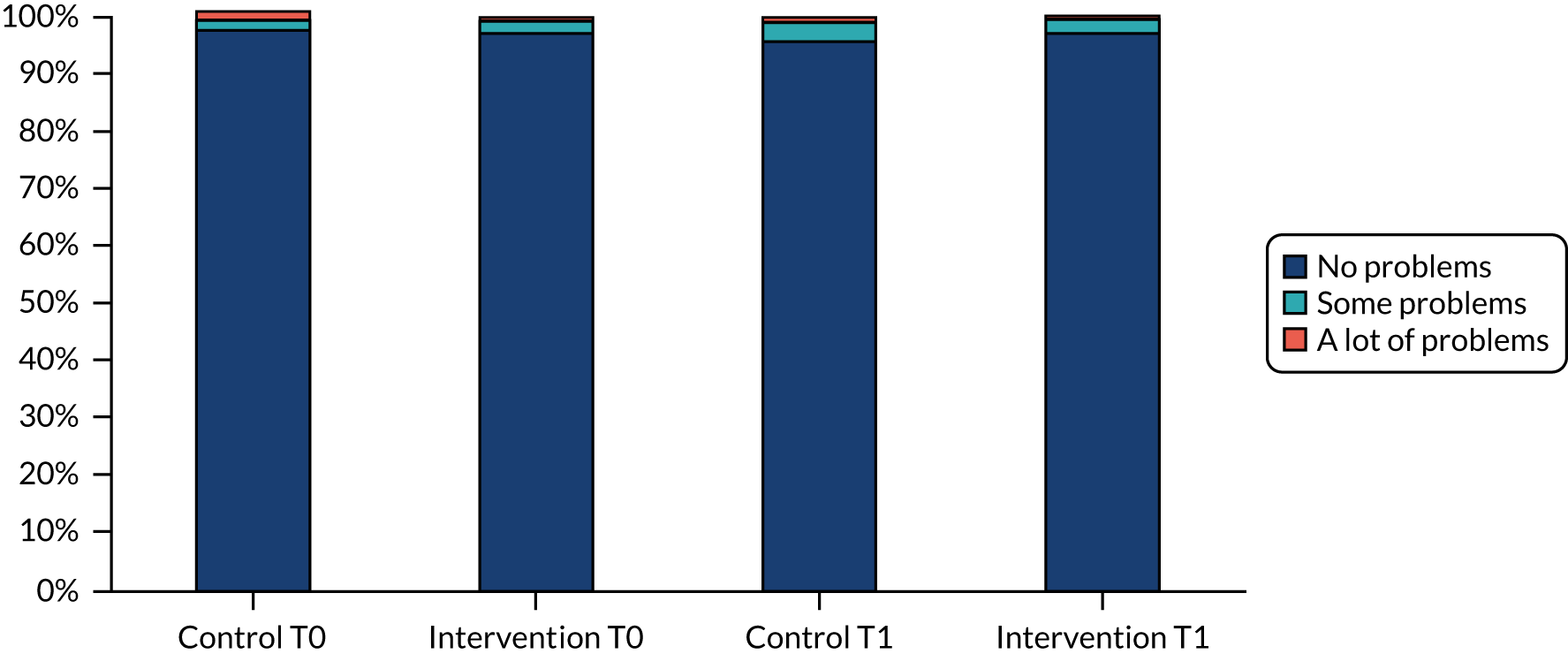

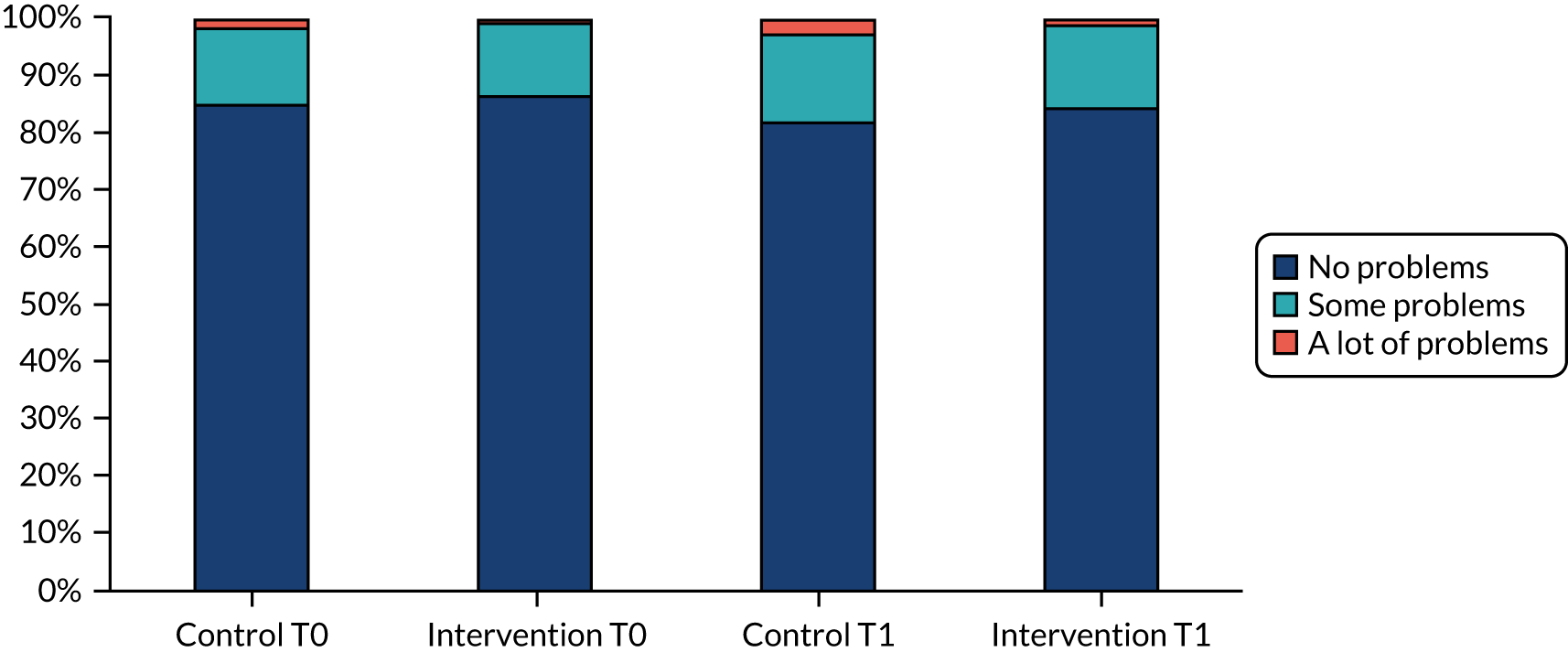

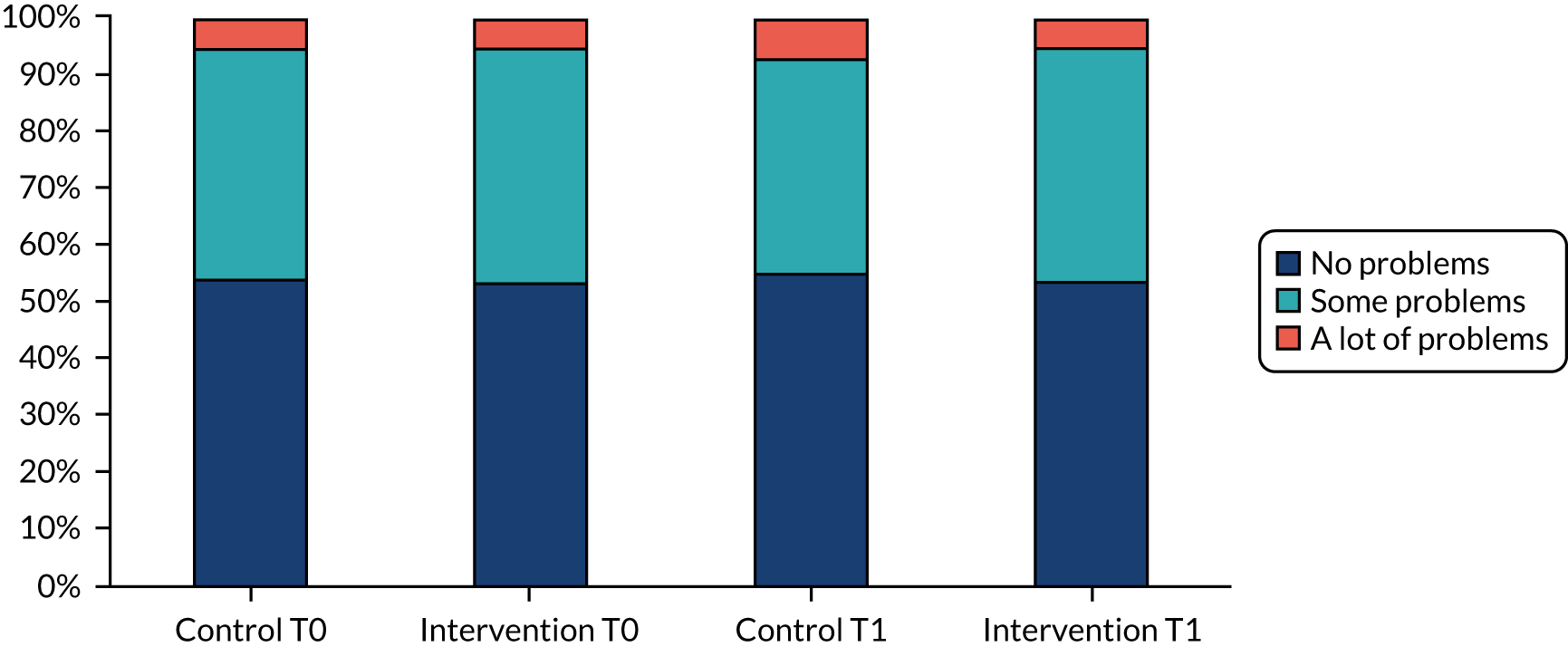

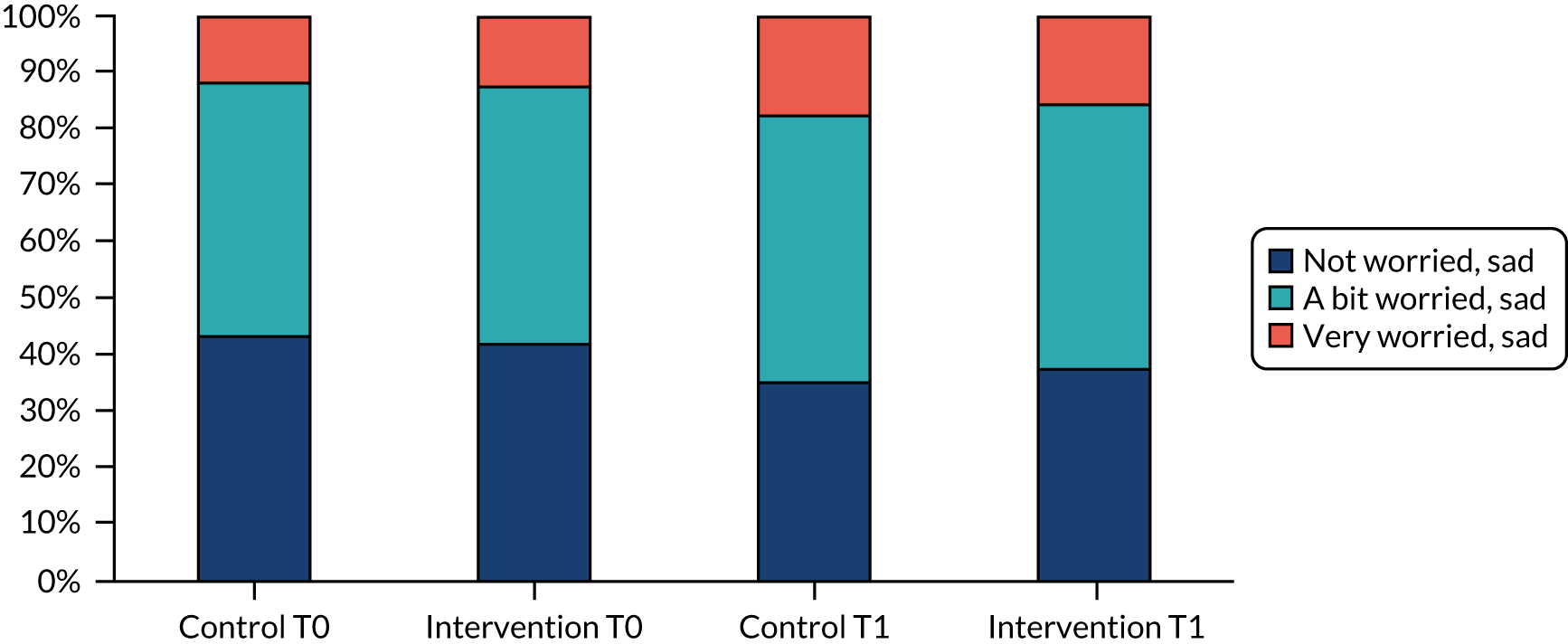

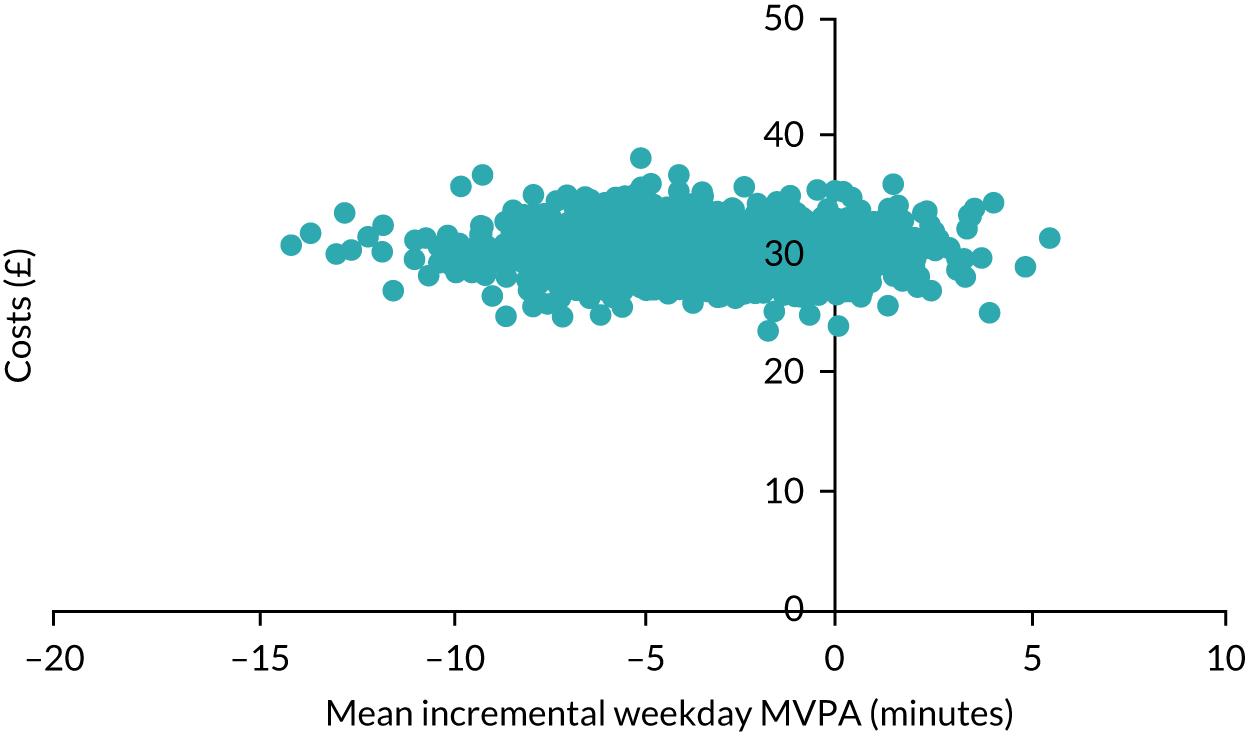

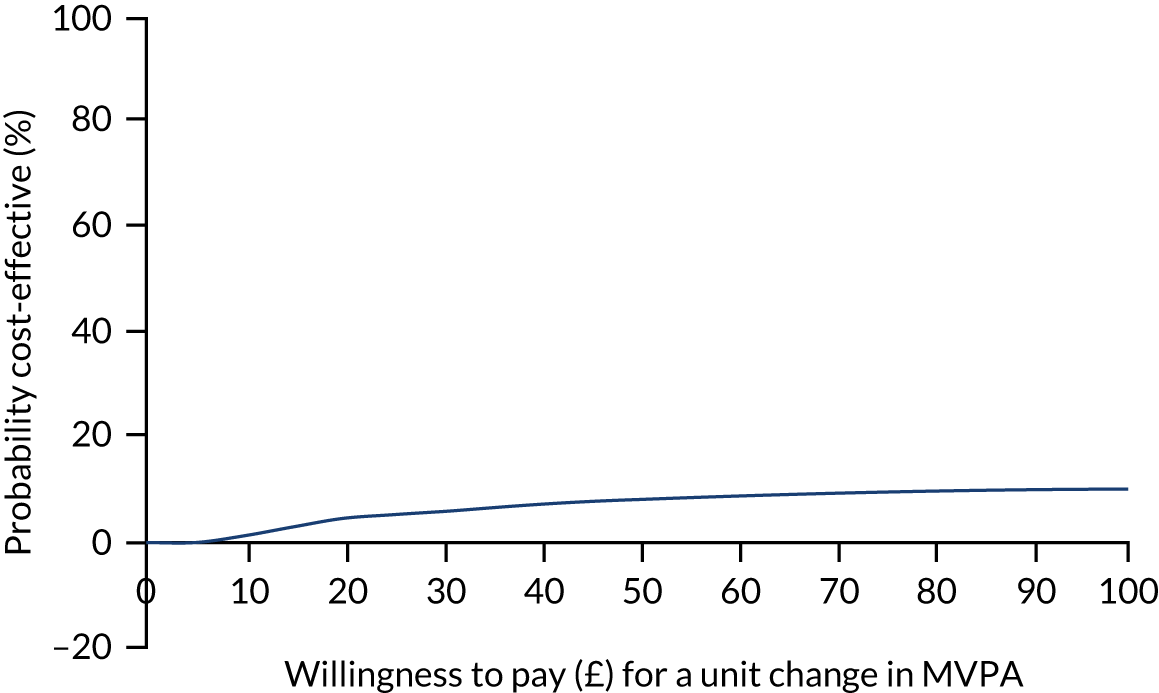

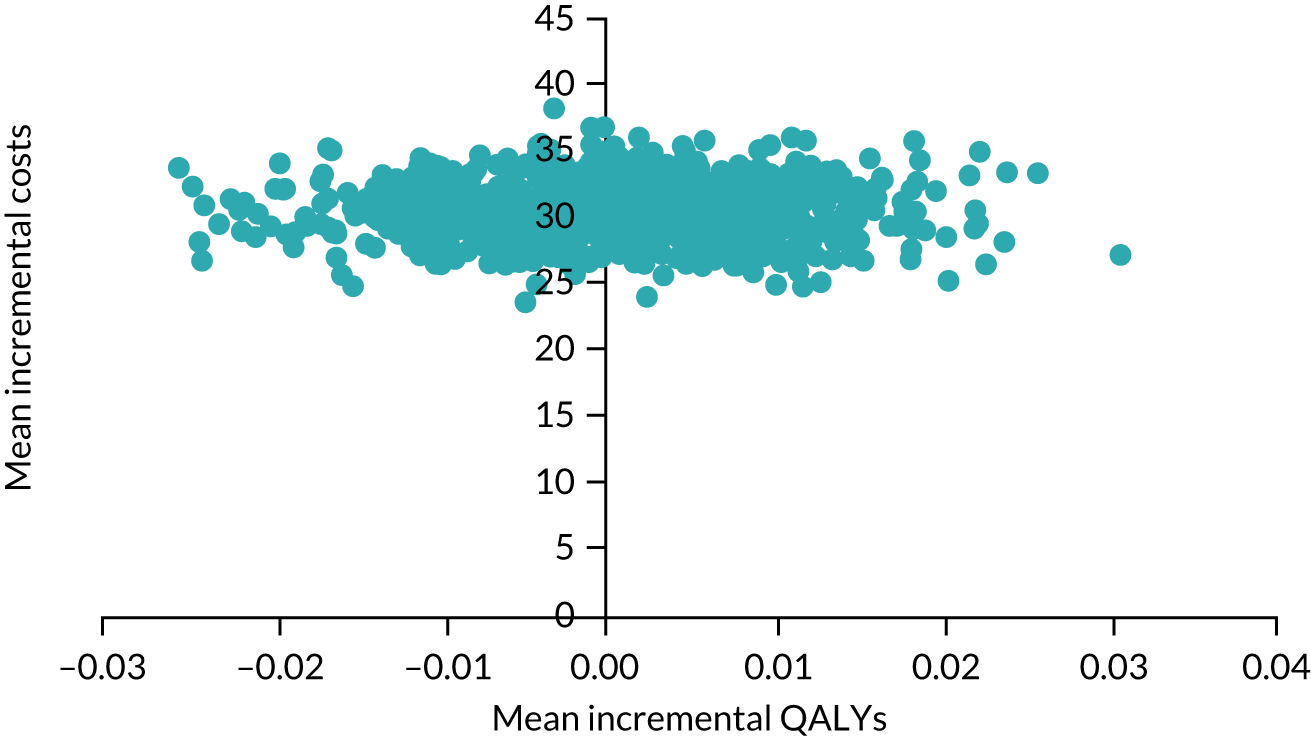

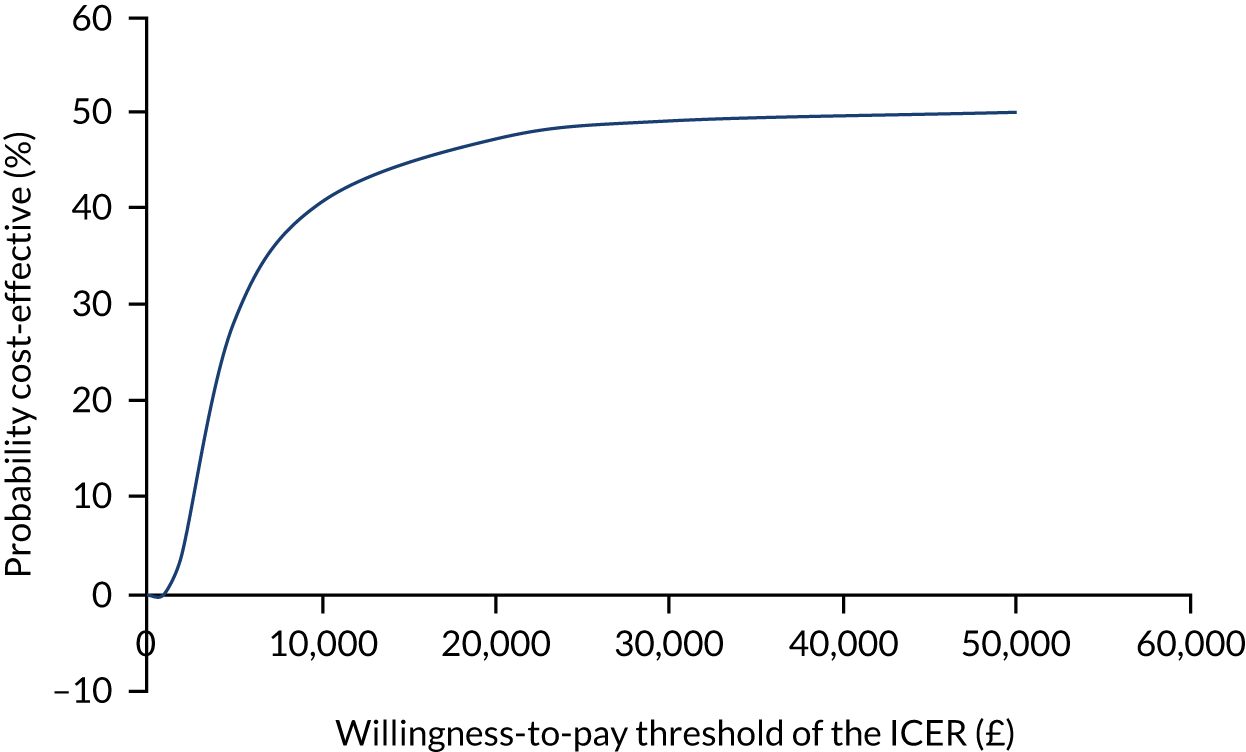

Outcomes