Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/197/65. The contractual start date was in July 2016. The final report began editorial review in July 2019 and was accepted for publication in February 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rachel Meacock is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Funding Committee (2019 to present). Prior to that, Rachel Meacock was an associate member of the NIHR HSDR Board (March 2016–December 2018). Richard Emsley is a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Clinical Evaluation and Trial Committee (November 2017 to present).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Forsyth et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Literature search

At present, approximately 850,000 people have a diagnosis of dementia in England and Wales, with the rate of diagnosis projected to double by 2040. 1 Dementia is currently an NHS priority. 2 In England and Wales, a social framework to support people with dementia in the community has been adopted,3,4 with a focus on quality of life. 5 National Institute for Health and Care Excellance guidelines6 outline a clear community pathway and provide a detailed referral process, including assessment tools, provision for patients across different community settings and suggestions for best practice7 for care co-ordination once a diagnosis is made.

Recent research has concentrated on dementia and the impact that it can have on individuals in hard-to-reach communities, such as those in prison, and has focused predominently on the suitability, or otherwise, of prison environments for individuals with dementia. 8

There are currently 82,525 people in prison in England and Wales. Sixteen per cent of the total prison population are older prisoners, defined as aged ≥ 50 years. 9 In England and Wales, prisoners aged ≥ 60 years are the fastest-growing group, followed by those aged 50–60 years. 9 Between 2011 and 2019 the number of male prisoners aged ≥ 60 years increased from 3038 to 4930 and the number of male prisoners aged ≥ 50 years increased from 8899 to 13,061. At the same time, the number of female prisoners aged ≥ 60 years increased from 79 to 128, and the number of women prisoners aged ≥ 50 years increased from 397 to 559. 9 A similar pattern has been shown in other countries, including the USA,10 Australia,11 Japan12 and Canada. 13 This trend is likely to continue. 14 This growth is in part due to an overall ageing population, but also to increases in sentence length and the increase for prisoners aged ≥ 50 years in historical sexual convictions. 15

It is widely accepted that those in prison are physiologically approximately 10 years older than their chronological age. 16 This is, in part, a result of drug and alcohol misuse and lower educational attainment, but also exacerbated by the prison environment. 17 It is recognised that adjustments are required to accommodate and address the mental and physical frailty associated with ageing,8,18,19 including those conditions more prevalent in older age (e.g. dementia). 18 Older prisoners often have suboptimal access to appropriate health-care services20 and may go unnoticed in large prisons. Unlike their younger counterparts, they tend to be quieter and less complaining, and their health and social care needs may not be as immediately obvious as those with severe, acute problems, such as active psychosis or substance withdrawal. This was notably emphasised in the thematic review published by the Chief Inspector of Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons in 2004, the title of which, ‘No Problems – Old and Quiet’: Older Prisoners in England and Wales,21 reflected an entry found in an elderly prisoner’s discipline record. However, this stereotype of a quiet, helpful, older prisoner is being challenged by a growing body of research that shows that older prisoners can have serious health, social and custodial needs that often go unidentified and unmet in the prison setting. A number of studies have shown that older men in prison have different needs from both the general (younger) prisoner population and older adults in the community. 21–27

According to the principle of the equivalence of care,28 prisoners are entitled to the same level of health care as that provided to the general population. 29 All NHS standards therefore apply to prison health care, including the National Service Framework for Older People. 30 However, the standards outlined in this framework remain largely unmet in prisons in England and Wales,21 and there remains no overarching national strategy for older prisoners, despite repeated recommendations that one be developed. 21 Although equivalence is a recognised priority, it is well established that community guidelines do not adequately address the logistical challenges of prison environments and, in practice, equivalence can be difficult to achieve. 31 Prison health-care services are under continuing strain to provide comparable health and social care provision, and the continued under-resourcing of health care contributes to inefficient service delivery. 17

Dementia in prison is understudied and research is yet to establish what systematic care should be provided for prisoners with dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Research so far has been centred on men8,32 and of limited geographical representation. 19,33 Before the study commenced, dementia rates among older male prisoners were estimated at 1–2%. 19,23,24 This figure was based on small samples that did not include women and may therefore not be representative of the whole older prison population. Prevalence estimates also varied as a result of discrepancies in assessment measures used. A previous study from our research group25 investigated a sample of older male prisoners drawn from a 1-day census in 12 prisons across the north-west of England. The study25 reported that 7% of participants achieved a score on the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)34 that indicated possible dementia.

Studies have shown that prisoners with dementia or MCI can suffer from multiple adverse consequences in relation to victimisation and punishment for non-adherence to prison rules. 35,36 Furthermore, the prison environment in its current form is not suitable to effectively provide dementia or MCI care. Excessive noise and poor lighting can be distressing and disorientating to those with dementia or MCI,37 and often prisons are dark and use inadequate artificial lighting. Likewise, the prison regime is restrictive and, if disorientated, an individual may find it increasingly difficult to follow a routine. 38 It is therefore imperative to establish an accurate prevalence rate to inform our understanding of the ability of current services to identify and manage prisoners with dementia or MCI, and to establish what systematic care should be delivered and what adjustments should be made to the prison environment.

Although government strategies regarding ageing prisoners and dementia have been published, no a specific dementia or MCI care pathway has been developed that is applicable and appropriate for use across different prison sites in England and Wales. Recommendations have been made to translate community-based guidelines into guidance suitable for prisons;39 however, a strategic pathway is yet to be developed. For example, although some UK prisons have developed wings for older prisoners, these services are delivered on an ad hoc basis, with support often disbanded as a result of financial limitations. 8 It has been postulated that the delivery of age-appropriate services could be cost-effective and that research must endeavour to develop pragmatic solutions to support staff and prisoners. 40

To achieve this, there are contextual constraints that should be acknowledged when considering the implementation of the community model into the prison environment. These constraints include a lack of understanding between prison service staff and prison health-care staff regarding how each other’s organisations work, with lack of role clarity resulting in problematic intervention implementation. 40 Care pathway development should therefore aim to support all members of staff and include clear role guidance.

The increasing age of the prison population is a relatively new concern in prison; therefore, current understanding and awareness of dementia and MCI among prison staff is low. 41 There is potential to misdiagnose early symptoms of dementia, for example regressive behaviour can present as anger or bad behaviour. 42 Therefore, there is a need to develop training for all prison staff. 39

The Dementia Training Standards Framework,43 updated by Skills for Health, Health Education England (HEE) and Skills for Care in 2018, provides a guide on what essential skills and knowledge are needed across the health and social care sector. The framework describes three tiers of training: awareness, which everyone should have (tier 1); basic skills that are relevant to all staff in settings where people with dementia are likely to appear (tier 2); and training for leadership (tier 3). With the principles of equivalence in mind, this framework should also guide the format of training interventions in the prison setting.

A systematic review of dementia education and training for the health and social care workforce found that educational programmes should to be relevant to participants’ roles and experience; involve active face-to-face participation; underpin practice-based learning with theory; be delivered by an experienced facilitator; have a total duration of at least 8 hours, with individual sessions of ≥ 90 minutes; support application of learning in practice; and provide a structured tool or guideline to guide care practice. 44

A scoping review of the literature on dementia training in the prison setting identified a general lack of research on training needs, preferences and content. Cipirani et al. 45 described dementia remaining ‘a hidden problem’ for many reasons, including prisoners not being proactively screened for MCI when they enter facilities, prison staff lacking the skills to identify possible dementia, prisoners tending not to report any cognitive or physical symptoms for fear of repercussions and mental health services focusing on other inmates whose behaviour is more challenging. 45 Recommendations for training content included covering the early warning signs of dementia (e.g. indecisiveness, confusion about time or place, mood changes, wandering and developing problems with handwriting) and increasing awareness of the impact of dementia on a prisoner’s ability to function, thereby reducing the potential for conflict arising from misunderstandings. 8,46 Moll8 further recommended the need to explore and clarify the role of peer carers in prison and provide them with appropriate training.

Study aims

This study aimed to

-

establish the prevalence of dementia and MCI in prisons in England and Wales (part 1; see Chapter 2)

-

establish the degree and type of impairment, risk level, needs and social networks of those who screen positive on the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination – Third Revision (ACE-III) (part 1; see Chapter 2)

-

validate the six-item cognitive impairment test (6-CIT) for routine use in prisons to aid the early and consistent identification of older prisoners with possible MCI or dementia (part 1; see Chapter 2)

-

identify gaps in current service provision (part 2; see Chapter 3)

-

understand the first-hand experiences of prisoners living with dementia and MCI in prison (part 3; see Chapter 4)

-

develop a prison-based care pathway for prisoners with dementia and MCI (part 4; see Chapter 5)

-

develop training packages for staff and prisoners in dementia and MCI awareness, assessment and management (part 5; see Chapter 6)

-

undertake health economic costings for the care pathway and training packages developed in parts 4 and 5 (part 6; see Chapter 7).

Chapter 2 Part 1

Method

Part 1 of the study aimed to:

-

estimate the current and likely future prevalence of dementia among the prison population in England and Wales

-

establish the degree and type of impairment, the risk of reoffending, the needs and the social networks of those who screen positive on the ACE-III

-

validate the 6-CIT for routine use in prisons to aid the early and consistent identification of older prisoners with possible MCI or dementia.

Sample

We aimed to recruit 860 prisoners (591 men and 269 women). This sample size was calculated to allow the estimation of a prevalence of 7% (based on Hayes et al. 25) with 2% precision [95% confidence interval (CI) 5% to 9%, applying finite sample corrections for each sex].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged ≥ 50 years.

-

Resident in one of the participating prison establishments on the day of the census.

Exclusion criteria

-

Considered by prison or health-care staff not safe to interview alone due to their current risk.

-

Previous inclusion in the study.

-

Does not have a functional command of the English language.

-

Lacking the capacity to provide informed consent and an appropriate personal or independent consultee could not be identified or contacted, was unwilling to be consulted or made the decision to refuse consent.

Participants were included only if they could speak and understand English to a sufficient level and researchers were satisfied that their English-language ability would not adversely have an impact on their test scores. There are significant language biases in some tests, which cannot be overcome by straightforward translation or use of an interpreter. Some tests are available in other language versions, but not all translations have been validated and test administration would still have required the presence of an interpreter. In previous prison-based studies, researchers have experienced considerable difficulties in accessing translation services by telephone. The equipment required to utilise these resources is scarce within prisons, and negotiating researcher access to it on an ad hoc basis was not realistic and would have threatened the feasibility of completing the research to time and budget.

Consent

The researcher explained the project to the eligible participants and gave them the information sheet as well as explaining their ethics rights (see Report Supplementary Material 1). The researcher read and explained the information in these documents to the eligible participant, showing sensitivity to the high levels of learning difficulties and literacy problems in this population, as well as to their potential MCI. The researcher explained what participation involved, how much time it would take and answered any questions. The researcher also explained that participation was voluntary, that the prisoner was free to withdraw at any point and that their decision to participate, or not, would have no adverse effect on the care that they received or their legal rights. The researcher also discussed the arrangements to ensure confidentiality (and limits of this) and data protection. Limits to confidentiality included information pertaining to:

-

behaviour that was against prison rules

-

information that suggested either a risk of harm to self or a risk of harm to others

-

information that referred to a new crime committed or planned, or undisclosed illegal acts

-

behaviour that would be harmful to the individual (e.g. intention to self-harm or to end one’s life)

-

information that raised concerns about terrorism, radicalisation or security issues.

Researchers had a duty to inform prison staff of any of the above, in line with our written protocol.

Potential participants were given the option of participating immediately after they were approached. The reason for interviewing people so soon after the initial approach was because of the complex and challenging nature of the prison environment, the difficulties in working around the prisons’ security needs (which take priority at all times) and the very short notice periods involved when moving people around the prison estate. It would have been unlikely that we could have achieved the recruitment targets for the study in the prison environment without such an approach. However, a process consent procedure was followed to ensure that participants had multiple opportunities to consider their involvement in the study and withdraw if they chose, without any negative implications for them. Further details of this process consent method are explained in Individuals lacking capacity. Eligible participants who wanted to have longer to consider their involvement were interviewed within 1 week of their initial approach and were given at least 24 hours to consider whether or not they wanted to participate. The consent form (see Report Supplementary Material 2) was explained to the participant before they signed it, and the researcher signed the form after it had been completed by the participant. A copy of the consent form was offered to the participant and one copy was retained by the researcher. Once informed consent had been obtained, the participant was invited to begin the interview.

Each person who agreed to participate in the interview was allocated a unique participant identification (ID) number and names were not recorded. Dependent on the outcome of the initial screening on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), participants were invited for a further interview. Those who did not want to continue with the study were thanked for their time and their participation in the study ended. For those who consented to a further interview, it was explained that they may be contacted in the next 3 months, but that they were under no obligation to complete the next interview should they change their mind.

The researchers taking consent were aware of the potential for any coercion and how the vulnerabilities of individuals might affect the decision they make. Researchers also received specific training in recognising MCI and working sensitively with individuals affected in this way. The prisoner population has high levels of illiteracy and learning difficulties, and researchers had an awareness of these difficulties when obtaining consent. Researchers ensured that participants could demonstrate a clear understanding of their involvement in the study and their rights within the study (e.g. the right to withdraw) prior to seeking informed consent. Researchers were sufficiently trained and experienced to assess whether or not patients had the capacity to give consent.

Individuals lacking capacity

Researchers received training in assessing capacity, as outlined in the Mental Capacity Act (MCA),47 as follows:

-

Gaining ‘permission to access’ the person with possible dementia from staff, a relative or a named person.

-

Establishing the basis for consent. As capacity is situational and variable, the researcher endeavoured to find out how the person usually consented to care or other activities in day-to-day life.

-

Seeking initial consent for the specific research. Information was provided that was appropriate for that person to help them understand the study. This step included recording non-verbal communication and facial expressions, and referring back to what was already known about how the person usually consented on a daily basis. It was important that the researcher did not rely only on a lack of verbal objection and assumed this to mean consent had been given.

-

Monitoring ongoing consent monitoring in line with the idea of consent as a process. Dewing48 described this stage as ‘ensuring initial consent is revisited and re-established on every occasion or even within the same occasion’. 48

-

Providing feedback and support. This included feeding back to staff any concerns the researcher might have had about the participant.

Researchers also sought an opinion from prison health-care staff regarding capacity. If the person lacked capacity, an attempt was made to identify a ‘personal consultee’, as defined by the MCA,47 to advise on the individual’s participation. In the first instance, even when participants were considered to lack the capacity to consent to participation, researchers asked if they could contact someone else to advise on the individual’s behalf. Potential consultees from outside the prison were contacted only if the research team had established that they were aware that the potential participant was in prison and that they had difficulties that limited their capacity to consent. The initial approach to anyone outside the prison was made by prison health-care staff.

Personal consultees were provided with study information (see Report Supplementary Material 3) and their role and the reason for them being approached was explained by researchers. If the participant was unable to nominate anyone or give consent to contact someone outside the prison, researchers identified an appropriate independent consultee (again, in line with the MCA47). This was usually a clinician or health-care worker from within the prison. No pressure was placed on any individual to act as a consultee and researchers fully briefed consultees regarding the study, to enable them to offer advice on the potential participant’s behalf. If a consultee or nominee advised that the individual would not want to take part, they were not be recruited.

Researchers also discussed the study with the person themselves, in a way that was appropriate to their level of understanding. If there was any indication that the individual did not want to participate in any part of the study then the individual did not take part, even if their participation has been advised by another person on their behalf. When this occurred, researchers informed the individual’s consultee that the individual was not taking part, despite their advice, and explained the reasons for this. There was clear potential for the research to benefit individuals with MCI and the study methods (interviews and observations) posed minimal risk to participants. All data collection was completed with sensitivity and respect for the autonomy and privacy of each participant.

The following safeguards were applied once an individual had been recruited in this way:

-

No actions were taken during any part of the study if the participant seemed to object to it (unless the action was vital to protect the individual from harm).

-

Researchers considered the interests of the participant above all else throughout the study.

-

The participant was withdrawn if any conditions pertaining to his or her inclusion in the project no longer applied and/or if he or she gave any indication that they did not want to continue or take part.

The consent form (see Report Supplementary Material 2 and 4) for all individuals included an option to indicate a preference ‘for’ or ‘against’ continued participation, should the individual lose the capacity to consent during the study.

Sampling procedure

The sample was drawn randomly from all women’s prisons and a representative range of adult men’s prisons across England and Wales, including local prisons holding those on remand, those serving short sentences and those in the early part of long sentences; training and dispersal prisons holding men part-way through long sentences; high-secure establishments holding those considered to be high risk; and open prisons holding short-term prisoners deemed low risk and those in the final stages of long sentences who are preparing for community release.

We selected sites based on the proportion of each prison type in the prison estate as a whole: one of the eight high-secure sites; 3 of the 31 local sites; 5 of the 51 category B or C training and dispersal prisons, and one of the seven category D or open prisons [as defined in the Justice prison index URL: www.justice.gov.uk/contacts/prison-finder (accessed 9 May 2016)]. We also included a prison that had a specific wing for older and disabled prisoners. This is one of only two prisons in the country with a dedicated wing for prisoners based on their age and health needs.

We estimated that we would need to initially approach approximately 415 female prisoners and 896 male prisoners to allow for 20% of prisoners refusing to participate and a further 14% of prisoners who might have been unavailable on the day, unable to consent or already interviewed for the study in a previous establishment. (These estimates were based on the Hayes et al. study,25 in which researchers conducted a 1-day census of all prisons in the north-west of England and interviewed all men aged ≥ 60 years resident in each establishment.)

The total number of prisoners aged ≥ 50 years in the recruiting prisons was established and these figures were used to calculate a sampling fraction, which informed the proportion of prisoners we approached at each site. We stratified our sample according to age, an important variable when investigating MCI, as prevalence doubles with every increase of 5 years. 49

To stratify by age, we collected an age breakdown of the prisoners present in the establishment on census day for each of the sites. The latest Dementia UK: Update1 stipulated that those aged 60–69 years had two to three times the prevalence of those aged 50–59 years. Additionally, those aged ≥ 70 years had three to five times the prevalence of the youngest group. We therefore obtained the number of prisoners aged 50–59, 60–69, 70–79 and ≥ 80 years at each site on a given census day. Within each site, we sampled 30% of those aged 50–59 years, 60% of those aged 60–69 years, 90% of those aged 70–79 years and all prisoners aged ≥ 80 years. The procedure is described as follows.

Procedure

Our exact procedure varied between sites, as certain elements depended on local factors or procedures, such as the size of the health-care suite or the holding room, the freedom of movement allowed to prisoners within the establishment and whether or not researchers were authorised as key holders. The research team therefore liaised with the prison governor and relevant staff to establish a procedure in each site, which broadly followed that detailed in the following steps.

Recruitment

We utilised a 1-day census approach, specifying a census date per site. (It would not have been feasible to have only 1 census day for all sites, as it took considerable time to collect data at each site, and a long delay between the census date and data collection would inevitably have resulted in increased attrition, especially at local prisons with transient, remand populations.)

A research nurse or another appropriate staff member in each prison acted as a single point of contact (SPOC) for the research team. This was a different role across study sites (such as a clinical studies officer, researcher or research facilitator), but to avoid the potential for coercion during recruitment we ensured that the individual was not in a directly caring role for prisoners and not a member of our research team. The research team provided the SPOC at each site with a census date and the SPOC then identified potential participants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The SPOC did this by running a search on all prisoners in their establishment on the prison computer system (Computer-National Offender Management Information System) or health-care system [SystmOne; The Phoenix Partnership (Leeds) Ltd, Leeds, UK]. Once a numbered list of all potential participants had been generated, the SPOC informed researchers of the number of eligible older prisoners identified. A member of the university-based research team then used a random number generator to identify the numbers of those randomly selected for potential participation. We communicated these to the SPOC (e.g. numbers 1, 3, 6, 7, 9 . . ., etc., on this list). The SPOC then conducted checks using the internal prison data systems to ensure that the individual met the inclusion criteria and that it was appropriate for them to be seen. They considered if the potential prisoner’s current risk assessment indicated whether or not they were safe to be seen. This was done by reviewing the records and discussing with health-care staff, as appropriate. They had a protocol that they used to determine appropriateness in a uniform way.

The SPOC then sent an information and appointment slip to each of the individuals who had been randomly selected and were both eligible and appropriate to be seen. The slip briefly outlined the study and invited each individual to a one-to-one interview with a researcher. The slip explicitly stated that, by attending their designated appointment, individuals would be meeting with a member of the research team to further discuss the potential for participation. Details of who to approach for further information or advice regarding the study, within the prison and prior to the appointment time, was also included. This procedure was considered more realistic and feasible than someone in the prison going to see each potential participant and asking for their consent to pass details on to the research team. There were in excess of 100 eligible participants at some establishments and, given the impact of austerity measures across the prison estate, requiring a member of staff to do this amount of work was considered unfeasible.

Interviews were held in health-care clinic rooms, in visits or in wing interview rooms, depending on the availability of rooms, procedures and governor preferences in each prison. At their appointment time, eligible participants met a researcher who provided them with, initially, verbal information and then, if they were willing, written information about the study and an opportunity for further discussion. During the briefing process, participants were made aware that if they chose to take part in the study, their data would be made available to other researchers, but that this would be in an anonymised format.

Following the procedure for obtaining consent, if an individual consented to take part, the researcher conducted an initial interview (see Report Supplementary Material 5), which included the collection of demographic data and completion of the MoCA. A proportion of the sample also completed the 6-CIT for validation purposes.

Researchers obtained the prison ID number of all who attended an appointment, regardless of whether or not they had consented to participate in the study. This list was then passed to the SPOC, who matched it against the list of those invited to appointments to identify anyone who failed to attend. If any individuals identified in the initial random sample failed to attend, the SPOC attempted to make contact with them to establish whether or not the reason for their failure to attend was related to an inability to comprehend the written information provided. This was an important step in ensuring that the sample was not biased by the indirect exclusion of those with a MCI or literacy problems. The SPOC took great care to avoid coercing individuals into taking part or making individuals feel that they had to account for their decision not to attend. Instead, they made it clear that the purpose of making contact was to check if any individuals wanted to attend but were unable to, in which case-appropriate arrangements and additional support was put in place to facilitate a meeting with the research team. At some sites, multiple census day random samples were generated until the target number was achieved.

Individuals who scored positive on the MoCA proceeded to a further needs assessment interview (see Report Supplementary Material 6). The interview took place immediately after the part 1 interview or, in some cases was delayed by a short time, depending on the operational arrangements at the study site and the individual’s preference or needs. A further, fairly lengthy interview may have been difficult and distressing for individuals with MCI, so researchers considered the needs and wishes of each participant prior to continuing with the second interview. If it was operationally viable and the individual was able and willing to continue with a full needs assessment, then both interviews were conducted at the same appointment. If this was not the case, the researcher arranged a new appointment via the research nurse and returned to complete the full needs assessment at a later stage.

Interviews and consent procedures followed the same format for the second interview as described above for the MoCA. Researchers first obtained additional, more detailed demographic information. Information on current physical and mental health, as well as any diagnosis of learning difficulties or disabilities, sensory difficulties and/or use of substances or medication, was gathered on a pro forma designed for the study. This information enabled us to gauge the presence of other factors known to have an impact on cognitive test scores (e.g. pain, strong medication, poor hearing or eyesight, learning issues, mood disorders). Information on this was supplemented by the use of information gathered from SystmOne. Researchers interviewed participants using a range of standardised assessments to assess the degree and type of their impairment, their activities of daily living (ADL) needs, their mental health needs, any brain injury, and their social networks.

Subject to each individual’s informed consent, risk and follow-up data were also collected at this stage. Information pertaining to risks of self-harm and reoffending was sought from the Offender Management Unit. The NHS number, name and date of birth of each participant was also obtained and recorded to allow for the long-term follow-up of key health and criminal justice outcomes at a later date (in a further potential study). Consent was sought from the participant (or advice was sought from the consultee; see Individuals lacking capacity) for researchers to access the individual’s electronic prison health-care record. Health-care records were screened for any indication of diagnosed MCI or dementia.

Follow-up

To enable us to examine the longer-term health and criminal justice outcomes of those who screened positively at a later date, and with further funding, we sought permission from participants to collect their NHS numbers as well as their full names and dates of birth.

If consent was granted, researchers obtained this information from a health-care administrator who already had access to this information, and data were shared via secure e-mail (gov.gsi.uk and nhs.net). Participants were allocated a unique study ID, so, once NHS numbers were received by the research team, these were held with other identifiable information (name, prison ID number) in a separate and secure location from the identifier key and other study data, including test responses.

Participants were able to opt out of allowing access to their data for follow-up and/or allowing access to their risk data as generated by the Offender Management Unit to maintain individual choice and avoid any potential adverse effect on recruitment. Participants were therefore given the option to continue to participate in the study as a whole, even if they opted out of allowing researchers to access their risk information or follow-up data.

No risk or follow-up information was sought in relation to participants deemed to lack the capacity to provide informed consent, as it would not have been appropriate for a personal or an independent consultee to grant researchers access to risk or follow-up data on another’s behalf.

Measures

All participants were invited to complete the MoCA. 50

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

The MoCA50 was designed as a rapid screening instrument for cognitive dysfunction. Different cognitive domains (including attention, memory, visuospatial skills and orientation) are assessed using a series of short tests. The time taken to administer the MoCA is approximately 10 minutes. The total possible score is 30 points, with a score of ≥ 26 points considered normal in the general population. Permission to use the MoCA for research purposes was granted for this study.

The literature clearly supports the MoCA as superior to the MMSE as a global assessment tool. 51 It reportedly has a higher classification accuracy than other measures for differentiating healthy control individuals from those with MCI, and it can identify impairment indicative of specific clinical conditions, including Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease and, Korsakoff syndrome. Although specialised assessment within a memory service is the ‘gold-standard’ assessment, the MoCA is considered to be the best of the short assessment measures.

However, several studies question whether or not the universal cut-off score of 26 points (developed originally on 90 Canadian healthy control individuals) is appropriate across populations.

Freitas et al. 52 compared the MoCA and MMSE for differentiating MCI from Alzheimer’s disease and healthy ageing in a large, Portuguese, clinical cohort, in which 90 patients with Alzheimer’s disease and 90 patients with MCI were compared with two groups of 90 age-matched controls. Freitas et al. 52 reported optimal cut-off scores of < 22 points for MCI and < 17 points for Alzheimer’s disease. Waldon-Perrine and Axelrod53 assessed 185 veterans referred by a physician for neuropsychological testing in Michigan, USA, and reported an optimal cut-off score of ≤ 20 points for detecting impairment. Larner54 recruited new referrals from a cognitive function clinic in Liverpool, UK. Using a cut-off score of 26 points, sensitivity was 0.97 but specificity was 0.60. A cut-off score of > 20 points for healthy control individuals increased overall test accuracy and improved specificity to 0.95, but reduced sensitivity to 0.63. Luis et al. 55 suggested a cut-off score of 23 points in a south-western US sample. Roalf et al. 51 assessed 321 people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, 126 people with MCI (from Penn Memory Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and 140 healthy control individuals. They developed an optimal cut-off score of 23 points to differentiate between healthy control and Alzheimer’s disease, a cut-off score of 25 points to differentiate between healthy control and MCI and a cut-off score of 19 points to differentiate between Alzheimer’s disease and MCI. Lee et al. 56 validated the MoCA-K, a Korean version of the MoCA, with 196 elderly persons from a Seoul hospital (mild AD, n = 44; MCI, n = 37; HC, n = 115). Using a cut-off score of 22 out of 23 points, the MoCA-K had an excellent sensitivity of 89% and a good specificity of 84% for screening MCI.

We therefore used a cut-off score of 23 points in this study. The high rate of false positives when using a cut-off score of 26 points could have threatened the feasibility of the study, as we planned to conduct a 1.5-hour battery of assessments with individuals who screened positively on the MoCA.

Six-item cognitive impairment test

We had originally planned to complete the 6-CIT with all 869 participants. However, it became apparent that this may be unnecessary and a waste of resources and participants’ time if it transpired that the 6-CIT was not a valid screening tool. We therefore conducted a sample size calculation to ascertain the number of participants that were required to validate the 6-CIT. This sample size calculation was based on 90% sensitivity and 100% specificity, assuming an estimated prevalence of 7% (error 0.15). We established that 470 individuals from our sample of 869 were required to complete the 6-CIT57 for validation purposes. We continued to conduct both the 6-CIT and the MoCA until the required number of 6-CIT responses was obtained. We stratified the sample at each prison by age and collected data from one prison before moving on to the next. We could therefore be confident that the 6-CIT sample was representative of the overall sample.

The 6-CIT57 is a short screening measure for dementia. It is administered in around 3–4 minutes and asks questions about the current time, month and year, as well as testing the participant’s ability to recall a five-component address and list the numbers 1–20 and the months of the year in reverse. Permission to use the measure was obtained from the authors.

The 6-CIT is a much shorter assessment than the MoCA and could therefore be more easily added into current health assessments used in prison. The 6-CIT was used so that we could compare its clinical effectiveness with that of the MoCA in identifying people with potential dementia and MCI.

Participants who scored < 23 points on the MoCA were invited to complete a further battery of assessments detailed as follows.

Demographic pro forma

A demographic pro forma was designed for the study, covering participants’ health (including self-reported ADL problems, eyesight and hearing problems, learning difficulties, head injuries and whether or not they were under the influence of any substances), criminal justice information and command of the English language.

History of comorbidities and medications pro forma

A pro forma was designed to ascertain past and current comorbidities and medications. The research team took this information from prison health-care notes.

Addenbrookes Cognitive Examination – Third Revision

The ACE-III58 is one of the most commonly used cognitive tests to assess dementia and other neurological disorders. It routinely takes around 15 minutes to administer and covers five domains: (1) attention, (2) memory, (3) fluency, (4) language and (5) visuospatial ability. The gold standard for diagnosing dementia and MCI is specialised assessment within a memory service. The ACE-III is, however, a validated screening tool for dementia syndromes. 58

The ACE-III consists of tasks associated with memory, language, verbal fluency and visuospatial functioning, and it has a possible total score of 100. This is a robust clinical tool, which is most commonly used to aid a clinical diagnosis of dementia. Cut-off scores of 82 and 88 are considered to indicate dementia and MCI, respectively. 58,59 These studies have also reported sensitivity of 93–100% and specificity rates of 96–100% at cut-off scores of 82 for dementia and 88 for MCI.

The following structured assessments scales were used to describe the ADL skills and comorbidities of those with suspected MCI or dementia.

Bristol Activities of Daily Living Survey (adapted version)

The Bristol Activities of Daily Living Survey (BADLS) (adapted version)60 was designed specifically for patients with dementia. The questions assess level of independence with regard to ADL abilities, such as preparing food, dressing, washing and using the telephone. The BADLS has 20 items, but these were reduced to 18 items for the purposes of this study, as questions relating to activities that are not relevant in prison (use of public transport and managing finances) were removed. In addition, questions referring to shopping and housework were rephrased to relate to canteen ordering and keeping one’s cell area clean. As a result, we looked not at the overall score but at individual items of the assessment. The survey can be administered in approximately 5 minutes.

Geriatric Depression Scale-15

The Geriatric Depression Scale-1561 (GDS-15) is an adapted version of the long-form Geriatric Depression Scale and is used to identify depression in elderly people. It can be administered in approximately 5 minutes.

PriSnQuest

PriSnQuest62 is an eight-item prison screening questionnaire validated to screen for mental illness in prison. The questions are in yes/no format and cover previous contact with services, suicidal ideation and the presence of psychotic symptoms. A score of ≥ 3 indicates the need for further, detailed examination, and the measure can be completed in < 5 minutes.

Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire

The Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire63 is designed to assess the presence of mild to moderate brain injury. Participants are asked to rate the severity of 16 cognitive, somatic and emotional symptoms that are commonly found after a traumatic brain injury. Symptoms are rated from 0 (not experienced) to 4 (severe problem) and are judged on their severity over the course of the last 24 hours. The questionnaire takes around 5 minutes to administer and was only used with participants who reported having had a brain injury, as it is not relevant otherwise.

Lubben Social Network Scale-18

The Lubben Social Network Scale-1864 is an 18-item self-report scale that assess ES social isolation in older adults. It measures perceived social support from family, friends and neighbours. The Lubben Social Network Scale-18 takes around 10 minutes to complete and assesses the size, closeness and frequency of contacts in a participant’s social network. For the purposes of this study, ‘neighbours’ were interpreted as friends or acquaintances in the prison (rather than in the individual’s neighbourhood), whereas the section on friends was completed in relation to friends external to the prison.

When permission was granted, we also obtained individuals’ NHS numbers to allow us to obtain funding to follow up these participants in the future.

Risk information

We sought the following information from the Offender Management Unit in each prison (for each individual who participated in stage 2, i.e. MoCA-positive individuals):

-

Offender Assessment System (OASys) rating of risk of harm to self and others: very high, high, medium or low

-

Risk Matrix 2000 score (in relation to risk of sexual reoffending), if applicable

-

risk markers: sexual offender; risk to children, women, staff; hate crime (e.g. racism).

Risk information was used to describe the sample in stage 2.

Data analysis

The prevalence estimates were directly age standardised using the age distribution of the national prison population as the reference. From age 50 years and older the following age strata were applied: 50–59, 60–69 and ≥ 70 years. Each stratum-specific weight was calculated as the proportion of the whole prison population that was in that age group, divided by the equivalent proportion for the study sample. The numerator was then calculated the adjusted by taking the product of the weight and the study sample size within each age stratum.

We produced age-specific prevalence estimates to allow comparison with community-based samples (e.g. Matthews et al. 65).

The battery of tests established the broader needs of each older prisoner, including social support, ADL skills, comorbidity and risk. Descriptive statistics were produced. This information informed the case vignettes that were generated in part 4 of the study (see Chapter 5).

In addition, we measured the agreement between categories of the MoCA and 6-CIT using kappa. 66–68 We also examined the relationship between the items and combinations of items on the scales and, with these ordered data, we used weighted kappa as the measure of agreement. 69,70 This approach allowed us to establish whether or not the 6-CIT has suitable psychometric properties to be used as a routine screen in prisons. We estimated the prevalence of MCI by calculating percentages and 95% CIs using the 6-CIT, so that we could compare these with prevalence estimates based on the MoCA.

We aimed to generate a matrix of future prevalence estimates according to various hypothetical projected scenarios of overall prison population growth and of rising numbers of older prisoners in both absolute and proportional terms. Unfortunately, data were not available to enable prediction of future numbers of older prisoners and therefore this task could not be completed. The increase in numbers of older prisoners over recent years has mainly been due to recent sentencing for historical crimes largely as a result of better forensic science procedures (e.g. DNA testing). The population of prisoners aged ≥ 50 years is projected to increase, both in absolute terms and as a proportion of the total prison population. This is because the number of offenders aged ≥ 50 years being sentenced to custody is currently greater than the number being released. 70 However, the extent to which the increase in sentencing of people for historical crimes will continue is largely unknown and therefore it is difficult to predict if this will increase, decrease or stay the same. Furthermore, this growth is offset by a declining imprisoned for public protection/lifer population, who constitute a higher proportion of offenders aged ≥ 50 years. The 50–59 years group is predicted not to grow between now and 2023. 71

Cumulative percentages were calculated throughout this report.

Results

Prevalence

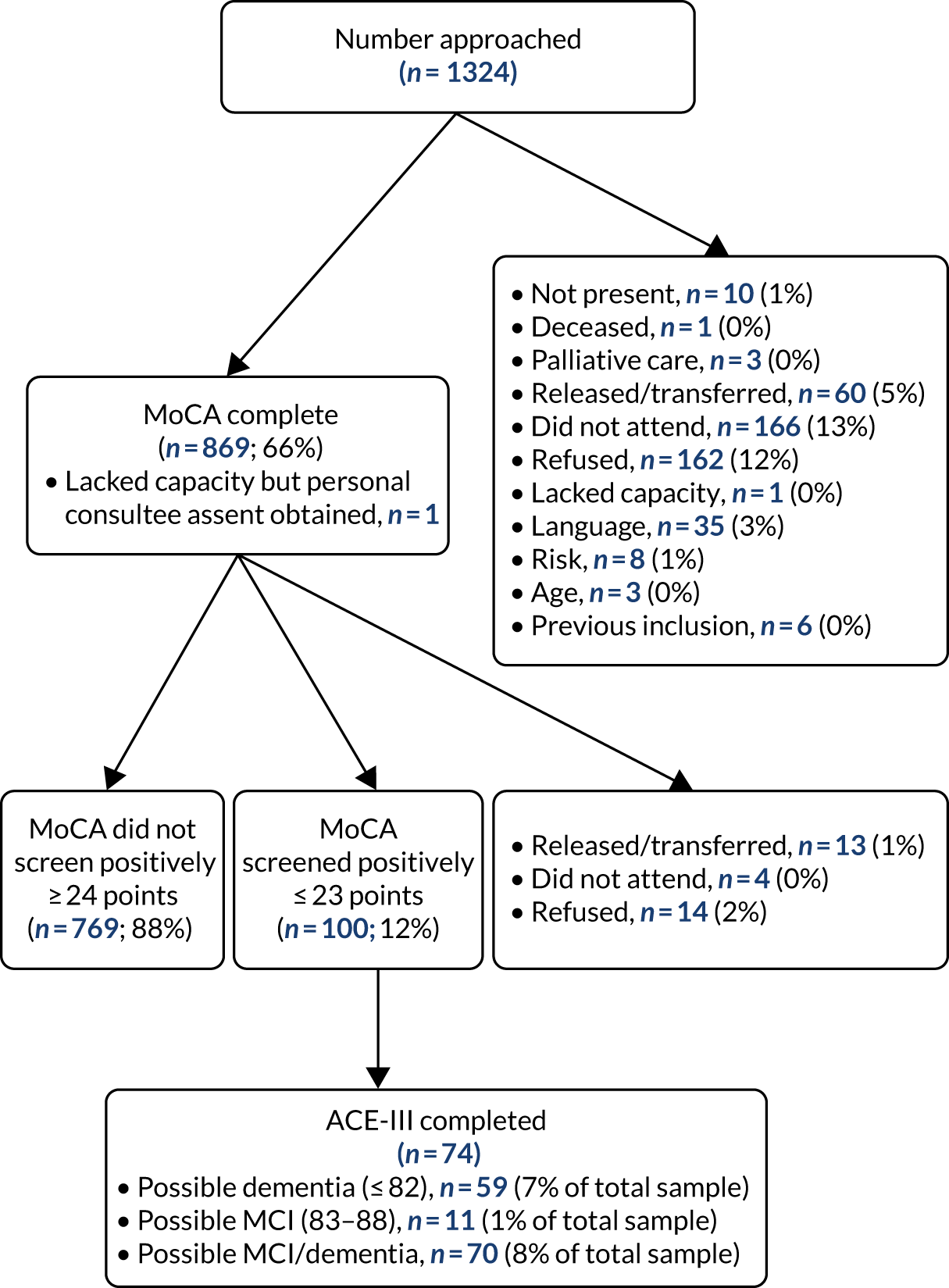

We recruited 869 prisoners (596 male and 273 female). Participant recruitment is detailed in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Part 1 participant details for prevalence study.

As shown in Figure 1, 100 participants screened positively on the MoCA (12%). Seventy (8%) of the total sample screened positively on the ACE-III. This included 11 individuals who screened positively for possible MCI (1% of the total sample) and 59 individuals who screened positively for dementia (7% of the total sample).

Table 1 shows the estimated prevalence of dementia and MCI among our sample of older prisoners. Across the whole sample, the prevalence was 8.1% (95% CI 6.4% to 10.1%). When this was stratified by age, the highest proportion was found among prisoners aged ≥ 70 years (16.9%, 95% CI 12.1% to 23.1%). Participants aged 50–59 years had the second highest estimated prevalence (6.4%, 95% CI 4.3% to 9.2%), followed by prisoners aged 60–69 years (4.0%, 95% CI 2.1% to 7.5%).

| Age group (years) | Number sampled | Number with suspected dementia/MCI in our sample | Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50–59 | 425 | 27 | 6.4 (4.3 to 9.2) |

| 60–69 | 249 | 10 | 4.0 (2.1 to 7.5) |

| ≥ 70 | 195 | 33 | 16.9 (12.1 to 23.1) |

| Total | 869 | 70 | 8.1 (6.4 to 10.1) |

We estimated a prevalence of 6.8% for dementia (95% CI 5.3% to 8.7%) and 1.3% for MCI (95% CI 0.7% to 2.3%). The total weighted estimate for dementia and MCI combined is 8.1% (95% CI 6.4% to 10.1%) (Table 2).

| Type of impairment | Number impaired | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia | 59 | 6.8 | 5.3 to 8.7 |

| MCI | 11 | 1.3 | 0.7 to 2.3 |

| Total | 70 | 8.1 | 6.4 to 10.1 |

Table 3 shows estimated prevalence of dementia and MCI among the older prisoner population weighted by sex and age. There are currently 13,620 prisoners aged ≥ 50 years in England and Wales. 9 It is estimated that 8% of these prisoners have MCI or dementia. This equates to an estimated 1090 older prisoners with MCI or dementia in England and Wales. It should be noted that these findings are based on validated cognitive impairment assessments and not on a clinical diagnosis.

| Sex | Age (years) | Prisoners in England and Wales | Prisoners in sample | Dementia/MCI | Crude, % (95% CI) | Weighted, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 50–59 | 8109 | 213 | 16 | 7.5 (4.7 to 11.9) | |

| 60–69 | 3233 | 193 | 10 | 5.2 (2.8 to 9.3) | ||

| ≥ 70 | 1727 | 190 | 30 | 15.8 (11.3 to 21.6) | ||

| Female | 50–59 | 426 | 212 | 11 | 5.2 (2.9 to 9.1) | |

| 60–69 | 90 | 56 | 0 | |||

| ≥ 70 | 32 | 5 | 3 | 60.0 (23.1 to 88.2) | ||

| Total | 13,617 | 869 | 70 | 8.1 (6.4 to 10.1) | 7.9 (6.3 to 9.9) |

Only two individuals (3%) who screened positively on the ACE-III had a diagnosis of dementia recorded in their prison health-care notes, suggesting current under-recognition.

There were no individuals in our sample who were female, aged 60–69 years and screened positively for symptoms of dementia or MCI on the MoCA. A smaller number of men aged 60–69 years screened positively than (men aged 50–59 years).

Table 4 shows that the prevalence of MCI weighted by age is 0.8%.

| Age (years) | Number | MCI | Crude (%) | Weighted (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50–59 | 425 | 1 | 0.2 (0.03 to 1.7) | |

| 60–69 | 249 | 0 | ||

| ≥ 70 | 195 | 10 | 5.1 (2.8 to 9.3) | |

| Total | 869 | 11 | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.3) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.7) |

Table 5 shows that the prevalence of dementia weighted by age is 6.3%.

| Age (years) | Number | Dementia | Crude (%) | Weighted (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50–59 | 425 | 26 | 6.1 (4.2 to 8.8) | |

| 60–69 | 249 | 10 | 4.0 (2.2 to 7.3) | |

| ≥ 70 | 195 | 23 | 11.8 (7.9 to 17.2) | |

| Total | 869 | 59 | 6.8 (5.3 to 8.7) | 6.3 (4.9 to 8.2) |

Comparison with the community

We aimed to compare the prevalence rates of dementia and MCI among the older prisoner population with those that exist for the wider community. Data were not available for individuals aged 50–59 years living in the community. Community prevalence estimates are broken into 5-year age brackets; however, we used 10-year age groups. It is estimated that 0.9% of individuals aged 60–64 years and 1.7% of individuals aged 65–69 years living in the community have dementia. 1 The prevalence rate among our sample of older prisoners (4%) is approximately two times higher for individuals aged 60–69 years than it is for those living in the community.

The prevalence of dementia for individuals living in the community varies greatly for individuals aged ≥ 70 years. For example, among those aged 70–74 years the estimated prevalence is 3% and among those aged ≥ 95 years the estimated prevalence is 41.1%. The median age of individuals aged ≥ 70 years in our sample of older prisoners was 73 years. Therefore, it is logical to compare the estimated prevalence of individuals aged 70–74 years (3%) in the community with our estimated prevalence of those aged ≥ 70 years (12%). Consequently, we can estimate that prisoners aged ≥ 70 years are approximately four times more likely to have a diagnosis of dementia than their age-matched counterparts living in the community. However, it should be highlighted that our evidence is based on cognitive assessments and not on a clinical diagnosis.

Characteristics of participants screening positive on the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination – Third Revision

Seventy participants screened positive on the ACE-III (for MCI or dementia). Demographic and criminogenic information for these participants is detailed in Tables 6 and 7.

| Demographic | Frequency (N = 70), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity | |

| White British | 55 (79) |

| White Irish | 4 (6) |

| Black African/Caribbean | 4 (6) |

| Asian/Pakistani | 1 (1) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 22 (31) |

| Separated/divorced | 8 (11) |

| Married/partner | 33 (47) |

| Widowed | 7 (10) |

| Employment status (before prison) | |

| Full- or part-time employment | 25 (36) |

| Unemployed | 13 (19) |

| Retired | 19 (27) |

| Long-term sick (benefits) | 12 (17) |

| Accommodation (before prison) | |

| Private house | 60 (86) |

| Temporary accommodation | 2 (3) |

| Homeless | 2 (3) |

| Supervised hostel | 3 (4) |

| Living circumstances (before prison) | |

| Alone | 33 (47) |

| With spouse/partner with children | 13 (19) |

| With parents | 1 (1) |

| With spouse/partner without children | 16 (2) |

| Criminogenic detail | Frequency (N = 70), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Prisoner status | |

| Convicted | 69 (99) |

| Remand | 1 (1) |

| Previously convicted | |

| Yes | 27 (39) |

| No | 43 (61) |

| Wing location | |

| Remand/induction | 2 (3) |

| Health care | 2 (3) |

| Normal location | 24 (34) |

| VPU | 41 (59) |

| Drug free | 1 (1) |

| Regime | |

| Standard | 31 (44) |

| Basic | 12 (17) |

| Enhanced | 26 (37) |

The majority of prisoners were white British (n = 55, 79%). Within the general prison population, 26% of prisoners identified as non-white;72 this varied greatly from the older prisoner population more specifically. Twenty-five (36%) of the sample were employed prior to prison; however, among the wider prison population, 68% were unemployed in the 4 weeks prior to custody. 73 Prior to imprisonment, 33 (47%) of our sample were married or living with a partner, 33 (47%) were living alone and 60 (86%) were living in a private house. Homelessness is more prominent among the wider prison population (15%) than it was in our sample of older prisoners (3%).

These differences are largely as a result of the nature of the older prisoner population. A high proportion (45%) of older prisoners are sex offenders73 and many of these will have been convicted for historical offences.

The mean number of previous convictions was 2.95 and the mean current sentence length was 18 months.

Other conditions causing mild cognitive impairment

There are several possible reasons for MCI in this sample, including severe depression, stroke, chronic serious alcohol misuse, the impact of serious head injuries, other neurological conditions and learning disabilities. We established the proportion of the ACE-III-positive people who had these comorbid conditions. Seven people had some difficulties understanding spoken English to an extent that it may have interfered with their performance on the ACE-III. Hearing impairment may also have affected performance on ACE-III. One participant had hearing impairment recorded in their medical records; however, 23 individuals reported some hearing problems at interview.

Three participants had learning difficulties reported in their health-care records; however, 21 participants self-reported a learning disability, including 10 who had attended a special educational needs school. One participant had a brain injury recorded in their medical records; however, 22 participants self-reported a previous brain injury.

It is not known whether or not these comorbid conditions were associated with MCI and are therefore responsible for the ACE-III-positive score. It is possible that some people may have dementia or MCI and one or other of the conditions listed above.

Characteristics of people scoring positive on Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination – Third Revision

Table 8 shows that 42 participants scored above the cut-off score of 5 on the GDS-15 (60%). Scoring above the cut-off score indicates that further clinical exploration is needed. Only 13 of these individuals had a diagnosis of depression recorded in the prison health-care records.

| Test | Participants scoring above cut-off points (N = 70), n (%) |

|---|---|

| GDS-15 (score ≥ 5) | 42 (60) |

| PriSnQuest (score ≥ 3) | 7 (10) |

Seven participants (10%) who screened positively on the ACE-III scored ≥ 3 on PriSnQuest, indicating that further clinical assessment for mental illness is required.

Nineteen (27%) participants reported a history of head injury on the Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire; nine participants (13% of ACE-III-positive participants) reported experiencing poor memory after the head injury.

Physical health

The most common comorbidities noted in the case notes were hypertension (n = 18) and diabetes mellitus (n = 13) (Table 9).

| Comorbidity | Frequency of people with an underlying comorbidity (N = 59), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Heart disease | 8 (14) |

| Hypertension | 18 (31) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 4 (7) |

| Angina | 1 (2) |

| COPD | 5 (8) |

| Asthma | 8 (14) |

| COAD | 1 (2) |

| Epilepsy | 1 (2) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 1 (2) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 13 (22) |

| Cancer | 7 (12) |

| Renal problems/failure | 1 (2) |

| Arthritis/osteoarthritis | 7 (12) |

| Osteoporosis | 4 (7) |

| Anaemia | 3 (5) |

| UTI | 2 (3) |

| Pneumonia | 1 (2) |

| Alcohol misuse | 3 (5) |

| Drug misuse | 4 (7) |

| Recent surgery | 2 (3) |

Table 10 shows the current medication prescribed according to the health-care records.

| Medication | Frequency of people taking medication (N = 59), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Antipsychotic drug | 7 (12) |

| Benzodiazepine | 1 (2) |

| Non-benzodiazepine anxiolytic | 1 (2) |

| Non-benzodiazepine hypnotic | 1 (2) |

| Antidepressant | 18 (31) |

| Dementia medication | 2 (3) |

| Anticonvulsant | 1 (2) |

| Mood stabiliser | 1 (2) |

| Pain relief | 33 (56) |

Table 11 shows the number and percentage of participants who screened positively on the ACE-III for ADL dependence in at least one area (n = 19, 27%). The domain in which the highest number of participants experienced difficulties was mobility (n = 21, 30%).

| Descriptive assessment | Frequency (N = 70), n (%) |

|---|---|

| BADLS dependence | 19 (27) |

| OASys risk of harm: high/very high | 32 (46) |

| Risk Matrix 2000: high/very high | 4 (6) |

Thirty-two (46%) participants had a high or very high risk of harm to self or others, as measured using the OASys. In addition, four (6%) participants had high or very high scores on the Risk Matrix 2000, indicating a high level of risk of sexual offending.

Table 12 shows the proportion of participants who screened positively on the ACE-III who had no friends to talk to about private matters (n = 35, 50%) or to call on for help (n = 35, 50%). In addition, over half of these participants (n = 37, 53%) stated that they ‘never’ had a friend to talk to when they had an important decision to make.

| Social network | Frequency (N = 70), n (%) |

|---|---|

| No friends to talk to about private matters | 35 (50) |

| No friends to call on for help | 35 (50) |

| Never has a friend to talk to when has an important decision to make | 37 (53) |

Six-item cognitive impairment test validation

A total of 495 of the participants completed the 6-CIT in addition to the MoCA for validation purposes. Table 13 shows that 41 individuals screened positively on the MoCA but did not screen positively on the 6-CIT.

| MoCA status | Screened positively on 6-CIT, n (%) | Not screened positively on 6-CIT, n (%) | Total (N = 495), n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screened positively | 24 (4.8) | 41 (8.3) | 65 |

| Not screened | 18 (3.6) | 412 (83.2) | 430 |

| Total | 42 | 453 | 495 |

An inter-rater reliability analysis using the kappa statistic was performed to determine the level of agreement between the screening tools, with respect to individuals who did or did not screen positively using the MoCA and the 6-CIT. The analysis indicated that the level of agreement between the MoCA and the 6-CIT was ‘fair’: the observed agreement was 88.1% compared with an expected agreement of 80.6% [this is the baseline agreement that we would expect to see by chance (6-CIT κ = 0.39; p < 0.001)].

Summary

-

We recruited 869 prisoners (596 male and 273 female).

-

A total of 100 participants screened positively on the MoCA (12%). Seventy (8%) of the total sample screened positively on the ACE-III. This included 11 individuals who screened positively for possible MCI (1% of the total sample) and 59 who screened positively for dementia (7% of the total sample).

-

Across the whole sample, the prevalence was 8.1% (95% CI 6.4% to 10.1%). When this was stratified by age, the highest proportion was found among prisoners aged ≥ 70 years (16.9%, 95% CI 12.1% to 23.1%). Participants aged 50–59 years had the second highest estimated prevalence at 6.4% (95% CI 4.3% to 9.2%), followed by prisoners aged 60–69 years (4.0%, 95% CI 2.1% to 7.5%).

-

The total weighted estimate for dementia and MCI combined is 8.1% (95% CI 6.4% to 10.1%).

-

We estimate that there are 1090 older prisoners with suspected MCI or dementia in England and Wales.

-

Only two individuals (3%) who screened positively on the ACE-III had a diagnosis of dementia in their prison health-care notes, suggesting current under-recognition.

-

The prevalence rate among our sample of older prisoners is approximately two times higher for individuals aged 60–69 years than it is for those living in the community.

-

We can estimate that older prisoners aged ≥ 70 years are approximately four times more likely to have a diagnosis of dementia than their age-matched counterparts living in the community.

-

It should be noted that estimates are based on structured assessments for MCI and not on a clinical diagnosis.

-

The 6-CIT was not considered an effective tool for identifying potential MCI or dementia among the older prisoner population.

Chapter 3 Part 2

Method

Part 2 established the current health and social care service provision, encompassing assessment, treatment and care for older prisoners with MCI and dementia in prisons, including how well multiagency services were integrated. Training needs were also explored.

Measures

Questionnaire

Two separate questionnaires were issued to governors and health-care managers of all prisons housing men and women in England and Wales (n = 109). The questionnaires included free-text sections, single-response questions and multiple-choice questions. The governor questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 7) included questions on service provision for people with dementia and MCI, including any modifications to the environment, training delivered and required, and social care provision. The health-care questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 8) included questions on training provision, training needs, current health and social care provision, and future care pathway delivery.

Procedure

An up-to-date list of names and contact details of all the health-care managers was obtained from NHS England and cross-checked with records held by regional offender health leads. Similarly, an up-to-date list of all prison governors was obtained from Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service.

The questionnaire was designed by the research team and piloted in prisons in the north-west of England before wider distribution. Small, mainly structural, changes were made to the questionnaires following feedback on the pilot.

The questionnaire was distributed electronically to prison sites where we had a direct e-mail contact. A postal questionnaire was sent if no direct contact was available. In either case, a cover letter was sent with the questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 9). A researcher followed up contacts 2 weeks after the initial distribution of questionnaires, by either e-mail or telephone, and then further contact was made 2 weeks later by letter. This process was repeated several times between August 2017 and June 2019. Named recipients were also given the option of completing the questionnaire in a telephone interview with a member of the research staff.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) for Windows, version 22 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA). Free-text responses were analysed thematically. 74

Results

Establishments

We collected data from 85 prison governors (78%) and 77 health-care managers (71%). There were four (3%) prisons from which we received no data (i.e. from neither the governor nor the health-care manager questionnaire).

Questionnaires were completed between August 2017 and June 2019. Table 14 shows a breakdown of establishments that responded by predominant prison function. Eleven (13%) were privately contracted prisons and 48 (62%) had either partially or fully privately managed health care.

| Prison function | Governor questionnaires, n (%) | Health-care questionnaires, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Category C | 35 (41) | 28 (36) |

| Local | 22 (26) | 22 (29) |

| Open | 7 (8) | 9 (12) |

| Female | 8 (9) | 6 (8) |

| Category B | 7 (8) | 6 (8) |

| High security | 6 (7) | 6 (8) |

Non-responder prisons were privately contracted in four (17%) cases and had partially or fully privately managed health care in 16 (50%) cases.

Prison and health-care staff were asked for their definition of an ‘older prisoner’ (Table 15). Sixty-four per cent of prison staff and 56% of health-care staff defined a ‘older prisoner’ as a prisoner aged ≥ 50 years. This fits with the definition in the literature. 8

| Definition | Governor questionnaires frequency (N = 85), n (%) | Health-care questionnaires frequency (N = 77), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Aged ≥ 50 years | 54 (64) | 43 (56) |

| Aged ≥ 55 years | 13 (15) | 17 (22) |

| Aged ≥ 60 years | 8 (9) | 7 (9) |

| Aged ≥ 65 years | 10 (12) | 9 (12) |

| Missing | 1 (1) |

For the remaining questions, ‘older prisoners’ were defined as those aged ≥ 50 years.

We asked health-care staff to estimate the number of people in their establishments with a confirmed diagnosis of dementia and/or MCI and the number of those awaiting assessment. Table 16 provides a breakdown of how many older prisoners were reported to have each diagnosis across all prisons.

| Diagnosis/status | Mean number | Cumulative number |

|---|---|---|

| Dementia diagnosis | 5 | 141 |

| Waiting or undergoing assessment for dementia | 3 | 45 |

| MCI diagnosis | 2 | 12 |

Most prisons reported that they had at least one identified older prison lead [n = 67 prisons (79%); 81 leads in total]. Most of these were at a governor grade (n = 42, 52%), followed by custodial managers (n = 18, 22%) and prison officers (n = 16, 20%).

Within health care, 45 of 77 (59%) prisons reported having an identified older prisoner lead (59 leads in total). Most commonly, these were nurses (n = 35, 59%), followed by health-care assistants (n = 11, 19%).

Activities that fell under the responsibility of the health-care older prisoner lead included producing individual care plans, conducting screening assessments for care needs, liaising with community providers, disseminating good working practices and well-being checks.

Current service provision

Health-care staff reported that prisoners with dementia or MCI were most commonly identified during a health consultation for another issue (n = 64, 83%) and/or through screening on reception (n = 62, 81%). Six prisoners (8%) were identified through screening on discharge from prison.

Routine dementia screening for all older prisoners on reception was conducted at 23 of 77 (30%) prisons. Fifteen out of 77 (19%) prisons reported that they routinely screened all older prisoners (not just new receptions) for dementia or MCI. Of these, most would reassess every 7–12 months (n = 9, 60%), three (20%) would reassess every 0–6 months, one (7%) would reassess every 13–18 months and the remainder would reassess on an individual basis. Routine screening prior to release as part of resettlement was conducted at only eight (10%) establishments.

Table 17 provides a breakdown of the screening tools used across the establishments (some establishments use more than one).

| Screening tool | Frequency (N = 23), n (%) |

|---|---|

| MMSE | 14 (61) |

| ACE-III | 8 (35) |

| MoCA | 5 (22) |

| 6-CIT | 4 (17) |

| GPCOG | 3 (13) |

| CAMCOG | 2 (9) |

| Other locally developed tool | 2 (9) |

| Clock-drawing test | 1 (4) |

Around half of prisons surveyed [46 (54%) governor questionnaires and 36 (47%) health-care questionnaires] described additional support or modifications to the prison environment that had been provided or developed specifically for prisoners with dementia or MCI.

Both health-care and prison staff were asked about all modifications, and there were some interesting discrepancies in their responses. For example, 87% of prison staff reported the use of prisoner carers, compared with 67% of health-care staff. Conversely, 59% of prison staff reported the use of regular health screening, compared with 72% of health-care staff. Table 18 provides a breakdown of types of modification taken from governor or health-care questionnaires. The sources of these data are given in Report Supplementary Material 7 and 8. The choice of source was made in relation to which would likely generate the most accurate information (e.g. information of health screening from the health-care questionnaire, information on exercise from the prison staff questionnaire).

| Modification | Frequency, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Handrailsa | 31 (67) |

| Provision of incontinence materialsb | 28 (78) |

| Regular health screeningb | 26 (72) |

| Bigger/more accessible prison cellsa | 25 (54) |

| Exercise/activity/canteena | 19 (41) |

| Signposting/highlighting of key areas or itemsa | 10 (22) |

| Improved lightinga | 6 (13) |

| Provision of easy to remove clothinga | 5 (11) |

| Removal of mirrorsa | 1 (2) |

Other modifications included alarm call bracelets and personal alarms, magnifying screens, long-handled equipment, memory boards and prompt cards, personal emergency evacuation plans, support and therapy groups, social care aids and specific older prisoner wings or units.

Eleven out of 77 (14%) of the prisons responded that there was a support group (or similar) specifically for individuals with dementia or MCI, most often run by prison staff, mental health teams or the older prisoner lead. Groups included a dementia-friendly music group or choir, gym groups, holistic care and support, memory cafes, an over ‘45s’ focus group, over 50s well-being and mindfulness, cognitive stimulation therapy, and arts and crafts.

More than half of the prisons (n = 44, 57%) reported that they had a clear referral process for more detailed assessment of older prisoners with suspected dementia or MCI, and 29 (38%) prisons reported that external health and social care services provided this assessment or treatment.

The majority of prisons reported that they did not have a defined care pathway for prisoners with dementia or MCI (n = 53, 69%); however, just under one-third of these (16/53, 30%) were in the process of developing one.

Care planning between health-care and prison staff occurred to varying degrees in 53 (69%) establishments. This was, on the whole, fairly rudimentary and involved attending care planning meetings (77%), employing prisoner carers (49%) and sharing guidelines and resources.

Social care

Health-care staff were asked about how social care needs were identified, assessed and met in their establishment. Very few prisons used standardised assessment tools for social care needs (n = 7, 9%). Staff indicated that needs would normally be identified through initial health screening on reception. Most respondents indicated that anyone could make the referral for assessment, but it was most commonly made by reception and induction staff.

The formal identification of social care needs most commonly fell to health-care and other clinical staff (n = 30, 39%) or social workers, including both prison-based social workers and local authority staff (n = 38, 49%).

The development of care planning was mostly attributed to social care staff (n = 33, 43%) or health-care staff (n = 12, 16%), with a clear link that in many cases this was multidisciplinary and involved complex case meetings with prison and safer custody staff (n = 13, 17%). In several cases, there was evidence that dementia and older prisoner leads took responsibility for this joint working (n = 4, 5%).

Almost half of health-care staff stated that they had advocacy arrangements in place for those with social care needs (n = 36, 47%). Some were internal to the prison, but others used local advocacy services, including from the local authority.

All health-care staff were asked who was responsible for meeting social care needs, as defined in the Social Care Act 2014. 75 The highest proportion attributed this responsibility to the social care team (n = 17, 22%), followed by health care (n = 13, 17%) and joint responsibility between health care and social care (n = 10, 13%). The prison was seen as having some responsibility by over one-quarter of respondents, with many (n = 15, 19%) suggesting that all three shared this responsibility or that it was down to ‘everybody’.

Both health-care staff and prison staff were asked about how well the local authority was meeting its responsibilities as outlined in the Social Care Act 2014. 75 Responses to this are detailed in Table 19.

| Response | Health-care staff frequency (N = 77), n (%) | Prison staff frequency (N = 85), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Very well | 23 (30) | 21 (25) |

| Fairly well | 30 (39) | 42 (49) |

| Not very well | 11 (14) | 11 (13) |

| Not at all well | 3 (4) | 5 (6) |

Ongoing issues with Social Care Act 2014 compliance