Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 17/22/02. The contractual start date was in November 2018. The draft report began editorial review in January 2021 and was accepted for publication in June 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Norman et al. This work was produced by Norman et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Norman et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Methods of birth in preterm birth

Preterm birth (PTB) (prior to 37 weeks’ gestation) affects 7% of UK livebirths and is the single largest cause of neonatal mortality and morbidity. Survival to 1 year of life and rates of disability are inversely proportional to length of gestation (i.e. babies born at lower gestational ages do worse than those born at higher gestational ages). Importantly, although survival rates have increased with time, rates of disability have remained unchanged. 1,2

Despite the relatively common nature of PTB, there is significant uncertainty about which mode of birth (MoB) [vaginal or caesarean section (CS)] is best. Current guidance advises clinicians to discuss the risks and benefits of vaginal and caesarean birth with women thought to be in preterm labour and to highlight the potential risks associated with CSs.

Despite this advice, the evidence base on risks and benefits is limited largely to observational studies. There is uncertainty as to whether or not a randomised trial is possible, in part because of established practice.

The research described in this monograph was in response to a Health Technology Assessment commissioned call (17/22 ‘Mode of delivery for preterm infants’) to:

. . . establish the scenarios in which there is equipoise in how best to deliver a preterm baby and to define the most important outstanding question(s) for clinicians and parents in this area that could be addressed by a future trial. If outstanding questions are identified in this first phase, then researchers are asked to conduct qualitative work with clinicians and potential participants to determine the acceptability of randomisation in order to inform the feasibility of future research.

Uncertainty about the best-planned mode of birth for women in spontaneous preterm labour

The majority of PTBs follow the premature initiation of spontaneous labour. There is clinical uncertainty about the optimal MoB in this scenario. A minority of women require CS (e.g. those with fulminating pre-eclampsia), and these women are not the focus of this study. For the remainder of women, there is significant clinical uncertainty, and some clinicians believe that birth by CS is best because of the hypothesised reduction in birth trauma and intrapartum hypoxia. Others believe that vaginal birth confers advantages for the baby (e.g. reducing respiratory morbidity), the mother (e.g. avoiding operative complications) and the NHS (e.g. costs). There are similar uncertainties about the best mode of planned PTB. Addressing these clinical uncertainties could significantly improve the health of the public and patients. Rates of intrapartum stillbirth and neonatal and long-term mortality and morbidity are higher in the 60,000 preterm babies born in the UK each year than with term babies.

In addition to these clinical uncertainties, there is very little evidence on the best MoB. To the best of our knowledge, there is only one systematic review3 of randomised trials on this topic. In this systematic review,3 only four studies (involving only 116 women) were considered to be sufficiently robust to be able contribute data to the analysis, and the most recent study was conducted 25 year ago. There were very few data of relevance to the two main (primary) outcomes for the baby considered in the review [i.e. birth injury to infant and birth asphyxia (as defined by the triallists)]. For the mother, there were very few data on the primary outcome of admission to intensive care/major maternal post-partum complications; however, women in the vaginal birth group had lower rates of puerperal pyrexia [relative risk (RR) 2.98, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.18 to 7.53; three trials, n = 89 women] and other maternal infection (RR 2.63, 95% CI 1.02 to 6.78; three trials, n = 103 women). The authors concluded that ‘there is not enough evidence to evaluate the use of a policy of planned immediate caesarean birth for preterm babies. Further studies are needed in this area’. 3

The Cochrane systematic review was updated by the Guideline Development Group for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Preterm Labour and Birth guideline (2015),4 which found no new randomised trials. A further update of this search was conducted in November 2017 prior to submission of the full grant application for this study using the medical subject headings premature birth AND delivery; obstetric AND randomised trial; premature birth AND caesarean delivery AND randomised trial; premature birth AND labor AND obstetric AND randomised trial, with publication date of January 2011–November 2017 (see Appendix 1). Again, we found no new randomised trials to address the question of the best MoB for women in preterm labour or undergoing planned PTB. A further scoping search was undertaken in preparation for the Delphi exercise on 18 May 2019 and, again, no new randomised trials were found. Both of our own searches identified some observational studies. An initial review of these observational studies shows the extent of the controversy, with evidence both of worse outcomes5,6 and of better outcomes7,8 in babies delivered by CS than in babies delivered vaginally, and also evidence of no difference. 9 It is plausible that planned birth by CS could reduce the frequency of either death or disability in preterm babies compared with the control standard of care of vaginal birth. Indeed, our recent retrospective study of 1575 UK babies born between 23 and 27 weeks’ gestation found that, after adjusting for confounders, babies born vaginally had a higher odds (OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.58) of intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH). 8 Another study has shown that neonatal mortality is lower in babies born by CS than in babies born vaginally. 10 Conversely, CS is associated with higher NHS costs and greater complications for the mother,11 and there is conflicting evidence of benefit for preterm babies. 3,5,6

Importantly, there is uncertainty about the subgroups of women (e.g. those with cephalic presentation only, those at a particular gestational age and those without any signs of intrauterine growth restriction) for whom there is equipoise about the appropriate MoB. A brief description of these subgroups of women follows. First, there may be one or more babies. The Cochrane review12 and the NICE guideline4 focused on singleton pregnancy (i.e. just one baby), and we intended to include discussion about multiple pregnancy in our research in order not to narrow the question too quickly. Second, the baby (or babies) may be presenting by the breech or cephalic. (It is assumed that babies with a non-longitudinal lie would require birth by CS.) Three of the four studies in the Cochrane review12 focused on babies with breech presentation. There is arguably less controversy about the optimal MoB in women delivering preterm with breech presentation, as randomised trials of term babies have provided evidence of the advantages of CS for these babies. 13 Indeed, the NICE guideline Preterm Labour and Birth4 acknowledges this and suggests that, for women in preterm labour with breech presentation, CS should be ‘considered’. 4 Last, it is plausible that the risks and benefits of CS and vaginal birth may be different when comparing women who are in preterm labour with women undergoing planned PTB. Both subsets of women are included in the commissioning brief and we have addressed both in our research described here.

Despite the lack of evidence and uncertainty in the national guidance,11 it is not clear whether clinicians and pregnant women are in equipoise about the best MoB. Acknowledging that published evidence is only one source of information that clinicians and women use for clinical decision-making, the purpose of this study was to determine ‘[i]n which groups of women and babies in preterm labour is there clinical uncertainty about planned mode of birth’.

Uncertainty about whether or not a trial to compare planned modes of birth is feasible

In addition to the uncertainty about the best-planned MoB, there is uncertainty about whether or not a trial to compare planned modes of birth is feasible. Clinicians may not wish to randomise women to CS or vaginal birth because they have firm beliefs about the optimal MoB (despite the lack of published evidence). Likewise, pregnant women may not wish randomisation for a variety of reasons, including the experience of friends or family. The uncertainty about whether or not women and clinicians would accept randomisation has been given prominence by the Cochrane review, which noted that ‘[f]urther studies are needed in this area [of best method of delivery], but recruitment is proving difficult’. 3 The comment on difficult recruitment arose because all four of the randomised trials, which provided data for the Cochrane review, closed without having reached their sample size. However, three14–16 out of four of these studies focused on women with breech presentation for whom there is less clinical uncertainty (as described above). The most recent of these studies (of breech presentation) was published over 20 years ago. 14 In addition, the rationale for early termination of the study of singleton babies with cephalic presentation was because of an ‘unacceptably high proportion (63%) of babies with birthweight > 1500 g’ and not because of poor recruitment. This fourth trial was published over 30 years ago. 17 Therefore, there is little evidence to determine whether or not recruitment to a randomised trial of MoB is feasible, and much of the available evidence is from women delivering over 25 years ago.

This project aims to determine which groups of women in preterm labour or with planned PTB would be willing to randomise to a potential future trial. Randomised trials have been performed to address optimal MoB for women with breech presentation13 and women with twin pregnancy,18 and these trials have (arguably) reduced uncertainty. However, there are few randomised trials to compare planned CS with vaginal birth for women with a singleton pregnancy and cephalic presentation at term. 19 Importantly, in a previous study of women with a previous CS at full-term gestation, comparing elective repeat CS with vaginal birth, the majority of women were allocated by patient preference rather than randomisation, implying reluctance to randomise or be randomised. 20

Rationale for research

Aims

This project, which we called the CASSAVA project, was funded by the National Institute for Health Research as part of the Health Technology Assessment programme. The overall aim of the project was to find out the groups of women and babies in preterm labour for whom there is clinical uncertainty about the optimal planned mode of birth and whether or not women and clinical staff would be willing to participate in a future randomised trial to address this question. We aimed to determine which of the four statements below is most accurate and to define any uncertainties:

-

There are no uncertainties about the best-planned MoB for any groups of women or babies presenting in preterm labour.

-

There are uncertainties about the best-planned MoB for specific subgroups of women (which we will define) presenting in preterm labour, and in the willingness of clinicians to recruit to, and of women to participate in, a randomised trial to address these uncertainties.

-

There are uncertainties about the best-planned MoB for specific subgroups of women (which we will define) presenting in preterm labour, and in the willingness of clinicians to recruit to, and of women to participate in, a randomised trial to address some, but not all, of these uncertainties.

-

There is uncertainty about the best-planned MoB for specific subgroups of women (which we will define) presenting in preterm labour, but women and/or clinical staff are not willing to participate in a randomised trial to address any of these uncertainties.

Objectives

To achieve our overall aim, our stated objectives were as follows:

-

To perform two surveys: one survey with health-care professionals to establish current practice and opinion in key clinical scenarios of women presenting in preterm labour (e.g. cephalic/breech, previous CS or not, growth restriction present or not, gestational age of 23–24, 24–28 or 28–36 weeks) (see Chapter 3) and a second survey with parents to establish current opinion about the best MoB (see Chapter 4).

-

To convene an interactive working group of clinicians to determine what kind of trials still need to be carried out and what groups of women should be included in these trials. Formal consensus methodology was used to resolve uncertainties (see Chapter 5).

-

To design a randomised trial that addresses the agreed most important clinical uncertainties. In line with the Health Technology Assessment brief, we anticipated that the ‘control’ in our randomised trial would be planned vaginal birth and the ‘intervention’ would be planned CS, but this would be informed by the survey.

-

To mock up a short trial protocol (see Chapter 6), together with a rich descriptive vignette of the trial scenario and participant information sheets, to facilitate the qualitative study described below.

-

To perform a qualitative study among clinicians and women to determine remaining key issues and the acceptability of randomisation (see Chapter 7). We aimed to conduct telephone interviews with health-care professionals and focus groups (FGs) with women, including those who have had, or who are at risk of, PTB.

Assuming that there are clinical uncertainties that can be addressed by a trial to which women and clinicians will support recruitment, we aimed to finalise the design (and approximate costs) of a randomised trial of CS compared with vaginal birth to determine the optimal MoB of women presenting in preterm labour.

Chapter 2 Study design

Study design

To achieve our staged aims, we planned two surveys: one with health-care professionals to establish current practice and opinion in key clinical scenarios of women presenting in preterm labour (e.g. cephalic/breech, previous CS or not, growth restriction present or not, gestational age of 23–24, 24–28 or 28–36 weeks) and one with parents to establish current opinion about the best MoB. These surveys are described in more detail, with results, in Chapters 3 and 4.

Informed by the surveys and by an updated literature review, we then convened an interactive working group of clinicians to determine what kind of trials still need to be carried out and what groups of women should be included in these trials. Formal consensus methodology (Delphi) was used to resolve uncertainties. More detail about this Delphi process and the results are described in Chapter 5.

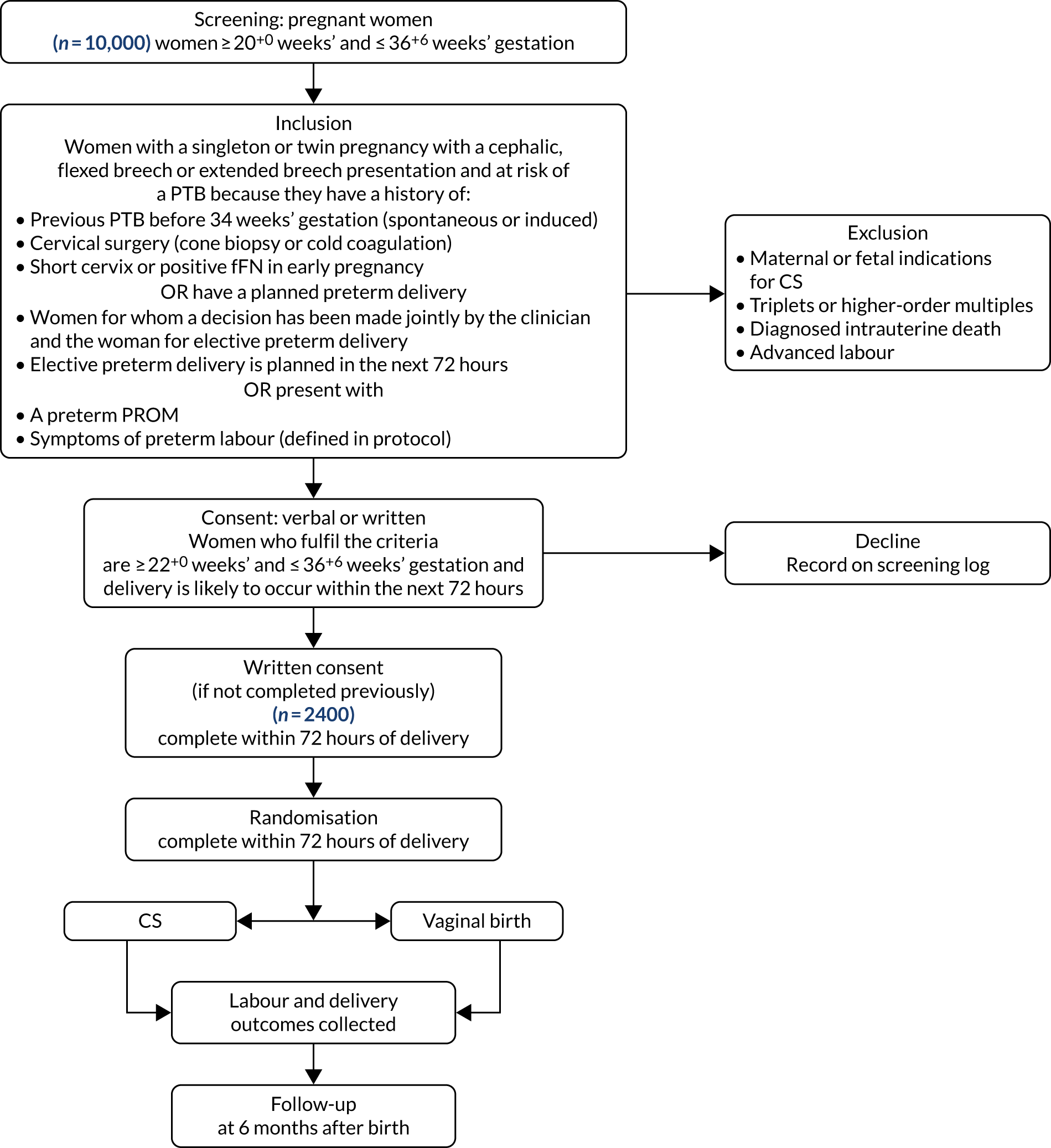

Next, we designed a randomised trial (CASSAVAplus) (see Chapter 6) that would address the agreed most important clinical uncertainties. In line with the Health Technology Assessment brief, the ‘control’ in our randomised trial was vaginal birth and the ‘intervention’ was planned CS, and this approach was validated by the clinician survey. In addition, we generated a rich descriptive vignette of the trial scenario and participant information sheets to facilitate the qualitative study.

Last, we performed a qualitative study among clinicians and women to determine remaining key issues and the acceptability of randomisation. We conducted telephone interviews with health-care professionals, and FGs with women, including those who have had, or who are at risk of, PTB. More details on the qualitative study and its results are provided in Chapter 7.

Thereafter, we had planned to finalise the design (and approximate costs) of a randomised trial of CS compared with vaginal birth to determine the optimal MoB of women presenting in preterm labour. In practice, the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020) curtailed further project development and so we have been unable to do this. However, Chapter 8 describes strategies for doing this in the future should a trial be commissioned or funded.

Ethics approval and research governance

A study protocol was written to include the surveys, the consensus workshops and Delphi process, and the qualitative interviews and FGs.

The protocol was approved by the London – City & East Research Ethics Committee on 30 April 2019 (reference 18/LO/1616). Local research and development approval was given in Edinburgh on 13 February 2019. Protocol amendments are described in Table 1 and sponsor (University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK) approval was obtained on 15 October 2018, with approval from the NHS Research Scotland Permissions Coordinating Centre and the Health Research Authority on 30 October 2018. The funder approved all versions of the protocol prior to submission to ethics.

| Amendment number | Date of amendment request | Classification | Reason for change | Approved by | Categorya | Approval process complete |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 29 October 2018 | Non-substantial | Funder requested addition of the REC reference number (i.e. 18/LO/1616) and that Section 18 – Protocol Amendments – should state that any amendments should also be submitted to the funder for authorisation prior to submission to ethics | Sponsor, HRA/NRS PCC, REC | C | 29 October 2018 |

| 2 | 25 March 2019 | Substantial 01 | Following the staff pilot survey, we made changes to the CASSAVA questionnaire for staff | Sponsor, HRA/NRS PCC, REC | C | 25 March 2019 |

| 3 | 30 January 2019 | Non-substantial | Change of PI for Edinburgh Royal Infirmary from Professor Jane E Norman to Dr Sarah Stock | Sponsor, NRS PCC | B | 30 January 2019 |

| 4 | 30 April 2019 | Substantial 02 | A new invitation to attend the Delphi meeting to be held in London on 5 July 2019 | Sponsor, HRA/NRS PCC, REC | A | 30 April 2019 |

| 5 | 24 October 2019 | Substantial 03 | New or updated documents:. CASSAVA_ PIS_HCP_V2_17092019. CASSAVA_HCP_Staff_Consent form _ V2_17092019. CASSAVA_PIS (women)_V2_17092019. Cassava_Women_Consent form_V2_17092019. Cassava_Women_OPT-IN_FORM women)_V2_17092019. HCP invitation email to interview_V1_03 Sep 19. CASSAVA_OPT_IN_FORM (HCP)_V1_03092019. CASSAVA Data Information Sheet v1.0_21072018. Social media adverts for CASSAVA focus Groups_V1_03Sep19 | Sponsor, HRA/NRS PCC, REC | A | 24 October 2019 |

| 6 | 16 December 2019 | Non-substantial | One change to the consent form for staff involved in interviews for the qualitative part of the study. The date of the CASSAVA data information sheet was incorrectly noted on the consent form: CASSAVA_HCP_Staff_Consent form _ V3_18 November 2019. CASSAVA Data Information Sheet v1.0_07082018 | Sponsor, HRA/NRS PCC | C | 16 December 2019 |

| 7 | 15 January 2020 | Non-substantial | Typographical correction to the original IRAS form dated 28 August 2018. Name of the hospital site amended | Sponsor, HRA/NRS PCC | B | 15 January 2019 |

| 8 | 15 April 2020 | Non-substantial | Owing to the restrictions imposed in relation to the COVID 19 pandemic, we were unable to arrange for women to attend FGs in person, as planned. It was, therefore, proposed that these meetings be held as virtual FGs in place of face to face interaction. The list of was follows: CASSAVA_PIS (women)_ V3_15042020; Cassava_Women_Consent form_ V3_15042020 | Sponsor, HRA/NRS PCC | C | 4 June 2020 |

Participants

Inclusion criteria

For the survey, we aimed to include consultant obstetricians, neonatologists and midwives working in hospitals with neonatal intensive care units (as these are the only hospitals that will deliver the extreme PTBs, which are included in the scenarios). For the patient survey, we included all parents who responded to the advertisement by Tommy’s (London, UK) and Bliss (London, UK), charities involved in patient support and campaigning for better care for PTB, for responses.

For the consensus workshop and qualitative interviews, we aimed to recruit clinicians (including obstetricians, anaesthetists, midwives, nurses, neonatologists and midwives) with ≥ 5 years experience of providing clinical care to women at risk of preterm labour or preterm infants.

For the consensus workshops and Delphi process, we included women and their partners who fulfilled the following criteria:

-

aged > 16 years

-

willing to consent

-

women with previous experience of preterm labour or delivery

-

women at risk of future preterm labour or delivery.

For the FGs, we recruited women who fulfilled the following criteria:

-

aged > 16 years

-

willing to consent.

Exclusion criteria

For the survey, we excluded clinicians working in units that did not have neonatal intensive care facilities. Women and their partners who experienced adverse events as a result of the issues above (e.g. neonatal death, stillbirth) were not actively excluded from the consensus workshops or FGs, but we were mindful of the need to manage this sensitively. The members of the research team have significant experience of conducting mixed-methods research with parents who have experienced adverse events, including perinatal death.

Recruitment procedure

We aimed to recruit health-care professionals for the survey through our professional networks of contacts. We focused on clinicians participating in existing PTB intervention studies currently led by co-applicants involved in this study. We invited participation through the NHS Preterm Birth Network and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) Preterm Birth Clinical Study Group (London, UK). In addition, we planned to advertise the survey through the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, the Royal College of Midwives (London, UK), the British Maternal and Fetal Medicine Society (London, UK), the British Association of Perinatal Medicine (London, UK) and the Neonatal Society (Edinburgh, UK). At the end of the survey, we planned to ask participating clinicians if they would be willing to be contacted to take part in an interview in the qualitative phase of the study.

We aimed to recruit patient participants for the survey through our charity partners Tommy’s and Bliss on an opt-in basis.

Those who agreed to further contact through the survey were invited by e-mail to participate in the consensus working group and Delphi survey.

Clinicians who indicated at the end of the survey that they would be willing to be contacted to take part in an interview were sampled purposefully for an in-depth interview according to their survey responses (ensuring a mix of those in favour of CS and vaginal birth, respectively). Some additional ‘snowball sampling’ was also undertaken to achieve representation of the different kinds of clinical staff who would be involved in recruiting into the proposed trial (e.g. obstetricians, neonatologists, midwives and research midwives) from different areas.

Women were identified for recruitment into the FGs by social media posts on Facebook (URL: www.facebook.com; Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), Twitter (URL: www.twitter.com; Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) and Instagram (URL: www.instagram.com; Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), and by charity partner connections with local community groups.

Informed consent

All participants were given an information sheet about the study. Completion of the survey was assumed to indicate consent. Those women/clinicians participating in the Delphi survey, FGs and interviews were asked to provide written consent before they did so.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures were participant opinions, as derived from the surveys, consensus workshops, Delphi, interviews or FGs.

Sample size

Our planned sample sizes were as follows: 200 participants for the clinician survey, 200 participants for the patient survey, 40 participants for the interactive working group and Delphi survey, between 30 and 60 participants for the FGs with women and 25 participants for the interviews with clinicians. No formal sample size calculations were made.

Statistical analyses

Survey data

We used a five-point Likert scale and analysed it with appropriate non-parametric and parametric tests. When > 85% of clinicians responding to the survey agreed on an answer to a clinical scenario, we designated the scenario as having good agreement and being accepted in clinical practice. When < 50% of clinicians agreed on an answer, we assumed that there was significant clinical uncertainty. When 50–70% of clinicians agreed, we designated the scenario as having moderate clinical uncertainty. When 70–85% of clinicians agreed, we designated the scenario as having some clinical uncertainty.

Interactive working group/Delphi survey

Data analysis involved graphical summation of the scores indicating the whole groups’ and individual participant groups’ responses using ‘DelphiManager’ software [www.liverpool.ac.uk/population-health/research/groups/comet-initiative/software/ (accessed October 2021)]. Participants were asked to score each scenario using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) scale for Delphi processes [accessed online: www.gradeworkinggroup.org (accessed October 2021)]. Participants were asked ‘[h]ow important is to include the following scenarios in a randomised trial of mode of delivery (caesarean/vaginal) for a preterm baby?’ A prespecified scale and criteria21 were used for dropping and retaining items in the longlist created from the survey. Scenarios with > 70% of participants scoring 7–10 and scenarios with < 30% of participants scoring 1–3 were included in subsequent rounds.

Qualitative research

Data analysis was undertaken by highly experienced qualitative researchers, with input from other members of the co-investigator team. Individual interviews were read through repeatedly and cross-compared to identify issues and experiences that cut across different accounts. 22 A similar approach was used for the FGs discussions, with particular attention being paid to differences and similarities in the perspectives and views of women belonging to different cultural and religious groups, and to those with prior experience of CS and vaginal birth. In line with recommendations,23–25 careful attention was also paid in the analysis to group interactions, including use of humour, as participants’ (different) assumptions can be revealed through the ways they challenge, question and support one another in the context of a group discussion. 23 Team members undertook separate analyses and wrote independent reports before meeting to discuss their interpretation of the data and reach agreement on key findings and themes, which were then used to inform development of a coding frame. Coded data sets were subjected to further analyses to allow more nuanced interpretations of the data to be developed and to identify illustrative quotations. NVivo software (version 11; QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to support data coding and retrieval.

Study oversight

A Study Steering Committee was appointed to provide oversight for the study and the members of this committee are listed in the Acknowledgements.

Chapter 3 The clinician survey

Introduction

This chapter describes a survey with clinicians to establish current practices regarding MoB (offering women planned CS or labour with the intention of achieving vaginal birth) and opinions in key clinical scenarios of women presenting at risk of PTB (e.g. cephalic/breech, previous CS or not, indicated birth for pre-eclampsia or not, twin pregnancy or not and 23, 26 or 32 weeks’ gestation). The results were used to inform the subsequent interactive consensus workshop and to provide context to the Delphi exercise.

Methods

We performed a survey of clinicians regarding current practices and opinions, offering examples of key clinical scenarios of women presenting in preterm labour or undergoing planned PTB. The purpose of this survey was to determine the opinions of clinicians (i.e. obstetricians, neonatologists, anaesthetists and midwives working in units with neonatal intensive care facilities) on the optimal MoB in different scenarios.

Prior to designing the survey, we consulted expert opinion at a multidisciplinary conference (the European Spontaneous Preterm Birth Conference, Edinburgh, 16–18 May 2018; ≈ 150 clinicians responded to the survey) to identify scenarios for which there appeared to be most clinical uncertainty. Informed by these discussions, the survey was designed focusing on five scenarios:

-

A woman with a singleton pregnancy with established preterm labour.

-

A woman with experience of a previous caesarean birth and in established preterm labour.

-

A woman with PTB indicated by worsening pre-eclampsia (not in labour).

-

A woman with PTB indicated by fetal growth restriction (not in labour).

-

A woman with twins with established preterm labour.

In each scenario, the clinicians were asked to give their opinion on MoB at different gestational ages (i.e. 23, 26 and 32 weeks’ gestation) and different presentations of baby (i.e. cephalic, flexed breech and footling breech). In each case, clinicians were asked to give their opinion on MoB on a scale from 1 to 7, with 1 being ‘very likely to recommend CS’, 7 being ‘very likely to recommend vaginal delivery’ and 4 indicating ‘equipoise’. There was also an option to indicate that ‘I am uncertain as it is not within my clinical expertise’.

The survey was piloted with 20 clinicians, five of whom repeated the questionnaire 2 weeks later. There was acceptable agreement with responses (75–92%). The wording of questions was modified for clarity in response to feedback.

The questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 1) was designed and administered through Jisc online surveys (URL: www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk; formerly Bristol Online Surveys), with options presented as ordinal rating scales. A free-text box for further communication was included at the end of the questionnaire. A request for demographic information of the respondent (including clinical specialty and experience) was included at the end of the survey, along with an option to provide contact details and consent for future contact for interviews and FGs.

The survey was distributed through our professional networks of contacts (including the NHS Preterm Birth Network and RCOG Preterm Birth Clinical Study Group), advertised at meetings (e.g. the British Maternal and Fetal Medicine Society annual meeting, Edinburgh, 28 and 29 March 2019) and promoted on social media.

We acknowledge, a priori, that when surveys are distributed through external organisations it is difficult to determine the proportion of people completing the survey. However, we aimed for completion from around 200 individuals and for representation from different groups of clinicians (e.g. obstetricians, neonatologists, anaesthetists and midwives). This large and diverse sample aimed to overcome any potential bias due to clustering of responses from any particular professional group.

Results were exported in a comma-separated values (CSV) file for analysis. To visualise variation in practice and clinical uncertainty, categories 1 and 2 were collapsed into ‘favours CS’, categories 3–5 were collapsed into ‘uncertain’ and categories 6 and 7 were collapsed into ‘favours vaginal birth’. Results are presented as percentages of clinicians surveyed. When < 50% of clinicians surveyed favoured one MoB (either CS or vaginal birth), then we categorised the scenario as an area of high variation in opinion. When 50–66% of clinicians favoured one MoB, then we classified the scenario as an area with considerable variation in practice. When > 66% of clinicians favoured one MoB, then we classified the scenario as an area with little variation in practice.

Results

We received 224 responses from clinicians working at 72 different UK hospitals and two European hospitals. Details of specialty and experience are included in Table 2.

| Clinician | Total (N = 224), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Specialty | |

| Obstetrics | 114 (50.9) |

| Neonatology | 33 (14.7) |

| Midwifery | 53 (23.7) |

| Anaesthetics | 10 (4.5) |

| Neonatal nursing | 13 (5.8) |

| Other (e.g. radiography) | 1 (0.2) |

| Level of experience | |

| Consultant for ≥ 5 years | 85 (37.9) |

| Consultant for < 5 years | 34 (15.2) |

| Specialty doctor | 5 (2.2) |

| Midwife/neonatal nurse for ≥ 5 years | 58 (25.9) |

| Midwife/neonatal nurse for < 5 years | 14 (6.3) |

| Subspecialty trainee | 5 (2.2) |

| Specialty trainee 4–5 | 8 (3.6) |

| Other (e.g. radiographer) | 1 (0.2) |

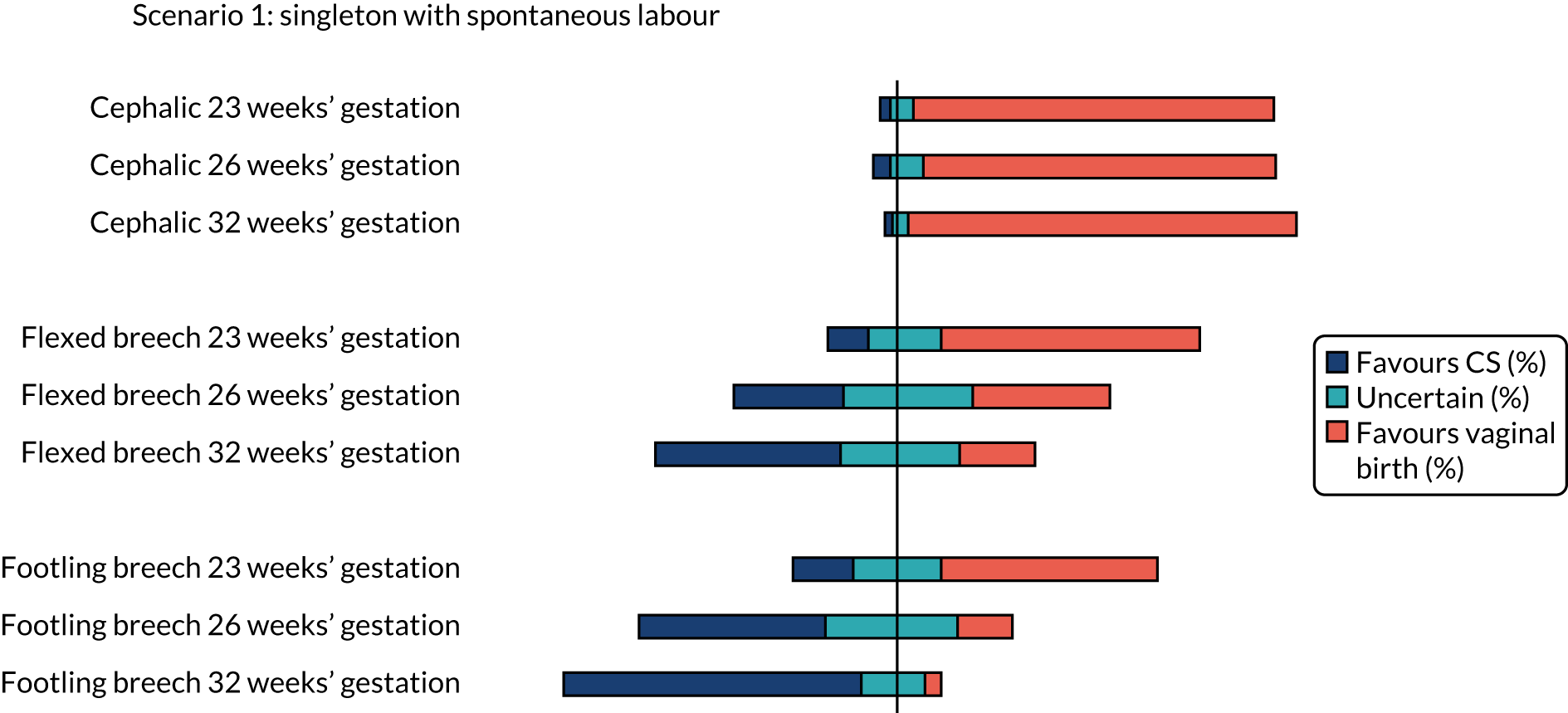

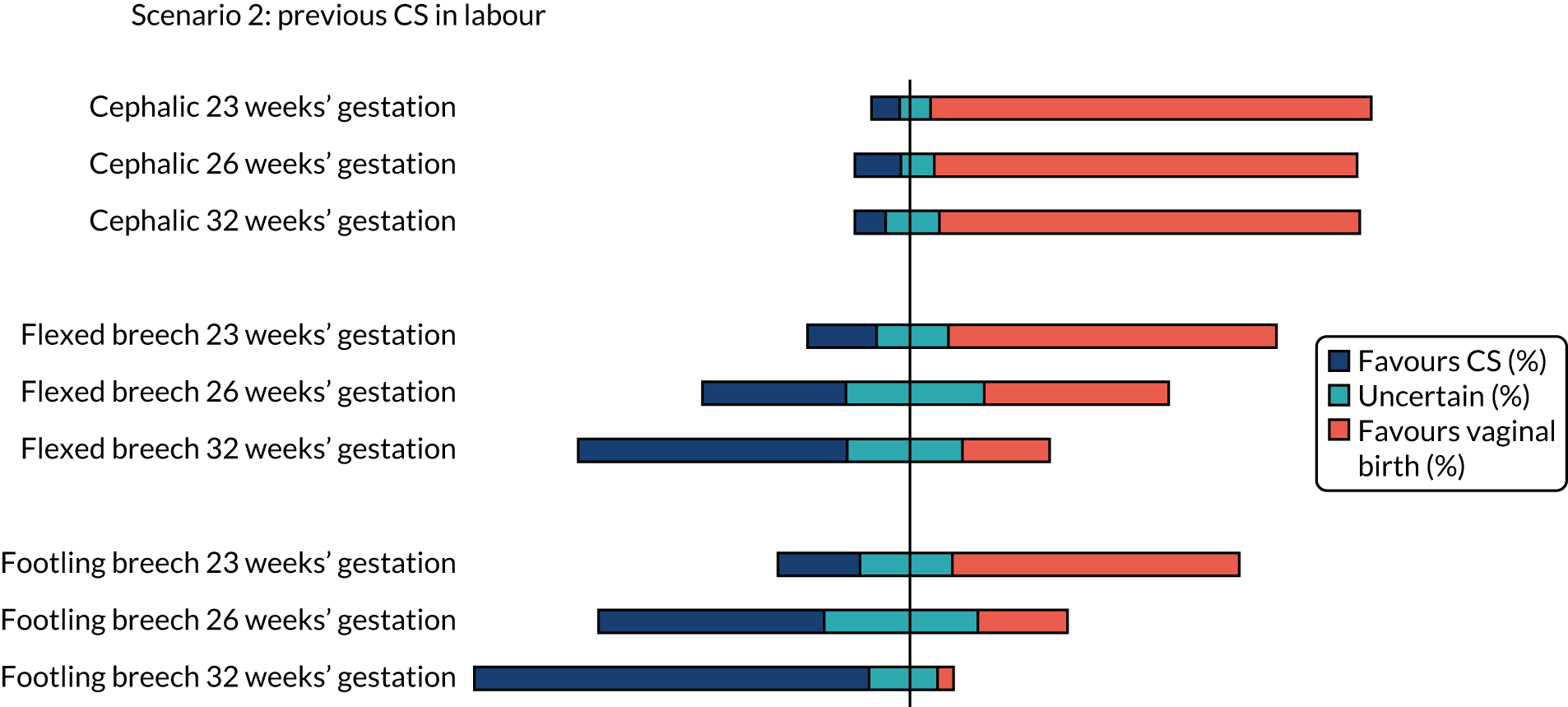

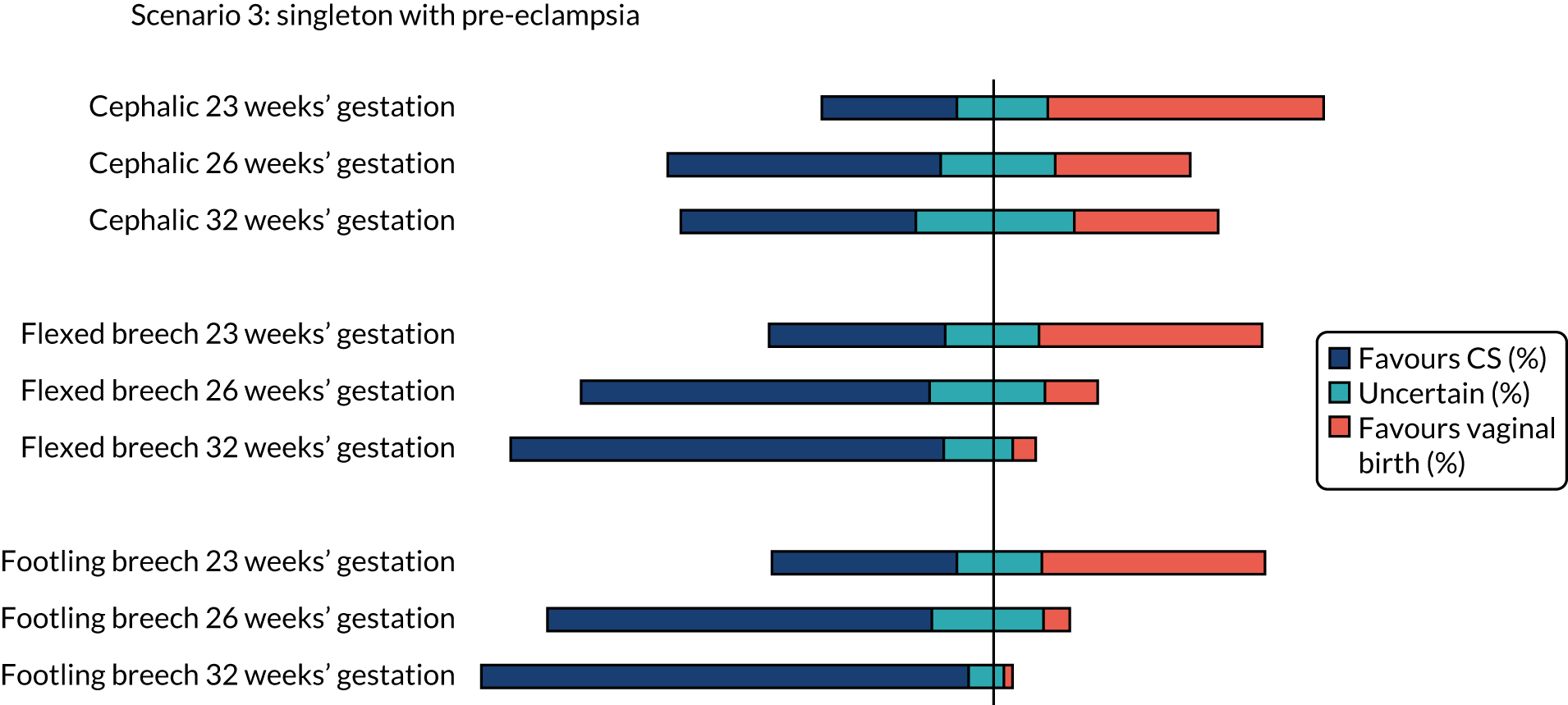

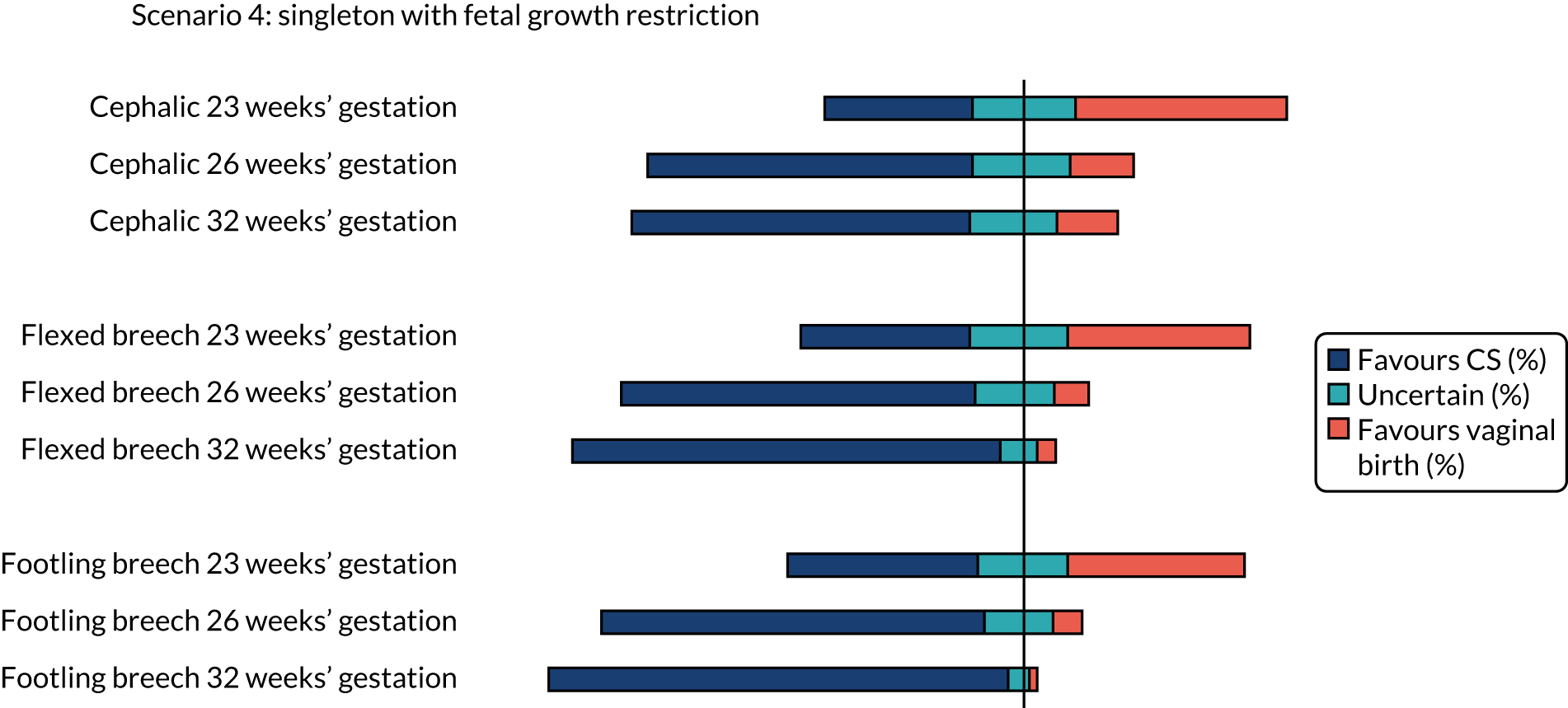

The results for each scenario are presented in Figures 1–5 and raw data are included in Report Supplementary Material 2.

Summary of findings for scenarios 1–5

The percentages of clinicians who favoured CS (scores 1 and 2), vaginal birth (scores 6 and 7) or who were uncertain (scores 3–5) on the clinician survey in scenarios relating to a woman with a singleton pregnancy in spontaneous labour are shown in Figure 1. Between 10% and 14% (i.e. between 23 and 31) of the 224 respondents did not feel that the questions on cephalic presentation were in their expertise, 17–18% (i.e. 39 to 41) of respondents did not feel that the questions on flexed breech presentation were in their expertise and 17–20% (i.e. 39 to 45) of respondents did not feel that the questions on footling breech presentation were in their expertise.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of clinician findings for scenario 1.

The percentages of clinicians who favoured CS (scores 1 and 2), vaginal birth (scores 6 and 7) or who were uncertain (scores 3–5) on the clinician survey in scenarios relating to a woman with a singleton pregnancy with previous CS in spontaneous labour are shown in Figure 2. Between 12% and 13% (i.e. between 27 and 30) of the 224 respondents did not feel that the questions on cephalic presentation were in their expertise, 18–19% (i.e. 40 to 42) of respondents did not feel that the questions on flexed breech presentation were in their expertise and 17–20% (i.e. 38 to 45) of respondents did not feel that the questions on footling breech presentation were in their expertise.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of clinician findings for scenario 2.

The percentage of clinicians who favoured CS (scores 1 and 2), induction of labour aiming for vaginal birth (scores 6 and 7) or who were uncertain (scores 3–5) on the clinician survey in scenarios relating to a woman with a singleton pregnancy with pre-eclampsia are shown in Figure 3. Between 18% and 24% (i.e. between 41 and 54) of the 224 respondents did not feel that the question on cephalic presentation was in their expertise, 20–25% (i.e. 45 to 55) of respondents did not feel that the question on flexed breech presentation was in their expertise and 19–25% (i.e. 43 to 56) of respondents did not feel that the question on footling breech presentation was in their expertise.

FIGURE 3.

Summary of clinician findings for scenario 3.

The percentage of clinicians who favoured CS (scores 1 and 2), induction of labour aiming for vaginal birth (scores 6 and 7) or who were uncertain (scores 3–5) on the clinician survey in scenarios relating to a woman with a singleton pregnancy with fetal growth restriction are shown in Figure 4. Between 18% and 22% (i.e. between 40 and 49) of the 224 respondents did not feel that the question on cephalic presentation was in their expertise, 1–24% (i.e. 40 to 54) of respondents did not feel that the question on flexed breech presentation was in their expertise and 17–23% (i.e. 38 to 51) of respondents did not feel that the question on footling breech presentation was in their expertise.

FIGURE 4.

Summary of clinician findings for scenario 4.

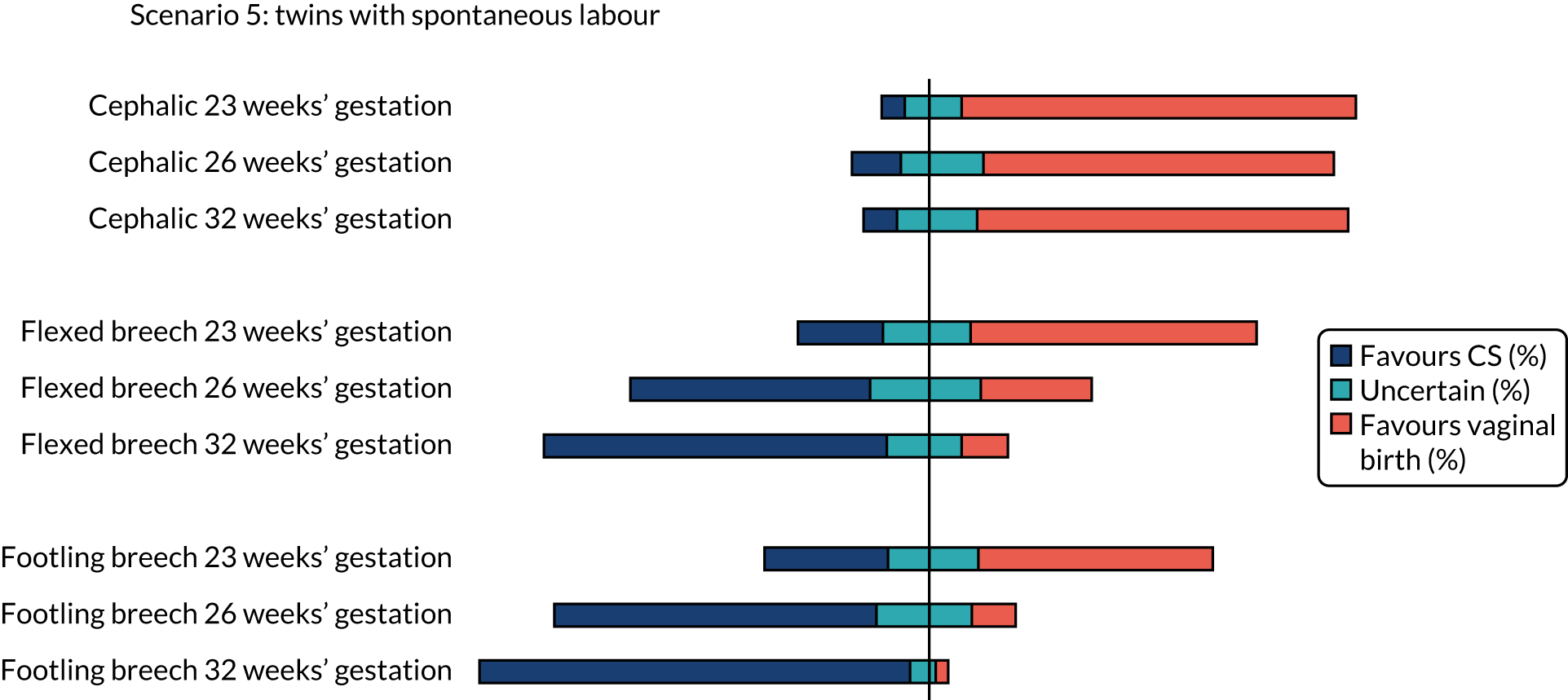

The percentage of clinicians who favoured CS (scores 1 and 2), vaginal birth (scores 6 and 7) or who were uncertain (scores 3–5) on the clinician survey in scenarios relating to a woman with twin pregnancy in spontaneous labour are shown in Figure 5. Between 16% and 18% (i.e. between 36 and 40) of the 224 respondents did not feel that the question on cephalic presentation was in their expertise, 20–21% (i.e. 45 to 47) of respondents did not feel that the question on flexed breech presentation was in their expertise and 19–22% (i.e. 42 to 50) of respondents did not feel that the question on footling breech presentation was in their expertise.

FIGURE 5.

Summary of clinician findings for scenario 5.

Cephalic presentation preterm infant

There was clear consensus for a recommendation of vaginal birth for women in spontaneous preterm labour with a cephalic presentation baby at all gestations assessed (23, 26 and 32 weeks), even with a previous CS or with twins (first twin cephalic) (see Figures 2 and 5). In the scenario of an indicated PTB for pre-eclampsia (see Figure 3) there was less agreement with no consensus at any gestation examined. If the scenario of indicated PTB for fetal growth restriction and a cephalic baby (see Figure 4) there was no consensus on MoB at 23 weeks; but some preference for birth by CS at 26 and 32 weeks.

Flexed breech presentation preterm infant

There was no consensus on recommendations for MoB for women with singleton babies in spontaneous preterm labour with flexed breech infants at 26 and 32 weeks’ gestation (with or without previous CS) (see Figures 1 and 2). At 23 weeks’ gestation, there was still considerable variation in practice, but vaginal birth was the more common recommendation (see Figures 1 and 2). In women requiring an indicated PTB for pre-eclampsia or fetal growth restriction there was no consensus on MoB for babies at 23 weeks’ gestation. However, at 26 weeks’ gestation, there was a slight preference for CS and at 32 weeks’ gestation there was a clear consensus for recommending CS in these scenarios (see Figure 4).

For women with twins in spontaneous preterm labour and first twin flexed breech there was variation, but more clinicians would recommend vaginal birth than CS at 23 weeks’ gestation. At 26 weeks’ gestation, there was no clear consensus. Last, at 32 weeks’ gestation, more clinicians would recommend CS than vaginal birth (see Figure 5).

Footling breech presentation preterm infant

The majority of clinicians would recommend vaginal birth for women with a baby with footling breech presentation in spontaneous preterm labour at 32 weeks’ gestation (regardless of whether or not there was a previous CS and whether or not there was a twin pregnancy, with the first twin presenting in footling breech). At 23 and 26 weeks’ gestation, there was no clear consensus in women with singleton pregnancies and no previous CS. In women who had a previous CS, more clinicians would favour vaginal birth at 23 weeks’ gestation and more clinicians would favour CS at 26 weeks’ gestation. In women with twins in spontaneous labour at 23 weeks’ gestation, there was no clear consensus, but at 26 weeks’ gestation more clinicians favoured CS (see Figure 5).

For women requiring indicated PTB for pre-eclampsia or fetal growth restriction with footling breech presentation, there was no consensus on MoB for babies at 23 weeks’ gestation; however, by 32 weeks’ gestation, there was a clear consensus for recommending CS in both these scenarios. In women with fetal growth restriction, there was also clear preference for birth by CS at 26 weeks’ gestation (see Figure 4). In women with pre-eclampsia, there was more variation, but more clinicians preferred CS than vaginal birth (see Figure 3).

Box 1 summarises the findings on current opinion.

Singleton with spontaneous labour at 23 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation.

Singleton with spontaneous labour at 26 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation.

Singleton with spontaneous labour at 32 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation.

Singleton with spontaneous labour at 23 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech presentation.

Singleton with spontaneous labour and previous CS at 23 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation.

Singleton with spontaneous labour and previous CS at 26 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation.

Singleton with spontaneous labour and previous CS at 32 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation.

Twins at 23 weeks’ gestation with cephalic first twin presentation.

Twins at 26 weeks’ gestation with cephalic first twin presentation.

Twins at 32 weeks’ gestation with cephalic first twin presentation.

Little variation in opinion: clinicians clearly favour CSSingleton with spontaneous labour at 32 weeks’ gestation with footling breech presentation.

Singleton with spontaneous labour and previous CS at 32 weeks’ gestation with footling breech presentation.

Singleton with pre-eclampsia at 32 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech presentation.

Singleton with pre-eclampsia at 32 weeks’ gestation with footling breech presentation.

Singleton with fetal growth restriction at 32 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech presentation.

Singleton with fetal growth restriction at 26 weeks’ gestation with footling breech presentation.

Singleton with fetal growth restriction at 32 weeks’ gestation with footling breech presentation.

Twins at 32 weeks’ gestation with footling breech first twin presentation.

Considerable variation in opinion: clinicians slightly favour vaginal birthSingleton with spontaneous labour at 23 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech presentation.

Singleton with spontaneous labour and previous CS at 23 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech presentation.

Singleton with spontaneous labour and previous CS at 23 weeks’ gestation with footling breech presentation.

Twins at 23 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech first twin presentation.

Considerable variation in opinion: clinicians slightly favour CSSingleton with spontaneous labour and previous CS at 26 weeks’ gestation with footling breech presentation.

Singleton with pre-eclampsia at 26 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech presentation.

Singleton with pre-eclampsia at 26 weeks’ gestation with footling breech presentation.

Singleton with fetal growth restriction at 26 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation.

Singleton with fetal growth restriction at 32 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation.

Singleton with fetal growth restriction at 26 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech presentation.

Twins at 32 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech first twin presentation.

Twins at 26 weeks’ gestation with footling breech first twin presentation.

High variation in opinion: no consensus among clinicians surveyedSingleton with spontaneous labour at 26 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech presentation.

Singleton with spontaneous labour at 32 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech presentation.

Singleton with spontaneous labour at 23 weeks’ gestation with footling breech presentation.

Singleton with spontaneous labour at 26 weeks’ gestation with footling breech presentation.

Singleton with spontaneous labour and previous CS at 26 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech presentation.

Singleton with spontaneous labour and previous CS at 32 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech presentation.

Singleton with pre-eclampsia at 23 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation.

Singleton with pre-eclampsia at 26 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation.

Singleton with pre-eclampsia at 32 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation.

Singleton with pre-eclampsia at 23 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech presentation.

Singleton with pre-eclampsia at 23 weeks’ gestation with footling breech presentation.

Singleton with fetal growth restriction at 23 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation.

Singleton with fetal growth restriction at 23 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech presentation.

Singleton with fetal growth restriction at 23 weeks’ gestation with footling breech presentation.

Twins at 26 weeks’ gestation with flexed breech first twin presentation.

Twins at 23 weeks’ gestation with footling breech first twin presentation.

The responses to the question ‘is there a lower limit of gestation before which you would not offer/recommend caesarean section?’ are shown in Table 3. Fifty-four per cent (122/224) of clinicians responded that they did have a lower limit, with the median gestation being 24 weeks (range 21–35 weeks). Thirty-two per cent (71/224) of clinicians had no set lower limit and 14% (31/224) felt that this was outside their expertise.

| Weeks’ gestation | Number (%) of clinicians |

|---|---|

| 21 | 2 (1) |

| 22 | 7 (3) |

| 23 | 28 (13) |

| 24 | 50 (22) |

| 25 | 15 (7) |

| 26 | 16 (7) |

| 28 | 2 (1) |

| 30 | 1 (0.5) |

| 35 | 1 (0.5) |

| No lower limit | 71 (32) |

| Outside expertise | 31 (14) |

Discussion

These findings show that there is considerable variation in UK practice regarding MoB for the preterm infant. However, the findings indicate that in later preterm babies (i.e. 32 weeks’ gestation or more) with malpresentation and/or indicated PTB, there is clear consensus for birth by CS and, therefore, focusing exclusively on these women and infants in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) may result in low recruitment. Similarly, at the extreme preterm gestation of 23 weeks, vaginal birth was generally strongly favoured. The survey suggests most variation in MoB of preterm babies in (1) spontaneous labour with breech presentation between 23 and 32 weeks’ gestation and (2) indicated PTBs (in women not already in preterm labour) with cephalic presentation. These scenarios informed discussions at the interactive consensus workshop and subsequent protocol design.

The survey was aimed to provide context for the subsequent interactive consensus workshop and identify areas where clinical uncertainty was likely. The strengths of the survey were that we surveyed a variety of clinicians from around the UK and that we piloted the survey. Weaknesses are that, although we did check the consistency of responses with a small number of participants (n = 5), there was no formal validation of the survey. Around one-fifth of participants did not feel qualified to respond to different scenarios. However, this information was useful to inform the range of clinician specialties and experience to include in the subsequent qualitative work.

Chapter 4 The public opinion survey

Introduction

This chapter describes a survey with the public to determine their opinions and preferences on MoB for preterm babies. We provided key clinical scenarios of women presenting in preterm labour or undergoing planned PTB and asked patients/the public to indicate their preferred option of vaginal birth or CS. The results were used to inform the subsequent interactive consensus workshop and provide context to the Delphi exercise.

Methods

A survey was designed and placed on Jisc online surveys, which is an online survey tool designed for academic research, education and public sector organisations. A website was set up for the survey and the link distributed, as described below. The survey was designed to be able to be completed on a smart phone or tablet computer, as well as on a laptop or desktop computer. If people did not have computer access, we offered to send a paper questionnaire.

Survey design

The survey asked for basic demographic information (i.e. gender, whether or not the individual had children and whether or not they had experienced PTB). Three clinical scenarios were presented (Table 4). The first clinical scenario was presented for each of the gestations of 23, 26 and 32 weeks. The remaining two scenarios focused on 28 weeks’ gestation only. Respondents were asked to indicate a single option for each scenario and each gestation on a five-point scale as follows:

-

strongly prefer vaginal delivery

-

moderately prefer vaginal delivery

-

no preference for either method of delivery

-

moderately prefer CS

-

strongly prefer CS.

| Scenario number | Description of scenario |

|---|---|

| 1 | Please describe your preferences for the method of delivery if the doctor tells you that a vaginal delivery and a CS are equally safe for you and the baby. (Tick one option for each of the gestations of 23, 26 and 32 weeks) |

| 2 | Please describe your preference for the method of delivery if the doctor tells you that a vaginal delivery is safer for you, and that both CS and vaginal delivery are safe for the baby. You are 28 weeks pregnant |

| 3 | Please describe your preferences for method of delivery if the doctor tells you that CS and vaginal delivery are equally safe for you and that a CS is safer for this baby, but might make a future pregnancy and birth more risky for you and your baby. You are 28 weeks pregnant |

In addition to this ‘tick-box’ question, participants were also asked to provide free-text comments in response to a question ‘[p]lease tell us what else you think the NHS should take into account in deciding whether to recommend a vaginal delivery or a caesarean section in women who are in labour before 37 weeks of pregnancy’.

Survey distribution

The survey was distributed through our charity partners Bliss and Tommy’s in late 2018. The following text was used to advertise the survey. A link to the survey was sent out by each charity, as described below.

Tommy’s advertised the survey on their Facebook page on 20 November 2018. A screenshot of the post is given in Report Supplementary Material 3:

Can you help @EdinburghUni? They’re looking for parents with experience of #prematurebirth to fill in a survey to help them understand the safest way for early babies to be born. To take part in the CASSAVA study or to find out more, go to bit.ly/2S21ICO.

The Tommy’s centre in Edinburgh advertised the survey on their Facebook page on 13 November 2018. A screenshot is given in Report Supplementary Material 3:

We would like to tell you about the CASSAVA study. This study is looking at babies and women who are in premature labour and for whom it is not known which way is the best for them to give birth: whether it is better (safer) by caesarean section (CS) or better (safer) to try and have a vaginal delivery. The first part of this research is to find out where clinicians and women feel that more research on this topic is needed – follow the link to the surveys to help us find out! We would really appreciate your time in filling out the survey appropriate for you. https://edinburgh.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/pilot-cassava-public- . . . (Public Survey). There is also plenty more information on the CASSAVA website www.ed.ac.uk/centre-reproductive-health/cassava Thank you. The Tommy’s team.

Bliss advertised on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram on 7 December 2018. A screenshot of the post is given in Report Supplementary Material 3:

The University of Edinburgh are researching the best way to manage the birth of women presenting in preterm labour. They are inviting parents to participate in an online survey to ask their opinions on the best mode of delivery for preterm labour. You can complete the study at https://edinburgh.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/pilot-cassava-public- . . . If you are interested in learning more about the project you can visit their website at www.ed.ac.uk/centre-reproductive-health/cassava.

By 9 December 2018, 72 people had responded to the survey. Following the Bliss posting, we had 307 further responses. The total number of responders was 379.

The survey closed on 9 January 2019.

Consent

An information sheet was provided to participants before completion of the survey. Those participants who wished to proceed were given access to the survey database. All responders to both the clinician and public surveys were invited to participate in the Delphi questionnaire process (two rounds) by accessing https://delphimanager.liv.ac.uk/Cassava/Delphi, which was active from 1 November 2018 to 9 January 2019 (see Report Supplementary Material 4). All participants who completed both rounds were invited to the consensus meeting in London (held on 5 July 2019).

Results

The summary output from public opinion survey is shown in Report Supplementary Material 5.

A total of 379 people completed the survey, of whom over 95% were female with children and having experienced a PTB. All surveys were completed electronically and there were no requests for completion on paper.

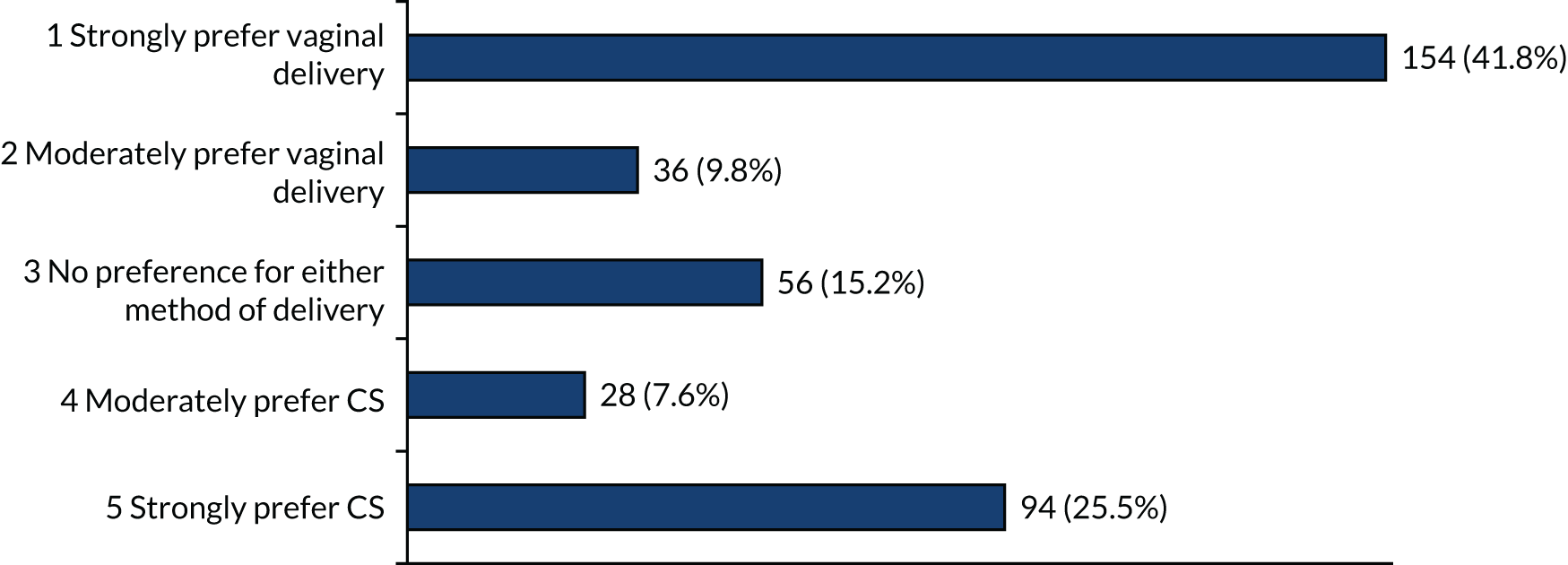

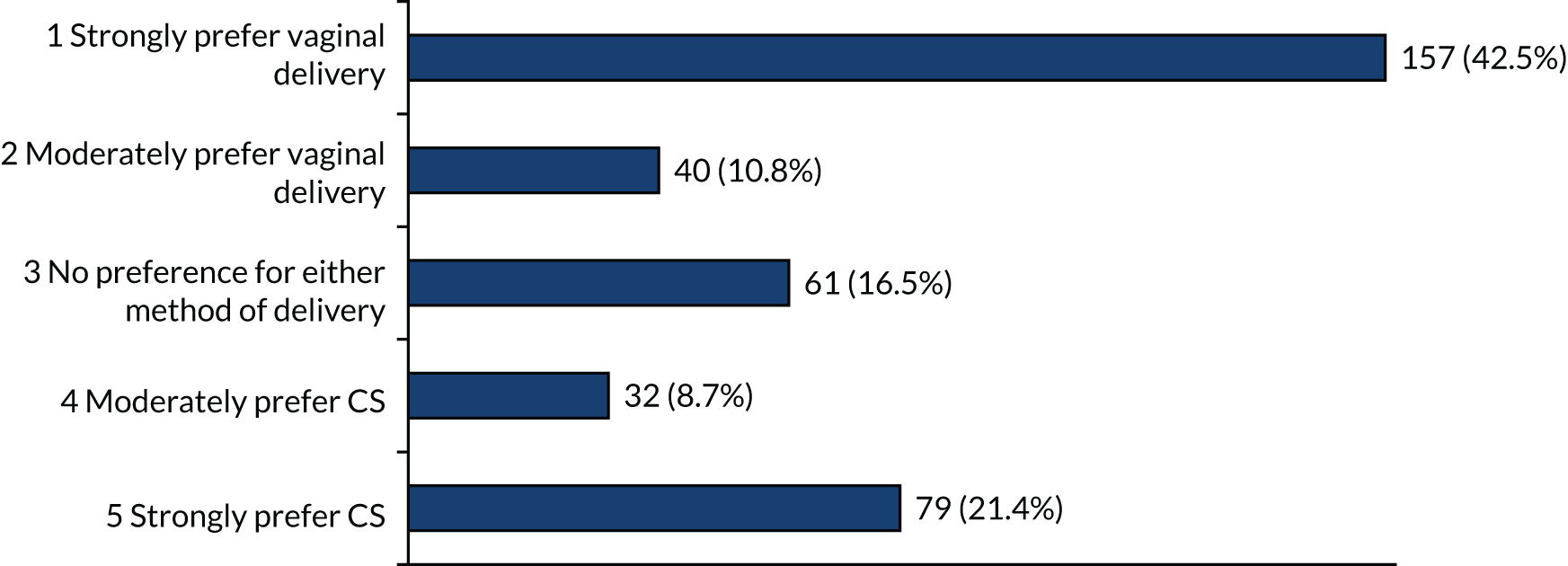

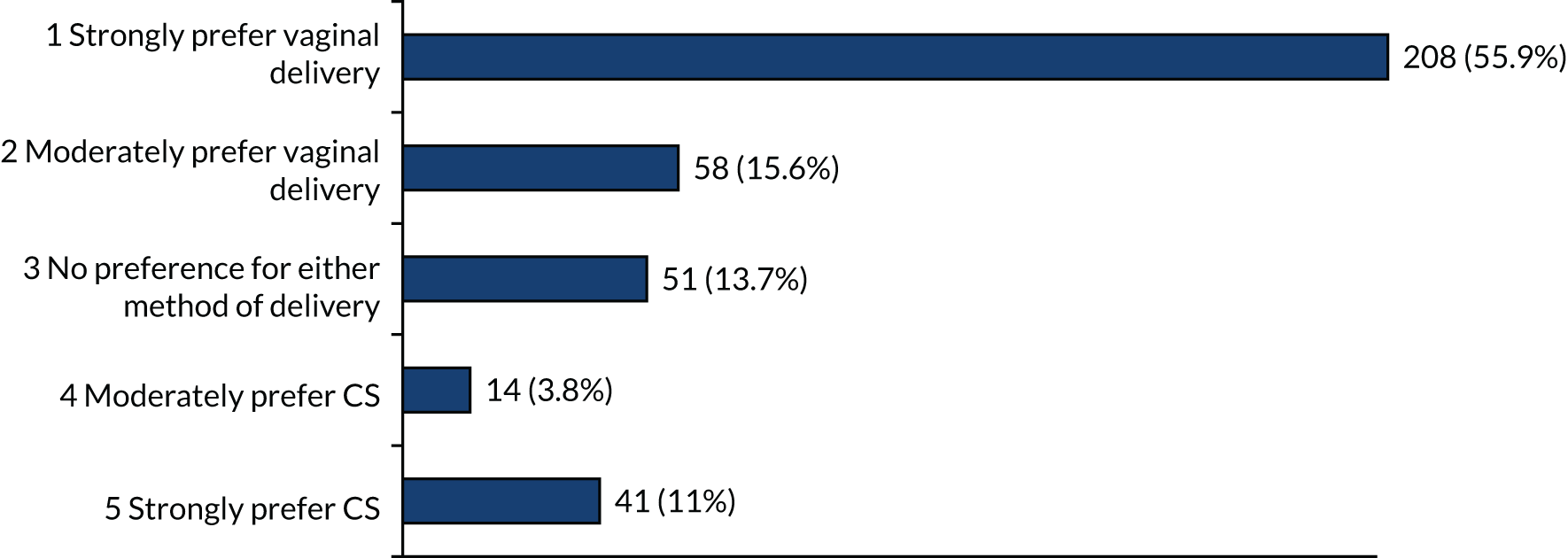

When offered the option of a particular mode of birth, in the scenario with the pregnancy being at 23 or 26 weeks’ gestation, there were strong preferences for vaginal birth (> 40%) and also strong preferences for caesarean birth (> 20%) (Figures 6 and 7). The other options (i.e. moderate or no preferences) were recorded by < 20% of respondents.

FIGURE 6.

Method of birth preferences at 23 weeks’ gestation if each (i.e. vaginal birth and CS) are equally safe for mother and baby.

FIGURE 7.

Method of birth preferences at 26 weeks’ gestation if each (i.e. vaginal birth and CS) are equally safe for mother and baby.

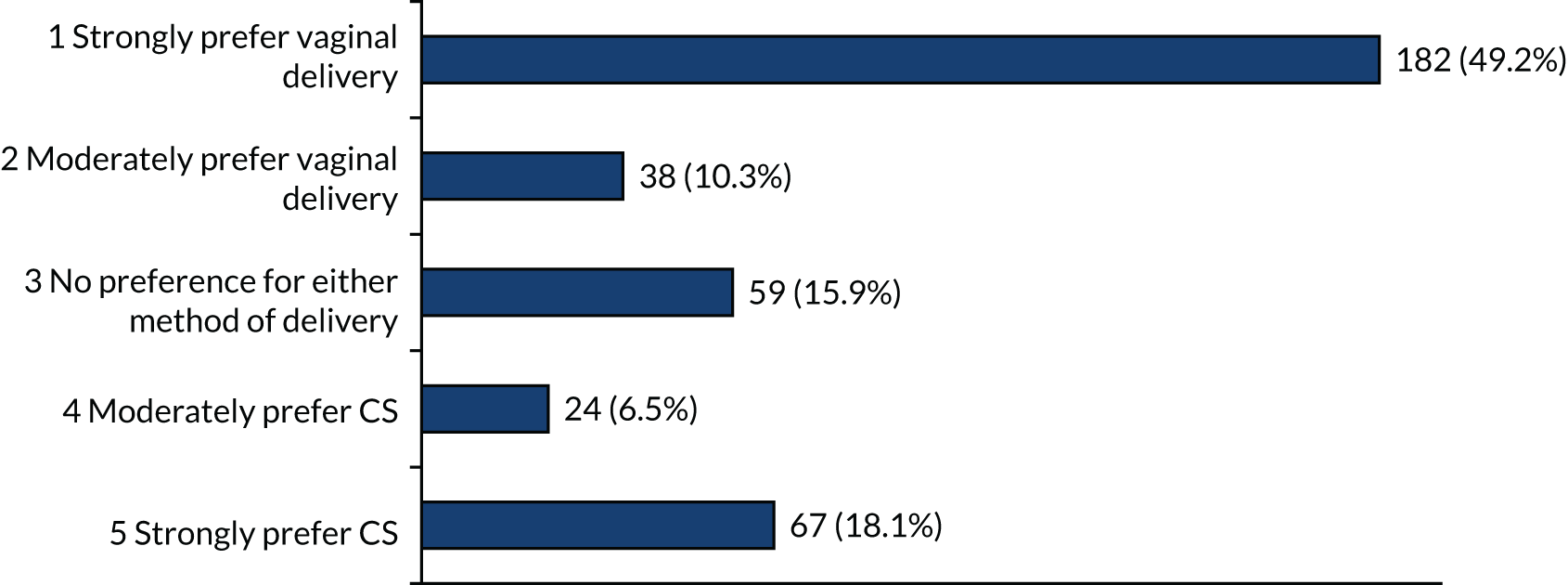

For women at 28 and 32 weeks’ gestation, again, there were high proportions of participants with strong preferences for vaginal birth (> 49%) (Figures 8 and 9). Smaller numbers of participants strongly preferred CS at 28 and 32 weeks’ gestation than at earlier gestations (18% at 28 weeks’ gestation and 11% at 32 weeks’ gestation).

FIGURE 8.

Method of birth preferences at 28 weeks’ gestation if each (i.e. vaginal birth and CS) are equally safe for mother and baby.

FIGURE 9.

Method of birth preferences at 32 weeks’ gestation if each (i.e. vaginal birth and CS) are equally safe for mother and baby.

Taken together, these data suggest that individual women have strong preferences for either vaginal birth or CS. Vaginal birth is the most frequent ‘preference’ and becomes more frequent with later gestations (most common at 32 weeks’ gestation). However, a strong preference for CS is most commonly expressed at earlier gestations [most common at 23 weeks’ gestation (26% of women)].

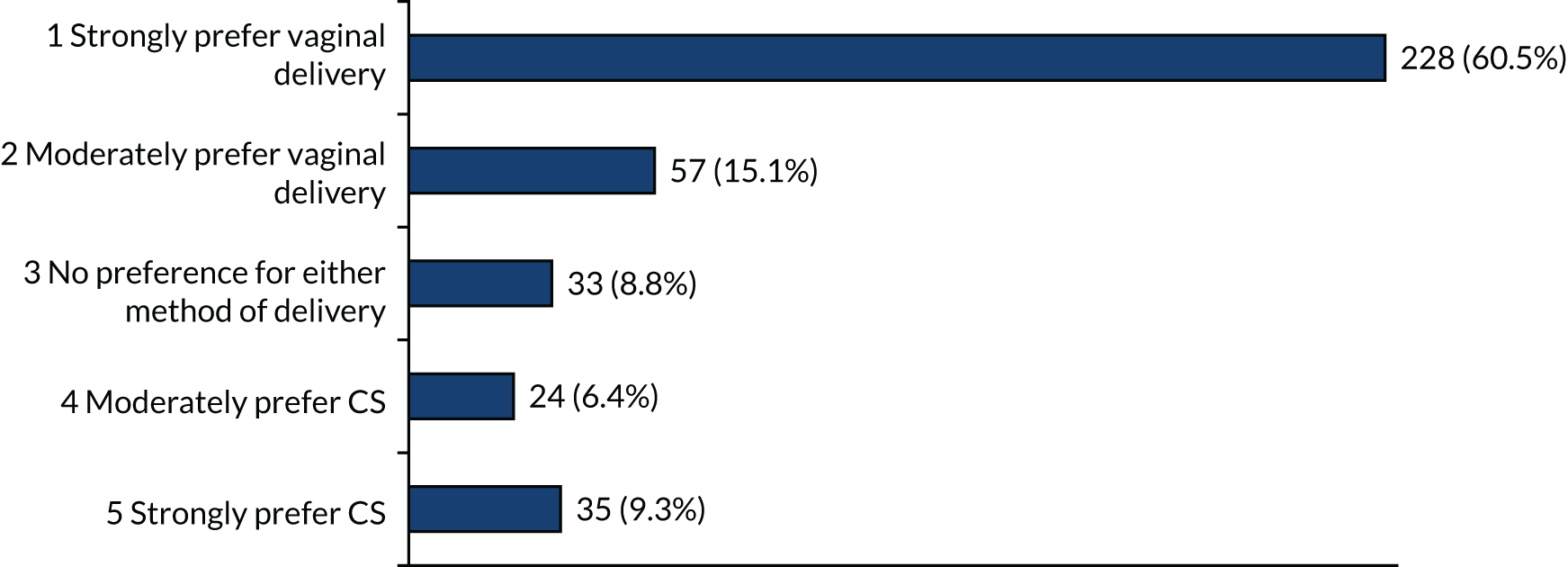

When faced with the scenario that both options are equally safe for the baby and vaginal delivery is safest for mother, there was a strong preference for vaginal delivery (61%) (Figure 10), although 9% of participants still strongly preferred CS.

FIGURE 10.

Method of birth preferences at 28 weeks’ gestation when vaginal delivery is safer for mother and both vaginal delivery and CS are equally safe for the baby.

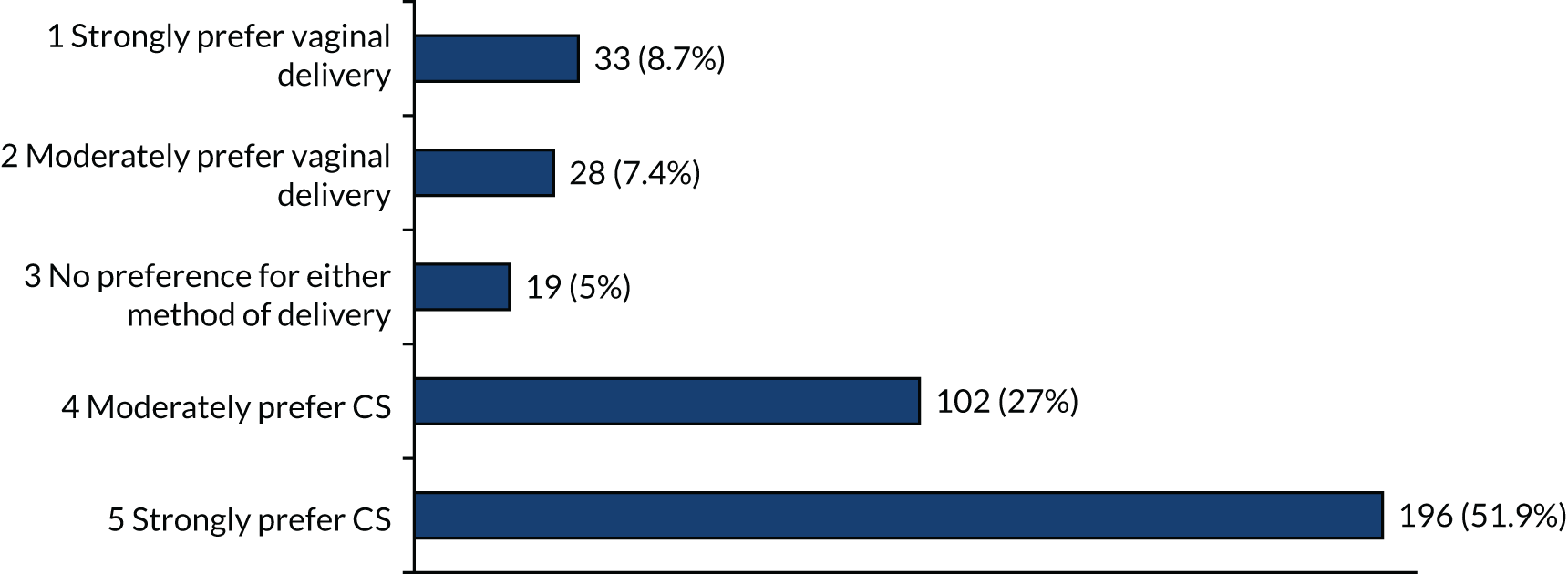

When faced with the scenario that CS is safer for the baby of the index pregnancy, but both CS and vaginal delivery are equally safe for the mother, then 52% of participants report a strong preference for CS and 27% of participants moderately prefer CS (Figure 11). These preferences were described, despite it being acknowledged that CS might make future pregnancies riskier for both mother and baby.

FIGURE 11.

Method of birth preferences at 28 weeks’ gestation when vaginal delivery and CS are equally safe for mother and CS is safer for the baby, but might make a future pregnancy and birth more risky.

Free-text comments are shown in Report Supplementary Material 5.

Key issues mentioned in the free-text comments (in order of frequency) were safety for baby, safety for the mother, recovery times and choice. Presentation of information was also clearly important for respondents.

Discussion

Use of charity partners to access patients and members of the public rapidly generated a large number of responses. Although it is likely that this approach has preferentially selected those who have an interest in this topic, and who have previously engaged with charities focused on this topic, we believe that this approach is likely to be generalisable to the population. It is possible that responses are influenced by people’s own experiences of birth. Importantly, a large majority of respondents had experienced PTB. Although we were able to collect basic demographic information, this did not include information on ethnicity or social exclusion. It is likely that those with limited English, and possibly those from lower socioeconomic groups, are poorly represented in our sample.

Men and women who have not previously experienced PTB were also poorly represented in our sample. Although the decision about MoB is formally made by the pregnant woman, partners, friends and families are influential in women’s decision-making. The demographics of our survey prevents us from knowing whether or not male partners might come to different conclusions and, therefore, alter decision-making in practice.

Many women faced with the decision about how their preterm baby should be born will not have experienced a previous PTB. Including more women for whom this would be a novel experience would have been helpful; however, these women are less likely to be interested in answering a query about PTB and may be less well represented in the contact lists of charities focused (in part) on preventing PTB complications.

The data from our survey suggest the following:

-

Many women are not in equipoise about the best method of birth for a preterm baby and have a strong preference for either vaginal birth (most common) or CS.

-

Women are more likely to choose vaginal birth at later gestations (than at other gestations).

-

A strong preference for CS is more likely to be expressed at very early gestations (than at other gestations).

-

Women prioritise safety of the baby of the index pregnancy ahead of their own safety and against safety of future babies.

These data were used to inform the protocol and the FGs, described in subsequent chapters.

Chapter 5 The Delphi survey

Purpose and rationale

Our aim was to convene an interactive working group of stakeholders to determine what kinds of trials still need to be carried out and which groups of women should be included in these trials.

Formal Delphi consensus methodology was used as a method of systematically collating expert consultation and building constructivist consensus to resolve uncertainties. The Delphi technique is a flexible method and can be adjusted to the respective research aims and purposes, as long as modifications are justified by a rationale and applied systematically and rigorously. There was no intention to arrive at any more than one trial option, but to agree on including or excluding different patient subgroups that could be recruited to a trial. This report follows the recommendations of the CREDES (Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies) guidance.

Planning and design

The multidisciplinary investigator team, including the two co-applicants representing patients and support groups, developed, in an interactive virtual meeting, a longlist of clinical scenarios with equipoise, based on the findings of the surveys described in Chapters 3 and 4 and a systematic literature search completed in May 2019, which identified 54 relevant papers. The scenarios were piloted and edited by the lay members of the investigator team.

In summary, the literature search identified the following prevalent issues: previous caesarean or not (cited in seven papers), number of previous pregnancies (cited in four papers), body mass index (cited in four papers), gestational age/degree of prematurity (cited in four papers), breech presentation (cited in four papers) and multiple (multifetal) pregnancy (cited in four papers).

Other issues identified in the literature included hypertensive disease, gestational diabetes, advancing maternal age, preterm rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, placental abnormalities, maternal cardiac conditions, uterine abnormalities, presence of cervical cerclage, fetal growth disorders, cephalic presentation, worrying cardiotocography trace of the fetal heart rate, presentation of twins, previous vaginal birth, previous CS during the second stage of labour (associated with risk of recurrence of preterm labour) and previous PTB. These issues informed decisions by the research team as to which scenarios to include in the rounds, alongside findings from the survey and proposals by participants in round 1.

A two-round three-step Delphi consensus methodology was planned to score and reach consensus on scenarios and subgroups to be included in a future trial. All stakeholder groups, including parents, health-care professionals, researchers and health-care regulators, were invited to participate in the two rounds of the Delphi survey (steps 1 and 2) and a final interactive consensus workshop (step 3).

The aim was for at least 40 participants in round 1 and more than 20 participants in round 2 and the consensus meeting, with at least two or three representatives from each group of participants.

Definition of consensus

A prespecified scale and criteria were used for dropping and retaining items in the longlist.

Scenarios with (1) > 70% of participants scoring 7–10 and (2) < 30% of participants scoring 1–3 were to be prioritised for discussion at the interactive consensus workshop.

Scenarios fulfilling only one of these two criteria were considered borderline.

Study conduct

Informational input

The literature search followed systematic search principles described in the Cochrane handbook. 26 The longlist of scenarios was developed through the clinician and patient surveys.

A summary of the literature and survey findings was presented at the final consensus meeting (i.e. step 3) using Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

External validation

The processes and results of all steps were presented to the Study Steering Committee, which made comments and approved the framework for study conduct and interpretation, and, specifically, recommended assessments for attrition bias.

Prevention of bias

To minimise attrition, DelphiManager (i.e. the software used to support the Delphi process) automatically sent reminders every week to registered participants who did not complete each stage and/or had missing data. The investigators did not participate in or influence the reminders.

Attrition bias was estimated by comparing the average scores for different groups of participants between those who completed both rounds and those who completed only round 1 for evidence of significant difference that implied biased participation in the second round as opposed to consensus.

Interpretation and processing of results

Consensus does not necessarily imply the ‘correct’ answer or judgement. Non-consensus and stable disagreement provide informative insights and highlight differences in perspectives concerning the topic in question.

Therefore, we decided a priori to retain all scenarios in both rounds and in all three steps, presenting at the final meeting how scores had evolved over the consensus process, differences between participants groups and the accompanying qualitative comments.

Study process and findings

Expert panel

The Delphi consensus invitees were agreed by the CASSAVA co-investigator team to include UK-based preterm trial leads, members of the RCOG Preterm Birth Clinical Study Group, members of the partners (i.e. Tommy’s and Bliss), other parent organisations (e.g. National Bereavement Care Pathway charities), national stakeholders (e.g. NHS Improvement, NHS England and the Saving Babies’ Lives programme) and all participants in the previous clinician and parent surveys (see Chapters 3 and 4). (Note that this is a more diverse group than described at grant application stage, when we described a Delphi focused on clinicians only, but after reading survey results we felt that it would be helpful to get perspectives from all stakeholders.)

Description of the methods

We used the web-based survey application (DelphiManager) that has been developed by the University of Liverpool (Liverpool, UK) and adopted by the COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) initiative. The web-based Delphi survey is feasible, cost and time efficient and is accepted by users. The survey was hosted within an online portal and infrastructure designed by the University of Liverpool. Before entering the exercise, participants were asked to register, provide demographic details and commit to two rounds.

After the details of participants and the commitment to contribute to two rounds had been reviewed, a unique identifier was allocated. The unique identifier anonymised participant responses but also provided a means to send completion reminders.

Participants were asked to score each scenario using the GRADE scale (accessed online). This scale was originally developed to score the quality of evidence of systematic reviews and has now been adopted in other research studies using Delphi methods (e.g. core outcome sets). Participants were asked ‘[h]ow important is it to include the following scenarios in a randomised trial of mode of birth (caesarean/vaginal) for a preterm baby’.

Free-text comments were also invited and facilitated by DelphiManager.

The Delphi questionnaire was piloted on the Study Management Group, the patient and public involvement (PPI) panel and a sample of stakeholders to ensure the ease of completion by participants prior to recruitment. This also ensured that the scenario terminology was understood by stakeholders before allowing them to decide which scenario was important to them in the Delphi.

In round 1, participants received an e-mail linking to the web-based questionnaire embedded within the study’s website. Initial questions included the option to add additional scenarios for use in round 2 before proceeding to scoring, as additional failsafe steps to identify any scenarios that are prominent with experts and/or parents and should still be considered. Participants scored each scenario listed using the Likert-type scale, as described above. The scores were summarised graphically and indicated the whole groups’ and individual participant groups’ responses that were automatically collated by DelphiManager, using its standard methodology.

After round 1, the data were analysed to produce a summary of results.

It was agreed in an interactive study management meeting that all scenarios would be carried forward to round 2 in addition to scenarios proposed by the participants of round 1 after they had been discussed by the study team and PPI representatives. An anonymous summary of the responses was fed back to participants according to each stakeholder group. Participants were asked to, again, score their preference to reach consensus.

An interactive consensus meeting involving key stakeholders took place following the completion of the Delphi process to consider the scores and agree on inclusions and exclusions, including any scenarios in Delphi round 2 where ‘no consensus’ was found. Only those stakeholders who completed both rounds of the Delphi study were invited to participate to the final consensus meeting.

Procedure framework

Delphi survey rounds (steps 1 and 2)

It was agreed that participants would represent stakeholders in three groups (i.e. the maximum allowed by DelphiManager):

-

parents

-

health-care professionals and researchers (academics)

-

health-care regulators and other stakeholders.

Although, ideally, equal numbers from the three groups would participate, it was agreed that this may not be possible to ensure within the pragmatic constraints of the study. The rules specified that all participants who completed the first two rounds were invited to the interactive workshop. In the lead’s experience, the final workshop was likely to include comparable numbers from the three groups of participants, even though the numbers in each group receiving the original invite to register to the Delphi website may not have been identical.

Each round was agreed to be left open for 2 weeks in view of time constraints. It was deemed essential to complete analysis of the surveys before the workshop and it was expected that analysis would take half a day.

Invitees received an e-mail with an invitation letter that provided a link to the web-based questionnaire. A postal questionnaire was offered but not used by any invitee. All responders to both the clinician and public surveys were invited to participate in the Delphi survey by accessing https://delphimanager.liv.ac.uk/Cassava/Delphi, which was active from 1 November 2018 to 9 January 2019 (see Report Supplementary Material 6). All participants who completed both rounds were invited to the Delphi consensus meeting in London (held on 5 July 2019).

The scenarios were presented in domains (a fixed terminology by DelphiManager that was not possible to amend). Scoring all scenarios on a page was mandatory by default.

The agreed domains, based on analysis of the previous surveys’ findings, were as follows:

-

Domain A [spontaneous PTB with baby flexed breech (the baby is bottom first with its feet right next to its bottom)] at:

-

< 24 weeks’ gestation (A1)

-

24–25+6 weeks’ gestation (A2)

-

26–27+6 weeks’ gestation (A3)

-

28–36 weeks’ gestation (A4).

-

-

Domain B [PTB for obstetric complications (e.g. pre-eclampsia and fetal growth restriction)] at:

-

< 24 weeks’ gestation with any breech presentation (B1)

-

< 24 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation (B2)

-

24–25+6 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation (B3)

-

26–27+6 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation (B4)

-

28–36 weeks’ gestation with cephalic presentation (B5).

-

Following the literature review, additional domains agreed were as follows:

-

Domain C [women with previous caesarean birth(s) in spontaneous labour] at:

-

< 24 weeks’ gestation with spontaneous preterm labour and cephalic presentation (C1)

-

24–25+6 weeks’ gestation with spontaneous preterm labour and cephalic presentation (C2)

-

26–27+6 weeks’ gestation with spontaneous preterm labour and cephalic presentation (C3)

-

28–36 weeks’ gestation with spontaneous preterm labour and cephalic presentation (C4).

-

-

Domain D [women with previous caesarean birth(s) and indicated preterm labour] at:

-

< 24 weeks’ gestation with indicated preterm labour (e.g. pre-eclampsia or growth restriction) (D1)

-

24–25+6 weeks’ gestation with indicated preterm labour (e.g. pre-eclampsia or growth restriction) (D2)

-

26–27+6 weeks’ gestation with indicated preterm labour (e.g. pre-eclampsia or growth restriction) (D3)

-

28–36 weeks’ gestation with indicated preterm labour (e.g. pre-eclampsia or growth restriction) (D4).

-

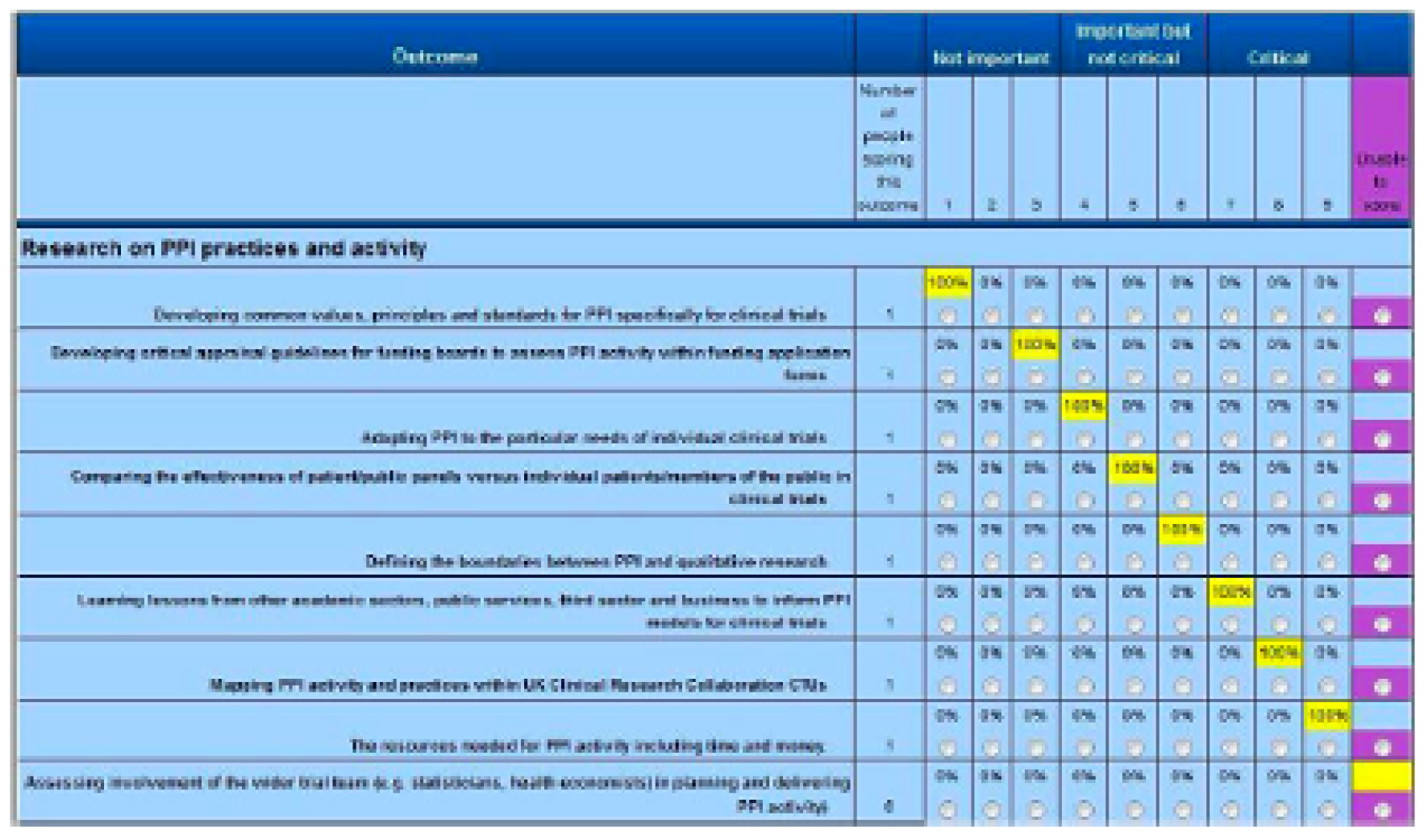

In round 2, participants were shown the distribution of scores from other participants, along with the score that they attributed to each scenario. Only participants who had scored all scenarios in round 1 were automatically invited by DelphiManager to round 2. Round 2 participants were asked to reflect on their responses, and re-score if they wanted to, having been shown the views of the other participants. DelphiManager facilitates this process by a simple setup followed by inbuilt functionality to calculate the distribution of scores for a particular round. Unlike other online survey tools, the score distribution is then automatically displayed to the participant in the next round, together with a reminder of their own score. An example of what a participant might be shown in round 2 (of a Delphi with a single panel throughout) is shown in Figure 12. Note that scenarios replaced outcomes.

FIGURE 12.

Mock up of Delphi output.

In Figure 12, the participant’s score from the previous round is highlighted in yellow.

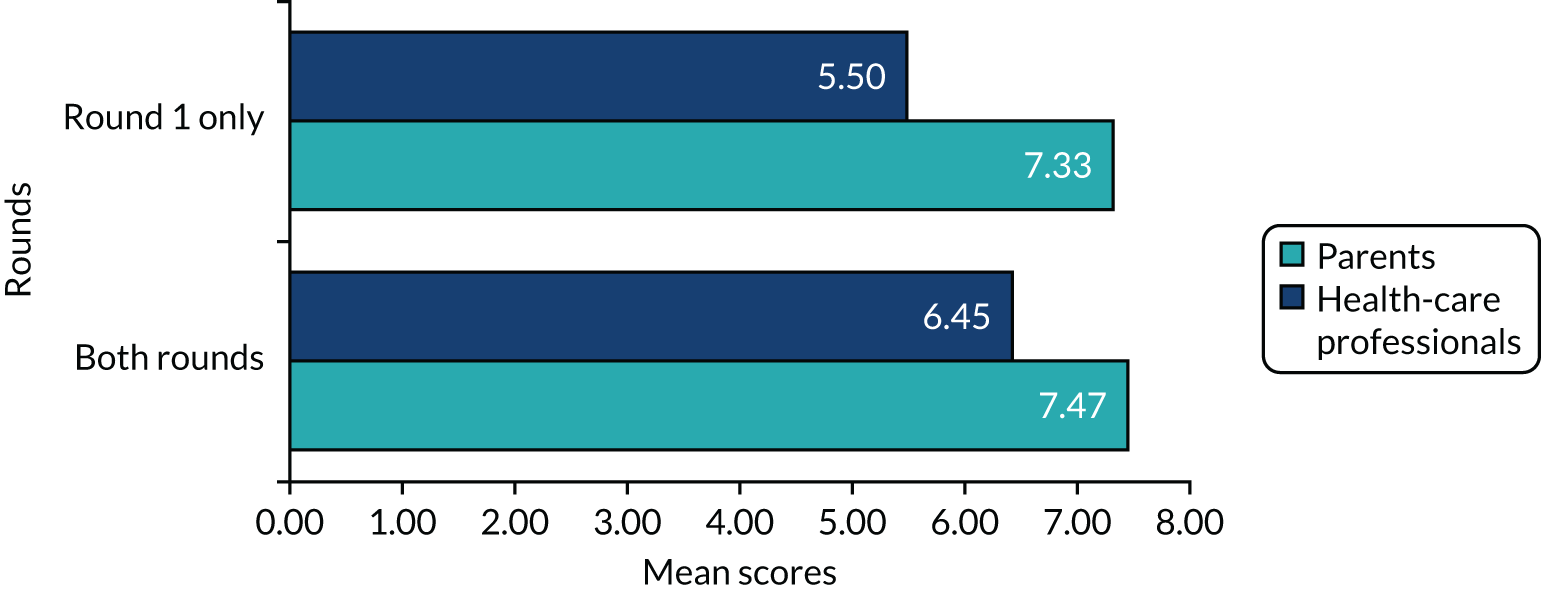

For the CASSAVA project, feedback in round 2 was intended to be split according to the three groups described previously. However, it became clear after round 1 that some national stakeholder representatives who had participated had declared themselves as a ‘health-care professional’ as opposed to a ‘stakeholder’. It was decided to amalgamate these two groups, for a final split of (1) parents and (2) health-care professionals/stakeholders.

Results were exported in a CSV file. Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) was used to generate charts.

For statistical tests, we used Stata/SE® 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Final consensus: step 3

The final consensus meeting was moderated by the Delphi lead, a clinical lecturer and a PPI representative. As the purpose of this meeting was to elicit scenario(s) that would be desirable and feasible for a trial, which meant the approach had to be inclusive as opposed to highly selective, participants were presented with the results of the two rounds and were invited to discuss each scenario from the final list in detail. Participants were invited to score any final uncertainties using the same scoring scale as in steps 1 and 2. It was intended that the final output would be a couple of inclusive scenarios with clear exclusion criteria (e.g. whether or not spontaneous cephalic labour with no comorbidity should be excluded).

Results

Rounds 1 and 2

Eighty-six participants were included in round 1 (parents, n = 27; health-care professionals, n = 59). Four parents did not score any scenarios and three parents scored only some (but not all) scenarios and were not invited, by DelphiManager, to round 2. Ten parents did not continue after round 1. Ten parents participated in both rounds. One health-care professional did not score any scenarios and two health-care professionals scored only some scenarios and were not invited to round 2. Twenty-eight health-care professionals did not continue after round 1. Twenty-eight health-care professionals participated in both rounds. One new health-care professional who missed the first round was allowed as an exception to join the second round for a total of 29 health-care professionals.

The total number of participants in round 2 was 39 (parents, n = 10; health-care professionals, n = 29), of whom 38 completed both rounds.

After round 1, participants recommended a list of scenarios that were considered by the Study Management Group and PPI representatives (Box 2).

Suspected chorioamnionitis, 22–24 weeks’ gestion.

Suspected chorioamnionitis in labour (> 3 cm), cephalic presentation, > 24–26 weeks’ gestation.

Suspected chorioamnionitis in labour (> 3 cm), cephalic presentation, > 24–26 weeks’ gestation.

Suspected chorioamnionitis in labour (> 3 cm), cephalic presentation, > 28 weeks’ gestation.

Suspected chorioamnionitis, > 24–26 weeks’ gestation.

Suspected chorioamnionitis, 26–28 weeks’ gestation.

Suspected chorioamnionitis, > 28 weeks’ gestation.

Spontaneous PTB with extended breech presentation, < 36 weeks’ gestation.

Indicated PTB with extended breech presentation, < 36 weeks’ gestation.

Admission to NICU in term babies.

Footling breech scenarios.

Abnormal middle cerebral artery doppler studies or ratio.

Previous laser twins, first twin cephalic, spontaneous labour.

Preterm twins with variations on presentation of the first twin, as per previous questions.

Spontaneous rupture of membranes.

Previous obstetric history.

Spontaneous labour.

Induction of labour.

Augmentation of labour.

Spontaneous labour, twin pregnancy, 25–28 weeks’ gestation.

Patient with lethal fetal anomaly at any gestation between 24 and 36 weeks’ gestation.

NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Bold text indicates scenarios that were added for round 2 of the Delphi.

The investigator team decided to add four more scenarios to round 2 of the Delphi (see bold text in Box 2). As the DelphiManager website did not allow for the inclusion of additional domains after round 1, it was decided to include the scenarios under domain A.

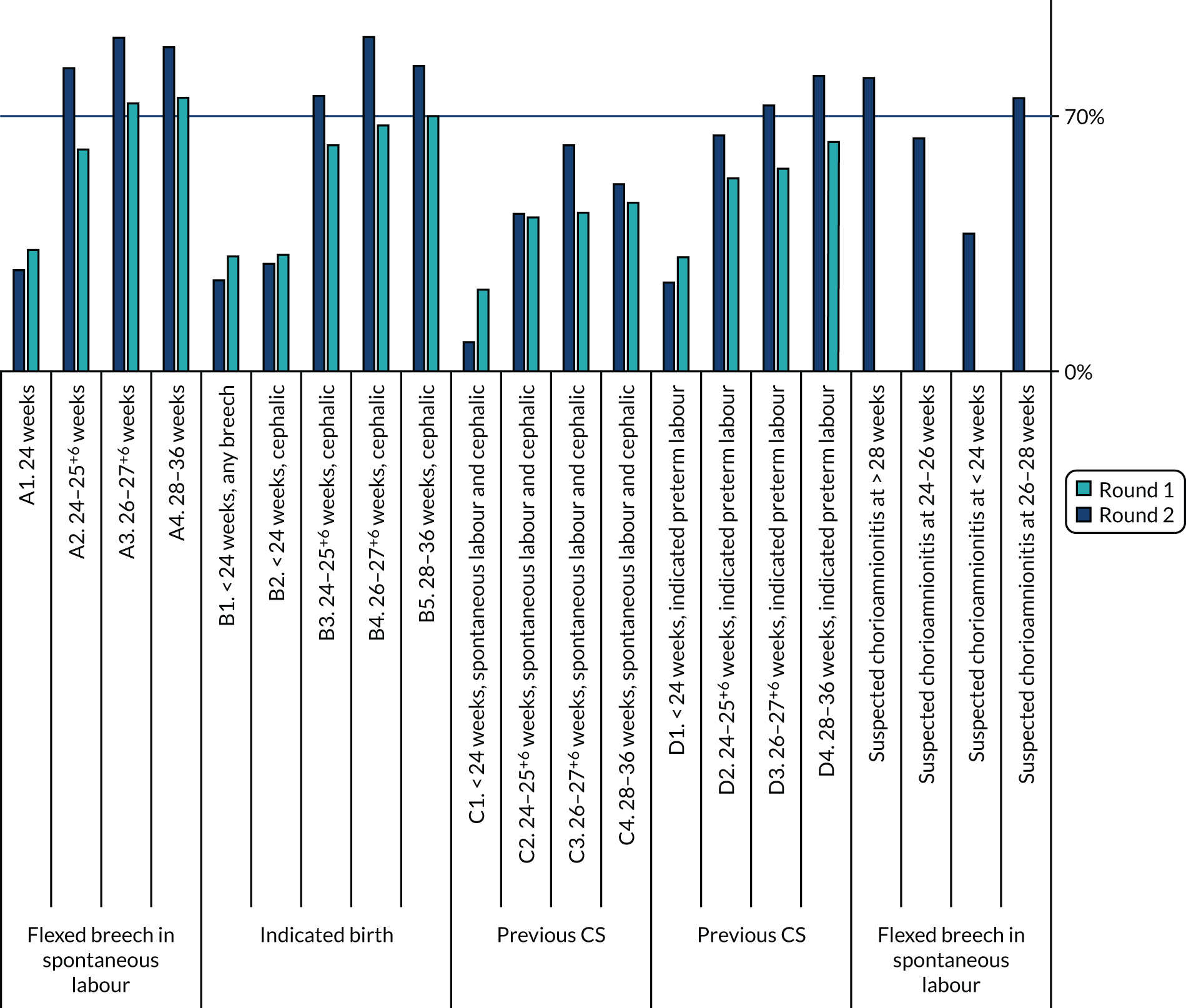

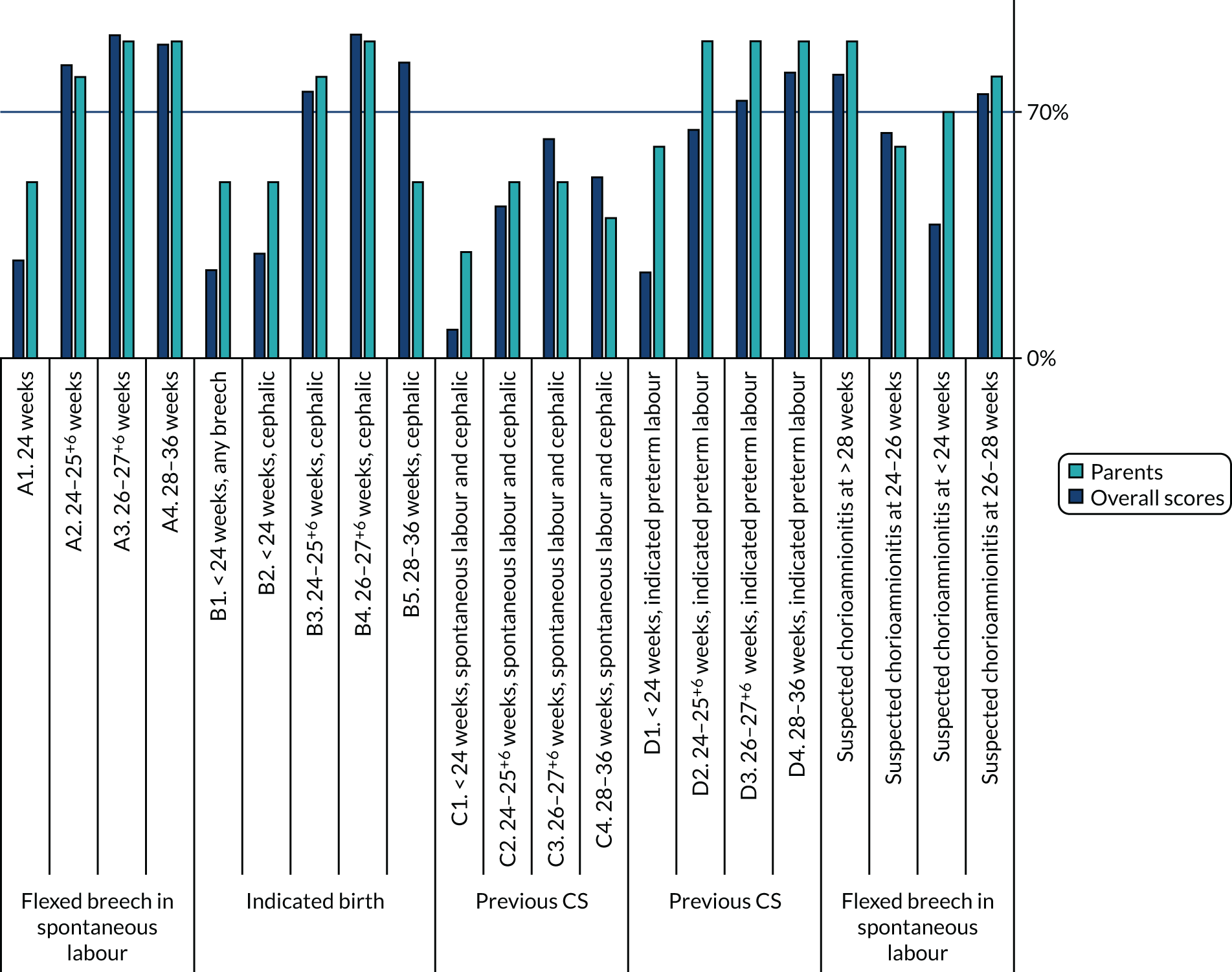

There was evidence of consensus over the two rounds, with scenarios more likely to be included after round 2 than after round 1 (Figure 13).

FIGURE 13.

Recommended scenarios in Delphi rounds 1 and 2.

Eighty-one (10.2% of 798 individual scores – 21 scenarios × 38 participants) individual scores were different between rounds 1 and 2.

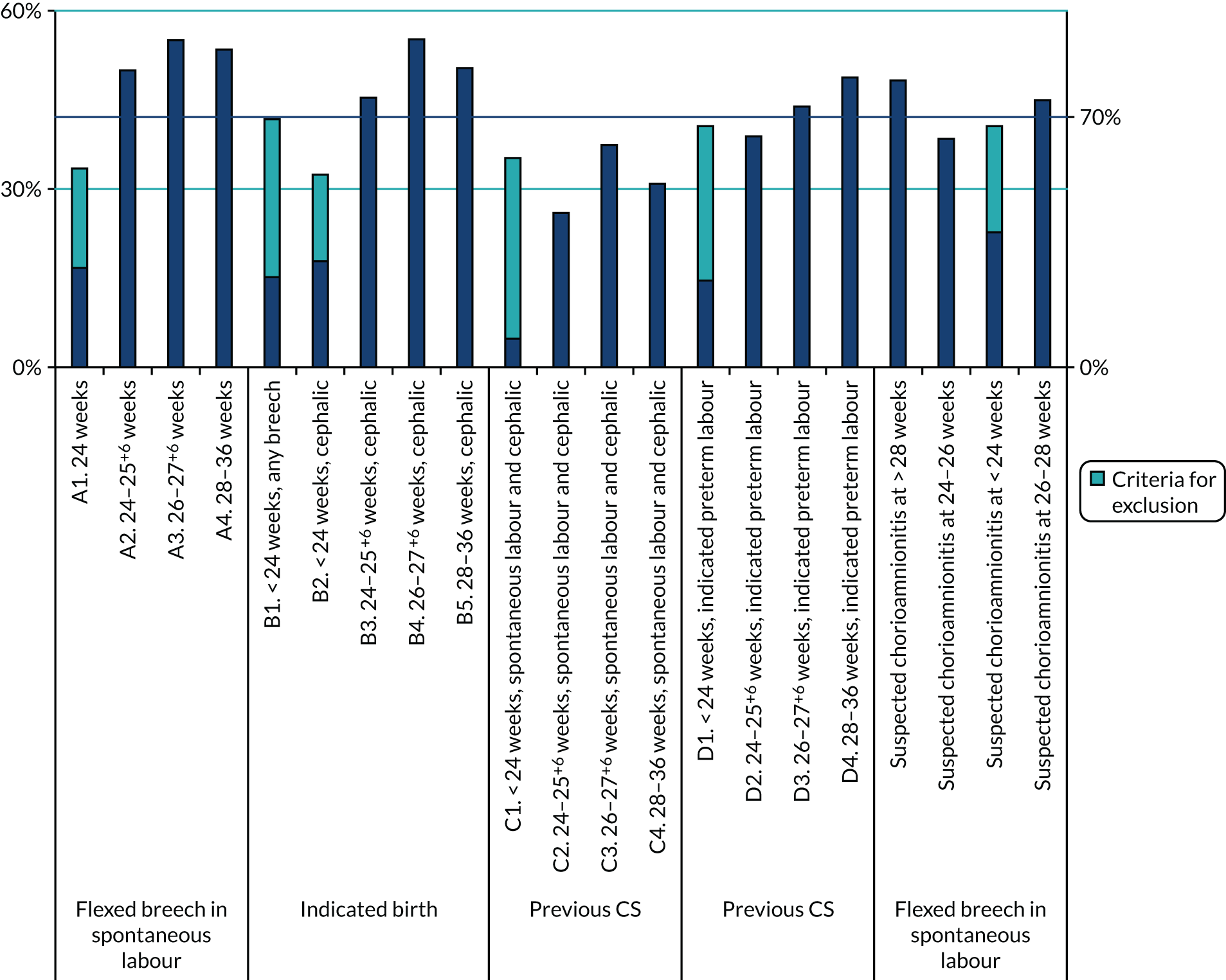

After round 2, few scenarios fulfilled criteria for exclusion, with most scenarios either qualifying for exclusion or being borderline (Figure 14).

FIGURE 14.

Percentage of participants scoring 1–3 (left axis) vs. 7–9 (right axis).